You’d have thought every wing and paw in the Woods and Fields (except the Bad Little Owls, of course) would have been glad to know that Silvertip the Fox was caught. ’Specially Nibble Rabbit, who started the hunt, and wise old Doctor Muskrat, who planned it, and Tommy Peele’s good dog, Watch, and Trailer the Hound, who were still barking on his trail way out in the middle of the Deep Woods. For Silvertip was just as clever as he was wicked; the very last thing he’d done was to fool those two dogs again.

I s’pose old Grandpop Snapping Turtle, who did the catching was—glad, I mean. But Doctor Muskrat just looked very, very sober, and Nibble felt the shivers run from the puff on his tufty tail to the tips of his tickly whiskers whenever he thought about it. They didn’t have a word to say while they waited for the two hunters to come back to the meeting-place by the flat stone at the edge of the Pond.

But they thought of course the dogs would bark the good news so loud that Tommy could hear it way down the road at the schoolhouse. Instead, Trailer just gasped, “How awful!” in a very awed voice. And Watch looked as if somebody’d rubbed him the wrong way.

“Awful!” repeated Trailer. “Poor Silvertip! Think of his being caught by a stupid old mud-grubber like that!” He drooped his tail and ears.

“Why, that’s just the way I felt about it!” Nibble exclaimed. “But I never dreamed you would. I thought you hated him.”

“Hate him!” said both dogs at once. “Why, he was the smartest Beast we ever chased. We hadn’t any reason to hate him.”

That certainly made Nibble open his eyes pretty wide. “Then why did you try to kill him?” he demanded. “Was it because you’re hungry?” He was glad to know that the Pickery Things were close behind him when he asked that.

Trailer laughed. “I’m always hungry.” But his tail went up when he said it, so Nibble didn’t run. “But that isn’t why I hunt. You have to know a beast to hate him. I’ve killed plenty of beasts I never saw before I found their trail. Lots that I don’t eat, either.”

“I couldn’t do that!” Nibble gasped and Doctor Muskrat nodded.

“Of course not,” said Trailer, quite proudly, too. “But that’s what I was made for. My mother taught me to use my nose before my eyes were open and to sing the trailing song as soon as I could talk above a whimper.”

“Sing it,” begged the woodsfolk. “Please.”

Trailer raised his head and bayed with an open throat:

“You see,” he explained, “one dog doesn’t do all the singing. He sings one line and someone else answers with the next one, round and round again.”

The sound sent a queer, scary thrill through Nibble Rabbit. But now he wasn’t really afraid of the smiling hound any more than he was of Watch.

Watch sat with his ears pricked and his nostrils twitching while he listened to the Hound’s Hunting Song. “Eh, but that’s grand!” he barked. “It puts the tickle into your feet to be up and running.”

Nibble Rabbit squirmed closer to the Pickery Things. He wasn’t afraid of the dogs, but he felt very queer. “It starts my feet tickling, too,” he sniffed. “And my fur’s all fluffed out like a moulting bird.”

Trailer laughed. “That’s partly what we sing it for,” he explained. “It rouses up you Game Beasts and gets you running, and when your coat stands up on end your scent is easier to follow.”

“You don’t say?” Nibble’s eyes were sparkling. “Then that’s why the Quail say ‘Hold your scent!’ when they mean ‘sleek down your feathers.’”

“Exactly,” nodded Trailer. “And they’re so clever that it takes a special dog, who makes a business of birds, to find them. He has a special song, too, but I never learned it. I only follow furry things.”

“That was splendid!” put in Doctor Muskrat, who had been listening thoughtfully to the talk. He wasn’t at all sorry because the dogs had politely left him a clear path to the water. He could have dived in a flash if he had wanted to. “You’ve made the frogs very jealous, Mr. Trailer.” Sure enough, the frogs were tuning up all over the pond. “There’s something very queer about this,” he went on. “Your song doesn’t do anything to me—because I’ve never been chased that way. But there was one dog, a noisy little one, who used to drive me nearly out of my wits when I was younger.”

“That might have been Spice the Terrier, who was here when I was a pup,” said Watch. “I know his song well enough. He was always shouting it at something.

Watch had fairly snapped out Spice’s song.

“That’s it!” squealed the Doctor. “That’s the very song—and look at my fur! It will take a dip in cold water to smooth it again.” He was as fluffy as Tad Coon’s tail. “Now, Watch, what’s your song?”

“Oh, I’m no regular kind of a dog, so I really haven’t any,” said Watch, looking a bit regretful. “I just do—whatever I’m told the best I can and”—here his ears pricked and his tail began to wag—“I look after Tommy Peele.”

“But why must you always do things?” said Nibble.

“Why, everyone has to have a job of some kind,” said Trailer. “Or else he’s a worthless old scrump not worth feeding. And, if it’s really your own special job, you enjoy doing it. I love to hunt, but I wouldn’t care much about driving cows.”

“Sure you would if you learned how,” said Watch. “I really do.”

“There, you see?” laughed Trailer. And Nibble nodded.

“Speaking of driving cows,” smiled Trailer, “who do you think drove up to Tommy Peele’s this morning?” He said it to tease Watch. He and Watch had gone out before daybreak to hunt Silvertip and now it was way past milking time.

But Watch wasn’t teased a bit.

“The cows slept in the barn,” he grinned. “Nobody had to drive them—so there! The only job I have waiting for me right now is to clean up my breakfast plate before Chirp Sparrow gets his scratchy little feet into it.”

Trailer forgot all about how tired he was. “Fine,” said he. “I’m ready to help you.” And off they trotted with their tails waving.

“I wonder why all the Tame Beasts have work to do or milk to give or eggs or whatever it happens to be?” Nibble Rabbit remarked. “We don’t What’s our job, Doctor Muskrat? Trailer says a Beast without a job isn’t worth feeding.”

“That’s just the point.” The doctor’s bright eyes were twinkling. “You silly rabbit! Do you think Trailer would be so nice and obedient to Watch and Tommy if he didn’t know the people up at the house would feed him? If he had to catch his breakfast or go hungry there wouldn’t be any bunny. He licked his lips every time he sniffed you. But so long as he does what he’s told, Tommy’ll feed him. We feed ourselves.”

“I see.” Nibble flicked his tail thoughtfully. “And we find our own holes and take care of ourselves and we like doing it.”

“Do we, indeed?” said a whiny, complainy voice from the bulrushes on the bank. “Is that dog gone?” It was Tad Coon. He came splashing out of the water and flopped down in the sun. Then he got very busy with his funny little paws. The front ones were handy ones, but the hind feet made a print like a baby’s would except that there was a little round hole, where the claw pricked, in front of every toe. He would wipe them in his warm fur and lick them, one by one, with his warm tongue. Nibble couldn’t think what he was doing.

“There,” he said at last, not quite so crossly. “I can feel with them. The water’s awfully cold. And I had to stand in it all the time you beasts were talking. That hound is my very worst enemy—I can’t yet see for the life of me why he didn’t make a snap at Nibble Rabbit.”

“Because I belong to Tommy Peele,” Nibble explained. “Why don’t you make friends with him?”

“Huh!” grunted Tad, crosser than ever. “Do you s’pose those dogs would let me? Never!”

You know Nibble Rabbit. First he’s scared and next he’s curious. That’s why he has such a very good time—he’s always finding out about new things. But you don’t know Tad Coon—not yet. There’s this about Tad Coon. First, he’s very, very unhappy and then suddenly he’s got a lovely joke on someone.

He was very unhappy on this particular morning, though he was spread out very comfortably in the warm sun where Trailer had lain. Still he kept on complaining.

“It isn’t any trouble to you fellows to find a hole,” he was saying. “A nice spot to dig and there you are. But I live in trees, and not every tree in the woods has a big enough hollow for me to hide in. I used to sleep in that big oak—it went and blew down in the Terrible Storm” (he said this exactly as though the poor old oak did it on purpose), “and I had another that the wood-duck nested in. Silvertip the Fox spoiled the nest and he didn’t leave me a single egg, either. And I had the nicest of all in a great big elm; now there’s a cross old mother coon with four young ones in it. I haven’t any place to go-o-o!”

“That’s too bad,” said Doctor Muskrat, edging nearer the water because Tad Coon’s temper isn’t very good.

“Get a square meal and then you won’t want to sit there squalling like a blind kitten.” And in he dove.

Tad Coon didn’t dive after him. He didn’t even get angry. He just went on wailing, “I haven’t eaten anything but frogs all spring and I’m so sick of them I can’t bear the sight of them.”

“Try fish, then,” advised Doctor Muskrat, from the pond.

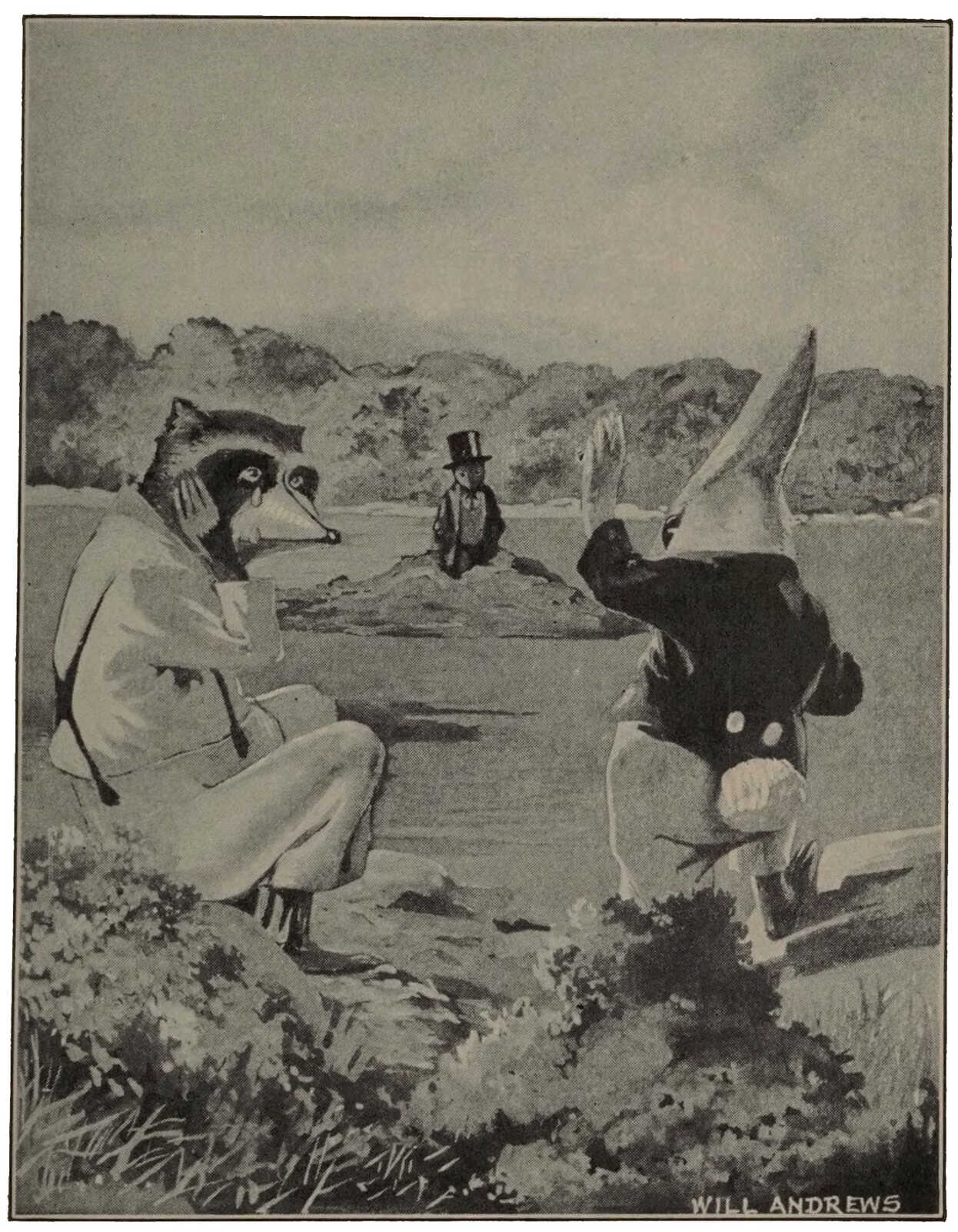

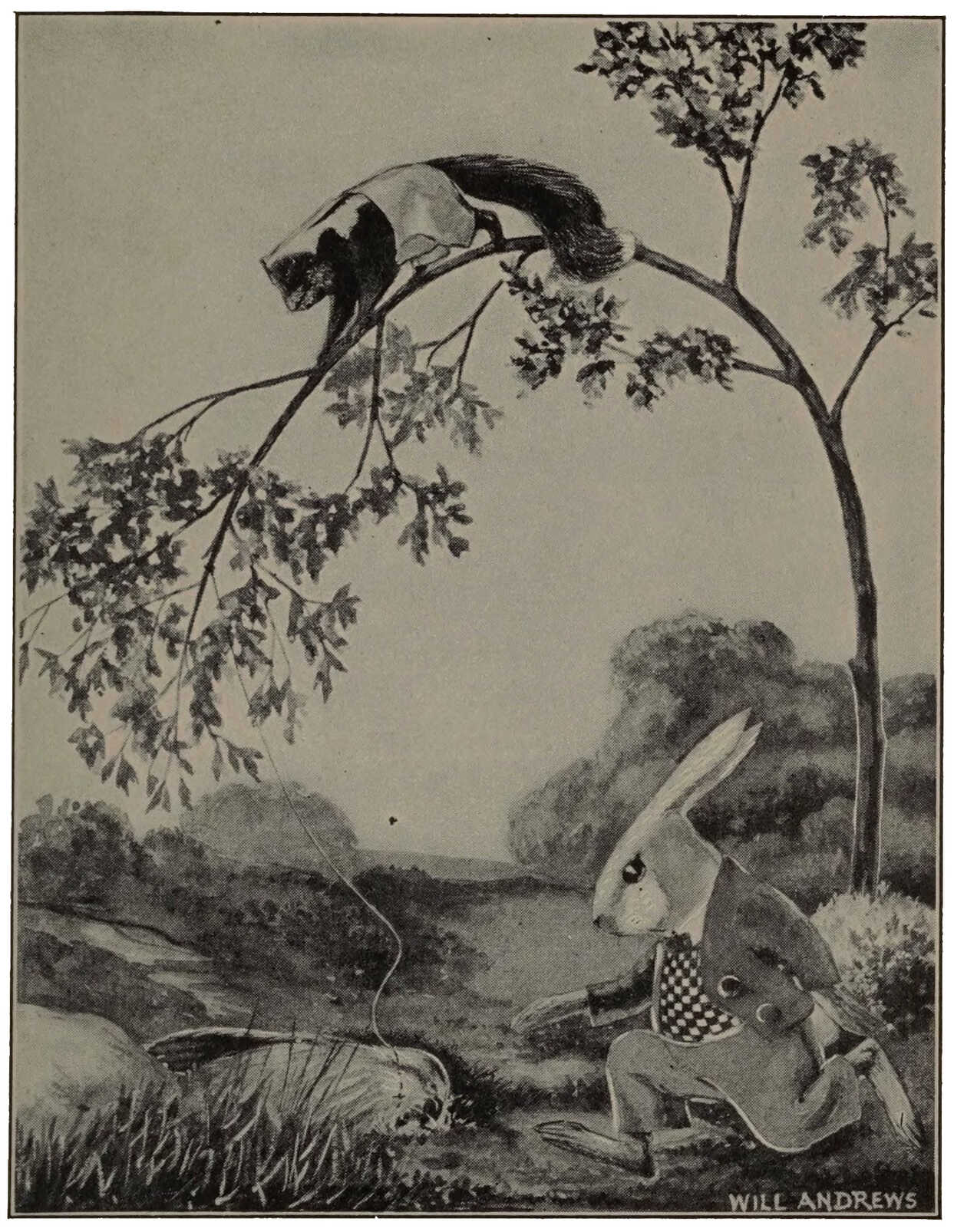

Tad Coon stopped whimpering. He looked at Doctor Muskrat, and then he looked at Nibble Rabbit. “I believe I will,” he said. And he looked at Nibble again. Then he walked out on the flat stone that used to be Doctor Muskrat’s.

“Don’t go in there,” warned Nibble. “That’s right where Grandpop Snapping Turtle just caught Silvertip the Fox.”

“I know that,” answered Tad. “I don’t dive; I go fishing. I take my tail—” and he did it—“like this. And I tickle the water—like this. And when a fish comes up, thinking it’s a fly just dropped in the water, I reach out my paw and catch him. Move around behind me, so you won’t cast a shadow. I must see what I’m doing.”

So Nibble moved around where Tad told him to and craned his neck. This looked interesting.

Swish, swish, swish, went Tad Coon’s bushy tail. He cocked his head. Swish—out went his hand—splash, went a great big wave all over Nibble Rabbit.

“Ugh! Snff-snff-choo-a-a-ka-choo!” he sneezed. He stamped his feet angrily.

Tad looked over his shoulder and then went back to his fishing as though he didn’t know what he had done, but Nibble could hear him snort as he tried to choke down his laughter, and his fur was shaking.

Tad was sitting right over the place where Grandpop Snapping Turtle had caught Silvertip the Fox. Tad knew perfectly well he was there, but it would take something smarter than a loggy old turtle to catch Tad Coon. Besides, he knew, too, that Grandpop Snapping Turtle wouldn’t pay attention to anything else until Silvertip was all eaten up. So he sat there flicking the water with the tip-end of his tail, pretending he was fooling the fish into thinking it was a fly alighting. He was trying to think up another trick to play.

But there was one thing Tad didn’t know. He didn’t know what Doctor Muskrat was doing. Doctor Muskrat was paddling around in the pond, diving now and then as though he were fishing—and so he was, fishing up trouble for Tad Coon. The first time he came up to find out the meaning of Tad’s splash he sniffed. And it wasn’t to blow the water out of his nose—it was to make Nibble look at him. Nibble did look. And Doctor Muskrat closed both of his eyes in a big wink. After that you can be pretty sure Nibble kept his eyes on that playful tail of Tad Coon.

Flick! it went. Swish! For Tad wasn’t thinking what he was doing. He had an idea for another joke. “Pop!” Up comes the ugly head of Grandpop Snapping Turtle, his beady eyes peering, his hissy mouth open. Snap! it went on the end of that playful tail. Jerk! And Tad Coon was bouncing up the bank, his fluffy breeches sticking straight out with fright. And when Grandpop Snapping Turtle’s ugly head sank back it was wearing whiskers—whiskers which used to belong to the very last tip-end of that smarty coon’s tail.

And then didn’t Doctor Muskrat and Nibble Rabbit have their turn to chuckle! Nibble laughed till he stamped, only this time he wasn’t the one who was angry. And Doctor Muskrat paddled away round and came up on the bank beside him.

“What made Grandpop Snapping Turtle wake up?” asked Nibble.

“Mussel shells,” giggled the wise muskrat. “You know Bobby Robin’s story about the Babes in the Woods that the robins covered with leaves? That’s just what I’ve been doing to Silvertip. Only leaves don’t sink, so I used empty mussel shells. I’ve shied them down at him until Grandpop Snapping Turtle couldn’t take a bite without getting his beak into one of them. He thinks Tad Coon did it.”

“He-he!” snickered Nibble Rabbit. “And Tad Coon blames it all right back on him!”

“Ow, ow, ow!” wailed Tad from way up the bank in the Pickery Things. And he had the tip of his tail in his mouth, so you could hardly make out what he was saying. “Ow, ow, my tail’s bitten right off!” “Do you think it’s really as bad as all that?” asked Nibble anxiously. Tad’s eyes were bulging so wide that they showed white all round them when he went bouncing off the flat stone. If he were really truly hurt it wouldn’t seem so funny. They liked him.

“Let’s go and see,” said the doctor, and he scuffled up the bank as fast as he could travel. “Did that turtle really bite you?” he asked. “Let me look so I’ll know what kind of a remedy to go after.”

So Tad took his tail out of his mouth and showed it to the doctor. He wouldn’t look at it himself for fear there would be blood on it. Tad’s very timid that way. And Doctor Muskrat examined it carefully. At last he said: “Why, Tad Coon, there’s nothing wrong with this tail.”

“Isn’t there?” asked Tad in a relieved voice. “It felt as if there was. It truly did.” So he took back his tail and combed the hair out and examined it most carefully with his little handy-paws, but all he could find was a tiny weeny bare spot at the very tip where Grandpop Snapping Turtle had pulled the hair out. “That’s good,” he smiled with a satisfied air. He wasn’t the least bit ashamed of having made such a fuss about nothing.

He wasn’t even thinking about it. Pretty soon he burst right out laughing. “Ho, ho! That old turtle’s got tickly coon hairs in his mouth. I hope they set him choking.” Then he cocked his head on one side and the most mischievous sparkle came into his dark brown eyes which peer out from a band of dark brown fur that lies across his nose like a pair of goggles. “I’ll get even with him,” he chuckled. “I’ll find his nest when his wife comes out to lay her eggs on the beach and I’ll eat every last one of them.”

“That won’t be till June,” answered Doctor Muskrat. “You’d better find something else in the meantime. I know where there are some marshmallow roots and we’ll all share them.”

“That sounds fine,” Tad agreed. “Just wait a minute.”

“What do you s’pose he’s up to now?” asked Nibble curiously.

But he knew in just a moment. Tad found himself a nice big rock. And he shoved and pushed and tugged and grunted until he worked it out on the edge of the flat stone and sent it crashing down on top of Grandpop Snapping Turtle.

Kerchug! went the rock. And that was the last straw that broke Grandpop Snapping Turtle’s temper. He came flopping up on land as fast as he could travel. And he had his wicked eye on Tad Coon.

Swish, went Doctor Muskrat back into the water. That was the safest place for him because he can swim as fast as any one and a little bit faster than any turtle who ever flipped a paddle. Bounce, went Nibble Rabbit clear through the woods and past the Brushpile and out into the head of the Broad Field before he stopped to listen. Scritch, scratch, went lazy Tad Coon to the top of a big stump where Grandpop Snapping Turtle couldn’t reach him. And that turtle was digging in his claws and tearing up the earth as he marched round and round it, reaching up his long neck and hissing: “Just you wait till I get hold of your leg with my bite that never lets go!”

“Grandpop’s lost his temper,” said Nibble to himself. “Something’s sure to happen. It always does. It happened to Chatter Squirrel and Silvertip the Fox, and Mrs. Hooter, and the Red Cow——” Here he pricked up his ears, for Watch the Dog was barking at the other end of the pasture. And Watch had Tommy Peele and Tommy’s big cousin Sandy and Trailer the Hound with him. So he signalled Watch to hurry. Then he hurried back to hide in the Pickery Things where he could see what that happening was going to be. He was so curious he forgot all about Tad Coon.

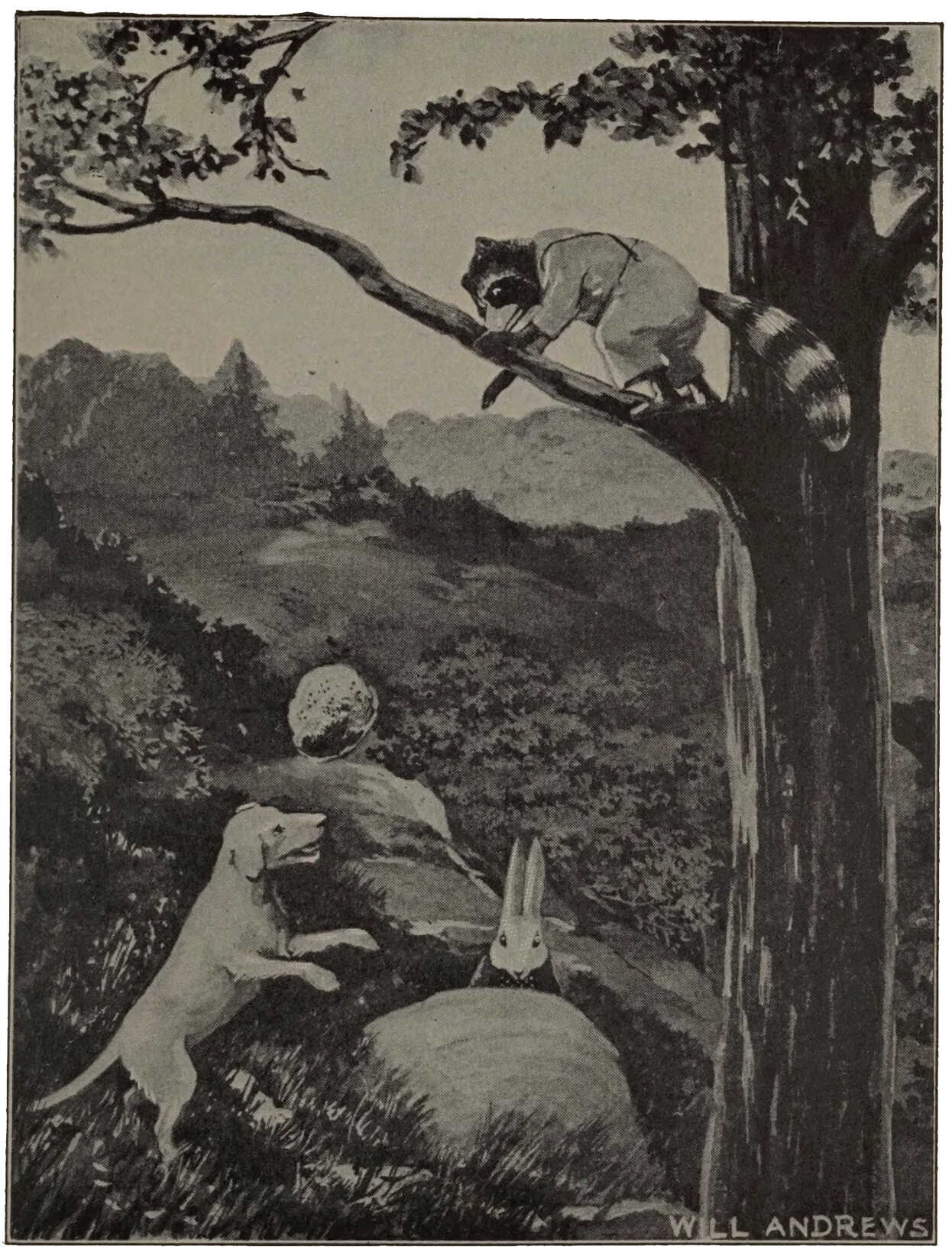

But Tad Coon hadn’t forgotten about himself. He hadn’t lost his temper. As soon as he heard the dogs coming he watched his chance while Grandpop Snapping Turtle was on the far side of the stump and jumped over to the nearest tree. And you should have seen his little handy-paws shin up it!

So all Tommy Peele and his cousin Sandy found was a spitting, swearing old shellback marching round and round that stump.

“Oh-h-h!” shouted Sandy. “Turtle soup for supper. Um-m!”

“Don’t hurt him!” cried Tommy. “He doesn’t do any harm.”

“Doesn’t he?” exclaimed Sandy. “He just spoils all the fishing in your pond, and he’s simply death on muskrats.”

Of course that settled Tommy Peele, because Doctor Muskrat was his friend.

So Sandy took up a long stick and held it out in front of Grandpop Snapping Turtle. “Ah-h-h!” he hissed triumphantly. And he grabbed it right in the middle with his bite that never lets go.

“Pick up the other end,” said Sandy. Tommy did, and there they had the turtle hanging between them, so blazing angry and so proud of his bite that won’t let go, that he never noticed that they were carrying him farther and farther away from his pond. And that was the last Nibble ever saw of him.

But there was a whole lot of excitement near the Pond. There was Tad Coon snug in the crotch of a tree, there was Trailer the Hound sniffing the top of the stump where Tad had sat to keep out of reach of the angry turtle, and there was Nibble Rabbit snuggled beneath the Pickery Things, so curious that he couldn’t sit still.

Pretty soon Trailer began to whimper. “Coon, coon, coon,” he said to himself. “Where did he come from? Where did he go?” And he was so puzzled that he shook his head until his ears flopped.

That was too much for Tad Coon. He pulled off a strip of bark and dropped it right on top of Trailer. The hound jumped as though something had stung him.

And wasn’t Nibble surprised? He didn’t see how Tad dared play tricks on the very dog he said was his worst enemy.

Pretty soon Tad began to call out: “Hey; you hound, go away! I want to come down before that Man with the gun gets back here.”

“Go away?” barked Trailer. “I most certainly won’t. I’ll stay right here and keep you until I see what Sandy and Tommy Peele want to do with you.”

“Tommy won’t hurt you,” shouted Nibble. “He’ll just make friends with you.”

“No, thank you,” grinned Tad Coon. “Not the way he makes friends. I don’t want to be trapped like you and Doctor Muskrat, and I don’t want to be hunted like Silvertip the Fox. I’m going.”

“But you haven’t been stealing his chickens like Silvertip did,” argued Nibble.

“How do you know?” asked Tad. For it was his guilty conscience that made him afraid. He didn’t exactly steal Tommy Peele’s chickens, but he had eaten some eggs that were very nearly hatched. And all this time Nibble could see him working away at something with his little handy-paws. Pretty soon he called again: “Mister Hound, I asks you for the last time, are you going to let me down?”

“Yah!” barked Trailer. “I ’most certainly am not.”

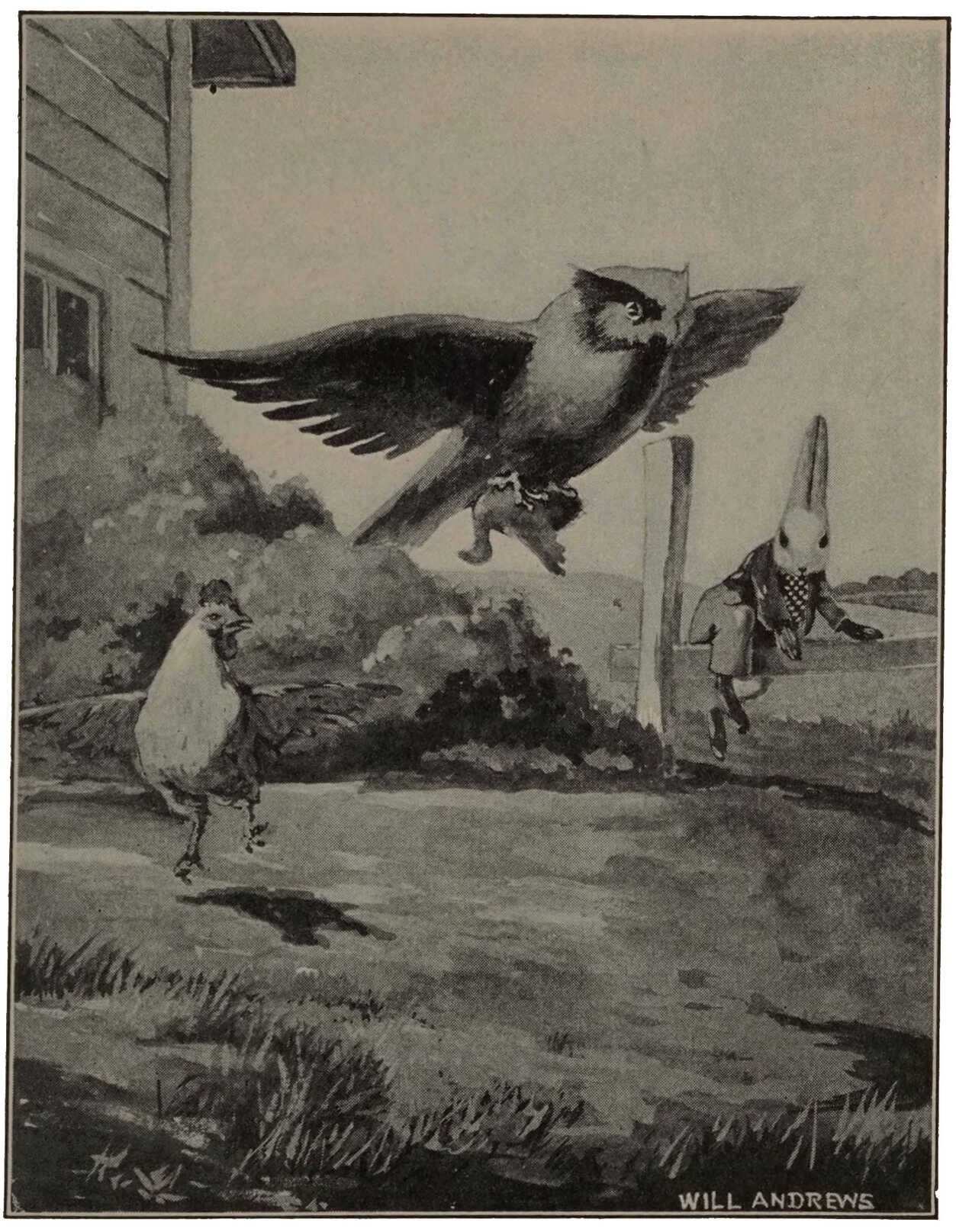

“Hm,” sniffed Tad Coon. “We’ll see about that, then.” Blam! He hit Trailer square on the head with something. And this time the hound jumped because he really was stung. “Ow, ow, ow!” he yelped, and he started for home on the run with a trail of buzzing insects strung out behind him.

“Run, run, run!” squalled Tad. “Look at that hound run! He’s only hitting the high spots. Ye-a-o-u-w! See him go!” And he danced about on the limb until the limb danced with him.

Trailer was surely running—faster than ever he’d run on any trail. But this time he wasn’t chasing any one—the buzzers were chasing him. For it wasn’t a piece of bark Tad threw down the last time—it was the fat round nest of some paper wasps.

Nibble Rabbit wasn’t seeing any of the fun. He knew something about paper wasps. They were buzzing all over everywhere, and they don’t care who they sting when they get angry. He sat very still in the Pickery Things with his twitchy nose tucked down between his furry feet, and his waggly ears laid flat back, and his bright eyes squinched up as tight as ever he could shut them. Some of those wasps flew right by him and never knew he was anything but a round stone—not even the one that tangled its legs in his whiskers. He did feel awfully sorry for poor Trailer; but all the same Tad Coon had been pretty smart to send him home.

But Tad Coon wasn’t quite as smart as he thought he was. Trailer ran so fast that he left most of those wasps behind him. And he went bouncing through the brush at such a rate that he scraped a lot more off of him. Pretty soon they began coming back to where their nest had been. And they couldn’t find it. That didn’t improve their tempers, I can tell you. But if they couldn’t find their nest, they certainly could find Tad Coon. And just didn’t they?

Now it was Tad’s turn to howl. “Ow-ow-ow!” he cried. And he squinched up his eyes as tight as ever Nibble did and began to scramble down as fast as ever his little handy-paws would let him. But when he opened his mouth a wasp stung him right on the tongue, and when he shut it his little black nose got the stinging. And when he tried to cover it with his paw he lost his hold and went tumbling down to the ground.

Blam! It almost knocked the breath out of him. But he rolled over and over till he found his feet and then he scuttled to Doctor Muskrat’s Pond as fast as he could limp on three of them. He kept trying to brush the wasps off his nose and ears with the other one, until he could jump into the water. And then he splashed around as hard as ever he could. The wasps didn’t like that a little bit, because they can’t fly when their wings get wet. So they went away and left him.

Then poor Tad Coon began shouting: “Do’ Mu’a! Do’ Mu’a!” Because his poor stung tongue couldn’t say Doctor Muskrat.

He wished he hadn’t dropped that wasps’ nest down on Trailer. And he wished those wasps hadn’t come back and stung him. And he wished he hadn’t fallen out of the tree and bumped himself. And he wished his nose wasn’t swollen up so he couldn’t see around it. And he wished his poor tongue wasn’t hanging out of the corner of his mouth with such a great big sting that he couldn’t say any of his wishes. All he could do was shout “Do’ Mu’a!” when he was trying with all his might to shout “Doctor Muskrat!” And Doctor Muskrat wouldn’t come.

But Nibble Rabbit did. And when he heard Tad Coon’s great big sobs and saw the tears in his eyes he felt mighty sorry for him. So he began to thump and pound for the doctor.

Pretty soon Doctor Muskrat came out on top of his house in the middle of the pond and answered. “I hear you,” he snapped. “And I heard Tad Coon in the first place. But I’m not going to do anything for him. I don’t mind the funny tricks he plays, but that one just played on Trailer the Hound was cruel.”

“I ’o,” sniffed Tad. “I i’ ‘o’ i’ u’ hu’ ho.”

“He didn’t know it would hurt so,” Nibble translated. “Don’t scratch your ears, Tad. Come over and let me lick them.”

“That’s no excuse,” said Doctor Muskrat severely. “What if Tommy Peele thinks we did it? That hound can’t explain. And he doesn’t know anybody else is here with us.”

“Yes, but Tad doesn’t know Tommy,” Nibble pleaded. “He’s awfully afraid of being caught. You know how that hurts your own self. And lots of times they put coons in cages, and I didn’t like my cage. But he’s sorry as anything that he did it.”

“So I see,” said the doctor, just as gruffly as ever, and he dove back into the pond. Poor Tad hitched himself over to the flat stone so Nibble could fix his ears while he splashed the cool water over his nose and tongue. My, but he was meek! He didn’t even blame Doctor Muskrat for being angry with him.

Then suddenly up popped a head right beside him. “Open your mouth,” said the doctor. “Bite on that.” And he slipped a soft, soothing chewed root poultice on to Tad’s tongue. “Now raise your head.” And he clapped a blue clay plaster on Tad’s nose. “Snort!” And Tad snorted a pair of holes to breathe through. “There,” said he; “you’ll be all right before long.”

But Nibble had his ears pricked. “There comes Watch,” he said. “I heard him bark. Tad can’t run.”

“You hide him in the Pickery Things,” ordered the doctor. “I’ll try to get this matter settled.”

“M-m-m-m!” grunted Tad Coon gratefully through his poultice. And he limped off after Nibble, still holding up his nose.

“Aough, aough!” barked Watch. “Yah!” he yapped breathlessly when he found Doctor Muskrat sitting out on the flat stone, waiting to meet him. “You’re just who I was looking for. Trailer just stumbled up to the house with his eyes bunged shut and his nose as big as a soupbone, mumbling something about a coon as near as I can understand him. But no coon ever did anything like that to him.”

The doctor cocked his ears. “Can’t talk, can’t he? Poor fellow. Did you try what blue clay will do for him? I’ll get you some.”

“Ok, he’ll be all right. His master Sandy’s working over him,” Watch answered. “But what did do it?”

“Those striped buzzers with hot spots in their tails. They’re over there guarding the nest that fell down on Trailer. The rest of them are building a new one up in that tree—and you just ought to have seen what they did to poor Tad Coon. He was up there hiding.”

“Well, you just tell him to stay hidden, too,” whined Watch, stretching his stiff legs thoughtfully. “I’ve had enough of hunting after Silvertip the Fox to last me awhile.”

“But what happened to Grandpop Snapping Turtle?” called Nibble from the Pickery Things.

“He’s in a pot on the fire right now,” answered Watch.

“What’s a pot? What’s a fire?” asked the two wild folks.

“Fire? You know fire. When men make that red spot that’s all hot—like a buzzer’s tail, you know—come out of the end of a stick—that’s fire,” he explained.

“They do it to the bulrushes,” nodded the doctor. “The red spot gets bigger and bigger until everything’s red and then the hot things disappear.”

“Exactly. But men don’t always let it make everything red. They keep it in one place and use it to cook with. They’re cooking Grandpop.”

“Cooking?” echoed Nibble and Doctor Muskrat.

“Bare bones and broken biscuits!” sniffed Watch. “I can’t explain that to you any more than I can explain about the buzzers to Tommy Peele. But I can show them to him—and I’d better.” So off he set with his tail drooping because he was puzzled.

“It isn’t so very queer that Tommy Peele’s own dog can’t tell him that Grandpop Snapping Turtle ate Silvertip, when you really come to think about it,” observed Nibble Rabbit thoughtfully. “Tommy can’t even talk to the tame beasts. That’s why Watch has to take him all the way down here to the pond to show him these striped buzzers before he’ll understand who bit Trailer. But I don’t see why Watch can’t tell us what Tommy did to Grandpop Snapping Turtle. They certainly didn’t put an ugly thing like that in any cage.”

“There!” exclaimed Doctor Muskrat. “He can’t make us understand what he’s talking about because we Woodsfolk haven’t the words for things we’ve never seen. Those man-words Watch uses don’t mean anything to us. You talk about a cage. I don’t know what you mean and you can’t even tell me.”

“Why, a cage,” Nibble began—“a cage is a sort of a cave, only it isn’t in the ground. It bites like wood, but it doesn’t look like any tree I ever saw, and it has something in front of it that you can see through and the wind can blow through, but you can’t jump through it.” Now we might guess that was a packing-box with a big open front of chicken-wire. But even Nibble couldn’t be sure of wood when its bark was off.

“Um-hm!” grinned Doctor Muskrat. “A cave that isn’t in the ground? Wood that isn’t in a tree? What does that mean?”

Nibble laughed at himself. To one of the Woodsfolk it did sound foolish.

“Now if a cage is like a barn, only little,” said the doctor, “I can think about it. I’ve seen a barn from the outside, and if it’s hollow like a tree I can guess what the inside is like.”

“It is! It is!” Nibble cried. “Why didn’t I think of that?”

“Then Grandpop Snapping Turtle can’t live in one. He can’t eat unless he’s under water. Watch says Tommy’s cooking him. I don’t know what that means, either, but I can guess. Tommy eats him. There isn’t anything that hasn’t someone who eats it and no one else can eat Grandpop unless Tommy Peele does.”

“Maybe,” Nibble agreed; “but the real question is what will Tommy do to Tad Coon. Tad can’t run away, and Watch knows he’s here. If Tommy is very angry because Tad made those striped buzzers bite Trailer he’ll make Watch find him.”

“If Tommy’s eaten Grandpop he won’t be a bit hungry,” began Doctor Muskrat hopefully. Then a bright idea struck him. “And Tommy’ll never know Tad’s to blame. No one can tell him!”

“That’s so!” Nibble exclaimed. “No one can!”

All the same, when Nibble heard Watch bringing Tommy to the woods to show him the paper wasps’ nest so he’d know who bit Trailer, the rabbit couldn’t help feeling that something would go wrong. Tommy would find out and then wouldn’t he be angry with Tad Coon! And neither Nibble nor Doctor Muskrat could bear to have Tad hunted like Silvertip the Fox. Poor Tad couldn’t even run.

Watch galloped up to the wasps’ nest and barked. “There they are, Tommy. They did it. Those are the buzzers with hot tails I’ve been trying to tell you about.”

“That’s funny,” said Tommy, and he looked right up into the tree. The wasps up there were buzzing over which was the best twig to begin building another nest on. “I wonder how it came to fall down.”

Of course Nibble didn’t understand him—but Watch did! “Yow!” he barked. “That coon made it fall. Trailer was trying to tell me. Coon, coon, coon!” he sang, sniffing around to find him.

“Lie still,” warned Doctor Muskrat, who was hiding with Tad in the Pickery Things.

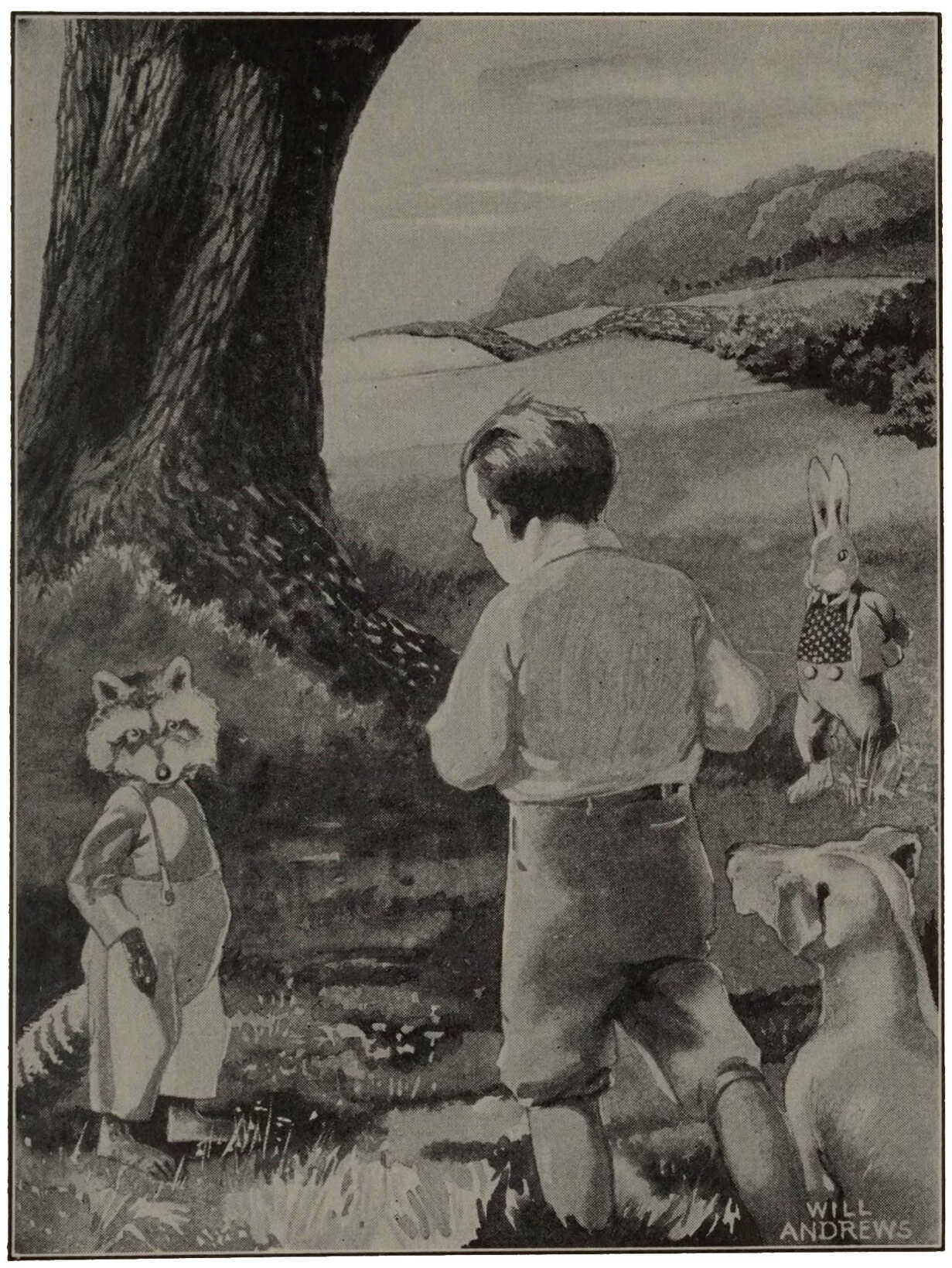

“I can’t,” whimpered Tad. “This place is all right for a rabbit, but the pond is where I belong.” And with that he staggered to his feet and started for it. But right on the edge of the bank he stumbled. Down he rolled, paws over fur, with Nibble Rabbit and Doctor Muskrat scuttling after him.

“Look out!” barked Watch. “Let me get at him. He’ll fight like anything! They always do.”

“Come here, Watch! Go lie down!” shouted Tommy Peele.

“Why?” whimpered Watch. But Tommy Peele never answered. He couldn’t! There was Tad Coon sniffling through his puffy nose, peering through his squinty eyes, snarling with his swollen lips, and all smeared with Doctor Muskrat’s mud plaster and chewed root poultice. He was making the awfullest faces you ever saw. Maybe you think Tommy Peele could help laughing at him. Well, you couldn’t your own self.

“You lucky coon!” squealed Nibble. “When he laughs he can’t stay angry.”

“Ha, ha, ha!” laughed Tommy. “You ought to see yourself. You look a funny picture of a coon with the lines all wiggly.” And Tad Coon certainly did.

But pretty soon Tommy stopped laughing. “You poor beast,” he said in a sorry voice; “it must hurt you awfully.” Nibble Rabbit knew that voice. It was the same one he had used when he took Nibble out of the wire trap and when he let Doctor Muskrat out of the cold steel jaws that had bitten his toe off.

“Er-yow!” argued Watch, Tommy’s dog. He meant it was all Tad’s fault.

“Bz-z-z!” went the wasps who were guarding their nest on the ground until the little white grubs in it should hatch. They meant that they had something to say about it.

But Tommy didn’t understand and he didn’t care. “Be still, Watch!” he ordered. Then he took a long branch and speared the nest on the tip of it. Splash! He sent it into the middle of Doctor Muskrat’s pond. Some of the wasps were drowned and the rest flew up into the tree, buzzing with all their wings that the old nest was bewitched and they wouldn’t have anything more to do with it. So there it floated wherever the wind blew it, like a deserted ship. And the wind began blowing it right back to Tad Coon.

“Come on, Tad,” called Doctor Muskrat from the pond. “Tommy isn’t going to hurt you.” So Tad limped down and took a drink and washed himself.

Then he felt a lot better. After all, there aren’t very many places where his fur is so short a wasp can sting him.

Nibble looked at Tad, and then he looked at Tommy. “I think Tommy means to be friends,” he said. “But he hasn’t brought you anything to eat yet.”

“He’s brought this,” answered Tad, and he waded out and caught the wasps’ nest. Then he sat himself down on Doctor Muskrat’s nice, warm stone and picked the fat white grubs out of it with his clever little fingery toes. “Mm’m!” he grunted contentedly with his mouth full.

He was so busy and sober about it that he set Tommy laughing all over again. Nibble twiddled his tail thoughtfully. “Doctor Muskrat,” he remarked, “I’m beginning to wonder if Tommy makes friends with us because he caught us or because he felt sorry we were hurt?”

Right then Watch spoke up. “I haven’t made friends with Tad, and you remember I don’t always take Tommy when I go hunting.”

“Be still, Watch!” Tommy ordered. “I want to see what’s going to happen next.”

“Nothing, now,” Watch answered. “But it will just as soon as you aren’t here to stop me.” And he laid his nose on his paws and rolled the whites of his eyes at Tad.

“Why?” demanded Nibble. Just the way he cocked his ears made Tommy understand that he and Watch were talking, though he couldn’t even hear the Woodsfolk.

“Because Tad’s just as bad as Silvertip the Fox,” snarled Watch. “He eats Tommy’s eggs and his chickens—and he eats rabbits, too, when he’s smart enough to catch them, you silly bunny. And you ought to see what he does to the green corn that’s sprouting in the Broad Field.”

“He doesn’t!” gasped Nibble. “He could have caught me a dozen times. I don’t believe it.”

But Tad Coon looked down his nose at his bad little handy-paws, he was so ashamed, and nodded. “Yes, I do,” he owned honestly. “After I’ve slept through the winter I come out in the spring so terrible starvation hungry. But I wouldn’t eat you. I’d rather dig grubs from a rotten log, even if we haven’t any compact.” And Nibble knew he meant it.

But Watch didn’t. “A lot of good that would do!” he snarled.

“That’s just what the cows said about their compact with you dogs in the First-Off Beginning,” interrupted Doctor Muskrat in his sober voice. “But you did keep it. Tad Coon isn’t one of the Things-from-under-the-Earth that Mother Nature herself can’t trust. Let’s all make a compact. Why fight unless you have to?”

Now this was very wise, because no dog likes to fight with a coon. “I’ll make this much of a compact,” said Watch. “I won’t bother Tad Coon as long as he behaves himself. If he doesn’t—Gr-r-rr!”

“All right,” Tad agreed cheerfully, for he meant to be very, very good. All the same, he floundered into the pond and brought up a clam to give Watch, just as though it were a regular compact. Watch didn’t eat it of course, but he did touch his tongue to it. “I s’pose you’d think it awfully funny if that shelly thing bit me,” he grinned, and he even wagged his tail. Then Nibble sniffed of it, and Doctor Muskrat—and of course Tommy was so puzzled he picked it up and put it in his pocket. He wanted to ask his father if there was anything the matter with it. But the beasts thought he was in the compact, too, so they were all happy.

Nobody dreamed that Bad One was hiding in the willows across the pond, listening to every word Watch had spoken and saying to himself: “It won’t take me long to start some trouble there.” And it didn’t.

The woods weren’t peaceful at all next morning. Watch came tearing down to Doctor Muskrat’s Pond with the bristles pricked up on his shoulders and his teeth snapping. “Where’s that coon?” he snarled. “Give me that coon. He’s broken his compact already. Now I will have to kill him, and you might just as well have let me do it yesterday.”

Doctor Muskrat popped his head out of the pond. “What’s the matter?” he asked. “And where’s Tommy Peele?”

“He’s coming,” snapped Watch. “And he knows who did it, too.”

“Then he knows more than you do,” called Nibble Rabbit, hurrying through the Pickery Things. “Tad Coon hasn’t been out of the woods a single minute.”

“He has!” snarled Watch. “He’s slit the throats of every chick belonging to old Topknot—the hen who was good to you, Nibble Rabbit. Perhaps that’s one of his jokes.”

“Oh-h-h!” gasped Nibble. “But what makes you sure it was Tad?”

“Topknot says it was someone who wore stripes. Who else could it be?”

“The cat!” guessed Nibble. “She wears them.”

“No, it wasn’t! I smelled, and it didn’t smell like her.”

“Then smell of me,” said Tad. And he marched right out of the Pickery Things, not a bit afraid because he did-n’t have a guilty conscience. “It won’t smell like me, either.”

So when Tommy Peele came running up, there stood Tad Coon with his fur all fluffed up to let the scent out (you remember how the quails sleeked their feathers to hold it), but he wasn’t snarling. He wasn’t even angry. And Watch was sniffing carefully all around him.

“Sic him! S-s-s-sic him!” called Tommy Peele. My, but he was the angry one.

“No,” barked Watch. “Beg pardon, Tad. It wasn’t your smell, either.”

“Whoever it was,” said Nibble, “I’m coming up to the barn to help find him.”

Maybe you think Tommy Peele wasn’t puzzled! “S-s-s-sic him!” he ordered impatiently. “Whatever is the matter with you, anyway? You aren’t scared of him, are you? Yesterday you wanted to kill him for nothing at all, and to-day you won’t touch him. But if he didn’t kill all poor Topknot’s little chicks, who did? It’s a regular coon trick—dad says so. S-s-sic him! Go on!”

“A-aour-r!” Watch whined unhappily. “If I only could tell you that it wasn’t Tad Coon!”

“We’ve just got to find out for ourselves and show him,” said Nibble Rabbit. “The sooner we start the fresher the scent,” he quoted from an old dog-song. “Come along.”

“I’m coming, too,” announced Tad Coon. “This is some of my business.”

“No, you’re not,” said Nibble. “We don’t want another paw-mark until we examine every trail up by the barn.”

“That’s right,” said Watch. “That kind of a thief doesn’t fly. I didn’t stop to look because I was so sure I knew who did it.”

“But you couldn’t make any mistake about mine,” protested Tad, holding up his handy-paw. “No one, not even my cousin Gurf Bear, who has hind feet like mine, has one anything like it.”

Now Tommy was angry enough about those chicks of Topknot the Hen’s, but he was angrier yet because Watch wouldn’t obey him. “You’re a bad, bad dog!” he scolded. “I’m going right over to get Trailer. He isn’t afraid.” And you know Trailer the Hound, who belonged to Tommy’s big cousin Sandy, was Tad Coon’s worst enemy.

“There!” Watch exclaimed. “You see you’d better keep away. Trailer won’t make any compact with you, and he wouldn’t even listen if I tried to explain how your tracks came to be there, but if you don’t leave any he’ll tell Tommy so the same way I’ve been trying to.” And Watch galloped off to catch up with the cross little boy.

But Tommy wouldn’t forgive him no matter how much Watch begged and explained. Only when he passed the place where the dead chicks had lain he cried, “Why, they aren’t all here! That killer must have come back after them.” He saw Watch sniff them just as carefully as he had sniffed Tad Coon down by the pond. And he knew just where Tad Coon had been every minute of the time. Tad didn’t take them. So now he understood. “All right, Watch. Good dog,” he said. “It wasn’t the coon. Then who was it? S-s-sic him!”

And maybe you think that didn’t make Watch happy!

If Nibble hadn’t been in such a hurry to get up to the barn and see Topknot’s little dead chicks he might have found who really killed them all the sooner. But here was a new killer whom no one had ever seen, so no one knew how to hide from him or where to expect him. No wonder Nibble was too excited to think of listening at the Brushpile for the Bad Little Owls.

Just about the time he went slipping down the fence row under the safe pickers of the blackberry canes they were having their first full meal since Chaik and his family mauled them for trying to help Silvertip. Chaik had pulled out so many feathers that they couldn’t hunt well. And now they had swallowed one of those fuzzy little chickens, fluff, legs, and all, because they were so hungry.

“My, but that chick tasted good,” said the Lady Owl. “Do you know, when Stripes came waddling by this morning and bragged about what he’d done, I didn’t believe him. I don’t see why he didn’t eat every last one of them instead of leaving them for us.”

“He didn’t leave them for us at all,” snapped the he owl. “And don’t you ever tell him we took one, either. He just killed them and laid them out in a neat row so it would look like one of Tad Coon’s tricks. Then that boy would think it was the coon and make all sorts of trouble for him.”

“Why doesn’t Stripes like Tad Coon?” said his mate thoughtfully.

“He’s jealous because Tad has a compact with that shaggy dog so it won’t chase him, and he’s mad because it’s getting to such a pass in the woods and fields that you hardly dare rob a nest for fear that rabbit will tell on you.”

“What happens then?” asked his wife, sleepily, for it was long after sunup.

“That’s the mystery,” he answered in an awed voice. “But Silvertip has disappeared, and Grandpop Snapping Turtle, and you know yourself that Foulfang the Rattlesnake was nothing more than ant food when we found him.”

“Then you aren’t going to help Stripes? He might feed us.”

“I’m not going to help any one but myself. And right now I’ll help myself to one more chicken. I could sleep right through a full moon if I had a full stomach. Stripes is asleep in the oak that blew down in the Terrible Storm. Keep your eye on him. We can take what he leaves without helping him fight that rabbit.” And off he flew, steering very badly with his ragged tail.

But Nibble Rabbit wouldn’t have known who Stripes was, even if he had overheard the little owls.

The very first thing Nibble did when he got to the barn was to hunt up poor Topknot. He had a hard time finding her. For he had to be very careful himself, I can tell you. He listened and peeked behind every corner, expecting to see the flashing eyes and snarling teeth of the killer no one knew.

That was why the Bad Little Owl didn’t see him when he came flipping by. “What’s he doing out this time of day?” thought Nibble. Then he saw, for the little owl swooped down and staggered off with a furry yellow chick. Its poor head was dangling, and it was such a load that he could scarcely lift it above the bushes, and he steered more crookedly than ever. As he passed a clump of burdock, out dashed Topknot, squawking and screeching, and it was only by sheer luck that he escaped her beak.

“That owl never killed them, did he?” asked Nibble when he came up with the hen.

“Not while I was with them,” she answered, ruffling up her feathers. “He wouldn’t dare. No. It was a furry thing with stripes. He’d reach in his paw and draw them out from under me—so gently at first I didn’t know what he was doing.”

Now that certainly did sound a lot like Tad Coon. “Did he have a black mask across his face?” Nibble wanted to know.

“It was so very dark I couldn’t see,” she clucked. “He had a bushy tail and no matter where I tried to attack him he kept his back turned.”

No wonder Watch the Dog had thought it was Tad. Even Nibble felt doubtful. He was a very sober rabbit when he hopped over to where Watch and Tommy Peele were examining the chicks.

“They’re not all here. The killer’s come back for them!” Tommy was just shouting excitedly. “We’ve been with him all the time, so it’s not the coon. What is it?” But Nibble knew that the little owl had taken them, and he certainly wasn’t the killer, either.

Watch sniffed very carefully. “It isn’t Tad’s smell,” he whined, circling about. Suddenly he barked, bristling. “But it certainly is his trail!” For there right beneath his nose was a hind footprint, something like a baby’s, and very much more like Tad Coon’s. “He won’t fool me again,” Watch raged. “I’ll fix him!”

“Wait a minute,” Nibble protested.

“That’s too small to be Tad. It might be another coon. No, no! It hasn’t a handy-paw. Look!” For the print of the forefoot was clawed and padded like Watch’s own, and not a bit like any coon’s.

Watch sat right down. This was too puzzling for him.

“We’ll find out yet,” Nibble encouraged him. “You look out up here—you might catch him, red-toothed, any minute. I’m going to see what the little owls know about him.”

But he didn’t tell why he was sure they knew.

Now if Nibble had gone straight to Doctor Muskrat and asked, “Who has a hind footprint like a little coon’s and a front one like a dog’s?” the wise old doctor would have told him in a moment.

But he didn’t. Because Tad was down at Doctor Muskrat’s Pond waiting for him, to know if Tommy Peele believed him. How could Nibble say, “Well, we’re pretty sure you told the truth, but we can’t find any one else to lay it to. The real killer must be too smart for us.” So he just crept into the Brushpile beneath the two little owls, asleep like two small knots on their limb.

They slept late, for they had feasted on those chicks that morning. It was almost dark before they stretched their wings and twiddled their stumpy tails. “Have you seen anything of Stripes?” asked the Lady Owl, polishing her beak on the rough bark, just the way you want to brush your teeth before breakfast. “Or are you going back for another chick?”

“No,” answered her mate. “I’d rather follow him.” And he flew over to the hollow in the fallen oak. “He’s gone!” he cried when he came back again. “He’s been gone a long time. His scent’s quite cold.”

“That’s no sign,” she said cheerfully. “Stripes can leave less scent than any fur I ever knew, when he pleases—and make more when he isn’t pleased!”

Nibble almost squealed. “Stripes is a skunk! I’ve never seen him, but Watch has. What a joke on that dog!” What Nibble had learned surely would have burst out of him if she hadn’t added: “Never mind, we’ll find him fast enough.” And off they flew.

“So will I,” chuckled Nibble, racing along behind them.

He’d have lost them in the dark, because they flew zig-zagging all about, if they hadn’t kept calling to each other all the while. “Where? Where?” they cried every other minute. Then “Here! Here!” shouted the little he owl “Under the bridge!” And, sure enough, Nibble could see a white thing moving around by the bridge across the brook that came out of the lower end of Doctor Muskrat’s Pond.

He could make out the queer blotchy streaks of white that Stripes was named from. The white tuft was probably the tip of his tail. Oh, yes, he could see that skunk all right enough—but he couldn’t see someone else who was hunting clams right beside Stripes. He could only hear.

“Get out! I’ve taken this hunting ground.” That was a horrid, snarly voice.

“All right. Then I’ll be moving right along.” That was the fat, smily voice of Tad Coon. In the dark you couldn’t see his stripes at all. There was splashing.

“Ah! Wah! Yah! Gr-r-r-yah!” yelped the snarly voice. Then Nibble smelled the awfullest smell you ever imagined—the smell of Stripes when he isn’t pleased.

Nibble’s nose was twitching so fast he had to wipe it on the nice damp earth, just as the little owl wiped her beak on the rough bark of her perch. But he stayed there, squeezed in between the stems of a leafy elder bush, trying to guess what had happened.

Pat-pat, came leisurely footsteps. “Uh-huh,” coughed a voice. Then someone snorted. Nibble’s ears flew up; he knew that sound. Tad Coon was trying to keep from laughing. Pat-pat, went his handy-paws, and then there was a splashing and a scrubbing. Nibble hopped down to the pond, and there was Tad squirming about in the damp sand.

“That you, Nibble?” Tad asked as he heard the soft lip-it, lip-it of Nibble’s furry feet. “Keep to windward. Keep to windward, if you don’t want to strangle, as I’m almost doing.” He was lying on his back and he stopped squirming while he spoke. Nibble could see his limp paws fairly shaking with laughter.

“Whew, I should say so! What happened? Did you have a fight with Stripes?” Nibble asked curiously as he moved around Tad. “You aren’t hurt, are you?”

“Hurt!” snorted Tad. “Of course not. Stripes Skunk won’t fight. He doesn’t have to. He wouldn’t face any one anywhere near his own size—he just turns around so you can’t find anything but the tip of his tail to chew on. And that’s all shaggy, slippery hairs, so you couldn’t possibly get a grip on it, and if you did he knows he could make you let go. He has this scent,” Tad sniffed disgustedly, “and it’s worse than any bite he could give because it shows all your enemies where you are.”

“But Watch was trying to follow Stripes, because he’s the killer of those poor little chicks up at the barn, and he could hardly trail him at all.”

“Of course not,” Tad giggled, “Stripes hates it himself. He’s so afraid of getting it on his own fur that he won’t use it unless someone’s foolish enough to plague him into it—like me,” he finished, sanding a new spot to get it clean. “But Watch can trail him now.”

“What did you do?” My, but Nibble was curious to know.

Tad looked half ashamed, the way he always does when his tricks come back on him. “Well, he just would turn his back on me—and he was so rude and there was a mussel, such a big one, with a big sharp shell—so all the time I was being so polite I was letting it close on the end of his tail. And he couldn’t make it let go when he wanted to. My, but wasn’t he scared!”

So that was Tad’s trick. It was certainly clever, but Nibble didn’t sleep very close to him that night.

Early, early in the morning Stripes Skunk came snooping into the Pickery Things. Of course they caught hold of him until Nibble Rabbit waked up. And as soon as he sniffed that scent in the air he said, “Is that you, Tad Coon?”

“No,” said a meek, whiny voice; “it’s me, Stripes Skunk. I’ve been talking with the little owls. Please, won’t you make a compact with me?”

“Compact!” Nibble exclaimed. “Of course I won’t! And no one else will!” At that Stripes began to cry. “Won’t you even try me?” he sobbed. “I’d not want to be friends. I just want to be let alone as long as I’m good. Won’t you give me a chance to show you how very good I can be?”

So Nibble finally promised to talk things over with Watch and Doctor Muskrat. Doctor Muskrat didn’t say anything, but he waited out on his flat stone for Watch. And when Watch came he fairly howled at the idea.

“Make a compact with that murderer?” he barked. “Not when he’s killed those little chicks that belong to Tommy Peele. I’ll kill him.”

“Watch,” said Doctor Muskrat, “who made you executioner of all the woods and fields? Killing Stripes won’t give back those chicks to Tommy Peele. But if you put Stripes to work instead, he can pay back for them. He can keep down the mice who steal Tommy’s grain; he can kill snakes, and locusts, and beetles, and all manner of grubs. If he just picks bugs off Tommy’s potatoes he’ll pay for all the harm he’s done.”

Watch put his head to one side. He could remember how Tommy hated to pick the bugs off those potatoes. “Wurff,” he growled at last. “I wish I knew what Tommy would think about it. I’ll wait until I know.”

As soon as Doctor Muskrat had finished speaking, Watch went rambling up to the old house with his ears laid back. He wanted to get a nice comfortable bone in a quiet corner and think about it. Doctor Muskrat was right; no one, not even Tommy Peele, had appointed him executioner of the woods and fields, and he’d been pretty quick about wanting to kill every one who did any harm, instead of letting them learn better—if they would. You see, a dog is so big and strong he has to be careful not to bully the other beasts. No decent dog can be happy if he does that. But he couldn’t make up his mind that Stripes Skunk deserved to be trusted.

Neither did Nibble Rabbit. He wanted to know what every other one of the Woodsfolk thought about it. Right now he knew that Stripes was waiting to find out what Watch had decided to do to him, and yet he couldn’t help shaking at the idea of going to talk with him. For the first thing every mother rabbit teaches the fluffy bunny babies, as soon as they open their eyes, is to run from anything that has the strange and scary scent of the Things-from-under-the-Earth, whether they wear scales or fur. Snakes have it just the same as Stripes the Skunk, or Slyfoot the Mink, or the weasel whom the Woodsfolk usually mean when they speak of the Killer. He’s so terribly bloodthirsty and cruel that they never give him any other name.

But when Nibble found Stripes waiting patiently beside his Pickery Things, right where the faithful thorns had warned him to stop when he came begging for help that morning, even a scarier rabbit than Nibble wouldn’t have been afraid. Stripes was trembling and trying his best not to cry. “What did he say?” he begged anxiously. “Please, Nibble, quick! What did that big dog say? It’s too late for me to try to run away from him. He could trail me anywhere, and I’m so slow he’d overtake me in just a little while.”

“He’s gone off to make up his mind,” said Nibble. “Doctor Muskrat put in a word for you. He said that if you hunted the mice in Tommy Peele’s grain and kept the potato bugs off his vines, you could pay Tommy back for those chicks you killed, if you didn’t do any more harm.”

“I will! I will!” chattered Stripes. “I just love mice and potato bugs, too. Only I thought those chicks belonged to a hen. Who’s Tommy Peele?”

“Why, Tommy Peele is a boy. He owns all these woods and fields, and the hen as well. That’s why Watch, his dog, takes care of them all,” Nibble began.

“But what’s a boy?” Stripes demanded, his eyes opened very wide.

“A boy? Why, he’s a man’s kitten,” Nibble explained patiently. (Kittens are what Stripes calls his own young.) “This is his hunting ground. But he only hunts Bad Ones. We Woodsfolk aren’t afraid of him, and Doctor Muskrat is his special friend.”

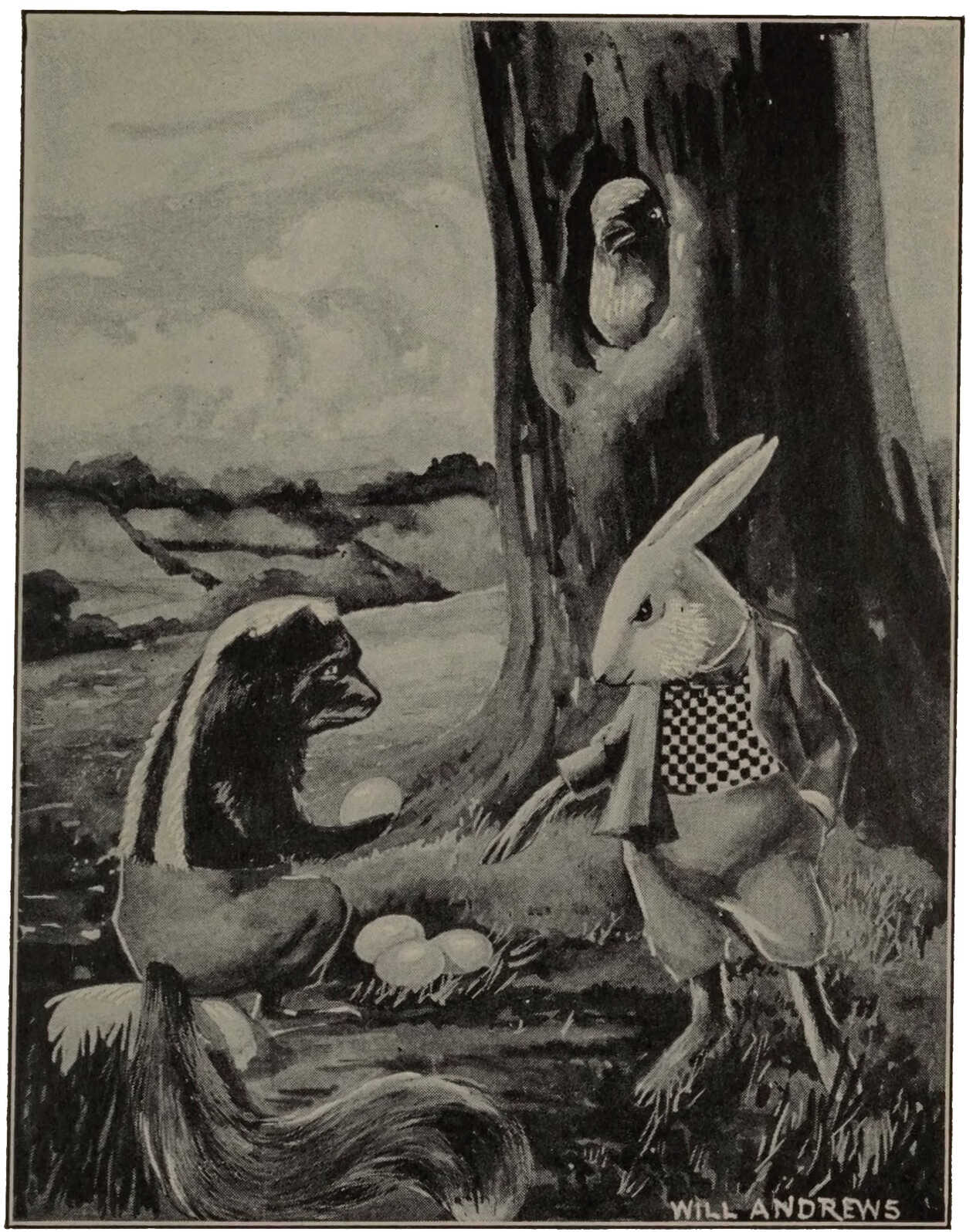

“I must thank Doctor Muskrat,” exclaimed Stripes very eagerly. “I’d like to bring him a present—how about a nice fresh egg? I just found some here.”

And just then Bob White’s wife, over in the Quail’s Thicket, began to scream. “Prr-whit! My nest! Someone’s spoiled my beautiful eggs! Prr-whit! Two of them are nothing but empty shells,” she wailed. And the air was filled with whirring wings. Every other quail in the covey who wasn’t sitting on eggs of her own had come to see what was the matter. And my, but weren’t they angry!

But Nibble Rabbit was angrier still. “You took those eggs!” he accused Stripes. “You just finished telling me so. And you were trying to pretend you would be good. Is that your way?” He looked savage enough to kick Stripes and send him end over end. That’s the rabbit way of fighting. He stamped his feet.

But Stripes never bared a tooth to defend himself. He just turned his back, just as Tad said he always did, and hunched himself into a little ball. “I did,” he confessed. “I did take them but I didn’t know it was bad. Truly I didn’t. Please don’t look that way. I don’t want to do anything more to be sorry for.”

“Then why did you steal?” Nibble demanded.

“I just found them,” Stripes pleaded. “There wasn’t any one with them at all. I knew I mustn’t kill any more quail, but eggs are different. Aren’t they?” he asked anxiously.

“No,” said Nibble. “They are not. This year’s eggs are next year’s quail. If we let every one help himself to all the eggs he came across there wouldn’t be any more quail to lay them.”

“But I’ve always done it,” whimpered Stripes, peeking over his shoulder to see how Nibble was bristling. “And I only took two.”

“That’s as bad as taking them all. Do you suppose she’ll go back to them now that she knows you’ve found them?” Nibble began to suspect that Stripes really didn’t know any better after all, but this was no time to teach him.

“Wouldn’t she if I promised never to do it again?” he asked hopefully.

“She wouldn’t believe you,” snapped Nibble decidedly. “Watch the Dog gave you one chance even after you killed Tommy Peele’s little chicks. Now you’ve been bad right over again. No one here ever will trust you. You’d better go back where you came from as fast as you can travel—Watch will certainly rage about this.”

“But I don’t wa-a-ant to go,” sniffed Stripes. “I want to stay right here and learn how to behave. Way back in the Deep Woods I heard about it. It’s the peacefulest place in the world——”

“So you came to see if you couldn’t make us a little trouble!” Nibble was in a terrible temper. “Tried to lay all on poor Tad Coon, didn’t you? You’d better foot it if you want to save your skin. That dog will most certainly kill you.”

So off trudged Stripes with his head hanging. And Nibble hopped over to the Quail’s Thicket just in time to hear them asking each other, “Where’s Bob? Where IS Bob?”

You know quail live together in the winter but separate when they nest in the spring. They mostly settle near enough together so that when anything goes wrong the covey call can bring them all in. They help each other if they can; if they can’t at least they learn about the danger to those precious nests of their own.

But when Bob White’s wife gave that horrified “Prr-whit!” that a quail’s ears can hear so far, her own husband did not come. The other birds might scatter all over the woods and fields calling anxiously, “Bob White, Bob White, Oh, Bob White!” but he did not answer.

Nibble was the only one who knew for sure who had taken the eggs. He didn’t tell on Stripes Skunk—not yet, for fear the little owls would hear of it. He called Chaik Jay and whispered, “Tell Watch the Dog to find my trail and follow it.” Then he set out after Stripes. “That bad killer knows what happened to Bob,” he said to himself. “I’m glad I didn’t let him fool me a second time. He wanted me to persuade Bob’s wife to go back to her nest and trust him—then he’d have caught her, and maybe I wouldn’t be in trouble! Just maybe!” And he ran as fast as ever he could.

But he was only half right. Stripes did know what had happened to Bob White, but he wasn’t to blame for it. Instead he was doing his best to help the poor bird. He was waddling back to the Quail’s Thicket with his tongue hanging out the side of his mouth and his long hairy tail waggling because he was too winded to gallop.

Nibble ran right straight into him. The first thing he said was, “What are you doing here?” and the next was “What about Bob White Quail?”

And wasn’t Stripes s’prised? “How ever did you hear?” he gasped. “I haven’t seen a single wing I could send for help, so I’ve ’most burst my sides coming after you my own self. He’s hanging upside down from a little tree. He’ll die if you don’t get him down soon. Hurry! Hurry!”

Hurry! You just better believe Nibble did. He knew what that meant. Bob was caught in exactly the same kind of a snare that Tommy Peele had set for Nibble. You remember he fastened a wire noose to the tip end of a springy sapling, and then he bent it over and pegged it down. The minute anything touched it, swish went the sapling and swish went whatever was caught in that wicked wire. This one had tight hold of Bob White’s foot, and there he hung with his head limp and his wings just weakly fluttering.

“I guess I’ll have to try to gnaw through this tree,” said Nibble anxiously. “I simply can’t climb.” And he looked at his furry feet that are made to run.

Stripes looked at them, too, and then he looked at his own. You remember the queer tracks he left up by the barn. His front feet were like a dog’s but his hind ones were something like Tad Coon’s, and you know how Tad could climb! “I never tried it,” he murmured doubtfully, “but maybe I can.”

Nibble almost squealed. “If you can get up there and bend that top down——” And right then Stripes clambered up on a log and sprang. He caught in the lower branches, and then he began—well, Tad Coon or Chatter Squirrel would never have called it climbing! It was scratch and scramble and grunt and whine, but he kept right on. And the higher he went the lower the sapling leaned. Down, down came Bob White till he lay on the ground. Nibble had hardly touched his teeth to that wicked wire when it let go its hold and Bob White was free. And just about then Stripes Skunk let go, too, and came tumbling down on top of them.

There lay Bob White, too weak to fly, his eyes closed, and his poor little thirsty beak half open. “Now,” thought Nibble, “that skunk is going to try and eat him.” Of course that’s what any bad Thing-from-under-the-Earth would do.

But Stripes didn’t. All that he scrunched was a couple of fat wood snails. Pretty soon he found what he was looking for—a fat, juicy grub. He knew Bob White would like it because skunks and birds eat so many of the same things. And Bob White did. The minute he smelled it he opened his eyes, and then he opened his beak. My, but that grub felt cool and moist on his tongue when he gulped it in! But didn’t he start when he saw who had given it to him?

And didn’t Nibble Rabbit prick up his ears when he heard what Stripes Skunk was saying? “I broke up your nest and stole your eggs this morning,” he told Bob White. “I thought maybe I’d pay you back even if I can’t be trusted to kill mice and potato bugs to pay back for those chickens of Tommy Peele’s I killed.” He still talked in his whiny, discouraged voice.

“What’s that?” cheeped Bob. He simply couldn’t believe his ears. “Well, I’ll be feathered! I’d as soon expect the Great Horned Owl to tell me such a thing. Eggs? You’re perfectly welcome. It’s not too late to nest over again. But for a skunk you’re certainly queer.”

“I—I—feel queer,” said Stripes in a funny, high voice, as though he were going to cry. “I feel queer and different.”

“You just feel happy,” said Nibble. “And you’ll feel happier yet when you’ve fixed those potato bugs for Tommy.”

You just ought to have heard the commotion in the Quail’s Thicket when Bob White came whirring home with his wild tale. But do you think he could make the quail believe that Stripes Skunk had helped Nibble Rabbit set him free again? Not until Nibble Rabbit himself came hopping along and told them exactly the same thing—only he gave Stripes all the credit.

“Eggs! Eggs!” exclaimed Bob White’s wife when Stripes explained he was trying to pay back because he’d mussed up her nest that morning. “What are a couple of eggs? I’ll scrape them back into the nest and lay a couple more in no time. I hadn’t begun to set on them.”

“Come along, Stripes,” said Nibble. “We must tell Doctor Muskrat. You know he told Watch the Dog to try you. If the quail can trust you, I guess I can. Your cousin Slyfoot the Mink would have eaten me long ago if I’d come this close to him. Why didn’t you?”

“I was afraid,” Stripes owned up. “The little owls warned me that if I did the dog would come after me. Anyway, I couldn’t catch you. Neither could Slyfoot if you only knew it.

“You know,” he went on to explain, “we things from under the earth are all scary—just as scary as you are. Only you’re so afraid of us that you never remember we have any one to be afraid of. When Slyfoot chases one of you silly bunnies you run round and round through the brush trying to hide yourself from him. But as long as you hide he’s hidden, too. All the time he’s trailing you. So he can take his time about finding you—and he always does. Now if you’d run straight out in the open, where the grass is short and there isn’t any place to hide, he wouldn’t dare to follow. He knows the owl would get him.”

“If he didn’t get us first,” was Nibble’s sly comment.

“But you’ve got twice as many chances to get away. You can dodge and run,” Stripes insisted. “Besides, your furry feet are so quiet; ours make much more noise when we’re galloping. And the big owl hears you before he looks for you.”

“He does?” Nibble exclaimed. “How do you know?”

“Why every one in the woods knows that an owl is either right-eared or left-eared. And whichever ear he uses most, that side of his head gets lop-sided from listening,” Stripes said.

“But his feathers are so fluffy I don’t see how any one would find out, if it’s really so,” Nibble objected.

“Killer (he meant the big weasel) ate one,” grinned Stripes. “I guess he ought to know. You see everything has something to be afraid of.”

They weren’t going very fast, Stripes was eating snails and licking little clusters of insect eggs from the under sides of leaves and digging grubs among the roots, while Nibble took a bite here and a bite there as is the way with rabbits. “Everything has something to be afraid of—and yet it’s terrible to be afraid,” he said.

“But if you’re not afraid, the others are afraid of you,” answered Stripes. “You’re the only rabbit who ever scared me. When you got so cross because I stole those quail eggs, I didn’t know what you’d do to me. Honest I didn’t.”

“I didn’t, either,” Nibble giggled, remembering how funny Stripes looked when he scrouched all up with his back turned and squinted over his shoulder. “I was too angry with you for being so bad. What could I have done, anyway?”

“I wouldn’t like you to kick me,” Stripes sniffed, nodding his head very earnestly. “You’ve got picky claws on those big furry kickers of yours. They’d rip a fellow worse than teeth do, and you’re awfully big for a rabbit.”

“Am I?” asked Nibble in great surprise. “It’s a long time since I’ve seen another bunny—not since the day my mother left me.”

“Well, you’ll see plenty before long, now that the news is going through the Deep Woods that this is such a peaceful place.” By now they were patting up the beach of Doctor Muskrat’s Pond. Stripes stopped suddenly. “Wait a minute,” he exclaimed, “I’ve got to do something before I meet the doctor.” And off he trotted, his long, hairy tail waggling behind him.

“Peaceful?” thought Nibble. “He calls this peaceful when something’s happening every minute. What must the Deep Woods and the Far Marshes be if this is peaceful? Wonder what that hairy scamp is up to now?” But he didn’t worry.

Pretty soon Stripes came running back with his mouth full. He laid a mouse on the doctor’s flat stone and then he laid something else beside it. “It’s so early,” he explained. “I had quite a hunt to find this potato bug.”

And then didn’t Nibble laugh! And didn’t Doctor Muskrat? But Stripes was deadly serious. “That’s to show you I mean to pay Tommy Peele for those chicks. He’ll have to hunt harder than I did if he wants to find any potato bugs after I’m through with them. I like being good, but how did you know I’d like it?”

“Ahem,” Doctor Muskrat cleared his throat. “Way back in the First-Off Beginning——”

And you know how that would please Nibble.

“Way back in the First-Off Beginning,” said Doctor Muskrat impressively, “there was one of the Things-from-under-the-Earth who really wanted to be good——”

“The skunk!” exclaimed Nibble Rabbit. “Wasn’t it?”

“Was it?” asked Stripes Skunk.

Doctor Muskrat didn’t answer right away. He sat there sleeking his whiskers with a clammy wet paw to hide a smile, and his little eyes were twinkling. “I was just wondering,” he went on at last, “whether they still tell this story in your family or whether you made up your mind on your own account.”

“On my own account,” owned Stripes truthfully. “I got awfully scared at what the little owls told me after you found out I’d been making trouble for Tad Coon. And I got to thinking. Then it seemed as if I just had to try how it would be to live so nice and peaceful—the way you want it.” He was squirming a pebble in his paw and squinting down his pointy nose, looking very much ashamed of himself.

“Ah,” cried Doctor Muskrat in a delighted voice. “That’s exactly the story of the First Skunk in the First-Off Beginning. He was bad—just as bad as all the other Things-from-under-the-Earth. He went running around, making all the trouble he could, while Mother Nature was away fixing up the other half of the world and this half all went wrong again. You remember, Nibble, how the sun and the wind and the rain didn’t take care of things the way she’d ordered them to, so winter came, and the plants hid in the earth and wouldn’t be eaten, and her very own new creatures got so terrible starvation hungry that some of them took to eating each other—like the wolves ate the cows.

“All the Things-from-under-the-Earth wore scales in the First-Off Beginning. When winter came most of them went right back under the earth and they stayed scaly, and are to this very day. But some of them found it was so easy to Mother Nature’s poor starved new creatures they couldn’t bear to stop eating them. They didn’t bother picking their poor lean bones; they just ate the tender parts that weren’t so starvation thin—like brains. They drank blood, and it went to their heads, so at last they killed for the sheer fun of killing.”

“Like Killer the Weasel,” nodded Stripes knowingly.

“Like some of Mother Nature’s own creatures, the wildcats and the wolves,” said Doctor Muskrat. “And they didn’t care a bit who they were killing, either. If the Things-from-under-the-Earth came near they took after them. They took after the First Skunk whenever they came across him—you’d better believe he was scared! The ground was so frozen by that time that he couldn’t dig down into it. So he hid in a hollow tree, with nothing but his scales on, and he was terribly cold and miserable and unhappy. And that was the first thing that set him to thinking.”

“Think of being in a windy tree with nothing but a clammy coat of scales on,” said Nibble, his teeth almost chattering. “Sometimes it’s bad enough in the Pickery Things, and they surely keep the wind off.”

“Well, he didn’t suffer very long,” went on the old doctor. “The first thing Mother Nature said was, ‘Any one can have fur that wants it.’ Now she didn’t say ‘my own creatures,’ nor she didn’t say ‘except the Bad Ones’—she just said ‘any one.’ And there was the First Skunk in a nice warm suit of fur, looking like any of her own things, except that his earholes were so far over the sides of his head his ears came too low down—and so did those of all the Things-from-under-the-Earth; that’s one way you can always tell them. And he was so happy. He said to himself, ‘This is all I wanted,’ and he curled right up tight and fell fast asleep.

“But when he woke up he began to think again. And by this time he could think of several things he wanted. So he started out to find how he’d get them. And it didn’t take him long to discover that he got his fur because Mother Nature gave it to him; or to learn not to hunt her up where she was busy trying to put things in order in this half of the world again.

“She was fairly discouraged at the way the sun and the wind and the rain had spoiled it and disgusted at the way some of her creatures had been behaving—’specially the wolves, for eating the poor cows, you know. So the First Skunk didn’t dare to trouble her; he just sat there listening. And he thought and thought, until his head was tired, for the Things-from-under-the-Earth aren’t used to thinking. Perhaps that’s why they always stay Bad Ones——”

“It is!” Stripes interrupted. “It certainly is.” And his little low ears were so pricked up over the idea that he didn’t look snaky and sneaky any more, but just nice and pert and interested.

“Well, anyway,” continued Doctor Muskrat, “at last the First Skunk crept up close and whined, ‘Won’t you have the earth fixed up the way it was before very long? I want to ask something before you’re all done.’

“‘I can’t do that,’ she answered sadly, ‘because it’s been lived, so it can’t be done over again. I’ll have to do the best I can with things as they are. But who are you?’ She didn’t know him at all because he was so different from the last time she’d seen him. But she knew right off from his ears that she’d never made him.

“‘I’m the skunk,’ he answered. ‘This is my new fur you gave me this morning!’ And then wasn’t she angry—angry with herself and angry with him! It was hard enough to have the sun and the rain and the wind be so careless that they let winter come, without having some of the Bad Ones stay up from under the earth to hunt her poor beasts all through it. If they had only scales on they couldn’t, but here was one with fur. Just because she was so hurried and flustered she hadn’t stopped to think what she’d been saying when she said ‘any one’ could have it.

“But the First Skunk didn’t know how she felt about it. He was so pert and proud because he’d been thinking a little. He said, ‘I like the way you want things. I want to be good and live up here in the sun with your own creatures instead of going back down under the Earth-that-is-common-to-all.’

“‘Well, be good, then,’ she snapped. She really didn’t believe him.

“‘But,’ he argued, ‘someone will have to show me how.’ You see her own creatures were all made good, and they had to learn how to be bad from the Bad Ones. A Bad One may want ever so much to be good, but he hasn’t any idea where to begin.

“She didn’t stop to think of that. She thought he was just making excuses, so she said, ‘You can stay up all winter now that you’ve got fur. I don’t see why you need anything else.’

“‘Because I’m so small and so slow it’s terribly scary for me now that your own beasts have taken to killing,’ he whimpered. ‘I don’t know how to run away.’

“‘Oho!’ Mother Nature was very sarcastic, but he didn’t know enough to know it. ‘You Bad Ones taught them how. I should think you’d be proud over the way they’ve learned it. What else do you want, then?’

“‘Lots of things,’ answered the First Skunk more cheerfully. ‘Paws, for instance.’”

“Did they have feet?” Stripes Skunk interrupted again. “Snakes haven’t.”

“They had then,” replied Doctor Muskrat; “splay-footed, lizardy ones. The First Skunk wasn’t sure which he wanted, handy-paws like Tad Coon or paddy ones like the wolves, so he could run away from them. He left all that to Mother Nature. ‘Anyway you want to fix me,’ he said, ‘so I’m not always being chased and they can’t hold me if they do catch me.’

“Mother Nature just stared at that First Skunk. ‘Well, of all the impudence!’ she exclaimed. ‘Of all the impudence! There you are, then!’

“And there he was, indeed! Only he had paddy-paws on in front, where he wanted the handy-ones, and Tad Coon’s paws behind, where he couldn’t run on them, and a long, hairy tail no tooth could hang on to, and that terrible scent so no one could even want to try. You can imagine how that First Skunk felt!”

“That poor First Skunk!” exclaimed Nibble Rabbit. “Mother Nature was mean to give him everything he asked for just the opposite to the way he wanted it. I’d have gone right off and been just as bad as ever I knew how to be.”

“Eh, Stripes Skunk?” asked Doctor Muskrat, “is that how you feel about it?”

“N-n-no,” Stripes answered slowly. “Being good is something even Mother Nature couldn’t give the First Skunk; he’d have to get it for himself. For the other things, I like being just the way we are. When I had to climb the tree to help Bob White Quail I’d have liked the handy-paws the First Skunk wanted. But that’s just because I’ve never practised climbing, like my little cousin Spotty. And handy-paws are no earthly good to dig with—you just ought to see these paddy-paws of mine make the dirt fly. But paddy-paws behind, where he wanted them, wouldn’t be half as nice as these good firm footy soles I stand on.

“I wouldn’t even give up my hairy tail. It’s heavy, but no one can bite it, and it’s wonderful to sleep in.” He whisked it into a billowy rug about his toes; then he finished contentedly, “I don’t mind Mother Nature making us so we can’t chase other folks, seeing that she gave us our scent so we’re not always being chased. She was perfectly fair.”

“Fair!” You ought to have seen Nibble turn his sniffy nose up at this. “She played you a horrid kind of a joke.”

“Not at all!” answered Stripes—and he was really quite indignant. “We don’t have to be unpleasant. Anyway, it’s better than fighting, and I notice even you bunnies don’t like to be eaten. Only nobody but Doctor Muskrat seems to understand.”

“Furry-foot,” chuckled that wise old beast, “Mother Nature played that joke on a lot of other fellows besides the skunk. We were all of us asking for scents, and she simply couldn’t understand it. She thought if she gave the First Skunk that one, the rest of us wouldn’t want them.”

“Why did you?” Nibble wanted to know. “We didn’t.”

“You didn’t, didn’t you?” Doctor Muskrat’s little eyes twinkled. “Why do you run around the Pickery Things each evening and give a stamp at every tunnel?”

“So if any other rabbit comes he’ll know that the place belongs to me.”

“How will he know?” asked the doctor. “He mightn’t see you or hear you——”

“He’d smell me, of course!” Nibble’s eyes were big and round.

“He would. Now do you see why nearly every one wanted some way of leaving messages for other Woodsfolk while he went off to hide or feed? You don’t dare make a noise; you can’t wait too long for fear someone will see you; so you leave that little smelly mark that stays and stays long after the warm smell of your body is blown away so you can’t be followed. But you’re so used to it you never think about it.”

“Oh-h-h!” said Nibble. “I hadn’t thought of that. I guess I’m beginning to understand.”