The Project Gutenberg eBook of The ward of Tecumseh, by Crittenden Marriott

Title: The ward of Tecumseh

Author: Crittenden Marriott

Illustrator: Frank McKernan

Release Date: September 26, 2022 [eBook #69052]

Language: English

Produced by: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

By CRITTENDEN MARRIOTT

SALLY CASTLETON,

SOUTHERNER

Six Illustrations by N. C. Wyeth. $1.25 net.

“A swiftly moving, entertaining tale

of love and daring secret service work.”

—Chicago Record Herald

OUT OF RUSSIA

Illustrated by Frank McKernan. $1.25 net.

“There is everything that goes to make

up a story wholesomely exciting.”

—The Continent, Chicago

THE

ISLE OF DEAD SHIPS

Illustrated by Frank McKernan. $1.00 net.

“Chapter after chapter unfolds new

and startling adventures.”

—Philadelphia Press

J. B. LIPPINCOTT CO.

PUBLISHERS PHILADELPHIA

ALAGWA COMES TO THE COUNCIL FIRE

Page 304

THE WARD OF

TECUMSEH

BY

CRITTENDEN MARRIOTT

AUTHOR OF “SALLY CASTLETON, SOUTHERNER,” “THE ISLE OF DEAD

SHIPS,” ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

FRANK McKERNAN

PHILADELPHIA & LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

1914

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY CRITTENDEN MARRIOTT

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER, 1914

PRINTED BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

AT THE WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

PHILADELPHIA, U. S. A.

| PAGE | |

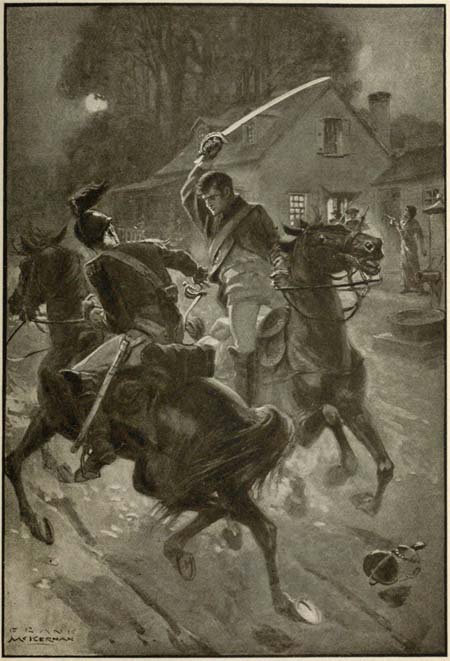

| Alagwa Comes to the Council Fire | Frontispiece |

| Alagwa, Being Wounded, is Rescued by Jack Telfair | 80 |

| Alagwa Shoots Captain Brito | 194 |

| Jack Telfair and Captain Brito Settle Their Dispute | 330 |

THE WARD OF

TECUMSEH

WHEN the beautiful Sally Habersham accepted Dick Ogilvie her girl associates rejoiced quite as much as she did, foreseeing the return to their orbits of sundry temporarily diverted masculine satellites. Her mother’s friends did not exactly rejoice, for Dick Ogilvie had been a great “catch” and his capture was a sad loss, but they certainly sighed with relief; for they had always felt that Sally Habersham was altogether too charming to be left at large. About the only mourners were a score or so of young men, whose hearts sank like lead when they heard the news.

The young men took the blow variedly, each according to his nature. One or two made such a vehement pretense of not caring that everybody decided that they cared a great deal; two or three laughed at themselves in the vain hope of preventing other people from laughing at them; several got very drunk, as a gentleman might do without disgrace in that year of 1812; others hurriedly set[8] off to join the army of thirty-five thousand men that Congress had just authorized in preparation for the coming war with Great Britain; the rest stayed home and moped, unable to tear themselves away from the scene of their discomfiture.

Of them all none took the blow harder than Jaqueline Telfair, commonly known as Jack. Jack was just twenty-one, and the fact that he was a full year younger than Miss Habersham, had lain like a blight over the whole course of his wooing. In any other part of the land he might have concealed his lack of years, for he was unusually tall and broad and strong, but he could not do so at his home in Alabama, where everybody had known everything about everybody for two hundred years and more. Still, Jack hoped against hope and refused to believe the news until he received it from Miss Habersham’s own lips.

Miss Habersham, by the way, was not quite so composed as she tried to be when she told him. Jack was so big and fine and looked at her so straight and, altogether, was such a lovable boy that her heart throbbed most unaccountably and before she quite knew what she was doing she had leaned forward and kissed him on the lips. “Good-by, Jack, dear,” she said softly. Then, while Jack stood petrified, she turned and fled. She did not love Jack in the least and she did love Dick Ogilvie,[9] but—Oh! well! Jack was a gentleman; he would understand.

Jack did understand. For a few seconds he stood quite still; then he too walked away, white faced and silent.

The next morning he went out to hunt; that is, he took a light shot-gun and tramped away into the half dozen square miles of tangled woodland that lay at the back of the Telfair barony along the Tallapoosa River. But as he left his dog and his negro body-servant, Cato, at home, he probably went to be alone rather than to kill.

Spring was just merging into summer, and the sun spots were dancing in the perfumed air across the tops of the grasses. Great butterflies were flitting over the painted buttercups and ox-eyed daisies, skimming the shiny gossamers beneath which huge spiders lay in wait. From every bush came the twitter of nestlings or the wing flash of busy bird parents. Squirrels, red and gray, flattening themselves against the bark, peered round the trunks of great trees with bright, suspicious eyes. Molly cottontails crouched beneath the growing brambles. Round about lay the beautiful woodland, range after range of cobweb-sheeted glades splashed with yellow light. Crisp oaks and naked beeches, mingled with dark green hemlocks and burnished quivering pines, towered above bushes of[10] sumach and dogwood, twined and intertwined with swift-growing dewberry vines. From somewhere on the right came the sound of water rippling over a pebbly bed.

Abruptly Jack halted, stiffening like a pointer pup, and leaned forward, gun half raised, trying to peer through the sun-soaked bushes of the moist glade. He had heard no sound, seen nothing move, yet his skin had roughened just as that of a wildcat roughens at the approach of danger. Instinct—the instinct of one born and brought up almost within sight of the frontier—told him that something dangerous was watching him from the jungly undergrowth before him. It might be a bear or a wolf or a panther, for none of these were rare in Alabama in the year 1812. But Jack thought it was something else.

He took a step backward, cocking his gun as he did so and questing warily to right and to left.

“Come out of those bushes and show yourself,” he ordered sharply.

From behind an oak an Indian stepped out, raising his right hand, palm forward, as he came. In the hollow of his left arm he carried a heavy rifle. Fastened in his scalp-lock were feathers of the white-headed eagle, showing that he was a chief.

“Necana!” he said. “Friend!”

Instinctively Jack threw up his hand. “Necana!” he echoed. The tongue was that of the Shawnees.[11] Jack had not heard it for ten years, not since the last remnant of the Shawnee tribe had left the banks of the Tallapoosa and gone northward to join their brethren on the Ohio; but at the stranger’s greeting the almost forgotten accents sprang to his lips. “Necana,” he repeated. “What does my brother here, far from his own people?”

Wonderingly, he stared at the warrior as he spoke. The man was a Shawnee; so much was certain, but his costume differed somewhat from that of the Shawnees to whom Jack had been accustomed, and the intonation of his speech rang strange. His moccasins, the pouch that swung to his braided belt, all were foreign. His accent, too, was strange. Moreover, though clearly a chief, he was alone instead of being well escorted, as etiquette demanded. Plainly he had travelled fast and long, for his naked limbs were lean and worn, mere skin and bone and stringy muscles. Hunger spoke in his deep-set eyes.

At Jack’s words his face lighted up. Evidently the sound of his own tongue pleased him. Across his breast he made a swift sign, then waited.

Dazedly Jack answered by another sign, the answering sign learned long ago when as a boy he had sat at a Shawnee council and had been adopted as a member of the clan of the Panther.

In response the savage smiled. “I seek the young chief Telfair,” he said. “He whom the Shawnees of the south raised up as Te-pwe (he who speaks[12] with a straight tongue). Knowest thou him, brother?”

Jack stared in good earnest. “I am Jack Telfair,” he said, haltingly, dragging the Shawnee words from his reluctant memory. “Ten years ago the squaw Methowaka adopted me at the council fire of the Panther clan.” He hesitated. Ten years had blurred his memory of the ritual of the clan, but he knew well that it required him to proffer hospitality.

“My brother is welcome,” he went on, stretching out his hand. “Will he not eat at the campfire of my father and rest a little beneath our rooftree?”

The Shawnee clasped the hand gravely. “My brother’s words are good,” he answered. “Gladly would I stop with him if I might. But I come from a far country and I must return quickly. I turn aside from my errand to bring a message and a belt to my brother.”

From his pouch the chief drew a belt of beautiful white wampum. “Will my brother listen?” he asked.

Jack nodded. “Brother! I listen,” he answered.

“It is well! Many years ago a chief of the elder branch of my brother’s house was the friend of Tecumseh. They dwelt in the same cabin and followed the same trails. They were brothers. Ten years ago the white chief travelled the long trail to the land of his fathers. But before he died he[13] said to Tecumseh: ‘Brother! To you I leave my one child. Care for her as you would your own. Perhaps in days to come men of my own house may seek her, saying that to her belong much land and gold. If they come from the south, from the branch of my house living in Alabama, at the ancient home of the Shawnees, let her go with them. But if they come from the branch of my house that dwells in England do not let her go. The men of that branch, the branch of the chief Brito, are wicked and vile, men whose hearts are bad and who speak with forked tongues. If they come for her, then do you seek out my brothers in the south and tell them, that they may take her and protect her. If they fail you then let her live with you forever.’

“Since the chief died ten years have passed, and the maid has grown straight and tall in the lodge of Tecumseh. Now the chief Brito has come, wearing the redcoat of the English warriors. He speaks fair, saying that to the maid belong great lands and much gold and that he, her cousin, would take her across the great water and give them into her keeping. He is a big man, strong and skilful, to all seeming a fit mate for the maiden. If his tongue is forked, Tecumseh knows it not. But Tecumseh remembers the words of his dead friend and wishes not to give the maid up to one whom he hated. Yet he would not keep her from her own. Therefore he sends this belt to his younger brother, he of whom[14] his friend spoke, he whom the mother of Tecumseh raised up as a member of the Panther clan, and says to him: ‘Come quickly. The maid is of your house; come and take her from my lodge at Wapakoneta and see that she gets all that is hers.’”

Jack took the belt eagerly. To go to the lodge of Tecumseh to bring back a kinswoman to whom had descended great estates and against whom foes—he at once decided that they were foes—were plotting—What boy of twenty-one would not jump at the chance.

And to go to Ohio—the very name was a challenge. The Ohio of 1812 was not the Ohio of today, not the smiling, level country, set with towns, crisscrossed with railways, plastered with rich farms where the harvest leaps to the tickling of the hoe. It was far away, black with the vast shadow of perpetual forests, beneath which quaked great morasses. Within it roved bears, deer, buffalo, panthers, venomous snakes, renegades, murderers, Indians—the bravest and most warlike that the land had yet known.

Across it ran the frontier, beyond which all things were possible. For thirty years and more, in peace and in war, British officers and British agents had crossed it and had passed up and down behind it, loaded with arms and provisions and rewards for the scalps of American men and women and children. Steadily, irresistibly, unceasingly, the Americans[15] had driven back that frontier, making every fresh advance with their blood, their sweat, and their agony; and as steadily the redcoats had retreated, but had ever sent their savage emissaries to do their devilish work. Ohio had taken the place of Kentucky as a watchword with the adventurous youth of the east; to grow old without giving Ohio a chance to kill one had become almost a reproach.

Besides, war with Great Britain was unquestionably close at hand. All over the country troops were mustering for the invasion of Canada. General Hull in Ohio, General Van Rensselaer at Niagara, and General Bloomfield at Plattsburg were preparing to cross the northern border at a moment’s notice. In Ohio, Jack would be in the very forefront of the fighting. Both by instinct and ancestry the lad was a born fighter, always on tip-toe for battle; he had shown this before and was to show it often afterwards. But the last three months had been an interlude, during which Sally Habersham had been the one real thing in a world of shadows. Now he had awakened. He would not dream in just the same way again.

With swelling heart he grasped the proffered belt.

“The maiden is white?” he questioned.

“As thyself, little brother. She is the daughter of Delaroche Telfair, the friend of Tecumseh, who[16] died at Pickawillany fifteen years ago. Moreover, she is very fair.”

The Indian spoke simply. He did not ask whether Jack would come; the latter’s acceptance of the belt pledged him to that course and to question him further would be insulting. He did not ask any pledge as to the treatment of the girl; apparently he well knew that none was necessary.

Jack considered. “I will find the maiden at Wapakoneta?” he questioned.

“If my brother comes quickly. My brother knows that war is in the air. If my brother is slow let him inquire of Colonel Johnson at Upper Piqua. The maiden is known as Alagwa (the Star). Has my brother more to ask?”

Jack shook his head. If he held been speaking to a white man he would have had a score of questions to ask; but he had learned the Indian taciturnity. All had been said; why vainly question more?

“No!” he answered. “I have nothing more to ask. My brother may expect me at Wapakoneta as quickly as possible. I go now to make ready.” He did not again press his hospitality on the chief. He knew it would be useless.

The Shawnee bowed slightly; then he turned on his heel and melted noiselessly into the underbrush.

Jack stared after him wonderingly. Then he stared at the belt in his hand. So quickly the chief[17] had come and so quickly he had gone that Jack needed the sight of something material to convince himself that he had not been dreaming.

Not the least amazing part of the chief’s coming had been the message he had brought. Jack had heard of Delaroche Telfair, but he had heard of him only vaguely. When his Huguenot forefathers had fled from France, a century and a quarter before, one branch had stopped in England and another branch had come to America. The American branch, at least, had not broken off all connection with the elder titled branch of the family, which had remained in France. Indeed, as the years went by and religious animosities died out, the connection had if anything grown closer. Communication had been solely by letter, but it is not rare that relatives who do not see each other are the better friends. A hundred years had slipped by and then the Terror had driven the Count Telfair and his younger brother, Delaroche, from France. The count had stayed in London and bye and bye had gone back to join the court of Napoleon. But Delaroche had shaken the soil of France from his feet and had crossed to America with a number of his countrymen and had founded Gallipolis, on the banks of the Ohio, the second city in the state. Later he had become a trader to the Indians and at last was rumored to have joined the Shawnees. That had[18] been fifteen years before and none of the Alabama Telfairs had heard of him since.

And now had come this surprising news. He was dead! His daughter had been brought up by the great chief Tecumseh and was nearly grown and was the heiress of great estates. Brito Telfair—Jack vaguely recalled the name as that of the head of the branch that had stopped in England—sought to get possession of her. Tecumseh liked him, but, bound by a promise to the girl’s dead father, had refused to give her up and had sent all the weary miles from Ohio to Alabama to seek out the American Telfairs and keep his pledge. More, he might have long contemplated the necessity of keeping it. It might have been at his suggestion that his mother, Methowaka, who had been born in Alabama, at Takabatchi, on the Tallapoosa River, not twenty miles from the Telfair barony, had revisited her old home about ten years before, shortly before her tribe had gone north for good and all, and had “raised up” Jack as a member of the great Panther clan.

And now he had sent for him, sent for him over nearly a thousand miles of prairie, swamp, and forest, past hostile Indian villages and suspicious white men. Jack thought of it and marvelled. Few white men would do so much to keep a pledge to a friend ten years dead!

As he pondered Jack had been pacing slowly homeward. At last he halted on a rustic bridge[19] thrown across a swift-flowing little creek that sang merrily through the woodland. On the hill beyond, at the crest of a velvety shadow-flecked lawn, rose the white-stoned walls of the home where he had been born and bred. Around it stretched acres of field and orchard, vivid with the delicate blossoms of apples and of plums, the pink-white haze of peach, the light green spears of corn, and the darker green of tobacco. Over his head a belted kingfisher screamed, a crimson cardinal flashed like a live coal from tree to tree, a woodpecker drummed at a tree. Below flashed the creek, a singing water pebbled with pearls. Jack did not see nor hear them; arms on rail he stared blankly, pondering.

A voice startled him and he swung round to face his body-servant, Cato, a negro a few years older than himself.

Cato was panting. “Massa Colonel’s home, suh,” he gasped. “An’ he want you, suh. He’s in a pow’ful hurry.”

Jack stared at the boy. “Father home!” he exclaimed, half to himself. “I didn’t expect him for hours.”

“He’s done got home, suh. He ride Black Rover most near to death, suh. Yes, suh! He’s in most pow’ful hurry.”

COLONEL TELFAIR was striding excitedly up and down the wide verandah, lashing as he went at the tall riding boots he wore. His plum-colored, long-skirted riding coat, his much-beruffled white shirt, and his tight-fitting breeches were dusty and spattered with dried mud. It needed not the white-lathered horse with drooping head that a negro was leading from the horseblock to show that he had ridden fast and furiously.

From one end of the porch to the other he strode, stopping at each to scan the landscape, then restlessly paced back again. A dozen negroes racing in every direction confirmed the urgent haste that his manner showed.

Abruptly he paused as Jack, followed by Cato, came hurrying up the drive. “Hurry, sir, hurry,” he bawled. “Don’t keep me waiting all day.”

Jack quickened his steps. “I didn’t know you were back, father,” he declared, as he came close. “I’m glad you are, sir. I’ve news, important news!”

The elder Telfair scowled. “News, have you, sir?” he rumbled. “So have I. Come inside, quick, and we’ll exchange.” Turning, he led the way through a deep hall into a great room, whose oak-panelled walls were hung with full-length portraits of dead and gone Telfairs—distinguished men and[21] women whose strong faces showed that in their time they had cut a figure in the world. There he faced round.

“Now, sir, tell your news,” he ordered. “I’ll warrant it’s short and foolish.”

“Perhaps!” Jack grinned; he and his father were excellent friends. “Did you know, sir, that our kinsman, Delaroche Telfair, was dead, leaving a daughter who is a ward of Tecumseh, the Shawnee chief?”

The elder Telfair blinked. “Good Lord!” he said, softly. He tottered a step or two backward and dropped heavily into a chair. “You’ve had a letter, too?” he gasped.

“A letter? No, sir; not a letter——”

“You must have, sir. Don’t trifle with me! I’m in no temper to stand it. Who brought you the letter?”

“I haven’t any letter, father. I haven’t heard of any letter. I met an Indian——”

“An Indian?”

“Yes. A Shawnee from Ohio, a messenger from Tecumseh——”

“Tecumseh! Good Lord! Do you know—But that can wait. Go on.”

“Delaroche seems to have pledged him to call on us in case certain things happened. They have happened and he has sent. He wants me to come and get the girl.”

[22]“Good God!” muttered the elder man once more. “Look—look at this, Jack!” He held out an open letter. “I got it at Montgomery, and I rode like the devil to bring it, and here a murdering Shawnee gets ahead of me and——” His words died away; clearly the situation was beyond him.

Jack took the letter doubtfully and unfolded it. Then he looked at his father amazedly.

“It’s from Capron, the lawyer for the Telfair estates in France,” interjected the elder man. “It’s in French, of course. Read it aloud! Translate it as you go.”

Jack walked to the window, threw up the blind, and held the letter to the light.

“My very dear sir,” he read. “It is my sad duty to apprise you that my so justly honored patron, Louis, Count of Telfair, passed away on the 30th ultimo, videlicet, December 30, 1811. The succession to the title and the estate now falls to the descendants of his brother, M. Delaroche Telfair, who, as you of course know, emigrated to America in 1790 and settled at Gallipolis on the Ohio, which without doubt is very close to your own estates in Alabama. Perhaps it is that you have exchanged frequent visits with him and that his history and the so sad circumstances of his death are to you of the most familiar. If so, much of this letter is unnecessary.

“In the remote contingency, however, that you may not know of his history in America, permit me to repeat[23] the little that is known to us here in France. It will call the attention; this:

“Among the papers of my so noble patron, just deceased, I have found a letter, dated June 10, 1800, with the seal yet unbroken, which appears to have reached the château Telfair many years ago but not to have been brought to his lordship’s attention. Of a truth this is not surprising, the year 1800 being of the most disturbed and the years following being attended by turbulence both of politics and of strife, during which his lordship seldom visited the château.

“This letter inclosed certificates of the marriage at Marietta, Ohio, of M. Delaroche Telfair to Mlle. Margaret De la War, on June 18, 1794, and of the birth of a daughter, Estelle, on Oct. 9, 1795. The originals appear to be on file at Marietta. M. Delaroche says that he sends the copies as a precaution.

“No other information of father or daughter or of any other children appears to be of record, but the late count had without a doubt received further news, for he several times spoke to me of his so sadly deceased brother.

“In default of a possible son the title of Count of Telfair devolves on M. Brito Telfair, representative of the branch of the family so execrated by his lordship now departed. Your own line comes last. The estates go to the Lady Estelle Telfair, or, if she be deceased, to Count Brito Telfair, whose ancestors have long been domiciled in England.”

Jack looked up. “Brito Telfair!” he exclaimed. “That’s the name the Indian mentioned. Who is he exactly?”

[24]“He’s the head of the British branch. His people moved there a hundred years or so ago, after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. We came to America and they stopped in England. I understand he’s an officer in the British army, heavily in debt, and a general roué. I reckon he’s about forty years old.”

With a shrug of his shoulders—a trick inherited from his Gallic ancestors—Jack resumed:

“Not knowing where to reach the Lady Estelle (or other descendants of M. Delaroche) I address you, asking that you convey to her my most humble felicitations. I can not close, my dear sir, without a word of the caution. The Lady Estelle would appear to be about seventeen years of age. Her property in France is of a value, ah! yes, but of a value the most great. Adventurers will surely seek her out and she will need friends. Above all she should not be allowed to fall into the hands of M. Brito, who would undoubtedly wed her out of all hand to gain possession of her estates. Both the late count and M. Delaroche (when I knew him) hated and despised the English branch of M. Brito. To you, beloved of my master the count, I appeal to save and protect his heiress from those he so execrated. I have the honor, my very dear sir, to be your obedient servant. Verbum sapientes satis est.

Henri Capron, avocat.

Postscriptum.—I open this to add that I have just learned that M. Brito sailed with his regiment for Montreal a month ago. He is of a repute the most evil.[25] If he gets possession of the Lady Estelle he will without the doubt wed her, forcibly if need be. And it would be of a shame the most profound if the Telfair estates should be squandered in paying the debts of one so disreputable.”

Jack crumpled the letter in his hand. “I should think it would be,” he cried. “Thank the Lord Tecumseh remembered Delaroche’s warning. But let me tell you my story.”

Rapidly Jack recounted the circumstances of the Shawnee’s visit and recited the message he had brought. “This explains everything,” he ended. “Brito Telfair wants to get possession of the girl and marry her before she knows anything about her rights. Well! He shan’t!”

Colonel Telfair laughed. “Lord! Jack! You’re heated,” he exclaimed. “Brito Telfair probably isn’t much worse than other men of his age and surroundings. You’ve got to allow for Capron’s prejudices, national and personal. Marriage with him mightn’t be altogether unsuitable. Still, we’ve got to make sure that it is suitable, and if it isn’t, we’ve——”

“We’ve got to stop it!” Jack struck in. “The first thing is to find the girl and bring her here. We can decide what to do after that.”

Colonel Telfair became suddenly grave. “Yes!” he answered, “I reckon we can, if—” He broke off and contemplated his son curiously. “How does[26] Tecumseh happen to send for you, sir?” he demanded. “But I reckon it comes of your running wild in their villages while they were down here. They adopted you or something, didn’t they?”

Jack nodded. “Yes! Tecumseh’s mother adopted me into the Panther clan. She was born down here, you know, and was back here on a visit when I knew her.”

“Humph!” The old gentleman pondered a moment. Then suddenly he caught fire. “Yes! Go, Jack, go!” he thundered. “Damme, sir! I’d like to go with you, sir. I envy you! If I was a few years younger I’d go, too, sir! Damme! I would.”

“I wish you could, father.” The boy threw his arm affectionately about the older man’s shoulders. “Lord! wouldn’t we have times together. We’d rescue the girl and then we’d help General Hull smash the redcoats and the redskins.”

“We would, sir! Damme, we would!” The old gentleman shook his fist in the air. “We’d—we’d——” He broke off, catching at his side, and dropped into a chair, which Jack hurriedly pushed forward. “Oh! Jack! Jack!” he groaned. “What d’ye mean by getting your old father worked up till he’s ill?” Then with a sudden change of front—“You—you’ll be careful, won’t you, Jack? Not too careful, you know—not when you face the enemy, but—but—damme, sir, you know what I mean.[27] You needn’t get yourself killed for the fun of it, sir. I—I’m an old man, Jack, and you’re my only son and if you——”

“Don’t fear, father! I know the woods. I know the trails. I know the Indian tongues. I am a member of the Panther clan. More, I am going to Ohio at the invitation of Tecumseh. Until war begins every member of my clan will be bound to help me because I am their clan brother; every Shawnee will be bound to help me because I am the friend of Tecumseh; every other warrior will befriend me once he knows who I am. If I travel fast I may rescue cousin Estelle before——”

“Estelle! Estelle! Good God! Yes! I’d forgotten her altogether. I wonder what she’ll be like: not much like our young ladies; that’s certain. Bring her back to us, Jack. We need a daughter in the family. And as for France, damme, I’ll go over with her myself, sir.”

“I’ll wager you will, father. I’ll get her before war begins if I can. If I can’t—well, I’ll get her somehow. Once war begins, my clan membership fails and——”

“Well! Let it fail, sir. I don’t half understand about this clan business of yours, sir. I don’t approve of it, sir. How will war effect that, sir?”

Colonel Telfair’s ignorance as to the Indian clans was no greater than that of nine-tenths of his fellow citizens, whether of his own times or of later[28] ones, dense ignorance having commonly prevailed not only as to the nature but as to the very existence of the clans.

But Jack knew them. Much had he forgotten, but in the last hour much had come back to him. Thoughts, memories, bits of ritual, learned long before and buried beneath later knowledge, struggled upward through the veil of the years and rose to his lips.

“They—they are like Masonic orders, father,” he began, vaguely. “They know no tribe, no nation. Mohawks and Shawnees and Creeks of the same clan are brothers, and yet—and yet—if the Shawnee sends a war belt to the Creeks, clan ties are suspended—just as between Masons of different nations. But when the battle is over, fraternity brothers are bound to succor each other, bound to ransom each other from the flame. This they may perhaps do by persuading the tribe to adopt them in place of some warrior who has been slain.”

“Humph! I thought they had been adopted already?”

“As members of the clan, yes! Adoption by the tribe is different. It changes the entire blood of him who is adopted. He becomes the man whose name and place he takes, and he is bound to live and fight as his predecessor would have lived and fought and to forget that he ever lived another life. Membership in the clans by birth is strictly[29] in the female line. The women control them and decide who shall be adopted into them.”

“All right. I don’t half understand. But I suppose you do. Anyway, I’m glad you’ve got your membership to help you—Look here, Jack!” An idea had struck the elder man. “D—d if I don’t believe that warrior of yours was Tecumseh himself. I started to speak of it when you first named him. I met Colonel Hawkins—he’s the Indian agent—this morning and he told me that a big chief from the north was down here, powwowing to the Creeks at Takabatchi—urging them to dig up the hatchet, I reckon. Tecumseh was here a year ago, you know. Maybe he’s come back!”

Jack nodded, absently. “Maybe it was Tecumseh, father,” he answered. He had just remembered Sally Habersham and he was wondering if she would grieve when she heard that he had gone away. For a time, perhaps! But not for long. She would have other thoughts to engross her. Jack knew it and was glad to know it. He wanted no one to be unhappy because of him—least of all Sally Habersham. She who had been so kind—so kind—His lips burned at the memory of her kiss. “I’ll prove myself worthy of it!” he swore to himself. “I’ll carry it unsullied to the end. No other woman——”

Telfair broke in. “Damme! sir! What are you moonshining about now?” he roared. “About your[30] cousin Estelle? Bring her back and marry her, Jack. She’s a great heiress, my lad, a great heiress.”

Jack drew himself up. Strangely enough he had thought little about the girl-child for whose sake he was going to undertake the long journey. His father’s words grated on him.

“I shall never marry, father,” he declared.

THE sun was about to climb above the rim of the world. Already the white dawn was silvering the grey mists that lay alike on plain and on river and half hid the mossy green boles of the trees that stood on the edge of the forest. From beneath it sounded the low murmur of the waters of the Auglaize, toiling sluggishly through the timbers that choked its bed and gave it its Indian name of Cowthenake, Fallen Timber river. High about it whimpered the humming rush of wild ducks. From the black wall of the forest that led northward to the Black Swamp came the waking call of birds.

Steadily the light grew. The first yellow shafts shimmered along the surface of the mist, stirring it to sudden life. Out of the draperies of fog, points seemed to rise, black against the curtain of the dawn. To them the mists clung with moist tenacious fingers, resisting for a moment the call of the sun, then shimmering away, leaving only a trace of tears to sparkle in the sunlight.

Steadily the sun mounted and steadily the mists shrank. The spectral points, first evidence that land and not water lay beneath the fog, broadened downward, here into tufts of hemlock, there into smoother, more regular shapes that spoke of human[32] workmanship. Louder and louder grew the rippling of the river. Then, abruptly, the carpet of mist rose in the air, shredding into a thousand wisps of white; for a moment it obscured the view, then it was gone, floating away toward the great forest, as if seeking sanctuary in its chilly depths. The black river was still half-veiled, but the land lay bare, sparkling with jewelled dew-drops.

Close beside the river, on an elevation that rose, island like, above the surrounding plain, stood the Indian village, row after row of cabins, strongly built of heavy logs, roofed with poles, and chinked with moss and clay. In and out among them moved half-wolfish dogs, that had crept from their lairs to welcome the rising of the sun.

No human being was visible, but an indistinct murmur, coming from nowhere and everywhere, mingled with the rush of the river and the whisper of the wind in the green rushes and the tall grass. The huts seemed to stir visibly; first from one and then from a score, men, women, and children bobbed out, some merrily, some grumpily, to stretch themselves in the sunshine and to breathe in the soft morning air before it began to quiver in the baking heat that would surely and swiftly come. For early June was no less hot in northern Ohio in 1812, when the whole country was one vast alternation of swamp and forest, than it is a hundred years later when the land has been drained and the forest cut away.

[33]From the door of a cabin near the centre of the town emerged a girl sixteen or seventeen years of age, who stood still in the sunbeams, eyes fixed on the trail that led away through the breaks in the forest to the south. Her features, browned as they were by the sun and concealed as they were by paint, yet plainly lacked the high cheek-bones, black eyes, and broad nostrils of the Indians. Some alien blood showed itself in the softness of her cheek, in the kindling color in her long dark hair, in the brown of her eyes. Her graceful body had the straight slenderness that in the quick-maturing Indian maids of her size and height had given place to the rounded curves of budding womanhood. Her head, alertly poised above her strong throat, showed none of the marks of ancestral toil that had already begun to bow her companions. In dress alone was she like them, though even in this the unusual richness of her doeskin garb, belted at the hips with silver, marked her as one of prominence.

For a little longer the girl watched the southward trail; then her eyes roved westward, across the rippling waters of the Auglaize, now veiled only by scattered wisps of mist, and across its border of sedgy grass, pale shimmering green in the mounting sun, and rested on a cabin that stood on the further bank, between an orchard and a small field of enormous corn. From this cabin two men were just emerging.

[34]They were too far away indeed for the average civilized man or woman to distinguish more than that they were men and were dressed as whites. The girl, however, was possessed of sight naturally strong and had been trained all her life amid surroundings where quickness of vision might easily mean the difference between life and death. She had seen the men before and she recognized them instantly.

One of them wore a red coat and carried himself with a ramrod-like erectness that bespoke the British officer; the girl knew that he was from Canada, probably from the fort at Malden, to which for three years the Indians from a thousand square miles of American soil had been going by tens and hundreds to return laden with arms and ammunition and presents from His Majesty, the King of Great Britain. The second was of medium height, shaggy, dressed in Indian costume, with a handkerchief bound about his forehead in place of a hat. He could only be James Girty, owner of the cabin, or his brother Simon, of infamous memory—more probably the latter.

As the girl watched them an Indian squaw crept out of a near-by cabin and came toward her.

“Ever the heart of Alagwa (the Star) turns toward the white men,” said she, harshly.

The girl started, the swift blood leaping to her[35] cheeks. “Nay!” she said. “These white men have red hearts. They are the friends of the Indian. Katepakomen (Girty) is an Indian; his white blood has been washed from his veins even as my own!”

“Your own!” The old woman laughed scornfully. “Not so! Your heart is not red. It is white.”

Alagwa’s was not the Indian stoicism that meets all attacks with immobility. Her lip quivered and her eyes filled with tears. “I am not white,” she quavered. “I am red, red.”

The old woman hesitated. She knew that between equals what she had said would have been all but unforgiveable. Alagwa had been adopted into the tribe years before in the place of another Alagwa who had died. She had been “raised up” in place of her. Theoretically all white blood had been washed out of her. She was the dead. To remind her of her other life and ancestry was the worst insult imaginable. The old woman knew that Tecumseh would be very angry if he heard it. But she had an object to gain and went on.

“Then why does Alagwa refuse my son?” she said. “Why does she defy the customs of her people—if they are her people. The council of women have decreed that she shall wed Wilwiloway. If her heart is red why does she not obey?”

The girl hung her head. “I—I am too young to wed,” she protested.

[36]“Bah!” the old woman spat upon the ground. “Alagwa has seen seventeen summers. Other girls wed at fifteen. Why should Alagwa scorn my son. Is he not straight and tall? Is he not first among the warriors in war and in chase? Has he not brought back many scalps? Alagwa’s heart is white—not red.”

“But——”

“Were Wilwiloway other than he is, he would long ago have taken Alagwa to his hut. But he will not. His heart, too, is white. He says Alagwa must come to him willingly or not at all. He will not let us compel her. He——” The old woman broke off with a catch in her voice—“he loves Alagwa truly,” she pleaded, wistfully. “Will not Alagwa make his moccasins and pound his corn!”

The girl, who had slowly straightened up under the assault of the old woman, weakened before the sudden change of tone.

“Oh!” she cried. “I will try. Truly! I will try. Wilwiloway is good and kind and brave. I am proud that he has chosen me. I wish I could love him. But—but I do not, and I must love before I give myself. I am bad! wicked! I know it. Yes! I have a white heart. But I will pray to Mishemanitou, the Great God, to make it red.”

The old woman caught the sobbing girl to her heart. “Do not weep!” she said, gently. “See! the sun burns red through the trees; it is the answer[37] of Manitou, the mighty. He sends it as a message that your heart shall turn from white to red. There! It is changed! Look up, Alagwa, and be glad.”

The girl raised her head and stared at the line of trees that curled away in a great crescent toward the east and the west. The sun did indeed burn red through them. Could it be an omen? As she stared the squaw slipped silently away.

Alagwa’s heart was burning hot within her. The squaw’s accusation that her heart was white had cut deep. All her remembered life she had been taught to hate and fear the white men. White men were the source of all evil that had befallen her. They had driven her and her people back, back, ever back, forcing them to give up one home after another. White men had slain her friends; never did she inquire for some dear one who was missing but to be told that he had been killed by the white men. Again and again in her baby ears had rung the cries of the squaws, weeping for the dead who would return no more. Of the other side of the picture she knew nothing. Of the red rapine the Shawnee braves had wrought for miles and miles to the south she had heard, but it was to her only a name, not the awful fact that it had been to its victims. To her the whites were aggressors, robbers, murderers, who were slowly but surely crushing her Indian friends.

[38]Only the year before they had destroyed her home at Tippecanoe on the banks of the Wabash. Well she remembered their advance, their fair speaking that concealed their implacable purpose to destroy her people. Well she remembered the great Indian council that debated whether to fight or to yield, the promises of the Prophet that his medicine would shield the Indians against the white men’s bullets, the night attack, the repulse, the flight across miles of prairie to the ancestral home at Wapakoneta. She remembered Tecumseh’s return—too late. Here, also, she knew nothing of the other side—of the absolute military necessity that the headquarters from which Tecumseh was preparing to sweep the frontier should be destroyed and its menace ended. It was she and her friends who had suffered and it was she and her friends who had fled, half starved, across those perilous miles of swamp and morass. It was the white men who had triumphed; and she hated them, hated them, hated them. The memory of it all was bitter.

And it was no less bitter because revenge seemed hopeless. Tecumseh was planning revenge, she knew, but he no longer found the support he had gained a year before. His own people, the Shawnees, implacable fighters as they had been, had wearied of war at last. Black Wolf, the chief at Wapakoneta, himself once a great warrior and a[39] bitter foe of the whites, now preached that further resistance was vain—that it meant only death. Many of the tribe sided with him, for the Indian, no more than the white man, unless maddened by long tyranny, cares to engage in a contest where triumph is hopeless. The only hope lay in the redcoats, soldiers of the great king across the water. They were planning war against the Long Knives. If they should make common cause with the red men, revenge might yet be won. If she could do anything to help!

A footstep startled her and she flashed about to find Simon Girty and the tall man in the red coat almost upon her. While she had dreamed of the return of Tecumseh they had crossed the Auglaize river and had come upon her unawares.

Girty was as she had many times remembered him—a deeply-tanned man perhaps forty years of age, with gray, sunken eyes, thin and compressed lips, hyena chin, and dark shaggy hair bound with a handkerchief above a low forehead, across which stretched a ghastly half-healed wound. In his arms he carried a great bale, carefully wrapped.

The other—Alagwa had never seen his like before—was tall and powerful looking. His carriage was graceful and easy. His dark face, handsome in a way though plainly not so handsome as it had been some years before, was characterized by a powerful[40] jaw that diverted attention from his strong mouth and aquiline nose. He was regarding the girl with an expression evidently intended to be friendly, but which somehow grated. It seemed at once condescending, appraising, and insolent.

All this Alagwa took in at a glance as she shrank backward, intent on flight. But before she could move Girty’s voice broke in.

“Stop!” he ordered, sharply, in the Shawnee tongue. “The white chief from afar would speak with the Star maiden.”

Alagwa paused, looking fearfully backward. But she did not speak and Girty went on.

“The white chief is of the House of Alagwa,” he declared. “His heart is warm toward her. He brings good news and many presents to lay at her feet.” He laid down the bale.

Alagwa looked from it to the man and back again. “Let him speak,” she said, in somewhat halting English.

At the sound of his own tongue the Englishman’s face lighted up and he took an impulsive step forward. “You speak English?” he exclaimed, with a note of wonder in his voice. “Why did nobody tell me that? How did you learn?” His surprise did not seem altogether complimentary.

Alagwa was studying him shyly. She found his pink and white complexion very pleasing after the[41] coppery skins of the Indians and the no less swarthy faces of most of the white men she had seen. Besides, this man wore a red coat and the redcoats were the friends of Tecumseh. “I speak it a little,” she said, hesitatingly. As a matter of fact she spoke it rather well, having picked up much from time to time from Colonel Johnson, the Indian agent, from two or three white prisoners, and from Tecumseh himself.

“That’s lucky. If I’d known that I’d have spoken to you before and settled the business out of hand. You wouldn’t guess it, of course, little forest maiden that you are, but you are a cousin of mine?”

“A cousin? I?” Startled, palpitating, Alagwa leaned forward, staring with wide eyes. No white man except her father had ever claimed kin with her. What did it mean, this sudden appearance of one of her blood?

“Yes! You’re my cousin and, egad, you’ll do the family honor! I’m Captain Count Brito Telfair, you know, and you are the Lady Estelle Telfair. Your father was my kinsman. I never met him, for he and his people lived in France, and I and my people lived in England. Your uncle was the Count Telfair. He died not long ago. He had neglected you shamefully, but when he died it became my duty as head of the house to come over here and fetch you back to France and give you everything you want. Do you understand?”

[42]Alagwa did not understand wholly. Not only the words but the ideas were new to her. But she gathered that she had white kinspeople, that they had not altogether forgotten her, and that the speaker had come to bring her gifts from them. Doubtfully she nodded.

“I saw Tecumseh two months ago,” went on Captain Brito, “and I saw you, too.” He smiled engagingly. “You were outside Tecumseh’s lodge as I came out and I remember wishing that my new cousin might prove to be half as charming. Of course I did not know you. Tecumseh told me that he knew where Delaroche’s daughter was, but he refused to tell me anything more. He said he would produce her in two months.” Captain Brito’s face darkened. “These Indians are very insolent, but—Well, I waited for a time, but when Tecumseh went away I made inquiries, and Girty here found you for me. I can’t tell you how delighted I am to find that you and the charming little girl I saw outside the lodge are one and the same. It makes everything delightful.”

Alagwa’s head was whirling. For ten years, practically all of her life that she could remember, she had lived the life of an Indian with no thought outside of the Indians. She had rejoiced with their joys, and grieved with their woes. Like them she had hated the Americans from the south and had looked upon the English on the north as her friends.

[43]And now abruptly another life had opened before her. A redcoat officer had claimed her as kinswoman. The easy, casual, semi-contemptuous air with which he spoke scarcely affected her, for she had been used to concede the supremacy of man. She did not know what this claim might portend, but it made her happy. No thought that she might have to leave her Indian home had yet crossed her mind. Brito’s assertion that he had come to take her to France had not yet seeped into her understanding. To her France and England were little more than words.

Uncertainly she smiled. “I am glad,” she murmured.

Captain Brito took her hand and raised it to his lips. “You will be more than glad when you understand,” he declared, patronizingly. “Of course you can’t realize what a change this means for you.” He glanced round and shuddered. “After this—ugh—England and France will be paradise to you. Get ready and as soon as Tecumseh comes back and gives me the proofs of your identity I’ll take you to Canada and then on to England.”

Alagwa shrank back. “I? To England?” she gasped.

“Of course.” Captain Brito smiled. “All of your house are loyal Englishmen and you must be a loyal Englishwoman. You really don’t know what[44] a wonderful country England is. It’s not a bit like this swampy, forest-covered Ohio. And the people—Oh! Well! you’ll find them very different from the Indians and from the bullying murdering Americans. You’ll learn to be a great lady in England, you know.”

A shadow fell between the two, and an Indian, naked save for a breech-clout and for the eagle feathers rising from his scalp-lock, thrust himself between the girl and the intruders.

“White men go!” he ordered, in Shawnee. “Take presents and go!”

Brito’s face flushed brick-red. He did not understand the words, but he could not mistake the tone. His hand fell to his sword hilt. Instantly, however, Girty stepped between. “Why does the Chief Wilwiloway interfere?” he demanded.

Wilwiloway leaned forward, his fierce eyes glittering into those of the renegade. “Tecumseh say white men no speak to Alagwa. White men go!” he ordered again. His words came like a low growl.

For a moment the others hesitated. Then Brito nodded and said something to Girty and the latter drew back, snarling but yielding. Brito himself turned to Alagwa. “Good-by, cousin,” he called. “Since this—er—gentleman objects I have to go. With your permission I’ll return later—when Tecumseh is back.” With a smile and a bow he[45] turned away. He knew he could not afford to quarrel with Tecumseh until he had secured the proofs of the girl’s identity.

Wilwiloway called Girty back. “Take presents,” he ordered, pointing; and with a savage curse the man obeyed.

Wilwiloway watched them go. Then he turned to Alagwa and his face softened. “They are bad men,” he said, gently. “Their words are forked. Tecumseh commands that Alagwa shall not speak with them.”

The girl did not look altogether submissive. Nevertheless she nodded. “Alagwa will remember,” she promised. “Yet surely Tecumseh is deceived. The white man speaks with a straight tongue. He brings Alagwa great tidings. And the redcoats are the friends of the Shawnees.”

The Indian shrugged his shoulders. “Tecumseh speaks; Alagwa must obey!” he declared, bluntly. Then he turned away, leaving the girl to wonder—quite as mightily as if she had lived all her life among her civilized sisters.

How long she stood and wondered she never knew. Abruptly she was roused by a sound of voices from the direction of the southern outposts. Steadily the sound grew, deepening into a many-throated chant—the chant of welcome to those returning from a journey—the chant of thanksgiving that those[46] arriving have passed safely over all the perils of the way:

Alagwa spun round. She knew what the song meant—Tecumseh was returning.

A moment later he passed her, striding onward to his lodge. His face was stern—the face of one who goes to face the great crisis of his life. Behind him came chief after chief, warrior after warrior, members of many tribes. Versed in Indian heraldry as she was, Alagwa could not read half the ensigns there foregathered.

FOR nearly a month Jack Telfair, with black Cato at his heels, had been riding northward through a country recently reclaimed from the wilderness and reduced to civilization. Day after day he passed over broad well-beaten roads from village to village and from farmstead to farmstead, where clucking hens and lowing cattle had taken the place of Indian, bear, and wildcat. Between, he rode through long stretches of wilderness, where the settlements lay farther and farther apart and the ill-kept way grew more and more rugged and silver-frosted boulders glistened underfoot in the dawn.

The route lay wholly west of the Alleghenies and the travellers had to climb no such mighty barrier as that which stretched between the Atlantic and the west. But the land steadily rose, and day by day the sunset burned across increasing hills. The two passed Nashville—a thriving town growing like a weed—and came at last to the Kentucky border and the crest of the watershed between the Cumberland and the Green river. Here, cutting across the headwaters of a deep, narrow creek, ice cold and crystal clear, filled with the dusky shadows of darting trout, they stumbled into the deep-cut trail[48] travelled for centuries by Indian warriors bound south from beyond the Ohio to wage war on tribes living along the Atlantic and the Gulf. This trail was nearly a thousand miles long; one branch started from the mouth of the Mississippi and the other from the Virginia seaboard, and the two met in southern Kentucky, crossed the Ohio, and followed the Miami toward the western end of Lake Erie. Jack had only to follow it to reach his destination.

Like all Indian pathways, the trail clung to the highest ground, following the route that was driest in rain, clearest of snow in winter and of brush and leaves in summer, and least subject to forest fires. Much of it was originally lined out by buffalo, which found the way of least resistance as instinctively as the red men, but long stretches of it had been made by the Indians alone. The buffalo trail was broad and deep and was worn five or six feet into the soil; the Indian trail was in few places more than a foot deep and was so narrow that it was impossible to see more than a rod along it. No one could traverse it without breaking the twigs and branches of the dense bushes that overhung it on either side, leaving a record that to the keen eye of the savage and of the woodsman was eloquent to the number who had passed and the time of their passage. No one who once travelled its vistaless stretches could fail to understand the ease with which ambushes and surprises could be effected.

[49]Though the trail clung to high ground the exigencies of destination compelled it in places to go down into the valleys. It had to descend to cross the Kentucky river and to descend again into the valley of the Licking as it approached the Ohio at Cincinnati. In such places it had often been overflowed and obliterated and its route was far less definite. However, this no longer mattered, for in all such parts it had long been incorporated into the white man’s road. Much of it, however, still endured and was to endure for more than a hundred years. Beyond the Ohio it climbed once more and followed the crest of the divide between Great and Little Miami rivers to Dayton, Piqua, and Wapakoneta.

Thirty years before men had fought their way over every inch of that trail, dying by scores along it from the arrow, the tomahawk, and the bullet. But that had been thirty years before. For twenty years the trail had been safe as far as the Ohio; for ten it had been measurably safe halfway up the state, to the edge of the Indian country.

Throughout the journey Jack tried hard to be mournful. Every dawn as he opened his eyes on a world new created, vivid, baptized with the consecration of the dew, he reminded himself that life could hold no happiness for him—since Sally Habersham had given her hand to another. Every noontide as he saw the fields swelling with the growing[50] grain, the apples shaping themselves out of the air, the vagrant butterflies seeking their painted mates above the deep, moist, clover-carpeted meadows, he told himself that for him alone all the vast processes of nature had ceased. Every evening, when the landscape smouldered in the setting sun, when the red lights burned across the tips of the waving grasses, when the burnished pines pointed aspiringly higher, when the rushing rapids on the chance streams glittered in sparkling points of multi-colored fire, he assured himself that to himself there remained only the hard, straight path of duty.

Yet, in spite of himself, the edge of his grief grew slowly but surely dull. The bourgeoning forests, the swelling mountains, the vast stretches of solitude were all so many veils stretched between him and the past. His love for Sally Habersham did not lessen, perhaps, but it became unreal, like the memory of a dear, dead dream that held no bitterness. It was hard to brood on the life of gallant and lady, of silver and damask, of polished floors and stately minuets, when his every waking minute had to be spent in meeting the intensely practical problems that beset the pioneers. It was hard to assure himself that he would live and die virgin and that his house should die with him, when, as often as not, he dropped off to sleep in the same house, if not the same room, with a dozen or more sturdy boys and girls that were being raised by one[51] of those same pioneers and his no less vigorous wife.

Besides, Cato would not let him brood. Cato had feminine problems of his own which he insisted on submitting to his master’s judgment. When rebuffed, he preserved an injured silence till he judged that Jack’s mood had softened and then returned blandly to the charge. Very early on the trip Jack gave up in despair all attempts to check his menial’s tongue; he realized that nothing short of death would do this, and he could not afford to murder his only companion, though he often felt as if he would like to do it.

“There ain’t no use a-talkin’, Marse Jack,” Cato observed one day. “The onliest way to git along with a woman is to keep her a-guessin’. Jes’ so long as she don’ know whar you is or what you’s a-thinkin’, you’s all right. But the minute she finds out whar you is, then whar is you? Dat’s what I ax you, Marse Jack?”

Jack shook his head abstractedly. “I’m sure I don’t know, Cato,” he said. “Where are you?”

“You ain’ nowhar, that’s what you is. Dar was Colonel Jackson’s gal Sue. Mumumph! Couldn’t dat gal make de beatenest waffles! An’ didn’t she make ’em foh me for most fo’ months till I done ax her to marry me! An’ didn’t she stop makin’ ’em right spang off? An’ didn’t she keep on stoppin’ till I tuk up with Sophy? An’ then didn’t she begin again? Yes, suh; it’s jes’ like I’m tellin’ you. Jes’[52] as long as a woman thinks she’s got you, you ain’t nobody; and the minute she thinks some other gal’s got you, then you’s everything. Talk to me about love! Gals don’t know what love is. All they wants is to spite the other gals.”

“Well! How did you make out, Cato. Did you fix on Sue or Sophy?”

“Now, Marse Jack, you know I ain’t a-goin’ to throw myself away on none of them black nigger gals. I’se too light complected to do that, suh. Besides, Sue and Sophy done disappointed me. They pointedly did, suh. Jes’ as I was a-makin’ up my mind to marry Mandy—Mandy is dat yaller gal of Major Habersham’s; I done met her when you was co’ting Miss Sally—Sue and Sophy got together and went to Massa Telfair and tole him about it and Massa Telfair say I done got to marry one of them two inside a week, an’ if you hadn’t done start off so sudden I reckon’s I’d a been married and done foh befo’ now, suh. Massa Telfair’s plumb sot in his ways, suh.”

Jack was tired of the talk. “Oh! Well! I reckon Mandy’ll be waiting for you when you get back,” he answered, idly.

Cato smiled broadly. “Ain’t dat de trufe?” he chuckled, delightedly. “I ain’t ax Mandy yit, but she ’spec’s me to. I tell you, Marse Jack, you got to keep ’em guessin’, yes, you is, suh. Jes’ as long as you does you got ’em.”

[53]Cato rung the changes on his tale with infinite variations. Jack heard about Sue and Sophonia and Mandy from Alabama to Ohio, from the Tallapoosa to the Miami. It was only when he reached Dayton that the loves of his henchman were pushed into the background by more urgent affairs.

Dayton was alive with the war fever. Governor Hull, of Michigan, who had been appointed a brigadier general, had started north from there nearly a month before with thirty-five hundred volunteers and regulars and was now one hundred miles to the north, cutting his way laboriously through the vast forest of the Black Swamp. At last reports he had reached Blanchard River, and had built a fort which he called Fort Findlay. So far as Ohio knew war had not yet been declared, but news that it had been was expected daily. The whole state awaited it in apprehension, not from fear of the British, but from terror of their ruthless red allies.

Not a man or woman in all Ohio but knew what Indian warfare meant. Not one but could remember the silent midnight attack on the sleeping farmhouse, the blazing rooftree, the stark, gashed forms that had once been men and women and little children, the wiping out of the labor of years in a single hour.

Every sight and sound of forest and of prairie mimicked the clash. The hammering of the woodpecker was the pattering of bullets, the thump of[54] the beaver was the thud of the tomahawk, the scream of the fishhawk the shriek of dying women, the scolding of the chipmunks in the long grass the chatter of the squaws around the torture post, the red reflection of the setting sun the gleam of blazing rooftrees.

Ah! Yes! Ohio knew what Indian war meant.

And Cato, for the first time, realized whither he was going. He ceased to talk of his sweethearts and began to pray for his soul.

At last Jack came to Piqua. Piqua stood close to the boundary of the Indian country, which then spread over the whole northwestern quarter of Ohio. North of it lay the great Black Swamp, through which roved thousands of Indians, nominally peaceful, but potentially dangerous. At Piqua, too, dwelt Colonel John Johnson, the United States Indian agent, whose business it was to keep them quiet.

As Jack rode into the outskirts of the tiny scattered village, a middle-aged man with long, gray whiskers, skull cap, and buckskin trousers came up to him.

“Hello, stranger!” he bawled. “What’s the news?”

Jack reined in. “Sorry, but I haven’t any,” he replied.

“Whar you from?”

“From Dayton and the south.”

“Sho! Ain’t Congress declared war yet?”

[55]“Not that I know of. The last news from Washington was that they were still debating.”

“Debatin’? Well! I just reckon they are debatin’. Lord sakes, stranger, don’t it make you sick and tired to hear a lot of full grown men a-talkin’ and a-talkin’ like a pack of women. Just say what you got to say and stop; that’s my motto. And here’s Congress a-talkin’ and a-talkin’ and a-wastin’ time while the Injuns are fillin’ up with fire-water and sharpenin’ their tomahawks and the country’s going to the devil. Strike first, and talk afterwards, say I. But then I never was much of one to talk. I guess livin’ in the woods makes you kinder silent, and——”

“What’s the news from the north?” Hopeless of a pause in the old man’s garrulity Jack broke in.

The old man accepted the interruption with entire good humor if not with pleasure, and straightway started on a new discourse. “Bad, bad, mighty bad, stranger,” he declared. “That red devil, Tecumseh, has been a-traveling about the country but he’s back now and the Injuns are getting ready to play thunder with everybody. Colonel Johnson says you ought to treat ’em kind and honeyswoggle ’em all the time, but that ain’t my way, and it ain’t the way of nobody that knows Injuns. How far north is you aimin’ to go, stranger?”

“To Wapakoneta, I think.”

“Then I reckon you’ll have to see Colonel Johnson.[56] What did you say your name was? Mine’s Rogers—Tom Rogers.”

Jack grinned. “I didn’t say,” he answered. “But it’s Jack Telfair.”

“Telfair! Telfair! Seems to me I kinder remember hearin’ of somebody of that name. But it’s mighty long ago. Let’s see, now, I wonder could it ha’ been that fellow that we whipped for stealin’—Pshaw, no, that was a fellow named Helden. He was——”

“Where’ll I find Colonel Johnson,” demanded Jack, in despair.

“Well, now, that’s mighty hard to tell. Colonel Johnson sloshes round a whole lot. Maybe you’ll find him at John Manning’s mill up at the bend here or maybe you’ll have to go to his place at Upper Piqua or maybe you’ll have to go further. I reckon you didn’t stop at Stanton as you come along, did you? Colonel Johnson’s mighty thick with Levy Martin down there, and he’s liable to be at his house, or at Peter Felix’s store.”

Jack shook his head. “No, I didn’t come by Stanton.”

By this time a number of other white men had come up. The old hunter insisted on making Jack known to all of them. Jack heard the names of Sam Hilliard, Job Garrard, Andrew Dye, Joshua Robbins, Daniel Cox, and several others. All of them were anxious for news in regard to the coming[57] war, and all shook their heads dubiously when they heard that Jack proposed to go further north.

“It’s taking your life in your hands these days, youngster,” remarked Andrew Dye, a patriarchal-looking old man. “There’s ten thousand Injuns pretendin’ to be tame between here and Wapakoneta and the devil only knows how many more there are north of it. Tecumseh’s sort of civilized, but his Shawnees ain’t Tecumseh by a long shot. And them d— British are stirrin’ ’em up. Course you may get there all right, but when you go trampin’ in where angels are ’fraid to, you’re mighty apt to get turned into an angel yourself.”

“I guess I’ve got to go,” said Jack. “I want to get somebody who knows the country to go along with me.”

“What’s the matter with me?” broke in Rogers. “I ain’t a-pining to lose my scalp, but I reckon if I won’t go nobody will. And I don’t want no big pay neither. You and me’ll agree on terms mighty easy. I can take you anywhere. I know all the Injuns. Why! Lord! They call me——”

Job Garrard laughed. “Yes,” he said. “Tom can take you anywhere. Tom’s always willing to stick in. He stuck in on Judge Blank’s court down in Dayton the other day, didn’t you, Tom? Haw! Haw! Haw!”

A burst of laughter ran round the group. Everybody laughed indeed, except Tom himself. “You[58] boys think you’re blamed funny,” he tried to interpose.

But the others would not hear him.

“Maybe you heard something about it as you come through Dayton, stranger!” said Dye. “Tom tromped right into court and he heard the judge dressin’ down two young lawyers that had got to fussin’. I reckon Tom had been a-practicin’ at another bar, for he yells out: ‘Give it to ’em, old gimlet eyes.’ The judge stops short. ‘Who’s that?’ he asked. Tom thinks he’s going to ask him upon the bench or something and he steps out an’ says: ‘It’s this yer old hoss!’ The judge he looks at him for a minute an’ then he calls the sheriff and says, ‘Sheriff, take this old hoss out and put him in a stall and lock the stable up and see that he don’t get stole before tomorrow mornin’.’ And the sheriff done it, too. Haw! Haw! Haw!”

The laughter was interrupted by the appearance of a wagon drawn by mules and driven by a man who looked neither to the right nor to the left.

Rogers, glad of any change of subject, jumped forward. “Hey!” he yelled. “What’s the news?”

The driver paid no attention to the call. His companion on the box, however, leaned out. “Go to h—l, you old grand-daddy long legs,” he yelled.

The old hunter’s leathery cheek reddened. But before he could retort a horseman appeared in the[59] road in front of the wagon and threw up his hand.

“Hold on, boys,” he called. “Hold on! I want to speak to you.”

The driver hesitated; then, compelled by something in the eyes of the man, he sulkily reined in. As he did so Jack and the little crowd about him moved over to the wagon.

“I’m Tom Rich, deputy of Colonel Johnson, the Indian agent up here,” the horseman was explaining, peaceably. “Colonel Johnson’s away just now and I’ve got to see everybody that goes north to trade with the Injuns.”

“We ain’t going to trade with no Injuns,” said the man who appeared to be the leader. “We’re taking supplies to Fort Wayne for the Government. I reckon you ain’t got no call to stop us.”

“Not a bit of it, boys. Not a bit of it. Just let me see your papers and you can go right along.”

The man sought in his pockets and finally extracted a paper which he passed to Rich, who scanned it carefully. “Your name’s David Wolf, is it?” he questioned, “and your friend’s name is Henry Williams?”

“That’s right and we ain’t got no time to waste. There ain’t no tellin’ when war’ll be declared an’——”

“No! There’s no telling. You can go along if you want to, but I’ve got to warn you—warn all of you.” Rich’s eye swept the group. “We got news[60] this morning that there was a big council at Wapakoneta last night. There was a British officer there in uniform and he and Tecumseh tried to get the Shawnees to go north. Black Hoof (Catahecasa) stood out against them, and our news is that less than two hundred braves went. Still, there’s no telling, and the country’s dangerous. Colonel Johnson’s at Wapakoneta now. Better wait till he gets back.”

“Wait nothin’.” Wolf spat loudly into the road. “General Hull rushed us here with supplies for Fort Wayne and we’re going through. If any darned Injun gets in our way he won’t stay in it long. My pluck is to shoot first and question after.”

The deputy’s brow grew stern. “You’ll be very careful who you shoot and when,” he ordered, sternly. “A single Indian murdered by a white man might set the border in flames and turn thousands of friendly Indians against us. I’ll let you go through, but I warn you that if you shoot any Indians without due cause Colonel Johnson will see that you hang for it. We’ve got the safety of hundreds of white people to consider and we’re not going to have them endangered by any recklessness of yours. You understand?”

Wolf shrugged his shoulders. “I reckon so,” he muttered.

“All right, see that you heed.” Rich turned[61] away from the men and greeted Jack. “And where are you bound, sir?” he asked smilingly.

“I’m looking for Colonel Johnson,” returned Jack. “I’m looking for a young lady who was to have been left in his care. Have you heard anything about her.”

“A young lady?” The deputy stared; then he laughed. “No! I’m not young enough,” he remarked, cryptically.

“Then, with your permission I’ll just tag along after our crusty friends in the wagon.”

The deputy hesitated. “I have no power to stop you,” he said. “But you’d better wait here for Colonel Johnson.”

“I can’t. The matter is urgent. Come, Cato! So long, boys!” Jack nodded to the group around him, shook his bridle and cantered off after the wagon, which had just vanished among the trees.

THE close of the Revolution had brought no cessation of British intrigue along the northern frontier. The British did not believe the confederacy of states would endure. In any event the western frontier was uncertain; miles upon miles of territory—land enough for a dozen principalities—lay open to whoever should first grasp it. Treaties were mere paper; possession was everything. Colonization in western Canada had always lagged and the British could supply no white barrier to hold back the resistless tide that was rolling up from the south. But this very dearth of colonists was in a way an advantage, for it prevented the pressure on the Indians for lands that had caused perpetual war further south. Desiring to check the Americans rather than to advance their own lines the British, through McKee and other agents, poured out money to win the friendship of the Indians. Arms, ammunition, provisions, gew-gaws in abundance were always ready. In the five years before the breaking out of the War of 1812 probably more than half the Indians about the Great Lakes had visited one British post or another in Canada and had come back home loaded with presents. The policy was wise, even if not humane.[63] When the conflict came it was to save Canada, which without Indian aid would have been lost forever to the British crown.

South of Canada, within the borders of the United States, ten thousand Indians hung in the balance, ready to be swayed by a hair. They were friendly to the British, and they hated the Americans. But they feared them, also—feared the men who had fought and bled and died as they forced their way westward past all resistance. Some would go north at the first word of war, but most would stay quiet, awaiting results.

The first British triumph, however small, would call hundreds of them to the British standard; a great British triumph would call them forth in thousands.

Tecumseh was the head and front of those Indians who favored war. For years he had urged that the red men should unite in one great league and should establish a line beyond which the white man must not advance. Behind this, no foot of land was to be parted with without the unanimous consent of all the tribes. Two long journeys had he made, travelling swiftly, tireless as a wolf, from one tribe to another, from Illinois to Virginia, from Florida to New York, welding all red men into a vast confederacy that in good time would rise against the ever-aggressive white man, crush his outposts, sweep back his lines, and establish a great[64] Indian empire that would hold him back forever.

A year before he had brought his plans nearly to perfection. He had accumulated great quantities of arms and ammunition and supplies at the town of his brother, the Prophet, on the banks of the Wabash, and had set out on his first long journey—a journey that was intended to rivet fast the league his emissaries had built. But he had gotten back to find that Harrison, the white chief, had struck in his absence, had defeated and scattered his chosen warriors, had destroyed his town, and had blotted out the work of three long years.

All afternoon long, from the protection of a near-by cabin, Alagwa watched that of Tecumseh, seeing the chiefs come and go. Simon Girty and the man in the red coat were among them.

When at last the sun was setting and the ridge poles of the cabin were outlined against the swirl of rose-colored cloud that hung in the west, Tecumseh sent for her.

Pushing through the mantle of skins that formed the door she found the great chief sitting cross-legged in the semi-gloom. Silently she sank down before him and waited.

For a long time Tecumseh smoked on in silence. At last he spoke, using the Shawnee tongue, despite the fact that he was a master of English and that Alagwa spoke it also, though not fluently. “Little daughter,” he began. “For ten years you have[65] dwelt in Tecumseh’s cabin and have eaten at his fireside. The time has come for you to leave him and take a trail of your own.”

Startled, with quivering lips and tear-filled eyes, Alagwa threw herself forward. “Why? Why? Why?” she cried. “What has Alagwa done that Tecumseh should send her away?”

“Alagwa has done nothing. Tecumseh does not send her away. And yet she must go. Listen, little daughter, and I will tell you a tale. Some of it you have heard already from the redcoat chief who spoke to you today against my will. The rest you shall hear now.

“Ten years ago, your father left you in my care. His name was Delaroche Telfair, a Frenchman, a Manaouioui. He came of a great chiefs family, from far across the water. All the chiefs of his house are now dead and all their lands have come down to him and from him to you. If you were dead the lands would go to another chief—the chief Brito, who spoke to you today. Two moons ago this chief came to Tecumseh, seeking you and speaking fair words and promising all things. He is the servant of the British King and the ally of Tecumseh, and if Tecumseh were free to choose, he would have let you go with him gladly. But he is not free. Before your father died he warned Tecumseh against Brito, saying of him all things that were evil. He told also of the other chiefs of[66] his house who dwelt far to the south, near the great salt water and near the ancient home of the Shawnee people before they were driven northward by the whites. He begged that Tecumseh should put you in the care of these chiefs rather than in that of the chief Brito. Does my daughter understand?”

Alagwa bowed. “I understand, great chief,” she answered, breathlessly.

“Therefore Tecumseh bade the chief Brito wait until he should return from a journey. He stationed the chief Wilwiloway to watch and protect you. For many moons he travelled. His moccasins trod the woods and the prairies. He visited the home of his friends’ people by the far south sea. Of them one is a young white chief, handsome and brave and skilful, called Te-pwe (he who speaks truth) by the Shawnees. His years are four or five more than Alagwa’s. Tecumseh saw him and gave him a belt of black and white and told him by what trail he should come to fetch you. The young chief took the belt and Tecumseh hoped to find him here when he came. But he has not come.”

Alagwa’s breast was heaving. The suggestion that she was to be sent far south into the land of the Americans filled her with terror. She had been trained in the stoicism of the Indian and she knew that it was her part to obey in silence, accepting the words of the chief, but her white blood cried out in protest.

[67]The chief went on. “Tecumseh has done what he can to keep his promise to his friend. But now Tecumseh’s people call him and he must leave all else to serve them. Tonight he holds a great council and tomorrow he and those who follow him go north to join the redcoats and fight against the Seventeen Fires (seventeen states). But before he goes he must decide what to do with Alagwa. He can not take her north with him. He can not leave her here, for that would be to give her to the chief Brito whether he wished it or not and whether she wished it or not. Two things only can he do. He can give her into the hands of her father’s foe or he can send her south to meet the young white chief, who is on his way to fetch her. Which shall he do, little daughter?”