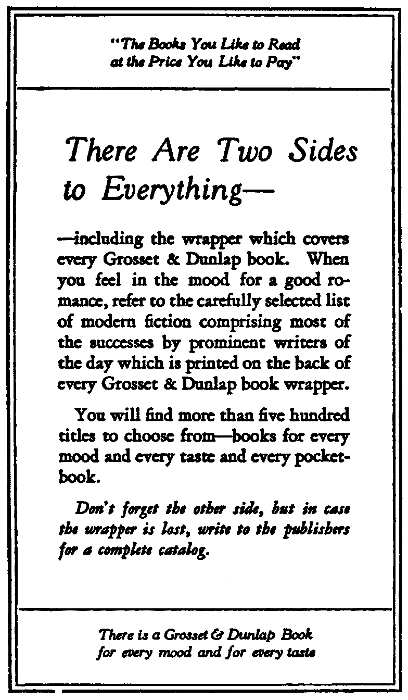

Transcriber's Note:

A Table of Contents has been added.

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

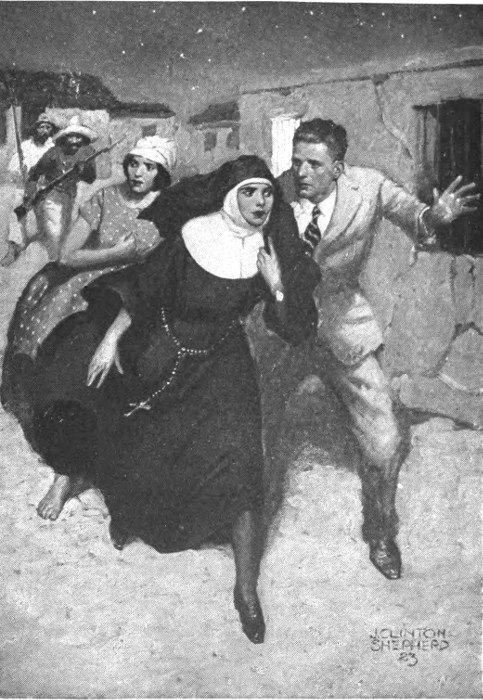

"I—I—how far do we have to run?" she gasped.

FOMBOMBO

BY

T. S. STRIBLING

AUTHOR OF

TEEFTALLOW, Etc.

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1923, by

The Century Co.

——

Copyright, 1923, by

T. S. Stribling

Printed in U. S. A.

TO MY UNCLE

LEE B. WAITS

Soldier, Fox-Hunter, and Philosopher

FOMBOMBO

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | 3 |

| CHAPTER II | 10 |

| CHAPTER III | 16 |

| CHAPTER IV | 23 |

| CHAPTER V | 28 |

| CHAPTER VI | 42 |

| CHAPTER VII | 50 |

| CHAPTER VIII | 64 |

| CHAPTER IX | 75 |

| CHAPTER X | 85 |

| CHAPTER XI | 96 |

| CHAPTER XII | 105 |

| CHAPTER XIII | 114 |

| CHAPTER XIV | 127 |

| CHAPTER XV | 139 |

| CHAPTER XVI | 149 |

| CHAPTER XVII | 155 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | 176 |

| CHAPTER XIX | 184 |

| CHAPTER XX | 198 |

| CHAPTER XXI | 211 |

| CHAPTER XXII | 222 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | 240 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | 252 |

| CHAPTER XXV | 257 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | 268 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | 289 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | 303 |

FOMBOMBO

In Caracas, Thomas Strawbridge called at the American Consulate, from a sense of duty. The consul, a weary, tropic-shot politician from Kentucky, received him with gin, cigars, and a jaded enthusiasm. He glanced at Mr. Strawbridge's business card and inquired if his visitor were one of the Strawbridges of Virginia. The young man replied that he lived in Keokuk, Iowa, and that his father had moved there from somewhere East. Upon this statement the consul ventured the dictum that if any family didn't know they had come from Virginia, they hadn't.

Having exhausted their native states as a topic of conversation, they swung around, in their talk, to the relatively unimportant Venezuela which sweltered outside the consulate in a drowse of endless summer. The two Americans damned the place, with lassitude but thoroughness. They condemned the character of the Venezuelan, his lack of morals, honesty, industry, and initiative. The Venezuelan was too polite; he was cowardly. He had not the God-given Anglo-Saxon instinct for self-government. But the high treason named in this joint bill of complaint was that the Venezuelan was unbusinesslike.

"I'm no tin angel," proceeded Mr. Strawbridge, emphatically, "but you know just as well as I do, Mr. Anderson, that the fellow who pulls slick stuff in a business deal has[Pg 4] hit the chutes for the bowwows. Business methods and strict business honesty will win in the long run, Mr. Anderson."

The consul nodded a trifle absent-mindedly at this recommendation of his nation's widely advertised virtue.

"In fact," continued Mr. Strawbridge, with an effect of having begun to recite some sort of creed he could not stop until he reached the end, "in fact, continual aggressive business policies coupled with an incorruptible honesty are bound to land the American exporter flat-footed on the foreign trade. And, moreover, Mr. Anderson—" Strawbridge had the traveling salesman's habit of repeating a companion's name over and over in the course of a conversation, so he would not forget it—"moreover, Mr. Anderson, we American traveling business men have got to set an example to these people down here; show 'em what to do and how to do it. Snap, vim, go, and absolute honesty."

"Yes, ... yes," agreed the consul, still more absently. He was holding Mr. Strawbridge's card in his fingers and apparently studying it. Presently he broke into the homily:

"Speaking of business, how do you find the gun-and-ammunition business in Venezuela, Mr. Strawbridge?"

"Rotten. I've hardly booked an order since I landed in the country."

The consul lifted his brows.

"Have you booked any at all?"

"Well, no, I haven't," admitted Strawbridge.

The consul smiled faintly and finished off his glass of gin and water.

"I thought perhaps you hadn't."

"What made you think that?"

"No one does who just passes through the country offering them to any and every merchant."

"Why not?"

"Isn't allowed."

Strawbridge stared at his consul—a very honest blue-eyed stare.

"Not allowed? Who doesn't allow it, Mr. Anderson? Why, look here—" he straightened his back as there dawned on him the enormity of this personal infringement of his right to sell firearms whenever and wherever he found a buyer—"why the hell can't I sell rifles and—"

"Forbidden by the Government," interposed Mr. Anderson, patly.

Strawbridge was outraged.

"Now, isn't that a hell of a law! No reason at all, I suppose. Like their custom laws. They don't tax you for what you bring into this God-forsaken country; they tax you for the mistakes you make in saying what you've brought in. They look over your manifest and charge you for the errors you've made in Spanish grammar. Venezuela's correspondence course in the niceties of the Castilian tongue!"

The consul again smiled wearily.

"They have a better reason than that for forbidding rifles—revolutions. You know in this country they stage at least one revolution every forty-eight hours. The minute any Venezuelan gets hold of a gun he steps out and begins to shoot up the Government. If he wings the President, he gets the President's place. It's a very lucrative place, very. It's about the only job in this country worth a cuss. So you see there's a big reason for forbidding the importation of arms into Venezuela."

Mr. Strawbridge drew down his lips in disgust.

"Good Lord! Ain't that rotten! When will this leather-colored crew ever get civilized? Here I am—paid my fare from New York down here just to find out nobody buys firearms in this sizzling hell-hole; can't be trusted with 'em!"

In the pause at this point Mr. Anderson still twirled his guest's card. He glanced toward the front of his consulate,[Pg 6] then toward the rear. The two Americans were alone. With his enigmatic smile still wrinkling his tropic-sagged face, the consul said in a slightly lower tone:

"I didn't say no one bought firearms in Venezuela, Mr. Strawbridge. I said they were not allowed to be sold here."

"O-o-oh, I se-e-e!" Mr. Strawbridge's ejaculation curved up and down as enlightenment broke upon him, and he stared fixedly at his consul.

"All I meant to say was that the trade is curtailed as much as possible, in order to prevent bloodshed, suffering, and the crimes of civil war."

Mr. Strawbridge continued his nodding and his absorbed gaze.

"But, still, some of it goes on—of course."

"Naturally," nodded Strawbridge.

"I suppose," continued the consul, reflectively, "that every month sees a considerable number of arms introduced into Venezuela, as far as that goes."

Strawbridge watched his consul as a cat watches a mouse-hole—for something edible to appear.

"Yes?" he murmured interrogatively.

"Well, there you are," finished the consul.

Strawbridge looked his disappointment.

"There I am?" he said in a pained voice. "Well, I must say I am not very far from where you started with me; am I?"

"It seems to me you are somewhat advanced," began the diplomat, philosophically. "You know why you haven't sold anything up to date. You know why you can't approach a Venezuelan casually to sell him guns, as if you were offering him stoves or shoe-polish." The consul was still smiling faintly, and now he drew a scratch-pad toward him and began making aimless marks on it after the fashion of office men. "In fact, to attempt to sell guns at all would be quite against[Pg 7] the law, as I have explained, for the reasons I have stated. It's a peculiar and I must say an unfortunate situation."

As he continued his absent-minded marking his explanation turned into a soliloquy on the Venezuelan situation:

"You may not know it, Mr. Strawbridge, but there are one or two revolutions which are chronic in Venezuela. There is one in Tachira, a state on the western border of the country. There is another up in the Rio Negro district, headed by a man named Fombombo. They never cease. Every once in a while the federal troops go out to hunt these insurrectionists, a-a-and—" the consul dragged out his "and" after the fashion of a man relating something so well known that it isn't worth while to give his words their proper stress—"a-a-and if they kill them, more spring up." His voice slumped without interest. He continued marking his pad. "Then there are the foreign juntas. About every four or five years a bunch of Venezuelans go abroad, organize a filibustering expedition, come back, and try to capture the presidency. Now and then one succeeds." The consul yawned. "Then the diplomatic corps here in Caracas have to get used to a different sort of ... of ... President." He paused, smiling at some recollection, then added, "So, you see, one can hardly blame the powers that be for wanting to keep rifles out of the country."

The young man was openly disappointed.

"Well, ... that's very interesting historically," he said with a mirthless smile, "and I am sure when I send in my expense account for this trip my house will be deeply interested in the historical reasons why I blew in five hundred dollars and landed nothing."

"Well, that's the state of affairs," repeated the consul, with the sudden briskness of a man ending an interview. "Insurrectionists in Tachira, old Fombombo raising hell on[Pg 8] the Rio Negro, and an occasional flyer among the filibusters." He rose and offered his hand to his caller. "Be glad to have you drop in on me any time, Mr. Strawbridge. Occasionally I give a little soirée here for Americans. Send you a bid." He was shaking hands warmly now, after the fashion of politicians. His air implied that Mr. Strawbridge's visit had been sheer delight. And Mr. Strawbridge's own business-trained cordiality picked up somewhat even under his unexpressed disappointment. In fact, he was just loosing the diplomat's hand when he discovered there was a bit of paper in Mr. Anderson's palm pressing against his own. When the consul withdrew his hand he left the paper in his countryman's fingers.

"Well, good-by; good luck! Don't forget to look me up again. When you leave Caracas you'd better give me your forwarding address for any mail that might come in."

The consul was walking down the tiled entrance of the consulate, floating his guest out in a stream of somewhat mechanical cordiality. Strawbridge moved into the dazzling sunshine, clenching the bit of paper and making confused adieus.

He walked briskly away, with the quick, machine-like strides of an American drummer. After a block or two he paused in the shade of a great purple flowering shrub that gushed over the high adobe wall of some hidden garden. Out of the direct sting of the sun he found opportunity to look into his hand. It held a sheet of the scratch-pad. This bore the address, "General Adriano Fombombo, No. 27 Eschino San Dolores y Hormigas." Inside the fold was the sentence, "This will introduce to you a very worthy young American, Mr. Thomas Strawbridge, a young man of discretion, prompt decision, strict morals, and unimpeachable honesty." It bore no signature.

Strawbridge turned it over and perused the address for[Pg 9] upward of half a minute. Now and then he looked up and down the street, then at the numbers on the houses, after the fashion of a man trying to orient himself in a strange city.

In the capital of Venezuela, ancient usage has given names to the street corners instead of to the streets. This may have been very well in the thinly populated days of the Spanish conquest, but to-day this nomenclature forms a hopeless puzzle for half the natives and all the foreigners.

To Mr. Thomas Strawbridge the address on the consul's note was especially annoying. He hardly knew what to do. He could not go back and ask Mr. Anderson where was Eschino San Dolores y Hormigas, because in a way there was a tacit understanding between the two men that no note had passed between them. On the other hand, he felt instinctively that it was not good revolutionary practice to wander about the streets of Caracas inquiring of Tomas, Ricardo, and Henrico the address of a well-known insurrectionary general. However, he would have to do just that thing if he carried out the business hint given him by the consul. It was annoying, it might even be dangerous, but there seemed to be no way out of it. It never occurred to the drummer to give the matter up. The prospect of a sale was something to be pursued at all hazards. So he put the note in his pocket, got out a big silver cigar-case with his monogram flowing over one of its sides, lit up, frowned thoughtfully at the sun-baked streets, then moved off aimlessly from his patch of shade, keeping a weather eye out for some honest, trustworthy Venezuelan who could be depended upon to betray his country in a small matter.

As the American pursued this odd quest, the usual somnolent street life of Caracas drifted past him: a train of[Pg 11] flower-laden donkeys, prodded along by a peon boy, passed down the calle, braying terrifically; native women in black mantillas glided in and out of the ancient Spanish churches, one of which stood on almost every corner; lottery-ticket venders loitered through the streets, yodeling the numbers on their tickets; naked children played in the sewer along foot-wide pavements; dark-eyed señoritas sat inside barred windows, with a lover swinging patiently outside the bars. Banana peels, sucked oranges, and mango stones littered the calles from end to end and advertised the slovenliness of the denizens.

All this increased in Strawbridge that feeling of mental, moral, and racial superiority which surrounds every Anglo-Saxon in his contacts with other peoples. How filthy, how slow, how indecent, and how immoral it all was! Naked children, lottery venders, caged girls! Evidently the girls could not be trusted to walk abroad. Strawbridge looked at them—tropical creatures with creamy skins, jet hair, and dark, limpid eyes; soft of contour, voice, and glance.

A group of four domino-players were at a game just outside a peluqueria. A fifth man, holding a guitar, leaned against a little shrine to the Blessed Virgin which some pious hand had built into the masonry at the corner of the adobe. He was a graceful, sunburned fellow, and as he bent his head over the guitar, during his intermittent strumming, Strawbridge was surprised to see that his hair was done up like a woman's, in a knot at the back of his head.

Just why the American should have decided to ask this particular man for delicate information, it is impossible to say. It may have been because he was leaning against a shrine, or because he showed splendid white teeth as he smiled at the varying fortunes of the players. There is a North American superstition that a man with good teeth also possesses good morals. If one can believe the dentifrice [Pg 12]advertisements, a good tooth-paste is a ticket to heaven. At any rate, for these or other reasons, the drummer moved across the calle and came to a stand, with his own hand resting on the base of the little clay niche that sheltered the small china Virgin. He was so close to the man that he could smell the rank pomade on his knob of hair. He stood in silence until his nearness should have established that faint feeling of fellowship which permits a question to be asked between two watchers of the same scene. Presently he inquired in a casual tone, but not loud enough for the players to hear:

"Señor, can you tell me where is Eschino San Dolores y Hormigas?"

The strumming paused a moment. The man with the knot of hair gave Strawbridge a brief glance out of the corners of his eyes, then resumed his desultory picking at the strings.

"How should I know where is Eschino San Dolores y Hormigas?" he replied in the same nonchalant undertone.

"I thought perhaps you were a native of this town."

"Pues, you are a stranger?"

"Yes."

"Un Americano, I would say?"

"Yes."

The strumming proceeded smoothly.

"Señor, in your country, is it not the custom in searching for an address to inquire of the police?"

A little trickle of uneasiness went through the American's diaphragm.

"Certainly," he agreed, with a faint stiffness in his undertone, "but when there is no policeman in sight, one can inquire of any gentleman."

The man with the knob of hair muted his guitar, then lifted his hand and pointed.

"Yonder stands one, two corners down, señor."

"Gracias, señor." Strawbridge had a feeling as if a path[Pg 13] he meant to climb along a precipice had begun crumbling very gently under his feet. "Gracias; I'll just step down there." He made a little show of withdrawing his attention casually from the game, glanced about, got the direction of the policeman in question, then moved off unhurriedly toward that little tan-uniformed officer.

As he went, Strawbridge tried quickly to think of some other question to ask the police. He wondered if it would be best not to go up to the officer at all. If he knew the man with the hair was not looking after him.... He was vaguely angry at everything and everybody—at Venezuela for making a law that would force an American salesman to go about the important function of business like a thief; at the consul for not giving him complete sailing instructions; at himself for asking ticklish questions of a man with a wad of hair. He might have known there was something tricky about a man like that!

Then his thoughts swung around to the nation again. He began swearing mentally at the basic reason of his slightly uncomfortable position. "Damn country is not run on business principles," he carped in his thoughts. "Looks like they're not out for business. Then what the hell are they out for? Why, they were all trying to pull crooked deals, overcharging, milking the customs! One honest, upright, strictly business American department-store down here in Caracas would grab the business from these yellow sons of guns like a burglar taking candy from a sick baby!" He moved along, pouring the acid of a righteous indignation over his surroundings. However, he was now approaching the policeman, and he stopped insulting the Venezuelan nation, to think of a plan to circumvent it.

He was again beginning to debate whether or not he should make a show of going to the officer at all, when he heard the thrumming of a guitar just behind him. He looked around[Pg 14] quickly and saw that the man with the knot of hair had followed him. Then Strawbridge realized that not only would he have to go to the policeman, but he would have to inquire for the actual address in order to maintain an appearance of innocence. Right here he lost his order! He damned his luck unhappily and was on the verge of crossing the street, when the man with the knob of hair continued their conversation, in the same low tone they had used:

"By the way, señor, I just happened to recall an errand of my own at the address you inquired for, if you care to go along with me."

"Why, sure!" accepted Strawbridge, vastly relieved. He drew out a silk handkerchief and touched the moisture on his face. "Sure! Be glad to have your company."

The man began tinkling again.

"I suppose you are going to ... er ... to the house with the blue front?" He lifted his eyebrows slightly.

"I'm looking for Number ... I never was there before, so I don't know what color the house is."

"No?" The guitarist lifted his brows still more. He seemed really surprised. But the next moment his attention broke away. He smote his guitar to a purpose, and broke out in a bold tenor voice:

The American was startled at this sudden outbreak of song, but no one else took any notice of it. That is, no one except a girl inside a barred window, who dropped a rose through the grille and withdrew. As the two men passed this spot, the singer stooped for the flower and in a shaken voice murmured into the window, "Little heaven!" and somewhere inside a girl laughed.

The two men walked on a few paces, when the guitarist shrugged, spread a hand, and said:

"They always laugh at you!"

Strawbridge stared at him.

"Who?" he asked.

"A bride ... that bride ... any bride."

The American had been so absorbed in the matter of the police and the street address that he had followed none of this by-play.

"A bride?" he repeated blankly.

"Yes, she married three nights ago. Caramba! The house was crowded, and everybody was tipsy. The guests overflowed out here, into the calle...." He broke off to look back at the window, after a moment waved his hand guardedly, then turned around and resumed his observations:

"Don't you think there is something peculiarly attractive ... well, now ... er ... provocative in a young girl who has just been married?"

The American stared at his new acquaintance, vaguely outraged.

"Why—great God!—no!"

The man with the knob of hair came to a halt, and pointed on a long angle across the street.

"That big blue house, señor. I'll come on more slowly and pass you. There is no use for two men to be seen waiting outside the door at one time."

This touch of prudence reassured Strawbridge more than any other thing the stranger could have said. The drummer nodded briskly and walked ahead of his companion toward the building indicated. It was one of a solid row of houses all of which had the stuccoed fronts and ornamental grilles that mark the better class of Caracas homes. The American paused in front of the big double door and pressed a button. He waited a minute or two and pushed again.

Nothing happened. A faint breeze moved a delicate silk curtain in one of the barred windows, but beyond that the casa might have been empty. The silent street of old Spanish houses, their polychrome fronts, and somewhere the soft, guttural quarreling of pigeons wove a poetic mood in Strawbridge's brain. It translated itself into the thought of a huge order for his house and a rich commission for himself. He began calculating mentally what his per cent. would be on, say, ten thousand cases of cartridges—or even twenty thousand. Here began a pleasant multiplication of twenty thousand by thirty-nine dollars and forty-two cents. That would be ... it would be....

The sonnet of his mood was broken by the guitarist, who walked past him, snarling:

"Diablo, hombre! You'll never get in that way! Ring once, then four short rings, then a second long, then three." He walked on.

This brought Strawbridge back to the fact that his order had not yet reached the stage where he could count his profits. He pressed the button again, using the combination the knob-haired man had given him.

Immediately a small panel in the great door opened and framed the head of a negro sucking a mango. The head withdrew and a moment later a whole panel in the door and a corresponding panel in the iron grille opened and admitted the drummer. Strawbridge stepped into a cool entrance of blue-flowered tiles which led into a bright patio. He looked around curiously, seeking some hint of the revolutionist in his casa.

"Is your master at home?" he asked of the negro.

The black wore the peculiarly stupid expression of the boors of his race. He answer in a negroid Spanish:

"No, seño', he ain't in."

"When'll he be in?"

The negro lowered his head and swung his protruding jaws from side to side, as though denying all knowledge of the comings and goings of his master.

Strawbridge hesitated, speculated on the advisability of delivering his note to any such creature, finally did draw it out, and stood holding it in his hand.

"Could you deliver this note to your master?"

"If de Lawd's willin' an' I lives to see him again, seño'."

Strawbridge was faintly amused at such piety.

"I don't suppose the Lord will object to your delivering this note," he said.

"No, seño'," agreed the black man, solemnly, and Strawbridge placed the folded paper in the numskull's hands.

The creature took it, looked blankly at the address, then[Pg 18] unfolded it and with the same emptiness of gaze fixed his eyes on the message.

"It goes to General Fombombo," explained Strawbridge.

"Gen'l Fombombo," repeated the negro, as if he were memorizing an unknown name.

"Yes, and inside it says that ... er ... ah ... it says that I am an honest man."

"A honest man."

"Yes, that's what it says."

"I thought you was a Americano, seño'."

Strawbridge looked at the negro, but his humble expression appeared guileless.

"I am an American," he nodded. "Now, just hand that to your master and tell him he can communicate with me at the Hotel Bolivia." Strawbridge was about to go.

"Sí, seño'," nodded the servant, throwing away the mango stone. "I tell him about de Americano. I heard about yo' country, seño', el grand America del Norte; so cold in de rainy season you freeze to death, so hot in de dry season you drap dead. Sí, seño', but ever'body rich—dem what ain't froze to death or drap dead."

"Sounds like you'd been there," said the drummer, gravely.

"I never was, but I wish I could go. Do you need a servant in yo' line o' business, seño'?"

"I don't believe I do."

"Don't you sell things?"

"Sometimes."

"What, seño'?"

"I sell—" then, recalling the private nature of this particular prospect, he finished—"almost anything any one will buy."

This answer apparently satisfied the garrulous black, who nodded and pursued his childish curiosity:

"An' when you sell something do you have it sent from away up in America del Norte down here?"

"Sure."

"An' us git it?"

Strawbridge laughed.

"If you're lucky."

The black man scratched his head at this growing complication of the drummer's sketch of the North American export trade. Then he discovered a gap in his information.

"Seño', you ain't said what it is you sell, yit."

"That's right," agreed Strawbridge, looking at the fool a little more carefully. "I have not." Then he added, "A man doesn't talk his business to every one."

The negro nodded gravely.

"Dat's right, but still you's bound to talk your business somewhere, to sell anybody at all, seño'."

"That's true," acceded the American, with a dim feeling that perhaps this black fellow was not the idiot he had at first appeared.

"And how would you git paid, away up there in America?" persisted the black.

The American decided to answer seriously.

"Here's the way we do it. We ship the ... the goods ... down here and at the same time draw a draft on a bank here in Caracas. We get our pay when the goods are delivered, but the bank extends the buyer six, nine, or twelve months' credit, whatever he needs. That is the accepted business method between North and South America."

The drummer was not sure the black man understood a word of this. The fellow stood scratching his head and pulling down his thick lips. Finally he said, speaking more correctly:

"Señor, I was not thinking about the time a person had to pay in. It was how you could get paid at all."

"How I could get paid at all?"

The negro nodded humbly, and his dialect grew a trifle worse:

"You see, if anybody was to go an' put a lot o' money in de banks here in Caracas, most likely de Guv'ment would snatch it right at once."

Strawbridge came to attention and stood studying the African.

"How would the Government ever know?" he asked carefully.

"How would you ever keep 'em from knowin'?" retorted the negro. "How could anybody, seño', even a po' fool nigger like me, drive a string o' ox-carts through de country, loaded wid gold, drive up to the bank do' an' pile out sacks o' gold an' not have ever'body in Caracas know all about it?"

The suggestion of gold, of wagon-loads of gold delivered to banks, sent a sensation through Strawbridge as if he had been a harp on which some musician had struck a mighty chord. As he stood staring at the black man his mouth went slightly dry and he moistened his lips with his tongue.

"I see the trouble," he said in a queer voice.

His vis-à-vis nodded silently.

The negro with the mango juice on his face and the trig white man stood studying each other in the blue entrance.

"Well," said Strawbridge, at last, "how will I get the money?"

"Where?"

"Here."

"Impossible, señor."

Strawbridge was getting on edge. He laughed nervously.

"You seem to know more about ... er ... certain conditions in this country than I do. What would you suggest?"

The black cocked his head a little to one side.

"Seño', did you know that the Orinoco River and the Amazon connect with each other up about the Rio Negro?"

"I think I've heard it. Didn't some fellow go through there studying orchids, or something? A man was telling me something about that in Trinidad."

"He went through studying everything, seño'," said the black man, solemnly. "You are thinking of the great savant, Humboldt."

"M—yes, ... Humboldt." Strawbridge repeated the name vaguely, not quite able to place it.

"I would suggest that you follow Herr Humboldt's route, seño'. You can carry the bullion down in boats and get it exchanged for drafts in Rio."

A dizzy foreshadowing of Indian canoes laden with treasure, pushing through choked tropical waterways, shook the drummer. He drew a long breath.

"Is it a practical route? I mean, does anybody know the way? Do you think it can be done?"

"I would hardly say practical, seño'. It has been done."

The negro and the white man stood looking at each other.

"How do I ... er ... how does any one get to Rio Negro?" asked the drummer, nervously.

"You will need some person to pilot you, seño': some black man would make a good guide."

"Now, I just imagine he would," said Strawbridge, drawing in his lips and biting them. "Yes, sir, I imagine he would—" He broke off and suddenly became direct: "When do we start?"

"When you feel like it, seño'—now, if you are ready."

"I stay ready. How do we get there?" He asked the question with a vague feeling that the black man might climb up to the roof of the blue house and show him a flying-machine.

"I have a little motor around at the garage, seño'."

"Uh-huh? Well, that's good. Let's go."

The negro went into a room for an old hat. He took a key from his pocket, opened the door, and courteously bowed the American into the calle. When he had locked the door behind them, he said, "Now you go in front, seño'," and indicated the direction down the street. Strawbridge did so, the negro following a little distance behind. They looked like master and servant set forth on some trifling errand.

They had not gone very far before Strawbridge observed that two or three blocks behind them came the guitarist. This fellow meandered along with elaborate inattention to either the white man or the negro.

Now that his rôle of ignoramus and lout had been played, the black man introduced himself as Guillermo Gumersindo and glided into the usual self-explanatory conversation. He was sure Señor Strawbridge would pardon his buffoonery, but one had to be careful when a police visitation was threatened. He was the editor of a newspaper in Canalejos, "El Correo del Rio Negro," a newspaper, if he did say it, more ardently devoted to Venezuelan history than any other publication in the republic. Gumersindo had been chosen by General Fombombo to make this purchasing expedition to Caracas just because he was black and could drop easily into a lowly rôle.

To the ordinary white American an educated negro is an object of curious interest, and Strawbridge strolled along the streets of Caracas with a feeling toward the black editor much the same as one has toward the educated pony which can paw out its name from among the letters of the alphabet.

Gumersindo's historical interest exhibited itself as he and Strawbridge passed through the mercado, a plaza given over to hucksters and flower-venders, in the heart of Caracas. The black man pointed out a very fine old Spanish house of blue marble, with a great coat of arms carved over the door:

"Where Bolivar lived." Gumersindo made a curving gesture and bowed as if he were introducing the building.

The American looked at the house.

"Bolivar," he repeated vaguely.

The editor opened his eyes slightly.

"Sí, señor; Bolivar the Libertador."

The black man's tone showed Strawbridge that he should have known Bolivar the Libertador.

"Oh, sure!" the drummer said easily; "the Libertador. I had forgot his business."

The black man looked around at his companion as straight as his politeness admitted.

"Señor," he ejaculated, "I mean the great Bolivar. He has been compared to your Señor George Washington of North America."

Strawbridge turned and stared frankly at the negro.

"Wha-ut?" he drawled, curving up his voice at the absurdity of it and beginning to laugh. "Compared to George Washington, first in war, first in—"

"Sí, ciertamente, señor," Gumersindo assured his companion, with Venezuelan earnestness.

"But look here—" Strawbridge laid a hand on his companion's shoulder—"do you know what George Washington did, man? He set the whole United States free!"

"But, hombre!" cried the editor. "Bolivar! This great, great man—" he pointed to the blue marble mansion—"set free the whole continent of South America!"

"He did!"

"Seguramente! And this man, who freed a continent, was at length exiled by ungrateful Venezuela and died an outcast, señor, in a wretched little town on the Colombian coast—an outcast!"

Strawbridge looked at Bolivar's house with renewed interest.

"Well, I be damned!" he said earnestly. "Freed all of South America! Say! why don't somebody write a book about that?"

Gumersindo pulled in one side of his wide-rolling lips and bit them. The two men walked on in silence for several blocks west. They passed the Yellow House, the seat of the [Pg 25]Venezuelan Government. On the south side of this building stands a monument with a big scar on the pedestal, where some name has been roughly chiseled out. The negro explained that this monument had been erected by the tyrant Barranca, who occupied the Venezuelan presidency for eight years, but that when Barranca was overthrown by General Pina, the oppressed people, in order to show their hatred of the fallen tyrant, erased his name from the monument.

Strawbridge stood looking at the scar and nodding.

"Did they have to rise against this man Barranca to get him out of office?" he asked in surprise.

"Rise against him!" cried Gumersindo. "Rise against him! Why, señor, the only way any Venezuelan president ever did go out of office was by some stronger man rising against him! But come: I will show you, on Calvario."

They moved quickly along the street, which was changing its character somewhat, from a business street to a thoroughfare of cheap residences. After going some distance Strawbridge saw the small mountain called Calvario which rises in the western part of the city. The whole eastern face of this mountain had been done into a great flight of ornamental steps. Half-way up was a terrace containing three broken pedestals.

"These," decried Gumersindo, "were erected by the infamous Pina, but when Pina was assassinated and the assassin Wantzelius came into power, the people, infuriated by Pina's long extravagances, tore down the statues he had erected and broke them to pieces." The black man stood looking with compressed lips at the shattered monoliths in the sunshine.

There was a certain incredulity in Strawbridge's face. The American could not understand such a social state.

"And you say they just keep on that way—one president overthrowing another?"

"Precisely. Wantzelius had Pina assassinated, Toro Torme overthrew Wantzelius, Cancio betrayed and exiled Toro Torme...."

The American arms salesman stood on the stairs of Calvario, beneath the broken pedestals, and began to laugh.

"Well, that's a hell of a way to change presidents—shoot 'em—run 'em off—exile 'em! It's just exactly like these greaser Latin countries!" He sat down on the stairs in the hot sunshine and laughed till the tears rolled out of his eyes.

The thick-set negro stood looking at him with a queer expression.

"It ... seems to amuse you, señor?"

Strawbridge drew out his handkerchief and wiped his eyes. He blew out a long breath.

"It is funny! Just like a movie I saw in Keokuk. It was called 'Maid in Mexico,' and it showed how these damned greasers batted along in any crazy old way; and here is the wreckage of just some such rough stuff." He looked up at the broken pedestals again with his face set for mirth, but his jaws ached too badly to laugh any more. He drew a deep breath and became near-sober.

Just below him stood the negro, like a black shadow in the sunshine. He stared with a solemn face over the city with its sea of red-tiled roofs, its domes and campaniles, and the blue peaks of the Andes beyond. Abruptly he turned to Strawbridge.

"Listen, señor," he said tensely, and held up a finger. "My country has lived in mortal agony ever since Bolivar himself fell from his seat of power amid red rebellion, but there is a man who will remedy Venezuela's age-long wounds; there is a man great enough and generous enough—"

At this point some remnant of mirth caused Strawbridge to compress his lips to keep from laughing again. The dark[Pg 27] being on the steps stopped his discourse quite abruptly; then he said with a certain severity:

"Let us understand each other, señor. You sell rifles and ammunition; do you not?"

"Yes," said Strawbridge, sobering at once at this hint of business.

Gumersindo took a last glance at the city sleeping in the fulgor of a tropical noon:

"Let's get to the garage," he suggested briefly.

Gumersindo's automobile turned out to be one of those cheap American machines which one finds everywhere. Its only peculiarity was an extra gasolene-tank which filled the greater part of the body of the car, and which must have given the old rattletrap a cruising-radius of a thousand or fifteen hundred miles.

Just as the negro and the white man were getting into the car the man with the knot of hair at the back of his head strolled into the garage. He called to Gumersindo that the Americano was to take him on the expedition which was just starting.

The black editor looked up and stared.

"Take you!"

"Sí, señor, me. This caballero—" he nodded at Strawbridge—"promised to take me along for the courtesy of directing him to ... well ... to a certain address."

Strawbridge heard this with the surprise an American always feels when a Latin street-runner begins manufacturing charges for his service.

"The devil I did! I said nothing about taking you along. I didn't know where I was going. I still don't know."

"Caramba!" The man with the hair spread his hands in amazement. "Did I not say we would go to the same address, and did not you agree to it!"

"But, you damn fool, you know I meant the address here in Caracas! Good Lord! you know I didn't propose to take you a thousand miles!"

The man with the hair made a strong gesture.

"That's not Lubito, señor!" he declared. "That's not Lubito. When a man attaches himself to me in friendly confidence, I'm not the man to break with him the moment he has served my purpose. No, I will see you through!"

"But—damnation, man!—I don't want you to see me through!"

"Cá! You don't! You go back on your trade!"

The American snapped his fingers and motioned toward the door of the garage.

"Beat it!"

The man with the hair flared up suddenly and began talking the most furious Spanish:

"Diantre! Bien, bien, bien! I'll establish my trade! I'll call the police and establish my trade! Ray of God, but I'm an honest man!" and he started for the door, beginning to peer around for a policeman before he was nearly out. "Yes, we'll have a police investigation!" He disappeared.

Strawbridge looked at Gumersindo, and then by a common impulse the black editor and the white drummer started for the door, after the man with the hair. The editor hailed him as he was walking rapidly down the calle:

"Hold on, my friend; come back!"

Lubito whirled and started back as rapidly as he had departed. His movements were extraordinarily supple and graceful even for Latin America, where grace and suppleness are common.

"We have decided that we may be able to carry you along after all, Señor Lubito. We may even be of some mutual service. What is your profession?"

"I am, señor, a bull-fighter." He tipped up his handsome head and struck a bull-ring attitude, perhaps unconsciously. The negro editor stared at him, glanced at Strawbridge, and shrugged faintly but hopelessly.

"Very good," he said in a dry tone. "We want you. No[Pg 30] expedition would care to set out across the llanos without a bull-fighter or two."

If he hoped by voice and manner to discourage Lubito's attendance, he was disappointed. The fellow walked briskly back and was the first man in the car.

The other two men followed, and as the motor clacked away down the calle Lubito resumed the rôle of cicerone, cheerfully pointing out to Strawbridge the sights of Caracas. There was the palace of President Cancio; there was an old church built by the Canary Islanders who made a settlement in this part of Caracas long before the colonies revolted against Spain.

"There is La Rotunda, señor, where they keep the political prisoners. It is very easy to get in there." Whether this was mere tourist information or a slight flourish of the whip-hand, which Lubito undoubtedly held, Strawbridge did not know.

"Have they got many prisoners?" he asked casually.

"It's full," declared the bull-fighter, with gusto. "The overflow goes to Los Castillos, another prison on the Orinoco near Ciudad Bolívar, and also to San Carlos on Lake Maracaibo, in the western part of Venezuela."

"What have so many men done, that all the prisons are jammed?" asked the drummer, becoming interested.

It was Gumersindo who answered this question, and with passion:

"Señor Strawbridge, those prisons are full of men who are innocent and guilty. Some have attempted to assassinate the President, some to stir up revolution; some are merely suspected. A number of men are put in prison simply to force through some business deal advantageous to the governmental clique. I know one editor who has been confined in the dungeons of La Rotunda for ten years. His offense was that in his paper he proposed a man as a candidate for the presidency."

Strawbridge was shocked.

"Why, that's outrageous! What do the people stand for it for? Why don't they raise hell and stop any such crooked deals? Why, in America, do you know how long we would stand for that kind of stuff? Just one minute—" he reached forward and tapped Gumersindo two angry taps on the shoulder—"just one minute; that's all."

Lubito laughed gaily.

"Yes, La Rotunda to-day is full of men who stood that sort of thing for one minute—and then raised hell."

Strawbridge looked around at the bull-fighter.

"But, my dear man, if everybody, everybody would go in, who could stop them?"

Gumersindo made a gesture.

"Señor Strawbridge, there is no 'everybody' in Venezuela. When you say 'everybody' you are speaking as an American, of your American middle class. That is the controlling power in America because it is sufficiently educated and compact to make its majority felt. We have no such class in Venezuela. We have an aristocratic class struggling for power, and a great peon population too ignorant for any political action whatsoever. The only hope for Venezuela is a beneficent dictator, and you, señor, on this journey, are about to instate such a man and bring all these atrocities to a close."

A touch of the missionary spirit kindled in Strawbridge at the thought that he might really bring a change in such leprous conditions, but almost immediately his mind turned back to the order he was about to receive, how large it would be, how many rifles, how much ammunition, and he fell into a lovely day-dream as the tropical landscape slipped past him.

At thirty- or forty-mile intervals the travelers found villages, and at each one they were forced to report to the police department their arrival and departure. Such is the law in Venezuela. It is an effort to keep watch on any considerable[Pg 32] movements among the population and so forestall the chronic revolutions which harass the country. However, the presence of Strawbridge prevented any suspicion on the part of these rural police. Americans travel far and wide over Venezuela as oil-prospectors, rubber-buyers, and commercial salesmen. The police never interfere with their activities.

The villages through which the travelers passed were all just alike—a main street, composed of adobe huts, which widened into a central plaza where a few flamboyants and palms grew through holes in a hard pavement. Always at the end of the plaza stood a charming old Spanish church, looking centuries old, with its stuccoed front, its solid brick campanile pierced by three apertures in which, silhouetted against the sky, hung the bells. In each village the church was the focus of life. And the only sign of animation here was the ringing of the carillon for the different offices. The bell-ringings occurred endlessly, and were quite different from the tolling which Strawbridge was accustomed to hear in North America. The priests rang their bells with the clangor of a fire-alarm. They began softly but swiftly, increased in intensity until the bells roared like the wrath of God over roof and calle, and then came to a close with a few slow, solemn strokes.

As is the custom of traveling Americans, Strawbridge compared, for the benefit of his companions, these dirty Latin villages with clean American towns. He pointed out how American towns had an underground sewage system instead of allowing their slops to trickle among the cobblestones down the middle of the street; how American towns had waterworks and electric lights and wide streets; and how if they had a church at all it was certainly not in the public square, raising an uproar on week-days. American churches were kept out of the way, up back streets, and the business part of town was devoted to business.

Here the negro editor interjected the remark that perhaps each people worshiped its own God.

"Sure we do, on Sundays," agreed Strawbridge; "or, at least, the women do; but on week-days we are out for business."

When the motor left the mountains and entered the semi-arid level of the Orinoco basin, the scenery changed to an endless stretch of sand broken by sparse savannah grass and a scattering of dwarf gray trees such as chaparro, alcornoque, manteco. The only industry here was cattle-raising, and this was uncertain because the cattle died by the thousands for lack of water during the dry season. Now and then the motor would come in sight, or scent, of a dead cow, and this led Strawbridge to compare such shiftless cattle-raising with the windmills and irrigation ditches in the American West.

On the fifth day of their drive, the drummer was on this theme, and the bull-fighter—who, after all, was in the car on sufferance—sat nodding his head politely and agreeing with him, when Gumersindo interrupted to point ahead over the llano.

"Speaking of irrigation ditches, señor, yonder is a Venezuelan canal now."

The motor was on one of those long, almost imperceptible slopes which break the level of the llanos. From this point of vantage the motorists could see an enormous distance over the flat country. About half-way to the horizon the drummer descried a great raw yellow gash cut through the landscape from the south. He stared at it in the utmost amazement. Such a cyclopean work in this lethargic country was unbelievable. On the nearer section of the great cut Strawbridge could make out a movement of what seemed to be little red flecks. The negro editor, who was watching the American's face, gave one of his rare laughs.

"Ah, you are surprised, señor."

"Surprised! I'm knocked cold! I didn't know anything this big was being done in Venezuela."

"Well, this isn't exactly in Venezuela, señor."

"No! How's that?"

"We are now in the free and independent territory of Rio Negro, señor. We are now under the jurisdiction of General Adriano Fombombo. You observe the difference at once."

By this time the motor was again below the level of the alcornoque growth and the men began discussing what they had seen.

"What's the object of it?" asked Strawbridge.

"The general is going to canalize at least one half of this entire Orinoco valley. This sandy stretch you see around you, señor, will be as fat as the valley of the Nile."

The idea seized on the drummer's American imagination.

"Why!" he exclaimed, "this is amazing! it's splendid! Why haven't I heard of this? Why haven't the American capitalists got wind of this?"

Gumersindo shrugged.

"The federal authorities are not advertising an insurgent general, señor."

After a moment the drummer ejaculated:

"He will be one of the richest men in the world!"

Gumersindo loosed a hand from the steering-wheel a moment, to hold it up in protest.

"Don't say that! General Fombombo is an idealist, señor. It is his dream to create a super-civilization here in the Orinoco Valley. He will be wealthy; the whole nation will be wealthy,—yes, enormously wealthy,—but what lies beyond wealth? When a people become wealthy, what lies beyond that?"

This was evidently a question which the drummer was to answer, so he said:

"Why, ... they invest that and make still more money." The editor smiled.

"A very American answer! That is the difference, señor, between the middle-class mind and the aristocratic mind. The bourgeois cannot conceive of anything beyond a mere extension of wealth. But wealth is only an instrument. It must be used to some end. Mere brute riches cannot avail a man or a people."

The car rattled ahead as Strawbridge considered the editor's implications that wealth was not the end of existence. It was a mere step, and something lay beyond. Well, what was it, outside of a good time? He thought of some of the famous fortunes in America. Some of their owners made art collections, some gave to charity, some bought divorces. But even to the drummer's casual thinking, there became apparent the rather trivial uses of these fortunes, compared with the fundamental exertion it required to obtain them. Even to Strawbridge it became clear that the use was a step down from the earning.

"What's Fombombo going to do with his?" he asked out of his reverie.

"His what?"

"Fortune—when he makes it?"

"Pues, he will found a government where men can forget material care and devote their lives to the arts, the sciences, and pure philosophy. Great cities will gem these llanos, in which poverty is banished; and a brotherhood of intellectuals will be formed—a mental aristocracy, based not on force but on kindliness and good-will."

"I see-e-e," dragged out the drummer. "That's when everybody gets enough wealth—"

"When all devote themselves to altruistic ends," finished the editor.

The drummer was trying to imagine such a system, when[Pg 36] Gumersindo clamped on the brakes and brought the car to a sudden standstill. Strawbridge looked up and saw a stocky soldier in the middle of their road, with a carbine leveled at the travelers.

Strawbridge gasped and sat upright. The soldier in the sunshine, with his carbine making a little circle under his right eye, focused the drummer's attention so rigidly that for several moments he could not see anything else. Then he became aware that they had come out upon the canal construction, and that a most extraordinary army of shocking red figures were trailing up and down the sides of the big cut in the sand, like an army of ants. Every worker bore a basket on his head, and his legs were chained together so he could take a step of only medium length.

The guard, a smiling, well-equipped soldier, began an apology for having stopped the car. He had been taking his siesta, he said; the popping of the engine had awakened him, and he had thought some one was trying to rescue some of the workers. He had been half asleep, and he was very sorry.

The cadaverous, unshaven faces of the hobbled men, their ragged red clothes gave Strawbridge a nightmarish impression. They might have been fantasms produced by the heat of the sun.

"What have these fellows done?" asked the American, looking at them in amazement.

The guard paused in his conversation with Gumersindo to look at the American. He shrugged.

"How do I know, señor? I am the guard, not the judge."

Out of the rim of the ditch crept one of the creatures, with scabs about his legs where the chains worked. He advanced toward the automobile.

"Señors," he said in a ghastly whisper, "a little bread! a little piece of meat!"

The guard turned and was about to drive the wretch back[Pg 37] into the ditch, when Strawbridge cried out, "Don't! Let him alone!" and began groping hurriedly under the seat for a box where they carried their provisions. When the other prisoners learned that the motorists were about to give away food, a score of living cadavers came dragging their chains out of the pit, holding out hands that were claws and babbling in all keys, flattened, hoarsened, edged by starvation. "A little here, señor!" "A bit for Christ's sake, señor!" "Give me a bit of bread and take a dying man's blessing, señor!" They stunk, their red rags crawled. Such odors, such lazar faces tickled Strawbridge's throat with nausea. Saliva pooled under his tongue. He spat, gripped his nerves, and asked one of the creatures:

"For God's sake, what brought you here?"

The prisoners were mumbling their gracias for each bit of food. One poor devil even refrained, for a moment, from chewing, to answer, "Señor, I had a cow, and the jefe civil took my cow and sent me to the 'reds.'" "Señor," shivered another voice, "I ... I fished in the Orinoco. I was never very fortunate. When the jefe civil was forced to make up his tally to the 'reds,' he chose me. I was never very fortunate."

An old man whose face was all eyes and long gray hair had got around on the side of the car opposite to the guard. He leaned toward Strawbridge, wafting a revolting odor.

"Señor," he whispered, "I had a pretty daughter. I meant to give her to a strong lad called Esteban, for a wife, but the jefe civil suddenly broke up my home and sent me to the 'reds.' She was a pretty girl, my little Madruja. Señor, can it be, by chance, that you are traveling toward Canalejos?"

The American nodded slightly into the sunken eyes.

"Then, for our Lady's sake, señor, if she is not already lost, be kind to my little Madruja! Give her a word from[Pg 38] me, señor. Tell her ... tell her—" he looked about him with his ghastly hollow eyes—"tell her that her old father is ... well, and kindly treated on ... on account of his age."

Just then the bull-fighter leaned past the American.

"You say this girl is in Canalejos, señor?" he broke in.

"Sí, señor."

"Then the Holy Virgin has directed you to the right person, señor. I am Lubito, the bull-fighter, a man of heart." He touched his athletic chest. "I will find your little Madruja, señor, and care for her as if she were my own."

The convict reached out a shaking claw.

"Gracias á Madre in cielo! Gracias á San Pedro! Gracias á la Vírgen Inmaculada!" Somehow a tear had managed to form in the wretch's dried and sunken eye.

"You give her to me, señor?"

"O sí, sí! un millón gracias!"

"You hear that, Señor Strawbridge: the poor little bride Madruja, in Canalejos, is now under my protection."

The drummer felt a qualm, but said nothing, because, after all, nothing was likely to come from so shadowy a trust. The red-garbed skeleton tried to give more thanks.

"Come, come, don't oppress me with your gratitude, viejo. It is nothing for me. I am all heart. Step away from in front of the car so we may start at once. Vamose, señors! Let us fly to Canalejos!"

Gumersindo let in his clutch, there was a shriek of cogs, and the motor plowed through the sand. The bull-fighter turned and waved good-by to the guard and smiled gaily at the ancient prisoner. The motor crossed the head of the dry canal, and the party looked down into its cavernous depths. As the great work dropped into the distance behind them, the dull-red convicts and their awful faces followed[Pg 39] Strawbridge with the persistence of a bad dream. At last he broke out:

"Gumersindo, is it possible that those men back there have committed no crime?"

The negro looked around at him.

"Some have and some have not, señor."

"Was the fisherman innocent? Was the old man with the daughter innocent?"

"It is like this, Señor Strawbridge," said Gumersindo, watching his course ahead. "The jefes civiles of the different districts must make up their quota of men to work on the canal. They select all the idlers and bad characters they can, but they need more. Then they select for different reasons. All the jefes civiles are not angels. Sometimes they send a man to the 'reds' because they want his cow, or his wife or his daughter—"

"Is this the beginning of Fombombo's brotherhood devoted to altruistic ends!" cried Strawbridge.

"Mi caro amigo," argued the editor, with the amiability of a man explaining a well-thought-out premise, "why not? There must be a beginning made. The peons will not work except under compulsion. Shall the whole progress of Rio Negro be stopped while some one tries to convince a stupid peon population of the advisability of laboring? They would never be convinced."

"But that is such an outrageous thing—to take an innocent man from his work, take a father from his daughter!"

The editor made a suave gesture.

"Certainly, that is simply applying a military measure to civil life, drafted labor. The sacrifice of a part for the whole. That has always been the Spanish idea, señor. The first conquistadors drafted labor among the Indians. The Spanish Inquisition drafted saints from a world of sinners.[Pg 40] If one is striving for an ultimate good, señor, one cannot haggle about the price."

"But that isn't doing those fellows right!" cried Strawbridge, pointing vehemently toward the canal they had left behind. "It isn't doing those particular individuals right!"

"A great many Americans did not want to join the army during the war. Was it right to draft them?" Gumersindo paused a moment, and then added: "No, Señor Strawbridge; back of every aristocracy stands a group of workers represented by the 'reds.' It is the price of leisure for the superior man, and without leisure there is no superiority. Where one man thinks and feels and flowers into genius, señor, ten must slave. Weeds must die that fruit may grow. And that is the whole content of humanity, señor, its fruit."

Two hours later the negro pointed out a distant town purpling the horizon. It was Canalejos.

Strawbridge rode forward, looking at General Fombombo's capital city. The houses were built so closely together that they resembled a walled town. As the buildings were constructed of sun-dried brick, the metropolis was a warm yellow in common with the savannahs. It was as if the city were a part of the soil, as if the winds and sunshine somehow had fashioned these architectural shapes as they had the mesas of New Mexico and Arizona.

The whole scene was suffused with the saffron light of deep afternoon. It reminded the drummer of a play he had seen just before leaving New York. He could not recall the name of the play, but it opened with a desert scene, and a beggar sitting in front of a temple. There was just such a solemn yellow sunset as this.

As the drummer thought of these things the motor had drawn close enough to Canalejos for him to make out some of the details of the picture. Now he could see a procession[Pg 41] of people moving along the yellow walls of the city. Presently, above the putter of the automobile, he heard snatches of a melancholy singing. The bull-fighter leaned forward in his seat and watched and listened. Presently he said with a certain note of concern in his voice:

"Gumersindo, that's a wedding!"

"I believe it is," agreed the editor.

Lubito hesitated, then said:

"Would you mind putting on a little more speed, señor? It ... it would be interesting to find out whose wedding it is."

Without comment the negro fed more gasolene. As the motor whirled cityward, the bull-fighter sat with both hands gripping the front seat, staring intently as the wedding music of the peons came to them, with its long-drawn, melancholy burden.

Strawbridge leaned back, listening and looking. He was still thinking about the play in New York and regretting the fact that in real life one never saw any such dramatic openings. In real life it was always just work, work, work—going after an order, or collecting a bill—never any drama or romance, just dull, prosy, commonplace business ... such as this.

Canalejos was no exception to the general rule that all Venezuelan cities function upon a war basis. At the entrance of a calle, just outside the city wall, stood a faded green sentry-box. As the motor drove up, a sentry popped out of the box, with a briskness and precision unusual in Venezuela. He stood chin up, heels together, quite as if he were under some German martinet. With a snap he handed the motorists the police register and jerked out, from somewhere down in his thorax, military fashion:

"Hup ... your names ... point of departure ... destination ... profession...."

It amused Strawbridge to see a South American performing such military antics. It was like a child playing soldier. He was moved to mimic the little fellow by grunting back in the same tones, "Hup ... Strawbridge ... Caracas ... Canalejos ... sell guns and ammunition...." Then he wrote those answers in the book.

An anxious look flitted across the face of the sentry at this jocularity. His stiff "eyes front" flickered an instant toward the sentry-box. While the negro and the bull-fighter were filling in the register, a peon came riding up on a black horse. He stopped just behind the motor and with the immense patience of his kind awaited his turn.

While his two companions were signing, Strawbridge yielded to that impulse for horse-play which so often attacks Americans who are young and full-blooded. He leaned out of the motor very solemnly, lifted the cap of the sentry, turned the visor behind, and replaced it on his head. The[Pg 43] effect was faintly but undeniably comic. The little soldier's face went beet-colored. At the same moment came a movement inside the sentry-box and out of the door stepped a somewhat corpulent man wearing the epaulettes, gold braid, and stars of a general. He was the most dignified man and had the most penetrating eyes that Strawbridge had ever seen in his life. He had that peculiar possessive air about him which Strawbridge had felt when once, at a New York banquet, he saw J. P. Morgan. By merely stepping out of the sentry-box this man seemed to appropriate the calle, the motor and men, and the llanos beyond the town. Strawbridge instantly knew that he was in the presence of General Adriano Fombombo, and the gaucherie of having turned around the little sentry's cap set up a sharp sinking feeling in the drummer's chest. For this one stupid bit of foolery he might very well forfeit his whole order for munitions.

Gumersindo leaped out of the car and, with a deep bow, removed his hat.

"Your Excellency, I have the pleasure to report that I accomplished your mission without difficulty, that I have procured an American gentleman whom, if you will allow me the privilege, I will present. General Fombombo, this is Señor Tomas Strawbridge of New York city."

By this time Strawbridge had scrambled out of the motor and extended his hand.

The general, although he was not so tall as the American, nor, really, so large, drew Strawbridge to him, somehow as if the drummer were a small boy.

"I see your long journey from Caracas has not quite exhausted you," he said, with a faint gleam of amusement in his eyes.

Strawbridge felt a deep relief. He glanced at the soldier's cap and began to laugh.

"Thank you," he said; "I manage to travel very well."

The general turned to the negro.

"Gumersindo, telephone my casa that Señor Strawbridge will occupy the chamber overlooking the river."

The drummer put up a hand in protest.

"Now, General, I'll go on to the hotel."

The general erased the objection:

"There are no hotels in Canalejos, Señor Strawbridge; a few little eating-houses which the peons use when they come in from the llanos, that is all."

By this time Strawbridge's embarrassment had vanished. The general somehow magnified him, set him up on a plane the salesman had never occupied before.

"Well, General," he began cheerfully, using the American formula, "how's business here in Canalejos?"

"Business?" repeated the soldier, suavely. "Let me see, ... business. You refer, I presume, to commercial products?"

"Why, yes," agreed the drummer, rather surprised.

"Pues, the peons, I believe, are gathering balata. The cocoa estancias will be sending in their yield at the end of this month; tonka-beans—"

"Are prices holding up well?" interrupted Strawbridge, with the affable discourtesy of an American who never quite waits till his question is answered.

"I believe so, Señor Strawbridge; or, rather, I assume so; I have not seen a market quotation in...." He turned to the editor: "Señor Gumersindo, you are a journalist; are you au courant with the market reports?"

The negro made a slight bow.

"On what commodity, your Excellency?"

"What commodity are you particularly interested in, Señor Strawbridge?" inquired the soldier.

"Why ... er ... just the general trend of the market," said Strawbridge, with a feeling that his little excursion into[Pg 45] that peculiar mechanical talk of business, markets, prices, which was so dear to his heart, had not come off very well.

"There has been, I believe, an advance in some prices and a decline in others," generalized Gumersindo; "the usual seasonal fluctuations."

"Sí, gracias," acknowledged the general. "Señor Gumersindo, during Señor Strawbridge's residence in Canalejos, you will kindly furnish him the daily market quotations."

"Sí, señor."

The matter of business was settled and disposed of. Came that slight hiatus in which hosts wait for a guest to decide what shall be the next topic. The drummer thought rapidly over his repertoire; he thought of baseball, of Teilman's race in the batting column; one or two smoking-car jokes popped into his head but were discarded. He considered discussing the probable Republican majority Ohio would show in the next presidential election. He had a little book in his vest pocket which gave the vote by states for the past decade. In Pullman smoking-compartments the drummer had found it to be an arsenal of debate. He could make terrific political forecasts and prove them by this little book. But, with his very fingers on it, he decided against talking Ohio politics to an insurgent general in Rio Negro. His thoughts boggled at business again, at the prices of things, when he glanced about and saw Lubito, who had been entirely neglected during this colloquy. The drummer at once seized on his companion to bridge the hiatus. He drew the espada to him with a gesture.

"General Fombombo," he said with a salesman's ebullience, "meet Señor Lubito. Señor Lubito is a bull-fighter, General, and they tell me he pulls a nasty sword."

The general nodded pleasantly to the torero.

"I am very glad you have come to Canalejos, Señor Lubito. I think I shall order in some bulls and have an[Pg 46] exhibition of your art. If you care to look at our bull-ring in Canalejos, you will find it in the eastern part of our city." He pointed in the direction and apparently brushed the bull-fighter away, for Lubito bowed with the muscular suppleness of his calling and took himself off in the direction indicated.

At that moment the general observed the peon on the black horse, who as yet had not dared to present himself at the sentry-box before the caballeros.

"What are you doing on that horse, bribon?" asked the general.

"I was waiting to enter, your Excellency," explained the fellow, hurriedly.

"Your name?"

"Guillermo Fando, your Excellency."

"Is that your horse?"

"Sí, your Excellency."

"Take it to my cavalry barracks and deliver it to Coronel Saturnino. A donkey will serve your purpose."

Fando's mouth dropped open. He stared at the President.

"T-take my caballo to the ... the cavalry...."

A little flicker came into the black eyes of the dictator. He said in a somewhat lower tone:

"Is it possible, Fando, that you do not understand Spanish? Perhaps a little season in La Fortuna...."

The peon's face went mud-colored. "P-pardon, su excellencia!" he stuttered, and the next moment thrust his heels into the black's side and went clattering up the narrow calle, filling the drowsy afternoon with clamor.

The general watched him disappear, and then turned to Strawbridge.

"Caramba! the devil himself must be getting into these peons! Speaking to me after I had instructed him!"

The completely proprietary air of the general camouflaged under a semblance of military discipline the taking of the[Pg 47] horse from the peon. It was only after the three men were in Gumersindo's car and on their way to the President's palace that the implications of the incident developed in the drummer's mind. The peon was not in the army; the horse belonged to the peon, and yet Fombombo had taken it with a mere glance and word.

Evening was gathering now. The motor rolled through a street of dark little shops. Here and there a candle-flame pricked a black interior. Above the level line of roofs the east gushed with a wide orange light.

The dictator and the editor had respected the musing mood of their guest and were now talking to each other in low tones. They were discussing Pio Barajo's novels.

In the course of their trip the drummer had that characteristic American feeling that he was wasting time, that here in the car he might get some idea of the general's needs in the way of guns and ammunition. In a pause of the talk about Barajo, he made a tentative effort to speak of the business which had brought him to Canalejos, but the general smoothed this wrinkle out of the conversation, and the talk veered around to Zamacois.

The drummer had dropped back into his original thoughts about the injustice and inequalities of life here in Rio Negro, and what the American people would do in such circumstances, when the motor turned into Plaza Mayor and the motorists saw a procession of torches marching beneath the trees on the other side of the square. Then the drummer observed that the automobile in which he rode and the moving line of torches were converging on the dark front of a massive building. He watched the flames without interest until his own conveyance and the marchers came to a halt in front of the great spread of ornamental stairs that flowed out of the entrance of the palace. A priest in a cassock stood at the head of the procession, and immediately behind him[Pg 48] were two peons, a young man and a girl, both in wedding finery. They evidently had come for the legal ceremony which in Venezuela must follow the religious ceremony, for as the car stopped a number of voices became audible: "There is his Excellency!" "In the motor, not in the palacio!" The priest lifted his voice:

"Your Excellency, here are a man and a woman who desire—"

While the priest was speaking, a graceful figure ran up the ornamental steps and stood out strongly against the white marble.

"Your Excellency," he called, "I must object to this wedding! I require time. I represent the father of the bride. It is my paternal duty, your Excellency, to investigate this suitor."

Every one in the line stared at the figure on the steps. The priest began in an astonished voice:

"How is this, my son?"

"I represent the father of this girl," asserted the man on the steps, warmly. "I must look into the character of this bridegroom. A father, your Excellency, is a tender relation."

A sudden outbreak came from the party:

"Who is this man?" "What does he mean by 'father'? Madruja's father is with the 'reds.'"

General Fombombo, who had been watching the little scene passively, from the motor, now scrutinized the girl herself. It drew Strawbridge's attention to her. She was a tall pantheress of a girl, and the wavering torchlight at one moment displayed and the next concealed her rather wild black eyes, full lips, and a certain untamed beauty of face. Her husband-elect was a hard, weather-worn youth. The coupling together of two such creatures did seem rather incongruous.

General Fombombo asked a few questions as he stepped out[Pg 49] of the car: Who was she? What claim had the man on the steps? He received a chorus of answers none of which were intelligible. All the while he kept scrutinizing the girl, appraising the contours visible through the bridal veil. At last he waggled a finger and said:

"Cá! Cá! I will decide this later. The señorita may occupy the west room of the palace to-night, and later I will go into this matter more carefully. I have guests now." He clapped his hands. "Ho, guards!" he called, "conduct the señorita to the west room for the night."

Two soldiers in uniform came running down the steps. The line of marchers shrank from the armed men. The girl stared large-eyed at this swift turn in her affairs. Suddenly she clutched her betrothed's arm.

"Esteban!" she cried. "Esteban!"

The groom stood staring, apparently unable to move as the soldiers hurried down the steps.

By this time General Fombombo was escorting the drummer courteously up the stairs into the deeply recessed entrance of the palace. Strawbridge could not resist looking back to see the outcome of this singular wedding. But now the torchbearers were scattering and all the drummer could see was a confused movement in the gloom, and now and then he heard the sharp, broken shrieks of a woman.

His observations were cut short by General Fombombo who, at the top of the stairs, made a deep bow:

"My house and all that it contains are yours, señor."

Strawbridge bowed as to this stereotype he made the formal response, "And yours also."

As the general led the way into the palace, through a broad entrance hall, the cry of the peon girl still clung to the fringe of Thomas Strawbridge's mind. He put it resolutely aside, and assumed his professional business attitude. That is to say, a manner of complimentary intimacy such as an American drummer always assumes toward a prospective buyer. He laid a warm hand on the general's arm, and indicated some large oil paintings hung along the hallway. He said they were "nifty." He suggested that the general was pretty well fixed, and asked how long he had lived here, in the palace.

"Ever since I seized control of the government in Rio Negro," answered the dictator, simply.

For some reason the reply disconcerted Strawbridge. He had not expected so bald a statement. At that moment came the ripple of a piano from one of the rooms off the hallway. The notes rose and fell, massed by some skilful performer into a continuous tone. Strawbridge listened to it and complimented it.

"Pretty music," he said.

"That is my wife playing—the Señora Fombombo."

"Is it!" The drummer's accent congratulated the general on having a wife who could play so well. He tilted his head so the general could see that he was listening and admiring.

"Do you like that sort of music, General?" he asked breezily.

"What sort?"

"That that your wife's playing. It's classic music, isn't it?"

The general was really at a loss. He also began listening, trying to determine whether the music was of the formal classic school of Bach and Handel, or whether it belonged to the later romantic or to the modern. He was unaware that Americans of Strawbridge's type divided all music into two kinds, classic and jazz, and that anything which they do not like falls into the category of classic, and anything they do is jazz.

"I really can't distinguish," admitted the general.

"You bet I can!" declared Strawbridge, briskly. "That's classic. It hasn't got the jump to it, General, the rump-ty, dump-ty, boom! I can feel the lack, you know, the something that's missing. I play a little myself."

The general murmured an acknowledgment of the salesman's virtuosity, and almost at the same moment sounds from the piano ceased. A little later the door of the salon opened and into the hall stepped a slight figure dressed in the bonnet and black robe of a nun.

For such a woman to come out of the music-room gave the drummer a faint surprise; then he surmised that this was one of the sisters from some near-by convent who had come to give piano lessons to Señora Fombombo. The idea was immediately upset by the general:

"Dolores," and, as the nun turned, "Señora Fombombo, allow me to present my friend, Señor Strawbridge."

The strangeness of being presented to a nun who was also the general's wife disconcerted Strawbridge. The girl in the robe was bowing and placing their home at his disposal. The drummer was saying vague things in response: "Very grateful.... The general had insisted.... He hoped that she would feel better soon...." Where under heaven Strawbridge had fished up this last sentiment, he did not[Pg 52] know. His face flushed red at so foolish a remark. Señora Fombombo smiled briefly and kindly and went her way down the passage, a somber, religious figure. Presently she opened one of the dull mahogany doors and disappeared.