GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXIV. January, 1849. No. 1.

Table of Contents

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

GRAHAM’S

AMERICAN MONTHLY

MAGAZINE

Of Literature and Art.

EMBELLISHED WITH

MEZZOTINT AND STEEL ENGRAVINGS, MUSIC, ETC.

WILLIAM C. BRYANT, J. FENIMORE COOPER, RICHARD H. DANA, JAMES K. PAULDING,

HENRY W. LONGFELLOW, N. P. WILLIS, CHARLES F. HOFFMAN, J. R. LOWELL.

MRS. LYDIA H. SIGOURNEY, MISS C. M. SEDGWICK, MRS. FRANCES S. OSGOOD,

MRS. EMMA C. EMBURY, MRS. ANN S. STEPHENS, MRS. AMELIA B. WELBY,

MRS. A. M. F. ANNAN, ETC.

PRINCIPAL CONTRIBUTORS.

G. R. GRAHAM, J. R. CHANDLER AND J. B. TAYLOR, EDITORS.

VOLUME XXXIV.

PHILADELPHIA:

SAMUEL D. PATTERSON & CO. 98 CHESTNUT STREET.

1849.

CONTENTS

OF THE

THIRTY-FOURTH VOLUME.

JANUARY, 1849, TO JUNE, 1849.

| All About “What’s in a Name.” By Caroline C——, | 62 |

| A Recollection of Mendelssohn. By J. Bayard Taylor, | 113 |

| A Voice from the Wayside. By Caroline C——, | 300 |

| Barbara Uttman’s Dream. By Mrs. Emma C. Embury, | 43 |

| Christ Weeping Over Jerusalem. By Joseph R. Chandler, | 189 |

| Cousin Fanny. By M. S. G. Nichols, | 354 |

| Doctor Sian Seng. From the French, | 123, 174 |

| Deaf, Dumb and Blind. By Agnes L. Gordon, | 347 |

| Editor’s Table, | 79, 153, 215, 273, 330, 387 |

| Eleonore Eboli. By Winifred Barrington, | 134 |

| Fifty Suggestions. By Edgar A. Poe, | 317, 363 |

| For and Against. By Walter Herries, Esq. | 377 |

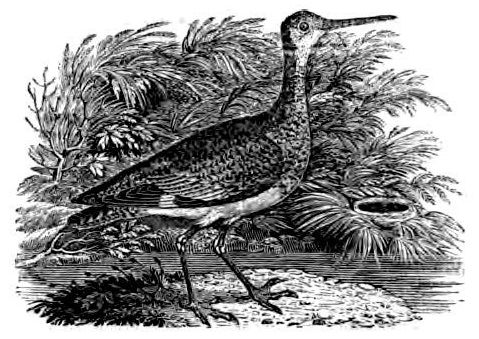

| Game-Birds of America. No. XII., | 68 |

| Gems from Late Readings, | 78, 149, 211 |

| History of the Costume of Men. By Fayette Robinson, | 71, 140, 196, 264, 319 |

| Honor to Whom Honor is Due. By Mrs. Lydia Jane Peirson, | 192 |

| Jasper Leech. By B., | 15 |

| Kate Richmond’s Betrothal. By Grace Greenwood, | 8 |

| Love, Duty and Hope. By Enna Duval, | 56 |

| Lessons in German. By Miss M. J. Browne, | 118 |

| Mormon Temple, Nauvoo, | 257 |

| Mr. and Mrs. John Johnson Jones. By Angele De V. Hull, | 277 |

| Montgomery’s House, | 330 |

| May Lillie. By Caroline H. Butler, | 365 |

| Passages of Life in Europe. By J. Bayard Taylor, | 307 |

| Passages of Life in Europe. By J. Bayard Taylor, | 373 |

| Reviews, | 81, 151, 213, 270, 334, 385 |

| Rose Winters. By Estelle, | 258 |

| Reminiscences. By Emma C. Embury, | 325 |

| Speak Kindly. By Kate Sutherland, | 53 |

| St. Valentine’s Day. By J. R. Chandler, | 110 |

| The Belle of the Opera. By J. R. Chandler, | 1 |

| The Illinois and the Prairies. By James K. Paulding, | 16 |

| The Letter of Introduction. By Mrs. A. M. F. Annan, | 26 |

| The Fugitive. By the Viscountess D’Aulnay, | 37 |

| The Old New House. By H. Hastings Weld, | 47 |

| The Wounded Guerilla. By Mayne Reid, | 50 |

| The Young Lawyer’s First Case. By J. Tod, | 85 |

| The Man in the Moon. By Caroline C——, | 91 |

| The Wager of Battle. By W. Gilmore Simms, | 99 |

| The Chamber of Life and Death. By Professor Alden, | 129 |

| The Lost Notes. By Mrs. Hughs, | 144 |

| The Naval Officer. By W. F. Lynch, | 157, 223, 286 |

| The Unfinished Picture. By Jane C. Campbell, | 182 |

| The Adventures of a Man who could Never Dress Well. | |

| By M. Topham Evans, | 199 |

| The Plantation of General Taylor, | 206 |

| The Poet Lí. By Caroline H. Butler, | 217 |

| The Recluse. By Park Benjamin, | 232, 298 |

| The Missionary, Sunlight. By Caroline C——, | 235 |

| The Brother’s Temptation. By Sybil Sutherland, | 243 |

| The Gipsy Queen. By Joseph R. Chandler, | 250 |

| The Darsies. By Emma C. Embury, | 252 |

| Taste. By Miss Augusta C. Twiggs, | 310 |

| The Man of Mind and the Man of Money. By T. S. Arthur, | 312 |

| The Picture of Judgment. By W. Gilmore Simms, | 337 |

| The Battle of Life. By Len, | 362 |

| The Birth-Place of Benjamin West, | 378 |

| The Young Dragoon. By C. J. Peterson, | 379 |

| Unequal Marriages. By Caroline H. Butler, | 169 |

| Western Recollections. By Fay. Robinson, | 178 |

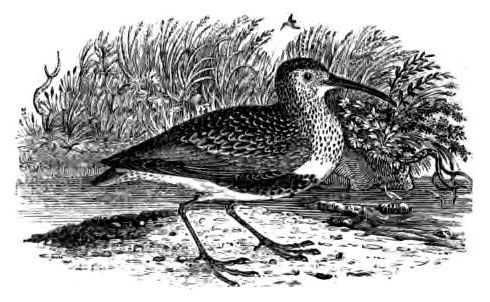

| Wild-Birds of America. By Prof. Frost, | 142 |

| Wild-Birds of America. By Professor Frost, | 208 |

| Wild-Birds of America. By Prof. Frost, | 267 |

| Wild-Birds of America. By Prof. Frost, | 322 |

| Wild-Birds of America. By Prof. Frost, | 382 |

POETRY.

MUSIC.

| Softly O’er My Memory Stealing. Words by S. D. Patterson. | |

| Music by John A. Janke, Jr. | |

| The Bells of Ostend. Words by W. L. Bowles. | |

| Music by J. Hilton Jones. | |

| Oh, Have I Not Been True to Thee? | |

| Written and adapted to a beautiful melody | |

| by John H. Hewitt. | |

| Adieu, My Native Land. Words by D. W. Belisle. | |

| Arranged for the piano by James Piper. | |

| Virtue’s Evergreen. Words by Theodore A. Gould. | |

| Music by Theodore Von La Hache. | |

| I Can’t Make Up My Mind. Words from Hood’s Magazine. | |

| Arranged for the piano by C. Grobe. |

ENGRAVINGS.

| Day on the Mountains, engraved by W. E. Tucker. | |

| The Belle of the Opera, engraved by W. E. Tucker. | |

| The Wounded Guerilla, engraved by Rice. | |

| Oglethorp University, engraved by Rawdon & Co. | |

| A Valentine, engraved by W. E. Tucker. | |

| Home Treasures, engraved by Addison. | |

| The Mirror of Life, engraved by Wilmer. | |

| Portrait of Mrs. Davidson, by Rawdon & Co. | |

| Christ Weeping Over Jerusalem, by W. E. Tucker. | |

| Why Don’t He Come, engraved by Addison. | |

| The Bridal Night, engraved by Addison. | |

| View of the Plantation of Gen. Taylor. | |

| The Gipsy Queen, engraved by Thomas B. Welsh. | |

| The Church of St. Isaac’s, engraved by A. L. Dick. | |

| The Miniature, engraved by an American Artist. | |

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | |

| May Morning, engraved by T. B. Welsh. | |

| View of Tortosa, engraved by J. Dill. | |

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. | |

| The Star of the Night, engraved by Addison. | |

| The Cottage Door, engraved by Humphreys. | |

| Col. Washington at the Cowpens. | |

| Paris Fashions, from Le Follet. |

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXIV. PHILADELPHIA, JANUARY, 1849. No. 1.

AN ESSAY UPON WOMAN’S ACCOMPLISHMENT, HER CHARACTER AND HER MISSION.

———

BY JOSEPH R. CHANDLER.

———

[SEE ENGRAVING.]

It is not a small thing to be an engaged writer for a magazine that has admittance into numerous families, and, by the costliness and adaptation of its decorations, and the general proclivity of its contents, is in no small degree the handbook of young females.

A good book, an octavo or quarto, upon sound morals or religious doctrines comes like a wholesome breeze, “stealing and giving odors”—but then, like that breeze, it is only occasional—a current rushing in but rarely, and seldom finding the right object within its healthful influence. But the magazine is the atmosphere in which the inmates dwell; they are constantly within its influence, and their general life, their mental sanative properties become imbued with its qualities: And this is the more important as the influence is commenced at home, and upon the female portion; so that it becomes constantly, permanently, and extensively operative upon, and through others.

The writers for this magazine seem to have been impressed with this idea of these consequences, and hence the importance of their contributions; or the editor has been exceedingly careful in his winnowing, to allow nothing to pass the sieve that might be productive of evil in the field which he is called to cultivate.

The writer of this article is deeply impressed with the importance of his position, and the danger of an error. A magazine that is devoted to taste, the arts and the fashions, it would seem, from the opinions of some, must be in a great degree light, and in no degree instructive, save in the very subject of taste, fashion and the arts, to which it is ostensibly devoted, and according to the general acceptation of the words, taste and fashion, and the ordinary uses to which the arts are applied.

“A magazine, then, of polite literature, of the arts and fashions, must be for the day—must treat of ephemeral subjects—must make the fashions of female dresses a leading and permanent matter of thought—must recommend amusements as matters of life-consideration, and erect the finer arts as an image of universal worship.”

We say plainly that we differ from those who make this estimate of periodical literature. We cannot consent to such a degrading standard for the monthly press—we certainly will not submit ourselves or our pen to this shortening process of the Procrustean bed of literature—we will do what we can to keep “Graham’s Magazine” from such debasement—we will do it for the long established character of the periodical, and for what we think it capable of—we will do it for our own credit—and, most of all, we will do it for the good of that large portion of society to which this magazine supplies the mental pabulum. When we furnish forth the table of those who look to our catering, we will take care that there shall be no poison in the ingredients, no “death in the pot.”

But in a secular magazine there must be light reading—all, or nearly all, the contents must be of a kind addressed to the fancy as well as the understanding—and consequently of a character to excite the censure, or at least forbid the approach, of the ascetic. Nay, it must greatly differ from the class of periodical literature devoted to, and sustained upon sectarian religious grounds. The task, the labor of the magazine editor is to sustain the high moral tone of his work, and yet have it the vehicle of fashion, taste and the arts—to take the pure, the good, and the beneficial, and give to them attractions for the young and gay—or, to take that which is attractive for the young and the gay, and make it the vehicle of high moral truth—of sober, solid reflection, the means of heart-improvement, and the promoter of home joys—to overlay the book with gold, and with sculptured cherubim, and all the magnificence of taste and ingenuity—but to be sure that within are the prophet’s rod—the shew-bread of the altar—and the written law of truth.

Our sense of the duty of a magazine writer of the present time, is rather hinted at than set forth in the above remarks. The subject is one that might command the pages of a volume, and if properly handled would be made eminently useful to writers and to readers. Our attention was awakened to the subject by an examination of the exquisitely executed picture of “The Belle of the Opera,” with which that accomplished artist, W. E. Tucker, has enriched the present number of this Magazine. We do not know that he who drew the figure had such a thought in his head as the improvement of magazine literature; and it is probable that Tucker when he exhausted the powers of engraving, or almost all its powers, to produce the figure, was impressed rather with the importance of his contribution to the artistic importance of periodicals, than to the high moral influence which he was aiding to promote. But true genius, wherever exercised, is suggestive—and the beautifully drawn figure is as promotive of useful reflection as the best composed essay. Hence the fine arts and literature are allied—allied in their elevating influence upon the possessors, and their power of meliorating and improving the minds of the uninitiated. Hence they go hand in hand in the path of usefulness—hence they are united in this Magazine.

The Belle of the Opera! Will the reader turn back once more and look at the picture? How full of life—how much of thought—how self-possessed—how desirable for the possession of others—how conscious of charms—and yet how charmed with the tasteful objects represented.

The Belle of the Opera! To be that—to be “the observed of all observers,” in a house crowded with objects for observation, to be made preeminent by exceeding beauty is “no small thing.” It must be costly—it must demand large contributions from other portions of the possessor of the proud object. If acres went to enrich the dress of the ancient nobility of England, something as desirable and as essential to the possessor, as those acres were to the British nobility, must have been sacrificed to perfect the attractions of the Belle of the Opera. Were they social duties? were they domestic affections? were they the means of womanly usefulness? of healthful and almost holy operation upon the minds of others? were they prospective or present? is present moderate but growing happiness sacrificed, or is the present enjoyment of distinction so great as to balance all of immediate loss, and to make the sacrifice that of future peace, future happiness, future domestic usefulness, future social consequence, all that makes mature womanhood delightful, all that makes age respectable and lovely?

Such reflections and such pregnant queries arise in the mind, when we contemplate the representation of such loveliness, so displayed. (I might say such loveliness displayed, for the representation is loveliness itself.) And the moralist has taken just such a beauty, (if his mind ever “bodied forth” the forms of things so unknown,) and marked upon all the display “vanity and vexation of spirit”—the very display, and especially the place of the display, warranting the conclusion.

We confess that we have looked at The Belle of the Opera until our mind has arrived at other conclusions. We think it fair to conclude that so lovely a face, and such a majestic form, are at least prima faciæ evidence of an elevated and beautiful mind, and that the enjoyment of opera music, nowhere to be enjoyed but at the opera, is by no means inconsistent with that elevation or that beauty. Music, that constitutes half our worship on earth, and all in heaven, shall that be regarded in itself as a sin or a means of degradation?

“But the display of the person, the vanity of the dress, the folly of the personal exhibition, these are against the character and usefulness of the Belle—”

How so? There is certainly no improper diminution of dress. The most that can be said is, that a beautiful woman, beautifully dressed, is sitting in the front seat of an opera-box, surrounded by hundreds of persons of both sexes, who have come with the same ostensible object, and who sit equally exposed.

But it is the exceeding beauty of the person and the elegance of the dress that make her conspicuous; and it is that conspicuousness which constitutes the ground of censure.

But fortunately The Belle of the Opera did not make herself beautiful. Those elegant proportions, those enticing charms, are the gift of Him who made human beings in his own image; and let it be confessed that half the elegance of the dress is attributable to the elegance of the form which it covers, and the exquisite beauty which it is not intended to conceal.

Beauty is a gift—a gift of God—like all personal or mental endowments, dangerous, it is confessed—but, like all, to be used for personal gratification and the promotion of social advantage.

If it is conceded to be a means of mental melioration to dwell among the beauties of artistic skill and lofty architectural efforts, then surely it must be still more advantageous to be reared within the influence of living charms; “to grow familiar day by day” with features and forms that constitute models for the representation of angels, and to pass onward through life with the sense of seeing constantly improved and gratified with objects of exquisite beauty exquisitely clothed. This is viewing The Belle of the Opera with an artist’s eye.

“But,” the moralist will say, “the high office of woman is vacated by such a sacrifice to display, and such a devotion of time to amusement. That The Belle of the Opera can never be The Bonne of the Nursery, and therefore woman is out of her place when out of such an exercise of her faculties as shall minister directly to domestic advantage.”

We take issue with the moralist on this question of the direct application of female faculties; and we do this because we feel that the narrow bigotry of the unenlightened, which leads them to condemn the elegant enjoyments of life, and to ground their condemnation on the demand which is constant upon human beings, “to do good and to communicate,” is founded on a want of a full appreciation of female powers, and a mistake as to what constitutes these, and their means of usefulness.

There will be no space for a discussion of the measure of female duties, though it is intended to enter upon such a discussion hereafter; but we may say that however extensive or however limited they may be, their discharge will be more or less effectual and complete, as she is qualified by the elegance of education, the improvement of her mind, the cultivation and adaptation of her faculties, to impart to others the graces of life, and to fix them by constant example.

Virtue is embraced for its charms—it is not admired for deformity or its negligence of mind; it has its attractions and its means of compensation, as much as has vice—but they are not always as obvious. The young must be made to trust in the results of a virtuous course; they must have their faith fixed by the graces of parental, of maternal precept and example—and this good cannot be hoped for if the mother is incapable of attracting, if she has not the means of charming—if, indeed, she cannot show that what constitute the pleasures of life (pleasures which in excess become crimes) are, while properly enjoyed, wholesome and advantageous, and at the same time can show the line of demarcation between their uses and their abuses. She must know what are the true accomplishments of life—she must understand the influence of refinement and cultivation on the mind—and she must bring herself to apply all these. She must know the difference, too, between the uses and the abuses of cultivated talents, and she must learn to discriminate.

She who would deny to the young the cultivation of talents, musical, literary or artistic, is like the beings who would pile up the snows of winter, that the accumulated heap might prevent the budding and the blossoming of spring; while she who would force the mind of her child to an unnatural development of merely ornamental faculties, is like one who would concentrate the rays of the sun through a burning-glass, in order to accelerate the growth of a delicate plant.

What we mean to assert is the obvious fact, that the female, the mother, cannot discharge the high responsibilities of her sex, without many of those acquisitions which are condemned as worthless in themselves, and perhaps the condemnation is in some measure correct; that is, the acquisition separately considered may be rather injurious than beneficial.

Music itself, if it be the only or the principal attainment of a woman, must be valuable only as a means of obtaining money or fame. So of dancing—so of painting—so of poetry, that divine gift—each one of these, allowed to become predominant, loses its meliorating influence, and devotes the possessor to a solitary enjoyment, or, at most, assists her in acquiring notoriety and a living.

It is our intention to laud the cultivation of tastes only as parts of the meliorating means of woman’s character—the acquisition or rather the improvement of ingredients to fit her for that office of delicate influence for which God evidently designed her. Her personal beauty may be a part of the means of her wholesome domestic influence—her love of, and attainments in, music, her improvement in drawing, her literary gifts and acquirements all go, when all are mingled, to give to her consequence and usefulness in the nursery, and to make her beloved and beneficially influential in the domestic circle, and to add attraction to her charms in social life. There is no incompatibility between all these acquisitions with great personal beauty, between a sense of that beauty, indeed, and the entire fulfillment of all domestic and social duties, that are likely to be devolved on one thus highly endowed, thus qualified by extensive attainments.

The Belle of the Opera is at a place of refined amusement, where the richest productions of musical science are properly delivered. She is dressed to suit her own means and the place which she occupies. There is as much propriety in the proper presentation of her charms, as in the appropriate delivery of the music. The place itself is one of enlarged social intercourse. Elegant attire is the requisite of the place, and is due from the female (who has it) to him who incurs the expense of the visitation, and receives the honor of her company.

“But she is admired in her display; her dress, her form, the beauty of her face, attract marked attention. She is the object of general observation.”

And why not? Is it inconsistent with good taste to admire beauty? Is not the whole opera a place where the taste is to be improved and gratified? Is it music alone that is to be relished? When went forth the decree from morals or religion that beauty—female beauty—should not be adorned? And to be adorned it must be seen.

Let us not hear the platitudes about the worthlessness of beauty; it is not worthless—it is of high price—of exceeding worth—of extensive usefulness; and, appropriately displayed, its influence is humanizing, tranquilizing, and every way beneficial.

To personal charms The Belle of the Opera adds a cultivated taste for music—a taste which she indulges at the fountain-head of such enjoyments. But does she less, on that account, or rather on these accounts, (beauty and musical taste, namely,) fulfill her mission at home? Does the lesson of virtue which the accomplished mother gives to her young child, fall less impressively on the heart because the infant pupil, in looking upward, gazes into a face replete with all of earthly beauty? Is there not a certain coincidence between the looks of his beloved teacher and the excellence of her delightful instruction? or rather, does not her beauty tend to make these lessons delightful? And if the charm for the child is the morning or evening hymn, does not the sacred simplicity of the text drop with extraordinary unction on the ear, if conveyed in the rich melody of a cultivated voice.

I might thus enumerate all the high attainments, and show how each becomes useful; but it is enough to have it understood, that the true, the great value of all these high gifts and extraordinary cultivation is derived from their influence, when combined, to form the character of the possessor. The Belle of the Opera is also The Belle of the Ball-room. The same variety of characteristics, without a necessity for the same attainment, marks each, and both are liable to be set down by a superficial observer, as destitute of any qualities, except those which distinguish them in the places of amusement.

May not the Belle of the Opera, or the Belle of the Ball-room, be the guardian genius of the sick chamber, the faithful, devoted director of the nursery?

I knew The Belle of the Opera, and she was as fond of the dance as of the song, and shared in both in the social circle, and enjoyed them in others in more public displays. Her buoyant spirits, her happy gayety of disposition, made her the marked object of admiration in all parties in which she shared—the first to propose that in which all could gracefully and appropriately join, and the last to propound a thought that could cast a gloom over the countenance of a single being around her. She seemed so much the spirit of the joyous assembly, that serious thought, deepth of feeling, or firm principles of good, were not suspected by those incapable of looking into the heart. The Belle of the Opera was deemed by such, one set apart for the enjoyment of the opera and the dance, and to be without life when without these means of life’s pleasures; to have no sympathy with her kind, excepting through music and display, and to reckon none among her intimates but the light-hearted and the gay.

Men may be thus exclusive, but women are not.

Returning one night from opera or route, the Belle entered her parlor wearied with, but not tired of the pleasure in which she had shared, when suddenly a cry of distress was heard; it was caused by the appearance of a case of small-pox in a neighboring house. At once the Belle changed her dress, and was at the bed of the sufferer.

“But, madam, have you had the small-pox?”

“No; but I have been vaccinated.”

“Ah! so was my sister.”

“But evidently not well. I will tarry and assist until she be removed, or some change take place.”

The change took place after a few days, and the Belle of the Opera carefully wrapped the body of the deceased in its grave-clothes, and having committed it to a coffin, she went to purify herself, give thanks for her preservation, and to enjoy again the fine arts which she so much admired.

The pleasant laugh could at times, and did, give place to tears of sorrow or of sympathy; and the appearance of indifference would promptly yield, when thoughtlessly or wickedly some sentiment opposed to strict morality, would drop from the lip of a companion. Never did hours of gayety tend to moments of unkindness, or the full enjoyment of the abundance to which all were happy to contribute, obliterate a sentiment of gratitude toward those whose earlier kindness might have assisted to prepare for that enjoyment.

Beneath the exterior of frequent devotion to admissible pleasure, there was a depth of feeling and a soundness of principle that sustained themselves in all circumstances, and exhibited themselves where-ever their exercise was requisite, that were seen, indeed, influencing even in the midst of gayety, and throwing a charm around that freedom of conversation in which those of well-regulated minds may indulge.

The virtues of The Belle of the Opera are not sudden, fitful, dependent upon excited feelings—they are constant, influencing, ruling. They appear in private conversations, they are manifest in delicate forbearance toward the errors of others, they exhibit themselves in unwavering attachment to known established principles, and a delicate tolerance of the views of friends; and they are set forth for admiration by the charms of those accomplishments which the world admires, and which that world supposes to be her principal attraction.

And that world judges in this case as in most others; it has no interest in the object before it, and it is not concerned to look into the effect of its own judgment upon that object. Ten thousand who saw the late laughter-moving Jefferson upon the stage, supposed that he never moved without laughing himself, and making others laugh. They supposed that he must delight in and be the delight of social life; and as they had nothing to do with his life off the stage, they never cared to correct their judgment—they never knew that the most pleasant of all comedians was fond of solitude, loved the quiet silence of angling—and was a prey to melancholy.

The inward man, the man to himself, the household man, the man of the fireside and social circle, is different from the man abroad, the man professionally, the man to others, and this not from hypocrisy, not from a difference of character throughout, but simply because the many who judge see only one phaze, and one, indeed, is all that is exhibited, all that is required to fill up the part in which the many know the man. But justly to judge, and fairly to decide, we must see the whole man, we must know how all his relations are sustained; we must see how he discharges the high, solemn duties of his life, and carries the influence of that discharge into minor relations. We must understand how much of himself, his better self, he gives to the amusements and light enjoyments of life, and how much he brings from them to influence his conduct elsewhere; or, if weak, how much of himself he leaves in scenes where artistic taste only is exercised; how much he sacrifices of himself to mere gratification—a burnt-offering never to be recalled.

And here we reach a point toward which we have attempted to steer; we mean the fullness of character, the entire inward person—the meeting—the combination—the fusion, indeed, of all those properties and qualities of the mind, by a well-directed education; the balancing of the various propensities and gifts by the skillful hand of instruction, so that no appetite, natural or acquired, shall have an undue predominancy, or serve to constitute the distinguishing characteristic of the possessor.

The Belle of the Opera, we have already said, brought to the place of amusements only the charms which God has bestowed and cultivated taste has well set off. She did not elect herself as The Belle of the Opera; she did not inaugurate herself as “the observed of all observers.” Such results, though made probable by the charms of her person, and promoted by the opportunities afforded by the indulgence of a high order of talents, was, nevertheless, the work of the admiring many, who felt and acknowledged the charms of person thus displayed, and at once rendered to them the kind of homage which their excellence and position seemed to suggest. They, the multitude, judged in part, judged by what they saw, and what they imagined—and deified the woman with the appellation of “Belle of the Opera;” it was all the attribute they had to bestow; they felt an influence that they did not comprehend; and not knowing of the charms concealed, that made effective what they saw, they gave to the visible and the ostensible, the regard which was only due to the concealed and the influencing, as the shepherds of old saw with admiration and delight the fiery part of the stars of the firmament in all their loveliness, and feeling an influence from the celestial display, adored the hosts of heaven for their beauty and their use, forgetful or ignorant of the power that made them seem beautiful—uninstructed in all the relations of those orbs by which their beauty and their usefulness are secured.

We have taken the reader to one scene, in which The Belle of the Opera showed how little the accomplishment of person, and the cultivation of taste had disturbed the feelings of humanity; and yet we confess, that such an example standing alone, seems to be a contradiction, or a sort of accidental effort, rather the result of impulse, rather dependent upon caprice or individual affection, than to be regarded as illustrative of, or consistent with, the ruling characteristics. We are speaking now of a whole character—and a character cannot be judged of by one strong propensity on one hand, and one great but contradictory act on the other.

Is the character of The Belle of the Opera complete? Is the distance between the lustre and display of the opera-box, and the devotion to the loathsomeness of the small-pox chamber, all occupied with corresponding virtues, and similar graces mingling, shading, combining, perfecting? If the great offices of the woman’s life, (we are speaking now of the Belle as a woman, looking at her higher vocation,) if all these offices are well discharged, if as mother, wife, as friend and neighbor, she stand unimpeachable; if she is as notable in all these relations as in the opera-box, still we want to inquire what is the influence exercised upon all these relations, by those qualities which made her The Belle of the Opera. How stand the opera-box and the nursery related? Because in the complete character of a woman are very few isolated qualities; they all bear upon each other, or exercise mutual influences, and each is less of itself by the qualities which it derives from others. The Belle of the Opera gave to her own fireside the attraction of her personal charms, if less gorgeously accompanied, still the more directly effective. The adventitious aid of ornaments, that was a sacrifice to public taste, was not required; and these charms gathered a circle which the exercise of mental accomplishments retained; and thus all within their influence derived the advantage which association with high gifts and large attainments necessarily impart, and the home was made gladsome by those charms which are attractive to their like, and compensating to their admirers.

The attainment of the science of music, and the display of that science at home, meliorated the manners of the inmates, and invited to association those whose taste was elevated, and whose talents were of a kind to sustain and appreciate high cultivation; and beyond the parlor these extended even to the nursery, or rather the nursery, by their exercise, was transferred to the parlor. That is what The Belle of the Opera understood by making all her accomplishments subservient to her duties as wife and mother. The mind of the child, by this constant intercourse with the gifted and the improved, became expanded, received character from the atmosphere in which it was placed, derived pleasure from the development which it witnessed, and had its habits formed to those graces which, in others, are only extraordinary results of extraordinary means, distinguishing the possessor only by one quality or attainment, making her The Belle of the Opera alone.

It is this association of the young with the beautiful and the accomplished, which infuses into their character, and fixes there those meliorating influences that constitute the charm of life, ruling, modifying, illustrating their whole character, making it whole, harmonious, consistent.

It must be understood that The Belle of the Opera was not a mere pianist, not a mere strummer upon the harp, she understood music as a science, and was therefore capable of conversing upon the subject as well as playing upon an instrument. This power of conversation, resting upon a deep knowledge of subjects, is the secret and charm of association; and it is worthy of remark, that gossip, even among the elevated, soon wearies; and what is more remarkable, it is wearisome and disgusting to children compelled to listen, while conversations or discussions upon subjects well understood by the interlocutors, are at once interesting to general listeners, and attractive, gratifying and instructive even to children. We appeal to general experience for this.

Eminently did The Belle of the Opera comprehend that truth, and practice upon it; hence a musical entertainment in her house was not a mere exercise of vocal powers, or a fearful attack upon the piano-keys. Music was discussed and then performed; and music, too, was not alone the theme. The well-lined walls denoted a taste for kindred arts; and the degrees of excellence of pictures, the distinguishing attributes of masters, were so lucidly illustrated, that the junior members of the family grew into connoisseurs without dreaming of study—grew directly and certainly into such characters without forethought, as a blade of corn, in all its greenness, is tending in the warmth of the sun, and the favor of the soil, to produce a golden harvest. But the discipline of mind necessary to acquire the advancement which The Belle of the Opera attained, gave to her habits of care with regard to the education of her children; and the superficial study which makes amateurs in any branch, was unknown in her family. Various degrees of perfection were observable, and in different branches of pursuits and studies there was a superiority among them, according to gifts; but compared with other families, these children evinced pre-eminence in almost every thing they undertook.

But it was as a wife that The Belle of the Opera most distinguished herself; we mean the special, particular duties of a woman to her husband—all the other qualifications to which we have referred, were of a kind to make her desirable as a wife—but in constant affection, manifested in various ways in those delicate arts, appreciable but inimitable by man, with which a beautiful and an accomplished woman makes attractive her home, preserves it at once from the restraints of affected knowledge, which is always chary of near display, because fearful of detection, and from that ostentatious exhibition of attainments which wearies and disgusts by obtrusiveness. In all these, and the graces of intimate and reciprocal affection, she made her husband proud of his home, happy in his companion, and gratified at her superiority in those things which belong more especially to her sex and made her beauty beautiful.

There was a cloud thrown suddenly across the brilliant prospects of the husband, a threatening of utter insolvency; the evil seemed inevitable. Who should tell The Belle of the Opera that the means of gratifying her highly cultivated taste, and displaying her admirable accomplishments were about to cease?

The husband had all faith in the affections of his wife; he appreciated the excellence of her character, for he was worthy of her. But it was a terrible blow to pride—to womanly pride—the pride of condition, which had never been straightened; it must be a terrible blow to her who knew how to use and how to give, but had never been called upon to suffer or acquire. He carried to her the fearful news of the anticipated disaster; he did not annoy her by the prelude of weeks of abstraction and painful melancholy, but with the first consciousness of danger he announced to her his fears, and awaited the consequences of the shock.

“And what, my dear husband, will become of us all—of you, of me, and of the children?”

“That is the misery of my situation. It is not only the loss of the property I received with you, and that which I had acquired, but it is the difficulty of pursuing any business without some of the means which I thought so safe. I know not now how to sustain my family even in the humble state which we must assume until I can again make a business. And you, with all your charms, with all your attainments, and all your power to enjoy, and means of affording pleasure—what a blow—what a fall!”

“And while you enumerate my attainments, do you forget that they are like yours, marketable; have you forgotten what that education cost? Will not others pay me as much for instruction as I have paid for my education? And will not the task of imparting be a pleasure rather than a pain, because it will be the exercise of those talents, and the uses of those attainments, whose employment has been the delight of our home, the pride of our social relations, and the solace of my solitary hours. Be assured, my dear husband, that with the exception of giving, most of the pleasures of wealth may be had in poverty—and the substitute for the pleasure of giving must be found in that of earning.”

The apprehended evil was never realized. The losses, though considerable, did not reach an amount that rendered necessary any diminution of style in the family.

“I think the alarm has not been uninstructive,” said The Belle of the Opera; “either that, or the approach of age,” (there was nothing in the lustre of her eye, or the brilliancy of her complexion that denoted the proximity of years—and she knew it when she said so—women seldom speak lightly of such foes when they are within hearing distance,) “either that or the approach of age has taught me to relish less many of the amusements which our means have allowed and with which my taste was gratified.”

“A natural gratification of so cultivated a taste,” said her husband, “could be nothing but correct; and it is only when others are acquired, that we need feel regret at indulging such as you have possessed. We, who approach the midsummer of life, find fewer flowers in our pathway than spring presented, but let us not complain of those who gather the vernal sweets; rather let us rejoice that we take with us the freshness of appetites that delights in whatever the path of duty supplies, and by discipline are made to enjoy those latent sweets that escape the observation of the uncultivated.”

We repeat our remarks, that to judge of a woman we must know her whole character. We must not suppose because a lady is at the opera, that she has no pleasure in other positions, or that a cultivated taste for music is inconsistent with the general cultivation of her talents. It is wrong to imagine that a beautiful woman is necessarily vain, or that her beauty is inconsistent with the discharge of all the high and holy duties that belong to her sex; the wife, the daughter, the mother, and the friend.

Excessive amusement, we know, vitiates the mind; and a woman, whose whole pride is to be The Belle of the Opera, has evidently no mission for domestic usefulness. But the domestic circle is blessed, and woman’s office honored, when an improved taste and generally cultivated talent, the charms of person and elegance of manners are made subservient to, and promotive of, the full discharge of the duties that belong to woman in her exalted sphere.

And, we may add, that religion itself is made more lovely, more operative, when the offices of humanity which it suggests, and the services of devotion by which it is manifested, are discharged by one who brings to the altar talent, beauty, acquirements, with a sense of their unworthiness, and takes thence a spirit of piety and devotion that throws a charm about all the graces that have been so attractive to the world.

We would have our Magazine commend to our fair readers for approval and acquisition, all the gifts and graces which belonged to The Belle of the Opera; we would not have them seek that title. She did not; as unconscious of the admiration of the audience, as the performers were of her individual presence; she came to enjoy the music, not to acquire fame. We would have those for whom we write bear in mind that the character of woman is incomplete, whatever talents or acquisition she may boast, if she has not the charm that attracts to and delights its domestic circle. And she should know that the basis of all those charms which give permanent beneficial influence, is religion; a fixed principle of doing right, from right motives. Upon that basis let the lovely fabric be erected; beauty, music, literature, science, social enjoyment, all become and all ornament the structure. And woman’s character with these is complete, if she add the discharge of the duties of a friend—a wife—a mother. She who is the charm of social life must be the benignant spirit of home—the source and centre of domestic affection.

———

BY AUGUSTA.

———

Flowers are beautiful—every hue

Colors their petals, and pearly dew,

The nectar the fairies love to sup,

Sparkles brightly in each tiny cup,

While the dark leaves of the ivy shine,

And its clustering tendrils closely twine

Round the old oak, and the sapling young,

And when it has lightly round them clung,

It laughs, and shouts, and it calls aloud,

Have I not now a right to be proud?

I’ve mastered the lordly forest-tree,

I’m King of the woods, come see, come see.

Night’s gems are beauteous, right rare are they,

Gloriously bright is each gentle ray,

Flashing and twinkling up so high,

Like diamonds set in the deep blue sky;

Who is there but loves night’s gentle queen,

Gorgeously robed in her silver sheen?

Shedding her pale, pure brightness round,

O’er hill and valley, and tree and ground;

Gilding the waters as on they glide

In their conscious beauty, joy and pride;

Or sending a quiet ray to rove,

And wake the shade of the deep-green grove.

The Sun is beautiful—“God of day,”

He sends o’er the earth a lordly ray,

He shames the sweet pensive Orb of night

By his radiant beams so fiercely bright.

Wind is beautiful—not to the eye—

You cannot see it—but hear it sigh

Lowly and sweet in a gentle breeze,

Rustling the tops of the lofty trees,

Sending the yellow leaves to the ground,

Playfully whirling them round and round,

Filling the sails with their fill of air,

Then dancing off on some freak more rare;

Scat’ring the snow and the blinding hail,

Shrieking aloud in the wintry gale,

Rudely driving the pattering rain

’Gainst the lonely cottage’s humble pane,

Uprooting the aged forest-tree,

Then whistling loud right merrily;

Owning no king save a mighty One!

Following His dictates, and His alone.

Water is beautiful—sounding clear,

Like distant music upon the ear,

Bubbling light, sparkling bright, bounding still

With a joyous laugh adown the hill,

Clapping its hands with a noisy glee,

Shouting I’m bound for the sea, the sea!

I’ll bear my spoils to the Ocean’s tide—

Hurrah! hurrah! the earth’s my loved bride;

I came through a lovely grassy glade,

And caught the dew-drops from every blade;

I stopped awhile in a shady spring

Hearing the summer-birds sweetly sing,

And I just ’scaped being pris’ner caught,

A maiden to fill her pail there sought;

But I laughed aloud with a careless ring,

As off I rolled from the crystal spring.

Small though I seem, I’m part of the tide

That’s to dash against a tall ship’s side,

Bearing silken goods far o’er the sea,

Bringing back ingots of gold for me—

For me to seize and to bury deep

Where thousands of pearls and diamonds sleep

Scorn me! who dares? I tell thee now,

I’m monarch, and mine is the lordly brow.

Oh! all is beautiful, all is fair—

High Heaven, and earth, and sea, and air,

The sun, the moon, and the stars on high,

The clouds, the waters, and sands that lie

Far away down where the mermaids roam

And the coral insects build their home.

———

BY GRACE GREENWOOD.

———

I must warn my readers given to sober-mindedness, that they will probably rise from the perusal of the sketch before them, with that pet exclamation of the serious, when vexed, or wearied with frivolity, “vanity, vanity, all is vanity!” I can, indeed, promise no solid reading nor useful information—no learning nor poetry—no lofty purpose nor impressive moral—no deep-diving nor high-flying of any sort in all that follows. For myself, I but seek to wile away a heavy hour of this dull autumn day, and for my reader, if I may not hope to please, I cannot fear to disappoint him, having led him to expect nothing—at least nothing to speak of.

As a general thing, I have a hearty horror of all manœuvring and match-making, yet must I plead guilty to having once got up a private little conspiracy against the single-blessedness of two very dear friends. There is a wise and truthful French proverb, “Ce que femme veut, Dieu le veut,” which was not falsified in this case. But I will not anticipate.

My most intimate friend, during my school-days, was a warm-hearted, brave, frank, merry and handsome girl, by name Kate Richmond. In the long years and through the changing scenes which have passed since we first met, my love for this friend has neither wearied nor grown cold; for, aside from her beauty and unfailing cheerfulness, she has about her much that is attractive and endearing—a clear, strong intellect, an admirable taste, and an earnest truthfulness of character, on which I lean with a delicious feeling of confidence and repose.

As I grew to know and love Kate better, and saw what a glorious embodiment of noble womanhood she was, and how she might pour heaven around the path of any man who could win her to himself, I became intensely anxious that her life-love should be one worthy and soul-satisfying. One there was, well known to me, but whom she had never met, who always played hero to her heroine, in my heart’s romances; this was a young gentleman already known to some few of my readers, my favorite cousin, Harry Grove.

I am most fortunate to be able to take a hero from real life, and to have him at the same time so handsome a man, though not decidedly a heroic personage. My fair reader shall judge for herself. Harry is not tall, but has a symmetrical and strongly-built figure. His complexion is a clear olive, and his dark chestnut hair has a slight wave, far more beautiful than effeminate ringlets. His mouth is quite small—the full, red lips are most flexible and expressive, and have a peculiar quiver when his heart is agitated by any strong emotion. His eyes are full and black, or rather of the darkest hue of brown, shadowed by lashes of a superfluous length, for a man. They are arch, yet thoughtful; soft, with all the tenderness of woman, yet giving out sudden gleams of the pride and fire of a strong, manly nature. Altogether, in form and expression, they are indescribably beautiful—eyes which haunt one after they are once seen, and seem to close upon one never.

In character my kinsman is somewhat passionate and self-willed, but generous, warm-hearted, faithful and thoroughly honorable. Yet, though a person of undoubted talent, even genius, I do not think he will ever be a distinguished man; for he sadly lacks ambition and concentration, that fiery energy and plodding patience which alone can insure success in any great undertaking. He has talent for painting, music and poetry, but his devotion to these is most spasmodic and irregular. He has quite a gift for politics, and can be eloquent on occasion, yet would scarcely give a dead partridge for the proudest civic wreath ever twined. As a sportsman, my cousin has long been renowned; he has a wild, insatiable passion for hunting, is the best shot in all the country round, and rare good luck seems to attend him in all his sporting expeditions.

For the rest, he is a graceful dancer, a superb singer, and a finished horseman; so, on the whole, I think he will answer for a hero, though the farthest in the world from a Pelham, a Eugene Aram, a Bruno Mansfield, or an Edward Rochester.

“In the course of human events,” it chanced that a year or two since, I received an urgent invitation from my relatives, the Groves, to spend the early autumn months at their home, in the interior of one of our western states. Now for my diplomatic address; I wrote, accepting, with a stipulation that the name of my well-beloved friend, Miss Catharine Richmond, who was then visiting me, should be included in the invitation, which, in the next communication from the other party, was done to my entire satisfaction. Kate gave a joyful consent to my pleasant plan, and all was well.

One fine afternoon, in the last of August, saw the stage-coach which conveyed us girls and our fortunes rolling through the principal street of W——, the county-seat, and a place of considerable importance—to its inhabitants. We found my uncle, the colonel, waiting our arrival at the hotel, with his barouche, in which he soon seated us, and drove rapidly toward his residence, which was about two miles out of town. On the way, he told me I would meet but two of his seven sons at home—Harry, and an elder brother, on whom, for a certain authoritative dignity, we had long before bestowed the sobriquet of “the governor.” He also informed us that his “little farm,” consisted of about eight hundred acres, and that the place was called “Elm Creek.”

As we drove up the long avenue which led to the fine, large mansion of my friends, I saw that my good aunt and Cousin Alice had taken steps to give us an early welcome. I leaped from the barouche into their arms, forgetting Kate, for a moment, in the excitement of this joyful reunion.

But my friend was received with affectionate cordiality, and felt at home almost before she had crossed the threshold of that most hospitable house. My grave cousin, Edward, met us in the hall—bowed profoundly to Kate, and gave me a greeting more courtly than cousinly; but that was “Ned’s way.” Harry was out hunting, Alice said, but would probably be home soon.

After tea, we all took a stroll through the grounds. These are very extensive, and the many beautiful trees and the domesticated deer, bounding about, or stretched upon the turf, give the place a park-like and aristocratic appearance. Elm Creek, which runs near the house, is a clear and sparkling stream, which would be pleasantly suggestive of trout on the other side of the Alleghanies.

Suddenly was heard the near report of a gun, and the next moment Harry appeared on the light bridge which spanned the creek, accompanied by his faithful Bruno, a splendid black setter. On recognizing me, he (Harry, I mean, not the dog) sprung forward with a joyous laugh, and met me with a right cousinly greeting. I never had seen him looking so finely—he had taste in his hunting-dress, which became him greatly; and it was with a flush of pride that I turned and presented him to Kate. Harry gave her a cordial hand-shake, and immediately after, his dog, Bruno, gravely offered her his sable paw, to the no small amusement of the company.

I soon had the satisfaction of seeing that there was a fine prospect of Kate and my cousin being on the very best terms with each other, as they conversed much together during the evening, and seemed mutually pleased.

The next morning my gallant and still handsome uncle took us out to the stable and invited us to select our horses for riding. He knew me of old for an enthusiastic equestrian, and Kate’s attainments in the art of horsemanship were most remarkable. Kate chose a beautiful black mare, Joan, the mate of which, Saladin, a fiery-spirited creature, was Harry’s horse, and dear to him as his life. I made choice of a fine-looking but rather coltish gray, which I shall hold in everlasting remembrance, on account of a peculiar trot, which kept one somewhere between heaven and earth, like Mohammed’s coffin.

The fortnight succeeding our arrival at Elm Creek, was one of much gayety and excitement—we were thronged with visiters and deluged with the most cordial invitations. Ah! western people understand the science of hospitality, for their politeness is neither soulless nor conventional, but full of heartiness and truth. Long life to this noble characteristic of the generous west.

Colonel Grove was an admirable host—he exerted himself for our pleasure in a manner highly creditable to an elderly gentleman, somewhat inclined to indolence and corpulency. Every morning, when it was pleasant, he drove us out in his barouche, and by the information which he gave, his fine taste for the picturesque, and the dry humor and genuine good nature of his conversation, contributed much to our enjoyment. In the sunny afternoons, we usually scoured the country on horseback—Harry always rode with Kate and I with “the governor,” who proved an interesting, though somewhat reserved companion. My Cousin Alice was unfortunately too much of an invalid for such exercises.

In our evenings we had music and dancing, and occasionally a quiet game of whist. Now and then we were wild and childish enough to amuse ourselves with such things as “Mr. Longfellow looking for his key-hole,” “Homeopathic-bleeding,” and the old stand-by, “Blind Man’s Buff.”

One rather chilly afternoon, about three weeks after our arrival, Alice Grove entered the chamber appropriated to Kate and myself, exclaiming, “Come, girls, put on some extra ‘fixings’ and come down, for you have a call from Miss Louisa Grant, the belle and beauty of W——, the fair lady we rally Harry so much about—you remember.”

We found Miss Grant dressed most expensively, but not decidedly à la mode, or with much reference to the day or season. She was surprisingly beautiful, however—a blonde, but with no high expression; and then she was sadly destitute of manner. She seemed in as much doubt whether to sit, or rise, nod or courtesy, as the celebrated Toots, on that delicate point of propriety whether to turn his wristbands up, or down; and like that rare young gentleman, compromised the matter.

Miss Louisa talked but little, and that in the merest commonplaces; she had a certain curl of the lip, and toss of the head, meant for queenly hauteur, but which only expressed pert superciliousness; so, undazzled by her dress and beauty, I soon sounded her depth and measured her entire circumference. But Kate, who is a mad worshiper of beauty, sat silent and abstracted, gazing on her face with undisguised admiration.

When the call was over, we accompanied our guest to the door, and while we stood saying a few more last words, Harry came up, having just returned from hunting. At sight of his fowling-piece, Miss Louisa uttered a pretty infantine shriek, and hid her eyes with her small, plump hands. Harry, taking no notice of this charming outbreak of feminine timidity, greeted her with a frank, unembarrassed air, and throwing down his gun and game-bag, begged leave to attend her home. She assented with a blush and a simper, which left me in no doubt as to her sentiments toward my handsome cousin. Ah! how perilously beautiful she seemed to me then, while I watched her proud step as she walked slowly down the avenue, with a bitter feeling, for all the world as though I was jealous on my own account. I was somewhat pacified, however, by Harry’s returning soon, and bringing Kate a bouquet from Louisa’s fine garden.

That evening we were honored by another call extraordinary, from a young merchant of the place—the village D’Orsay—by name, La Fayette Fogg, from which honorable appellation the gentleman, by the advice of friends, had lately dropped the “Marquis”—his parents, at his christening, having been disposed to go the whole figure. But he had a title which in our “sogering” republic would more than compensate for any of the mere accidental honors of rank—he had recently been appointed captain of a company of horse, in W——, and had already acquired a military bearing, which could not fail to impress the vulgar. A certain way he had of stepping and wheeling to the right and left, suggestive at once of both a proud steed and a firm rider—a sort of drawing-room centaur. But Captain Fogg was beyond all question strikingly handsome. I never saw so perfect a Grecian head on American shoulders. There was the low, broad forehead, the close, curling hair, the nose and brow in one beautiful, continuous line, the short upper lip, round chin, small ears, and thin nostrils. A classical costume would have made him quite statuesque; but, alas! he was dressed in the dandiacal extreme of modern fashion. His entire suit of superfine material, fitted to an exquisite nicety, and he revealed a consciousness of the fact more Toots-ish than Themistoclesian. He moved his Phidian head with slow dignity, so as not to disturb his pet curls, slumbering in all the softness of genuine Macassar. His whiskers and imperial were alarmingly pale and thin, but seemed making the most of themselves, in return for the captain’s untiring devotion and prayerful solicitude.

The expression of this hero’s face, malgré a Napoleonic frown which he was cultivating, and a Washingtonish compression of the lips, was soft, rather than stern—decidedly soft, I should say,—and there was about him a tender verdancy, an innocent ignorance of the world—all in despite of his best friends, the tailor, the artist in hair, and the artist in boots.

During the first half hour’s conversation, I set the gallant captain down as uneducated, vain and supercilious; but I was vexed to see that Kate, dazzled by his beauty, regarded him more complacently. It was evident from the first, that Kate pleased him decidedly, and he “spread himself,” to use a westernism, to make an impression on her heart, whose admiration for his physique spoke too plainly through her eyes. While he talked, Kate watched the play of his finely chiseled lips, and when he was silent, studied with the eye of an artist, the classic line of his nose. The attentive, upward look of her large, dark eyes, was most dangerous flattery—it loosened the tongue of our guest marvelously, till he talked quite freely, almost confidentially. Among other things, he informed us that he “was born in the chivalrous south,” and had been “a native of W—— for only the five years past.” I glanced mischievously at Kate, and she, to turn the tide of talk, exclaimed—“Oh, Mr. Fogg, we had a call from Miss Grant to-day! Exquisitively beautiful—is she not?”

“Why,” drawled the captain, stroking his imperial affectionately, “she is rather pretty, but wants cultivation; I can’t say I admire her greatly, though she is called the Adonis of this country.”

Kate colored with suppressed laughter, bit her lip, and rising, opened the piano, saying—“Do you sing, Mr. Fogg?”

Fortunately, Mr. Fogg did sing, and that very well. He declined accompanying Kate in “Lucy Neal,” saying that he “never learned them low things;” but on many of Russell’s songs he was “some,” and acquitted himself with much credit.

During all this time Harry had taken little part in the conversation, and when asked to sing, drily declined. I thought him jealous, and was not sorry to think so. I saw that Kate also perceived his altered mood, yet she showed, I regret to say, no Christian sympathy for his uneasiness, but chatted gayly, sung and played for all the world as though earth held neither aching hearts nor dissatisfied Harrys.

At last my cousin rose hastily and left the room. I said to myself, “He has gone out to cool his burning brow in the night air, and seek peace under the serene influences of the stars.” But no, he crossed the hall, and entered the family sitting-room. Soon after I followed, and found him having a regular rough and tumble with Bruno, on the floor. He raised his head as I entered, and said with a yawn,

“Has that bore taken himself off?”

“No,” I replied.

“Well, why the deuce don’t he go—who wants his company?”

“I don’t know,” said I, “Kate, perhaps.”

“Very likely,” growled Harry, “you intellectual women always prefer a brainless coxcomb to a sensible man.”

“Yes, Cousin Harry, in return for the preference you men of genius give to pretty simpletons.”

The captain’s “smitation,” as we called it, seemed a real one, and his sudden flame genuine—at least there was some fire, as well as a great deal of smoke. He laid resolute siege to Kate’s heart, till his lover-like attentions and the manifestations of his preference were almost overwhelming. In a week or two Kate grew wearied to death of her conquest, and was not backward in showing her contemptuous indifference, when Harry Grove was not by. But, oh, the perverseness of woman! in the presence of my cousin, she was all smiles and condescension to his rival; and he, annoyed more than he would confess, would turn to Miss Louisa Grant with renewed devotion.

Yes, Harry was plainly ill at ease to mark another’s attentions pleasantly received by my friend—that was something gained; but such jealousy of a mere tailor-shop-window-man, was unworthy my cousin, as well as a wrong to Kate; and for my part, I would not stoop to combat it.

In the captain’s absence, however, all went admirably. Harry seemed to give himself up to the enjoyment of Kate’s brilliant society, her cleverness, her liveliness, her “infinite variety,” with joyous abandon. They sung, read, danced, strolled, and rode together, always preserving the utmost harmony and good-will.

For Kate’s success in the part I wished her to play, I had never any fear. Aside from her beauty, which is undeniable, though on the brunette order, and her accomplishments, which are many, she has a certain indescribable attractiveness of manner, an earnest, appealing, endearing way—a “je-ne-sais-quoi-sity,” as a witty friend named it, which would be coquetry, were it not felt by all alike, men, women, and children, who find themselves in her presence. It is without effort, a perfectly unconscious power, I am sure.

Thus, I did not fear for Kate, provided Harry was heart-whole; but this fact I could not settle to my entire satisfaction. My Cousin Alice sometimes joked him about a certain fair maid he had known at New Haven, while in college, evidently wishing it to appear that she knew vastly more than she chose to reveal; and then Miss Grant was certainly a dangerous rival—far more beautiful, according to the common acceptation of the term, than my friend, with the advantage, if it be one, of a prior acquaintance.

One morning, as we were returning home, after having made a call on Miss Louisa, Harry, who once, for a wonder, was walking with me, began questioning me concerning my opinion of her. I evaded his question for awhile, but at length told him frankly that I could not speak freely and critically unless assured that I should give him no pain thereby.

“Oh, if that’s all,” replied Harry, with a laugh, “go on, and ‘free your mind, sister’—I shall be a most impartial auditor.”

“Indeed, Harry!—has there, then, been no meaning to your attentions in that quarter?”

“Why, as to that,” he replied, “I have always admired the girl’s beauty, and have flirted with her too much, perhaps, but there is not enough in her to pin a genuine love to; I have found her utterly characterless; and then, she affects a ridiculous fear of fire-arms, and behaves like a sick baby on horseback.”

“But, cousin,” I rejoined, “you do not want a wife to hunt with you, and ride horseback; Miss Grant is a young lady of domestic virtues and refined tastes—is she not?”

“Yes, and no. I believe she is a good housekeeper; she takes pains to let one know that—a perfect walking cookery-book; but for her refinement! Have you never noticed her coarse voice, and how much use she makes of provincialisms? She might sing well, but always makes mistakes in the words. She professes a passion for flowers; but last spring, coz, I helped her make her garden, and heard her say ‘piney’ and ‘layloc’—I never could marry a woman who said ‘piney’ and ‘layloc!’ and then she called pansies—‘pansies, that’s for thoughts’—those flowers steeped in poetry as in their own dew—‘Jonny-jump-ups!’ Bah! and then, she vulgarizes her own pretty name into Lo-izy!”

Need I confess that I was far from displeased with this little speech of my cousin’s. I was silent for a few moments, and then, with my head full of Kate and her fortunes, said, while pulling to pieces a wild-flower, which Harry had just gallantly presented to me,

“Well, then, cousin, you don’t love any body in particular, just now, do you?”

I raised my eyes when I had said this, to meet Harry’s fixed on my face, with a strange, indefinable expression—something of what is called a “killing look,” so full of intense meaning was it; but around his mouth lurked a quiet drollery, which betrayed him, even while he replied to my singular question in a tone meant to tell,

“Why, my dearest cousin, at this moment, I cannot say that I do not.”

I broke at once into a laugh of merry mockery, in which he joined at last, though not quite heartily; and we hastened to rejoin Ned, Kate and Alice, who were somewhat in advance.

On reaching our room I told Kate enough of my conversation with Harry to prove that he was really not the lover of Louisa Grant; and with a blush and a smile, she kissed and thanked me. Why should she thank me?

Thus matters went on—Captain Fogg’s star declining visibly, and Harry Grove’s evidently in the ascendant, until the last week of our stay, when a little incident occurred which had quite a disturbing influence on the pleasant current of my thoughts and Kate’s. One afternoon, while Harry was out shooting woodcock, of which Kate was very fond, on going up to my room, I perceived the door of Harry’s open, and saw his easil standing before the window, with a picture upon it. I could not resist the temptation of seeing what this might be, and entered the room. The picture was a small female head—the face rather fair, with dark blue eyes. It was probably a portrait, still unfinished. The likeness I did not recognize, though it looked like half a dozen pretty faces I had seen—Kate’s and Miss Grant’s among the number. To the bottom of the picture was attached a slip of paper, bearing these lines:

“Glow on the canvas, face of my beloved!

Smile out upon me, eyes of heavenly blue!

Oh! be my soul’s love by my pencil proved,

And lips of rose, and locks of auburn hue,

Come less obedient to the call of art,

Than to the pleading voice of my adoring heart!”

When I had read this verse, I remained standing before the picture in a thoughtful trance. I was finally startled by a deep sigh, and turning, saw Kate just behind me. She had also seen the portrait of the unknown, and read those passionate lines. She turned immediately and passed into her room.

When I rejoined her, a few moments after, she was reading, apparently deep in “Martin Chuzzlewit,” but tears were falling on the page before her.

“Martin’s return to his grandfather is a very affecting scene,” she observed.

I naturally glanced over her shoulder; the book was open at that “tempest-in-a-teapot” scene, the memorable misunderstanding between Sairey Gamp and Betsey Prig.

Oh, Kate, Kate! thy heart had gone many days’ journey into the life and fortunes of quite another than Martin.

In the evening Captain Fogg honored us, and Kate was unusually affable and gay. She sung none but comic songs, and her merry laugh rang out like a peal of bells.

During the evening we played a game of forfeits, and it was once adjudged that the captain should relate a story, to redeem his turquoise breastpin. He told a late dream, which was, that once, on taking a morning walk to hear the birds sing, he found Miss Richmond completely lost in a fog, and refused to help her out!

Oh, how he sparkled, as he fairly got off his witticism, and saw that it took!

“Ah, captain,” said I, “you must have a gift for punning.”

“Something of one, Miss,” he replied, with a complacent pull at his imperial. “I was into White’s, the other day, buying some music, and White offered me a song called ‘Mary’s Tears,’ which I told him must have a tremendous run! White laughed till he cried, and threatened to expose me in our paper! ’Pon honor, he did so!”

The captain informed us that the following would be a great day for the militia, as there was to be on the village-green of W——, a parade and review; and he gallantly begged the honor of our presence. We graciously testified our willingness to patronize the show, provided Harry would drive us into town for the purpose. On leaving, the captain requested the loan of Harry’s noble horse, Saladin, which had been trained to the field, for the grand occasion. He would come for him in the morning, he said. Harry consented, with rather a bad grace, I thought. He is a perfect Arab in his loving care for his horse.

The next morning, about ten, the captain called and found us all ready—the barouche waiting at the door. Colonel Grove, who is a gentleman of the ancien régime, invited the young officer, who was in complete uniform, to take wine with him. It was really laughable—the captain’s affectation of a cool, bon-vivantish indifference, as he tossed off glass after glass of the sparkling champagne, showing himself to be far from familiar with that exhilarating and insidious beverage. He grew elevated momentarily; his very words soared majestically above mere common sense, and his eyes winked of strange mysteries, and flashed unutterable things.

At length were we civilians seated in the barouche and driving toward W——, at a brisk rate, the captain causing Saladin to wheel and caracole beside us in a most remarkable manner. Ah, how did the harmless lightning of his wit play around us! how were his compliments showered upon us like bonbons in carnival-time! How beautifully was he like the sparkling wine he had so lately quaffed—what was he but a human champagne-bottle, with the cork just drawn!

About half way to the village we saw before us an old Indian woman, well known in all the country round as a doctress, or witch, according to most people. She was bent almost double, and looked very feeble, though she was said to be still marvelously active and vigorous.

Suddenly the captain, who had galloped on a little to display his horsemanship, came dashing back, exclaiming—“Now, young ladies, for some glorious fun! Do you see that old squaw yonder?”

“Yes,” said Alice Grove, “that is old Martha—what of her?”

“Why, I mean to have some rare sport. I’ll invite her to take a ride behind me. I’ll ride up to the fence for her to get on, and then, just as she makes her spring, spur Saladin, and let her land on the ground.”

“Oh, don’t! don’t!” cried we all in chorus; but the captain was off and already speaking to old Martha. She evidently liked his proposition, for she quickly climbed the fence, preparatory to mounting. The captain wheeled his horse to within about two feet of her—she gave a spring—he spurred his steed, which leaped wildly forward—but too late! Old Martha was safe on Saladin’s back, her long, bony arms clasped closely round the waist of his rider—and, hurrah, they were off at a dashing rate.

Harry whipped up his grays, and we presently overtook the equestrians. Captain Fogg had succeeded in checking Saladin, and was striving to persuade old Martha to dismount, but in vain; she would ride to the village, as he had invited her. He coaxed, threatened, and swore—but all to no purpose; she would go on to the village!

At last, in endeavoring forcibly to unclasp her arms, Fogg dropped the rein, and Saladin, worried and frightened, started off at a furious gallop, and tore down the street like mad. Oh, the rich, indescribable ludicrousness of the sight! Such a conspicuous figure was the captain, so splendidly mounted, with “sword and pistols by his side,” and all his burnished buttons and buckles glistening in the morning sun; and then that ridiculous old woman, in her tattered Indian costume, seated behind him, clinging convulsively to his waist, and bounding up half a foot with every leap of the frantic steed. The ends of the captain’s scarlet sash floated back over her short black petticoat, and the white horse-hair of his military plume mingled ingloriously with her long elf-locks streaming in the wind.

The dirty woollen blanket of old Martha became loose, and flew backward, held only by one corner, exposing her bright blue short-gown, trimmed with wampum, while her red leggings got up quite a little show on their own account.

As thus they dashed on, faster and faster, they spread astonishment and consternation as they went.

A farmer, who with his son was gathering apples from a tree near the road, saw the vision—dropped his basket, and knocked down his first born with an avalanche of pippins. An old lady, who was hanging out clothes in her yard, struck with sudden fright and sore dismay, fell backward into her clothes-basket, as white as a sheet, and as limp as a wet towel.

Young urchins let go the strings of kites, leaving them to whirl dizzily and dive earthward—left “terrestrial pies” unfinished, and took to their heels! A red-haired damsel who was milking by the road-side, on beholding the dread apparition, turned pale, and ran, and the cow, following her example, also turned pail and ran!

But most excruciatingly and transcendentally ridiculous was the scene when Saladin, over whom the captain had lost all control, reached the parade-ground, and dashed in among the soldiers and spectators. Hats were tossed into the air, and shouts of laughter and derisive hooras resounded on every side. But fortunately for poor Fogg, Saladin suddenly perceived a part of the cavalry company, who, in the absence of their captain, were going through some informal and supererogatory exercises, and obedient to his military training, wheeled into line, and stood still, with head erect and nostrils distended.

“For Heaven’s sake, boys,” cried the captain, “haul off this old savage!”

But the worthy Martha, wisely declining such rough treatment, leaped to the ground like a cat—made a profound courtesy, and with a smile rather too sarcastic for so venerable a person, said,

“Me tank you, cap’en—old Martha no often have such fine ride, with such pretty man, all in regiments!”

After this rare comedy, the review was a matter of little moment, and we soon returned home, not even waiting for the tragedy of the sham-fight.

On the afternoon of the following day, Harry invited Kate to take a horse-back ride—and the incidents of that ride, as I received them from my friend, I will relate to the best of my ability.

The equestrians took a route which was a favorite with both—up a glen, wild and unfrequented, through which ran a clear, silver stream. It happened that Harry was in one of his lawless, bantering moods, and teazed Kate unmercifully on the gallant part played by her lover, the captain, on the preceding day.

Kate, who was not in the most sunny humor, began to rally him about “Lo-izy” Grant, and the New Haven belle.

Suddenly Harry became grave, and said, in an earnest tone, “Shall I tell you, Kate, just the state of my heart?”

“Don’t trouble yourself,” she coolly replied, “it is a matter of no moment to me.”

“There, now, you are insincere,” said Harry, with a saucy smile, leaning forward to strike a fly from Saladin’s neck, “it is a matter of some moment to you, for you know that I love you, and that you are not entirely indifferent to my love.”

“Sir, you mistake in addressing such language to me—you are presuming,” said Kate, with a petrifying hauteur; and giving her horse a smart cut with the whip, galloped on. Surprised, and somewhat angry, Harry checked his own horse, and gazed after her till she was lost in a bend of the winding road. As he stood by the side of the rivulet, Saladin reached down his head to drink. In his troubled abstraction, Harry let go the rein, which fell over the head of his horse. With a muttered something, which was not a benediction, Harry dismounted to regain it, when Saladin, in one of his mad freaks, gave a quick leap away and galloped up the glen after his mate. Harry was about to follow, but an odd thought coming into his brain, he threw himself on the turf instead, and lay perfectly still, with closed eyes, listening to the gallop of the two steeds, far up the glen. Presently he heard them stop—then turn, and come dashing down again with redoubled speed. Nearer and nearer came Kate. She was at his side—with a cry of alarm she threw herself from her horse and bent above him.