The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. A LETTER—AND A SURPRISE.

CHAPTER IV. MOTOR MATT’S DUTY.

CHAPTER V. HOW MCGLORY WAS FOOLED.

CHAPTER VI. ON THE BOSTON PIKE.

CHAPTER VII. THE JOURNEY’S END.

CHAPTER VIII. CHUMS IN COUNCIL.

CHAPTER XIII. IN AND OUT OF LEEVILLE.

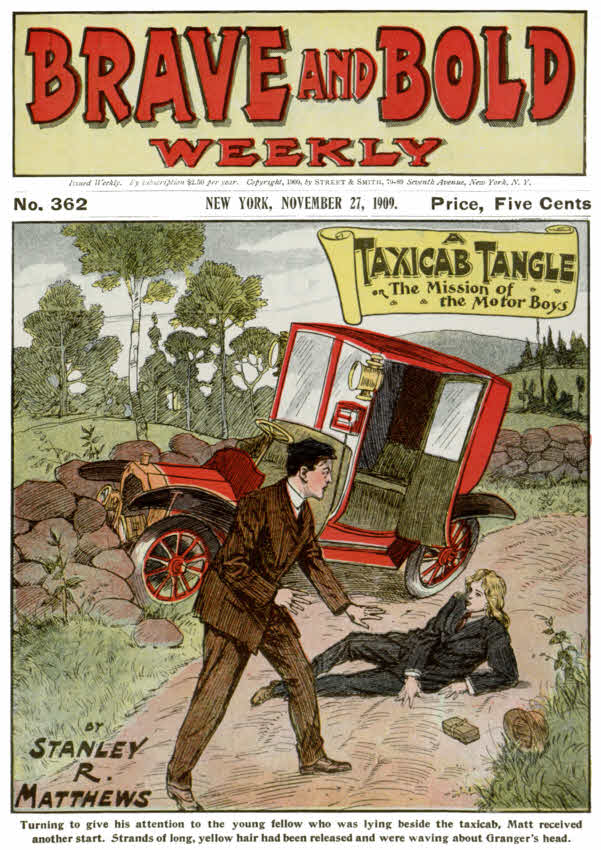

Turning to give his attention to the young fellow who was lying beside the taxicab, Matt received another start. Strands of long, yellow hair had been released and were waving about Granger’s head.

BRAVE AND BOLD

WEEKLY

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Copyright, 1909, by Street & Smith, 79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

No. 362. NEW YORK, November 27, 1909. Price Five Cents.

By STANLEY R. MATTHEWS.

“For its size, pard, I reckon this is about the biggest town on the map. We’ve been here five days, and the traffic squad has been some busy with our bubble-wagon, but if there’s any part of this burg we haven’t seen, now’s the time to get out a search warrant, and go after it. What’s on for to-day?”

Joe McGlory was the speaker. He and his chum, Matt King, known far and wide as Motor Matt, were in the lobby of the big hotel in which they had established themselves when they first arrived in New York. In a couple of “sleepy-hollow” chairs they were watching the endless tide of humanity, as it ebbed and flowed through the great rotunda.

For five days the gasoline motor had whirled the boys in every direction, an automobile rushing them around the city, with side trips to Coney Island, north as far as Tarrytown, and across the river as far as Fort Lee, while a power boat had given them a view of the bay and the sound. Out of these five days, too, they had spent one afternoon fishing near City Island, and had given up several hours to watching the oystermen off Sound Beach.

Matt, having lived in the Berkshires, and having put in some time working for a motor manufactory in Albany, had visited the metropolis many times. He was able, therefore, to act as pilot for his cowboy pard.

“I thought,” he remarked, “that it’s about time we coupled a little business with this random knocking around. There’s a man in the Flatiron Building who is interested in aviation—I heard of him through Cameron, up at Fort Totten—and I believe we’ll call and have a little talk. It might lead to something, you know.”

“Aviation!” muttered the cowboy. “That’s a brand-new one. Tell me what it’s about, pard.”

“Aviation,” and Matt coughed impressively, “is the science of flight on a heavier-than-air machine. When we used that Traquair aëroplane, Joe, we were aviators.”

“Much obliged, professor,” grinned the cowboy. “When we scooted through the air we were aviating, eh? Well, between you and me and the brindle maverick, I’d rather aviate than do anything else. All we lack, now, is a bird’s-eye view of the met-ro-po-lus. Let’s get a flying machine from this man in the Flatiron Building, and ‘do’ the town from overhead. We can roost on top of the Statue of Liberty, see how Grant’s Tomb looks from the clouds, scrape the top of the Singer Building, give the Metropolitan——”

“That’s a dream,” laughed Matt. “It will be a long time before there’s much flying done over the city of New York. I’m going to see if we have any mail. After that, we’ll get a car and start for downtown.”

McGlory sat back in his chair and waited while his chum disappeared in the crowd. When Matt got back, he showed his comrade a letter.

“Who’s it from?” inquired McGlory.

“Not being a mind reader, Joe,” Matt replied, “I’ll have to pass,” and he handed the letter to the cowboy.

“For me?” cried McGlory.

“Your name’s on the envelope. The letter, as you see, has been forwarded from Catskill.”

“Speak to me about this! I haven’t had a letter since you and I left ’Frisco. Who in the wide world is writing to me, and what for?”

McGlory opened the letter and pulled out two folded sheets. His amazement grew as he read. Presently his surprise gave way to a look of delight, and he chuckled jubilantly.

“This is from the colonel,” said he.

“Who’s the colonel?” asked Matt.

“Why, Colonel Mark Antony Billings, of Tucson, Arizona. Everybody in the Southwest knows the colonel. He’s in the mining business, the colonel is, and he tells me that I’m on the ragged edge of dropping into a fortune.”

A man of forty, rather “loudly” dressed, was seated behind the boys, smoking and reading a newspaper. He was not so deeply interested in the paper as he pretended to be, for he got up suddenly, stepped to a marble column near Matt’s chair, and leaned there, still with the cigar between his lips, and the paper in front of his eyes. But he was not smoking, and neither was he reading. He was listening.

“Bully!” exclaimed the overjoyed Matt, all agog with interest. “I’d like to see you come into a whole lot of money, Joe.”

“Well, I haven’t got this yet, pard. There’s a string to it. The colonel’s got one end of the string, ’way off there in Tucson, and the other end is here in New York with a baited hook tied to it. This long-distance fishing is mighty uncertain.”

“What is it? A mining deal?”

“Listen, pard. About a year ago I had a notion I’d like to get rich out of this mining game. Riding range was my long suit, but gold mines seemed to offer better prospects. I had five hundred saved up and to my credit in the Tucson bank. The colonel got next to it, and he told me about the ‘Pauper’s Dream’ claim, which needed only a fifty-foot shaft to make it show up a bonanza. I gave the colonel my five hundred, and he got a lot more fellows to chip in. Then the colonel went ahead, built a ten-stamp mill, and started digging the shaft. When that shaft got down fifty feet, ore indications had petered out complete; and when it got down a hundred feet, there wasn’t even a limestone stringer—nothing but country rock, with no more yellow metal than you’d find in the sand at Far Rockaway. I bade an affectionate farewell to my five hundred, and asked my friends to rope-down and tie me, and snake me over to the nearest asylum for the feeble-minded if I ever dropped so much as a two-bit piece into another hole in the ground. After that, I forgot about the colonel and the ‘Pauper’s Dream.’ But things have been happening since I’ve been away from Tucson. Read the letter for yourself, pard. It will explain the whole situation to you. After you read it, tell me what you think. You might go over it out loud, while I sit back here, drink in your words, and try to imagine myself the big high boy with a brownstone front on Easy Street.”

Matt took the sheet which McGlory handed to him, and read aloud, as follows:

“My Dear Young Friend: I knew the ‘Pauper’s Dream’ was all right, and I said all along it was the goods, although there were some who doubted me. Within the last three months we have picked up a vein of free milling ore which assays one thousand dollars to the ton—and there’s a mountain of it. Your stock, just on this three months’ showing, is worth, at a conservative estimate, five hundred dollars a share—and you paid only five dollars a share for it! You’re worth fifty thousand now, but you’ll be worth ten times that if the deal I have on with certain New York parties goes through.

“Now, from an item I read in the papers, I find you are at Catskill, New York, with that young motor wonder, Matt King, so I am hustling this letter right off to you. By express, to-day, I am sending, consigned to the Merchants’ & Miners’ National Bank, for you, two gold bars which weigh-up five thousand dollars each. Inclosed herewith you will find an order on the bank to deliver the bars to you. On Wednesday evening, the twenty-fourth, there will be a meeting of the proposed Eastern Syndicate in the offices of Random & Griggs, No. — Liberty Street. You can help the deal along by taking the bullion to these capitalists, along with my affidavit—which is with the bars—stating that the gold came out of a week’s run at the ‘Pauper’s Dream’ with our little ten-stamp mill. That will do the business. Random & Griggs have had an expert here looking over the mine. After you show the bullion at the syndicate’s meeting, return it to the bank.

“I am not sure that this letter will reach you. If it doesn’t, I shall have to get some one else to take the gold to the meeting. Would come myself, but am head over heels in work here, and can’t leave the ‘Dream’ for a minute. Wire me as soon as you get this letter. I hope that you are in a position to attend to this matter, my lad, because there is no one else I could trust as I could you, with ten thousand dollars’ worth of gold bullion.

“Catskill is only a little way from New York City, and you can run down there and attend to this. Let me know at once if you will.

“Sincerely yours,

“M. A. Billings.”

“Fine!” cried Matt heartily, grabbing his chum’s hand as he returned the letter.

“It sounds like a yarn from the ‘Thousand and One Nights,’” returned the cowboy, “and I’m not going to call myself Gotrox until the ‘Pauper’s Dream’ is sold, and the fortune is in the bank, subject to Joe McGlory’s check.”

“This is Monday,” went on Matt, “and the meeting of the syndicate is called for Wednesday evening.”

“Plenty of time,” said McGlory. “I’m not going to let the prospect of wealth keep me from enjoying the sights for the next three days.”

“Well,” returned Matt, “there’s one thing you’ve got to do, and at least two more it would be wise for you to do, without delay.”

“The thing I’ve got to do, Matt, is to wire the colonel that I’m on deck and ready to look after the bullion. What are the two things it would be wise for me to do?”

“Why, call at the bank and see whether the bullion is there.”

“I don’t want to load up with it before Wednesday afternoon.”

“Of course not, but find out whether it has arrived in New York. Then I’d call on Random & Griggs, introduce[3] yourself, and tell them you’ll be around Wednesday evening.”

“Keno! You’ll go with me, won’t you?”

“I don’t think it will be necessary, Joe. While you’re attending to this, I’ll make my call at the Flatiron Building.”

“I’ll have to hunt up Random & Griggs, and I haven’t the least notion where to find the Merchants’ & Miners’ National Bank.”

“We’ll get all that out of the directory.”

“Then where am I to cross trails with you again?”

“Come to the Flatiron Building in two hours; that,” and Matt flashed a look at a clock, “will bring us together at ten. You’ll find me on the walk, at the point of the Flatiron Building, at ten o’clock.”

“Correct.” McGlory put the folded papers back into the envelope, and stowed the envelope in his pocket. “I reckon I won’t get lost, strayed, or stolen while I’m attending to this business of the colonel’s, but from the time I take that bullion out of the bank, Wednesday afternoon, until I get it into some safe place again, you’ve got to hang onto me.”

“I’ll be with you, then, of course,” Matt laughed. “Now, let’s get the street addresses of the bank and the firm of Random & Griggs, and then our trails will divide for a couple of hours.”

The boys got up and moved away. The man by the marble column stared after them for a moment, a gleam of growing resolution showing in his black eyes. Turning suddenly, he dropped his newspaper into one of the vacant chairs and bolted for the street.

His mind had evolved a plan, and it was aimed at the motor boys.

Matt and McGlory decided that they would not use an automobile for their morning’s work. The cowboy would go downtown by the subway and Matt would use a surface car. They separated, McGlory rather dazed and skeptical about his prospective fortune, and Matt more confident and highly delighted over his chum’s unexpected good luck.

It chanced that Matt had spent some time in Arizona, and he knew, from near-at-hand observation, how suddenly the wheel of fortune changes for better or for worse in mining affairs.

One of Matt’s best friends, “Chub” McReady, had leaped from poverty to wealth by such a turn of the wheel, and Matt was prepared to believe that the same dazzling luck could come McGlory’s way.

Within half an hour after leaving his chum, the young motorist was in the Flatiron Building, asking the man on duty at the elevators where he could find Mr. James Arthur Lafitte, the gentleman whom Cameron had mentioned as being interested in the problem of aëronautics. Lafitte, Cameron had told Matt, was a member of the Aëro Club, had owned a balloon of his own, and had made many ascensions from the town of Pittsfield, Massachusetts—which was near Matt’s old home in the Berkshire Hills; but, Cameron had also said, Lafitte had given up plain ballooning for dirigibles, and, finally, had turned his back on dirigibles for heavier-than-air machines. He was a civil engineer of an inventive turn, and with an adventurous nature—just the sort of person Matt would like to meet.

Having learned the number of Lafitte’s suite of rooms, Matt stepped aboard the elevator and was whisked skyward. Getting out under the roof, he made his way to the door bearing Lafitte’s name, and passed inside.

A young man, in his shirt sleeves, was working at a drawing table. Matt asked for Mr. Lafitte, and was informed, much to his disappointment, that he was at his workshop on Long Island, and would probably not be in the city for two or three days.

Matt introduced himself to the young man, who was a draughtsman for Lafitte, and who immediately laid aside his compasses and pencil, and climbed down from his high stool to grasp the caller’s hand.

“Mr. Lafitte has heard a good deal about you,” said he, “and has followed your work pretty closely. He’ll be sorry not to have seen you, Motor Matt. Can’t you come in again? Better still, can’t you run out to his workshop and see him?”

“I don’t know,” Matt answered. “I’m in the city with a friend, and he has a little business to attend to which will probably take up some of our time.”

“I think,” went on the other, “that you won’t regret taking the time to talk with Mr. Lafitte. He’s working on something, out there at his Long Island place, which is going to make a big stir, one of these days.”

“Something on the aëroplane order?”

The draughtsman looked thoughtful for a moment.

“Suppose,” said he, “that something was discovered which had fifty times the buoyancy of hydrogen gas, that the buoyancy could be regulated at will by electrically heated platinum wires—would that revolutionize this flying proposition?”

Matt was struck at once with the far-reaching influence of the novel proposition.

“It would, certainly,” he declared. “Is that what——”

“I’m not saying any more than that, Motor Matt,” broke in the young man; “in fact, I can’t say anything more, but you take the trouble to talk with Mr. Lafitte. It may be worth something to you.”

Matt lingered in the office for a few minutes longer, then went away. The spell cast over him by the clerk’s words went with him. He had often thought and dreamed along the lines of the subject the draughtsman had mentioned.

The drawback, in the matter of dirigible balloons, lay in the fact that the huge bag, necessary to keep them aloft, made them the sport of every wind that blew. If the volume of gas could be reduced, then, naturally, the smaller the gas bag, the more practicable the dirigible would become. With the volume of gas reduced fifty times, a field opened for power-driven balloons which fairly took Matt’s breath away. And this lifting power of Lafitte’s was under control! This seemed to offer realization of another of Matt’s dreams—of an automobile flying machine, a surface and air craft which could fly along the roads as well as leap aloft and sail through the atmosphere above him.

Carried away by his thoughts, Matt suddenly came back to his sober senses and found himself staring blankly into a window filled with pipes and tobacco at the V-shaped point of the Flatiron Building. He laughed under his breath as he dismissed his wild visions.

“I won’t take any stock in this new gas,” he muttered,[4] “until I can see it demonstrated. Just now I’m more interested in Joe and his good luck than in anything else.”

He looked at his watch. It was only half-past nine, and it would be half an hour, at least, before he could expect his chum. Matt had suddenly remembered, too, that it would probably be ten o’clock before Joe could finish his business at the bank, and that would delay his arrival at the Flatiron Building until after the appointed time.

Crossing over into Madison Square, Matt idled away his time, roaming around and building air castles for McGlory. The cowboy was a fine fellow, a lad of sterling worth, and fortune could not have visited her favors upon one more deserving.

By ten o’clock Matt was back at the Flatiron Building. As he came around on the Fifth Avenue side, a taxicab drew up at the curb, the door opened, and a lad sprang out. The youth was well dressed and carried a small tin box.

Matt supposed the lad was some one who had business inside the building, and merely gave him a casual glance as he strolled on. Matt had not gone far, however, before he felt a hand on his shoulder. He whirled around, thinking it was McGlory, and was a little surprised to observe the youth who had got out of the taxicab.

“Are you Motor Matt?” came a low voice.

“That’s my name,” answered Matt.

“And you’re waiting here for your friend, Joe McGlory?”

“He was to meet me here at ten,” said Matt, his surprise growing.

“Well,” went on the lad, a tinge of color coming into his face, “he—he won’t be able to meet you.”

“Won’t be able to meet me?” echoed Matt. “Is business keeping him?”

“That’s it. I’m from the office of Random & Griggs, and Mr. McGlory wants you in a hurry.”

“What does he want me for?”

“That’s more than I know. You see, I’m only a messenger in the brokers’ office.”

He was a well-dressed young fellow, for a messenger, but Matt knew that some of the messengers, from the Wall Street section, spend a good share of their salary on clothes, and, in fact, are required to dress well.

“I can’t imagine what Joe wants me for,” said the wondering Matt, “but I’ll go with you to Liberty Street and find out.”

“He’s not at the office, now,” went on the messenger, “but started into the country with Mr. Random just as I left the office to come after you.”

“What in the world is Joe going into the country for?”

“That’s too many for me. All he told me to tell you was that it had something to do with the ‘Pauper’s Dream.’ He said you’d understand.”

This was startling news for Matt, inasmuch as it seemed to indicate that McGlory had encountered a snag of some kind in the matter of the mine.

“We’d better hurry,” urged the messenger, as Matt stood reflecting upon the odd twist the “Pauper’s Dream” matter was taking.

“All right,” said Motor Matt.

Accompanying the young fellow to the taxicab, Matt climbed inside and the messenger followed and closed the door. The driver, it appeared, already had his instructions, and the machine was off the moment the door had closed.

“My name is Granger, Motor Matt,” observed the messenger, “Harold Granger.”

“You don’t look much like a granger,” laughed Matt, taking in the messenger’s trim, up-to-date garments.

Harold Granger joined in the laugh.

“What’s in a name, anyhow?” he asked.

“That’s so,” answered Matt good-naturedly. “I’d give a good deal to know what’s gone crossways with McGlory. I suppose you haven’t any idea?”

“There are not many leaks to Mr. Random’s private room,” answered Harold, “and I can’t even guess what’s going on. Mr. Random seemed excited, though, and it takes a lot to make him show his nerves.”

“Where are we going?”

“To Rye, a small place beyond Mamaroneck.”

“Great spark-plugs!” exclaimed Matt, watching the figures jump up in the dial, recording the distance they were covering in dollars and cents. “What’s the use of using a taxicab for a trip like that? You ought to have hired a touring car by the hour.”

“Oh, this was the only car handy, and Mr. Random never stops at expense.”

“Why couldn’t he and McGlory have come by way of the Flatiron Building and picked me up?”

“I think Mr. McGlory said you were not expecting him until ten o’clock.”

“That needn’t have made any difference. Joe knew where I was to be in the Flatiron Building and he could have come for me.”

“He and Mr. Random seemed to be in a hurry,” was the indefinite response, “and that’s all I know.”

When the taxicab got beyond the place where the eight-miles-an-hour speed limit did not interfere, the driver let the machine out, and the figures in the dial danced a jig. But Random & Griggs were furnishing the music for the dance, and Matt composed himself.

“You’re a stranger in New York, aren’t you?” Harold inquired.

“I haven’t been in the city for a long time,” Matt answered.

“This is the Pelham Road,” the messenger went on, “and that’s the sound, over there.”

“I was never out this way before,” said Matt, “but——”

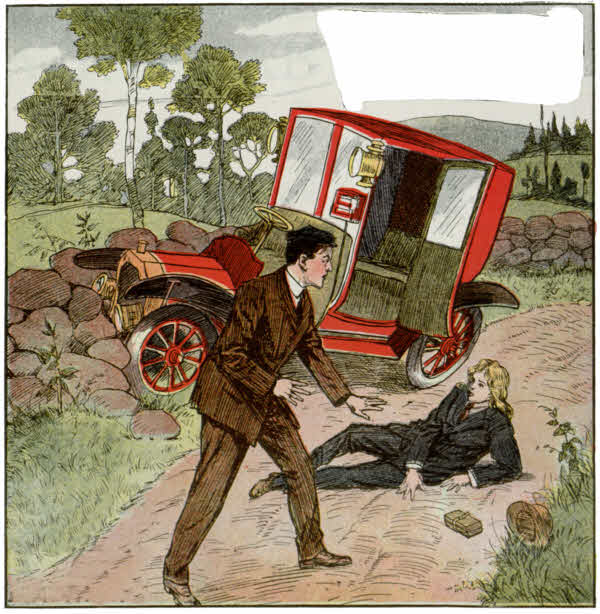

Just at that moment something went wrong with the taxicab. There was a wobble, a wild lurch sidewise, a brief jump across the road, and a terrific jolt as the machine came to a halt. The body of the car was thrown over to a dangerous angle, Matt was flung violently against Harold Granger, and both of them struck the door. Under the impact of their bodies, the door yielded, and they fell out of the vehicle and into the road.

Malt had given vent to a sharp exclamation, and his companion had uttered a shrill cry. The next moment they were on the ground, Matt picking himself up quickly, a little shaken but in no wise injured.

The taxicab, he saw at a glance, had dived from the road into a stone wall. The driver had vanished, and Matt took a hurried glance over the wall to see if he had landed on the other side of it. He was not there, and the mystery as to his whereabouts deepened.

Turning to give his attention to Granger, Matt received another start. The young fellow was lying beside the taxicab, lifting himself weakly on one arm. His tin box had dropped near him, and his derby hat had fallen off. Strands of long, yellow hair, which must have been[5] done into a coil and hidden under a wig of some sort, had been released and were waving about Granger’s shoulders.

A woman! Here was a pretty tangle, and Motor Matt was astounded.

As though a taxicab, minus its driver and running amuck into a stone wall, was not enough hard luck to throw across the path of Motor Matt, he had also to deal with a young woman masquerading in man’s attire. But for the mishap to the taxicab, Matt would probably never have discovered that the supposed youth was other than “he” seemed.

There were a number of details that perplexed our young friend just then, and among them—and not the least—was the strange disappearance of the driver of the machine. This problem, however, would have to wait. Matt felt that the young woman should claim his first attention.

“Are you hurt?” he asked, feeling more concern on that point than he would have done had his companion been of the other sex.

“No,” answered the girl, her face reddening with mortification.

Matt started to help her up, but she regained her feet without his aid and picked up the tin box and the hat.

“I suppose, Miss Granger,” said he, “that I should have known, from the way those yellow tresses were smoothed upward at the back of your head, that—that you were not what you were trying to appear; but, of course, I wasn’t looking for any such deception as this.”

Tears sprang to the girl’s eyes.

“I—I don’t know what you will think of me,” she murmured. “You see, a man has so much better chance for getting on in the world that I—I have been obliged to play this—this rôle in—in self-defense.”

“You have played the rôle for some time?”

“For—for a year, now.”

“You can’t expect me to believe that, Miss Granger,” said Matt calmly.

“Why not?” she flashed.

“Well,” he answered, “you would have cut off those long locks if you had made a business of playing such a part for a year. That would have been the reasonable thing to do, and I am sure you would have done it.”

“Do you doubt my word?” she asked defiantly.

“I don’t want to doubt your word, Miss Granger, but I have to take matters as I find them. You’re not a messenger for Random & Griggs, either, are you?”

She did not reply.

“And all this about my chum, Joe McGlory, going into the country and wanting me to join him, isn’t true, is it?”

“Yes, it’s true,” she declared desperately. “You’ll have to go with me if you want to find Mr. McGlory.”

“Did McGlory go into the country in a touring car with Mr. Random?”

This was another question which the girl did not see fit to answer.

“You’re not frank with me,” continued Matt, “and how can you expect me to have any confidence in you? Have you any idea what became of the driver of the taxicab?”

“No,” she replied.

“I’m going back down the road to look for him. While I’m gone, Miss Granger, you do a little good, hard thinking. I guess you’ll make up your mind that it’s best to be perfectly frank with me.”

Without saying anything further, Matt turned away and started back along the road. He was caught in a twisted skein of events, and was the more perturbed because he could not think of any possible object the girl might have in trying to deceive him.

But, whatever plot was afoot, Matt was positive that the accident to the taxicab had nothing whatever to do with it. That had been something outside the girl’s calculations, and an investigation might lead to results.

The driver had not been long off the seat of the taxicab when the machine collided with the wall. This was self-evident, for the machine could not have proceeded any great distance without a controlling hand on the steering wheel.

Less than a hundred feet from the spot where the accident had happened, Matt found the driver sitting up at the edge of some bushes by the roadside. He was covered with dust, and was holding his hat in his hands. There was a vacant stare in his eyes as he watched Matt approach.

“What’s the matter with you?” queried Matt.

The driver acted as though he did not understand. He began turning the hat around and around in his hands and peering into the crown in the abstracted fashion of one who is struggling with a hard mental problem.

A little way back, Matt remembered that they had passed a road house. If he could get the driver to the road house, perhaps the people there could do something for him.

“Come,” said he, catching the man by the arm and trying to lift him. “You are sick, and I’ll help you to a place where they can look after you.”

Mechanically the driver put his hat on his head and got to his feet. For a moment he stood still, staring at Matt speculatively, as though trying to guess who he was and where he had come from; then, suddenly, he whirled and broke from Matt’s grasp, running farther back into the bushes.

In half a dozen leaps Matt was upon him again, and had caught him firmly by the collar.

“I’m a friend of yours,” he said soothingly, “and I want to take you to a place where you can be cared for. You’re not right in your head.”

“Who are you?” mumbled the driver.

“Can’t you remember me? I was in your taxicab; you picked me up at the Flatiron Building.”

“What taxicab?” the man asked, drawing one hand across his forehead.

“Yours.”

The man’s blank look slowly yielded to a glimmering of reason.

“Oh, yes,” he muttered, “I—I remember. The young chap hired me at Herald Square. I was to take him to the Flatiron Building, pick up another fare, and then go along the Pelham Road as far as Rye. I guess I’ve got that straight.”

“Sure it was at Herald Square that the young fellow hired you?”

“Yes, I’m positive of it.”

The driver was getting back his wits by swift degrees.

“What was the matter with you?” asked Matt.

“Sort of a fit. I used to have ’em a whole lot, but this is the first that’s come on me for purty nigh six months. No matter what I’m doin’, I jest drop an’ don’t know a thing for a minute or two; then, after I come out of it, I’m gen’rally a little while piecin’ things together.”

“You shouldn’t be driving a taxicab, if you’re subject to such spells.”

“Thought I’d got over ’em. I won’t have another, now, for two or three weeks, anyway. Didn’t you see me when I tumbled from the seat?”

“No.”

“That’s blamed queer! Didn’t you hear me, either?”

“No.”

“How did you find out I was gone from up front?”

“The taxi jumped into a stone wall,” answered Matt dryly, “and threw us out. If you’ll step out of this patch of brush you can see the machine.”

“Was it damaged much?” asked the man anxiously.

“It doesn’t seem to be.”

“Think I can tinker it up so as to take you and that other young chap on to Rye?”

“That’s where you’re to take us, is it?”

“Yes.”

“And the young fellow hired you at Herald Square?”

“Say, my brain’s as clear as yours, now. I know jest what I’m sayin’. I was hired at Herald Square to take him to the Flatiron Buildin’, and then to pick you——”

“All right,” cut in Matt. “Do you know who the young fellow is?”

“Don’t know him from Adam. Never saw him before.”

“After you get to Rye, what——”

The drumming of a motor car, traveling swiftly, was heard at that moment. The car was close and, through the bushes, Matt caught a glimpse of its fleeting red body as it plunged past.

Thinking that the car, which seemed to be big and powerful, might be used for towing the taxicab—in case it was very seriously damaged—to the nearest garage, Matt jumped for the road.

By the time he had gained the road, however, the touring car was abreast of the taxicab and forging straight onward at a tremendous clip. Matt’s intention of hailing the machine was lost in a spasm of astonishment the moment he had caught sight of the single passenger in the tonneau. There was one man in front with the driver, but the passenger in the tonneau—there could be no doubt about it—was Joe McGlory!

By the time Matt had recovered full possession of his senses, the touring car was out of sight.

For Matt, in this queer taxicab tangle, one mystery was piling upon another. Joe McGlory, in a faster car than the “taxi,” had left New York after Matt and the girl had taken their departure. Joe might be with Mr. Random, but the girl had certainly made a misstatement when she said that the cowboy and the broker had hurried off in advance of the taxicab. But then, the girl had made many misstatements.

By the narrow margin of no more than thirty seconds, Matt had failed to reach the road in time to hail the touring car. Fate works with trifles, drawing her thread fine from the insignificant affairs of life.

The driver came unsteadily through the bushes and stood at Matt’s side, gazing toward the taxicab.

“What was you intendin’ to do?” he asked of Matt.

“I was thinking we could hail that automobile and, if the taxicab was too badly injured to proceed under its own power, we could have the machine towed to the nearest garage.”

“We won’t have any trouble findin’ a car to tow us—if we have to. If the machine ain’t too badly smashed, I’m goin’ to take you on to Rye.”

“Perhaps I’d better do the driving,” suggested Matt.

“Bosh! I’m all right for two or three weeks. The spells ain’t bad, but they’re mighty inconvenient.”

“I should say so!” exclaimed Matt. “That other passenger and myself might have been killed.”

“You wasn’t either of you hurt, was you?”

That was the first remark the driver had made that showed any solicitude for his passengers.

“No,” Matt answered. “Let’s get back and see if we can repair the taxi.”

When they reached the taxicab, the girl was sitting on a stone near the machine. Her long tresses had been replaced under the derby hat, and she looked sufficiently boyish to keep up the deception—so far as the driver was concerned. Matt passed her with hardly a glance, and helped the driver make his investigation.

No serious damage had been done to the taxicab. A lamp was smashed, and some of the electric terminals had been jarred from their posts, but not a tire had been punctured, and the machine seemed as capable as ever of taking the road.

If the girl was curious as to the sudden disappearance and reappearance of the driver, she kept her curiosity to herself. When the driver had backed the machine into the road and headed it eastward, Matt turned to the girl.

“Rye is the place we are bound for?” he said tentatively.

She gave him a quick, troubled glance.

“Yes,” she answered.

Probably she was wondering whether he was intending to keep on with the journey.

“Then,” proceeded Matt, “let’s get inside. We’ve lost a good deal of time.”

He held the door open and the girl got into the vehicle. He followed her, after telling the driver to make his best speed.

“The driver had some sort of a fit,” Matt explained, when they were once more under way, “and fell off the seat. You didn’t see him when he dropped, did you?”

“If I had,” she answered, somewhat tartly, “I should have spoken about it.”

“Of course,” returned Matt calmly. “So many peculiar things are happening, though, that I wasn’t sure but the disappearance of the driver might have had something to do with your plans.”

“My plans?” she echoed.

“I don’t know whose plans they are, but I suppose, if some one else laid them, you are pretty well informed or you couldn’t carry them out. What are we to do when we get to Rye?”

“There will be another automobile there—a fast car—waiting to take us on along the Boston Post Road.”

“How far?”

“Somewhere between Loon Lake and Stoughton, on the Boston Pike.”

Again Matt was astounded.

“That’s pretty close to Boston, isn’t it?” he inquired.

“It’s a good deal closer to Boston than it is to New York.”

“When do you think we’ll get to—to where we’re going?”

“Some time to-night,” was the careless response.

“You don’t seem to realize,” said Matt, just the barest riffle of temper showing itself, “that I hadn’t any intention of taking such a long ride as this when I left the Flatiron Building.”

“Your friend wants you,” said the girl. “If that’s not enough to keep you on the long ride, then you can get out at Mamaroneck—we’ve already passed New Rochelle—and take the train back to New York.”

The girl’s indifferent manner puzzled him. She must have seen the touring car pass the taxicab, and she must have known that Joe McGlory was in the car. What this had to do with her present attitude, if anything, Matt could not guess. For all that, he felt positive she did not think he had seen the touring car dash along the road with McGlory.

“You told me McGlory had left New York ahead of us,” said he.

“That’s what I was told.”

“As a matter of fact, he didn’t leave until after we did, for he passed us while I was looking for the missing driver.”

She shot a quick look at him.

“You saw that, did you?” she inquired.

“Yes.”

“Then why didn’t you stop the car and find out what Mr. McGlory wanted?”

“The car was going too fast. Besides, I didn’t know my friend was in the car until it was too far away.”

She laughed softly.

“Then you do have a little confidence in me, after all?”

“Not a bit,” answered Matt, with a little laugh. “For reasons of your own, I believe you’re going to take me to the place where some one else is taking McGlory. I don’t know why, but I suppose I’ll find out if I wait long enough. Anyway, if Joe McGlory is in any sort of trouble, my place is at his side. And if you try to get away from me before I find McGlory,” he threatened, “I shall turn you over to the police in one of these small towns we’re passing through.”

“You couldn’t do that without a legal excuse.”

“Haven’t I a legal excuse? You got me away from New York by telling me something that wasn’t true.”

“You don’t know, yet, that what I told you isn’t true. I don’t think you could have me arrested for something that hasn’t happened.”

Some desperate purpose was urging the girl on. What it was, and why it should be desperate, were beyond Matt’s comprehension.

“You’re a young man with a mission,” said the girl, turning a pair of frosty blue eyes upon the young fellow beside her, “and the mission is to get to where we’re going, and find Mr. McGlory. You’ll be a whole lot wiser after that.”

Matt, in his own mind, did not doubt this statement. But that reflection in no wise helped him just then.

Presently the girl began peering through the window in the top of the door, watching the roadside as they scurried along.

“What are you looking for, Miss Granger?” asked Matt, after the girl had been peering steadily through the glass for several minutes.

“For the other car,” she answered, without looking around.

“You said that was to be waiting for us at Rye.”

“It may have come this way to meet us, and——Ah, stop!” she cried, lifting her voice. “We’ll get out here, driver.”

The driver was a surprised man as he brought the taxicab to a halt. It was a lonely piece of road where they had come to a stop, shadowed deeply, as it was, by a thick growth of trees on either side.

“It’s a mile, yet, before we get to the town,” demurred the driver.

“We’ll stop here,” said the girl decisively.

“I can’t see the other car,” spoke up Matt, looking in vain for the automobile that was to take them on.

Although he did not see another car, yet his eye was caught and held by something white fluttering from a bush. While the girl was settling with the driver, Matt made his way to the roadside and examined the fluttering object. It was a white cloth, and had evidently been tied to the bush as a signal.

“Wait a minute!” shouted Matt, as the driver was climbing back into his seat.

Both the driver and the girl whirled around and stared in his direction.

“I may want to go back to New York in the taxicab,” continued Matt. “I’d like to talk with you a minute, Mr. Granger,” he added, putting a little emphasis on the “mister.”

The girl advanced slowly toward him.

“Go back, if you’re afraid to go on and do what your friend wants you to do,” said she.

“I’m not at all certain,” said Matt, “that I’m doing what my friend wants me to do. The only reason I’m keeping on with you is because I saw McGlory pass me in that red touring car. I’d like to ask you, Miss Granger, if you stopped because you saw this signal,” and Matt turned and pointed to the white cloth.

“That’s the reason I stopped, Motor Matt,” the girl replied promptly.

“The plans you are following seem to have been laid with a good deal of care, and to point to something that may prove pretty serious. I think, Miss Granger, that you and I will go on to Rye, and stop there.”

“I’m not going to stop at Rye,” answered the girl, with spirit.

“I think you will,” answered Matt coolly. “On second thought, I believe it’s my duty to turn you over to the authorities until I can find out something more about my chum. You can explain to the judge why you’re disguised as you are.”

“You don’t mean that!” gasped the girl, starting back.

“I do,” declared Matt. “As I said, I believe it’s my duty, and——”

At that precise juncture, something descended over Matt’s head, thrown from behind. It might have been a shawl, or an automobile coat, or a piece of cloth—there was no time to take particular note of it. The attack came so suddenly, and so unexpectedly, that he was not able to defend himself.

With his face smothered in the thick folds, he was[8] drawn roughly backward. A foot tripped him, and he measured his length on the ground. The next moment he was seized by strong hands and dragged through the bushes and into the woods. He struggled blindly and fiercely against his unseen captors, but they were too many of them. He was powerless to free himself, and the smothering cloth that covered his head and shoulders made it impossible for him to call for help.

McGlory found his way to the address in Liberty Street without any difficulty. But he was too early. The Stock Exchange had not yet opened, and only a few clerks were at work in the brokerage offices of Random & Griggs.

The cowboy sat down in a room where there were a number of chairs facing a big blackboard. There were a stepladder and a chair in front of the blackboard, and off to one side was a machine in a glass case with a high basket standing under it. A ribbon of paper hung from the machine into the basket. This, of course, was the “ticker” which received and recorded the quotations of stocks at the Exchange, but it was not yet time for it to begin work.

McGlory and Matt were at least an hour too early in setting about their morning’s business.

While the cowboy sat in his chair in front of the blackboard, wondering how long he could wait for Random or Griggs and yet be at the Flatiron Building as per appointment with Matt, a man sauntered in, looked at an office boy who was just going out with an armful of ticker tape, and then approached McGlory.

He was the gentleman in the noisy apparel—he of the cigar, and the newspaper, and the listening ear and scheming brain. He was playing boldly, for the stakes were worth the risk.

“Young man,” said he to McGlory, “are you waiting for some one?”

“I’m waiting for one of the big high boys that boss the layout,” answered McGlory.

“Indeed!” The man flashed a quick look around and made sure that only he and McGlory were in the room. “Well,” he went on, “I am Mr. Random.”

“Fine!” exclaimed the cowboy, getting up. “I’m Joe McGlory, from the land of sun, sand, solitude, and pay-streaks. I’ve run in here to——”

McGlory got no further. Random grabbed his hand effusively.

“We’ve been expecting you,” said he. “We have a meeting of the syndicate on Wednesday evening, and a letter from the colonel gives your name and informs us that you will be on deck with the bullion from the test run of the mill. If the gold shows up properly, there’s no doubt about our people coming across with the money. But we can’t talk here—some one is liable to drop in on us at any moment. This business is private, very private. Come with me, Mr. McGlory, and I’ll find a place where we can have a little star-chamber session.”

“I don’t want to tear you away from business,” protested McGlory.

Random waved his hand deprecatingly.

“Griggs will look after the office,” said he. “This ‘Pauper’s Dream’ matter is a big deal to swing, and I guess it’s worth a few hours of my time. This way.”

Random walked out into Liberty Street, rounded a corner, entered a door, passed through a barroom, and finally piloted the cowboy into a small apartment, furnished with two chairs, a table, and an electric fan.

After he and McGlory had seated themselves, Random pushed an electric button. A waiter appeared.

“What are you drinking, Mr. McGlory?” inquired Random. “I can recommend their Scotch highballs, and as for cocktails, they put up a dry Martini here that goes down like oil, and stirs you up like a torchlight procession.”

“Elegant!” cackled McGlory. “I reckon, neighbor,” and he cocked up his eye at the waiter, “that I’ll trouble you for a seltzer lemonade, mixed with a pickled cherry and the cross-section of a ripe orange.”

“You don’t mean to say that you’re from Arizona, and don’t irrigate!” gasped Random.

“We irrigate with water, and that’s always been good enough for your Uncle Joseph. Besides, I’m training with Motor Matt, and our work calls for a clear brain and a steady hand. Seltzer lemonade for mine.”

“You’ll have a cigar?”

“That’s another thing I miss in the high jump.”

“Give me the same as usual, Jack,” said Random, to the waiter. “You’re a lad of high principles, I see,” remarked the broker, when the waiter had retired.

“It’s a matter of business, rather than of principle. Whenever an hombre gets his trouble appetite worked up, the first thing he does is to take on a cargo of red-eye. That points him straight for fireworks and fatalities.”

“I don’t know but you’re right,” said Random reflectively.

The waiter returned, and Random mixed himself something while McGlory fished around in his lemonade for the “pickled” cherry. Over their glasses they talked at some length, the broker seeking information about the section of Arizona where the colonel had begun operations on the “Pauper’s Dream.”

“What time is it, Mr. Random?” asked McGlory, in the midst of their talk.

“Just ten,” replied Random, with a look at his watch.

“Sufferin’ schedules!” cried the cowboy, starting up. “I’m to meet Pard Matt at ten, at the Flatiron Building. On my way there, I’ve got to drop in at the bank.”

“Why are you to call at the bank?” asked Random.

“To find out whether the bullion has got here, and to show them my order for it from the colonel.”

“You have the order with you?”

“Sure thing. Just got it this morning.”

“It won’t be necessary for you to go to the bank, Mr. McGlory,” said Random. “I’ve been there, myself, and I know the bullion has arrived. As for showing the order, you won’t have to do that until you take out the gold, on Wednesday.”

“Wouldn’t it be a good scheme to get acquainted with the bank men?”

“Not at all! If they doubt your authority to receive the bullion, in spite of the colonel’s order, a word from me will make everything all right. I believe I will go with you to the Flatiron Building. I’ve heard of this Motor Matt, and should like to meet him.”

McGlory wondered a little at the cheerful way in which Random left Griggs to look after the brokerage business; at the same time, the cowboy felt not a little flattered to[9] have Random neglect his personal affairs for the purpose of meeting Matt.

A cab carried them to the Flatiron Building, and Random waited on the walk while McGlory went bushwhacking for Matt. But Matt wasn’t in evidence.

“Perhaps he got tired waiting for you,” suggested Random, “and went away?”

“Nary, he wouldn’t,” returned the puzzled McGlory, “I reckon he’s talking with an aviator, upstairs, and has lost track of the time. I’ll go find Lafitte, and, ten to one, my pard will be with him. Wait here for a brace of shakes, Mr. Random, and——”

Just then a man pushed forward from the entrance to the cigar store. The man wore a cap and gloves, and looked like a chauffeur.

“I beg your pardon,” said he, addressing McGlory, “but are you Motor Matt’s chum?”

“That’s me,” answered the cowboy.

“McGlory’s your name, isn’t it?”

“Joe McGlory, that’s the label.”

“Well, Motor Matt had a hurry-up call into the country. It’s a long ride, and he went by automobile. He wants you to follow him, and he hired me to wait for you and then take you after him. That’s my chug cart,” and the man pointed to a red touring car at the curb.

“Speak to me about this!” cried McGlory. “What’s to pay? Do you know?”

“Motor Matt didn’t say. All he wanted was for me to follow him with you in my car.”

“I’ll bet a bushel of Mexican dollars it has something to do with Lafitte,” hazarded the cowboy. “Of course, I’ll go. Mr. Random,” and he turned to the broker, “I’m sorry you couldn’t meet up with my pard, but I’ll bring him around to your office Wednesday.”

“Just a minute, Mr. McGlory,” and the broker took the cowboy’s hand and drew him to one side. “I don’t like the looks of this thing,” he went on, in a low tone.

“How’s that?” asked McGlory, surprised.

“I don’t know, but I’ve got a presentiment that something’s wrong.”

“There’s something unexpected happened to Pard Matt,” said McGlory, “or he wouldn’t have piked off like this. But his orders are clear enough. I’m to follow him, so it’s me for the country.”

“Perhaps,” and Random wrinkled his brows, “this has something to do with the ‘Pauper’s Dream.’”

McGlory laughed incredulously.

“I can’t see how,” he answered.

“Neither can I, but it’s possible, all the same. We’re to get a good fat commission for placing that property, and I don’t intend to let the commission slip through my fingers.”

“It’s a cinch, Mr. Random, that you’re barking up the wrong tree. This business of Matt’s has more to do with flying machines than with mines, and I’ll bet my moccasins on it.”

“If you haven’t any objections, Mr. McGlory, I’d like to ride with you and make sure.”

“The shuffer says it’s a long trip.”

“I don’t care how long it is, just so I can assure myself that nothing is going crossways with the ‘Pauper’s Dream.’”

“All right, neighbor. If that’s how you feel about it, you’re welcome to one corner of the bubble-wagon.”

The three of them climbed into the touring car, Random in front with the driver, and McGlory in the tonneau. As soon as they were seated, the car began working its way through the crowded streets toward a section less congested with traffic. As the way cleared, the speed increased. Once on the Pelham Road, the chauffeur “hit ’er up,” and the red car devoured the miles in a way that brought joy to McGlory’s soul.

When they passed a taxicab, with its nose rammed into a stone fence, the chauffeur remarked that the taxi was a good ways from home. Mr. Random looked thoughtful, but he made no request that the red car slacken its speed. McGlory saw a young fellow sitting on a bowlder, but the spectacle afforded by the taxicab and the supposed youth meant nothing to him. His mind was circling about Motor Matt.

Motor Matt, helpless and half stifled among the bushes, felt lashings being put on his arms and legs; then, while some one laid a hand on the cloth and pressed it tightly over his lips, a bit of conversation was wafted to him from the road. Because of the smothering cloth, the voices seemed to come from a great distance, although the spoken words were distinct enough.

“What’re you tryin’ to do with that chap?”

This was the driver of the taxicab. His curiosity, as was quite natural, had been aroused by the treacherous attack on Matt.

“That’s all right, my friend,” replied a voice—a voice Matt had not heard before.

“Maybe it’s all right, but it looks mighty crooked to me. Two of you threw a cloth over that chap’s head, downed him, an’ dragged him into the brush. I got a warm notion of goin’ on to Rye and gettin’ a constable.”

The other man laughed.

“You’d be making a fool of yourself, if you did. I’m from Matteawan, and the young fellow is an escaped lunatic. He’s a desperate chap to deal with, and we had to take him by surprise in order to capture him.”

A long whistle followed those words.

“Great Scott! Say, he didn’t look like he was dippy.”

“Some of ’em never look the part—until they find you’re after ’em.”

“Why didn’t you nab him in New York, instead o’ bringin’ him ’way out here?”

“He’s armed, and he’d have put up a fight. In a crowded street, some one would have been hurt. It was better to lure him off here, into the country.”

“I guess you know your business. Who’s the other young chap?”

“He’s the lunatic’s brother.”

“I see.”

“You needn’t say anything about this, driver. The family wouldn’t like to have it known. You’ve been put to a little extra trouble, and here’s a ten to make up for it.”

“That’s han’some, an’ I’m obliged to you.”

It can be imagined, perhaps, what Matt’s feelings were as he listened to this. He tried frantically to burst the cords that secured his arms, but the tying had been too securely done. He made an attempt, too, to call out and inform the driver of the taxicab that the tale he was listening[10] to was false, but the hand over his face pressed the cloth more firmly down upon his lips.

Resigning himself to the situation, Matt listened while the purr of a motor came to his ears and died away in the direction of New York. A friend who might have saved him was gone, and Matt was completely at the mercy of his captors.

Some one came through the bushes; there were two of them, it seemed, and they talked as they approached.

“I was up in the air when I heard Motor Matt say he was to stop at Rye,” said the voice that had talked with the taxi driver. “What was the matter, Pearl?”

It was the girl who answered, and she told briefly how the driver had fallen from the seat of the taxicab, how Matt had discovered her disguise, and how his suspicions had been aroused.

“I was up in the air myself, dad,” finished the girl, drawing a deep breath of relief. “But we’re all right, now. The way you pulled the wool over the eyes of that taxicab man was splendid.”

“Doing the right thing at the right time, Pearl, is your father’s long suit. Where were you when Tibbits went past in the red car?”

“Sitting on a stone at the roadside.”

“Where was Motor Matt?”

“Back along the road in the brush, looking for the driver.”

“And those in the red car never saw him!”

“No, but he saw them and recognized McGlory.”

“Oh, well, this is our day for luck, and no mistake. Watch the road, Pearl, while we’re getting out our own car. We don’t want to be seen lifting a bound man into it.”

“I’ll watch,” the girl answered.

Matt was still further impressed with the comprehensive nature of the plans launched against him and McGlory. Three motor cars had been used in the game, and there must be at least four men in the plot besides the girl. But what was the purpose of the plotters? What end were they seeking to gain by all this high-handed, criminal work?

From off to the left Matt could hear the pounding of a motor as it took up its cycle. After the engine had settled into a steady hum, the crunching of the bushes indicated that a heavy car was being forced through them into the road.

“All right, Dimmock!” called a voice.

“Is the road clear, Sanders?” answered Dimmock.

“There’s not a soul in sight.”

“Then come here and help me. We’ll take this coat from Motor Matt’s head and replace it with a gag—a twisted handkerchief will do. The quicker we can get him into the car, now, the better.”

The next moment the smothering cloth was jerked from Matt’s head and shoulders. He had just time to gulp down a deep breath of air when the twisted handkerchief was forced between his teeth and knotted in place.

He saw a slender, wiry man, soberly but richly dressed, and another, short, thick-set, and wearing a long dust coat and cap.

“Take him by the feet, Sanders,” said the slender man, who, from this, Matt knew to be Dimmock.

Between them Matt was lifted, carried out to the road, and shoved into the tonneau of a touring car, while the girl held the door open. There was a top to the car, and Matt was made to sit on the floor and lean back against the seat.

By every means in his power Matt tried to let his captors know that he wanted to talk with them, but they either could not understand him, or else had no intention of letting him relieve his mind. The girl and Dimmock seated themselves on either side of Matt, and the same coat that had been used in effecting Matt’s capture was dropped over him.

In this manner the strange party started away along the road, the prisoner unable to see anything of the route they were taking.

Matt was sensible of the swiftness of their flight, and of the driver’s perfect mastery of the machine. The explosion in the cylinders was unfailing, the mixture of air and gasoline was perfect, and the coils hummed their beautiful rhythm to the well-timed spark.

Gradually there was forming, in Matt’s mind, an idea that these desperate plotters had made some huge mistake. He could not account, in any other way, for the execution of such a plan as they were carrying out.

He and McGlory were not being kidnapped to be held for ransom. Such an idea was preposterous. Matt had no relatives, so far as he knew, rich or poor; and neither had McGlory.

Yes, Matt was sure that Dimmock, and his daughter, and Tibbits, the man who had dashed past with McGlory in the red car, were blundering in some way. At the end of the journey, wherever that might be, the mistake must be discovered, and the motor boys would be released.

The point that troubled Matt a little was the fact that his cowboy pard was not a prisoner. He appeared to be traveling in the red car of his own free will. Was that because he had been lured away, and had not yet had his suspicions aroused?

There was little talk between Dimmock and his daughter, and Sanders was attending strictly to his driving. Now and then, however, a word was dropped as the car slowed down which gave Matt an inkling as to the course they were taking.

“Stamford,” and “Bridgeport” were on the line of their flight, and this proved conclusively that they were proceeding in the direction of Boston.

The day was warm, and Matt, crouched uncomfortably under the coat, was having anything but an enjoyable ride. By twisting about, however, he managed to give some relief to his cramped limbs.

Hour after hour the car swept on. Once they halted at a filling station to replenish their supply of gasoline, but the man in charge of the supply tank was kept adroitly in ignorance of the fact that there was a prisoner in the tonneau.

By degrees a numbness crept along Matt’s limbs, and a drowsiness enwrapped his brain. He slept, in spite of his many discomforts, and was awakened, finally, by a rattle from somewhere forward of the tonneau.

The car was at a stop.

“What was the trouble, Sanders?” called the voice of Dimmock.

“Nothing much,” answered Sanders. “It’s fixed now.”

“Why not let Motor Matt sit up here on the seat between us?” suggested the girl. “It’s so dark no one could see him—even if we happened to be passed by another car.”

“We might as well give him a little comfort, I suppose,” answered Dimmock.

Thereupon the coat was pulled away, and Matt found that it was night. Dimmock reached down and helped him up on the seat.

“We’re doing this for your comfort, Motor Matt,” said Dimmock. “I hope you’ll appreciate it, and not try to make any trouble for us.”

Matt moved his cramped joints and stretched his legs the full width of the tonneau. There were shadowy bluffs on each side of the road, and a tracery of boughs lay against the lighter background of sky. From the fragrant odor, Matt gathered that they were in the depths of a pine forest. He gurgled ineffectively behind the gag.

“He wants to talk, dad,” said the girl. “Why not let him? If any one comes you can prevent him from calling out.”

“You’ve got too much heart, girl, for this kind of work,” returned Dimmock. Nevertheless, he fumbled with the knots at the back of Matt’s head, and removed the handkerchief.

Matt inhaled deep breaths of the pine-scented air. The ozone held tonic properties and freshened him wonderfully.

“It’s been a long time since I had breakfast, Mr. Dimmock,” were his first words.

“You’ve skipped dinner,” returned Dimmock, evidently pleased to note that the prisoner was taking recent events in such a matter-of-fact way, “but you’ll have a fine supper to make up for it. In less than an hour from now we’ll be where we’re going.”

Sanders cranked up, climbed into his seat, and the car moved on through the forest aisle, the searchlights boring bright holes in the dark.

“Where is the journey’s end to be?” inquired Matt.

“Somewhere between Loon Lake and Stoughton. That’s all you’re to know.”

“This is the Boston Pike?”

“We’ve been traveling the Boston Pike for a long time—but I guess that knowledge won’t help you much if you ever wanted to find the house again.”

“We’re about due at Matteawan, aren’t we?”

Dimmock laughed at that, and the laugh was echoed by the girl.

“I had to tell the taxicab driver something,” said Dimmock.

“This is quite a plot you’re working out,” pursued Matt.

“It was rather hastily evolved by Tibbits, but it seems to be doing the work.”

“Tibbits, if I’ve got it right, is the man with McGlory?”

“You’ve got it right.”

“Did you bring my chum from Liberty Street?”

“Of course, Motor Matt, I hadn’t anything to do with that part of it. Pearl and Sanders and I were to look after you.”

“How did you happen to be hidden away on the Boston Post Road?”

“We thought that was safer than to meet you at Rye.”

Dimmock had a complaisant air—entirely the air of a man whose plans are succeeding, and with ultimate victory assured.

“What was the use of all this juggling with taxicabs and touring cars?” continued Matt.

He was groping for information, in order to lead up to the announcement that Tibbits, Dimmock, and the rest were having their trouble for their pains.

“You see,” explained Dimmock, “it was easier for Pearl to work alone, and pretend to be a messenger for the brokers. If Sanders and I had been along, you’d have suspected something.”

“I suspected something, anyhow, and if you hadn’t resorted to violence, back there on the road, your daughter would have been held in the Rye police station until I could have learned more about what was going on.”

“Which shows our wisdom in waiting for you on the other side of Rye,” commented Dimmock.

“What’s back of all this, Dimmock?” demanded Matt.

“You’ll find that out later,” was the reply. “Tibbits is at the head of this little conspiracy, and most of the talking must be left for him.”

“How did you know I was to meet my chum at the Flatiron Building at ten o’clock?”

“That’s something else you’ll have to learn from Tibbits.”

“Do you know how Tibbits got McGlory to take his ride into the country?”

“Just as we got you, if the business worked out according to plan. You were told that your chum wanted you, and McGlory was told that you wanted him. That seemed to be enough,” and Dimmock laughed under his breath.

“There’s been a mistake, Dimmock,” said Matt earnestly.

“Not on our side,” answered Dimmock.

“Ever since ten o’clock this morning you and your pals have played fast and loose with the law, and you’re under a delusion of some sort.”

“You’re the one who is under a delusion.”

“I believe you’ll find out differently. I feel so sure of that, that I’m perfectly willing to go with you to the end of the journey. The facts will come out, at that time.”

“They will,” said Dimmock, with emphasis.

“My mission is to find my chum——”

“You’ll have fulfilled your mission when we get to where we’re going.”

“McGlory will be there?”

“Yes.”

“That’s all I can ask. Take these ropes off me, can’t you? I’m too anxious to find McGlory to try to get away.”

“The ropes won’t be removed until we reach the house.”

“What’s to be done at the house?”

“Nothing to your physical harm. You and McGlory will be entertained there for a few days. You’ll be able to eat, drink, and enjoy yourselves—within certain prescribed limits.”

“But we can’t do that!” cried Matt, suddenly remembering that his chum had to be back in New York by Wednesday afternoon.

“You’ll have to stay at the house,” was the decided answer.

“Why? What’s the reason?”

“I have talked all I’m going to about the whys and[12] wherefores. Whatever else you learn you’ll have to get from Tibbits.”

Matt relapsed into silence, while the car continued to speed along the gloomy, tree-bordered road, following the long shafts of light like a phantom locomotive on gleaming rails.

Suddenly there was a lessening of the speed, a swerve to the right, a quick stop, and the touring car was nosing a big iron gate, hung between square brick pillars.

“Here we are,” said Sanders.

“See if the gates are locked, Sanders,” ordered Dimmock. “They shouldn’t be. Tibbits said he would leave them unfastened.”

Matt leaned forward to watch the glow from the searchlights as it played over the massive iron work, penetrated the heavy bars, and lost itself in a dense mass of trees and shrubbery beyond.

The gates were not fastened, and Sanders pushed them wide. After running the car into the yard, the driver left it standing on a graveled drive while he returned to close the gates, and lock them.

“What sort of a place is this, Dimmock?” asked Matt, peering around, but seeing little, except the heavy shadows cast by trees and bushes.

“It’s a fine old place,” replied Dimmock, “and you and your chum should feel highly flattered at being entertained here. The family, as it fortunately happens for Tibbits and the rest of us, are in Europe this summer.”

“Then you haven’t any right here?”

“We have borrowed the use of the house. Tibbits has the run of the place, and we’re here by his invitation.”

Sanders got back and started the car slowly. The gravel road wound through the trees, and finally the searchlights flashed out upon the front of a large mansion. The great house was silhouetted against the sky, and the car lights swept the front door as the machine turned and halted at the broad front steps.

A glow appeared suddenly in the fanlight over the door. Sanders gave three quick, sharp blasts of the horn. This seemed to be a signal, for the door opened as if by magic, and a man showed darkly in the entrance.

“That you, Dimmock?” called the man.

“Who else could it be, Tibbits?” answered Dimmock. “Did you get here safely with McGlory?”

“Yes. And you? Have you got Motor Matt?”

“We have.”

An exclamation of satisfaction fell from Tibbits’ lips.

“I was afraid Pearl had had trouble,” said he. “We passed her on the road, sitting beside a taxicab that had run head-on into a stone wall. Motor Matt was nowhere in sight, and I thought he had suspected that something was wrong, and had escaped. I didn’t dare stop and ask any questions, you see, because McGlory was with us.”

“We came near having a streak of hard luck there, Tibbits, but we pulled through all right. What shall we do with Motor Matt?”

“Bring him in, of course. His chum’s anxious to see him, and I suppose he’s equally anxious to see McGlory.”

“He’s tied,” said Dimmock.

“Then untie him. He won’t get away.”

Tibbits pulled something from his pocket that flashed in the lamplight.

“I’ll keep him under the point of this,” Tibbits went on, “until he gets where I want him to go.”

Sanders, standing on the footboard of the car, leaned into the tonneau and helped Dimmock remove the cords that bound Matt’s arms and legs. When the cords were removed, Matt tried to stand, but tottered back upon the seat.

“Pretty rough treatment you’ve had, eh?” laughed Dimmock. “Well, you’ll be entertained so royally here, Motor Matt, that you’ll forget all the unpleasant things that have happened to you.”

In a few moments, Matt was able to climb out of the tonneau. Tibbits’ revolver was leveled at him the instant he dropped down from the footboards.

“Walk straight up the steps, Motor Matt,” ordered Tibbits, “and on into the house. I’ll follow and tell you which way to go. Be nice about it, and nothing will happen.”

Matt mounted the steps. Tibbits backed to one side, to let him pass, and the hall light shone over his face. Matt looked at him sharply. The man was a stranger, and he was positive he had never seen him before. This was another fact to clinch Matt’s theory that Tibbits and his pals were making a mistake.

Up the steps, through the great doors, and into a richly furnished hall Matt passed, Tibbits, still with the revolver aimed, following him closely.

“Keep straight on along the hall,” ordered Tibbits.

Matt kept on. The musty, close odor of a house, long shut up, assailed his nostrils, and offered proof that Dimmock had told the truth when he asserted that the family were in Europe.

“That door on the right,” said Tibbits. “Go in there.”

Matt opened the door. As he closed it behind him he heard the rasp of a key in the lock, and the “click” of a thrown bolt.

“Pard!” came an overjoyed yell.

The next moment Matt was caught and given a bear’s hug.

“Joe!” exclaimed the delighted Matt.

“Sure, it’s Joe,” whooped the cowboy. “What’s going on here, anyhow? What do you want me for?”

McGlory was under the impression that Matt had sent for him. In spite of the strange proceedings through which the cowboy had passed, he still believed that Tibbits had brought him on that long ride according to the wishes of his friend. Even the locking of the door, after Matt had entered the room, did not appear to have aroused any suspicions in McGlory’s mind.

Matt looked around. He was in a large room, lined with bookcases. At one end of the apartment was a magnificent fireplace. A thick carpet, that gave one the impression of walking on down, covered the floor. White busts looked out from niches in the wall, and comfortable chairs were scattered around. A light, suspended from the ceiling, cast a warm glow over the room, and over a table, heaped with food, and set with places for two.

“I’ve been waiting here for an hour,” grumbled McGlory. “Where have you been, pard, and what sort of a layout is this that you’ve brought me into?”

Matt removed his hat and threw it upon a couch; then,[13] seating himself in a chair, he began rubbing his hands and arms and staring at his chum.

“What’s the trouble with you, pard?” asked McGlory. “You act as though you were in a trance.”

“I am,” returned Matt. “I’m hardly able to credit my senses. In the first place, Joe, I never sent for you and asked you to come here.”

The cowboy gave a jump.

“Why, the driver of that red car told me——”

“I guess he told you what some one else told me. I was informed that you had come into the country with Mr. Random, of Random & Griggs, and that you wanted me to follow you. That’s why I’m here.”

McGlory slumped into a chair, and brushed a hand across his forehead.

“Sufferin’ brain twisters!” he muttered. “I came out here to find you, and you came out here to find me!”

“And here we are,” laughed Matt.

“And what are we here for?” gasped McGlory.

“Give it up. But I think somebody has made a big mistake, and that they’re going to find it out before they’re many hours older. If that’s our supper on the table, suppose we get busy with it. I haven’t had anything to eat since morning.”

“I had dinner in Bridgeport,” said McGlory. “I was mighty well treated, I’ll say that—and that only makes it harder for me to understand what’s in the wind. I don’t think any one would run away with us just for the fun of the thing.”

“It would be more of a joke on the other fellows than it would on us,” averred Matt, moving to the table and taking a seat. “How long has this supper been here, Joe?”

“About half an hour,” returned the cowboy, taking a chair opposite his chum. “Random is here,” he said suddenly.

“Random, of Random & Griggs?” inquired Matt, showing some surprise.

“What other Random could it be?”

Matt helped himself to a cold roast beef sandwich and a glass of lemonade.

“Tell me what happened to you, Joe,” said he. “I can eat and listen at the same time. Besides, I guess I’m hungrier than you are. You had dinner, and I didn’t.”

McGlory told of his call at the Liberty Street office, of meeting Random, of his talk with Random in the restaurant, of Random’s going with him to the Flatiron Building, of the failure to find Matt, and of the yarn told by the driver of the red car.

“We came through the country lickety-whoop,” the cowboy finished, “but it was the longest kind of a ride, and I wondered what in Sam Hill you were doing ’way over in Massachusetts. It was after sundown when we got to this place. Some one met the driver of the red car at the door, and said that Motor Matt hadn’t come yet, and that we were to wait for him. Random and I came into this room. By and by, a servant began to spread the table for chuck-pile, but layin’ covers for only two. I guessed a little about that, and asked the servant who he was intending to leave out, Random or Motor Matt. It was orders, he said, and that was all he knew about it.

“After a while, Random got up, told me to wait, and said he would try and find some one who could tell him something. Next thing I know, you walk in on me, and the door is locked behind you. Speak to me about this! Where’s Random?”

“The man’s name isn’t Random, Joe,” said Matt, “but Tibbits.”

“Tibbits?” echoed McGlory blankly. “But he met me at Random’s office.”

“That may be, but he’s Tibbits, just the same.”

“If he’s Tibbits, why did he tell me his label was Random?”

“Because that was part of the plot. By posing as Random, Tibbits knew he would have a lot more influence over you. He kept you from going to the bank, he accompanied you to the Flatiron Building, and he came out here with you. He might not have been able to do all that if you had known he wasn’t Random, and that he wasn’t interested in the ‘Pauper’s Dream.’”

The cowboy scowled, and drummed his fingers on the table. Matt helped himself to a piece of pie, and another glass of lemonade.

“Can’t you choke off, pard,” begged the cowboy, “and tell me how they played tag with you? Sufferin’ tenterhooks, but this business has got me all at sea.”

“I’m at sea, too,” said Matt, “but we’re pretty comfortable, so far, and I guess we can wait a little for the thing to work itself out. That’s the way with most mysteries. If you leave them alone they’ll solve themselves.”

“What happened to you? Bat it up to me!”

Matt recounted the manner in which he had been beguiled into the open country by the supposed messenger; and he told about the accident to the taxicab, the revelation that the supposed youth was a girl, the finding of the driver, the passing of the red touring car with McGlory in the tonneau, the work of Dimmock and Sanders, a mile west of Rye, and the journey through Connecticut and into Massachusetts, finishing with his meeting with McGlory.

The cowboy listened, spellbound.

“You’ve had the hot end of this, so far, pard,” said he, “and no mistake. But wouldn’t the whole game just naturally rattle your spurs? What’s the good of it? How are Tibbits, Dimmock, and the rest going to make anything by their work?”

“That’s where I’m muddled, too,” acknowledged Matt, drawing away from the table and resuming his easy-chair. “I think, Joe, that Tibbits, who seems to have been the one that planned this thing, has made an error.”

“That he’s bobbled, and thinks we’re some other fellows?”

“Not that, exactly, for they appear to know a whole lot about us, and our business. Where they’ve made their mistake, it strikes me, is in thinking that we’re mixed up in some affair we don’t know anything about. If that’s the case, then the fact will come out, before very long. All we’ve got to do is to wait until Tibbits comes for a talk with us.”

“I’m hanged if I want to wait!” fumed McGlory. “They’ve fooled us, they’ve got us here, and I’m a Piute if I’m going to stay!”

Jumping up, he ran to one of the two windows of the room. Pushing back the heavy hangings, he raised the lower sash. As he did so, a voice called up from the darkness outside:

“Git back in there, an’ close the winder! If ye don’t, I’ll shoot.”

The cowboy appeared dashed.

“You might have expected that, Joe,” laughed Matt. “You didn’t think, did you, that Tibbits would go to all[14] this trouble and then leave us free to leave the house if we wanted to?”

McGlory closed the window and returned dazedly to his chair.

“Sufferin’ poorhouses!” he mumbled. “I reckon they think we’re millionaires in disguise, and that our folks will hand over a lot of money to ransom us. The laugh’s on them, and no mistake.”

“Let’s take things easy,” advised Matt, “until we can learn more about the game the gang are playing.”

As Matt finished, the key rattled in the lock, the door was pushed open, and Tibbits entered. He had some wearing apparel thrown over his arm, and dropped it the moment he was inside the room. The door was closed behind him, by unseen hands, and again locked.

With an angry exclamation, McGlory sprang to his feet and started toward Tibbits. The latter, with a quick movement, brought out the weapon which Matt had already become acquainted with.

“Steady,” warned Tibbits, smiling, but none the less determined. “Let’s all be nice and comfortable,” he begged, “and no harm will be done. You lads are my guests. Consider yourselves so, and we’ll get along swimmingly. It was a cold supper I provided, but it was the best I could do, under the circumstances. If you——”

“See here, you!” shouted McGlory. “Tell me whether your name is Tibbits or Random.”

“Tibbits,” was the reply.

“And you haven’t anything to do with that brokerage firm in Liberty Street?”

“Not a thing. The first time I was ever there was this morning.”

“What did you——”

“If you’ll give me a chance, McGlory,” interposed Tibbits, “I’ll explain everything to the complete satisfaction of Motor Matt and yourself.”

“‘Complete satisfaction!’” muttered McGlory. “That means you’re to fill a pretty big order. But go ahead, Tibbits, and let’s find out where we stand.”

“Let me assure you, in the first place,” said Tibbits, still keeping his revolver prominently displayed, “that no harm is intended either of you lads. You are to remain here in these comfortable surroundings for a week. At the end of that time you will be released, and can make your way back to New York.”

“Guess again about that,” spoke up the cowboy. “There are important doings for me in New York Wednesday, and we’ll have to tear ourselves away from you by to-morrow afternoon, at the latest.”

“You’ve got to stay here a week,” insisted Tibbits.

“You don’t understand,” went on McGlory. “There’s a meeting at the office of Random & Griggs Wednesday evening, and I’ve just got to be there. That’s all there is to it.”

Tibbits fixed his glittering eyes on McGlory for a moment.

“That excuse won’t do,” said he. “You can’t make up a yarn like that out of whole cloth, and expect me to swallow it.”