Wedded and Murdered Within an Hour!

THE CRUEL MURDER

OF

MINA MILLER

BY

KENKOUWSKY, alias “KETTLER.”

The Guttenberg-Hoboken Tragedy.

A THRILLING AND REMARKABLE CASE, WHICH

RECALLS THE MURDER OF MARY RODGERS,

“THE SEGAR GIRL,” WHICH TOOK PLACE ON

THE SAME SPOT, THE SCENE OF OTHER

MURDERS OF A LIKE CHARACTER.

THE ONLY LIFE OF MINA MILLER PUBLISHED

BARCLAY & CO., Publishers,

21 North Seventh Street, Philadelphia, Pa.

AGENTS WANTED AT ALL TIMES.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1881, by

BARCLAY & CO.,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C.

THE MINA MULLER MURDER.

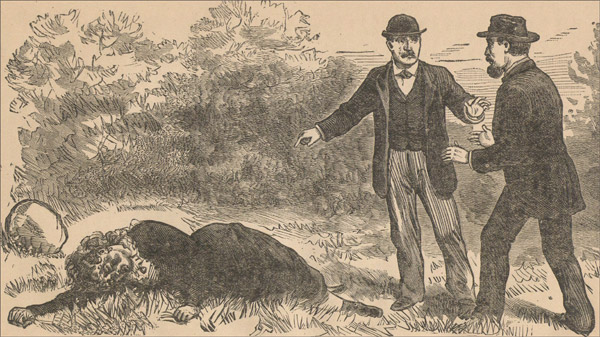

On Friday morning, the 13th of last May, a German, whose purpose was to gather green leaves to sell to florists in N. Y. city, entered the path leading from Bergen avenue, in the district known as Bull’s Ferry, north of Weehawken. He had followed it eastward toward the river about 100 feet, and had turned aside to the right about twenty feet, when he was appalled by almost stepping upon the dead body of a woman. He hurried away to inform the police.

Early in the afternoon Coroner Wiggins, of Hoboken, visited the spot and made a careful examination. He judged that the woman had not been over 25 years old. Along the top of the head, on the left side, was a deep gash, and beneath it the skull was fractured. There was another gash over the right eye. Both of these gashes were apparently made with the edge of a stone. The nose was broken in the middle. The right side of the head had apparently been crushed by a stone. The left ear was injured as if an ear-ring had been torn from it. Search was made for the missing ear-ring, but it was not found. Her face had become blackened by the sun, which shone upon the spot where the body lay. The features were small and symmetrical. She wore number one or number two buttoned shoes.

An investigation was at once begun by the coroner, but without much success.

On the 18th the young woman was completely identified as Mrs. Philomena Muller, the wife of Simon Muller, a tobacconist, at 502 West20 Thirtieth street, N. Y. Mr. Muller called at the Morgue at 3 o’clock on the afternoon of May 18th, in company with a lady whom he introduced as Miss Maria Schmidt, his wife’s sister. He said they desired to look at the body. They were led into the damp vault, and at sight of the body Miss Schmidt was overcome, and she retired to the adjoining basement. Mr. Muller gazed upon the body calmly. The jewelry and clothing of the dead woman were shown to him, and he positively identified them as the property of his wife. He said that he had given her the cameo brooch. Mr. Muller said that some time ago his wife deserted him, and since then she had not lived with him. Miss Schmidt had seen her sister about two weeks before. Mrs. Muller then informed her that she had found a decent man, who was going to marry her and take her to Germany in the steamer L’Amerique, which was to sail on the 4th of May. When Miss Schmidt told Mr. Muller of this he went to the wharf of the Transatlantic Steamship Company on the morning of May 4th, and remained at the gang plank of the vessel until all the passengers had gone aboard. He was certain that his wife was not among them, but he did not know her paramour.

Before this identification was made, the authorities of Hudson county had obtained conclusive evidence of the fact that the murdered woman was Mrs. Philomena Muller, and that her assassin had married her on the morning of the day on which he killed her, and had taken passage on the following day for Europe. As Mrs. Finck, the wife of an alehouse keeper in Pierce Avenue, West New York, was sitting in her saloon on the afternoon of Tuesday, the 3d of May, a man and a woman entered and sat down at a table. The woman ordered drinks, and called for a glass of beer. Her companion drank soda water. While they were there the woman talked almost incessantly. She said that they came from Morrisania. She seemed to have plenty of money. When she paid for the refreshments, Mrs. Finck noticed a large roll of bank notes in her pocketbook, besides some silver and gold. Before going away, the woman borrowed a corkscrew to open a bottle of Rhine wine which she had with her. She said she had bought the bottle in Union Hill. Mrs. Finck minutely described the woman, and the description tallied exactly with that of the woman who was murdered. Prosecutor McGill was so impressed with the accuracy of Mrs. Finck’s description, that he specially detailed Detectives Swinton and Fanning to trace the movements of the unknown couple. They began their search on Tuesday evening, May 17th, and Wednesday the 18th they submitted to the Prosecutor a circumstantial account of their discoveries.

21 They began by looking for the person from whom the bottle of Rhine wine had been purchased. Every saloon along the Boulevard and the Hackensack plank road was visited, but to no purpose. Continuing their inquiries, they entered an inn kept by Edward Stabel, on the Weaverstown road. When they questioned him he said he remembered that on the day indicated by them a woman had called at his place and asked for a bottle of Rhine wine. As he did not have any he sent his granddaughter, Lizzie Haas, to Mr. Eberling’s store, in Bergenline avenue, for a bottle of it. While the girl was absent the woman chatted pleasantly with Stabel. She told him, among other things, that she had just been married by the Rev. Mr. Mabon, the pastor of the Grove Reformed Dutch Church, and that she wanted the wine to celebrate the event, and to treat the minister. She also said that she was about to sail for France. When the girl came back with the bottle of wine the woman paid her fifty cents for it, and gave her ten cents additional out of a $5 gold piece that Stabel changed for her. On leaving the saloon the woman was joined by a man. Stabel could not recollect anything in particular about the man, except that he had stood outside on the street while the woman bought the wine. But he gave a very accurate description of the woman and her dress, which tallied both with Mrs. Finck’s description of the woman she had seen, and with that of the murdered woman. Mrs. Stabel furnished additional details. She said the woman came to the saloon on the 3d of May. She was sure of the date, because on the same day there was a burial in the Grove Church Cemetery which is only a short distance from the inn. The woman told Mrs. Stabel of her marriage, and explained that it had been secretly performed, because her brother disliked her husband, and had objected to the match. She also said that she had been married once before, and had attended a cigar store which her former husband kept in N. Y. city. Mrs. Stabel’s circumstantial description of the woman tallied yet more accurately than her husband’s with that of the murdered woman.

The detectives then went to the parsonage of the Grove Reformed Dutch Church, where they found the Rev. Dr. Mabon. He recollected having married a couple on May 3d. The woman, he said, entered his residence alone, leaving the man in the yard, where he paced up and down as if absorbed in meditation. The woman asked Mr. Mabon if he would perform a marriage, and upon being told yes, she went out and returned immediately with the man. As the couple had not provided a witness, the clergyman called in John Schuman, a barber in Union street, Union Hill.22 The man and woman made satisfactory replies to the usual questions, and they were married in legal form. After the ceremony they subscribed the following record of the marriage, which is now in Mr. Mabon’s possession:

On Tuesday, May 3, 1881, Louis Kettler, single, aged 33, bricklayer by occupation, and residence 1511 Second avenue, New York, married to Mina Schmidt, single, aged 34, residence, 1247 Third avenue, New York. Father of bridegroom, Louis Kettler; father of bride, Anastasius Schmidt. Both of the contracting parties were born in Katenheim, Germany.

The woman did most of the talking, and seemed to be in excellent spirits. She exhibited a bulky pocketbook, and asked Mr. Mabon how much his charge was. He replied that she might pay him whatever she thought proper. As she had no small bills she went out to get change, and came back presently with the money and a bottle of Rhine wine, which she offered to the clergyman. When he refused it she tried to persuade him to take a drink, but he declined, and, after a few more words, the strange couple quitted the parsonage. Mr. Mabon could not recollect anything about the dress of either of the parties, but his colored servant girl told the detectives that she had particularly noticed the man as he was striding up and down the garden, and acting as if his mind was troubled. She said he was stout, with a full face and dark moustache, and wore a high, flat-topped Derby hat.

Mrs. Sarah Rigler, who lives in the neighborhood of the church, saw the couple before their marriage. They came along the road, and the woman stopped and asked Mrs. Rigler:

“Can you please direct me to a priest?”

“Do you want a priest or a minister?” Mrs. Rigler inquired.

“I want a Protestant priest,” the woman responded. “I am going to be married, and I want him to marry us.”

Mrs. Rigler’s description of the woman was almost precisely the same as Mrs. Stabel’s. The man, she said, was quiet, and did not say anything in her hearing. When the couple were last seen by the people in the neighborhood of the church they were walking together toward West New York by a road that led in the direction of Finck’s saloon and the Guttenberg ferry.

The detectives next went to 1247 Third avenue, N. Y. city, the number that had been given to Mr. Mabon by the bride as her residence. There they were unable for a long time to find any trace of Mina Schmidt. Finally the daughter of the janitor remembered that a woman answering25 Miss Schmidt’s description had been living at service with a family in the house. But the family had moved, and the servant had gone with them. An expressman named Body had taken away her trunks. After a tedious search Body was found. The young woman whose trunks he had removed proved not to have been the murdered woman. But Body said that about the 1st of May a woman whom he knew as Mrs. Mina Muller offered to sell him some articles of furniture, as she was about to move. They were unable to agree on the price. Mrs. Muller returned shortly afterward and left an order to have an express wagon call for her baggage at 1511 Second avenue, where she was then staying. Body sent William Norke, one of his drivers, to the place, and the man received from Mrs. Muller four trunks, a bundle of bedding, and a valise, which, by her directions, he carried to Theodore Scherrer’s Hotel, at 178 Christopher street. Body and Norke described Mrs. Muller, and the detectives were satisfied that she was the woman who, under the name of Mina Schmidt, was married by Mr. Mabon in the Grove Church. A man whom the driver did not know, but who, from his appearance, he believed to have been the murderer, superintended the transfer of her packages, and rode in the wagon with Norke to the hotel. On the way there he told Norke that he intended soon to sail for Europe.

At 1511 Second avenue, whither the detectives next proceeded, they found a German woman named Mrs. Schwan, who keeps a dyeing establishment. She did not know any man named Kettler, but she said that a man who answered in every respect the description of Kettler had lived in the house, but had moved about the first of May. He had lived, she said, with a young widow, to whom she had heard he was married. Mrs Schwan described the woman, and again the description tallied with that of the murdered woman. Mrs. Schwan had been told that the woman had another husband living in Thirty-ninth street. Charles Rost, the landlord, said that on March 3d Mrs. Muller had engaged three rooms, front, on the top floor, and had furnished them comfortably. She told Rost that she was working for Hahn, the butcher, in Third Avenue. Her husband, Mr. Muller, she said, had died of consumption, and had left her $1,000 insurance on his life. She was away all day as a rule, and returned to her apartments in the evening.

“One day,” said Mr. Rost, “about five weeks after she came here, I had occasion to go to the roof. Her room door was wide open, and Mrs. Muller was at work within fixing up her curtains and arranging her room. I said to her in fun:

26 “You ought to have a husband here, Mrs. Muller.”

“‘Oh! I’ve got one,’ she said. ‘My name is Mrs. Kettler now. I’m not Mrs. Muller any longer.’” She said, too, that her new husband was a mason, kalsominer and paper hanger, and was getting good wages. A few days after that Mr. Rost met him in the hallway of the house for the first time, and asked if he lived there. He also told Kettler that he believed Mrs. Muller had another husband living. His suspicions had been excited by the woman’s talk of her dead husband and her inconsistent lack of mourning attire or demeanor. On May 2nd, they sold their furniture, and moved their trunks and bedding, no one then knew whither. “The man,” said Mrs. Rost, “was a greenhorn,” and this was the testimony of others in the building who had noticed him.

Among the persons by whom the woman had been employed was Moise Hahn, a butcher in Third avenue. He said that she worked for him until May 1st, when she quitted, as she intended to go to Europe. She was then living with a foreigner whose name Hahn did not know, but whose description corresponded with that of the groom in the marriage ceremony in Mr. Mabon’s house. She told Hahn that she was going with him to Mulhausen in Alsace.

Mr. Scherrer of Scherrer’s Hotel at 178 Christopher street, to which place Norke had carried the trunks and bundles belonging to the woman who gave her name as Mina Miller, informed the detectives that on Monday evening, May 2, a German went there with an express wagon containing four trunks, a bundle of bedding, and a valise.

“The man,” Scherrer said, “afterwards introduced a woman who he said was his wife. She was very talkative and had all the money and paid all the bills. The man told me that they were going to sail in the steamship L’Amerique on the 4th inst., and were going to Mulhausen, in Alsace. On the day they came to my place the man, who said his name was Kettler, left the trunks here, but spent the night at Mr. Boker’s place, two doors further down the street. On Monday, May 3, Mr. and Mrs. Kettler and I had a long chat about the old country, and about noon they left my place and went to the direction of the Christopher Street Ferry. Mrs. Kettler promised my wife that she would come back to bid us good-by. Late on Tuesday night Mr. Kettler returned alone. I asked him where his wife was, and he said she had gone to spend the night at her sister’s house, and was to meet him on board the steamship in the morning. He seemed to me to be very much excited and uneasy, and his behaviour struck me at27 the time as peculiar. The next morning he had his trunks sent to the steamship wharf, and went away. That is the last I saw of him.”

Louis Groth keeps a lager beer saloon in Thirty-ninth street, near Ninth avenue. A friend of his living at 1511 Second avenue, in the same house with Mrs. Muller, told Groth of her being there with Kettler. Groth told Mr. Schmidt, Mrs. Muller’s brother, who lives at 555 Ninth avenue, and he informed Mr. Muller of his wife’s whereabouts.

Mr. Schmidt was at his home at 555 Ninth avenue last evening. He told our reporter who called that he saw his sister for the last time on the Sunday before the murder. Previous to that, upon the information from Louis Groth that she was living with Kettler in Second avenue, he saw her there, and remonstrated with her. He also had a talk with Kettler, who, however, said nothing of any proposed marriage. He said, however, that he knew Muller. Muller told Schmidt that he didn’t know Kettler. Schmidt says that when his sister Mina called at his house on Sunday she got a bank book containing $40 which he had been keeping for her, and told him that she had sold her furniture, and had altogether $116. She was going to marry Kettler on Tuesday, May 3, and go with Kettler to Alsace, which was his former home. Her brother says he told her he did not want her to marry again while she had a husband, but she said she was determined to do so.

Mr. Schmidt has a brother August, a musician, living at 49 Avenue A. and two sisters now living one of whom is married. Muller, he says, was attentive to the unmarried sister, and Mrs. Muller and he continually quarrelled about this intimacy. Their disputes were so violent as to attract the attention of the people in the house where they lived in Thirty-ninth street, and once Mr. Muller was badly whipped, it is reported, by some friends of Mrs. Muller.

Muller and his wife were married in 1874, and lived for three and a half years in the house at 338 West Thirty-ninth street. Muller made cigars and kept a small store there. When he and his wife could stand each other no longer, said Mr. Schmidt, they separated, and Mrs. Muller for a while lived in a house in the same block. About three months previous to the murder she left the neighborhood and secured employment in the butcher shop of Moise Heahn in Third avenue. Muller sold his store out on April 1, and removed to his present place in Thirtieth street. Mr. Schmidt said that Kettler, after marrying his sister, undoubtedly led her to the lonely place of the murder for the sole purpose of28 killing and robbing her of the $116 which she had, and the gold watch and chain.

As Mrs. Muller left her brother’s house on Sunday she said to the saloon-keeper on the ground floor, “I’ve got another man—a nice man now—and I’m all right again.”

Kettler had been only seven months in this country.

Attorney-General Stockton directed Mr. McGill to telegraph to the authorities at Havre, describing Kettler, and requesting his arrest on a charge of murder. Detective Edward Stanton was to sail for Europe on Saturday in pursuit of the murderer, but subsequent events proved this unnecessary, as the reader will learn by following this complete and dramatic recital.

Wildly Declaring his Innocence, yet admitting that he was in Hoboken with the murdered woman—“She Led Me Astray”—A very Touching Scene with his Wife.

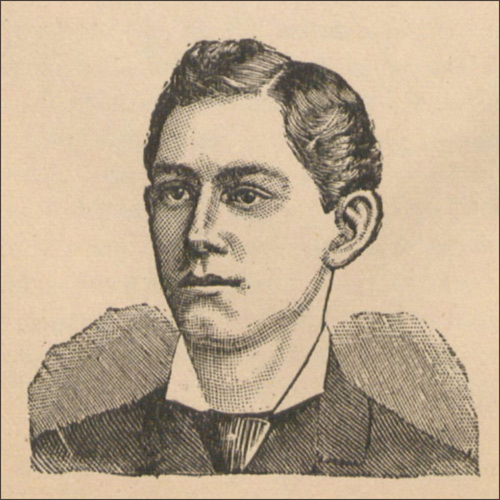

Martin Kenkouwsky, alias Louis Kettler, the murderer of Mrs. Mina Muller, was captured on the night of May 19th, 1881, by Policemen Morris Fitzgerald and Richard Tregonning of the Thirty-seventh street police station, as he was walking in Thirty-sixth street, near Tenth Avenue, New York City. The clue which led to his detection was discovered and followed out almost to the end by Gustavus A. Seide, a reporter for a Jersey City newspaper, and compares, as a piece of amateur detective work, with the detection of Chastine Cox, the murderer of Mrs. Hull. Seide recognized that there was a flaw in the theory that the alleged murderer had gone to Europe in the Amerique. There was no certainty that the baggage which was taken from Sherrer’s house on the day the steamer sailed was delivered at the pier of the French line, nor was there positive evidence that Kettler himself had been seen on the pier that morning. Superintendent West of the French pier said that on the day the Amerique sailed, a man answering somewhat Kettler’s description had applied to him for a ticket, and he had referred him to the purser.29 Baggage corresponding to what Kettler was supposed to have taken with him the Superintendent had not seen on the pier.

Seide came over to New York early Thursday morning, May 19th, and proceeded at once to look for the man who was supposed to have taken Kettler’s baggage from Scherrer’s Hotel to the pier. Scherrer had seen the man in the neighborhood quite frequently, but did not know his name or where he kept. He, however, described him to Seide as a tall, well-built man, with dark moustache and dark complexion. The reporter started out, and visited the truck stands between Christopher and Twentieth streets, but could not find his man. Returning to Scherrer’s, he found a man, whom he describes as a “dilapidated individual,” taking a drink at the bar. Seide again asked Scherrer for a description of the truckman. Scherrer gave it as before, adding that he drove a red truck with one brown horse. Here the “dilapidated individual” spoke up and said, the truckman might be found at Christopher and Bleecker streets. On inquiring there Seide learned that he changed his stand a few days before; but where he had gone no one in the immediate vicinity could tell. He, however, discovered that his name was C. A. Strang. He then made inquiries for Strang’s whereabouts in various smithies and liquor stores, and in one of the latter he ascertained that Strang lived in Greenwich street, on the west side, a few doors below Christopher street.

At this point Seide telegraphed over to Detective Stanton of the New Jersey force, and awaited his arrival. Then they went to Strang’s house, where Mrs. Strang informed them that her husband was at the new market, corner of West and Gansvoort streets. There they found him. They asked him if, on the morning of the sailing of the Amerique, he had taken baggage belonging to Kettler to the steamship wharf. He replied that he had not; he had taken the baggage to a Mrs. Clifford’s, at 179 Charles street, and about ten days afterward he had removed the valise and three ordinary yellow trunks to 510 West Thirty-sixth street. The other trunk, which was long and black, he had not seen again. He was not sure whether he had taken the first load on the 3d or 4th instant. He at first refused to go with them to the house in Charles street, saying he was too busy; but when Seide and Stanton offered to pay him for his time, he consented.

Mrs. Clifford said that a man answering Kettler’s description had come to the house either on the 3d or 4th inst., and she remembered that Strang had brought a valise and four trunks. Kettler had remained at30 the house about ten days, paying her regularly. Once he paid her with a five-dollar gold piece. She did not notice anything peculiar or restless in his behaviour. He kept to the house pretty closely, though he was generally out nights. She saw, however, that he read the newspapers very closely. He told her that he was going to California. When asked if on his departure he had taken all his baggage, she said, no, he had left a long black trunk, which they would find in the wood-shed. They opened the trunk, and found it full of crockery and cooking utensils. They carried it to Strang’s truck, and directed Strang to carry it to the house in Thirty-sixth street, to ask for Kettler, and if Kettler was there, to give them a sign, as they would remain outside. Strang inquired for Kettler, but was told that no man of that name lived there; but that a man corresponding to the description lived one flight up with a wife and two children. Strang took the trunk up stairs, and found a woman, a young boy, and a little girl in the room designated. The woman said the trunk belonged to Martin Kenkouwsky, her husband, and offered to pay fifty cents for its delivery. Strang then signalled to Seide and Stanton that the man was not in, and the reporter and detective went to an adjoining house, and received permission to watch from the windows. Seide went out again to speak to Strang, and while he was talking to him in front of 510 West Thirty-sixth street, both were arrested by Policeman Tregonning. The police of Capt. Washburn’s precinct had been looking for the same man, and had traced him to this same house. This was the cause of the arrest of Seide and Strang. When they got to the station, Seide explained to the Captain who he was, and the Captain sent him back with a policeman to get Stanton to identify him. At first they couldn’t find Stanton, and the policeman wanted to take Seide back. In the meantime the Captain had sent Policeman Fitzgerald to aid Tregonning in arresting Kenkouwsky. The policemen, Seide, and Stanton, who had meanwhile relieved Seide of his embarrassment, waited for about three hours, when they saw a man answering the description of the murderer walking up the street. Policeman Fitzgerald arrested him. He offered no resistance, and his only exclamation was in German: “Was ist? was ist? was ist?” He was at once taken to the station, where he was locked up. Sergeant Brown was sent down for Scherrer, and a policeman was despatched for Strang. Scherrer arrived about twenty minutes after the arrest, and identified the prisoner as the man who had been at his house under the name of Kettler. Strang also soon appeared, and he too identified Kettler. Meanwhile Policemen had31 entered the room at 510 West Thirty-sixth street, notified the woman of her husband’s arrest, and taken the four trunks and the valise to the station. Our reporter was present when the trunks were opened. Almost the first thing found when one of the yellow trunks was opened was a letter addressed to Mrs. Mina Muller, 338 West Thirty-ninth street. In a corner of the envelope was printed “Germania Lodge, No. 70, K. of H.” It contained a request for her to attend a lodge meeting on Jan. 10. The trunks were full of articles of female attire, and in one of them was a pair of men’s gloves of white leather, stained with dirt and badly torn, as though whoever wore them had been handling some rough object. It is thought that Kenkowski wore these gloves when he was married and when he crushed Mina Muller’s skull with stones. A gray wrapper, and a straw bonnet and table covers were among the other objects found.

At about half-past 9 the prisoner’s wife arrived at the station with her boy, who was crying bitterly. She asked why her husband had been arrested, and why the trunks had been taken away. When asked what his name was, she replied, “Martin Kenkouwski,” and added that they had been married ten years ago in Alsace, and had only been in this country a little more than half a year. Her husband was a mason and kalsominer. When asked if he had been at home regularly lately, she said he had been away about ten days in the beginning of the month.

“Do you know,” asked the interpreter (the woman and her husband spoke in German), “that he married another woman, and killed her?”

“I don’t believe it,” she replied firmly, while the boy cried more loudly than before. “I don’t believe it!” she reiterated. “Let me see him! Don’t cry my child” (turning to the boy), “or you will make me weep. Don’t cry!” Here her voice faltered, and she burst into tears.

She was then led to the cell. Here a heart-rending scene occurred. She threw herself with her child against the grating, sobbing and calling for her husband. He was far back in the cell, and when he heard her and the child, he shrieked from out of the darkness:

“Katrina! Katrina! Merciful Heavens! My child! My child! Great God, are you here!”

Then he rushed forward to the cell door, pressed his face against the iron trellis work, lifted his hands and called out: “Before God I stand a guiltless man, and if I die I die guiltless. I was misled by the wicked woman; she led me astray. My God, Katrina! Katrina! Give me your hand!”

34 Here he thrust his hand through the cell gate, and his wife clasped it. She was too much overcome to speak for a while, and the child moaned and sobbed. Kenkouwski continued reiterating his innocence, when he called out again. “The wicked woman misled me; she led me astray.”

His wife exclaimed: “Have I not been a good wife? Have I not prayed to God for you?” Then she sobbed again. After a while she said to him: “I don’t believe you killed her! I don’t believe it!” After this she and the child were led away, and he called after them: “By God, Katrina, I am innocent. I am innocent.”

The woman said he had always been a good husband to her, nor did she seem to know anything of Mina Muller. She said nothing when asked what she had thought when her husband came back with three yellow trunks after an absence of ten days.

Shortly after the woman left, Kenkouwski was led before the Sergeant for examination. He looked wild and nervous, and gesticulated violently. “He must be watched well to-night,” said one of the policemen, “or he’ll hang himself.” As he approached the desk, he suddenly threw up his arms and exclaimed:

“Now, I will tell you the truth. If it is not the truth you may take a knife and cut my throat, like this,” (here he pulled his finger across his neck.) “Mina Schmidt told me the other day that she knew I was married, but she wanted me to marry her and go to Germany with her, where she had very good parents living. At that time I didn’t know she was married. We went to Guttenberg to get married, and when we got over there we went to the Schutzen Park. Two men there came up to me and told me that she did not love me, that she loved another. When she heard this she sprang up and ran away from me, and I have not seen her since.”

He was then led back to his cell. He was again brought from his cell at about 11 o’clock to be looked at by the reporters assembled in the Thirty-seventh street station. He had been lying down, and the light dust from the cell floor covered his back. He looked in a bewildered manner at the throng about him, spoke a few words in German, reasserting what he had previously said in regard to the murder, and was taken back again. His eyes were bloodshot, and he spoke in a nervous manner.

“Mon Dieu! Mon Dieu!” exclaimed Kenkouwsky, “does any one speak French?

“I do!” replied another reporter, addressing him in French.

35 Kenkouwsky sprang from his seat and, with tears falling fast, seized the reporter by the hand and said: “Tell them that as our Saviour, who was crucified, was innocent, so am I!”

“Of what?” asked the reporter.

“Of the murder of Mina Schmidt. I married her that day, although I have a wife here. She told me she loved me. I did not tell her I was married. After we were married we went to Schuetzen Park. There we sat at a table drinking, when two men came by. They greeted Mina as old friends, and we all drank together. One of the men took her away, and the other then told me that Mina had said that she did not love me. They all left me, and I, after hunting for them, came back to this city and tried to find her.”

Chief of Police Donovan of Hoboken, who had been standing by all this time and listening to what the reporter quickly translated, touched the reporter on the shoulder and said: “Ask him if he was not in Jersey City last night.”

The reporter asked the question. Kenkouwsky staggered back and repeated, “Jersey City! Jersey City! Where is that?” The reporter repeated the question.

Kenkouwsky replied: “I was with my wife last night.”

“In Jersey City?” asked the reporter.

“No; I was with a woman there.”

Chief Donovan’s eyes brightened, and he then said: “Last Monday a young girl, whose name I cannot now mention, was taken into a house by this man. He made her drink wine, and as she was partly stupefied, he locked the doors and assaulted her. It was for this offence that I and my detectives were hunting him up to-day. We did not then suspect that he was the murderer of Mrs. Schmidt. Last night he was to meet another girl, but she became frightened and did not stay where he told her to until he came. He eluded us by ten minutes.”

In the prisoner’s pocket was found a clipping from a German paper of the account of the hanging of Mrs. Meierhoffer and her paramour last winter. To the reporter he said he had not read any account of the Guttenberg murder until the day previous to his arrest.

At midnight Chief Donovan had the trunks of Mrs. Mina Schmidt taken over to Hoboken.

Detective Stanton told our reporter that an empty watch case had been found in the room at 510 West Thirty-sixth street. On the yellow trunks labels were pasted with the address:

Monsieur Joseph Reymann,

No. 52 Rue Clissant,

Paris (France).

The purpose of this address was, it is supposed, to induce Scherrer to believe that he was to take the French steamer.

Seide says he has ascertained that on Monday night, May 2, Kenkouwsky applied at Becker’s Hotel in Christopher street, for a room, but refused to write his name. The entry is in the hotel clerk’s hand. “Louis Kettler, Room No. 1.”

Coroner Wiggins began an inquest in the case in Hoboken on the afternoon of May 19th. Simon Muller, the husband of the murdered woman, testified: “Coroner Wiggins told me on Wednesday that my wife had been found murdered in Guttenberg. I told him that it could not be so, for that she had gone to Germany with a man from Alsace. I went to the French steamship wharf on the day I heard they were to sail, and watched for her until the ship sailed, but she did not come. I was married to her five years ago. Our married life was unhappy, and on the 5th of last January she left me. She had then between $75 and $100.”

Carl Schmidt, the brother of the murdered woman, testified: “I last saw my sister Philomina at my place, 555 Ninth avenue, New York. She came to my house on Sunday, May 1, at about 5 o’clock in the afternoon. She told me she was going with a man named Louis Kettler to Mulhausen, in Alsace. I asked her why she was going. She replied that Kettler was well off at home. ‘You know,’ she said, ‘what treatment I have had from my husband.’ I told her that I knew he did not treat her right, but that she should not go with this man, as she did not know him at all. And further, I told her that she must first get a separation from Muller before she could go with another man. She answered, ‘I don’t care how it will result, I will go with him. My husband tried to shoot me.’ She also told me that she had known Kettler for four weeks, and he had told her that he had property in Mulhausen, and that he would give her a good home there. Kettler, she said, was richer than the whole Schmidt family. She left me at about 6½ o’clock to go to my other sister’s house in Tenth avenue, between Nineteenth and Twentieth streets. I never saw Kettler but once, and that was on a Sunday in April in Second avenue, near Seventy-ninth street, in my sister’s apartments. On May 2nd a cousin of my wife met Kettler on the street and asked him when he and Mina were going to Europe. He replied that he was not going to Europe. The cousin then asked what Mina would do, and he said she would go to the country, where she had friends to stay with. Kettler then suggested that the cousin37 and he should go off together, and leave Mina behind. Since the 3rd of May, on the 9th or 10th of the month, I think, the woman Sacks saw Louis Kettler passing up on the opposite side of the street. When she noticed him she called my wife, who was in the room with her, to the window.”

The Rev. Dr. Mabon, the pastor of the Grove Reformed Dutch Church, on the Weavertown road, at whose house the murdered woman and Kettler were married, testified that he had performed the ceremony.

“When I asked the man,” he said, “if he took the woman for his lawful wife, he answered ‘Yes,’ and at the time I noticed a tear in his eye.”

The inquest was suddenly adjourned on the news of the murderer’s arrest in N. Y. city.

The Scene at his Parting from his Wife and Children—Angry Throngs in Hoboken—Giving Away the Murdered Woman’s Watch—The Testimony.

Over in New York Martin Kenkowsky was closely watched. He was so agitated when he was led back to his cell on Thursday night, that Policeman Finerty was detailed to watch him, as it was feared he might attempt to kill himself. The policeman says that the prisoner was restless until after sunrise. At first he paced the cell like a caged animal, stopping now and then and pressing his face against the gate, his bloodshot eyes glaring through the trellis work. This continued several hours. Then, for the first time, he gave way to his feelings. He threw himself upon the floor and moaned piteously. Then he sprang up again, leaped to the gate, and tried to shake it. After that he again paced the cell, wringing his hands wildly and calling out German words which the policeman could not understand. Toward morning he became more quiet, but even when lying down he tossed about and did not sleep. Finerty says that Kenkowsky is one of the most powerful men he has seen; that when he tried to shake the cell gate he could see the muscles moving beneath his sleeves.

The news that the Guttenberg murderer had been captured spread rapidly in the neighborhood, and by eight o’clock in the morning some 400 persons were in Thirty-seventh street, pressing toward the police station and standing on either side of the station nearly all the way to Ninth and Tenth avenues. A little after 8 o’clock a woman with a young boy at her side and a little girl in her arms was seen trying to make her way through the crowd. Whenever it was so dense as to impede her progress she spoke a few words, and those in the immediate vicinity fell back and allowed her38 to pass. The boy was crying bitterly, but the woman’s features were firmly set, and the little girl, who seemed to be about 6 years old, was quiet. When the woman had made her way to the station door she hesitated a moment. Then she entered, dragging the boy, who seemed unwilling to follow, after her. She was the prisoner’s wife. People now began to climb upon some empty trunks near by, and even women with babies in their arms were seen on the wagons. Up to this point the crowd had been quiet. But when the coach in which Kenkowsky was to be conveyed to the Jefferson Market Police Court appeared, some one shouted, “Kill him!” and an angry howl went up from the dense throng.

“Lynch him! Hang him to a lamp post!” was shouted by others. No attempt, however, was made to carry out these threats.

Meanwhile Chief of Police Donovan of Hoboken and Detective Stanton had arrived, and the prisoner had been led from his cell. When he saw his wife and children he burst into tears. His wife also wept and called out:

“Why did you not take my advice? Why did you not stay away from her?”

“I swear to God I am innocent,” he called out. “Let me kiss you, Katrina; let me kiss you and my children!”

He stepped toward her with arms spread as though to embrace her, but she started back in a half frightened way. The boy, however, sprang toward him and clasped his arms around his neck. The woman turned her face away and only allowed him to kiss her neck, while the little girl pushed him off and then shrank away. Just then the crowd without howled. Kenkowsky turned ghastly pale and trembled, while his wife fainted and fell upon the floor, and the boy wept louder than ever. The little girl leaned over her mother and patted her cheek with one hand, while with the other she made a repelling motion toward her father. The prisoner was led away, and as soon as the wife came to her senses she went away with her children. When the door closed on her she stood for a moment gazing in a dazed manner at the crowd. The people seemed to pity her. One man took her hand and led her down the steps, and then she passed through the crowd unmolested by either word or act. Her face was pale but calm, and the little girl was as quiet as she had been throughout all the trying scenes, but the boy, who clung to his mother’s skirt, was still crying bitterly.

Kenkowsky was again led back before the sergeant at the desk as soon as his family had gone. He was then quite calm and collected. He turned to a policeman and said in German: “I am innocent. I suppose you will let me go home soon.”

“Why,” replied the policeman, “whether you’re guilty or not, you’ll be mighty lucky if you get off.”

The prisoner was then asked if he would go quietly to court, and he said he would. He was manacled, and between two policemen was marched out of the station. His appearance was a signal for another howl from the 39 crowd, who pressed around the party so closely that the policemen used their clubs. The prisoner turned pale, and trembled as he had done in the station when he heard the angry cry without. He was hustled into the coach, and as soon as the door was closed the driver whipped up his horses, and they started off at such speed that the crowd had to fall back. Many, however, ran after the coach several blocks down Ninth avenue, and some boys followed it all the way to the Jefferson Market Police Court.

41 The prisoner was taken into a small room, and when court was opened he was led before Justice Morgan. Capt. Washburn, Coroner Wiggins, Chief Donovan, Detective Stanton, and G. A. Seide were in court. Capt. Washburn stated the case to the Justice, and said the New Jersey authorities wished to have the custody of the prisoner. The Justice called up Kenkowsky and asked if he knew why he was to be taken to New Jersey. The French interpreter translated the question, but the prisoner said he understood German better than he did French, so the German interpreter was called in. Kenkowsky replied in the affirmative. He further said that he knew his legal rights, but that he was willing to go to New Jersey without any formal proceedings. The Justice then endorsed the warrant and Capt. Washburn handed over the prisoner to Chief Donovan. Kenkowsky’s manacles had been taken off, and he asked that he be allowed to have his arms free. His request was granted.

Kenkowsky was then again placed in the coach, which was driven hurriedly through West Tenth street to the Hoboken ferry and upon the ferryboat Moonachie.

Kenkowsky’s coming had been anticipated in Hoboken, and an immense throng had gathered at the ferry on the Hoboken side, rendering the streets leading to the river almost impassable. As each boat reached the slip the policemen on duty there experienced the utmost difficulty in restraining the crowd that pressed forward eagerly in the desire to get a glimpse of the prisoner. When at last he landed on the New Jersey shore the carriage was driven as rapidly as possible through the multitude in the direction of Police Headquarters. Some one in the throng recognized Chief Donovan in the vehicle and shouted to the bystanders:

“There’s the murderer! There’s the murderer!”

The news spread like wildfire, and was received with mingled threats and shouts of exultation. Cries of “Hang him!” “Lynch the wretch!” “We’ll fix him!” were heard on all sides. The coach dashed up Newark street to Hudson street, pursued by over 2,000 persons, shouting at the top of their voices. Chief Donovan deemed it prudent to avoid the still larger crowds that swarmed around the police station on Washington street. He therefore directed the driver to pull up his horses at the end of an alley that led to the rear of the building. The prisoner was conducted through this passage to the station. He was placed in a cell at the end of the corridor.

While he was lying in jail awaiting the opening of the inquest, which42 had been adjourned until 2 o’clock, another link in the chain of circumstantial evidence against him was being prepared. Regina Herkfeldt, 20 years old, of 153 Newark avenue, told the police that on Monday, May 9, she went to an intelligence office in Mott street to get a situation as a servant. There she met a man answering Kenkowsky’s description. He engaged her to do housework, and took her to 149 Charles street. There he locked her in a room and assaulted her. He then led her to the street and left her. Afterward he followed her into a saloon and took her pocketbook and a ring from her finger, and left the saloon with them. She followed him to Thirty-fifth street and Tenth avenue, where she lost him. Three or four days afterward the man went to her brother’s place of business (her brother is a galvanizer in the Pennsylvania Railroad shops), and told him that he wanted to marry the girl. After that he went to her house and told her he would marry her, and they went to Canal street, New York, to her sister’s house. Last Sunday the man went to her house and told her he was going to Chicago. He said he wanted to give her a gold watch and a ring. The watch was a lady’s hunting case gold watch, with flowers engraved on the outside case. The inside case did not look like gold. The ring was chased, and had one round dark blue stone set in a crown setting, with four claws which held the stone. He would not let her keep the ring, but said he would send her one from Chicago. He went back on Wednesday, the 18th, and told her she must get a situation, and he would send for her from Chicago. The girl could not remember the man’s name.

When Chief Donovan heard this story he telegraphed to Jersey City for the girl, and she was taken to Hoboken by Detective Bowe. Kenkowsky and a number of other persons were admitted to the large drill room of the station, and the girl was then led in and requested to point out the man. No sooner had she entered the apartment than she walked opposite to Kenkowsky, looked at him steadily for an instant, and then, as she waved her umbrella toward him, exclaimed:

“Das ist der man.”

“Ask him,” said Chief Donovan to Aid Ringe, “whether he has ever seen this woman before.”

The aid interpreted the question and the prisoner grunted out a negative answer.

At 2 o’clock in the afternoon, the hour appointed for the continuation of the inquest, a great throng swarmed in Washington street between Police Headquarters and the Morgue. Kenkowsky was led through this crowd by Chief Donovan and an escort of policemen. The prisoner’s appearance was greeted with the same threatening cries that had been uttered on his arrival in Hoboken, but he bore up against the clamor with real or well-feigned indifference. When he entered the hall and was being led to a seat at the side of the Coroner’s chair his eyes accidentally fell upon the lay figure that had been draped with the clothing of the murdered woman. When he saw43 it he averted his face with a perceptible tremor. He almost immediately recovered his composure and dropped into his seat.

The Rev. Dr. Mabon, the pastor of the Grove Reformed Dutch Church, testified: “To the best of my knowledge I think the prisoner is the man that I married under the name of Louis Kettler.”

Sarah Jane Rigler, who had directed the couple to Dr. Mabon’s house on May 3, testified: “I recognize the prisoner as the man who was with the woman who asked me where she could get a minister to marry them.”

John E. Schumann, the barber who had been called in by Dr. Mabon to witness the ceremony, said that he believed the prisoner to be the man who was married on that occasion.

Regina Herkfeldt testified concerning her acquaintance with Kenkowsky. She identified a watch that was produced as the one that he gave her. On cross-examination she considerably modified her previous account of the prisoner’s assault upon her.

John E. Luthy, a watchmaker of 315 West Thirty-fifth street, testified that the prisoner called at his place on May 16 with the watch and left it there, taking a receipt for it.

Charles H. Peters, a roundsman of the Twentieth Precinct, this city, testified to a conversation he had had with the prisoner at the station on the night of the arrest. Kenkowsky admitted to him that he knew Mina Muller. He at first denied but afterward confessed that he had given a watch to Luthy to have repaired, and that it belonged to Mina Muller. He told the roundsman that after the trunks had been taken to Christopher street, Mina proposed to him to take a walk, and they went over to New Jersey and visited the Scheutzen Park. They strolled into a saloon on the Guttenberg road and had some beer. After leaving it he told her he wanted to go back to New York, and she objected. As they were talking, two men, he asserted, came along the road. One of them said to the woman: “Hello, Mina! what are you doing over here?” When he heard this familiar language he turned to his companion, and said: “If you are that kind of a woman, I’ll have nothing to do with you,” and then he parted from her, leaving her with the two men.

While the inquest was going on the wife of the prisoner entered the room and managed to force her way through the throng. When she turned her eyes toward her husband she threw up her arms and fell unconscious. She was carried down stairs to the station, where restoratives were applied.

In the evening Kenkowsky was taken to the county jail and placed in the cell formerly occupied by Covert D. Bennett.

In the trunks in Kenkowsky’s possession was found, in addition to a lot of female clothing, a white shirt. The sleeves from the wrists to the elbows were spotted with blood; the bosom, too, was marked with similar stains. On each side of the shirt at about the waist there were marks of bloody fingers. A pair of buckskin gloves with very small spots of blood on the back was also found; the palms were soiled, as if they had been used to handle some rough and dusty article.44

At 11 o’clock on the morning of May 20th, Martin Sanger, an undertaker, removed the body of Mina Muller from the Hoboken Morgue and placed it in a plain coffin, which was put in a hearse and driven to the residence of the deceased woman’s brother, Carl Schmidt, 555 Ninth avenue. On the lid of the coffin was a silver plate with the inscription: “Mina Muller, died May 3, 1881, aged 34 years.” A shield bearing the words “Ruhe in Frieden,” was also on the coffin. A wreath of flowers inwoven with the dead woman’s name rested upon the head of the coffin, surrounded by bouquets. A throng of Germans, mostly women, were waiting in front of the house for the arrival of the body. When the hearse appeared at about two o’clock, the sidewalks for nearly a block were almost impassable. Vehicles blocked the street in some places, and many men and boys had climbed upon the elevated railroad columns. Six carriages containing the husband and brothers of the deceased woman, and the officers of Lodge No. 70, Knights and Ladies of Honor, accompanied the hearse to the grave in the Lutheran Cemetery. Louis Schlisenger, the president of the lodge, read its ritual. Mr. Muller wept during the service.

Mr. Schlisenger said the Lodge would pay the sister of Mrs. Muller $1,000. Mrs. Muller joined the Lodge several years ago. She originally assigned the money she was entitled to as a member to her husband, but on May 3 she revoked this and assigned it to her sister. When Mrs. Muller saw Mr. Schlisenger she told him she was going to France, and in case of her death she desired that her sister should receive the money.

At half-past one o’clock on the morning of May 22d, Detectives Heidelberg and Dolan arrested Philip Emden of 414 West Thirty-ninth street, on the charge that he was an accomplice of Martin Kenkowsky. Emden was locked up in a cell at the Police Headquarters. In the morning, however, he was liberated. It was said that he was arraigned at the Jefferson Market Police Court and liberated; but on the other hand it was reported that he was not taken to court at all, but that Captain Washburn of the Twentieth Precinct called at headquarters, and that after a conversation the captain had with Inspector Byrnes, Emden was liberated. The police were reticent about the procedure, but the result was that Emden was freed.

Capt. Washburn was indignant at Emden’s arrest. He said: “Emden was the first man to give a clue to Kenkowsky, and I promised to keep his name a secret. We are in the habit of taking informers’ names in confidence; otherwise people wouldn’t give us information. Prosecutor McGill also promised me that he would not disclose the name. I think Kenkowsky’s wife found out that Emden had given me information, and she45 tried, out of revenge, to throw suspicions on him. Emden has lived three years in the district, and is a quiet, well-behaved man. Chief Donovan was perfectly willing that Emden should be set at liberty. Emden will accompany me to testify at the inquest. He certainly has not behaved like a man who has committed a murder.”

Philip Emden was found at his house, 414 West Thirty-ninth street. According to his statement he met Kenkowsky shortly after the latter came to this country. Emden is a mason, and found odd jobs for Kenkowsky, who is of the same trade. On Feb. 19 last Emden married Bertha Himmelsbach, and Kenkowsky was one of the witnesses to the ceremony, though on the certificate his name appears as Martin Karkowsky. Shortly after the marriage Emden was told by Kenkowsky that Mina Muller, a friend of his, knew Bertha Himmelsbach, who, she said, was a bad woman. This led to difficulties between Emden and his wife, which ended in their separation on April 17. Since that time he has seen very little of Kenkowsky, but he says that on one occasion the prisoner showed him a gold watch and chain corresponding to those owned by Mina Muller. Emden does not know whether this was before or after the murder.

On Thursday morning he read of the identification, and in H. Luhr’s liquor store, 587 Tenth avenue, he mentioned that Kenkowsky had known Mina Muller. Luhr, who knew Kenkowsky, suggested that the description of the man who was married in Guttenberg tallied with Kenkowsky’s appearance. Emden made up his mind to see if Kenkowsky was still at his house, 510 West Thirty-sixth street. As his pretence for calling, he determined to say that he had a job for the alleged murderer. He found him in bed, and, when he asked if he wanted the job, Kenkowsky said that he was engaged as a cook in a Jewish family on Fifth avenue, and only came home nights. After working hours, Emden went to Capt. Washburn and informed him of his suspicions, and a policeman was sent with him to watch the house. In front of the house they found Strang, the trunkman, who in the meantime had been tracked by Seide. Strang asked Emden if he could speak German, and, when the latter answered in the affirmative, requested him to ask the German woman up stairs if a trunk he was to deliver belonged to her, saying he had left three trunks there some time previously. Emden went up stairs and asked Mrs. Kenkowsky if three trunks had been delivered there, and she said they had not. When Emden came back to Strang with this answer, Strang requested him to ask again, and this time she replied in the affirmative; and when Strang brought up Kenkowsky’s trunk, she said, in surprise: “Why, he told me he had taken it to where he was working in Fifth avenue.”

Kenkowsky’s wife was found at 510 West Thirty-sixth street. She had just returned from a visit to her husband in jail. Her eyes were red as though she had been weeping.

“Philip Emden,” she said, “has been a good friend to me and my poor little ones. When I told my husband this afternoon in jail that Philip46 had been arrested, he threw up his arms and exclaimed: ‘Philip arrested! Philip, who has always been so good to us? He is innocent, Katrina, as innocent as I am myself.”

Martin Kenkowsky spent Sunday quietly in his cell in the Hudson County Jail at Jersey City. He ate his meals regularly and with much relish, and slept for an hour after dinner. In the afternoon his wife and two children visited him. He embraced them and had a long conversation with them in the presence of a turnkey. In the course of their talk the woman charged him with having stolen a five-dollar gold piece from her room on the evening of May 3d. That was the day on which the murder was committed. Kenkowsky admitted that he had taken the money. He said that after he had left Mina with the two men at Union Hill, he returned to New York city and went home. There he found the $5 piece, which his wife had saved, and put it in his pocket. When he was told of the arrest of Emden he seemed to be very much surprised. He said he knew Emden, and had become acquainted with him only a short time ago.

“But,” he exclaimed, “he is as innocent as I am.”

The prisoner referred frequently to his former narrative as to the circumstances under which he parted with Mrs. Muller in New Jersey. He stated that one of the two men who accosted her in the Schuetzen Park, and with whom he says he left her, was tall, and had a red moustache, and the other was shorter and thinner. He was convinced, he declared, that they murdered her.

City Missionary Verrinder held divine service in the corridor of the jail on Sunday morning. Kenkowsky, at his own request, was permitted to attend the exercises. He sat on the foremost bench, directly in front of the minister, and although he did not understand the sermon, he bowed his head reverently whenever the name of Jesus was uttered by the preacher. At an early hour he went to bed, and fell asleep a few moments later.

The reader who has followed us thus far will perceive that scarcely ever in the records of modern murder cases has such a steel coil of circumstantial evidence, in such a small space of time, so completely woven itself around a murderer. Kenkowsky attempted to prove an alibi by asserting that on the day of the murder, and several hours before it could have taken place, he was on his way to cross the river, and that on his way he had asked the direction to the ferry of a carpenter whom he saw putting up posts for a fence. This carpenter was found, and testified that a man on that date had asked him the way to the ferry, but he failed to recognize Kenkowsky as that man. The bottom of the alibi leaked, however, when the gentleman on whose property the fence was being put up showed his diary, in which was recorded a mem. of that particular job, dated several days after the date of the murder. What verdict could a coroner’s jury bring in but one fastening the crime on Kenkowsky? The trial will be read with great interest.

THE END.

Transcriber’s Note

Efforts have been taken to transcribe this work as originally published, including inconsistent capitalization and punctuation, and alternative titles, names and spelling, except on page 37 where “ogether” has been changed to “together”.