The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Minor War History Compiled from A Soldier

Boy's Letters to "The Girl I Left Behind Me, by Martin A. Haynes

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: A Minor War History Compiled from A Soldier Boy's Letters to "The Girl I Left Behind Me"

1861-1864

Author: Martin A. Haynes

Release Date: August 25, 2020 [EBook #63040]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A MINOR WAR HISTORY COMPILED ***

Produced by Quentin Campbell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

See the end of this document for details of corrections and changes.

COMPILED FROM

A SOLDIER BOY’S LETTERS TO “THE GIRL

I LEFT BEHIND ME”

1861–1864

* *

*

DRAMATIS PERSONÆ

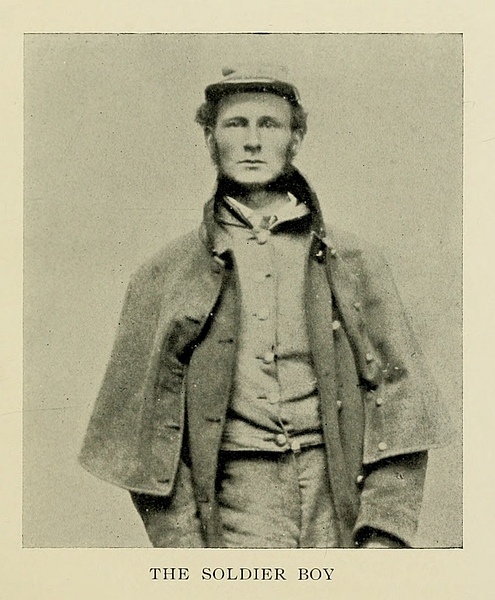

| The Soldier Boy | Martin A. Haynes | |

| Company I, Second New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry | ||

| “The Girl I Left Behind Me” | Cornelia T. Lane | |

| Now and for more than Fifty Years the Wife of the Soldier Boy | ||

* *

*

LAKEPORT, N. H.

PRIVATE PRINT OF MARTIN A. HAYNES

1916

************************

EDITION SIXTY COPIES

THIS IS NO.

AND IS PRESENTED TO

WITH COMPLIMENTS OF

MARTIN A. HAYNES

************************

IN gathering material for a history of the Second Regiment, one of my sources of information was a big bundle of letters, even then yellowing with age—my letters, covering a period of over three years, written to “The girl I left behind me.” These—with the elimination of such strictly personal matters as concerned only the two of us—were carefully copied, and the letters then given to the flames. Thirty years later, breaking the seals of that bundle of manuscript, I read with indescribable interest my own story of more than half a century ago. And the whim came upon me to put those scraps of war history into type and print a few copies, especially for members of the family. I can see an opening for only one regret. It will probably destroy an illusion of those four grandchildren—Marjorie and Warren, Martin and Eugene—as to their grandfather’s relative importance in the war, and while Grant and Sherman will be moved up one notch on the roll of those who put down the Great Rebellion, I will, very likely, have to be content with third place.

There is lots of history here—minor history, to be sure—and while there is a sequence of events, it is not a connected story, nor even complete. A series of letters rarely is. They do not deal, like Sherman’s letters, in the grand strategy of campaigns, but they do give an idea of what the men in the ranks were talking and thinking and doing. Their interest lies almost entirely in the fact that they deal with the trivialities of army life. Here is recorded the small talk of the camp, and many incidents that are too trivial for big history, but are really interesting and worth saving. I have preserved the personality of some of those royal old comrades of mine, who but for these letters would be remembered only through the cold lines of the official record. In these sketches—“right off the bat,” as it were—they seem to live again, and one can get a very fair idea of what manner of men they were. It is sometimes with moistened eyes that I catch the step with them again in these pages and in memory live over those stirring days when comradeship was so close and meant so much.

I feel lonesome when I realize that I am almost the last survivor of those who live and move in the following pages. Not one member of the old “Abbott Guard”—a Manchester company and largely composed of Manchester men—now remains as a living resident of that city, and the survivors, scattered far and wide, can be counted upon the fingers of one hand. As often happened in the old army days, I am once more a straggler, dusty, footsore and weary. But I know that before long I will swing around the bend in the road and come upon the whole precious bunch in bivouac. There will be Rod. Manning and George Slade, Hen. Everett and Bill Ramsdell, “Heenan” and “Gunny,” old Dan. Desmond—a hundred of the rarest aggregation that ever touched elbows in a common cause. And with the old familiar whoop they will greet the belated straggler and give him a place at their campfire.

M. A. H.

Lakeport, New Hampshire, October, 1916.

*

* * *

* * * * *

* * * * * * *

* * * * *

* * *

*

IF you could look in on this scene you would rate it as about as good a comedy as we ever took in at Bidwell and Marston’s. I am writing on a rough board table, and right opposite me the fellow who has set up as company barber is skinning a poor victim alive. I don’t think he is much of a barber, and from the spasmodic and at times profane remarks of the patriot he is practicing on, I gather that I am not alone in that opinion.

I have been very busy this week and have hardly had time to write the letters I promised Farnsworth for the American. But I am going to give you a little idea of the routine of camp life. We are in camp on the Merrimack County fair grounds, across the river from the city. Our barracks are rough board buildings with ample ventilation through a thousand cracks. One continuous bunk, bedded with straw, extends along one side. Into this we tumble at night, wrapped in our thick army blankets, warm and cozy, and go to sleep after about so much laughing and joking and blackguarding.

The drum beats to marshal us to our meals, and each company falls into line, single file. At the command we march around by the commissary’s stand, each man, as he passes, helping himself to plate and dipper with rations upon them. I have seen richer food and a more comprehensive bill of fare, but it is all right and there is plenty of it: fish hash (and I always did like fish hash,) bread (white and brown,) pickles, coffee. No butter, no condiments. But the whole outfit seems to agree with me, and I never was in better health and spirits in my life.

There are now about 550 men here in camp—over 240 from Manchester. It is a rattling jolly crowd, and there is something[2] doing about all the time. At night we gather around the campfires and amuse ourselves with songs and stories and badinage until nine o’clock, when “Tattoo” sounds and we tumble into our bunk. As many as are needed are detailed each night to stand guard. I have had one round at it—routed out of my warm nest at one o’clock in the morning and posted at the main gate of the camp. It was very cold, and every star was out with a broad grin on as I paraded up and down with a ten-pound musket on my shoulder.

I shall try to get leave to run down to Manchester Saturday and stop over Sunday. I want to “see my sister.”

We have not got our uniforms yet. We all expected to have them by the last of the week, so hardly anybody brought any change of clothing. I borrowed a collar of Cochrane [W. H. D.] until I could send home for wardrobe supplies. We have got to go to church at Concord this afternoon, in a body.

There are lots of Manchester folks here today, and I have to stop every minute and shake hands with some friend who comes along. Kelley’s [Capt. John L.] recruits came up yesterday. I met them as I was going to the city. Jim Atherton was among them. He brought me lots of things from my friends—pastry from mother, a mince pie from Mrs. Currier, a pin cushion from Augusta Currier, and a great big sugar heart from Mrs. Logue, bless her dear old Irish soul.

Address, Camp Union, Company A, Concord, N. H.

AM writing in great haste to let you know that the Guard are going to Portsmouth this afternoon, to join the Second Regiment, under Tom Pierce. We get away in a hurry, in order to get position on the right of the regiment—if we can. I will write to you in a day or two—by Sunday, sure. Shall run back to Manchester before we go to the war. Direct letters to Abbott Guard, Portsmouth.

RECEIVED a letter from you a few moments before the company left Concord, enclosing a note from Sally [Shepherd] and a fine picture of yourself. I don’t think, however, it is quite as good as the one I have with me in a little round velvet case.

The Second Regiment are quartered in an old ropewalk, four or five hundred feet long and about eighteen feet wide. Our bunks extend along each side, with a walk through the center and a rack over our heads to place our muskets in. Our quarters and food are much better than they were at Concord.

There are now five companies here, all of us raw recruits fast enough, but the Guard are just conceited enough to imagine their military education is a little more advanced than that of the other fellows. You know, we’ve been sworn in almost three weeks, and naturally know it all. There was a little friction night before last. A guard from the Great Falls company was posted around the quarters, and word got around that they were acting mighty “cocky.” They would not let our men even pass around in the yard, where they had a perfect right to go. I had had no intention of leaving the quarters that night, but was determined not to be cooped up that way. So I recruited two desperate outlaws, and we ran the guard and went over to the city. There we ran across our Orderly Sergeant [George W. Gordon] and he was as mad as we were. At a late hour we marched back to camp. When the guard at the outer gate hollered “Whoa, there!” and tried to block our way, we upset him and went right along. We didn’t get a proper challenge down the whole line, but there was a succession of wild calls for the Officer of the Guard. The last I heard as I passed into the barracks was the assurance of the officer, to a sentry who had narrated his tale of woe, that the “Manchester boys” were right—that a proper challenge would doubtless have been heeded and saved all trouble.

Our boys are all pleased with Portsmouth, but are afraid we shall not be ordered away as soon as if we had stayed in Concord. There are many points of interest here—the navy yard, where 1100 men are employed fitting out three large war vessels, and the forts down the harbor, where they are putting in garrisons and mounting heavy guns.

Nich. Biglin, alias “Heenan,” one of our boys, had a thumb badly crushed in showing how strong he was. Up at the arsenal there are rows of big iron cannon, relics of the war of 1812, resting at each end on blocks. “Heenan” lifted an end of one of these, which was quite a feat, but his grin of triumph faded out when he let the gun back smash onto one thumb.

I received today a very welcome present from the Manchester High School—a splendid waterproof blanket. John Johnson is the committee to distribute similar favors among the M. H. S. boys in camp here.

I am detailed for guard and my round commences soon. You need have no fear that I shall not run up to Manchester before leaving here.

HAVE been expecting all this week that I would have an opportunity to run up home today, but have just learned that Gen. Stark has issued orders that no man is to leave camp till the regiment is uniformed, which he expects will be next Monday or Tuesday. There is a rumor circulating that this regiment will not be ordered into active service unless we enlist for three years or until the war is ended; but Fred. Smith told me, yesterday, he would warrant we should be ordered off within ten days. If we are not, I think nearly all the boys will enlist for the war. We started out to see the rebels put down, and we are not willing to go home without seeing it done and having a hand in it. I do not think the war will last more than a few months.

Since our little affair with the Commissary we have had first rate grub. [This refers to the “rag hash war,” when the Abbott Guard rebelled against the rations and marched over to the city, in a body, for something to eat.] We were placed under arrest when we got back and kept under guard twenty-four hours. I gave a pretty plain statement of the affair in my letter to the American, and yesterday down came Fred. Smith to see about it. With one of the Governor’s Aides he went around and investigated pretty thoroughly, and there are already signs of a decided improvement.

YOU have, doubtless, been expecting me every day for a week. I wrote Tuesday throwing out a hint that I might be up Wednesday; but when Wednesday came there was no move to uniform us, and I had to wait. But today something definite has transpired. We are officially informed that an opportunity will be given us to re-enlist for three years or the war, or to be discharged. We can take it or leave it. The Abbott Guard had a meeting this afternoon, and a majority voted to offer the services of the company to the President, for the war. Several of them will not go, but I, of course, could not be dogged back to Manchester while the company is headed for the South. A possible three years from home is a long stretch, but you can be pretty sure the war will not last many months. At any rate, my fortunes are cast with the Abbott Guard, and its fortunes I am bound to follow, wherever they lead.

General Abbott told us, this afternoon, that we should all have a chance to go home and put our affairs in order.

THE regiment is now uniformed—the queerest-looking uniform in the world. You have probable seen some like them in the streets of Manchester, on the First Regiment boys. The suit is gray throughout, with a light trimming of red cord. The coat is a “swallow-tail,” with brass buttons bearing the New Hampshire coat-of-arms; a French army cap to top off with.

We have the Manchester Cornet Band here with us now—they came yesterday. They played in front of the barracks last evening—lots of the good old tunes that you and I have enjoyed together, many a time.

DO not know how much longer we will be here, but not more than a few days—perhaps not over a week. Yesterday the First Maine Regiment passed through here. I wish this regiment had been in their place.

EXPECTED I would have a chance to write a long letter today. I was on guard last night, and in the natural course should have had the day to myself. But our company was mustered this forenoon—sworn in for three years’ service—and the regiment has been marching and parading all the afternoon. I was never more tired in all my life. We shall be off in a day or two. Next Tuesday is the time set, but we may not get away until a day or two later. We are very busy getting ready to leave.

A number of the boys have taken a notion to get married before leaving for the front, among the number being Eugene Hazewell, E. Norman (nicknamed “Enormous”) Gunnison, and Johnny Ogden, the round-faced Englishman I pointed out to you down by the cemetery, one day.

We have lots of fun with the fellows who come creeping into the barracks late at night or early in the morning. All sorts of traps are set, and some one of them generally gets the bird. Sometimes it is the old trick of tinware over the door, which is bound to rouse the whole camp, no matter how carefully the door is opened; or a gun box set on end in the aisle; or a rope stretched across it.

Just to bring myself to a realization of how long the three years ahead ought to seem, I have been measuring back to events that transpired three years ago. Three years seems a long time looking into the future, and yet many things that took place three years ago do not seem so very far away. In the depot at Manchester I met Ike Sawyer, who has just got back from sea. I asked him how long he had been gone this time, and he said, “Over three years.” I was[7] surprised that it was so long, and hope the coming three will sort of shorten up in the same way.

Our company is now stocking up on mascots. The latest additions are a splendid Newfoundland dog and a pretty maltese cat.

Nich. Biglin is going up tomorrow to bid good bye to a large and enthusiastic circle of female admirers. Just now he and Dan Mix are engaged in an animated dispute as to whether a man will get tight on gin sweetened with sugar sooner than if sweetened with molasses, and “Heenan” proposes that they go out and experiment.

STILL in Portsmouth, in spite of all prophecies, augurs and omens. The excuse now is that the baggage wagons and some other camp equipage are not ready. The time now set is next Monday, but I am not counting on going before Wednesday, as a precaution against being disappointed. All our baggage wagons, harnesses, horses, and other field stuff are in Concord, and it is more than probable that we shall go there to get it, and thence to New York through Manchester. I hope so, as it will give me a chance to see you once more just for a moment.

I was somewhat surprised to hear that Frank had gone to Washington. I wish he was going with this regiment; but I shall have as good care as I could wish for if I am sick, as my uncle, Dr. John, is going out with us in the hospital department. My aunt wrote me that if the doctor went she should put on the breeches and go too.

And, by the way, I am not sure that you would recognize me now that I have followed the prevailing fashion and had my flowing locks shaved off close to my scalp.

Yesterday morning, before breakfast, a party of us boys went down to the beach and had a glorious frolic, swimming, digging clams, and catching crabs.

In the regimental organization we are designated as Company I. It is explained to us that this gives us a post of honor, as the color company, in the center of the regiment; but I am a little skeptical.

The boys have been singing sentimental songs, but just now have switched off onto cheers over the taking of Big Bethel, in Virginia, by Gen. Butler. “Hooray!” The way they are tearing it off is a caution. All are at fever heat to be off and helping in the war.

WE know, at last, just when we are going away—“sure.” Next Thursday, at 7 o’clock in the morning, we are off. As we go direct to Boston, and not through Manchester, it is good bye until I come home from the war.

Si. Swain is under guard today. He refused to do duty and invited Rod. Manning, one of the sergeants, to go to H——ot place.

My ribs are sore from laughing over the regatta we had today out on the mill pond. Some of the boys gathered together from somewhere a number of hogsheads, halved by being sawed in two, and went voyaging in them. They were not a very manageable craft. They rolled around every-which-way, capsized, collided, and went through all sorts of ridiculous stunts.

We have had issued to us blue flannel blouses, thin, loose, and far more comfortable than our uniform dress coats.

Some of the boys have been fishing down at the fort today. They brought home a lobster they caught, and while a kettle of water is heating to boil him in, are teasing the poor fellow with sticks. “Heenan” is taking an active part in the persecution. He holds up long enough to say to me, “Tell her I want to keep the first two months’ pay to buy my liquor with; but after that I will remit enough so that, with her own efforts, the family will be insured from want.”

OFF we go at 7 o’clock tomorrow morning, and everything is bustle and excitement. Have seen lots of Manchester folks here within a day or two. Mary Rice was on the parade ground yesterday. Dr. Nelson, Henry A. Gage, A. C. Wallace, policeman Bennett, Parker Hunt and his mother, and many more of my friends and acquaintances. We have been drilling today with knapsacks and equipments on, and my shoulders are as lame as if I had been beaten with a club. Twenty rounds of cartridges have been issued to us. You will direct letters to Company I, 2d Regt. N. H. Vols., Washington, D. C. We may not be at Washington, but there is no mail south of there, and it will be distributed from that point.

There was quite an excitement here last night, resulting from a fire on the frigate “Santee.” It was set near the magazine, in which was forty tons of powder.

HERE we are at last, in Washington, safe and sound, but stewed with the heat. We left Portsmouth on schedule time, Thursday morning. At Boston, we met with a grand reception. The boys will never forget the superb collation that was served us there—not merely the toothsome meats and substantials, but all the little niceties, such as strawberries and cream, &c. From Boston we went to Fall River, where we took the steamer “Bay State” for New York. I roosted on the hurricane deck and never had a better night’s sleep in my life. At New York the Sons of New Hampshire gave us a flag and a feast, after which we were ferried to Amboy, 16 miles, and took cars for Baltimore. I got in a good night’s sleep between Harrisburg and Baltimore, and Sunday noon we arrived in Washington.

Our camp reminds me of the old-fashioned tin oven my grandmother used to set before the fireplace to bake biscuits in. On the sunny slope of a ridge, with not a tree for shade and shelter. Hot![10] And the flies! I know now how to pity those poor old Egyptians. We have plenty of unusual happenings now. I am not sure but that some of the boys are seeing spooks. Sunday night several of the sentinels reported exchanging shots with prowlers about the camp. I was on guard that night, where there were plenty of bushes, but the best I could do I couldn’t find anything to get excited over. Dan Mix, one of the teamsters, says he was fired at four times while coming into camp with his team last night. And it is currently reported that the Zouaves, camped next to us, captured a spy a day or two ago, and he will be hanged today or tomorrow. I can understand how some secessionists around here might be tempted to take a pot shot at a Yankee sentinel out of pure cussedness; but I haven’t got it through my head yet what a spy could find to spy out that isn’t perfectly open to anybody who cares to look about in broad daylight, unmolested.

Just before I left Portsmouth I had a letter from my mother that touched a sensitive nerve. My dear old Grandmother Knowlton came down from New London to see me, but I had just gone back to Portsmouth. As the first and favorite grandchild I always filled a big space in her little world. She mourned over her disappointment, and grieved that she should never see me again. My mother could not even conceal her own blue streak. She and father were in Boston when we went through, and I had a chance just to shake hands and say good bye to them.

I have seen Dave Perkins here two or three times. [David L., of Manchester, then connected with one of the Departments.] He asked me if I wanted to send any word to that little girl away up in New Hampshire, for he was going back in a few weeks. I gave him lots of messages, and have no doubt he will forget every one of them before he sees you.

Our grub, since we got here, has not been quite up to the Astor House standard, but the army stores will be here today, which will improve the bill of fare. So far it has consisted of hard bread bearing the stamp “1810”—whatever that may signify—ham or salt pork and coffee.

SATURDAY was quite an eventful day with me. I went over to the city on a sight-seeing trip with Hen. Morse, one of my tentmates [killed, three weeks later, at Bull Run.] Went first to the Capitol, and viewed the paintings and statuary. Thence to the Smithsonian Institute and spent several hours in its wonderful museum, where I could have interested myself for days. From there to the Washington monument. Among the stone blocks there, contributed from various sources and to be built into the walls, was one inscribed: “From the Home of Stark. From the Ladies of Manchester, N. H.” We wound up our sight-seeing in the parks around the President’s house; and when we got back to camp I was tired enough to pile onto my blankets and go to sleep.

Not much sleep, though. I had hardly lost myself when somebody shook me and said the Captain wanted me up at his tent. I went up, in no very amiable mood. Found Commissary Goodrich there, who said he wanted me to be his clerk. I chewed the matter over and decided I’d take the assignment. It relieves me from guard duty and drill, and gives me very nice quarters with the Commissary. I jumped into my work the next day—Sunday. Issued three days’ rations to the regiment, and had a pretty busy time keeping track of the provisions. Monday and Tuesday I had my hands full straightening up accounts and opening a set of books; and not until today have I had any chance to write letters and attend to private affairs.

Last night we had a rain—and such a rain! The board floor in my tent kept me high and dry above the flood, but the fellows down in camp came pretty near being carried out to sea.

I am not starving now. I don’t think anybody does in the commissary department. Yesterday I had all the cherries I could eat, and some day, when I have a little leisure, I think I’ll go blackberrying.

YESTERDAY I received orders to deliver four days’ rations of beef, bread and coffee, and the cooks were ordered to cook the meat, ready for a march. We are now expecting marching orders at any moment. I have an idea that they will come about night, so as to avoid marching in the heat of the day. I am going, you bet. Captain Goodrich told me this camp is not to be broken up at present. The commissary stores are to be left here, the tents to remain standing, with the surplus baggage, all under guard of the cripples and invalids. When it came to details, I found the plan was for the Captain to go with the expedition, while I remained behind to look after things in camp. That didn’t suit me; so I asked him to hunt up another clerk, and notified the Captain that I wanted my gun again and to go with the company.

Where we are going we do not know, but inasmuch as twelve regiments are going with us, and we are to take no knapsacks, but four days’ rations and a large supply of ammunition, it is fair to presume we will be looking for trouble. I hope we are going down to Manassas to drive the secessionists out of that stronghold. Very likely some of the boys have not many days to live, but they are jolly eager to be off, and will give a good account of themselves.

I went to a ride into the country yesterday to find a boarding place for Captain Goodrich’s wife.

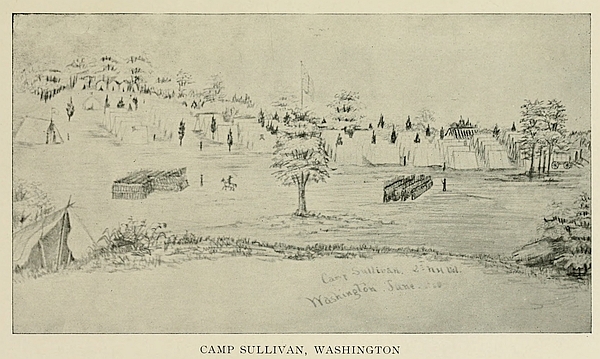

WE are still here in Camp Sullivan, our marching orders having been countermanded at the last moment; but are sure to be off before many days. We have been expecting to march today, but probably will not.

A day or two ago there was a dreadful accident in our brigade. The Rhode Island battery were drilling upon the parade ground in front of our camp, when the ammunition in one of the limbers exploded and the three men seated on the box were hurled high in[13] the air, two being killed instantly—literally blown all to pieces. I was on the spot almost instantly, and with the single exception of the Pemberton Mills horror, which I viewed as a newspaper reporter, it was the most sickening sight I ever saw.

We certainly do have gay times here in camp. The days are frightfully hot, but the evenings are cool and nice, and somehow or other the camp scenes then remind me—and I can’t tell just how—of an old-fashioned country fair. I suppose it’s the canvas, the lighted tents like open booths, the men swarming hither and thither, the bustle and frolic and singing—and we have some very fine singers in our company.

P. S.—Monday Morning.—We have received orders to march tomorrow at two o’clock, with three days’ rations and without camp equipage. The orders are imperative and we are sure of going. We shall probably see some of the business we came for before long. I will write at the first opportunity and let you know what happens.

I INTENDED to write to you yesterday, but after what I have been through in the past week I simply couldn’t get up steam. Last Tuesday—a week ago yesterday—this regiment crossed the Potomac at Long Bridge, with the other regiments and batteries of Burnsides’ brigade, and advanced into Virginia. Saturday night we were encamped about a mile from Centreville. At two o’clock Sunday morning we were up and on the march, and at ten o’clock we came upon the secessionists at Bull Run and engaged them. The battle lasted several hours, when we were obliged to withdraw. It was a very disorderly retreat. We expected to be followed sharply, of course, and there was no halt worth talking about until we straggled into Washington, every man for himself. Coming and going we got in about sixty miles of travel, to say nothing of several hours on the battlefield. I was about all in when, midday Monday, I reached the Virginia end of Long Bridge. We were then inside the fortifications, and there were kettles of hot coffee and boxes of hard[14] bread set out for everybody to help themselves. It did seem as if I never could drag myself over to our camp. But I finally negotiated with a huckster who was over there with his team, and having purchased his remaining stock of pies and distributed them among the crowd of refugees, he gave me a ride across the bridge and up into the city well toward Camp Sullivan.

The battle was the hardest fought so far, and the losses on both sides were heavy. At the roll call this morning 175 were missing from the Second Regiment, but this number will doubtless be cut down as stragglers come in. Of my eight tentmates, six went. Two [Harvey Holt and Henry Morse] were killed outright, and one [George F. Lawrence] was severely wounded in the head. I got my little upset at the very tail-end of the fight. The regiment had crossed over to the opposite hill, and about a hundred of us had taken cover in a cut in the road. We had a house on our front, some secessionist cannon up near it, and enough of the enemy to give us a real lively time. There was a rail fence along the edge of the cut, and I rested my musket on one of the rails, and carefully sighted on a fellow who seemed to be showing off. Then something happened. A cannon ball struck the rail, one of the fragments hit me in the head and neck, and I rolled down the bank. I heard one of the boys cry out “Mart is killed!” and for about half a minute I didn’t know but what I was. But when we had to break for the rear, a few minutes later, I had no trouble in keeping up with the procession.

In all my life I never suffered from thirst as I did that day. On the advance, our regiment was right at the ford of Bull Run creek when the head of the column sighted the enemy. A staff officer rode back with the announcement and called to the men to fill their canteens. I waded up a few feet and filled my canteen with good clear river water. A little while after, I took a drink, spat out the tepid mouthful in disgust, and emptied the canteen. I learned my lesson and will never do that again. Before that day was over I would have given dollars for one square drink of that same water. On the retreat I one time scooped up a few sips from a mud puddle through which men and horses and wheels were ploughing their way. Before reaching Centreville I filled up clear to the ears from a little trickling rivulet, and filled my canteen as well. Laid down in the[15] old bivouac, and went to sleep. After two or three hours was waked up and told to keep agoing. The old thirst was on me, but when I lifted my canteen it was empty—drained to the last drop. If I could have got hold of that sneak thief the casualty list would have been one bigger, I think.

You will be pleased to know that “Heenan” behaved finely. His tin dipper, hanging by his side, was desperately wounded—otherwise all right. Frank Wasley had one or more fingers hurt by a bullet. Col. Marston was not more than twenty or thirty feet from me when he was shot in the shoulder. It was rather a wild scene just then—a dead man stretched out here and there; a stream of wounded men staggering or being helped to the rear; the Rhode Island battery, shrouded in smoke and with several horses down, soaking it to the batteries across the valley, on the other hill. A little later we were farther down the slope, lined up in a cornfield, helping drive the enemy out of woods and bushes where they were strongly posted. While here we saw the Black Horse, a famous secessionist cavalry corps, charge the Fire Zouaves, and then go back with lots of empty saddles.

I find I must hurry to get this into the mail, but will write again in a day or two.

JUST to let you know that I was alive and kicking, I wrote a week ago, but did not write half I wanted to. I got a letter from Roger [Woodbury] a few days ago. He has an idea of enlisting in the Third Regiment. I advised him, as he is situated, not to do it. It may seem inconsistent in me to advise him against doing what I myself have done; but he has others dependent on him, while I have not.

Things are getting straightened out so we can now tell about how many men we lost in the unfortunate battle of Bull Run. Our total loss in killed, wounded and missing is only about eighty or ninety. I lost some of my best friends. Mose Eastman was wounded in the leg. I saw him carried to the rear. If still living he is probably a[16] prisoner. Frank Wasley has had a finger cut off. I had a letter from mother today. She says they do not know yet, in Manchester, who is missing, and there is the deepest anxiety there.

By the way, I may as well remind you that this is my birthday, and I am nineteen years old. If some one with the gift of prophecy had told me, a year ago, that at my next birthday I would be in the army and a participant in the greatest battle ever fought on this continent, wouldn’t it have seemed a wild piece of fortune telling?

THE heat today is something awful. We are all just about dead from it—lying about camp and sweltering. I received your letter of the 30th and will answer your questions in turn.

Charlie Farnam is in our regiment as a drummer.

All the boys you specially inquired after are well. Hen. Pillsbury inquires often where “the woman” is and how she is getting along.

As to the talk that we are going to be beaten in this war, that is the veriest bosh. The next time we march towards Richmond we will have force enough to crush our way. We were not beaten this time in the fighting, but by an unfortunate combination of adverse circumstances. Had Johnston’s division been held back by Patterson, as it was expected it would be, we should have beaten them anyway. And even with that reinforcement I am not sure we would not have whipped them in the end, but for that unaccountable panic communicated to two or three broken regiments by teamsters who had driven their teams into places where they were not wanted, and who took the order to change positions as a signal for retreat. Then everything went to pieces before anybody really knew what had happened.

My tentmates Holt and Morse were both awfully nice boys. Holt was the first man killed in the regiment. He was not with the company, but with the corps of pioneers, a detachment of axe-men, made up of details from the various companies. He was killed very early in the action, while crouching in a ditch, by a piece of shell[17] which struck him in the shoulders. Morse was killed late in the day. The regiment was crossing from the slope where it had been fighting over to the opposite hill. It was halted in the valley, while Gen. Burnside rode up the hill a little piece and took an observation. We were under very sharp fire from a battery further up. I heard a shot from it come roaring down the slope, ending in a “thud” which told it had got a victim down the line. Looking back, I saw a prostrate form sprawled in the dust of the road, with Johnny Ogden bending over it. “Who is it, Johnny?” I called back. “Hen. Morse,” he answered me.

We expect to change our position before long—are hoping to spend a few of these hot weeks at Fort McHenry, in Baltimore, or at Fortress Monroe. I don’t know where the idea started from, but it would be fine.

I hear from Manchester often. Roger Woodbury, George Dakin, Ruthven Houghton and Frank Morrill have enlisted into the Third Regiment. How I wish that crowd was in this company!

Some of our officers are now in New Hampshire after recruits to fill the gaps in the Second Regiment.

DIDN’T wake up very early this morning; but when I did I got up, quick—rolled out of a puddle of water I had been sleeping in. We moved over to this camp last Friday morning, and are in a most delightful location. It is about five miles from Washington, on the field where the battle of Bladensburg was fought in 1814. There is a little village, a little river, little hills, &c., and plenty of the very best of water close at hand. The place has quite a reputation for its mineral springs. There is one right in the village, and the water is so clear, so cool, so refreshing—only the merest suggestion of a mineral flavor.

It is surprising how many of my old friends I manage to run across. Gust. Hutchinson, who used to work with me in the old American office, is in the Massachusetts Eleventh, which is camped here. Almost every day I run across somebody I have known before.

August 15.—I have been about used up for the past two days, but now I must finish my letter. You can assure your rebel-sympathizing friends that the rebels cannot take the capital, and I do not believe they will attempt it. I hope they will try.

I have just received a paper with a list of the second company of Abbott Guards. I note that Roger Woodbury, Frank Johnson, Johnny Stokes and others of my old friends are in it. My uncle John has gone home. The climate did not agree with him as well as it does with me.

PRESIDENT LINCOLN, accompanied by Secretaries Seward and Welles, reviewed the brigade this forenoon. Friday afternoon we were reviewed by Gen. McClellan, who is next in command to Gen. Scott. We expect to stay here several weeks—perhaps till the first of October. We are so very pleasantly situated that we would not object to lying around here for a few weeks. If the rebels should be bold enough to attack Washington there will be lots of music. The city is being fortified against any such emergency. Our brigade is working on a fort near here that would prove a hard nut to crack. Three of our regiments were at Bull Run. The First Massachusetts was in the Thursday fight at Blackburn’s Ford, and the Eleventh Massachusetts was in the Sunday fight.

There was a most laughable scene here today. Colonel Fiske’s horse ran away with him and bolted smack into [Lieut.] Joe Hubbard’s tent. Down went tent, horse and rider all in one grand mix-up. And while they were trying to save something from the wreck out of the ruins crawled the worst-scared man ever seen in these parts since Bull Run. He was reading a newspaper, all unsuspecting, when the heavens fell.

A day or two ago I read a letter from a daughter of old John Brown. It was written to a brother-in-law of hers in my company—Willard P. Thompson—whose brother, her husband, was one of John Brown’s men killed at Harper’s Ferry two or three years ago. It was a gem of patriotic sentiment, and with a fine womanly instinct she expressed her sorrow that Avis, who was her father’s jailer, was killed at Bull Run—he was so very kind to the old prisoner.

ORDERS came tonight to pack and be ready to march at a minute’s notice with two days’ cooked rations. I learn from headquarters that we are going over into Virginia again. We want a chance to try the Southern Chivalry on again, and I guess we will have it before long. We hear there was a scrimmage over there today, and our troops took possession of Munson’s Hill, which the rebels had fortified. It is after ten o’clock at night. “Taps” beat an hour ago, and I must close. Perhaps in my next letter I will tell of a battle, and if I do, it will be a battle won.

I AM somewhat surprised to hear that M—— has, as you write me, given her secession-sympathizing lover the mitten. I can not work up any more sympathy for a rebel in New Hampshire than for one in Virginia, and a Manchester man who would jubilate over our defeat at Bull Run ought to be taken out into a back pasture and shot. As for my never getting home again, I’m not worrying about that. I went through Bull Run safe and sound, and I don’t believe we will ever see a harder fight than that, and there is no reason why I should not come out of the rest of the battles equally well.

There has been some sort of a shake up in the commissary department. Capt. Goodrich has had three clerks since I got out, all of whom threw up the position. He and the Brigadier General [Hooker] didn’t hitch up together very well, and now, I understand, he has quit the service.

Am I homesick? you ask. Not a bit. And that does not mean that I would not like to see you and the “old folks at home.” We are very comfortably situated just now. No signs of immediate starvation. Government rations are excellent, and we can piece out with any luxury we are willing to pay for. And drill and camp duties are so arranged that we have much time for pleasure.

I got a letter from Roger Woodbury Wednesday. He is camped on Long Island and is enjoying camp life immensely. The Division he is in will consist of ten New England regiments, and is probably designed to operate somewhere along the coast when the time comes for the grand move.

We are building a line of forts to encircle Washington on the north. Details from this brigade have worked upon two near our camp. One of these now has twenty guns mounted, commanding the country for miles around. How soon we will move, we cannot tell—perhaps in a day, perhaps not for a month. We have two days’ rations constantly in readiness. The Massachusetts First has gone over into the country somewhere for a few days.

I ran into a little bunch of excitement this noon. Had gone over to a huckster’s on the road running between the camps of the Pennsylvania Twenty-sixth and Massachusetts Eleventh, to buy a pie for dinner. Saw a commotion over in the Eleventh camp which seemed worth looking into, so I went over. Had just passed the camp guard when I saw one of the boys rushing a negro out of the crush and over to the Pennsylvania camp. The negro was almost paralyzed with fright. He was a runaway, and had been with the Massachusetts boys quite a little time. His master got track of him and sent two slave catchers to get him. But when they tried to execute their mission, some of the boys promptly knocked them down and got the negro out of the way.

LAST Wednesday I went down to the Third Regiment and saw lots and lots of the old crowd. Roger Woodbury had not come on yet from Long Island. I met Frank Morrill, Jack Holmes, Ruthven Houghton, and many others. Frank and I had such a good long talk over the happy old times. The regiment is camped about three miles from here, and the men are worrying for fear they may be ordered back to Long Island.

So you think, do you, it would be a good plan to go down to the city once in a while for something good to eat. Why, bless you, we[21] don’t have to do that now. We have sutlers here, and hucksters out from the city, and farmers with their truck, and can buy most anything we want to piece out the army rations, from sweet potatoes to pound cake.

COMPANY I goes on guard today, and I can manage to pick out a little time for writing letters. I wish you could be in camp here Sundays and see the colored people come in. Sunday is the negro’s holiday, and they swarm into camp with their apples, peaches, chickens, or whatever they happen to have that can be turned into money or old clothes. Each one has a basket, with a crooked stick on which to swing it over the shoulder. These plantation negroes—mostly slaves—are a quaint lot, not a bit like the bright colored people you see north. We used to think the stage negro at the minstrel show was a burlesque. He wasn’t.

Fast Day some four hundred of the regiment marched down to the camp of the Third and had a jolly time. Roger had got along, but I saw him for only a moment. Frank Morrill and I took a most cheerful stroll down to that most cheerful public institution, the Congressional Cemetery, and saw the tombs of Gen. Macomb, Gov. Clinton, and no end of generals, commodores and other big men.

The Fourth N. H. Regiment passed here today. I do not know where they will camp. I have many acquaintances in its ranks.

Have you read about the taking of Munson’s Hill? Wasn’t that a pretty neat trick the rebels turned on us—mounting stovepipes and wooden cannons on the forts? The boys are borrowing trouble now through fears that McClellan will not take us with him when he advances over into Virginia. It would be decidedly ungrateful not to give us a chance to square accounts for Bull Run and the run we made after it. I shall never forgive the rebels for that affair until we have paid them in their own coin.

The First Michigan Regiment came in today and camped right beside us. They were at Bull Run as a three months’ regiment, and enlisted again, for three years, when their time was up.

The fort we have been working on is about ready for business. It mounts thirteen 32-pounder guns, and would be a lovely thing for a few thousand men to butt their heads against.

The days are very hot and the nights terribly cold. I put my overcoat on and wrap my blanket about my legs and feet when I bunk down nights, and then I am almost frozen. This is a good time to catch the fever and ague, and I may be in for it.

THE Fourth Regiment are encamped about two miles below here. I went down to see them one day last week and had a good time. Saw Kin. Foss, Sam. Porter, “Tulip” Bunten and many others. As I went strolling through the camp, I noted one street down ahead where there appeared to be half a dozens fights going on, in various stages of development. I said to myself, I’ll bet a dollar that’s Charlie Hurd’s company. I won the bet.

The Third Regiment has gone to Annapolis. This afternoon we are to be reviewed by Gen. McClellan. He has reviewed us once before, and it may be that he intends putting us ahead somewhere, and that we shall leave Bladensburg before long.

So you want me to learn a lot of songs, do you? Well, I have anticipated your wishes and already commenced. There is one pathetic local ballad that I have been practicing on and can do pretty well for a green hand. Here is the first verse, which will give you some idea of its high artistic merits:

Then there is another that is very popular with the boys. It is easy to learn, notwithstanding there are 147 verses to it. I will give you the first verse, and when you’ve got that you’ve got the whole thing, for they’re all alike. One, two, sing:

Our entire company was out yesterday cutting down woods that interfered with the range of the guns on the forts we have been building. My mother, having in recollection her experiences with the family wood box when I was a boy, would probably have advised against taking me out. But I am inclined to think that, as a wood chopper I achieved some reputation this time, as after I had gnawed down a tree of considerable size some of the boys called the others to come and admire “Mart’s stump.”

Well, I have strung out a long letter, and some of it you can credit to the delightful surroundings and conditions under which I am working. Here is the picture: A big tent—the Quartermaster’s—overlooking from its back a railroad cut twenty-five or thirty feet deep; an enormous oak tree deeply shading a large space, with a delicious breeze rustling its branches; several of the boys sitting around reading the newspapers, chatting, and looking down upon the numerous trains that pass below; and your own correspondent, with a big pile of army overcoats for a backrest.

WE are having some of the worst weather the almanac can dish out to us, and the hospital is full of sick men, some seriously ill. I have, myself, been off duty for several days, but am now on deck again all right. It is surprisingly cold, and tents are not the warmest sleeping apartments in the world. I hope they will take us off down south before long or give us good barracks.

I had a letter from my uncle Nathaniel the other day. [Nathaniel Columbus Knowlton of New London.] He wrote that after he went back from Boston, where he went to see me off, a girl came to my father’s house, whom they introduced as Miss Lane, and who seemed to be very well acquainted. About a month after, Addie told him who you was. He approves.

The two aunts you met at my house are all right. Aunt Polly is the wife of my father’s eldest brother, Joshua. Aunt Olivia was reared down south, in a Catholic seminary at Charleston, South Carolina. Her father, Captain Bailey, was an old time sea captain. Until recently she has been very decided in her southern predilections. But a summer spent in Charleston two years ago changed her sentiment very radically. Her husband—my uncle William—is in the Massachusetts Eighteenth, which is now at Baltimore.

There is quite a little force of cavalry here with us now. They make a brave show in their drilling. Gen. Hooker, who commanded this brigade, now has a division, and Col. Cowdin, of the First Massachusetts, commands the brigade. I believe we shall move from here before long. The boys are getting impatient, and will be very discontented if they hold us here much longer.

You write me of your fingers being cold. If you could only know how cold I am this very minute, you would realize the pleasures of letter-writing in camp. It is a cold day, and I am writing in a wide open tent, which is just the same as out of doors. But we have lots of good times, notwithstanding the cold; and when we get around the campfires at night, we talk of home and the jolly times we will have when we get back to Manchester.

YOU will take note that we have changed our location at last. We are now forty or fifty miles below Washington, on the Potomac river, below Budd’s Point. The other side of the river is lined with rebel batteries for a distance of ten miles, up and down, and we are here with ten or twelve thousand men to watch them. We have cavalry and artillery with us. With our regiment is Doubleday’s battery of 12- and 32-pounders. Most of the Fort Sumter men are in this battery. We left Bladensburg Thursday and got here last night—a march of four days. As we were in heavy marching order, all our earthly possessions strapped or hung to us in some way, you can be sure it was a pretty tired crowd that landed in here.

Tuesday Morning.—I tried to write last night, but it was so cold I had to give up. We are camped down in a deep hollow, where the sun doesn’t get in till pretty late. Every morning the ground is white with frost. It takes all our dry goods to keep us anywhere near comfortable, day or night. Our grub is neither rich nor varied, but it appears to agree with me—with what I have been able to pick up on the side. A man who is enterprising can occasionally get hold of a piece of fresh meat. Until last night, since leaving Bladensburg, every man has been his own cook. Our tin plates served very well as stew- or fry-pans, and coffee drank out of the tin dipper in which it was boiled on the coals of the campfire, has a flavor all its own. But last night the company cooks got into action again and served out boiled corned beef, hardbread, and coffee. As it never rains but it pours, our sutler also got along and opened up shop.

Guard duty in this place is not what it was at Bladensburg. Our company goes on picket today down by the mouth of the creek we are camped on [Nanjamoy,] to watch the rebels over across the river. Mail will leave here three times a week.

Yesterday the rebel batteries were busy throwing shells over to this side of the river, but our regiment was far out of range of fire. Before we came down here the rebels used to come over and visit and forage and gather recruits and scout around with impunity.

The infantry of this division consists of our own brigade—the First and Eleventh Massachusetts, Twenty-sixth Pennsylvania, and the Second—and General Sickles’ “Excelsior Brigade” of five New York regiments. The regiments are strung along for a distance of probably seven or eight miles, we being the farthest south.

WHEN I wrote you last we were camped in a hollow by Nanjamoy Creek. Well, we got driven out. It was so infernally uncomfortable that Col. Marston moved the camp up onto the hill. It is not probable that we shall stay in this camp a very[26] great while, but when or where we will move is a riddle. For all that, we are doing a good deal of fixing up that belongs to a permanent camp. Have built log huts for the company cooks, which will probably be labor thrown away. But we are having a good time. The woods are full of small game, although we do practically no hunting. But the darkies bring in coons, possums, gray squirrels, rabbits and chickens, all cooked, and well cooked. We have not seen any soft bread since we left Washington. Our hard bread certainly does not belie its name. But given a good soaking in coffee, and well lubricated with butter, I manage to dispose of my share.

Our mail is regular in nothing but its irregularity. A three days’ mail for this regiment got as far as the Massachusetts First, and then, in some fool freak, was shipped back to Washington. Everybody is swearing—except, possibly, the chaplain.

SINCE my last letter we have moved up several miles and are now encamped with the rest of our brigade, near General Hooker’s headquarters. Our location here is a most attractive one, the camp being in the edge of woods thick enough to afford a perfect wind-break. This insures us against such a calamity as we were up against at wind-swept Hill Top, when several tents were overturned.

Yesterday I had a reserved seat at a first-class show. I heard the rebel batteries on the other side of the Potomac banging away at something, so I went down to the river—not a very great distance—to find out what the trouble was. It was a saucy little schooner skimming down the river, and the rebels trying to hit her. They fired about sixty shots and never made a score. But it was an inspiring sight all the same, the big guns flashing from battery after battery as the vessel came in range, and puffs of smoke in the air or a big splash on the water marking the grand finish.

It looks very much as though we were going into winter quarters here. Logs of suitable size and length are being hauled in,[27] to be used as an underpinning for our canvas houses, and the boys, in squads of five or six, are already at work on their quarters. My crew is already made up, a picked squad of congenial souls, and we will get at our building operations next week.

We had a thunder shower night before last, and it has cleared off very cold. But there is an abundance of fuel, and half a dozen campfires agoing in each company street.

FOR amateurs, the association of house builders I joined has done a good job. It is on the same general plan as most of the others. First, you start in to build a log cabin. When the walls are four or five feet high, you stop, fasten your tent on top—and there you are. It is astonishing, the room you gain over a plain tent. On the right-hand corner fronting the street is a fireplace—a big one—built, with its chimney, of small logs laid cob-house fashion and thickly plastered with Maryland mud. The bottom is sunk a foot or more, and around the front is a one-log pen or barrier, which serves a double purpose. It is just right for a seat before the fire, and it keeps our thick carpet of straw out of mischief. When we are all fixed up we’ll have bunks and a table and shelves and pegs and a gun rack and everything required in a well-regulated family. I am writing by the light of a candle. Roberts [Orsino,] one of the tent’s crew, is warming himself at the fire and going over all the songs he has in stock, and the rest of the gang seem to have no higher ambition, just at present, than to “break up” both me and him.

Sunday our company went up to “the landing” to help unload two or three small steamers that bring our supplies down from Washington. The landing is at Rum Point, over three miles from here, but as near as boats can get to us, on account of the rebel batteries. As we did not start to return until after dark, we had a sweet time of it. The roads here are now nothing but a ditch through woods and fields, filled with mud of terrible adhesive qualities and of fabulous depth. I thought, for the life of me, I should never get home.[28] If I tried to follow the road, I wallowed up to my knees in mud. If I switched off to one side or the other, I had, in addition to the mud, a butting match with every tree in the county. It was pitch dark when I landed in camp just ahead of a smart shower.

Tomorrow is Thanksgiving Day in New Hampshire, and we New Hampshire boys out here on the Potomac will observe it in a befitting manner. In our tent we have a big fat goose up on the shelf, with a rabbit- or chicken-pie or two and a few other fixings. Beat that if you can.

I AM just in from our standard show—a little schooner running up the river and thumbing her nose at the rebel batteries. In all, they fired seventy shots at her, with the usual result—no damage done. There was much noise and smoke, a great splashing of the water, and lots of fun for the boys in the gallery. As every shot they fire costs them from ten to fifteen dollars, each schooner trip up or down the river must be an expensive job for them. They must burn up about a thousand good dollars every time, mainly to amuse a lot of Yankee soldiers over on the Maryland shore.

Next Tuesday there is to be a grand review of this division, together with an inspection. These functions are doubtless a military necessity, but not very popular with the men—especially the inspections. You are toled out with your entire outfit, and everything is hauled over, peeked into and examined. They say Gen. McDowell, the old fellow who led us to Bull Run (and back,) is down at headquarters. The last time I saw him he was riding down the front of Burnsides’ brigade, in the corn field at Bull Run, and telling us we had won a victory.

There are a thousand-and-one rumors afloat as to our leaving here, but I am not expecting to move in any other direction than straight across the river. Any man with a vivid imagination can make a guess, whisper it to one or two, and before night it is all over camp as an authentic tip from headquarters, Gen. Heintzelman’s division is advanced on the other side almost down to the[29] rebel position, and my guess is that he will come down on them before long, while we will cross here and give them Jessie, with the aid of the gunboats. They are getting ready for us. We can see them digging and throwing up intrenchments on the opposite hills.

TOMORROW rounds out just seven months of my three years’ term. The other night, at the meeting of a literary society some of the First Massachusetts boys have started, the Lieutenant-Colonel of the regiment said he thought the regiment would be home by March. There’s the cheerful optimist for you! Our regiment has been in the service just about the same length of time as the First, and the two will probably be sent home about the same time. Presumably the regiments first in the field will go out first, and so we may get home many months before the later regiments from New Hampshire. They will have to keep them as a sort of police for a while after the war is really over.

For a day or two we have been having splendid weather. But under foot it is simply awful. The “Maryland salve” is everywhere. The roads are a terror now, and in a short time will be absolutely impassible except where corduroyed with logs laid crossways to make some sort of a platform for teams.

We were reinforced last week by a brigade of New Jersey troops. Just below the blockade is a large fleet of gunboats, ready to co-operate in any move we may make. Last night a big steamer ran the blockade in the darkness and there was a terrific hullaballoo.

Joe Hubbard has got back from New Hampshire, but the boxes confided to him have not yet arrived. He says there is one for me, and I am, of course, very anxious to get it.

I WISH you could take a peek-in on my luxurious surroundings. I have a barber’s chair to sit in. It has a canvas back and seat, and was built by Damon [George B.,] the Jack-at-all-trades of my tent’s party. There is a good fire, plenty of apples at my elbow, and, all in all, I am a pampered child of luxury. There are only two besides myself occupying the castle just at present—George Slade and George Damon—very companionable fellows, and who have seen a great deal of the world. Two—George Cilley and Bill Wilber—are in the hospital, and E. Norman Gunnison (a fellow with a decided talent for writing poetry) is in the guard house for some infraction of camp discipline. So we three that are left have plenty of room and get along mighty comfortably. Slade and Damon are good cooks. We buy flour, butter, sugar, &c., and cook a big slack of fritters whenever the spirit moves us. And we have rabbits, chickens, wheat biscuits, and various other camp luxuries. And occasionally we make molasses candy of an evening. All this, you will understand, is outside of and in addition to our regular army rations.

Here is our schedule of duty: Reveille beats at sunrise, when we turn out and answer to roll call. Then comes the breakfast call. At 9 o’clock is guard mount—that is, the company which has been on guard duty is relieved by another. The remaining companies drill from 9 to 11 and 3 to 5—but now only occasionally, owing to weather conditions. Dinner call at 12. Dress parade at sunset. Tattoo is beat at 8, when the roll is called and the men can go to bed. The Colonel says we will not have much drilling for the rest of the winter.

The boys find plenty to amuse themselves with, and things are by no means dull here in camp. Quite a number of musical instruments have found their way in, and there are men here who know how to play them too—fiddles and banjos and such.

We had a large party of New Hampshire people in camp today—E. H. Rollins, John P. Hale, Daniel Clark, Waterman Smith, E. A. Straw and others. There were also four good-looking New Hampshire women, and they got three rousing cheers at dress parade.

The old rumor factory now has it that the Second is going to Washington within a few days, to act as provost guard. Joe Hubbard’s boxes have not yet arrived, and may not for some time yet. The railroads leading into Washington are buried in freight and express matter, but I suppose our stuff will get through in due time.

You inquire what sort of a place this is. Well, it comes about as near to being no place at all as it could and still be on the map. There are but few houses hereabouts, and a good part of these are just negro cabins. There is a store a little ways from here, but I have yet to discover where enough local trade can come from to keep it going. The Potomac is only about an eighth of a mile from our camp. From the western edge of the strip of woods in which we are camped one can see the river for a long distance, with the rebel batteries, and the upper works of their gunboat “George Paige,” which sticks close up in Quantico Creek, out of reach of our gunboats. The river here is less than two miles wide and the deep-water channel runs very near the other side, so a large vessel has to run close in to the rebel batteries to get through at all.

We witnessed a lively little brush the other day. The rebels started to throw up some works on Shipping Point, and the “Harriet Lane” and five other gunboats dropped down and told them to stop it. The way they pitched shells onto that point was a caution. And a few nights ago—just for fun, as near as I could figure it out—one of our gunboats dropped down to the upper battery and had some sport for a while. I always did like fireworks, so I got the countersign and went out to take in the display. It was worth the money.

You have thought to inquire for “Heenan.” Alas! Poor Heenan! It grieves me to inform you that the other night he got into an argument with a Company D boy. Just what condition the other fellow was left in—if still alive—I don’t know. But when Heenan returned to the bosom of his family he was a sight. His face was badly bruised, both eyes in mourning, and one thumb chewed to a jelly. He says he wanted his thumbs to be mates, and the other was crushed out of shape before he left Portsmouth.

OUR friends over the river have got another battery in good working order. It mounts a 64-pounder rifled gun, and the other night they dropped two shells within the camp limits of the New Jersey brigade, forty or fifty rods from our camp.

The boxes sent on by Joe Hubbard have at last arrived, and you may be sure we were glad to see them. I presume you know what was in mine as well as I do myself. The pies went into the common stock and disappeared as though they had legs. The various articles of clothing filled my knapsack as full as it would hold. And I must say to you that the little knitted smoking-cap or skating-cap or sleeping cap, or whatever you call it, is the gayest fez in camp. There are quite a number in the company, built on the same general lines, but no two alike, and mine takes first premium. I wish I could see you long enough to thank you for it.

I took one of the big boxes and made a cupboard to keep my things in. I have my eating utensils on one shelf, writing materials, bundles of letters, &c., on another, papers, magazines and books on the third.

Col. Marston was wounded last Sunday by the accidental discharge of a pistol, so Lieut.-Col. Fiske is in command. He is a great fellow for drilling the men, and we are not having as easy a time as we did with Marston.

One of the boys has just come in, bringing a fragment of a shell fired by the rebels at our battery down near the river. All the mementos I have picked up so far are a sand-bag from the rebel works at Fairfax Court House and a few insignificant trifles.

I AM feeling pretty ragged just now, but I see a glimmer of comfort ahead in the shape of a big lot of biscuits Damon is making for supper. We have not had any rations of soft bread since we left Bladensburg, but better days are coming. They are putting in[33] a bakery for the Second Regiment, and when it is done I expect the boys will feel like getting up a celebration. Really, though, it won’t make so much difference in this tent, where we have had a very efficient private bakery in operation for some time. Even I, as a lover of toast, have developed some skill in making good buttered toast out of our hardbread. I soak and boil it a long, long time, then stack the crackers up, buttering each, and it is a pretty palatable dish, if I do say it as shouldn’t.

NIGHT before last we had a regular old-fashioned hail-storm. I lay on the ground in my tent, rolled up in my blankets and overcoat, cozy, snug and warm in spite of the hail that was hammering my canvas roof, and pitied the poor people who didn’t have a fireplace, a snug nest, and a roof. But last night the boot was on the other leg. I was on guard, and it was miserably cold, with ice a quarter of inch thick over everything. When I came off, along in the night, I headed for my tent and comfort for a while. Had just got comfortably settled when some one stuck his head in and hollered, “Your chimney’s on fire!” I rolled out, broke through the ice in a water-hole, mixed some mud, and plastered it into the crevices. In about an hour, another good angel sang the same song, and I went through the same performance. Another hour, and the third alarm came. I was now thoroughly mad and utterly demoralized, and I howled back, “Well, let her burn if she wants to.” It smouldered until morning, when we doctored it so we hope it will behave for a few days at least.

The rebels have not been very demonstrative lately. I hear that Gen. Hooker has orders not to grant any more furloughs, as Heintzelman is advancing on the other side and is liable to have a fight any day, in which event we will be called upon to support him. And besides this, Gunnison has had a dream. He believes in all sorts of uncanny manifestations, and the other night he dreamed that the regiment was in a battle, and in an awful hot place too. I am not[34] very anxious to get out of my present comfortable quarters, unless it might be to go home or farther south where it is warmer. If it were not for that glorious old fireplace of ours we should not be as comfortable or as cheerful as we are.

I HAVE been working like a beaver all day and am awfully tired. It was that infernal chimney. Last night it got afire again and was roaring gloriously before we found it out. So today the whole crew put in their time reconstructing it. It is a pretty substantial piece of work, and it ought to stand the wear and tear for a long time. This is one of the most enjoyable days of the season—warm and with a refreshing breeze. But O, the mud! And not a bit of snow on the ground.

Last night the rebels fired a great many random shots across the river, hit or miss, here and there, and have been keeping at it, intermittently, today. They know, of course, the location of our camps, and it is really surprising that not a speck of damage has been done. A number of the shells struck quite near to our camp. Today one shell struck square in the New Jersey camp, but did not explode. And this afternoon, while I was sitting in my tent half asleep, there was a wild screech a few feet overhead, and a shell landed on the parade ground a few rods beyond the camp, but did not explode. A crowd ran out from the camp, but Damon captured the prize and brought it into our tent. A little while after, he sold it for ten dollars. [Major Stevens was the purchaser. For several years, properly labeled, it was one of the exhibits in the Adjutant-General’s office at Concord.]

You inquire of me why we don’t fight. I don’t know. Suppose the time hasn’t come yet. I have no doubt it will before long, however, and there will be a lively time.

HORRIBLE weather! It is almost inconceivably muddy, and today it is raining. I went out to watch the batteries work, today, and it was a question sometimes whether I wouldn’t have to leave my boots in the mud. We have spells of cold weather, with a little snow, but it soon gets warm and rains.

Jim Carr, of our company, cut his foot terribly with an axe, yesterday. The blade went right through the bones, and he will be crippled for a long time.

I have studied it out that we will not trouble the rebels on the other side for some time yet. We are building big mortar rafts up at Baltimore, to be used in shelling out the rebel batteries. It will take some time to get them ready, of course; but when the time does come there will be music in the air.

Last week I helped dig out a rebel shell. It was buried seven feet in the solid earth and must have traveled over four miles.

YOU never saw a lovelier day than this—clear as a whistle, with breeze enough to set the whitecaps running on the river. In the forenoon I went down to our battery, near the river, just for the walk. One of the lookout pickets I passed on the bluff had a powerful spy-glass, through which I got a good view of the rebel fort on Shipping Point. Down by the battery I picked up an Indian arrow head. Some contrast between this stone weapon of a dead and gone race and those long 32-pounders close by.

I see a good many old Manchester acquaintances here who drop down sight-seeing. Kimball the shoe man, John B. Chase the tanner, and Cy. Mason, Washington agent for the Associated Press, were here day before yesterday; and yesterday Dr. Hawkes came down.

Would you like a picture of myself and my surroundings right at[36] this moment? Well, here it is. See me sitting in front of a cheerful wood fire, my boots off, and your gorgeous smoking cap on my head. By my side, a cup of steaming hot cocoa, a cookie and a quarter of mince pie. Slade is at my right, writing, and similarly provided for in the eatable line. Just at this moment he is digging down into his box hunting for a big lump of candy that came to him from home.

We had chickens, from New Hampshire, for supper. I am getting to be an expert, myself, in certain branches of cookery. I can toss and turn fritters now, without dropping them in the ashes. Can you? Our “oven” is very simple, but it does its work to perfection. We set a deep iron pan on a bed of coals. In this, four or five little rocks as supports for the plate carrying the dough. The whole covered with another iron pan filled with coals. The biscuits and plum cake we turn out cannot be beat anywhere by anybody.

EVERY night, almost, I dream that I am home again, and those dreams are perhaps a forerunner or premonition of something that is going to happen. The signs are decidedly more promising for an early termination of the war. We have worsted the rebels in every fight we have had for some time, and the tone of the Southern press indicates that the Southern people begin to appreciate what a scrape they have gotten themselves into. I expect we will move from here before long. The Quartermaster says he does not expect to stay in this place much longer, and has especially charged his teamsters to keep their equipments in condition for a quick movement. Besides, a road is now being built down to Liverpool Point, about twelve miles below here on the Potomac. This indicates that when we go we will embark for somewhere—perhaps only to be ferried across the river.

In all your life, travels and experience you never ran across such a mud hole as this is at this season. I heard, this afternoon, that we would have to back our supplies up from the landing, as it is pretty near impossible for teams to get through. The landing is two miles[37] and a half from here, and we would have a fine time toting up boxes of hardbread, beef, and other fixings. I saw one of our boys coming up from the landing last night who had evidently misjudged the depth of the mud in some place, for clear to his waist he was cased in Maryland salve. A man is fortunate if he can find a place to cross the road without going in to his knees.

My tentmate Damon is on furlough. He was not in condition for duty, having strained his back, so they gave him a furlough of thirty days. His time is about half up, and we do miss the boy. Frank Robinson has got back, looking pleasant and happy, as a newly-married man should.

FOR a day or two I have been laid up with a bad cut on my foot, which I got chopping wood for my tent. I can not get a boot or a shoe on, but hope it won’t bother me a great while. I guess—in fact almost know—that we are to leave here soon. Gen. Hooker has been to Washington to confer with the commanding General. Rahn, our Commissary Sergeant, thinks we are going on an expedition to Galveston, Texas. Wouldn’t we have a time down there among those Spaniards, Greasers, Negroes, and those perfectly awful Texas Rangers!

Damon has not got back yet. We have a letter from him saying he was at Lunenburg, Vt., laid up with a lame leg.

We have been rigged out with new uniforms. Dark blue dress coats with light blue cord trimmings, and light blue pants.

OF course you have rejoiced over Burnsides’ victory at Roanoke Island and the success of the Kentucky army at Fort Henry. If we can keep on with the good work, this rebellion will be crushed and we home again before long. We are under orders[38] to be ready to march at short notice and will soon be doing our share of the business. A Vermont brigade is expected here, any day, to reinforce us; and some big guns are being brought down from Washington, probably to be used in shelling the rebel batteries. The gunboats have not had their full armament until lately.

That foot of mine, that I was fool enough to cut over a week ago, is a beauty now. I got cold in it, or something, and it now looks more like a parboiled pig than a foot. If we get orders to march right now, I shall have the foot swathed up in some way and go with the regiment.

Slade is sorting over his stuff, to see what he shall send home. He actually has more than he can lift.

A few days ago there came an order to find out how many men in this division wanted to go on the Mississippi river gunboat flotilla. They proposed to transfer forty out of each regiment, and I suppose the idea was that they would find lots of sailors in the regiments from the coast. The order was quickly rescinded, however.

MY foot is most well now, much to my gratification. I would not like a furlough just now. There will be some fighting before long and I want to be in it. The rebels over the way have not fired a gun for a week, and it is surmised that they have evacuated. Everything indicates that we will move soon—very soon. A Brigadier General has been assigned to command of this brigade, Col. Marston is coming back from Washington, and the officers on recruiting service in New Hampshire have been ordered back to the regiment. The Quartermaster assures me we will be off within a few days.

VERY cold just now, and the mud is drying up fast, so it is getting to be very good traveling. You know we are going to move when the roads are in condition. McClellan says so, and he ought to know. All the signs point to a movement before long. We have shipped the company property to Washington, and also our dress coats. We will not take any tents, and only two wagons, for ammunition. We drill now about six hours a day. The musicians have an “ambulance drill”—learning to get men into and out of ambulances, to staunch wounds, and to generally care for wounded men. Senator Hale told one of our boys, a while ago, that he thought we would be home by July.

Damon got back today, and we celebrated his return by cooking and eating two or three pounds of molasses candy. I got one valentine, and I know who backed it. Perhaps Sally [Shepherd] does too. It’s nearly midnight, and I’m off to bed.