HORACE WALPOLE

After Rosalba

A MEMOIR

WITH AN APPENDIX OF BOOKS PRINTED AT THE STRAWBERRY-HILL PRESS

BY

AUSTIN DOBSON

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

Publishers

Copyright, 1890,

By Dodd, Mead and Company.

University Press:

John Wilson and Son, Cambridge, U.S.A.

| CHAPTER I. | Page |

| The Walpoles of Houghton.—Horace Walpole born, 24 September, 1717.—Lady Louisa Stuart's Story.—Scattered Facts of his Boyhood.—Minor Anecdotes—'La belle Jennings.'—The Bugles.—Interview with George I. before his Death.—Portrait at this time.—Goes to Eton, 26 April, 1727.—His Studies and Schoolfellows.—The 'Triumvirate,' the 'Quadruple Alliance.'—Entered at Lincoln's Inn, 27 May, 1731.—Leaves Eton, September, 1734.—Goes to King's College, Cambridge, 11 March, 1735.—His University Studies.—Letters from Cambridge.—Verses in the Gratulatio.—Verses in Memory of Henry VI.—Death of Lady Walpole, 20 August, 1737 | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Patent Places under Government.—Starts with Gray on the Grand Tour, March, 1739.—From Dover to Paris.—Life at Paris.—Versailles.—The Convent of the Chartreux.—Life at Rheims.—A Fête Galante.—The Grande Chartreuse.—Starts for Italy.—The tragedy [vi]of Tory.—Turin; Genoa.—Academical Exercises at Bologna.—Life at Florence.—Rome; Naples: Herculaneum.—The Pen of Radicofani.—English at Florence.—Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.—Preparing for Home.—Quarrel with Gray.—Walpole's Apologia; his Illness, and return to England. | 27 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Gains of the Grand Tour.—'Epistle to Ashton.'—Resignation of Sir Robert Walpole, who becomes Earl of Orford.—Collapse of the Secret Committee.—Life at Houghton.—The Picture Gallery.—'A Sermon on Painting.'—Lord Orford as Moses.—The 'Ædes Walpolianæ.'—Prior's 'Protogenes and Apelles.'—Minor Literature.—Lord Orford's Decline and Death; his Panegyric.—Horace Walpole's Means. | 57 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Stage-gossip and Small-talk.—Ranelagh Gardens.—Fontenoy and Leicester House.—Echoes of the '45.—Preston Pans.—Culloden.—Trial of the Rebel Lords.—Deaths of Kilmarnock and Balmerino.—Epilogue to Tamerlane—Walpole and his Relatives.—Lady Orford.—Literary Efforts.—The Beauties.—Takes a House at Windsor. | 82 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The New House at Twickenham.—Its First Tenants.—Christened 'Strawberry Hill.'—Planting and Embellishing.—Fresh [vii]Additions.—Walpole's Description of it in 1753.—Visitors and Admirers.—Lord Bath's Verses.—Some Rival Mansions.—Minor Literature.—Robbed by James Maclean.—Sequel from The World.—The Maclean Mania.—High Life at Vauxhall.—Contributions to The World.—Theodore of Corsica.—Reconciliation with Gray.—Stimulates his Works.—The Poëmata-Grayo-Bentleiana.—Richard Bentley.—Müntz the Artist.—Dwellers at Twickenham.—Lady Suffolk and Mrs. Clive. | 107 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Gleanings from the Short Notes.—Letter from Xo Ho.—The Strawberry Hill Press.—Robinson the Printer.—Gray's Odes.—Other Works.—Catalogue of Royal and Noble Authors.—Anecdotes of Painting.—Humours of the Press.—The Parish Register of Twickenham.—Lady Fanny Shirley.—Fielding.—The Castle of Otranto. | 141 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| State of French Society in 1765.—Walpole at Paris.—The Royal Family and the Bête du Gévaudan.—French Ladies of Quality.—Madame du Deffand.—A Letter from Madame de Sévigné.—Rousseau and the King of Prussia.—The Hume-Rousseau Quarrel.—Returns to England, and hears Wesley at Bath.—Paris again.—Madame du Deffand's Vitality.—Her Character.—Minor Literary Efforts.—The Historic Doubts.—The Mysterious Mother.—Tragedy in England.—Doings of the Strawberry Press.—Walpole and Chatterton. | 166 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | [viii] |

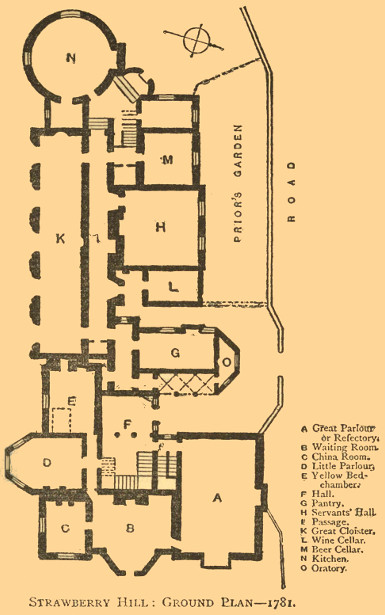

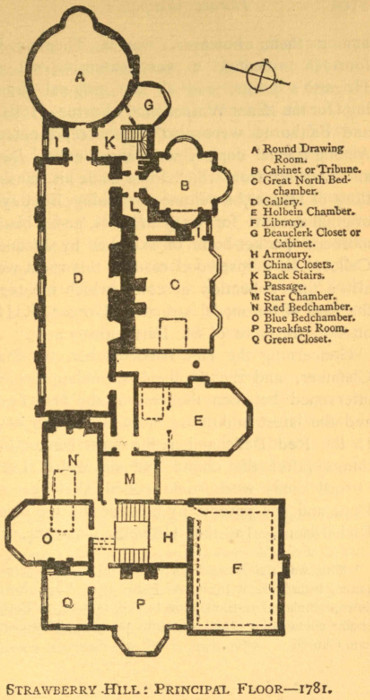

| Old Friends and New.—Walpole's Nieces.—Mrs. Damer.—Progress of Strawberry Hill.—Festivities and Later Improvements.—A Description, etc., 1774.—The House and Approaches.—Great Parlour, Waiting Room, China Room, and Yellow Bedchamber.—Breakfast Room.—Green Closet and Blue Bedchamber.—Armoury and Library.—Red Bed-chamber, Holbein Chamber, and Star Chamber.—Gallery.—Round Drawing Room and Tribune.—Great North Bed-chamber.—Great Cloister and Chapel.—Walpole on Strawberry.—Its Dampness.—A Drive from Twickenham to Piccadilly. | 201 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Occupations and Correspondence.—Literary Work.—Jephson and the Stage.—Nature will Prevail.—Issues from the Strawberry Press.—Fourth Volume of the Anecdotes of Painting.—The Beauclerk Tower and Lady Di.—George, third Earl of Orford.—Sale of the Houghton Pictures.—Moves to Berkeley Square.—Last Visit to Madame du Deffand.—Her Death.—Themes for Letters.—Death of Sir Horace Mann.—Pinkerton, Madame de Genlis, Miss Burney, Hannah More.—Mary and Agnes Berry.—Their Residence at Twickenham.—Becomes fourth Earl of Orford.—Epitaphium vivi Auctoris.—The Berrys again.—Death of Marshal Conway.—Last Letter to Lady Ossory.—Dies at Berkeley Square, 2 March, 1797.—His Fortune and Will.—The Fate of Strawberry. | 232 |

| CHAPTER X. | [ix] |

| Macaulay on Walpole.—Effect of the Edinburgh Essay.—Macaulay and Mary Berry.—Portraits of Walpole.—Miss Hawkins's Description.—Pinkerton's Rainy Day at Strawberry.—Walpole's Character as a Man; as a Virtuoso; as a Politician; as an Author and Letter-writer. | 271 |

| Appendix | 299 |

| Index | 325 |

HORACE WALPOLE:

A Memoir.

The Walpoles of Houghton.—Horace Walpole born, 24 September, 1717.—Lady Louisa Stuart's Story.—Scattered Facts of his Boyhood.—Minor Anecdotes.—'La belle Jennings.'—The Bugles.—Interview with George I. before his Death.—Portrait at this time.—Goes to Eton, 26 April, 1727.—His Studies and Schoolfellows.—The 'Triumvirate,' the 'Quadruple Alliance.'—Entered at Lincoln's Inn, 27 May, 1731.—Leaves Eton, September, 1734.—Goes to King's College, Cambridge, 11 March, 1735.—His University Studies.—Letters from Cambridge.—Verses in the Gratulatio.—Verses in Memory of Henry VI.—Death of Lady Walpole, 20 August, 1737.

The Walpoles of Houghton, in Norfolk, ten miles from King's Lynn, were an ancient family, tracing their pedigree to a certain Reginald de Walpole who was living in the time of William the Conqueror. Under Henry II. there was a Sir Henry de Walpol of Houton and Walpol; and thenceforward an orderly procession of Henrys and Edwards and Johns (all[2] 'of Houghton') carried on the family name to the coronation of Charles II., when, in return for his vote and interest as a member of the Convention Parliament, one Edward Walpole was made a Knight of the Bath. This Sir Edward was in due time succeeded by his son, Robert, who married well, sat for Castle Rising,[1] one of the two family boroughs (the other being King's Lynn, for which his father had been member), and reputably filled the combined offices of county magnate and colonel of militia. But his chief claim to distinction is that his eldest son, also a Robert, afterwards became the famous statesman and Prime Minister to whose 'admirable prudence, fidelity, and success' England owes her prosperity under the first Hanoverians. It is not, however, with the life of 'that corrupter of parliaments, that dissolute tipsy cynic, that courageous lover of peace and liberty, that great citizen, patriot, and statesman,'—to borrow a passage from one of Mr. Thackeray's graphic vignettes,—that these pages are concerned. It is more material to their purpose to note that in the year 1700, and on the 30th day of July in that year (being the day of the death of the Duke of Gloucester, heir presump[3]tive to the crown of England), Robert Walpole, junior, then a young man of three-and-twenty, and late scholar of King's College, Cambridge, took to himself a wife. The lady chosen was Miss Catherine Shorter, eldest daughter of John Shorter, of Bybrook, an old Elizabethan red-brick house near Ashford in Kent. Her grandfather, Sir John Shorter, had been Lord Mayor of London under James II., and her father was a Norway timber merchant, having his wharf and counting-house on the Southwark side of the Thames, and his town residence in Norfolk Street, Strand, where, in all probability, his daughter met her future husband. They had a family of four sons and two daughters. One of the sons, William, died young. The third son, Horatio,[2] or Horace, born, as he himself tells us, on the 24th September, 1717, O. S., is the subject of this memoir.

With the birth of Horace Walpole is connected a scandal so industriously repeated by his later biographers that (although it has [4]received far more attention than it deserves) it can scarcely be left unnoticed here. He had, it is asserted, little in common, either in tastes or appearance, with his elder brothers Robert and Edward, and he was born eleven years after the rest of his father's children. This led to a suggestion which first found definite expression in the Introductory Anecdotes supplied by Lady Louisa Stuart to Lord Wharncliffe's edition of the works of her grandmother, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.[3] It was to the effect that Horace was not the son of Sir Robert Walpole, but of one of his mother's admirers, Carr, Lord Hervey, elder brother of Pope's 'Sporus,' the Hervey of the Memoirs. It is advanced in favour of this supposition that his likeness to the Herveys, both physically and mentally, was remarkable; that the whilom Catherine Shorter was flighty, indiscreet, and fond of admiration; and that Sir Robert's cynical disregard of his wife's vagaries, as well as his own gallantries (his second wife, Miss Skerret, had been his mistress), were matters of notoriety. On the [5]other hand, there is no indication that any suspicion of his parentage ever crossed the mind of Horace Walpole himself. His devotion to his mother was one of the most consistent traits in a character made up of many contradictions; and although between the frail and fastidious virtuoso and the boisterous, fox-hunting Prime Minister there could have been but little sympathy, the son seems nevertheless to have sedulously maintained a filial reverence for his father, of whose enemies and detractors he remained, until his dying day, the implacable foe. Moreover, it must be remembered that, admirable as are Lady Louisa Stuart's recollections, in speaking of Horace Walpole she is speaking of one whose caustic pen and satiric tongue had never spared the reputation of the vivacious lady whose granddaughter she was.

With this reference to what can be, at best, but an insoluble question, we may return to the story of Walpole's earlier years. Of his childhood little is known beyond what he has himself told in the Short Notes of my Life which he drew up for the use of Mr. Berry, the nominal editor of his works.[4] His godfathers, he [6]says, were the Duke of Grafton and his father's second brother, Horatio, who afterwards became Baron Walpole of Wolterton. His godmother was his aunt, the beautiful Dorothy Walpole, who, escaping the snares of Lord Wharton, as related by Lady Louisa Stuart, had become the second wife of Charles, second Viscount Townshend. In 1724, he was 'inoculated for the small-pox;' and in the following year, was placed with his cousins, Lord Townshend's younger sons, at Bexley, in Kent, under the charge of one Weston, son to the Bishop of Exeter of that name. In 1726, the same course was pursued at Twickenham, and in the winter months he went to Lord Townshend's. Much of his boyhood, however, must have been spent in the house 'next the College' at Chelsea, of which his father became possessed in 1722. It still exists in part, with but little alteration, as the infirmary of the hospital, and Ward No. 7 is said to have been its dining-room.[5] With this, or with some other reception-chamber at Chelsea, is connected one of the scanty anecdotes of [7]this time. Once, when Walpole was a boy, there came to see his mother one of those formerly famous beauties chronicled by Anthony Hamilton,—'la belle Jennings,' elder sister to the celebrated Duchess of Marlborough, and afterwards Duchess of Tyrconnell. At this date she was a needy Jacobite seeking Lady Walpole's interest in order to obtain a pension. She no longer possessed those radiant charms which under Charles had revealed her even through the disguise of an orange-girl; and now, says Walpole, annotating his own copy of the Memoirs of Grammont, 'her eyes being dim, and she full of flattery, she commended the beauty of the prospect; but unluckily the room in which they sat looked only against the garden-wall.'[6]

Another of the few events of his boyhood which he records, illustrates the old proverb that 'One half of the world knows not how the [8]other half lives,' rather than any particular phase of his biography. Going with his mother to buy some bugles (beads), at the time when the opposition to his father was at its highest, he notes that having made her purchase,—beads were then out of fashion, and the shop was in some obscure alley in the City, where lingered unfashionable things,—Lady Walpole bade the shopman send it home. Being asked whither, she replied, 'To Sir Robert Walpole's.' 'And who,' rejoined he coolly, 'is Sir Robert Walpole?'[7] But the most interesting incident of his youth was the visit he paid to the King, which he has himself related in Chapter I. of the Reminiscences. How it came about he does not know, but at ten years old an overmastering desire seized him to inspect His Majesty. This childish caprice was so strong that his mother, who seldom thwarted him, solicited the Duchess of Kendal (the maîtresse en titre) to obtain for her son the honour of kissing King George's hand before he set out upon that visit to Hanover from which he was never to return. It was an unusual request, but being made by the Prime Minister's wife, could scarcely be refused. To conciliate etiquette and avoid precedent, however, it was arranged that the audience [9]should be in private and at night. 'Accordingly, the night but one before the King began his last journey [i. e., on 1 June, 1727], my mother carried me at ten at night to the apartment of the Countess of Walsingham [Melusina de Schulemberg, the Duchess's reputed niece], on the ground floor, towards the garden at St. James's, which opened into that of her aunt, ... apartments occupied by George II. after his Queen's death, and by his successive mistresses, the Countesses of Suffolk [Mrs. Howard] and Yarmouth [Madame de Walmoden]. Notice being given that the King was come down to supper, Lady Walsingham took me alone into the Duchess's ante-room, where we found alone the King and her. I knelt down, and kissed his hand. He said a few words to me, and my conductress led me back to my mother. The person of the King is as perfect in my memory as if I saw him but yesterday. It was that of an elderly man, rather pale, and exactly like his pictures and coins; not tall; of an aspect rather good than august; with a dark tie-wig, a plain coat, waistcoat, and breeches of snuff-coloured cloth, with stockings of the same colour, and a blue ribband over all. So entirely was he my object that I do not believe I once looked at the Duchess; but as I could not[10] avoid seeing her on entering the room, I remember that just beyond His Majesty stood a very tall, lean, ill-favoured old lady; but I did not retain the least idea of her features, nor know what the colour of her dress was.'[8] In the Walpoliana (p. 25)[9] Walpole is made to say that his introducer was his father, and that the King took him up in his arms and kissed him. Walpole's own written account is the more probable one. His audience must have been one of the last the King granted, for, as already stated, it was almost on the eve of his departure; and ten days later, when his chariot clattered swiftly into the courtyard of his brother's palace at Osnabruck, he lay dead in his seat, and the reign of his successor had begun.

Although Walpole gives us a description of George I., he does not, of course, supply us with any portrait of himself. But in Mr. Peter [11]Cunningham's excellent edition of the Correspondence there is a copy of an oil-painting belonging (1857) to Mrs. Bedford of Kensington, which, upon the faith of a Cupid who points with an arrow to the number ten upon a dial, may be accepted as representing him about the time of the above interview. It is a full length of a slight, effeminate-looking lad in a stiff-skirted coat, knee-breeches, and open-breasted laced waistcoat, standing in a somewhat affected attitude at the side of the afore-mentioned sundial. He has dark, intelligent eyes, and a profusion of light hair curling abundantly about his ears and reaching to his neck. If the date given in the Short Notes be correct, he must have already become an Eton boy, since he says that he went to that school on the 26th April, 1727, and he adds in the Reminiscences that he shed a flood of tears for the King's death, when, 'with the other scholars at Eton College,' he walked in procession to the proclamation of his successor. Of the cause of this emotion he seems rather doubtful, leaving us to attribute it partly to the King's condescension in gratifying his childish loyalty, partly to the feeling that, as the Prime Minister's son, it was incumbent on him to be more concerned than his schoolfellows; while the spectators, it is hinted, placed it to the[12] credit of a third and not less cogent cause,—the probability of that Minister's downfall. Of this, however, as he says, he could not have had the slightest conception. His tutor at Eton was Henry Bland, eldest son of the master of the school. 'I remember,' says Walpole, writing later to his relative and schoolfellow Conway, 'when I was at Eton, and Mr. Bland had set me an extraordinary task, I used sometimes to pique myself upon not getting it, because it was not immediately my school business. What, learn more than I was absolutely forced to learn! I felt the weight of learning that, for I was a blockhead, and pushed up above my parts.' That, as the son of the great Minister, he was pushed, is probably true; but, despite his own disclaimer, it is clear that his abilities were by no means to be despised. Indeed, one of the pièces justificatives in the story of Lady Louisa Stuart, though advanced for another purpose, is distinctly in favour of something more than average talent. Supporting her theory as to his birth by the statement that in his boyhood he was left so entirely in the hands of his mother as to have little acquaintance with his father, she goes on to say that 'Sir Robert Walpole took scarcely any notice of him, till his proficiency at Eton School, when a lad of some[13] standing, drew his attention, and proved that whether he had or had not a right to the name he went by, he was likely to do it honour.'[10] Whatever this may be held to prove, it certainly proves that he was not the blockhead he declares himself to have been.

Among his schoolmates he made many friends. For his cousins, Henry (afterwards Marshal) Conway and Lord Hertford, Conway's elder brother, he formed an attachment which lasted through life, and many of his best letters were written to these relatives. Other associates were the later lyrist, Charles Hanbury Williams, and the famous wit, George Augustus Selwyn, both of whom, if the child be father to the man, must be supposed to have had unusual attractions for their equally witty schoolmate. Another contemporary at school, to whom, in after life, he addressed many letters, was William Cole, subsequently to develop into a laborious antiquary, and probably already exhibiting proclivities towards 'tall copies' and black letter. But his chiefest friends, no doubt, were grouped in the two bodies christened [14]respectively the 'triumvirate' and the 'quadruple alliance.'

Of these the 'triumvirate' was the less important. It consisted of Walpole and the two sons of Brigadier-General Edward Montagu. George, the elder, afterwards M.P. for Northampton, and the recipient of some of the most genuine specimens of his friend's correspondence, is described in advanced age as 'a gentleman-like body of the vieille cour,' usually attended by a younger brother, who was still a midshipman at the mature age of sixty, and whose chief occupation consisted in carrying about his elder's snuff-box. Charles Montagu, the remaining member of the 'triumvirate,' became a Lieut.-General and Knight of the Bath. But it was George, who had 'a fine sense of humour, and much curious information,' who was Walpole's favourite. 'Dear George,'—he writes to him from Cambridge,—'were not the playing fields at Eton food for all manner of flights? No old maid's gown, though it had been tormented into all the fashions from King James to King George, ever underwent so many transformations as those poor plains have in my idea. At first I was contented with tending a visionary flock, and sighing some pastoral name to the echo of the cascade under the bridge. How happy[15] should I have been to have had a kingdom only for the pleasure of being driven from it, and living disguised in an humble vale! As I got further into Virgil and Clelia, I found myself transported from Arcadia to the garden of Italy; and saw Windsor Castle in no other view than the Capitoli immobile saxum.' Further on he makes an admission which need scarcely surprise us. 'I can't say I am sorry I was never quite a schoolboy: an expedition against bargemen, or a match at cricket, may be very pretty things to recollect; but, thank my stars, I can remember things that are very near as pretty. The beginning of my Roman history was spent in the asylum, or conversing in Egeria's hallowed grove; not in thumping and pummelling King Amulius's herdsmen.'[11] The description seems to indicate a schoolboy of a rather refined and effeminate type, who would probably fare ill with robuster spirits. But Walpole's social position doubtless preserved him from the persecution which that variety generally experiences at the hands—literally the hands—of the tyrants of the playground.

The same delicacy of organisation seems to have been a main connecting link in the second or 'quadruple alliance' already referred to,—an [16]alliance, it may be, less intrinsically intimate, but more obviously cultivated. The most important figure in this quartet was a boy as frail and delicate as Walpole himself, 'with a broad, pale brow, sharp nose and chin, large eyes, and a pert expression,' who was afterwards to become famous as the author of one of the most popular poems in the language, the Elegy written in a Country Church Yard. Thomas Gray was at this time about thirteen, and consequently somewhat older than his schoolmate. Another member of the association was Richard West, also slightly older, a grandson of the Bishop Burnet who wrote the History of My Own Time, and son of the Lord Chancellor of Ireland. West, a slim, thoughtful lad, was the most precocious genius of the party, already making verses in Latin and English, and making them even in his sleep. The fourth member was Thomas Ashton, afterwards Fellow of Eton College and Rector of St. Botolph, Bishopsgate. Such was the group which may be pictured sauntering arm in arm through the Eton meadows, or threading the avenue which is still known as the 'Poet's Walk.' Each of the four had his nickname, either conferred by himself or by his schoolmates. Ashton, for example, was Plato; Gray was Orosmades.

On 27 May, 1731, Walpole was entered at Lincoln's Inn, his father intending him for the law. 'But'—he says in the Short Notes—'I never went thither, not caring for the profession.' On 23 September, 1734, he left Eton for good, and no further particulars of his school-days remain. That they were not without their pleasant memories may, however, be inferred from the letters already quoted, and especially from one to George Montagu written some time afterwards upon the occasion of a visit to the once familiar scenes. It is dated from the Christopher Inn, a famous old hostelry, well known to Eton boys,—'The Christopher. How great I used to think anybody just landed at the Christopher! But here are no boys for me to send for; there I am, like Noah, just returned into his old world again, with all sorts of queer feels about me. By the way, the clock strikes the old cracked sound; I recollect so much, and remember so little; and want to play about; and am so afraid of my playfellows; and am ready to shirk Ashton; and can't help making fun of myself; and envy a dame over the way, that has just locked in her boarders, and is going to sit down in a little hot parlour to a very bad supper, so comfortably! And I could be so jolly a dog if I did not fat,—[18]which, by the way, is the first time the word was ever applicable to me. In short, I should be out of all bounds if I was to tell you half I feel,—how young again I am one minute, and how old the next. But do come and feel with me, when you will,—to-morrow. Adieu! If I don't compose myself a little more before Sunday morning, when Ashton is to preach ['Plato' at the date of this letter had evidently taken orders], I shall certainly be in a bill for laughing at church; but how to help it, to see him in the pulpit, when the last time I saw him here was standing up funking over against a conduit to be catechised.'[12]

This letter, of which the date is not given, but which Cunningham places after March, 1737, must have been written some time after the writer had taken up his residence at Cambridge in his father's college of King's.[13] This he did in March, 1735, following an interval of residence in London. By this time the 'quad[19]ruple alliance' had been broken up by the defection of West, who, much against his will, had gone to Christ Church, Oxford. Ashton and Gray had, however, been a year at Cambridge, the latter as a fellow-commoner of Peterhouse, the former at Walpole's own college, King's. Cole and the Conways were also at Cambridge, so that much of the old intercourse must have been continued. Walpole's record of his university studies is of the most scanty kind. He does little more than give us the names of his tutors, public and private. In civil law he attended the lectures of Dr. Dickens of Trinity Hall; in anatomy, those of Dr. Battie. French, he says, he had learnt at Eton. His Italian master at Cambridge was Signor Piazza (who had at least an Italian name!), and his instructor in drawing was the miniaturist Bernard Lens, the teacher of the Duke of Cumberland and the Princesses Mary and Louisa. Lens was the author of a New and Complete Drawing Book for curious young Gentlemen and Ladies that study and practice the noble and commendable Art of Drawing, Colouring, etc., and is kindly referred to in the later Anecdotes of Painting. In mathematics, which Walpole seems to have hated as cordially as Swift and Goldsmith and Gray did, he sat at the feet of the blind[20] Professor Nicholas Saunderson, author of the Elements of Algebra.[14] Years afterwards (à propos of a misguided enthusiast who had put the forty-seventh proposition of Euclid into Latin verse) he tells one of his correspondents the result of these ministrations: 'I ... was always so incapable of learning mathematics that I could not even get by heart the multiplication table, as blind Professor Saunderson honestly told me, above threescore years ago, when I went to his lectures at Cambridge. After the first fortnight he said to me, 'Young man, it would be cheating you to take your money; for you can never learn what I am trying to teach you.' I was exceedingly mortified, and cried; for, being a Prime Minister's son, I had firmly believed all the flattery with which I had been assured that my parts were capable of anything. I paid a private instructor for a year; but, at the year's end, was forced to own Saunderson [21]had been in the right.'[15] This private instructor was in all probability Mr. Trevigar, who, Walpole says, read lectures to him in mathematics and philosophy. From other expressions in his letters, it must be inferred that his progress in the dead languages, if respectable, was not brilliant. He confesses, on one occasion, his inability to help Cole in a Latin epitaph, and he tells Pinkerton that he never was a good Greek scholar.

His correspondence at this period, chiefly addressed to West and George Montagu, is not extensive, but it is already characteristic. In one of his letters to Montagu he encloses a translation of a little French dialogue between a turtle-dove and a passer-by. The verses are of no particular merit, but in the comment one recognizes a cast of style soon to be familiar. 'You will excuse this gentle nothing, I mean mine, when I tell you I translated it out of pure good-nature for the use of a disconsolate wood-pigeon in our grove, that was made a widow by the barbarity of a gun. She coos and calls me so movingly, 'twould touch your heart to hear her. I protest to you it grieves me to pity her. She is so allicholly[16] as any [22]thing. I'll warrant you now she's as sorry as one of us would be. Well, good man, he's gone, and he died like a lamb. She's an unfortunate woman, but she must have patience.'[17] In another letter to West, after expressing his astonishment that Gray should be at Burnham in Buckinghamshire, and yet be too indolent to revisit the old Eton haunts in his vicinity, he goes on to gird at the university curriculum. At Cambridge, he says, they are supposed to betake themselves 'to some trade, as logic, philosophy, or mathematics.' But he has been used to the delicate food of Parnassus, and can never condescend to the grosser studies of Alma Mater. 'Sober cloth of syllogism colour suits me ill; or, what's worse, I hate clothes that one must prove to be of no colour at all. If the Muses cœlique vias et sidera monstrent, and quâ vi maria alta tumescant; why accipiant: but 'tis thrashing, to study philosophy in the abstruse authors. I am not against cultivating these studies, as they are certainly useful; but then they quite neglect all polite literature, all knowledge of this world. Indeed, such people have not much occasion for this latter; for they shut themselves up from it, and study till they know less than any one. [23]Great mathematicians have been of great use; but the generality of them are quite unconversible: they frequent the stars, sub pedibusque vident nubes, but they can't see through them. I tell you what I see; that by living amongst them, I write of nothing else: my letters are all parallelograms, two sides equal to two sides; and every paragraph an axiom, that tells you nothing but what every mortal almost knows.'[18] In an earlier note he has been on a tour to Oxford, and, with a premonition of the future connoisseur of Strawberry Hill, criticises the gentlemen's seats on the road. 'Coming back, we saw Easton Neston [in Northamptonshire], a seat of Lord Pomfret, where in an old greenhouse is a wonderful fine statue of Tully, haranguing a numerous assemblage of decayed emperors, vestal virgins with new noses, Colossus's, Venus's, headless carcases and carcaseless heads, pieces of tombs, and hieroglyphics.'[19] A little later he has been to his father's seat at Houghton: 'I am return'd again to Cambridge, and can tell you what I never expected,—that I like Norfolk. Not any of the ingredients, as Hunting or Country Gentlemen, for I had nothing to [24]do with them, but the county; which a little from Houghton is woody, and full of delightfull prospects. I went to see Norwich and Yarmouth, both which I like exceedingly. I spent my time at Houghton for the first week almost alone. We have a charming garden, all wilderness; much adapted to my Romantick inclinations.' In after life the liking for Norfolk here indicated does not seem to have continued, especially when his father's death had withdrawn a part of its attractions. He 'hated Norfolk,'—says Mr. Cunningham. 'He did not care for Norfolk ale, Norfolk turnips, Norfolk dumplings, or Norfolk turkeys. Its flat, sandy, aguish scenery was not to his taste.' He preferred 'the rich blue prospects' of his mother's county, Kent.

Of literary effort while at Cambridge, Walpole's record is not great. In 1736, he was one of the group of university poets—Gray and West being also of the number—who addressed congratulatory verses to Frederick, Prince of Wales, upon his marriage with the Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha; and he wrote a poem (which is reprinted in vol. i. of his works) to the memory of the founder of King's College, Henry VI. This is dated 2 February, 1738. In the interim Lady Walpole died. Her son's[25] references to his loss display the most genuine regret. In a letter to Charles Lyttelton (afterwards the well-known Dean of Exeter, and Bishop of Carlisle), which is not included in Cunningham's edition, and is apparently dated in error September, 1732, instead of 1737,[20] he dwells with much feeling on 'the surprizing calmness and courage which my dear Mother show'd before her death. I believe few women wou'd behave so well, & I am certain no man cou'd behave better. For three or four days before she dyed, she spoke of it with less indifference than one speaks of a cold; and while she was sensible, which she was within her two last hours, she discovered no manner of apprehension.' That his warm affection for her was well known to his friends may be inferred from a passage in one of Gray's letters to West: 'While I write to you, I hear the bad news of Lady Walpole's death on Saturday night last [20 Aug., 1737]. Forgive me if the thought of what my poor Horace must feel on that account, obliges me to have done.'[21] Lady Walpole was buried in Westminster Abbey, where, on her monument in Henry VIIth's Chapel, may be read the piously eulogistic [26]inscription which her youngest son composed to her memory,—an inscription not easy to reconcile in all its terms with the current estimate of her character. But in August, 1737, she was considerably over fifty, and had probably long outlived the scandals of which she had been the subject in the days when Kneller and Eckardt painted her as a young and beautiful woman.

Patent Places under Government.—Starts with Gray on the Grand Tour, March, 1739.—From Dover to Paris.—Life at Paris.—Versailles.—The Convent of the Chartreux.—Life at Rheims.—A Fête Galante.—The Grande Chartreuse.—Starts for Italy.—The tragedy of Tory.—Turin; Genoa.—Academical Exercises at Bologna.—Life at Florence.—Rome; Naples; Herculaneum.—The Pen of Radicofani.—English at Florence.—Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.—Preparing for Home.—Quarrel with Gray.—Walpole's Apologia; his Illness, and Return to England.

That, in those piping days of patronage, when even very young ladies of quality drew pay as cornets of horse, the son of the Prime Minister of England should be left unprovided for, was not to be expected. While he was still resident at Cambridge, lucrative sinecures came to Horace Walpole. Soon after his mother's death, his father appointed him Inspector of Imports and Exports in the Custom House,—a post which he resigned in January, 1738, on succeeding Colonel William Townshend as Usher of the Exchequer. When, later in the year, he came of age (17 September), he 'took possession of two other little[28] patent-places in the Exchequer, called Comptroller of the Pipe, and Clerk of the Estreats,' which had been held for him by a substitute. In 1782, when he still filled them, the two last-mentioned offices produced together about £300 per annum, while the Ushership of the Exchequer, at the date of his obtaining it, was reckoned to be worth £900 a year. 'From that time [he says] I lived on my own income, and travelled at my own expense; nor did I during my father's life receive from him but £250 at different times,—which I say not in derogation of his extreme tenderness and goodness to me, but to show that I was content with what he had given to me, and that from the age of twenty I was no charge to my family.'[22]

He continued at King's College for some time after he had attained his majority, only quitting it formally in March, 1739, not without regretful memories of which his future correspondence was to bear the traces. If he had neglected mathematics, and only moderately courted the classics, he had learnt something of the polite arts and of modern Continental letters,—studies which would naturally lead his inclination in the direction of [29]the inevitable 'Grand Tour.' Two years earlier he had very unwillingly declined an invitation from George Montagu and Lord Conway to join them in a visit to Italy. Since that date his desire for foreign travel, fostered no doubt by long conversations with Gray, had grown stronger, and he resolved to see 'the palms and temples of the south' after the orthodox eighteenth-century fashion. To think of Gray in this connection was but natural, and he accordingly invited his friend (who had now quitted Cambridge, and was vegetating rather disconsolately in his father's house on Cornhill) to be his travelling companion. Walpole was to act as paymaster; but Gray was to be independent. Furthermore, Walpole made a will under which, if he died abroad, Gray was to be his sole legatee. Dispositions so advantageous and considerate scarcely admitted of refusal, even if Gray had been backward, which he was not. The two friends accordingly set out for Paris. Walpole makes the date of departure 10 March, 1739; Gray says they left Dover at twelve on the 29th.

The first records of the journey come from Amiens in a letter written by Gray to his mother. After a rough passage across the[30] Straits, they reached Calais at five. Next day they started for Boulogne in the then new-fangled invention, a post-chaise,—a vehicle which Gray describes 'as of much greater use than beauty, resembling an ill-shaped chariot, only with the door opening before instead of [at] the side.' Of Boulogne they see little, and of Montreuil (where later Sterne engaged La Fleur) Gray's only record, besides the indifferent fare, is that 'Madame the hostess made her appearance in long lappets of bone lace, and a sack of linsey-woolsey.' From Montreuil they go by Abbeville to Amiens, where they visit the cathedral, and the chapels of the Jesuits and Ursuline Nuns. But the best part of this first letter is the little picture with which it (or rather as much of it as Mason published) concludes. 'The country we have passed through hitherto has been flat, open, but agreeably diversified with villages, fields well cultivated, and little rivers. On every hillock is a windmill, a crucifix, or a Virgin Mary dressed in flowers and a sarcenet robe; one sees not many people or carriages on the road; now and then indeed you meet a strolling friar, a countryman with his great muff, or a woman riding astride on a[31] little ass, with short petticoats, and a great head-dress of blue wool.'[23]

The foregoing letter is dated the 1st April, and it speaks of reaching Paris on the 3rd. But it was only on the evening of Saturday the 9th that they rolled into the French capital, 'driving through the streets a long while before they knew where they were.' Walpole had wisely resolved not to hurry, and they had besides broken down at Luzarches, and lingered at St. Denis over the curiosities of the abbey, particularly a vase of oriental onyx carved with Bacchus and the nymphs, of which they had dreamed ever since. At Paris, they found a warm welcome among the English residents,—notably from Mason's patron, Lord Holdernesse, and Walpole's cousins, the Conways. They seem to have plunged at once into the pleasures of the place,—pleasures in which, according to Walpole, cards and eating played far too absorbing a part. At Lord Holdernesse's they met at supper the famous author of Manon Lescaut, M. l'Abbé Antoine-François Prévost d'Exilles, who had just put forth the final volume of his tedious and scandalous Histoire de M. Cléveland, fils naturel de Cromwel. They went to the spec[32]tacle of Pandore at the Salle des Machines of the Tuileries; and they went to the opera, where they saw the successful Ballet de la Paix,—a curious hotchpot, from Gray's description, of cracked voices and incongruous mythology. With the Comédie Française they were better pleased, although Walpole, strange to say, unlike Goldsmith ten years later, was not able to commend the performance of Molière's L'Avare. They saw Mademoiselle Gaussin (as yet unrivalled by the unrisen Mademoiselle Clairon) in La Noue's tragedy of Mahomet Second, then recently produced, with Dufresne in the leading male part; and they also saw the prince of petits-maîtres, Grandval, acting with Dufresne's sister, Mademoiselle Jeanne-Françoise Quinault (an actress 'somewhat in Mrs. Clive's way,' says Gray), in the Philosophe marié of Nericault Destouches,—a charming comedy already transferred to the English stage in the version by John Kelly of The Universal Spectator.

Theatres, however, are not the only amusements which the two travellers chronicle to the home-keeping West. A great part of their time is spent in seeing churches and palaces full of pictures. Then there is the inevitable visit to Versailles, which, in sum,[33] they concur in condemning. 'The great front,' says Walpole, 'is a lumber of littleness, composed of black brick, stuck full of bad old busts, and fringed with gold rails.' Gray (he says) likes it; but Gray is scarcely more complimentary,—at all events is quite as hard upon the façade, using almost the same phrases of depreciation. It is 'a huge heap of littleness,' in hue 'black, dirty red, and yellow; the first proceeding from stone changed by age; the second, from a mixture of brick; and the last, from a profusion of tarnished gilding. You cannot see a more disagreeable tout ensemble; and, to finish the matter, it is all stuck over in many places with small busts of a tawny hue between every two windows.' The garden, however, pleases him better; nothing could be vaster and more magnificent than the coup d'œil, with its fountains and statues and grand canal. But the 'general taste of the place' is petty and artificial. 'All is forced, all is constrained about you; statues and vases sowed everywhere without distinction; sugar-loaves and minced pies of yew; scrawl work of box, and little squirting jets d'eau, besides a great sameness in the walks,—cannot help striking one at first sight; not to mention the silliest of laby[34]rinths, and all Æsop's fables in water.'[24] 'The garden is littered with statues and fountains, each of which has its tutelary deity. In particular, the elementary god of fire solaces himself in one. In another, Enceladus, in lieu of a mountain, is overwhelmed with many waters. There are avenues of water-pots, who disport themselves much in squirting up cascadelins. In short, 'tis a garden for a great child.'[25] The day following, being Whitsunday, they witness a grand ceremonial,—the installation of nine Knights of the Saint Esprit: 'high mass celebrated with music, great crowd, much incense, King, Queen, Dauphin, Mesdames, Cardinals, and Court; Knights arrayed by His Majesty; reverences before the altar, not bows, but curtsies; stiff hams; much tittering among the ladies; trumpets, kettle-drums, and fifes.'[26]

It is Gray who thus summarises the show. But we must go to Walpole for the account of another expedition, the visit to the Convent of the Chartreux, the uncouth horror of which, with its gloomy chapel and narrow cloisters, seems to have fascinated the Gothic soul of the future author of the Castle of Otranto. Here, [35]in one of the cells, they make the acquaintance of a fresh initiate into the order,—the account of whose environment suggests retirement rather than solitude. 'He was extremely civil, and called himself Dom Victor. We have promised to visit him often. Their habit is all white: but besides this he was infinitely clean in his person; and his apartment and garden, which he keeps and cultivates without any assistance, was neat to a degree. He has four little rooms, furnished in the prettiest manner, and hung with good prints. One of them is a library, and another a gallery. He has several canary-birds disposed in a pretty manner in breeding-cages. In his garden was a bed of good tulips in bloom, flowers and fruit-trees, and all neatly kept. They are permitted at certain hours to talk to strangers, but never to one another, or to go out of their convent.' In the same institution they saw Le Sueur's history (in pictures) of St. Bruno, the founder of the Chartreux. Walpole had not yet studied Raphael at Rome, but these pictures, he considered, excelled everything he had seen in England and Paris.[27]

'From thence [Paris],' say Walpole's Short Notes, 'we went with my cousin, Henry Conway, to Rheims, in Champagne, [and] staid there three [36]months.' One of their chief objects was to improve themselves in French. 'You must not wonder,' he tells West, 'if all my letters resemble dictionaries, with French on one side, and English on t'other; I deal in nothing else at present, and talk a couple of words of each language alternately from morning till night.'[28] But he does not seem to have yet developed his later passion for letter-writing, and the 'account of our situation and proceedings' is still delegated to Gray, some of whose despatches at this time are not preserved. There is, however, one from Rheims to Gray's mother which gives a vivid idea of the ancient French Cathedral city, slumbering in its vast vine-clad plain, with its picturesque old houses and lonely streets, its long walks under the ramparts, and its monotonous frog-haunted moat. They have no want of society, for Henry Conway procured them introductions everywhere; but the Rhemois are more constrained, less familiar, less hospitable, than the Parisians. Quadrille is the almost invariable amusement, interrupted by one entertainment (for the Rhemois as a rule give neither dinners nor suppers); to wit, a five o'clock goûter, which is 'a service of wine, fruits, cream, sweetmeats, crawfish, and cheese,' [37]after which they sit down to cards again. Occasionally, however, the demon of impromptu flutters these 'set, gray lives,' and (like Dr. Johnson) even Rheims must 'have a frisk.' 'For instance,' says Gray, 'the other evening we happened to be got together in a company of eighteen people, men and women of the best fashion here, at a garden in the town, to walk; when one of the ladies bethought herself of asking, Why should we not sup here? Immediately the cloth was laid by the side of a fountain under the trees, and a very elegant supper served up; after which another said, Come, let us sing; and directly began herself. From singing we insensibly fell to dancing, and singing in a round; when somebody mentioned the violins, and immediately a company of them was ordered. Minuets were begun in the open air, and then came country dances, which held till four o'clock next morning; at which hour the gayest lady there proposed that such as were weary should get into their coaches, and the rest of them should dance before them with the music in the van; and in this manner we paraded through all the principal streets of the city, and waked everybody in it.' Walpole, adds Gray, would have made this entertainment chronic. But 'the women did not come into it,' and[38] shrank back decorously 'to their dull cards, and usual formalities.'[29]

At Rheims the travellers lingered on in the hope of being joined by Selwyn and George Montagu. In September they left Rheims for Dijon, the superior attractions of which town made them rather regret their comparative rustication of the last three months. From Dijon they passed southward to Lyons, whence Gray sent to West (then drinking the Tunbridge waters) a daintily elaborated conceit touching the junction of the Rhone and the Saône. While at Lyons they made an excursion to Geneva to escort Henry Conway, who had up to this time been their companion, on his way to that place. They took a roundabout route in order to visit the Convent of the Grande Chartreuse, and on the 28th Walpole writes to West from 'a Hamlet among the mountains of Savoy [Echelles].' He is to undergo many transmigrations, he says, before he ends his letter. 'Yesterday I was a shepherd of Dauphiné; to-day an Alpine savage; to-morrow a Carthusian monk; and Friday a Swiss Calvinist.' When he next takes up his pen, he has passed through his third stage, and visited the Chartreuse. With the convent itself neither Gray [39]nor his companions seem to have been much impressed, probably because their expectations had been indefinite. For the approach and the situation they had only enthusiasm. Gray is the accredited landscape-painter of the party, but here even Walpole breaks out: 'The road, West, the road! winding round a prodigious mountain, and surrounded with others, all shagged with hanging woods, obscured with pines, or lost in clouds! Below, a torrent breaking through cliffs, and tumbling through fragments of rocks! Sheets of cascades forcing their silver speed down channelled precipices, and hastening into the roughened river at the bottom! Now and then an old foot bridge, with a broken rail, a leaning cross, a cottage, or the ruin of an hermitage! This sounds too bombast and too romantic to one that has not seen it, too cold for one that has. If I could send you my letter post between two lovely tempests that echoed each other's wrath, you might have some idea of this noble roaring scene, as you were reading it. Almost on the summit, upon a fine verdure, but without any prospect, stands the Chartreuse.'[30]

The foregoing passage is dated Aix-in-Savoy, 30 September. Two days later, passing by Annecy, they came to Geneva. Here they [40]stayed a week to see Conway settled, and made a 'solitary journey' back to Lyons, but by a different road, through the spurs of the Jura and across the plains of La Bresse. At Lyons they found letters awaiting them from Sir Robert Walpole, desiring his son to go to Italy,—a proposal with which Gray, only too glad to exchange the over-commercial city of Lyons for 'the place in the world that best deserves seeing,' was highly delighted. Accordingly, we speedily find them duly equipped with 'beaver bonnets, beaver gloves, beaver stockings, muffs, and bear-skins' en route for the Alps. At the foot of Mont Cenis their chaise was taken to pieces and loaded on mules, and they themselves were transferred to low matted legless chairs carried on poles,—a not unperilous mode of progression, when, as in this case, quarrels took place among the bearers. But the tragedy of the journey happened before they had quitted the chaise. Walpole had a fat little black spaniel of King Charles's breed, named Tory, and he had let the little creature out of the carriage for the air. While it was waddling along contentedly at the horses' heads, a gaunt wolf rushed out of a fir wood, and exit poor Tory before any one had time to snap a pistol. In later years, Gray would perhaps have celebrated this[41] mishap as elegantly as he sang the death of his friend's favourite cat; but in these pre-poetic days he restricts himself to calling it an 'odd accident enough.'[31]

'After eight days' journey through Greenland,'—as Gray puts it to West,—they reached Turin, where among other English they found Pope's friend, Joseph Spence, Professor of Poetry at Oxford. Beyond Walpole's going to Court, and their visiting an extraordinary play called La Rappresentazione dell' Anima Dannata (for the benefit of an Hospital), a full and particular account of which is contained in one of Spence's letters to his mother,[32] nothing remarkable seems to have happened to them in the Piedmontese capital. From Turin they went on to Genoa,—'the happy country where huge lemons grow' (as Gray quotes, not textually, from Waller),—whose blue sea and vine-trellises they quit reluctantly [42]for Bologna, by way of Tortona, Piacenza, Parma (where they inspect the Correggios in the Duomo), Reggio, and Modena. At Bologna, in the absence of introductions, picture-seeing is their main occupation. 'Except pictures and statues,' writes Walpole, 'we are not very fond of sights.... Now and then we drop in at a procession, or a high mass, hear the music, enjoy a strange attire, and hate the foul monkhood. Last week was the feast of the Immaculate Conception. On the eve we went to the Franciscans' church to hear the academical exercises. There were moult and moult clergy, about two dozen dames, that treated one another with illustrissima and brown kisses, the vice-legate, the gonfalonier, and some senate. The vice-legate ... is a young personable person of about twenty, and had on a mighty pretty cardinal-kind of habit; 'twou'd make a delightful masquerade dress. We asked his name: Spinola. What, a nephew of the cardinal-legate? Signor, no; ma credo che gli sia qualche cosa. He sat on the right hand with the gonfalonier in two purple fauteuils. Opposite was a throne of crimson damask, with the device of the Academy, the Gelati;[33] [43]and trimmings of gold. Here sat at a table, in black, the head of the Academy, between the orator and the first poet. At two semicircular tables on either hand sat three poets and three; silent among many candles. The chief made a little introduction, the orator a long Italian vile harangue. Then the chief, the poet, the poets,—who were a Franciscan, an Olivetan, an old abbé, and three lay,—read their compositions; and to-day they are pasted up in all parts of the town. As we came out of the church, we found all the convent and neighbouring houses lighted all over with lanthorns of red and yellow paper, and two bonfires.'[34]

In the Christmas of 1739, the friends crossed the Apennines, and entered Florence. If they had wanted introductions at Bologna, there was no lack of them in Tuscany, and they were to find one friend who afterwards figured largely in Walpole's correspondence. This was Mr. [44](afterwards Sir Horace) Mann, British Minister Plenipotentiary at the Court of Florence. 'He is the best and most obliging person in the world,' says Gray, and his house, with a brief interval, was their residence for fifteen months. Their letters from Florence are less interesting than those from which quotations have already been made, while their amusements seem to have been more independent of each other than before. Gray occupied himself in the galleries taking the notes of pictures and statuary afterwards published by Mitford, and in forming a collection of MS. music; Walpole, on the other hand, had slightly cooled in his eagerness for the antique, which now 'pleases him calmly.' 'I recollect'—he says—'the joy I used to propose if I could but see the Great Duke's gallery; I walk into it now with as little emotion as I should into St. Paul's. The statues are a congregation of good sort of people that I have a great deal of unruffled regard for.' The fact was, no doubt, that society had now superior attractions. As the son of the English Prime Minister, and with Mann, who was a relation,[35] at his elbow, all [45]doors were open to him. A correct record of his time would probably show an unvaried succession of suppers, balls, and masquerades. In the carnival week, when he snatches 'a little unmasqued moment' to write to West, he says he has done nothing lately 'but slip out of his domino into bed, and out of bed into his domino. The end of the Carnival is frantic, bacchanalian; all the morn one makes parties in masque to the shops and coffee-houses, and all the evening to the operas and balls.' If Gray was of these junketings, his letters do not betray it. He was probably engaged in writing uncomplimentary notes on the Venus de' Medici, or transcribing a score of Pergolesi.

The first interruption to these diversions came in March, when they quitted Florence for Rome in order to witness the coronation of the successor of Clement XII., who had died in the preceding month. On their road from Siena they were passed by a shrill-voiced figure in a red cloak, with a white handkerchief on its head, which they took for a fat old woman, but which afterwards turned out to be Farinelli's rival, Senesino. Rome disappointed them,—especially in its inhabitants and general desolation. 'I am very glad,' writes Walpole, 'that I see it while it yet exists;' and he goes on to[46] prophesy that before a great number of years it will cease to exist. 'I am persuaded,' he says again, 'that in an hundred years Rome will not be worth seeing; 'tis less so now than one would believe. All the public pictures are decayed or decaying; the few ruins cannot last long; and the statues and private collections must be sold, from the great poverty of the families.' Perhaps this last consideration, coupled with the depressing character of Roman hospitality ('Roman conversations are dreadful things!' he tells Conway), revived his virtuoso tastes. 'I am far gone in medals, lamps, idols, prints, etc., and all the small commodities to the purchase of which I can attain; I would buy the Coliseum if I could.' Meanwhile as the cardinals are quarrelling, the coronation is still deferred; and they visit Naples, whence they explore Herculaneum, then but recently exposed and identified. But neither Gray nor Walpole waxes very eloquent upon this theme,—probably because at this time the excavations were only partial, while Pompeii was, of course, as yet under ground. Walpole's next letter is written from Radicofani,—'a vile little town at the foot of an old citadel,' which again is at 'the top of a black barren mountain;' the whole reminding the[47] writer of 'Hamilton's Bawn' in Swift's verses. In this place, although the traditional residence of one of the Three Kings of Cologne, there is but one pen, the property of the Governor, who when Walpole borrows it, sends it to him under 'conduct of a sergeant and two Swiss,' with special injunctions as to its restoration,—a precaution which in Walpole's view renders it worthy to be ranked with the other precious relics of the poor Capuchins of the place, concerning which he presently makes rather unkindly fun. A few days later they were once more in the Casa Ambrosio, Mann's pleasant house at Florence, with the river running so close to them that they could fish out of the windows. 'I have a terreno [ground-floor] all to myself,' says Walpole, 'with an open gallery on the Arno, where I am now writing to you [i. e., Conway]. Over against me is the famous Gallery; and, on either hand, two fair bridges. Is not this charming and cool?' Add to which, on the bridges aforesaid, in the serene Italian air, one may linger all night in a dressing-gown, eating iced fruits to the notes of a guitar. But (what was even better than music and moonlight) there is the society that was the writer's 'fitting environment.' Lady Pomfret, with her daughters, Lady Charlotte,[48] afterwards governess to the children of George III., and the beauty Lady Sophia, held a 'charming conversation' once a week; while the Princess Craon de Beauvau has 'a constant pharaoh and supper every night, where one is quite at one's ease.' Another lady-resident, scarcely so congenial to Walpole, was his sister-in-law, the wife of his eldest brother, Robert, who, with Lady Pomfret, made certain (in Walpole's eyes) wholly preposterous pretentions to the yet uninvented status of blue-stocking. To Lady Walpole and Lady Pomfret was speedily added another 'she-meteor' in the person of the celebrated Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.

When Lady Mary arrived in Florence in the summer of 1740, she was a woman of more than fifty, and was just entering upon that unexplained exile from her country and husband which was prolonged for two-and-twenty years. Her brilliant abilities were unimpaired; but it is probable that the personal eccentricities which had exposed her to the satire of Pope, had not decreased with years. That these would be extenuated under Walpole's malicious pen was not to be expected; still less, perhaps, that they would be treated justly. Although, as already intimated, he was not[49] aware of the scandal respecting himself which her descendants were to revive, he had ample ground for antipathy. Her husband was the bitter foe of Sir Robert Walpole; and she herself had been the firm friend and protectress of his mother's rival and successor, Miss Skerret.[36] Accordingly, even before her advent, he makes merry over the anticipated issue of this portentous 'triple alliance' of mysticism and nonsense, and later he writes to Conway: 'Did I tell you Lady Mary Wortley is here? She laughs at my Lady Walpole, scolds my Lady Pomfret, and is laughed at by the whole town. Her dress, her avarice, and her impudence must amaze any one that never heard her name. She wears a foul mob, that does not cover her greasy black locks, that hang loose, never combed or curled; an old mazarine blue wrapper, that gaps open and discovers a canvas petticoat.... In three words, I will give you her picture as we drew it in the Sortes Virgilianæ,—Insanam vatem aspicies. I give you my honour we did not choose it; but Gray, Mr. Coke, Sir Francis Dashwood, and I, with [50]several others, drew it fairly amongst a thousand for different people.'[37] In justice to Lady Mary it is only fair to say that she seems to have been quite unconscious that she was an object of ridicule, and was perfectly satisfied with her reception at Florence. 'Lord and Lady Pomfret'—she tells Mr. Wortley—'take pains to make the place agreeable to me, and I have been visited by the greatest part of the people of quality.'[38] But although Walpole's portrait is obviously malicious (some of its details are suppressed in the above quotation), it is plain that even unprejudiced spectators could not deny her peculiarities. 'Lady Mary,' said Spence, 'is one of the most shining characters in the world, but shines like a comet; she is all irregularity, and always wandering; the most wise, the most imprudent; loveliest, most disagreeable; best-natured, cruellest woman in the world: "all things by turns, but nothing long."'[39]

By this time the new pope, Benedict XIV., had been elected. But although the friends were within four days journey of Rome, the fear of heat and malaria forced them to forego [51]the spectacle of the coronation. They continued to reside with Mann at Florence until May in the following year. Upon Gray the 'violent delights' of the Tuscan capital had already begun to pall. It is, he says, 'an excellent place to employ all one's animal sensations in, but utterly contrary to one's rational powers.' Walpole, on the other hand, is in his element. 'I am so well within and without,' he says in the same letter which sketches Lady Mary, 'that you would scarce know me: I am younger than ever, think of nothing but diverting myself, and live in a round of pleasures. We have operas, concerts, and balls, mornings and evenings. I dare not tell you all of one's idlenesses; you would look so grave and senatorial at hearing that one rises at eleven in the morning, goes to the opera at nine at night, to supper at one, and to bed at three! But literally here the evenings and nights are so charming and so warm, one can't avoid 'em.' In a later letter he says he has lost all curiosity, and 'except the towns in the straight road to Great Britain, shall scarce see a jot more of a foreign land.' Indeed, save a sally concerning the humours of 'Moll Worthless' (Lady Mary) and Lady Walpole, and the record of the purchase of a few pictures, medals, and busts,—[52]one of the last of which, a Vespasian in basalt, was subsequently among the glories of the Twickenham Gallery,—his remaining letters from Florence contain little of interest. Early in 1741, the homeward journey was mapped out. They were to go to Bologna to hear the Viscontina sing, they were to visit the Fair at Reggio, and so by Venice homewards.

But whether the Viscontina was in voice or not, there is, as far as our travellers are concerned, absence of evidence. No further letter of Gray from Florence has been preserved, nor is there any mention of him in Walpole's next despatch to West from Reggio. At that place a misunderstanding seems to have arisen, and they parted, Gray going forward to Venice with two other travelling companions, Mr. John Chute and Mr. Whitehed. In the rather barren record of Walpole's story, this misunderstanding naturally assumes an exaggerated importance. But it was really a very trifling and a very intelligible affair. They had been too long together; and the first fascination of travel, which formed at the outset so close a bond, had gradually faded with time. As this alteration took place, their natural dispositions began to assert themselves, and Walpole's normal love of pleasure and Gray's retired studiousness became more[53] and more apparent. It is probable too, that, in all the Florentine gaieties, Gray, who was not a great man's son, fell a little into the background. At all events, the separation was imminent, and it needed but a nothing—the alleged opening by Walpole of a letter of Gray[40]—to to bring it about. Whatever the proximate cause, both were silent on the subject, although, years after the quarrel had been made up, and Gray was dead, Walpole took the entire blame upon himself. When Mason was preparing Gray's Memoirs in 1773, he authorized him to insert a note by which, in general terms, he admitted himself to have been in fault, assigning as his reason for not being more explicit, that while he was living it would not be pleasant to read his private affairs discussed in magazines and newspapers. But to Mason personally he was at the same time thoroughly candid, as well as considerate to his departed friend: 'I am conscious,' he says, 'that in the beginning of [54]the differences between Gray and me, the fault was mine. I was too young, too fond of my own diversions, nay, I do not doubt, too much intoxicated by indulgence, vanity, and the insolence of my situation, as a Prime Minister's son, not to have been inattentive and insensible to the feelings of one I thought below me; of one, I blush to say it, that I knew was obliged to me; of one whom presumption and folly perhaps made me deem not my superior then in parts, though I have since felt my infinite inferiority to him. I treated him insolently: he loved me, and I did not think he did. I reproached him with the difference between us when he acted from conviction of knowing he was my superior; I often disregarded his wishes of seeing places, which I would not quit other amusements to visit, though I offered to send him to them without me. Forgive me, if I say that his temper was not conciliating. At the same time that I will confess to you that he acted a more friendly part, had I had the sense to take advantage of it; he freely told me of my faults. I declared I did not desire to hear them, nor would correct them. You will not wonder that with the dignity of his spirit, and the obstinate care[55]lessness of mine, the breach must have grown wider till we became incompatible.'[41]

'Sir, you have said more than was necessary' was Johnson's reply to a peace-making speech from Topham Beauclerk. It is needless to comment further upon this incident, except to add that Walpole's generous words show that the disagreement was rather the outcome of a sequence of long-strained circumstances than the result of momentary petulance. For a time reconciliation was deferred, but eventually it was effected by a lady, and the intimacy thus renewed continued for the remainder of Gray's life.

Shortly after Gray's departure in May, Walpole fell ill of a quinsy. He did not, at first, recognise the gravity of his ailment, and doctored himself. By a fortunate chance, Joseph Spence, then travelling as governor to the Earl of Lincoln, was in the neighbourhood, and, [56]responding to a message from Walpole, 'found him scarce able to speak.' Spence immediately sent for medical aid, and summoned from Florence one Antonio Cocchi, a physician and author of some eminence. Under Cocchi's advice, Walpole speedily showed signs of improvement, though, in his own words in the Short Notes, he 'was given over for five hours, escaping with great difficulty.' The sequel may be told from the same source. 'I went to Venice with Henry Clinton, Earl of Lincoln, and Mr. Joseph Spence, Professor of Poetry, and after a month's stay there, returned with them by sea from Genoa, landing at Antibes; and by the way of Toulon, Marseilles, Aix, and through Languedoc to Montpellier, Toulouse, and Orléans, arrived at Paris, where I left the Earl and Mr. Spence, and landed at Dover, September 12th, 1741, O. S., having been chosen Member of Parliament for Kellington [Callington], in Cornwall, at the preceding General Election [of June], which Parliament put a period to my father's administration, which had continued above twenty years.'

Gains of the Grand Tour.—'Epistle to Ashton.'—Resignation of Sir Robert Walpole, who becomes Earl of Orford.—Collapse of the Secret Committee.—Life at Houghton.—The Picture Gallery.—'A Sermon on Painting.'—Lord Orford as Moses.—The 'Ædes Walpolianæ.'—Prior's 'Protogenes and Apelles.'—Minor Literature.—Lord Orford's Decline and Death; his Panegyric.—Horace Walpole's Means.

Although, during his stay in Italy, Walpole had neglected to accumulate the store of erudition which his friend Gray had been so industriously hiving for home consumption, he can scarcely be said to have learned nothing, especially at an age when much is learned unconsciously. His epistolary style, which, with its peculiar graces and pseudo-graces, had been already formed before he left England, had now acquired a fresh vivacity from his increased familiarity with the French and Italian languages; and he had carried on, however discursively, something more than a mere flirtation with antiquities. Dr. Conyers Middleton, whose once famous Life of Cicero was published early in 1741, and who was him[58]self an antiquary of distinction, thought highly of Walpole's attainments in this way,[42] and indeed more than one passage in a poem written by Walpole to Ashton at this time could scarcely have been penned by any one not fairly familiar with (for example) the science of those 'medals' upon which Mr. Joseph Addison had discoursed so learnedly after his Italian tour:—

The poem from which these lines are taken—An Epistle from Florence. To Thomas [59]Ashton, Esq., Tutor to the Earl of Plimouth—extends to some four hundred lines, and exhibits another side of Walpole's activity in Italy. 'You have seen'—says Gray to West in July, 1740—'an Epistle to Mr. Ashton, that seems to me full of spirit and thought, and a good deal of poetic fire.' Writing to him ten years later, Gray seems still to have retained his first impression. 'Satire'—he says—'will be heard, for all the audience are by nature her friends; especially when she appears in the spirit of Dryden, with his strength, and often with his versification, such as you have caught in those lines on the Royal Unction, on the Papal dominion, and Convents of both Sexes; on Henry VIII. and Charles II., for these are to me the shining parts of your Epistle. There are many lines I could wish corrected, and some blotted out, but beauties enough to atone for a thousand worse faults than these.'[44] Walpole has never been ranked among the poets; but Gray's praise, in which Middleton and others concurred, justifies a further quotation. This is the passage on the Royal Unction and the Papal Dominion:—

That the refined and fastidious Horace Walpole of later years should have begun as a passable imitator of Dryden is sufficiently piquant. But that the son of the great courtier Prime Minister should have distinguished himself by the vigour of his denunciations of kings and priests, especially when, as his biographers have not failed to remark, he was writing to one about to take orders, is more noticeable still. The [61]poem was reprinted in his works, but he makes no mention of it in the Short Notes, nor of an Inscription for the Neglected Column in the Place of St. Mark at Florence, written at the same time, and characterized by the same anti-monarchical spirit.

His letters to Mann, his chief correspondent at this date, are greatly occupied, during the next few months, with the climax of the catastrophe recorded at the end of the preceding chapter,—the resignation of Sir Robert Walpole. The first of the long series was written on his way home in September, 1741, when he had for his fellow-passengers the Viscontina, Amorevoli, and other Italian singers, then engaged in invading England. He appears to have at once taken up his residence with his father in Downing Street. Into the network of circumstances which had conspired to array against the great peace Minister the formidable opposition of disaffected Whigs, Jacobites, Tories, and adherents of the Prince of Wales, it would here be impossible to enter. But there were already signs that Sir Robert was nodding to his fall; and that, although the old courage was as high as ever, the old buoyancy was beginning to flag. Failing health added its weight to the scale. In October Walpole tells his correspondent that[62] he had 'been very near sealing his letter with black wax,' for his father had been in danger of his life, but was recovering, though he is no longer the Sir Robert that Mann once knew. He who formerly would snore before they had drawn his curtains, now never slept above an hour without waking; and 'he who at dinner always forgot that he was Minister,' now sat silent, with eyes fixed for an hour together. At the opening of Parliament, however, there was an ostensible majority of forty for the Court, and Walpole seems to have regarded this as encouraging. But one of the first motions was for an inquiry into the state of the nation, and this was followed by a division upon a Cornish petition which reduced the majority to seven,—a variation which sets the writer nervously jesting about apartments in the Tower. Seven days later, the opposition obtained a majority of four; and although Sir Robert, still sanguine in the remembrance of past successes, seemed less anxious than his family, matters were growing grave, and his youngest son was reconciling himself to the coming blow. It came practically on the 21st January, 1742, when Pulteney moved for a secret committee, which (in reality) was to be a committee of accusation against the Prime Minister. Walpole defeated this[63] manœuvre with his characteristic courage and address, but only by a narrow majority of three. So inconsiderable a victory upon so crucial a question was perilously close to a reverse; and when, in the succeeding case of the disputed Chippenham Election, the Government were defeated by one, he yielded to the counsels of his advisers, and decided to resign. He was thereupon raised to the peerage as Earl of Orford, with a pension of £4,000 a year,[46] while his daughter by his second wife, Miss Skerret, was created an Earl's daughter in her own right. His fall was mourned by no one more sincerely than by the master he had served so staunchly for so long; and when he went to kiss hands at St. James's upon taking leave, the old king fell upon his neck, embraced him, and broke into tears.

The new Earl himself seems to have taken his reverses with his customary equanimity, and, like the shrewd 'old Parliamentary hand' that he was, to have at once devoted himself to the difficult task of breaking the force of the attack which he foresaw would be made upon himself by those in power. He contrived adroitly to [64]foster dissension and disunion among the heterogeneous body of his opponents; he secured that the new Ministry should be mainly composed of his old party, the Whigs; and he managed to discredit his most formidable adversary, Pulteney. One of the first results of these precautionary measures was that a motion by Lord Limerick for a committee to examine into the conduct of the last twenty years was thrown out by a small majority. A fortnight later the motion was renewed in a fresh form, the scope of the examination being limited to the last ten years. Upon this occasion Horace Walpole made his maiden speech,—a graceful and modest, if not very forcible, effort on his father's side. In this instance, however, the Government were successful, and the Committee was appointed. Yet, despite the efforts to excite the public mind respecting Lord Orford, the case against him seems to have faded away in the hands of his accusers. The first report of the Committee, issued in May, contained nothing to criminate the person against whom the inquiry had been directly levelled; and despite the strenuous and even shameless efforts of the Government to obtain evidence inculpating the late Minister, the Committee were obliged to issue a second report in June, of[65] which,—so far as the chief object was concerned,—the gross result was nil. By the middle of July, Walpole was able to tell Mann that the 'long session was over, and the Secret Committee already forgotten,'—as much forgotten, he says in a later letter, 'as if it had happened in the last reign.'