The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Dickens Country, by Frederic G. Kitton This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Dickens Country Author: Frederic G. Kitton Illustrator: T. W. Tyrrell Release Date: December 3, 2017 [EBook #56105] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DICKENS COUNTRY *** Produced by Chris Curnow, Stephen Hutcheson, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE SCOTT COUNTRY

BY W. S. CROCKETT

Minister of Tweedsmuir

THE THACKERAY COUNTRY

BY LEWIS MELVILLE

THE INGOLDSBY COUNTRY

BY CHAS. G. HARPER

THE BURNS COUNTRY

BY C. S. DOUGALL

THE HARDY COUNTRY

BY CHAS. G. HARPER

THE BLACKMORE COUNTRY

BY F. J. SNELL

PUBLISHED BY

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK, SOHO SQUARE, LONDON

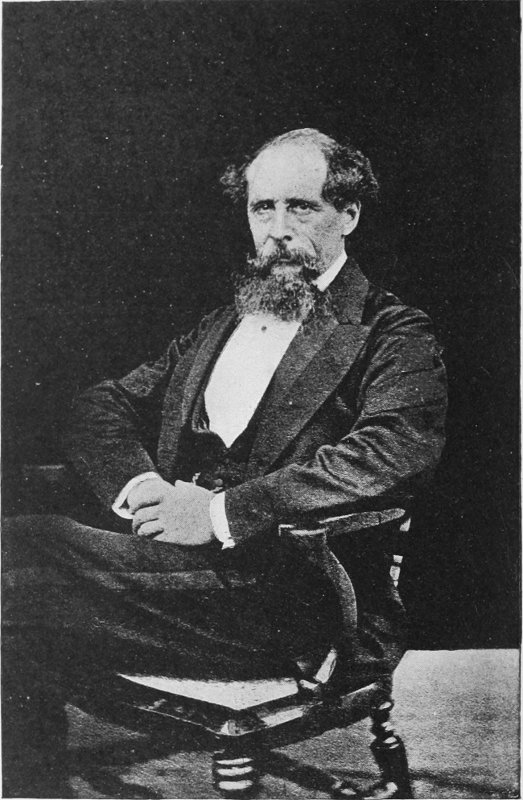

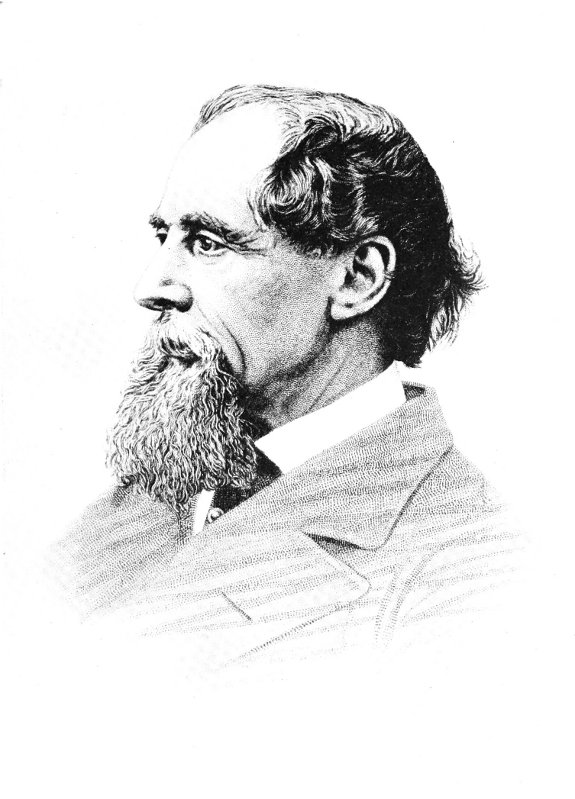

CHARLES DICKENS IN 1857.

From a hitherto unpublished photograph by Mason.

BY

FREDERIC G. KITTON

AUTHOR OF

“CHARLES DICKENS BY PEN AND PENCIL,” “DICKENS AND HIS ILLUSTRATORS,” “CHARLES DICKENS: HIS LIFE, WRITINGS, AND PERSONALITY,” “DICKENSIANA,” ETC.

WITH

FORTY-EIGHT FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

MOSTLY FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

BY T. W. TYRRELL

LONDON

ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK

1911

First published February, 1905

Reprinted September, 1911

It seems but a week or two ago that Frederic Kitton first mentioned to me the preparation of the volume to which I have now the melancholy privilege of prefixing a few words of introduction and valediction. It was in my office in Covent Garden, where he used often to drop in of an afternoon and talk, for a spare half-hour at the end of the day, of Dickens and Dickensian interests. We were speaking of a book which had just been published, somewhat similar in scope to the volume now in the reader’s hand, and Kitton, with that thoroughly genial sympathy which always marked his references to other men’s work, praised warmly and heartily the good qualities which he had found in its composition. Then, quite quietly, and as though he were alluding to some entirely unimportant side-issue, he added: “I have a book rather on the same lines on the stocks myself, but I don’t know when it will get finished.” That was a little more than a year ago, and in the interval how much has happened! The book has, indeed, “got finished” in the pressure of that indefatigable industry which his friends knew so well, but its author was never to see it in type. Almost before it had received his finishing touches, the bright, kindly, humane spirit of Frederic Kitton was “at rest and forever.” He died on Saturday, September 10, 1904, and left the world appreciably poorer by the loss of a sincere and zealous student, a true and generous man.

As I turned over the pages of the book in proof, and recalled this passing conversation, it seemed to me that the whole character of its author was displayed, as under a sudden light, in that quite unconscious attitude of his towards the two books—the one his friend’s, the other his own. For no one that I ever met was freer from anything like literary jealousy or the spirit of rivalry in art; no one was ever more modest concerning his own achievements. And in this case, it must be remembered, he was speaking of a vi particular piece of work for which no writer in England was so well qualified as himself. His work had its limitations, and he knew them well enough himself. For treatment of a subject on a broad plane, critically, he had little taste; indeed, many of his friends may remember that at times, when they may have indulged too liberally in a wide literary generalization, he was inclined, quietly and almost deprecatingly, to suggest some single contrary instance which seemed to throw the generalization out of gear at once. He saw life and literature like a mosaic; his eye was on the pieces, not upon the piece; and this microscopic view had its inevitable drawbacks and hindrances. On the other hand, when it came to a subject like that of the present volume, his method was not only a good one, but positively the best and only certain method possible. His laborious care for detail, his unfailing accuracy—never satisfied till he had traced the topic home under his own eye—his loving accumulation of little facts that contribute to the general impression—all these conspicuous traits made him the one man qualified to speak upon such a subject with confidence and authority. One sometimes felt that he knew everything there was to know about Dickens and the circle in which Dickens lived. The minuteness of his knowledge could only be appreciated by those who had occasion to test it in actual conversation, in that give-and-take of question and answer by which showy, shallow information and pretentious ignorance are so quickly discomfited and exposed. He had not only, for example, traced almost every published line and letter of Dickens himself, but he could tell you, in turning over old numbers of Household Words, the author of every single inconsiderable contribution to that journal; he was familiar with the manner and the production of all the infusoria of Wellington Street. It was a wonderful wealth of information, and his habit of acquiring and fostering it was born and bred in his very nature. In this, as in many other respects, he was essentially his father’s son.

When I ventured, a page further back, to call his method “microscopic,” the word slipped naturally from my pen, but in a moment its indisputable propriety asserted itself. Frederic George Kitton was trained in the school of microscopy. He was born at Norwich on May 5, 1856, and his father, who had then only just completed his twenty-ninth year, was already known among his associates as a scientist of much research and no little originality of observation. Frederic Kitton the elder was the son of a Cambridge vii ironmonger, and had been intended for the legal profession; but his father’s business did not prosper, and the whole family was obliged to remove to Norwich, there to take up work in a wholesale tobacco business, the proprietor of which was one Robert Wigham, a botanist of some repute. This Mr. Wigham soon saw that Kitton was a clever lad, and, finding him interested in the studies which were his own diversion, trained him in botany and other scientific branches of research. The young man soon surpassed his tutor in knowledge and resource, and by the time that he was married and the father of our own friend, Frederic George Kitton, he had made a name among the leading diatomists of his time, and was reputed to be more successful in finding rare specimens than any other man in the country. His reputation and his industry increased together, with the result that the son grew up in an atmosphere of unsparing research and conscientious accuracy of observation which never failed him as an example for life. We may fairly attribute the general outlines of F. G. Kitton’s method to the inspiration he received at his father’s desk.

This inspiration found its first expression upon the lines of art. The boy showed great ability with his pencil, and was apprenticed to wood engraving, joining the staff of the Graphic, and contributing any number of pencil drawings and woodcuts to its columns, in the days before the cheap processes of reproduction had supplanted these genuine forms of art-workmanship. His landscapes and his pictures of old buildings and romantic architecture were full of breadth and feeling, and some of the best of them were devoted to an early book of travel in the Dickens country, in which he collaborated with the late William R. Hughes. Indeed, much of the most picturesque work of his life was done in the way of black and white.

At the age of twenty-six, however, he decided to be less of an artist and more of a writer, and retired finally from the ranks of illustrated journalism. He settled about this time at St. Albans in Hertfordshire, and began his long series of books, most of them dedicated to his lifelong study of Dickens and his contemporaries. His first books of the kind treated, not unnaturally, of the various illustrators of Dickens’s novels, and monographs on Hablot K. Browne and John Leech attracted attention for their fidelity and sympathetic taste. Following these came “Dickensiana: a Bibliography of the Literature relating to Charles Dickens and His Writings” (1886); “Charles Dickens by Pen and Pencil” (1890); viii “Artistic London: from the Abbey to the Tower with Dickens” (1891); “The Novels of Charles Dickens: a Bibliography and a Sketch” (1897); “Dickens and His Illustrators” (1899); “The Minor Writings of Charles Dickens” (1900); “Charles Dickens: His Life, Writings, and Personality” (1902); and innumerable editorial works, among which must be mentioned his notes to the Rochester Edition of Dickens, his recension of Dickens’s verse, and his general conduct of the Autograph Edition now in course of publication in America—a laborious undertaking, which included a series of bibliographical notes from his pen of the very first value to all students of “Dickensiana.” He had also in MS. a valuable dictionary of Dickens topography, illustrated by descriptive quotations from the novels themselves; and, finally, he left the “copy” for the present book, which will rank among the most useful and characteristic of all his contributions to the study of the author whom he so much admired and so sincerely served.

Kitton was only forty-eight when he died, and the work which he had done was large in bulk and rich in testimony to his industry; but he was far from accomplishing the volume of work which he had already set before himself. It is no secret that the short “Life of Dickens” which he published two and a half years ago was only regarded by himself as the framework upon which he proposed to construct a much more elaborate biography, to be at least as long as Forster’s “Life,” fortified by a vast array of facts which Forster had not been disposed, or careful enough, to collect. The book would have been full of material and value; but there were some of us who believed that Kitton’s talent might be even better employed in a work which none but himself could have satisfactorily accomplished—the preparation of an elaborate annotated edition of Forster, constructed upon the scale of Birkbeck Hill’s monumental Boswell, and illustrated by all the fruits of Kitton’s profitable research. We talked the matter over together, and he was enthusiastically willing to essay the task. But obstacles arose at the moment, and now the work can never be done as he would have done it. His talent was peculiarly adapted to annotation; his knowledge of the subject was unparalleled. If the work is ever done (and I suppose it is bound to be done some day), it can never be done now with that surety and deliberate finality which he would have had at his disposal.

But one must not speak of Kitton only as a student of literature and an artist; any picture of him that seemed to suggest that he ix was rooted to his desk and his desk-work, to the exclusion of outside interests and social activities, would give a very false impression of his energetic and amiable temperament. There are many books standing to Kitton’s name in the catalogue of the British Museum, and innumerable articles of his writing in the files of the reviews, magazines, and newspapers of the last twenty years, but his work extended far beyond the limits of print and paper. He was not only an industrious man of letters, but a most helpful and self-sacrificing citizen. His adopted town of St. Albans, and the county of Hertfordshire at large, had no little cause for gratitude in all he did in their interests. Despite the amount of literary work he got through, there was scarcely a day that passed without finding him at work at the Hertfordshire County Museum, where he took sole charge of the prints and books, a collection which his care and judgment made both exhaustive and invaluable. He was continually at work, arranging and adding to the books and prints, and outside the walls of the museum he did inestimable service in preserving the ancient buildings of the town of St. Albans. Had it not been for his intervention, many of the most interesting old houses in the town would have been pulled down; he argued with callous owners and vandal jerry-builders, and managed to retain for the town those characteristic and historic buildings around the abbey which in days to come will be the chief attraction of the picturesque county town he loved to serve.

And so, with hard work at his desk and unsparing energy out of doors, his bright, unselfish spirit wore itself out. He never looked strong, but I do not think he seemed actually ill when one spring morning in this last year he came in to see me at my office, and told me, with his easy, unapprehensive smile, that he was about to undergo an operation. “It is only a small matter,” he said, “but the doctors say I ought to have it done. I hope I shall soon be back again, and we will have a further talk over that book you know about.” We parted, as men part at the cross-roads, feeling sure of meeting on the morrow. But I never saw him again. The operation he had made so light of proved too much for a constitution already undermined by hard, unselfish work. He lingered on, but never really rallied, and the end came very quietly, to close a life that had always brought with it a sense of peace and gentle will, wherever it had touched, whomsoever it had influenced.

For, when other shifting recollections of Frederic Kitton fade x away—accidents of a common interest, chances of a brief and busy acquaintanceship—the impression that remains, and will always remain with those who knew him, is the haunting impression of a sweet and winning simplicity, an absolute sincerity of life and word, that knew no use for the thing he said but that it should be the thing he thought, and that never (so it seemed) thought anything of man, or woman, or child but what was kind and Christian and noble-hearted. He looked you in the eyes in a fearless, open fashion, as a man who had nothing to conceal and nothing to pretend; he smiled with a peculiarly sunny and unhesitating smile, as one who had tried life and found it good. And yet, as the common rewards of life go, he had less cause to be thankful than many who complain; he had to work hard (how hard it is not ours to say) for the ordinary daily gifts of homely comfort. He had little time to rest or play, and little means of recreation. Yet no friend of his, I believe, however intimate, ever heard him grumble about work and the badness of the times. He had a happy home, bright and blithe with the carol of the cricket on the hearth, and brighter and blither for his own affectionate nature; and his happy spirit seemed to ask for nothing that lay outside the four walls of his plain contentment. He knew the secret of life—a simple secret, but hard to find, and harder to remember. He had no touch of self in all his composition, no taint of self-interest or self-care. He lived for others: and in their memory he will survive so long as earthly recollections and earthly examples return to encourage and to inspire. Arthur Waugh.

Owing to the untimely death of the author, the page proofs were not revised by him for the press, though Mr. Kitton corrected proofs at an earlier stage.

Mr. Kitton’s friends—Mr. B. W. Matz, Mr. T. W. Tyrrell, and Mr. H. Snowden Ward—have kindly read the final proofs, without, however, making any material alterations.

From Photographs by T. W. Tyrrell, etc.

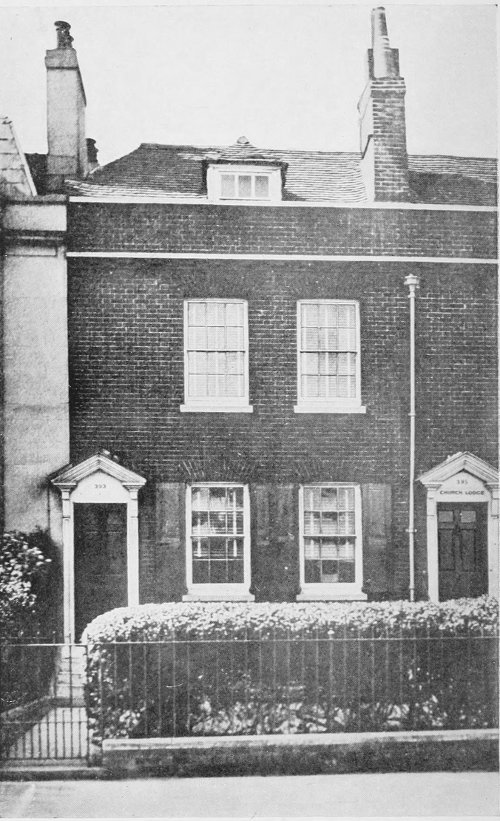

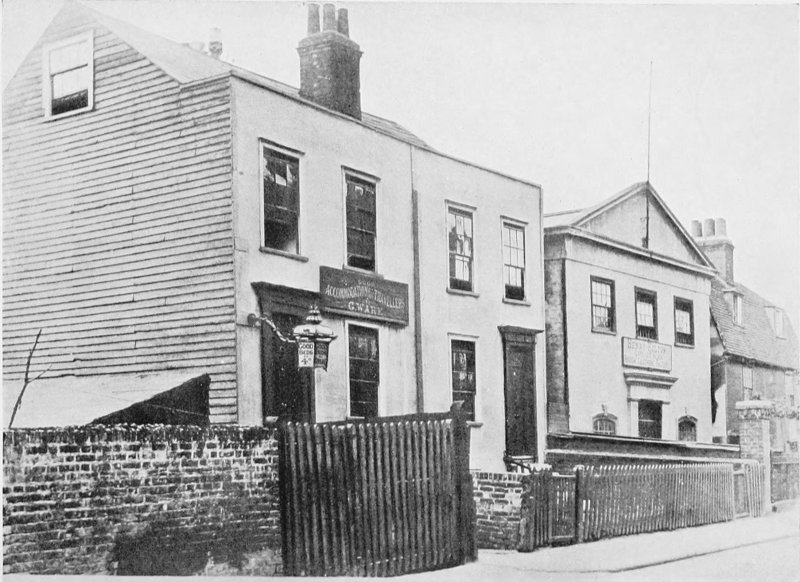

1 MILE END TERRACE, PORTSEA

(NOW 393 COMMERCIAL ROAD, PORTSMOUTH). (Page 2.)

The birthplace of Charles Dickens.

The writer of an article in a well-known magazine conceived the idea of preparing a map of England that should indicate, by means of a tint, those portions especially associated with Charles Dickens and his writings. This map makes manifest the fact that the country thus most intimately connected with the novelist is the south-eastern portion of England, having London as the centre and Rochester as the “literary capital,” and including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk, Essex, Kent, Surrey, Sussex, Hampshire, and Warwickshire, with an offshoot extending to the northern boundary of Yorkshire.

All literary pilgrims, and particularly the devotees of Charles Dickens, regard as foremost among literary shrines inviting special homage the scene of the nativity of “Immortal Boz.” Like the birthplaces of many an eminent personage who first saw the light in the midst of a humble environment, the dwelling in which Dickens was born is unpretentious enough, and remains unaltered. The modest abode 2 rented shortly after marriage by John Dickens (the future novelist’s father), from June, 1809, to June, 1812, stands in Commercial Road, Portsmouth, the number of the house having been recently changed from 387 to 393. The district was then known as Landport, in the Island of Portsea, but is now incorporated with Portsmouth; a comparatively rural locality at that time, it has since developed into a densely populated neighbourhood, covered with houses and bisected by the main line of the municipal tramways.[1] It is, however, yet within the memory of middle-aged people when this area of brick and mortar consisted of pasture land in which trees flourished and afforded nesting-places for innumerable birds—a condition of things recalled by the names bestowed upon some of the streets hereabouts, such as Cherry Garden Lane and Elm Road—but now “only children flourish where once the daisies sprang.”

The birthplace of Charles Dickens, which less than half a century ago overlooked green fields, is an interesting survival of those days of arboreal delights; and the broad road, on the west side of which it is situated, leads to Cosham and the picturesque ruin of Porchester Castle. In 1809 John Dickens was transferred from Somerset House to the Navy Pay-Office at Portsmouth Dockyard, and, with his young wife, made his home here, in which 3 were born their first child (Frances Elizabeth) in 1810, and Charles on February 7, 1812. This domicile is a plain, red-brick building containing four rooms of moderate size and two attics, with domestic offices; in front there is a small garden, separated from the public roadway by an iron palisading; and a few steps, with a hand-rail, lead from the forecourt to the hooded doorway of the principal entrance. The front bedroom is believed to be the room in which Dickens was born. From the apartments in the rear there is still a pleasant prospect, overlooking a long garden, where flourishes an eminently fine specimen of the tree-mallow. On the death of Mrs. Sarah Pearce, the owner and occupier (and last surviving daughter of John Dickens’s landlord), the house was offered for sale by public auction on Michaelmas Day, 1903, when, much to the delight of the townspeople as well as of all lovers of the great novelist, it was purchased by the Portsmouth Town Council for preservation as a Dickens memorial, and with the intention of adapting it for the purposes of a Dickens Museum. The purchase price was £1,125, a sum exceeding by five hundred pounds the amount realized on the same occasion by the adjoining freehold residence (No. 395), which is identical in character—an interesting and significant testimony as to the sentimental value attaching to the birthplace of “Boz.”

Charles Dickens, like David Copperfield, was ushered into the world “on a Friday,” and, when less than a month old, underwent the ordeal of baptism at the parish church of Portsea, locally and popularly known as St. Mary’s, Kingston, and dating from the reign of Edward III. In 1882 a plan for its restoration 4 and enlargement was proposed, but a few years later the authorities resolved to demolish it altogether and build a larger parochial church from designs by Sir Arthur Blomfield, A.R.A., the foundation stone of which was laid by Queen Victoria early in the spring of 1887, one half of the estimated cost being defrayed by an anonymous donor. On its completion the people of Portsmouth expressed a desire to perpetuate the memory of Charles Dickens by inserting in the new building a stained-glass window, but were debarred by a clause in the novelist’s will, where he conjured his friends on no account to make him “the subject of any monument, memorial, or testimonial whatever,” as he rested his claim to the remembrance of his country upon his published works. It is not common knowledge that three baptismal names were bestowed upon Dickens, viz., Charles John Huffam, the first being the Christian name of his maternal grandfather, the second that of his father, while the third was the surname of his godfather, Christopher Huffam (incorrectly spelt “Huffham” in the church register), who is described in the London Postal Directory of that time as a “rigger in His Majesty’s Navy”; he lived at Limehouse Hole, near the lower reaches of the Thames, which afterwards played a conspicuous part in “Our Mutual Friend” (“Rogue Riderhood dwelt deep and dark in Limehouse Hole, amongst the riggers, and the mast, oar, and block-makers, and the boat-builders, and the sail-lofts, as in a kind of ship’s hold stored full of waterside characters, some no better than himself, some very much better, and none much worse”). It is interesting to know that the actual font used at the ceremony of Charles Dickens’s 5 baptism has been preserved, and is now in St. Stephen’s Church, Portsea.

John Dickens, after a four years’ tenancy of No. 387, Mile End Terrace, went to reside in Hawke Street, Portsea. Here he remained from Midsummer Day, 1812, until Midsummer Day, 1814, when he was recalled to London by the officials at Somerset House.

I have spared no trouble in endeavouring to discover the house in Hawke Street which John Dickens and his family occupied. Mr. Robert Langton, in his “Childhood and Youth of Charles Dickens” (second edition), states that it is the “second house past the boundary of Portsea,” which, however, is not very helpful, as the following note (kindly furnished by the Town Clerk of Portsmouth) testifies:

“I cannot understand what the connection can be between Hawke Street and the borough boundary. The town of Portsea, no doubt, had a recognised boundary, because at one time the greater part of it was encircled by ramparts, but Hawke Street did not come near those ramparts. The old borough boundary was outside the ramparts, both of Portsmouth and Portsea, and therefore Hawke Street did not touch that boundary. Since then the borough boundary has been extended on more than one occasion, and, of course, these boundaries could not touch Hawke Street.” A letter sent by me to the Portsmouth newspapers having reference to this subject brought me into communication with a Southsea lady, who informs me that an old gentleman of her acquaintance (an octogenarian) lived in his youth at No. 8, Hawke Street, and he clearly 6 remembers that the Dickens family resided at No. 16. Hawke Street, in those days, he says, was a most respectable locality, the tenants being people of a good class, while there were superior lodging-houses for naval officers who desired to be within easy reach of their ships in the royal dockyard, distant about five minutes’ walk. No. 16, Hawke Street is a house of three floors and a basement; three steps lead to the front door, and there are two bay-windows, one above the other. The tenant whom John Dickens succeeded was Chatterton, harpist to the late Queen Victoria.

Forster relates, as an illustration of Charles Dickens’s wonderfully retentive memory, that late in life he could recall many minor incidents of his childhood, even the house at Portsea (i.e., his birthplace in Commercial Road), and the nurse watching him (then not more than two years old) from “a low kitchen window almost level with the gravel walk” as he trotted about the “small front garden” with his sister Fanny.

Dickens’s memory obviously failed him on this point, for he was a mere infant of barely five months old when his parents left Commercial Road to reside in Hawke Street, a fact which he had probably forgotten, and of which Forster had no knowledge, as no mention is made by him of the latter street. Here the family had lived two years when John Dickens was recalled to London. I therefore venture to suggest that the novelist vaguely recalled certain incidents of his childhood associated with Hawke Street. True, there is no “small front garden” at No. 16 (indeed, all the houses here are flush with the sidewalk), but at the back is a garden overlooked 7 by the kitchen window, which has an old-fashioned, broad window-seat.

On quitting Portsea for the Metropolis, John Dickens and his family occupied lodgings in Norfolk Street (now Cleveland Street), on the east side of the Middlesex Hospital. In a short time, however, he was again “detached,” having received instructions to join the staff at the Navy Pay-Office at Chatham Dockyard. The date of departure is given by Forster as 1816, and in all probability the Dickens family again took lodgings until a suitable home could be found. After careful research, the late Mr. Robert Langton discovered that from June, 1817 (probably midsummer), until Lady Day, 1821, their abode was at No. 2 (since altered to No. 11), Ordnance Terrace. There little Charles passed some of the happiest years of his childhood, and received the most durable of his early impressions.

Chatham, on the river Medway, derives its name from the Saxon word Ceteham or Cættham, meaning “village of cottages.” It is anything but a “village” now, having since that remote age developed into a river port and a populous fortified town. Remains of Roman villas have been found in the neighbourhood, thus testifying to its antiquity. Chatham is one of the principal royal shipbuilding establishments in the kingdom. The dockyard was founded by Elizabeth before the threatened invasion of the Spanish Armada, and removed to its present site in 1662; it is now nearly two miles in length, and controlled by an Admiral-Superintendent, with a staff of artisans and labourers numbering about five thousand. Dickens describes and mentions Chatham in several of his writings, and in one 8 of the earliest he refers to it by the name of “Mudfog.”[2]

In “The Seven Poor Travellers” he says of Chatham: “I call it this town because if anybody present knows to a nicety where Rochester ends and Chatham begins, it is more than I do.”[3]

Mr. Pickwick’s impressions of Chatham and the neighbouring towns of Rochester, Strood, and Brompton were that the principal productions “appear to be soldiers, sailors, Jews, chalk, shrimps, officers, and dockyard men,” and that “the commodities chiefly exposed for sale in the public streets are marine stores, hard-bake, apples, flat-fish, and oysters.” He observed that the streets presented “a lively and animated appearance, occasioned chiefly by the conviviality of the military.” “The consumption of tobacco in these towns,” Mr. Pickwick opined, “must be very great, and the smell which pervades the streets must be exceedingly delicious to those who are extremely fond of smoking. A superficial traveller might object to the dirt, which is their leading characteristic, but to those who view it as an indication of traffic and commercial prosperity it is truly gratifying.” Were Mr. Pickwick to revisit Chatham, he would find many of these characteristics still prevailing, and could not fail to note, also, that during the interval of more than sixty years the town had undergone material changes in the direction of modern improvements. When poor little David Copperfield fled from his distressing experiences at Murdstone and Grinby’s, hoping to meet with a welcome from Betsy Trotwood at Dover, he wended his weary way through Rochester; and as he toiled into Chatham, it seemed to him in the night’s aspect “a mere dream of chalk, and drawbridges, and mastless ships in a muddy river, roofed like Noah’s arks.”[4]

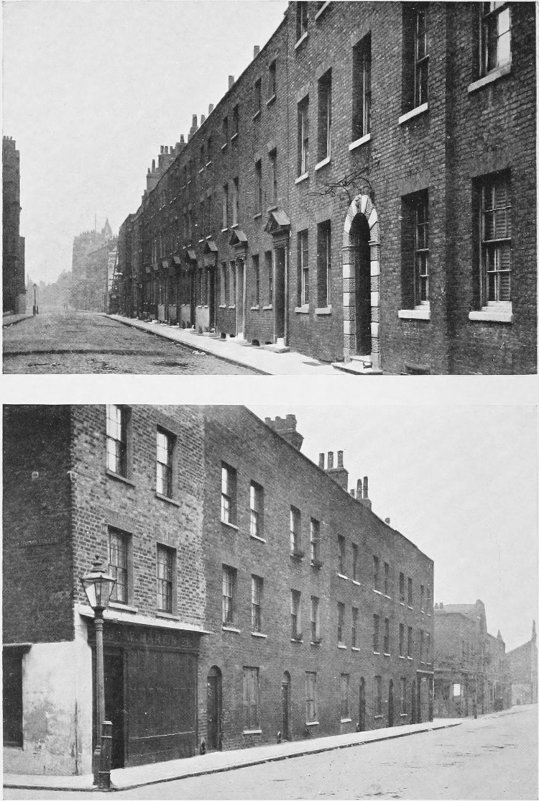

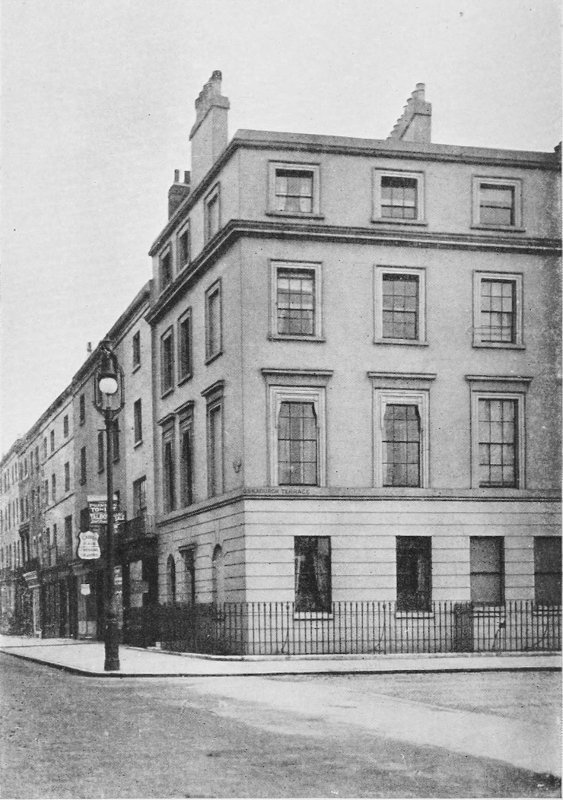

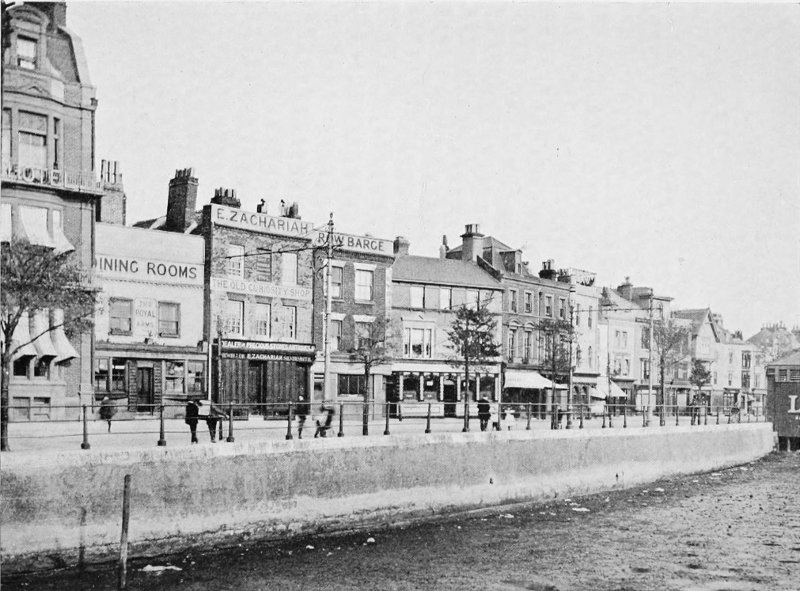

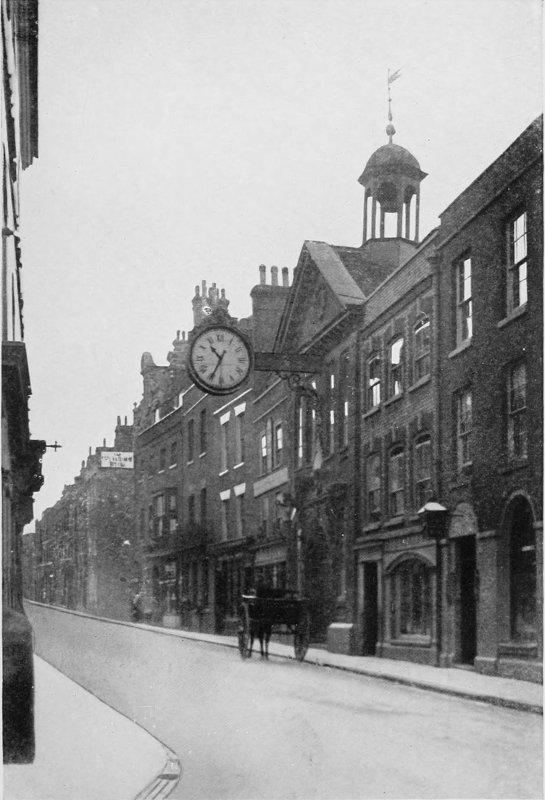

NORFOLK (NOW CLEVELAND) STREET, FITZROY SQUARE. (Page 7.)

Dickens and his parents resided in Norfolk Street in 1816, after their removal from Hawke Street, Portsea.

Dickens himself, when a boy, must have seen the place frequently under similar conditions. The impressions he then received of Chatham and the neighbourhood were permanently fixed upon the mental retina, to be recalled again and again when penning his stories and descriptive pieces. In an article written by him in collaboration with Richard Hengist Horne, he supplies a picture of Chatham as it subsequently appeared when the military element on the main thoroughfares seemed paramount: “Men were only noticeable by scores, by hundreds, by thousands, rank and file, companies, regiments, detachments, vessels full for exportation. They walked about the streets in rows or bodies, carrying their heads in exactly the same way, and doing exactly the same thing with their limbs. Nothing in the shape of clothing was made for an individual, everything was contracted for by the millions. The children of Israel were established in Chatham, as salesmen, outfitters, tailors, old clothesmen, army and navy accoutrement makers, bill discounters, and general despoilers of the Christian world, in tribes rather than in families.”[5]

John Dickens’s official connection with the Navy Pay Department offered facilities for little Charles to roam unchecked about the busy dockyard, where he experienced delight in watching the ropemakers, 10 anchor-smiths, and others at their labours, and in gazing with curious awe at the convict hulks (or prison ships), and where he found constant delight in observing the innumerable changes and variety of scenes; on one day witnessing the bright display of military tactics on Chatham “Lines,” on another enjoying a sail on the Medway with his father, when on duty bound for Sheerness in the Commissioners’ yacht, a quaint, high-sterned sailing-vessel, pierced with circular ports, and dating from the seventeenth century; she was broken up at Chatham in 1868.

The boy unconsciously stored up the pictures of life, and character, and scenery thus brought to his notice, to be recalled and utilized as valuable material by-and-bye. Of the great dockyard he afterwards wrote: “It resounded with the noise of hammers beating upon iron, and the great sheds or slips under which the mighty men-of-war are built loomed business-like when contemplated from the opposite side of the river.... Great chimneys smoking with a quiet—almost a lazy—air, like giants smoking tobacco; and the giant shears moored off it, looking meekly and inoffensively out of proportion, like the giraffe of the machinery creation.”[6]

The famous Chatham Lines (constituting the fortifications of the town), are immortalized in “Pickwick” as the scene of the review at which Mr. Pickwick and his friends were present and got into difficulties; and the field adjacent to Fort Pitt (now the Chatham Military Hospital, standing on high ground near the railway station), was the locality selected for the intended duel between the irate 11 Dr. Slammer and the craven (but innocent) Mr. Winkle, both field and the contiguous land surrounding Fort Pitt being now a public recreation ground, whence is obtainable a fine panoramic view of Chatham and Rochester. The “Lines” are today locally understood as referring to an open space near Fort Pitt, which is used as an exercising ground for the soldiers at the barracks near by. All this portion of the country possessed great attractions for Dickens in later years; it was rendered familiar to him when, as a lad, he accompanied his father in walks about the locality, thus hallowed by old associations.

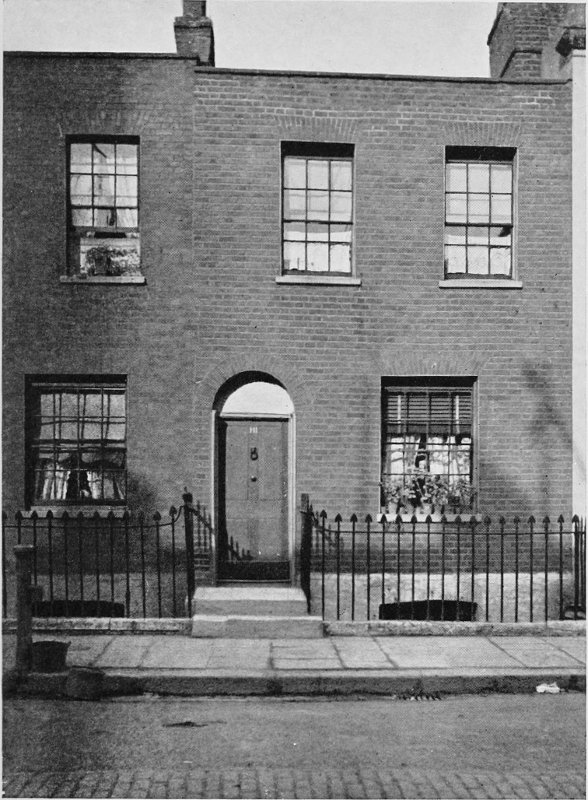

Ordnance Terrace, Chatham, retains much the same aspect it possessed at the time of John Dickens’s residence there (1817-1821)—a row of three-storied houses, prominently situated on high ground within a short distance of the Chatham railway station. The Dickens abode was the second house in the terrace (now No. 11), whose front is now overgrown with a Virginia creeper, and so redeems its bareness. In describing the place, the late Mr. W. R. Hughes says: “It has the dining-room on the left-hand side of the entrance and the drawing-room on the first floor, and is altogether a pleasantly-situated, comfortable and respectable dwelling.” At Ordnance Terrace, we are assured by Forster, it was that little Charles (“a very queer, small boy,” as he afterwards described himself at this period) lived with his parents from his fifth to his ninth year; the child’s “first desire for knowledge, and his greatest passion for reading, were awakened by his mother, who taught him the first rudiments, not only of English, but also, a little later, of Latin.” The same authority 12 states that he and his sister Fanny presently supplemented these home studies by attending a preparatory day-school in Rome Lane (now Railway Street), and that when revisiting Chatham in his manhood he tried to discover the place, found it had been pulled down “ages” before to make room for a new street; but there arose, nevertheless, “a not dim impression that it had been over a dyer’s shop, that he went up steps to it, that he had frequently grazed his knees in doing so, and that, in trying to scrape the mud off a very unsteady little shoe, he generally got his leg over the scraper.” Other recollections of the Ordnance Terrace days flashed upon him when engaged upon his “Boz” sketches; for example, the old lady in the sketch entitled “Our Parish” was drawn from a Mrs. Newnham who lived at No. 5 in the Terrace, and the original of the Half-Pay Captain (in the same sketch) was another near neighbour: at No. 1 there resided a winsome, golden-haired maiden named Lucy Stroughill, whom he regarded as his little sweetheart, and who figures as “Golden Lucy” in one of his Christmas stories,[7] while her brother George, “a frank, open, and somewhat daring boy,” is believed to have inspired the creation of James Steerforth in “David Copperfield.”

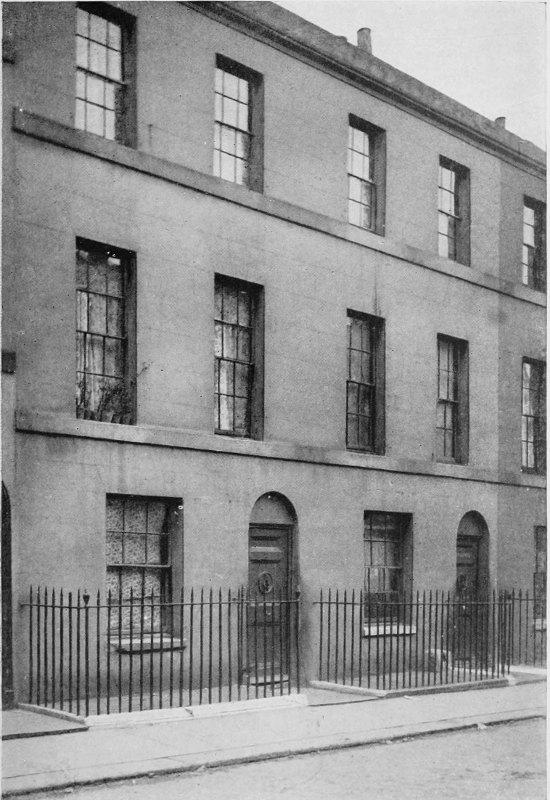

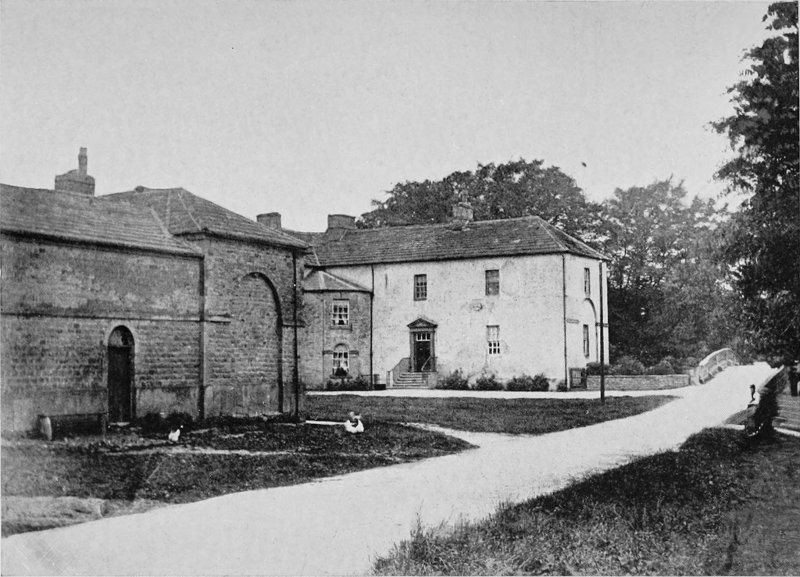

2 (NOW 11) ORDNANCE TERRACE, CHATHAM. (Page 11.)

Occupied by John Dickens and his family, 1817-1821.

Little Charles must have been acquainted, too, with the prototype of Joe, the Fat Boy in “Pickwick,” whose real name was James Budden, and whose father kept the Red Lion Inn at the corner of High Street and Military Road, Chatham, where the lad’s remarkable obesity attracted general attention. The Mitre Inn and Clarence Hotel at Chatham, described in 1838 as “the first posting-house in the town,” is also associated with Dickens’s early years, and remains very much as it was when he knew it as a boy. At the period referred to the landlord of this fine old hostelry was a Mr. Tribe, with whose family Mr. and Mrs. John Dickens and their children were on visiting terms; indeed, it is recorded that, at the evening parties held at the Mitre, Charles distinguished himself by singing solos (usually old sea songs), and sometimes duets with his sister, both being mounted on a dining table for a stage. The Mitre is historically interesting by reason of the fact that Lord Nelson used to reside there when on duty at Chatham, a room he occupied being known as “Nelson’s Cabin.”[8]

In the eighteenth chapter of “The Mystery of Edwin Drood” we find the place disguised as “The Crozier”—“the orthodox hotel” at Cloisterham (i.e., Rochester)—and in “The Holly-Tree Inn” it is thus directly immortalized: “There was an inn in the cathedral town where I went to school, which had pleasanter recollections about it than any of these.... It was the inn where friends used to put up, and where we used to go and see parents, and to have salmon and fowls, and be tipped. It had an ecclesiastical sign—the Mitre—and a bar that seemed to be the next best thing to a bishopric, it was so snug.”[9]

John Dickens had by nature a very generous 14 disposition, which inclined him to be too lavish in his expenditure. This idiosyncrasy, coupled with the ever-increasing demands of a young and growing family, compelled him to realize the immediate necessity for retrenchment. Hitherto his income (ranging from £200 to £350 per annum) amply sufficed to provide for the comfort of wife and children; but the time had arrived when rigid economy became imperative, and early in 1821 he removed into a less expensive and somewhat obscure habitation at No. 18, St. Mary’s Place (otherwise called “The Brook”), Chatham, situated in the valley through which a brook (now covered over) flows into the Medway. The house on “The Brook,” with a “plain-looking whitewashed plaster front, and a small garden before and behind,” still exists; it is a semi-detached, six-roomed tenement, of a much humbler type than that in Ordnance Terrace, and stands next to what is now the Drill Hall of the Salvation Army, but which, in John Dickens’s time, was a Baptist meeting-house called Providence Chapel. While the Dickens dwelling-place remains unaltered, the neighbourhood has since greatly deteriorated. The locality was then more rural and not so crowded as now, many of the people living there being of a quite respectable class. The minister then officiating at Providence Chapel was William Giles, whose son William had been educated at Oxford, and afterwards kept a school in Clover Lane (now Clover Street, the playground since covered by a railway station), Chatham, whence he moved to larger premises close by, still to be seen at the corner of Rhode Street and Best Street. Both Charles and his elder sister Fanny attended here as 15 day scholars, and the boy, under Mr. Giles’s able tuition, made rapid progress with his studies. Apropos of Mr. Giles, it should be mentioned that when his intelligent pupil had attained manhood and achieved fame as the author of “Pickwick,” his old schoolmaster sent him, as a token of admiration, a silver snuff-box, the lid bearing an inscription addressed “To the Inimitable Boz.” For a considerable time afterwards Dickens jocosely alluded to himself, in letters to intimate friends, as “the Inimitable.” By the way, where is that snuff-box now?

St. Mary’s Place is in close proximity to the old parish church of St. Mary, where the Dickens family worshipped during their residence in Chatham. It dates from the early part of the twelfth century, but having lately undergone a process of rebuilding, the edifice no longer possesses that quaintness which formerly characterized it, both externally and internally. The present structure, standing on a site which has been occupied by a church from Saxon times, has been erected from the designs of the late Sir Arthur Blomfield, already mentioned as the architect of the new parochial church of St. Mary, Kingston. Happily, there are preserved in St. Mary’s, Chatham, some interesting remains of the Norman edifice (A.D. 1120), notably a fine doorway and staircase, and the columns of the central arch of the nave. Instead of the diminutive bell-turret originally surmounting the roof of the nave, a lofty detached tower now constitutes the most striking feature of the church, which was consecrated on October 28, 1903, in the presence of Lord Roberts. It has been suggested that the description of Blunderstone 16 Church in “David Copperfield” recalls in some respects the old parish church of Chatham, so familiar to Dickens in his boyhood, although the picture was partly drawn from Blundeston Church, Suffolk: “Here is our pew in the church. What a high-backed pew! with a window near it, out of which our house can be seen, and is seen many times during the morning’s service by Peggotty, who likes to make herself as sure as she can that it’s not being robbed, or is not in flames.”[10] Dame Peggotty was no doubt to some extent depicted from Charles Dickens’s nurse of those days, Mary Weller, who afterwards married Thomas Gibson, a shipwright in the dockyard, and whose death took place in 1888.

In the registers at Chatham Church are recorded the entries of the baptism of three children born in the parish to John and Elizabeth Dickens, the parents of the novelist; and Mary Allen, an aunt of Charles, was married by license there on December 11, 1821, to Dr. Lamert, a regimental surgeon, who afterwards figured in “Pickwick” as Dr. Slammer. In the church registers may be found several names subsequently used by Dickens in his stories—names of persons who lived in the district—Sowerby (Sowerberry), Tapley, Wren, Jasper, Weller, etc., the Tapleys and the Wellers being well-known cognomens, for there are vaults in the church belonging to the former family, and a gravestone in the churchyard erected to the latter. At the west end of the church there are two inscriptions to the family of Stroughill, who lived in Ordnance Terrace, and to whom reference has already been made. The Vicar, in his appeal for subscriptions in aid of the restoration fund, expressed a hope that the people of Chatham would contribute towards the cost of a memorial in the church to Charles Dickens. Apropos, I may mention that the Council of that flourishing institution the Dickens Fellowship have, very rightly, approached the Corporation of Chatham with the suggestion that they should place commemorative tablets on the two houses in Chatham in which he spent some of the happiest years of his boyhood, and the Corporation have consented.

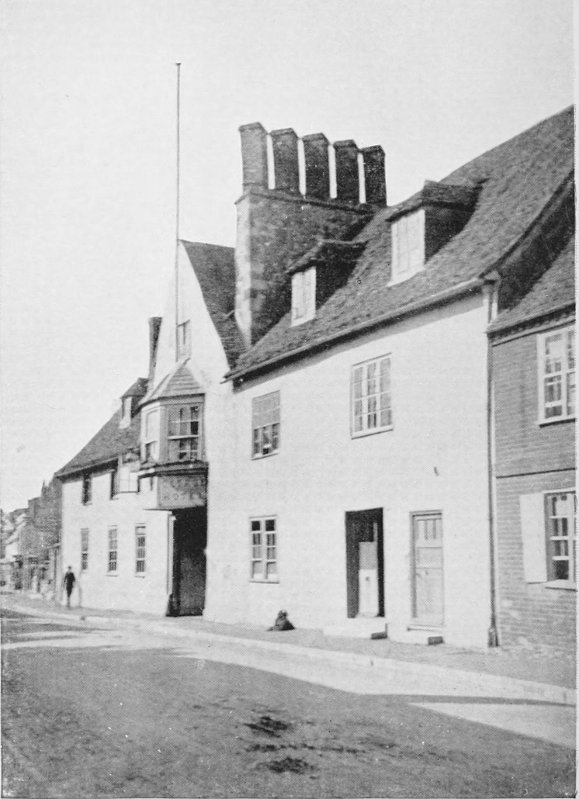

18 ST. MARY’S PLACE, THE BROOK, CHATHAM. (Page 14.)

The Dickens family resided in the house next to Providence Chapel, 1821-1823.

From an upper window at the side of the house, No. 18, St. Mary’s Place, an old graveyard was plainly visible, and frequently at night little Charles and his sister would gaze upon the God’s-acre and at the heavens above from that point of vantage. Some thirty years later he recalled the circumstances in a poetical little story entitled “A Child’s Dream of a Star,”[11] a touching reminiscence of these early days, where he says: “There was once a child, and he strolled about a good deal, and thought of a number of things. He had a sister, who was a child too, and his constant companion. These two used to wonder all day long. They wondered at the beauty of the flowers; they wondered at the height and blueness of the sky; they wondered at the depth of the bright water; they wondered at the goodness and the power of God who made the lovely world.

“They used to say to one another sometimes, Supposing all the children upon earth were to die, would the flowers and the water and the sky be sorry? They believed they would be sorry. For, said they, the buds are the children of the flowers, and the little playful streams that gambol down the 18 hillsides are the children of the water, and the smallest bright specks playing at hide-and-seek in the sky all night must surely be the children of the stars; and they would all be grieved to see their playmates, the children of men, no more.

“There was one clear shining star that used to come out in the sky before the rest, near the church spire, above the graves. It was larger and more beautiful, they thought, than all the others, and every night they watched for it, standing hand in hand at a window. Whoever saw it first cried out, ‘I see the star!’ and often they cried out both together, knowing so well when it would rise, and where. So they grew to be such friends with it that, before lying down in their beds, they always looked out once again to bid it good-night; and when they were turning round to sleep they used to say, ‘God bless the star!’”

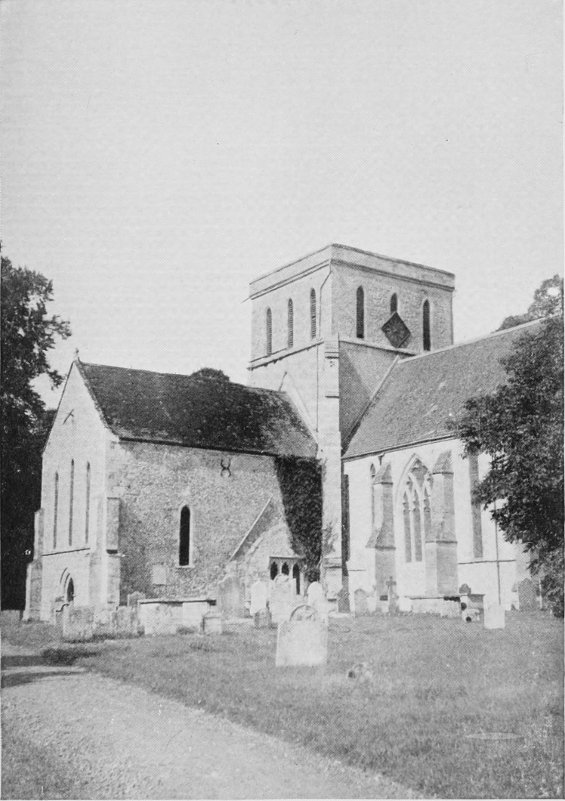

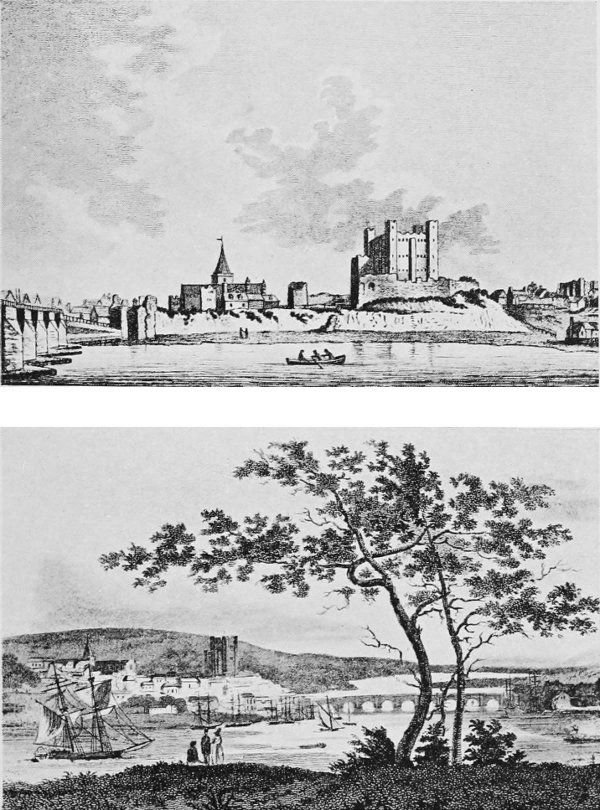

FORT PITT, CHATHAM. (Page 18.)

The playground of Dickens in his childhood, and the scene of the duel in “Pickwick.”

The Chatham days were replete with innocent delights for little Charles, whose young life overflowed with the happiness resulting therefrom. He and his schoolfellows often went to see the sham fights and siege operations on the “Lines,” and he enjoyed many a ramble with his sister and nurse in the fields about Fort Pitt; and “the sky was so blue, the sun was so bright, the water was so sparkling, the leaves were so green, the flowers were so lovely, and they heard such singing birds and saw so many butterflies, that everything was beautiful.” In “The Child’s Story,” whence these extracts are culled, we find the following undoubted allusions to some of the juvenile pleasures in which the children indulged while at Chatham: “They had the merriest games that ever were played.... They had holidays, too, and ‘twelfth-cakes,’ and parties where they danced till midnight, and real theatres, where they saw palaces of real gold and silver rise out of the real earth, and saw all the wonders of the world at once. As to friends, they had such dear friends and so many of them that I want the time to reckon them up.”[12] At home there were picture-books and toys—“the finest toys in the world and the most astonishing picture-books”—and, above all, in the little room adjoining his bedchamber a small library, consisting of the works of Fielding, Smollett, Defoe, Goldsmith, the “Arabian Nights,” and “Tales of the Genii,” which the boy perused with avidity over and over again. “They kept alive my fancy,” he said, as David Copperfield, “and my hope of something beyond that place and time ... and did me no harm, for whatever harm was in some of them was not there for me; I knew nothing of it.”[13] In referring afterwards to the “readings” and “imaginations” which he described as brought away from Chatham, he again observes with David: “The picture always rises in my mind of a summer evening, the boys at play in the churchyard, and I, sitting on my bed, reading as if for life. Every barn in the neighbourhood, every stone in the church, and every foot of the churchyard, had some association of its own in my mind connected with these books, and stood for some locality made famous in them”[14]—words that were written down as fact some years before they found their way into the story.

Happily for the boy, he remained in ignorance of 20 the changes impending at home, and unconscious of the fact that he was about to relinquish for ever the delectations afforded by those daily visions of his childhood; the ships on the Medway, the military paradings and manœuvres, the woods and pastures, the delightful walks with his father to Rochester and Cobham—all were to vanish, as Forster says, “like a dream”; for in 1822 John Dickens was recalled to Somerset House, and in the winter of that year he departed by coach for London, accompanied by his wife and children, excepting Charles, who was left behind for a few weeks longer in the care of the worthy schoolmaster, William Giles. Presently the day arrived when the lonesome lad followed his parents to the Metropolis, leaving behind him, alas! everything that gave his “ailing little life its picturesqueness or sunshine”; for he was really a very sickly boy, and for that reason unable to join with zest in the more vigorous sports of his playfellows, which explains his fondness for reading, so unusual in lads of his age.

Little Charles was only ten years old when he bade farewell to Chatham, and took his place as a passenger in the stage-coach “Commodore.” “There was no other inside passenger,” he afterwards observed, “and I consumed my sandwiches in solitude and dreariness, and it rained hard all the way, and I thought life sloppier than I expected to find it.” Like Philip Pirrip, he might with more justice have thought that henceforth he “was for London and greatness.” Undoubtedly he experienced the same sensations as those of that youthful hero who, under similar circumstances, realized that “all beyond was so unknown and great that in a moment with a 21 strong heave and sob I broke into tears.”[15] Reminiscences of that memorable journey are recorded in one of that charming series of papers contributed by him to All the Year Round under the general title of “The Uncommercial Traveller.” Dickens here calls his boyhood’s home “Dullborough”—“most of us come from Dullborough who come from a country town”—informing us that as he left the place “in the days when there were no railways in the land,” he left it in a stage-coach, and further takes us into his confidence by saying that he had never forgotten, nor lost the smell of, the damp straw in which he was packed, “like game, and forwarded, carriage paid, to the Cross Keys, Wood Street, Cheapside, London.” These words were written in June, 1860, and a few months later, when penning the twentieth chapter of “Great Expectations,” he again recalled the episode: “The journey from our town to the Metropolis was a journey of about five hours. It was a little past mid-day when the four-horse stage-coach by which I was a passenger got into the ravel of traffic frayed out about the Cross Keys, Wood Street, Cheapside, London.... The coach that had carried me away was melodiously called ‘Timpson’s Blue-Eyed Maid,’ and belonged to Timpson, at the coach-office up-street.... Timpson’s was a moderate-sized coach-office (in fact, a little coach-office), with an oval transparency in the window, which looked beautiful by night, representing one of Timpson’s coaches in the act of passing a milestone on the London road with great velocity, completely full inside and out, and all the passengers dressed in the first style of fashion, and enjoying 22 themselves tremendously.” He found, on a later visit to Rochester and Chatham, that Timpson’s had disappeared, for “Pickford had come and knocked Timpson’s down,” and “had knocked two or three houses down on each side of Timpson’s, and then had knocked the whole into one great establishment....”[16] The late Mr. Robert Langton states that Timpson was really Simpson (the coach proprietor at Chatham), and that the “Blue-Eyed Maid” was a veritable coach, to which reference is also made in the third chapter of “Little Dorrit.”

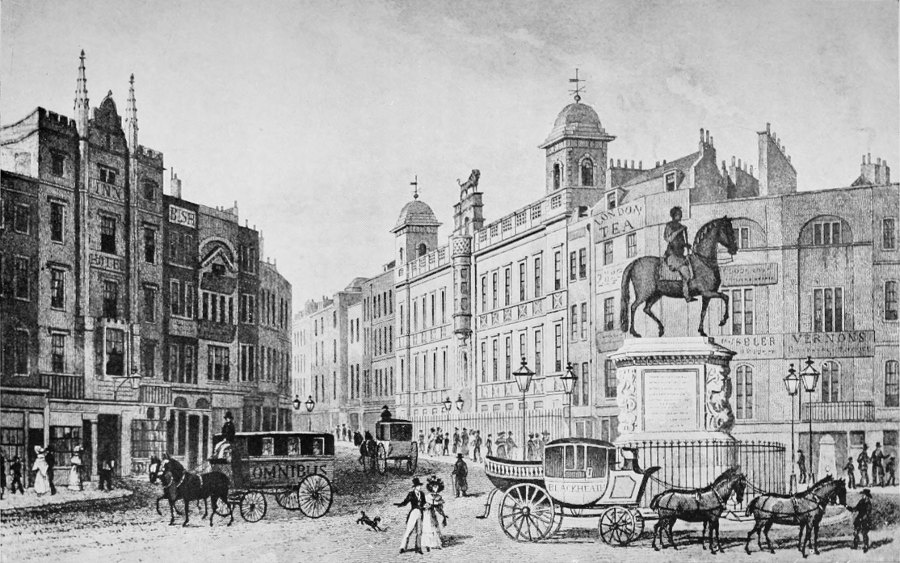

If, as Forster tells us, the “Commodore,” and not the “Blue-Eyed Maid,” conveyed little Charles to London, it was the identical vehicle by which Mr. Pickwick and his companions travelled from the Golden Cross at Charing Cross to Rochester, as duly set forth in the opening chapter of “The Pickwick Papers”; this coach was driven by old Cholmeley (or Chumley), who is said to have been the original of Tony Weller, and concerning whom some amusing anecdotes are related in “Nimrod’s Northern Tour.”

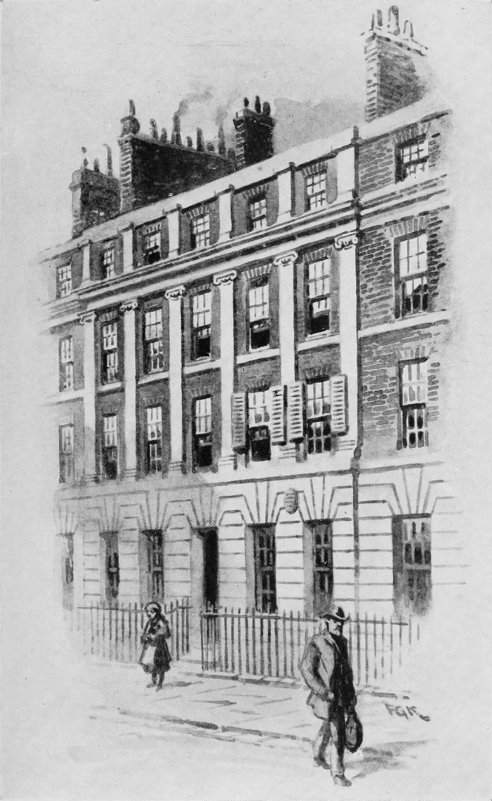

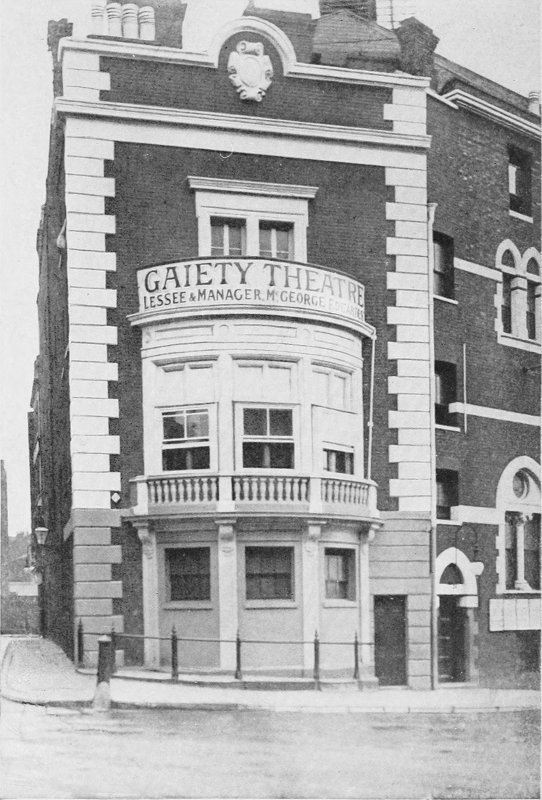

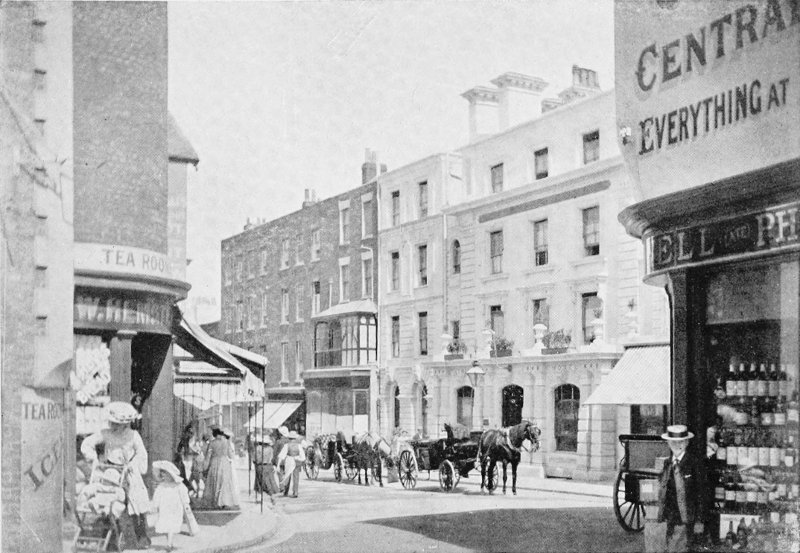

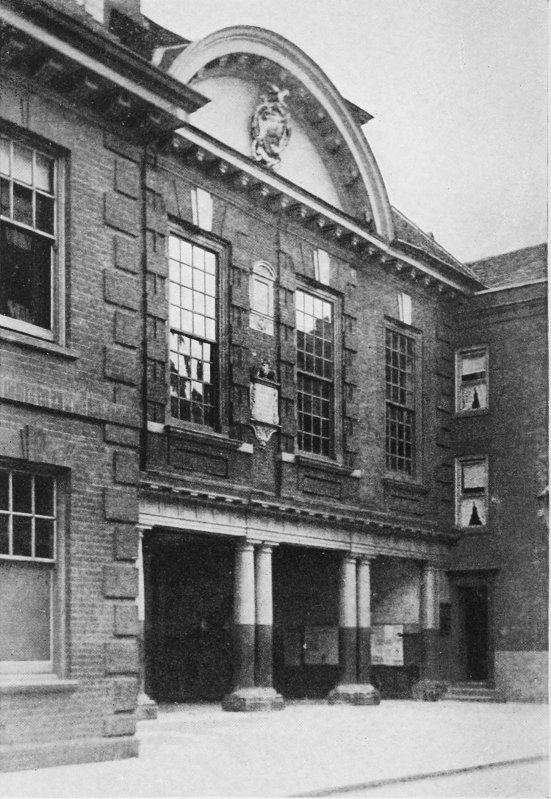

THE GOLDEN CROSS, CHARING CROSS, CIRCA 1827. (Page 22.)

Showing the hotel as it was in the Pickwickian days.

From a print in the collection of Councillor Newton, Hampstead.

It was in the early spring of 1823 that Charles Dickens made acquaintance with London for the second time, that vast Metropolis which henceforth continued to exercise a fascination over him, and in the study of which, as well as of its various types of humanity, he found a perpetual charm. His early impressions, however, were not of the brightest, having (as he subsequently observed) exchanged “everything that had given his ailing little life its picturesqueness or sunshine” for the comparatively sordid environment of a London suburb, and suffered the deprivation of the companionship of his playfellows at Chatham to become a solitary lad under circumstances that could not fail to make sorrowful the stoutest heart, not the least depressing being his father’s money involvement with consequent poverty at home. John Dickens, whose financial affairs demanded retrenchment, had rented what Forster describes as “a mean, small tenement” at No. 16 (now No. 141), Bayham Street, Camden Town, to-day one of the poorest parts of London, but not quite so wretched then as we are led to suppose by the reference in Forster’s biography. The cottages in Bayham Street, built in 1812, were comparatively 24 new in 1823, and then stood in the midst of what may be regarded as rural surroundings, there being a meadow at the back of the principal row of houses, in which haymaking was carried on in its season, while a beautiful walk across the fields led to Copenhagen House. Dickens averred that “a washer-woman lived next door” to his father, and “a Bow Street officer lived over the way.” We learn, too, that at the top of the street were some almshouses, and when revisiting the spot many years later Dickens told his biographer that “to go to this spot and look from it over the dust-heaps and dock-leaves and fields at the cupola of St. Paul’s looming through the smoke was a treat that served him for hours of vague reflection afterwards.” A writer who vividly remembered Camden Town as it appeared when John Dickens lived there has placed upon record some interesting particulars concerning it. He says: “In the days I am referring to gas was unknown. We had little twinkling oil-lamps. As soon as it became dark, the watchman went his rounds, starting from his box at the north end of Bayham Street, against the tea-gardens of the Mother Red Cap, then a humble roadside house, kept by a widow and her two daughters, of the name of Young. Then the road between Kentish and Camden Towns was very lonely—hardly safe after dark. These certainly were drawbacks, for depredations used frequently to be committed in the back premises of the houses.... The nearest church was Old St. Pancras, then in the midst of fields.”[17] Exception has been taken to Forster’s use of the 25 word “squalid” as applied to the Bayham Street of 1823, and with justification, for persons of some standing made it their abode, and we learn that in certain of the twenty or thirty newly-erected houses there lived Engelhart and Francis Holl, the celebrated engravers, the latter the father of Frank Holl, the Royal Academician; Charles Rolls and Henry Selous, artists of note; and Angelo Selous, the dramatic author. Thus it would appear that Bayham Street, during the early part of its history, was eminently respectable, and we are compelled to presume that Dickens’s unfavourable presentment of the locality was the outcome of his own painful environment, such as would be forcibly impressed upon the mind of a sickly child (as he then was) and one keenly susceptible to outward influences. Undoubtedly, as Forster remarks, “he felt crushed and chilled by the change from the life at Chatham, breezy and full of colour, to the little back garret in Bayham Street,” and, looking upon the dingy brick tenement to-day, it is not difficult to realize this fact; for, although the house itself could not have been less attractive than his previous home on “the Brook” at Chatham, the surroundings did not offer advantages in the shape of country walks and riverside scenery such as the immediate neighbourhood of Chatham afforded.[18]

16 (NOW 141) BAYHAM STREET, CAMDEN TOWN. (Page 24.)

Dickens and his parents lived here in 1823. The house was also the residence of Mr. Micawber, and the district is mentioned in “Dombey and Son” under the name of Staggs Gardens.

Bayham Street was named after Bayham Abbey in Sussex, one of the seats of the Marquis Camden. Eighty years ago this part of suburban London was but a village, and Bayham Street had grass struggling through the newly-paved road. Thus we are forced to the conclusion that the misery and depression of spirits, from which little Charles suffered while living here, must be attributed to family adversity and his own isolated condition rather than to the character of his environment. At this time his father’s pecuniary resources became so circumscribed as to compel the observance of the strictest domestic economy, and prevented him from continuing his son’s education. “As I thought,” said Dickens on one occasion very bitterly, “in the little back-garret in Bayham Street, of all I had lost in losing Chatham, what would I have given—if I had had anything to give—to have been sent back to any other school, to have been taught something anywhere!”

Instead of improving, the elder Dickens’s affairs grew from bad to worse, and all ordinary efforts to propitiate his creditors having been exhausted, Mrs. Dickens laudably resolved to attempt a solution of the difficulty by means of a school for young ladies. Accordingly, a house was taken at No. 4, Gower Street North, whither the family removed in 1823. This and the adjoining houses had only just been built. The rate-book shows that No. 4 was taken in the name of Mrs. Dickens, at an annual rental of £50, and that it was in the occupation of the Dickens family from Michaelmas, 1823, to Lady Day, 1824, they having apparently left Bayham Street at Christmas of the former year. No. 4, Gower Street North stood a little to the north of Gower Street 27 Chapel, erected in 1820, and still existing on the west side of the road; the house, known in recent times as No. 147, Gower Street, was demolished about 1895, and an extension of Messrs. Maple’s premises now occupies the site. When, in 1890, I visited the place with my friend the late Mr. W. R. Hughes (author of “A Week’s Tramp in Dickens Land”), we found it in the occupation of a manufacturer of artificial human eyes, a sort of Mr. Venus, with his “human eyes warious,” as depicted in “Our Mutual Friend”; while there was a dancing academy next door, reminiscent of Mr. Turveydrop, the professor of deportment in “Bleak House.” The Dickens residence had six small rooms, with kitchen in basement, each front room having two windows—altogether a fairly comfortable abode, but minus a garden. The result of Mrs. Dickens’s enterprise proved as disastrous as that of Mrs. Micawber’s. “Poor Mrs. Micawber! She said she had tried to exert herself; and so, I have no doubt, she had. The centre of the street door was perfectly covered with a great brass plate, on which was engraved, ‘Mrs. Micawber’s Boarding Establishment for Young Ladies’; but I never found that any young ladies had ever been to school there; or that any young lady ever came, or proposed to come; or that the least preparation was ever made to receive any young lady.” The actual facts are thus recorded in fiction, and the futility of Mrs. Dickens’s excellent intention to retrieve the family misfortunes seemed inevitable, in spite of the energy displayed by the youthful Charles in distributing “at a great many doors a great many circulars,” calling attention to the superior advantages of the new seminary. The blow proved 28 a crushing one, rendering the prospect more hopeless than ever. Importunate creditors, who could no longer be kept at bay, effected the arrest of John Dickens, who was conveyed forthwith to a prison for debtors in the Borough of Southwark; his last words to his heart-broken son as he was carried off being similar to those despondingly uttered by Mr. Micawber under like circumstances, to the effect that the sun was set upon him for ever.

Forster says that the particular prison where John Dickens suffered incarceration was the Marshalsea, and this statement appears correct, judging from the fragment of the novelist’s autobiography which refers to the unfortunate incident: “And he told me, I remember, to take warning by the Marshalsea, and to observe that if a man had twenty pounds a year, and spent nineteen pounds nineteen shillings and sixpence, he would be happy; but that a shilling spent the other way would make him wretched.” Another of Mr. Micawber’s wise sayings, be it observed. That impecunious gentleman (it will be remembered) suffered imprisonment at the King’s Bench, and it may be surmised that the novelist purposely changed the locale that old memories should not be revived. Of debtors’ prisons considerable knowledge is displayed in his books, his personal acquaintance with them dating, of course, from those days when the brightness of his young life was obscured by the “falling cloud” to which he compares this distressing time. Realistic and accurate pictures of the most noteworthy of these blots upon our social system may be found in the forcible description in the fortieth chapter of “Pickwick” of the Fleet Prison, of which the last vestiges were removed 29 in 1872, and the site of which is now covered by the Memorial Hall, Farringdon Street, and by Messrs. Cassell and Co.’s printing works; the King’s Bench Prison (long since demolished) figures prominently in “David Copperfield”; while many of the principal scenes in “Little Dorrit” are laid in the departed Marshalsea, which adjoined the burial-ground of St. George’s Church in the Borough. The extreme rear of the Marshalsea Prison, described by Dickens in the preface to “Little Dorrit,” was transformed into a warehouse in 1887.

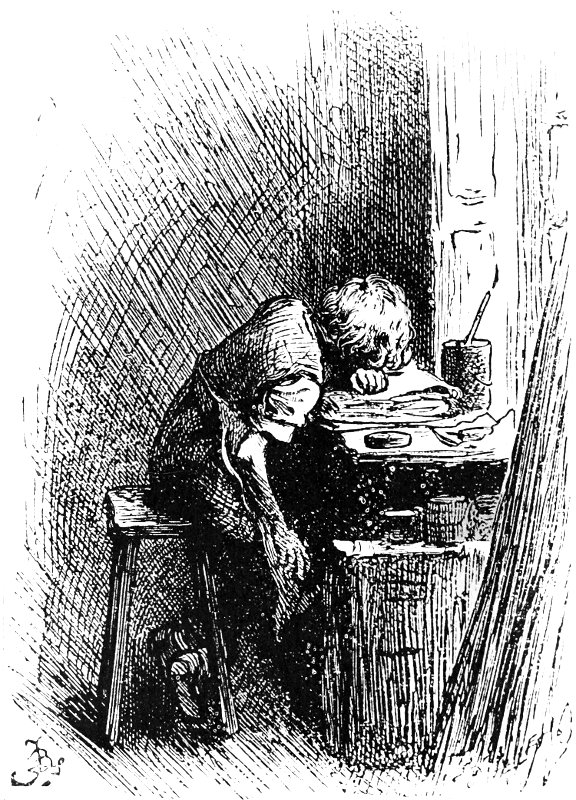

The second chapter of Forster’s biography makes dismal reading, relating, as it does, the bitter experiences of Charles Dickens’s boyhood—experiences, however, which yielded abundant material for future use in his stories. With the breadwinner in the clutches of the law, the wife and children, left stranded in the Gower Street house, had a terrible struggle for existence; we are told that in order to obtain the necessaries of life their bits of furniture and various domestic utensils were pawned or otherwise disposed of, until at length the place was practically emptied of its contents, and the inmates were perforce compelled to encamp in the two parlours, living there night and day. At this juncture a relative, James Lamert (who had lodged with the family in Bayham Street), heard of their misfortunes, and, through his connection with Warren’s Blacking Manufactory at 30, Hungerford Stairs, Strand, provided an occupation there for little Charles by which he could earn a few shillings a week—a miserable pittance, but extremely welcome under the circumstances, as, by exercising strict economy, it enabled him to support himself, thus making one mouth less to provide 30 for at home. Hungerford Stairs (in after-life he used to declare that he knew Hunger-ford well!) stood near the present Charing Cross railway bridge (which usurps the old Hungerford Suspension Bridge, transferred to Clifton), and the site of Hungerford Market is covered by the railway station. Dickens has recorded that “the blacking warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting, of course, on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscotted rooms and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up vividly before me, as if I were there again.” The blacking factory, which disappeared when Hungerford Market went, is faithfully portrayed in the eleventh chapter of “David Copperfield,” thinly disguised as Murdstone and Grinby’s Warehouse, “down in Blackfriars.” Dickens, like David, was keenly sensible of the humiliation of what he could not help regarding as a very menial occupation—the tying-up and labelling innumerable pots of paste-blacking—which he was now destined to follow, and for the remainder of his life he never recalled this episode without a pang.

He reminded Forster how fond he was of roaming about the neighbourhood of the Strand and Covent Garden during the dinner hour, intently observing the various types of humanity with precocious interest, and storing up impressions which were destined to prove invaluable to him. One of his favourite localities was the Adelphi, and he was 31 particularly attracted by a little waterside tavern called the Fox-under-the-Hill; doubtless the incident narrated in the just-mentioned chapter of “Copperfield”—the autobiographical chapter—is true of himself, when he causes little David to confess to a fondness for wandering about that “mysterious place with those dark arches,” and to wonder what the coalheavers thought of him, a solitary lad, as he sat upon a bench outside the little public-house, watching them as they danced.[19] The pudding-shops and beef-houses in the neighbourhood of St. Martin’s Lane and Drury Lane were familiar enough to him in those days; for, with such a modest sum to invest for his mid-day meal, he naturally compared notes as to the charges made by each for a slice of pudding or cold spiced beef before deciding upon the establishment which should have the privilege of his custom. He sometimes favoured Johnson’s in Clare Court, which is identical with the place patronized by David Copperfield—viz., the “famous alamode beef-house near Drury Lane,” where he gave the waiter a halfpenny, and wished he hadn’t taken it. In the recently demolished Clare Court there existed in those days two of the best alamode beef-shops in London, the Old Thirteen Cantons and the New Thirteen Cantons, and we read in a curious 32 book called “The Epicure’s Almanack” (1815), that “the beef and liquors at either house are equally good, and the attention of all who pass is attracted by the display of fine sallads in the windows, which display is daily executed with great ingenuity, and comprehends a variety of neat devices, in which the fine slices of red beetroot are pleasingly conspicuous.” The New Thirteen Cantons was kept by the veritable Johnson himself. We are further informed that he owned a clever dog called Carlo, “who once enacted so capital a part on the boards of Old Drury,” and whose sagacity “brought as many customers to Mr. Johnson as did the excellence of his fare.” Dickens, however, did not become acquainted with Carlo, who, a few years before the lad knew the shop, paid the penalty of a report that the famous animal had been bitten by a mad dog. “There were two pudding-shops,” said Dickens to his biographer, “between which I was divided, according to my finances.” One was in a court close to St. Martin’s Church, where the pudding was made with currants, “and was rather a special pudding,” but dear; the other was in the Strand, “somewhere in that part which has been rebuilt since,” where the pudding was much cheaper, being stout and pale, heavy and flabby, with a few big raisins stuck in at great distances apart. The more expensive shop stood in Church Court (at the back of the church), demolished when Adelaide Street was constructed about 1830, and may probably be identified with the Oxford eating-house, then existing opposite the departed Hungerford Street; the other establishment, where Dickens often dined for economy’s sake, flourished near the spot covered until quite recently by that children’s paradise, the Lowther Arcade. The courts surrounding St. Martin’s Church were formerly so thronged with eating-houses that the district became popularly known as “Porridge Island.”

DICKENS AT THE BLACKING WAREHOUSE. (Page 29.)

From a drawing by Fred Barnard. Reproduced by kind permission of Messrs. Chapman and Hall.

Failing, by means of a certain “deed,” to propitiate his creditors, John Dickens continued to remain within the gloomy walls of the Marshalsea. The home in Gower Street was thereupon broken up, and Mrs. Dickens, with her family, went to live with her husband in the prison. Little Charles, however, was handed over as a lodger to a Mrs. Roylance, a reduced old lady who afterwards figured as Mrs. Pipchin in “Dombey and Son.” Mrs. Roylance, long known to the family, resided in Little College Street, Camden Town; it became College Street West in 1828, and the portion north of King Street has been known since 1887 as College Place. The abode in question was probably No. 37, for, according to the rate-book of 1824 (the period with which I am dealing), the house so numbered (rated at £18) was occupied by Elizabeth Raylase[20] until the following year, and demolished about 1890, at which time the street was rebuilt.

The boy still carried on his uncongenial duties at the blacking warehouse with satisfaction to his employers, in spite of the acute mental suffering he underwent. Experiencing a sense of loneliness in being cut off from his parents, brothers, and sisters, he pleaded to his father to be allowed to lodge nearer the prison, with the result that he left Mrs. Roylance, to take up his abode in Lant Street, Borough, where, in the house of an insolvent court agent, a back attic 34 had been found for him, having from the little window “a pleasant prospect of a timber-yard.” Of Lant Street, as it probably then appeared, we have a capital description in the thirty-second chapter of the “Pickwick Papers,” for here it was that Bob Sawyer found a lodgment with the amiable (!) Mrs. Raddle and her husband, in the identical house, maybe, as that tenanted by the insolvent court agent. “There is a repose about Lant Street, in the Borough, which sheds a gentle melancholy upon the soul. There are always a good many houses to let in the street; it is a by-street, too, and its dulness is soothing. A house in Lant Street would not come within the denomination of a first-rate residence in the strict acceptation of the term, but it is a most desirable spot, nevertheless. If a man wished to abstract himself from the world, to remove himself from within the reach of temptation, to place himself beyond the possibility of any inducement to look out of the window, he should by all means go to Lant Street.

“In this happy retreat are colonized a few clear-starchers, a sprinkling of journeymen bookbinders, one or two prison agents for the insolvent court, several small housekeepers who are employed in the docks, a handful of mantua-makers, and a seasoning of jobbing tailors. The majority of the inhabitants either direct their energies to the letting of furnished apartments, or devote themselves to the healthful and invigorating pursuit of mangling. The chief features in the still life of the street are green shutters, lodging-bills, brass door-plates, and bell-handles, the principal specimens of animated nature, the pot-boy, the muffin youth, and the baked-potato man. The population is migratory, usually disappearing on the verge of quarter-day, and generally by night. His Majesty’s revenues are seldom collected in this happy valley; the rents are dubious, and the water communication is very frequently cut off.”

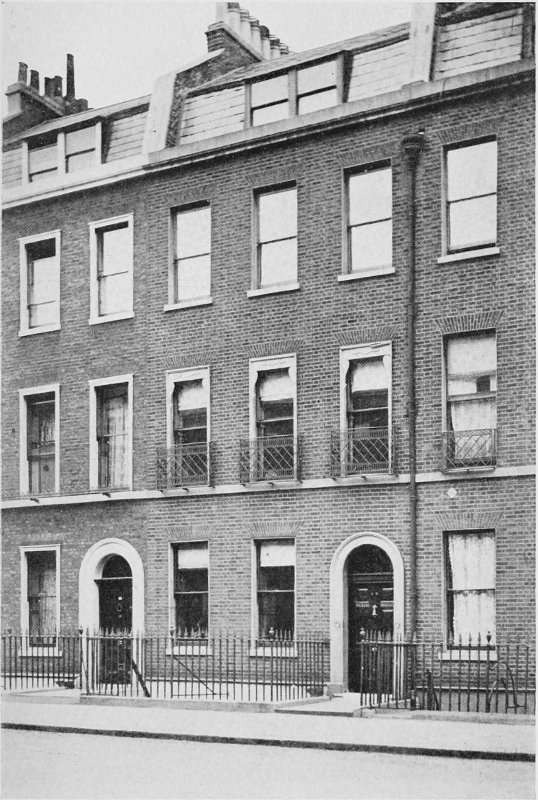

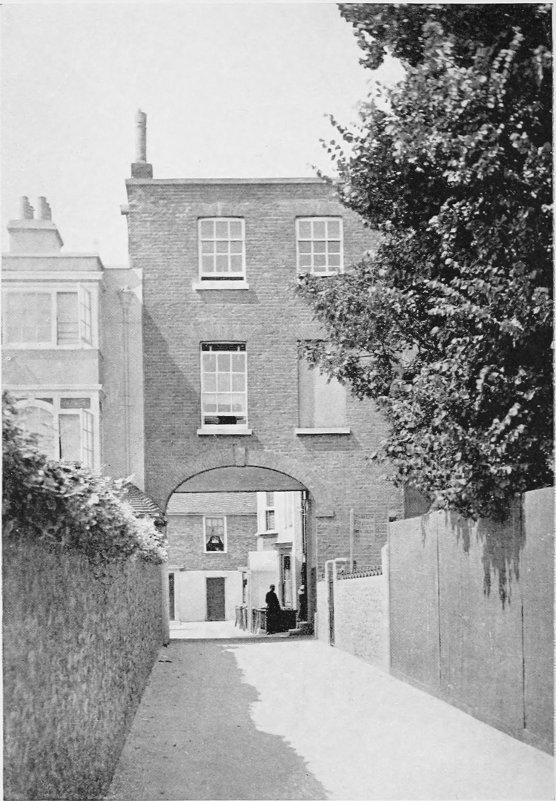

LANT STREET, BOROUGH. (Page 34.)

Showing the older residential tenements. The actual house in which Dickens lived as a boy is now demolished.

Lant Street, as Bob Sawyer informed Mr. Pickwick, is near Guy’s Hospital, “little distance after you’ve passed St. George’s Church—turns out of the High Street on the right-hand side of the way.” It has not altered materially in its outward aspect since the time when little Charles Dickens slept there, on the floor of the back attic, an abode which he then thought was “a paradise.” We may suppose that such accommodation, poor as it must have been, yielded some consolation to the lonely child by reason of the fact that he was within easy reach of his parents, and also because his landlord—a fat, good-natured old gentleman, who was lame—and his quiet old wife were very kind to him; and it is interesting to know that they and their grown-up son are immortalized in “The Old Curiosity Shop” as the Garland family. Little Charles looked forward to Saturday nights, when his release from toil at an earlier hour than usual enabled him to indulge his fancy for rambling and loitering a little in the busy thoroughfares between Hungerford Stairs and the Marshalsea. His usual way home was over Blackfriars Bridge, and then to the left along Charlotte Street, which (he is careful to tell us) “has Rowland Hill’s chapel on one side, and the likeness of a golden dog licking a golden pot over a shop door on the other,” a quaint sign still existing here. He was sometimes tempted to expend a penny to enter a show-van which generally stood at a corner of the 36 street “to see the fat pig, the wild Indian, and the little lady,” and for long afterwards could recall the peculiar smell of hat-making then (and now) carried on there.

The autobiographical record discloses another characteristic incident, which was afterwards embodied in the eleventh chapter of “Copperfield.”

One evening little Charles had acted as messenger for his father at the Marshalsea, and was returning to the prison by way of Westminster Bridge, when he went into a public-house in Parliament Street, at the corner of Derby Street, and ordered a glass of the very best ale (the “Genuine Stunning”), “with a good head to it.” “The landlord,” observes Dickens, “looked at me, in return, over the bar from head to foot, with a strange smile on his face; and instead of drawing the beer, looked round the screen and said something to his wife, who came out from behind it, with her work in her hand, and joined him in surveying me. Here we stand, all three, before me now, in my study at Devonshire Terrace—the landlord in his shirt-sleeves, leaning against the bar window-frame, his wife looking over the little half-door, and I, in some confusion, looking up at them from outside the partition. They asked me a good many questions, as what my name was, how old I was, where I lived, how I was employed, etc., etc. To all of which, that I might commit nobody, I invented appropriate answers. They served me with the ale, though I expect it was not the strongest on the premises; and the landlord’s wife, opening the little half-door and bending down, gave me a kiss that was half-admiring and half-compassionate, but all womanly and good.” I am 37 sure “so juvenile a customer was evidently unusual at the Red Lion”; and he explains that “the occasion was a festive one,” either his own birthday or somebody else’s, but I doubt whether this would prove sufficient justification in the eyes of the rigid total abstainer. In “David Copperfield” we find an illustration of the scene depicted in a clever etching by “Phiz.” The public-house here referred to is the Red Lion, which has been lately rebuilt, and differs considerably from the unpretentious tavern as Dickens knew it; unfortunately, the sign of the rampant red lion has not been replaced, but in its stead we see a bust of the novelist, standing within a niche in the principal front of the new building.

By a happy stroke of good fortune, a rather considerable legacy from a relative accrued to John Dickens, and had been paid into court during his incarceration. This, in addition to the official pension due for long service at Somerset House, enabled him to meet his financial responsibilities, with the result that the Marshalsea knew him no more. Just then, too, the blacking business had become larger, and was transferred to Chandos Street, Covent Garden, where little Charles continued to manipulate the pots, but in a more public manner; for here the work was done in a window facing the street, and generally in the presence of an admiring crowd outside. The warehouse (pulled down in 1889) stood next to the shop at the corner of Bedford Street in Chandos Street (the southern corner, now the Civil Service Stores); opposite, there was the public-house where the lad got his ale. “The stones on the street,” he afterwards observed to Forster, “may be smoothed by my small feet 38 going across to it at dinner-time, and back again.” The basement of the warehouse became transformed in later years into a chemist’s shop, and the sign of the tavern over the way was the Black Prince, closed in 1888, and demolished shortly afterwards to make room for buildings devoted to the medical school of the Charing Cross Hospital. His release from prison compelled the elder Dickens to seek another abode for himself and family, and he obtained temporary quarters with the before-mentioned Mrs. Roylance of Little College Street. Thence, according to Forster, they went to Hampstead, where the elder Dickens had taken a house, and from there, in 1825, he removed to a small tenement in Johnson Street, Somers Town, a poverty-stricken neighbourhood even in those days, and changed but little since. Johnson Street was then the last street in Somers Town, and adjoined the fields between it and Camden Town. It runs east from the north end of Seymour Street, and the house occupied by the Dickens family (including Charles, who had, of course, left his Lant Street “paradise”) was No. 13, at the east end of the north side, if we may rely upon the evidence afforded by the rate-book. At that time the house was numbered 29, and rated at £20, the numbering being changed to 13 at Christmas, 1825. In July of that year the name of the tenant is entered in the rate-book as Caroline Dickens, and so remains until January, 1829, after which the house is marked “Empty.”

THE SIGN OF THE DOG’S HEAD IN THE POT, CHARLOTTE STREET, BLACKFRIARS. (Page 35.)

“That turning in the Blackfriars Road which has Rowland Hill’s Chapel on one side, and the likeness of a golden dog licking a golden pot over a shop door at the other” (Forster).

Brighter days were in store for the Dickens family, and especially for little Charles, whose father could now afford to send him to a good school in the neighbourhood, much to the boy’s delight. Owing to a quarrel (of which he was the subject) between John Dickens and James Lamert, the father declared that his boy should leave the blacking warehouse and go to school instead. Thus terminated, suddenly and unexpectedly, that period of his life which Charles Dickens ever regarded with a feeling of repugnance. “Until old Hungerford Market was pulled down,” he tells us, “until old Hungerford Stairs were destroyed, and the very nature of the ground changed, I never had the courage to go back to the place where my servitude began.” He never saw it, and could not endure to go near it, and, in order that a certain smell of the cement used for putting on the blacking-corks should not revive unpleasant associations, he would invariably, when approaching Warren’s later establishment in Chandos Street, cross over to the opposite side of the way.