Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

The Story Of

THE RESTORATION OF BAXTER’S MILL

By

A. HAROLD CASTONGUAY

1962

Copyright 1962

by

A. Harold Castonguay

Sketches by Gordon Brooks

Printed on Cape Cod

by

The Wayside Studio

SOUTH YARMOUTH, MASSACHUSETTS

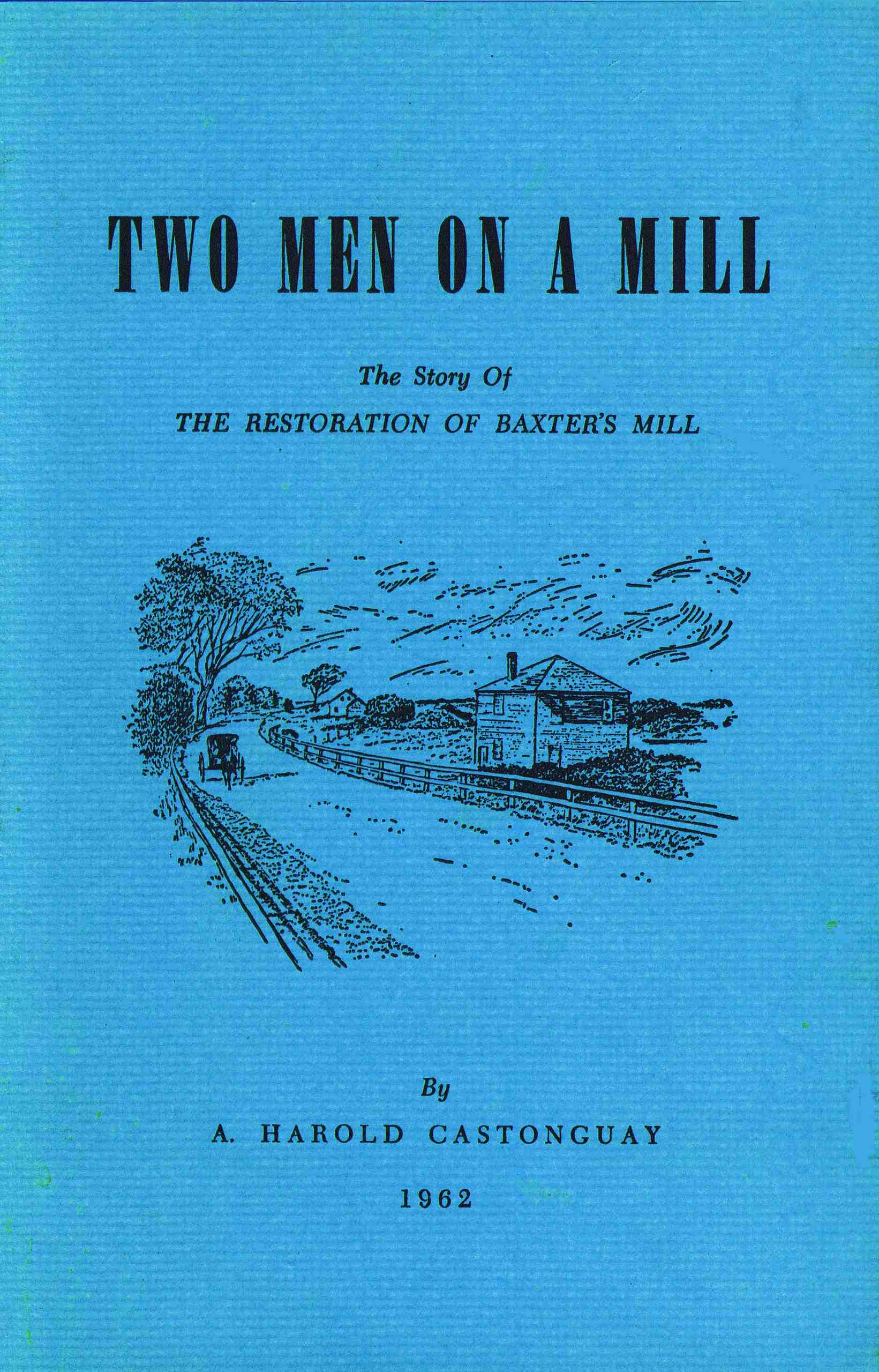

This

OLD WATER MILL

Is Being Restored

(IT IS HOPED)

BY

Two Local Characters

1

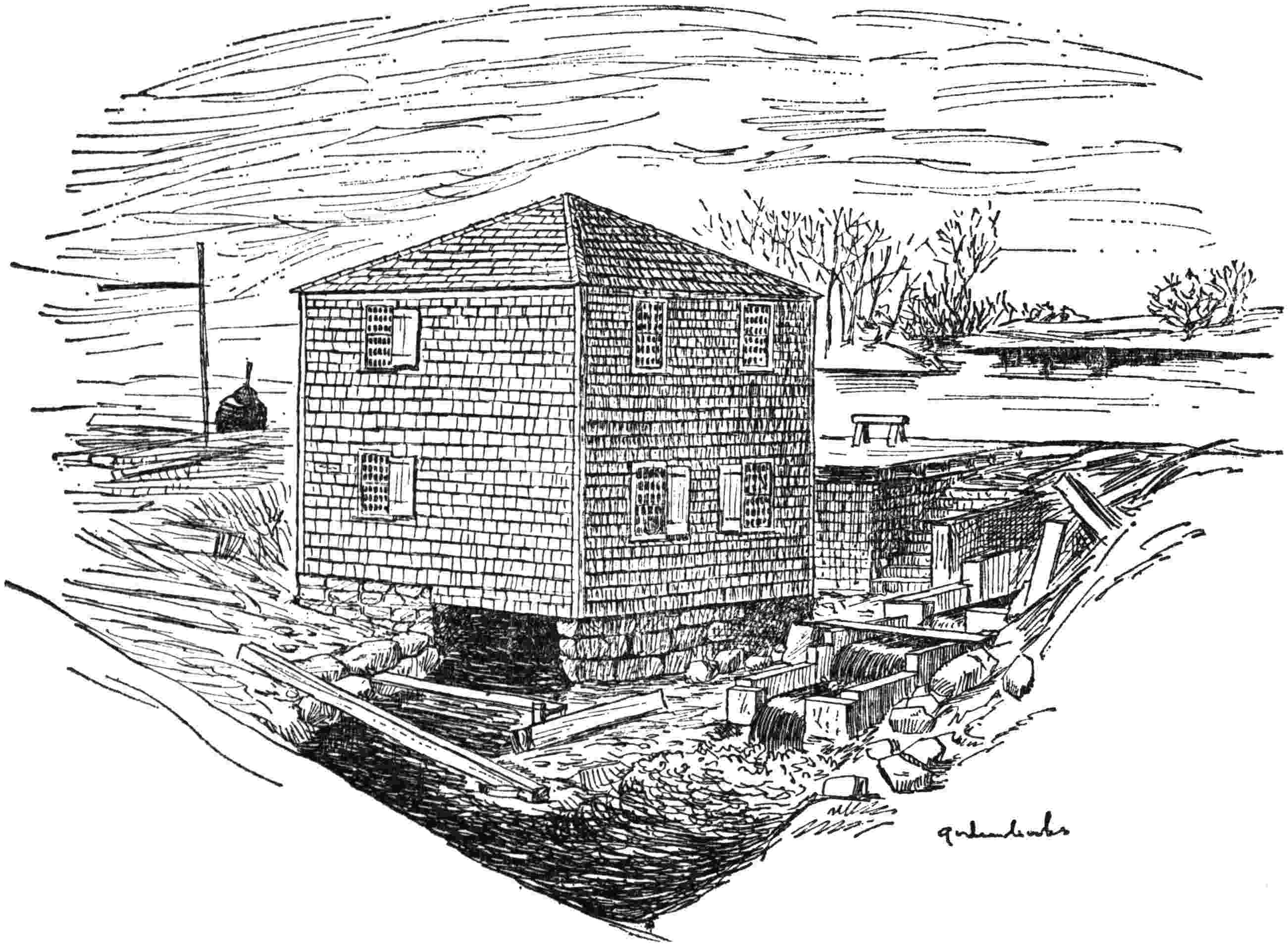

A few days before Christmas of 1961 we will raise a pen gate in a flume adjoining the Mill Pond in West Yarmouth, on Cape Cod, and a 250-year old water grist mill will again grind corn into corn meal.

And so, a vanishing part of Americana, especially old New England dating to our colonial days, has been restored. Hundreds and perhaps thousands of people have been going by this little old building, especially in the summer, without giving it a thought but the mill’s visitors from now on, growing up in our modern world of television, jet airplanes, and high-powered automobiles, to say nothing of electric can openers, will get a glimpse of early America, a view of the simplicity of the mechanism, and the quiet dignity of the building itself.

The mill is the only one of its kind on Cape Cod, the few others being either windmills or outside water wheels.

The original mill was probably built about 1710 by John and Shubael Baxter, sons of Thomas, who arrived in Yarmouth from Rhode Island after the close of King Philip’s War. Originally a mason, the loss of a hand in the war made it impossible for Baxter to continue his trade, and he became a millwright. His will, probated in 1714, disposes of fulling mill equipment. This equipment was from the fulling mill which he built on Swan Pond, now Parker’s River, in West Yarmouth.

2

He probably offered no more than advice to his sons when they built the grist mill near the South Sea neighborhood, but it is undoubtedly these sons who are immortalized in the little verse on the frontispiece of this saga. The poem was already old when Amos Otis reproduced it in his 1880 Genealogy of Barnstable Families.

The Baxter mill passed from John and Shubael to their children, Richard and Jennie, first cousins who were wed. From them, it went to their son, Prince, and from him to his son, Prince, Jr., whose guardian, David Scudder, sold one-half of the mill to Timothy Baker and his son, Eleazer, and the other half to Alexander Baxter, a remote cousin of Prince, Jr., through their common great-grandfather, John.

Extensive repairs were made to the Baxter mill around 1850. It is likely that Prince, Sr., who inherited the mill on the death of his father, Richard, in 1785, either made the repairs or caused them to be made.

After about two hundred years of continuous operation, the mill was finally abandoned around the turn of the century, the last miller being a man aptly named Dustin Baker, who earned the magnificent sum of 68¢ per day for his work.

The mill did lend itself as a gift shop and a lobster stand in the past few years, but as it stands today, completely restored in all authenticity it is doing exactly the work it did originally, with the same machinery, except the turbine which had to be replaced.

3

So many people have asked me,

“What are you doing this for?”

“Is there any money to be made grinding corn?”

“What are you ever going to do with this useless old building?”

And most people, when they get an answer, sadly walk away shaking their heads, wondering.

I suppose no one person or no one episode gave rise to my thought in acquiring the mill and entering upon a program of restoration, unless it could be what I have heard in the various entertaining stories of people such as C. Milton Chase, Dean of the Massachusetts Town Clerks, and retired Town Clerk of Barnstable, who tells most engaging tales of his trips as a young lad to the mill with a horse and team, carrying corn to be ground.

Perhaps I was fired by my friend, George Kelley, a ponderous, phlegmatic, Cape Codder, attempting to perpetuate some of the characters of old Cape Cod, personified in Joe Lincoln’s stories; and perhaps by the stories of Walter B. Chase and Howard Hinckley of their nostalgic remembrances of the old mill.

If you ever meet Milton Chase, see if you can get him to tell you of the adventures, and strange doings of an old-time travelling barber, one Frank Clifford, who went around to all the business places, livery stables, and grain stores with his little black bag, plying his barber trade, and who employed a most ingenious method of warming the shaving lather for his customers.

4

Or perhaps it was enthusiasm of Margaret Perkins. Maggie, as we affectionally call her, spent long hours in tedious searching of the records at the Deed Registry, Town Clerk’s office, Proprietor’s Records of the Town of Yarmouth, and interviewing everyone she could think of who might know something of the history of the old mill. Maggie was the motivating force in presenting an article at our Town Meeting about a year ago, requesting the Town to purchase the mill or take it by so-called eminent domain proceedings, so that it might be preserved and restored, but the townspeople were not eager to invest in the past.

Strange how so many people insist upon their rights and forget their obligations. Strange again, how so many people are looking for something without giving part of themselves.

Whatever it was, or however it arose, I found myself engulfed in the middle of hard but fascinating work.

Having lived for thirty-five years close by the old Baxter Mill in West Yarmouth, it is not surprising that my curiosity and interest were aroused. Somehow, I felt called upon to restore this old mill, perhaps to keep a way of life now forgotten in our present civilization, perhaps merely as a means of self-expression.

A clipping from the Yarmouth Register, November of 1935, speaks for itself of the lethargy of present day thought, when the old Farris Mill that stood for many years at the corner of Berry Avenue and Main Street in West Yarmouth was purchased by Henry Ford and moved to Dearborn, Michigan, despite violent protest. The clipping reads as follows:

5

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AGO—From the files of the Register—November, 1935.

It is reported that the oldest windmill on Cape Cod is to be moved from West Yarmouth. The West Yarmouth Association is attempting to obtain the sentiments of Cape Cod residents, both permanent and seasonal, on the rumored removal of one of the Cape’s most picturesque objects of great historical value to the Cape—the old windmill in West Yarmouth. Mrs. George Breed of Englewood and Germantown has wired Mr Ford, the new owner, direct, expressing her individual feelings in the matter, and the West Yarmouth Improvement Society has done the same.

We quote from a letter also dispatched, “If the windmill is to be retained by you upon its present location, we are delighted, but if it is to be removed it is a calamity.” “It may be well to explain that there is no record in the offices of the Town of Yarmouth whereby any offer was ever made and presented to the voters that the windmill was to be a gift or offered to be purchased; thus the townspeople have never been allowed to express their opinion on this matter, nor have they been allowed to visit and inspect the mill. The door is always locked.”

I can distinctly remember at about this time the concern and heated meetings held by civic groups, the letters and telegrams of indignation sent to high public officials, and the angry voice of the people protesting the removal of this old landmark, but it struck me as being a bit strange that not one person (including myself) came forward with donations to purchase the Farris Mill and keep it where it belonged. Needless to say, it was the usual story of “Let George do it.”

In looking back, it was probably George Kelley and Walter Chase who finally prodded me into action. George Kelley is engaged in a flourishing insurance business in Hyannis and is very handy and exceptionally good with tools. As a matter of fact, he is better than the usual expert, and has an extensive knowledge of craftsmanship. He is meticulous,6 patient, and without his assistance I don’t think we could ever have accomplished the project.

Walter B. Chase and his brother, Milton, are two of the last old-school gentlemen left on the Cape, both of them well-known and beloved by everyone and the living examples of young boys graduating from high school and immediately starting in business as a clerk or as an ordinary laborer. One rose to be the Dean of Massachusetts Town Clerks and the other rose to be the President of the Hyannis Trust Company, the largest commercial bank on the Cape. They represent a living contrast to the average youth of today, the product of our so-called schools.

These gentlemen, through their own efforts and by virtue of the simple, ordinary and basic fundamentals learned in their school days, made a complete success of their lives and are vigorously engaged today in directing the affairs of two banks. Both are in their 80’s, alert, and enterprising, as were their contemporaries, young men of 18, 20 and 22 who became masters and captains of deep-sea sailing vessels going all over the world, purchasing cargo, handling all kinds of men, and making money and profit for their employers.

I mention this because of the things uncovered in working on the mill to show the sharp contrast of the average youth of today who is taken to school on the bus so that he can engage in physical exercise and who, when graduating from the glamorous schools, hasn’t the slightest idea of fundamental mathematics, of figuring simple interest, or of handling ordinary division or multiplication.

7

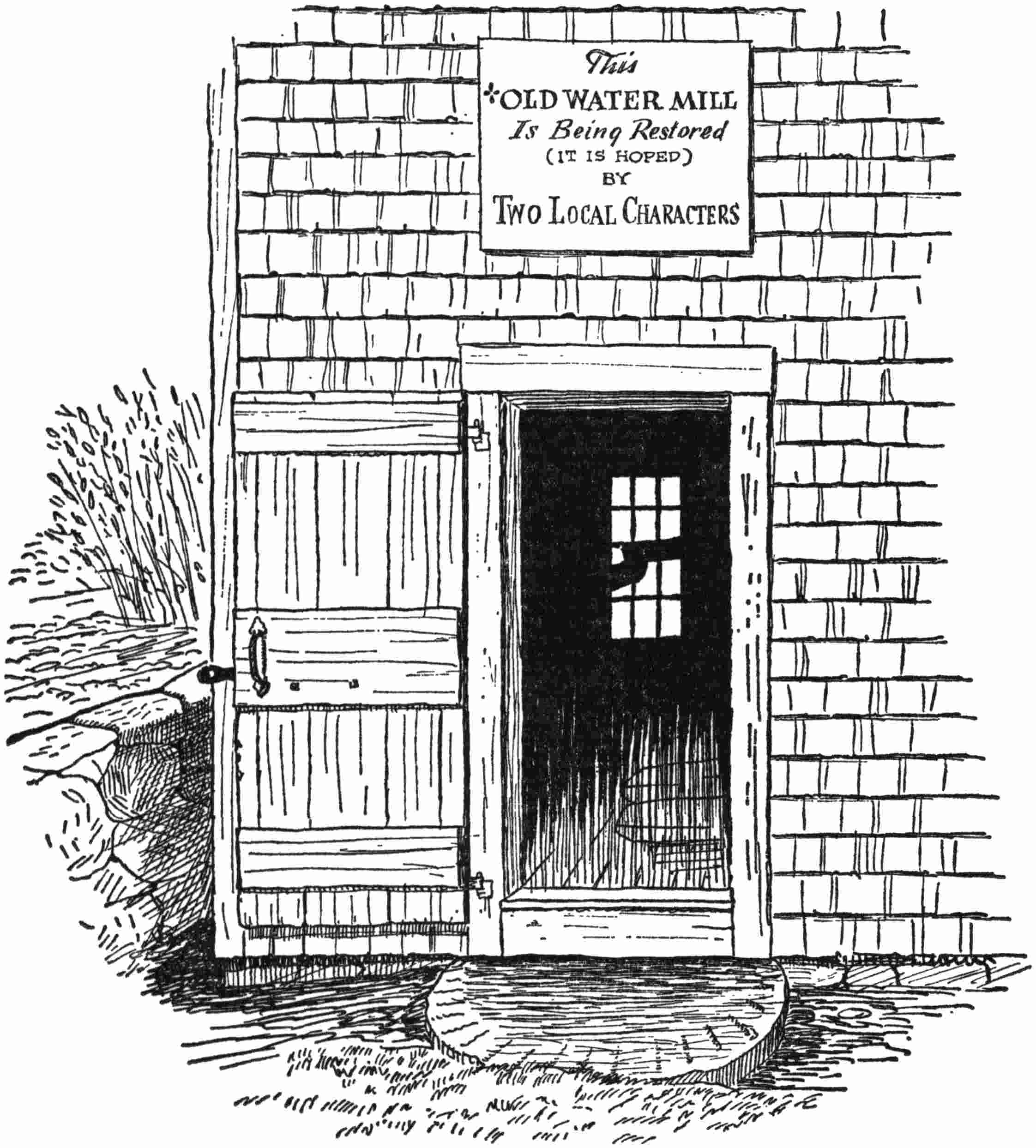

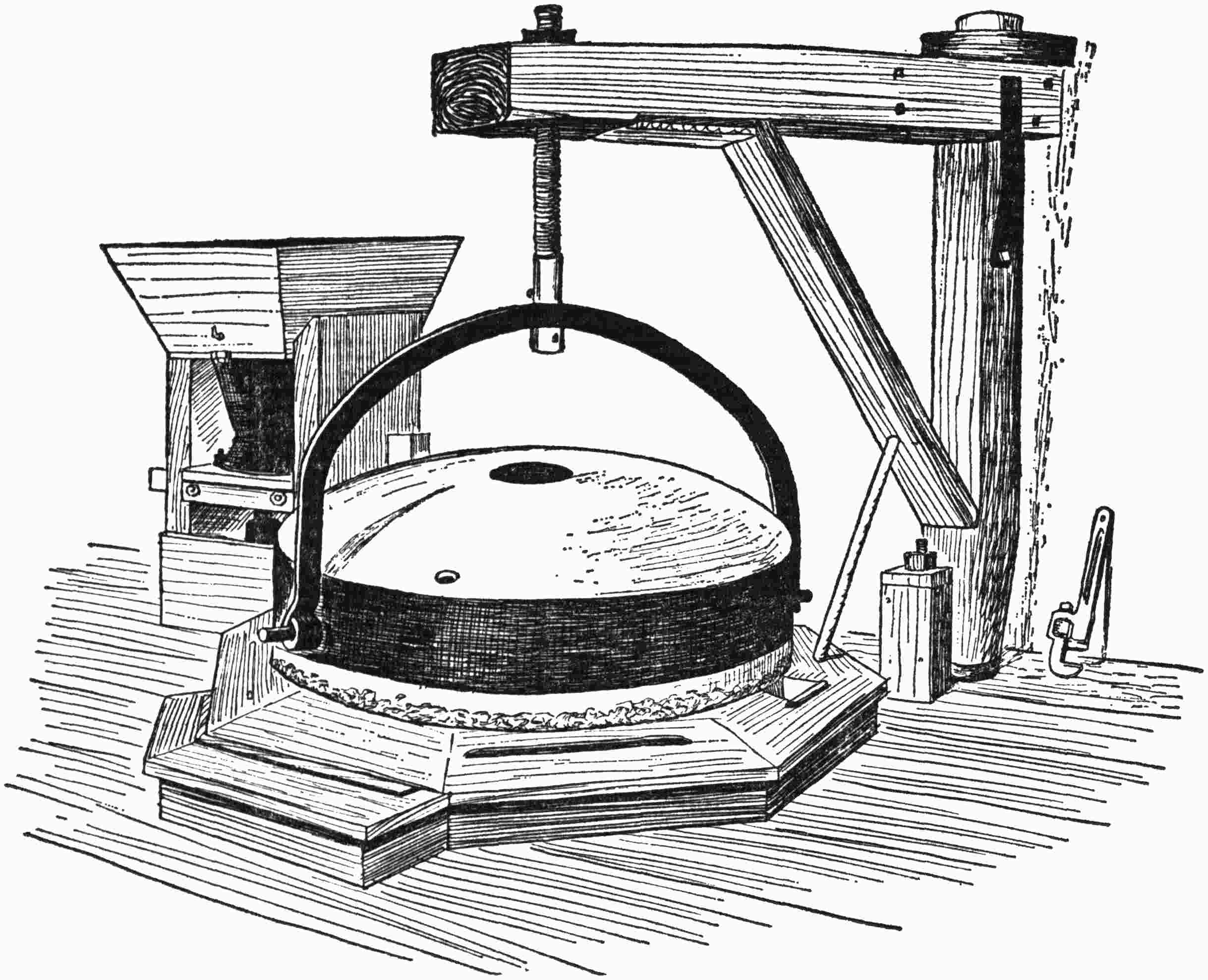

Around 1870 the water wheel was disposed of and a so-called “new and improved” metal turbine was installed for a few very good reasons.

The old outside wooden water wheel in the winter became lopsided with ice forming on the paddles and the uneven motion was undoubtedly disconcerting to the miller to feel the building and the machinery wobbling about. Whenever solid ice blocked the wheel, it was useless. Further, the mill pond was limited in its volume of water (“head,” to you engineers), so that when the pond was low there wasn’t very much water to turn a large outside wheel.

Ingenious engineers of that era came up with the so-called “improved” iron turbine to rest under the water and under the mill where ice could not get at it and where there would always be some water in the pond to turn it.

8

About two or three months after we started reconstruction, my friend, George Kelley, came up with an old pamphlet put out by the J. Leffel Company of Springfield, Ohio, dated 1870, and sure enough the pamphlet referred to a “satisfied customer” as “J. Baker and Company, Hyannis,” who were successors in title at that time to the Baxter boys.

I wrote to the Company in Springfield, Ohio, and much to my surprise received a most magnificent brochure showing they were still in business after all these years, now supplying turbines to great power dams, but ready to build a small turbine. I thought it very interesting that at least there was one company left that could turn out and furnish a small turbine.

Everyone likes to play in the water, so we went to work about August 1, 1960. You can well imagine the condition of the mill. Windows were shattered, the sills were powder, the roof practically gone, and the building had a definite cant to the east’ard. It really looked hopeless.

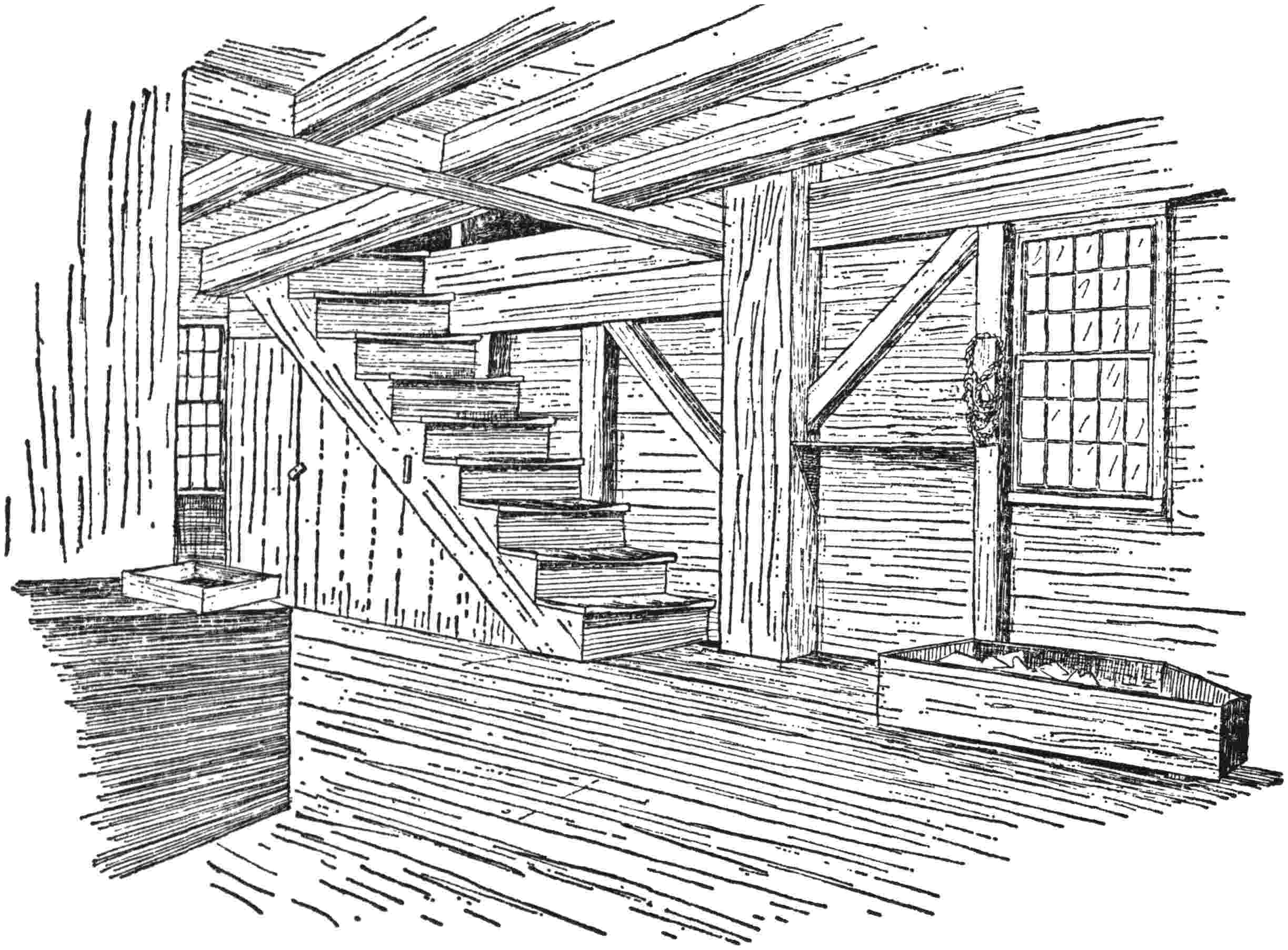

Fortunately, most of the ancient machinery—the stones, gears, brakes, and chutes—were still intact, even the miller’s little desk where he kept his records, and the ancient bin for storage.

The beams, the corner post studs, etc. are of tremendous size and all mortised, tenoned and dowelled, and hard as rock. The stairs were worn paper thin; the floor was practically gone. Dirt and dust, of course, were everywhere.

The stones are the French buhr type, which are practically impossible to obtain today, to say nothing of the fact that probably no stone could be obtained, except in upper New England, so many of the old mills having been raided and the equipment, especially the stones, taken away for steps and other decorative purposes.

9

Eric Sloane, in his exceptionally fine and exhaustive research entitled “The Vanishing Landscape,” refers to the pattern of the stones, meaning the furrows or grooves cut in the stone, against which the corn was ground.

Directly underneath the first floor of the mill were the remains of a wooden pit, which was filled with sand, gravel, and debris, accumulated over the years, particularly because of the raising of the adjacent State Highway from time to time, and more or less by the action of the elements.

Sticking out of the debris beneath the first floor was an iron bar or shaft, about five inches in diameter, so George and I and a couple of hired help went to work, and on hands and knees we finally managed to dig enough away to stand upright and eventually came to the top of the old turbine which was so far rusted as to be beyond reconditioning. We uncovered the complete wheel pit, the floor of which was about twelve to fifteen feet below the level of the first floor10 of the mill. This pit was made of hard pine, 2½ inch planks, set against 12 × 12 hard pine uprights, and was about 10 foot square and probably 12 feet deep to the lower shelf, called the “tail race.”

We had a rough time removing the old turbine with some hydraulic jacks, muscle power, and the sage advice and help of friend George.

Now, George is a married man, blessed with three children, and I noticed in our local newspaper one evening shortly after we had started work that his wife had experienced another happy event. George had not mentioned this to anyone, including me so when I suggested the next day that this was a bit of a surprise, he said,

“You know, it was news to me, too. Last night about three o’clock, my wife woke me up and said, ‘George, I think you have to take me to the hospital.’

“I muttered, ‘What for?’, and she replied that she was going to have a baby.

“You know”, said George, “I do declare that is just what happened.”

I suppose everyone has a desire to investigate, to explore into the past, and to relive some of our history and past traditions. This mill and its restoration has provided us an excellent opportunity to test our ability to do what the old folks did. They were able, with their crude tools, to build this mill and to actually make it grind corn in excellent fashion, even to the extent of doing a thriving business. It is interesting to reflect that they did not have the modern power tools available today, nor did they really have the time we have today, but these folks really built for permanence.

Eric Sloane aptly puts it by saying,

11

“What a shame that with all our timesavers and with our abundance of wealth, we do not have the time today and apparently cannot afford to build the way they did or to use the excellent material they did.”

Why is it impossible for our builders and architects to construct a house with a bow roof, for instance, a little more overhang on the rake, a box return with gutters, a decent-sized chimney, and many of those small things that lend charm to a house and give it character and dignity? Why are we satisfied with chicken houses, or is it that we have not made the progress we thought we had?

All these things we thought about as we went about the business of restoration.

12

The peace and quiet of the mill pond every Saturday morning was shattered by the rumblings of two water pumps. These pumps had to suck out the water from the pit in the flume to enable us to even see what we were trying to do. Three or maybe four, very muddy characters, attired in the necessary garments to withstand the cold, were always in the depths of the mill, working in the mud, sand, gravel and debris, and at times it seemed as though we were merely moving these from one place to another, rather than disposing of them.

We finally managed to extricate the old turbine. The simple mechanism and design of this ancient piece of machinery to me is always marvelous. We had hoped to renovate the old turbine and put it back in its place, but age and rust made this impossible, and the turbine now rests on the shore of the pond for all to see.

In the process of moving all the mud and sand, we uncovered the remains of the original flume or sluiceway leading from the mill pond to the wheel pit. We found the flume to be about five and a half feet wide and originally about ten feet high and, roughly, thirty feet long. The sides were planked against 8 × 8 hard pine timbers which were in turn cut or tenoned into 8 × 8 mortised supports, twelve on each side of the flume, about two feet apart, and each dowelled or pinned with one and a half inch hard pine trunnells (wooden pins to you).

We were now down about twelve feet in the dike of the flume, and we had to hand shovel and excavate all around each stub of these timbers, knocking back the dowels and prying out each stub. These uprights had been broken off when the flume was filled in. Every one of the stubs and13 the pins was bright and new as the day it was put in. Packed around each section of each stub was about six inches of semi-hard blue clay.

Apparently wood or any substance long immersed in water will last forever and undoubtedly the clay we found packed around each helped to preserve this wood. We threw the stubs upon the top of the dike, and they were not in the air and light two or three days before they turned gray, discolored and aged looking.

George Woodbury, in his book, “John Goffe’s Mill”, says:

“Wood can be almost indefinitely preserved if it is kept either consistently dry or consistently wet all the time. Let it get wet and dry out a few times and it quickly decomposes. In Egypt where it never rains, wooden objects are found well preserved after countless centuries of burial. In Switzerland, the piles driven into the Lac Neuchatel by the aboriginal lake dwellers are still sound after two thousand years.”

We could not obtain any proper hard pine 8 × 8, but we did find some creosote 6 × 8 hard pine timber creosoted, about twenty feet long. Friend George very carefully made the tenons, and we were able to replace them in the old position from whence they came. This may sound easy, but just try it!

After a few hours of this work, the writer became exhausted. Hot baths and horse liniment helped somewhat, but I think I can still feel the effects. The chances are, our tenacious forefathers had no trouble whatsoever in this work.

We were able to re-use about fifty per cent of the old pine pins, or trunnells, recovered from the joints. The new ones we made by hand. I would suggest to anyone contemplating such a venture as this that he would be wise to anticipate endless frustration, hard work, and snide and14 caustic comments from onlookers and discouraging prospects of completion.

The embankment would cave in every few minutes, notwithstanding our amateurish shoring attempts, but we managed to keep ahead of the cave-ins by shoring up quickly before the whole dam caved in on top of us.

During all this, the level of the water in the mill pond had to be lowered so that we could work in this spot, which is about two or three feet below the bottom of the mill pond. The lowering of the water level resulted in great consternation to the inhabitants thereabouts, whose only concern seemed to be when were we going to raise the pond. No one seemed to care about our sudden demise from the pond breaking through the dam.

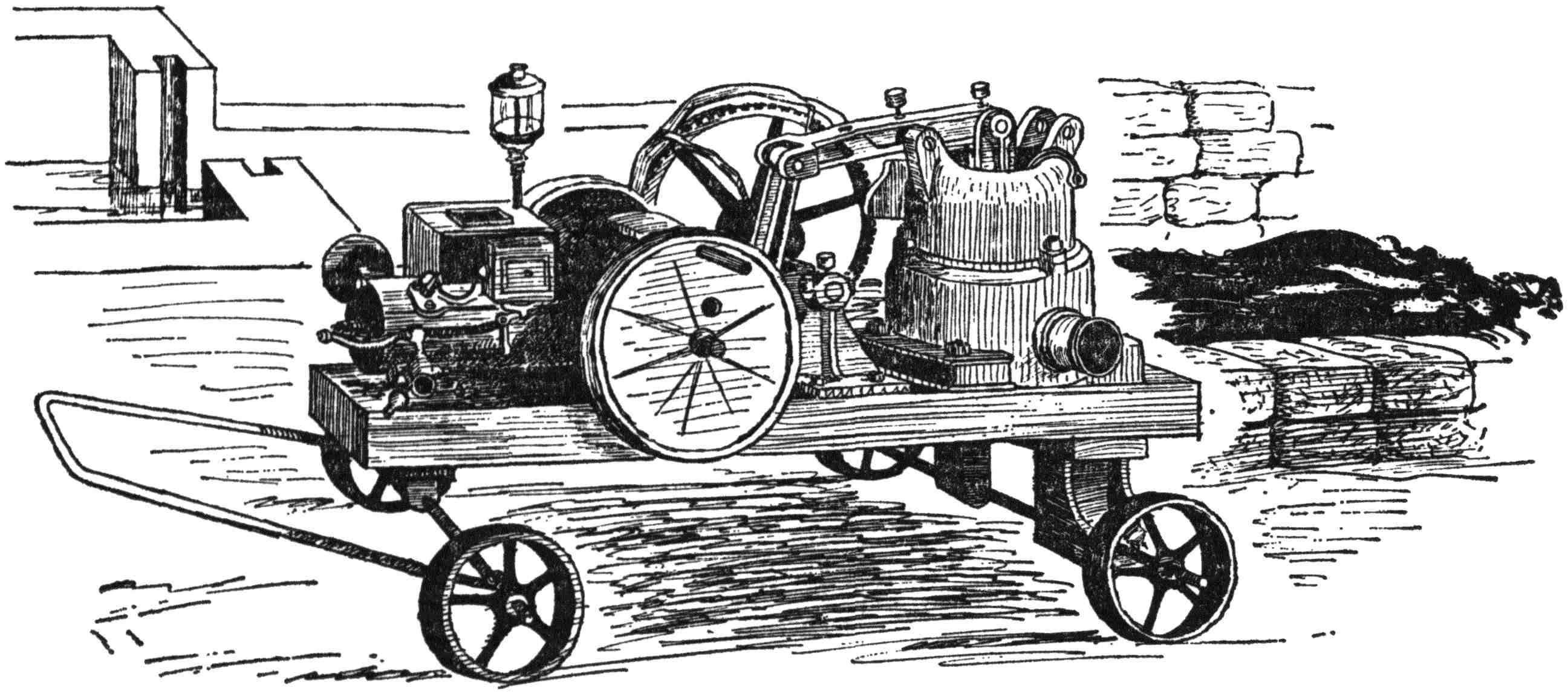

Of course, the pumps had to be working constantly while we were employed in this operation. One of these pumps was loaned to us by S. R. Nickerson of Hyannis, and the other was given us by Colonel Ralph Thacher of the Cape Cod Shipbuilding Corporation, some of the few persons who were sympathetic with our cause.

Although this pump from Colonel Thacher was probably around fifty years old, it proved to be a most reliable and excellent piece of apparatus, consisting of a large, horizontal, single cylinder, “make and break” engine, driving a heavy, eighteen-inch rubber diaphragm pump. It certainly puts to shame some of the modern pump equipment of today, chugging along hour after hour like a patient old horse without much noise and clatter.

We all became very fond of this sturdy antique which, to my mind, combines functional beauty with gratifying simplicity and reliability. Cooling was a simple matter of a pail of water in the cylinder jacket tank; lubrication was15 by a few grease cups and an outside glass oil container about the size of a large tea cup; and the starting was easy and positive, all by hand.

All the visitors seemed to be drawn to this piece of equipment when it was operating, and we signified our tribute by mounting a small flag on the pump every Saturday morning.

I should not forget to relate how Harvey Studley, a young, local contractor, sent up three men and all the shingles necessary to entirely re-do the roof of the mill itself. Harvey also gave us a goodly supply of 10 × 10 hard pine timbers which we put to good use in the sills and otherwise.

About six months before this project got underway, Harvey, who is generally a quiet, peaceful soul, delivered an impassioned speech at our annual Town Meeting, decrying the lack of interest by the townspeople in the preservation of some of our own landmarks.

The building itself had to be raised by Bob Hayden and his crew, and a new foundation completely made on the old. When this was done, new sills put in and the building lowered, things looked a little better, for at least the building sat upright.

16

Harvey gave concrete help, but although a good many people expressed their admiration of the job we were doing and the task which we had undertaken, we didn’t get too much actual help. It is always more fun to watch work being done.

We did, however, among other people, receive help from a photogenic barrister, Harold Hayes, who spent an afternoon in his boots with a shovel helping us to disturb the mud of the centuries. One kind gentleman, whom I do not know, was watching us one day as we were trying to pry off some of the rusted bolts and nuts from the old turbine. He showed up the next afternoon with a large, much-needed, Stilson wrench which he donated to the cause.

Ben Baxter, one of the living heirs of the “Baxter boys”, and a descendant of some of the best sea captains the Cape has ever produced, gave much of his time and effort and loaned us considerable equipment. Ben is an expert mariner, engaged in ferrying cargo back and forth to Nantucket, virtually bring “oil to the lamps of China”. I don’t think anyone knows Nantucket Sound better than Ben Baxter. Between his trips to the island, Ben found time to be with us every Saturday. He is a stout fellow.

My friend, John Doherty, who is engaged in the building of homes and selling of real estate, has delivered to us many loads of loam, fill, and sand.

Charles Cunningham, a local contractor and builder of large buildings, was most generous in offering the use of his stock pile, where a treasure was found of different sizes and shapes of all kinds of lumber and materials. He told us to take anything we could use, and the offer was music to our ears.

17

I do hope Mr. Cunningham didn’t feel too chagrined when he saw how much we were taking, but nevertheless he grinned and said to go ahead and take whatever we wanted.

The Hinckley Lumber Company of Hyannis graciously offered, and we quickly accepted, lumber and supplies from their mill and warehouse.

Our busy surveyor of highways, Chris Marsh, loaned to us from time to time a machine called a back hoe, which does marvelous things, and some men to help with the hard digging.

One generous soul, Tom Powers, has given us several beautiful trees which we are planting and hope will live to beautify the structure and the landscaping. Tom is a director and officer of several banks, owns most of the real estate on Cape Cod, and is a teller of tall tales in any dialect you wish.

The two signs, and especially the final sign, which grace the mill property were made by a sign painter and artist extraordinary, one H. O. Thurston, of Centerville, a friend of long-standing.

There were many times when it seemed to me we would never finish this job; that it really was perhaps too much for us to have ever started, what with our limited knowledge and seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Somehow we all kept going, hoping that we would finally have the mill completed as we envisioned from the beginning. It reminded me of the chap who had the tiger by the tail and didn’t dare let go.

18

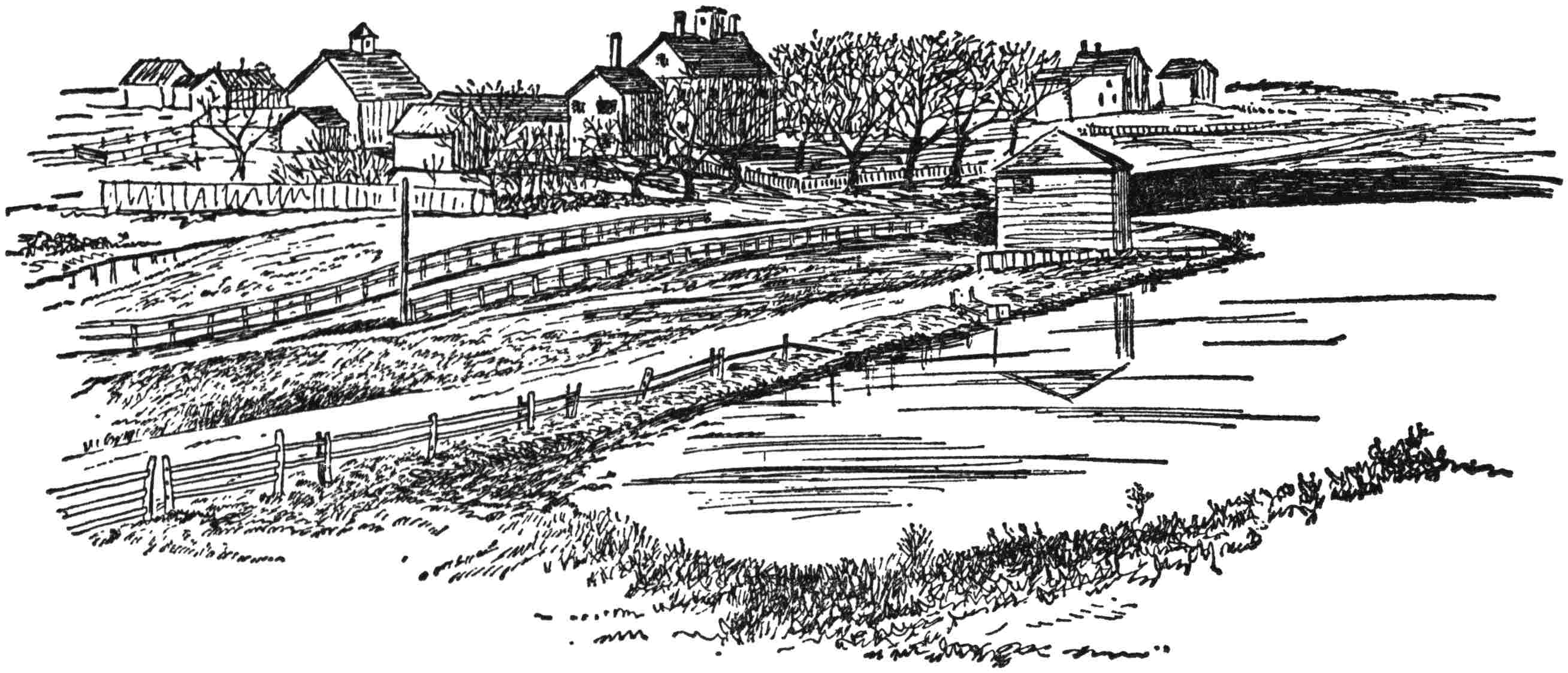

This land on which we live, called Cape Cod, is visited by hundreds of tourists in the summer and dwelt upon by the year-round residents, most of whom are totally unaware of the richness of the tradition and of the way of life which is found here. This way of life is quite different than any one finds in any other part of our country. We do live close to the sea, and we have many little villages nestled around quiet, patient roads. We have innumerable ponds and lakes, and the vast seas on either side of us. Express highways bring crowds to the Cape, but there are many villages and communities not encroached upon as yet to a great degree by speed and hasty living.

Being close to Plymouth, the birthplace of liberty, and the second landing place of the Pilgrims, we, of course, are bound to history by close ties.

I think and I hope many people are becoming more and more aware of the gradual loss and decay of our historical landmarks, and my thought is to preserve the rich but dwindling heritage of our traditional land, not by or through the Federal Government or by the State Government, but by all the people in local communities through our own Town Government.

There are a few restoration projects now under way and some have been completed in the past few years. I can think quickly of the West Parish Meeting House in West Barnstable, which can be seen from the Mid-Cape Highway; the old Hoxie House in Sandwich; the Sandwich Water Mill, now being restored by the Town of Sandwich, which, by the way, has a most excellent setting at Shawme Pond, in which are reflected the tall, white buildings surrounding it; the Brewster Mill at Stony Brook, having been restored19 about three years ago by the Town of Brewster, where one can purchase corn meal every Saturday afternoon at twenty cents per pound.

I recently purchased some of the corn meal from the Brewster Stony Brook Mill, where it is slowly ground between old millstones, and if you have never tasted corn meal muffins made from this flour, you are in for a real treat. Ground in this manner, the corn apparently keeps the goodness and the natural nutrients of the grain. It is not processed and bleached to a point where it tastes like a blotter. It actually tastes like corn. We have also tried some of the wheat flour, and the bread made from it is something to be experienced.

Other restoration projects that come to mind are two or three windmills in Chatham and Eastham which have been restored or reproduced, and a few herring runs, but there are many other places and sites that are gradually going unless we all make some effort to preserve them.

We cannot, of course, entirely recapture the way of life in the 1800’s, nor probably would we want to, but it would seem that we could preserve and keep that which was good and those methods which were efficient, employed so long ago. I don’t think anyone wants to give up our electric lights for the old oil lamps, nor indoor bathrooms for the outside “privy” (notwithstanding hearsay that the outdoor “privy” was quite pleasant on a balmy summer afternoon), but there are many things which we can learn from the old people that certainly would make our mode of living and our existence a bit more pleasant, tranquil and serene.

Although it may cost a bit more to “post and beam” a house, a bit more for a bow roof, or box returns, or dental work on the trim, I do believe that many people would really20 prefer this type of construction once they have seen it, and I do know that most people could afford it. I will also go farther out on a limb and say that this type of construction is actually cheaper in the long run, and the long run means the lifetime of a house.

Plymouth is now embarking on a very ambitious program of rebuilding the old “Plimouth Plantation”.

I do not think that we on the Cape can do another Williamsburg, nor do I think that we should try to restore everything we find, but each town could do a little bit each year toward setting aside some of its historical treasures.

We have all kinds of beaches, public landing places, swimming pools, both public and private, for the two-week visitor in the summer, all kinds of dance halls and bowling alleys for their entertainment; but what a great wealth of information, interest, and education could be aroused through the restoration of some of the old buildings and landmarks.

The Yarmouth Historical Society, like many other similar groups, has been doing an excellent job. The Captain Bangs Hallett house has been authentically repaired, restored, and reconstructed by and through the Historical Society. Captain Bangs Hallett was one of the deep-water sailors who commanded some of the well-known clipper ships, the giants of the sea. This house is open to the public every afternoon in the summer and reflects the way of living at that time of the more well-to-do sea captains.

My idea is not to restore the Baxter Mill just as another museum which would be filled with all kinds of ancient bric-a-brac, furniture, glassware and curios for people to look at and pass by. My thought is that we should restore and21 reconstruct this mill, holding to exact authenticity, so that the final result would be exactly the same mill with its fundamental mechanisms and its simple dignity, and turn out the same products.

22

Snow and bitter weather came early to Cape Cod in December, 1960. We have always bragged about the mild winters enjoyed on the Cape, but we certainly had a real old fashioned one this year. Every Saturday it seemed that the very nastiest weather prevailed, but on Monday it was beautiful.

It was really hard work in this flume and in the wheel pit at ten and twelve above zero, notwithstanding our heavy winter clothing, but nevertheless about ten o’clock a welcome coffee break was taken. Time after time ice would form and congeal around our boots while we were working, and a penetrating, deadly chill arose from the wheel pit. I don’t know how many hours were spent in breaking up the ice before we could even start to work. Fortunately, no one seemed the worse for wear.

We collected all kinds of lumber, materials, and supplies of various descriptions, widths, and lengths, piling all of this around the mill site. It was a great source of concern to many passers-by where we possibly could be putting all this vast amount of lumber and supplies. Those that took the time to see could readily understand the large amount of lumber necessary to go into the wheel pit and the flume.

Joe Carapezza, the stone mason, was then employed and did a most excellent job in renewing the foundation and rebuilding the retaining walls, mostly out of old dressed granite blocks. These old fashioned dressed granite blocks are about two and a half feet long and about ten to twelve inches square and make a most attractive addition to the landscape of the mill. Not being accustomed to this heavy work, which was indeed difficult for a professional like Joe, you can well imagine that I gradually gravitated to an assistant23 hired hand, but in this weather one did not stand around and become solidified. It was necessary, for self preservation, to keep moving, and while you are moving you might as well be doing some work.

We did indulge in a welcome respite at ten o’clock on a Saturday morning of adjourning to my homestead where we would have some hot coffee and doughnuts. I don’t know how many gallons of coffee and how many doughnuts we consumed over this year and a half, and I don’t know how much mud my wife had to clean up in the kitchen after we all tramped in and out. We were all very thankful to her, however, for putting up with us.

Friend George is slow, meticulous, and very exacting. As for myself, I know that I am impatient and I have to do everything in a hurry. Naturally, both our natures at times clashed, but I think one was good for the other.

I did object strenuously to George’s most annoying habit of suddenly standing up and shouting,

“Harold, where is the rule?”

I found that ignoring him did not help, so I acquired some earmuffs which worked admirably until George resorted to making signs and perhaps lifting up one of the earmuffs and gently requesting the rule. Incidentally, the rule most of the time was sticking out of his own pocket.

Everyone slept fairly well after a day’s work at the mill, but I asked George one morning how he slept. He replied,

“Not too well. I had to turn over once.”

I furnished no small amount of amusement to my co-workers as I tried to fashion a fifteen-foot board to the floor of the mill. The board had to be fitted in about five places, and I would saw and cut and chisel and then saw and cut24 some more, finally ending up with a board about three feet long, much to the gratification and mirth of my so-called assistants.

It seems that shingles are always in demand no matter whether you are rebuilding an old building or building a new one. I never realized how handy shingles were until we began this project. Apparently, shingles were made not only for roofs and side-walls, but to take up the error in the professional’s work.

Somewhere in Maine George made a large speech to an assembled populace about the necessity of everyone having shingles at hand.

25

New England is especially favored with many rivers, streams, ponds and lakes, and it is with never-ending admiration that one reflects on the ingenuity of the early settlers putting to practical use all of the water power. Throughout the whole region will be found hundreds of remains of water mill sites, small and large, and the settlers soon found ways of putting a harness on them for water power.

If the stream happened to be small, the early millwright built a dam across it and in no time he acquired a small pond. The higher the dam, the greater the head of water.

Where there were large rivers, you can now find tremendous power plants, textile mills and other manufacturing establishments all using this water power.

Most of us today, when we think of power, think of electricity, gas, or steam, but it is very simple to consider the water in an ordinary little stream and the amount of power it can deliver.

Although the machinery built by the early millwrights was a bit crude, nevertheless it was functional and worked with efficient success.

On a recent scouting trip George and I took through Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Connecticut, we visited a few restored mills. One of them was in Rowley, Massachusetts, just off the Main Road, called the “Jewel Mill”. Here an enterprising and resourceful chap had rebuilt the outside water wheel on a fairly small stream and he was driving a small D C generator supplying electricity to his house and to a small lathe shop. This, he told me, had been going on for five or six years without interruption. The lights were steady and there was no fuss, clamor, or noise. The only26 thing one heard was the splashing of the water over the wheel. His mill was so named because he was actually cutting and polishing small, local, semi-precious stones.

I find that there is a small group of enthusiasts who are gradually picking up and collecting all the old turbines they can find of ancient vintage, so if one wishes to invest in the future, he might consider picking up one of these old turbines which in a few years will be extinct.

Another interesting site we visited was John Goffe’s Mill near Manchester, New Hampshire. Having read with fascination George Woodbury’s tale of restoring this mill, we were very anxious to actually see it. Mr. Woodbury, a very learned gentleman, former archaeologist and now author, had performed a most remarkable job.

Another mill, farther along the trail, was in Alstead, New Hampshire, where Heman Chase was conducting a class in woodworking, the power being supplied by an old refinished turbine. Mr. Chase, in addition, is a land surveyor, a teacher of mathematics and the philosophy of Henry George, as you can see from his letterhead.

At Weston, Vermont, at the Artists’ Guild, will be found a real old mill where they are grinding corn and wheat and other grains.

Late the first night of this expedition, George and I holed up in a modern motel somewhere in New Hampshire. I was not quite prepared for George’s night attire. It seems he still wears an old fashioned nightshirt, split up on each side, and I got a bit of a start to observe this character climbing into bed with this on. George will deny this, but he also had on an old night-cap.

27

Coming home we went to Monson, Massachusetts, and there found all kinds of mill apparatus in various states of repair, gradually rusting out and disappearing into the ground. I was a little sad to observe how the owner was tenaciously clinging to his old way of life: his machinery, tools, and all the things he had collected all his life. But how his eyes did light up with enthusiasm when he learned we were attempting to restore our own mill.

A tall, gaunt man, weather-beaten, with hands that had known many a piece of machinery, he was a living figure of the old millwright and gave us a great amount of information on the revolutions per minute and various other facets of millwrighting.

Most of us think of antique things as so many curios and objects to be placed in museums to be passed by, but we do not realize how much better some of these things did work than the ones we buy today. For instance, I have a small hand garden trowel, forged perhaps fifty or sixty years ago, and it is much more practical than the new trowels on sale in the hardware stores. I have often wondered why they couldn’t make one like this rather than the ones on display but perhaps this kind would last too long and the factory would go out of business.

We did not find on our pilgrimage a turbine suitable for us, but we did find the brilliant foliage of the hills and mountains, the quiet patience of the roads, and the beauty of the small towns of New England.

A few weeks later our fast trip in upper New England paid off, for we heard by mail of a turbine that seemed might be just right for our purposes. Chuck Stanley gave us the loan of his truck and George and I, fortified by a28 packed lunch, hot coffee, and sandwiches, started out at 4:00 A. M. one Sunday morning for Livermore Falls, Maine.

There, we found on the side of a hill an old turbine weighing about two ton, and after poking about this monster we decided we could use it.

The task of loading this beast upon the truck seemed formidable, so we finally located a mountaineer who possessed an oversized auto wrecker, and backing our truck against a strategic hump on the side of the hill we proceeded to load the turbine on the truck. The wrecker hooked onto the turbine, but the turbine proved too much for it, so much so that it turned it over on its side.

A goodly crowd had by this time gathered to watch the operation, and enlisting the aid of some husky boys, we finally managed to push the wrecker back on its four wheels.

Friend George, in his unruffled manner, soon had the turbine on the truck, and we fell to the task of shoring it up with chunks of wood, plank and chalks. We could vividly imagine what would happen if this baby got away from us going down some mountain, so we took a long time in lashing it securely to the truck.

Of course, George could not let the day go by without shouting,

“Harold, where is the shingle?”

“Didn’t bring one,” I replied.

Then followed an impassioned speech by friend George from the tailboard of the truck to the assembled populace, extolling the virtues of shingles and decrying the negligence of the author in not bringing at least one shingle to Maine.

29

A brief glimpse of the Cape Cod Village in the 1800’s and its everyday life in those days would be interesting and would also throw some light on the fascination of the mill.

This mill and many others like it played a most important role in our small towns, as did the country store, the blacksmith shop and, of course, the church.

On the Cape at about that time, there were between thirty and forty mills, either powered by wind or water, and these mills supplied flour and corn in its various stages to the villages. Corn then was more important than gold. The meal, of course, was used for corn meal muffins and corn bread, and the cracked corn for the chickens and pigs.

Every family was practically self-sufficient, growing their vegetables, and if they did not have a cow, trading eggs or other produce for milk or cream with their neighbors. Almost everyone would supplement their food supply with shellfish from the shores and flats and fish from the various boats that plied the sound and bays. There were many orchards, most of which have now disappeared. One can hardly find a grape arbor left, but in those days apples and other tree-grown fruit were found in every other home or homestead. Cranberries played no small part, but they were just about developing in the 1880’s, and I can remember distinctly, while growing up in Brewster, of earning small amounts of money from time to time helping the farmers harvest their cranberry crop, together with asparagus, turnips and strawberries.

I cannot remember any people being on Old Age Assistance, and I recall distinctly there was no Social Security program. There was always something for everyone to do30 whether they were young, middle-aged, or old. For us young children there were ordinary chores in and about the house to be done morning and evening, cutting the kindling, getting wood ready for the fires, and generally being handy boys around the house and barn. I can definitely say there were no gangs of teenagers with switchblades. “Mac the Knife” was wholly unknown. The only knives we had were pocket jackknives used for whittling and playing mumbley-peg.

I can remember that there were many things to do the night before the Fourth, but I can remember no destruction of property. Perhaps a few privies might be displaced, and on Halloween fences might disappear, but they were always found somewhere, and the culprits made to replace them.

In the Fall almost everyone would gather seaweed from the beaches and bank it around the house, because only the very rich could afford full basements and what we call central heating. The small, round Cape Cod cellars were used to keep fruits and vegetables.

I can also distinctly remember working on the town roads, helping to get in ice for the ice houses, and I can also remember that almost every boy knew how to handle a hammer, a saw, screw driver, or chisel, which did not seem work to us at the time.

The mill was not exactly a gathering place for the country folk; that was left to the country store. In Brewster, the mail would come in about 6:00 P. M., and it was a great thing for us younger boys to gather at the Knowles’ store at about the time the mail was due and listen to some of the older men around the stove discuss the events of the day and the nation.

I do not recall many critical periods of wars and threats of war, but I do recall the fusion of the wonderful odors of31 the country store, the far off cry of the lonely whistle of the mail train, the hard candy, and the attractive chocolate-colored tobacco. I can also recall vividly the old time “drummer” with his fancy, gay, colored straw hat, the horse drawn carts that would bring groceries, meat and fish once or twice a week.

All around the towns, almost everyone had a horse and some more well-to-do people had two or three. It was not necessary to turn in the horse every year, because the model never changed. The horses sometimes died, but only after twelve or fourteen years of good service. Almost everyone owned a so-called Cape Cod truck wagon, painted a faded blue color.

I can remember the May baskets, the sleigh rides, and sliding down the hill in High Brewster in the winter-time.

All this is in sharp contrast to the children on the present day and the problems of juvenile delinquency. Undoubtedly lack of parental care and instruction, to say nothing of planned obsolescence, time payments, and lack of individual initiative, can be blamed for the conditions. Being fortunate to have been born at about the turn of the century, when the era of the horse was just about departing and the automobile beginning, I think I am in a fairly good position to compare conditions of that day with today.

I might say that I do recall when I was about ten years of age, my mother and grandmother sadly declaring that things at that time were different when they were children, and that they did not know where we then were going. I put this in to show that there may be an answer to all this through the process of evolution. I do not know.

32

I do know that the flour and the meal coming from these old and ancient mills produced much better food than the present day processed flour and meal.

I can remember many of the older figures of that time. Seth Rogers, a typical country gentleman, and many other well-known men about that time, who were not looking for something for nothing. They all did work of one form or another, either on their farms or their cranberry bogs, or in some business or trade. They did not have much time, but the time they had was put to great use in production. They did not have too much money because they did not need it. A man that died leaving an estate of $5,000.00 or $6,000.00 was considered reasonably wealthy. These men would do something for their town without expecting great pay in return; they were not constantly looking to the town, state, or government for handouts. They produced and developed a way of life totally different from the way we have today.

33

Now, after the machinist has repaired and fixed up the old coupling, and other parts of the old turbine which could not withstand our battering, it becomes necessary to drop the turbine in place and hope everything will work.

First, we have to pull out the temporary retaining walls next to the tailrace, dig down below the pool, and put in a brand new wall, so that the rush of water will not tear away the earth next to the State Highway which would stop all the dear people from dashing about on the State Highway, especially the tourists.

I have often wondered what I would do if this mill doesn’t work when we get through. All sorts of suggestions have come from skeptics, the practical ones being to install a gas engine or electric motor to turn the stones. I doubt very much that we will ever do this. We are still convinced that if the early settlers and tenacious people could make this work with their cumbersome and crude tools, we can do the same thing with our so-called improved modern equipment and tools.

So now the flume is finished, a good solid bridge is built over it, and we must go and dig out and repair the tailrace and get ready to place the new turbine in its position.

This tailrace runs from underneath the building, from the bottom of the turbine out to the pool near the State Highway and then under the State Road into Lewis Bay. All the rocks which attempted to retain the embankment adjoining the State Highway were merely dumped there by someone hoping they would shore up the embankment. The result was, over the years they were gradually disturbed and found their way into the pool, and, of course, a lot of the dirt and34 sand from the embankment slipped off into the pool and the bottom of the tailrace.

So we again call in our stout and genial mason, Joe Carapezza, and a machine to dig out the rocks, dirt and mud. Putting the rocks back into a firm and complete wall turned out to be a little more of a job than we planned on.

Every one of the rocks, some of which weighed from five hundred to a thousand pounds, had to be handled manually, as there was no room for cranes and the like to lift them up and work them around. After about two weeks of this, we finally managed to build a fairly solid retaining wall next to the tailrace.

Just about this time the herring began their annual migration to their spawning ground, so we had to raise the level of the mill pond so that nature could take her course.

It would seem that every time a weekend came around there was either rain, snow, drizzle, or some other sort of foul weather, which didn’t help things along a bit.

In browsing through some old pamphlets by one Daniel Wing, a school master who taught school in Yarmouth about 1900, I ran across the following interesting paragraph:

“The old gristmill directly opposite the Captain Baxter residence was known as Baxter’s mill. It was at one time owned by Captain Timothy Baker, Senr., (born in the first half of the eighteenth century) and later by his son, Captain Joshua Baker, born in 1766. The mill pond was fed by several streamlets which came down from the north, but its work having been completed, the dam has been allowed to wash away; and, there being some question as to ownership, we learn that this once beautiful and interesting spot is now grown up with rushes. It seems as if the water power here might, in this day of improved machinery, be made again to serve a useful purpose.”

I wonder if Daniel can see the mill now.

35

The old turbine that we excavated from a side hill in Maine was lowered into place after much straining, blocking, and running around. George’s careful measurements and minute calculations paid off, because it fitted perfectly in the large hole cut in the bottom of the wheel pit. We had to call upon the machinist to fashion a coupling in order to fit the old coupling still left on the shaft coming down through the first floor into the wheel pit from the gears above.

While this was being done, George, Dick McElroy, and I managed to make a decent pen gate with the necessary worm gear attached to it so that we could block off the water in the flume and raise the gate when necessary.

36

At this point I happened to mention to one of my friends that I would like to find, somewhere, a metal wheel similar to a freight car brake wheel that we could use on the shaft to raise and lower the pen gate. A few days later, my friend left at the mill a real old timer. It was a wheel which was about two and one-half feet in diameter, and which was nicely adapted to the top of the rod of the pen gate. This wheel suspiciously looked similar to a wheel that would toll a bell on a church steeple, and when I suggested the possibility of this to my friend, he merely smiled and walked away.

37

We have used to a great extent Oliver Evans’ “The Young Mill-Wright and Miller’s Guide.” This book was printed about 1800, and I think I have referred to it before, but it has proved invaluable to us in the course of our work. The words and references in the book may have meant something to the millers one hundred years ago, but not us poor amateurs of 1961, the words millseat, flutterwheels, cockheads, cubocks, to say nothing of “tailflour,” confused us no end, but on closer reading and more attention to the details of the book, we did finally make some sense from it.

Under Article 108 in this ancient volume is found the following:

“Of Regulating the Feed and Water in Grinding.”

“The stone being well hung, proceed to grind, and when all things are ready, draw as much water as is judged to be sufficient; then observe the motion of the stone, by the noise of the damsel, and feel the meal; if it be too coarse, and the motion too slow, give less feed and it will grind finer, and the motion will be quicker; if it yet grind too coarse, lower the stones; then, if the motion be too slow, draw a little more water; but if the meal feel to be ground, and the motion right, raise the stones a little, and give the motion right, raise the stones a little, and give a little more feed. If the motion and feed be too great, and the meal be ground too low, shut off part of the water. But if the motion be too slow, and the feed too small, draw more water.”

I doubt very much that the venerable Mr. Evans would have relished “the noise of the damsel” if he had observed George one sunny afternoon pick up a luscious creature of the female sex, heave her over his shoulder and transport her into the depths of the mill, all in plain sight of the general public. It seems that it was a little too muddy for this fair lady to walk to the mill, but the following week, however, the same damsel was there and took the same ride on George’s shoulders into the mill.

38

We could not and did not observe either the motion or the noise of the damsel, which probably is just as well.

The damsel referred to by Evans, however, is nothing more or less than a square wooden shaft which turns against a shoe suspended under the spout of the hopper to regulate the flow of grain into the stones themselves.

There is, of course, a definite rhythm to the clatter created by the damsel, and this is what Evans was speaking about in “noise of damsel.”

Farther on in Evans’ book, it states that we must “pick up the stones” and sharpen them, but as I said before, we found that we were too ignorant of the art of sharpening the stones, and that is why we obtained the services of Mr. Mattson, who did an excellent job in “picking up” the stones.

It is interesting to read Evans’ book, and I have taken the time to copy directly from the book the chapter on the “Duties of the Miller.”

“CHAPTER XVIII

Directions for keeping the mill and the business of it in good order.

Article 116

The Duty Of The Miller

The mill is supposed to be completely finished for merchant work, on the new plan; supplied with a stock of grain, flour casks, nails, brushes, picks, shovels, scales, weights, etc., when the millers enter on their duty.

If there be two of them capable of standing watch, or taking charge of the mill, the time is generally divided as follows. In the day-time both attend to business, but one of them has the chief direction. The night is divided into two watches, the first of which ends at one o’clock in the morning, when the master miller should enter on his watch, and continue till day-light that he may be ready to direct other hands to their business early. The first thing he should do, when his watch begins, is to see39 whether the stones are grinding, and the cloths bolting well. And secondly, he should review all the moving gudgeons of the mill, to see whether any of them want grease, etc.; for want of this, the gudgeons often run dry, and heat, which bring on heavy losses in time and repairs; for when they heat, they get a little loose, and the stones they run on crack, after which they cannot be kept cool. He should also see what quantity of grain is over the stones, and if there be not enough to supply them till morning, set the cleaning machines in motion.

All things being set right, his duty is very easy—he has only to see to the machinery, the grinding, and the bolting once in every hour; he has, therefore, plenty of time to amuse himself by reading, or otherwise.

Early in the morning all the floors should be swept, and the flour dust collected; the casks nailed, weighed, marked, and branded, and the packing begun, that it may be completed in the forepart of the day; by this means, should any unforseen thing occur, there will be spare time. Besides, to leave the packing till the afternoon, is a lazy practice, and keeps the business out of order.

When the stones are to be sharpened, everything necessary should be prepared before the mill is stopped, (especially if there is but one pair of stones to a water-wheel) that as little time as possible may be lost: the picks should be made quite sharp, and not be less than 12 in number. Things being ready, the miller is then to take up the stone; set one hand to each, and dress them as soon as possible, that they may be set to work again; not forgetting to grease the gears and spindle foot.

In the after part of the day, a sufficient quantity of grain is to be cleaned down, to supply the stones the whole night; because it is best to have nothing more to do in the night, than to attend to the grinding, bolting, gudgeons, etc.”

Shades of the coffee break and the forty-hour week! Apparently Evans and his millers hardly found time to stop and get a bite to eat.

Interesting, the old methods and way of life compared with our present day methods and ways of existence.

40

The summer of 1961 is now hard upon us, as is the horde of vacation seekers; so, at least for a while, we are forced to give up our labors at the mill and go to other pursuits, but just as soon as autumn comes around we start in again Saturday mornings at the old mill site.

The mill stones had to be sharpened and we found out that this was really beyond the scope of our knowledge and skill.

Inquiries at Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, Massachusetts led us to finding one of the few men left who could “pick up” the stones. This gentleman, Arthur Mattson, of Plainville, Connecticut, consented to come, and finally did come to the Cape, and in a matter of hours had sharpened the stones to the nth degree.

While he was here, we gleaned as much information from him as we could, in the course of which we found that he owned five mill stones which were grinding out stone ground flour, and that he had been supplying, for many years, the stone ground flour to the Pepperidge Farm Mills in Connecticut, famous for their Pepperidge Farm Bread.

Among other things, he showed us how to construct a “damsel” (which is nothing but a small flutter board hung below the mouth of the hopper) and wiggles just enough to let the grain drop into the stones at the proper quantity.

About a year from the date we started to work on the mill, to wit: August 3, 1960, we are able to open the pen gate, let the rushing water fill up the flume and wheel pit, raise the skirt in the turbine, and with a feeling of great self-satisfaction, see and hear the stones turn, albeit, a little slow at first, since the stones were not properly balanced, but, nevertheless, lo and behold, all our work finally paid off.

41

Someone shouted, “Ho, ho, she starts, she moves, she feels a spark of life.” You can well imagine who that was.

As near as we can figure, these stones had not been turning for exactly seventy-one years, and frankness would be lacking if we did not feel proud of our hard work and efforts.

The mill actually ran smoothly, and with very little noise, but to be sure that we were not subject to hallucinations we spent the better part of the afternoon turning the wheel off and on. The wheel and its heavy but simplified gears responded with slow speed and gradual pick-up of revolutions to a very deliberate cadence.

Again I was struck with the simplicity of the working of the turbine and wheel, and perhaps the economy of the whole affair was intriguing. One had only to look at the water pouring into the wheel pit to see the power of the stream and to reflect upon the fact that it cost absolutely nothing for this power. Gear grease, oil or other lubrication was absolutely unnecessary to maintain the operation.

The stones were originally enclosed and covered with a wooden casing, half of which we found in the mill, but the other half we had to build ourselves and make them, of course, exactly as the first half. As usual the boards that were available at any lumber yard were not the same thickness, so again we had to have proper boards milled out to match up with the old. Finally, George found an old blade adequate to make the same beading on the edge of these new boards as the original beading, and it was not too difficult to do with the aid of this old fashioned plane.

About this time we received in the express from Mr. Mattson, the genial gentleman from Connecticut, who had sharpened the stones, a cradle and a shoe. The cradle is to42 hold the hopper and the shoe is for support, as I said before, underneath the spout of the hopper.

The cradle was practically a perfect fit on the top of the wooden casing, and the hopper fitted the cradle perfectly. This was one time something really did fit.

And so - - - - just before the Christmas Holidays of 1961 everything seemed to be about finished. We procured a bag of whole corn, part of which we dropped into the hopper, opened up the pen gate, and lo and behold, yellow gold came flowing out of the chute. To be sure, at first the meal was a bit coarse, but after George maneuvered the “tenterer,” we obtained about the correct texture of meal.

It has been said that the end of something is better than the beginning, but I think I felt a little sad that we were finished and somewhat surprised that the mill actually worked. Sad, perhaps, because we had no more to do to complete the mill project. We were constantly uncovering new sights in the ancient mill. The actual work, the research, the conversations with new people, the reading of stories of old mills, seeing the old mills, some of which were restored and others abandoned, and being able to finally rebuild this old mill and to renew a small part of life now long forgotten, has been most fascinating.

George just called me on the phone, saying,

“Harold ... you know what?”

“No, what?”

“I think I have found an old tide mill - - - -”

Punctuation, hyphenation, and spelling were made consistent when a predominant preference was found in the original book; otherwise they were not changed.

Simple typographical errors were corrected; unbalanced quotation marks were remedied when the change was obvious, and otherwise left unbalanced. Two typographical errors in quoted text on page 37 were corrected after consulting a copy of the book from which the quotation was taken.

The illustrations at the ends of chapters I, II, VI, VIII, and X are simple decorative tailpieces.