| Vol. III.—No. 120. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, February 14, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

Electa Eliza was never seen without that baby. Ever since it was three weeks old—it was born in August and now it was February—she had taken the whole care of it every day, excepting Sundays, from morning until night.

Mrs. Googens, her mother—her father was dead—when she wasn't out washing and ironing, was washing and ironing at home and having no other children besides Electa Eliza and the baby, of course the care of the small boy fell almost entirely on his sister.

This was rather hard, for she was only twelve years old, and lame besides, and it requires a great deal of patience and good nature to mind a baby, especially a lively, wide-awake baby who jumps, and "pat-a-cakes," and "goos," and "guggles," and wants to go "day-day" all the time.

It wasn't a pretty baby, and it wasn't an ugly baby. It had round blue eyes, round red cheeks, round wee nose, and a very bald head, and sometimes it looked so wise you couldn't help thinking it wasn't a baby at all, but a jolly, lazy old gentleman dwarf just making believe to be one, to be carried around and waited upon.

Electa Eliza had gone to school before the baby came, and had been a very good scholar—at the head of her class, in fact; but ever since she had been obliged to stay at home altogether, and it was but seldom she got a chance to look at her books.

Now around the corner from the house where Electa Eliza lived was a church, and on the steps of this church, sheltered by the porch, she often rested when tired walking with the baby.

Indeed, it was her favorite resting-place, and even when the weather was quite cold, she spent many hours there, watching most of the time the house directly opposite, at whose windows often appeared another girl and another baby.

This young girl, who was about three years older than Electa Eliza, and whose name was Theodora Judson, and her little brother were her mother's only children, just as Electa Eliza and her baby were her mother's only children.

But, ah! how far apart their paths in life were!

The Judson baby had a nurse-maid in constant attendance upon him, his sister only playing with him when she felt so inclined, and Miss Theodora had a French and German teacher, and a music teacher, and a riding-master, besides being one of the day-pupils at a celebrated academy famous for its excellent scholars. And her father and mother were the most indulgent of parents, refusing her nothing that she desired.

But yet Theodora was not contented, but was continually wishing to be something that would make her of more importance in the world, and wondering when, if ever, she would find a mission. On St. Valentine's morning—Valentine's Day happening that year to fall on a Saturday—she was holding forth, as she had held forth a hundred times before to her mother, who was listening patiently, as mothers usually do, on the subject which always lay nearest her heart.

"I'd like to become famous," said Theodora, her eyes sparkling and her cheeks glowing; "be an artist, or an author, or an inventor, or somebody great. It seems so hard to live in this big world, and be a woman and nothing more. To paint a lovely picture, to write a beautiful book, to make a discovery that would gain me the praise and thanks of thousands of people—ah! if I dared to dream I should ever do any of these things, I should be perfectly happy."

"My dear," said her mother, mildly, "there are many other ways besides those which you have mentioned by which praise, and thanks, and love, and happiness can be gained. It isn't easy to become famous, but it is easy—that is, if one's heart is in the work—to do a great deal of good to one's fellow-beings. Young as you are, I have no doubt there are many sad hearts you might gladden, and many gloomy homes to which you might bring brightness."

"Oh, mother, can you show me one?" said Theodora, eagerly.

"I could, many a one," answered the mother, smiling; "but surely so bright and intelligent a girl as yourself ought to be able to find out who needs your help and encouragement without my assistance."

It was now just about the hour for the morning's mail to come in, and within ten minutes of the time when this serious conversation took place, Miss Theodora and her friend Bessie Lee were on their way to the post-office.

What a hurrying and skurrying there was! what a laughing and shouting!

How did the deaf old clerk in the post-office ever manage to take charge of such dainty missives? There were big valentines and little valentines, valentines with coarse figures accompanied by bad poetry, and valentines that were marvels of art. There were hearts, and darts, and Cupids, and roses, and posies, and everything that goes to make the valentine a wonder and delight.

No one had a larger supply than Theodora and Bessie, and arm in arm they walked down the street displaying their treasures, and demanding everybody's sympathy, from the old doctor, on his way to treat a critical case, to Pussie Evans, the minister's little girl, who was forbidden to leave the door-step, and had to wait for somebody to bring her valentines to her.

Not one of the merry party noticed Electa Eliza. Yet there she was, and without the baby—a fact so remarkable that it might well have attracted attention had there been a person in the world to give the poor child a thought.

But Electa Eliza had a special interest in this Valentine's Day. Not that she expected a valentine; such a thing would have been too absurd. Still, her interest in those wonderful missives at the post-office was quite sufficient to induce her to give up fully one-half of her dinner to a friend who agreed to mind the baby for an hour. Then with her little crutch she mounted the hill to the post-office, waiting quietly about until Miss Theodora received the gay envelopes addressed to her.

Now when this young lady reached home she found among the great bundle handed her by the old clerk a large yellow envelope on which her name was written in a print-like hand.

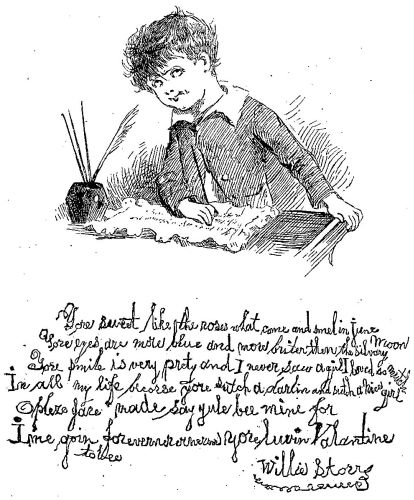

With rather a scornful expression on her pretty face Theodora opened it, and found a rude drawing of two babies looking smilingly at each other—at least it had been intended that they should be looking smilingly at each other—one with very round eyes, nose, and mouth, and plain dotted slip; the other with indistinct features, but a most elaborately embroidered dress, over which floated an immense sash. Underneath the picture was this verse:

"You are such a pretty girl

With your lovely hair in curl

With your lovely eyes of blue

How I wish that I was you."

And underneath the verse was the following letter:

"Dear young Lady,—I am a poor, little girl and I'm lame too because of a dreadful fall I got once and broke something in my knee. Maybe you have saw me sittin cross the way from your house on the church steps with a baby. Hese awful heavy but hese good but I cant go to school cause I have to mind him and he wants to mused ever so mutch but hese very good and I love pictures and books and now Alonzo that's my baby's name is a beginin to go to sleep erly and if I had some Ide be so glad. I named him out of a story I read once and[Pg 243] I thort maybe you had some picktures and books you dident want no more and you might give them to me. I wrote this potry I had to say pretty girl cause lady woodent go with curl and I drawed the babies I coodent make his face right cause I never seen him close but I think his dress is right my mother washes dresses like them sometimes I did it when Alonzo was asleep he dont sleep mutch days hese a very lively baby but hese good If you will let me have some of your old picktures and books I will thank you ever so mutch and so will Alonzo when hese big enuf cause he rely is a very good baby Your baby's nurse told me your name and she says your baby is a sugar plum from Heaven.

"Electa Eliza Googens."

"What a queer valentine!" said Theodora, laughing, as she finished reading it.

"What a nice one!" said her mother. "Far above half of those all lace and nonsense that you have received to-day. And, Dora, those babies are drawn better than you could have drawn them."

"Yes," said Theodora, frankly, "they are."

"So it appears this poor child has more artistic talent than you."

"And the verse is but little worse than I might have done myself. I'll save you the trouble of saying that, mother," said the daughter, merrily; "and so she may stand just as good a chance of becoming a writer or an artist as I do, she being so much younger. Poor little thing! I've seen her sitting on the church steps, with the baby that is so 'good,' many a time, but I am ashamed to say I never gave her a second thought."

"And yet, my dear," said Mrs. Judson, "there was your mission right before your eyes waiting for you to take it up. Help this poor child to the learning for which it is evident she longs so much. Give her and Alonzo some happy hours. And who knows?—you may at the same time be helping the world to a noble woman and a noble man, and what greater work than that could be found?"

"I will, mother—dear, wise, good mother, I will," said Theodora, and she flew to the window and beckoned to Electa Eliza, who had resumed the charge of Alonzo, and although the snow was falling fast, sat under the church porch, with Alonzo, well wrapped in an old woollen shawl, in her arms.

And that was the beginning of the "Star in the East Mission School." From one little girl and a baby it grew in a year to forty children small and large, and now—for the valentine was sent and the mission founded several years ago—a hundred and more bless the name of their pretty young teacher and friend, Miss Theodora Judson, and look up with affection and pride to her clever assistant, still younger than herself, Miss Electa Eliza Googens.

There is a beautiful little French story which has been translated into English, and called "Picciola," the Italian for little flower. It is the story of a French nobleman who was thrown into prison on an unjust charge of plotting against the government of his country. He was a man of talent and education, as well as of wealth and position. Somehow, with all his life had given him, it had never taught him to look with open eyes at nature, or to see beyond nature a God who had created it.

He was restless and impatient in his close cell and the little strip of court-yard where he paced up and down, and up and down, in his misery, longing to be free. One day he saw between the heavy paving-stones of the yard the earth raised up into a tiny mound. His heart bounded at the thought that some of his friends were digging up from below to reach him, and give him his liberty again.

But when he came to examine the spot closely he found it was only a little plant pushing the earth before it in its effort to reach the light and the air. With the bitter sense of disappointment which this discovery brought, he was about to crush the little intruder with his foot, and then a feeling of compassion stopped him, and its life was spared.

The plant grew and throve in its prison, and the Count de Charney became every day fonder of his fellow-prisoner; he spent hours, which had before been empty, watching it as it grew and developed, until it became the absorbing interest of his life. As he watched it day by day, and saw the contrivances by which it managed to live and grow, he was compelled to believe that there must be somewhere a great and wonderful power that could design and make so marvellous a thing. The little flower was like a little child taking him by the hand; and leading him away from his dark, bitter, unbelieving thoughts into the light of God's love.

I want to take some common flower, something you have seen a hundred times every summer of your lives, and show you a few of the marvellous contrivances that make it able to live and grow and bear blossoms and fruit. If you will study them closely for a while, it will not seem so strange then that the Count de Charney, who had lived so many years without learning anything of the wonders of nature, should have had them opened for him by one little flower that he had carefully watched and studied.

Most plants are alike in having roots, stems, and leaves, and some sort of flower and seed-vessel. But the parts look so very different in different plants that it is sometimes a little hard to tell which is which. In some the roots grow in the air, and in others the stems grow underground. It is only by studying what the parts do that it is possible to be sure what they are. The most important part of every living thing is its stomach, because everything that lives must eat and drink, or die. There are some very curious plants which have regular stomachs into which their food goes, just as it does in an animal, and is digested, but these are not very common. Some day, however, when we have learned a little more about simpler things, I mean to tell you something about these strange plants. Ordinary plants have roots to supply them with food and water in the place of a stomach.

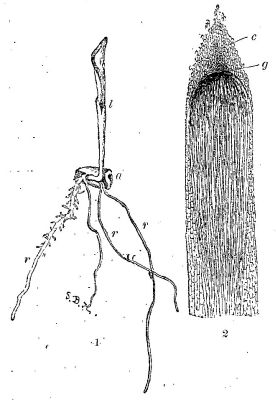

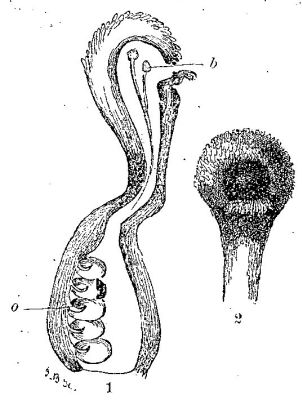

Fig. 1.—Corn and Magnified Root.

Fig. 1.—Corn and Magnified Root.Let us study the roots of some plant. Almost anything will do. If you can do so, get a hyacinth glass and bulb. The bulb is the root, and looks very much like an onion; the glass is a vase made for the purpose of growing hyacinths in water. It slopes in from the bottom upward, and then bulges out suddenly. The bulb rests in this bulging part, and has water below it and around its lower part. The glass being clear, you can see the roots grow as plainly as you can see a leaf or a flower bud unfold. Perhaps you have no hyacinth glass, and can not get one; then try to make one for yourself out of a small glass jar. There will certainly be a pickle bottle or a preserve jar about the house that will answer perfectly well. All you want is to have the bulb rest half in and half out of the water, with room below for the roots to spread through the water. Be careful to keep the water up to the right mark by adding a little every day as the plant soaks it up.

Or you may take a dozen grains of seed corn, soak them overnight, and then plant them an inch deep in a box, having about six inches or more depth of good earth. In about three days the blade will come above ground. Put your hand or a trowel down beside one of the plants, and scoop it gently up. Be sure you make your hand or trowel go away down below where the seed was planted, so as not[Pg 244] to bruise the tender growth. Shake and blow the dust away, and you will see several little white thread-like roots coming from the grain. If you take up in this way all the young plants, one or two every day, you will see how they sprout and grow.

If you have a microscope[1] and a sharp knife, carefully split the end of one of these roots and look at it. If you have not, you will have to trust me so far as to take this drawing as correct (Fig. 1). All these tiny roots have a cap over their growing end, so that when they have to push their way among the hard earth and stones, the growing part will not get bruised. These roots take in all the water and the food which the earth supplies to the plant.

Fig. 2.—Geranium Pistil.

Fig. 2.—Geranium Pistil.The hyacinth can grow in water alone, because it has been a provident little body, and stored away enough food in the little round carpet-bag of a bulb to supply the plant for the few weeks of its life. It only asks for the water it needs to keep it alive and growing. When the thirsty little roots have sucked up water enough, the bulb begins to grow in the other direction. If you look, you will see a solid lump of pale green come up from the top like the horns of a calf, or a baby's tooth. This is the young plant coming up out of its dark cradle into the light and air and sunshine. The delicate growing end of the plant, which will after a while bear its beautiful spike of bells, is very tenderly wrapped up in the leaves. After it gets through the tough skin of the bulb, the plant grows straight up. It stretches itself after its long sleep in the sweet air and light, the leaves lengthen and broaden and open out, and the stem with its little knobby buds comes up in the midst. These will soon grow and unfold into beauty and fragrance, and you will be rewarded for all your long waiting, if watching the wonderful growth day by day has not carried its own reward with it.

Many plants are grown from roots or bulbs, but a greater majority by far come from seed. Tulips and lilies, onions and potatoes, are all instances of plants grown from roots which sprout out from the old ones. The root is in every case the beginning, the seed the ending, of the life of a plant.

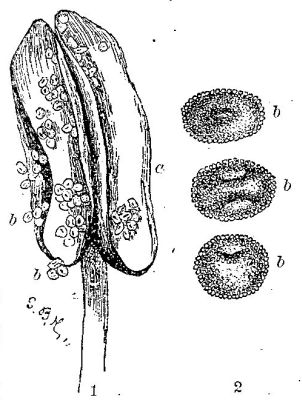

Fig. 3.—Geranium Stamen and Pollen Grains.

Fig. 3.—Geranium Stamen and Pollen Grains.Take two of the commonest of our window and garden plants—the geranium and the heart's-ease. Let us take the geranium first. On the cluster of bloom we will probably find flowers partly withered, flowers full blown, and buds nearly ready to open. Look at a full-blown flower. You will see with your naked eye something standing up in the middle which looks like a tiny pink lily; around it are little rounded white spikes. If you carefully strip off the green cap outside, and then the colored petals, you will find a lily like the one in the figure (Fig. 2); this is called the pistil. Now open one of the nearly blown buds; you will find the lily pistil still closed, and on two of the spikes around it two double-barrelled rosy pods. When the pods, or stamens, are nearly ripe, they look for all the world like a pink gum-drop made in the shape of a French roll. If they are ripe they look as you see in Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.—Pistil of Heart's-Ease.

Fig. 4.—Pistil of Heart's-Ease.To make a perfect seed the stamen and pistil have to enter into partnership. The stamen sends out thousands of clear orange pollen grains (Fig. 3, b), and when these fall on the top of the lily or pistil, as some have done in. Fig. 2, they stick fast. The lily, for all its innocent look, has laid a trap for them; it is covered with a sticky substance that holds them fast. The tiny little grain begins to send out a tube like a little hose-pipe, which grows down and down to the bottom of the lily. There it finds some very small egg-shaped bodies called ovules (Fig. 2, o). The busy little hose-pipe pushes its way into a little opening at the end of one of the ovules, pumps away till the pollen grain is empty, and the liquid out of it is all safely stored in the ovule, and then it withers away. The ovule when it is ripe is a seed, but if the pollen has not emptied itself in the way just described, the ovule dies.

If you look at Fig. 4 you will see the pistil of a pansy, or heart's-ease. No. 1 is a side view of the pistil sliced down so you can see into it, as you can into a baby-house. You see the pollen grains, b, sending down their tubes to the ovules, o. No. 2 in this drawing is the front view of the heart's-ease pistil. The beautiful colored leaves of a flower are only meant to cover and protect the pistil and the pollen of the plant, as the fruit is meant to cover its seed. There has been a tender care for us in all this that the covering for both should have been made so beautiful and so delicious.

ortune had been hard upon Bill and his two mates, or at least they thought so. The trees to which they had been tied by the Lipans were so situated that it was only necessary for them to turn their heads in order to have a good view of what was doing on the plain to the westward. They saw their captors ride out, and heard their whoops and yells of self-confidence and defiance.

"Don't I wish I was with the boys just now!" growled Bill. "Three more good rifles'd be a good thing for 'em."

"Skinner'll fight, you see 'f he don't. He'll stop some of that yelling."

"He's great on friendship and compromise," groaned Bill. "He may think it's good sense not to shoot first."

The three gazed anxiously out toward the scene of the approaching conflict, if there was to be one. They could not see the advance of their comrades, but they knew they were coming.

"Hark!" suddenly exclaimed Bill. "That's the boys. Opened on 'em. Oh, don't I wish I was thar!"

The other two could hardly speak in their excitement and disgust. It was a dreadful thing for men of their stamp to be tied to trees while a fight was going on which might decide whether they were to live or die.

Suddenly a squad of Lipans came dashing in; the cords that bound them were cut—all but those on their hands; they were rudely lifted upon bare-backed ponies, and led rapidly away to the front of the battle. They could not understand a word of the fierce and wrathful talking around them; but the gesticulations of the warriors were plainer than their speech. Besides, some of them were attending to wounds upon their own bodies or those of others. Some were on foot, their ponies having been shot under them. More than all, there were warriors lying still upon the grass who would never again need horses.

"It's been a sharp fight," muttered Bill, "for a short one. I wonder if any of the boys went under? What are they gwine to do with us?"

A tall Lipan sat on his horse in front of him, with his long lance levelled as if only waiting the word of command to use it. It remained to be seen whether or not the order would be given, for now To-la-go-to-de himself was riding slowly out to meet Captain Skinner.

"He can't outwit the Captain," said one of the miners. "Shooting first was the right thing to do this time. Skinner doesn't make many mistakes."

It was their confidence in his brains rather than in his bones and muscles which made his followers obey him, and they were justified in this instance, as they had been in a great many others. The greetings between the two leaders were brief and stern, and the first question of old[Pg 246] Two Knives was: "Pale-faces begin fight. What for shoot Lipans?"

"Big lie. Lipans take our camp. Tie up our men. Steal our horses. Ride out in war-paint. Pale-faces kill them all."

The chief understood what sort of men he had to deal with, but his pride rebelled.

"All right. We kill prisoners right away. Keep camp. Keep horse. Kill all pale-faces."

"We won't leave enough of you for the Apaches to bury. Big band of 'em coming. Eat you all up."

"The Lipans are warriors. The Apaches are small dogs. We are not afraid of them."

"You'd better be. If you had us to help you, now, you might whip them. There won't be so many of you by the time they get here. Pale-faces are good friends. Bad enemies. Shoot straight. Kill a heap."

Captain Skinner saw that his "talk" was making a deep impression, but the only comment of the chief was a deep, guttural "Ugh!" and the Captain added: "Suppose you make peace. Say have fight enough. Not kill any more. Turn and whip Apache. We help."

"What about camp? Wagon? Horse? Mule? Blanket? All kind of plunder?"

"Make a divide. We'll help ourselves when we take the Apache ponies. You keep one wagon. We keep one. Same way with horses and mules—divide 'em even. You give up prisoners right away. Give 'em their rifles and pistols and knives."

"Ugh! Good! Fight Apaches. Then pale-faces take care of themselves. Give them one day after fight."

That was the sort of treaty that was made, and it saved the lives of Bill and his mates, for the present at least.

It was all Captain Skinner could have expected, but the faces of the miners were sober enough over it.

"Got to help fight Apaches, boys."

"And lose one wagon, and only have a day's start afterward."

The chief had at once ridden back to announce the result to his braves, and they too received it with a sullen approval, which was full of bitter thoughts of what they would do to those pale-faces after the Apaches should be beaten and the "one day's truce" ended.

The three captives were at once set at liberty, their arms restored to them, and they were permitted to return to the camp and pick out, saddle, and mount their own horses.

"The Captain's got us out of our scrape," said Bill. "I can't guess how he did it."

"Must ha' been by shootin' first."

"And all the boys do shoot so awful straight!"

That had a great deal to do with it, but the immediate neighborhood of the Apaches had a great deal more. To-la-go-to-de knew that Captain Skinner was exactly right, and that the Lipans would be in no condition for a battle with the band of Many Bears after one with so desperate a lot of riflemen as those miners.

The next thing was to make the proposed "division" of the property in and about the camp. The Lipan warriors withdrew from it, all but the chief and six braves. Then Captain Skinner and six of his men rode in.

"This my wagon," said Two Knives, laying his hand upon the larger and seemingly the better stored of the two.

"All right. Well take the other. This is our team of mules."

So they went on from one article to another, and it would have taken a keen judge of that kind of property to have told, when the division was complete, which side had the best of it. The Lipans felt that they were giving up a great deal, but only the miners knew how much was being restored to them. It was very certain that they would take the first opportunity which might come to "square accounts" with the miners. Indeed, Captain Skinner was not far from right when he said to his men:

"Boys, it'll be a bad thing for us if the Apaches don't show themselves to-morrow. We can't put any trust in the Lipans."

"Better tell the chief about that old man and the boy," said one of the men.

"I hadn't forgotten it. Yes, I think I'd better."

It was easy to bring old Two Knives to another conference, and he received his message with an "Ugh" which meant a good deal. He had questions to ask, of course, and the Captain gave him as large an idea as he thought safe of the strength and number of the Apaches.

"Let 'em come, though. If we stand by each other, we can beat them off."

"Not wait for Apaches to come," said To-la-go-to-de. "All ride after them to-night. Pale-faces ride with Lipans."

That was a part of the agreement, but it had not been any part of the intention of Captain Skinner.

"We're in for it, boys," he said, when he returned to his own camp. "We must throw the redskins off to-night. It's time to unload that wagon. We're close to the Mexican line. Every man must carry his own share."

"Guess we can do that."

"I don't believe we can. It'll be as much as a man's life's worth to be loaded down too much with all the riding we've got before us."

"We won't leave an ounce if we can help it."

"Well, not any more'n we can help."

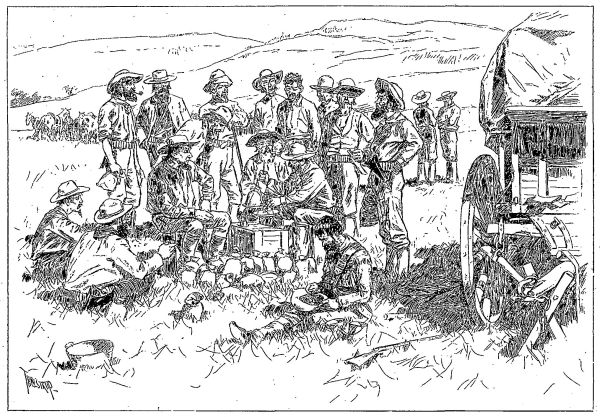

It was a strange sight, a little later, the group those ragged, weather-beaten men made around their rescued wagon, while their leader sat in front of it with a pair of scales before him.

"Some of the dust is better than other some."

"So are the bars and nuggets."

"EVERYTHING'S GOT TO GO BY WEIGHT. NO ASSAY-OFFICE IN

THIS CORNER OF ARIZONA."

"EVERYTHING'S GOT TO GO BY WEIGHT. NO ASSAY-OFFICE IN

THIS CORNER OF ARIZONA."

"Can't help that," replied Captain Skinner. "Everything's got to go by weight. No assay-office down in this corner of Arizona."

So it was gold they were dividing in those little bags of buckskin that they stored away so carefully. Yellow gold, and very heavy.

Pockets, money-belts, saddle-bags, all sorts of carrying places on men and horses were brought into use, until at last a miner exclaimed:

"It's of no use, boys. I don't care to have any more load about me. Specially if there's to be any running."

"Or any swimming," said another.

"Swimming! I've got enough about me to sink a cork man."

"And I've got all I keer to spend. Enough's as good as a feast, I say."

One after another came to the same opinion, although Captain Skinner remarked:

"We're not taking it all, boys. What'll we do with the rest?"

"Cache it. Hide it."

"For the Lipans to find the next day? No, boys; we'll leave it in the wagon, under the false bottom. That's the safest place for it, if any of us ever come back. No redskins ever took the trouble to haul a wagon across the mountains. It'll stay right here."

The "false bottom" was a simple affair, but well made, and there was room between it and the real bottom to stow a great deal more than the miners were now leaving.

They would have had no time to dig a hiding-place in the earth if they had wanted to, for messengers came from To-la-go-to-de before sunset to tell them he was nearly ready to start, and from that time forward the keen eyes of strolling Lipan horsemen were watching every step that was taken in the camp of their pale-face allies.

"If they want to know how much supper we eat," said the Captain, "we can't help it. I only hope I can blind 'em in some way before morning."

"Any sign of a breeze yet, Mr. Brown?"

"No, sir."

"Humph!"

The Captain's discontented grunt, as he ran his eyes over the lifeless sea and the hot, cloudless sky, was certainly not without reason. To be suddenly becalmed when one is in special haste to get home is at no time the most agreeable thing in the world; but to be becalmed off the pestilential coast of Western Africa, with food and water beginning to run short, and good cause to expect an attack at any moment by an overwhelming force of savages, might overtask the patience of Job himself.

"I guess we've just got to grin and bear it," muttered the Captain. "If the niggers'll only keep as still as the air does! But I'll bet my last dollar they won't. They must have seen us by this time, and a ship in distress to them is like an open door to a tramp."

As he spoke, his keen eye wandered with a troubled look along the endless line of the African coast, one impenetrable mass of dark thicket as far as the eye could reach, except at one single point. Just opposite, the becalmed vessel, a long, low reef of brown rock, masking the mouth of a small river, broke the interminable perspective of clustering leaves; and it was to this point that the Captain's watchful look was most often and most anxiously directed.

His uneasiness seemed to have infected the officers and the crew likewise. Just abaft the foremast a tall, wiry Portlander was turning a grindstone, upon which another sailor was sharpening in turn five or six rusty cutlasses; while a gaunt, keen-looking fellow from Maine was hard at work cleaning the Captain's double-barrelled shot-gun—unluckily the only fire-arm on board.

But there was one on board who seemed to trouble himself very little about the matter. This was the cabin-boy—a brown-faced, curly-haired, bright-eyed little fellow, active as a leopard and fearless as a lion. The way in which he was employed, amid all this bustle and anxiety, would have rather astonished a stranger. With a piece of raw meat in his hand, he dived down the fore-hatchway, ran along the low narrow passage that led between-decks, and opening the door of a small dark recess just abaft the store-room, called out, "Tom!"

A very strange sound answered him, partly like the squall of a cat, and partly like the growl of a wild beast.

"He's hungry, poor old boy," said the lad, stepping forward and holding the meat to the bars of a cage in the farther corner, through which was dimly visible the gaunt outline of a young tiger, bought cheap in Southern India by the Captain, who expected to make a profit by selling it to some menagerie when he got home. For a tiger, it was tame enough; but the only one of the crew for whom it showed any liking was the little cabin-boy, who had named it Tom, after his favorite brother, and never lost a chance of talking to it, always insisting that it understood him perfectly.

"You see, Tom," said he, as the tiger seized the meat, "there ain't much for you, 'cause we're gittin' short ourselves; but you'll have plenty by-and-by, never fear."

The beast rubbed its huge yellow head caressingly against the hand which Jack thrust into the cage as unconcernedly as if he were only petting a kitten, and lifted, in obedience to the familiar call of "Shake hands, Tom," the mighty fore-paw, one stroke of which would have crushed the boy like an egg-shell.

But just as the two strangely assorted playmates were in the height of their sport, a sudden clamor of voices from above startled them both.

"Can't stop now, Tom," said the boy, as gravely as if he were excusing himself to one of his messmates. "There's something up, and the Captain'll want me to help him manage the ship, you know. By-by."

And up he went like a rocket.

When he reached the deck, the cause of the tumult at once became apparent. From behind the low reef five rudely built native boats, each with ten or twelve men on board, were creeping out toward the doomed vessel.

"They're coming now, sure enough," muttered the Captain through his set teeth; "but I guess they won't be here for another twenty minutes yet, for them boats o' their'n are too heavy and lubberly built to go fast. Say, boys, we must fight for it now, for them black sarpints won't leave a man of us livin' if they git the best of it. You that hain't got cutlasses, take boat-hooks or capstan bars, and jist break a few bottles, and scatter the glass around the deck: it'll astonish their bare feet some, I reckon. Hickman, lay that grindstone on the gunnel, and be ready to tip it over on to the first boat that comes alongside. If these black-muzzled monkeys want our scalps, they've got to pay for 'em."

The men obeyed his orders; but they did so with a subdued air which showed how little hope they had of anything beyond selling their lives as dearly as possible.

In truth, the bravest man might have been pardoned for despairing in such a situation. Even including the officers, the ship's company (already thinned by storm and sickness) could muster only sixteen men, while the savages numbered nearly sixty, all big and powerful fellows, whose huge muscles stood out like coils of rope on their bare black limbs. In weapons, again, the advantage, if there was any, was on the side of the assailants; for although the latter appeared at first sight to be unarmed, the Captain's spy-glass soon showed him clubs and spears and bows, with one or two muskets as well.

On came the human tigers over the smooth bright water, with the cloudless blue of the tropical sky overhead, and the dark green mass of clustering leaves, surmounted here and there by the tall slender column of a palm-tree in the background. They had evidently chosen the heat of noon for their hour of attack in the expectation of finding the white men asleep; and there was a visible start among them as the Captain's tall figure appeared from behind the main-mast, gun in hand.

"Keep off!" roared he, as they made signs of wishing to trade. "Keep off! you ain't wanted here."

But seeing that they swept on unheeding, he let fly both barrels into them, the double report being followed by a sharp howl from the foremost boat as the buckshot rattled among its crew. Four out of the twelve oarsmen were struck down, overthrowing several others in their fall, and the clumsy craft, turning half round, lay completely helpless for several minutes. But on came the other four boats, and ran alongside, two to port and two to starboard. The carpenter launched his grindstone, but the ponderous missile splashed harmlessly into the water within a foot of the nearest boat, and in another moment the whole deck was flooded with yelling savages, thirsting for blood.

All that followed was like the confusion of a hideous dream—blows raining, blood flowing, men falling, and death coming blindly, no one knew whence or how. Despite the fearful odds against them, the American sailors, fighting like men who fight for their lives, were still holding their ground, when an exulting yell from behind made them turn just in time to see the eight surviving rowers of the fifth boat (which had crept up unperceived in the heat of the fray) clambering over the stern.

Another moment and all would have been over, but just then a tremendous roar shook the air, and a huge gaunt, yellow body shot up through the after-hatchway, right among the startled assailants. Little Jack had crept aft and let loose the tiger, which fell like a thunder-bolt upon the blacks, four or five of whom lay mangled on the deck almost before they could look round.

This unexpected re-enforcement ended the battle at one blow. The superstitious savages, taking the beast for an evil spirit raised against them by the white men's magic, leaped panic-stricken into their boats (some even tumbling into the sea in their hurry), and made off with all possible speed. A light breeze, springing up from the eastward, soon bore the vessel far beyond their reach.

"Well done, Jack, my hearty!" cried the Captain, grasping the little hero's slim brown hand with a force that made every joint crackle. "That was a mighty cute trick of yours, and no mistake. I guess you'll make a smarter sailor than any of us before you've done; and it sha'n't be my fault if you don't git something good for this when we see New York again."

And the Captain kept his word.

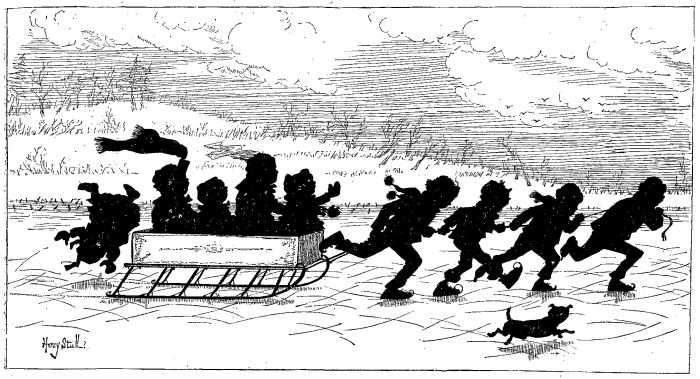

Curling is a Scotch game. For centuries past everybody who has been anybody in the Land o' Cakes has played golf in the spring, summer, and autumn, and curling in the winter; and wherever Scotchmen have gone to live they have introduced their national games.

For a good game of curling a sheet of clear ice and a number of curling-stones are necessary. But what is a curling stone, or "channel stane," as it is sometimes called, from the fact that stones found in the channels of rivers were formerly used in the game? It is a large stone, of such a shape as an orange would be if it were crushed down so that its sides bulged out without breaking. The stone is generally about twelve inches in diameter, and four or five inches high. It is polished until it is perfectly smooth, and on the upper side it has a handle, something like that of a smoothing-iron, so that it may be thrown with greater ease and accuracy. Its weight is from thirty to fifty pounds, but in days gone by heavier weights were used. One well-known curler played with a stone weighing seventy pounds, and his uncle used one that was even heavier. What a remarkable family that must have been!

A match at curling is called a "bonspiel," and many a tale of hard-fought bonspiels in the "auld countree" can an old Scot tell. But we have bonspiels even here. On January 30 the great bonspiel of the year in this country was played on one of the lakes in Central Park, New York, and our artist has depicted the scene on this page. Americans were matched against Scotchmen, and were not ashamed to suffer defeat at their hands, for of late years American curlers have enjoyed more than their share of victory. In this match eight rinks were prepared, and four players of each side played at each rink. And now let us describe the rink.

It is a stretch of ice swept perfectly clean, and measuring forty-two yards by eight or nine. A few feet from each end is a mark, called the "tee," and around this a circle is drawn measuring fourteen feet in diameter. This circle is called the "hoose." Each player has two stones, and they take turns to throw their stones along the rink, and try to let them stop as near the "tee" as they can.

It may seem easy to throw the stone along the glassy surface of the ice to that distance, and so it is. There are instances on record of a curling-stone having been thrown across a pond a mile in width; but it is not so easy to make the stone stop just where the player wants it to. There are all sorts and varieties of play in this game. See,[Pg 249] nearly all the men have played their stones. The rink is thick with them at the far end. Some are right up close to the "tee," most of them have reached the "hoose," but some have fallen short.

There is only one opening left by which a stone can reach the "tee." The next player is unsteady. Can he get through, or had he better send a slow one to close the "port" against the next player, his adversary? He is a young player, and old heads are better than young ones in curling. His "skip" (Captain) advises the latter course. But, alas! he throws too gently. The stone seems tired out almost before it has reached the middle of the rink. Then there arise shouts of "Soop! soop!" (sweep, sweep), and his comrades fall to with a will, and sweep the ice in front of the lagging stone as if life depended on it.

What is the meaning of this? Well, it means that when a stone is travelling very slowly, the least bit of snow is liable to bring it to a stand-still, and so the players are armed with brooms to clear away whatever snow may have been blown on the rink.

Perhaps next to skill in throwing the stone, judgment in sweeping is the most valuable accomplishment for a curler. It is very like working the brake on a horse-car. If you do it too much, you stop the car too soon, and the ladies have to get off in the mud instead of at the clean crossing. So, in curling, if you do not sweep enough, the stone will stop before it reaches the hoose; but if, on the other hand, you sweep too much, the stone reaches the hoose, and perhaps passes the tee, and then your opponents begin to "soop," and make the ice so smooth that your stone passes clear out of the hoose, and so is lost, amid cries of "Weel soopit!" (well swept).

The last play of the "head," or end, is reserved by the "skips" of the two sides, for they are always the best players, being chosen skips on that account. The excitement grows intense. The way is blocked, but the experienced eye of the skip sees how the stones lie. "Wick, and curl in," cries an eager comrade, by which he means carom off an outlying stone, and curl in so as to avoid the stones that lie in front. This the skip does. By a peculiar turn of the wrist he gives a twist to his stone, so that when it touches another stone it glances sharply off, and avoiding the block, makes straight for the tee.

When the last stone of the head has been played, the excitement of counting begins. Only one side can count at one time, and that side can only count as many as it has stones nearer to the tee than the nearest stone belonging to the other side. Thus the nearest stone may belong to the Scotchmen, and the next to the Americans, and after that the Scotchmen may have three or four nearer than the next American stone; but the Scotchmen can only count one. It often happens that the distance is so nearly equal that it is impossible to decide between two stones, and then the measuring string is produced to settle the claims of the rival players. A bonspiel generally consists of twenty-one ends at each rink, and as many rinks are used as are necessary to accommodate the players, eight playing at each.

MR. THOMAS CATT AND FAMILY AT DINNER.

MR. THOMAS CATT AND FAMILY AT DINNER.

Presence of mind is that quality which leads a person to do the right thing at the right moment. There are times of sudden peril, times of accident, and times of illness when the person who has presence of mind becomes the leader, and helps everybody else.

If a fire break out in a building where a crowd is assembled, there is often a panic, and people trample upon and kill each other in their fright. Some months ago an alarm of fire was caused by the appearance of smoke in a New York public school. Fortunately the lady principal was a person who had presence of mind. She controlled herself and her pupils, and they all marched safely into the street, without hurry or riot. She knew what ought to be done, and she did it promptly.

People who know what ought to be done do not always do it at once, however, or they are flustered, lose their wits, and do something dreadful. A very loving mother once scalded her baby so that it will bear the marks of the burn for its life, because she lost her presence of mind. She knew that a child in a convulsion should be put into a warm bath, and in her terror she immersed her little one in a boiling bath, the hot water running from a faucet at that point of heat.

A person whose clothing catches fire should be rolled at once in a rug, or quilt, or large shawl, to stifle the flame. When a fire breaks out anywhere the doors and windows should be shut as quickly as possible, to prevent a draught. But most people rush out-of-doors, screaming, in their terror, and others rush after them, throwing pails of water, or doing anything but the right thing. If a person is wounded or cut, the way to stop the flow of blood is to bandage tightly above the wound, between that and the heart; but instances are not rare where people bleed to death because nobody at hand has enough knowledge or presence of mind to attend to this simple thing at once. Like other desirable qualities, this one can be cultivated, and you may possess it as well as another.

"Mr. North!—please, Mr. North!"

The voice, a delicate, childish one, seemed to be almost caught up and whirled away in the snow-flakes. The speaker—a little boy of about twelve years, scantily clad, and carrying a heavy basket—was running as well as he could along the dreary country road, while he tried to make himself heard by the invisible occupant of a wagon lumbering ahead of him.

It was a covered wagon, and to the boy's eyes it seemed to be the embodiment of comfort and warmth. He was chilled to the bone, thoroughly tired, and disheartened. What could he do if Mr. North failed to hear him?

But he did not. Suddenly he pulled up his horses, and peered around him in the gloomy twilight.

"Be some one a-calling?" he said, loudly.

"Yes, sir, please." The boy's voice was just audible.

"Why," said Mr. North to himself, "derned if that bean't Miss Holsover's boy!"

It was Miss Holsover's nephew, Jesse Grey, and he was soon at the side of the wagon, looking up into the driver's kindly weather-beaten face.

"Oh, please, Mr. North," the little fellow said, trying to get his breath, "I'm so tired! and I thought, perhaps, you'd give me a lift."

"Of course I will," Mr. North answered, good-humoredly. "Come, can ye git in there?" and he lifted the little figure into the back of the wagon, where, with many bundles, there was a pile of straw. "You be about as wet as water. I declare to mercy! Where hev you been?"

Jesse was comfortably seated on the straw by this time behind Mr. North's burly figure, and as the wagon jogged on he almost forgot his fright and fatigue.

"I've been in to market with butter and eggs," he said, "and brought back a basketful of things for Aunt Jemima."

"Humph!" Mr. North's exclamation was characteristic as he looked around at the delicate face of the child, which had about it so many tokens of refinement that it was hard to believe he really was the nephew of the coarse, hard-featured woman who lived in grim seclusion at Holsover Farm.

"I say, Jesse," he said, shortly, "how comes it you be a relation o' hern?" He jerked his head toward the cross-roads they were approaching.

Jesse's face flushed. "I'm not, really," he said, with a little quiver of the lip. "I know I have a real aunt somewhere in Boston, if I could only find her; but Aunt Jemima never will tell me anything about her." There was a pause, and then Jesse added, quickly: "Oh, Mr. North, do you suppose you could hunt for her when you go to Boston next time? Oh, I know her name—Marian Lee. I know that because I have a book of hers. 'From Helen to Marian Lee,' it says in it, and Helen was my mother"—the child's eyes looked very wistful and pleading. "And when Bill was home he told me it was my aunt's, and she lived in Boston. I never could get him to say any more."

"Why, how come you to be up to Miss Holsover's?"

Jesse shook his head. "I don't know," he answered. "I've always been there."

They jogged on a few minutes in silence. Jesse felt the soothing effect of the warmth and stillness, and half dozed. Mr. North turned a compassionate gaze on the sad young face which in sleep showed such worn lines.

"No Holsover blood there!" he muttered.

Mr. North was the only expressman, or carrier, in this very obscure part of the country. Twice a week he came and went, carrying letters and packages, as well as occasionally a traveller, to the different villages of towns about. Once a month he visited Boston. His own house stood on a country road about three miles from Holsover Farm. There he lived almost alone, his widowed mother being too infirm to be considered very much of a companion for a hearty, burly, good-humored man like himself.

The old farm-house in which Miss Holsover lived stood near the cross-roads. It was a long low building with one story and an attic, above which rose the slanting roof. Some old trees grew at one side, but everything about it was dismal and uninviting to visitors. Miss Holsover said she was glad of this. She liked to shut herself away as much as possible from her fellow-creatures.

Not a human being in all the country about ever remembered a sympathetic word or look from her. She was a tall grim woman of sixty, with bushy eyebrows, gray hair, and thin, bluish lips. What comfort she could take in life every one wondered, but it was whispered that she was hoarding money; that if the truth was but known, untold sums lay hidden somewhere in the old house.

Certainly Jesse Grey saw nothing of the kind. As the boy had said to Mr. North, he did not know how he had come to Holsover Farm. Jesse only knew that he had "always been there." There were no dim remembrances in his mind of any past which did not include the desolate house, and Miss Holsover's cruel face and figure. The only variations in his surroundings had been visits from the one human being Miss Holsover had ever shown any fondness for. This was her reprobate nephew Bill.

The boy had appeared and disappeared so many times in the course of Jesse Grey's remembrance that he had felt as if he might expect him any particularly windy night,[Pg 251] or any time when things were going on a little comfortably. For Bill's visits to the farm were his seasons of terror. Bill was a coarse, violent-tempered lad, who delighted in terrifying him in every way possible, who forced his so-called aunt into new cruelties to the helpless child, and who seemed only to know that he could suffer.

Of late Jesse had begun to wonder when Bill would reappear. Last year, just at this season, he had suddenly arrived, and how well Jesse remembered his saying with a coarse laugh that he had come back as a valentine! What was a valentine? Jesse wondered. He looked at Mr. North's spacious back a moment before he said,

"Mr. North, can you tell me what a valentine is like?"

Mr. North peered around with a queer smile at his little companion. "Wa'al," he said, slowly, "there's all kinds. I think it's sort o' good luck, or good wishes, like as if you wuz to do me a favor. I don't know as I've seen many in my day. They hev 'em in store winders—paper things, with Cupids; but they say on 'em, 'I'm your valentine.' Neow ef eny one wuz to say he wuz my valentine, he'd oughter do me a good turn; seems to me as if a valentine oughter be good luck."

It was a long speech, and Mr. North delivered it with some difficulty, flecking his horses with his whip now and then, and apparently taking a great interest in the weather.

"I wish I could have something like a valentine, then," sighed Jesse.

"Wa'al," said Mr. North, "ter-morrow's the day."

But the boy only laughed sadly.

The dark road suddenly seemed to come to an end. Jesse jumped up and looked out. There across the fields lay the gloomy brown farm-house. He felt his heart sink within him as he thanked Mr. North, got down from the wagon, and taking the basket turned in at the gate.

The door was opened with a click, and Miss Holsover stood there holding a candle-light above her head.

"'Sthat you?" she said, in a shrill voice.

"Yes," answered Jesse. His entrance into the house was helped by Miss Holsover giving him a decided push by the shoulders.

Jesse put the basket down, and began at once taking off his coat. In spite of his rest and little sleep, he was shivering with cold and fatigue.

"What's the matter?" said Miss Holsover, giving him another shake by the shoulder.

"I'm wet and tired," said Jesse, timidly.

"Wet and fiddlesticks!" retorted the old lady. "None of that nonsense! You've plenty to do to-night, let me tell you. I'm goin' across fields."

Jesse knew what this meant. Once in a while Miss Holsover took it into her head to pay a visit to a cousin of hers living at the next village—"across fields," as she called it. These nights were the child's especial horror. Unhappy as was the farm-house with Miss Holsover, it had an element of terror for the child when he was left alone—and then on such a night! Jesse stood still a moment looking at Miss Holsover with dilated eyes, anticipating all the horrors of the lonely evening; not all the work he knew there was left for him to do would keep him from being frightened at every gust of wind that blew around the old house, or moaned in the group of cedar-trees.

"Don't stand gapin' like that," exclaimed Miss Holsover. "Sit down and eat your tea, and then go out and do your chores."

Jesse obeyed. The supper—some weak milk and stale bread—was soon eaten, and then he followed Miss Holsover, who laid his work out, and gave him his instructions for the night. He was to perform the tasks she had set him, and not think of going to bed until she returned.

Jesse was too well accustomed to the hardships of his life to rebel against anything. He stood still, listening quietly, and even helped the old lady to go away in comfort.

Instead of going at once to work, he knelt down a moment before the fire, thinking about the questions Mr. North had asked him.

Jesse never knew how it came into his head that perhaps there might be some escape for him. I suppose that in the loneliness of his position that evening, and with the fear of being by himself in the desolate house, there came a certain sense that he could do as he pleased. Then, too, he knew absolutely nothing of the world, and it gradually seemed to him quite feasible that he should run away, and try to find his real aunt in Boston.

His plan, childish as it was, developed very quickly. Jesse had an idea that he could walk very far before morning, and that he might meet Mr. North somewhere on the way. He knew there was no time to lose, and so, running up to his little attic room, he began hastily putting together such things as seemed necessary for his long journey. The book with his aunt's name was carefully tied up in the bundle. Jesse thought that the name written there might perhaps help him in some way.

He had only a small bit of candle, and it so happened that this went out before he had quite finished his preparations. He was standing by the little dormer window, and almost at once he felt rather than saw the gleam of a lantern. It was moving, and seemed to come from the barn loft. In a moment there was a second flash, and this time it illumined a man's figure.

Jesse shrank back in fear and trembling. Who could it be? But though afraid of the lonely house, it frightened him still more to think of not finding out who was in the barn. He hesitated but a moment, and then sped down stairs, and creeping across the space between the house and barn, slowly unlatched the door. He was scarcely inside the barn before he caught the sound of voices. Two men were speaking, and Jesse's heart sank within him as he recognized one voice as that of Bill Holsover.

The boy's feet seemed rooted to the spot. He was standing just by the ladder leading to the loft, and in the absolute stillness and darkness it was easy to hear what the men were saying. The first sentences were of no importance, but suddenly the strange voice said,

"Do you know where she keeps it?"

Then came Bill's answer: "I'm most sure it's in the cupboard to the right of the fire-place, under the floor."

"Will there be trouble getting it?"

"Not if we make sure she's in bed. There's that little young 'un around; but we won't have any trouble keepin' him quiet."

There is not the slightest doubt that Bran had a conscience. No dog who was not fully aware that he had misbehaved himself, and deeply penitent on account of it, could have shown so much sorrow and contrition.

We were staying at Yarmouth, and Bran, who was allowed perfect liberty, was lost for one entire day.

At night, just before the house was shut up, he made his appearance, very tired and travel-stained. Being met at the hall door, he was rebuked, and his offered paw not taken, in token that he was in disgrace.

His nightly resting-place was a cellar, where he had a comfortable straw couch provided for him, and his usual custom was to run down stairs immediately to his bed and supper; but on this evening he remained at the top of the stairs, and cried and whined piteously.

Presently my brother said, "You must come and make it up with Bran, or the poor fellow will cry there all night."

Accordingly we opened the door, and one by one shook Bran's paw in sign of forgiveness, whereupon he quietly walked down stairs, and after eating his supper with avidity, curled himself up on the straw and went to sleep.

I've made up my mind that half the trouble boys get into is the fault of the grown-up folks that are always wanting them to improve their minds.

I never improved my mind yet without suffering for it. There was the time I improved it studying wasps, just as the man who lectured about wasps and elephants and other insects told me to. If it hadn't been for that man I never should have thought of studying wasps.

One time our school-teacher told me that I ought to improve my mind by reading history, so I borrowed the history of Blackbeard the Pirate, and improved my mind for three or four hours every day. After a while father said, "Bring that book to me. Jimmy, and let's see what you're reading," and when, he saw it, instead of praising me, he— But what's the use of remembering our misfortunes? Still, if I was grown up, I wouldn't get boys into difficulty by telling them to do all sorts of things.

There was a Professor came to our house the other day. A Professor is a kind of man who wears spectacles up on the top of his head and takes snuff and doesn't talk English very plain. I believe Professors come from somewhere near Germany, and I wish this one had staid in his own country. They live mostly on cabbage and such, and Mr. Travel's says they are dreadfully fierce, and that when they are not at war with other people, they fight among themselves, and go on in the most dreadful way.

This Professor that came to see father didn't look a bit fierce, but Mr. Travers says that was just his deceitful way, and that if we had had a valuable old bone or a queer kind of shell in the house, the Professor would have got up in the night, and stolen it and killed us all in our beds; but Sue said it was a shame, and that the Professor was a lovely old gentleman, and there wasn't the least harm in his kissing her.

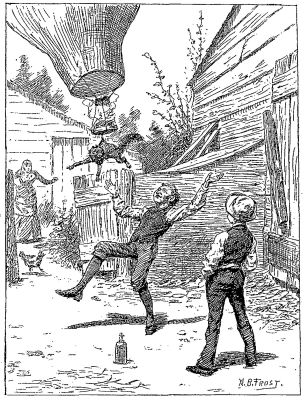

Well, the Professor was talking after dinner to father about balloons, and when he saw I was listening, he pretended to be awfully kind, and told me how to make a fire-balloon, and how he'd often made them and sent them up in the air; and then he told about a man who went up on horseback with his horse tied to a balloon; and father said, "Now listen to the Professor, Jimmy, and improve your mind while you've got a chance."

The next day Tom Maginnis and I made a balloon just as the Professor had told me to. It was made out of tissue-paper, and it had a sponge soaked full of alcohol.[3] and when you set the alcohol on fire the tumefaction of the air would send the balloon mornamile high. We made it out in the barn, and thought we'd try it before we said anything to the folks about it, and then surprise them by showing them what a beautiful balloon we had, and how we'd improved our minds. Just as it was all ready, Sue's cat came into the barn, and I remembered the horse that had been tied to a balloon, and told Tom we'd see if the balloon would take the cat up with it.

"PRESENTLY IT WENT SLOWLY UP."

"PRESENTLY IT WENT SLOWLY UP."

So we tied her with a whole lot of things so she would hang under the balloon without being hurt a bit, and then we took the balloon into the yard to try it. After the alcohol had burned a little while the balloon got full of air, and presently it went slowly up. There wasn't a bit of wind, and when it had gone up about twice as high as the house, it stood still.

You ought to have seen how that cat howled; but she was nothing compared with Sue when she came out and saw her beloved beast. She screamed to me to bring her that cat this instant you good-for-nothing cruel little wretch won't you catch it when father comes home.

Now I'd like to know how I could reach a cat that was a hundred feet up in the air, but that's all the reasonableness that girls have.

The balloon didn't stay up very long. It began to come slowly down, and when it struck the ground, the way that cat started on a run for the barn, and tried to get underneath it with the balloon all on fire behind her, was something frightful to see. By the time I could get to her and cut her loose, a lot of hay took fire and began to blaze, and Tom ran for the fire-engine, crying out "Fire!" with all his might.

The firemen happened to be at the engine-house, though they're generally all over town, and nobody can find them when there is a fire. They brought the engine into our yard in about ten minutes, and just as Sue and the cook and I had put the fire out. But that didn't prevent the firemen from working with heroic bravery, as our newspaper afterward said. They knocked in our dining-room windows with axes, and poured about a thousand hogsheads of water into the room before we could make them understand that the fire was down by the barn, and had been put out before they came.

This was all the Professor's fault, and it has taught me a lesson. The next time anybody wants me to improve my mind I'll tell him he ought to be ashamed of himself.

Oh dear! what a fuss! It is certainty true.

Sweet Love is our ruler, whatever we do.

The lions and tigers his dainty whip feel;

He harnesses both to his chariot wheel.

Oh, none can escape. The eagle's fleet wing

Is no manner of use, or the hare's rapid spring.

The ostrich may stride, the eagle may fly,

But Love is their ruler—he ever is nigh.

The quick little rogue, with his whip and his wings,

He is ever about, and he ruleth all things;

And Mollie and Ted, as they hurry along,

Are only two more in his worshipping throng.

Oh, Love in the school-room has tenses and moods.

And Love in the kitchen quite often intrudes,

And Love o'er the ledger drops fancies of bliss.

Till the figures get mixed with the thought of a kiss;

And Love on the avenue raises his cap

To Love in the parlor with work in her lap,

And Love in a cottage or Love in a palace

Drink nectar alike from a cup or a chalice:

Let cross people scold, and let prim people frown.

Love reigns like a prince both in country and town.

Hurra for sweet Cupid! Ye laggards, give way,

While the lads and the lasses greet Valentine's Day.

This is a very common saying indeed, and is used to denote the extreme of stupidity, and as regards geese in general it is near enough to the truth.

But all geese are not stupid. History tells us that the cackling of geese once saved the city of Rome, and we find in a Scotch newspaper the following instance of sagacity and reasoning on the part of a persecuted goose:

"A haughty and tyrannical chanticleer, which considered itself the monarch of a certain farm-yard, took a particular antipathy to a fine goose, the guardian of a numerous brood, and accordingly, wheresoever and whenever they met, chanticleer immediately set upon his antagonist. The goose, which had little chance with the nimble and sharp heels of his opponent, and which had accordingly suffered severely in various rencontres, got so exasperated against his assailant that one day, during a severe combat, he grasped the neck of his foe with his bill, and dragging him along by main force, he plunged him into an adjoining pond, keeping his head, in spite of every effort, under water, and where chanticleer would have been drowned had he not been rescued by a servant who witnessed the proceeding. From that day forward the goose received no further trouble from his enemy."

Another writer gives the following incident, which he says was witnessed in the north of England:

"One morning, during very cold weather, the geese on a large farm were, as usual, let out of their roosting-place, and, according to their custom, went directly to the pond on the common. They were observed by the family to come back immediately, but you may guess their astonishment when in a few minutes the geese were seen to return to the pond, each of the five with a woman's patten in its mouth. The women, to rescue so useful a part of their dress from the possession of the invaders of their property, immediately made an attack, but the waddling banditti presented such a stout resistance that it was not till some male allies were called in that a victory could be obtained."

It would have been interesting had the geese been let alone, as we shall never know what they intended doing with those pattens. Who knows but they might have devoted them to some purpose that would have won geese a reputation for wisdom for all time?

So much for the saying, "As stupid as a goose."

"Unlearned is he in aught

Save that which love has taught,

For love has been his tutor."

The sweetest of letters.

Miss Bessie, for you,

From bonny Prince Charlie

Or Little Boy Blue.

The brightest of letters,

Sir Arthur, for you.

From fair Lady Edith

Or dear little Sue.

Your name is not Arthur?

Your name's not Bess?

Peep into your letter;'

You'll find it, I guess.

For the loveliest missives

Are flying all round

As thick as the white flakes

That fly to the ground.

And Our Post-office Box,

Like a ship in the bay,

Is crammed and is jammed

This Valentine's Day.

Detroit, Michigan.

The other night, about eleven o'clock, as my father and Mr. Sherrill (he is a student, and my father is a doctor) were reading in the office, they heard a noise on the steps, and my father went out, and saw a large owl right before him. So he threw a rubber cloak over him, and brought him in, and Mr. Owl screamed and yelled like anything, but he was put safely into a bushel basket, and a cover clapped over it. The next morning we went out on the steps, and found a large dead rat, which the owl had brought there with the purpose of eating. The following night we let him go.

Royal T. F.

New York City.

My name is Paul. I live in New York, near Central Park. I am five years old, and go to school. My teacher is my beau. My teacher is Miss Lizzie C. I love her. I printed this all on my slate myself, and my mamma copied it off for me. I can draw a boat; and I can draw it nice, too. My big brother has a big boat. Susie helped me spell all the big words in this letter. Susie is eight. She is my sister, and she had a big French doll named Eva. Naughty Charlie broke Eva's head, and Susie cried. Charlie is our baby girl. We haven't any cat or dog, but the firemen on our block have a nobby little dog named Prince, and we boys all play with him. He sometimes follows me into our house, and we think he is so cute. I drew the boat all myself. Don't you think it a nice one?

Paul L. L.

Yes, Paul, the boat you drew in your letter was very well done indeed for such a little boy. You must send us some Wiggles.

Cambridge, Massachusetts.

I live in Cambridge, very near the famous Washington Elm, of which you gave an illustration in Vol. I., No. 25, page 340. It does not look very much like that now, but resembles any other large old tree, and has an iron fence around it, and an upright slab, with an inscription, saying,

Under This Tree

Washington

First Took Command

of the

American Army.

July 3d. 1775.

It is on Garden Street. On the north side is the Common, on the southwest is the Shepard Congregational Church. Near to this, though on another street, is Longfellow's house. I had Miss Anna Longfellow for my Sunday-school teacher last Sunday. I very much liked the picture in Young People entitled "Little Dreamer." I have had the two volumes of Harper's Young People bound in your handsome cover. I am glad to have Tuesday come, because I get my paper on that day.

Arthur M. M.

Washington, D. C.

My name is Eugenia A. I am nine years old, and my sister Bessie is five. Every summer we go to visit our Aunt Ella in Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh. Last summer we made the journey alone, changing cars at Cumberland. The conductor helped us, and a gentleman was at the last station to help us off, and take care of us. We had a trunk and a lunch basket. When mamma was packing, papa said she might as well take the trunk for our lunch and the basket for our clothes. Aunt Ella came down for us, and bought me a large doll, which I named Mignonette, and a set of dishes, and Bessie two dolls and a rocking-chair. We hunted eggs, and tried to milk, and had a good time. Aunt Ella sends me Young People, and Bessie Our Little Folks.

Chicago, Illinois.

I am going to tell Young People about my great fishing last summer. I went to Milwaukee on an excursion, and staid there a few days. While there I thought I would go a-fishing. So I went one morning early, and staid on the pier until noon, but did not catch a single fish, missed a half-day's pleasure while there (because there were other places I could have gone to), spent nearly all my money for car fare, lost my fishing-tackle, and, besides, broke my fishing-pole, and since that time I have not been fishing.

F. E. K.

You had quite a day of disappointment. But we have no doubt other fishermen have at times had equally bad luck, and the only way to do is to take such misfortunes philosophically.

New York City.

I am nothing but a little white mouse, and I am almost two years old. I was born in a market, and my mate and I were bought by a little girl. I have had over twenty babies, and have only one left. My mistress lets us run around the room once a day to exercise ourselves. One evening she let us run out as usual, and my son that I have now and his little sister were about two weeks old. My grandmistress had company, and my mate ran right under the rockers, and was killed instantly. My troubles seemed to come right in a bunch, for a few days after, my little daughter was carried down stairs by the old cat. My mistress weighed me and my little son this morning, and I heard her say I weighed one-sixteenth of an ounce, and my son one-fourth of an ounce. My mistress takes Young People, and I often hear her say it is the nicest little paper she ever read. I have travelled about a great deal, and my name is

Little Mother Mouse.

Ever so many thanks to Maud for helping her pretty white mouse to write this tragic tale.

Clanton, Alabama.

I live in a little town of about three hundred inhabitants. It is only eleven years old, though, and builds up tolerably fast; don't you think so? About half a mile from this place there is an old field in which we think there must have once been an Indian battle fought, because the ground is almost covered with broken arrow and spear heads. My brother and I found some that were perfect. He found one that was stained with blood.

John Nat T.

Newark, New Jersey.

I go to school every day. We have Harper's Young People in our school, and I have taken it at home from the first number. We are soon to have an entertainment, which is going to be splendid. I wish you could attend it. Our principal is a very nice man when he has no boys to punish. I think he does not like to punish boys. We have a very nice teacher. At the end of the last term the pupil who had received the greatest number of merits was rewarded by an elegant medal. Her name was Nellie A. The best writer received a story-book, and the scholar with the highest average a silver napkin-ring. Do you not think it is very nice for the teachers to present the best scholars with handsome presents? In the last class that I was in I received the medal. It was made out of solid silver, with a bar attached to a round plate by a little chain. On the bar the word Merit was engraved: on the medal there was a wreath, inside of which were my initials.

C. F. K.

Mount Pulaski, Illinois.

I am a little girl eight years old. My home is in Mount Pulaski, Illinois. I am not going to school this winter. I have had the typhoid fever, and now have the whooping-cough. My papa hears me say my lessons at home, so that I may not get behind my class. I read in the Fourth Reader, and study spelling, arithmetic, and geography. I have two pet rabbits, and I keep them in a cage. They are black and white. I shall turn them out in the spring. We have a little niece at our house. She is two years old, and her name is Ella. Her mother died last fall.

Lena A. A.

We are glad, dear, that you are safely through the typhoid fever, and we advise you to study very little, and play a great deal for a good while to come. Never mind if your class does get on a little faster than you can. Health is more important for you just now than rapid progress in study.

Urbana, Ohio.

I have taken Harper's Young People from the first number. My mamma reads me all the stories and letters, and I enjoy them very much. I have several pets: a white rabbit, which is very pretty, a large-yellow-striped cat named Tiger, but called Tige for short, and two canaries. I have also quite a case of butterflies, which I caught last summer. Some of them I took when caterpillars, and fed them until they spun their cocoons, and then watched them as they came out. I am learning to read, write, and draw, but can not write well enough yet, so mamma is writing this for me. I will not be seven years old until next spring.

James A. N.

Stockton, California.

I think Young People is a very nice paper. I am nearly eleven years old. I have a sister nine years old. A friend of mamma's told me this story one day: A father was telling his little daughter that the earth turned around once every twenty-four hours. The little girl sat quietly on his knee for a few minutes, and then said, 'Papa, I do think I feel a little dizzy.' She lisped a little bit. I got a great many nice things Christmas. Papa gave me a gold pen. We have a pet canary-bird.

Louie E. P.

Did you write your letter with your new pen? We think so, it was so beautifully written.

Wentworth, New Hampshire.

My brother Harry has taken Young People a year, and we like it very much. I read about the little girls' dolls in their letters, and want to tell them about mine. I have eight. Papa says he don't know about supporting so many children for me. I had a large wax doll at Christmas last year; her name is Jennie, a small one this year, named Florence, and one named Mamie, and others named Budge, Todie, and George. I have a very large cat named Nicodemus. There are no children but my brother Harry and myself. He is thirteen, and I am seven. Harry takes Harper's Young People and Wide Awake magazine, and I Our Little Ones and the Pansy. I go to school when we have one, and can read all our papers; but can only write in printing, so I asked mamma to write this for me. Please give my love to all the little girls.

L. Addie M.

South Amboy, New Jersey.

I am twelve years old. I am going to tell you about the little canary-bird we have. When we first got him, several years ago, his eyesight was perfectly good. We used to let him fly around the room with another canary-bird we had. That canary-bird died, and the other bird gradually got blind in one eye, and then in the other; and now he is perfectly blind. But he sings from morning until night. We have to cover him in the morning, he sings so early he wakes us up before the time. You can hear him singing all over the house during the day. Children, how much happier ought we to be, who have our eyesight, than this poor little blind canary!

Julia S.

Hastings.

I write to tell you that I have learned the names of all the Kings and Queens of England, and the dates of their coronation; I learned them in just one week. I have to walk nearly two miles to school. I have no brother or sister; my sister Ella died one year ago, and was buried on my ninth birthday. I want to tell you about a trout-pond we have on our farm, and how we raise the little speckled trout. We put their spawn on wire screens in a wooden trough, and let spring water run through it. It takes about fifty days for them to hatch. When they are hatched, they have something attached to their stomach which is called a food sac, and on which they live for about forty days. After that is gone we have to feed them. Last winter we hatched twenty thousand,[Pg 255] and expect to raise as many more this year. Trout spawn in November and December, and the eggs are hatched in the winter. A few weeks ago my father noticed his screens had been disturbed in the night. We set a trap, and in the morning it had a musk-rat caught in it. My auntie takes Harper's Young People for me, and I am very glad every week when it comes.

Bert Campbell.

In what State is your Hastings? You forgot to tell us.

Bardstown, Kentucky.