|

THRILLING ADVENTURE |

MOTOR FICTION |

|

No. 31 SEPT. 25, 1909. |

FIVE CENTS |

|

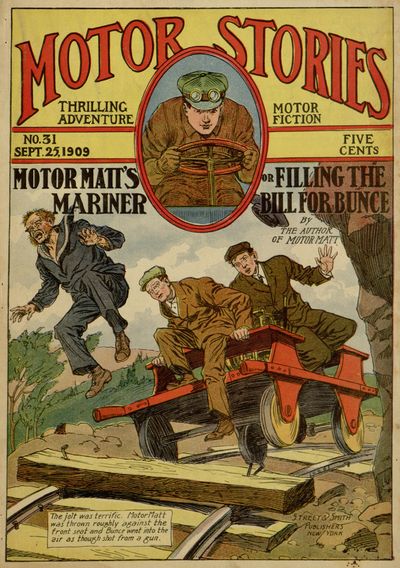

MOTOR MATT'S MARINER | or FILLING THE BILL FOR BUNCE |

| By THE AUTHOR of MOTOR MATT | |

|

Street & Smith Publishers NEW YORK |

| MOTOR STORIES | |

| THRILLING ADVENTURE | MOTOR FICTION |

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Copyright, 1909, by Street & Smith, 79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

| No. 31. | NEW YORK, September 25, 1909. | Price Five Cents. |

MOTOR MATT'S MARINER;

OR,

Filling the Bill for Bunce.

By the author of "MOOR MATT."

CHAPTER I. "BUDDHA'S EYE."

CHAPTER II. THE GREEN PATCH.

CHAPTER III. MOTOR MATT—TRUSTEE.

CHAPTER IV. BUNCE HAS A PLAN.

CHAPTER V. BUNCE SPEAKS A GOOD WORD FOR HIMSELF.

CHAPTER VI. THE HOMEMADE SPEEDER.

CHAPTER VII. TRAPPED.

CHAPTER VIII. THE CUT-OUT UNDER THE LEDGE.

CHAPTER IX. BETWEEN THE EYES.

CHAPTER X. THE MAN FROM THE "IRIS."

CHAPTER XI. ABOARD THE STEAM YACHT.

CHAPTER XII. GRATTAN'S TRIUMPH.

CHAPTER XIII. FROM THE OPEN PORT!

CHAPTER XIV. LANDED—AND STUNG.

CHAPTER XV. A CRAFTY ORIENTAL.

CHAPTER XVI. THE MANDARIN WINS.

JERRY STEBBINS' HOSS TRADE.

THE PHANTOM ENGINEER.

Matt King, otherwise Motor Matt.

Joe McGlory, a young cowboy who proves himself a lad of worth and character, and whose eccentricities are all on the humorous side. A good chum to tie to—a point Motor Matt is quick to perceive.

Tsan Ti, Mandarin of the Red Button, who proves adept in the ways of Oriental craft, and shows how easy it is for a person to shift his dangers and responsibilities to other shoulders—if only he goes about it in the right way.

Philo Grattan, a talented person who devotes himself to "tricks that are dark and ways that are vain," and whose superb assurance leads him to flaunt his most memorable crime in the face of the authorities through the medium of moving pictures. A man fitted by nature for a worthier part than he plays, and whose keen mind is not able to save him from deception.

Bunce, the mariner, and a pal of Grattan.

Pardo, who charters a power-boat and uses it in forwarding a plot of Grattan's.

Bronson, a railroad superintendent, who appears briefly but creditably.

"BUDDHA'S EYE."

"It's three long and weary hours, pard, before the boat for New York ties up at the landing. You don't want to cool your heels in the hotel, do you, while we're waiting? How about doing something to fill in the time?"

It was about seven o'clock in the evening, and Motor Matt and his cowboy chum, Joe McGlory, were sitting on the porch of their hotel in Catskill-on-the-Hudson. The hotel was on an elevation, and the boys could look out over the river and see the lights of steamers, tugs, motor boats, and other craft gliding up and down in a glittering maze.

Matt had been looking down at the river lights, and dreaming. He aroused himself with a start at the sound of his chum's voice.

"What would you suggest, Joe?" he asked.

"Let's take in the moving-picture shows. Say, they're the greatest thing for a nickel that I ever saw. Some yap gets into trouble, and then ladies and gents, and workmen, and clerks, and nurses with baby cabs take after the poor duffer, and there's a high old time for all hands. I'm plumb hungry for excitement, Matt. This town has become mighty tame since we parted company with Tsan Ti."

"If you think the moving-picture shows will furnish what you need in the excitement line, Joe, we'll go out and take them in."

Matt got up with a laugh, and he and McGlory left the hotel, and laid a course for the main street of the town. At the first nickel theatre they came to, they gave up a dime, and moved into the darkened room. An illustrated song was in the lantern, and a young man with a husky voice was singing something about a "stingy moon."

The motor boys stumbled around in the dark, and McGlory tried to slip into a seat that was already occupied. A stifled scream made him aware of his mistake, and he tumbled all over himself to get somewhere else.

"Speak to me about that!" he whispered to Matt, with a choppy chuckle. "That's the trouble with these moving-picture honkatonks when you come in after the lights are out. Oh, bother that stingy moon! I wish the[Pg 2] chap with the raw voice would cut it out, and let the rest of the show get to climbing over the screen."

"Don't be so impatient, old chap," returned Matt. "You've got to have something happening to you about once every fifteen minutes, or you get so nervous you can't sit still. In that respect, you're a lot like Dick Ferral, a sailor chum I cruised with a while ago. Now——"

"Sh-h-h!" interrupted the cowboy. "The piano has had enough of the moon, and now here comes the first moving picture."

White letters quivered on the screen. "Buddha's Eye" was the title of the series of pictures about to be shown. McGlory gulped excitedly, and Matt stared. The motor boys had just finished a wild entanglement with a great ruby called the "Eye of Buddha," and this, the first picture in the first theatre that claimed them, reminded them, with something like a shock, of recent experiences.

"Sufferin' sparks!" muttered McGlory. "What's the difference between 'Buddha's Eye' and the 'Eye of Buddha,' Matt?"

"No difference, Joe," answered Matt. "This is just a coincidence, that's all."

The interior of a Buddhist temple was thrown on the screen. The views were colored, and priests in gray and yellow robes could be seen moving back and forth and prostrating themselves before a huge gilt idol. The idol was of a "sitting Buddha" and must have measured full twenty feet from the temple floor to the top of the head.

With a flash, the interior of the temple gave way to an enlarged view of the idol's head. The head had but one eye, placed in the centre of the forehead—a huge ruby, which glowed like a splash of warm blood.

"The Honam joss house, in the suburbs of Canton!" whispered McGlory excitedly. "If it ain't, I'm a Piute!"

Motor Matt kept silence, wondering.

The boys were next afforded a view of two men, plotting aboard a sampan near the island of Honam. One was tall and had a dark face and sinister eyes. He wore a solar hat with a pugree. The other had on sailor clothes, had a fringe of mutton-chop whiskers about his jaws and a green patch over his right eye. McGlory grabbed Matt's arm in a convulsive grip.

"What do you think of that?" demanded the cowboy, in a husky whisper. "The tinhorn in the sun hat is Grattan, and the webfoot is Bunce. Am I in a trance, or what?"

"Watch!" returned Matt, fully as mystified as was his chum.

The next picture was labeled, "The Egyptian Balls—view of excavations at Karnak, on the Upper Nile."

Ponderous ruins were brought into view, showing Egyptian fellahs digging in a subterranean chamber. An urn was lifted up and uncovered. From this urn the wondering workmen removed a number of crystalline spheres. One of the spheres dropped from an awkward hand, crashed to fragments on the floor of the chamber, and instantly all the workmen staggered, flung their hands to their faces, and fell sprawling, lying on the stones prone and silent.

Two men stole in upon them, covered with flowing Arab robes, and their faces masked in white. Swiftly they gathered up some of the balls, and the camera followed them as they left the chamber and stood under the broken columns of the ancient temple of Karnak. The robes were flung away, and the masks removed. Grattan and Bunce, the sampan plotters, stood revealed.

"I've got the blind staggers, I reckon!" mumbled McGlory, rubbing his eyes. "It was in Egypt Grattan got his dope balls—the glass spheres filled with the knock-out fumes. This—this—sufferin' brain twisters! It's more'n I can savvy."

After Grattan and Bunce had gone through a pantomime expressive of their wild delight on securing the balls, the films entered into another series, entitled, "The Theft of the Great Ruby from the Honam Joss House, near Canton, China."

The walls outside the temple were shown, and an avenue bordered with banyan trees, with rooks flapping among the branches. Grattan and Bunce were seen making their way along the avenue, entering the temple court, and coming into the chamber which had been flashed on the screen at the beginning.

Here was the huge idol again, and the yellow-robed priests moving about. For a space, Grattan and Bunce stood and gazed; then, suddenly, Grattan pulled a hand from his coat, held one of the glass balls over his head for a space, then sent it crashing among the priests. The priests started up in amazement, recovered their wits, and rushed toward the foreign devils. But the priests were suddenly stricken before Grattan and Bunce could be roughly dealt with.

White masks had been pushed over the faces of the two plotters, and the pair watched while the priests, overcome by the paralyzing, sense-destroying fumes from the broken balls, reeled to the temple floor, and lay there in inert heaps. The masks protected Grattan and Bunce from the baneful influence of the balls.

As soon as the priests were stretched silent upon the floor, Grattan unwound a ladder of silk from about his waist. One end of the ladder was weighted with a bit of lead, and this end was thrown over the idol's head. Thereupon, Grattan mounted the ladder, and dug out the ruby with a knife. Upon descending, he and Bunce went through another pantomime, suggesting their joy over the success of their shameless work, and then passed quickly from the court, stuffing their white masks into their pockets as they went.

The next scene was in the room of a house in the foreign quarter, on the sea wall, called Shameen. Grattan was secreting the ruby in the head of a buckthorn cane. Barely was the secreting done, when a fat mandarin burst in on them with a number of armed coolies at his heels.

The mandarin seemed to be accusing Grattan. Grattan could be seen to shake his head protestingly. Then Grattan and Bunce were searched thoroughly, and the room ransacked. In the utmost chagrin, the mandarin and his coolies left, without having been able to discover anything. A few minutes later, the thieves took their triumphant departure, Grattan exultantly waving the buckthorn stick.

Scarcely breathing, and with staring eyes, the motor boys continued to watch the pictures as they raced over the white screen. What wonder work was this? From Grattan's own lips Matt had heard of the robbery at the Honam joss house, in which Grattan had played such an important part. So far, the pictures had shown it substantially as the details had come from Grattan; there were a few minor differences, but they were insignificant.

From this point, however, Grattan's story and the story as told by the pictures were at variance.

The thieves got into a couple of sedan chairs, each chair carried by four coolies. Apparently, Grattan and Bunce were on their way to the river to embark for other shores. When near the landing, one of the poles supporting the chair in which Grattan was riding broke. The chair fell, the bamboo door burst open, and Grattan tumbled out. One of the coolies picked up the buckthorn cane, and another the sun hat with the pugree. Grattan, in anger, knocked down the coolie who had picked up his hat. The other, coming to his countryman's aid, struck at Grattan with the head of the cane. Grattan dropped to his knees. The cane passed over his head, and the force the coolie had put into the blow carried the stick out of his hand, and sent it smashing against the side of a "go-down."

The head of the cane was broken, and the great ruby rolled over the earth out of the débris, and lay gleaming in the sun under the eyes of the astounded coolies. Then, with the inexplicable timeliness so prevalent in motion pictures, the fat mandarin and his coolies came upon the scene, the mandarin gathering in "Buddha's Eye" with extravagant expressions of joy, and Grattan and Bunce writhing desperately in the hands of the chair men and the mandarin's guard.

That was all. The scenes to follow were of a humorous order, and probably had to do with some unfortunate getting into trouble and leading a varied assortment of people a gay chase, but McGlory had lost interest in the show. So had Matt.

As by a common impulse, the boys got up and groped their bewildered way out of the room and into the street. They were dazed, thunderstruck, and hardly knew what to think.

THE GREEN PATCH.

Distracted by their mental speculations, the motor boys presently found themselves back on the porch of their hotel, occupying the same chairs they had left a little while before. Once more Matt was looking down on the river lights, coming and going across the broad stream like so many fireflies.

"Am I locoed, I wonder?" inquired McGlory, as though speaking to himself. "Did I see that moving picture, with Grattan and Bunce in it and stealing the 'Eye of Buddha,' or didn't I?"

"You saw the picture, Joe," returned Matt, "and so did I."

"I reckon I did; and jumpin' tarantulas, how it got on my nerves! But how does it happen that the picture is being shown like it is? Grattan told you, Matt, just how the ruby was stolen from the Honam joss house by himself and Bunce; he told you how he went to Egypt after the glass balls that were more than two thousand years old, and had been dug up at Karnak. He didn't get the balls from Karnak just exactly in the way the picture shows it, but he did steal the ruby in exactly the same fashion those films brought the tinhorn trick under our eyes. Not only that, but Grattan hid the ruby in the head of his cane. Right up to that point the whole game is a dead ringer for the yarn Grattan batted up to you. The rest of the pictures are pure fake. It was you who helped recover 'Buddha's Eye,' and it happened right here in the Catskill Mountains, near the village of Purling, and not in China. But it was the smashing of the head of the cane that revealed the ruby."[A]

[A] The thrilling adventures of the motor boys in recovering the Eye of Buddha were set forth in No. 30, Motor Stories.

"We know," said Matt, his mind recovering from the shock occasioned by the strange series of pictures so suddenly sprung upon him and McGlory, "we know, pard, that Grattan was in the motion-picture business at the time he conceived the idea of stealing the ruby. He was traveling all over the world with his camera apparatus. Probably his line of work has something to do with his putting the robbery into the form we have just seen it."

"But why should Grattan want to publish his criminal work all over the country in moving pictures? And he put himself into the pictures, too—and that old sea dog, Bunce."

"That part of it is too many for me, Joe," answered Matt. "However, I can't see as the moving pictures of the robbery cut much figure now. The mandarin, Tsan Ti, has recovered the ruby, and is on his way to San Francisco to take ship for China. Grattan and Bunce made their escape, and are probably getting out of the country, or into parts unknown, as rapidly as they can. So far as we are concerned, the incident is closed. But it was certainly a startler to come face to face with a set of pictures like those—and so unexpectedly."

"First nickelodeon we struck, and the first picture shoved through the lantern," muttered the cowboy.

"Are you positive, Joe," went on Matt, "that the two thieves who figured in the picture were really Grattan and Bunce?"

"It's a cinch!" declared McGlory. "There can't be any mistake. I never saw a clearer set of pictures, and I'd know Grattan and Bunce anywhere—could pick 'em out of a thousand."

"That's the way it looked to me, and yet there's one point I can't understand. It's a point that doesn't agree with your assertion that Bunce was really in the picture."

"What point is that?"

"Why, it has to do with the green patch Bunce wears over his eye."

"The patch was in the picture, all right."

"Sure it was! But which of Bunce's eyes did it cover?"

"The right eye!"

"Exactly! The green patch was over Bunce's right eye, in the picture of the robbery, which we just saw; but when we had our several encounters with Bunce, a few days ago, the patch was over the mariner's left eye."

McGlory straightened up in his chair and stared at his chum through the electric light that shone over them from the porch ceiling.

"Glory to glory and all hands round!" he exclaimed. "You're right, pard. When we were trotting that heat with Bunce, here in the Catskills, it was his left eye that was gone. Now, in the picture, it's his right eye. How do you explain that?"

"The explanation seems easy enough," answered Matt. "Bunce must have two good eyes, and he simply covers up one for the purpose of disguise. Either that, or else [Pg 4]some one represented him when the moving pictures were taken, and got the patch over the wrong eye."

"What good is a green patch as a disguise, anyway?" demanded McGlory.

"Give it up. The difference in the position of the patch merely led me to infer that Bunce might not have really been in that moving picture. And if Bunce wasn't in it, then it's possible that Grattan wasn't in it, either. Two men might have been made up to represent the two thieves. I can't think it possible that Grattan and Bunce, as you said a moment ago, should want to publish their crime throughout the country by means of these moving pictures. The films are rented everywhere, and travel from place to place."

McGlory heaved a long breath.

"Well, anyhow, I don't want to bother myself any more with the Eye of Buddha," said he. "It's a hoodoo, and I never went through such a lot of close shaves, or such a series of rapid-fire events, as when we were helping Tsan Ti, the mandarin, recover the ruby. Let's forget about it. We can't understand how those pictures came to be shown, and we're completely at sea regarding the green patch. But it's nothing to us, any more. We're for New York by the night boat, and then it'll be 'Up the river or down the bay, over to Coney or Rockaway' for the motor boys. Sufferin' cat naps! A spell of pleasure in the metro-polus is all that brought me East with you, anyhow. It's us for the big town, and with you along to see that no one sells me a gold brick, I reckon I'll be able to pan out a good time."

The prospect of a week or two in New York, with a little rest and a little motoring, was also appealing powerfully to Matt. He had not been in the big town for some time, and he longed to renew his acquaintance with its many "sights" and experiences.

"We'll be there in the morning, Joe," Matt answered. "As you say, we need not bother our heads any longer about the Eye of Buddha, or Grattan, or Bunce, or Tsan Ti. We'll take our toll of enjoyment out of Manhattan Isle, and we'll forget there ever was such a thing as the big ruby."

"You don't intend to think of business at all while you're there, eh?"

"No. We'll just knock around for a couple of weeks and enjoy ourselves. Of course we'll be more or less among the motors—I couldn't be happy myself if we weren't—and then, when we've had enough of that, I want to take a run up to my old home in the Berkshire Hills."

Great Barrington had been very much in Motor Matt's mind for several weeks. He felt a desire to go back to the old place, and revisit the scenes of his earlier life. There was a mystery concerning his parents which had never been solved. He did not have any idea that a return to Great Barrington would settle that problem, but, nevertheless, it had something to do with luring him in the direction of the Berkshires.

"Speak to me about that!" murmured McGlory. "You've always been a good deal of a riddle to me, pard. You've never let out much about your early life, and I come from a country where it's a signal for fireworks if you press a man too closely about his past, so I've just taken you as I picked you up in 'Frisco, and let it go at that. But there are a few things I'd like to know, just the same."

"I'll tell you about them sometime, Joe," Matt answered. "Just now, though, I'm not in the mood. When we're ready to start for the Berkshires——"

He paused. The night clerk of the hotel had come out on the porch and was standing at his elbow, a small package in his hand.

"Motor Matt," said he, in a voice of concern, "here's something that came for you by express, about five-thirty in the afternoon. It's been lying in the safe ever since. The day clerk couldn't find you, when the package came, so he receipted for it. He didn't tell me anything about it, when I went on duty, and he just happened to remember and to telephone down from his room. I'm sorry about the delay."

"We're taking the ten-o'clock boat for New York," spoke up McGlory. "It would have been a nice layout if we'd got away and left that package behind."

"I'm mighty sorry, but it's not my fault."

"Well," answered Matt, taking the package, "no great harm has been done. It's an hour and a half, yet, before the New York boat gets here, and I have the package."

The clerk went back into the hotel and Matt examined the package under the light.

"What do you reckon it is, pard?" queried McGlory curiously.

"You can give as good a guess as I can, Joe," Matt answered. "I'm not expecting anybody to send me anything. It's addressed plainly enough to Motor Matt, Catskill, New York, in care of this hotel."

"And covered with red sealing wax," added McGlory. "Rip off the cover and let's see what's on the inside. Sufferin' tenterhooks! Haven't you got any curiosity?"

Matt cut the cord that bound the package and took off the wrapper. A small wooden box was disclosed, bound with another cord.

The box was opened, and seemed to be filled with cotton wadding. Resting the box on his knees, Matt proceeded to remove the wadding. Then he fell back in his chair with an astounded exclamation.

A round object, glimmering in the rays of the electric light like a splash of blood against the cotton, lay under the amazed eyes of the motor boys.

"Buddha's Eye!" whispered McGlory.

Around the end of the veranda, in the wavering shadows, a face had pushed itself above the veranda railing—a face topped with a sailor cap and fringed with "mutton-chop" whiskers—a face with a green patch over one eye.

MOTOR MATT—TRUSTEE.

Matt and McGlory had seen the Eye of Buddha, and they were not slow in recognizing it. But the bewildering events of the evening were crowned by this arrival of the ruby, by express, consigned to Motor Matt. By all the laws of reasoning and logic, the gem, worth a king's ransom, should at that moment have been in the possession of Tsan Ti, en route to the Flowery Kingdom.

"Oh, tell—me—about this!" stuttered McGlory.

Matt picked the ruby up in his fingers and held it in the palm of his hand. Apparently he was loath to credit[Pg 5] the evidence of his senses. From every angle he surveyed the glittering gem.

"Wouldn't this rattle you?" he murmured, peering at his chum.

"Rattle me!" exploded McGlory. "Why, pard, it leaves me high and dry—stranded—gasping like a fish. Tsan Ti must be locoed! At last accounts, he was in a flutter to get that ruby back to the Honam joss house and replace it in the idol's head, where it belongs. What came over the mandarin to box it up and ship it to you? I'm fair dazed, and no mistake. This cuts the ground right out from under me."

Matt, with a hasty look around, dropped the ruby into his pocket; then he pulled out some more of the wadding and discovered, in the bottom of the box, a folded sheet of white paper.

"Here's a letter," said he. "This will explain why the ruby was sent to me, I guess."

"What good's an explanation?" grunted the cowboy. "I wouldn't be tangled up with that thing for a mint of money. Sufferin' centipedes! It's a regular hoodoo, and hands a fellow a hard-luck knock every time he turns around. What's in the letter, anyway? If it's from Tsan Ti, I'll bet his paper talk is heavy with big words and all kinds of Class A 'con' lingo. Read it, do. I can't tell how nervous you make me hanging fire."

"It's from Tsan Ti, all right," said Matt, "and is dated New York."

"New York! Why, he was hitting nothing but high places in the direction of 'Frisco, when he left here. How, in the name of all his ten thousand demons of misfortune, does he happen to be in New York?"

"Listen," answered Matt, and began to read.

"'Esteemed and illustrious youth, whose never-to-be-forgotten services to me shine like letters of gold on a tablet of silver: Behold——'"

"Oh, the gush!" growled McGlory.

"'Behold,'" continued Matt, "'I send you the Eye of Buddha, the priceless jewel which belongs in the temple of Hai-chwang-sze, in my beloved Canton. You ask, of your perplexity, why is the jewel sent to you? and I reply, for the security's sake. Upon my trail comes Grattan, of the evil heart, weaving his plans for recovering the costly gem. I fear to keep it about me, and so I send to you asking that you remain with it in the Catskill Mountains until such time as I may come to you and receive it from your hands. This will be when the scoundrel Grattan is safely beheaded, or in prison, and clear of my way for all time. I turn to you of my perfect trust, and I adjure you, by the five hundred gods, not to let the ruby get for one moment out of your possession. Leave it nowhere, keep it by you always, either sleeping or walking, and deliver it to no one except to me, who, at the right time, will come and request it of you in my own person. Will it be an insult to offer you one thousand silver dollars and expense money for consummating this task? I commend you to the good graces of the supernal ones whose years are ten thousand times ten thousand!

"'Tsan Ti, of the Red Button.'"

The reading finished, McGlory eased himself of a sputtering groan.

"Loaded up!" he exclaimed. "You and I, pard, just at the time we thought we were rid of Tsan Ti and Buddha's Eye for good, find the thing shouldered onto us again, and trouble staring us in the face! Why didn't the mandarin deposit the ruby in some bank, or safe-deposit vault? Better still, if Grattan was on his trail, why didn't he have the express company take it to San Francisco for him instead of sending it to you, at Catskill? He knows less, that Tsan Ti, than any other heathen on top of earth. In order to keep himself out of trouble he hands us the Eye of Buddha, and switches the responsibility to us. Wouldn't that rattle your spurs?"

McGlory was profoundly disgusted.

"I reckon," he went on, "that this sidetracks us, eh? The big town is cut out of our reckoning until the mandarin shows up and claims the ruby. He may do that to-morrow, or next week, or next month—and, meanwhile, here we are, kicking our heels in this humdrum, back-number, two-by-twice town on the Hudson! Say, pard, I'd like to fight—and I'd just as soon take a fall out of that pesky mandarin as any one else."

"He offers us a thousand dollars and expenses," said Matt. "Tsan Ti wants to do the right thing, Joe."

"A million dollars and expenses won't pay us for hanging onto that ruby. It's a hoodoo, and you know that as well as I do, pard. We can expect things to happen right from this minute. Say, put it somewhere where it'll be safe! Put it in the hotel safe, or in a bank, or any place. Pass the risk along."

"Tsan Ti expressly stipulates that I am to keep the ruby about me," demurred Matt.

"What of that?" snorted McGlory. "Are you working for Tsan Ti? Are you bound to do what he tells you to? What business is it of his if we choose to show a little sense and get some one else to take charge of the ruby? The mandarin's an old mutton-head! If he wasn't he'd know better than to send the Eye of Buddha to us. And in a common express package, at that. What value did he put on it?"

McGlory picked up the wrapper that had covered the box and looked over the address side.

"No value at all!" he exclaimed. "Either he didn't think of that, or else he didn't want to pay for the extra valuation. If there had been a railroad wreck, and the ruby had been lost, our excellent mandarin would have collected just fifty plunks from the express company—and I reckon the Eye of Buddha is worth fifty thousand if it's worth a cent."

"Sometimes," said Matt reflectively, "it's safer to trust to luck than to put such a terrific value on a package that's to be carried by express."

"Well," grunted McGlory, "I don't like his blooming Oriental way of doing business, and that shot goes as it lays. I'll tell you what we can do," he added, brightening.

"What?"

"We can jump aboard that New York boat and tote the ruby back to New York; then we can hunt up Tsan Ti and return the thing to him and tell him not any—that we have done as much for him as we're going to. Where's his letter sent from? What's the name of the hotel?"

In his eagerness, McGlory snatched the letter from Matt's knee and began looking it over.

"There's no address," said Matt.

"Tsan Ti may be in Chinatown," went on McGlory.[Pg 6] "Such a big high boy couldn't get lost in the shuffle around Pell and Doyer Streets. Let's go on by that boat and take our chances locating him!"

"No," and Matt shook his head decidedly, "that's a move we can't make, Joe. I'm no more in love with this piece of work than you are, but we're in for it, and there's no way to dodge. Tsan Ti has unloaded the ruby upon us and we've got to stand for it."

"But we're responsible——"

"Of course, up to a certain point. If the stone should be taken away from us, though, Tsan Ti couldn't hold us responsible. We didn't ask for the job of looking after it, and we don't want the job, but we're doing what we can, you see, because there's no other way out of it."

"You could stow it away in a safer place than your pocket," grumbled McGlory.

"In that event," returned Matt, "we might be responsible. The thing for us to do is to follow out our instructions to the letter. If anything happens to the Eye of Buddha then it's the mandarin himself who's responsible."

"And we're to hang out in the Catskill Mountains until Tsan Ti comes for the ruby!" mused McGlory, in an angry undertone; "and he's not going to come until Grattan is 'beheaded' or clapped into jail. We're liable to have a long wait. Of all the tinhorns I ever saw, or heard of, that Grattan is the sharpest of the lot. Fine job this red-button heathen has put onto us!"

Matt disliked the work of taking care of the valuable gem, and he would have shirked the responsibility if he could have done so, but there was no way in which this could be brought about. He and Joe would have to stay in the Catskills, for a while anyway, and wait for Tsan Ti to present himself. Meanwhile, the trip to New York would have to be postponed.

More to soothe his friend than as an expression of his own feelings, the king of the motor boys began taking a pleasanter view of the situation.

"We know, pard," said he, "that Tsan Ti is a man of his word. When he says he'll do anything, he does it. He'll come for the ruby, and I think he's clever enough to fool Grattan, and we know he'll pay us a thousand dollars. That money will come in handy while we're in New York."

"If we ever get there," growled the cowboy. "We may get into so much trouble on account of that Eye of Buddha that we'll be laid up in the hospital when Tsan Ti presents himself in these parts."

Matt laughed.

"You're so anxious to see the sights in the big town, Joe," he observed, "that it's the delay, more than anything else, that's bothering you."

"When I get started for anywhere," answered McGlory, "a bee line and the keen jump is my motto. But, so long as we have anything to do with Tsan Ti, we never know what's going to happen. I wish the squinch-eyed heathen would leave us alone."

Just then a form rounded the front of the hotel, gained the steps leading up to the porch, and climbed to a place in front of the motor boys.

McGlory lifted his eyes. The moment they rested on the form, and realization of who it was had flashed through his brain, he jumped for the man and grabbed him with both hands.

"Bunce!" he whooped. "I told you things would begin to happen, pard, and right here is where they start!"

Then, with considerable violence, McGlory pushed the old sailor against one of the porch posts, and held him there, squirming.

BUNCE HAS A PLAN.

"Avast, there!" gurgled Bunce, half choked, trying to pull the cowboy's hands from his throat.

The green patch was over his left eye, and the right eye gleamed glassily in the electric light.

Matt was as much surprised at Bunce's appearance as was McGlory, but he held his temper better in hand. The cowboy, profoundly disgusted with the trend of recent events, showed a disposition to take it out of the sailor.

Had Bunce been even the half of an able seaman he would have given McGlory a hard scramble, but he seemed a wizened, infirm old salt, although he had proved active enough during the experiences the motor boys had already had with him.

"Don't strangle him, Joe!" called Matt. "Take your hands from his throat and grab his arm. He came here openly, and he must have known we were here. Judging from that, I should say that his intentions are peaceable."

"Ask him," gritted McGlory, "why he doesn't change eyes with the patch. Let's get to the bottom of this moving-picture business, too. We can have a little heart-to-heart talk, I reckon, and find out a few things before we turn the old webfoot over to the police."

"Right you are, my blood," gasped the half-suffocated Bunce, as the cowboy dropped his hands to his arm and dragged him down into a chair, "a heart-to-heart talk's the thing. Didn't I bear away for this place for nothin' else than to fall afoul o' ye? Ay, ay, that was the way of it, but split me through if I ever expected such treatment as this what I'm a-gettin'. Motor Matt's the lad, says I to myself, to fill the bill for Bunce, so I trips anchor an' slants away, only to be laid holt of like I was a reg'lar skull-and-crossbones, walk-the-plank pirate, with the Jolly Roger at the peak."

"Oh, put a crimp on that sort of talk," growled McGlory. "Sufferin' freebooters! If you're anything better than a pirate, I'd like to have you tell me."

"So, ho!" and Bunce's eye glittered wrathfully, "if I had a cutlass, my fine buck, I'd slit ye like a herrin' for that. I'm a fair-weather sort of man, an' I hates a squall, but stir up nasty weather an' then give me somethin' to fight with, an' I'm a bit of a handful. Nigh Pangool, on the south coast o' Java, I laid out a hull boat's crew with my fists alone, once, not so many years back. That was when I was mate o' the brig Hottentot, as fine a two-sticker as ever shoved nose into the South Seas—reg'lar bucko mate, I was, an' a main hard man when roused."

At the time the Eye of Buddha was recovered, Bunce had made his escape with Grattan; and he had been equally guilty, with Grattan, in the theft of the ruby from the Honam joss house. That the sailor should have shown himself at all, in those parts, was a wonder; and that he should have shown himself to Matt and McGlory, who knew of his evil deeds, was a puzzle past working out.

"You say you came here to see me?" inquired Matt.

"Ay, ay, my hearty," answered Bunce. "Motor Matt,[Pg 7] says I to myself, is the lad to fill the bill for me, an' I luffed into the wind an' bore down for Catskill. Here I am, an' here's you, an' if I blow the gaff a bit that's my business, ain't it? But take me to the cabin; what I has to say is between us an' the mainmast with no other ears to get a sizing of it."

McGlory glared at Bunce as though he would have liked to bore into him with his eyes and see what he had at the back of his head.

"If you're trying to play double with us, you gangle-legged old hide rack," he threatened, "you'll live to wish you'd thought twice before you did it."

"Now, burn me," snorted Bunce, "d'ye take me for a dog fish? By the seven holy spritsails, I'm as good a man as you, an' ye'll l'arn——"

"Enough of that, Bunce," broke in Matt sharply, getting up from his chair. "You want to say something to us in private, and I'm going to give you the chance. Come after me; you trail along behind him, Joe," and, with that, Matt went into the hotel and up the stairs to the room jointly occupied by himself and McGlory.

At the door, Matt pushed a button that turned on the lights. As soon as McGlory and Bunce were in the room, the door was locked and Matt took charge of the key.

"That's the stuff, pard," approved McGlory, with great satisfaction. "If the old tinhorn don't spout to please us, we can phone the office for a policeman."

"Ye're not sending me to the brig this trip, mates," spoke up Bunce. "'Cos why? 'Cos in fillin' the bill for me, ye're givin' the mandarin a leg up out of a purty bad hole."

"What have you got to tell us?" inquired Matt curtly. "Out with it, Bunce."

"When ye last seen me, my lad," said Bunce, "I was sailin' in convoy with Philo Grattan. But he's doin' things I don't approve of, not any ways. It was all right to put our helm up an' bear down on a chink joss house to lift the Eye o' Buddha, an' it was all right, too, when ye helped the big high boy get the ruby back. That was all in the game, an' we'd ought to've made the most of it. But not Philo Grattan. D'ye know what he's layin' to do? Nothin' more, on my soul, than to strangle Tsan Ti with a yellow cord an' take the ruby away from him. My eye, mates, but Grattan's a clever hand at overhauling his locker for a game like that. The boss of the Chinee Empire sends these yellow cords to the chinks he don't like an' don't want around. When the cords come to hand, then the chinks receivin' thereof uses them to choke out their lives. Tsan Ti is found, dead as a mackerel, with the yellow cord twisted into his fat neck. Eye o' Buddha is missin' from his clothes. What's the answer? Why, that Tsan Ti lost the ruby, an' used the cord sent him from the home country. That'll seem plain as a burgee flyin' from the gaff o' one o' these fresh-water yachts. Won't it, now?"

Matt knew that Tsan Ti had received the yellow cord from China, and that he had been allowed two weeks in which either to find the stolen ruby or to use the cord. Of course, the ruby had been recovered, and there was no necessity for using the hideous cord; but, if he was found strangled, it would have seemed as though he himself had committed the deed in compliance with orders from the Chinese regent.

Bunce may have been romancing, but there was a little plausibility back of his words.

"Where is Grattan?" demanded Matt.

"In these here hills, shipmate," replied Bunce.

"Tsan Ti isn't in the Catskills!"

"No more he ain't, which I grant ye offhand an' freely, but supposin' he's in Noo York, held a pris'ner in a beach comber's joint in Front Street? An' supposin', furthermore, this same beach comber is a mate o' Grattan's, an' waitin' only for Grattan to come afore he makes Tsan Ti peg out? Put that in your pipe an' smoke it careful."

"You mean to say that Tsan Ti is a prisoner in New York—a prisoner of a confederate of Grattan's?"

"That's gospel truth! It happened recent—no longer ago than early mornin'. I bore the word to the beach comber in a letter of hand from Philo, an' the beach comber met me in a snug harbor on the front where sailormen are regularly hocused an' shipped for all parts. I don't know where the beach comber's place is, not me, but I did get him topping the boom an' he reported the whole matter entire. However Tsan Ti fell into the net is a notch above my understandin', but there he is, hard an' fast, an' when I'd done with the beach comber I took the train for Catskill to find Grattan an' tell him what's been pulled off."

Bunce was a trifle hard to follow.

"Let's see if I've got this right," said Matt, "When you and Grattan escaped from the officers, at the time the ruby was recovered, you hid yourselves away among the Catskills?"

"Ay, so we did!"

"And then Grattan gave you a letter to some man in New York and you carried it personally?"

"Personally, that's the word. I carried it personally."

"And this man in New York entrapped the mandarin and is holding him a prisoner until he can hear what Grattan wants done?"

"Ye've got the proper bearin's, an' no mistake."

"And you came back on the train to tell Grattan?"

Bunce nodded, and pulled at his fringe of whiskers.

"Then, why didn't you go and tell Grattan," asked Matt, "instead of coming and telling me?"

"I'm no blessed cut-an'-slash pirate," protested Bunce. "So long as the ruby was to be come by without any stranglin', I was willin' to bear a bob an' do my share; an' while mebby there ain't anythin' morilly wrong in chokin' the breath out of a heathen Chinee, yet they'll bowse a man up to the yardarm for doin' the same. Mates, on the ride back to the Catskills I overhauled the hull matter, an' I makes up my mind I'd sailed in company with Grattan as long as 'twas safe. If I can save the mandarin, I thinks to myself, mebby Motor Matt'll play square with me an' let me off for what I done in helpin' lift the ruby. If so be he thinks that way, says I to myself further, then he's the one to fill the bill for Bunce. So, instid o' slantin' for the cove where the motor car is hid away, I 'bouts ship an' lays a course for this hotel."

"What's your plan, Bunce?" queried Matt.

"Easy, does it; simple as a granny's knot. You kiss the Book that I'm free as soon's I do my part, then I takes you to where Grattan is, an' you lays him by the heels—just us three in it an' not a man Jack else. The beach comber don't do a thing to Tsan Ti till he hears from Grattan; an' how'll he ever hear from Grattan if he's safe in irons in some jail in these hills? That's my plan, an' you take it or leave it. If ye don't follow the course I've laid, then Grattan gets the ruby back, an' the[Pg 8] mandarin's life along with it. If ye think I'm talkin' crooked, an' put the lashings on me an' hand me over to the police, then not a soul'll ever know where Grattan's hid, an' he'll clear out an' get to Noo York whether I see him or not—but Tsan Ti'll be for Davy Jones' locker, no matter what ye try to do to prevent it. I've said my say an' eased my mind; now it's you for it."

With that, Bunce calmly drew a plug of tobacco from his pocket and nibbled at one corner reflectively.

BUNCE SPEAKS A GOOD WORD FOR HIMSELF.

Matt made a brief study of Bunce, leaning back in his seat and gazing at the mariner through half-closed eyes. The sailorman's get-up reminded Matt of Dick Deadeye in "Pinafore." Whether Bunce was really a deep-water humbug, and whether he was to be taken seriously, were questions that gave Matt a good deal of bother.

"He's stringing us, pard," averred McGlory bluntly. "That tongue of his is hung in the middle and wags at both ends."

"Avast, my man-o'-war!" came hotly from the mariner. "I'm no loafing longshore scuttler to let go my mudhooks in these waters and then begin splicing the main brace out of hand. You'll get your whack, my blood, and get it hard, if you keep on in the style ye're goin'. Belay a bit, can't you?"

McGlory snorted contemptuously and put his tongue in his cheek. Bunce began fingering his knife lanyard.

"No more of that give-and-take," said Matt.

"I'm a hard man," observed Bunce, "an' I've lived a hard life, winnin' my mate's berth on the ole Hottentot off Trincomalee by bashing in the skull of a Kanaka. More things I've done as would make your blood run cold just by listenin' to, but I'm straight as a forestay for all that, d'ye mind, an' I've a clean bill from every master I ever sailed with. 'He ain't much fer looks, Bunce ain't,' as Cap'n Banks, of the ole Hottentot used to say, 'but in a pinch you don't have to look twice for Bunce.' An' there ye have it, all wrapped up, tied small, an' ready for any swab as doubts me."

"Bunce," said Matt dubiously, "I'm frank to say I don't know just how to take you. By your own confession you're a thief——"

"Only when chinks has the loot," cut in Bunce hastily, "an' when it takes a bit of headwork an' a matchin' o' wits to beat 'em out."

"You helped Grattan steal the Eye of Buddha. Plotted it on a sampan off Canton, didn't you?"

Bunce shoved in his chair and showed signs of consternation.

"Scuttle me!" he gulped. "Wherever did you find that out? Grattan never told you where we had our chin-chin in the river of Honam."

"It's all pictured out," said Matt, "and you can drop into a theatre, in this town of Catskill, and see yourself and Grattan committing the robbery."

Bunce fell limply back.

"So, ho!" he mumbled. "Then them pictures are out, eh? They wasn't to come out for a month yet—it was in the agreement."

"Agreement?"

"Ay, no more nor less. It was on the trip from 'Frisco, east, mate, when Grattan an' me had the ruby but not a sou markee in our pockets. We needed money. Grattan knew some of these moving-picture swabs in Chicago, and he allowed he could turn a few reds by givin' 'em the plan of the robbery an' helpin' act it out. 'Avast,' says I, feelin' a warnin' twinge, 'don't touch it, Philo!' But he would—an' did, first gettin' an' agreement from the swabs that they wouldn't put out the pictures for two months. We got a couple of hundred yen for the work, an' that's what brought us on to the Catskills. So it's out, so it's out," and Bunce wagged his head forebodingly.

"Did you play a part in the pictures, Bunce?" went on Matt.

"Not I, mate! I may be lackin' in the head, once in a while, but there's a few keen thoughts rollin' around in my locker. I wouldn't go in for it, an' you can smoke my weather roll on that."

"There's a one-eyed sailor in the picture," said Matt.

"And he's a dead ringer for you," added McGlory.

"Which it ain't me, d'ye see?" scowled the mariner. "It's a counterfeit, got up to look like me—an' nothin' more."

"Then it's a mighty good counterfeit," averred the cowboy.

"I'm a man o' high principles, mate, even though I do say it as shouldn't. I was brought up right, by a Marblehead fisherman who hated rum, couldn't abide playin' cards, an' believed the-ay-ters was milestones on the road to the hot place. Actin' in a play I wouldn't think of, an' that's the flat of it. But what's the good word, shipmate? Are you sailin' this cruise wi' me to save the life o' the mandarin? I must know one way or t'other."

"Where is Grattan?"

"Five miles away, snug as a bug in a rug where he'll never be found onless I con the course. We'll have to go to him soon, if he's captured. I'm due at the meetin' place to-night."

"You spoke of a motor car——"

"Ay, that I did. It's hid in the woods beyond the railroad yards. We'll use that."

"You had a couple of motorcycles," said Matt.

"Which you and Grattan stole from us," supplemented McGlory. "What's become of them, Bunce?"

"Wrecked an' sunk," answered Bunce. "Mine sprung a leak an' went over a cliff in fifty fathoms of air; Grattan's bounced up on a reef an' went to pieces. Then we lifted the motor car, usin' of it for night cruises."

"You stole a motor car, eh?" said McGlory grimly. "And on top of that you have the nerve to come along here and speak a good word for yourself."

"Stow it," growled Bunce, "or you an' I'll be at loggerheads for good. What's the word?" and he turned his gleaming eye on Matt. "You can use the telephone an' hand me over to the police, or you can do as I say an' save the mandarin. What's the word?"

"When will we have to start after Grattan?" asked Matt.

"By early mornin', mate, just when it's light enough to see."

"And where'll we meet you?"

"In the woods beyond the railroad yards. Go there, stand on the track, an' whistle. I'll whistle back, then we'll come together—an' fill the bill."

"You can expect us at six o'clock," said Motor Matt, unlocking the door and pulling it open.

"Brayvo, my bully!" enthused Bunce. "An' ye'll come armed? Grattan is a hard man, an' sizable in a scrimmage."

"We'll be prepared to take care of Grattan," answered Matt. "Good night, Bunce."

"Good night it is," and the mariner vanished into the hall.

As soon as the door was again closed, Matt turned to find McGlory staring at him as though he thought he was crazy.

"Sufferin' tinhorns!" exclaimed the cowboy. "You can't mean it, pard?"

"Yes, I do," was the answer.

"Why, that old fore-and-after never told the truth in his life! He was using his imagination overtime."

"The chances are that he was, but there's a bare possibility he was telling the truth. We know Tsan Ti is in New York, and we can't feel absolutely sure that the Chinaman hasn't fallen into some trap laid by Grattan. If that's the case, the mandarin may lose his life."

"There's about as much chance of that, pard, as that you and I will get struck by lightning."

"We'll say the chance that Bunce is telling the truth is about one in a hundred. Well, Joe, that hundredth chance is what we can't take. Besides, Grattan is wanted. If he is really in the hills, and we can capture him, that will clear the road for Tsan Ti."

"But what will you do with the Eye of Buddha?"

Matt was in a quandary about that.

"Will you tote it along on a trip of this kind?" proceeded Joe, "or will you leave it in the hotel safe? Maybe that's what Bunce is playing for."

"He don't know we have the ruby. How could he?"

"I'm by. But he's up to something, and that's a cinch."

"We'll have to give him the benefit of the doubt—on account of Tsan Ti."

"Consarn that bungling chink!" grunted the cowboy, venting his anger on the mandarin as the original cause of their perplexing situation. "You can't do a thing with that red stone but lug it along."

"If the banks were open between now and the time we start, I might leave it with one of them for safe-keeping."

"And go dead against your letter of instructions! Then you would be responsible."

"I'll think it over to-night," said Matt, and began his preparations for turning in.

But sleeping over the question didn't answer it. Matt's quandary lasted until far into the night.

He had no faith in Bunce; he couldn't understand why Tsan Ti should have sent the ruby to him for safe-keeping; he doubted the wisdom of going into the hills with the mariner, and he understood well the risk of carrying the priceless Eye of Buddha with him on the morning's venture.

When McGlory opened his eyes in the first gray of the morning, Matt was tying up the box in which the ruby had come by express.

"What are you going to do, pard?" inquired the cowboy, jumping out of bed and beginning to scramble into his clothes.

"I guess, after all," answered Matt, "that I'll leave this box with the clerk."

"Wish I knew whether that was the proper caper, or not, but I don't. One thing's as good as another, I reckon."

At five-thirty they had a hurried breakfast, and, a little before six, Matt handed the small box to the hotel clerk and asked him to put it away in the office safe. Then the motor boys started for the railroad track and followed it away from the river and into the wooded ravine beyond the yards.

"This is far enough, I guess," said Matt, and began to whistle.

The signal was promptly returned from a place on the left, and the head of the mariner was pushed through a thicket of bushes.

"Ahoy, my hearties!" came from Bunce. "Come up here and bear a fist with the car, will ye?"

Puzzled not a little at this request, Matt and McGlory climbed the bank of the ravine and came alongside the mariner on a small, cleared shelf on the bank side. The "motor car" was before them, and at sight of it McGlory exploded a laugh.

"Speak to me about this!" he exclaimed. "Had you any notion it was this sort of a bubble, Matt?"

THE HOMEMADE SPEEDER.

What Matt saw was an ordinary hand car equipped with a two-cylinder gasoline engine. Across one end of the car was a bench, tightly bolted to the framework; back of this was a shorter bench for the driver of the queer machine. The king of the motor boys examined the car with a good deal of curiosity. Power was communicated to the rear axle by chain and sprocket. The gasoline tank was under the driver's bench, and he unscrewed the cap and tested the fuel supply by means of a clean twig picked up from the shelf.

"Oh, she's loaded full," wheezed Bunce. "I filled her myself, not more'n ten minutes ago."

"Do you know anything about motors, Bunce?" inquired Matt, giving the mariner a sharp look.

"Ay, that I do—in a way. I can turn on the oil and the spark when I wants to start, an' I can cut 'em off an' jam on the brakes when I wants to stop. That's all ye got to know in runnin' these benzine machines."

"Where does this belong?"

"Track inspector owns it. Grattan an' me borried it." Bunce grinned. "When we're done with the machine, we'll give it back."

"We'll make a picture, pard," grumbled McGlory, "trailin' along with this tinhorn on a stolen speeder."

"Avast, I say!" growled Bunce. "Ye're too free with your jaw tackle. Lend a hand, an' let's get her on the track an' make off. The section gang'll be out purty soon, an' we want to be away afore they see us."

"Sure you do," agreed McGlory sarcastically. "It'll be healthier for my pard and me, too, I reckon, if we're absent when the section men come along. That's why you wanted to make such an early start, eh?"

Without more ado, the motor boys helped Bunce get the speeder down the slope and upon the rails.

"Any trains coming or going at this hour?" asked Matt, with sudden thought.

"Say," jeered McGlory, "it would be fine if we went head on into a local passenger!"

"No trains comin' or goin', mate," said Bunce. "That's another reason for the early start. Want me to run the thing?"

"I'll do the running," answered Matt. "You climb up in front with McGlory."

Bunce and McGlory got on the front bench. Matt "turned the engine over" by running with the speeder for a few steps, then climbed to his seat, and they began laboring up a stiff grade through the ravine.

The road was full of curves, and when it couldn't go around a hill it went over it.

From his talk with Bunce, the night before, Matt had been under the impression that the stolen car was an automobile, and he had made up his mind to return the car to its owner—if the man's name could be learned—after it had been used for running down Philo Grattan. Now, that he had discovered that the car was a track speeder, he was no less resolved to hand it over to the railroad company on the return to Catskill.

The speeder performed fairly well, considering that it must have been knocked together in the company's shops by men whose knowledge of their work was not extensive. A secondhand automobile engine had furnished the motor.

"This isn't so bad," remarked McGlory, as they ducked around the shoulder of a hill, still on the up grade, with the motor fretting and pounding. "A motor ride's a motor ride, whether you're on an aëroplane, or rubber tires, or steel rails."

"This is what they call a joy ride, Joe," called Matt, from the rear. "The owner of the car doesn't know we're out with it. I'll return it to the railroad company when we're through with our morning's work."

"That's you. I hope the railroad company don't find out we've got it before we give it back. Gee, man, how she's workin'!"

"Fine day an' clear weather for fillin' the bill," remarked Bunce. "Did ye come armed, mateys?"

"Sufferin' hold-ups!" exclaimed McGlory. "Did you think for a minute, Bunce, we'd jump into this without being heeled?"

The cowboy, as he spoke, reached behind him and drew a short, wicked-looking six-shooter from his hip pocket.

Bunce recoiled.

"Where'd you get that, Joe?" asked Matt.

"Borrowed it from the hotel clerk."

"Well, put it away. I don't think we're going to need it. If we find Grattan there'll be three of us to take care of him. He's alone, I suppose, Bunce?"

"Sailin' by himself, mate," answered the mariner. "Better le' me take the gun, my hearty," he added, to McGlory.

"Speak to me about that!" scoffed the cowboy. "Why?"

"I'll have to go for'ard when we come close to the place, an' if Philo gets vi'lent, I'll look at him over the gun, an' it'll be soothin'."

"I'm able to soothe him, I reckon, no matter whether you're ahead or behind."

The speeder was making a terrific clatter. Everything rattled—the brake shoes barged against the wheel flanges, the engine rocked on its bed, and the levers jarred in their guides. In order to talk, and make themselves heard, those aboard had to lift their voices.

"Sufferin' Bedlam!" cried McGlory. "It's a wonder Grattan and Bunce were ever able to steal a rattletrap like this and get away with it. We're making more noise than a limited express."

Suddenly the motor gave a flash and a sputter and went out of business. In a twinkling the car lost headway and began sliding back down the grade toward Catskill. Matt threw on the brakes. The rear wheels locked, but still the car continued to slide downward. Shutting off the power, Matt dropped into the roadbed over the back of the bench, cleared the rails at a leap, and wedged one of the wheels with a stone. He had been obliged to work rapidly, for the car was on the move, and going faster and faster, as its weight gathered headway. But the stone sufficed, and the speeder was brought to a standstill.

"What took us aback, like that?" demanded Bunce.

"Too much gasoline," answered Matt, tinkering with the supply pipe, "and I couldn't check it with the lever control."

"This is a great old chug cart," laughed McGlory. "The railroad company ought to have been willing to pay somebody for running away with it. How'd you ever get over this road with it, Bunce?"

"When I came over the road it was downhill," answered the mariner, "an' all I had to do was to keep the craft on her course, an' scud along under bare poles."

"You had to climb a hill before you took the down grade, didn't you?"

"Ay, so I did, but the car came up the hill easy enough."

Matt soon had the valve in the supply pipe adjusted, and all hands had to push in giving the car a start. When they were going, and the engine had taken up its cycle, there followed a wild scramble to get aboard. This was finally accomplished, and once more they were puffing up the hill, but with less pounding than before.

"Say, Bunce," demanded McGlory suddenly, "did you take the speeder off the track and up the slope into those bushes alone?"

"Ay, ay, mate," was the answer. "But I had a rope and tackle to help."

McGlory was convinced that Bunce was wide of the truth, and Matt inclined to the same opinion, although why the mariner wanted to deceive them in such a small matter was difficult to understand.

Presently, to the great relief of the motor boys, the top of the hill was reached. The descent angled downward, around rocky uplifts and through thick timber, so that it was impossible to watch the track in advance for any considerable distance.

The descent, on such a makeshift power car as the speeder, was fraught with greater perils than the climb up the mountain. No power would be necessary, for the car would go fast enough without any added impetus. In order to keep it from going too fast, and jumping the track, the brakes would have to be judiciously used.

"We're off!" cried McGlory, as the speeder began coasting down the grade.

Matt tried out the brakes. They were capable of slackening the pace, but as for stopping the car, no appliance could have done that.

With rear wheels locked, the speeder hurled itself[Pg 11] down the mountain, acquiring greater and greater speed as it went. In and out of cuts the car dashed, here and there rumbling over a trestle which gave the passengers fearful glimpses of space below them.

McGlory and Bunce hung to their bench with both hands. There was no talking, now, for all three passengers were holding their breath.

Finally the descent became less steep. As the grade flattened out slowly into something approaching a level, Matt's work with the brakes began to achieve results. By degrees the mad flight of the car commenced to slacken.

"Sharp curve ahead!" sang out McGlory, heaving a deep breath of relief as the car continued to slow down.

Matt saw the sharp turn in the track where it rounded a shoulder of rock. Naturally he could not see around the turn, and he was speculating as to whether their reduced speed would be sufficient to throw the speeder off the rails at the bend, or whether the car would make it safely.

Before his calculations had been brought to an end, the problem was working itself out.

The speeder struck the curve, whirled around it with a shrieking of flanges against the rails, and then there went up a wild yell from McGlory and Bunce.

Directly in front of the car was a tie across the track!

A collision with the tie was inevitable. Matt foresaw it, and clung desperately to his bench.

"Brace yourselves!" he yelled.

The next moment they struck the tie.

The jolt was terrific. Motor Matt was thrown roughly against the seat in front, and Bunce went into the air as though shot from a gun.

TRAPPED.

Matt saw that McGlory had managed, like himself, to stay with the car, then both motor boys had a flash-light glimpse of the mariner ricochetting through the atmosphere and striking earth right side up by the track. But Bunce did not remain in an upright position. The force with which he had been thrown launched him into a series of eccentric cartwheels, and when he finally stopped turning he was in a sitting posture, with his back against a bowlder.

Apparently he had escaped serious injury, which was a remarkable fact, in view of the circumstances. A broken neck might easily have resulted, or, at the least, a fractured arm or leg.

"Shiver me!" gasped Bunce, dazed and bewildered by the suddenness of it all.

Then Motor Matt's and McGlory's shocked senses laid hold of another detail of the situation which was most astounding.

The green patch had been shaken from the mariner's head, and he was peering around him with two good eyes!

"Tell me about that!" roared McGlory, pointing. "Look at his lamps, Matt! He's got two!"

"I see," answered Matt grimly. "Suppose we approach closer, Joe, and find out about this."

Bunce watched the boys descend from the speeder and advance upon him, but there was still a dazed gleam in his eyes which proved that he was slow in recovering his wits.

"Are you all right, Bunce?" asked Matt, reaching the mariner's side and bending down.

"That—that craft must have—have turned a handspring," mumbled Bunce. "Purty tolerable blow we had, mates, an' I was snatched away from the bench, an' tossed overboard. It was done so quick I—I hardly knowed what was goin' on. By the seven holy spritsails! it's a wonder I'm shipshape an' all together." He got up slowly and began feeling gingerly of his arms and legs. "Nothin' busted, I guess," he added.

The ground where he had landed was cushioned with sand. To this fact, more than to anything else, he owed his escape from injury.

McGlory picked up the green patch.

"Here's an ornament you dropped during that ground-and-lofty tumbling, you old tinhorn," said he. "What did you wear it for, anyhow?"

"Blow me tight!" exclaimed Bunce, staring at the patch with falling jaw. "Ain't that reedic'lous?" he added, with a feeble attempt to treat the matter lightly.

"It is rather ridiculous, Bunce, and that's a fact," answered Matt. "You've a pair of very good eyes, it seems to me, and what's the good of that patch?"

The mariner grabbed the bit of green cloth and pulled the string over his head.

"I never said I'd lost one o' my lamps," he averred, settling the patch in place. "Off Table Mountain, South Africy, a cable parted on the ole Hottentot, an' I was hit in the eye with a loose rope's end. For a while, I thought I was goin' blind. But I didn't, only the eye has been weak ever sence, an' needs purtection. That's why I wear the patch."

"You've got it over the wrong eye, Bunce," observed McGlory. "You've been wearing it over the left eye, and now it's over the right. Have you got any clear notion which eye was hit with that rope's end?"

Bunce hastily changed the position of the patch.

"I'm that rattled," said he, "that I'm all ahoo, an' don't rightly know what I'm about. I——"

For an instant he stared up the track, breaking off his words abruptly; then, without any further explanation, he whirled and rushed for the timber.

With a yell of anger, McGlory started after him.

"Come back, Joe!" shouted Matt. "Here come some men who seem to have business with us."

The cowboy whirled to an about face, and followed with his eyes the direction of his chum's pointing finger.

Four men in flannel shirts and overalls, and carrying spades, picks, and tamping irons, were hurrying up the track in the direction of the curve.

"The section gang!" muttered McGlory.

"A good guess," laughed Matt. "We've been trapped."

"Trapped?"

"That's the way it looks to me. We were seen coming down the mountain and those men, recognizing the speeder, laid the tie across the rails to catch the thieves."

"Sufferin' kiboshes, but here's a go! This comes of trying to fill the bill for an old tinhorn like Bunce."

"Ketched!" yelled one of the approaching men, flourishing a tamping iron; "we've ketched the robbers that run off with Mulvaney's speeder! Don't you make no[Pg 12] trouble," he added, slowing his pace and coming more warily.

The other three men spread out and then closed in, barring escape for the motor boys in every direction.

"You've made a mistake," said Matt.

"Oh, sure!" jeered the section boss, "but I reckon we'll take ye to Catskill, an' let ye tell the superintendent all about the mistake."

"Don't be in a rush about taking us to Catskill," threatened McGlory. "You listen to what Motor Matt says, and I reckon he'll make the layout clear to you."

"Motor Matt!" returned the boss ironically. "Why don't ye say ye're the governor o' the State, or somethin' like that? Ye might jest as well. Motor Matt ain't stealin' speeders an' runnin' off with 'em."

The king of the motor boys had become pretty well known in the Catskills through his previous work in recovering the ruby for Tsan Ti. Even these section men had heard of his exploits. Matt, seeing the impression his cowboy pard's words had made, resolved to prove his identity in the hope of avoiding trouble.

"What my chum says is true, men," he declared. "I am Motor Matt. We didn't steal the railroad speeder. That was done by the man who was with us—the fellow who ran away. You saw him, didn't you?"

"Sure we saw him," answered the section boss, "but I wouldn't try to put it all off onto him, if I was you."

"Sufferin' blockheads!" rumbled McGlory. "Use your brains, if you've got any, can't you? Do we look like thieves?"

"Can't most always tell from a feller's looks what he is," returned the boss skeptically. "And this other chap can't be Motor Matt, nuther, or he wouldn't have stole the speeder. That there speeder has been missin' for three days, an' orders has gone out, up an' down the line, for all hands to watch out for it. When I seen it comin' down the grade, I knowed we had ye. All we done was to throw that tie acrost the track, an' the trick was done. Ye'll have to go to Catskill, that's all about it."

"Are you men from Catskill?" inquired Matt.

"No, Tannersville, but Catskill's the place you're wanted. We'll put ye on the passenger, when it comes along."

"But we don't want to go back to Catskill just yet," Matt demurred. "We've got business here, and it can't be put off."

Matt believed that Bunce had run to get away from the section men, who, he must have realized, had caused the speeder's mishap in the hope of catching the ones who had stolen the car. There was yet a chance, Matt thought, to overhaul Bunce and find Grattan. To go back to Catskill, just then, would have been disastrous to the work he and McGlory were trying to do under the mariner's leadership.

"Sure ye don't want to go to Catskill," went on the section boss, "right now, or any other time. But ye're goin', all the same. Grab 'em, you men," and the boss shouted the order to the three who had grouped themselves around Matt and McGlory.

"Hands off!" shouted the cowboy.

Matt saw him jerk the revolver from his pocket, and aim it at the man who was reaching to lay hold of him. The man fell back with an oath of consternation.

"Don't do that, Joe!" cried Matt.

"Oh, no," sneered the boss, "you fellers ain't thieves, I guess! What're you pullin' a gun on us for, if ye ain't?"

"I'm not going to argue the case with you any further," Matt answered shortly. "We're going back to Catskill after a while, but not now. When we get there we'll report to your superintendent and explain how we happened to be aboard the stolen speeder. I was intending to return the car to the railroad company as soon as we had got through with it, and then——"

"Sure ye was!" mocked the boss. "Ye wasn't intendin' to do anythin' but what was right an' lawful—to hear ye tell it. We got ye trapped, an' I ain't goin' to fool with ye any longer. Put down that gun, you!" and he whirled savagely upon McGlory. "We're goin' to take ye, an' if you do any shootin' ye'll find yerselves in a deeper hole than what ye are now."

"You keep away from me," scowled McGlory, still holding the weapon leveled, "and keep your men away from me. Try to touch either of us, and this gun will begin to talk. We're not thieves, but that's something we can't pound into your thick head, so we're going to attend to our business in spite of you."

The section boss was a man of courage, and was resolute in his intention to take the boys to Catskill. Certainly, so far as appearances went, he had the right of the matter, and Matt didn't feel that he could explain the exact situation with any chance of having his words believed.

"Here's where I'm comin' for ye," proceeded the section boss, "an' if you shoot, you'll be tagged with more kinds o' trouble than you can take care of. Now——"

The section boss got no farther. Just at that moment the rumble of a train coming up the grade could be heard. Instantly the attention of the section boss was called to another matter.

"The passenger!" he cried, jumping around and staring at the speeder and the tie. "There'll be a wreck if we don't clear the track. Come on, men! Hustle!"

The peril threatening the passenger train banished from the minds of the section men all thought of the boys. All four of the gang ran to remove the obstructions from the rails.

"Come on, pard!" said McGlory; "now's our chance."

Matt, with a feeling of intense relief, bounded after his chum, and they were soon well away in the timber.

THE CUT-OUT UNDER THE LEDGE.

McGlory was inclined to view recent events in a humorous light.

"Speak to me about that, pard!" he laughed, when he and Matt had halted for breath, and to determine, if possible, which way Bunce had gone. "I told you what was on the programme if you became trustee for the Eye of Buddha. We never know when lightning's going to strike, or how."

"I don't like episodes of that sort," muttered Matt. "It puts us in a bad light, Joe."

"Oh, hang that part of it! We can explain the whole thing to the railroad superintendent as soon as we get back to Catskill. That section boss was a saphead. You[Pg 13] couldn't pound any reason into his block with a sledge hammer. Forget it!"

"But you drew a gun on the section men. That makes the business look bad for us."

McGlory chuckled. "See here, pard," said he. With that, he "broke" the revolver and exposed the end of the cylinder.

There were no cartridges in the weapon!

"Now, what do you think?" laughed the cowboy. "I borrowed the gun in a hurry, and didn't think to ask whether it was loaded—and I reckon the hotel clerk didn't think to tell me. It's about as dangerous as a piece of bologna sausage, but it looks ugly—and that's about all there is to this revolver proposition, anyhow."

Matt enjoyed the recent experience, in which the harmless revolver had played its part, fully as much as his chum.

"Well," said the king of the motor boys, "what's done can't be helped, and we'd better be about our business with Bunce. But what's become of the mariner? He ought to be around here, somewhere."

"He's ducked," returned McGlory, "and I'll bet it's for good. We've found out he had a pair of good eyes, and he's got shy of us."

"If we don't find him," mused Matt, "it's a clear case that he was playing double with us. If we do find him, then we can take a little more stock in what he tells us about Tsan Ti. It will be worth something to feel sure, either way."

"Maybe you're right, but how are we going to pick up the webfoot's trail?"

Matt studied the ground. The earth was soft from a recent rain, and the fact gave him an idea.

"Track him, Joe. You're used to that sort of thing. Put your knowledge to some account."

"In order to track the mariner," said McGlory, "we'll have to go back to the place where we saw him duck into the timber. It'll be a tough job, but I'm willing to try if we can once pick up the trail."

"That's the only thing for us to do. If Bunce was intending to deal squarely with us, he'd have shown himself before this."

"Let's see," mused the cowboy. "He said that Grattan was hiding out about five miles from Catskill, didn't he?"

"Yes."

"Then I reckon the place is somewhere around here. We're about five miles from the town, I should judge. Still," and disgust welled up in the cowboy as he voiced the thought, "you can't tell whether Bunce was giving that part of it straight, or not. He's about as crooked as they make 'em, that tinhorn."

The boys, during their talk, had been moving slowly back in the direction of the railroad track. Cautiously they came to the edge of the timber, close to the right of way, on the alert not only for the tracks left by Bunce, but for the presence of the section men, as well.

The section gang, they discovered, had left the vicinity of the sharp curve, and were nowhere in sight. The speeder, badly shaken by the jar of its collision with the tie, was off the rails, and the tie lay beside it.

"No sign of the section men," announced Matt, after a careful survey of the track.

"Mighty good thing for us, too, pard," said McGlory. "Here's Bunce's trail, and he traveled so fast he only hit the ground with his toes. Come on! I can run it out for a ways, anyhow."

McGlory's life on the cattle ranges had made him particularly apt in the lore of the plains. The trail was very dim in places, but even the disturbed leaves under the trees, and the broken bushes told McGlory where the mariner had passed.

The course taken by Bunce led across a timbered "flat" and down into a rocky ravine, then along the ravine to a ledge of rock which jutted out from a side hill. The under side of the ledge was perhaps a dozen feet over the bottom of the ravine, and under it was a sort of "pocket" in the hill.

Here there were evidences of a primitive camp. The soft earth under the ledge was trampled by human feet, and there was a large, five-gallon can that had once held gasoline, but which was now empty. A small mound of dried leaves had been heaped up at the innermost recess of the "pocket," and the bed still bore the faint impression of a man's body.

"Bunce was right about Grattan being in hiding near Catskill," observed Matt. "Here's the place, sure enough."

"And Bunce came here, pard," went on McGlory; "he made tracks straight for this hang-out as soon as he got clear of us. Judging from what we see, I should say Bunce met Grattan, and that they both hurried off. But what was that gasoline for?"

"For the speeder, maybe," replied Matt.

"They wouldn't keep the gasoline supply for the speeder so far from the track, would they?"

"I shouldn't think so; still, I can't imagine what else they'd want gasoline for."

"What sort of a game was Bunce up to? If Grattan was here, then everything was going right, so far as the plan to capture Grattan was concerned. Why didn't Bunce wait for us, back there in the timber, and give us the chance to come on here and put the kibosh on the man we want?"

"It's a mystery, Joe," said the puzzled Matt. "Perhaps Bunce believed that we'd be captured by the section men and that it wouldn't be possible to get hold of Grattan. If he thought that, he might have come on to this place, given his New York report to Grattan, and made up his mind to see the rascally game through to a finish. Bunce couldn't have any idea that we'd escape from the section gang."

"Well," growled McGlory, "he might have waited and made certain of it."

There was no accounting for the queer actions of the mariner. It seemed as though, after the collision with the railroad tie and the coming of the section men, he had changed his mind about helping the boys capture Grattan.

Matt and McGlory moved around under the ledge, trying to find something else that would point positively to the presence of Grattan in the "pocket."

There was a strong odor of gasoline—much stronger than would have come from the uncorked, empty can. Suddenly Matt found something, and hurriedly called his chum.

"What is it?" inquired McGlory, running to Matt's side.

Matt pointed to two straight lines in the earth, leading out and up the ravine.

"Motorcycles," said he laconically, "two of them!"

McGlory struck his fist against his open palm.

"Well, what do you think of that!" he cried. "Motorcycles and speeders! Say, those tinhorns were well fixed in the motor line. And Bunce told us both motorcycles had been destroyed! Sufferin' Ananias, but he's a tongue twister!"