CÆDWALLA

Cædwalla

OR

THE SAXONS IN THE ISLE OF WIGHT

A Tale

BY

FRANK COWPER, M.A.

QUEEN'S COLLEGE, OXFORD

With Illustrations by the Author

SECOND EDITION

LONDON

SEELEY & CO. 46 47 & 48 ESSEX STREET, STRAND

(LATE OF 54 FLEET STREET)

1888

All Rights Reserved.

TO

H.R.H. PRINCE HENRY OF BATTENBERG, K.G.

Hon. Colonel 5th (Isle of Wight "Princess Beatrice's")

Volunteer Battalion. The Hants Regiment.

THIS TALE

OF THE DEEDS OF TEUTONIC WARRIORS IN OLDEN TIME

IN THE ISLE OF WIGHT

IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED

BY

THE AUTHOR

PREFACE.

In writing a story of the Isle of Wight in the seventh century, which shall at the same time be suitable for young people as well as historically truthful, there are many difficulties. The authorities for this period are Bede and the Saxon Chronicle. The former obtained his information of the South Saxons and the Wihtwaras from Daniel, Bishop of Winchester, who was evidently well-informed of the state of the southern people during the later half of the seventh century. Eddius, Asser, Ethelweard, Florence of Worcester, and Henry of Huntingdon all supply information, more or less accurate, as they are nearer to or more remote from the time of which they treat; and the valuable remarks of the modern specialists Dr. Guest, Kemble, and Lappenberg, are useful in leading the student to a right judgment of the facts. The historians, Dr. Milman, Dr. Lingard, and Mr. Freeman are also important helps, especially the first-named writer. Neander's "Memorials of Christian Life" and Montalembert's "Monks of the West," have been consulted, with a view to becoming acquainted with the theology and religious fervour of the times; and Mallet's "Northern Antiquities" has been largely laid under contribution for a clue to the mythology of the period, although properly belonging to a later time, and to the Scandinavian form of Teutonic religion. The author has also had the learned assistance of the Rev. J. Boucher James, M.A., Vicar of Carisbrooke, and late Fellow and Tutor of Queen's College, Oxford, whose antiquarian knowledge of the Isle of Wight is accurate and profound.

The scenes are all well known to the writer, who has many times threaded the channels at the entrance to Chichester Harbour, and climbed the steep slopes of Bembridge and Brading Downs.

As the story has been written for young people, sentiment has been entirely omitted, the ideas of the author differing from those of other writers who make their youthful heroes and heroines suffer the sentimental pangs of a Juliet and a Romeo.

The mode of spelling the Saxon names has been carefully thought over, and the most commonly received method has been generally adopted.

The name of the outlaw, West Saxon King, and enthusiastic convert to Christianity, Cædwalla, himself, has offered considerable difficulties, since there are many ways of writing his name, and probably not a few of pronouncing it. Cæadwalla, Cædwalla, Cadwalla, are the most common forms; while perhaps the most correct pronunciation would be represented by Kadwalla.*

* The name of Cædwalla bears a singular resemblance to that of Cadwalla, the British prince who made war upon Ædwin, king of Northumbria. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, Cadwalla was succeeded by Cadwallader, who died at Rome AD. 689, the very place and date of Cædwalla's death, according to Bede. Could Cædwalla have really been of British descent?

His brother, Mollo, Wulf, or Mul, as he is indifferently called, is also a very ambiguous personage as regards nomenclature, and it has even been suggested that his name was "Mauler," as though he were an awkward man to deal with in a personal encounter!

A few simple foot-notes have been appended; not that they were necessary to students of history, into whose hands the author hardly ventures to hope the little book will fall, but because it seemed some explanation was required for younger readers.

That the state of the south of England during the latter half of the seventh century was a very dismal one, is sufficiently clear from all contemporary evidence, and the author has not attempted to give a more couleur de rose view of it than his materials justified.

It is, however, quite evident from Bede and other authorities that the English or Saxons had already developed great intellectual powers, and where law and order were more firmly established than in the south of England, general culture and the arts of peace were making steady progress.

Such learning as that of Bede, such architecture as that introduced by St. Wilfrid at Ripon and Hexham, such artistic work as that of the Royal MS. preserved in the British Museum, which may have been the very one presented by Wilfrid to his church of York, show that the Saxons, who are so often described as mere jovial, hard fighting, hard drinking, blustering dullards, had in many instances reached a comparatively high standard of civilization.

- Lisle Court, Wootton, I.W.,

-

July, 1887.

CONTENTS.

CHAP.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

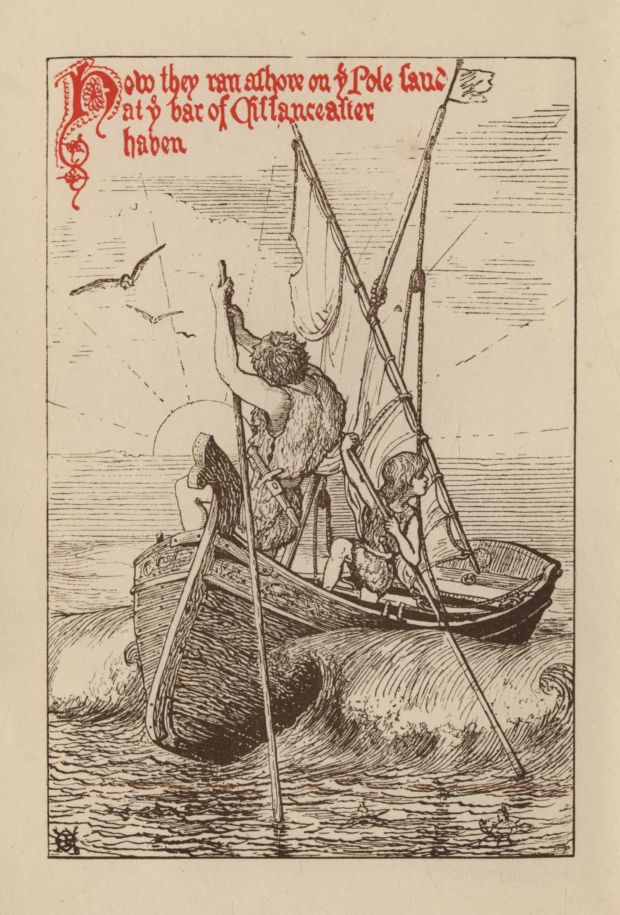

How they ran ashore on the Pole Sand at the Bar of Cissanceaster Haven . . . Front.

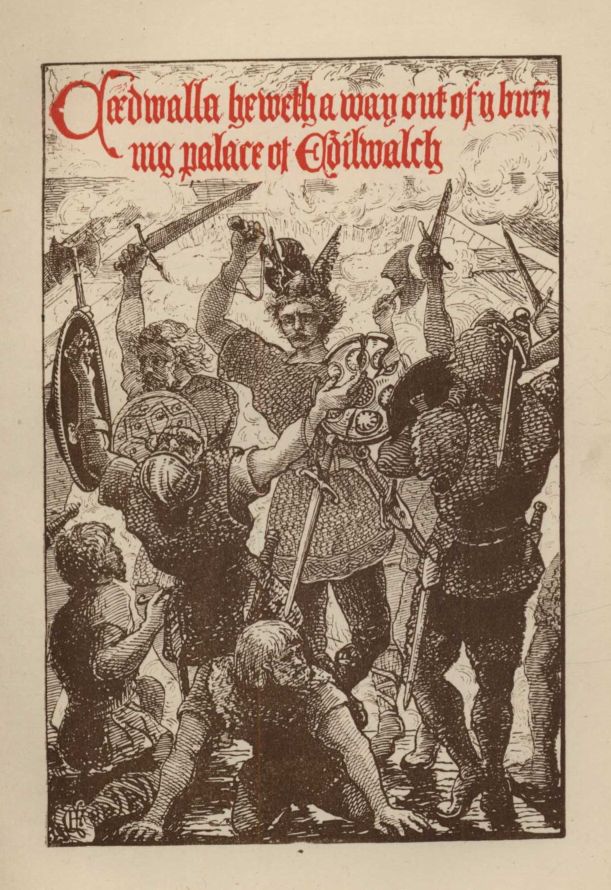

Cædwalla heweth a way out of the burning Palace of Edilwalch

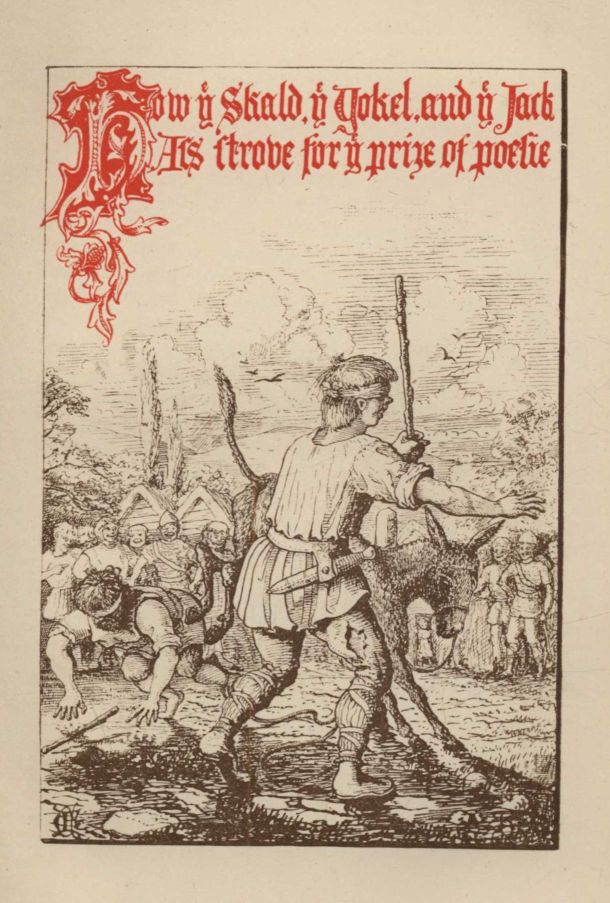

How the Skald, the Yokel, and the Jackass strove for the Prize of Poesie

How they talked of many things as they mended the boat at Boseham

How Dicoll and Ædric saw the boat depart

How Deva, Malachi, and Wulfstan were surprised by the Wihtwaras

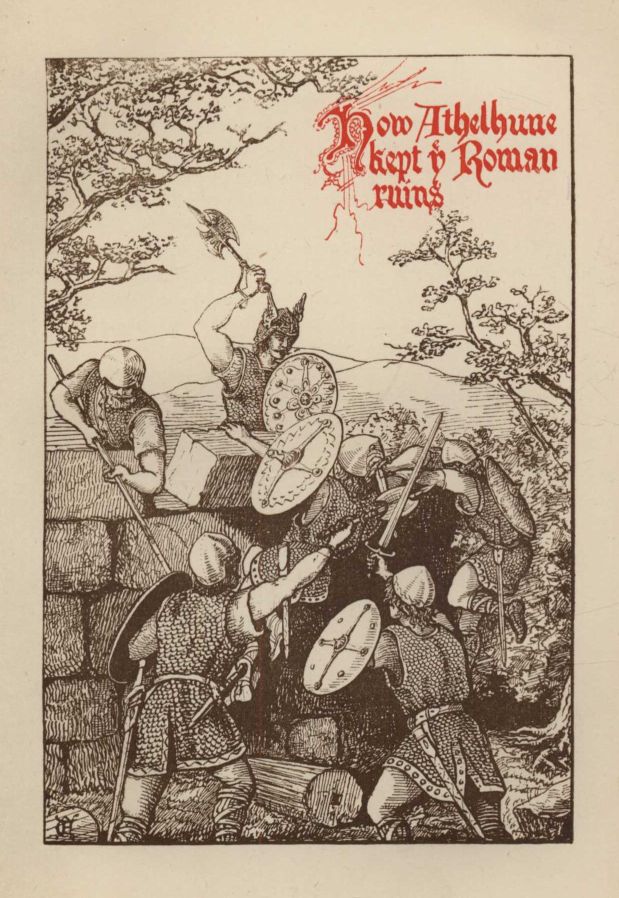

How Athelhune kept the Roman Ruins

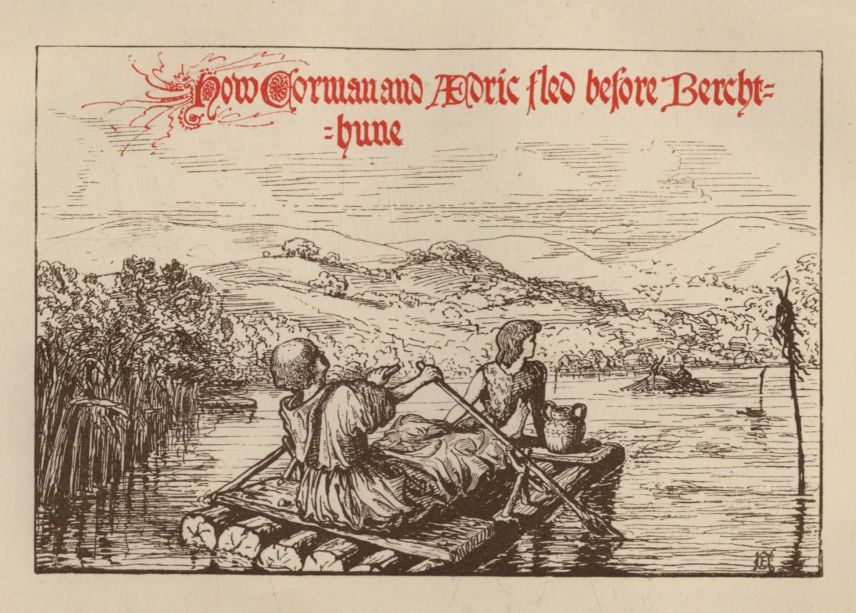

How Corman and Ædric fled before Berchthune

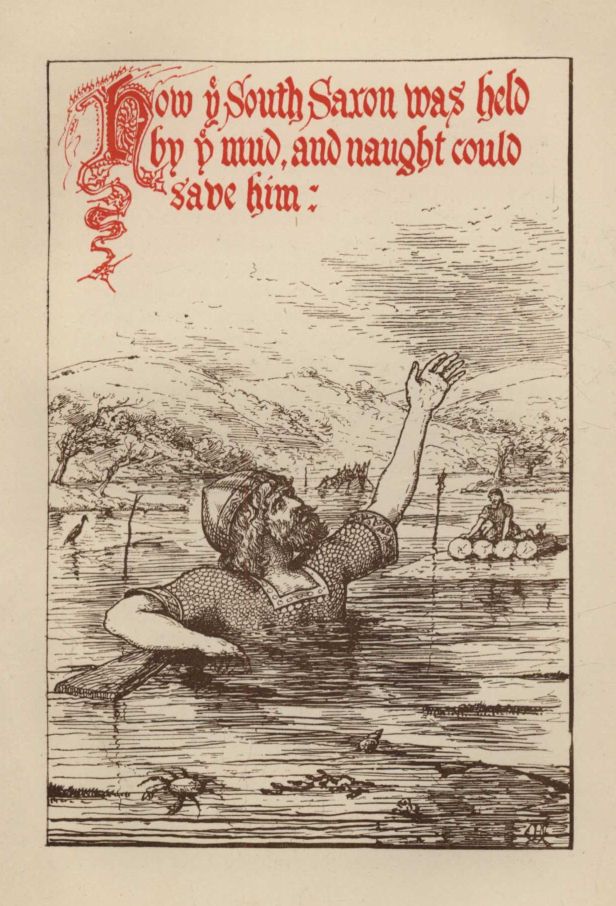

How the South Saxon was held by the mud, and naught could save him

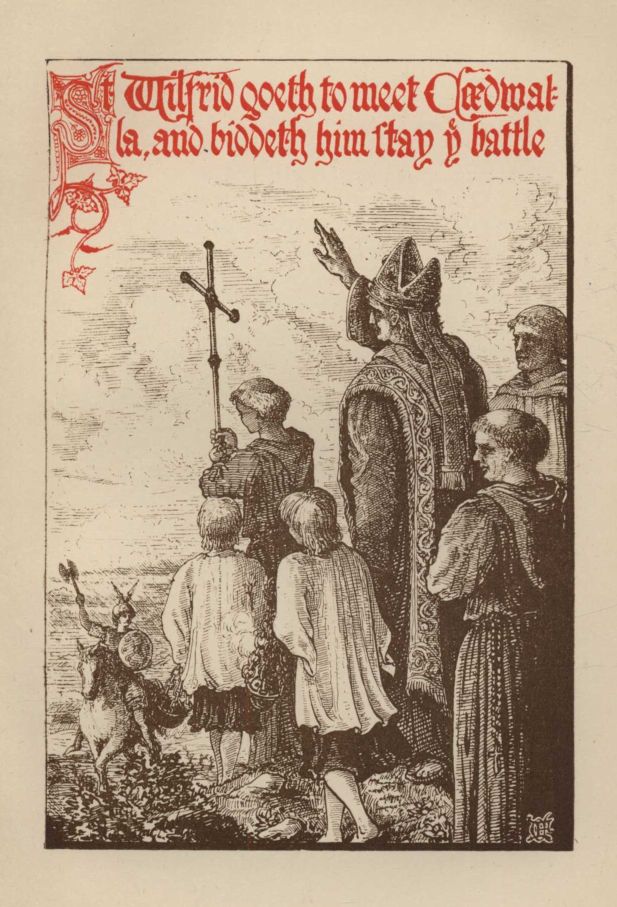

How Wilfrid goeth forth to meet Cædwalla, and biddeth him stay the Battle

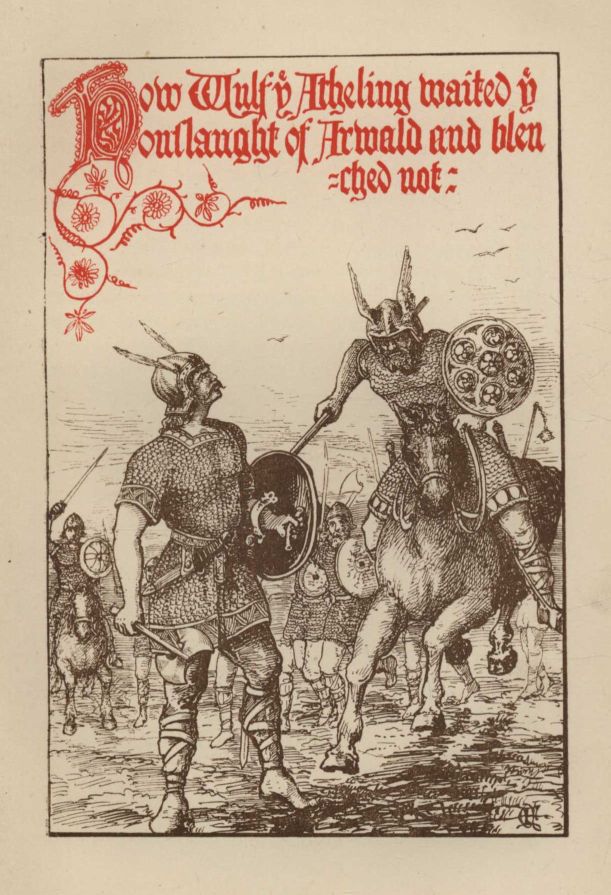

How Wulf the Atheling waited for the onslaught of Arwald, and blenched not

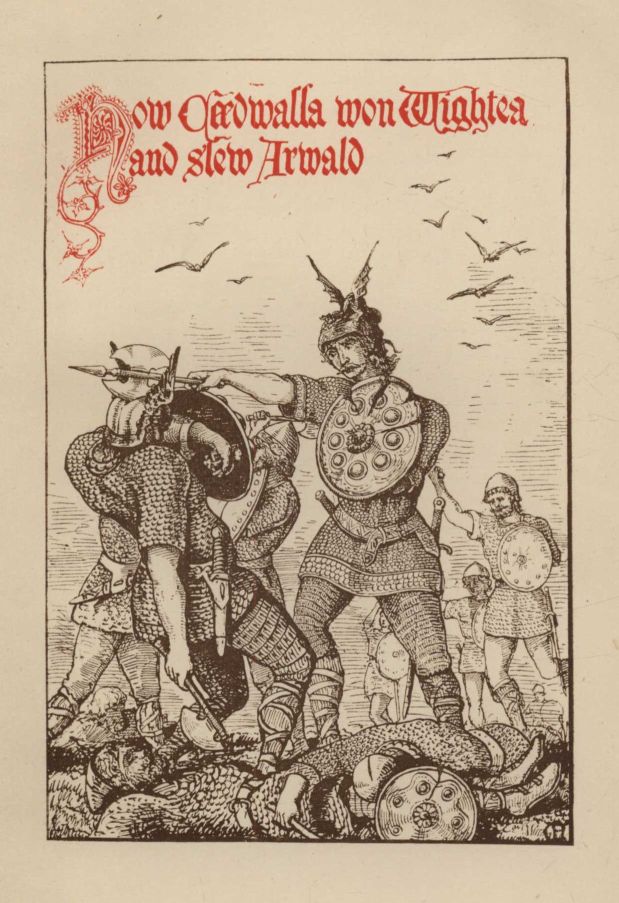

How Cædwalla won Wihtea, and slew Arwald

CÆDWALLA

OR, THE SAXONS IN THE ISLE OF WIGHT

CHAPTER I.

STRANDED.

"How much longer, thinkest thou, must we be here, Biggun?"

To this question no answer was returned, and after a moment the same voice spoke again rather more feebly.

"Biggun, why answerest thou not? What ails thee? Oh, how she does bump!" And the child's voice became tremulous with pain.

"It won't be a long time now, Ædric, before she floats, I'm thinking; the tide is making up fast—only if she don't go to pieces first I'm a weala,"[1] added the speaker, under his breath.

[1] The general name for foreigners, but applied especially to the conquered, and therefore despised, British. The words Wales and Welsh are the modern equivalents.

"Art thou much in pain, Eddie?" said another younger and brighter voice.

"Oh! Wulf, it does hurt here so much. It wouldn't hurt like this, I think, if the weary old boat wouldn't bump so dreadfully—oh!—" exclaimed the boy, as a rolling wave came in and raised up the large, awkwardly-built boat; and then, as the white crest of the wave passed on to break in a long frothy cataract over the shallow sand-bank beyond, the boat fell back with a bump that made every timber in her strain and creak and work as though she would go to pieces.

The old man addressed as "Biggun," whose real name was Ceolwulf, but who was always called Biggun by reason of his height and breadth of chest, had gone to the bows of the boat as he saw the wave coming, and, calling to the boy who was addressed as Wulf to take his pole and push hard, had leant with all his might on his own long pole; and, as the wave lifted the awkward craft, their united efforts made her give a little.

"There she goes, there she goes; her head is coming round. Ah, now she's aground again! Well, never mind, the next roller is coming, and she'll come off then. There, have a care not to overstrain thyself, Wulfstan," said the old man cheerily. "Wait for the next swell; we want all our strength, and it is not much either that we've got."

The position of the boat was not a very safe one, considering the condition she was in. She was lying aground on a sand-bank at the entrance of a harbour which was then, as it is now, very difficult for a stranger to find his way into.

The boat had got aground fortunately at the time when the tide was just beginning to rise, and there was, therefore, every hope that she would float off again as the tide rose; but there was also the great danger of her breaking up first, considering how old she was and how badly built, and the difficulty of getting her off was considerably increased by the long rollers that came in, with their green and glassy swirl, and lifted her farther and farther on. Had there been more strength in the crew it would have been an easy matter to get her off, or had the boat drawn less water; but she was such a heavy, clumsy, thing, drawing quite four feet of water, that it would have done no good to get overboard and push, for her weight would have only been imperceptibly lightened, while the depth of the water would have prevented any great strength being applied by pushing her. There was nothing to be done, therefore, but stand in the bows and push with all their might against the sand with two long poles they had with them.

It was early in the morning of an October day, and owing to the dim light of the hour before sunrise they had got aground; for although Ceolwulf, or Biggun, had never been in here before, yet he was accustomed to find his way into creeks and out-of-the-way harbours, and would have avoided this bank could he have seen the long rollers breaking ahead; but in the white mist of the early morning he could not make them out. It was true that their dull sound in the still morning air should have told him there were dangers near; yet the waves were breaking all around on many similar sand-banks, and it was difficult to tell how near they were. As the glow of the coming sun spread over the sky they could make out their position better. About two hundred yards on their right was a high bank of shingle, with nothing whatever to be seen above it; this bank stretched away to the west until it was lost in the mist, but immediately ahead of the boat it ended in a point of shingle, steeply sloping down to the sea; beyond this point nothing could yet be seen but the oily sea blending with the grey mist; directly under the bows of the boat the sea was breaking in long glassy rollers, while beyond them a low and shingly beach stretched away into the mist again; overhead the grey fog was rolling off in ever-changing wreaths, and towards the east a warm rosy light told of the rising sun; behind them the impalpable mist and sea faded into one, only now and then a dark ridge would rise up and come majestically rolling onwards, the boat would give a gentle heave, then come down with a heavy bump, and the wave would pass on to curl over in a sounding deluge of foam, and spread out in white froth over the bank to join the eddying current on the other side.

The occupants of the boat were two boys, about ten and twelve years of age, and the old man. The eldest boy, who was addressed as Eddie, and whose name was Ædric, was lying down in the most comfortable position he could obtain in the bottom of the boat. He was covered up with a few skins, and from time to time moved in a feverish, restless way. His head was all that could be seen, and showed a pale, handsome countenance, with blue eyes and yellow hair; but the evident expression of pain made the face look older than it was. The unkempt hair lay in curling masses on a pillow of rough cow-hide, and it would have been difficult to tell if the figure were that of a boy or girl.

Beside him lay a bow and some arrows, a couple of spears, and a formidable-looking axe. There were no other articles in the boat, and the only means of propelling her were three long and very rude oars, a mast, and one old and patched sail bent to a yard, and hoisted like a lug-sail, only quite incapable of being set properly, both by reason of its shape and the weakness of its material. The halyards which hauled the sail up were old and worn, and they would have given way at the least strain put upon them.

There had been a light draught of air from the south during the night, but it had blown rather heavily from the south-west for two or three days previously.

The old man called Biggun was a hard, weather-beaten, grim-looking fellow, his reddish-grey beard and stubbly moustache surrounded a sunburnt face seamed with wrinkles, and two sharp grey eyes looked out from under heavy, bushy eyebrows. He wore no covering on his head, and his dress chiefly consisted of a leathern coat or jacket, covering a rough woollen kind of jersey, which formed a kilt below his waist. On his legs he wore pieces of leather with the hair on, strapped round with thongs of hide, and rough leather sandals protected his feet. He was armed with a sharp knife at his waist-belt.

The other boy was a bright-looking little fellow, of about ten years of age, fine and well-made; his hair, like that of his brother, hung in thick masses round his neck, and would have been all the better for a little brushing and combing. He was fair, like his brother, and gave promise of developing great strength in later life. He was dressed in a tight-fitting tunic of coarse woollen stuff, and wore short drawers of the same material, and bare legs. He also carried a small dagger suspended from a leathern belt, and leather sandals, strapped on to his feet and round his ankles, completed his equipment.

"Now, Wulf, hold on to thy pole," called out Biggun, as a dark ridge rose up silently astern and came rolling on. The stern of the boat lifted, and as the wave passed under her, the old man and the boy leant with all their might on their poles, and Ædric called out: "That's it, I feel her moving—there she goes; that's right, keep her going. Ah! now we are off," as Biggun and Wulfstan kept pushing with their poles as the boat moved astern.

"Well, Wulfstan, thou didst that well, I will say; and thou wilt grow up yet to pay off the debts of last night upon that nithing Arwald. Ah, the robber! I wish I had got my axe into him, that I do. That's right, keep her head round; the tide will swing us in now, and we can see all the banks."

The boat was now fairly afloat, and was, as Biggun said, being rapidly carried into the narrow channel of deep water that led between the steep shingle point and the outlying spit of sand on which they had bumped.

The sun had risen over the mist, and the grey bank ahead gradually resolved itself into a low island, covered with bushes and a few wind-blown trees, which all looked as if a violent gale was then blowing, although everything was perfectly still. Their branches stretched away to the north-east, and all the side towards the south-west was bare and branchless. On each side of the island the sea flowed up in winding channels, with wide reaching mudbanks between the water and the shore; beyond the lowland and water, rose thickly-wooded hills, standing back some distance from the immediate foreground.

Slowly the boat passed the shingle point, and was paddled with difficulty towards the channel on the right. They had now got into perfectly still water, and Wulfstan was amused to see how curious the waves looked as they stood up astern like a low dark wall, and then suddenly broke up into foam, followed by a dull, heavy sound like distant thunder.

"Thou art in less pain now, Eddie?" said Wulfstan.

"Yes, Wulf; but the leg hurts a good deal—it aches so. I wonder what became of father? Think of our home all burnt down! and father killed. Dost thou think he was killed, Biggun?"

"I am greatly afraid of it. He wasn't the man to let his goods go without a fight, and we know how the fight went."

It was an age when men did not sorrow long; they were so accustomed to slaughter, and robbery, and misery, that the loss even of the nearest and dearest relations stirred more the feelings of revenge than the softer emotions.

The South of England in the latter part of the 7th century was not a place where sentiment could flourish; men had no time then for the luxury of sorrow. Hard knocks and little pity was the order of the day. Ninety, or rather eighty-four years ago, Augustine the Monk had set foot in the Island. But that part of it where the events just related were taking place had not yet heard the Gospel tidings, or, if a faint rumour had reached the leading Eorldomen, the common people knew little of it. Quite recently, a few strange men, speaking an unknown tongue, had come to the inlet, the entrance of which has just been described; they had come by land, and had forced their way through the vast impenetrable forest that separated the South Seaxa, or Sussex, from the rest of England. There were but four of these men, and their habits were very simple and harmless, and the rude men of the country saw nothing to gain by doing them harm. They let them live therefore; and they had settled at a convenient spot at the head of a creek that had its outlet to the sea, upon the sandy bar of which the boat had struck. This place was called Boseam, or Boseham, and is known to-day by the very little altered name of Bosham.

There had also lately arrived a wonderful man, a Skald or Priest, as Biggun had heard, who had all sorts of charms and spells, and who had come from foreign parts. He, like the strange men of Bosheam, never fought; he wore splendid clothes, and talked in a wonderful way. Edilwalch, the king of the South Saxons, stood greatly in awe of him, and so did all the country round.

"But what tongue does he talk?" said Ædric, who was greatly interested in what Biggun was telling them about this wonderful man.

"He talks English, only in a different way to what we do; rather more like those men who were wrecked on our coast last year."

"What, those men who came from Bernicia, as they called it, and wanted to go across the sea? But, Biggun, what's that thing standing up in the water there?" added the boy with eagerness.

Biggun looked, and saw a thing that seemed like a man's head and shoulders standing out above the water. But the face was very flat and badly formed, with large bristles over the mouth, and bright eyes the skin nearly black and covered with long hair. For the first moment or so he was puzzled, not being a man of quick apprehension, but directly afterwards he called out: "Why, it's a seal! You have seen many of them off our point at the Foreland, Wulf."

The creature did not seem at all afraid of them, but was presently joined by another, who rose awkwardly up on the shallow sandbank and flapped its fins at them. They were approaching the Isle of Seals, or Sealsea.

Wulfstan picked up the bow from beside his brother, and was going to let an arrow fly at the creatures, when Biggun stopped him, saying: "We may want all our arrows, and we can't pick up the beast if thou dost hit it. Hark! there's somebody hallooing," and Biggun rested on his oar to listen.

A loud voice from the shingly promontory they were passing hailed them. Old Biggun looked leisurely round, and saw a tall, well-made young man. He was armed with a long bow, and a quiver, full of arrows, hung over his shoulder by a broad leather strap, and carried a stout boar spear in his hand, while a bright two-edged battle-axe hung in another belt, and balanced a long, straight sword that hung at his left hip. He wore a loose tunic of leather, covered with little steel rings, sewn one over the other in a careful manner, and in such a way that the upper ring lapped over the one below at the spot where it was attached to the leather tunic; he wore a close-fitting cap on his head, protected by steel plates and ornamented with a heron's crest; his legs were encased in tight leather leggings and stout leathern boots. Altogether he looked a thoroughly well armed and gallant young fellow—one who would help a friend, and be likely to make himself respected by a foe. His fair, curling hair and laughing blue eyes added to his free and handsome appearance.

Wulfstan, boy-like, was instantly taken with him, and admired him immensely. He thought he must be Balder the Beautiful, or perhaps Thor himself—at least, they could not be finer looking; and he insensibly let his oar dip into the water, which, as he was rowing on the port or left side of the boat, had the effect of holding the water and turning the boat towards the shore.

"What art thou doing that for, Wulf?" growled old Ceolwulf, or Biggun. "We don't want to take that stripling on board, and we don't want to get too near him neither, until we know who he is and what he wants."

"Ho, there! put me across, will you?" shouted the stranger.

"Aye, aye; but we must know thy business first," bawled Ceolwulf in return, resting on his oar.

"I want to go to Cymenesora. Thy crew seems weak. I might lend thee a hand at an oar if thou art bound for the same place."

"Maybe we are, and maybe we aren't," said the cautious Ceolwulf; "but I don't see how we're going to get thee in. See how the tide is setting us up?"

"Yes; but, Biggun, if I back water and thou pullest we shall swing round, and not many strokes will bring us ashore, thou knowest well," said Wulfstan.

"That's all very fine, Wulf; but how am I to know if it's safe to take him on board? We're strangers in a strange land, seest thou, and it's better to keep to ourselves until we know who's who. That young man there is too fine a bird not to be somebody, and he may not be friends with them who have the rule in these parts, dost understand? or he might take a fancy to our boat perhaps. There's no knowing."

"Now, old man, art going to put me across or not?"

"Do, Biggun, row ashore. If he is somebody important, we shall be all the better for having done him a good turn; and, besides, he can get us to Boseham, or wherever we are going, all the quicker, and then poor Eddie can be attended to. And I am dying of hunger, too."

"Well, I don't much like it, but I don't see that we can come to much harm anyway. Let me paddle a bit, Wulf; she will come round into the slack water under that point. There—that's it."

The tide had already carried them close to the point, and a few strokes brought the bow of the boat grating against the steep shingle, but not sufficiently near for the stranger to get in without wetting his feet. However, taking a run, and using his spear as a leaping pole, he sprang lightly on board without touching the water at all.

"Well, old man, I don't see what thou would'st have gained by going off without me, and thou mayest get some good by taking me with thee. Hollo, my fine boy! what's thy name? and what's the matter with thee?" he added, seeing Ædric in the bottom of the boat.

Ædric now for the first time saw the well-armed handsome stranger, and, like Wulfstan, he thought him the most splendid man he had ever seen, and, boylike, never connecting any thoughts of suspicion with so frank and prepossessing an outside, did not hesitate a moment to answer him.

"My name is Ædric, and I broke my leg last night when our house was burnt down."

"And how was that?"

"Ah! that's a long tale," said Ceolwulf, who did not at all like this way of telling all about themselves while he knew nothing of the new comer. "We can be telling all we know when we are a little nearer the place we want to go to. Come, lend us a hand, and let's get off this point."

"Why, we are off already," cried Wulfstan. "How the tide is rising!"

"Here, my boy, let me have thy oar, and go thou and sit down by that poor fellow there. Thou art a brave lad, I can see, but thou must not overdo thyself," said the stranger, with a smile. "Where dost want to go, old man?" he added, turning to Ceolwulf.

"Well, to tell the truth, I don't much care as long as I can find some shelter and food for those boys. They want it. They've had none since last evening, and one has had a deal of pain, poor weakling," said Ceolwulf, grimly and sadly.

"If that's all thy want, there's naught better to do than go to Boseham, and it will do as well for me as Cymenesora; or, better still," he added, "thou canst put me out just opposite, it's all in the way to Boseham."

The old boat went along much faster now, propelled by the vigorous arm of the young man, and the entrance to the creek was entirely shut out, the two banks of shingle appearing to join; but before this happened Wulfstan had turned his head and called out, "There it is. There's the island; good-bye, dear home," and then he burst into tears.

"Don't cry, Wulfy, perhaps father wasn't killed; we don't know, and we can always go back and see," said Eddie, manfully. But the tears were welling up in his eyes too.

"Poor little fellows," said the stranger, looking at them with pity. "If thou wert to tell me all about them, I might be able to help them one of these days; what sayest thou, old man?"

"Well, I don't rightly know; thou seemest a good sort of young fellow, and I don't see it can do much harm. Well, thou must know that these boys' father is, or was—for I fear he was knocked on the head last night—Ælfhere the Eorldoman, who owns all the land at the east end of Wihtea,[2] where the Wihtwaras dwell, has had a quarrel with Arwald who held the land round Wihtgarsbyryg,[3] and who has been wanting for some time to get the upper hand among us Wihtwaras. Last night, when all were sleeping, we were roused by smoke, and rushing out, we found Arwald and his men ready to receive us. My lord Ælfhere, seeing that matters were likely to go hard with us, bid me take his two sons here and place them in a boat, and get what help I could to bring them over to his wife's sister's people, who dwell about Portaceaster.[4] But all the men were eager for the fight, and I could only manage this boat, and the drift of the tide carried us during the night to this harbour, and now thou knowest our story."

[2] Now Isle of Wight.

[3] Now Carisbrooke.

[4] Porchester.

"But how came the boy to break his leg?"

"In running for the boat in the dark, and as he was turning to look at the blazing house, he was struck by a spear, and, falling, broke his leg. I picked him up as tenderly as I could, but he has suffered a great deal, poor little one."

"The best thing thou canst do is to take him to the good monks at Boseham; they will take care of him, and cure him too. They are wonderful men at healing, but they are no good at fighting. So these are the sons of Ælfhere the Eorldoman, are they? They come of good stock; I know their mother's family too. Their blood is the same as mine, for their grandfather was Cynegils, and I am a great grandson of Ceawlin."

"What, the great Bretwalda of the house of Cerdic?" said Ceolwulf, with awe.

"Even so; and since thou hast been so open to me I will return thy faith. I am Cædwalla; and now if thou wilt rest on thy oar, I will just push the boat to the shore, for I must get out here."

In a few minutes more the boat neared the beach, and, using his spear as a leaping pole again, Cædwalla sprang to the land, and, waving his hand, disappeared among the scrub on the top of the shingle bank.

CHAPTER II.

"FREELY YE HAVE RECEIVED—FREELY GIVE."

"So that's Cædwalla, is it! I have heard tell of him many a time! And if, poor youth, he had his due, he'd be King of Wessex and Bretwalda[1] to boot. And who is king now? Centwine is it, or Æscuin? Well, that I don't rightly know. Gytha, the old nurse who came from Readbryg,[2] now she told me that one of them had been killed at a fight with the king of Mercia. Anyhow, Cædwalla is the rightful heir, that I do know; but what's he doing here? Well, he can't do any harm to me and my boys, that's certain; and if he gets his own he may help us to pay out that Arwald over there. Well, well, we shall see. Here, Wulf, come and see what thou canst do with that oar again; we can't be far from Boseham now. It's a very good thing the tide hasn't covered the mud, or we should never see all these lakes[3] hereabouts. Let me see, that's the way to Boseham, down there. Why, there's a man fishing! he'll tell us the way. But he's a mighty odd-looking man. What's the matter with his head? Look, Wulf, he's got his hair cut off like a half moon on the top of his head."

[1] The title conferred on, or assumed by, the most powerful among the various Saxon kings, from Ælla of Sussex to Egbert of Wessex. The word occurs first in the "Chronicles" under the year 827, and probably meant "Wielder, of Britain." See Freeman's "Norman Conquest," note B in the Appendix, vol. i.

[2] Now Redbridge, at the head of Southampton Water.

[3] A lake is the local word for a creek running in among the mud banks.

As the boat passed slowly through the water, it took them some minutes before they came up to the fisherman, who was seated on three or four logs rudely nailed together with two cross planks, and moored by a rope to a stick stuck in the mud. The man had long hair, cut or shaved in a peculiar half moon on the top of his head, and wore a long loose robe made of coarse frieze and fastened round his waist by a cord. His feet were bare, and he was sitting on his raft placidly, feeling his line from time to time, and muttering to himself a low, monotonous chant.

"What's he saying, Biggun?"

"That's more than I know. It isn't English; it's a saga of some kind. Listen!"

"Verbum caro, panem verum verbo carnem efficit;Fitque sanguis Christi merum, et si sensus deficit,Ad firmandum cor sincerum sola fides sufficit."

These words the man on the raft sang in a low, deep, melodious voice, and Eddie longed to know what they meant.

"Ho! there; are we in the right track for Boseham?" called Biggun.

The man paused in his chant and looked up, showing a wistful, anxious countenance, that made Biggun form a poor opinion of him; but Wulfstan took directly to him, because of his honest, fearless, trustful eyes.

"Thou art in the right way. There it is, round that point on thy left, among those trees," he answered, with a peculiar accent and foreign way of expressing himself.

"Ask him if he knows where those men live whom that man told us about. He called them some name I never heard before," said Wulfstan.

"Canst tell me where some men live who know how to cure wounds?"

"Meanest thou the monks of Boseham, or, as some call us, the Irish?"

"Those are the men. I met a youth who said they could cure a poor lad I have here who is wounded."

"Row alongside of me and let me look at him. I am one of the monks myself."

"Praise be to Thor," said old Biggun, "but the gods seem determined to make up for their treatment of us last night. Easy, Wulf, and let the old boat come alongside."

Gently they glided up to the rude raft, and the monk, who had cast off his moorings, made his rope fast to their boat, and got over the side into it. They now observed that he had a few fish lying on his raft, and Wulfstan was much delighted at the sight.

"My son," said the monk, stooping over Ædric, "where is the hurt?"

"Here, in this leg," said Ædric, uncovering the skins with difficulty.

"Let me do it, my child," said the monk, gently rolling them back and exposing a large and deep wound in the fleshy part of the calf, which had now become very stiff from cold and loss of blood.

"Ah! we will soon put that right," he said, cheerfully, "if there are no bones broken. It is only about a mile to our huts, and Brother Dicoll knows what herbs soothe wounds of body, as well as of mind."

"Shall we find food there? We are all hungry, and I could eat a bit of wolf and say thank-you if you would give it me."

"There is not much, but such as we have is freely thine, for what saith holy Peter: 'Hospitales invicem sinemurmuratione.'"

"What curious words he does use, Eddie, doesn't he?" said Wulf, in an undertone, to his brother.

"Yes; but I like him. He's quite as tender as Nurse Gytha, and does not make so much fuss; and I am sure he can tell us lots of sagas and stories."

"And he can show me how to fish and make lines," said Wulfstan.

They were now nearing the little settlement on the banks of the creek or inlet that has existed from these early days—the year 680—down to our own, and without much change; in fact, since Harold, about 320 years afterwards, started from Boseham on his luckless expedition to Normandy, the addition to the number of houses has probably been very small, although all have, of course, been frequently rebuilt. But the church is, in all likelihood, the one in which Harold worshipped, and, if tradition is correct, the great king Knut, or Canute, himself.[4] The piece of sharp practice by which Earl Godwine obtained it from the Archbishop of Canterbury is hardly worthy of credence or mention.[5] A few roofs scattered here and there could be seen nestling among thick woods which came down from the great Andredesweald, or Forest, which then spread from where Lewes now is to the borders of Dorset. This vast wilderness of trees and bush and scrub was then a great and impenetrable barrier, which shut off the little kingdom of the South Saxons, founded by the first Bretwalda Ælla, from the rest of their kin.

[4] According to a well sustained theory the church of Bosham is built on the site, and its walls partly consist of those, of a Roman basilica erected by Vespasian. The tower of the church, tradition says, was founded by St. Wilfrid. Thus this obscure Sussex village has been trodden by Vespasian, Titus, Wilfrid, Canute, Harold.

[5] Walter Mapes (quoted by Camden in his "Britannia," translated by Philemon Holland, edit. 1637) says:—"This Boseam, underneath Chichester, Goodwin saw, and had a minde to it. Being accompanied therefore with a great traine of gentlemen, he comes smiling unto the Archbishop of Canterburie, whose towne then it was. 'My lord,' sayth he, 'give you me Boseam.' The Archbishop, marvelling what he demanded by that question answered, 'I give you Boseam.' Then he, with his company of knights and soldiers, fell down, and, kissing his feet with many thanks, went back to Boseam and kept it." The point appears to be in the play upon the word Boseam and Basium, kiss or "buss" which was used in performing homage—so says Camden.

The abode of the wild boar, the wolf, and all other game that then roamed free in England, it was also the legendary home of the pixies, the gnomes, the wehr-wolves, and the witches, in all of whom the Saxons firmly believed. It also afforded a secure shelter for all outlaws and robbers, and had protected Cædwalla from the jealousy of his kinsman, Centwine.

"There are our poor huts, and there is our Dominus, or Abbas," said the monk, pointing to a small cottage built of wooden logs, before which stood a tall and gaunt man, with hollow eyes and sunken checks, but with the same patient, wistful look that the other monk had. He was dressed in exactly the same way, and had his head shaven also.

There were one or two children playing about, and a few men were helping to push down an unmanageable boat, not unlike the one now arriving. These all stopped to gaze at the new comers, and before they got much nearer one of the men called out to know who they were and how many they had on board. The monk replied, and the answer appearing satisfactory, no further notice was taken of their arrival, except that the children crowded down to the landing-place, and stood open-mouthed with curiosity to see the strangers get out.

There was a rude kind of quay, made of rough logs laid one on the top of the other, and kept in their places by piles driven into the mud. The tide had now risen sufficiently to allow the boat to come alongside this, and as she glided up the tall monk came down to meet them. He spoke a few words in a language Biggun could not understand to the monk who had been fishing; and he then said to one of the children:

"Call brother Corman, and bid him bring down a bench, or settle."

Meanwhile Ceolwulf had got on shore, and made the boat fast, and then slung the axe over his shoulder by a thong, and told Wulfstan to take one of the spears. But the monk advised him to put them down again, as no one was disposed to hurt them, and any signs of suspicion or defiance might arouse angry feelings.

"What is thy name, my boy?" said the superior monk to Eddie, whom he was now examining with the other monk, whom they had first met.

Ædric told his name, and the rank of his father, and what had happened. Such events in that lawless time were far too frequent to cause much surprise; but the monk seemed distressed nevertheless, more apparently at this fresh instance of the treachery, rapacity, and cruelty of man, than by reason of the actual circumstances related to him; for he sighed and murmured: "O generatio incredula et perversa quousque ero vobiscum!"

By this time another monk had joined the party, and now, under the directions of the abbot or superior, they carefully lifted Ædric out of the boat and up to the hut, before which the monk had been standing. They took him inside, and laid him down on a rough couch, in one corner, and then they gave him some bread and a little water.

"We will get better food presently," said the superior; "but there is great difficulty in getting food here at all now, and the people suffer much."

"Ah! thou mayst well say that," said the first monk, whom the superior addressed by the name of Malachi. "Ever since that fearsome summer, when everything died for want of water, after the sun was darkened, the dearth has been dreadful; and after the dearth and drought came the plague. Verily God hath visited us! but what we have ye are welcome to; for did not our blessed Master say: 'Beati misericordes quoniam ipsi misericordiam consequentur.'"

In attending to Ædric, the good monks had not forgotten Ceolwulf and Wulfstan, but had given them some of the same coarse fare they had set before Eddie.

"It strikes me," said Ceolwulf, "that these woods ought to produce something better than this; and, after we've had enough to satisfy our hunger, we will go out and see if we can't kill something."

"Oh, do let us, Biggun; they will think much more of us if we can bring them something we have killed."

The abbot of the little community, whose name was Dicoll, having finished his attention to Ædric's leg for the present, came and stood by Wulfstan, and, stroking him kindly on the head, said that now he knew who he was, and what accident had driven them on their shore, he should like to ask him what he was going to do. "Did they know that Edilwalch, the king, had an alliance with Arwald, and had received Wihtea[6] as a grant from King Wulfhere,[6] of Mercia, as a reward for his having been christened?"

[6] Isle of Wight.

This was news to Biggun, and he did not understand how Wulfhere could give away what he had not got. However, it was quite clear if Edilwalch was a friend of Arwald, he could not well be anything else but an enemy to Ælfhere, who had always supported the West Saxon domination, and had fought at Pontisbyryg, by the side of Coinwalch, the last powerful West Saxon king, when Wulfhere, of Mercia, defeated him. Biggun began to think they had only got from the frying-pan into the fire.

"As soon as possible it will be well to go to Wilfrid the Bishop, who has lately come to Sealchea,[7] and has received eighty-seven hides of land, and a great number of slaves, all of whom, I hear, he has set at liberty. Truly, although he does observe Easter at a different time to us, and also shaves his head in a way that would have vexed the soul of the blessed Columba, yet he hath wrought a good work among these rude and pagan South Saxons, and may the Lord pardon him for his other irregularities."

[7] Selsea.

"But how can we take the boy there? he has already had enough journeying."

"Leave him with us. Edilwalch is now engaged on an expedition against the men of Kent; at least, I know that two of his chief Thanes, Berethune and Andhune, have set out, and I understood he was to follow; so that, busied as he is, he will not have occasion to inquire about the sons of Ælfhere, even if he should hear that they have come. It is not, my sons, that I wish to be inhospitable, but we are poor people, and cannot treat our guests as we should like, nor could we protect the boys if Edilwalch were to demand them."

"Well, I think that will be the best thing to do, and may Woden and Thor shield thee for thy kindness. If ever Ædric there gets his own again, he will give thee land over at Wihtea, where thou canst worship Thor in thine own way, and eat plenty and drink more."

"Heathen, may the Holy One grant thee His blessing, and bring thee out of the darkness of iniquity wherein thou dwellest, and guide thee to a knowledge of His most blessed faith. And in that I doubt if thou ever heardest the name of our blessed Lord, there is much hope that thou mayest yet be saved. The Bishop Wilfrid will do much to lead thee to the right way; but be not led astray as to the time thou shouldest keep the holy feast of Easter. And, above all, reverence not the way in which that proud and erring man would have the servants of God to shave the crowns of their heads. I much mourn that I may not teach thee myself, for I perceive there are many errors thou mayest fall into; but the course I have prescribed I believe to be the best one for the safety of all. Wilfrid is a holy man in most respects, but I have cautioned thee beforehand of his errors."

"Well, Wulf, we will go and get these good people something to eat. There's no danger of meeting any who will do us harm, is there, Father?" said Biggun, yawning.

"Not if thou goest into the forest behind us, and I have heard there are plenty of four-footed beasts there; but beware of wolves and boars, for men say they have increased much of late, since all the land has been withered and wasted under the heavy hand of the Almighty, who has visited these poor people for their heathenish ways, I doubt not. We will care for Ædric here till thy return, and then brother Malachi shall show thee the road to Wilfrid to-morrow morning, after thou hast had a good night's rest."

"Oh, Biggun! I am so tired of all this talk, let's go to the forest. Good-bye, Eddie; we won't be gone long, and we shall be sure to bring back something better than they have got here."

"I wish I could go too," said Ædric, wistfully; "it seems such a long time since I walked, and, really, it is only yesterday that I was all right. Oh, what things have happened since yesterday!"

He watched the two figures out of the door, and the tears would well up in his eyes in spite of himself.

Brother Corman, who was just like the other two monks, except that he was not quite so sad-looking, came and sat down by him, while Malachi proceeded to prepare the fish he had caught, singing to himself the while, and occasionally exchanging a gentle remark with the children that came to look on as he scraped and cleaned the fish.

The tide had now risen to its full, and the scene was pretty. The still grey tones of the autumn day, the silent water, and the falling leaves, were all in harmony with the monkish chaunt, and the listless forms of the half-starved children. For, as Malachi had well said, the times were dreadful. Such a sore disease had followed the terrible famine, that men in these South Saxon marshes had begun to despair of life altogether, and many times he had seen as many as forty or fifty men, women, and children, drowning themselves for very weariness. They had no strength to till the land, and the land would not produce if they did till it. Their condition had become very desperate and pitiful. They did not seem to know how to fish, and, until Wilfrid had come, they had never attempted to get any food out of the sea. They were able to catch eels, but had become so utterly weary of life that they had rather perish than take any trouble to support themselves.

The worthy monks, who, as some men said, came from Scotland, and others from Ireland, had been doing a noble work. In the true spirit of missionaries, taking their life in their hands, they had left their lonely, but to them dearly loved, island home of Hii, or Iona, hallowed to them by the life and teaching of Columba, and had gone penniless and with nothing but the clothes they wore to teach the Gospel of Christ. "Freely ye have received, freely give," was their motto. "Humility and the fear of the Lord" were their weapons, and they did not seek the blessings attached to these, viz., "riches, and honour, and strength," except as they would redound to the glory of Him whom they served. Simple men they were as regards worldly affairs, naturally clinging to that wherein they were instructed; they put implicit faith in the precepts of their predecessors, who had professed and taught Christianity long before Augustine the Monk had set foot in England. They felt and believed that their Spiritual Father had been a Martyr for the Faith centuries before the hated Saxon, or Jute, or Angle, had left his swampy shore; and that they had received the faith from St. John, from Anatolius, and from Columba. While all Europe was overrun with the waves of barbarism, they had kept the pure light of the Gospel shining in the Western Islands, and it was gall and bitterness that now they were to change their customs and their fashions at the bidding of the emissary of the Bishop of Rome. Were these matters trifles? they urged. Be it so, then; and why make all this disturbance about them? Trifles, alas! in the poor mind of humanity, are very frequently more fought over than essentials. And to both Augustine and Wilfrid after him, zealous for the visible unity of the Church, it seemed a ridiculous thing, as well as pernicious, that these lowly monks, whom they affected to despise, should obstinately cling to their obsolete and unorthodox fashion. Alas! that the charity which suffereth long and is kind was so early forgotten. The poor Irish or Scotch missionaries were worsted in the controversy, because the power of the See of Rome was in the ascendant; but the purity and simplicity of their lives, their utter self-denial, and the piety of their teaching, made the way easier for the more famous men who followed after them, and who combined the fervour of a missionary with the grand ideal of Christian unity.

Corman, who was sitting by Ædric's side, talked to him from time to time if he appeared restless, but tried chiefly to get him to go to sleep. The boy, however, was too much excited by the rapidity of the past events, and the fever caused by his wound, to be able to sleep, and an occasional restless sigh showed that he was thinking of his father and his home.

"When I grow up," he burst out impatiently, "I will wreak full vengeance on that nithing Arwald, for all that he has done to my house and father. I swear by Wod——"

"Hush! Ædric, hush!" broke in Corman, interrupting him, and putting his cool hand upon the boy's fevered brow. "Swear not, my son, by anything; least of all by the false gods of the heathen. And when thou hast lived longer with us, thou wilt not, I hope, wish to avenge thyself on any being, whatever may be the wrongs he has done thee."

Ædric stared at him in open-mouthed astonishment.

"What, not make those suffer who have made me suffer? Why, I have always heard it is the first duty of a hero to deal starkly with his foe!" exclaimed the boy, indignantly. "What would my father say when I meet him in Valhalla if I have not cleft the head of Arwald or died in the attempt?"

"My son, I trust thou wilt meet him in a better Valhalla; but thou must not talk too much now. Thou wilt make thy leg worse. Drink this cooling drink, and I will tell thee tales which may, perchance, lull thee to sleep."

Then Corman began to tell in soft, melodious words, a wondrous tale, the like of which Ædric had never heard before, but which is now so well known that its very familiarity tends to weaken its beauty. He told how all things were lovely, how all things pleased the Creator, how sin entered in, and then came death, and how death ended in victory. But he told it all so simply, and made it so like a saga, that Ædric thought he was listening to one of old Deva's tales, and gradually sleep stole over him, and he sank into profound slumber.

Corman sat silently by his side, fearing to move, lest he should disturb him.

Presently Dicoll and Malachi came in, and they began the morning service, but in low tones; while outside the door of the hut a few women and children stood round to listen.

The inherent reverence of the Teutonic nature showed itself strongly in these rude, suffering, untaught South Saxons, and the monks already saw promise of future good.

By the welcome aid of healing arts they had gradually obtained a hold on the little settlement; and as their practical sympathy with physical suffering found ready scope in their power to deal with it, so the purity of their worship attracted the gentler natures of the more reflecting among the people.

The religion of the South Saxons, like that of all the Teutonic tribes, was calculated to promote reverence, and was yet so vague in its teaching as to oppose but slight obstacles to the approaches of Christianity. Their deities were the elements, and, like the Greeks, they worshipped a divinity in every object of nature. Rude temples they seem to have had, which, as in the story of Coifi, appear to have had but little hold on the people; and as there were no material advantages at stake, so the opposition offered to the Christian missionary was much less envenomed than is usually the case where vested interests are at hazard.

Indeed, the Christian missionaries found, in one very important particular, a decided gain in dealing with the Teutonic peoples as compared with the Christian but Romance nations. The sanctity of domestic life contrasted strongly with the habits and customs of the laxer peoples of the South, habituated to vice in all its forms, and among whom the pursuit of pleasure had become almost a science as well as a passion.

The spirit of scoffing, of ridicule, was absent. Such a spirit seems inconsistent with the gloom of the vast primeval forest, of the solitudes of the hunter, and the earnestness produced by the stern fight for existence. Luxury, laziness, the energy of the body directed to the amusement of a debased intellect, and an intellect pandering to the unwholesome passions of the body, all these were absent, and the Christian missionaries found themselves confronted with an almost primitive state of life.

CHAPTER III.

"UNDER THE GREENWOOD TREE."

Ceolwulf and Wulfstan, after leaving the hut of the kind monks, went first to look to the boat, and moored her securely. Then they walked into the thick wood, which was immediately behind the little settlement, and which stretched without intermission right up to the great Andredesweald. There were occasional clearings here and there, especially to the east of Boseham towards Cissanceaster, but owing to the dreadful drought and consequent famine, and demoralisation of the inhabitants resulting from it, most of these clearings had relapsed into a wilderness again.

They had not gone far when Biggun remarked that they had better take a look at the sun, and see how they were to find their way back again; and while he was taking a careful look round Wulfstan noticed a rustling noise amongst the dry leaves on his right, and directly afterwards an old pig and several little ones came grunting through the wood followed by a miserable, unhealthy-looking boy, who instantly stopped on seeing the two strangers, and stared at them with suspicion.

"Whose pigs are those?" said Biggun.

The young swineherd only stared at him the more, and especially eyed Wulfstan with curiosity, as though such a healthy-looking boy were quite surprising. At last, on the question being repeated two or three times, he shook his head to intimate that he did not understand.

"Come along, Wulf, we've no time to lose; let us go down this glade and keep thy spear ready. That boy is a Weala."

They now reached a long and natural glade in the forest, and as they got farther away from the sea the trees grew larger and straighter, and the view under the branches was more extended, being only interrupted by clumps of brushwood here and there. There was no sign of any road or track whatever, only the vast forest stretched in endless solitude to right and left, and as far ahead as the eye could see.

Wulfstan was delighted with the size of the forest, and eagerly looked on each side for the chance of some game appearing. They had now walked about four miles from Boseham, and were going in a north-westerly direction, when a gleam through the trees ahead told them they were approaching some water, and in a few minutes more they had reached a long winding pool, or lake, from which a large heron rose slowly as they came out of the forest.

"Biggun, look! Take a shot at that heron! I can swim for him if he does drop in the water."

"He's too far off, Wulf; we must not waste our arrows. Wait till we get a sure mark; we shan't have to wait long. If this is salt water, animals won't come to drink, but I doubt not we shall find a fresh brook running into it farther on; and if we find the marks where the beasts come down to water, we can hide in the bushes, as we used to do at home, and then we shan't miss."

They had hardly gone three steps more when a large hare darted out of a thicket by the side of the water and ran into the wood; but Biggun was too quick for him, carefully watching as he passed behind a tree, the instant he appeared on the other side of it, an arrow whizzed from his bow and rolled the hare over on the ground.

"By Woden, Biggun, that was a good shot; thou timedst it well," cried Wulf admiringly, as he ran up to the hare and pulled the arrow out, carefully wiping the shaft and point, and smoothing the feathers; then taking the animal up by his hind legs he hit it behind the neck to kill it, for it was not quite dead, then he ran back to Biggun and gave him his arrow again.

"Be still, my son, and hurry not, if thou wouldst hit anything," said Biggun complacently, as he put the arrow back in the quiver. They then went on again, Wulf carrying the hare and looking with sharp glances all round him. Presently they came to a very marshy place and had to leave the side of the water and enter the forest again. Skirting the marsh they came to a kind of track that led them to a deep pool which was trodden all round and was evidently a place where animals came down to water.

"We ought to come here to-night, Wulf, but we ought to come in a large gang, for here be marks we don't see in our island," said Biggun, stooping down and examining the "spoor" of the animals that frequented this place to quench their thirst.

"Hark, Biggun, there is something coming!" whispered Wulfstan, as a crackling of twigs was heard a little way off.

"Quick, Wulf, climb up that tree there; up with thee!" cried Biggun, as he hurried the boy hastily to a wide-spreading oak, whose large and low branching limbs stretched over the pool. In an instant Wulfstan was ensconced among the branches, and Biggun had handed him up his spear, and was just pulling himself up after him, when, with a crash and a squeal, a huge wild boar rushed through the brushwood, and charged at poor Biggun, who, old and stiff, was with difficulty getting up into the first low fork of the old tree.

"Oh, Biggun, get thy legs out of the way!" shrieked Wulfstan in terror, and without pausing a moment he hurled the boar spear he held right at the advancing beast. He threw it with such good aim that it struck the animal in the shoulder, and although it did not stop his charge, by reason of the wound it caused, it yet pulled the beast up by catching in one of the overhanging boughs, and the shaft being made of stout ash did not break, but widened the wound in the shoulder, and caused the poor animal to squeal aloud with pain. Biggun had now got his legs over the first branch, and, taking steady aim, he shot an arrow into the animal's eye. Such was the vitality and courage of the brute that, although it had the spear still sticking in its shoulder, and was pierced in one eye with an arrow, it yet charged home to the trunk of the tree, and buried its tusks in the bark. Then it stood looking round for its enemy, and grunting and squealing fiercely. Biggun drew another arrow up to its head, and the shaft went home to the boar's heart, and he fell over dead.

"Well, I think we have got enough game now, Wulf, for the monks and ourselves, and we had better make the best of our way home, and carry as much as we can of this beast with us," said Biggun, scrambling out of the tree again, followed by Wulfstan, who was very delighted at the death of the big animal, and greatly admired his formidable tusks and the thick crest of bristles which grew down his strong neck and shoulders.

Ceolwulf proceeded to cut up the body with his long hunting knife, and slinging the two hind quarters over his shoulders, and replacing the arrows in the quiver, they hung the rest of the quartered boar on the lowest bough of the oak that had saved their lives, and started to make their way home again.

Suddenly Ceolwulf pulled his young companion behind a tree, and then, before Wulf could ask him the reason, he had whispered to him to be perfectly still, as he saw some men a little way ahead of them. Very cautiously Biggun and Wulf crouched down, and crawled to the cover of some bushes that were near, and from this shelter they saw several men coming in their direction. They were all armed, and looked a strong and formidable body of men. There were about thirty or forty in all, and most wore iron helmets, and two or three had hawberks, or jackets of mail, like that which the young man wore whom they had met in the morning. Some carried stout spears, and others large clubs, with a heavy ball of metal attached by a short piece of chain to the head of the club, and studded with spikes. Most had shields of a round shape, and nearly all carried, in addition to the arms already mentioned, long swords and battle axes. The men who had not got jackets of mail wore leathern tunics, which appeared to be of double thickness over the chest and shoulders, and which were no doubt sufficiently tough to ward off a sword cut or spear thrust. Many of the men appeared to be quite young: none of them seemed over forty, and the youngest might have been between eighteen and twenty. They were a handsome and picturesque-looking set of men, with their bushy hair flowing out from under their helmets, their bronzed faces and martial appearance. Some wore close-cut beards, and some were shaved, with the exception of the "knightly fringe that clothed the upper lip," and Ceolwulf knew that they must be the body-guard of some powerful Thane or Eorldoman, and he crouched all the closer, for the times were very perilous. They did not seem to be in any hurry, for they sauntered along, talking among themselves, and appearing to be under no leadership. Suddenly one of them uttered a cry, and walked hastily to the tree where the remains of the wild boar were hanging, fresh and bleeding from the knife of Ceolwulf.

"Ah, they will track us by the drops of blood from the joints I have over my shoulders!" said Biggun. "Well, I must even drop them here, and perchance they won't find them," he added, with a sigh, as he unstrung the quarters, and hung them on a bough above him. He then took Wulfstan by the hand, and pulled him into the thickest of the bushes, and crouched down again. They could hear the men talking about the boar, and laughing at the unexpected piece of good luck they had fallen in with.

"This will just do," said one. "I was getting very hungry, and here we are where he told us to wait for him. Let us make a fire and roast some of these joints."

"That we will," cried another. "Here's water to drink and flesh to eat. What more do we want? Why the heroes in Valhalla can't have much more! This boar, I warrant, is every bit as good as Sæhrimnir[1] the everlasting, and we can do for once without mead."

[1] The author has put into the mouths of the Saxons the mythological allusions of the Scandinavian sagas, thinking that probably the same tales were common to the Scandinavian and Jutland peninsula, as well as to the Saxons and Frisians.

"Aye, and we can cut our enemies to pieces after our dinner just as well as before; so waste no more time, but get some sticks and make a fire," rejoined a third.

"Well, thou canst begin making afire," said the man who had first seen the pieces of boar's flesh. "I shall follow this trail of blood, and see where they are who have killed the boar. They can't be far off, or the track wouldn't be so fresh, and they can't be many, or they wouldn't let us take their game so easily. But, after all, there's no knowing; these South Saxons, since the plague, have lost all heart."

Hearing these words, several others began to follow on the trail, and it was not long before they came to the bushes, where Ceolwulf and Wulfstan lay hid. A loud shout soon told that they had found the rest of the animal, and then they were apparently baffled. But not for long, for a keen-eyed man saw where a twig had recently been broken off, and then another where dead leaves had been trodden on and the damp side turned up, and in another moment Biggun and Wulfstan rose to their feet, face to face with a bronzed and powerful man peering through the bushes at them.

"Hark, here! So! so! my masters. Here's the game come to bay!" he cried merrily, and all the others broke through the bushes to get a view. Ceolwulf saw instantly it was no use showing fight, and he and Wulfstan came out and gave themselves up.

They were led to where the others were making a fire, and all crowded round to look at the captives.

"Well, and who are ye?" said the oldest-looking man.

Biggun had no idea who these men were, and after what he had heard from Father Dicoll about Edilwalch and his friendship for Arwald, he thought it better to conceal as long as possible who he was and where he came from.

"My name is Ceolwulf."

"Where dost come from?"

"From Boseham."

"Why, we know every one who lives in Boseham, and we never saw thee before, so that won't pass."

"Nevertheless I come from Boseham."

"Look here, old man, thou hadst better tell us at once all about thyself and the boy there, both for thy sake and his. We are not used to be trifled with, and thou art old enough to know what being made a spread eagle means."

Ceolwulf scratched his head and looked at Wulfstan, who, boy-like, could not see what there was to hide, for if they knew every one in Boseham they must know the kind monks who had so befriended them.

"Now, old man, be quick," said his questioner.

"Well, we come from Wihtea, over there, and have been in a good deal of trouble," said Ceolwulf, hoping to mollify his interrogator; "and when we got to Boseham we found some queer sort of men, who gave us some bread, and we thought we would go out and get something better to eat, for there seems no heart left in those South Saxons to help themselves."

"Thou art in the right there, my man. Since the yellow plague all spirit has gone out of them, and they care to do nothing now but die—which, after all, isn't so bad, if thou diest with thine axe in the skull of thine enemy, but any other way is disgraceful," from which remark it was clear that this man was a philosopher in his way, although somewhat crude in his ideas.

"And whose boy is this? He isn't thy son, I'll be bound. An old wooden head like thee couldn't have a son like that," said another man.

"Let me stand out there with my axe, and I'll soon show thee whether my head is any more wooden than thine, thou young Weala!"

"He has called me a Weala," cried the young man to the others. "He belongs to me to punish; let me have him out here, that I may split his old timber skull."

"No, no," said the older man. "We have got to have our dinner first, and, I think, as he has provided it, he ought to be asked to share it."

"But thou hast not told us who the boy is, old man."

"He is the son of a noble eorldoman in Wihtea."

"What, Arwald's son?" cried the man with eagerness.

"Now I wish I knew whether he wanted him to be his son or not," thought Ceolwulf. Then he added, "Dost thou know Arwald, then?"

"It is not thy business to ask me questions, but to answer mine, and take care thou doest it," said the man, sternly.

"No, he's not Arwald's son."

"All the better for him, then," muttered his interrogator.

But at this moment a most delicious smell of fragrant roast pork floated past their nostrils, and neither Biggun nor the man could avoid sniffing it admiringly.

"Well, we can ask thee these questions presently quite as well as now, and if we are not quick the others will have all the best bits. Now promise me thou wilt not attempt to escape, and I will let thee sit down and eat with us."

Biggun was very hungry, and so was Wulfstan, and they both promised at once, and then they all sat down, while three of the youngest were told to divide the joints and distribute them to the others.

It was a picturesque scene: the blue smoke from the fire curled up among the fast falling leaves of the great forest trees; beyond, fading into grey dimness, was the forest, while the sinking sun cast its warm rays aslant the stems of the trees, and turned the red bracken to golden sprays; the men lay about in careless attitudes, their flashing weapons gleaming in the setting sun, and above all were the ruddy leaves and great limbs of the wide-spreading oaks.

Merrily the talk went on, and coarse jest and practical joke made the echoes of the forest ring, until the noise reminded the man who had questioned Ceolwulf of the errand they were upon, and which apparently demanded some measure of secrecy, for he told four of the young men who had eaten enough to go some distance off and act as scouts, and he also tried to get the others to be a little less boisterous. Wulfstan enjoyed the whole feast immensely, and had won universal applause when old Ceolwulf told how he had speared the boar, and they all vowed he should be one of them, and should live to be a hero and do great deeds, to all which Wulfstan listened complacently; but at times he thought of Ædric, and longed to take him the hare, and he would have liked the good monks to have had some of that delicious boar, for he thought he never had tasted anything so good, as he held the end of a chop in his fingers and munched the juicy flesh. This was the fourth he had eaten, and he felt that the world was much more pleasant than it had been lately.

The others were now nearly satisfied, and little of the boar remained, which, fortunately for the happiness of the party, was a full grown animal, and in very good condition. As the men leant back with dreamy faces, and meditatively gave themselves up to the joys of tranquil digestion, there came a desire for amusement, and it occurred to the younger and more mischievous among them to think of the reproach cast by Biggun on the young man he had called a "Weala," which was regarded as an insult by the conquering Saxons.

"I say, Beornwulf, I wouldn't be called a Weala by that old red beard," said one, throwing a bone at the young man he addressed, which alighted on his hand just as he was putting a choice morsel into his mouth, and knocked the piece of flesh out of his hand on to the ground.

A loud and general burst of laughter greeted this practical joke, which did not add to the young man's good humour, and he, being of a fiery disposition, and so the very fittest subject for a practical joker, rose up in a rage and hurled the bone back at his aggressor, who, being prepared for it, ducked his head, and it passed harmlessly over him.

"There, Beorney, don't get angry. If thou wantest to fight, fight the old man there, and then, after he has thrashed thee, thou canst come and fight us. We shan't be afraid of thee then, but thou'rt too strong a man now, and aimest too straight."

"What is all this about, boys?" said the older man, who had been comfortably stretched on his back with Ceolwulf and Wulfstan on each side of him, placidly enjoying the pleasant reminiscences of that estimable boar. "What's all this about? Why can't ye enjoy the blessings the gods give ye without wanting to make a disturbance?"

"Beornwulf here wants to fight that old red beard we caught in the bushes, who called him a Weala."

"Well, and Beornwulf called him a wooden head first, so I think they are quits."

"Let them fight, Athelhune. We've nothing to amuse us, and they might just as well have a round."

"Why, what's the good, boys? We want all our strength for to-night's work, and he might be here any moment. Ye see the sun is sinking fast."

"Then they can leave off when he comes."

Athelhune, who really did not much care one way or the other, made no answer, and this being taken as a consent, the young men, now that they had roused Beornwulf, set to work to get old Ceolwulf excited, who had gone tranquilly off to sleep.

They proceeded therefore to pitch a chop bone neatly on to his nose, and when he started up full of bewilderment at the unexpected shock, another bone, adroitly thrown, though not very hard, struck him on the mouth. Boiling with rage, old Biggun got up and glared round for his assailant.

"Here he is, old man; here's the Weala that did it!" cried several voices, pushing Beornwulf forward.

"Thou didst, thou nithing thou? I'll teach thee to insult a free born Wihtwara!" cried old Ceolwulf, whose blood was now thoroughly up.

"There, Beornwulf, he has called thee a nithing. Nothing but blood can wipe out that," called out the others, delighted at the success of their stratagem.

Ceolwulf was going at once to strike the young man with his boar-spear, but two or three young men knocked up the point, and told him he must wait until they had made a ring, and he must have the same arms as his antagonist.

They proceeded, therefore, to cut wands of hazel and fix them round in a circle, leaving ample room in the middle for the two combatants, and then they explained to Ceolwulf that whosoever drew first blood or drove his opponent out of the ring was to be considered conqueror. They then gave Ceolwulf the choice of several battle-axes, and allowed him to have a helmet like Beornwulf and a shield, and then they led the two combatants into the ring.

All had now risen from their recumbent position, and were showing much interest in the approaching fray. Opinion was divided as to which of the two was likely to win. Most inclined to Beornwulf, who was younger far and likely to be much more active. The older men, however, augured well from Ceolwulf's size and experience that victory might declare for him.

Wearing their shields on their left arms, and holding their battle-axes in their right, the two men eyed each other steadily, and in order to rouse them to greater animosity, several young men called out: "Remember, Beorney, he called thee a Weala." "And worse than that, he called thee a nithing," added others.

While to provoke Ceolwulf they called out: "He called thee a wooden head, and threw bones in thy face."

Poor little Wulfstan looked on with anxious eyes. He did not much fear for Ceolwulf, in whom he had always had unbounded confidence, but the thought would occur to him that were anything to happen to their old servant what would become of himself and Ædric? He was their only friend left in the whole world now. So he thought, and looked on, angry-eyed and wistful.

And now the fight began. Beornwulf stepped up close to Ceolwulf and made a feint at his right arm, which Ceolwulf parried with his axe, and caught the next blow, aimed with all the young man's might at his head, with his round shield. The force of the blow split the shield and exposed the arm, so that all thought the old man was wounded, but Ceolwulf at the moment that the blow descended, struck slanting at the exposed right side of his opponent, and cut through his leathern jerkin, causing a crimson stream to flow down his armour.

"A hit! a hit!" they all cried, and then, forgetting their own rules in their excitement, they called out to Beornwulf to revenge himself. But Ceolwulf parried every blow, and called out that the victory was his. He was very anxious the combat should have a speedy termination, for he did not wish to kill his opponent, foreseeing that if he did his position and that of Wulfstan would be rendered much more unpleasant, and he naturally had no wish to be killed himself. While all were excited at the contest a voice suddenly called out, "Why, men, what is all this to do? Haven't ye work enough in hand to-night that ye must needs be splitting each other's heads now?"

All turned round astonished, and a universal cry of "Cædwalla!" told Wulfstan that his handsome friend of the morning was among them.

CHAPTER IV.

THE SURPRISE.

The arrival of Cædwalla put an end to the combat, to the great joy of Wulfstan, who ran up to Ceolwulf with eager congratulations.

"I knew that fellow couldn't do thee any harm, Biggun; he didn't know thee as well as I do, or he wouldn't have dared to stand up to thee; but I am glad thou gavest it him as thou didst."

"Aye, Wulf, they will respect us all the more after this. I thought I should give him a good trouncing," said Ceolwulf complacently.

"Why, whom have we here?" cried Cædwalla, now for the first time seeing Ceolwulf and Wulfstan. "Why, it's the old greybeard I met this morning, and the stout little son of Ælfhere! And what art thou doing here?"

The whole of the circumstances were quickly narrated to him, and, patting Wulfstan on the head, he told him he should make him one of his Huscarles, or body-guard, which delighted the boy much. He reproved Beornwulf for being so quarrelsome, and advised old Ceolwulf not to call people "nithings" again, or worse would come of it. As it had turned out he had drawn Beornwulf's blood first, and therefore, according to the laws of the Holmgang, or duel, Beornwulf ought to pay the fine of the conquered; but, considering how great a provocation Ceolwulf had given, he should decide that the two were now quits, and there the matter had better end. "And now, my men, we must be up and doing. I have learnt that the greater part of Edilwalch's men have gone with the two eorldomen to Kent, and the king is spending the night at Cissanceaster; we are now about six miles off, and it will take us till near midnight to get there and arrange our plans. Beornwulf, as thou art wounded, thou hadst best take this boy back to his brother at Boseham, and take care of him until I come. Bid the monks treat him well, or, by Freja, I will skin the shavelings; but they are good men," he added, "and will do that without my bidding. And as to thee, old man, thou hadst best take Beornwulf's place, and make good the damage thou hast done. And now, men, fall in. Athelhune, you will take command of the rear, I will lead the advance, and do thou, old man, take Beornwulf's arms and give him thine to take back to Boseham; after to-night I trust thou wilt have some of thine own, or else that there will be no want of any. Remember all of ye that in worsting Edilwalch we are winning a victory for Wessex, and each victory for Wessex is a step towards my rightful crown. Ye have feasted on the flesh of the wild boar which Woden has put before ye as an omen of victory; remember the sagas, and how he who dies in battle will feast for ever on Sæhrimnir the Eternal, and quaff mead from the never-dying Heidrun, and shall for ever and for ever hack his enemies in pieces. Who would not rather go there than live here? But to obtain honour there we must kill our enemies here, and the more we kill, the greater our joy hereafter. Up, men, and earn an undying name!"

Excited by this speech, and eager for the fray, each warrior clashed his axe against his shield, and the wild din caused the birds, that were going to roost, to fly screaming out of the branches, and scared the beasts of the forest in their distant lair.

"See, the wild ravens there,Woden's wild birds of air,Call us to Nastrond's fare,Call us to battle!"

shouted a warrior, whose eyes glowed with the joy of approaching fight.

"Hark to the wolves' wild cry,Baying towards the sky,Knowing the prey is nigh,Hearing death's rattle!"

cried another answering, tossing his battle-axe high in the air, and catching it again; for every warrior who wished to be distinguished affected a talent for verse, and all leaders who desired fame surrounded themselves with "Skalds," or gleemen, as they were called, who should proclaim their doughty deeds.

Wulfstan longed to go with the expedition, but Cædwalla would not hear of it, and he was sent off with Beornwulf, both sulky at their dismissal, but Beornwulf especially enraged, and vowing vengeance on Ceolwulf when he got the chance.

"Never mind, Beorney, thou canst practice fighting with the monks, they won't hurt thee," shouted some of the young men.

"And thou canst throw stones at the seals, they won't run away," called another, as they went off laughing; while Beornwulf, grinding his teeth with rage, and having no retort ready, disappeared with Wulfstan in the direction of Boseham.

The others directed their march through the forest towards Cissanceaster, proceeding at a rapid pace; all noise had now ceased, and each man settled down to his step with the air of men accustomed to long expeditions, and who all knew their business thoroughly. Ceolwulf wished much his master Ælfhere had had a few dozen men like these the night before, and he hoped if he could only induce Cædwalla to take up the cause of his young lords, that they might recover their lands and revenge themselves on Arwald; he had seen therefore Wulfstan go off with Beornwulf less reluctantly than he otherwise would have done.

The sun had set, and the mists of the forest rendered it a difficult matter to see their way, but Cædwalla led them on without pausing or appearing to be once in doubt as to which way to go. After they had gone on in almost absolute silence for about a couple of miles they came to a circular clearing in the forest; in the centre of this clearing was a large stone, and Cædwalla went up to it, and, raising his battle-axe aloft, chanted the following verses:—