![[Image of the cover

is unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

|

Contents. (In certain versions of this etext [in certain browsers] clicking on the image will bring up a larger version.) (etext transcriber's note) |

THE ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE

OF SCOTLAND

FROM THE EARLIEST CHRISTIAN TIMES TO THE

SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.

{ii}

| Edinburgh: Printed by George Waterston & Sons | |

| FOR | |

| DAVID DOUGLAS. | |

| LONDON, | SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT, AND CO., LIMITED |

| CAMBRIDGE, | MACMILLAN AND BOWES |

| GLASGOW, | JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS |

BY

DAVID MACGIBBON AND THOMAS ROSS

AUTHORS OF “THE CASTELLATED AND DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE OF SCOTLAND”

VOLUME ONE

![[Image unavailable.]](images/title.png)

EDINBURGH: DAVID DOUGLAS

MDCCCXCVI

All rights reserved.

While engaged upon their work on The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland, the authors were frequently brought in contact with the various ecclesiastical structures throughout the country, and they naturally availed themselves of such opportunities to make notes and sketches of these interesting edifices.

These notes and sketches, together with others made during a long series of years, formed a considerable fund of information and a collection of drawings, the possession of which has induced the authors to undertake the completion of the illustration and description of the Ancient Architecture of Scotland, by adding an account of the Ecclesiastical to that of the Castellated and Domestic Architecture of the country already given to the public.

The size of the former book has been found to be somewhat restricted for many of the illustrations of the churches, but it has been thought best, for the sake of uniformity, to adhere to the same size and style as in the former work.

The subject of the Castles and Mansions, having been previously little investigated, afforded a fresh field for enquiry. The history and gradual development of the design and construction of these buildings had to be wrought out and arranged in periods according to the dates and the peculiarities of the structures, and an appro{vi}priate nomenclature had to be invented. These considerations added greatly to the interest of the subject.

In Ecclesiastical Architecture the case is different. The various styles and periods of Gothic architecture, both in this country and abroad, have for long been carefully investigated and defined. It thus only remains to apply to our Scottish edifices the system already adopted in the rest of Europe. An attempt is made in this work to do so, and attention is drawn to the various points in which Scottish Church Architecture agrees with and differs from that of other countries.

It has been suggested that our Ecclesiastical Architecture might be arranged in connection with the various orders of ecclesiastics by whom it was employed, and the specialities of the architecture of the various orders pointed out. This matter has not escaped attention; but it has been found impossible to form a system of nomenclature on that foundation.

The more this subject is investigated, the stronger is the conviction that there is, in this country at least, practically no difference in the style of architecture of the different orders of Churchmen from the twelfth to the sixteenth century. The cathedrals and parish and other churches were all built on general and well understood principles. The monasteries also were all constructed on the same general plan. Whether the occupants were Canons Regular or Monks of the Cistercian, Tyronensian, Premonstratensian or other order, or even Franciscans or Dominicans, their convents were all designed on one general system.

The plan consisted of an open court or cloister, sur{vii}rounded by a covered walk, having on one side (generally the north side) the nave of the church; while on the east side, in connection with the transept, lay the sacristy, chapter house, and frequently the fratery or day-room of the monks, on the upper floor of which range extended the dormitory, library, &c. The south side of the cloister was occupied by the refectory and kitchen; and the west side contained cellars and stores, and apartments for the lay brothers and guests.

These dispositions were sometimes extended and modified, but were invariably adhered to on the whole.

None of our Scottish monasteries are sufficiently well preserved to exhibit these arrangements in their entirety; but the various portions of the different convents which survive always correspond with the parts which would be expected in the positions they occupy.

As regards the style of the architecture and ornamentation, the only difference observable is that which is common to all the structures of the respective periods.

While it is intended to include in this work all the examples of ancient church architecture discoverable in Scotland, such subjects as ancient sites, demolished structures, and mere foundations do not fall within its scope, and are only referred to incidentally. These matters belong to the province of archæology, not to that of architecture.

Most of the ancient ecclesiastical structures of the West Highlands and Islands, and also those of Orkney and Shetland, being of a special and somewhat indefinite, although very interesting, character, are treated separately, before the main subject of the work is entered on.{viii}

In connection with the churches of Orkney and Shetland, the authors have to express their obligation to Sir Henry E. L. Dryden for his kindness in allowing his drawings and descriptions of these buildings to be incorporated in this work. They have also to thank the Council of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, with whom these drawings and descriptions are deposited, for their permission to use them.

The descriptions of the churches of the Highlands and Islands are, as stated in the book, chiefly abstracted from the late Mr. T. S. Muir’s interesting volumes.

The authors further take this opportunity of returning their sincere thanks to the many friends and well-wishers who have rendered them assistance in their labours. The names of many of these gentlemen are mentioned in connection with a number of the different structures. They would also express their indebtedness to all those whose permission was necessary to enable them to visit and make drawings of public and private buildings, which permission was invariably freely given.

They have specially to acknowledge their indebtedness to Dr. Joseph Anderson, of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, for his goodness in revising the portion of the work dealing with Celtic Art; to Mr. T. S. Robertson, Architect, Dundee, and Mr. William Galloway, Architect, Wigton, for their assistance in supplying drawings, and otherwise; and to Dr. Dickson, late of the Register House, Edinburgh, for valuable aid in many ways.

Edinburgh, January 1896.

| INTRODUCTION. | ||

| Various branches of early art in Scotland—Cells of Anchorites—Celtic art—Round towers and sculptured monuments, succeeded by Norman and Gothic architecture—Native developments—Previous writers on Celtic art (3)—Primitive Christianity—Candida Casa—Crosses and caves—St. Palladius—Irish monasteries—Wattles—Beehive cells (7)—Cashels—“Deserts”—Christian structures (9)—Irish MSS. and slabs—Symbolic sculptures—St. Columba—Iona—Missionaries from Northumbria—Lindisfarne—Roman influence—St. Augustine—Benedict Biscop—St. Winifred (12)—Pre-Norman churches—Columbans expelled—Culdees—Roman system introduced (14)—Revival of Celtic system—Celtic art (15)—Symbols (16)—Upright slabs (17)—Development of design of—Sculptures, origin of—Western crosses (20)—Early Ecclesiastical Structures in Scotland (24)—Beehive huts—Churches—Round towers (26)—Brechin and Abernethy—St. Regulus—Churches erected by Queen Margaret—Alexander I.—David I.—Parochial system (31)—Romanesque architecture (32)—Vaulting, development of (34)—Subordination of members (35)—Norman Style, examples (36)—Norman Style in Scotland (38)—First Pointed Style (39)—Salisbury Cathedral (41)—France and England compared (43)—Examples of the style (45)—First Pointed Style in Scotland (46)—Derived from England (47)—Examples (48)—Architecture of Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Sixteenth Centuries in Scotland (50)—Divided into Decorated and Late Pointed (52)—Middle Pointed or Decorated Style (53)—Middle Pointed or Decorated Style in Scotland (55)—Examples—Third or Late Pointed Style (58)—Examples—Third or Late Pointed Style in Scotland (60)—Effects of English and French influence (62). | ||

| {x} CELTIC MONASTIC AND ECCLESIASTICAL STRUCTURES IN SCOTLAND. | ||

|---|---|---|

| I.Simple Oblong Churches, associated with Beehive Cells and Churches in Groups. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Eilean Naomh, | Argyleshire, | 66 |

| Skeabost, | Skye, | 68 |

| Mugstot, | Do., | 69 |

| Howmore, | South Uist, | 70 |

| Kilbar, | Barra, | 71 |

| II.Hermits’ Cells, | 73 | |

| The Chapel of St. Ronan, | North Rona, | 73 |

| Teampull Sula Sgeir, | 75 | |

| Flannain Isles, or Seven Hunters, | 77 | |

| Teampull Beannachadh, | 77 | |

| III.Celtic Churches standing alone, | 78 | |

| 1. One oblong chamber. 2. Do., with modifications. 3. With architecturally distinguished chancel. 4. With chancel or nave added. 5. With pointed arches, | 79 | |

| (A) Churches dry-built and Churches with sloping jambs, | 80 | |

| Tigh Beannachadh, | Lewis, | 80 |

| Dun Othail, | Do., | 81 |

| Carinish, | North Uist, | 81 |

| (B) Simple oblong Churches with modified features, | 82 | |

| Cara, off Gigha, | Kintyre, | 82 |

| Eilean Munde, | Lochleven, | 83 |

| Church of Holy Cross, South Galston, Lewis, | 83 | |

| Teampull Pheadair, | Lewis, | 83 |

| St. Aula, Gress, | Do., | 83 |

| Toehead, | Harris, | 83 |

| Nuntown, | Benbecula, | 83 |

| Pabba, | Sound of Harris, | 84 |

| Kilmuir, | Skye, | 84 |

| Trumpan, | Do., | 84 |

| Churches showing signs of Norman influence:— | ||

| St. Carmaig, Kiels, | Knapdale, | 84 |

| Kilmory, | Do., | 85 |

| Kirkapoll, | Tiree (Ithica Terra), | 87 |

| Kilchenich, | Do., | 88 |

| {xi} (C) Churches with Chancel, or Nave added to an older structure, | 88 | |

| St. Columba, Balivanich, | Benbecula, | 88 |

| Eilean Mor, | Knapdale, | 89 |

| St. Columba’s, Ey., | Lewis, | 91 |

| St. Columba, Kiels, | Kintyre, | 92 |

| Kilchouslan, Campbeltown, | Do., | 92 |

| Kilchenzie, | Do., Do., | 93 |

| IV.Churches built with Chancel and Nave. | ||

| St. Mary’s, Lybster, | Caithness, | 93 |

| Church of John the Baptist, South Bragair, Lewis, | 95 | |

| St. Michael’s, Borve, | Barra, | 95 |

| (D) Churches with pointed or late features. | ||

| St. Catan’s, Gigha, | Kintyre, | 95 |

| Kildalton, | Islay, | 96 |

| Kilnaughton, | Do., | 96 |

| Kilneave, | Do., | 96 |

| Kilchieran, | Do., | 96 |

| St. Ninian’s, Sanda, | Kintyre, | 97 |

| St. Columba’s Isle, | Lewis, | 97 |

| Pennygowan, | Mull, | 98 |

| Laggan, | Do., | 98 |

| Inchkenneth, | Ulva, | 98 |

| St. Moluac, | Raasay, | 98 |

| Killean, | Kintyre, | 98 |

| Kilbride, | Knapdale, | 98 |

| Eorrapidh, | Lewis, | 99 |

| Olrig, | Caithness, | 99 |

| Kilchieven or Kilcoiven, | Kintyre, | 100 |

| CHURCHES IN ORKNEY AND SHETLAND. | ||

| Drawn and described by Sir Henry Dryden, Bart. | ||

| Chapel on the Brough of Deerness, | 101 | |

| Chapel on the North Shore of Head of Holland, | 105 | |

| Halcro Chapel, | South Ronaldshay, | 105 |

| St. Tredwell’s Chapel, | Papa Westray, | 106 |

| Church at Swendro, | Rousay, | 108 |

| St. Ola, | Kirkwall, | 109 |

| {xii} Churches of type containing Chancel and Nave. | ||

| Church on the Island of Wyre, | 113 | |

| Church on the Island of Enhallow, | 116 | |

| Chapel at Linton, Shapinsay, | 122 | |

| Chapel in Westray, | 124 | |

| Church on Island of Egilsey, | 127 | |

| Church on Brough of Birsay, | 135 | |

| Church at Orphir, | 141 | |

| Churches in Shetland (145). | ||

| Chapel of Noss, | Bressay, | 146 |

| Kirkaby, Westing, | Unst, | 147 |

| Meal, Colvidale, | Do., | 148 |

| St. John’s Kirk, Norwick, | Do., | 148 |

| Church at Uya, | 149 | |

| Kirk of Ness, | North Yell, | 151 |

| Church at Culbinsbrough, | Bressay, | 157 |

| General Characteristics, | 159 | |

| Monuments, | 160 | |

| Proportions, | 161 | |

| Dates, | 162 | |

| Chapel at Lybster, Reay, Caithness, | 162 | |

| Chapel, Effigy, and Cross on Inch Kenneth, Mull, Argyleshire, | 165 | |

| TRANSITION FROM CELTIC TO NORMAN ARCHITECTURE. | ||

| Abernethy Round Tower, Perthshire, | 175 | |

| Restennet Priory, Forfarshire, | 178 | |

| St. Regulus’, or St. Rule’s, St. Andrews, Fifeshire, | 185 | |

| NORMAN ARCHITECTURE. | ||

| Markinch Tower, | Fifeshire, | 193 |

| Muthill Church, | Perthshire, | 196 |

| St. Serf’s, Dunning, | Do., | 204 |

| Cruggleton Church, | Wigtonshire, | 212 |

| Monymusk Church, | Aberdeenshire, | 215 |

| St. Brandon’s, Birnie, | Morayshire, | 218 |

| St. Oran’s Chapel, Iona, | Argyleshire, | 220 |

| Chapel in Edinburgh Castle (St. Margaret’s Chapel), | 224 | |

| Dunfermline Abbey, | Fifeshire, | 230 |

| {xiii} St. Magnus’ Cathedral, Kirkwall, | Orkney, Dunfermline Abbey, | 259 |

| St. Blane’s Church, | Buteshire, | 292 |

| Dalmeny Church, | Linlithgowshire, | 298 |

| Leuchars Church, | Fifeshire, | 309 |

| Bunkle Church, | Berwickshire, | 314 |

| Edrom Church, | Do., | 316 |

| Legerwood Church, | Do., | 320 |

| Chirnside Church, | Do., | 322 |

| St. Helen’s Church, | Do., | 323 |

| Tynninghame Church, | Haddingtonshire, | 326 |

| Stobo Church, | Peeblesshire, | 329 |

| Duddingston Church, | Mid-Lothian, | 333 |

| St. Andrew’s, Gullane, | Haddingtonshire, | 339 |

| Uphall Church and St. Nicholas’, | Strathbroc, Linlithgowshire, | 342 |

| Abercorn Church, | Linlithgowshire, | 346 |

| Kelso Abbey, | Roxburghshire, | 347 |

| St. Martin’s Church, | Haddington, | 362 |

| Kirkliston Church, | Linlithgowshire, | 366 |

| St. Mary’s, Ratho, | Mid-Lothian, | 371 |

| St. Peter’s, Peterhead, | Aberdeenshire, | 371 |

| St. Mary’s, Rutherglen, | Lanarkshire, | 372 |

| Lamington Church, | Do., | 376 |

| St. Boswells Church, | Roxburghshire, | 377 |

| Smailholm Church, | Do., | 378 |

| Linton Church, | Do., | 379 |

| Duns Church, | Berwickshire, | 381 |

| St. Lawrence, Lundie, | Forfarshire, | 382 |

| Kirkmaiden Church, | Wigtonshire, | 383 |

| Herdmanston Font, | Haddingtonshire, | 384 |

| THE TRANSITION STYLE. | ||

| Dundrennan Abbey, | Kirkcudbrightshire, | 388 |

| Jedburgh Abbey, | Roxburghshire, | 398 |

| Kinloss Abbey, | Morayshire, | 416 |

| The Nunnery, Iona, | Argyleshire, | 421 |

| St. Nicholas’, | Aberdeen, | 426 |

| Coldingham Priory, | Berwickshire, | 437 |

| Dryburgh Abbey, | Do., | 448 |

| Airth Church, | Stirlingshire, | 465 |

| Lasswade Church, | Mid-Lothian, | 471 |

| Bathgate Church, | Linlithgowshire, | 474 |

Among the various branches of Mediæval Art in Europe, the Church Architecture of Scotland fills an interesting and valuable place. This country cannot claim to have originated a new style in the sense in which the Ile de France gave birth to pointed Gothic, but it can show a continuous series of Christian structures, beginning with the primitive cells and oratories of the early Anchorites, and extending through all the periods of Mediæval Art.

Two distinct phases of artistic development are exemplified in the History of Scotland—the first comprises the rise and decline of Celtic Art in early Christian times, and the second is allied to the various stages of general European culture.

Of the former period abundant illustrations exist in the almost prehistoric examples of Celtic structures of early Christian recluses, together with specimens of round towers and innumerable sculptured memorials and crosses, somewhat similar to those found in Ireland. These indicate the intimate connection which formerly existed with that country, whence Scotland derived her name, as well as her early instruction in religion.

The round towers and sculptured monuments are followed by primitive examples of Norman work, pointing to the direction from which the later phases of religious and artistic development in the country took their origin. The Saxon and Norman influence of the eleventh century produced a complete revolution in the artistic elements of the country, and led to a full development of the Romanesque or Norman style of architecture—a style similar to the round arched architecture of other countries of Europe in the twelfth century. Of this new departure the signs are still visible in the numerous remains of Norman structures which are spread over the country. These consist chiefly of small parish churches,{2} but they also include some large and elaborate buildings, almost entirely monastic, and one cathedral.

The succeeding Gothic styles are also well represented in Scotland, and include a great variety of churches, monasteries, and cathedrals. These exhibit many fine examples of the various styles of Gothic art, and, although comprising certain local peculiarities, show a general correspondence with the arts of the different periods in France and England.

The “first pointed” style is fully represented in Scotland during the thirteenth century; but, owing to the disastrous situation of the country during the fourteenth century, the number of “decorated” buildings is comparatively small.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when the “perpendicular” style prevailed in England and the “Flamboyant” in France, the architecture of Scotland was distinguished by a style peculiar to the country, in which many features derived from both the above styles may be detected.

While the Mediæval Architecture of Scotland thus corresponds on the whole with that of the rest of Europe, there exists in the Ecclesiology of the country an amount of native development sufficient to give it a special value as one of the exponents of the art of the Middle Ages. Its buildings further contribute largely to the illustration of the history of the country by showing in their remains the condition and growth of its religious ideas and observances at different epochs, and the manner in which its civilisation advanced. We observe striking evidences of the Irish influence in the relics of the primitive Celtic Church. The Norman and Early English influences are clearly traceable up to the invasion of Edward I., and the political and commercial connection with France and the Netherlands is distinctly observable in the period of the Jameses.

Till comparatively modern times the early history of Scotland was involved in obscurity, but much light has within recent years been thrown upon it by the works of Robertson, Skene, and others. The religious and political conditions of the country have now been placed upon a reliable historical basis, while its archæology has been expounded in the works of the late Sir Daniel Wilson, and those of Dr. Joseph Anderson and Mr. J. Romilly Allen. The numerous prehistoric monuments of Scotland have been collected by the late Dr. John Stuart, in his great work on the Sculptured Stories, and the Sepulchral Slabs of the West Highlands have been beautifully illustrated by the late James Drummond, R.S.A.

A wide field has been explored through the patient and devoted labours of the late T. S. Muir, by his searching out the architectural fragments scattered over the land, and especially by bringing to light many unknown examples of the retreats and primitive oratories of the early Anchorites which still exist in the remote and in many cases uninhabited islands of the{3} West. Similar explorations have been accomplished by Sir Henry Dryden in Orkney and Shetland, and by Captain White and Captain Thomas in Kintyre and the Hebrides. To all these authors we are indebted for much valuable information and guidance, as will appear in the following pages.

The structures and monuments of the early Celtic inhabitants of Scotland have formed the special subject of careful investigation by Dr. Joseph Anderson, and the exposition of the history of the remarkable and previously mysterious Sculptured Stones has been successfully accomplished by him in his lectures on Scotland in early Christian times. In these lectures he has not only clearly explained the origin and significance of these monuments and their order of succession, but he has extended his view over the whole field of Celtic culture, both in this country and in Ireland, and has explained the relations of its different phases to one another, thus disclosing the unity and beauty of that remarkable and independent development of art culture which existed in these countries from the sixth to the twelfth centuries.

We have also the benefit of Dr. Reeves’ and Dr. Petrie’s well-known works on Irish History and Archæology, and the magnificent volumes of Lord Dunraven on Early Irish Architecture, so ably edited by Miss Stokes. In the following introductory sketch of the Early History and Artistic Development of Scotland, free use has been made of the above and other works, in order to place before the reader a continuous account of the religious and artistic progress of the country from the earliest dawn of Christianity till the great Revolution of the sixteenth century, which severed the connection between mediæval and modern times.

The earliest trace of Christianity in Scotland is connected with the founding of a church, the name of which still survives in a structure of a much later date. This primitive church was erected by St. Ninian, a Briton, who seems to have settled in the end of the fourth century amongst the Picts, on the south coast of Galloway, with the view of there maintaining the Christian faith already introduced by the Romans.

St. Ninian is said to have studied in Rome, and, on his return journey, to have visited St. Martin, at Tours, who supplied him with masons to assist in the erection of a church, built of stone, in the Roman manner. This was known as the Candida Casa (now Whithorn), which was built about the year 412, and dedicated to St. Martin of Tours. It became a great school of instruction in Christian doctrine,[1] but after a time the Christianity of this locality appears to have died out, or was transferred to Ireland. It is believed that some of the emissaries from this school in the fifth century may be traced in the dedications of churches amongst the Picts, as, for example, St. Ternan, at Banchory-Ternan; St. Mocholmoc,{4} at Inchmahome; and St. Fillan, at the place named after him on Loch Earn. At Abernethy, in Perthshire, King Nectan is said to have been raised from the dead by St. Bœthius or Buitte, who came from Ireland, accompanied by St. Bridget and her ten virgins. The Saint, as a reward for his miracle, was presented with the fortress which existed at the place, just as the Irish ecclesiastics were established (as will be pointed out) by the chiefs in their raths or strongholds.[2] This king also built a church at Abernethy in honour of St. Bridget (about 480)—a foundation which afterwards became famous.

It tends to confirm the truth of the early mission of St. Ninian to the Southern Picts, that the monumental stones which still survive in that region are engraved with incised crosses of the oldest form, and are accompanied with inscriptions in debased Roman capital letters, containing the formula “hic jacet”—all marks which indicate a very early date.[3] Such are the crosses near Whithorn and those at Kirkmadrine, in a neighbouring parish, which all bear the simple cross with equal arms enclosed in a circle,[4] and contain the chi-rho symbol. (Fig. 1.){5}

It should further be noted that on the south coast of the Bay of Luce, not far from Whithorn, there exists a cave in the rocks which is believed to have been the retreat of an early Anchorite, perhaps of St. Ninian himself. Numerous crosses of early type, incised on the rocky walls and on the steps of a short stair leading down to the cave, prove that it has been occupied for religious purposes at an early date;[5] while on the Isle of Whithorn are the ruins of a church, which may possibly occupy the site of the original Candida Casa of St. Ninian.[6]

Another cave in the rocks on the shore of the opposite side of the Bay of Luce, still known as St. Medan’s Cave,[7] has also apparently served as the abode of an Anchorite. It consists, like the retreat of St. Cuthbert at Farne (to be afterwards described), of an oratory and an outer apartment for ordinary uses.

Numerous similar caves, which have been used for the like sacred purpose, are still to be found in many parts of the country, particularly on the West Coast.

After the decadence of the School of Candida Casa, Christianity in Scotland seems to have been in abeyance, till it was revived in the sixth century by the arrival of fresh light and energy from Ireland. From that period till the twelfth century the religion and culture of Scotland were entirely derived from that country. It is therefore necessary, in order to follow the origin and development of ecclesiology and art in Scotland, to trace generally their history in Ireland, and to mark the influence of the latter country on the former.

Owing to the disturbed state of Britain after the withdrawal of the Romans in the beginning of the fifth century, and the eruptions of the Goths in Gaul, many Christian refugees found their way to Ireland. Christianity was thus introduced, and, during the fifth century, spread rapidly under the instructions of St. Palladius, a reputed emissary of Rome, and St. Patrick, the patron Saint of Ireland. At first the Church seems to have assumed a peculiar collegiate form, consisting of groups of seven bishops placed together in one church; but in the sixth century the monastic rules were introduced, and at once took root and spread with wonderful rapidity amongst the various tribes. Under St. Finnian, after a short time, there are said to have been three thousand monks in the monastic school of Clonard. Columba, one of his twelve disciples, born in 521, founded several monasteries in Ireland, amongst others those of Derry and Kells, Raphoe in Donegal, and Durrow in Meath.

In 558 the great monastery of Bangor was founded by St. Comgall,{6} one of Columba’s companions, and is said to have contained thousands of monks.[8]

These monasteries were tribal institutions, and were well suited to the social relations of the country. The abbots were connected with the leading families of the tribes, and succeeded one another according to the rules of succession which prevailed amongst the chiefs. Many of the monasteries were established with the consent of the chiefs, and it frequently happened that on such occasions a “rath,” or native fortress, was presented to the founder by the head of the tribe, as a place of security in which his monastic dwellings might be erected.[9] These structures were generally of a slight and simple nature, consisting of huts made of branches or wattles, covered with turf or clay. The churches or oratories were also constructed with wood. The whole establishment seems to have resembled the primitive fortresses of the Celts, consisting of a great enclosing wall or rampart, with temporary erections within. At a later time wooden boards were substituted for wattles, and the roofs were covered with thatch. Dr. Reeves states that St. Palladius erected three churches of oak, while St. Patrick is said to have built one with stone, because no wood was to be found in the locality.[10]

The practice of building with wood was the favourite one amongst the “Scots”[11] in Ireland, and we shall find further examples amongst their disciples both in Scotland and England. Dr. Reeves states that the “Scotic” attachment to wooden churches continued in Ireland till the twelfth century, and that although stone churches existed, they were regarded as of foreign introduction. These wooden structures, it is needless to remark, have all long since disappeared, having been replaced by more permanent edifices.

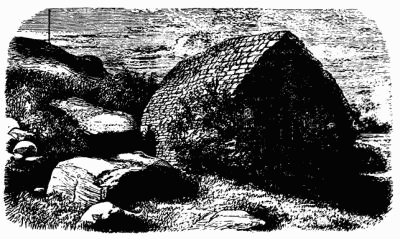

Although building with wattles and wood was the usual form of construction in Ireland in the early centuries, it was not the only one. When monasteries were established (as above mentioned) within the “raths” or fortresses by the chiefs, certain native forms of building in stone were found to exist in connection with these structures.[12] The{7} rath was invariably surrounded with a lofty wall of great thickness, composed of unhewn stones mingled with earth. The exterior face of the wall was carefully built with “headers,” and in many instances chambers were constructed in the thickness of the wall, and roofed with overlapping stones in the form of an arch, but without the radiating structure of a true arch.[13] Chambers of similar construction are also often found in the walls of the brochs, and in the Eirde houses and other Celtic structures in Scotland.

Besides the great “cashel” or enclosing rampart, other stone buildings existed within the rath. These consisted of circular or oval huts, built with unhewn stones without mortar. They are generally about 6 to 10 feet in diameter, and the interior has sometimes square angles. The walls are 3 to 4 feet in thickness, and rise perpendicularly to about 6 feet in height, when they begin to converge towards the centre, the stones overlapping as they rise with a curve till they nearly meet, when the aperture is covered in on top with flagstones. The external appearance of these primitive abodes presents a domed form like that of a beehive,{8} from which circumstance they are called “beehive huts” (Fig. 2). There is invariably a small doorway about 4 feet high, with a straight lintel on top, and the jambs are always built, not perpendicularly, but with an inclination inwards as they rise. A small square opening in the roof, greatly splayed towards the interior, forms the window of the hut. Stone structures of this description were common in certain parts of Ireland in Pagan times.[14] These were the native originals from which the Irish monks derived the style of stone building which was afterwards adopted by them in certain localities, with modifications as time progressed.

The Celtic monks of the early centuries showed a strong predilection for islands as the sites of their monasteries. Almost every loch and river show evidence of this choice in the ruins scattered over the country, and some small detached and rocky islands situated a few miles from the West Coast of Ireland (where they have been little exposed to disturbance) yet contain specimens of the above primitive structures. The great enclosing cashels and the singular beehive huts have been beautifully illustrated and described in the splendid work of the late Lord Dunraven on Ancient Irish Architecture, edited by Miss Stokes.

It was one of the peculiarities of the Irish monastic system to encourage the members to retire occasionally for a lengthened period to some solitary place, where they might do penance and worship undisturbed. These places of retreat were called “deserts,” and were sought for in the uninhabited and rocky islands lying at a distance from the mainland. It is surmised that the islands of St. Michael, Ardoilean, and others in a similar position off the West Coast of Ireland, containing monastic remains, were retreats of this description.

We have seen that these establishments exhibit in their beehive huts and cashels the tradition of the native Pagan style of building derived from the raths of the converted chiefs. In addition to these primitive erections, they further contain evidences of certain structural elements imported in connection with the introduction of Christianity.[15] For, besides the circular cells of the monks, they invariably comprise one or more small churches or oratories. These are structurally distinguished by having square angles on plan, both externally and internally, and by having the joints of the stones generally cemented with a certain amount of mortar. The roofs were constructed like those of the huts, with overlapping stones carried up with a curve to a pointed ridge. These churches are of small dimensions, and form a simple oblong chamber set with its greater length towards the east and west. They have a small door in the west end with inclined jambs and straight lintel, and a small square-headed window to the east. The above Christian form of church was, however, not fully adopted at first, many of the early{9} Irish churches retaining the native form of construction—i.e., the walls, both of sides and ends, rise in a curve from the foundation to the ridge of the roof, which is formed of overlapping stones, and the whole presents the appearance of an inverted boat with a sharp keel. These churches are built with dry stones, carefully constructed.[16] They are often associated with pillar stones, inscribed with crosses and inscriptions in Roman letters of the most ancient form,[17] and are supposed to be of the age of the Saints whose names they bear, dating from the fifth to the seventh centuries.[18] They were succeeded in the seventh and eighth centuries by a somewhat more advanced type, forming a transition from the dry-built and rough stone structures to buildings cemented with mortar, and having the stones dressed. To these were added chancels in the ninth and tenth centuries, having radiating chancel arches, which are invariably semi-circular, and have inclined jambs. The church of St. Kevin at Glendalough presents a good example of a chancel added to a primitive single-chambered church. Ornament was gradually introduced, but the Irish characteristic of the stone roof, supported on an arch, was retained in small structures up to the twelfth century. As time progressed the original overlapping form of arch was superseded by the true radiating arch. In the case of the larger churches, however, the roof seems generally to have been constructed with wooden rafters and shingles.[19]

The radiating arch appears to have been introduced about the same time as the chancel, and was by degrees applied both to doors and windows, but the sloping form of the jambs continued in use till the introduction of the Norman style.[20]

The religious enthusiasm which pervaded the Irish monasteries was very great, and displayed itself in the numerous offshoots and missions which they sent out, not only to the neighbouring countries of England and Scotland, but also to Gaul, Switzerland, Germany, and Italy. Rude and primitive as were their dwellings, the Celtic monks excelled in several departments of art and literature. Their chronicles of events are almost our only guide to the history of the country in those early times, and the writings and illuminations of their religious books are marvels of beautiful caligraphy and design. The forms and features of their drawings and illuminations are of a marked and special character, and are found prominently displayed not only in their MSS., but on all objects of Celtic production, such as gold and silver ornaments and shrines, and the sculptured crosses and architectural enrichments of a somewhat later date.[21]

The earliest stone monuments in Ireland consist, as in Scotland, of rude pillar stones, bearing plain incised crosses, accompanied with inscriptions in debased Roman capitals. These are succeeded by sepulchral{10} slabs, shaped and dressed, which were laid flat over the graves, and were carved with various forms of the cross extending over the entire surface, and sometimes covered with interlacing ornament. But the upright cross-bearing slabs, which we shall find are so common in Scotland, were almost unknown in Ireland. At Clonmacnoise there are 179 of these recumbent cross-bearing slabs, the ascertained dates of which extend from 628 to 1278; of these only sixty-seven bear any ornament except the cross. The earliest with ornament dates from 806, and many others belong to the ninth, tenth, and eleventh centuries.[22] Free standing crosses of fine design are also numerous in Ireland. They are generally covered with pictorial sculpture of Scriptural subjects; they date from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. They usually bear on the obverse a representation of the Crucifixion,[23] and on the reverse a figure of Christ in glory. These sculptures occupy the principal place at the junction of the arms with the upright shaft, and the remainder of the cross contains figure subjects, arranged in panels, representing events symbolical of the Redemption, and leading the mind up to the principal subject. Amongst the most common are the Temptation of Adam and Eve, the Sacrifice of Isaac, Jonah and the Whale, Daniel in the Lions’ Den, &c.

Symbolic sculptures, representing hunting scenes, grotesque animals, &c., so common on the Scottish monuments, are also occasionally found on the Irish crosses, but do not occur so frequently as on the former. The peculiar and unexplained symbols so universally found on the Scottish monuments are, however, entirely absent from those of Ireland.

Amongst the earliest fields in which the energy and enterprise of the Irish monastic missionaries found an outlet were naturally the adjoining lands of Kintyre and the islands on the West Coast of Scotland. From the beginning of the sixth century an emigration had been going on from Dalriada, in Ulster, to these regions, and settlements had been formed and a large part of the country taken possession of, extending as far north as Mull, and including part of the mainland of Argyll. In 560, however, Brude, King of the Northern Picts, led an expedition against the invaders, and drove them back from most of their possessions. A desire to retrieve this reverse, combined with zeal to spread the benefits of religion amongst the heathen Picts, is supposed to have led to St. Columba’s mission, and to the foundation of the Monastic Church in Scotland. In 563 St. Columba, with twelve disciples, sailed from Ireland for Dalriada, in Scotland. After visiting some of the islands and founding a cave-chapel at Loch Coalisport, which is still traceable, he finally, with consent of the Picts, settled at Iona. There he found a remnant of an early Church of Secular Bishops, but they yielded to the stronger monastic element now prevailing.[24]{11}

The monastery founded by Columba at Iona was of the ordinary style of the Irish establishments above described. Adamnan, in his Life of Columba, mentions that the buildings were constructed with wattles and turf, and the roofs covered with thatch. Besides the church and the huts for the brethren, there was a special cell for the abbot, a larger hut for a refectory, and another for strangers. The whole was enclosed, as usual, with a high wall or rampart. About a century after Columba’s time some improvement seems to have been made on the rude system of building with wattles. Adamnan, who lived about that date, describes how, in renewing the structures of the monastery, oak boards were used, and the roof was covered with thatch.

The Church established in Iona followed the example of its Irish founders, and sent out missionaries in all directions. In 565 St. Columba visited King Brude in his stronghold on the river Ness, and succeeded in converting the king and the Northern Picts. This mission seems to have been partly political, as it was also successful in establishing the Irish colony of Dalriada in possession of its territory under its own king.[25] During the sixth century numerous churches were founded throughout Scotland and in the Western Islands by St. Columba and his companions, St. Brendan, St. Comgall, and St. Cainnech,[26] whose names still survive in the dedications of many of these structures.

The Pictish King Brude was succeeded by King Gartnaid, who fixed his royal seat at Abernethy, in Perthshire. There he is said to have built a monastery (580-590) and dedicated it to St. Bridget, to whom, as we have seen, an earlier church had been dedicated in the same locality. St. Cainnech is said to have established himself in a “desert” at Kilrimont (St. Andrews),[27] thus indicating the early foundation of these well-known religious sites. The Cumbrian Church was also founded about this time at Glasgow by St. Kentigern, a friend of Columba’s. St. Columba died in 597, and, after his death, Iona was acknowledged as the head of all the churches and monasteries which had been established in Scotland.

But the influence of this Church soon spread beyond the boundaries of that kingdom. Oswald, son of Aidilfrid, having been driven from Northumbria, found refuge in Iona, and there acquired a knowledge of religion and literature. Having regained his throne, he sent, in 635, to Iona for monks to introduce the Christian faith amongst his people. St. Aidan was the first of these missionaries sent, and, with the king’s consent, he fixed his monastery on the island of Lindisfarne. He also founded monasteries at Old Melrose and Coldingham, then within the bounds of Northumbria. It was to the Columban Church thus established that the Angles between the Humber and the Forth owed their permanent conversion to Christianity. After a time St. Aidan was succeeded by St. Cuthbert, who continued and extended this pious work. But after being{12} twelve years in charge of Lindisfarne, St. Cuthbert retired, like so many of the same monastic school, to a “desert” or hermitage, situated on the solitary island of Farne, more distant from the mainland than Lindisfarne. Here he erected his hermit’s cell, the account of which, given by Bede,[28] is most interesting, as it so fully explains the nature of such structures. The enclosure was circular, and about 4 or 5 perches in diameter. Externally the wall was about the height of a man, but in the interior somewhat higher, owing to the soil and rock having been excavated. The wall was composed of massive unwrought stones and turf. The enclosure contained a dwelling-place divided into two parts, one being an oratory and the other a room suitable for common uses. The roof was formed of rough beams and thatched with straw. At the landing-place outside the enclosure a large house was erected to give shelter to the monks when they visited the hermit. Although called for a time to the Bishopric of Lindisfarne, St. Cuthbert again retired to his hermitage, and there expired A.D. 687.

When the Columban Church had existed in Northumbria for about thirty years, new influences arose, before which that monastic form gradually declined. The principal of these influences came from the South, and was part of that steady pressure from Rome which by degrees brought all Churches into uniformity of doctrine and observance. England was to a great extent the spiritual child of Rome, having been reconverted to the faith by the direct intervention of the Pope after the desolation caused by the heathen Danes. This was accomplished by the mission of St. Augustine, who was sent by Pope Gregory to England in 596 for the reformation of religion. The ecclesiastics from Rome brought with them the Roman forms and observances and the Roman mode of building. Thus St. Augustine, so soon as he was established in Kent, set about the erection, at Canterbury, of a cathedral, with two towers attached to the nave and a circular baptistry, in imitation of St. Peter’s at Rome. Other instances occur of the introduction of building with stone after the Roman manner. Bede describes how Benedict Biscop, in 676, brought masons from Gaul to carry out buildings in stone, and how the churches of St. Peter at Monkwearmouth, and St. Paul at Jarrow, were erected by Benedict Biscop (670-80) with stone, “according to the manner of the Romans.” Bede further mentions that Nectan, King of the Northern Picts, sought, in 710, for masons to be sent to him from Monkwearmouth, who should build churches for him according to the fashion of the Romans.

St. Winifred, Bishop of York, the great opponent of the Columbans in Northumbria, had also erected stone churches in the seventh century after the Roman manner at Hexham, York, and Ripon.

Northumbria was at this period (during the seventh and part of the{13} eighth centuries) the most powerful and advanced portion of England. It was the nursery of learning and poetry, the home of Bede and Caedmon. Religion also flourished, as is proved by the remains of the pre-Conquest churches which still survive.[29] Many of these show traces of the works of the ancient Romans in the country, being built, partly at least, with Roman wrought stones from the ruins in the district. The influence of the Columban period is observable in the numerous crosses carved with Celtic work which still survive in Northumbria.

The pre-Norman churches have some peculiarities. They are remarkable for the height of the walls, as compared with the width of the building. Thus at Monkwearmouth and Jarrow (erected by Benedict Biscop in the seventh century), the width of the nave is 18 feet, while the height of the walls is 30 feet. The carved lacertine figures of the porch at Monkwearmouth have likewise a Celtic character. Square towers at the west end of the nave form common features of these churches, and the jambs of the doors and windows are often inclining, like those of Ireland. Some of these features may be observed in one or two of our Scottish churches, such as that of St. Regulus at St. Andrews and Restenot Priory.

As the Roman influence prevailed, that of the Columbans waned, till, finally, that of Rome was, after the Synod of Whitby in 664, definitely adopted, and the Columbans were driven off. After the expulsion of the Columbans from Northumbria, the Roman forms and observances were gradually extended over the southern parts of Scotland, then included in the dominions of Oswy, King of Northumbria. Various circumstances tended to aid this process. When the victory of the Picts at Dunichen, in 685, terminated the rule of the Angles in Scotland, Nectan, king of the Celtic kingdom, was brought into contact with the Roman missionaries, whom he found in his extended southern provinces, and became, in 710, a convert to their ideas. He seems to have warmly espoused their cause, and desired that their rules and forms should be universally adopted throughout his kingdom. But the Columbans still clinging to their own observances, King Nectan at length, in 717, issued a decree, expelling from his dominions all ecclesiastics who refused to conform to the Roman practices.

Up to this period there had been an increasing tendency to asceticism in the Columban Church, leading the monks to forsake the cœnobitical or monastic life in common, and to adopt that of the hermit or Anchorite. This had the effect of breaking up the monastic system which had hitherto succeeded so well amongst the Celtic tribes of Ireland and Scotland, and also tended to encourage the introduction of the secular hierarchy of the Roman system.[30]

The hermits were known on the Continent as Deicolæ, or Worshippers{14} of God, and in this country by the title of Keledei or Culdees. The similar order which arose in the Celtic Church afterwards played an important part in Scottish ecclesiastical matters. They first appear in Scotland after the expulsion of the Columbans—the establishment of St. Serf on an island in Lochleven being of this school.

The Deicolæ were organised in 747 as an order of Secular Canons with the object of bringing the secular clergy into a cœnobitical life, so as to help to counteract the then prevailing tendency to the eremitical mode of living. The nature of the structures erected under the latter form of religious observance is well illustrated in the cells and oratories already alluded to, which were erected in such numbers on the lonely and deserted islands on the West Coasts of Ireland and Scotland.

The advent of the Roman emissaries in Scotland is embodied in several mythical legends. Such is the story of the arrival of St. Boniface with a complete following of persons representing all the offices of the Roman service, and his favourable reception by King Nectan indicates the goodwill with which they were welcomed.[31] The dedications of churches to St. Peter, superseding the dedication to the ancient native Saints, further mark the change from Iona to Rome.

The assimilation of the Church to the Roman system, and the introduction of the secular clergy, led in Scotland, as it had done in Northumbria, to the secularisation of the monasteries. Through the operation of the Celtic rules of succession they fell into the hands of laymen, who retained the title of abbot, and with it the possession of the monastic lands, but without any pretence to clerical office.[32] The old Celtic system of monasticism thus perished, first, from internal decay and change to the eremitical system; and, second, from its being gradually superseded by the introduction of the secular clergy on the Roman system.

Meanwhile at Iona, and in all the Western Islands and coasts, a new enemy to the Columban establishments sprung up. In 794 the Northern Rovers made their first appearance, and during many succeeding years the monastery of Iona was frequently attacked and pillaged, the monks being slain or driven to seek safety in Ireland. The connection between Ireland and Scotland was thus almost entirely severed during the ninth century, and the Columbans having (as above stated) been expelled from the Pictish kingdom, the previous active relations between the Church in the two countries was for the time entirely brought to a close.

In Alban or Pictland a revolution seems to have occurred about the year 850, and Kenneth M‘Alpine, a king of the Scotic race, ascended the throne of the Picts. By him an effort was made to re-establish the Columban Church. For this purpose he erected a chief religious centre at Dunkeld, and brought to it some of the relics of St. Columba, with the view of making it an inland Iona. However, in the latter half of{15} the ninth century, the see of the primacy was removed to Abernethy, in Perthshire. Here, Cellach, Abbot of Kildare and also of Iona, had sought refuge from the persecution of the Norsemen in Ireland, and there he died in 865. Irish clergy who had returned to Scotland are thus found at this period at Abernethy, and Dr. Skene supposes that the round tower which still stands there was probably erected about this date.[33] The increasing strength of the Roman influence may be gathered from the fact that in 878-89 King Giric is said to have “given liberty to the Scottish Church;” the meaning of which is, that he decreed that all church lands should be free from secular exactions.[34] In 908 the primacy was transferred to St. Andrews, and Cellach was appointed first Bishop of Alban.[35] A church was founded at Brechin about the year 1000, and was dedicated to the Holy Trinity. It was probably a monastery after the Irish model, with a College of Culdees. The round tower there is a mark of its early association with Ireland.

The Culdees long continued to assert their position and maintain their rights, but they became gradually absorbed into the cathedral chapters established in the country. We thus finally arrive at the period when, in the eleventh century, the adoption of the Roman system in Scotland, under Malcolm Canmore and Queen Margaret, was completed.

We have now followed the history of the Church in Scotland up to the point where the two streams of influence we have been observing, one from Ireland and the other from Rome through England, meet. We have noticed the powerful influence of the former in imparting to Scotland, under the Columban system, its early rudiments of education, religion, and art. Although this phase of culture did not display itself prominently in architectural results, yet there are other departments in which it excelled. It is to it we are indebted for the beautiful examples of caligraphy and decorated metal work of which the relics are preserved in the MSS., shrines, croziers, and ornaments of the Celtic race.[36]

The marvellous sculptured ornaments and crosses in which Scotland still abounds are also relics of the culture and artistic elements introduced by the missionaries from Ireland. These features of Celtic art form one of the most remarkable series of monuments in any country.

In Ireland, as we have already seen, this monumental art is chiefly exhibited in the recumbent cross-bearing slabs at Clonmacnoise and other ecclesiastical sites, while its later development assumes the form of free standing crosses of the Celtic pattern carved with the interlacing ornaments{16} characteristic of the style, or with figure sculptures enclosed in panels, each panel representing a Scriptural or symbolic subject.

The Scottish sculptured monuments, although bearing a general resemblance to the Irish, have several peculiarities. The earliest form of sculptured monuments in Scotland, as in the other Celtic divisions of Britain, consists of rude upright stones, engraved with an equal-armed cross enclosed in a circle, accompanied with an inscription in debased Roman capital letters, generally comprising the formula “hic jacet” and the chi-rho symbol. The carving is invariably incised in the stone. We have already met with examples of this class of monument, probably of the fifth century, in the South-West of Scotland, in connection with the Candida Casa of St. Ninian. (See Fig. 1.)

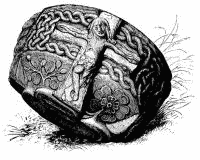

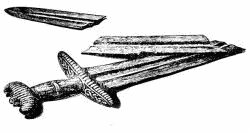

Certain peculiar forms of sculptured symbols, carved on undressed upright stones, seem to have originated amongst the Northern Picts. These symbols (Fig. 3) consist of the well-known symbol of (a) the “crescent and sceptre,” (b) the “double disc” or “spectacles,” (c) the above with sceptre, (d) the oblong with sceptre, (e) the “elephant,” and other forms which are very common in the East of Scotland north of the Forth, but are unknown anywhere else. The meaning of these symbols has never been satisfactorily explained. In the earliest monuments the symbols and occasional figures are the only ornaments found on the stones. They are invariably incised and plain, containing no interlaced or other ornament. It has been pointed out by Dr. J. Anderson that these simple incised symbols probably belong to the period before the beginning of the eighth century, when the Columbans were expelled from Pictland by King Nectan, while the later form of decorated monuments which succeeded them possibly dates from the return of the Columban clergy from Ireland in the middle of the ninth century, when they were re-established in the land by King Kenneth.

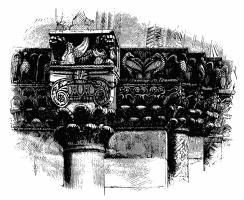

That period probably marks the later style of ornamentation which is found on the monuments. The original idea of an upright stone with sculptured symbols is retained, but the monument is no longer a rough unhewn block. It is now a shaped slab, dressed on both sides and on the edges, and the ornamental work is no longer incised, but carved

in relief (Fig. 4). The oblong slabs are always upright, and ornamented on both sides, not recumbent like the Irish slabs. They generally bear on the obverse a cross of the Celtic form occupying the full size of the stone. This form of cross has the four angles at the junction of the arms with the upright shaft hollowed out with a circular or square recess, and the junction surrounded with a circular band. The oblong form of the slab is preserved entire, and the portions of the surface on each side of the cross are usually covered with sculptures representing symbols or interlaced patterns arranged in panels (Fig. 5). The cross itself and the other figures are carved with elaborate designs of interlaced work, or with frets or divergent spirals. The reverse of the slabs is also covered with sculpture representing symbols and conventional or symbolic figures (Fig. 6). The sculpture on these stones bears a close resemblance to the designs of the Celtic MSS., so close, indeed, that each sculptured monument might be a page of MS. carved in stone. This indicates, as pointed out by Dr. J. Anderson, that the designs were first wrought out and brought to perfection on the pages of the MSS., and reproduced at a subsequent

period on the stone monuments. The earliest Celtic MSS. date from the end of the seventh century, while the decorated slabs are probably of the ninth to the twelfth centuries.[37]

A distinct change or progressive development is observable in the forms of the sculptures and ornaments of the above monuments. The{18} Celtic design gradually gives place to new features which bring it into conformity with the decorations of the MSS. and metal work and the general progress of the country. It thus at length becomes merged in the general design of the twelfth century, as introduced from the South along with the other effects of the Roman influence. The interlaced work, spirlets, and fret work give place in course of time to scrolls and leaf ornaments (Fig. 7). The crosses, formerly enriched with divergent spirals, become carved with leaf or flower patterns, the peculiar Pictish symbols disappear, and the Celtic cross gives place to the more ordinary Norman form. Upright cross slabs are abandoned and recumbent slabs take their place.

Amongst the later examples, Scripture scenes similar to those on the Irish crosses are introduced in the panels, together with numerous hunting pieces and figures of men and animals. Dr Anderson[38] shows distinctly that the Scriptural scenes are debased and barely intelligible representations of symbolic subjects from the Bible, such as Adam and Eve, the Sacrifice of Isaac, David Slaying the Lion, &c. Similar subjects are common in the Catacombs of Rome, where they are painted so as to be easily recognised; but in course of time, and after many imperfect efforts to copy them, they became reduced to the conventional forms seen in the Celtic sculptures, the meaning of which can only be explained by following the designs back to the originals. Dr. Anderson also shows that the hunting scenes, with men on horseback, dogs, &c., and the grotesque

animals represented, often with much spirit in the sculptures, are derived from the symbolic mediæval bestiaries. These figures, which at first sight might be regarded as secular or grotesque, are thus proved to be symbolic of Christian doctrine and moral teaching, like many of the later and more naturalistic carvings in the Gothic churches. In the hunting scenes the hart panting after the waterbrooks represents the soul pursued by its worldly enemies; the shooting of the wild boar with arrows symbolises the conversion of heathen savages to Christianity; the pelican, with its young, is a symbol of the Resurrection; the lion, the eagle, the phœnix are types of Christ; the fox and hyena of the devil.[39]

The above monuments of the East of Scotland are, as we have seen, almost all of the upright slab form, bearing the cross on the obverse. Only a very few free standing crosses exist in that region. Some examples of transition character are, however, found which form a connecting link between the upright slabs and the free standing crosses. These consist of cross bearing slabs having the circles, at the junction of the arms with the shaft, cut through the stone. It then only remained to cut away the remainder of the slab and leave the cross free.

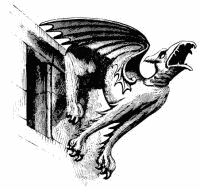

In the West of Scotland, on the other hand, the principal form of cross is the free standing one. In consequence of the invasions of the Northmen, this part of the country was in a great state of disturbance for a long period after the expulsion of the Columbans from the East, and little monumental work seems to have been done.[40] There are, however, a few fragments of free standing crosses at Iona, and one fine specimen at Kildalton, in Islay, which exhibit the same characteristics in their sculpture as the pure Celtic upright slabs of the East. (Fig. 8.) When monumental sculpture was revived in the West, at a considerably later date, its style indicates connection with Ireland rather than with the East of Scotland. Free standing crosses abound, and the upright slabs carved on both sides are rare; the grave slabs being recumbent, like those of Ireland. The symbols peculiar to the East are also entirely wanting. It seems also that the monuments of Argyllshire and the Western Islands (as at Iona, &c.) were influenced by a style of sculpture imported from the Continent, of which examples exist at Durham and Hexham. These “are not Celtic, but a debased local survival of Romanesque forms.”[41]

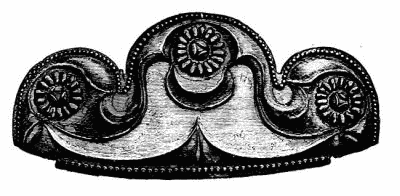

The late Western crosses have, further, this peculiarity, that the circular band round the head of the cross is not cut free, so as to present an independent ring of stone, but forms a solid disc, from which the ends of the arms and top project. (Figs. 9 and 9A.) These crosses generally contain a representation of the Crucifixion, which is almost unknown in pure Celtic work. The carving also ceases by degrees to be distinctively Celtic, and consists generally of scroll work and foliage. (Fig. 10.) These features were adhered to in this region for centuries after the Celtic work of the East had entirely given place to the general Gothic art of the rest of Europe. (Fig. 11.) The monuments of the West thus retain a very special character, the foliage of the designs being unique and original, and in many cases of much beauty. This peculiar design continued as late as the sixteenth century, several good dated examples of that period being still preserved, mixed with debased Gothic{21} features. The architecture of the locality is naturally much influenced by this style, as will be pointed out when Iona is described.

It can scarcely be doubted that many of the Scottish sculptured stones are of about twelfth century date. The sculptures on them represent the

same scenes, and are derived from the same source, as many of those carved on the tympana and fonts of Norman churches. Such sculptures are found on churches dating from 1135 to 1190, and almost no figure sculpture is found on churches of an earlier date. The subjects carved on the{22} churches are similar to those on the crosses, such as Adam and Eve, David and the lion, Daniel and the lions, hunting scenes, animals, monsters, and symbolic figures derived from the bestiaries. (See Dalmeny below.) The latter figures continued to be used on Gothic structures till a comparatively late date.

![[Image unavailable.]](images/ill_pg_022.png)

|

Fig. 9a.—Island of Oronsay. |

Fig. 10.—Kilchoman Cross, Islay. |

The sculptured crosses of the East of Scotland thus naturally connect{23} themselves with the current design of the period in other countries. They are no longer the mysterious and unintelligible monuments they

were once supposed to be. By the able investigations and expositions of the writers above referred to, they are brought into harmony with the{24} general art of Europe prior to the twelfth century, and are shown to hold a prominent place in the artistic history of the country.

It is remarkable, notwithstanding the abundance of sculpture on the early monuments, that, until the advent of the Norman influence, scarcely any indication of architectural details or sculpture occurs on the churches of either Ireland or Scotland.

The earliest sign of decoration on buildings in Ireland is seen in the form of a cross, composed of five white pebbles, inserted over the doorway, in the dark stone of which the beehive cells of Ardoilean are built. Some of the round towers contain very early instances of symbolism in the Celtic cross carved on the lintel, while late examples (such as Brechin) show a further advance in the introduction of a Crucifixion on the lintel, and other figures on other parts of the doorway. The carving of the cross on the above and other lintels is probably symbolic of the blood of the lamb which was struck on the doorposts of the Israelites in Egypt at the Passover.[42]

The ecclesiastical structures of the early centuries which still survive in Scotland are of the type of the stone erections above described in the monasteries of Ireland. The beehive huts and oratories of the parent eremitical establishments in the latter country are represented by a few similar collections of structures which yet remain in the remote islands and distant parts of Scotland.

Groups of dry-built beehive huts (or the remains of them), surrounding one or more primitive churches, can still be pointed to in several localities. These are surrounded with the wall or cashel which was always present around the Irish monasteries.

Diminutive dry-built stone cells or oratories, with sloping or curved walls, having the roof closed in with overlapping stones, converging towards the centre, and covered with flag-stones, are still found in the remote islands. One oratory also exists at Inchcolm where the stone roof is supported by a true arch, as in some of the latest Irish examples. It should, however, be pointed out that huts of similar construction to the above are known to have been erected and inhabited in recent times in the Outer Hebrides.[43] The hermitages above referred to, although belonging to this oldest type of structure, may thus possibly not be the oldest buildings in the country.

At a later time the rude monastic cells and hermitages were{25} followed by the churches established by the missionaries from Iona. The Scottish churches erected by the Columbans were, like those of Ireland, of extreme simplicity, and generally of small dimensions. They consisted of a simple oblong chamber, with a single door and a single small window. The walls were often built without mortar, and the wall apertures were finished with undressed stones. These structures were sometimes covered with a plain barrel vault, and sometimes with rafters and thatch. The jambs of the doorway incline inwards and have straight lintels; the windows are either square-headed or rudely arched. Until the Romanesque influence is felt, not a trace of any kind of ornament is to be found on these churches. Latterly, a few details resembling Norman work are introduced.

In other examples of this type the details are more advanced. The door jambs are upright and are covered with semi-circular arches, and the windows are also similarly treated. The buildings, however, possess few features to enable the date of their erection to be determined. They may possibly have all been erected during a long course of years at different times in different localities, according to local circumstances; but it is natural to suppose that those of the more refined type are the latest.

Another class of churches forms a distinctly later type than the above simple quadrilateral structures. These are the churches consisting of a nave and chancel. Not that the method of construction or the details of these churches show any advance on the previous class. On the contrary, the details are in many cases as simple and rude as those of the one-chambered churches; but the alteration of the ground plan, by the addition of a separate chancel, shows a development of the religious service, leading to the inference that the type of churches with chancels is later than the single-chambered ones. This, however, only shows that the idea is later, not that single-chambered churches did not continue to be erected after the chancel had, in some instances, been introduced.[44] The persistence of an original form of plan is remarkable and is well exemplified in the history of the castles of Scotland, which shows how the primitive keep-plan of the thirteenth century continued to be adopted up to the seventeenth century, long after other and more developed forms of castles had been introduced.

The tendency in churches, however, seems to have been to adhere to the chancel plan after its introduction, and even to alter older simple churches by the addition of a chancel to one-chambered structures. Of this we have mentioned an instance in Ireland at St. Kevin’s oratory at Glendalough, and we shall meet with examples in Scotland as we proceed. In other instances, primitive oratories have been converted into churches with chancels by the addition of a nave, the original oratory being retained as the chancel. We have thus a transitional plan{26} forming the link which connects these primitive single-chambered churches with the more advanced type of church with nave and chancel. In most of these early churches the chancel forms a separate apartment from the nave, the entrance to the chancel being by a doorway only, generally similar in size and form to that of the western entrance to the nave.

The chancel arch occurs, in some instances, as a later development. This, together with a few other details, seems to point to the influence of the Continental or Romanesque style which was slowly beginning to make itself felt in some parts of the country. All the above types of structures have been thoroughly examined and described by Mr. Muir, and will be more fully dealt with in the detailed descriptions of the churches derived from Mr. Muir’s works.

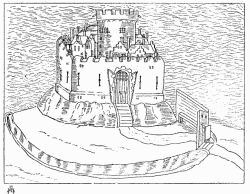

There still remain some special examples of Celtic structures to be mentioned. These are the well-known round towers, of which those at Abernethy and Brechin have already been referred to. A third round tower is also found attached to the church of Egilsay, in Orkney.[45] These towers are, undoubtedly, all examples of a style imported from Ireland. They are detached specimens of a group, of which no fewer than seventy-six examples still exist in that country, besides twenty-two others which are known to have existed formerly. It has been shown by Dr. Petrie that the Irish round towers were erected as places of refuge in connection with monasteries, to which the monks might repair with their relics and treasures in case of alarm. Such shelter was only too much required, as the valuables of the monastic institutions formed a very tempting bait for pillage by the Norsemen, whose depredations were so alarming during the ninth century.

The history of the round towers of Ireland is easily traced in their architecture, and has been fully explained and illustrated by Dr. Petrie in his well-known book on the subject, and in the late Lord Dunraven’s beautiful work on the early structures of Ireland. These towers are always found associated with religious sites. The earliest examples are comparatively rude in structure, while the later ones gradually improve in style of masonry and finish, until the latest are built with ashlar work, and contain some Romanesque ornaments and details. In all, however, the leading principles of their construction are the same. (Fig. 12.) The tower is round on plan, and is finished on top with a conical roof. The door is narrow, and is placed, for security, at a considerable height above the ground, and the lower floor is sometimes built up solid, so as to resist conflagration. The windows are small, except those on the top story, which are generally set facing the cardinal points, and are larger, so as to allow the sound of the bell to be heard—one of the uses of the tower being to serve as a belfry. The Irish practice of inclining the jambs of the doors is maintained, and in the early examples the lintel is straight,{27} while in the later ones the door is finished with a semi-circular arch, and enriched with several orders of mouldings and ornaments bearing a markedly Norman character. This remark applies also to the four windows of the top story, which are plain in the early examples, and gradually become more ornamental and Norman like. The Irish towers are almost invariably built alone, and free from other structures; but some late examples are constructed in connection with churches, and enter from them by a door on the level of the floor of the church. The idea of using these towers as a place of security is thus departed from, and they are then simply of use as belfries.[46] Finally, they become absorbed into the structure of the church, and are erected merely to serve as belfries on the gable.

In the three Scottish round towers we find the same characteristics as in those of Ireland. The tower at Egilsay (q.v.) is rude in style of masonry, but as

it enters from the church on the level of the floor, it is evidently of the late type above referred to. The towers at Brechin and Abernethy (q.v.) are built with more carefully selected and wrought materials, and both have the door, which is built with inclined jambs, set some feet above the ground. The latter has the four upper windows covered with semi-circular arches,{28} showing a considerable amount of Norman character in the mouldings and enrichments, as well as in the style of masonry. That at Brechin has a door with sloping jambs, having a Crucifixion carved above it and dragonesque sculptures at the base, and other details connecting it in a marked manner with the style of the round towers of Ireland. There can be no doubt that these are outlying examples of the Irish class of towers, while they exhibit also some features of the Romanesque architecture which, in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, had penetrated thus far northwards.

The next step in architectural progress consists of another structure, comprising a tower of a character somewhat related to the above, but having the Norman character more fully developed. This is the church of St. Regulus at St. Andrews (q.v.), the tower of which is lofty and square. This tower may be compared to the square tower of Cormac’s Chapel at Cashel, in Ireland, which is stated by Dr. Petrie, on good authority, to have been finished by 1135.[47] They both possess Norman features, well developed, and their square form and close attachment to a church are elements which distinguish them from the other and older round towers. Probably, however, they were also intended, like the latter, to form places of secure retreat as well as belfries. Both bear the signs of being late buildings of their class.

The dates of all the Irish round towers are somewhat uncertain, but probably extend from the ninth to the twelfth centuries, having, as already stated, been erected at the time of the invasions of the plundering Northmen. The dates of the destruction of several are recorded, and have been collected by Dr. Petrie, who also shows that many churches which had been destroyed by the Northmen were repaired and rebuilt about 1150.[48]

It is believed that in Ireland a form of Romanesque was introduced before the Anglo-Norman invasion,[49] and many of the early ornamented churches show a style of carving in which the Irish interlaced work and other special details are introduced. But in Scotland there are no traces of churches containing any similar work, although, possibly, some may have existed and been swept away in the great rebuilding epoch which followed the Norman Conquest.

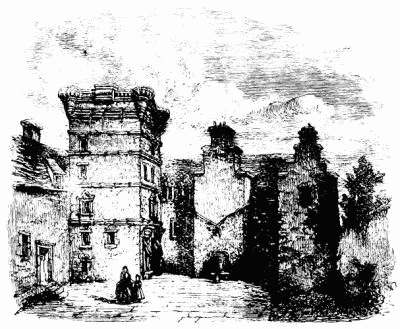

The earliest examples of anything like ornament in Scottish churches within the historic period are undoubtedly the outcome of the Roman influence introduced under the Normans. We have already referred to the effects of early Roman influence at St. Regulus; and the next earliest building, the date of which is thought to be recorded, is the Reilig Oran at Iona (q.v.), a simple single-chambered structure, with a west doorway containing Norman ornament. This is said to have been erected by Queen Margaret before 1093.[50]{29}

The chapel in Edinburgh Castle bearing St. Margaret’s name is also attributed to her, and is supposed to have been erected during her lifetime, or shortly afterwards. It would, in that case, be the first example in Scotland of a church terminating with an eastern apse (which, however, is square on the exterior).

Whether these buildings were actually erected in Queen Margaret’s lifetime or not, they certainly belong to a period not long subsequent. The life of that Queen and Saint marks the period of transition in Scotland from the old system to the new, not only in building, but in every other department.

Edgar Aetheling, the heir of the old Saxon kings, having been driven out by the Conqueror, found refuge, along with his mother and sisters, in the Court of his relative, Malcolm Canmore. There Margaret, having become Malcolm’s wife, soon introduced many of the reforms and ameliorations she had learned in England. Particularly, she gave a distinct impetus to the Roman influence, then very strong in the South, and encouraged the hosts of Saxon refugees who now crowded to Scotland, bringing their advanced notions with them. The same tendency was manifested by Margaret’s sons, Edgar and Alexander, who followed her footsteps in endeavouring to assimilate the Scottish Church to that of England.

It was King Alexander who, being driven by a storm on the Island of Inchcolm, in the Frith of Forth, was rescued and sustained by a hermit, who then occupied a primitive cell, built on the island, similar to those of the Columbans above referred to. The king vowed, in thankfulness for his deliverance, to found a monastery on the spot, and in 1123 he here introduced a colony of Canons Regular. He also endeavoured to bring the Episcopacy of St. Andrews into conformity with the Roman model.

Under Alexander,[51] Turgot, the Prior of Durham, and biographer of St. Margaret, was appointed to the long vacant See of St. Andrews. This king also founded the Bishopric of Moray, and restored that of Dunkeld. In the former wild Diocese the churches of Birnie, Spynie, and Kinedor appear to have existed, but it was not till 1203 that Bricius, the sixth bishop, was able to fix his cathedral at Spynie.

In 1115 Alexander introduced a colony of Canons Regular to Scone, from Nastley Abbey, in Yorkshire, and some years later he brought canons to the Diocese of Dunkeld, and in 1122 he founded a Priory of Canons Regular on an island at the east end of Loch Tay.[52]