Transcriber’s Notes:

COMPANY “G”

FIRST ARKANSAS REGIMENT

INFANTRY

MAY, 1861 TO 1865

| Page | ||

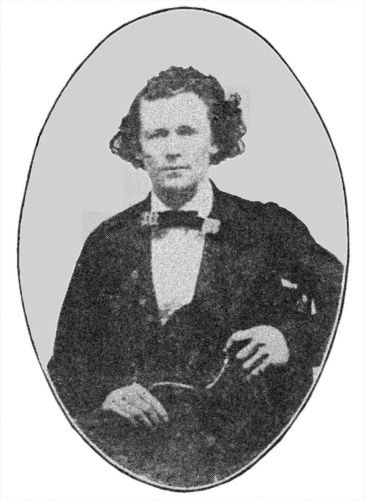

| W. E. BEVENS—1861. | 2 | |

| W. E. BEVENS—1912. | 3 | |

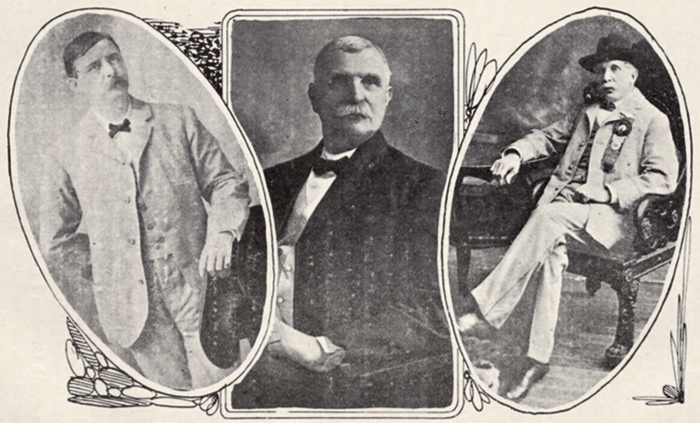

| THREE VETERANS OF COMPANY “G”. | 4 | |

| CAPT. A. C. PICKETT. | 9 | |

| L. C. GAUSE. | 21 | |

| CLAY LOWE. | 22 | |

| LYMAN B. GILL. | 50 | |

| LON STEADMAN. | 55 | |

| BEN ADLER. | 64 | |

| W. T. BARNES. | 67 | |

| ROBT. D. BOND. | 72 | |

| THAD KINMAN, ED DICKINSON, BEN ADLER. | 74 |

Reminiscences Of A Private.

When our children come from other states and from foreign lands to visit Jacksonport, the old home of their parents, they find the pitiful remnant of a village. Streets overgrown with weeds, dilapidated wooden cottages, a tumbled down brick court house, meet their eyes. One or two well-kept homes and a prosperous general store only emphasize the prevailing air of decay. The visitors may walk a mile down the road to the old town Elizabeth, and find no trace of habitation. The persimmon, the paw paw and the muscadine flourish in spaces that were once busy streets. When they remember that this place lacked only one vote of being made the capital of the state they may ponder on the uncertainty of human destiny.

But in 1861 Jacksonport was an important town. It was the county seat when Jackson county was much larger than it is now. Woodruff was a part of it and the whole formed a wealthy section of the state, the rich “bottoms” producing the finest cotton. Jacksonport was situated where Black River flows into White River, and was the center of distribution for many counties. At low water, which was the greater part of the year, it was at the head of navigation and people came from fifty miles to trade there, hauling overland all freight for Batesville and upper points.

It was then one of the great river towns, and one of the most fascinating occupations of my boyhood was watching the steamboats. We had two mail steamers, side-wheelers, up-to-date, with all kinds of accommodations for passengers and freight, and I have seen nine steamers loading and unloading at once. One packet from Louisville, one from St. Louis, two from Memphis, two from Upper Black River, and two from New Orleans. I [Pg 6] have seen one of the last, “The Seminole,” with a load of fifteen hundred bales of cotton.

At that time Jacksonport had a population of twenty-five hundred. The surrounding farms and plantations, cultivated by negro slaves, were owned by the Tunstalls, Waddells, Robinsons, Gardners and others. Old fashioned Southern hospitality prevailed in town and country, and we who were fortunate enough to live there “Befo de wah” think no other can ever equal it, no other town can ever boast of such beautiful girls, such handsome boys, such noble women, such brilliant men.

When the war cry sounded, Captain A. C. Pickett, a fine lawyer and an old Mexican War veteran, made up our company, and called it the “Jackson Guards.” This company to the number of one hundred and twenty was formed of the best boys of the county. Sons of plantation-owners, lawyers, doctors, druggists, merchants,—the whole South rose as one man, to defend its rights. The young men, many of us barely twenty years of age, knew nothing of war. We thought we could take our trunks and dress suits. We besieged Capt. Pickett and nearly drove him to distraction with questions as to how many suits we should take. He nearly paralyzed us by telling us to leave behind all fancy clothes, and to take only one suit, a woolen top shirt and two suits of underwear.

The noble women of Jacksonport made our flag. The wife of Judge Robinson bought the silk in Memphis. Mrs. Densford made the stars and all the ladies, old and young, worked on it, for love of those who were to bear it in battle.

On the Fifth of May, 1861 we were ready. It was a gloomy day. The rain poured in torrents, but our company formed and marched to the Presbyterian church where the flag was to be presented. Every living soul in town was there, streets, yard and church overflowed with people, notwithstanding the rain. We had seats reserved for us, and felt very grand as we watched the young ladies on the platform. We thought they were the sweetest girls living, and the most beautiful. Misses Mary Thomas Caldwell, Fannie Board, Pauline Hudson, and others were [Pg 7] there. Miss Caldwell presented the colors with a short and touching speech. Sydney S. Gause received it in the name of the company, replying beautifully. There was not a dry eye in the throng. Mothers were there who saw their sons perhaps for the last time. Fathers bade adieu to noble boys whom they had brought up to manly deeds of honor. Sisters separated from brothers. Sweethearts gave farewell to those whom they would love unto death. Who would not be moved to tears? We marched to the boat, and on the bank we stopped to give a last embrace to mother, wife sister, sweetheart. That spot was hallowed with the tears that dropped upon the ground.

The boat was the Mary Patterson, named for an Augusta lady, wife of one of our great lawyers. Its owner, Captain Morgan Bateman with great generosity, offered to take us to Memphis. He was a man of commanding ability, or he could never have handled so many wild young men. He never received a cent for his liberality, but he did not care. (He afterwards came back and made up a company of his own, with the assistance of his brother who went with him.)

When we were on board at last the boat pulled off from shore, amid waving handkerchiefs and shouts, “Good-bye, good-bye,” and no one present ever forgot that day.

We had with us an Italian Band which had come up from New Orleans and became stranded in Jacksonport. It was a great band and afforded us much pleasure until we got to Memphis.

At every town, landing and woodpile there was a crowd to cheer us. At Grand Glaize there happened a near-tragedy, which was averted by Captain Pickett and Captain Morgan. When we reached Des Arc, from which place we expected to march overland to Little Rock, Captain Pickett received a telegram from the governor to send in by wire our votes for Colonel of the Regiment and then proceed to Memphis. By Captain’s Pickett’s advice our company voted for Flournay. The rest of the Regiment voted for Fagin, who was elected. Fagin [Pg 8] ever afterward felt hard toward Captain Pickett.

We arrived at Memphis Thursday, May 9th. We marched to the Fair Grounds to await the arrival of the rest of the Regiment, and were put into the same quarters with an Irish Regiment from Tennessee.

I was put on guard inside the Fair Grounds. It rained all night, I had on new pump-soled boots, and being by mistake, left on duty, these tight boots caused me considerable pain. When the sergeant asked me how long I had been on duty I answered “all night.” He informed me that I should have been on guard only two hours. I thought it a part of the game to stay on all night. So much for being a soldier fool!

The next day we were organized and officers were elected for the twelve months. They were.

When the captain took charge there were only two men in the company who knew anything about military tactics or could even keep step. We stayed in Memphis four days. On Sunday afternoon with our new banner proudly waving, we marched through Memphis to the depot of the Memphis and Charleston Railway, where we entrained for Richmond, Va. Along the line of march were thousands of people and at every station was shown such enthusiasm as was never before known in the South. Everyone came down to greet us. Old men and women, young girls, even the negroes. We were showered with bouquets. We were delayed at different stations by the crowds. They came to see the Arkansas Troops, and to [Pg 10] hear Captain Bob Crockett speak. He was a conspicuous character from the manner of his dress, and also a celebrity from being a grandson of old David Crockett, hence was often called on for a speech. On one occasion, however, some of the soldiers asked several citizens to call for Private J. R. Fellows, one of the best orators in the South. He so far eclipsed Captain Crockett that the latter ever after took second place.

We passed through Knoxville and Bristol, debatable territory because Etheridge Brownlow and Andy Johnson, Union men of great ability and influence, lived in these places. To say there were hot times in these old towns would be putting it mildly—“red hot” would be about right.

At Bristol John M. Waddell took sick and I was detailed to stay with him at the hotel to which he was carried. He was delirious and kept calling for his mother, who lived in North Carolina. He was a Christian boy, and was ready to die, but how natural to want his mother in his distress. But he got better and we resumed our journey to Richmond, where we rejoined our regiment. We camped in the fair ground and were reviewed often by President Davis at dress parade.

I think that to him we must have looked very cheap indeed. We did not know what discipline was, and resented being shown. The boys used to steal through the lines and spend most of their time in the city. Bill Barnes drew some pictures of “Company G in Richmond,” which caused quite a little trouble at home.

We went from Richmond to Fredericksburg and there camped in the city awhile. We then moved to Brooks Station, and at this camp had cadets from Richmond to drill us. And I should say they did drill us! Eight hours a day, with a big gun, knapsack and accoutrements weighing us down, the hot sun blazing over us. How we did perspire! We were not used to such strenuous exercise. The town boys, clerks and young fellows could stand it better than the robust country boys, and that seemed queer to us.

At this camp John M. Waddell took sick with measles. [Pg 11] The Regiment lost over fifty men from this disease. Waddell was discharged and went home. After his recovery he joined a North Carolina Regiment, and served with them through the war. He Was a gentleman in the truest sense of the word. We hated to lose him. From Brooks Station we went to Aquia Creek, and from there to Marlboro Point on the Potomac. We camped at a point where this beautiful stream was four miles wide. W. M. Maltens, our company color-bearer waded into the river and unfurled our flag, the handsome silk one given us by the Jacksonport ladies. “Jackson Guards” was very plain upon it, and it was displayed in full sight of the enemy’s war vessels. We were lined up on the bank to defend our colors. This shows how green we were in knowledge of warfare and we realized it later.

From Fredericksburg, five companies of our Regiment and five companies of Col. Bates’ Second Tennessee Regiment were under Col. Cary. He was a West Pointer, a fine man and officer, but he certainly did drill us eight hours every day. During drill our orderly sergeant, a regular army man, used to prompt us when new moves were given. One morning he was angry at Captain Pickett. When Col. Cary gave the command “Double quick by companies” there was no prompting and Captain Pickett failed to repeat the command. The sergeant had his revenge for we were double-quicking by fours to the line on the right and proceeded by ourselves. Col. Cary shouted “Captain Pickett, where are you going with your company?” amid the laughter of the rest of the regiment.

At this camp Bill Shackelford used to go fishing for crabs in the Potomac. He would miss roll-call and have to serve extra duty. The boys begged him to stop this but he said if he could get crabs to eat he did not mind extra duty. One night Bill had some fun at the expense of the officer whose duty it was to pass through the tents and see that all were in bed. We had a big Sibley tent in which twenty-two men slept. As the officer passed through the tent, Bill who was a ventriloquist, squealed like a pig. Of course the officer looked everywhere for the pig. As he passed to the other side of the tent Bill [Pg 12] barked like a dog. Then the officer asked for the man that did it. Of course all were asleep and knew nothing about it. He said he would arrest the entire company if it occurred again. Bill did not try it again.

One day Clay Lowe had cooked some corn-bread and left it on the table, feeling that he had done a good piece of work. After dinner a big man in uniform stepped up and broke open a piece of bread. Clay was about to call him to account in words not very choice, when the big man explained that he was General Holmes, commander of the troops. Clay had to beg his pardon and salute the General, and the General in return complimented Clay on his bread.

At this camp we had jumping matches. Bob Bond was our champion and no one could beat him in the whole command of one thousand troops, and he was never beaten in the army.

We also gave dances, and tied handkerchiefs on the arms of the smallest boys to take the part of ladies in making up square dances. Joe Hamilton, Rich Hayden and Billie Barnes were as fine musicians as any and we often had hilarious times along the Potomac.

On July 17th, 1861, we were ordered to cook three days’ rations, and be ready at daylight to join our regiment and march to Manassas Gap. We marched forty-seven miles and on July 21, were camped in an orchard at the extreme right of our army, with orders to be ready at a moment’s notice. We were in line of battle all afternoon and chafed to be in the fight. We could hear the cannonading. It seems that the courier who was bringing our orders to move at once was captured and we did not get the command. “The third time is the charm” and finally the third courier brought news of the battle with orders to double-quick eight miles. We made this in one hour and forty minutes. On this hot July day the red dust stirred up by our running made us look like red men. We hardly knew the features of our file leader. While on this run we saw some sizzling looking things streaming through the air. One of the boys said, “Captain, what are [Pg 13] those things going through the air?” Captain Pickett replied, “You damned fool, you will know soon.”

We got there in the nick of time. We were thrown into line of battle and could see in front of us the enemy, with glistening bayonets, forward marching, line after line of them. We had a four gun battery, belonging to Holmes’ Brigade, commanded by Captain Walker. He was ordered to place his guns on a small hill in our front. He unlimbered and was ready for action. We were ordered to load our guns and lie down behind the battery to protect it if charged. The captain gave the order to fire upon some Yankees who were advancing boldly. As he gave the order he was sitting on his big horse with his feet across the horse’s neck. The first shot did not reach the spot; so he got down, sighted the gun himself, and got back on his horse to watch the result. As the shot plowed through the enemy’s ranks it looked like cutting wheat, and the Captain said: “Give them hell.” The four guns made roads through them and with the Infantry on the other flank they could not stand the fire. The Yankees broke in every direction and never did stop. As this was their last stand we moved forward, and the Black Horse Cavalry passed. This was the finest cavalry I ever saw. All the horses were black and the uniforms of the men were handsome to behold. After the Cavalry Johnson, Beauregard and President Davis with all their staff, were near us, and the sight was beautiful. We turned the flank of the enemy and the Black Horse Cavalry did the rest. The first battle of Manassas was a great battle and a perfect success.

After the break we were ordered to be down in line of battle and await orders. Part of the Washington Battery was near us. This was an organization of fine boys from New Orleans. After fighting all day they had become separated, part of their battery being in one part of the field, and part in another. After the battle they were hunting their comrades and trying to get the full battery together. Such chatter! Such individual accounts of the battle! They told us of their share in the fight. How they fought the enemy from rear and front and side, and how the Yankees had run off! It was inside history of [Pg 14] the battle from privates who were in it. The whole truth of the first battle of Manassas is this: It was fought by undisciplined troops, without previous experience in battle, on a field they had never trod before. They fought as individuals, and if the officers had not been with them they would have fought just the same.

This was proved, for had they been disciplined troops they would have surrendered when cut off from their command, but not having any better sense they did not know when they were whipped. On this field they fought regular army troops with all the advantage of years and experience. Even our General was doubtful and thought they could not cope with the great army of Scott. But when he saw the Southern boys in action, he saw what, to this day, is the wonder of the world, that we were not to be whipped in six months.

This battle was a hard rap to those who intended to profit by it had it gone the other way. The Grand Army left Washington commanded by the invincible General Scott, having placards on their hats bearing the motto, “On to Richmond.” Congressmen, with their wives followed, together with the elite of Washington, all riding in carriages. They also wore badges with the ever-ready slogan, “On to Richmond.” They had trunks plastered with the same motto. They carried champagne and were ready for the celebration of a great fete when they should have witnessed the downfall of the Confederacy. Before the battle it was a holiday for them, with their wine, and their hope of an easy rout of the rebels, and the pleasant anticipation of the capture of soldiers and congressmen of the Confederacy. But after the battle—ah, it was no holiday then! What a blow to their pride was the result. How they tore back to Washington. Their own account of the first battle of Manassas was truly pitiful. We could have easily gone into Washington, but at that time we did not want to go into their territory, all we desired was to defend our own homes, property and states, which were ours according to the constitution.

At daylight we marched to Dumfries, thirty miles back from the station, then to Culpepper court house, and [Pg 15] from there to the pine thicket back from Evansport. With us were Captain Walker’s battery (Captain Walker afterwards became General of Artillery) and the Thirteenth North Carolina Infantry. With their assistance, working at night with great secrecy, we built batteries to blockade the Potomac, which was only a mile and a half wide at this point. We built three batteries in one mile and mounted large siege guns. The enemy was greatly astonished on the morning we cut the pine thicket and laid our guns open to view.

We next made sail boats and tug boats and schooners. These captured a three masted vessel. When the tugs came towing it to shore we went out and got it. Later we had a hard time finding a sailor to set the sails. Finally one was discovered in our own company, and as soon as he got on the vessel he ran up the rigging like a genuine sailor. We found the rooms of the captured vessel very fancy. It had a piano on board, and a good deal of nice grub. We unloaded her and then burned her.

We certainly did blockade that river and stop transportation to Washington by way of the Potomac. Then the Yankees built a railroad on the opposite side back from the river and supplied the gap in that manner. We used to bombard the men over there and kill them and their six mule teams. This caused consternation as you may guess.

A small yacht with two on board ran the blockade. Our batteries opened up on them. The balls exploded above and around them, sometimes splashing the water so that we could not see them for the spray. For awhile it seemed as if we had them, but they got through. The yacht was so small that we could not hit it. When they got by, the men waved their hats, as much as to say, “Goodbye”, but they never tried to repeat the performance.

One night the enemy ran up a creek by the upper battery, where we had a schooner out and away from the river. In the darkness they passed our guards and burned the schooner. The guards were new recruits and very green. They sent to headquarters to ask what they could do. Of course the Yanks had plenty of time to get [Pg 16] back to the Potomac. We built huts out of logs, placing them in the side of the hill and roofing them with a foot and a half of earth to keep out the rain. A few of the boys had tents, but I think our log huts were more comfortable, for we covered the floors over with straw. We passed most of the winter here. Our Maryland boys used to cross the river in skiffs at night to visit their homes, and return before daylight.

The Second Tennessee, commanded by Colonel Bates, camped along with us that winter. One day Colonel Bates ordered some work done which did not agree with the dignity of his men. They refused to do it, saying they “were gentle,” and asking him to resign. He at once wrote out his resignation and gave it to them. He told them he would as soon be a private as be an officer. That a private must obey, and he was as willing to obey any officer over him as they should be to obey an officer over them. He was a great man, and a fine speaker. At the close of his speech they tore up his resignation and re-elected him colonel.

Colonel Fagin once ordered some boys of our company to set up his tent but they refused. They came back to the company and told us about it, also informed Captain Pickett who went to Colonel Fagin and got them out of it.

So much for raw undisciplined troops.

Christmas was at hand. Our first Christmas in a soldier’s camp! How homesick we were as we thought of the people at home and wondered how they were spending Christmas. Here were their boys fifteen hundred miles from them, living in dark huts, wading snow a foot and a half deep. We did not know that the time would come when these dark, rude huts would seem luxurious quarters.

Our mess was composed of George Thomas, Clay Lowe, Bob Bond and myself. George had been left behind at Fredericksburg, where he was ill for some time. He and a private from another company decided to come to camp and spend Christmas with the boys. They left the train and tramped a mile and a half to surprise the mess, arriving in the nick of time. George said they could not [Pg 17] bring us turkey, so they brought some whiskey and eggs. They began beating eggs early Christmas morning, and they made a huge pan full of egg-nog. We invited the officers and our friends to take some with us. In the evening the boys went for Col. Fagin and invited him to drink egg-nog. By that time they were pretty full and Clay Lowe told Col. Fagin that he wanted him to understand that he was “Fifth Sergeant of Company G.” He succeeded in impressing the Colonel with his rank. Then everyone began to make things lively.

I did not touch the egg-nog, therefore did not enjoy their hilarity. I left the hut, found Sam Shoup in his hut, and we went out and sat by the fire thinking we were away from the crowd. But the boys did not intend to let us off so easily. When we came back into the hut we could not see very well. The cabin was dark, as the only light came from the doorway, and the snow had blinded us. The boys made a rush for us. I got into a dark corner, and after they were all in we both ran out. They caught Sam, but failed to get me.

Clay Lowe, followed by about twenty-five of the boys, went down to the middle of the company grounds and commenced to make a speech, which he could do so well. Some of the boys, not wishing Clay to have all the glory, put John Loftin on the stump to make an address and he began: “My friends, I am not as eloquent as Clay, but I speak more to the point.”

That evening at dress parade, Sam Shoup as corporal had to march out and present arms, reporting two commissioned officers, four non-commissioned officers, and twenty-seven privates drunk. The rest of the regiment was there, and to our consternation, we were ordered to cook three days’ rations and be ready to march at daylight. The order read that any private who straggled or failed to keep up with the command would be court martialed.

When we stopped late next evening on the march, Clay was nearly dead and could hardly walk, from the effect of the Christmas spree. Colonel Fagin rode along by our company and seeing how Clay was said, “Hello, Fifth Sergeant of Company G, how do you feel?” Clay [Pg 18] replied, “Colonel, I am damned dry; how are you?”

December 26, 1861, we reached Aquia Creek and went into winter quarters in log huts and tents. Here we had “Sunday Soldiering.” We were close to Fredericksburg, and could order what we wanted to eat. Confederate money was good and we could grab things cheap with it. Fifty cents a gallon for shelled oysters; twenty-five cents a pound for butter; pies and cakes every day. Think of such grub for a soldier! But, ah, to stay in the snow, eighteen inches deep, and guard the Potomac river all night! No shelter, but a corn stalk house; no fire, but a driftwood blaze, not very bright either, as it would be a signal for the enemy to cannonade. That was like war and soldier duty.

We had three points to guard on the river, one on the island with battery, and one at the lower end of the line. It required a whole company for all points at night, since the guard had to be relieved every twenty minutes. Otherwise he would have been frozen by the snow and sleet which swept across the Potomac.

One night a squad from our company under a sergeant was ordered to the island, which was only guarded at night. We had to cross over in a flat boat. The evening before supplies had been sent to the island for the use of the Battery Company and they had failed to haul them. The squad on the lower part of the guard line found them, all unused, in a pile on the landing. The night was bitter cold, the snow was deep, the wind blowing a gale, no wood was in sight. The supplies were bacon. It was good to eat, and in this emergency it was good to burn, so the boys proceeded to burn it. Dawn revealed other things besides bacon. They discovered two jugs of red liquor, which they immediately confiscated. At daylight they were ordered to camp two miles away and proceeded to march—and drink on empty stomachs until the whole squad was drunk. We, on the upper part of the guard line, had to wait in the snow and wind until they came up, for all must report in camp together. We did not know what caused their delay, but we were in no pious [Pg 19] frame of mind when we saw them coming, wabbling from side to side, yelling like Commanches. The officers with us were red-headed and said things to that squad that “were bad”.

But the boys from the lower end knew how dry the officers were after being out all night, so they offered the jug of snake bite medicine. The officers found it so good they did not let it go in a hurry. After that the privates could not refuse for fear of making the boys angry. By the time we reached camp almost everybody was overcome. The officers went to sleep, and when they awoke they forgot all about discipline. So nobody suffered but the Battery fellows, and they could never prove who captured their supplies.

Sometimes a company would buy a barrel of oysters, take it to their hut and open it, and find in the center a five gallon jug of red rye. It was so concealed to pass the provost guard on train. But the boys did even worse. Seven of them from other commands, went to Fredericksburg, bought a coffin and filled it with jugs. With sad faces and measured steps they carried it solemnly to the train. But the joke was too good to keep. The boys unscrewed the lid and yelled at the guard. Of course, when the train returned no one could name the offenders.

But our “Sunday Soldiering” did not last long. The regiment was composed of one year troops, who now re-enlisted for three years, or for the war. The re-enlisted men were ordered to rendezvous at Memphis, to reorganize the regiment, but later were ordered to Corinth, Mississippi.

The Virginia people had been good to us, and had tried to make us feel at home. Some of the boys had gone into society at Fredericksburg, and found it hard to part from their new friends. George (my old friend, George Thomas) “had it mighty bad.” He said to me, “Bill, I must go to Fredericksburg to see my girl. Will you cook my three days’ rations? I’ll meet you at the train tomorrow.” “But Pard, how will you get off?” “I’ll ask Col. Fellows.” He went to Colonel Fellows, who was in charge that day and told his tale of woe. The colonel was in [Pg 20] deep sympathy with the boy (perhaps he had had the disease himself sometime,) and agreed to help him. George went to Fredericksburg, and the next day I saw him there with his girl. Our train pulled out, I yelled at him, but still he lingered. They gazed and gazed at each other, and it seemed that George did not have the nerve to tear himself away. Finally they parted and by hard running he caught the train and stood waving to her until we were out of sight. The mails were kept hot after that. Poor George was killed at Atlanta. He was the bravest man I ever knew, and if he had lived, would have made that girl a noble husband.

March 17, 1862, at Corinth, Mississippi, the re-organization of the regiment took place. The newly elected officers of Company G were:

We camped at Corinth, Mississippi, and the army was under General Beauregard until General Albert Sydney Johnston arrived. April 4th we marched to Shiloh, arriving there April 5th. The constant rains had made the roads so bad that we had to pull the cannon by hand as the horses mired in the mud. But by this time we were used to hardships, and nothing discouraged that superb commander, General Albert Sydney Johnston. Every soldier loved him and was ready to follow him to the death. At the battle of Shiloh we were placed in the Gibson Brigade, Braggs’ Division. On the night before the battle the Medical Department ordered six men from each company to report to headquarters for instructions.

I was one of the six to report from our company. The Surgeon General ordered us to leave our guns in camp and follow behind the company at six paces, as an infirmary corps to take care of the wounded. We reported our instructions to Captain Shoup, telling him we would not leave our guns, as we intended to fight. After hard pleading Captain Shoup consented. We took our guns and also looked after the wounded.

At four o’clock in the morning we began the march on the enemy. Each man had forty cartridges, all moving accoutrements and three days’ rations. General Johnston was cheered as he rode by our command and I remember his words as well as if they had been today, “Shoot low boys; it takes two to carry one off the field.”

Before we started Captain Scales of the Camden Company, begged his negro servant to stay in camp at Corinth, but the old negro would not leave his master. When we were in line of battle the captain again begged the negro to return to camp, but he refused to go. Just after the last appeal the fight began. A cannon ball whizzed through the air and exploded, tearing limbs from trees, wounding the soldiers. One man fell dead in front of the old negro. Then there was a yell, and old Sam shouted, “Golly, Marster, I can’t stand this,” and set out in a run for Corinth.

We moved forward with shot and shell, sweeping everything before us. We drove the officers from their hot coffee and out of the tents, capturing their camp and tents. Captain Shoup and John Loftin and Clay Lowe each got a sword. In the quartermaster’s tent we found thousands of dollars in crisp, new bills, for they had been paying off the Yankee soldiers.

Thad Kinman of the 7th Arkansas, who was under Ellenburg, quartermaster department, had loaded a chest into a wagon when he was ordered to “throw that stuff away.” He told us afterwards, “That was one time that I was sick,” but Ellenburg would not let him keep it.

Our command moved steadily forward for a mile or more. The Yankees had time to halt the fleeing ones, form a line of infantry and make a stand in an old road in a thicket. We were to the left of the thicket, fighting all the time in this part of the field. I saw Jim Stimson [Pg 24] fall, and being on the Infirmary Corps, I went to him. I cut his knapsack loose and placed it under his head, tied my handkerchief about his neck, and then saw that he was dead. I took up my gun again, when in front I saw a line of Yankees two thousand strong, marching on the flank. I could see the buttons on their coats. I thought I would get revenge for my dead comrade, so I leveled beside a tree, took good aim at a Yankee, and fired. About that time the Yankees fronted and fired. Hail was nothing to that rain of lead. I looked around and found only four of our company. One was dead, two were wounded and I was as good as dead I thought, for I had no idea I could ever get away. To be shot in the back was no soldier’s way, so I stepped backward at a lively pace until I got over the ridge and out of range, assisting the wounded boys at the same time. I had not heard the command to oblique to the right and close up a gap, and that was how we four happened to be alone in the wood. But I did some running then, found my regiment at the right of the thicket and fell into rank. When I got there the company was in a little confusion through not understanding a command, whether they were to move forward or oblique to right. Captain Shoup thought his men were wavering, so he stepped in front of the company, unsheathed his new sword and told the boys to follow him. He had scarcely finished with the words when a bullet struck his sword and went through wood and steel. The boys were red-headed. They told him he did not have to lead them. They were ready to go anywhere. So we went forward into the hottest of the battle where the roar of musketry was incessant, and the cannonading fairly shook the ground. Men fell around us as leaves from the trees. Our regiment lost two hundred and seventy, killed, wounded and captured. The battle raged all day and when night came the enemy had been pushed back to the verge of the Tennessee river. But our victory had been won at a great price, in the loss of our beloved General, Albert Sydney Johnston, who was killed early in the action.

General Beauregard, next in command, succeeded [Pg 25] Johnston, and the battle opened again at daylight the next morning. During the night the enemy had been strongly re-inforced, and our men were steadily pressed back.

John Cathey, John R. Loftin, Waddell and I were among the wounded. We were sent to the field hospital several miles back in the wood. When the Surgeon General went to work on me he gave me a glass of whiskey, saying it would help me bear the pain. I told him I would not drink it. He then handed me a dose of morphine. I refused that. He looked me squarely in the face, saying, “Are you a damned fool?”

Our men, fighting stubbornly all the while, were pushed back by superior force through and beyond the Yankee camps we had captured so easily the day before, and at last retreated to Corinth, amidst a terrible storm of rain and sleet. We had lost about ten thousand men. That was the beginning of our real soldiering and the greatest battle we had been in. About thirty thousand men were killed, wounded and captured in those two days, the loss on each side being fifteen thousand.

At Corinth we awaited re-inforcements and prepared to renew the struggle. The Yankee forces advanced to Farmington, and we had a little more fighting. They captured one of our outposts, then we drove them back to their lines. Colonel Fellows was always on the front line. At this battle he plunged after some cavalry, following them he struck low, boggy ground. He got stuck in the mud and lost his hat, but succeeded in capturing the enemy.

We kept heavy guards at night. One night eighteen of our company were put on out-post, but our cavalry was still further out. George Thomas and I were stationed inside a fence row. We were told not to fire, and we were to be relieved before daybreak. We were not relieved however, and when day came we found ourselves only a short distance from the Yankee breastworks. We could have kept concealed by the grass and bushes, but George, who knew not the meaning of fear, stood in his corner of the fence-row. As he watched the Yankees walking their [Pg 26] beats on the breastworks he thought it a good opportunity, and before I knew it, he had shot his man. Oh, then three cannon and two thousand infantry turned loose on us! The fence was knocked to smithereens. The rails, filled with bullets, crashed over us. Limbs falling from trees, covered us, and we were buried beneath the debris like ground hogs. We could not get out until darkness fell again. Then we found some of our cavalry, and tried to get back to our regiment, but the Yanks were between us and our command. The cavalry said we could fight our way through their lines, and we did. The cavalry soon left us behind. Yankees were shooting all around us and yelling for us to surrender, but we ran into a ravine, where we were hidden by the thick undergrowth, and so we got away.

On May 29, 1862, General Beauregard evacuated Corinth. We retreated on a dark night through a densely wooded bottom road. About two o’clock we halted. As soon as we stopped we dropped in the road anywhere, anyhow, and were fast asleep. Some devilish boy got two trace chains and came running over the sleeping men, rattling the chains, yelling “Whoa! Whoa!” at the top of his voice. Of course all the commotion—we had it then. Soldiers grasped the guns at their sides, officers called, “Fall in, fall in men.” When the joke was discovered it would have been death to that man, but no one ever knew “who struck Billy Patterson.”

We marched forty miles and camped at Twenty Mile Creek on the Mobile and Ohio railroad. On June 5th we reached Tupelo. We were put in Anderson’s Division of General Walker’s Brigade and camped at Tupelo until August 4th, when we were ordered to Montgomery, Ala.

We went on the train to Mobile. Here I went up into the city with Colonel Snyder and two of his friends, I being the only private among them. It seemed ages since we had enjoyed a square meal. We went into a fine restaurant near the Hotel Battle House, four half-starved Confederate soldiers. Just at the smell of oyster stew I collapsed. But we ordered everything—oysters raw, fried, stewed, fresh red snapper; just everything. We ate. I hope we ate! I think that proprietor was astounded, but it was only our pocketbooks that suffered. At last [Pg 27] when we could eat no more, we had fine cigars, and as Dr. Scott said later, “This was good enough for a dog.”

We went from Mobile to the railroad station on the bay, where the water flows under the platform. The train was two hours late, so the boys shed their clothes, and in ten minutes there were a thousand men in the bay. They swam about splashing, kicking, diving, having fun until some of the boys went in where the palm flags were growing and espied a large alligator with his mouth wide open. In less time than it takes to tell it there was not a soldier in the bay. Strange! Men, who had stood firm in battle, had faced cannon, had endured shot and shell, now fled from one alligator!

We went by rail to Montgomery, where we arrived August 7th. We went into camp near the river and had a chance to swim without fear of alligators.

Montgomery, as the first capital of the Confederacy, was a noted place and many celebrated people lived there. Dr. Arnold and I had bought ourselves “boiled” white shirts, thinking we might be invited into society, but we seemed to have been forgotten by the “haut ton.” But it was a beautiful city and we inspected it thoroughly. We were too many for the police, so they “gave us rope to hang ourselves.”

We went on next day to Atlanta. When we got there we hoped to eat a big Georgia watermelon, but to our consternation, found the provost guard destroying every watermelon in the city. They were fresh, red and juicy and made our mouths water, but discipline had improved and we touched not, tasted not, handled not the unclean watermelons. The doctor said they would make us sick. Citizens and negroes might eat them. For soldiers they were sure poison.

We passed up the Sequatchie Valley with its fine springs, stone milk houses, and rich bottom land. We camped on Cumberland Mountain and we camped on Caney Fork. We marched thirty-five miles to Sparta, Tennessee, and camped, and there we were ordered to wash our clothes and to cook three days’ rations. All this marching was on the famous Bragg Kentucky Campaign [Pg 28] and the old general trained us to walk until horses could not beat us. We marched eleven, twelve, thirteen____ ____fifty miles. We waded the Cumberland river, and it was very swift and deep. My messmate, Bob Bond, found a sweetheart here, but he could not tarry and they parted in tears. We camped at Red Sulphur Springs, marched thirty-eight miles and camped on the Tennessee and Kentucky line. We passed through Glasgow, marching all night. These forced marches were hard on us, seasoned infantry as we were. Dr. Arnold, my file leader said:

“Bill, I can’t go any further, don’t you see I go to sleep walking? I can’t stand it any longer.”

“You’re no good,” I replied, “you can stand it as well as I can, besides if you leave the road you will be captured and will have to eat rats.”

“Goodbye, old friend, I am gone,” was his answer. He ran into the wood twenty or thirty feet from the road, dropped down and was asleep by the time he hit the ground.

He said when he awoke he heard sabres clashing and cavalry passing. He thought he “was a goner”, but he soon heard the familiar voice of General Hardee. He was calling to get up and go on. He said even a soldier’s endurance had a limit, and that limit was now reached. We would not go much further without a rest. Then he ordered his body guard to charge the sleeping men. Dr. Arnold had to run for his command or be court martialed. Panting for breath, he joined us after we had gone into camp, and exclaimed, “Bill, I wish I had come on, for I am nearly dead, and old General Hardee is after me hot and heavy.”

On September 17th we left Case City at daybreak, and marched fifteen miles to Mumfordsville, which we surrounded, placing a battery on every hill and knoll that commanded the town. We had eighty cannon ready to open fire, and then demanded the surrender of the garrison, and on September 18th six thousand men marched out, laying down six thousand guns. While Will Reid of our company was loading guns into a wagon, one went off accidentally and shot off his arm. General Hardee was riding over the battlefield, and seeing Reid with his arm [Pg 29] dangling at his side asked his staff surgeon, Dave Yandell, “Who is that man’s surgeon?” Yandell pointed out Dr. Young. Dr. Young had gone out in our company a graduate surgeon. He was young and up to that time he had made no operation of note. He begged the staff-surgeon to help him, but Yandell refused, saying he had no time. He stayed, however, to look on, and embarrassed the young surgeon still more. When Dr. Young took the knife his hand shook like a leaf, but he performed the operation successfully and according to all the laws of surgery. After the war he returned to his home at Corinth, Mississippi, where he stood high in his profession. He died in 1892.

At Mumfordsville while in line of battle, marching slowly and stopping often, we passed through an orchard. Nice juicy apples were lying all over the ground and one of the boys of a Louisiana Regiment, stooped down and picked up two or three. His colonel happened to be looking in his direction, and he had that boy gagged and buckled every time the line stopped. After that every soldier thought hell was too good for that colonel.

On the 20th we marched all night and camped at daylight at New Haven. On the 21st we marched seventeen miles, and camped at Haginsville. On the 22nd we passed fine orchards. My partner, Dr. Arnold said to me, “If you will carry my surplus luggage, I will take the risk and get some of those apples.” “Now Pard, you are in for more trouble.” But he would not listen, and taking his blanket to hold the apples he started off.

He was not the only soldier under the trees, and while on a limb getting his share of the apples, lo and behold, the provost guard came to arrest them! He fairly fell from the tree, broke through the high corn and ran for his life, the guard calling after, “Halt, or I shoot.”

He got back to us with the fruit but said the apples had cost him so much labor and so much fright that they did not taste good. Because we laughed at him, running with his load, he would not give us any until the next day.

We marched fifteen miles and camped at Bardstown until October 4th, when we marched seventeen miles. We marched twelve miles and camped at Springfield. The heat was terrible on those long sunny pikes, with never [Pg 30] a sign to mark the grave of a hero, noble sacrifice to their cause.

One day an assistant surgeon carrying an umbrella was marching along the pike in the rear of his regiment when General Hardee came along. The General had nothing to shield him from the sun but a little cap. He rode up to the surgeon and said, “What is your name?”

The man told him his name, rank and regiment.

“Well sir,” said General Hardee, “just imagine this whole army with umbrellas.”

The doctor shut up his umbrella and pitched it over into the field.

General Hardee was always joking his men on the march, but when the fight was on no one did his part better than he.

On October 6th we marched through Perryville, but on the 7th we marched back and camped in the main street of the town.

Some of the boys stole a bee-hive and many of them got stung so their faces were swollen and eyes closed. Dr. Arnold was one of the injured ones, but he did not fail to eat his honey. As we lay on the ground that night I teased him, saying General Hardee would need no further proof; that he carried his guilt in his face. The doctor did not relish this so I turned over to go to sleep when a bee stung me on the cheek.

“Who’s the guilty one now?” laughed the doctor and the joke was surely on me. But I knew where the medicine wagon was, and went and got some ammonia. I bathed my face, and the swelling went down at once, so I came out ahead after all.

By daylight we were in line of battle and honey and bee-stings were forgotten. The Battle of Perryville was fought October 8th, 1862. We were on the extreme left and our battery, on a hill at our rear, was not engaged until late in the day. The heaviest fighting was on the extreme right. Both sides were contending stubbornly for a spring of water between the lines and were dying for water. Sometimes one side would have the advantage, sometimes the other. When called into action we crossed a bridge in the center of the town, formed a line and advanced [Pg 31] to the top of the hill. Our battery was planted and had begun its work when we received orders to recross the bridge and occupy our former lines. We had to retreat under battery fire, and after we had got our battery over the bridge we marched along the pike. The enemy opened on us with grape and cannister and did deadly work. We double-quicked into line and their sharp-shooters gave us a terrible assault from behind the houses. But when our line was formed, our sharp-shooters deployed and our battery opened fire, they had to retreat. So the battle went on, but finally we had to give up the struggle and evacuate the town. The loss was heavy on both sides, about eight thousand men being killed, captured and wounded.

October 9th we marched fifteen miles and passed Harrodsburg. On the 10th we marched sixteen miles to Camp Dick Robinson. Here a council was held while General Bragg gave his wagons time to go South. It was the greatest wagon train ever seen in the army; was three days passing at one point. Here George Thomas and I each bought three yards of undyed jeans to make ourselves some trousers when we got back South.

The defeat at Perryville and the failure of the Kentuckians to join us as we had hoped, made our campaign anything but a brilliant success from a military point of view, notwithstanding our victories at Mumfordsville and Richmond.

But we had captured six thousand men, we had secured arms and ammunition which were sorely needed, we had gotten enormous quantities of supplies which were a great help to the Confederacy, and the men who did get back were tough as whit-leather, ready for anything.

October 13th we marched twenty-three miles, passing through Lancaster, October 14th we marched seventeen miles, going through Mount Vernon, and halted a little before dark.

Dr. Arnold and I went down to a creek about a mile from camp, and there in a field we found a fine pumpkin. He said if I would help him cook it I might help him eat it. He said it would have to cook until one o’clock to be well [Pg 32] done. I told him I would help take it to camp but I’d be dinged if I’d stay up until one o’clock to cook it. I was too nearly dead for rest and sleep. We got it to camp, cut it up, put it in the famous old army camp kettle and Doc began the Herculean task of staying awake to cook his pumpkin. He did stay awake until one o’clock and got it nicely done, but was afraid to eat it at that unusual hour, as he might have cramp colic. He found an old fashioned oven with a lid, put his pumpkin into it, fastened the lid, placed the oven under the knapsack beneath his head and went to sleep. But first he took the trouble to wake me and tell me I should not have a bite of his pumpkin because I would not stay up to help him cook it.

When reveille sounded he woke up and began to guy me, saying “You shall not have a bite.” He took up his knapsack and behold, the oven, pumpkin and all, was gone! Oh, he was furious, and fairly pawed the ground. He thought I had taken it for a joke, but soon found that to be a mistake. We decided that some soldier had stolen and eaten it. If he had found the man he would have fought him to a finish. He never did see the joke.

October 19th we marched eleven miles. We passed over a battlefield, where General Buckner had fought, and crossed Wild Cat River. We marched thirteen miles and passed through Barkersville. This was a strong Union town in the mountains. The “Jay Hawkers” shot at us from the top of the mountains; women and boys pelted us with stones, shouting, “Hurrah, for the Union.” As they were women and children, we had to take it.

Once we were marching on a road cut out of the mountain side. On one side was a cliff of solid rock, on the other a deep precipice. The command to halt was given and the men fell down to rest, completely filling the road. Arnold and I were in the rear, and one of the ambulance drivers, seeing the crowded condition of the road, told us to get up with him, which we did. There was a trail just wide enough for the horsemen, single file, and along this trail rode General Hardee looking after his men. When he reached this ambulance he stopped opposite Arnold and said to him, “Are you sick?” “No, sir.” [Pg 33] “Well, get down off that wagon.”

“Are you sick?” he called to me, but by that time I was out on the ground. Then he said to the driver, “Let no soldier ride unless he is sick or wounded.”

A Kentucky Colonel brought with him his five hundred dollar carriage, and had his negro drive it at the rear of the regiment. In his rounds General Hardee had found some sick men and told them to get into that carriage. The negro and rear officers explained whose carriage it was, but the General only said, “No use going empty when it can serve so good a purpose. By tomorrow perhaps none of us will need it.”

So the umbrella man, Arnold and myself were not the only ones upon whom General Hardee kept an eye.

October 19th we marched fourteen miles, crossed Cumberland River, then on through Gibraltar, Cumberland Gap, and on across Powell River into Tennessee. We marched past Taswell, crossed Clinch River at Madisonville, and, on October 24th, camped about six miles from Knoxville. Here we were given time to wash and dry our clothes. On this raid we had only one suit and to get it clean meant to strip, wash, let the clothes dry on or hang them on bushes to dry, while we waited. With our battles and forced marches we could not stop for that; so creeping companions were large and furious, and made deadly war. But at Knoxville everybody got busy, went into warfare with our creeping enemy, and the thousands destroyed in that fierce combat will never be known.

George Thomas and I brought out our white jeans which we had bought in Camp Dick Robinson, and had carried all these miles. We got some copperas from a kind old rebel lady, took walnut hulls and dyed our cloth. It was a good job too.

The boys were getting short on tobacco, and it looked as if the whole army would be forced to reform on this line. But they borrowed Dr. Ashford’s horse and sent me to buy tobacco, chewing tobacco, smoking tobacco, hand tobacco, giving me plenty of Confederate currency.

I rode into the beautiful town which I had not seen since we were flying into Virginia. Then we wore good [Pg 34] clothes and had Sunday Soldiering. Now we were soldiers with the dust of a thousand mile march, ragged and unkempt, bleeding from the wounds of two hard-fought battles and numerous skirmishes. Then we were raw, undisciplined troops, now we were seasoned veterans. Such was the change in a few short months.

Riding to a drug store, I hitched my horse, went in, and bought my wholesale bill of tobacco. When I came out again to the sidewalk I saw a policeman leading off my horse. I yelled at him to stop, but he went on, I rushed up and grabbed the reins. He told me it was against the law to hitch a horse to a post in that city. About that time twenty of our boys came running to my rescue. They lined up and told the policeman to turn the horse loose. He did the wise thing, or there would have been a “hot time” right there. I took the horse and I made a bee-line for General Braggs’ Brigade, and took joy and delight to my tobacco-starving friends.

November 2nd we passed through Knoxville and camped on the railroad. At daylight the 154th Regiment Band awoke us with the sweetest music I ever heard. It brought back such poignant memories of home, of the boys and girls around the piano, of charming plantation melodies.

But the next tune was not so sweet. It came to the tune of orders to “cook three days’ rations, and be ready to move at a moment’s notice.” We rode cars to Chattanooga, from there on November 10th we went to Bridgeport, Alabama. From Bridgeport we crossed the Tennessee River, marched fifty miles and camped at Alisonia. November 24th we marched twenty miles, passing through Tullahoma; November 25th we marched fifteen miles and camped on Duck River at a short distance from Shelbyville. At this time the Medical department decided to give all the one-course Medical students then in the army a chance to pass the examination for promotion to assistant surgeon. Dr. Arnold was one of these one-course students and decided to try the examination. We diked him out in the best clothes we could get together in the company. I contributed my white shirt, other boys [Pg 35] brought him hat, coat, shoes, and collar. When he stood before us for inspection he could have passed for a lawyer or preacher just from town. With his book, “Smith’s Compends,” he walked twenty miles to the Board of Examiners, stood before the “saw-bones,” shook and answered questions. Perhaps his borrowed plumage helped him, at any rate he passed, and was given a certificate. He walked back, changed from the rank of a private to that of a captain! When he came in sight two hundred braves met him; when shown his certificate they rode him on a rail and kept up a rough house for an hour or two. He had no horse, no money, and no books except his Smith’s Compends, but the older doctors helped him, and soon he was fully up in medical affairs and made a good surgeon too.

December 8th we marched twenty miles and camped at Eaglesville. From there we marched to College Hill.

December 28th we marched to Murfreesboro, and camped on Stone River within cannon shot of the town. Here we prepared to meet Rosecrans with his army, forty-five thousand in number. We were in line of battle on the extreme right. After dark on the thirtieth, still in line of battle, we moved our position to extreme left and camped, without fire, in a cedar rough. Our orders were to advance as soon as it was light enough to see. At dawn, December 31, we moved promptly on the enemy, advancing through an open field. The enemy, protected by a fence and the trees, received us with deadly fire and our loss was great. But we flew after them and our work was just as disastrous to them. Dead bluecoats were thick in every direction. We soon had them on the run.

Our company Color Bearer William Mathews, the same who had defied the Yankee fleet on the Potomac, had been ill and this was his first fight. As we followed the fleeing Yanks he said, “Boys, this is fun.” One of the men answered, “Stripes, don’t be so quick, this is not over yet; you may get a ninety-day furlough yet.” In twenty minutes Mathews’ arm was shot to pieces.

George Thomas was in front of all the company. He had killed two men and was pulling down on the third, [Pg 36] when one, but a short distance away, shot him, wounding him in the arm. But George spotted the man who shot him and wanted to go on with one good arm. However, he was taken off the field and sent to the hospital.

We drove the enemy three miles. The fire all along the line was terrific. The cannonading could be heard for miles. The rattle of small arms was continuous. Our line on the left was pressing on over a terrible cedar rough. Anyone who understands a cedar rough can understand what that means. Limestone rocks, gnarly cedar trees, stub arms sticking out of the ground, make it almost impassable at best. How much more difficult with an enemy in front concentrating his fire upon us. We pressed on through rocks and thicket. One of our brave boys, Arthur Green, was struck by a cannonball and torn all to pieces. Other parts of the line were as hot as ours. We got possession of the thicket but could not get the cannon through it; so we hardly got a man of their line.

When we got through, we found the Yanks with sixty cannon in line fronting the cedar rough. Our ranks were so depleted we could not charge two lines of infantry and sixty cannon. There was nothing to do but hold our position and await re-inforcements.

We lay in line all night. Orders were sent to the quarter-master to send rations, if he had any. Two negroes, belonging to two of the officers, arrived, bringing food for their masters.

As all was quiet then, and it was raining, they decided to sleep by the fire until daylight. To keep off the rain they drove forked branches into the ground, laid a brace across them, stretched their blankets over all, and pegged them to the ground at the four corners. Before long hard firing was heard on the outpost. Bullets rained on their tent, struck the logs of the fire, cut loose the corners of the blankets, letting the rain on their faces. When they saw the flying bullets, they awaited no instructions from their masters. With eyes popping out of their heads, they grabbed their blankets and set out for the wagon [Pg 37] train. They were not long in getting there.

Next day the struggle was renewed with fearful carnage.

Each side fought with grim and settled purpose, finally a fierce onslaught scattered our forces. In twenty minutes we lost two thousand men, and the day was lost. Orders for retreat were given.

General Braggs’ loss was about ten thousand men, while Rosecrans reported his at twelve thousand.

In the battle our Lieutenant Colonel Don McGregor was mortally wounded. When he was taken to the hospital, his faithful old Samuel was by his side. The Colonel’s sister, who lived a few miles from Murfreesboro, had come to relieve the suffering and nurse the wounded. (Ah, those brave, never-to-be-forgotten daughters of the South!) When she drove up to the hospital in her carriage she found Sam waiting with his own and his master’s horse saddled ready for the trip to her home. When we retreated General Rosecrans’ men came in, and his guard took the two horses, and drove off in the carriage. What could be done? Samuel said, “I will get them back.”

At this particular time of the unpleasantness, the Yankees were burning with sympathy for the poor, oppressed negro, and negroes were permitted to do pretty much as they pleased. Samuel went to Rosecrans’ headquarters, told him the horses were his, that he had a wounded friend in the hospital and he wanted a pass to the country. All his requests were granted. He drove the Colonel and his sister to her home, and nursed his master until he died.

After Colonel McGregor died Samuel got a pass through the lines and returned to our camp. He delivered the Colonel’s horse but kept his own and asked our Regiment Colonel for a pass to Arkansas. He then told the boys to write to their fathers, mothers and sweethearts, as he was going back home to see his mistress. We received answers to these letters, showing that Samuel had made the journey safely, faithful to the end.

We retreated by night. We were nearly starved. It was raining, cold, cold rain, and we were wet to the skin. We were so sleepy that if we stopped for a moment we would go to sleep. We had gone almost as far as human [Pg 38] nature could go.

One of the boys thought he would rest a few moments beside a fire left by some wagons. He took pine boughs and laid them on the wet ground, dropped down with all his accoutrements, and went to sleep. General Hardee came up, spied him, called to his Adjutant, “Roy, come here; here is a fellow who has gone regularly to bed.”

About then the soldier woke up very much frightened. He thought he would be shot. He got away from there in a hurry, and was with his command before his absence was discovered.

January 5th, 1863, we marched forty-two miles to Manchester. January 6th we marched eighteen miles to Alisonia. From Alisonia we marched to Tullahoma, and there we camped for the winter.

We were in General Hardee’s Division. We had tents and were comfortable. We drilled four hours a day, and by way of diversion General Hardee had contests in drilling. We become so expert that we could have made the Virginia Cadets ashamed of themselves. Our company was third best and that took good practice. A Louisiana company was ahead of us. It beat us in quickness at “trail arms”, “lie down”, at “double quick.” At walking or running none excelled us at any army maneuver. We had other amusements, too. We played “town ball” and “bull pen” and had some lively games. We dressed up the smaller fellows as girls and we danced. Joe Hamilton, Dick Hayden, Sam Shoup and Bill Barnes were the musicians. Bill Shackleford was ready to play pranks, and made fun for the crowd. Now and then we got a pass and sent our best foragers out for “fancy grub” and vegetables. Then we would have a big dinner and a big day.

April 23rd, real fun began again, but we were alive, active, young, healthy, well-drilled, well-disciplined—in perfect fighting trim. For fear we would forget how to march a walking track was opened up from Tullahoma, and we marched daily five, ten, eighteen, twenty, thirty miles, making expeditions to all the surrounding towns—Wartrace, Bellbuckle, Hoover’s Gap, Duck River, Bridge, [Pg 39] Railroad Gap, Manchester. Manchester was a nice little town in the hills, where there were numerous springs and streams in which we could swim. June 22nd we went there to relieve a Louisiana Regiment. When we arrived they were on dress parade, eleven hundred strong and their drill was simply fine, but they had never smelt powder nor marched at all. They wore nice caps, fine uniforms, white gloves, fine ——shop-made laced high shoes. They carried fat haversacks and new canteens, fine new fat knapsacks with lots of underclothing and even two pairs of shoes. They laughed at us in our shabby dress, with our dirty haversacks and no knapsacks. We had one suit of underwear wrapped in our blankets and our accoutrements were reduced to the lightest weight possible. They said we were too few to meet the enemy, but we told them we would stay with any who came to engage us. We also told them that they couldn’t get through one week’s campaign with such knapsacks. Some of the boys said, “We will follow in your wake and replenish our wardrobes.”

This was a sad camp to us. One of our men, Garret, got angry with Mr. Bragden, the Beef Sergeant, who divided the company rations. Taking his gun, he went to Bragden’s tent where he was unarmed and shot him like a dog. Garrett would have been lynched if the officers had not hurried him off to another part of the army.

June 27th we marched to Wartrace, June 29th to Tullahoma, June 30th we were deployed to build breastworks, but we retreated at eleven o’clock at night to Alisonia on Elk River.

July third, we camped in the Cumberland Mountains, near the school which had been established by General Polk and the Quintards. It was an ideal place for a school and I am glad to say it bears, today, an honored name among educators as the University of the South.

We had marched all day in the hot July sun, clouds of dust had parched our throats, and we were almost perishing for water when we reached the spring. As we rested at the side of the road whom should we see but our crack Louisiana Regiment—the one we had relieved at Manchester only ten days before. They were dusty, dirty, lame and halt, with feet sore and swollen in their tight shoes, [Pg 40] a bedraggled and woe begone set of youngsters. How we joshed them.

“Don’t cry, mama’s darling;” “Straighten up and be men;” “Brace up like soldiers, so the army won’t be ashamed of you.” These were some of the commands we hurled at them. They would have fought us if they could have stopped, but a soldier cannot break ranks.

July 4th, 1863, we camped in the valley on the Tennessee River. Then we crossed the River at Kelly Ford to Lookout Valley. July 9th we marched through Chattanooga and camped at Turner’s Station.

August 17th we marched to Graysville. Here Dr. T. R. Ashford got a four days’ furlough. Dr. Ashford had married in Georgia and had gone with his bride to Arkansas and established himself as a physician. When the war broke out he joined the army from his adopted home, going out as assistant surgeon in our regiment. His wife returned to her mother in Georgia and he had not seen her for two years. As Graysville was near her home, she came to visit him and there they had a happy meeting.

Dr. Ashford, always kind and sympathetic, was a great favorite with the boys. Highly educated and a fine surgeon, he was modest and unassuming, a sincere Christian gentleman. After the war he settled in Georgia. Dr. Ashford, Dr. Arnold and I were close friends through those long dreadful years.

August 21st we camped at Harrison on the Tennessee River. On August 23rd we marched fourteen miles and camped at Gardner’s Ferry.

Here several of the boys went foraging and got some nice green apples. George Thomas, Captain Shoup and others made apple dumplings and put them in a large camp kettle to cook.

They were standing around the fire, with mouths watering, thinking every minute an hour, when the Yankees on the other side of the river began to shell the camp. They had run up four globe-sighting 16 shotguns to the top of a small hill. We were too far from our guns and [Pg 41] there were no orders given to shoot, so they shelled us a plenty.

While the boys were watching the kettle a cannon ball struck the fire, upset the kettle, passed between the legs of one of the men and exploded a little farther on. This did not seem to cause any alarm. They had heard cannon balls explode before, but a mighty wail went up over the loss of the apple dumplings. The air was blue around there, and at that particular moment the boys would have charged the enemy joyously.

I was with the doctors that day. They had a negro who was a fine forager. He even brought us fried chicken. We had a royal spread in front of the doctors’ tent and were consuming the good things with great relish, when a cannon ball went through the tent! It looked like it was going to smash us to smithereens, grub and all! We got away from there. We grabbed the grub and, went down the line where we finished our meal. Not royally as we would have done, but hastily and stealthily.

But our sharp-shooters in the dumps on the river got even with them. The Yanks drove out into the field with two six-mule wagons to get some fine rebel fodder. There were about thirty men in all, teamsters and guards. Some of them stood on the rail pen surrounding the fodder, others climbed on the shock to begin at the top. Our sharp-shooters shot the mules first, then the men, and few lived to tell the tale. Sherman said, “War is Hell.” In this case it was hell to them.

September 10th we marched down the valley toward Lafayette. As the dust was a foot deep and water scarce we moved slowly and we went into camp about ten o’clock.

Dr. Scott of our Division, was sent for to see a citizen who was very ill. He went and relieved him, and left medicine, not asking pay for his services. After he had returned to camp a negro brought him a huge tray heaped with good things to eat. The doctor looked at the pile of grub, and said, “You boys must dine with me today, I can’t eat all of this.” We needed no further urging for our blue beef and water corn-dodger was rather poor fare. We lit into it, and as hungry wolves devour a sheep, so we devoured that pile of grub. Then the darkey took his [Pg 42] tray and departed with a note of thanks. Our gratitude was truly sincere.

September 19th battle was on hand. We were in General Polk’s Brigade, to which the Hardee Corps had been transferred. When orders were read we found ourselves named as reserves. Cannonading began on our right, and we were moved quickly to the sound of the shot, about three miles. As we drew nearer to it we were ordered to double-quick. When we came to Chickamauga Creek we began to pull off our shoes to wade when General Cleburne came along saying, “Boys, go through that river, we can’t wait.”

Through the creek we went, and were among the first to be engaged instead of being reserves. When our line was deployed and ordered forward we were the very first. We struck stubborn western troops who knew how to fight. The conflict was terrific and raged all day. When night fell the engagement was stopped. Throwing out skirmishers we found that the lines were mixed up terribly. We were among the Yankees and they were calling, “What command is this?” It was midnight before the lines were reformed. Then we had a night’s sleep on the ground, knowing that on the morrow some of us would fall in defense of our country—some of us would never see home and mother again. General Longstreet arrived in the night with re-inforcements, bringing a division from Virginia. At daybreak the struggle was renewed. On both sides was the determination, “God being our helper, we will win this day.” Wave after wave of deadly lead was sent against those Western troops, who contested every inch of the ground, who would stand a charge, and stay on the field. But our blood was hot, we fought for home, and against an invading foe and we could not give up at all. At the end of two days a battle of battles had been fought and won for the Confederate cause. But alas, how many Southern boys had bitten the dust. The field was so thickly strewn with dead we could scarcely walk over it without stepping on the corpses. Our Regiment lost 42 killed and 103 wounded, and of the 120,000 [Pg 43] men engaged on both sides, 28,000 were killed and wounded.

Longstreet’s men said to us, “Boys, you have tougher men to fight than we.”

If we had followed up our victory and had Forrest cut off the enemy’s supplies what a difference it would have made. We might have stretched our lines to the Kentucky border. Such are the mistakes of war.

At this battle one of the boys captured two horses and gave them to Dr. Arnold. He said he would draw feed for them and on the march I could ride one of them. I named my horse “General Thomas” but before we left our first camp the assistant surgeons could draw feed only for one horse so I was afoot as I had been for two years.

We established a line of breastworks on Missionary Ridge and held Lookout Mountain, a mountain over a mile in height, and, as we thought, commanded Chattanooga.

The Yankees saw that something must be done or things would be booming in Dixie. They brought to the front Dutch, Irish, Hottentots and all kinds of troops, and by the last of October the Sequatchie (?) (Wauhatchie?) Valley was swarming like a beehive.

Once a Dutch corps of 15,000 went down the valley through a gap to reach our rear. Bragg sent to meet them about 15,000 troops, placing them arrowed in front. He had a line under General Hindeman with orders, at a certain signal, to rush across, cutting them off entirely from the main army. The signal was never given and we do not know why to this day. At that signal we were to follow across the valley at double-quick but Mr. Dutch discovered he was in a trap and he marched out again.

There was a Union man living on the route of this Dutch Devil, who had not joined either army. He had lived on his farm unmolested by the Southern troops, and supposed that of course he would be protected by the Northern troops. As the Dutch marched down to attack us they stopped at this man’s home, searched the place, insulted his wife and knocked him down. As they came running back they had no time to tarry, but one at a time, a straggler, would drop into his smokehouse to see if there was one ham left. The Union man took a long, [Pg 44] keen bowie-knife and stood in the dark corner of the smokehouse; when only one man entered he stabbed him to the heart and put his body into the well. He killed three men. Next morning, he with his wife and children, walked into our camp. He said he was ready to fight to the bitter end. He took his family South and came back and made a bad soldier for them.

November 23, 24 and 25 we fought the “Battle Above the Clouds,” the terrible conflict of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge. We were fighting continuously during those three days. We were in breastworks on the ridge near Lookout Mountain, but when the fighting was fiercest we were sent to relieve the commands at the extreme right of the Yankee army. They came in solid front five columns deep and charged our breastworks but were driven back hour after hour with terrible slaughter. Late in the afternoon they made a concentrated attack on our center and drove our men out of line. We had to give up Lookout Mountain and we retreated to the Ridge about midnight. Throughout the night Sherman’s troops were coming up, and next day we were attacked in front and flank. Our breastworks were of no use as Lookout Mountain commanded the Ridge, so in spite of desperate struggles we were ordered to retreat.

At Chattanooga it had been agreed that there should be no firing on the line of pickets without notification. Here between the picket line and the main line of battle our sporting boys sought “sheckle luck,” those who were fortunate enough to have a few sheckles of Confederate money. One day when General Hardee was officer of the day he ordered a regiment deployed around the gamblers, but soldiers from all parts of the field yelled to the boys to run, and run they did. General Hardee did not get many.

In our company was a Kentucky lad named Barnett who had a brother in the Union Army. They got permission to spend the day together. When the day was over they separated, each going back to his command. That [Pg 45] was a war! Brother against brother, father against son, arrayed in deadly combat.

We went to Dalton, marching all night. As we crossed the river it seemed the coldest night our thinly clad men had ever experienced. Our corps under Hardee was the rear guard. General Cleburne’s Division was immediately in the rear. General Polk was our Brigadier General. About two o’clock we passed General Cleburne.

[ … ]

mountain, looking and thinking.

“Something is going to happen” I said to the boys.

“Why?”

“Look at General Cleburne, don’t you see war in his eyes?”

We had crossed Ringold Mountain, but we were sent back to take the horses from the cannon, put men in their places, and pulled it quickly to the top of the mountain, so to the summit over rocks and between trees two pieces were carried. Our regiment was sent to the top with them. Two minutes more would have been too late. Not fifty yards away on the other side of the hill were Yankees climbing for the same goal. Then the firing began. We had the advantage in having a tree to use as breastworks, and in being able to see them. Whenever one stepped aside from his tree to shoot our men got him. Captain Shoup and John Baird rolled rocks down the hill and when a Yankee dodged the other boys shot him. We picked off dozens. When the cannon was got ready and began shelling the woods, breaking the trees, tearing up rocks and showering them on the lines below, they had to break and retreat in haste down the hill.

If we had not got there as soon as we did our line would have been the one to retreat.

General Cleburne took us next to Ringold Gap, a gap dug by the railroad through the mountain. He made a talk to the boys, telling us that we were there to save the army, which was five miles away and could not possibly get help to us. Our task would require nerve and will of which he knew we had plenty. We were to form two lines of battle across the gap and were not to fire until he gave the signal, (by signs, as commands would not be [Pg 46] heard in the roar of guns.)

The Yankees having failed to break our line on the mountain had massed their forces at the gap, determined to break Cleburne’s line, when the rest would be easy for them.