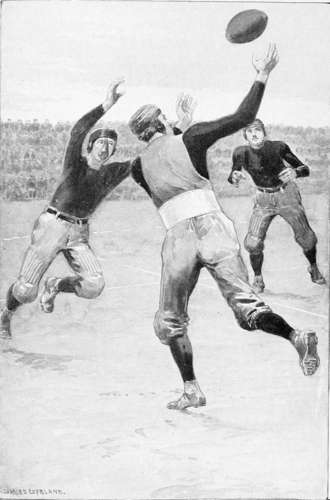

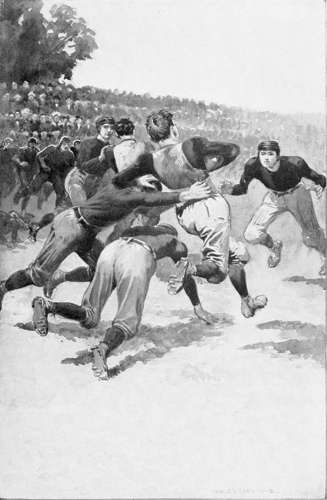

The Westcott man clutched the ball over his rival’s head.

“The School Four” is a story of football and rowing, its scene laid in a private school in an Eastern city. As in the Phillips Exeter books, the aim has been to keep the athletics practical and technically correct, and at the same time to present such conceptions of life and conduct as may encourage the boy reader to face his own school problems with the right spirit. Later volumes will treat successively of the city high school and the country boarding-school.

To Mr. John Richardson, Jr., captain of the undefeated Harvard crew of 1908, the author owes a special debt for expert counsel, for the freedom of the Harvard coaching launch, and, above all else, for personal inspiration.

A. T. DUDLEY.

The first suggestion of the Triangular League came from a certain aspiring and nimble-witted graduate of the Newbury Latin named John Smith, whose surname, occurring on every page of every daily paper, should safely conceal his identity from any over-curious reader of this story. Moreover, it may be asserted with truth that the particular John Smith who called the first meeting of representatives of the three schools is not to be found on any of the eighteen pages of Smiths in the last Boston directory. It is enough for our purpose to know that he looked over the material in the upper half of the Newbury Latin and found it to his liking—good for the present and promising for the future. He considered within himself, with what he imagined to be uncommon shrewdness, that it is better for a school to be at the head of a small league than to swell the troop at the conqueror’s heels in a larger one. His reason for selecting Westcott’s and the Trowbridge School as complements to the Newbury Latin in this laudably patriotic scheme was that while they contained decent fellows and were nominally fair rivals, they were probably beatable without killing exertion. This last item was not included in the argument for the organization which he presented to the first meeting. His speech here took loftier grounds, such as the charms of an alliance between naturally friendly schools, and the splendid athletic ideals for which the new league would stand.

Either John Smith’s idea or John Smith’s argument carried weight, for the league was formed, and the three schools pledged themselves to maintain it and abide by its rules. In recognition of his unselfish services in behalf of the cause, and at the suggestion of Mr. Snyder, an instructor at Trowbridge, who insisted that the direction of affairs should be in the hands of some mature person, Mr. John Smith was elected president. It was voted that a managing committee consisting of two representatives from each school, together with the president, ex officio, should be empowered to draw up rules, arrange schedules, select officials, and act as general board of control.

The first meeting of this permanent committee was held at Westcott’s, in Boston, just before the end of the school year. After the visitors had departed, Sumner and Talbot remained behind to discuss events from the Westcott point of view.

“It’s going to be great!” opined Sumner, with his usual outburst of enthusiasm for what he approved. “Everything was pleasant and straight, and nobody tried to get the advantage of anybody else.”

“I’m not so sure about that,” answered Joe Talbot, commonly called “Pete.” The origin of this nickname is involved in obscurity. Some boys derived it from a character in a play; some asserted that Joe’s family had given him the name in jest when he was a toddler. Steve Wilmot, the wag of the class, maintained that it was descriptive,—he was called Pete because he looked Pete,—and this explanation was on the whole popular, especially as Talbot stoutly protested against it.

“Why not?” demanded Sumner.

“I’ve no confidence in that Smith. He’s too oily and smug. He’s got some scheme he means to work.”

“Shucks!” retorted Jack. “Your brother Bob has prejudiced you against him with his talk about that old football squabble. If I were a junior in college, like Bob, I’d try to forget about school rows.”

“Those are the things you remember longest,” Pete answered wisely. “You can’t change the facts, can you? You can’t make a low trick any better by forgetting it. If it happened, it’s history, as much as Bunker Hill. It shows the kind of man Smith is.”

“Was!” corrected Jack. “That was a long time ago, and he’s probably changed as much as we have since we came into the sixth together. Just think what little fools we were then, how we thought the verb amo was too hard to learn, and cried when Mr. Lawton lectured us, and Mussy used to send us out of French every day for whispering in class.”

“We weren’t anything but kids then. Neither of us was over twelve.” Talbot spoke as if seventeen, which was their present age, represented the climax of maturity.

“I was just trying to make you see that people change. Smith has changed too.”

“Perhaps he has,” growled Talbot, “but I don’t believe it’s for the better. He’s got us into the league just because he thinks Newbury can beat us. You don’t suppose he’s doing it out of love for us, do you?”

“No doubt he thinks we are a good crowd for his school to tie up with,” answered Sumner, with ready complacency. “I really believe those fellows would rather beat us than any other school, but that’s because they are jealous of us. We are only a private school, more than half of us little kids in knickerbockers, but we have the inside track in Harvard, and we’re on the top socially. They don’t like that.”

“It’s the little kids and getting into college so early that spoils our athletics,” remarked Talbot. “Newbury is a public endowed school with lots of big fellows who don’t go to college, and Trowbridge is a boarding-school in the country where the fellows have nothing to do but play games all day. We aren’t anything but a school building in town and a playground in Brookline.”

“And Adams’s,” put in Sumner.

Adams’s was the house of the instructor who lived at the athletic field. It contained a schoolroom for such boys as were condemned to prepare the next day’s lessons before they left the field in the afternoon, and quarters for a limited number of boarding pupils.

“Adams’s!” exclaimed Pete. “What good is that? A half-dozen little kids who play on the fourth or third, and a few older fellows whose parents are abroad or can’t stand them at home. There wasn’t a fellow there last year who did anything for the school.”

“There was Pitkin,” Sumner remarked. “He’d have made the second crew if he hadn’t caught the measles.”

“He might,” responded Talbot, in a tone which implied that he probably wouldn’t. “But what’s Pitkin, anyway?”

“Ben Tracy is going there next year,” went on Sumner, “and that cousin Louis of his who lives in Worcester, and some one from New Jersey. There may be some other new fellows.”

“The usual orphan asylum!” commented Talbot, savagely. “It’s four to one that none of ’em will be good for anything. You always see things about one hundred per cent better than they really are.”

“That’s not half so bad as seeing them one hundred per cent worse than they are, as you do, you old growler!” retorted his friend, with a laugh.

“They can’t be a hundred per cent worse,” maintained Talbot. “That’s a logical impossibility. It would bring ’em below the zero point.”

And then, being boys, in spite of their advanced age and the seriousness of their interest and the fact that both, avowedly at least, were putting every available minute into their preparation for the next week’s battle with the Harvard preliminaries, they wrangled for a good quarter of an hour over the possibility—logical, actual, or theoretical—of things being a hundred per cent worse than they were without reaching the vanishing point. The reader will be spared this argument. If he is a boy, he can manufacture it for himself; if a grown-up, he has only to listen quietly to a knot of boys waiting in idleness for a bell to ring or a train to appear, and he will understand how it is done.

When the discussion had run its length, they recurred naturally to the first theme of conversation. It was Pete who reintroduced the topic of the new league.

“Whether Smith is straight or crooked,” he said, “he certainly expects his school to come out ahead. I’d give something to beat him at his little game.”

“Wouldn’t it be great!” Sumner’s exclamation was like an anticipatory smack of the lips; his eyes were fixed in a fervent but unseeing stare on the blank wall, his face beamed with delight at the mental foretaste of the joys of triumph. “We may do it, too!”

“And we may not!” answered Talbot, rising. “Let’s get after those French sentences.”

Whatever his faults, the president of the new league possessed unquestionably the virtue of activity. While the Westcott boys, scattered up and down the coast from Long Island Sound to Bar Harbor, were amusing themselves in their own idle but wholesome fashion,—camping, cruising, racing boats, playing tennis matches, and exchanging visits,—Mr. John Smith was devoting his surplus energy to the cause. One tangible result of his labors formed the basis of much curious questioning when Westcott’s gathered at the end of September for the year’s work. A prize was to be offered to stimulate interest in the contests of the league. Though many of the Westcott graduates had been laid under contribution and might be supposed to know definitely the purpose for which their money had been expended, it was soon discovered that no one possessed information extending beyond the statements in the newspapers. These began with encomiums on Mr. John Smith for his enthusiastic and efficient services and the success with which he had “rallied about him his hosts of friends”; they ended with congratulations to the new league on having a man of Mr. Smith’s caliber and influence at its head. In between was sandwiched the meagre news that a cup was to be competed for by the schools on terms to be announced later.

But Westcott’s had no notion of waiting until later. The boys stirred up the contributing graduates, and the graduates addressed to Mr. Smith certain pointed inquiries which suggested to the astute leader that it would be wise to announce the conditions immediately, even at the risk of losing some advantage for his own school. He appeared, therefore, at Westcott’s, one day during the second week of the term, bearing a big box of tinted cardboard, and made a speech to the assembled school in which he set forth the conditions of the gift and the high hopes of the givers. Then, with great impressiveness and in the midst of quivering expectancy, he removed the cover of the box, undid a bag of canton flannel and held forth the glittering thing to the general admiration.

“To remain from year to year in the possession of the school which shall last have won it, and to be held permanently when three times won.”

To this announcement the school gave bountiful applause. The older boys, though harassed by grave doubts of their ability to fulfil the conditions, understood the privilege offered them and were grateful; while the knee-trousered, flattering themselves with the assurance that the splendid, two-handled vase, like a reward for good behavior, must ultimately be theirs, smote their hands together long and violently. Whereupon Mr. John Smith, who showed himself to be a sharp-featured, somewhat over-dressed young man, with no semblance of that personal diffidence with which great men are often handicapped, smiled blandly, restored the treasure to its double envelope, shook hands with Mr. Westcott, gave the school another benevolent and congratulatory smirk, and departed—bearing his cup with him.

At the recess period for the first and second, four fellows took places round the small table in the corner of the lunch room; a fifth seized a chair and pushed in among them as if he belonged there. Others bought themselves handfuls of munchable food at the other end of the room and hurried to get a position at the railing which separated the hot-lunchers from those who patronized the counter. The confusion of half a dozen talking at once obscured the opening of the discussion.

“The crew’s in it. That’s good for us,” declared Rolfe, getting the first hearing in the babel. “We’ll trust you to win that for us, Pete.”

Talbot, the captain of the crew, would probably have disputed this loud assumption if he had been given an opportunity to speak; but others were readier of tongue.

“And the track’s out!” cried Seamans. He held a sandwich untasted within three inches of his lips and stared over the railing into Rolfe’s face with an expression of disgust.

“Bad for you, Sim,” called out Jack Sumner. “You’ll have to go in for baseball.—Some soup, please.”

“Newbury lost all her track men last year, that’s why the track’s out.” Talbot had found his tongue.

“That’s not the reason,” proclaimed Sumner. “Mr. Westcott doesn’t believe in track work for schoolboys. He thinks it’s too much of a strain for young fellows like us. Your brother Bob has the same idea. He told me just the other day that it usually spoiled fellows for college running.”

“Smithy would have put it in all the same, if Newbury had any show for it.”

“I don’t quite understand about those conditions,” came from the lips of a boy at the railing, who was poising a buttered bread stick before a broad, big-featured face crowned with shaggy hair.

“You never understand anything, Fluffy,” cut in Wilmot. “A fellow who asks ‘why’ about the laws of falling bodies—”

He hesitated, giving Fluffy a chance to ejaculate, “You don’t know yourself—”

“And don’t care!” retorted Wilmot. “I know they fall, and there’s a rule about it.”

“I don’t mean falling bodies, I mean about the cup!” Fluffy got this out in the face of a storm that threatened to sweep him the whole length of the railing. No one wanted to hear a debate between Fluffy Dobbs and Wilmot on the laws of falling bodies.

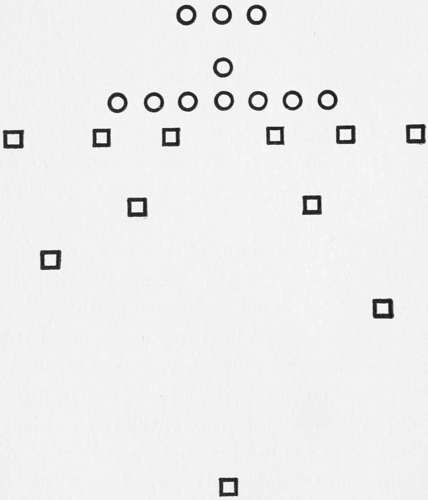

“It’s clear enough,” said Sumner. “There are three sports that count, football, baseball, and crew. Whoever wins two of them gets the cup for a year. The school that gets it three times has it to keep.”

“Do you understand that, Fluffy?” called Wilmot. “Because if you don’t, we’ll get you a map and a guide-book.”

“But supposing each of the three schools wins at one sport?” proposed Fluffy, undisturbed by Wilmot’s jeers, to which he was evidently well accustomed.

“No score!” returned Sumner, quickly.

“Are they going to have special crew races with Newbury and Trowbridge?” asked Tracy.

“No, we all row in the Interscholastic.”

“Then the first thing for us to do is to win at football,” said Trask. “It’s up to you fellows to start the thing right.”

“Easy enough for you to say when you don’t play,” said a tall, wiry, light-haired boy who up to this time had been listening in silence. “Give us the material, and we’ll do it. We can’t make bricks without straw.” Harrison was captain of the eleven.

“Oh, yes, you can, only it’s harder. A really good captain could make a team out of ’most anything. Any fool captain can win with a bunch of stars.” Wilmot’s significant grin disarmed this seemingly insulting remark of all its sting. Everybody respected Eliot Harrison, and Wilmot enjoyed a liberty of his own.

“The lot we had out yesterday was more like a flock of goats than a bunch of stars,” growled Pete.

“A goat ought to be mighty good in the centre of the line,” said Wilmot, reflectively. “He could butt a hole right through the other side, and that’s about all guard and centre have to do. Now if you could only get a few good butting goats into the line—”

“Or teach your own goats to butt,” suggested Tracy.

Wilmot slammed the table. “That’s the best idea yet! Get a goat as assistant coach, a good old side-hill, can-eating, whiskered billy that’s practiced butting from his youth up. He’d show the line how to open holes!”

The audience warmed noisily to Wilmot’s proposition.

“He’d look fine on the side-lines, wouldn’t he?” This sarcastic comment came from sober-faced little Stanley Hale of the sixth, whose class, by the necessities of the school schedule, shared the recess hour of the older boys. The influence of the kindergarten and the fairy tale was still effective in Stanley’s mind. Ideas still translated themselves for his intelligence into pictures, and the picture of the goat stood out vividly before him.

“He could be a mascot, Stan,” said Sumner, turning to smile at Stanley.

“He’d be a great help in the cheering,” went on Wilmot. “The sixth could give him lessons. He’d cheer bass to their soprano.”

By this time there was a general and hilarious interest in the development of Wilmot’s suggestion which rendered impossible all serious discussion of the morning’s announcement. Foolish jesting became epidemic, and wit soon ran into silliness. Two boys showed no disposition to share in the levity. Harrison smiled but rarely, and then feebly and against his will; Talbot’s scowl grew deeper and blacker as Wilmot’s fancy spread from the centre, where it had originated, out into the ranks of the clumsy-wits who seized upon it with rough hands, tossed it to and fro, squeezed it dry of whatever freshness and cleverness it might have contained, and dropped it in ennui for some new catchword ten minutes later.

The bystanders drifted forth for a walk, the sixth ran into the yard and played goat tag, the pursuer being the goat.

“I wish you wouldn’t say that kind of thing, Steve,” began Harrison, when the coast was clear. “It hurts the team to make sport of it or any one on it.”

Wilmot opened his eyes. “I didn’t make sport of it. I just offered a suggestion. You don’t have to take it, if you don’t want to.”

“We’ve got to have the respect and support of the school if we are going to do anything,” went on Harrison, trying to be sensible and keep his temper. “All that talk about goats makes the team ridiculous.”

“It puts everything to the bad right at the beginning of the season,” broke in Talbot, roughly. “If you want to spoil all our chances, just keep it up. You don’t care, of course, as long as you get your fun out of it, but the rest of us have a little school spirit left and a little self-respect!”

“Who introduced the subject, anyway?” demanded Wilmot, triumphantly. “It was you that did it, and it was you that called the team goats. I just built on your suggestion.”

“I won’t argue it,” answered Pete, savagely. “You’d twist my words against me. But just try the goat business with the crew, and see what you’ll get. Harry may put up with it if he wants to. I wouldn’t!”

“Now you’re getting peevish.” Wilmot rose from the table, still keeping his smile of indifference, but by no means content at heart. “I don’t like you when you’re peevish!”

The bell rang; the boys came flocking in and crowded up the stairway. Harrison took Tracy’s arm as they leisurely followed the stream.

“Isn’t that new fellow at Adams’s coming out?”

“Who? Hardie?”

“Yes. He sat opposite us at luncheon to-day with the kids and didn’t peep.”

“He hasn’t said much to any one yet. He’ll be out to-day if he gets his clothes.”

“Do you think he’ll be good for anything?” pursued the captain, anxiously. “We need about six more good men.”

Tracy gave his chin a side tip that might have expressed doubt, or merely reserve of judgment. “I don’t know. He isn’t very heavy, but if you’d seen him chucking trunks around this morning, you’d think him fairly strong.”

“Trunks?”

“Yes, we piled a few in front of his door last night.”

“It’s a good thing to be strong, but a lot depends on spirit,” began Harrison. What further he may have intended to say, we shall never know, for the sight of Mr. Spaulding standing at the head of the stairs put a sudden gag upon his lips.

Roger Hardie knew absolutely no one at Westcott’s when he moved into his room at Adams’s that fall. His father was engaged in the Argentine trade; and the day after Roger was safely established in school the whole family sailed for Buenos Aires to spend the winter there. He took his fate stoically, trying hard to persuade himself that he should soon feel at home, but he could not avoid the sense of isolation and exclusion which comes naturally to one of a very few new boys among a great many very intimate old ones; and he lacked entirely the aptitude for quick friendships. Boys are seldom temperate in their opinions of their own merits. Eliminate the over-confident who run to freshness and the under-confident who lack courage to assert themselves, and there remain but a small percentage who wisely follow the middle course. The over-modest in the end is likely to outstrip the over-bold, whose rash spirit is easily broken by unexpected and humiliating defeats. The average boy, however, takes very little thought for ultimate results. He lives vividly in the present, is captivated by boldness and dash and ready wit, ranks caution with timidity, and suspects steadiness to be mere feebleness in disguise.

Roger was naturally reticent; he was likewise inclined to regard himself as neither attractive nor clever. The first impression which he produced on his mates at Adams’s was that of mediocrity. They took him at his own valuation and disregarded him. The consciousness that he wasn’t considered worth while increased his reticence, and at the same time stirred his obstinacy. He certainly didn’t care for the boys if they didn’t care for him. He would go one way, and let them go another.

Hardie’s pique was enhanced by the apparently different reception accorded to another new Adamsite, Archibald Dunn. As a matter of fact, the principle followed by the boys in the treatment of the two cases was identical: each was accepted at the outset at his face value. While Hardie made no claim to ability, importance, or friends among the great, Dunn’s method was to assume everything, to throw himself frankly on the credulity and friendliness of his new companions. Of course he played football; he had been end on the Westport High School at the beginning of last season, but a shoulder bruise got in the practice had thrown him out of the regular games. He liked baseball better; he and a friend of his, who made the Yale Freshmen, used to be the battery of a corking little nine they got up at their summer place. His favorite sport was automobiling; in his first half-hour in Tracy’s room he told five astonishing stories of marvellous escapes from death or the police. He sailed, too,—used to take charge of his uncle’s forty-footer in cruises. Dunn’s manners were undeniably easy. In twenty-four hours he knew all the small boys at Adams’s by their nicknames, and treated the older ones as if they were intimates of years’ standing.

The Tracys, Ben and Louis, might smile a little incredulously at the broadest of Dunn’s claims, but he amused them, and, provisionally at least, they accepted him. “He’s good sport, anyway,” said Ben, on the second day of school, while describing the Adams household to Sumner. “He can talk more than any person I ever saw, and he likes himself to beat the band, but he seems to be a good fellow to have round.”

“What about Hardie?”

“Oh, he’s a zero, a good little boy that never speaks unless he’s spoken to. He sat up in his room all last evening, grinding at algebra and Latin. Just think of being so fierce about the first day’s lessons!”

“All the new ones do that,” opined Sumner; “they’re scared.”

“Dunn didn’t. He loafed round Louis’s room, telling stories, the first two hours, and spent the rest of the evening looking for a trot to Xenophon. He says it’s a waste of time trying to get along without one.”

“Flunked to-day, didn’t he?”

“Don’t know. He’s not in any of my classes.”

By favor of chance, Dunn did not flunk. He was called up in Latin on grammar questions which he happened to know. Hardie did not escape so easily. His lot fell upon a difficult passage which in his preparation he had not fully understood. Confused by the new surroundings and agitated by a nervous eagerness to do well, he floundered along like a pig in the mud, getting nowhere and accomplishing nothing but the amusement of a cruelly grinning class.

To escape unscathed without having prepared a lesson was, of course, a piece of good fortune which a boy could not expect to experience often. Before the week was out, Dunn had been pretty well gauged by his teachers, and one of the most conscientious had already begun in the simple old-fashioned way—which Dunn reviled as antiquated—to detain him after school to make up neglected work. But what he lost in prestige by classroom deficiencies—boys never charge such failures up against a good comrade—he made ample amends for by marked success on the football field, where he was generally regarded as the most promising addition to the available material which the new season had brought.

Here Dunn’s own lively tongue had prepared for him a favorable reception. While he did not actually declare himself a great player, his ready vocabulary of football terms, his anecdotes of games which he had seen or taken part in, the air of familiarity with styles of play which he showed—all marked him as a veteran. Besides this, he was an end, and the eleven lacked an end. With Harrison, the captain, at one extremity of the line and Dunn at the other, the two important wings of the fighting force would be well equipped. The idea pleased the school fancy and produced a strong prejudice in Dunn’s favor. The boys believed in him because they needed him, and it was more agreeable to believe than to doubt.

The first week’s work on the football field, as every one knows, is largely concerned with the individual elements of the game,—tackling, dropping on the ball, running down under punts, charging. Through these Dunn’s self-confidence and previous experience carried him with flying colors. He threw himself on the ball with admirable spirit; and the way in which he scampered down the field after punts, getting the direction of the kick by a single, quick, accurate glance over his shoulder, and fairly hugging the waiting receiver, was a joy to the beholder. In open work he was not quite so successful. He missed a few hard tackles, but he made some good ones, and the balance remained in his favor. Talbot was so malevolent as to remark that Dunn got the smaller fellows and let the big ones by, but Talbot was from aye a surly growler. The opinion which Dunn himself delivered in the dressing rooms after the first tackling practice found by far the wider acceptance.

“Nobody can tackle in the open in cold blood,” he averred. “A fellow might get his man every time in a game when he feels the excitement and forgets everything but the play, and yet miss every tackle when you put him out to show what he can do. There was a half-back we had in school who afterwards made the Dartmouth eleven; he couldn’t make one out of a dozen of those practice tackles. They’re dangerous, too. If I was a coach, I’d cut ’em out altogether.”

After the middle of the week there were short line-ups in which Dunn played left end. Behind him was all the superior weight and prestige of the first backs, and before him as opposing tackle only “Skinny” Fairbanks, who had barely made the third the year before. Dunn’s work here was of the lively, striking kind that sets partial spectators agog with delight. He shoved Fairbanks back for holes as if Fairbanks were a dummy. When the ball by way of variety was given to the second, he lay outside like a keen-eyed bird of prey and fell upon the fearful seconders with a sudden, calamitous swoop. Hardie stood on the side-lines the day before the first real game, and reproached himself for a feeling of envy. Apparently he and Dunn had started fair in school but a few days before, and now Dunn was leagues beyond him. He felt inclined to send word to the dilatory outfitter that he shouldn’t want any football clothes at all.

Then on the first Saturday came the game with the Suffolk school, which Newbury had just soundly beaten. It was a discouraging contest that took the fire out of the hearts of the players and set the school to jesting about the team. Westcott’s won in the last five minutes through a long run by Harrison, who got the ball on a fumble and carried it half the length of the field; but the record of six to nothing looked very small alongside of Newbury’s twenty-six to eight. The plan of the coach had been to push the attack generally through the left side of the line behind Eaton and Dunn; and when Suffolk had the ball to concentrate the secondary defence behind centre and right, leaving the strong wing to make its own resistance. The scheme did not work, and after much waste of time was abandoned. Holes did not develop where they were expected, and Suffolk pounded the left with great success. The fault was not easy to place. Dunn seemed so devoted to playing a safe outside that he rarely got into the path of the Suffolk runner; and the Suffolk right, it was generally conceded, had been greatly strengthened since the Newbury game. Two bad fumbles that lost Westcott the ball at critical moments were charged against Horr, the half-back.

“You could have saved us the ball both times if you’d only dropped quick enough!” Talbot remarked with undisguised frankness to Dunn, as the team walked moodily into the dressing rooms after the game.

“I couldn’t, really!” protested Dunn. “Once some one piled into me just as I was going to drop, and the other time I tried to pick it up because I had a clear field, and my foot slipped. It was the correct thing to do, wasn’t it, Harry?”

“I didn’t see,” answered the captain. “I thought you might have got Jefferson, though, on that crisscross.”

“The end blocked me off just as I was going to tackle. Eaton really ought to have taken him.”

“It’s your business not to be blocked off!” snapped Talbot.

“Shut up, Pete!” called the captain. “What’s the good of kicking now? None of us played well.”

“My playing was rotten, I know,” rejoined the pessimist, “but I don’t shirk the responsibility for it.”

“It takes time for a team to get shaken together,” said Dunn. “We’ll all do better when we’ve had more practice.”

Dunn’s remark showed a forgiving and conciliatory spirit that by all the rules of story-book morality should have extracted from a contrite Talbot an apology; but the surly half-back went his way unappeased.

On the following Tuesday—the day of the imposing appearance before the school of President John Smith—Hardie, having at last secured his playing clothes, presented himself on the field. His arrival aroused no very flattering comment, partly because nothing in particular was expected from him, partly because of the company in which he came. Saturday’s disappointment had caused a flurry of energy on the part of the football leaders, and the school had been sifted anew for material. As a result Fat Bumpus was strained out, and little McDowell, who, though lithe and sinewy as an alley tomcat, and eager as a hound tugging at the leash, was manifestly below the standard of weight. He came via the third team, on which he had distinguished himself in the game with Wood’s third, played on the Saturday on which the first had failed so conspicuously at Suffolk. These three, Bumpus the fat, McDowell the small, and Hardie the unpretending, formed the last group of recruits available to reënforce the battle line of Westcott’s.

The side-line comments would have been sufficient to put all three to speedy flight, if the contemptuous words had reached their ears. Stover, the ball player, stood with Hargraves who didn’t like football and Reeves whose forte was dancing and “fussing,” and made very merry over the faults of their schoolmates, dwelling with unwearied if not brilliant wit on the appearance of the newcomers, and enjoying the audience of gaping small boys who surrounded them.

“They ought to tie a string to it and give Fatty the end,” said Stover, as Bumpus groped sprawling after the ball which Harrison had rolled toward him. “It’s cruelty to animals to make him root around like that.”

“The best way would be to put him sideways in the line on his hands and knees. No one could get past him then,” remarked Reeves.

“They’d have to call time to get him up again.”

“Did you see that?” broke in Hargraves. “Hardie got the ball at the first try!”

“It must have been an accident; he hasn’t sand enough in him to do it purposely.” This was Stover’s opinion.

A furious but futile charge on the part of Marshall, a clumsy but energetic hanger-on of the second, drew the fire of the trio. “That’s the spirit!” chuckled Hargraves. “Dig up the dirt with your face, my boy! Football is the game!”

“There goes Mac!” cried a shrill voice close at hand.

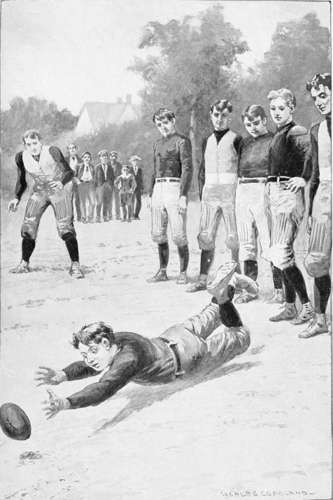

“McDowell the infant wonder,” commented Stover, as the boy dropped sharply and cleanly on the ball, falling along knee, thigh, and hip, in one continuous and perfectly easy motion.

“What’s the sense in wasting time on a kid like him?” muttered Reeves. “Firman of Newbury would carry half a dozen of him on his back.”

The coach evidently had his own views as to the usefulness of McDowell, for he made the boy repeat his performance several times to show the less skilful how the trick should be done. Meantime Talbot, who was catching punts, drew over near the criticising group, and the comments became less audible. As regards side-line ridicule, Talbot held forcible opinions which he had no hesitation in expressing nor reluctance to defend. The trio moved farther down the line, and their wit flowed anew.

“They ought to tie a string to it and give Fatty the end.”

All three of the newcomers got into the line-up of the second that afternoon. Bumpus thrashed about with more uproar than success at guard, while McDowell and Hardie were placed at right end and right tackle respectively. Harrison gave them a general exhortation to “play sharp now,” and Talbot urged Hardie in specific terms to “get right into Dunn.”

“You can manage him all right, if you stand right up to him,” he said. “Forget everything but the play!”

Hardie nodded gratefully. He felt no fear, nor was he by any means new to football, but he was conscious that the school did not expect much of him, and the personal interest of an important fellow like Talbot was, therefore, especially gratifying. In the big athletic school from which he had come to Boston, he had learned to think modestly of his prowess. While he had made his class eleven there, the school team lay beyond all reasonable hope. It was not easy for him to think of himself as ‘varsity material, even at Westcott’s!

Talbot kicked off, the ball sailing over Roger’s head down into McDowell’s territory. Lingering long enough to see the boy gather in the ball and tuck it safely under his arm, Hardie ran forward at three-fourths speed to take the first onset of the school linesmen and permit Mac to slip by. The first comer was Dunn, who caromed off Roger’s shoulder without so much as touching the runner. Eaton, the left tackle of the first, McDowell dodged by an abrupt stop and a dart outside; and beyond Eaton again, Hardie was at his side to take Channing, the right guard. The two disentangled themselves and followed after as McDowell zigzagged on, emerging from between Lowe’s hands and leaving Talbot on the ground behind him. Sumner, the quarter-back, at last drove him outside at the forty-yard line.

The coach carried the ball in and put it down for the scrimmage, first giving the little end a deserved compliment, and then scoring the first severely for careless tackling. The glory of the second faded quickly. The quarter fumbled and lost a yard. Bumpus let Eaton through on the waiting half; the third down was followed by a feeble punt which Sumner ran back twenty yards. Then came a quick reversal. The first had the men and the signals. The ball was pushed rapidly through the centre, through the right side, again through the centre and again through right. At a new signal Hardie caught a change of expression in Dunn’s face, and knew that his own turn had come.

“Look out, Mac!” he shouted, and leaped for his opening with the first movement of the ball. Dunn held him but an instant; with a side buffet of the open hand the new tackle slipped by, ruined the interference, and drove the convoy straight into Mac’s sure grip.

“This feels like it again,” Roger said to himself as he took his place once more. “They’re not up to a Hillbury class team after all.”

“Whose fault was that?” demanded the coach.

“Mine!” said Talbot, shortly.

Hardie looked in wonder over at the friendly half-back. It wasn’t Talbot’s fault, or at least not primarily. Dunn had failed to block his man, Talbot only to make his protection wholly effective—a difficult task at best. The essential weakness lay with Dunn.

“Tackle and end must take care of the opposing tackle,” said the coach. “Get down in front of him, Dunn, spread your elbows, dive into him with your shoulder, but hold him—you hear?”

“He started before the ball was snapped,” pleaded Dunn.

“Shut up! Play the game!” commanded Talbot. “I said it was my fault.”

They bucked the centre once more, by way of variety, and then made another trial of the left side. Horr went ahead to push out the end, and Talbot carried the ball. This time Dunn made frantic efforts to hold his man by use of body and arms without much regard for the rules of the game; but Hardie, keeping him at arm’s length, made a dash at the runner that staggered him, and the line half-back laid him low. At the third attempt Dunn and Eaton together contrived to box the second tackle, and the play went through, over the line half-back.

Mr. Adams, who feared overdoing at the beginning of the season, cut into the coach’s programme after the first had made two touch-downs, and put an end to the practice. Bumpus limped in like an exhausted dray-horse, sweating at every pore. Stover and Hargraves hailed him as he crossed the road to the dressing rooms.

“How’d you like it, Bump?” asked Stover. “You look warm.”

“You played a bully game,” said Hargraves.

“Did I?” Bumpus gave them a glance of suspicion. “It didn’t seem so.”

“It was great playing,” continued Stover. “Going to keep it up?”

“Of course he is!” interrupted Harrison, as he came up from behind. “Bump won’t go back on the school as long as it needs him.”

“That’s right!” said Bumpus, beaming with his whole red, swollen face. “I’m not stuck on the game, but if you really think I’m any help, I’ll come out till the end of things!”

“That’s the talk,” answered Harrison. “I wish you fellows showed as good a spirit.”

“We’ve been trying to encourage him,” claimed Hargraves. “What more do you want?” They went off, snickering, to Stover’s automobile.

Inside the dressing rooms, boys shouted and jested and laughed over their bathing and dressing. Talbot leaned a smooched arm and a grimy paw on the top of a locker, and smiled across at Hardie.

“You’ve played football before.”

“Only on a class team at Hillbury.”

“That’s more than most of us have done. You ought to make our team easily.”

“I’d like to,” said Hardie, wistfully.

“Ever play end?”

“That’s where I’ve always played.”

“See here!” Talbot raised his eyes level with his companion’s and gave him a square, direct look. “We need just the kind of fellow you are, but Harry doesn’t know it yet. You keep your mouth shut, play for all that’s in you, try to do what the coach tells you, and you’ll make the team before the first league game. Understand?”

“Yes.”

“All right.” Talbot turned toward the door. “Where’s that ’Lijah with the towels? He hasn’t given me a clean one for two days.”

A sober-faced negro with close-cut side whiskers appeared round the corner.

“Aren’t you going to give me a clean towel, Lije?”

“Not ontil you pay me,” returned Elijah. “I ain’t trustin’ nobody this year.”

“You old Shylock!” grumbled Talbot. “I’ve only got five cents, and I want that for car-fare.”

“I’ll lend you a quarter,” proposed Hardie, eagerly.

“Thanks. He’s more generous than you are, ’Lijah. He’ll lend me a quarter, and you won’t trust me for a towel.”

“He’s new here,” answered Elijah, solemnly, as he handed over the clean towel and pocketed the quarter. “If he’d lost as much by you fellows as I have, he wouldn’t lend you a cent.”

“That pays for a week, now, Lije,” urged Talbot. “Don’t forget!”

“I never forgets. It’s you that forgets;” and the janitor went forth to seek other business opportunities.

“A good fellow Lije is, but he’s too avaricious,” commented Talbot, hurrying for the shower.

Half an hour later, Roger Hardie was giving the last tug to his necktie before a square of looking-glass that still adhered to the end of the locker tier near the window, and Talbot, swinging a couple of books by a strap, lounged near. Eaton was getting into his clothes a few feet distant, bravely chanting away on a ragtime song in the face of derisive comments from Wilmot, the manager, who sat on the bench nursing a couple of footballs. Farther down, Dunn’s tongue was running wild before an audience of worthies of uncertain intent, whose grins might denote either innocent amusement or guile. Harrison was minding his own business in his usual quiet fashion.

“That’s the second time my socks have disappeared!” sputtered Dunn. “This is the worst gang of thieves I ever got into. You couldn’t keep a thing here if you had a steel vault and a watchman.”

“You’ve probably got ’em on,” suggested Wilmot.

As Dunn had very little on, and was notably bare as to feet, this suggestion could not have been serious. He glanced down, none the less, and earned thereby a unanimous jeer.

“I don’t see how you could lose them,” observed Sumner. “They’re the most conspicuous things in school. I recognized you by ’em this morning a block away, before I could see your face.”

“Oh, you did!” was the best Dunn could do in rejoinder.

“I never saw anything like them but once,” Wilmot observed thoughtfully. “A clown had ’em on in the circus. They seemed all right there.”

“They cost two dollars, anyway!” ejaculated Dunn, who was turning over football trousers on the floor and kicking shoes into corners.

“Tyrian purple always did come high,” Wilmot said softly. “Aren’t you ready yet, Jim? This excitement is getting on my nerves. I feel as if there was an officer here with a search warrant. Perhaps Lije took ’em, Dunn. He might use ’em for a necktie.”

“If I could find the fellow who swiped ’em, I’d use him for a necktie!” exploded Dunn. “It’s a low-down trick to hide a man’s clothes. No one but a kid would do it. You fellows belong with the rubes who tie knots in shirts at the village swimming-hole!”

This violent arraignment awoke new chuckles of merriment. Dunn was becoming interesting.

“That’s a good suggestion,” said Wilmot. “Harrison might try that next time.”

“Shut up, Baldie, and get dressed!” admonished Ben Tracy, in a low tone. “You’re playing right into their hands. You don’t need the socks to get to your room.”

At this advice, the wisdom of which he recognized, Dunn smothered his indignation and went on with his dressing in silence. The crowd, perceiving that the fun was over, began to scatter. Eaton put on his coat and turned to Wilmot. “All ready, Steve! Come on, Pete!”

“I’m going up to Hardie’s room for a while,” said Talbot, who had been talking in the corner with Roger.

Wilmot slid over toward the door. “There are your socks on the bench, Dunn!” called Eaton.

“I must have been sitting on them all the time,” Wilmot explained contritely from the doorway. “I felt something hot under me. Hope I didn’t hurt them.”

“They seem all right, just as bright and sporty as ever. Want ’em, Dunn?” Eaton held out the lost socks toward their owner; but Dunn, having definitely adopted a policy of indifference, turned his back on his tormentors and continued the conversation with Tracy as if he had lost all interest in the object of dispute—in the end taking possession of his property without let or hindrance.

Talbot, having explained the point in physics which was the nominal object of his call on Hardie, sat by the window and talked about school affairs.

“The trouble with our athletics is that we are in a big city,” he said, “with lots of interesting things to take up our time outside of school. Then we’re mostly too young to be very serious about anything. In the big schools like Hillbury the fellows are older; and in the boarding-schools they haven’t any outside attractions nor any liberty, and there’s really nothing else to do but play something.”

“You always have men on the college teams,” remarked Roger.

“Oh, they do well in college, but they’re more mature then. Here there’s always a whole lot of fooling going on such as you saw this afternoon. You can’t change a fellow like Wilmot. He’s an awfully nice chap, but he’s never serious, and he spoils the atmosphere for the hard, determined kind of work that makes good teams.”

“Harrison seems serious enough,” said Hardie. “I should think he’d make a mighty good captain.”

“That’s right! He’s about the best fellow we’ve got. That’s the reason I had hopes of the football, but it looks now as if it was going in the same old way. If we could only win in football, we could go to work with more courage on the crew.”

“The crew is always good, isn’t it?”

“We seem to do better with rowing than anything else. There’s no fooling there, I can tell you. From the time you lift out the boat until you put her away on the supports there isn’t a minute wasted.”

“I should think it would be monotonous, just pulling an oar with the same motion all the time. Of course the race is exciting, but the training must be terribly tiresome.”

“That shows you’ve never tried it,” answered Talbot, laughing. “The race is hard and disagreeable because you try to pull yourself completely out, but the practice is fun all the time. We have good coaching, and every day we try to get into the swing a little better, and overcome some one of our faults. Then the movement of the boat is fine. You can’t imagine what a pleasure it is to feel it going under you right—to know that there is no check between strokes, that everybody is getting away quick and sharp, and pulling just as he ought to.”

“I don’t understand,” returned Roger, “but I’d like to try it.”

“You must come out. You have the right build for rowing.”

Talbot glanced out at the window and waved his hand at Tracy, who was crossing the yard to the dormitory. “We’re a long way from that yet,” he went on. “We might possibly beat Newbury and Trowbridge in rowing, but we can’t get the cup without football.”

“There’s baseball,” suggested Roger.

“No hope there. What can you expect with a fellow like Stover running things? We never were a baseball school, anyway. It’s the fellows who play on the corner lots that make the baseball players. Our fellows do too much sailing and rowing and playing golf in the summer to have time for baseball practice.”

He rose to leave. “Just go in hard on the football, and don’t give up if you don’t get all the credit you deserve. They have a way here of starting with a team made up on paper and keeping to it through the season; but it’s a bad custom which I want to see broken. I give Dunn about three weeks to talk himself off the field. Then if you don’t get in, it’ll be your own fault.”

The door closed behind the first really sympathetic visitor Roger Hardie had yet received. He had been in school long enough to know that the captain of the crew on the whole outranked any other captain, and that Talbot, in spite of his marked tendency to see the dark spots in the future, and to be over-frank in his criticism, was yet one of the steady-flowing springs of school energy, respected perforce even by those who did not like him. To have Talbot as a friend was to be sure of a stout defender, if not of a persuasive advocate.

Thrilled with gratitude for the attention shown him, his ambition kindling into flame from the spark of hope which Talbot had struck, Roger resolved to show himself worthy of his patron’s favor; he would make something of himself in the school life for the honor of the boy who had befriended him, if such a result lay within the reach of hard work, or patience, or devotion. That making something of himself in the school life meant to him mainly achieving a success in the school athletics, was but natural. We who are older may rightly insist that there are other ways of serving one’s school than by scoring touch-downs or pulling on a winning crew; but a boy cannot be expected to see life through the spectacles of the aged. He must grow through his own ideals, not those of his parents. If his opinion as to the importance of athletics is a fallacy, it is at least a far more wholesome one to hold than many cherished by adults.

Roger held his head higher than usual as he went downstairs to dinner, and in his plain but not unintelligent face the look of stolidity had given place to a brighter expression.

“I was glad to see you playing to-day,” said Mr. Adams, pleasantly. “It seemed to me that you were starting in very well.”

“Thank you,” returned Roger, quietly.

“Didn’t you say you hadn’t played before?” asked Ben Tracy.

Hardie shook his head. “I didn’t mean to. I’ve never played on a school team. At Hillbury I played end on my class team in some of the games.”

“That’s not bad,” said Louis, with respect. “They have great class teams at those schools.”

“It isn’t like playing on a school team, though,” offered Dunn. “You don’t have any great responsibility.”

“The class feeling is pretty strong sometimes,” replied Roger, “and the games are always hard.”

“I liked the way you got into the play,” said Mr. Adams. “The house ought to give a good account of itself on the playground this year.”

“I couldn’t do anything at all to-day,” observed Dunn. “I have to feel just right to do myself credit. I didn’t sleep very well last night.”

Redfield exchanged a glance of intelligence with Louis Tracy. They knew what had disturbed Dunn’s slumbers,—the memory of a late lunch in Number Six.

“You must be careful about food and bed hours if you want to be in good condition,” observed Mr. Adams, apparently oblivious to the exchange of messages. “It takes some self-control to keep in training with a pocket full of money.”

“I’d like to have a chance to try it once,” sighed Redfield, to whose mind the suggestion of a pocket full of money conveyed the idea of a continuously replenished supply. Much of his allowance never reached his pocket at all; it was spent in paying back bills.

Hardie’s appearance on the football field unquestionably raised him from the condition of nonentity into which he had fallen, but it did not materially help him to get into the charmed circle of the initiate who occupied the social centre of the school on a kind of ancestral tenure. He felt himself an outsider, even more after Talbot had shown him favor than before, for friendliness on the part of one served only to emphasize the lack of interest of others. It was not that he was objectionable or disliked; his schoolmates were merely content without him, seeing nothing in the newcomer that commended him especially to their notice. His mother’s name was not on their mothers’ calling lists; he possessed no cousins or near friends who knew their cousins or friends; he lacked the ready tongue which creates on short acquaintance a reputation for wit. He had no special resources to enhance his attractiveness—no fast auto waiting for him at the corner, no shooting lodge in the marsh to which his friends might be invited. He was just plain, undistinguished, unvalued Hardie, a new boy who lived at Adams’s and played tackle on the second.

Dunn still floated with the tide. Judgment regarding him was still in a measure suspended, but aside from Talbot, who was silent about him, and Wilmot, who jollied him, the trend of opinion was in his favor. As a prospective member of the first eleven, he possessed prestige, and as a good-natured loafer whose excuses and garrulity were entertaining, he appealed to the indiscriminate humor of the mob. But with one of the smaller, though not altogether impotent, members of the school, he early fell into conflict.

“Mike” McKay was a red-headed, freckle-faced, wing-eared urchin, filled to the brim with activity and energy, who dominated the fifth class. He lived at Adams’s, and held the proud position of captain and half-back on the fourth eleven. Mike was no lover of lessons, but they constituted a part of his day, and with his natural habit of putting into everything that he undertook all the vim he possessed, he labored on them devotedly until they were accomplished. Behind Mike in the schoolroom sat Archibald Dunn. Dunn lacked the zeal of his little neighbor; he could endure about ten minutes of mental effort at a stretch, after which his brain demanded rest. In these intervals of rest he often refreshed himself by slouching down in his seat and bracing his toes against the chair in front of him, achieving, in the meantime, some distraction by a languid survey of the room. Mike, intent on the French sentences which he was laboriously manufacturing, word upon word, like a conscientious bricklayer, would feel the tip of Dunn’s toe thrust into his exposed haunch, and violently reacting, would make a scrawl or drop a blot to disfigure the work of his hands.

Expostulations served only to convert what had at first been accidental into a deliberate and repeated annoyance. Dunn had discovered a diversion for the idle moments of brain recuperation.

Stung one day by this persecution, Mike turned fiercely and attacked the exposed ankle of the offender with his pen. A teacher, sharp-eyed but not far-sighted, caught the boy in the act and gave him long minutes after school. This result appeared to Dunn exquisitely amusing; he could hardly wait for the lunch hour to bring him the opportunity of telling the story.

“You’d better let Mike alone,” said Ben Tracy. “He’s a miniature fire-eater when he’s mad.”

Dunn sniffed contemptuously. “What do I care for him? I could lick a couple of such little fresh kids with one hand.”

“He seems to me a rather nice little chap,” Redfield remarked.

“That shows he isn’t,” answered Dunn. “You never get things right.”

Silenced by this blunt personality, which Dunn would classify under the head of wit, Redfield abandoned the conversation and devoted himself to his luncheon. Bumpus came rolling in just in season to hear Redfield’s remark and Dunn’s rejoinder.

“Who’s the nice little chap?” he asked, as he removed one chair and took possession of the territory belonging to two.

“You!” sang out Wilmot, giving Bumpus a slap as he tripped past to another table.

Bumpus beamed with joy, not at the jest, which indeed was worn as smooth as a pebble in a pot-hole, but at Wilmot’s cordial manner, and at the intimacy suggested by the playful tap on the shoulder. Word had gone out from Captain Harrison that Bumpus was to be encouraged.

“Captain Mike McKay,” explained Tracy. “Dunn’s got him stung!”

“You don’t suppose I’m going to have him jabbing pens into my legs, do you?” protested Dunn, disappointed to be thrown upon his defence when he had expected to be amusing.

Of course no one did suppose any such thing, and the conversation zigzagged gayly off to distant fields. Meantime Mike was temporarily allaying his indignation by a brisk and noisy game of indoor baseball in the playroom. Later on he paid his penance with stoicism, working out half his home arithmetic problems during the period of his detention.

On the next day Mike endured two or three toe thrusts with Christian forbearance. By squeezing himself against his desk he could put a neutral zone between his own person and the convenient range of the prods. By this pretence of retreat he tempted the enemy into an incautious advance. To reach his prey in spite of bars, Dunn slid farther down in his own seat, and bent his foot around the chair back, so as to come within striking distance.

Instantly the boy recognized his opportunity. Seizing the foot with both his nimble hands, he twisted off the shoe and passed it across the aisle to a faithful clansman, who handed on the emblem of victory to another, who as speedily got rid of it in his turn. By the time Dunn recovered himself sufficiently to demand its restoration, the whereabouts of the shoe was actually unknown to the first plunderer. It ultimately found its way, wrapped in a page of a returned exercise, to the waste-basket.

The call to recitation broke in upon Dunn’s efforts, greatly handicapped by the presence of a teacher at the other end of the room, to make clear to Pirate Mike the fate in store for him if the shoe were not immediately returned to its owner. The fifth Latin rose with cheerful readiness and crowded to the door. Dunn fell in behind them, though he had no recitation at that time, hoping in the confusion to get his hand on his enemy. Once out of sight of the room teacher, he pressed on hotly, scattering the fifth like a flock of sheep, and with an imprecation on his lips reached for his quarry,—only to be met by the stern face of Mr. Westcott as he emerged from his room at the foot of the stairs.

Dunn was questioned in the office in a most unpleasant secret session, while the fifth in their Latin room were forced to trace the route between Mike’s desk and the waste-basket. When the different stations on this underground railroad were located, and the shoe was produced by the boy who had consigned it to its last resting-place, the guilty received the regular penalty for small misdemeanors, and the Latin lesson took its usual course.

Dunn’s session was longer. He emerged with a very red face, and sat with a book open before him, staring angrily and unprofitably at its pages for many minutes. He was very late for football practice for several days after, on an excuse that was evidently valid. This, however, might have been but a passing experience, forgotten in a fortnight, had not a heartless sally from Wilmot perpetuated the memory of the unpleasantness and given Mike a telling advantage over his bigger foe.

As was to be expected, Dunn had no history lesson that morning. He never did compass more than half a lesson, but to-day he was as ignorant on the subject of Greek Oracles and Greek Colonization as the Esquimau in his hut of ice on the edge of No Man’s Land.

More than this, he showed himself distrait, and totally impervious to the cleverly pointed shafts with which Mr. Downs sought to pierce a way to thick-crusted brains. The patient instructor, ignorant, of course, of the disturbance of the morning, and faithful to duty even under discouraging circumstances, detained Dunn after the class was dismissed for recess to admonish him of the evil consequences of idleness and inattention. As a result, Dunn arrived at the lunch room late, facing with an uneasy and unnatural grin a full collection of unsympathetic teases.

“Jason!” cried Wilmot, loudly. “Beware of the man with one shoe!”

About one first class boy in five understood the reference, and this one was immediately besought by his four ignorant companions to explain the joke, for joke they were sure it must be. Johnny Cable, the book-learned but otherwise incapable, was in excessive demand for the next few minutes to clear up the mystery. These few minutes Dunn employed in strengthening his defence of indifference and preparing himself for the coming questions as to what Mr. Westcott had said to him, and what he was going to do to Mike. He answered the questions in very ambiguous terms, but his threats against the chief agent in his misfortunes were no less awful because of their vagueness, while the grins of a dozen fifth class boys at the long table opposite kept his wrath at the boiling-point. Ben Tracy at last succeeded in diverting the general interest to Redfield, who had made a new record that morning in the smashing of glass tubes in the laboratory.

But the fifth were not to be diverted. They had no need of Cable’s learning to explain Wilmot’s comparison. Having fought their way, line by line, through sundry tales of Greek heroes presented in simple Latin, they knew the stories from end to end. “Jason Dunn!” they whispered ecstatically to one another along the table. The names fitted as if made to go together. No combination could be better!

“We’ll call him Jason after this,” proposed Dickie Sumner, Jack’s younger brother. “Nobody can help saying it after he’s heard it once.”

This suggestion was put into practice as soon as the youngsters left the table. They gathered at the door and sang out in chorus three times before they scattered: “Jason Dunn! Jason Dunn! What has Jason done?”

“Fresh little mutts!” exclaimed Tracy, in disgust. “That’s the result of being tied up with a kindergarten. Let’s go out and wring their necks!”

“Don’t notice ’em,” said Wilmot. “They’ll forget it to-morrow if you let ’em alone.”

But the title stuck. Before a week was out, the name, Archie Dunn, or Baldie Dunn, ceased to be heard on a boy’s lips. It had become Jason Dunn.

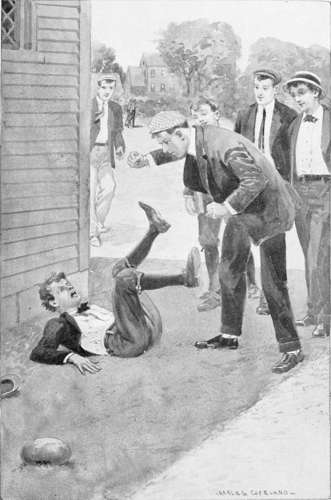

The first skirmish in the feud that was bound to arise came on the following day at Adams’s, when a group of fifth and sixth lads, thinking themselves safe in the shadow of the dormitory, sang out the new nickname derisively across the field to Dunn. Dunn, who was still in a state of irritation, and by no means ready, as yet, to accept the inevitable nickname, made a dash for the group, which broke into screaming flight round the corner of the locker house. The first lad whom Jason met as he rounded the corner in full pursuit, was Mike, engaged in tossing a football against the side of the building. Without stopping to raise the question whether Mike had been one of the offenders, Dunn proceeded to the agreeable task of teaching the urchin a lesson. The boy resisted with hands, feet, voice, and teeth. The older fellows, hurrying forth at the shrill cries for help, found Mike lying on his back, like the arms of a hay tedder, squirming to keep his antagonist at bay and squawking like a hen in distress.

His feet going like the arms of a hay tedder.

The majority of the newcomers lined up in good positions, to enjoy the amusement which chance had thrown in their way; but Talbot, who had seen the beginning of the incident from a distance, pushed through the line, jerked the boy to his feet, and commanded him to stop his noise.

“He knocked me down when I wasn’t doing a thing!” screamed Mike, weeping more from rage than because of any hurt which he had received. “Let me get a stone, and I’ll kill him!”

“You won’t do anything of the sort,” said Talbot, firmly. He turned to Dunn. “What’s the row, anyway? What’s the use of pitching into a little fellow like him?”

“I’m not going to have him calling me names,” said Dunn, defiantly. “He thinks because he’s small he can be as fresh as he wants to, without getting hurt.”

“I didn’t call him names,” sobbed Mike. “I wasn’t doing a thing.”

“It wasn’t him,” offered Dickie Sumner, who had been tempted back by all-compelling curiosity. “He wasn’t with us at all.”

Talbot turned and seized the rash youngster by the arm. “So it was you, was it? Now, look here! We aren’t going to have any calling names or any other freshness from you young kids round this place. If we catch you at it, we’ll duck you under the cold-water faucet and forbid you the grounds. Understand?”

Dickie understood. “All right,” he answered faintly, and tried to pull away; but Talbot still held him in a tight grip.

“What do you say, Jack?” he added, turning to Dick’s older brother, who shared with him the responsibility for order on the grounds.

“That’s right!” replied Jack Sumner, sacrificing his fraternal obligation in the cause of justice with surprising equanimity. “He’s a good one to begin on.”

Talbot released the youngster, who speedily escaped from the circle of danger to join his confederates over by the tennis courts, where they discussed for a time in subdued voices the probability that Pete meant business. They were soon diverted by tag.

“All the same, Dunn is a fool to notice them,” murmured Talbot in Hardie’s ear as they returned to the locker room to finish their dressing.

“I don’t believe he can shake off the nickname, now,” said Roger.

“No, it’s branded in. He isn’t showing much of the good-nature they talk about, is he?”

In fact, Dunn’s good-nature didn’t extend far below the skin. It was a mannerism assumed to win him the popularity which he craved. He was vain, lazy, and characterless. In the football field his fine physique, together with the professional air with which he bore himself, for some time blinded the eyes of critics to his shortcomings. Yards, the coach, felt sure that something could be made of a man of Dunn’s vigor and apparent knowledge of the game. Yet a strong player opposite him, or the grinding strain of an uphill contest, invariably produced slackened effort and excuses.

“It’s come to be the weakest place in the team,” said the coach, a few days before the Groton game. “If we could brace up the left end and quarter-back, we should have some hope of giving Newbury a tussle.”

“Is Sumner so bad as all that?” asked Harrison, disturbed. “I thought he was running the play very well.”

“He runs the play well enough, but look at the errors! He fumbles, muffs punts, misses tackles. A quarter-back has no right to do anything of the kind.”

“No one plays perfectly,” Harrison hastened to offer in defence of his friend. “Besides, he’s the only man we’ve got for the place.”

“Hardie is coming on well,” observed the coach. “He’s going to push Ben Tracy pretty hard for tackle. We might give him a trial at quarter.”

“I don’t think he’d do at all,” answered Harrison, quickly. “He’d be entirely new to the position, and we shall need him as a substitute tackle before the season is over.”

The coach considered for a time in silence. Yards was a loyal Westcott graduate, whose devotion to his school was strong enough to make him sacrifice his afternoons at the Law School for the sake of helping the Westcott team. He knew the game well and could teach it, but he lacked confidence in his own judgment of the comparative merits of individuals, and he was morbidly anxious to avoid the foolish jealousies which he remembered as a source of weakness to the school in his own day. It was clear that Harrison’s heart was set on keeping Sumner in his place. To insist on a change which would be at best an experiment with an unknown quantity, and which might give rise to factions, seemed at present unwise.

“We’ll give McDowell a chance on the end, anyway,” he said, “and let Dunn rest.”

To this proposition Harrison assented eagerly, and went hot foot to warn Sumner that he must bestir himself if he wanted to keep his post.

“Am I as bad as that?” asked Sumner, in consternation.

“You’re not bad, but you’ve got to be better.”

In place of replying, Sumner swung his sweater to the other shoulder and gazed, a sober, startled expression in his eyes, across the field. Harrison stole a side glance at his friend’s face and took his arm affectionately. “It’s all right, Jack; don’t worry,” he said. “Just play your best game, and I’ll stand back of you.”

“You’re wrong there, Harry,” Jack said quietly. “You’ve no right to stand back of me. My playing has been rotten lately, and I know it. I’m fumbling punts and missing tackles all the time. If you’ve got some one else who can do better, I won’t have you keep me on just out of friendship.”

“You’re talking rot,” returned Harrison, impatiently. “Stubby Weldon is no use, as you know perfectly well. There’s no one else.”

Sumner breathed easier. “I’ll do better if I can,” he said.

So McDowell went to Groton to play left end, and Dunn was told to stay at home and rest. He neither stayed at home nor rested. Stover took him to the game with Hargraves and Reeves in his flyer. He amused himself watching the play incognito, and got back before the return train delivered the weary, disheartened team at the station in Boston.

Westcott’s fared ill at Groton. Sumner’s game was worse than ever. McDowell strove like a hero against men a whole head taller and many pounds heavier, tackling fiercely and surely whenever he got within striking distance of the ball; but his opponents brushed his interference aside, charged through him in the line and blocked him off from the play almost at will. The score was eighteen to nothing at the end of the first half.

“I can’t do it!” groaned McDowell, as the players tried to hearten each other during the intermission. “I’m not big enough. Put Hardie in.”

As Dunn was out, there was nothing else to do. Hardie went in at left end, and fat Bumpus, who had lost in weight but gained in muscle and wind by his patriotic exertions on the field, relieved Kimball at guard. The team sallied forth once more, crestfallen but determined.

Groton got the ball on Talbot’s kick-off, and tried the old trick of circling Westcott’s left end, but Hardie could not be disposed of, and the play came to grief. They bucked the centre, only to find big Bumpus sprawling effectually in the path. A forward pass found its way into Horr’s hands. Then Sumner gave the ball to Talbot, who discovered a hole where McDowell had failed to make one. Encouraged, he repeated the play and made the first down. A lucky forward pass which, to his great delight, fell into Hardie’s hands, saved Westcott’s at the next third down, and carried the ball to the centre of the field. Twenty yards farther they pressed, and then Talbot was forced to kick. Groton started on a return journey, which proved to be slow and frequently interrupted. A fumble by Westcott’s before the goal posts gave the home eleven the only score which they made during the second half.

Roger Hardie felt very happy as he took his seat in the barge with his mates to drive to the station, for he knew, without regard to the compliments paid him by his polite opponents, that his chance had come and he had not missed it.

The leaders, however, were in no exultant mood. Twenty-three to nothing is a big score for a coach and captain to swallow, especially when it is clear that two-thirds of it is due to avoidable errors. On the train Mr. Adams, who had accompanied the team, sat with Yards, Harrison, and Talbot in a double seat, and tried to point out signs of hope for the future in the day’s disaster.

“I should like to suggest two changes,” he said at length, “which may help the team. One I think you will accept. The other I have my doubts about.”

The trio looked at him expectantly. “Hardie should play regularly at left end,” went on the teacher. “His work to-day was almost equal to Harrison’s.”

“Better, sir!” said Harrison, quickly. “We accept that suggestion on the spot, don’t we, Yards?”

Yards nodded. “We ought to have had him there before. What’s the other suggestion,—Bumpus?”

“No. Bumpus can take care of himself. I want to propose that you try McDowell at quarter. He’s out of place in the line, but he’s a good tackler, catches punts well, and has a good head.”

Talbot looked at Yards, and Yards looked at Harrison, who pressed his lips together and looked at no one. There was an interval of silence.

“I don’t see why he should be any better than Sumner!” said the captain, defiantly.

“I don’t see how he could be any worse!” ejaculated Talbot.

“I don’t urge it,” said Mr. Adams, kindly. “I merely suggest it for consideration.”

“He couldn’t run the game as Jack does,” said Harrison.

“He could save touch-downs as Jack doesn’t,” asserted Talbot. “I think as much of Jack as you do, but my thinking a lot of him can’t make him play well.”

“He has been on the team all the season. It is hard to put him off now.”

“No one stays on the crew because he’s been on all the season—I’ll tell you that in advance!” blurted Pete, savagely. “I’ll fire myself if there are four better men.”

Harrison smiled faintly. “It’s easy to say that now. Wait till spring.”

“Sh! Here he comes,” exclaimed Yards, speaking for the first time. “We’ll think it over during the night.”

Sumner came oscillating down the aisle from the seat which he had occupied, dismally brooding alone, during half the journey. He stopped at the end of the double seat and addressed Harrison, but his gaze, as he spoke, wandered uneasily away over the captain’s head; while his flushed cheek and hurried tones betrayed the strain under which he had been laboring.

“I’ve been thinking the thing all over,” he began, “and I see perfectly plainly what’s the right thing to do. I’ve gone to the bad in my play. I know it as well as anybody. I want you to put little Mac into my place at quarter and give him a good, fair show to prove what he can do. He’s no good in the line because he’s so light, but he tackles like a little fiend in the open, and he can catch anything that can be kicked. I could tell him all he doesn’t know about signals and plays in twenty minutes. I believe the change would give the team a new start.”

“By Jove, you’re the stuff, Jack!” cried Talbot, as he clutched his friend’s hand and gave it a wring. “If we win anything this year, that’s the spirit that’ll bring it. There’s something in a name, after all.”

“Give McDowell the place and wrest it back from him,” suggested Mr. Adams, who felt the tension of the scene.

“I shan’t wrest it back, if he has a fair show, sir,” answered Sumner, with a melancholy laugh.

“We’ll try him, then,” concluded Harrison; “shan’t we, Yards?”

Yards acquiesced with a vast sense of relief. He had already determined on this very change, though how he was to bring it about had greatly perplexed him. Sumner’s magnanimity relieved him of all anxiety.

Only a week remained before the first league game—that with Newbury. Having already had experience in the position, and being a lad who used his eyes and ears more than his lips, Hardie needed very little coaching to fit well into the game at left end. Though he lacked Harrison’s sureness in play, as well as the instinctive readiness in translating signals into action which is to be expected of one who has practiced long in a single position, he was better than Harrison in making holes and quite as fast in getting down the field. Each showed a fine keenness of scent after the ball in the enemy’s hands; each was master of the art which belongs especially to a good end, of appearing where he is most useful, and not somewhere else. Deprived of the support of the first team and handicapped by the weakness of the second, Dunn made an inconspicuous figure in the practice. When on the first, he had at times, under favorable conditions, shown effective dash and vigor; degraded to the second, he became sulky and listless. Little remained of the aggressiveness of the early days but a chronic ugliness which manifested itself in fault-finding and in the practice of certain mean tricks which he had learned at a former school.

Sumner’s conduct stood out in strong contrast. Having undertaken to furnish the school a quarter-back better than himself, he pushed his sacrifice to its full limit. He drilled Mac in signals, schooled him in receiving and passing—a part of the play in which Sumner himself excelled—and put him in possession, as far as was possible, of such facts respecting likely plays and dangers to be avoided as his own experience had furnished. Harrison immediately made him captain of the second eleven, and in this capacity he went energetically to work to build up a team which should give the first the best possible practice. By this course, it is safe to say, he gained more respect among the boys whose opinion was worth having than if he had kept his place and won a game. When kid-brother Dick, who, imp-like, found amusement in his elder’s misfortune, referred slightingly to Jack as having been “fired,” Mike McKay threatened to lick him on the spot.

“You’re a big fool, Dick Sumner, or you’d know that it’s a lot harder thing to get off a team of your own accord when you’re on it, than to get put on when you’re off. I’d be proud of him if he was my brother. Besides, he’ll get back.”

“The team’s playing a lot better since he’s off; everybody says so,” answered Dick, bound to maintain his position, yet secretly pleased at this authoritative recognition of his brother’s merits.

“It isn’t because he’s off, it’s because Jason Dunn’s off. He never was any good. I knew it all the time. He’s afraid of any fellow his size.”

Dick had nothing to say in favor of Jason Dunn, so he took another tack.

“Newbury’ll beat ’em anyway, so what difference does it make?”

“It may make a lot of difference,” answered the oracle of the fifth. “Newbury may beat us, and they may not. If big Bumpus doesn’t bust, we’re going to have a solid line, and the ends are great! It’ll be a corking game all right, whichever wins. And you don’t want to go around saying we’re going to be licked!”

“I don’t say it to anybody but you,” Dick interposed hastily.

“You don’t want to say it to any one,” continued Mike, with a severity quite judicial. “Just try to make everybody think we’re going to win. You know how Phillips had us all scared when the fourth played Suffolk, with his talk about how big and strong they were, and how we couldn’t possibly down ’em, and all that, till we lost our nerve and almost let ’em beat us?”

Dick remembered.

“It’s the same with the big team; they’ve got to be encouraged. Harrison deserves it, too, for firing Jason.”

This principle Mike had an opportunity to put into practice the next morning when he passed a knot of older boys gathered at the corner of the school building, where they waited for the nine o’clock bell to ring and meantime swapped news and jokes and covertly watched the girls who by twos and threes and fours passed on the other side of the street on the way to Miss Wheeler’s school. Eaton reached out and seized the boy by the shoulder. “Ticket for the game?” he demanded.

“Got one,” said Mike, coolly, shaking himself free.

“What do you say, Mike,” asked Wilmot; “are we going to beat Newbury?”