Please see the Trascriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The Rural Science Series

Edited by L. H. Bailey

THE FARMSTEAD

BY

ISAAC PHILLIPS ROBERTS

Director of the College of Agriculture and Professor of Agriculture in

Cornell University; author of “The Fertility of the Land”

FIFTH EDITION

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd.

1910

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1900

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

Set up and electrotyped January, 1900

Reprinted August, 1902; January, 1905;

August, 1907; June, 1910

Mount Pleasant Press

J. Horace McFarland Company

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

[v]

| CHAPTER | PAGES | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Rural Homes | 1-11 |

| II. | The Farm as a Source of Income | 12-42 |

| III. | Educational Opportunity on the Farm | 43-53 |

| IV. | Selection and Purchase of Farms | 54-64 |

| V. | The Relation of the Farmer to the Lawyer (By Hon. DeForest VanVleet) | 65-73 |

| VI. | Locating the House | 74-86 |

| VII. | Planning Rural Buildings | 87-131 |

| VIII. | Building the House—General Lay-out | 132-157 |

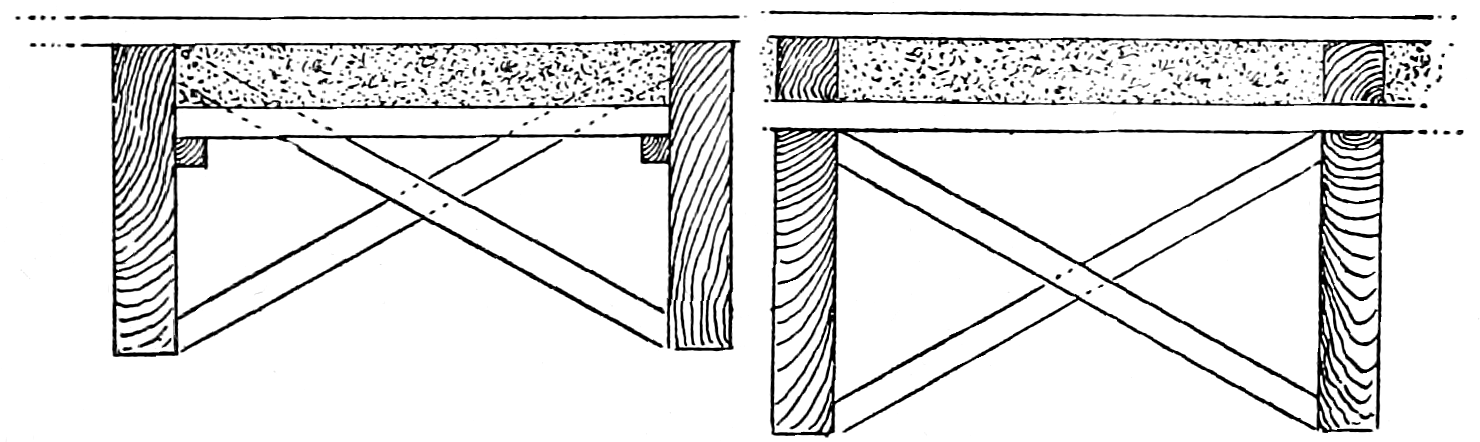

| Building the Foundations | 138 | |

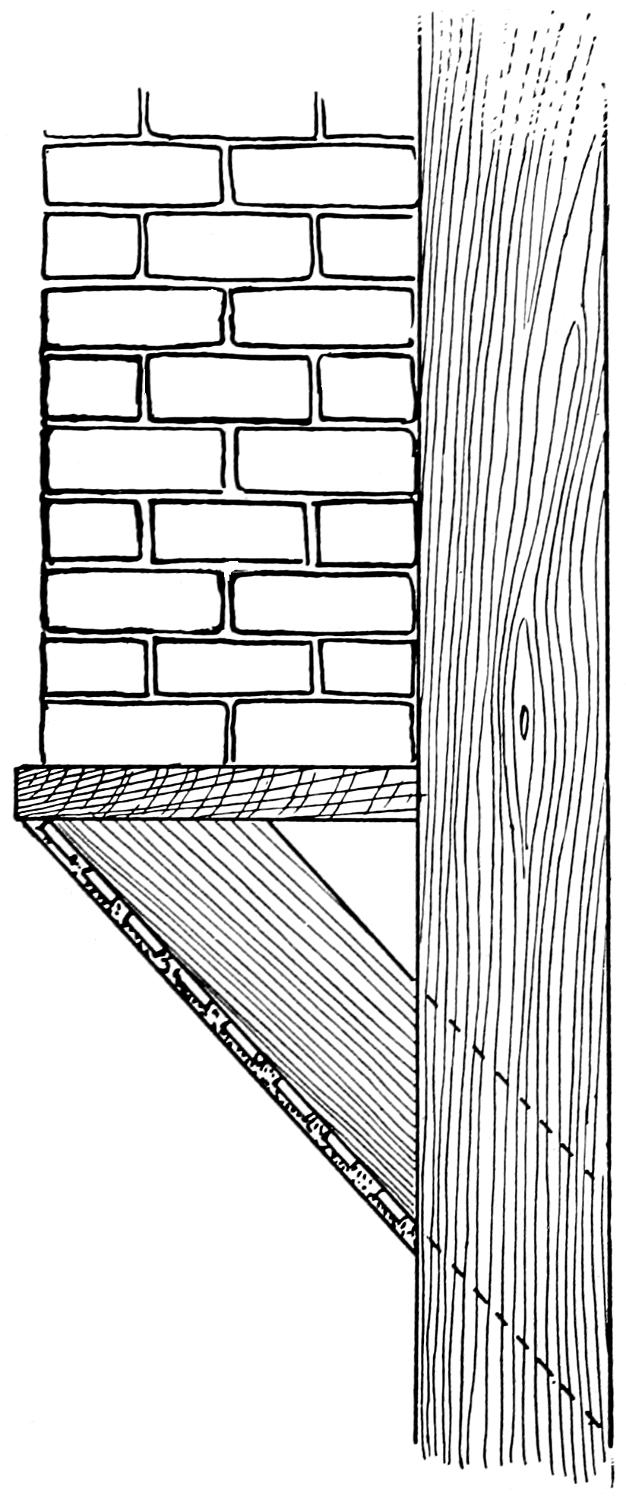

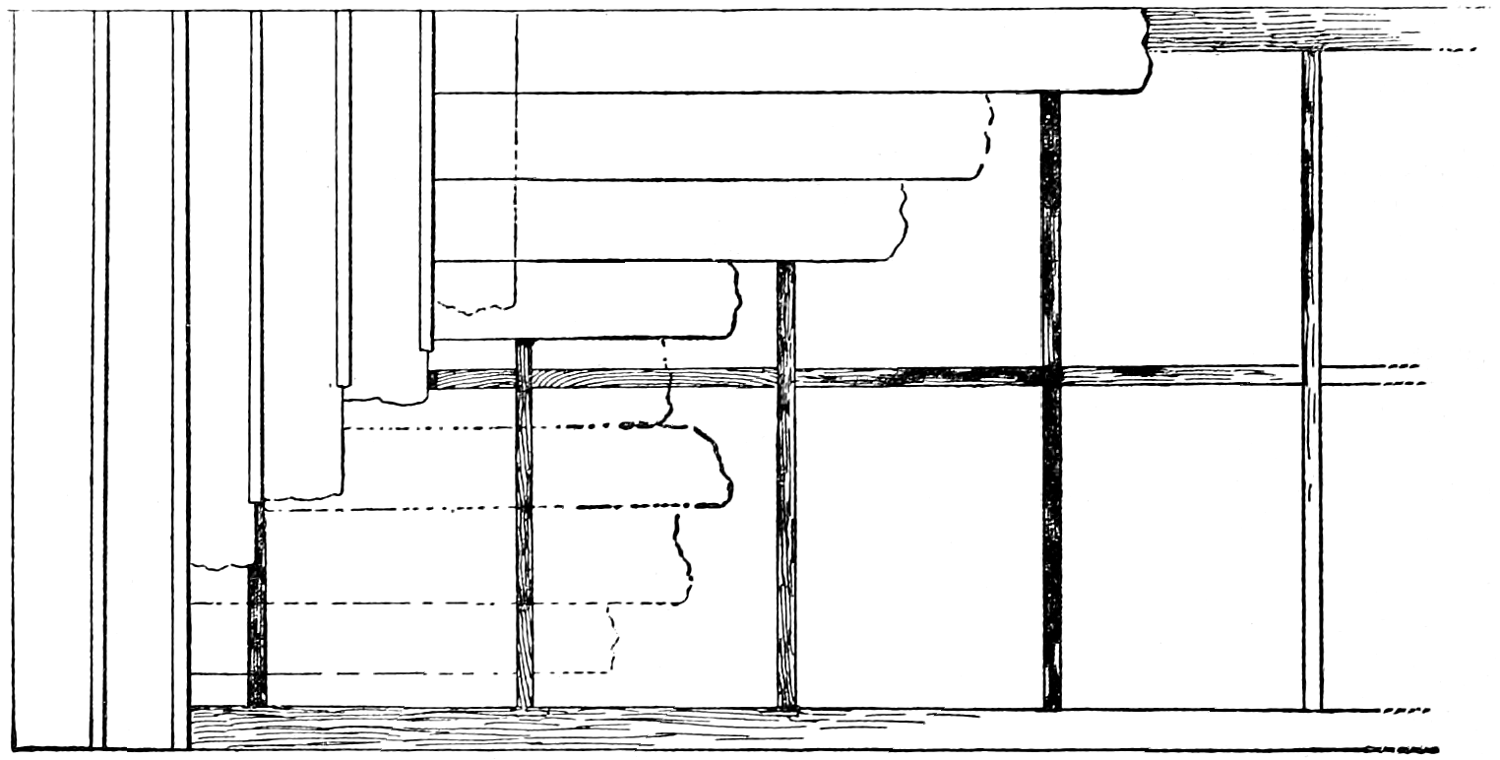

| Wooden Houses—The Frame | 142 | |

| IX. | Building the House, Concluded—Outside Covering, Painting | 158-180 |

| Veneered Houses | 168 | |

| Old Houses | 170 | |

| Painting the House | 173 | |

| X. | Inside Finish, Heating, and Ventilation | 181-192 |

| Heating and Ventilation | 190 | |

| XI. | House Furnishing and Decoration (By Professor Mary Roberts Smith) | 193-203 |

| XII. | Cleanliness and Sanitation—Water Supply and Sewage (By Professor Mary Roberts Smith) | 204-223 |

| Water Supply and Sewage | 217 | |

| XIII. | Household Administration, Economy, and Comfort (By Professor Mary Roberts Smith)[vi] | 224-236 |

| XIV. | The Home Yard (By Professor L. H. Bailey) | 237-248 |

| XV. | A Discussion of Barns | 249-265 |

| Location | 255 | |

| Planning the Barn | 259 | |

| Water Supply | 261 | |

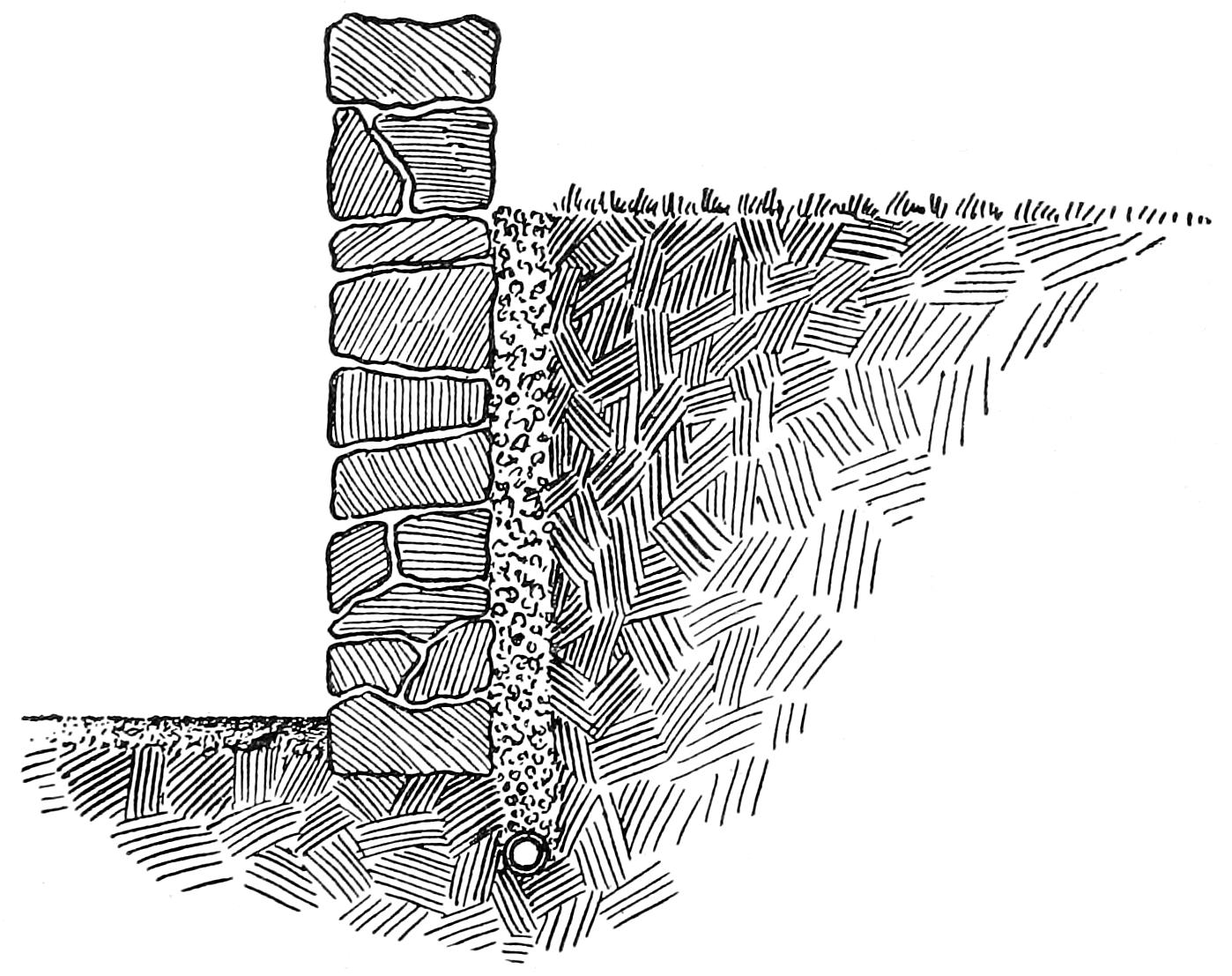

| XVI. | Building the Barn—The Basement | 266-287 |

| Excavation | 268 | |

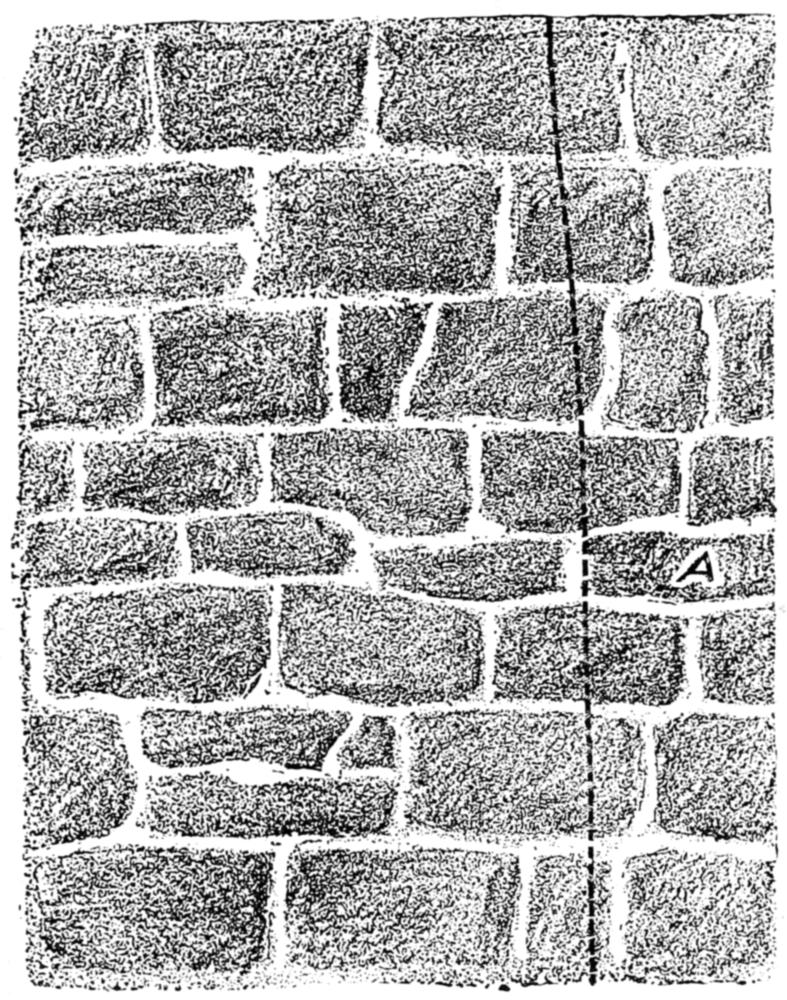

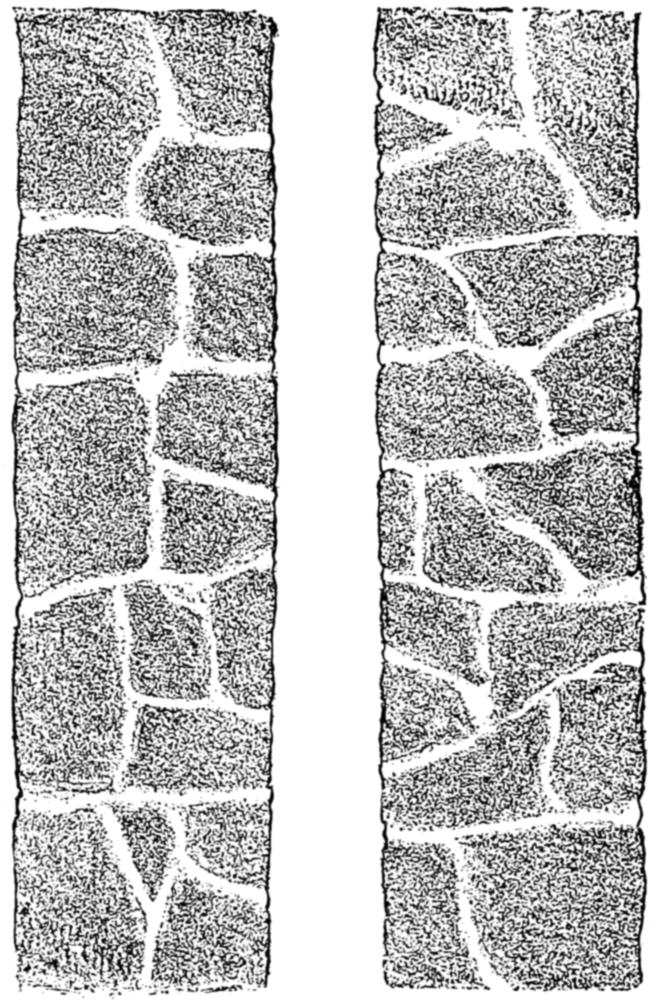

| Walls | 271 | |

| Floors | 277 | |

| Stalls | 280 | |

| Mangers and Ties | 285 | |

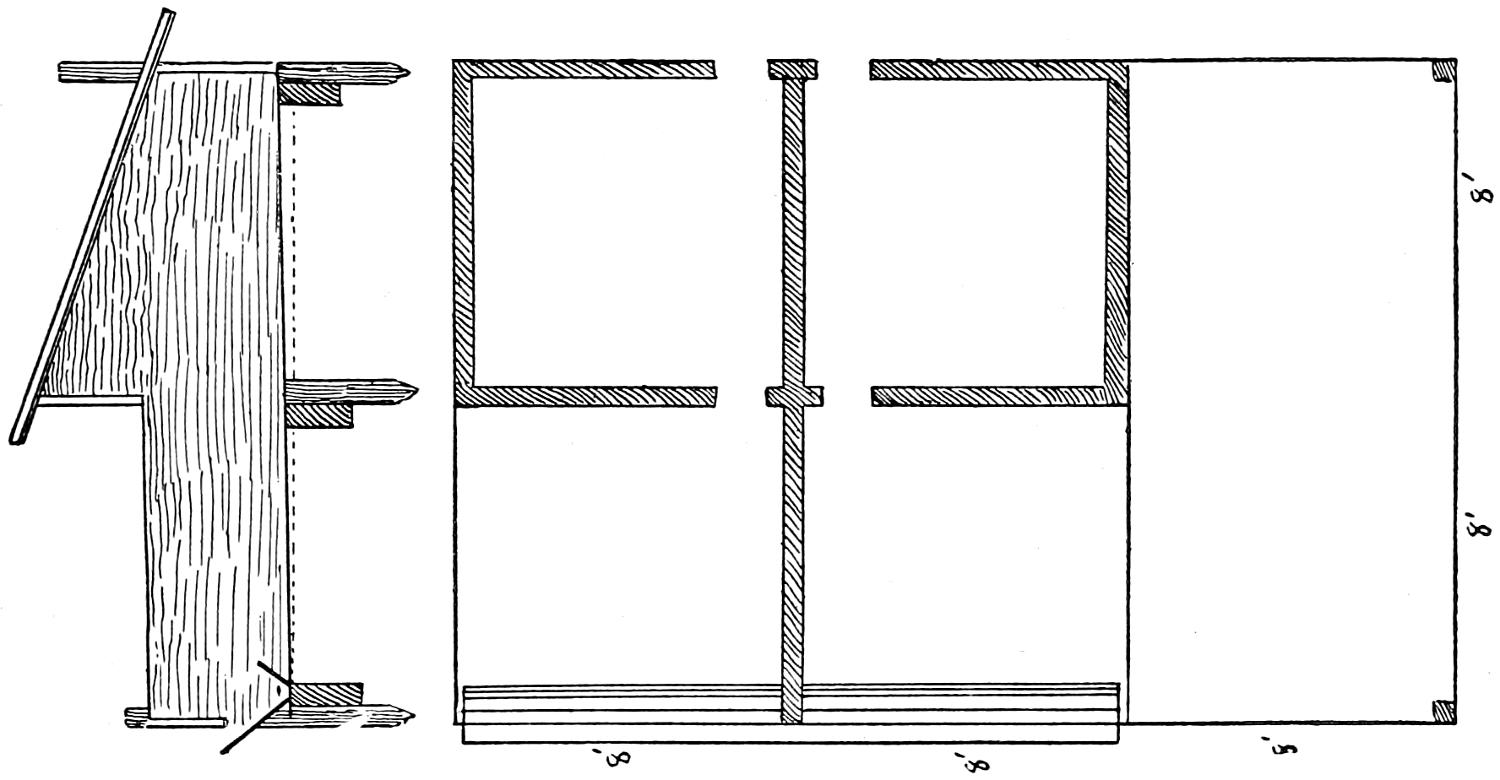

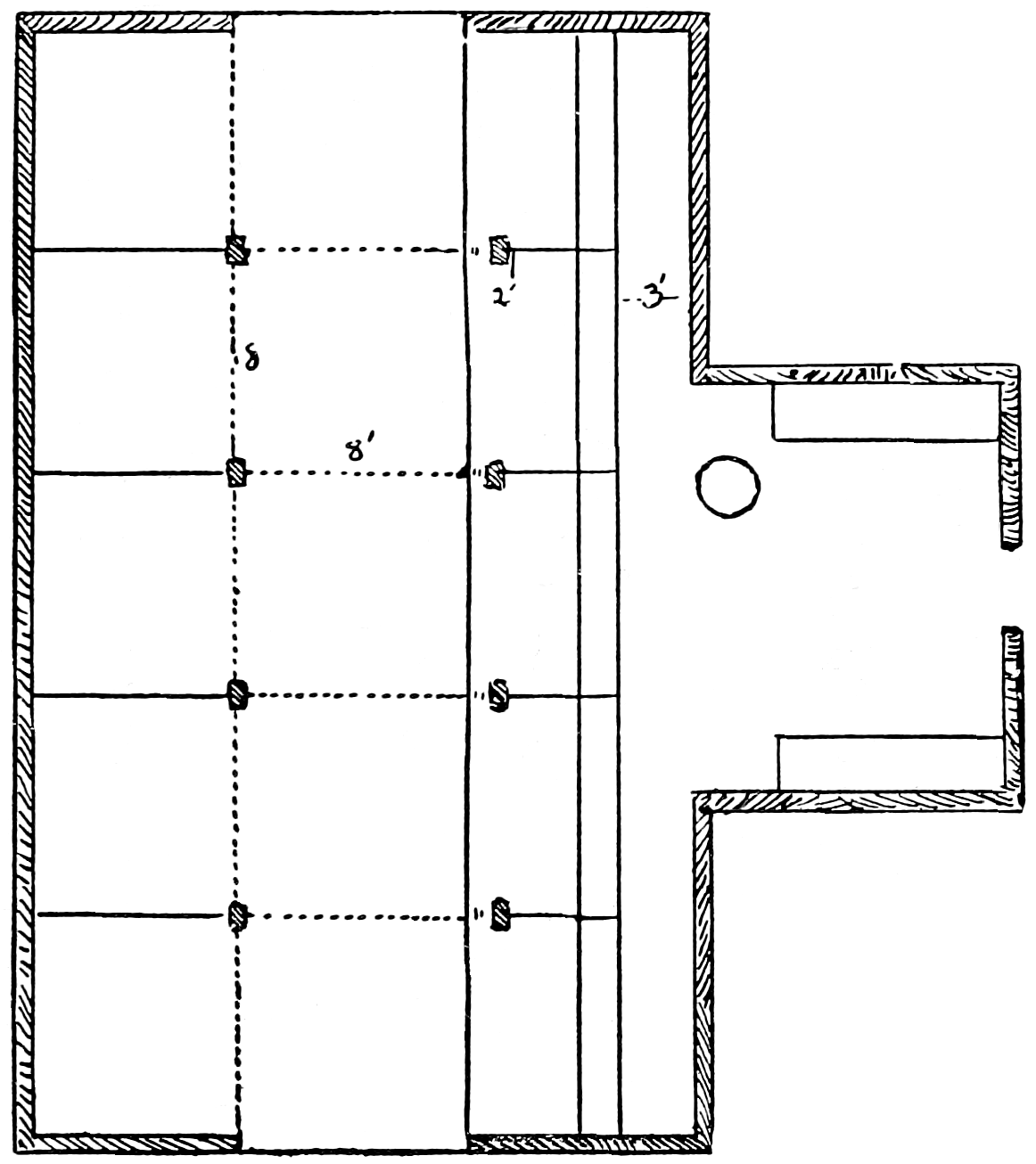

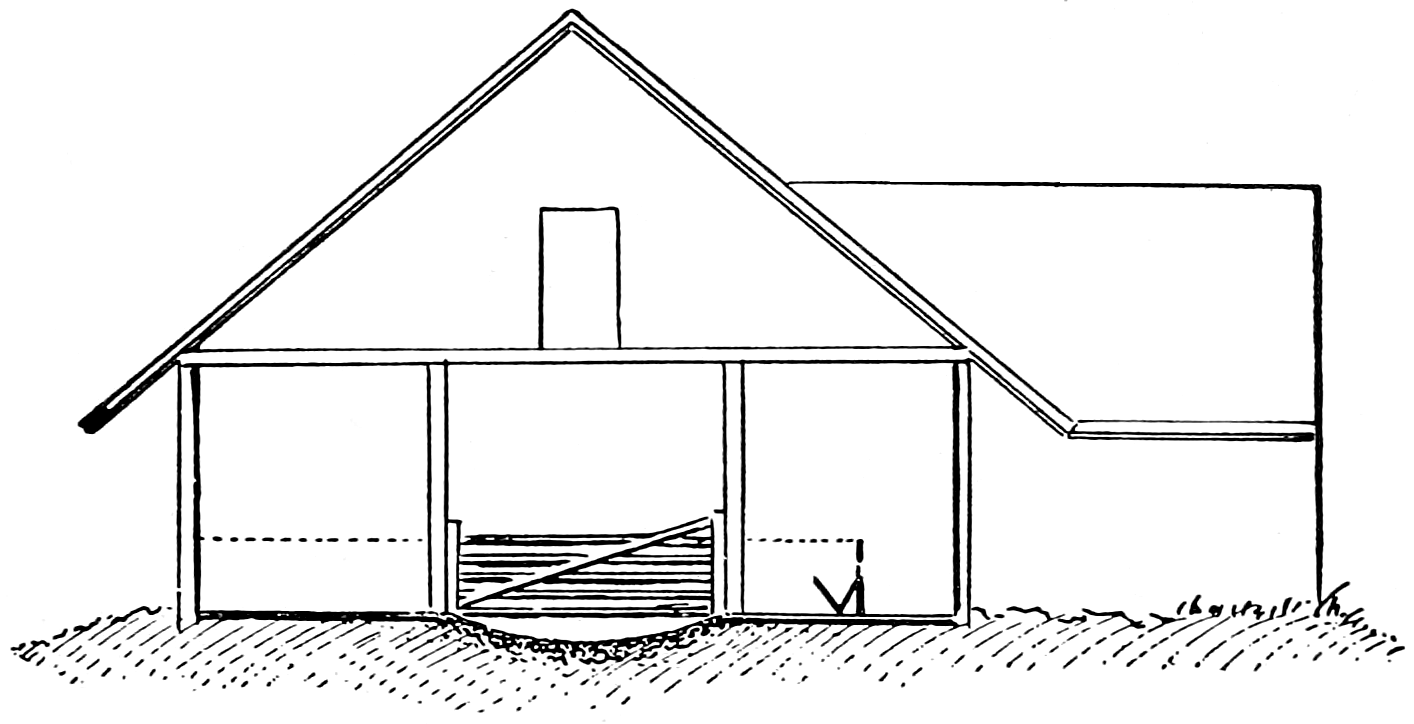

| XVII. | Building the Barn—The Superstructure | 288-297 |

| XVIII. | Remodeling Old Barns | 298-305 |

| XIX. | Outbuildings and Accessories | 306-320 |

| Poultry Houses | 306 | |

| Piggeries | 311 | |

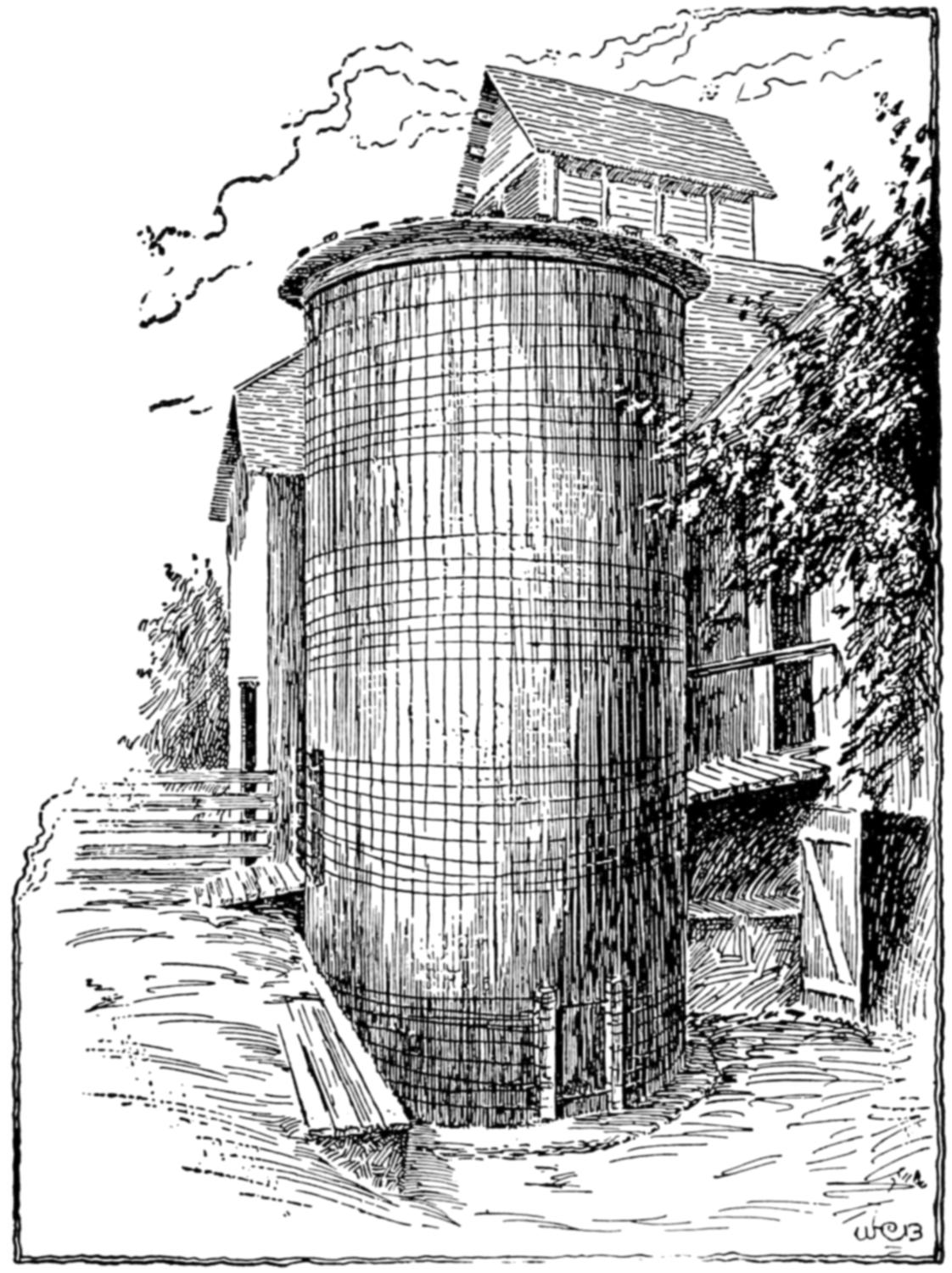

| The Silo | 316 | |

| XX. | Lightning Protection (By H. H. Norris, M.E.) | 321-335 |

| Metal Roofs | 324 | |

| Protecting Wooden Roofs | 326 | |

| XXI. | The Fields | 336-345 |

| Fences | 336 | |

| Orchards | 340 | |

| Farm Garden | 341 | |

| Index | 346 | |

THE FARMSTEAD

[1]

Man is made partly by heredity, partly by environment; both may be controlled and modified to a far greater extent than is generally supposed. In speaking of farm life, its disadvantages are frequently emphasized, while its possible advantages as an environment for the development of the finest quality of human nature are as often ignored or overlooked.

Nature, with her ever-varying form and color, beauty and symmetry, is forgotten in the city; the shady forest, the meadow brook, the waving fields, are unknown. There, instead, is incessant noise, the clang and clash of trade, towering and ugly buildings, skies darkened by the smoke of factories, children who never saw a tree or played elsewhere than upon a hard and filthy pavement; and worst of all is the nerve-destroying haste and unequal competition, wearing out[2] body and soul. In rural life, however tame and lonely, the home is not merely a few square feet hedged in by brick walls, but the whole wide countryside: the barns, the fields, the woods, the orchards, the animals wild and domesticated, the outlook over hill and valley—these all constitute the farmer’s home.

The manufacturer locates his factory in some by-street or suburb where land is cheap, and as far as possible from the residence part of the city; his home is far removed from these unsightly surroundings. But the farmer must live within a few hundred feet of his barns and outbuildings, and if these be ugly and dirty, the beauty and comfort of the home are sadly marred. If the farmer, then, has the whole landscape as a background for his home, he must on the other hand modify his immediate surroundings so as to overcome their almost inevitable unsightliness.

Besides the ever-present beauties of nature, country life has certain other advantages over the city: it is the place to develop the strong health-physique. The luxury of rich and populous communities tends to produce puny and enervated citizens; the excessive toil, bad air, limited space and scant food of the poor tend to degrade and destroy body and soul; but the comfortable simplicity, space, air, sunlight and[3] abundant food of the open country give opportunity for the finest development of the human animal. It is true that even on the farm there are sometimes overwork and privation; but, at the worst, these cannot be so severe as in cities so long as the sun shines, the wind blows, and green things grow for the worker out of doors. Here the child may be born right and nourished by pure food and air. It is surrounded by animals whose life and motion become an incentive to action, and who become its companions without danger of moral contamination. The lamb, the calf, the colt, are far safer playmates than the city urchin precociously wise in evil ways.

Professor Amos G. Warner says that “children reared in institutions are much below par because they lack the power of initiative.” The farm child has an incessant, varied and unconscious training of the eye, the hand, and the mind. While he is developing strength, symmetry, courage, the mental is being coördinated with the physical. The hand is made to obey the will, while the fact that the handicraft is made useful lends charm and delight to the work. The city child must try to learn, by a course of manual training in some public school, what the country child picks up unconsciously in the natural process of play and work.

[4]

After half a century, I look back to one of the happiest moments of my life, when I presented my mother with a dove-tailed wooden flower box, painted bright red. That flower box first taught me how to make wood take the form desired. While the flower box has long since rotted, the board-runner sled smashed, the water wheel broken, and the boat lies rotten in the bottom of the lake, the time spent upon them was not thrown away, for they gave me the inspiration and power to “boss” wood, and this power has served me well in many an emergency.

As knowledge begins to dominate the hand and train it to change the form and character of things, certain physical laws are discovered. If the sail is made too large or the boat too narrow, a cold bath is the result. If the sled runners are too short and rough, the school-mate arrives at the bottom of the hill first. No schoolmaster was needed, for when one of these natural laws was broken or ignored, the penalty followed quickly and with full force. So, in a thousand ways, the youth is taught respect for the laws which govern matter. All this leads the youth on the farm, if full play and direction are given, to investigate everything in sight, to discover that there are other than physical laws. The higher laws puzzle him greatly,[5] give him much concern, lead to doubts, for they are too abstract and too far-reaching for his youthful comprehension. The physical laws have been found by experience to be ever true and stable, and the youth cannot but believe that moral and spiritual laws are equally so. This is the sheet anchor which holds him to belief in them, however imperfectly he may understand them. He is anxious to investigate, even to experiment along these lines, but is disappointed because the results cannot be set down in pounds or feet or units of energy. If here on the farm the mental and physical have been kept healthy and active, the moral and spiritual will develop as naturally as the fruit from the blossom. The development of spiritual fruit to high perfection is slow, because the power to think and reason correctly and abstractly comes only with age, experience and mental development.

But the greatest advantage of country life lies in the opportunity for the promotion of healthy family relations. Parents naturally find their chief happiness in the education and development of their children; and in time the children stimulate the parents. The sharing of common labors from babyhood up, the working together for common interests and ambition, which farm life especially entails, produce the most wholesome[6] family relations. The most valuable part of any person’s education is really in the home. To “help father and mother” becomes the keynote of a child’s life, and unselfish, willing service is the first and last and best lesson of morality and religion. The pride in honest and capable ancestors, the natural and wholesome ambition for the future of the children, fill up a measure of contentment difficult to find elsewhere. In such a family there need be nothing to conceal; life takes on dignity in place of affectation, honesty instead of sham; it has simplicity, pure affections, fidelity. Artificial sex distinctions disappear; men and women may do that which is needful and human, the woman in the field, the man in the house, if desirable, sharing their common, healthful activities.

All this is very well, some will say, but how shall such a home be maintained on the income of the farm? “Farming doesn’t pay.” This statement is unverified, and, carrying on its face, as it does, a little truth, is misleading. Does farming pay? Does anything pay? What is pay? All depends upon how you value the currency in which the pay is received. Is “wisdom better than rubies?” Are the sayings of the wisest and best of men true? “Give me neither riches nor poverty. Get wisdom, get understanding. Take fast hold of instruction.”

[7]

A modern thinker, Professor L. H. Bailey, in the report of the Secretary of the Connecticut Board of Agriculture, 1898, puts it in this wise: “But there is another cause of apprehension which I ought to mention, perhaps founded upon the probable tendencies of our sociological and economic conditions, especially as they apply to rural communities. There is a tendency towards a division of estates as population increases, and the profits of farming are often so small that educated tastes, it is thought, cannot be satisfied on the farm. There are those who believe that because of these two facts we are ourselves drifting towards an American peasantry. Let us take the second proposition first,—that the profits of farming are so small that educated tastes cannot be satisfied and gratified on the farm. Now I grant this to be true if the measure of the satisfaction of an educated taste is money; but I deny it most strenuously if the satisfaction of an educated taste lies in a purer and better life. We must make this distinction very deep and broad, for it is a fundamental one. I believe we have made a mistake in teaching agriculture, during the last few years, by putting the emphasis on the money we make out of it. I do not believe that people are to become wealthy on the farm, as a few do in manufacturing; I should not hold out that hope to men.[8] There are certain men here and there who have great executive ability, who see the strategic points and take advantage of them, who can make a success of farming the same as they would at the making of shoes, or harnesses, or buttons, or anything else. But as a general thing, the farmer should be taught that the farm is not the place to become wealthy. I do not believe it is. Certainly I should not go on the farm with that idea in view. But if I wanted to live a happy life, if I wanted to have at my command independence and the comforts of living, I do not know where I could better find them than on the farm; for those very things which appeal to an educated taste are the things which the farmer does not have to buy,—they are the things which are his already.”

The wealthy few of the cities give voice to the thought that the farming classes in the United States are always on the verge of poverty, yet in the last century they have rescued from barbarism and solitude nearly all of the arable land of the two billion acres of which the United States are composed. More than four million five hundred thousand farm homes have been planted, valued at more than thirteen billion dollars. Much hue and cry has been raised of late about farm mortgages. If the facts were known, it is more than probable that[9] the farmers, as a whole, have assets in mortgages, promissory notes and savings banks amply sufficient to liquidate all such outstanding obligations. Added to the real estate, the farmers own implements and machines valued at five hundred millions of dollars, and their live stock, upon ten thousand hills, numbers one hundred and seventy-five millions, valued at more than two billions of dollars, while the annual value of the farm products is between two and three billions of dollars. It should be remembered that these values are nominal, the true value being in most cases more than double these amounts. The farmers are not now in danger of becoming paupers. From the farms come more than half of the college students. At the present time it is probable that the income of the farmers exceeds three billion dollars annually. When it is considered that there is little or no direct outgo for rent of house, and that nearly three-fourths of the food is produced at home, and that these items are seldom taken into account in the statistics of income, it appears that the farmer’s real income is much larger than is usually estimated in money. In other words, a five hundred dollar net income on the farm, under the conditions which now prevail, provides for a more comfortable living than does a thousand dollars in the city.

[10]

But these results of the labors of the farmer as set forth in figures, tell but half the story, for nothing is said in these census reports of an empire redeemed, of the thousands upon thousands of miles of road constructed, of rivers spanned, of the school house by every roadside, or of the church spires which mark the progress of agriculture and civilization in countryside, in village and in hamlet. The census report does not give the number or value of the great men and noble women which the rural homes have produced, though they are the most valuable product of the farms. It says nothing about the perennial rural springs from which flow, in a never-ending stream, statesmen, divines, missionaries, teachers, students and business men. Although more than half of these life-giving energies of the nation and civilization come directly from the rural homes, the census report gives no clue by which the value of these, the nation’s wealth and power, can be ascertained.

Looking over all the trades and professions which are followed by civilized and barbarous peoples, none give opportunity for rearing the family under so nearly ideal conditions as does the profession of agriculture: none furnish such good conditions for rearing children and for developing them into strong, natural and useful men and women. Here, then, on[11] these broad acres of America, under the flag which we love, we are to help transform the rude surroundings of the pioneer and the slovenly homes of the careless into pure and beautiful nurseries of American citizenship. Having shown, in part, what a rural life has to offer to those who are trained to appreciate the beauties of nature and to obey her laws, and having shown that the average farmer always has an assured though modest income, and that the better farmers have an ample income for maintaining improved rural homes, the further discussion of how they may be made to minister to the natural longings for broader and more refined lives may be taken up.

[12]

If it cannot be shown that the profession of agriculture offers as good opportunities for securing, with a fair degree of certainty, what all should prize,—a beautiful and comfortable home and a modest surplus,—then this little volume will be for the most part useless and uncalled for, as the following chapters presuppose an income sufficient for maintaining a home, and for gratifying, in part at least, the simple, educated tastes of the better class of American farmers.

In “The Fertility of the Land” I attempted to set forth some fundamental principles which, if followed, should result in such increased incomes as to justify the present book. A comfortable home must be secured from the products of field and stable, with a reasonable expenditure of physical energy, or farming in its highest sense is a failure. In addition, farming must give fair opportunity for training and educating families, and for making provision for old age and unforeseen contingencies.

[13]

In the previous chapter the annual income of the farmer has been set forth, and, approximately, the accumulated earnings of the rural population. Unfortunately, we are so short-sighted that the present—the dollar—blunts the appreciation of the higher and more enduring values which spring from well conducted farms. This being so, of necessity much stress must be laid on immediate benefits which flow from a well ordered farm life. While it is not proposed to write here of the details of farm management along the lines of greatest financial results, yet something must be said, at least in general, about the methods most likely to produce the necessary competence.

A fairly liberal income and financial reserve give, or should give, some leisure. Leisure gives opportunity for study and recreation, without which life becomes one ever-revolving round of work, and results in producing an automatic animal. If this is to be avoided, far-reaching plans must be laid, energy directed into its most efficient channels, and time and resources economized. All this implies training and education directed, primarily, along the lines which broaden and ennoble, and those of the occupation to be followed.

For centuries, the higher education has been in the direction of the humanities, while educa[14]tion along technical and non-professional lines, until recently, has been conspicuous by its absence. Prior to the present century, what provision was made for coördinating the hands and intellects of the industrial classes? None at all. Is it any wonder, then, that the farmer and mechanic, until recently, received but meager rewards for their efforts?

All this is now changed. Already the industrial classes are enabled to secure far more of the necessaries and luxuries of life for a given period of work than could their ancestors. In every state and territory one or more colleges have been equipped and endowed to teach, among other things, “such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, ... in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions of life.” In addition to this provision, Congress gives to each state and territory $15,000 annually for conducting experiments and investigations in agriculture. In 1890 the Federal government supplemented the benefactions of 1862 by appropriating annually $15,000 to each of the Land Grant colleges; this sum has now been increased and finally fixed at $25,000, for the purpose of strengthening the departments of agriculture and mechanic arts. Most, if not[15] all, of the states have made additional appropriations for agriculture, in some cases very liberal ones. At first, there was a strong prejudice against these colleges devoted to the improvement of the industries and those engaged in them, but this has nearly disappeared.

A broader view of education now prevails than formerly. The modern colleges and universities think it not undignified to offer other than four year courses of study preceded by difficult entrance requirements. Many courses of from six weeks to one or two years are now open to those who prize knowledge above a diploma. Most of these courses are given at such seasons of the year as best suit the pupils. In America all doors which lead to knowledge have at last been opened, and all earnest students may enter and find teachers awaiting them. The effect of the recent changes in college courses has been most marked and beneficial. Many of the colleges have, as far as possible, adopted the words of the founder of Cornell University: “I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study.”

The following data show the incomes of the United States Land Grant colleges for the year ending June 30, 1897. The table is condensed from one recently published by the United States Department of Agriculture:

[16]

Income of the U. S. Land Grant Colleges for the Year Ending June 30, 1897

| States and Territories |

Interest on Land Grant of 1862 |

Interest on Other Funds |

U. S. Appropri- ations, Act of 1890 |

State Appropri- ations |

Miscella- neous |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama (Auburn) | $20,280.00 | ... | $12,012.00 | $8,746.83 | $2,821.20 | $43,860.03 |

| Alabama (Normal) | ... | ... | 9,988.00 | 4,000.00 | 16,898.44 | 30,886.44 |

| Arkansas (Fayetteville) | 10,400.00 | ... | 16,000.00 | 26,911.00 | 1,200.00 | 54,611.00 |

| Arkansas (Pine Bluff) | ... | ... | 6,000.00 | ... | 418.25 | 6,418.25 |

| California (Berkeley) | 43,619.33 | ... | 22,000.00 | 133,415.46 | 12,180.48 | 311,212.45 |

| Colorado (Fort Collins) | 3,238.99 | $109,997.18 | 22,000.00 | 38,892.01 | ... | 64,131.00 |

| Connecticut (Storrs) | 6,750.00 | ... | 22,000.00 | 26,800.00 | ... | 55,550.00 |

| Delaware (Newark) | 4,980.00 | ... | 17,600.00 | ... | 1,620.74 | 24,200.74 |

| Delaware (Dover) | ... | ... | 4,400.00 | 4,000.00 | ... | 8,400.00 |

| Florida (Lake City) | 9,107.00 | ... | 11,000.00 | 5,000.00 | 1,896.88 | 27,003.00 |

| Florida (Tallahassee) | ... | ... | 11,000.00 | 4,000.00 | ... | 15,000.00 |

| Georgia (Athens) | 16,954.00 | ... | 14,666.66 | 29,000.00 | 1,600.00 | 62,220.66 |

| Georgia (College) | ... | ... | 6,333.00 | ... | ... | 6,333.00 |

| Idaho (Moscow) | ... | ... | 22,000.00 | 6,000.00 | 339.80 | 28,839.80 |

| Illinois (Champlain) | 23,241.10 | 500.00 | 22,000.00 | 121,214.93 | 41,305.09 | 211,591.60 |

| Indiana (Lafayette) | 17,000.00 | 3,830.48 | 22,000.00 | 58,562.96 | 29,552.35 | 127,115.31 |

| Iowa (Ames) | 47,729.75 | ... | 23,000.00 | 37,232.10 | 49,397.49 | 157,359.34 |

| Kansas (Manhattan) | 50,689.50 | ... | 22,000.00 | 16,557.70 | 9,323.88 | 98,571.08 |

| Kentucky (Lexington) | ... | ... | 18,810.00 | 32,429.32 | 6,680.61 | 57,819.93 |

| Kentucky (Frankfort) | ... | ... | 3,190.00 | 5,000.00 | 76.00 | 8,266.00 |

| Louisiana (Baton Rouge) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| Louisiana (New Orleans) | ... | ... | 11,346.00 | 9,000.00 | 439.46 | 20,785.46 |

| Maine (Orono) | 5,915.00 | 4,000.00 | 22,000.00 | 20,000.00 | 20,001.13 | 71,916.13 |

| Maryland (College Park) | 6,142.30 | ... | 22,000.00 | 9,000.00 | 18,000.00 | 55,142.30 |

| Massachusetts (Amherst) | 7,300.00 | 3,820.23 | 14,666.66 | 15,000.00 | 1,920.00 | 42,706.89 |

| Massachusetts (Boston) | 5,896.00 | 35,000.00 | 7,666.67 | 25,000.00 | 253,076.23 | 318,638.90 |

| Michigan (Agricultural College) | 39,009.66 | 386.34 | 22,000.00 | 10,000.00 | 12,825.62 | 84,221.62 |

| Minnesota (St. Anthony Park) | 27,410.55 | 21,856.00 | 23,000.00 | 174,332.59 | 74,496.48 | 321,095.62 |

| Mississippi (Agricult’l College) | 5,914.50 | ... | 10,217.08 | 22,500.00 | 14,597.96 | 53,227.54 |

| Mississippi (West Side)[17] | 6,814.50 | ... | 11,000.00 | 7,000.00 | ... | 24,814.50 |

| Missouri (Columbia) | 16,100.00 | 6,469.58 | 20,804.02 | 3,762.34 | 5,022.73 | 52,158.67 |

| Missouri (Rolla) | 4,025.00 | 6,469.58 | 5,201.00 | 5,476.65 | 2,192.16 | 23,364.39 |

| Missouri (Jefferson City) | ... | ... | 1,195.98 | ... | ... | 1,195.98 |

| Montana (Bozeman) | ... | ... | 22,000.00 | 2,500.10 | 2,439.57 | 26,939.57 |

| Nebraska (Lincoln) | ... | ... | 22,000.00 | 123,572.50 | 7,801.53 | 153,374.03 |

| Nevada (Reno) | 4,464.89 | 1,803.55 | 22,000.00 | 16,250.00 | 327.35 | 44,845.79 |

| New Hampshire (Durham) | 4,800.00 | 3,880.50 | 23,000.00 | 5,500.00 | 1,148.00 | 40,328.50 |

| New Jersey (New Brunswick) | 6,644.00 | ... | 22,000.00 | ... | 21,170.37 | 49,814.37 |

| New Mexico (Mesilla Park) | ... | ... | 22,000.00 | 19,792.01 | 875.70 | 42,667.71 |

| New York (Ithaca) | 34,428.80 | 314,407.51 | 22,000.00 | 25,000.00 | 191,660.07 | 587,496.38 |

| North Carolina (West Raleigh) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| North Carolina (Greensboro) | ... | ... | ... | 12,500.00 | 157.92 | 12,657.92 |

| North Dakota (Agri. College) | ... | 392.96 | 22,000.00 | 27,000.00 | 3,446.62 | 52,839.58 |

| Ohio (Wooster) | 31,450.58 | 1,511.63 | 22,000.00 | 118,906.53 | 175,140.39 | 349,009.13 |

| Oklahoma (Stillwater) | ... | ... | 22,000.00 | 500.00 | 3,391.00 | 25,591.00 |

| Oregon (Corvallis) | 7,164.68 | ... | 22,000.00 | 1,854.79 | 1,342.37 | 32,361.84 |

| Pennsylvania (State College) | 25,637.43 | 5,382.57 | 22,000.00 | 45,000.00 | 8,340.27 | 106,360.27 |

| Rhode Island (Kingston) | 1,500.00 | 1,000.00 | 22,000.00 | 10,000.00 | 6,000.00 | 40,500.00 |

| South Carolina (Clemson College) | 5,754.00 | 3,512.36 | 11,000.00 | 54,053.29 | 700.00 | 75,019.65 |

| South Carolina (Orangeburg) | 5,000.00 | ... | 11,000.00 | 13,000.00 | 1.00 | 29,001.00 |

| South Dakota (Brookings) | ... | ... | 22,000.00 | 5,900.00 | 8,038.12 | 35,938.12 |

| Tennessee (Knoxville) | 23,760.00 | 1,650.00 | 22,000.00 | 1,674.00 | 7,271.89 | 56,355.89 |

| Texas (College Station) | 14,280.00 | ... | 16,500.00 | 22,500.00 | 9,361.39 | 62,641.39 |

| Texas (Prairieview) | ... | ... | 5,500.00 | 15,700.00 | 10,836.78 | 32,036.78 |

| Utah (Logan) | ... | ... | 22,000.00 | 22,000.00 | 5,811.83 | 49,811.83 |

| Vermont (Burlington) | 8,130.00 | 1,500.00 | 22,000,00 | 6,000.00 | 16,603.09 | 54,233.09 |

| Virginia (Blacksburg) | 20,658.72 | ... | 14,666.67 | 15,750.00 | 12,352.48 | 63,427.87 |

| Virginia (Hampton) | 10,329.36 | 30,264.61 | 7,333.33 | ... | 109,110.46 | 157,037.76 |

| Washington (Pullman) | ... | ... | 22,000.00 | 29,000.00 | ... | 51,000.00 |

| West Virginia (Morgantown) | 5,223.00 | 1,485.00 | 17,000.00 | 38,060.00 | 10,315.13 | 72,083.13 |

| West Virginia (Farm) | ... | ... | 5,000.00 | 14,500.00 | 600.00 | 20,100.00 |

| Wisconsin (Madison) | 12,250.00 | 14,000.00 | 23,000.00 | 285,000.00 | 47,000.00 | 381,250.00 |

| Wyoming (Laramie) | ... | ... | 22,000.00 | 7,425.00 | 775.59 | 30,200.59 |

| Total | $609,992.64 | $574,120.08 | $1,009,097.07 | $1,821,072.01 | $1,239,902.90 | $5,203,580.82 |

[18]

It has been thought strange that the farmers did not more quickly see and appreciate the valuable opportunities offered to their children. But why should they at once appreciate and value the princely provisions which were being made for them? With no opportunity for education along the lines of their profession, following a more or less despised calling, from being the butt and jest of those who had had educational advantages from time immemorial, how could they at once understand the value and far-reaching effects of the new order of things? Then, too, these liberal provisions were made somewhat in advance of the times. The pioneer must first redeem the land from the wilderness, fight the physical battles and endure the hardships of a new country. As soon as these primitive conditions passed away, the farmers made an effort to bring their profession up to a high intellectual plane and make it a delightful and honorable calling. The evolution from the primitive to the complex, from the age of toil to the age of thought, from excessive muscular effort to a more intelligent direction of energy, from the narrow and prejudiced to the broad and liberal, from the coarse and ugly to the refined and beautiful, is proceeding rapidly, and is in part realized. What happier task than to give direction and help, sympathy and encouragement[19] to these new-born desires! The part which the youths on the farm are taking in this evolution leads naturally to a higher intellectual plane, and hence to a more rational understanding and fuller comprehension of what the rural home should be. This desire to gratify the love for the true and beautiful, which has been growing up by reason of the better education, leads directly to the securing of an income sufficiently large to gratify the more refined and newly acquired tastes.

Taking the rural population as we find it, with added wants and new aspirations, and with a somewhat better understanding of the value of a more extended culture, it will be seen that a more rational system of agriculture, a more economic expenditure of energy, and a clearer comprehension of the highest and most economical use of money must be secured if the objects sought are attained. To secure the results desired, it must be shown how a competence can be secured without excessive toil, how the results of work may be put to the best uses, and lastly, but not least, it must be shown what is really valuable, what real, what substantial, what polite, what beautiful, what worthy of intelligent Americans. On the other hand, vulgar display must be shown to be vulgar, shoddy must be unmasked, the effect of aping the uncultured[20] rich set forth, and that which is unreal and that which goes for naught but vanity displayed under their true colors,—that comparisons may be made, and that truer conceptions of life, its duties and obligations, may be secured.

How may a competence be obtained? Briefly, by securing a knowledge of the laws which govern the business or undertaking entered into, and by conducting the business or undertaking in obedience to the modes of action or laws which apply to the specific case in hand. What are some of the dominant laws which should govern the farmer and farm practices? The farmer should specialize along those lines for which his taste and training, in part at least, fit him. To be more specific: A farmer will show you his potato patch with pride, but not a word will be said about his work animals and their offspring, which look like Barnum’s woolly horse. Then the first principle of agriculture is, follow up successes. In this case, the man has land and skill in potato culture which should lead him directly to success. Why not each year increase the output of potatoes, and let some horseman breed the horses? I have no ear or taste for music; why should I spend time in thrumming a piano and in making the life of my neighbors miserable? I love a bird and am interested in all its ways, its beauty and its life.[21] Why not study the birds, and let them make the music?

Much of life’s energy is spent in trying to adjust square pegs to round holes and round pegs to square holes, and life may be spent before the adjustment is complete. Modern civilization tends to specialization. Men vary as widely as do the stars. There is a place for everyone and some one to fill the place, if this great mass of unlike units can only be sorted and fitted into the complex problem of civilization.

The first question, and the question which should be repeated often is, What am I good for; what branch or branches of agriculture will give me the greatest pleasure and profit? Having answered this question, pursue the work through all discouragements to a successful issue. It is possible you have no capacity for farm life, and, since you cannot buy a capacity, better go directly to town and there fit yourself into your environment. I have known men to toil many years on a farm, and near the close of life to be driven to town by the sheriff. There they made not only a living, but secured a modest competence in conducting some little one-horse business, the profits or losses of which could be counted up every night. The farm, with all its complexities, with its profits and losses a year or five years in the future, was too large and[22] far-reaching for their narrow understandings. All are not so fortunate. Some remind us of the Quaker’s dog which he sold to his friend and recommended as a good coon dog. The dog proved to be a failure and was returned to the seller, who said, “I am much surprised. Thee believes that nothing was created in vain, does thee not, Ephraim?” “Most certainly I believe that the Creator made all things for some beneficent purpose.” “I, too, believe this, and I had tried that dog for everything else under the heavens but coons, so I was certain he must be a good coon dog.”

A competency is always in sight in this country for those who do well those things which are suited to their tastes and training. A competence may be secured by following those branches of farming which require the minimum of labor and the maximum of skill and training. My friend of Westfield, Mr. G. Schoenfeld, from Germany, has six acres of land, a part of which is covered with glass. He did that terrible thing,—ran in debt for the full purchase price of the land. It and the valuable improvements upon it are now paid for. His modest home is valued at $6,000. While paying for it a large family has been raised and educated, the eldest boy entering Annapolis Naval Academy with a high standing. It is possible that this[23] son will one day be acknowledged as the intellectual and social equal of the aristocracy of Germany should he ever visit the fatherland of his parents. But why this long account of a not infrequent occurrence? To show how it was done: This German, though untrained, succeeded from the first in producing superior carnations. He followed up his successes, and sold the product of brains instead of the fertility of his little farm. Mr. Schoenfeld sold in Buffalo during one year—October 1, 1896, to September 30, 1897—carnations (80,946 flowers) for the net sum, over commissions, of $719.08. The amount of plant-food removed by the 80,946 carnations was as follows:

| Nitrogen | Phosphoric acid | Potash | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 lbs. 4 ozs. | 2 lbs. 3 ozs. | 10 lbs. 8 ozs. | (valued at $1.32) |

The table below shows the amount of plant-food removed by 856 bushels of wheat, being the amount which, at 84 cents per bushel (the average price of wheat for the last ten years in central New York), would bring $719.08, the amount received for the carnations.

| Nitrogen | Phosphoric acid | Potash | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 904 lbs. | 437 lbs. | 298 lbs. | (valued at $158.34) |

In addition, 20,000 flowers used in making flower displays for weddings, and the like, were[24] sold at retail, by the dozen, for $450.80. The net returns for flowers sold during the fiscal year ending September 30, 1897, amounted to $1,169.88. The expenses, including taxes, insurance and 10 per cent on the capital, were $790.67. This includes the cost of raising 12,000 plants, about 6,000 of which netted $263.24. In round numbers, then, the net income from the one leading industry—flowers—after paying 10 per cent on invested capital, coal, commission and workmen’s bills, was $642.45, with an additional prospective income from the 6,000 plants which remained unsold.

When I last visited this gentleman, he informed me that he had all the land he wanted. Since that time he has purchased eight acres adjoining, has made some improvements upon the land, and now values it at $2,000. He stated incidentally that the reason he made his purchase was that the land was in the market, and he wanted control of it that he might choose his neighbor. The land, he says, is now in the market, although it paid 9 per cent, clear of all expenses, on a valuation of $2,000. The question is often discussed as to how much land is necessary to secure a competence. Here we find that six acres suffices. A large family has been fed chiefly from the products of the orchards, vineyard and garden, and the children[25] are receiving a practical and, in some cases, a liberal education. All this has been accomplished because the man quickly learned the value of scientific agriculture and was wise enough to follow up his successes.

Not only follow up success, but learn to do the difficult things; there will always be a throng seeking to do the easy things,—things which require the maximum of muscle and the minimum of brains. Why do such multitudes seek this hard, easy work? Because they will not consent to endure the toil, shall I say, of acquiring the power to think deeply, accurately and effectively. Some of our sympathy is thrown away upon these muscular workers. Their desires are few, their wants simple, their appetites good, and their sleep peaceful. Let us show them the way to a higher life, open the doors to those who choose to enter, and fret not because all will not enter in.

The man who fells the trees in the woods may receive 15 cents per hour; the man who controls the carriage of the great sawmill and decides on the instant what shape and dimensions the lumber shall take may receive 25 cents[26] per hour for simply moving a little lever; a third man causes a piece of the wood to take on the forms of beauty for the great staircase, and may receive 50 cents per hour; the fourth furnishes the design for this beautiful staircase, and may receive $1 an hour. The man who does the so-called “hard” work receives the least pay. Why? Because it is the least difficult. This difference of remuneration holds good on the farm. Mushrooms sell for 50 cents per pound; maize for one-half cent per pound. Why? Because anybody, even a squaw, can raise maize, but only a specially skilled gardener can succeed in mushroom culture. Hothouse lambs bring from $6 to $10 when two months old; a poorly bred sheep at two years of age may bring from $2 to $4. Why? The breeding and feeding of the one is easy; of the other difficult.

In 1897 the raising of potatoes was difficult. The blights, the bugs and the beetles were present in full force. Good potatoes in the middle and eastern states rose to 65 cents per bushel wholesale. The man who watched and fought intelligently secured 300 bushels per acre and a ready market; the careless man and the man who should have been raising horses or chickens secured 30 bushels per acre and a slow market. Why? Because unusual difficulties were present,[27] and the man who was able to cope with them drew the prize of $195 per acre for his potatoes. This successful potato raiser the previous year secured more than 300 bushels per acre, and sold them for 25 cents per bushel, but even at this low price they brought more than $75 per acre. If from 200 to 300 per cent profit can be secured and the limit of profit not reached by raising one of the most common products of the farm, what possibilities loom up for securing a competence from those products which require greater skill and knowledge than the raising of potatoes?

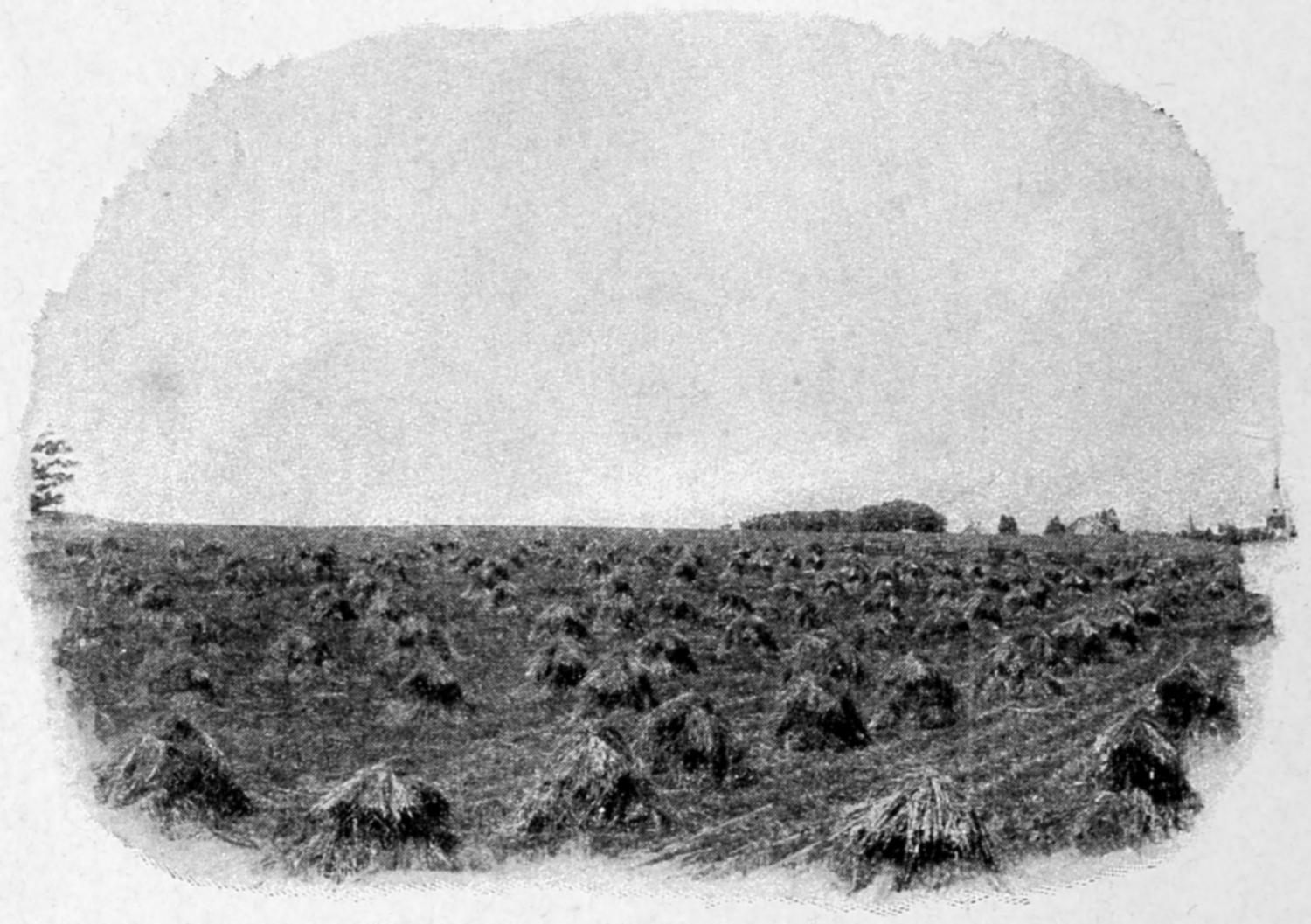

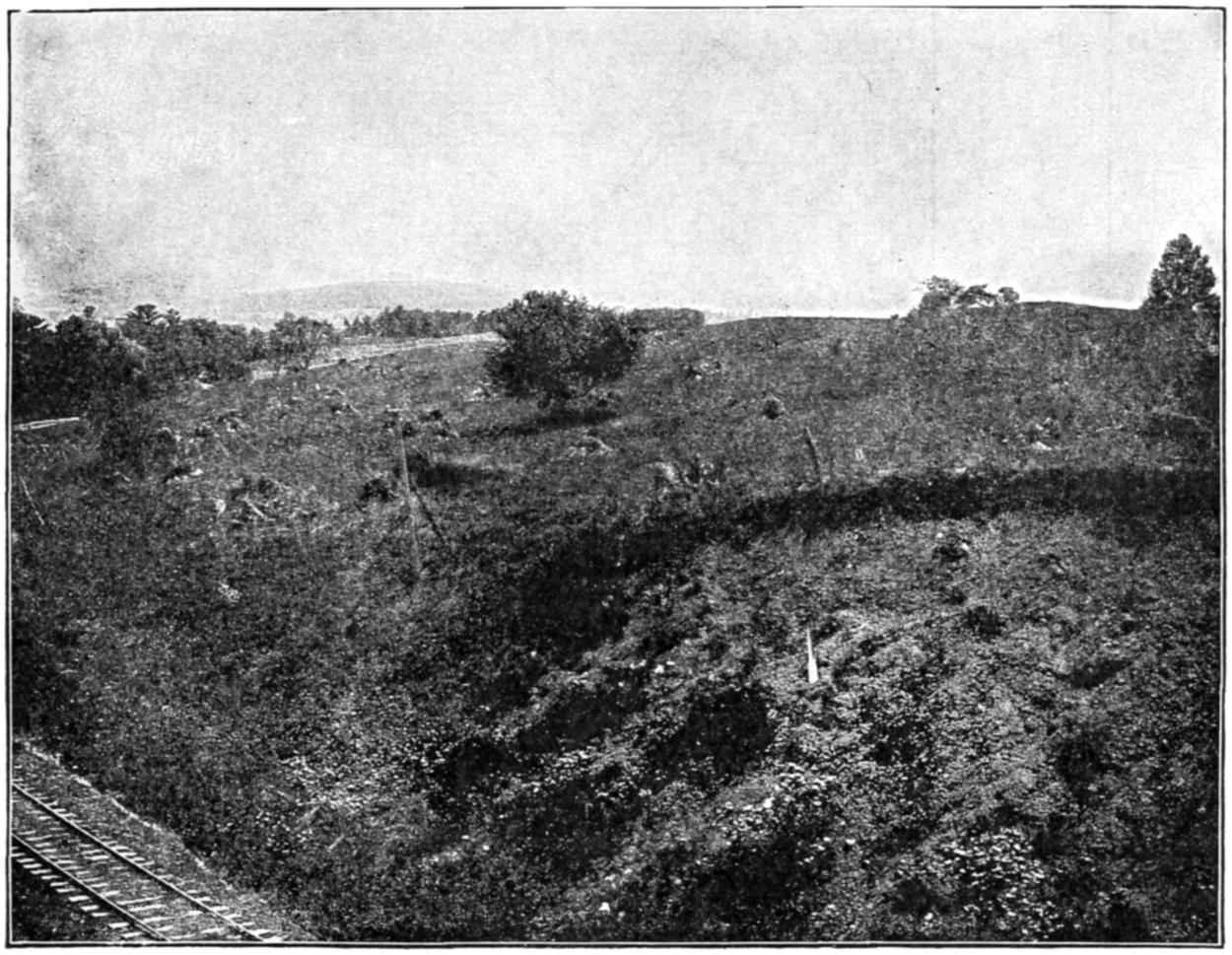

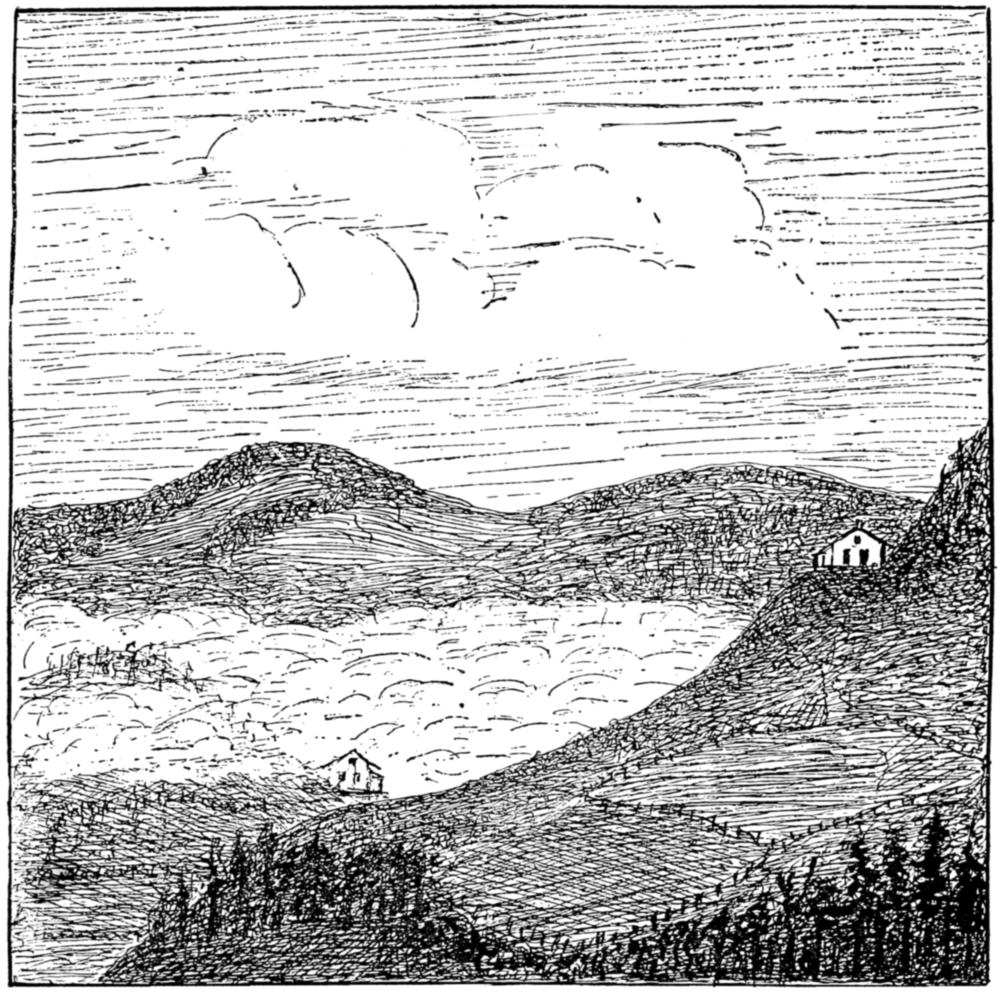

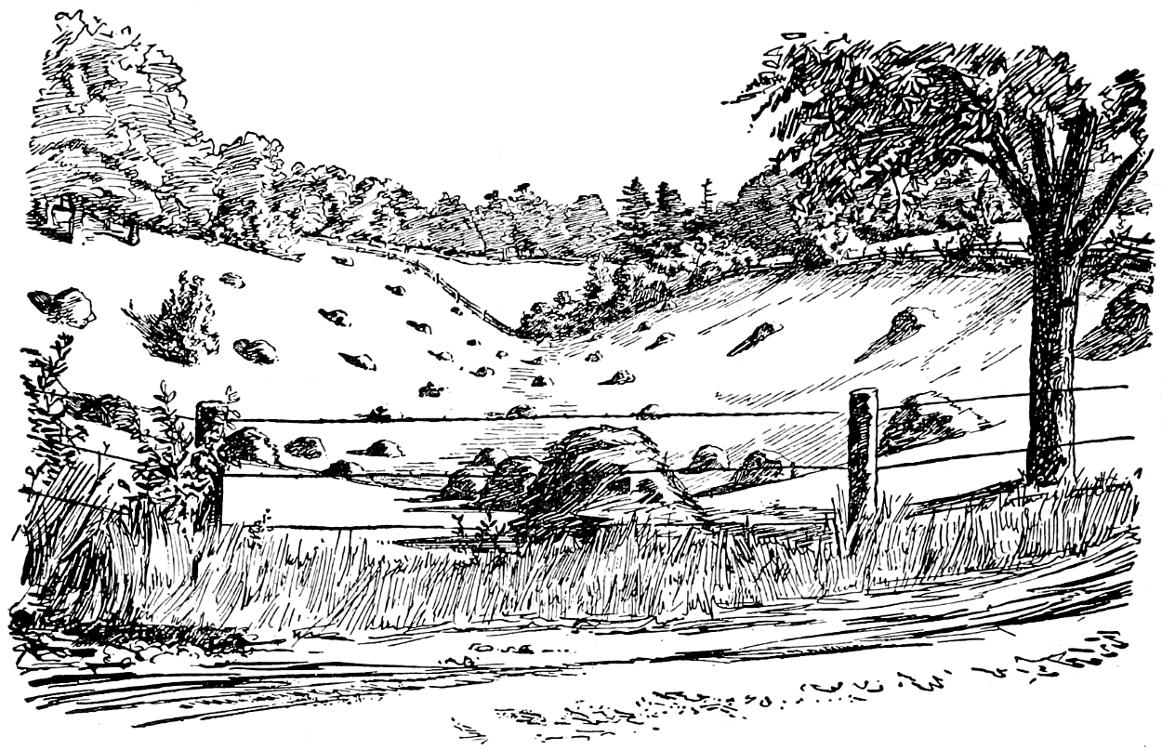

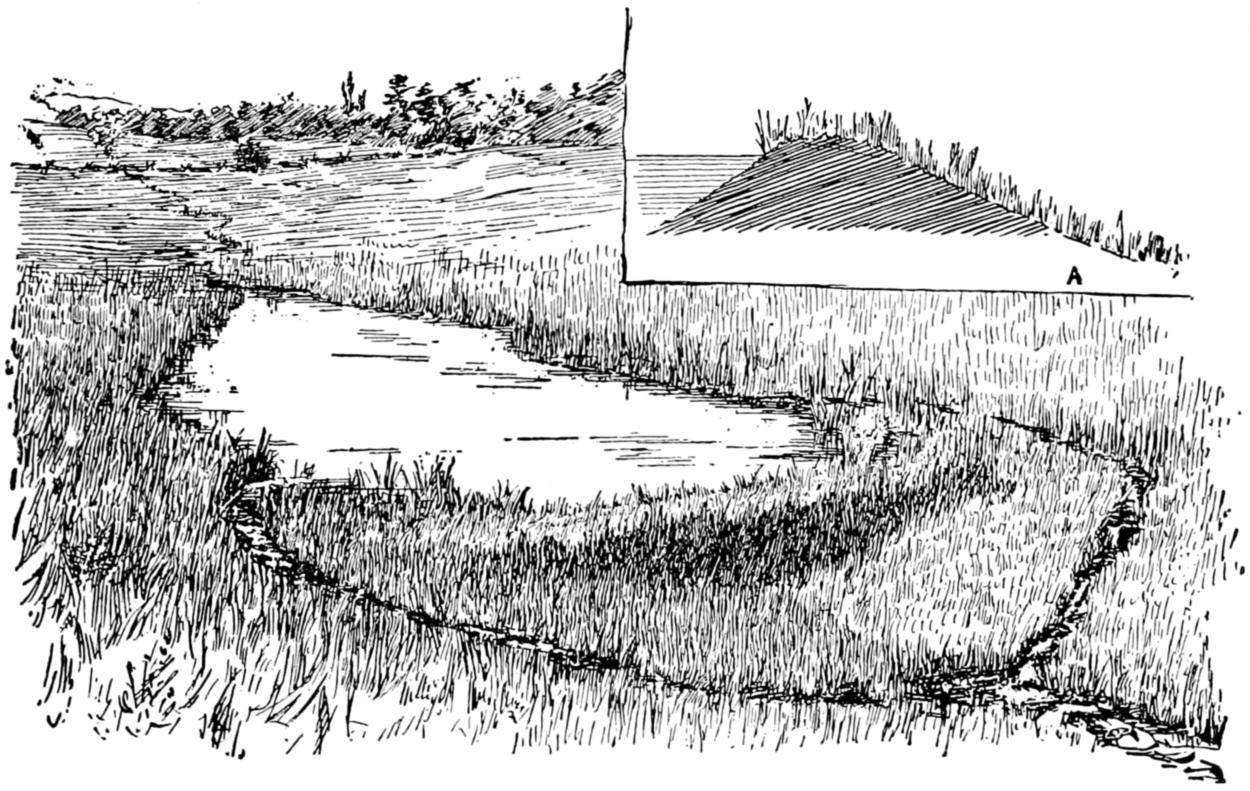

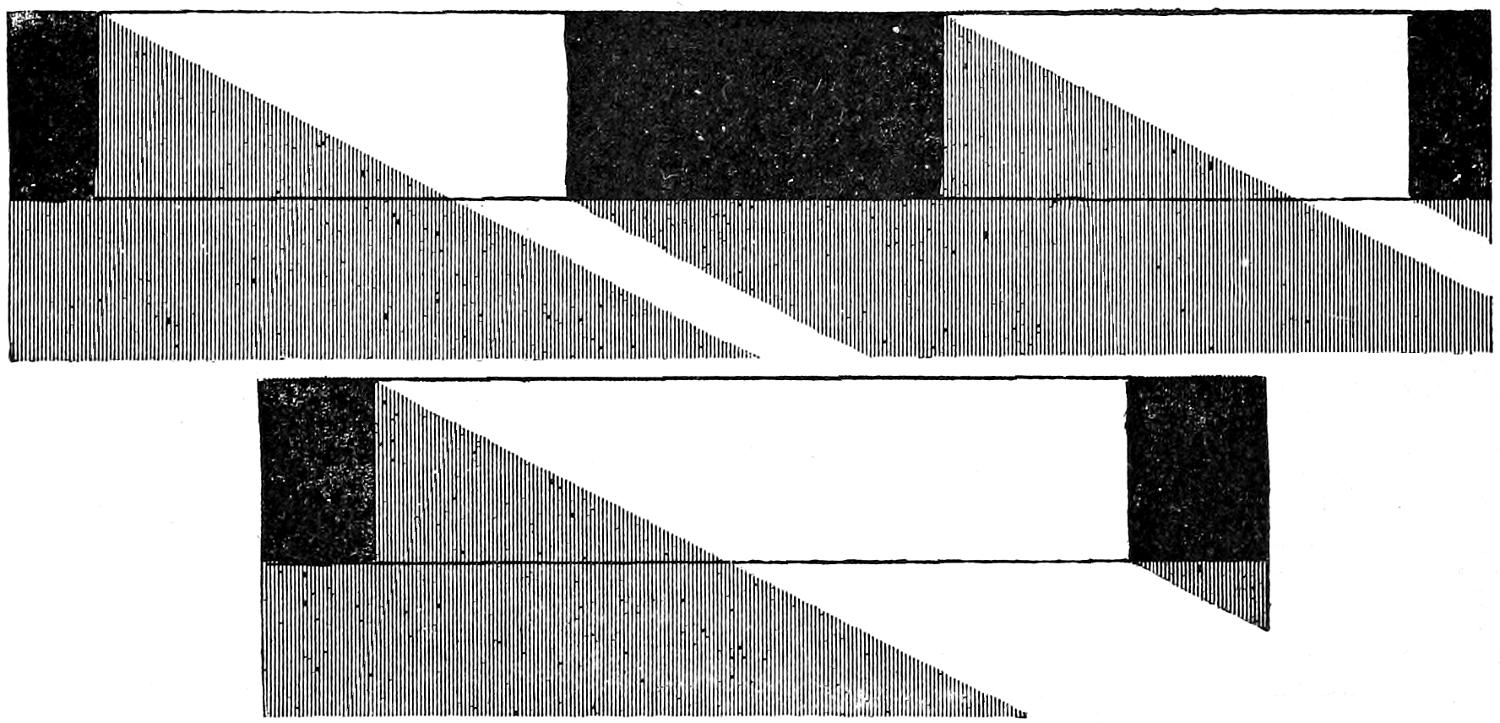

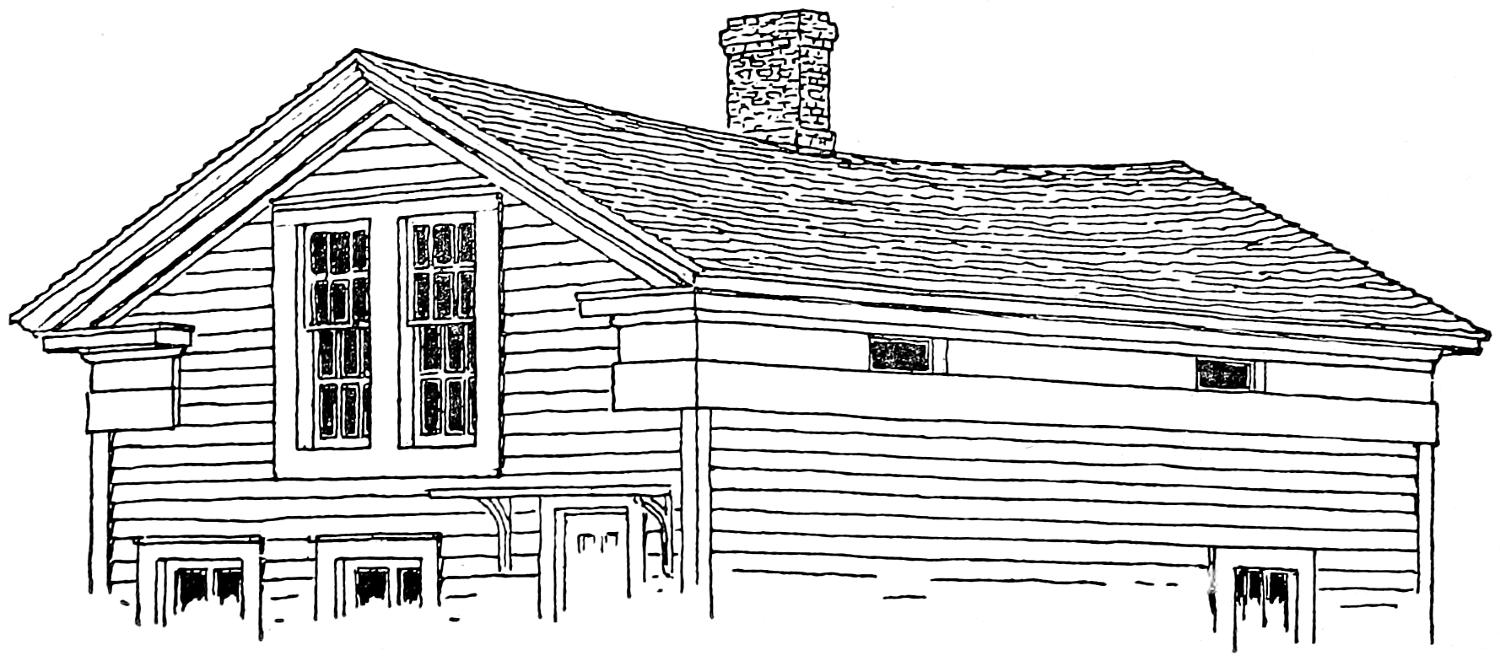

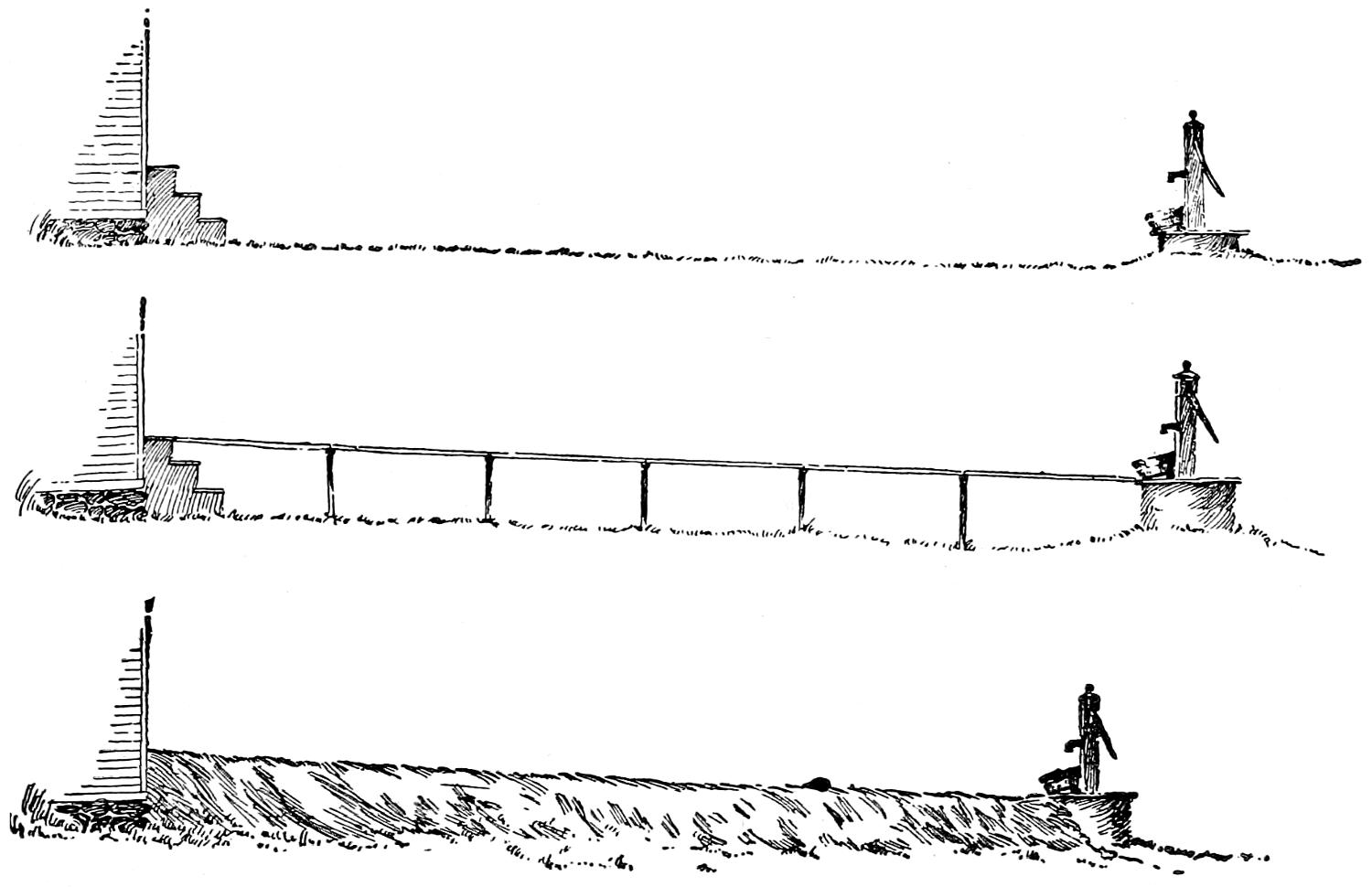

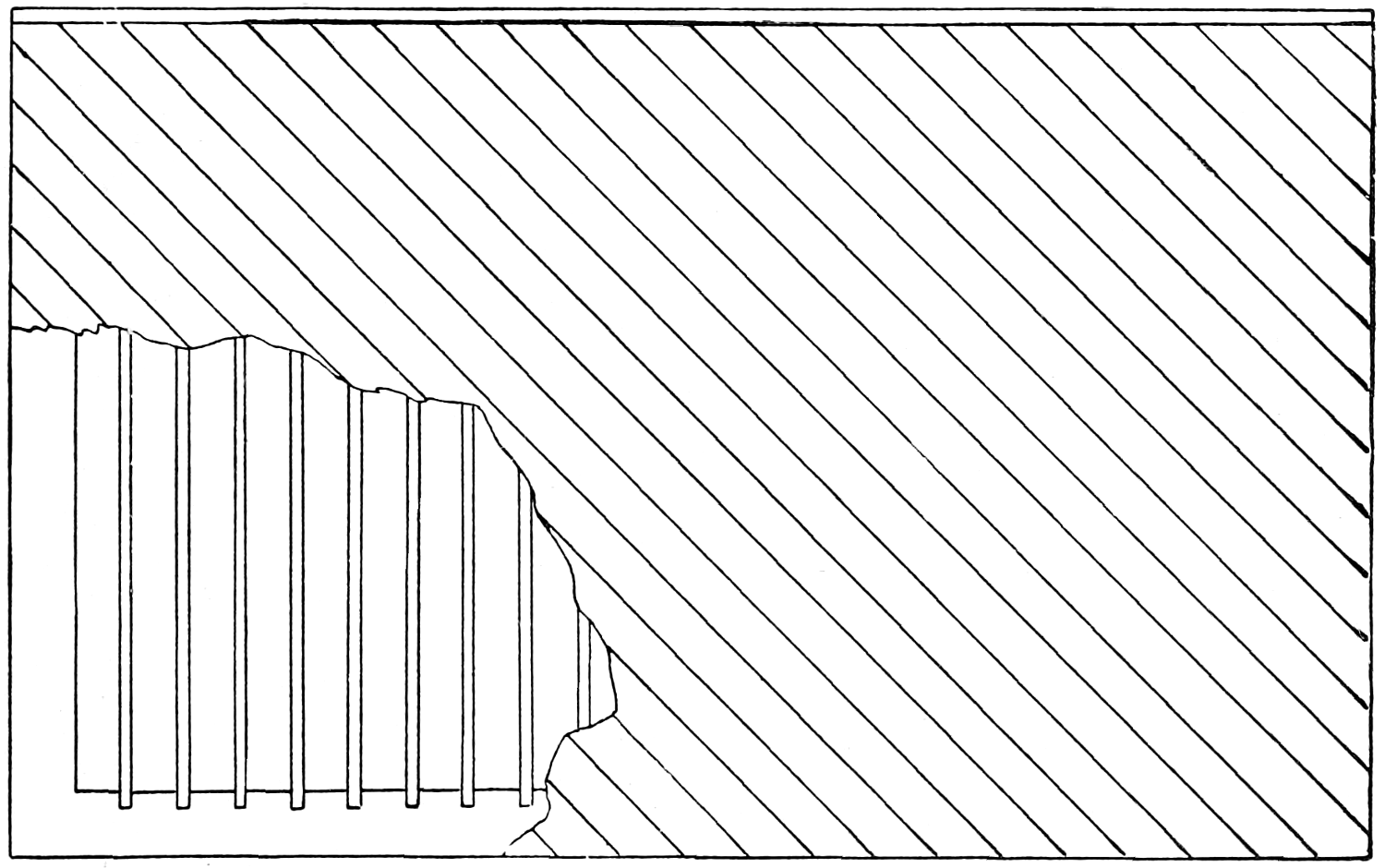

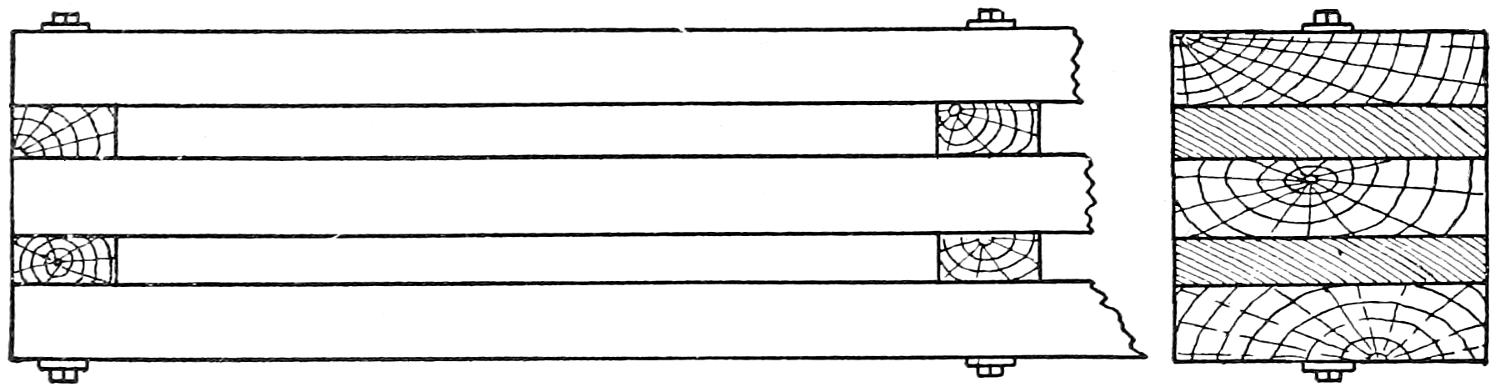

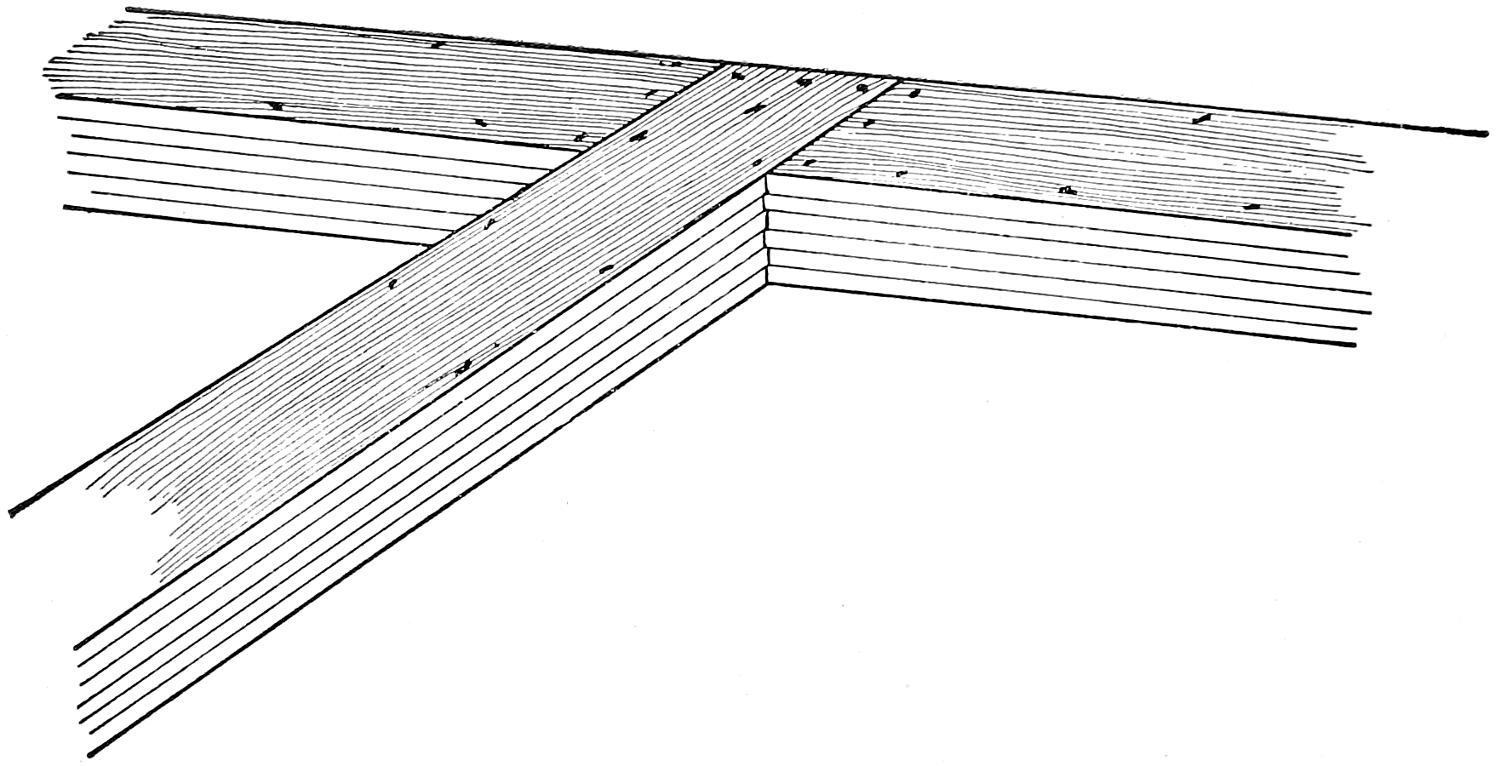

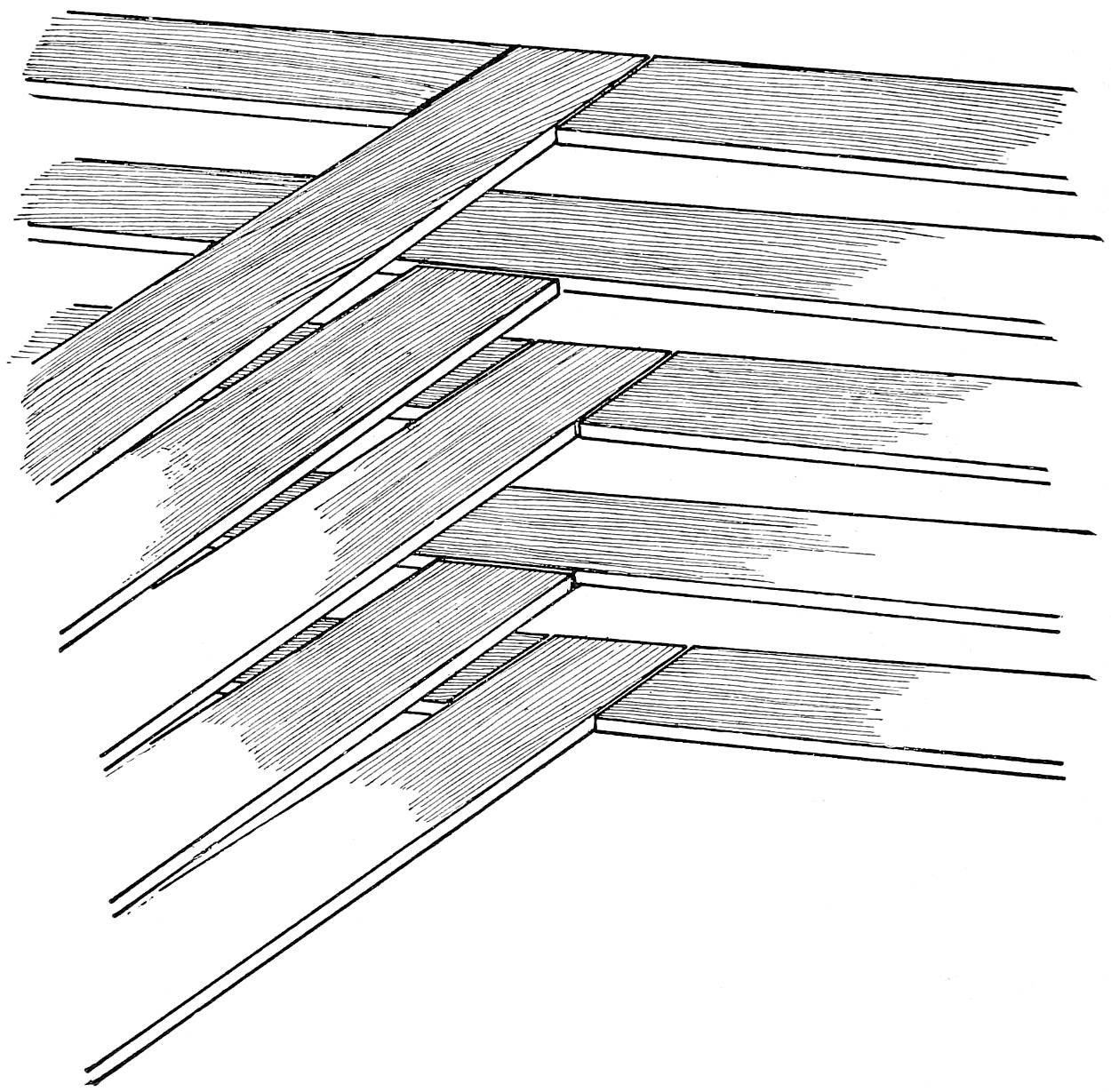

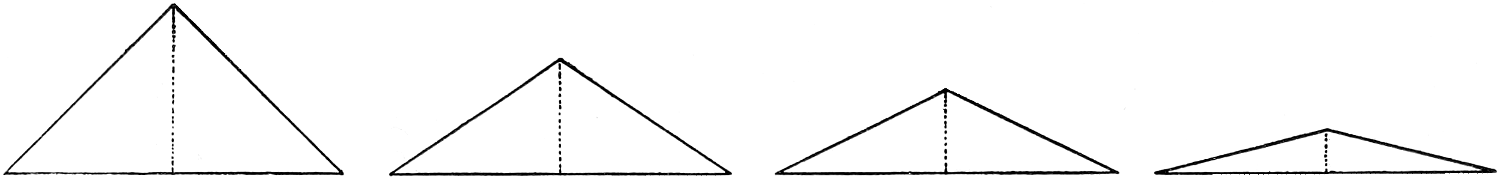

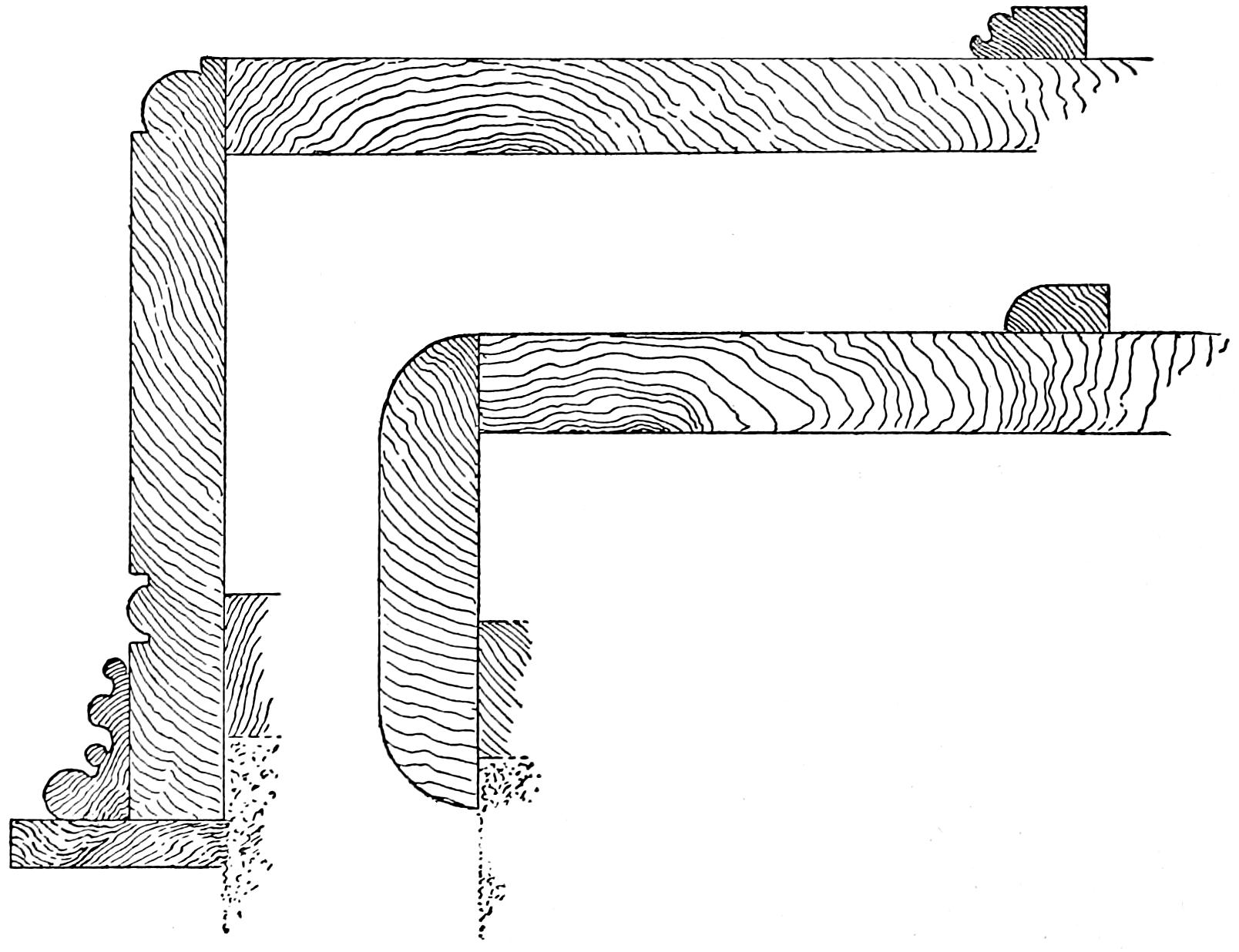

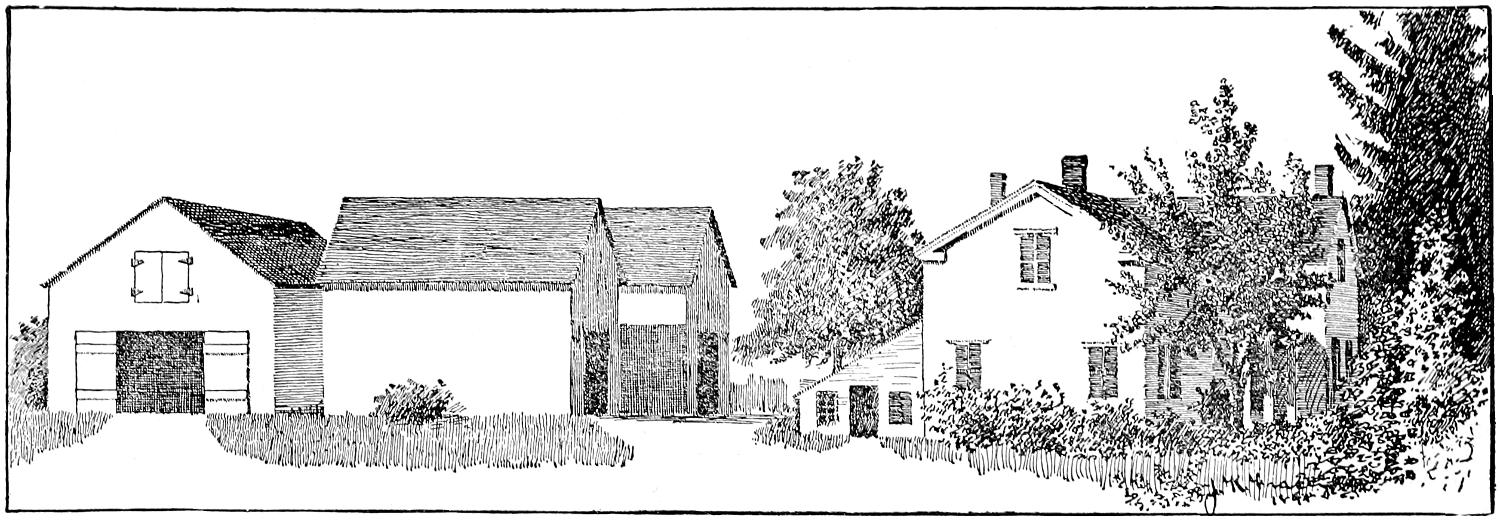

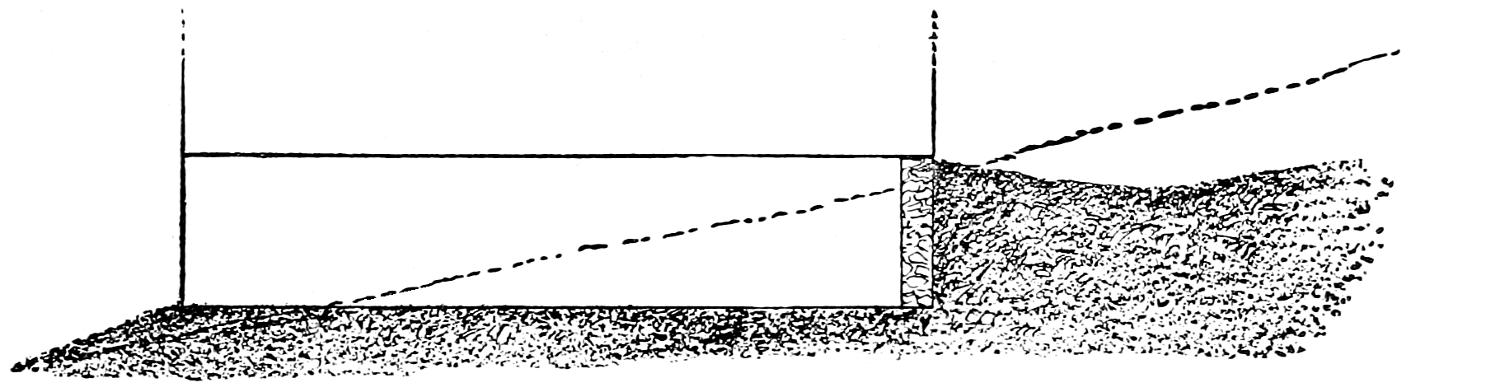

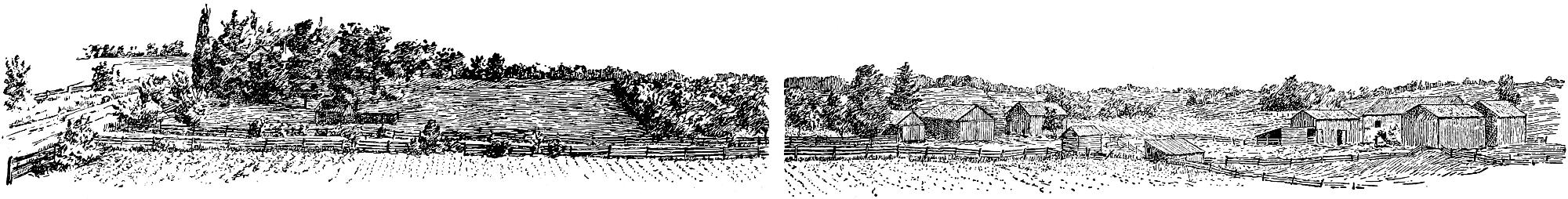

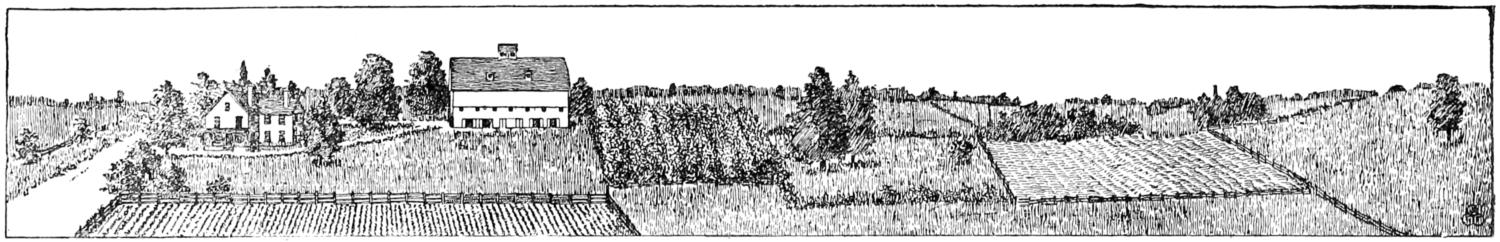

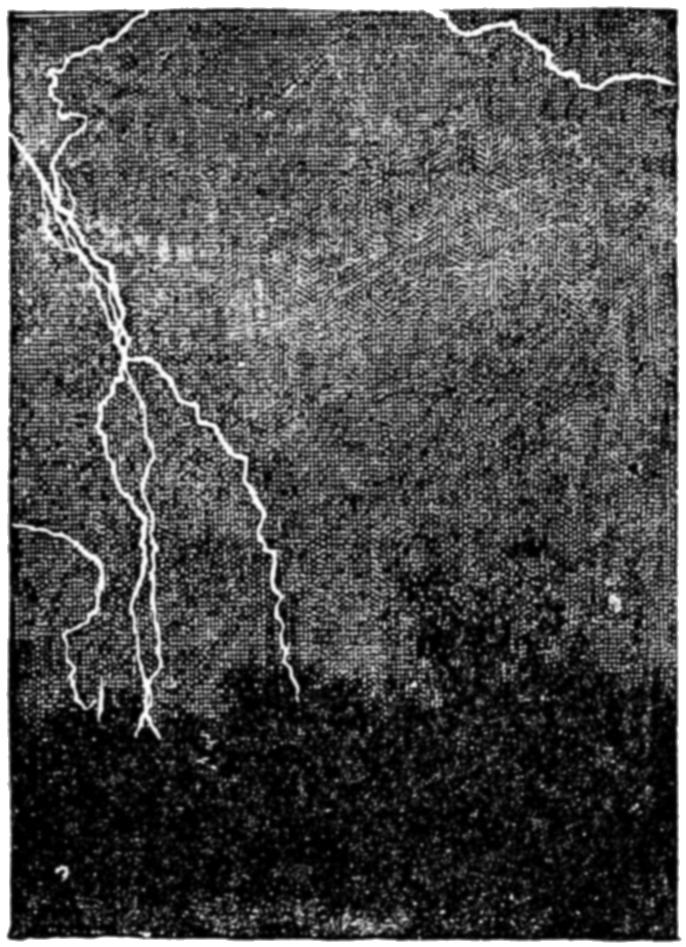

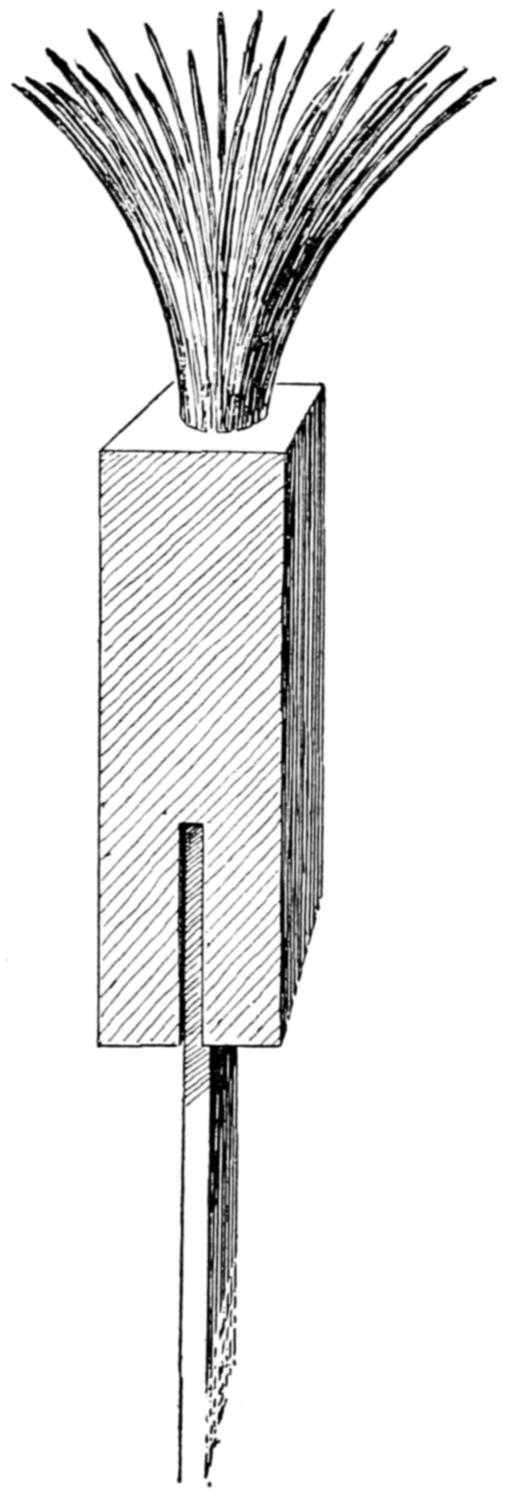

Consider the crops which are supposed to give promise of securing little or no profits at the present low prices, as wheat, maize, hay and oats. One man, on land naturally below the average, has secured during the last fifteen years an average of nearly 35 bushels of wheat, and in a few cases 40 bushels per acre. The average yield for the whole United States in 1889 was a shade less than 14 bushels per acre. During the same year the average yield of oats was 28.57 bushels per acre, and hay, including such other crops as are used for forage, averaged 1.26 tons per acre. Good farmers secure 40 to 50 bushels of oats, and 2 to 2¹⁄₂ tons of hay, and in propitious years 50 to 60 bushels of oats and 3 tons of hay per acre. (Compare Figs. 1 and 2.) These[28] latter yields always show large profits and lead to a competency, while the average yield usually gives no profit. If the average yield gives only a bare subsistence, what must be the condition of those who secure much less than the average? If one man raises 35 bushels of wheat, five other men must each raise 10 bushels to secure an average yield of 14 bushels per acre. Some entire states—as, for instance, Mississippi, North Carolina and Tennessee,—have an average of 6, 6 and 9 bushels, respectively, per acre. What is the remedy? Stop raising wheat, and raise something better adapted to soil and climate, or[29] go to town and sell peanuts. Some of these men who utterly fail to comprehend the laws of wheat culture may be good “coon dogs,” after all.

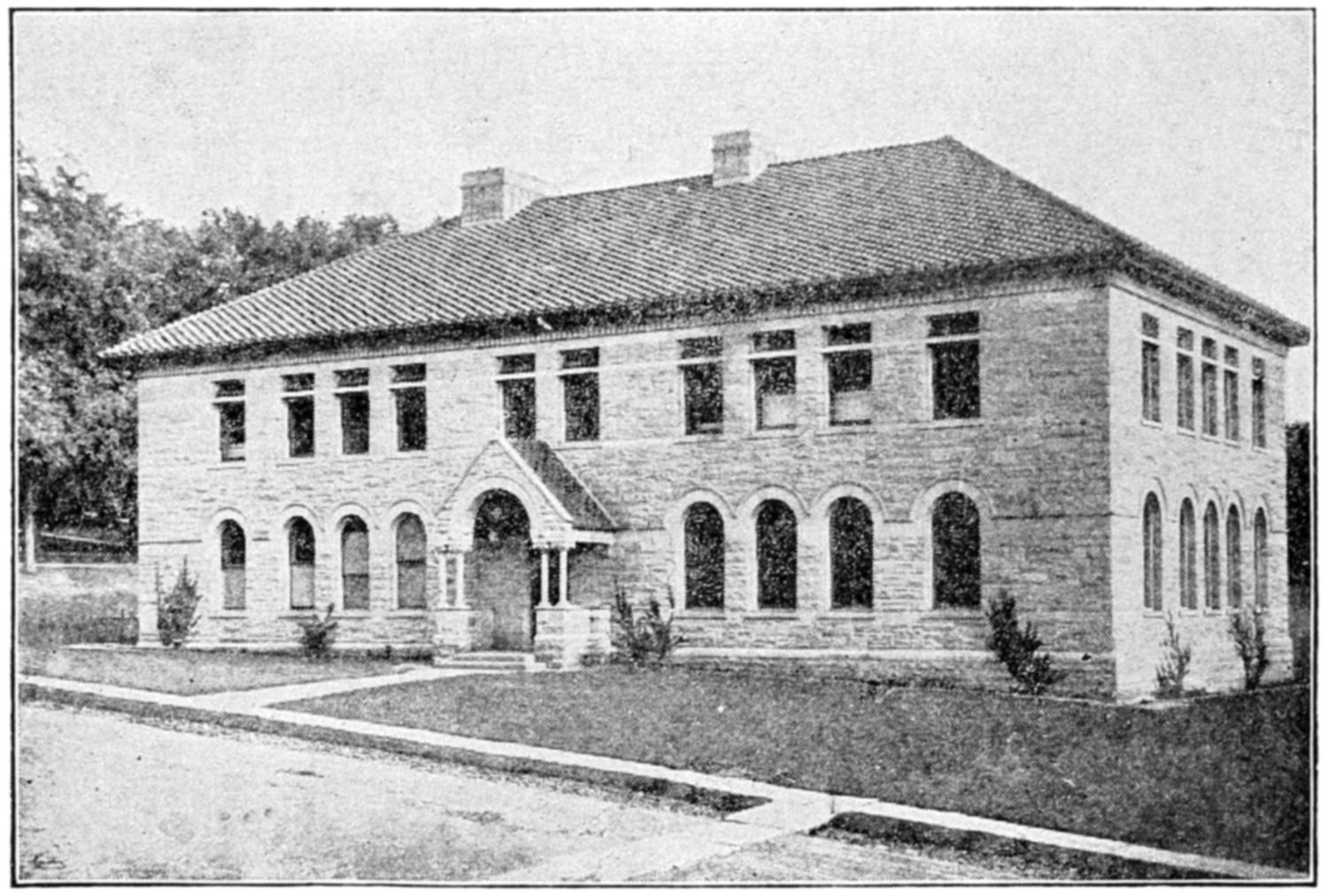

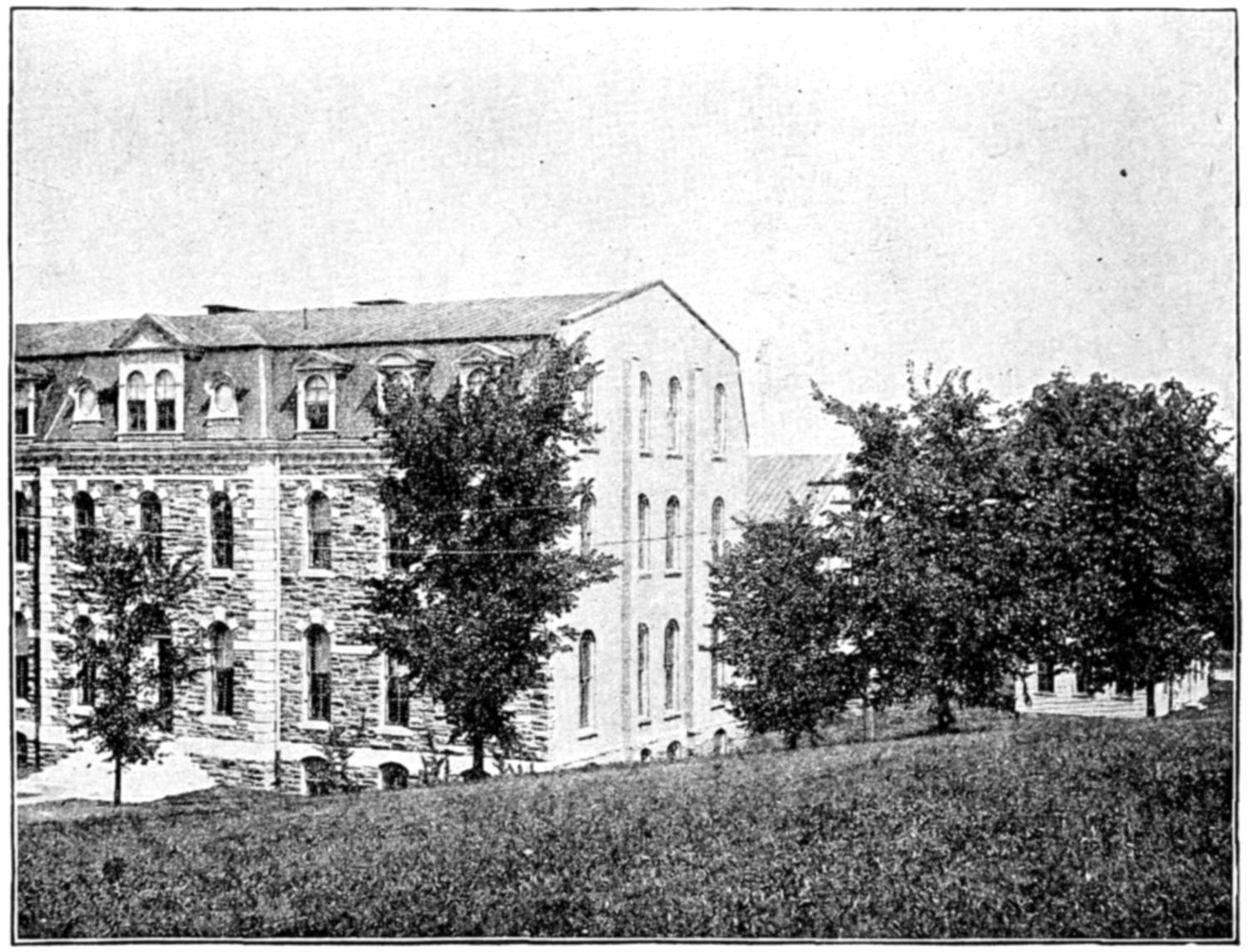

Fig. 1. Thirty-five-bushel wheat field (Cornell University).

Fig. 2. Eight-bushel wheat field, on a farm adjoining that shown in Fig. 1.

It will be said that if the yield per acre be doubled, the market will be so flooded that no one will receive profits. This is the old scarecrow. No farmer can control the prices of his product. The law of supply and demand is inexorable. What he may do is to improve quality, diminish cost, reduce area, find the best market and the products most sought, and increase the[30] production from a given area. If he raises the yield from 20 to 35 bushels, while the yield of his neighbor remains at 10 bushels and prices remain low, we shall soon see a fine illustration of “the survival of the fittest.” The 35 bushels will yield a fair remuneration for the work expended in production when prices are at the lowest. When they are high the profits are 200 to 300 per cent. Wheat, for the last ten years, has averaged 84 cents per bushel in June in central New York. Allow $3 for the straw of the lower yield, and if the wheat was sold at the average price, the total income per acre would be $11.40. For the straw of the larger yield allow $6, which, added to the wheat at the average price, would give a gross income per acre of $35.40.

The cost of raising and marketing an acre of wheat, including $5 for rental of land and $2 for fertilizers, may be set down at from $15 to $20 in New York. If the most successful compels the less successful farmer to stop raising wheat at a loss, what will the latter do with his land? Better give it away than lose by farming it. Better abandon the farm and go to town and set up a second-hand clothing store. There is always at least a small profit in that business.

In central New York a large herd of dairy cows was tested, and the owner of the herd[31] was informed that about one-fourth of his cows were quite profitable, one-half paid their board bill and a little more, and one-fourth were kept at a considerable loss. He was advised to dispose of the unprofitable cows. His answer was, “But what will I do for cows?”

Then, to secure a competence, the crops and the land which uniformly produce loss must be abandoned. How it worries the city penny-a-liner and how it rejoices the successful farmer to see land thrown out of cultivation—“abandoned.” To me nothing is so encouraging in agriculture as this lately acquired knowledge which reveals the fact that vast areas have been cleared and brought under cultivation which should have been left undisturbed, except to harvest the mature trees and protect the young plants from ravages of fire and cattle. As the blackberry bushes, year by year, creep down the steep hillsides and over the rock-covered fields, one rejoices at the pioneer work these modest, hardy, tap-rooted plants are accomplishing. How wisely and well they fit the soil for a higher and more noble class of plants, and how surely in time they cover the shame and nakedness of mother earth!

The rural population has made many serious mistakes, toiling to reclaim land which was not worth reclaiming, not worthy of an intelligent[32] farmer. But how could they know better? Not one college of forestry in all this great land up to 1898, and as yet but one in its infancy! Until the last generation not a single school of agriculture, scarcely a book obtainable which might give direct help to the rural American boy and girl! Therefore, the farmer should not be blamed for the wasteful and unscientific treatment of forest and field. All this leads to the conclusion that to secure a competence, lands of high and varied agricultural capabilities, lands worthy of an intelligent American, should be selected upon which to build and maintain rural homes.

Quantity of farm products we have in abundance; better quality is what is wanted, since quality may improve prices and widen markets. To assist in securing a competence some specialization is advisable. Sometimes this has been carried so far as to work serious disaster. Many farms in western New York have been almost exclusively devoted to the raising of grapes, which, when abundant or moderately so, sold at ruinous prices. It is noticed that where only an eighth or a fourth of the farm was devoted to vines, the yield was not only proportionately larger but the quality better than where nearly all the land was used as a vineyard. Wherever diversified agriculture was carried[33] on to a limited extent and plantations were restricted, the low price of grapes made no serious inroads on the income. Where all the land was given up to grapes, work was intermittent, the farmer being overtasked at one season of the year and idle at another. The demoralizing effect on the farmers and their families of this army of unrestrained youths and loungers of the city, which, for a brief period, swarms in the districts devoted to specialized crops, as grapes, berries and hops, is marked.

The baleful result of raising a single or few products in extended districts may be seen in California and the great wheat districts of the northwest. In such localities there is little or no true home life, with its duties and restraints; men and boys are herded together like cattle, sleep where they may, and subsist as best they can. The work is hard, and from sun to sun for two or three months, when it abruptly ceases, and the workmen are left to find employment as best they may, or adopt the life and habits of the professional tramp. It is difficult to name anything more demoralizing to men, and especially to boys, than intermittent labor; and the higher the wages paid and the shorter the period of service, the more demoralizing the effect. If there were no other reason for practicing a somewhat diversified agriculture, the welfare of the[34] workman and his family should form a sufficient one. Happily, many large and demoralizing wheat ranches are being divided into small farms, upon which are being reared the roof-tree, children, fruits and flowers.

To secure a competence, no more activities should be entered into than can be prosecuted with vigor and at a profit. On the other hand, too few activities tend to stagnation and degeneration. Mental power, like many other things, increases with legitimate use and diminishes with disuse. The farmer who simply raises and sells maize is often poor in pocket and deficient in understanding. The college graduate who attempts but a few easy things seldom becomes a ripe scholar.

To secure a competence, the petty outgoes should be met by weekly receipts from petty products. I have known so many farmers to succeed by specializing moderately along one or two lines, while holding on to diversified agriculture, in part at least, that I am tempted to give a single illustration as a sample of thousands which have come under my notice.

A Scotchman and his family of four little children landed in northern Indiana with three to four hundred dollars; to this was added as much more by day labor. A farm of about one hundred and fifty acres was purchased, one hundred[35] acres of which were adapted to wheat, corn and clover. Thirty acres were marshy pasture land; the balance, timber. Wheat was selected as the great income crop, which was supplemented by the sale of one to three horses yearly. The butter from a dozen cows, the chickens, ducks, and their eggs, were taken to the city once each week. The result was that at the end of the year there were no debts of subsistence to be paid. This left all the money received for the wheat and horses to be applied towards liquidating the mortgage. In a few years a large, comfortable house was built. This was followed by the purchase of another farm, and still another, until each child was provided with a home and facilities for securing a modest income. This shrewd Scotchman succeeded because he neglected neither little nor great things.

With what pride the writer, in 1863, deposited $1,700 in bank, the product of a single wool crop!—and the little farm of one hundred and twenty acres was not all devoted to wool-raising. If a young man can secure a loving, helpful wife, four good cows and enough land to produce feed for them, with room left for an ample garden, a berry patch and a small orchard, he may consider himself rich, and if he be able and intelligent he will soon have a competence.

[36]

The farmer, of necessity, goes to the city or village once each week for supplies which cannot well be produced on the farm. He should return, if possible, with more money than he had when he left home. It is not the big mortgage which was given for part of the purchase price of the farm which should make him unhappy, but the steadily increasing little charges accumulating on the tradesmen’s ledgers until this “honest” farmer dreads to meet a score of his town acquaintances.

The farmer who, from his well-painted covered democrat wagon, sells the product of his skill and labor looks to me quite as dignified as does the merchant who sells nails and codfish, turpentine and bobbins, patent medicines and jews’-harps, none of which represents his own skill or labor.

Farming will never be carried on in America by trusts or syndicates. A combine can run fifty nail factories or breweries, but not fifty farms, at a profit, because farming is too difficult, requires too close supervision and frequent change of details and combinations, and new plans to meet the ever-changing conditions of climate and soil. The conditions which surround agriculture in America put a quietus forever on “bonanza farming,” and tend to the rearing of ideal homes and the accumulation of[37] modest incomes. Mining-farming on virgin, fertile, unobstructed areas can be successfully prosecuted only for a time.

“The Red river valley native soils contain from .35 to .40 of nitrogen, while the soils which have been under cultivation (in wheat) for twelve to fifteen years contain from .2 to .3 of a per cent.”[1] Another important point: When humus is taken out of the native soil as above, only .02 of a per cent of the phosphoric acid is soluble by ordinary chemical methods, while in the native soil three or four times as much phosphoric acid is soluble and is associated with the humus. Allowing that an acre of soil one foot deep weighs 1,800 tons, the native soil would contain from 12,600 to 14,400 pounds of nitrogen per acre, while the cultivated soil would contain from 7,200 to 10,800 pounds per acre. If the average amount of nitrogen in native soils (13,500 pounds per acre), and the average in the soil after it had been cropped twelve to fifteen years (9,000 pounds per acre), are compared, it will be seen that the soil has lost 4,500 pounds of nitrogen per acre, or more than one-third (probably one-half) of the nitrogen which could well be made available, and this in less than a quarter of a century.

[1] Henry Snyder, Bulls. 30, 44, Minn. Exp. Sta. See “Fertility of the Land,” p. 256.

[38]

Fifteen crops of wheat of 25 bushels per acre require 433 pounds of nitrogen, or one-tenth of the amount which the soil lost during the years of cropping. This soil, under “bonanza farming,” has lost outright nitrogen sufficient for 155 crops, each requiring as much nitrogen as does a crop of 25 bushels of wheat per acre. When the amount wasted on a single acre is multiplied by the acres of the vast, fertile wheat plains of the west, where “bonanza farming” is carried on, the loss of nitrogen to our country is seen to be so great as to appal the thoughtful man who looks forward to the generations who will want this element in the not distant future. Happily, this “bonanza farming” has its own cure. When mining-farming reduces the yield so that profits vanish, then these great farms will be cut up into modest-sized ones, true homes will rise, intermittent labor and the tramp harvest-hand will disappear, and the last and only condition which tends to produce an uninstructed peasant class will cease to exist.

The other great “bonanza” industry which still remains and which affects agriculture, and the land directly, is lumbering. This, like “bonanza” wheat farming, may be classed as a mining industry, carried on at the surface instead of in the bowels of the earth. Without rational[39] direction, restraint or control, this agricultural mining goes on until the sources from which the profits are drawn are so depleted as to be no longer profitable. There is no home or competency for the farm boys in the lumber camp or on the great wheat farm. Here the rule is to take all and return nothing. After the ax and the binder, comes the fire to complete the wanton destruction. The shade-giving and moisture-conserving brush, stubble and straw, and all living plants, are destroyed, and nothing but the mineral matter, unmixed with surface humus, remains. A blackened waste, devoid of animal or vegetable life, is left behind. No homes can be reared here, no competence secured until nature, assisted by man in the coming years, slowly restores the covering and productivity of the soil. This unwise treatment of the land must soon come to an end; then the hardy home-builder will have opportunity to repair, by more rational methods, some of the wanton and unnecessary waste.

Is it too much to hope that before the close of another decade every state and territory will have a school of forestry, and that all national forest domains will have been brought under rational supervision and control? The future home-builders will need them, and the present owners of homes have a right to a share of[40] the benefits which flow from intelligently managed forest preserves. It is not enough to show that intelligent farming is highly remunerative at the present time; provision must be made by which the children and the children’s children, for all generations, may have opportunity for securing a competence from rural pursuits.

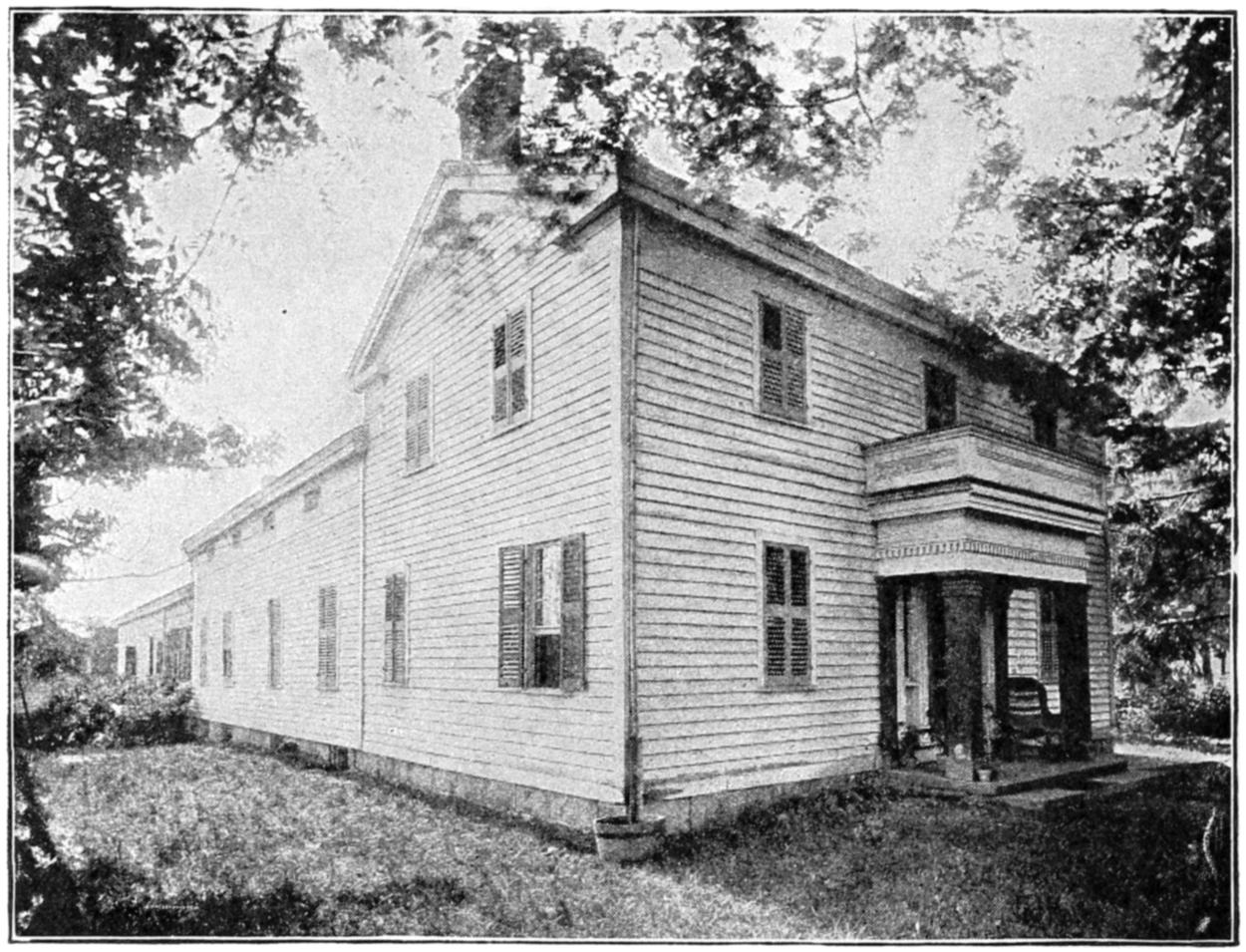

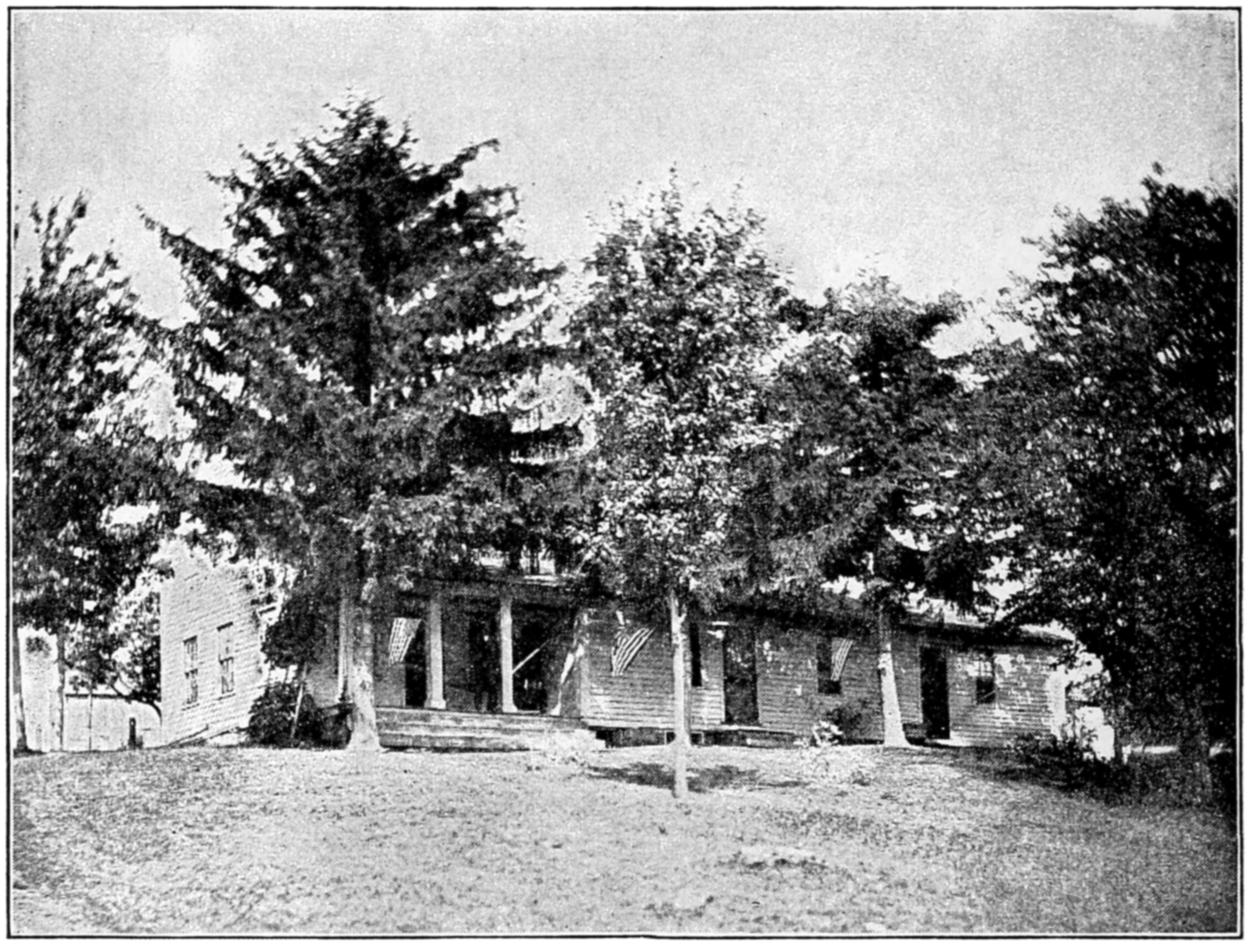

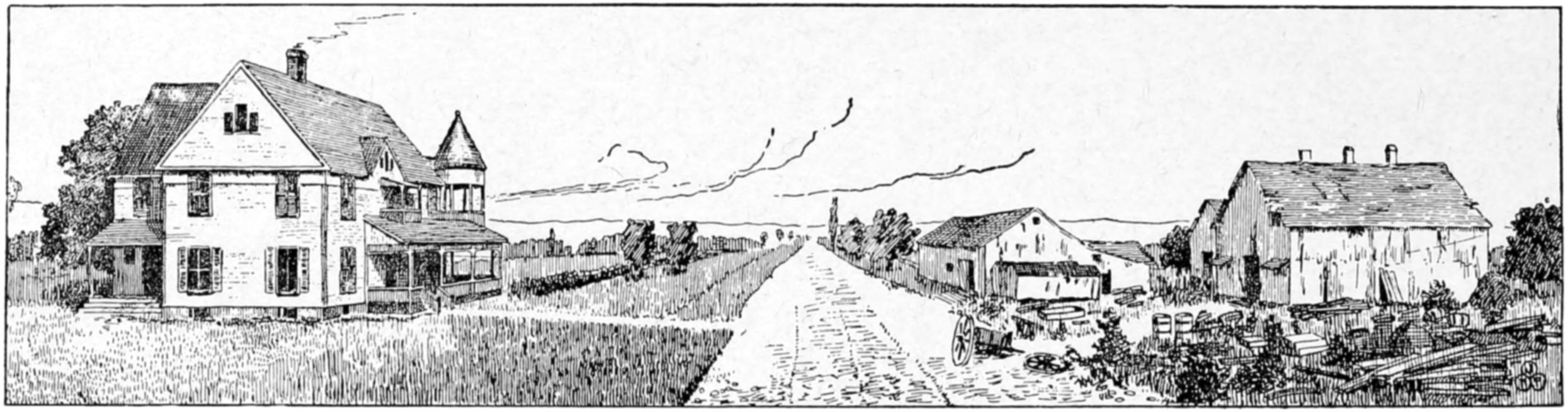

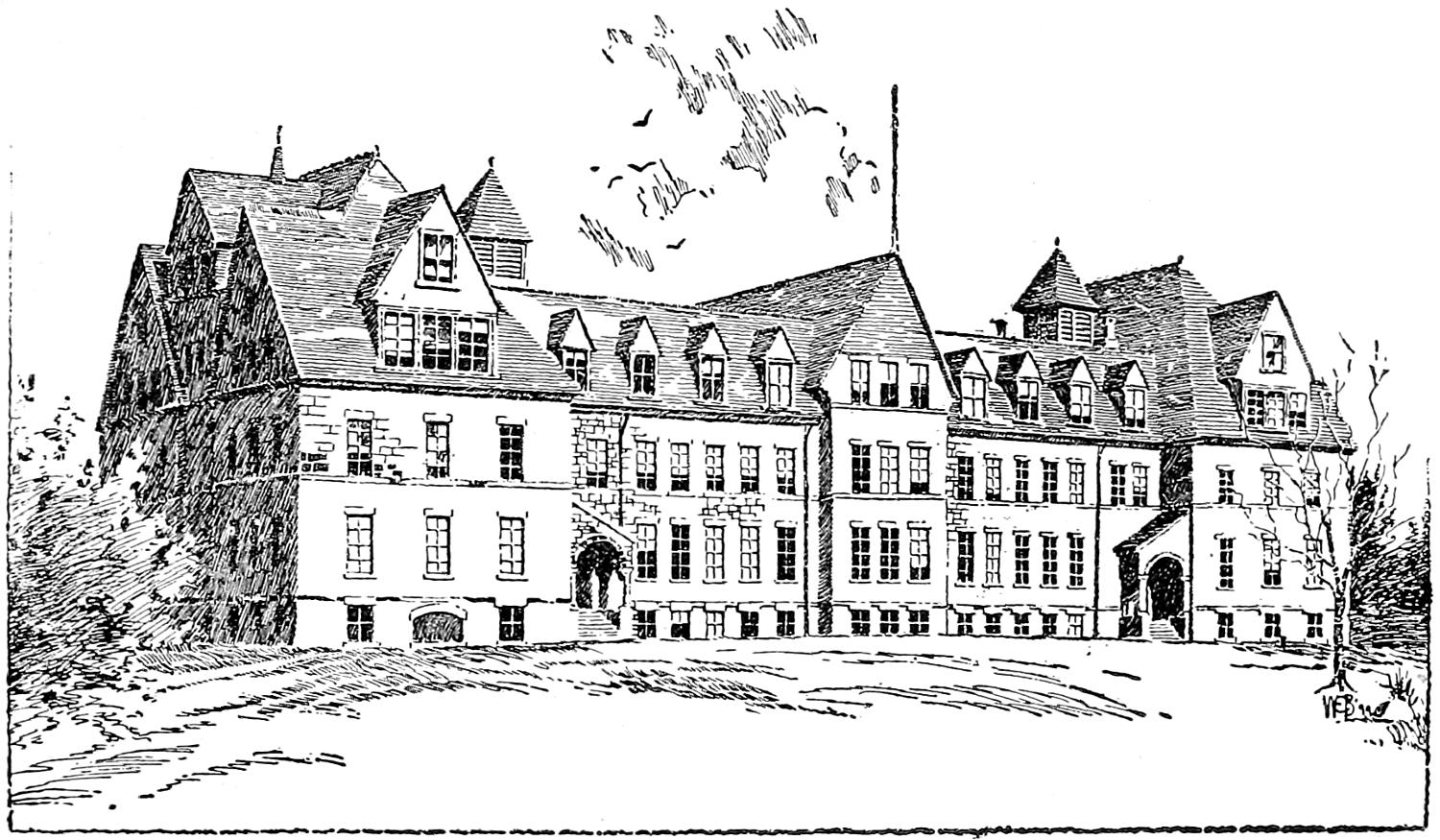

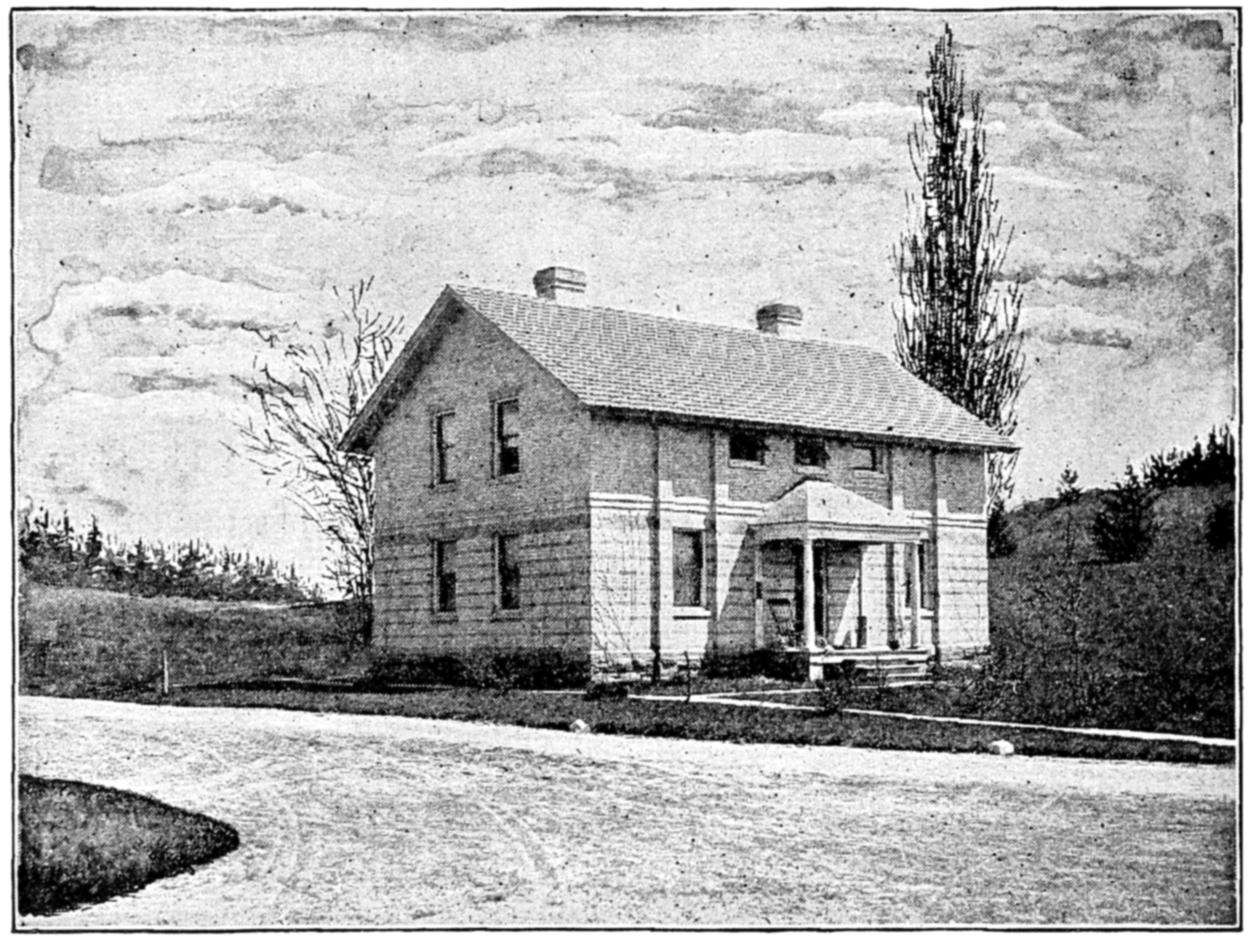

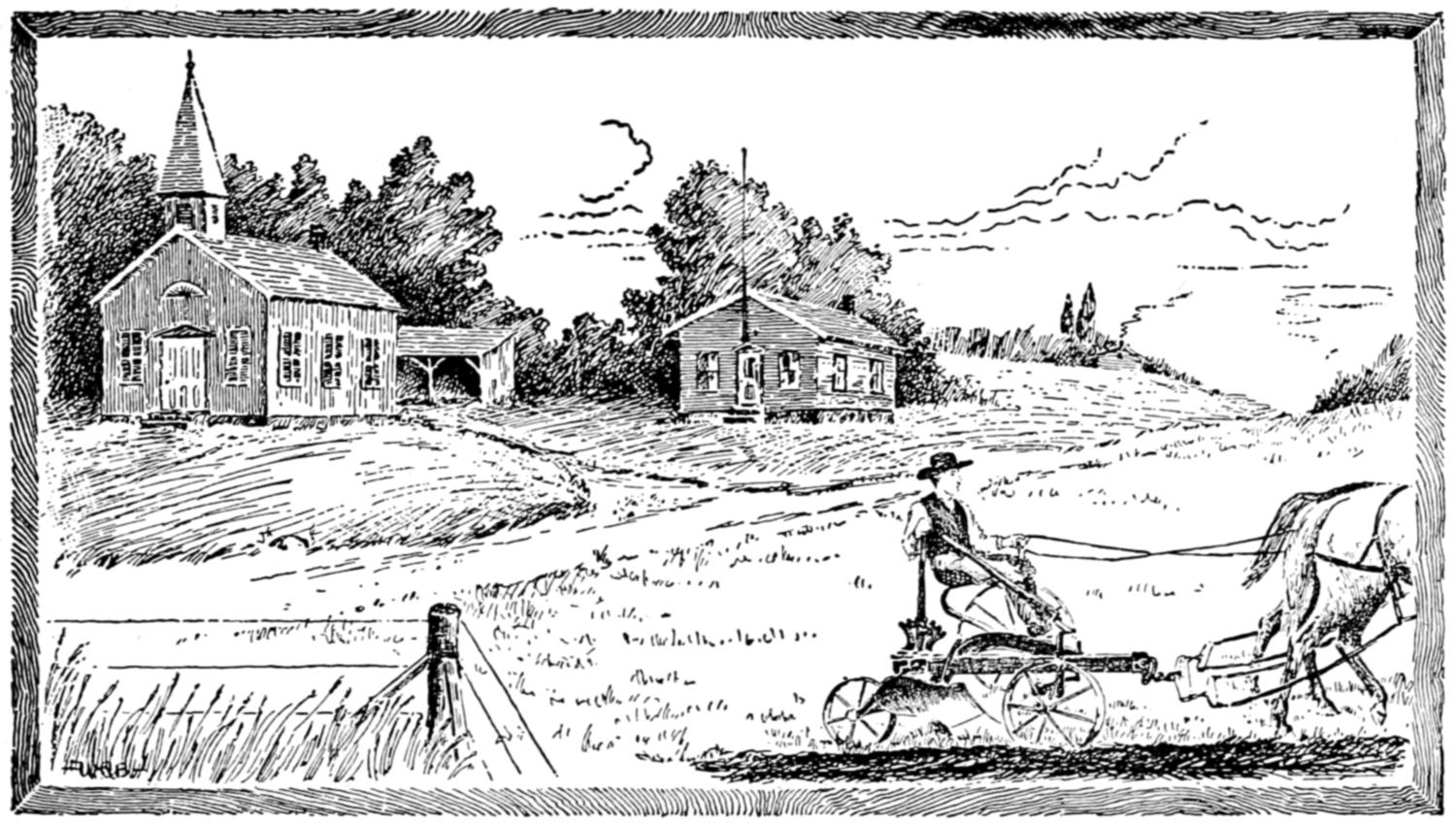

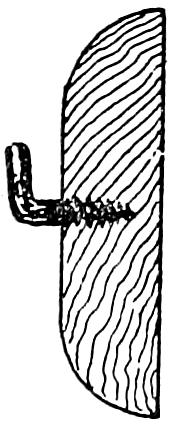

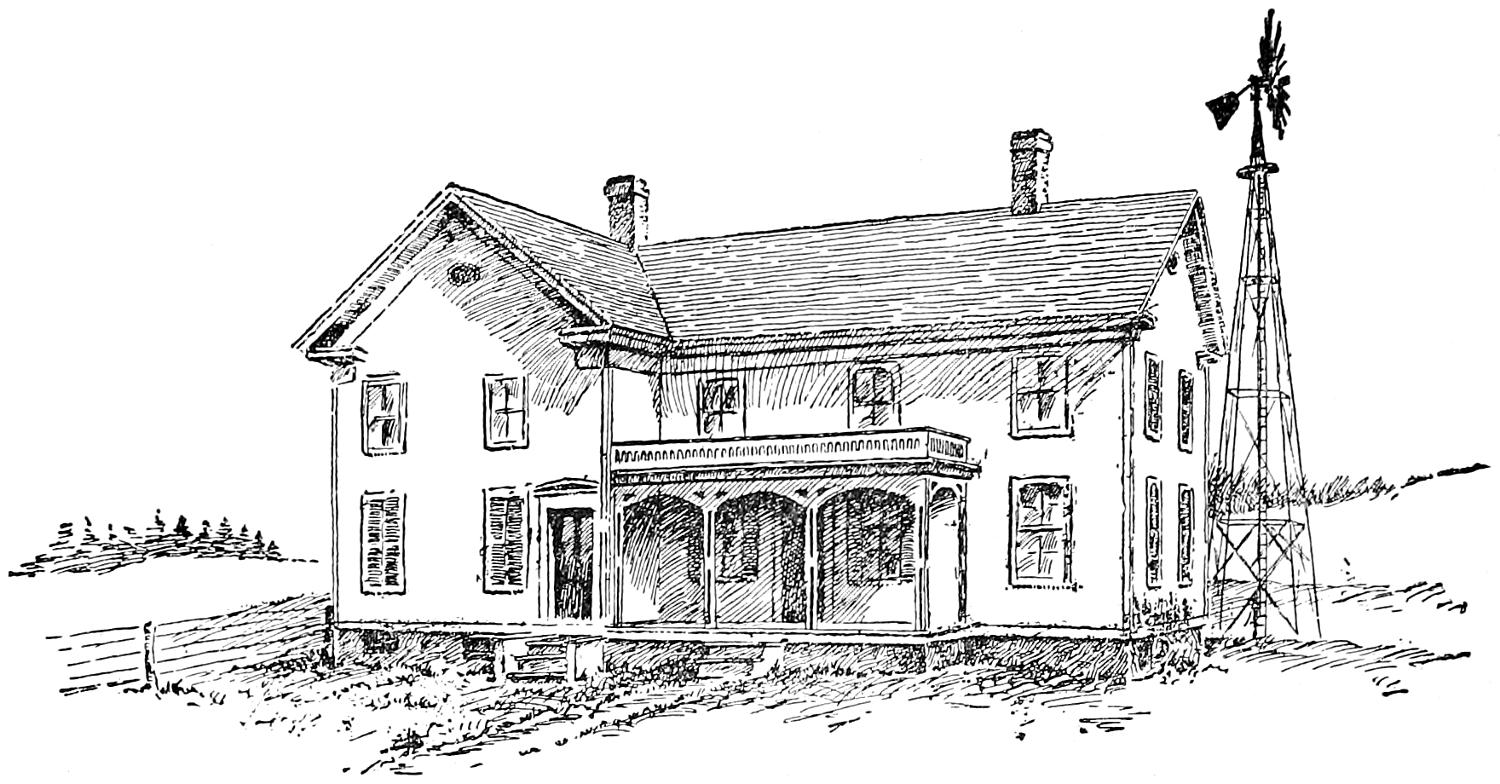

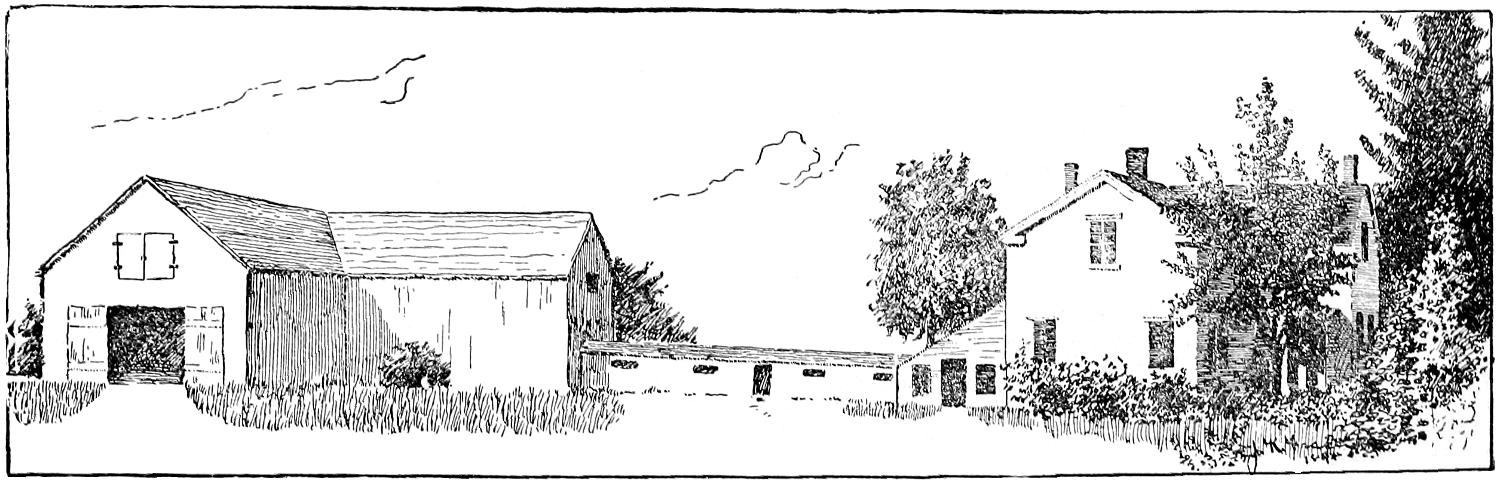

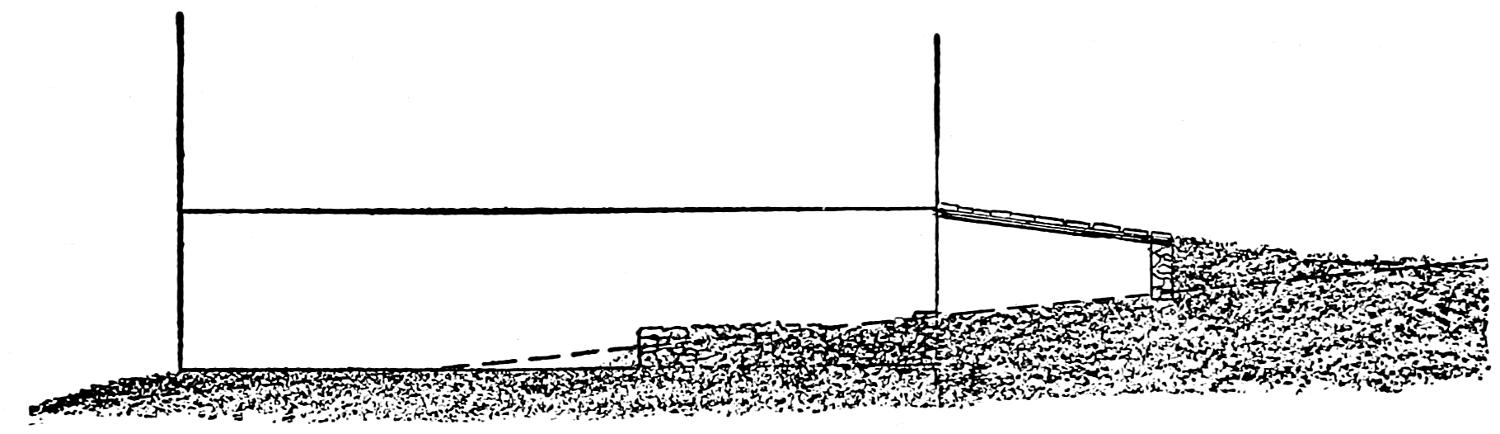

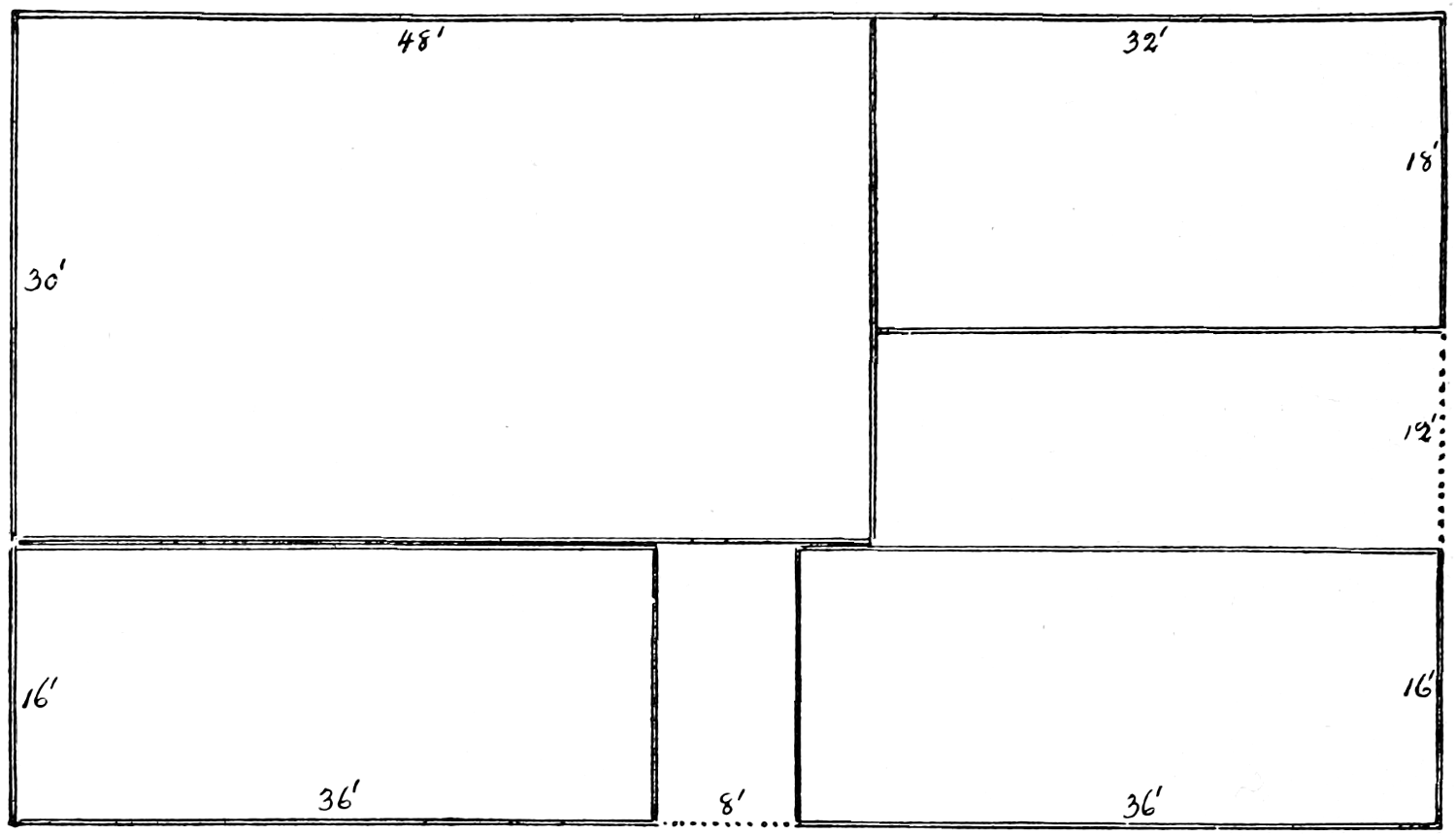

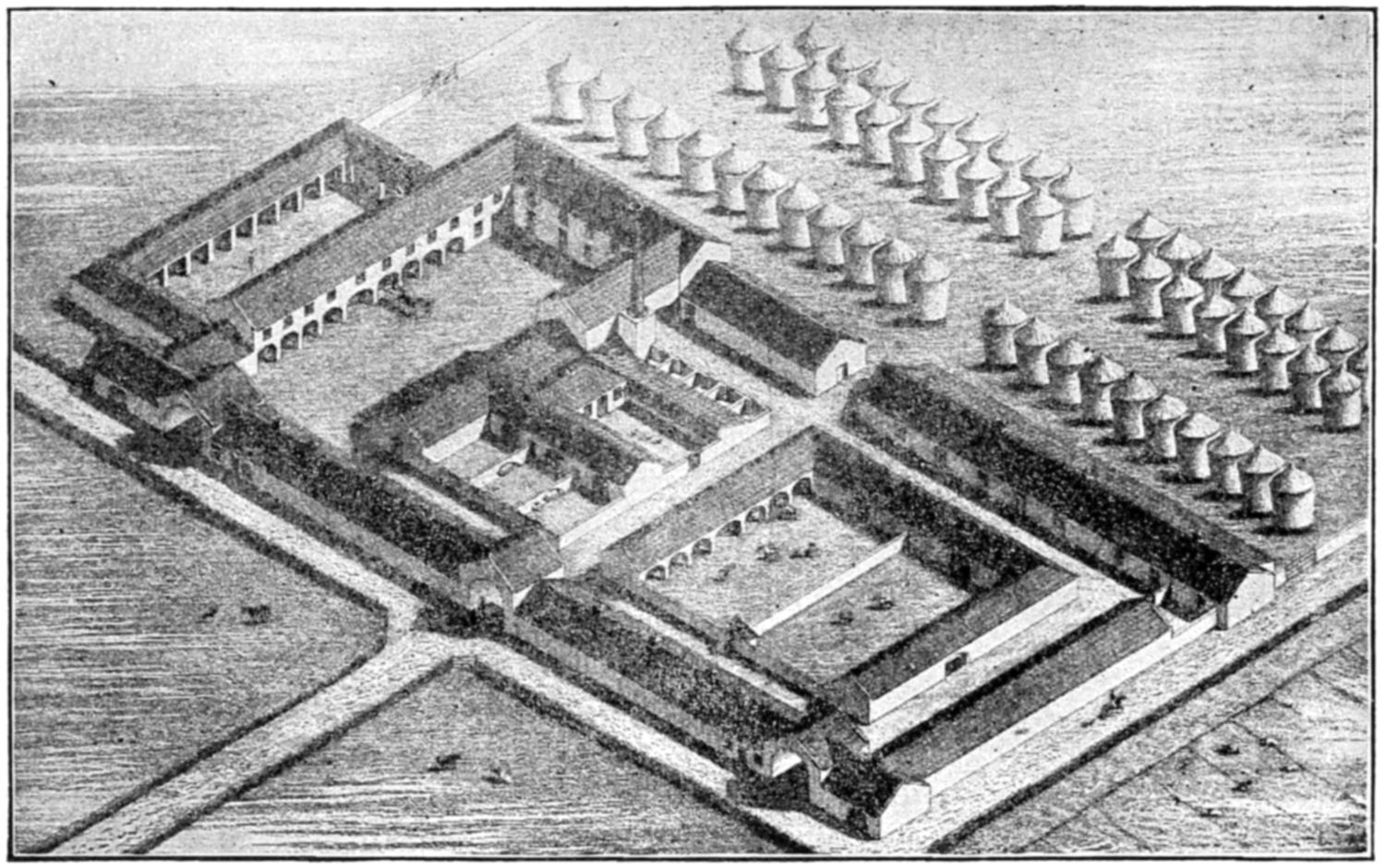

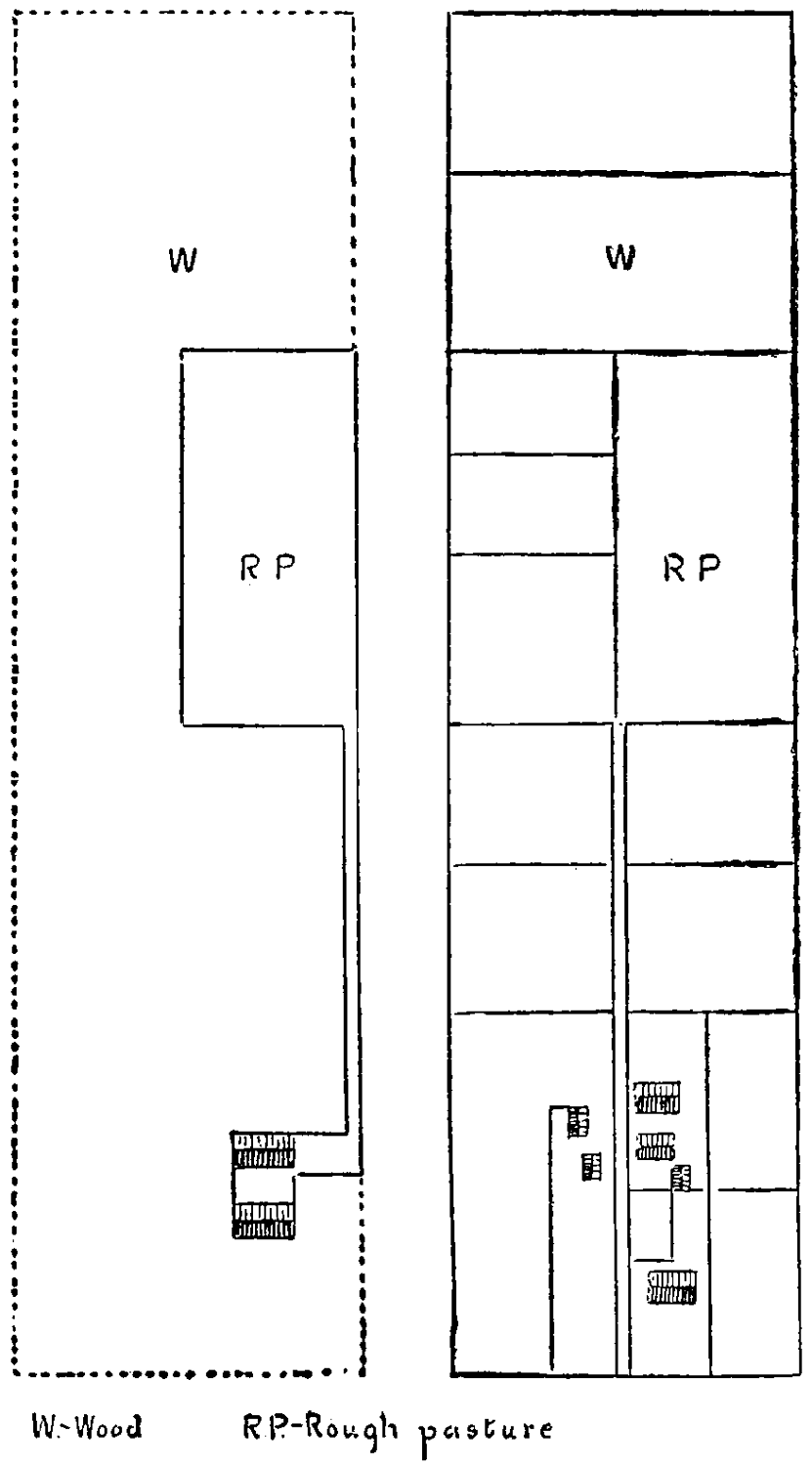

Can a competence and a comfortable home be secured by the renter? If not, why not? Shall the farmer put his little capital into a home and run in debt for supplies and necessary equipment; or had he better rent, and start even? This depends to a large extent upon the individual. A successful country life does not depend upon owning the land in fee simple. Here is a picture of what may be called “a country gentleman” (Fig. 3). He, his father and his grandfather, all have been renters of the same farm. He has a competence and an assured income. This hue and cry about renting has no terrors for those who have been renters and have found that this is often the most satisfactory way to start when capital is limited. The merchant of limited means invariably rents the building in which he does business, because it is safer and usually more economical to rent than to purchase the business block.

[41]

Fig. 3. A farmer and a renter.

In an old city of 12,000 inhabitants, it was found that 84 per cent of the business was carried on in rented rooms. The trouble in renting farms in the United States lies chiefly in the fact that there are no well digested laws or old customs which help to guide the renter and rentee. A few simple laws would provide for adjusting the value of betterments removed from[42] or put upon the farm at any time. Long leases, with inducements to long occupancy, would give the rentee a permanent occupier. The renter has quite as good a chance of finally securing a home in fee simple as has the man who purchases and mortgages heavily. The possession of a valuable farm and an assured income, especially in a new country, is often most surely and easily secured by renting for a series of years. Good farming pays liberal profits even on rented land. If there is failure, it is the man and not the occupation which causes it. The fault will not be “in the moon,” but in ourselves if we fail or become underlings.

[43]

More and more we are coming to believe that the rural district schools offer but few opportunities for educating the farmers’ children. Various schemes have been recommended for providing better and more convenient educational facilities. One proposition is first to improve the principal highways. This, it is thought, will make it possible to run ’buses or carriages twice daily to transport the children to and from some centrally located graded school. Such schemes are usually proposed by some one who has seldom seen a country school-house and who is totally unacquainted with the conditions which prevail in rural communities.

Admitting, for the sake of comparison, that teacher and pupil in the country are not so far advanced in book-lore as they are in the city, how does it happen that the country youths are able to maintain themselves on an educational level with the pupils of the graded schools when they meet them in the academy and college? Is it not quite possible that the wide opportunities[44] enjoyed by the country youth for becoming acquainted with natural objects of use and beauty are a full offset, so far as training is concerned, for the more systematic instruction given in the city schools?

I can but look with some degree of solicitude on the effect on civilization and on the home, of palatial hotels, and great school buildings, filled with heterogeneous masses of children, in which love, solicitude and sacrifices, each for all, have little opportunity for growth and development. The family seems to be the sacred unit of civilization and morality. A full and sufficient reason must be given for massing men, much more children, in a single great structure, thereby destroying the quiet and breaking the sacred ties of the home. What good reasons can be offered for massing children between the ages of six and twelve in an uncomfortable school-room? Children do not study; they learn little except when they read the lesson in the immediate presence of the teacher who is able to amplify and explain the lesson in hand. Sending these little ones to school is a relic of the primeval days, when, by reason of large families, lack of training and excessive toil of the parents, there was no other way but to make nursery maids of the school-teachers.

I have a vivid recollection of those early[45] days when I was crowded into a 16 × 20 school-house, with two score other bounding, mischievous urchins, all seated on the hard side of unbacked, long-legged slab benches, which left our bare legs, for which the flies had a liking, to dangle between heaven and earth. True, all this has now been improved, and good and appropriate seats are usually provided, but this only ameliorates the conditions; it does not cure them. If the parents who have lost something of their first love for their children, or who are too lazy or careless or ignorant to teach them, will go to these patent-seated school-rooms and sit for five mortal hours on one of these hard, wooden, uncushioned seats, they will no longer place their tender children in these modernized stocks. You who no longer have the hot blood and restless nervous energy of youth make long faces and complain bitterly from your well cushioned pew, if the over-earnest pastor prolongs his sermon ten minutes beyond the customary time. It may be said that many, nevertheless, secured a primary education under these unfavorable conditions. But I did not; I received it at my mother’s knee in the old kitchen, some of it before daylight. About all I got in that old school-house were kicks and cuffs from boys who were older and stronger than I, and round shoulders from sitting through many[46] weary hours on backless benches, and blistered hands in punishment for my unrestrained interest in things in general, and in my school-mates in particular.

But what has all this to do with the opportunities which a farm life gives for education? It is to emphasize the need of more home training, more personal attention by the parents, and a more natural and rational education of those whom it has been our responsibility to bring into existence, and upon whose shoulders will rest the weal or woe of our country. In these rural homes, children should be reared and educated until they have reached the point beyond which their parents or the older children cannot carry them. The child, when only two or three years old, begins to learn handicraft, performs some little helpful act for another; it is being taught to work. As it becomes more mature it is to do useful things; but who thinks of keeping the child of eight to ten years of age at continuous work for five or six hours daily? Why not carry on the child’s mental education along these natural lines in the same manner as it receives its primary technical education?

I am almost persuaded that the farmers’ children would be better off if the old red school-house on the dusty, treeless four corners was abandoned, and the responsibility for the[47] education of the children up to twelve or fourteen years of age was thrown upon the parents. As it is, the parents who have received a fairly good primary education become rusty and illiterate simply from non-use of the education which they had when they left the schools. If the unexcelled opportunities which rural life offers for securing a primary education were only utilized, there would be fewer country youths hating even the sight of that red school-house which has received such honorable mention. It has been glorified in every Fourth of July oration, but it still remains not only unevolutionized but even degenerated.

If you ever imagined that the best provision has been made for teaching the little ones, spend a day in one of these school-houses. Take some book with you that is as abstract and useless to you as the children believe their books to be to them, and make the attempt to memorize a single page, or essay to write a composition on “The Immortality of the Soul,” or on “The Wisdom of Annexing the South Sea Islands.” Meantime, classes are reciting in falsetto voices; the teacher is giving many admonitions and making dire threats; a festive bumblebee has found its way through the open window and makes as much commotion among the timid girls as a mouse at a tea-party. Now a[48] dog barks, and the boys know that Bowser has safely treed a squirrel. Before you have had time to collect your thoughts a lusty farm boy, perched on a creaking wain, whooping loudly to his team, goes rattling by. Stay a week and finish your composition, and see how fast your children are securing disjointed fractions of an education. A half-hour of continuous, quiet, intensified study at home is worth more than a day in many a school-room where little muddy driblets of knowledge are being doled out to the children.

You may say that you have no time to teach children. Business is too pressing, and you are already overworked. You should have thought of that sooner, and been wholly selfish and saved the money and time you spent to persuade that beautiful maiden to join you and help perform the duties and functions of life.

You will certainly agree that home education is the best, the ideal education. For a child, an hour or two of study and recreation a day, an equal time employed in useful work, and the rest of the day spent in picking up fun and facts, both of which may be found in abundance on the old farm, is the natural way to secure a broad primary foundation, upon which to rest a liberal education.

After the child has reached the age of ten or twelve and has had careful home training,[49] what provision can be made for continuing its education during the next four to six years? Two or more districts might be joined to form one, for graded school purposes. On every farm is, or should be, a spare horse and a light wagon; a few dollars would provide a stable near the school building. Such an arrangement would permit the children to drive to and from the central school, although the distance might be two or three miles. All this means that the children will be around the family fireside in the evening instead of on the street, as is too frequently the case when they are sent to the village or city school and remain during the week. All this keeps the boys and girls in sympathy and healthful touch with home life and their parents, until character has been strengthened by age and knowledge. Here, in these country and village graded schools, the home life, with its restraints and duties, is preserved. Only the mentally strong or the courageous and aspiring will seek the halls of higher learning, from which, if they tend to go astray or neglect their work, they are quickly returned to the bosom of their families. If the central graded school is impracticable in some cases, then a few families might join and employ a private instructor; this would be far cheaper and more satisfactory than to send the children away from home.

[50]

It is not so much lack of facilities as a lack of an appreciation of the true value of an education which debars the country youth from securing even a wholesome and logical primary education. The value of an education for citizenship must be placed first, and its value as a money-making power second. Now the first question that is usually asked is, Will an education help to secure a position or to make money? The question, Will an education help to a nobler citizenship? is not even thought of. We shall have no evolution in rural training until the parents secure a clearer conception of the true value of an education.

Evolution along educational lines has already begun, and it is not difficult to see many beneficial effects of the changed methods. M. Demolins’ recent book has this to say: “‘It is useless to deny the superiority of the Anglo-Saxons. We may be vexed by this superiority, but the fact remains, despite our vexation.’... Considering the superiority conclusively proved, the author proceeds to search for the cause of this superiority. He finds the secret of this irresistible power of the Anglo-Saxon world in the education of its youth, in the direction given to studies, to the spirit which reigns in the school. The English and the people of the United States have perceived that the needs of[51] the time require that youth should be trained to become practical, energetic men, and not public functionaries or pure men of letters, who know life only from what they learn in books. M. Demolins has personally studied with care some prominent English schools. In these he found the school buildings, not as in France, immense structures with the aspect of a barrack or a prison, but the pupils were distributed among cottages, in which efforts were made to give the place the appearance of a home. They were not surrounded by high walls, but there was an abundance of air and light and space and verdure. In place of the odious refectories of the French colleges, the dining-room was like that of a family, and the professors and director of the school, with his wife and daughters, sat at table with the pupils.”[2]

[2] Editorial, “Literary Digest,” July 2, 1898.

Here is seen the beginning of better methods in primary education. In the rural districts of America, this system needs but little modification to fit it to the rural home. All else must yield to the inborn rights of the children. If that Brussels carpet which adorns the dark and unused parlor must be pulled up and some of the worst pictures relegated to the garret, in order that provision for a school-room for the children of the family or for those of the immediate neighborhood may be made, then pull[52] it up. Receive the visitor in the sitting-room or on the veranda, and let the neighborly chat be where there is “air, and light, and space, and verdure.”

Reduce the above picture of an English school to suit environment, and we have the family as a unit; the mother and her companion as teachers; and we shall have not only the appearance of home, but a true home, where duty commands and love obeys. This is no far-fetched picture; it is one drawn from many observed instances of these farm home schools. The youths on the farm have a right to a liberal education if they desire it; they own the earth, and why should they not have the best it affords if they make good use of what the earth and all that therein is has to offer.

When we come to the higher education, there are good and sufficient reasons why pupils should be massed. At the college, expensive and rare appliances, great laboratories and museums, ample and expensive libraries, and distinguished and able teachers, must be provided. Then, too, the pupils of the college have arrived at that period of maturity which gives them a fair degree of self-restraint and discretion.

Connected, as I have been for more than a quarter of a century, with college life, I have had many opportunities to observe the freshness,[53] vigor and purity of many of the country lads and lasses who come directly from the healthy, solid home instruction of their parents.

I am well aware that this chapter will not revolutionize rural primary education. I do not want it to do so. Revolution destroys; evolution builds. But if these brief words of one who received until near manhood the thoughtful, loving home training of a mother, who said, “I received a better education than my parents did, and, come what will, I determine that my children shall have better opportunities for securing an education than I had,” shall persuade some that the farm home is the natural, the appointed place for training children until they have passed the critical mental and physical period of life, I shall be content.

[54]

In selecting a farm, many things should be considered. One purchaser may lay stress on the quality or productivity of the land, another on its location as to market, another as to the outlook or scenery, and another as to the society in the immediate locality. Some would be unhappy if far removed from city or town, while others delight in many broad acres far removed from the busy crowd. All these different phases of the subject, with many others, should be considered before the purchase is made. It is seldom that a farm can be secured which fulfils all desirable conditions; therefore, such choice should be made as will most fully meet the desires and tastes of the purchaser.

Some farms are purchased with little or no thought of their producing a livelihood, while others are selected largely for the purpose of securing profits in their cultivation, and others are bought because they are expected to furnish safe and profitable investments. It is evident[55] that no specific or even general rule can be formulated which will be applicable to all purchasers, since tastes, training, needs and desires of the purchaser vary widely; nevertheless, a discussion of the subject may be profitable. Those who secure their income and profits by agriculture alone should lay stress on four things; viz., healthfulness, environment, quality of land, and water supply.

Without health, life often becomes a burden; therefore, climatic conditions, soil and surroundings, so far as they relate to physical and mental vigor, should be considered first. But health and vigor are not all, for if the moral, intellectual and social conditions of the people in the neighborhood are undesirable, the children may take the road which leads towards semi-barbarism. This road is open to all, in city and country, but parents should avoid thrusting their children into it. Church, and social congenial and God-fearing associates should be accessible to the growing family. Children are and must be active, physically and mentally, if they are to grow straight; and if provisions are not made for directing their energies into proper channels, they are likely to find improper ones. Wherever the farmer sows not a full abundance of good seeds, weeds are certain to spring up. The farm must provide a fair and liberal income,[56] because want brings lack of true pride, breeds carelessness, even hatred of others, filches self-respect and courage. Therefore, if profits are desired, good land, land of wide agricultural capabilities, should be selected. The greater variety of crops the land is capable of producing and the more varieties the farmer raises, provided he does not exceed his mental and executive capabilities, the better will be his education and training.

Frequently the purchaser has too little means, and feels that he must secure cheap lands, which too often are situated far from the railway markets and centers of activity. In such a case, he places himself outside the activities of the towns, which are extremely helpful to him if he be wise enough to choose the good and refuse the evil which they offer. Of course, much depends on the good sense of the parents and the inheritance and training of the children as to how much they will imbibe of that which is good and how much they will refuse of that which is evil. Children cannot be placed entirely beyond evil influences, but they can be prevented from becoming too familiar with them.

[57]

Already something has been said with regard to an abundant supply of water, but it may not be out of place to emphasize the necessity of securing healthful water for household purposes. Modern science has revealed the fact that a large number of diseases are introduced into the system by means of drinking water (see Chapter XII). All drinking water may be boiled; it may be said that it should be, for in too many cases water that appears limpid and pure, drawn from sources which have every appearance of being uncontaminated, is not only dangerous but sometimes deadly. Careful physicians recommend that all water be filtered, but so many of the filters are imperfect and are so badly neglected that there is no certainty that filtered water is entirely safe; therefore, it may be said that the only safe way is to boil all drinking water. As the streams and soil become more and more contaminated by unsanitary conditions, it is only in rare cases that safe water can be secured naturally. When wells or streams become low, or when streams are quickly flushed by heavy rains, invariably there is danger that the water which they contain may be impure. Care should be taken to provide an abundance of water, and that used for household purposes should be treated in such manner as will make it entirely healthful.

[58]

Having discussed the subject from four leading standpoints, those of less importance may be taken up. It is usually not wise to purchase a farm, however well it may fulfil the requirements of healthfulness, desirable environment and productivity, if the lands by which it is surrounded are poor, since man, in one respect, is like the tree toad, which partakes largely of the color of the thing to which it adheres. The French have a proverb which runs in this wise: “Tell me where you live, and I will tell you your name.” Translated into modern thought, it would read: “Tell me your environment, and I will tell you your character.”

Beauty of natural scenery may not be entirely ignored, although utility, the dollar, must be kept prominently in view. One can afford to economize in the living expenses in many ways not dreamed of by those who load the farm table with a superabundance of good things, if it be necessary to do so, to secure beautiful surroundings. It may be only a question of choice between a moderate subsistence and a reposeful environment, or an overloaded table with uninspiring surroundings. Natural as well as artificial beauty and pleasurable environment have their values. A certain lot on one street sells for $1,000, another one on the same street for $500. They are both within easy reach of[59] the business center, on the same street-car line, of the same size, and have the same elevation. Why the difference in price? Because of environment. A seat in the dress circle at the theater costs a dollar, one in the peanut gallery ten cents. The play can be seen as well with a glass in the cheap seat as in the more expensive one. Then environment has value, as well as land and buildings.

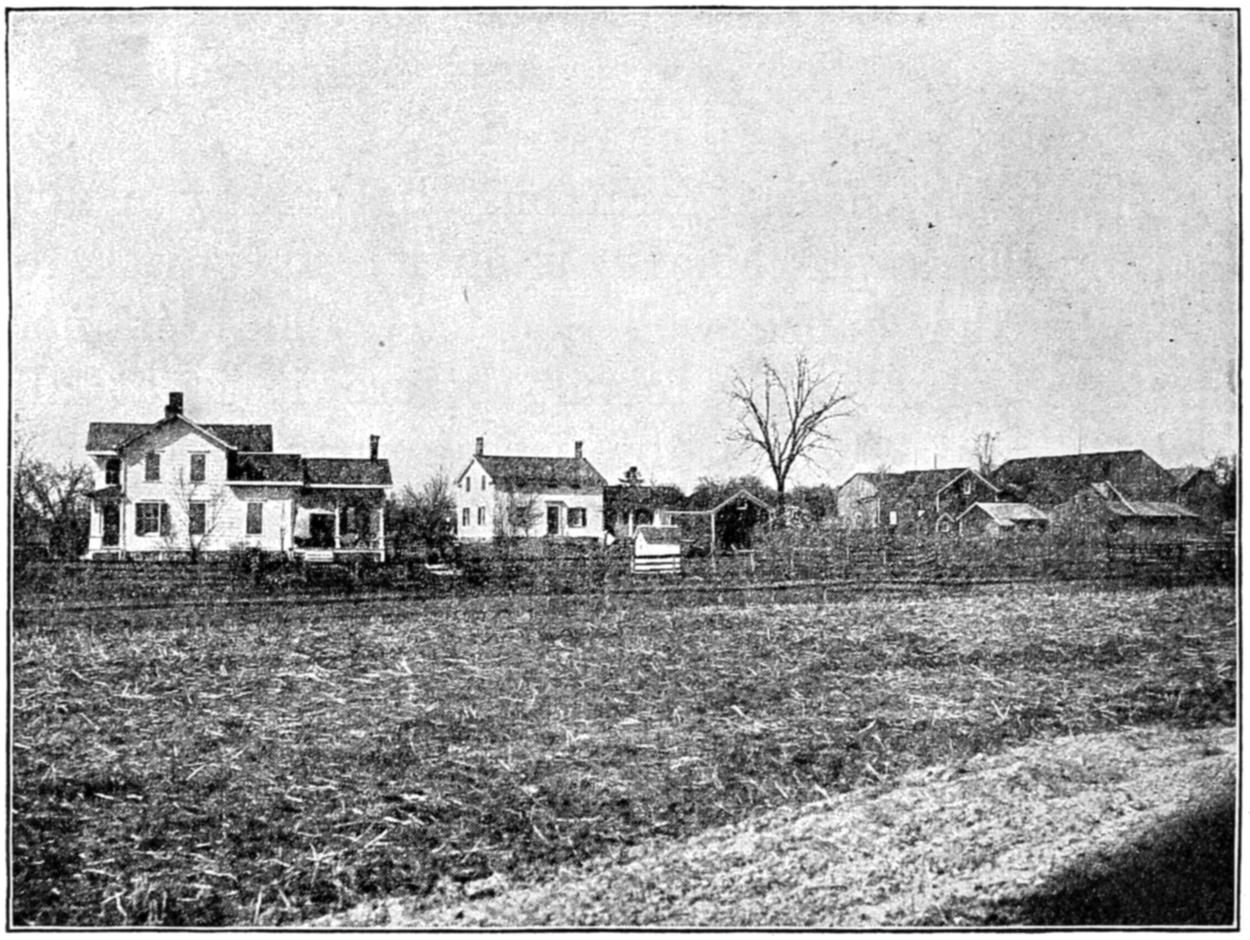

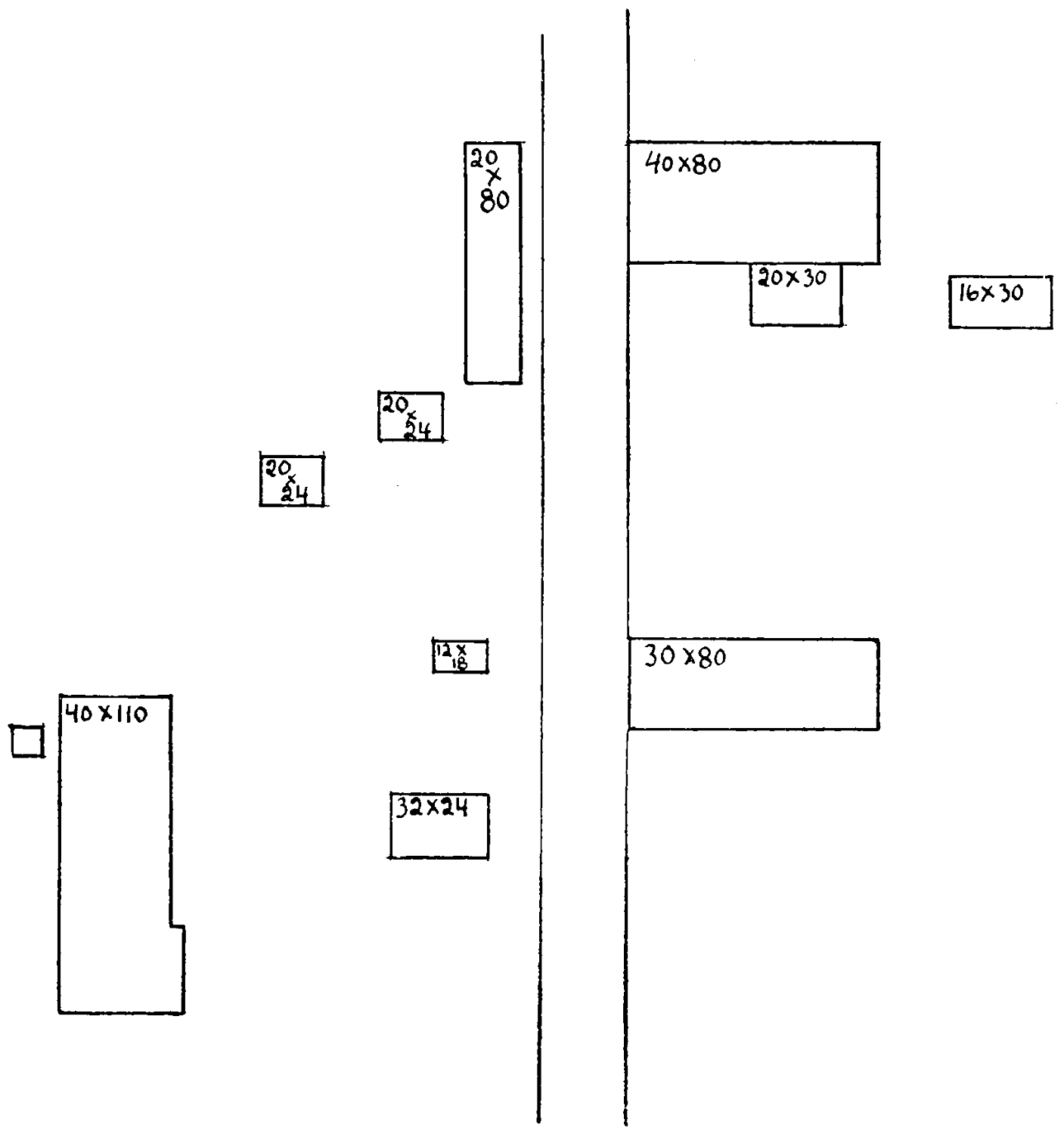

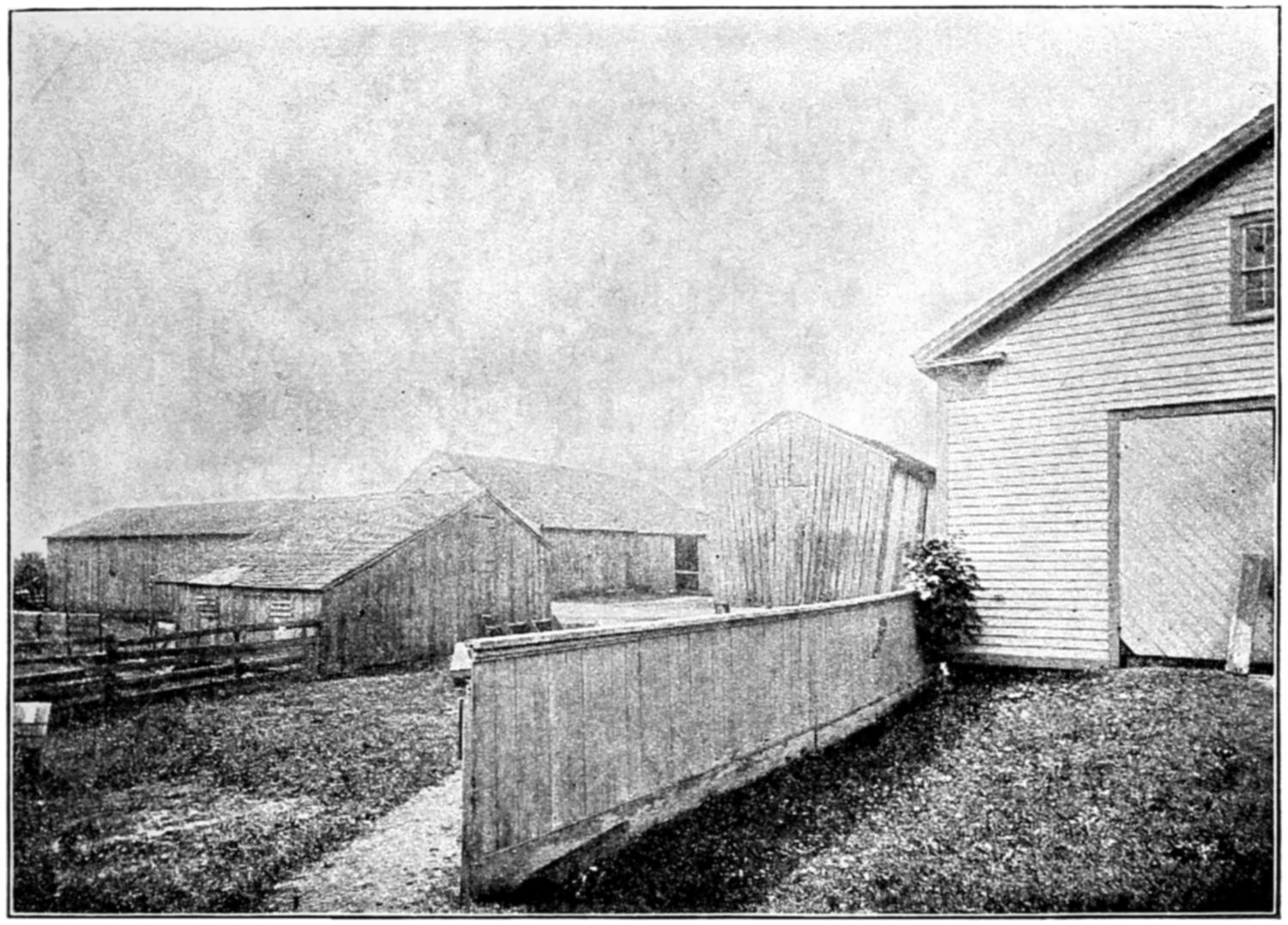

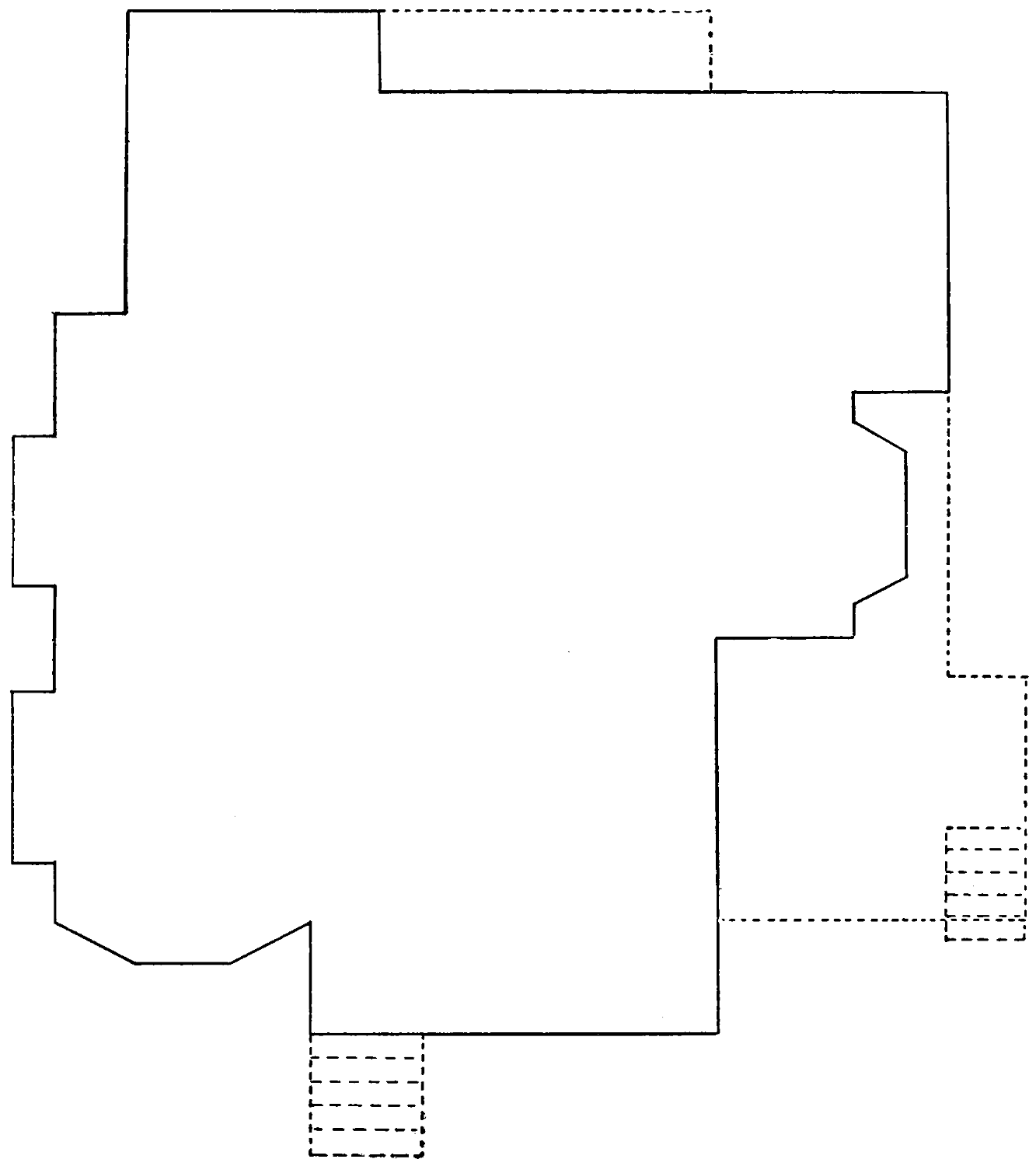

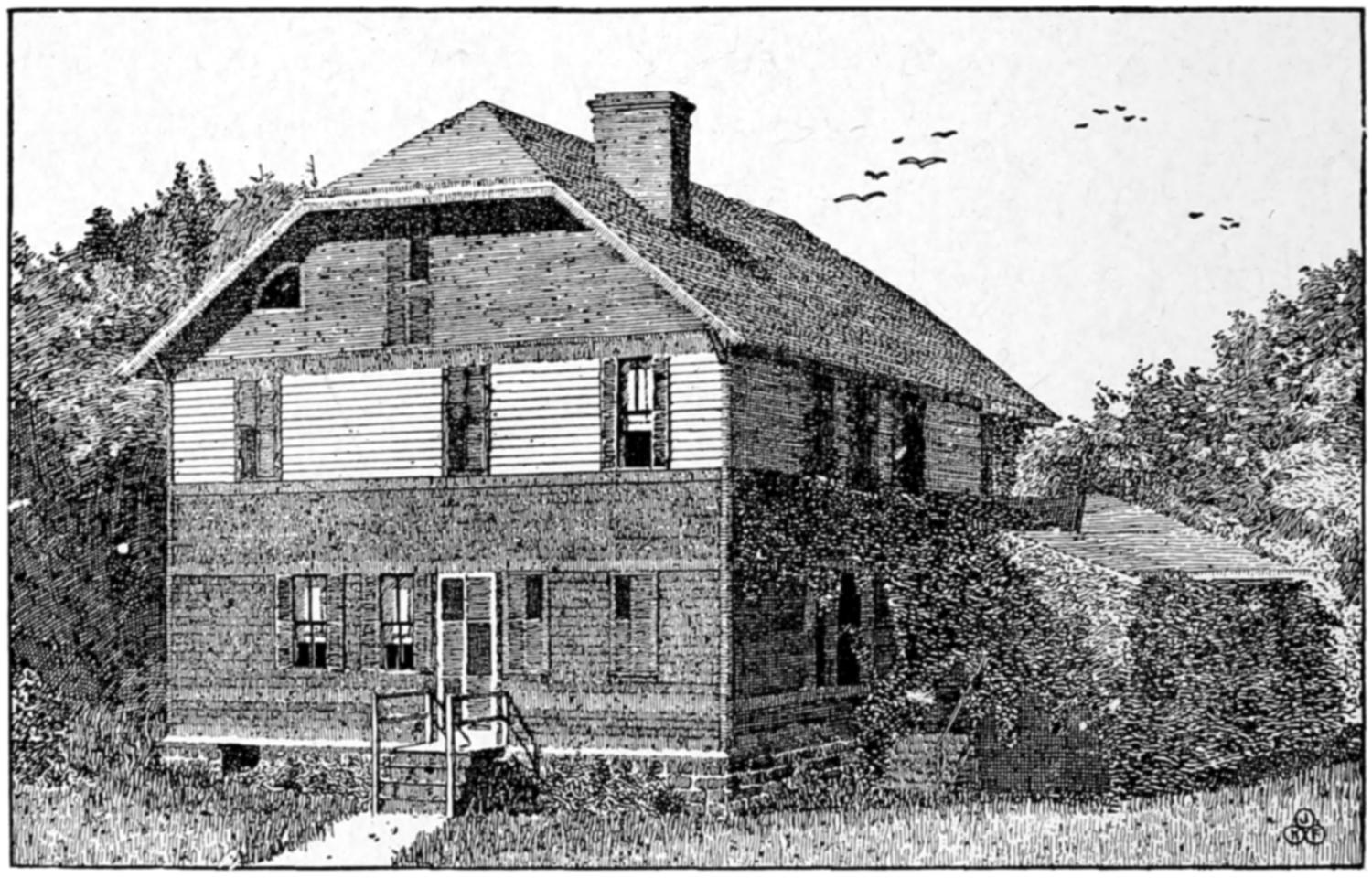

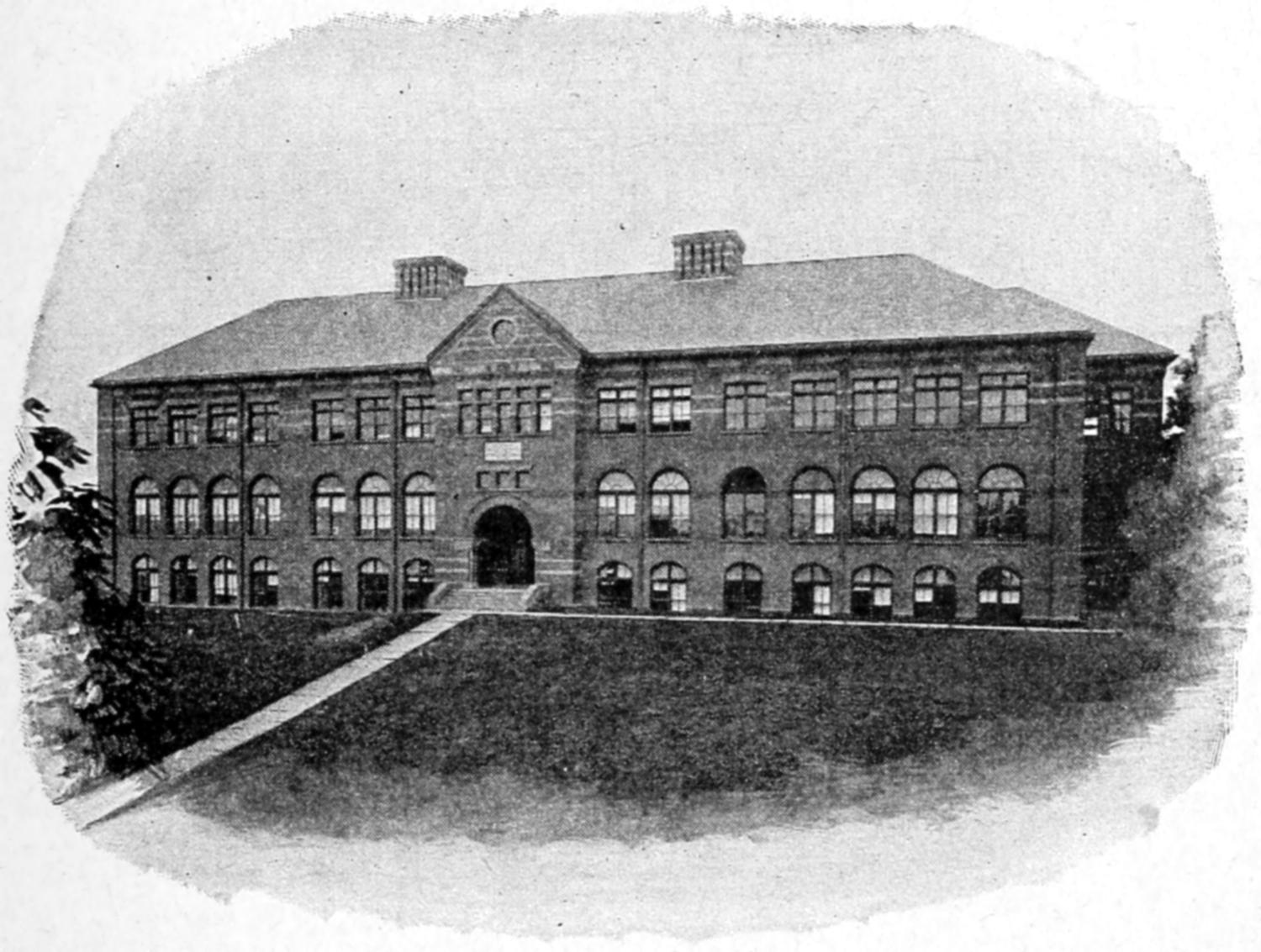

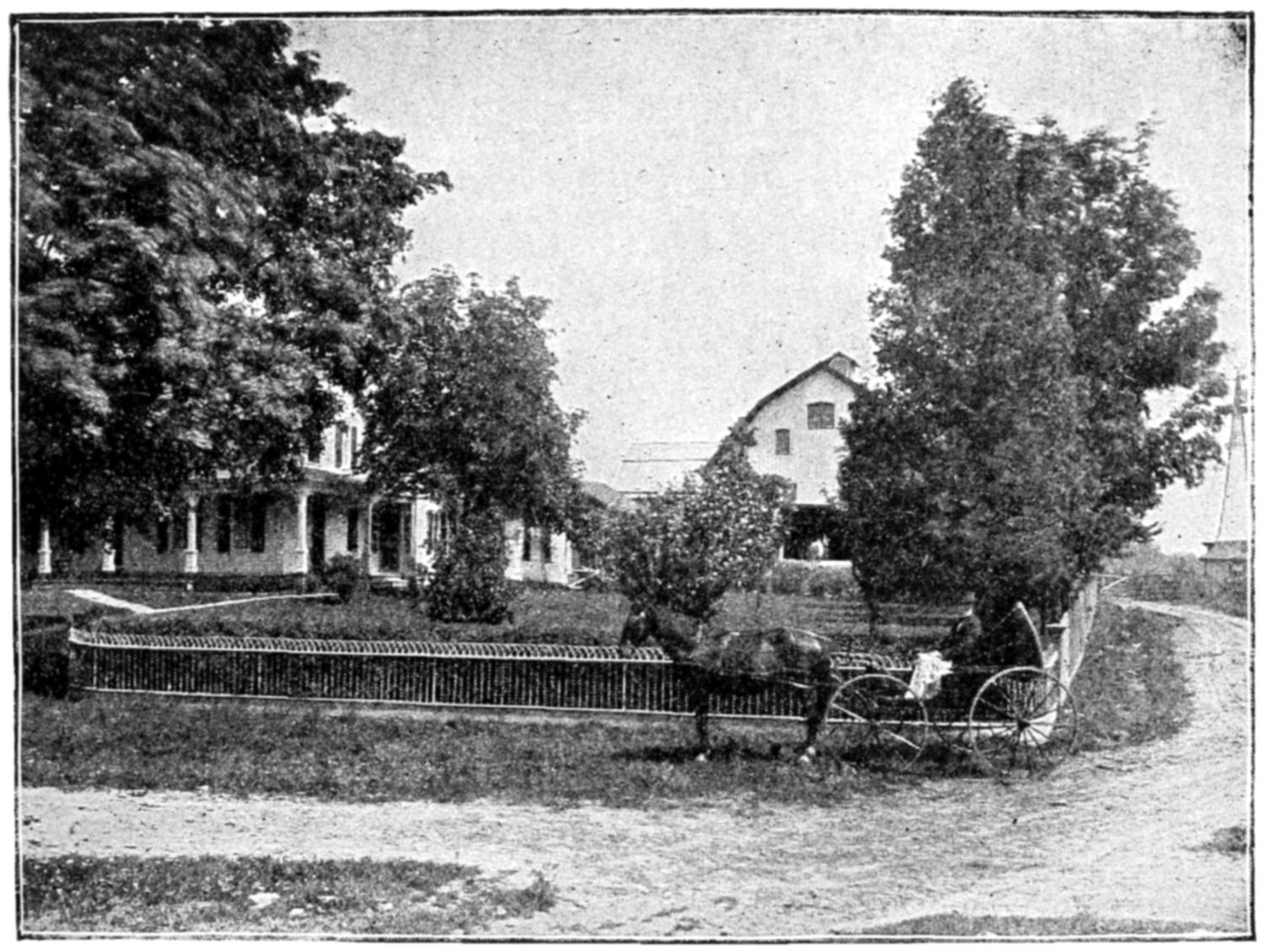

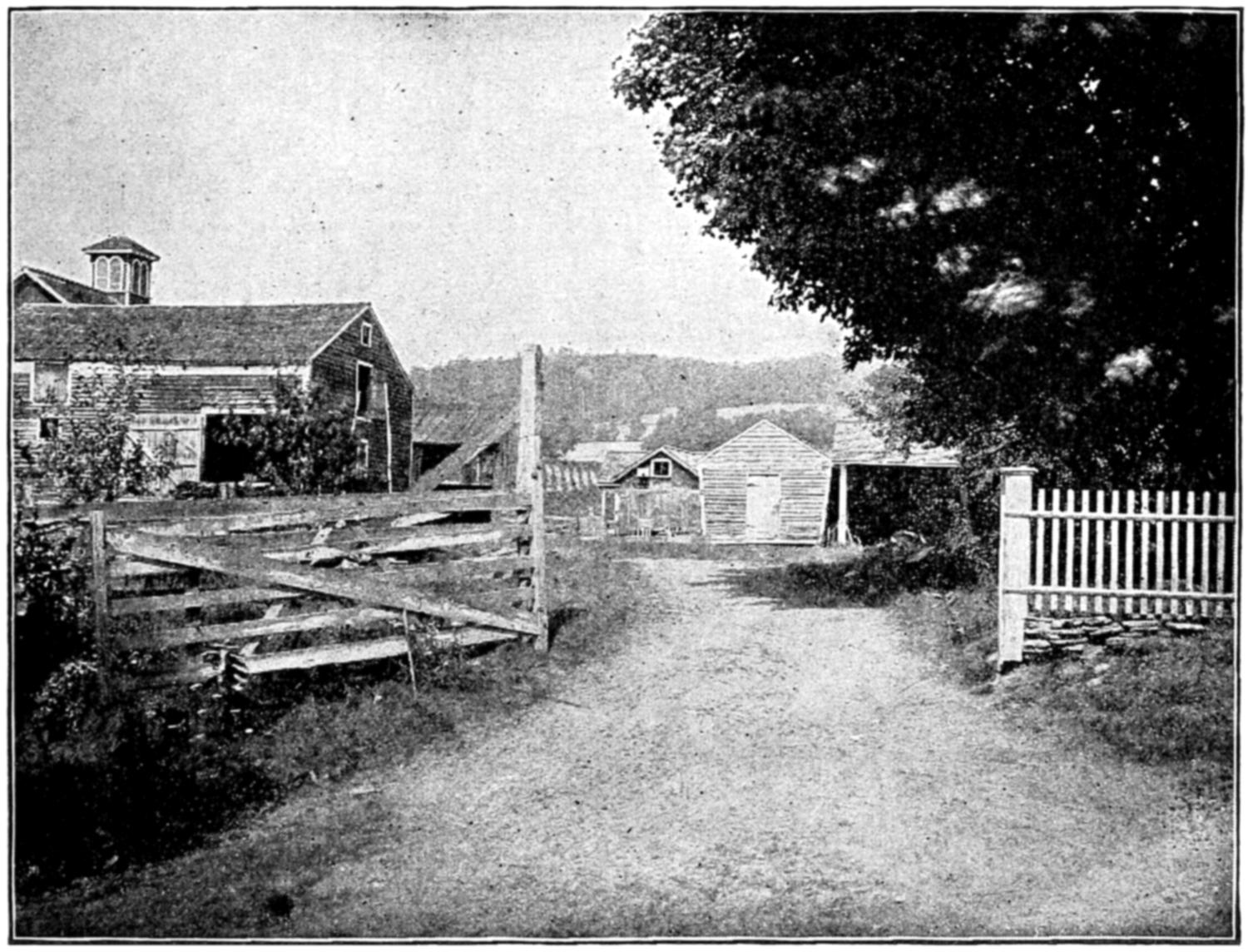

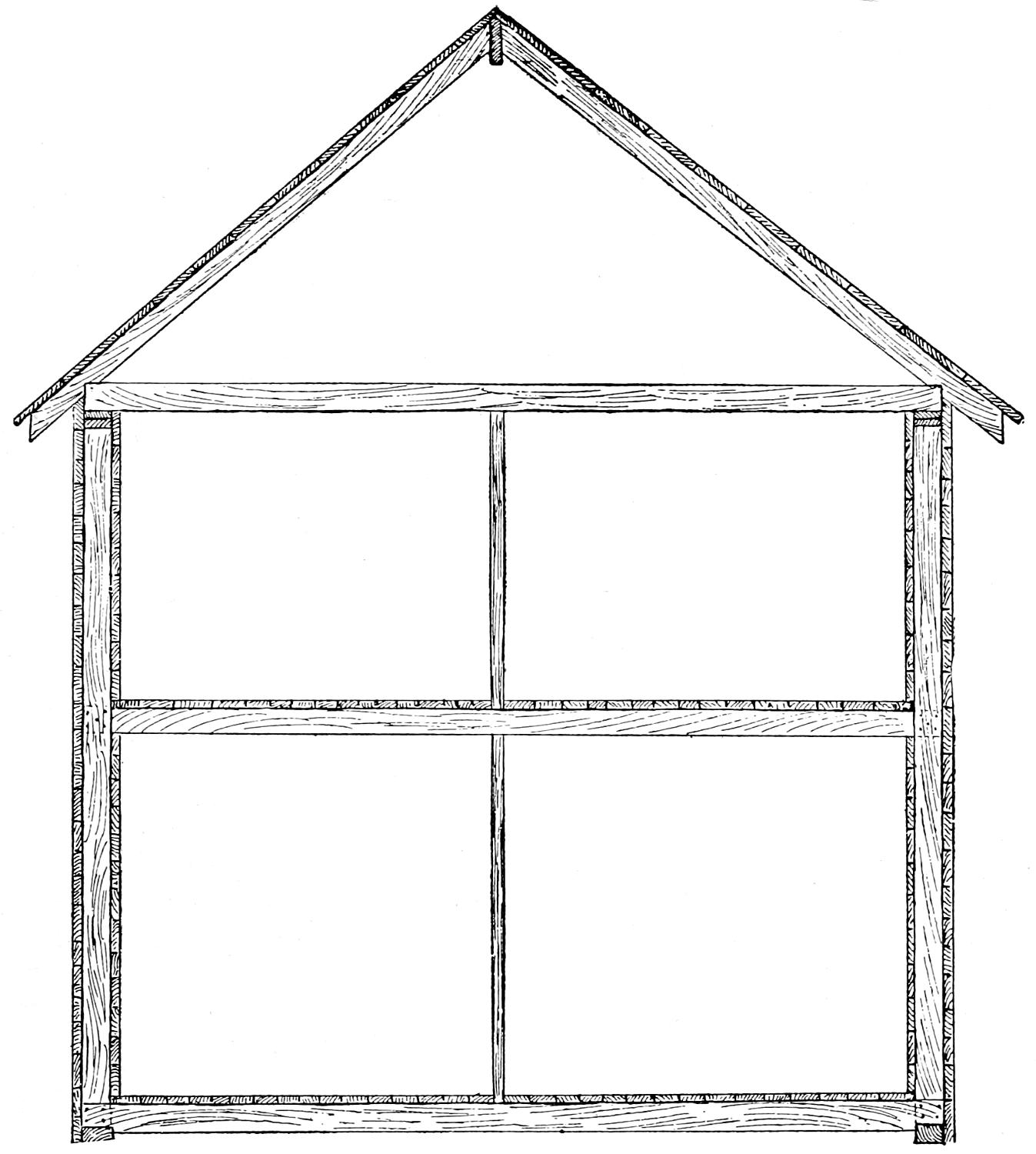

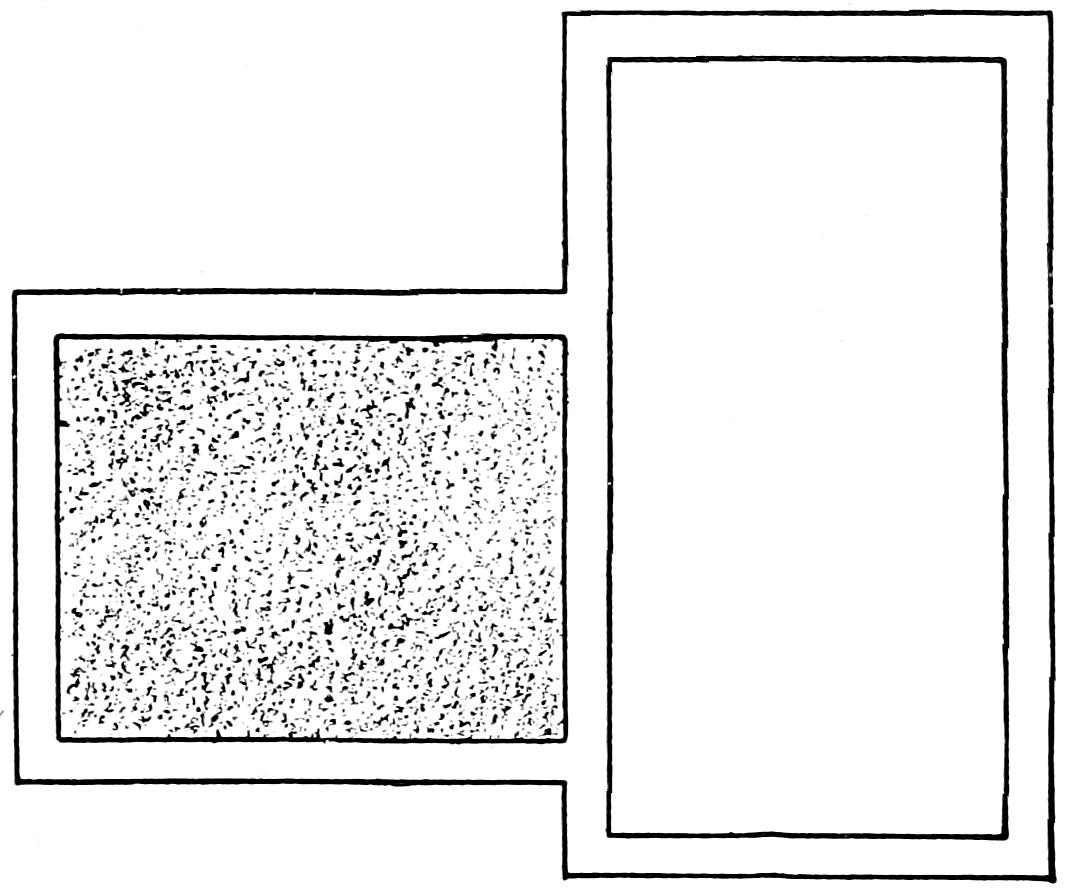

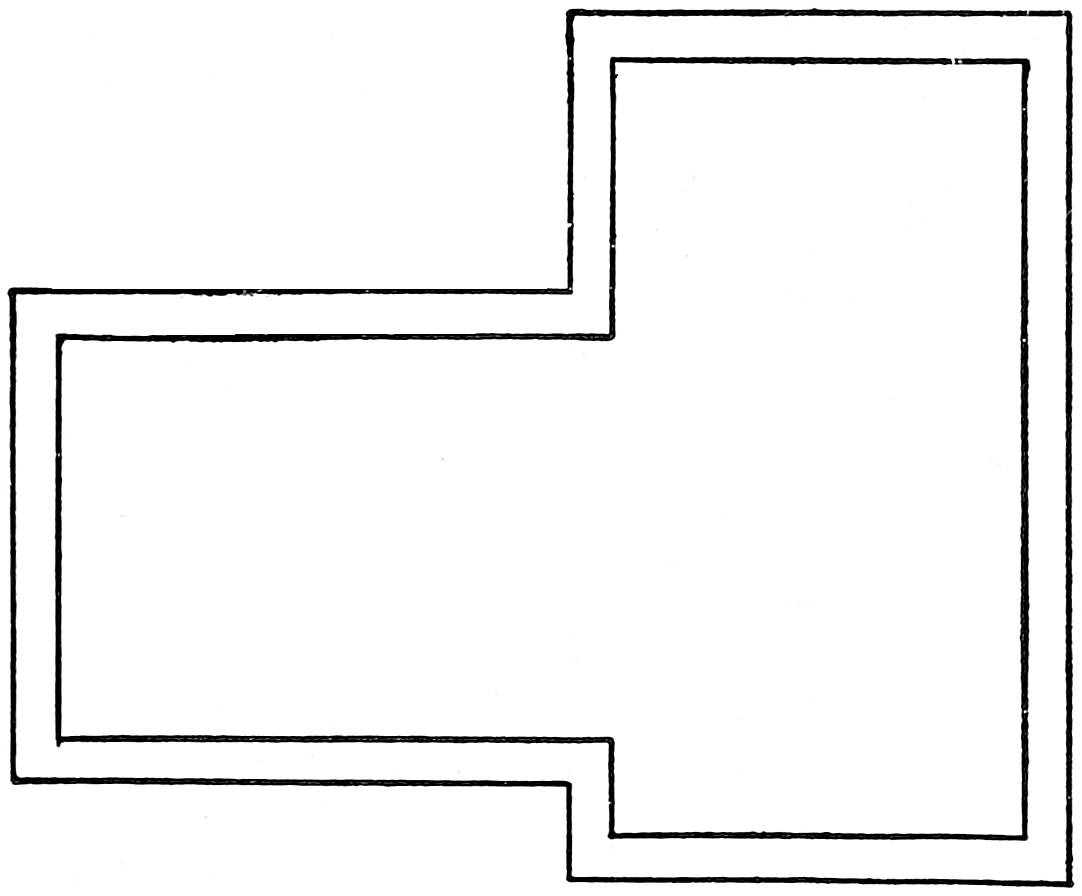

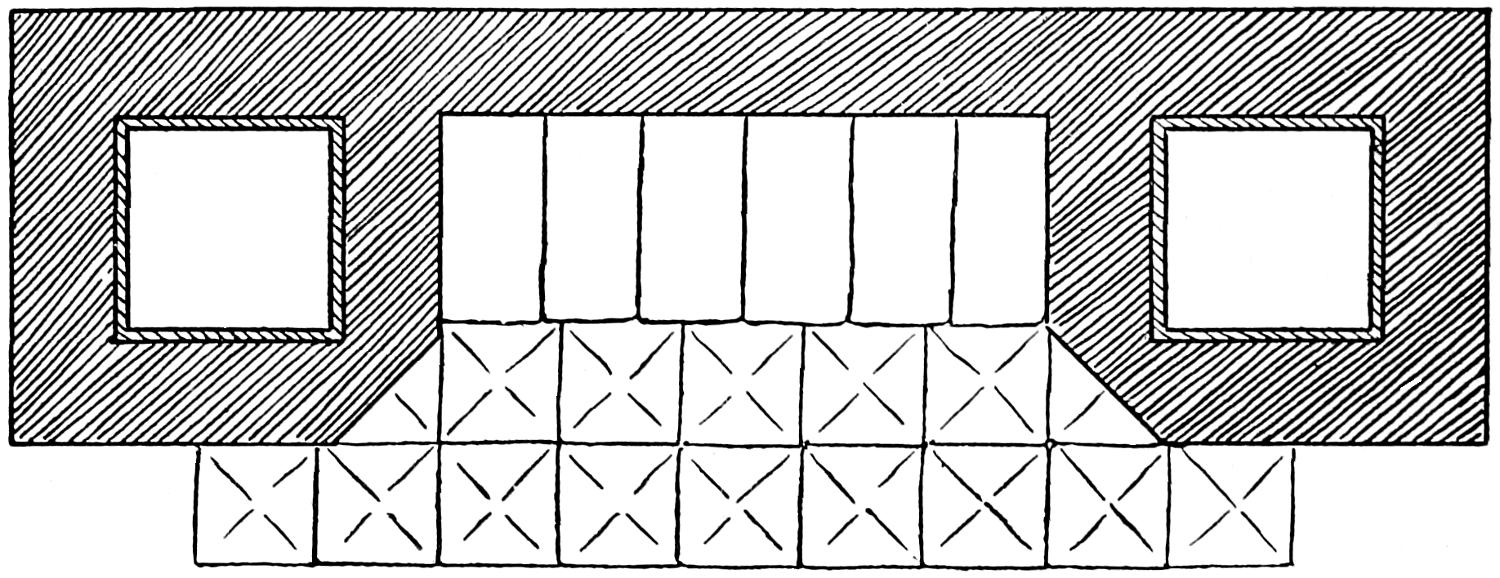

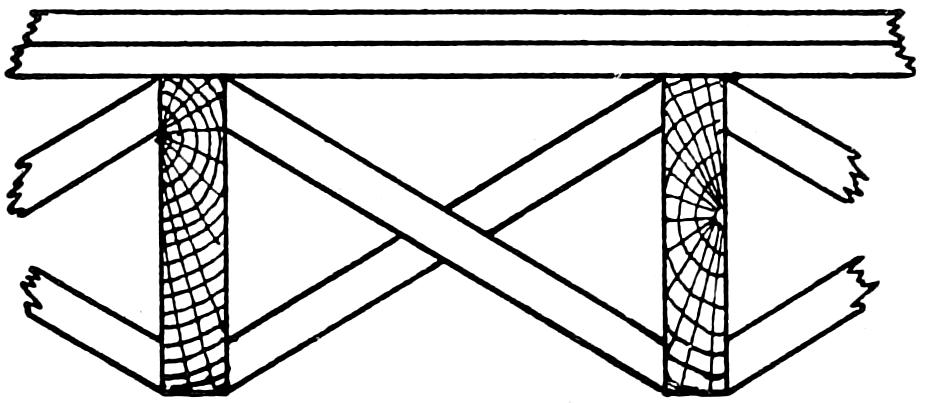

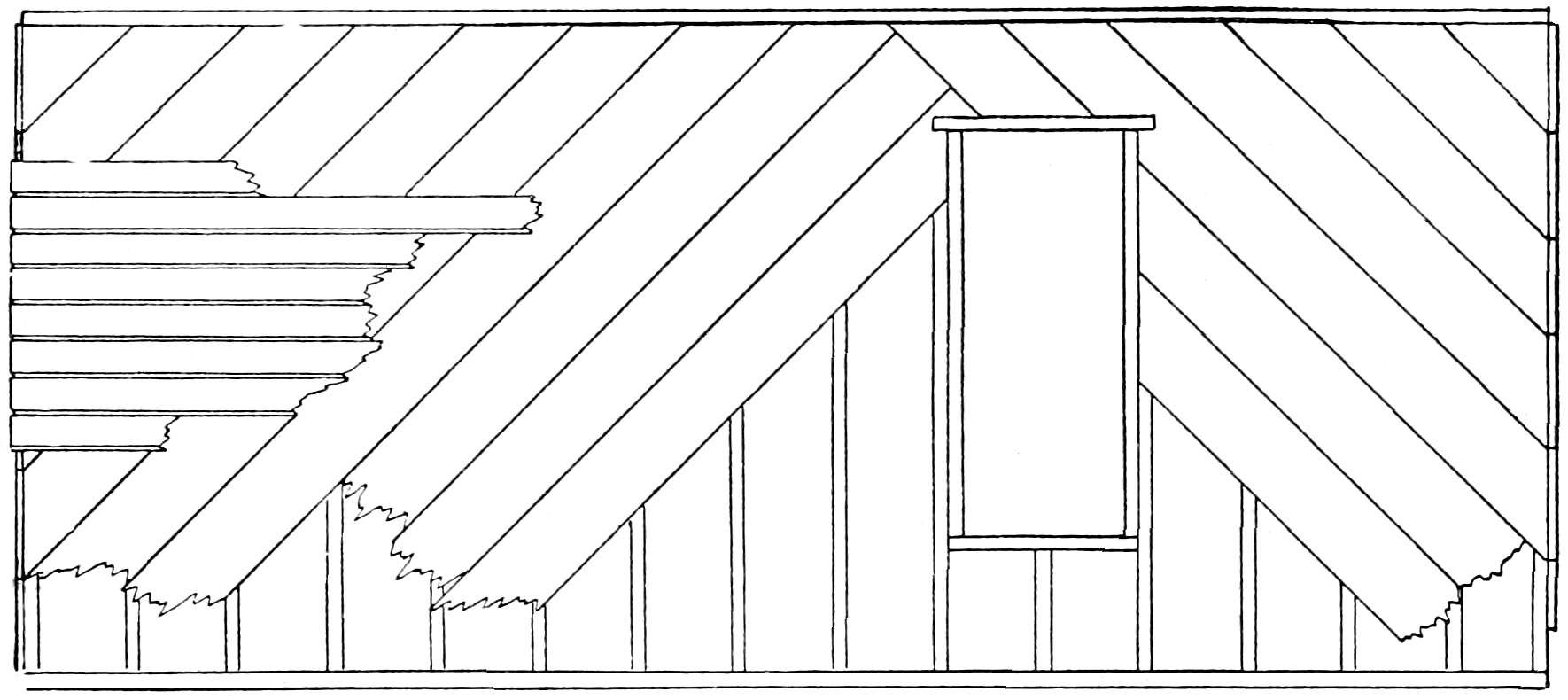

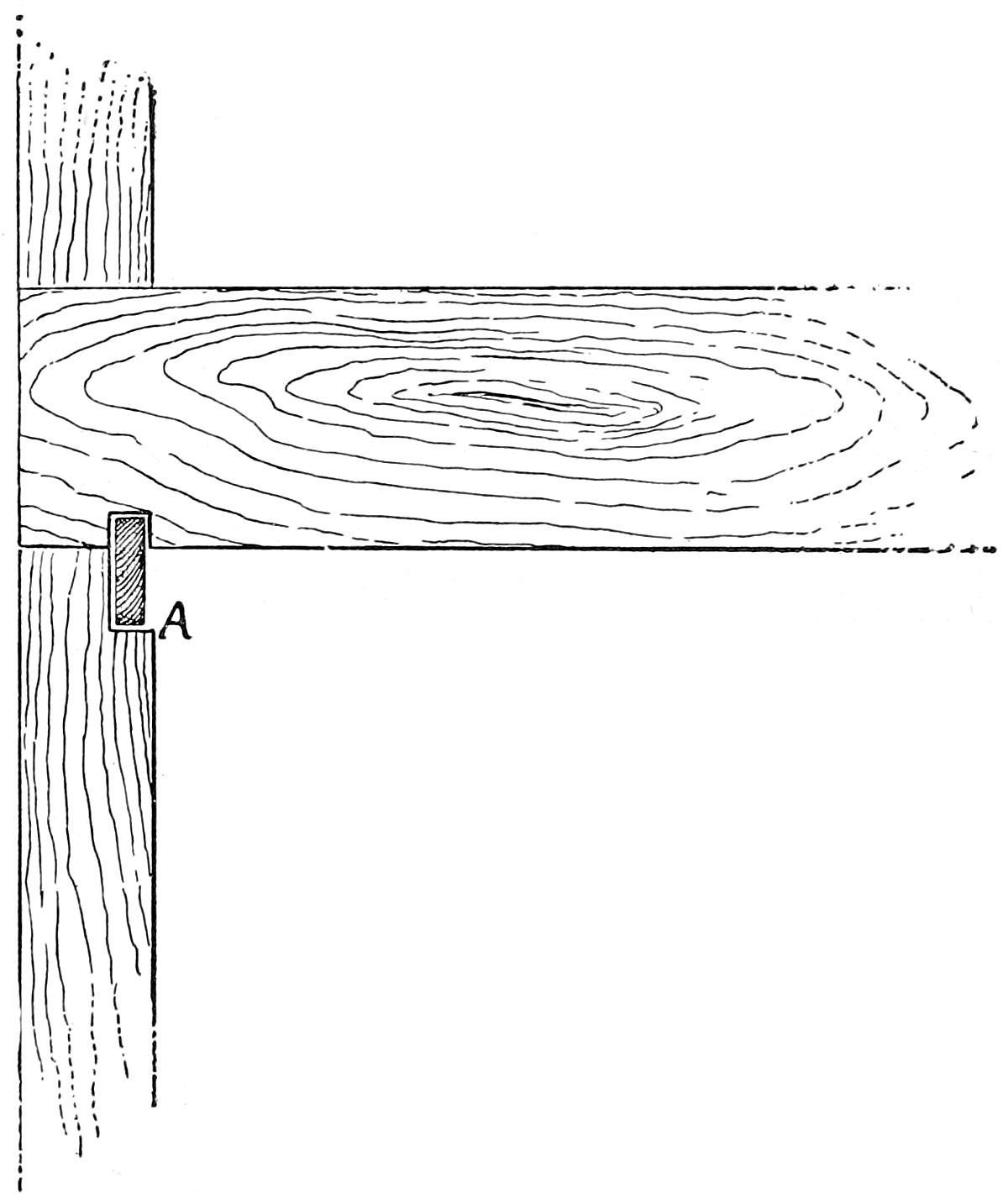

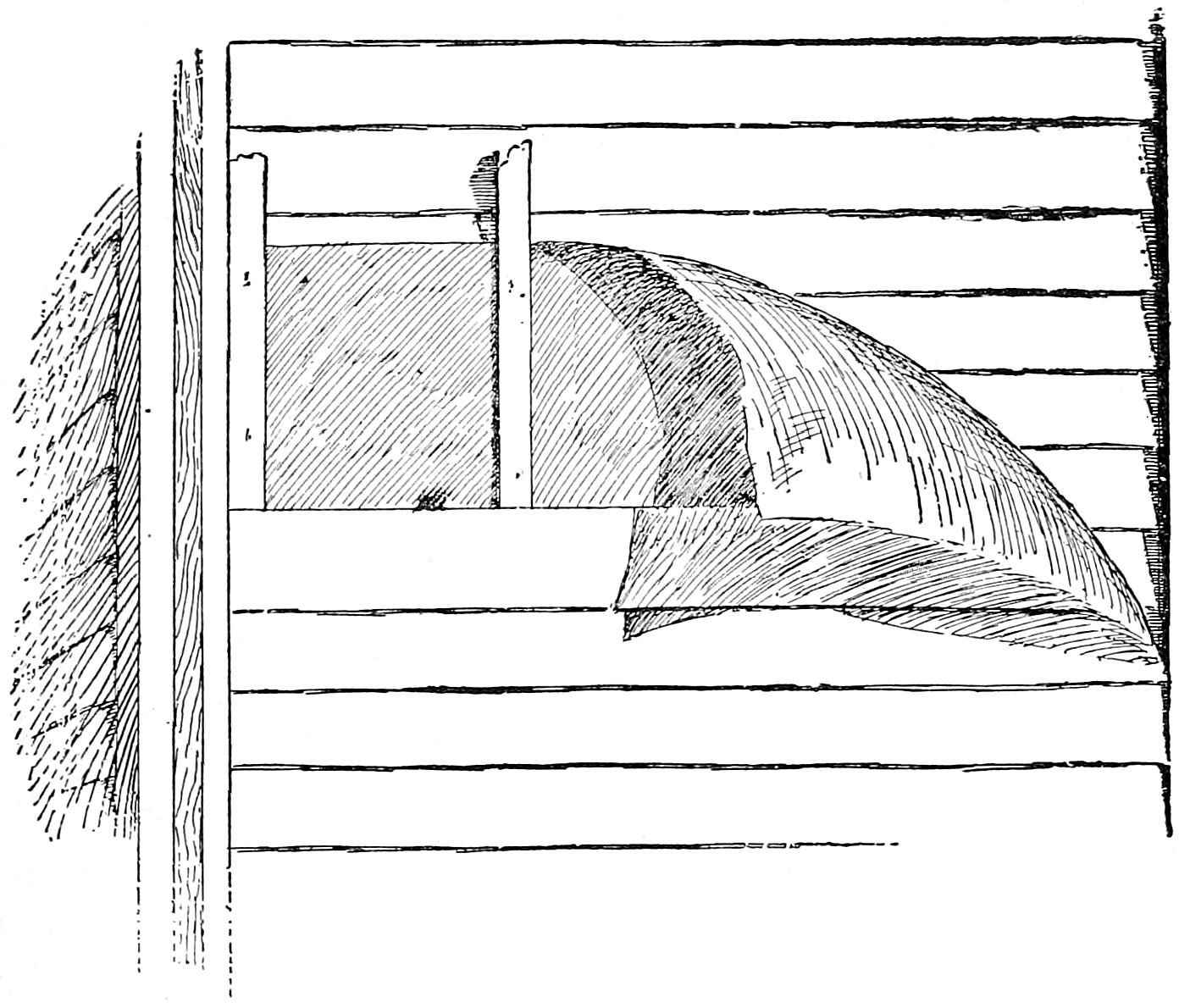

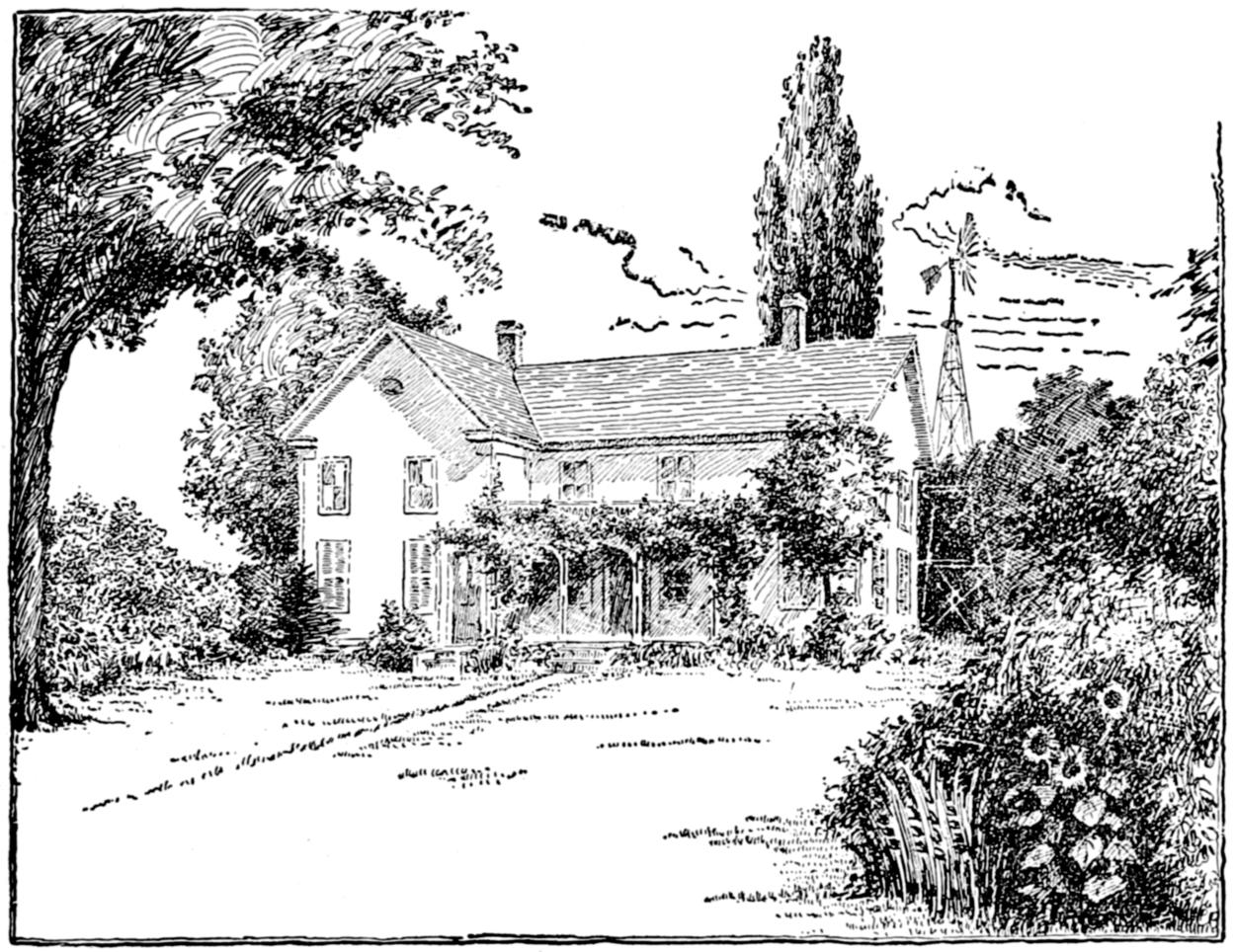

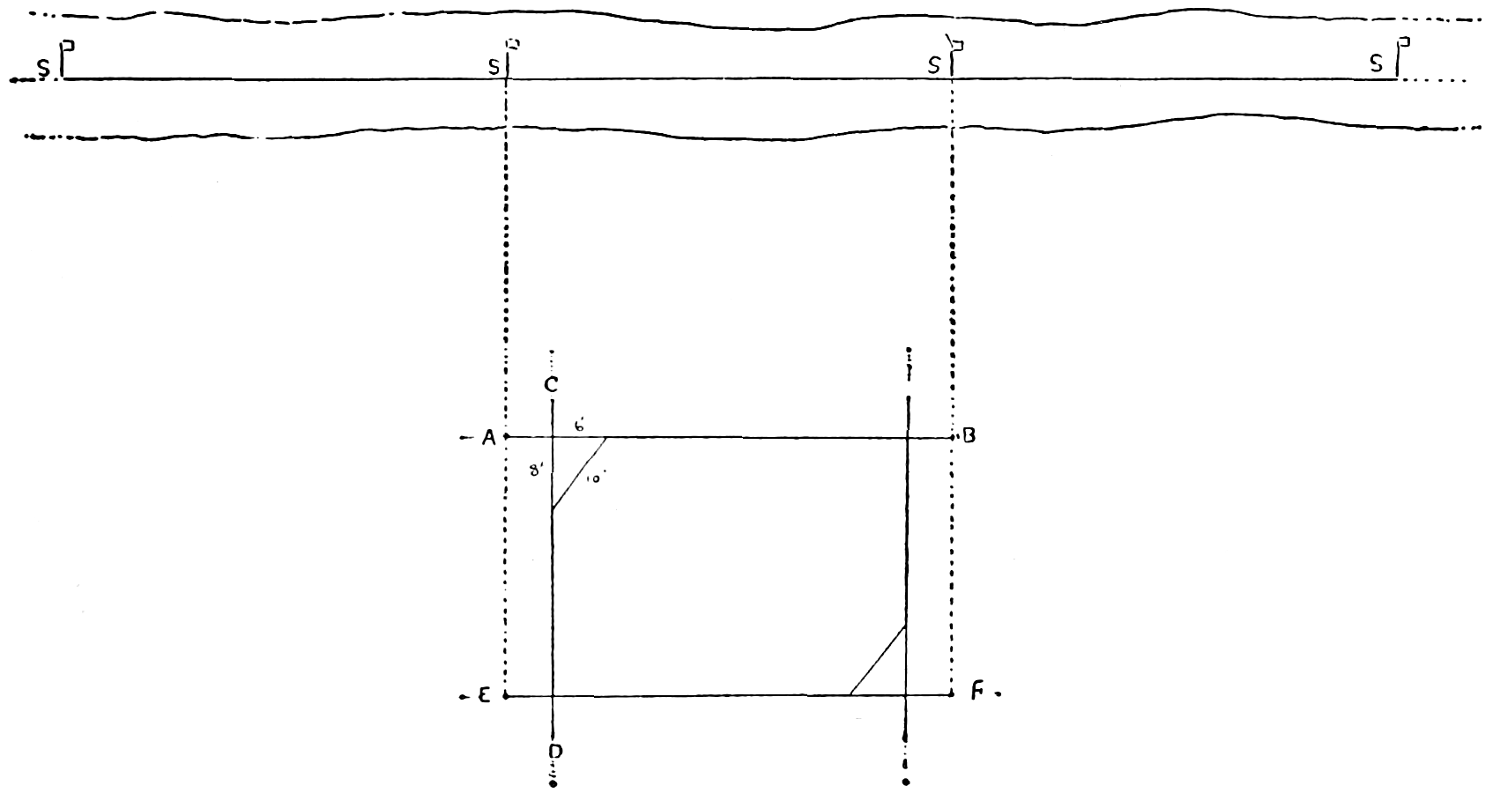

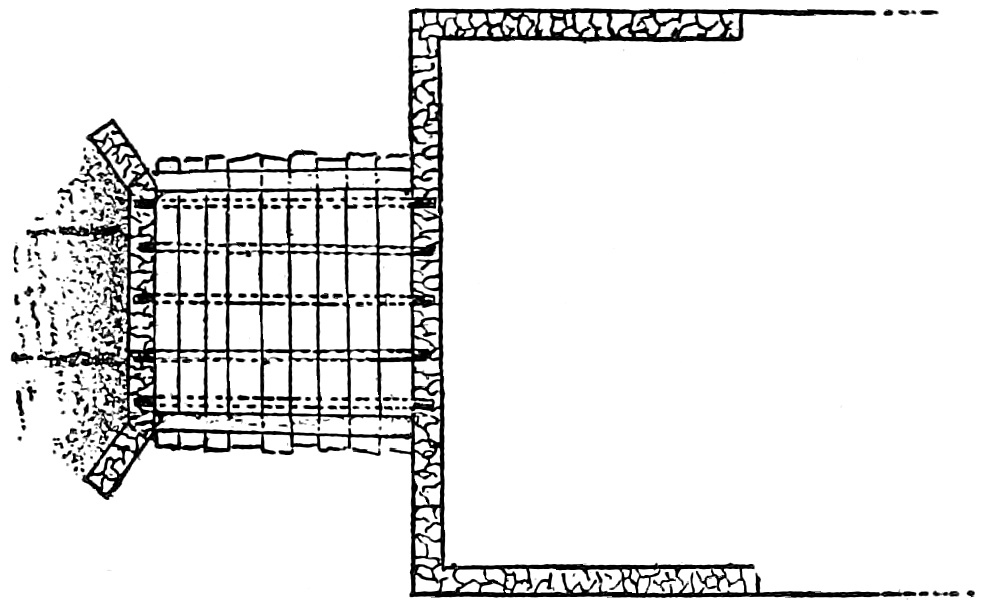

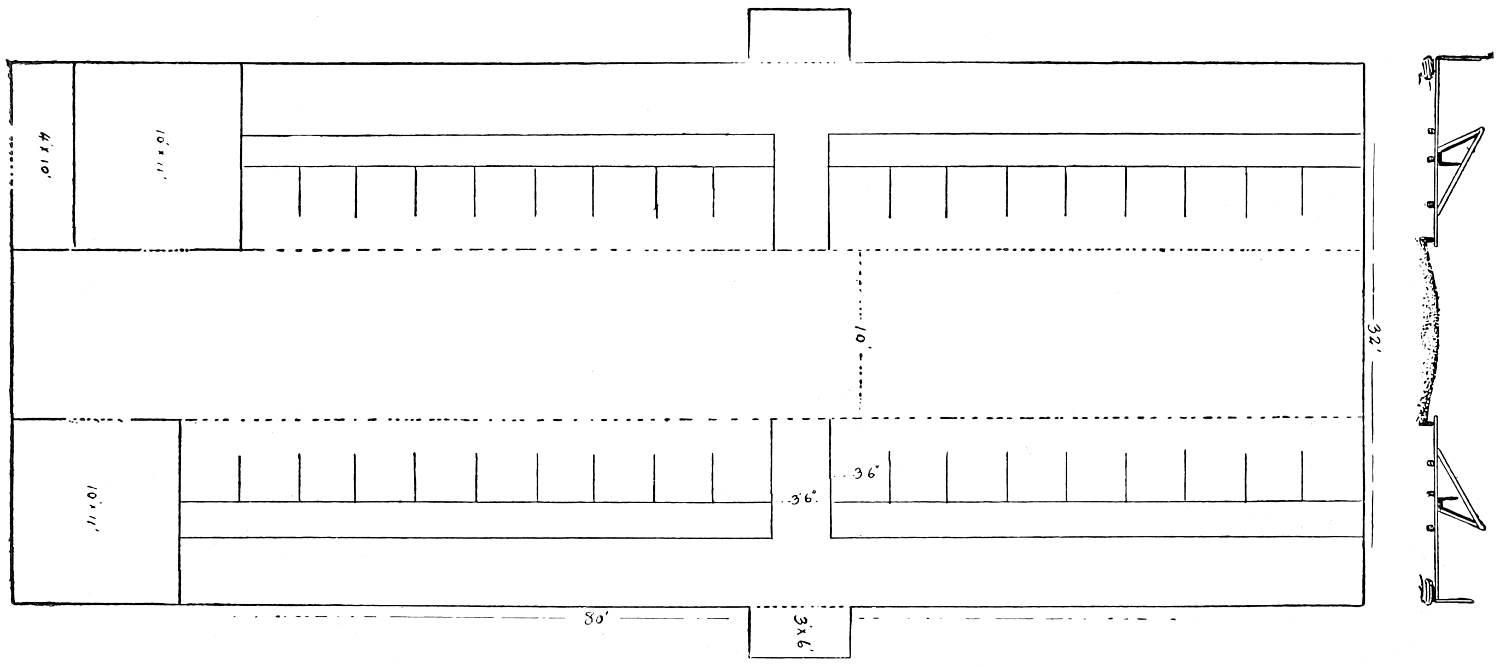

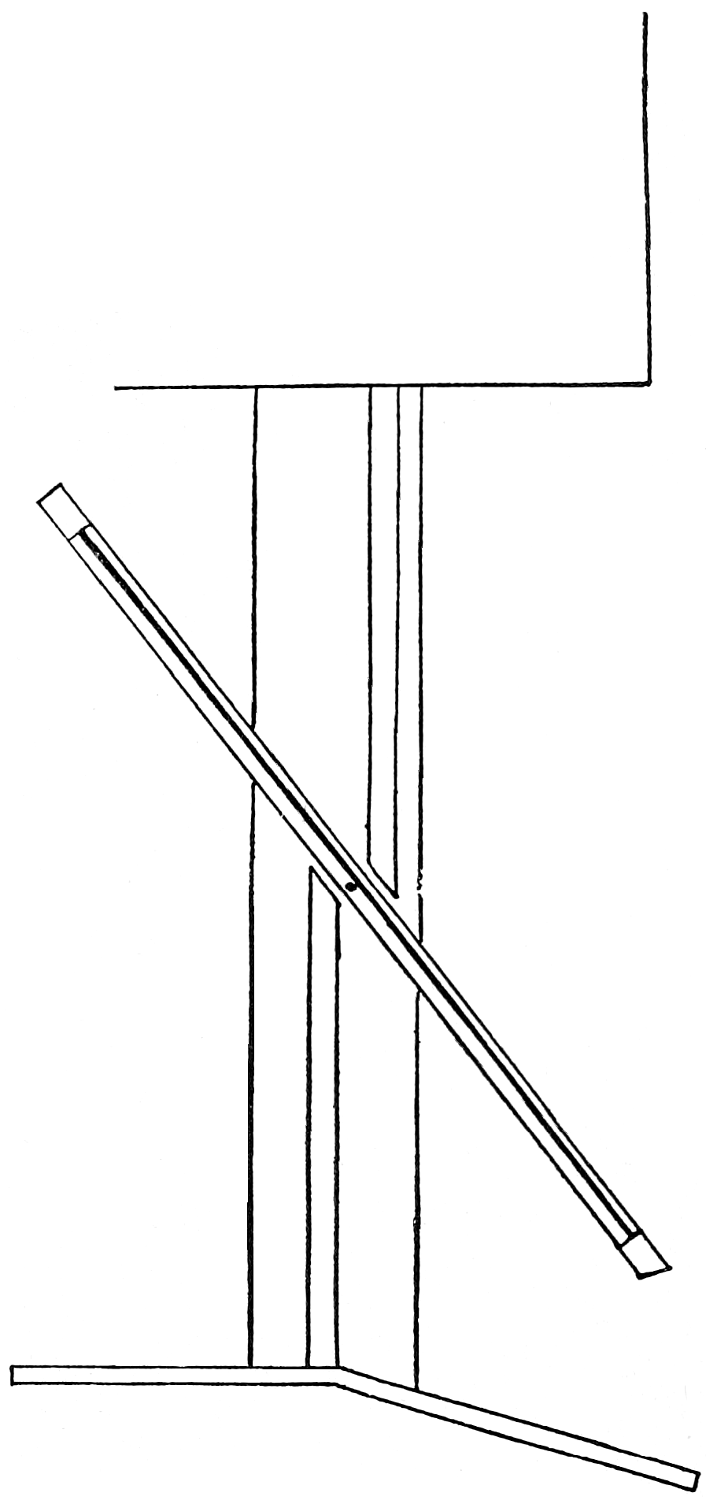

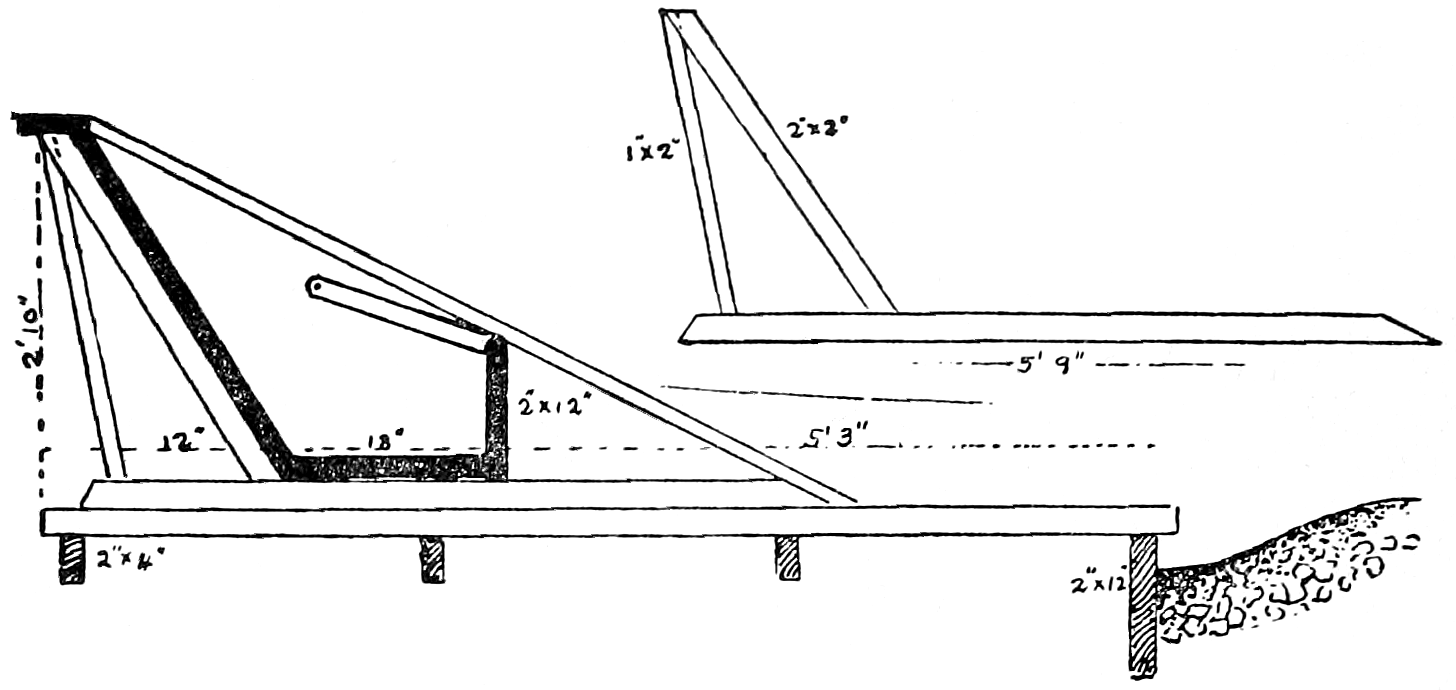

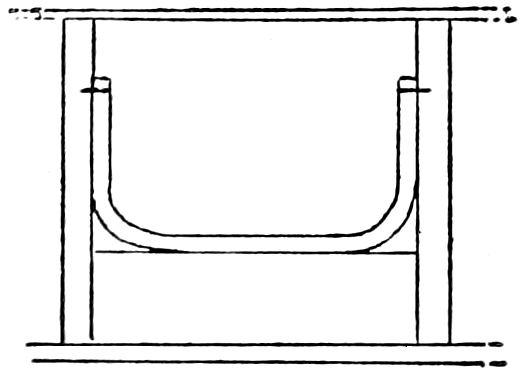

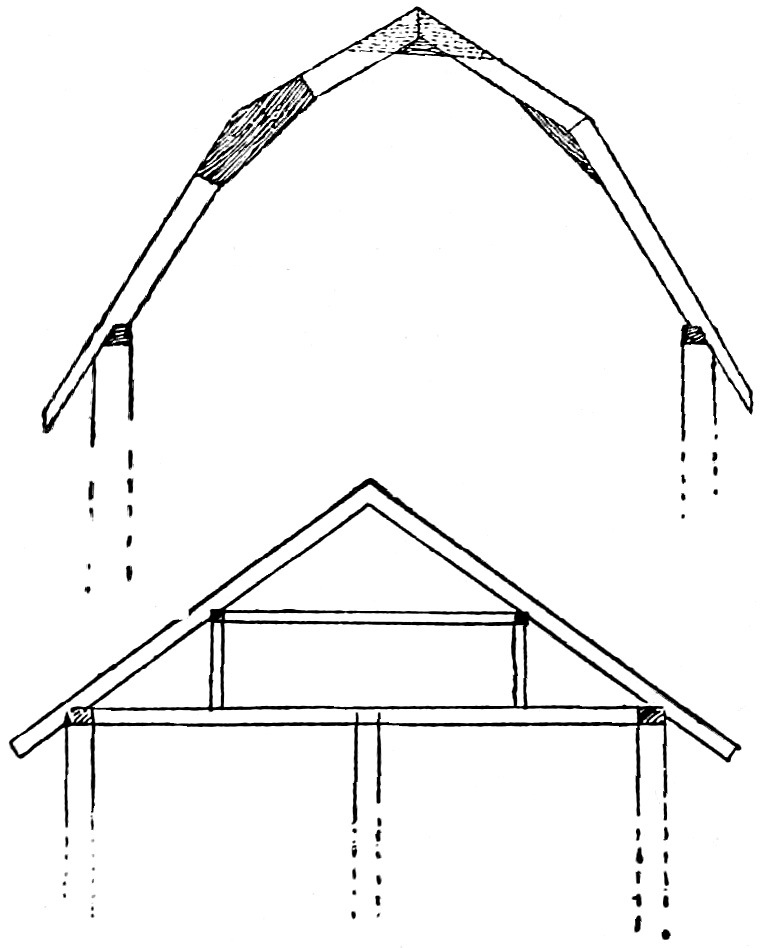

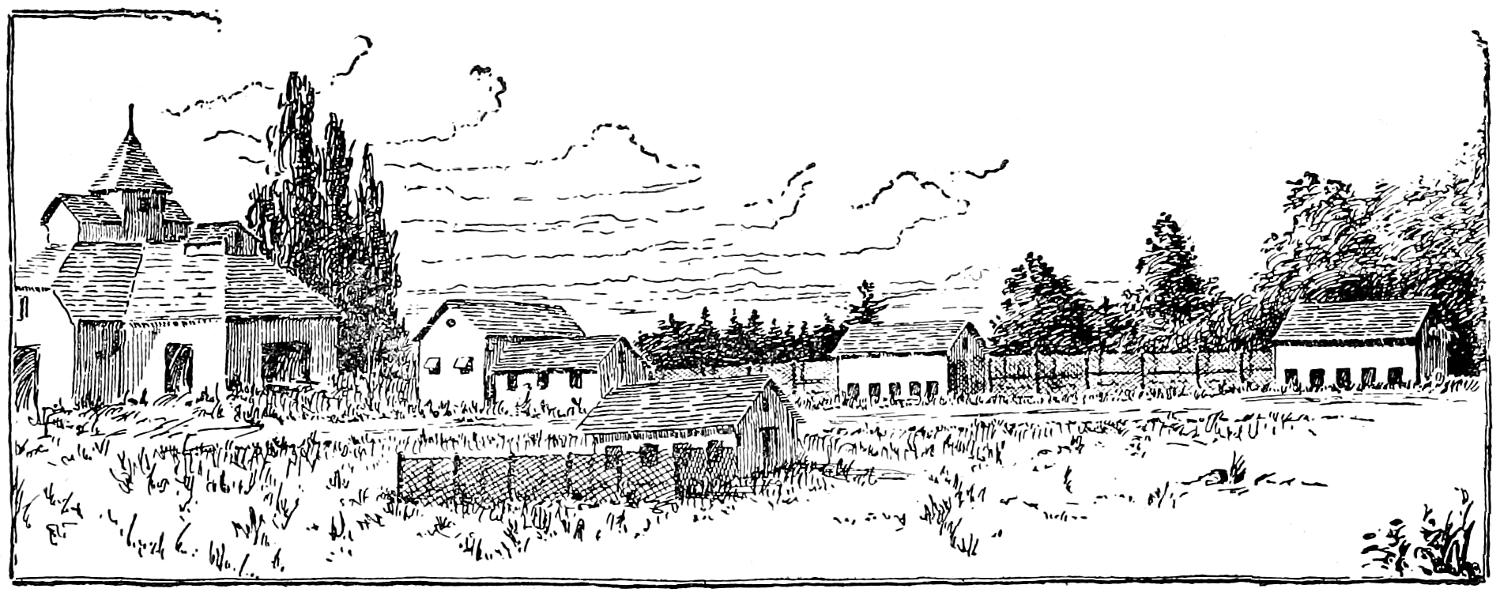

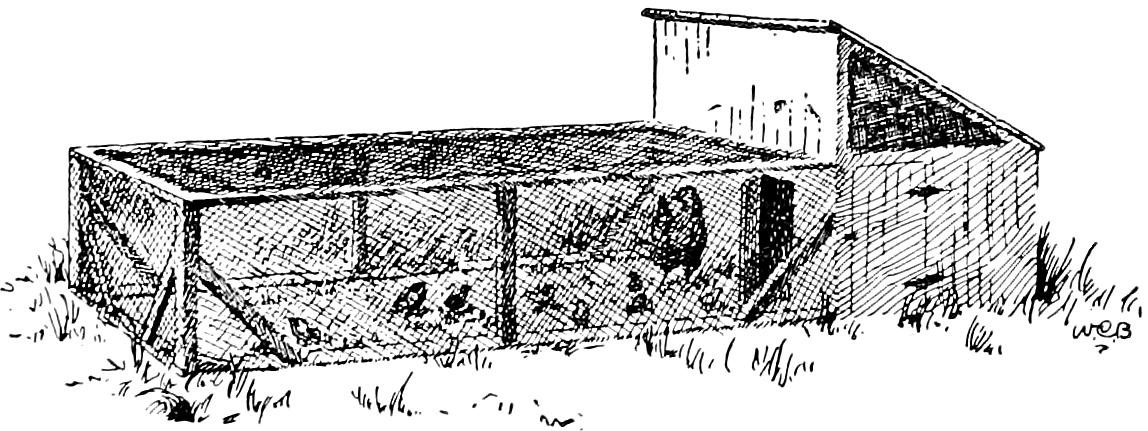

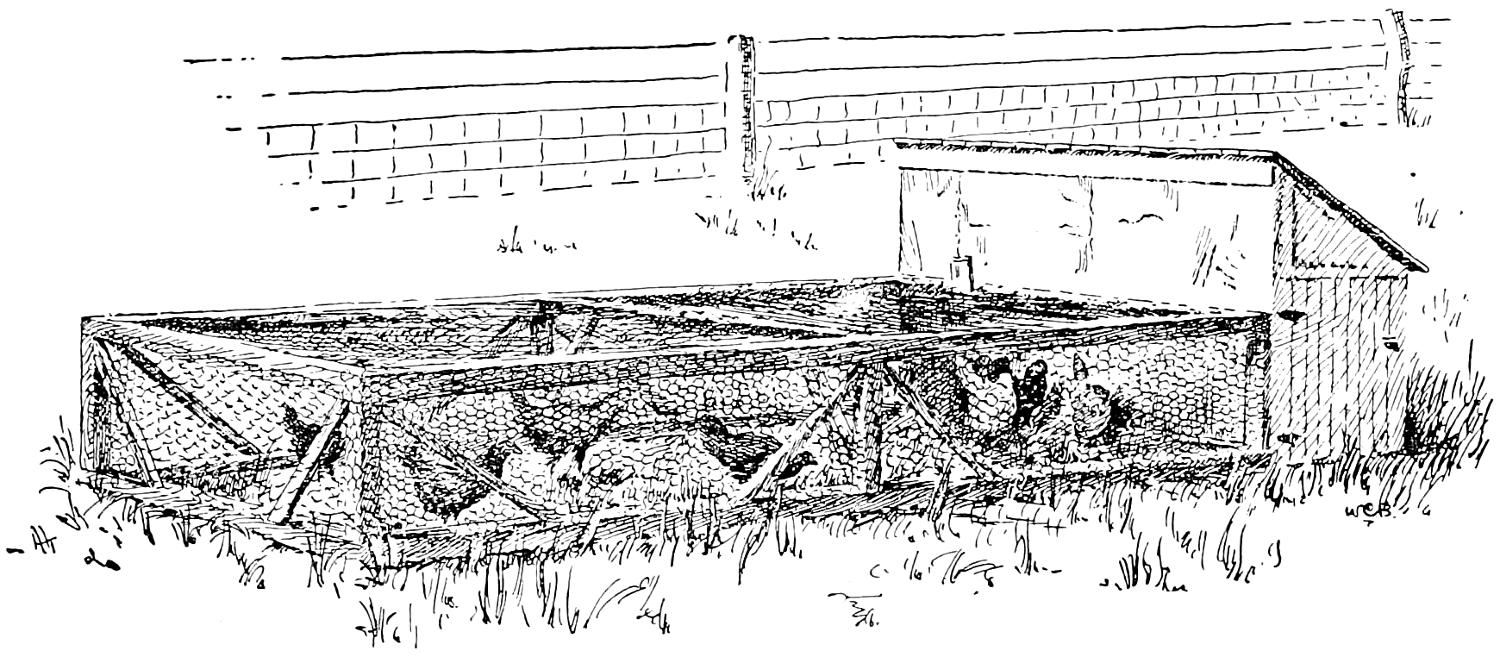

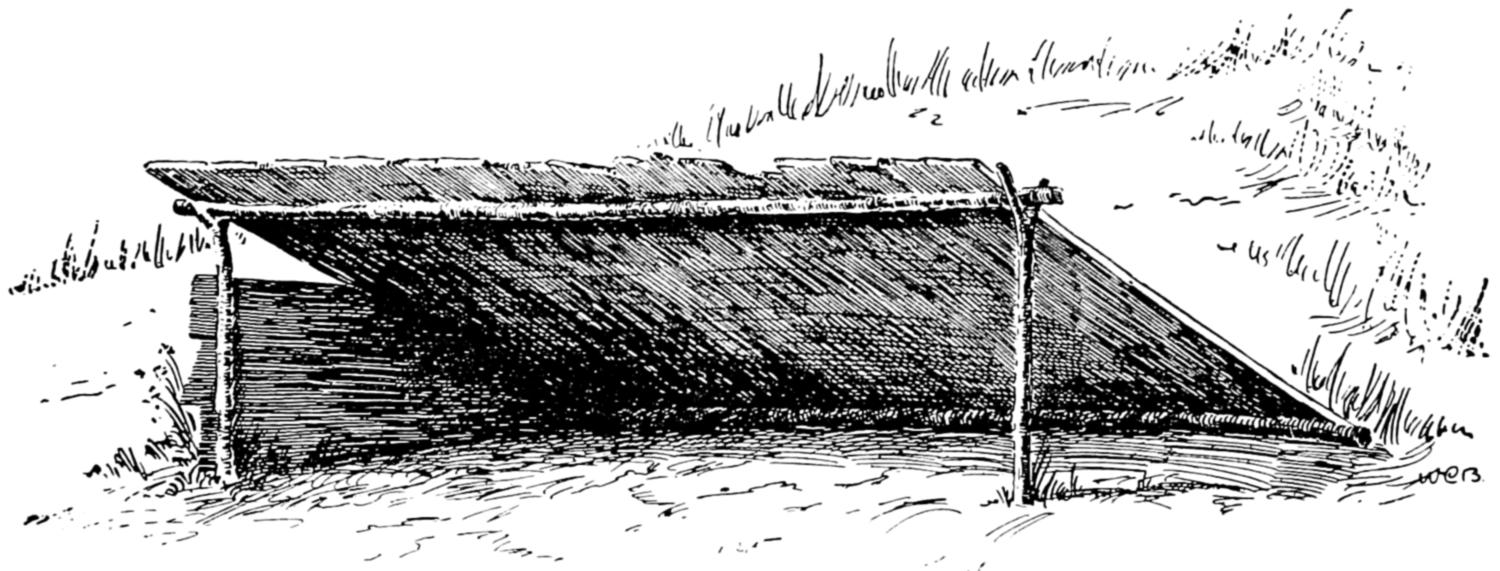

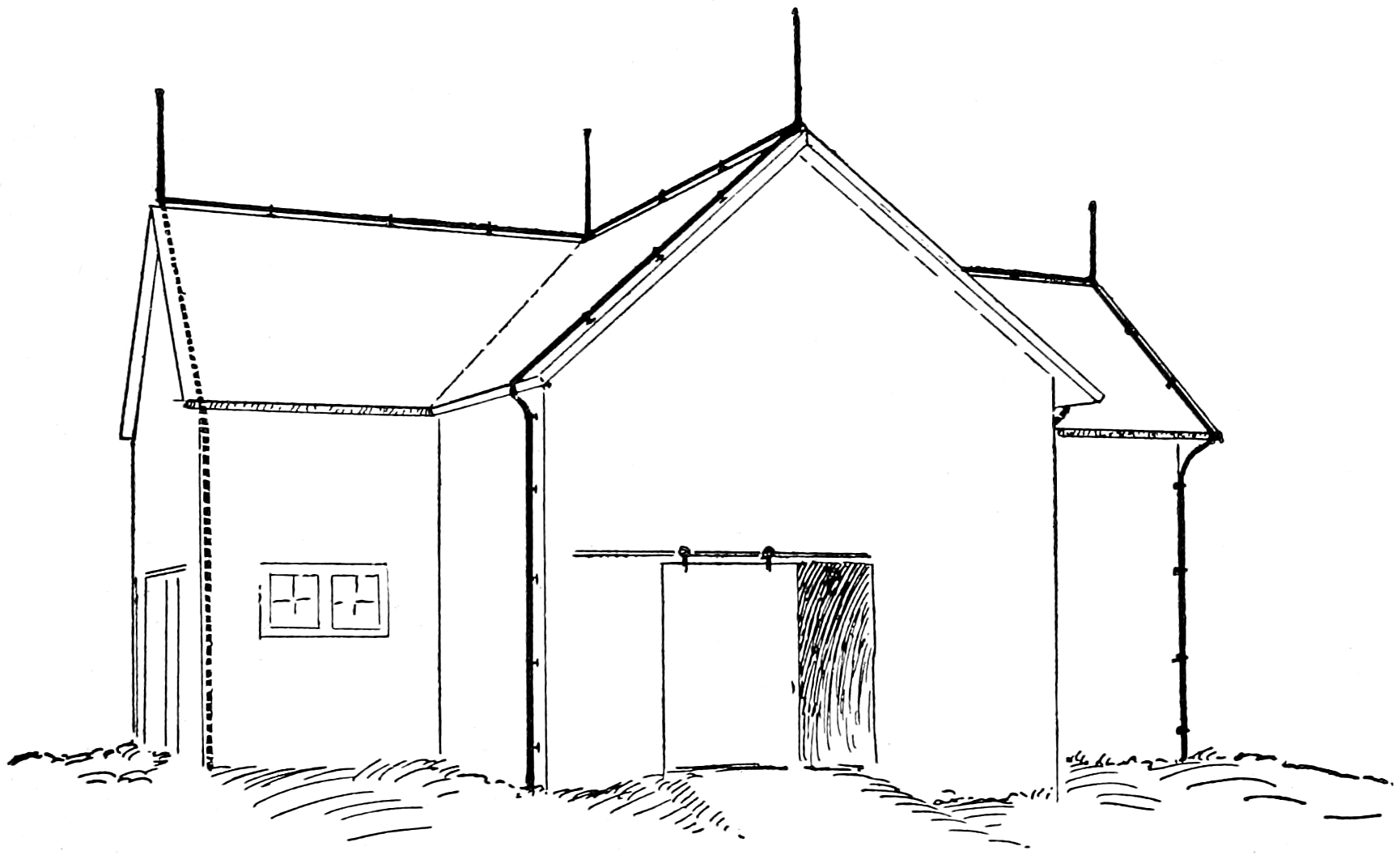

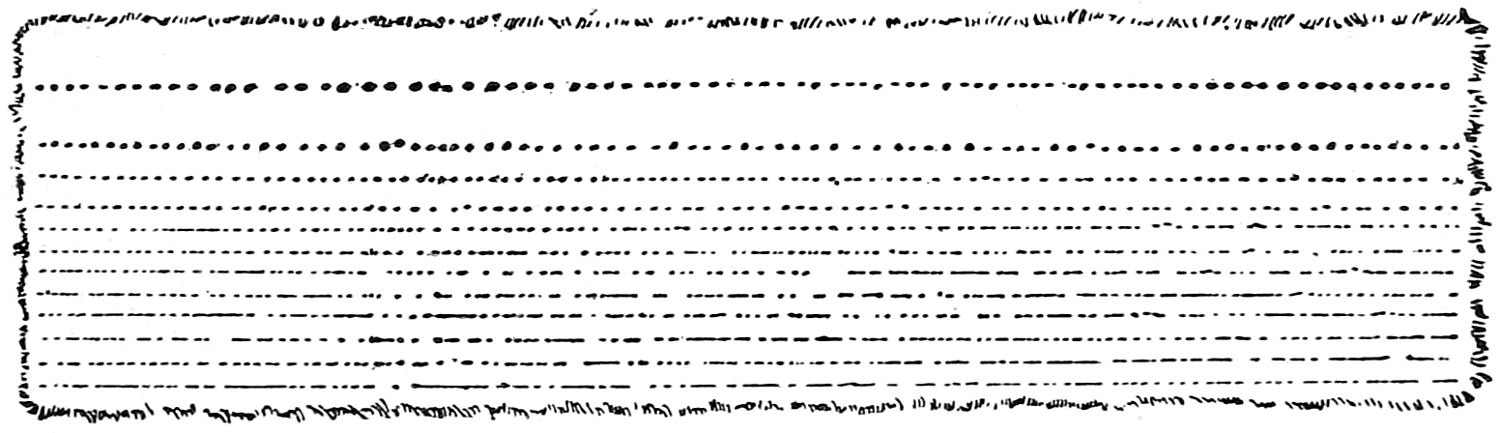

The value of the farm may be greatly modified by the improvements upon it. It is well to ask, Is the house well located? May it not have to be virtually rebuilt before it is at all satisfactory? Will it be necessary to move and repair barns before they are at all suited to their purposes? The improvements may be too extended for the needs of the purchaser. Some farms are overloaded with buildings (Fig. 4); some have badly arranged, unsightly buildings, too good to destroy and too ugly and unhandy for either economy or pleasure. Farm buildings are not a direct source of income and are expensive to keep in repair; therefore, there would better be a slight deficiency of them than an ill arranged surplus. All other permanent improvements, such as orchards, plantations, fences, and the like, should be carefully considered. A good bearing orchard of only a few acres may serve to furnish enough profit each year to liquidate[60] taxes and interest charges. The orchard may be cheaper at $500 per acre than the balance of the farm is at $75 per acre, or it may be only an incumbrance of good land. Is the farm naturally or artificially drained? If not, will $35 per acre have to be spent in thorough draining before the land is really satisfactory? If not drained, will it bring constant disappointment? Fences, lanes and the necessity for them, the amount and location of inferior land as pasture land, the kind of weeds about the farm, as[61] well as the amount, kind and location of timber, should be considered.

Fig. 4. Too many buildings for eighty acres of land.