He turned to look at her; her lips were slightly parted as she lifted her lovely face toward his.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Startling Stories, February 1953.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I

Director Unterbaum of the Intercolonial Office rose from his chair as the pair came in. "I take it you haven't met before?" he said. "Mr. and Mrs. Lanzerotti, this is Ann Starnes, the recording photographer, and Robert Heidekopfer, one of our better writers."

There were smiles and acknowledgments. Unterbaum touched a pair of buttons on his desk and two chairs slid out of the walls to make a group of five. "Sit down, please," he said. "Now I'm not going to mince words. The reason you're here is because the Council wants you—three of you, at least—to undertake a mission. Vincent—" he indicated Lanzerotti, who nodded a dark head—"already knows something about it, but for the benefit of Miss Starnes and Mr. Heidekopfer, I will say that we want to send you to Tolstoia."

Heidekopfer smiled and said, "Sounds better than that trip to the polar mines on Mars, eh Ann?"

"Warmer, anyhow," said the girl, turning a carefully-kept blonde head. "But I thought Tolstoia was closed to visitors."

"The patriarch has agreed to let a delegation in for this visit," said Unterbaum, "so we can render a fair and unbiased report on Tolstoia, in word, picture and observation. The point is this; there are some islands about three hundred miles off the coast of Tolstoia, between it and South Bergenland—the Wrightley Islands. They have no resources, but Tolstoia wants to colonize them." He touched buttons again, and a map appeared on the wall showing the almost-round shape of the island nation, with the islands and the tip of South Bergenland at the right.

Unterbaum went on: "They're uninhabited, so there isn't any objection from the Demographic Commission, although it's unusual for one of the hermit-states to expand. But there are certain features of the request that make the Council inclined to go slow; or at least to want more information."

He stopped, seeming to wait for a question, so Heidekopfer asked it. "What are they?"

Lanzerotti answered, "To begin with, the place was founded in accordance with the philosophy of Count Leo Tolstoi, a Russian writer of some centuries back. The Russians discovered that a sect of people who believed in his ideas was growing up in their country, and considered it a threat to the organization of their state. They couldn't dispose of the Tolstoians under the genocide laws, so they appealed to the Council and it agreed to expatriate all the Tolstoians the Russians could identify."

"Then it was a penal colony, like the Moon mines?" inquired Heidekopfer.

"No," said Lanzerotti. "As a matter of fact, when the announcement was made, the Tolstoians came forward in numbers and identified themselves. But they thought they were going to have a reservation set apart for them in Russia itself, and when they found they were going to an island on Venus, there was a certain amount of resentment."

"Do you think it still exists? That if they're allowed to get hold of the islands, they'll do something drastic—say start a war?"

"Not after all these years," said Lanzerotti. "It's nearly three centuries, and national resentments don't last that long without something to feed on. Besides, pacifism was one of Tolstoi's doctrines."

"Then what are we supposed to look for?"

Lanzerotti spread his hands. "We don't know. That's what's worrying the Diplomatic Division. Asking for more territory indicates a rising birth-rate, but the kind of territory they're asking for doesn't promise a rise serious enough to worry the Demographic Commission. We don't consider it likely that Tolstoianism has become militant. But to be honest, we just don't know."

Ann Starnes smiled. "It sounds like hunting for a needle in a haystack when you don't even know whether there's any needle," she said.

"On the contrary," said Unterbaum, "we're fairly certain there is a needle, and a sharp one. What we need to know is what kind of needle it is before someone gets stuck with it. Listen—" He snapped up one of the lids in his desk and spun a wheel of recording tape. "Planes aren't allowed to land in Tolstoia, of course, but every once in a while one comes down there, and occasionally a yacht or fishing-craft gets wrecked on the coast. Now the normal procedure in such a case with a hermit-state is that they hold survivors and notify someone to come and get them. They stopped doing that about eighty years ago."

"What do you mean?" said Heidekopfer. "Stopped notifying or stopped rescuing survivors?"

"It isn't quite certain," said Unterbaum, "but here's the sequence, such as it is. Seventy-eight years ago Bernard Jones and his wife disappeared while on a flight from MacNider to South Bergenland." He indicated the map. "You see, that would carry them close to Tolstoia. Three months later one of the fishing vessels, which are the only form of communication the Tolstoians have, turned up at MacNider. It had a letter from Mrs. Jones. She said her husband had died in a crash landing, and she was staying in Tolstoia with the permission of the authorities."

"Anything wrong about that?" asked Heidekopfer.

"There's nothing wrong with any of this," said Unterbaum, "at least as far as that instance goes. It's other things. Nothing has been heard of Mrs. Jones since. Seventy-six years ago, a musician named Bruno Zaleski went on a yachting trip in the South Ocean with a party of three. They never came back. After the usual interval letters came through from all of them. They said they found Tolstoia a Venusian paradise and were going to stay. Zaleski was heard from again. At the time of the next incident, one year later, his brother received a letter telling how happy he was."

He paused for a moment. "The incident sixty-seven years ago was the beginning of a new series. It concerned a man named Walter Artem, another plane case. Like Jones, he disappeared. One of the Tolstoian fishing-craft brought him back, but he was dead. They had preserved his body carefully. I'll show you the picture."

He touched the stud and the watchers found themselves gazing at a coffin, partly glassed so the occupant was visible to the waist. Rose Lanzerotti gave a little cry and with reason, for the face within was peculiarly horrible; bloated and suffused with blood, the neck swelling out over a clearly visible rope.

"They explained he had hanged himself," Unterbaum continued.

"I have a question," said Ann Starnes. "Why did they go to all the trouble of preserving him just the way he died? It sounds as though they were afraid somebody might get suspicious."

"That's what I thought," said Unterbaum. "But there's an explanation. The records show that the Tolstoians, even while they were in Russia, showed a peculiar reverence for their dead when they were important people. It's a hold-over from their twentieth century leader Lenin. They preserve bodies this way so they're visible. The explanation that came with Artem's body was that the Tolstoians didn't know how important he was, but thought he might be big enough to deserve preservative treatment."

"Polite of them," murmured Lanzerotti.

"Very," said Unterbaum. "Almost too polite. Because it was repeated—since Artem there have been six cases of castaways on Tolstoia committing suicide and being delivered at MacNider in preserved form."

"All hangings?" asked Heidekopfer.

"No. One stabbing, three shootings, two overdoses of soporifics. There are autopsy records on those, and they're legitimate."

"Seems a high proportion of suicides among the castaways," said Heidekopfer. "Can anything be made of that?"

"Nobody seemed to think so," said Unterbaum. "Seven suicides out of a given group over a period of eighty years isn't much, after all. The thing that stirred up our office was the discovery that in the past eighty years not one castaway has come back alive. They've either been crated out as suicides or sent through letters saying they have decided to become citizens of Tolstoia."

He paused a moment to let that sink in. "A number of these cases are rather special. There was Carmenilla Baio, forty-four years ago. She was a video dancer on a flight from MacNider to South Bergenland. Sent out the usual letter saying she had decided her future lay in Tolstoia, and followed it with another one a couple of years later. That's ordinary enough, but the case made the news, and when we went through the records, we found that when she disappeared she had been married only three months and was passionately devoted to her husband. Her second letter was written in a kind of code, and asked him to fake an accident and join her there."

"Did he?" asked Ann Starnes.

"Any possibility of forgery in those letters?" asked Heidekopfer at the same time.

Unterbaum turned to the girl. "No to your question. As for the other one, Carmenilla Baio's private code was certainly no forgery."

Heidekopfer said, "It appears that the Tolstoians compel them to stay there, and if they argue, bump them off. Is that it?"

"That would be a charge of genocide. I do not think—" began Lanzerotti.

"I don't either," said Unterbaum. "The Tolstoians wouldn't expose themselves to such a thing, especially in view of their origins. No, I'm convinced they have been quite honest, leaning over backward—as witness the preserved suicides—but there's some factor in the equation we don't know. And I won't deny that there's danger in the trip."

"Then I'm going," said Rosa Lanzerotti, decisively. She was a small woman with vivid Italiote coloring.

Ann Starnes said, "Might as well square the party off, hadn't we? It would be nice to have someone to handle the recording tapes and films."

Unterbaum frowned. "The Intercolonial Office—" he began.

Lanzerotti said, "I believe that psychologists recognize it as a temperamental danger to send two men and one woman on a protracted expedition."

"I ought to know better than to argue with a diplomat," said Unterbaum.

II

The low spit guarding the harbor entrance was only a slightly deeper blue than the water and perpetual overcast of Venus. Captain Ratterman sighed, reported "No charts," and spoke into the communicator, "Cut speed to eight knots, use full automatics on the bottom sonics," then he turned to the pair beside him on the bridge. "I'm not being inhospitable. In fact, you're welcome to stay as long as you please. But it's fair to warn you that we won't be docking for another three hours."

"We love your company," said Ann Starnes, but Heidekopfer picked at her arm, and led her toward the gangway. When they had reached the low, flat bow with the water whispering softly beneath, he said, "How about it, Ann? Why not marry me now and save trouble? You're going to anyway, some day, and it might be a protection here."

She put a hand over one of his. "No, Bob. Not now. I'll give you first place on the list, but I'm not going to marry you—or anybody else—until I'm something more than a failure."

"You're no failure. The fact that you were selected for this job proves it."

"Just a competent mechanical photographer, Bob—you needn't tell me. I was picked because I had worked with you before, and your work is important."

"Look ..." he started to say, then let it trail off. They had argued the point so often it was like another trip on a merry-go-round. Ann said, "I don't want to be just a wife, like Rosa Lanzerotti."

He moved. "Do you think she's—a failure?"

"No-o. Not within her own dimension. It just isn't mine. I want to be something more important than a good mechanical photographer."

"Did it ever occur to you—" he began, and let it trail off as he watched a formation of the odd Venusian batfish soar from the water under the bow and sweep overhead to dive again in perfect alignment. The ship swung. The long blue tongue of land came round on their right and the harbor opened before them. There was a little grove of masts at its depth clustered around what seemed to be docks, but he saw no town on the shore behind.

"Think you can handle the language all right now?" asked Ann, a note of banter in her question.

"If there hasn't been too much development in it since Tolstoia was closed off. Communications thought a good many special terms might have developed. What worries me more is the system of ideas. You were lucky, not having to study Tolstoi. He had a philosophy, all right, but I can't conceive how it could be translated into a practical method of living, and neither can Vincent. Unless we do understand, it's going to be hard to present a sympathetic picture."

"Photos are always sympathetic," said Ann. "The question is, do we want to be? Let's go down and have a cup of coffee. The betting is there won't be any where we're going."

The other two were in the cabin and the cup of coffee lasted until a cessation of movement and a slight bump indicated they had arrived. There was a bustle of gathering luggage; they went topside to find the gangplank already laid to a dilapidated dock with holes in the planking, alongside which little Tolstoian fishing-craft rose and fell rhythmically to the swell. At the shore end of the dock a little group of men in embroidered white smocks with square caps on their heads looked on with an air of complete uninterest as the ambassadors disbarked. There were four droshkies behind them; a house was visible among drooping-branched Venusian trees.

Ann set her camera to automatic and hooked it to her belt as Lanzerotti led the way along the dock. Three of the men detached themselves from the group and waited. As the ambassadors approached, one of them clasped his hands together, said, "Behrmann, Andrei Pavlich" and took a step back. "Vikhranov, Nicolai Leonovich," said the second, and the third, "Kazetzky, Pyotr Ilyich." He was a tall man, with a long, hooked nose and an expression of deep melancholy.

Lanzerotti stepped forward. "We are the representatives of the Interplanetary Council," he said. "My name is Vincent Lanzerotti with the rank of ambassador. This is Mrs. Lanzerotti, and Miss Starnes, our photographer and Mr. Heidekopfer, the official observer. We have a good deal of baggage."

The three looked at each other. Behrmann was a short man with a broad Slavic face. He said, "Bring it forward. Transportation has been provided to the seat of the patriarch."

Heidekopfer remembered that somewhere in Tolstoi there was something about not waiting on other people; also, that he was not going to have as much difficulty with the language as he had feared. Behrmann's accent was a little funny, but he put his sentences together in the classical manner and with the right words. The sailors were loading their baggage onto power-dollies. Vikhranov said, "The ambassador will take the first droshky, with myself and Pyotr Ilyich. Andrei Pavlich will accompany you in the second." He waved a hand toward Ann and Heidekopfer.

As their guides led the way toward the vehicles, Heidekopfer said, "One thing surprises me, if you don't mind a snap judgment. I would have expected to find more of a city around your port."

Behrmann turned his head with a smile. "We have no cities," he said. "They are destroyers of nature, and without communion with nature there is no happiness."

That was good Tolstoi, all right, thought Heidekopfer, and said to Ann, "They don't take very good care of their roads here, do they?"

"I should say not—and my mud-shedders are all nicely packed in the baggage, too." She lifted a neatly clad foot that was already plentifully marked with black Venusian mire. "Their trees are nice, though, and look how even the rows in that field are." She aimed the camera at it for a moment, and spoke to Behrmann in Russian; "Where are the fishermen for the boats?"

"Oh, this is Thursday," he said, standing aside so she could get in the droshky. "On this day they work in the fields. It is good to work in the fields, and we have a law that all who follow other forms of work shall do so for one day a week."

"That's not a bad law for an agricultural community," observed Heidekopfer. "I suppose you are practically all agriculture? But what do you do for manufactured articles—like shoes and glass and newspapers?"

In the droshka ahead Vikhranov raised his hand; both drivers shouted something like "Ya-ya!" simultaneously, cracked their whips tremendously, and the procession was off along a dirt road in a decidedly poor state of repair.

"I am not sure I understand your question," said Behrmann. "Shoes or glass, when we want them we make them. As for newspapers, they are forbidden by the word of the Master. I know there must be such things, because they are mentioned, but I have never seen one and do not really know what they are."

The road had begun to rise toward a cut in a range of low hills. "Uh-huh," said Heidekopfer, "and I suppose radio falls under the prohibition on newspapers. Well, let me put it this way; suppose someone had an idea for a new kind of machine. Would he have to make all the parts himself?"

"There is a law against machines. They interfere with simplicity."

"But doesn't anyone ever have an idea for a machine so brilliant that he simply has to make it in spite of the law?"

"How could he? It is against the law."

"Do you mean that the law here is always obeyed?"

"Always. That is the superiority of Tolstoia to all other peoples. Those who come to our happy country by accident never wish to leave when they find that through the doctrines of the Master we have established the brotherhood of men."

Ann gave a little giggle. "I know," said Heidekopfer rapidly in English, "I think we can take that with a cellar full of salt." He switched to Russian; "Then you have no crime?"

"In our happy country?" said Behrmann. "No. Look how beautiful is the arrangement of the cows in that field?"

Heidekopfer sighed. Then he said, "Tell me something about the government of your country. I don't want to be too inquisitive, but I have to report on these things when I get back."

Behrmann's face flashed a frown. "It is hard to explain this to an outsider, but we know of what you call government only from the works of the Master, who spoke of it as it was in the old days, in the old Russia, the holy Russia." He lifted a hand to his face, and Heidekopfer was dumbfounded to see the man was wiping away a tear. "There is the patriarch, but he is only the general secretary of the Supreme Soviet."

"Well, who makes the laws?"

"The Supreme Soviet."

"How are they elected—or chosen?"

"We all agree on them."

Heidekopfer was saved from going mad by a cry from Ann Starnes. They had passed through the cut into the hills and now, as they swung round the brow of one, a wide valley lay spread before them under the soft Venusian light. It was dotted with little clumps of trees and had houses here and there, mostly low and with curiously bound-down thatched roofs. With the green fields and grazing animals, it made a scene of truly pastoral beauty. Ann said, "Tell him to stop for a minute, will you? I want to get this."

Behrmann looked at Heidekopfer. "Is it your will also that we stop?"

"Sure, why not," said he. "Isn't even necessary to ask if the girl-friend wants it. Do you have a law about women getting permission for what they want to do, too?"

"No. Stop, Pavel Josephovitch." He turned to Heidekopfer; "But the will of one must become the will of all."

"Now I don't understand," said Heidekopfer, as Ann adjusted her camera to take a sweeping panorama of the valley. "Would you mind explaining?"

"In happy Tolstoia when the desire of one person would cause others to do what they might not desire, all must agree before it is done. To allow anything else would be compulsion, and as the Master says; 'Anything that savors of compulsion is harmful.'"

"I can see where there must be some prize family arguments in happy Tolstoia," said Ann, in English. "Would I like to be married to a man if I had to get his agreement every time I wanted to buy a new hat? No."

"If you'll marry me you won't have to—" began Heidekopfer, but Behrmann was speaking again:

"It was not always so. When our people came from holy Russia, they were like others on earth, with only the desire for universal brotherhood and the writings of the Master to guide them. But there was so much love among them and they obeyed the law so well that a hundred thirty-one of our years ago, brotherhood was attained and the will of all became the will of the one. Now it is possible for us to extend the privilege of agreement to outsiders. This is why none who have felt it wish to leave."

By this time, they had almost caught up to the leading droshky, which was just turning into a tree-lined alley at the end of which stood quite the largest house they had yet seen. It had two stories and a couple of jutting wings beside the central door. "This where we're going?" asked Ann.

"The residence of the Patriarch Pitrim Androvich Samsonov," said Behrmann, with the sonorous accents of one who is aware of saying something impressive.

The others got out and waited for them. When they had assembled Vikhranov led the procession, opening the door himself, and they found themselves in a neat hall with whitewashed walls and plain chairs standing against them. The light from the door was helped out by a couple of candles in bracket holders on the wall. Vikhranov said, "You will wait here," and turned through a door to the right. It could not have been more than a couple of minutes before a tall, strong man came out, wiping his hands on his smock, as though he had just been interrupted in something. Heidekopfer experienced an almost physical shock at the emanation of personality that seemed to flow from him. He might equally have been a general or a prophet, but either way there was no doubting that if he wanted somebody to do something, they would probably do it. Ann too was affected. She lifted her camera and let the photographing light play on the patriarch, but he moved his head slightly, the light went out and she put the camera back to her belt, an expression of awe suffusing her face.

Vikhranov said, "Little Father, these are the ambassadors from the Council. They did not tell me their names."

Lanzerotti gave him a peculiar look and said, "I am the ambassador and my name is Lanzerotti. This is—"

The big man lifted a hand. "It is good for simplicity to address all persons by their patronymics," he said. "Mine is Pitrim Androvich." Instead of looking at Lanzerotti he was, staring fixedly at Ann.

"Oh, I see," said the diplomat. "Well by that system, I suppose you'd have to call me Vincent Guidovich. And this is my wife, Rosa—uh—Mariovna."

Heidekopfer and Ann similarly identified themselves. Samsonov said, "We will show you your rooms. Is it your custom to change the clothes after travelling?"

Rosa Lanzerotti spoke for the group, "I think I'd like to change my shoes at least. They got rather muddy."

Samsonov turned to Kazetzky: "Pyotr Ilyich, will you and the horse-drivers bring the baggage of the ambassadors to the rooms in the west wing, in the name of the Master? There is a special law that this service may be performed for them."

He reached out a hand, calmly took one of Ann's, and began to lead her along the hall toward a door on the opposite side. There didn't seem to be anything to do but follow.

"Do you have any children?" said Samsonov, as he turned down a corridor at right angles to the first. "It is Nature's way of life for women to have children."

Ann laughed. "I'm afraid not yet. I'm going to leave that until after I'm married."

"It is not against our law for women to have children before." Still holding the girl's hand, he touched a door. "This room will belong to you, Vincent Guidovich."

The next was for Heidekopfer. The opened door showed a clean, plain room with Venusian yellow poppies in a vase on a writing table, a bed and a washstand with a pitcher of water. The walls were bare and there didn't seem to be any plumbing. Outside the baggage was arriving. Heidekopfer claimed his own, unpacked and put on a pair of clean shoes, and went out to find Ann's door open and the girl engaged in a similar task.

He grumbled, "If that big bruiser keeps on making such a play for you, it's going to be bad for international relations."

She laughed. "He said he loved me—but in the brotherhood of man, everyone must love everyone else. Then he let me take his picture. Let's go check with the Lanzerottis before going to the audience." She stood up.

III

Lanzerotti was zipping open a bottle-container. "Well, Robert Murrayovich, first impressions."

"About what I would have expected from a regime founded on the ideas of Tolstoi," said Heidekopfer, "and a rather screwy set-up. But my general impression was not unfavorable. They seem to be running the place with a decent respect for human values and each other."

"'The will of all is the will of one,'" quoted Lanzerotti. "Did they say that to you, too?" He took a couple of bottles of champagne from the container. "I'm going to give our hosts a treat. It never hurts in opening diplomatic negotiations. I suppose it's too early to ask yet, but you didn't run onto anything that might be a clue to why we aren't getting the castaways back?"

"Nothing that you'd call a clue, but something that might have a connection. Our guide told us that Tolstoia had attained the brotherhood of man a hundred thirty-one Venus years ago. That's eighty-one earth years, and strikes awful close to the date when Unterbaum said the disappearances began."

"Even so," said Ann, "I can't see a whole group of people who have been brought up in civilization giving it up for this." She swept her hand around the room, which was as bare as the others. "Especially that dancer he mentioned."

"A point," conceded Lanzerotti. "Shall we go?"

He led the way back to the main hall. The door from which Samsonov had emerged stood open, and there was a wide table in the room beyond, laid with an array of dishes which held any number of hors d'oeuvres, while eight or nine men and women were gathered about Samsonov. "You know your Russian customs, all right," Heidekopfer murmured to Lanzerotti as the patriarch came forward.

He explained that these were the central committee of the Supreme Soviet; there were introductions and Lanzerotti presented his champagne, which Heidekopfer had to open because none of the Tolstoians seemed to know how.

Vikhranov said admiringly, "How beautiful is the play of bubbles in this beverage!" as the ambassador lifted his glass, saying, "To the future of Tolstoia!" bowed to Samsonov and drank.

The patriarch's return bow was a trifle stiff, but he sipped—and immediately appeared to become the victim of a revolution, spitting the champagne on the floor and coughing with bulging eyes, while the others gathered round him with expressions of sympathy. After a moment of gasping recovery, he pushed them aside and said to Lanzerotti, "I taste alcohol! Is it not so?"

"To be sure," said the ambassador. "You can't very well make champagne without it. Please accept my sincerest apologies for offering it to you if it offends you, however."

"We have a law against it in Tolstoia! The drinking of alcohol leads to failure to recognize the brotherhood of man!"

Heidekopfer said to Ann, "They had a law against alcohol in America once, too, but as far as I can remember, it didn't keep people from drinking."

"Hush," she said, "I like to watch the way he holds his head."

Her eyes were fixed on Samsonov, who was returning the glance with interest as he talked to the ambassador. Heidekopfer growled, helped himself to some of the zakuski (which seemed to consist largely of various kinds of pickled fish and vegetables, with some of the soft Venusian kara nuts) and moved over to join the group around Rosa Lanzerotti. Kazetzky was just saying, "It would pleasure me greatly, little mother, if it is your will to allow me to show you some of the natural beauty of happy Tolstoia tomorrow, while the others are making their official observations."

"Thank you," she said, "but I usually go with my husband on inspection trips, when there are any, and I think I'd rather like to—" She broke off suddenly with a frown between her brows, and Heidekopfer noticed that the others in the group were staring at her with a quite peculiar intensity. Kazetzky was swinging in his fingers some kind of little bright ornament that he wore on a chain around his neck.

Rosa Lanzerotti said slowly, "I think it would be very nice. You'll have to call for me, though. I have no idea of what hours you keep in Tolstoia."

Kazetzky's lugubrious countenance took on an expression that was almost a smile. "It shall be as you desire, little mother. The will of one is the will of all."

The group seemed to split apart, and Vikhranov's voice said in Heidekopfer's ear, "Will you try some of our Tolstoian beer, Robert Murrayovich?"

"I thought you had a law against alcohol," said Heidekopfer, accepting the proffered mug.

"But beer is not alcohol. No one could become drunken from it. Besides, we have a law against becoming drunken, too."

The hell you say, thought Heidekopfer privately, and quaffed. It was about as he suspected; the beer was certainly not 3.2. He said, "What's the official schedule for us tomorrow?"

"In the morning we visit a school and see how children are educated in happy Tolstoia. If there is time we will also visit the grave of the Patriarch Ilarion Triunfovich. In the afternoon, you will see one of our collective farms. On the following day a picnic has been arranged. It will last all day in accordance with our custom."

Heidekopfer frowned. "The school may be some help, and I don't doubt that the farm will be. But in the nature of the report we have to make, a visit to one of your law courts would be a lot more interesting than a picnic, and a sitting of your Supreme Soviet more interesting still."

Vikhranov's flat face showed disapproval. "The sittings of the Supreme Soviet are in secret by law," he said. "We would have to pass a special law admitting you, and I am not sure but it would be concisionary."

"Excuse me. You seem to have developed a term there I have not heard before. What does 'concisionary' mean?"

The guide's disapproval surprisingly became sullenness. "Am I to blame if you cannot understand good Russian?"

"We went to some trouble to learn it, even getting records of Russian as it was spoken at the time Tolstoia was founded, and I'm sorry if I've given offense. But my friend, I'd have you remember that we're here to do you a favor, not the other way round. Have you got a dictionary?"

"We have no need of dictionaries in happy Tolstoia. They are a part of culture and culture is fatal to happiness. It is set down in the Master's own words."

It was saved from developing into a hassle as someone touched Heidekopfer's arm to present him to Anna Golyevna Samsonova, a small woman with dark hair, high cheek-bones and a mouth that seemed set in a perpetual mysterious smile. She said, "Have you been in holy Rrrrrussia, on earth, Robert Murrayovich?"

"No, I haven't had that pleasure," he said, and added gallantly, "But I'm sure this is better. You have made life so much simpler."

"Yes, that is true. Here in happy Tolstoia the will of all is the will of one, and the will of all is toward the good of all. All are happy."

Her eyes darted past him, and he half-turned in time to see that Samsonov was certainly displaying indisputable signs of happiness as he talked to Ann, and what was a good deal worse, the girl was showing no signs of unhappiness. Rather hastily, he said, "Don't you ever have disagreements?"

"Oh, yes. But they do not last long. And if one is not attuned, then he takes the cure."

"I see," said Heidekopfer, although he was reasonably sure he did not, and was saved from more of this disjointed conversation by the ringing of a bell, which Mrs. Samsonov said announced dinner. She led the way through the side door to another large room, where there was a table laid for dinner with steaming dishes already in place. Heidekopfer noticed that the plates were of wood, and of the flatware beside them only the knife-blades were metal. Everyone seemed to seat him or herself where they pleased and fell to work at once on the food without ceremony.

Mrs. Samsonov said, "You may find our food difficult. People who come here often do at first. But we have a law against eating meat except while taking the cure."

Difficult was the word for it, reflected Heidekopfer, munching away at something that appeared to be a combination of cabbage and boiled nuts with a sour sauce. He said, "You seem to have laws about almost everything. Clothes, too?"

She surveyed him with an air of puzzlement, and he noticed that in the candlelight her eyes had a singularly deep quality. "Of course. How would we know how to act without laws?"

"Tell me, what does 'concisionary' mean?"

"It means—" she gave him that glance again "—I don't quite know how to define it, but something against the will of all. As you stay in happy Tolstoia, you will understand." For a moment, looking into her eyes, it seemed to Heidekopfer that he almost did understand. Then she said, "Alexei Ivanovich is concisionary."

"Who?"

"Alexei Ivanovich Dubrassov. The traditionalist. He wished to become patriarch when Pitrim Androvich did, but he would have led Tolstoia back to the days before the brotherhood of man was achieved." She looked around the table and clapped her hands as a signal that the meal was over, and a couple of girls came hurrying in to gather the plates.

Heidekopfer said, "Pardon me, but didn't someone tell me that you had a law against serving one another?"

"It is the will of all that the patriarch be served," she said. Nobody seemed to be leaving the table and the reason became apparent when two men with goose-necked stringed instruments came in, accompanied by a girl who began to sing as they played. The music had certain haunting strains, but was so disjointed that Heidekopfer decided he didn't like it, and looked down the table to see how the others were taking it. He got a shock. Samsonov, seated between Rosa Lanzerotti and Ann, had his arm around the latter's shoulders, and she was leaning back with her eyes half-closed and the smile of a smug kitten.

IV

Ann's voice sounded vaguely apologetic as she explained to Heidekopfer. "His wife didn't seem to mind," she said. "I was watching her."

"That isn't the point," said Heidekopfer. "It isn't even the point that I minded a hell of a lot. As you have so often informed me, I don't own you or even have a claim on you, much as I'd like to. I just want to know why you did it."

The girl's lips closed and her pretty face set in obstinate lines. "Because I wanted to. Because I felt like it. For the same reason I've kissed you a few times."

"But you've never kissed me with about sixteen people looking on. And may I point out that the reason the castaways stayed in Tolstoia was because they wanted to, too. I want to know what made you want to do it."

"And you're going to put the whip on me to find out," said the girl, but with a smile. "No use, Bob—call it an uncontrollable impulse."

Someone tapped at the door and it was Lanzerotti. "Want to come into my room?" he said. "I'd like to compare notes, and if we do it here, two of us will have to sit on the bed."

"All right," said Heidekopfer. "Rosa back yet?"

"No, still communing with nature and Pyotr Ilyich Kazetzky." He glanced at his watch, saying, "I forgot that's no good here on the different system of time, but I'd guess that it's a good hour before bedtime, so I'm not going to worry. Come on." He led the way down the hall, and threw open the door.

"Notice there isn't a lock in the place?" said Heidekopfer. "It may really be true that they've abolished crime."

"I didn't see any either," said Lanzerotti, "but we have to be careful about drawing conclusions from guided tours. The Russians have always been great on setting up Potemkin villages."

"Oh, back in the old imperial days an Empress named Catherine went on a progress through the country to see how it was getting along under her prime minister, Potemkin. He went ahead of her and had villages set up, just the dummy fronts of houses, with actors to play the part of villagers. Back in the Soviet period they used to pull the same trick, to show tourists how prosperous the country was, only they did it with real model villages and factories and people working in them."

"I don't think they're doing that with us," said Heidekopfer. "On the way to the school, I asked to turn off and see one of the farms we passed, and it all seemed perfectly normal and in key with the rest."

"Shall I get the pictures?" said Ann. "That white wall is rather rough, but I imagine it will take projection."

"No, they're for the record," said Lanzerotti. "I just want a verbal report and impressions." He stepped across the room and opened the sound box for recording.

"Well," said Heidekopfer, "we went to a school this morning. It was quite small, but had children of all ages up to about sixteen. It was more like a manual training institute than what we'd call a school. Most of them were learning to use tools, and some of them working in a garden, and doing a pretty good job of it, I'd say. There was only one class with books."

"I asked about that," said Ann. "They practically don't have any books, and those they do have are hand set and hand printed."

"Of course, I can understand their not using microfilm," said Heidekopfer. "That would run into their prohibition of machines. But I don't quite see how they can claim a printing press isn't a machine."

Lanzerotti smiled. "Logic isn't the long suit of most theorists," he said. "However, my opinion is generally favorable. They seem to be decent people with a high standard of morality, and in spite of the Potemkin village angle, it looks good. There's just one thing—we still haven't found any explanation of why the castaways didn't come back. And that is primarily why we came here."

Heidekopfer said, "We can add a second point to that now—or perhaps it's part of the same one. Did you notice Ann after dinner last night while the music was playing?"

Lanzerotti said, "I did notice that she seemed on fairly good terms with our host on somewhat short notice, but I assumed it was her own business."

"The trouble is that she can't tell why she did it," said Heidekopfer.

A little spot of red appeared in the girl's cheeks. "I told you because I felt like it," she said, "and I'm not particularly grateful for being pumped about it! Excuse me, I've got to charge my camera while you discuss my case." She got up, avoided Heidekopfer's protesting hand, and slipped out the door.

Lanzerotti said, "The case seems to call for diplomacy, and as the diplomat of the expedition, I prescribe a cooling-off period. Meanwhile, continue."

"There isn't much to continue with," said Heidekopfer, rubbing his chin thoughtfully. "You know as well as I do that her behavior with Samsonov wasn't—well, what you'd normally expect, even if it wasn't disgraceful or anything. But it seems to me that it's of a piece with the behavior of the castaways who decided to stay in Tolstoia. In both cases, there was what she herself described as an uncontrollable impulse to do something not normally done."

"Evidence of pattern," said Lanzerotti. "You think pressure was applied from outside. But how? Was the food or the beer drugged? No, it couldn't have been that; we ate and drank the same things, and weren't affected."

"I don't know," said Heidekopfer. "It could have been a special for her. Samsonov hardly took his eyes off her from the first time he saw her."

"I—" began Lanzerotti, when a tap sounded on the door and Rosa Lanzerotti came into the room. "Hello, dear," she said, "have a good day?"

"Good with a little mystery in it, which we were just discussing. And you?"

She laughed. "The same. In fact, if you're up to a trip, the day isn't over yet."

"What do you mean?"

"There's a man outside with a droshky to take us to see someone who wants to meet you. I'll tell you the rest as we go. It might be a good idea if you come along, too, Bob. Wait till I get a recorder." She went over to get one of the small size that fits in a pocket, and the other two stood up. Heidekopfer stopped to tap at Ann's door, but she didn't answer, so he stopped at his own room long enough to slip a light in his pocket, as it had grown quite dark outside. There was no one in the dimly-lighted halls; apparently most good Tolstoians had decided to call it a night. Outside, the heavy night mist which pinch-hits for most of Venus' rain was drifting past in streamers, condensing on everything it touched; Heidekopfer felt drops run down his face.

Rosa said, "He's waiting at the corner of the road, and I was warned not to let myself be seen, so you had better not put on the light now.

"Damn!" said Lanzerotti, stumbling. "All right, Rosa, what's the story?"

"We drove around most of the day looking at various views, while this Kazetzky person explained to me how beautiful it all was. It was, too. Stopped at a house where they were weaving cloth on a wooden hand loom and had some lunch, then drove around again. Kazetzky is not an interesting talker, as I began to realize about the fifteenth time he repeated his line about nature and happiness being connected. But toward dinner time he said, 'Ah! I shall take you to have a repast with a man who has in him much of the spirit of the Master.'"

They had reached the end of the drive, and in the dark could just make out the loom of the droshky. A voice said, "Little mother?" Rosa answered, "Okay, it's me," and Heidekopfer flashed his light briefly to enable them to climb into the vehicle. When they were seated and the driver had stirred his horse into action with the inevitable crack of the whip, Rosa went on, "He took me a little distance, little enough so it looked as though he'd been intending to do that all along, to a house almost as big as the one we're living in. Only the owner wasn't living in it, he was living in a tent pitched in a field outside by a stream. His name is Dubrassov, by the way. Kazetzky introduced me, and then went to the house and brought the family out and introduced them, too, ten or twelve of them. Dubrassov said I must bring you here at once, tonight, before it was too late, to hear something terribly important. They all said yes, I must, and then asked me whether I wanted to eat with the family or Dubrassov. Of course I said Dubrassov, and that was my big mistake. The meal consisted of a whitish liquid that tasted like turpentine and burned like it—"

"Kumiss," said Heidekopfer. "It has a kick, too."

"Apparently they have exceptions to their law about liquor. Anyway, I drank water. As I say, the meal consisted entirely of this kumiss and meat, nothing else, and we had to eat it with our fingers. He apologized for it, I will say, and said he was taking a cure of some kind. A diet like that would cure me of wanting to live."

For a moment there was silence as the droshky jounced along. Then Lanzerotti's voice said out of the dark, "Evidently there are disagreements, even in happy Tolstoia, and I'm grateful for the opportunity to learn what they are. But this whole business has a rather conspiratorial odor, and I'm not sure that a diplomatic representative should be mixed up in it. If you don't mind my saying so, Rosa, you might have given us a chance to discuss all the angles before getting us out of the house."

"But I couldn't do anything else, could I?" Her voice sounded hurt.

The horse's feet clopped in the muddy road. Heidekopfer made a sound like the beginning of speech, then stopped.

"Beg pardon?" said Rosa.

"I just wondered—why didn't you come with us to see the school today? I should have thought you'd find it interesting."

"Oh, there's plenty of time. Besides, if I hadn't gone out to see the country with Kazetzky, I wouldn't have met Dubrassov."

Lanzerotti stirred in his place and said, "By the way, Bob, while you and Ann were looking over that farm this afternoon, I addressed myself to the matter of communications. They don't have to have any, except by word of mouth; the society is so static that there isn't anything requiring quick action by a large number of people, and they can afford to wait."

"Find out anything more about the governmental system?"

"They're disinclined to talk, but I gather it's an almost unchanged adaptation of the Soviet system. Which might be expected, seeing their ancestors came from there, and there's nothing in Tolstoi that would conflict with the system. As a matter of historical process, I'm a bit surprised that there should have been so little evolution—"

"Hell!" said Heidekopfer. "Vincent, when you get to talking theory, you're three parsecs over my head. I just want to know what makes things tick in a practical way."

"The difference is doubtless one of the reasons why we were associated in this mission," said Lanzerotti evenly, and that seemed to put a period to the conversation in the dark until Rosa said, "This must be it. See that light in the tent?"

Heidekopfer flipped on his light and set it in the catch-ring of his hat. The beam diffused through the drifting mist to catch a wooden house painted white and with shutters, on quaint, old-fashioned lines. It was all dark. The droshky pushed on past, bumping off the road across a field toward where a light showed dimly through the wall of a circular tent, and came to a halt. Lanzerotti jumped out and handed Rosa down after him. She approached and said, "May I come in?"

A deep voice boomed, "In the name of the Master, enter, little mother," and the three went in. They saw a powerful looking man, not as big as Samsonov, but with the same indefinable air of force, who barked, "Dubrassov, Alexei Ivanovich," and promptly sat down in the only chair in the tent.

This time the ambassadors knew the right reply. They made it, Rosa sat down on the bed, the others curled up on the ground floor of the tent and waited. Dubrassov glanced from Lanzerotti to Heidekopfer and back with quick motions of his head and neck thrust forward, as though he were trying to see into their minds. Finally he said, "They make me take the cure as concisionary, but it is not I who am the concisionary, it is Pitrim Androvich."

"Indeed," said Lanzerotti.

"It is Pitrim Androvich," Dubrassov repeated. "The will of all is the will of one, but he makes the will of one the will of all."

"I thought the two went together," said Heidekopfer.

The burning eyes were fixed on him. "Are you the ambassador? It is anti-social to interrupt deliberations."

Heidekopfer felt himself flush a little, but said nothing. He could hear the buzz of Rosa's recorder.

"I am the ambassador," said Lanzerotti smoothly. "But I am accredited to the government of Tolstoia, and so far as I am aware, you are a private citizen. However, I will be glad to hear anything you have to say that may affect the question of whether the World Council should allow Tolstoia to colonize the Wrightley Islands."

"Pitrim Androvich wishes the world, even holy Russia." He paused and blew his nose at the name, his Adam's apple moving. Heidekopfer remembered Behrmann. "You should n-n-n—" He stopped suddenly, gagging for breath, his eyes bulging, and then closed his mouth and tried again. "The achievement of universal brotherhood makes the will of all the will of one. It is possible to control the will of one for—" He gagged again, his mouth open, then closed his eyes with a grimace and said, "It is against the law to say more. Beware! And go, in the name of the Master."

V

The fact that Venusian trees of every species tend to trail their branches on the ground makes no particular difference; with approximately one day's direct sunshine during a Venusian year, shade is less important than what the tree produces and the decoration it provides. Neither, reflected Heidekopfer, would it particularly matter to people who were used to it that everything was mildly damp to the touch. The members of the Supreme Soviet scattered on the bank of the little natural amphitheatre around him seemed to be having a thoroughly good time, laughing, talking, drinking beer and listening to the music of the goose-necked instruments, which tinkled from group to group. He felt lonely, and Ann was somewhere else.

There was a touch on his shoulder and Lanzerotti sat down beside him, saying in a low voice, "All right, but talk fast. And smile now and then, so it will look casual. I understand how you couldn't discuss it last night with Rosa in the droshky."

"She got angry," said Heidekopfer. "Just like Ann."

"And you think you have the explanation?"

"You said something about pattern. It makes one. Mass hypnotism."

Lanzerotti gestured with one hand, as though he were pointing to the group around them. "I find that difficult to credit. The thing hasn't existed since the days of the dictators and their wars."

"Remember that these people are the overflow of a totalitarian state. And I don't mean mass hypnotism with one person hypnotizing many, as among the old dictators, but with the group exerting mass pressure on one person. The will of all is the will of one."

Lanzerotti smiled. "I think you misinterpret. There is undoubtedly some pressure from what might be called public opinion, but—"

"Listen!" cried Heidekopfer, desperately. "It all fits together. Kazetzky twirled something bright in his fingers when he asked Rosa to spend the day with him, and all of them rallied round. They've achieved some kind of mental integration and they want to expand—"

Lanzerotti laid a hand on his knee. "You're talking too loud. And I think on the wrong lines. The nature of this development is essentially elymosynnary—"

Heidekopfer experienced a sensation of being surrounded by stone walls as two of the Tolstoians stood over them. One was a member of the Supreme Soviet whose name he had, of course, forgotten, and the other was a remarkably pretty girl with ash-blond hair pulled back from a well-shaped forehead. He got up, as the man from the Supreme Soviet said, "Sonia Grigorevna is the cousin of the patriarch Pitrim Androvich."

"Heidekopfer, Robert Murrayovich," said Heidekopfer, dutifully.

Lanzerotti repeated his part of the formula, but the girl seemed to be concentrating on the reporter. "Is it not a joy to be in this beautiful countryside?" she said, looking at him directly.

"I find it so."

"Would it be your will to let me show you some of the flowers of happy Tolstoia?" she said.

If he were right, this was his chance to get one of them apart from the rest, where the group pressure would presumably be less effective. He said, "It would please me very much."

She reached out a hand to take his. "Come," and led the way across the bowl of green. A group of men and women stood in their path. "We are going to look at flowers together," the girl announced gaily. "Pitrim Androvich thinks it would be good."

They all seemed to find something delightfully humorous in this, and there was a burst of laughter as they crowded round. "Flowers are nature's key to happiness!" boomed one of the men, patting Heidekopfer on the shoulder. "You will see what fine ones we produce in happy Tolstoia."

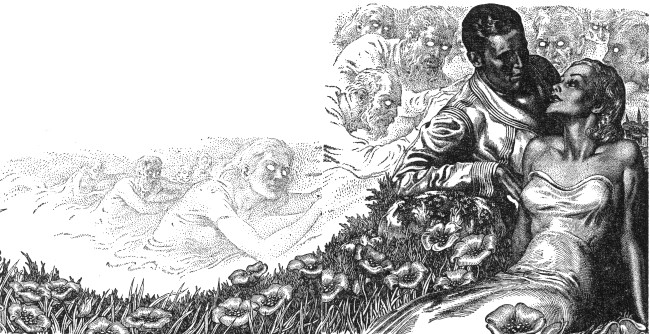

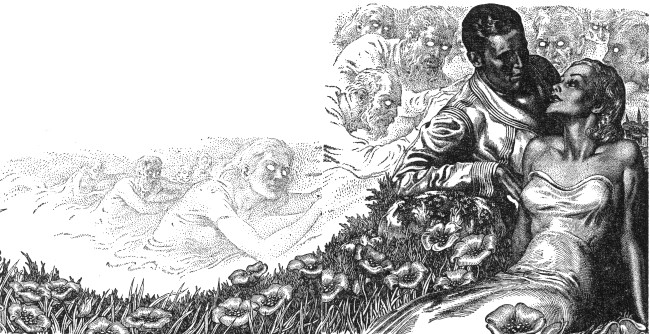

He was suddenly aware that they were staring at him with a peculiar intensity in the midst of their animated movements, and of a slight tension, like the beginning of a headache, at the back of his neck. This must be it; he was being high-pressured for some purpose. It was understandable how they would call this the brotherhood of man ... how they had developed the ability to put mass hypnotic pressure on any individual ... how the castaways had been similarly pressured into adopting the Tolstoian way of life ... how—

Sonia Grigorevna's voice came through his reverie, "Are you dreaming, little father? Let us go."

He shook himself a little, like a dog coming out of water. "By all means, let us go." She was really beautiful, not with the broad Slavic features at all, but a narrow face and high cheek-bones that must have come from some remote Nordic ancestor.

The others waved hands as she led him up the gentle slope at the edge of the bowl, and pushed through a screen of trees into a field of lush grass. There was a string of bushes toward the river-bank. "The best flowers are there," said Sonia.

"Tell me," he said, "when someone really does not want to do something the rest want, how do you make them do it?"

She gave him a glance of puzzlement. "I do not understand. We do not make them do it. It is the word of the Master that everything savoring of compulsion is harmful."

Pretty neat, he thought ... just like the Russian Soviets of the old days, who got away with dictatorship by calling it democracy. Aloud he said, "I know. But don't you ever have—deviationists?"

"Oh no. The will of all is the will of one. That is the brotherhood of man. But if a person doubts whether his will is fully given, he takes the cure. That is the law. This way."

She pushed through the bushes and they were on a slope above the river, starred with red poppy-like flowers. "Are they not beautiful? Let us sit here and contemplate them. The contemplation of nature is the source of happiness."

Heidekopfer lowered himself to the damp grass, blessing the forethought that had led him to dress in waterproof nylon. "They're very nice," he said, "but when did you Tolstoians discover the brotherhood of man?"

She settled herself comfortably against him. "I am not certain of the date. But it was in the time of the Patriarch Ilarion Triunfovich, long ago. Is it your will that we cease talking of material things and address ourselves to what we see?" She snuggled against him, and the pressure was not at all unendurable.

He placed a hand on one of hers. "Just one more question. When people come from the—outside, do you always will them to stay?"

"We do not need to. Everyone wishes to stay in happy Tolstoia. See how that blossom shakes on its stalk."

Except those who come back in boxes, he thought, and wondered how he could broach the subject, but before he could think out a way, she lifted his hand beneath her own and pressed it softly against her cheek. He turned to look at her; her lips were slightly parted as she lifted her lovely face toward his....

He turned to look at her; her lips were slightly parted as she lifted her lovely face toward his.

And it struck him like a thunderbolt why the others had laughed when Sonia said they were going to see flowers at Samsonov's suggestion, and what the pressure had been on him for. He said abruptly, "Do you know where Ann went—the photographer who was with us?"

"To look at flowers with Pitrim Androvich." Her glance was neither disappointed nor hostile, merely a trifle wide-eyed as though she had just discovered something frightening. She let his hand drop.

VI

So that was the play, thought Heidekopfer, a trifle grimly. The Patriarch was going to make off with Ann while providing him with a substitute and putting the heat on him to accept. He scrambled up and reached a hand to Sonia Grigorevna. "Let's get back to the others, if it is your will."

Later, back with the others Heidekopfer confided his ideas. "If you will forgive me," said Lanzerotti, "I find your theory slightly fantastic."

"So do I," said Rosa. "I haven't been conscious of any sense of pressure or the headachy feeling you mention, and I haven't done a thing I didn't really want to do."

They were sitting in the ambassador's room at the Samsonov house, and it was not yet dark enough to make the candles necessary, although they were lighted. Ann wasn't there. Heidekopfer drew a long breath. "The only thing I can suggest is that you have been influenced too, to some extent. Come on, look at it objectively. Won't you admit the possibility?"

"As a matter of principle, yes," said Lanzerotti. "This is an island culture in the sense that it has been cut off from contact with others, and I'm well aware that island races often develop on aberrant lines. But I see no signs of the compulsions you mention."

"Not even Dubrassov? When he tried to warn us about something and couldn't?"

Lanzerotti smiled. "I'm afraid Dubrassov's case is a rather simple one of hallucination. It was explained to me this afternoon. They don't lock up their mental cases here; they simply let them take that cure, which amounts to a kind of shock-treatment in view of their usual habits."

"Damn it!" said Heidekopfer, but Lanzerotti held up a hand. "Listen, Bob," he said, "I quite understand your annoyance and the reason for it. And I will say that I'm a little surprised at Ann's behavior with our friend the Patriarch. But that's a purely personal matter, and shouldn't be allowed to cloud the diplomatic issue, which is above personalities. And on that level I haven't encountered anything to justify your apprehensions."

"The evidence of pattern? You mentioned it once before. The suicides?"

"The suicides were just suicides. I hinted at the matter and one of them—I think it was Vikhranov—came right out with the explanation without even being asked. It seems that the suicide cases among the castaways were people who had some strong tie or reason for going back, but still couldn't bear to leave Tolstoia once they got here. A simple case of a conflict they were unable to resolve."

Heidekopfer got up and began to pace the floor, his brow set in a frown. "Well, anyway," he said at last, "I might as well tell you that I'm doing something practical about what you call my apprehensions. After what developed at the picnic I radioed South Bergenland for a helio. It will be here tonight, and I'm going back on it and taking Ann with me. I advise you to come, too."

Rosa Lanzerotti trilled a little laugh. "I don't think you'll find Ann particularly grateful—or particularly willing," she said.

"Then by God I'll get help to make her willing!" cried Heidekopfer.

"Wait—" began Lanzerotti, but he was already out the door and almost running down the corridor toward the apartment occupied by the Samsonovs. Not knowing what the custom was, he knocked. A female voice said, "Enter, in the name of the Master."

Mrs. Samsonov, looking as mysterious as ever, was sitting beside a table with one of the girls who served at table, sewing on something. "Good evening, Robert Murrayovich," she said. "Pitrim Androvich is out this evening."

"As a matter of fact, it was you that I wanted to see," he said, "and alone, if possible."

She glanced at the girl. "Is it your will to leave at the desire of the little father?"

"The will of one is the will of all," said the girl, picked up her sewing and went through a door at the back as Mrs. Samsonov faced Heidekopfer. "What is it you desire to say, Robert Murrayovich?"

He hesitated. "Well, it's rather difficult, and I hope you won't be offended—but—"

"In happy Tolstoia we do not take offense at what Nature gives us to do."

"That's very nice of you. Well, it's about Miss Starnes—Ann Samuelovna."

"She is very beautiful."

"That's just the trouble, I'm afraid. Did you know that she went to look at flowers with your husband this afternoon?"

Anna Gulyevna's smile became a trifle more Mona Lisa than before, if possible. "Yes, I knew it."

"And it doesn't worry you? Not even a little bit?"

"Not even a little bit, Robert Murrayovich."

"And he told her she should have children."

"It is good to have children." She smiled again at his hopeless expression and laid down her sewing. "Listen, Robert Murrayovich, and I will tell you how it is in happy Tolstoia. We have a law that a husband and wife must remain faithful to each other. So that if Pitrim Androvich looks at flowers with Ann Samuelovna, or even touches and kisses her, it is because he thinks she is beautiful, like a part of nature. Even though he is Patriarch he cannot break the law."

"But damn it!" said Heidekopfer. "I want to marry her myself!"

"Is it her will also? The will of one must become the will of all."

Heidekopfer experienced a violent sense of frustration. "Look here," he said, "I know you have means of influencing the way people think about things. Can't you give me a little help with Ann?"

She lifted one hand and placed it beside her cheek. "She has achieved the brotherhood of man, and I think she will want to become a citizen of happy Tolstoia," she said. "If she does, the only way would be for the Supreme Soviet to pass a law that she must marry you. Thus the will of all becomes the will of one."

"But I don't want to stay in Tolstoia," said Heidekopfer, "I—"

Outside the door someone shouted, "In the name of the Master, may I enter?"

"Enter," called Anna Gulyevna, and the door opened on Kazetzky. His expression looked even more morose than usual. He said to Heidekopfer, "I am glad you are here, little father. Good evening Anna Gulyevna—I am the bearer of unhappy news."

"Unhappiness cannot remain long in happy Tolstoia," said Anna Gulyevna gravely. "What is your news, Pyotr Ilyich?"

"Pitrim Androvich is very desirous of the foreign woman. He has called a session of the Supreme Soviet for tonight, and will propose a law that a man may have two wives, so that he can marry her."

Heidekopfer saw Anna Gulyevna's hands tense in her lap and the secret smile dropped from her face. "That is most unhappy news, Pyotr Ilyich," she said.

"See here," said Heidekopfer, "can't something be done about this?" He looked at Kazetzky. "You're a member of the Supreme Soviet, aren't you? Can't you oppose the bill on the ground that it's—concisionary, or something?"

But they shook their heads, looking at him gloomily. "Well, by God, I'm going to do something about it if nobody else does," he said, getting to his feet. "Where's this meeting being held?"

Kazetzky did not move. "It is even worse than you think, little father. Pitrim Androvich will propose a law of suicide against you."

Anna Gulyevna gasped and put one hand to her mouth. Heidekopfer looked bewildered. "What have I done and what's a law of suicide?" he asked.

"You are a resistant," said Kazetzky. "It was the will of all that you fall in love with the girl Sonia Grigorevna whom you took to look at flowers this afternoon, but it did not become your will. Therefore, it is evident that you are resistant to the will of all. We always pass laws of suicide against resistants, especially if they are foreigners. It is the only way of maintaining the brotherhood of man."

"I see," said Heidekopfer, and he did, with a sudden horrible clarity. So this was what had happened to the castaways! And how many others had been wiped out in these self-inflicted purges since they established their "brotherhood of man?" The hackles on his neck were rising, but he managed a laugh. "Well, if I'm a resistant, I guess I'm not going to worry about it too much."

Anna Gulyevna's face looked a trifle pale, even in the candlelight. "You do not know the strength of a law of suicide," she said. "It makes use of the death-wish, and those against whom it is passed cannot sleep until they sleep forever."

"Do you mean I have to take it lying down? I'm damned if I do!" He took four quick steps across the room, tore open the door and started down the hall. Kazetzky's voice behind him said, "A moment, little father."

Heidekopfer faced him. "Well?"

"What are you going to do, little father?"

"See Lanzerotti—Vincent Guidovich. He's the ambassador of the Council, and he isn't going to let anything like this go on."

"It will do you no good. This has happened before. He has accepted the will of all, and will not believe you until the law has been passed. When the two new laws are passed and the foreign woman has married Pitrim Androvich, then you will commit suicide, and he will say, 'Ah, that is the reason he did it.'"

"You're so full of bright ideas you just slay me," said Heidekopfer with a wry twist to his mouth. "But I don't think you'd be batting them up unless you had something in mind. Come on, out with it."

Kazetzky said, "If you could leave Tolstoia and return where you came from before the law was passed, I do not think you would be in danger. There would be too many people around you with confused thoughts who do not belong to the brotherhood of man."

"And leave Ann behind to marry that old goat? No, I think not."

Kazetzky said, "Then there is only one thing to do. That is to go to the session of the Supreme Soviet and try to prevent the laws being passed. You are a resistant, and it is possible you could make their thinking confused enough."

Heidekopfer glanced at him sharply. "You want me to, don't you? What's your interest in this?"

"I am a supporter of Alexei Ivanovich Dubrassov. He is a traditionalist who does not believe happy Tolstoia should be extended as Pitrim Androvich wishes. If the law of suicide is not passed and you report against giving us the islands, there will be a law of suicide against Pitrim Androvich, and Alexei Ivanovich will be Patriarch."

Heidekopfer laughed shortly. "I thought there'd be some chestnut-pulling connected with this somewhere. How come that the will of all the others to follow the Patriarch's plan didn't affect you and Dubrassov, too?"

The man's face went sullen. "You have no right to ask me questions like that," he said.

Heidekopfer reflected that the development of their mental integration had not made the Tolstoians any the less Russian. "All right, let's go," he said. "Is it far?"

"At the schoolhouse. I have a droshky which I took to bring Anna Gulyevna the news. It is not good to let bad news delay until the will of one becomes a resistance."

"Okay. Wait just a minute, will you, while I get my pocket radio. I've got some friends coming who may be some help, and I might want to get in touch with them."

VII

The lights behind the windows of the schoolhouse made vague islands in the dark pennons of mist. Kazetzky got out and tied the horse to the hitching-rail as Heidekopfer dismounted. "Go in, little father," he said. "I will stay outside as long as I can." He was breathing hard, as though trying with all his strength to resist some kind of compulsion.

Heidekopfer checked the sets of his radio, walked to the door and flung it open. The fifteen or twenty men and women of the Supreme Soviet were seated in chairs scattered in no particular order around the classroom, with Samsonov at the teacher's desk, his back to Heidekopfer as the latter entered. But the thing that made the reporter catch his breath as the faces turned toward him like flowers toward the sun was the sight of Ann Starnes, sitting just to the right of the Patriarch. Her glance was coldly unfriendly.

For a second or two the tableau held. Then Samsonov turned round and rose majestically to his feet. "The session of the Supreme Soviet is secret," he said, and glared.

Heidekopfer once more felt the headache sensation at the back of his neck, accompanied by an almost overwhelming impulse to get out of there, to escape from that place before something dreadful happened, a strange malaise, which he could not name possessed him. He staggered back a step, then caught Ann's eye fixed on him with the same quality as the rest, and was abruptly seized by another impulse, even more overwhelming.

The second one struck him as a better idea, anyway, so he yielded to it. He took three rapid steps toward the Patriarch Samsonov and let him have one fetched up from the region of the belt-line.

It took the big man flush on the button, and down he went, thrashing and kicking, as the room burst into a turmoil of shouts and chairs knocked to the floor. Ann screamed. Heidekopfer grabbed her by the arm. "You're coming with me whether you like it or not," he said in English, and turned to face the group menacingly. But nobody seemed inclined to offer him any opposition, and the thought flashed through his head that they probably had a law against physical violence, too.

Samsonov had hauled himself to his feet with the aid of the desk. There was a little trickle of blood from his mouth and his eyes were deadly. The last thing Heidekopfer heard him say as he pulled the girl through the door was, "There will be a law—"

Kazetzky had disappeared. Ann was limp as he bundled her into the droshky, and didn't say anything until he had unhitched the horse, climbed to the driver's seat, and with a combination of yells and jerking on the reins, urged it into plodding motion. Then she said, "Oh, Bob!"

He didn't turn around. "Yeah. What is it?"

"I was hating you. I knew they were going to pass a law that you should commit suicide, and I was going to help them."

"Nice of you."

"When you hit him, something happened. It was like coming out of a dark room into the sunlight.... Bob!"

"What is it?"

"I think I need a keeper. I'll marry you when we get back—if we ever do." She began to cry.

This time he swung round on the seat. "Listen, angel," he said, "I want you just enough to take you up on that, whether it's on a rebound or not. But are you sure you're out from under the control that big lug seemed to have snapped on you?"

"I—I—think so. But I don't know how long it will last. Get me out of here, quick!"

Overhead, a beam of light stabbed down through the crowding mist, just picking out the corner of Samsonov's house a few hundred yards beyond them, and there was a sound of ghostly wings. The beam shifted, ran along a line of trees, and then satisfied itself with an open field.

"The helio," said Heidekopfer. "I radioed for one on the chance I could get you away." He tried to urge the horse to greater speed as lights came on in the building and the aircraft swung in for a landing in a pool of its own illumination. Abruptly, the headache sensation took him in the back of the neck again, stronger than ever, accompanied by an intolerable sense of depression, and the night was suddenly full of horrors ahead. It was not worth the trouble. He felt the reins loosening in his hands. "Ann!" he cried, "Ann ..." and blacked out.

He came to to the sound of purring motors and struggled to sit up. Someone said, "Give him this," and a cup of coffee was held against his lips. He looked up into Ann's face.

"Still feel the same way you did in the droshky?" was the first thing he said as he drank.

"Sssh. Yes," she said, and he looked round to see the Lanzerottis smiling at him across the cabin of the helio. He struggled upright on the transom. "That was a narrow one," he said. "I think they must have passed the law of suicide against me. But I can't figure out how it would affect me so. They said I was a resistant."

Lanzerotti said, "Thought can operate without physical presence. The Christian Scientists and Theosophists on earth knew that years ago. And this was a rather massive impact."

Heidekopfer shook his head. "Give me a little more of that stuff, will you? I'm still a little groggy. What I can't figure out is how you two got away and came along."

"We were talking about that," said Lanzerotti. "Rosa and I were just getting ready for bed, when it suddenly struck us that everything you had said was true, and the Tolstoians had us under control and were showing us, in effect, a Potemkin village. When you knocked Samsonov out, even for only a moment, the control snapped on us as it did on Ann. Then he got so interested in passing the law of suicide against you that he didn't have time to rebuild his fences. So we got away, but we had to leave most of the records."

Heidekopfer drank again. "I don't suppose it makes much difference, though," he said. "Our verbal report ought to be enough to keep the Council from giving them the Wrightley Islands. My God, if that thing got loose! With what they've developed they'd be able to take over every inch of the three worlds, little by little, and turn them into more Tolstoias."

"No," said Lanzerotti emphatically.

"No what?"

"My recommendation will be that we grant them the Wrightley Islands and any other bits of uninhabited territory they happen to want—but only for so long as Samsonov remains Patriarch."

Heidekopfer's mouth fell open. "What!" he exclaimed aghast, "Has he still got you under?"

Lanzerotti's smile was bland. "Not at all. They've attained the goal of the totalitarian state. They've got everybody thinking alike. Remember, Dubrassov couldn't warn us, even when he wanted to, although he couldn't bring himself to go along with Samsonov's expansionist policy. Samsonov showed us Potemkin villages, all right. But don't you see what all this crazy set-up adds up to? These people can't change. They've lost their adaptability.

"The system has to be rigid, because the first time anyone expresses an individual idea, the whole totalitarian structure will collapse. They're inbred and interlocked, and Samsonov has complete control of their thinking and their behavior—for the time being, at least. But as soon as the Tolstoians expand to the Wrightley Islands, or anywhere else, they'll be facing conditions they've never before encountered. They'll have to learn to think for themselves again—"

"—And as soon as they start to think new thoughts, Samsonov's power will evaporate. He'll lose his grip, just like he did on me!" finished Heidekopfer, reaching for Ann's hand.

"You see," concluded Lanzerotti, "Dubrassov was the really dangerous one. He didn't have new ideas, and whether they were castaways or not, more people would have been drawn in on him."

The little group was quiet, contemplative, then they smiled knowingly at one another.

"Let's get home," said Ann, "and make our—my last picture."