| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/disraelistudyinp00sichrich |

DISRAELI

A STUDY IN

PERSONALITY AND IDEAS

BY

WALTER SICHEL

AUTHOR OF “BOLINGBROKE AND HIS TIMES”

WITH THREE ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY

LONDON: METHUEN & CO.

1904

Page 22, line 2 note, for “called to the bar” read “entered at Lincoln’s Inn”

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION. ON THE IMAGINATIVE QUALITY | 1 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| DISRAELI’S PERSONALITY | 21 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| DEMOCRACY AND REPRESENTATION | 53 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| LABOUR—“YOUNG ENGLAND”—“FREE TRADE” | 112 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| CHURCH AND THEOCRACY | 145 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| MONARCHY | 180 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| COLONIES—EMPIRE—FOREIGN POLICY | 199 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| AMERICA—IRELAND | 246 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| SOCIETY | 268 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| LITERATURE: WIT, HUMOUR, ROMANCE | 289 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| CAREER | 316 |

| INDEX | 327 |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

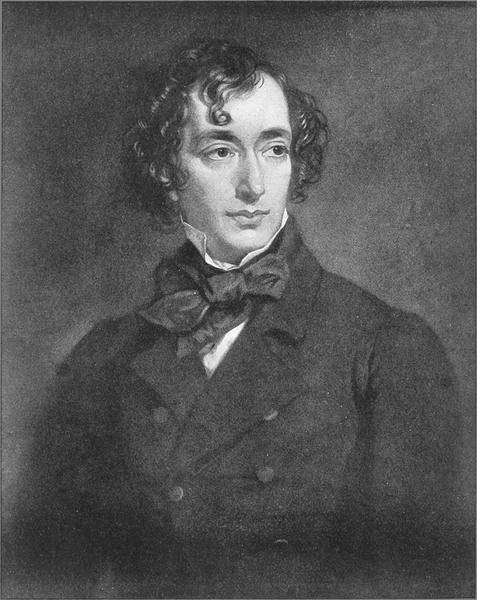

| PORTRAIT OF THE YOUNG DISRAELI. FROM THE MINIATURE BY KENNETH MACLEAY IN THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY Frontispiece | |

| PORTRAIT OF DISRAELI THE YOUNGER. AFTER A WATER COLOUR BY A. E. CHALON | 23 |

| PORTRAIT OF DISRAELI IN 1852. AFTER A PAINTING BY SIR FRANCIS GRANT, P.R.A. | 289 |

“TIME IS REPRESENTED WITH A SCYTHE AS WELL AS WITH AN HOUR-GLASS. WITH THE ONE HE MOWS DOWN, WITH THE OTHER HE RECONSTRUCTS.”—Disraeli, in The Press, 1853.

“GREAT MINDS MUST TRUST TO GREAT TRUTHS AND GREAT TALENTS FOR THEIR RISE, AND NOTHING ELSE.”

“TRUE WISDOM LIES IN THE POLICY THAT WOULD EFFECT ITS AIMS BY THE INFLUENCE OF OPINION, AND YET BY THE MEANS OF EXISTING FORMS.”

“... THE PAST IS ONE OF THE ELEMENTS OF OUR POWER.”—Speech on Mr. Cobden’s death, April 3, 1865.

The power of imagination is essential to supreme statesmanship. Indeed, no really originative genius in any domain of the mind can succeed without it. In literature it reigns paramount. Of art it is the soul. Without it the historian is a mere registrar of sequence, and no interpreter of characters. In science it decides the end towards which the daring of a Verulam, a Newton, a Herschel, a Darwin, can travel. On the battle-field, in both elements, it enabled Marlborough, Nelson, and Napoleon to revolutionise tactics. In the law its influence is perhaps less evident; but even here a masterful insight into the spirit of precedent marks the creative judge. By lasting imagination, far more than by the colder weapon of shifting reason, the world is governed. “Even Mormon,” wrote Disraeli, “counts more votaries than Bentham.” For imagination is a vivid, intellectual, half-spiritual sympathy, which diverts the flood of human passion into fresh channels to fertilise the soil; just as fancy again is the play of intellectual emotion. Whereas reason, the measure of which varies from age to age, can only at best dam or curb the deluge for a time. Reason educates and criticises, but Imagination inspires and creates. The magnetic force which is felt is really the spell of personal influence and the key of public opinion. It solves problems by visualising them, and kindles enthusiasm from its own fascinating fires. And more: Imagination is in the truest2 sense prophetic. Could one only grasp with a perfect view the myriad provinces of suffering, enterprise, and aspiration with which the Leader is called upon to grapple, not only would the expedients to meet them suggest themselves as by a divine flash, but their inevitable relations and meanings would start into vision. For what the herd call the Present, is only the literal fact, the shell, of environment. Its spirit is the Future; and the highest imagination in seeing it foresees. Imagination, once more, is the mainspring of spontaneity. Its vigour enables the will to beget circumstance, instead of being the creature of surroundings; “for Imagination ever precedeth voluntary motion,” says Bacon. It empowers the will of one to sway and mould the wills of many. And it is the very source of that capacity for idealism which alone distinguishes man from the brute. Viewing in 1870 the general purport of his message, Disraeli wrote with truth that it “... ran counter to the views which had long been prevalent in England, and which may be popularly, though not altogether accurately, described as utilitarian;” that it “recognised imagination in the government of nations as a quality not less important than reason;” that it “trusted to a popular sentiment which rested on an heroic tradition, and was sustained by the high spirit of a free aristocracy;” that its “economical principles were not unsound,” but that it “looked upon the health and knowledge of the multitude as not the least precious part of the wealth of nations;” that “in asserting the doctrine of race,” it “was entirely opposed to the equality of man, and similar abstract dogmas, which have destroyed ancient society without creating a satisfactory substitute;” that “resting on popular sympathies and popular privileges,” it “held that no society could be durable unless it was built upon the principles of loyalty and religious reverence.”

How comes it, then, that, in the art of governing a free people, this imaginative fellowship with unseen ideas, this power which men call Genius, “to make the passing shadow serve thy will,” is so constantly suspected and mistrusted; that uncommon sense, until it triumphs, is a stone of stumbling to the common sense of the average man? That Cromwell was called a self-seeking maniac for his vision of3 Theocracy; William of Orange, a cold-blooded monster for his quest after union and empire; Bolingbroke, a charlatan for his fight against class-preponderance, and on behalf of united nationality; Chatham, an actor for his dramatic disdain of shams; Canning, by turns a charlatan and buffoon, for preferring the traditions of a popular crown to the innovations of a crowned democracy, and at the same time seeking to break the charmed circle of a patrician syndicate; that Burke was hounded out by jealous oligarchs for refusing to confound the “nation” with the “people,” and cosmopolitan opinions with national principles? The main answer is simple. What is above the moment is feared by it, and malice is the armour of fear: “It is the abject property of most that being parcel of the common mass, and destitute of means to raise themselves, they sink and settle lower than they need. They know not what it is to feel within a comprehensive faculty that grasps great purposes with ease, that turns and wields almost without an effort plans too vast for their conception, which they cannot move;” and there are always the jealous who—

There are the puzzled whom novelty bewilders, and there are the cautious who suspect it. And there is the wholesome instinct of the plain majority to pin itself to immediate “measures” without recognising that a “principle” may change expedients for bringing its idea into effect. Again, there are many—especially in England—who, in their genuine scorn of pinchbeck, mistake the great for the grandiose, and certain that nothing which glitters can be gold, invest imaginative brilliance with the tinsel spangles of Harlequin. There are, too, the second-rate and the second-hand, whose life is one long quotation, and who doubt every coin unissued from the nearest mint; and there is, moreover, a sort of stolid crassness readily dignified into sterling solidity. All this is natural. Institutions and traditions4 themselves have been aliens until naturalised in and by the community. Imagination gave them birth, national needs accept them; and the contemporary sneer is often succeeded by the posthumous statue.

Perhaps the most curious feature of the prosaic and imperceptive man is his ready confusion of the dramatic with the theatrical, of attitude with posture, of pointed effects for a big purpose with affectations for a small. Flirtation might just as well be confounded with love, or foppery with breeding. And yet these same unimaginative censors have often contradicted their protests by their actions, and squandered great opportunities by futile strokes of the theatre.

So early as 1837, Sheil, who from the first admired the young Disraeli (then Bulwer’s intimate and the meteor of three seasons), whom Disraeli praised in one of his earliest election speeches, and who was surely no mean judge of intellectual eloquence, warned him after his début that “the House will not allow a man to be a wit and an orator, unless they have the credit of finding it out.... You have shown the House that you have a fine organ, that you have an unlimited command of language, that you have courage, temper, and readiness. Now get rid of your genius for a session; speak often, for you must not show yourself cowed, but speak shortly. Be very quiet, try to be dull, only argue and reason imperfectly, for if you reason with precision, they will think you are trying to be witty. Astonish them by speaking on subjects of detail. Quote figures, dates, calculations, and in a short time the House will sigh for the wit and eloquence which they all know are in you; they will encourage you to pour them forth, and then you will have the ear of the House, and be a favourite.” Seventeen years afterwards, when the dashing littérateur had become Chancellor of the Exchequer and leader of the House of Commons, Mr. Walpole thus defended him against his enemies on the Budget. “... Whence is it that these extraordinary attacks are made against my right honourable friend? What is the reason, what is the cause, that he is to be assailed at every point, when he has made two financial statements in one year, which have both met with the approbation of this5 House, and I believe also with the approbation of the country? Is it because he has laboured hard and long, contending with genius against rank and power and the ablest statesmen, until he has attained the highest eminence which an honourable ambition may ever aspire to—the leadership and guidance of the Commons of England? Is it because he has verified in himself the dignified description of a great philosophical poet of antiquity, portraying equally his past career and his present position—

Yes! This is the sort of barrier piled in the path of the brilliant by the “practical” man—“the man who practises the blunders of his predecessors,” the “prophet of the past.” Still greater, because deeper laid, are the obstacles which confront him when he has mastered the drudgery of office and the strategy of debate; when, from the vantage-ground of political pre-eminence and public approval, he dares to look over the heads of his compeers and prepare strong foundations for the future of his country. Then that becomes true which Bolingbroke has so splendidly expressed: “The ocean which environs us is an emblem of our government, and the pilot and the minister are in similar circumstances. It seldom happens that either of them can steer a direct course, and they both arrive at their port by means which frequently seem to carry them from it. But as the work advances, the conduct of him who leads it on with real abilities clears up, the appearing inconsistencies are reconciled, and when it is once consummated, the whole shows itself so uniform, so plain, and so natural, that every dabbler in politics will be apt to think that he could have done the same.”

It is this that Disraeli effected by reverting to fundamental elements and substituting the generous, inclusive, and “national” Toryism of Bolingbroke, Wyndham, and Pitt, for the perverted Toryism of Eldon; the “party without principles,” the “Tory men and Whig measures,” the “organised hypocrisy” that followed on the “Tamworth Manifesto;” the Conservatism that “preserved” institutions as men “preserve”6 game, only to kill them; and the outworn Whiggism that excluded all but a few governing families from power; and, after its great achievement of religious liberty, exploited the extension of civil privileges as the mere muniment of its own title. He ended the confederacies and revived the creed.1 He repudiated the system under which “the Crown had become a cipher, the Church a sect, the nobility drones, and the people drudges.” “... But we forget,” he urges in Sybil, “Sir Robert Peel is not the leader of the Tory party—the party that resisted the ruinous mystification that metamorphosed direct taxation by the Crown into indirect taxation by the Commons; that denounced the system which mortgaged industry to protect property;2 the party that ruled Ireland by a scheme which reconciled both Churches, and by a series of parliaments which counted among them lords and commons of both religions; that has maintained at all times the territorial constitution of England as the only basis and security for local government, and which nevertheless once laid on the table of the House of Commons a commercial tariff negotiated at Utrecht, which is the most rational that was ever devised by statesmen; a party that has prevented the Church from being the salaried agent of the State, and has supported the parochial polity of the country which secures to every labourer a home. In a parliamentary sense that great party has ceased to exist; but I will believe that it still lives in the thought and sentiment ... of the English nation. It has its origin in great principles and noble instincts; it sympathises with the lowly, it looks up to the Most High; it can count its heroes and its martyrs.... Even now, ... in an age of political materialism, of confused purposes and perplexed intelligence, that aspires only to wealth because it has faith in no other accomplishment;3 as men rifle cargoes7 on the verge of shipwreck, Toryism will yet rise from the tomb ... to bring back strength to the Crown, liberty to the subject, and to announce that power has only one duty—to secure the social welfare of the people.”

And, again, this from the close of Coningsby: “... he looked upon a government without distinct principles of policy as only a stop-gap to a widespread and demoralising anarchy; ... he for one could not comprehend how a free government could endure without national opinions to uphold it.... As for Conservative government, the natural question was, ‘What do you mean to conserve?... Things or only names, realities or merely appearances? Do you mean to continue the system commenced in 1834, and with a hypocritical reverence for the principles and a superstitious adherence to the forms of the old exclusive constitution, carry on your policy by latitudinarian practice?’”

His lifelong purpose as a statesman was to refresh institutions with reality, and to show by practice, as well as by precept, that, in all classes, an aristocracy without inherent superiority is doomed. De Tocqueville, in his famous treatise on “The Old Régime and the Revolution,” does the same.

Eighteenth-century Toryism, a smitten cause espousing popular privileges, taught that unless the Crown ruled for the people as well as reigned over them, unless the nobles led them independently to high issues, unless the people themselves recognised that they were the privileged order in a nation, and that their representatives should form “a senate supported by the sympathy of millions,” the traditional principles of England had dwindled into a sham.

“No one,” says Disraeli in Coningsby, again adverting to the critical issues of 1834, “had arisen either in Parliament, the Universities, or the Press, to lead the public mind to the investigation of principles; and not to mistake in their reformations the corruption of practice for fundamental ideas. It was this perplexed, ill-informed, jaded, shallow generation,8 repeating cries which they did not comprehend, and wearied with the endless ebullitions of their own barren conceit, that Sir Robert Peel was summoned to govern. It was from such materials, ample in quantity, but in all spiritual qualities most deficient; with great numbers, largely acred, consoled up to their chins, but without knowledge, genius, thought, truth, or faith, that Sir Robert Peel was to form ‘a great Conservative party on a comprehensive basis....’” Even Sir Robert’s single-mindedness and supremacy over Parliament failed to secure strength of Government. By universal consent, including his own avowal, he wrecked a great party in a country where great parties form the main pledge for the due representation of political opinion, and under a system where they remain the chief preventive against public corruption.

The first two Georges had reigned over the towns, but not over the country. After the Reform Bill it seemed as though the great cities themselves would swamp the land. How was Sir Robert to save the situation in 1834? Speaking with respect for Sir Robert, but with contempt for his “Tamworth Manifesto,” Disraeli, in his discussion of that famous document, repeats his message once more: “... There was indeed considerable shouting about what they called Conservative principles; but the awkward question naturally arose, ‘What will you conserve?’ The prerogatives of a Crown, provided they are not exercised; the independence of the House of Lords, provided it is not asserted; the ecclesiastical estate, provided it is regulated by a commission of laymen. Everything, in short, that is established, as long as it is a phrase and not a fact.”4

It is thus that the man of ideas is, in the long run, eminently practical; and it is thus, too, that in the realm of art ideas are the surest realities. But here also the immediate appeal constantly falls to the lot of what is called “realism,” and few feel what they cannot touch until the popular voice tells them that it is “real.” “Madame,” says Heine in his “Buch Legrand,” “have you the ghost of an idea what an idea is? ‘I have put my best ideas into this coat,’ says9 my tailor. My washerwoman says the parson has filled her daughter’s head with ideas, and unfitted her for anything sensible; and coachman Pattensen mumbles on every occasion, ‘That is an idea.’ But yesterday, when I inquired what he meant, he snarled out, ‘An idea is just an idea; it is any silly stuff that comes into one’s head.’”

No memorial of Disraeli’s magical career can be adequate without access to the papers confided to the late Lord Rowton, as well as to much private and unpublished correspondence. It is no slur on the “Lives” that have already appeared to say that they lack the materials for a complete picture. The best of these beyond question is Mr. Froude’s; but not only is it tinged with considerable prejudice, but it is very faulty in its facts; and, moreover, in common with Mr. Bryce’s cursory essay and Herr Brandes’s minuter study, it has perhaps fallen into the error of misreading Disraeli’s mature character and career from isolated and indiscriminate use of such sidelights as they are pleased to discover in his earliest novels. To trace Disraeli’s development, it is necessary to follow the long and continuous thread of his words and actions, to consider the changes experienced during the fifty years of his political outlook in England and in Europe, and to ascertain how many of these tendencies were foreseen, produced, or modified by him. The criticisms current are either those of men (often partisans) who lack this length of view, and interpret the latter manifestations of Disraeli’s genius, with which alone they are even outwardly acquainted, in the light of preconceived notions, or the few circulated comparatively early in his career, before its eventual drift was revealed, and while the full blaze of hostile bitterness was raging. There exists, it is true, a most able, a most appreciative, a most detailed account of his political career, compiled by Mr. Ewald shortly after Lord Beaconsfield’s death, but this is mainly a long parliamentary chronicle. Mr. Kebbel’s enlightening edition of selected speeches is illustrative though limited. To both of these, among many other sources, direct and indirect, I here gratefully acknowledge my obligation.

A real biography, therefore, is at present impossible. Disraeli’s acknowledged debt to his darling sister and devoted10 wife (“Women,” he has said, “are the priestesses of pre-destination”); his correspondence and commerce with many eminent men, including both Louis Philippe and Napoleon III.; his letters to our late Queen; his notes of policy; the rough drafts for compositions, both literary and parliamentary; his State papers and official memoranda; his relations to many men of letters and leading; such known, though unpublished, correspondence as even that with Mrs. Williams; the glimpses of him as a youth through Mrs. Austin, Bulwer, Lord Strangford, the Sheridans, with many others; in his age, through a privileged circle of distinguished and devoted associates—all these, and many more, must be pressed into service if even the rudiments are to be portrayed. And none of these are yet available.

I have therefore thought that, pending such an enterprise, some account, however imperfect, of the ideas that governed him throughout—a slight biography, as it were, of his mind—might prove acceptable. It will endeavour to depict the spirit of his attitude to the world in which he moved and for which he worked. It will aim at representing the temperature of his opinions immanent alike in his writings and speeches. His utterance was never bounded by the mere occasion, and light and guidance may be found in it for the problems of to-day. In most that he wrote or said, a certain swell of soul, a sweep and stretch of mind are strikingly manifest.

“How very seldom,” he has written, “do you encounter in the world a man of great abilities, acquirements, experience, who will unmask his mind, unbutton his brains, and pour forth in careless and picturesque phrase all the results of his studies and observations, his knowledge of men, books, and nature!”

Such a contribution is anyhow feasible, and is fraught with more than even the glamour linked with the person by whom these ideas were clothed in words and deeds. For principles are applied ideas; habits are applied principles. Disraeli’s ideas have, to some extent, become ruling principles, several of them are at this moment national habits; while some of them, unachieved during his lifetime, seem in process of accomplishment. Disraeli was a poet—one of those “unacknowledged legislators of the world” described by “Herbert”11 in Venetia; but his imaginative fancy was allied to a very strong character. It is a rare combination. To Bolingbroke’s youthful genius he united that force of will and purpose for which Bolingbroke had long to wait, and which, perhaps, he never fully attained. This analogy was pressed on Disraeli on the threshold of his career by a distinguished friend.

Above all things Disraeli was a personality. Personality is independent of training, except in the rare cases where education accords with predisposition. It is the will. And in authorship, when expression chimes with intention, it is the style. Personality is the clue to history, for events proceed from character, more than character from events. Commenting on the adoption of the “Charter” by non-chartists groaning under the injustice of industrial slavery, Disraeli observes most truly: “... But all this had been brought about, as most of the great events of history, by the unexpected and unobserved influence of individual character.” Personality is the salt of politics; it is the spirit of our party system; and woe betide every era in England when figure-heads replace head-figures. It is an atmosphere enchanting the landscape. “... It is the personal that interests mankind, that fires their imagination and wins their hearts. A cause is a great abstraction, and fit only for students: embodied in a party, it stirs men to action; but place at the head of that party a leader who can inspire enthusiasm, he commands the world....” Association, groups, co-operative principles, these are the mechanisms invented by the brain, and guided by the hand of individuality, the fuel that individuality gathers and enkindles. Without it they remain dead lumber, and can never of themselves prove originative forces. What men crave is, once more in Disraeli’s parlance, “... A primordial and creative mind; one that will say to his fellows, ‘Behold, God has given me thought, I have discovered truth, and you shall believe.’” Personality is the contradiction of the mechanical and of the dead level; it is the soul of influence. How depressing is the reverse side of the medal!—“Duncan Macmorrogh” (the utilitarian in The Young Duke), “cut up the Creation and got a name. His attack upon mountains was most violent, and proved, by its personality12 that he had come from the lowlands. He demonstrated the inability of all elevation, and declared that the Andes were the aristocracy of the globe. Rivers he rather patronised, but flowers he quite pulled to pieces, and proved them to be the most useless of existences.... He informed us that we were quite wrong in supposing ourselves to be the miracle of the Creation. On the contrary, he avowed that already there were various pieces of machinery of far more importance than man; and he had no doubt in time that a superior race would arise, got by a steam-engine on a spinning-jenny....”

To impress his ideas through his will on his generation, was Disraeli’s ruling purpose from the first; but to attain the position which would entitle him to do so he never regarded as more than a ladder towards his main ambition. Ambition5 spurred him from the first. But, as the present Duke of Devonshire generously owned in the heat of party contest, Disraeli was never prompted by mean or unworthy motives; and—added the speaker—it would be the merest cant to pretend that honourable and honest ambition is not a main incitement to public life. At the outset he was convinced of a mission, and the visions over which he had long brooded in silent solitude became realised in the world of action. Both reverie and energy alternated even in his boyish being. “I fully believed myself the object of an omnipotent Destiny over which I had no control”—and yet “Destiny bears us to our lot, and Destiny is perhaps our own will.” “... There arose in my mind a desire to create things beautiful as that golden star;” and yet “... Nor could I conceive that anything could tempt me from my solitude ... but the strong conviction that the fortunes of my race depended on my effort, or that I could materially forward that great amelioration, ... in the practicability of which I devoutly believe.” As a boy he dreamed of “shaking thrones and founding empires;” and yet, he felt that he must not13 “pass” his “days like a ghost gliding in a vision.” These are among the echoes and glimpses afforded by his earliest fiction of his earliest self, and to this topic I shall recur in my last chapter. I mention them here for a material reason. In treating his thoughts we must distinguish between those notions which merely concern success or career, and those ideas which assured victory was to achieve. Nor should we omit the very vital distinction between personality and egotism, for confusion in this regard constantly obscures our estimates. Individuality with the forces that make for it is not “individualism;” yet the two are often confused.

The essential egotist is a sort of buccaneer. He roams the seas to rifle cargoes, and his conquests are the spoils of a freebooter. He seeks to exploit society for his own benefit—to burn down his neighbour’s roof-tree that he may boil his egg. He gives nothing that he can keep, and takes all he can grasp by whatever methods may advantage him. He leaves the world poorer when he goes, and as he leaves it, he wishes it. In Cowper’s words—

The man, on the other hand, of overwhelming personality, aspires honourably to power, the very condition of which in his eyes is to guide and elevate the country which entrusts him with it. The responsibility of privilege, great position on the tenure of great duties, ambition not as a right but as the sole means of enforcing his ideals—these are his characteristics. He never covets place without power, and never power without influence; whereas some kind of covetousness is essential to the egotist. “He who has great honours,” Disraeli has urged, “must have great burdens.” And again: “... My conception,” he said, in a signal speech during 1846, “of a great statesman is of one who represents a great idea; an idea which he may and can impress on the mind and conscience of a nation.... That is a grand, that is indeed an heroic position. But I care not what may be the position of a man who never originates an idea—a watcher of the atmosphere, a man who ... takes his observations, and when14 he finds the wind in a certain quarter trims to suit it. Such a person may be a powerful Minister, but he is no more a great statesman than the man who gets up behind a carriage is a great whip. Both are disciples of progress; both perhaps may get a good place. But how far the original momentum is indebted to their powers, and how far their guiding prudence regulates the lash or the rein, it is not necessary for me to notice.”

Disraeli never stooped to trim; he always aspired to steer. When he started as a brilliant author, electric with ideas derided but since accepted—as an imaginative originator, “full of deep passions and deep thoughts”—it would have been easy for him to have followed the triumphal car of the Whigs who invited him.6 It would have been easy for him to have suited himself to Sir Robert Peel’s vicissitudes of private, and desertion of public opinion, embodied in a great party which had raised him to power. In obeying again the central ideas which quickened him from the first, Disraeli broke up the “Young England” party, which looked up to and cheered him, whose main objects he inspired, and eventually realised. And in 1867, as we shall see, so far from “dishing” the Liberals with their own measure of Reform, he carried, in the teeth of his own supporters, one on lines peculiar to his own perpetual view of the subject, and at length achieved what he had urged in the ’thirties, the ’forties, and the ’fifties.

In the stubborn pursuit of his aims Disraeli even courted unpopularity. On every occasion when the object of the Jew bill was involved with other measures which he considered prejudical to its due interests, he risked misconstruction by withholding his vote. During the long spell of 1859–66, when a dispirited, and sometimes disloyal following often left him alone in his seat, he continued the pronouncements alike and the reticence which they disrelished. During the six years previous he dared to offend them equally by hammering the Government’s foreign policy, and insisting on his own convictions. Nobody, again, more regretted the precipitancy of Lord Derby in 1852, although his rash assumption of office15 afforded Disraeli his first hard-won opportunity of leadership. During three separate sets of discreditable intrigues to dethrone him, he kept place, counsel, and temper without wheedling concessions or recriminating revenges, though none could strike home harder when he chose.

“... Ah, why should such enthusiasm ever die? Life is too short to be little. Man is never so manly as when he feels deeply, acts boldly, and expresses himself with frankness and with fervour.”

The fact that both the mere egotist, and the man of intense personality, must, from the need of their respectively low and lofty concentrations, be self-centred, and infuse their temperaments into the objects of their energy, favours, it is true, the mistake to which I have referred. But the one is pettily fixed on self, the other intent on ideals. He leads a life of ideas which form his atmosphere, and which emanate from it. He mounts the chariot to drive it to a distant goal, while the other borrows or pilfers it for his own immediate convenience. Egoism—if I may coin a distinction—is one thing, egotism another. Goethe was an egoist—he is full of a radiating self; but such egoism is, if we reflect, the very opposite of the egotist, who is full of a shrivelled selfishness. Such were the later phases of Napoleon, who changed from a generous imparter into an absorbing monopolist. That was egotism. All genius, however, has been egoist, and ever will be; for genius is at once the ear, sensitive to the subtlest appeals of existence, and the voice which constrains others to enter the realm of its ideas. Its sensitiveness is part of its strength, and in this respect it shares the self-consciousness of the artist. It is in the real sense auto-suggestive; it implants ideas which its will generates into events. It is in some degree that—

And its faults, as I shall show in my closing chapter, are associated with its very qualities.

16 Genius is both light and heat; it combines enthusiasm with insight. Such a genius was Disraeli. He was eminently a man of ideas, and not merely of abnormal perceptions. This distinction again is material, and too often ignored.

The eminently perceptive man is at root a critic, while the man of ideas is by prerogative a creator; and yet the quick perceiver is often mistaken for a creative genius, and keenness confused with originality. In politics, for instance, this was the case with such different beings as Peel and Gambetta; in literature, with Addison and Arnold; in art, with Kneller and Lawrence. Disraeli’s ideas were at once his creations and companions, and he moved in their inner circle with a sort of extravagant intensity. They were no shadows. He was convinced of their substance almost to fatalism, and his immense will-power forced and projected them into movement. In his extreme youth, before his character had matured, these ideas flickered as fantasies. The restlessness of a volition felt, but not yet freed or directed, caused some masquerade of guise, and a perpetual strain on the intuition that sought to forestall experience. Realisation alone, with power and experience, brought repose. But at all periods an idea that had once seized him tinged his whole being. Its reality haunted him till he had given it place and shape.7 An inward and ideal energy possessed him. Ideas were for him far more tangible, even far more sociable, than the outward and fleeting phantasms around him, as is evidenced in his fiction by his constant habit of transferring environment and transplanting personalities to accentuate their ideal essence. Thus, in Venetia, the soul of Lady Byron animates the form of Shelley’s wife, while the very date is put back some thirty years, that Shelley himself might be enabled to have braved in action what he mused in poetry. So, again, in Contarini, the hero’s development blends something of his own with something of his father’s character; while Baron Fleming is his grandfather reincarnated as a noble.8 About17 the ironies of these, the arabesques of his playful fancy flickered. For him they were mostly the pretexts of things, but ideas were the causes, and he loved to contrast “the pretext with the cause;” but even here romance blent with irony, and invested the seemingly trivial with wonder. Some, too, of his ideas hovered, as it were, over the present scene, in a flight bound other-whither and beyond. In a word, Disraeli was an artist, conscious and confident of an over-mastering call. As he has written in a striking passage from the work of his youth, Contarini Fleming: “I never labour to delude myself; and never gloss over my own faults. I exaggerate them; for I can afford to face truth, because I feel capable of improvement.... I am never satisfied.... The very exercise of power teaches me that it may be wielded for a greater purpose.... No one could be influenced by a greater desire of knowledge, a greater passion for the beautiful, or a deeper regard for his fellow-creatures.... I want no false fame. It would be no delight to me to be considered a prophet, were I conscious of being an impostor. I ever wish to be undeceived; but if I possess the organisation of a poet, no one can prevent me from exercising my faculty, any more than he can rob the courser of his fleetness, or the nightingale of her song.”

The “ill-regulated will,” “the undercurrent of feelings he was then unable to express,” portrayed in Vivian Grey, developed into the higher and more elevating purposes of which his transforming imagination was all along capable. That very book contained the germs of what its composition revealed to his own mind—that out of a young adventurer with purpose and genius, the school of life forms a strong character and a great man. In Contarini Fleming the irresistible power of predisposition, the hollowness of a nurture which ignores it and substitutes “words” for “ideas,” the interactions of imagination and experience, the fatuity of contradicting or overstraining Nature, are pursued; nor, as regards this novel, should it be forgotten that in some portions of its analysis18 there are traces in allusive undertone to the fatalities of the great and stricken Dean of St. Patrick’s.9

In Disraeli’s case, as so often before him, “the dreaming part of mankind” has “prevailed over the waking.” His flouted dreams came true. They still hold sway. To give effectual substance to these higher and abiding dreams, those other dreams of ascendency, through which alone his will could realise his ideas, were also verified. “It is the will”—he speaks by the lips of the young “Alroy”—“that is father to the deed, and he who broods over some long idea, however wild, will find his dream was but the prophecy of coming fate.” “All is ordained,” he had said as a stripling, “yet man is master of his own actions.”10 Disraeli’s career was itself a romance—a romance of the will that defies circumstance, and moulds the soil where ideas are to flourish. An inward, personal energy is the parent of faith, and faith in oneself is the sole security for the issue of faith among others. He lived to triumph, but not in order to triumph; and he remains a standing protest against those who believe in cliques and disbelieve in personal influence. The former are only compact in appearance; they are unsympathetic associations, welded together by interest alone. Joint-stock enterprise is not fellowship, and the test of direction is liability. Nor is it without significance that “Fortune,” even in the ancient world a real though blind goddess, has come, in the modern, to mean little more than cash; so that capital leans away from labour, plutocracy is cemented, solidarity declines, and worth too often is resolved by the question, “Worth how much?”

It is this idea of personality that lies at the very root of united nationality; for a nation is an idealised individual, no aggregate of atoms. Still less is it the experimenting room of doctrinaires or the dumping-ground of the Tapers and Tadpoles, the Paul Prys of politics, who “whisper nothings that sound like somethings;” or of those “Marneys,” “Fitz-Aquitaines,” and “Mowbrays” who deem that the end of an administration is “two garters to begin with;” or again of19 “the good old gentlemanlike times, when Members of Parliament had nobody to please, and Ministers of State nothing to do;” of those who, like “Rigby,” mistake peddling with constituencies for representing the country; or of those petty placemen to whom, as he has said, party means the machinery for receiving “£1200” a year, career the pursuit of it, and success its attainment.

“... I prefer” (the passage is from Sybil) “association to gregariousness.... It is a community of purpose that constitutes society ... without that men may be drawn into contiguity, but they will continue virtually isolated....” What does this imply but the sympathetic power of personality? The more individual societies become, the greater their efficacy. The less individual they are the more they display the tameness and unfruitfulness that enfeeble a copy.

“But what is an individual,” exclaimed “Coningsby,” “against a vast public opinion?”

“Divine,” said the stranger. “God made man in His own image; but the Public is made by newspapers, Members of Parliament, excise officers, Poor Law guardians. Would Philip have succeeded, if Epaminondas had not been slain? And if Philip had not succeeded? Would Prussia have existed, had Frederick not been born? And if Frederick had not been born? What would have been the fate of the Stuarts, if Prince Henry had not died, and Charles I., as was intended, had been Archbishop of Canterbury?”

This was written in 1844. Since then, would Germany have been united if Bismarck had not been born? And if Bismarck had not been born? In 1865 a powerful party, promising success, reinforced by commanding talent, and concerting an intelligible plan with immense vigour, began to demand the disintegration of Great Britain. And if Disraeli had not been born?——

Nothing is more striking in modern parliamentary life than the growing neglect of the past. Great issues are mooted by men ignorant of, or ignoring, their historical origin. Young members discuss weighty problems with no study save that of20 omniscience. The ancestry of events is disregarded. Development is relegated to musty students and mouldy volumes. The fact that statesmanship is able to look forward because it has already looked back, is flouted or forgotten. Public interest is gradually being withdrawn from debate, just because it is getting out of touch with the organic changes of national life. The genius which transfigures facts with imagination has been replaced by the opportunism which invests emptiness with solemnity; and this, in a country where national growth depends on continuous tradition.

The utterances of Disraeli from the early ’twenties to the latest ’seventies display a wonderful harmony of coherence in progress. They form one long suite of variations on the central motif of persistent and consistent ideas. To understand them aright one must view them successively, both in his books and his speeches, which illustrate each other; nor in so doing should the contexts of personal development, events private as well as public, be lost from sight.

This I have endeavoured to accomplish in the following chapters. I have classified their themes in groups broad enough to admit of kindred topics. After a fresh portrait of Disraeli’s personality, I treat first of his constitutional ideas, because these are at the root of his political standpoint; they underlie, too, his conception of the State. Then follows his attitude towards Labour and the causes it involved. Next come his distinctive views on Church and Christianity; his views, equally distinctive, on Monarchy occupy a separate chapter. Colonies, Empire, and Foreign Policy are then grouped together; and it may excite surprise to mark the earliness and the correctness of his prophecies. Under this head I also consider his thoughts on India. America and Ireland succeed; and here again his justified originality is most remarkable. Perhaps the light chapters on Society, Literature, Wit, Humour, and Romance, with the closing study of Career, may be considered not the least suggestive. I have not drawn on Mr. Meynell’s delightful “Disraeliana” (the pleasure of reading which I purposely postponed), because I wished this portraiture of the man and his mind to be wholly original.

“A great mind that thinks and feels is never inconsistent and never insincere.... Insincerity is the vice of a fool, and inconsistency the blunder of a knave.... Let us not forget an influence too much underrated in this age of bustling mediocrity—the influence of individual character. Great spirits may yet arise to guide the groaning helm through the world of troubled waters—spirits whose proud destiny it may still be at the same time to maintain the glory of the Empire and to secure the happiness of the people.”

So wrote “Disraeli the Younger” during the perplexed crisis of 1833 in his rare pamphlet, What is he?11 which embodies his own large attitude. The sentence is characteristic and prophetic. Its last words were repeated more than forty years afterwards in the message of farewell to his constituents, when he quitted the lively scene of his triumphs for that grave assemblage, of which he once said that its aptitudes were best rehearsed among the tombstones.

In my last three chapters I shall touch on some unique phases of his boyhood, and outline several of his relations to his home, to society, to literature, to character, and to career. But here I shall attempt a less detailed account of his individuality and of the main ideas which flowed from it.

And first let me venture on two glimpses—one of his youth, the other of his age.

22 It is not difficult to collect from many scattered presentments some likeness of

Imagine, then, a romantic figure, a Southern shape in a Northern setting, a kind of Mediterranean Byron; for the stock of the Disraelis hailed from the Sephardim—Semites who had never quitted the midland coasts, and were powerful in Spain before the Goths. The form is lithe and slender, with an air of repressed alertness. The stature, above middle height. The head, long and compact; its curls, fantastic. The oval face, pale rather than pallid, with dark almond eyes of unusual depth, size, and lustre under a veil of drooping lashes. The chin, pointed with decision. The expression holds one, by turns keen and pensive; about it hovers a strange sense of inner watchfulness and ambushed irony, half mocking in defiance, half eager with conscious power. A languid reserve marks his bearing; it conceals a smouldering vehemence; its observant silence prepares amazement directly interest excites intercourse. Then indeed the scimitar, as it were, flashes forth unsheathed, and dazzles by its breathless fence of words with ideas. This ardour is not always pleasant; it breathes of storm; it speaks out elemental passions and grates against the smooth edges of civilisation. In the London medley he, like his friend Bulwer, studies a purposed posture. Dandyism and listlessness mask unsleeping energy. But at Bradenham, his constant retreat, the “Hurstley” of his last novel, all is natural and unconstrained. Here at least he is free. Here he “drives the quill” with his famous father, reads and rides, meditates and is mirthful. Here, with that gifted sister “Sa”—“Sa,” a name soon afterwards doubly endeared to him through Lord Lyndhurst’s daughter; “Sa,” who, while others doubt or twit, ever believes in and heartens him—he dreams, improvises, discourses. The rest may treat him as a moonstruck Bombastes,12 but his lofty visions are real23 to the gentle insight of affection. In the language of Shakespeare’s fine colloquy:—

DISRAELI THE YOUNGER

After a water colour by A. E. Chalon

Already, like one of those his biting pen had satirised, he too, it must be owned, teems with “confidence in the nation—and himself.” There was a daredevilry about him, and in those days a romantic melancholy, akin to that of the Spanish artist Goya. Far behind have faded those consuming pangs of boyish restlessness, when fevered imagination played vaguely on inexperience. Far behind, those schools of “words” which never slaked his thirst for ideas, and where he ran wild as rebel ringleader.13 Far away now, those boxing bouts witnessed by Layard’s mother. Past, that earliest and unpublished novel of Aylmer Papillon,14 which Murray praised but would not print. Past, that fugitive satire of the “New Dunciad,” which does not deserve to remain waste-paper.15 Past, that abortive journal, which in transforming an old periodical while adopting its name was to have revolutionised opinion.16 Vanished, too, those first outbursts of unchastened brilliance under the favouring auspices of the Layards’ fair kinswoman, Mrs. Austin. And the vista of his two long24 journeys have receded; the alternate spells of Venice, the Rhine and Rome, and afterwards of Athens, Constantinople, Jerusalem. Past, also, the strange malady for which his Eastern travels proved the stranger cure. As he muses, the ball is at his feet. Yet, when the daydream fades, is he, perhaps, after all, only Alnaschar of the broken glass, bemoaning vain reveries amid the ruined litter of his overturned basket in the jeering market-place? The seed-time of reflection is over: he pants for action. No more for him the beaten tracks. Hitherto he had fed on books and dreams. The former had led him to a pondered plan, with Bolingbroke for clue and Pitt as example. The latter fired his ambition—his presumption—to realise them by restoring vanished life to a now mouldering party—by suiting old forms to new phases and heading them.

Next morning the secluded scholar, so friendly a contrast with his daring son, is bound for Oxford to receive his long delayed honours. This very day that son’s earliest election-procession starts from the doorway of the tranquil manor house.17 Already the budding genius has descried the dim future of his country, which he has proclaimed must be governed for and through the nation; of which, too, he has already sung in halting verse:—

What matter now the debts, the duns, the embarrassments for which he blushes?18 What matter the heartless allurements of siren fashion? His course is clear before him. He must win. He “has begun several times many things, and25 has often succeeded at last.” As for the taunt of “adventurer,” what are all original spirits that “burst their birth’s invidious bar” but adventurers? Such were Chatham,19 and Burke, and Canning, and Peel himself. But when the “adventurer” is one by temperament as well as occasion, how miraculous becomes his progress! “Adventures are to the adventurous.”

Many of us remember Disraeli in his age as he sauntered dreamily and slowly with the late Lord Rowton, and none who ever heard one of his last orations in the House of Lords can forget how, even when he was in pain, he sprang from his seat with the quick step of youth. The physical charm had disappeared. Few who gazed on that drawn countenance could have discerned in it the poetry and enthusiasm of his prime; only the unworn eyes preserved their piercing fires, and the sunken jaw was still masterful. A long discipline of iron self-control, much disillusion, growing disappointments with crowning triumphs, and latterly a great desolation, had subdued the fiercer force and the elastic buoyancy of his hey-day. Yet the intellectual charm, and the spell of mind and spirit had deepened their outward traces. Fastidious discernment, dispassionate will, penetrating insight, courage,20 patience, a certain winning gentleness underneath the scorn of shams, stamp every lineament. Below habitual insouciance, intensity, bigness of soul and purpose are prominent. The arch of the noble brow retains its height and curve. Surrounded though he be by friends and flatterers, he looks lonelier than of old. “I do not feel solitude,” he said, “it gives one repose.” Interested in every movement, and even in every trifle that engages thought, his gaze appears more turned within.

26 We know from Lady John Manners,21 and from other sources, how he loved flowers, and forestry, and study during the dinner-hour, more than all the social glitter; how he communed with the unseen; how far-reaching were his sympathies; what interest and curiosity he displayed in every form of career and purpose; how often to all the splendour which he had conquered he preferred converse with the weak, the lowly, the suffering; how his wise counsel and inexhaustible resource were sought and coveted by cottagers, by the toilers whose cause he made his own, by princes; how delicately considerate he was in his appointments, and for all in contact with him, how he would sacrifice a keen personal wish rather than disturb a pleasure or abridge a holiday; and yet how his playfulness of fancy mixed in pithy ironies with his very considerateness. A familiar instance—that of the attached servant who was to enjoy “the pleasures of memory”—occurred as he lay dying from the illness long and bravely concealed even from his intimates. He was truly unselfish, and he was never known to blame a subordinate. If things went wrong, he took the whole burden on his own shoulders. He exerted infinite pains to understand the conditions of and the organisations affecting labour.22 The Buckinghamshire peasants still cherish his memory; and it may be said with truth that the deepest affections of this extraordinary man, whom vapid worldlings sneered at as a callous cynic, were reserved for his country, his county, his home, and his friends, for effort and for distress. Many a young aspirant to fame, moreover, in literature or public life, has owed much to his generous encouragement. He liked to dwell on the vicissitudes of things,23 and his own motto, “Forti nihil difficile,” represents his conviction. In private, when he was not entertaining, his habits were of the simplest. In two things only he was profuse; books and light. He loved to27 see every room of Hughenden illuminated with candles. He was utterly careless of money. It is related, that when he accepted the Chancellorship of the Exchequer, he sent for the celebrated Mr. Padwick, and asked for a necessary advance. “On what security?” inquired the sporting speculator. “That of my name and my career,” was the answer. And the money was at once forthcoming, and punctually repaid. As is well known, he would often make his greatest efforts half dinnerless; and his delight was, after the strain and the plaudits had ceased, to betake himself in the dim hours of dawn to the supper which his devoted wife, who spared him every detail of management, had prepared, and there to recount to her the excitements of the debate. The pair would certainly have endorsed those verses of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, of which Byron was so fond—

His public and touching tribute to Mrs. Disraeli deserves repetition here; nor will the reader forget, among many hackneyed stories, that stern rebuke to the triflers overheard discussing the reasons for his marriage—“Because of a feeling to which such as you are strangers—gratitude.”

It was at Edinburgh, in 1867, when his old ally, Baillie Cochrane (Lord Lamington), toasted Mrs. Disraeli as her illustrious husband’s helper and his own dear friend for many years before Disraeli met her.24 Disraeli opened with the characteristic remark that their mutual intimate “certainly had every opportunity of studying the subject to which he has drawn attention.” And he went on to say, “I do owe to that lady all I think that I have ever accomplished, because she has supported me with her counsel, and consoled me by the sweetness of her mind and disposition.” Six years after his28 marriage, he had dedicated the three volumes of his Sybil, “To one whose noble spirit and gentle nature ever prompt her to sympathise with the suffering; to one whose sweet voice has often encouraged, and whose taste and judgment have ever guided their pages; the most severe of critics, but—a perfect wife.”

Several of his nice things were said in Scotland, and one of the nicest was his compliment when he was installed Rector of Glasgow University. He described his visit to Abbotsford, whither he had repaired in his extreme youth with an enthusiastic letter from John Murray the First, his father’s old friend, to Sir Walter Scott, that father’s old acquaintance. “He showed me,” he said of the laird, “his demesne, and he treated me, not as if I was an obscure youth, but as if I were already Lord Rector of Glasgow University.”25

Disraeli’s marriage was the happiest turning-point in his career; and that which had begun partly in interest, soon developed into the warmest, the most entire and the most mutual affection. Mrs. Disraeli, at a great country house, always used to commence conversation by the query, “Do you like my Dizzy? Because, if you don’t——” From another, on a visit most advantageous to him, Disraeli departed, despite pressing remonstrance, on the plea that the “air” disagreed with Mrs. Disraeli—because she had complained of their host’s rudeness. It will one day be found that to this gifted and selfless woman, English history owed much at several serious conjunctures. I cannot resist relating a good story in another vein. Shortly after Disraeli’s marriage, a guest at Grosvenor Gate, pointing to a portrait of the late Mr. Wyndham Lewis, Mrs. Disraeli’s first husband and with Disraeli member for Maidstone, asked him whom it represented. “Our former colleague,” was the rejoinder. At a much later date Mr. Frith was painting a group in which Disraeli figured. As her husband was going, Mrs. Disraeli whispered to the artist, “Remember one thing, if you don’t mind, his pallor is his beauty.” She was afraid that his complexion would be coloured. To the last she would say,29 as she did during his interrupted speech at Aylesbury in 1847:—“He mind them! Not a bit of it. He’s a match for them all.” Sir Horace Rumbold has just told us how, at the scene of Disraeli’s investiture as Earl, a sob was heard from the crowd. It was the grief of an old and faithful servant sighing, “Ah! If only she had lived to see him now!”

Like childless men in general, he was devoted to children. More than one still living remembers his happy words of playful intimacy. To women from the days of his pet Sheridans to those of the present Lady Currie, he appealed with magnetism throughout his career, and there are few more romantic episodes than his meetings, after hesitation, with the elderly Mrs. Bridges Williams at the fountain in the Exhibition of 1862, the existing correspondence which ensued, and the thumping legacy which crowned it. One who has read that correspondence has assured me that its gentle chivalry is most striking. In the midst of engrossing occupation he never ceased to cheer the old lady with gossip of his doings, and even to argue with her, as on an affair of state, regarding the advisability of Struve’s seltzer water as a remedy.

Of Queen Victoria’s affection for him I will only say that it was because he treated her as a woman. She grew to lean on his wisdom and his judgment. On more than one occasion he acted as mediator in her family. He was sincerely attached to her. His witticism, when asked for a reason of her favour, will bear repetition: “I never argue, I never contradict, but I sometimes forget.”

His influence over the late Queen was more remarkable even than has hitherto been disclosed. And in this regard I am able to state that, while out of office, he negotiated with extreme tact, under delicate circumstances, the peerage conferred on a most amiable prince, now no more; and further, that at each stage of all its bearings Queen Victoria consulted and deferred to his counsel, kindness, and resource. I may add that he also devised a means of providing the same lamented prince with an absorbing occupation.

He was a firm friend; loyalty he always extolled as a sovereign virtue. Not many have the faculty for friendship in old age as Lord Beaconsfield had it. His passion for30 mastery, his addiction to mystery were rivalled by his immense faithfulness. If he was always “the man of destiny,” he was also ever “faithful unto death.” And his real friendships were warm as well as constant. While he was at Glasgow to be inaugurated Lord Rector of its University, he heard good tidings of an old associate. “Mrs. Disraeli and I,” he wrote, “were over-joyed, and we danced a Highland fling in our nightgowns.” The picture raises a smile,26 but it also strikes an unexpected chord.

Of music and of art in general he was a devotee, as many passages in his novels attest. He had his own theories of their influence on composition and on literature. Murillo was his favourite painter, Mozart his favourite composer. He ever deplored the insensibility of the Government to the duty of elevating taste for the beautiful. When the Blacas collection of gems was in the market at the price of £70,000, the Administration of the day at first refused to entertain the purchase, but Disraeli persuaded them by offering to find the money himself, if they persisted. In this case, as in so many others (notably that of the Suez Canal shares), imagination forwarded the public interest; for this collection is now worth some threefold of what was expended. When a great work by Raphael was offered to the Government, and Disraeli’s colleagues were in doubt, Disraeli sent for the leading dealer, in whose hands the commission had been placed, inspected the picture himself, discoursed charmingly and critically of its merits, with the result that it is now in the National Gallery. Since even trifles about the eminent possess interest, I may add the following story of his old age. He was showing a distinguished visitor (still living) his family portraits at Hughenden. He paused before a pastel of a lovely child wafted by seraphs through the skies. “That,” he exclaimed, “is a pet picture; observe how exquisitely the draperies of the angels are arranged. The baby’s me!” His fondness for beautiful form extended to his own handwriting.

31 In matters of courtesy he was old-fashioned and punctilious. To the last he resented that grotesque disfigurement which was beginning to make manners ugly before he died. Even at an earlier date, “Manners are easy,” said “Coningsby,” “and life is hard.” “And I wish to see things exactly the reverse,” said “Lord Henry,” “the modes of subsistence less difficult, the conduct of life more ceremonious.”

In his fiction it was often objected that he over-depicted great splendour and supreme beauty; that it was thronged with “daughters” and mansions “of the gods.” But, if he erred in these respects, it was from familiarity and not from ostentation, as Lady John Manners has pointed out at some length. “It must be recollected,” she wrote, thinking of Lothair, “that many of those who most appreciated him, and whose friendship he warmly reciprocated, are surrounded in daily life by a certain amount of state which employs their dependants.” So, too, with regard to the peaceful and prosperous marriages of those homes of forty years ago on which he delighted to dwell. He loved the gentle Buckinghamshire landscape, with its treasures of association in every cranny, more than all the remembered luxuriance of the South and glare of the East. And it should also be remembered that his works abound in sympathetic descriptions of all kinds and conditions of men, including the strangest and humblest. They were taken from personal observation, and he himself would penetrate the queerest haunts to gain the most curious insight. The common and the uncommon people fascinated him, for in them he found ideas; the middling charmed him less. He delighted to invest the seemingly commonplace with significance, and also to strip the pretentiously important of its wonder. Not even Dickens, as I shall hint hereafter, knew or loved his London better. I shall also, in the proper place, touch on the exotic element in his style and accent. Mr. John Morley has aptly compared it to Goethe’s dictum about St. Peter’s, that, though it is baroque; it is always the expression of something great and not merely grandiose. His big words are never for little things. Undoubtedly some of his earliest works are deficient in taste; and there is a certain fierce hardness in their abrupt violence. Mrs. Austin advised him32 in omissions from the original manuscript of Vivian Grey; it was to women that he owed his training in these directions. His knowledge was vast and profound, and he exercised the habit of pursuing long trains of thought in reflection. He seldom worked at night, preferring that season for brooding over his ideas. But at all times, contrary to the superficial opinion, he worked long and hard, sometimes over ten hours a day. His gift of divination never dimmed his passion for study, until old age and ill-health warned him that it must pause. He never ceased to deplore the want of “that boundless leisure which we literary men need.” To the last, as Lord Iddesleigh has pointed out, he studied the Bible in the earliest hours. In church attendance he was what Mr. Gladstone used to call a “oncer.” He was a regular communicant.

By success he was never inflated, by reversals never depressed, although by nature elastic.27 It was not until 1874 that his power became wholly unfettered, and then foreign crisis claimed the attention that he longed to bestow on social improvements and Colonial Confederation. His three previous spans of office had been equally brief. For some twenty years he headed, at intervals, a despairing Opposition, whose mistrustful murmurs had to be stilled, whose doubts had to be dispelled, and the immense difficulties of whose management he has graphically portrayed in a notable passage from his Life of Lord George Bentinck. To the printed diatribes which assailed him he was indifferent. In parliamentary generalship, demanding an infinite insight and management, an instant recognition of movements in the mass, and “creation of opportunity,” he was unsurpassed even by Peel, who played on Parliament “as on an old fiddle.” To his urgent control even so early as 1854, and when out of office, the correspondence with Spencer Walpole affords a striking insight. “My dear Walpole,” he writes on November 29 of that year, “remember to write to the Queen if anything of interest happens to-night. Tell somebody, Harry Lennox or another, to send me a bulletin by this messenger of what is taking place, but not later than ten o’clock, as I shall retire33 early, that being my only chance. Be positive that the financial statement will be made on Friday.”28

What he really valued in power was its faculty of influence. Otherwise it was bitter-sweet. He once told a high aspirant for high office, that as for its pleasures, they lay chiefly in contrasting the knowledge it afforded of what was really being done with the ridiculous chatter about affairs in the circles that one frequented.

His wit, his brightness of humour, and lightness of touch, long prevented many of his contemporaries from taking him seriously. Literary statesmen are often belittled by their generation; imaginative statesmen, always. They have usually to await a career after death. The stereotyped character imposed on him till his pluck and power appealed to the nation at large was largely due to the old Whigs (“oligarchy is ever hostile to genius”29), who for years refused to regard him with anything but amusement, yet whose drawing-rooms had been the readiest to applaud those sparkling sallies of 1845 and 1846 that demolished the premier whom they too wished to destroy; that coterie so long trained to make popular causes preserve their exclusive power, and of whom he wrote in 1833, “A Tory, a Radical, I understand; a Whig, a democratic aristocrat, I cannot comprehend.” It was not due to the Peelites, who frankly hated him as an open foe. Even the Liberals (many of whom he counted as personal friends), when he warned them of the underground rumblings, ominous of social earthquake in Ireland, shrugged their shoulders; and when he was reported, glass in eye, to have answered a duchess inquisitive about the exact date of the dissolution with “You darling,” they split their sides, and guffawed, “There he is again!” They agreed with his old family acquaintance, Bernal Osborne (if it was he), to whom the heartlessness was attributed of saying, when Lord Beaconsfield was stricken with his lingering illness, “Overdoing it, as usual.”

And yet how interesting it is to find Disraeli in the34 Grant-Duff diaries discoursing eagerly in the faint dawn on Westminster Bridge of Lord John Russell. Perhaps Disraeli’s greatest admirer among opponents was Cobden, and that admiration was warmly returned. Both of them had one great virtue in common, and a rare one, especially in public life—gratitude; and both could afford to be generous. Read the letter now first disclosed by Mr. John Morley, whose literary appreciation of Disraeli is manifest, in which Disraeli sought to win Gladstone with “deign to be magnanimous.”

Disraeli’s own magnanimity—frankly owned by Mr. Gladstone—was conspicuous though it is unfamiliar. During the decade of the ’fifties, on at least four occasions30 he offered to sacrifice his personal position to Graham, Palmerston, and Gladstone successively for the interests of his country and his party. In 1868 and 1869 he indignantly defended the last against the carping “tail” of his supporters, rebuking alike the “frothy spouters of sedition,” and those who preferred remembrance of “accidental errors” to gratitude for “splendid gifts and signal services.” His unstinted praise of worthy foes, his conduct even towards the ostracised Dr. Kenealy, are constant proofs of a leading trait. He always forebore to strike an opponent to please the whim or the passion of the popular breeze.

À propos of Mr. Gladstone, who himself paid a tribute to the absence of rancour in his rival, I may be permitted to recall an anecdote told me by the late Sir John Millais. When Disraeli stood (though then suffering, he refused to sit) for his last portrait, his “dear Apelles” noticed his gaze riveted on an engraving of the artist’s fine portrait of the great premier. “Would you care to have it?” he inquired. “I was rather shy of offering it to you.” “I should be delighted to have it,” was the reply. “Don’t imagine that I have ever disliked Mr. Gladstone; on the contrary, my only difficulty with him has been that I could never understand him.” And Carlyle himself thawed when Disraeli, whom he had so long hysterically abused, but many of whose ideas, as I shall prove, he shared, offered him public recognition in a letter which gave as a reason for uninheritable honours, “I have remembered that you too, like myself, are childless.” But35 Carlyle, who had aspersed him, never denied that he looked facts in the face without mistaking phantoms for them. Even from the first he owned length of view. In his old age a certain far-awayness of expression was very noticeable.

I have mentioned Mr. Gladstone. It was well for England that two great attitudes towards great questions should have been thrown into sharp relief for nearly a score of years by the duel between two great personalities; and it was also well for Disraeli that “England does not love coalitions.” We know from Mr. Gladstone’s own lips that much in his rival had won his respect, while from Mr. Morley we glean that Mr. Gladstone even struggled with a sort of subacid liking for one whom he too could “never comprehend.”31 The letters of both after Lady Beaconsfield’s death are refreshing instances of how sworn enemies of the arena may grasp hands under the softening solemnity of bereavement, and for a moment forget the hard words which, under irritation, they certainly used of each other.

Disraeli was older than Gladstone, and had been early acquainted with him. In the ’thirties he sat next to “young Gladstone” at the Academy dinner, and regretted that he had been relegated from “the wits,” with whom he had been ranged in the year previous, to “the politicians.” In the ’forties Disraeli made one of his few mistakes in prognostic, when he wrote to his sister, “I doubt if he has an ‘avenir’;” but the significance of Gladstone’s resignation at this juncture on “Maynooth,” and the peculiar circumstances of the Peelites must be borne in mind. Disraeli could scarcely then divine the surprises of oscillation in store.

Except in vigour of undaunted character, and in a sort of inward loneliness, their qualities were opposed. The intensity of the one was austere, imperious, imposing, and didactic; of the other, buoyant, lively, and poignant. Frequently the36 flippancy of certain leaders provoked his gravity; more frequently the solemnity of others upset his own. Gladstone moved by violent reaction and hasty rebound; Disraeli, by a spring of step, it is true, but of a step measured, wary, and equal. Disraeli stamped himself on his age; it was often the “Time-Spirit” that impressed itself on Mr. Gladstone, a list of whose changeful “convictions”32 from 1836 to 1896 might fill a small volume. Again, Disraeli’s utterance left a stronger sense of reserve power, of something serious behind the veil. Mr. Gladstone’s phases, always sincere, in the main struck more the conscience of certain sections; Disraeli’s ideas, the national feelings. Mr. Gladstone’s subtleties were those of a theologian; they did not quicken the lay mind. Disraeli’s were the subtleties of an artist; they put things in new perspectives. It might be said that by nature and unconscious bent, the one hid simplicity under the form of subtlety, while with the other the process was the converse. In oratory, Mr. Gladstone convinced by height and redundance of enthusiasm, by depth of feeling and weight or wealth of words and gestures; Disraeli, more by grasp, incisiveness, and point; his imagination played all round many sides of his subject. Gladstone’s eloquence resembled the storminess and the mist of the North Sea; Disraeli’s, the strange lights and shadows, the subtle and tideless lustre of the Mediterranean. As Mr. Gladstone warmed to his theme, he increased in eloquence; his perorations are always great. It was in peroration that Disraeli sometimes failed, except in his after-dinner speeches, which never missed fire from start to finish.

Mr. Gladstone was saturated, Disraeli tinctured, with the classics. Mr. Gladstone was essentially the scholar, and he was Homeric, while Disraeli was Horatian and Tacitean. His ready acquaintance with Latin masterpieces was shown when he first37 took the oaths as Chancellor of the Exchequer, and hit off a most happy quotation on the spur of the moment; nor will it be forgotten that once, when he was citing a classic in the House, he added, “Which, for the sake of the successful capitalists around me, I will now try to translate.”

Again, despite Mr. Gladstone’s immense versatility, there was always something cloistral about him. He himself confessed that till he was fifty he did not “know the world.” I venture to doubt if he ever knew it, and it was just this academic simplicity that so often led his huge brain-power to deal with unsubstantial material.

Mr. Gladstone will not live through his books. He was far more a writer than an author, though he was always distinguished in all his undertakings. But he was doctrinaire; and he was almost devoid of any real sense of humour. On the appearance of “Nicholas Nickleby” he owned its merit, but singled out its pathos with the criticism that he was grieved by the absence from it of the religious sentiment—“No Church!” In this respect Disraeli and Gladstone were brought into amusing contrast during the Bulgarian atrocity campaign. Mr. Gladstone had characterised the Premier’s attitude as “diabolical.” Disraeli, in a speech, referred to Mr. Gladstone’s having called him “a devil.” Mr. Gladstone denied the impeachment, and asked for verse and chapter. Disraeli rejoined by writing that “the gentlemen who so kindly assist me in the conduct of public affairs” had used their best endeavours to ascertain the precise time and place when the Prince of Darkness had been named, but hitherto without success.

A famous bookseller, with whom both statesmen frequently conversed, used to recount that Disraeli once inquired, as was his wont, what of new interest was forthcoming. He mentioned one of Mr. Gladstone’s Vatican pamphlets. “No,” was the answer; “please not that. Mr. Gladstone is a powerful writer, but nothing that he writes is literature.”

In the House of Commons Disraeli had schooled himself from the first to conceal the emotions of a nature naturally quick and sensitive. He early lit on two mechanical devices for this purpose: the one was to stroke his knees regularly38 with his hand, the other to scan the clock. When he was much angered it was only by a change of colour that his agitation was ever betrayed. It must be confessed that he loved to “draw” Mr. Gladstone, and those who remember how, when Disraeli sat down and relapsed into impassivity, Mr. Gladstone jumped up with a look of rage and a voice of thunder, will admit that both performances were perfect. But the audience expected the scene which became habitual, and even supreme actors are influenced by the expectation of their audience. Neither Gladstone nor Disraeli ever stooped to ill-nature. Great men are not petty. But the moral indignation of the one, and the intellectual indignation of the other, which sometimes exchanged places, lent the semblance of pique or of quarrel. Disraeli’s dislike of spleen is well displayed by what he once said of Abraham Hayward, the caustic reviewer: “If that man were to be run over in the streets, you would see his venom swimming in the gutters.”

In debate, Disraeli’s characteristics were a quick readiness and an inexhaustible power of diverting discussion to new channels and of defeating expectation. The occasion when, in reply to Mr. Whalley concerning the Jesuits, he answered that one of their pet devices was to send over Jesuits in disguise to decry the Jesuits, will recur to the memory. His power of literary illustration needs no comment. Two brilliant instances are that of the boots of the Lion embracing the chambermaid of the Boar in connection with the Edinburgh and Quarterly Reviews, and that charming one about the Abyssinian expedition, where he reminded us that the standard of St. George was flying over the mountains of Rasselas.33 In retort he was supreme. Two of the best instances are to be noted in the rejoinder to Peel about “candid friends” and Canning, and in the pause he made when in a much later speech he said, “I have never attacked any one” (cries of “Peel”) “unless I was first assailed.” I shall relate some others hereafter. His self-imposed impassiveness of demeanour in the House was that of a sentinel on bivouac; it became exaggerated by the contrast of his illustrious compeer’s39 extreme excitability. Disraeli was very zealous for the honour of the House in which he passed the greater portion of his life. On one occasion a young and violent adversary insinuated that Disraeli had told a lie. Disraeli calmly cleared himself to the general satisfaction, and his denouncer began to feel uncomfortable; still more so when he was sent for to the great man’s private room. What was his surprise when he was shaken warmly by the hand. “We all make mistakes,” said Disraeli, “when we are young. But please to remember all your life that the House of Commons is a house of gentlemen.”