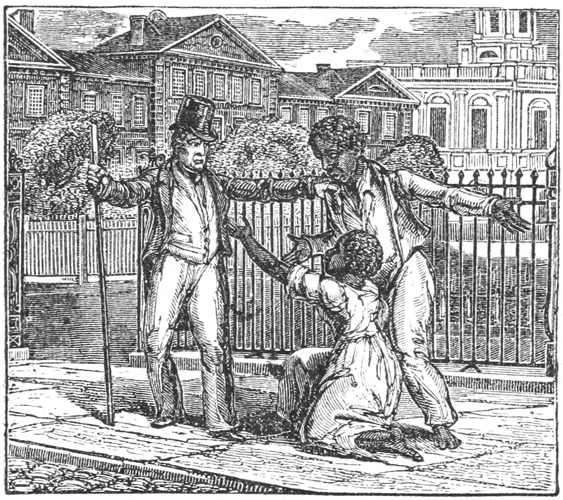

[See page 63.]

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Anti-Slavery Record, Volume 1, No. 7, by Various

Title: The Anti-Slavery Record, Volume 1, No. 7

Author: Various

Release Date: May 10, 2022 [eBook #68042]

Language: English

Produced by: Carol Brown and The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE

VOL. I. JULY, 1835 NO. 7.

[See page 63.]

STEPHEN DOWNING.

This man was arrested as a fugitive, by a Virginia planter, and imprisoned in Bridewell, where he remained eighteen months. The inmates of the prison knew him well, and they were always ready to speak a good word for Downing. After the planter had got his legal right allowed, either because his lawyer’s bill was so heavy, or because he hoped Downing’s friends would buy him, he neglected to take him away for three months. By this delay he forfeited his right to do so, as was decided by Judge Edwards. But Downing’s release was referred to the Supreme Court, which was to meet in two weeks. To the disappointment of every body, this was prevented by another Judge,[1] who, contrary to his promise, secretly wrote for, and by a partial statement, obtained from the Supreme Court, at Albany, an order for the removal of poor Downing, and, before his friends were aware of the plot, he was shipped for Virginia.

Here we see intrigue and perfidy used with impunity to deprive this poor man of his liberty, which, had it been used in the case of a dog, would have consigned its perpetrators to remediless disgrace.—Such is the strength of a pro-slavery public sentiment!

[1] See Emancipator for November 4, 1834.

FRANCIS SMITH

Was a young man of small stature, but of keen eye and intelligent countenance. While a lad, in the time of the last war, he and his master were taken prisoners at sea and carried to Nova Scotia. His servile condition becoming known to the British officers, they compelled his master to give him free papers. But when the prisoners were exchanged, his master persuaded him to return with him to Virginia, by the promise that he should still be free. But he was sold. In Richmond he for some years had hired his time, and kept a well known fruit shop. At last he became the marriage portion of his master’s daughter, and was speedily to be removed as part and parcel of the set out of the bride. To this he demurred, threw himself upon his inalienable rights, and came to New York. Here he occupied himself for some months as a waiter, much to the satisfaction of his employer. The object of his affections, a very worthy and industrious free colored girl, had found her way to New Haven, Connecticut. Thither it was fixed that Francis should follow, and after their marriage they should proceed with their united means to a place of greater safety. But the kind Christian white bridegroom had come on from Virginia to search for his runaway property, and by the aid of a professed slave taker in the city, discovered the retreat of Francis and his intended movements. At the appointed hour for the steamboat to start, the colored young man came quietly on board with his little bundle. The fell tigers were in ambush—the slave-taker Boudinot, a constable, and the lily-fingered white bridegroom aforesaid. The latter delicately pointed at the victim. A pounce was made upon him by Boudinot. Smith, after a scuffle of a moment, in which his antagonist received a scratch from his knife, darted on shore, cried “kidnappers,” and fled. The pursuers raised the cry of “murderer, stop the murderer.” The crowd thus deceived ran after him. Clubs, stones, and brickbats, were hurled at the poor fugitive without mercy, and he was at last brought to the ground, weltering in his blood. The owner took care to save his “property” from farther injury by having it conveyed to the old Bridewell. Thus was the happiness of this humble pair frustrated, that the delicate fingers of another pair might be spared the vulgar necessity of doing something for the support of their owners. And all this was done by law. During the law’s delay, Francis for months occupied one of the coffin cells, the heat and smothering stench of which, added to his disappointment and his galling manacles, were too much for his brain. Often were his wild ravings heard by the passengers on the outside.

His intended bride, in the bitterness of her grief and disappointment, offered her little all, amounting to about $300, for his ransom, but it was of no avail.

[From the Declaration of Sentiments of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Convention.]

We believe slavery to be a sin—always, every where, and only sin. Sin in itself, apart from the occasional rigors incidental to its administration, and from all those perils, liabilities, and positive inflictions to which its victims are continually exposed, sin in the nature of the act which creates it, and in the elements which constitute it. Sin, because it converts persons into things; makes men property, God’s image, merchandise. Because it forbids men to use themselves for the advancement of their own well being, and turns them into mere instruments to be used by others solely for the benefit of the users. Because it constitutes one man the owner of the body, soul, and spirit of other men—gives him power and permission to make his own pecuniary profit the great end of their being, thus striking them out of existence as beings possessing rights and susceptibilities of happiness, and forcing them to exist merely as appendages to his own existence. In other words, because slavery holds and uses men, as mere means for the accomplishment of ends, of which ends their own interests are not a part,—thus annihilating the sacred and eternal distinction between a person and a thing, a distinction proclaimed an axiom by all human consciousness—a distinction created by God,—crowned with glory and honor in the attributes of intelligence, morality, accountability and immortal existence, and commended to the homage of universal mind, by the concurrent testimony of nature, conscience, providence, and revelation, by the blood of atonement and the sanctions of eternity, authenticated by the seal of Deity, and in its own nature, effaceless and immutable. This distinction, slavery contemns, disannuls, and tramples under foot. This is its fundamental element,—its vital constituent principle, that which makes it a sin in itself under whatever modification existing. All the incidental effects of the system flow spontaneously from this fountain-head. The constant exposure of slaves to outage, and the actual inflictions which they experience in innumerable forms, all result legitimately from this principle, assumed in the theory and embodied in the practice of slave holding.

That our readers may know familiarly the horrors of the American “Middle passage,” we extract from the report on the free colored population of Ohio the case of Mary Brown. Let the dainty sentimentalists, who tremble to approach the “delicate” subject, stand off; but if there are any who wish to help their suffering fellow creatures, let them come and look at the naked ugliness of things as they are, till they feel something like an honest and practical indignation against the whole system of man-driving.

“Mary Brown, another colored girl who was kidnapped in 1830, was the daughter of free parents in Washington city. She lived with her parents until the death of her mother; she was then seized and sold. The following are the facts as she stated them. One day when near the Potomac bridge, Mr. Humphreys, the sheriff, overtook her, and told her that she must go with him.—She inquired of him, what for? He made no reply, but told her to come along. He took her immediately to a slave auction. Mary told Mr. Humphreys that she was free, but he contradicted her, and the sale went on. The auctioneer soon found a purchaser, and struck her off for three hundred and fifty dollars. Her master was a Mississippi trader, and she was immediately taken to the jail. After a few hours, Mary was handcuffed—chained to a man slave, and started in a drove of about forty for New Orleans. Her handcuffs made her wrists swell so that they were obliged to take them off at night, and put fetters on her ankles. In the morning her handcuffs were again put on. Thus they travelled for two weeks, wading rivers, and whipped up all day, and beaten at night, if they did not get their distance. Mary says that she frequently waded rivers in her chains with water up to her waist. It was in October, and the weather cold and frosty. After traveling thus twelve or fifteen days, her arms and ankles became so swollen that she felt that she could go no farther. Blisters would form on her feet as large as dollars, which at night she would have to open, while all day the shackles would cut into her lacerated wrists. They had no beds, and usually slept in barns, or out on the naked ground—was in such misery when she lay down that she could only lie and cry all night. Still they drove them on for another week. Her spirits became so depressed, and she grieved so much about leaving her friends, that she could not eat, and every time the trader caught her crying, he would beat her, accompanying it with dreadful curses. The trader would whip and curse any of them whom he found praying. One evening he caught one of the men at prayer—he took him, lashed him down to a parcel of rails, and beat him dreadfully. He told Mary that if he caught her praying he would give her Hell!! (Mary was a member of the Methodist Church in Washington.) There were a number of pious people in the company, and at night when the driver found them melancholy, and disposed to pray, he would have a fiddle brought, and make them dance in their chains. It mattered not how sad or weary they were, he would whip them until they would do it.

“Mary at length became so weak that she could travel no further. Her feeble frame, was exhausted and sunk beneath her accumulated sufferings. She was seized with a burning fever, and the trader, fearing he should lose her, carried her the remainder of the way in a wagon.

“When they arrived at Natchez, they were all offered for sale, and as Mary was still sick, she begged that she might be sold to a kind master. She would sometimes make this request in presence of purchasers—but was always insulted for it, and after they were gone, the trader would punish her for such presumption. On one occasion he tied her up by her hands, so that she could only touch the end of her toes to the floor. This was soon after breakfast; he kept her thus suspended, whipping her at intervals through the day—at evening he took her down. She was so much bruised, that she could not lie down for more than a week afterwards. He often beat and choked her for another purpose, until she was obliged to yield to his desires.

“She was at length sold to a wealthy man of Vicksburg at four hundred and fifty dollars, for a house servant. But he had another object in view. He compelled her to gratify his licentious passions and had children by her. This was the occasion of so much difficulty between him and his wife, that he has now sent her up to Cincinnati to be free.

“We have no reason to doubt the account of Mary as given above. The person from whom we heard this took it down from her own lips. Her manner of relating it was perfectly simple and artless, and is here written out almost verbatim. We have also the testimony of a number of individuals who knew her in Vicksburg; they have no doubt of her integrity, and say that we may rely implicitly upon the truth of any statement which she may make.”

[From a Report on the Free Colored Population of Ohio.]

“Calling upon a family not long since, whose children did not come to school very regularly, we found the father and mother were out at work. On saying to the eldest child, aged about ten years, “why dont you come to school, my girl?” she replied, “I’m staying at home to help buy father.”

“As this family attend the sabbath school, we will state some particulars respecting them, to illustrate a general fact. Their history is, by no means, a remarkable one. Conversing with them one day, they remarked: “We have been wonderfully blessed; not one in a hundred is treated so well as we have been.” A few years since, the mother, an amiable woman, intelligent, pious, and beloved by all who knew her, was emancipated. But she lived in continual dread lest her husband, who was still a slave, should be sold and separated from her forever. After much painful solicitation, his master permitted him to come to Cincinnati, to work out his freedom. Although under no obligation, except his verbal promise, he is now, besides supporting a sickly family, saving from his daily wages the means of paying the price of his body. The money is sent to a nephew of his master, who is now studying for the ministry, in Miami University. The following is an extract from the correspondence of this candidate for the ministry. It is addressed to this colored man.

“Mr. Overton:

Sir, I have an order on you for $150, from your old master. It is in consideration of your dues to him for your freedom. I am in great want of the money, and have been for some time. I shall only ask you 10 per cent interest, although 12 is common. The money has been due two months. If you cannot pay it before the last of March, I shall have to return the order to Uncle Jo,—for I cannot wait longer than that time. It must also run at 12 per cent interest henceforth. If you cannot pay it all, write to me, and let me know when you can. Uncle Jo requests me to let him know when you would have any more money for him.

Yours in haste.”

“This is only one of a series of dunning letters which came every few weeks. Soon after the reception of this, Mr. Overton scraped together the pittance he had earned, and sent the young man $100, with interest. And he is now going out at days work, and his wife, when able, is taking in washing, to pay the balance.”

We have heard the claim that some men are born slaves, but from the following fact we see that the all-grasping genius of slavery is not always contented to wait for birth. It claims a right of property in men BEFORE they are born.

“Another individual had bargained for his wife and two children. Their master agreed to take $420 for them. He succeeded at length in raising the money, which he carried to their owner. ‘I shall charge you $30 more than when you was here before,’ said the planter, ‘for your wife is in a family-way, and you may pay thirty dollars for that, or not take her, just as you please.’ ‘And so,’ said he, (patting the head of a little son three years old, who hung upon his knee,) ‘I had to pay thirty dollars for this little fellow, six months before he was born.’”—Ohio Report.

Our colored brethren have always understood that colonization means expatriation, a cruel driving out of the country. And it is remarkable how few of them, by all the art, and argument, and benevolence too, of the colonization community, have been persuaded to embrace the scheme. An old colored woman, who had been most of her life a slave in Virginia, said to the writer of this, when he spoke to her of the bright prospects of Liberia, “Ah, sir, if it’s going to be so good a place, the white folks will come and take it, by and by. I know them well enough. They always take what’s best.” It is needless to say that this woman could not be convinced of the benevolence of colonization. It is not to be denied by any body, that there is in this country a very general hatred of the colored people. And it might have been predicted with certainty, that any plan for their general removal, however benevolent its motive, and however careful it might be to act only by their own consent, would bring into life and action a general desire to drive them out. Such has been the fact in regard to the American Colonization Society. We have abundance of proof, but at present have only room for the following.

Extract from the Maryland Temperance Herald, of May 30, 1835. “We are indebted to the committee of publication, for the first number of the Maryland Colonization Journal, a new quarterly periodical, devoted to the cause of colonization in our state. Such a paper has long been necessary; we hope this will be useful.

“Every reflecting man must be convinced, that the time is not far distant when the safety of the country will require the EXPULSION of the blacks from its limits.—It is perfect folly to suppose that a foreign population, whose physical peculiarities must forever render them distinct from the owners of the soil, can be permitted to grow and strengthen among us with impunity. Let hair-brained enthusiasts speculate as they may, no abstract considerations of the natural rights of man will ever elevate the negro population to an equality with the whites. As long as they remain in the land of their bondage, they will be morally, if not physically, enslaved, and indeed, as long as their distinct nationality is preserved, their enlightenment will be a measure of doubtful policy. Under such circumstances, every philanthropist will wish to see them removed, but gradually, and with as little violence as possible. For effecting this purpose, no scheme is liable to so few objections as that of African Colonization. It has been said that this plan has effected but little—true, but no other has done any thing. We do not expect that the exertions of benevolent individuals will be able to rid us of the millions of blacks who oppress and are oppressed by us. All they can accomplish, is, to satify the public of the practicability of the scheme—they can make the experiment—they are making it, and with success. The state of Maryland has already adopted this plan, and before long, every southern state will have its colony. The whole African coast will be strewn with cities, and then should some fearful convulsion render it necessary to the public safety TO BANISH THE MULTITUDE AT ONCE, a house of refuge will have been provided for them in the land of their fathers.”

At a convention of gradualists and colonizationists, held on the 23d of May, 1835, at Shelbyville, Kentucky, the following resolutions were passed.

“Resolved, That the system of domestic slavery, as it exists in this commonwealth, is both a moral and political evil, and a violation of the natural rights of man.

“Resolved, That no system of emancipation will meet with our approbation, unless colonization be inseparably connected with it; and that any scheme of emancipation which shall leave the blacks within our borders, is more to be deprecated than slavery itself.”

So the only condition on which the slaves are to be emancipated is exile. This is no emancipation at all. For if a man is free, he must be free to stay in the land of his birth. The plain meaning of these resolutions is, that the resolvers are so bent upon expatriating their poor colored laborers, that they rush on to a “violation of the natural rights of man” to effect their purpose. Would it be any worse in principle to free the slaves by cutting their throats? And again, is it not wrong to advocate a scheme which gives the least countenance to such iniquity?

At the anniversaries in New Hampshire, the Rev. R. R. Gurley, secretary of the American Colonization Society, being called upon by Mr. May to give his opinion concerning the Maryland scheme, gave utterance to the following remarkable sentiment. With regard to direct legislation he would confess his mind was not clear. This he would say, on his own responsibility, that when the time arrived that slavery should become a great political question, he conceived it might be justifiable for a state to select a spot, here or in Africa, and carry the blacks there, willing or unwilling. But he should object to the Maryland scheme, because, at the present time, such rigorous laws were unnecessary.

Here is a sentiment as murderous to the peace of the colored people as a dagger thrust into the heart.

There have recently been two most interesting anti-slavery meetings in Pittsburgh, which were addressed by a number of members of the Presbyterian General Assembly. In this connection, we have the pleasure to state, that forty-eight members, or about one fourth part of that body, this year, were found to be favorable to immediate emancipation: of these, six are ministers from slave states. Last year there were only two known abolitionists in the Assembly. The speeches at the anti-slavery meetings were Christian-like, eloquent, and rich in facts. We make a few extracts.

FROM THE REV. DR. BEMAN OF TROY.

“Admitting, as all do, that slavery is a great evil, existing in the land, we would anxiously inquire, Is there no remedy? Is there any evil for which God has provided no remedy? No, I would not slander the Bible, by making such an assertion. Let us all come up to the work, shoulder to shoulder, in a pleasant way, (I don’t like scowls,) and there is no danger but we can get right. I have heard many remedies proposed; and one very queer one: ‘Better let it alone.’ This is a very popular remedy. In case of slight pain, or momentary head-ach, it will do very well. But who ever heard that an acute disease, which racks the whole frame, and threatens speedy dissolution, if left to the operations of nature, will cure itself? Sin is an inveterate disease—it has no curative principle—it never gets well of itself. Slavery will never cure itself.—This let-alone policy—if it were in the church, I would call it heresy—it is moral heresy.

“But, I have heard of another remedy: ‘Just leave that question to the slave states. What have we at the north to do with slavery?’ But, here is ground for caution. Have not we at the north our share in the government of the District of Columbia? Do we not in fact govern it? Yet, that district is the central mart of the traffic in human flesh. Yes, sir, we at the north do govern slave shambles. Our hands are not quite so clean as we have supposed—as in the dusty atmosphere of Pittsburgh, we often get them a little smutty before we are aware of it.

“My southern brethren never heard me slander them. I am candid on this subject. Often do we hear it said, ‘What do northern people know about slavery?’ Sir, I am not a stranger to slavery. I have resided eleven years at the south, and three or four winters into the bargain, and I know something about it. It is an immense evil. I can go, chapter and verse, with the able document that has been read.[2] It is even so—the very picture of slavery. Are our southern brethren infallible? They are very kind-hearted brethren; yet some of them SELL THE IMAGE OF JESUS IN THEIR SLAVES! Are they competent judges in the case?—The wise man says, ‘A gift blindeth the eyes.’ They judge with the price of human flesh in their hands.”

FROM REV. A. RANKIN OF OHIO.

Mr. Rankin is brother to Rev. John Rankin, author of “Letters on Slavery,” and is, if we mistake not, by birth a southern man.

“But we are told, ‘You at the north know nothing of slavery—why meddle with what you do not understand?’ Sir, we do know what slavery is. It is usurped authority—a system of legalized oppression. If we could show what is this moment transpiring in the land of slavery, every bosom in this house would thrill with horror. I will state a case: A minister of the gospel owned a female slave, whose husband was owned by another man in the same neighborhood. The husband did something supposed to be an offence sufficient to justify his master in selling him for the southern market. As he started, his wife obtained leave to visit him. She took her final leave of him, and started to return to her master’s house. She went a few steps, and returned and embraced him again, and then started the second time to go to her master’s house; but the feelings of her heart overcame her, and she turned about and embraced him the third time. Again she endeavoured to bear up under the heavy trial, and return; but it was too much for her—she had a woman’s heart. She returned the fourth time, embraced her husband, and turned about—A MANIAC. To judge what slavery is, we must place ourselves in the condition of the slave. Who that has a wife, who that has a husband, could endure for a moment the thought of such a separation! Take another case: A company of slave dealers were passing through Louisville with a drove of slaves, of all classes and descriptions. Among them were many mothers with infants in their arms. These often become troublesome to the drivers: and in this case, in order to get rid of the trouble, the inhuman monsters severed the cords of maternal affection, and took these infants, from three to five months old, and sold them in the streets of Louisville, for what they could get. Do we know nothing of slavery? Can we shut our eyes to such facts as these, which are constantly staring us in the face?”

[2] The Declaration of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Convention.

FROM REV. MR. BOARDMAN OF N. Y.

Mr. Boardman directed his address especially to ladies, and we should think not without effect. He said:

“In slavery, marriage is unknown. Men and women live together: but the tie is not formally sanctioned. There is no minister, no magistrate, to give religious or civil authority to the relation. It is a system of concubinage. And this state of things is encouraged, or rather marriage is discouraged, because it throws an obstacle in the way of the sale of these human chattels. Notwithstanding, the ties of affection are not less strong on account of the absence of legal or religious sanction. Indeed, the fellowship of suffering binds still stronger the hearts of husband and wife. It is the only channel of affection. The children of the slave are not his own—they are not subject to his authority, and they may be torn from him without a moment’s warning. Pent up in every other direction, the affections of husband and wife naturally centre entirely upon each other. Yet, even this tie is rudely severed. A slave in the west, who had a wife belonging to another master, learned, to his great grief, that his wife had been sold for the southern market. He went to his master, and requested that he might be sold, so as not to be separated from his wife. In order to dissuade him from it, his master described the hardships to which he would be exposed in the south; but he was firm to his purpose, choosing the severe servitude of the sugar plantations of the south, in preference to a separation from the wife of his bosom. His master then offered him money to satisfy him; but no, he said he could not leave his wife. ‘O,’ says his master, ‘You can get another!’ ‘Why, massa, don’t you think I am a man!’

“Another case, I will mention, to show the legitimate effects of slavery upon the relations of life. A colored man, who was a member of the church, and who had been living with a woman, according to the customs of the slaves, went to his master, who was an elder in the Presbyterian church, and told him that he did not feel right to be living so, and requested permission to be lawfully married. And, how do you suppose this reasonable request was received? Although it was a request from one Christian brother to another to be permitted to cease from sin, yet it was received with a laugh, and positively denied.

“It is in behalf of woman, to woman that this appeal is made, It is woman in bondage that calls for woman’s sympathies, woman’s efforts, and woman’s prayers. And I feel confident that this appeal will not meet a cold repulse, because the object of it has a black skin. I remember, in my boyhood, of seeing a colored man driving a cart, and by some accident he was precipitated from his seat, and crushed to death. But when the alarm began to spread, I heard it said, ‘O, its only a poor negro that is killed.’ But O, thought I, it is a man. And, boy as I was, I remembered that he had an immortal soul. Ah, think you woman would have said that? No. Woman has a heart that can be moved with the sufferings of the poor negro.

“Woman did much for the abolition of slavery in Great Britain and her dependencies. When the petition was presented to parliament, it required four men to carry it to the speaker’s desk. It was signed by 182,000 ladies. A noble lord arose, and with much emotion, said, ‘It is time for us to move in this matter, when we are called upon in this manner by our wives, and sisters, and mothers!’ And I rejoice that the ladies of this country are already lifting up their voices on this subject. Sir, I was much gratified to hear the voice of 1,000 of my countrywomen raised in the General Assembly, in behalf of suffering humanity. And, I feel assured that woman’s voice will be heard. But, if man will not hear, there is an audience where you can appear with the assurance of being heard. O, then, mothers, sisters, wives, let your voice be heard at the throne of grace, pleading in behalf of your enslaved sisters, and of suffering bondmen.

“But, the question is asked and reiterated, ‘What has abolition done?’ What has abolition done! It has done much, sir. It has so modified the sentiments of many colonizationists that they speak a language in reference to slavery, which would not have been tolerated in 1830. Its voice is now heard in Maryland, in Kentucky, in Tennessee, in Missouri—in some places, indeed, it is feeble—in others it is the voice of thunder. What has abolition done? On the first day of August, 1834, it broke the manacles of 800,000 slaves. The sun set upon them in bondage, and rose upon them in freedom.”

FROM REV. MR. DICKEY OF OHIO.

“Sir,” said Mr. D., “I am not ignorant of slavery. Having passed thirty years of my life in a slave state, and having been a slave-holder myself, I know something about it.

“Slavery in the church exposes her to the scoffs of the world. Infidels despise a religion which they suppose sanctions such oppression. I once heard a professor of religion laboring to justify slavery from the Bible, in the presence of an infidel; who turned from him with contempt, saying he despised such a religion.

“It exerts an influence upon the mind of the slave, prejudicial to the reception of instruction. Suppose the master himself attempt to instruct his slaves in the truths of religion—what confidence can he have in the man, who deprives him of his liberty, and robs him of his labor? I will state a case: An old slave told me, “Massa bery ’ligious—he bery good Christian. He hab prayers e’vry Sunday wid the slaves—but he sure to read ’em dat chapter what say servants be ’bedient to massa.”

INTO THE TREASURY OF THE AMERICAN ANTI-SLAVERY SOCIETY

From May 16, 1835, to June 12, 1835.

| Donations received by the Treasurer. | ||

| Amherst College, | E. C. Pritchett, | 2 50 |

| “ | H. G. Pendleton, | 2 50 |

| Boston, Mass., | M. Hayward, | 6 00 |

| “ | Rev. H. Foote, | 1 00 |

| “ | B. Kingsbury, | 5 00 |

| “ | Joshua Southwick, | 5 00 |

| “ | Wm. Loyd Garrison, | 1 50 |

| “ | Isaac Knapp, | 1 50 |

| “ | David H. Ela, | 5 00 |

| “ | Rev. S. J. May, | 1 00 |

| “ | Geo. A. Baker, | 1 00 |

| “ | H. W. Mann, | 1 00 |

| “ | David L. Child, | 3 00 |

| “ | Moses Kimball, | 3 00 |

| Providence, R. I., | Female A. S. Society, | 25 00 |

| “ | A Friend, | 0 50 |

| “ | Samuel H. Gould, | 1 00 |

| Kennebunk, Me., | Ladies and Gentlemen, | 26 00 |

| “ | Dr. B. Smart, | 1 00 |

| Hallowell, Me., | E. Dole, | 10 00 |

| “ | Robert Gardner, | 5 00 |

| Portland, “ | John Winslow, | 5 00 |

| Bangor, “ | Rev. S. L. Pomeroy, | 10 00 |

| Irville, Ohio, | Miss Lewis, | 2 00 |

| “ | Huntn. Lyman, | 1 00 |

| Catskill, N. Y., | W. H. Smith, | 1 00 |

| “ | William Adams, | 1 00 |

| Albany, N. Y., | Timothy Fassett, | 1 00 |

| “ | A. G. Alden, | 3 00 |

| New York City, | Jeremiah Wilbur, | 1 00 |

| “ | Rev. J. N. Sprague, | 1 00 |

| “ | Michael Flagg, | 2 00 |

| “ | Andrew Savage, | 1 00 |

| “ | J. N. McCrommell, | 2 00 |

| “ | James Linnon, | 1 00 |

| “ | A few Friends, | 7 00 |

| Poughkeepsie, N. Y., | S. Thompson, | 1 00 |

| Troy, N. Y., | H. Z. Hayner, | 1 00 |

| Holden, Mass., | Charles White, | 1 00 |

| York, N. Y., | Anti-Slavery Society, | 4 00 |

| Perry, N. Y., | S. F. Phoenix, | 2 45 |

| Madison, N. Y., | Rev. M. Hart, | 8 50 |

| Greenwich, Con., | Rev. J. Mann, | 10 00 |

| “ | E. Griffen, | 1 00 |

| New Haven, Con., | Dr. I. Ide, | 1 00 |

| “ | Daniel Hoyt, | 1 00 |

| Stratford, Con., | Lewis Bears, | 5 00 |

| “ | Charles H. True, | 1 00 |

| “ | Rev. J. Horton, | 1 00 |

| “ | Thomas Huntington, | 1 00 |

| Princeton, N. J., | Anthony Simmons, | 5 00 |

| “ | F. Wright, | 1 00 |

| Philadelphia, Pa., | Arnold Buffum, | 1 00 |

| “ | W. H. Scott, | 1 00 |

| “ | Anti-Slavery So., | 50 00 |

| Ferrisburg, Vt., | Mary D. Bird, | 1 87 |

| New York, | Henry Green, on $10 subscription, | 5 00 |

| New York, | J. Rankin, for June subscription, | 100 00 |

| New York, | William Green, for May and June, | 166 66 |

| Mass., | Anti-Slavery Society, | 500 00 |

| New York, A subscription made in Chatham-st. Chapel one year ago, | 1 00 | |

| Philadelphia, Pa., | Ladies A. S. S., | 10 00 |

| Flushing, L. I., | L. Van Bokkelin, | 2 00 |

| Providence, R. I., | Juvenile A. S. S., | 30 00 |

| Total, | $1059 98 | |

| New York, June 12, 1835. | ||

| John Rankin, Treasurer, | ||

| No. 8 Cedar St. | ||

| Monthly Collections received by Publishing Agent from May 12 to June 12, 1835. | ||

| Albany, N. Y., | Mrs. Hester Gibbons, | 1 00 |

| Buffalo, N. Y., | by E. A. Marsh, | 11 50 |

| Brooklyn, Con., | by Rev. S. J. May, | 11 13 |

| Brighton, N. Y., | by Dr. W. W. Reid, | 2 00 |

| Carlisle, Pa., | by H. Duffield, | 5 00 |

| Catskill, N. Y., | Robert Jackson, | 3 00 |

| Dover, N. H., | by William H. Alden, | 20 00 |

| Dunbarton, N. H., | 5 00 | |

| Darien, Con., | 1 38 | |

| East Rutland, Vt., | Dea. S. Cotting, | 63 |

| Farmington, N. Y., | by Wm. R. Smith, | 6 25 |

| Ferrisburgh, Vt., | by R. T. Robinson, | 4 00 |

| Hudson, O., | by F. W. Upson, | 5 00 |

| New Garden, O., | by William Griffith, | 5 00 |

| New York Mills, N. Y, | by Rev. L. H. Loss, | 14 00 |

| Oneida Institute, N. Y, | by Wm. J. Savage, | 24 00 |

| Plattekill, N. Y., | Rev. J. M‘Cord, | 25 |

| Philadelphia, Pa., | Ladies A. S. So., | 5 00 |

| Rochester, N. Y., | by Dr. W. W. Reid, | 25 00 |

| Springfield, N. J., | James White, | 1 00 |

| “ | Jonath. Parkhurst, | 1 00 |

| Starksboro, Vt., | Joel Battey, | 1 50 |

| Schenectady, N. Y., | by I. G. Duryee, | 6 00 |

| Whitesboro, N. Y., | by T. Beebee, | 10 00 |

| Records sold at office. | 66 35 | |

| Books and Pamphlets sold at office. | 645 68 | |

| Total. | $880 65 | |

| R. G. Williams, | ||

| Publishing Agent Am. A. S. S. | ||

| 144 Nassau St. | ||

| Total Receipts. | $1940 63 | |

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated below. Misspelled words were not corrected.

The page number in the caption to the illustration on the title page refers to an earlier issue.

Footnotes were numbered sequentially and moved to the end of the section in which the anchor occurs. Obvious printing errors, such as backwards, upside down, or partially printed letters, were corrected. An open quote was changed from single to double in the blockquote; unprinted commas in the lists of receipts were added for consistency.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.