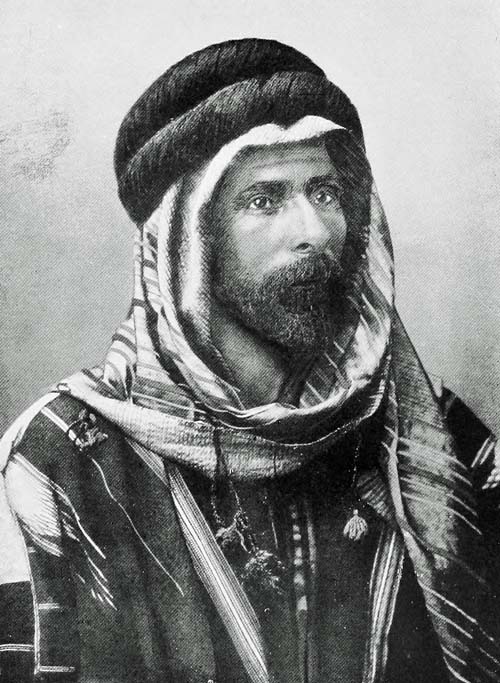

ARAB SHEIKH

(Photo: The Photochrome Co. Ld.)

[i]

ARAB AND DRUZE

AT HOME

A RECORD OF TRAVEL

AND INTERCOURSE WITH THE PEOPLES

EAST OF THE JORDAN

BY

WILLIAM EWING, M.A.

FIVE YEARS RESIDENT AT TIBERIAS

THIRTY-ONE ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAP

LONDON: T. C. & E. C. JACK

16 HENRIETTA STREET W.C.

AND EDINBURGH

1907

[ii]

TO

MY FATHER

TIBERIAS FROM THE SEA

[iv]

The number of books published regarding Palestine proves the exhaustless fascination of the subject. Most of them, however, deal with Western Palestine; and even of this, beyond the districts traversed by the annual stream of tourists, comparatively little is heard.

The lands beyond the Jordan are seldom visited. For the ordinary sight-seer the difficulties and dangers are considerable; but these almost entirely vanish before one who can speak the language and is able to mingle freely with the people.

This book is an attempt to lift a little way the veil which still so largely obscures that region, in spite of its great and splendid history; where picturesque and beautiful scenery, the crumbling memorials of grey antiquity, and the life of villager and nomad to-day, cast a mysterious spell upon the spirit.

While the information given in the following pages is woven round the narrative of a single journey, it is the outcome of frequent travel and familiar intercourse with the peoples both east and west of Jordan.

[vi]During a residence of over five years in Palestine the writer was privileged often, quite alone or with a single native attendant, to visit the peasantry and the Beduw, to share the shelter of mud hut and goat’s-hair tent, to enjoy their abounding hospitality and friendly converse in the medāfy, on the house-top, and around the camp-fire in the wilderness.

What is here related regarding these strange but deeply interesting peoples was either learned from their own lips or verified in converse with them.

The author offers his tribute of affection and gratitude to the memory of Dr. H. Clay Trumbull of Philadelphia, U.S.A., surely the most generous and friendly of editors, who first moved him to write on Oriental subjects.

For many of the photographs taken on the journey he is indebted to his companions in travel, Rev. J. Calder Macphail, D.D., Edinburgh, and Dr. Mackinnon of Damascus; for others, to Dr. Paterson of Hebron and to the Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. He also gratefully acknowledges assistance received from the Rev. J. E. H. Thomson, D.D., and Oliphant Smeaton, Esq., M.A., F.S.A., Edinburgh.

Edinburgh, December 1906.

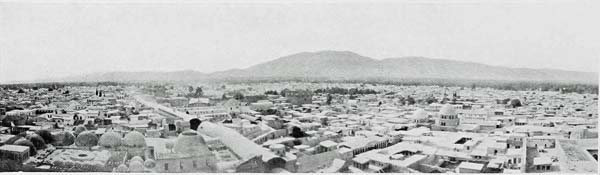

DAMASCUS FROM MINARET OF GREAT MOSQUE

| CHAPTER I | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| Damascus—Haurân Railway—Great Moslem pilgrimage—The plains of Damascus—Great Hermon—El-Kisweh—Bridges in Palestine—Ghabâghib—Es-Sanamein—Medical myth—A Land of Fear—Grain-fields of Haurân—An oppressed peasantry—Nowa | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Arab courtesy—Sheikh Saʿad—Egyptian monuments—Traditions of Job—El-Merkez—Religious conservatism—Holy places—Sheikh Meskîn—A ride in the dark—Zorʿa—El-Lejâʾ | 16 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| A landscape of lava—Deserted cities—Caverns—Cultivation—A land of ruins—The guide’s terror—Damet el-ʿAliâ—The sheikh’s welcome—A state of siege—An ugly incident—Druze hospitality—Arab and Druze in el-Lejâʾ—St. Paul in Arabia—The well of the priest—Story of the priest | 30 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Hidden treasure—The Bedawy’s treasure-trove—The sheikh’s farewell—A savage tract—Jebel ed-Druze—Umm ez-Zeytûn—Tell Shihân—Shuhba—An ancient house—A stingy entertainer—The ruins—Pharaoh’s “grain-heaps”—The house of Shehâb | 48 |

| CHAPTER V[viii] | |

| Ride to Kanawât (Kenath)—Impressive situation and remains—Place-names in Palestine—Israelites and Arabs—Education—A charming ride through mountain glades—Suweida | 63 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Healing the sick—A strange monument—Telegraph and post in Haurân—Cruel kindness—The Ruins of Suweida—Turkish methods of rule—ʿIry—Sheyûkh ed-Druze—Jephthah’s burial—Enterprise of Ismaʿîl el-ʿAtrash | 74 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Druzes—Their religion—Their character—Druze and Jew—Recent history in Haurân—Druze and Bedawy—War | 86 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Bozrah—First Syrian mosque—The physician the reconciler—The “House of the Jew”—The great mosque—Cufic inscription—Boheira and Mohammed—The fortress—Bridal festivities—Feats of horsemanship—History—Origen’s visit—Capture by Moslems | 102 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Travellers’ troubles—A corner of the desert—The mirage—Dangerous wadies—Lunch in the desert—A “blind” guide—The clerk to the sheyûkh—A milestone—Kalʿat Esdein—Thirst—The uplands of Gilead—Search for water—A Bedawy camp—Terrific thunderstorm | 117 |

| CHAPTER X[ix] | |

| Morning on the mountains—Arab time—Tents and encampments—The women and their work—Arab wealth—Scenes at the wells—Dogs—Arabian hospitality—Desert pests—Strange code of honour—The blood feud—Judgment of the elders—Arab and horse—The Arabs and religion—The Oriental mind—Arab visit to Damascus | 129 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

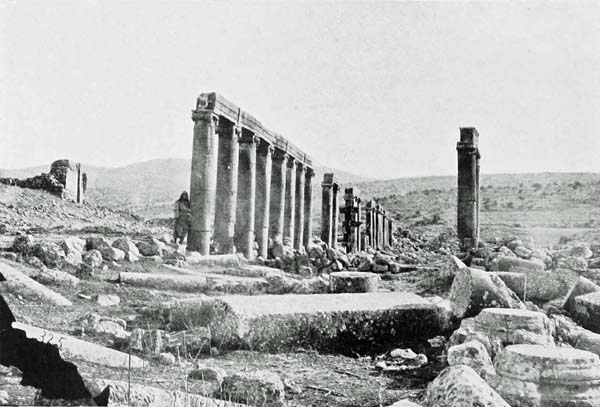

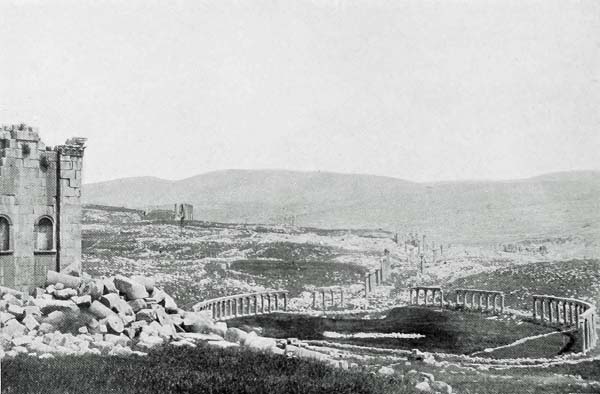

| Ride to Jerash—Magnificent ruins—Circassian colonists—History—Preservation of buildings—East of Jordan—Sûf—A moonlight scene—Down to the Jabbok | 145 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| “Time is money”—Rumamain—Priestly hospitality—Fair mountain groves—Es-Salt—The springs—Relation to Arabs—Raisins—Descent to the Jordan—Distant view of Jerusalem—View of the river, the plains of Jordan, the Dead Sea, and the mountains beyond—The bridge—The “publican’s” shed—The men from Kerâk | 158 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| The banks and thickets of the Jordan—Bathing-place—The Greek convent—A night of adventures in the plains of Jericho—The modern village—Ancient fertility—Possible restoration—Elisha’s fountain—Wady Kelt—The Mountain of Temptation—The path to Zion | 169 |

[x]

| PAGE | ||

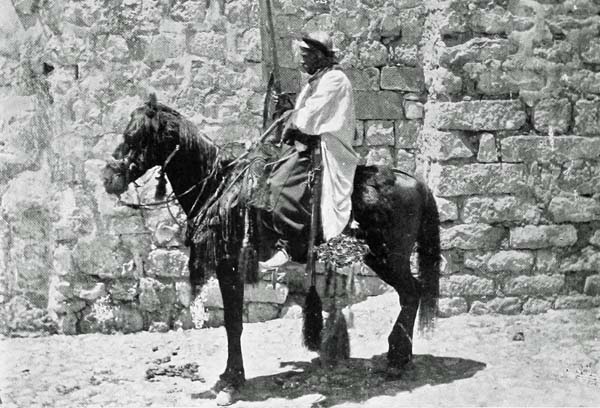

| Arab Sheikh | Frontispiece | |

| Tiberias from the Sea | Facing | iii |

| Damascus from Minaret | ” | vii |

| Pilgrimage leaving Damascus | ” | 2 |

| The Cook’s Tent | ” | 8 |

| Treading out the Corn | ” | 14 |

| “Wild Ishmaelitish Men” | ” | 25 |

| Peasant Ploughman | ” | 33 |

| Well in the Desert | ” | 47 |

| Shuhba: Baths and Roman Pavement | ” | 54 |

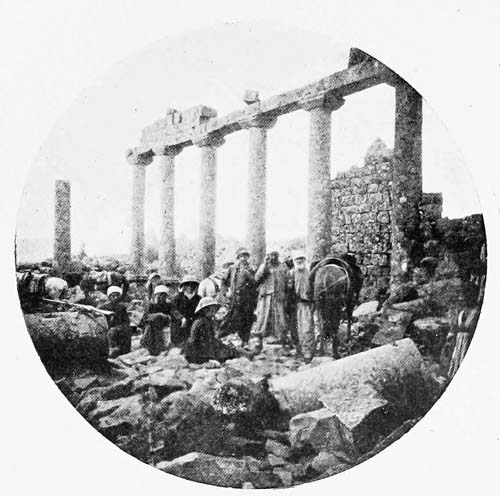

| Kanawât: Ruins of Temple | ” | 66 |

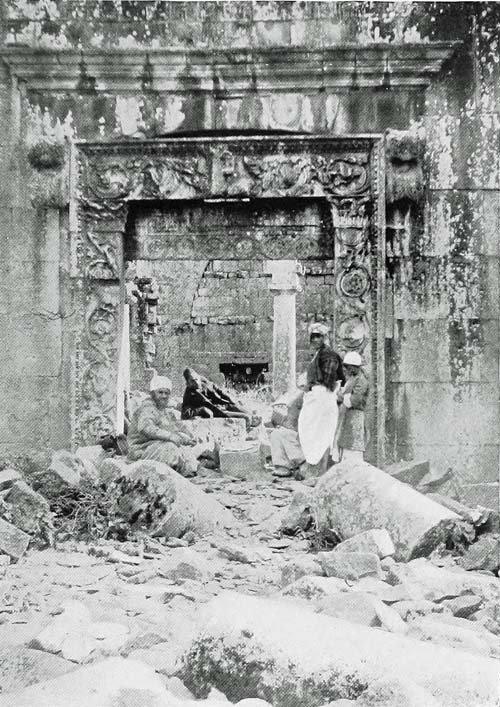

| Kanawât: Sculptured Doorway in Temple | ” | 70 |

| Sheyûkh ed-Druze: a Council of War | ” | 83 |

| Bozrah: Bab el-Howa | ” | 102 |

| Bozrah: at the Cross Ways | ” | 114 |

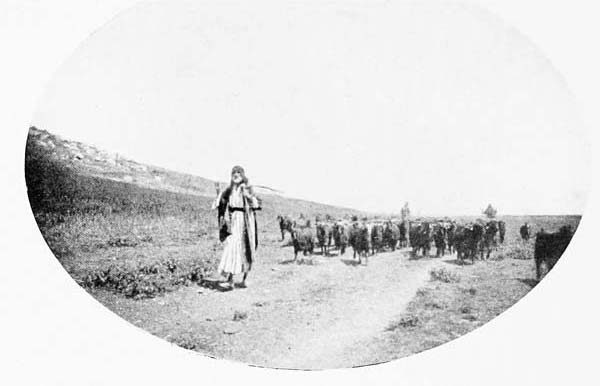

| Palestinian Shepherd and Flock | ” | 122 |

| Arab Camp in Gilead | ” | 126 |

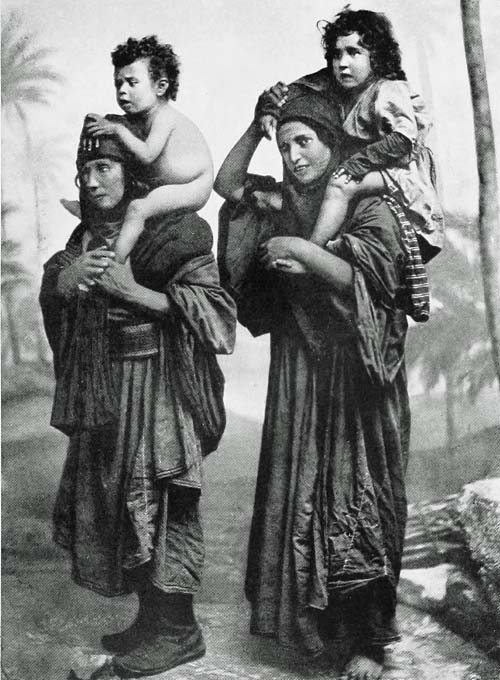

| Arab Women and Children | ” | 133 |

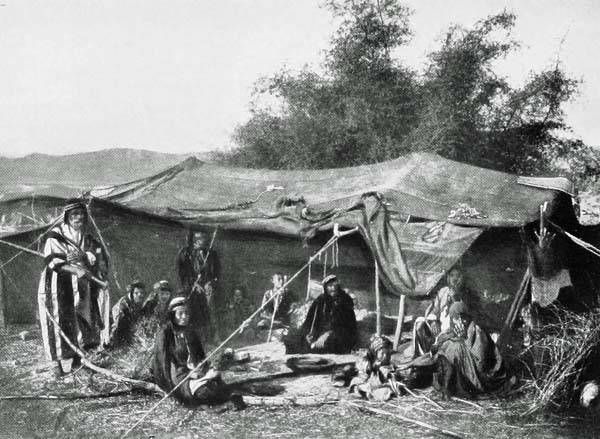

| Arabs at Home | ” | 136[xii] |

| Arab Horseman | ” | 140 |

| Jerash: Gateway | ” | 145 |

| Jerash: Temple of the Sun | ” | 148 |

| Jerash: Street of Columns | ” | 152 |

| Jerash: General View | ” | 154 |

| Gorge of the Jabbok | ” | 156 |

| Rumamain | ” | 159 |

| Es-Salt: the Fountain | ” | 162 |

| Jordan, showing Terraces | ” | 164 |

| Fords of Jordan: Pilgrims Bathing | ” | 170 |

| Elisha’s Fountain | ” | 175 |

| Mouth of Wady Kelt | ” | 178 |

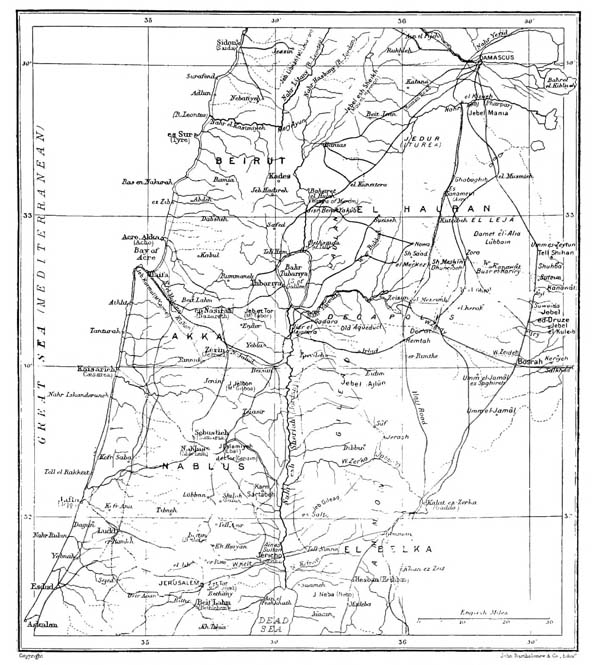

| Map | ” | xii |

MAP OF THE COUNTRY EAST AND WEST OF THE JORDAN

Damascus—Haurân Railway—Great Moslem pilgrimage—The plains of Damascus—Great Hermon—El-Kisweh—Bridges in Palestine—Ghabâghib—Es-Sanamein—Medical myth—A Land of Fear—Grain-fields of Haurân—An oppressed peasantry—Nowa.

There is a pleasant excitement in the prospect of a journey through long-forgotten lands, where hoary age is written on dark ruin and carved stone, which lends its influence to while away the monotonous days of preparation. But even amid surroundings of entrancing interest in the queenly city on the Barada, the traveller soon grows impatient to find himself in the saddle with his friends, heading away towards the hills that bound the green plains of Damascus. Fortunately, we could dispense with a dragoman, often more an imperious master than an obliging servant, and were able to arrange our routes and carry out our programme according to our own wishes.

Leaving the city by Bawabbat Ullah, we took the Hajj road to the south-west. This for many centuries was, what in the southern reaches it still is, a mere track, not always clear, and often to be kept only by[2] observance of landmarks. To facilitate the passage of troops to and from Haurân, the Government had made a fairly good road from Damascus to some distance within that province. A railway has now been built, and is in working order as far south as Mizerîb. One day, perhaps, it will reach the sacred cities in el-Hejaz. If this do not greatly expedite the hâjj’s enterprise, it will at least add variety to his peril. The first trains east of the Jordan were objects of surpassing interest to the camels. Unaccustomed to give way to anything else on the road, a strange mingling of curiosity and pride brought many of these “ships of the desert” to grief.

MOSLEM PILGRIMAGE LEAVING DAMASCUS

Our journey fell in the late spring of 1890. The Hajj, the great annual pilgrimage to Mecca and Medîna, fell that year in the month of April. A few days before we started, we had seen the pilgrims and their guard setting out. Most were mounted on mules, but there were also a few horses and camels. Conspicuous among these last was that which bore the Mahmal—the canopy in which is carried the Sultan’s gift—a covering for the shrine at Mecca. The canopy is of green silk, richly embroidered, supported by silver posts. On its apex a gilt crescent and globe flash in the bright sun. The occasion stirs the city to its depths. The roofs all along the line of route were crowded, and every point of vantage was occupied by eager spectators. The procession passed amid the hum of suppressed conversation. From the faces in the crowd it was plain to see that many had gone of whose return there was but little hope. The[3] weary, painful journey through the pitiless desert, beset by marauding Arabs, and the insanitary conditions of the “holy places,” prepare a sure path for not a few to Firdaus—“the garden” par excellence of Moslem dreams, the unfailing portion of him who dies on pilgrimage. The stir caused by their passage through the country quickly subsides. When we followed in their footsteps, things had already assumed their drowsy normal.

Passing the gates, we were at once in the open country; for the famous orchards do not extend thus far in this direction. On every side the plains were clad with heavy crops of waving green; the whir of the quail and the crack of the sportsman’s fowling-piece mingled with the frequent sound of running waters—sweetest music to the Syrian ear. Stately camels came swinging along, each with a great millstone balanced on his back. One of these forms a camel-load. The basaltic quarries in the mountains southward, from which these stones, celebrated for hardness and durability, are hewn, have been long and widely esteemed. Full thirty miles away, yet, in the clear April afternoon, seeming almost on the edge of the nearer plain, lay the magnificent mass of Hermon, clad in his garment of shining white—a huge snowy bank against the horizon, twenty miles long and ten thousand feet high. Those who have seen this majestic gleaming height, when the snows lie deep in the early year, can understand how appropriately the Amorites named it Senir—the breastplate, or shield. Syria owes much to Hermon.[4] Cool breezes blow from his cold steeps; his snows are carried now, as in ancient days, to moisten parched lip and throat in the streets of Sidon and Damascus. Many of the streams “that fill the vales with winding light” and living green are sweet daughters of the mighty mountain, while his refreshing dews descend, as sang the Psalmist, even on the distant and lowly Zion.

Looking back a moment from the rising ground, ere passing down behind the Black Mountain, we caught a parting glimpse of the fair city, renowned in Arab song and story. Rich flats now stretched between us and the thick embowering orchards, over which rose tall minaret and glistening dome. A light haze hung over the city, obscuring the immediate background; but away beyond appeared the high shoulders and peaks of Anti-Lebanon, many capped with helmets of snow, standing like guards around the birthplace of the city’s life; for thence comes the Abana, the modern Barada, without which there could have been no Damascus.

A gentle descent brings us to the Aʿwaj, in which many find the Bible Pharpar—a name still to be traced, perhaps, in Wady Barbar, higher up but not a tributary of this stream. On the nearer bank stands el-Kisweh, a Moslem village of some pretensions, with khan mosque and minaret, and ancient castle, while the stream is spanned by an old-time bridge. No new bridges in Palestine are of any account. The only two that span the Jordan from Banias to the Dead Sea—the Jisr Benât Yaʿkûb, below the waters of[5] Merom, and Jisr el-Mejamiʿa above Bethshan—are both survivors of the old Roman system. Around and below el-Kisweh, as in all places where water comes to bless the toil of the husbandman, are beautiful orchards; olive and willow, fig, apricot, and pomegranate mingle their foliage in rich profusion; and high over all rise the stately cypress trees—the spires and minarets of the grove. Here, when the Hajj falls in summer or autumn, pilgrims take leave of greenness and beauty, and press forward on their long desert march to the Haramein. As our evening song of praise rose from the river’s bank, for centuries accustomed to hear only the muttered devotions of the Moslem, we could not but think of the time when the voice of psalms shall roll with the sweet waters down the vale—a time surely not far distant now; and in the thought we found new inspiration for our work.

Continuing southward, a dark mountain lies to the left, well named Jebel Māniʿa, which may be rendered “Mount of Protection,” or “The Protector.” In its difficult recesses the peasant cultivators of the rich open land around find a home, secure against marauding Beduw and lawless bands. Jedûr, the old Iturea, stretches away to the right; we are now in Haurân, part of the land of Bashan, corresponding in name to the ancient Auranitis. At Ghabâghib, where we halt for lunch, great cisterns and scattered ruins tell of an important place in times past. It has fallen on evil days, only a few wretched hovels occupying the site. The poor inhabitants, demoralised by[6] the yearly Hajj, expect much more than value for anything they supply; but neither here nor anywhere east of Jordan did we once hear the irritating cry Bakhshîsh.

From this point the road deteriorates. First there are patches of some thirty yards in length thickly laid with broken stones, then occasional stretches of ground cleared, and finally the ancient track, with no claim to be called a road. These patches illustrate the Government method of road-building. All is done by forced labour. A certain length of road is allocated to each town or village in the district concerned, and this the inhabitants are bound to construct themselves, or pay for its construction. The stone-laid patches represent the diligence and promptitude of some villages; the intervals suggest the evasions of work, in the practice of which the Arab is an adept.

The country now becomes more open. The view stretches far in front over the waving grain-fields which have given Haurân its fame. Westward, the rolling downs of Jaulân, the New Testament Gaulanitis, corresponding to the ancient Golan, reach away towards the roots of Hermon, with their beautiful conical hills, once grim smoking volcanoes, now grass-covered to the top; while beyond Jordan we catch glimpses of the Safed hills. To the left, at a somewhat lower level, through a light mist we see indistinctly the dark lava-fields of el-Lejâʾ, and dim on the eastern horizon rises the mountain-range Jebel ed-Druze.

[7]Es-Sanamein, “the two idols,” where we spent the Sunday, stands to the west of the Hajj road. This is a typical Haurân village. The houses are built throughout of basalt, the oldest having no mortar whatever—doors, window-shutters, and roofs all of the same durable material. They have outlived the storms of many centuries, and, if left alone, might see millenniums yet. The modern houses are built from the ruins, the mortar being mud. Carved and inscribed stones that once adorned temple or public building may often be seen, usually upside down, in these rickety new structures. Many houses are fairly underground, being literally covered with rubbish, accumulated through the long years, as generation after generation grew up within these walls and passed away. One temple, built also of basalt, is well preserved, the ornamentation on pillar, niche, and lintel being finer than most to be seen in Haurân. A Greek inscription[1] tells us that this temple was dedicated to Fortuna. An olive-press occupies the centre of the temple. Near by a large water-tank is connected by channels still traceable with an elaborate system of baths. The ancients loved these more than do their degenerate successors. Several tall square towers are evidently of some antiquity; but awkwardly placed hewn stones, certainly taken from other buildings, show them to be modern compared with the city whose ruins lie around.

The doctor’s name is a passport to favour all over[8] the land: Christian, Moslem, and Druze, however fanatical, have ever a welcome for him. His presence brought a perpetual stream of afflicted ones. The people are in many respects simple and primitive. Myth and mystery grow and flourish among them. Most extraordinary tales are told, and accepted with unquestioning faith. The traveller who goes thither leaves modern times behind, sails far up the dark stream of time, and lives again in the dim days of long ago.

Grateful patients sang the doctor’s praise and celebrated his skill. From lip to lip the story and the wonder grew. Some with sore eyes had been relieved. By and by we heard that a great doctor had passed through the country, who took out people’s eyes, opened them up, washed them thoroughly, and replaced them in their sockets, when the aged and weak-eyed saw again with the brightness of youth!

These lands offer a tempting and promising field for the medical missionary. His profession would act like magic in securing entrance to the people’s homes and confidence. And it is practically virgin soil. He would build on no other man’s foundation.

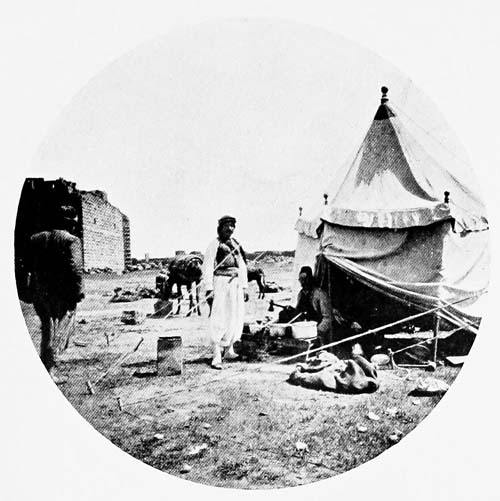

THE COOK’S TENT

About sunset the owner of a flock from whom we wished to buy a lamb was brought to our tents. The flock was sheltered only a little way from the village, but, as the shadows deepened, he displayed no little unwillingness to go thither. At last, armed with sword, musket, and pistols, and accompanied by one similarly accoutred, he sallied forth, not without signs of alarm. Soon he returned, the[9] lamb under his arm, and looks of evident relief on his face. Neither fear nor relief was without reason. In that lawless land, he who goes abroad after sundown takes his life in his hand. Even the hardy shepherd, with tough, well-knit frame, fed on the milk of the flocks, exercised in the invigorating air of the uplands, used from infancy to face the dangers of the solitary wilderness by day, trembles until his knees knock together at the thought of falling into the hands of the enemy who lurks privily for him in the dark.

From es-Sanamein two tracks branch off, one to the east, the other to the west of the Hajj road. The former leads down to the villages on the borders of el-Lejâʾ; the latter to Nowa, Sheikh Saʿad, and el-Merkez, the last being the seat of the Governor of Haurân, who is also military commander in the province. The main part of our company went eastward. Two of us turned towards el-Merkez to visit the Governor, who had been ordered by his superior in Damascus to show us what attention and kindness might be possible. Our arrangement was to meet at night by a city in the south-west corner of el-Lejâʾ, whence we hoped to penetrate that forbidding region. We rode down a ruin-covered slope, on a paved road—monument of the wise old warrior Romans, and crossed, by an ancient bridge, the little brook which, fed by springs on the southern slopes of Hermon, affords a perennial supply of water. The bridge, having served men for centuries, now failing, is almost dangerous to horsemen. A few stones and a little[10] mortar judiciously applied would quite restore it. But where shall we find an Arab with public spirit enough to do that from which another might reap benefit?

Here we entered the far-famed grain-fields of Haurân. What magnificent stretches they are! These vast plains of waving green, here and there tending to yellow, were our wonder and delight for many days. Such land as this, with rich, dark soil, yielding royally, might well sustain a teeming population. Often, in the West, had I watched the interminable strings of camels, laden with wheat, on all the great caravan roads leading from the east to Acre, the principal seaport, and mused as to whence these well-nigh fabulous streams of golden grain should come—from what mysterious land of plenty. Now I could understand it all. As that scene opens to view, visions of the future inevitably rise—but even in fancy one cannot easily exhaust the possibilities enclosed in these generous plains. What it once was, as attested by grim ruins around—a land studded with beautiful cities and prosperous villages—that, at least, it may be again. We see what it is under the hand of the ignorant peasant, with antique methods and implements of husbandry. Who shall say what it might become with enlightened care? This is of special interest now, when the eyes of the world are turning toward Palestine to find a home for the descendants of the men to whom long since it was given by God. Far more of the land in western Palestine than appears to the passing[11] traveller would bear heavy crops of grain; while of the remainder, although much was probably never cultivated, there is very little which, in the hands of patient, industrious people, might not be made to yield fair returns. Evidence of the wealth and immense possibilities of the soil of Bashan meets one on every hand.

As the eye wanders over the wide green expanse, the thought naturally arises, whence the reapers are to come who shall gather in the harvest; for the population, as represented by the little villages seen at long intervals, is certainly quite inadequate to the task. Should the traveller return six weeks hence, he will find the whole country alive. Men and women, youths, maidens, and little children, come trooping up from the deep depression of the Jordan valley; reapers pour down in streams from the mountain glens. And right swiftly must they ply their task; for soon the burning suns and hot winds of the desert will drive the wild Beduw and their flocks hither in search of pasture and water, when woe betide the owner of unreaped or ungathered grain. The robber bands that afflicted the patriarch Job in these same fields, according to local tradition, have worthy successors to-day in the bold wanderers from the sandy wastes.

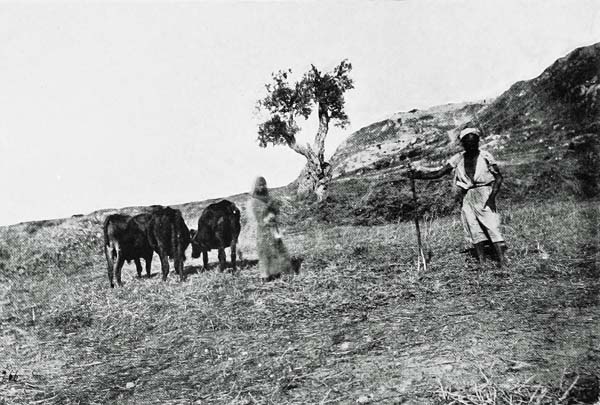

No scythe ever flashes among the bending heads of wheat and barley here. Everything is reaped with the hook—not changed in form, I should say, for at least three thousand years. Faithfully, too, is the law befriending the gleaners observed; and many a[12] golden armful is carried off at evening by modern Ruth, widow and orphan, to store in the clay vats that stand in the corners of their little houses, against the cheerless winter days. When the grain is cut, it is swiftly gathered into heaps on threshing-floors, in the neighbourhood of villages or other protected spots, ready for the “treading out,” the process that still stands for threshing here.

Donkeys and camels are the carrying animals chiefly employed in the fields. They are constant companions everywhere, even in the desert, where the former has almost as good a claim to the honourable title “ship of the desert” as his better-known comrade. The grain is bound in bundles of equal weight, one of which is tied on either side, over a broad, wooden saddle. Seen in motion from a little distance, the animals are quite concealed: they seem like so many animated “stacks” making their way home. Reaping and gathering are soon accomplished, but threshing and winnowing are tedious. The most primitive methods are still employed. Round each heap the ground is covered about knee-deep with grain, and over this, round and round, oxen or horses are driven, trampling it under foot; or the old tribulum, a strong piece of board, with small stones fastened in its under surface, is drawn, until the straw is beaten small and the wheat or barley thoroughly separated. This is then drawn aside, and a second supply, taken from the grain-heap, treated in the same way. The process is repeated until all has been thus reduced. Winnowing is done only when there is sufficient wind[13] to “drive the chaff away.” Then the new heap of threshed stuff is attacked with a wooden fork of three prongs and tossed high in the air. The grain falls at once, forming a heap beside the workman, while the chaff or crushed straw is blown into a bank farther off. This may be repeated several times, until the wheat or barley is quite clean. Then it is put into goats’-hair sacks, ready for transport, since only a fraction of what the land produces is used in the country.

Indeed, it is but little of anything that the poor husbandman has, in the end, for his labour. The Government tax is a first charge upon the entire crop. A tenth is the legal proportion to be paid to officials. But the season for the collection of ʿashâr, or tithe, is often one of oppression and terror for the wretched villagers. Soldiers are quartered upon them, who practise all manner of excesses at the expense of their poverty-stricken hosts; and scenes of violence and rapine are all too common. The tithe has often to be paid over and over again to purchase peace. There is no other way; for if the despised fellah lifts his voice in protest or appeal, there is no ear to hear and none to sympathise. He can only thus bring down the iron hand more heavily on his own head. Of what remains, he must sell the most. But in the country there are no buyers; he must needs send it to the coast or sell it to agents for shipment abroad. Camels afford the only means of transport, and the cost is ruinous. A camel-load consists of two bags, and one of these must go to pay the hire of each camel. Only[14] half thus remains to be sold at Acre in the name of the grower; and happy is the man who receives from cameleers and agents all his due for this miserable remnant of his harvest.

What would our western agriculturists say to such conditions as these? Who can wonder if the people are utterly heartless, having neither spirit to cherish dreams of improvement nor courage to give them effect? What wonder if the thief and the robber increase in a land where honesty and industry are so severely punished? One can see what an incalculable blessing the opening up of this country by rail should be, putting it into connection with the outside world, and bringing all the civilising influences that elsewhere follow the wheels of the steam-engine. What the result will be remains to be seen. Should Israel come back with the returning tides of civilisation, he will find the land almost like an empty house, waiting for the return of its tenants. The scanty population would heartily welcome the advent of masters who could both instruct them in improved arts of husbandry and protect them against unrighteous exactions and oppressions.

TREADING OUT THE CORN

The black remains of Nowa cover a large area. In its essential features the village resembles es-Sanamein, but lacks the relief afforded by the temples. A few fragments of ancient sculpture and architecture are scattered through the village, which also boasts a large tower, its most conspicuous feature, corresponding to those at es-Sanamein. Some have sought to identify Nowa with Golan, the ancient city of[15] refuge. It commands a wide and beautiful prospect over the district for which Golan was appointed; beyond this there appears to be no reason for the identification. The place is associated in local tradition with the patriarch Noah. Whether the name was derived from this association or vice versa, who shall now determine? In any case, the grave of Noah is pointed out, a little to the north-west of the present village,—which suggests the reflection that, if we are to trust tradition, these old worthies must have been often buried; for I have stood by another grave where Noah was buried, and that at no little length, near Zahleh in Mt. Lebanon. The grave is many yards long, and even then, it is said, the patriarch’s legs are doubled down. The mother of our race, also according to the Moslems, lies within sound of the Red Sea waves, in the sacred soil of el-Hejaz, while the Jews with equal earnestness maintain that she sleeps beside Abraham and Sarah, with Adam, within the holy precincts of Machpelah. The prophet Jonah has tombs almost anywhere, from Mosûl to the Mediterranean Sea.

Arab courtesy—Sheikh Saʿad—Egyptian monuments—Traditions of Job—El-Merkez—Religious conservatism—Holy places—Sheikh Meskîn—A ride in the dark—Zorʿa—El-Lejâʾ.

One trait in Arab character must appear to strangers peculiar—the general unwillingness to say anything to a man’s face which may be unpleasant. Truth may be stretched far beyond vanishing-point to avoid this. The results to the stranger are often unpleasant enough. If the traveller, still distant from his destination, ask one whom he meets how far he has to go, he may be told that in half-an-hour, or an hour at most, he will be there, when he may still have six or seven hours before him. The object is to make the traveller mabsût, or pleased, with the reply. Truth is sacrificed for a moment’s pleasure,—typical of how much of the Arab’s improvident life. On the other hand, if the destination is nearly reached, the traveller may be told it is hours away, that so he may be “much contented” to find himself suddenly there. We soon found that the only trustworthy means of learning the distance of a place was to go there.

Sheikh Saʿad and el-Merkez are both seen from[17] Nowa. A stretch of almost level ground, soon covered at a smart gallop, we begin threading our way through the rocky flats surrounding the eminence on which the old village stands. We are in the very thick of the memories of Job, which linger more or less over all Haurân. On the southern shoulder of the little hill stands a small white-domed building, covering the spot, saith tradition, where Job sat during his afflictions. This contains “Job’s Stone,” a large block which Dr. G. Schumacher discovered to be an Egyptian monument, with a figure of Ramses II. Some years later Prof. G. A. Smith found at Tell-esh-Shehâb a stone with the cartouch of Sety I., the father of Ramses II. These are the only two Egyptian monuments yet known in Haurân. Immediately below is the Hammâm Eyyûb, “the bath of Job,” where the man of patience is said to have washed when he was finally healed. The waters are held in high estimation by the country people as possessing marvellous healing virtue. Sweeping round to the right, we pass through the modern village, where a singular scene presents itself. Throughout all Syria and Arabia, one often meets the ʿabîd—“slave,” as every negro is called—but here only is a village community entirely black to be seen. At the sudden apparition of black faces and limbs, one might almost fancy himself transported to some strange hamlet in the Sudân. For these are Sudanese, whose parents and grandparents were brought hither, in the early days of the nineteenth century, by Sheikh Saʿad, of pious memory;[18] and as yet they have kept their lineage pure. The change was a delightful one, from the sandy burning wastes of their native land to this sweet vale, which, with its lines of olive, groves of fruit trees, and musical ripple of cool water, must have seemed almost a paradise to those who had known the thirsty desert. It was inevitable that such a benefactor as their leader should be enshrined in grateful memory. We are not surprised to find him canonised, and the fruitfulness of the place ascribed to his saintly blessing. Thus, in these latter days, has the patriarch found in the modern saint a rival in popular regard; the dark man thinking little of Job and much of his own Sheikh Saʿad, while the native fellah, overborne by the majesty of hoary tradition, bows in reverence before the old-world saint, esteeming the village sheikh a mere upstart. Chiefly round the banks of the little stream are the rival honours canvassed; for this has been regarded, from of old, as the gift of the patriarch of Uz, and now it is attempted to reverse the verdict of the grey centuries in favour of one who is revered only by a handful of immigrant ʿabîd (“slaves”). But who that knows the religious idiosyncrasies of the Arab will venture to say how soon the modern sheikh may not find a place in the Arab Valhalla? Sheikh Saʿad’s grave lies to the west of the village.

The appearance of el-Merkez is deceptive. Red tile roofs, rising above the foliage of surrounding trees, are associated in our minds with the comfort[19] and cleanliness of the West. And verily, were the hand of civilisation here, nothing is wanting in nature to make a pleasant village; but, alas! here is only the mailed hand of the Turk, which seems to crush while it protects, to ruin even while it builds. A sharp canter along a soft green meadow brought us to the entrance of a new street, partly paved. Young fruit trees were planted confusedly around; and over to the left, on open ground, in front of their green tents, a company of Turkish soldiers were engaged in drill. Much of the village is new; but the building is poor, and the houses have already assumed the dreary, untidy aspect common to the Arab village. Deir Eyyûb, “the monastery of Job,” covers an extensive area, but is now almost entirely ruinous. The Moslems claim the honour of its erection, but it certainly existed centuries before the prophet of Arabia was born. Part of the monastery is used as a barrack, and, close by the gate, another part contains the post and telegraph office. To the west is Makâm Eyyûb, where the reputed graves of Job and his wife are shown. In the early centuries of our era, the Christian inhabitants were wont here to celebrate an annual “Festival of Job.” The antiquity of the tradition connecting the place with the patriarch’s name is beyond all question. Dr. Schumacher found in the neighbourhood a place called by the common people “the threshing-floor of Uz.” The towns whence came Job’s comforters have been traced in the names of existing hamlets or ruins; notably Tēmā, the home of Eliphaz,[20] in the northern end of Jebel ed-Druze, two days’, or perhaps only one long day’s, journey eastward.

The Governor himself had gone on a tour of inspection through the towns of Gilead; but his wakîl, or representative, treated us with all courtesy, furnishing us with letters to the subordinate officers in the province, and drinking coffee with us to seal our friendship. We entered one of the least forbidding of the hovels in the bazaar, seating ourselves on upturned measures or logs of firewood. After negotiations with the host, there were set before us on the earthen floor a pan with eggs fried in samn—clarified butter, universally used in cooking—coffee in a pot remarkable for blackness, brown bread not free from ashes, milk, and pressed curd, which passes for cheese. During the progress of the repast, soldiers and natives came, in turns, to view the strangers; probably also with the hope of sharing the coffee. Wondrously acute is the Arab’s perception of the odour of coffee, and swift are his feet in carrying him to it. Coffee-drinking, and more especially tobacco-smoking, consume a large proportion of the Arab’s time. What a vacant life theirs must have been before the introduction of the fragrant weed! This latter now grows profusely all over the country. The coffee-beans of el-Yemen are esteemed superior to all others.

Mounting again, we turned our faces eastward. Not far from el-Merkez we found a copious cool spring, into which our horses dashed with delighted eagerness. Then we galloped away over a beautiful[21] country of rounded hill and soft vale, cultivated plain, and slopes of sweet pasture; anon our horses plunge to the saddle-girths in the stream that sheds fertility over wide acres. Far before us spread the rolling downs of Haurân, dotted all over with ruined towns and villages, like dark rocks amid the verdant ocean, that swayed in the spring breeze. Here and there were seen the Moslem weleys—little square buildings with white domes, sacred as covering the last resting-places of reputed saints. One of these we passed, perched on what must have been in times past a strongly fortified hill. A stream washes the foot of the mound, and on the opposite bank the music of a water-mill greets the traveller’s ear. These weleys or makâms—“places” of the saints—witness to the marvellous continuity of religious thought and association in Eastern lands; for there is no doubt that most of these, situated as they are on high ground, are simply survivals of the ancient “high places,” frequented by the inhabitants before the dawn of history, against which in later times the prophets raised their voices, taken over bodily by the religious system of Islâm. To these, at certain seasons, pilgrimage may be made by the faithful for prayer, in the belief that the spirit of the saint thus appealed to will by intercession secure an answer. But with the growing disposition to avoid all that savours of inconvenience, or that, lacking ostentation, brings no immediate credit to the performer among his fellows, such pilgrimages are now infrequent.

But the makâms are not without use. In lawless,[22] unsettled lands it is well to have some spots where property may be safe. What is placed under one of these domes even the most abandoned will hardly dare to touch, so strong is the superstitious dread of kindling the saint’s wrath, whose protection has been thus invoked. In each of these a grave is found, with one marked exception. There are numerous weleys in the East, dedicated to el-Khudr—“the immortal wanderer,” variously identified with St. George and the prophet Elijah. He is not dead, therefore he has no tomb; these are only his resting-places in his ceaseless wanderings to and fro upon the earth, destined once again to appear, declare all mysteries, and right all wrongs. Strange, weird tales are afloat of lights kindled by no mortal hand, appearing in these lonely weleys by night, and fading away with returning dawn. Then it is known that the Lord Elijah has visited his shrine, and passed forth again on his invisible circuit.

It is interesting to note the methods of measuring time adopted by those to whom watches are still unknown. We asked the miller how far it was to Sheikh Meskîn, or Sh-Meskin, as the natives call it. “You will go there,” he said, “in the time it takes to smoke a cigarette.” This is a common expression to denote a short time. It is like a flash revealing the extent to which cigarette-smoking prevails among these benighted peoples. Even in the remote wilds of el-Lejâʾ we found the little coloured boards with elastic bands in which the white cigarette paper is secured, no other signs of civilisation being seen, save[23] the weapons carried. It is a sad reflection that these are the only heralds of her approach our boasted civilisation sends before her into these darker places of the earth.

Sheikh Meskîn is a large village, with many ancient remains and Greek inscriptions, situated on the western side of the Hajj road. Notwithstanding the cordial invitations of the inhabitants to stay with them until the morrow, for “the day was far spent and night was at hand,” we were constrained to press onward to Zorʿa, where we knew our party must be awaiting our arrival, not without anxiety. Crossing the Hajj road, and wading deep pools in the bed of a winter stream which passes the village, we struck again through the fields, nearly due east, and over a beautifully rounded hill which seemed literally groaning under the heaviest crop of wheat I had ever seen. From the summit we saw across a narrow valley the border of el-Lejâʾ, within which, in the fading light, we could distinguish the outlines of Zorʿa. A low rocky hill, rising abruptly from the valley on the side next el-Lejâʾ, is crowned by a little village. This we knew to be Dhuneibeh, owned, with its lands, by a wealthy citizen of Damascus, a Christian; occupied entirely by Christians—Greek, of course—who cultivate the soil for him. Ere we reached the village the sun set, and a moonless night closed around us. Here we were overtaken by a soldier magnificently mounted and thoroughly armed. The kindly colonel at Sheikh Saʿad, fearing that dangers might beset us in the darkness, ordered the horseman[24] to follow, and see us safely to our destination. His fine horse, notwithstanding his rapid journey, showed not one drop of perspiration; and for his wonderful instinct in keeping the way in the dark we had soon reason to be thankful. Our road led over the mound, past Dhuneibeh—a most difficult ascent, and no easier descent, by reason of the unequal rocks, which we could no longer see. This is a great danger in travel by night over volcanic country. All is black under foot, and the path cannot be distinguished from its surroundings. The hospitable sheikh would have us await the first light of breaking morning; but finally, with many warnings to be on our guard, he gave us a guide who should conduct us past the immediate dangers of open ditch and cistern around the village. Even he lost the way several times in this short distance.

When we emerged from the labyrinth, the soldier’s noble horse took the lead. His feet once fairly in the road, he went swiftly forward, and without a moment’s hesitation conducted us triumphantly to our journey’s end. At times we were cheered by seeing a light swinging away in the darkness, which we felt sure our friends had hung out to guide us. Occasionally we lost sight of it behind intervening obstacles, and, when seen again, owing to the windings of our path, it appeared to be now on this side, now on that, and but for observing the position of the stars we might have been perplexed. What a blessing these glorious luminaries have been for ages to the desert wanderer! As one gazes upward into[25] the clear Syrian sky, beholding them in all their splendour, he is forcibly reminded of Carlyle’s graphic sentences: “Canopus shining down over the desert, with its blue diamond brightness [that wild, blue, spirit-like brightness, far brighter than we ever witness here], would pierce into the heart of the wild Ishmaelitish man, whom it was guiding through the solitary waste there. To his wild heart with all feelings in it, with no speech for any feeling, it might seem a little eye, that Canopus, glancing out upon him from the great, deep eternity, revealing the inner splendour to him. Cannot we understand how these men worshipped Canopus,—became what we call Sabeans, worshipping the stars?” But the difficult threading of one’s path among basaltic rocks, with the howlings of wolf and jackal around, varied with the higher treble of the hyena, are not conditions favourable to such meditations. The district, moreover, has an evil reputation for quieter but more dangerous foes. It was with feelings of satisfaction that we found ourselves under the battlements of the old city of Zorʿa. Messengers came with lanterns to meet us, without which I know not how we should have avoided the pitfalls that surrounded the last part of our way. With no little thankfulness the whole company met again around the table in our tent, to recount and hear the adventures of the day.

WILD ISHMAELITISH MEN

Our friends had enjoyed a pleasant ride along the border of el-Lejâʾ; nor had their day been quite without adventure. In crossing a stream of some depth, one rider was treated to an involuntary bath—his[26] horse suddenly plunging down and rolling over. Happily no harm was done. It is not easy in such circumstances to preserve dignity on the one part and gravity on the other. Our friends, however, were quite equal to the occasion, and what might have been an awkward incident was soon a subject of pleasant jest to all concerned. But the occurrence indicates a real danger, of which the traveller ought to be aware. Walking in the great heat, with constant perspiration, if the saddle is not a good fit and skilfully padded, the horse’s back is easily fretted and wounded. Then the animal naturally seeks relief when a chance comes, by rolling over and trying to remove the offending saddle. If the rider is in his seat, it may go hard with him. In passing through water there is a peculiar temptation to cool the injured spot by plunging down.

We awoke next morning to find ourselves fairly within the limits of el-Lejâʾ. This is a tract of country famous from of old as a refuge for fugitives from law or justice. And no better land could be desired for this purpose. El-Lejâʾ is equivalent to meljâʾ—the word most commonly employed—and means a retreat or refuge. A more savage and forbidding rocky wilderness it would be impossible to imagine. It probably answers to Trachonitis of Josephus and the New Testament. Some have sought in it also the “Argob” of the Old Testament; but this identification is extremely precarious. Argob can hardly be rendered “stony.” It seems rather to indicate rich arable soil, and the district is now generally located[27] to the south-east. “Chebel Argob” is the invariable biblical phrase, and “Chebel” would here be peculiarly appropriate. The word signifies primarily “a cord,” then a measuring-line, then a district marked off as by a measuring-line, like a tribal portion, the boundaries being well known. This vast lava outbreak terminates abruptly all round in the fertile plains, almost suggesting the idea of a gigantic cord, drawn right round, marking it off distinctly from the surrounding country. It is admirably adapted for defence, and its capacities in this respect have been put to stern trial in many a hard-fought battle. The attacking force is completely exposed to the defenders’ fire, the latter being as entirely sheltered. Often has a handful of men held the place against numbers which, in other circumstances, it would have been supreme folly to oppose. Notably was this the case when the celebrated Ibrahîm Pasha, the Egyptian, led his hitherto unconquered veterans to the attack, and was ignominiously repulsed by an insignificant company of Druzes. Within these adamantine walls, until quite recently, the Government was impotent; nor can we say its power is yet great. The suspected criminal, be he innocent or guilty, if he can only outstrip his pursuers and cross that rugged coast, will find a surer retreat than the Cities of Refuge ever afforded in ancient days. Among the inhabitants he will receive an unquestioning welcome. There he may dwell secure until a messenger of peace comes to call him again to home and friends, or until the King of Terrors summons him away.

[28]Before us lay the ruins of a great old-world city, with much to declare its ancient splendour. Zorʿa is held by many to be the city Edrei, in the neighbourhood of which Og, king of Bashan, and his people met their crushing defeat at the hands of Israel. While I am disposed to favour its more southern rival, Derʿat, the claims of this city cannot be lightly passed over. It has been a position of great strength, and, lying on the border of the huge natural fortifications of el-Lejâʾ, the country’s central citadel, it is not unnatural to suppose that this spot may have been chosen for the last desperate struggle with the victorious invaders. This city taken, foothold would be obtained within the great fortification itself—a basis for further operations against it. The defenders demoralised by this piece of singularly evil fortune, it fell a prey to the enemy, as it is safe to say it never has done since. The ruins of the city have often been described, in so far as they can now be seen; but much lies buried many yards deep under accumulations of debris. When the excavator shall have rescued ancient structures from their dark tombs, much may be learned regarding the city’s past, of which so little now is known.

The soldier who followed us the previous night would have gone with us in any other direction, but one foot farther into el-Lejâʾ he would not move. We were told that his uniform would act, on Arab and Druze alike, as a red rag acts on a bull. We had great difficulty in finding a guide. Between the Druzes of the interior and the Christians around there is naturally little affection; there is less love,[29] if possible, between the former and their Moslem neighbours. Blood feud’s are common; and here the pursuit of the “avenger of blood” is no mere ruse, as it often is elsewhere, to extract money or goods from the tribe or village of the offender, but an earnest seeking for vengeance. Blood for blood is the law; and if the actual manslayer cannot be found, any one of his tribe or village may be taken. This explains the difficulty travellers often have in finding suitable guides. Men do not care to be seen far from their own homes and comrades. Our difficulty was finally overcome, partly by the promise of handsome payment, partly by the exercise of the sheikh’s authority on our behalf; and at last a sturdy Arab, shouldering his club, stalked away over the rocks before us, under bond to conduct us safely to the Druze village, Damet el-ʿAliâ.

A landscape of lava—Deserted cities—Caverns—Cultivation—A land of ruins—The guide’s terror—Damet el-ʿAliâ—The sheikh’s welcome—A state of siege—An ugly incident—Druze hospitality—Arab and Druze in el-Lejâʾ—St. Paul in Arabia—The well of the priest—Story of the priest.

From Zorʿa our course lay north-east by east, and we hoped on the way to pass more than one ruin which should tell of the ancient glory of el-Lejâʾ. What a wild solitude it is! Far on every hand stretched a veritable land of stone. The first hour or two of our march no living thing was seen. Even the little ground-lark, which hitherto we had seen everywhere, seemed now to have deserted us. Wherever we looked, before us or behind, lay wide fields of volcanic rock, black and repulsive, swirled and broken into the most fantastic shapes; with here and there a deep circular depression, through which in the dim past red destruction belched forth, now carefully walled round the lip to prevent wandering sheep or goat from falling in by night. The general impression conveyed was as if the dark waters of a great sea, lashed to fury by a storm, had been suddenly petrified; as if the fierce lineaments of the[31] tempest, and all its horror, had been caught and preserved forever in imperishable rock by the hand of a mighty sculptor.

At times we passed over vast sheets of lava, which, in cooling, had cracked in nearly regular lines, and which, broken through in parts, appeared to rest on a stratum of different character, like pieces of cyclopean pavement. Curious rounded rocks were occasionally seen by the wayside, like gigantic black soap-bubbles, blown up by the subterranean steam and gases of the active volcanic age, often with the side broken out, as if burst by escaping vapour; the mass, having cooled too far to collapse, remained an enduring monument of the force that formed it. Scanty vegetation peeped from the fissures in the rocks, or preserved a precarious existence in the scanty soil, sometimes seen in a hollow between opposing slopes. In a dreary, waterless land, where the cloudless sun, beating down on fiery stones, creates heat like that of an oven, it were indeed a wonder if anything less hardy than the ubiquitous thistle could long hold up its head.

We passed several deserted cities, built of the unvarying black stone, and surrounded by strong walls. Many of the houses are still perfect, and seem only waiting the return of their inhabitants. In one of these towns we found a church. It may be about fifty feet in length by about thirty feet in breadth, and is built in two stories, the roof of the first being composed of lava slabs, many of which are still in position. A Greek inscription containing the[32] name of Julios Maximos probably fixes its date about the time of Philip the Arabian. These walled towns were doubtless places of considerable strength in ancient days, and their stone gates may once have been secured by bolts and bars of brass. But, in the largest of them, not more than about four thousand inhabitants could ever have been comfortably housed. If this is remembered, it may aid towards correct impressions of the “cities” taken by the Israelites, and of the exploits of the warrior Jair.

There is not a stream or a perennial spring in all el-Lejâʾ. The water supply of its ancient and even of its present sparse population has therefore long been a subject of wonder. Near one of these towns by the wayside, we saw what probably suggests the solution of the mystery. This was a large natural cave, the roof partly broken through, and underneath a deep hollow in the rock, now brimming over with water from the winter’s rains. It would have been next to impossible to pierce that hard rock with cisterns numerous and large enough to afford refreshment and water for other necessary purposes to man and beast. The work was not required. Nature had provided liberally herself. This cave may be taken as a type of the natural reservoirs in which this formation abounds. Josephus tells of the caves in Trachonitis, inhabited by robber bands and wild outlaws, whose inaccessible retreats secured immunity from punishment. No modern traveller has seen these; but this is not strange, for the few who have ventured within the borders of el-Lejâʾ have not been[33] too curious in examining the wilder and more remote parts. The natives, however, know them well, and would resort thither in times of stress or danger. Indeed, some say that under the rough surface rocks it is nearly all hollow; so that one acquainted with the labyrinth could go from one end to the other of el-Lejâʾ and never once show his head above-ground. From all this it is evident there is no lack of accommodation for storage of water; and, considering the quantity of rain which falls in its season, it would be a long drought indeed which would exhaust the supplies.

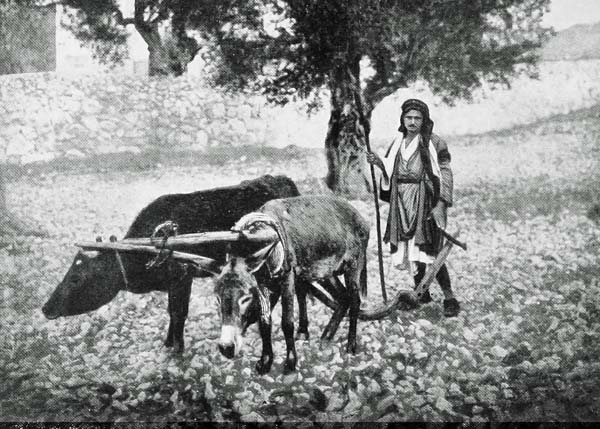

PEASANT PLOUGHMAN

(Photo. The Photochrome Co. Ld.)

From this point onward the little openings among the rocks grow larger and occur more frequently. Our little friend, the lark, appears again; and the voice of the partridge and the whir of his wings, to right and left, relieve the dull monotony. When the traveller has fairly penetrated the rough barriers that surround el-Lejâʾ, he finds not a little pleasant land within—fertile soil which, if only freed a little more from overlying stones, might support a moderate population. In ancient times it was partly cleared, and the work of these old-world agriculturists remains in gigantic banks of stones carefully built along the edges of the patches they cultivated. The hands that laid these courses have been cold for ages; the lichens have crept slowly over all, adorning the home of multitudinous snakes and lizards, now long held by its reptile tenants in undisturbed possession. These wise old husbandmen have had no worthy successors. The neighbouring rocks that echoed to[34] the sower’s eager tread and the reaper’s merry song lie under brooding age-long silence, broken only by the voice of the wild game, the cry of the solitary shepherd, or the bleat of the browsing herds. But here, as so often, generous Nature comes with a fold of her loveliest garment to hide the neglect of men. These patches were everywhere blushing with fair anemones and great ranunculi, which, seen in the distance, often appeared like a soft crimson haze, showing beautifully against the black of surrounding lava. The cyclamen, already past on the other side of Jordan, still clung to the clefts in the rocks; and the most delicate little irises were blooming in the interspaces, as if to soften with their sweet beauty the harsher aspect of the savage wilderness.

From every higher eminence we could trace, near and far away, the outlines of numerous ancient towns and villages. Nearly all are utterly deserted and desolate, haunts of wild beasts and birds of night. Here, and in other parts, we were deeply impressed with the fact that we were travelling through a land of ruins. How eloquent are these solitudes with lessons of warning for the great world of to-day! It would have been as difficult for the dwellers in these towns, and in the magnificent cities of the neighbouring country, to conceive of the “stranger” one day coming from “a far land” to walk through their desolate homes, and over the wreck of their architectural splendours, as it would be for the legislators who sit in Westminster to realise Macaulay’s famous vision of the New-Zealander[35] sitting on the ruins of London Bridge, musing, like the noble Roman amid the ruins of Carthage, on the desolation around. But what has happened once may happen on a much grander scale again; for is it not the doing of the Almighty Himself, before whom all earthly splendour is but as the passing reflection of His own sun’s light on the broken surface of the water? It is but the fulfilment of the wrath denounced by the prophet upon the rebellious and disobedient: “In all your dwelling-places the cities shall be laid waste, and the high places shall be desolate; that ... your works may be blotted out.”

Coming nearer the centre of el-Lejâʾ, fresh signs of the husbandman’s presence were seen. Fields of waving wheat and barley alternated with rough knolls, dotted with furze and thorn, while scattered oaks and terebinths lent variety to the scene. Once, not long ago, large tracts were covered by a forest of terebinth; this has now almost entirely disappeared, the natives finding a ready market for the timber beyond their rocky confines, and the branches serving well for charcoal. This depletion of the forest is greatly to be deplored in a land where trees are such a blessing.

Some distance to the right, on lower ground, lay a town of the usual type, somewhat larger than those we had seen, with a tall square tower rising from the centre. The guide called it Lubbain. Directly in front, crowning a slight eminence, was Damet el-ʿAliâ, where we hoped to spend the night, protected by the[36] hospitable and friendly Druzes. We doubted not of our welcome, and our faith was justified right handsomely by the event.

Another incident, however, was necessary to bring our experience into line with that of other travellers in these parts.

When we came within sight of Dama—so “Damet el-ʿAliâ” is contracted—crowning a little eminence in front, our guide slowed his pace, hesitated, and finally halted. “There,” he said, “is Dama; you can now reach it alone; I must return”; and nothing could induce him to move one step nearer the village. We would have had him see us safely there in fulfilment of his contract. But fear was written on every line of his face, so we were fain at last to give him his money and let him go. At once his countenance brightened, his frame became all energy and sprightly motion. In about three minutes he was out of sight. A horseman, fully armed and well mounted, swept down from the gate of the town, and, halting at some little distance, surveyed our party. His soldierly eye was soon satisfied that we were bound on no military exploit, and he came forward frankly to bid us welcome. For the entertainment of his guests he careered around, affording a fine exhibition of horsemanship. He proved to be the son of the sheikhly ruler of Dama; so we were already under the protecting influence of the Druze inhabitants—the sheikh’s guests being the guests of all, among the dwellings of all his people. Stalwart, white-turbaned Druze[37] warriors came down from the roofs, whence they had watched our approach, to second the welcome of their chief’s soil, and accompany us to the sheikh’s house. Thus we entered Dama, which early in the nineteenth century was the reputed capital of el-Lejâʾ. It is still the chief of inhabited towns not situated on the borders, but now the proud title of capital would be a misnomer. It is the most central of all towns in el-Lejâʾ. From its high position it commands a wide view, extending almost to the borders in every direction—a prospect not the less interesting because seen so seldom by European eyes. Enterprising travellers, one or two, may have been here in past years; but probably now for the first time ladies from the civilised West penetrated thus far into this famous but forbidding land.

The sheikh advancing, offered the heartiest of welcomes. He bade his subordinates attend to our horses, and with great dignity led the way under his hospitable roof. His house was most substantial, built of large basaltic blocks, well fitted, without mortar. The roof was composed of great slabs of the same material, covered with earth. The floor was earthen, with a hollow in the centre where blazed a great wood fire. What of the smoke passed our throats and eyes escaped by the door and a small opening in the opposite wall. A rude wooden door took the place of the ancient slab of stone, which might be seen forming part of the pavement in front.

We found a baitâr, or farrier, deftly plying his[38] hammer at the sheikh’s threshold, making the nails which should hold the shoes of the village horses in place until another wanderer should come to make a new supply. These men, and occasionally the makers of the red shoes and flimsy long boots worn by the Arab, are often met in the remotest parts, making long journeys even into the unkindly desert, in search of livelihood for wife and little ones, left far behind in the shelter of their native towns.

Ushered into his dwelling, we sat upon straw mats spread on the floor, and leaned against straw-stuffed cushions arranged along the walls. Delicious buttermilk was brought to refresh us; also cool water to drink, and to wash withal. The good sheikh and his sons sat down on the floor, and busied themselves preparing coffee for their guests. This beverage is universally offered to the visitor on his arrival; but, while in western towns it is made by domestics, its preparation is an accomplishment held in high esteem among the sheikhly families of Druze and Arab. Those who are liberal with their coffee are called “coffee sheikhs”—a name held in honour, and much coveted by men of high spirit and generosity. A handful of coffee-beans was put into a large iron ladle, which, resting on a small tripod, was held over the fire. The beans were stirred with a strip of iron, attached by a light chain to the ladle handle. When roasted to a rich brown colour, they were put into a large wooden mortar, brass-bound, and pounded with a hard-wood pestle, which resembled the heavy turned foot of an arm-chair. With marvellous precision the[39] youth who wielded the pestle raised it over his shoulder and struck fairly into the centre of the mortar. No little training and skill are necessary to beat such music from dull instruments as he produced with pestle and mortar, the pleasing cadences varying with the different stages of the process. The music of the pestle is esteemed as great an accomplishment as that of guitar or violin among ourselves. The fine brown powder was ready for the pot; a flavouring berry of cardamom was added, as a distinguished mark of honour; hot water poured on, it was left for a little to simmer by the fire. The first cup was thrown upon the fire as a libation to the tutelary spirit of the house—an interesting survival of old superstitious rites. A second cup was drunk by the sheikh himself, as an assurance to his guests that they might drink in safety—an assurance not wholly unnecessary in a country where men not seldom die from the effects of “a cup of coffee” adroitly manipulated. Then with his two little cups—about the size of china egg-cups, and without handles—he distributed the strong-tasting dark liquid to each in turn, repeating this a second and a third time as a mark of distinguished honour.

Meantime we were able to observe the general appearance of our host and his friends. The sheikh was rather over middle age, of average stature. His frame was well knit and athletic. The sandy whiskers, pointed beard, and light moustache left visible the firm, finely-chiselled lines of a face that had something royal in it. He wore the common red slippers; a[40] yellow striped ghumbaz, that reached to the ankles, gathered at the waist with a leathern girdle; over his shoulders was thrown an ʿabâʾ or cloak of goat’s hair, of the characteristic Druze pattern, striped alternately black and white. His red tarbush was surrounded by a thick turban of spotless white. He bore himself with an air of quiet dignity. Of a taciturn habit, he spoke but little. When he did speak his word secured instant attention and obedience. In such a position, constantly calling for wisdom, self-reliance, self-control, swift decision, and energetic action, with any basis of real character, a truly noble type of simple manhood is easily developed.

In the matter of dress, his followers resembled their chief. Every man of them, from the sheikh downwards, was a sort of walking armoury. They literally bristled with lethal weapons. Rifle and sword might be laid aside on entering the house, but the girdle contained pistols and daggers enough to make each man formidable still. The town is an outpost of the Druzes, taken by the strong hand, and maintained against the Arabs only by constant watchfulness and readiness to fight. This explained the careful scouting of us on our approach. For ourselves, however, we had nothing to fear. Since the fateful year in the history of Mount Lebanon, 1860, when the Druzes in their extremity were befriended by the British, every man who speaks English is sure of a cordial welcome among this people.

The Druzes well sustain the ancient tradition of hospitality in these parts. Our host invited the whole[41] party to supper. We were many, and hesitated to accept, lest it might seem imposing on his generosity. He silenced all objections by an intimation that supper was already in course of preparation; and with great thoughtfulness he ordered it to be served in our tents, judging that this would be more comfortable for us. These were pitched in the enclosed threshing-floor, in a hollow north of the village, sheltered from the night winds, which here blow cold, and overlooked by the sheikh’s house.

We had soon further evidence that these men did not carry instruments of death for mere ornament. Two villagers accompanied some of us who went to shoot partridges. We were strictly warned to be home by sunset, but we were yet far off when the shadows began to thicken. Passing over a little hill in the dim twilight, we saw a solitary figure gliding swiftly along the bottom of the valley below. Our two companions unslung their rifles, and, with far-echoing alarum, dashed down the hill in full career upon the stranger. There was no mistaking their purpose. We stood with strange forebodings of evil to follow which we were powerless to prevent. The dark figure halted on hearing the shouts of his pursuers, turned, and approached them. To our infinite relief, they parted peacefully. Our guards, returning, said he belonged to a friendly tribe. Asked what would have happened had it been otherwise, they replied at once, “He should have died as a spy.”

Returning with the fall of night, we found the table spread, and tray after tray of steaming viands was laid[42] out until it literally groaned—for a tent table, ours was strong—under the load. First a lamb roasted whole, then a kid stewed whole in leban, then a great tray of rice cooked with samn (clarified butter) as the Arabs know how, each grain whole and separate. A number of smaller dishes completed the repast, such as stuffed cucumber, kibbeh (a preparation resembling white or oatmeal puddings), leban (the ordinary thickened milk of the country), and bread in abundance. A light of pleasure gleamed in the kindly eye of the sheikh as he saw the ample justice done to his supper by the hungry travellers, whom he encouraged, by every means in his power, to eat and spare not. Loath was he to see anything remain uneaten.

Supper over, the sheikh and his followers set themselves for general conversation. It was particularly noteworthy that no question was asked and no subject started which might have disturbed the equanimity of the guests. It was inevitable that with such warlike spirits martial subjects should be discussed. We were interested in the sheikh’s narration of some of the recent history of el-Lejâʾ. The Druzes and the main Arab tribes in el-Lejâʾ are hereditary foes. The memory of suffering and loss incurred in old strifes rankles in their bosoms, ever urging them to seek revenge. There is chronic blood feud between them. Some time ago the Druzes held only positions near the south-east borders, but, waxing bolder, they advanced and took Dama, then a town utterly deserted. The position being strong, and the neighbouring land[43] fruitful, they thought it worth defending. The Arabs, unwilling to lose so valuable a prize, assembled in force, and, coming down upon the isolated occupants of Dama, were, after a tough fight, victorious. But the Druzes, while they retired, did not relinquish their claim. Securing themselves in the fastnesses in the south-east, they sent messengers through Jebel ed-Druze to rouse their friends, as the Scottish Highlands were roused of old by the fiery cross. These doughty warriors, as much at home in the turmoil of battle as in the peaceful work of field or vineyard, rushed forward in wild joy to redress their brothers’ wrongs. Before the chosen men of the Druze nation the Arab irregulars could make no serious stand. They were defeated and driven away into the inhospitable, stony land to the north-west. In the morning light, straining our eyes in that direction, we thought we could dimly descry their black tents among the hardly less black surroundings. And since that time they have never mustered courage to renew the attack. They might, by a supreme effort, dislodge again the little colony in Dama; but they know the terrible vengeance that would be taken by the bold mountain men.

The conversation was intensely interesting, as, indeed, was the whole situation. These calm, dignified men before us, discoursing on the various chances of war in which they had themselves borne a part, and into which they might soon be plunged again; a head here and there, enveloped in a cloud of smoke from pipe or cigarette; sparkling eyes,[44] glittering in eager faces that grew gradually darker as the lines receded into the night, leaving strange memories behind, when at last the sheikh and his followers went forth and vanished in the darkness.

Only the houses in the north-east of Dama are occupied. The most interesting structure in the town is an old church with Greek inscriptions, in the south-west quarter. Probably it corresponds in date with that we saw on the way. Such buildings are of frequent occurrence. The presence of so many remains of Christian antiquity over all these parts suggests reflections as to the extent to which Christianity had laid hold on the then inhabitants, in the beginning of its world-conquering career. The land enjoyed a second day of grace before the final outpouring of wrath and fulfilment of prophetic doom; and for a time it seems to have been roused to improve its privileges. By what agency was the evangel brought hither? Perhaps we may never fully know. But the Romans proudly styled these regions the province of Arabia; and through this the converted persecutor Saul at least passed, if he did not spend his three years’ sojourn here ere going up, in his new capacity as apostle, to Jerusalem. The reasons for believing that the desert of the exodus was the scene of his retirement are not convincing. It harmonises ill with our ideas of the tireless energy of the apostle, who had just consecrated all his fiery devotion to his Lord, and in the first flush of his new-born zeal had proclaimed the truth to his countrymen in Damascus, to picture him haunting[45] the solitudes, where no ear could hear and no heart respond to the wonder of new-found love and joy which he was panting to express. May not these early years of discipleship have been bright years of missionary activity, more immediately successful than those covered by the record of the beloved physician? And, although their history has long been lost amid the darkness of ages, it is pleasant to think that, when the books are opened on high, the fresh light may reveal another brilliant in the glorious crown of the apostle, to be cast down at the Saviour’s feet.

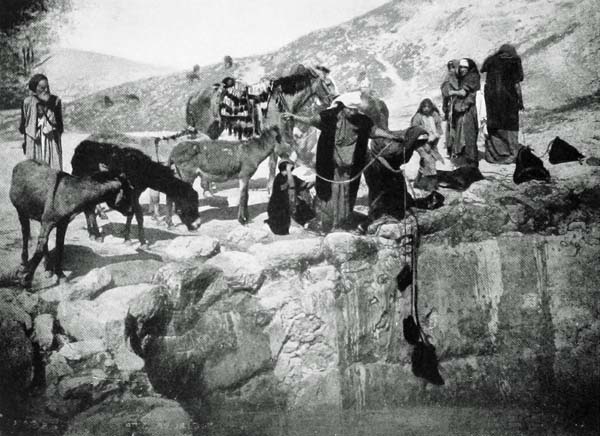

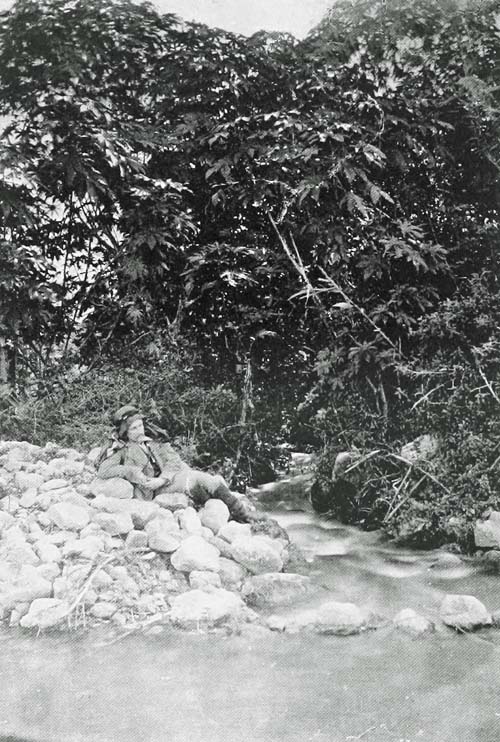

One took a jar and went to fetch water for us to drink. Wishing us to have the best and coolest, the sheikh called after him, “Bring it from the well of the priest.” The name struck me as curious at the moment, but, knowing how persistently ancient names cling to particular spots, and not thinking it at all likely that a “priest” should be found in a Druze village, I thought no more of the matter. Afterwards, however, I heard a story of disinterested self-sacrifice for the sake of Christ which, told of a Syrian, was peculiarly refreshing to a missionary’s ear; and, quite unexpectedly, the sheikh’s words afforded valuable confirmation of its truth. The average Syrian character is the despair of the missionary. Those calling themselves Christians are most disappointing. What time one hopes to see a spirit of self-forgetfulness developing, and a disposition to give the best of life and ability to Christ’s service, among the strangely varied peoples of Syria, he will probably be surprised by a request for some personal[46] favour or advancement. There are noble exceptions, of course, and I have known some, acquaintance with whom forms a permanent enrichment of life. It is well to remember, too, that the conditions in Syria are peculiar. Cut up as the population is into so many little communities, it is the very home of religious fanaticism. The mutual repulsions existing among these sections are terribly strong, each believing itself to be the true and only conservator of God’s truth, and all others, in slightly varying degrees of blackness, simply children of the devil. In such surroundings the feeling grows slowly that those who possess the light are debtors to all who sit in darkness. They must be patiently dealt with; and the story of the priest is a help to patience, as showing of what self-devotion the Syrian character is really capable.

I received the story in fragmentary form, but so much is clear: A young priest of the Greek Church, a native of Mount Lebanon—the district which has contributed most of the native Christian workers in the country—had laid on his heart the necessities of the great dark land east of Jordan, and, in a spirit of true Christian heroism, he resolved to go forth, single-handed, to the work of evangelisation. He left the comparative comforts of his mountain home for the rude life of these wild regions, with no protection but that of his divine Master, counting the salvation of Moslem and Druze equally precious with that of his own people. He made his way into el-Lejâʾ, staying in villages where he could find a[47] home for a little, and, when his position grew dangerous, passing on to others, carrying some little of the light of civilisation, as well as the evangel. Thus, arriving at Dama, he took possession of an empty house, put wooden frames with glass in the windows, swung a wooden door on hinges in the doorway, and arranged his scanty furniture within. The village lacked good water, so he had an old well cleaned out and repaired, and soon it was filled with wholesome rain-water. For about a year he went out and in among the warlike inhabitants, seeking to teach them the way of the Prince of Peace. A belief got abroad that he had found treasure among the ruins, and had it concealed in the house. A conspiracy was formed to kill and plunder him. He got news of the fact, and, seeing that his life was no longer safe, he was fain to move to another village, leaving a well of clear, cold water to preserve his memory, and, let us hope, also in some hearts a light that will lead to the Fountain of living waters. Exactly where he is now, I do not know, but some years later he was still in the district. “Persecuted in one city, he flees unto another.”

WELL IN THE DESERT

(Photo. The Photochrome Co. Ld.)

Hidden treasure—The Bedawy’s treasure-trove—The sheikh’s farewell—A savage tract—Jebel ed-Druze—Umm ez-Zeytûn—Tell Shihân—Shuhba—An ancient house—A stingy entertainer—The ruins—Pharaoh’s “grain-heaps”—The house of Shehâb.

The lust for treasure, which almost proved fatal to the priest, is common among all these semi-barbarous people. They are firmly persuaded that among the black ruins everywhere great hoards lie buried. Inscriptions, they think, contain directions how the precious stores are to be found, if they could only be read. But unfortunately they are in some mysterious speech which only the Franj—civilised foreigners—are supposed to understand. Interest in old ruins, in architectural remains, in anything that may shed light on former days, they regard as mere subterfuge. Many travellers have been struck with their unwillingness to show the whereabouts of inscriptions. They have a kind of dim hope that one day they may stumble upon the treasure themselves. Sometimes, however, they become confidential, and offer, for a consideration, say, half of what is found, to show the traveller all they know. They tell many stories, with full circumstantial details, of discoveries[49] of such heaps of gold. The noble metal is usually found by means of magical incantations, and every stranger is suspected of being the happy master of some such charm. At other times a mysterious conjunction of natural circumstances guides the lucky man to fortune.