[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astonishing Stories, October 1942.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Old Cobber's hand trembled slightly as he turned his tankbox so that his guns would point at the crew working outside.

Wilson, atop the white hill, watching the men clear away the ammonia snow drifts from the jets of the rocket, was the first to notice the challenging position of Cobber in his tankbox.

"Are you getting in or out of the airlock?" he radioed to Cobber. "Make up your mind."

The old man's lips were dry and his voice was hoarse as he spoke into the mouthpiece.

"I am going to blow up the ship," he said.

Instantly the work of clearing the field stopped. Through the haze of poison air that surrounded the planet, Cobber could see them wheel into a semi-circle not more than thirty yards away from him and the airlock that he held.

Wilson's tank rumbled a few feet forward from the semi-circle.

"You don't dare shoot, Cobber," he said quietly. "You're outnumbered thirty to one."

"Stand back! All of you!" Cobber shouted into the mike. "I'll blow up the first one that moves!"

"Don't be a fool, Cobber," Wilson said. "There's enough catalytic rock stored in the ship for all of us. I can make you a rich man. Put down those guns and we'll forget what has happened. Put down those guns."

"This ship is not going back to Earth," Cobber said.

"Put down those guns, Cobber!" Wilson shouted. "You can't win!"

Cobber turned the knob and shut off Wilson's loud voice. He then opened one of the dinatro bombs that lay beside him, unscrewed the cap and tossed it into the back of the car with the other neatly stacked-up explosives.

"Ten seconds!" he yelled.

The men were stunned for a moment by the suddenness of his decision to blow up the ship. They stood dumfounded, not knowing what to do, until one of them screamed "Dinatro!" Panic-stricken, they dashed their tanks for the meager protection of the nearby cliffs.

Wilson's tank stood still, not moving.

"You're bluffing, Cobber," he called out. "You want to scare the men away so you can seize the ship and get back to Earth. All right, Cobber, you win. Only you and I will share the cargo. I'm coming in."

One second.

Two.

Three.

"There's more than a cargo at stake," Cobber said.

Four seconds.

Five.

Six.

"Remember me, Kama!" Cobber said softly to himself.

Seven.

Eight....

The silent bulbous mass that was the Great Kama extended an undulating growing finger and pointed. When Cobber saw the charred bodies of the Kamae he knew what it meant to have one's people ravaged and killed. In that moment he forget the rosy glow of ammonia snow on the mountain tops and the purple clouds that battled majestically over the planet.

Here and there the anhydrous bodies of the Kamae lay stone still. The small village, tucked away by the shores of the russet sea, was wiped out. Many of the bodies were ripped apart, torn to shreds as if by some monster from the depths of the methane sea.

He had seen death before and he had seen brother kill brother on a hundred different planets in as many solar systems. Each time its horror and tragedy cut him deep. Cobber felt sick at heart.

"I did not know ..." he began despairingly.

His words were cut short by the overwhelming emotion of pain and hurt anger that forced itself out of the organ-less body of the Great Kama, through the poison atmosphere of the planet, through the walls of the tank-car and into Cobber's consciousness. It was held back, its power could overwhelm him, but Cobber could sense the enormity of the tragedy that racked the bubbly form of his Kama friend.

He looked through the window of his small car and watched his strange comrade leave him, gliding like a living liquid over the knolls and hills. Other men of Earth could feel only revulsion and disgust when their eyes fell on one of the Kamae. But Cobber was not like other men.

He had seen, in the years of his wanderings, enough of creation's mysteries to realize that the surface manifestations and expression of life were meaningless. Where men like Wilson would reach for a gun to blast it, Cobber would reach out to it with understanding and friendship.

Be it a crystal that grew into pulsating life with every sun ray, or the flesh and blood of Earth, or the singing strings of Orion—it did not matter. Life alone made them brothers. It was this realization that enabled him to be a friend to Kama. It was this knowledge that made him feel the immensity of the tragic despair which engulfed his strange other-world companion.

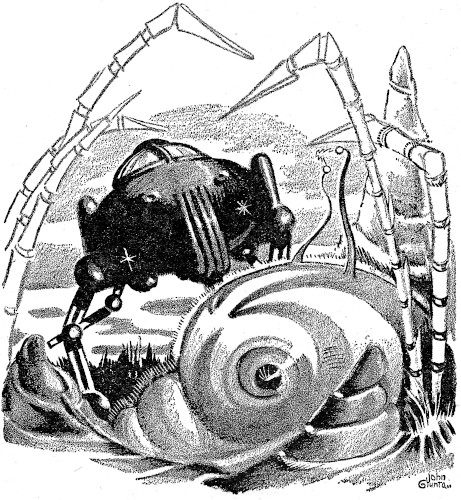

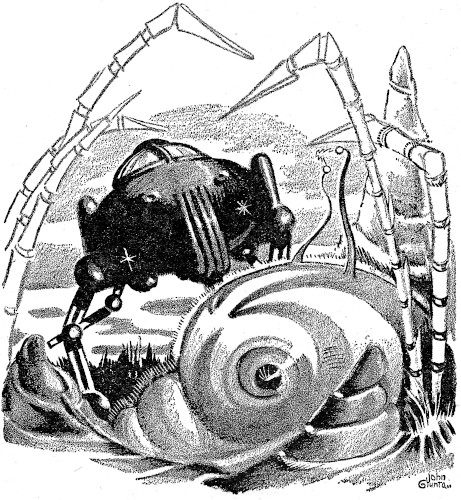

Gingerly he adjusted the controls of the tank-car so that it would walk carefully through the village. Years ago the crude spacesuits with which planetary explorers were encumbered were found to be too clumsy and dangerous for use. In their place were developed the tank-cars.

They were miniature houses on wheels and legs, faintly reminiscent of ancient battle-tanks, equipped for travel on sand, rock, hill, water and a thousand other fields. Tentacles, mechanical arms and legs were finally developed, making the tank-cars a thousand times superior to clumsy, inefficient spacesuits.

The metallic legs of the car, immune to the gaseous atmosphere, carefully stepped over the bodies. On the hilltop, through the mist that clouded the vision plates of the car, he could see the other villages being destroyed, as this one was.

Cobber shuddered. The planet of Kama was like death itself without the ghastly war that had descended upon it.

Seeing the crimson thunderhead clouds rear high into the stratosphere and knowing the approach of another storm, he hastened the speed of his car towards the huge mother-ship.

In an hour's time he found it, half buried among the great ammonia snow drifts. He folded the legs of his car, let it descend into a riding position and, metallic treads rumbling, rode into the airlock that opened to meet him. As it rolled in, the wall in back descended, imprisoning the car.

He waited patiently as the poison air was extracted from the lock. When the indicators registered the absence of carbon disulphide vapor he opened the top of his car and crawled out. The door leading into the airlock opened. Jina's face greeted him as Cobber walked through.

"Welcome home, Cobber!" he said. "We were beginning to worry about you."

Cobber tapped his feet experimentally on the floor of the ship. "It feels good to stretch out again after fourteen days in the tank. Air would have run low soon."

As was the ship's rule, Jina replaced the empty food drawers, stored up the fuel tanks, replenished the air supply and turned to the stacks of dinatro bombs in the back of the car.

"Shall I clear these out?" Jina asked.

"No. Let them stay," Cobber said. Before he could leave the dressing room the other officers and members of the crew came into the room.

"What did you hear?" they asked. Anxiety was written over their faces. Evidently they had already seen the effects of war. They waited, intent upon him.

"The peace is ended among the Kamae," he told them.

"Is it nation against nation?"

"No. They have not developed as far as that. Isolated tribes have attacked others, wiping them out. One by one the advanced cities that have schools and teachers are being laid low by wandering bands. I saw some of the ruins—"

He broke off and, as if seeing them again in his mind, said, "Old and young. Burnt out bodies buried in snow drifts. No prisoners. Savage war."

"Barbarians!" Jina said.

"Teachers of barbarians!" Cobber said, looking at the men under his command. "They were shown how they might pillage one another in order to bring catalytic to us for trade. Who else would teach them?

"I left explicit orders," he said angrily, walking back and forth among them, "to give only machinery and gas-proof metals in exchange for their catalytics. I said there was to be no interference with the private life of the Kamae. Why was I disobeyed?" he demanded. "Who told you to change the trade agreements that I had prepared?"

When no answer came he looked at his assistant officer.

"You, Jina. Who handled the trade accounts with the Kamae?"

"Wilson, sir."

Cobber swore, brushed past his men and made his way to the private quarters of Fogarth Wilson. Several of the men moved as if to stop him, but none dared. In the event of a quarrel between the man who ran the ship and the man who owned it, it was best to stay neutral.

Wilson was yawning lazily as Cobber walked in.

"Hello, Cobber," he greeted casually. "I was afraid your Kamae friends might have kept you. What did you find out?"

Cobber's voice shook. "You broke the trade agreement!"

Wilson looked up at him, and saw the anger in his eyes. He got up from his bed and walked across the narrow room and stood next to the older man.

"Did you see the store room?" he demanded. "It's one third full. One third full after two weeks of trade! We were here six months and got only a quarter ton of catalytic for the power machines of Earth. In one day I purchased more than you could buy in a month!"

"But at what a price, you fool!"

"Price? Yes! I sold oxygen!" Wilson laughed. "What did you offer them, Cobber? Books and machinery! Books for a savage king and machinery for fools! I gave them what they wanted—pure oxygen!"

Cobber prayed for the strength of a man twenty years his junior. But his weak and old hands would prove of little value against the youthful strength of Wilson.

"Oxygen! In an atmosphere of carbon disulphide and methane you sell them tanks of oxygen!"

"Yes."

"You know what you sell the Kamae?" Cobber asked, gripping him by the shoulders. "Death! A single spark—one rock striking another, a simple stroke—and that oxygen becomes a bursting, fuming flame! In this atmosphere it is worse than the most powerful dynamite. Whole villages have been wiped out. Entire cities have been burned to the ground by your oxygen. You showed them how to use it. You made flame-throwers. You showed them how to kill one another to bring you more catalytics for more weapons!"

"Why not?" Wilson demanded. "I sell them what they want—weapons of war. In selling it I've made enough to outfit a new ship and a new captain."

Cobber looked again at the man he hated. Unlike other sons of the rich who hired ships and captains to squire them in their adventurous tours of other planets, Wilson was not soft. A sensuous line about his lips hid their cruelty. Years of breeding and care, without the knowledge of poverty and the crushing weight of mature responsibility, had given him a smooth powerful body and a quick agile mind that was more callous and hard than the palms of old Cobber's hands.

Wilson owned not only the ship, but Cobber's soul as well. There were debts to be paid back at home. It was so with every man in the crew. Each would suffer if Wilson failed to come back safe and sound. Cobber knew this and Wilson knew it as well. Wilson was the master here—not Cobber.

"I spoke with the Great Kama today," Cobber said, remembering his friend.

"Yes. And what did the Messy One have to say?"

"The learned men of the villages, the educated ones, want revenge for the breaking of our trading treaties. They will attack us. They will break off all relations with Earthmen forever unless—"

"Unless what?"

"Unless I surrender you to them."

There was the beginning of a smile on Wilson's lips. It stayed there grimly as he watched indecision, hesitation and conflicting emotions battle in Cobber's eyes.

"You wouldn't dare!" he whispered softly. "In fact," he added, smiling as the thought gave him reassurance, "in fact, you couldn't!" He tried to smile again, but this time found little weakness in Cobber's eyes.

"The whole future of Kama's contact with the Earth depends upon me now," Cobber told him, stepping back a foot and then drawing his ancient revolver from his hip pocket.

Wilson looked at the gun calmly. "You're a fool, Cobber—a doddering old fool!" he said. "If you had done your work as captain without interfering with me I could have made you a rich man."

As he talked he gestured with his hand. With a swift, sudden movement he slapped the gun from Cobber's grip, grasped the old man by his neck and turned quickly, flinging Cobber against the wall. There was a dull thud as Cobber collapsed in a crumpled heap.

Wilson switched on the call board. "Attention! All officers please report to my quarters immediately. Wilson speaking. That is all."

Turning it off he came back again to the slowly rising Cobber.

"You're finished," he said. "Finished!"

The men drifted in one by one. When all had assembled, facing Wilson and Cobber, the younger man spoke.

"In view of the critical situation now facing us and the imminence of an attack by the savage Kamae, I have deemed it advisable to make some changes in the commanding personnel of my ship. With due respect for his splendid accomplishments in the past, I now relieve Cobber of his duties as commanding captain of this ship. He will henceforth function as second assistant navigator. Commanding Captain Jina, you will carry on."

Cobber ripped off the single star that emblazoned his sleeve and gave it to Jina. He walked past the stunned officers and men, past them all, into the corridor, down the steps and to the airlock.

The raging storm above had died. At times a lonely star peered through crimson clouds and then, as if frightened at the sight, disappeared from view. White flakes, so reminiscent of snow on Earth, settled softly upon the planet. From time to time he would brush the windows of his tankbox and peer out to watch for the approach of his friend.

He saw him, a white globule-like mass, slithering over the rolling hill and coming towards him. He raised one of the arms of the car in recognition. Instantly a gray finger extended from the bulbous mass in answer.

The strange being was standing beside the tankbox that enclosed Cobber. No message came from its brain as it waited for the thoughts to form in Cobber's mind.

I am ashamed, Cobber thought.

There was no answer, but a wave of pained bewilderment flooded upon him. Then the accusing words, You failed.

Yes, I failed, Cobber said, the bitterness of complete defeat rankling in his heart. The man your people want for revenge is my chief. I cannot deliver him. I cannot!

When Cobber first came to our planet, the Great Kama's thoughts rang in his head, who welcomed him? Who crossed the barriers between our different forms of life? Who told Cobber the tragic history of our people? Who told him the secrets of our learned teachers?

There was a long pause and then the Great Kama answered his own questions.

I did these things, for I thought Cobber was my friend.

Cobber wanted to shout, "I am your friend, believe me!" but he knew that the Great Kama could not look upon him as one single individual apart from his men. He was a symbol, the embodiment of the best that a different people could offer. If Cobber had failed him—Cobber, the wisest—then friendship between the planets was doomed forever.

I gave friendship—and what has Cobber's answer been? Your people sold weapons to the ignorant and brutal of my people. You taught them to kill and burn. You aroused the greed and lust in us with the offer of power. We reached for knowledge—and you pushed us back into the depths of savagery. Are you my friend, Cobber?

Cobber could not answer. Powerless, impotent, he could not fulfill the demand for just revenge that Kama had asked. A thousand plans pursued their way through his mind. A thousand solutions leapt up, offering themselves. He could have killed Wilson and shown them the body. But it would have meant death for all them in the courts of Earth.

What was the alternative? In his mind he could see the story. The spaceship would return home with a cargo full of catalytic and the story of ignorant beings willing to mine the metal for tanks of oxygen. Cheap, easy to manufacture oxygen in exchange for power! Other ships would come and other men like Wilson, greedy men, powerful men, men with lust in their hearts.

Kama's people, scarcely on the first rung of civilization's ladder, would be thrust back into the darkness. Tribal warfare, spurred on and encouraged by Earthmen, would deplete the planet. A new culture, just born, would die. Was this a fair price for the greed markets of Earth?

Are you my friend? He heard the thought again.

Slowly he rode back to the spaceship. The storm was over. The crew of the ship were clearing the ammonia drifts away in preparation for the blasting.

The airlock was open. Cobber rode to it and turned around, guns facing his men.

Six seconds.

Seven.

"I am your friend, Kama," Cobber said softly to himself. "Remember me!"

Eight seconds.

Nine.

There was a blinding flash of light as jagged white flames reached into a blood-red sky, tearing apart like a paper box the last ship commanded by Cobber.

From a hilltop in the distance Kama saw the flash and heard the rumble. When it died down the evening silence fell again he knew what Cobber had done.

Other years would bring other ships from Earth. If in them were men like Cobber, the barrier between different peoples might yet be crossed.