The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Yale Literary Magazine (Vol. LXXXVIII, No. 6, March 1923), by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: The Yale Literary Magazine (Vol. LXXXVIII, No. 6, March 1923)

Author: Various

Release Date: May 8, 2022 [eBook #68030]

Language: English

Produced by: hekula03 and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE YALE LITERARY MAGAZINE (VOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 6, MARCH 1923) ***

Vol. LXXXVIII No. 6

The

Yale Literary Magazine

Conducted by the

Students of Yale University.

“Dum mens grata manet, nomen laudesque Yalenses

Cantabunt Soboles, unanimique Patres.”

March, 1923.

New Haven: Published by the Editors.

Printed at the Van Dyck Press, 121-123 Olive St., New Haven.

Price: Thirty-five Cents.

Entered as second-class matter at the New Haven Post Office.

THE YALE

LITERARY MAGAZINE

has the following amount of trade at a 10%

discount with these places:

| ALEXANDER—Suits |

$32.00 |

| CHASE—Men’s Furnishings |

10.00 |

| GAMER—Tailors |

32.00 |

| KLEINER—Tailors |

32.00 |

| KIRBY—Jewelers |

63.00 |

| KNOX-RAY—Silverware |

30.00 |

| PACH—Photographers |

24.00 |

| PALLMAN—Kodaks |

32.00 |

| ROGER SHERMAN—Photographers |

46.50 |

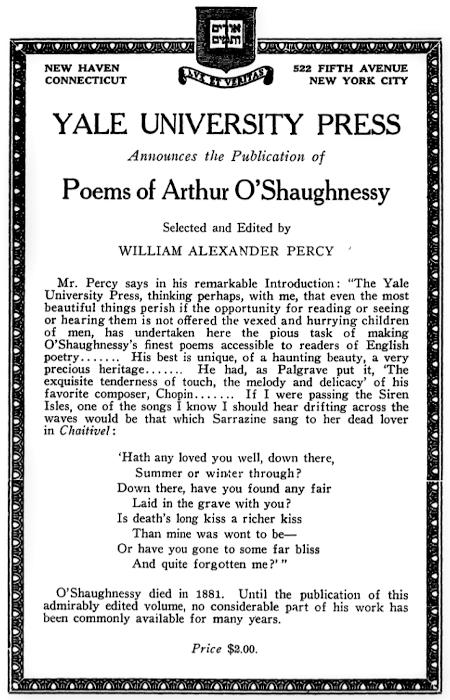

| YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS—Books |

111.50 |

If you want any of this drop a card to the

Business Manager, Yale Station, and a trade

slip will be returned on the same day.

ESTABLISHED 1818

MADISON AVENUE COR. FORTY-FOURTH STREET

NEW YORK

Telephone Murray Hill 8800

- Clothing Ready made or to Measure for Spring

- Evening Clothes, Cutaways, Sack Suits

- Sporting Clothes and Light weight Overcoats

- English and Domestic Hats & Furnishings

- Boots and Shoes for Dress, Street and Outdoor Sport

- Trunks, Bags & Leather Goods

The next visit of our representative

to the HOTEL TAFT

will be on April 6 and 7

BOSTON

Tremont cor. Boylston

NEWPORT

220 Bellevue Avenue

THE YALE CO-OP.

A Story of Progress

At the close of the fiscal year, July, 1921, the

total membership was 1187.

For the same period ending July, 1922, the

membership was 1696.

On January 18th, 1923, the membership was

1905, and men are still joining.

Why stay out when a membership will save

you manifold times the cost of the fee.

THE YALE LITERARY MAGAZINE

Contents

MARCH, 1923

| Leader |

Maxwell E. Foster |

181 |

| A Drama for Two |

Russell W. Davenport |

184 |

| Five Sonnets |

Maxwell E. Foster |

187 |

| This Modern Generation |

Russell W. Davenport |

192 |

| The Soul of a Button |

L. Hyde |

207 |

| Book Reviews |

|

213 |

| Editor’s Table |

|

220 |

[181]

The Yale Literary Magazine

Leader

“... being firmly persuaded that every time a man

smiles,—but much more so, when he laughs that it adds

something to this Fragment of Life.”—Dedication to

Tristam Shandy.

There is, of course, the Campus and Osborn Hall. There

is Mory’s. There is Yale Station. There is the Bowl.

Enumeration is unnecessary. That will serve well enough at the

twenty-fifth reunion. For the moment we are affluent in detail,

and comprehend suggestion. We still remember a great deal

about Yale.

But there is a wistfulness about even specific memories that

hardly expresses our attitude. For we take with us something

we are glad to have. The Comic Spirit has quietly insinuated its

existence into our point of view. Undoubtedly we have found

cherished mansions set on fire and destroyed, but in general we

have discovered the delights of roast pig amidst their ruins. You

will find the Senior more capable of laughing at the serious than

the Freshman. He sees the humor abroad, and is more sensitive

to the divine comedy.

[182]

Comedy particularizes, whereas tragedy deals in the general.

When one laughs one is beginning to see things in detail. In

Freshman year one contents oneself with the infinite, but in Senior

year one becomes concerned with the finite. The Freshman poet

will write about Death and Eternity, the Senior about life. After

all the latter is merely more sincere.

For Yale does not influence one to become a golden mean, or

to idealize a mens sana in corpore sano. It has a more brilliant

bit of philosophy than that. It satirizes the affectations out of a

man, so that he learns the proportion of the everyday and of the

eternal, and adapts his decisions to that proportion. He is capable

of rendering unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, because he

has learned to recognize what things are Caesar’s. He has won

his scales.

Seeing things in proportion is not materialism, any more than

it is idealism. It is seeing with sincerity. Material things are

not then idealized, and ideals are not made material. Each is

treated in its own terms, the question of emphasis and relativity

being left to the temperament. Shelley, for instance, in most of

his writing, exemplifies a disproportioned point of view of life.

It is not quite real, because it is not quite sincere. He died at the

point where he was beginning to imagine balance. Chaucer lived

long enough to find it and employ it in his art. He is the greater.

For it is just as foolish to think that the soul is without a body,

as to think that the body is without a soul; or to fancy a man as

completely aetherial, when it is perfectly obvious that he walks

with feet of clay.

I may seem to have maligned the Freshman, and the Freshman

of feeling will be hurt. But I am using the sobriquet as generic.

It really applies to most of the outside world. Experience there

is a hard task-master, and only the exception finds mirth under

her schooling. The majority there remain Freshmen always,

lacking the knowledge of the comic. At Yale there are few who

remain so. Ultimately they are laughed out of their position.

Yale has always fastened its banner to this criticism of life.

For years it was “Harvard affectation” that Yale ridiculed. To-day[183]

freaks are not seriously condemned; it is the dilettante who plays

into the hands of satire. Insincerity is the unpardonable sin. But

the method of punishing is humor. The world crushes the

apocryphal with an iron heel, but Yale kicks it deftly out of a

college window. It is the intelligent method. And naturally. For

common sense has become almost a Yale idiom.

Maxwell E. Foster.

“If men are dust, I do not understand

What women are. What language does she speak,

Who plays with me as children with the sand,

Who shapes me with a gesture of her hand,

And floods me in the crimson of her cheek?

Our fingers in our passion did entwine,

Like ivy growing in the lap of Spring:

A moment, and she was a deathless thing—

A woman? Nay, the spirit of the vine!”

“Ah, but I did not love to make him glad;

But, if I could, to make him more than wise.

I found, in the strange silence of his eyes,

The same unuttered fear that Dante had,

Lest Beatrice should die and he go mad!

And so I let him dream a paradise

Upon my lips; and with love’s quick disguise

Appeared in white robes and in roses clad.”

“I think that love is like a leaning sail

Swept toward a far horizon, swift in flight.

The seas are blue. But soon the wind must fail,

And all of Heaven’s will cannot avail

To keep the ship from drifting toward the night.

I am not sure of this: but yesterday

There was no eager passion in her lips;

And so I said, ‘My dear, we are but ships

Passing away in time—leaning away’.”

“How quickly do our blushes leave the cheek:

How like a withered ghost goes modesty!

[185]

I loved him not. The devil played with me,

And still plays on—instructing me to speak

In soft words—sounding truer in a shriek.

Would I had vanished into destiny!

Ah, God! When they pretend that love is free,

The women buy the freedom that they seek.”

“Of Beauty in immortal guise beware!—

For even women’s bodies are of dust.

I do not hate her, but I cannot bear

The subtle isolation of her stare,

As though she’d changed ‘I love’ into ‘I must’.

But in me there’s no sorrow or regret,

I am not by a jealousy distraught;

Love’s neither here nor there—for I have sought,

And found, and lost—and now I can forget.”

“Ah, when I told him everything, he said:

‘I love you still, but not as yesterday.

Life is a laughing art. Our passions play

So madly that it is in vain to wed.

I’m glad you feel the way I do,’ he said.

And had he washed my body quite away

In tears, I would not have had less to say.

I merely smiled, pretending I was dead.”

“Then where is Beauty, now that she had fled,

And where is Paradise without her arms?

Surely I did not know how much I said,

When I complained that the old love was dead:

’Tis thinking of to-morrow that disarms!

How her remembered hair makes sadness live,

And how her absent voice is young with power!

Yea, for the recollection of one hour

Turns the soul nightward, like a fugitive.”

[186]

“I find that being in the house alone

Is gruesome, for the worn and creaky floors,

The wind outside, the rain, the empty doors,

Sing with a wild and ghostly undertone—

Not quite articulate—but yet a moan.

Often I long for the white surf that roars,

Or for the rapture of the gull that soars,

Or for the splendor of a silent throne.”

Perplex me not with words I understand,

Nor gracefully demolish the unborn.

You tell me that my fantasies are torn,

But I have only written them on sand.

You answer with a gesture of your hand

Though I have asked not, I have only sworn.

Would you then burn green shoots with withered scorn?

My lady, you do waste your flaming brand.

I draw the pictures you desire to hide,

When you return such compliments for mine,

For love makes bitter poison into sweet.

And there’ll be memory, when our quick eyes meet,

To stir into a bubbling the gay wine.

—Which of us will have fallen in our pride?

[188]

But is it pride that motivates the play,

Or brings the climax and the curtain call?

—I question the new lilies that are tall,

For wiser than a Solomon are they.

But they have only parables to say,

And only nod against the mossy wall,

Pale blossoms of the sacrifice and gall,—

They do not answer those who cannot pray?

Their quick renascence from the tragedy

We do not act. We play the witty parts,

And do not veil with curtains our decease.

It is a trifle of a comic piece?

We wear upon our sleeves our naked hearts?

—Pride is not on, for we are two, not three.

[189]

But there’s the dialogue that must confuse.

It is not swift or brilliant otherwise.

We make a parody of paradise,

That it may fascinate, not to amuse.

I grant it’s a lost quaint, uncommon ruse.

But if it serves to open wide our eyes,

Would it be well to fancy or devise

New strange unheard of fables to abuse.

Love is a clever scene that you have set,

You the beginning, I will do the end.

—It is a bargain of an enemy?

Perhaps, but as a bargain let it be,

For it is fair I should not be your friend

—Now the dénouement of the cruel coquette.

[190]

You laugh again at this my imagery,

But I will turn your laughter from my soul,

Explain this love has humor as its goal,

That you are quainter than the simile.

You who have bound yourself so to be free,

You who will lose the part to keep the whole,

You who will quench with fire the living coal,—

O strange and unaccounted mystery.

Yes, I have flung you back your worn derision,

Cast to you all my precious, secret oaths.

Now as the curtain’s falling, take the applause.

Foolish to fight with bastard natural laws,

Even the ones that all of nature loathes.

Lady, you have the worth of their decision.

[191]

Charming?—A little long-drawn out?—or dead?

It matters not. Open the exit doors,

And let them out, and sweep the theatre floors,

The dazzle of the footlights takes my head.

—Good-night, and I shall totter off to bed.

To-morrow’s play? God, how these lines are bores!

You say it’s just the thing the crowd adores?

—It likes the pretty ending where we’re wed?

Thank God for night that is not made with lights,

Stars that are quiet, unpainted, distant things,

Wind that is dustless, fresh, and water-cool.

—Some day I shall give over my new school,

Permit myself the luxury of wings,—

Yes, I can hear you: “And a pair of tights?”

[192]

This Modern Generation

What is more exasperating, more insistent, and still more

exasperating because of its insistence, than a telephone

ringing beside one’s bed at two A. M.? There is indeed some

doubt as to whether these modern appliances, together with the

modern world which they purport to make happy, are not altogether

out of place on this earth. In striving to be great, perhaps

we mortals have obscured our immortality. At any rate, Mr.

Harrow thought so, as he hurled his corpulent shape from the

bed, crashed into the small table upon which the offensive instrument

rested, swore, and put the receiver to his ear. A terrific

buzzing ensued, and a vibration which was actually painful.

“Dammit,” he said, “hello, dammit.”

And now the reader will excuse us if we leave Mr. Harrow

struggling with this all too mortal instrument, and proceed to an

explanation of the causes of his disturbance; which task will

require the remainder of the story for its consummation.

Betty Harrow lived with her father in this very modest house

somewhere in New York City. The two of them were an affectionate

pair, in spite of a large discrepancy in their characters.

For, while the implacable gruffness of Mr. Harrow prevented him

from understanding the youth and the beauty of his daughter’s

emotions, still he was able to make allowances for what seemed

to him too modern and dashing in her character. She filled a

place in the old gentleman’s life which the death of his wife had

left vacant. If Mr. Harrow had ever understood his wife, he

was the only person that believed it. But there is a kind of understanding

which arises from a tender and lasting affection, and

which is really the main prerequisite to a happy married life. This

Mr. Harrow possessed to a degree. He never tired of watching

his wife manage the house, and never failed to kiss her tenderly,

after an argument, even when his impatience had been aroused to

the point of swearing at her. When she died, he felt strangely[193]

that it was a rebuke. He tried to compensate by increased tenderness

toward his débutante daughter.

He found this especially easy because Betty was the image of

her beautiful mother. Indeed if it had not been that she possessed

one of those intrinsically virtuous characters, in whom moral

principles are realized quite naturally without a struggle and

without being mentally formulated—if she had not owed much to

heredity—Betty would have been spoiled by her father’s attentions.

As it was, however, she came out successfully, being one

of the belles of that season; and had since lived with her father

for three years. She was now just twenty-one.

Of course, Mr. Harrow was not one of those disagreeable

early-Victorian fathers who force their daughters into undesirable

marriages; but he had nevertheless a choice for Betty in the back

of his mind, and allowed no opportunity to slip by without a sly

hint concerning the desirability of this gentleman. The gentleman’s

name was Conrad, and he had lately risen to a responsible

position in one of the largest of the down-town brokerage houses.

He was noted for his cleverness, his cool head, and for the

astoundingly impersonal way in which he looked out at the world.

He was one of those “objective” persons, who, if any criticism is

to be made of them, regard life with too slight an emphasis upon

the heart. Betty liked him well enough, though she did not

perceive those same virtues in him which had attracted her father.

But she was not yet prepared to sacrifice for a man already past

thirty-five, her present life of laughter, young love, and gayety.

Do not let me give you a false impression of this young lady.

If you had seen her in any one of a number of “scrapes” into

which her gay life had led her, you would, I think, form a very

high estimation of her character. Clandestine parties in automobiles,

with silly young men who know little beyond the recent

baseball scores, and who really do not know how to kiss a woman—these

kinds of things she had no use for. They bored her, and

did not tempt her. Romance, for her, was much more artistic

than this, and much more fundamental.

She had, indeed, managed to scare up a real romance which

served, for the present at least, as an added enjoyment to a life

that was already a happy one. Betty was cruel in such affairs.[194]

She made it quite plain to her lovers that she was very much in

love with them: but she never allowed them to approach her with

anything more forceful than their eyes. And as her present

favorite one day exclaimed to a confidential friend, “I might as

well hang her picture on the wall and flirt with that.”

This exclamation was carried to Betty’s ears by the said friend,

who, notwithstanding his vows of secrecy, was only human. A

few days after the disclosure Betty sent the following note by way

of consolation:

“Dearest Charles:

“Monty tells me that you want to look at my picture,

but that you haven’t got one to hang on the wall. I’m

sorry for this; I don’t wish to lose any opportunities,

even if it only is with a picture; so I am sending you the

very best photograph I have, hoping that you will not

fail to make use of it.

“Yours for the winter,

“Betty.”

This note, and the photograph which followed it, astounded

Charles, in spite of the fact that he was becoming used to Betty’s

impetuosity. Yet, he reflected, he had only known her a few

months and could be excused for his astonishment. He very dutifully

placed the picture upon his dresser, and very dutifully made

love to it. He liked to fill in the colors which the photograph did

not reveal. There was nothing to distinguish them from other

observations than a lover’s except possibly the hair, which was a

strange mixture of brown and gold. The eyes were blue and

large. And the nose had a peculiar curve of its own, which was

extremely feminine. Charles sighed and decided that he would

pay a visit to New York; for he was at that time occupied with

journalism in Boston.

Now Betty was no more anxious to fall seriously in love with

Charles than she was with Mr. Conrad. While the latter was

somewhat uninteresting and unromantic, the former acquitted

himself of those faults only at the expense of poverty and an

unpretentious position on a Boston newspaper. Mr. Conrad could

offer her everything that money could buy; Charles could only

bring her those sacrifices which love often demands. She was no[195]

more willing to save her pennies for Charles than she was to

forfeit her freedom to the middle age of Conrad. And although

she did not reason this out, she decided that something ought to

be done in the way of intimating her convictions to both lovers.

The direct antithesis which they presented amused her and gave

her an inspiration. She would pit them against one another and

see what would happen. Perhaps it was the restless tendency of

her generation which made her want to find out what would

happen. Perhaps it was the skepticism of the age which had

entered her heart and had led her to doubt which of the two goods

wielded the greatest motive—romance or a life of ease. Perhaps,

in the true spirit of the modern débutante, she preferred empirical

methods. Or perhaps it was merely femininity.

At any rate, she invited them both to dinner on the same evening,

and noted with satisfaction Mr. Conrad’s apparent uneasiness upon

perceiving the attractive features and the youthful bearing of the

new arrival. She laughed also to see that Charles merely regarded

Mr. Conrad as an uncle or as an old family friend, and had not,

as yet, a suspicion of the true nature of the case. So she devoted

the evening to Charles.

They were discussing the last Yale Promenade—for Charles

was a Yale man, having graduated only a year ago. Conrad, who

had never gone to college, leaned over with his elbows on his

knees, and tried to enter into the conversation, though puffing

nervously his cigar. Mr. Harrow was getting out the chess board,

for he was an enthusiastic player, and made it a habit to challenge

Conrad for an evening bout—usually, we fear, to that gentleman’s

annoyance, and always to his disgrace.

“Christy,” said the old man, having set up the chess-men and

arranged the chairs, “what do you say to a game of chess?”

The question was asked in this identical manner every evening,

and Christy, who had never yet found the method of avoiding

such elaborate preparations, invariably answered in the affirmative.

This evening he sat down even more reluctantly, since he had no

sooner begun to play than Betty delicately suggested to Charles

that they go into the parlor to see the family photograph albums.

“That old gentleman looks as if he needed a rest,” said Charles

after they were seated side by side.

[196]

Betty gasped. “Do you mean Christy?”

“Christy?—Is that what you call him?”

“Christopher Conrad of Wall Street,” said Betty, puckering

her lips and making a serious frown. Then she laughed. “The

idea of your calling him an old gentleman! Why—why—he’s

one of my best friends!”

“Oh.”

“And he’s just the kind of man to make a woman happy, don’t

you think, Charlie? Plenty of money—and—a fortunate disposition.”

Charles flushed. This seemed something of a pickle. “I’m

sorry,” he said. “I didn’t understand.”

Betty, having achieved that victory, sat back and opened a large

album, which she presently spread out across her knees, and his,

and leaned very close to him in order to point to the pictures of

principal interest.

After many oh’s and ah’s, Charles noticed a distinguished individual

and said: “There’s another man, I suppose, who could

make a woman happy.”

“Why, yes,” said Betty, “that’s Uncle Alfred. But he’s the

romantic type—like you. He hasn’t got a cent of money because

he spends it as fast as he gets it. I’m sure Aunt Susan must

have been very much in love with him before she married him.”

“Hm,” said Charles, “you seem to emphasize the economic side

of things to-night.”

Betty looked at him quietly. “I always make a point of it when

I’m with you,” she said; “but look here—that’s me when I was

six.”

Charles leaned as far over toward her as possible, in order to

get a clear view of the situation. She offered no objection.

Presently they were talking very seriously about his future.

Suddenly Charles said: “I say, Betty, are you engaged to—that—that

young gentleman?”

Betty eyed him. “Of course not,” she said. “Whatever put

that into your head?”

“Oh nothing, except that you have been continually praising

him all evening; and I thought perhaps you had some reason

for it.”

[197]

“Well, I have,” she said. “I think you ought to profit by his

example. He’s so industrious and calm and dignified. People

all talk about him. We’ve sort of made a model out of him.”

Saying which, she lighted a second cigarette and sat back to

look at Charles in a tantalizing way.

Meanwhile the chess players had been discussing very personal

matters between moves. Conrad had suggested to Mr. Harrow,

who knew his heart, that it was high time for a proposal of

marriage to the young lady in the adjoining room. “Especially,”

he said, “since she seemed to have her head turned by the attentions

of this young man Charles what-do-you-call-him.”

“Saunders,” said Mr. Harrow.

“Yes, Saunders. He hasn’t a cent in the world, has he?”

“No,” said Mr. Harrow, “but you mustn’t be alarmed at that.

If you had brought up a daughter, you wouldn’t be alarmed at

that. Your move.”

“Precisely,” said Conrad, moving his bishop into a position of

extreme peril, where it was promptly snatched up by the opponent’s

queen. “But I believe, sir—and surely you must agree

with me—that the better portion of a woman’s life is that which

is devoted to the care of the home; and that your daughter—”

“Your move again,” said Mr. Harrow, who was now commencing

the final drive of his attack.

“Certainly. That your daughter has seen enough of the world

to realize the futility of flirtation with—”

“Hold on—that move puts you in check. Besides, Christy, it’s

obvious that you ought to protect this rook here, if you want to

break my attack.”

“Certainly. But don’t you agree with me?”

“Eh-what? Yes. But I’ll tell you what, Christy. This modern

generation can’t be forced to do a damn thing. Haven’t I argued

with her? Haven’t I told her she’d end up in a scandal? ’Pon

my word, Christy, you’d better get a hustle on—check.”

Thus the party broke up, somewhat after ten o’clock, much to

the dissatisfaction of both lovers, and much to Betty’s enjoyment.

She was not surprised when Conrad called up the next day and

wished to have tea with her that afternoon—alone, if possible.[198]

“Why, yes,” she said; “it would be delightful. But one can

never tell who will drop in.”

It was easy enough, however, to arrange matters so that no one

could drop in. This she did. She was knitting in the parlor when

Conrad arrived. He was resplendent in gray spats and shiny

shoes. She asked him to sit down beside her on the sofa, and

poured him a cup of tea. After this was finished, he began, quite

abruptly:

“Elizabeth, you must have noticed that even during your childhood

I have looked upon you, not with the eyes of an elderly

friend—which might, indeed, have been the case—but with those

of a lover. I have never been entirely happy out of your sight,

and never so supremely happy as when favored with a glance of

your eyes” (here he looked at her), “or a touch of your hand”

(here he took her hand, which she allowed him to retain). “I

have, of course, understood, my dear, that your youth and extreme

beauty entitled you to—ah—your little fling in—ah—society. I

have for this reason stood aside, and have offered not the slightest

objection, either to your—ah—modernism, or to your—ah—gayety.

But I feel now that you have reached the age of full

discretion. I regard you openly as a woman with whom I am in

love. And I ask you, humbly, to become my wife.”

If Betty was laughing she did not show it. “Oh, Christy!”

she exclaimed. “I—I hadn’t thought. I don’t know. It is such

a step.”

“Why, dearest? How would it change you so very much?”

“Change? That’s just it. I’m afraid it wouldn’t change me

at all. I would still love dances and parties and music and Harry

Fisher (here Mr. Conrad started) and Charles Saunders (here

he jumped perceptibly), and cabarets. These things you can’t give

me, dear. I should have to be such a dutiful wife.”

She looked at him in a manner which simply denied the words

she spoke. He thought to himself “This is feminine resistance,”

and sought to embrace her. But she pushed him away gently.

“No, dear. Think it over; you will understand then.”

They talked on for some time—Conrad very ill at ease, Betty

quite delighted with the situation. She felt no compassion for[199]

him. He was such a stupid man not to realize these things. After

an hour or so he left, to think it over.

He had no sooner gone than Charles arrived, breathlessly, and

wanted to know if Betty could go on a party that night.

She laughed at his young enthusiasm. “What kind of a party?”

she asked.

“Oh, just you and I—down to Greenwich Village. We could

go to the Green Wagon and dance and have a little punch—I

know them down there.”

The temptation was almost overpowering. Ordinarily she might

have gone. “Why, Charlie,” she exclaimed, “how perfectly

absurd! How could I think of being seen in a place like that—alone—with

you?”

Charles grinned, in spite of his disappointment, and said that

she wasn’t likely to be “seen” by anybody she knew—“unless you

are in the habit of going there,” he added.

“Well, I’m not! And I don’t think you ought to have asked

me. I think it’s something of an insult.” Upon which she pouted

her lips just a trifle and fingered one of the books on the table.

To Charles this seemed the extreme of perversity. He gazed

at her for some time without knowing whether to become angry

or humble. To most young lovers, the situation would have

called for a certain amount of humility, inasmuch as the lady

seemed to consider herself deeply insulted. We venture the opinion

that the reader would have asked Betty’s pardon and offered his

services in some other and more refined amusement. In other

words, most of us with Charles’ meagre experience in matters of

love, would have taken a healthy bite to the hook. But Charles

was impetuous and possessed of a quick temper, which, while it

never lasted for any length of time, often asserted itself in precarious

situations. It had already ducked him into much hot water

and had been the cause of a broken engagement with a young

Boston girl, who, far from having Betty’s nice scruples, was too

much devoid of them in the eyes of her lover. Meanwhile, we

have left Charles and Betty standing there silent. And the former,

being keenly disappointed (for he had come there to offer her

nothing but the best intentions) suddenly looked up and said,[200]

“Well, I’m sorry you see it that way.—So long.” Whereupon he

turned and left the house.

You may imagine Betty’s surprise, which soon turned into

anger, for it seemed that one of the actors in her little play was

growing recalcitrant. She was decidedly not the mistress of the

situation, since Charles had done this most unexpected thing. It

was really horrid of him to react in such a manner. She boiled

over considerably.

On the other hand, Conrad rose immensely in her estimation,

because he reacted precisely as she had intended. As if he had

received written instructions, he announced his arrival as usual

by telephone, had tea with her the following afternoon, and said

that “he had thought the situation over with extreme care, and

had come to the conclusion that, in spite of his more advanced

age, he was perfectly capable of supplying Betty with that life of

gayety, music, and dancing which she so loved: in proof of which

he desired her to accompany him to Greenwich Village that very

night.” Betty was so flattered at the success of her anticipations

that she acquiesced somewhat too enthusiastically, although she

had intended to go with him from the very beginning. By way

of making her acceptance a trifle more lady-like, she urged him

to pick some cabaret obscure enough so that they would not be

seen.

Now, in case the reader should accuse me of relying too much

upon Fate in the relation of this tale, I had better acquaint him

before hand with certain facts: namely, that Conrad, having made

his decision, found himself at a loss to know of an obscure and

poorly frequented establishment in Greenwich Village, which

should at the same time be fairly respectable; that he had an artist

friend named Peter, to whom he went for advice; and that Peter,

who owned an establishment himself which seemed to suit Conrad’s

needs, was an intimate friend of Charles Saunders.

Charles, whatever may be said of his good qualities as a lover,

was not the kind to deny himself pleasure on account of a perverse

mistress. In fact, her very perversity aroused in him such

a craving to forget her, such a desire to avoid what he considered

a sickly and unmanly pining, that he was driven to indulge in

those passions, which, without the proper settings, the world considers[201]

un-Christian. Charles would merely have called them unbeautiful.

But it is a well-known fact that the loss of a very

delicate and tender beauty, which we have coveted, leads us to

madness, in a vain attempt to beautify anything which happens

to be at hand. Thus it happened that Charles had been drunk

twice since leaving Betty’s house (for that young lady had been too

proud to relent), and had spent his evenings at his friend Peter’s

establishment, called the Green Wagon, in company with Peter

himself and a couple of not-too-respectable girls.

It is not surprising, therefore, that Charles had no sooner seated

himself and ordered cocktails, than his gaze fell upon what appeared

to him the most beautiful back in the room. He gazed at

it steadily, doubting his own senses, which, however, insisted that

the color of the lady’s hair was a strange mixture of brown and

gold. He glanced at her partner, who was none other than the

dignified Conrad, and who was leaning far over the edge of the

table, tea-cup in hand, and talking with her earnestly. Charles

thought that he could even perceive the reflection of her beautiful

eyes in Conrad’s loathsome ones. Charles shuddered, and muttered

to himself, and drank his liquor violently, ordering more.

Meanwhile, Betty and Conrad were enjoying themselves hugely.

He had been very liberal, and she had taken rather more than she

would ordinarily have considered prudent. Perhaps it was the

fact that she was safe in the care of this old and reliable friend.

Perhaps, too, she wished to compensate for the good time which

she had denied herself with Charles.

“You know, my dear,” said Conrad, gazing at her intensely,

“I have never enjoyed any experience in my life quite so much

as this one. I must thank you for delivering me out of what was

proving to be a monotonous routine. I could be happy forever,

this way, with you.” Whereupon he took her hand, which she

had placed carelessly on the table, and which she allowed him to

hold. Indeed, she even gave his an affectionate squeeze, not

realizing perhaps that even old family friends can be fools. We

would, however, blush to set down on paper the thoughts which

were now in Conrad’s mind. We fear he had attempted to transfer

the cruel tactics of business into the affairs of love. For he saw

plainly that there was only one way of winning Betty for his wife,[202]

and that he could never do so while she was in her more rational

environment at home. And although Conrad was not an unscrupulous

man, his present plan could be considered little less than

diabolical.

“You have been such a good girl to come out with me to-night,”

he said—“to give me this little pleasure which I have lacked all

my life.”

Betty met his eyes. She could not see or hear things very distinctly.

Yet she was conscious that he had said something kind.

She really liked him a great deal. She squeezed his hand again,

and asked him to light a cigarette for her.

“Dear Christy,” she said, “you have always been such a good

friend to me.”

Soon after this the music started. They rose to dance, and

Betty allowed his cheek to touch hers; for although she was not

in the habit of doing this with everybody, she chose to make an

exception to-night. She had her reasons to justify this. One

was that she wanted to show Conrad how things were done; the

other, she said, was that he was perfectly safe anyway. Whatever

motive lay beneath this we will leave the reader to judge.

At present she closed her eyes and felt rather happy and a trifle

drowsy. She was a little surprised, however, in the middle of

the dance, to feel him tighten his arm about her body and move

his lips closer to hers. This was so unlike the Conrad she knew—the

dignified Wall Street broker. She opened her eyes and

looked up at him, and smiled.

Her glance had no sooner left Conrad’s eyes than it fell upon

Charles, who was not far away, and who was watching her over

the head of his partner, with a look of dismay, and, as it seemed

to Betty, even disgust. Her first reaction was one of terror. What

a frightfully compromising meeting. Then she remembered how

she had refused Charles an invitation to this very establishment,

without any reason for so doing. Whereupon she hated herself

for the part which she was now playing. She next looked at

Charles’ partner, whose lips and cheeks were painted, and hated

Charles.

“Let’s sit down a moment,” she said to Conrad. “I’m tired.”

She changed seats with him, saying that she wanted to see the[203]

dancers better. What was Charles doing down here, anyway,

with a disreputable woman like that? And after professing to

be in love with her! But he had never—yes, she knew he was in

love with her! Well, she did not love Charles, so it did not

matter; only she wished he had not seen her down here with

Conrad; and especially after her refusal to go with him!

Oh, it all went in such hopeless circles; and here was Conrad

trying to make her take another drink. “It will revive you, my

dear,” he said, “and brace you up.”

She looked at him. “Thank you; I’ve had enough.”

What was to be done?

The dance ended. Charles took his partner to their table. He

sat down, facing Betty. Suddenly Betty had an inspiration. She

quite unexpectedly exclaimed, “Oh!” and waved her hand toward

Charles, who, though surprised by this enthusiasm, responded

with a laugh. He presently arose and walked over to their table,

said hello to Conrad, and rallied Betty on the inconsistencies of

Fortune, “Which,” he said, “will never allow the most secret

conspiracies to pass unobserved by others.” Betty laughed and

promised to take the next dance with him, “If Christy didn’t

mind”; and Christy, scowling heavily, said he did not.

The next dance came, and Charles, realizing that Conrad’s eye

was upon them, retired with her to a corner, where they danced

in slow circles.

“Betty,” he exclaimed, “why did you come here with him—after

refusing, the other day?”

She laughed. “Why, Charles, dear, how foolish. Were you

offended at that? There’s quite a difference in your ages, you

know. He is a very old friend of mine. And he’s such a nice,

respectable man.”

“Hm. Well, to tell you quite frankly, I didn’t see anything very

respectable going on during the last dance.”

Betty flushed and bit her lip, and would have been angry had

not embarrassment overcome her.

Charles continued ruthlessly: “The woman I was with said,

‘There’s a happy party for you’, and I looked up—and saw—you.”

“Charles—” began Betty.

[204]

“Now wait a minute. Tell me one thing truthfully. Have you

ever been out like this with him before?”

“Why?”

“Because—well, because I don’t believe you ever have.”

“No, I haven’t. But I don’t see that that has anything to do

with it. I—”

“Just this. I don’t like his looks—that’s all. I judge men by

their eyes, and I don’t like his eyes. They seem especially bad

to me to-night. If you don’t believe me—”

“Well, I don’t believe you. And what I’d like to know is, what

are you doing down here with that—that creature. I should think

you would be ashamed to speak to me!”

It was her turn now to lash him, which she did, a trifle unjustly,

in the manner of a woman.

“I see,” he said, “that we can’t agree.” He began leading her

back to her table.

“You will perhaps think it over to-morrow morning. As for

that fellow there, I warn you, he’s drunk and not altogether

responsible for what he is doing.”

This ended the conversation, and they returned to the table

in silence. Although he did not show it, Charles was overcome

with grief. It seemed like such an unnecessary misunderstanding.

He adopted, in despair, a bravado mood, ordered some more liquor

quite loudly, and consciously acted as brazenly as possible. It was

unfair to him to do this. Betty sat and watched him, on the verge

of tears. She talked in an absent-minded way with Conrad, who

was so provoked that he suggested that they return home.

“No,” replied Betty, “I want to stay until the end.” As a

matter of fact, she could not tear herself away from Charles.

She could not keep her eyes from gazing at him, nor her heart

from wishing that he would stop. She hated Conrad now. He

seemed like a silent, grim barrier between herself and Charles.

She would not drink anything else, but sat there. She saw

Charles take the pudgy hand of the woman next to him. She

saw him give her a drink out of the white china cup. She saw

him put his arm around her and kiss her—passionately it seemed.

Oh horrible, horrible! This modernism!

She felt suddenly ashamed of herself, as though she had driven[205]

Charles to do this. She wished she had not come down here.

But she could not leave.

Just before closing time, she saw Charles and his partner rise

and make preparation to go. The other two members of the

party remained seated. Charles never looked over in her direction,

but took the woman by the arm and escorted her out of the

room. They disappeared behind the green plush curtains.

The room seemed to whirl before her eyes. She arose to follow

them.

“Are you going?” asked Conrad, jumping up. This reminded

her that she had forgotten him.

“Christy,” she said, “I’m sorry. But, Christy, go and bring

Charles back here.”

“I certainly shall not,” he said. “What business have I with

Charles Saunders?”

“Please, Christy, I want to speak to him.”

“No, I shan’t do it.”

“Very well, I’ll go myself.”

He held her arm. “What do you want to speak to him about?”

It seemed to her almost like a snarl.

“Something personal. You shall go.” She eyed him, and he

obeyed.

She sat down and tapped a cup impatiently with her finger.

Presently a figure emerged from the green curtain. It was Conrad.

He crossed the now empty dance-floor at what seemed to her an

infinitely slow pace.

“He’s gone,” he said finally.

She knew then, suddenly, that he lied; that he had been lying

to her all evening; that Charles was right. She rose abruptly and

almost ran across the room, forgetting her dignity. Pushing aside

the curtains she saw Charles, with his hat and coat on, just going

out the door.

“Charlie,” she cried—“Charlie!”

He turned quickly and looked at her in a perplexed way. There

was not a trace of humility on his features, until he saw her distressed

condition, and realized that the three or four strangers

standing around were laughing at her. He was then overcome[206]

with compassion and led her into a small hallway where they

could talk.

“Is anything the matter?” he asked.

“Just you,” she replied. “You probably think I have had too

much, but I am perfectly sober. Oh, Charlie, you—where were

you going?”

“I wasn’t going home,” he said, looking toward the ground.

“Charlie, you can’t take care of yourself. You don’t know

how.” She was much disturbed over the thought, although it

was a new one to him. He had just been thinking the same thing

about her.

She took hold of the lapels of his coat. “Charlie, don’t go back

with that awful woman?”

He looked at her defiantly. “Why not?” he asked. But the

expression of her eyes was so pitiful and so serious that his heart

relented.

“All right,” he said, “provided that you won’t let Conrad take

you home.”

Betty smiled then. There was humor in the situation.

“It’s all my fault,” she said.

“What’s all your fault?”

“Oh, I’ll tell you about it—soon—soon.”

“Tell me about it on the way home.”

“But Christy?”

“Oh, Christy be damned!” he said. “Here’s a back way out.

You can get your hat and coat to-morrow.”

He led her down a long corridor and out into the street; where

he took off his overcoat and gave it to her. They walked around

the block and climbed into the car which Charles had borrowed

for the evening, from the friend who “notwithstanding his vows

of secrecy, was only human”.

Thus, when they started down the deserted street, it was after

one o’clock. Christopher Conrad remained behind in the Green

Wagon for nearly an hour, where he ordered a search to be made,

at large expense, and strode imperiously up and down the room.

At two o’clock he called up Mr. Harrow.

RUSSELL W. DAVENPORT.

Long ago, when I had just reached the age of walking and

talking, a young lady friend of my own age was called by

the curious name of “Buttons”. Possibly the additional touch

that her father was the author of this, that he also called her

“Butterball”, and that she was plump as all properly healthy young

ladies of that age should be, will seem proper explanation for

such a christening. But mere physical attributes can scarcely be

hoped to give complete satisfaction, for the subject is one so much

of the spirit that we might almost call it intangible. Little did I

know in those younger years why my lady was called “Buttons”;

little, likewise, did I care; for the name seemed quite suited to

her. “Buttons” and the more formal, less Christian title which

a minister had pronounced over her fitted this childish personality

equally well. Indeed, how remarkable an artistic sense the girl’s

father must have been blessed with, in order to bestow on his

daughter such a charming sobriquet! How he could have thought

of the romance in the conception buttons embodied so delightfully

in his child I could never tell. A happy creative gift he must have

had indeed, since meditation on this whim has inspired in no small

measure the following remarks.

During the period when I thus heard the word buttons for the

first time, my mother habitually dressed me in a white suit, white

stockings and shoes. However much ridicule the white shoes

themselves may have occasioned as I and my fellows more nearly

approached the state of manhood, the buttons on the white shoes

made amends. Occasionally, when my nurse was with a large

button-hook “squeezing tight” a powdery shoe, one of these pearly

buttons would pop off. She was in such a case forced to search

out another one, for I at once engaged the attentions of the stray

sheep. Have you ever imagined a pearly thing more beautiful,

and therefore more precious, than a pearl? Perhaps on account

of a semi-opacity and semi-transparency and yet a transcendency[208]

of translucency—or perhaps it was the slippery smugness of these

little objects that attracted me. At any rate, I was brought to

wonder why father did not have one mounted to wear instead of

his pearl scarf-pin. Possibly it would be too expensive, I thought.

For long—I dare not say how long—they became of an afternoon

the center of my observation. I would watch rather than look at

their round surface backed up by a little metal ring. They seemed

to live. But in the midst of such reveries one of the little things

would slip from my fingers and, rolling along the edge of the

carpet, disappear, for all I knew, in the way most fairies did.

Buttons were kept in a button-house—that is, the buttons which

were not in contemporary use. The button-house on the outside

was brown and oblong and said “Huyler’s Chocolates, New York”

in black script on the top. But, though this might have at first

furnished an allurement to the house, the shining interior sides

and a sea of buttons—white, black, grey, yellow, blue, and green—surging

over the bottom, invited continual revisitations which in

the end caused a far firmer friendship, or love, to be formed

between me and this object than any mere acquaintance could

have brought about. As a violinist flees in dark moments to

expression through his violin, a painter through his pictures, and

a writer through his pen, so might you have seen a child poring

over his little button-house, poking in a finger once in a while to

stir the occupants to life, entirely absorbed. But had you peered

in, you would not have seen what he saw in the little tin box. And

I doubt if anyone ever will know what he saw. For I have

forgotten.

With the discarding of childish thoughts and childish ways, one

acquires boyish successors to these respective qualities. And so,

after learning to dress myself, I came to the struggle of buttoning

up clothes. My underwear gave me the most trouble. For who

can hope, except by dint of great practicing, to engineer in a

controlled manner a whole row of buttons up one’s back when, in

the hurry of getting up, a trying task is presented even by the

side ones. Although the appearance of these buttons fell short of

attaining a standard of beauty worthy of present description, the

sight of one (say a side one) at last becoming visible through an[209]

obstinate buttonhole inspired me with no less joy than that felt

by children at a puppet show when they see Humpty Dumpty

suddenly burst forth from a covered box.

Aye! The struggle with these buttons gave them their meaning.

Perhaps we may rather call them villains than heroes. Or perhaps

big, plain-faced dubs with vacant eyes, hard to shove out of

the way because of their very clumsiness. Yet in a temper one

way remained—the sinful, easy road to Hell—the last resort—tearing

them off.

A young man does not need to wait till his brass wedding anniversary

(if there be such a one) for his first dealing with that

deceptive, goldlike metal. He owns it first on his blue coat. Supposing

the whole coat not to be brass, we will by elimination and

hypothesis proceed to the buttons. A correct supposition—and

more, for the brass is embossed with an anchor and chain, together

with a crest or other insignia of the kind. These have the virtue

(a) of shininess, and (b) of being like a policeman’s—or a trolley

car conductor’s, bellboy’s, naval officer’s, etc.,—all of whom,

finally, are pretty much policemen. Elders may presume such a

coat—or such buttons—to be unhealthy since they tend to make

the wearer stick out his stomach, to show them off. But critics

must as well realize that this attitude increases the morale, and

while mortifying the flesh, tends to exalt the spirit. Possibly the

spirit in this case is not of the purely heavenly quality that some

would-be angels might desire,—yet it is higher and more serene

than the majority of sensualists would admit.

When Chris, the coachman (pardon me, the chauffeur) stalks

into the kitchen of a wintry evening, mayhap to see Marie,—how

could a person of the brass-button age be expected to conceive of

the use of those great orbs stationed at intervals along the front

of Chris’s great, fuzzy coat. They are mammoth. Their very

size confounds one, especially since, in common with many great

objects, preciousness of detail or surface and delicacy of effect

have declined their rightful position in favor of a world of the

gigantesque, to be widely wondered at. Even thus Chris’s buttons.

But wonderful to say, they are useful. For after Marie had helped

him off with his greatcoat, I tried to lift it slightly from the back[210]

of the chair in the corner. My wonder henceforth was not that

the buttons were so big, but that such a great mountain of heavy

stuff as this could be held together by anything at all!

How broadly the influence of the button world is felt you have

had as yet, dear reader, but little indication. In matters great as

the height and age of a child and in the relations which, physically,

at any rate, he may bear to his father, buttons are most subtle

indicators. Thus when one morning my parents asked me to stand

up beside my father to see how tall I was, we found among us

that my topmost crest of hair reached the second button of his

waistcoat. Feet and inches were no longer needed in the mathematical

scale:—their place was superseded by buttons and buttonholes.

“How tall are you, my boy?” I might be asked. With

romantic evasion of the point and still with a certain exactitude

I answered, “Well, I come up as far as the second button on

father’s vest.”

Some day I hope to write An Historie on the Romance of

Buttonholes. Buttonholes, however, are such unbodied beings

and taken on the whole without their buttons, are such lonely

objects that I fear lest the ambitious author should, in entertaining

a morbid affinity for the Universal Desolate, fall a prey to his

own affections and die of an heavenly grief. Have you never

felt the pitiful sentiments put forward at the mere suggestion of

the lost buttonhole? The classic illustration of this type is, of

course, the one on the lapel of a coat. Perhaps the scholar will

here accuse me of having incorrectly used the word buttonhole

for a little slit fashioned to receive no button. In reality this is

a buttonhole of many buttons. At the age when one is just too

old to be spanked the aperture first becomes fully a buttonhole—it

accommodates a youth with provision for his innumerable

colored, enamelled buttons emblazoned with advertisements of

charity drives, political campaigns, circus days, wholesale houses,

and the like. The only visible regret on these occasions is that

there is but one of its kind. In necessity invention presses even

normal ones into service. Later on, this receptacle receives buttonhole

bouquets from frail lady-fingers—fragrant forget-me-nots,

spring flowers, or dainty garden nosegays. And in empty declining[211]

years it may clasp only an infrequent bachelor’s button

or an onion blossom.

About two years after the father-vest-second-button age, which

would land me in the father-vest-third-and-a-half-button stage, I

fell to wondering about buttons in a scientific way. Buttons were

awkward. The world, I knew, had been going on for hundreds

of centuries and men had discovered no more graceful fashion

of fastening their clothes together than by these round discs,

dangling ridiculously from clothes and yet anchored there with

an amount of pains out of all proportion to the achievement.

Furthermore the cloth was sloppy. The combination sufficed, you

may judge, to drive any young neurotic into a very unenviable

state. I fell to inventing. Pins would not do (this was an instinct).

Hooks and eyes were worse still (I had experienced all

too intense agony at the canniness of “doing up” mother’s dress).

Sewing in for the winter was obviously unchristian. In a desperate,

fevered condition of mind clothes pins, railroad spikes,

patent clasps, a series of bands like a Michelin man’s, box fasteners,

padlocks, rings, thongs, strings, and lobster claws whirled

by as a giddy panorama of substitutes, leaving me at last faint and

content necessarily with the extant order of things, yet peaked

at the impotency of my inventive genius. After carefully revolving

the matter in my mind, picturing many modes of clothes

and corresponding sorts of buttons, I finally concluded that this

whole section of the world—buttons—instead of falling under the

rule of science, was an art.

In this manner I became artistic—such mammoth results do

transpire from buttons. Whether this be the cause, or whether

the grey years are dulling with their sepulchral dust the gloss of

my golden hair, I know not. But I am now largely unconscious

of buttons. They are only miserable little nuisances flying off

and rolling across the floor at the most inconvenient moments.

They are intensely realistic. How in truth could anyone, save a

fool, suck romance from their marrow? Fie upon you!—collar

buttons—but tread softly,—we will not embark there. One exception

only to this indifference do I know—the comfort of sitting

in an easy-chair and unbuttoning a tight vest. This sensation is[212]

the most agreeable immediately after a large meal—say, an over-large

meal. And however gross the indulgence, it causes buttons

again to swim into my ken—this time on the side of mine enemies;—and

as great ones indeed do they loom over me when I, by

yielding to the order of unbuttoned vests, am constrained to

think—

“... now ’tis little joy

To know I’m farther off from heaven

Than when I was a boy.”

L. HYDE.

The Story of Mankind. By Hendrick Van Loon. (Boni &

Liveright.)

“The Story of Mankind” by Hendrick Van Loon is an original

and valuable contribution to education. Those who have

read little or no history will find here a well-drawn picture of the

life of the world and its people from the earliest times we know

of. And those who have read much of these things will find the

book an acute survey of the whole—a survey which sets off

individual races and periods and changes in definite perspective.

Mr. Van Loon’s viewpoint of history and its presentation varies

very radically from that of the average historian. History to

him is no long list of wars and kings and papal edicts; it is

primarily dramatic. Here before you are the greatest plots,

intrigues, heroes, heroines, villains that you could ever imagine—now

playing a comedy, now a tragedy, now a farce. No wonder

you are startled to find your attention so completely held by “an

old history book”.

But beneath this we find a more fundamental viewpoint. In

the author’s own words you are to “try to discover the hidden

motives behind every action and then you will understand the

world around you much better and you will have a greater chance

to help others, which (when all is said and done) is the only true

satisfactory way of living”. Here we have Mr. Van Loon’s ideal

as an historian; and the spirit which runs through the book proves

how well he lived up to it.

As I turn back over the pages the treatment of three or four

subjects is particularly significant. Another of the author’s precepts—“it

is more important to ‘feel history’ than to know it”—perhaps

explains why the chapters on the religions of the world

are so impressive. That on Joshua of Nazareth, when the Greeks

called Jesus, is indeed a unique presentation of the story of Christ.[214]

And for the first time in my life I feel that Mohammed and

Buddha and Confucius have ceased to be names—have become

very wise men who actually lived and whose words one may well

listen to. Napoleon is criticized very severely, but with unprejudiced

insight into his character. The last chapters—those on the

Great War and the New World—sum up all that has gone before.

Mr. Van Loon turns from his backward glance into the ages and

looks with all his optimistic philosophy to the greater drama that

is still to be enacted. In all you feel the man’s sympathetic touch;

he believes in mankind—in its past and in its future.

W. E. H., JR.

Martin Pippin in the Apple Orchard. By Eleanor Farjeon.

(Frederick A. Stokes Company.)

In these enlightened days when the past is a memory only and

life but the illusion of our daily experience, it is rather startling

to have a “grown-up person” talk to us of fairies, and magic

spells, and the beauty of an apple orchard. Such things are all

very well in the nursery, but really, now that we have grown wise

enough to put away childish things—. So let this be a warning

to all who by chance might read the first page of “Martin Pippin”,

for he who once exposes himself to the magic spell of this fairy

tale may well find himself an object for mockery by his scornful

companions. At least, here is one man’s experience, and he speaks

for many others. Mr. J. D. Beresford, who read the manuscript,

writes in the introduction: “Before I had read five pages ... I

had forgotten who I was or where I lived. I was transported

into a world of sunlight, of gay inconsequence, of emotional

surprise, a world of poetry, delight, and humor. And I lived and

took my joy in that rare world until all too soon my reading was

done.” A better expression could not be found for the fancy,

the whimsy, the delicate beauty of this fairy tale. Its spirit

touches in us a chord that is rarely awakened in our modern

environment or in the literature of to-day.

[215]

To clothe her richness of imagination, Miss Farjeon possesses

a richness of language most worthy of so high a service. Quite

unconsciously you run across striking metaphors, most subtle

bits of philosophy. You may look far before discovering quite

as beautiful a combination of language and imagination as this:

“‘I am not so old, young shepherd, that I do not remember

the curse of youth.’

“‘What’s that?’ he said moodily.

“‘To bear the soul of a master in the body of a slave,’

she said; ‘to be a flower in a sealed bud, the moon in a

cloud, water locked in ice, Spring in the womb of the year,

love that does not know itself.’”

There will be few who will not find delight in this fairy tale;

and there shall be some, even, who will see beyond their illusions

for a day and an hour and follow Martin Pippin where his fancy

may lead.

W. E. H., JR.

Finders. By J. V. A. Weaver. (Alfred Knopf.)

Dramatic Legends and Other Poems. By Padraic Colum.

(Macmillan.)

These two volumes are similar in intention and to a certain

extent in method. Padraic Colum is attempting to communicate

some of the nuances of Irish character and life, more

especially as it is lived in the farms and villages of the countryside.

Mr. Weaver, substituting the subway for the lonely roads, is performing

the same service for America. Both poets use the language

of the people with whom they are dealing, either because

they believe it beautiful in itself or because it adds to their effect.

The sole but enormous difference between the two men is in the

measure of their success. Mr. Weaver, in choosing the American

language, was admittedly under great disadvantage at the start.

He was forced to assume a defensive attitude and as a result lost

sight of most of the important things which constitute poetry. He

seemed to think that the fact he was writing in a new language

was sufficient, that he need use no fine discretion in the choice of

his words in that language, or the manner in which those words[216]

were arranged. We imagine he is trying to write in metrical

verse, although few of the lines have meter. In short, the novelty

of his medium was too much for Mr. Weaver. He was so overcome

by the thought of writing in American slang that he forgot

the essential elements of poetry. Moreover, if Mr. Weaver fails

in his language, there is little other interest to be found in the

book. His themes are as sentimental and inconsequential as ever.

But Padraic Colum is primarily a poet and only incidentally

the exponent of a new form of expression. He does not take the

speech of his people as spoken in the dull hours, but only when it

is lifted to eloquence by the vision and poignancy of rare moments.

He is a master of the words in his language, their sounds, their

colors, their subtle shadings. Furthermore, the things he writes

about, however local they might at first appear, have always something

permanent and universal in them—death, poverty, thwarted

heroes and remembered queens. Perhaps the first lyric, To a

Poet, is the most significant in the book, both in its relation to the

author and in its expression of the ancient problem of the artist

and his race. He is speaking of his own people:

“White swords they have yet, but red songs;

Place and lot they have lost—hear you not?

For a dream you once dreamed and forgot!”

Despite the many fine things in the present volume it is greatly

inferior to the earlier Wild Earth. Every lyric in that collection

was cast in the same mood and attained the same high degree of

perfection. Dramatic Legends would almost make us believe

that Mr. Colum has abandoned the particular type of poetry which

he can write so much better than anyone else in the language.

W. T.

The Interpreters. By A. E. (Macmillan & Co.)

“The Interpreters” is a product of the present-day groping

for an explanation of man’s purpose on earth as conceived

by the Creator and the instrument of government—or non-government—best

adapted to fulfill this purpose; as A. E. has put it,

“the relation of the politics of time to the politics of eternity”.[217]

Like the rest of the world A. E. is not able to completely pierce

the mist which conceals our conception of things eternal, so that

this book is rather a seeking along a path illumined by the white

light of a superbly analytical reasoning, and the path seems to

lead somewhere.

It is A. E.’s belief that there is a spiritual law operating above

all intellectual and physical laws in such a way that our affairs

are linked with the vast purpose that the Creator has for His

universe. This is not, however, a doctrine of fatalism, for A. E.

believes we have control of our own destinies in proportion as we

work in harmony with the Eternal—“I think it might be truer to

say of men that they are God-animated rather than God-guided”.

In this sentence he has precluded the possibility of interpreting

his doctrine as a disguised fatalism.

A. E. is moving in an extremely rarified atmosphere in his

discussion. To keep the book somewhere near the ground, he

provides a simple mechanism. During a revolution against an

autocratic world state two centuries hence a number of revolutionary

leaders are brought together in a prison, where they devote

the night before their death to a discussion of their ideals for the

union of world politics with the spiritual Will. Each one takes a

different stand as to the methods to be employed, one supporting

socialism, another nationalism, a third individualism, and it is in

the arguments over governmental forms that some of the finest

logic comes out. The following quotation is an example, taken

from Leroy’s statement for individualism: “You and I see different

eternities.... It is our virtue to be infinitely varied.

The worst tyranny is uniformity.”...

It is possible to call A. E. a visionary. Doubtless, “The Interpreters”

was written under the press of an immense surge of

inspiration, for there is much of poetical fervor in its pages. But

it is for this very reason that it can hold us with the spell of its

sincerity and the intensity of its philosophy. The world of the

world has been inspired by visionaries, and there is a place for a

vision to-day.

S. M. C.

[218]

The Eighteen Nineties. A Review of Art and Ideas at the Close

of the Nineteenth Century. By Holbrook Jackson. (Published

by Alfred A. Knopf, 1922. $5.00.)

This fine volume, whose thrillingly beautiful format is alone

enough to recommend it to any collector of unique books, is

a reprint, with a few addenda, of a work of the same name issued

in 1913. It is to be doubted whether the former copy could have

been as effective as the present one which, with its clear, round

type, and profuse illustrations, and magenta and purple covers,

make up a volume that no true book-lover can afford not to own.

Mr. Jackson, intimately connected with British periodicals of

note since 1897, the author himself of such noteworthy pieces as

“The Eternal Now” and “Romance and Reality”, is admirably

qualified to write on “The Eighteen Nineties”, a creative period

in English literature, which for the quality as well as the quantity

of its output, is second only to the Elizabethan era. He knew

intimately the men about whom he writes, and whose work he

appraises. In the admirable introduction he sets forth his aim as

“interpretative rather than critical ... to interpret the various

movements of the period not only in relation to one another, but

in relation to their foreign influences and the main trend of our

national art and life.” The following passage exemplifies as well

as any the illuminating quality of mind that makes all Mr. Jackson’s

comments valuable: “Anybody who studies the moods and

thoughts of the Eighteen Nineties cannot fail to observe their

central characteristic is a widespread concern for the correct—that

is the most righteous, the most effective, the most powerful

mode of living. For myself, however, the awakening of the

nineties does not appear to be the realization of a purpose, but the

realization of a possibility.”

The book deals in twenty-one chapters with every important

phase of art and life that came into the crowded hour of the last

decade of the last century. To the present reviewer, at least, the

most substantial and most unusual interpretations are those in

the cases of Francis Thomson, Rudyard Kipling, and George

Bernard Shaw. “Consciously or unconsciously,” the author says,

“men were experimenting with life, and it would seem also as if[219]

life were experimenting with men. It was a revolution precipitated

by the Time Spirit. Francis Thomson represented the revolt

against the world. He did not, as so many had done, defy the

world; he denied it, and by placing his condition beneath contempt,

he conquered it.” Of Shaw he says, “he strove to add to

the heritage of the race a keener sense of reality.... To look

at life until you see it clearly is Bernard Shaw’s announced aim....

His sense of reality does not take reason for its basis. The

basis of the new realism is the will.”

The predominating trends of the decade are summed up under

the discussion called “Fin de Siecle” under the three headings,

“The So-called Decadence; the introduction of a Sense of Fact

into life literature and art; and the development of a Transcendental

View of Social Life”.

Each chapter, with its astounding collection of facts, never

pedantically, often brilliantly, and always intelligently presented,

are brightened by comment that is often epigrammatical: “Wilde

was the playboy of the Nineties.” “Aubrey Beardsley’s art would

have been untrue had it been imitable or universal.” “The decade

began with a dash for life and ended with a retreat—but not a

defeat.” Speaking of Shaw’s wit, the author says, “It was the

sharp edge of the sword of purpose.... Although the majority

of those who go to his plays go to laugh and remain to laugh

(often beyond reason), many remain to laugh and pray.” It is

a sane book, carefully written, and clamors to be read—and read

again.

F. D. T.

The Egoist was engaged to, or at least with a Silent Woman, so of course

he knows nothing about it. And anyway, according to Ahasuerus, he

had resigned. So that’s that.

But perhaps it was a little like this. “Wet!” “Not quite good enough.”

“Mi-mi-mi-mi-ha-ha.” “Oh, come on...”—the interstices being filled with

a long silence, by the howling of the wind, or what you will.

No chaos this time—it’s serious, this last “Lit”.—

Or perhaps the dependable, or rather, more dependable four were not all

on deck: perhaps—perhaps—but then, Mr. Benson or Bukis can tell better

than the enamored Egoist. Or perhaps Richard Cory—ask one of them if

you would know.... It is of small moment now. Nothing matters any more.

Nothing.—

“They are not long, the days of wine and laughter,

Love, desire, and hate:

I think they have no portion in us after

We pass the gate....”

We have passed the gate. “It is gone like time gone, a track of dust and

dead leaves that merely led to the fountain.” Gone.

Good-bye, good-bye, good-bye, good-bye, good-bye.

Sic transit gloria Yalensis!

Yet must it be so, O Ahasuerus, Richard Corey, Bukis, Mr. Benson—must

it be?...

Yale Lit. Advertiser.

Compliments

of

The Chase National Bank

HARRY RAPOPORT

University Tailor

Established 1884

Every Wednesday at Park Avenue Hotel,

Park Ave. and 33rd St., New York

1073 CHAPEL STREET NEW HAVEN, CONN.

DORT SIX

Quality Goes Clear Through

$990 to $1495

Dort Motor Car Co.

Flint, Michigan

$1495

The Knox-Ray

Company

Jewelers, Silversmiths,

Stationers

- Novelties of Merit

- Handsome and Useful

- Cigarette Cases

- Vanity Cases

- Photo Cases

- Powder Boxes

- Match Safes

- Belt Buckles

- Pocket Knives

970 CHAPEL STREET

(Formerly with the Ford Co.)

Steamship

Booking

Office

Steamship lines in all parts

of the world are combined

in maintaining a booking

agent at New Haven for

the convenience of Yale

men.

H. C. Magnus

at

WHITLOCK’S

accepts booking as their direct

agent at no extra cost to

the traveler. Book Early

Hi! There!

Time to re-hat.

Pension off the

old “kelly” and

choose one of these

new derbies or “softies.”

Our new arrivals

have distinctive

styles not found elsewhere.

MADE BY

KNOX

SHOP OF JENKINS

940 Chapel Street New Haven, Conn.

The Nonpareil Laundry Co.

The Oldest Established

Laundry to Yale

We darn your socks, sew

your buttons on, and make

all repairs without extra

charge.

PACH BROS.

College

Photographers