Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

“There is no man so high-hearted over earth, nor so good in gifts, nor so keen in youth, nor so brave in deeds, nor so loyal to his lord, that he may not have always sad yearning towards the sea-faring, for what the Lord will give him there.

“His heart is not for the harp, nor receiving of rings, nor delight in a wife, nor the joy of the world, nor about anything else but the rolling of the waves. And he hath ever longing who wisheth for the Sea.”

“The Seafarer”

(Old English Poem).

THE NORTHMEN

IN BRITAIN

BY

Eleanor Hull

AUTHOR OF

‘THE POEM-BOOK OF THE GAEL’ ‘CUCHULAIN, THE HOUND OF ULSTER’

‘PAGAN IRELAND’ ‘EARLY CHRISTIAN IRELAND’

ETC.

WITH SIXTEEN FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS BY

M. Meredith Williams

NEW YORK

THOMAS Y. CROWELL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

5

Turnbull & Spears, Printers, Edinburgh

Two great streams of Northern immigration met on the shores of Britain during the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries. The Norsemen from the deep fiords of Western Norway, fishing and raiding along the coasts, pushed out their adventurous boats into the Atlantic, and in the dawn of Northern history we find them already settled in the Orkney and Shetland Isles, whence they raided and settled southward to Caithness, Fife, and Northumbria on the east, and to the Hebrides, Galloway, and Man on the western coast. Fresh impetus was given to this outward movement by the changes of policy introduced by Harald Fairhair, first king of Norway (872–933). Through him a nobler type of emigrant succeeded the casual wanderer, and great lords and kings’ sons came over to consolidate the settlements begun by humbler agencies. Iceland was at the same time peopled by a similar stock. The Dane, contemporaneously with the Norseman, came by a different route. Though he seems to have been the first to invade Northumbria (if Ragnar and his sons were really Danes), his movement was chiefly round the southern shores of England, passing over by way of the Danish and Netherland coast up the English Channel, and round to the west. Both streams met in Ireland, where a sharp and lengthened contest was fought out between the two nations, and where both6 took deep root, building cities and absorbing much of the commerce of the country.

The viking was at first simply a bold adventurer, but a mixture of trading and raiding became a settled practice with large numbers of Norsemen, who, when work at home was slack and the harvest was sown or reaped, filled up the time by pirate inroads on their own or neighbouring lands. Hardy sailors and fearless fighters they were; and life would have seemed too tame had it meant a continuous course of peaceful farming or fishing. New possessions and new conquests were the salt of life. “Biorn went sometimes on viking but sometimes on trading voyages,” we read of a man of position in Egil’s Saga, and the same might be said of hundreds of his fellows.

It was out of these viking raids that the Dano-Norse Kingdoms of Dublin and Northumbria grew, the Dukedom of Normandy, and the Earldom of Orkney and the Isles.

The Danish descents seem to have been more directly for the purpose of conquest than those of the Norse, and they ended by establishing on the throne of England a brief dynasty of Danish kings in the eleventh century, remarkable only from the vigour of Canute’s reign.

The intimate connexion all through this period between Scandinavia, Iceland, and Britain can only be realized by reading the Northern Sagas side by side with the chronicles of Great Britain and Ireland, and it is from Norse sources chiefly that I propose to tell the story.

7

| THE AGE OF THE VIKINGS | ||

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The First Coming of the Northmen | 11 |

| II. | The Saga of Ragnar Lodbrog, or “Hairy-breeks” | 15 |

| III. | The Call for Help | 22 |

| IV. | Alfred the Great | 29 |

| V. | Harald Fairhair, First King of Norway, and the Settlements in the Orkneys | 36 |

| VI. | The Northmen in Ireland | 45 |

| VII. | The Expansion of England | 52 |

| VIII. | King Athelstan the Great | 56 |

| IX. | The Battle of Brunanburh | 65 |

| X. | Two Great Kings trick each other | 78 |

| XI. | King Hakon the Good | 82 |

| XII. | King Hakon forces his People to become Christians | 85 |

| XIII. | The Saga of Olaf Trygveson | 91 |

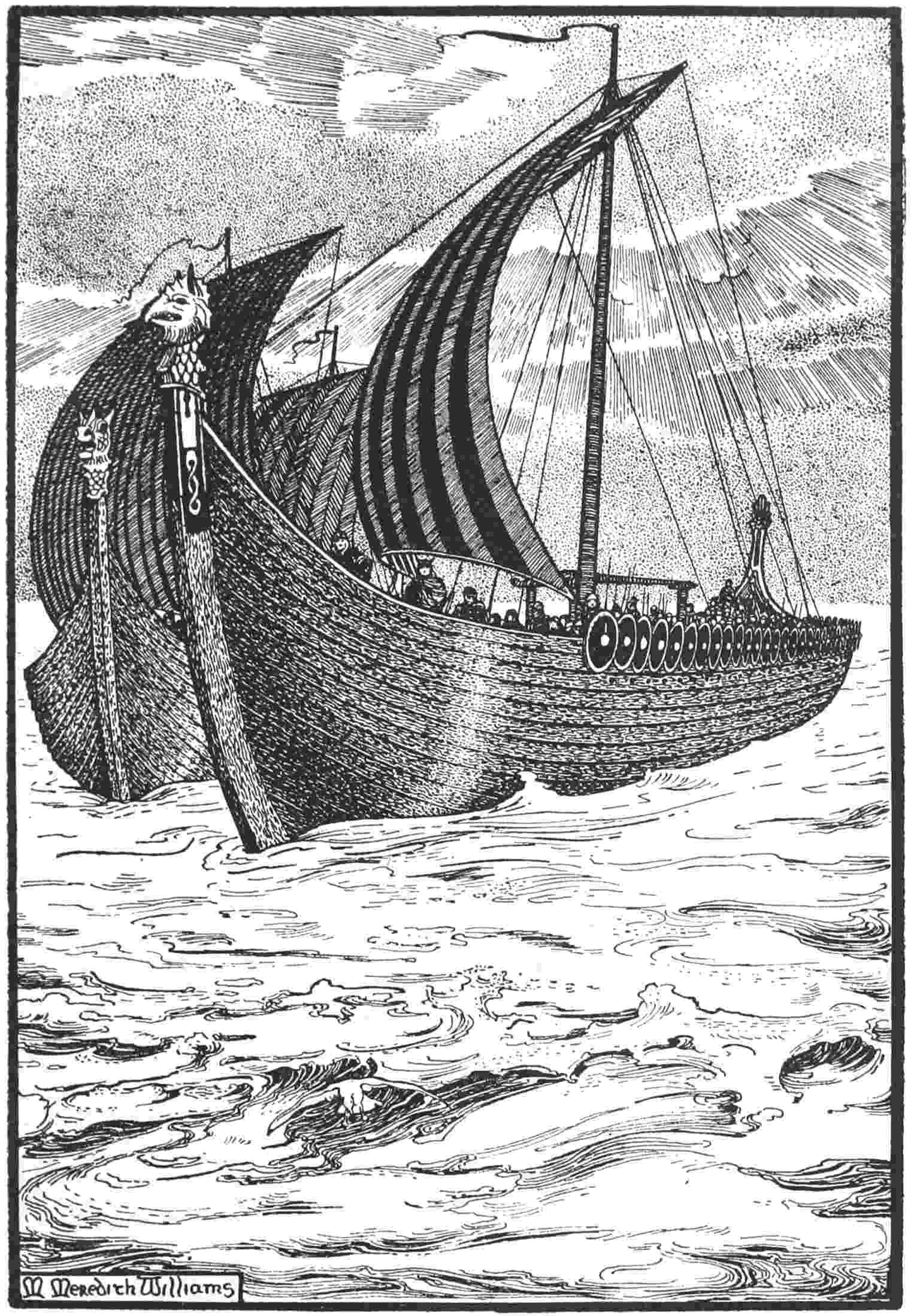

| XIV. | King Olaf’s Dragon-ships | 100 |

| XV. | Wild Tales from the Orkneys | 108 |

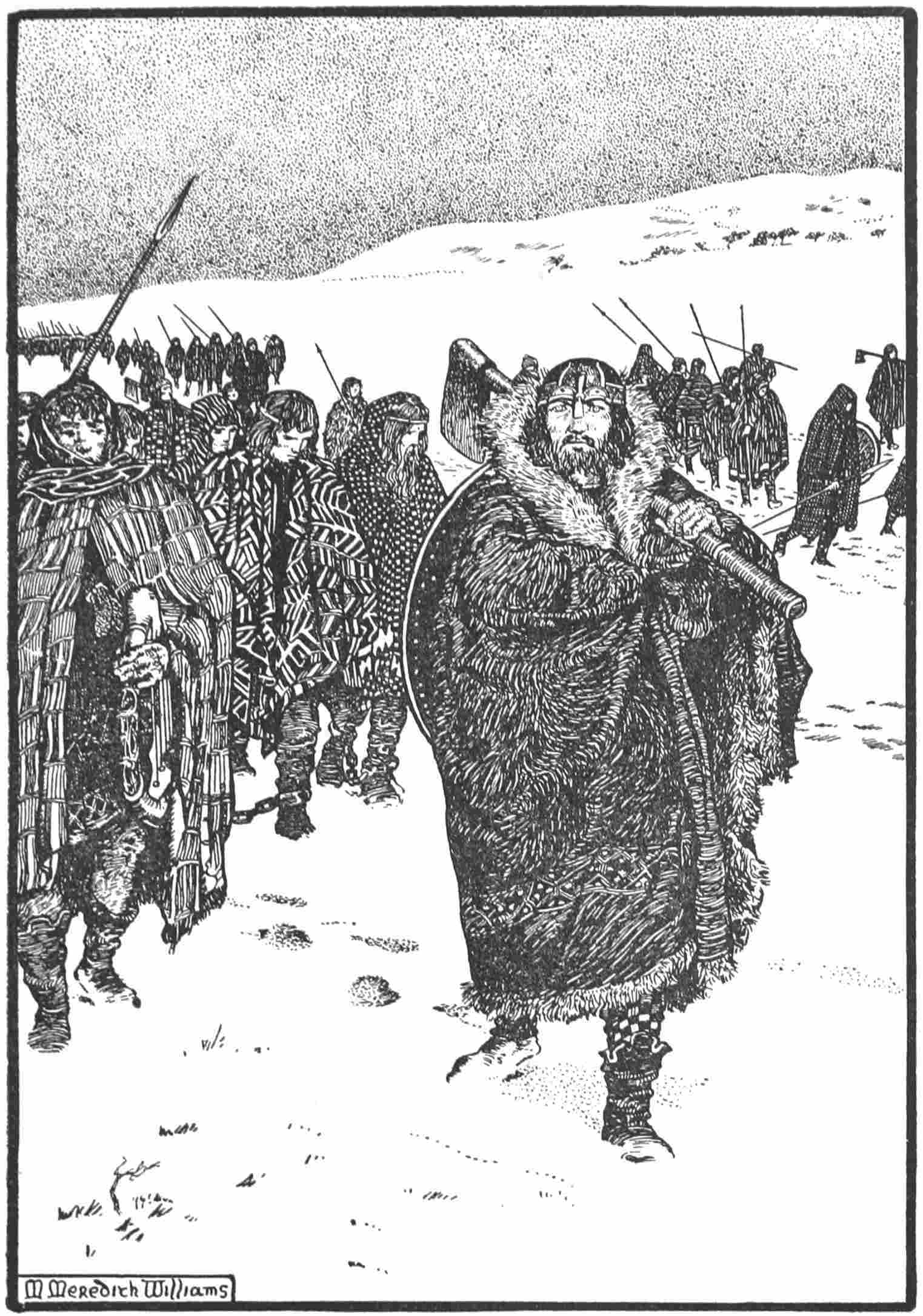

| XVI. | Murtough of the Leather Cloaks | 117 |

| XVII. | The Story of Olaf the Peacock | 1228 |

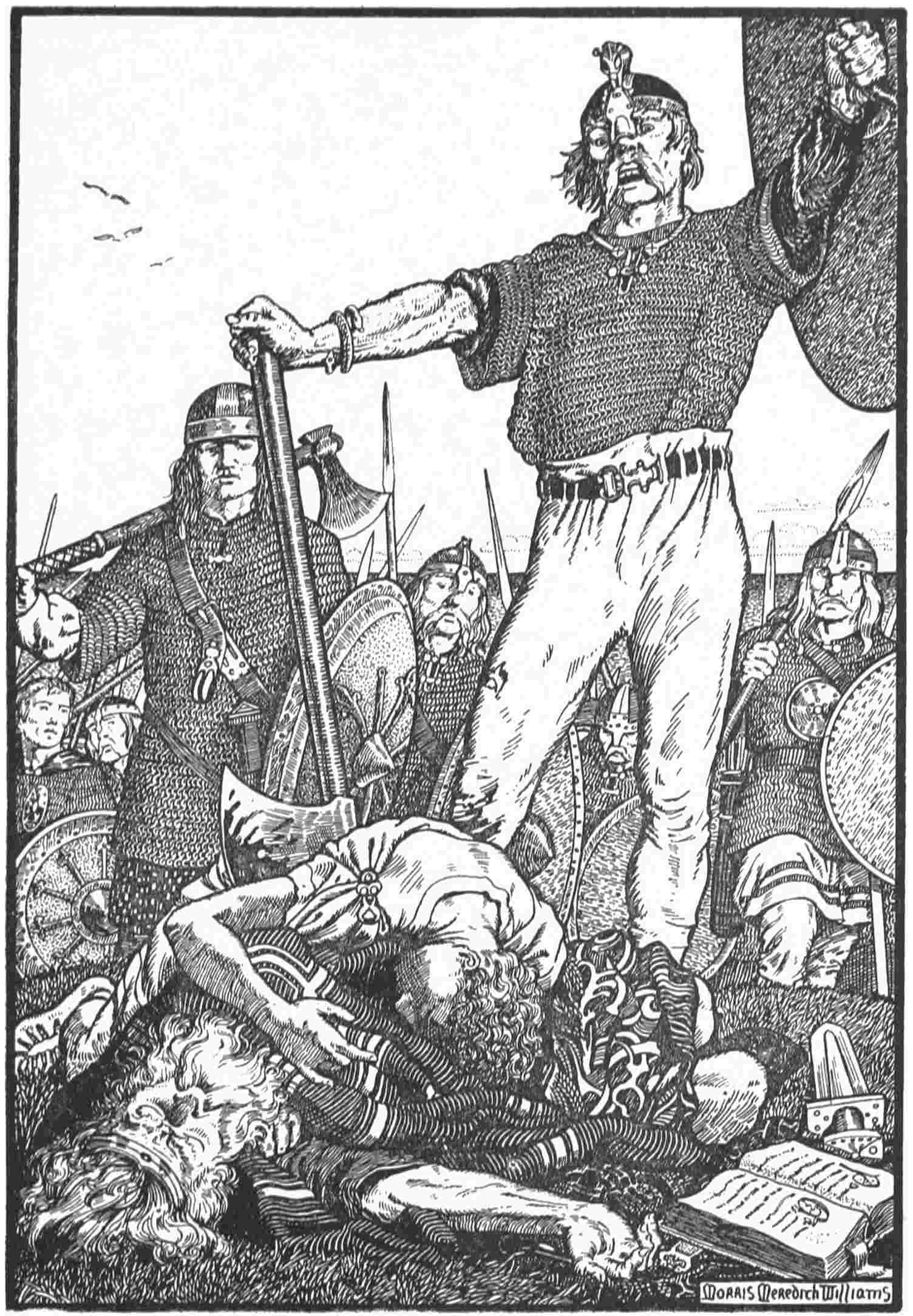

| XVIII. | The Battle of Clontarf | 135 |

| XIX. | Yule in the Orkneys, 1014 | 144 |

| XX. | The Story of the Burning | 157 |

| XXI. | Things draw on to an End | 166 |

| THE DANISH KINGDOM OF ENGLAND | ||

| XXII. | The Reign of Sweyn Forkbeard | 179 |

| XXIII. | The Battle of London Bridge | 186 |

| XXIV. | Canute the Great | 191 |

| XXV. | Canute lays Claim to Norway | 198 |

| XXVI. | Hardacanute | 211 |

| XXVII. | Edward the Confessor | 221 |

| XXVIII. | King Harold, Godwin’s Son, and the Battle of Stamford Bridge | 226 |

| XXIX. | King Magnus Barelegs falls in Ireland | 237 |

| XXX. | The Last of the Vikings | 244 |

| Chronology | 249 | |

| Index | 251 | |

9

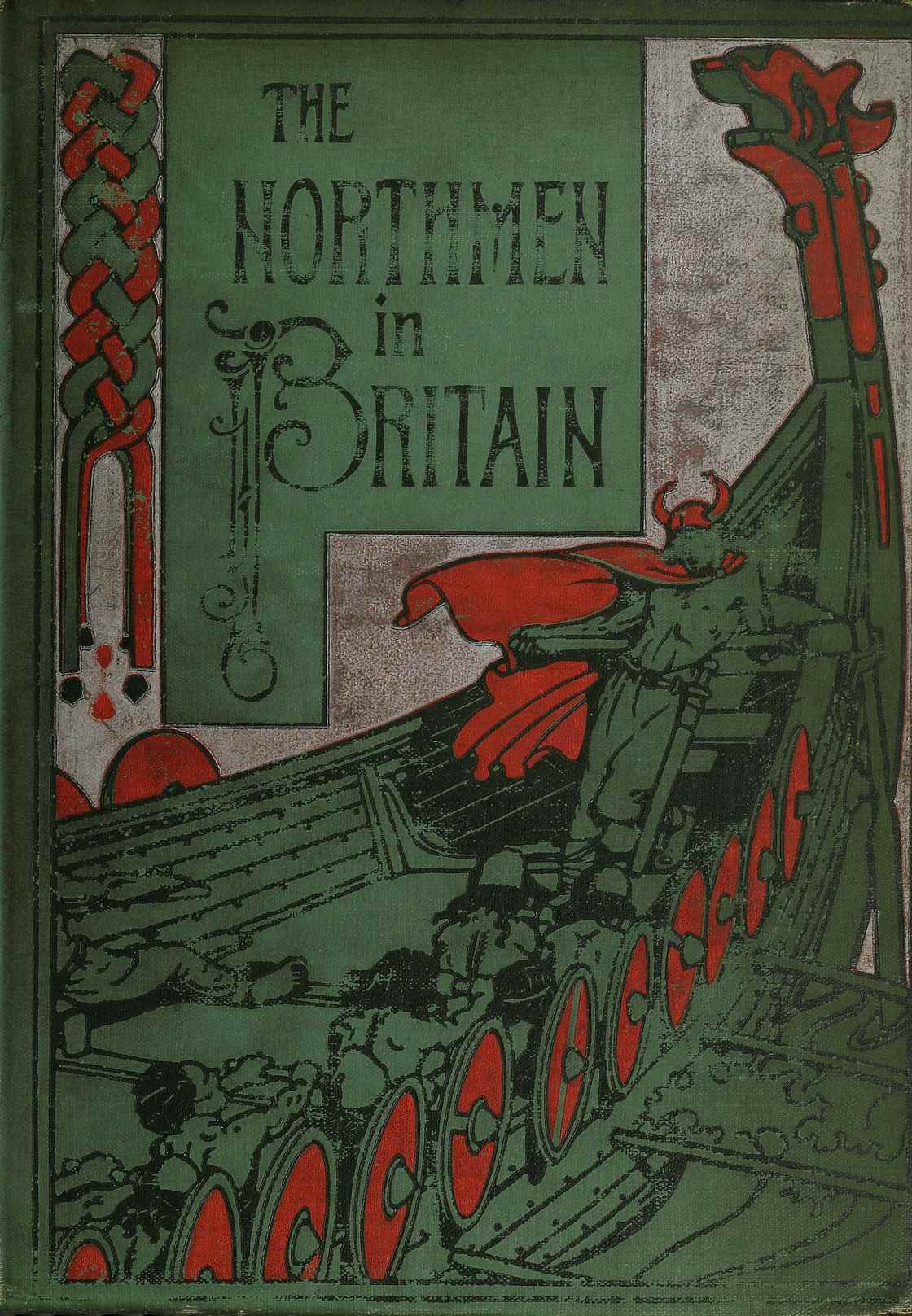

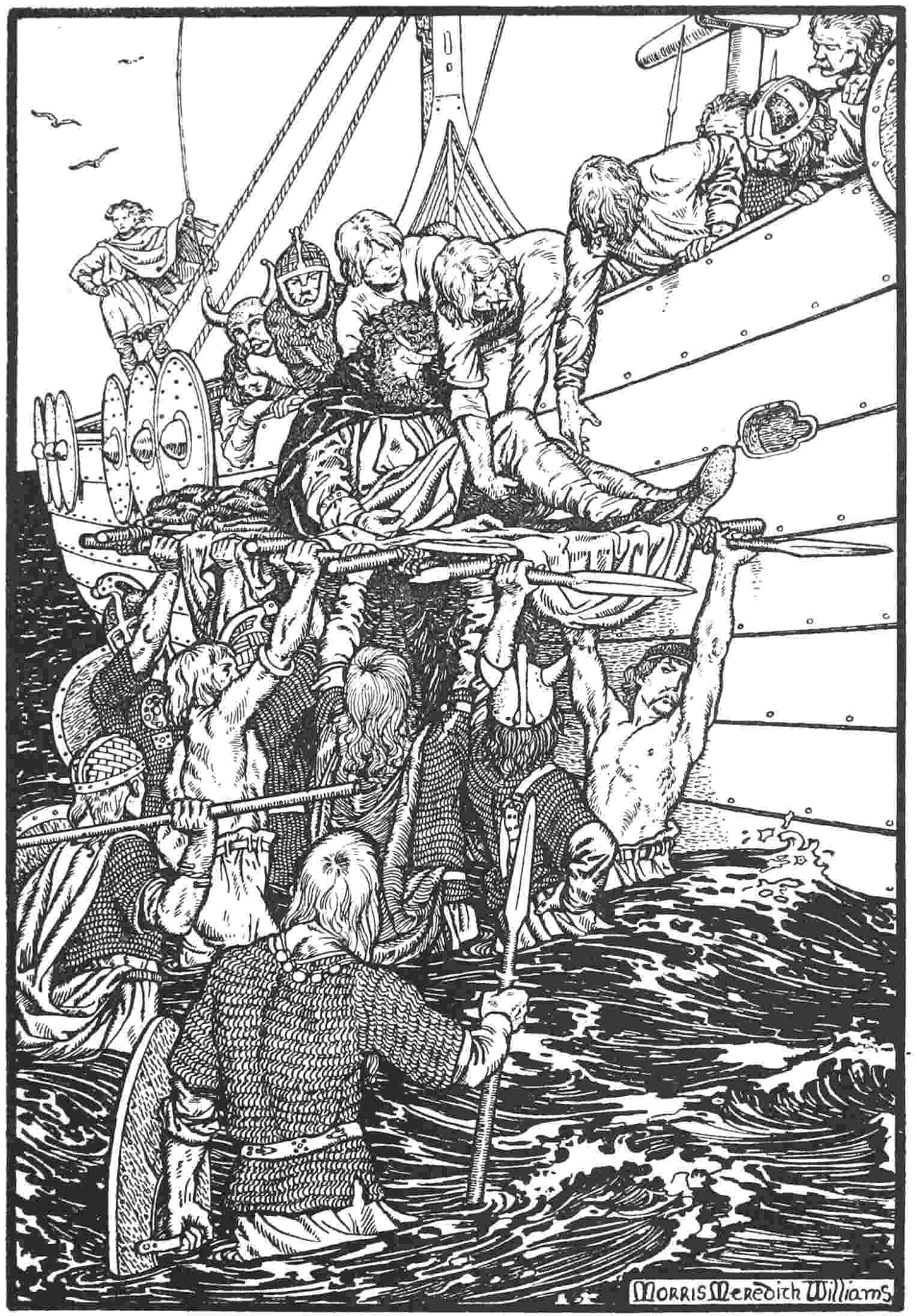

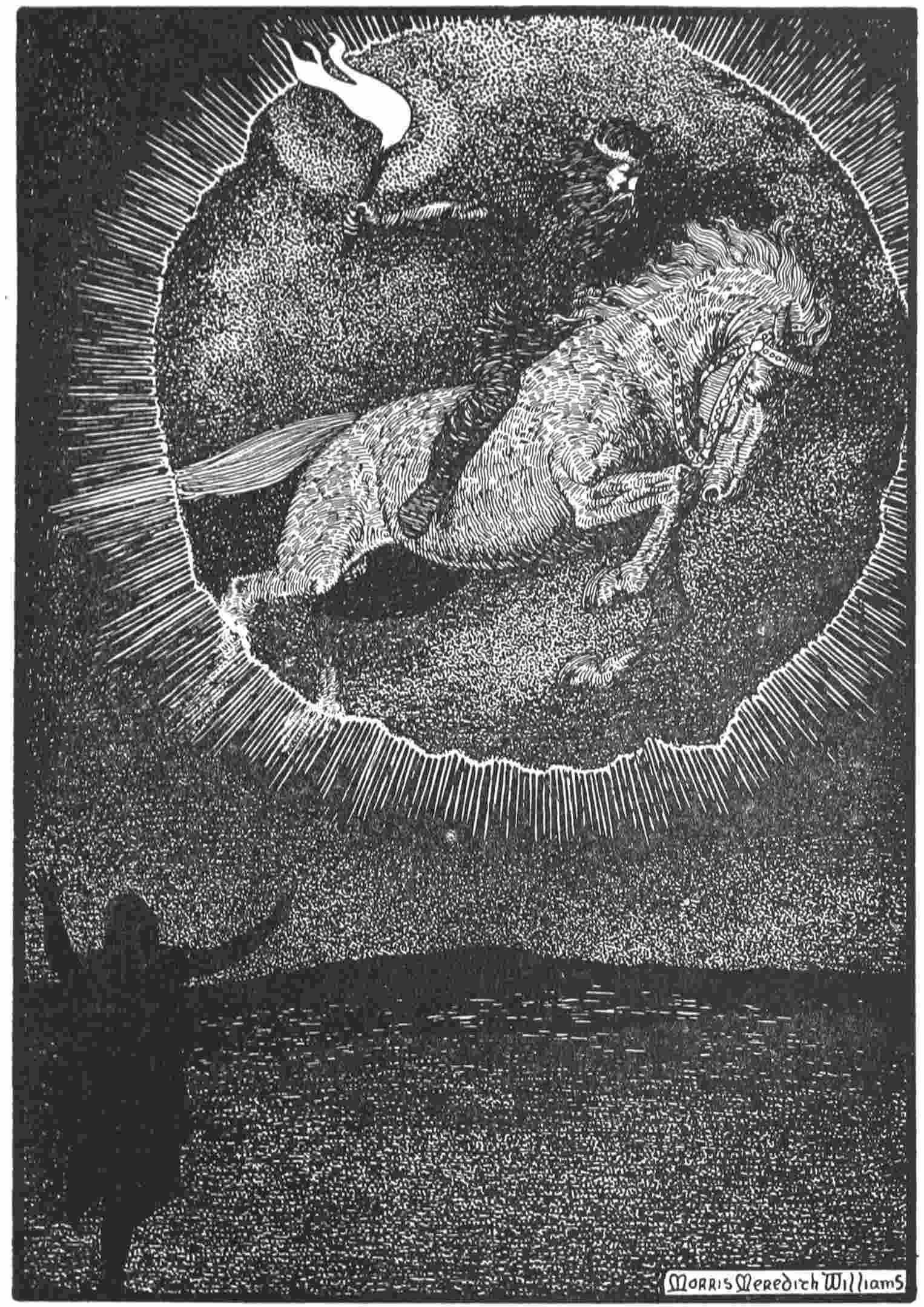

| The Coming of the Northmen | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

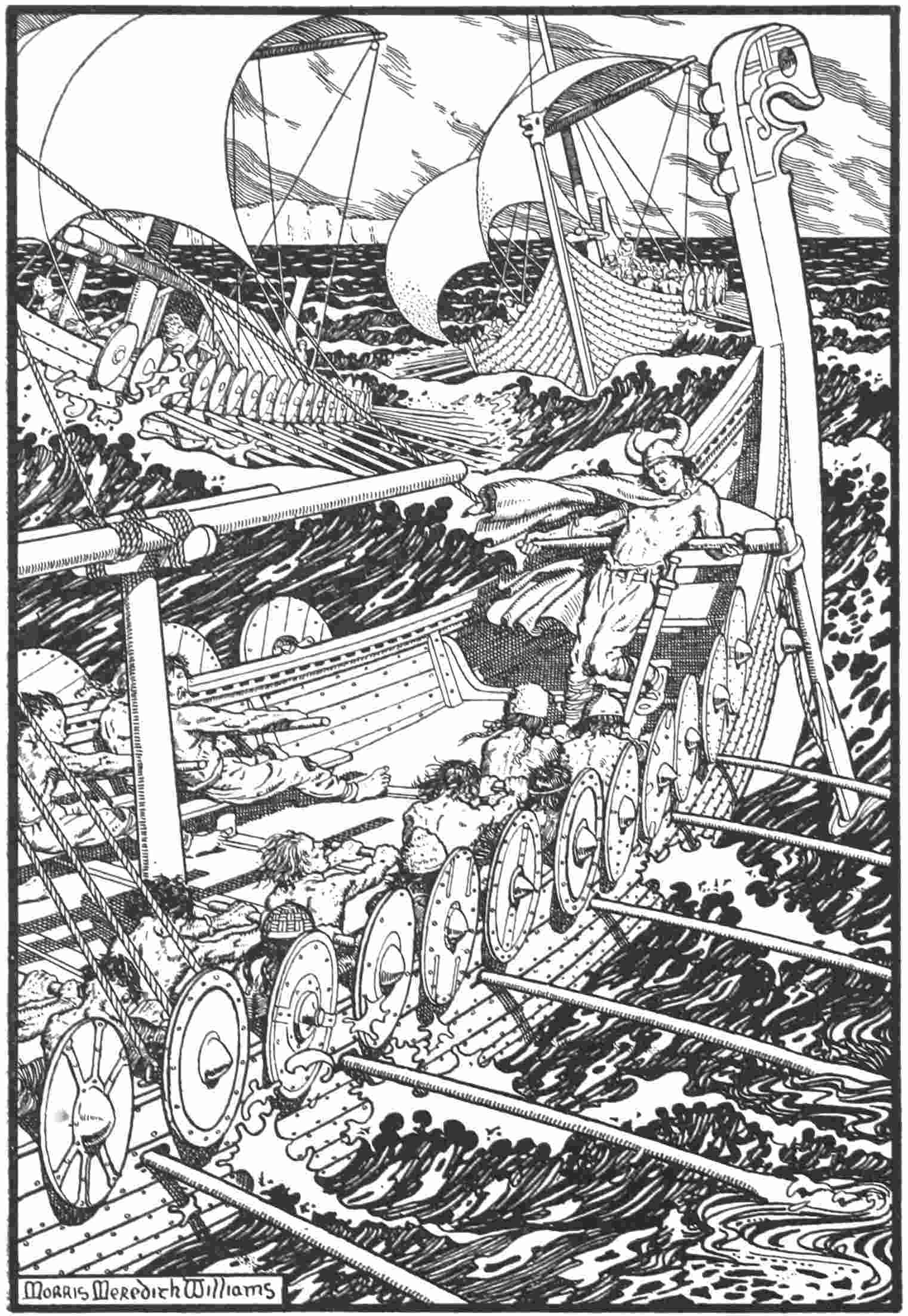

| Ladgerda | 16 |

| Alfred at Ashdune | 26 |

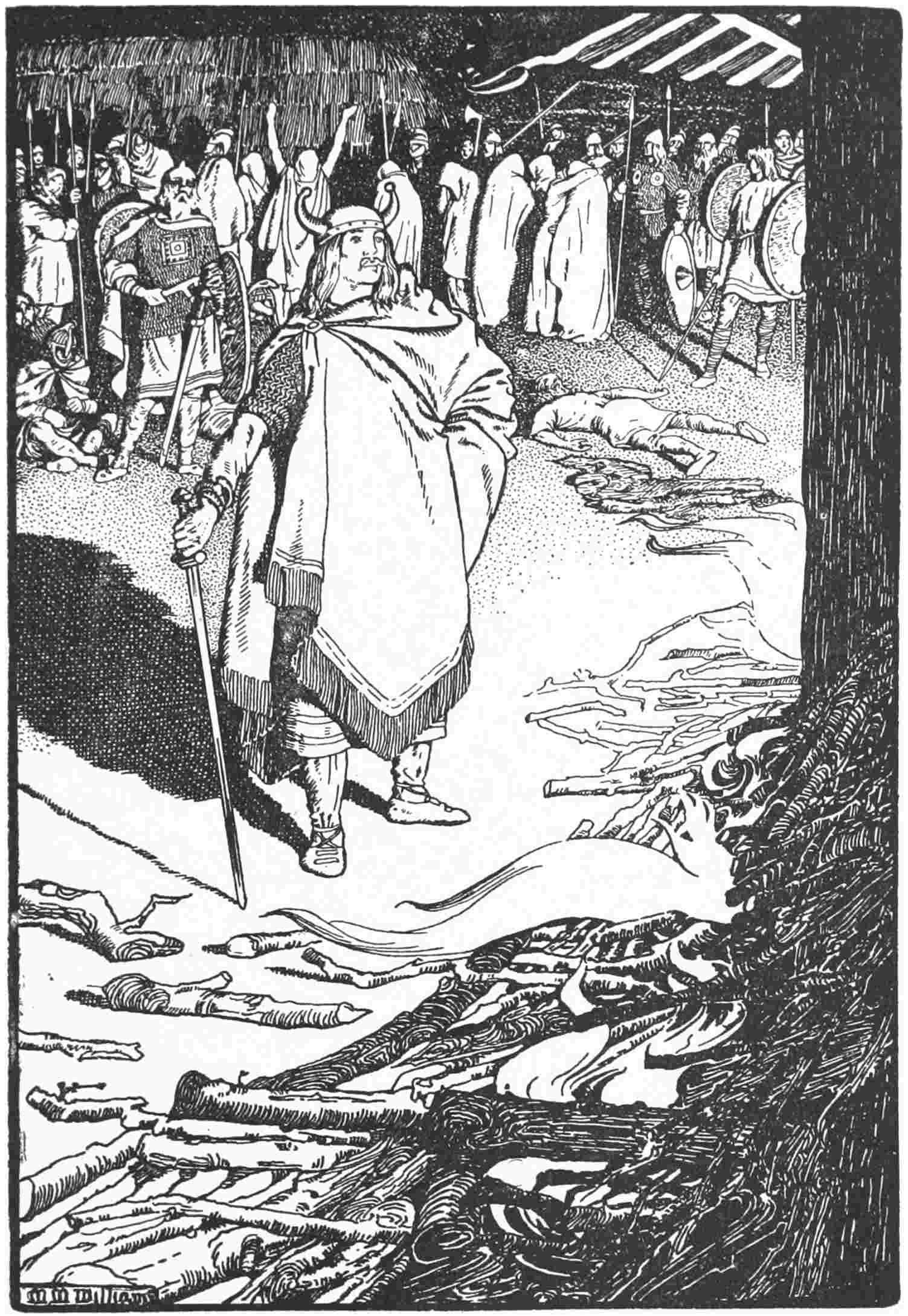

| Harald Fairhair | 42 |

| Olaf Cuaran | 62 |

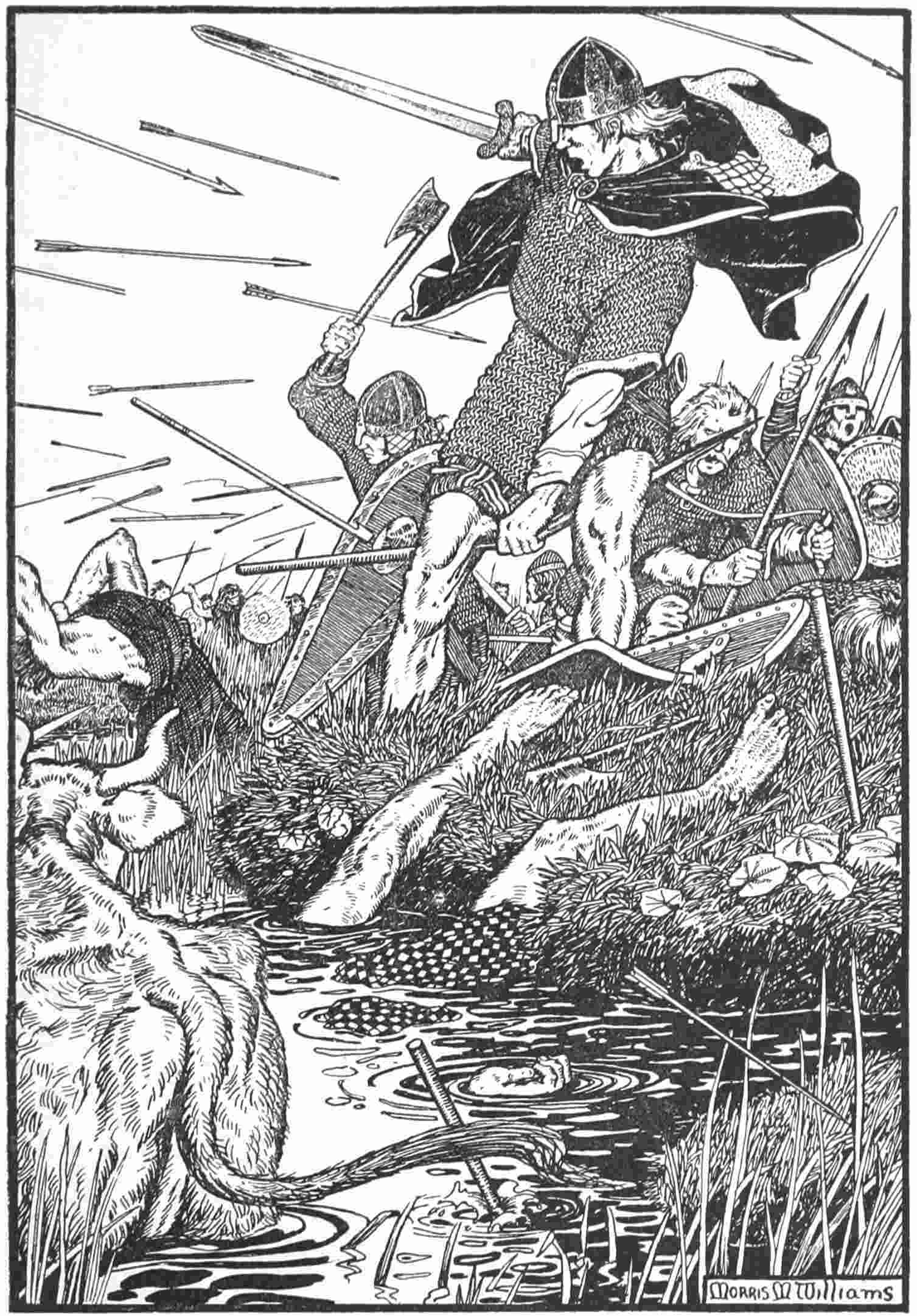

| Thorolf slays Earl Hring at Brunanburh | 72 |

| The dying King Hakon carried to his Ship | 88 |

| King Olaf’s “Long Serpent” | 102 |

| Murtough on his Journey with the King of Munster in Fetters | 118 |

| “Olaf took the Old Woman in his Arms” | 132 |

| Death of Brian Boru at Clontarf | 152 |

| “The Vision of the Man on the Grey Horse” | 166 |

| “Come thou out, housewife,” called Flosi to Bergthora | 172 |

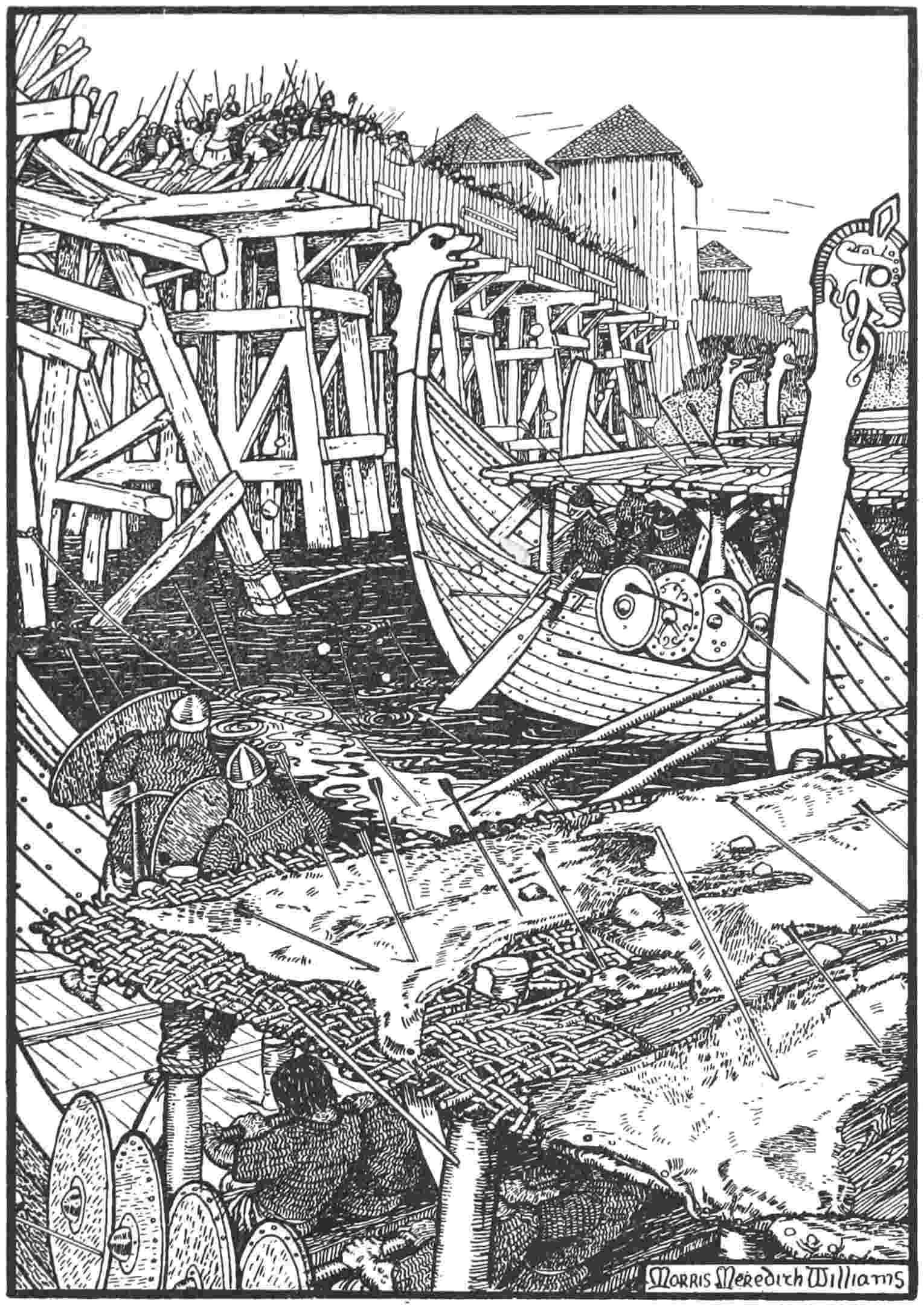

| The Battle of London Bridge | 188 |

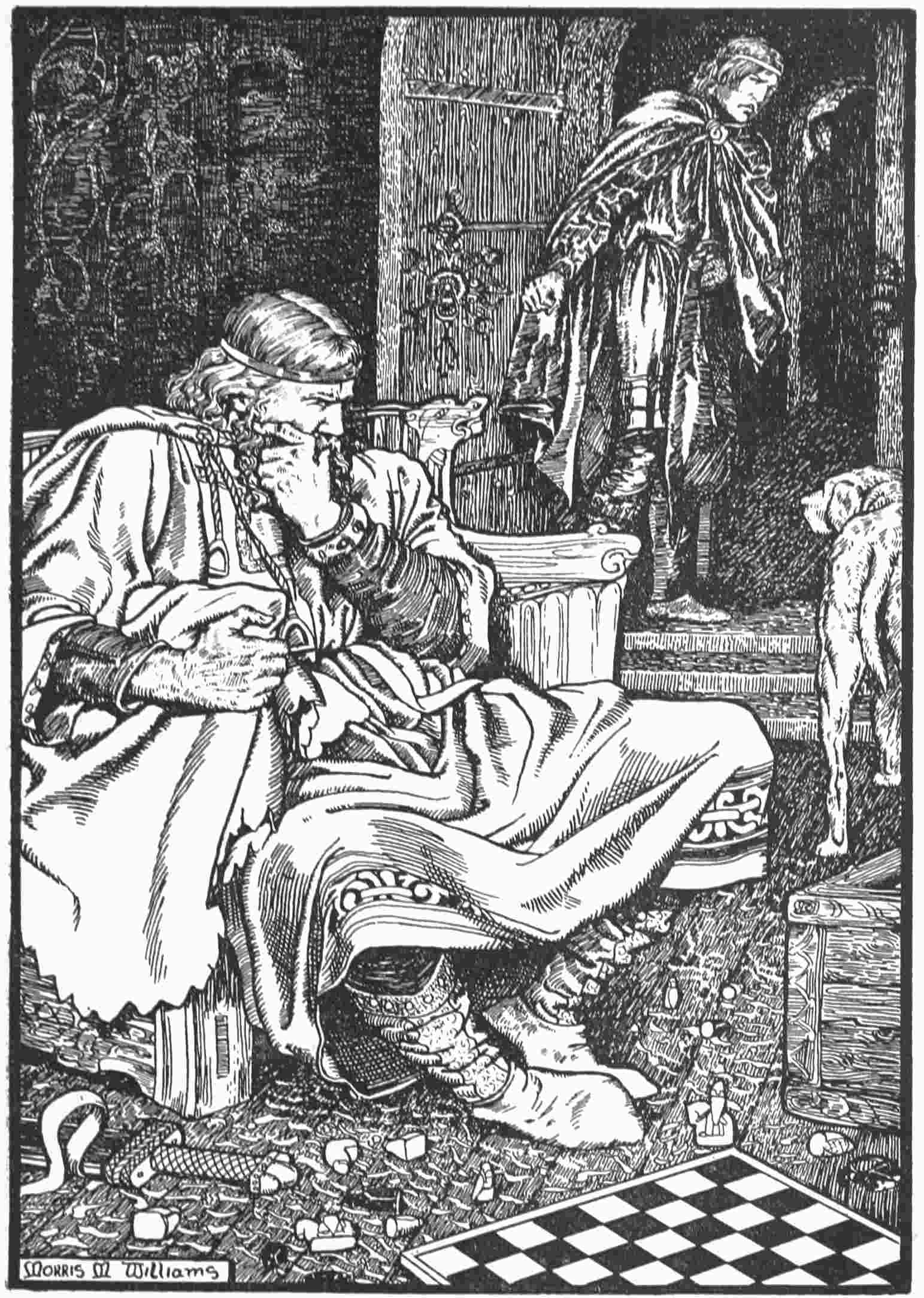

| King Canute and Earl Ulf quarrel over Chess | 214 |

| King Magnus in the Marsh at Downpatrick | 240 |

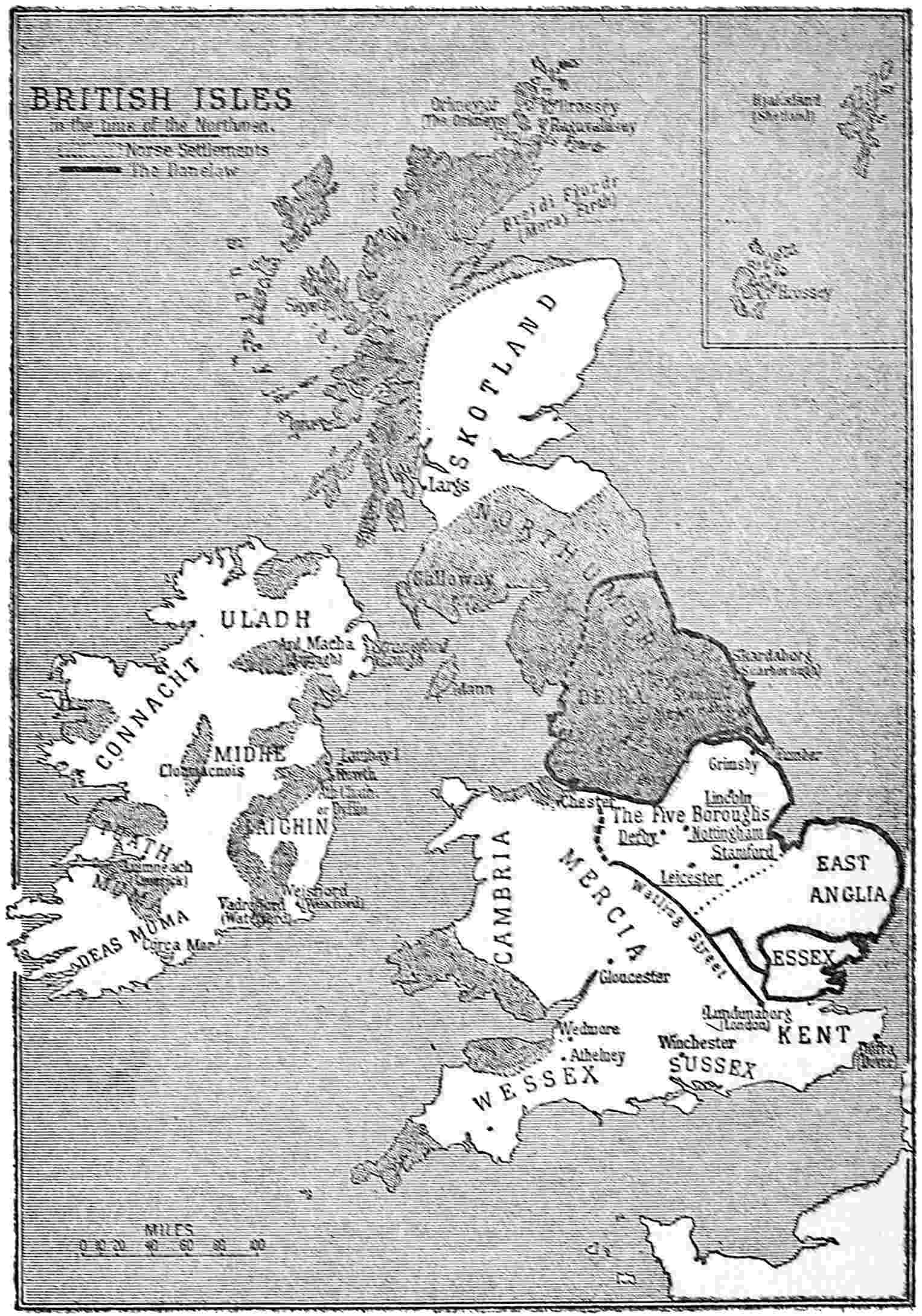

| MAP | |

| British Isles in the time of the Northmen | 176 |

10

For the Sagas of the Norwegian Kings: Snorri Sturleson’s Heimskringla, or Sagas of the Kings of Norway. Translated by S. Laing and by W. Morris and E. Magnüsson

For Ragnar Lodbrog: Saxo Grammaticus and Lodbrog’s Saga

For Ragnar Lodbrog’s Death Song: Corpus Poeticum Boreale. Vigfusson and York Powell

For the Orkneys: Orkneyinga Saga

For the Battle of Brunanburh: Egil Skallagrimson’s Saga. Translated by W. C. Green

For the Story of Olaf the Peacock and Unn the Deep-minded: Laxdæla Saga. Translated by Mrs Muriel Press

For the Story of the Burning: Nial’s Saga. Translated by G. W. Dasent

For the Battle of Clontarf: Wars of the Gael and Gall. Edited by J. H. Todd; Nial’s Saga, and Thorstein’s Saga

For Murtough of the Leather Cloaks: The bard Cormacan’s Poem. Edited by J. O’Donovan (Irish Arch. Soc.)

English Chronicles: The English Chronicle; William of Malmesbury’s, Henry of Huntingdon’s, Florence of Worcester’s Chronicles; Asser’s Life of Alfred

Irish Chronicles: Annals of the Four Masters; of Ulster; Chronicum Scotorum; Three Fragments of Annals, edited by J. O’Donovan

I desire to thank Mrs Muriel Press and Mr W. C. Green for kind permission to make use of portions of their translations of Laxdæla and Egil’s Sagas; also Mr W. G. Collingwood for his consent to my adoption in my map of some of his boundaries from a map published in his Scandinavian Britain (S.P.C.K.); and to the Secretary of the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge for giving his sanction to this.

11

The first actual descent of the Northmen is chronicled in England under the year 787, and in Ireland, upon which country they commenced their descents about the same time, under the year 795; but it is likely, not only that they had visited and raided the coasts before this, but had actually made some settlements in both countries. The Ynglinga Saga tells us that Ivar Vidfadme or “Widefathom” had taken possession of a fifth part of England, i.e. Northumbria, before Harald Fairhair ruled in Norway, or Gorm the Old in Denmark; that is to say, before the history of either of these two countries begins. Ivar Vidfadme is evidently Ivar the Boneless, son of Ragnar Lodbrog, who conquered Northumbria before the reign of Harald Fairhair. There are traces of them even earlier, for a year after the first coming of the Northmen to Northumbria mentioned in the English annals we find that they called a synod at a place named Fingall, or “Fair Foreigners,” the name always applied to12 the Norse in our Irish and sometimes in our English chronicles. Now a place would not have been so named unless Norse people had for some time been settled there, and we may take it for granted that Norse settlers had made their home in Northumbria at some earlier period. We find, too, at quite an early time, that Norse and Irish had mingled and intermarried in Ireland, forming a distinct race called the Gall-Gael, or “Foreigners and Irish,” who had their own fleets and armies; and it is said that on account of their close family connexion many of the Christian Irish forsook their religion and relapsed into the paganism of the Norse who lived amongst them. We shall find, as we go on in the history, that generally the contrary was the case, and that contact with Christianity in these islands caused many Norse chiefs and princes to adopt our faith; indeed, it was largely through Irish and English influence that Iceland and Norway became Christian. Though we may not always approve of the way in which this was brought about, the fact itself is interesting.

The first settlers in Iceland were Irish hermits, who took with them Christian books, bells, and croziers, and the first Christian church built on the island was dedicated to St Columba, the Irish founder of the Scottish monastery of Iona, through whom Christianity was brought to Scotland.

Yet there is no doubt that the coming of the Northmen was looked upon with dread by the English, and there is a tone of terror in the first entry in the chronicles of their arrival upon the coast. This entry is so important that we will give it in the words of one of the old historians: “Whilst the pious King Bertric [King of Wessex] was reigning over the western13 parts of the English, and the innocent people spread through the plains were enjoying themselves in tranquillity and yoking their oxen to the ploughs, suddenly there arrived on the coast a fleet of Danes, not large, but of three ships only: this was their first arrival. When this became known, the King’s officer, who was already stopping in the town of Dorchester, leaped on his horse and galloped forwards with a few men to the port, thinking that they were merchants rather than enemies, and commanding them in an authoritative tone, ordered them to go to the royal city; but he was slain on the spot by them, and all who were with him.”1

This rude beginning was only a forecast of what was to follow. We hear of occasional viking bands arriving at various places on the coast from Kent to Northumbria, and ravaging wherever they appeared. At first they seem to have wandered round the coast without thought of remaining anywhere, but about sixty years after their first appearance (in 851), we find them settling on the warmer and more fertile lands of England during the winter, though they were off again when the summer came, foraging and destroying. This became a regular habit with these visitors, and led gradually to permanent settlements, especially in Northumbria. The intruders became known as “the army,” and the appearance of “the army” in any district filled the inhabitants with terror. Our first definite story of the Northmen in England is connected with the appearance of “the army” in Yorkshire A.D. 867. We learn from the English chronicles that violent internal discord was troubling Northumbria at this time. The king of the Northumbrians was Osbert,14 but the people had risen up and expelled him, we know not for what reason,2 and had placed on the throne a man named Ælla, “not of royal blood,” who seems to have been the leader of the people.

Just at this moment, when the country was most divided, the dreaded pagan army advanced over the mouth of the Humber from the south-east into Yorkshire. In this emergency all classes united for the common defence, and we find Osbert, the dethroned king, nobly marching side by side with his rival to meet the Northmen. Hearing that a great army was approaching, the Northmen shut themselves up within the walls of York, and attempted to defend themselves behind them. The Northumbrians succeeded in making a breach in the walls and entering the town; but, inspired by fear and necessity, the pagans made a fierce sally, cutting down their foes on all sides, inside and outside the walls alike. The city was set on fire, those who escaped making peace with the enemy. From that time onward the Northmen were seldom absent from Northumbria. York became one of their chief headquarters, and the constant succession of Norse ships along the coast gradually brought a considerable influx of Norse inhabitants to that part of England. It became, in fact, a viking kingdom, under the sons of Ragnar Lodbrog, whose story we have now to tell. This was in the time of the first Ethelred, when Alfred the Great was about twenty years of age. Ethelred was too much occupied in warring with the pagans in the South of England to be able to give any aid to the Northumbrians.

15

According to the Danish and Norse accounts, the leader of the armies of the Northmen on the occasion we have just referred to was the famous Ragnar Lodbrog, one of the earliest and most terrible of the Northern vikings. The story of Ragnar stands just on the borderland between mythology and history, and it is difficult to tell how much of it is true, but in some of its main outlines it accords with the rather scanty information we get at this time from the English annals. An old tradition relates how Ragnar got his title of Lodbrog, or “Hairy-breeks.”

It is said that the King of the Swedes, who was fond of hunting in the woods, brought home some snakes and gave them to his daughter to rear. Of these curious pets she took such good care that they multiplied until the whole countryside was tormented with them. Then the King, repenting his foolish act, proclaimed that whosoever should destroy the vipers should have his daughter as his reward. Many warriors, attracted by the adventure, made an attempt to rid the country of the snakes, but without much success. Ragnar also determined to try to win the princess. He caused a dress to be made of woolly material and stuffed with hair to protect him, and put on thick hairy thigh-pieces that the snakes16 could not bite. Then he plunged his whole body, clad in this covering, into freezing water, so that it froze on him, and became hard and impenetrable. Thus attired, he approached the door of the palace alone, his sword tied to his side and his spear lashed in his hand. As he went forward an enormous snake glided up in front, and others, equally large, attacked him in the rear. The King and his courtiers, who were looking on, fled to a safe shelter, watching the struggle from afar like affrighted little girls. But Ragnar, trusting to the hardness of his frozen dress, attacked the vipers boldly, and drove them back, killing many of them with his spear.

Then the King came forward and looked closely at the dress which had withstood the venom of the serpents. He saw that it was rough and hairy, and he laughed loudly at the shaggy breeches, which gave Ragnar an uncouth appearance. He called him in jest Lodbrog (Lod-brokr), or “Hairy-breeks,” and the nickname stuck to him all his life. Having laid aside his shaggy raiment and put on his kingly attire, Ragnar received the maiden as the reward of his victory. He had several sons, of whom the youngest, Ivar, was well known in after years in Britain and Ireland, and left a race of rulers there.

Meanwhile the ill-disposed people of his own kingdom, which seems to have included the districts we now know as Zealand or Jutland, one of those small divisions into which the Northern countries were at that time broken up,3 during the absence of Ragnar stirred up the inhabitants to depose him and set up one Harald as king. Ragnar, hearing of this, and having few men at his command, sent envoys to Norway to ask for assistance.17 They gathered a small host together, of weak and strong, young and old, whomsoever they could get, and had a hard fight with the rebels. It is said that Ivar, though he was hardly seven years of age, fought splendidly, and seemed a man in courage though only a boy in years. Siward, or Sigurd Snake-eye, Ragnar’s eldest son, received a terrible wound, which it is said that Woden, the father of the gods of the North, came himself to cure. The battle would have gone against Ragnar but for the courage of a noble woman named Ladgerda, who, “like an Amazon possessed of the courage of a man,” came to the hero’s assistance with a hundred and twenty ships and herself fought in front of the host with her loose hair flying about her shoulders. All marvelled at her matchless deeds, for she had the spirit of a warrior in a slender frame, and when the soldiers began to waver she made a sally, taking the enemy unawares on the rear, so that Harald was routed with a great slaughter of his men. This was by no means the only occasion in the history of these times that we hear of women-warriors; both in the North and in Ireland women often went into battle, sometimes forming whole female battalions. The women of the North were brave, pure, and spirited, though often fierce and bitter. They took their part in many ways beside their husbands and sons.

About this time Thora, Ragnar’s wife, died suddenly of an illness, which caused infinite sorrow to her husband, who dearly loved his spouse. He thought to assuage his grief by setting himself some heavy task, which would occupy his mind and energies. After arranging for the administration of justice at home, and training for war all the young men, feeble or strong, who came to him, he determined to cross over to Britain, since18 he had heard of the dissensions that were going on, and the weakness of the country. This was before the time of Ælla, when, as the Danish annals tell us, his father, Hame, “a most noble youth,” was reigning in Northumbria. This king, Ragnar attacked and killed, and then, leaving his young and favourite son to rule the Danish settlers of Northumbria, he went north to Scotland, conquered parts of Pictland, or the North of Scotland, and of the Western Isles, where he made two others of his sons, Siward Snake-eye and Radbard, governors.

Having thus formed for himself a kingdom in the British Isles, and left his sons to rule over it, Ragnar departed for a time, and the next few years were spent in repressing insurrections in his own kingdom of Jutland, and in a long series of viking raids in Sweden, Saxony, Germany, and France. His own sons were continually making insurrections against him. Ivar only, who seems to have been recalled and made governor of Jutland, took no part in his brothers’ quarrels, but remained throughout faithful to his father, by whom he was held in the highest honour and affection. Another son, Ubba, of whom we hear in the English chronicles, alternately rebelled against his father and was received into favour by him. Then, again, Ragnar turned his thoughts to the West, and, descending on the Orkneys, ravaged there, planting some of those viking settlements of which we hear at the opening of Scottish history as being established on the coasts and islands. But two of his sons were slain, and Ragnar returned home in grief, shutting himself up in his house and bemoaning their loss, and that of a wife whom he had recently married. He was soon awakened from his sorrow by the news that Ivar, whom he had left in19 Northumbria, had been expelled from the country, and had arrived in Denmark, his own people having made him fly when Ælla was set up as king.4 Ragnar immediately roused himself from his dejection, gave orders for the assembling of his fleet, and sailed down on Northumbria, disembarking near York. He took Ivar with him to guide his forces, as he was now well acquainted with the country. Here, as we learn from the English chronicles, the battle of York was fought, lasting three days, and costing much blood to the English, but comparatively little to the Danes. The only real difference between the Danish and English accounts is that the Northern story says that Ælla was not killed, but had to fly for a time to Ireland, and it is probable that this is true. Ragnar also extended his arms to Ireland, after a year in Northumbria, besieged Dublin, and slew its king, Maelbride (or Melbrik, as the Norse called him), and then, filling his ships with the wealth of the city, which was very rich, he sailed to the Hellespont, winning victories everywhere, and gaining for himself the title of the first of the great viking kings.

But it was fated to Ragnar that he was to die in the country he had conquered, and when he returned to Northumbria from his foreign expeditions he was taken prisoner by Ælla, and cast into a pit, where serpents were let loose upon him and devoured him. No word of complaint came from the lips of the courageous old man while he was suffering these tortures; instead, he recounted in fine verse the triumphs of his life and the dangers of his career. This poem we still possess. Only20 when the serpents were gnawing at his heart he was heard to exclaim: “If the little pigs knew the punishment of the old boar, surely they would break into the sty and loose him from his woe.” These words were related to Ælla, who thought from them that some of Ragnar’s sons, whom he called the “little pigs,” must still be alive: and he bade the executioners stop the torture and bring Ragnar out of the pit. But when they ran to do so they found that Ragnar was dead; his face scarred by pain, but steadfast as in life. Death had taken him out of the hand of the king.

In Ragnar Lodbrog’s death-song he recites in succession his triumphs and gallant deeds, his wars and battles, in England, Scotland, Mona, the Isle of Man, Ireland, and abroad. Each stanza begins, “We hewed with our swords!” Here are the final verses, as the serpents, winding around him, came ever nearer to his heart.

Ragnar Lodbrog’s Death-song

We hewed with our swords!

Life proves that we must dree our weird. Few can escape the binding bonds of fate. Little dreamed I that e’er my days by Ælla would be ended! what time I filled the blood hawks with his slain, what time I led my ships into his havens, what time we gorged the beasts of prey along the Scottish bays.

We hewed with our swords!

There is a never-failing consolation for my spirit: the board of Balder’s sire [Woden] stands open to the brave! Soon from the crooked skull-boughs5 in the splendid house of Woden we shall quaff the amber mead! Death blanches not the brave man’s face. I’ll not approach the courts of Vitris6 with the faltering voice of fear!

21

We hewed with our swords!

Soon would the sons of Aslaug7 come armed with their flaming brands to wake revenge, did they but know of our mischance; even that a swarm of vipers, big with venom, sting my aged body. I sought a noble mother for my children, one who might impart adventurous hearts to our posterity.

We hewed with our swords!

Now is my life nigh done. Grim are the terrors of the adder; serpents nestle within my heart’s recesses.

Yet it is the cordial of my soul that Woden’s wand8 shall soon stick fast in Ælla! My sons will swell with vengeance at their parent’s doom; those generous youths will fling away the sweets of peace and come to avenge my loss.

We hewed with our swords!

Full fifty times have I, the harbinger of war, fought bloody fights; no king, methought, should ever pass me by. It was the pastime of my boyish days to tinge my spear with blood! The immortal Anses9 will call me to their company; no dread shall e’er disgrace my death.

I willingly depart!

See, the bright maids sent from the hall of Woden, Lord of Hosts, invite me home! There, happy on my high raised seat among the Anses, I’ll quaff the mellow ale. The moments of my life are fled, but laughing will I die!

22

It seemed, toward the close of the ninth century, that England would gradually pass into the power of the Danes and cease to be an independent country. They had established themselves not only in Northumbria, but in East Anglia and parts of Mercia. We have to think of England at this period not as one united kingdom, but as a number of separate principalities, ruled by different kings. The most powerful of these principalities was Mercia, which occupied the whole central district of England, from Lincolnshire in the north to Oxford and Buckingham in the south, and west to the borders of Wales. It was governed by a king named Burhred, who found great difficulty in holding his own against incursions from the Welsh on the one hand and from the Danes of Northumbria on the other.10

In the south the kingdom of Wessex was coming into prominence. During the reigns of Alfred and his brother, Edward the Elder, Wessex not only held back the Danes from their tide of progress, but gave its kings to the larger part of England. The kingdom of Wessex extended from Sussex in the east to Devon in the west, and included our present counties of Hants,23 Dorset, Somerset, Berks, and Wilts. It was from this small district that the saviour of England was to come, who, by his courage, perseverance, and wisdom, broke the power of the Danes and kept them back from the conquest of the whole country, which at one time seemed so probable. This saviour of England was Alfred the Great.

We know the history of Alfred intimately, for it was written for us during the King’s lifetime by his teacher and friend, Asser, who tells us that he came to Alfred “out of the furthest coasts of western Britain.” He was Bishop of St David’s, in South Wales.

The account of his coming at Alfred’s request to give him instruction and to act as his reader must be told in his own interesting words. He tells us that at the command of the King, who had sent in many directions, even as far as Gaul, for men of sound knowledge to give him and his sons and people instruction, he had come from his western home through many intervening provinces, and arrived at last in Sussex, the country of the Saxons.

Here for the first time he saw Alfred, in the royal “vill” in which he dwelt, and was received with kindness by the King, who eagerly entered into conversation with him, and begged him to devote himself to his service and become his friend. Indeed, so anxious was he to secure Asser’s services, that he urged him then and there to resign his duties in Wales and promise never to leave him again. He offered him in return more than all he had left behind if he would stay with him. Asser nobly replied that he could not suddenly give up those who were dependent on his ministrations and permanently leave the country in which he had been bred and where his duties lay; upon which the24 King replied: “If you cannot accede to this, at least let me have part of your service; stay with me here for six months and spend the other six months in the West with your own people.” To this Asser, seeing the King so desirous of his services, replied that he would return to his own country and try to make the arrangement which Alfred desired; and from this time there grew up a lifelong friendship between these two interesting men, one learned, simple, and conscientious, the other eager for learning, and bent upon applying all his wisdom for the benefit of the people over whom he ruled.

From the life of Alfred, written by his master, we might imagine that the chief part of the monarch’s time was devoted to learning and study. “Night and day,” Asser tells us, “whenever he had leisure, he commanded men of learning to read to him;” so that he became familiar with books which he was himself unable to read. He loved poetry, and caused it to be introduced into the teaching of the young. He with great labour (for his own education had been sadly neglected) translated Latin works on history and religion, so that his people might read them. He kept what he called a “Manual” or “Handbook,” because he had it at hand day and night, in which he wrote any passage they came upon in their reading which especially struck his mind. Asser tells us in a charming way how he began this custom. He says that they were sitting together in the King’s chamber, talking, as usual, of all kinds of subjects, when it happened that the master read to him a quotation out of a certain book. “He listened to it attentively, with both his ears, and thoughtfully drew out of his bosom a book wherein were written the daily psalms and prayers which he had read in his25 youth, and he asked me to write the quotation in that book. But I could not find any empty space in that book wherein to write the quotation, for it was already full of various matters. Upon his urging me to make haste and write it at once, I said to him: ‘Would you wish me to write the quotation on a separate sheet? For it is possible that we may find one or more other extracts which will please you; and if this should happen, we shall be glad that we have kept them apart.’

“‘Your plan is good,’ he said; and I gladly made haste to get ready a fresh sheet, in the beginning of which I wrote what he bade me. And on the same day, as I had anticipated, I wrote therein no less than three other quotations which pleased him, so that the sheet soon became full. He continued to collect these words of the great writers, until his book became almost as large as a psalter, and he found, as he told me, no small consolation therein.”

But, studious as was naturally the mind of Alfred, only a small portion of his life, and that chiefly when he became aged, could be given to learning. His career lay in paths of turmoil and war, and his earlier days were spent in camps and among the practical affairs of a small but important kingdom. Already as a child of eight or ten he had heard of battles and rumours of war all around him. He heard of “the heathen men,” as the Danes were called, making advances in the Isle of Wight, at Canterbury and London, and creeping up the Thames into new quarters in Kent and Surrey. There his father, King Ethelwulf, and his elder brothers had met and defeated them with great slaughter at Aclea, or Ockley, “the Oak-plain,” and they returned home to Wessex with the news of a complete victory. It was probably to keep his favourite child out of the26 way of warfare and danger that Ethelwulf sent him twice to Rome; the second time he himself accompanied him thither, and they returned to find that one of Alfred’s elder brothers, Ethelbald, had made a conspiracy against his own father, had seized the kingdom, and would have prevented Ethelwulf from returning had he been able. But the warm love of his people, who gathered round him, delighted at his return, prevented this project from being carried into effect, and the old man, desiring only peace in his family, divided the kingdom between his two eldest sons; but on the death of Ethelbald, soon after, Ethelbert joined the two divisions together, including Kent, Surrey, and Sussex in the same kingdom with Wessex. When Alfred was eighteen years of age this brother also died, and for five years more a third brother, Ethelred, sat on the throne of Wessex.

It was at this time, when Alfred was growing up to manhood, that the troubles in Northumbria of which we have already given an account took place. The reign of Ælla, and his horrible death at the hands of Lodbrog’s sons, was followed by the advance of the pagan army into Mercia, and it was here that Alfred came for the first, time face to face with the enemy against whom much of his life was to be spent in conflict. Burhred, King of the Mercians, sent to Ethelred and Alfred to beg their assistance against the pagan army. They immediately responded by marching to Nottingham with a large host, all eager to fight the Danes; but the pagans, shut up safely within the walls of the castle, declined to fight, and in the end a peace was patched up between the Danes and the Mercians, and the two Wessex princes returned home without a battle. It was not long, however, before the army was needed27 again; for, three years later, in the year 871, when Alfred was twenty-three years of age, “the army of the Danes of hateful memory,” as Asser calls it, entered Wessex itself, coming up from East Anglia, where they had wintered. After attacking the then royal city of Reading, on the Thames, they entrenched themselves on the right of the town. Ethelred was not able to come up with them at so short notice, but the Earl of Berkshire, gathering a large army, attacked them in the rear at Englefield Green, and defeated them, many of them taking to flight. Four days afterwards the two princes of Wessex, Ethelred and Alfred, came up, and soon cut to pieces the Danes that were defending the city outside; but those Danes who had shut themselves in the city sallied out of the gates, and after a long and hot encounter the army of Wessex fled, the brave Earl of Berkshire being among the slain.

Roused by this disaster, the armies of Wessex, in shame and indignation, collected their whole strength, and within four days they were ready again to give battle to the Danes at Ashdune (Aston), “the Hill of the Ash,” in the same county. They found the Danes drawn up in two divisions, occupying high ground; while the army of Wessex was forced to attack from below. Both parties began to throw up defences, and the Danes were pressing forward to the attack; but Alfred, who was waiting for the signal to begin the battle, found that his elder brother, Ethelred, was nowhere to be seen. He sent to inquire where he was, and learned that he was hearing mass in his tent, nor would he allow the service to be interrupted or leave his prayers till all was finished. It had been arranged that Alfred with his troops should attack the smaller bodies of the Danes, while Ethelred, who was to lead the centre, took the general command;28 but the enemy were pushing forward with such eagerness that Alfred, having waited as long as he dared for his brother, was forced at length to give the signal for a general advance. He bravely led the whole army forward in a close phalanx, without waiting for the King’s arrival, and a furious battle took place, concentrating chiefly around a stunted thorn-tree, standing alone, which, Asser tells us, he had seen with his own eyes on the spot where the battle was fought. A great defeat was inflicted on the Danes; one of their kings and five of their earls were killed, and the plain of Ashdune was covered with the dead bodies of the slain. The whole of that night the pagans fled, closely followed by the victorious men of Wessex, until weariness and the darkness of the night brought the conflict to an end.

29

It was in the midst of incessant warfare that Alfred ascended the throne of Wessex. Ethelred, his brother, died a few months after the battle of Ashdune, and in the same year, that in which Alfred came to the throne, no less than nine general battles were fought between Wessex and the Danes. Both armies were exhausted, and a peace was patched up between them, the Danish army withdrawing to the east and north, and leaving Wessex for a short time in peace. But they drove King Burhred out of Mercia, and overseas to Rome, where he soon afterwards died. He was buried in the church belonging to an English school which had been founded in the city by the Saxon pilgrims and students who had taken refuge in Rome from the troubles in England.

It would seem that Alfred’s chief troubles during the years following were caused by the fierce sons of Ragnar Lodbrog, brothers of Ivar the Boneless of Northumbria. These three brothers, Halfdene, Ivar, and Ubba, overran the whole country, appearing with great rapidity at different points, so that, as one historian says, they were no sooner pushed from one district than they reappeared in another. Alfred tried by every means to disperse the Danish army. He made them30 swear over holy relics to depart, but their promise was hardly given before it was broken again; he raised a fleet after their own pattern and attacked them at sea; and he laid siege to Exeter, where they had entrenched themselves, cutting off their provisions and means of retreat. It was like fighting a swarm of flies; however many were killed, more came overseas to take their place. “For nine successive years,” writes William of Malmesbury, “he was battling with his enemies, sometimes deceived by false treaties, and sometimes wreaking his vengeance on the deceivers, till he was at last reduced to such extreme distress that scarcely three counties, that is to say, Hampshire, Wiltshire, and Somerset, stood fast by their allegiance.” He was compelled to retreat to the Isle of Athelney, where, supporting himself by fishing and forage, he, with a few faithful followers, led an unquiet life amid the marshes, awaiting the time when a better fortune should enable them to recover the lost kingdom. One hard-won treasure they had with them in their island fortress. This was the famous Raven Banner, the war-flag which the three sisters of Ivar and Ubba, Lodbrog’s daughters, had woven in one day for their brothers. It was believed by them that in every battle which they undertook the banner would spread like a flying raven if they were to gain the victory; but if they were fated to be defeated it would hang down motionless. This flag was taken from the brothers in Devon at the battle in which Ubba was slain, and much booty with it. No doubt it was cherished as an omen of future victory by the followers of the unfortunate Alfred in their retreat.

But Alfred was not idle. Slowly but surely he gathered around him a devoted band, and his public reappearance31 in Wiltshire some months afterwards, in the spring or summer of 878, was the signal for the joyous return to him of a great body of his subjects. With a large army he struck camp, meeting the foe at Eddington or Ethandun, and there defeated the pagans in so decisive a battle that after fourteen days of misery, “driven by famine, cold, fear, and last of all by despair, they prayed for peace, promising to give the King as many hostages as he desired, but asking for none in return.” “Never before,” writes Asser, “had they concluded such an ignominious treaty with any enemy,” and the king, taking pity on them, received such hostages as they chose to give, and what was more important, a promise from them that they would leave the kingdom immediately. Such promises had been given by the Danes before, and had not been kept. But the Danish chief or prince with whom Alfred was now dealing was of a different type from the sons of Ragnar. He was a man of high position and character; not a viking in the usual sense, for he had been born in England, where his father had settled and been baptized, and Alfred knew that in Gorm, or Guthrum, he had a foe whom he could both respect for his courage and depend on for his fidelity.

This Gorm is called in the Northern chronicles, “Gorm the Englishman,” on account of his birth and long sojourn in this country. Though a prince of Denmark, he had spent a great part of his life in England, and he had held the Danes together, and been their leader in many of their victories against Alfred. It was during his absence from England, when he had been forced to go back to Denmark to bring things into order in his own kingdom, that the English had gathered courage, under Alfred’s leadership, to revolt against him. His absence was short, but he was unable32 on his return to recover his former power, and the result was the great defeat of the Danes of which we have just spoken. It had been one of Alfred’s stipulations that Gorm, or Guthrum (as he was called in England), should become a Christian; this he consented to do, the more inclined, perhaps, because his father had been baptized before him; accordingly, three weeks after the battle, King Gorm, with about thirty of his most distinguished followers, repaired to Alfred at a place near Athelney, where he was baptized, Alfred himself acting as his godfather. After his baptism, he remained for twelve days with the King at the royal seat of Wedmore; and Alfred gave him and his followers many gifts, and they parted as old friends. His baptismal name was Athelstan. For a time he seems to have remained in East Anglia, and settled that country; but soon afterwards he returned to his own kingdom, where the attachment of his people seems to have been all the greater on account of his ill-luck in England. Though he irretrievably lost his hold on this country, he remained firmly seated on the throne of Denmark. He was the ancestor of Canute the Great, joint King of Denmark and of England, who regained all, and more than all, that his great-grandfather had lost in this country, for Canute ruled, not over a portion of England, but over an undivided kingdom. Gorm died in 890.

The latter part of Alfred’s reign was devoted to the affairs of his country. He gave his people good laws; dividing the kingdom into divisions called “hundreds” and “tythings,” which exercised a sort of internal jurisdiction over their own affairs. He rebuilt London, and over the whole of his kingdom he caused houses to be built, good and dignified beyond any that had hitherto been known in the land. He encouraged33 industries of all kinds, and had the artificers taught new and better methods of work in metals and gold. He encouraged religion and learning, inviting good and learned men from abroad or wherever he could hear of them, and richly rewarding their efforts. He devoted much time to prayer; but his wise and sane mind prevented him from becoming a bigot, as his activity in practical affairs prevented him from becoming a mere pedant. One of his most lasting works was the establishment of England’s first navy, to guard her shores against the attacks of foreigners. All these great reforms were carried out amid much personal suffering, for from his youth he had been afflicted with an internal complaint, beyond the surgical knowledge of his day to cure, and he was in constant pain of a kind so excruciating that Asser tells us the dread of its return tortured his mind even when his body was in comparative rest. There is in English history no character which combines so many great qualities as that of Alfred. Within and without he found his kingdom in peril and misery, crushed down, ignorant and without religion; he left it a flourishing and peaceful country, united and at rest. When his son, Edward the Elder, succeeded him on the throne, not only Wessex but the whole North of England, with the Scots, took him “for father and lord”; that is, they accepted him, for the first time in history, as king of a united England. This great change was the outcome of the many years of patient building up of his country which Alfred had brought about through wise rule. He was open-handed and liberal to all, dividing his revenue into two parts, one half of which he kept for his own necessities and the uses of the kingdom and for building noble edifices; the other for the poor, the encouragement of learning,34 and the support and foundation of monasteries. He took a keen interest in a school for the young nobles which he founded and endowed, determining that others should not, in their desire for learning, meet with the same difficulties that he had himself experienced. In his childhood it had not been thought necessary that even princes and men of rank should be taught to read; and the story is familiar to all that he was enticed to a longing for knowledge by the promise of his stepmother Judith, daughter of the King of the Franks, who had been educated abroad, that she would give a book of Saxon poetry which she had shown to him and his brother to whichever of them could first learn to read it and repeat the poetry by heart. Alfred seems to have learned Latin from Asser, for he translated several famous books into Saxon, so that his people might attain a knowledge of their contents without the labour through which he himself had gone. When we consider that he was also, as William of Malmesbury tells us, “present in every action against the enemy even up to the end of his life, ever daunting the invaders, and inspiring his subjects with the signal display of his courage,” we may well admire the indomitable energy of this man. In his old age he caused candles to be made with twenty-four divisions, to keep him aware of the lapse of time and help him to allot it to special duties. One of his attendants was always at hand to warn him how his candle was burning, and to remind him of the special duty he was accustomed to perform at any particular hour of the day or night.

The latter years of Alfred were comparatively free from incursions by the Danes or Norsemen; this was the period during which the attention of the Norse was attracted in other directions. The conquests of35 Rollo or Rolf the Ganger or “the Walker” in the North of France were attracting a large body of the more turbulent spirits to those shores which in after-times they were to call Normandy, or the land of the Northmen. After Gorm the Englishman’s submission to Alfred many of the Danes from England seem to have joined these fresh bands of marauders, advancing up the Seine to Paris, and devastating the country as far as the Meuse, the Scheldt, and the Marne on the east and Brittany on the west. In time to come, under Rollo’s descendant, William the Conqueror, these people were once more to pour down upon English shores and reconquer the land that their forefathers had lost through Alfred’s bravery and statesmanship. Rollo overran Normandy for the first time in the year 876,11 and William the Conqueror landed at Pevensey in 1066, nearly two hundred years later. William’s genealogy was as follows:—He was son of Robert the Magnificent, second son of Richard the Good, son of Richard the Fearless, son of William Longsword, son of Rollo or Rolf the Walker—six generations. The direct connexion between the Anglo-Norman houses was through Emma, daughter of Richard the Fearless, who married first Ethelred the Unready, King of England, and afterwards his enemy and successor, Canute the Great. It was on account of this connexion that William the Conqueror laid claim to the Crown of England.

36

There were yet other directions toward which the Norse viking-hosts had already turned their eyes. Not far out from the coasts of Norway lay the Orkney and Shetland Islands, and beyond them again the Faröe Isles rose bleak and treeless from the waters of the northern sea. The shallow boats of the Norsemen, though they dreaded the open waters of the Atlantic, were yet able, in favourable weather, to push their way from one set of islands to another, and from the earliest times of which we know anything about them they had already made some settlements on these rocky shores. To the Norseman, accustomed to a hardy life and brought up to wring a scanty livelihood almost out of the barren cliff itself, even the Orkney and Shetland Isles had attractions. Those who have seen the tiny steadings of the Norwegian farmer to-day, perched up on what appears from below to be a perfectly inaccessible cliff, with only a few feet of soil on which to raise his scanty crop, solitary all the year round save for the occasional visit of a coasting steamer, will the less wonder that the islands on the Scottish coast proved attractive to his viking forefathers. Often, in crossing that stormy sea, the adventurous crew found a37 watery grave, or encountered such tempests that the viking boat was almost knocked to pieces; but on the whole these hardy seamen passed and repassed over the North Sea with a frequency that surprises us, especially when we remember that their single-sailed boats were open, covered in only at the stem or stern,12 and rowed with oars. We hear of these settlers on our coasts before Norwegian history can be said to have begun; and from early times, also, they carried on a trade with Ireland; we hear of a merchant in the Icelandic “Book of the Settlements” named Hrafn, who was known as the “Limerick trader,” because he carried on a flourishing business with that town, which later grew into importance under the sons of Ivar, who settled there and built the chief part of the city.

But during the latter years of Alfred’s reign and for many years after his death a great impetus was given to the settlements in the North of Scotland by the coming to the throne of Norway of the first king who reigned over the whole country, Harald Fairhair. He established a new form of rule which was very unpopular among his great lords and landowners, and the consequence of this was that a large number of his most powerful earls or “jarls” left the country with their families and possessions and betook themselves to Iceland, the Orkneys and Hebrides, and to Ireland. They did not go as marauders, as those who went before them had done, but they went to settle, and establish new homes for themselves where they would be free from what they considered to be Harald Fairhair’s oppressive laws. Before his time each of these jarls had been his own master, ruling his own district as an38 independent lord, but paying a loose allegiance to the prince who chanced at the time to prove the most powerful. From time to time some more ambitious prince arose, who tried to subdue to his authority the men of consequence in his own part of the country, but hitherto it had not come into the mind of any one of them to try to make himself king over the whole land.

The idea of great kingdoms was not then a common one. In England up to this time no king had reigned over the whole country; there had been separate rulers for East Anglia, Wessex, Northumbria, etc., sometimes as many as seven kings reigning at the same time in different parts of the country, in what was called the “Heptarchy.” It was only when the need of a powerful and capable ruler was felt, and there chanced to be a man fitted to meet this need, as in Alfred’s time and that of his son, Edward the Elder, that the kingdoms drew together under one sovereign. But even then it was not supposed that things would remain permanently like this; under a weaker prince they might at any moment split up again into separate dynasties. In Ireland this system remained in force far longer, for centuries indeed, the country being broken up into independent and usually warring chiefdoms. Abroad, none of the Northern nations had united themselves into great kingdoms up to the time of Harald Fairhair, but about this date a desire began to show itself to consolidate the separate lordships under single dynasties, partly because it chanced that men of more than usual power and ambition happened to be found in them, and partly for protection from neighbouring States; in the case of Harald himself, his pride also led him to desire to take a place in the world as important39 as that of the neighbouring kings. In Sweden King Eirik and in Denmark King Gorm the Old were establishing themselves on the thrones of united kingdoms. The effort of Harald to accomplish the same task in Norway was so important in its effects, not only on the future history of his own country, but on that of portions of our own, that it is worth while to tell it more in detail.

Harald was son of Halfdan the Black, with whose reign authentic Norwegian history begins. Halfdan ruled over a good part of the country, which he had gained by conquest, and he was married to Ragnhild, a wise and intelligent woman, and a great dreamer of dreams. It is said that in one of her dreams she foretold the future greatness of her son Harald Fairhair. She thought she was in her herb-garden, her shift fastened with a thorn; she drew out the thorn with her hand and held it steadily while it began to grow downward, until it finally rooted itself firmly in the earth. The other end of it shot upward and became a great tree, blood-red about the root, but at the top branching white as snow. It spread until all Norway was covered by its branches. The dream came true when Harald, who was born soon afterwards, subdued all Norway to himself.

Harald grew up strong and remarkably handsome, very expert in all feats, and of good understanding. It did not enter his head to extend his dominions until some time after his father’s death, for he was only ten years old at that time, and his youth was troubled by dissensions among his nobles, who each wanted to possess himself of the conquests made by Halfdan the Black; but Harald subdued them to himself as far south as the river Raum. Then he set his affections40 on a girl of good position named Gyda, and sent messengers to ask her to be his wife. But she was a proud and ambitious girl, and declared that she would not marry any man, even though he were styled a king, who had no greater kingdom than a few districts. “It is wonderful to me that while in Sweden King Eirik has made himself master of the whole country and in Denmark Gorm the Old did the same, no prince in Norway has made the entire kingdom subject to himself. And tell Harald,” she added, “that when he has made himself sole King of Norway, then he may come and claim my hand; for only then will I go to him as his lawful wife.” The messengers, when they heard this haughty answer, were for inflicting some punishment upon her, or carrying her off by force; but they thought better of it and returned to Harald first, to learn what he would say. But the King looked at the matter in another light. “The girl,” he said, “has not spoken so much amiss as that she should be punished for it, but on the contrary I think she has said well, for she has put into my mind what it is wonderful that I never before thought of. And now I solemnly vow, and I take God, who rules over all things, to witness, that never will I clip or comb my hair until I have subdued Norway, with scat,13 dues, and dominions to myself; or if I succeed not, I will die in the attempt.”

The messengers, hearing this, thanked the King, saying that “it was royal work to fulfil royal words.”

After this, Harald set about raising an army and41 ravaging the country, so that the people were forced to sue for peace or to submit to him; and he marched from place to place, fighting with all who resisted him, and adding one conquest after another to his crown; but many of the chiefs of Norway preferred death to subjection, and it is stated of one king named Herlaug that when he heard that Harald was coming he ordered a great quantity of meat and drink to be brought and placed in a burial-mound that he had erected for himself, and he went alive into the mound and ordered it to be covered up and closed. A mound answering to this description has been opened not far north of Trondhjem, near where King Herlaug lived, and in it were found two skeletons, one in a sitting posture, while in a second chamber were bones of animals. It is believed that this was Herlaug’s mound where he and a slave were entombed; it had been built for himself and his brother King Hrollaug, to be their tombs when they were dead, but it became the sepulchre of the living. As for Hrollaug, he determined to submit to Harald, and he erected a throne on the summit of a height on which he was wont to sit as king, and ordered soft beds to be placed below on the benches on which the earls were accustomed to sit when there was a royal council. Then he threw himself down from the king’s seat into the seat of the earls, in token that he would resign his sovereignty to Harald and accept an earldom under him; and he entered the service of Harald and gave his kingdom up to him, and Harald bound a shield to his neck and placed a sword in his belt and accepted his service; for it was his plan, when any chief submitted to him, to leave him his dominions, but to reduce him to the position of a jarl, holding his rights from himself and owning fealty to him.

42

In many ways the lords were richer and better off than before, not only because they had less cause to fight among themselves, being all Harald’s men, but because they were made collectors of the land dues and fines for the King, and out of all dues collected the earl received a third part for himself; and these dues had been so much increased by Harald that the earls had greater revenues than before; only each earl was bound to raise and support sixty men-at-arms for the King’s service, while the chief men under them had also to bring into the field their quota of armed men. Thus Harald endeavoured to establish a feudal system in Norway similar to that introduced into England by William the Conqueror, and in time the whole country was subdued outwardly to his service, and Harald won his bride. But although he cut off or subdued his opponents and there was outward peace, a fierce discontent smouldered in the minds of many of the nobles who hitherto had been independent lords, and they would not brook the authority of Harald, but fled oversea, or joined the viking cruisers, so that the seas swarmed with their vessels and every land was infested with their raids. It was at this time that Iceland and the Faröe Islands were colonized by people driven out of Norway, and others went to Shetland and the Orkneys and Hebrides and joined their countrymen there; others settled in Ireland, and others, again, lived a roving life, marauding on the coasts of their own country in the summer, and in other lands in the winter season; so that Norway itself was not free from their raids. King Harald fitted out a fleet and searched all the islands and wild rocks along the coast to clear them of the vikings. This he did during three summers, and wherever he came the vikings took to flight, steering43 out into the open sea; but no sooner was the King gone home again than they gathered as thickly as before, devastating up into the heart of Norway to the north; until Harald grew tired of this sort of work, and one summer he sailed out into the western ocean, following them to Shetland and the Orkneys, and slaying every viking who could not save himself by flight. Then he pushed his way southward along the Hebrides, which were called the Sudreys14 then, and slew many vikings who had been great lords in their time at home in Norway; and he pursued them down to the Isle of Man; but the news of his coming had gone before him and he found all the inhabitants fled and the island left entirely bare of people and property. So he turned north again, himself plundering far and wide in Scotland, and leaving little behind him but the hungry wolves gathering on the desolate sea-shore. He returned to the Orkneys, and offered the earldom of those islands to Ragnvald, one of his companions, the Lord of More, who had lost a son in the war; but Ragnvald preferred to return with Harald to Norway, so he handed the earldom of Orkney and the Isles over to his brother Sigurd. King Harald agreed to this and confirmed Sigurd in the earldom before he departed for Norway.

When King Harald had returned home again, and was feasting one day in the house of Ragnvald, Earl of More, he went to a bath and had his hair combed and dressed in fulfilment of his vow. For ten years his hair had been uncut, so that the people called him Lufa or “Shockhead”; but when he came in with his44 hair shining and combed after the bath, Ragnvald called him Harfager, or “Fair Hair,” and all agreed that it was a fitting name for him, and it clung to him thenceforward, so that he is known as Harald Harfager to this day.

45

There is yet another direction to which we must turn our attention, if we would understand the grip that the Northmen at this time had taken on the British Islands, and the general trend of Norse and Danish history outside their own country. Their conquests and influence in Ireland were even more widespread and equally lasting with those in England. We find them from the beginning of the ninth century (from about A.D. 800 onward) making investigations all round the coast of Ireland, and pushing their way up the rivers in different directions. The Norse, many of whom probably reached Ireland by way of the Western Isles and Scotland, consolidated their conquests in the north under a leader named Turgesius (perhaps a Latinized form of Thorgils), who ruled from the then capital of Ireland and the ecclesiastical city of St Patrick, Armagh. Thorgils was a fierce pagan, and he established himself as high-priest of Thor, the Northman’s god of thunder, in the sacred church of St Patrick, desecrating it with heathen practices; while he placed his wife Ota as priestess in another of the sacred spots of Ireland, the ancient city of Clonmacnois, on the Shannon, with its seven churches and its high crosses, from the chief church of which she gave forth her oracles.

46

Soon after this there arrived in Ireland another chief, named Olaf the White, who chose Dublin, then a small town on the river Liffey, as his capital, building there a fortress, and establishing a “Thing-mote,” or place of meeting and lawgiving, such as he was accustomed to at home. From this date the importance of Armagh waned, and Dublin became not only the Norse capital of Ireland and an important city, but also the centre from which many Norse and Danish kings ruled over Dublin and Northumbria at once. We shall see when we come to the time of Athelstan, and the story of Olaf Cuaran, or Olaf o’ the Sandal, who claimed kingship over both Ireland and Northumbria, how close was the connexion between the two.

The Danes, who succeeded the Norwegians, first came to Ireland in the year 847, probably crossing over from England. They had heard much of the successes of the Northmen or Norwegians in Ireland, and they came over to dispute their conquests with them and try to take from them the fruit of their victories. They did not at first think of warring with the Irish themselves, but only with their old foes, the Norsemen, whom they were ready to fight wherever they could find them; but as time went on we find them fighting sometimes on one side and sometimes on the other, mixing themselves up in the private quarrels of the Irish chiefs and kings, often for their own advantage. On the other hand, the Irish chiefs were often ready enough to take advantage of their presence in the country to get their help in fighting with their neighbours.

The Kings of Dublin in the later time were Danish princes, who passed on to other parts of Ireland, building forts in places which had good harbours and could easily be fortified, such as Limerick and Waterford,47 which were for long Danish towns, ruled by Danish chiefs, most of them of the family of Ivar of Northumbria. Though their hold on their settlements was at all times precarious, and they met with many reverses, and several decisive defeats from the Irish, the Danes gradually succeeded in building up their Irish and Northumbrian kingdom. The official title of these rulers was “King of the Northmen of all Ireland and Northumbria.”

The story we have now to tell is connected with a prince who probably was not a Dane, but a Norseman, or a “Fair-foreigner,” as the Irish called them, to distinguish them from the Danes, or “Dark-foreigners.” This was Olaf the White, who came to Ireland in 853. In the course of a warring life he succeeded in making himself King of the Norse in Dublin. He seems to have been of royal descent, and he was married to Aud, or Unn, daughter of Ketill Flatnose, a mighty and high-born lord in Norway. Aud is her usual name, but in the Laxdæla Saga, where we get most of her history, she is named Unn the Deep-minded or Unn the Very-wealthy. All this great family left their native shores after King Harald Fairhair came to the throne, and they settled in different places, Ketill himself in the Orkney Isles, where some of his sons accompanied him; but his son Biorn the Eastman and Helgi, another son, said they would go to Iceland and settle there. Sailing up the west coast, they entered a firth which they called Broadfirth. They went on shore with a few men, and found a narrow strip of land between the foreshore and the hills, where Biorn thought he would find a place of habitation. He had brought with him the pillars of his temple from his home in Norway, as many of the Icelandic settlers did, and he flung them overboard,48 as was the custom with voyagers, to see where they would come ashore. When they were washed up in a little creek he said that this must be the place where he should build his house; and he took for himself all the land between Staff River and Lava Firth, and dwelt there. Ever after it was called after him Biorn Haven.

But Ketill and most of his family went to Scotland, except Unn the Deep-minded, his daughter, who was with her husband, Olaf the White, in Dublin, though after Olaf’s death she joined her father’s family in the Hebrides and Orkneys, her son, Thorstein the Red, harrying far and wide through Scotland. He was always victorious, and he and Earl Sigurd subdued Caithness, Sutherland, and Ross between them, so that they ruled over all the north of Scotland.15 Troubles arose out of this, for the Scots’ earl did not care to give up his lands to foreigners, and in the end Thorstein the Red was murdered treacherously in Caithness.

When his mother, Unn the Deep-minded, heard this, she thought there would be no more safety for her in Scotland; so she had a ship built secretly in a wood, and she put great wealth into it, and provisions; and she set off with all her kinsfolk that were left alive; for her father had died before that. Many men of worth went with her; and men deem that scarce any other, let alone a woman, got so much wealth and such a following out of a state of constant war as she had done; from this it will be seen how remarkable a woman she was. She steered her ship for the Faröe Islands, and stayed there for a time, and in every place at which she stopped she married off one of her granddaughters,49 children of her son, Thorstein the Red, so that his descendants are found still in Scotland and the Faröes. But in the end she made it known to her shipmates that she intended to go on to Iceland. So they set sail again, and came to the south of Iceland, to Pumicecourse, and there their good ship went on the rocks, and was broken to splinters, but all the sea-farers and goods were saved.

All that winter she spent with Biorn, her brother, at Broadfirth, and was entertained in the best manner, as no money was spared, and there was no lack of means; for he knew his sister’s large-mindedness. But in the spring she set sail round the island to find lands of her own; she threw her high-seat temple pillars into the sea, and they came to shore at the head of a creek, so Unn thought it was well seen that this was the place where she should stay. So she built her house there, and it was afterwards called Hvamm, and there she lived till her old age.

When Unn began to grow stiff and weary in her age she wished that the last and youngest of Thorstein the Red’s children, Olaf Feilan, would marry and settle down. She loved him above all men, for he was tall and strong and goodly to look at, and she wished to settle on him all her property at Hvamm before she died. She called him to her, and said: “It is greatly on my mind, grandson, that you should settle down and marry.” Olaf spoke gently to the old woman, and said he would lean on her advice and think the matter over.

Unn said: “It is on my mind that your wedding-feast should be held at the close of this summer, for that is the easiest time to get in all the provision that is needed. It seems to me a near guess that our friends50 will come in great numbers, and I have made up my mind that this is the last wedding-feast that shall be set out by me.”

Olaf said that he would choose a wife who would neither rob her of her wealth nor endeavour to rule over her; and that autumn Olaf chose as his wife Alfdis, and brought her to his home. Unn exerted herself greatly about this wedding-feast, inviting to it all their friends and kinsfolk, and men of high degree from distant parts. Though a crowd of guests were present at the feast, yet not nearly so many could come as Unn asked, for the Iceland firths were wide apart and the journeys difficult.

Old age had fallen fast on Unn since the summer, so that she did not get up till midday, and went early to bed. She would allow no one to come to disturb her by asking advice after she had gone to sleep at night; but what made her most angry was being asked how she was in health. On the day before the wedding, Unn slept somewhat late; yet she was on foot when the guests came, and went to meet them, and greeted her friends with great courtesy, and thanked them for their affection in coming so far to see her. After that she went into the hall, and the great company with her, and when all were seated in the hall every one was much struck by the lordliness of the feast.

In the midst of the banquet Unn stood up and said aloud: “Biorn and Helgi, my brothers, and all my other kinsmen and friends, I call as witnesses to this, that this dwelling, with all that belongs to it, I give into the hands of my grandson, Olaf, to own and to manage.”

Immediately after that Unn said she was tired and would return to the room where she was accustomed51 to sleep, but bade everyone amuse himself as was most to his mind, and ordered ale to be drawn out for the common people. Unn was both tall and portly, and as she walked with a quick step out of the hall, in spite of her age, all present remarked how stately the old lady was yet. They feasted that evening joyously, till it was time to go to bed. But in the morning Olaf went to see his grandmother in her sleeping-chamber, and there he found Unn sitting up against her pillow, dead.

When he went into the hall to tell these tidings, those present spoke of the dignity of Unn, even to the day of her death. They drank together the wedding-feast of Olaf and funeral honours to Unn, and on the last day of the feast they carried Unn to the burial-mound that they had raised for her. They laid her in a viking-ship within the cairn, as they were wont to bury great chiefs; and they laid beside her much treasure, and closed the cairn, and went their ways.

One of the kinsmen was Hoskuld, father of Olaf the Peacock, whose story will be told later on.

52

While Harald Fairhair was occupied in settling the Hebrides and Orkneys with inhabitants from Norway, and Rollo and his successors were possessing themselves of the larger part of the North of France, England and Ireland were enjoying a period of comparative repose. The twenty-three years of Edward the Elder’s reign were devoted largely to building up the great kingdom which his father, Alfred, had founded, but not consolidated; he brought Mercia more immediately into his power, and subdued East Anglia and the counties bordering on the kingdom of Wessex; before his death Northumbria, both English and Danish, had invited him to reign over them, and he was acknowledged lord also of Strathclyde Britain, then an independent princedom, and of the greater part of Scotland. In all his designs Edward was supported by the powerful help of his sister, Ethelfled, “the Lady of the Mercians,” as her people called her, a woman great of soul, beloved by her subjects, dreaded by her enemies, who not only assisted her brother with advice and arms, but helped him in carrying out his useful projects of building and strengthening the cities in his dominions, a matter which had also occupied the attention of their father. This woman had inherited the high spirit of Alfred; she was the53 widow of Ethelred, Prince of Mercia, and she ruled her country with vigour after her husband’s death, building strong fortresses at Stafford, Tamworth, Warwick, and other places; she bravely defended herself at Derby, of which she got possession after a severe fight in which four of her thanes were slain. The following year she became possessed of the fortress of Leicester, and the greater part of the army submitted to her; the Danes of York also pledged themselves to obey her. This was her last great success, for in 922 the Lady of Mercia died at Tamworth, after eight years of successful rule of her people. She was buried amid the grief of Mercia at Gloucester, at the monastery of St Peter’s, which she and her husband had erected, on the spot where the cathedral now stands.

The most severe attack of the Danes in Edward the Elder’s reign was made by two Norse or Danish earls who came over from the new settlements in Normandy and endeavoured to sail up the Severn, devastating in their old manner on every hand. They were met by the men of Hereford and Gloucester, who drove them into an enclosed place, Edward lining the whole length of the Severn on the south of the river up to the Avon, so that they could not anywhere find a place to land. Twice they were beaten in fight, and only those got away who could swim out to their ships. They then took refuge on a sandy island in the river, and many of them died there of hunger, the rest taking ship and going on to Wales or Ireland. One of the great lords of the Northern army, well known in the history of his own country, Thorkill the Tall, of whom we shall hear again, submitted to Edward, with the other Norse leaders of Central England, in or about Bedford and Northampton. Two years afterwards we read that Thorkill the Tall,54 “with the aid and peace of King Edward,” went over to France, together with such men as he could induce to follow him.

Great changes had been brought about in England during the reigns of Edward and his father. Everywhere large towns were springing up, overshadowed by the strong fortresses built for their protection, many of which remain to the present day. Commerce and education everywhere increased, and there was no longer any chance of young nobles and princes growing up without a knowledge of books. Edward’s large family all received a liberal education, in order that “they might govern the state, not like rustics, but like philosophers”; and his daughters also, as old William of Malmesbury tells us, “in childhood gave their whole attention to literature,” afterwards giving their time to spinning and sewing, that they might pass their young days usefully and happily.

This was a change of great importance. The ruler who succeeded Edward, his son, the great and noble-minded Athelstan, was a man of superior culture, and the daughters of Edward and Athelstan sought their husbands among the reigning princes of Europe. England was no longer a mere group of petty states, always at war with each other, or endeavouring to preserve their existence against foreign pirates; it was a kingdom recognized in the world, and its friendship was anxiously sought by foreign princes.

Another thing which we should remark is that it was at this time that the Norse first came into close contact with England. Hitherto her enemies had been Danes, and the kingdom of Northumbria seems to have been a Danish kingdom. But Thorkill the Tall, King Hakon, the foster-son of Athelstan, King Olaf Trygveson, who55 all came into England at this period, were Norsemen; and henceforth, until the return of the Danish kings under Sweyn and Canute the Great and their successors, it is principally with the history of the Kings of Norway that we shall have to deal, in so far as these kings were connected with the history of England.

Hitherto the connexion between Great Britain and Norway had been confined to the settlements of the Norse in the Western Isles and in Northern Scotland; but the partial retirement of the Danes from the South of England, and the importance to which the country had recently grown, brought her into closer relationship with the North of Europe generally, and with Norway in particular. This we shall see as our history proceeds.

56

England was fortunate in having three great kings in succession at this critical period, all alike bent upon strengthening and advancing the prosperity of the kingdom.