| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/olgaromanoff00grif |

OLGA ROMANOFF

MORRISON AND GIBB, PRINTERS, EDINBURGH.

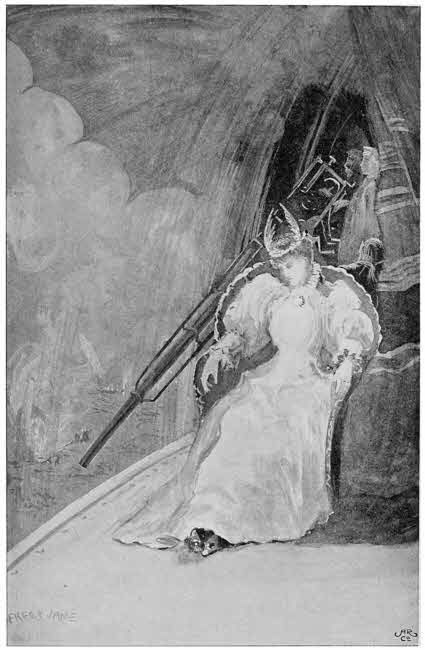

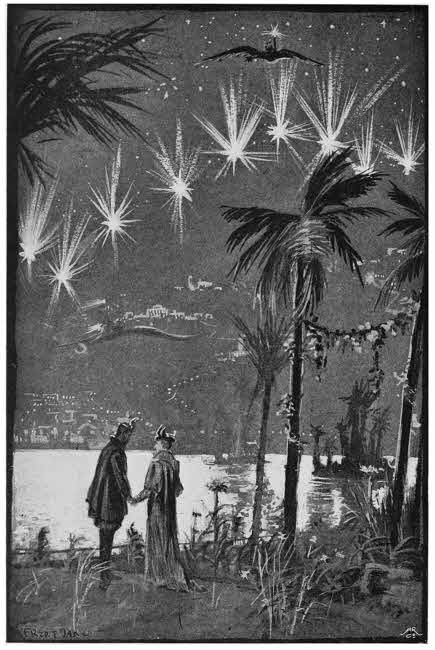

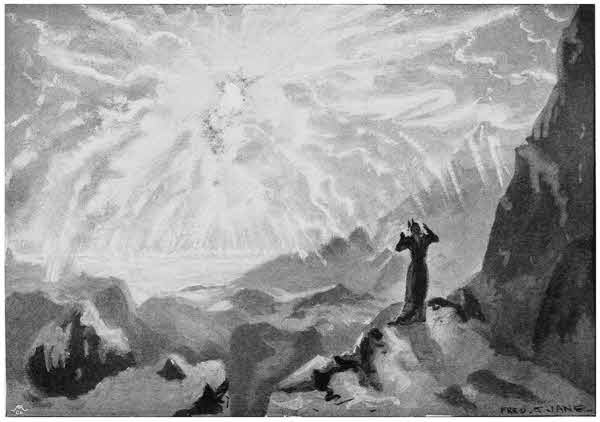

Evil in such a Shape might be something more than Good. (Frontispiece.) See page 176.

BY

GEORGE GRIFFITH.

AUTHOR OF

“THE ANGEL OF THE REVOLUTION,” “THE OUTLAWS

OF THE AIR,” “VALDAR THE OFT-BORN,” “BRITON

OR BOER?” “THE ROMANCE OF GOLDEN STAR,”

ETC., ETC.

“And so they waited—waited while the ages-old snow and ice melted from the bare, black rocks under the fierce breath of the fire-storm; while the ocean of flame seethed and roared and eddied about them, licking up the seas and melted snows, and fighting with them as fire and water have fought since the world began; while the foundations of the Southern Pole quivered and rocked beneath their feet, and the walls of their refuge quaked and cracked with the throes of the writhing earth, and cosmos was dissolved into chaos once more.”—p. 368.

WITH SIXTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS

BY FRED T. JANE.

LONDON:

SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT & CO., Ltd.

1897.

Copyrighted Abroad.][All Foreign Rights Reserved.

TO

HIRAM STEVENS MAXIM

THE FIRST MAN WHO HAS FLOWN

BY MECHANICAL MEANS

AND SO APPROACHED MOST NEARLY

TO THE LONG-SOUGHT IDEAL

OF

AERIAL NAVIGATION

THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE INSCRIBED

BY

THE AUTHOR

| PAGE | ||

| PROLOGUE | 1 | |

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | THE SURRENDER OF THE WORLD-THRONE | 8 |

| II. | A CROWNLESS KING | 14 |

| III. | TSARINA OLGA | 26 |

| IV. | A SON OF THE GODS | 35 |

| V. | A VISION FROM THE CLOUDS | 47 |

| VI. | DEED AND DREAM | 53 |

| VII. | THE SPELL OF CIRCE | 66 |

| VIII. | THE NEW TERROR | 75 |

| IX. | THE FLIGHT OF THE “REVENGE” | 83 |

| X. | STRANGE TIDINGS TO AERIA | 94 |

| XI. | THE SNAKE IN EDEN | 102 |

| XII. | THE BATTLE OF KERGUELEN | 110 |

| XIII. | THE SYREN’S STRONGHOLD | 129 |

| XIV. | FROM THE SEA TO THE AIR | 138 |

| XV. | OLGA IN COUNCIL | 146 |

| XVI. | KHALID THE MAGNIFICENT | 159 |

| XVII. | AN UNHOLY ALLIANCE | 174 |

| XVIII. | A MOMENTOUS COMMISSION | 188 |

| XIX. | FACE TO FACE AGAIN | 202[viii] |

| XX. | THE CALL TO ARMS | 215 |

| XXI. | THE HOME-COMING | 226 |

| XXII. | THE EVE OF BATTLE | 243 |

| XXIII. | THE FIRST BLOW | 253 |

| XXIV. | WAR AT ITS WORST | 271 |

| XXV. | A MESSAGE FROM MARS | 289 |

| XXVI. | SENTENCE OF DEATH | 303 |

| XXVII. | ALMA SPEAKS | 314 |

| XXVIII. | THE SIGN IN THE SKY | 319 |

| XXIX. | THE TRUCE OF GOD | 325 |

| XXX. | THE SHADOW OF DEATH | 338 |

| XXXI. | THE LAST BATTLE | 350 |

| XXXII. | THE SHE-WOLF TO HER LAIR | 359 |

| EPILOGUE | 369 |

| PAGE | |

| EVIL IN SUCH A SHAPE MIGHT BE SOMETHING MORE THAN GOOD | Frontispiece |

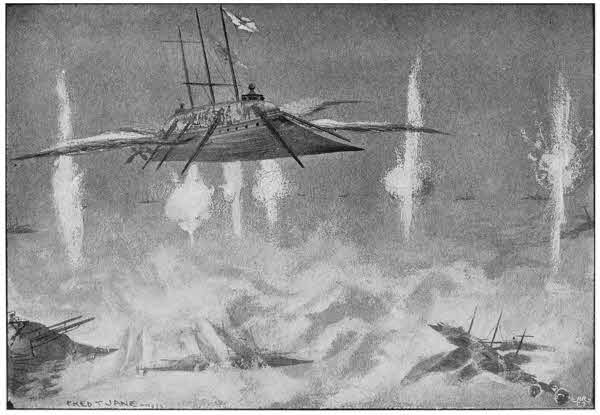

| NOT A VESTIGE OF OUR AIR-SHIP OR HER CREATORS REMAINED | 22 |

| AS SHE GAZED UPON IT, THE FIRES DIED AWAY | 57 |

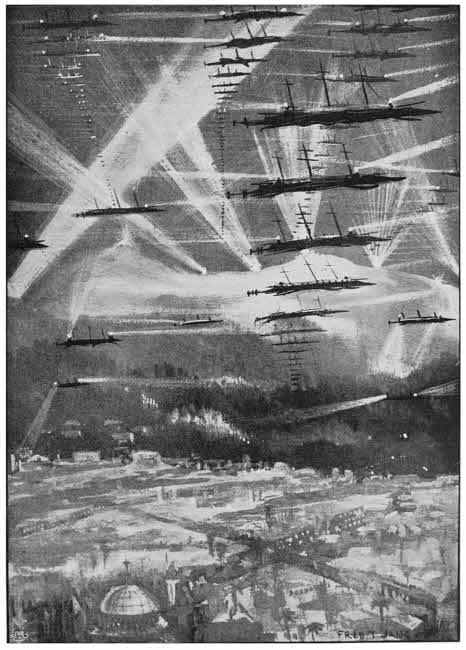

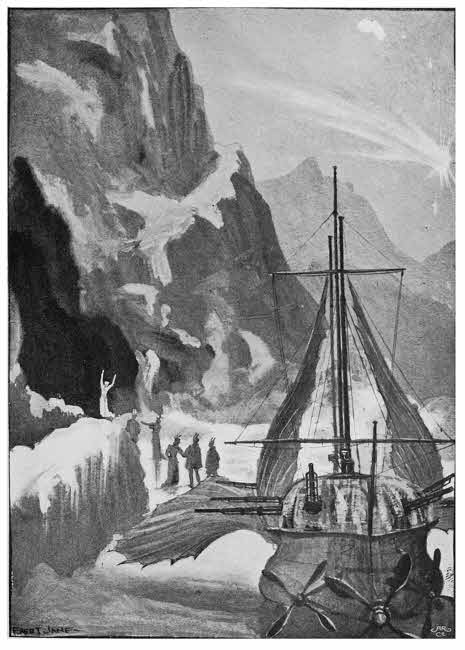

| FLINGING LONG STREAMS OF RADIANCE FOR MILES INTO THE SKY | 83 |

| THE CLOUDS WERE RENT AND ROLLED UP INTO VAST SHADOWY BILLOWS | 122 |

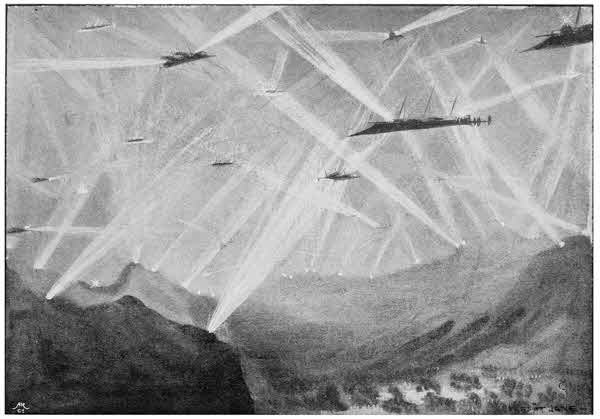

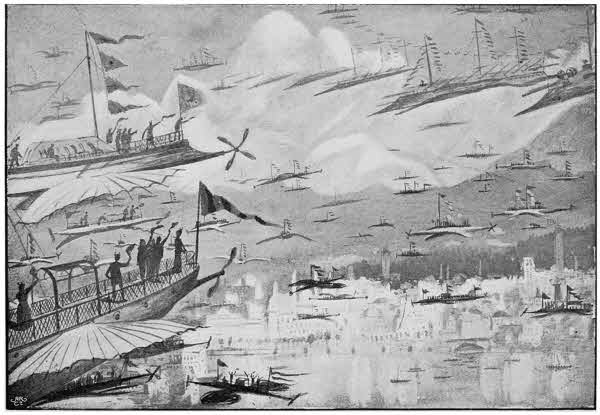

| THE COMBINED SQUADRONS SWEPT ACROSS THE MOUNTAIN BARRIER | 237 |

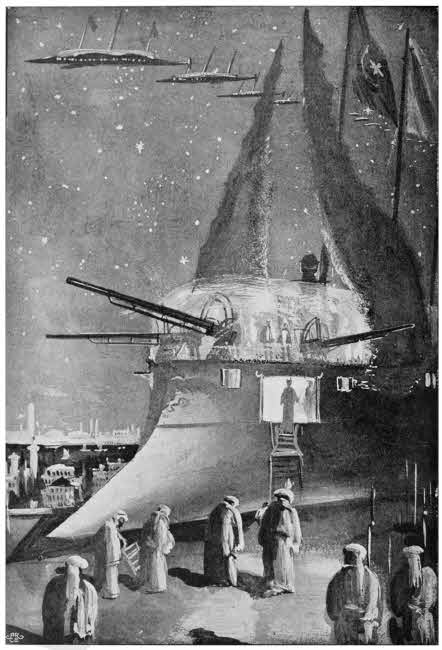

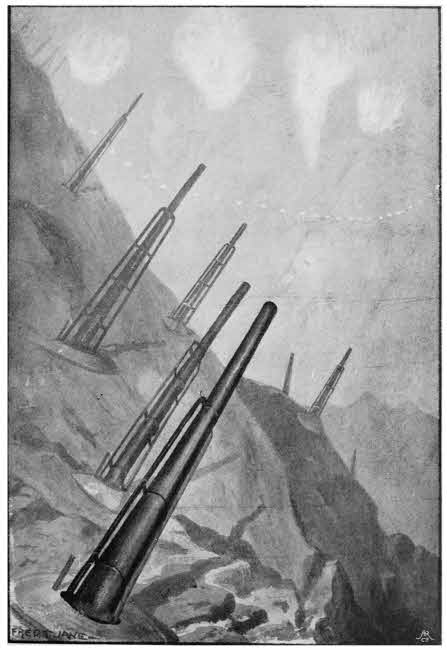

| BATTERIES WHICH WOULD BE ABLE TO SURROUND AERIA WITH A ZONE OF STORM AND FLAME | 248 |

| THE FOUR HUNDRED BATTLESHIPS OF THE TWO SQUADRONS ROSE INTO THE AIR | 252 |

| THREE OF THE AIR-SHIPS SEEMED TO BREAK-UP AND ROLL OVER | 259 |

| A GREAT BATTLESHIP LEAPT UP OUT OF THE NETHER WATERS | 266 |

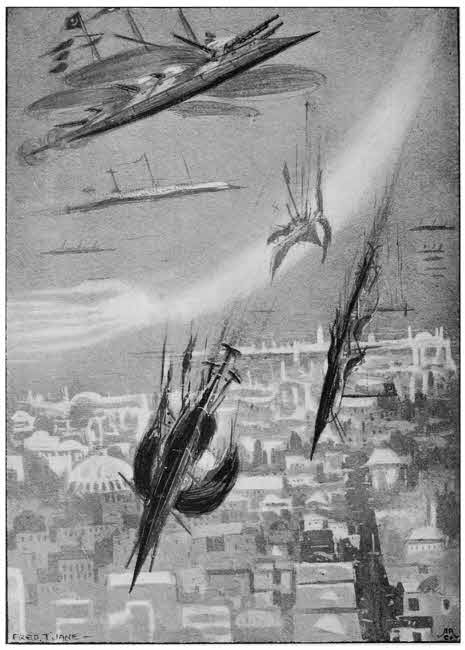

| THE “ISMA” SWOOPED DOWN | 281 |

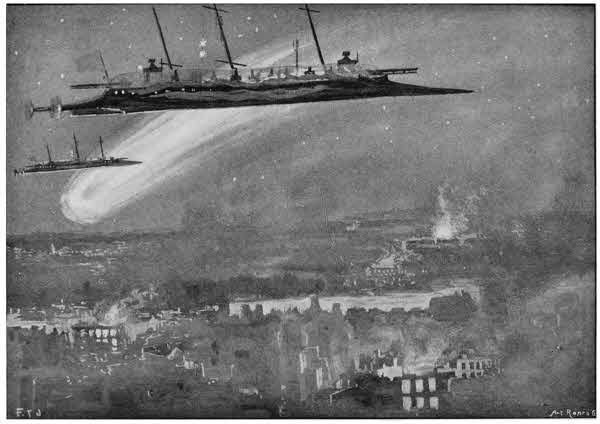

| A FEARFUL SCENE UNFOLDED ITSELF AS THEY SWEPT UP OVER PARIS | 286 |

| “ONLY YOU CAN BID ME LIVE, ALMA” | 317 |

| STILL THE FIGHT WENT ON AT LONG RANGES | 354 |

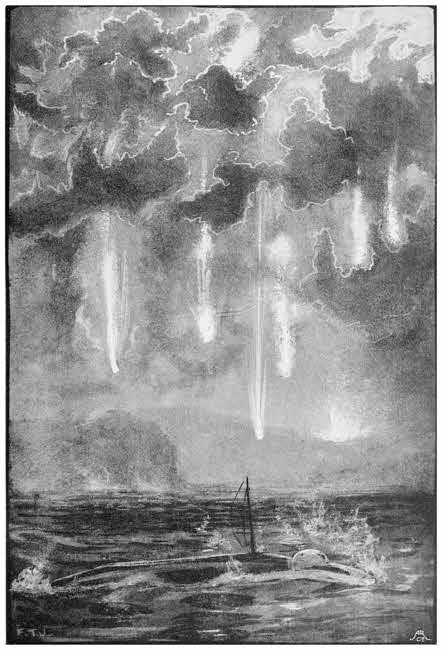

| THE BLAZING SKY WAS LITERALLY RAINING FIRE OVER SEA AND LAND | 367 |

| OLGA ROMANOFF HAD SURVIVED THE DOOM OF THE WORLD | 374 |

OLGA ROMANOFF.

These are the last words of Israel di Murska, known in the days of strife as Natas, the Master of the Terror, given to the Children of Deliverance dwelling in the land of Aeria, in the twenty-fifth year of the Peace, which, in the reckoning of the West, is the year nineteen hundred and thirty.

MY life is lived, and the wings of the Angel of Death overshadow me as I write; but before the last summons comes, I must obey the spirit within me that bids me tell of the things that I have seen, in order that the story of them shall not die, nor be disguised by false reports, as the years multiply and the mists gather over the graves of those who, with me, have seen and wrought them.

For this reason the words that I write shall be read publicly in the ears of you and your children and your children’s children, until they shall see a sign in heaven to tell them that the end is at hand. No man among you shall take away from that which I have written, nor yet add anything to it; and every fifth year, at the Festival of Deliverance, which is held on the Anniversary of Victory,[1] this writing of mine[2] shall be read, that those who shall hear it with understanding may lay its warnings to heart, and that the lessons of the Great Deliverance may never be forgotten among you.

It was in the days before the beginning of peace that I, Natas the Jew, cast down and broken by the hand of the Tyrant, conceived and created that which was known as the Terror. The kings of the earth and their servants trembled before my invisible presence, for my arm was long and my hand was heavy; yet no man knew where or when I should strike—only that the blow would be death to him on whom it should fall, and that nowhere on earth should he find a safe refuge from it.

In those days the earth was ruled by force and cunning, and the nations were armed camps set one against the other. Millions of men, who had no quarrel with their neighbours, stood waiting for the word of their rulers to blast the fair fields of earth with the fires of war, and to make desolate the homes of those who had done them no wrong.

In the third year of the twentieth century, Richard Arnold, the Englishman, conquered the empire of the air, and made the first ship that flew as a bird does, of its own strength and motion. He joined the Brotherhood of Freedom, then known among men as the Terrorists, of whom I, Natas, was the Master, and then he built the aerial fleet which, in the day of Armageddon, gave us the victory over the tyrants of the earth.

At the same time, Alan Tremayne, a noble of the English people, into whose soul I had caused my spirit to enter in order that he might serve me and bring the day of deliverance nearer, caused all the nations of the Anglo-Saxon race to join hands, from the West unto the East, in a league of common blood and kindred; and they, in the appointed hour, stood between the sons and daughters of men and those who would have enslaved them afresh.

The chief of these was Alexander Romanoff, last of the[3] Tsars, or Tyrants, of Russia, whose armies, leagued with those of France, Italy, Spain, and certain lesser Powers, and assisted by a great fleet of war-balloons that could fly, though slowly, wherever they were directed, swept like a destroying pestilence from the western frontiers of Russia to the eastern shores of Britain; and when they had gained the mastery of Europe, invaded England and laid siege to London.

But here their path of conquest was brought to an end, for Alan Tremayne and his brothers of the Terror called upon the men of Anglo-Saxondom to save their Motherland from her enemies, and they rose in their wrath, millions strong, and fell upon them by land and sea, and would have destroyed them utterly, as I had bidden them do, but that Natasha, who was my daughter and was known in those days as the Angel of the Revolution, pleaded for the remnant of them, and they were spared.

But the Russians we slew without mercy to the last man of those who had stood in arms against us, saving only the Tyrant and his princes and the leaders of his armies. These we took prisoners and sent, with their wives and their children, to die in their own prison-land in Siberia, as they had sent thousands of innocent men and women to die before them.

This was my judgment upon them for the wrong that they had done to me and mine, for in the hour of victory I spared not those who had not known how to spare. Now they are dead, and their graves are nameless. Their name is a byword among men, for they were strong and they used their strength to do evil.

So we made an end of tyranny among the nations, and when the world-war was at length brought to an end, we disbanded all the armies that were upon land and sank the warships that were left upon the sea, that men might no more fight with each other. War, that had been called honourable since the world began, we made a crime of blood-guiltiness, for which the life of him who sought to commit it should pay; and as a crime, you, the children of those who have delivered the nations from it, shall for ever hold it to be.

We leave you the command of the air, and that is the command of the world; but should it come to pass—as in the progress of knowledge it may well do—that others in the world outside Aeria shall learn to navigate the air as you do, you shall go forth to battle with them and destroy them utterly, for we have made it known through all the earth that he who seeks to build a second navy of the air shall be accounted an enemy of peace, whose purpose it is to bring war upon the earth again.

Forget not that the blood-lust is but tamed, not quenched, in the souls of men, and that long years must pass before it is purged from the world for ever. We have given peace on earth, and to you, our children, we bequeath the sacred trust of keeping it. We have won our world-empire by force, and by force you must maintain it.

In the day of battle we shed the blood of millions without ruth to win it, and so far the end has justified the means we used. Since the sun set upon Armageddon, and the right to make war was taken from the rulers of the nations, we have governed a realm of peace and prosperity which every year has seen better and happier than that which went before.

No man has dared to draw the sword upon his brother, or by force or fraud to take that which was not his by right. The soil of earth has been given back to the use of her sons, and their wealth has already multiplied a hundredfold on every hand. Kings have ruled with wisdom and justice, and senates have ceased their wranglings to soberly seek out and promote the welfare of their own countries, and to win the respect and friendship of others.

Yet many of these are the same men who, but a few years ago, rent each other like wild beasts in savage strife for the meanest ends; who betrayed their brothers and slaughtered their neighbours, that the rich might be richer, and the strong stronger, in the pitiless battle for wealth and power. They have become peaceful and honest with each other, because we have compelled them to be so, and because they know that the[5] penalty of wrong-doing in high places is destruction swift and certain as the stroke of the hand of Fate itself.

They know that no man stands so high that our hand cannot cast him down to the dust, and that no spot of earth is so secret and so distant that the transgressor of our laws can find in it a refuge from our vengeance. We stand between the few strong and cunning who would oppress, and the many weak and simple who could not resist them; and when we are gone, you will hear the voice of duty calling you to take our places.

When you stand where we do now, remember who you are and the tremendous trust that is laid upon you. You are the children of the chosen out of many nations, masters of the world, and, under Heaven, the arbiters of human destiny. You shall rule the world as we have ruled it for a hundred years from now. If in that time men shall not have learnt the ways of wisdom and justice, you may be sure that they will never learn them, and deserve only to be left to their own foolishness. Since the world began, the path of life has never lain so fair and straight before the sons of men as it does now, and never was it so easy to do the right and so hard to do the wrong.

So, for a hundred years to come, you shall keep them in the path in which we have set them, and those that would wilfully turn aside from it you shall destroy without mercy, lest they lead others into misery and bring the evil days upon earth again.

At the twenty-fifth celebration of the Festival of Deliverance, you shall give back the sceptre of the world-empire into the hands of the children of those from whom we took it,—because they wielded it for oppression, and not for mercy. At that time you shall make it known throughout the earth that men are once more free to do good or evil, according to their choice, and that as they choose well or ill so shall they live or die.

And woe to them in those days if, knowing the good, they shall turn aside to do evil! Beyond the clouds that gather[6] over the sunset of my earthly life, I see a sign in heaven as of a flaming sword, whose hilt is in the hand of the Master of Destiny, and whose blade is outstretched over the habitations of men.

As they shall choose to do good or evil, so shall that sword pass away from them or fall upon them, and consume them utterly in the midst of their pride. And if they, knowing the good, shall elect to do evil, it shall be with them as of old the Prophet said of the men of Babylon the Great: Their cities shall be a desolation, a dry land and a wilderness; a land wherein no man dwelleth, neither shall any son of man pass thereby.

For from among the stars of heaven, whose lore I have learned and whose voices I have heard, there shall come the messenger of Fate, and his shape shall be that of a flaming fire, and his breath as the breath of a pestilence that men shall feel and die in the hour that it breathes upon them.

Out of the depths beyond the light of the sun he shall come, and your children of the fifth generation shall behold his approach. The sister-worlds shall see him pass with fear and trembling, wondering which of them he shall smite, but if he be not restrained or turned aside by the Hand which guides the stars in their courses, it shall go hard with this world and the men of it in the hour of his passing.

Then shall the highways of the earth be waste, and the wayfaring of men cease. Earth shall languish and mourn for her children that are no more, and Death shall reign amidst the silence, sole sovereign of many lands!

But you, so long as you continue to walk in the way of wisdom, shall live in peace until the end, whether it shall come then or in the ages that shall follow. And if it shall come then, you shall await it with fortitude, knowing that this life is but a single link in the chain of existence which stretches through infinity; and that, if you shall be found worthy, you shall be taught how a chosen few among your sons and daughters shall survive the ruin of the world, to be the parents of the new race, and replenish the earth and possess it.

Out of the Valley of the Shadow of Death I stretch forth my hands in blessing to you, the children of the coming time, and pray that the peace which the men of the generation now passing away have won through strife and toil in the fiery days of the Terror, may be yours and endure unbroken unto the end.

A HUNDRED years had passed since Natas, the Master of the Terror, had given into the hands of Richard Arnold his charge to the future generations of the Aerians—as the descendants of the Terrorists who had colonised the mountain-walled valley of Aeria, in Central Africa, were now called; since the man, who had planned and accomplished the greatest revolution in the history of the world, had given his last blessing to his companions-in-arms and their children, and had “turned his face to the wall and died.”

It was midday, on the 8th of December 2030, and the rulers of all the civilised States of the world were gathered together in St. Paul’s Cathedral to receive, from the hands of a descendant of Natas in the fourth generation, the restoration of the right of independent national rule which, on the same spot a hundred and twenty-five years before, had been taken from the sovereigns of Europe and vested in the Supreme Council of the Anglo-Saxon Federation.

The period of tutelage had passed. Under the wise and firm rule of the Council and the domination of the Anglo-Saxon race, the Golden Age had seemed to return to the world. For a hundred and twenty-five years there had been peace on earth, broken only by the outbreak and speedy suppression of a few tribal wars among the more savage races of Africa and Malaysia. Now the descendants of those who had been victors[9] and vanquished in the world-war of 1904, had met to give back and assume the freedom and the responsibility of national independence.

The vast cathedral was thronged, as it had been on the momentous day when Natas had pronounced his judgment on the last of the Tyrants of Russia, and ended the old order of things in Europe. But it was filled by a very different assembly to that which had stood within its walls on the morrow of Armageddon.

Then the stress and horror of a mighty conflict had set its stamp on every face. Hate had looked out of eyes in which the tears were scarcely dry, and hungered fiercely for the blood of the oppressor. The clash of arms, the stern command, and the pitiless words of doom had sounded then in ears which but a few hours before had listened to the roar of artillery and the thunder of battle. That had been the dawn of the morrow of strife; this was the zenith of the noon of peace.

Now, in all the vast assembly, no hand held a weapon, no face was there which showed a sign of sorrow, fear, or anger, and in no heart, save only two among the thousands, was there a thought of hate or bitterness.

For three days past the Festival of Deliverance had been celebrated all over the civilised world, and now, in the centre of the city which had come to be the capital, not only of the vast domains of Anglo-Saxondom, but of the whole world, a solemn act of renunciation was to be performed, upon the issues of which the fate of all humanity would hang; for the members of the Supreme Council had come through the skies from their seat of empire in Aeria to abdicate the world-throne in obedience to the command of the dead Master, from whom their ancestors had derived it.

At a table, drawn across the front of the chancel, sat the President and the twelve men who with him had up to this hour shared the empire of the human race. Below the steps, on the floor of the cathedral, sat, in a wide semicircle, the rulers of the kingdoms and republics of the earth, assembled to hear the last word of their over-lords, and to receive from them[10] the power and responsibility of maintaining or forfeiting, as the event should prove, the blessings which had multiplied under the sovereignty of the Aerians.

The President of the Council was the direct descendant not only of Alan Tremayne, its first President, but also of Richard Arnold and Natasha; for their eldest son, born in the first year of the Peace, had married the only daughter of Tremayne, and their first-born son had been his father’s father.

Although the average physique of civilised man had immensely improved under the new order of things, the Aerians, descendants of the pick of the nations of Europe, were as far superior to the rest of the assembly as the latter would have been to the men and women of the nineteenth century; but even amongst the members of the Council, the splendid stature and regal dignity of Alan Arnold, the President, stamped him as a born ruler of men, whose title rested upon something higher than election or inheritance.

At the last stroke of twelve, the President rose in his place, and, in the midst of an almost breathless silence, read the message of Natas to the great congregation. This done, he laid the parchment down on the table and, beginning from the outbreak of the world-war, rapidly and lucidly sketched out the vast and beneficent changes in the government of society that its issues had made possible.

He traced the marvellous development of the new civilisation, which, in four generations, had raised men from a state of half-barbarous strife and brutality to one of universal peace and prosperity; from inhuman and unsparing competition to friendly co-operation in public, and generous rivalry in private concerns; from horrible contrasts of wealth and misery to a social state in which the removal of all unnatural disabilities in the race of life had made them impossible.

He showed how, in the evil times which, as all men hoped, had been left behind for ever, the strong and the unscrupulous ruthlessly oppressed the weak and swindled the honest and the straightforward. Now dishonesty was dishonourable in fact as well as in name; the game of life was played fairly, and its[11] prizes fell to all who could win them, by native genius or earnest endeavour.

There were no inequalities, save those which Nature herself had imposed upon all men from the beginning of time. There were no tyrants and no slaves. That which a man’s labour of hand or brain had won was his, and no man might take toll of it. All useful work was held in honour, and there was no other road to fame or fortune save that of profitable service to humanity.

“This,” said the President in conclusion, “is the splendid heritage that we of the Supreme Council, which is now to cease to exist as such, have received from our forefathers, who won it for us and for you on the field of the world’s Armageddon. We have preserved their traditions intact, and obeyed their commands to the letter; and now the hour has come for us, in obedience to the last of those commands, to resign our authority and to hand over that heritage to you, the rulers of the civilised world, to hold in trust for the peoples over whom you have been appointed to reign.

“When I have done speaking I shall no longer be President of the Senate, which for a hundred and twenty-five years has ruled the world from pole to pole and east to west. You and your parliaments are henceforth free to rule as you will. We shall take no further part in the control of human affairs outside our domain, saving only in one concern.

“In the days when our command was established, the only possible basis of all rule was force, and our supremacy was based on the force that we could bring to bear upon those who might have ventured to oppose us or revolted against our rule. We commanded, and we will still command, the air, and I should not be doing my duty, either to my own people or to you, if I did not tell you that the Aerians, not as the world-rulers that they have been, but as the citizens of an independent State, mean to keep that power in their own hands at all costs.

“The empire of earth and sea, saving only the valley of Aeria, is yours to do with as you will. The empire of the air[12] is ours,—the heritage that we have received from the genius of that ancestor of mine who first conquered it.

“That we have not used it in the past to oppress you is the most perfect guarantee that we shall not do so in the future, but let all the nations of the earth clearly understand, that we shall accept any attempt to dispute it with us as a declaration of war upon us, and that those who make that attempt will either have to exterminate us or be exterminated themselves. This is not a threat, but a solemn warning; and the responsibility of once more bringing the curse of war and all its attendant desolation upon the earth, will lie heavily upon those who neglect it.

“A few more needful words and I have done. The message of the Master, which I have read to you, contains a prophecy, as to the fulfilment of which neither I nor any man here may speak with certainty. It may be that he, with clearer eyes than ours, saw some tremendous catastrophe impending over the world, a catastrophe which no human means could avert, and beneath which human strength and genius could only bow with resignation.

“By what spirit he was inspired when he uttered the prophecy, it is not for us to say. But before you put it aside as an old man’s dream, let me ask you to remember, that he who uttered it was a man who was able to plan the destruction of one civilisation, and to prepare the way for another and a better.

“Such a man, standing midway between the twin mysteries of life and death, might well see that which is hidden from our grosser sight. But whether the prophecy itself shall prove true or false, it shall be well for you and for your children’s children if you and they shall receive the lesson that it teaches as true.

“If, in the days that are to come, the world shall be overwhelmed with a desolation that none shall escape, will it not be better that the end shall come and find men doing good rather than evil? As you now set the peoples whom you govern in the right or the wrong path, so shall they walk.

“This is the lesson of all the generations that have gone before us, and it shall also be true of those that are to come after us. As the seed is, so is the harvest; therefore see to it that you, who are now the free rulers of the nations, so discharge the awful trust and responsibility which is thus laid upon you, that your children’s children shall not, perhaps in the hour of Humanity’s last agony, rise up and curse your memory rather than bless it. I have spoken!”

LATE in the evening of the same day two of the President’s audience—the only two who had heard his words with anger and hatred instead of gratitude and joy—were together in a small but luxuriously-furnished room, in an octagonal turret which rose from one of the angles of a large house on the southern slope of the heights of Hampstead.

One was a very old man, whose once giant frame was wasted and shrunken by the slow siege of many years, and on whose withered, care-lined features death had already set its fatal seal. The other was a young girl, in all the pride and glory of budding womanhood, and beautiful with the dark, imperious beauty that is transmitted, like a priceless heirloom, along a line of proud descent unstained by any drop of base-born blood.

Yet in her beauty there was that which repelled as well as attracted. No sweet and gentle woman-soul looked out of the great, deep eyes, that changed from dusky-violet to the blackness of a starless night as the sun and shade of her varying moods swept over her inner being. Her straight, dark brows were almost masculine in their firmness; and the voluptuous promise of her full, red, sensuous lips was belied by the strength of her chin and the defiant poise of her splendid head on the strongly-moulded throat, whose smooth skin showed so dazzlingly white against the dark purple velvet of the collar of her dress.

It was a beauty to enslave and command rather than to woo and win; the fatal loveliness of a Cleopatra, a Lucrezia, or a Messalina; a charm to be used for evil rather than for good. In a few years she would be such a woman as would drive men mad for the love of her, and, giving no love in return, use them for her own ends, and cast them aside with a smile when they could serve her no longer.

The old man was lying on a low couch of magnificent furs, against whose dark lustre the grey pallor of his skin and the pure, silvery whiteness of his still thick hair and beard showed up in strong contrast. He had been asleep for the last four hours, resting after the exertion of going to the cathedral, and the girl was sitting watching him with anxious eyes, every now and then leaning forward to catch the faint sound of his slow and even breathing, and make sure that he was still alive.

A clock in one of the corners of the room chimed a quarter to nine, as the old man raised his hand to his brow and opened his eyes. They rested for a moment on the girl’s face, and then wandered inquiringly about the room, as though he expected someone else to be present. Then he said in a low, weak voice—

“What time is it? Has Serge come yet?”

“No,” said the girl, glancing up at the clock; “that was only a quarter to nine, and he is not due until the hour.”

“No; I remember. I don’t suppose he can be here much before. Meanwhile get me the draught ready, so that I shall have strength to do what has to be done before”—

“Are you sure it is necessary for you to take that terrible drug? Why should you sacrifice what may be months or even years of life, to gain a few hours’ renewed youth?”

The girl’s voice trembled as she spoke, and her eyes melted in a sudden rush of tears. The one being that she loved in all the world was this old man, and he had just told her to prepare his death-draught.

“Do as I bid you, child,” he said, raising his voice to a querulous cry, “and do it quickly, while there is yet time. Why do you talk to me of a few more months of life—to me,[16] whose eyes have seen the snows of a hundred winters whitening the earth? I tell you that, drug or no drug, I shall not see the setting of to-morrow’s sun. As I slept, I heard the rush of the death-angel’s wings through the night, and the wind of them was cold upon my brow. Do as I bid you, quick—there is the door-telephone. Serge is here!”

As he spoke, a ring sounded in the lower part of the house. Accustomed to blind obedience from her infancy, the girl choked back her rising tears and went to a little cupboard let into the wall, out of which she took two small vials, each containing about a fluid ounce of colourless liquid. She placed a tumbler in the old man’s hand, and emptied the vials into it simultaneously.

There was a slight effervescence, and the two colourless liquids instantly changed to deep red. The moment that they did so, the dying man put the glass to his lips and emptied it at a gulp. Then he threw himself back upon his pillows, and let the glass fall from his hand upon the floor. At the same moment a little disc of silver flew out at right angles to the wall near the door, and a voice said—

“Serge Nicholaivitch is here to command.”

“Serge Nicholaivitch is welcome. Let him ascend!” said the girl, walking towards the transmitter, and replacing the disc as she ceased speaking.

A few moments later there was a tap on the door. The girl opened it and admitted a tall, splendidly-built young fellow of about twenty-two, dressed, according to the winter costume of the time, in a close-fitting suit of dark-blue velvet, long boots of soft, brown leather that came a little higher than the knee, and a long, fur-lined, hooded cloak, which was now thrown back, and hung in graceful folds from his broad shoulders.

As he entered, the girl held out her hand to him in silence. A bright flush rose to her clear, pale cheeks as he instantly dropped on one knee and kissed it, as in the old days a favoured subject would have kissed the hand of a queen.

“Welcome, Serge Nicholaivitch, Prince of the House of[17] Romanoff! Your bride and your crown are waiting for you!”

The words came clear and strong from the lips which, but a few minutes before, had barely been able to frame a coherent sentence. The strange drug had wrought a miracle of restoration. Fifty years seemed to have been lifted from the shoulders of the man who would never see another sunrise.

The light of youth shone in his eyes, and the flush of health on his cheeks. The deep furrows of age and care had vanished from his face, and, saving only for his long, white hair, if one who had seen Alexander Romanoff, the last of the Tsars of Russia, on the battlefield of Muswell Hill could have come back to earth, he would have believed that he saw him once more in the flesh.

Without any assistance he rose from the couch, and drew himself up to the full of his majestic height. As he did so the young man dropped on his knee before him, as he had done before the girl, and said in Russian—

“The honour is too great for my unworthiness. May heaven make me worthy of it!”

“Worthy you are now, and shall remain so long as you shall keep undefiled the faith and honour of the Imperial House from which you are sprung,” replied the old man in the same language, raising him from his knee as he spoke. Then he laid his hands on the young man’s shoulders, and, looking him straight in the eyes, went on—

“Serge Nicholaivitch, you know why I have bidden you come here to-night. Speak now, without fear or falsehood, and tell me whether you come prepared to take that which I have to give you, and to do that which I shall ask of you. If there is any doubt in your soul, speak it now and go in peace; for the task that I shall lay upon you is no light one, nor may it be undertaken without a whole heart and a soul that is undivided by doubt.”

The young man returned his burning gaze with a glance as clear and steady as his own, and replied—

“It is for your Majesty to give and for me to take—for you[18] to command and for me to obey. Tell me your will, and I will do it to the death. In the hour that I fail, may heaven’s mercy fail me too, and may I die as one who is not fit to live!”

“Spoken like a true son of Russia!” said the old man, taking his hands from his shoulders and beckoning the girl to his side. Then he placed them side by side before an ikon fastened to the eastern wall, with an ever-burning lamp in front of it. He bade them kneel down and join hands, and as they did so he took his place behind them and, raising his hands as though in invocation above their heads, he said in slow, solemn tones—

“Now, Serge Nicholaivitch and Olga Romanoff, sole heirs on earth of those who once were Tsars of Russia, swear before heaven and all its holy saints that, when this body of mine shall have been committed to the flames, you will take my ashes to Petersburg and lay them in the Church of Peter and Paul, and that when that is done, you will go to the Lossenskis at Moscow, and there, in the Uspènski Sobōr, where your ancestors were crowned, take each other for wedded wife and husband, according to the ancient laws of Russia and the rites of the orthodox church.”

The oath was taken by each of the now betrothed pair in turn, and then Paul Romanoff, great-grandson of Alexander, the Last of the Tsars, raised them from their knees and kissed each of them on the forehead. Then, taking from his neck a gold chain with a small key attached to it, he went to one of the oak panels, from which the walls of the room were lined, and pushed aside a portion of the apparently solid beading, disclosing a keyhole into which he inserted the key.

He turned the key and pulled, and the panel swung slowly out like a door. It was lined with three inches of solid steel, and behind it was a cavity in the wall, from which came the sheen of gold and the gleam of jewels. A cry of amazement broke at the same moment from the lips of both Olga and Serge, as they saw what the glittering object was.

Paul Romanoff took it out of the steel-lined cavity, and laid it reverently on the table, saying, as he did so—

“To-morrow I shall be dead, and this house and all that is[19] in it will be yours. There is my most precious possession, the Imperial crown of Russia, stolen when the Kremlin was plundered in the days of the Terror, and restored secretly to my father by the faith and devotion of one of the few who remained loyal after the fall of the Empire.

“In a few hours it will be yours. I leave it to you as a sacred heritage from the past for you to hand on to the future, and with it you shall receive and hand on a heritage of hate and vengeance, which you shall keep hot in your hearts and in the hearts of your children against the day of reckoning when it comes.

“Now sit down on the divan yonder, and listen with your ears and your hearts as well, for these are the last words that I shall speak with the lips of flesh, and you must remember them, that you may tell them to your children, and perchance to their children after them, as I now tell them to you; for the hour of vengeance may not come in your day nor yet in theirs, though in the fulness of time it shall surely come, and therefore the story must never be forgotten while a Romanoff remains to remember it.”

The old man, on whom the strange drug that he had taken was still exercising its wonderful effects, threw himself into an easy-chair as he spoke, and motioned them with his hand towards a second low couch against one of the walls, covered with cushions and draped with neutral-tinted, silken hangings.

Olga, moving, as it seemed, with the unconscious motion of a somnambulist, allowed her form to sink back upon the cushions until she half sat and half reclined on them; and Serge, laying one of the cushions on the floor, sat at her feet, and drew one of her hands unresistingly over his shoulder, and kept it there as though she were caressing him. Thus they waited for Paul Romanoff to teach them the lesson that they had sworn to teach in turn to the generations that were to come.

The old man regarded them in silence for a moment or two, and as he did so the angry fire died out of his eyes, and his lips parted in a faint smile as he said, rather in soliloquy to himself than to them—

“As it was in the beginning, it is now and for ever shall be until the end! Empires wax and wane, and dynasties rise and fall! Revolutions come and go, and the face of the world is changed, but the mystery of the sex, the beauty of woman, and the love of man, endure changeless as Destiny, for they are Destiny itself!”

As he spoke, the fixed, rigid look melted from Olga’s face. The bright flush rose again to her cheeks, and she bowed her royal head, and looked almost tenderly at the blond, ruddy, young giant at her feet. After all, he was her fate, and she might well have had a worse one.

Then after a brief pause, Paul Romanoff began to speak again, slowly and quietly, with his eyes fixed on the glittering symbol of the vanished sovereignty of his House, as though he were addressing it, and communing with the mournful memories that it recalled from the past.

“It is a hundred and twenty-five years since the hand of Natas, the Jew, came forth out of the unknown, and struck you from the brow of the Last of the Tsars. On the day that Natas died, I was born, a hundred years ago. There are barely a score of men left on earth who have seen and spoken with the men who saw the Great Revolt and the beginning of the Terror, and I alone, of the elder line of Romanoff, remain to pass the story of our House’s shame and ruin on, so that it may not be forgotten against the day of vengeance, that I have waited for in vain.

“But I have no time left for dreams or vain regrets. Listen, Children of the Present, and take my words with you into the future that it is not given to me to see.”

He passed his hands upwards over his eyes and brow, and then went on, speaking now directly to Olga and Serge, in a quick, earnest tone, as though he feared that his fictitious strength would fail him before he could say what he had to say—

“When Alexander, the last of the crowned Emperors of Russia, fell down dead on the morning after he reached the mines of Kara, to which the Terrorists had exiled him as a convict for life, those who remained of his family, and who had[21] taken no part in the war, were allowed to return to Europe, on condition that they lived the lives of private citizens and sought no share in the government of any country to which they were allied by marriage or otherwise.

“Only two of those who had survived the march to Siberia were able to avail themselves of this permission, and these were Olga, the daughter of Alexander, and Serge Nicholaivitch, the youngest son of his nephew Nicholas. These two settled at the Court of Denmark, and there, two years later, Olga married Prince Ingeborg. Her first-born son, the only one of her children who lived beyond infancy, was my father, as my own first-born son was yours, Olga Romanoff.

“Serge married Dagmar, the youngest daughter of the House of Denmark, three years later, and from him you, Serge Nicholaivitch, are descended in the fourth generation. Thus in you will be united the only two remaining branches of the once mighty House of Romanoff. May the day come when, in you or your children, its ancient glories shall be restored!”

“Amen!” said Olga and Serge in a single breath, and as she uttered the words, Olga’s eyes fell on the lost crown upon the table, and for the moment they seemed to flame with the inner fires of a quenchless rage. Paul Romanoff’s eyes answered hers flash for flash, for the same hatred and longing for revenge possessed them both—the old man who had carried the weight of a hundred years to the brink of the grave, and the young girl whose feet were still lingering on the dividing line between girlhood and womanhood.

Then he went on, speaking with an added tone of fierceness in his voice—

“From the day of my birth until this, the night of my death, it has been impossible to do anything to recover that which was lost in the Great Revolt. Not that stout hearts and keen brains and willing hands have been wanting for the work; but because the strong arm of the Terror has encircled the earth with unbreakable bonds; because its eye has never slept; and because its hand has hurled infallible destruction upon all who have dared to take the first step towards freedom.

“Natas spoke truly when he said that the Terrorists had ruled the world by force, and Alan Arnold to-day spoke truly after him when he said that the supremacy of the Aerians was based upon the force that they could bring to bear upon any who revolted against them, through their possession of the empire of the air.

“It is this priceless possession that gives them the command of the world, and for a hundred years they have guarded it so jealously, that they have slain without mercy all who have ventured to take even the first step towards an independent solution of the mighty problem which Richard Arnold solved a hundred and twenty-six years ago.

“The last man who died in this cause was my only son, and your father, Olga. Remember that, for it is not the least item in the legacy of revenge that I bequeath to you to-night. He had devoted his life, as many others had done before him, to the task of discovering the secret of the motive power of the Terrorists’ air-ships.

“The year you were born, success had crowned the efforts of ten years of tireless labour. Working with the utmost secrecy in a lonely hut buried in the forests of Norway, he and six others, who were, as he thought, devoted to him and the glorious cause of wresting the empire of the world from the grasp of the Terrorists, had built an air-ship that would have been swifter and more powerful than any of their aerial fleet.

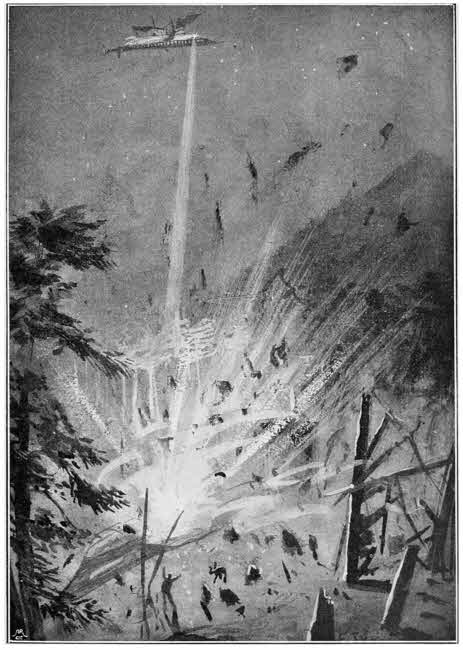

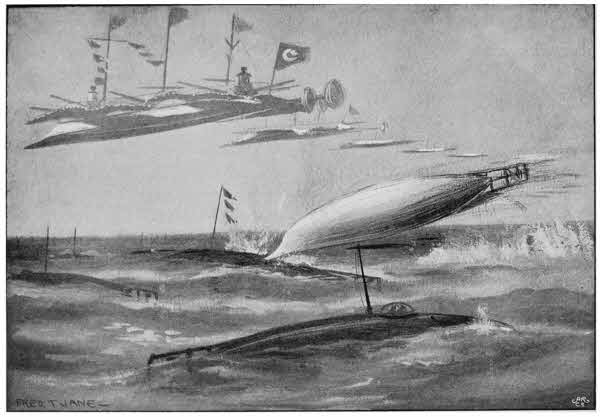

“Two days before she was ready to take the air, one of his men deserted. The traitor was never seen again, but the next night a Terrorist vessel descended from the clouds, and in a few minutes not a vestige of our air-ship or her creators remained. Only a blackened waste in the midst of the forest was left to show the scene of their labours. Within forty-eight hours, it was known all over the civilised world that Vladimir Romanoff and his associates had been killed by order of the Supreme Council, for endeavouring to build an air-ship in defiance of its commands.

Not a Vestige of our Air-Ship or her Creators remained. Page 22.

“Such are the enemies against whom you will have to contend. They are still virtually the masters of the world, and the[23] task before you is to wrest that mastery from them. It is no light task, but it is not impossible; for these Aerians are, after all, but men and women as you are, and what they have done, other men and women can surely do.

“The Great Secret cannot always remain theirs alone. While they actively controlled the nations, nothing could be done against them, for their hand was everywhere and their eyes saw everything. But now they have abdicated the throne of the world, and left the nations to rule themselves as they can. For a time things will go on in their present grooves, but that will not be for long.

“I, who am their bitterest enemy on earth, am forced to confess that the Terrorists have proved themselves to be the wisest as well as the strongest of despots. Under their rule the world has become a paradise—for the canaille and the multitude. But they have curbed the mob as well as the king, and abolished the demagogue as well as the despot. Now the strong hand is lifted and the bridle loosed; and before many years have passed, the brute strength of the multitude will have begun to assert itself.

“The so-called kings of the earth, who rule now in a mockery of royalty, will speedily find that the real kings of the old days ruled because, in the last resource, they had armies and navies at their command and could enforce obedience. These are but the puppets of the popular will, and now that the moral and physical support of the Supreme Council and its aerial fleet is taken from them, they will see democracy run rampant, and, having no strength to stem the tide, they will have to float with it or be submerged by it.

“In another generation the voice of the majority, the blind, brute force of numbers, will rule everything on earth. What government there may be, will be a mere matter of counting heads. Individual freedom will by swift degrees vanish from the earth, and human society will become a huge machine, grinding all men down to the same level until the monotony of life becomes unendurable.

“Hitherto all democracies in the history of the world have[24] been ended by military despotisms, but now military despotism has been made impossible, and so democracy will run riot, until it plunges the world into social chaos.

“This may come in your time or in your children’s, but it is the opportunity for which you must work and wait. Even now you will find in every nation, thousands of men and women who are chafing against the limitations imposed on individual aspirations and ambition; and as the rule of democracy spreads and becomes heavier, the number of these will increase, until at last revolt will become possible, nay, inevitable.

“Of this revolt you must make yourselves the guiding-spirits. The work will be long and arduous, but you have all your lives before you, and the reward of success will be glorious beyond all description.

“Not only will you restore the House of Romanoff to its ancient glories in yourselves and your children, but you will enthrone it in an even higher place than that which your ancestor had almost won for it, when these thrice-accursed Terrorists turned the tide of battle against him on the threshold of the conquest of the world.

“Do not shrink from the task, or despair because you are now only two against the world. Think of Natas and the mighty work that he did, and remember that he was once only one against the world which in the day of battle he fought and conquered.

“Above all things, never let your eyes wander from the land of the Aerians. That once conquered and the world is yours to do with as you will. To do that, you must first conquer the air as they have done. Aeria itself, by all reports, is such a paradise as the sun nowhere else shines upon. Some day, whether by force or cunning, it may be yours; and when it is, the world also will be yours to be your footstool and your plaything, and all the peoples of the earth shall be your servants to do your bidding.

“Yes, I can see, through the mists of the coming years and beyond the grave that opens at my feet, aerial navies, flying the Eagle of Russia and scaling the mighty battlements of Aeria,[25] hurling their lightnings far and wide in the work of vengeance long delayed! Behind the battle, I see darkness that my weak eyes cannot pierce, but yours shall see clearly where mine are clouded with the falling mists of death.

“The shadows are closing round me, and the sands in the glass are almost run out. Yet one thing remains to be done. Since Alexander Romanoff died at the mines of Kara, no Tsar of Russia has been crowned. Now I, Paul Romanoff, his rightful heir, will crown myself after the fashion of my ancestors, and then I will crown you, the daughter of my murdered son, and you will place the diadem on your husband’s brow when God has made you one!”

So saying, the old man rose from his seat, with his face flushed and his eyes aglow with the light of ecstasy. Olga and Serge rose to their feet, half in fear and half in wonder, as they looked upon his transfigured countenance.

He lifted the Imperial crown from the table, and then, drawing himself up to the full height of his majestic stature, raised it high above his head, and lowered it slowly down towards his brow.

The jewelled circlet of gold had almost touched the silver of his snowy hair when the light suddenly died out of his eyes, leaving the glaze of death behind it. He gasped once for breath, and then his mighty form shrank together and pitched forward in a huddled heap at their feet, flinging the crown with a dull crash to the floor, and sending it rolling away into a corner of the room.

“God grant that may not be an omen, Olga!” said Serge, covering his eyes with his hands to shut out the sudden horror of the sight.

“Omen or not, I will do his bidding to the end,” said the girl slowly and solemnly. Then her pent-up passion of grief burst forth in a long, wailing cry, and she flung herself down on the prostrate form of the only friend she had ever known and loved, and laid her cheek upon his, and let the welling tears run from her eyes over those that had for ever ceased to weep.

THREE days after his death, the body of Paul Romanoff was reduced to ashes in the Highgate Crematorium, a magnificent building, in the sombre yet splendid architecture of ancient Egypt, which stood in the midst of what had once been Highgate Cemetery, and what was now a beautiful garden, shaded by noble trees, and in summer ablaze with myriads of flowers.

Not a grave or a headstone was to be seen, for burial in the earth had been abolished throughout the civilised world for nearly a century. In the vast galleries of the central building, thousands of urns, containing the ashes of the dead, reposed in niches inscribed with the name and date of death, but these mostly belonged to the poorer classes, for the wealthy as a rule devoted a chamber in their own houses to this purpose.

The body was registered in the great Book of the Dead at the Crematorium as that of Paul Ivanitch, and the only two mourners signed their names, “Serge Ivanitch and Olga Ivanitch, grand-children of the deceased.” The reason for this was, that for more than a century the name of Romanoff had been proscribed in all the nations of Europe. It was believed that the Vladimir Romanoff who had been executed by the Supreme Council, for attempting to solve the forbidden problem, was the last of his race, and Paul had taken great pains not to disturb this belief.

Long before his son had met with his end, he had called himself Paul Ivanitch, and settled in London and practised his profession as a sculptor, in which he had won both fame and fortune. Olga had lived with him since her father’s death, and Serge, who at the time the narrative opens had just completed his studies at the Art University of Rome, had passed as her brother.

They took the urn containing the ashes of the old man back with them to the house, which now belonged, with all its contents, to Olga and Serge. On the morning after his death, a notice, accompanied by an abstract of his will, had been inserted in The Official Gazette, the journal devoted exclusively to matters of law and government.

Paul Romanoff had, however, left two wills behind him, one which had to be made public in compliance with the law, and one which was intended only for the eyes of Olga and Serge. This second will reposed, with the crown of Russia, in the secret recess in the wall of the octagonal chamber; and the instructions endorsed upon it stated that it was to be opened by Serge in the presence of Olga, after they had brought his ashes back to the house and had been legally confirmed in their possession of his property.

Consequently, on the evening of the 11th, the two shut themselves into the room, and Olga, who since her grandfather’s death had worn the key of the recess on a chain round her neck, unlocked the secret door and gave the will to Serge. As she did so, a sudden fancy seized her. She took the crown from its resting-place, and, standing in front of a long mirror which occupied one of the eight sides of the room from roof to floor, poised it above the lustrous coils of her hair with both hands, and said, half to Serge and half to herself—

“What age could not accomplish, youth shall do! By my own right, and with my own hands, I am crowned Tsarina, Empress of the Russias in Europe and Asia. As the great Catherine was, so will I be—and more, for I will be Mistress of the West and the East. I will have kings for my vassals and[28] senates for my servants, and I will rule as no other woman has ruled before me since Semiramis!”

As she uttered the daring words, whose fulfilment seemed beyond the dreams of the wildest imagination, she placed the crown upon her brow and stood, clothed in imperial purple from head to foot, the very incarnation of loveliness and royal majesty. Serge looked up as she spoke, and gazed for a moment entranced upon her. Then he threw himself upon his knees before her, and, raising the hem of her robe to his lips, said in a voice half choked with love and passion—

“And I, who am also of the imperial blood, will be the first to salute you Tsarina and mistress! You have taken me as your lover, let me also be the first of your subjects. I will serve you as woman never was served before. You shall be my mistress—my goddess, and your words shall be my laws before all other laws. If you bid me do evil, it shall be to me as good, and I will do it. I will kill or leave alive according to your pleasure, and I will hold my own life as cheap as any other in your service; for I love you, and my life is yours!”

Olga looked down upon him with the light of triumph in her eyes. No woman ever breathed to whom such words would not have been sweet; but to her they were doubly sweet, because they were a spontaneous tribute to the power of her beauty and the strength of her royal nature, and an earnest of her future sway over other men.

More than this, too, they had been won without an effort, from the lips of the man whom she had always been taught to look upon as higher than other men, in virtue of his descent from her own ancestry, and the blood-right that he shared with her to that throne which it was to be their joint life-task to re-establish.

If she did not love him, it was rather because ambition and the inborn lust of power engrossed her whole being, than from any lack of worthiness on his part. Of all the men she had ever seen, none compared with him in strength and manliness save one—and he, bitter beyond expression as the thought was[29] to her, was so far above her as she was now, that he seemed to belong to another world and to another order of beings.

As their eyes met, a thrill that was almost akin to love passed through her soul, and, acting on the impulse of the moment, she took the crown from her own head and held it above his as he knelt at her feet, and said—

“Not as my subject or my servant, but as my co-ruler and helpmate, you shall keep that oath of yours, Serge Nicholaivitch. We have exchanged our vows, and in a few days I shall be your wife. We will wed as equals; and so now I crown you, as it is my right to do. Rise, my lord the Tsar, and take your crown!”

Serge put up his hands and took the crown from hers at the moment that she placed it on his brow. He rose to his feet, holding it on his head as he said solemnly—

“So be it, and may the God of our fathers help me to wear it worthily with you, and to restore to it the glory that has been taken from it by our enemies!”

Then he laid it reverently down on the table and turned to Olga, who was still standing before the mirror looking at her own lovely image, as though in a dream of future glory. He took her unresisting in his arms, and kissed her passionately again and again, bringing the bright blood to her cheeks and the light of a kindred passion to her eyes, and murmuring between the kisses—

“But you, darling, are worth all the crowns of earth, and I am still your slave, because your beauty and your sweetness make me so.”

“Then slave you shall be!” she said, giving him back kiss for kiss, well knowing that with every pressure of her intoxicating lips she riveted the chains of his bondage closer upon his soul.

To an outside observer, what had taken place would have seemed but little better than boy-and-girl’s play, the phantasy of two young and ardent souls dreaming a romantic and impossible dream of power and glory that had vanished, never to be brought back again. And yet, if such a one had been[30] able to look forward through little more than a single lustrum, he would have seen that, in the mysterious revolutions of human affairs, it is usually the seemingly impossible that becomes possible, and the most unexpected that comes to pass.

The secret will of Paul Romanoff, to the study of which the two lovers addressed themselves when they awoke from the dream of love and empire into which Olga’s phantasy had plunged them both, would, if it had been made public, have given a by no means indefinite shape to such vague dreams of world-revolution as were inspired in thoughtful minds, even in the thirty-first year of the twenty-first century.

It was a voluminous document of many pages, embodying the result of nearly eighty years of tireless scheming and patient research in the field of science as well as in that of politics. Paul Romanoff had lived his life with but one object, and that was, to prepare the way for the accomplishment of a revolution which should culminate in the subversion of the state of society inaugurated by the Terrorists, and the re-establishment, at anyrate in the east of Europe, of autocratic rule in the person of a scion of the House of Romanoff. All that he had been able to do towards the attainment of this seemingly impossible project was crystallised in the document bequeathed to Olga and Serge.

It was divided into three sections. The first of these was mostly of a personal nature, and contained details which it would serve no purpose of use or interest to reproduce here. It will therefore suffice to say, that it contained a list of the names and addresses of four hundred men and women scattered throughout Europe and America, each of whom was the descendant of some prince or noble, some great landowner or millionaire, who had suffered degradation or ruin at the hands of the Terrorists during the reorganisation of society, after the final triumph of the Anglo-Saxon Federation in 1904.

The second section of the will was of a purely scientific and technical character. It was a theoretical arsenal of weapons[31] for the arming of those who, if they were to succeed at all, could only do so by bringing back that which it had cost such an awful expenditure of blood and suffering to banish from the earth in the days of the Terror. The designs of Paul Romanoff, and the vast aspirations of those to whom he had bequeathed the crown of the great Catherine, could have but one result if they ever passed from the realm of fancy to that of deeds.

If the clock was to be put back, only the armed hand could do it, and that hand must be so armed that it could strike at first secretly, and yet with paralysing effect. The few would have to array themselves against the many, and if they triumphed, it would have to be by the possession of some such means of terrorism and irresistible destruction as those who had accomplished the revolution of 1904 had wielded in their aerial fleet.

By far the most important part of this section of the will consisted of plans and diagrams of various descriptions of air-ships and submarine vessels, accompanied by minute directions for building and working them. Most of these were from the hand of Vladimir Romanoff, Olga’s father; but of infinitely more importance even than all these was a detailed description, on the last page but two of the section, of the solution of a problem which had been attempted in the last decade of the nineteenth century, but which was still unsolved so far as the world at large was concerned.

This was the direct transformation of the solar energy locked up in coal into electrical energy, without loss either by waste or transference. How vast and yet easily controlled a power this would be in the hands of those who were able to wield it, may be guessed from the fact that, in the present day, less than ten per cent. of the latent energy of coal is developed as electrical power even in the most perfect systems of conversion.

All the rest is wasted between the furnace of the steam-engine and the dynamo. It was to electrical power, obtained direct from coal and petroleum, that Vladimir Romanoff trusted[32] for the motive force of his air-ships and submarine vessels, and which he had already employed with experimental success as regards the former, when his career was cut short by the swift and pitiless execution of the sentence of the Supreme Council.

The remainder of this section was occupied by a list of chemical formulæ for the most powerful explosives then known to science, and minute instructions for their preparation. At the bottom of the page which contained these, there was a little strip of parchment, fastened by one end to the binding of the other sheets, and covered with very small writing.

Olga’s eyes, wandering down over the maze of figures which crowded the page, reached it before Serge’s did. One quick glance told her that it was something very different to the rest. She laid one hand carelessly over it, and with the other softly caressed Serge’s crisp, golden curls. As he looked round in response to the caress, their eyes met, and she said in her sweet, low, witching voice—

“Dearest, I have a favour to ask of you.”

“Not a favour to ask, but a command to give, you mean. Speak, and you are obeyed. Have I not sworn obedience?” he replied, laying his hand upon her shoulder and drawing her lovely face closer to his as he spoke.

“No, it is only a favour,” she said, with such a smile as Antony might have seen on the lips of Cleopatra. “I want you to leave me alone for a little time—for half an hour—and then come back and finish reading this with me. You know my brain is not as strong as yours, and I feel a little bewildered with all the wonderful things that there are in this legacy of my father’s father.

“Before we go any further, I should like to read it all through again by myself, so as to understand it thoroughly. So suppose you go to your smoking-room for a little, and leave me to do so. I shall not take very long, and then we will go over the rest together.”

“But we have only a couple more pages to read, sweet one,[33] and then I will go over it all again with you, and explain anything that you have not understood.”

As he spoke, Serge’s eyes never wavered for a moment from hers. Could he but have broken their spell, he might have seen that she was hiding something from him under her little, white hand and shapely arm. She brought her red, smiling lips still nearer to his as she almost whispered in reply—

“Well, it is only a girl’s whim, after all, but still I am a girl. Come, now, I will give you a kiss for twenty minutes’ solitude, and when you come back, and we have finished our task, you shall have as many more as you like.”

The sweet, tempting lips came closer still, and the witching spell of her great dusky eyes grew stronger as she spoke. How was he to know what was hanging in the balance in that fateful moment? He was but a hot-blooded youth of twenty, and he worshipped this lovely, girlish temptress, who had not yet seen seventeen summers, with an adoration that blinded him to all else but her and her intoxicating beauty.

He drew her yielding form to him until he could feel her heart beating against his, and as their lips met, the promised kiss came from hers to his. He returned it threefold, and then his arm slipped from her shoulder to her waist, and he lifted her like a child from her chair, and carried her, half laughing and half protesting, to the door, claimed and took another kiss before he released her, and then put her down and left her alone without another word.

“Alas, poor Serge!” she said, as the door closed behind him; “you are not the first man who has lost the empire of the world for a woman’s kiss. Before, I saw that you were my equal and helpmate, now you and all other men—yes, not even excepting he who seems so far above me now—shall be my slaves and do my bidding, so blindly that they shall not even know they are doing it.

“Yes, the weapons of war are worth much, but what are they in comparison with the souls of the men who will have to use them!”

In half an hour Serge came back to finish the reading of[34] the will with her. The little slip of paper had been removed so skilfully that it would have been impossible for him to have even guessed that it had ever been attached to the parchment, or that it was now lying hidden in the bosom of the girl who would have killed him without the slightest scruple to gain the unsuspected possession of it.

ON the day but one following the reading of Paul Romanoff’s secret will, Olga and Serge set out for St. Petersburg, to convey his ashes to their last resting-place in the Cathedral of SS. Peter and Paul in the Fortress of Petropaulovski, where reposed the dust of the Tyrants of Russia, from Peter the Great to Alexander II. of Russia, now only remembered as the chief characters in the dark tragedy of the days before the Revolution.

The intense love of the Russians for their country had survived the tremendous change that had passed over the face of society, and it was still the custom to bring the ashes of those who claimed noble descent and deposit them in one of their national churches, even when they had died in distant countries.

The station from which they started was a splendid structure of marble, glass, and aluminium steel, standing in the midst of a vast, abundantly-wooded garden, which occupied the region that had once been made hideous by the slums and sweating-dens of Southwark. The ground floor was occupied by waiting-rooms, dining-saloons, conservatories, and winter-gardens, for the convenience and enjoyment of travellers; and from these lifts rose to the upper storey, where the platforms and lines lay under an immense crystal arch.

Twelve lines ran out of the station, divided into three sets[36] of four each. Of these, the centre set was entirely devoted to continental traffic, and the lines of this system stretched without a break from London to Pekin.

The cars ran suspended on a single rail upheld by light, graceful arches of a practically unbreakable alloy of aluminium, steel, and zinc, while about a fifth of their weight was borne by another single insulating rail of forged glass,—the rediscovery of the lost art of making which had opened up immense possibilities to the engineers of the twenty-first century.

Along this lower line the train ran, not on wheels, but on lubricated bearings, which glided over it with no more friction than that of a steel skate on ice. On the upper rail ran double-flanged wheels with ball-bearings, and this line also conducted the electric current from which the motive-power was derived.

The two inner lines of each set were devoted to long-distance, express traffic, and the two outer to intermediate transit, corresponding to the ordinary trains of the present day. Thus, for example, the train by which Olga and Serge were about to travel, stopped only at Brussels, Berlin, Königsberg, Moscow, Nijni Novgorod, Tomsk, Tobolsk, Irkutsk, and Pekin, which was reached by a line running through the Salenga valley and across the great desert of Shamoo, while from Irkutsk another branch of the line ran north-eastward viâ Yakutsk to the East Cape, where the Behring Bridge united the systems of the Old World and the New.

The usual speed of the expresses was a hundred and fifty miles an hour, rising to two hundred on the long runs; and that of the ordinary trains, from a hundred to a hundred and fifty. Higher speeds could of course be attained on emergencies, but these had been found to be quite sufficient for all practical purposes.

The cars were not unlike the Pullmans of the present day, save that they were wider and roomier, and were built not of wood and iron, but of aluminium and forged glass. Their interiors were, of course, absolutely impervious to wind and dust, even at the highest speed of the train, although a[37] perfect system of ventilation kept their atmosphere perfectly fresh.

The long-distance trains were fitted up exactly as moving hotels, and the traveller, from London to Pekin or Montreal, was not under the slightest necessity of leaving the train, unless he chose to do so, from end to end of the journey.

One more advantage of railway travelling in the twenty-first century may be mentioned here. It was entirely free, both for passengers and baggage. Easy and rapid transit being considered an absolute necessity of a high state of civilisation, just as armies and navies had once been thought to be, every self-supporting person paid a small travelling tax, in return for which he or she was entitled to the freedom of all the lines in the area of the Federation.

In addition to this tax, the municipality of every city or town through which the lines passed, set apart a portion of their rent-tax for the maintenance of the railways, in return for the advantages they derived from them.

Under this reasonable condition of affairs, therefore, all that an intending traveller had to do was to signify the date of his departure and his destination to the superintendent of the nearest station, and send his heavier baggage on in advance by one of the trains devoted to the carriage of freight. A place was then allotted to him, and all he had to do was to go and take possession of it.

The Continental Station was comfortably full of passengers when Olga and Serge reached it, about fifteen minutes before the departure of the Eastern express; for people were leaving the Capital of the World in thousands just then, to spend Christmas and New Year with friends in the other cities of Europe, and especially to attend the great Winter Festival that was held every year in St. Petersburg in celebration of the anniversary of Russian freedom.

Ten minutes before the express started, they ascended in one of the lifts to the platform, and went to find their seats. As they walked along the train, Olga suddenly stopped and said, almost with a gasp—

“Look, Serge! There are two Aerians, and one of them is”—

“Who?” said Serge, almost roughly. “I didn’t know you had any acquaintances among the Masters of the World.”

The son of the Romanoffs hated the very name of the Aerians, so bitterly that even the mere suspicion that his idolised betrothed should have so much as spoken to one of them was enough to rouse his anger.

“No, I haven’t,” she replied quietly, ignoring the sudden change in his manner; “but both you and I have very good reason for wishing to make their distinguished acquaintance. I recognise one of these because he sat beside Alan Arnold, the President of the Council, in St. Paul’s, when they were foolish enough to relinquish the throne of the world in obedience to an old man’s whim.

“The taller of the two standing there by the pillar is the younger counterpart of the President, and if his looks don’t belie him, he can be no one but the son of Alan Arnold, and therefore the future ruler of Aeria, and the present or future possessor of the Great Secret. Do you see now why it is necessary that we should—well, I will say, make friends of those two handsome lads?”

Olga spoke rapidly and in Russian, a tongue then scarcely ever heard and very little understood even among educated people, who, whatever their nationality, made English their language of general intercourse. The words “handsome lads” had grated harshly upon Serge’s ears, but he saw the force of Olga’s question at once, and strove hard to stifle the waking demon of jealousy that had been roused more by her tone and the quick bright flush on her cheek than by her words, as he answered—

“Forgive me, darling, for speaking roughly! Their hundred years of peace have not tamed my Russian blood enough to let me look upon my enemies without anger. Of course, you are right; and if they are going by the express, as they seem to be, we should be friendly enough by the time we reach Königsberg.”

“I am glad you agree with me,” said Olga, “for the destinies of the world may turn on the events of the next few hours. Ah, the Fates are kind! Look! There is Alderman[2] Heatherstone talking to them. I suppose he has come to see them off, for no doubt they have been the guests of the City during the Festival. Come, he will very soon make us known to each other.”

A couple of minutes later the Alderman, who had been an old friend of Paul Ivanitch, the famous sculptor, had cordially greeted them and introduced them to the two Aerians, whose names he gave as Alan Arnoldson, the son of the President of the late Supreme Council, and Alexis Masarov, a descendant of the Alexis Mazanoff who had played such a conspicuous part in the war of the Terror. They were just starting on the tour of the world, and were bound for St. Petersburg to witness the Winter Festival.

Olga had been more than justified in speaking of them as she had done. Both in face and form, they were the very ideal of youthful manhood. Both of them stood over six feet in the long, soft, white leather boots which rose above their knees, meeting their close-fitting, grey tunics of silk-embroidered cloth, confined at the waist by belts curiously fashioned of flat links of several different metals, and fastened in front by heavy buckles of gold studded with great, flashing gems.

From their broad shoulders hung travelling-cloaks of fine, blue cloth, lined with silver fur and kept in place across the breast by silver chains and clasps of a strange, blue metal, whose lustre seemed to come from within like that of a diamond or a sapphire.

On their heads they wore no other covering than their own thick, curling hair, which they wore somewhat in the picturesque style of the fourteenth century, and a plain, broad band of the gleaming blue metal, from which rose above the temples a pair of marvellously-chased, golden wings about four inches high—the insignia of the Empire of the Air, and the[40] sign which distinguished the Aerians from all the other peoples of the earth.

As Olga shook hands with Alan, she looked up into his dark-blue eyes, with a glance such as he had never received from a woman before—a glance in which he seemed instinctively to read at once love and hate, frank admiration and equally undisguised defiance. Their eyes held each other for a moment of mutual fascination which neither could resist, and then the dark-fringed lids fell over hers, and a faint flush rose to her cheeks as she replied to his words of salutation—

“Surely the pleasure will rather be on our side, with travelling companions from the other world! For my own part, I seem to remind myself somewhat of one of the daughters of men whom the Sons of the Gods”—

She stopped short in the middle of her daring speech, and looked up at him again as much as to say—

“So much for the present. Let the Fates finish it!” and then, appearing to correct herself, she went on, with a half-saucy, half-deprecating smile on her dangerously-mobile lips—

“You know what I mean; not exactly that, but something of the sort.”

“More true, I fancy, of the daughter of men than of the supposed Sons of the Gods,” retorted Alan, with a laugh, half startled by her words, and wholly charmed by the indescribable fascination of the way in which she said them; “for the daughters of men were so fair that the Sons of the Gods lost heaven itself for their sakes.”

“Even so!” said Olga, looking him full in the eyes, and at that moment the signal sounded for them to take their places in the cars.

A couple of minutes after they had taken their seats, the train drew out of the station with an imperceptible, gliding motion, so smooth and frictionless that it seemed rather as though the people standing on the platform were sliding backwards than that the train was moving forward. The speed[41] increased rapidly, but so evenly that, almost before they were well aware of it, the passengers were flying over the snow-covered landscape, under the bright, heatless sun and pale, steel-blue sky of a perfect winter’s morning, at a hundred miles an hour, the speed ever increasing as they sped onward.

The line followed the general direction of the present route to Dover, which was reached in about half an hour. Without pausing for a moment in its rapid flight, the express swept out from the land over the Channel Bridge, which spanned the Straits from Dover to Calais at a height of 200 feet above the water.

Travelling at a speed of three miles a minute, seven minutes sufficed for the express to leap, as it were, from land to land. As they swept along in mid-air over the waves, Olga pointed down to them and said to Alan, who was sitting in the armchair next her own—

“Imagine the time when people had to take a couple of hours getting across here in a little, dirty, smoky steamboat, mingling their sorrows and their sea-sickness in one common misery! I really think this Channel Bridge is worthy even of your admiration. Come now, you have not admired anything yet”—

“Pardon me,” said Alan, with a look and a laugh that set Serge’s teeth gritting against each other, and brought the ready blood to Olga’s cheeks; “on the contrary, I have been absorbed in admiration ever since we started.”

“But not apparently of our engineering triumphs,” replied Olga frankly, taking the compliment to herself, and seeming in no way displeased with it. “It would seem that the polite art of flattery is studied to some purpose in Aeria.”