CONTENTS

One day, in the middle of a long literary conversation, Théodore Duret said to me: “I have known in my life two men of supreme intelligence. I knew of both before the world knew of either. Never did I doubt, nor was it possible to doubt, but that they would one day or other gain the highest distinctions—those men were Léon Gambetta and Émile Zola.”

Of Zola I am able to speak, and I can thoroughly realise how interesting it must have been to have watched him, at that time, when he was poor and unknown, obtaining acceptance of his articles with difficulty, and surrounded by the feeble and trivial in spirit, who, out of inborn ignorance and acquired idiocy, look with ridicule on those who believe that there is still a new word to say, still a new cry to cry.

I did not know Émile Zola in those days, but he must have been then as he is now, and I should find it difficult to understand how any man of average discrimination could speak with him for half-an-hour without recognising that he was one of those mighty monumental intelligences, the statues of a century, that remain and are gazed upon through the long pages of the world’s history. This, at least, is the impression Émile Zola has always produced upon me. I have seen him in company, and company of no mean order, and when pitted against his compeers, the contrast has only made him appear grander, greater, nobler. The witty, the clever Alphonse Daudet, ever as ready for a supper party as a literary discussion, with all his splendid gifts, can do no more when Zola speaks than shelter himself behind an epigram; Edmond De Goncourt, aristocratic, dignified, seated amid his Japanese watercolours, bronzes, and Louis XV. furniture, bitterly admits, if not that there is a greater naturalistic god than he, at least that there is a colossus whose strength he is unable to oppose.

This is the position Émile Zola takes amid his contemporaries.

By some strange power of assimilation, he appropriates and makes his own of all things; ideas that before were spattered, dislocated, are suddenly united, fitted into their places. In speaking, as in writing, he always appears greater than his subject, and, Titan-like, grasps it as a whole; in speaking, as in writing, the strength and beauty of his style is an unfailing use of the right word; each phrase is a solid piece of masonry, and as he talks an edifice of thought rises architecturally perfect and complete in design.

And it is of this side of Émile Zola’s genius that I wish particularly to speak—a side that has never been taken sufficiently into consideration, but which, nevertheless, is its ever-guiding and determinating quality. Émile Zola is to me a great epic poet, and he may be, I think, not inappropriately termed the Homer of modern life. For he, more than any other writer, it seems, possesses the power of seeing a subject as a whole, can divest it at will of all side issues, can seize with a firm, logical comprehension on the main lines of its construction, and that without losing sight of the remotest causes or the furthest consequences of its existence. It is here that his strength lies, and his is the strength which has conquered the world. Of his realism a great deal, of course, has been said, but only because it is the most obvious, not the most dominant quality of his work. The mistletoe invariably hides the oak from the eyes of the vulgar.

That Émile Zola has done well to characterise his creations with the vivid sentiment of modern life rather than the pale dream which reveals to us the past, that he was able to bend, to model, to make serviceable to his purpose the ephemeral habits and customs of our day, few will now deny. But this was only the off-shoot of his genius. That the colour of the nineteenth century with which he clothes the bodies of his heroes and heroines is not always exact, that none other has attempted to spin these garments before, I do not dispute. They will grow threadbare and fall to dust, even as the hide of the megatharium, of which only the colossal bones now remain to us wherewith to construct the fabric of the primeval world. And, in like manner, when the dream of the socialist is realized, when the burden of pleasure and work is proportioned out equally to all, and men live on a more strictly regulated plan than do either the ant or the bee, I believe that the gigantic skeleton of the Rougon-Macquart family will still continue to resist the ravages of time, and that western scientists will refer to it when disputing about the idiosyncrasies of a past civilization.

In the preceding paragraph, I have said neither more nor less than my meaning, for I am convinced that the living history of no age has been as well written as the last half of the nineteenth century is in the Rougon-Maequart series. I pass over the question whether, in describing Renée’s dress, a mistake was made in the price of lace, also whether the author was wrong in permitting himself the anachronism of describing a fête in the opera-house a couple of years before the building was completed. Errors of this kind do not appear to me to be worth considering. What I maintain is, that what Émile Zola has done, and what he alone has done—and I do not make an exception even in the case of the mighty Balzac—is to have conceived and constructed the frame-work of a complex civilization like ours, in all its worse ramifications. Never, it seems to me, was the existence of the epic faculty more amply demonstrated than by the genealogical tree of this now celebrated family.

The grandeur, the amplitude of this scheme will be seen at once. Adélaïde Fouque, a mad woman confined in a lunatic asylum at Plassans, is the first ancestor; she is the transmitter of the original neurosis, which, regulated by his or her physical constitution, assumes various forms in each individual member of the family, and is developed according to the surroundings in whieh he or she lives. By Rougon this woman had two children; by Macquart, with whom she cohabited on the death of her husband, she had three. Ursule Macquart married a man named Mouret, and their children are therefore cousins of the Rougon-Macquarts. This family has some forty or fifty members, who are distributed through the different grades of our social system. Some have attained the highest positions, as, Son Excellence Eugène Rougon, others have sunk to the lowest depths, as Gervaise in “L’Assommoir,” but all are tainted with the hereditary malady. By it Nana is invincibly driven to prostitution; by it Etienne Lantier, in “Germinal,” will be driven to crime; by it his brother, Claude, will be made a great painter. Protean-like is this disease. Sometimes it skips over a generation, sometimes lies almost latent, and the balance of the intelligence is but slightly disturbed, as in the instance of Octave in “Pot-Bouille,” and Lazare in “La Joie de Vivre.” But the mind of the latter is more distorted than is Octave’s. Lazare lives in a perpetual fear of death, and is prevented from realizing any of his magnificent projects by his vacillating temperament; in him we have an example how a splendid intelligence may be drained away like water through an imperceptible crack in the vase, and how what might have been the fruit of a life withers like the flowers from which the nourishing liquid has been withdrawn.

And so in the Rougon-Macquart series we have instances of all kinds of psychical development and decay; and with an overt and an intuitive reading of character truly wonderful, Émile Zola makes us feel that as the north and south poles and torrid zones are hemmed about with a girdle of air, so an ever varying but ever recognisable kinship unites, sometimes, indeed, by an almost imperceptible thread, the ends the most opposed of this remarkable race, and is diffused through the different variation each individual member successively presents. Can we not trace a mysterious physical resemblance between Octave Mouret in “Le Bonheur des Dames” and Maxime in “La Curée?” Is not the moral something by which Claude Lantier in “Le Ventre de Paris” escapes the fate of Lazare made apparent? Then, again, does not the inherited neurosis that makes of Octave a millionaire, of Lazare a wretched hypochondriac, of Claude Lantier a genius, of Maxime a symbol of ephemeral vice, reappear in a new and more deadly form in Jeanne, the hysterical child, in that most beautiful of beautiful books, “Une Page d’Amour?”

As beasts at a fair are urged on by the goads of their drivers, so certain fate pushes this wretched family forward into irrevocable death that is awaiting it. At each generation they grow more nervous, more worn out, more ready to succumb beneath the ravages of the horrible disease that in a hundred different ways is sweeping them into the night of the grave.

Even from this imperfect outline, what majesty, what grandeur there is in this dark design! Does not the great idea of fate receive a new and more terrible signification? Is not the horror and gloom of the tragedy increased by the fact that the thought was born in the study of the scientist, and not in the cloud-palace of the dreamer? What poet ever conceived an idea more vast! and if further proof of the epic faculty with which I have credited Émile Zola be wanting, I have only to refer to Pascal Rougon. Noah survived the deluge. Pascal Rougon, by some miracle, escapes the inherited stain—he, and he alone, is completely free from it He is a doctor, an advanced scientist, and he, in the twentieth volume, will analyse the terrible neurosis that has devastated his family.

In the upbuilding of this enormous edifice, Émile Zola shows the same constructive talent as he did in its conception. The energy he displays is marvellous. Every year a wing, courtyard, cupola, or tower is added, and each is as varied as the most imaginative could desire. Without looking further back than “L’Assommoir,” let us consider what has been done. In this work, we have a study of the life of the working people in Paris, written, for the sake of preserving the “milieu,” for the most part in their own language. It shows how the workers of our great social machine live, and must live, in ignorance and misery; it shows, as never was shown before, what the accident of birth means; it shows in a new way, and, to my mind, in as grand a way as did the laments of the chorus in the Greek play, the irrevocability of fate. “L’Assommoir” was followed by “Une Page d’Amour,” a beautiful Parisian idyl. Here we see the “bourgeois” at their best. We have seven descriptions of Paris seen from a distance of which Turner might be proud; we have a picture of a children’s costume ball which Meissonier might fall down and worship; we have the portrait of a beautiful and virtuous woman with her love story told, as it were, over the dying head of Jeanne (her little girl), the child whose nervous sensibilities are so delicate that she trembles with jealousy when she suspects that behind her back her mother is looking at the doctor. After “Une Page d’Amour” comes “Nana,” and with her we are transported to a world of pleasure-seekers; vicious men and women who have no thought but the killing of time and the gratification of their lusts. Nana is the Messaline of modern days, and, obeying the epic tendency of his genius, Émile Zola has instituted a comparison between the death of the “gilded fly,” conceived in drunkenness and debauchery, and the harlot city of the third Emperor, which, rotten with vice, falls before the victorious arms of the Germans.

“Nana” and “Une Page d’Amour” are psychological and philological studies of two radically different types of women; in both works, and likewise in “L’Assommoir,” there is much descriptive writing, and, doubtless, Émile Zola had this fact present in his mind when he set himself to write “Pot-Bouille,” that terrible satire on the “bourgeoisie.” He must have said, as his plan formulated itself in his mind, “this is a novel dealing with the home-life of the middle-classes; if I wish to avoid repeating myself, this book must contain a vast number of characters, and the descriptions must be reduced to a bare sufficiency, no more than will allow my readers to form an exact impression of the surroundings through which, the action passes.”

“Pot-Bouille,” or “Piping Hot!” as the present translation is called, is, therefore, an inquiry into the private lives of a number of individuals, who, while they follow different occupations, belong to the same class and live under the same roof. The house in the Rue de Choiseul is one of those immense “maisons bourgeoises,” in which, apparently, an infinite number of people live. On the first floor, we find Monsieur Duveyrier, an “avocat de la cour,” with his musical wife, Clotilde, and her father, Monsieur Vabre, a retired notary and proprietor of the house, who is absorbed in the preparation of an important statistical work; on the fourth floor are Madame Josserand, her two daughters, whom she is always trying to marry, her crazy son Saturnin, and her husband who spends his nights addressing advertising circulars at three francs a thousand, in order to eke out an additional something to help his family to ape an appearance of easy circumstances. On the third floor is an architect, Monsieur Campardon, with his ailing, yet blooming, wife Rose, and her cousin, “l’autre Madame Campardon.” There is also one of Monsieur Vabre’s sons, and “a distinguished gentleman who comes one night a week to work.”

These are the principal “locataires” but, in various odd corners, “des petits appartements qui donnent sur la cour,” we find all sorts and conditions of people. First on the list is the government clerk Jules and his wife Marie. She is a weak-minded little thing who commits adultery without affection, without desire, and the frequency of her confinements excites the ire of her mother and father. Then come two young men, Octave and Trublot. The former plays a part similar to that of a tenor in an opera; he is the accepted lover of the ladies. The latter is equally beloved by the maids. From the frequency of his visits, he may almost be said to live in the house; he is constantly asked to dine by one or other of the inmates, and in the morning he is generally found hiding behind the door of one of the servants’ rooms, waiting for an opportunity of descending the staircase unperceived by the terrible “concierge,” the moral guardian of the house.

Other visitors who figure prominently in the story are Madame Josserand’s brother, Uncle Bachelard, a dissipated widower, and his nephew Gueulin; the Abbé Mouret, ever ready to throw the mantle of religion over the back-slidings of his flock, and Madame Hédouin, the frigid directress of “The Ladies’ Paradise,” where Octave is originally engaged. The remaining “locataires” are Madame Juzeur, a lady who only reads poetry, and who was deserted by her husband after a single week of matrimonial, bliss; a workwoman who has a garret under the slates; and last, but not least, an author who lives on the second floor. He is rarely ever seen, he makes no one’s acquaintance, and thereby excites the enmity of everyone.

All these, the author of course excepted, pass and repass before the reader, and each is at once individual and representative; even the maid-servants—who only answer “yes” and “no” to their masters and mistresses—are adroitly characterised. We see them in their kitchens engaged in their daily occupations: while peeling onions and gutting rabbits and fish they call to and abuse each other from window to window. There is Julie, the belle of the attics, of whose perfume and pomatum Trublot makes liberal use when he honours her with a visit; there is fat Adèle whose dirty habits and slovenly ways make of her a butt whereat is levelled the ridicule and scorn of her fellow-servants; there are the lovers, Hippolyte and Clémence, whose carnal intercourse affords to Madame Duveyrier much ground for uneasiness, and in the end necessitates the intervention of the Abbé. Never were the manners and morals of servants so thoroughly sifted before, never was the relationship which their lives bear to those of their masters and mistresses so cunningly contrasted. The courtyard of the house echoes with their quarrelling voices, and it is there, in a scene of which Swift might be proud, that is spoken the last and terrible word of scorn which Émile Zola flings against the “bourgeoisie.” From her kitchen window a fellow-servant of Julie’s is congratulating her on being about to leave, and wishing that she may find a better place. To which Julie replies, “Toutes les baraques se ressemblent. Au jour d’aujourd’hui, qui a fait l’une a fait l’autre. C’est cochon et compagnie.”

I do not know to what other work to go to find so much successful sketching of character. I had better, I think, explain the meaning I attach to this phrase, “sketching of character,” for it is too common an error to associate the idea of superficiality with the word “sketch.” The true artist never allows anything to leave his studio that he deems superficial, or even unfinished. The word unfinished is not found in his vocabulary; to him a sketch is as complete as a finished picture. In the former he has painted broadly and freely, wishing to render the vividness, the vitality of a first impression; in the latter he is anxious to render the subtlety of a more intellectual and consequently a less sensual emotion. The portrait of Madame Josserand is a case in point, it is certainly less minute than that of Hélène Mouret, but is not for that less finished. In both, the artist has achieved, and perfectly, the task he set himself. “Piping Hot!” cannot be better defined than as a portrait album in which many of our French neighbours may be readily recognized.

This merit will not fail to strike any intelligent reader; but the marvellous way the almost insurmountable difficulties of binding together the stories of the lives of the different inhabitants of the house in the Rue de Choiseul are overcome, none but a fellow-worker will be able to appreciate at their full value. Up and down the famous staircase we go, from one household to another, interested equally in each, disgusted equally with all. And this sentence leads us right up to the enemies’ guns, brings us face to face with the two batteries from which the critics have directed their fire. The first is the truthfulness of the picture, the second is the coarseness with which it is painted. I will attempt to reply to both.

M. Albert Wolff in the “Figaro” declared that in a “maison bourgeoise” so far were “locataires” from being all on visiting terms, that it was of constant occurrence that the people on one floor not only did not know by sight but were ignorant of the names of those living above and below them; that the spectacle of a “maison bourgeoise,” with the lodgers running up and down stairs in and out of each other’s apartments at all hours of the night and day, was absolutely false; had never existed in Paris, and was an invention of the writer. Without a word of parley I admit the truth of this indictment. I will admit that no house could be found in Paris where from basement to attic the inhabitants are on such terms of intimacy as they are in the house in the Rue de Choiseul; but at the same time I deny that the extreme isolation described by M. Wolff could be found or is even possible in any house inhabited over a term of years by the same people. Émile Zola has then done no more than to exaggerate, to draw the strings that attach the different parts a little tighter than they would be in nature. Art, let there be no mistake on this point, be it romantic or naturalistic, is a perpetual concession; and the character of the artist is determined by the selection he makes amid the mass of conflicting issues that, all clamouring equally to be chosen, present themselves to his mind. In the case of Émile Zola, the epic faculty which has been already mentioned as the dominant trait of his genius naturally impelled him to make too perfect a whole of the heterogeneous mass of material that he had determined to construct from. The flaw is more obvious than in his other works, but in “Piping Hot!” he has only done what he has done since he first put pen to paper, what he will continue to do till he ceases to write. We will admit that to make all the people living in the house in the Rue de Choiseul on visiting terms was a trick of composition—et puis?

This was the point from which the critics who pretended to be guided by artistic considerations attacked the book; the others entrenched themselves behind the good old earthworks of morality, and primed their rusty popguns. Now there was a time, and a very good time it must have been, when a book was judged on its literary merits; but of late years a new school of criticism has come into fashion. Its manners are very summary indeed. “Would you or would you not give that book to your sister of sixteen to read?” If you hesitate you are lost; for then the question is dismissed with a smile and you are voted out of court. It would be vain to suggest that there are other people in the world besides your sister of sixteen summers.

I do not intend putting forward any well known paradox, that art is morals, and morals are art. That there are great and eternal moral laws which must be acted up to in art as in life I am more than ready to admit; but these are very different from the wretched conventionalities which have been arbitrarily imposed upon us in England. To begin with, it must be clear to the meanest intelligence that it would never do to judge the dead by the same standard as the living. If that were done, all the dramatists of the sixteenth century would have to go; those of the Restoration would follow. To burn Swift somebody lower in the social scale than Mr. Binns would have to be found, although he might do to commit Sterne to the flames. Byron, Shelley, yes, even Landor would have to go the same way. What would happen then, it is hard to-say; but it is not unfair to hint that if the burning were argued to its logical conclusion, some of the extra good people would find it difficult to show reason, if the intention of the author were not taken into account, why their most favourite reading should be saved from the general destruction.

Many writers have lately been trying to put their readers in the possession of infallible recipes for the production of good fiction; they would, to my mind, have employed their time and talents to far more purpose had they come boldly to the point and stated that the overflow of bad fiction with which we are inundated is owing to the influence of the circulating library, which, on one side, sustains a quantity of worthless writers who on their own merits would not sell a dozen copies of their books; and, on the other, deprives those who have something to say and are eager to say it of the liberty of doing so. It may be a sad fact, but it is nevertheless a fact, that literature and young girls are irreconcilable elements, and the sooner we leave off trying to reconcile them the better. At this vain endeavour the circulating library has been at work for the last twenty years, and what has been the result? A literature of bandboxes. Were Pope, Addison, Johnson, Fielding, Smollet, suddenly raised from their graves and started on reviewing “three vols.,” think you that they would not all cry together, “This is a literature of bandboxes?”

We judge a pudding by the eating, and I judge Messrs. Mudie and Smith by what they have produced; for they, not the ladies and gentlemen who place their names on the title pages, are the authors of our fiction. And what a terrible brood to admit the parentage of! Let those who doubt put aside pre-conceived opinions, and forgetting the bolstered up reputation of the authors, read the volumes by the light of a little common sense. Cast a glance at those that lie in Miss Rhoda Broughton’s lap. What a wheezing, drivelling lot of bairns they are! They have not a virtue amongst them, and their pinafore pages are sticky with childish sensualities.

And here we touch the keynote of the whole system. For, mark you, you can say what you like provided you speak according to rule. Everything is agreed according to precedent. I could give a hundred instances, but one will suffice. On the publication of “Adam Bede” a howl was raised, but the book was alive; it finished by being accepted, and the libraries were obliged to give way. The employment of seduction in the fabulation of a story was therefore established. This would have been a great point gained, if Mr. Mudie had not succeeded in forcing on all succeeding writers George Eliot’s manner of conducting her story. In “Adam Bede” we have Hetty described as an extremely fascinating dairymaid and Arthur as a noble-minded young man. After a good deal of flirtation they are shown to us walking through a wood together, and three months after we hear that Hetty is enceinte. Now, ever since the success of this book was assured, we have had numberless novels dealing with seductions, but invariably an interval of three months is allowed wherein the reader’s fancy may disport until the truth be told.

Not being a select librarian I will not undertake to say that the cause of morality is advanced by leaving the occurrence of the offence unmarked by a no more precise date than that of three months, but being a writer who loves and believes in his art, I fearlessly declare that such quibblery is not worthy of the consideration of serious men; and it was to break through this puerile conventionality that I was daring enough in my “Mummer’s Wife” to write that Dick dragged Kate into the room and that the door was slammed behind her. And it is on this passage that the select circulating libraries base a refusal to take the book. And it is such illiterate censorship that has thrown English fiction into the abyss of nonsense in which it lies; it is for this reason and no other that the writers of the present day have ceased even to try to produce good work, and have resigned themselves to the task of turning out their humdrum stories of sentimental misunderstanding. Yet, strange to say, in every other department of art, an unceasing intellectual activity prevails. Our poetry, our histories, our biographies, our newspapers are strong and vigorous, pregnant with thought, trenchant in style; it is not until we turn to the novel that we find a wearisome absence of everything but drivel.

Though much that I would like to have said is still unsaid, the exigencies of space compel me to bring this notice to a close. However, this one thing I hope I have made clear: that it is my firm opinion that if fiction is to exist at all, the right to speak as he pleases on politics, morals, and religion must be granted to the writer, and that he on his side must take cognizance of other readers than sentimental young girls, who require to be provided with harmless occupation until something fresh turns up in the matrimonial market. Therefore the great literary battle of our day is not to be fought for either realism or romanticism, but for freedom of speech; and until that battle be gained I, for one, will continue fearlessly to hold out a hand of welcome to all comers who dare to attack the sovereignty of the circulating library.

The first of these is “Piping Hot!” and, I think, the pungent odour of life it exhales, as well as its scorching satire on the middle-classes, will be relished by all who prefer the fortifying brutalities of truth to the soft platitudes of lies. As a satire “Piping Hot!” must be read; and as a satire it will rank with Juvenal, Voltaire, Pope, and Swift.

George Moore.

In the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin, a block of vehicles arrested the cab which was bringing Octave Mouret and his three trunks from the Lyons railway station. The young man lowered one of the windows, in spite of the already intense cold of that dull November afternoon. He was surprised at the abrupt approach of twilight in this neighbourhood of narrow streets, all swarming with a busy crowd. The oaths of the drivers as they lashed their snorting horses, the endless jostlings on the foot-pavements, the serried line of shops swarming with attendants and customers, bewildered him; for, though he had dreamed of a cleaner Paris than the one he beheld, he had never hoped to find it so eager for trade, and he felt that it was publicly open to the appetites of energetic young fellows.

The driver leant towards him.

“It’s the Passage Choiseul you want, isn’t it?”

“No, the Rue de Choiseul. A new house, I think.”

And the cab only had to turn the corner. The house was the second one in the street: a big house four storeys high, the stonework of which was scarcely discoloured, in the midst of the dirty stucco of the adjoining old frontages. Octave, who had alighted on to the pavement, measured it and studied it with a mechanical glance, from the silk warehouse on the ground floor to the projecting windows on the fourth floor opening on to a narrow terrace. On the first floor, carved female heads supported a highly elaborate cast-iron balcony. The windows were surrounded with complicated frames, roughly chiselled in the soft stone; and, lower down, above the tall doorway, two cupids were unrolling a scroll bearing the number, which at night-time was lighted up by a jet of gas from the inside.

A stout fair gentleman, who was coming out of the vestibule, stopped short on catching sight of Octave.

“What! you here!” exclaimed he. “Why, I was not expecting you till to-morrow!”

“The truth is,” replied the young man, “I left Hassans a day earlier than I originally intended. Isn’t the room ready?”

“Oh, yes. I took it a fortnight ago, and I furnished it at once in the way you desired. Wait a bit, I will take you to it.”

He re-entered the house, though Octave begged he would not give himself the trouble. The driver had got the three trunks off the cab. Inside the doorkeeper’s room, a dignified-looking man with a long face, clean-shaven like a diplomatist, was standing up gravely reading the “Moniteur.” He deigned, however, to interest himself about these trunks which were being deposited in his doorway; and, taking a few steps forward, he asked his tenant, the architect of the third floor as he called him:

“Is this the person, Monsieur Campardon?”

“Yes, Monsieur Gourd, this is Monsieur Octave Mouret, for whom I have taken the room on the fourth floor. He will sleep there and take his meals with us. Monsieur Mouret is a friend of my wife’s relations, and I beg you will show him every attention.”

Octave was examining the entrance with its panels of imitation marble and its vaulted ceiling decorated with rosettes. The courtyard at the end was paved and cemented, and had a grand air of cold cleanliness; the only occupant was a coachman engaged in polishing a bit with a chamois leather at the entrance to the stables. There were no signs of the sun ever shining there.

Meanwhile, Monsieur Gourd was inspecting the trunks. He pushed them with his foot, and, their weight filling him with respect, he talked of fetching a porter to carry them up the servants’ staircase.

“Madame Gourd, I’m going out,” cried he, just putting his head inside his room.

It was like a drawing-room, with bright looking-glasses, a red flowered Wilton carpet and violet ebony furniture; and, through a partly opened door, one caught a glimpse of the bed-chamber with a bedstead hung with garnet rep. Madame Gourd, a very fat woman with yellow ribbons in her hair, was stretehed out in an easy-chair with her hands clasped, and doing nothing.

“Well! let’s go up,” said the architect.

And seeing how impressed the young man seemed to be by Monsieur Gourd’s black velvet cap and sky blue slippers, he added, as he pushed open the mahogany door of the vestibule:

“You know he was formerly the Duke de Vaugelade’s valet.”

“Ah!” simply ejaculated Octave.

“It’s as I tell you, and he married the widow of a little bailiff of Mort-la-Ville. They even own a house there. But they are waiting until they have three thousand francs a year before going there to live. Oh! they are most respectable doorkeepers!”

The decorations of the vestibule and the staircase were gaudily luxurious. At the foot of the stairs was the figure of a woman, a kind of gilded Neapolitan, supporting on her head an amphora from which issued three gas-jets protected by ground glass globes. The panels of imitation white marble with pink borders succeeded each other at regular intervals up the wall of the staircase, whilst the cast-iron balustrade with its mahogany hand-rail was in imitation of old silver with clusters of golden leaves. A red carpet, secured with brass rods, covered the stairs. But what especially struck Octave on entering was a green-house temperature, a warm breath which seemed to be puffed from some mouth into his face.

“Hallo!” said he, “the staircase is warmed.”

“Of course,” replied Campardon. “All landlords who have the least self-respect go to that expense now. The house is a very fine one, very fine.”

He looked about him as though he were sounding the walls with his architect’s eyes.

“My dear fellow, you will see, it is a most comfortable place, and inhabited solely by highly respectable people!”

Then, slowly ascending, he mentioned the names of the different tenants. On each floor were two separate suites of apartments, one looking on to the street, the other on to the courtyard, and the polished mahogany doors of which faeed eaeh other. He began by saying a few words respecting Monsieur Auguste Vabre; he was the landlord’s eldest son; since the spring he had rented the silk warehouse on the ground floor, and he also occupied the whole of the “entresol” above. Then, on the first floor the landlord’s other son, Monsieur Théophile Vabre and his wife, resided in the apartment overlooking the courtyard; and in the one overlooking the street lived the landlord himself, formerly a notary at Versailles, but who was now lodging with his son-in-law, Monsieur Duveyrier, a judge at the Court of Appeal.

“A fellow who is not yet forty-five,” said Campardon, stopping short. “That’s something remarkable, is it not?”

He ascended two steps, and then suddenly turning round, he added:

“Water and gas on every floor.”

Beneath the tall window on each landing, the panes of which, bordered with fretwork, lit up the staircase with a white light, was placed a narrow velvet covered bench. The architect observed that elderly persons could sit down and rest. Then, as he passed the second floor without naming the tenants.

“And there?” asked Octave, pointing to the door of the principal suite.

“Oh! there,” said he, “persons whom one never sees, whom no one knows. The house could well do without them. Blemishes, you know, are to be found everywhere.”

He gave a little snort of contempt.

“The gentleman writes books, I believe.”

But on the third floor his smile of satisfaction reappeared. The apartments looking on to the courtyard were divided into two suites; they were occupied by Madame Juzeur, a little woman who was most unhappy, and a very distinguished gentleman who had taken a room to which he came once a week on business matters. Whilst giving these particulars, Campardon opened the door on the other side of the landing.

“And this is where I live,” resumed he. “Wait a moment, I must get your key. We will first go up to your room; you can see my wife afterwards.”

During the two minutes he was left alone, Octave felt penetrated by the grave silence of the staircase. He leant over the balustrade, in the warm air which ascended from the vestibule; he raised his head, listening if any noise came from above. It was the death-like peacefulness of a middle-class drawing-room, carefully shut in and not admitting a breath from outside. Behind the beautiful shining mahogany doors there seemed to be unfathomable depths of respectability.

“You will have some excellent neighbours,” said Campardon, reappearing with the key; “on the street side there are the Josserands, quite a family, the father who is cashier at the Saint-Joseph glass works, and also two marriageable daughters; and next to you the Pichons, the husband is a clerk; they are not rolling in wealth, but they are educated people. Everything has to be let, has it not? even in a house like this.”

From the third landing, the red carpet ceased and was replaced by a simple grey holland. Octave’s vanity was slightly ruffled. The staircase had, little by little, filled him with respect; he was deeply moved at inhabiting such a fine house as the architect termed it. As, following the latter, he turned into the passage leading to his room, he caught sight through a partly open door of a young woman standing up before a cradle. She raised her head at the noise. She was fair, with clear and vacant eyes; and all he carried away was this very distinct look, for the young woman, suddenly blushing, pushed the door to in the shame-faced way of a person taken by surprise.

Campardon turned round to repeat:

“Water and gas on every floor, my dear fellow.”

Then he pointed out a door which opened on to the servants’ staircase. Their rooms were up above. And stopping at the end of the passage, he added:

“Here we are at last.”

The room, which was square, pretty large, and hung with a grey wall-paper with blue flowers, was furnished very simply. Close to the alcove was a little dressing-closet with just room enough to wash one’s hands. Octave went straight to the window, which admitted a greenish light. Below was the courtyard looking sad and clean, with its regular pavement, and the shining brass tap of its cistern. And still not a human being, nor even a noise; nothing but the uniform windows, without a bird-cage, without a flower-pot, displaying the monotony of their white curtains. To hide the big bare wall of the house on the left hand side, which shut in the square of the courtyard, the windows had been repeated, imitation windows in paint, with shutters eternally closed, behind which the walled-in life of the neighbouring apartments appeared to continue.

“But I shall be very comfortable here!” cried Octave delighted.

“I thought so,” said Campardon. “Well! I did everything as though it had been for myself; and, moreover, I carried out the instructions contained in your letters. So the furniture pleases you? It is all that is necessary for a young man. Later on, you can make any changes you like.”

And, as Octave shook his hand, thanking him, and apologising for having given him so much trouble, he resumed in a serious tone of voice:

“Only, my boy, no rows here, and above all no women! On my word of honour, if you were to bring a woman here it would revolutionize the whole house!”

“Be easy!” murmured the young man, feeling rather anxious.

“No, let me tell you, for it is I who would be compromised. You have seen the house. All middle-class people, and of extreme morality! between ourselves, they affect it rather too much. Never a word, never more noise than you have heard just now. Ah, well! Monsieur Gourd would at once fetch Monsieur Vabre, and we should both be in a nice pickle! My dear fellow, I ask it of you for my own peace of mind: respect the house.”

Octave, overpowered by so much virtue and respectability, swore to do so. Then, Campardon, casting a mistrustful glance around, and lowering his voice as though some one might have heard him, added with sparkling eyes:

“Outside it concerns nobody. Paris is big enough, is it not? there is plenty of room. As for myself, I am at heart an artist, therefore I think nothing of it!”

A porter carried up the trunks. When everything was straight, the architect assisted paternally at Octave’s toilet. Then, rising to his feet he said:

“Now we will go and see my wife.”

Down on the third floor the maid, a slim, dark, and coquettish looking girl, said that madame was busy. Campardon, with a view of putting his young friend at ease, showed him over the rooms: first of all, there was the huge white and gold drawingroom, highly decorated with artificial mouldings, and situated between a green parlour which the architect had turned into a workroom and the bedroom, into which they could not enter, but the narrow shape of which, and the mauve wall-paper, he described. As he next ushered him into the dining-room, all in imitation wood, with an extraordinary complication of baguettes and coffers, Octave, enchanted, exclaimed:

“It is very handsome!”

On the ceiling, two big cracks cut right through the coffers, and, in a corner, the paint had peeled off and displayed the plaster.

“Yes, it creates an effect,” slowly observed the architect, his eyes fixed on the ceiling. “You see, these kind of houses are built to create effect. Only, the walls will not bear much looking into. It is not twelve years old yet, and it is already cracking. One builds the frontage of handsome stone, with a lot of sculpture about it; one gives three coats of varnish to the walls of the staircase; one paints and gilds the rooms; and all that flatters people, and inspires respect. Oh! it is still solid, it will certainly last as long as we shall!”

He led him again across the ante-room, which was lighted by a window of ground glass. To the left, looking on to the courtyard, there was a second bed-chamber where his daughter Angèle slept, and which, all in white, looked on this November afternoon as sad as a tomb. Then at the end of the passage, came the kitchen, into which he insisted on conducting Octave, saying that it was necessary to see everything.

“Walk in,” repeated he, pushing open the door.

A terrible uproar issued from it. In spite of the cold, the window was wide open. With their elbows on the rail, the dark maid and a fat cook, a dissolute looking old party, were leaning out into the narrow well of an inner courtyard, which lighted the kitchens of each floor, placed opposite to each other. They were both yelling with their backs bent, whilst, from the depths of this hole, arose the sounds of vulgar voices, mingled with oaths and bursts of laughter. It was like the overflow of some sewer: all the domestics of the house were there, easing their minds. Octave’s thoughts reverted to the peaceful majesty of the grand staircase.

Just then the two women, warned by some instinct, turned round. They remained thunderstruck on beholding their master with a gentleman. There was a gentle whistle, windows were shut, and all was once more as silent as death.

“What is the matter, Lisa?” asked Campardon.

“Sir,” replied the maid, greatly excited, “it’s that filthy Adèle again. She has thrown a rabbit’s guts out of the window. You should speak to Monsieur Josserand, sir.”

Campardon became very grave, anxious not to make any promise. He returned to his workroom, saying to Octave:

“You have seen all. On each floor, the rooms are arranged the same. I pay a rent of two thousand five hundred francs, and on a third floor, too! Rents are rising every day. Monsieur Vabre must make about twenty-two thousand francs a year from his house. And it will increase still more, for there is a question of opening a wide thoroughfare from the Place de la Bourse to the new Opera-house. And he had the ground this is built upon almost for nothing, twelve years ago, after that great fire caused by a druggist’s servant!”

As they entered, Octave observed, hanging above a drawing-table, and in the full light from the window, a richly framed picture of a Virgin, displaying in her opened breast an enormous flaming heart. He could not repress a movement of surprise; he looked at Campardon, whom he had known to be a rather wild fellow at Plassans.

“Ah! I forgot to tell you,” resumed the latter slightly colouring, “I have been appointed diocesan architect, yes, at Evreux. Oh! a mere bagatelle as regards money, in all barely two thousand francs a year. But there is scarcely anything to do, a journey now and again; for the rest I have an inspector there. And, you see, it is a great deal, when one can print on one’s cards: ‘government architect.’ You can have no idea what an amount of work that procures me in the highest society.”

Whilst speaking, he looked at the Virgin with the flaming heart.

“After all,” continued he in a sudden fit of frankness, “I do not care a button for their paraphernalia!”

But, on Octave bursting out laughing, the architect was seized with fear. Why confide in that young man? He gave a side glance, and, putting on an air of compunction, he tried to smooth over what he had said.

“I do not care and yet I do care. Well! yes, I am becoming like that. You will see, you will see, my friend: when you have lived a little longer, you will do as every one else.”

And he spoke of his forty-two years, of the emptiness of life, posing for being very melancholy, which his robust health belied. In the artist’s head which he had fashioned for himself, with flowing hair and beard trimmed in the Henri IV. style, one found the flat skull and square jaw of a middle-class man of limited intelligence and voracious appetites. When younger, he had a fatiguing gaiety.

Octave’s eyes became fixed on a number of the “Gazette de France,” which was lying amongst some plans. Then, Campardon, more and more ill at ease, rang for the maid to know if madame was at length disengaged. Yes, the doctor was just leaving, madame would be there directly.

“Is Madame Campardon unwell?” asked the young man.

“No, she is the same as usual,” said the architect in a bored tone of voice.

“Ah! and what is the matter with her?”

Again embarrassed, he did not give a straightforward answer.

“You know, there is always something going wrong with women. She has been in this state for the last thirteen years, ever since her confinement. Otherwise, she is as well as can be. You will even find her stouter.”

Octave asked no further questions. Just then, Lisa returned, bringing a card; and the architect, begging to be excused, hastened to the drawing-room, telling the young man as he disappeared to talk to his wife and have patience. Octave had caught sight, on the door being quickly opened and closed, of the black mass of a cassock in the centre of the large white and gold apartment.

At the same moment, Madame Campardon entered from the ante-room. He scarcely knew her again. In other days, when a youngster, he had known her at Plassans, at her father’s, Monsieur Domergue, government clerk of the works, she was thin and ugly, as puny-looking as a young girl suffering from the crisis of her puberty; and now he beheld her plump, with the clear and placid complexion of a nun, soft eyes, dimples, and a general appearance of an overfed she-cat. If she had not been able to grow pretty, she had ripened towards thirty, gaining a sweet savour and a nice fresh odour of autumn fruit. He remarked, however, that she walked with difficulty, her whole body wrapped, in a mignonette coloured silk dressing-gown, moving; which gave her a languid air.

“But you are a man, now!” said she gaily, holding out her hands. “How you have grown, since our last journey to the country!”

And she gazed at him: tall, dark, handsome, with his well kept moustache and beard. When he told her his age, twenty-two, she scarcely believed it: he looked twenty-five at least. He, whom the presence of a woman, even though she were the lowest of servants, filled with rapture, laughed melodiously, enveloping her with his eyes of the colour of old gold, and of the softness of velvet.

“Ah! yes,” repeated he gently, “I have grown, I have grown. Do you recollect, when your cousin Gasparine used to buy me marbles?”

Then, he gave her news of her parents. Monsieur and Madame Domergue were living happily, in the house to which they had retired; they merely complained of being very lonely, bearing Campardon a grudge for having taken their little Rose from them, during a stay he had made at Plassans on business. Then, the young man tried to bring the conversation round to cousin Gasparine, having a precocious youngster’s old curiosity to satisfy, in the matter of an hitherto unexplained adventure: the architect’s mad passion for Gasparine, a tall lovely girl, but poor, and his sudden marriage with skinny Rose who had a dowry of thirty thousand francs, and quite a tearful scene, and a quarrel, and the flight of the abandoned one to Paris, to an aunt who was a dressmaker. But Madame Campardon, whose placid complexion preserved a rosy paleness, did not appear to understand. He was unable to draw a single particular from her.

“And your parents?” inquired she in her turn. “How are Monsienr and Madame Mouret?”

“Very well, thank you,” replied he. “My mother scarcely leaves her garden. You would find the house in the Rue de la Banne, just as you left it.”

Madame Campardon, who seemed unable to remain standing for long without feeling tired, had seated herself on a high drawing-chair, her legs stretched out in her dressing-gown; and he, taking a low chair beside her, raised his head when speaking, with his air of habitual adoration. With his large shoulders, he was like a woman, he had a woman’s feeling which at once admitted him to their hearts. So that, at the end of ten minutes, they were both talking like two lady friends of long standing.

“Now I am your boarder,” said he, passing a handsome hand with neatly trimmed nails over his beard. “We shall get on well together, you will see. How charming it was of you to remember the Plassans youngster and to busy yourself about everything, at the first word!”

But she protested.

“No, do not thank me. I am a great deal too lazy, I never move. It was Achille who arranged everything. And, besides, was it not sufficient that my mother mentioned to us your desire to board in some family, for us to think at once of opening our doors to you? You will not be with strangers, and will be company for us.”

Then, he told her of his own affairs. After having obtained a bachelor’s diploma, to please his family, he had just passed three years at Marseilles, in a big calico print warehouse, which had a factory in the neighbourhood of Plassans. He had a passion for trade, the trade in women’s luxuries, into which enters a seduction, a slow possession by gilded words and adulatory glances. And he related, laughing victoriously, how he had made the five thousand francs, without which he would never have ventured on coming to Paris, for he had the prudence of a Jew beneath the exterior of an amiable giddy-headed fellow.

“Just fancy, they had a Pompadour calico, an old design, something marvellous. No one would bite at it; it had been stowed away in the cellars for two years past. Then, as I was about to travel through the departments of the Var and the Basses-Alpes, it occurred to me to purchase the whole of the stock and to sell it on my own account. Oh! such a success! an amazing success! The women quarrelled for the remnants; and to-day, there is not one there who is not wearing some of my calico. I must say that I talked them over so nicely! They were all with me, I might have done as I pleased with them.”

And he laughed, whilst Madame Campardon, charmed, and troubled by thought of that Pompadour calico, questioned him: “Little bouquets on an unbleached ground, was it not?” She had been trying to obtain the same thing everywhere for a summer dressing-gown.

“I have travelled for two years, which is enough,” resumed he. “Besides, there is Paris to conquer. I must immediately look out for something.”

“What!” exclaimed she, “has not Achille told you? But he has a berth for you, and close by, too!”

He uttered his thanks, as surprised as though he were in fairy land, asking, by way of a joke, whether he would not find a wife and a hundred thousand francs a-year in his room that evening, when a young girl of fourteen, tall and ugly, with fair insipid-looking hair, pushed open the door, and gave a slight cry of fright.

“Come in and don’t be afraid,” said Madame Campardon. “It is Monsieur Octave Mouret, whom you have heard us speak of.”

Then, turning towards the latter, she added:

“My daughter, Angèle. We did not bring her with us at our last journey. She was so delicate! But she is getting stouter now.”

Angèle, with the awkwardness of girls in the ungrateful age, went and placed herself behind her mother, and cast glances at the smiling young man. Almost immediately, Campardon reappeared, looking excited; and he could not contain himself, but told his wife in a few words of his good fortune: the Abbé Mauduit, Vicar of Saint-Roch, had called about some work, merely some repairs, but which might lead to many other things. Then, annoyed at having spoken before Octave, and still quivering, he rapped one hand in the other, saying:

“Well! well! what are we going to do?”

“Why, you were going out,” said Octave. “Do not let me disturb you.”

“Achille,” murmured Madame Campardon, “that berth, at the Hédouins’—”

“Why, of course! I was forgetting,” exclaimed the architect. “My dear fellow, a place of first clerk at a large linen-draper’s. I know some one there who has said a word for you. You are expected. It is not yet four o’clock; shall I introduce you now?”

Octave hesitated, anxious about the bow of his necktie, flurried by his mania for being neatly dressed. However, he decided to go, when Madame Campardon assured him that he looked very well. With a languid movement, she offered her forehead to her husband, who kissed her with a great show of tenderness, repeating:

“Good-bye, my darling—good-bye, my pet.”

“Do not forget that we dine at seven,” said she, accompanying them across the drawing-room, where they had left their hats.

Angèle followed them without the slightest grace. But her music-master was waiting for her, and she at once commenced to strum on the instrument with her bony fingers. Octave, who was lingering in the ante-room, repeating his thanks, was unable to make himself heard. And, as he went downstairs, the sound of the piano seemed to follow him: in the midst of the warm silence other pianos—from Madame Juzeur’s, the Vabres’, and Duveyriers’—were answering, playing on eaeh floor other airs, whieh issued, distantly and religiously, from the calm solemnity of the doors.

On reaching the street, Campardon turned into the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin. He remained silent, with the absorbed air of a man seeking for an opportunity to broach a subject.

“Do you remember Mademoiselle Gasparine?” asked he, at length. “She is first lady assistant at the Hédouins’. You will see her.”

Octave thought this a good time for satisfying his curiosity.

“Ah!” said he. “Does she live with you?”

“No! no!” exelaimed the architect, hastily, and as though feeling hurt at the bare idea.

Then, as the young man appeared surprised at his vehemence, he gently continued, speaking in an embarrassed way:

“No; she and my wife no longer see each other. You know, in families— Well, I met her, and I could not refuse to shake hands, could I? more especially as she is not very well off, poor girl. So that, now, they have news of each other through me. In these old quarrels, one must leave the task of healing the wounds to time.”

Octave was about to question him plainly on the subject of his marriage, when the architect suddenly put an end to the conversation by saying:

“Here we are!”

It was a large linen-drapers, opening on to the narrow triangle of the Place Gaillon, at the corner of the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin and the Rue de la Michodière. Across two windows immediately above the shop was a signboard, with the words, “The Ladies’ Paradise, founded in 1822,” in faded gilt letters, whilst on the shop windows was inscribed, in red, the name of the firm, “Deleuze, Hédouin, & Co.”

“It has not the modern style, but it is honest and solid,” rapidly explained Campardon. “Monsieur Hédouin, formerly a clerk, married the daughter of the elder Deleuze, who died a couple of years ago; so that the business is now managed by the young couple—the old Deleuze and another partner, I think, both keep out of it. You will see Madame Hédouin. Oh! a woman with brains! Let us go in.”

It so happened that Monsieur Hédouin was at Lille buying some linen; therefore Madame Hédouin received them. She was standing up, a penholder behind her ear, giving orders to two shopmen who were putting away some pieces of stuff on the shelves; and she appeared to him so tall, so admirably lovely, with her regular features and her tidy hair, so gravely smiling, in her black dress, with a turn-down collar and a man’s tie, that Octave, not usually timid, could only stammer out a few observations. Everything was settled without any waste of words.

“Well!” said she, in her quiet way, and with her tradeswoman’s accustomed gracefulness, “you may as well look over the place, as you are not engaged.”

She called one of her clerks, and put Octave under his guidance; then, after having politely replied to a question of Campardon’s that Mademoiselle Gasparine was out on an errand, she turned her back and resumed her work, continuing to give her orders in her gentle and concise voice.

“Not there, Alexandre. Put the silks up at the top. Be careful, those are not the same make!”

Campardon, after hesitating, at length said to Octave that he would call again for him to take him back to dinner. Then, during two hours, the young man went over the warehouse. He found it badly lighted, small, encumbered with stock, which, overflowing from the basement, became heaped up in the corners, leaving only narrow passages between high walls of bales. On several different occasions he ran against Madame Hédouin, busy, and scuttling along the narrowest passages without ever catching her dress in anything. She seemed the very life and soul of the establishment, all the assistants belonging to which obeyed the slightest sign of her white hands. Octave felt hurt that she did not take more notice of him. Towards a quarter to seven, as he was coming up a last time from the basement, he was told that Campardon was on the first floor with Mademoiselle Gasparine. Up there was the hosiery department, which that young lady looked after. But, at the top of the winding staircase, the young man stopped abruptly behind a pyramid of pieces of calico systematically arranged, on hearing the architect talking most familiarly to Gasparine.

“I swear to you it is not so!” cried he, forgetting himself so far as to raise his voice.

A slight pause ensued.

“How is she now?” at length inquired the young woman.

“Well! always the same. It comes and goes. She feels that it is all over now. She will never get right again.”

Gasparine resumed, in compassionate tones:

“My poor friend, it is you who are to be pitied. However, as you have been able to manage in another way, tell her how sorry I am to hear that she is still unwell—”

Campardon, without letting her finish, seized hold of her by the shoulders and kissed her roughly on the lips, in the gas-heated air already becoming heavy beneath the low ceiling. She returned his kiss, murmuring:

“To-morrow morning, if you can, at six o’clock; I will remain in bed. Knock three times.”

Octave, bewildered, and beginning to understand, coughed, and showed himself. Another surprise awaited him. Cousin Gasparine had become dried up, thin and angular, with her jaw projecting, and her hair coarse; and all she had preserved of her former self were her large superb eyes, in a face that had now become cadaverous. With her jealous forehead, her ardent and obstinate mouth, she troubled him as much as Rose had charmed him by her tardy expansion of an indolent blonde.

Gasparine was polite, without effusiveness. She remembered Plassans—she talked to the young man of the old times. When they went off, Campardon and he, she shook their hands. Downstairs, Madame Hédouin simply said to Octave:

“To-morrow, then, sir.”

Out in the street the young man, deafened by the cabs, jostled by the passers-by, eould not help remarking that this lady was very beautiful, but that she did not seem particularly amiable. On the black and muddy pavement, the bright windows of freshly-painted shops, flaring with gas, east broad rays of vivid light; whilst the old shops, with their sombre displays, lit up in the interior only by smoking lamps, which burnt like distant stars, saddened the streets with masses of shadow. In the Rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin, just before turning into the Rue do Choiseul, the architect bowed on passing before one of these establishments.

A young woman, slim and elegant, dressed in a silk mantlet, was standing in the doorway, drawing a little boy of three towards her, so that he might not get run over. She was talking to an old bareheaded lady, the shopkeeper, no doubt, whom she addressed in a familiar manner. Octave eould not distinguish her features in that dim light, beneath the dancing reflections of the neighbouring gas-jets; she seemed to him to be pretty, he only saw two bright eyes, whieh were fixed a moment upon him like two flames. Behind her yawned the shop, damp like a cellar, and emitting an odour of saltpetre.

“That is Madame Vabre, the wife of Monsieur Théophile Vabre, the landlord’s younger son. You know the people who live on the first floor,” resumed Campardon, when he had gone a few steps. “Oh! a most charming lady! She was born in that shop, one of the best paying haberdashers of the neighbourhood, which her parents, Monsieur and Madame Louhette, still manage, for the sake of having something to occupy them. They have made some money there, I will warrant!”

But Octave did not understand trade of that sort, in those holes of old Paris, where at one time a piece of stuff was sufficient sign. He swore that nothing in the world would ever make him consent to live in such a den. One surely caught some rare aches and pains there!

Whilst talking, they had reached the top of the stairs. They were being waited for. Madame Campardon had put on a grey silk dress, had arranged her hair coquettishly, and looked very neat and prim. Campardon kissed her on the neck, with the emotion of a good husband.

“Good evening, my darling; good evening, my pet.”

And they passed into the dining-room. The dinner was delightful. Madame Campardon at first talked of the Deleuzes and the Hédouins—families respected throughout the neighbourhood, and whose member’s were well known; a cousin who was a stationer in the Rue Gaillon, an uncle who had an umbrella shop in the Passage Choiseul, and nephews and nieces in business all round about. Then the conversation turned, and they talked of Angèle, who was sitting stiffly on her chair, and eating with inert gestures. Her mother was bringing her up at home, it was preferable; and, not wishing to say more, she blinked her eyes, to convey that young girls learnt very naughty things at boarding-schools. The child had slyly balanced her plate on her knife. Lisa, who was clearing the cloth, missed breaking it, and exclaimed:

“It was your fault, mademoiselle!”

A mad laugh, violently restrained, passed over Angèle’s face. ‘Madame Campardon contented herself with shaking her head; and, when Lisa had left the room to fetch the dessert, she sang her praises—very intelligent, very active, a regular Paris girl, always knowing which way to turn. They might very well do without Victoire, the cook, who was no longer very clean, on account of her great age; but she had seen her master born at his father’s—she was a family ruin which they respected. Then as the maid returned with some baked apples:

“Conduct irreproachable,” continued Madame Campardon in Octave’s ear. “I have discovered nothing against her as yet. One holiday a month to go and embrace her old aunt, who lives some distance off.”

Octave observed Lisa. Seeing her nervous, flat-chested, blear-eyed, the thought came to him that she must go in for a precious fling, when at her old aunt’s. However, he greatly approved what the mother said, as she continued to give him her views on education—a young girl is such a heavy responsibility, it is necessary to keep her clear even of the breaths of the street And, during this, Angèle, each time Lisa leant over near her chair to remove a plate, pinched her in a friendly way, whilst they both maintained their composite, without even moving an eyelid.

“One should be virtuous for one’s own sake,” said the architect learnedly, as though by way of conclusion to thoughts he had not expressed. “I do not care a button for public opinion; I am an artist!”

After dinner, they remained in the drawing-room until midnight. It was a little jollification to celebrate Octave’s arrival. Madame Campardon appeared to be very tired; little by little she abandoned herself, leaning back on the sofa.

“Are you suffering, my darling?” asked her husband.

“No,” replied she in a low voice. “It is always the same thing.”

She looked at him, and then gently asked:

“Did you see her at the Hédouins’?”

“Yes. She asked after you.”

Tears came to Rose’s eyes.

“She is in good health, she is!”

“Come, come,” said the architect, showering little kisses on her hair, forgetting they were not alone. “You will make yourself worse again. You know very well that I love you all the same, my poor pet!”

Octave, who had discreetly retired to the window, under the pretence of looking into the street, returned to study Madame Campardon’s countenance, his curiosity again awakened, and wondering if she knew. But she had resumed her amiable and doleful expression, and was curled up in the depths of the sofa, like a woman who has to find her pleasure in herself, and who is forcibly resigned to receiving the caresses that fall to her share.

At length Octave wished them good-night. With his candlestick in his hand, he was still on the landing, when he heard the sound of silk dresses rustling over the stairs. He politely stood on one side. It was evidently the ladies of the fourth floor, Madame Josserand and her two daughters, returning from some party. As they passed, the mother, a superb and corpulent woman, stared in his face; whilst the elder of the young ladies kept at a distance with a sour air, and the younger, giddily looked at him and laughed, in the full light of the candle. She was charming, this one, with her irregular but agreeable features, her clear complexion, and her auburn hair gilded with light reflections; and she had a bold grace, the free gait of a young bride returning from a ball in a complicated costume of ribbons and lace, like unmarried girls do not wear. The trains disappeared along the balustrade: a door closed. Octave lingered a moment, greatly amused by the gaiety of her eyes.

He slowly ascended in his turn. A single gas-jet was burning, the staircase was slumbering in a heavy warmth. It seemed to him more wrapped up in itself than ever, with its chaste doors, its doors of rich mahogany, closing the entrances to virtuous alcoves. Not a sigh passed along, it was the silence of well-mannered people who hold their breath. Presently a slight noise was heard; Octave leant over and beheld Monsieur Gourd, in his cap and slippers, turning out the last gas-jet. Then all subsided, the house became enveloped by the solemnity of darkness, as though annihilated in the distinction and decency of its slumbers.

Octave, nevertheless, had great difficulty in getting to sleep. He kept feverishly turning over, his brain occupied with the new faces he had seen. Why the devil were the Campardons so amiable? Were they dreaming of marrying their daughter to him later on? Perhaps, too, the husband took him to board with them so that he might amuse and enliven the wife? And that poor lady, what peculiar complaint could she be suffering from? Then his ideas got more mixed; he saw shadows pass—? little Madame Pichon, his neighbour, with her clear empty glances; beautiful Madame Hédouin, correct and grave in her black dress; and Madame Vabre’s ardent eyes, and Mademoiselle Josserand’s gay laugh. How they swarmed in a few hours in the streets of Paris! It had always been his dream, ladies who would take him by the hand and help him in his affairs. But these kept returning and mingling with fatiguing obstinacy. He knew not which to choose; he tried to keep his voice soft, his gestures cajoling. And suddenly, worn-out, exasperated, he yielded to his brutal inner nature, to the ferocious disdain in which he held woman, beneath his air of amorous adoration.

“Are they going to let me sleep at all?” said he out loud, turning violently on to his back. “The first who likes, it is the same to me, and all together if it pleases them! To sleep now, it will be daylight to-morrow.”

When Madame Josserand, preceded by her young ladies, left the evening party given by Madame Dambreville, who resided on a fourth floor in the Rue de Rivoli, at the corner of the Rue de l’Oratoire, she roughly slammed the street door, in the sudden outburst of a passion she had been keeping under for the past two hours. Berthe, her younger daughter, had again just gone and missed a husband.

“Well! what are you doing there?” said she angrily to the young girls, who were standing under the arcade and watching the cabs pass by. “Walk on! don’t have any idea we are going to ride! To waste another two francs, eh?”

And as Hortense, the elder, murmured:

“It will be pleasant, with this mud. My shoes will never recover it.”

“Walk on!” resumed the mother, all beside herself. “When you have no more shoes, you can stop in bed, that’s all. A deal of good it is, taking you out!”

Berthe and Hortense bowed their heads and turned into the Rue de l’Oratoire. They held their long skirts up as high as they could over their crinolines, squeezing their shoulders together and shivering under their thin opera-cloaks. Madame Josserand followed behind, wrapped in an old fur cloak made of Calabar skins, looking as shabby as cats’. All three, without bonnets, had their hair enveloped in lace wraps, head-dresses which caused the last passers-by to look back, surprised at seeing them glide along the houses, one by one, with bent backs, and their eyes fixed on the puddles. And the mother’s exasperation increased still more at the recollection of many similar returns home, for three winters past, hampered by their gay dresses, amidst the black mud of the streets and the jeers of belated blackguards. No, decidedly, she had had enough of dragging her young ladies about to the four corners of Paris, without daring to venture on the luxury of a cab, for fear of having to omit a dish from the morrow’s dinner!

“And she makes marriages!” said she out loud, returning to Madame Dambreville, and talking alone to ease herself, without even addressing her daughters, who had turned down the Rue Saint-Honoré. “They are pretty, her marriages! A lot of impertinent minxes, who come from no one knows where! Ah! if one was not obliged! It’s like her last success, that bride whom she brought out, to show us that it did not always fail; a fine specimen! a wretched child who had to be sent back to her convent for six months, after a little mistake, to be re-whitewashed!”

The young girls were crossing the Place du Palais-Royal, when a shower came on. It was a regular rout. They stopped, slipping, splashing, looking again at the vehicles passing empty along.

“Walk on!” cried the mother, pitilessly. “We are too near now; it is not worth two francs. And your brother Léon, who refused to leave with us for fear of having to pay for the cab! So much the better for him if he gets what he wants at that lady’s, but we can say that it is not at all decent. A woman who is over fifty and who only receives young men! An old nothing-much whom a high personage married to that fool Dambreville, appointing him head clerk!”

Hortense and Berthe trotted along in the rain, one before the other, without seeming to hear. When their mother thus eased herself, letting everything out, and forgetting the wholesome strictness with which she kept them, it was agreed that they should be deaf. Berthe, however, revolted on entering the gloomy and deserted Rue de l’Echelle.

“Oh, dear!” said she, “the heel of my shoe is coming off. I cannot go a step further!”

Madame Josserand’s wrath became terrible.

“Just walk on! Do I complain? Is it my place to be out in the street at such a time and in such weather? It would be different if you had a father like others! But no, the fine gentleman stays at home taking his ease. It is always my turn to drag you about; he would never accept the burden. Well! I declare to you that I have had enough of it. Your father may take you out in future if he likes; may the devil have me if ever again I accompany you to houses where I am plagued like that! A man who deceived me as to his capacities, and who has never yet procured me the least pleasure! Ah! good heavens! there is one I would not marry now, if it were to come over again!”

The young ladies no longer protested. They were already acquainted with this inexhaustible chapter of their mother’s blighted hopes. With their lace wraps drawn over their faces, their shoes sopping wet, they rapidly followed the Rue Sainte-Anne. But, in the Rue de Choiseul, at the very door of her house, a last humiliation awaited Madame Josserand: the Duveyriers’ carriage splashed her as it passed in.

On the stairs, the mother and the young ladies, worn out and enraged, recovered their gracefulness when they had to pass before Octave. Only, as soon as ever their door was closed behind them, they rushed through the dark apartment, knocking up against the furniture, and tumbled into the dining-room, where Monsieur Josserand was writing by the feeble light of a little lamp.

“Failed!” cried Madame Josserand, letting herself fall on to a chair.

And, with a rough gesture, she tore the lace wrap from her head, threw her fur cloak on to the back of her chair, and appeared in a flaring dress trimmed with black satin and cut very low in the neck, looking enormous, her shoulders still beautiful, and resembling a mare’s shining flanks. Her square face, with its drooping cheeks and too big nose, expressed the tragic fury of a queen restraining herself from descending to the use of coarse, vulgar expressions.

“Ah!” said Monsieur Josserand simply, bewildered by this violent entrance.

He kept blinking his eyes and was seized with uneasiness. His wife positively crushed him when she displayed that giant throat, the full weight of which he seemed to feel on the nape of his neck. Dressed in an old thread-bare frock-coat which he was finishing to wear out at home, his face looking as though tempered and expunged by thirty-five years spent at an office desk, he watched her for a moment with his big lifeless blue eyes. Then, after thrusting his grey locks behind his ears, feeling very embarrassed and unable to find a word to say, he attempted to resume his work.

“But you do not seem to understand!” resumed Madame Josserand in a shrill voice. “I tell you that there is another marriage knocked on the head, and it is the fourth!”

“Yes, yes, I know, the fourth,” murmured he. “It is annoying, very annoying.”

And, to escape from his wife’s terrifying nudity, he turned towards his. daughters with a good-natured smile. They also were removing their lace wraps and their opera-cloaks; the elder one was in blue and the younger in pink; their dresses, too, free in cut and over-trimmed, were like a provocation. Hortense, with her sallow complexion, and her face spoilt by a nose like her mother’s, which gave her an air of disdainful obstinacy, had just turned twenty-three and looked twenty-eight; whilst Berthe, two years younger, retained all a child’s gracefulness, having, however, the same features, but more delicate and dazzlingly white, and only menaced with the coarse family mask after she entered the fifties.

“It will do no good if you go on looking at us for ever!” cried Madame Josserand. “And, for God’s sake, put your writing away; it worries my nerves!”

“But, my dear,” said he peacefully, “I am addressing wrappers.”

“Ah! yes, your wrappers at three francs a thousand! Is it with those three francs that you hope to marry your daughters?”

Beneath the feeble light of the little lamp, the table was indeed covered with large sheets of coarse paper, printed wrappers, the blanks of which Monsieur Josserand filled in for a largo publisher who had several periodicals. As his salary as cashier did not suffice, he passed whole nights at this unprofitable labour, working in secret, and seized with shame at the idea that any one might discover their penury.

“Three francs are three francs,” replied he in his slow, tired voice. “Those three francs will enable you to add ribbons to your dresses, and to offer some pastry to your guests on your Tuesdays at home.”

He regretted his words as soon as he had uttered them; for he felt that they struck Madame Josserand full in the heart, in the most sensitive part of her wounded pride. A rush of blood purpled her shoulders; she seemed on the point of breaking out into revengeful utterances; then, by an effort of dignity, she merely stammered, “Ah! good heavens! ah! good heavens!”

And she looked at her daughters; she magisterially crushed her husband beneath a shrug of her terrible shoulders, as much as to say, “Eh! you hear him? what an idiot!” The daughters nodded their heads. Then, seeing himself beaten, and laying down his pen with regret, the father opened the “Temps” newspaper, which he brought home every evening from his office.

“Is Saturnin asleep?” sharply inquired Madame Josserand, speaking of her younger son.

“Yes, long ago,” replied he. “I also sent Adèle to bed. And Léon, did you see him at the Dambrevilles’?”

“Of course! he sleeps there!” she let out in a cry of rancour which she was unable to restrain.

The father, surprised, naively added,

“Ah! you think so?”

Hortense and Berthe had become deaf again. They faintly smiled, however, affecting to be busy with their shoes, which were in a pitiful state. To create a diversion, Madame Josserand tried to pick another quarrel with Monsieur Josserand; she begged him to take his newspaper away every morning, not to leave it lying about in the room all day, as he had done with the previous number, for instance, a number containing the report of an abominable trial, which his daughters might have read. She well recognised there his want of morality.

“Well, are we going to bed?” asked Hortense. “I am hungry.”

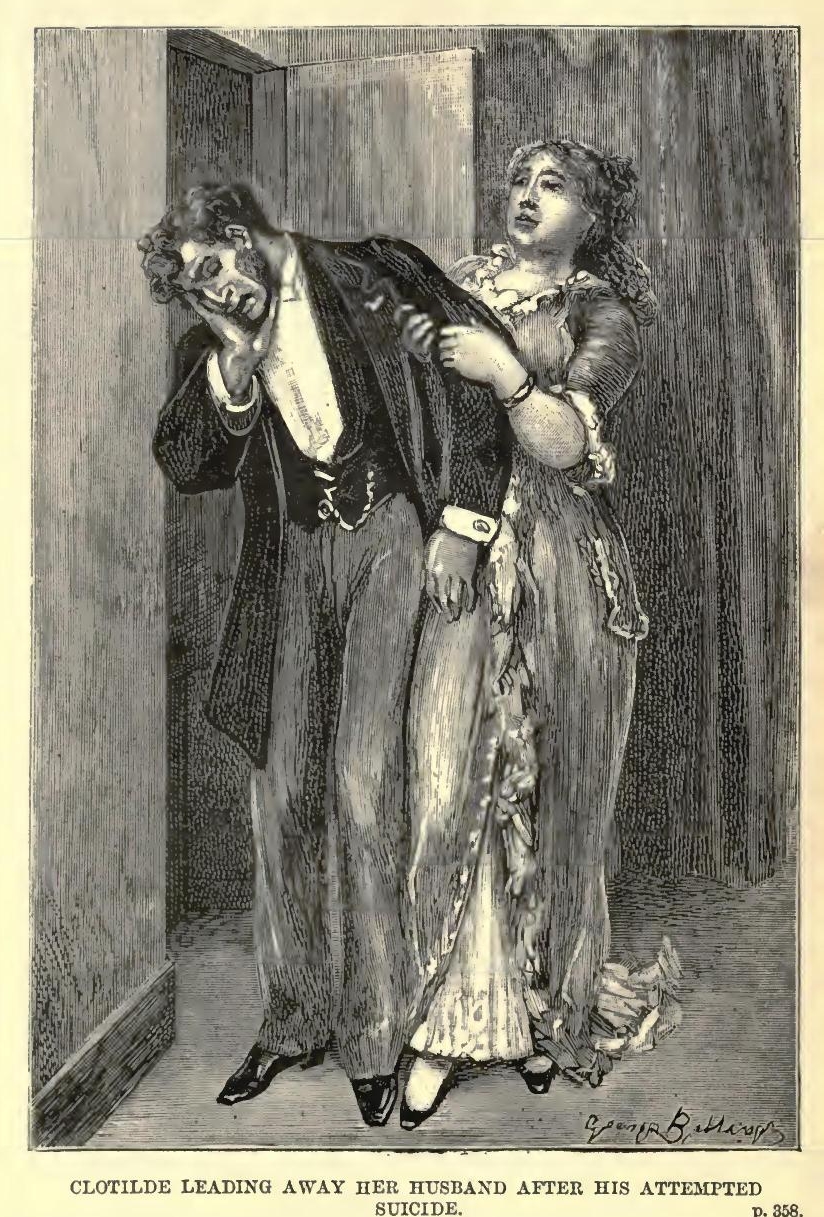

“Oh! and I too!” said Berthe. “I am famishing.”