BADEN-POWELL

OF MAFEKING

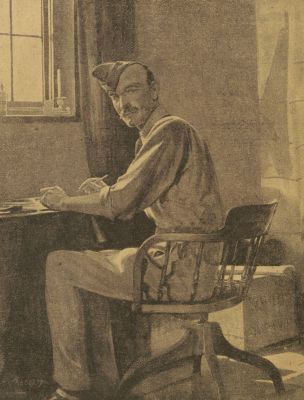

BADEN-POWELL IN HIS OFFICE

BADEN-POWELL

OF MAFEKING

BY

J.S. FLETCHER

AUTHOR OF "THE BUILDERS," "THE PATHS OF THE PRUDENT," ETC.

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

CONTENTS

| Introduction |

||||

| TO THE MAN IN THE STREET | ||||

| Part I. | ||||

| BADEN-POWELL—THE MANNER OF MAN HE IS | ||||

| Page | ||||

| I. | The Boy and His People | 11 | ||

| II. | "Bathing-Towel" | 18 | ||

| III. | Learning the Trade | 24 | ||

| IV. | Scout and Sportsman | 29 | ||

| V. | The Kindly Humorist | 42 | ||

| Part II. | ||||

| AN EXPEDITION AND A CAMPAIGN | ||||

| I. | The Ashanti Expedition, 1895-6 | 47 | ||

| II. | The Matabele Campaign, 1896 | 64 | ||

| Part III. | ||||

| THE STORY OF THE SIEGE OF MAFEKING, 1899-1900 | ||||

| I. | The Warm Corner | 89 | ||

| II. | Warmer and Warmer | 97 | ||

| III. | Sitting Tight | 104 | ||

| IV. | The Last Days | 111 | ||

| V. | The Relief and the Empire | 119 | ||

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | ||

| Baden-Powell in his Office | Frontispiece | |

| A Merciful Man | (Sketch by the Author) | 14 |

| The Horse Guard | " " | 26 |

| Following up the Spoor | " " | 29 |

| Britannia | " " | 45 |

| Sketch Map of the March to Kumassi | " " | 48 |

| Human Sacrifice at Bantama | " " | 51 |

| Portrait of King Prempeh | " " | 55 |

| King Prempeh watching the arrival of Troops | " " | 59 |

| Embarkation of King Prempeh | " " | 63 |

| Sketch Map of the Theatre of Operations | " " | 65 |

| Mafeking to Buluwayo—Ten Days and Nights by Coach | " " | 66 |

| The Umgusa Fight: June 6th | " " | 67 |

| Eight to One | " " | 70 |

| Scout Burnham | " " | 73 |

| The Peace Indaba with the Matopo Rebels | " " | 75 |

| The Battle of August 5th | " " | 75 |

| A Human Salt-Cellar | " " | 79 |

| Fresh Horse-Beef | " " | 81 |

| Dolce far Niente | " " | 87 |

| An every-day Scene in the Market | 95 | |

| Strolling Home in the Morning | (Sketch by the Author) | 104 |

| "Halt! who comes there?" | " " | 104 |

| A Cape Boy Sentry | " " | 113 |

| Rough Map of Brickfields | 116 |

NOTE

THE AUTHOR DESIRES TO EXPRESS HIS OBLIGATIONS TO MISS BADEN-POWELL AND TO THE REV. CANON HAIG-BROWN FOR THEIR KINDNESS IN AFFORDING HIM HELP AND INFORMATION IN PREPARING THE FOLLOWING ACCOUNT OF MAJOR-GENERAL BADEN-POWELL'S CAREER.

TO THE MAN IN THE STREET

It may well and fittingly be complained that of late years we English folk have shown an unpardonable spirit of curiosity about things which do not concern us. We have brought into being more than one periodical publication full of gossip about the private life and affairs of folk of eminence, and there are too many of us who are never so much pleased as when we are informed that a certain great artist abhors meat, or that a famous musician is inordinately fond of pickled salmon. There was a time when, to use a homely old phrase, people minded their own business and left that of their neighbours' alone—that day in some degree seems to have been left far behind, and most of us feel that we are being defrauded of our just rights if we may not step across the threshold of my lady's drawing-room or set foot in the statesman's cabinet. The fact is that we have itching ears nowadays, and cherish a passion for gossip which were creditable to the old women of the open doorways. We want to know all—which is to say as much as chance will tell us—about the people of whom the street is talking, and the more we can hear of them, even of the things which appertain in reality to no one but themselves, the better we are pleased. But even here, in what is undoubtedly an evil, there is an element of possible good which under certain circumstances may be developed into magnificent results. Since we must talk amongst ourselves, since we must satisfy this very human craving for what is after all gossip, let us find great subjects to gossip about. If we must talk in the streets let us talk about great folk, about great deeds, about great examples, and since our subjects are great let us talk of them in a great way. There is no need to chatter idly and to no purpose—we shall be all the better if our gossip about great men and great things leads us to even a faint imitation of both.

We English folk possess at this moment a magnificent opportunity of talking and thinking about the things and the men which make for good. It may be that ever since the Empire rose as one man to sustain the honour and glory of England we have glorified our fighting man a little too much. It may be that we have raised our voices too loudly in the music-halls and been too exuberant in our conduct in the streets. But after all, what does it mean? We are vulgar, we English, in our outward expression of joy and delight—yes, but how splendidly our vulgarity is redeemed and even transformed into a fine thing by our immense feeling for race and country! What is it, after all, that we have been doing during this time of war but building up, renewing, strengthening that mysterious Something which for lack of a better word we call Empire? War, like sorrow, strengthens, chastens, and encourages. Just as the heart of a strong man is purified and made stronger by sorrow, so the spirit of a nation is lifted up and set on a higher pedestal by the trials and the awfulness of war. Heaven help the people which emerges from a great struggle broken, sullen, despondent!—Heaven be thanked that from the blood of our fellows spilt in South Africa there have already sprung the flowers of new fortitude and new strength and new belief in our God-given destiny as the saviours of the world. It is as it ever was:—

"We are a people yet!

Tho' all men else their nobler dreams forget,

Confused by brainless mobs and lawless Powers;

Thank Him who isled us here, and roughly set

His Britons in blown seas and storming showers,

We have a voice with which to pay the debt

Of boundless love and reverence and regret

To those great men who fought and kept it ours."

We have a voice!—yes, and is it not well that at this juncture it should be raised in honour of the men who have mounted guard for us at the gates of Empire? It is well, too, that our ears should listen to stories of them—surely there is no taint of unpardonable curiosity in that, but rather an inquisitiveness which is worthy of praise. No man can hear of great men, nor think of brave deeds, without finding himself made better and richer. It is in the contemplation of greatness that even the most poorly-equipped amongst us may find a step to a higher place of thought.

Here then is an excuse for attempting to tell plain folk the story of Baden-Powell (no need to label him with titles or prefixes!) in a plain way. It is a task which has already been attempted and achieved by more than one person: the only reason why it should be attempted again is that a good story cannot be told too often, and that in its variations there may be something of value added to it by the particular narrator. It seems to me that this story of Baden-Powell finds its great charm in its revelation of character, and as being typical of the British officer at his best. I do not find Baden-Powell so much a prodigy as a type of the flower of a class which of late has been much maligned. We have been told, over and over again since we became involved in our struggle with the Boer, that our officers are badly trained, incompetent, and careless. It is not to be denied that there is room for improvement in their military education and training, but I think we shall have hard work to improve them in one matter of some slight importance—their cheerful, brave, steady devotion to Duty. When one comes to think of it, seriously, what a great quality that is! To be ready to go anywhere, to do anything, or to attempt its doing with all the strength one possesses, to face whatever a moment may bring forth with the cheery pluck with which a schoolboy goes into a scrimmage—are these not qualities which make for greatness? It seems to me that they are found in the British officer in an extraordinary degree, and that the life of Baden-Powell as we know it is typical of the results of the possession of them. I do not mean to say that every British officer is a Baden-Powell, but I cherish a strong conviction that Baden-Powell himself has said, more than once, when overwhelmed with congratulations, "Oh, any other fellow would have done the same!" Of course, that is all wrong—we all know that not every other fellow would. But I believe every other fellow would have Tried—and to Try means a world of things. After all, the greatest thing in this world, and the surest passport to happiness in the next, is doing one's Duty, cheerfully, fearlessly, and confidently, and it is because there is so much evidence of the way in which the British officer attempts to do his, in the story of Baden-Powell's career, that I make no excuse for begging the man in the street to read it again, and again, and yet again—whoever writes, or tries to write it.

J.S.F.

East Hardwick, Yorks

September, 1900

BADEN-POWELL OF MAFEKING

BADEN-POWELL—THE MANNER OF MAN HE IS

THE BOY AND HIS PEOPLE

If it seems something of an impertinence to write about the life of a man who is still alive and apparently determined to be so for many years of energy and activity, it appears to be almost in the nature of a sacrilege to draw aside the veil which ought to shroud the privacy of his family life. Most English folk, whether they show it or not, are deeply in love with the sentiment expressed in Browning's lines,—

"A peep through my window if some should prefer,

But, please you, no foot over threshold of mine"—

but in the case of the Baden-Powell family many feet have already crossed the threshold, and many hands have drawn aside the curtain. It is not often that the lifting of the veil which usually hides English family life from the world's gaze reveals as charming and instructive a picture as is found in the contemplation of the people to whom the hero of Mafeking belongs. We all know that it is not necessary to spring from a great family in order to be a great man; we all know, too, that many a great family has produced a great fool. But when a great family does produce a great man the result is greater than could be obtained in any other way. Baden-Powell comes of a family-stock great in many ways, and were there reason or time for it, nothing could be more delightful or instructive than to endeavour to trace the connection between the main features and characteristics of his life and the hereditary influences which must needs have acted upon him. His ancestors have done so many fine things that one feels something like amazement to find their present day representative still adding lustre to the family name. According to the ordinary laws all the strength and virtue should have been exhausted in the stock ere now, but just as Baden-Powell himself is in certain ways a mysterious contradiction to things in general, laughing where other men would weep, and rising to great heights where most men would turn back to the valley in despair, so his family, after many generations of great activity, contradict the usual laws by increasing in strength and giving evidence of that growth and development which, as Dr. Newman told us in a remarkable sentence, is the only evidence of life.

Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell was born at 6, Stanhope Street, London, on the 22nd February, 1857. He was the seventh son of the late Rev. Baden-Powell, sometime Savilian Professor in the University of Oxford, and of Henrietta Grace, daughter of Admiral W.H. Smyth, K.S.F. Of his father the future defender of Mafeking can have known little; Professor Baden-Powell died when his seventh son was only three years old. He was a man of great talents, widely known as a profound student in the physical sciences and as an exponent of broad and tolerant theology, a frequent contributor of learned papers to the transactions of the Royal Society, and a whole-hearted lover of nature and of the sights and sounds of country life. One would like to know more of him, and of such intercourse as existed between him and his children. They, however, were separated from him at an early age and were left to the sole guidance and friendship of their mother. It is rarely that children have a mother so well equipped for the performance of a difficult task—Mrs. Baden-Powell is in all respects a great woman and eminently fitted to be the mother of a hero. She, like her husband, came of a stock eminent for its qualities. Her father, Admiral W.H. Smyth, was a well-known seaman of his day, and his children have all achieved eminence in one way or another. One of his sons, Warington, became Mineral Inspector to the Crown; another, Fiazzi, Astronomer Royal for Scotland; a third, General Sir Henry Smyth, after a distinguished military career, was Governor and Commander-in-Chief at Malta from 1890 to 1893. Of his two daughters, the younger, Georgina Rosetta, was married in 1858 to Sir W.H. Flower, the eminent scientist; the elder, Henrietta Grace, had previously married Professor Baden-Powell.

A Merciful Man.

It is often said that a boy is what his mother makes him, and no one will deny that there is a certain amount of truth in the saying. A boy naturally turns rather to his mother than to his father when he first feels the need of sympathy, and it is well for him if his mother has not merely sympathy but perception and understanding to give him. Mrs. Baden-Powell appears to have been singularly fitted to help her children with her love, sympathy, and tact during the earlier years of their youth. Herself a brilliantly clever woman, she recognized intuitively the workings of dawning talent and ability in her own children, and she encouraged and helped them as only a woman of great gifts could. As a linguist, an artist, a musician, a mathematician, and a lover of science and of nature, Mrs. Baden-Powell has many attainments, and it must be evident to the most obtuse that her children received a liberal education in merely knowing her. When Professor Baden-Powell died his widow was left with a responsibility from which the bravest woman might well have shrunk. She had been married fifteen years, and there were ten children of the marriage, and the eldest was not fourteen years of age. That Mrs. Baden-Powell had no shrinking, that she devoted herself to her task with courage, determination, and skill is proved by the results with which the world, for its good, has been familiarized. The training of her children, as far as one may speak of it with reserve and respect, seems to have been marked by the greatest good sense. She took an interest in everything that interested them; she inculcated a strict regard for honour in their minds; she taught them to bear pain as strong men should; above everything she strove to bring all the influence of nature into their lives. Such an education as this could scarcely fail to produce men well fitted to do something, and Mrs. Baden-Powell's sons have done much. Her eldest son attained considerable distinction as the author of an important work on the Land Systems of British India, and occupied a high judicial post in that country ere his death. Her second son, Mr. Warington Baden-Powell, after serving some years in the navy, turned from the sea to the atmosphere of the Law Courts, and is now a Queen's Counsel of eminence. Her third son, the late Sir George Baden-Powell, who died in 1898, was, until recent events brought his younger brother's name more prominently before the public, the best-known member of the family. His record was a particularly brilliant and useful one. He took the Chancellor's Prize at Oxford in 1876. He was private secretary to the Governor of Victoria, 1877-78; Joint Special Commissioner in the West India Colonies, 1882-84; Assistant to Sir Charles Warren in Bechuanaland, 1884-85; Joint Special Commissioner in Malta, 1887-88; British Commissioner in the Behring Sea Question, 1891; and British Member of the Washington Joint Committee in 1892. He was a Fellow of the Royal Society and an LL.D., and represented the Kirkdale Division of Liverpool in Parliament from 1885 until his death. He wrote several important works and papers on scientific, economic, and political subjects, and was created a baronet in 1888. Other sons of this fortunate and gifted mother are Mr Frank Baden-Powell, who, after a distinguished career at Oxford, became a barrister and is well known as an artist of great merit, and Major B.F.S. Baden-Powell, of the Scots Guards, whose invention of war-kites was of great value during the operations at Modder River. Of the seventh son it is the province of this book to speak more fully and particularly than of his brothers, but this brief reference to Mrs. Baden-Powell's family would be incomplete if it did not include some notice of the sister of all these clever boys, who, clever and brilliant herself, must needs have watched the development of their lives with true pride and affection. I ventured to ask Miss Baden-Powell the other day two questions which seemed to me peculiarly pertinent to the matter I had just taken in hand. The first arose out of a passage in General Baden-Powell's work on the Ashanti Expedition of 1896, wherein he declares that "a smile and a stick will carry you through the world." I asked Miss Baden-Powell if this saying formed a sort of keynote to her brother's character as she knew it. She replied that she found it impossible to conceive of his using a stick in any case. So, in my estimate of him, whatever it may be worth, the stick disappears from Baden-Powell, but the smile remains and has gained much in potency. My second question had perhaps a much deeper significance. I asked if in his sister's view—and it has been my experience, founded on much cynical observation of things, that if one wants honest criticism of one's self one can get it, in all truth, from one's sister—the future warrior was in his boyhood at all phenomenal, if he gave, as some embryonic geniuses unfortunately do give, any notable evidence of the greatness that was coming. And I rejoiced to hear that he did not, that he was a human boy, neither precocious nor a prig—just a healthy, fun-loving English boy, full of kindliness and of delight in the joys of life's morning.

That is exactly what one likes to feel about Baden-Powell's boyhood. From what one can gather from many sources about his early days they appear to have been marked chiefly by the sunniness of his own disposition. His education was conducted under a tutor at home until he was eleven years old, and he spent much of his time in outdoor pursuits. He learned to ride at a very early age, and was fond of exploring unknown regions in company with his brothers. Much of the future scout's boyhood was spent at a country house near Tunbridge Wells, and in the neighbouring woods he lived many hours of glorious life. But he appears to have had almost as many pursuits in boyhood as he has shown himself fond of in manhood. He began to draw and paint at a very early age. Before he was three years old he executed a pen-and-ink drawing of camels and camel drivers, the execution of which was wonderful for so young a child. It was quickly perceived in the family circle that he used his left hand, which he has always used throughout his life with equal facility to his use of the right, and his mother consulted Ruskin as to the advisability of checking this propensity. Ruskin advised her to let the boy use his left hand as freely as his mind wished, with the result that he has always been able to work at his sketches and drawings with both hands at the same time, drawing with the left and shading with the right—a performance which is surely rarely equalled. Another of his boyish amusements was to play with dolls, and to make their clothes; another, succeeding, one supposes, the doll era, was to take part with his brothers in the performance of plays. He has always been passionately devoted to dramatic art, and showed his love for theatrical matters at a very early age. It is only what one would expect from his extraordinary versatility to hear that he used to write the plays himself, invariably fitting himself with a "fat" low-comedy part.

Although he was in no sense of the word that most unspeakable thing, a precocious child, Baden-Powell showed in his boyhood some signs of the inclinations which were working in him. Nothing pleased him so much as to explore new ground in the shape of woods and fields; it was an exquisite delight to him to get lost in an unfamiliar part of the country and to be obliged to find a way out. He showed great pleasure in drawing maps and charts, with which he took infinite pains, and he was very fond of cutting figures of animals out of paper, and of imitating the cries and calls of birds and voices of animals. Then, again, he showed at an early age the resourcefulness and dependency upon self which have been such marked characteristics of his military career. He entirely dispensed with the services of a nurse before he was three years old; he kept a very careful account of the expenditure of his pocket money, and in everything seems to have shown a wisdom not at all out of keeping with his light-hearted disposition. It may be that much of his light-heartedness has unconsciously sprung from his thoroughness in doing things. It was fortunate for him that he possessed a great friend in his brother, Mr. Warington Baden-Powell, who, being ten years his senior, was able to give him not merely advice but excellent example. In company with his brothers the future soldier lived a great part of his holiday-time as a sailor, roughing it in small yachts around the coast and over the seas. The yachts were designed by Mr. Warington Baden-Powell, who also acted as skipper, and were managed entirely by himself and his younger brothers. Now and then the small craft and its crew happened upon tight places, and on one occasion, while off Torquay in a ten-tonner named the Koh-i-noor, they had an experience which would have frightened most boys to such an extent that the sea and its perils would have been eschewed for ever. A violent storm broke over them one dark evening, raged throughout the night and far into the next day, and necessitated a battling with wind and wave which only the bravest dare face. But Baden-Powell and his brothers appear to have been boys of infinite bravery and resource. They travelled extensively about the English and Welsh coasts, and spent some of their holidays in Norway, and wherever they went they depended upon themselves for whatever was necessary to be done in the way of cooking, repairing, and boat-mending. No better schooling than this, developing as it did the priceless qualities of energy, self-reliance, and confidence, could have been devised for the boy who was destined in after years to safeguard the honour of England in beleaguered Mafeking.

"BATHING-TOWEL"

After being under the care of a tutor until he was eleven years old, Baden-Powell was sent to a preparatory school at Tunbridge Wells, and remained there for two years, leaving it at the end of that time with the sincere regret of his master, who had found him an admirable example to his fellows. In 1870 he was admitted, on the Duke of Marlborough's nomination, to the Foundation of Charterhouse, then in its ancient quarters near Smithfield. Two years later he went with the Foundation to its new home near Godalming, and there remained, an inmate of Mr. Girdlestone's house, until 1876. Of these six years of Baden-Powell's life it is necessary to say something, if one wishes to form an accurate idea of their importance in moulding and strengthening his character. School-life exercises a vast influence upon a boy's future career; it may make or mar it; it is certain, indeed, that he cannot go through it without receiving influences of the most paramount importance. All the world knows now what manner of man Baden-Powell is; all the world has no doubt wondered what sort of boy he was in his days of school-life.

I recently visited the Charterhouse in order to ask Dr. Haig-Brown, who was Headmaster of the Charterhouse School from 1863 to 1897, and has since then been Master of the Charterhouse, if he would tell me something about his old pupil. There was a certain amount of satisfaction in setting foot within the precincts of a place so closely associated with one of the men of the moment; there was a strong and restful sense of relief, too, in escaping from the whirl and roar of London's crowded streets into so delightful a haunt of peace as that which lies in their very midst. Between the noise and bustle of the much-thronged thoroughfares about Smithfield and the cloistral quiet of the Master's Lodge in the Charterhouse there was a difference intensely welcome to a lover of quiet places, and I could not help thinking as I sat in Dr. Haig-Brown's study, with the noise of the outer world reduced to a low and easy murmur, that there must have been moments during the siege of Mafeking when Baden-Powell's mind turned to the grey walls and quaint gables of his old school with perhaps a little longing for the peace which broods there always. It was easy to see that the thought and memory of the old Carthusian was cherished there. In Dr. Haig-Brown's study hung a picture of the face now familiar to all of us through the medium of innumerable illustrated newspapers and magazines, the good-humoured, strong face, shadowed by the big hat, and in one of the drawing-rooms stood a small table gaily decorated with red, white and blue ribbons, whereon had been gathered together a collection of little objects—some of them the penny wares of the London street vendors—associated with the name of the hero of Mafeking. It was easy to see, too, that Baden-Powell was deeply placed in the affections of his old schoolmaster. Dr. Haig-Brown spoke of him in simple words which showed more feeling than the mere sound of them implied. He spoke of his great truthfulness, his love of fun and of sport, of his self-respect, and of his interest in his old school. He showed me a volume of the school magazine, The Greyfriar, which contained several contributions, literary and artistic, by the man who has so ably sustained all the best traditions of a great school, and has thought of it when far away and busily engaged in fighting his country's cause. And perhaps no greater tribute could be paid to Baden-Powell's greatness than Dr. Haig-Brown paid him in a few words, words which convey a great and deep meaning—"He was a boy whose word you could not doubt."

Dr. Haig-Brown was kind enough to give me a copy of an article on Baden-Powell which he wrote for a recent number of The Church Monthly, and to allow me to make use of any of the remarks which he there made as regards his old pupil. It is an article which shows that in the opinion of his schoolmaster the recent brilliant achievements of Baden-Powell were foreshadowed in his early youth. Quoting Wordsworth's famous line,

"The child is father of the man,"

Dr. Haig-Brown goes on to say that though it is not always easy to found on observation of early life a prophecy of the future career, it is not so difficult when characteristics have found a field for display, to trace in the memories of youth the qualities that have formed a great man, and that the boyish life of Baden-Powell furnishes an illustration in point. Then he proceeds to speak of Baden-Powell's joyousness of spirit, of his indomitable energy, his versatility of talent, his wit, kindliness, and activity of body and mind, and of his judgment and fidelity in positions of trust and responsibility. And there is one passage in Dr. Haig-Brown's article which, to my mind, is of supreme importance to anyone endeavouring to form an estimate of Baden-Powell's character as illustrated by his school-days. "In his attitude to the younger boys," says Dr. Haig-Brown, "he was generous, kind and encouraging, and in those early days gave no slight indication of the qualities which have since gained for him the confidence, respect, and love of all the soldiers who have been under his command." Here, indeed, the promise of the boy has been amply fulfilled in the performance of the man.

Another foreshadowing of Baden-Powell's future career is found in a characteristic entry in the school's Football Annual for 1876, wherein it is recorded that "R.S.S.B.-P. is a good goalkeeper, keeping cool, and always to be depended upon." Keeping cool—always to be depended upon—what a magnificent endowment! How many of us, fighting our little battles in life's war-time, would give all that we possess if we could always keep cool—if we knew that other folk could always depend upon us! Those of us who believe in athletic exercises as forming no inconsiderable part of a boy's training will find no difficulty in believing that much of the coolness and resource which have distinguished Baden-Powell in his various campaigns were deepened and strengthened by the fact that he was very fond of football. The two qualities were there before, of course, but the goalkeeping added a new fibre or two of strength to them. Dr. Haig-Brown took me out upon a terrace which commanded a view of the old Charterhouse playground. It, like the school buildings, is now used by the Merchant Taylors' School, and in one corner stood two or three practice-nets for cricket, while at each end of the playing area a certain wornness of aspect showed where many a struggle had taken place around the goal-posts during the bygone spring and winter. Dr. Haig-Brown told me that his old pupil played other games than football, notably cricket and racquets, but added that football was his chief love, and goalkeeping his great forte. One characteristic he possessed as goalkeeper which is not often found on the football field. When the fight was raging far off in the enemy's quarters, and he himself was relieved of immediate duty for the moment, he used to delight the onlookers who crowded round about the goal which he was defending by cracking all sorts of extraordinary jokes, which only ceased when he rushed forward to repel an attack with a vigour and force not less strenuous than his wonderful flow of spirits. Naturally enough, there was always a little group of spectators round the goal-posts where "Bathing-Towel" (a nickname which has clung to him always in the minds of old Carthusians) stood intent and alert, but not so entirely preoccupied as to forget the humour which was always bubbling up within him.

During his school-days, either in the precincts of the ancient Charterhouse or in the new home of the school at Godalming, where he was an inmate of Mr. Girdlestone's house, "Bathing-Towel," in true promise of his later years, appears to have been very fully occupied, and to have had quite a multitude of interests. He was extremely fond of theatrical representations, and became such a favourite that his mere appearance on the stage invariably evoked wild applause from his schoolfellows. He wrote for the school magazine, and helped to illustrate it; he was a member of the chapel choir, assisted in forming the school rifle corps, which he represented as one of the Charterhouse VIII. for three consecutive years at Wimbledon, and persuaded the powers that were into instituting a school orchestra. He played various instruments, and notably the violin, with some skill, and it is said that he was on one occasion discovered playing the piano with his toes. He was always in high spirits, always making jokes, always good-humoured. The whoop in which he was wont to indulge when he became excited by the struggles of the football field is still remembered by those of his old schoolfellows who heard it, and there is scarcely an old Carthusian of "Bathing-Towel's" day who has not some quaint story to tell of him, or whose manner in telling it does not suggest that the defender of Mafeking must have been one of the sunniest-natured boys that one could wish to meet.

But all this, of course, only deals with one side of "Bathing-Towel's" school-days—the side which after all has more to do with the pleasant things of life than with the serious things. Now that everybody knows what manner of man he is who held Mafeking against the Boers through seven long months of privation, no one will be surprised to hear that "Bathing-Towel" was just as earnest in his work at school as he was joyous in his play. Dr. Haig-Brown says of him that he never showed want of respect for his masters or lack of consideration for his schoolfellows. He speaks with some stress of his liberality of feeling and of his natural gift as a leader. He worked hard and seriously, and though he was very reserved he was never shy, and approached his masters on any subject on which he desired advice and enlightenment with a total absence of timidity or embarrassment. Naturally, then, he was a great favourite in the school. He entered Charterhouse by a low form, for there had very wisely been no attempt to force his education, but so well did he work there that by 1875—five years after his admission—he had reached the sixth form, and on the recommendation of Mr. Girdlestone, his house-master, was made a monitor. Dr. Haig-Brown says that he discharged the duties of this responsible position with judgment and fidelity, bringing his intelligence to bear on the interpretation of the school's traditions, and being especially considerate and thoughtful in his attitude to the younger boys.

It is scarcely necessary to say that "Bathing-Towel's" memory is much cherished by his old schoolfellows, nor that he himself keeps a very warm corner in his heart for the great foundation to which he now belongs in a stronger sense than ever. Whenever he is in England he quickly makes his way to Godalming, there to renew his youth, and it was to Dr. Haig-Brown, whom he visited at the Charterhouse just before sailing for South Africa, that he expressed the wish—very soon to be amply satisfied!—that the authorities would give him a warm corner. The Greyfriar, the illustrated school magazine which possesses a peculiar charm for all Carthusians, past and present, has at various times been enlivened by contributions from his pen and pencil, and on more than one occasion he has made another appearance on the stage where his boyish jokes used to find such favour. No wonder that Charterhouse cherishes his memory and is proud of his career. "Baden-Powell," says Dr. Haig-Brown, "has already secured a distinguished place among Carthusian heroes. Probably, if his youth had been spent elsewhere, he would not have fallen short of the high distinction he has won; but those who love Charterhouse (and they are many) may be excused if they feel some pride in this association with a man who has devoted such varied and sterling qualities to the service of his country."

LEARNING THE TRADE

It seems somewhat strange to learn that when Baden-Powell left school it was with no definite notion of entering the army. One would have thought, considering all his subsequent brilliant achievements, that his mind had been set on being a soldier from some very early age. This, however, was not the case. When he said good-bye to the Charterhouse he had no definite idea as to the character of his future career, beyond a strong impulse to engage in some pursuit which would show him the wild places of the world. There was some talk of his going into the Indian Civil Service, especially as he wanted to study life and nature in that country, but it was pointed out to him that military life in India would give him equal if not superior facilities to that of the civilian. His first intention, however, was to proceed to Oxford, and by the advice of his godfather, the late Professor Jowett, he was entered at Christ Church, where he meant to spend two years. Then came one of those curious events, which, looked at in the light of after happenings, seem to work as special interpositions of Providence. Hearing that an army examination was about to be held, Baden-Powell, apparently more out of whimsicality than anything else, decided to go in for it. The examination over, he set out for a yachting cruise in company with his brother, quite careless, so far as one may be permitted to judge, of the immediate results of this testing of his abilities. The immediate results were, to say the least of them, surprising and even startling. The examination took place in the summer of 1876; ere summer was over he received an official communication from the Duke of Cambridge, as Commander-in-Chief, informing him that out of 718 candidates he had passed fifth (ranking as second place for a cavalry regiment), and that in consequence of his success he had been gazetted to a second lieutenancy in the 13th Hussars, his commission being ante-dated by two years as a reward for the uniform good work shown in his papers. This was the beginning of Baden-Powell's military career. Within a few days of his receipt of the official communication he was on his way to join his regiment, which at that time was stationed in India.

The 13th Hussars, thus suddenly reinforced by this bright and lively young prodigy, prides itself greatly on the fact that it figured in the great affair at Balaklava, when in company with the 4th and 5th Dragoon Guards, the 1st, 2nd and 6th Dragoons, the 4th, 8th and 11th Hussars, the 17th Lancers, and the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, it assisted in performing certain deeds and affairs which have made military critics wonder ever since in more ways than one. It was then known as the 13th Light Dragoons. Like nearly every British regiment it possesses numerous nicknames. It is sometimes called "The Green Dragoons," sometimes "The Ragged Brigade." It has a third nickname in "The Evergreens," a fourth in "The Geraniums," a fifth in "Gardner's Dragoons." These five varying sobriquets are much more pleasant than a sixth—"The Great Runaway Prestonpans"—which seems to imply certain things that one would rather not think of. Its motto is "Vivet in Æternum"; its badge a V.R. in a Garter, crowned. When Baden-Powell joined it in India in 1876 it was in command of Sir Baker Russell, a fine soldier who had served through the terrible times of the Indian Mutiny and recently passed through the Ashanti War of 1873.

The light-heartedness which characterized Baden-Powell's early days appears to have increased rather than deteriorated when he entered upon the serious business of life. There is a curious story told of one of his first doings on joining his regiment in India which serves to show what high spirits and whimsical notions were his in those days. Assembling all the European children he could find or hear of, he produced from his kit an ocarina—an instrument from which most people would surely despair of extracting much music!—and forming his youthful following into procession, marched at their head through the streets playing "The Girl I Left Behind Me." One learns a good deal about Baden-Powell from that little incident, and it is not surprising that it should have done a good deal to make him popular with the folk amongst whom he had suddenly appeared. But his popularity with his brother officers seems to have been assured from the first. Just as he had been the life and soul of Charterhouse in all things appertaining to gaiety and amusements, so he speedily became a moving spirit in regimental jinks and jollities. It was not long ere his fellows discovered that they had got a veritable prodigy amongst them where theatrical matters were concerned, and that behind the new-comer's somewhat reserved manner there lay such funds of light and original humour as are too seldom met with in this world. At this time, no doubt, Baden-Powell's wonderful versatility was widening and deepening, and his extraordinary facility in doing anything that had to be done must have been nothing short of astonishing to those who witnessed it. Always ready and always willing to take anything in hand, it is little wonder that those who remember him in those early days in India speak of him with an affection which is not the less real because there is always a vein of merriment in it.

The Horse Guard.

But while Baden-Powell was continuing his old pranks and cultivating his old spirit of laughter, he lost no opportunity of learning his trade as a soldier. It is characteristic of the man that though until he entered the army he had cherished no very definite notion of a military career, he had no sooner taken the final step than he began to devote himself to his profession with all his might. He speedily became a perfect horseman, made himself fully acquainted with regimental duties and details, and began to read systematically. He took a first class and special certificate for topography in the Garrison Class Examination of 1878. Coming back to England soon afterwards for musketry instruction at Hythe, he soon took a first class extra certificate, and on his return to India was appointed Musketry Instructor at Quetta. His advancement in his profession, indeed, if not extraordinarily rapid, was sure and certain. It is not pertinent to the character of such a necessarily brief sketch of his life as this to lay too much stress on all that he did ere he came into special prominence some few years ago. But when one considers the brief facts of his military career one easily sees how thoroughly Baden-Powell—to use a well-understood phrase—learnt his trade. He served with his regiment (of which he was adjutant for many years) in India, Afghanistan, and South Africa; he was on the Staff as Assistant Military Secretary in South Africa in 1887-89; he was in the operations in Zululand in 1888, and was mentioned in despatches; he acted as Assistant Military Secretary at Malta from 1890 to 1893; he went on special service to Ashanti in 1895, and was Chief Staff Officer in the Matabele Campaign of 1896, and was promoted from his old regiment to the command of the 5th Dragoon Guards in 1897. It required little knowledge of military life and matters to realize how thoroughly the future hero of Mafeking had made himself acquainted with the duties of the perfectly-equipped soldier during the twenty-one years dealt with in this brief outline of his doings. Such an outline is indeed less than brief, for it records scarcely anything but the main facts of his military advancement. When one comes to remember that in addition to all the active service here mentioned he contrived to find time to write books, some of them about Tactics, some about Sport, some describing his participation in or conduct of important military operations, one is amazed to find that a single brain can compass so many things. But the amazement deepens when it is remembered that in addition to all this Baden-Powell also found time to do many other things—to act, sing, paint, etch, make innumerable sketches, hunt, shoot, yacht, get up theatrical entertainments and stage-manage them, attend foreign military evolutions, and travel extensively. To an ordinary mortal the question must needs occur,—How does he manage to do it all? To that the only possible answer can be that Baden-Powell, in addition to possessing many qualities denied to other men, is blessed with yet another of which most men are not so keen to take advantage—that of always being occupied, and of being thoroughly absorbed in the thing that occupies him. He has never shown this quality more thoroughly, perhaps, than during those portions of his career when duty called him to play—or rather, work—the part of regimental officer. Most of us know how such a part may be played—how the officer in barracks may spend his time in doing a minimum of duty and a maximum of pleasure, how he may ignore the men under him, and generally behave as if the service were a bore and all its surroundings unpalatable. Some officers do order their lives after such a fashion; others again affect a languid indifference to things in general, which is scarcely less hurtful to the best interests of the service. Baden-Powell, as regimental officer, was neither bored nor indifferent. He was always doing something for his men, interesting himself in games and amusements, lecturing to them, acting, reciting, and making fun for them, and there was not a man in his troop who did not feel that he had a friend in his energetic captain. It is not difficult to realise what all this means. The man who can command the respect and affection of those serving under him to such an extent that they would go anywhere and do anything at his lightest word must needs possess a personal magnetism which proves him worthy of leading not merely a troop but an army.

SCOUT AND SPORTSMAN

Following up the Spoor.

In his youthful days Baden-Powell was very fond of exploring such unknown regions as are accessible to a small boy, and it is related of him that nothing gave him so much pleasure as to find himself and his companions lost and his own ingenuity taxed to restore them to the paths of safety. When he arrived at years of discretion this passion for wandering did not desert him—on the contrary it increased within him, and finally culminated in a devotion to scouting, which has made his name famous all over the world. It is needless to say that in this matter, as in most other matters closely affecting him, Baden-Powell has largely depended upon himself for success and mastery. As he remarks in his "Aids to Scouting," a little military handbook the proofs of which accompanied the last despatches got through the Boer lines at Mafeking, "Scouting is a thing that can be learnt, but cannot be taught. A man must pick up much of it for himself by his own effort." How much of it Baden-Powell has not picked up for himself can only be guessed by a careful perusal of this little treatise, which is packed with the results of keen observation, and gives one perhaps a better notion of what its author really is as a born soldier and leader of soldiers than anything else of his. It was, no doubt, with sublime unconsciousness that he describes himself in describing the perfect scout, the man of pluck, self-reliance, and discretion, the man who can use his ears and eyes, his sense of smell and touch, who can keep himself hidden and track others, who can make his way across strange lands and take good care of himself and his horse, and who in everything he does is always dominated by the desire to secure valuable information. And it is with perhaps still more sublime unconsciousness that he insists that the first three necessary qualifications spring from—confidence in one's own powers.

Of the many wonderful things done by Baden-Powell nothing seems to me so wonderful as the way in which the man who has had so many and such varied occupations has perfected himself in scouting. He seems to be all eyes and ears, to never lose cognizance of anything that happens, and to give an attention to little points of detail which less extraordinary men would feel tempted to ignore. "It should be a point of honour with a scout," he remarks, "that nobody sees any object that he has not already seen for himself. For this your eyes must be never resting, continually glancing round in every direction, and trained to see objects in the far distance. A scout must have eyes in the back of his head. Riding with a really trained scout, such as Buffalo Bill or Burnham, you will notice that while he talks with you his eyes scarcely look you in the face for a moment, they keep glancing from point to point of the country round from sheer force of habit." Then he quotes a slight incident from his own experience to show how a little reflection and common-sense will suggest the most likely point for which to look for the presence of an enemy. He and a Shikari in Kashmir were having a match as to which of them could see furthest. The Shikari, pointing out a hillside rising at some distance, inquired if his opponent could say how many cattle were grazing along its slopes. Baden-Powell could only see the cattle with great difficulty, but he presently astonished the Shikari by asking him if he could see the man who was herding the cattle. He could not see the man himself, but he had argued the thing out and knew where the man was. First of all, where there were cattle there would be a herd in charge of them. Secondly, it was most likely that he would be up-hill, above them. Thirdly, up-hill above them stood a solitary tree. Fourthly, the day was very hot, and the tree was the only means of affording shade. Because of these reasons the man must be under the tree—and when Baden-Powell and the Shikari brought their glasses into operation there the man was.

An instance of Baden-Powell's careful attention to small details is given in the same chapter of "Aids to Scouting." "I was once acting as scout for a party in a desert country," he says, "where we were getting done up for want of water. I had gone out two or three miles ahead to where I thought the ground seemed to slope slightly downwards, but except a very shallow, dry water-course, there was no sign of water. As I was making my way slowly back again, I noticed a scratching in the sand, evidently recently made by a buck, and the sand thrown up was of a darker colour, therefore damper, than that on the surface. I dismounted and scooped up more with my hands, and found the under-soil quite moist, so water was evidently near, and could probably be got by digging. But at that moment two pigeons sprang up and flew away from under a rock near by; full of hope, I went to the spot and found there a small pool of water, which yielded sufficient for the immediate requirements of the party. Had I not noticed the buck-scratching, or the pigeons flying up, we should have had a painful toil of many miles before we struck on the river, which we eventually did come to."

There are abundant evidences in "Aids to Scouting" of the extraordinary patience which its author possesses, and of the way in which he has exercised it in perfecting himself as a scout. He mentions, as if it were a mere nothing, that he once took up a position amongst some rocks overhanging a path, and so close to it that he could have touched passers-by with a fishing-rod, and remained there for two hours in order to see how many people who passed him would perceive him. He took no pains to conceal himself, but merely sat down, a little above the level of a man's eye. During the two hours fifty-four persons passed him, and he was only noticed by eleven of them. But how many of us are there who have the patience to remain motionless for two hours?—all for the sake of an experiment! But Baden-Powell's patience gains a great deal in its value to him as a scout by its being linked with a marvellous power of deduction. He likes to find out everything he can about all that he sees, keeps a sharp eye on the people he meets, tries to deduce what they are from their personal appearance, outward signs, and chance observations, and is all the better satisfied if he finds that his conclusions are true. When he was in India he used to go out in the early mornings looking for what he could find and deducing arguments from signs and things thus found. He gives numerous illustrations of this exercise of his logical faculties in "Aids to Scouting," of which the following is a typical example:—

Example of Deduction from Signs. ("Aids to Scouting," p. 75.)

Locality.—A mountain path in Kashmir.

Weather.—Dry and fine. There had been heavy rain two days before, but the ground had dried the same night.

Signs observed.—Passing a tree stump, I noticed a stone lying on it about the size of a cocoa-nut. I wondered for the moment how it came to be there, and soon discovered the reason.

On the stump, and also sticking to the stone, were some bits of bruised walnut-rind, green, but dried up. Bits of shell of about four walnuts were lying about the ground near a leaning rock about 30 yards away south of the stump. The only walnut-tree in sight was about 150 yards north of the stump.

At the foot of the stump, just where a man would stand to use the stone on it, was a cake of hardened mud that had evidently fallen from the sole of a grass sandal.

Deduction.

That a man was carrying a load.—Had it been anyone not carrying a load he or she would not have sat down on the stump or close to it; instead of that, he had gone 30 yards away to where a slanting rock was; this would support his load while he leant back against it to rest and eat his walnuts (whose shells were lying there). Women do not carry loads on their backs.

He was on a long journey.—As he wore sandals instead of bare feet.

Towards the south.—He had got the walnuts 150 yards north of the stump, had stopped there to break them with the stone, and had gone 30 yards further on his road to the rock to eat them.

He had passed there two days ago.—The cake of mud off his sandal showed that when he was there the ground was wet, and the dried husk of the walnuts corroborated this deduction.

Total information.—A man had passed here two days ago, on a long journey, carrying a load southward.

It goes without saying that Baden-Powell has had plenty of adventures and excitement out of his love of scouting. How often his life has been in such danger that it was apparently not worth a moment's purchase, it is probable he himself does not know. But if there is anybody who knows what an extraordinarily watchful life it is that has thus risked itself a thousand times, it is the Matabele against whom Baden-Powell brought his keen senses to bear during the campaign of 1896, and who conferred upon him a sobriquet which is likely to stick to him as long as his old nickname of "Bathing-Towel," or the modern "B.-P." of admiring crowds. Writing of his work during July, 1896 ("The Matabele Campaign," p. 127-8), he says: "Many of the strongholds to which I had at first learned the way with patrols, I have now visited again by myself at nights, in order to further locate the positions of their occupants. In this way I have actually got to know the country and the way through it better by night than by day, that is to say, by certain landmarks and leading stars whose respectively changed appearance or absence in daylight is apt to be misleading. The enemy, of course, often see me, but are luckily very suspicious, and look upon me as a bait to some trap, and are therefore slow to come at me. They often shout to me; and yesterday my boy, who was with my horse, told me they were shouting to each other that 'Impeesa' was there—i.e., 'The Wolf,' or, as he translated it, the beast, that does not sleep, but sneaks about at night." Since then a good many folk have learnt much of the Wolf that does not sleep. But if this same sleepless Wolf were asked if there had not been many compensations for his sneaking about at night, he would probably be able to say that for every moment of anxiety he had spent a thousand of satisfaction. To how many men leading hum-drum stay-at-home lives is it ever granted to see one such picture as that Baden-Powell records in his journal under date July 29th, 1896? ("The Matabele Campaign," p. 175.)

"To-day, when out scouting by myself, being at some distance from my boy and the horses, I lay for a short rest and a quiet look-out among some rocks and grass overlooking a little stream; and I saw a charming picture. Presently there was a slight rattle of trinkets, and a swish of the tall yellow grass, followed by the sudden apparition of a naked Matabele warrior standing glistening among the rocks of the streamlet, within thirty yards of me. His white war ornaments—the ball of clipped feathers on his brow, and the long white cow's-tail plumes which depended from his arms and knees—contrasted strongly with his rich brown skin. His kilt of wild cat-skins and monkeys' tails swayed round his loins. His left hand bore his assegais and knobkerrie beneath the great dapple ox-hide shield; and, in his right, a yellow walking-staff.

"He stood for almost a minute perfectly motionless, like a statue cast in bronze, his head turned from me, listening for any suspicious sound. Then, with a swift and easy movement, he laid his arms and shield noiselessly upon the rocks, and, dropping on all fours beside a pool, he dipped his muzzle down and drank just like an animal. I could hear the thirsty sucking of his lips from where I lay. He drank and drank as though he never meant to stop, and when at last his frame could hold no more, he rose with evident reluctance. He picked his weapons up, and then stood again to listen. Hearing nothing, he turned and sharply moved away. In three swift strides he disappeared within the grass as silently as he had come. I had been so taken with the spectacle that I felt no desire to shoot at him—especially as he was carrying no gun himself."

But lest those who read these words should imagine that the life of a scout is all pleasurable excitement with a little danger thrown in to give it an added zest, let them read an extract from one of Baden-Powell's letters to the Daily Chronicle, to which he at one time acted as special correspondent. It describes setting out on reconnaissance with a patrol:—

"Is it the cooing of doves that wakes me from dreamland to the stern reality of a scrubby blanket and the cold night air of the upland veldt? A plaintive, continuous moan, moan, reminds me that I am at one of our outpost forts beyond Buluwayo, where my bedroom is under the lee of the sail (waggon tilt) which forms the wall of the hospital. And through the flimsy screen there wells the moan of a man who is dying. At last the weary wailing slowly sobs itself away, and the suffering of another mortal is ended. He is at peace. It is only another poor trooper gone. Three years ago he was costing his father so much a year at Eton; he was in the eleven, too—and all for this.

"I roll myself tighter in my dew-chilled rug, and turn to dream afresh of what a curious world I'm in. My rest is short, and time arrives for turning out, as now the moon is rising. A curious scene it is, as here in shadow, there in light, close-packed within the narrow circuit of the fort, the men are lying, muffled, deeply sleeping at their posts. It's etiquette to move and talk as softly as we are able, and even harsh-voiced sentries drop their challenge to a whisper when there is no doubt of one's identity. We give our horses a few handfuls of mealies, while we dip our pannikins into the great black 'billy,' where there's always cocoa on the simmer for the guard. And presently we saddle up, the six of us, and lead our horses out; and close behind us follow, in a huddled, shivering file, the four native scouts, guarding among them two Matabele prisoners, handcuffed wrist to wrist, who are to be our guides.

"Down into the deep, dark kloof below the fort, where the air strikes with an icy chill, we cross the shallow spruit, then rise and turn along its farther bank, following a twisting, stony track that leads down the valley. Our horses, though they purposely are left unshod, make a prodigious clatter as they stumble adown the rough uneven way. From force of habit rather than from fear of listening enemies, we drop our voices to a whisper, and this gives a feeling of alertness and expectancy such as would find us well prepared on an emergency. But we are many miles as yet from their extremest outposts, and, luckily for us, these natives are the soundest of sleepers, so that one might almost in safety pass with clattering horses within a quarter of a mile of them.

" ... Dawn is at hand. The hills along our left (we are travelling south) loom darker now against the paling sky. Before us, too, we see the hazy blank of the greater valley into which our present valley runs. Suddenly there's a pause, and all our party halts. Look back! there, high up on a hill, beneath whose shadow we have passed, there sparkles what looks like a ruddy star, which glimmers, bobs, goes out, and then flares anew. It is a watchfire, and our foes are waking up to warm themselves and to keep their watch. Yonder on another hill sparks up a second fire, and on beyond, another. They are waking up, but all too late; we've passed them by, and now are in their ground. Forward! We press on, and ere the day has dawned we have emerged from out the defile into the open land beyond. This is a wide and undulating plain, some five miles across to where it runs up into mountain peaks, the true Matopos. We turn aside and clamber up among some hills just as the sun is rising, until we reach the ashes of a kraal that has been lately burned. The kraal is situated in a cup among the hills, and from the koppies round our native scouts can keep a good look-out in all directions. Here we call a halt for breakfast, and after slackening girths, we go into the cattle kraal to look for corn to give our horses. (The Kaffirs always hide their grain in pits beneath the ground of the 'cattle kraal' or yard in which the oxen are herded at night.) Many of the grain-pits have already been opened, but still are left half-filled, and some have not been touched—and then in one—well, we cover up the mouth with a flat stone and logs of wood. The body of a girl lies doubled up within. A few days back a party of some friendlies, men and women, had revisited this kraal, their home, to get some food to take back to their temporary refuge near our fort. The Matabele saw them, and just when they were busy drawing grain, pounced in upon them, assegaing three—all women—and driving off the rest as fast as they could go. This was but an everyday incident of outpost life."

It may be that Baden-Powell would never have been so great an exponent of the art and science of scouting if he had not always been a thoroughly good sportsman. To sport his devotion has invariably been marked since the days when he first felt the charm of wild life. He hunts and shoots, and in Mrs. Baden-Powell's house in St. George's Place there are innumerable trophies of his skill, including lions and tigers. Perhaps his favourite sport is pig-sticking, of which he became a devotee soon after he joined the 13th Hussars in India. In 1883 he won the Kadir Cup—the highest distinction open to followers of this very fascinating sport—and in 1885 he published his work on "Pig-sticking," from which the following characteristically written account of a fight which he once witnessed between a tiger and a boar is extracted:—

" ... He eagerly watched the development of this strange rencontre. The tiger was now crouching low, crawling stealthily round and round the boar, who changed front with every movement of his lithe and sinewy adversary, keeping his determined head and sharp, deadly tusks ever facing his stealthy and treacherous foe. The bristles of the boar's back were up at a right angle from the strong spine. The wedge-shaped head poised on the strong neck and thick rampart of muscular shoulder was bent low, and the whole attitude of the body betokened full alertness and angry resoluteness. In their circlings the two brutes were now nearer to each other and nearer to us, and thus we could mark every movement with greater precision. The tiger was now growling and showing his teeth; and all this, that takes such a time to tell, was but the work of a few short minutes. Crouching now still lower, till he seemed almost flat on the ground, and gathering his sinewy limbs beneath his lithe, lean body, he suddenly startled the stillness with a loud roar, and quick as lightning sprang upon the boar. For a brief minute the struggle was thrilling in its intense excitement. With one swift, dexterous sweep of the strong, ready paw, the tiger fetched the boar a terrific slap right across the jaw, which made the strong beast reel, but with a hoarse grunt of resolute defiance, with two or three sharp digs of the strong head and neck, and swift, cutting blows of the cruel, gashing tusks, he seemed to make a hole or two in the tiger's coat, marking it with more stripes than Nature has ever painted there; and presently both combatants were streaming with gore. The tremendous buffet of the sharp claws had torn flesh and skin away from off the boar's cheek and forehead, leaving a great ugly flap hanging over his face and half blinding him. The pig was now on his mettle. With another hoarse grunt he made straight for the tiger, who very dexterously eluded the charge, and, lithe and quick as a cat after a mouse, doubled almost on himself, and alighted clean on the boar's back, inserting his teeth above the shoulders, tearing with his claws, and biting out great mouthfuls of flesh from the quivering carcase of his maddened antagonist. He seemed now to be having all the best of it, so much so that the boar discreetly stumbled and fell forward, whether by accident or design I know not, but the effect was to bring the tiger clean over his head, sprawling clumsily on the ground ... the tables were turned. Getting his forefeet on the tiger's prostrate carcase, the boar now gave two or three short, ripping gashes with his strong white tusks, almost disembowelling his foe, and then exhausted seemingly by the effort, apparently giddy and sick, he staggered aside and lay down, panting and champing his tusks, but still defiant...." One can conceive, after reading this passage, that Baden-Powell must needs have a considerable respect for the wild pig of India, and find in him a foe worthy his own skill and courage.

An extract from the journal which he kept during the Matabele Campaign shows Baden-Powell in the character of lion-hunter:—

"October 10th (to be marked with a red mark when I can get a red pencil).—Jackson and a native boy accompanied me scouting this morning; we then started off at three in the morning, so that by dawn we were in sight of one of the hills we expected might be occupied by Paget, and where we hoped to see his fires. We saw none there; but on our way, in moving round the hill which overlooks our camp, we saw a match struck high up near the top of the mountain. This one little spark told us a good deal. It showed that the enemy were there; that they were awake and alert (I say 'they' because one nigger would not be up there by himself in the dark), and that they were aware of our force being at Posselt's (or otherwise they would not be occupying that hill). However, they could not see anything of us, as it was then quite dark; and we went further on among the mountains. In the early morning light we crossed the deep river-bed of the Umchingwe River, and, in doing so, we noticed the fresh spoor of a lion in the sand. We went on, and had a good look at the enemy's stronghold; and on our way back, as we approached this river-bed, we agreed to go quietly, in case the lion should be moving about in it. On looking down over the bank, my heart jumped into my mouth, when I saw a grand old brute just walking in behind a bush. Jackson could not see him, but was off his horse as quick as I was, and ready with his gun; too ready, indeed, for the moment that the lion appeared, walking majestically out from behind the bush that had hidden him, Jackson fired hurriedly, striking the ground under his foot, and, as we afterwards discovered, knocking off one of his claws. The lion tossed up his shaggy head and looked at us in dignified surprise. Then I fired, and hit him in the ribs with a leaden bullet from my Lee-Metford. He reeled, sprang round, and staggered a few paces, when Jackson, who was firing a Martini-Henry, let him have one in the shoulder; this knocked him over sideways, and he turned about, growling savagely.

"I could scarcely believe that we had actually got a lion at last, but resolved to make sure of it; so, telling Jackson not to fire unless it was necessary (for fear of spoiling the skin with the larger bullet of the Martini), I got down closer to the beast, and fired a shot at the back of his neck as he turned his head away from me. This went through his spine, and came out through the lower jaw, killing him dead. We were pretty delighted at our success, but our nigger was mad with happiness, for a dead lion—provided he is not a man-eater—has many invaluable gifts for a Kaffir, in the shape of love-philtres, charms against disease or injury, and medicines that produce bravery. It was quite delightful to shake hands with the mighty paws of the dead lion, and to pull at his magnificent tawny mane, and to look into his great deep yellow eyes. And then we set to work to skin him; two skinning, while the other kept watch in case of the enemy sneaking up to catch us while we were thus occupied. In skinning him, we found that he was very fat, and also that he had been much wounded by porcupines, portions of whose quills had pierced the skin and lodged in his flesh in several places. Our nigger cut out the eyes, gall-bladder, and various bits of the lion's anatomy, as fetish medicine. I filled my carbine bucket with some of the fat, as I knew my two boys, Diamond and M'tini, would very greatly value it. Then, after hiding the head in a neighbouring bush, we packed the skin on to one of the ponies, and returned to camp mightily pleased with ourselves.

"On arrival there, the excitement among the boys was very great, for, as we rode into camp, we pretended we had merely shot a buck; but when Diamond turned out to take my horse from me, he suddenly recognized the skin, and his eyes almost started from his head as he put his hand over his mouth and ejaculated, 'Ow! Ingonyama!' ('Great Scott! a lion!') Then, grinning with excitement, he asked leave to go and get some more of it. In vain I told him that it was eight miles away, and close under the enemy's stronghold. He seized up an assegai and started off at a steady trot along our back-spoor. And very soon one nigger after another was doubling out of camp after him, to get a share of the booty. In the evening they came back quite happy with various tit-bits, and also the head. The heart was boiled and made into soup, which was greedily partaken of by every boy in camp, with a view to gaining courage. Diamond assured me that the bits of fat, &c., of which he was now the proud possessor, would buy him several cattle when he got back to Natal."

In addition to his fame as a sticker of pigs, a hunter of hogs, a slayer of lions and tigers, Baden-Powell has also greatly distinguished himself as a hunter of big game and an expert polo-player. But there is scarcely anything in the shape of sport and the pursuit of outdoor life which he does not care for. Nature in her wildest and loneliest moods he loves with a whole-hearted devotion, and it is easy to perceive when reading his books and journals that he knows her in all her phases and attitudes, and loves her in them all. It would be strange if it were not so in the case of a man who has so often laid down in the loneliness of the African veldt and slept as trustfully as if he were in his own bed—always taking care, though, with his usual caution, to be sure that his revolver is under his knees, and its lanyard round his neck. To such as him the open air is as the breath of heaven to the saint, and communion with the wild places and wild life of the earth as meat to the hungry.

THE KINDLY HUMORIST

It seems to me that the distinguishing quality of Baden-Powell's life and character, so far as the man in the street has been permitted to inform himself about them, is a sense of humour, so strong as to dominate everything else within him. He is essentially the man who, whatever happens, will come up smiling. It is only necessary to look at him to feel sure of that—there is something in the tall, spare figure, in the well-cut, determined face and quick, observant, fun-loving eyes which gives the beholder a sense of very pleasant security. Everybody who knows Baden-Powell bears testimony to the great and unvarying quality of his humour. It is the humour of a great nature—now exuberant even to the verge of mischief, now dry and caustic enough to suit an epigram-loving philosopher, now of a whimsical sort that makes it all the more charming. But it has a further quality which may not be overlooked—it is always kindly. Only a good-natured, sunny-tempered, laughter-loving man could or would have done all the things which are credited to Baden-Powell—things which have been done more for the pleasure which a great nature always feels in lightening life for others than for the mere desire of provoking laughter. The man who was always ready as regimental officer to amuse his men by his powers as an actor, maker of jokes, and general entertainer, differs only from the schoolboy who was always full of fun and high spirits in the sense that his abilities were being turned to more serious account.

The humour which is Baden-Powell's great characteristic is of much variety and shows itself in the most astonishing ways. It is wonderfully whimsical, and sometimes appears when one would never dream of seeing it. What a whimsical notion, for instance, to assemble the European children, on joining his regiment in India, and march them through the streets to the tune of "The Girl I left behind me," played upon an ocarina! Or to send a dispatch from Mafeking which laconically said, "All well, four hours' bombardment—one dog killed." Or to present himself at a picture exhibition, and on being informed that he must leave his stick outside, to turn away and return a moment later limping so badly that the tabooed stick was perforce allowed to accompany him. Or to seat himself, a full-grown English officer, upon a kerb-stone and pretend to sob bitterly until a constable inquired as to his woes, and then to inform the astonished man that he had just fallen out of his nurse's arms, and that the unfeeling woman had gone on and left him. This sort of thing is not merely whimsical, but in the last two cases closely allied to practical joking. But it is characteristic of the man who, when Commandant Eloff surrendered to him at Mafeking, said, "How do you do?—come and have some dinner." That strong, saving sense of humour—which really means a total lack of miserable, morbid self-consciousness—must have been strong in Baden-Powell at a very early age. There is a story told of him in his very youthful days which shows that when little more than a baby his sense of humour was already strong. While staying at the seaside he had the ill-luck to fall into a somewhat deep hole in the rocks, just when the tide was coming in, and was promptly treated to a ducking, which, as he phrases it, "comed up all over my head," and made him think that he should never "tum out adain." But he fought, tooth and nail, to "tum out adain," and was met a few minutes later, a dripping and bedraggled figure, by a lady to whom he coolly explained what had happened. There was no howling and crying about the thing now that it was over—that was Baden-Powell's sense of humour. Many a long year after that we find him jotting down in his journal some particulars of a narrow escape from sudden death, or at least from serious injury. When the mule battery moved off from Beresford's position, after the fight of August 5th, 1896, during the proceedings of the Matabele Campaign, one of the mules carried a carbine strapped on its pack-saddle. The carbine had very carelessly been left loaded, and at full cock, and in passing a bush it was discharged, the bullet nearly hitting Baden-Powell, who was close behind. Most men would have made this incident the text for nauseous thankings of Providence, for self-reflection, and the like—Baden-Powell merely remarks: "Many a man has nearly been shot by an ass, but I claim to have been nearly shot by a mule." It is a fortunate gift to possess, this saving sense of humour, but it strikes some folk as gruesome, all the same. There is a story told to the effect that when the siege of Mafeking began, some individual who had offended very seriously was brought before Baden-Powell. The delinquent's account of what happened is full of charm. "He told me that if I ever did it again he would have me shot immediately—and then he began to whistle a tune!" Exactly—but the wrongdoer did not know that it is one of the defender of Mafeking's great beliefs that when one is very much bothered by naughty people or awkward things it is a very good thing to—whistle a tune. What the Boers thought of Baden-Powell's humour we shall possibly find out in time to come. Commandant Eloff, captive at last, and receiving his captor's off-hand, cheery invitation to dine, was, no doubt, not surprised by it, for he had already experienced something of his antagonist's methods of regarding things. During the siege Eloff wrote to Baden-Powell saying that he learnt that the beleaguered garrison amused itself with balls, concerts, tournaments, cricket matches, and the like on Sundays, and hinted that he and his men would very much like to come in and take part, life being pretty dull amongst the Boer forces. To this Baden-Powell replied that he thought the return match had better be postponed until the one then proceeding was finished, and suggested that as Cronje, Snyman, and others had been well tried without effect on the garrison, which was then 200 and not out, there had better be another change of bowling. All which Commander Eloff, no doubt, read with mixed feelings, in which, let us hope, a sense of amused agreement with his correspondent predominated.

Of purely amusing stories about Baden-Powell there have been quite enough given in the public prints to fill a small volume. Whether it is exactly pertinent to the understanding of his character to continually harp on the mirth-provoking side of it is a question which need not be answered, but no one doubts that a great man is made all the more human and all the more attractive to ordinary mortals if he happens to possess a wholesome love of fun. Love of fun, even of what very young ladies call mere frivol, appears to have possessed Baden-Powell ever since he was a small boy. He was always in for a lark. There was a master at the Charterhouse whose usual answer to any boy who bothered him with a question was a more or less testy, "Don't you know I'm engaged?" It happened to be noised abroad that this gentleman had succeeded in persuading some young lady to share his fortunes, and Baden-Powell was one of the first to hear the news. His brilliant, and one may righteously say mischievous mind, conceived a brilliant notion. He approached the Benedict-to-be as the latter stood amidst a group of other masters, and made some remark or request. Quick came the usual question: "Don't you know I'm engaged?" "Bathing-Towel" assumed one of the looks which only he could assume. "Oh, Sir!" he exclaimed in accents that expressed—himself best knew what.

Britannia.