Transcriber’s Note: Readers may wish to be warned that the Colonel’s tales, and the accompanying illustrations, contain outdated racial stereotyping and language.

TOLD BY THE COLONEL.

BY

W. L. ALDEN,

Author of “A Lost Soul,” “Adventures of Jimmy Brown,”

“Trying to Find Europe,” etc., etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

RICHARD JACK AND HAL HURST.

NEW YORK

J. SELWIN TAIT & SONS

Copyright, 1893, by

J. SELWIN TAIT & SONS

| PAGE | |

| An Ornithological Romance, | 1 |

| Jewseppy, | 12 |

| That Little Frenchman, | 26 |

| Thompson’s Tombstone, | 38 |

| A Union Meeting, | 52 |

| A Clerical Romance, | 63 |

| A Mystery, | 80 |

| My Brother Elijah, | 93 |

| The St. Bernard Myth, | 108 |

| A Matrimonial Romance, | 124 |

| Hoskins’ Pets, | 139 |

| The Cat’s Revenge, | 153 |

| Silver-Plated, | 168 |

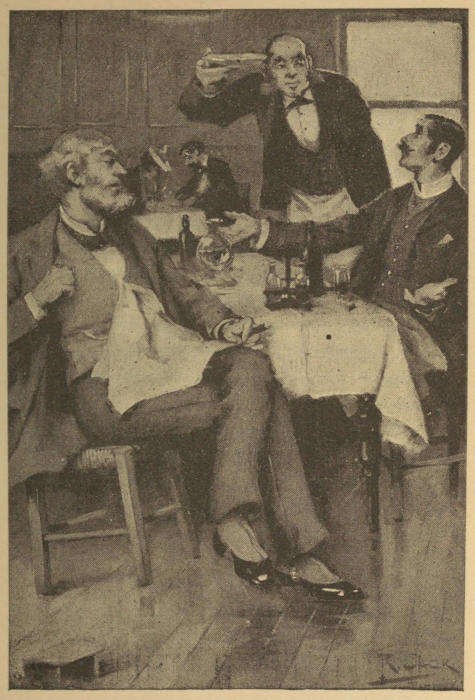

Four Americans were sitting in the smoking-room of a Paris hotel. One of them was a grizzled, middle-aged man, who sat silent and apart from the others and consumed his heavy black cigar with a somewhat gloomy air. The other three were briskly talking. They had been three days in Paris, and had visited the Moulin Rouge, the tomb of Napoleon, and the sewers, and naturally felt that they were thoroughly acquainted with the French capital, the French government, and the French people. They were unanimously of the opinion that Paris was in all things fifty years behind the age, and at least sixty behind Chicago. There was nothing[2] fit to eat, drink, or smoke in Paris. The French railway carriages were wretched and afforded no facilities for burning travellers in case of an accident. The morals of French society—as studied at the Moulin Rouge—were utterly corrupt, owing possibly to that absence of free trade in wives and husbands which a liberal system of divorce permits. The French people did not understand English, which was alone sufficient to prove them unfit for self-government, and their preference for heavy five-franc pieces when they might have adopted soft and greasy dollar bills showed their incurable lack of cleanliness.

Suddenly the silent man touched the bell and summoned a waiter.

“Waiter,” he said, as that functionary entered the room, “bring me an owl.”

“If you please, sir?” suggested the waiter, timidly.

“I said, bring me an owl! If you pretend to talk English you ought to understand that.”

“Yes, sir. Certainly, sir. How would you please to have the nowl?”

“Never you mind. You go and bring me an owl, and don’t be too long about it.”

The waiter was gone some little time, and, then returning, said, “I am very sorry, sir, but we cannot give you a nowl to-night. The barkeeper is out of one of the materials for making nowls. But I can bring you a very nice cocktail.”

“Never mind,” replied the American. “That’ll do. You can go now.”

“I beg your pardon, sir,” said one of the three anatomizers of the French people, speaking with that air of addressing a vast popular assemblage which is so characteristic of dignified American conversationalists. “Would you do me the favor to tell me and these gentlemen why you ordered an owl?”

“I don’t mind telling you,” was the answer, “but I can’t very well do it without telling you a story first.”

“All right, Colonel. Give us the story, by all means.”

The elderly American leaned back in his chair searching for inspiration with his gaze[4] fixed on the chandelier. He rolled his cigar lightly from one corner of his mouth to the other and back again, and presently began:

“A parrot, gentlemen, is the meanest of all creation. People who are acquainted with parrots, and I don’t know that you are, generally admit that there is nothing that can make a parrot ashamed of himself. Now this is a mistake, for I’ve seen a parrot made ashamed of himself, and he was the most conceited parrot that was ever seen outside of Congress. It happened in this way.

“I came home one day and found a parrot in the house. My daughter Mamie had bought him from a sailor who was tramping through the town. Said he had been shipwrecked, and he and the parrot were the only persons saved. He had made up his mind never to part with that bird, but he was so anxious to get to the town where his mother lived that he would sell him for a dollar. So Mamie she buys him, and hangs him up in the parlor and waits for him to talk.

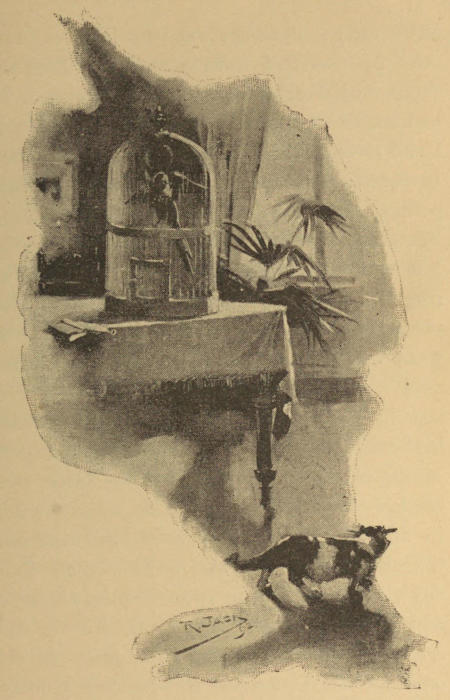

“ASKING THE CAT IF HE HAD EVER SEEN A MOUSE.”

“It turned out that the parrot couldn’t talk anything but Spanish, and very little of that. And he wouldn’t learn a word of English, though my daughter worked over him as if he had been a whole Sunday-school. But one day he all at once began to teach himself English. Invented a sort of Ollendorff way of studying, perhaps because he had heard Mamie studying French that way. He’d begin by saying, ‘Does Polly want a cracker?’ and then he’d go on and ring the changes. For example, just to give you an idea of the system, he’d say, ‘Does Polly want the lead cracker of the plumber or the gold cracker of the candlestick maker?’ and then he’d answer, ‘No, Polly does not want the lead cracker of the plumber nor the gold cracker of the candlestick maker, but the large steel cracker of the blacksmith.’ He used to study in this way three hours every morning and three every afternoon, and never stop for Sundays, being, as I suppose, a Roman Catholic, and not a Sabbath-keeping bird. I never saw a bird so bent on learning a language as this one was, and he fetched it. In three months’ time that parrot could talk English as well as[7] you or I, and a blamed sight better than that waiter who pretends that he talks English. The trouble was the parrot would talk all the time when he was not asleep. My wife is no slouch at talking, but I’ve seen her burst into tears and say, ‘It’s no use, I can’t get in a word edgewise.’ And no more could she. That bird was just talking us deaf, dumb, and blind. The cat, he gave it up at an early stage of the proceedings. The parrot was so personal in his remarks—asking the cat if he had ever seen a mouse in his whole life, and wanting to know who it was that helped him to paint the back fence red the other night, till the cat, after cursing till all was blue, went out of the house and never showed up again. He hadn’t the slightest regard for anybody’s feelings, that bird hadn’t. No parrot ever has.

“He wasn’t content with talking three-fourths of the time, but he had a habit of thinking out loud which was far worse than his conversation. For instance, when young Jones called of an evening on my daughter, the parrot would say, ‘Well, I suppose that young idiot will stay till[8] midnight, and keep the whole house awake as usual.’ Or when the Unitarian minister came to see my wife the parrot would just as likely as not remark, ‘Why don’t he hire a hall if he must preach, instead of coming here and wearing out the furniture?’ Nobody would believe that the parrot made these remarks of his own accord, but insisted that we must have taught them to him. Naturally, folks didn’t like this sort of thing, and after a while hardly anybody came inside our front door.

“And then that bird developed a habit of bragging that was simply disgusting. He would sit up by the hour and brag about his superiority to other birds, and the beauty of his feathers, and his cage, and the gorgeousness of the parlor, and the general meanness of everything except himself and his possessions. He made me so tired that I sometimes wished I were deaf. You see, it was the infernal ignorance of the bird that aggravated me. He didn’t know a thing of the world outside of our parlor; and yet he’d brag and brag till you couldn’t rest.

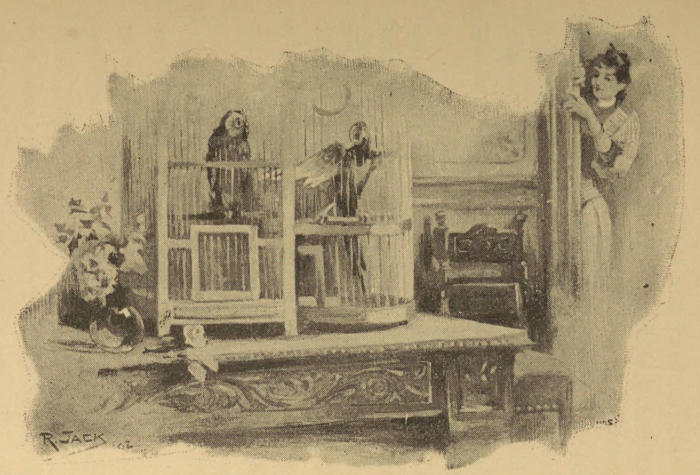

“THE PARROT BEGAN BY TRYING TO DAZZLE THE OWL WITH HIS CONVERSATION, BUT IT WOULDN’T WORK.”

“You may ask why didn’t we kill him, or sell him, or give him to the missionaries, or something of that sort. Well, Mamie, she said it would be the next thing to murder if we were to wring his neck; and that selling him would be about the same as the slave-trade. She wouldn’t let me take the first step toward getting rid of the parrot, and the prospect was that he’d drive us clean out of the house.

“One day a man who had had considerable experience of parrots happened to come in, and when I complained of the bird he said, ‘Why don’t you get an owl? You get an owl and hang him up close to that parrot’s cage, and in about two days you’ll find that your bird’s dead sick of unprofitable conversation.’

“Well, I got a small owl and put him in a cage close to the parrot’s cage. The parrot began by trying to dazzle the owl with his conversation, but it wouldn’t work. The owl sat and looked at the parrot just as solemn as a minister whose salary has been cut down, and after a while the parrot tried him with Spanish. It wasn’t of any use. Not a word would the[11] owl let on to understand. Then the parrot tried bragging, and laid himself out to make the owl believe that of all the parrots in existence he was the ablest. But he couldn’t turn a feather of the owl. That noble bird sat silent as the grave, and looked at the parrot as if to say, ‘This is indeed a melancholy exhibition of imbecility!’ Well, before night that parrot was so ashamed of himself that he closed for repairs, and from that day forth he never spoke an unnecessary word. Such, gentlemen, is the influence of example even on the worst of birds.”

The American lit a fresh cigar, and pulling his hat over his eyes, fell into profound meditation. His three auditors made no comment on his story, and did not repeat the inquiry why he had asked the waiter for an owl. They smoked in silence for some moments, and then one of them invited the other two to step over to Henry’s and take something—an invitation which they promptly accepted, and the smoking-room knew them no more that night.

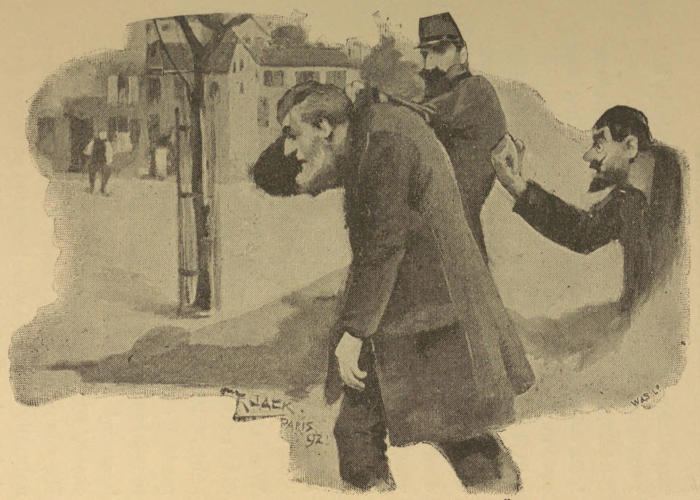

“Yes, sir!” said the Colonel. “Being an American, I’m naturally in favor of elevating the oppressed and down-trodden, provided, of course, they live in other countries. All Americans are in favor of Home Rule for Ireland, because it would elevate the Irish masses and keep them at home; but if I were living in Ireland, perhaps I might prefer elevating Russian Jews or Bulgarian Christians. You see, the trouble with elevating the oppressed at home is that the moment you get them elevated they begin to oppress you. There is no better fellow in the world than the Irishman, so long as you govern him; but when he undertakes to govern you it’s time to look out for daybreak to westward. You see, we’ve been there and know all about it.

“Did I ever tell you about Jewseppy? He[13] was an organ-grinder, and, take him by and large, he was the best organ-grinder I ever met. He could throw an amount of expression into ‘Annie Rooney,’ or, it might be, ‘The Old Folks at Home,’ that would make the strongest men weep and heave anything at him that they could lay their hands to. He wasn’t a Jew, as you might suppose from his name, but only an Italian—‘Jewseppy’ being what the Italians would probably call a Christian name if they were Christians. I knew him when I lived in Oshkosh, some twenty years ago. My daughter, who had studied Italian, used to talk to him in his native language; that is, she would ask him if he was cold, or hungry, or ashamed, or sleepy, as the books direct, but as he never answered in the way laid down in the books, my daughter couldn’t understand a word he said, and so the conversation would begin to flag. I used to talk to him in English, which he could speak middling well, and I found him cranky, but intelligent.

“He was a little, wizened, half-starved-looking man, and if he had only worn shabby black[14] clothes, you would have taken him for a millionaire’s confidential clerk, he was so miserable in appearance. He had two crazes—one was for monkeys, who were, he said, precisely like men, only they had four hands and tails, which they could use as lassoes, all of which were in the nature of modern improvements, and showed that they were an advance on the original pattern of men. His other craze was his sympathy for the oppressed. He wanted to liberate everybody, including convicts, and have every one made rich by law and allowed to do anything he might want to do. He was what you would call an Anarchist to-day, only he didn’t believe in disseminating his views by dynamite.

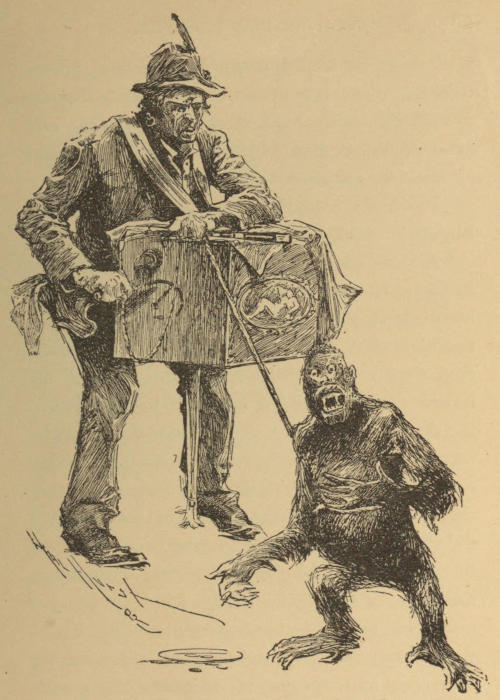

“SHE WOULD ASK HIM IF HE WAS COLD OR HUNGRY.”

“He had a monkey that died of consumption, and the way that Jewseppy grieved for the monkey would have touched the heart of an old-fashioned Calvinist, let alone a heart of ordinary stone. For nearly a month he wandered around without his organ, occasionally doing odd jobs of work, which made most people think that he was going out of his mind. But one[16] day a menagerie came to town, and in the menagerie was what the show-bill called a gorilla. It wasn’t a genuine gorilla, as Professor Amariah G. Twitchell, of our university, proved after the menagerie men had refused to give him and his family free tickets. However, it was an animal to that effect, and it would probably have made a great success, for our public, though critical, is quick to recognize real merit, if it wasn’t that the beast was very sick. This was Jewseppy’s chance, and he went for it as if he had been a born speculator. He offered to buy the gorilla for two dollars, and the menagerie men, thinking the animal was as good as dead, were glad to get rid of it, and calculated that Jewseppy would never get the worth of the smallest fraction of his two dollars. There is where they got left, for Jewseppy knew more about monkeys than any man living, and could cure any sick monkey that called him in, provided, of course, the disease was one which medical science could collar. In the course of a month he got the gorilla thoroughly repaired, and was giving him lessons[17] in the theory and practice of organ-grinding.

“The gorilla didn’t take to the work kindly, which, Jewseppy said, was only another proof of his grand intellect, but Jewseppy trained him so well that it was not long before he could take the animal with him when he went out with the organ, and have him pass the plate. The gorilla always had a line round his waist, and Jewseppy held the end of it, and sort of telegraphed to him through it when he wanted him to come back to the organ. Then, too, he had a big whip, and he had to use it on the gorilla pretty often. Occasionally he had to knock the animal over the head with the butt end of the whip-handle, especially when he was playing something on the organ that the gorilla didn’t like, such as ‘Marching through Georgia,’ for instance. The gorilla was a great success as a plate-passer, for all the men were anxious to see the animal, and all the women were afraid not to give something when the beast put the plate under their noses. You see, he was as strong as two or three men, and his[18] arms were as long as the whole of his body, not to mention that his face was a deep blue, all of which helped to make him the most persuasive beast that ever took up a collection.

“Jewseppy had so much to say to me about the gorilla’s wonderful intelligence that he made me tired, and one day I asked him if he thought it was consistent with his principles to keep the animal in slavery. ‘You say he is all the same as a man,’ said I. ‘Then why don’t you give him a show? You keep him oppressed and down-trodden the whole time. Why don’t you let him grind the organ for a while, and take up the collection yourself? Turn about is fair play, and I can’t see why the gorilla shouldn’t have his turn at the easy end of the business.’ The idea seemed to strike Jewseppy where he lived. He was a consistent idiot. I’ll give him credit for that. He wasn’t ready to throw over his theories every time he found they didn’t pay. Now that I had pointed out to him his duty toward the gorilla, he was disposed to do it.

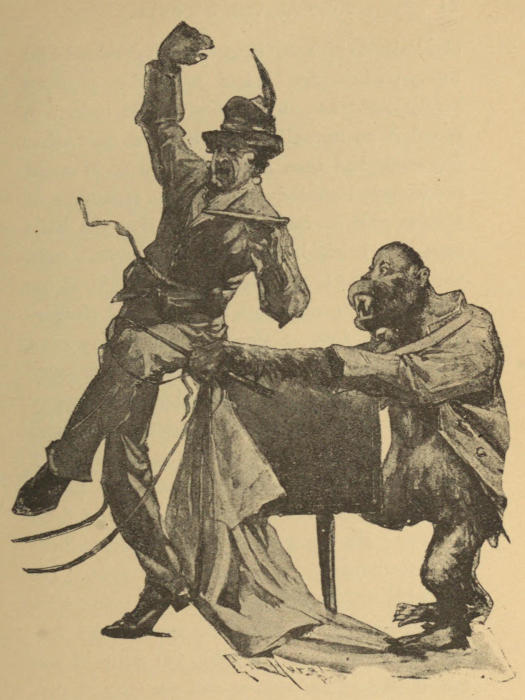

“THE GORILLA WAS A GREAT SUCCESS.”

“You see, he reasoned that while it would only be doing justice to the beast to change places with him, it would probably increase the receipts. When a man can do his duty and make money by it his path is middling plain; and after Jewseppy had thought it over he saw that he must do justice to the gorilla without delay.

“It didn’t take the beast long to learn the higher branches of hand-organing.

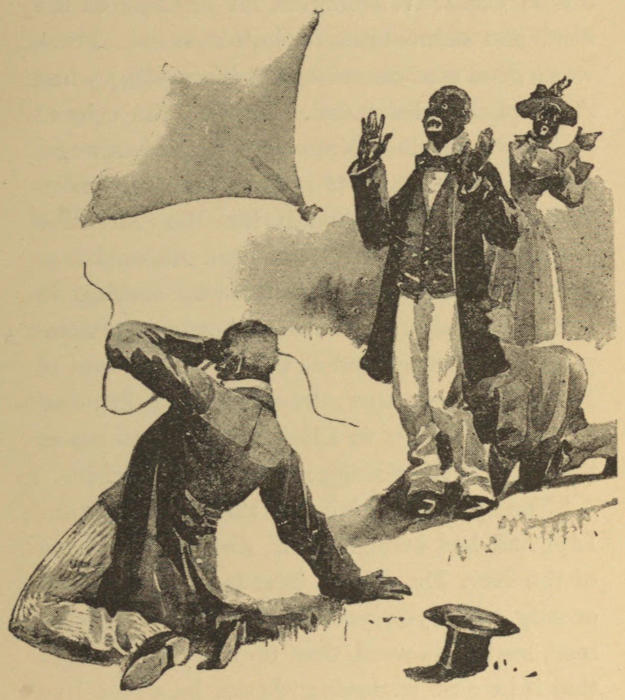

“He saw the advantages of putting the money in his own pocket instead of collecting it and handing it over to Jewseppy, and he grasped the idea that when he was pushing the little cart that carried the organ and turning the handle, he was holding a much better place in the community than when he was dancing and begging at the end of a rope. I thought, a day or two after I had talked to Jewseppy, that there was considerable uproar in town, but I didn’t investigate it until toward evening, when there seemed to be a sort of riot or temperance meeting, or something of the kind, in front of my house, and I went out to see about it. There were nearly two thousand people there watching Jewseppy and his gorilla, or rather the gorilla and his Jewseppy. The little man had been[21] elevating the oppressed with great success. A long rope was tied around his waist, and he was trotting around among the people, taking up the collection and dancing between times.

“The gorilla was wearing Jewseppy’s coat, and was grinding away at the organ with one hand and holding Jewseppy’s rope with the other. Every few minutes he would haul in the rope, hand over hand, empty all the money out of Jewseppy’s pocket, and start him out again. If the man stopped to speak to anybody for a moment the gorilla would haul him in and give him a taste of the whip, and if he didn’t collect enough money to suit the gorilla’s idea, the animal would hold him out at arm’s length with one hand and lay into him with the other till the crowd were driven wild with delight. Nothing could induce them to think that Jewseppy was in earnest when he begged them to protect him. They supposed it was all a part of the play, and the more he implored them to set him free, the more they laughed and said that ‘thish yer Eyetalian was a bang-up actor.’

“As soon as Jewseppy saw me he began to tell[22] me of his sufferings. His story lacked continuity, as you might say, for he would no sooner get started in his narrative than the gorilla would jerk the rope as a reminder to him to attend strictly to business if he wanted to succeed in his profession. Jewseppy said that as soon as he tied the rope around his waist and put the handle of the organ in the gorilla’s hand the beast saw his chance and proceeded to take advantage of it. He had already knocked the man down twice with the handle of the whip, and had lashed him till he was black and blue, besides keeping him at work since seven o’clock that morning without anything to eat or drink.

“WEARING JEWSEPPY’S COAT, AND WAS GRINDING AWAY AT THE ORGAN.”

“At this point the gorilla hauled Jewseppy in and gave him a fairly good thrashing for wasting his time in conversation. When the man came around again with the plate I told him that he was taking in more money than he had ever taken in before, and that this ought to console him, even if the consciousness that he was doing justice to the oppressed had no charms for him. I’m sorry to say that Jewseppy used such bad language that I really couldn’t stay[24] and listen to him any longer. I understood him to say that the gorilla took possession of every penny that was collected, and would be sure to spend it on himself, but as this was only what Jewseppy had been accustomed to do it ought not to have irritated a man with a real sense of justice. Of course I was sorry that the little man was being ill treated, but he was tough, and I thought that it would not hurt him if the gorilla were to carry out his course of instruction in the duty of elevating the oppressed a little longer. I have always been sort of sorry that I did not interfere, for although Jewseppy was only a foreigner who couldn’t vote, and was besides altogether too set in his ideas, I didn’t want him to come to any real harm. After that day no man ever saw Jewseppy, dead or alive. He was seen about dusk two or three miles from town on the road to Sheboygan. He was still tied to the rope and was using a lot of bad language, while the gorilla was frequently reminding him with the whip of the real duties of his station and the folly of discontent and rebellion. That was the last anybody[25] ever saw of the Italian. The gorilla turned up the next day at a neighboring town with his organ, but without anybody to take up the collection for him, and as the menagerie happened to be there the menagerie men captured him and put him back in his old cage, after having confiscated the organ. No one thought of making any search for Jewseppy, for, as I have said, he had never been naturalized and had no vote, and there were not enough Italians in that part of the country to induce any one to take an interest in bringing them to the polls. It was generally believed that the gorilla had made away with Jewseppy, thinking that he could carry on the organ business to more advantage without him. It’s always been my impression that if Jewseppy had lived he would have been cured of the desire to elevate the down-trodden, except, of course, in foreign countries. He was an excellent little man—enthusiastic, warm-hearted, and really believing in his talk about the rights of monkeys and the duty of elevating everybody. But there isn’t the least doubt that he made a mistake when he tried to do justice to that gorilla.”

“Does anybody doubt my patriotism?” asked the Colonel. We all hastened to say that we should as soon doubt our own existence. Had he not made a speech no longer ago than last Fourth of July, showing that America was destined to have a population of 1,000,000,000 and that England was on the verge of extinction? Had he not perilled his life in the cause of freedom, and was he not tireless in insisting that every Chinaman should be driven out of the United States? If there ever was one American more patriotic than another it was the Colonel.

“Well, then,” continued the speaker, “you won’t misunderstand me when I say that the American railroad car is a hundred times more dangerous than these European compartment cars. In thirty years there have been just four[27] felonious assaults in English railroad cars. There have been a few more than that in France, but not a single one in Germany. Now, I admit that you are in no danger of being shot in an American car, unless, of course, two gentlemen happen to have a difficulty and shoot wild, or unless the train is held up by train robbers who are a little too free with their weapons. But I do say that the way in which we heat our cars with coal-stoves kills thousands of passengers with pneumonia and burns hundreds alive when the trains are wrecked.

“You see, I’ve looked into this thing and I’ve got the statistics down fine. I’m the only man I know who ever had any trouble with a passenger while travelling in Europe, and I don’t mind telling you about it, although it will be giving myself away. Kindly push me over those matches, will you? These French cigars take a lot of fuel, and you have to encourage them with a match every three minutes if you expect them to burn.

“When I was over here in Paris, ten years ago, there was a fellow here from Chicago who[28] was trying to introduce American cars, and he gave me a pamphlet he had got up showing the horrors of the compartment system. It told of half a dozen murders, fifteen assaults, eleven cases of blackmail, and four cases in which a solitary traveller was shut up in a compartment with a lunatic—all these incidents having occurred on European railways. I was on my way to Egypt, and when I had read the pamphlet I began to wonder if I should ever manage to live through the railroad journey without being killed, or blackmailed, or lunaticked, or something of the kind. You see, I believed the stories then, though I know now that about half of them were false.

“I took the express train—the Peninsular and Oriental they call it—from Paris about twelve o’clock one night. I went early to the train, and until just before we started I thought I was going to have the compartment to myself. All at once a man very much out of breath jumped in, the door was slammed, and we were off.

“‘DOES ANYBODY DOUBT MY PATRIOTISM?’ ASKED THE COLONEL.”

“I didn’t like the looks of the fellow. He was a Frenchman, though of course that wasn’t his fault. He was small but wiry-looking, and his sharp black eyes were not the style of eyes that inspires me with confidence. Then he had no baggage except a small paper parcel, which was queer, considering that the train was a long-distance one. I kept a close watch on him for a while, thinking that he might be one of the professional lunatics that, according to the Chicago chap’s pamphlet, are always travelling in order to frighten solitary passengers; but after a while I became so sleepy that I decided to lie down and take a nap and my chances of being killed at the same time. Just then the man gets up and begins to talk to me in French.

“Now, I needn’t say that I don’t speak French nor any of those fool languages. Good American is good enough for me. One reason why these Europeans have been enslaved for centuries is that they can’t make each other understand their views without shouting at the top of their lungs, and so bringing the police about their ears. But I did happen to know, or thought I did, the French word for going to sleep,[31] and so I thought I would just heave it at this chap so that he would understand that I didn’t require his conversation. I have always found that if you talk to a Frenchman in English very slowly and impressively he will get the hang of what you say. That is, if he isn’t a cabman. You can’t get an idea into a French cabman’s head unless you work it in with a club. So I said to the fellow in the train: ‘My friend! I haven’t any time to waste in general conversation. I’m going to sleep, and I advise you to do the same. You can tell me all about your institutions and your revolutions and things in the morning.’ And then I hove in the French word ‘cochon,’ which I supposed meant something like ‘Now I lay me down to sleep.’

“The fellow staggered back as if I had hit him, and then he began to sling the whole French language at me. I calculate that he could have given Bob Ingersoll fifty points in a hundred and beaten him, and, as you know, Bob is the ablest vituperator now in the business. The Frenchman kept on raving and getting madder and madder every minute, and I[32] saw that there wasn’t the least doubt that he was a dangerous lunatic.

“I stood up and let him talk for a while, occasionally saying ‘non comprenny’ and ‘cochon,’ just to soothe him, but presently he came close to me and shook his fist in my face. This was too much, so I took him by the shoulders and slammed him down in a corner seat, and said, ‘You sit there, sonny, and keep quiet, or you’ll end by getting me to argue with you.’ But the minute I let go of him he bounced up again as if he was made of India-rubber, and came at me just as a terrier will come at a horse, pretending that he is going to tear him into small pieces. So I slammed him down into his corner again, and said, ‘This foolishness has gone far enough, and we’ll have it stopped right here. Didn’t you hear me say cochon? I’m going to cochon, and you’d better cochon, too, or I’ll make you.’

“This time he jumped up as soon as I had let go of him and tried to hit me. Of course I didn’t want to hit so small a chap, letting alone that he knew no more about handling his fists[33] than the angel Gabriel, so I just took and twisted his arms behind his back and tied them with a shawl-strap. Then, seeing as he showed a reprehensible disposition to kick, I put another strap around his legs and stretched him on the seat with his bundle under his head. But kindness was thrown away on that Frenchman. He tried to bite me, and not content with spitting like a cat, he set up a yell that was the next thing to the locomotive whistle, and rolling off the seat tried to kick at me with both legs.

“I let him exercise himself for a few minutes, while I got my hair-brush and some twine out of my bag. Then I put him back on the seat, gagged him with the handle of the hair-brush, and lashed him to the arm of the seat so that he couldn’t roll off. Then I offered him a drink, but he shook his head, not having any manners, in spite of what people say about the politeness of Frenchmen. Having secured my own safety and made the lunatic reasonably comfortable, I turned in and went to sleep. I must have slept very sound, for although the train stopped two or three times during the night, I never woke up[34] until we pulled up for breakfast about eight o’clock the next morning. I sat up and looked at my lunatic, who was wide awake and glaring at me. I wished him good-morning, for I couldn’t bear any grudge against a crazy man; but he only rolled his eyes and seemed madder than ever, so I let him lie and got out of the train.

“Two policemen were walking up and down the platform, and I took one of them by the arm and led him to the car, explaining what had happened. I don’t know whether he understood or not, but he pretended that he didn’t.

“As soon as he saw the lunatic there was a pretty row. He called two more policemen, and after they had ungagged the fellow they hauled us both before a magistrate who had his office in the railroad station. At least he acted like a magistrate, although he wore the same uniform as the policemen. Here the fellow I had travelled with was allowed to speak first, and he charged me, as I afterward found, with having first insulted and then assaulted him. He said he rather thought I was a lunatic, but at any rate he must have my blood. Then an interpreter was sent for, and I told my story, but I could see that nobody believed me.

“THEY HAULED US BOTH BEFORE A MAGISTRATE.”

“‘Accused,’ said the magistrate very sternly, ‘you called this gentleman a pig. What was your motive?’

“Of course I swore that I had never called him a pig, that I hardly knew half a dozen words of his infamous language, and that I had used only one of those. Being asked what it was, I said ‘cochon.’ And then that idiot ordered me to be locked up.

“By rare good luck there happened to be an American secretary of legation on the train. You know him. It was Hiram G. Trask, of West Centreopolis. He recognized me, and it didn’t take him very long to explain the whole affair. It seems that the Frenchman had asked me if I objected to smoking, and when I tried to tell him that we ought to go to sleep, I said ‘cochon,’ which means pig, instead of ‘couchons,’ which was the word I ought to have used. He was no more of a lunatic than a Frenchman naturally is, but he was disgusted at being carried two hundred miles beyond his destination,[37] which was the first stopping-place beyond Paris, and I don’t know that I blame him very much. And then, too, he seemed to feel that his dignity had been some ruffled by being gagged and bound. However, both he and the policemen listened to reason, and the man agreed to compromise on my paying him damages and withdrawing the assertion that he was morally or physically a pig. The affair cost considerable, but it taught me a lesson, and I have quit believing that you can’t travel in a European railroad car without being locked up with a lunatic or a murderer. I admit that the whole trouble was due to my foolishness. When the Frenchman began to make a row, I ought to have killed him and dropped the body out of the door, instead of fooling with him half the night and trying to make him comfortable. But we can’t always command presence of mind or see just where our duty lies at all times.”

We had just dined in the little Parisian restaurant where Americans are in the habit of going in order to obtain those truly French delicacies, pork and beans, buckwheat cakes, corned beef, apple pie, and overgrown oysters. I knew a man from Chicago who dined at this restaurant every day during the entire month spent by him in Paris, and who, at the end of that time, said that he was heartily sick of French cookery. Thus does the profound study of the manners and customs of foreign nations enlighten the mind and ripen the judgment.

The Colonel had finished his twelfth buckwheat cake and had lighted his cigar, when he casually and reprovingly remarked to young Lathrop, who, on principle, was disputing the bill with the waiter, that “he was making more trouble than Thompson’s tombstone.” Being[39] called upon to explain this dark saying, he stretched his legs to their limit, tipped back his chair, knocked the ashes of his cigar among the remnants of his pork and beans, and launched into his story.

“In the town where I was raised—and I’m not going to give away the name of it at present—there were two brothers, James and John Thompson. They were twins and about forty years old, as I should judge. James was a bachelor and John he was a widower, and they were both pretty well to do in the world, for those times at least. John was a farmer and James was a wagon maker and owned the village hearse besides, which he let out for funerals, generally driving it himself, so that any profit that was to be made out of a melancholy occasion he could make without sharing it with anybody. Both the men were close-fisted, and would look at a dollar until their eyesight began to fail before they could bring themselves to spend it. It was this miserly spirit that brought about the trouble that I’m going to tell you of.

“After John Thompson had been a widower[40] so long that the unmarried women had given up calling on him to ask his advice about the best way of raising money for the heathen, and had lost all expectation that any one of them would ever gather him in, he suddenly ups and marries Maria Slocum, who used to keep a candy store next door to the school-house and had been a confirmed old maid for twenty years. She had a little money, though, and folks did say that she could have married James Thompson if she had been willing to take the risk; but the fact that James always had the hearse standing in his carriage-house made him unpopular with the ladies. She took John because his views on infant baptism agreed with hers, and he took her because she had a good reputation for making pies and was economical and religious.

“The Thompson brothers owned burial lots in the new cemetery that were close together. James, of course, had, so far, no use for his lot, but John had begun to settle his by burying his first wife in about the middle of it. The lot was a good-sized one, with accommodation for a reasonably large family without crowding them,[41] and without, at the same time, scattering them in any unsocial way. I don’t know how it came about, but no sooner was John married than he took a notion to put up a tombstone over his first wife. He thought that as he was going to incur such an expense he would manage it so that he wouldn’t have to incur it again; and so he got up a design for a combination family tombstone, and had it made, and carved, and lettered, and set up in his burial lot.

“Near the top of the stone was John Thompson’s name, the date of his birth, and a blank space for the date of his death. Next came the name of ‘Sarah Jane, beloved wife of the above,’ and the date of her birth and death. Then came the name of ‘Maria, beloved and lamented wife of the above John Thompson,’ with the date of her birth and a space for the date of her death. You see, John worked in this little compliment about Maria being ‘lamented’ so as to reconcile her to having the date of her birth given away to the public. The lower half of the tombstone was left vacant so as to throw in a few children should any such[42] contingency arise, and the whole advertisement ended with a verse of a hymn setting forth that the entire Thompson family was united in a better land above.

“The cost of the affair was about the same as that of one ordinary tombstone, the maker agreeing to enter the dates of John’s death and of his wife’s death free of charge whenever the time for so doing might arrive; and also agreeing to enter the names of any children that might appear at a very low rate. The tombstone attracted a great deal of attention, and the summer visitors from the city never failed to go and see it. John was proud of his stroke of economy, and used to say that he wasn’t in danger of being bankrupted by any epidemic, as those people were who held that every person must have his separate tombstone. Everybody admitted that the Thompson tombstone gave more general amusement to the public than any other tombstone in the whole cemetery. Every summer night John used to walk over to his lot and smoke his pipe, leaning on the fence and reading over the inscriptions. And then he[43] would go and take a fresh look at the Rogers’ lot, where there were nine different tombstones, and chuckle to think how much they must have cost old man Rogers, who had never thought of a combination family tomb. In the course of about three years the inscriptions had grown, for there had been added the names of Charles Henry and William Everett Thompson, ‘children of the above John and Maria Thompson,’ and John calculated that with squeezing he could enter four more children on the same stone, though he didn’t really think that he would ever have any call so to do.

“Well, a little after the end of the third year John’s troubles began. He took up with Second Advent notions and believed that the end of the world would arrive, as per schedule, on the 21st of November, at 8:30 A.M. Maria said that this was not orthodox and that she wouldn’t allow any such talk around her house. Both of them were set in their ways, and what with John expressing his views with his whip-handle and Maria expressing hers with the rolling-pin, they didn’t seem to get on very well together,[44] and one day Maria left the house and took the train to Chicago, where she got a divorce and came back a free and independent woman. That wasn’t all: James Thompson now saw his chance. He offered to sell out the hearse business, and after waiting ten months, so as to give no opportunity for scandal, Maria married him.

“John didn’t seem to mind the loss of his wife very much until it happened to occur to him that his combination family tombstone would have to be altered, now that Maria was not his wife any longer. He was a truthful man, and he felt that he couldn’t sleep in peace under a tombstone that was constantly telling such a thumping lie as that Maria was resting in the same burying-lot and that she was his beloved wife, when, in point of fact, she was another man’s wife and would be, at the proper time, lying in that other man’s part of the cemetery. So he made up his mind to have the marble-cutter chisel out Maria’s name and the date of her birth. But before this was done he saw that it wouldn’t be the square thing so far as Charles Henry and William Everett[45] were concerned. It would be playing it low down on those helpless children to allow that tombstone to assert that they were the children of John Thompson and some unspecified woman[46] called Maria, who, whatever else she may have been, was certainly not John Thompson’s wife. Matters would not be improved if the name of Maria were to be cut out of the line which stated the parentage of the children, for in that case it would appear that they had been independently developed by John, without the intervention of any wife, which would be sure to give rise to gossip and all sorts of suspicions.

“DIDN’T SEEM TO GET ON VERY WELL TOGETHER.”

“Of course the difficulty could have been settled by erasing from the tombstone all reference to Maria and her two children, but in that case a separate stone for the children would some day become necessary, and, what was of more consequence, John’s grand idea of a combination tombstone would have to be completely abandoned. John was not a hasty man, and after thinking the matter over until the mental struggle turned his hair gray, he decided to compromise the matter by putting a sort of petticoat around the lower half of the tombstone, which would hide all reference to Maria and the children. This was easily done with the aid of an old pillow-case, and the tombstone[47] became more an object of interest to the public than ever, while John, so to speak, sat down to wait for better times.

“THE TOMBSTONE BECAME MORE AN OBJECT OF INTEREST TO THE PUBLIC THAN EVER.”

“Now, James had been thinking over the tombstone problem, and fancied that he had found a solution of it that would put money in his own pocket and at the same time satisfy[48] his brother. He proposed to John that the inscription should be altered so as to read: ‘Maria, formerly wife of John and afterward of James Thompson,’ and that a hand should be carved on the stone with an index-finger pointing toward James’ lot, and a line in small type saying, ‘See small tombstone.’ James said that he would pay the cost of putting up a small uninscribed stone in his own lot over the remains of Maria—waiting, of course, until she should come to be remains—and that John could pay the cost of altering the inscriptions on the large stone. The two brothers discussed this scheme for months, each of them being secretly satisfied with it, but John maintaining that James should pay all the expenses.

“This James would not do, for he reasoned that unless John came to his terms the combination tombstone would be of no good to anybody, and that if he remained firm John would come round to his proposal in time.

“There isn’t the least doubt that this would have been the end of the affair, if it had not been that James chuckled over it so much that[49] one day he chuckled a fishbone into his throat and choked to death on the spot. He was buried in his own lot, with nothing but a wooden headboard to mark the spot. His widow said that if he had been anxious to have a swell marble monument he would have made provision for it in his lifetime, and as he had done nothing of the kind, she could not see that she had any call to waste her money on worldly vanities.

“How did this settle the affair of the combination tombstone? I’m just telling you. You see, by this time the world had not come to an end, and John, who always hated people who didn’t keep their engagements, seeing that the Second Adventists didn’t keep theirs, left them and returned to the regular Baptist fold. When his brother died he went to the funeral, and did what little he could, in an inexpensive way, to comfort the widow. The long and short of it was that they became as friendly as they ever had been, and John finally proposed that Maria should marry him again. ‘You know, Maria,’ he said, ‘that we never disagreed except about that Second Advent nonsense. You were right[50] about that and I was wrong, as the event has proved, and now that we’re agreed once more, I don’t see as there is anything to hinder our getting married again.’

“Maria said that she had a comfortable support, and she couldn’t feel that it was the will of Providence for her to be married so often, considering how many poor women there were who couldn’t get a single husband.

“‘Well,’ continued John, ‘there is that there tombstone. It always pleased you and I was always proud of it. If we don’t get married again that tombstone is as good as thrown away, and it seems unchristian to throw away a matter of seventy-five dollars when the whole thing could be arranged so easy.’

“The argument was one which Maria felt that she could not resist, and so, after she had mourned James Thompson for a fitting period, she married John a second time, and the tombstone’s reputation for veracity was restored. John and Maria often discussed the feasibility of selling James’ lot and burying him where the combination tombstone would take him in,[51] but there was no more room for fresh inscriptions, and besides, John didn’t see his way clear to stating in a short and impressive way the facts as to the relationship between James and Maria. So, on the whole, he judged it best to let James sleep in his own lot, and let the combination tombstone testify only to the virtues of John Thompson and his family. That’s the story of Thompson’s tombstone, and if you don’t believe it I can show you a photograph of the stone with all the inscriptions. I’ve got it in my trunk at this very moment, and when we go back to the hotel, if you remind me of it, I’ll get it out.”

“Well, sir,” said the Colonel, “since you ask me what struck me most forcibly during my tour of England, and supposing that you want a civil answer to a civil question, I will say that the thing that astonished me more than anything else was the lack of religious enterprise in England.

“THE LACK OF RELIGIOUS ENTERPRISE IN ENGLAND.”

“I have visited nearly every section of your country, and what did I find? Why, sir, in every town there was a parish church of the regulation pattern and one other kind of church, which was generally some sort of Methodist in its persuasion. Now, in America there is hardly a village which hasn’t half a dozen different kinds of churches, and as a rule at least one of them belongs to some brand-new denomination, one that has just been patented and put on the market, as you might say. When I lived in[53] Middleopolis, Iowa, there were only fifteen hundred people in the place, but we had six kinds of churches. There was the Episcopalian, the Methodist, the Congregational, the Baptist, the Presbyterian, the Unitarian, and the Unleavened Disciples church, not to mention the colored Methodist church, which, of course, we didn’t count among respectable white denominations.[54] All these churches were lively and aggressive, and the Unleavened Disciples, that had just been brought out, was as vigorous as the oldest of them. All of them were furnishing good preaching and good music, and striving to outdo one another in spreading the Gospel and raising the price of pew-rents. I could go for two or three months to the Presbyterian church, and then I could take a hack at the Baptists and pass half a dozen Sundays with the Methodists, and all this variety would not cost me more than it would have cost to pay pew-rent all the year round in any one church. And then, besides the preaching, there were the entertainments that each church had to get up if it didn’t want to fall behind its rivals. We had courses of lectures, and returned missionaries, and ice-cream festivals till you couldn’t rest. Why, although I am an old theatrical manager, I should not like to undertake to run a first-class American church in opposition to one run by some young preacher who had been trained to the business and knew just what the popular religious taste demanded. I never was[55] mixed up in church business but once, and then I found that I wasn’t in my proper sphere.”

The Colonel chuckled slowly to himself, as his custom was when anything amused him, and I asked him to tell me his ecclesiastical experience.

“Well, this was the way of it,” he replied. “One winter the leading citizens of the place decided to get up a series of union meetings. Perhaps you don’t know what a union meeting is? I thought so. It bears out what I was saying about your want of religious enterprise. Well, it’s a sort of monster combination, as we would say in the profession. All the churches agree to hold meetings together, and all the preaching talent of the whole of them is collected in one pulpit, and each man preaches in turn. Of course every minister has his own backers, who are anxious to see him do himself and his denomination credit, and who turn out in full force so as to give him their support. The result is that a union meeting will always draw, even in a town where no single church can get a full house, no matter what attractions it may offer.

“Now, a fundamental rule of a union meeting is that no doctrines are to be preached to which any one could object. The Baptist preacher is forbidden to say anything about baptism, and the Methodist can’t allude to falling from grace in a union meeting. This is supposed to keep things peaceful and to avoid arguments and throwing of hymn-books and such-like proceedings, which would otherwise be inevitable.

“The union meetings had been in progress for three or four nights when I looked into the Presbyterian church, where they were held one evening, just to see how the thing was drawing. All the ministers in town, except the Episcopalian minister, were sitting on the platform waiting their cues. The Episcopalian minister had been asked to join in the services, but he had declined, saying that if it was all the same to his dissenting and partially Christian friends he would prefer to play a lone hand; and the colored minister was serving out his time in connection with some of his neighbors’ chickens that, he said, had flown into his kitchen and[57] committed suicide there, so he couldn’t have been asked, even if the white ministers had been willing to unite with him.

“The Presbyterian minister was finishing his sermon when I entered, and soon as he had retired the Baptist minister got up and gave out a hymn which was simply crowded with Baptist doctrine. I had often heard it, and I remember that first verse, which ran this way:

“The hymn was no sooner given out than the Methodist minister rose and claimed a foul, on the ground that Baptist doctrine had been introduced into a union meeting. There was no manner of doubt that he was right, but the Baptists in the congregation sang the hymn with such enthusiasm that they drowned the minister’s voice. But when the hymn was over there was just a heavenly row. One Presbyterian deacon actually went so far as to draw on a Baptist elder, and there would have been blood[58] shed if the elder had not knocked him down with a kerosene lamp, and convinced him that drawing pistols in church was not the spirit of the Gospel. Everybody was talking at once, and the women who were not scolding were crying. The meeting was beginning to look like an enthusiastic political meeting in Cork, when I rapped on the pulpit and called for order. Everybody knew me and wanted to hear what I had to say, so the meeting calmed down, except near the door, where the Methodists had got a large Baptist jammed into the wood-box, and in the vestibule, where the Unitarians had formed a ring to see the Unitarian minister argue with an Unleavened Disciple.

“I told the people that they were making a big mistake in trying to run that sort of an entertainment without an umpire. The idea pleased them, and before I knew what was going to be done they had passed a resolution making me umpire and calling on me to decide whether the Baptist hymn constituted a foul. I decided that it did not, on the ground that, according to the original agreement, no minister[59] was to preach any sectarian doctrines, but that nothing was said about the hymns that might be sung. Then I proposed that in order to prevent any future disputes and to promote brotherly feeling, a new system of singing hymns should be adopted. I said, as far as I can recollect, that singing hymns did not come under the head of incidental music, but was a sort of entr’acte music, intended to relax and divert the audience while bracing up to hear the next sermon. This being the case, it stood to reason that hymn-singing should be made a real pleasure, and not an occasion for hard feeling and the general heaving of books and foot-stools. ‘Now,’ said I, ‘that can be managed in this way. When you sing let everybody sing the same tune, but each denomination sing whatever words it prefers to sing. Everybody will sing his own doctrines, but nobody will have any call to feel offended.’

“The idea was received with general enthusiasm, especially among the young persons present, and the objections made by a few hard-headed old conservatives were overruled. The[60] next time singing was in order the Unitarian minister selected a familiar short-metre tune, and each minister told his private flock what hymn to sing to it. Everybody sang at the top of his or her lungs, and as nobody ever understands the words that anybody else is singing, there did not seem to be anything strange in the singing of six different hymns to the same tune. There was a moment when things were a little strained in consequence of the Presbyterians, who were a strong body, and had got their second wind, singing a verse about predestination with such vigor as partly to swamp their rivals, but I decided that there was no foul, and the audience, being rather tired with their exertions, settled down to listen to the next sermon.

“The next time it was the Methodist minister who gave out the tune, and he selected one that nobody who was not born and bred a Methodist had ever heard of. We used to sing something very much like it at the windlass when I was a sailor, and it had a regular hurricane chorus. When the Methodist contingent started in to[61] sing their hymn to this tune, not a note could any of the rival denominations raise. They stood it in silence until two verses had been sung, and then——

“Well, I won’t undertake to describe what followed. After about five minutes the Methodists didn’t feel like singing any more. In fact, most of them were outside the meeting-house limping their way home, and remarking that they had had enough of ‘thish yer fellowship with other churches’ to last them for the rest of their lives. Inside the meeting-house the triumphant majority were passing resolutions calling me a depraved worldling, who, at the instigation of the devil, had tried to convert a religious assemblage into an Orange riot. Even the Unitarians, who always maintained that they did not believe in the devil, voted for the resolutions, and three of them were appointed on the committee charged with putting me out. I didn’t stay to hear any more sermons, but I afterward understood that all the ministers preached at me, and that the amount of union displayed in putting the blame of everything on[62] my shoulders was so touching that men who had been enemies for years shook hands and called one another brothers.

“Yes! we are an enterprising people in ecclesiastical matters, and I calculate that it will be a long time before an English village will see a first-class union meeting.”

“If you want to know my opinion of women-preachers,” said the Colonel, “I can give it to you straight. They draw well at first, but you can’t depend upon them for a run. I have had considerable experience of them, and at one time I thought well of them, but a woman, I think, is out of place in the pulpit.

“Although I never was a full member of the New Berlinopolisville Methodist church, I was treated as a sort of honorary member, partly because I subscribed pretty largely to the pastor’s salary, the annual picnics, and that sort of thing, and partly because the deacons, knowing that I had some little reputation as a theatrical manager and was a man of from fair to middling judgment, used to consult me quietly about the management of the church. There was a large Baptist church in the same town,[64] and its opposition was a little too much for us. The Baptist house was crowded every Sunday, while ours was thin and discouraging. We had a good old gentleman for a minister, but he was over seventy, and a married man besides, which kept the women from taking much interest in him; while his old-fashioned notions didn’t suit the young men of the congregation. The Baptists, on the other hand, had a young unmarried preacher, with a voice that you could hear a quarter of a mile off, and a way of giving it to the Jews, and the Mormons, and other safe and distant sinners that filled his hearers with enthusiasm and offended nobody. It was growing more and more evident every day that our establishment was going behindhand, and that something must be done unless we were willing to close our doors and go into bankruptcy; so one day the whole board of trustees and all the deacons came round to talk the matter over with me.

“My mind was already made up, and I was only waiting to have my advice asked before giving it. ‘What we want,’ said I, ‘is a[65] woman-preacher. She’ll be a sensation that will take the wind out of that Baptist windmill, and if she is good-looking, which she has got to be, I will bet you—that is, I am prepared to say—that within a fortnight there will be standing-room only in the old Methodist church.’

“‘But what are we to do with Dr. Brewster?’ asked one of the deacons. ‘He has been preaching to us now for forty years, and it don’t seem quite the square thing to turn him adrift.’

“‘Oh! that’s all right,’ said I. ‘We’ll retire him on a pension, and he’ll be glad enough to take it. As for your woman-preacher, I’ve got just what you want. At least, I know where she is and how much we’ll have to pay to get her. She’ll come fast enough for the same salary that we are paying Dr. Brewster, and if she doesn’t double the value of your pew-rents in six months, I will make up the deficit myself.’

“The trustees were willing to take my advice, and in the course of a few days Dr. Brewster had been retired on half-pay, the church had extended a call to the Rev. Matilda Marsh, and[66] the reverend girl, finding that the salary was satisfactory, accepted it.

“She was only about twenty-five years old, and as pretty as a picture when she stood in the pulpit in her black silk dress with a narrow white collar, something like the sort of thing that your clergymen wear. I couldn’t help feeling sad, when I first saw her, to think that she did not go into the variety business or a circus, where she would have made her fortune and the fortune of any intelligent manager. As a dance-and-song artiste she would have been worth a good six hundred dollars a week. But women are always wasting their talents, when they have any, and doing exactly what Nature didn’t mean them to do.

“THE REV. MATILDA MARSH.”

“Miss Marsh was a success from the moment that she came among us. Being both unmarried and pretty, she naturally fetched the young men, and as she let it be understood that she believed in the celibacy of the clergy and never intended to marry under any circumstances, the greater part of the women were willing to forgive her good looks. Then she could preach a first-class sermon, and I call myself a judge of sermons, for at one time I managed an agency for supplying preachers with ready-made sermons, and I never put a single one on the market that I hadn’t read myself. I don’t mean to say that Miss Marsh was strong on doctrinal sermons, but every one knows that the public doesn’t want doctrinal sermons. What it wants is poetry and pathos, and Miss Marsh used to ladle them out as if she had been born and bred an undertaker’s poet.

“As I had prophesied, the Baptists couldn’t stand the competition when we opened with our woman-preacher. Their minister took to going to the gymnasium to expand his chest, and by that means increased his lung-power until he could be heard almost twice as far as formerly, but it didn’t do any good. His congregation thinned out week by week, and while our church was crowded, his pew-rents fell below what was necessary to pay his salary, not to speak of the other incidental expenses. A few of the young men continued to stick by him until our minister began her series of sermons ‘To Young Men[69] Only,’ and that brought them in. I had the sermons advertised with big colored posters, and they proved to be the most attractive thing ever offered to the religious public. The church was crammed with young men, while lots of men of from fifty to seventy years old joined the Young Men’s Christian Association as soon as they heard of the course of sermons, and by that means managed to get admission to hear them. Miss Marsh preached to young men on the vices of the day, such as drinking, and card-playing, and dancing, and going to the theatre, and she urged them to give up these dissipations and cultivate their minds. Some of them started a Browning Club that for a time was very popular. Every time the club met one of Browning’s poems would be selected by the president, and each member who put up a dollar was allowed to guess its meaning. The man who made the best guess took all the money, and sometimes there was as much as thirty dollars in the pool. The young men told Miss Marsh that they had given up poker and gone in for Browning, and of course she was greatly[70] pleased. Then some of the older men started a Milton Club, and used to cut for drinks by putting a knife-blade into ‘Paradise Lost’—the man who made it open at a page the first letter of which was nearer to the head of the alphabet than any letter cut by any other man winning the game. Under Miss Marsh’s influence a good many other schemes for mental cultivation were invented and put into operation, and everybody said that that noble young woman was doing an incalculable amount of good.

“As a matter of course, at least half the young men of the congregation fell in love with the girl-preacher. They found it very difficult to make any progress in courting her, for she wouldn’t listen to any conversation on the subject. When Christmas came, the question what to give her kept the young men awake night after night. The women had an easy job, for they could give the preacher clothes, and lace, and hairpins, and such, which the young men knew that they could not give without taking a liberty. If she had been a man, slippers would, of course, have been the correct thing, but the[71] young men felt that they couldn’t work slippers for a girl that always wore buttoned boots, and that if they did venture upon such a thing the chances were that she would feel herself insulted. One chap thought of working on the front of an underskirt—if that is the right name of it—I mean one of those petticoats that are built for show rather than use—the words, ‘Bless our Pastor,’ in yellow floss silk, but when he asked his sister to lend him one of her skirts as a model, she told him that he was the champion fool of the country. You may ask, why didn’t the preacher’s admirers give her jewelry? For the reason that she never wore anything of the kind except a pair of ear-rings that her mother had given her, and which she had promised always to wear. They represented chestnut-burs, and it is clear to my mind that her mother knew that no young man who had much regard for his eyesight would come very near a girl defended by that sort of ear-ring. Miss Marsh used to say that other people could wear what they thought right, but she felt it to be inconsistent with her holy calling to wear[72] any jewelry except the ear-rings that her sainted mother had given her.

“The best running was undoubtedly made by the cashier of the savings bank and a young lawyer. Not that either of them had any real encouragement from Miss Marsh, but she certainly preferred them to the rest of the field, and was on what was certainly entitled to be called friendly terms with both of them. Of the two the cashier was by far the most devoted. He was ready to do anything that might give him a chance of winning. He even wanted to take a class in the Sunday-school, but the bank directors forbade it. They said it would impair the confidence of the public in the bank, and would be pretty sure to bring about a run which the bank might not be able to stand. They consented, however, that he should become the president of the new temperance society which the Rev. Miss Marsh had started, as the president had the right to buy wines and liquors at wholesale in order to have them analyzed, and thus show how poisonous they were. As the cashier offered to stand in with the bank directors[73] and let them fill their cellars at wholesale rates, both he and the directors made a good thing of it.

“The other young man, the lawyer, was a different sort of chap. He was one of those fellows that begin to court a girl by knocking her down with a club. I don’t mean to say that he ever actually knocked a woman down, but his manner toward women was that of a superior being, instead of a slave, and I am bound to say that as a general thing the women seemed to like it. He wasn’t a handsome man, like the cashier, but he had a big yellow beard that any sensible girl would have held to be worth twice the smooth-shaved cheek of his rival. He never tried to join the Sunday-school or the temperance society, or do anything else of the kind to curry favor with the minister; but he used occasionally to give her good advice, and to tell her that this or that thing which she was doing was a mistake. Indeed, he didn’t hesitate to tell her that she had no business in the pulpit, and had better go out as a governess or a circus rider, and so conform to the dictates of Nature.

“MAKING THE RUNNING.”

“I used to watch the game pretty closely, because I had staked my professional reputation on the financial success of the girl-preacher, and I didn’t want her to marry and so put an end to her attractiveness with the general public. I didn’t really think that there was much danger of any such thing, for Miss Marsh seemed to be[75] entirely absorbed in her work, and her salary was exceptionally large. Still, you can never tell when a woman will break the very best engagement, and that is one reason why they will never succeed as preachers. You pay a man a good salary, and he will never find that Providence calls him elsewhere, unless, of course, he has a very much better offer; but a woman-preacher is capable of throwing up a first-class salary because she don’t like the color of a deacon’s hair, or because the upholstery of the pulpit doesn’t match with her complexion.

“That winter we had a very heavy fall of snow, and after that the sleighing was magnificent for the next month or two. The cashier made the most of it by taking the minister out sleigh-riding two or three times a week. The lawyer did not seem to care anything about it, even when he saw the minister whirling along the road behind the best pair of horses in the town, with the cashier by her side and her lap full of caramels. But one Saturday afternoon, when he knew that the cashier would be detained at the bank until very late—the president[76] having just skipped to Canada, and it being necessary to ascertain the amount of the deficit without delay—the lawyer hired a sleigh and called for the minister. Although she was preparing her next day’s sermon by committing to memory a lot of Shelley’s poetry, she dropped Shelley and had on her best hat and was wrapped in the buffalo robe by the side of the lawyer in less than half an hour after she had told him that she positively wouldn’t keep him waiting three minutes.

“CALLED FOR THE MINISTER.”

“You remember what I said about the peculiar pattern of her ear-rings. It is through those ear-rings that the Methodist church lost its minister, and I became convinced that a female ministry is not a good thing to tie to. Miss Marsh and her admirer were driving quietly along and enjoying themselves in a perfectly respectable way, when one runner of the sleigh went over a good-sized log that had dropped from somebody’s load of wood and had been left in the road. The sleigh didn’t quite upset, but Miss Marsh was thrown against the lawyer with a shock for which she apologized, and he[78] thanked her. But it happened that one of her ear-rings caught in the lawyer’s beard, and was so twisted up with it that it was impossible to disentangle it. Unless Miss Marsh was ready to drag about half her companion’s heard out by the roots, there was nothing to be done except for her to sit with her cheek close against his until some third person could manage to disentangle the ear-ring. While she was in this painful position—at least she said at the time that it was painful—a sleigh containing two of her deacons and a prominent Baptist drove by. Miss Marsh saw them and saw the horrified expression on their faces. She knew quick enough that her usefulness as a minister in New Berlinopolisville was at an end and that there was going to be a terrible scandal. So, being a woman, she burst into tears and said that she wished she were dead.

“But the lawyer was equal to the occasion. He told her that there was nothing left to be done except for them to be married and disentangled at the next town. Then he would take her on a long wedding-trip, stopping at[79] Chicago to buy some clothes, and that if she so wished they would afterward settle in some other town, instead of coming back to New Berlinopolisville. Of course she said that the proposal was not to be thought of for a moment, and of course she accepted it within the next ten minutes. They drove to the house of the nearest minister, and the minister’s wife disentangled them, to save time, while the minister was engaged in marrying them.

“That was the end of the experiment of playing a woman-preacher on the boards of the First Methodist Church of Berlinopolisville. Everybody was content to call a man in the place of Miss Marsh, and everybody agreed to blame me for the failure of the experiment. I don’t know whether the lawyer ever had any reason to regret his marriage or not, but when I saw his wife at a fancy dress hall at Chicago, a year or two later, I could see that she was not sorry that she had given up the ministry. Ever since that time I have been opposed to women-preachers, and consider a woman in the pulpit as much out of place as a deacon in the ballet.”

“Do I believe in spiritualism?” repeated the Colonel. “Well, you wouldn’t ask me that question if you knew that I had been in the business myself. I once ran a ‘Grand Spiritual Combination Show.’ I had three first-class mediums, who did everything, from knocking on a table to materializing Napoleon, or Washington, or any of your dead friends. It was a good business while it lasted, but, unfortunately, we showed one night in a Texas town before a lot of cowboys. One of them brought his lasso under his coat, and when the ghost of William Penn appeared the cowboy lassoed him and hauled him in, hand over hand, for further investigation. The language William Penn used drove all the ladies out of the place, and his want of judgment in tackling the cowboy cost him all his front teeth. I and the other mediums[81] and the doorkeeper had to take a hand in the manifestation, and the result was that the whole Combination was locked up over-night, and the fines that we had to pay made me tired of spiritualism.

“No, sir! I don’t believe in spiritualism, but for all that there are curious things in the world. Why is it that if a man’s name is Charles G. Haseltine he will lose his right leg in a railway accident? The police some years ago wanted a Charles G. Haseltine with a wooden right leg in the State of Massachusetts, and they found no less than five Charles G. Haseltines, and every one of them had lost his right leg in a railway accident. What makes it all the more curious is that they were no relation to one another, and not one of them had ever heard of the existence of the others. Then, will someone tell me what is the connection between darkies and chickens? I say ‘darkies’ instead of ‘niggers’ because I had a colored regiment on my right flank at the battle of Corinth, and that night I swore I would never say ‘nigger’ again. However, that don’t concern[82] you. What I meant to say was that there is a connection between darkies and chickens which nobody has ever yet explained. Of course no darky can resist the temptation to steal a chicken. Everybody knows that. Why, I knew a colored minister who was as honest a man as the sun ever tried to tan—and failed—and I have known him to preach a sermon with a chicken that he had lifted on his way to meeting shoved up under his vest. He wouldn’t have stolen a dollar bill if he was starving, but he would steal every chicken that he could lay his hands on, no matter if his own chicken-house was crowded with chickens. It’s in the blood—or the skin—and no darky can help it.

“What was I going to say about the connection between darkies and chickens? I had very nearly forgotten it. This was what I was referring to. A chicken will draw a darky just as a dead sheep will draw vultures in Egypt, though there may have been no vultures within twenty miles when the sheep was killed. You may be living in a town where there isn’t a single darky within ten miles, but if you put[83] up a chicken-house and stock it there will be darkies in the town within twenty-four hours, and just so long as your chicken-house has a chicken in it fresh darkies will continue to arrive from all sections of the country. This beats any trick that I ever saw a spiritual medium perform, and I can’t see the explanation[84] of it. You may say that some one carries word to the darkies that there is a new chicken-house waiting to be visited, but the answer to this is that it isn’t true. My own idea is that it is a matter of instinct. When you carry a cat twenty miles away from home in a bag and let her out, we all know that her instinct will show her the way home again before you can get there yourself. Just in the same way instinct will draw a darky to a chicken-house he has never seen or heard of. You’ll say that to talk about instinct doesn’t explain the matter. That is true enough, but it makes you feel as if you had struck the trail, which is some satisfaction at any rate. So far as I can see, that is about all that scientific theories ever do.

“PREACH A SERMON WITH A CHICKEN UNDER HIS VEST.”

“If you care to listen, I’ll tell you what happened within my knowledge in connection with darkies and chickens. I was located a little after the war in the town of South Constantinople, in the western part of Illinois, and my next-door neighbor was Colonel Ephraim J. Hickox, who commanded the 95th Rhode Island Regiment. The town was a growing place, and[85] it had the peculiarity that there wasn’t a darky in it. The nearest one lived over at West Damascus, seven miles away, and there was only two of him—he and his wife. Another curious thing about the place was the scarcity of labor. There weren’t above a dozen Irishmen in the place, and they wouldn’t touch a spade or a hoe under three dollars a day, and wouldn’t work more than four days in a week. You see, a certain amount of digging and gardening had to be done, and there wasn’t anybody to do it except these Irishmen, so they naturally made a good thing of it, working half the time and holding meetings for the redemption of Ireland the rest of the time in the bar-room of the International Hotel.

“One day Colonel Ephraim, as I always used to call him, wanted to drain his pasture lot, and he hired the Irishmen to dig a ditch about a quarter of a mile long. They would dig for a day, and then they would knock off and attend to suffering Ireland, till Ephraim, who was a quick-tempered man, was kept in a chronic state of rage. He had no notion of going into politics,[86] so he didn’t care a straw what the Irishmen thought of him, and used to talk to them as free as if they couldn’t vote. Why, he actually refused to subscribe to a dynamite fund and for a gold crown to be presented to Mr. Gladstone, and you can judge how popular he was in Irish circles. I used to go down to Ephraim’s pasture every once in a while to see how his ditch was getting along, and one afternoon I found the whole lot of Irishmen lying on the grass smoking instead of working, and Ephraim in the very act of discharging them.

“‘Perhaps it’s “nagurs” that you’d be preferring,’ said one of the men, as they picked themselves up and made ready to leave.

“‘You bet it is,’ said Ephraim, ‘and, what’s more, I’ll have that ditch finished by darkies before the week is out.’ This seemed to amuse the Irishmen, for they went away in good spirits, in spite of the language that had been hove at them, and it amused me too, for I knew that there were no darkies to be had, no matter what wages a man might be willing to pay. I said as much to Ephraim, who, instead of taking it[87] kindly, grew madder than ever, and said, ‘Colonel! I’ll bet you fifty dollars that I’ll have that ditch finished by darkies inside of four days, and that they’ll do all the digging without charging me a dollar.’

“‘If you’re going to send over into Kentucky and import negro labor,’ said I, ‘you can do it, and get your ditch dug, but you’ll have to pay either the darkies or the contractor who furnishes them.’

“‘I promise you not to pay a dollar to anybody, contractor or nigger. And I won’t ask anybody to send me a single man. What I’m betting on is that the darkies will come to my place of their own accord and work for nothing. Are you going to take the bet or ain’t you?’

“I didn’t hesitate any longer, but I took the bet, thinking that Ephraim’s mind was failing, and that it was a Christian duty in his friends to see that if he did fool away his money, it should go into their pockets instead of the pockets of outsiders. But, as you will see, Ephraim didn’t lose that fifty dollars.

“Early the next morning Ephraim had a[88] couple of masons employed in turning his brick smoke-house into a chicken-house, and he had two dozen chickens with their legs tied lying on the grass waiting for the chicken-house to be finished. The masons broke a hole through the side of the house and lined it with steel rods about four feet long, which Ephraim had bought to use in some experiments in gun-making that he was always working at. The rods were set in a circle which was about a foot and a half wide at one end and tapered to about four inches at the other end. The arrangement was just like the wire entrance to a mouse-trap, of the sort that is meant to catch mice alive and never does it. It was nothing less than a darky-trap, although Ephraim pretended that it was a combined ventilator and front door for the chickens. The masons, so far as I could judge, thought that Ephraim’s mind was going fast, and I made up my mind that it would be a sin to let the man bet with anybody who would be disposed to take advantage of his infirmity.

“‘DUNNO!’”