The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. THE CAR THAT WOULDN’T BEHAVE.

CHAPTER II. MATT KING’S RESOLVE.

CHAPTER III. A DEMON IN CONTROL.

CHAPTER IV. THE MANILA ENVELOPE.

CHAPTER VI. A DIFFERENCE OF OPINION.

CHAPTER VIII. THE COLONEL TRIES PERSUASION.

CHAPTER IX. WHAT AILS M’GLORY?

CHAPTER XII. A STARTLING MYSTERY.

CHAPTER XIII. IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES.

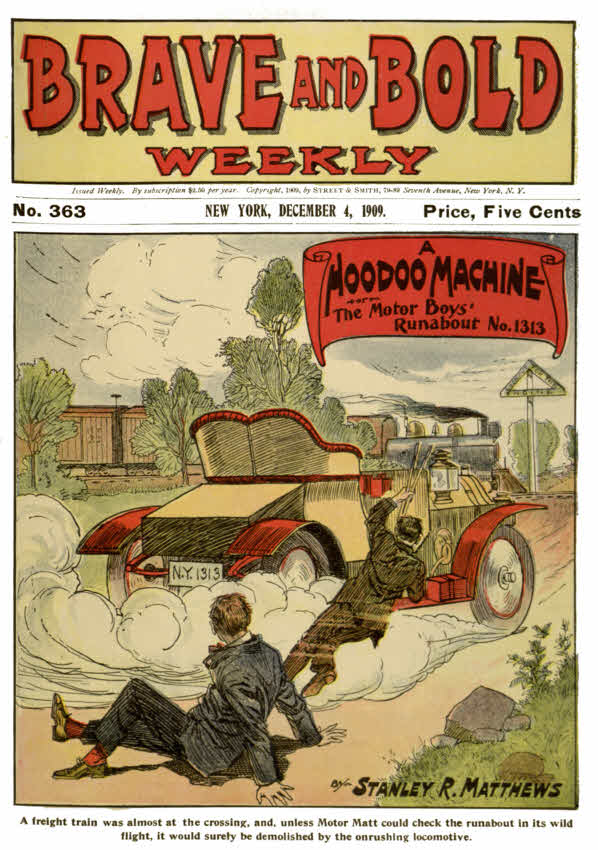

A freight train was almost at the crossing, and, unless Motor Matt could check the runabout in its wild flight, it would surely be demolished by the onrushing locomotive.

BRAVE AND BOLD

WEEKLY

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Copyright, 1909, by Street & Smith, 79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

No. 363. NEW YORK, December 4, 1909. Price Five Cents.

By STANLEY R. MATTHEWS.

“Sufferin’ whirligigs, Pard Matt! Look at that bubble wagon! Is it trying to turn a handspring, or ‘skin the cat,’ or climb that telephone pole? I reckon the longhorn up front don’t know how to run the thing. Either that, or else he’s ‘bug’ with a big ‘B.’”

“I should say it’s the car that’s ‘bug,’ Joe. The driver seems to be trying to control the machine in the proper manner, but it won’t be controlled. What’s your notion of it, Billy?”

“Hoodoo car, Matt. Look at the number of her—thirteen thirteen. Double hoodoo. You couldn’t expect no chug wagon with such a tag to behave anything else than disgraceful. Lo and behold you, if she don’t turn turtle in the ditch before she goes many more miles then my name’s not Billy Wells. Watch ’er; keep your eye on ’er an’ I’ll bet you see something.”

The three boys were driving along the Jericho Pike well toward Krug’s Corner—Matt King, Joe McGlory, and Billy Wells. Billy belonged with a New York garage from which the boys had secured the touring car they were using that morning. He was a living road map, this Billy, and could go anywhere up-state, or over Long Island, or in Jersey on the darkest night that ever fell, and he knew every minute just where he was.

Matt was doing the driving, and Billy sat beside him as guide, counselor, and friend. In the back of the machine was McGlory.

That was Thursday. Matt and his chum were heeding a summons that carried them toward the Malvern Country Club, near Hempstead. After transacting their business at the Country Club—they did not know what it was, but believed it would not take them long—they were planning to return to Krug’s Corner for their noon meal, and then back to Manhattan by Jackson Avenue and the Williamsburg Bridge. But plans are easily made, sometimes, and not so easily carried out.

The day was bright, the roads were good, and the motor boys were enjoying themselves. Well along the Jericho Pike they had come up with a white runabout, two seats in front and a deck behind, and the actions of this car aroused their curiosity to such an extent that Matt slowed down the big machine in order that he and those with him could follow and watch the performance.

There was only one passenger in the white car, and he was having his hands full.

The runabout would angle from one side of the road to the other, in apparent defiance of the way the steering wheel was held, and sometimes it would go its eccentric course slowly and sometimes with a rush—so far as those in the other car could see—without any change in the speed gear.

The driver of the runabout worked frantically to keep the machine where it ought to be, but the task was too much for him.

Once a telephone pole gave him a close shave, and[2] once his unmanageable car gave a sidewise lurch that almost hurled it into a machine going the other way.

“What’s the matter?” Matt hailed.

The man in the runabout looked around with a facial expression that was far from angelic.

“If I knew what was the matter with this confounded car,” he cried in exasperation, “do you think I’d be side-stepping all over the road the way I am?” Then, muttering to himself, he humped over the steering wheel again.

“He’s happy—I don’t think,” chuckled McGlory. “The car’s getting on his nerves.”

“A car like that would get on anybody’s nerves,” commented Billy. “The number’s enough to set mine on edge. Thirteen’s unlucky, no matter where you find it. That’s right. And when you get two thirteens bunched together, you’ve sure got a combination that points a car for the scrap heap. I wouldn’t hold down the cushions in that roadster for all the money in New York. No, sir, that I wouldn’t,” and Billy shook his head forebodingly.

“Oh, splash!” scoffed Matt. “When a car fools around like that, Billy, there’s something wrong with its internal apparatus.”

“Matt,” went on Billy solemnly, “I’ve seen cars that hadn’t a thing wrong with ’em, but they was just naturally crazy and never’d run right. Steer ’em straight, an’ they’d go crooked; point ’em crooked, an’ they’d go straight; throw on the reverse, an’ they’d go for’ard; give ’em the third speed an’ they’d crawl; give ’em the first an’ they’d tear away like lightnin’—and all the while, mind you, the engine was running as sweet as any engine you ever see. The Old Boy himself takes charge of some cars the moment they’re sold and in a customer’s hands. I’ve worked in a garage for five years, and I know.”

Matt laughed. McGlory laughed, too, but not so mirthfully. The cowboy had a little superstition in his make-up and Billy’s remarks had left a fleeting impression.

“Gammon, Billy, gammon,” said Matt. “If a car is built right, and works right, it is going to run right. That stands to reason.”

“A lot of things happen,” insisted Billy, “that don’t stand to reason. Now, take that runabout. The engine’s working fine—from the sound of it. Eh?”

Matt admitted that, so far as the hum of the motor was concerned, the machinery seemed to be doing its part.

“Well, then,” cried the triumphant Billy, “why don’t the blooming car run like it ought to?”

“It’s the steering gear that’s wrong,” Matt answered, “not the engine, or——”

Bang!

Just then the runabout blew up a forward tire. The machine tried to turn a somersault, and its passenger went over on the hood and tried to knock off one of the gas lamps with his head. When Matt brought the touring car to the side of the runabout, and halted, the man was on his feet, shaking his fist at the silent white tormentor.

“If I had a stick of dynamite,” he declared wrathfully, “I’d blow this infernal machine to kingdom come! I’ve been fiddling around the Jericho Road for two mortal hours, and I could have made better time if I’d left the car and gone on afoot. But I’ll hang to it, and make it take me where I’m going. By George, I’ll not be beaten by a senseless contraption of tires, mud guards, and machinery.”

Matt had jumped out of the touring car and was sniffing at the damaged tire.

“What makes that smell of gasoline?” he asked.

“I put in a tube this morning, and washed out the chalk with gasoline,” said the man.

“Never use gasoline for cleaning the tubes,” counseled Matt. “Get all the chalk you can from the outer tube, and then soak it in wood naphtha or ordinary alcohol. No wonder your tire blew up. You left gasoline in the shoe, and when it got hot, it mixed with a little air in the tube and something had to happen. Have you got another shoe?”

“Yes.”

“And a jack?”

“Of course. When a man goes out with a car like this he ought to carry a small garage around with him.”

“Well, we’ll help you get on the shoe.”

Matt and Billy worked. McGlory stood near, watching and talking with the owner of the car.

After the tire had been repaired, Matt looked over the runabout critically. Much to his amazement, he could find nothing wrong.

“It’s the double hoodoo,” whispered Billy; “that’s all that’s the trouble.”

“Much obliged to you,” said the man, cranking up. “Now we’ll see how she acts.”

He got in, went through the operations for a fresh start, but the runabout began backing. While the man shouted, and said things, the runabout backed in a circle around the big touring car, then dropped rearward down a shallow embankment at the roadside—and its passenger had another spill, out over the rear deck this time. For a second, he stood on his head and shoulders, then turned clear over and made a quick move sideways in getting to his feet. He was afraid, evidently, that the runabout was coming on top of him. But the car, almost in defiance of the laws of gravitation, hung to the side of the steep bank, its position nearly perpendicular.

“Speak to me about that!” gasped McGlory.

Matt was scared. From the top of the bank he stood staring while the man got out of the way.

“Are you all right?” Matt asked.

“No thanks to that fiendish machine if I am,” sputtered the man, laboring frantically up the slope. “It has tried to kill me in a dozen different ways since I left home with it. I’m done. Life’s too short to bother with such an infernal car as that.”

Fairly boiling with rage, he started along the road on foot.

“Wait a minute!” shouted Matt. “Where you going?”

The man turned.

“Krug’s,” he answered. “I’ll get a decent, respectable car there to take me on.”

“You can telephone to a garage from Krug’s,” suggested Billy, “and they can send some one to get the runabout home.”

“I’m done with the runabout, I tell you. It can stay where it is until the tires rot, for all of me.”

“I’ll agree to get it back to the city for you,” said Matt. “My name’s King, Matt King, and I’m staying at——”

The man’s rage subsided a little.

“You’re Matt King?” he inquired.

“Yes.”

“I understand, now, how you happen to know so much about tubes. They say you’re pretty well up in motors, too. Well, here’s where I give you the job of your life. Matt King, I make you a present of that runabout. Take it—but Heaven help you if you try to run it.”

Thereupon the man whirled around and strode off.

“Oh, I say,” yelled Matt, “you don’t mean it. Wait, and I’ll——”

But the man swung onward, paying no heed to what Matt was calling after him.

Matt King turned and peered in amazement at his cowboy chum.

“Sufferin’ tenterhooks!” exclaimed McGlory. “You’re loaded up with a bunch of trouble now, pard.”

“Come on,” urged Billy, moving toward the touring car with considerable haste. “Don’t lay a finger on that runabout—don’t have a thing to do with it.”

But Matt was face to face with a proposition that caught his fancy. A refractory automobile! Never yet had he encountered a machine that had got the best of him. And this runabout couldn’t do it—he was positive of that.

“That man was so mad he was locoed,” observed the cowboy.

“Certainly he was, Joe,” agreed Matt. “If he hadn’t been, he’d never have given away that machine. It’s a powerful car and worth twenty-five hundred of any man’s money.”

“Don’t tamper with it, Matt,” implored Billy. “When that fellow gets over his mad spell he’ll want the runabout back. Let him have it—and let him find it right where he left it.”

“If he hadn’t been worked up like he was,” said Matt, “he wouldn’t have given the car to me. I won’t take it, of course, but Joe and I will use it to take us to the Malvern Country Club, and then back to Manhattan. By to-morrow that fellow will be looking for me and wanting his car back.”

“You wouldn’t think of such a thing as wanting to bother with that runabout!” gasped Billy, from his seat in the touring car.

“Yes, I would,” answered Matt. “Why not?”

“The number—thirteen thirteen!”

“Bosh!”

“It’s a hoodoo car.”

“Never mind about that, Billy. You go on to Krug’s Corner and get a stout rope. If you overtake the owner of the runabout you can give him a lift. See him, anyhow, and tell him we’ll take the runabout to New York and that he can have it whenever he wants it.”

“Don’t do it!” begged Billy. “I’ve seen enough of these hoodoo cars to know they’ll prove the death of somebody. Don’t let that runabout prove the death of you!”

“Go get the rope, Billy,” said Matt sharply, “and hustle back with it.”

There was that in the voice of Matt King which proved that he had made up his mind, and that there was no shaking his determination. With an ominous movement of the head, Billy started for Krug’s Corner.

“Pard,” remarked McGlory earnestly, “I reckon the runabout is heap bad medicine. Do you think you ought to mix up with it?”

“Are you going back on me, Joe?” asked Matt.

“Not so you can notice. I’d get on a streak of greased lightning with you, if you said the word, and help you ride it to the end of the One-way Trail, but I think this is too big an order for us. Sufferin’ thunderbolts! Why, pard, that car won’t mind the helm or do the thing it ought to do even when you pull the right thing. When it began to crawfish around the road, the reverse wasn’t on.”

“I don’t know about that. It’s on now,” and he looked down at the runabout. “I guess the man must have thrown on the reverse instinctively when the tire blew up. Think of rinsing the chalk from the outer tube with gasoline!” Matt laughed. “There was good cause for the tire going wrong, and there may be other good and sufficient causes for the machine’s sizzling around like it did. Anyhow, we’ll try it, and see how it will behave for us.”

“But how can we lay a course for the Malvern Country Club? Billy will have to show us.”

“Billy can tell us how to go, and we’ll get to the Country Club all right. Hello! What’s this?”

Matt began slipping and sliding down the slope at the side of the runabout. Just at the point where the driver of the car had taken his header, the young motorist picked up a long manila envelope, unsealed.

“I reckon that dropped out of the man’s clothes while he was upside down,” ventured McGlory.

“That’s a cinch,” said Matt. “There’s no address on the envelope, and no printed card in the corner, but it may be we can find the man’s name and address on the papers inside. If he won’t come for his car, we’ll take it to him.”

“I’m a Piute,” mumbled McGlory, “if I feel right about this runabout business.”

“Billy’s talk about hoodoo cars has got you on the run,” grinned Matt. “You’ll feel different when we’re slamming along the pike with the runabout under perfect control. It’s my opinion that man doesn’t know a whole lot about running a car.”

While Matt was moving here and there about the steep bank, making a few investigations of the “hoodoo” machine, Billy came racing back.

“There’s your rope, Matt,” said he, tossing a coiled cable into the road.

Matt crept warily up the bank to the front of the runabout.

“Did you see the man, Billy?” he asked.

“Sure I did. Let him ride with me for half a mile.”

“You told him what we were going to do?”

“I did. He says that if you get that car back to the city, and try to turn it over to him, he’ll have you arrested for assault with intent to do great bodily damage. He says the runabout is a powder mine, and liable to blow up at any minute. ‘Tell Matt King to keep it,’ he said, ‘providing he’s got the nerve.’ That’s the way he handed it to me. Take my advice,” Billy clamored desperately, “and leave it alone!”

“Joe and I are going to use it,” answered Matt.[4] “Hand me an end of that rope, pard,” he added to the cowboy.

McGlory passed him the rope, and Matt made it secure to the front of the runabout.

“Back up, Billy,” called Matt, “and tie the other end of the rope to the touring car. You’ve got to give us a lift into the road.”

“What if something should happen?” demurred Billy.

“Nonsense!” said Matt impatiently.

“You can’t give the car back to that fellow if he won’t take it.”

“We’ll make him take it. He’s a very foolish man, and he’s going to feel differently when his temper cools.”

Billy, not in a very comfortable frame of mind, backed the touring car close to the edge of the bank. The rope was made fast, and Matt and McGlory went to the foot of the bank to push while the big machine pulled.

The attempt was successful. The runabout sputtered—perhaps defiantly—as it yielded to the tugging and rolled up the slope. Matt looked the machine over and could not find that it had suffered any by the slide down the slope.

“It’ll hang together till it gets you, Motor Matt,” observed Billy grewsomely. “That’s the way with these hoodoo cars. They never go to pieces till they kill somebody.”

“You’re too good a driver, Billy, to talk such foolishness,” returned Matt. “Now, tell us how to get to the Malvern Country Club.”

“Ain’t I going with you?”

“Three of us couldn’t ride very comfortably in the runabout.”

“But hadn’t I better go along in the touring car so as to be handy in case of accidents?”

“Oh, Joe and I will get along. We’re not going to have any accidents if we can help it—and I feel pretty sure we can.”

Billy laid out the course the boys were to take with considerable detail. When he was through, Matt felt that he had the route clearly fixed in his mind.

“If the runabout’s too much for you,” Billy finished, “all you’ve got to do is to phone the garage, and I’ll come a-runnin’.”

“Where did you get the rope?” asked Matt.

Billy told him he had borrowed it at Krug’s.

“We’ll leave it there,” said Matt, “on our way past the Corner.”

“You may never get to Krug’s,” answered Billy, in extreme dejection.

“Pile in, Joe,” said Matt, “and we’ll throw in the clutch and scoot.”

McGlory, it must be admitted, climbed into the runabout in a way that proved his lack of confidence. Matt cranked up, listening with deep satisfaction to the smooth singing of the engine, and then got into the driver’s seat.

Billy, in the touring car, watched tremulously and waited. From his appearance, he was plainly expecting that the white car would turn a few cartwheels and perhaps land upside down in the middle of the road with Matt and McGlory underneath.

But nothing of the sort happened. Car No. 1313 moved off in the direction of Krug’s as nice as you please—moved on a hair line, with none of the distressing wabbling which characterized its previous performance with its owner at the wheel.

The cowboy gathered confidence. Looking behind, he waved his hat at Billy.

“Don’t whistle till you’re out of the woods!” yelled Billy.

He shouted something else, but his words faded out in the increasing distance.

“Speak to me concerning this!” laughed McGlory, straightening around in his seat. “This little old chug cart is a false alarm, after all. It seems to understand that there’s a fellow in charge who knows the ropes up and down and across. Fine!”

“We’ll see the owner of the machine at Krug’s,” said Matt, “and get his address.”

“But he can’t have the runabout till we’re done with it,” protested McGlory.

“I should say not! We’ve sent Billy home, and that leaves us only this car to take us back. Ah, there’s Krug’s! We’ll stop for a few minutes.”

Matt tried to stop, but he couldn’t. He went through all the motions for cutting off the flow of gasoline and switching off the spark. The clutch was out, but the engine still had the car, and the engine wouldn’t stop.

An automobile was just coming out of the sheds. The runabout came within an ace of a head-on collision. Fortunately the steering gear still worked, and Matt scraped mud guards with the other car and he and his cowboy chum bounded on along the road.

McGlory yelled frantically. “Jump!” he cried; “let the old contraption run its blooming head off!”

But Matt wouldn’t jump, and he wouldn’t let his chum go over the flying wheels. Dazed and bewildered, he bore down on the brake.

The speed slackened, but they were half a mile beyond Krug’s before the car made up its mind to stop. Then McGlory tumbled out, while Matt sat astounded, his arms folded over the steering wheel and such a look on his face as the cowboy had never seen there before.

“Get out of that, pard! Get out!” McGlory was wild with apprehension, and sprang up and down at the roadside and waved his arms. “The way that car acts would make the hair stand up on a buffalo robe! What are you staying there for?”

“I’m trying to guess how that happened,” said Matt.

“Then stop guessing. You can guess till you’re black in the face and you’ll still be up in the air. Cut loose from that bubble wagon—that’s your cue and mine.”

“There’s a reason for the car acting as it does,” declared Matt, “and I’m going to get down to the bottom of the mystery. We might just as well put in a little time right here. It’s not a very long run to the Malvern Country Club, and we can waste another half hour without missing your appointment.”

“If you took my advice,” muttered McGlory, “you wouldn’t touch that machine with a ten-foot pole.”

There was a determined look on Matt’s face as he leaped into the road and began an exhaustive examination. He could find nothing wrong; nevertheless, he[5] went over the ignition system carefully, step by step; then he took the carburetor to pieces, ran pins through the spray nozzle and sandpapered the float guides; and, after that, he went under the car, broke the gasoline connections and drew wires through the tubes.

The cowboy heaved a long breath of relief as Matt reappeared from under the car.

“Find anything out of whack, pard?” McGlory asked.

“Not a thing,” answered the mystified Matt.

“Then you’re about ready to admit there’s a demon in control of the car?”

“I don’t believe in demons.”

“If a car won’t stop when it ought to stop, and if it won’t go straight when you’re steering that way, and if it backs up when everything is set for going ahead, I’m a Piute if I don’t think there’s something else got a hand in running it.”

Matt was silent. He was facing a proposition that was new to him, but he was dealing with motor details with which he was perfectly familiar. Here was an ordinary four-cycle engine, and an ordinary float-feed carburetor; the transmission was of the common sliding-gear variety; the fuel tank was under the seat, and the gasoline was fed into the engine by gravity. Why was it that the different parts did not coöperate as they should?

“Come on, Joe,” said Matt, putting on the coat which he had laid off while at work, “we’ll go back to Krug’s and see if my tinkering has helped any.”

“I can’t pass up the invitation, pard,” returned McGlory, “but if any one else gave it to me, I’d say manana. Every minute we’re aboard that runabout, we’re sitting on a thunderbolt that’s not more than half tame. Here goes, anyhow.”

The cowboy climbed to his place, and Matt “turned the engine over” and got in beside him. Then they backed until the runabout was headed the other way, whereupon Matt changed speeds and they slid over the pike as easily as a girl tripping to market. No. 1313 behaved like the prince of cars. No one, from its present performance, could ever have dreamed that it was anything but the mildest-mannered little buzz wagon that had ever come out of the shop.

“I’m stumped,” declared McGlory. “She acts as though she had never thought of such a thing as taking the bit in her teeth. I reckon, pard, you must have done something that started her to working in the right way.”

“I’ll never be able to understand how she ran for half a mile without any gas in the cylinders or any spark to cause an explosion,” said Matt, as he came to a stop in front of Krug’s. “Return the rope, Joe,” he added, “and see if you can find the owner of the runabout.”

McGlory was gone for ten minutes. When he came back he reported that the man who had cut loose from the runabout was nowhere to be found, and that a fellow answering his description had been taken into a car by a friend and had motored off in the direction of Hempstead.

“Then,” said Matt, “we’ll stop thinking about the owner of the car and continue to use it just as though it belonged to us.”

They turned south from the Corner and moved away in the direction of Hempstead at a good rate of speed. The runabout kept up its excellent behavior, answering instantly Matt’s slightest touch on steering wheel or levers.

“You’ve got the best of her, pard,” observed McGlory. “When you hip-locked with her, after she ran away from Krug’s, you must have poked a wire into something that was causing all the trouble.”

“I couldn’t have done that,” answered Matt. “Still, no matter what the reason, the car is acting handsomely now, and we’ll let it go at that. Read that telegram to me again, Joe.”

McGlory fished around in his pocket until he had brought up a folded yellow sheet. Opening it out, he read as follows:

“‘Meeting of syndicate in the matter of ”Pauper’s Dream“ Mine postponed from Wednesday night to Thursday night. Meet me eleven o’clock Thursday Malvern Country Club, near Hempstead, Long Island. Important.

“‘Joshua Griggs.’”

The “Pauper’s Dream” Mine was located near Tucson, in Arizona. It was owned by a stock company, and the cowboy had a hundred shares of the stock. A friend of his, named Colonel Mark Antony Billings, had induced him to invest in the “Pauper’s Dream” when it was little more than an undeveloped claim. Development seemingly proved the claim worthless, and McGlory had been surprised, while he and Matt were in New York, to receive a letter stating that a rich vein had been struck, and that the colonel was planning to sell the property at a big figure to a syndicate of New York capitalists. Random & Griggs, brokers, in Liberty Street, were the colonel’s New York agents, and the meeting of the syndicate was to be held in their office.

Two bars of gold bullion from the “Pauper’s Dream” mill had been sent by the colonel to New York, and McGlory had been requested to get the bullion and exhibit it to the members of the syndicate at the meeting. Matt and McGlory had had a good deal of trouble with that bullion, and the cowboy was not intending to take it from the bank, to whose care it had been consigned, until three o’clock in the afternoon.

Meanwhile, this telegram from Griggs was taking the boys to the Malvern Country Club; but just why it was necessary for McGlory to talk with Griggs was more than either of the lads could understand.

“Griggs, I reckon,” said McGlory, as he returned the telegram to his pocket, “is one of the members of the firm of Random & Griggs.”

“That’s my guess,” returned Matt; “but, if he is, why couldn’t he talk with you at the office in Liberty Street instead of having you come all the way out here?”

“I’ll have to shy at that, pard. Maybe Griggs is a plutocrat, and is accustomed to having people jump whenever he cracks the whip. Like as not he didn’t want to go in to the office to-day and just shot that message at us to save him the trouble of going too far for a palaver.”

“He told you all it was necessary for you to know, in the message. The meeting was postponed from last night to to-night. What else is there that he could want to tell you?”

“Pass again. Maybe he wants to ask about the colonel’s health, or——”

The cowboy bit off his words suddenly. Without the least warning, the runabout had made a wild lunge toward the side of the road.

“She’s cut loose again!” yelled McGlory, hanging to the seat with both hands.

Matt was holding the steering wheel firmly. So far as he could see, there was not the least excuse for the car’s making that frantic plunge toward the roadside.

Just ahead of the machine was a railroad track, and the noise of an approaching train was loud in the boys’ ears. Matt was thinking that, if the runabout repeated the performance it had given at Krug’s Corner, he, and Joe, and the car, stood a grave chance of being hung up on the pilot of a locomotive.

Before he could disengage the clutch or give a kick at the switch, one of the forward wheels struck a bowlder. The car jumped, throwing McGlory out on one side and Matt on the other.

As Matt fell, he caught at the two levers on the right of the driver’s seat and clung to them desperately. Although the car was running wild, with no hand on the steering wheel, yet it bounded away along the centre of the road, dragging Matt along with it.

With his elbows on the footboard, and the lower half of his body trailing in the dust, Matt endeavored again and again to get back on the running board and regain a grip on the steering wheel.

A freight train was almost at the crossing. Unless Matt could check the runabout in its wild flight, it would surely be demolished by the locomotive or else hurl itself to destruction against the sides of the swiftly moving box cars.

The situation was desperate to the last degree. Unless he could get hold of the steering wheel and regain his seat, nothing could be done to avert the threatening catastrophe. If he let go, and abandoned the runabout to its fate, he was in danger of being thrown under the racing wheels.

A demon of perversity seemed to possess the car and to be bent upon the destruction of Matt King.

Again and again the young motorist tried to reach the steering post with one hand and wriggled up onto the running board. Each attempt was unsuccessful until a lurch of the car helped in executing the manœuvre.

Hanging to the wheel, Matt threw himself over the upright levers, dropped into the driver’s seat, disengaged the clutch and jammed both brakes home.

Even then he was in doubt as to whether he would succeed in stopping the car. If it continued mysteriously to refuse control, there was certain destruction for both Matt and the car against the side of the train, the box cars of which were already flashing over the crossing.

But the car stopped—stopped within a yard of the rushing box cars!

Matt dared not throw in the reverse, fearing the machine might move forward instead of backward, so he dropped into the road and lay there, panting and exhausted, while the freight rolled on.

“Sufferin’ doom! I’m beginning to think Billy had a bean on the right number, pard, when he said this car would have to kill somebody before it settled down and acted as though it was civilized.”

Matt looked up and saw his cowboy chum. McGlory was rubbing a bruise on the side of his face and was carrying the long manila envelope in his hand.

“Why didn’t you let the car go to blazes?” demanded the cowboy. “What did you want to hang on to it for? The best place for the blamed thing is the junk pile.”

“I couldn’t let go without getting run over,” explained Matt, rising to his feet.

“Well, you’d feel a heap more comfortable under a pneumatic tire than you would under a train of box cars!”

McGlory’s face was white, and his voice trembled. The strain he had been under was just beginning to tell on him.

“The owner of the runabout,” he went on, “showed his good sense when he cut loose from it. The car’s like a broncho, Matt, and you never can tell when its fiendishness is going to break loose. If we had a keg of powder, I’m a Piegan if I wouldn’t scatter that sizz wagon all over this part of Long Island.”

McGlory glared savagely at the white, innocent-looking machine.

The freight train had passed, and Matt was leaning against the car and cudgeling his brains to think of some reason for the runabout’s acting as it did.

“It brought us out of Krug’s Corner as nice as you please,” he mused.

“Which is just the way it took us into Krug’s Corner,” proceeded the cowboy. “That’s the way the pesky thing works. First it lulls you into thinking it wouldn’t side-step, or buck-jump, or do anything else that was crooked or underhand for the world; then, when you think you’re all right, the runabout hauls off and hands you one. That’s the meanest kind of treachery—reaching out the glad hand only to land on you with a bunch of fives. There’s something human about that car, Matt.”

“Inhuman, I should say,” muttered Matt. “Well, it’s too much for me. Get in, Joe, and we’ll cross the track to those trees over there and rest up a little before we go on to the Malvern Country Club.”

“Damaged much, pard?”

“Jolted some, that’s all.”

“Same here. I landed in the road like a thousand of brick. This is my first experience with a crazy automobile, and you can bet your moccasins it will be the last. I didn’t know there was such a thing.”

“There isn’t,” said Matt. “How can you put together a lot of machine and have anything but a senseless piece of mechanism?”

“I’m by, when you pin me right down, pard, but if this car isn’t locoed, then what’s the matter with it?”

“Something must go wrong.”

“Goes wrong and then fixes itself,” jeered the cowboy. “If you’d look the blamed thing over this minute, you wouldn’t be able to find anything out of order.”

Once more Matt started the car, and once more it[7] acted like a sane and sensible machine, carrying the boys to the shade of the trees and stopping obediently to let them alight.

Matt flung himself down on the grass at the roadside and examined his watch to ascertain whether it had been injured. He found the timepiece in good condition.

“Ten-fifteen, Joe,” he observed, replacing the watch in his vest and noticing that his chum was still carrying the manila envelope in his hand as he sat down beside him. “What are you holding that envelope for?” he inquired.

“I reckon I’ve gone off the jump myself, Matt,” laughed McGlory. “It dropped out of my pocket when I fell into the road. I picked it up, but have been too badly rattled ever since to do anything but hold it in my hand.”

McGlory was about to put it in his pocket when Matt suggested that he examine the contents and see if he could discover the name and address of the man who owned the runabout.

The cowboy pulled out a couple of papers. Unfolding one of them, he read some typewritten words and gave a gasp and turned blank eyes on his chum.

“What’s wrong?” queried Matt.

“Listen to this,” was the answer. “‘Private Report on the Pauper’s Dream Mine, by Hannibal J. Levitt, Mining Engineer, of New York City.’ Wouldn’t that rattle your spurs, Matt?” cried McGlory. “The syndicate had an expert go out to Arizona and make an examination of the ‘Pauper’s Dream,’—you remember the colonel told me about that, in his letter. Here’s the report! It drops into our hands by the queerest happen-chance you ever heard of. Mister Man takes a header from a crazy chug cart, unloads the machine onto you, and then hustles for Krug’s, leaving the report behind. He’s not at Krug’s when we get there, so the report is left in our hands. This couldn’t have happened once in a million times, pard!”

Matt was rubbing his bruised shins and allowing the amazing event to drift through his brain. It was queer, there was no mistake about it. In fact, all the experiences of the boys that Thursday morning were on the “queer” order.

“You say,” said Matt, “that the document is headed ‘Private Report.’ Why should it be a private report if it is for the syndicate?”

“Private for the syndicate, I reckon.”

“Hardly that, Joe. Unless there’s some skullduggery that report ought to be public property—public enough so that it could go into a prospectus. What’s the other paper?”

McGlory opened the other document, and found it to be a letter from Colonel Billings, dated nearly a month previous.

“It’s a letter from the colonel, Matt,” the cowboy announced, “and is addressed to Levitt. The colonel says he will not pay Levitt the balance due until Levitt sends him the private report on the ‘Pauper’s Dream’ proposition.”

“Great spark plugs!” exclaimed Matt.

“What’s strange about that?” demanded McGlory. “If Levitt made an examination of the property he certainly expects pay for it.”

“But not from the colonel, Joe! Levitt was examining the mine for the syndicate, and he’s not entitled to any money from the colonel unless he’s doing shady work of some kind.”

“Speak to me about that!” muttered McGlory. “It looks as though we’d grabbed a live wire when we got hold of this yellow envelope.”

“I don’t like the way the business stacks up,” said Matt earnestly. “The owner of this troublesome runabout happens to be Hannibal J. Levitt, and he’s playing an unscrupulous double game. Glance through that report and give me the gist of it.”

Eagerly—and a little apprehensively—McGlory looked through the private report. His face grew longer and longer as he read.

“Sufferin’ poorhouses!” he cried at last. “Levitt says, in this report, that the ‘Pauper’s Dream’ isn’t a mine, but a pocket, and that the pocket has been worked out. In other words, pard, my hundred shares of stock are worth just about what they’ll bring for scrap paper. And the colonel had me worked up till I thought I was going to be a millionaire! Riddle: Where was Moses when the light went out?”

McGlory fell back on the grass and kicked up his heels dejectedly.

“Can’t you see through the dodge your Tucson colonel is working, Joe?” asked Matt.

“Dodge?” echoed McGlory. “The ‘Pauper’s Dream’ is just a hole in the ground. We can’t any of us dodge that.”

“The colonel,” went on Matt quietly, “is paying Levitt to make a false report to the syndicate. To-night the syndicate meets and decides whether or not it will buy the ‘Pauper’s Dream.’ Levitt’s false report has already been submitted, I suppose, and read. You show up at the meeting with the two bars of bullion, and a sworn statement from the colonel that they came out of the ten-stamp mill on the ‘Dream’ during one week’s run. That clinches the proposition. The syndicate, relying on Levitt’s honesty, and, incidentally, on the colonel’s, pay over a big sum for a worthless hole in the ground, and——”

The cowboy leaped erect, flushed and excited.

“And the colonel,” he cried, “divides the proceeds among the stockholders! That gives me a big profit on my five hundred. Oh, well, I reckon I’ve got my dipper right side up during this rain.”

McGlory chuckled. Matt stared at him as though he hardly believed what he heard.

“Pard,” said Matt quietly, “it’s a game of out-and-out robbery.”

“That’s the syndicate’s lookout, not mine. If they want to drop half a million into that hole in the ground, what is it to me?”

“I don’t think you mean that, Joe,” said Matt, getting up. “We’ll go on to the Malvern Country Club and find out what Griggs has to say to you. We’ve got plenty of time to figure the matter over before the Syndicate meets to-night.”

Matt’s face was set and determined, and there was a smouldering light in his gray eyes, which proved that he had nerved himself for some duty which might be disagreeable. McGlory was wrapped in thought—so concerned in his own affairs that he forgot Matt, forgot the treacherous nature of the runabout, forgot everything but the “Pauper’s Dream” and his chances for winning or losing a fortune.

The unexpected happened at least twice to the motor boys between ten-thirty and eleven o’clock that Thursday morning. First, they naturally expected to have trouble with the runabout, but it carried out its work handsomely and deposited them in the Malvern Country Club garage at precisely five minutes of eleven.

There was not much talk between the boys during the ride. McGlory was concerned with his “Pauper’s Dream” reflections—and Matt had reflections of his own. Besides his thoughts, which were none too agreeable, Matt had to recall Billy’s instructions for finding the way, and also to be on the alert for any sudden tantrum on the part of the runabout. But the tantrum did not develop, and the boys left the garage and made their way across the broad lawn of the clubhouse to a porch which extended along the front of the building.

“I’d like to see Mr. Joshua Griggs,” said McGlory to a stout person wearing side-whiskers and knee breeches. The servant looked the boys over.

“Wot nyme?” he asked.

“Matt King and Joe McGlory—two nymes.”

“’E’s hexpecting you. This w’y, please.”

The boys were ushered through a great apartment with a beamed ceiling and a fireplace that covered half of one end of the room, up a flight of broad stairs, and along a wide hall. Here the servant paused by a door and knocked. A mumble of voices, coming from the other side of the door, ceased abruptly.

“What’s wanted?” demanded some one.

“Mr. McGlory hand friend, sir.”

“Send ’em in.”

The servant pushed open the door, drew to one side, and bowed the boys out of the hall. Then the unexpected happened for the second time.

There were two men in the room, and the atmosphere was thick with tobacco smoke and a reek of liquor. A box of cigars was on a table; also a decanter and two glasses, a bowl of cracked ice, and a bottle of “fizz” water.

A man was seated in a comfortable chair, rocking and smoking. This man was Hannibal J. Levitt, owner of the unmanageable runabout.

The other man was tall and gaunt. He wore a black frock coat and gray trousers, a flowing tie, and a big diamond in the front of his pleated white shirt. His hair was a trifle long and a trifle thin on the crown. A mustache spread widely from his upper lip; and a wisp of pointed beard decorated his chin.

This latter individual exploded a hearty laugh as McGlory recoiled and stared like a person in a trance.

“Howdy, son?” barked the man in the long coat, sweeping down on the cowboy and seizing his hand. “Something of a surprise, hey? Lookin’ for Griggs, by gad, and you find me!”

“Colonel!” gulped McGlory. “Speak to me about this! Why, I thought you were in Tucson?”

“Made up my mind at the last minute that I’d better trek eastward and make sure the deal for the ‘Dream’ went through.” He slapped McGlory on the back. “A fortune, my boy, for all of us, by gad! The ‘Dream’s’ a bonanza—gold from the grass roots down. But present your friend; present your friend.”

The colonel turned beamingly toward Matt.

“My pard, Matt King,” said McGlory. “Everybody has heard of him, I reckon.”

“You do me proud,” bubbled the colonel, seizing Matt’s hand and pumping his arm up and down. “A friend of McGlory’s is a friend of mine. Allow me”—and he turned toward Levitt, only to find Levitt leaning across the table, his jaws agape. “Well, well, well!” mumbled the colonel. “What’s flagged you, Levitt?”

“We’ve met before,” grinned Levitt.

“How’s that?”

“These are the young fellows to whom I gave that confounded runabout.”

“A conspiracy, by gad, to keep me from meeting McGlory! How’d you expect him to get here in a motor wagon you couldn’t run yourself?”

“I didn’t know who the lads were, colonel, or I’d have been more considerate. But”—and here he turned to Matt—“how did you do it?”

“We had plenty of trouble with the machine,” said Matt, “but we made it bring us.”

The situation was clearing. Levitt, at the time Matt and McGlory had met him that morning, was also on his way to the Malvern Country Club.

“Re-markable!” cooed the colonel. “But it’s a terrible land for dust, ain’t it?” He poured something from the decanter into the glasses. “Irrigate!” he said. “Advance by file, my young friends, and refresh the inner man.”

“None for me, colonel,” answered Matt, whose opinion of the colonel was dropping by swift degrees.

“That’s the way I stack up, too, colonel,” grinned McGlory.

The colonel looked horrified.

“From Arizona, Joseph,” he murmured, “and you won’t indulge? Ex-traordinary, I must say. Smoke?” And he indicated the box of cigars.

“No, colonel,” declined Matt.

A sheepish look crossed McGlory’s face as he met the colonel’s inquiring eye.

“I’m in line with my pard,” said he.

“Astounding!” gasped the colonel. “Both habits are reprehensible—exceedingly so. I honor you highly, my lads, but—ahem!—your shining example is one by which I may not profit.” He turned to the mining engineer. “The fire-water is before us, Levitt,” said he; “charge!”

Two hands gripped the glasses simultaneously, and a gurgling followed. The colonel dried his lips elaborately with a large yellow handkerchief.

“The day, Joseph,” he resumed, “is not far distant when you can own a private yacht, a racing stable, an imported car, and a lordly mansion. I have come personally to New York to drive the business through and clinch it. To-night we show the moneyed interests what we’ve got up our wide and flowing sleeves. Half a million in coin, my son, will rise to the bait like a speckled trout to the alluring fly. But be seated, be seated; let’s all be seated.”

Matt took a chair by an open window, and McGlory dropped into another at a little distance.

“The telegram I received, colonel,” observed the cowboy, “was signed ‘Joshua Griggs.’”

“Even so, my dear youth,” smiled the colonel, lowering himself into a chair and lifting his feet to the top of the table. “Mr. Griggs lives in Hempstead. I am enjoying his hospitality, and he has put me up at this most[9] delightful club. I arrived yesterday afternoon, and I yearned to clasp your honest palm before we met in Liberty Street to-night. Incidentally, I will relieve you of further responsibility in the matter of the bullion. Being somewhat fatigued after my long and arduous railroad journey, the Syndicate meeting was put off. To-night, however, we shall be there; and to-night, my son, we put our fortunes to the touch.”

The colonel was altogether too loquacious to suit Matt—too fluent and insincere. That he was entirely capable of engineering a huge swindle Matt felt sure. And Matt regretted to note that the colonel exerted a powerful influence over McGlory.

“Is this deal for the ‘Pauper’s Dream’ on the level, colonel?” inquired the cowboy.

A lighted bomb, suddenly dropped in front of the colonel and Levitt, would not have caused more consternation. The colonel’s feet fell from the table with a bang, and the mining engineer once more threw himself half-way across the table top.

There followed a period of silence. The colonel, after an odd look at Levitt, was first to speak.

“McGlory,” said he, “you are my friend, and I would take a good deal from a friend. Has my integrity ever been questioned? Have you any reason to believe that this mining deal is not on the level?”

“Shucks!” deprecated McGlory. “Is the syndicate anxious to buy a pocket that’s been worked out? Have they got so much money, these Syndicate fellows, that they want to drop some of it into a mine that’s a ‘dream’ in more senses of the word than one?”

This was another bomb. Levitt went white, and breathed hard. Colonel Billings drew a deep breath, studied McGlory’s face, and then looked at the ceiling. Then once more he was first to speak.

“My son,” said he, “you talk like a buck ’Pache with more tizwin aboard than is good for him. And yet you must be in your sober senses. What are your grounds for expressing yourself in that—er—preposterous manner? I wait to learn!”

“Well,” answered the cowboy, “when Levitt took his header from that runabout of his, on the Jericho Pike, a long yellow envelope dropped from his pocket——”

“I breathe again!” interjected the colonel. “You found it, McGlory?”

“That’s the size of it.”

“And you read the contents of that yellow envelope?”

“Matt and I wanted to find out the name of the man who owned the runabout. That’s how we happened to read the ‘private report.’ It wasn’t good reading, colonel.”

“It was for private perusal by the inner circle, my son,” said the colonel. “Levitt and I were vastly worried over the loss of that report. I will trouble you for it, my boy.”

The colonel reached out his hand. McGlory took the envelope from his pocket, and was about to pass it over when Matt reached forward and caught it from his fingers.

“I beg your pardon,” said Matt, “but I was the one who found this envelope. I gave it to Joe when I threw off my coat, east of Krug’s Corner, to tinker with the runabout. I am going to take care of it.”

All four were on their feet—Matt determined, McGlory puzzled and bewildered, the colonel wrathful, and Levitt with a dangerous gleam in his eyes.

“Well, by gad!” exclaimed the colonel, realizing suddenly what sort of a lad he had to deal with in Matt King.

“What’s that for, pard?” inquired McGlory.

“It don’t belong to you, or to McGlory, or to any one but me!” said Levitt. “If you try to keep that document, King, you’re nothing more nor less than a thief.”

The red ran into Matt’s face.

“Softly, softly,” breathed the colonel. “This talk of thieves, Levitt, is a little premature. Matt King is a friend of McGlory’s, and he could not be that if there was any yellow streak in his nature. No, by gad! We are all gentlemen here. King, sir, if that manila envelope contains papers belonging to our mutual friend, Levitt, you will return them to him, will you not?”

“After a while,” said Matt; “not immediately.”

The colonel seemed thunderstruck.

“You hear?” muttered Levitt, between his teeth. “He’s trying to play double with us, Billings! Those papers mean a whole lot to me, and I’m going to have them!”

The colonel’s mood underwent a change. Attempts at conciliation having failed, there now remained nothing but vigorous action. His first move was to pass rapidly to the door, turn a key in the lock, and drop the key into his pocket. Then he once more approached Matt.

“May I inquire, young man,” he bristled, “what you mean by this most remarkable conduct?”

“I’m trying to protect Joe and myself,” Matt answered.

“Protect? Protect yourself and Joe against what, in Heaven’s name?”

“Against being drawn into a criminal act by you and Levitt, and being compelled to take the consequences.”

“He talks like a fool!” snapped the mining engineer.

“He is misinformed, that’s all,” said the colonel.

“I’m not misinformed,” went on Matt sturdily. “These New York capitalists hired Levitt to go to Arizona and investigate the ‘Pauper’s Dream.’ He made two reports, one private and the other for the members of the Syndicate. One says the mine is no good, and the other, of course, gives it a glittering recommendation.”

“How do you know,” asked Levitt, his voice shaking with anger, “that the Syndicate’s report is different from the other?”

“Because Colonel Billings is paying you for making it,” replied Matt. “Would the colonel give you good money for handing that private report over to the Syndicate? Hardly. Colonel Billings is here to sell the mine.”

“How do you know Billings is paying me anything?”

“He has already paid you a little, and you came out here this morning to receive the rest of it. If that crazy runabout of yours hadn’t interfered, you’d have been able to turn the private report over to the colonel, and no one would ever have been the wiser.”

“How do you know all this?” Levitt’s voice was husky.

“There was a letter from the colonel in the envelope along with the report.”

“By gad!” Billings whirled on the mining engineer.[10] “You don’t mean to say, Levitt,” he asked, “that you had so little sense as to keep that letter of mine?”

“Why shouldn’t I keep it? It was the only thing in the way of an agreement that I had with you.”

“Then”—and the colonel tossed his hands—“that lets in the search light on the two of us.”

“And we’ve caught a tartar in this meddling young whelp,” ground out Levitt, waving his hand toward Matt.

“He’s an intelligent youth, Levitt,” declared the colonel, “and amenable to reason. Let me talk with him. My dear young man,” said the colonel to Matt, “assuming that what you say about the report is true, in what way are you legally liable through association with Levitt and myself?”

“You’re trying to swindle a company of New York capitalists,” answered Matt, “and Joe and I, not knowing the deal was crooked, have already been dragged into it. If we allowed the plot to go on we would be equally guilty with you and Levitt, and we could be arrested and sent to prison.”

A tolerant smile crossed the colonel’s face.

“Suppose I assure you that there is not the remotest possibility of any of us going to prison,” said he; “will you give up that report and letter?”

Matt hesitated, not because his determination was wavering, but because he wanted to put his thoughts in the right words.

“It means a fortune to McGlory,” urged the colonel; “and what kind of a fellow are you to euchre a friend out of a fortune?”

“It’s not an honest fortune,” declared Matt, “and Joe can’t afford to accept it. Besides, what good would it do him if he found himself in the penitentiary for obtaining money under false pretenses?”

The colonel was beginning to lose patience.

“You’ve got less sense than any cub of your years I ever met up with!” he cried irritably. “How much money do you want for that report and letter? That’s your play, I reckon; and I’d rather shell out a hundred or two than have any trouble with you. How much do I bleed?”

The colonel measured Matt with wrathful and inquiring eyes.

“You haven’t money enough to buy me!” declared Matt.

“Aw, cut it short!” broke in Levitt savagely. “What’s the use of fooling with him any longer?

“Wait!” cautioned the colonel. “McGlory,” he went on, to the cowboy, “what do you mean by lugging such a two-faced longhorn into a private and important council like this?”

“You’re wide of your trail, colonel,” said McGlory, with spirit. “There’s nothing two-faced about Matt King, and you can spread your blankets and go to sleep on that. He’s the clear quill from spurs to sombrero, and the best pard that ever rode sign with me. Don’t you make any mistake in taking his sizing.”

“Well, what is he trying to rope down and tie your bright prospects for?”

“He’s got more sense in a minute than I have in a year, and you can bet your boot straps he knows what he’s doing—even if I don’t.”

“You’re far wide of your trail, Joseph. Matt King is committing an illegal act this minute. He has property belonging to Levitt and refuses to give it up. He could be jailed for a thief. But we’re not going to jail him. We’ll just take that report and letter from him.”

“Then you’ll have to walk over me to do it, colonel!” asserted McGlory.

“By gad!” muttered the colonel. “You’ve got as little sense as he has.”

“Brainwork never was my long suit, but I’ve seen enough of Pard Matt to feel safe in banking on any notion that he bats up to me.”

“Bah!” gibed the colonel. “I’ll talk with you later, McGlory, and take pains to show you the error of your way. As for Matt King, he’s a false friend. He’s jealous because you’re about to come into a fortune, and he’s doing all he can to shift the cut and leave you stranded.”

“That’s not true!” said Matt. “Joe knows me better than that.”

“Sure I do, pard. Come on, and let’s get out of here.”

The actions of the two men were threatening. McGlory started toward the door; but happened to remember that it was locked, and that the colonel had the key in his pocket.

“Cough up the key, colonel,” said the cowboy. “Don’t force me to yell and have up that fellow with the knee pants and the lilocks.”

“It will be better for you youngsters,” growled the colonel, “if you don’t raise a commotion. The surest way to see the inside of a lockup is by calling for help. Are you going to hand over those papers?” And he turned to Matt. “Last call.”

“I’ll return them,” said Matt, “but not till after that meeting to-night.”

He slipped the manila envelope into the breast of his coat. Having planned what he considered was the best move, the young motorist was never more resolute in seeking to carry it out. Even though he was retaining Levitt’s property, yet right and justice upheld him in doing so.

“By Jupiter,” murmured Levitt, his eyes flaming, “he’s intending to take that private report to the Syndicate meeting to-night! If he does——” He gulped on his words, finishing with a significant glance at Billings.

Matt was wondering how he and McGlory could get out of the room without making too much of a scene. He understood very well that the colonel could inaugurate a pursuit, in case he and his chum succeeded in getting away with the envelope and its contents, and that, for a time at least, any story the colonel and Levitt chose to tell would be accepted. Temporary advantage was all on the side of the colonel and the mining engineer.

“He won’t show that paper at the meeting, Levitt,” gritted the colonel, now thoroughly aroused. “We’re done fooling with him.”

He stepped toward Matt from one side, while Levitt advanced from the other. The cowboy tried to push closer to his chum, but the colonel held him back. One of the colonel’s hands went groping in the direction of a hip pocket. Matt guessed what the hand was after.

“The window, Joe!” he called.

Simultaneously with the words, the king of the motor boys whirled, pushed through the window, lowered himself swiftly from the sill, and dropped.

The colonel grabbed at the hands on the sill, but they pulled out from under his gripping fingers; then, looking[11] downward, he saw the lithe, agile form of Matt King lift itself from a flower bed and fade from sight around a corner of the building.

Two young fellows with golf sticks were crossing the lawn and had witnessed Matt’s drop from the window. Naturally they were surprised at the peculiar proceeding and stood looking up at the colonel.

“Catch him!” bawled the colonel; “he’s a thief!”

That was enough. The two members of the Country Club darted away after Matt.

McGlory was making preparations to drop from the other window, but the colonel grabbed him at the critical moment and forced him into a chair.

“Off with you, Levitt!” the colonel called. “You can catch that young cub! And when you do overhaul him get the report and the letter at any cost.”

As he finished the colonel flung the door key toward the engineer. The latter let himself out of the room and bounded excitedly down the stairs.

Matt hoped that McGlory would be able to follow him; but, if the cowboy found this to be impossible, then Matt would do his best to prevent the report from falling into the hands of the colonel and Levitt. That report was the one thing of vital importance. On it alone hinged the success or failure of the colonel’s gigantic swindling operations. Matt must escape capture at any cost, in order to retain possession of the report.

The course of his flight carried him toward the rear of the Country Club grounds. He heard the colonel’s shout to the young men just in from the golf links, and he knew there would be a pursuit. Of course Matt could explain the situation and perhaps escape legal complications, but if caught he would be compelled to give up the report.

He darted across a tennis court, leaped the net, dodged behind a clump of lilac bushes, and ran toward the edge of a grove that bordered the Country Club grounds on that side. Between the lilacs and the grove was a rustic pavilion. A flower bed was near the pavilion, and an old negro was kneeling beside the bed, his back toward Matt, and industriously pulling weeds. Matt had not much time to give to the negro, but hoped that he was giving his whole attention to his work. As he came around the pavilion Matt heard sounds which indicated that more pursuers were after him—these coming from the direction of the garage and the stables.

To reach the timber without being seen seemed hopeless, and Matt looked hurriedly around for some place in which he could secrete himself.

The floor of the pavilion was elevated some two feet or more above the surface of the ground. The opening between the floor and the ground was filled in with panels of close latticework. One of the panels was broken, and Matt dropped to his knees and crawled through it.

This was not as secure a hiding place as he would have selected, if he could have had his choice, but his emergency was such that he had no time to look farther.

Lying flat on the ground, so that his form would not be visible to his pursuers, Matt watched and waited.

The two young men with the golf sticks broke into view around the lilac bushes. They were closely followed by three others, employees of the club, evidently, for they wore overclothes. Matt recognized one of them as having been in the garage when he and McGlory left the runabout there.

The old negro had lifted himself to his feet and was facing the five pursuers. Freedom or capture for Matt depended upon what the old negro knew. Scarcely breathing, the king of the motor boys listened for what was to come.

“Say, uncle,” panted one of the young men from the links, “did you see a fellow running this way?”

“Ah did, suh,” replied the negro. “Ah was as close tuh him as whut me an’ yo’ is, boss.”

Levitt at that instant rushed around the bushes. He was in time to hear the negro’s answer to the question.

“Which way did he go?” Levitt demanded. “He’s a thief, and we’ve got to capture him and recover some stolen property. Which way did he run? Quick!”

The old darky turned and deliberately pointed away from the pavilion and to a point in the encompassing timber which led toward the road, well to the north of the clubhouse.

“Dat’s de way he went, boss,” said he, “an’, by golly, he went jess a-hummin’.”

“This way, men!” shouted Levitt, leaping off in the direction indicated by the negro.

The six pursuers disappeared at a run, and left Matt gasping with astonishment. Why had the old darky put them on the wrong track? It was preposterous to think that the negro had himself been deceived.

While Matt was turning the matter over in his mind, and puzzling his brain with it, the negro began to whistle softly and to limp in the direction of the pavilion. On reaching the broken panel of latticework, he leaned against the railing of the pavilion.

“How yo’ lak dat, Marse Matt?” he chuckled. “Didn’t Ah done send um on de wrong track, huh? En yo’ all thought Ah wasn’t lookin’ at yo’, en dat Ah didn’t know who yo’ was! Har, har, har!”

The darky laughed softly as he finished talking.

Matt’s wonderment continued to grow.

“Great spark plugs!” he muttered, recognizing an old acquaintance. “Is it—can it be—Uncle Tom?”

“Dat’s who Ah is, marse! Hit’s been a right sma’t of er while since Ah had de pleasuah ob seein’ yo’. De las’ time we was togedder was in Denvah. ’Membah all dem excitin’ times we had in Arizony, dat time dat Topsy gal en me was wif dat Uncle Tom’s Cabin comp’ny? Golly, I ain’t nevah gwineter fo’git dat! Who’s been doin’ yo’ mascottin’ lately, huh? ’Pears lak no one had, f’om de ha’d luck yo’ is in.”

Matt recalled Uncle Tom very vividly. The aged negro had belonged to a stranded company of players, and Matt had helped them out of their difficulties. But that had happened in the Southwest, and here was Uncle Tom about as far East as he could get. The world is not so large, after all, and many strange and unexpected meetings occur.

“I’m more surprised than I can tell, Uncle Tom,” said Matt, “to run across you, here on Long Island, and at a time when I certainly needed a friend. It may be that you can help me even more, but——”

“Ah’s pinin’ tuh do all dat Ah can fo’ yo’, Marse Matt,” interposed the darky earnestly.

“But,” went on Matt, “this is hardly a safe place for me. If the coast is clear I guess I’d better crawl out and get into the woods.”

“Yo’s right erbout dat, marse. Ah’s so plumb tickled tuh see yo’ dat I come mighty nigh fo’gittin’ yo’s bein’ hunted fo’. Wait twell Ah take er look erroun’.”

Uncle Tom stepped away from the pavilion and swept a keen glance over the grounds in that vicinity.

“De coast am cleah, Marse Matt,” he announced, returning to the side of the pavilion. “Yo come out an’ hike fo’ de woods, en Ah’ll foller yuh. Den we can talk a li’l, en you can tell me whut mo’ de ole man can do.”

Matt pushed through the broken lattice and gained the timber line at a point opposite the place where his pursuers had vanished. Here, for a time, he was safe, and he sank down behind a mask of brush. Uncle Tom was not long in reaching his side.

“Golly,” he beamed, looking Matt over, “but hit’s good fo’ sore eyes jess tuh see yo’, marse. Ah nevah expected nuffin’ lak dis. Mouty peculiah how folks meets up wif one anotheh sometimes, dat-er-way.”

“How did you happen to wander in this direction, Uncle Tom?” Matt asked.

“Mascottin’,” answered the old man gravely. “Ah be’n mascottin’ fo’ er prize fighteh. Terry, de Cricket, is whut he called himse’f, en Ah won a fight fo’ him in Denvah, en another in Kansas City; but in New Yawk Terry, de Cricket, done ’spected me tuh do all de wo’k, en he went down wif er chirp, en dey counted ten on him. Ah couldn’t help dat, but Terry he ’low Ah was losin’ mah mascottin’ ability, en he turned me loose. Topsy done got er job in er house in Hempstead, en Ah picked up dis place at de Country Club. But Ah doan’ like hit, marse. Ah’s er ole man, en hit’s backachin’ wo’k. Yo’ needs er mascot bad, en now’s de time tuh take me on.”

Uncle Tom was a humorous old rascal, and professed to believe that he possessed mystical powers as a luck bringer. He declared that he had helped Matt, and Matt humored him by letting him think so, giving him a few dollars now and then to help him keep body and soul together.

“I’m not in shape just now, Uncle Tom,” said Matt, “to hire a private mascot of your abilities. You see, I’m mixed up in a bit of trouble that I’ve got to work through alone.”

“Bymby, Marse Matt, mebby yo’ all can make er place fo’ Uncle Tom?” pleaded the negro. “Jess remembah whut Ah’s done fo’ yo’ in de past. Ah nevah mascotted fo’ anybody dat Ah liked so well as yo’se’f. Dat’s right. Has yo’ got a dollah yo’ can let go of wifout material damage to yo’ own welfare?”

Matt extracted a five-dollar bill from his pocket and pushed it into the negro’s yellow palm. Uncle Tom’s gratitude was so intense it was almost morbid.

“Yo’s de fines’ fellah dat evah was,” he declared, grabbing Matt’s hand and hanging to it. “Dat’s de trufe. Ah’d raddah wo’k fo’ you fo’ nuffin dan fo’ some odders fo’ er millyun dollahs er day. Dat’s right. Yo’s de same ole Marse Matt, en yo’——”

“I haven’t much time to talk, Uncle Tom,” interrupted Matt. “When I left the clubhouse I had to drop from a second-story window. I made it all right, but I left a friend behind. My friend’s name is Joe McGlory. Do you think you could get word to him?”

“Shuah Ah can!” replied the old negro promptly. “What kin’ ob a lookin’ fellah is dat ’ar Joe McGlory?”

Matt described his chum’s appearance, and the darky listened closely.

“Find out,” Matt finished, “whether McGlory is still upstairs in the clubhouse. If he is I don’t suppose you can communicate with him, for you will have to do it privately. Providing you can get word to him, tell him to meet me in the grove at the roadside, a quarter of a mile north of the clubhouse. Got that?”

“Yas, I done got dat, marse.”

“If you can’t get word to McGlory inside of an hour, then you come and tell me, will you?”

“Yo’ knows, Marse Matt, yo’ can count on Uncle Tom. Ah’ll do whut yo’ say, en Ah’ll wo’k mah ole haid off mascottin’ fo’ yo’ while Ah’m doin’ it.”

The old darky slipped away through the edge of the timber, and Matt, none too sanguine, proceeded to lay a course for the spot where he hoped to be joined by his cowboy chum.

For a few moments McGlory struggled in the grasp of Colonel Billings. He was excited, and angry over the way Matt had been treated, and he would not have hesitated to do the colonel an injury if he could thereby have escaped from the room and followed his pard.

“Quiet!” ordered the colonel sternly. “You don’t understand this thing, McGlory, or you wouldn’t be fighting to escape from me. I’m the best friend you ever had, if you only knew it.”

“Nary, you ain’t!” panted the cowboy. “My best friend just risked his neck dropping out of the window. You’re trying to get me into trouble, and Pard Matt is trying to keep me out. Take your hands off me, colonel!”

“I will, Joe, just as soon as you promise to sit still and hear what I have to say.”

McGlory reflected that it was too late to follow Matt, who was probably doing his best to evade Levitt and the others who were hot on his trail. The cowboy reasoned that he could find his chum later, and that there could be no harm in listening to what the colonel had to say.

“Go on,” said he curtly.

“You’ll stay right where you are until I’m done?” asked the colonel.

“Yes.”

Billings drew back, dropped into a chair, and laid a friendly hand on the cowboy’s knee. His voice changed, sounding the depths of friendly interest and personal regard.

“Joe,” he remarked, “ever since your father took the One-way Trail I’ve sort of felt that I was responsible for your welfare. I knew your father mighty well—better than any one else in Tucson, I reckon—and him and me was bosom friends.”

McGlory had no personal knowledge on this point, but he was willing to take the colonel’s word for it.

“If I can do anything for Joe,” the colonel went on,[13] “I says to myself that I won’t leave a stone unturned to do it. When the ‘Pauper’s Dream’ proposition came under my management I knew I had the chance I wanted to turn your way. I sold you a hundred shares of the stock at five dollars a share, and we went on to develop the claim.”

“And there wasn’t any more gold in the shaft,” spoke up the cowboy dryly, “than there was in a New England well.”

“That’s what everybody thought,” returned the colonel, “but I knew better.”

He got up, went to the table, and helped himself to a drink from the decanter.

“Better have a nip, son, eh?” he asked, as by an afterthought, before leaving the table.

“Not for me,” replied McGlory stoutly. “Pard Matt don’t believe in that sort of thing, and I get along better when I make his notions my own. I’ve found that out more than once.”

The colonel sighed resignedly, but did not press the point. Returning to his chair, he continued his persuasions.

“I knew when I sold you that stock that there was a reef of rich gold ore under the ‘Pauper’s Dream.’ I didn’t want it found until the right minute. Those who had bought stock in the claim got scared. Some of them sold their stock back to me for a song. When I’d got enough of the stock to give me a controlling interest I found the gold vein.”

“That was a double play,” said McGlory bluntly. “There wasn’t anything fair about that, colonel.”

“It was all fair. Some of the stockholders were trying to freeze me out. By letting them think there wasn’t any gold in the ‘Dream’ I turned the tables and froze them out. It was simply a game of diamond cut diamond—and I was a little too sharp for my enemies. That was all right, wasn’t it?”

McGlory thought the colonel had a fair excuse for acting as he had done.

“When we laid open that gold vein,” pursued the colonel, “buyers flocked around the ‘Pauper’s Dream’ like crows around a cornfield. They wanted to buy. I saw a chance to deal with this New York syndicate for big money, so I had the syndicate send out an expert to examine our property. Levitt came. I asked him to make out a true report for the syndicate and a private, false report for—other uses.”

McGlory opened his eyes.

“I see I’ve got you guessing,” laughed the colonel gently. “This is how that private report came to be made out—that private report on which your misguided friend has built such a fabric of unjust suspicions. The men I had frozen out of the company began to threaten legal proceedings. The proceedings wouldn’t have amounted to that”—and the colonel snapped his fingers—“for those fellows hadn’t a leg to stand on; but do you know what they could have done? Why, they’d have tied up the mine for a year or two and prevented the sale to the syndicate. In order to get around that I hired Levitt to make out that fake report, and leave it where those soreheads could see it. Now my hands are free. The sale can be made to the syndicate, and we’ll all win a fortune—providing your misguided friend doesn’t take that cock-and-bull story of his to the meeting to-night.“

“Couldn’t you explain the matter to the syndicate, colonel, just as you have to me?” asked the cowboy.

“I could, yes; but they’d shy off. A little thing like that sometimes knocks a big deal galley-west. It’s best not to let any intimation of that fake report reach the ears of the syndicate until we have the syndicate’s money safely in our clothes. Young King means well—I’ll give him credit for that—but he’s shy a couple of chips this hand, and if he butts in we’re going to be left out in the cold. That’s all there is to it.”

“Why didn’t you explain this to Matt?”

“The explanation is for our own stockholders, and not for outsiders. A word, a whisper might leak through and reach the fellows who could block the deal. We mustn’t allow that. My boy, my boy”—and here the colonel became very gentle, very fatherly—“I’m doing the best I can for you. I’m trying to hand you a fortune, and you’ve got to help me—in spite of Pard Matt. It’s your duty to help me. You’ll never have such a chance to pick out a brownstone front on Easy Street, and you mustn’t let the opportunity slip through your fingers.”

To say that Joe McGlory was not influenced by the colonel’s words would be to say that he was not human. The cowboy wanted money, not for its own sake, but for the great things he felt he could do with it. Not the least of the cowboy’s desires was to help Matt in some of his far-reaching aims in the motor field. He accepted Billings’ story, and he reached out and gripped his hand heartily.

“I’m with you, chaps, taps, and latigoes!” he exclaimed. “But say, can’t I tell Pard Matt? If he knew——”

But the colonel was afraid of “Pard Matt.” The king of the motor boys had a brain altogether too keen.

“Not a word, not a syllable,” adjured Billings. “All that I have said, Joe, you must keep under your hat—until after the meeting to-night and until after the ‘Dream’ is sold. You must buckle in and help me and let Matt think what he will. Afterward, when the money is divided, you can show Pard Matt where he was wrong, and he’ll be glad to think that he did not interfere with us in our work.”

“But he’s going to interfere,” murmured McGlory. “Whenever Matt King sets out to do a thing he does[14] it. That’s his style. He’s got the fake report, and he’ll use it at the meeting to-night—thinking he’s doing me a good turn.”

“I believe that Levitt will catch him,” asserted the colonel.

“You don’t know my pard as well as I do,” returned the cowboy dejectedly. “I wonder if I couldn’t——” McGlory paused.

“Couldn’t what?” urged the colonel.

“Never mind now. I’m going out and see if I can’t do something.”

Billings stared steadily at the lad for a moment.

“All right,” said he, “go and do what you can. Remember I have confidence in you, and you’re not to breathe a word regarding what we have talked about. I shall have to get to New York before three o’clock. The bank closes then, and I’ve got to get that bullion. I’ll have to start in a fast car by one. Come back and report to me before I leave.”

“I’ll do it,” replied the cowboy, hurrying out of the room.

The colonel chuckled, threw himself back in a chair, and lighted a cigar.

“Easy, easy, easy!” he muttered. “I can wrap McGlory around my fingers and not half try. Now, if King is captured, and if I can be sure he won’t meddle with me to-night, everything will be serene.”

The resourceful colonel accepted his worries calmly. He had too much dignity to take part in a foot race, so he remained in a comfortable chair by the window and waited for news.

McGlory was back in ten minutes. His face was glowing.

“Matt King dodged Levitt and all the rest who were trailing him,” he reported.

“What!” The colonel arose excitedly from his seat.

“Don’t fret, colonel,” grinned the cowboy, “it’s not so bad as that. An old darky who works around the club grounds helped Matt make his getaway. Matt asked him to tell me to meet him in the woods at the roadside, a quarter of a mile north. That’s where I’m going now. You’ll hear from me before one o’clock, colonel.”

“What are you going to do?” rapped out the colonel.

“Something that will make the deal a sure go. I haven’t time to talk much. Adios, for now.”

McGlory was away again like a shot, leaving the colonel wondering—and fretting a little.

A few minutes later Levitt came gloomily into the room.

“That young cub gave us the slip,” said he savagely, “and I never had such a run in my life. The fat’s in the fire, Billings.”

“Not so, my friend,” returned the colonel, his quick wit grasping something that looked like an opportunity. “Can you get hold of a man who will help you? Are you acquainted with any one about the club grounds who can be trusted to do a little brisk work and then keep quiet about it?”

“Well, yes. The man in the garage is known to me, and he’s out for anything that’s got a dollar in it. But what of it?”

The colonel’s plan was based on the information just communicated to him by McGlory. He went into the matter swiftly, but exhaustively, and when he had done the gloom had vanished from Levitt’s face.

“It will work, it will work,” murmured the mining engineer, rubbing his hands.

“Then go and work it,” said the colonel briskly.

Matt King, in a clump of bushes a quarter of a mile north of the Malvern Country Club, watched the road and waited for his chum. He had not much hope that McGlory would join him, for he believed that the cowboy would be held a prisoner by the colonel.

What Matt was doing, in this particular matter, was all for his friend. McGlory had become entangled with a gang of confidence men, who were playing boldly for big stakes. Whether the dishonest game won out or failed, Joe McGlory must have nothing to do with it. If he profited by the crime he would be called on to suffer at the hands of the law; and, even if the law never reached him, his conscience would make him miserable all his life for the part he had played in such a huge swindling scheme.