Transcribed from the [1855] George Lewis edition by David Price.

COMPRISING

THE

BRITISH, SAXON, NORMAN, AND ENGLISH

ERAS;

THE

TOPOGRAPHY OF THE BOROUGH;

AND

ITS

ECCLESIASTICAL AND CIVIC HISTORY:

WITH NOTICES

OF

BOTANY, GEOLOGY, STATISTICS, ANGLING, AND BIOGRAPHY:

TO WHICH ARE

ADDED

SKETCHES OF THE ENVIRONS.

ILLUSTRATED WITH WOOD-ENGRAVINGS,

By MR. PERCY

CRUIKSHANK, after Sketches by MR. ROBERT

CRUIKSHANK.

WRITTEN AND COMPILED

BY WILLIAM CATHRALL,

AUTHOR OF

“THE HISTORY OF NORTH WALES,”

“WANDERINGS

IN NORTH WALES,” &c.

OSWESTRY:

PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY GEORGE LEWIS.

ENTERED AT STATIONERS’ HALL.

The issue of this volume has been “the accident of an accident.” I was called by commercial business last autumn to Oswestry, where I found, temporarily located, a man with humour at his finger-ends, and of “infinite jest” on paper. I allude to Mr. Robert Cruikshank, an artist scarcely inferior to his celebrated brother, Mr. George Cruikshank—par nobile fratrum, who have both successfully laboured in their vocation to

—“Shoot folly as it flies,

And catch the living manners as they rise.”

Mr. Robert Cruikshank, pleased with the rich and diversified scenery of the neighbourhood of Oswestry, undertook to illustrate the present book. To be thus pictorially aided was a distinction, and I therefore cheerfully complied with the wish of the respectable publisher, to try my “’prentice hand” at a History of the Borough. Mr. Cruikshank has well executed his task. What may be my portion of merit will be determined by the judgment, not critically severe, I hope, of my readers.

The History of Oswestry and its neighbourhood is, however, worthy of a more elaborate and carefully-wrought p. ivvolume than that which I now send forth; and I should have been glad had some pen, abler than my own, been employed in the completion of so desirable a work. Oswestry is not deficient in the talent or learning necessary to produce a voluminous history; but until the historic mantle fall upon some kindred spirit, that can evoke with magic skill the dramatis personæ and chequered incidents of bye-gone ages, and beguile his readers with beautiful delineations of his native hills and vallies, the good citizens of Oswestry must, I fear, content themselves with the present volume, whose chief excellence, if it possess any, may be found to consist in supplying a collection of interesting facts, connected with the town and district, hitherto dispersed through many publications.

In preparing this volume for the press much delay has occurred from the pressure of other and more anxious engagements. In wading, however, through musty tomes and modern books, I have been instructed and solaced by the way. The Past reveals little else than vandal darkness and the pride and pomp of feudal power. Lords and their vassals figure chiefly in the discordant scene, and ignorant dependence is too commonly seen prostrate at the feet of favourites, in court or field, of ambitious and despotic monarchs. The Present has a more genial and encouraging aspect. Religion, with her gentle handmaids, Literature, Science, and Art, is shedding its radiance even over this district, so long the theatre of Border-feuds, strife, and injustice. The Future, therefore, indicates still more agreeable promise; and those of the present generation who are co-operating in the good work already begun, of endeavouring to make the world better than they found it, will have the consolation of leaving to posterity an inheritance more precious than silver or gold.

p. vI cannot close these remarks without thankfully acknowledging the assistance I have derived, from several gentlemen of the town and neighbourhood, in the prosecution of my labours. If I could have stirred up many others to the grateful task of elucidating the history of their native or adopted place of residence, I should have been still more satisfied. I take this opportunity of mentioning the names of The Rev. Thomas Salwey, Vicar of Oswestry, Richard Redmond Caton, Esq., F.S.A., Edward Williams, Esq., of Lloran House, R. J. Croxon, Esq., Charles Sabine, Esq., and one or two other gentlemen, who, with a becoming feeling of respect for the ancient borough, have kindly aided me by various contributions.

I am sensible of many imperfections in the volume; but I trust, by the generous support of the Public, I may be enabled, at some not far distant day, to revise my pages, and render them still more worthy of acceptance.

WILLIAM CATHRALL.

Oswestry, October, 1855.

Asterley Miss, Willow-street

Attree R. W., Esq., Plasmadoc

Bassett Joseph, Esq., solicitor

Berry Joseph, Accountant

Bennion Edward David, Esq., Summer Hill

Baugh Robert, Llanymynech

Bull William Isaac, Esq., solicitor

Bickerton George Morrel, brazier

Bartlett Charles Archibald, 32, Paternoster Row, London

Buckley Miss Eliza

Broughall John, Esq., Fernhill, Whittington

Barlow Thomas, Esq., postmaster, Worksop

Barnes William, Osberton Hall, Notts

Bayley Joseph, Quadrant

Cashel Rev. Frederick, Incumbent of Trinity Church

Corbett Vincent, Esq.

Caton Richard Redmond, Esq., F.S.A.

Croxon Richard Jones, Esq., Town Clerk

Crutchloe Henry, Lloran Cottage

Cooper George, Esq., Salop-road

Cullis William, Lower Brook-st.

Corney William, confectioner and spirit merchant

Churchill Benjamin, Esq., Bellan House

Cross Thomas, Ornithologist

Cox J., porter merchant, Birmingham

Clarke Mrs., 3, Devonshire-terrace, Paddington, London

Cruikshank Percy, Pentonville, London

Churchill Miss, Bellan House (2 copies)

Crippin R., Church-street

Cross William B., Cross-street

Cartwright Samuel, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury

Donne Rev. Stephen, the Schools (12 copies)

Dovaston John, Esq., Nursery, West Felton

Davies Henry, Esq., solicitor

Davies John, draper

Davies Edward, confectioner

Davies Captain, Llanymynech

Dicker Phillip Henry, Esq., surg.

Davies Messrs. R. & W., Golden Eagle

Downes Richard, Esq., Haughton Grange

p. viiDavies Edward, Esq., surgeon, Llansilin

Davies Henry, schoolmaster, Llandrinio

Duckett Mrs. Tamar, the Lodge

Davies Mrs. E., Chirk

Duncan John, Esq., solicitor, 2, New Inn, Strand

Davies W. M., Waterloo-house

Davies Giles, Lower Brook-street

Davies Thomas, Greenwich

Davies John, Erwallo, Glyn

Edwards James, Esq., Upper Brook-street (2 copies)

Edmunds Rev. Edw., M.A., Vicar of St. Michael’s, Southampton

Eddy Walter, Mine Agent, Fron, Rhuabon

Evans Edward, auctioneer

Edwards Thomas, Esq., Cae Glas

Edwards Ed., Commercial Hotel

Eyeley Edward, organist

Evans R. D., Esq., Meifod

Edwards James Coster, Trefynant

Edwards Thomas, chandler

Evans John, ship builder, Morbum, Machynlleth

Edwards Alfred, Hanwell, Middlesex

Edmunds Griffith, Albion Hill

Edisbury James, Esq., Wrexham

Edisbury J. F., Esq., Holywell

Ellis Henry, English Walls

Evans Edward, Liverpool Gas Co.

Evans William, Glascoed

Edwards Edward, currier

Edwards William, Queen’s Head

Evans John, Church-street

Ewing John, gardener, Osberton Hall

Fitz-William, The Right Hon. The Earl (4 copies)

Fitz-William, The Hon. Lady Charlotte Wentworth, Wentworth House

Fitz-William, The Hon. M. S. C. Wentworth

Fitz-William, The Hon. Lady Dorothy H. Wentworth

Francis Captain, Aberystwith

Fallon Rev. J. M., Bailee Rectory, Ireland

Fuller William, Esq., Salop-road

Furnin The Rev. J. P., Rode Parsonage, near Lawton, Cheshire

Faulder F. J., Esq., St. Ann’s-square, Manchester

Fox John, accountant

Gore William Ormsby, Esq., M.P. for North Shropshire

Grey William, Esq., New Burlington-street, London

Gray Thos., Esq. architect, Chester

Greenwood J. W., Esq., London

Goodwin John, Beatrice-street

Galloway Charles, Halston

George Roger, Willow-street

Giles Henry, Cross-street

Gornall Mrs. Jane, Swan Inn

Griffiths William, Esq., solicitor, Dolgelley

Hill The Right Hon. The Viscount, Lord Lieutenant of the County of Salop

Hales John Miles, Esq., Lower Brook-street

Hill T. Esq., Upper Brook-street

Hill T. W., Esq., Upper Brook-st

Hargraves James, Esq., Whittington (2 copies)

Hayden Wm. Henry, 17, Warwick-square, London

Higgins Samuel, draper

Holland George, Whittington

Husband Rev. J., Rectory, Selattyn

Hopwood F. A., Station Master, Gobowen

Hardman Thomas, 14, Slater-street, Liverpool

Hughes T., Esq., solr., Wrexham

Hughes Miss Catherine, Church-street

Hughes Alexander, Willow-street

Hughes Miss Anne, Salop-road

Humphreys Edmund, East Sheen, Richmond (2 copies)

Hughes John, Savings’ Bank

Hilditch George, Esq., Salop-road

Heaton Rev. H. E., M.A., perpetual curate of Llangedwin

Hodgkinson R., Esq., estate agent, Osberton, Worksop

Howell David, Willow-Street (2 copies)

p. viiiHughes Thos., Esq., Plasnewydd, Llansilin

Jones, Rev. Llewelyn Wynn, M.A., Curate of Oswestry (2 copies)

Jacob Rev. L. R., Rhuabon

Jones John, Esq., solicitor

Jones Miss Harriette, Church-st.

Jones Thomas, Esq., Boughton, Chester

Jones Joseph, wine merchant

Jones Edward, Plas Issa, Rhuabon

Jones Mrs. Frances, London House

Jones John, hair dresser

Jones Edwin, Union-place

Jones James Thomas, Esq., Brynhafod (2 copies)

Jones Oswald Croxon, Esq., Enfield, Middlesex

Jones Mrs. Mary Watkin, Cross-street

Jacques Edwin William, Esq., Llangollen

Jones Henry, tobacconist

Jones Thomas, Esq., Brook-street

Jones John, Esq., Domgay, Llandisilio

Jervis Geo. Boot Inn, Whittington

Jones Rev. D. L., Meifod

Jones Rev. Walter, Llansilin

Jones Richard, Cross-street

Jones Richard, Salop-road

Jones Thomas, builder, Chester

Jones Gwen, Cross-street

Jones Henry, grocer, Cross-street

Jones John Pryce, Willow-street

Jones John, Cross

Jones Richard, Esq., Bellan Place, Rhuabon

Jones Edward, Mine Agent, Llwynymapsis

Kenyon John Robert, Esq., Recorder of Oswestry

Kinchant Richard Henry, Esq., Park Hall

King John Edward, Cross Keys Hotel

Kilner Richard, Britannia Inn

Lovett Joseph Venables, Esq., Belmont

LLoyd, Mrs., Aston Hall

Longueville Mrs., Pen-y-lan

Longueville Thomas Longueville, Esq.

Lloyd Rev. Albany Rosendale, Hengoed

Large Joseph, Esq., surgeon

Lewis Richard, Osberton Hall, Notts (4 copies)

Lloyd David Edward, Cross

Lloyd David, Wynnstay Arms Hotel

Lewis Charles Thomas, 38–9, Holloway Head, Birmingham (6 copies)

Lewis Henry, painter, Beatrice-st.

Lloyd Rev. David, Trefonen

Lewis William, Elephant and Castle, Newtown

Leah John, Esq., Willow-street

Lewis Henry, building surveyor & contractor, Chester (2 copies)

Lever William H., Esq., Chirk

Lewis Miss Margaret, Cross

Lees S. S., National Schools

Lyons Aaron, Jeweller, Leg-street

Lloyd Miss M. A., Willow-street

Milton The Hon. Viscountess, Osberton, Notts

Milton The Hon. Selina, Viscountess, Osberton Hall, Notts

Mickleburgh Chas. Esq., Montgomery (2 copies)

Minshall Thomas, Esq., solicitor

Morris Edward, Esq., Salop-road

Morris William, builder

M’Kie William Hay, Scybor Issa

Morgan Captain, 54, Terrace, Aberystwith

Minett William, Esq., Maesbury

Meredith Edward, Rednal

Morris Joseph, Esq., Shrewsbury

Morgan John, Wynnstay

Moreton and Son, Cross

Morgan Thomas, Willow-street

Mytton John, Church-street

Manning Benjamin, Esq., Warwick-square, London

Martin John, Esq., Gold Mine, Dinas Mowddy (3 copies)

Monk Charles, Llangollen

Morris George, Porkington

Morgan R., Aberystwith

p. ixM’Kie William H., Melbourne, Australia

Morris John, builder (2 copies)

Morris Thomas, chemist, Worksop, Notts

Norfolk The Most Noble His Grace the Duke of (Baron of Oswestry), Arundel Castle, Sussex (4 copies)

Nicholson J. Esq., Upper Brook-street

Oswell Edward, Esq., solicitor

Owen M. Wynne, Esq., Plas Wilmot

Owen George, Esq., Park Issa (2 copies)

Oliver Irwin, Leg-street

Owen Elizabeth, 5, Upper Parade, Leamington

Oliver John, druggist, Liverpool

Powis The Right Hon. the Earl of (Lord of the Manor of Oswestry), Powis Castle

Portman The Right Hon. Lord, Bryanstone House, Dorset

Portman The Hon. William Berkeley, M. P.

Phillips John, Esq., Cross

Porter Isaac, Esq., Salop-road

Pryce Thomas, Cross-street

Powell John Richard, Esq., Preesgwene

Price William, Esq., Fulford, York

Phillips the Rev. John Croxon, Tynyrhos

Pearson Mr. S., clothier, 2, Lamb’s Conduit-street, London

Penson Richard Kyrke, Esq., Willow-street

Price Miss Mary, The Cross

Phillip and Son Messrs., Liverpool

Penson Thomas Mainwaring, Esq., Chester

Price Miss Elizabeth, Confectioner, Cross

Peate Jane, Porkington Terrace

Pierce Mrs. H., 87, Park Terrace, Green Heys, Manchester

Perkins Samuel, Bailey Head

Pearson W., J. Munn and Co., Manchester (4 copies)

Powell William, Salop Road

Parry Thomas Price, Willow-st.

Provis William A., Esq., Cross-street

Pearce R.A., Esq., Worksop, Notts

Rogers Thomas, Esq., Stone House

Roberts Thomas Vaughan, Esq., solicitor

Roberts Thomas, Esq., Glyndwr, St. Asaph

Roberts John, Esq., Cross-street

Roberts Maurice, draper

Roberts David, Leg-street

Rogers E., Church-street

Roberts John Askew, Bailey Head

Rodenhurst Charles, Whittington

Roderick William, Esq., surgeon

Redrobe James, Royal Oak

Roberts Miss, Brook-st. Cottage

Roberts R., gas proprietor

Roberts E., Willow-street

Roberts William Whitridge, Melbourne, Australia

Reed Mrs., London

Ruscoe John, Horse Shoe Inn

Salwey Rev. Thomas, Vicar of Oswestry

Sabine Charles, Esq., solicitor

Smith Frederick William, Esq., Ruthin (3 copies)

Smale William, chemist

Sharwood Messrs. S. and T., 120, Aldersgate-street, London (2 copies)

Saunders George James, chemist

Sage Mrs. Catherine, Middleton-road

Smith Captain, Dinas Mowddy

Smith Henry, Supervisor, Inland Revenue

Savin Thomas, draper

Stokes Mrs., Rock Ferry

Sides Miss Sarah, Fron, Rhuabon

Sissons Henry, stationer, Worksop, Notts

Shaw Henry, ironmonger, Worksop, Notts

Smith Benjamin, innkeeper, Norton, Notts

p. xTipton Edward Blakeway, Esq., Distributor of Stamps for Shropshire and North Wales

Thomas Edward Wynne, Esq., Cross

Tomkies John, Esq., Manchester (2 copies)

Thomas Rev. John, Liverpool

Thomas John, maltster

Tucker St. Felix, Esq, H.M.C., West Derby-road, Liverpool

Taylor John, shoemaker

Tyley Thomas, Sun Inn

Thomas Henry, Coney Green

Thompson John, Leg-street

Towers Mr., Angel Hotel, Dale-street, Liverpool

Thompson Thomas, Chester

Venables Rowland Jones, Esq., Oakhurst

Vaughan Robert Chambre, Esq., Burlton, Shrewsbury

Venables Mrs. Eliz., Whittington

West Frederick Richard, Esq. M.P., Ruthin Castle

West Frederick Myddleton, Esq.

Williams Edward, Esq., Lloran House (4 copies)

Wilding John Powell, Esq., Montgomery

Whalley George Hammond, Esq., Plasmadoc

Waite George, Esq., New Burlington-street, London

Williams Rev. Rt., Rhydycroesau

Webster Benjamin Esq., Adelphi Theatre, Strand, London

Wood Richard, Leg-street

Woods Richard, farmer, Osberton, Worksop

Williams J. Vincent, Accountant

Wright Edmund, Esq., Halston

Wynn Edward, Black-gate

Williams Edward, Belle Vue, Wrexham

Williams Rt., draper (2 copies)

Williams Samuel, The Llys

Winter John, Chirk

Webb Miss J. C., Melbourne, Australia

Windsor William, Babin’s Wood

Windsor Samuel, Powis Castle

Wilson William, upholsterer

Williams G. H., Esq., The Lymes

Williams William, Esq., 295, Kent-St., Southwark, London

Williams Michael, Railway Station

Whitridge Mr., bookseller, Carlisle

Page |

|

Agricultural Statistics |

|

Album Monasterium |

|

Aldermen and Common-Councilmen |

|

Alfred the Great |

|

Ancient Customs |

|

Ancient Houses |

|

Ancient Relics |

|

Angling |

|

Aston Hall |

|

Attack on the town |

|

Baptist Chapel |

|

Banks |

|

Battle of Oswestry |

|

Belmont |

|

Benevolent Institutions |

|

Bethesda Chapel |

|

Blanc-Minster |

|

Bleddyn ab Cynvyn |

|

Biography |

|

Botany of the Parish |

|

Bray, Dr. Thomas |

|

British Period |

|

British Schools |

|

Broom Hall |

|

Brunswick Dynasty |

|

Brynkinalt |

|

Cadwaladr’s reign |

|

Cae Nef |

|

Carreg Hofa Castle |

|

Castle of Oswestry |

15–172 |

Overton |

|

Ceiriog, the |

|

Civil Wars |

|

Charitable Donations |

|

Church or Chapel-Field |

|

Charles I., Character of |

|

Charter, First Royal |

|

Charter of Charles II. |

|

Charter the Third |

|

Chirk |

|

Chirk Castle |

|

Clawdd Coch |

|

Coed Euloe, Battle of |

|

Cranage’s Daring |

|

Crogen, Battle of |

|

Croes-Oswallt (Oswald’s Cross) |

|

Croes Wylan |

|

Death of Oswald |

|

Derivation of Name, &c. |

|

Derwen |

|

Dispensary and Baths |

|

Dissenting Places of Worship |

|

Dovaston, John Freeman Milward |

|

Drenewydd |

|

Ecclesiastical History |

|

English Period |

|

Extension Line (Oswestry and Newtown) Railway |

|

Famine |

|

Felton West |

|

Fernhill |

|

Fitz-Alan, William |

|

Fletcher, Philip Lloyd |

|

Fitz-Gwarine |

|

Free Grammar School |

|

Friendly Societies |

|

Gas-works |

|

Gates |

|

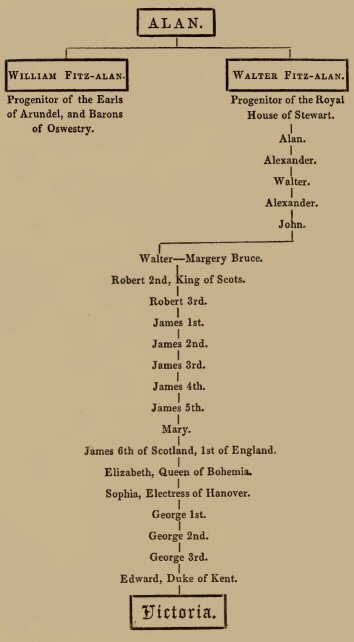

Genealogical Table |

|

Geology, &c. |

|

Glorious Age |

|

Glyndwr Insurrection |

|

Reverses |

|

Death of |

|

Great Western Railway Company |

|

Greenfield Lodge |

|

Griddle Gate |

|

Grufydd ab Cynan |

|

Guto (y Glyn) |

|

Halston |

|

Hen Dinas |

|

Hengoed |

|

Hotels |

|

House of Industry |

|

Humphreys, Humphrey, D.D. |

|

Hywel Dda (the Welsh Justinian) |

|

Independent Methodist Chapel |

|

Ingratitude of (Common Wealth) Parliament |

|

Invasion of Wales |

|

Jones, Thomas |

|

King Oswald |

|

Knockin |

|

Kynaston, Humphrey |

|

Le Strange, Roger |

|

Lighting |

|

Lodge, the |

|

Llanforda |

|

Llangollen Vale |

|

Llanymynech |

|

Llanyblodwel |

|

Llansilin |

|

Lloyd, Colonel |

|

Lloyd, Bishop |

|

Llynclys (or Llynclis) Pool |

|

Lupus, Hugh |

|

Llwyd, Edward |

|

Llywarch Hen |

|

Llywelyn ab Jorwerth |

|

Madog |

|

Maelor |

|

Marrow’s Assault |

|

Marches Lordships |

|

Margery Bruce |

|

Markets and Fairs |

|

Markets |

102–3 |

Maserfield |

|

Mathrafal |

|

Maud Verdon |

|

Maurice, William |

|

Mayors, List of |

|

Mayor’s Blunders |

|

Mediolanum |

|

Montgomery, Roger de |

|

Morda, the |

|

Morlas, the |

|

Morus, Hugh |

|

Monuments within the Church |

|

in the Church-yard |

|

in the New Church-yard |

|

Morva Rhuddlan |

|

Mortimers, the |

|

Mount Pleasant |

|

Municipal and Civil Government |

|

Officers |

|

Myddelton, Sir Thomas |

|

Mytton, Major-General |

|

Mytton, the late John, Esq. |

|

National Schools |

|

Natural History |

|

Newport, Mr. |

|

Norfolk, Duke of |

|

Norman Period |

|

Notabilia |

|

Oakhurst |

|

Offa’s Dyke |

|

Old Chapel |

|

Oswald’s Well |

|

Oswestry Race-course |

|

Castle, Burning of |

|

Government of |

|

As it was |

|

recent History of |

|

Castle Hill |

|

Owain Brogyntyn |

|

Oswald and Penda |

|

Parliament, the Great |

|

Parish Church |

|

Sunday School |

|

Park Hall |

|

Penda, the Mercian King |

|

Pengwern |

|

Pentre Pant |

|

Pentre Poeth |

|

Penylan |

|

Perry, the |

|

Plague, records of |

|

Plot to remove the markets |

|

Poor Rate Return—Oswestry town and parish (1855) |

|

Population |

|

Porkington |

|

Post Office |

|

Powys Vadog |

|

Preesgwene House |

|

Primitive Methodist Chapel |

|

Public Establishments and Institutions |

|

Quinta, the |

|

Railway Communication |

|

Restoration, the |

|

Review of Ancient History |

|

Revolution, the |

|

Reynolds, John |

|

Richard II., death of |

|

Rivers |

|

Rhyd-y-croesau Church |

|

Roberts, the Rev. Peter |

|

Rug |

|

Sacheverell, Dr. |

|

Salter, Mr. Robert |

|

Savings’ Bank |

|

Saxon Period |

|

Selattyn |

|

Shrewsbury, the Battle of |

|

Siarter Cwtta, the Short Charter |

|

Site of the town |

|

Sketches of the Environs of Oswestry |

|

Social Improvement |

|

Society for Bettering the Condition of the Poor |

|

Spot, Dick |

|

St. Martin’s |

|

Stamp Office |

|

Statistics |

|

Streets |

|

Sweeney Hall |

|

Tenants’ Service |

|

Theatre |

|

Topographical History |

|

Town Walls |

|

Tre’r Cadeiriau |

|

Tre’r Fesen |

|

Trefaldwyn |

|

Trefonen Church |

|

Tre Meredydd |

|

Trevor, Sir John |

|

Trinity Church |

|

Tyn-y-Rhos |

|

Visit of Baldwin and Giraldus |

|

Vicars, List of |

|

Walter the Stewart |

|

Watt’s Dyke |

11–12–13 |

Welsh Cloth Market |

|

Wesleyan Methodist Chapel |

|

Whittington |

|

William the Conqueror |

|

Wood Hill Hall |

|

Wynnstay |

|

Young Men’s Institute |

|

Zion Chapel |

|

Page |

|

Beatrice Gate |

|

Church Gate and Avenue |

|

Cross Market and Street Views |

(facing the Title-page) |

Dispensary and Public Baths |

|

Free Grammar School |

(facing) 107 |

Griddle Gate |

|

New Gate |

|

National Schools |

|

Oswestry Castle (from an ancient drawing belonging to an inhabitant of Dudleston) |

(facing) 172 |

The Old Chapel |

|

Parish Church |

(facing) 132 |

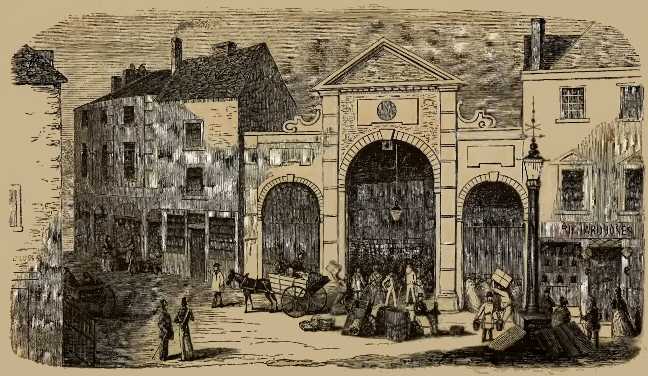

Powis Market, Guildhall, and Bailey Head |

(facing) 103 |

St. Oswald’s Well |

|

Trinity Church |

Brynkinalt |

(facing) 243 |

Chirk Castle |

(facing) 244 |

Halston |

(facing) 249 |

Llanymynech Church |

|

Park Hall |

(facing) 263 |

Porkington |

(facing) 266 |

Selattyn Church |

|

Whittington Castle |

(facing) 281 |

Wynnstay |

(facing) 287 |

A celebrated writer has said, that “History is philosophy teaching by example.” Local History was doubtless included in the reflection of the distinguished essayist, when he penned the memorable sentence, which has for years past been adopted as a national maxim. In Local History we have handed down to us facts and fiction, both grave and gay; traditions and customs illustrative of popular habits and manners; records of national edicts and social laws; municipal mandates, and parochial practice; doleful notes of superstition and ignorance, with gratifying statistics of the progress of truth and enlightenment; pleasing reports of the advancement of science and art, mechanical ingenuity, and industrial pursuits; and, speaking comprehensively, with a keen glance at the past, we descry enough, in the chequered examples of byegone times, to help us on in wisdom’s ways.

With these preliminaries, let us now lead our readers pleasantly onward through the devious paths and labyrinths of Oswestry’s varied history, beguiling them, perchance, by the way, with all that is agreeable pertaining to the Ancient and Loyal Borough, which, from its antiquity, its scenes of martial daring and prowess, the tranquil beauty of its surrounding landscapes, and its primitive, as well as modern p. 2relation to some of the sweetest spots of Cambria, has commanded the admiration and homage of historians, painters, and poets.

The derivation of the name of the Borough is still, and perhaps ever will be, involved in obscurity. As a place of retreat for the Cymry, or early Britons, when chased from the south by the Roman invaders, it is not unlikely to have had a primitive name that has been lost in the flood of ages. Pennant, whose industry and historical research have earned for him lasting fame, dates the commencement of its history in the Saxon period, not anterior to the celebrated conflict at Oswestry, between Oswald, the Christian King of the Northumbrians, and Penda, the Pagan King of the Mercians, which occurred in the year 642. Other Welsh biographical and historical writers trace the origin of its name to a much earlier period, and contend that Oswal, a son of Cunedda Wledig, sovereign of the Stratclyde Britons, and who lived in the early part of the fifth century, received from his father, as a tribute for special military services, an extensive grant of land, called from him Osweiling, in which the present town of Oswestry is situated. The coincidence is extraordinary that two distinguished chieftains should have flourished—although upwards of two centuries had rolled between their reigns—bearing names so similar to each other, that from either, it may be presumed, the town could, not inappropriately, have derived its present designation. The evidence in favour of Oswald’s right to the sponsorship of Oswestry is, however, in our opinion, so strong, that we must accord the honour to the Northumbrian Monarch, until the Cambrian or British claim shall be more authoritatively established. In the battle between Oswald and Penda, history informs us that the former was defeated and fell; that the barbarian victor ordered that the body of the slain monarch should be cut in pieces, and “stuck on stakes dispersed over p. 3the field as so many trophies; or, according to the ancient verses that relate the legend, his head and hands only were thus exposed:—

‘Three crosses, raised at Penda’s dire command,

Bore Oswald’s royal head and mangled hands.’”

After this battle the Welsh, or Cymry, (who seemed to have possessed for some time the district including Oswestry,) had called it Croes-Oswallt (Oswald’s Cross), in allusion to Penda’s ignominious exposure of Oswald’s slaughtered body. The spot where the battle was fought is said to have borne the name of Maeshir (the long field), as marking the length and obstinacy of the conflict. In the fulness of the Saxon period the town was known as Oswald’s Tree, in evident reference to Oswald’s death, and subsequently, to the present day, “without let or impediment,” by the name of Oswestry.

Industrious and talented antiquarian writers have given to the town other names and derivations. For instance, we are told that it was termed by the Saxons Blanc-Minster, White-Minster, Album-Monasterium, from its “fair and white Monastery,” whilst the Cymry, or “Old Britons,” as Williams denominates them, “called the town Tre’r Fesen, Tre’r Cadeiriau, the Town of the Oak Chairs,” or, as another writer has it, “the Town of Great Oaks.” These terms bear special allusion to Oswald’s unfortunate arrival in this district; for the ancient seal of the town, cut in brass, represents King Oswald sitting in his robes on a chair, holding a sword in his right hand, and an oak branch in his left, with the words around, “De Oswaldestre sigillum commune.” In repeating the long and tedious catalogue of names and derivations, it will be proper to mention that one writer renders the designation Tre’r Cadeiriau as follows:—“Oswestry was called by the Britons Tre’r Cadeiriau, literally the Town of Chairs, or Seats, commanding an extensive view, (as Cadair Idris, the chair of Idris, and others,) as there are several eminences commanding such views in the neighbourhood.”

p. 4Here is a chapter on civic nomenclature and varied derivation, very curious, perhaps, to many readers, but little edifying to those who ask with the poet, “What’s in a name?” And yet, ancient civic names, like many other ancient relics, have valuable and salutary uses. They are as finger-posts to the Past; in some instances inviting us to the honest path of truth and honour; in others deterring us from the rugged ways of ignorance and error. In almost all respects they enable us to institute comparisons and form contrasts between men and manners in ancient and modern days. Whilst looking at such names, we are too frequently reminded of times when Might overcame Right, and are gently led with thankful spirits to the Present, when, in our own happy and highly-privileged age, every Briton can sit “under his vine and under his fig-tree,” none daring to make him afraid.

For ages the site of the town, with the surrounding district, was the theatre of brutal contention, rapine, and aggrandisement. Here, as in the Border-Lands of Scotland, it was

“The good old rule,

* * * the simple plan,

That they should take who have the power,

And they should keep who can.”

Education had not spread her benign wings over the people, to hush them into peace; and too commonly they who possessed the strongest physical power and the wildest barbarism became, in turns, “Lords of the Ascendant.” There is no record extant that the Roman invaders of Britain pitched their tents within the Oswestrian district; and yet it is more than probable that part of the legion, which traversed p. 5from the south of our island, actually touched at Llanymynech Hill (a Roman settlement beyond doubt), and most likely constituted a portion of the army which, under Suetonius, found its way along the mountain-passes of North Wales into Anglesey, may have halted there, if the ground was pre-occupied by the invaded Britons, or the ancient encampment, Hen Dinas, had then stood. We can produce nothing more than conjectural evidence of such a visit. There is no Roman architecture in the town, to mark the presence of the invaders, nor are there Roman relics rich as those discovered at Llanymynech. If the Britons occupied Hen Dinas during the Roman visit to the district, the destruction of that encampment may have been accomplished by the Roman marauders; and yet it is believed by some that the Britons possessed Oswestry, intact, from before the death of Oswald to the invasion of Offa. A Roman invasion of Oswestry, and the real history of Hen Dinas (or Old Oswestry, as it is termed,) are therefore alike still involved in mystery.

On this “vexed question” we may add the following:—“Remarking to a gentleman,” says Mr. Hutton, “that I had gleaned some anecdotes relative to Oswald, he asked me if I had seen Old Oswestry, where, he assured me, the town had formerly stood. I smiled, and answered him in the negative. He then told me, ‘that the town had travelled three quarters of a mile to the place where it had taken up its present abode.’ This belief, I found had been adopted by others with whom I conversed.”

The earliest sovereign possession of Oswestry, noted in the Welsh historic page, was in the beginning of the fifth century, as already referred to. Oswal, son of Cunedda Wledig, is there represented to have been its first monarch. The Welsh Chroniclers, however, furnish no details of his reign; and no event connected with the town is subsequently recorded, till the memorable one of King Oswald’s attack upon the Mercian King Penda, August 5th, A.D. 642. Oswald and Oswy p. 6were sons of Adelfrid, the seventh King of Northumberland. These young Princes had been driven out of the kingdom of their father by Cadwallawn, who had before been expelled from Wales, his rightful possession, by Edwin. Oswald, after seventeen years’ exile in Scotland, was restored to his kingdom by the overthrow and death of Cadwallawn. During his exile Oswald is said to have been baptized in a Christian church. He brought with him from Scotland a Christian bishop, Aidan, who preached Christianity to the people, and Oswald assisted him in his ministrations. The young Northumbrian King appears to have been zealous in the Christian cause, both in the pulpit and the field. Penda was a pagan prince, and had united with Cadwallawn in laying Northumbria waste. Oswald’s Christianity was not strong enough, it would seem, to subdue his revenge against Penda. The two monarchs at length met, a bloody conflict ensued, and Oswald was slain. The site of the closing scene of this memorable battle is said to have been a field called Cae Nef (Heaven’s Field), “situated on the left of the turnpike road leading to the Free School.” The writer from whom we quote mentions, that “Oswald approached with his army to what is called Maes-y-llan, or Church Field, then open.” “About four hundred yards west of the church,” he adds, “is a rising ground, where the battle began. The assailant appears to have driven Penda’s forces to a field nearer the town, called Cae Nef. Here Oswald fell.” These minute particulars give increased interest to the combat; but the writer does not state any authority for the details. We suppose it must have been merely traditionary. At the present time the sites of Cae Nef, and Church or Chapel Field, are well known to most of the inhabitants of the town. Oswald’s remains were first interred in the monastery of Bradney, in Lincolnshire, and afterwards, in 909, removed to St. Oswald’s, in Gloucestershire. The memory of the deceased King seems to have been held in great veneration, for churches, in various parts of the kingdom, still bear his name, as patron saint. p. 7Speed, in his “History of Great Britaine,” with his accustomed quaintness and minute graphic description, sums up Oswald’s closing scene in the following language:—

“But as the sunne hath his shadow, and the highest tide her ebbe, so Oswald, how holy soeuer, or gouernment how good, had emulators that sought his life, and his Countries mine: for wicked Penda the Pagan Mercian, enuying the greatnesse that King Oswald bare, raised warres against him, and at a place then called Maserfeild, in Shrop-shire, in a bloudie and sore fought battle slew him; and not therewith satisfied, in barbarous and brutish immanitie, did teare him in peeces, the first day of August, and yeere of Christ Iesus six hundred forty two, being the ninth of his raigne, and the thirty eighth of his age: whereupon the said place of his death is called to this day Oswaldstree, a faire Market Towne in the same Countie. The dismembred limmes of his body were first buried in the Monastery of Bradney, in Lincolnshire, shrined with his standard of Gold and Purple erected ouer his Tombe, at the industry and cost of his neece Offryd, Queene of Mercia, wife vnto king Ethelred, and daughter to Oswyn that succeeded him. From hence his bones were afterwards remooued to Glocester, and there in the north side of the vpper end of the Quire in the Cathedrall Church, continueth a faire Monument of him, with a Chapell set betwixt two pillers in the same Church.”

From the death of Oswald to 777, Oswestry is reported, as already mentioned, to have been in undisputed possession of the Britons. What its faithful history was during that long period we are unable to state. If the Britons did really occupy it, no event worthy of record seems to have occurred. If the Britons were preserved in peace, no chronicle is handed down to us of their social or industrial habits within the halcyon time. Whether they improved their land, instructed their minds in arts useful to their tribe, or were sunk in ignorance, sloth, and selfishness, there is no voice or pen to p. 8inform us. Three centuries later than this period the domestic architecture of the Cymry was in the lowest state of rudeness. One of the regal mansions of Hywel Dda, their great law-giver, was made of peeled rods; the people lived in wattled huts; and a gentleman’s hall was valued according to the number of posts it contained. These were filled up with wattled twigs and clay. The only notice we have of the period is in the Welsh Chronicles, and from them we learn that Cadwaladr (son of the Cadwallawn who was defeated and slain in a battle with King Oswald, near Denisbourne, in Northumberland,) the last of the Welsh Princes who assumed the title of Chief Sovereign of Britain, reigned over the Britons from A.D. 634 to 703, and was succeeded by Idwal Iwrch, or the Roe. In one of the Welsh Triads, Cadwaladr is called “one of the three canonized kings of Britain,” for the protection which he gave to the primitive Christians when dispossessed by the pagan Saxons; and his long reign is mentioned as having been peaceable, mainly in consequence, we are told, of his mother being sister to Penda, the Mercian king. Rhodri Molwynog, a brave and warlike prince, and grandson of Cadwaladr, succeeded to the western part of Britain about the year 720, and was engaged in constant hostilities with the Saxons until near the close of his life, in 755. These dottings from Welsh history show that the Britons had not peace within their borders during the long period already mentioned, and that “battles and murders” were still the constant theme and employment of the Britons and Saxons. It is hardly probable that the Britons possessed this district peaceably, and not unlikely that they still had to fight for their lives and property, inch by inch, and foot to foot. War, even in the present day, is the curse of nations; it fosters animosities, engenders ignorance and vice, and brutalizes man. What, then, must have been the effect of constant wars and incursions upon the British people by their invaders? The Britons had among them, about this period, their great bard, Llywarch Hen, a man ranked among p. 9the wise bards of the Court of Arthur, and whose poetical effusions display profound talent, if not genius, for so rude an age; but we have no proofs that they profited much by his vigorous instructions, although his life was lengthened out to one hundred and fifty years. The art of printing was unknown in Llywarch’s days, otherwise his humanizing productions might have wrought peace and harmony amongst both the oppressors and the oppressed.

The period had now arrived when the sovereignty of the Britons was so powerfully disputed that they were compelled to yield to the cohort strength of the impetuous Offa, King of the Mercians. Mercia was the largest of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, and London was its capital. Offa passed the Severn with a mighty force, drove the Britons from their fertile and lovely plains, and limited the princedom of Powys to the western side of the celebrated ditch still known by the name of Offa’s Dyke. Offa enjoyed a victorious reign, from the year 755 to 794. During that period the finest part of Powys became a confirmed part of the Mercian territory, and Shropshire was permanently annexed to England. Owen and Blakeway, in their invaluable “History of Shrewsbury,” remark, “Though there can be no doubt that the cession of Shropshire was obtained from the British Prince (Eliseg, it is supposed,) only by the military preponderance of the Saxon, yet it seems equally certain that it must finally have been the subject of a pacific negociation. A work of so much labour as Offa’s Dyke, evidently designed, according to his practice in other places, as the line of demarkation between two kingdoms, could never have been carried into execution without the concurrence of the sovereign on each side of that boundary. * * * * The prince, thus despoiled of the fairest portion of his dominions, retired to Mathrafal, on the Vyrnwy, five miles beyond Welshpool, while Pengwern, p. 10degraded from the dignity of a metropolis, passed under the yoke of an English conqueror, and henceforth to be known by the name of Shrewsbury, a name of Saxon origin.”

Offa’s Dyke, called by the Britons Clawdd Offa, extended nearly a hundred miles along the mountain border of Wales, from the Clwydian hills to the mouth of the Wye. Part of the Dyke may be traced at Brachy Hill, and Leintwardine, in Herefordshire, continuing northward from Knighton, in Radnorshire, over part of Shropshire, entering Montgomeryshire between Bishop’s Castle and Newtown. It again appears in Shropshire, near Llanymynech, crosses Cern-y-bwch (the Oswestry race-course), descends to the Ceiriog, near Chirk, where it again enters Wales, and terminates in the parish of Mold, beyond which no traces of it are discovered. Offa may have imagined that the Clwydian hills, and the deep valley that lies at their base, would serve as a continuance of the prohibitory line. Pennant tells us, that in all parts the Dyke was constructed on the Welsh side, and that there are numbers of small artificial mounts, the sites of small forts along its course. In the MS. “Historia Wallica,” we are informed, that the work of forming this Dyke, forty feet in height, occupied a numerous band of men, “able and accustomed to work in the fields,” more than seven years. This great line of demarcation answered but little purpose as a line of defence, or even of boundary. The Border Lands were still the scenes of sanguinary contests, and superior force alone repelled the Britons. Severe laws were enacted against any that should transgress the limits prescribed by Offa; and one of these enactments declared, that “the Welshman who was found in arms on the Saxon side of the Dyke was to lose his right hand.” These laws, however, were unheeded by the Britons. They deeply felt their injuries, and concerted means of revenge, and, as they hoped, emancipation. They formed an alliance with the kings of Sussex and Northumberland, broke through the boundary, p. 11attacked Offa’s camp, slew great numbers, and the Mercian king himself narrowly escaped with a small remnant of his army. On this disaster Offa retired into his own dominions, meditating vengeance. Hostages having been given to him by the Britons, a short time before, during a brief period of peace, he now dealt out to them severe treatment, strictly confining them, and selling, or reserving for perpetual slavery, their wives and children. Still breathing destruction he marched into the confines of Wales with a powerful army, but for years was gallantly repelled by the Britons. At length the contending forces met on Rhuddlan Marsh (now the scene of peaceful arts, the Chester and Holyhead Railway passing over it), and the Britons, under the command of Caradog, were entirely defeated with terrific slaughter, their leader being slain in the conflict. The fury of the Saxon prince did not cease with victory. He savagely massacred the men, women, and children who fell into his hands; and, according to tradition, the remaining Britons, who had escaped the enemy’s sword, fleeing with haste over the marsh, perished in the waters by the flowing of the tide. This tragedy has been carried down to posterity by a plaintive Welsh melody, called Morva Rhuddlan, the notes of which are amongst the most touching and deeply-pathetic of Cambrian minstrelsy.

Having traced Offa’s Dyke, it is necessary to describe the course of Watt’s Dyke, as the space between these two great lines of demarcation was deemed neutral ground both by the Britons and their invaders, and subsequently, during the Norman period, became part of what is denominated the Marches, although it is difficult to define correctly the precise extent of territory they occupied. Watt’s Dyke is supposed by various writers to have been constructed anterior to the time of Offa. Its course is marked by Pennant as follows:—

“It appears at Maesbury, in the parish of Oswestry, and terminates at the river Dee, below Basingwerk Abbey. The southern end of the line is lost in morassy grounds; but was p. 12probably continued to the river Severn. It extends its course from Maesbury to the Mile Oak [on the old road from Oswestry to Shrewsbury]; from thence through a field [now belonging to Edward Williams, Esq., Solicitor, of Oswestry], called Maes-y-garreg-llwyd, between two remarkable pillars of unhewn stone [strongly resembling Druidic altar stones]; passes by the town [below the Shelf-bank’ Field], and from thence to Old Oswestry, and by Pentreclawdd to Gobowen, the site of a small fort called Bryn-y-Castell, in the parish of Whittington; runs by Prys Henlle and Belmont; crosses the Ceiriog, between Brynkinallt and Pont-y-blew Forge, and the Dee, below Nant-y-Bela; from whence it passes through Wynnstay Park, by another Pentreclawdd, to Erddig, where there was a strong fort on its course; from Erddig it runs above Wrexham, near Melin Puleston, by Dolydd, Maesgwyn, Rhos-ddû, Croes-oneiras, &c.; goes over the Alûn, and through the township of Llai, to Rhydin, in the county of Flint, above which is Caer-estyn, a British post; from hence it runs by Hope church along the side of Molesdale, which it quits towards the latter place, and turns to Mynydd Sychdyn, Monachlog, near Northop, by Northop Mills, Bryn-Moel, Coed-y-Llys, Nant-y-Flint, Cefn-y-Coed, through the Strand Fields, near Holywell, to its termination below the Abbey of Basingwerk.”

The Chester and Shrewsbury Railway intersects these two ancient dykes. At the junction of the branch line to Brymbo, Minera, &c., the railway crosses Watt’s Dyke, and continues to run on the left side of it, travelling from Chester, for about fourteen miles, until Gobowen is reached, where the line again crosses the dyke; the superintendants of modern improvements, especially railway engineers and contractors, paying little if any deference to mere antiquities. By this route the railway traveller passes a considerable distance on the neutral ground, where alone, for many years, the trade and commerce of the Britons, the Saxons, and the Danes, were transacted. Offa’s Dyke at Brymbo is about two miles to the right, from Chester, and p. 13runs parallel with the railway for about eighteen miles. Churchyard, in his “Worthies of Wales,” thus chronicles, in his quaint verse, the use to which the “free ground” was applied in early days:—

“Within two miles, there is a famous thing

Called Offa’s Dyke, that reacheth farre in lengthe;

All kind of ware the Danes might thither bring;

It was free ground, and called the Britaines’ strength.

Watt’s Dyke, likewise, about the same was set,

Between which two, both Danes and Britaines met.”

For many years after Offa’s memorable defeat of the Britons on Rhuddlan Marsh, the history of the district conveys but little information interesting in the present day. “Wars, and rumours of wars,” are the only topics on which past historians have filled their pages in reference to this period. Rhodri Mawr (Rhoderick the Great), one of the most celebrated warriors and princes of Wales, succeeded to the sovereignty of North Wales and Powys in 843. In the year of his succession his territories were invaded by Berthred, King of Mercia, whom he defeated with great loss. Rhodri left three sons, and, according to the law of gavel-kind, he divided his dominions among his children. His son Mervyn had the principality of Powys, with the palace of Mathraval. His three sons were called y tri thywsog taleithiog, or diademed princes, from their wearing diadems of gold set with precious stones; and Anarawd, his eldest son, received a yearly tribute from the Prince of Powys. Contentions still continued, and intestine divisions kept the Britons in as violent commotion as if they were battling with their avowed enemies on the border. Mervyn did not long enjoy his dominion, as he was slain in 892 by his own subjects, headed by his brother Cadell, who took possession of the throne. The reign of Cadell was also brief, and his son Hywel Dda (Howel the Good) succeeded him. The Welsh Justinian, as Hywel has been called, died in 984, deservedly honoured by his subjects, and leaving four sons, all of whom perished in the desolating wars to which his country soon after fell a prey.

Saxon dominance was now rapidly approaching to its close; and the Britons were about to be exposed to the incursions of a new body of invaders, under the usurpation of William, surnamed the Conqueror. Bleddyn ab Cynvyn, with his brother, obtained in 1062 the sovereignty of North Wales and Powys, through the influence of the Saxon King Edward. Bitter hostilities subsequently occurred between Bleddyn and his kindred; at length the succession to the whole principality passed from his children, but Powys-land devolved to his sons, and came at length entire to Meredydd, the eldest born, after the contentions and slaughter incident in those days to such partitions. Oswestry, we are told, was called Trefred (a contraction of Tre Meredydd, Meredydd’s Town), in honour of this prince, but after his death the name was soon discontinued, and the town resumed its former appellation of Oswald’s-tree, or Oswestry. His eldest son, Madog, inherited from his father the tract known by the name of Powys Vadog, which consisted, according to the division of the times, of five cantrevs, or hundred townships; and these were subdivided into fifteen commots, or cwmwds:

CANTREVS. |

CWMWDS. |

COUNTIES. |

Y Barwn, |

Dinmael |

Denbighshire. |

Edeyrnion |

Merionethshire. |

|

Glyndyfrdwy |

Ibid. |

|

Y Rhiw, |

Yale, or Ial |

Denbighshire. |

Ystrad Alun, or Mold |

Flintshire. |

|

Hope |

Ibid. |

|

Uwchnant, |

Merffordd |

Ibid. |

Maelor Gymraeg, or Bromfield |

Denbighshire. |

|

Maelor Saesnaeg |

Flintshire. |

|

TREFRED, |

Croes-Vaen |

Denbighshire. |

Tref-y-Waun, or Chirk |

Ibid. |

|

Croes-oswallt, or Oswestry |

Shropshire. |

|

Rhaiadr, |

Mochnant-is-Rhaiadr, Cynllaeth, &c. |

Denbighshire. |

Nanheudwy |

Ibid. |

|

Whittington |

Shropshire. |

p. 15To Madog is assigned the honour of erecting the Castle of Oswestry. Whether he is entitled to this distinction it would be difficult now to prove. Welsh historians assert, that he built also the Castles of Overton (Flintshire) and Caereinion, and that in the former, which received the additional name of Madog, he resided. Powell says of him, that he was “ever the King of England’s friend, and was one that feared God, and relieved the poor.” Madog married Susanna, daughter of Grufydd ab Cynan, Prince of North Wales, by whom he had two sons, Grufydd Maelor and Owain ab Madog. To the first he gave the two Maelors, Yale, Hopedale, Nanheudwy, Mochnant-is-Rhaiadr, &c.: to Owain, the land of Mechain-is-Coed; and to his natural son, Owain Brogyntyn, a nobleman of distinguished talents, he granted the lordships of Edeirnion and Dinmael. The last-named Owain resided at Brogyntyn, near Oswestry, now called Porkington, whence he assumed his surname. His dagger and cup are still preserved at Rûg: and many families in Merionethshire and Denbighshire are directly descended from him. Madog’s second wife was Maud Verdon, an Englishwoman of noble lineage. He died in 1159 at Winchester, whence his body was conveyed to Meivod, in Montgomeryshire, where it was deposited in the Church of St. Mary, which he himself had built some years before. His widow is stated to have been married to William Fitz-Alan, Lord of Clun, and he, in right of his wife, obtained the town and castle of Oswestry. Fitz-Alan was a descendant of Alan, one of the companions of the Conqueror, and was the first of his name who bore the title of “Baron of Oswaldestre.” Alan was progenitor of the entire noble family which from him derived the name of Fitz-Alan, and for many succeeding centuries were the most distinguished personages in Shropshire. From this powerful race is descended the present Duke of Norfolk, who holds the title of “Baron of Oswaldestre,” in addition to his other patrician honours. His Grace’s ancestor, Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, married Lady Mary, daughter of Henry, p. 16the last Earl of Arundel named Fitz-Alan, 13th Elizabeth, when the barony of “Oswaldestre” was conveyed to the Duke.

The Norman conquest was “a heavy blow and great discouragement” to the impetuous Britons. During that eventful period almost the whole of Shropshire was parcelled out, and bestowed by William the Conqueror on his kinsman, Roger de Montgomery, as a reward for his great military services in the conquest. The Earl of Shrewsbury, whilst thus taking possession of Powys, among his other newly-acquired lands, brought under his subjection the town and castle of Trefaldwyn, (from Baldwin, Montgomery’s lieutenant,) which fortress he strongly fortified, and afterwards called it after his own family name. Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester, (the founder of the Grosvenor family,) likewise did homage for Englefield and Rhûvoniog, with the country extending along the sea shore from Chester to the waters of Conway. Ralph Mortimer did the same for the territory of Elvel; as did Hugh de Lacie for the lands of Eulas; and Eustace Cruer for Mold and Hopedale. Brady relates out of Domesday, that William the Conqueror granted to Hugh Lupus North Wales in farm, at the rent of £40 per annum, besides Rhos and Rhûvoniog. These Norman Barons erected fortresses on their lands, and, so far as they were able, settled in them English and Norman defenders. In a MS., relating to the Welsh Marches, from the library of the late Philip Lloyd Fletcher, Esq., of Gwernhaylod, in Flintshire, it is stated “that about this time, Bristol, Gloucester, Worcester, Shrewsbury, and Chester were rebuilt and fortified, and formed a line of military posts upon the frontiers.” Thus the last asylum of the Welsh was invested on almost every side, or broken into by their enemies. The kingdom of North Wales, reduced to the island of Anglesey, to Merioneth and Caernarvonshire, and to part of the present counties of Denbigh and Cardigan, still preserved the national character and p. 17importance. The natives of Wales, aided by the virtue and courage of their Princes, became more formidable than ever to the English; and at times, as they acquired union with additional vigour from despair, their invaders, instead of being able to make new conquests, held those which they had already obtained by a precarious tenure. William’s policy, in giving to his barons the power to make such conquests in Wales as they were able, led to the erection of the Marches Lordships, of which Oswestry formed a part. These lordships consisted of more than a hundred petty sovereignties, and were the fruitful source of innumerable disorders, till their partial suppression in the reign of Henry VIII. Pennant says, that William’s design was, in establishing these seignories and jurisdictions, to give to those whom he had brought over to England the power of providing for themselves, and to reduce, at the same time, the opposition of the Welsh people. The precise extent of the Marches Lordships it is difficult, as we have already said, to define. During the Saxon period the Severn was considered the ancient boundary between England and Wales. The lands conquered by Offa on the western side of that river were annexed to Mercia, and afterwards incorporated with the monarchy by Alfred the Great. The term Marches signifies generally the limits or space between England and Wales, of which the western part of Shropshire, Oswestry included, formed a principal portion. Of the Norman Barons, besides the first Earl of Shrewsbury, who did homage for royal grants of territory, were Fitzalan for Oswestry and Clun; Fitz-Gwarine for Whittington; and Roger le Strange for Ellesmere. The tenure by which the Baronies Marches were held, was, that—

“in case of war the lords should send to the army a certain number of their vassals; that they should garrison their respective castles, and keep the Welsh in subjection. In return for these services the lords had an arbitrary and despotic power in their own domains. They had the power of life and death, in their respective courts, in all cases except those of high treason. p. 18In every frontier manor a gallows was erected; if any Welshman passed the boundary line fixed between the two countries, he was immediately seized and hanged. Every town within the Marches had a horseman armed with a spear, who was maintained for the express purpose of taking these offenders. If any Englishman was caught on the Welsh side of the line, he suffered a similar fate. The Welsh considered everything that they could steal from their English neighbours as lawful prize.”

After the conquest of Wales by Edward I. the Baronies Marches were continued, but under regulations somewhat different from the former. In the reign of Edward IV. they were governed by a Lord President and Council, consisting of the Chief Justice of Chester, and three Justices of Wales. In cases of emergency other parties were called in. By a statute passed in the reign of Henry VIII. the principality and dominion of Wales became formally annexed to England; and all the Welsh laws, and most of their peculiar customs and tenures, were by this statute entirely abolished. By this statute also four new counties were formed, Brecknockshire, Denbighshire, Montgomeryshire, and Radnorshire. The Marches became annexed partly to England, and partly to the new counties of Wales. The President and Council of the Marches were however allowed to continue as before, and their general court was held at Ludlow. A statute was passed in the reign of William III., by which the government of the entire principality was divided between two peers of the realm, on whom was conferred the title of Lords Lieutenant of North and South Wales. From that period the Lordship Marches were entirely abolished.

There is another salient point in the history of Wales which it will not be inappropriate here to mention. Many of our readers have heard or read of the Royal Tribes of Wales.

“The five regal Tribes, and the respective representative of each, were considered as of royal blood. The fifteen common Tribes, all of North Wales, and the respective p. 19representative of each, formed the nobility, were lords of distinct districts, and bore some hereditary office in the palace. Grufydd ab Cynan, Prince of North Wales, Rhys ab Tewdwr, of South Wales, and Bleddyn ab Cynvyn, of Powys, regulated both these classes, but did not create them; as many of the persons, placed at their head, lived before their times, and some after. Their precedence, as it stands, is very uncertain, and not governed by dates; the last of them were created by Davydd ab Owain Gwynedd, who began his reign in 1169. We are left ignorant of the form by which they were called to this rank. Mr. Vaughan, of Hengwrt, informs us that Grufydd ab Cynan, Rhys ab Tewdwr, and Bleddyn ab Cynvyn made diligent search after the arms, ensigns, and pedigrees of their ancestors, the nobility and kings of the Britons. What they discovered by their pains in any paper or records, was afterwards by the Bards digested, and put into books, and they ordained five Royal Tribes, there being only three before, from whom their posterity to this day can derive themselves, and also fifteen special Tribes, of whom the gentry of North Wales are for the most part descended!’”

It will be seen from the foregoing pages that we have abstained from all minute detail in our description of the continued struggles for mastery between the Welsh and their own kindred, as well as of the strife for power and dominion between the Cambrian princes and their foreign invaders. These scenes in the history of Wales are nothing more, to use the eloquent language of Warrington, than “a recital of reciprocal inroads and injuries—a series of objects unvaried and of little importance, which pass the eye in a succession of cold delineations, like the evanescent figures produced by the camera obscura. The characters and events are not brought distinctly into view, nor are they sufficiently explained, to enable the historian to judge of their proportions, their beauty, or defects; whence he can neither develope the principles of action, nor trace the connection of causes with effects, by p. 20leading incidents, or by the general springs which govern human affairs.” “The story of our country under its native princes,” observes another impartial writer on Welsh history, “is a wretched calendar of crimes, of usurpations, and family assassinations; and in this dismal detail we should believe ourselves rather on the Bosphorus than the banks of the Dee.” The British or Welsh rulers had doubtless much to complain of against their Roman, Saxon, and Norman invaders; but their own conduct towards their own people—to those who by affinity claimed their protection and regard—was quite as guilty as that of their foreign foes.

Throughout the entire reign of Henry I. we read in the Welsh annals of nothing but “a series of retaliated injuries arising in regular succession; evils naturally springing from the passions, where they usurp the sword of justice.” Henry died about the year 1135, and Stephen succeeded to the English throne, and was soon embarked in a sea of troubles. Engaged in continual hostilities, and in supporting a doubtful title, he prudently concluded a peace with the Welsh, and allowed them to retain the territories they had lately recovered, free of homage or tribute. The incidents of Stephen’s reign were marked by no feature of national interest; and the only reference made to it in connection with this district is William Fitz-Alan’s espousal of the claim made by the Empress Maud to the English crown. His union with other noblemen, to dethrone Stephen, exposed him to danger, and he was compelled to leave the kingdom, abandoning his lands and other property to the incensed monarch. Whilst an exile from England he remained faithful to the interests of the Empress; and on his return to this country on the death of Stephen, and the accession to the throne of Henry II., he reaped the reward of his spirit and fidelity, by receiving back all his forfeited honours and estates, including the Castles of Oswestry and Clun. Of Oswestry Castle we shall speak particularly in subsequent pages. Of Clun we may at p. 21present say, that it remained in the direct line of William Fitz-Alan down to the reign of Queen Elizabeth, when the last Earl died. By the marriage of Mary Fitz-Alan with Philip Howard, the son of Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, it became vested in that noble family. From them it passed to the Walcotts, and afterwards, by purchase, to Lord Clive, in whose family it continues. The Duke of Norfolk still retains the title of “Baron of Clun,” as well as that of “Baron of Oswaldestre.”

Henry was an inveterate and formidable enemy to the interests of Wales. He speedily employed his utmost force in attempting to subjugate the Cambrian people; and it is recorded of Madog ab Meredydd, Prince of Powys, who had united with the enemies of his country, that he incited the English king to an invasion of North Wales. Henry listened to the solicitations of the Powysian prince, and eagerly exerted every means for the conquest of the country. He quickly raised a powerful army, and marched without delay into North Wales. Mathew Paris states that the levy of Henry, raised at this time, amounted to 30,000 men. Owain Gwynedd, in this campaign, gallantly led the Welsh, and in one of the actions, at Coed Euloe, near Hawarden, Flintshire, the monarch himself, who had encamped near the field of battle, escaped from the hands of the Welsh with the greatest difficulty. The English forces, having been strengthened, pursued the Welsh, and at length Prince Owain, fearful that his army would perish for want of provisions, concluded a peace with the King of England. He himself and his chieftains submitted to do homage to Henry, and to yield up the castles and districts in North Wales which, in the last reign, had been obtained from the English. Lord Lyttleton tells us, that to complete this humiliating position, Owain was obliged to deliver up two of his sons as pledges of his future obedience. The year after this important event a general p. 22peace took place between England and Wales; the princes and all the chieftains of South Wales repaired to the court of England, where Henry granted peace, on the Welsh doing homage for their own territories, and formally ceding to him the districts recovered from the English in the last reign. This peaceful state of things was but of short duration. Rhys, the son of Grufydd ab Rhys, immediate heir to the sovereign power of South Wales, having been outraged by several English lords, threw off his allegiance, commenced a revolt, and rallied around him a numerous force, which perplexed and baffled the English monarch. Shortly afterwards, fired by the gallant example of Rhys, the Prince of North Wales (Owain Gwynedd), and all his sons, his brother Cadwaladr, and the chieftains of Powys, united with him, in the endeavour to regain their independence and honour. After some slight skirmishes with the Welsh, Henry gathered together a formidable force, with which he marched into Powys, breathing slaughter and extermination against the inhabitants. All the historical writers, in describing this fearful onslaught, admit that few events of ancient times were more deeply stained with the blood of innocence. The English army, formed of the choicest troops, from Normandy, Anjou, Flanders, Brittany, and other territories which Henry possessed in France, entered the Welsh confines at Oswestry, where it was encamped for some time. The forces of North Wales were collected under the command of Owain Gwynedd and his brother Cadwaladr; the army of South Wales was headed by the chivalrous Rhys ab Grufydd; and the men of Powys were led by Owain Cyveiliog, and the sons of Madog ab Meredydd. The combined forces of the Welsh assembled at Corwen, where they awaited the approach of the English. Henry, burning with ardour to attack the enemy, marched his army to the banks of the Ceiriog, near the present village of Chirk, and at once ordered that the woods on each side of the river be cut down, to prevent ambuscades and sudden approaches of the enemy. It is related by some writers, that p. 23on the passage of the Ceiriog Henry was in imminent danger of losing his life: attempting to force a bridge, an arrow aimed at him by the hand of a Welshman must inevitably have pierced his body, if Hubert de St. Clare, Constable of Colchester, perceiving the danger, had not in a moment sprang before his sovereign and received it into his own bosom, and thereby met with his death-wound. Whilst the English soldiers were employed in felling the woods, a detachment of the Welsh forces forded the river, and suddenly attacked the van of Henry’s army, composed of pikemen, considered to be the most daring and gallant portion of his soldiers. A fierce battle ensued; many were killed on both sides, but at length Henry gained the passage, and advanced onward to the Berwyn mountains, to recruit his troops. There he remained in camp for several days. The Welsh were posted on the mountain-heights opposite, watching with lynx-eyed care every movement of the enemy. They succeeded in cutting off his supplies, and his army was reduced to extreme distress and privation, for want of food for man and horse. To increase his difficulties, sudden and heavy rains fell, which rendered the country on the Berwyn side so slippery and dangerous, that neither men nor horses could stand on their feet. Torrents of water, from the incessant rains, poured down from the mountains into the vale where Henry was encamped; and, unable to maintain his ground amidst all these unexpected disasters, he retired, with great loss of men, and, what was more annoying to his vaunting spirit, with defeat and disgrace. Fired with revenge, and urged by the barbarism which ever marks the tyrant, he commanded that the eyes of all the hostages which had been placed in his hands should be put out. The two sons of Rhys ab Grufydd, Prince of South Wales, and the two sons also of Owain Gwynedd, Prince of North Wales, became the unfortunate victims of Henry’s cruelty. Holinshead, in his Chronicles, tells us, that besides these young chieftains, the atrocious monarch caused the sons and daughters of several Welsh lords to be treated with the same severity; ordering p. 24the eyes of the young striplings to be pecked out of their heads, and the ears of the gentlewomen to be stuffed.

In the annals of Wales this battle is ranked among the brightest achievements of the Welsh, in their long-continued struggles for liberty. The site is known by the mournful designation of Adwy’r Beddau, or the Pass of the Graves. The conflict is called in most of the ancient books, “The Battle of Crogen.” Yorke observes, “it has been erroneously said that the term Crogen was used in contempt and derision of the Welsh; but that was not the truth: the English meant to express by it animosity, and the desire of revenge.” “Many of the English,” he adds, “were slain, and buried in Offa’s Dyke, below Chirk Castle, and the part so filled up is to be seen, and forms a passage over it, called to this day Adwy’r Beddau, or the Pass of the Graves.” The late Mr. William Price, in an annotated edition of his “History of Oswestry,” published in 1815, has the following note on the Battle of Crogen:—

“Owain Gwynedd slept at Tyn-y-Rhos, the present residence of Richard Phillips, Esq., who has still in preservation the bedstead he at that time lay upon. Likewise a Deed or Lease of a piece of land, of five acres, for 2s. 8d. per year; with a cock and hen at Christmas, and a man a day in the harvest; which still preserves the name.”

Turning for a moment to the civil government of Oswestry, it may be mentioned that in the reign of Henry II, the first Charter was granted to Oswestry, by William, Earl of Arundel. The Welsh called it “Siarter Cwtta,” the Short Charter. It was a Charter of protection, of which there were many granted about this period. It states, “I have received in protection my Burgesses of Blanc-Minster. Richard de Chambre was Constable of White-Minster. Thomas de Rossall held Rossall, of John Fitz-Alan, in chief, of one knight’s fee at White-Minster.” Guto (y Glyn), an excellent poet who flourished from 1430 to 1460, a native of p. 25Llangollen, and domestic bard to the Abbot of Llanegwestl, or Valle Crucis, near that romantic town, speaks of White-Minster in his days. He says, “I know not of any Convent of Monks superior to White-Minster.”

About the year 1188, William Fitz-Alan, Earl of Arundel, gave a sumptous banquet in the Castle of Oswestry, to Giraldus Cambrensis, and Baldwin, Archbishop of Canterbury, on their return from Wales, the bleak and barren mountains of which they had just travelled over, in an attempt to incite the people to the intended Crusade to the Holy Land. Giraldus seems to have considered that the entertainment given by the Norman Earl was too luxurious for saintly personages. He speaks, however, with much complacency of the comfortable accommodations provided for him and the Archbishop at Shrewsbury, whither they repaired from this town. “From Oswestry,” says he, “that Prelate and his retinue came after Easter (1188) to Slopesbury, where they remained some days to recruit and refresh themselves, and many assumed the cross in obedience to the precepts of the Archbishop, and the gracious sermon of the Archdeacon of St. David’s. Here also they excommunicated Oen de Cevelioc (Owain Cyveiliog, Prince of Powys), because he alone of all the Welsh princes, had not advanced to meet the Archbishop.” The visit of Giraldus and Baldwin to Oswestry might have been induced by a two-fold motive, namely, to partake of the princely hospitality of Fitz-Alan, in his baronial castle, and to hold “ghostly communication” with Regner, Bishop of St. Asaph, who at this period resided in Oswaldestre.

The succeeding portion of Henry II’s long reign was largely occupied with plans and movements to subdue the Welsh princes and their people. After repeated struggles, the English monarch saw, with exulting spirit, that he had reduced Cambrian independence to a bye-word of contempt, by seducing them from patriotism and virtue, and rendering p. 26them a disunited and improvident people. When he had accomplished this signal victory over them, and hoped to enjoy further years of sovereign power in comparative ease and tranquillity, the fate even of monarchs was dealt out to him. His mortal career was ended, and he was “gathered to his fathers:”—

“The glories of our blood and state are shadows, not substantial things;

There is no armour against fate; Death lays his icy hand on kings.”

Henry was succeeded by Richard, his son, surnamed Cœur-de-Lion, whose reign continued for about ten years, when he was slain at the siege of Chalons, in France, and John, his brother, ascended the throne. During Richard’s monarchy the town of Oswestry was not marked by any event worthy the record of the contemporary historian.

The reign of John was distinguished by strong enmity to the Welsh. In 1211 he assembled a large army at Oswestry, and was there joined by many of the Welsh Chieftains, his vassals, with whom he marched to Chester; resolving to exterminate the people of North Wales. It is revolting to trace the history of this feeble-minded and capricious king. His reckless attacks upon Wales, and his inveterate quarrel with his son-in-law, Prince Llywelyn ab Jorwerth, added to his troubles, and probably hastened his end. As a last effort against Wales, resenting Llywelyn’s stern defence of Cambrian independence, John demolished the castles of Radnor and Hay; and then, proceeding to the Marches, he set fire to Oswestry Castle, then under the governorship of John Fitz-Alan, (who had united with the barons of England in renouncing allegiance to the English Monarch, on his refusal to confirm their constitutional rights,) and burnt it to the ground.

In the reign of Henry III. John Fitz-Alan, who was reconciled to the king, procured for his Manor of Blanc-Minster p. 27the grant of a Fair on the eve, the day, and the day after St. Andrew’s feast. The Bailiffs were also made clerks of the market, with privilege to imprison any person detected in forestalling; for which they were paid twenty marks as a consideration. These petty officers, “dressed in a little brief authority,” abused their power, and gave occasion to frequent remonstrances from the inhabitants. Powel, who seems to have paid great deference to “the powers that be,” concludes, not very logically, we think, that it was “no wonder that so many of the grievances which the Welsh so much complained of to Edward I. should originate from this place.”

The historic facts recorded subsequent to this period are brief and meagre. We are told that in 1233 Oswestry was again destroyed by fire. Llywelyn ab Jorwerth had just made an inroad into the county of Brecknock, destroying all the towns and fortresses belonging to that territory; he then invested the castle, lay before it a month, raised the siege, finding his efforts to be fruitless, set fire to the town, and pursued his way to the Marches. Conflagration and ruin marked his progress: he burnt the town of Clun, in Salop, demolished Redde Castle, in Powys, and laid Oswestry in ashes. A few months afterwards, Llywelyn and Lord Pembroke, having joined their forces, made another inroad into the English Marches, and having rendered all that country a scene of devastation, they finished their fiery career by laying part of the town of Shrewsbury (Frankwell, it is supposed,) in ashes.

Early in the reign of Edward I. that monarch was intent on bowing the stubborn neck of Llywelyn ab Grufydd (the last native sovereign Prince of Wales). Llywelyn was refractory, and ambitious to maintain his order. Edward summoned him to a parliament in London, but Llywelyn refused to comply with the royal command. In reply, he offered (Oct. 14, 1276–7,) to repair to Montgomery, or to “the p. 28White Monastery of John Fitz-Alan,” as Oswestry was then called, but declined a journey to the metropolis of England. On the receipt of this answer, by which Edward, resolute to exact a personal obedience, was, or affected to be, greatly enraged, the Parliament immediately condemned Llywelyn as a rebel, for his non-appearance. The melancholy end of the Welsh prince is well known. “If,” says an elegant historian, “the valour of Llywelyn, his talents, and his patriotism, had been exhibited upon a more splendid theatre,—on the plains of Marathon, or in the straits of Thermopylæ,—his name would have been recorded in the classic page, and his memory revered, as an illustrious hero, and as a gallant assertor of the rights of nature.”