Project Gutenberg's Historical Characters, by Henry Lytton Earle Bulwer

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Historical Characters

Mackintosh, Talleyrand, Canning, Corbett, Peel

Author: Henry Lytton Earle Bulwer

Release Date: October 15, 2016 [EBook #53285]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORICAL CHARACTERS ***

Produced by Clarity and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet

Archive/American Libraries.)

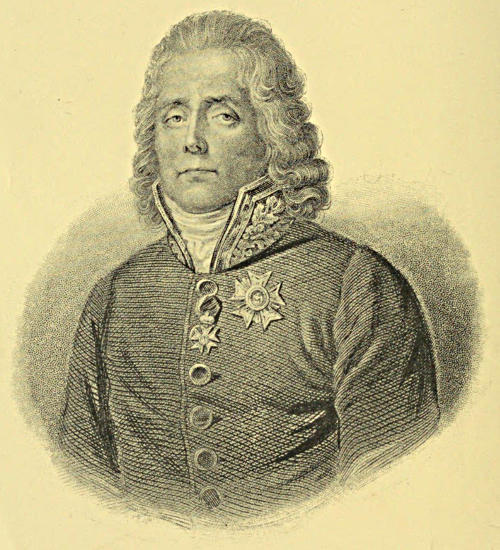

TALLEYRAND

HISTORICAL CHARACTERS

| MACKINTOSH | TALLEYRAND |

| CANNING | COBBETT |

| PEEL | |

BY

SIR HENRY LYTTON BULWER

(LORD DALLING)

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1900

All rights reserved

First Edition, in 2 vols., demy 8vo, 30s., November 1867. Second Edition, in 2 vols., demy 8vo, 30s., March 1868. Third Edition, in one volume, crown 8vo, 6s., December 1869. Fourth Edition, in which was included, for the first time, the Life of Sir Robert Peel, in one volume, crown 8vo, 6s., December 1875. Transferred to Macmillan and Co., Ltd., August 1898. Reprinted May 1900.

My dear Edward,

The idea of this work, which I dedicate to you in testimony of the affection and friendship which have always united us, was conceived many years ago. I wished to give some general idea of modern history, from the period of the French Revolution of 1789 down to our own times, in a series of personal sketches. In these sketches I was disposed to select types of particular characters, thinking that in this way it is easier to paint with force and clearness both an individual and an epoch. The outlines of Talleyrand, Cobbett, and others, were then imperfectly traced; and Canning and Mackintosh have been little altered.

The manuscript, however, was laid aside amidst the labours of an active professional career, and only thought of since complete leisure created the wish for some employment. It was then that I resumed my task.

I need not say that the portraits I give here are but a few of those I commenced, but the constant change of residence, rendered necessary by the state of health in which I left Constantinople, interfered with the completion of my design, and added to the defects which, under any circumstances, would have been found in the following pages.

Ever yours affectionately,

H. L. Bulwer.

13, Rue Royale, Paris,

Oct 10, 1867.

The sale which this work has had in its original form has induced my publisher to recommend a cheaper and more popular one; and I myself gladly seize the opportunity of correcting some of the errors in print and expression which, though gradually diminished in preceding editions, left even the last edition imperfect. An author with ordinary modesty must always be conscious of many defects in his own work. I am so in mine. Still I venture to say that the portraits I have drawn have, upon the whole, been thought truthful and impartial; and though I have been often reminded of the difficulty which Sir Walter Raleigh, when writing the History of the World, experienced in ascertaining the real particulars of a tumult that took place under his windows—almost every anecdote one hears on the best authority being certain to find contradiction in some of its particulars—I have not refrained from quoting those anecdotes which came to me[viii] from good authority or the general report of the period; since a story which brings into relief the reputed character of the person it is applied to, and which, to use the Italian proverb, ought to be true if it is not so, is far from being indifferent to history.

In conclusion, I cannot but express my thanks, not only to public, but to private and previously unknown critics, whose remarks have always received a willing and grateful attention, and to whose suggestions I am greatly indebted.

Nov. 6, 1869.

Different types of men.—M. de Talleyrand, the politic man.—Character of the eighteenth century, which had formed him.—Birth, personal description, entry into church.—Causes of revolution.—States-General.—Talleyrand’s influence over clergy; over the decision as to the instructions of members, and the drawing up of the rights of man.—Courage in times of danger.—Financial knowledge.—Propositions relative to church property.—Discredit with the Court party.—Popularity with the Assembly.—Charged to draw up its manifesto to the nation.—Project about uniformity of weights and measures.

There are many men in all times who employ themselves actively in public affairs; but very few amongst these deserve the title of “Men of action.”

The rare individuals who justly claim this designation, and whose existence exercises so important an influence over the age in which they appear, must possess, in no ordinary degree, intelligence, energy, and judgment; but these qualities are found blended in different degrees in the different classes or types of men who, as soldiers, sovereigns, or statesmen, command the destiny of their times.

They in whom superior intelligence, energy, and judgment are equally united, mount with firm and rapid pace the loftiest steeps of ambition, and establish themselves permanently on the heights to which they have safely ascended. Such men usually pursue some fixed plan or[2] predominant idea with stern caution and indomitable perseverance, adapting their means to their end, but always keeping their end clearly in view, and never, in the pursuit of it, overstepping that line by which difficulties are separated from impossibilities. Cardinal de Richelieu in France, and William III. in England, are types of this heroic race.

On the other hand, they in whom the judgment, however great, is not sufficient to curb the energy and govern the intellect which over-stimulates their nature, blaze out, meteor-like, in history, but rather excite temporary admiration than leave behind them permanent results. Their exploits far surpass those of other men, and assume for a moment an almost supernatural appearance: but, as their rise is usually sudden and prodigious, their ruin is also frequently abrupt and total. Carried on by a force over which they gradually lose all control, from one act of audacity to another more daring, their genius sails before the wind, like a vessel with overcrowded canvas, and perishes at last in some violent and sudden squall. Charles XII. of Sweden was an example of this kind in the last century, and Napoleon Bonaparte, if we regard him merely as a conqueror, a more striking one in our own days.

Thirdly, there are men whose energy though constant is never violent, and whose intellect, rather subtle than bold, is attracted by the useful, and careless of the sublime. Shrewd and wary, these men rather take advantage of circumstances than make them. To turn an obstacle, to foresee an event, to seize an opportunity, is their peculiar talent. They are without passions, but self-interest and sagacity combined give them a force like that of passion. The success they obtain is procured by efforts no greater than those of other candidates for public honours, who with an appearance of equal talent vainly struggle after fortune; but all their exertions are made at the most fitting moment, and in the happiest manner.

A nice tact and a far-sighted judgment are the predominant qualities of these “politic” persons. They think rarely of what is right in the abstract: they do usually[3] what is best at the moment. They never play the greatest part amongst their contemporaries: they almost always play a great one; and, without arriving at those extraordinary positions to which a more adventurous race aspires, generally retain considerable importance, even during the most changeful circumstances, and most commonly preserve in retirement or disgrace much of the consideration they acquired in power. During the intriguing and agitated years which preceded the fall of the Stuarts, there was seen in England a remarkable statesman of the character I have just been describing; and a comparison might not inappropriately be drawn between the plausible and trimming Halifax and the adroit and accomplished personage whose name is inscribed on these pages.

But although these two renowned advocates of expediency had many qualities in common—the temper, the wit, the knowledge, the acuteness which distinguished the one equally distinguishing the other—nevertheless the Englishman, although a more dexterous debater in public assemblies, had not in action the calm courage, nor in council the prompt decision, for which the Frenchman was remarkable; neither is his name stamped on the annals of his country in such indelible characters, nor connected with such great and marvellous events.

And yet, notwithstanding the vastness of the stage on which M. de Talleyrand acted, and the importance of the parts which for more than half a century he played, I venture to doubt whether his character has ever been fairly given, or is at this moment justly appreciated; nor is this altogether surprising. In a life so long, brilliant, and varied, we must expect to find a diversity of impressions succeeding and effacing each other; and not a few who admired the captivating companion, and reverenced the skilful minister of foreign affairs, were ignorant that the celebrated wit and sagacious diplomatist had exhibited an exquisite taste in letters, and a profound knowledge in legislation and finance. Moreover, though it may appear singular, it will be found true, that it is precisely those public men who are the most tolerant to adverse opinions, and the least prone to personal enmities, who oftentimes[4] gather round their own reputation, at least during a time, the darkest obloquy and the most terrible reproaches. The reason for this is simple: such men are themselves neither subject to any predominant affection, nor devoted to any favourite theory. Calm and impartial, they are lenient and forgiving. On the other hand, men who love things passionately, or venerate things deeply, despise those who forsake—and detest those who oppose—the objects of their adoration or respect. Thus, the royalist, ready to lay down his life for his legitimate sovereign; the republican, bent upon glorious imitations of old Rome and Greece; the soldier, devoted to the chief who had led him from victory to victory, could not but speak with bitterness and indignation of one who commenced the Revolution against Louis XVI., aided in the overthrow of the French Republic, and dictated the proscription of the great captain whose armies had marched for a while triumphant over Europe.

The most ardent and violent of the men of M. de Talleyrand’s time were consequently the most ardent and violent condemners of his conduct; and he who turns over the various works in which that conduct is spoken of by insignificant critics,[1] will be tempted to coincide with the remark of the great wit of the eighteenth century: “C’est un terrible avantage de n’avoir rien fait; mais il ne faut pas en abuser.”[2]

How far such writers were justified will be seen more or less in the following pages, which are written with no intention to paint a character deserving of eulogy or inviting to imitation, but simply with the view of illustrating a remarkable class of men by a very remarkable man, who happened to live at a period which will never cease to occupy and interest posterity.

Charles Maurice Talleyrand de Périgord was born February 2, 1754.[3] The House of Périgord was one of the noblest in France, and in the earliest ages of the French monarchy possessed sovereign power. The principality of Chalais, the only one which existed, I believe, in the time of Louis XIV. (for the other personages called princes at the French court took their titles as princes of the Roman States or the German Empire, and ranked after French dukes), is said to have been eight centuries in this family. Talleyrand, a name usually attached to that of Périgord, and anciently written Tailleran, is supposed to have been a sort of sobriquet, or nickname, and derived from the words, “tailler les rangs” (cut through the ranks). It was borne by Helie V., one of the sovereign counts of Périgord, who lived in 1118; and from this prince (Helie V.) descended two branches of the Talleyrand-Périgords; the one was extinct before the time of Louis XVI., the other, being the younger branch, was then represented by a Comte de Périgord, Captain of the Guards, and Governor of the States of Languedoc. A brother of this Comte de Périgord was the father of Charles Maurice Talleyrand de Périgord (the subject of this memoir), whose mother, Eléonore de Damas, daughter of the Marquis de Damas, was also of a highly noble family, and a lady alike remarkable for her beauty and her virtue.[4]

The seal which marks our destiny has usually been stamped on our childhood; and most men, as they look back to their early youth, can remember the accident, the[6] book, the conversation, which gave that shape to their character which events have subsequently developed.

M. de Talleyrand was in infancy an exile from his home; the fortune of his parents did not correspond with their rank: his father,[5] a soldier, was always at the court or the camp; his mother held a situation in the household at Versailles. To both a child was an incumbrance, and Maurice immediately at his birth was put out to nurse (as was indeed at that time frequently the custom) in the country, where, either by chance or neglect, he met with a fall which occasioned lameness. This infirmity, when the almost forgotten child at the age of twelve or thirteen was brought up to Paris for the purpose of receiving rather a tardy education, had become incurable; and by a conseil de famille, it was decided that the younger brother, the Comte d’Archambaud—subsequently known as one of the handsomest and most elegant of the courtiers of Louis XVI., and whom I can remember under the title of Duc de Périgord—(a title given by Louis XVIII.), should be considered the elder brother, and enter the army, whilst the elder son should be pronounced the younger son, and devoted to the clerical profession, into which the Périgords knew they had sufficient influence to procure his admission, notwithstanding the infirmity which, under ordinary circumstances, would have been a reason for excluding him from the service of the church. From this moment the boy—hitherto lively, idle, and reckless—became taciturn, studious, and calculating. His early propensities remained, for nature admits of no radical change; but they were coloured by disappointment, or combated by ambition. We see traces of gaiety in the companion who, though rarely smiling himself, could always elicit a laugh from others; we see traces of indolence in the statesman who, though always occupied, never did more than the necessity of the case exacted; we[7] see traces of recklessness in the gambler and politician who, after a shrewd glance at the chances, was often disposed to risk his fortune, or his career, on a speculation for money or power: but the mind had been darkened and the heart hardened; and the youth who might easily and carelessly have accepted a prosperous fate, was ushered into the world with a determination to wrestle with an adverse one.

Nor did any paternal advice or maternal care regulate or soften the dispositions which were thus being formed. From the nurse in the country, the lame young Périgord—for Périgord was the name which at this time he bore—was transplanted to the “Collége d’Harcourt,” since called that of St. Louis. He entered it more ignorant, perhaps, than any boy of his years; but he soon gained its first prizes, and became one of its most distinguished scholars.

At the “Séminaire de St. Sulpice,” to which he was removed in 1770, his talent for disputation attracted attention, and even some of his compositions were long remembered and quoted by contemporaries. Whilst at the Sorbonne, where he subsequently completed his studies, this scion of one of the most illustrious French houses was often pointed out as a remarkably clever, silent, and profligate young man: who made no secret of his dislike to the profession that had been chosen for him, but was certain to arrive at its highest honours.

With such prospects and such dispositions, M. de Talleyrand entered, in 1773, the Gallican Church.

At this time we have to fancy the young ecclesiastic—a gentleman about twenty years of age, very smart in his clerical attire, and with a countenance which, without being handsome, was singularly attractive from the triple expression of softness, impudence, and wit. If we are to credit the chronicles of that day, his first advance in his profession was owing to one of those bon mots by which so many of the subsequent steps of his varied career were distinguished.

There were assembled at Madame Dubarry’s a number of young gentlemen, rather free in their conversation and prodigal in their boasts: no beauty had been veiled to their desires, no virtue had been able to resist their attacks. The subject of this memoir alone said nothing. “And what makes you so sad and silent?” asked the hostess. “Hélas! madame, je faisais une réflexion bien triste.” “Et laquelle?” “Ah, madame, que Paris est une ville dans laquelle il est bien plus aisé d’avoir des femmes que des abbayes.”

The saying, so goes the story, was considered charming, and being reported to Louis XV., was rewarded by that monarch with the benefice desired. The Abbé de Périgord’s career, thus commenced, did not long linger. Within a few years after entering the church, aided by his birth and abilities, he obtained (in 1780) the distinguished position of “Agent-General” of the French clergy—this title designating an important personage who administered the ecclesiastical revenues, which were then immense, under the control of regular assemblies.

It is a curious trait in the manners of these times that, whilst holding this high post as a priest, the Abbé de Périgord fitted out a vessel as a privateer; and, it being his intention to plunder the English, received from the French government the cannon he required for so pious a purpose.[6]

I am unable to say what success attended M. de Talleyrand’s naval enterprise; but when, in 1785, he had to give an account of his clerical administration, the very clear and statesmanlike manner in which he did so, raised him, in the opinion of the public, from the position of a clever man, into that of an able one. Nor was this all. The peculiar nature of the first public duties which he thus exercised, directed his mind towards those questions which the increasing deficit in the French treasury, and the acknowledged necessity of supplying it, made the fashion: for every one at that time in Paris—ladies, philosophers, wits, and men of fashion—talked finance.[9] Few, however, troubled themselves with acquiring any real insight into so dry a subject. But M. de Talleyrand, although constitutionally averse to hard or continued study, supplied this defect by always seeking and living with men who were the best informed on those subjects with which he wished to become acquainted. In this manner his own information became essentially practical, and the knowledge he obtained of details (furnishing him with a variety of facts, which he always knew how to quote opportunely), attracted the attention and patronage of M. de Calonne, then at the head of the French government, and who, being himself as much addicted to pleasure as to affairs, was not sorry to sanction the doctrine that a man of the world might also be a man of business.

Still, though thus early marked out as a person who, after the example of his great ecclesiastical predecessors, might rise to the highest dignities in the Church and State, the Abbé de Périgord showed an almost ostentatious disregard for the duties and decorum of the profession which he had been forced to embrace. Indeed, he seemed to make in this sort of conduct a kind of protest against the decree by which his birthright had been set aside, and almost to glory in the publication of profane epigrams and amorous adventures which amused the world but scandalised the Church. Thus, each year, which increased his reputation for ability, added to the stories by which public rumour exaggerated his immorality; and in 1788, when the bishopric of Autun, to which he had for some time been looking forward, became vacant, Louis XVI. was unwilling to confer the dignity of prelate on so irregular an ecclesiastic. For four months the appointment was not filled up. But the Abbé de Périgord’s father lay at that time on his death-bed: he was visited by the kind-hearted Louis in this condition, and he begged the monarch, as the last request of a dying and faithful servant, to grant the bishopric in question to his son. The King could not withstand such a prayer at such a moment, and the Abbé de Périgord was consecrated Bishop of Autun on the 17th of January, 1789—four months before the assembling of the States-General.

The period which had elapsed between the time at which M. de Talleyrand had entered the Church, and that at which he attained the episcopal dignity, is, perhaps, the most interesting in modern civilization. At no epoch did society ever present so bright and polished a surface as it did in the French capital during these fourteen or fifteen years. The still great fortunes of the grand seigneur, the profuse expenditure of the financier, the splendour of a court embellished by that love for the arts and for letters which the Medici had imported from Italy, and which Louis XIV. had made a part of his royal magnificence, all contributed to surround life with a taste in luxury which has never been surpassed. Rich manufactures of silk, exquisite chiseling in bronze, china equally beautiful in form and decoration, and paintings somewhat effeminate, but graceful, and which still give celebrity to the names of Watteau, Boucher, and Greuze, mark the elegant refinement that presided over those days.

Nothing, however, in those courtly times had been carried to such perfection as the art of living, and the habits of social intercourse. People did not then shut up their houses from their friends if they were poor, nor merely open them in order to give gorgeous and pompous entertainments if they were rich. Persons who suited and sympathised, assembled in small circles, which permitted the access of new members cautiously, but received all who had once been admitted without preference or distinction.

In these circles, the courtier, though confident of the fixed superiority of his birth, paid homage to the accident of genius in the man of letters; and the literary man, however proud of his works, or conscious of his talents, rendered the customary tribute of respect to high rank and station.

Thus poets and princes, ministers of state, and members of learned academies—men of wit, and men of the world—met on a footing of apparent equality, and real familiarity, on a stage where Beauty, ambitious of universal admiration,[11] cultivated her mind as much as her person, and established one presiding theory—“that all had to make themselves agreeable.”

The evening parties of Madame de Brignole, and of Madame du Deffand, the little suppers of Madame Geoffrin, the dinners of Baron Holbach and Helvetius, the musical receptions of the Abbé Morelet, and the breakfasts of Madame Necker, were only specimens of the sort of assemblies which existed amongst different classes, and throughout every street and corner of Paris and Versailles.

Here, all orders mingled with suitable deference towards each other. But beneath this brilliant show of actual gaiety and apparent unity there lay brooding a spirit of dissatisfaction and expectation, which a variety of peculiar circumstances tended, at that time, to exaggerate in France, but which is in fact the usual characteristic of every intellectual community, when neither over-enervated by luxury and peace, nor over-wearied by war and civil commotion. Its natural consequence was a desire for change, which diffused its influence over all things—great and small. Léonard revolutionized the head-dress of the French lady: Diderot and Beaumarchais, the principles of the French stage: Turgot and Necker, the political economy and financial system of the French state: and just at this moment, when the imagination was on the stretch for novelty, as if Providence designed for some mysterious end to encourage the aspiring genius of the epoch, the balloon of Montgolfier took its flight from the Tuileries, and the most romantic dreams were surpassed by a reality.

It was not, however, a mere discontent with the present, a mere hope in the future, a mere passion after things new, however violent that passion might be, which constituted the peril, nor, indeed, the peculiarity of the hour.

In other seasons of this kind, the wishes and views of men have frequently taken some fixed form—have had some fixed tendency—and in this way their progress has been regulated, and their result, even from a distance, foreseen.

But at the period to which I am referring, there was no general conception or aim which cast a decisive shadow over coming events, and promised any specific future in exchange for the present, evidently passing away.

There still lived, though on the verge of the tomb, an individual to whom this distinguishing misfortune of the eighteenth century was in no small degree attributable. The keen sagacity of Voltaire, his piercing raillery, his brilliant and epigrammatic eloquence, had ridiculed and destroyed all faith in old abuses, but had never attempted to give even a sketch of what was to come in their room. “Magis habuit quod fugeret quam quod sequeretur.” The effect of his genius, therefore, had been to create around him a sort of luminous mist, produced by the blending of curiosity and doubt; an atmosphere favourable to scepticism, favourable to credulity; and, above all things, generative of enthusiasts and empirics. St. Germain the alchymist, Cagliostro the conjurer, Condorcet the publicist, Marat the politician, were the successive produce of this marvellous and singular epoch. And thus it was,—amidst a general possession of privileges, and a general equality of customs and ideas—amidst a great generosity of sentiment, and an almost entire absence of principle in a society unequalled in its charms, unbounded in its hopes, and altogether ignorant of its destiny,—that the flower of M. de Talleyrand’s manhood was passed.

I have dwelt at some length upon the characteristics—

I have dwelt, I say, at some length upon the characteristics of those times; because it is never to be forgotten that the personage I have to speak of was their child. To the latest hour of his existence he fondly cherished their memory; to them he owed many of those graces which his friends still delight to recall: to them, most of those faults which his enemies have so frequently portrayed.

The great test of his understanding was that he totally escaped all their grosser delusions. Of this I am able to give a striking proof. It has been said that M. de Talleyrand was raised to the episcopal dignity in January, 1789, four months previous to the assembling of the States-General. To that great Assembly he was immediately named by the baillage of his own diocese; and perhaps there is hardly to be found on record a more remarkable example of human sagacity and foresight than in the new bishop’s address to the body which had chosen him its representative.

In this address, which I have now before me, he separates all the reforms which were practicable and expedient, from all the schemes which were visionary and dangerous—the one and the other being at that time confused and jumbled together in the half-frenzied brains of his countrymen: he omits none of those advantages in government, legislation, finance—for he embraces all these—which fifty years have gradually given to France: he mentions none of those projects of which time, experience, and reason have shown the absurdity and futility.

A charter giving to all equal rights: a great code embodying and simplifying all existing and necessary laws: a due provision for prompt justice: the abolition of arbitrary arrest: the mitigation of the laws between debtor and creditor: the institution of trial by jury: the liberty of the press, and the inviolability of private correspondence: the destruction of those interior imposts which cut up France into provinces, and of those restrictions by which all but members of guilds were excluded from particular trades: the introduction of order into the finances under a well-regulated system of public accounts:[14] the suppression of all feudal privileges: and the organization of a well-considered general plan of taxation: such were the changes which the Bishop of Autun suggested in the year 1789. He said nothing of the perfectibility of the human race: of a total reorganization of society under a new system of capital and labour: he did not promise an eternal peace, nor preach a general fraternity amongst all races and creeds. The ameliorations he proposed were plain and simple; they affiliated with ideas already received, and could be grafted on the roots of a society already existing. They have stood the test of eighty years—now advanced by fortunate events, now retarded by adverse ones—some of them have been disdained by demagogues, others denounced by despots;—they have passed through the ordeal of successive revolutions; and they furnish at this instant the foundations on which all wise and enlightened Frenchmen desire to establish the condition of government and society in their great and noble country. Let us do honour to an intelligence that could trace these limits for a rising generation; to a discretion that resisted the temptation to stray beyond them!

About the time of the assembling of the States-General, there appeared a work which it is now curious to refer to—it was by the pen of Laclos—entitled Galerie des États-Généraux. This work gave a sketch under assumed names of the principal personages likely to figure in the States-General. Amongst a variety of portraits, are to be found those of General Lafayette and the Bishop of Autun; the first under the name of Philarète, the second under that of Amène; and, assuredly, the author startles us by his nice perception of the character and by his prophetic sagacity as to the career of these two men. It is well, however, to remember that Laclos frequented the Palais Royal, which the moral and punctilious soldier of Washington scrupulously avoided. The criticism I give, therefore, is not an impartial one. For, if General Lafayette was neither a hero nor a statesman, he was, take him all in all, one of the most eminent personages of his[15] time, and occupied, at two or three periods, one of the most prominent positions in his country.

“Philarète,” says M. Laclos, “having found it easy to become a hero, fancies it will be as easy to become a statesman. The misfortune of Philarète is that he has great pretensions and ordinary conceptions. He has persuaded himself that he was the author of the revolution in America; he is arranging himself so as to become one of the principal actors in a revolution in France.

“He mistakes notoriety for glory, an event for a success, a sword for a monument, a compliment for immortality. He does not like the court, because he is not at his ease in it; nor the world, because there he is confounded with the many; nor women, because they injure the reputation of a man, while they do not add to his position. But he is fond of clubs, because he there picks up the ideas of others; of strangers, because they only examine a foreigner superficially; of mediocrity, because it listens and admires.

“Philarète will be faithful to whatever party he adopts, without being able to assign, even to himself, any good reasons for being so. He has no very accurate ideas of constitutional authority, but the word ‘liberty’ has a charm for him, because it rouses an ambition which he scarcely knows what to do with. Such is Philarète. He merits attention, because, after all, he is better than most of his rivals. That the world has been more favourable to him than he deserves, is owing to the fact that he has done a great deal in it, considering the poverty of his ability; and people have been grateful to him, rather on account of what he seemed desirous to be, than on account of what he was. Besides, his exterior is modest, and only a few know that the heart of the man is not mirrored on the surface.

“He will never be much more than we see him, for he has little genius, little nerve, little voice, little art, and is greedy of small successes.”

Such was the portrait which was drawn of Lafayette; we now come to that of M. de Talleyrand.

“Amène has charming manners, which embellish virtue.[16] His first title to success is a sound understanding. Judging men with indulgence, events with calmness, he has in all things that moderation which is the characteristic of true philosophy.

“There is a degree of perfection which the intelligence can comprehend rather than realise, and which there is, undoubtedly, a certain degree of greatness in endeavouring to attain; but such brilliant efforts, though they give momentary fame to those who make them, are never of any real utility. Common sense disdains glitter and noise, and, measuring the bounds of human capacity, has not the wild hope of extending them beyond what experience has proved their just limit.

“Amène has no idea of making a great reputation in a day: such reputations, made too quickly, soon begin to decline, and are followed by envy, disappointment, and sorrow. But Amène will arrive at everything, because he will always profit by those occasions which present themselves to such as do not attempt to ravish Fortune. Each step will be marked by the development of some talent, and thus he will at last acquire that general high opinion which summons a statesman to every great post that is vacant. Envy, which will always deny something to a person generally praised, will reply to what we have said, that Amène has not that force and energy of character which is necessary to break through the obstacles that impede the course of a public man. It is true he will yield to circumstances, to reason, and will deem that he can make sacrifices to peace without descending from principle; but firmness and constancy may exist without violent ardour, or vapid enthusiasm.

“Amène has against him his pleasing countenance and seductive manner. I know people whom these advantages displease, and who are also prejudiced against a man who happens to unite the useful chance of birth with the essential qualities of the mind.

“But what are we really to expect from Amène in the States-General? Nothing, if he is inspired with the spirit of class; much, if he acts after his own conceptions, and remembers that a national assembly only contains citizens.”

Few who read the above sketch will deny to the author of the “Liaisons Dangereuses” the merit of discernment. Indeed, to describe M. de Talleyrand at this time seems to have been more appropriate to the pen of the novelist than to that of the historian. Let us picture to ourselves a man of about thirty-five, and appearing somewhat older: his countenance of a long oval; his eyes blue, with an expression at once deep and variable; his lips usually impressed with a smile, which was that of mockery, but not of ill-nature; his nose slightly turned up, but delicate, and remarkable for a constant play in the clearly chiseled nostrils. “He dressed,” says one of his many biographers, “like a coxcomb, he thought like a deist, he preached like a saint.” At once active and irregular, he found time for everything: the church, the court, the opera. In bed one day from indolence or debauch, up the whole of the following night to prepare a memoir or a speech. Gentle with the humble, haughty with the high; not very exact in paying his debts, but very scrupulous with respect to giving and breaking promises to pay them.

A droll story is related with respect to this last peculiarity. The new Bishop had ordered and received a very handsome carriage, becoming his recent ecclesiastical elevation. He had not, however, settled the coachmaker’s “small account.” After long waiting and frequent letters, the civil but impatient tradesman determined upon presenting himself every day at the Bishop of Autun’s door, at the same time as his equipage.

For several days, M. de Talleyrand saw, without recognising, a well-dressed individual, with his hat in his hand, and bowing very low as he mounted the steps of his coach. “Et qui êtes vous, mon ami?” he said at last. “Je suis votre carrossier, Monseigneur.” “Ah! vous êtes mon carrossier; et que voulez-vous, mon carrossier?” “Je veux être payé, Monseigneur,” said the coachmaker, humbly. “Ah! vous êtes mon carrossier, et vous voulez être payé; vous serez payé, mon carrossier.” “Et quand,[18] Monseigneur?”[7] “Hum!” murmured the Bishop, looking at his coachmaker very attentively, and at the same time settling himself in his new carriage: “Vous êtes bien curieux!” Such was the Talleyrand of 1789, embodying in himself the ability and the frivolity, the ideas and the habits of a large portion of his class. At once the associate of the Abbé Sieyès, and of Mademoiselle Guimard: a profligate fine gentleman, a deep and wary thinker; and, above all things, the delight and ornament of that gay and graceful society, which, crowned with flowers, was about to be the first victim to its own philosophy. As yet, however, the sky, though troubled, gave no evidence of storm; and never, perhaps, did a great assembly meet with less gloomy anticipations than that which in the pomp and gallantry of feudal show, swept, on the 1st of May, through the royal city of Versailles.

Still, there was even at that moment visible the sign and symbol of the approaching crisis; for dark behind the waving plumes and violet robes of the great dignitaries of Church and State, moved on the black mass, in sable cloak and garb, of the Commons, or tiers-état, the body which had, as yet, been nothing, but which had just been told by one of its most illustrious members,[8] that it ought to be everything.

The history of the mighty revolution which at this moment was commencing, is still so stirring amongst us,—the breath of the tempest which then struck down tower and temple, is still so frequently fancied to be rustling about our own dwellings,—that when the mind even now wanders back, around and about this time, it is always with a certain interest and curiosity, and we pause once again to muse, even though we have often before meditated, upon that memorable event which opened a new chapter in the history of the world. And the more we reflect, the[19] more does it seem surprising that in so civilised an age, and under so well-meaning a sovereign, an august throne and a great society should have been wholly swept away; nor does it appear less astonishing that a monarch with arbitrary sway, that a magistracy with extraordinary privileges, each wishing to retain their authority, should have voluntarily invoked another power, long slumbering in an almost forgotten constitution, and which, when roused into activity, was so immediately omnipotent over parliament and king.

The outline of Louis XVI.’s reign is easily, though I do not remember where it is briefly, and clearly traced. At its commencement, the influence of new opinions was confined to the library and drawing-room. The modern notions of constitutional liberty and political economy prevalent amongst men of letters, and fashionable amongst men of the world, had not been professed by men in power, and were consequently disdained by that large class which wishes in all countries to pass for the practical portion of the community. At this time, an old minister, himself a courtier, and jealous lest other courtiers should acquire that influence over his master which he possessed, introduced into affairs a set of persons hitherto unknown at court, the most eminent of whom were Turgot, Malesherbes, and Necker; and no sooner had these three eminent reformers obtained a serious political position, than their views acquired a political consideration which had not before belonged to them, and the idea that some great and general reform was shortly to take place entered seriously into the public mind. Each of these ministers would have wished to make the reforms that were most necessary with the aid of the royal authority; and, had they been able to do so, it is probable that they would have preserved the heart and strength of the old monarchy, which was yet only superficially decayed. But the moderate changes which they desired to introduce with the assent of all parties, were opposed by all parties, in spite of—or, perhaps, on account of—their very moderation: for losers are rarely satisfied because their losses are[20] small, and winners are never contented but when their gains are great.

In the meantime, Maurepas, who would have supported the policy of his colleagues, if it had brought him popularity, was by no means disposed to do so when it gave him trouble. Thus, Malesherbes, Turgot, and Necker were successively forced to resign their offices, without having done anything to establish their own policy, but much to render any other discreditable and difficult.

The publication of the famous “Compte Rendu,” or balance-sheet of state expenses and receipts, more especially, rendered it impossible to continue to govern as heretofore. And now Maurepas died, and a youthful queen inherited the influence of an old favourite. M. de Calonne, a plausible, clever, but superficial gentleman, was the first minister of any importance chosen by the influence of Marie-Antoinette’s friends. He saw that the expenses and receipts of the government must bear some proportion to each other. He trembled at suddenly reducing old charges; new taxes were the only alternative; and yet it was almost impossible to get such taxes from the lower and middle classes, if the clergy and nobility, who conjointly possessed about two-thirds of the soil, were exempted from all contributions to the public wants. The minister, nevertheless, shrunk from despoiling the privileged classes of their immunities, without some authorization from themselves. He called together, therefore, the considerable personages, or “notables,” as they were styled, of the realm, and solicited their sanction to new measures and new imposts, some of the former of which would limit their authority, and some of the latter affect their purses.

The “notables” were divided into two factions: the one of which was opposed to M. de Calonne, the other to the changes which he wished to introduce. These two parties united and became irresistible. Amongst their ranks was a personage of great ambition and small capacity—Brienne, Archbishop of Toulouse. This man was the most violent of M. de Calonne’s opponents. The court turned round suddenly and chose him as M. de[21] Calonne’s successor. This measure, at first, was successful, for conflicting opinions end by creating personal antipathies, and the “notables,” in a moment of exultation over the defeated minister, granted everything with facility to the minister who had supplanted him. A new embarrassment, however, now arose. The notables were, after all, only an advising body: they could say what they deemed right to be done, but they could not do it. This was the business of the sovereign; but his edicts, in order to acquire regularly the force of law, had to be registered by the Parliament of Paris; and it is easy to understand how such a power of registration became, under particular circumstances, the power of refusal. The influence of that great magisterial corporation, called the “Parliament of Paris,” had, indeed, acquired, since it had been found necessary to set aside Louis XIV.’s will by the sanction of its authority, a more clear and positive character than at former periods. This judicial court, or legislative assembly, had thus become a constituent part of the State, and had also become—as all political assemblies, however composed, which have not others for their rivals, will become—the representative of popular opinion. It had seen, with a certain degree of jealousy, the convocation, however temporarily, of another chamber (for such the assembly of notables might be called), and was, moreover, as belonging to the aristocracy, not very well disposed to the surrender of aristocratical privileges. It refused, therefore, to register the new taxes proposed to it: thus thwarting the consent of the notables, avoiding, for a time, the imposts with which its own class was threatened, and acquiring, nevertheless, some increase of popularity with the people who are usually disposed to resist all taxation, and were pleased with the invectives against the extravagance of the court, with which the resistance of the parliament was accompanied.

The government cajoled and threatened the parliament, recalled it, again quarrelled with it, attempted to suppress it—and failed.

Disturbances broke out, famine appeared at hand, a bankruptcy was imminent; there was no constituted[22] authority with sufficient power or sufficient confidence in itself to act decisively. People looked out for some new authority: they found it in an antique form. “The States-General!” (that is, an assembly chosen from the different classes, which, in critical periods of the French nation had been heretofore summoned) became the unanimous cry. The court, which wanted money and could not get it, expected to find more sympathy in a body drawn from all the orders of the State than from a special and privileged body which represented but one order.

The parliament, on the other hand, imagined that, having acquired the reputation of defending the nation’s rights, it would have its powers maintained and extended by any collection of men representing the nation. This is why both parliament and court came by common accord to one conclusion.

The great bulk of the nobility, though divided in their previous discussions, here, also, at last agreed: one portion because it participated in the views of the court, and the other because it participated in those of the parliament.

In the meantime, the unfortunate Archbishop, who had tried every plan for filling the coffers of the court without the aid of the great council now called together, was dismissed as soon as that council was definitively summoned: and, according to the almost invariable policy of restoring to power the statesman who has increased his popularity by losing office, M. Necker was again placed at the head of the finances and presented to the public as the most influential organ of the crown.

It will be apparent, from what I have said, that the court expected to find in the States-General an ally against the parliament, whilst the parliament expected to find in the States-General an ally against the court. Both were deceived.

The nobility, or notables, the government, and the parliament, had all hitherto been impotent, because they had all felt that there was another power around them[23] and about them, by which their actions were controlled, but with which, as it had no visible representation, they had no means of dealing.

That power was “public opinion.” In the Commons of France, in the Deputies from the most numerous, thoughtful, and stirring classes of the community, a spirit—hitherto impalpable and invisible—found at once a corporate existence.

Monsieur d’Espremenil, and those parliamentary patricians who a year before were in almost open rebellion against the sovereign, at last saw that they had a more potent enemy to cope with, and rallied suddenly round the throne. Its royal possessor stood at that moment in a position which no doubt was perilous, but which, nevertheless, I believe, a moderate degree of sagacity and firmness might have made secure. The majority of the aristocracy of all grades, from a feudal sentiment of honour, was with the King. The middle classes also had still for the monarch and his rank considerable respect; and were desirous to find out and sanction some just and reasonable compromise between the institutions that were disappearing, and the ideas that had come into vogue. It was necessary to calm the apprehensions of those who had anything to lose, to fix the views of those who thought they had something to gain, and to come at once to a settlement with the various classes—here agitated by fear, there by expectation. But however evident the necessity of this policy, it was not adopted. Suspicions that should have been dissipated were excited; notions that should have been rendered definite were further disturbed; all efforts at arrangement were postponed; and thus the revolution rushed onwards, its tide swelling, and its rapidity being increased by the blunders of those who had the greatest interest and desire to arrest it. The fortune of M. de Talleyrand was embarked upon that great stream, of which few could trace the source, and none foresaw the direction.

I have just said that none foresaw the direction in which the great events now commencing were likely to run. That direction was mainly to be influenced by the conduct and character of the sovereign, but it was also, in some degree, to be affected by the conduct and character of the statesman to whom the destinies of France were for the moment confided.

M. Necker belonged to a class of men not uncommon in our own time. His abilities, though good, were not of the first order; his mind had been directed to one particular branch of business; and, as is common with persons who have no great genius and one specialty, he took the whole of government to be that part which he best understood. Accordingly, what he now looked to, and that exclusively, was balancing the receipts and expenditure of the State. To do this, it was necessary to tax the nobility and clergy; and the class through whose aid he could best hope to achieve such a task was the middle-class, or “tiers-état.” For this reason, when it had been decided to convoke the States-General, and it became necessary to fix the proportionate numbers by which each of the three orders (viz. the nobility, clergy, middle-class, or “tiers-état,”) which composed the States-General, was to be represented, M. Necker determined that the sole order of the “tiers-état” should have as many representatives as the two other orders conjointly; thinking in this way to give the middle-class a greater authority, and to counterbalance the want of rank in its individual members, by their aggregate superiority in numbers.

But when M. Necker went thus far he should have gone farther, and defined in what manner the three orders should vote, and what power they should separately exercise. This precaution, however, he did not take; and therefore, as soon as the States-General assembled, there instantly arose the question as to whether the three orders were to prove the validity of their elections together as members of one assembly, or separately as members of three distinct assemblies. This question, in point of fact,[25] determined whether the three orders were to sit and vote together, or whether each order was to sit and vote apart; and after M. Necker’s first regulation it was clear that, in one case, the order of the Commons would predominate over all opposition; and that, in the other, it would be subordinate to the two rival orders. A struggle then naturally commenced.

The members of the “tiers-état,” who, as the largest of the three bodies forming the States-General, had been left in possession of the chamber where all the orders had been first collected to meet the sovereign—an accident much in their favour—invited the members of the two other orders to join them there. The clergy hesitated; the nobles refused. Days and weeks passed away, and the minister, seeing his original error, would willingly have remedied it by now proposing that which he might originally have fixed, namely, that the three orders should vote together on questions of finance, and separately on all other questions. This idea was brought forward late; but, even thus late, it might have prevailed if the court had been earnest in its favour. The King, however, and those who immediately influenced him, had begun to think that a deficit was less troublesome than the means adopted to get rid of it; and fancying that the States-General, if left to themselves, might ere long dissolve amidst the dissensions which were discrediting them, were desirous that these dissensions should continue. Nor would this policy have failed in its object if negotiation had been much further prolonged.

But it is at great moments like these that a great man suddenly steps forth, and whilst the crowd is discussing what is best to be done, does it. Such a man was the Comte de Mirabeau; and on the 15th of June, this marvellous personage, whose audacity was often prudence, having instigated the Abbé Sieyès (whose authority was at that time great with the Assembly) to bring the subject under discussion, called on the tiers-état, still doubting and deliberating, to constitute themselves at once, and without further waiting for the nobility, “The Representatives[26] of the French people.” They did so in reality, though not in words, declaring themselves duly elected, and taking as their title “The National Assembly.” The government thought to stop their proceedings by simply shutting up the chamber where they had hitherto met, but so paltry a device was insufficient to arrest the resolutions of men whose minds were now prepared for important events. Encouraging each other, the Commons rushed unhesitatingly to a tennis-court, and in that spot, singularly destined to witness so solemn a ceremony, swore, with but one dissentient voice, to stand by each other till France had a constitution. After such an oath, the alternative was clearly between the old monarchy, with all its abuses, and a new constitution, whatever its dangers. On this ground, two orders in the State stood hostilely confronted. But another order remained, whose conduct at such a juncture was all-decisive. That order was the clergy,—which, still respected if not venerated,—wealthy, connected by various links with each portion of society, and especially looked up to by that great and sluggish mass of quiet men who always stand long wavering between extremes—had been endeavouring to effect some compromise between the privileged classes and their opponents, but had as yet taken no prominent part with either. The moment was come at which it could no longer hesitate.

M. de Talleyrand, though but a new dignitary in the church, was already one of its most influential members. He had been excluded by a prejudice of the nobility from the situation to which his birth had entitled him amongst them. He had long resolved to obtain another position at least as elevated through his own exertions. His views, as we have seen, at the time of his election, were liberal, though moderate, whilst he was sufficiently acquainted with the character of Louis XVI. to know that that monarch would never sincerely yield, nor ever sturdily resist, any concession demanded with persistency. Partly, therefore, from a conviction that he was doing what was best for the public, and partly, also, from the persuasion[27] that he was doing what was best for himself, he separated boldly from the rest of his family (who were amongst the most devoted to the Comte d’Artois and Marie-Antoinette), and laboured with unwearied energy to enlist the body he belonged to on the popular side.

To succeed in this object he had the talents and advantages most essential. His natural courtesy flattered the curates; his various acquirements captivated his more learned brethren; his high birth gave him the ear of the great ecclesiastical dignitaries; and, finally, a majority of his order, instigated by his exertions and address, joined the Third Estate, on the 22nd of June, in the Church of Saint-Louis.

From that moment the question hitherto doubtful was determined; for at no time have the clergy and the commons stood side by side without being victorious. It was in vain, therefore, that even so early as the day following, the descendant of Louis XIV., in all the pomp of royalty, and in the presence of the three orders—whom he had for that day summoned to assemble—denounced the conduct which the tiers-état had pursued, annulled their decisions, and threatened them with his sovereign displeasure.

The tiers-état resisted; the King repented—retracted,—and showing that he had no will, lost all authority. Thus, on the 27th of June, the States-General, henceforth designated by the title which had been already assumed by the Commons (the National Assembly), held their deliberations together, and the three orders were confounded.

But one step now remained in order to legalise the revolution in progress. Each deputy had received a sort of mandate or instruction from those who named him at the moment of his election. Such instructions or mandates, which had been given at a time when people could hardly anticipate the state of things which had since arisen, limited, or seemed to limit, the action of a deputy to particular points which had especially attracted the attention of his constituents.

The conservative party contended that these mandates were imperative, the liberal party that they were not. According to the first supposition, the States-General could do no more than redress a few grievances; according to the other, they could create a perfectly new system of government.

The Bishop of Autun, in the first speech he delivered in the National Assembly—a speech which produced considerable effect—argued in favour of his own liberty and that of his colleagues, and his views were naturally enough adopted by a body which, feeling its own force, had to determine its own power. Hence, on the record of two great decisions—the one solving the States-General into the “National Assembly;” the other extending and fixing that Assembly’s authority—decisions which, whatever their other results, were at least fatal to the power and influence of the class to which he belonged by birth, but from which he had, in spite of himself, been severed in childhood—was indelibly inscribed the name of the once despised and still disinherited cripple of the princely house of Périgord.

There was nothing henceforth to impede the labours of the National Assembly, and it commenced those labours with earnestness and zeal, if not with discretion. One of its first acts was to choose by ballot a committee of eight members, charged to draw up the project of a constitution, which was subsequently to be submitted to the Assembly. The Bishop of Autun was immediately placed upon this select and important committee. It had for its task to render practical the political speculations of the eighteenth century. Things, however, had commenced too violently for them to proceed thus peaceably; and as the success of the popular party had been hitherto obtained by braving the crown, it was to be expected that the crown would seize the first opportunity that presented itself for boldly recovering its authority. A well-timed effort of this kind might have been successful. But neither Louis XVI., nor any of the counsellors in whom he confided, possessed that instinct in political affairs which is the soul of action,[29] inspiring men with the resolve to do the right thing at the right moment. It has often been found easy to crush a revolution at its commencement, for the most ardent of its supporters at such a time act feebly, and doubt about the policy they are pursuing. It has often been found possible to arrest a revolution at that subsequent stage of its progress when the moderate are shocked by some excess, or the sanguine checked by some disappointment; but a revolution is invincible at that crisis, when its progress, begun with boldness, has neither been checked by misfortune, nor disgraced by violence.

Nevertheless, it was just at such a crisis that the unfortunate Louis XVI., guided in a great degree by the fatal influence of his brother, after having gradually surrounded Versailles and the capital with troops, suddenly banished M. Necker (July 10th), whose disgrace was instantly considered the defeat of those who advised the King to renovate his authority by concessions, and the triumph of those who counselled him to recover and re-establish it by force. But the measures which were to follow this act were still in suspense, when a formidable insurrection broke out at Paris. A portion of the soldiery sided with the people. The Bastille was taken, and its commandant put to death, the populace got possession of arms, the prevôt or mayor of the city was assassinated, whilst the army which had been so ostentatiously collected in the Champ de Mars and at St. Denis was left an inactive witness of the insurrection which its array had provoked. The results were those which usually follow the strong acts of weak men: Louis XVI. submitted; M. Necker was recalled; the Comte d’Artois emigrated.

It was M. de Talleyrand’s fortune not merely at all times to quit a falling party at the commencement of its decline, but to stand firm by a rising party at the moment of its struggle for success. This was seen during the contest we have just been describing. Throughout that contest the Bishop of Autun was amongst the most determined for maintaining the rights of the nation against the designs of the court. His decision and courage added not a little to the reputation which had[30] been already gained by his ability. We find his name, therefore, first in the list of a small number of eminent men,[9] whom the Assembly, when surrounded by hostile preparations for restoring the despotism which had been abolished, charged, in a bold but not imprudent spirit of defiance, with the task of at once completing and establishing the constitution which had been promised, and which it had become evident there was no intention to accord. The labour of these statesmen, however, was not easy, even after their cause was triumphant, for political victories often leave the conquerors—in the excess of their own passions, and the exaggeration of their own principles—worse enemies than those whom they have vanquished. Such was the case now.

In the exultation of the moment all moderate notions were laid aside, and succeeded by a blind excitement in favour of the most sweeping changes. Nor was this excitement the mere desire of vulgar and selfish interest stirring the minds of those who hoped to better their own condition: nobler and loftier emotions lit up the breasts of men who had only sacrifices to make with a generous enthusiasm. “Nos âmes,” says the elder Ségur, “étaient alors enivrées d’une douce philanthropie, qui nous portait à chercher avec passion les moyens d’être utiles à l’humanité, et de rendre le sort des hommes plus heureux.”[10] On the 4th of August, “a day memorable with one party,” observes M. Mignet, “as the St. Bartholomew of property, and with the other as the St. Bartholomew of abuses,”—personal service, feudal obligations, pecuniary immunities, trade corporations, seignorial privileges, and courts of law,—all municipal and provincial rights,—the whole system of judicature,—based on the purchase and sale of judicial charges, and which, singular to state, had, however absurd in theory, hitherto produced in practice[31] learned, able, and independent magistrates,—in short, almost all the institutions and peculiarities which constituted the framework of government and society throughout France, were unhesitatingly swept away, at the instigation and demand of the first magistrates and nobles of the land, who did not sufficiently consider that they who destroy at once all existing laws (whatever those laws may be), destroy at the same time all established habits of thought;—that is, all customs of obedience, all spontaneous feelings of respect and affection, without which a form of government is merely an idea on paper.

In after times, M. de Talleyrand, when speaking of this period, said, in one of his characteristic phrases, “La Révolution a désossé la France.” But it is easier to be a witty critic of by-gone history, than a cool and impartial actor in passing events; and at the time to which I am alluding the Bishop of Autun was, undoubtedly, amongst the foremost in destroying the traditions which constitute a community, and proclaiming the theories which captivate a mob. The wholesale abolition of institutions, which must have had something worth preserving or they would never have produced a great and polished society honourably anxious to reform its own defects, was sanctioned by his vote; and the “rights of man,” the acknowledgment of which did so little to secure the property or life of the citizen, were proclaimed in the words that he suggested.

It is difficult to conceive how so cool and sagacious a statesman could have imagined that an old society was to be well governed by entirely new laws, or that practical liberty could be founded on a declaration of abstract principles. A sane mind, however, does not always escape an epidemic folly; any more than a sound body escapes an epidemic disease. Moreover, in times when to censure unnecessary changes is to pass for being the patron, and often in reality to be the supporter, of inveterate abuses, no one carries out, or can hope to carry out, precisely his own ideas. Men act in masses: the onward pressure of one party is regulated by the opposing resistance of another: to pursue a policy, it may be expedient for[32] those who do not feel, to feign, a passion; and a wise man may excuse his participation in an absurd enthusiasm by observing it was the only means to vanquish still more absurd prejudices.

Still, if M. de Talleyrand was at this moment an exaggerated reformer, he at least did not exhibit one frequent characteristic of exaggerated reformers, by being so wholly occupied in establishing some delusive scheme of future perfection, as to despise the present absolute necessities. He saw from the first that, if the new organization of the State was really to be effected, it could only be so by re-establishing confidence in its resources, and that a national bankruptcy would be a social dissolution. When, therefore, M. Necker (on the 25th of August) presented to the Assembly a memoir on the situation of the finances, asking for a loan of eighty millions of francs, the Bishop of Autun supported this loan without hesitation; demonstrating the importance of sustaining the public credit; and shortly afterwards (in September), when the loan thus granted was found insufficient to satisfy the obligations of the State, he again aided the minister in obtaining from the Assembly a tax of twenty-five per cent. on the income of every individual throughout France. A greater national sacrifice has rarely been made in a moment of national distress, and has never been made for a more honourable object. It is impossible, indeed, not to feel an interest in the exertions of men animated, amidst all their errors, by so noble a spirit, and not to regret that with aspirations so elevated, and abilities so distinguished, they should have failed so deplorably in their efforts to unite liberty with order—vigour with moderation.

But Providence seems to have prescribed as an almost universal rule that everything which is to have a long duration must be of slow growth. Nor is this all: we must expect that, in times of revolution, contending parties will constantly be hurried into collisions contrary to their reason, and fatal to their interests, but inevitably suggested by their anger or suspicions. Hence the wisest intentions are at the mercy of the most foolish incidents. Such an incident now occurred.

A military festival at Versailles, which the royal family imprudently attended, and in which it perhaps idly delighted to excite a profitless enthusiasm amongst its guards and adherents, alarmed the multitude at Paris, already irritated by an increasing scarcity of food, and dreading an appeal to the army on the part of the sovereign, as the sovereign dreaded an appeal to the people on the part of the popular leaders. The men of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and the women of the market-place, either impelled by their own pressing wants and indefinite fears, or guided (as it was then—I believe falsely—reported) by the secret influence of the Duc d’Orléans, were soon seen pouring from the dark corners of the capital, and covering the broad and stately road which leads to the long-venerated palace, where, since the time of the “Great Monarch,” his descendants had held their court. In the midst of an accidental tumult, this lawless rabble entered the royal residence, massacreing its defenders.

The King was rescued from actual violence, though not from insult, and escorted with a sort of decorum to the Tuileries, which he henceforth inhabited, nominally as the supreme magistrate of the State, but in reality as a prisoner. The National Assembly followed him to Paris.

The events of which I have been speaking took place on the 5th and 6th of October; and were, to the advocates of constitutional monarchy, what the previous insurrection, in July, had been to the advocates of absolute power. Moderate men began to fear that it was no longer possible to ally the dignity and independence of the crown with the rights and liberties of the people: and MM. Mounier and Lally-Tollendal, considered the leaders of that party which from the first had declared the desire to establish in France a mixed constitutional government, similar to that which prevailed in England—disheartened and disgusted—quitted the Assembly. Hitherto, M. de Talleyrand had appeared disposed to act with these statesmen, but he did not now imitate their conduct: on the contrary, it was precisely at the moment when they[34] separated themselves from the Revolution, that he brought forward a motion which connected him irrevocably with it.

Had affairs worn a different aspect, it is probable that he would not have compromised himself so decidedly in favour of a scheme which was certain to encounter a determined and violent opposition: still it is but just to observe that his conduct in this instance was in perfect conformity with the course he had previously pursued, and the sentiments he had previously expressed, both with respect to the exigencies of the State and the property of the Church. I have shown, indeed, the interest he had manifested in maintaining the public credit, first by supporting a loan of eighty millions of francs, and secondly by voting a property tax of twenty-five per cent. But the one had proved merely a temporary relief, and the other had not given an adequate return; for, as the whole administration of the country had been disorganized, so the collection of taxes was precarious and difficult. Some new resource had to be sought for. There was but one left. The clergy had already resigned their tithes, which at first had only been declared purchasable, and had also given up their plate. When M. de Juisné, Archbishop of Paris, made the two first donations in the name of his brethren, he had been seconded by the Bishop of Autun; and it was the Bishop of Autun who now proposed (on the 10th of October) that all that remained to the clergy—their land—should, on certain conditions, be placed at the disposal of the nation.

M. Pozzo di Borgo, a man in no wise inferior to M. de Talleyrand, though somewhat jealous of him, once said to me, “Cet homme s’est fait grand en se rangeant toujours parmi les petits, et en aidant ceux qui avaient le plus besoin de lui.”[11]

The propensity which M. Pozzo di Borgo somewhat bitterly but not inaccurately described, and which perhaps[35] was in a certain degree the consequence of that nice perception of his own interests which guided the person whom I designate as “politic” through life almost like an instinct, was especially visible in the present instance. No one can doubt that, at the moment when every other institution was overturned in France, a great change in the condition of the French church, against which the spirit of the eighteenth century had been particularly directed, was an event not to be avoided. Alone amidst the general prodigality, this corporation by its peculiar condition had been able to preserve all its wealth, whilst it had lost almost all its power.

The feeble and the rich in times of commotion are the natural prey of the strong and the needy; and, therefore, directly the nation commenced a revolution to avoid a bankruptcy, the ecclesiastical property was pretty sure, a little sooner or a little later, to be appropriated to the public exigencies. Such an appropriation, nevertheless, was not without difficulties; and what the laity most wanted was a churchman of position and consideration who would sanction a plan for surrendering the property of the church. The opinions expressed by a man of so high a rank amongst the nobility and the clergy as the Bishop of Autun, were therefore of considerable importance, and likely to give him—those opinions being popular—an important position, which was almost certain (M. Necker’s influence being already undermined) to lead—should a new ministry be formed on the liberal side—to office. Mirabeau, in fact, in a note written in October, which proposes a new ministerial combination, leaves M. Necker as the nominal head of the government “in order to discredit him,” proposes himself as a member of the royal council without a department, and gives the post of minister of finance to the Bishop of Autun, saying, “His motion on the clergy has won him that place.”[12]

The argument with which the Bishop introduced the motion here alluded to has been so often repeated since the period to which I am referring, and has so influenced the condition of the clergy throughout a great portion of[36] Europe, that it cannot be read without interest. “The State,” said M. de Talleyrand, “has been for a long time struggling with the most urgent wants. This is known to all of us. Some adequate means must be found to supply those wants. All ordinary sources are exhausted. The people are ground down. The slightest additional impost would be justly insupportable to them. Such a thing is not to be thought of. Extraordinary means for supplying the necessities of the State have been resorted to: but these were destined to the extraordinary wants of this year. Extraordinary resources of some kind are now wanted for the future; without them, order cannot be established. There is one such resource, immense and decisive: and which, in my opinion (or otherwise I should reject it), can be made compatible with the strictest respect for property. I mean the landed estate of the church.

…

“Already a great operation with regard to this estate is inevitable, in order to provide suitably for those whom the relinquishment of tithes has left destitute.

…

“I think it unnecessary to discuss at length the question of church property. What appears to me certain is, that the clergy is not a proprietor like other proprietors, inasmuch as that the property which it enjoys (and of which it cannot dispose) was given to it—not for its own benefit, but for the performance of duties which are to benefit the community. What appears to me also certain is, that the nation, exercising an almost unlimited power over all the bodies within its bosom, possesses—not the right to destroy the whole body of the clergy, because that body is required for the service of religion—but the right to destroy any particular aggregations of such body whenever they are either prejudicial or simply useless; and if the State possesses this right over the existence of prejudicial or useless aggregations of the clergy, it evidently possesses a similar right over the property of such aggregations.

“It appears to me also clear that as the nation is bound to see that the purpose for which foundations or endowments[37] were made is fulfilled, and that those who endowed the church meant that the clergy should perform certain functions: so, if there be any benefices where such functions are not performed, the nation has a right to suppress those benefices, and to grant the funds, therefrom derived, to any members of the clergy who can employ them according to the object with which they were given.

…

“But although it is just to destroy aggregations of the clergy which are either prejudicial or useless, and to confiscate their property—although it is just to suppress benefices which are no longer useful for the object for which such benefices were endowed—is it just to confiscate or reduce the revenue of those dignitaries and members of the church, who are now actually living and performing the services which belong to their sacred calling?

…

“For my own part, I confess the arguments employed to support the contrary opinion appear to me to admit of several answers. I shall submit one very simple answer to the Assembly.

“However the possession of a property may be guaranteed and made inviolable by law, it is evident that the law cannot change the nature of such property in guaranteeing it.