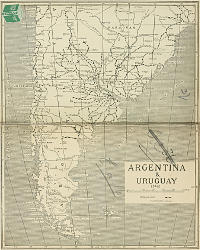

ARGENTINA & URUGUAY

ARGENTINA AND URUGUAY

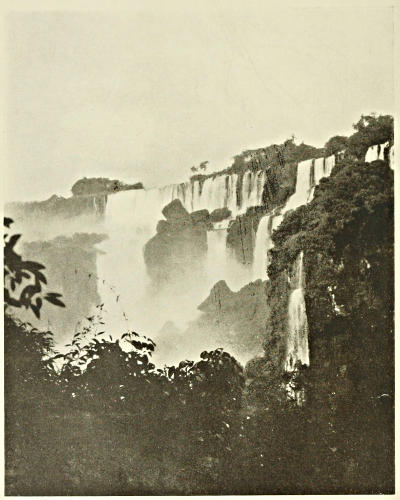

A PART OF THE IGUAZÚ FALLS

ARGENTINA AND

URUGUAY

BY

GORDON ROSS

FORMERLY FINANCIAL EDITOR OF “THE STANDARD,” BUENOS AIRES

AND OFFICIAL TRANSLATOR TO THE CONGRESS OF AMERICAN

REPUBLICS, BUENOS AIRES, 1910

WITH TWELVE ILLUSTRATIONS, FOUR DIAGRAMS

AND A MAP

METHUEN & CO. LTD.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published in 1917

TO

Sir ROBERT JOHN KENNEDY, K.C.M.G.

THIS BOOK

IS DEDICATED IN GRATEFUL REMEMBRANCE

OF THE MANY KINDNESSES SHOWN

AND VALUABLE AID GIVEN

BY HIM

TO THE AUTHOR

IN HIS

LITERARY WORK AT MONTEVIDEO

IN 1911

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I INTRODUCTORY |

|

| An allegory of the Pampa—Patriarchs and Oligarchies—National and local politics and administration—Patrician government—The landed aristocracy—Patriotism and foreign railways—The problem of agricultural labour—Propaganda, in theory and in practice—Needed and unneeded immigration—The peon of to-day and the gaucho—Urgent need of rural population—Industries in waiting—The INCALCULABLE future of the River Plate countries—Lack of Uruguayan statistics | 1 |

| CHAPTER II THE WAR |

|

| The shock falls on existing local depression—Vigorous and prompt action of the River Plate governments and banks—No “Mañana”—Mr. C. A. Tornquist’s views—Again the need of rural population—Socialism from above and below—Buoyancy of national securities | 18 |

| CHAPTER III HISTORY AND POLITICS |

|

| The Declaration of Independence—Subsequent chaos—Rozas and Artígas—Sarmiento—Mitre—Juarez Celman—The Argentine financial crash of 1891—Uruguay; “Whites” and “Reds”—Uruguayan patriotism and honesty—“State socialism gone mad”—The commencements of modern River Plate history—Dr. Saenz Peña—Sound financial policy—Future peace and prosperity—The ballot in Argentina and former electoral corruption—The people a new factor in Argentine politics | 29 |

| CHAPTER IV RACIAL ELEMENTS AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS |

|

| The Argentine of the future (?) and of the past—Spanish and Italian immigration—Young patriots—Argentine and Uruguayan[viii] sources of immigration—River Plate Spanish and philology—Argentines and Uruguayans contrasted—Manners and characteristics—The true signification of “Mañana”—Some advice to immigrants—Land and the foreigner—Much learning and little application—Lower-class illiteracy—Argentine women, households, and children—Jeunesse dorée—Further contrast of Argentines and Uruguayans | 40 |

| CHAPTER V NATIONAL, PROVINCIAL, AND MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT |

|

| The constitutions of Argentina and Uruguay, advantages and defects of each—Dr. Figueroa Alcorta—“Revolución de arriba”—A “Coup d’État”—Former Argentine electoral practices—Doctrinaire government in Uruguay—An autocratic democrat—General strike and general festivities—Certified milk-cans—Provincial authorities—Freedom from corruption of National governments—The “making” of internal politics—Finance—“A fat thief better than a lean one”—Childish things, soon to be put away | 62 |

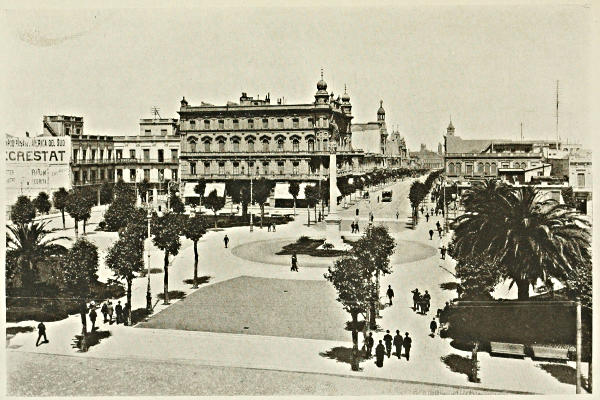

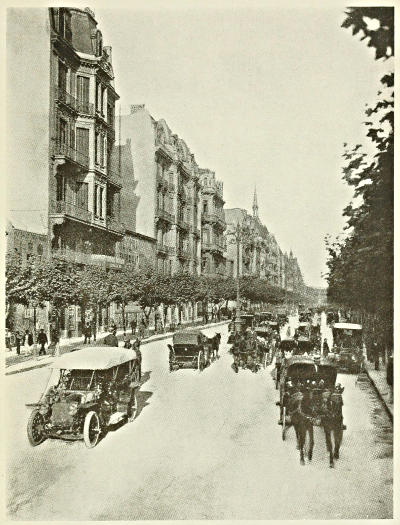

| CHAPTER VI MONTEVIDEO AND BUENOS AIRES |

|

| History and modernity; music and verdure—Theatres and Bathing—The ambition of Montevideo—Carnival—The origins of two great fortunes—More historic buildings and the “Palace of Gold”—The Buenos Aires “tube”; its tramways—Comparative expense of living—Opera houses and theatres—Night and day—Ever-changing Buenos Aires—The Jockey Club—Palermo and the Avenida de Alvear—Fashion moves northwards—Corso and race-course—Gambling—The agricultural show—Hurlingham—The Tigre—The Recoleta—“The Bond Street of the South”—Hotels—Buenos Aires not a hot-bed of vice—Marriage and mourning—“Conventillos”—Fashion in Buenos Aires and Montevideo | 79 |

| CHAPTER VII FINANCE AND COMMERCE |

|

| Susceptibility of South America to conditions of the European money markets; early fear of Balkan complications—Relatively bad times—Transient “crises”—August, 1914—Protective measures—“It’s an ill wind that blows no one any good”—Still further insistence on the need of agricultural population—Currencies—The Argentine “Conversion” Law—Former gold speculation and banks of issue—Golden opportunity for British trade—A South American view of the Monroe doctrine—The “Hustler”—British manufacturers and the South American trade—How to lose it—How to keep[ix] it—Uruguay’s creditable reputation—General commercial conditions in Argentina and Uruguay—The Buenos Aires Stock Exchange—Gambling—Sound securities: the Argentine Hypothecary Bank, and National, Provincial, and Municipal Debenture Bonds—The new and the old Buenos Aires corn exchanges—More about the “Bolza”—Fictitious booms—A great bear—The death of public speculation—Cedulas and Cedulas—Credito Argentino | 93 |

| CHAPTER VIII RAILWAYS, PORTS AND IMMIGRATION |

|

| An Imperium in Imperio—Foreign capital in River Plate railways—Gauges—The “Mitre” Law—Luxurious travelling—An U.S. Syndicate—Argentine national railways—The Transandine and Entre Rios lines—The projected southern transandine line—Maritime accessibility of the River Plate Republics—Chief ports—Spanish immigration | 122 |

| CHAPTER IX GENERAL STATISTICS |

|

| Increase of trade during past two decades—United Kingdom imports of grain and meat—U.K. exports, showing importance of Argentina and Uruguay—British capital invested in Argentina during first half of 1914—Trade of the U.S. with S. America—U.S. exports, showing importance of Argentina—Argentine imports from Europe in 1913—The rich productiveness of Uruguay—Increase of Argentine and Uruguayan exports—Public works and small budget surpluses—Buenos Aires commercial and industrial census, 1914; bread and smoke(!)—Italian and Spanish retail traders—Russians and Jews | 127 |

| CHAPTER X A GLANCE AT THE PROVINCES AND NATIONAL TERRITORIES OF ARGENTINA, AND THE INTERIOR OF URUGUAY |

|

| BUENOS AIRES, the “Queen” Province: Its stillborn capital—Famous museum and university—Bahia Blanca—Mar-del-Plata, a veritable round of gaiety; the new Port—Potatoes—Other chief towns of the province—Cereals and live stock—Great agricultural and industrial activity—Generally uninteresting scenery: model farms and fine country houses | 139 |

| SANTA FÉ: Forests, live stock and agriculture—An old-world capital—Busy Rosario—Other ports—Mixed agriculture and stock farming—Milling and other industries | 144 |

| CÓRDOBA: The gaucho wars—The learned city—The Cathedral and university—Monks and nuns—Mediæval atmosphere—Some[x] personal recollections: religion and roulette—Alta gracia—Mar chiquita—Chief towns—The Dique San Roque—A projected canal | 145 |

| ENTRE RIOS: No longer the “Poor Sister”—The railway ferry service—City of Paraná; Urquíza and Sarmiento—Concórdia—Large land holdings—Extract of meat | 150 |

| CORRIENTES: Where the Diligence still runs—Descendants of the Conquistadores—San Juan de la Vera de las siete Corrientes—Other chief towns—Good possibilities but commercial apathy—Lake Iberá—A zoological invasion—General San Martin | 153 |

| SAN LUIS: Alfalfa—Irrigation—Grapes and wine—Minerals—Native indolence | 156 |

| SANTIAGO DEL ESTERO: Irrigation and cereal cultivation—Alfalfares—Quebracho and charcoal—Amenities of the Santiagueño—Quack doctors and wise women; a cure for toothache—Dangers of quackery | 158 |

| TUCUMÁN: Smallest Argentine province, but important—Sugar—Former difficulties and present progress—The city of Tucumán—The Declaration of Independence—Palatial villas—The Plaza Independencia, theatre and casino—Irrigation—Snow-capped mountains and fertile valleys | 160 |

| CATAMARCA: Sparse population—Irrigation and transport; a new government line—Minerals—The Campo del Pucara and the city of Catamarca; a sleepy hollow—Native lethargy; a Spanish aristocracy—Unexploited mineral wealth | 163 |

| LA RIOJA: Water, labour and transport needed—Maize and tropical fruits—Wine—Irrigation—A new national railway—Mineral wealth; La Famatina—The city of La Rioja; arrested development—Remains of Inca civilization—Mountain and plain | 165 |

| JUJUY: The brothers Leach—A picturesque province—The Humahuaca dialect—General Lavalle—The blue and white flag and the “Sun of May”—A primitive population | 167 |

| SALTA: “The Cradle of the Republic”—Jabez Balfour—The gaucho—Coya Indians—Need of intelligent and energetic population—Ponchos—Rubber—Hot springs—No soldiery, only armed police | 169 |

| MENDOZA: Wine—“Entre San Juan y Mendoza”—Alfalfa—San Rafael—Irrigation—Earthquakes—Public gardens and the West Park—Wine manufacture—Table grapes—Peaches—Coal and petroleum—The Puente del Inca—Hot springs | 174 |

| SAN JUAN: Former financial recalcitrance—Depreciated paper—Irrigation and enforced prosperity—A new railway—The defeat of the Buenos Aires grape ring—Old colonial charm | 178 |

| THE PAMPA CENTRAL: The fifteenth province?—Wheat, linseed and maize—Rapid development—Shifting sand-hills—Three great railways—Wool and hides—The latent landlord in excelsis—Need of a real colonization policy; settlers wanted | 182 |

| [xi]NEUQUEN: Chilean colonies and trade—Wheat, alfalfa and vegetables—“Tronador”; Scandinavian scenery—Lake Nahuel Huapí and Victoria Island—Hot and medicinal springs—Future wealth—Vast irrigation—Rich, virgin soil—Deep-water ports | 185 |

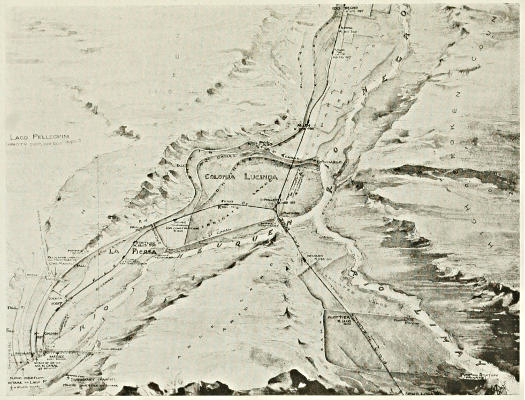

| RIO NEGRO: Fertile soil, but no rainfall—Irrigation and the Lago Pellegrini—Regulation of the flow of the river—Former disastrous floods—A climatic transformation—New railway lines—San Blas—Copper, salt, and petroleum—Furious winds—A scheme which failed | 188 |

| CHUBUT: Petroleum—The Welsh colony—“Foreigners” not admitted—Lazy descendants of active forefathers—Sparse population—Wool and alfalfa—A new railway | 193 |

| SANTA CRUZ: English climate, orchards and gardens; far from the madding crowd—Sheep—Wind!—Cold storage—Wheat, oats and alfalfa; apples and pears | 196 |

| TIERRA DEL FUEGO: No volcanoes in “Fire Land”—A cure for anarchy—Hardy sheep—Seal and whale fishing—Potatoes and table vegetables—The Silesian mission—Mr. Bridges’ refuge—The new gaol—Gold prospecting—“De Gustibus!” | 197 |

| MISIONES: The “Imperio Jesuitico”—Practical religion—Fairyland—The Iguazú Falls—Timber—Mate—Maize, sugar and fruit—Granite—Neglected industries—Need of suitable labour—Indians then and now—A projected railway to the junction of three republics | 200 |

| FORMOSA: Not the most beautiful—No man’s land—A projected railway—Quebracho—Alfalfa and maize—Again the Latifundío question—A fiscal land scandal—Landlords and squatters—Smuggling—Tobacco and sugar—Timber—Pleasant memories of the River Plate | 205 |

| URUGUAY: General physical and climatic characteristics—Flora—The Uruguayan Rio Negro the dividing line of general physical features—Fruit and vegetables—Flour—Soil—Minerals and the Mining Laws | 212 |

| THE CHACO and LOS ANDES: Timber and Minerals | 214 |

| CHAPTER XI AGRICULTURE |

|

| Comparative values of agricultural exports—Railways not the only causes of agricultural extension—Railway policy—Ambassadorial managers—Intensive and extensive farming—“Secondary” industries—Bread versus meat—Minerals, petroleum and pigs—Uruguayan agriculture—River Plate cereal exports—Wheat and alfalfa; Agricultural dolce far niente—Again “population!”—An economic deadlock—“Colonists”—Mr. Herbert Gibson’s views—Dr. Francisco Latzina—Cultivable land in Argentina—The Defensa Agricola—Señor Ricardo Pillado—Tabular statistics—Latest Argentine harvest and cereal export estimates—Deficiency of official Uruguayan statistics—General soil characteristics | 215 |

| [xii]CHAPTER XII LIVE STOCK |

|

| The “History of Belgrano”—The first horses on the River Plate—The Goes’ cattle—The first goats and sheep—Early export trade—The first freezing establishment—Amazing pastoral and agricultural changes—The “discovery” of alfalfa—Sheep—Fine stock—Horses—Pigs and poultry—Tired land—Tabular statistics—Favourite breeds—Comparative absence of disease—British prohibition of import of animals on the hoof—Drought—Water supplies of Uruguay and Argentina—A windmill which was not erected—Fencing—Anglo-Saxon enterprise—The Argentine Rural Society; its herd and flock books—The agricultural and live stock show—Trees—The coming colonist and mixed farming—Tabular statistics—The meat trade: its history from the seventeenth to the present century—Market classification—Predominance of U.S. interests in cold storage industry—Influence of cold storage companies on fine breeding—Tabular statistics | 249 |

| CHAPTER XIII FORESTRY |

|

| River Plate timber and fancy woods—Señor Mauduit’s lists and descriptions—Argentina and Uruguay considered as one arboricultural area—Importance of this subject—Railway coach building—Shelter for cattle | 277 |

| CHAPTER XIV LITERATURE AND ART |

|

| Historians and poets—Other writers—Art awaits development—Painting, architecture, literature and music—The native Drama—Oratory—Heroes and history—An Argentine sculptress—Wanted: an author | 299 |

| Index | 303 |

| Map | Front Endpaper |

| A Part of the Iguazú Falls | Frontispiece |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

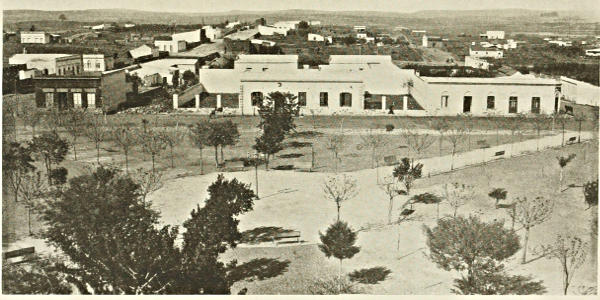

| The Plaza Libertad, Montevideo | 80 |

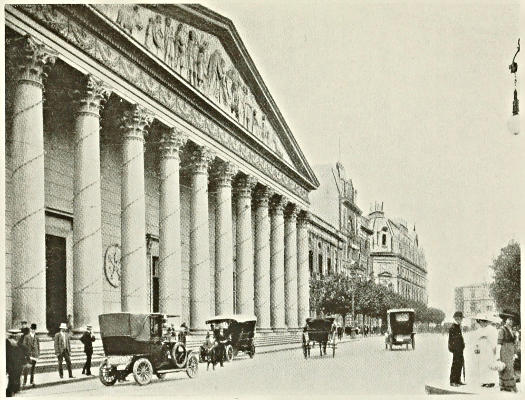

| The Avenida de Mayo, Buenos Aires | 84 |

| The Cathedral and Plaza Victoria, Buenos Aires | 86 |

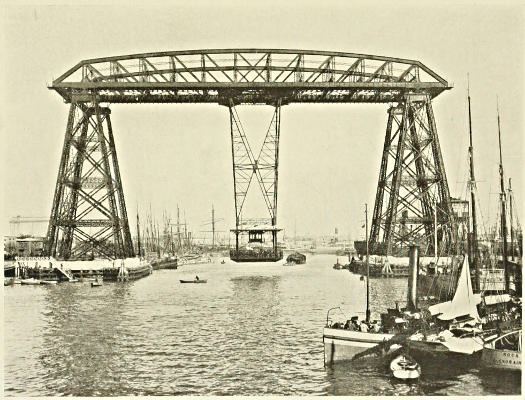

| Transporter Bridge, Port of Buenos Aires | 122 |

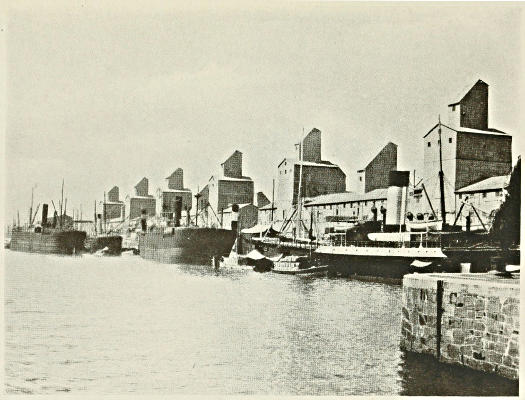

| Grain Elevators, Madero Dock, Buenos Aires | 126 |

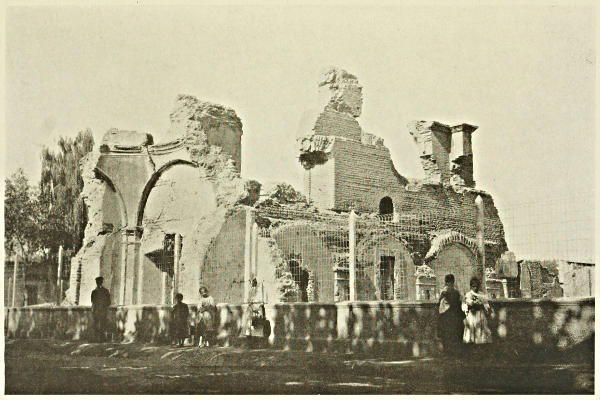

| Ruins of Jesuit Buildings, Mendoza, Argentina | 174 |

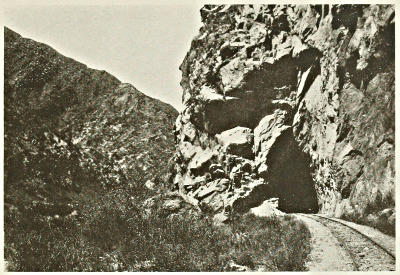

| A Bit of the Transandine Railway, Argentina | 176 |

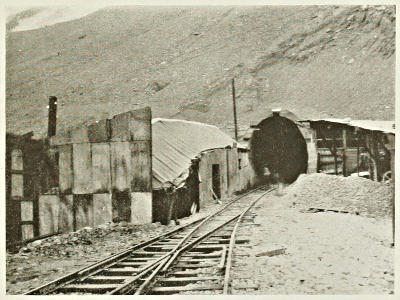

| Entrance to the Summit Tunnel through the Andes (Chilean Side) | 176 |

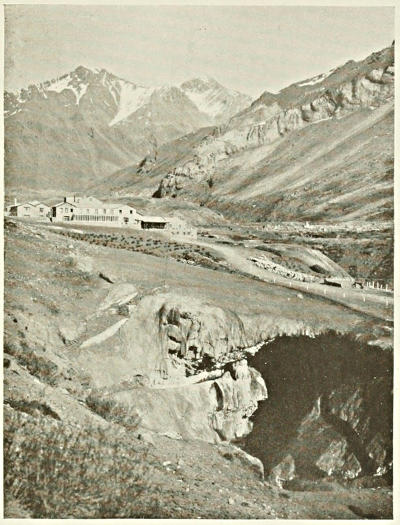

| Puente del Inca; Mendoza, Argentina | 178 |

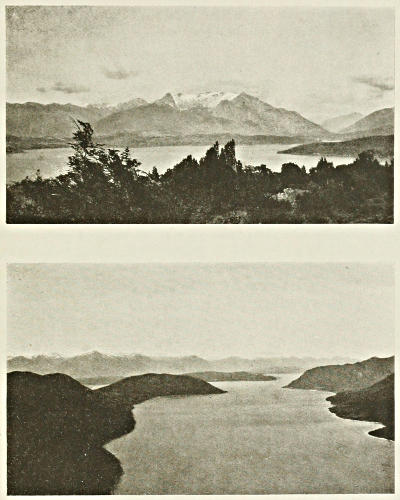

| Views on Lake Nahuel Huapí, Argentine National Territory of Neuquen | 186 |

| Head Portion of the Rio Negro, Argentina, Great Irrigation and Control Works. (Bird’s-Eye View) | 188 |

| A Typical Small “Camp” Town (Rivera, Uruguay) | 212 |

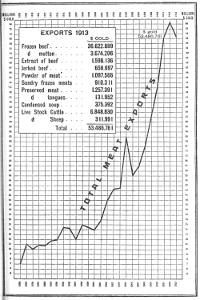

| I. | International Trade of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay | 133 |

| II. | Development of Argentine Agriculture | 243 |

| III. | Argentine Meat Trade | 273 |

| IV. | Argentine Frozen and Chilled Meat Exports | 275 |

For the majority of the Statistics and Statistical Diagrams contained in this book the Author is indebted to the Division of Commerce and Industry of the Argentine Ministry of Agriculture and particularly to the kindness and courtesy of Señor Ricardo Pillado, the Director-General of that Division, for permission for their reproduction; for others to Señor Emilio Lahitte, the Director-General of the Division of Rural Economy and Statistics in the same Ministry. And in Uruguay to Dr. Julio M. Llamas, Professor of Political Economy in the University of Montevideo, and Dr. Daniel García Acevedo, of the Uruguayan Bar, eminent as an authority on Commercial Law.

The Author’s sincere thanks are also tendered to the Buenos Aires Great Southern, the Buenos Aires Pacific, and the Central Uruguay of Montevideo Railway Companies, the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company, Mitchell’s Library, Buenos Aires, and several private persons for permission to reproduce photographs with which this book is illustrated; to the Proprietors of The Times for their consent to the embodiment under the heading “Currency” of the material portions of an article by the Author which appeared in the Special South American Number of that Newspaper under date December 28th, 1909; to the Argentine Committee for the National Agricultural and Pastoral Census taken in 1908 for much information; to Mr. Herbert Gibson for his very kind permission to quote portions of his pamphlet, “The Land We Live On.” And to very many official and other friends of different Nationalities for help freely given to the literary work of the Author in the past, much of which help has borne fruit in this book.

A tale of the Pampa[1] tells how a River Plate farmer of bygone days, seeing his wife and child dead of pestilence and his pastures blackened by fire, fell into a magic slumber born of the lethargy of despair.

He was awakened, many years afterwards, by the scream of a railway engine at his boundary; to find his land fenced in, his flocks and herds improved beyond recognition, and maize and wheat waving where only coarse grass had been before.

This allegory is true.

It tells the whole story of the real development of the River Plate Territories, a development in which the descendant of the original settlers has but comparatively recently begun to take an active part.

He, the Patriarch of the soil, lived on his land while English capital and Italian labour opened up its treasures to the world. In the beginnings of Argentina as a nation, his property consisted of vast herds of long-horned, bony cattle, valuable only for their hides, which roamed the Pampa in savage freedom; untended, save for periodic[2] slaughter and skinning and the yearly rounding up for the marking of the calves.

Later, came the acknowledgment between neighbours, living at vast distances from one another, of boundaries which indicated the huge areas over which each had grazing rights. Later still came the time when the more far-sighted of such men bought wire and, with quebracho posts, ringed in those areas as their own. The foreigner and his railway did the rest to build up the huge fortunes of the children and grandchildren of those far-sighted Patriarchs. For Patriarchs they were, Pastoral Kings surrounded by half-caste gauchos who lived in the familiar vassalage of the great mud-walled, grass-thatched house, and spoke in the familiar second person singular still in use among Argentines towards their servants; otherwise only employed between members of the same family or close friends. Until a very few years ago, these great Argentine families constituted Oligarchies which ruled almost absolutely each over one of the more distant Provinces, the people of which were the descendants of the vassals of their forefathers. The full power of these Provincial Oligarchies was only broken by the centralizing policy of President Dr. Figueroa Alcorta (1906 to 1910). The curtailing of their power was very necessary for the credit of National Finance and Justice, for that power was often exercised with a mediæval high-handedness unsuited to twentieth-century ideas.

The disintegration of the power of local Oligarchies, each of which completely dominated the Congress of its province, was one of the final but quite necessary steps towards putting the house of Argentina into perfect political and financial order; especially as Provincial Governors, hitherto always members of the Oligarchic families, were also almost invariably members of the National Senate. Add to these considerations the further one that the Provincial Courts had somehow or other gained a reputation for not meting out justice to political friend and foe alike, and that much[3] complaint was heard about the difficulties encountered by some persons in even working the way of their cases up to the admirably impartial hearing of the Federal High Court of Appeal; since, for instance, it is difficult to appeal from a decision which has not been given, and which you seem to possess no means to obtain, even as against you.

All these inconveniences and scandals had long called imperatively for reform, but it was reserved for Dr. Figueroa Alcorta to discover the way to successfully bell these powerful provincial cats.

The way he found (which is referred to more fully in a later chapter) was essentially South American; but, as many things in South America which at first sight appear strange to European eyes do, it worked very well.

It is desirable here, however, to make quite clear the fact that any political South Americanisms which may still survive in Argentina are strictly confined to her internal and local politics and administration. Within that sphere it might almost be said that only the Judges of the Federal High Court of Appeal keep themselves completely clear of any shadow of suspicion. If you get to the Federal High Court you have the Law of the Land administered with unflinching impartiality. The only leaning of which that Tribunal has ever been accused (and that only jokingly) is that of an inclination to decide against the Government. Because, its judges, once appointed, cannot be removed unless on the ground of gross misconduct; whereas all other functionaries in the country are more or less liable to feel the effects of political influence. The National foreign or commercial policy is also as transparently pure and fair as it is possible to be. Argentina knows her best interests much too well to seem even to offend against European ethical standards in anything which touches external policy or Foreign interests, however remote.

As for her internal politics, these have been, until very recently, at all events, left by common consent of foreigner[4] and native alike to the sweet will of the caste of professional politicians. These people intrigue for place and profit and have vicissitudes, triumphs and defeats, without the real wealth-producers of the country knowing or caring one way or another. The doings of the Ministries of Finance, Agriculture (embracing Commerce and Industry) and Public Works and the legislation affecting matters appertaining thereto are all that matter to the Bankers, Traders and Agriculturists or the great Railway Companies; and these leading Official and Commercial and Industrial Classes are the only people of real consequence in the land; unless one adds the Municipal Authorities of the Cities of Buenos Aires and Bahia Blanca.

The actual Government, however, is jealously kept in native patrician hands. If one finds a foreign name in the list of high officials it may safely be assumed that the bearer of it is connected by marriage with one of what may be called the great ruling Argentine families, with names recurrent in the country’s History.

These families constitute the real aristocracy of the Republic, and are mostly possessed of very great wealth. Kind and sympathetically courteous to the stranger as are all Argentines, one cannot but smile when one finds writers implying that entrance into Argentine Society is easily effected by anyone who, as I once saw it stated, could play a good hand at bridge.

As a fact, no stranger ever becomes a member of the best Argentine Society; he may find himself in it at brief, fleeting moments, but he is never of it. As in the aristocracies of the old world, all its members are connected more or less remotely by blood or marriage, usually both, with one another. One may know intimately many men prominent in Argentine Society, may be received by them at their houses now and again and mingle there with other men, their kindred; but the charming conversation one enjoys when there is not that which was going on when one[5] entered, and will continue after one has left again. Argentine ladies only receive on set, formal occasions; unless in such public places as the Palermo Race-course or the Rambla at Mar-del-Plata. Small and select dinners take place rather at the Jockey Club than in private houses. Under a somewhat effusive external manner, the Argentine has all the reserved exclusiveness of his Spanish ancestors. Gold has its weight in Argentina as elsewhere; but it has more efficacy as a key to society in many European capitals than in Buenos Aires; notwithstanding the almost childish fondness of Argentines for the display of their own wealth, a characteristic which makes them (and other Americans) beloved in Hotels and Restaurants throughout the world. The one characteristic for which the Argentine does not get full credit from the superficial observer is the very strong vein of common sense which underlies his more immediately noticeable affectation of manner and behaviour. A great deception is always in store for those who do not appreciate the fact that the most boisterously extravagant Argentine never really loses sight of the fact that 2 and 2 make 4 and no more and no less. Yet this should be apparent in a nation which has known so well during the fifty or sixty years of its real development how to let the foreigner work out that development at a good profit for himself, of course, but at a much greater one for them. The Argentine, while availing himself of every advantage derivable from the influx into his country of foreign Capital and Labour, has never really loosed his hold on his own independent Government nor the land. His land is and has always been the source of his fortune, and to his land he clings with unrelaxing tenacity. If there is a good bargain to be made in real property, it is an Argentine who immediately takes advantage of it to increase his probably already large holding.

He it is who most readily lends money on mortgage, at a high rate of interest, on real property. He knows only of one way in which to invest the surplus of his income—in[6] land or the things intimately connected with land and its immediate productivity. Agricultural enterprise he understands and daily appreciates more and more its scientific working. Intensive farming is already practised by him in those parts of the country where land is most valuable. He breeds as fine cattle and sheep as any foreign breeder or colonizing company.

But for commerce other than purely agricultural he has no bent. So he wisely leaves it in the hands of the stranger, who thereby develops his towns, and builds railways and tramways; all of which go to the enhancement of the values of Argentine real property.

Now and again there is a pseudo-patriotic clamour in certain sections of the Native Press over what is denounced as the exploitation of Argentina by the foreigner. But all this is mere froth born of journalistic need of “copy”: mere great-gooseberry matter for a dull season. That it is no more was proved a few years ago by the great English Railway Companies.

They became weary of being denounced as the worst kind of exploiters of an innocent bucolic people; and, in reply, published broadcast an announcement that they would transfer a certain large quantity of their shares at par (the market price being considerably higher) to Argentines who might thereby qualify themselves not only for a share in the Companies’ profits, but for seats on the Boards of Directors; where they could have a voice in the management of what was being denounced as a vast system of exploitation. To this very liberal, almost quixotic, offer there was no response. For the simple reason that, whilst the railway dividends did not exceed 7%, land mortgages carried 10% or 12%, and the yield from immediate agricultural enterprise proportionately more.

Every branch line opened by the railways, often at huge expense of expropriation, spells fortune to Argentines. If the railway gains in a less degree who should complain?[7] No one really does, everyone really concerned being much too well aware on which side his own particular bread is buttered. As I have said, the Argentine is possessed of a quite preponderating amount of common sense.

His attitude towards the foreigner is, “I give you all liberty and protection for any enterprise you may wish to carry out in my country, by which you may become very rich; but the country itself and nearly all the land in it is mine and will remain so.”

The last thing the Argentine will part with as an individual or as a nation is land.

Grants of fiscal lands were made in the past with scandalous liberality for political services, but to Argentines. Mighty little of such lands, none of any, then, apparent value, went to foreigners; whatever they might have done for the country’s development and good. Now, few grants of such lands are made to anyone; the National and Provincial Governments appreciating too fully the advantages of their retention as aids to power and wealth.

In all this the Argentine is right from his natural point of view; but his obstinate maintenance of it is gradually bringing certain economic problems of vital importance to a stage when some way will have to be found out of the dilemmas which they already present.

The chief of these problems is that of agricultural labour. What inducement does Argentina offer to the class of colonist she needs most, the man with a wife and family to aid him in his work and with, perhaps, a small amount of Capital?

He will find plenty of work and people to employ his labour at a liberal wage as soon as he lands. He will be taken, if he so wish, free of all cost to himself, to one or other of the more or less distant parts of the Republic, where he may be set to work on virgin soil at a wage, or, may be, on a half share of profits for a period of three years. On the scene of his industry he will find an Italian or Galician[8] storekeeper who will supply his every reasonable want on credit, taking as security the share to come to him of the profits from the land to be worked. The storekeeper will also charge a high rate of interest on prices of his own fixing, unembarrassed by any competitors within a radius of very many miles; or, if there be such, he and they will know well enough how to preserve a rate of profit which would astonish an European shopkeeper.

At the end of three years the landlord will have his land in good working order,[2] and the storekeeper will have most, if not all, of the new colonist’s share of profits. The latter can then, if he likes, have some more virgin land on similar terms. He is a mere labourer, a worker for others, with no betterment on his own horizon.

There is as yet no real practically working official machinery by which he can obtain a direct grant of land in freehold to himself; such as exists, with other added facilities, in each of our own great agricultural dependencies such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

For this reason alone, the rural population of Argentina has almost ceased to show much more than a vegetative increase. The population of the whole Republic is that of greater London spread over an area only a very little less than that of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, Holland, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and Switzerland put together.

This lack of increase in the rural population is not due to Argentina being a country unknown to the appropriate class of people. There are thousands of Italian peasants who go there regularly every year as harvesters, and who return to their own country as soon as the crops are gathered in. They know Argentina and the natural richness of her resources as well as do born Argentines, but they also know that they cannot get land. Only wages; the purchasing power of which is so much greater in Italy that there they[9] can live on them in semi-idleness for the remainder of the year, whereas they would attain no greater pecuniary advantage by remaining and working permanently in Argentina, where the cost of living is relatively very great. So they remain “swallows” as they are called, coming and going with the beginning and close of the harvest season.

If Argentina wants settlers, and she does need them badly, she must make up her mind to give them land.

And she must also make a thorough overhaul of the titles to all lands as yet not under cultivation. Because many of such lands are merely traps for the unwary who may be induced to occupy and develop them only to find himself, after he has ploughed and planted, called upon to pay rent to some resident in Buenos Aires or some other town whose property they turn out to be, under some long-forgotten Government grant, and who has not only never visited them, but has also practically lain in wait for some innocent settler to develop them under the impression that they were his own. Cases of this kind have happened over and over again; and the deluded settler, who may have even purchased the land in question at a public auction or have obtained it from some self-styled colonizing Company, finds himself with nothing but a vista of wearisome and costly litigation before he can hope to grasp a usually very elusive remedy for his wrong. Generally, he gives the whole thing up in despair and becomes a tenant of the land on which he has already spent all his small capital. These things are also known to the Italian harvester, and the knowledge of them acts as a further deterrent to his becoming a settler.

As Argentina is blessed with almost the best possible laws about everything sublunary, she has, naturally, first-rate colonization regulations. Only these are confined to her statute books and sundry pamphlets which lie in dust-covered heaps in the Ministry of Agriculture. But there is as yet no real working machinery for the carrying out in practice of all these excellent embodiments of the results[10] of experience of farming colonization all the world over. There are no officials whose exclusive duty it is to attend to the multiple exigencies of true colonization, and none capable of such work if they were suddenly called upon to do it, for lack of the necessary experience.

An intending colonist may therefore land in Buenos Aires with a small but sufficient amount of capital for a reasonable start in, say, Australia or Canada, and may wander about that city till, if he be foolish enough, his money is all spent without ever having found any Government office or official willing or in a position to put him into possession of the land he wants.

He usually, after a few weeks of fruitless search, goes back to Australia or New Zealand or wherever else he may have come from, disgusted with Argentina and her ways; of which he, on getting back, gives an account which effectually damps off any existing enthusiasm in his neighbourhood for emigration to the River Plate for a long while to come.

The Argentine Government spends plenty of money in advertisement, and true advertisement, of the fertility and marvellous climates of a Republic which extends over 35 degrees of latitude, but neglects to make provision for those who may desire to respond actively to its propaganda. This neglect is due, really, to an inherent incapacity for detail, part of the Argentine nature which, therefore, is terribly prone to get tired half-way through a job. In South America, generally, a wonderful amount of enthusiasm is always available for the planning of new schemes. The declamatory exposition of their sovereign virtues and glory amid the acclamations of sympathetic Board or Committee meetings is a grateful task; as is that of the dissemination of these discourses in pamphlet form, in which also the full list of the names of the originators and supporters of the scheme appears. It is, however, when practice shows unworkable flaws in splendid theories, when the drudgery of[11] adapting high-flown principles to plain everyday drab facts must take the place of inaugural banquets and florid speeches, that Argentine enthusiasm has a regrettable way of petering out. Soon, something newer and of a different kind is started by someone else. The meetings and banquets are held in its honour by other groups and the former scheme passes to a shadowy land, the way to which is always kept paved with a plenitude of good intentions.

Capital will always be forthcoming for profitable enterprise; as will Labour if that enterprise be made profitable to the worker—a good and useful class of whom can only be induced to emigrate by the prospect of permanent betterment of the conditions of life. The natural ambition of every man is to work for himself, to be the master of the results of his own efforts and to possess those results as a provision for his old age and his children. This a new country or colony must offer if it would obtain the high level of intelligent labour which it needs for its fullest and best development.

On the other hand no one need starve or go hungry for long in any of the countries of the River Plate; unless he elects to be and to remain a persistent loafer in one of the large towns. Even then he has only to ask and he will receive food, at almost any restaurant or private house. If he refuse to beg or to leave town, he may suffer hunger and thirst, otherwise he cannot. To begin with he can always get a job at one thing or another from any of the numerous private agencies which have standing orders for labour, and even schoolmasters, for the “Camp,” and which are as avid of candidates for such jobs as any crimp of the old days was for men of any kind to sling aboard a ship.

Once in the camp any man who has had the grit to go there is sure of finding someone wanting some kind of work which he can do in some sort of fashion. There he will recover such of his normal health and strength as he may have lost as a city unemployed, and will soon shake into[12] a capacity for, and get, something better to do than his first job.[3]

The native agricultural labourer or “peon” is a very free and easy and light-hearted kind of person, and must be treated accordingly if his services are to be retained. He is never rude unless in answer to obviously intentional offence offered to himself, and will work very much harder for an employer he likes than for one he finds unsympathetic. Indeed he will only remain with the latter on his own tacit understanding that he takes things easily.

When he has accumulated a few dollars of wages he will take himself off to the nearest store or township and indulge in such dissipation as the place affords. From thence he departs with perhaps a few cheap handkerchiefs or other small finery, in the breast of his blouse, which he bestows as gifts at various friendly cottages; at each of which he may while away a day, partaking of pot luck, a shake down on the floor, and innumerable mates and cigarettes, making himself merrily agreeable to his hosts. When he gets tired of this, or has exhausted the immediate circle of his friends, he will return to work on the property on which he left off; or somewhere else should he find himself not as well received on his return as he had hoped.

It is pretty much all one to him. An experienced native peon need never go far begging for a job.

These men are strong and wiry, capable of spurts of very hard work indeed; so that, even with frequent intervals for chat with everyone available, their average day’s work is usually by no means a bad one. Severity in an employer[13] they will take with perfect good humour; but any affected superiority, or “side,” on his part will meet with a very contemptuous resentment. They are true sons of a Republic, though holding school-learning in the deep respect observable in peasantry almost all the world over.

The Argentine peon inherits much of the ready wit and extraordinary gift of repartee of his immediate ancestor the GAUCHO; of whom he is the modern representative. With whom, however, a concertina has most unfortunately taken the place of the guitar. But as a bachelor he is the same flirtatious, lady-killing scamp; loving often and riding away from, most frequently instead of with, the lady of his ephemeral choice.

His wit, and hers, most frequently take the form of double entente. An interchange of chaff has always one perfectly innocent superficial meaning and another the realization of which would redden the ears of a British bargee. Both parties to this skilled contest of phrases keep perfectly immobile countenances and neither gives a sign, except by his or her, always latent, reply, of any perception of the underlying significance of the conversation.

This exchange of wit is a form of art derived from the gaucho Payadores or minstrels, who improvised their songs in verses which, on the face of them, were hymns to Nature in its purer forms, and contrived simultaneously to either hugely amuse ribald company or else to convey insult to a present rival payador who answered in like manner in his turn; hidden insult being thus intentionally heaped on insult till a fight with knives succeeded singing. A fight in which all present took sides and joined.

Thus were Sundays enjoyed in the PULPERIAS (canteens) of the older times, over a quarter of a century ago.

A now almost lost art of those days was the knife play in which the gaucho was then an extraordinary adept. Even now gauchos may be found, in the distant northern Provinces,[14] who in a duel, according as it be a serious or a playful one, can kill or just draw a pin-prick’s show of blood at will from their adversary. In these duels the knife is kept in constant rapid, dazzling movement, while the poncho or gaucho shawl, with a slit through which the head is passed when wearing, is wrapped round the left arm which is used as a guard.

The gaucho was a picturesque figure in his chiripá[4] or festal, wide-bottomed, lace-frilled trousers, a broad leathern girdle studded with silver coins and his silver-mounted, high-pommelled saddle. The chiripá and girdle remain; and one may still see a camp dandy glorious on feast-days in a saddle adorned with silver mountings.

But the cow-boy utility of the gaucho waned with the advent of scientific farming. He had no taste nor aptitude for such new-fangled ideas; and now his sons are mostly to be found in the army, the police, or that very useful body of firemen and soldiers too, the corps of “Bomberos,” men who can be relied on at any moment to quell a fire or a riot in their own very effective way. They fear neither flames nor turbulent strikers, and are only too ready, in the case of the latter, to shoot first and listen to orders afterwards. Another body of men drawn almost exclusively from gaucho sources is the “Squadron of Security”; a mounted corps of steel-cuirassed and helmeted semi-military police, also used to clear the streets of political or other disturbances. Three trumpet blasts sounded in quick succession are the signal for a charge in lines extending, for instance, over the whole breadth of the Avenida de Mayo. Such is the law and everyone, as in England, is presumed to know it. If he do not, and therefore fail to take prompt refuge down a side street or in a shop, so much the worse for him. The Avenida will be cleared even if he be taken to the Asistencia Publica as a consequence of the[15] process, without any valid claim for damages. He heard the “Clarion” and is assumed to have contumaciously disregarded its warning.

It might be thought that the vegetative increase of such a hardy nucleus of native population would suffice for the Labour needs of the country. There are, however, many reasons for the fact that it does not. The chief of these is the general refractoriness of the Indian to the process of education on the lines of the white races. You cannot by any means make a white man out of an Indian any more than you can of a Negro. And the gaucho has usually more Indian (and Negro, from the slave days) blood in him than he has white.

Unrivalled in the days when vast hordes of semi-savage cattle needed rounding up and cutting out with his lazo and boleadora, the gaucho has not always the patience nor the regard for detail needed for the care of prize Durhams, Polled Angus or Herefords; nor is he at his best with modern agricultural machinery. Neither does his character lend itself to the dull discipline expected and necessary on a farm to-day. He can no longer with impunity stay the extra day or two at the canteen to which his savings entitle him; and on the farm he finds himself confined to the more subservient work. Against all this his native pride rebels, and he gradually drifts into the army or the police, where he is gradually being exterminated by the disintegrating effects of idleness and lack of the hard physical exercise which kept his ancestors in health. A greedy meat-eater, he succumbs as often to stomach as to lung trouble.

Population! In every other way nature is most bountiful on the River Plate. If only Argentina were more thickly peopled her wealth would be phenomenal in the world. For it must not be thought that grain and cattle sum up the whole extent of her possible productivity. Far from it: her output has hitherto been confined to these commodities because they were so obviously those which most readily[16] yield immediate profits, without in the first place demanding any great outlay of capital or scientific acquirements. Cattle there have always been on the Pampa since the time of the Goes’ cows;[5] and as for grain, the virgin soil barely needed scratching for its growth. Thus cereal cultivation and cattle raising naturally became the national industries, and the population has never been sufficient to attend even to all the possibilities of these, let alone others. Nevertheless, there are many more which Nature has in store for these marvellous countries with their great variety of climates.

Sugar (pretty badly exploited till recently), coffee, cotton, tobacco (already grown in the North and even, to a comparatively small extent, in the Province of Buenos Aires) and timber of many and valuable kinds are among the future produce of the Southern Republics; while the wool output of Argentina could be greatly increased.

No lack of capital would be felt were there the necessary skilled management and labour available for the production of, leaving sugar and timber apart for the moment, let us say cotton and tobacco.

In the cultivation of both of these, much depends on selection of kinds according to soil and climate and on the right moment for gathering. It is owing to ignorance in these regards as well as to labour difficulties that several attempts to cultivate these crops on a large scale have hitherto only resulted in failure.

Given the necessary science and labour, soil and climate may well be trusted to do the rest for assured success.

Nothing is lacking to the countries of the River Plate but population. Given adequate human agency to exploit their evident and latent treasures, they have before them a future[17] prosperity which can only be called incalculable in its marvellous immensity.

Note.—A fact that cannot escape observation by the reader of this book is that of the comparative absence of exact statistical information disclosed in it in regard to Uruguay in comparison with that which appears relating to Argentina. The reason of this is that while the latter country has now had many decades in which to put its house in order, the former is still so busily occupied in that necessary task that its officials have as yet had little time to devote to compiling authoritative statistics of a progress of which it must not, therefore, be inferred that they and their country are not very justly proud.

Thus figures which are easily available through the patriotic ability and industry of Dr. Francisco Latzina, the chief of the National Argentine Statistical Department, and so clearly and strikingly digested by Señor Ricardo Pillado, the Director of the Division of Commerce and Industry in the Argentine Ministry of Agriculture, a Ministry the scope of whose work is extremely wide and all-important in the Republic, have really yet no counterparts in Uruguay, where one is rather left to guess at the general effect of such isolated agricultural trade statistics as alone are immediately available. Figures are to be had by the private courtesy of individuals connected with various administrations, and these, if not exact, are no doubt approximately so; but they do not bear the stamp nor the proof of comparison which should be found in authoritative figures.

The author knows from the test of his own previous experience that such few figures as he has given concerning Uruguay are substantially correct, and must therefore, though reluctantly, ask the reader to take his word for it that they are so.

As has been indicated elsewhere in these pages, the shock of the commencement of the Great War found the River Plate Republics already in a condition of considerable local depression. This was owing to relatively poor harvests, due to a long continuance of exceptional and ill-timed rains; a consequent collapse of land speculation and the usually sinister effects of slump after a long period of boom; and the condition of money markets, for some time past disturbed by the fear of the results of political complications in the Balkans.

The Governments of Argentina and Uruguay must be most warmly congratulated on the vigour and promptitude with which they faced the fact that, with the declaration of war in Europe, they were suddenly left to their own resources to an extent they had never experienced during the few decades which really form the whole period of their true economic history.

Lucky it was for Argentina that such a veteran statesman as Dr. Victorino de la Plaza occupied the Presidential chair, and that he had the aid of a man of such high intelligence and reputation as Dr. Carbó as Minister of Finance; fortunate also for Uruguay in having Dr. Viera (since elected President) at the head of her Ministry of Finance.

Honour is also due to the Officials of the State Banks of both nations and to the private Banks and financiers who[19] lent such an untiring and efficacious aid to both Governments in the hour of pardonable alarm; alarm which was prevented from developing into panic by the prompt and statesmanlike measures adopted.

Really, as Mr. C. A. Tornquist justly observes in an article cited in these pages, it cannot be said that a “crisis” exists in a country while its vital forces are in full development.

Still, in Argentina and Uruguay these forces had not for some time been in full operation, from causes stated above; and, therefore, panic would not have been a surprising result from alarm falling on depression, before cool reason had time to assert its reassuring influence.

It soon did so, however, thanks to the virile and sound handling of the situation by the heads of Government and Finance.

Congresses assembled and their usually heterogeneous political elements unanimously and swiftly agreed to pass the several measures of economic defence placed before them.

During seven days’ Bank Holiday the finance of both Republics was set in good order; not only to avoid ill consequences from the initial and any likely future shocks, but to enable the countries to profit—as there can now be little doubt they are doing and will do—from the political and economic disturbance of Europe.

As Señor Carlos F. Soares, writing in La Nacion (Buenos Aires) under date January 1st, 1915, said:—

The laws and financial and economic measures necessitated by the European conflagration have proved opportune and efficacious.

Thanks to them, danger to the Credit Houses and Institutions was avoided; Internal and Foreign commercial pressure was lessened, the gold stock in the “Caja de Conversión,” which guarantees the value of the paper currency, was preserved; the escape of gold from the country was avoided; the lack of foreign bills of exchange was compensated for by deposits of[20] gold at the various Argentine Legations; shortage of coal and dearness of wheat and flour were foreseen; and, finally, means of obtaining its value were assured to the natural wealth of the country.

Only one Buenos Aires Bank (of comparatively small importance) failed to reopen its doors after the seven days’ holiday; a failure which there is some reason to believe was by no means entirely due to the War.

Not one Bank and very few Commercial Houses availed themselves of the Moratorium; a fact which is highly creditable to the Local Banking and Commercial community.

The arrangements for the deposits of gold at the Legations constitute a feature novel to the system of International Exchange.

After all this accomplished in so short a space of time, who will continue to throw the reproach of “Mañana” at either Argentines or Uruguayans? A reproach long since unjustified by the attitude of the inhabitants of either of the River Plate Republics towards any matter the advantages of which they grasp.

No European Statesmen and Bankers could have more promptly realized and carried out the necessary measures for the economic protection of their country.

The present of Argentina and Uruguay was thus assured. What of their future?

Prophecy, which is generally counted as hazardous, is especially so when it is about to be printed, and may still be read by the light of the experience of several years hence. Still, some Commercial and Financial angels have not feared to tread the ground of prophecy as to the immediate and post-bellum future of Argentina and Uruguay; and not only has competent authority not feared to forecast results in this regard, but there is a remarkable unanimity of influential opinion as to the probably favourable effects of European affairs on the economy of the River Plate Republic. Always supposing, as there seems every reason[21] to suppose, that these Republics continue to have the commercial and common sense to manage their internal affairs in such manner as to be able to derive the greatest possible pecuniary benefits from the troubles of European nations.

One, perhaps the chief, in his courage of declaration of these prophetic authorities is Mr. C. A. Tornquist; a man having very large financial and commercial interests on the River Plate and enjoying a very high local reputation for business acumen and honour. His whole life has been spent in the higher financial circles of Argentina.

Therefore the author has thought well to cite here some portions of an article published by him in the Argentine Press, a translation of which appeared in The Review of the River Plate, under date December 25th, 1914.

In this article Mr. Tornquist says:—

From this chaos (that of the European War) there will arise perhaps an Asiatic country, and, quite certainly, some American countries, and in the first place the Argentine Republic, which, on account of the class and special conditions of its products, is called upon to benefit from the situation more than any other country in the world, as even the United States cannot export in any quantity the noble products produced by Argentina as they require them for home consumption. This war not only does not create difficulties for our economic development, as will happen to nearly all the other countries in the world, but, on the contrary, it will stimulate it, and for this reason, the longer the war lasts the more our national economy will gain at the expense, sad as it is to say it, of the countries now at war. Whilst the war lasts the prices of the majority of our products will not decline, for many of the countries which produce the same goods as we do are at war, and on this account the demand is bound to increase. The first effects of this advantageous situation will bring about the disappearance of what we call here “crisis,” but which is nothing more than a “commercial indigestion,” brought about by excessive speculation, and which has principally affected speculators, and has done absolutely no harm to pastoral or agricultural industries, which are our principal[22] sources of wealth. … It cannot be said that a country is in “crisis” when its vital forces are in full development. This does not mean, nevertheless, what many erroneously think, that if the next crop is good they will be able in 1915 to sell their lands in the vicinity of cities and summer resorts and speculative regions at the prices ruling when they purchased them. Nothing of this will occur, and only the value of revenue-producing property will normalize itself, and will be placed at a value corresponding to a return of 8 to 9 per cent per annum. On the other hand, I believe that several, perhaps many, years will pass before it will be possible to liquidate properties which do not give revenue at the prices which their owners desire. … A favourable factor which might become important, perhaps in the not distant future, is the immigration of the “capitalist” farmer from Belgium and other European countries, who prefer to liquidate their affairs there and come to Argentina with what remains to them, and so get away from the taxes which of necessity the Government of the conquering or conquered countries must impose so as to re-establish their finances. It is a very interesting fact for ourselves that after all large wars or revolutions in Europe in modern times there has been an enormous increase of good immigration in new countries, and especially to America, from which the United States has been the first to benefit, because in that epoch the future of South America was based solely on the gold mines of Peru and the coffee and diamonds of Brazil, whilst the Argentine Republic was only known by its “sterile Pampa and Patagonia,” and its internal revolutions. To-day these things have changed, and if any country is to interest the capitalist immigrant it will without doubt in the first place be the Argentine Republic, because it is in the best condition to receive them, especially if they are convinced that the value of property is not inflated. It is the duty of our Government to make all this known to future immigrants by means of serious propaganda. … Then we shall have to struggle against the lack of tonnage for exporting our crop, but we should not forget that whereas to export with regularity is for us an economic question, for the belligerent countries, purchasers of our produce, the matter is of vital importance, as it is a material question not to die of hunger, and of indispensable necessity to be able to carry on the war, so that those countries are even more interested than ourselves that we should be able to dispose of the necessary means of transport. We take as[23] our basis of the probable assets of our balance of payments an exportation to the value of $580,000,000 gold. At first sight this figure appears high, but let us analyse it. Our record of exports was in 1912-13 $513,500,000 gold, of which $306,000,000 corresponded to cereals and the remainder to produce not affected by locusts, droughts, rain or frost, that is to say, the crop of that year represented $306,000,000 gold for produce exported, and we will suppose $104,000,000 remained in the country, making a total of $410,000,000. If the crop of this year should be 25 per cent less than our “record” crop we should have “at the prices of that time” $307,000,000 as the value of the harvest, and there would remain, deducting what the country requires for consumption and seed, over $200,000,000 for export. But the actual prices and those in perspective are 25 per cent higher than the others, so that would give $250,000,000 for exports of cereals, besides which there are the other products (meat, wool, hides, tallow, etc.), which then represented a value of $207,000,000 gold, and which to-day are worth 20 per cent more, that is to say, $250,000,000 gold, making a total of $500,000,000 gold. To this we must add the value of 2,500,000 tons of maize, the balance of last year’s crop which remained to be exported on October 1st, 1914; the possible value of the export of horses; the value of the sugar exported, which is more than 60,000 tons, and which will probably be duplicated; the export of woven goods (ponchos, cloths, etc.) and articles of saddlery and tanned goods for the European governments; alcohol and other products of lesser importance, which come under the heading of extraordinary exports. It would not therefore be at all extraordinary if we reached $600,000,000 or even passed that figure, which will be the case if our harvest exceeds our estimate. … If the crop turned out to be a “bad” one[6] (that is to say, that it failed in certain parts, as due to the great extension of area, it is not possible to-day for a whole crop to be lost) and it only results in 50 per cent of that of 1912-13, we should still obtain a total value of $205,000,000, and there would remain after deducting the necessities for home requirements $100,000,000 gold for export, calculated on prices of two years ago, but in this case the prices would rise much more than 25 per cent, and for this reason the consumption of cereals in the country, as well as imports in general, would show such a marked decrease, that[24] the favourable superavit in the balance of payments would never completely disappear.

I take as my starting-point the sum of $460,000,000 gold, made up as follows:—[7]

(a) Imports $270,000,000 gold. (b) Service of the Public Debt payable abroad $50,000,000 gold. (c) Interest on Cedulas and on capital placed by foreign companies on mortgage $31,000,000 gold. (d) Interest and dividends on foreign capital in railways $42,000,000 gold. (e) Interest and dividends on other foreign capital $27,000,000 gold. (f) Savings of immigrants and emigrants $24,000,000 gold. (g) Expenses of Argentines abroad $6,000,000 gold.

The sum total of all these items is $460,000,000 gold, so that we have

| $ Gold. | |

|---|---|

| Assets | 580,000,000 |

| Liabilities | 460,000,000 |

| Total balance | 120,000,000 |

in favour of the Argentine Republic, a sum which can be increased if the harvest is very good and imports are less than I estimated, and decreased if the harvest is bad and imports greater than $246,000,000 gold. From this it will be seen that if my calculations are confirmed Argentina will receive from abroad the sum of $120,000,000 gold for balance of accounts for the commercial year of 1914-15. To demonstrate the importance of this fact I will mention that for the year 1913-14 the balance was $185,000,000 against Argentina; in 1912-13 it was $200,000,000 in contra, and in 1911-12 $202,000,000 in contra, so that compared with the three previous years Argentina will have a difference in its favour in the balance of payments of $300,000,000 gold!

What do these figures signify?

$120,000,000 gold is equivalent to the service of the National Debt for two and a half years, and is more than half the amount actually deposited in bullion in the Caja de Conversión. It also represents the half of all that the country owes abroad for mortgages.[25] On the other hand, $300,000,000 are three-fourths of all our national external debt, are two annual national budgets, as well as the total value of a good harvest. Practically speaking, it results that the Argentine Republic will receive with these $120,000,000 gold a sum which exceeds the average of the new foreign capital which has come to the country in the last few years, which will compensate for the absence of capital which formerly came to the country seeking investment, and will contribute to develop the economic forces of the country. Outside of this $120,000,000 gold it is logical to imagine that some capital will come, as some railways and other foreign companies have recently made issues abroad and others will place their profits here. There are also the various financial operations of the National and Provincial Governments and the Municipality of the capital for the payment of debt services or to consolidate the floating debt, for although money does not come to the country this will diminish by these operations the emigration of capital in respect of items b, d and e of the balance of payments, that is to say, the dividends and interest on foreign capital placed in commercial enterprises and railways, and thus also the service of the external debt, which otherwise would have to be remitted and all of which I have not taken into account. Besides, where will Europeans place their savings? In European bonds which continue to depreciate on account of the issue which will have to be made for the war debt and to consolidate the monetary situation? Assuredly more money will come here than many believe in search of investment. The United States with its new monetary law does not require as much as before. To Brazil and Chile it will not go for some time, neither to Mexico or the Balkans.

An interesting point is the manner in which these $120,000,000 will come into the country.

It should come in the form of Argentine bonds (“Cedulas” principally), and in coined gold all that is not employed to cover debts payable to our commerce and industry to European banks and manufacturers, which sums cannot be very considerable, although it is difficult to fix them. … The reaction will bring about the investment of savings in Argentine revenue-producing bonds instead of in purchases of land on monthly payments; it will bring about a reduction in interest and as a consequence of this an abundance of money which will stubbornly withstand speculation in land. The movement of the Stock Exchange will[26] reawaken—it has been dead since 1906—and there will be money for mortgages and business, replacing that which came from abroad and which has to be repaid. All of this will bring in time an immigration of Cedulas of our external debt bonds and of railway and industrial shares. What will probably not take place for several years, perhaps for many, is what I mentioned at the commencement, namely, that land and other objects of speculation which do not produce anything will rise to prices which their owners dream about and pretend to obtain, as neither banks nor capitalists will invest their money in such objects, neither will they stimulate speculation, all of which are circumstances which will contribute to develop the economic forces of the country and to foment its industries and its commerce until there arrives for the Argentine Republic the psychological moment of being able to produce all that it consumes, that is to say, become self-supporting, without having to fall back on European industry, a situation at which the United States of North America have arrived after great efforts.

Remains only to be added that Mr. Tornquist appears to have omitted consideration of the possibility of money being withdrawn from South America by European investors, not on account of any lack of confidence, but simply because such investors may under existing conditions have actual need of all the pecuniary resources they are able to realize.

For the getting in of the 1914-15 harvests there has been sufficient labour available; because of the stoppage of much municipal and building work, on account of retrenchment rendered necessary by the situation. But for the future, if, indeed, they are to occupy the prominent place in the world’s economy for which Nature appears to have destined them, the River Plate Republics will have to increase their agricultural populations greatly and speedily.

The need of this is now fully realized in both countries, but, strange to say, it is in Uruguay where there are no fiscal lands that proposals for probably useful legislation to this end have attained the greater maturity. It is there proposed, in effect, that the Government should purchase, at least portions of, the present holdings of the large landowners[27] and colonize the land so purchased on systems similar to that obtaining in, for instance, Canada.

Argentina still has large tracts of fiscal land, but no doubt her large landowners will also aid towards the colonization by granting to colonists greater fixity of tenure and greater facilities for mixed farming than the latter have been hitherto able to obtain.

With regard to Belgian emigration to the River Plate, the fact which cannot be lost sight of is that the Belgian, especially the Fleming, is a person deeply attached to his own land and his own ways of living. It seems certain that if Belgians of the agricultural class are to be colonized in South America, such colonization will have to be effected by means of settlements like those of the Welsh colony in Chubut and the Swiss colony in Colonia.

A Flemish family would view with vehement disgust the ramshackle home of an Argentine or Uruguayan CHACRERO (small farmer); a disgust which, communicated to their friends in Europe, would effectually stop further Belgian immigration.

The Belgian is a good worker, but he is much more “insular” than the British in his scorn of ways of living which differ from his own. He is not adaptable enough, in any way, to be put to live or work among the composite Spanish-Italian-American rural classes of the River Plate.

Probably both Argentine and Uruguayan will continue to work out his own salvation in this vital matter of attracting agricultural colonists to his land. Already the spirit of democratic unrest menaces privilege in Argentina, privilege which has already been destroyed in Uruguay. And the greatest political danger which now seems to threaten Argentina and has for some time past been the bane of Uruguay is doctrinairism; a tendency to pursue to most unpractically illogical consequences theories which seem to their initiators and supporters to be destined to cure all the social and economic ills to which man is prone.

State socialism from high places in Uruguay and socialism[28] of all kinds and varieties from lower social spheres in Argentina are each set on the adoption of its own empiric policy.

Like all young things, these Republics must pick themselves up again when they fall (and, in truth, they display great capability for doing so), but it would be well if, just at the present moment, they were to adopt and fully carry out some provedly sound colonizing policy. Afterwards they might experiment with single-tax, rural Banks, state ownership of land and all upon and within it, as much as they might find themselves able to afford to do.

Meanwhile they must work patiently, in unadventurous fashion, towards the most soundly rapid possible development of their rich natural resources.

During 1915, all extension of activity was at a standstill in both Republics. Little or no land changed hands, unless under practically forced sale; city improvements and private building projects were stayed, and no new railway extensions were put under construction.[8]

A few good harvests[9] will put these things as they were; but the lesson of the War will have been lost for Argentina and Uruguay if they do not see to the matter of the extension of their agricultural industries.

It seems, however, that they now are solidly determined to do so; and that, far from the lesson of recent events being lost for them, the finding of themselves cast on their own resources has led to a most beneficial and self-sacrificing examination of what those resources are in contrast with what they so easily might be.

The real vitality of these countries can be measured by the fact that the prices of their National Securities, which fell with the world-wide shock of July-August, 1914, were by the following September already on the high road to the practically complete recovery they have now attained.

The political history of the River Plate Republics begins with the wars which made possible the great Declaration of Independence from the dominion of Spain on the 25th of May, 1810. Their most romantic history is that of those wars and that of the old Colonial days immediately preceding them. As, however, the only slight pretension of the present book is to be informative on matters of fact, romance must wait on, perchance, the author’s more leisured moments and some outline be presented now of the events which had most influence in making Argentina and Uruguay what they are to-day.

Having overthrown the rule of Spain the former River Plate colonies became involved in a long internecine struggle for supremacy of power. For fifty years the United States of the River Plate were most disunited by local jealousies and the rural districts were only usually unanimous in their refusal to submit to the Government at Buenos Aires, composed of men who, as the rural populations said with a great amount of truth, were endeavouring to rule even more despotically than did the Viceroys and by purely Viceregal methods. Were that submitted to, the revolution would have been in vain as far as concerned the substitution of democratic principles for those of tyranny. This was no doubt true, for the politicians of Buenos Aires neither knew, nor had had any opportunity of knowing, methods of Government other than those under which they themselves had been brought up. Had they known it, though it is only[30] just to them to say that they did not in the least realize the fact, rule under them in the way they proposed to rule, would have been merely an exchange of King Stork for King Log. The country was, however, quick to grasp the menace, and it is only very regrettable that rivalry between its several contemporary would-be saviours produced so long a continuance of political chaos, during which newly acquired Liberty and Independence had no chance to develop the vast natural resources which had lain idle in consequence of the Spanish policy of squeezing the life out of the goose which would otherwise have laid so many golden eggs for Spain. In consequence of civil war it was, as has been indicated, not much before 1860 that it began to lay any appreciable number of such eggs for itself or anyone else. It only began to do so under two tyrants: Rozas in the South and Artígas in the North. Both were strong men and patriots; and both held power, in spite of opposition both open and treacherous, for, as later history has shown, the good of the respective territories they had brought under their sway. Harsh as were their methods, these were suited to lawless times. Of each of them it has been said that he permitted no thief but himself to live.

As a fact neither were thieves nor sought nor attained overmuch wealth for themselves. Both, however, forestalled otherwise inevitable assassination by giving their enemies no shrift at all; once these had been ascertained. And both succeeded in establishing police systems throughout their territories which would rival the European secret services of to-day.

Nothing went on unknown to them; from short-lived conspiracies to petty thefts. And the punishment for each offence inflicted by them was swift and closely fitted to the crime.

No one has yet attempted a complete whitewashing of Rozas; though, in every political crisis in which the Government has shown any apparent weakness, old men have[31] sighed for his reincarnation. Artígas, on the other hand, whose memory not so long ago rivalled those of the most traditionally cruel old-world potentates, is now become the Saviour and National hero of Uruguay. The apostle of the democratic principle.

Truth about his personality probably lies somewhere between these two views, but there is no doubt but that he and Rozas were men needed for and suited to their times. Fearless and far-sighted, they made order out of chaos, and individually cruel as may have been many of their acts, it was their iron rule which laid the foundations of the admirable constitutions of what are now the separate Republics of Argentina and Uruguay. Rozas really founded the Argentine Republic as much as Artígas did the “Banda Oriental,” part of which is now Uruguay. But the period of strife which succeeded the Declaration of the Independence of the whole of the River Plate Territories had lasted just over half a century when General Mitre was chosen as the first President of a United Federal Argentina.

He was succeeded by Sarmiento, who did much to develop agriculture and was the great pioneer of education. Sarmiento had been a political exile in Europe, where he learned much; and, being a man of exceptional intellect, stored up his acquired knowledge and enlightenment for his country’s subsequent great good.

Since the first Presidency of General Mitre there has only been one political revolution which affected the whole of Argentina, the one which in 1890 ousted President Juarez Celman and was immediately succeeded by the financial crisis with which the name of Baring is chiefly associated in the European mind.

Both that revolution and the crisis were the natural outcome of a disease which would have completely ruined any country less rich in natural resources than Argentina. That disease was complete political and financial corruption; which then came to a head and necessitated drastic operation.[32] Since then the Argentine nation has advanced in political and financial health with extraordinary and unparalleled rapidity.

The history of Uruguay has run on different lines since she emerged from the older Banda Oriental. She has been the almost constant victim, until very recent years, of the fervent patriotism of her rural population; in rebellion, often with much apparent justice, against what it has from time to time considered to be the prejudicial doctrinarianism of the town-bred men who have directed her Government in Montevideo. In any case the rural population has always been in a more or less declared state of rebellion against the Government. For many years the “White” party was in power and the “Red” in revolution. Now for a long period the “Reds” have kept place and nominal power, from which until comparatively very recently the “Whites” have never ceased to endeavour to oust them.

Let it not, however, be thought that either the retention of power by one party or its attempted overthrow by the other has in Uruguay been due to personal ambition or corrupt greed on either side; as has been, unfortunately but very frequently, the case in other South American Republics. To think this would be to do a cruel injustice to the national character, the leading characteristics of which are uprightness and honesty in thought or deed. No Uruguayan would ever have rebelled had he not thought that the policy of the existing Government was gravely prejudicial to the vital interests of his country, nor would an Uruguayan statesman have ever clung to power unless he had been conscientiously convinced that the policy of his party was the only true way to that country’s best development and prosperity.