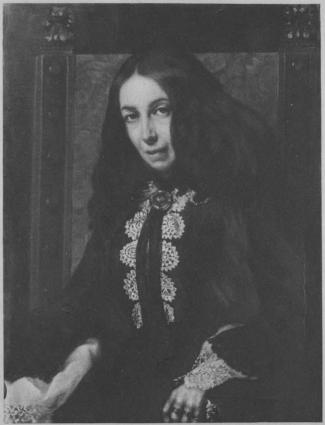

Walker & Boutall ph. sc.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

From an oil painting by Gordigiani

London: Published by Smith, Elder & Co. 15, Waterloo Place.

WITH PORTRAITS AND FACSIMILES

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. II.

SECOND IMPRESSION

LONDON

SMITH, ELDER, & CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE

1899

[All rights reserved]

Walker & Boutall ph. sc.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

From an oil painting by Gordigiani

London: Published by Smith, Elder & Co. 15, Waterloo Place.

| PORTRAIT OF ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING | Frontispiece |

| After the picture by Gordigiani | |

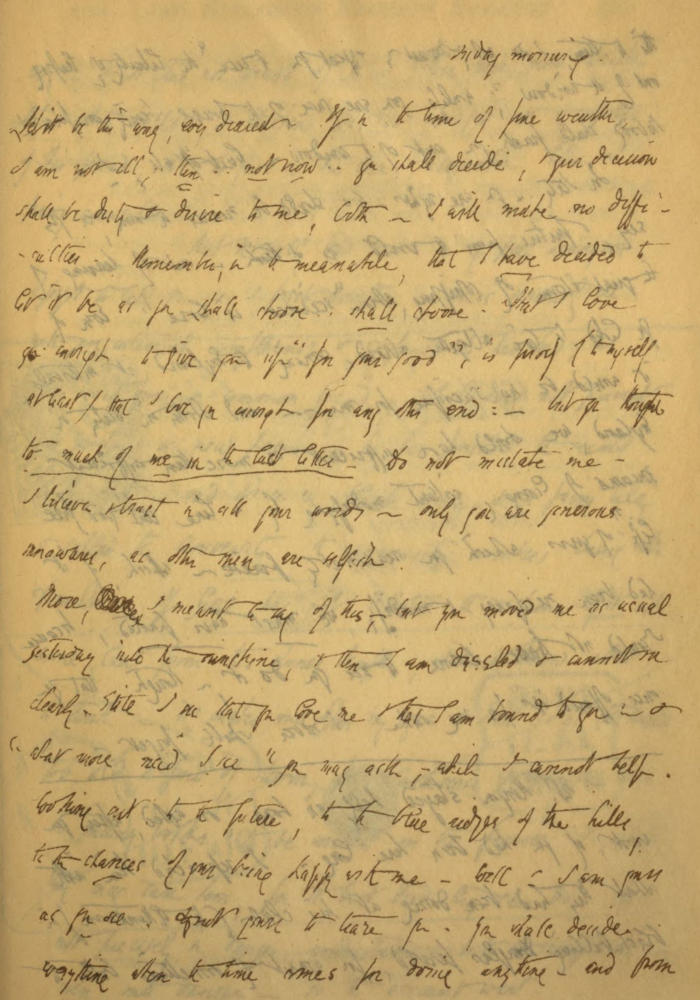

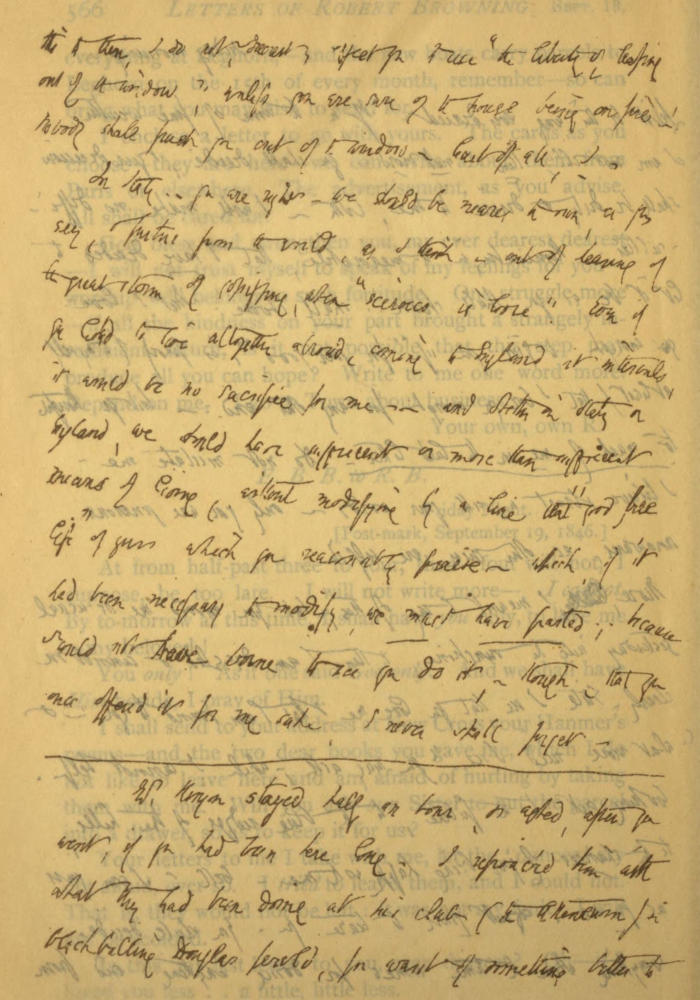

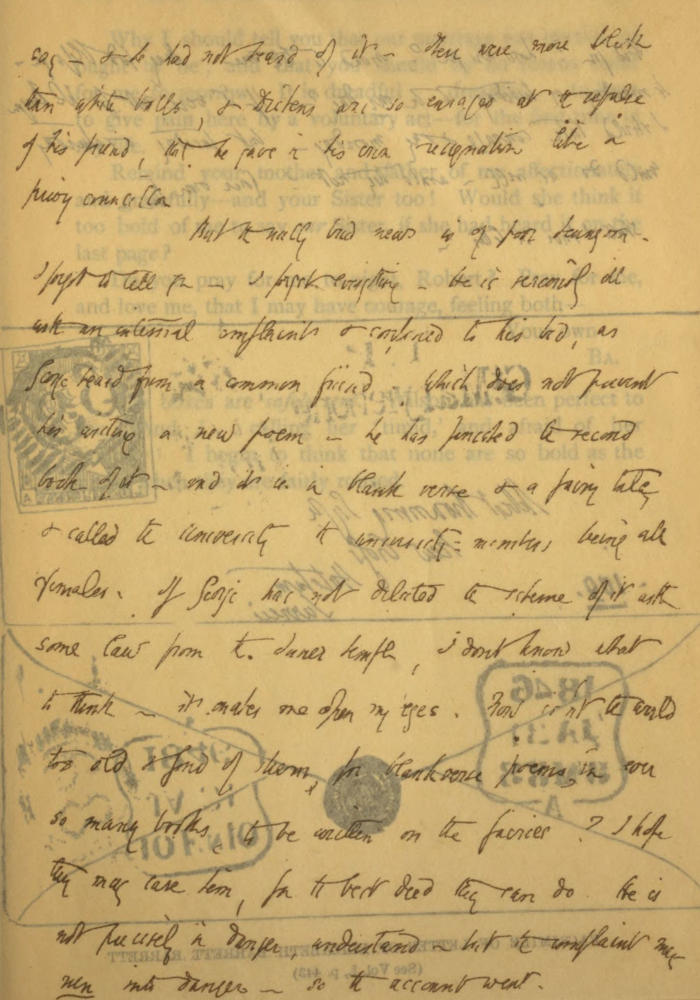

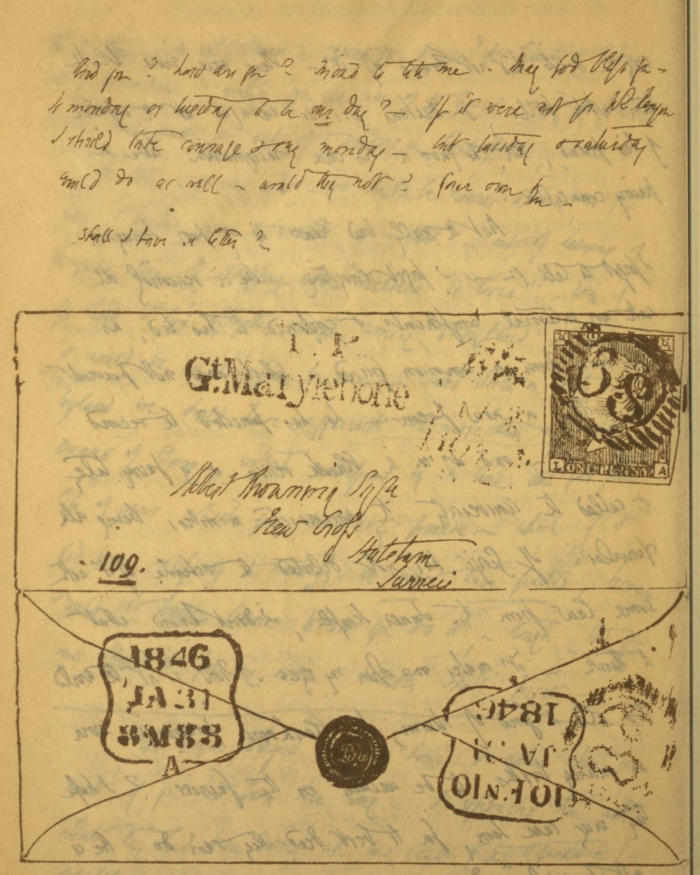

| FACSIMILE OF LETTER OF ELIZABETH BARRETT BARRETT | 566 |

Wednesday.

[Post-mark, March 25, 1846.]

You were right to bid me never again wish my poor flowers were ‘diamonds’—you could not, I think, speak so to my heart of any diamonds. God knows my life is for you to take just as you take flowers:—these last please you, serve you best when plucked—and ‘my life’s rose’ ... if I dared profane that expression I would say, you have but to ‘stoop’ for it. Foolish, as all words are.

You dwell on that notion of your being peculiarly isolated,—of any kindness to you, in your present state, seeming doubled and quadrupled—what do I, what could anyone infer from that but, most obviously, that it was a very fortunate thing for such kindness, and that the presumable bestower of it got all his distinction from the fact that no better ... however, I hate this and cannot go on. Dearest, believe that under ordinary circumstances, with ordinary people, all operates differently—the imaginary kindness-bestower with his ideal methods of showing and proving his love,—there would be the rival to fear!

Do not let us talk of this—you always beat me, beside, turn my own illustrations into obscurations—as in the notable case of the cards and stakes and risks—I suppose, (to save my vanity!) that if I knew anything about cards, I might go on, a step at least, with my argument. I once heard a dispute in the street between the proprietor of an oyster-stall and one of his customers—who was in the wrong ... that is, who used the clenching argument you shall hear presently, I don’t remember; but one brought the other to this pass—‘Are there three shells to an oyster?’—Just that! If there were not—he would clearly be found in the wrong, that was all!—‘Why,’ ... began the other; and I regret I did not catch the rest—there was such a clear possibility contained in that ‘Why ... an oyster might have three shells!’

Note the adroitness,—(calm heroic silence of the act rather than a merely attempted word,) the mastery with which, taking up Ba’s implied challenge, I do furnish her with both ‘amusement and instruction’—moreover I will at Ba’s bidding amuse and instruct the world at large, and make them know all to be known—for my purposes—about ‘Bells and Pomegranates’—yes, it will be better.

I said rather hastily that my head ‘ached’ yesterday: that meant, only that it was more observable because, after walking, it is usually well—and I had been walking. To-day it is much better; I sit reading ‘Cromwell,’ and the newspaper, and presently I shall go out—all will be better now, I hope—it shall not be my fault, at least, depend on that. All my work (work!)—well, such as it is, it is done—and I scarcely care how—I shall be prouder to begin one day—(may it be soon!—) with your hand in mine from the beginning—that is a very different thing in its effect from the same hand touching mine after I had begun, with no suspicion such a chance could befall! I repeat, both these things, ‘Luria’ and the other, are manqué, failures—the life-incidents ought to have been acted over again, experienced afresh; and I had no inclination nor ability. But one day, my siren!

Let me make haste and correct a stupid error. I spoke to my father last night about that tragedy of the studs—I was wholly out in the story—the sufferer was his uncle, and the scene should have been laid on the Guinea coast. À propos of errors—the copyright matter is most likely a case of copy-wrong by reporters—I never heard of it before—to be sure, I signed a petition of Miss Martineau’s superintending once on a time—but long ago, ‘I, I, I’—how, dear, all important ‘I’ takes care of himself, and issues bulletins, and corrects his wise mistakes, and all this to ... just ‘one of his readers of the average intelligence.’ Are you that, so much as that, Ba? I will tell you—if you do not write to me all about your dear, dearest self, I shall sink with shame at the recollection of what this letter and its like prove to be—must prove to be! Dear love, tell me—that you walk and are in good spirits, and I will try and write better. May God bless my own beloved!—Ever her own

R.

I think, am all but sure, there is a Mrs. Hornblower something!

Just a minute to say your second note has come, and that I do hate hate having to write, not kiss my answer on your dearest mouth—kindest, dearest—to-morrow I will try—and meantime—though Ba by the fire will not be cold at heart, cold of heart, at least, and I will talk to her and more than talk—My dearest, dearest one!

Wednesday Evening.

[Post-mark, March 26, 1846.]

But if people half say things,—intimate things, as when your disputant in the street (you are felicitous, I think, in your street-experiences) suggested the possible case of the ‘three oyster shells to an oyster,’—why you must submit to be answered a little, and even confuted at need. Now just see—

... ‘Got all his distinction from the fact that no better’ ... That is precisely the fact ... so ... as you have stated it, and implied ... ‘The fact that no better’ ... is to be found in the world—no better ... none. There, is the peculiar combination. The isolation on one side, and the best in the whole world, coming in for company! And I ‘dwell’ upon it, never being tired ... and if you are tired already, you must be tired of me, because the ‘dwelling’ has grown to be a part of me and I cannot put it away. It is my especial miracle à moi. ‘No better?’ No, indeed! not in the seven worlds! and just there, lies the miraculous point.

But you mean it perhaps otherwise. You mean that it is a sort of pis aller on my part. A pis aller along the Via lactea ... is that what you mean?

Shall I let you off the rest, dearest, dearest? though you deserve ever so much more, for implying such monstrous things, and treading down all my violets, so and so. What did I say to set you writing so? I cannot remember at all? If I ‘dwell’ on anything, beloved, it is that I feel it strongly, be sure—and if I feel gratitude to you with the other feelings, you should not grudge what is a happy feeling in itself, and not dishonouring (I answer for that) to the object of it.

Now I shall tell you. I had a visitor to-day—Mrs. Jameson; and when she went away she left me ashamed of myself—I felt like a hypocrite—I, who was not born for one, I think. She began to talk of you ... talked like a wise woman, which she is ... led me on to say just what I might have said if I had not known you, (she, thoroughly impressed with the notion that we two are strangers!) and made me quite leap in my chair with a sudden consciousness, by exclaiming at last ... ‘I am really glad to hear you speak so. Such appreciation’ &c. &c. ... imagine what she went on to say. Dearest—I believe she rather gives me a sort of credit for appreciating you without the jealousy ‘de métier.’ Good Heavens ... how humiliating some conditions of praise are! She approved me[5] with her eye—indeed she did. And this, while we were agreeing that you were the best ... ‘none better’ ... none so good ... of your country and age. Do you know, while we were talking, I felt inclined both to laugh and to cry, and if I had ‘given way’ the least, she would have been considerably astounded. As it was, my hands were so marble-cold when she took leave of me, that she observed it and began making apologies for exhausting me. Now here is a strip of the ‘world,’ ... see what colour it will turn to presently! We had better, I think, go farther than to your siren’s island—into the desert ... shall we say? Such stories there will be! For certain, ... I shall have seen you just once out of the window! Shall you not be afraid? Well—and she talked of Italy too—it was before she talked of you—and she hoped I had not given up the thoughts of going there. To which I said that ‘I had not ... but that it seemed like scheming to travel in the moon.’ She talked of a difference, and set down the moon-travelling as simple lunacy. ‘And simply lunatical,’ ... I said, ... ‘my thoughts, if chronicled, would be taken to be, perhaps’—‘No, no, no,! ...’ she insisted ... ‘as long as I kept to the earth, everything was to be permitted to me.’

How people talk at cross-purposes in this world ... and act so too! It’s the very spirit of worldly communion. Souls are gregarious in a sense, but no soul touches another, as a general rule. I like Mrs. Jameson nevertheless—I like her more. She appreciates you—and it is my turn to praise for that, now. I am to see her again to-morrow morning, when she has the goodness to promise to bring some etchings of her own, her illustrations of the new essays, for me to look at.

Ah—your ‘failures in “Luria” and the “Tragedy”’—Proud, we should all be, to fail exactly so.

Dearest, are you better indeed? Walk ... talk to the Ba in the chair ... go on to be better, ever dearest. May God bless you! Ah ... the ‘I’s.’ You do not see that the[6] ‘I’s’—as you make them, ... all turn to ‘yous’ by the time they get to me. The ‘I’s’ indeed! How dare you talk against my eyes? For me, I was going down-stairs to-day, but it was wet and windy and I was warned not to go. If I am in bad or good spirits, judge from this foolish letter—foolish and wise, both!—but not melancholy, anywise. When one drops into a pun, one might as well come to an end altogether—it can’t be worse with one.

Nor can it be better than being

Your own

‘No better’!!.

Thursday Morning.

[Post-mark, March 26, 1846.]

Sometimes I have a disposition to dispute with dearest Ba, to wrench her simile-weapons out of the dexterous hand (that is, try and do so) and have the truth of things my way and its own way, not hers, if she be Ba—(observe, I say nothing about ever meeting with remarkable success in such undertakings, only, that they are entered on sometimes). But at other times I seem as if I must lie down, like Flush, with all manner of coral necklaces about my neck, and two sweet mysterious hands on my head, and so be forced to hear verses on me, Ba’s verses, in which I, that am but Flush of the lower nature, am called loving friend and praised for not preferring to go ‘coursing hares’—with ‘other dogs.’ So I will lie now, as you will have it, and say in Flush-like tones (the looks that are dog’s tones)—I don’t don’t know how it is, or why, or what it all will end in, but I am very happy and what I hear must mean right, by the music,—though the meaning is above me,—and here are the hands—which I may, and will, look up to, and kiss—determining not to insist any more this time that at Miss Mitford’s were sundry dogs, brighter than ‘brown’—See where, just where, Flush stops discreetly! ‘Eternity’ he would have added, ‘but stern death’ &c. &c.

I treat these things lightheartedly, as you see—instead of seriously, which would at first thought seem the wiser course—‘for after all, she will find out one day’ &c. No, dearest,—I do not fear that! Why make uneasy words of saying simply I shall continue to give you my best flowers, all I can find—if I bring violets, or grass, when you expected to get roses,—you will know there were none in my garden—that is all.

And for you—as I may have told you once,—as I tell myself always—you are entirely what I love—not just a rose plucked off with an inch of stalk, but presented as a rose should be, with a green world of boughs round: all about you is ‘to my heart’—(to my mind, as they phrase it)—and were it not that, of course, I know when to have done with fancyings and merely flitting permissible ‘inly-sayings with heart-playing,’ and when it is time to look at the plain ‘best’ through the lock of ‘good’ and ‘better’ in circumstances and accident—I do say—were the best blessing of all, the blessing I trust and believe God intends, of your perfect restoration to health,—were that not so palpably best,—I should catch myself desirous that your present state of unconfirmed health might never pass away! Ba understands, I know! After all, it will always stay, that luxury,—if but through the memory of what has been, and may recur, that deepest luxury that makes my very heartstrings tremble in the thought of—that I shall have a right, a duty—where in another case, they would be uncalled for, superfluous, impertinent. Tapers ordinarily burn best let alone, with all your light depending on the little flame, the darkest night but for it—why, stand off—what good can you do, so long as there is no extraordinary evil to avert, breaking down of the candlestick to prevent? But here—there will be reason as well as a delight beyond delights in always learning to close over, all but holding the flame in the hollow of one’s hand! I shall have a right to think it is not mere pleasure, merely for myself, that I care and am close by—and that which thus is called ‘not for myself’ is,[8] after all, in its essence, most for myself,—why it is a luxury, a last delight!—

In the procurement of which there will be this obstacle, or grave matter to be first taken into consideration,—that the world will ‘change colour’ about it, will have its own thoughts on the subject I have my own thoughts, on its subject, the affairs of the world and pieces of perfect good fortune it approves of, and stamps for enviable—and on the whole the world has quite a right to treat me unceremoniously,—I having begun it. As for the ‘seeing out of the window once’—those who knew nothing about us but our names had better think that was the way, than most others; and the half-dozen who knew a little more, may hear the true account if they please, when they hear anything—those who know all, all necessary to know, will understand my 137 letters here and my 54 visits ... see, I write as if this were to be pleaded to-night—would it were! As if you had to write the meeting between Hector and Andromache, not the parting! By the way, dearest, what enchanted poetry all your translations for Miss Thomson are—as Carlyle says! ‘Nobody can touch them, get at them!’ How am I the better for Nonnus, and Apuleius? Now, do you serve me well there?

I shall hear to-morrow of Mrs. Jameson’s etchings and discourses? and more good news of you, darling? I am quite well to-day—going out with my sister to dine next door—then, over to-morrow, and the letter, will come Saturday, my day.

Bless you, my own best, dearest—I am your own.

R.

Thursday.

[Post-mark, March 27, 1846.]

Not the ‘dexterous hand’—say rather the good cause. For the rest, when you turn into a dog and lie down, are you not afraid that a sorcerer should go by and dash the[9] water and speak the formula of the old tales. ‘If thou wert born a dog, remain a dog, but if not’.... If not ... what is to happen? Aminè whipped her enchanted hounds ever so often in the day ... ah, what nonsense happens!

Dear, dearest, how you ‘take me with guile,’ or with stronger than guile, ... with that divine right you have, of talking absurdities! You make it clear at last that I am so much the better for being bad ... and I ... shall I laugh? can I? is it possible? The words go too deep ... as deep as death which cannot laugh! And I am forbidden to ‘dwell’ on the meaning of them—I! There are ‘I’s’ to match yours!

I shall have the right of doing one thing, ... (passing to my rights). I shall hold to the right of remembering to my last hour, that you, who might well have passed by on the other side if we two had met on the road when I was riding at ease, ... did not when I was in the dust. I choose to remember that to the end of feeling. As for men, you are not to take me to be quite ignorant of what they are worth in the gross. The most blindfolded women may see a little under the folds ... and I have seen quite enough to be glad to shut my eyes. Did I not tell you that I never thought that any man whom I could love, would stoop to love me, even if I attained so far as the sight of such. Which I never attained ... until ... until! Then, that you should care for me.!! Oh—I hold to my rights, though you overcome me in most other things. And it is my right to love you better than I could do if I were more worthy to be loved by you.

Mrs. Jameson came late to-day, ... at five—and was hurried and could not stay ten minutes, ... but showed me her etchings and very kindly left a ‘Dead St. Cecilia’ which I admired most, for its beautiful lifelessness. She is not to be in town again, she said, till a month has gone—a month, at least. Oh—and ‘quite uneasy’ she was, about my ‘cold hands’—yesterday—she thought she had put me to death[10] with over-talking!—which made me smile a little ... ‘subridens.’ But she is very kind and affectionate; and you were right to teach me to like her—and now, do you know, I look in vain for the ‘steely eyes’ I fancied I saw once, and see nothing but two good and true ones.

Well—here is an end till Saturday. It is too late ... or I could go on writing ... which I do not hate indeed. Talking of hating, ... ‘what you love entirely’ means that you love entirely ... and no more and no less. If it did not mean so, I should be unhappy about the mistake ... but to ‘love entirely’ is not a mistake and cannot pass for one either on earth or in Heaven. May God bless you, ever dearest. Such haste I write in—as if the angels were running up Jacob’s ladder!—or down it, rather, at this close!

Your own

Ba.

Friday.

[Post-mark, March 27, 1846.]

‘Qui laborat, orat’; so they used to say, and in that case I have been devotional to a high degree this morning. Seven holes did I dig (to keep up inversions of style)—seven rose-trees did I plant—(‘Brennus’—and ‘Madame Lafarge’! are two names I remember; very characteristic of old Gaul and young France—) and, for my pains, the first fruits, first blossoms some two or three months hence, will come, and will go to dearest Ba who first taught me what a rose really was, how sweet it might become with superadded memories of the room and the chair and the vase, and the cutting stalks and pouring fresh water ... ah, my own Ba!—And did you think to warn me out of the Flush-simile by the hint of Aminè’s privilege which it would warrant? If the ‘ever so much whipping’ should please you!... And beside it was, if I recollect, for the creature’s good, those poor imprisoned sisters, all the time. Moreover, I was ‘born’ all this and[11] more, that you will know, at least—and only walked glorious and erect on two legs till dear Siren, an old friend of, and deep in the secrets of Circe, sprinkled the waters ... perhaps on those roses—No, before that!—

Well, to-morrow comes fast now—and I shall trust to be with you my beloved—and, first, you are to show me the portrait, remember.

I am glad you like Mrs. Jameson—do not I like her all the better, much the better! But it is fortunate I shall not see her by any chance just now—she would be sure to begin and tell me about you—and if my hands did not turn cold, my ear-tips would assuredly turn red. I daresay that St. Cecilia is the beautiful statue above her tomb at Rome; covered with a veil—affectingly beautiful; I well remember how she lies.

Now good-bye; and to-morrow! Bless you, ever dear, dearest Ba—

Your own

R.

Sunday Afternoon.

Now, I think, if I had been ‘pricked at the heart’ by dear, dearest Ba’s charge yesterday,—if I did not certainly know why it might sometimes seem better to be silent than to speak,—should I not be found taking out three or four sheets of paper, and beginning to write, and write! My own, dearest and best, it is not so,—not wrong, my heart’s self tells me,—and tells you! But, for the rest, there shall never pass a day till my death wherein I will not write to you, so long as you let me, excepting those days I may spend with you, partly or ... altogether—Love, shall I have very, very long to be hating to write, yet writing?

You see sometimes how I talk to you,—even in mere talking what a strange work I make of it. I go on thinking quite another way; so, generally, I often have thought,[12] the little I have written, has been an unconscious scrawling with the mind fixed somewhere else: the subject of the scrawl may have previously been the real object of the mind on some similar occasion,—the very thing which then to miss, (finding in its place such another result of a still prior fancy-fit)—which then to see escape, or find escaped, was the vexation of the time! One cannot, (or I cannot) finish up the work in one’s mind, put away the old projects and take up new. Well, this which I feel on so many occasions, do you wonder if—if!

I should write on this for ever! It is all so strange, such a dream as you say!

Indeed, love, the picture is not like, nor ‘flattered’ by any means, yet I don’t know how it is, I cannot be cross with it—there is a touch of truth in the eyes,—would one have believed that? I know my own way with portraits; how I let them master eventually my most decided sense of their unlikeness—and this finds me very prepared—still—it seems already more faithful than last night ... how do I determine where the miraculousness ends? (My Mother was greatly impressed by it—and my sister, coming (from my room) into the room where I was with a visitor, before whom she could not speak English, said ‘È molto bella’!)

Here is my ‘proof’—I found it as I expected. I fear I must put you to that trouble of sending the other two acts—I hate to think of so troubling you! But do not, Ba, hurry yourself—nor take extraordinary pains—what is worth your pains in these poor things? I like Luria better now,—it may do, now,—probably because it must; but, as I said yesterday, I seriously hope and trust to shew my sense of gratitude for what is promised my future life, by doing some real work in it; work of yours, as through you. I have felt, not for the first time now, but from the beginning vexed, foolishly vexed perhaps, that I could not without attracting undesirable notice, ‘dedicate,’ in the true sense of the word, this or the last number to you. But if any[13] really worthy performance should follow, then my mouth will be unsealed. All is forewritten!

I wonder if you have ventured down this sunny afternoon—tell me how you are, and, once again, do not care about those papers; any time will do.

So, bless you, my own—my all-beloved Ba.

Your R.B.

Sunday Evening.

[Post-mark, March 30, 1846.]

Dearest, I have been trying your plan of thinking of you instead of writing, to-day, and the end is that I am driven to the last of the day and have scarcely room in it to write what I would. Observe if you please, how badly ‘the system works,’ as the practical people say. Then Mr. Kenyon came and talked,—asked when I had seen you, ... and desired, ‘if ever I saw you again,’ (ah, what an ‘if ever’!) that I would enquire about the ‘blue lilies’ ... which I satisfied him were of the right colour, on your authority.

But, to go to the ‘Tragedy’—I am not to admire it ... am I? And you really think that anyone who can think ... feel ... could help such an admiration, or ought to try to help it? Now just see. It is a new work with your mark on it. That is ... it would make some six or sixteen works for other people, if ‘cut up into little stars’—rolled out ... diluted with rain-water. But it is your work as it is—and if you do not care for that, I care, and shall remember to care on. It is a work full of power and significance, and I am not at all sure (not that it is wise to make comparisons, but that I want you to understand how I am impressed!)—I am not at all sure that if I knew you now first and only by these two productions, ... ‘Luria’ and the ‘Tragedy,’ ... I should not involuntarily attribute more power and a higher faculty to the writer of the last—I should, I think—yet ‘Luria’ is the completer work.... I know it[14] very well. Such thoughts, you have, in this second part of the Tragedy! a ‘Soul’s Tragedy’ indeed! No one thinks like you—other poets talk like the merest women in comparison. Why it is full of hope for both of us, to look forward and consider what you may achieve with that combination of authority over the reasons and the passions, and that wonderful variety of the plastic power! But I am going to tell you—Certainly I think you were right (though you know I doubted and cried out) I think now you were right in omitting the theological argument you told me of, from this second part. It would clog the action, and already I am half inclined to fancy it a little clogged in one or two places—but if this is true even, it would be easy to lighten it. Your Ogniben (here is my only criticism in the ways of objection) seems to me almost too wise for a crafty worldling—tell me if he is not! Such thoughts, for the rest, you are prodigal of! That about the child, ... do you remember how you brought it to me in your first visit, nearly a year ago?

Nearly a year ago! how the time passes! If I had ‘done my duty’ like the enchanted fish leaping on the gridiron, and seen you never again after that first visit, you would have forgotten all about me by this day. Or at least, ‘that prude’ I should be! Somewhere under your feet, I should be put down by this day! Yes! and my enchanted dog would be coursing ‘some small deer’ ... some unicorn of a ‘golden horn,’ ... (not the Kilmansegg gold!) out of hearing if I should have a mind to whistle ever so, ... but out of harm’s way perhaps besides.

Well, I do think of it sometimes as you see. Which proves that I love you better than myself by the whole width of the Heavens; the sevenfold Heavens. Yet I think again how He of the heavens and earth brought us together so wonderfully, holding two souls in His hand. If my fault was in it, my will at least was not. Believe it of me, dear dearest, that I who am as clear-sighted as other women, ...[15] and not more humble (as to the approaches of common men), was quite resolutely blind when you came—I could not understand the possibility of that. It was too much ... too surpassing. And so it will seem to the end. The astonishment, I mean, will not cease to be. It is my own especial fairy-tale ... from the spells of which, may you be unharmed...! How one writes and writes over and over the same thing! But day by day the same sun rises, ... over, and over, and nobody is tired. May God bless you, dearest of all, and justify what has been by what shall be, ... and let me be free of spoiling any sun of yours! Shall you ever tell me in your thoughts, I wonder, to get out of your sun? No—no—Love keeps love too safe! and I have faith, you see, as a grain of mustard-seed!

Your own

Ba.

Say how you are ... mind!

Monday.

[Post-mark, March 30, 1846.]

‘The system,’ Ba?—Were you to stop writing, as if for my reasons? Could I do without your letters, on any pretence? You say well—it was a foolish fancy, and now—have done with it!

And do you think you could have refused to see me after that visit? I mean, do you think I did not resolve so to conduct myself; so to ‘humble myself and go still and softly all my days’; that your suspicion should needs insensibly clear up ... (if it had been so pre-ordained, and that no more was in my destiny,) and at last I should have been written down your friend for ever, and let come and stay, on that footing. But you really think the confirmation of that sentence must have been attended with such an effect—that I should have forgotten you or so remembered you? You think that on the strength of such a love as that, I would[16] have ventured a month of my future life ... much less, the whole of it? Not you, Ba,—my dearest, dearest!

How you surprise me (what ever may you think) by liking that ‘Tragedy’! It seems as if, having got out of the present trouble, I shall never fall into its fellow—I will strike, for the future, on the glowing, malleable metal; afterward, filing is quite another process from hammering, and a more difficult one. Note, that ‘filing’ is the wrong word,—and the rest of it, the wrong simile,—and all of it, in its stupid wrongness very characteristic of what I try to illustrate—oh, the better, better days are before me there as in all else! But, do you notice how stupid I am to-day? My head begins again—that is the fact; it is better a good deal than in the morning—its œconomy passes my comprehension altogether, that is the other fact. With the deep joy in my heart below—this morning’s letter here—what does the head mean by its perversity? I will go out presently and walk it back to its senses.

Dearest, did you receive my ‘proof’ this morning? Do not correct nor look at it, nor otherwise trouble yourself—there is plenty of time. But what day is ours to be? Of that you say nothing, and of my poems a great deal, ‘O you inverter!’ But I am, rather, a reverter—and you shall revert, and mind the natural order of things, and tell me first of all—(in to-night’s letter, dearest?)—that it is to be on—?

Now let me kiss you here—my own Ba! Being stupid makes some difference in me—I am no poet, nor prose-writer, nor rational ‘Christian, pagan nor man’ this afternoon—but I am now—as yesterday—as the long ‘year ago’—your own, utterly your own! May God bless you! (I wondered yesterday if you had gone down-stairs—‘no’ I infer!)

Monday.

Dearest, I send you back the two parts of the ‘Soul’s Tragedy,’ and the proof. On a strip of paper are two or three inanities in the form of doubts I had in reading the first part. I think upon the whole that you owe me all gratitude for the help of so much high critical wisdom—of which this paper is a fair proof and expression.

The proof, the printed ‘Luria’ I mean, has more than pleased me. It is noble and admirable; and grows greater, the closer seen. The most exceptionable part, it seems to me, is Domizia’s retraction at the last, for which one looks round for the sufficient motive. But the impression of the whole work goes straight to the soul—it is heroic in the best sense.

I write in such haste. Oh—I should have liked to have read again the second part of the ‘Tragedy,’ but dare not keep it though you give me leave. I think of the printers—and you will let me have the proof, in this case also.

Your letter shall be answered presently. Your sister’s word about the picture proves very conclusively how wonderfully like it must be as a portrait! That would settle the question to any ‘Royal Commission’ in the world—only we need not go so far.

Dearest I end here—to begin again in another half hour. Ah—and you promise, you promise—

No time—but ever your own

Ba.

Monday Evening.

[Post-mark, March 31, 1846.]

Ah now, now, you see! Held up in that light, it is ‘a foolish fancy,’ and unlawful, besides! ‘Not on any pretence’[18] will you do without letters ... you! And you count it among the imaginations of your heart that I could do without them better perhaps ... I ... to whom they are sun, air, and human voices, at the very lowest calculation? Why seriously you don’t imagine that your letters are not a thousand times more to me, than letters ever in the world were before, ... since ‘Heaven first brought them to some wretch’s aid.’ If you do, that is the foolishest fancy of all.

So foolish as to be unspeakable. We will ‘have done with it,’ as you say. I only ‘revert’ and innocently,—I do not reproach, even ignorantly,—I am grateful rather. What you said in the letter this morning made me grateful, ... and oh, so glad! so glad! what you said, I mean, of writing to me on every day that we did not meet on otherwise. That promise seemed to bring us nearer (see how I think of letters!), nearer than another word could, though you went for it to the end of the universe, ... that other word. So I accept the promise as a promise of pure gold, and thank you, as pure gold too, which you are, or rather far above. Only my own dearest, you shall not write long letters ... long letters are out of the agreement.... I never feel the need of length as long as the writing is there ... just the little shred of the Koran, to be gathered up reverently ... (Inshallah!)—and then, you shall not write at all when you are not well ... no, you shall not. So remember from henceforth! Shall I whip my enchanted dog when he is so good and true?—not to say that the tags of the lashes (do you call them tags?) would swing round and strike me on the shoulders? Dearest, you are the best, kindest in the world—such a very, very, very ‘little lower than the angels!’ If ever I could take advantage of your goodness and tenderness, to teaze and vex you, ... what should I be, I have been seriously enquiring to-day, head on hand, when I had sent away ‘Luria.’ For I sent it away, and the ‘Tragedy’ with it, and I hope you will have all to-morrow morning at the[19] furthest, ... before you get this letter. There was a note too in the parcel.

As to dedications ... believe me that I would not have them if I could ... that is, even if there were no dangers. I could not bear to have words from you which the world might listen to ... I mean, that to be commended of you in that way, on that ground, would make me feel cold to the heart. Oh no, no, no! It is better to have the proof-sheet as I had it this morning: it is the better glory ... as glory!

‘Not worthy of my pains’ ... you are right! But infinitely worthy of my pleasures—such pleasure as I could gather from nothing else, except from your letters and your very presence. Do you think that anything beside in the whole world could bring pleasure to me, as pleasure goes, ... anything like reading your poetry? My ‘pains’ indeed! It is a felicitous word—‘je vous en fais mon compliment.’

And all this time, while I write lightly, you are not well perhaps—you were unwell when you wrote to me; you were unwell a little yesterday even. Say how you are to-morrow—do not forget. For the cause of the unwellness, I see it, if you do not. It was the proof-correcting—I expected that you would be unwell—it is no worse than was threatened to my thoughts. The comfort is that all this wrong work is coming to an end, and that it is covenanted between us for you to rest absolutely from henceforth. Say how you are, dearest dearest. And walk, walk. For me, I have not been down-stairs. It has been cold—too cold for that, I thought.

Oh—but I wanted to say one thing! That wonderful picture, which is not much like a unicorn or even ‘a whale’ ... but rather more perhaps than like me, you may keep for weeks or months, if you choose; if it continues ‘not to make you cross.’ Because it does not flatter, and because you do not flatter (in such equal proportions!): the[20] sympathy accounts for the liking ... or absence of dislike; on your part.

Now I must end. Thursday is our day, I think:—and it is easier to say ‘Thursday’ on Monday than on Saturday ... a discovery of mine, that, as good as Faraday’s last!

Say how you are. Do not forget. I had to say.... What I cannot, to-night.

But I am your own

Ba.

Tuesday

[Post-mark, March 31, 1846.]

Dear, dear, Ba, what shall I say or not say? On a kind of principle, I have tried before this to subdue the expression of gratitude for the material, worldly good you do me—for my poor store of words would all pay themselves away here, at the beginning, and so leave the higher, peculiar, Ba’s own gifts even without a cry of acknowledgment, not to say of thanks. But somehow you, you my dearest, my Ba, look out of all imaginable nooks and crevices in the materiality—I see you through your goodness,—I cannot distinguish between your acts now,—the greater, indeed, and the lesser! Which is the ‘lesser’? With you all their heap of work seems no more than——. (I cannot even think of what may serve for some lesser act of kindness! That is just what I wanted to say—‘the effect defective comes by cause’ here—there is no ‘lesser’ blessing in your power, as I said!)

Now, darling,—it is late in the afternoon, as posts go—I have been out all the morning in town, and while I was happy with one letter (found waiting my return)—the parcel comes—so I will just say this much, (this little, this least)—this word now—and by to-night all shall be corrected, I hope, and got rid of fairly. And to-morrow, I will have you[21] to myself, my best one, and will write till you cry out against me. I go now. God bless you and reward you—prays your very own

R.B.

Tuesday Evening,

[Post-mark, March 31, 1846.]

If people were always as grateful to other people for being just kind to themselves, ... what a grateful world we should have of it! The actual good you get out of me, may be stated at about two commas and a semi-colon—do I overstate it, I wonder? You, on the other side, never overstate anything ... never enlarge ... never exaggerate! In fact, the immense ‘worldly’ advantages which fall to you from me, are plain to behold. Dearest, what nonsense you talk some times, for a man so wise! nonsense as wonderful in its way for ‘Robert Browning’ as the dancing of polkas! The worst is, that it sets me wishing impotently, to do some really good helpful thing for you—and I cannot,—cannot. The good comes to me from you, and will not go back again. Even the loving you, ... which is all I can, ... have I not had to question of it again and again.... “Is that good?” Now see.

I shall be anxious to hear your own thoughts of the ‘Soul’s Tragedy’ when you have it in print. You liked ‘Luria’ better for seeing it printed—and I must have you like the ‘Tragedy’ in proportion. It strikes me. It is original, as they say. There is something in it awakening ... striking:—and when it has awakened, it won’t let you go to sleep again immediately.

And of yourself, not a word. You might have said one word—but you have been in London which makes me hope that you are perhaps a little better ... or at least not worse. Oh, I do not hope much while you are about this printing. You are sure not to be well. That is to be accepted as a[22] necessary consequence—it cannot be otherwise. The comfort is, that the whole will be put away in a week or ten days, and that then I may set myself to hope for you, as the roses to blow in June. Fit summer-business, that will be! And you will help me, and walk and take care.

What do you think I have been doing to-day to Mr. Kenyon? Sending him the ‘enchanted poetry’ which such as you are never to see ... the translation about Hector and Andromache!—yes, really. Yet after all it is not that I like him so much better than you ... I do not indeed ... it is just that Miss Thomson and her book are of consequence to him, and that he hears through Miss Bayley and herself of the attempt here and the failure there, ... and so, being interested altogether, he asked me to let him see what I did with Homer. And it is not much. Old Homer laughs his translators to very scorn ... and he does not spare me, for being a woman. Surpassingly and profoundly beautiful that scene is. I have tried it in blank verse. About a year ago, when I had a sudden fit of translating, I made an experiment on the first fifty lines of the Iliad in a rhymed measure which seemed to me rather nearer to the Greek cadence than our common heroic verse. Listen to what I remember—

And so we get to the arrows you talked of ... ah, do you remember ... do you remember? ... which were to kill dogs and mules, you said! But they didn’t. I have an enchanted dog (‘which nobody can deny’!) and am not far to seek in my Apollo.

To-day I had a letter from Miss Mitford who says that, inasmuch as she does not go to Paris, she shall come for a[23] fortnight to London and ‘see me every day.’!! No time is fixed—but I look a little aghast. Am I not grateful and affectionate? Is it right of you, not to let me love anyone as I used to do? Is it in that sense that you kill the dogs and mules? Perhaps. The truth is, I would rather she did not come—far rather. And she may not, after all— ... now I am ashamed of myself thoroughly

I have not been down-stairs to-day—the weather seemed so doubtful. To-morrow, if it is possible, I will ... must ... do it. So ... goodbye till the day after—Thursday. May God bless you every day! and if only as I think of you ... you would not lose much!

Your Ba.

[Post-mark, April 1, 1846.]

Now—dear, dearest Ba—let me begin the only way!—And so you are kissed whether you feel it or not—through the distance, what matter? Dear love, I return from town—my writing has gone away—you remain, and we are together—as I said, it would be, so it is! And here is your letter, and here are recollections of all the letters for so long, all the perfect kindnesses which I did not answer, meaning to answer them one day—and, one day, look to receive (I may write you) a huge sheetful of answers to bygone interrogatories,—sins of omission remedied according to ability—and you will stare like a man, I read of somewhere, who asked his neighbour ‘how he fed that mule of his, so as to keep it in such good case?’—and then, struck by some other fancy, went on to talk of other matters till the day’s end—when, on alighting at their Inn (for these two were journeying, and the talk began with the stirrup-cup)—the other, who had been watching his opportunity, breaking silence for the first time, answered—‘With oats and hay.’ Observe that the only part of the story I parallel is the surprise at the end—for I am not going to get whipped before[24] I deserve, Aminè (Ba mine). At all events I will answer this last dear note. The ‘good’ you do me, I see you cannot see nor understand yet—there is my answer! Here, in this instance, I corrected everything,—altered, improved. Did you notice the alterations (curtailments) in ‘Luria’? Well, I put in a few phrases in the second part of the other,—where Ogniben speaks—and hope that they give a little more insight as to his character—which I meant for that of a man of wide speculation and narrow practice,—universal understanding of men and sympathy with them, yet professionally restricted claims for himself, for his own life. There, was the theology to have come in! He should have explained, ‘the belief in a future state, with me, modifies every feeling derivable from this present life—I consider that as dependent on foregoing this—consequently, I may see that your principles are perfectly right and proper to be embraced so far as concerns this world, though I believe there is an eventual gain, to be obtained elsewhere, in either opposing or disregarding them,—in not availing myself of the advantages they procure.’ Do you see?—as a man may not choose to drink wine, for his health’s sake, or from a scruple of conscience &c.—and yet may be a good judge of what wine should be, how it ought to taste—something like this was meant—and when it is forgotten almost, and only the written thing with a shadow of the meaning stays,—you wonder that the written thing gets to look better in time? Do you think if I could forget you, Ba, I should not reconcile myself to your picture—which already I love better than yesterday—and which, to revenge, I know I shall by this time to-morrow like less, so far less. Well, and then there is Domizia—I could not bring her to my purpose. I left the neck stiff that was to have bowed of its own accord—for nothing graceful could be accomplished by pressing with both hands on the head above! I meant to make her leave off her own projects through love of Luria. As it is, they in a manner fulfil themselves, so far as she has any power over them, and then, she[25] being left unemployed, sees Luria, begins to see him, having hitherto seen only her own ends which he was to further. Oh, enough of it! I have told you, and tell you and will tell you, my Ba, because it is simple truth,—that you have been ‘helping’ me to cover a defeat, not gain a triumph. If I had not known you so far these works might have been the better:—as assuredly, the greater works, I trust will follow,—they would have suffered in proportion! If you take a man from prison and set him free ... do you not probably cause a signal interruption to his previously all ingrossing occupation, and sole labour of love, of carving bone-boxes, making chains of cherry-stones, and other such time-beguiling operations—does he ever take up that business with the old alacrity? No! But he begins ploughing, building—(castles he makes, no bone-boxes now). I may plough and build—but there,—leave them as they are!

Here an end till to-morrow—my best dearest. I am very well to-day—I forgot to say anything yesterday. You did not go down-stairs, for all your good intentions, I hope—this morning I mean: observe how the days are made—the mornings are warm and sunny—after gets up such a wind as now howls—what a sound! The most melancholy in the whole world I think.

No—I can’t do what I had set down—keep my remonstrance and upbraiding on the Homer-subject till to-morrow and then speak arrows. What do you mean, Ba, by ‘remembering’ those lines you give me—have you no more written down, Quite happy and original they are—but to-morrow this is waited for—dearest, bless you ever! your

R.

Friday

[Post-mark, April 3, 1846.]

Dearest, your flowers make the whole room look like April, they are so full of colours ... growing fuller and[26] fuller as we get nearer to the sun. The wind was melancholy too, all last night—oh, I think the wind melancholy, just as you do,—or more than you do perhaps for having spent so many restless days and nights close on the sea-shore in Devonshire. I seem now always to hear the sea in the wind, voice within voice! But I like a sudden wind not too loud,—a wind which you hear the rain in rather than the sea—and I like the half cloudy half sunny April weather, such as we have it here in England, with a west or south wind—I like and enjoy that; and remember vividly how I used to like to walk or wade nearly up to my waist in the wet grass or weeds, with the sun overhead, and the wind darkening or lightening the verdure all round.

But none of it was happiness, dearest dearest. Happiness does not come with the sun or the rain. Since my illness, when the door of the future seemed shut and locked before my face, and I did not tire myself with knocking any more, I thought I was happier, happy, I thought, just because I was tranquil unto death. Now I know life from death, ... and the unsorrowful life for the first time since I was a woman; though I sit here on the edge of a precipice in a position full of anxiety and danger. What matter, ... if one shuts one’s eyes, and listens to the birds singing? Do you know, I am glad—I could almost thank God—that Papa keeps so far from me ... that he has given up coming in the evening ... I could almost thank God. If he were affectionate, and made me, or let me, feel myself necessary to him, ... how should I bear (even with my reason on my side) to prepare to give him pain? So that the Pisa business last year, by sounding the waters, was good in its way ... and the pang that came with it to me, was also good. He feels!—he loves me ... but it is not (this, I mean to say) to the trying degrees of feeling and love ... trying to me. Ah, well! In any case, I should have ended probably, in giving up all for you—I do not profess otherwise. I used to think I should, if[27] ever I loved anyone—and if the love of you is different from, it is greater than, anything preconceived ... divined.

Mrs. Jameson, the other day, brought out a theory of hers which I refused to receive, and which I thought to myself she would apply to me some day, with the rest of what Miss Mitford calls ‘those good-for-nothing poets and poetesses.’ She maintained, (Mrs. Jameson did) that ‘artistical natures never learn wisdom from experience—that sorrow teaches them nothing—leaves no trace at all—that the mind is modified in no way by passion—suffering.’ Which I disbelieved quite, and ventured to say on the other side, that although practically a man or woman might not be wiser, through perhaps the interception of a vivid apprehension of the present, which might put back the influence of the future over actions, ... yet that it was impossible for a self-conscious nature (which all these artistic natures are) and a sensitive nature, not to receive some sort of modification from things suffered—‘No’—she said, ‘they did not! she had known and loved such—and they were like children, all of them,—essentially immature.’ But she did not persuade me. What is inequality of nature, as Dugald Stewart observed it, (and did he not say that men of genius had lop-sided minds?) is different, I think, from immaturity in her sense of the word. We were talking of her friend Mrs. Butler, which brought us to the subject. Presently she will say of you and me ... ‘Just see there! she meant no harm, poor thing, I dare say—but she acts like a child! And, for him, his is the imbecility of most regent genius ... such as I am to live to see confessed imperial, or I die a disappointed woman.’!

Do you hear? I do, distinctly. You, in the meantime, are looking at the ‘locks’ ... just as poor Louis Seize did when they were preparing his guillotine.

May God bless you, my own dearest—Think of me a little—as you say!

Your

Ba.

Friday.

[Post-mark, April 3, 1846.]

I want to tell you a thing before I forget it, my own Ba—a thing that pleased me to find out this morning. A few days ago there was a paragraph in the newspaper about Lord Compton and his ways at Rome. His address was to be read in the general list of working-artists kept for public inspection at Monaldini’s news-room, and the Earl’s self was to be found in fraternal association with ‘young art,’ at board and sporting-place, wearing the same distinctive blouse and Louis II. hat with great flaps; even his hair as picturesquely disordered as the best of them—(the artists, not flaps)—at all which the reporter seemed scarcely to know whether he ought to laugh or cry. This I read in the Daily News with other gossip about Rome, last Wednesday. But this morning a Cambridge Advertiser of the same day reaches me—and there, under the head of College news (after recording that Mr. A. has been appointed to this vicarage, and Mr. B. licensed to the other curacy)—one finds this—‘The Earl Compton, M.A. (Hon. 1837)—is of great fame in Rome as a Painter!’—which the other authority wholly forgot to mention; supposing, no doubt, all the love went to the blouse and flapped hat aforesaid! Now, is it not a good instance of that fascination which the true life at Rome (apart from the stupidities of the travelling English) exercises every now and then on susceptible people? The best thing for an English Earl to do,—(who will be a Marquis one day)—would be to stay here and vindicate his title by honest work with the opportunities it affords him—but if he cannot rise to the dignity of the best part, surely this, he chooses, is better than many others—being caught as some noblemen were yesterday, for instance, superintending a dog-fight in some horrible den of thieves in St. Giles’s. I don’t know, after all, why I tell you this,—but[29] that amid all the dull doings of the notable dull ones there, and their ‘honours’—(such a wonder of a man was Smith’s prize-man,—another had got to be gloriously first in the Classical Tripos)—this bit of ‘fame at Rome’ seemed like a break of blue real sky with a star in it, shining through the canvas sham clouds and oil-paper moons of a theatre.

Now I get to you, my Ba! How strange! It does so happen that I took the pen and laid out the paper with, I really think, a completer, deeper yearning of love to you than usual even—I seemed to have a thousand things that I could say now—and on touching the paper ... see—I start off with a foolish story and still foolisher comment as if there were no Ba close at my head all the time, straight before my eyes too! So it is with me—I give the expressing part up at once! It must be understood, inferred,—(proved, never!) All nonsense, so I will stay—and try to be wise to-morrow—now, I have no note to guide me and half put into my mouth what I ought to say. So, dear, dear Ba, goodbye! I very well know what this letter is worth—yet because of the love and endeavour unseen, may I not have the hand to kiss—and without the glove? It is kissed, whether you give it or no,—for there are two long days more to wait—and then comes Monday! Bless you till then, and ever, my dearest: My own Ba—

Your R.

Friday Evening.

[Post-mark, April 4, 1846.]

Shall the heir to a Marquisate ‘justify his title’ in these days? Is not the best thing he can do for himself, to forget it in a studio at Rome?—and one of the best things he can do for his country, perhaps, to desecrate it at dog-fighting before the eyes of all men? I should not like to have to[30] justify my Marquisate to reasonable men now-a-days,—should you ... seriously speaking? It would be a hard task, and rather dull in the performance. On the other hand, the noble dog-fighters (unconscious patriots!) find it easy and congenial occupation down in St. Giles’s, rubbing out (as in the old game of fox and goose) figure by figure, prestige by prestige, the gross absurdity of hereditary legislators, lords, and the like. Yet of the three positions, I would rather be at Rome, certainly a man looks nobler there, is better, is happier ... a good deal nearer the angels than on his ‘landed estates’ playing at feudal proprietor, or even in St. Giles’s dog-fighting. See what a republican you have for a ... Ba. Did you fancy me capable of writing such unlawful, disorderly things? And it isn’t out of bitterness, nor covetousness ... no, indeed. People in general would rather be Marquises than Roman artists, consulting their own wishes and inclination. I, for my part, ever since I could speak my mind and knew it, always openly and inwardly preferred the glory of those who live by their heads, to the opposite glory of those who carry other people’s arms. So much for glory. Happiness goes the same way to my fancy. There is something fascinating to me, in that Bohemian way of living ... all the conventions of society cut so close and thin, that the soul can see through ... beyond ... above. It is ‘real life’ as you say ... whether at Rome or elsewhere. I am very glad that you like simplicity in habits of life—it has both reasonableness and sanctity. People are apt to suffocate their faculties by their manners—English people especially. I admire that you,—R.B.,—who have had temptation more than enough, I am certain, under every form, have lived in the midst of this London of ours, close to the great social vortex, yet have kept so safe, and free, and calm and pure from the besetting sins of our society. When you came to see me first, I did not expect so much of you in that one respect. How could I? You had lived in the world, I[31] knew, and I thought ... well!—what matter, now, what I thought?

I will tell you instead how to-day has gone by with me. Not like yesterday, indeed! In the first place, I went down-stairs, walked up and down the drawing-room twice, and finding nobody there (they were all having luncheon in the dining-room) came up-stairs again ... half-way on the stairs met Flush, who having been asleep, had not missed me till just then, and was in the act of search. I was lost for ever, thought poor Flush. At least I think he thought so by his eyes. They were three times their usual largeness—he looked quite wild ... and leaped against me with such an ecstasy of astonished joy, that I nearly fell backward down the stairs (whereupon, you would have had to go to the Siren’s island, dearest, all by yourself!) After which escape of mine and Flushie’s, and when I had persuaded him to be good and quiet and to believe that I was not my own ghost, I came home with him and prepared to see....

I will tell you. She is a Mrs. Paine who lives at Farnham, and learns Greek, and writes to me such overcoming letters, that at last, and in a moment of imprudent reaction from an ungrateful discourtesy on my part, I agreed to see her if she ever came to London. Upon which, she comes directly—I am taken in my trap. She comes and returns the same day, and all to see me. Well—she had been kind to me ... and she came at two to-day. Do you know, ... for the first five minutes, I repented quite? Dearest ... she came just with the sort of face which a child might take to see a real, alive lioness at the Zoological Gardens ... she just sate down on a chair, and stared. How can people do such things in this year of grace when they are abolishing the Corn Laws, I wonder? For my part it was so unlike anything civilized I had ever been used to that I felt as if my voice and breath went together. It would have saved me to be able to stare back again, but that was out of my power. So I endured—and, after a[32] pause, ran violently down a steep place into some sort of conversation (thinking of your immortal Simpson, and vowing never to be drawn into such a situation again) and in a little while, I was able to recognize that there was nothing worse than bad manners—ignorant manners—and that, for the rest, my antagonist was a young, pretty woman (rather pretty), enthusiastic and provincial, with a strong love for poetry and literature generally, loving Carlyle and yourself, (could I hold out against that?) and telling me all her domestic happinesses with a frankness which quite appeased me and prevented my being too tired ... though she stayed two hours, and wasn’t you!—

So there is my history of to-day for you! To-morrow you will have the proof—and perhaps, I shall! Monday will bring a better thing than a proof. May God bless you, beloved. Say how you are ... to-morrow! Mind to do it ... or I will not sit any more in your gondola-chair. How can you make me, unless I choose?

And you speak against my letter to-night? you shall not dare do such things. It is a good, dear letter, and it is mine to call so ... and I knew its fellows before I knew you and loved them before I loved you, and so you are not to be proud and scornful and try to put them down ‘in that way.’

Your own

Ba.

Saturday.

[April 4, 1846.]

Oh, my two letters—and to turn from such letters to you, to my own Ba!—I very well know I am not grateful enough, if there is any grace in that, any power to avert punishment, as one hopes! But all my hope is in future endeavour—it is, my Ba,—this is earnest truth. And one thing that strikes me on hearing such prognostications of[33] Mrs. Jameson’s opinion on our subject—is that—as far as I am concerned ... or yourself, indeed—we must make up our mind to endure the stress of it, and of such opinions generally, with all resignation ... and by the time we can answer,—why, alas, they are gone and forgotten, so that there’s no paying them for their impertinence. I mean, that I do not expect, as a foolish fanciful boy might, that on the sudden application of ‘Hymen’s torch’ (to give the old simile one chance more) your happiness will blaze out apparent to the whole world lying in darkness, like a wondrous ‘Catherine-wheel,’ now all blue, now red, and so die at the bed amid an universal clapping of hands—I trust a long life of real work ‘begun, carried on and ended,’ as it never otherwise could have been (certainly by me ... and if I dare hope, you, dearest, it is because you teach me to aspire to the height)—that the attainment of all that happiness of daily, hourly life in entire affection, which seeing that men of genius need rather more—ah, these words, I cannot look back and take up the thread of the sentence,—but I wanted to say—we will live the real answer, will we not, dearest, all the stupidity against ‘genius’ ‘poets,’ and the like, is got past the stage of being treated with patient consideration and gentle pity—it is too vexatious, if it will not lie still, out of the way, by this time. What is the crime, to his fellow man or woman (not to God, I know that—these are peculiar sins to Him—whether greater in His eyes, who shall say?)—but to mankind, what is crime which would have been prevented but for the ‘genius’ involved in it? A man of genius ill-treats his wife—well, take away the ‘genius’—does he so naturally improve? See the article in to-day’s Athenæum, about the French Duel—far enough from ‘men of genius’ these Dujarriers &c.—but go to-night into half the estaminets of Paris, and see whether the quarrels over dice and some wine present any more pleasing matter of contemplation au fond. Sin is sin everywhere and the worse, I think, for[34] the grossness. Being fired at by a duellist is a little better, I think also, than being struck on the face by some ruffian. These are extreme cases—but go higher and it is the same thing. Poor, cowardly miscreated natures abound—if you could throw ‘genius’ into their composition, they would become more degraded still, I suppose!

I know I want every faculty I can by any possibility dare—want all, and much more, to teach me what you are, my own Ba, and what I should do to prove that I am taught, and do know.

I will write at length to you to-morrow, my all beloved. I am, somehow, overflowing with things to say, and the time is fearfully short—my proofs have just arrived, here they are, not even glanced over by me—(To-morrow, love! not one thing answered in my letters, as when I read and read them to-night I shall say to myself). Bless you, dearest, dearest

R.

Sunday.

[April 5, 1846.]

It seems to me the safest way to send back the proofs by the early Monday post: you may choose perhaps to bring the sheet corrected into town when you come, and so I shall let you have what you sent me, before you come to take it ... though I thought first of waiting. To-morrow I shall force you to tell me how you like the ‘Tragedy’ now! For my part, it delights me—and must raise your reputation as a poet and thinker ... must. Chiappino is highly dramatic in that first part, and speaks so finely sometimes that it is a wrench to one’s sympathies to find him overthrown. Do you know that, as far as the temper of the man goes, I am acquainted with a Chiappino ... just such a man, in the temper, the pride and the bitterness ... not in other things. When I read your manuscript I was[35] reminded—but here in print it, seems to grow nearer and nearer. My Chiappino has tired me out at last—I have borne more from him than women ought to bear from men, because he was unfortunate and embittered in his nature and by circumstances, and because I regarded him as a friend of many years. Yet, as I have told him, anyone, who had not such confidence in me, would think really ill of me through reading the insolent letters which he has thought fit to address to me on what he called a pure principle of adoration. At last I made up my mind (and shall keep it so) to answer no letter of the kind. Men are ignoble in some things, past the conceiving of their fellows. Again and again I have said ... ‘Specify your charge against me’—but there is no charge. With the most reckless and dauntless inconsistency I am lifted halfway to the skies, and made a mark there for mud pellets—so that I have been excited sometimes to say quite passionately ... ‘If I am the filth of the earth, tread on me—if I am an angel of Heaven, respect me—but I can’t be both, remember.’ See where your Chiappino leads you ... and me! Though I shall not tell you the other name of mine. Whenever I see him now, I make Arabel stay in the room—otherwise I am afraid—he is such a violent man. A good man, though, in many respects, and quite an old friend. Some men grow incensed with the continual pricks of ill-fortune, like mad bulls: some grow tame and meek.

Well—I did not like the spirit of the Athenæum remarks either. I like what you say. These literary men are never so well pleased, as in having opportunities of barking against one another—and, for the Athenæum people, if they wanted to be didactic as to morals, they might have taken occasion to be so out of their own order, and in their own country. And then to bring in Balzac so! The worst of Balzac (who has not a fine moral sense at any time, great and gifted as he is), the very worst of him, is his bearing towards his literary brothers ... the manner in which he, who can so[36] nobly present genius to the reverence of humanity in scientific men (as he describes them in his books), always dishonours and depreciates it in the man of letters and the poet. See his ‘Grand Homme de Province à Paris,’ one of the most powerful of his works, but the remark is true everywhere. I go on writing as if I were not to see you directly. It is past four oclock—and if Mr. Kenyon does not come to-day, he may come to-morrow, and find you, who were here last Thursday to his knowledge!—Half I fear.

Observe the proof. Since you have two, you say, I have not scrupled to write down on this ever so much improvidence, which you will glance at and decide upon finally.

‘Grateful’ ... ‘grateful’ ... what a word that is. I never would have such a word on any proof that came to me for correction. Do not use such inapplicable words—do not, dearest! for you know very well in your understanding (if not in your heart) that if such a word is to be used by either of us, it is not by you. My word, I shall keep mine,—I am ‘grateful’—you cannot be ‘grateful’ ... for ineffable reasons....

For the rest, it is certainly very likely that you may ‘want all your faculties, and more’ ... to bear with me ... to support me with graceful resignation; and who can tell whether I may not be found intolerable after all?

By the way (talking of St. Catherine’s wheels and the like torments) you wrote ‘gag’ ... did you not? ... where the proof says ‘gadge’—I did not alter it. More and more I like ‘Luria.’

Your Ba.

Mr. Kenyon has been here—so our Monday is safe.

Sunday.

[Post-mark, April 6, 1846.]

I sent you some even more than usual hasty foolish words,—not caring much, however—for dearest Ba shall have to forgive my shortcomings every hour in the day,—it is her destiny, and I began unluckily with that stupidest of all notions,—that about the harm coming of genius &c., so I fell with my subject and we rolled in the mud together—pas vrai? But there was so many other matters alluded to in your dearest (because last) letter—there are many things in which I agree with you to such a tremblingly exquisite exactness, so to speak, that I hardly dare cry out lest the charm break, the imaginary oscillation prove incomplete and your soul, now directly over, pass beyond mine yet, and not stay! Do you understand, dear soul of my soul, dearest Ba? Oh, how different it all might be! In this House of life—where I go, you go—where I ascend you run before—when I descend it is after you. Now, one might have a piece of Ba, but a very little of her, and make it up into a lady and a mistress, and find her a room to her mind perhaps when she should sit and sing, ‘warble eat and dwell’ like Tennyson’s blackbird, and to visit her there with due honour one might wear the finest of robes, use the courtliest of ceremonies—and then—after a time, leave her there and go, the door once shut, without much blame, to throw off the tunic and put on Lord Compton’s blouse and go whither one liked—after, to me, the most melancholy fashion in the world. How different with us! If it were not, indeed—what a mad folly would marriage be! Do you know what quaint thought strikes me, out of old Bunyan, on this very subject? He says (with another meaning though) ‘Who would keep a cow, that may buy milk at a penny the quart’—(elegant allusion). Just so,—whoever wants ‘a quart’ of this other comfort, as solace of whatever it may be (at breakfast[38] or tea time too), why not go and ‘buy’ the same, and having discussed it, drink claret at dinner at his club? Why did not Mr. Butler read Fanny Kemble’s verses, paying his penny of intellectual labour, and see her play ‘Portia’ at night, and make her a call or ride with her in the middle of the day—why ‘keep the cow’? But—don’t you know they prescribe to some constitutions the perpetual living in a cow-house? the breath, the unremitting influence is everything,—not the milk—(now, Ba—Ba is suddenly Ἴω πλανωμένη and Mrs. Jameson is the Gadfly—and I am laughed at—not too cruelly, or the other lock of hair becomes mine—with which locks ... and not with Louis Seize iron knick-nack ones, I rather think I was occupied last time, last farewell taking—)

From all which I infer—that I shall see you to-morrow! Yes, or I should not have the heart to be so glad and absurd.

Well, to-morrow makes amends—dear, dear Ba! Why do you persist in trying to turn my head so? It does not turn, I look the more steadfastly at the feet and the ground, for all your crying and trying! But something shocking might happen—would happen, if it were not written that I am to get nothing but good from Ba,—and who, who began calling names—who used the word ‘flatterer’ first?

Bless you my own dearest flatterer—I love you with heart and soul. Are you down-stairs to day? it is warm, the rain you like—yes you are down, I think. God keep you wherever you are!

Your own.

I went last night to Lord Compton’s father’s Soirée,—and for all our deep convictions, and philosophic rejoicing, I assure you that of the two or three words that we interchanged—congratulation on the bright fortune of his son formed no part,—any more than intelligence about ordering Regiments to India whenever I met the relatives of the[39] ordered. And yesterday morning I planted a full dozen more rose-trees, all white—to take away the yellow-rose reproach!

Monday Morning.

[April 6, 1846.]

I shall receive a note from you presently, I trust—but this had better go now—for I expect a friend, and must attend to him as he wants to go walking—so, dearest—dearest, take my—last work I ever shall send you, if God please!

A word about a passage or two,—I had forgotten to say before—gadge is a real name (in Johnson, too) for a torturing iron—it is part of the horror of such things that they should be mysteriously named,—indefinitely,—‘The Duke of Exeter’s Daughter’ for instance ... Ugh!—Besides, am I not a rhymester? Well, who knows but one may want to use such a word in a couplet with ‘badge’—which, if one reject the old and obsolete ‘fadge,’ is rhymeless?

Then Chiappino remarks that men of genius usually do the reverse ... of beginning by dethroning &c. and so arriving with utmost reluctancy at the acknowledgment of a natural and unalterable inequality of Mankind—instead of that, they begin at once, he says, by recognizing it in their adulation &c. &c.—I have supplied the words ‘at once,’ and taken out ‘virtually,’ which was unnecessary; so that the parallel possibly reads clearlier. I know there are other things to say—but at this moment my memory is at fault.

Can you tell me Mrs. Jameson’s address?

My sea-friend’s opinion is altogether unfavourable to the notion of an invalid’s trusting himself alone in a merchant vessel—he says—‘it will certainly be the gentleman’s death.’ So very small a degree of comfort can be secured amid all the inevitable horrors of dirt, roughness, &c. The expenses are trifling in any case, on that very account. Any number[40] of the Shipping Gazette (I think) will give a list of all vessels about to sail, with choice of ports—or on the walls of the Exchange one may see their names placarded, with reference to the Agent—or he will, himself, (my friend Chas. Walton) do his utmost with a shipowner, we both know, and save some expense, perhaps. I made him remark the difference between my carelessness of accommodations and an invalid’s proper attention beforehand—but he persisted in saying nothing can be done, nothing effectual. My time is out—but I must bless you my ever dearest Ba—and kiss you—

Ever your own.

Tuesday.

[Post-mark, April 7, 1846.]

Dearest, it is not I who am a ‘flatterer’—and if I used the word first, it is because I had the right of it, I remember, long and long ago. There is the vainest of vanities in discussing the application of such a word ... and so, when you said the other day that you ‘never flattered’ forsooth ... (oh no!) I would not contradict you for fear of the endless flattery it would lead to. Only that I do not choose (because such things are allowed to pass) to be called on my side ‘a flatterer’—I! That is too much, and too out of place. What do I ever say that is like flattery? I am allowed, it may be hoped, to admire the ‘Lurias’ and the rest, quite like other people, and even to say that I admire them ... may I not lawfully? If that is flattery woe to me! I tell you the real truth, as I see the truth, even in respect to them ... the ‘Lurias’....

For instance, did I flatter you and say that you were right yesterday? Indeed I thought you as wrong as possible ... wonderfully wrong on such a subject, for you ... who, only a day or two before, seemed so free from[41] conventional fallacies ... so free! You would abolish the punishment of death too ... and put away wars, I am sure! But honourable men are bound to keep their honours clean at the expense of so much gunpowder and so much risk of life ... that must be, ought to be, ... let judicial deaths and military glory be abolished ever so! For my part, I set all Christian principle aside, (although if it were carried out ... and principle is nothing unless carried out ... it would not mean cowardice but magnanimity) but I set it aside and go on the bare social rational ground ... and I do advisedly declare to you that I cannot conceive of any possible combination of circumstances which could ... I will not say justify, but even excuse, an honourable man’s having recourse to the duellist’s pistol, either on his own account or another’s. Not only it seems to me horribly wrong ... but absurdly wrong, it seems to me. Also ... as a matter of pure reason ... the Parisian method of taking aim and blowing off a man’s head for the sins of his tongue, I do take to have a sort of judicial advantage over the Englishman’s six paces ... throwing the dice for his life or another man’s, because wounded by that man in his honour. His honour!—Who believes in such an honour ... liable to such amends, and capable of such recovery! You cannot, I think—in the secret of your mind. Or if you can ... you, who are a teacher of the world ... poor world—it is more desperately wrong than I thought.

A man calls you ‘a liar’ in an assembly of other men. Because he is a calumniator, and, on that very account, a worse man than you, you ask him to go down with you on the only ground on which you two are equals ... the duelling-ground, ... and with pistols of the same length and friends numerically equal on each side, play at lives with him, both mortal men that you are. If it was proposed to you to play at real dice for the ratification or non-ratification of his calumny, the proposition would be laughed to scorn ... and yet the chance (as chance) seems much the[42] same, ... and the death is an exterior circumstance which cannot be imagined to have much virtue. At best, what do you prove by your duel? ... that your calumniator, though a calumniator, is not a coward in the vulgar sense ... and that yourself, though you may still be a liar ten times over, are not a coward either! ‘Here be proofs.’

And as to the custom of duelling preventing insults ... why you say that a man of honour should not go out with an unworthy adversary. Now supposing a man to be withheld from insult and calumny, just by the fear of being shot ... who is more unworthy than such a man? Therefore you conclude irrationally, illogically, that the system operates beyond the limit of its operations.—Oh! I shall write as quarrelsome letters as I choose. You are wrong, I know and feel, when you advocate the pitiful resources of this corrupt social life, ... and if you are wrong, how are we to get right, we all who look to you for teaching. Are you afraid too of being taken for a coward? or would you excuse that sort of fear ... that cowardice of cowardice, in other men? For me, I value your honour, just as you do ... more than your life ... of the two things: but the madness of this foolishness is so clear to my eyes, than instead of opening the door for you and keeping your secret, as that miserable woman did last year, for the man shot by her sister’s husband, I would just call in the police, though you were to throw me out of the window afterwards. So, with that beautiful vision of domestic felicity, (which Mrs. Jameson would leap up to see!) I shall end my letter—isn’t it a letter worth thanking for?—

Ever dearest, do you promise me that you never will be provoked into such an act—never? Mr. O’Connell vowed it to himself, for a dead man ... and you may to me, for a living woman. Promises and vows may be foolish things for the most part ... but they cannot be more foolish than, in this case, the thing vowed against. So promise and vow. And I will ‘flatter’ you in return in the lawful way ... for[43] you will ‘make me happy’ ... so far! May God bless you, beloved! It is so wet and dreary to-day that I do not go down-stairs—I sit instead in the gondola chair ... do you not see? ... and think of you ... do you not feel? I even love you ... if that were worth mentioning....

being your own

Ba.

How good of you to write so on Sunday! to compare with my bad!

Tuesday.

[Post-mark, April 7, 1846.]

They have just sent me one proof, only—so I have been correcting everything as fast as possible, that, returning it at once, a revise might arrive, fit to send, for this that comes is just as bad as if I had let it alone in the first instance. All your corrections are golden. In ‘Luria,’ I alter ‘little circle’ to ‘circling faces’—which is more like what I meant. As for that point we spoke of yesterday—it seems ‘past praying for’—if I make the speech an ‘aside,’ I commit Ogniben to that opinion:—did you notice, at the beginning of the second part, that on this Ogniben’s very entry (as described by a bystander), he is made to say, for first speech, ‘I have known so many leaders of revolts’—‘laughing gently to himself’? This, which was wrongly printed in italics, as if a comment of the bystander’s own, was a characteristic circumstance, as I meant it. All these opinions should be delivered with a ‘gentle laughter to himself’—but—as is said elsewhere,—we profess and we perform! Enough of it—Meliora sperumus!