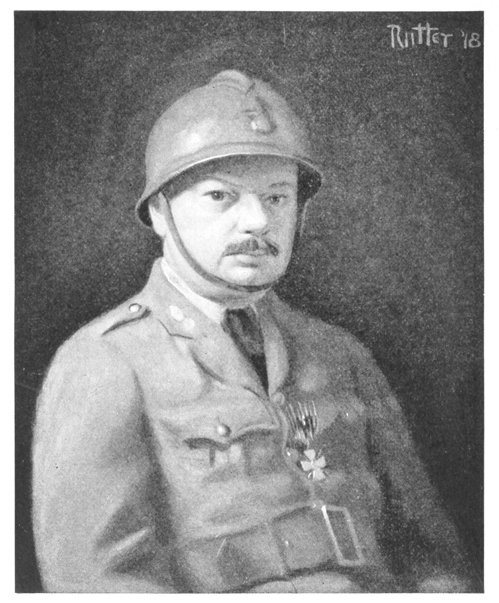

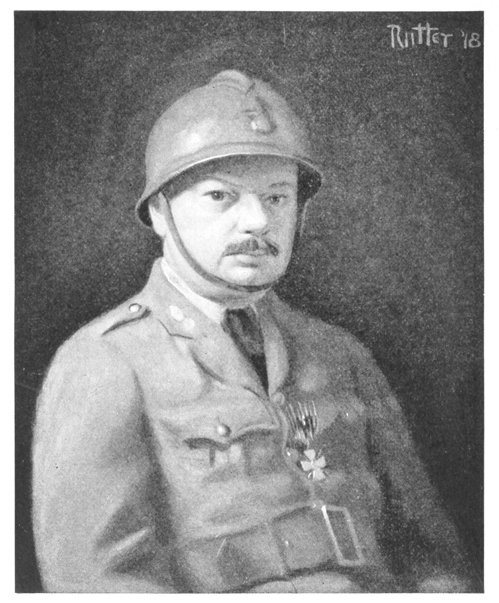

Philip Sidney Rice

Project Gutenberg's An American Crusader at Verdun, by Philip Sidney Rice This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: An American Crusader at Verdun Author: Philip Sidney Rice Release Date: October 21, 2020 [EBook #63520] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AN AMERICAN CRUSADER AT VERDUN *** Produced by Carol Brown and The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Philip Sidney Rice

By

Published by the Author,

at Princeton, N. J.

1918

Copyright, 1918,

By Philip Sidney Rice

Published October, 1918

Printed in the United States of America

I hesitate to write of my experiences because so many books have been written about the war, and the story of the ambulancier has been told before.

Many young Americans in sympathy with the Allied cause, and particularly the cause of France, and many Americans anxious to uphold the honor of their own country, when others were holding back the flag, went over as “crusaders” in advance of the American Army. Many had gone over before I went; some have come back and told their story and told it well—and so, although I went as a “crusader,” I am not the first to tell the story.

But if my story interests a few of my friends and kin I shall be satisfied with the telling of it.

Philip Sidney Rice.

Rhodes Tavern,

Harvey’s Lake, Pa.

A citation in general orders, by the Commanding General of the 69th Division of Infantry of the French Army, which declares that Driver Philip S. Rice “has always set an example of the greatest courage and devotion in the most trying circumstances during the evacuation of wounded in the attacks of August and September, 1917, before Verdun,”[1] ought to be sufficient introduction in itself to this story of an American Ambulance Driver who bore himself valiantly in those days of the great tragedy at Verdun. And yet for the story itself, and for the man who has written it, something can be said by one of his friends in appreciation of both the story and the man.

The literature that is coming out, and which will come out, of the great war, will never cease as long as history shall recite the efforts of the German Spoiler to gain the mastery of the world, and fill the world with hate and hunger. Therefore, every bit of evidence that shall touch even so lightly on every phase of the conditions, and reveal even in the slightest sense a picture of what happened, will have its value.

Of Mr. Rice, I can say that as a youngster the spirit of adventure was strong in him. He tried his best to break into the War with Spain in 1898, but his weight and heart action compelled his rejection by the surgeons. He later, however, served with credit under my command, as an enlisted man, and as an officer of the Ninth Infantry, National Guard of Pennsylvania.

When the United States entered the conflict on the side of the Entente Allies in the present war, Mr. Rice, knowing that he could not gain a place in the fighting forces, volunteered for service in the American Ambulance Corps in France. Herein is written the story of that service simply told, without vainglory or boasting. It is a story of a soldier’s work—for it was as a soldier he served.

Simply told, yes; but well told. For instance, the recital of the story of that evening of July 13, in the after dusk, when the guns had silenced forever the voice of his comrade, Frederick Norton, when they laid him to rest on the side of the hill in view of the enemy, and the towers of the desecrated Cathedral of Rheims. And that other time, when in front of Verdun, the “slaughter house of the world,” when nerve-racked he had stopped his car on the road, in the midst of the shells and gas clouds, when he said to himself: “If I do go and am hit, the agony will be over in a few minutes, but, if I turn back, the agony will be with me all the rest of my life”—so he put on his gas mask and drove on.

The “Cross of War” is not given by France for any but deserving action. The men of France who commended and recommended Phil Rice for the distinguished honor conferred upon him knew that in every day of his service he deserved what the French Government, through General Monroe, Commanding the 69th Division of Infantry, gave to him—the Croix de Guerre.

It is something to have been a part of it, to have visioned with your own eyes the scenes and the places that now lie waste upon the bosom of fair France; to have witnessed the horrors of the deadly gigantic monster War as it is now being conducted “Over There.” To have heard singing in your ears the whirr of the avions in the night air—to have seen with your own eyes the tragic diorama of the hateful and cruel side of war—and it is something for your children’s children in the years that are yet to come to tell that in the Great War their forebear bore an honorable part.

C. B. Dougherty,

Major General National Guard of

Pennsylvania, Retired

| PAGE | |

| I | |

| The Voyage | 1 |

| II | |

| “Over There” at Last! | 11 |

| III | |

| In the Champagne Region | 15 |

| IV | |

| Qualifying as a Driver | 18 |

| V | |

| “Car No. 13” | 21 |

| VI | |

| The “Crusader” | 24 |

| VII | |

| “Raising Hell Down at Epernay” | 29 |

| VIII | |

| Norton’s Last Ride | 35 |

| IX | |

| Bastille Day | 40 |

| X | |

| Here Kultur Passed | 45 |

| XI | |

| Verdun | 49 |

| XII | |

| Awaiting the Big Attack | 54 |

| XIII | |

| Under Fire in an Ambulance | 56 |

| XIV | |

| The Big Shells Come Over | 63 |

| XV | |

| Under the Shell Shower | 68 |

| XVI | |

| Aftermath of Battle | 72 |

| XVII | |

| In the Valley of the Shadow | 76 |

| XVIII | |

| In Paris | 81 |

| XIX | |

| Aillianville | 90 |

| XX | |

| Vive l’Amérique! Vive la France! | 98 |

| XXI | |

| Afterthoughts | 102 |

It was a glorious afternoon in Spring, to be exact, May 19, 1917, at about three bells, that the French liner Chicago moved out of her dock and started down the North river on the voyage to France, crowded for the most part with volunteers, entering various branches of service in the World War. There were doctors, camion drivers, aviators, ambulanciers—also a few civilians, half a dozen members of the Comédie Française returning to their native land and stage; and more than likely there were one or two spies. It was the largest crowd of “Crusaders” that had embarked for France since the war began.

The deck was crowded, too, with relatives and friends of those who were sailing; there was waving of flags, cheering and shedding of tears, and it was my observation that those who were being left behind took the departure harder than those who were leaving. But I suppose that is true when one starts on any long journey and I suppose it is especially true when one starts on the last long journey to a better world.

Those of us on the boat were not bound for a better world, we were just bound by going to help make the world a little better if we could. But some whom I met on the voyage have since passed on to a better world.

I am sure that most of the men on board were imbued with a spirit of seriousness. I was serious about the journey myself. Practically since the war began, I had been moved with a desire to get into it. I resented the invasion of Belgium, as have all red-blooded people, no matter what their nationality. I resented the murder of Edith Cavell; I resented the sinking of the Lusitania; I resented the atrocities committed, not against the people of any race in particular, but against fellow human beings; I resented the loud clamorings of white-blooded pacifists and Prussian propagandists who would have kept us out of war at any price, even at the price of honor. When I finally reached the decision to take a small part in the war and acted upon that decision by enlisting as a volunteer ambulance driver, I felt touched with a spirit of rest.

I did not know a single soul aboard when the liner cast off and backed out into the river. I knew quite a few before we reached Bordeaux. Shipboard is the easiest place in the world to make acquaintances, and being alone I drifted about, perhaps, more than if I had gone on board with a crowd of my own friends.

That morning in the Waldorf I had been told by Fred Parrish that a young fellow by the name of Meeker was going over for aviation and I had been told to look him up. A little later that same morning, while walking down Fifth avenue, bound for a bookstore to purchase a French dictionary and a volume of Bernard Shaw’s plays (I already had a Testament), I ran into my literary friend, Mr. George Henry Payne. It seemed perfectly natural to run into George on Fifth avenue—he seemed perfectly at home there. George is cosmopolitan—he is at home anywhere. He had sometimes been in my “Little Red House on the Hill,” my summer home in Dallas, Pennsylvania. “Darkest Dallas,” George called it.

This meeting with George on Fifth avenue has a bearing on my trip across. He informed me that a friend of his, a Miss Katherine G——, was sailing on the same boat. George told me to introduce myself to her and said he would communicate with her and vouch for the meeting. There was no time for a full description. George merely informed me that she was charming, though intellectual—that she had translated the works of Brandes into English and done a lot of heavy stuff like that. I confess I was a little terrified at the prospect of meeting Miss Katherine G——.

The boat was soon headed down the river and the crowd of friends and relatives on the dock faded from view, still waving farewell. Before we passed the Statue of Liberty I ran into Meeker—a fine, wholesome looking young chap—dressed in a light spring suit—a flower in his buttonhole. I saw a lot of Meeker before we reached the other side. He had spirit, and speaking of going as a “Crusader,” he remarked: “I would rather be a ‘went’ than a ’sent.’” At dinner I met a number of other fellows, among them a young aviator just out of Princeton. His name was Walcott.[2]

I only kept a diary for a few days. I found that everyone was keeping a diary. One day on deck I heard a man reading a page of his to an acquaintance and I heard him remark with a show of pride that the other fellows in his stateroom were keeping their diaries by copying from his. I heard him read: “Arose at seven o’clock, took a bath at seven-fifteen; had breakfast at eight, on deck at eight-thirty, sea is choppy.” And I thought to myself as I moved about the deck: “What an inspiring document to leave to one’s descendants.” So after about four pages of the brief one that I kept I find the following:

“I wonder what the intellectual Miss G—— looks like—whether she is prematurely old, anaemic or possibly has a tuft of hair on her chin. I have never read Brandes but he sounds heavy. I called on Miss G—— last evening after dinner. Ports were masked—curtains drawn, the decks were black except for spots of fire indicating a cigarette here and there. But in the darkness there was singing, and it was good, too. The submarines have not ears—only one eye like the witches in ‘Macbeth.’ I decided to call on Miss G—— and I approached her stateroom thinking of Brandes, of high-brow feminine youth prematurely blighted, of a tuft of hair and anaemia. The stateroom door was open and there were lights. The room was littered with roses and clothes and things. There was a feminine, human touch to that stateroom, but Miss G—— was not within. Perhaps she was on the deck somewhere among those cigarettes glowing like fireflies in the dark. I hastily tossed my card upon her pillow and returned to the deck. Miss G—— has not returned my call—I have not seen her to my knowledge.”

Later that first evening on board I went up into the smoking room and a cloud of blue smoke hung low over the occupants who crowded the room. They did not look like members of a peace commission—some were dressed in khaki, some wore yellow driving coats, one wore the uniform of the American Ambulance. Over at a corner table three French officers, in their light blue uniforms, were seated with ladies who I afterward learned were their wives. One of the officers wore the Croix de Guerre, which filled me with admiration and envy. At another table was a young French girl surrounded by admiring men. She was vivacious, possessed of a high color and beautiful teeth—even if she did smoke cigarettes. Her friends called her “Andree.” At another table a lively card game was going on—later I got to know the participants—Harris, Lambert, Bixby, Branch, Foltz and others.

Down in the music room it was crowded, too. Some one was playing the piano, and playing well. Altogether it was a likely looking crowd that I found on the boat.

Among my early acquaintances was a promising young poet who I was told had already begun to fulfil his promise. He was just out of Harvard and lived at South Orange, New Jersey. We discovered that we had some things in common—we both liked cigarettes and disliked white-corpuscled pacifists. We were photographed together by a friend. I have always been willing to have my photograph taken with a successful poet, providing he wore good clothes and did not wear long hair. I was glad to be photographed with Bob Hillyer. He wore a blue serge suit, a light blue necktie and had rather sad eyes, though I thought he was too young to have suffered much. The well-to-do never suffer much at Harvard. He had a slight cold and I prescribed for him out of a medicine chest which had been presented to me before sailing. The next day he told me he felt much better. I did not tell him that I discovered too late that I had given him the wrong medicine.

I met another young fellow who was not a poet. He introduced himself to me and said he had met me before somewhere. I could not recall the incident, though his name was familiar. On better acquaintance I got to call him “Bridgey” for short. He suggested that we take a walk around the deck, which was in darkness except for the cigarettes glowing here and there. “Bridgey” fell over a coil of rope before we had covered the starboard side, after which he inquired the number of his stateroom and retired for the night. The next morning he came to me and confided that he was rooming in a cabin with a begoggled person of strong religious propensities who had taken him to task for his levity of the night before. I inquired what form his levity had taken, and he confessed “I tried to feed grapes to him when he wanted to go to sleep and then accidentally smashed an electric light globe while taking off my shoe.” I tried to comfort him with the thought that religion was not merely a matter of goggles.

There were two fellows on the boat whom I was destined to know intimately later on after reaching the front. They were from Providence, Rhode Island. One was tall and slender and had red hair. His name I learned was Harwood B. Day. He will always be known affectionately to me as “Red” Day. The other was tall and slender and had dishevelled hair from constant reading. His name I learned was Frank Farnham. To me he will always be just “Farney.” Day was returning to the service after a visit in the States.

On a later page in my brief diary, from which I have already quoted, I find the following:

“Sapristi! I have just met Miss Katherine G——. She may be intellectual but she certainly is charming. She may have translated Brandes into English and done other heavy stuff like that, but she is not prematurely old. She is not anaemic and there is not a tuft of hair on her chin. She is young, she has black hair and black eyes and a kindly smile like a practical Christian. She is feminine. Her stateroom told the story—littered with flowers, clothes and things. If the boat is hit I shall certainly be one of several who will offer her a life belt.” There my diary ended.

The voyage was calm enough and without many exciting incidents. One of the passengers died. He was very old and feeble when he came on board, bound for his home I believe, in Greece. He was buried at sea early one morning before those who had gone to bed had risen.

Many passengers slept on deck while passing through the war zone. The ship’s concert took place a couple of nights before we landed. Many passengers stayed on deck during the ship’s concert. Miss G—— and the two aviators, Meeker and Walker, took part in a one-act play. I wrote the play originally but Miss G—— rewrote it because she said it was too “high-brow,” which convinced me that she was wonderfully human though highly intellectual.

Reaching France, we “crusaders” who had become intimate on the long voyage, which was all too short, went our various ways—some to aviation fields—some to camion camps—some to the American Field Headquarters at 21 Rue Reynouard, Paris, France. Some I have seen since—some I will never see again.

Coming out of an Eleventh Century Cathedral in Bordeaux with a couple of friends, I saw “Andree” pass by in an open carriage. She was smiling happily, showing her white teeth when she turned and waved to us as the carriage disappeared around the corner.

I last saw Meeker and Walcott in front of the Café de la Paix in Paris. I wished them luck in their undertakings for the cause. Meeker and Walcott, aviators, have since fallen on the field and I am sure the world is bound to be just a little better for the inspiring sacrifice they have made.

In Paris I met Frederick Norton, of Goshen, New York.

Friday, the twenty-second day of June, I arose upon a birthday anniversary. I had no intention of observing it, but I felt in a vaguely definite way that something interesting was to happen before the day was over; and this feeling was not long in growing from the vague to the definite.

From the time of reaching Paris I was busily engaged in various ways at the headquarters of the American Field Service while impatiently waiting my turn to go to the front. I was more than impatient—at times I was fretful. I even believe that upon cross-examination the heads of the service would admit that I was absolutely annoying. I supposed that I would be assigned to a new ambulance section soon to be organized, but on this day I have mentioned, I was informed that I was to fill a vacancy in Section Number One, the oldest American Field Section serving with the French army. I was in luck. Section One had been at the Battle of the Marne, it had served in Belgium—it had been at Verdun in 1916 and had gained a glorious record for itself at various places along the Western Front. I was to be prepared to leave Paris on Sunday morning, and to my delight I learned that Frederick Norton was also to join the same Section.

While working together in the Paris headquarters we discovered that we had many mutual friends and this naturally put us on a friendly footing from the beginning. We found that our ideas coincided about many things and about people. I thought Norton had some pretty good ideas and was an excellent judge of people. Sometimes when we were talking together he would say about someone: “How do you size him up?” And I would tell him. Usually our ideas coincided. Norton had been a traveller—he had been to Alaska—he had been North with Peary—he had been to Japan—he already knew something of France—he had been a hunter—he had a pilot’s license to drive an aeroplane—he had done some toboganning and skiing in Switzerland, which are not sports for the timid. These things I learned from him slowly, for he was extremely modest and not given to talking about his exploits. I was glad when I found that we were to start for the battle front together, and he was kind enough to say that he was glad, too.

Saturday night and a short “Good-night” to Paris. A short “Good-night” because cafés close at nine o’clock, and besides I must be up early the following morning. In company with my delightful pagan friend “Bridgey,” I went around to a little quiet out of the way café, which was hardly known to Americans. The little café was kept by an elderly lady whose husband had been killed in the war and by her daughter whose husband had also been killed in the war. This mother and daughter were excellent cooks, but their place was plain and comfortable. There was sawdust on the floor. Sitting in the little back dining room we could see into the kitchen and watch the meal being prepared. Across the street in the “Chinese Umbrella” there was more ostentation, style and atmosphere. The “Chinese Umbrella” was patronized mostly by Americans and the atmosphere was not Parisian.

“Bridgey” had invited me there for a quiet, exclusive farewell supper, and as we sat in the back room of the café he regaled me with an account of how he had tried for aviation the day before. He was nearsighted and wore spectacles, without which he could scarcely see across the room. From a friend he had procured a copy of the alphabet eye test and had tried to commit it to memory; he reported for examination with spectacles in his pocket. He missed on the third letter, and being brusquely informed that he had failed, “Bridgey,” who certainly had a sense of humor, smilingly adjusted his spectacles and bade adieu to the inspecting officer.

Supper finished, I said “Au ’voir” to Madame and her daughter, the two war widows, and then went off to bed.

“Bridgey” was on hand next morning to see us start for the front. A few other acquaintances were at the station, too. I have not seen “Bridgey” since but I heard that he was at Verdun during the big offensive.

Norton and I boarded the twelve o’clock train bound for the front. The train was crowded with French officers, grey haired Generals, Colonels, officers of all ranks and of various branches of the service. There were very few civilians and not half a dozen women. Twelve o’clock, and Paris faded behind us as we started for the battle front.

We left the train at Epernay, an important city some twenty miles back from the battle lines, but subject to air raids, as I observed from demolished and dilapidated buildings in various parts of the town, and as I was to learn from personal experience before many days had passed.

Here we were met by a member of Section One, a young fellow by the name of Stout, well named, of stocky build and robust appetite. Norton and I had eaten lightly and suggested that we repair to a café for luncheon before proceeding on to where Section One had its cantonment near the front. Stout said he would join us for company’s sake, but that he had finished dinner just a short while before. As we ate and talked a large plate of pastry was placed upon the table and Stout was prevailed upon to take one, and as we talked Stout emptied the plate and we called for more which we divided with Stout. After luncheon I caught Norton’s ear and said to him: “You heard Stout say he had his Sunday dinner?”

“Yes.”

“You noticed the vanishing plate of sweets?”

“Yes.”

“Well, it looks to me,” I said, “as if Section One is starving.”

That was before we knew Stout of robust appetite. But Stout had plenty of vim and vigor and was untiring, and later won the Croix de Guerre at Verdun. Stout and I quarrelled at Verdun, after which I had a genuine affection for him.

We clambered into a motor truck, Stout driving, and were on the second stage of our journey to the front. We reached the town of Louvois about six o’clock. Here Section One had its cantonment. Louvois is a picturesque village, far enough back from the lines not to be entirely deserted by its civilian population, mostly simple people living in simple homes just as their forebears had lived in the same homes a hundred years and more before. Here we began to breathe the atmosphere of the war—here, night and day, we saw the movement of the troops to and from the front—we saw the procession of camions carrying munitions and supplies—large cannons being drawn by many horses—the little machine guns—sometimes a fleet of armored cars equipped with anti-aircraft guns. Overhead we saw the large observation balloons and heard the whirr of aeroplanes. In the distance we could hear the firing at the front.

Supper was being served underneath a shed, and it was a good supper, too. Section One was not starving. We were cordially received by the members of the Section. “Red” Day and “Farney” were in the gathering. “Red” had served with the Section in Belgium. After supper we strolled along the street and listened while Purdy, a bright young fellow, told us all about the war. Purdy was six feet tall and as I later observed every inch a soldier.

That night we were billeted in the second story of a dilapidated barnlike building from which the windows were all gone, and lying on my cot I could see the stars through the roof. That night a rat ran across my face. At last I was getting into the war.

The following morning Norton and I, not having been assigned to cars, were set to work changing a tire. Down on our hands and knees we began to struggle—a few of the men were standing about. Norton laughed softly and whispered to me:

“Have you ever changed a tire before?”

“No,” I said; “have you?”

“No,” chuckled Norton, but we quickly finished the job and felt very proud of our first effort.

A little later I was taken out for a trial ride to prove whether or not I could really drive a Ford car. William Pearl, our volunteer mechanician, went with me on the run. Pearl had been a Rhodes scholar and had joined the Section some time before. A couple of months after that trial drive he and I were destined to have a thrilling and trying experience, in which he was the principal actor.

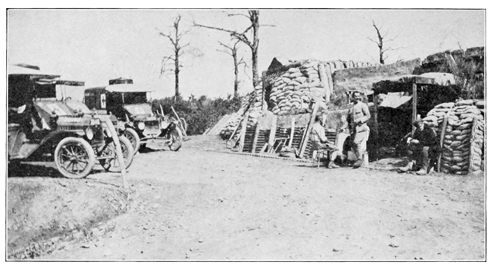

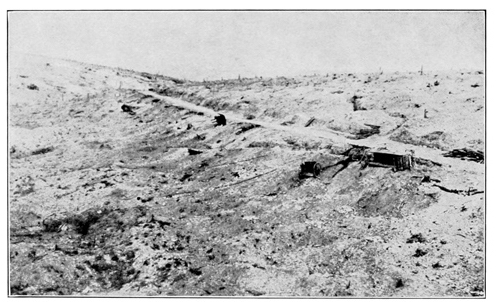

Cars Waiting for a Run

The trial ride took us along a road for about seven miles, where we came to the brow of a hill. Here we stopped the car and walked out into an open field and there I obtained my first glimpse of the war, spread out before us in a panorama. In the distance, to the left, I could see the city of Rheims, the towers of its desecrated cathedral looming up distinctly. I could see the shells falling and bursting in the city. Pearl informed me, as we stood there, that an average of two thousand shells a day were being dropped on the city. In front of us I could see the hills laid barren by shell fire and scarred by the lines of trenches. Overhead a German aeroplane had crossed the French lines—the anti-aircraft guns had opened fire—little puffs of cloudlike smoke appeared in the sky underneath the plane as it rose to higher altitudes. French planes arose in pursuit and finally the German plane disappeared from sight over its own lines. Directly overhead a bird was singing in a tree just as cheerfully as if there was no such thing as trouble in the world. Looking back in the opposite direction I could see women and young girls working in the vineyards.

As we started to leave the spot Pearl pointed to a town nearby on our left.

“That is the town of Ludes,” he said. “Notice where it is, because you will have to go there when on duty.”

I looked in the direction that he pointed, little realizing that the town of Ludes would be forever associated in my mind with the most tragic incident of my service in France.

Then we turned and drove back to Louvois. That was the full extent of my training for front line work. I was informed that I had qualified as an ambulance driver.

Having been duly declared a qualified driver, I was assigned to a car which happened to be number 13, but as I am not particularly superstitious this did not make me nervous.

Then I was sent to post for duty out at the town of Ludes. Here we had our headquarters in a little Swiss chalet hidden behind a clump of trees; though within sight and sound of the war, it was peaceful enough, at least for those on war duty. Everything is comparative. Before many days had passed I was to see that peaceful little chalet stained with blood. The place was equipped with a telephone bell, which would signal when a car was needed at a front line post. Those on duty here answered the calls in rotation.

About noon of my first day on duty a call came in for two cars. One of the cars was to carry wounded men back to the town of Epernay, the other car was to go to the extreme front line post. One of the calls was for Joe Patterson of Pittsburgh, the other call was for me. Out of politeness to a new man “Pat” gave me the choice of runs.

It seemed to be much easier to get right into the serious work than to have the suspense of waiting, so I chose the run to the front line post. I started off over the hills, through the ancient town of Verzeney, famous for its wines—through the winding streets, turning sharply at a corner—down a long steep hill hidden from view of the enemy by camouflage—past what was known as the Esperance farm till finally I reached the post. Here I stopped my car and waited. Here there was a canal, the waters of which had been let out, and into the canal banks had been built little dug-outs. In the one where I was to wait and sleep until needed were two rough cots, a shelf on which there were some rather dirty eating utensils and a loaf of dry bread.

During the afternoon there was intermittent firing but no great activity on either side of the lines. Occasionally an aeroplane would fly overhead. Once during the afternoon a German plane flew over in an effort to attack an observation balloon, but was successfully driven off by the French.

The afternoon passed quickly enough without having my services called for and at supper time I had my first meal of trench fare with French poilus for company, a cup of hot soup, a chunk of meat, a slice of bread and a cup of coffee. The cook who served us was a big fellow with a black beard. He was killed a short time after and his body lay all day in a nearby dug-out.

After supper I clambered over the canal bank and walked along the empty canal bed observing the marks of German shells. Then there was a sudden volley of shots from a French battery near at hand, the guns of which were so carefully concealed that I had not observed it. I quickly clambered back over the “safe” side of the canal bank and waited.

I began to feel restless and to wonder when I would be called to get out into the battle of the night.

In the meantime the firing had increased on both sides of the lines.

It was some time after nine o’clock and growing dark when a French soldier came up and handed me a slip of paper bearing a message which had just come over the telephone. The message conveyed instructions for me to drive down the road a couple of miles to a front line dressing station, where I would find wounded who had just been carried in. I was informed that the call was urgent. Though I am not fearless by any means, I did not feel frightened as I walked out to my car and started the engine; but I noticed that my heart was beating rapidly.

A few French soldiers waved to me and called “Au ’voir” as I got in the seat and was off down the road, first to the left, then to the right, then straight ahead as fast as I dared drive. The road took me directly in front of the French batteries, and in the growing darkness the flashes of fire from the guns and the concussion in my face made it seem as if they were firing directly at me, not over me. I drove on till I reached the post to which I had been sent, then backed up my ambulance around near the entrance to the dug-out and stopped. An officer stepped up and shook hands with me and in English said: “The American drives fast.”

He explained to me that the wounded were being cared for and would soon be ready for the journey. A small group of silent stretcher bearers were standing near the entrance to the dug-out. The firing increased in intensity—the battle of the night was on. The officer remarked to me: “The Germans are very angry.” I handed the officer a cigarette and lighted one myself. I have found that tobacco is a great solace to the nerves when under fire. We continued our broken conversation. “Do you come from New York?” he asked.

“Near New York,” I replied. Every place east of Chicago is near New York when you are over three thousand miles away.

“Do you like champagne?” he inquired. It was not an invitation, he was merely getting my point of view. We were standing within a few miles of the richest champagne producing vineyards in the world. Then I looked in the direction of the dug-out, into the dimly lighted entrance, and I saw stretcher bearers slowly coming out bearing a wounded soldier and I braced myself for the first shock of the horrors of war. Gently the wounded soldier was lifted into my ambulance, then two more wounded were carried out. I closed and fastened the back curtain of the car, started the engine and climbed into the seat. “Drive gently,” said the officer, shaking hands with me. “Thank you, good-night,” and I started on the return trip, in the dark without lights.

As I drove back to the town of Ludes, troops were moving to the front under the cover of darkness and I was obliged to blow my whistle continually. Now and then a large camion would loom up suddenly in the darkness directly in front of me—a little blacker than the darkness itself—that is how I could see it. I would turn quickly to avoid being hit. We always drove without lights at the front. Half way up the long hill leading to the town of Verzenay the water was boiling in the radiator and the engine was hitting on three cylinders—I wondered if I would make the heavy grade; I wondered if a bursting shell would sweep the road; I wondered if I would get the wounded safely back; I wondered about many things in those moments on my first night drive in the dark. On through the dark winding narrow streets of the town of Verzeney, at one place driving with difficulty through a flock of sheep, on in safety to the town of Ludes to the building which served as a field hospital. I felt a great sense of relief when I drew up at the entrance safely back with my wounded.

Then I drove back to the little Swiss chalet to await my next call. Before turning in for a little sleep I stood in the entrance listening to the continual firing along the front and watching the signal rockets, the star shells, and the flashes of the guns. Then I went inside, climbed over a sleeping companion, found a vacant space on the floor, rolled up in my blanket, put my coat under my head and went to sleep.

I had not been sleeping long when the telephone bell rang. It was my turn out again. This time I received instructions to drive over into another direction to a château which served as the headquarters of a French General. Château Romont it was called. There I was to await further instructions. So I parked my car in the courtyard and was led down into the dark cellar of the château. As I entered I could hear heavy breathing—evidently some one was sleeping there. A light was made and I was shown a rough cot where I might sleep until needed. Again I curled up in my blanket and was quickly asleep. I had only been asleep for a few minutes when some one touched me on the shoulder and awakened me. This time I was to drive over to the shell wrecked town of Sillery. It was then about four in the morning, the dawn was grey and then a streak of red in the east over the line of German trenches. The firing had subsided to some extent.

Into the shell wrecked town of Sillery I drove, and I could see in the growing light that many houses had been levelled to the ground and there were none at all that did not bear the marks of battle. I drove into a court yard, inside the gate of which there was a large shell hole. Stretcher bearers were waiting for me—there was no delay this time. Two men were lifted into the car. They were suffering very great agony but I could see no marks of blood. I understood at once—they were victims of poison gas.

This time there was no need to drive slowly back again to the town of Ludes to the hospital. It was broad daylight when I reached there. A sleepy stretcher bearer came out carrying a lantern, which was not needed. The two men were lifted out of the car and lowered to the ground. They were writhing in agony—one of them rolled off his stretcher into the gutter, and died at my feet. That was my first night on duty at the front—that was my baptism of fire.

Sir Philip Sidney, for whom I believe I was more or less hopefully named, gained immortal fame by giving his last drop of water to a dying comrade on the field of battle. I desire to mention that I gave my last cigarette to a perfectly live stretcher bearer while under shell fire. For twenty-four hours I had been stationed at the dug-out in the canal bank in front of the Esperance farm; the place where I had been the first time I went to post. Several time since I had gone there and now felt quite at home in those surroundings.

During the last twenty-four hours shells had been coming in with a fair regularity. The Germans were endeavoring to drive out a battery which evidently had given them some annoyance. In a comparatively short period I counted more than a hundred shells, shrieking over my head, striking and bursting a hundred yards in front of me, throwing the earth in every direction, the rocks and pieces of shell spattering around close to where I stood. Several trees were cut down by the bombardment and they fell like so many twigs.

I had been alone during those twenty-four hours and had begun to realize that waiting for a run was quite as trying as the run itself, particularly as I could observe that when I did start I would be obliged to pass uncomfortably close to the corner where the shells were hitting. Toward the end of the afternoon some wounded came straggling in. After twenty-four hours under whistling shells I was glad to start back to Ludes and to a cigarette.

I spent the early evening at the little Swiss chalet. About nine o’clock I received a call to carry two wounded officers back to the town of Epernay. It was a beautiful, cool, moonlight evening and I enjoyed the prospect of the peaceful drive away from the sound of the war, not realizing that there was a rather interesting evening in store for me. I drove across the Marne into the town of Epernay at about eleven o’clock and took one of the wounded officers to the principal hospital there. The other officer I was instructed to take on to another hospital, located at the top of a hill on the outskirts of the town. Epernay is an old town and the streets are narrow, winding, and quite as confusing as Boston, particularly when driving at night without lights.

As I pulled up the hill out on an open road in sight of the hospital, I saw a flash of light in the sky, followed by a sharp report—then there was a shower of lights much like rockets followed by a series of reports. As I stopped the car in the hospital grounds and was assisting stretcher bearers to lift out the wounded officer, I could hear the droning of several aeroplanes overhead but could not see them. Hospital aides, half dressed in white trousers, and in bare feet, were crowded in the doorway. Everyone understood what was happening. The Germans had come over in numbers for one of their periodical raids.

Incendiary bombs were now dropping down in the heart of the town where I had just passed. Church bells were ringing as a warning for all civilians to take to their caves—a warning which seemed quite superfluous. There was a terrific explosion, followed by a burst of flames which lighted up the sky. A building had been set on fire. Standing beside my car, I took off my fatigue cap and substituted my steel helmet, which I always carried with me when not actually wearing it. Steel helmets have saved many lives. The bombardment became more furious as time went on—bombs were dropping on various parts of the city. Several powerful searchlights began to sweep the heavens and two broad shafts of light crossed, and in the cross they held in view a German plane. It was flying low and not far overhead from where I stood. The two searchlights followed the movement of the plane and held it in the cross while the anti-aircraft guns opened fire. I could see the shells bursting underneath the plane but none hit and quickly the plane flew out of range and disappeared from sight. But the raiders continued the bombardment.

Having waited for some time for the firing to cease I decided to start back for post at Ludes. Unless there was very good reason for not doing so, we were expected to return to post as soon as we had finished the errand which had taken us away. To drive back it was necessary for me to return through the heart of the town were the bombs had fallen and were still falling. So far as possible I kept on the “shady” side of the street out of the moonlight, pausing at every corner for a moment. Sometimes there would be a deafening crash near by. I would stop—put my head down and my arms over my face, then would drive quickly into the next street. I passed the postoffice just after it was hit—pieces of shutters, doors and glass were littered about the street and I feared for punctured tires. I drove on a short distance, turned around and went back, pausing in front of the demolished building, but could hear no sound. The street was absolutely deserted. As I continued my drive over the deserted streets the only sign of humanity I would see was an occasional soldier with his gun standing in the comparative shelter of a doorway.

Before leaving the town I stopped for a moment at the hospital where I had first been and an officer who could speak a little English asked me to stay all night in the “cave.” “It is a bad night to be out,” he said. The invitation was alluring, but I decided to push on to Ludes.

To get out of the town I must recross the bridge over the Marne, close to the railroad station, and I had been informed that raiders were making a particular effort to hit the station. As I shot out across the bridge in the broad moonlight, in full view from above, I could see some freight cars burning. I wished that some friend were sittting beside me, but I often wished that on these lonely nerve-racking night drives.

When I drew out into the open country I felt no inclination to turn on my lights, for I had heard of a staff car just a short while before driving over the same road. The driver had turned on his lights. The target was seen from an aeroplane—a bomb was dropped with accurate aim, demolishing the car and killing all the occupants.

Reaching Ludes some time in the middle of the night, I stepped over the form of Curtis, who, curled up in his blankets, was asleep on the floor. He awoke and sleepily inquired: “Who’s there?” I told him. “Anything going on?” he inquired still sleepily.

“Seem to be raising hell down at Epernay,” I told him quietly, so as not to awaken anyone who might be sleeping.

“That so?” muttered Curtis, and with no more show of interest went back to sleep.

The next day I learned that many houses had been destroyed. Five wounded soldiers had been killed in the hospital where I had been invited to spend the night.

Frederick Norton and I were new men in an old Section. We were new men in an old crowd, consequently when we joined the Section we made no effort to break into any old established circles. When off duty together, he and I were accustomed to taking long walks across the fields and to the towns behind the lines and on these walks I learned to know what I already believed—that he was a man of exceptional character, quiet, unassuming, modest; a gentleman in the best sense of the word; a delightful companion, an ideal soldier. On one of our walks we talked some of spending “permission” together on the coast of Brittany.

I remember when I went to post for the first time Norton stepped up to me and shook hands, wishing me luck and an interesting trip. That established a custom between us. After that we always shook hands when either one or the other of us started for post.

When we had been in the Section for a short while we were invited to join three of the older fellows and to transfer our cots to a tent underneath the trees just outside the grounds of a very beautiful château, owned, I believe, by M. Chandon, of Möet & Chandon. We naturally accepted the invitation with pleasure and thus we became established as members of the old crowd. Formalities ceased from that time.

The château had been converted into a hospital and at night a lighted red cross over the large iron gates showed the entrance to approaching cars.

We had some pleasant evenings under the trees when off duty, even though we could hear the distant firing of the guns. We sang some, a guitar and mandolin also furnished music. We listened to New Townsend reminisce about his experiences in Belgium in the early part of the war. Frank Farnham and “Red” Day occasionally sang a duet without much persuasion. With difficulty “Farney” was prevailed on to yodel. On one occasion Ned Townsend danced the dance of the seven veils by moonlight. Sometimes we would hear the whirr of an aeroplane overhead. The light in our tent would be extinguished by the first man who could reach it and silence would reign.

So in spite of the war there were many pleasant moments. A spirit of comradeship grew up between us all. Under such conditions, sharing the same dangers, the some hardships, the same pleasures, we grew to know each other better in a short space of time than would have been possible in years in the ordinary peaceful walks of life.

Ned Townsend, the oldest man in point of service, remarked that the best of fellowship had always prevailed in Section One—that it had always been more like a club in that respect than a military organization. He also mentioned casually that Section One had almost always been lucky—very few casualties had marked its long, arduous and dangerous career at the front.

On the afternoon of July 12 I saw Frederick Norton starting for the front, and, following our custom, I went over to his car, shook hands with him and wished him “good luck.” I told him the next time we were off duty together we must take a walk over the neighboring hills to inspect a windmill which had been erected about the time Columbus discovered America. Then he was off to the town of Ludes—to the little Swiss chalet hidden behind the trees.

That night was a bright moonlight night—an ideal night for avions. Early in the evening those of us at Louvoise were having music under the trees. A few convalescent soldiers from the château hospital were sitting about in the grass, listening. As the moon came up and shone through the trees I recall “Red” Day remarking: “The avions will be over to-night,” and a short while after we heard the unmistakable crash of an avion bomb down the road in the direction of Epernay.

It must have been pretty close to eleven o’clock that Frederick Norton was standing in the back window of the little Swiss chalet at Ludes, from which place he could get a glimpse of the battle lines through the boughs of the trees. He was waiting for his call to go to the front. His call was soon to come. He no doubt heard the whirr of the approaching aeroplane overhead—he may have heard the deafening crash of the bomb as it struck the ground, making a crater in the earth and riddling the walls of the peaceful chalet. But then the sound of the war was forever silenced—for him. A piece of the shell had cut his throat—another had pierced his heart. He pitched forward, then fell backward on the floor. He had answered his final call.

The following night I walked beside my friend Frederick Norton for the last time. He was not laid to rest until after dusk because his burial place was on the side of a hill in view of the enemy—in view of the towers of the desecrated cathedral at Rheims—as fine a place as any for a volunteer who had earned an honorable rest.

There were French officers of high rank in the gathering to pay homage to the Volunteer American—a priest, a Protestant chaplain, his friends in Section One—a squad of soldiers under arms. As we stood there in the growing dusk a German aeroplane flew overhead and swept the roadside nearby with its rapid fire gun. All looked up but no one moved. The benediction being said, we walked slowly away.

July 14, 1917, was “Bastille Day,” the great French national holiday, and the troops were greatly heartened by the fact that at last America was coming over to help them win the war. French and American troops were to parade together in Paris—the fighters at the front were to have a special dinner, with a cup of champagne and a cigar. A few of the men in our Section who had a short leave of absence coming due were going into Paris for a couple of days.

Personally, I was glad that I was going out to the front on duty. I felt the need of active, strenuous work. During the forenoon several shells came shrieking over the little Swiss chalet, striking in a field a short distance back. A little while later I saw a dead soldier being carried into the town by his comrades. One shell struck in a field outside the town where a young girl was working in the vineyard and she was obliged to desert her work and run for shelter. I wondered if the Germans had observed the movements of our ambulances in and out of the grounds of the chalet or whether they were merely observing the French holiday. Some one remarked that following a custom of three years standing, they would do what they could to disturb the holiday dinner of the French soldiers. About noon a couple of shells struck in the town of Ludes but did no great amount of damage. A few civilians were still living in Ludes and in the kitchen of a little French woman we ate our meals when not out on a run. We supplied the food and she cooked for us. I remember during my first luncheon in that kitchen seeing her send her little daughters off to school with gas masks flung across their shoulders.

“Bastille Day” was a fairly busy afternoon and that night there was no time to rest. Sometimes it was a call to go out to the Esperance farm—sometimes a call to run into the town of Sillery—sometimes to report at the Château Romont back of Sillery to await further orders.

That night I had no sleep at all, though I made several efforts. Early in the evening I found myself at the Château Romont, and when I was going to retire for a little rest I was not shown down into the dark cellar where I slept for a short while the first night I had been there. I was invited into a large back room in the château which had once evidently been a handsome billiard room. On the walls were deer antlers and a boar’s head. The billiard table had been pushed over in a corner of the room out of the way and in its place was a table at which officers sat poring over maps and reports. A telephone was on the table and on the walls were large maps. I stretched out on a bare rough “crib” to rest. One of the officers called an orderly and said something to him which I did not hear. The orderly went into another room and returned with an armful of rugs. He placed them in the crib and once more I stretched out on this most comfortable couch. But just then the telephone rang. I got up, pulled on my boots, put on my coat, and as I started out the officer at the table smiled sympathetically at me and said “Bon nuit.”

Midnight in the little Swiss chalet. I had returned from a run and had lain down to sleep just outside the room where two nights before Frederick Norton had fallen. Again there was a call. Some time after one o’clock, at the dug-out in the canal bank in front of the Esperance farm, I again lay down, only to be called a few minutes later. I drove down the road to a post I had not visited before, and while the wounded were being placed in the car I was instructed to shut off my motor for fear the Germans might hear and open fire. The car being filled with three wounded men on stretchers inside, and one less seriously wounded on the front seat with me, I started off for Ludes. Along the road I struck a small shell hole which gave the car a severe jolt and the wounded inside cried out: “Oh, comrade! comrade!” In the morning I discovered that the jolt had cracked the front spring of the car but the wounded had forgiven me for my poor driving.

At Ludes the hospital was filled and I must push on back to the town of Epernay to one of the hospitals there. As I drove into the town at daylight I saw a strange sight. Straggling into the town were old men, women and children, all looking worn and bedraggled. Some carried blankets, some were pushing little carts in which were piled up household belongings. Some of the women were carrying babies in their arms.

The night before a warning had gone out that an air raid was expected and these civilians living under the shadow of the war had taken to the “caves” on the outskirts of the city for protection.

I reached the principal hospital in the town and, as frequently happened, was sent to another hospital further on. When I arrived there I was feeling tired, bedraggled, hungry and out of sorts myself after the all night strain. But if I felt like complaining I promptly changed my mind and decided to be cheerful.

Stopping my car, I went around to the back and raised the curtain. One of the wounded, a young fellow, looked up at me with the pleasantest expression in the world and said: “Hello, boy Americaine! Good morning!”

But that is the spirit of the French.

Toward the end of July we received orders that we were to move from the Champagne region, but we did not know just where we were to be sent. Early one morning, the order to move having come, we had loaded our cars with tents, supplies, automobile parts, all the paraphernalia of an ambulance section, and our personal belongings, and had formed in a line on the main thoroughfare of the picturesque town of Louvois. Stevenson drove up to the head of the procession, blew his whistle once and every engine was started; he blew his whistle twice, and we were off down the road in the direction of Epernay. The villagers of Louvois were on the street to wave us “Au ’voir.” There were old men, women and girls. The young men were all at the front.

Outside the town of Epernay we drew up alongside the road and waited further instructions. Some thought we were going to Belgium, others said we were going down into the Verdun sector. Our French Lieutenant, Reymond, had gone on ahead in his car for orders. Presently he returned and we learned that we were to drive in the direction of Verdun.

Stevenson, at the head of the procession, blew his whistle and once more all cars were started—soon we were rolling along the road.

At noon we reached Châlons, where we had luncheon in a café crowded with French officers. By late afternoon we reached the outskirts of the town of Vietry, and as we drove into the town we saw a squad of German prisoners, under guard, marching along the road. If they noticed that we were Americans, they showed no emotion even if they felt any. At Vietry we were to spend the night. We were shown to a large barn in which to sleep. Some Russian troops had occupied the barn a short while before and the straw littered about looked rather risky. As it promised to be a clear night some of us decided to sleep out in the open field under the trees. The cows were less to be feared than the straw in the barn or even the avions above.

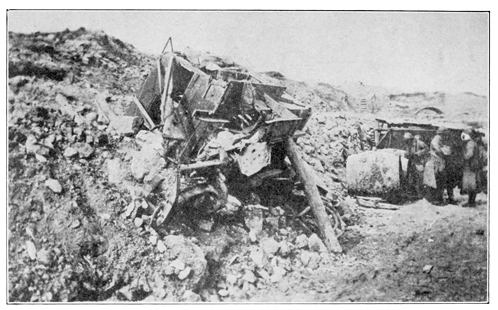

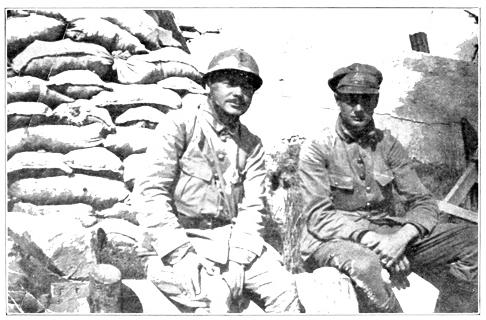

The Last of Ambulance No. 4

Having parked our cars, several of us strolled to the banks of the historic Marne and were quickly splashing around in the refreshing though muddy water. Then over to a café in the city for supper. The supper developed into a banquet. It was the first time in a great while that the entire Section and its French attachés had all sat together at one time and everyone off duty. Singing commenced before the meal was half over, and if not all harmonious it was at least hearty. The darkness came on but no lights were made in the room on account of danger from the avions, but the hilarity did not die out in the growing gloom.

Roy Stockwell was obliged to sing several verses of a war song which was called “Around Her Leg She Wore a Purple Ribbon,” in which every one joined in the chorus, singing:

“Winnie” Wertz, the French cook, sang a pastoral song of peaceful life on the farm after the war was over. One or two men tried to make speeches but received scant encouragement. The singing continued till late in the evening, when we wended our way back to the open field for a night of peaceful sleep under the trees. As we walked through the city on the way a quartette was lustily singing:

No doubt the French inhabitants awoke to shrug a shoulder and patiently mutter: “Oh, those terrible Americans.”

The next morning we were on our way to Bar le Duc, a picturesque city nestled between high hills. At the top of one of these hills, as we started the steep descent into the city, we passed a large convent almost totally destroyed by avion bombs. Bar le Duc is always subject to air raids and shows many marks of the war on its principal streets. Again we stopped for the night and here I slept on the sidewalk with my head against a sentry box so that no one would fall over me.

On to the town of Evres through a country, as we advanced, showing more and more plainly the desolation and waste of the war. Through towns deserted of all civilians, over roads dry in the midsummer sun and unspeakably dusty from the continual travel toward the front. One afternoon in Evres, Curtis and I dropped into the home of an elderly French peasant woman for a lunch of delicious cottage cheese and a jug of fresh milk. The peasant woman had a sad story to tell. Her husband was dead; her son’s home in the village had been destroyed; he had been taken prisoner and his wife had fallen victim to the advance of Prussian kultur.

At Evres we waited to move on to Verdun and there we learned of the great offensive that was soon to take place and we watched the preparations for it on a vast scale. We were deeply impressed.

When we moved up on the morning of August first to take our small part in the big offensive, we established our cantonment in the town of Houdainville, within about three miles of the city of Verdun. The town of Houdainville was conspicuously a war town, being deserted by all civilians, crowded with troops and subject to intermittent shelling. The houses were all old and many bore the marks of battle. Some of our men were billeted together in the second story of a building which was infested with rats. The quarters were so small that it was necessary to crowd the cots uncomfortably close together. Others of us pitched a tent in a barnyard. It was muddy, unsavory and very different from the place at Louvais, where we had our tent pitched under the trees outside the château of M. Chandon. We realized that we were not to see the war at its worst and we felt reconciled to added hardships by the fact that our Section had been assigned to the very serious work ahead.

That there was very serious work ahead, indeed, had been brought home to us while having seen for days and nights the continual stream of troops, heavy guns, supplies and munitions moving toward the front. We had been told that preparations for this offensive had been going on for months.

Had I been so inclined, which I was not, there was little time to complain of our surroundings—barely time to note them before I was sent out to post duty. Now we were to be on post duty for twenty-four hours and then off duty for twenty-four hours, in which to work on our cars and rest. This schedule was based on all of the cars in the Section being able to run, but there were times when some of the cars were not available.

I was sent out to a post at Cassairne Marceau, at the top of a hill about three miles in front of Verdun, near the spot which marks the extreme advance of the Crown Prince in his attack of 1916. Near here the French had stood and said: “They shall not pass.” They never did, and I am sure they never will.

Looking back from Cassairne Marceau I could see the ancient fortified city of Verdun, crowned by its cathedral on a hill. Close at hand were the remains of barracks built shortly before the war. All about was desolation, shell holes, pieces of exploded shells. In front of the post was a graveyard and during my many times at that post there was not a day that I did not see the dead being laid to rest. Here the war was seen in its most hideous aspect. Sometimes a wagon would come rumbling up to the post with dead piled up like so much cordwood.

My first call to go from here to a front line post came before sunset. The post was near Fort Vaux. An officer rode with me to observe whether the road could be covered by a car. It was a road that no sane person would undertake in peace times under any consideration. Down a ravine between two hills, in a country laid absolutely barren by continual shell fire, the sides of the hills were pock-marked with shell holes; and where at one time, three years before, there had been a beautiful forest, there was not now a tree stump, a bush or a patch of grass. We drove along the road very slowly indeed, for there was danger of breaking springs and axles in passing, as we drove close to the artillery as they were firing. I was later glad for the opportunity of seeing that road before sunset, for I sometimes covered it afterward in the darkness without lights.

We reached the poste de secour, picked up three wounded artillerymen and returned with added caution to Cassairne Marceau. It was very trying when we wanted to drive fast, in order to get back as quickly as possible to a place of comparative safety, that we were obliged to drive most slowly to save our wounded and our cars.

Sometime around eleven o’clock that night I lay down on a stretcher in the dug-out at Cassairne Marceau to snatch a little sleep while waiting for my next call. At that time I was still in good condition and had not yet suffered from great fatigue or undue nervous strain and consequently could sleep at any time and in any place that the opportunity offered. Later on I was to become so fatigued and my nerves were so shaken from the continual strain that I could not sleep at all. The dug-out served as a dressing station and was equipped for operations—surgeons were in attendance there. The place had the odor of a hospital, with the added unpleasant damp odor of the underground. Not a very satisfactory place in which to sleep, but we slept there many times.

I was just dozing off when I heard voices, footsteps and a moaning which was very distressing; and I was sufficiently conscious to realize that some one badly wounded was being carried in. But I must rest—I must sleep while the opportunity offered, so I dozed fitfully, never being quite unconscious of the fact that close by me an operation was being performed. Finally I was fully awakened by some one touching my foot. I sat up—the operation had been completed and I was to take the desperately wounded man back to a hospital in Verdun.

It was well past midnight when the man was lifted into the car and I started on my dark ride, driving slowly. I had not yet been inside the walled city of Verdun. I did not know just where the hospital was. I had simply been informed that by crossing a certain bridge, entering a certain gate and turning down a certain street I would find it. I carried few wounded men who moaned in greater agony than did this soldier as I drove on back to Verdun. I found the bridge and crossed it. I passed through the gate inside the city walls and I drove slowly through the dark, silent, apparently deserted city. It seemed indeed like a city of the dead. I came to a square and in the darkness took the wrong street. I was doing the best that could be done, and I hoped the wounded soldier would live till we reached the hospital. I wished for someone to talk to—for some one to help me find the way. Finally I saw a sentinel on duty and he directed me down the right street and before long we came to the house which was serving as a hospital.

That was my first entrance into the ancient fortified city of Verdun. When I saw the inside of my car at daylight I was glad that we had met with the sentinel when we did, for I think there could have been but little time to lose.

We had not been many days at Houdainville when we received orders to move up to Beveaux, just a short distance outside the walled city of Verdun. The big attack had not yet taken place but was expected at any time. In the meanwhile the artillery activity was daily increasing.

At Beveaux there was a large hospital which was almost vacant when we moved up there and pitched our tents. It had been made ready for the big attack and would probably accommodate fifteen hundred wounded. The preparations for the offensive were most impressive and tended to make us thoughtful. Though we were now closer to the front, the location of our cantonment on high, open ground was a welcome change to all of us. Those of us who in Houdainville had our tent in that muddy, unsavory barnyard were glad to get out. Those in the Section who had slept in the crowded, rat-ridden house, were more than glad of the change. That we were close to the war, in fact actually under it, even when off duty, was impressed upon us at supper time that first evening at Beveaux, when several shells struck within the hospital grounds and some hit the large stables adjoining, killing horses and wounding men. We all ran for shelter, and supper was delayed for some time. The hospital was shelled on several occasions after that.

During our stay at Beveaux we usually retired at night with most of our clothes on, partly on account of the avions and partly because our work was so arduous that we were likely to be called in the night, even when supposedly off duty. On retiring we always had our steel helmets and gas masks within reach. Frequently at night when the avions came over we were obliged to get out of bed and run for the nearby trenches. A canvas tent affords mightly little protection against shell fire!

We expected to be at Beveaux for but a very short time before being sent back for a rest, but the days went on, the long nights went on and the weeks rolled around before we were relieved.

Twenty-four hours on duty—twenty-four hours off duty: that was the schedule in the Verdun sector, based on all the cars being able to run, but there was not a day or night that cars were not put out of commission, which meant that the work of those who were running was increased. Theoretically speaking that was the schedule; practically speaking there was no schedule. Sometimes we were on duty thirty hours at a stretch, though perhaps in that time we could snatch a little sleep between runs; sometimes there was no sleep at all. The days were bad, the nights were worse, and day or night, either on or off duty, we were always under fire. Almost every time a man came back from post he had an experience to tell—it seemed that on our runs we escaped by a matter of seconds; shells were always hitting just behind us, in front of us and around us. We saw bloodshed all the time. The Twenty-third Psalm speaks of “the valley of the shadow of death.” That describes the desolate land about where we were. Verdun will go down in history as the slaughter house of the world. This was real warfare.

We were working hard all the time but we were buoyed up by the fact that soon, almost any day, the big attack would take place and then we would be sent back for a rest. The attack was to have taken place on August first but was postponed from day to day so that more guns might be moved into position, and more supplies, munitions and men moved up. Every night on the road we saw that endless procession of supply trucks, munitions, guns and men.

We were covering many posts—we were getting very tired even before the attack took place. One night the General commanding a division at Fort Houdrement asked for more cars to be stationed there and he was informed that were no more cars to spare.

He asked “Why?” and was informed that all of our cars were out.

He asked “Where?” and he was informed of the various posts that we were covering. He expressed great surprise. He thought we were merely serving his division. We were serving an entire Army Corps.

Fort Houdrement was a bad spot and it was a hard road to travel to reach there, but bad as it was there were other posts which most of us came to dread more. I first saw Fort Houdremont in broad daylight. Before that our cars had only gone there at night, because the road was so exposed. That I first went there in daylight was not because of bravery on my part or because of a desire to establish a precedent. It was just the result of an accident.

I had turned in to sleep one night—or to sleep as much of the night as might be possible. A couple of my friends had also lain down to sleep. As we lay in the darkness under the shelter of the tent we could hear the firing of the artillery all along the front. Then a sudden gust of cool wind blew the flaps of the tent and we heard the patter of rain above our heads. A thunder storm was coming on. The sound of the thunder was mingled with the noise of the artillery. Our tent was occasionally lighted by flashes of lightning and I could see my companions lying awake on their cots. The rain came down in torrents, the lightning became louder and the roar of the artillery less distinct, until when the storm had reached its height the pouring rain and the sound of the thunder drowned out the sound of the artillery. And as we lay there one of my friends spoke up in the darkness and said quietly: “Phil, it sounds as if God in Heaven is still omnipotent.” And I said: “Yes, I am glad that God in Heaven is still omnipotent in spite of the fact that the tent is leaking right over my face.” Then I pulled the blankets over my head and dozed off to sleep—but not for long.

I was soon awakened and told it was my turn out. It was still raining hard and I could hear the thunder and see the flashes of lightning as I bundled up and went out to my car and started out to find Fort Houdremont. I had never been there. I merely had a general direction as to where it was. It was a bad night for a ten-mile ride to a post I had never been to. It was not quite midnight when I started. The roads were slippery and crowded with traffic and progress was slow. About four miles out traffic was blocked for over half an hour, part of which time I dozed sitting at the wheel. Then once more motors began to whirr, trucks were groaning, horses were pulling and tugging, officers on horseback were shouting orders.

The procession moved on, getting nearer the battle, and along the road we could see the flashes of fire from the artillery and the exploding shells as they struck. On through the town of Bras, a desolate shell wrecked place, then on about a half a mile beyond. There I saw a chance to make time and gain ground by pulling out of the procession, driving ahead and crowding into an opening further on. A large motor truck loomed up in front of me. I turned sharply to escape being hit and ran into a ditch. I was hopelessly stalled.

One of our cars, driven by Holt, came directly back of me. He stopped to see if he could give me help. I told him it was impossible for us to pull the car out. He saw that for himself and as he drove on he shouted “Good-night” to me and I called back “Good-night” to him.

He could not have gone far when I saw a shell burst directly down the road over which he had gone. I wondered how close a call he had. Next day he told me he had jumped out of his car and was crouching in a ditch when the shell struck.

I stood alongside of my car in the rain and mud, shells coming in along the road as the procession of the night moved past me. Every one had his work to do and must move on. Once four poilus paused long enough to see whether they could help push my car out of the ditch, but it was useless and they went on.

There was nothing to do but to wait for daylight; and it was a long wait. During the night two horses were killed beside my car.

The dawn came on slowly, the rain stopped, the firing became less intense. The procession of the night had disappeared I knew not where. An empty ammunition wagon came clattering up the road, the driver cracking his whip and urging the four horses to greater speed. When the sun finally appeared I found myself alone in view of the enemy. Alone, excepting for the two dead horses lying in the road. Then I went for help.

I walked back to the town of Bras and if it looked forlorn at night it looked even more so in the daylight. Places where some houses had once stood were now merely marked by débris tumbled into the cellars—dead horses were lying about. A French ambulance gave me a lift back to Verdun and there I found one of our cars which took me back to our cantonment, where I reported my difficulties. Stevenson called to Hanna, who was off duty, and in his car we three drove back over the road to where I had abandoned my ambulance.

I really was sceptical about finding anything more than a pile of wreckage, but the car was still there and so were the two dead horses. Before we proceeded to pull my car out with the aid of Hanna’s car, I tenderly lifted an unexploded shell from under the rear wheel, carried it over to the other side of the road and laid it down.

Then on to Houdrement—Stevenson riding with me and Hanna following in his car. Reaching there, we walked up the side of a steep hill to the dressing station and inquired for any wounded that might be there. I was caked with mud from head to foot. A French officer smiled at my appearance. I saluted and he extended his hand. The French officers were usually quite as polite to us as if we were officers ourselves.

We found some wounded who would otherwise have been kept there until darkness had set in. After that our Section covered the run to Fort Houdremont in daylight with regularity; and in spite of the fact that the road was exposed to view, most of us found the daylight run much less nerve-racking than in the night.

“Do the boche fire on ambulances?” I have sometimes been asked.

“Certainly!” I have answered.

The days and nights went on, but still the attack did not take place, but the artillery duels were growing in intensity every night.

If there was any belief that preparations for the attack were not known, this belief was dispelled when the Germans erected a sign over their trenches reading—

“We will be waiting for you on the fifteenth”—but the fifteenth passed by and—the attack did not take place. We were getting very tired—we were becoming conscious that we had nerves—the driving became more hazardous and terrifying with the increased activity of the artillery.

Early on the evening of August seventeenth, I was off duty and was standing talking to some of the fellows, enjoying an after supper pipe and watching the anti-aircraft guns popping at a German aeroplane when Stevenson walked up. He said a telephone message had just come in informing him that Stockwell had broken the front spring of his car out at Fort Houdremont. I was to take a new spring out and Pearl was to go along to help make the repairs.

William Pearl was our volunteer mechanician and had been with the Section for some time. Before that he had been a Rhodes scholar. After the war he would practice law.

Pearl and I started off and we had not gone far when it began to rain—it frequently rained at Verdun. We stopped to slip our rubber ponchos over our heads. Perhaps that brief delay was the cause of what happened shortly after. A matter of seconds sometimes changes destiny when at the front. I recall that on one occasion I slowed down my car for a few seconds, just long enough to light a cigarette, and as I paused a shell struck on the road, not far in front of me. I am sure but for the lighting of that cigarette, the shell would have scored a direct hit. Yet some people say that cigarettes are an unmixed evil!

We drove on in the rain along the bank of the Meuse past the city of Verdun, up a long hill along which were formed the troops, the munition trucks, the cannon, the camions waiting to move toward the front under darkness; and when the procession once started to move, we knew from experience that progress would be slow along the road. So we drove as rapidly as possible, and as we drove, we got into conversation and Pearl told me that in all his experience Section One had never known anything worse that what we had been through at Verdun. I had heard Ned Townsend say the same thing, and Townsend had been at the front most of the time since the war started.

As we began to descend the long hill, we could see shells striking near the road and when we reached the bottom of the hill, we came to a large camion ditched and deserted on one side of the road and on the other side of the road a large shell hole. It was now dusk and I stopped my car to see whether I could pass without running into the hole. Then we heard the terrific shriek to which our ears had become accustomed—and then the crash. Pearl had stepped partly from the seat and had crouched down—I had put my head down and covered my face with my arms. The pieces of shell and rocks spattered around the car and hit it in several places. Each fraction of a second I expected to feel a stinging sensation but I quickly came to a realization that I was not scratched. I raised my head and asked—“Are you all right, Pearl?” Then I saw a magnificent display of calm courage. As he stood up, Pearl replied as quietly as if he had discovered something wrong with the front tire: “I think my arm is gone.”

It was not gone but badly shattered. With nerves calm and head cool, though he was bleeding badly, he got up on the seat beside me. The nearest dressing station was at Houdrement and we drove on. I am not sure, but I think a shell must have struck behind us at that moment because I later discovered a hole in the rear curtain of the car and the rear hub cap was cut as if by a steel chisel.