Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

BY

EGLANTON THORNE

AUTHOR OF "THE OLD WORCESTER JUG,"

"WORTHY OF HIS NAME," ETC., ETC.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56 PATERNOSTER ROW AND

65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

BUTLER & TANNER

THE SELWOOD PRINTING WORKS

FROME, AND LONDON.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. HER DEVOTED SUBJECT

CHAPTER III. THE PRINCESS DEPARTS

CHAPTER IV. THE PRINCESS'S LETTER

CHAPTER VI. BERT GAINS A FRIEND

CHAPTER VII. THE QUEEN'S JUBILEE

CHAPTER IX. AN INTERVIEW WITH THE PRINCESS

CHAPTER X. THE PRINCESS RETURNS

CHAPTER XII. AT THE LAST EXTREMITY

CHAPTER XIII. DEAD AND ALIVE AGAIN

A SHAM PRINCESS

Her Devoted Subject

"COULD it be that the Princess was going to die?" Bert held his breath as the thought smote him. He could almost hear the beating of his heart as he stood motionless, arrested by the painful idea, and gazed with anxious eyes on his sleeping sister.

Prin had been ill for more than a week, so ill that the parish doctor had come every day to see her; but Bert had never thought of death before.

The idea having presented itself, was not easily to be dismissed. He looked at Prin's white, sunken face, at the dark veins on her forehead, at the thin, white hands that were folded on her bosom; he listened to her quick, difficult breathing, and his fear deepened. How could he bear it if Prin died?

It was a small, mean room in which the brother and sister lived. The dirty, sodden paper hung in strips from the wall; the flooring was rotten, with holes gaping here and there; the place reeked of damp and worse; the window, dim with dirt, looked on to a foul area; it was hardly a room in which any patient was likely to make a good recovery.

The bed on which the sick girl lay looked very comfortless. Yet some one had arranged the grimy pillows in the best way possible, so that she lay at ease, and tended her so carefully that her white skin and fair hair had a purity which contrasted strangely with her dingy surroundings. This was their neighbour, Mrs. Kay, a woman who lived on the floor above, a native of Scotland, but who retained few traces of her Scotch upbringing save a faint and somewhat intermittent belief in the virtues of cleanliness. Bert had been wont to speak of her as the "cross old woman," for she had a sharp tongue and little patience with the ways of children; but she had not been cross at all since Prin fell ill, a fact which now struck Bert as ominous.

Bert knew what was the matter with his sister. She had had measles, and now, as he had heard the doctor say, they were succeeded by bronchitis. Bert himself had had measles; in fact, he had conveyed the infection to the Princess; but his ailment had been over in a couple of days. Clearly this "brownkitus," as he called it, was a much more serious thing.

Prin had been fretful and restless all day, but now at last she slept. As he watched her deep slumber, Bert took comfort from it. "If she sleep, she shall do well," he said to himself, not aware that he was making a quotation, though the words were a fleeting reminiscence of a Scripture lesson.

Suddenly, as he thought thus, there arose an uproar in the street above. It was never a quiet street by day or night. Fights and rows were of frequent occurrence, so that Bert was not surprised, though he was much annoyed when the sound of angry voices in hot altercation broke on his ear. If Prin were suddenly roused and affrighted, she would lose all the good that this sleep was doing her.

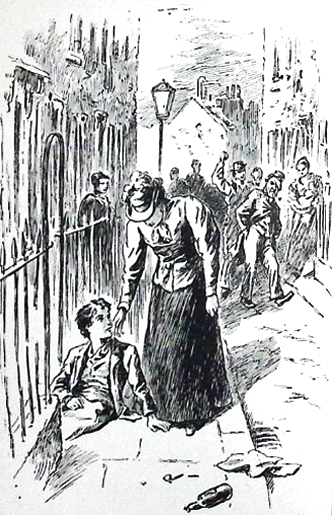

Bert was up the area steps in a moment, to see what he could do. Some lads, considerably bigger than himself, were causing the disturbance. The ringleader of the mischief had taken up his position, with his back against the railings of the area, and was inviting the others to "come on." With more pluck than discretion, Bert flew at him.

"Get out of this," he cried, shoving against him with all his might; "you don't stand here and make a row. Get out, I say. My sister's below very ill, and I won't have her woke by you, you big, hulking brutes!"

It was not a conciliatory mode of address, and it was hardly calculated to secure quiet. On the contrary, it created a greater hubbub.

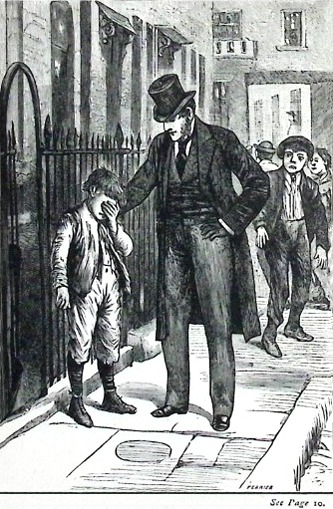

The lad thus assailed by Bert turned upon him with an oath, and dealt him a violent blow on the head. The others, foreseeing a new diversion, forgot their common quarrel and closed around Bert. It would have gone badly with him—for these young street ruffians had no hesitation in attacking one so unequally matched with them—had not the doctor's trap at that moment driven up to the door.

"What is all this about?" he demanded as he stepped out. At the sound of his authoritative voice the cowards took to their heels, and Bert emerged from their midst with a bleeding face and torn clothing.

"What have they done to you? Let me see," said the doctor, in sharp but not unkindly tones. "Why do you go with such boys as those? You did something to provoke them, I suppose?"

"I only told them to move on because my sister was asleep, and I did not want them to wake her," said Bert.

"Ah, and they did not choose to be commanded by you?" said the doctor. "Well, I advise you to be more diplomatic the next time you hold parley with the enemy. But now wash the blood from your face, and I'll put a piece of plaster over that cut for you. Oh, you live here, do you? So, I see it is your sister I am attending."

Bert wondered that the doctor should not know him again. He followed him down the dirty steps of the area. In a few minutes Bert's face was dressed, and the doctor turned his attention to the sleeping child, whom the noises without had failed to rouse.

"Please, sir, is she better?" asked Bert anxiously.

"She is," said the doctor decidedly, when he had made his examination, only partially waking the girl in doing so; "she really is better."

"Then you don't think, sir, that she will die?" said Bert.

"Die! What put that into your head? No, if only—" he paused, and glanced round the dismal room with rather a hopeless expression—"if only she could have good air and good food, I should say she might do well. What she wants is to be sent into the country as soon as she is a little better."

Bert's face fell. The country seemed to him as far-away as heaven. If Prin's recovery depended on her going there, the chances were sorely against her.

"Where is your mother?" asked the doctor.

Bert stared for a moment ere he replied,—

"We ain't got none. Our mother died ever so long ago; before I can remember."

"Then who is the woman I have always seen with you?"

"You mean Mrs. Kay. She's out just now, sir."

"Then Mrs. Kay takes care of you, I suppose?"

"Yes," said Bert, with considerable hesitation, however; "she does when—"

"When she is not drunk," he had been about to say, but he checked himself. He was not willing to expose the failings of one who during the last few days had proved herself so kind a neighbour.

"You have a father, of course?" said the gentleman.

"No, sir, not now," replied Bert; "he died in the hospital last summer."

Dr. Hurst looked keenly at the boy. His face was honest; his blue eyes had a frank, open expression. It was plain he was speaking the truth.

"Then who keeps you children?"

"We keeps ourselves, sir."

"What do you mean? You're too young to work for your living."

"I shall soon be eleven, sir," said Bert, stretching his diminutive frame to its utmost height, "and Prin's two years older. I sells papers of an evening, and sometimes matches, and runs errands for people; and Prin, she minds babies and helps Mrs. Kay. But the worst of it is, Prin is not strong, and she soon gets tired. I often have to work for her as well as myself."

"Upon my word you are a brave little man," said the doctor, looking at him admiringly. He had already perceived that these children—the boy with his open, intelligent face, the girl with her pretty, delicate features—were of another type from most of the children who swarmed in that narrow slum. But he had taken it for granted that Mrs. Kay was their mother.

"Who was your father?" he asked.

"He was a scene-shifter at the theatre, sir, and mother was one of the ladies of the theatre," said Bert, with evident pride in the announcement. "We used to live near Drury Lane at one time."

He did not explain that his father had lost his work through drink, and drifted lower and lower until his death.

Dr. Hurst stood musing on the facts thus presented to him. He felt that he had not sufficiently interested himself in these children. He was naturally a kind-hearted man, but long familiarity with the squalid homes amid which his work lay had blunted his susceptibilities.

His own life was a disappointment to him. Partly through his faults, partly by the force of circumstances, his medical career had proved somewhat of a failure. He had not anticipated that in mid-life he would hold the position of parish doctor in one of the lowest districts of London. The failure of his hopes had embittered him. He had grown cynical, morose, and inclined to take the darkest view of human nature. He was more often swayed by suspicion than by sympathy in his dealings with the poor. But he was touched by this boy's simple account of the life which he and his sister led. He looked on him with eyes softened by pity, and longed to do something to help these orphan children.

"What is your name, boy?" he asked.

"Bertram Sinclair," replied the boy promptly.

"And your sister's?"

"Eleanor Eliza," said Bert.

"But I thought you called her something else—some name beginning with P?"

"Oh, Prin, sir—that's short for Princess, you know; but that's not her real name. Father used to call her Princess, because she once took part in a pantomime as a little princess. My! And didn't she look a princess too! You should just have seen her. Her frock was all white, and it sparkled so it made your eyes water to look at it. And she had diamonds in her hair and on her neck, and white satin shoes, and a fan that sparkled too. You couldn't have known her from a real princess."

"As real as the diamonds, no doubt," said the doctor drily. "Ah, so you call her Princess still."

He turned to look again at his patient. She was sleeping soundly once more. Her face was flushed now with a delicate rose, like the lining of a shell. She looked pretty and refined enough to be a princess; but the dingy pillows, the dark, unlovely room were a strange setting for that dainty, fairy-like head and face.

The doctor had smiled as he turned towards her; but the smile died away and a sad expression took its place. His eyes grew moist for a moment as he murmured, "Poor little Princess!"

It was so unusual for him to yield to such emotion that he felt ashamed of the momentary weakness, and with a quick assumption of his ordinary manner turned to the little lad, saying briskly,—

"Well, good day. Don't forget that the Princess needs feeding. Give her plenty of milk and good beef-tea, if you can get it."

That if was very much to the point. A look came into the boy's eyes that made the doctor feel that his words were cruel in their carelessness. "I might as well have ordered her champagne and oysters," he said to himself. Then Dr. Hurst did something which astonished himself. He put his hand in his pocket, drew out a shilling and threw it on the bed.

"There, lad, spend that on milk or beef for the Princess. It is to go for nothing else, mind."

Bert nodded gravely as he picked up the coin. He looked wonderfully relieved. He stood gazing at the coin with an air of extreme satisfaction, and it did not occur to him to utter a word of thanks.

But the doctor felt that he had been abundantly thanked as he hurried away from the miserable room. He entered the children's names in his note-book ere he drove away.

"A case for Mrs. Thornton," he said to himself. "I must interest her in these young waifs."

A Fairy's Visit

THE Princess was better. She was no longer in bed. Mrs. Kay had helped her to rise and dress herself; and now, in her shabby, threadbare frock, with thin, broken shoes on her feet, she sat on a hard, wooden chair, beside the little handful of fire which Bert had managed to kindle in the rusty grate.

She was a very miserable princess. She had felt ill enough as she lay on her comfortless bed, but she felt far worse now as she tried to sit upright on the hard chair, with its straight, uneasy back. Her limbs ached, her head throbbed, and every now and then she was conscious of a sick, giddy sensation, when the room seemed to go round with her, and she had to clutch at the chair to keep herself from falling. If only she had had a mother to care for her, and could have felt the comfort of a mother's love in the sore depression which was the result of weakness!

Mrs. Kay was well-meaning; but since she knew the young patient to be out of danger, her manner had grown stern again. Her better self, the self of long ago, had re-asserted itself during the days when Prin needed to be watched and tended from hour to hour; but already the good influence was past. Evil habits had resumed their sway over her. She was the "cross old woman" again, and when she was not at the laundry, where she earned her living, she was drinking in the public-house over the way.

Bert was kneeling by the fire, dividing his attention between a small saucepan, which was simmering on the hob, and his sister, on whom, from time to time, he cast glances expressive of anxiety.

"Do you feel better, Prin?" he asked, not for the first time.

"I do wish you wouldn't keep asking me if I feel better," she answered pettishly; "I feel worse, I tell you, a great deal worse than I did when I was in bed. Can't you believe me?"

"But you can't really be worse," said Bert, seeking to reassure himself. "The doctor says you are better, and Mrs. Kay says so, so you must be better."

"I suppose they know my feelin's better than I do," replied the Princess scornfully; "I tell you I am worse, and I ought to know, I should think."

"Well, p'raps you'll feel better to-morrow," said Bert cheerfully.

"No, I shan't; I shall never feel well again. I only wish I was dead."

"Oh, Prin!" exclaimed Bert reproachfully. "When I want you so much to live! What could I do without you?"

"You would do just as well without me as with me," she said.

"I shouldn't do at all. I should die too," said Bert. "But don't talk of dying; just wait till you've had some of this beef-tea, and you'll feel as fit as possible."

As he spoke he lifted the lid of the saucepan, and a savoury odour was emitted. Bert's nostrils inhaled it with avidity. He was so hungry that he could have despatched in a few minutes all that the saucepan contained. But he had no intention of tasting more than a few drops, just to assure himself of the success of his cookery. Bert was feeling rather proud of his first attempt at making beef-tea. He had spent the last of the doctor's shilling on the beef—which was not of the primest quality—had got a hint from Mrs. Kay how to set to work, and the result was now to be tested. But the odour which Bert found so savoury only sickened the Princess, and to his keen disappointment she could not drink the weak, greasy decoction which he presently set before her.

"Take it away," she cried impatiently; "I don't like it; I don't want it."

And then to Bert's dismay, her head sank forward on her hands, and she began to sob helplessly. This was unlike the Princess, who was usually quick and imperious in her ways, and, though by no means sweet-tempered, perfectly self-controlled.

She signed to Bert to help her back to bed, and he obeyed. She sank down, hid her face in the pillow, and sobbed with hysterical violence, crying between her sobs,—"I wish I were dead. I do—I do!"

Bert stood looking at her in utter helplessness. He was devoted to his sister; but he was wont to regard her as one far stronger and more spirited than himself. She was his ruler, and her government was not of the gentlest description; but her faithful slave never rebelled. Their father had always petted and indulged her, while he made small account of Bert, whose appearance was mean and insignificant. The Princess was ever the Princess, to be treated with the first consideration, and given the best of everything it was possible to obtain. Bert had learned the lesson well. It never occurred to him to question her right to supremacy. He was as obedient to her now as he had been in the days when his father was at hand to insist upon his doing as she told him. It was positively alarming to Bert to see his sovereign thus prostrate.

"Don't cry, Princess," he pleaded; "oh, please, don't cry! It ain't no manner of use to cry. If things is bad to-day, they'll be better to-morrow."

"They will never be better for us," sobbed the Princess. "Look what a hole we live in! Could any one be well here?"

Bert thought he might be well enough there, if only he had something to stay the gnawing pain of hunger, of which he was just then disagreeably conscious. But he did not speak of his own feelings.

"If only you could go into the country, you would soon be well," he remarked; "the doctor said so."

"What is the good of saying it when I can't go?" asked the Princess peevishly. "You make me feel worse by talking of it. Oh, I am so thirsty! If only I had an orange!"

Bert looked around him in despair. He wished he had bought oranges instead of beef! Now he had not a penny left. His eyes searched for something that he could pawn; but there seemed nothing of any value that could be spared. Bert, however, was a boy of hopeful spirit.

"Just take a drink of this now," he said, bringing his sister a mug of water, "and I'll see if I can't get you an orange by-and-by."

The Princess drank a little of the water. Bert made a clumsy but well-meaning attempt to set her pillows comfortably, and then was off into the street. There was a metropolitan station not far from the street in which he lived. Bert made for this, in the hope of earning a penny by carrying a parcel or calling a cab. But there was no such luck for him this afternoon. Numbers of persons passed out of the station while he waited; but none of them wanted a boy. The ladies seemed to prefer to carry their own parcels, and there was no demand for cabs. He had no capital with which to start paper or match-selling.

He waited till the March evening closed in, and then, chill and weary, and hungrier than ever, he went home to see how the Princess was faring.

He halted for a moment at the top of the area steps. He did not like to present himself to the Princess without the orange which he had hoped to bring her. He dreaded her reproaches, and still more her tears. But there was no help for it. Slowly he opened the door and stole in. But the sight that met his eyes made him think for a moment that he had mistaken the house. He stood on the threshold and fairly gasped with surprise.

The first thing that met his astonished eyes was a heap of golden oranges lying on the dingy coverlid of the Princess's bed. Then he saw that the little rickety table beyond was spread with quite festal fare, and Prin, looking like her old self, and wearing a wonderful pink flannel jacket, was presiding over the feast, while Mrs. Kay, her bonnet on one side and her face suspiciously flushed, stood before the bright little fire engaged in toasting what looked remarkably like a muffin.

"Oh, come along, Bert!" exclaimed the Princess. "Here you are at last! I thought you never were coming!"

"Oh, Prin," gasped Bert, "where did you get those oranges and all those things?"

"Ah, you may well ask. There's been a fairy here since you went away. She brought me those oranges, and some tea and sugar, and that strengthening jelly; and she gave Mrs. Kay money to get firing and milk. Oh, you needn't look like that, Bert; it's quite true."

"A fairy!" stammered Bert. "There ain't no such things."

"Oh, ain't there! That's all you know. This fairy came in her carriage; but she wasn't a bit proud. She spoke as kind as kind to me. She said she'd heard of me from Dr. Hurst, and how I should never be better till I got into the country, and she's going to send me into the country. I'm going to-morrow, Bert. Only think of that!"

There was no need to bid Bert think of it. The news was startling in its unexpectedness.

"To-morrow," he repeated; "do you mean that you are going away to-morrow, Prin?"

"Yes, to-morrow," she repeated delightedly. "There's a nurse coming to fetch me, and I'm to have new clothes, and to go away in a cab. Won't it be lovely?"

"Yes," he said slowly, "it's the best thing possible for you. The doctor said the country would make you well."

He tried to think that he was glad, very glad, that Prin was going; but his heart felt strangely heavy.

"Where are you going, Prin?"

"Oh, I don't know—somewhere in Hampshire, I think the lady said. Oh, do take that muffin from Mrs. Kay, Bert; she'll burn it, to a dead certainty."

Bert rescued the muffin from Mrs. Kay's unsteady hand. It appeared that she had spent some of the lady's money at the public-house, though she explained that she was suffering from a swimming of the head caused by a chill on the liver.

"Come and have some tea, Mrs. Kay?" said Prin, beginning to pour out the beverage from a brown teapot with a broken spout.

Mrs. Kay consented, but she did not drink the tea Prin poured out for her. She fell asleep with her head lolling uncomfortably on the back of the chair.

"Isn't that muffin done yet?" asked Prin presently. "What are you thinking of, Bert? I declare you are as bad as Mrs. Kay."

"Yes, it's done," said Bert, bringing it to the table. "I was thinking of you, Prin. You're better already, just for the thought of going."

"Of course I am. I feel almost well," replied Prin. "Now let us have some tea; I guess you're hungry."

There could be no question of that. Bert began to eat with keen appetite, and when the meal was over he felt much better for it. But there was still a weight on his mind.

"What time are you going to-morrow, Prin?" he asked.

"Eleven o'clock," she answered promptly.

"And how long will you be away?"

"Oh, I don't know—all the summer, p'raps, the lady said."

"And what'll I do?" asked Bert.

"You? Oh, I don't know," replied his sister.

"Stay here with Mrs. Kay, I suppose."

"Didn't the lady say nothing about me?" he asked wistfully.

"Why, no, she didn't," said Prin; "I don't think she knew I had a brother."

"Didn't you tell her?" he said.

"I never thought of it," she said. "I could think of nothing but what she was a-saying about the fields, and the trees, and the flowers, and the good the country air would do me. You should have been here."

Bart heaved a deep sigh.

"Well," he said slowly, "if you come back strong and rosy, I shall be very glad that you went."

"Of course you will," she said.

"And I am glad now," he said slowly. "Oh yes, I am glad that you are going."

But his tone was hardly joyful.

The Princess Departs

THE hour of the Princess's departure had come. Already she appeared to belong to another place than the dingy underground room. A lady dressed in nursing costume had arrived in a cab, bringing with her a large bag. With the deft, quick manner of one used to such tasks, she proceeded to wash and dress the patient, arraying her in fresh, neat garments produced from the bag.

When her toilette was completed, Prin, wearing a serge frock and jacket and a sailor hat, looked a very different being from the forlorn, sick girl who had been lying on the wretched bed. She was one who "paid for dress," as people say. Even Bert, accustomed to do homage to her, was surprised at the new grace and dignity with which the Princess seemed to be invested by her change of garb.

The nurse looked with satisfaction on the result of her efforts. She noted what a pretty, gracefully-formed girl her patient was. Then her eyes fell on the little brother, shrinking back against the wall, as if suddenly smitten with awe of his transformed sister, and she was conscious of a painful contrast. Bert was not handsome, and his thin, stunted form, clad in hopelessly ragged garments, looked its worst at this moment. He had not washed his hands since he made the fire, and his fingers had conveyed various black touches to his face, the features of which were twitching grotesquely, partly from nervousness, partly as the result of a heroic resolve not to cry.

His was a queer little face at all times, with its snub nose and the sensitive mouth, which gave itself readily to contortions; but it was redeemed from ugliness by a pair of deep blue eyes, keen in their glance, from the swift intelligence of a boy who gets his living on the London streets. As she looked into those eyes, the heart of the nurse went out to him.

"Is he your brother?" she asked.

Prin looked as if she would have liked to disown him; but she nodded in reply to the question.

The nurse moved nearer to the deplorable little figure, and spoke gently to him. "What will you do when your sister is gone, my little man? Will you be quite alone?"

Bert nodded.

The nurse looked troubled.

"I don't believe Mrs. Thornton understood that there was a brother," she said to herself. "Yet she has no home for boys, and she never sends them into the country."

Aloud she said, addressing Bert, "Would you not like to go to school with other little boys?"

"I do go to school," replied the boy. "I goes every day when we haven't measles. I'm in the fifth standard."

"Ah, that's well," said the nurse; "but would you not like to go to school altogether—to live in a school, I mean, with other boys, where they would be very kind to you and teach you a trade? I could write to Dr. Barnardo about you, if you liked, and I daresay he would take you into one of his homes."

Bert looked gravely at her. He had heard of Dr. Barnardo.

"And I should have to stay there always, and I should never see Prin," he said.

"Oh, you might see your sister sometimes; not very often, of course; but you would be allowed to see her occasionally."

Bert shook his head.

"And when I grew big enough he would send me over the sea, wouldn't he?" he asked.

"I daresay he would send you to Canada, and a grand thing it would be for you."

"Where's Canada?" asked Bert. "It's further off than Hampshire, ain't it?"

The nurse smiled. "Oh yes, a great deal farther off."

Bert shook his head again, still more decidedly.

"Then I won't go," he said. "No Dr. Barnardo for me. I wouldn't leave Prin for the world. I promised father I'd always be good to her, and it wouldn't be keepin' my promise to go off to the other side of the sea."

And his mind was not to be changed by anything the nurse could say. She had no time to waste in useless persuasions.

"Now you must bid your brother good-bye," she said to Prin; "it is time we started."

Fatigued by the exertion of dressing, Prin had sunk wearily on to a chair; but, as the nurse spoke, she rose with fresh elasticity in her bearing.

"Good-bye, Bert," she said carelessly. "Oh, do you want me to kiss you? Then you should not have such a black face. It's not fit to kiss."

Nevertheless she kissed it, though in gingerly fashion.

"You'll send me a letter, won't you, Prin?" he said imploringly.

"Oh yes, I'll send you a letter," she said.

"And you'll come back—you'll be sure to come back?"

"Yes, I'll come back—some time," said the Princess loftily.

Then with the nurse's help, she got into the cab; and seating herself, looked round with an air of queenly importance on the little crowd which had gathered to witness her departure.

"Good-bye," she said, nodding graciously to those she recognised; "Good-bye."

The cab drove off, pursued for some little distance by a number of ragged and shouting children. But Bert was not amongst these. He stood on the edge of the pavement and watched till the cab turned the corner of the street; then he ran down the area steps, and crouching in the gloomiest corner of the dismal place he called his home, he gave way to the tears which could no longer be held back. The Princess had been his ruler and tyrant, but he loved her as even those who tyrannize are sometimes loved. She was the centre of his life, and his existence seemed empty and meaningless now that she had left him alone.

Bert soon found that he had lost his home, such as it was, in losing the Princess. On the evening of the next day, when he came back after selling newspapers with more than usual success, Mrs. Kay met him with the news that the landlady had let his room to some one else.

"She says you'll be getting behind with the rent now that your sister's gone, and a boy like you does not want a room to himself; but the truth is, she sees her way to making more money by it."

"What a shame!" exclaimed Bert. "Here, I've got the money for the rent now, and if I don't want the room, we shall want it when Prin comes back."

"Yes, when she does," said Mrs. Kay significantly.

"Why do you speak in that way?" asked the boy quickly. "Prin is coming back. Do you mean to say she won't?"

"Oh, I say nothing," said Mrs. Kay; "only I shouldn't wonder if now she's gone, she were to stay away altogether. It's not such a very nice place to come back to."

"But she will come back," exclaimed Bert passionately, "I know she will! Prin is not the girl to go away and never come back. She wouldn't do such a thing as that."

"Well, I don't know," said Mrs. Kay. "You're too young to think of such things; but if there was a girl I loved, I would not have her come to a place so full of sin and evil as this is."

"What is sin?" asked Bert.

"Oh, you know," said Mrs. Kay.

"I don't think I do," said Bert.

"Well, you know those girls that drink and swear and do everything that's bad? You would not have Prin become like one of them?"

"No," said Bert decidedly, "not like one of them noisy, rough girls. Is it sin to drink, then?"

"Oh, don't ask me!" exclaimed Mrs. Kay, with sudden and unreasonable impatience. "You should go to Sunday-school if you want to know about such things."

And she slammed her door in Bert's face.

He retreated, wondering how he had made her so angry. He could not know the power his words had to sting her.

There had been a time when Mrs. Kay had been far from thinking of herself as a sinner. In the home of her childhood, away in the north of Scotland, she had received a religious training. No child could repeat more promptly the answers in the Catechism, or had a better knowledge of Bible history. As she grew up, the minister found her the most satisfactory scholar belonging to his "kirk." In those days she could have explained glibly enough the nature of sin and the remedy God had provided for it. Yet now, in middle life, she was a woman degraded and enslaved by sin, living without hope, and craving only to forget the happier past, having dropped, one by one, all the good habits of her earlier life.

It was through drink that she had begun to go wrong.

"Was it sin to drink?" the boy had asked. Mrs. Kay had no doubt as to the answer to that question.

In simple, boyish fashion, Bert reflected on what Mrs. Kay had said. He had ample time for reflection now, for he was much alone. Naturally it had never occurred to him that he and Prin were surrounded by a moral atmosphere as bad for their souls as the tainted air of the slums was for their bodies. But now there came back to him certain things which he had heard his father say, without at the time comprehending their meaning.

Bert's father had been that strange anomaly, a man of strong religious beliefs, yet a hopeless slave to drink. He had not succumbed to temptation without a struggle. Many times had he signed the pledge, and he had kept it for intervals, sometimes of weeks, sometimes of months. During these periods of sobriety, he had done his best to instil religious truth into the minds of his children. He had warned them against his own vice. He had besought them to be true, and honest, and sober.

He was wise enough to know that his intemperance would probably involve his children's ruin as well as his own, yet this consideration was powerless to restrain him in the moment of weakness. Living where the enemy met him at every turn, his destruction was sure and swift. He had loved his children to the end; and Bert remembered that almost the last words he had heard from his father's lips were the prayer,—

"Deliver them from the evil."

He had felt sure that the words referred to himself and the Princess, but he had never thought about their meaning. Only now did a vague notion of the evil from which their father had prayed that they might be delivered begin to form itself within his mind.

The Princess's Letter

BERT found an early opportunity of pleading his own cause with the landlady. But in vain he begged her to let him remain longer in the miserable room he had called his home. He had no right to it. The poor furniture it contained was the property of the landlady, and she saw her way to letting the room to better advantage.

"What does a boy like you want with a room?" she asked. "You're always in the street. All you need is a place to sleep in. I'll put a shake-down for you in the corner under the stairs, and you'll be as cosy there as possible."

"But we shall want a room when Prin comes back," said Bert.

"Oh, well, it will be time enough to talk of that when she does come back," said the woman; and the words sent a chill to Bert's heart.

He had to content himself with the arrangement she proposed. She had no unkind intentions towards the boy; she only wanted to do the best she could for herself. In the days that followed, she was good to Bert in her way, sometimes giving him a basin of broth or a few potatoes for his supper, and demanding no rent of him, save a few simple services, which he willingly rendered instead of payment.

But the boy's life was very desolate. He had no "chum" amongst the boys in the street. His devotion to the Princess had prevented him from forming any friendship, and some instinct now withheld him from entering into alliance with these rude, low lads. He went regularly to school, and his quickness and intelligence made him a favourite with his master, who showed him much kindness in a careless fashion, little thinking how he was brightening Bert's life, or what a lonely life it was.

Out of school hours, Bert earned his living by selling papers, and having no longer to provide delicacies for the Princess, he soon found himself able to save some of his pennies. This was a great satisfaction to Bert. He set his heart on accumulating a hoard of pennies by the time Prin returned, and his imagination was largely occupied in arranging the details of the feast which he meant his money to furnish in honour of her return.

Meanwhile a week passed by, and the letter Prin had promised her brother did not arrive. He was growing impatient for news of her, and watched eagerly every night and morning for the coming of the postman. But that functionary always gave the same reply to his eager question. There was no letter for him. Probably the Princess was too absorbed in her new surroundings to give a thought to her little brother.

One evening when Bert came in, having sold all his papers, the landlady had news for him.

"There's been a gentleman here asking a lot of questions about you," she said. "He wants you to go into a home or something."

"Then I ain't going into a home," said Bert, stamping his foot by way of giving emphasis to his words. "I hope you told him so."

"Oh, I told him nothing," said the landlady, with a cunning look, "except that you no longer lived in that room down there. Did I know where you was? he said; and of course I didn't know where you was—I never know where you are when you ain't here."

"Of course not," said Bert, with a twinkle in his eyes. He understood that she had purposely misled the gentleman.

"I'm glad you didn't tell him nothing. I don't want to go away and be shut up in a home. What would the Princess say if she came back and found me gone?"

"Oh, as for that—" The woman laughed significantly. She did not believe that the lady who had taken the girl away would ever let her come back to that street. But she felt no compunction for having done her best to prevent the gentleman from tracing Bert. The boy was useful to her, and she wished to keep him at hand.

"Why, I declare!" she exclaimed the next moment, as the form of the postman suddenly appeared at the end of the passage, obscuring the light. Bert started at the sound of the loud rat-tat, then sprang eagerly to the door.

"Here, young man," cried the postman good-temperedly. "Isn't it you who are always asking me for a letter, and isn't your name Bertram Sinclair? Here you are then."

Bert could hardly believe in his good fortune as he seized the letter. The Princess had written at last, when he had ceased to hope that she would. Yes, the direction was written by her in a clear, though somewhat straggling hand. Carefully Bert opened the envelope. He would not tear it more than he could help, for even that was precious, as coming from the Princess. The light was waning in the passage, so he went to the door and seated himself on the step to read his precious letter. It was not very long, and he soon mastered its contents. The spelling was somewhat peculiar, but what Prin said was this:—

"DEAR BERT,—

"Perhaps you think that I might have written before, but really

everything is so lovely here that I couldn't be bothered to write.

It's not a bit like London here. There's a garden full of flowers, and

fields, and woods with lots of primroses and violets that any one may

pick. The lady keeps cows, and I have as much milk as I can drink,

and every day I drive about in a beautiful carriage. Every one says

how well I look, so different from what I was when I came. I am to

stay here all the summer, and the lady says I must go to school of a

morning, which I shall not like so much. She says she would like to

keep me altogether, for I am so quick and clever she could teach me

anything. Would you mind If I never came back at all?

"How is old Mother Kay? Does she drink as much as ever? I hate to

think of how horrid everything used to be. I am so much better off

here. Hoping you are as well as this leaves me.

"I remain,

"Yours truly,

"PRIN."

It was not a very affectionate or sisterly letter, but, such as it was, it was the only letter Bert had ever had from the Princess, and he regarded it with considerable admiration. Yet there was that in it which stung him. Would he mind if she never came back? Surely Prin might have known that he would mind.

The New Lodger

BERT read the Princess's letter over and over again, till he knew the words by heart. To keep it safely, he pinned it within his ragged jacket; but it was often in his hands, till from constant handling the paper became soiled and ragged. It was well he treasured it, for he got no second letter from Prin.

Week after week passed on. Spring grew into summer, and the sun's heat was fervid, and the air close and tainted in the narrow street in which Bert lived; but Prin, enjoying the fresher, sweeter atmosphere, and more wholesome life of the country, sent no token of remembrance to her brother. She did not write again, and it never occurred to Bert to write to her.

He could write, after a fashion, but it was an accomplishment he never practised out of school hours, and he had not written a letter in his life. He began to long for the summer to pass, for he believed that in the autumn Prin would come back to him.

"When will the summer be over?" he asked Mrs. Kay one day.

"Over!" she repeated. "Why, it's hardly begun yet. This is only the beginning of June, though it's hot enough for August. You are in a hurry."

Bert sighed. It was of no use to be in a hurry. He could not make the days move faster.

That June was a memorable one in the life of London. It was the June of 1887. Already every one was talking of the magnificence with which the Queen's Jubilee was to be celebrated. Even amongst the poorest dwellers in the metropolis it was a subject of absorbing interest. Most persons meant to see something of the splendour, and many hoped to turn the occasion to good account for themselves.

Bert eagerly gleaned all the information he could on the subject. He likened as people talked of the decorations, the illuminations, the grand stands for the spectators, the horses and carriages, the royal personages who were to appear, and all the pomp and show which were to mark the occasion. The thought of it excited and bewildered him. If only Prin were with him, what a time they would have! The Princess would know what to do. She would manage to see everything. No one was more clever than the Princess in pushing her way to the front and securing the best possible position when there was anything to be seen or gained. Bert was profoundly conscious of his inferiority to her in this respect.

Another new interest had come into Bert's life, and shared, with the Jubilee, his thoughts. This was the landlady's new lodger. He took possession of the room in the area three days after Prin's departure. He was an old sailor, and earned his living by bill-sticking and kindred occupations of a somewhat precarious nature. Apparently he was poor, as were all the inhabitants of that street; but his poverty was not, like that of most of the dwellers there, caused by drink. Watching the new lodger with a boy's keen curiosity, which lets nothing escape it, Bert soon observed that he never entered any of the public-houses in the neighbourhood, and that he drank nothing stronger than tea or ginger-beer. This was enough to distinguish him from every other man with whom Bert was acquainted.

Though he had brought nothing with him to the room that could be called furniture, the man had a few possessions on which he seemed to set great value. Among these was a great black cat, between which and his master there seemed to be a perfect understanding, and which was evidently very dear to him. Bert had never seen so fine a cat. The cats belonging to that street were a poor, half-starved race, with the mean and treacherous habits fostered by ill-treatment. This was a noble animal, with a coat as black as jet and as glossy as satin. He was supremely conscious of his superiority, and bore himself with much dignity. Nor would he suffer any familiarity; for when Bert once ventured to touch him, the cat instantly arched his back, spat fiercely, and showed a formidable set of claws. But with his master he was very different. Bert, peering down from the street between the railings, noted how the cat would spring on the man's shoulder and rub his head lovingly against his cheek. And whatever his master was doing, the cat was sure to be close beside him, and evidently he shared all his meals.

The stranger also possessed several books, and from what Bert saw, he judged him to be fond of reading. There was one book, a somewhat bulky, well-worn book, which was constantly in his hands. He would sit reading this by the open window with his cat perched on his shoulder, and the noises of the street did not seem to disturb him, nor did he appear aware of the little boy who stood so often by the railings, furtively watching his every movement.

Like most sailors, this man was very cleanly in his habits. Bert was amazed to see how clean he made his room, scrubbing the floor and polishing the window till they looked as Bert had never seen them look. Then he pasted clean paper over the soiled and torn wall-paper, and put up a bright picture here and there, and did a little carpentering where it was necessary.

"It looks like another room," thought Bert, as he caught glimpses through the open window of the improvement within; "Prin would not know it, if she saw it now." Then he sighed as he thought of Prin, who had been gone so long.

The new lodger seemed to have no friend save his cat. Not that he was unfriendly in his ways. He was ready enough to bid his neighbours "good day," and to exchange a kind word with them; but his manner of life was so different from theirs that they instinctively held aloof from him. But, if lonely, he was not unhappy. He was generally singing as he tidied his room or cooked his bit of food. Sometimes Bart caught the words he was singing.

"I've found a Friend, oh, such a Friend!" he heard him sing one day.

"Then he has got a friend," thought Bert. "It seemed as if he were as much left to himself as I am. I did not want a friend as long as Prin was with me, but now—"

And Bert sighed. He would have liked the old sailor to be his friend, but he was far too shy to make the first advances.

One day Bert heard the landlady tell Mrs. Kay that the old sailor was going away.

"Going away!" he exclaimed in dismay. "Going to give up his room?"

"Now then, what business is it of yours, Mr. Sharp-ears?" asked the landlady. "I wasn't a-speaking to you. But don't you make no mistake. He ain't giving up his room. He's just going away for a day or two—to Liverpool, he tells me."

"When does he go?" asked Mrs. Kay.

"Early to-morrow morning. He's a rare hand at getting up early. He's up at four most mornings, and off to his work."

"That's how it is I never see him, I suppose," said Mrs. Kay. "Funny, ain't it? I've never set eyes on your new lodger yet."

"Well, he ain't much to look at, but he's a good 'un," said the landlady; "pays his rent reg'lar to the day, which is more than many folks do."

The words had a significance which made Mrs. Kay uneasy. She remembered that her rent was over-due. When she was "on the drink," she was wont to forget that there was such a thing as rent.

Just then Bert tugged at her gown.

"There he is Mrs. Kay," he whispered. "Look, if you ain't seen him, there he is."

Mrs. Kay glanced into the street. A man stood at the top of the area steps—a bundle of papers was strapped to his back, and he carried a paste-pot and a big brush. He had paused for a moment to adjust his burden ere he descended to his room. Mrs. Kay had a good view of him. The next moment she staggered back into the passage, her face wearing such a startled look that Bert exclaimed in alarm,—

"Oh, what is the matter, Mrs. Kay? Do you know him? Have you seen him before?"

For answer, she dealt him a stinging box on the ears, then vanished into her room, slamming the door behind her.

The landlady laughed at Bert's discomfiture. "She's a queer one, she is," she said, "but it serves you right for asking impertinent questions. You want to know too much, you do."

Very early the next morning, Bert, sleeping in his corner under the stairs, was roused by the noise of the area gate swinging on its hinges. Noiselessly, on bare feet, he sped to the house door, which was never locked—for the lodgers came in at all hours of the night—and opening it a few inches peeped out. It was as he thought, the sailor was departing on his trip to Liverpool. He was wearing the blue pilot coat and peaked cap which he usually reserved for Sundays, and he carried in his hand a neatly-made bundle.

Bert saw him walk away with regret.

There was a fascination in watching the ways of this man, and the boy was sorry to think that some days must elapse ere he saw him again.

"I wonder if he's gone to see that friend he's always singing about," he said to himself. Then a grand idea came like a sudden inspiration to Bert. What if he were to go to see the Princess! If she would not come to him, why should he not go to her? If only he had money enough, no doubt a train would take him to the place where she was. Thrilled with excitement at the thought, Bert hastened to count his precious hoard. His coppers amounted to eleven-pence half-penny—almost a shilling! Surely, if he went on saving, he would soon have money enough to pay his fare to Hampshire. The idea acted on him like a stimulant. He rose at once and began to don his ragged clothes. He would lose no time in seeking to earn money. He hurried away, first to a coffee stall to get his breakfast, and then to secure his papers.

Fortune smiled on him this morning. He was lucky enough to make sixpence ere it was time for him to go to school.

When he came back to the house at mid-day, he found a crowd of children gathered at the top of the area steps. The cause of their gathering was soon evident. Loud and distressful mews resounded from the sailor's room. It was clear that his cat, shut up within, was both hungry and indignant.

"Did you ever hear anything like that cat?" cried the landlady, as she stood at her door, to the assembled neighbours. "It drives me frantic to hear it, and there's no getting to the creature, for he's locked the door and taken the key with him, and the shutters are fastened on the inside."

"What a shame to leave a poor dumb animal like that! He did ought to know better than to do such a thing," was the opinion expressed by more than one.

"Oh, as for that, he did not mean to do it. He must have forgot it just at the last, for he asked me to look after his cat, and he gave me money to buy it milk and meat. He'll be as mad as mad when he knows what he's done."

Bert knew that this was true. The lodger was far too fond of his cat to willingly cause it to suffer. Bert ran down the steps into the area, and standing by the door said, "Poor puss! Poor puss!" several times in encouraging tones. The cat's cries ceased for a few moments, then quickly began again, louder than ever.

A happy thought occurred to Bert. He remembered that the door was ill-fitting, and that a wide crevice at the top used to let in many a cruel draught upon him and Prin. If he stood on a chair, he might be able to drop some pieces of meat through the aperture.

He confided his plan to the landlady, and she helped him to carry it out. The lodger had nailed a piece of cloth along the top of the doorway to keep out the draught; but this Bert succeeded in tearing away, and then there was room for him to push the pieces of meat through. He soon heard sounds that told him that the cat was snapping them up as they fell. In this way he got a good meal. He still continued to mew, for he missed his master and disliked the confinement; but gradually his cries grew fainter, till at last they ceased.

"I suppose he has gone to sleep," thought Bert. "Well, I'm glad I remembered that hole. I can keep him from starving anyhow."

Then he went off to get his own dinner, which was not a very sumptuous repast.

When he came back from selling his papers late that evening, he found that the cat needed his supper, and was announcing the fact by loud and piercing mews. Bert hastened to beg some food for him from the landlady, and then proceeded to feed him as before. He was standing on a chair, stretching upward on tip-toe in order to supply the cat's wants, when he was startled by a voice which said:

"What are you doing at my door?"

Bert started, and almost fell off the chair. He could hardly believe his eyes when he saw the old sailor descending the steps.

"I'm feeding your cat," he said; "I—I didn't know you was coming home to-night."

"Nor did I mean to," he said. "It's just my cat that has brought me back. I can't think how I came to forget him. I couldn't bear to think of the poor beastie being shut up here without food or drink."

"Well, I never!" exclaimed the landlady, leaning over from the doorstep above. "To think of your coming back, all the way from Liverpool, Mr. Corney, just for the sake of an old cat! And you meant to stay there three days!"

The old sailor smiled, and made no attempt to defend his conduct as he advanced to where Bert was stationed.

Bert Gains a Friend

BERT felt rather shamefaced as he scrambled off the chair and drew it on one side, that the sailor might enter the room. But the sight he saw as the door opened made him forget his self-consciousness. The cat sprang towards his master with a cry that was almost human, so clearly did it express delight. Then he began rubbing his head and body against the old man's legs, purring loudly the while. Finally the cat sprang on his master's shoulders and rubbed his head lovingly against his check.

"Good old Cetywayo," said the old man tenderly; "you're better than most Christians to forgive me thus. 'Twas a scurvy trick to leave you shut up here. The truth is, I clean forgot you. You slept so soundly under the bed that I never thought of you till after the train started. Then when I remembered that I must have locked you up here, I hadn't a moment's peace. I did not think that you would find such a kind friend." And he turned to look for Bert.

"Come in, boy; come in. You must make the acquaintance of my cat, since you've been so good to him. Ah, Cetywayo does not like strangers," as the cat arched his back and retreated at the sight of Bert; "but he'll soon be friendly with you, if you treat him well. I've often seen you looking down on us; but I didn't want you to come any nearer, for boys are not friends to cats as a rule. But I see now that I wronged you."

"I like your cat," said Bert timidly; "but Prin does not like cats. I brought a kitten home once, but she would not let me keep it."

"Who's Prin?" asked his new acquaintance.

And presently Bert was telling him all his history, and the stranger learned with surprise that the boy and his sister had occupied that room before he came.

"Well, if I'd known that you would look after my cat, I need not have troubled to come back to-night. It's a long way to go and come in one day."

"Is Liverpool farther off than Hampshire?" asked Bert.

"Why, yes, a good bit farther I should say; but it's wonderful how them trains whirl you along. Now, I'm going to have some supper, and you must have some with me. Yes, yes, that's only fair, since you've been feeding my cat."

"Ah, but Mrs. Brown gave me the meat for him," said Bert.

"No matter. You had the trouble of feeding him," said the old man, liking the boy the better for the acknowledgment.

Bert watched with interest as the old man made up his fire and set the kettle on it, preparatory to making some cocoa.

"Did you go to Liverpool to see a friend, Mr.—?" he hesitated, not being sure of the name.

"I'm called Corney," said the sailor; "not that it's my real name, but it does as well as any other. My mother, who was a wonderful hand at Bible names, called me Cornelius Theophilus, and my mates soon shortened that into 'Corney.' No, I didn't go to Liverpool to see a friend; I went to try to get some news of my sister; but I don't suppose it would have been any good if I'd stayed longer. All who knew her and me have disappeared."

"Then you had a sister, Mr. Corney?"

"Yes, I had a sister; and I don't know now whether she's living or dead. Her name was Priscilla. That's in the Bible, too, you know."

Bert did not know much about the Bible, nor was he desirous of such knowledge; but he was full of curiosity respecting this lodger, and anxious to make the most of this opportunity of gratifying it.

"But you've got a friend, haven't you, Mr. Corney?" he said.

"No," said Mr. Corney, looking sad and shaking his head; "I don't believe I have a friend left in the world."

"There's that one you're always singing about," said the boy. "Who's he?"

And then, as the old sailor looked at him with a puzzled expression, the boy tried to sing, in his shrill little voice:—

"I've got a Friend, oh, such a Friend!"

The old man's face suddenly lit up.

"Ah, that Friend!" he said. "I did not know what you meant. Ah, yes, I've that Friend, and he that has Him can do without any other."

And then in his quavering voice he began to sing:—

"'I've found a Friend, oh, such a Friend!

He bled, He died, to save me;

And not alone the gift of life,

But His own self He gave me.'

"You know who that Friend is, surely, boy?"

Bert's face had suddenly taken a serious, thoughtful expression. "I don't know," he said.

"The Lord Jesus. You have heard of Him?"

Bert nodded gravely.

"What do you know of Him?"

Bert did not reply immediately. When he spoke it was with evident reluctance.

"He is our Lord," he said, "and He died for us."

"Yes, He died that we might be saved from sin. Was not that love? Have we another friend like Him?"

Bert shook his head. He was silent for a minute. Then he ventured to put a question.

"What is sin?" he asked.

"Sin!" said Mr. Corney, surprised at the question. "Sin is the worst thing in the world. It is that which makes all the misery of this world."

"Yes; but what is it?" asked Bert.

The old sailor looked at him with a puzzled expression.

"You know," he said; "surely, boy, you know the difference between right and wrong?"

Bert made no reply.

"You know that it's wrong to tell lies, or steal, or do murder?"

Bert nodded. He had once received a beating from his father for telling a lie. He knew how the law punished the other offences.

"Well, those are sins. And yet sin means more than that, for one may do none of those things and yet be a great sinner. Paul called himself the chief of sinners, and yet he was no law-breaker. Really, I never thought till now how difficult it is to say what sin means, and yet, I know! I know! Sin, it seems to me, is just loving ourselves instead of God, and doing what pleases ourselves instead of what pleases God."

"But how can we know what pleases God?" asked Bert, with wonder in his eyes.

"Oh, in many ways. There's a little voice in our hearts that warns us when we are going to do what is wrong; and then there is Jesus Christ to show us what God would have us to be. He is our example, our copy, you know. You write copies at school, don't you?"

Bert nodded.

"And there's a fine bit of writing at the top of the page, and you have to look at that and try to make your writing like it?"

Bert nodded again.

"Well, Jesus is our great copy. We look at Him and see what our lives should be. This Book tells us about Him, you know."

And the old sailor laid his hand on the well-worn volume Bert had often seen him reading.

"The Gospels are just one grand lesson in love," he said. "What made Jesus so different from every other man? I take it was just that His heart was overflowing with love to God and love to man. That's why He was the sinless One, in my opinion. If our hearts were full of love to others, we could not do them wrong; and if we loved God perfectly, we could not break His commandments. But our love is so different from God's. There was one I thought I loved, but I grieved her sore. Ay, lad, I should know what sin is, if anybody does, for I've been an awful sinner."

Bert looked at the old man in astonishment. His voice had quavered as he spoke, and it seemed to the boy that there were tears in his eyes.

"Why, Mr. Corney," Bert exclaimed, "I shouldn't think that you had been so bad!"

"Ay, but I was bad," said Mr. Corney, still speaking with emotion. "I broke my mother's heart by my sin. She was so fond of her children. There were only the two of us—my sister and I. Priscilla was always well-behaved, but I—I brought my mother sore sorrow and disgrace, and then I ran away to sea, and I never saw her again, for a year later she died."

The old man paused, as if the recollection was too painful for him to dwell upon. While he talked, he had been spreading the table for their simple meal. The kettle was boiling now, so he proceeded to make the cocoa.

Bert brought a hearty appetite to the table. He had not enjoyed a meal so much since Prin left him. He felt that he had gained a friend in the old sailor. When the time came to say "good-night," Cetywayo too showed himself friendly, for he suffered the boy to stroke his head without arching his back and spitting. Bert lingered for a moment on the doorstep ere he crept into the corner where he slept.

Many persons were in the street on this warm night. The sound of drunken revelry came from the public-house close by. A crowd had gathered about a house on the opposite side of the street to witness a fierce dispute between a husband and wife. At another time Bert would have rushed into the thick of the crowd to see what was going on; but to-night he felt no curiosity on the subject.

He stood looking up at the clear, calm sky above his head, studded with stars. How peaceful and far-away heaven looked! How noisy and ugly earth was! As he gazed into the grey vault, the boy had a momentary consciousness of a vast, unfathomable Love bending over him. But to the west, a great black cloud was slowly rising above the houses. Bert watched it as it gradually rose and spread, till it seemed to fill all the sky, and the stars were blotted out.

"That is like sin," the boy said to himself, and he turned indoors with a sigh.

As he passed Mrs. Kay's door, he saw that a light was burning within, and he could hear her moving about, with a noise as though she were lifting heavy things.

"She's not drinking to-night, then," he said to himself. He crept into bed, and was soon sound asleep.

Early in the morning, he was wakened by a great commotion in the passage. Emerging from his hole to see what it meant, he perceived that the place was strewn with Mrs. Kay's belongings, and that a cart stood at the door, waiting to receive them. Tumbling as quickly as possible into his clothes, he ran to learn more.

"Why, Mrs. Kay!" he cried. "Are you shifting?"

"Does it no look like it?" she asked grimly.

"I'm sorry for that," said Bert, who bore no malice on account of harsh words and blows received from her in the past. "Where are you going?"

"That's no business of yours," she replied. "Just hold your tongue, can't you? I've enough to do without your bothering me with questions."

"Can't I help you?" asked Bert.

"Yes, you may, if you'll be careful," she said, somewhat mollified; here, "you may carry these books out to the cart."

Bert looked curiously at the pile of shabby books she gave him. On the top lay a small old Bible. As he carried it out, the breeze lifted the old, broken cover, almost carrying it away, and Bert caught sight of a name written on the fly-leaf, "Priscilla Grant, from her loving mother."

Slowly he spelt out the long name, then tried in a whisper to pronounce it.

"Pris—cilla! That sounds like the name Mr. Corney said was his sister's. How odd that it should be in this book! I wonder if it's Mrs. Kay's?"

But Bert kept his wonder to himself. He did not dare to ask any more questions.

Mrs. Kay's possessions were not very numerous. In a short time they were all packed into the cart, and having given up the key of her room to the landlady, she took her departure, walking beside the cart.

"So she's gone," said Bert, with a sigh. "I'm sorry."

"Then it's more than I am," said Mrs. Brown, as she glanced round the dusty, littered room her lodger had vacated. "She's good riddance, I say, for I never knew when I should get her money, and she was a nasty-tempered woman."

"Where has she gone?" asked Bert.

"I'm sure I don't know," returned the landlady; "that's no business of mine. She's paid me what she owed, and that's all I care about."

The Queen's Jubilee

IT was the morning of the 21st of June. Bert had risen almost as soon as it was light, and, having made very special ablutions ere he donned the ragged garments, which had anything but a festive appearance, he was going to supply himself with a goodly number of the papers and programmes for which he hoped to find a ready sale that day. But ere he started, he stood for a moment at the area railings, and looked down into the sailor's room. Early as it was, Mr. Corney was astir. Bert saw him busy brushing his boots, with Cetywayo perched on his left shoulder, making the work more difficult, though it went on briskly notwithstanding, to the accompaniment of one of the sailor's favourite hymns.

Mr. Corney ceased singing when he caught sight of the boy.

"Hullo!" he cried. "So you're up betimes?"

"And so are you," returned the boy. "Are you going to see the Jubilee, Mr. Corney?"

"Ay, I'm going to see what I can see. Such a day will never come again in my life. I mean to have a look at Queen Victoria, anyway. It's years and years since I last sighted her. It was in London too—the first time that ever I came to London from Scotland."

"From Scotland!" exclaimed Bert, in surprise. "Are you Scotch, then, Mr. Corney?"

"Ay, I'm a Scotchman," he replied.

"How strange I never thought of that!" said Bert. "Now you say so, I notice that you speak very much like Mrs. Kay."

"And who is Mrs. Kay?" he asked.

"Why, she used to live in the first front room; but she shifted a fortnight ago. You could tell she was Scotch directly she opened her mouth."

"And you can't find me out so quickly? Ah, well, I suppose I have lost a bit of my Scotch tongue, knocking about the world. But a Scot I am, and a loyal one too, for I mean to see the Queen to-day. It's thirty years since I saw her, and her family has grown considerably since then. Such an array of Princes and Princesses there'll be in the procession to-day as never was seen before, they tell me."

Bert sighed. "I wish my Princess were here to see it all," he said to himself.

Then he consoled himself with the thought that, if only he made a nice sum of money this day, he would start on the morrow for Hampshire. "And won't the Princess be surprised and pleased to see me!" he thought.

"Well, good-bye, Mr. Corney; I'm off," he shouted. "I hope you'll get a good place and see 'everythink.'"

The dreary street in which Bert lived lay at no great distance from the stately squares and crescents of West London. Laden with papers, he soon found his way to the Marble Arch, and taking up his station there, did a brisk trade amid the ever-swelling stream of persons which swept by, intent on gaining a good position from which to view the show.

London wore an entirely new aspect on that brilliant morning. Its sombre streets, with their prosaic monotony of outline and hue, were transformed by vivid touches of colour and artistic decorative effects, till they glowed with a beauty few Oriental cities could surpass. Everywhere there was a lavish display of flags, bunting, floral decorations, and emblazoned mottoes proclaiming a nation's love and loyalty.

Early as was the hour, the streets were full of people, for many had risen with the lark, and not a few, busied with final preparations, had been astir all night. Already the church bells were making a merry din, and giving the keynote of the engagements of that festive day. Carriages, cabs, and omnibuses went by, carrying people to their chosen places along the route. Every minute the crowds increased. All seemed in good temper. The true spirit of jubilation was abroad.

Bert's spirits rose as he saw the signs of general festivity. He, too, grew excited, and his shrill little voice rose eagerly in the cry: "Now then, here you are! Special edition. Corr'ct account of the Jub'lee. Order of the processions. List of Roy'lties. All you want to know, for one penny."

Faster than he could have hoped, his papers disappeared. Some who bought them looked pityingly at the boy's odd little figure in the short, tight, ragged jacket which he had outgrown, small though he was for his years. They noted how thin and white was the little face, lit up by those eager eyes. But Bert had no pity for himself at that moment. As he dropped the pennies into the pocket of his ragged coat—there was no hole in the pocket; he had seen to that—he felt as proud and elate as a man who is making his fortune. He was getting quite rich, and his riches opened up to him such a joyous prospect. To-morrow he would be off to Hampshire to see the Princess.

There! The last paper had gone. Now he was free to go and see what he could, and take his share in the excitement of the day. He had already decided whither he would turn his steps. From the Marble Arch to Hyde Park Corner was not very far. Bert had been told that here the finest possible view of the procession might be had, and, undeterred by the crowds already pressing in that direction, he too made for this point of vantage.

Although it still wanted more than an hour to the time when the procession was to start, there were thousands of men and women, boys and girls, packed together on the broad pavements. The roadway, too, was blocked with vehicles. The squeezing was intense, the heat stiffing, yet Bert dauntlessly pushed forward into the crowd, and continued to work his way towards the front. He wanted to see what passed, and he would see nothing if he remained at the back of the pavement behind lines and lines of people.

In vain people pushed him back and told him to keep behind. Bert was small and thin and wiry, and he pushed his way through every slightest opening, and got the better of persons bigger than himself with a skill which excited the ire of some and the amusement of others. Yet Bert would have had a poor chance of seeing the procession had not a woman who blocked his way suddenly fallen forward, unconscious from the heat and pressure. Instantly there was a cry for the ambulance officers. Some of these came forward to remove the sufferer, and in the hustling that resulted from the disturbance Bert found himself carried to the very edge of the pavement, close to a mounted constable, who, seeing what a little chap he was, moved his horse a pace or two, so as not to intercept his view.

Just as Bert was congratulating himself on his good luck, there passed before him the stretcher on which the policemen had placed the woman who had swooned. To Bert's consternation, he recognised in the still, purple, apparently lifeless visage of the woman, the face of Mrs. Kay. He uttered a cry, and would have run after the ambulance, had not the mounted constable called to him sharply to come back. Bert watched as the policemen bore their burden across the broad road, now clear of all traffic, for the procession was momentarily expected, to the ambulance station below the arch at the top of Constitution Hill. Poor Mrs. Kay! Was she dead? Had the sun's heat killed her? For Bert had heard of people dying of sunstroke.

But now there rose from the direction of the Green Park the sound of swelling voices raised in joyous acclamation. Louder and louder rose the cries, and with a thrill of strange emotion, which brought tears to his eyes, Bert realized that the supreme moment had arrived. The Queen was coming!

In a few moments, the splendid cavalcade appeared. When the Queen came, attended by her magnificent body-guard of princes, the public enthusiasm knew no bounds. Foreign royalties were all very well; but here was the one whom her people loved, and whom they had gathered in such numbers to greet with every sign of loyalty and rejoicing. Next in interest to the Queen came the members of her family. Bert's shrill little voice had shouted lustily for the Queen; but as the carriages containing the princesses went slowly by he was too lost in admiration of their gentle looks and pretty dresses—the laces and satins and furbelows, which to his childish imagination suggested lives of unlimited luxury and enjoyment—to think of cheering.

"There's princesses for you!" he said to himself. "They're the real thing, they are; and yet if my Princess was rigged up like that, I guess she'd look just as well."

And there passed before his mind a picture of Prin, as she had appeared in her old, shabby frock and broken shoes. Then he remembered how different she had looked when she went away with the nurse.

"But she'll get shabby again when she comes back," he thought with a sigh. "We shall never get enough money to buy nice clothes."

But now the last carriage belonging to the procession had gone by. The police relaxed the restraint under which they had held the crowd. To the relief of every one, the great pressure was at an end. People were free to wander across the road and into the Green Park. Bert made use of his liberty to run to the ambulance station and inquire for Mrs. Kay.

"Oh, she's coming round," said the policeman of whom he made inquiry. "What do you know about her? Is she your mother?"

Bert shook his head, and explained that she was only an acquaintance, lately a neighbour, whereupon the policeman pushed him with little ceremony out of the way; but the boy had caught sight of Mrs. Kay, lying with her eyes closed, and that purplish tint still on her face, and it struck him that she looked very bad.

He turned towards the Green Park; but as he passed through the gateway, some one touched him on the shoulder. He looked round, and to his surprise found Mr. Corney beside him.

"What, you here, Mr. Corney!" he exclaimed. "It seems as if I was to see people I know. There's poor Mrs. Kay in there." And he pointed towards the little room in the base of the arch where the ambulance patients were sheltered.

"Mrs. Kay?" repeated Mr. Corney, in momentary bewilderment, till he remembered when he had heard mention of this individual before. "Was it she they carried in there just before the procession came? I saw her face as they went by, and, do you know, she reminded me of my sister! A very different sort of person, of course—not too respectable, I am afraid—older and stouter than Priscilla would be too, but still like her. It's strange how one sees likenesses sometimes."

Bert nodded; but he was not paying great heed to what the old sailor said. There was so much to divert him in all he saw.

In the relief of being able to move freely, the crowd was waxing merry. Vendors of fruit and sherbet had come to the fore, and little picnic parties were being formed here and there on the grass. Carriages too, most of them empty, were passing by, for the road was open again for traffic for a little while.

Bert became aware that he had eaten nothing since a very early hour, and that he was parched with thirst. He resolved to spend one of his halfpence on a glass of sherbet, and was turning to look for the seller of this cooling refreshment, when his attention was attracted by an open carriage which was driving towards the Park.

There were several prettily dressed children in the carriage, accompanied by a woman, who appeared to be their nurse. On the back seat was a girl older than the other children, and more quietly dressed than they were. Her complexion was very fair, and long golden locks fell over her shoulders. Bert's gaze was instantly arrested by this girl; she was so like Prin. He had no idea, however, that it was his sister, and could hardly believe his eyes when, as the carriage passed, the girl turned in his direction with a movement of the head familiar to him, and he saw that it was indeed Prin.

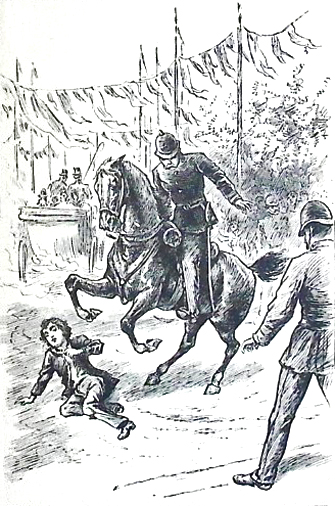

"Prin! Prin!" he cried aloud the next moment, and darted after the carriage, heedless of danger to himself.

Prin heard the cry and looked back. She recognized the ragged, dusty, deplorable little form pursuing the carriage. For a moment her eyes met those of her brother, and he knew that she saw him. But suddenly her face grew very red. She turned round quickly and looked in the opposite direction.

Instantly Bert understood. The Princess did not wish to see him. She was ashamed to call him her brother. The thought smote him with a pang of sharpest pain. He fell back at once, heedless of the perils of the busy road. A mounted policeman, suspecting the boy of begging to the annoyance of those within the carriage, was following at his heels.

Bert's sudden halt took him by surprise. He tried to pull up his horse, but there was not time. The animal reared wildly, but struck Bert as it reared. The boy fell senseless on the road.

Again the ambulance stretcher was in requisition. Bert was placed in it, and carried at once to St. George's Hospital, for it was feared that his hurt was serious.

In the Hospital

BERT was not likely to die. His worst injury was a broken rib, and that having been skilfully set, he was likely to do well. He did not suffer acute pain; yet the boy was miserable enough as he lay on his little bed in the hospital ward. He was enduring pangs which he could not describe, and which the best of nurses could not have relieved.

Shakespeare pronounced it "sharper than a serpent's tooth" to have a thankless child, and the sting of the ingratitude that sins against love is under all circumstances hard to bear. Bert could not have put his feelings into words, but his heart ached at the remembrance of how Prin had turned from him. It seemed cruel of her, for she must have known how he had suffered from loneliness and heartache since she went away.

"I could never have treated her so," Bert said to himself; "no, not if I had become the greatest swell that ever was."

It appeared that the Princess had risen in the world. How came she to be driving in that grand carriage with those smartly-dressed children? Had she left Hampshire for good?

"Oh, she might have written and told me," groaned Bert; "and to-day I meant to go down there to see her!"

The boy grew restless and feverish under the strain of his mental trouble. Mr. Corney, who had been greatly distressed to see him borne off to the hospital, and quite at a loss to understand how the accident had happened, had quickly followed him thither, and he came again and again to see him. But he, kind though he was, could not enter into Bert's state of mind. He was convinced that the boy was under a delusion regarding his sister. It was not really Prin, but some one very like her whom he had seen. Bert shook his head, and pressed his lips firmly together at the suggestion.

"It was Prin, and she saw me," he said; and it was impossible to persuade him otherwise.

In vain, Mr. Corney tried to argue with him.