PAM AND THE COUNTESS

PAM

AND THE COUNTESS

BY

E. E. COWPER

Illustrated by Gordon Browne, R.I.

BLACKIE & SON LIMITED

LONDON AND GLASGOW

(1920)

By E. E. Cowper

Gill and the Beanstalk.

Camilla's Castle.

The Forbidden Island.

Nancy's Fox Farm.

White Wings to the Rescue.

The Haunted Trail.

The Girl from the North-west.

The Mystery Term.

Ann's Great Adventure.

The White Witch of Rosel.

The Brushwood Hut.

The Mystery of Saffron Manor.

The Island of Secrets.

Pam and the Countess.

Jane in Command.

Maids of the "Mermaid".

Printed in Great Britain by Blackie & Son, Ltd., Glasgow

Contents

CHAP.

Illustrations

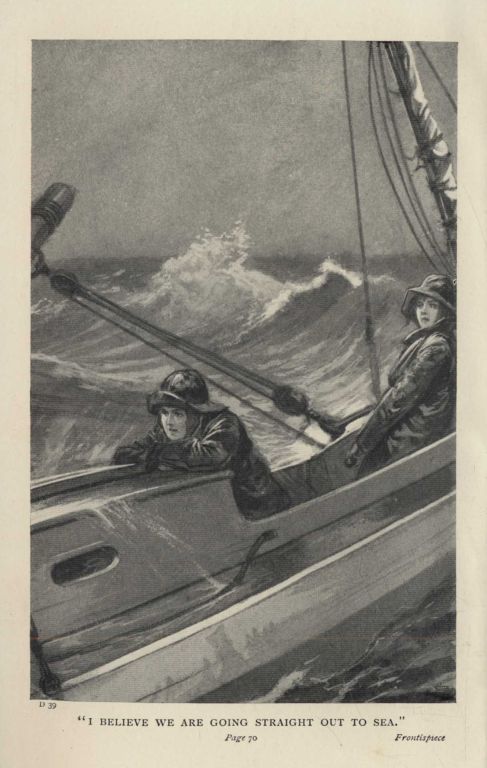

"I believe we are going straight out to sea" . . . Frontispiece

PAM AND THE

COUNTESS

CHAPTER I

In which Pam does a Good Deed,

and sees a Strange Thing

Pamela sat among the rocks with her elbows on her knees and her chin on her hands. In spite of the entrancing loveliness of her surroundings she had been reading with such interest that she had scarcely looked up in an hour. The book now lay face down on another round-topped rock, while Pamela stared at the sea, and thought about the contents of the book.

It was spring-time, and in spring Bell Bay was perhaps a thought more perfect than at any other time in the year. The wonderful little horse-shoe of its quiet haven was a jewel of colour in the dark setting of its cliff entrance. The semicircle of the high, rough stone sea-wall above the rock-strewn sands seemed to take on light from the flowering of the tiny rock plants, while the gardens at the Bell House behind that wall were just a mass of greenness and bloom.

Outside and above those gardens rose the sides of the valley, towering up into the blue of the clean, clear sky, and melting away into the woods inland. The bay was so small that the Bell House and its grounds filled the centre of it, as it were. There was no room for a "sea-front". No room for another house even--Bell Bay belonged to the Bell House.

Farther up the valley was Paramore's--the Temperance Tea Inn--to which parties came in the season by the one narrow road that ran along below the Bell Ridge--on the north side, that was. Farther still up the valley--also on the roadside--stood the tiny church, no bigger than a room, Fuchsia Cottage, where lived Anne Lasarge, and a few more cottages--not enough to make a village--that tailed away to Folly-Ho, a hamlet on the Peterock road.

On the south side of the valley--facing the long, grey front of the old Bell House--the woods fringed the heights like a green rampart. Just in one place glimmered the white walls of Crown Hill, the beautiful country place of Sir Marmaduke Shard, K.C.

That was all there was of Bell Bay--unless you count Mainsail Cottage, sitting like a gull's nest over the sea on the south headland, and Woodrising, the empty house so long "To Let", buried in dense woods right up at the back of the valley.

In the former lived Penberthy--pensioner--who looked after Sir Marmaduke's little yawl--the Messenger.

In the latter lived nobody but Mrs. Trewby, a caretaker; a mournful widow afflicted by bilious attacks, and living therefore in a cloud of her own creation.

Finally, as a last word in this explanation, the Bell House was the ancestral home of the Romilly family, and Mrs. Romilly was living there with all "the family" except its head, away in command of that first-class battleship Medusa; and her eldest son, Malcolm, who was busy as lieutenant on the destroyer Spite.

Now Pamela, already introduced reading a book among the rocks of this miniature haven, was absorbed in a new idea, of which the book was an outward and visible sign. Pamela was by no means a self-constituted martyr, but at the same time she believed herself to be a sort of "odd man out" in the family circle. She was thirteen--not even a long way on the road to fourteen. It must be allowed then that thirteen bore no comparison to Adrian and Christobel, who had reached sixteen and seventeen, or to Hughie, who was but seven. Malcolm, of course, was out of it altogether, being nearly twenty, and at sea.

Christobel was the one other girl in a party of five. She was undoubtedly Adrian's chum, and when he was at Harrow her particular friend and companion lived close at hand as a rule--Mollie Shard, that is to say, the only child of Sir Marmaduke and Lady Shard. Mollie was eighteen, Christobel seventeen and a half; Mollie exceptionally clever, Christobel exceptionally in earnest, and tenacious as her father, whom she resembled so closely that in babyhood she had been nicknamed "Jim Crow", being a darker edition of the elder "Jim".

Pamela's admiring affection for her one sister never failed, but it must be admitted that the gap between "nearly eighteen" and thirteen is considerable. Moreover, Christobel had been to school, the same school as Mollie Shard. They had left for good together this Easter, and Pamela hugged the thought that she was to share the same rule, going to school next Easter, when she would be fourteen, for four years. At the same term, Hughie would go to a preparatory school, and the reign of Miss Violet Chance, their governess, would be over.

That was how the matter stood; also, it was the reason why Pamela studied a Girls' Guide Handbook, with zeal that was seldom present in the case of Arithmetic or French Grammar. Her high aim--her secret ambition--was to become a Girl Guide, a "Silver Fish" with power to wear at least twenty badges on her sleeve, and, by the time she was sixteen, a Patrol Leader.

Pamela was bitten deeply by the thought of this wonderful army of girls, who could do practically everything possible for girls to do. But there was no chance of joining in Bell Bay. The nearest corps would be at Peterock, four miles to the north; or Salterne, the big town on the estuary harbour, eight or ten miles to the south. Mrs. Romilly did not know anything about companies and patrols, and did not like the idea of Pam getting mixed up with all sorts of girls. She knew about the ambition, but had asked for it to wait till her anxious daughter should join the school company at Somerton.

So there it was. Pamela meanwhile fought with difficulties. She wanted to learn to cook; Mrs. Jeep, who had ruled long years in the kitchen, would not let her. She wished to wash and iron; but Miss Chance thought it was not quite nice for her to associate with Patty Ingles--between maid--who did these things three days a week. It was tiresome, but had to be put up with. Pamela perforce spent her zeal on the book, and on making secret signs whenever opportunity occurred. She tried to fulfil Scout Law, including one good deed every day, and she tried to hide what she was doing from Hughie--which was impossible, as he possessed an uncanny power of seeing everything, no matter how carefully hidden.

With intent grey-blue eyes fixed on the distance, Pamela considered life as matters stood.

At that moment Miss Chance came up to the sea-wall from the garden, and called her. When she looked round Miss Chance asked questions. It was a way she had, and quite exasperating at times, because she seemed to have a perfect genius for asking questions to which answers were obvious.

"Isn't the sand rather damp, Pam dear?" she inquired in an even voice. "I think you ought to be careful about chills now we have so much influenza about. Are you reading? Wouldn't it be better to come up to the garden?"

Pamela answered neither of these questions, but she got up, stretched, and shook her skirt.

"The others are not back yet, are they?" went on Miss Chance, shading her eyes with a knuckly hand and gazing towards the shining horizon. "Why didn't you go with them, dear?"

Pamela said she wanted to read; then she came across the rock-strewn sand towards the rugged steps that led up to a gap in the wall, and as she came certain sentences in "The Knight's Code" repeated themselves:--

"Defend the poor, help them that cannot defend themselves."

"Do nothing to hurt or offend anyone."

"Perform humble offices with cheerfulness and----"

There are certainly moments when fulfilment is not easy----

"When do you suppose they will be back?" asked Miss Chance.

Pamela explained that there was a strong tide, and a light wind, but they'd said they would be back by tea-time--meaning six o'clock and solid high tea, not the afternoon variety.

"How tiresome!" exclaimed the governess, "I do wish they would hurry."

"You can't hurry sailing-boats," suggested Pamela patiently, as she went up the steps.

"I should have thought you could put up more sails, dear," said Miss Chance, who had spent none of her valuable time in mastering the intricacies of yachts and their habits, "it really is most annoying!"

"They don't know anybody wants them back before ten. I believe they've gone up to Peterock; the tide served--Penberthy said so--besides Salterne is too far; they didn't start till after lunch, you see, there was a lot to do at Crown Hill, Mollie couldn't come before."

"Your mother wants a message taken to the station about the stores she expects to-morrow," said Miss Chance, as they walked along the terrace, "they may come to-night by the 9.20 from Salterne. She wants them sent out specially at once, because there is too much, she thinks, for Timothy Batt; besides, his cart won't go to the station again till Saturday."

"Did she want Addie to go?" asked Pamela, waking to the situation. Then she continued quickly: "He won't want to go after tea, Miss Chance, he's arranged with Penberthy to do some painting on the yawl."

"He must put that off," said Miss Chance firmly.

"I'll go to the station--now, before tea," was Pamela's answer, "I cleaned my bicycle this morning. It looks smart enough to go out calling even on the station-master at Five Trees."

She said this so gravely that Miss Chance was a little uncertain as to whether she herself was not being laughed at. You could not quite be sure about Pamela, she was rather an inscrutable young person--tall and slim like her lovely mother, with a small face, a square chin, and firmly closing mouth. She owned a distinguishing nose also, very delicately modelled and turning up the least bit in the world. The family alluded to it as a "snub" at times, but there was nothing at all snubby about it, and it was full of character. For the rest, she owned a plaited rope of hair that fell below her waist, brown with more than a hint of red in it. Hughie was like her, but the other three followed rather faithfully in Captain Romilly's pattern, except that Adrian was on the way to be tall--had outgrown his sixteen-year-old strength, in fact, which was no doubt why the influenza fiend had driven him home in term time.

"Well," Pamela concluded with a question, "will that do?"

Miss Chance thought it would. Mrs. Romilly, finishing letters in a hurry for the 5.30 post, thought it would too. The stores were very important, as Mrs. Jeep was "out" of nearly everything that made life pleasing, and there was no fruit yet in the garden to help out puddings.

"Don't tire yourself, darling," murmured Mrs. Romilly, writing an address.

"I shan't be back by six o'clock, Mummy--at least most likely not--coming back is easy but going will be uphill most of the way."

"So it will." Mrs. Romilly spoke as though this was a new idea. Then she turned her head and smiled at Pamela with serene large blue eyes, "I dare say the Messenger won't be punctual," she said, "so the others will be late, and anyway, dear child, tea can be kept for you, so don't hurry--and thank you so much for going."

Pamela wheeled the bicycle up the drive into the narrow road that ran up and up close under a towering hill-side. All along it, hanging over the road, were banks of fuchsia trees--in summer the whole track would be a sheet of fallen fuchsia blossom. She passed the Temperance Inn on her right, then the church upon the height among the fuchsias, and soon after that the little fairy house called "Fuchsia Cottage", where lived Miss Anne Lasarge, the small grey lady called "The Little Pilgrim" by the Romilly family, because she was like a character in a book they loved.

Miss Anne had done wonders during the War; she had been out in the devastated regions of France working among the homeless peasants. She had only been back since Christmas. Pamela looked at the cottage as she passed. It was like a lovely toy--an ideal cottage--the atmosphere of Miss Anne made a distinct sense of peace cling to it all the year round. No one was in the garden, no one working on the three little terraces bright with flowers, that rose one above another to the lattice-paned bow window of Miss Anne's sitting-room.

Pamela was the least bit disappointed. There was perfect understanding between her and Miss Anne--who possessed a genius for understanding everybody, and everybody's worries. She knew that it was rather lonely to be a middle person in a family--cut off above and below. Pamela vaguely wondered where she was gone to; a natural conclusion being that some one must be ill in one of the farms.

Wheeling the bicycle on up the clean even road she left all trace of houses behind and came to the woods at the back of the valley. The road ran between an over-shadowing height on one side, and thick woods on the other--they bridged the centre of the deep to where the southern heights towered up, covered with more woods.

Presently a white wall began, and the trees behind it thinned a good deal. The wall was high and had broken glass along the top of it. There was a distinct suggestion of rebuff to an inquiring public. Pamela, looking at it, remembered Kipling's story in which "the invasion of privacy" is spoken of as a danger. In this part of the far west land there did not seem much need for walling yourself in, she thought. Moreover, no one lived at Woodrising but Mrs. Trewby the pessimistic caretaker, and it belonged to Sir Marmaduke, who wanted to let it, and had wanted to let it ever since he bought it before the War. There was the big square board--"To be let un-furnished". There were several boards at different points, but no one took the house. It required much money spent on the inside, and the large pretty gardens were neglected. No one worked in them but Peter Cherry, son of Mrs. Rebecca Cherry, the widow who ran the Temperance house in conjunction with her sister Mrs. Paramore.

As Pamela passed the big double gates in the wall, she glanced up at the house behind them. Little could be seen of it but slate roof and chimneys. It was a square, white house of moderate size; not pretty, but comfortable. There was smoke going up from four chimneys. Pamela noticed this as she noticed most things, and deduced from it that Mrs. Trewby was airing the rooms. She also decided that Sir Marmaduke must find the house--still unlet--a great expense. People said he had bought it because he did not want anyone in the valley of an uncongenial kind. He and the Romilly family owned the whole place in present circumstances. A third family--the sort that could afford a house and grounds like Woodrising, might be in the way! That is what people said; no one knew anything actually, because the great K.C. was not a man to confide his affairs to the general public.

Pamela, having glanced at the chimneys went on her way still alongside the white wall with glass on its top. She was walking in the road and some impulse caused her to glance back at the gates when she had gone some little distance. She could just see that one of them had opened inwards, and within the opening stood two people in earnest conversation. One was short and slight, the other was tall and leaned on a stick. The short and slight person was Anne Lasarge, her grey cloak and grey bonnet with white strings proved her; the other was Major Hilton Fraser, the invalided army doctor, lodging at Mainsail Cottage, with the Penberthys. He was lame from shell splinters in the thigh; also four years spent in Mesopotamia and front-line dressing-stations in France had left their mark. Major Fraser was the hero of the Romilly family; Pamela could not mistake his figure. The question was: what could he and the Little Pilgrim be at, meeting at Woodrising?

She paused to gaze, making sure. Then she went on her way, wondering and interested. Pamela was always interested; some people called her "inquisitive", which is not so pleasant an accusation to have tacked on to one! But she could not help herself, for it was that which her nose stood for, with its delicate, keen lines and sharp outline. Just inquiry and the liveliest intuition.

"I daresay they are in love with each other," considered Pamela, reviewing the situation mentally, "they ought to be, they've gone through a lot together, but what has Woodrising to do with it, unless they know somebody who wants to live there!"

This seemed to her a reasonable explanation. She decided that he had friends who wished to take the house, and he had asked Miss Anne to come and look at the rooms for him. He might find difficulty in measuring rooms perhaps.

All the same he'd better not have depended on Miss Anne for that sort of thing. "I'd sooner be nursed by that angel than any living soul," thought Pamela, "but I don't believe she knows about houses, and paint, and carpets. She's perfectly vague and unpractical about prices. He'd better have asked Miss Chance--or Jim Crow--she'd be better than anybody. I wish he'd marry Jim Crow, then we could keep a hero in the family."

Pamela sighed as she decided that there was no hope of this glorious conclusion to friendship. "It's a pity she's too young--but he likes her better than Mollie Shard."

She reached the top of the long hill at the back of the valley, and, mounting, began the easier part of the journey--down and up, down and up, over the loveliest scented moorland road--till presently she came in sight of the miniature railway station, looking like a good-sized hen-coop on its platform, and the shining rails stretching away north and south as far as eye could see, until the hills swallowed them.

Nobody was in the hen-coop. The booking office was locked. The person who did most things had gone off for some meal. There would be a train from Salterne through to Peterock at 6.45, and then the last one at 9.20. No rush of trains let it be said, as of course the up trains from Peterock did not count in this connection.

Pamela sat down on a seat to wait for a human being to appear. She hoped they would not be long, because she was hungry, but she was not in the least dull. She was always looking and thinking--years ago by instinct, nowadays with intention; it was part of the Scout training. She looked once at the shed of the platform opposite, then she shut her eyes and counted mentally how many posts supported it, how many scallops edged the roofing, how advertisements were hung within against the wall behind, and what they were all about. It was good practice. Anything could be used. The great idea, of course, was accuracy, and the power of noticing every detail in the quickest time. Pamela loved doing it, and she did not know yet, of course, that she had a special gift that way.

Time passed. At 6.30 a man sauntered into view wiping his mouth. Pamela went to him, and gave her instructions about the cases from London in a concise and definite manner. Then she hurried off to her bicycle, and made speed on the way home. She calculated that she should be back before seven; the sooner the better, because sun had set, and a veil of dusk was falling over the uplands--faint, sweet twilight.

Just at that moment the front tyre burst. There was a bit of broken glass on the road. As Pamela picked it up and threw it aside into the heather, she thought of Woodrising and that strongly-guarded wall--quite irrelevant, but better than losing one's temper. It was maddening, but there was nothing to do but walk home--about two miles from where she stood.

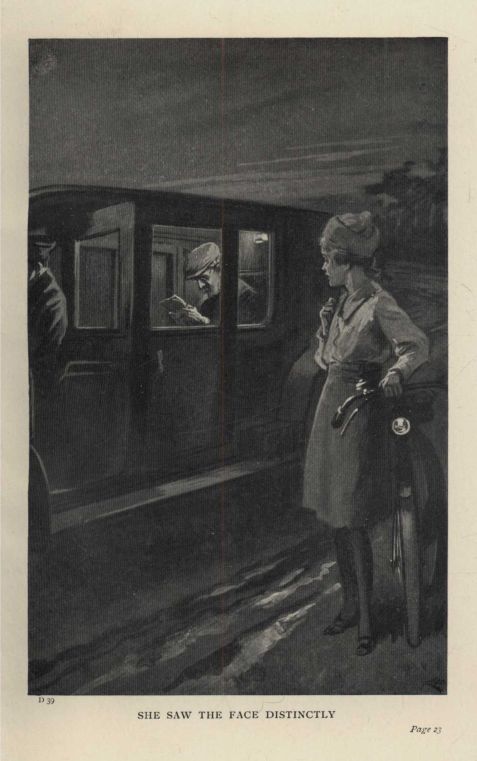

First, however, she made a try at mending the rent, and it was while she was at work--on what resulted in nothing but a waste of time--that a motor-car passed. It was a large car and strange to Pamela, which was not a surprising thing perhaps, though many cars paid visits in summer to beautiful Bell Bay.

The car was showing lights, and hummed past the girl at a good pace, but Pamela took in all details with her usual swift inclusion.

Luggage--a good deal. Certainly three people inside, and the window on her side closed. It was a large car, but, she felt certain, a hired one. The driver was no smart chauffeur, and the girl felt certain that no gorgeous private touring-car would have been allowed to carry miscellaneous trunks.

It was not the Shards' car. She knew that; it was a huge thing and painted grey; besides, the Shards would have turned off seaward earlier, for Crown Hill was reached by a road that went to Ramsworthy, the other side of the southern heights. This road was the direct route to Bell Bay, and though Peterock could be reached by turning off to the right lower down, any car for that town would have followed a straight line past the station and away northward.

Who could be coming to Bell Bay, then, in a big, hired car, laden with luggage, at that hour?

Now here was a mystery, and if Pamela could have imagined all that was to come out of it, she would have felt even more thrilled than she did.

CHAPTER II

Mollie Departs, but Comes Back

at Breakfast Time

Pamela failed to make anything of her repairing job, so, after fifteen minutes loss of time, she started off to walk it, wheeling the bicycle, for there was no place on the lonely way where she could leave it.

Dusk was now falling in earnest. Pam lighted her little lamp for company and made all speed. She had lost time over the tyre, but felt she was not far from home when the turn to Peterock was reached. From the top of this height now she could see over the long stretch of the Bell Bay valley, and the shimmer of grey sea beyond the trees--just a peep between the great headlands, Bell Ridge on the north above her home, and The Beak on the opposite side of the cove.

The evening was so still that the far-off mutter of the everlasting tide on the rocks came up to her. She lifted her head and sniffed the faint salt breath of the wind, and in that instant caught the throb of a motor. She checked and listened. Then went on again quickly. There was no doubt about it, a motor was coming up the long hill, out of the valley shadows. Then it must have gone to Bell Bay, for she was convinced it was the same car.

In a minute or two it passed her, going back to Salterne. The same car--big and dark, with powerful lights. The luggage was gone from the top where it had been placed, protected by a low fenced enclosure. Pamela saw all that at a glance, but her attention was centred on the occupant of the car--there must be someone inside there still, because she could see an electric lamp alight within the carriage. She stopped at the roadside, waiting for it, and as it went by fixed all her attention on the person who was reading a newspaper by the light of the brilliant lamp on the wall.

She saw the face distinctly--clean shaven, the powerful heavy features so often associated with great lawyers. He was reading intently, and his soft hat was pushed backward from his eyes. Pamela opened her lips in a little gasp of astonishment. The last person in the world she had thought of!

It was Sir Marmaduke Shard. Alone. But he had not been alone when the car passed her the first time.

Pamela stared after the receding car till it was lost in the dusk; then she went on again at her best pace, very much surprised, for it would really seem that the great Sir Marmaduke had actually brought someone to Bell Bay, left them behind somewhere, and gone back to Salterne. It really was exciting, because there was nowhere to come to except his own house, and had he been going there he would surely have chosen the direct road.

Moreover, to leave again at once, like this! Pamela could find no answer to the riddle.

When she reached home, nobody questioned her lateness, because they were all, so to speak, rather busy being low-spirited--a condition that nearly always takes people's attention off others.

Poor Adrian was very sorry for himself; very sorry indeed; and there was much excuse for him. It seemed likely that there would be no more sailing in the beloved Messenger.

Christobel, on her part, was passionately sorry for Adrian. She understood fully what such a blow meant to him who found more delight in sailing than in anything else in life.

Mrs. Romilly was grieving for both of them, but as usual was most absorbed in trying to think of a way out of the wood, and how to substitute something that would do--nearly as well.

Finally, there was Miss Violet Chance--nicknamed the "Floweret" in happier moments, by the way--who paralysed Mrs. Romilly's efforts and made matters worse by bright endeavours at dispersing the cloud.

"After all," said the Floweret, "what is a yacht? Surely we can find something quite as jolly! What about rounders? Wouldn't it soon be good weather for croquet?" She suggested to Adrian a collection of moths, and asked him where he had put the stamps he had been so proud of the year before last?

Adrian said:

"I've got them all, thank you, Miss Chance," in a voice that went to Jim Crow's heart, because the suppressed torture in it was so acute.

Because, then, this gloomy company was assembled in the drawing-room, Pamela found no one about, and going straight to the dining-room proceeded to make a good tea; and Hughie, hearing her come in, entered on the tips of his toes, sat down at a distance on the big leather sofa, curled up his toes under him--till he looked like a small soapstone "god"--and waited patiently.

"Why aren't you in bed?" asked Pamela, as she helped herself to some fresh cocoa brought in for her.

"It isn't eight," said Hughie.

"My dear child, it's ten past!"

"Well," Hughie glanced at the clock unashamed, "they've forgotten me, you see. That's why I came out here, for fear they should remember."

"Miss Chance won't forget," warned Pamela with conviction.

Hughie set that aside.

"They are in a state of miserableness, so nobody is remembering things," he said, "it's rather beastly, Pam, they can't sail the Messenger any more----"

"Who can't?" interrupted Pamela sharply, pausing with a glass of potted meat in her hand.

"All of them--Mollie, and Jim Crow, and Addie, and the worst is that Addie will be cross most of the time now, which is a fearful pity; he won't help me do my rigging, because it will remind him of the yawl. It's most unlucky for everybody."

"Why can't they sail the Messenger any more?" asked Pamela, going on with her supper. The thought flashed through her mind that the sudden and brief appearance of Sir Marmaduke was going to be explained simply.

"Because the gardens at Crown Hill are in a mess," Hughie went on with slow emphasis, "they are in a fearful mess, and everything is growing too fast, and Mr. Jordan can't do it, and there aren't any men, because they're mostly dead in the War. Miss Ashington says Penberthy has got to go in the gardens the whole while. Not a minute on the sea--and you know they can't go without Penberthy, Sir Marmaduke won't let them."

"Beastly hard luck," said Pamela firmly.

"I expect it's Fate," Hughie suggested thoughtfully.

"Why can't they have Peter Cherry from Woodrising?" said Pamela, ignoring fate.

"It isn't any good asking me," answered Hughie, "because, how can I tell? But anyway Woodrising is simply bursting with weeds, and the more there are, the more they come. He must stay and pull them out, and plant greens for Mrs. Trewby. She eats greens, she told Mrs. Jeep she has to. He can't possibly go to Crown Hill, and Miss Ashington is worried about the garden, Mollie says she is."

The door opened and Miss Chance looked round the edge of it.

"Ah, there you are, little runaway!" she said with her usual sprightliness, "I've found you."

"I wasn't lost, Miss Chance. I was only talking to Pam," remarked the little runaway, letting himself drop over the back of the sofa in an ingenious and complicated manner.

Miss Chance turned her attention to Pamela.

"You've come back, dear," she suggested, "I hope it's all right about the Stores' cases; Mrs. Jeep will be so glad to have them."

Pamela explained her accident, mentioned that she had been obliged to walk back, and gave the message from Five Trees, namely, that the cases had not come, but should be sent on at once when they did. She added that she was just going in to tell her mother. She said everything she could think of to forestall the inevitable questions, and good Miss Chance swept Hughie away to bed, remarking that it was late, but that the days were getting longer, and the summer would soon be here.

"That's what will make it harder for poor old Addie, about the yawl," thought Pamela, as she got up from the table, and departed for the scene of woe. She was very glad that Hughie's information had "put her wise", as the folk of the far west say--it would have been so galling for Adrian if she had plunged in, and asked what the matter was to start off with. That was Pam's way of looking at it.

So she gave the story of her mishap; said she would have to send the bicycle to Salterne, it must go in on Saturday by Timothy Batt's cart; gave her message about the stores, and made talk of a mildly distracting nature.

Adrian was gloomily turning a magazine; he looked up.

"It's all knocked on the head about our sailing, Pam," he said, "pretty rotten! Fancy having to see the old Messenger moored out there the whole blessed summer, and have nothing but our dinghy to go out in! It's enough to make a person of sense commit suicide."

"Hughie told me something when I got in," said Pamela with sympathy, "I was awfully sorry; he said Penberthy is wanted at Crown Hill. Of course the gardens are too much for Jordan--there used to be three men."

Adrian muttered something biting about gardens generally.

Christobel broke in.

"Mollie told us--she is most horribly disappointed herself--it cuts off her fun too, but she says the gardens must come first, as Lady Shard hates seeing things go--as they are; and men are so scarce, they want every creature they can get on the farms, of course. Oh dear, I wish one could get at Sir Marmaduke, he's always nice about the yawl."

"Why don't you ask him yourself?" suggested Pamela.

Both the others began to answer together in their eagerness; then Christobel dropped out, and Adrian went on.

"How can we, my good child? We can't exactly write letters to him asking him to hand over his yawl to us! As for talking, we shan't meet till goodness knows when--August at earliest."

Pamela suggested cautiously that Sir Marmaduke usually came for week-ends in the summer.

"Well, he may have, once in a way," allowed Adrian gloomily, "but he won't do it this year. Not a dreg of hope. He hasn't been down, and he's not coming. Government has put him on one of these hundred and fifty thousand commissions about miners' bath-rooms, or railway men's sofa cushions! It makes one ill. I wish the whole lot were at the bottom of Vesuvius. We can burn wood, and drive coaches, and go back to decent life. Anyway there it is. We can't get at Sir Marmaduke. Penberthy has got to do gardening----" his voice ceased in a sigh that was a positive groan.

"One would almost think you three--I mean Mollie and Crow and you--would do as well without Penberthy," said Pamela, "Penberthy does nothing ever but talk, does he? Mollie is as good as any man, she's pretty well trained her muscles on the land--and all that----" this was an allusion to the heroic efforts of Miss Shard on the Ensors' farm at Hawksdown during the holidays of two war years at least.

"Of course she could, Pam," Christobel interrupted hastily, noting Adrian's rising irritation, "but you see Mollie won't be here either."

"Mollie not here!" Pamela's face of startled dismay was satisfactory to the distressed pair.

"You see," said Adrian, "things have pretty well tumbled about our ears this afternoon! Well, the bottom has been knocked out of the whole show."

Pamela looked from one to the other, she did not ask another question, but her expression did, so Christobel answered:

"Mollie is going up to town this week-end to see her mother about crowds of things. She believes they've taken a cottage on the river just for--well, airing themselves. Mollie says Crown Hill is too far to come for week-ends; it is a long way, we know. If they have a cottage they can live out of London, and he can go up--I mean Sir Marmaduke can; he can't get down here, Mollie says--not yet anyway. The only person who will be here much will be Miss Ashington, and she'll look after things for Lady Shard, who says she can't possibly live here and leave Sir Marmaduke in London; besides she wants to present Mollie."

"Present Mollie!" echoed Pamela with awe. The world was simply changing swiftly.

Mrs. Romilly folded the paper she was reading, and said in her even, restful voice.

"I should have liked to have presented Crow at the same garden-party as Mollie, but it isn't convenient this year, so we must wait till next summer."

"When Hughie and I are at school," suggested Pamela, a little smile quivering round her firm lips.

Her mother's eyes smiled back sympathy.

"It's unlucky for Mollie and Crow not to be together," she said, "but of course Lady Shard wants Mollie and of course she can't leave Sir Marmaduke alone, so we others must e'en put up with it all. Something will turn up presently. I feel it in my bones," said Mrs. Romilly, "and meanwhile don't let's cross bridges before we come to them. I know nothing will be as bad as one fears, it never is."

She looked at Adrian, who made no response.

"Let's hope," said Crow.

"Has Mollie gone?" asked Pamela, suddenly thinking of an explanation for the motor-car. She put her foot in it, of course.

"My good girl, do have a grain of sense," begged Adrian, "how could she be gone, when she was out on the Messenger with us till nearly seven o'clock?"

"She goes to-morrow," explained Christobel, "not finally of course. She comes back about Tuesday--she's got to pack and take up things Lady Shard wants, you see. Then she'll go for good--I mean for about six weeks--after that."

Pamela made no comment. She was trying to fit that car piled with luggage into this sudden development of Bell Bay doings. Hitherto, the great K.C. and his wife had been to and fro constantly winter as well as summer. Miss Ashington--commonly called "Auntie A.", as her name was Adelaide Ashington--had been in residence nearly always. She was Lady Shard's sister, and a person positively made up of schemes--which never seemed to come off, and were, as a rule, dropped in favour of something more arresting. At present, the farming problem was her hobby, and she was full of an idea for milking cows once a day at eleven o'clock in the morning, so that land-girls need not get up so early, and farmers could do with less labour. The trouble, though, seemed to be that the cows would not agree to this excellent plan. However, Auntie A. did not despair of bringing them also to a sense of duty, and meanwhile she stayed at Crown Hill doing no one any harm, which was something to be thankful for.

It appeared then a settled question that the Shards would not come to Bell Bay until summer was well nigh through. Penberthy would no longer be available, and the lovely yacht would be on her moorings--useless to the Romilly party. It certainly was a sorrowful outlook for Adrian. As Christobel said afterwards to Pamela: "If Addie had never been able to use the yawl almost like his own it wouldn't have mattered." But he had; and of course nothing could make up for it.

Pamela thought that week-end was one of the most dismal she had ever spent. Indeed it was so gloomy that she forgot about the motor-car mystery and surprising visit of Sir Marmaduke; all her mind and efforts--hers and Crow's--were spent in trying to devise a new and interesting way of passing time. Mrs. Romilly was willing to fall in with any plan, even to the extent of hiring a sailing-boat of a size suitable. She was ready to suppress her own feelings in the matter--they would have been distinctly anxious--and let Adrian go to Salterne and find something; an open boat with a sail.

However, on Monday, Adrian, as his manner was, shook himself free of this weight of care and announced that no one was to bother about him and his needs. The dinghy--which was bigger than the average dinghy carried by an eight-ton yacht, and which belonged to the Romillys--would do well enough for fishing, he said. And for the rest, he had made various appointments with John Badger of Champles--the farm on the Down above Bell House--connected with rats and young rabbits.

"Besides the lawn must be kept decent," he concluded; which was his way of saying that the ancient gardener, "Hennery" Doe, could not be left to bear what Mrs. Jeep called "the blunt" of the Bell House gardens.

So content was restored, and Mrs. Romilly wrote to her husband that "the children were perfectly sweet"; they were certainly of the kind that has a sense of responsibility very much awake.

On that day--Monday--Miss Lasarge came down to the Bell House, stayed to tea, and was a joy to everybody--especially Hughie, who adored her--but it struck Pamela that she was a little less talkative than usual; perhaps even a little absent-minded. She went away early and said she had gardening to do.

Nobody noticed this but Pam, and she, sitting at her window in the evening looking straight across the sea-wall, the rocks, and the tide rippling out over the golden sand, decided that the Little Pilgrim was in love with Major Fraser. "Why don't people settle things comfortably and be done with it," thought Pamela vexedly. "They are both nice, and they could live at Fuchsia Cottage."

On Tuesday morning, so early as the nine-o'clock breakfast hour, came a surprise.

It had been raining in the night, and was still drizzling, with an inclination to clear up, when Mollie Shard burst upon the scene in an atmosphere of wet wind and scent of salt.

She had not had breakfast. It appeared that Auntie A. was not down, and as Miss Shard had something to communicate that refused to be kept back till conventional hours she had left Crown Hill, in a "trench" coat and no hat, racing down to the Bell House to see her friends, and tell her tale.

Everybody was down and beginning, except Pamela, and the conversation was a perfect rattle of questions and answers.

"Suppose," said Mrs. Romilly, "you let Mollie tell us what she has been doing."

Mollie explained that what she had been doing was entirely uninteresting. It was only what she expected--a little house on the river near Weybridge. "Yes, the usual little cottagey thing--with a lawn." Mollie liked it, and anyway it had to be because Dad couldn't leave London for ages. "It'll have to be put up with," said Mollie, "one must look forward to better times," but it seemed that was not the matter that was causing all this bubble of excitement and beam of smiles.

"Addie, I've got a message for you and Crow from Dad. Very special. You can have the Messenger to play with, till he wants her."

"We can!" gasped Christobel.

Adrian murmured "My hat!" and flushed red all over his tanned face.

"Yes. That's why I came bursting down, because why shouldn't we go out to-day? Do let's. I've got to do reams of packing, and I'm vowed to go back with the goods, next Monday. Mother lets me off till Monday. Well, anyway Dad says he sees that Crow and Adrian can manage the yawl just as well as he can, and he trusts her to you--only he says if you wreck her you'll have to give him another--that's all. Of course he knows Penberthy isn't vital. Especially when he has lumbago. She's not a heavy boat, and yawls are awfully convenient, Mrs. Romilly--aren't they, Addie?"

"Rather," agreed Adrian ecstatically; his hands shook a little with the thrill of the moment. Crow's grey eyes, so like her father's, seemed to shine with an inner light.

"Well, then, that's all settled. No, don't thank. Dad hates Messenger being on the moorings, just wasting. Hullo, here's Pamela, just in time to join in this jubilee. I say, Pam, why didn't you stop when I called you?"

Pamela slipped into her chair, took an egg, realized the amazing news from a few words of Crow's, looked from her mother's happy face to Adrian's, then attended to Mollie's question.

"How do you mean--'stop'--stop when?"

"Why, just now--when I was coming down the bay drive from Crown Hill, I was nearly at the end lodge, and you came down the road from Hawksdown, went to the edge of the cliff above Penberthy's and stared down into the cove. I called out to you, but you wouldn't answer, you must have heard."

Everybody looked at Pamela, who went on eating her egg slowly.

"It was my wraith," she said, "it wasn't me."

"Jolly solid wraith," declared Mollie, laughing.

"Well, but where did I go?" demanded Pamela, half laughing. "I mean, where did you think I went?"

"Don't know, my dear; I lost sight of you. It's for you to say where you went."

Pamela shook her head, and helped herself to marmalade.

"Well, it wasn't me," she repeated.

"'I', Pamela dear, 'I', please," put in Miss Chance urgently. And everybody laughed.

CHAPTER III

In which Hughie is Ill-used

Some days after that joyous breakfast--Mollie being deeply engaged in the arduous duty of packing--the Romilly crew took out the white yawl in force.

Jim Crow was admittedly skipper. She was the eldest, and had a "sailing" bent undoubtedly. Captain Romilly, in training his family to understand the true inwardness of boats, had discovered the natural gift in his elder daughter. Adrian loved it--and loved the sea, but he was going to be a soldier in due course; Crow and Hughie were following faithfully in the Romilly record.

On this warm still evening--for the day was drawing to a close--Messenger floated lazily on a heaving oily sea. The sky was full of brassy clouds that seemed to have a copper lining; these, drifting, with scarcely perceptible movement, from the north and east, formed rather a serious barrier to getting home, because, given a good strong tide running out also, what is the cleverest yacht to do?

Earlier in the day, with mainsail set as well as mizzen, with big jib ballooning out in fine style, in fact, looking exactly what a well-kept yawl should look, Messenger had gone away down to the southwest straight before the wind and with the tide. The skipper had acted on a sound principle in this; but she was not very sure of her tides, and, having decided that the tide should be in their favour for the homeward run, was now disturbed and puzzled to find it had not turned yet--and the hour was six o'clock or after.

"Of course," said Pam, leaning with her head back against the deck-house, "of course that was where old Penberthy came in. He didn't do anything. He was fearfully lazy, but he was a perfect clock for tides."

"So shall we be, soon," murmured Adrian peacefully from under the brim of a battered hat, "but anyway what does it matter! We shall be home some day. Great Scot, isn't this A1!"

"It would be if I wasn't afraid Mother would worry. It's our first day without anybody, you see----" Christobel suggested this in an apologetic tone.

"My good Crow--what do you call anybody, might I ask? Old Pen was simply luggage. And Mollie is only one more hand, naturally. I mean she couldn't effect a rescue if we went to smash, could she?"

"Of course not, but Mother----"

"Mother is full of sense," said Adrian with decision, as he sat up and looked about appreciatively. "I never in all my life saw anything more perfect than the colours on the old Beak and Bell Ridge. I wouldn't have missed this evening for--well--really, Crow, what does time matter? It's as calm as a plate."

That was true, but the skipper's eye glanced uneasily towards the dipping sun.

Hughie, sitting as usual like a small image of contemplation in a comfortable corner of the well, had said nothing, but listened to the argument.

"If I was at home I could say to Mum there's no wind," he suggested.

"But you're not at home; the Floweret can say so," said Adrian.

"She won't. She'll say 'dear Mrs. Romilly, don't be anxious'," remarked Hughie with grave assurance.

It was so very true that the elders looked at each other and laughed.

Then Christobel said humbly:

"It's all my fault. I made sure the tide turned in our favour at five o'clock. That seemed to give us heaps of time to pick up moorings and make all snug by half-past seven."

"For any sake, Crow, don't be in a repentant mood," urged Adrian, "the tide is keeping a pleasant surprise up its sleeve. At present it's pretending it never comes in at all! Keep it in a good temper whatever happens. It will get tired of the merry jest in two jiffs and remember how jolly and warm the little bays are all along; then it'll go home in a hurry! Oh, I say--what a coast this is! I don't believe you can beat it round England anywhere."

Adrian thus refused to be roused into worry, but Pamela was sorry for Crow. Crow had such a terribly tender conscience! She pulled herself together and sat upright with a decisive little movement.

"Give me the dinghy," she said, "and I'll go ashore and carry a message. Then, when you get back, the boat will be in the cove all right to take you off. There's no difficulty about it--it's as simple as--as anything."

"Pam, it's three miles! You can't possibly----" Christobel objected.

"Oh, my dear--it isn't. Not nearly three miles even from Bell Bay. What are you thinking of? I don't believe we are a mile from the Beak. It's nothing of a row. Just look----"

Christobel looked. First at the big headland, then at Adrian, who had made no comment.

Pamela went on explaining her plan.

"Suppose you make a little tack in towards Ramsworthy and the lighthouse. That will bring us quite near the easiest side of the Beak. Then Hughie can come with me. I'll land him and he can go up the sloping part into Ramsworthy, over Hawksdown, and into Bell Bay as quick as he likes--how far is it? Only about a mile and a half. I'll row the dinghy along the shore. We'll just see which of us gets back first, won't we, Hughie?"

"I shall," answered the small person without hesitation.

"Depends on the tide," said Pamela, "if it turns pretty quick, I shall."

"My young friends, you are both in error," Adrian stretched amazingly as he spoke, "we shall--if the tide turns. You others won't have a look in."

"Well, if you do, you can pick up the moorings and wait for me to fetch you off. And anyway Mother will see you from the windows so she will be comfortable, and everybody will be comfortable," was Pamela's conclusion of the whole matter, as she got up.

Christobel was not satisfied, though she had acted on the suggestion of a tack in the direction of Ramsworthy Cove, to the right of the Beak head--looking at it from the sea.

"I don't like to think of you and Hughie going ashore--all that way--alone," she said.

"Crow, you are hatching difficulties," retorted Pamela, "what else can we do? If Addie puts us ashore he'll have to leave you. Ought you to be left all alone on the yawl? What do you think, Addie?"

Adrian cut the Gordian knot by a new division of labour and a very decided opinion.

"Mother wouldn't like you and Hughie to go home--I mean, go ashore, from here--by yourselves. We know she wouldn't, so it's no use arguing. I vote Pam stays aboard with Crow while I put Hughie ashore at Ramsworthy Cove. Hughie can cut away home over Hawksdown, and race us, because the tide's turning already. When I've put him out I'll come back here. That's all about it, come on, youngster."

Pamela was disappointed, but she said nothing. A sailing boat in a calm is deadly dull most certainly, and Pamela objected strongly to dullness and monotony. Her inquiring mind was always seeking new interests, and she loved surprises--she was always trying to surprise herself, in small ways. The idea of rowing Hughie ashore and then going along round the headland to Bell Bay had appealed to her desire for adventure. However--of course Adrian was right, Mrs. Romilly would not have been pleased at such an independent excursion on the part of her younger children.

The dinghy started, and the mile of sea between lazily floating Messenger and the shadowy bay beyond the lighthouse point was quickly crossed. Adrian came back as quickly, and, as he sprang aboard and bent to tie up the tow rope, announced that the tide was flowing strongly.

"Wind or no wind," he said, "we shall get back before old Hughie. What a rum thing it is how that always happens. As long as you wait--you don't get it. Start doing something else, and there you are! Moral is--never wait. Always do something else. May as well tack, Crow--here's the wind too; breeze getting up with the tide of course!"

So the white yawl, leaning over very gently, gathered speed, and skimming through the smooth placid sea, made two tacks and picked up her moorings easily in half an hour.

The interest of this event is--what happened to Hughie, the human messenger.

Hughie, silent at all times, and almost as keen an observer as his sister Pamela, said nothing when this arrangement was made. At the same time he was well pleased to be put ashore with the responsibility of this small excursion upon his own shoulders. It was an adventure, and to Hughie, whose imagination was riotous, it might lead into all kinds of strange happenings.

Adrian landed him in the tiny cove beyond the great headland, on the point of which was a kind of fortress, walled and powerful--the barricaded strength of the lighthouse, which faced Atlantic gales through weather indescribable.

Outward and inner walls were white; all the low strong buildings were white, and the tower itself stood at the outer guard, smooth, round, and amazingly strong. Looking up at this as they rowed in Hughie felt a thrill--next to being a sailor like his father, he would have wished to be a lighthouse man--but this was a secret.

In the steep little cove lay the scattered bones of an old ship; weed grew in the staring ribs, and the massive keel was sunk deep into the sand. This was nothing new. The wreck had been there many years; it was that kind of thing that made Government build such a lighthouse. The Beak in old days had been one of the most relentless murderers of all the western headlands.

"There you are, old chap. Cut along home now, and tell Mother we'll be there before you," instructed Adrian as he pushed off, looking behind him as he went.

Hughie nodded, picked his way over the strewn wreckage, and went up the broken sloping steep at the back of the cove till he reached the road on the top. This went from the small village, Ramsworthy, over Hawksdown--which was the bare lovely height on the moor above the lighthouse--and down into Bell Bay. Several roads branched off; one went along the point to the lighthouse settlement; one led away back across Ramsworthy moor to the station at Five Trees. Yet another went to Clawtol, the Ensors' farm, and on past that and the principal lodge of Crown Hill to join the main road from Salterne.

This was the way Pamela's mysterious motor-car should have come, had it been behaving in a reasonable manner.

Hughie ran and walked alternately till he reached the top of Hawksdown. Then he stopped to look round. The sun was dipping into the sea--far, far out. Here and there upon the sea was a sailing vessel, looking like a painted toy. Not distant a great way from the lighthouse was the Messenger, a glistening model of perfection, with her white sails drawing on this new breeze that rippled the water.

Hughie, gazing at the straining sail and the ripple, saw that they would get home first if he waited, so he started off at a trot, making quite straight across the moorland for the drop into Bell Bay between Penberthy's cottage and the Crown Hill gate. It was the shortest way home.

The sun had gone into the sea, and a purply shadow was creeping over the land--the whole world was a happy hunting ground for adventures, and Hughie would have asked nothing better than to follow one of the farm tracks and go on till he met something surprising. At the crossroad to Clawtol Farm he paused, and looked along it because it was pretty. It dipped away from the high pitch of the moor and went down and down between banks covered with gorse and heather. It was sheltered as well as pretty, and was one way to Bell Bay, of course, though roundabout.

Hughie, stopping to look along this road, saw something immensely surprising--about the last thing he dreamed of--indeed a dragon or a giant would have been less astonishing, because he was always expecting creatures of that kind. What he saw was his sister Pamela. She was walking rather slowly between the gorsy banks in the direction of Clawtol Farm. Even as he looked, she paused, went up the left-hand bank two steps, picked some flower, jumped back into the road, and walked slowly on.

Hughie stared at this vision. At first in unbelief; then with a rapid calculation of time; then in amaze. It certainly was Pam; but she must have been amazingly quick to get up there, though it was possible--well, of course it was possible, because there she was! His mind reviewed rapidly the idea that Addie must have gone back very quickly and taken Pam off at once, and put her ashore on the home side of the Beak--you could climb it, but it was an awful bit of cliff. Altogether that explanation did not appeal to a reasoning mind. Then he remembered the ripples on the sea, and the straining mainsail of the yawl as she gathered speed on the homeward track. Of course that must be it. The Messenger had picked up her moorings and they had put Pam ashore to come up and meet him, while they stowed the sails. That was what would have been done--supposing they reached home first. Hughie concluded that he must have taken too much time over his journey--it was a most annoying conclusion to arrive at. Hughie shouted with vigour:

"Pam--I say--Pam!" and then stayed to watch the effect.

The tall, slim figure in neat skirt and jumper--such as Hughie connected with both his sisters--went on at a steady pace. It seemed that the headgear was a cap of the tam-o'-shanter kind. Pamela had one undoubtedly, but her small brother could not quite remember whether she had been wearing it this afternoon. Most likely she had. Anyway, the long, thick plait of polished hair was very obvious, hanging to the waist-line and below.

"Pam!" he shouted again, with greater energy.

The girl checked. She looked up and round, but not back. She seemed by the movements of her head to be listening.

"Hullo-o-o!" hailed Hughie, with force.

Pamela stood still with a startled pull-up, and turned round and glanced behind her. Hughie was conscious of surprise at the way she did it. He could not have explained clearly perhaps what it was that shocked him just a little in his sister's manner. His feeling was instinctive only.

She acted in a guilty manner.

Now this sort of thing was not only foreign to Pamela, but to the entire Romilly family. They did unexpected and independent things at times, of course--and explained afterwards. They did not do things they were ashamed to own up to, which was what Pamela appeared to be guilty of at this moment. Hughie flushed at the thought of it. Why was she running away; why wouldn't she make a sign?

He raised an arm, waved it round his head and started to catch her. She seemed to hesitate. Then she also distinctly made a gesture of the hand, and ran too. Away from him--in the direction of Clawtol.

Hughie had not a chance when Pamela ran. He knew that by long experience. His sister was a real "sprinter"; her long legs, light body, and excellent "wind" left him nowhere every time. At the same time he had no intention of giving in, though he was angry. It was a mean thing to do; especially after she had seen him and answered his wave.

He ran on steadily, though he knew the distance between them must be increasing fast, till he came in sight of Clawtol ricks and roofs, and the hedge-row fencing that began at the turn of the road. The dog was barking monotonously in that maddening way tied-up dogs do bark when anything interests them, and Hughie reasoned that the dog had heard Pamela run by along the road.

He stopped at the gate to see if there was a person about, and became interested in the distant doings of Mrs. Ensor, who was trying to induce several families of chickens--thoroughly mixed up among themselves--to go to bed in correct parties. The open coops stood in a row; Hughie looked through the gate, as it was a high one, and observed the manoeuvres.

Mrs. Ensor was a short, dark woman, with pretty eyes and a distinct moustache. Besides the moustache she owned six little boys, in ages ranging from eight down to eighteen months. This last--an important member of the Ensor family--was staggering about among the rebellious chickens, like them, he had no particular bed-time, and fought against it whenever it was decreed. As Hughie watched, drawn away from his intention of questioning Mrs. Ensor about Pam, a small pig charged through the mêlée, upset the Ensor baby, scattered the chickens and caused an uproar that brought more little Ensors to the scene of action.

One of these saw Hughie, and pulled his mother's skirt to make her notice the visitor. Hughie therefore pushed open the gate, and advanced rather gingerly, because the noise was deafening and Mrs. Ensor was shaking the baby--as an example to its brothers of what happens when people are naughty enough to fall over a pig.

"Mother," urged Reube Ensor, who was six, and very small, "here be Master Hughie."

The tumult ceased as by magic, and Mrs. Ensor advanced to meet her visitor, with the baby surprised into silence.

Hughie shook hands politely. Then he asked if his sister had just been to the farm.

"I thought I saw her," he explained, "she was in the road, and I thought she might have come up for eggs."

This idea had occurred to him when he saw the hen-coops as a very possible explanation for Pamela's conduct. Her gesture to him might have meant that she was going on to Clawtol Farm in a hurry.

Mrs. Ensor had not seen anybody. Miss Pamela had not called for eggs. She turned to the row of listening little boys and demanded of them, "had anybody seen Miss Pamela?"

There was a certain amount of whispering and nudging, from which the farmer's wife seemed to gather that Pamela had been seen. It was "young Reube" who volunteered information, twisting his cap round and round in very small nervous hands.

Hughie looked at him with shy sympathy. He liked Reube, but could not explain why.

"Did you see my sister?" he asked gravely.

"Yes, I seen the young lady," admitted Reube.

"Where did she go?" asked Hughie again.

"She went down along Crown Hill. She was running."

That was all Reube said, or knew apparently. As he gave this answer he looked from Hughie to his mother with a puzzled expression which neither interpreted to mean anything but shyness.

"I think I'd better go home now, Mrs. Ensor," said the visitor rather ceremoniously. "I shall be rather late for our tea, shan't I? I expect my sister has gone to Crown Hill to see Miss Ashington, so I shan't go that way--it's much longer."

Mrs. Ensor and family--with an inquisitive escort of chickens and little pigs--came to the gate with Hughie and let him out.

"Good-night, Mrs. Ensor," said Hughie, and lifted his cap with precision.

Young Reube stood in the background with a troubled expression on his small dark face. After Hughie was gone he ran about and drove chickens into coops, but all the while there was a sense of confusion in his mind, because he had no power to explain--words do not come easily when you are six!

Hughie raced back along the road to the top of Hawksdown. From there it was not very far to the drop of the hill down into Bell Bay. At a turn he came in full view of the lovely cove, and paused to look for the white yawl. There she was on her moorings. Sails stowed too, and he could see someone getting out of the dinghy on to the big flat rock where they usually landed. There was not enough light for him to distinguish persons, but seeing the Messenger was safely back home nothing else mattered.

He took to his heels and ran headlong down the steep road, past the lodge gate of the cove road. To Crown Hill, round the corner, down, and down, till he came to the sea-wall and gardens of the Bell House; and as he ran he became increasingly angry, which was a rare state of mind with Hughie. He considered himself swindled. He had been put ashore on purpose to carry a message, and had felt the importance of the trust.

It was a small thing that the yawl should be home first, though, as he had seen the dinghy coming ashore that would not have happened had he not been tricked into turning aside by Pamela.

The thing was distinctly unfair. Pamela, his partner in many interesting episodes, had gone back on him in this, she had treated him meanly and put him in a silly position.

CHAPTER IV

In which Pam Makes a Move

The first thing people said to Hughie was, of course, "What a long time you were!" It was exactly what he expected, and he felt extremely bitter about it.

There was supper on this night, everybody was hungry, and they had so much to tell Mrs. Romilly about the events of the day that no more than that comment was made at the moment.

Mrs. Romilly had not been anxious. She had observed the calm, had guessed the tides, and simply given orders that "high tea" would be supper. She was rejoiced that this first attempt had been a success, but decided that her youngest son was tired out--he was so silent. She remembered the climb out of Ramsworthy Cove, the walk over Hawksdown--thought of the long day of hot calm--and put no questions at all about it. Indeed she diverted those that the rest of the crew would have asked.

Pamela, as usual, came in rather late. Hughie looked at her. She sat down, saw him, and said:

"I saw you running down the hill, aren't you hot, poor Midget? It is stuffy as thunder, Mummy, and the wind is coming in little puffs over Bell Ridge; presently there'll be a row--we shall hear the thunder tanks come wheeling along over our heads! I am hot!"

Hughie decided she had been running also. But he felt this was not the time or place to go into the question. He ate his supper in silence, and matured a telling and desperate plan for paying his sister back. He would ignore her presence. He would not say good-night to her.

Thus when bed-time came, Hughie, busy as usual with some infinitely small carpentering work connected with his latest boat, got up, put away his tiny blocks, pulleys, and fine cord, and went to kiss his mother. She was making sails for him--perfect sails with amazingly neat reefing knots and cord-stiffened edges. Nobody could make model boat-sails like Mrs. Romilly.

"Oh, Mum----" said Hughie very low, and smiled.

"Tired boy," answered 'Mum', also smiling, "go to bed and go to sleep, and don't wake till eight."

Hughie said good-night to Adrian, Christobel, and the Floweret; then he went off to bed, deliberately missing out Pam.

Nobody thought about it but Pam herself. The others were all busy, Addie and Crow playing chess and too much absorbed, the Floweret reading the newspaper to Mrs. Romilly. Pamela, very intently taking notes from her precious handbook, had turned her head ready for Hughie's kiss. He always kissed her as well as his mother. But Hughie walked down the room with short quick steps, opened the door, shut it very softly, and was gone.

This action was in no way lost on his sister. She not only saw it all, but she realized that it was a case of extreme measures on Hughie's part, and made up her mind to get to the bottom of the business.

Pamela's bedroom was a small one at the end of the house, and it looked out over the sea-wall and into the rocky cove. Hughie's room was a pair to it, farther along the little cross passage that barred the end of the long corridor down the centre of the house. Hughie's window looked the same way as Pamela's, and they were exactly alike--strong casements, deep window seats, with a view passing description for peace and beauty.

At nine o'clock Pam went up to bed; but she walked by her own door, to Hughie's, and without knocking, opened it softly and went in.

A young clear moon was rising up the purple sky, and there was light enough to show any movements, especially as the blind was up. The owner of the room was in bed, and no doubt ought to have been asleep, but the excitements already narrated had kept him awake--combined with the expectation of a visit from his sister.

He turned his head on the pillow and looked at her. Pamela closed the door gently, came to the foot of the bed, and leaning her crossed arms on the brass foot, said:

"What's the matter, Midget?"

Hughie was not the sort of person to pretend he did not know what she was thinking of. He retorted by another question.

"Why didn't you stop when I called you, Pam?"

"Called me! Where? When?"

"On the top of Hawksdown--where the road goes to Clawtol," said Hughie.

"But when?"

"Why, this evening, when I was coming home, of course."

There was a pause. Pamela seemed to be thinking deeply. Hughie made use of the interval to sit up in bed--indeed he sat on his pillow, holding the small pyjama-clad ankles of his crossed legs in either hand. He looked very much like an enlarged soapstone figure of an Indian god.

After a sufficiently long pause to make Hughie feel sure his sister was very guilty in the matter, Pamela said:

"What was I doing?"

"I should think you ought to know," answered Hughie coldly.

"No, but tell me. I want to know just what you saw."

Hughie complied.

"So I waved--when I'd called; and you looked back and put up your hand. And then you ran away. I ran too, but I couldn't catch you--I never can--you know that perfectly well," he concluded.

He could see his sister's face quite plainly in the moonlight. She was frowning with a sort of puzzled intentness, and her keen features looked very sharp. Hughie, quick as she to observe, began to explain further. He told how he went to Clawtol, and how he inquired from Mrs. Ensor and her family.

"And Reube said he'd seen you," he ended.

"Reube said he'd seen me," echoed Pamela, "are you sure, Midget?"

Hughie considered; then he repeated carefully:

"Mrs. Ensor said 'did you see the young lady?' and Reube said 'yes'."

"Ah!" breathed Pamela, low, to herself. Then she left her position at the bed foot, and moved about the room in a restless silent fashion, her eyes on the ground. At last she came to a stand by the window.

Hughie made no remark; his eyes followed her, and he was much interested; there was plainly something on foot not understandable at first.

"How was I--she--dressed?" asked Pamela suddenly.

"Oh, your usual things--what you had on the boat," said Hughie vaguely.

"Brown shoes and stockings?" Pam demanded.

Hughie thought about it. Then he said he couldn't see so far.

"But I saw your pigtail hanging down. There was a bit of light on it, and it shone."

Pamela went back to the foot of the bed, and leaned there.

"Look here, Hughie," she said seriously, "if I say a thing you'd believe me, wouldn't you?"

Hughie gripped his ankles with either small brown hand and gazed back at her thoughtfully.

"I should believe you--if you said a true thing," he said.

"Well, I'm going to say a true thing. The girl you saw wasn't me--I mean, I."

"Oh!" said Hughie, "who was she, then?"

"I don't know any more than you do, but I'd venture to bet a shilling that she's the same girl Mollie Shard saw. Don't you remember when Mollie said she saw me, out by Mainsail Cottage on Tuesday morning. Well, I wasn't."

"Oh," murmured Hughie again--then, "I remember what Mollie said, but why didn't you say it wasn't you, Pam?"

"I was thinking about something rather queer that I saw myself; kind of adding them together."

"What did you see yourself?"

Pamela did not answer this question at once, her mind was searching round for points, at last:

"One thing is plain;" she said, "there's a girl about who looks like me; but goodness knows who she is, or where she comes from. Look here, Hughie, will you keep your eyes open--now you know. I'll try and follow it up too, and I promise I'll tell you what I find out even if I don't tell other people."

"I see. Yes, all right, Pam," agreed the Midget with dignity. As a matter of fact he was really not quite sure whether he did see. It was all rather startling; why should there be a girl exactly like Pam--and with the same pigtail even? However, there it was. He had said he would believe what his sister told him.

"Well, good-night, Hughie; we shall see what happens next," said Pamela. She was not laughing at all, her face wore the same keen look. "And remember you promised not to say one word to a living soul, whatever happens."

"All right. I promise. Good-night, Pam," and Hugh raised his face to be kissed rather meekly. He felt as though all this was rather serious.

Pamela went away to her own room and sat down in the low window-seat to puzzle out the position.

There was a girl in Bell Bay so like herself that two people who knew her well had been completely deceived, yet nobody had arrived in the cove--publicly. Indeed, there was no place for them to arrive at, without the inhabitants being aware.

"The queer part is," thought Pamela, "that nobody is worrying with curiosity, because whenever anyone sees her they think it's I, and naturally they don't notice any more. Whatever that girl does will be put on my shoulders, and I can't go and say she's there because I don't know."

She looked at the silver, clear, clean moon, riding so gaily up and up, and at the inky shadows of rocks away down on the white shining sand of the cove. Everything was painted black and white, and the ripple of the sea was a laughing whisper.

Pamela was used to this fairy scene in all sorts of phases, but to-night--probably because of the Mystery Girl--she felt as though something uncanny were abroad, and to shake herself free from the feeling she opened her precious handbook, and proceeded to search through it from end to end. "What should a person do--what would a Patrol Captain, or any experienced Guide do, if she found she had a 'double'? Practical information about making jam tins into candlesticks, or how to meet a mad dog! Splendid directions for camping and tracking--tracking!"

Pamela paused and thought about that. She studied the means for finding out a bicycle-track, what sort of bicycle--which way going. That might be useful if the girl rode a bicycle. Footprints might be followed up if she could be sure what sort of shoe the girl wore.

She shut up the book, and began to undress, gazing dreamily out at the moonshine all the time, utterly unconscious what that moonshine was to show her one night--in the near future.

Just before she went to sleep her mind fixed itself again on a previous idea. This business had surely got to do with Woodrising--with the strange motor-car--and with the secret visit of Sir Marmaduke Shard. She had no proof that he went that night to Woodrising, but she was perfectly certain he had done so. The first thing, of course, was to find out if anybody had come to Woodrising.

The next morning, warm, lovely--and far removed from any sort of mystery--arrived, in about five minutes. Mornings do arrive swiftly when you are thirteen and have been out sailing nearly all day before. Everything looked the same downstairs, and Pamela felt it difficult to believe she had a "double" and Bell Bay was the innocent scene of a surprising secret. She found that Christobel and Adrian were already planning a sail of some importance, and was met by a pressing invitation to go too.

"Where?" asked Pam lazily.

"Peterock. Addie wants his hair cut, and it can be cut at Peterock just as easily as Salterne. Besides, it's much nearer."

Christobel said this with intent, for though nearness was nothing to her and Adrian, she knew instinctively that her mother rather cherished the thought of their "keeping near home". So many people who have no experience of sailing believe that the safety is increased by keeping near land, whereas it is just as possible to drown in one fathom of water, as forty fathoms.

However, Christobel threw out the bait with purpose, and Mrs. Romilly, smiling happily, said:

"That would be nice, darlings. Won't you want lunch and tea on board? Ask Jeep for all you need."

Both Pam and Hughie excused themselves from this expedition. The day promised to be unusually hot and breathless, and Pamela, knowing exactly what it would be like, preferred a bathe and a book. Hughie wanted to test the new sails to his model boat.

This division of forces was so often practised that Mrs. Romilly took no notice. She was sure that the two elders could manage the yawl--and for the rest, a day in which there seemed to be neither wind nor waves, was very satisfying to her mind. Pamela liked being alone--she and Hughie spent hours in the cove contented and harmless. All would be well.

The morning wore on in peace, and about midday the voyagers went down, basket-laden, and very happy.

"It will be thunder," prophesied Pam, who was sitting on a low rock, with her back against another, learning certain enthralling rules by heart from a certain book, "it will be quite calm and oily, and presently you'll have a cracking storm. I feel it in my head. Glad I'm not going. Crow, do you remember the day when we couldn't get anywhere, and we threw the slices of beef overboard and they went with us for miles--sort of cheek by jowl, sitting on the sea."

"That was before the War," said Crow, evading the thought, "one doesn't have slices of meat now, of anything, thank goodness. Beef and ham pies would sink."

"Not before we've eaten them," put in Adrian calmly, "come along, Crow. I say, Pam--supposing we don't get to Peterock, but go to somewhere down coast beyond Ramsworthy, do you mind suggesting to Mother that we are playing on the sands at Netheroot or Tamerton? Either would do, 'fraid there'll be no wind for Salterne."

"Can you get your hair cut at Netheroot?" asked Pamela.

"No, don't suppose so; why?"

"Only because Mother likes to picture you on shore most of the time, when you go sailing, I mean--it's so nice and dry; and the sea is wet as wet can be! If there is a thunderstorm you'll go ashore, shan't you?"

"Like a shot," declared Adrian, as he pushed against the rocky landing platform, and drove the dinghy dancing over the breaking ripples.

Pamela watched, sleepily, as the boat made for the white yawl. She rejoiced that she had remained on land, when the sails went up under Addie's strenuous hauling, yet admired wholeheartedly as the flop of the moorings' buoy set free the yacht, and, leaning over very gently, she drifted broadside on towards Bell Ridge--the northern headland.

Even as she drifted, silent as a shadow, the far faint rumble of summer thunder murmured from inland, and Pam said "thought so" contentedly. After that she shut her eyes and reviewed a succession of plans; something ought to be done now she had a day to herself, or an afternoon at any rate, no one to ask inconvenient questions either, for Hughie being in the secret required but a hint. He was the most circumspect person living.

Sitting there with her eyes closed Pamela arranged a practical plan. She would go for a walk after lunch, on the pretext of taking her bicycle to Timothy Batt's house at Folly Ho. Timothy was the carrier, and lived with his old horse, at the very small hamlet on the Peterock road beyond the turn to the station--and also, of course, beyond Woodrising. She would leave the bicycle, and coming back she would take stock of that empty house, going round the big grounds encircled by the white wall. Surely something could be discovered that might help to elucidate this mystery.

The plan was excellent; when Pam and Hughie went in to dinner, she asked leave, and got it easily. Then came the thunderstorm--about which all details will be given presently--not only the details, but the results and consequences.

It was an exceedingly unusual and violent thunderstorm, frightening the household not a little; all except Pamela and Hughie, who for their own reasons did not mind in the least. Hughie wanted to test small boats in the water that rushed, seething, into the big horse-trough in the yard, and Pamela pictured footprints of a revealing nature, marking the wet soil all round Woodrising.

Good may come out of anything. And surely advantages might be expected from such rain as fell into Bell Bay on that afternoon.

Mrs. Romilly was certainly worried on account of the yawl, but Pamela told her what Addie had said about Netheroot or Tamerton. Also when the storm had passed she could see for herself that the water was hardly more rough. There was nothing to suggest danger. Later on the telegram came; but not till after Pamela had started off on her delayed walk.

She went after five-o'clock tea, into a wonderful washed world, where every plant, bush and hedge seemed to have been touched with a magic brush, and set in jewels. The sandy soil oozed beneath her feet, and rills of water streamed down the hill in winding gullies.

Pamela whistled softly to herself as she went; it was good to be alive on such an evening, and she felt very hopeful about her chances of making discoveries, chiefly because she felt so buoyantly cheerful.