KING TAWHIAO.

OR,

EXPLORATIONS IN NEW ZEALAND.

A NARRATIVE OF 600 MILES OF TRAVEL THROUGH MAORILAND.

BY

J.H. KERRY-NICHOLLS.

THE AUTHOR.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP.

SECOND EDITION.

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON,

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET STREET.

1884

[All rights reserved.]

THIS WORK IS DEDICATED

BY PERMISSION

TO

SIR GEORGE GREY, K.C.B., F.R.S.,

WHOSE CAREER

AS GOVERNOR, STATESMAN, ORATOR, AUTHOR, AND EXPLORER,

HAS SHED LUSTRE

UPON

THE HISTORY OF AUSTRALASIA.

In publishing this record of travel, I have deemed it advisable to arrange my narrative under four principal divisions. In the introductory portion I refer to the leading physical features of that part of the North Island of New Zealand known as the King Country, relate the leading incidents connected with its history, describe the condition of the native race, and explain the object with which my journey was undertaken. The succeeding chapters deal with my visit to the Maori King when presenting my credentials from Sir George Grey at the tribal gathering held at Whatiwhatihoe in October, 1882. The description of the Lake Country includes my route from Tauranga, on the East Coast, to Wairakei, and which led me through the marvellously interesting region familiarly termed the Wonderland of New Zealand, while in the pages embracing my explorations in the King Country I record events as they occurred from day to day over a lengthy journey which was delightful on account of its novelty and variety, and exciting by reason of the difficulties, both as regards natural obstacles inseparable from the exploration of an unknown region under[Pg viii] the unfavourable conditions by which I was constrained to carry it out, and the deep-rooted jealousy of the native race against the intrusion of Europeans into a portion of the island which is considered by them to be exclusively Maori territory.

When it is considered that in company only with my interpreter, and with but three horses—ultimately reduced to two—and with what scant provisions we could carry, I accomplished considerably over 600 miles of travel, discovered many new rivers and streams, penetrated almost inaccessible regions of mountainous forest, found extensive areas of open plains suitable for European settlement, traced the sources of three of the principal rivers of the colony, examined the unknown shores of its largest lake, ascended one of the highest mountains of the southern hemisphere, experienced degrees of temperature varying from 80° in the shade to 12° below freezing-point, and successfully traversed from South to North, through its entire length, a territory with an area of 10,000 square miles, and which had been from the early history of the colony rigorously closed to Europeans by the hostility of the native tribes, it may be readily seen that the explorations, by their varied nature, disclose many important facts hitherto unknown concerning a vast and beautiful portion of New Zealand; and while they cannot fail to prove of practical utility to the colony, they will, I venture to think, be a welcome addition to geographical science.

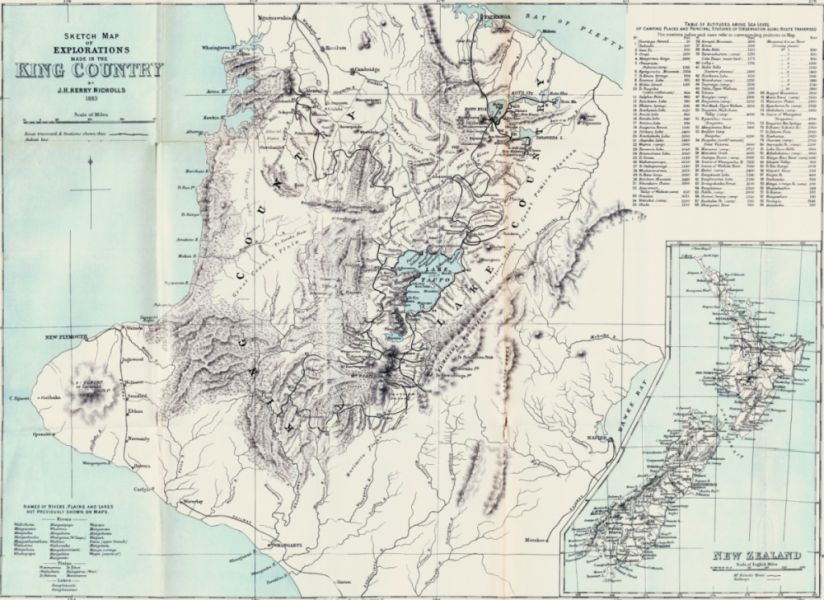

The map appended to this work may be said to form[Pg ix] the most complete chart of the interior of the North Island as yet published. Up to the present time the extensive territory embraced by the King Country has, owing to the obstruction of the natives, never been surveyed, and consequently many of its remarkable physical features have remained unknown, the existing maps of this part of the colony being mere outlines. As, therefore, considerably more than half of the country traversed was through a region which was, to all intents and purposes, a terra incognita from the commencement of my journey, I adopted a system of barometrical measurements and topographical observations, and thus secured a supply of valuable material, which I mapped out from day to day, while the names of mountains, rivers, valleys, and lakes were obtained from the natives by the skilful assistance of my interpreter, who was at all times unceasing in his endeavours to carry out this part of the work with accuracy.

The table of altitudes of the various camping-places and stations of observation throughout the country explored will be found to be of considerable interest and importance. By these results the conformation of a large portion of the island may be arrived at. Thus, beginning at Tauranga, and taking that place at ten feet above sea-level, it will be seen that the land rises rapidly from the coast-line for a distance of about twenty miles, when, at the Mangorewa Gorge, it attains to an altitude of 1800 feet; from that point it falls towards the South until the table-land of the Lake[Pg x] Country is reached, when, at Lake Rotorua, it has an altitude of 961 feet. From the latter place, still going southward, the table-land rises with an elevation varying from 1000 to 1500 feet, until it falls towards the valley of the Waikato, when at Atea-Amuri it is not more than 650 feet above the level of the sea. Further along it gradually rises until it reaches Oruanui, some fifteen miles distant, where an altitude of 1625 feet is attained, until the country again falls to the extensive table-land of Taupo, where over a large area it maintains an elevation varying from 1000 to 1400 feet, the great lake itself standing at an altitude of 1175 feet. Southward of Lake Taupo the Rangipo table-land varies from 2000 to 3000 feet, until it falls towards the South Coast, giving an altitude at Karioi, on the Murimotu Plains, of 2400 feet. Westward of this point the country falls gradually to 560 feet to the valley of the Whanganui, and from that region going eastward to the Waimarino Plains it attains to an elevation of 2850 feet in a distance of about thirty miles. Northward again along the western table-land of Lake Taupo it varies in height from 1000 to 2420 feet, until the Takapiti Valley is reached, where it is only 900 feet. In the Te Toto Ranges an altitude of 1700 feet is attained, until at Manga-o-rongo, a deep basin-like depression in the valley of the Waipa, the land is not more than 200 feet above sea level.

The wood engravings contained in this work are from original sketches by the author, with the excep[Pg xi]tion of that of the native village of Lake Rotoiti, which is from a painting by the talented artist Mr. Charles Bloomfield. They were engraved by Mr. James Cooper of Arundel Street, Strand. The portraits of the native chiefs are from photographs taken by E. Pulman and J. Bartlett of Auckland. They have been reproduced by the Meisenbach process.

In the Appendix will be found a synopsis of the principal flora met with during the journey, together with that of Mount Tongariro and Mount Ruapehu, up to the highest altitude attained by plant-life in the North Island. A synopsis of the fauna is also added. Biographical sketches are given of King Tawhiao and several noted chiefs, with a list of the principal tribes and their localities. There is likewise a brief reference to the Maori language, with a compendium of the most useful native words.

In bringing this volume to its completion, I desire to acknowledge my indebtedness to Sir George Grey, K.C.B., for his letter of introduction to King Tawhiao; to Mr. C.O. Davis, for the willing way he at all times placed his scholarly knowledge of the Maori language at my disposal; to Mr. T.F. Cheeseman, F.L.S., for the classification of the flora of Tongariro and Ruapehu; to Mr. James McKerrow, Surveyor-General, for maps and charts of the colony; to Mr. Percy Smith, Assistant-Surveyor-General, for a correction of altitudes; to Mr. Robert Graham, of Ohinemutu, for voluntarily placing his best horses at my disposal; to[Pg xii] J.A. Turner, for an unceasing earnestness of purpose in fulfilling his duties as interpreter; and to the Whitaker Ministry, for their recognition of the usefulness of my work.

| INTRODUCTION. | ||

| PAGE | ||

| Geographical description of the King Country—Its political state—Efforts made to open it—Condition of the natives—Origin of the journey—Letter of introduction to the king | ||

| 1 | ||

| THE FRONTIER OF THE KING COUNTRY. | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| THE KING'S CAMP. | ||

| Alexandra—Crossing the frontier—Whatiwhatihoe—The camp—King Tawhiao—The chiefs—"Taihoa" | ||

| 17 | ||

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| THE KORERO. | ||

| The Kingites—Half-castes—An albino—The king's speech—Maori oratory—The feast | ||

| 27 | ||

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| ASCENT OF PIRONGIA. | ||

| Mount Pirongia—Geological features—The ascent—A fair prospect | ||

| 36 | ||

| THE LAKE COUNTRY. | ||

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| AUCKLAND TO OHINEMUTU. | ||

| The flank movement—Auckland Harbour—Tauranga—Whakari—The [Pg xiv]tuatara—En route—The Gate Pa—All that remains—Oropi—A grand forest—Mangorewa Gorge—Mangorewa River—A region of eternal fire | ||

| 46 | ||

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| HOT-SPRING LIFE. | ||

| Ohinemutu and Lake Rotorua—Te Ruapeka—The old pa—Native baths—Delightful bathing—A curious graveyard—Pigs—Area of thermal action—Character of the springs—Chemical constituents—Noted springs—Whakarewarewa—Te Koutu—Kahotawa—"Tenakoe, pakeha"—Hot and cold | ||

| 56 | ||

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| TRADITION, IDOLATRY, AND ROMANCE. | ||

| Origin of the Maoris—Te Kupe—First canoes—The runanga house—Maori carving—Renowned ancestors—Tama te Kapua—Stratagem of the stilts—Legend of the whale—The Arawa canoe—Noted braves—Mokia—A curious relic—Gods of the Arawas—Mokia by night—Hinemoa—A love song | ||

| 68 | ||

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| EN ROUTE TO THE TERRACES. | ||

| Over the mountains—Rauporoa Forest—The hotete—Tikitapu—Rotokakahi—Te Wairoa—The natives—Waituwhera Gorge—The boat—A distinguished traveller—Sophia—Lake Tarawera—Mount Tarawera—Te Ariki—Te Kaiwaka | ||

| 81 | ||

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| THE TERRACES. | ||

| Te Tarata—Beauty of the terrace—The formation—The crater—A sensational bath—Ngahapu—Waikanapanapa—A weird gorge—Te Aua Taipo—Kakariki—Te Whatapohu—Te Huka—Te Takapo—Lake Rotomahana—Te Whakataratara—Te Otukapurangi—The formation—The cauldron | ||

| 94 | ||

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| OHINEMUTU TO WAIRAKEI. | ||

| Te Hemo Gorge—Mount Horohoro—Paeroa Mountains—Orakeikorako—Atea -Amuri—Pohaturoa—The land of pumice—Te Motupuke—The glades [Pg xv]of Wairakei | ||

| 109 | ||

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| WAIRAKEI. | ||

| The first view—The Geyser Valley—Curious sights—Tahuatahe —Terekirike—The Whistling Geyser—A nest of stone—Singular mud-holes—The Gas and Black Geyser—The Big Geyser—The great Wairakei—The Blue Lake—Hot mud-holes—Kiriohinekai—A valley of fumaroles—Te Karapiti Te Huka Falls—Efforts to pass under the falls—A cave—An enormous fissure—Another trial—A legend | ||

| 115 | ||

| EXPLORATION OF THE KING COUNTRY. | ||

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| THE START. | ||

| Reason of the journey—How I succeeded—My interpreter—Our horses—The Hursthouse difficulty—Departure from Wairakei—Tapuwaeharuru—The natives—Release of Hursthouse, nd capture of Te Mahuki—The council of war | ||

| 131 | ||

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| THE REGION OF LAKE TAUPO. | ||

| Natural phenomena—The great table-land—Position and dimensions of the lake—Water-shed—Geological features—The lake an extinct crater—Crater lakes—Areas of thermal action | ||

| 139 | ||

| CHAPTER XIII. | ||

| EASTERN SHORE OF LAKE TAUPO. | ||

| A grand view—True source of the Waikato—The river of "streaming water"—Our first camp—Variation of temperature—Roto Ngaio—Te Hatepe—Te Poroporo—The lake beneath us—A canoe—Motutere—Tauranga—Southern shore of the lake—Delta of the Upper Waikato | ||

| 149 | ||

| CHAPTER XIV. | ||

| TOKANU. | ||

| Scenery—The springs—The natives—Old war-tracks—Te Heuheu—A [Pg xvi]Maori lament—Motutaiko—Horomatangi | ||

| 161 | ||

| CHAPTER XV. | ||

| THE RANGIPO TABLE LAND. | ||

| Along the delta of the Upper Waikato—Mount Pihanga—The Poutu River and Lake Rotoaira—Boundaries of the Rangipo—Scenery—A fine night—A rough time—A great storm—The karamu as fodder—Banks of the Upper Waikato—Another start—More bad weather—Flooded creeks—Pangarara—Te Hau | ||

| 168 | ||

| CHAPTER XVI. | ||

| ASCENT OF TONGARIRO. | ||

| Physical and geological features—Legend of Tongariro—A break in the clouds—The start for the ascent—Maories in the distance—The Waihohonu valley—The ascent—The brink of Hades—The great crater—The inner crater—The lower cones—Crater lakes—The descent—A valley of death—Tongariro by moonlight—A cold night—The start for Ruapehu | ||

| 179 | ||

| CHAPTER XVII. | ||

| ASCENT OF RUAPEHU. (First Day.) |

||

| Approaching the mountain—A field for research—Physical and geological features—Plan of attack—Curious icicles—A lava barrier—Natives in the distance—Horse camp—Scoria hills and lava ridges—The start for the snow-line—Up the great spur—Head of the spur—Our camp—A wind-storm—Ruapehu by night—A picture of the past—Waiting for sunrise—Sunrise | ||

| 199 | ||

| CHAPTER XVIII. | ||

| RUAPEHU. (Second Day.) ASCENT OF THE GREAT PEAK. |

||

| The start—A lava bluff—Last signs of vegetation—Wall of conglomerate rock—The Giant Rocks—Ancient crater—Difficult climbing—A frightful precipice—The ice crown—Cutting our way over the ice—The summit—Peaks and crater—A grand coup d'œil—The surrounding country—Taking [Pg xvii]landmarks—Point Victoria | ||

| 217 | ||

| CHAPTER XIX. | ||

| THE KAIMANAWA MOUNTAINS. | ||

| Further plans—Across the plains—In memoriam—The Onetapu Desert—Mamanui camp—Grilled weka—A heavy frost—The Kaimanawas—Geological formation—A probable El Dorado—Reputed existence of gold | ||

| 229 | ||

| CHAPTER XX. | ||

| SECOND ASCENT OF RUAPEHU. SOURCES OF THE WHANGAEHU AND WAIKATO RIVERS. | ||

| Curious parterres—Supposed source of Whangaehu—-A gigantic lava bed—A steep bluff—The Horseshoe Fall—The Bridal Veil Fall—The Twin Falls—A dreary region—Ice caves—Source of the Waikato—The descent—Our camp on the desert | ||

| 237 | ||

| CHAPTER XXI. | ||

| KARIOI. | ||

| Our commissariat gives out—The Murimotu Plains—The settlement—The homestead—The welcome—Society at Karioi—The natives—The Napier mail | ||

| 252 | ||

| CHAPTER XXII. | ||

| FOREST COUNTRY. | ||

| The start from Karioi—On the track—Te Wheu maps the country—The primeval solitude—Terangakaika Forest—The flora—Difficulties of travel—The lakes—Birds—Pakihi—Mangawhero River—Gigantic vines—Fallen trees—Dead forest giants—Mangatotara and Mangatuku Rivers—A "Slough of Despond"—Dismal swamp | ||

| 258 | ||

| CHAPTER XXIII. | ||

| RUAKAKA. | ||

| The wharangi plant—Enormous ravines—Ruakaka—Reception by the Hauhaus—The chief Pareoterangi—The parley—Hinepareoterangi—A repast—Rapid fall of country—The Manganui-a-te-Ao—Shooting the rapids—The natives—Religion—Hauhauism—Te Kooti's lament—A [Pg xviii]Hauhau hymn | ||

| 269 | ||

| CHAPTER XXIV. | ||

| NGATOKORUA PA. | ||

| Departure from Ruakaka—A legend—Rough forest—Crossing the Manganui-a-te-Ao—Scenery of the river—Mount Towai—The plains in sight—Rapid rise in the country—Ruapehu from the west—The Waimarino plains—Arrival at the pa—The chief's family—A Hauhau chief—Inter alia—Pehi on the decay of the Maoris—A war-dance—The mere | ||

| 281 | ||

| CHAPTER XXV. | ||

| HOT SPRINGS OF TONGARIRO. | ||

| Departure from Ngatokorua—Okahakura Plains—Tongariro from the north—Source of the Whanganui—The hot springs—A marvellous sanatorium—Crater of Ketetahi—Te Perore—A strategic position—Kuwharua—Maori cakes—A grand region—Site for a public park | ||

| 295 | ||

| CHAPTER XXVI. | ||

| WESTERN TAUPO. | ||

| Supposed forest country—The western table-land—Soil and flora—Terania—Okarewa—Te Kaina Valley—Maoris on the track—Pouotepiki pa—A tangi—The natives—A friendly invitation—An old warrior—The women—Our quarters | ||

| 304 | ||

| CHAPTER XXVII. | ||

| THE NORTHERN TABLE-LAND. | ||

| The Whanganui stream—Oruapuraho Valley—Waihaha River—Kahakaharoa—The sweetbriar—The kiwi—The moa—A gigantic lizard—Waikomiko and Waihora Rivers—Te Tihoi Plains—Scenery—Mount Titiraupenga—Mangakowiriwiri River—Mangakino River—Swimming horses—Our camp—The Maoris as travellers—A Maori joke—Good horsemen—Their knowledge of the country—Their endurance—The Waipapa—Te Toto Ranges—The Waipari—Te Tauranga—The Upper Puniu—A fine specimen of tattooing—A night [Pg xix]at Hengia | ||

| 315 | ||

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | ||

| THE AUKATI LINE. | ||

| Manga-o-rongo—Mangatutu River—The encampment—A sumptuous repast—The kainga—Surrounding scenery—Old warriors—The tribes—The Korero—Arrival of Te Kooti—His wife—His followers—A tête-à-tête—A song of welcome—A haka—Departure from Manga-o-rongo—Waipa River—Valley of the Waipa—Our last difficulty | ||

| 328 | ||

| APPENDIX. | ||

| Potatau II. | 345 | |

| Major Te Wheoro, M.H.R. | 348 | |

| List of the New Zealand Tribes, with their localities | 351 | |

| The Flora | 352 | |

| The Fauna | 360 | |

| The Maori language | 366 | |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. | ||

| King Tawhiao | Frontispiece | |

| The Maori Queen, Pare Hauraki | 21 | |

| Wahanui, chief of the Ngatimaniapoto tribe | 24 | |

| Manga Rewi, a chief of the Ngatimaniapoto tribe | 25 | |

| Major Te Wheoro, M.H.R. | 28 | |

| Te Tuhi, a chief of the Waikato tribe | 29 | |

| Albino woman | 30 | |

| Whitiora Wirouiru te Komete, a chief of the Waikato tribe | 32 | |

| Paora tu Haere, head chief of the Ngatiwhatua tribe | 34 | |

| Hati Wira Takahi, chief of the Ngapuhi tribe | 37 | |

| Tawhao Ngatuere, a chief of the Ngatikahunu tribe | 38 | |

| A chief of the Ngatiproa tribe | 39 | |

| Paratene te Manu, a chief of the Ngatiwai tribe | 40 | |

| Tukukino, head chief of the Ngatitematera | 42 | |

| Te Raia Ngakutu te Tumuhuia, head chief of the Ngatitematera tribe. Last of the New Zealand Cannibals | [Pg xx]43 | |

| Whakari, or White Island | 48 | |

| The Tuatara | 49 | |

| Native woman and child, Ohinemutu | 58 | |

| Native village (Lake Rotoiti) | 62 | |

| Specimen of Maori carving | 72 | |

| Native woman, Lake Country | 86 | |

| Pohaturoa | 113 | |

| Section of valley of Waikato River at Huka Falls | 126 | |

| Transverse section of North Island from S.W. to N.E. | 140 | |

| Terrace formation and hot springs (Valley of the Waikato) | 146 | |

| Lake Taupo | 150 | |

| Source of the Waikato at Lake Taupo | 153 | |

| Tongariro | 180 | |

| Tongariro by moonlight | 197 | |

| Mount Ruapehu | 200 | |

| Summit of Ruapehu | 204 | |

| Waiting for sunrise | 213 | |

| Wall of lava conglomerate | 219 | |

| The ice crown, Point Victoria | 227 | |

| Great trachytic lava bed | 240 | |

| The Bridal Veil Fall | 245 | |

| Ruakaka | 272 | |

| A chief armed with "mere" and "huata" | 293 | |

| A "mere" | 294 | |

| Native girl | 312 | |

| Moa and apteryx | 317 | |

| Native girl | 330 | |

| Woman of the Waikato tribe | 333 | |

| Te Kooti, from a sketch by the author | 335 | |

| Te Kooti's wife | 336 | |

Geographical description of the King Country—Its political state—Efforts made to open it—Condition of the natives—Origin of the journey—Letter of introduction to the king.

That portion of the North Island of New Zealand known as the King Country extends (as near as the boundary can be defined) from lat. 38° to 39° 20' S., and from long. 174° 20' to 176° E. Its approximate area is equivalent to 10,000 square miles. In the north the aukati, or boundary-line—separating it from the European portion of the colony—passes by the southern shores of Aotea Harbour, thence easterly through the Pirongia Ranges in a direct line to the Waikato River, along which it follows nearly to Atea-amuri, from which point it strikes directly south to Lake Taupo. It takes in the whole of the western half of that lake; it then stretches south along the Kaimanawa Mountains to the Murimotu Plains, whence it goes westerly, round the southern base of Mount Ruapehu to the mouth of the Manganui-a-te-Ao River, and[Pg 2] thence north-westerly until it joins the coast at a point a little to the north of Pukearuhe.

The physical features of this vast region present not only many beauties, but many natural advantages for European settlement, while it is one of the best watered parts of the island. In its southern portion the Whanganui River passes through it in a long winding course to the sea, fed by many tributaries flowing from the high mountain-ranges, both in the south and central divisions of the island. In the west the Mokau River and its affluents flow from its central region to the coast. In the north the Waipa Puniu and various other streams, having their sources in the Titiraupenga and Rangitoto Mountains, wind through it to the Waikato River; the high, wooded ranges of the central table-land form the sources of many watercourses disemboguing into Lake Taupo; while in the south-east the snow-clad heights of Tongariro and Ruapehu pour down their rapid waters in a perfect network of creeks and rivers. In the west it has a coast-line of over sixty miles, and it possesses one of the largest harbours in the island. Extensive forests cover a large portion of its southern area, and extend northerly over the broken ranges of the Tuhua to Mount Titiraupenga and the Rangitoto Mountains. Westward of this division there is a considerable area of open country, including the valley of the Waipa, which in its turn is bounded in the west by high, fern-clad hills and wooded ranges. In the vicinity of the high, snow-clad mountains in the south, there are vast open table-lands; while immediately to the west of Lake Taupo and north of Titiraupenga to the banks[Pg 3] of the Waikato, there are again extensive open plains.

Geologically considered, the King Country possesses in extensive depositions all the strata or rock-formations in which both gold, coal, iron, and other minerals are found to exist, while its extensive forests are rich in timber of the most varied and valuable kind. Geysers and thermal springs possessing wonderful medicinal properties are found in the vicinity of its many extinct craters; and, while it possesses one of the largest active volcanoes in the world, its grand natural features are crowned by the snowy peaks of some of the highest mountains of Australasia. In the north the trachytic cones of Titiraupenga and Pirongia rise to an elevation varying from 3000 to 4000 feet, near to its south-western boundary the snowy peak of Taranaki, or Mount Egmont, attains to an altitude of 8700 feet, on its eastern confines the rugged crater of Tongariro sends forth its clouds of steam from a height exceeding 7000 feet, while on its southern side the colossal form of Mount Ruapehu rears its glacier-crowned summit to an altitude of over 9000 feet above the level of the sea.[1] With these important features nature has endowed it with scenery of the grandest order, and with a climate unsurpassed for its variety and healthfulness.

The political state of the King Country forms one of the most interesting chapters in the history of New[Pg 4] Zealand. In the early days, before the colony was founded in 1840, and long after that event, there were no such obstacles to travelling through the island as existed in later times. The Maoris rather welcomed Europeans, who were free to go anywhere, except on places which were tapu,[2] or sacred in their eyes, and in consequence what little has been hitherto known of the King Country has been derived from the experiences of one or two travellers who penetrated into portions of it some thirty years ago. Among the most active of the early travellers was Ferdinand Von Hochstetter, a member of the Austrian Novara Expedition, who, in 1859, at the instance of Sir George Grey, at that time Governor of the Cape of Good Hope, made a tour through a portion of the North Island in company with Drummond Hay, Koch, Bruno, Hamel, and a number of European attendants and natives. At this time the Maoris were ready to welcome Europeans; hostilities between the two races had never broken out, and Hochstetter and his party were received and fêted everywhere with almost regal honours. But in the course of years, as it was evident to the natives that the Europeans were the coming power in the land, suspicion and distrust were excited, and at last the tocsin sounded.

The native chiefs, seeing that their influence was declining, and that in proportion to the alienation of the land, their mana or authority over the tribes decreased, began to bestir themselves in earnest. It was considered that a head was needed to initiate a form of Government among the tribes to resist the encroachments daily made by the[Pg 5] Europeans, and which seemed to threaten the national extinction of the native race.

The first to endeavour to bring about a new order of things was a native chief named Matene Te Whiwi, of Otaki. In 1853 he marched to Taupo and Rotorua, accompanied by a number of followers, to obtain the consent of the different tribes to the election of a king over the central parts of the island, which were still exclusively Maori territory, and to organize a form of government to protect the interests of the native race. Matene, however, met with but little success. Te Heuheu, of Taupo, the great chief of the Ngatituwharetoa, at that time the most warlike tribe in the island, had no idea of any one being higher than himself, and therefore refused to have anything to do with the new movement, nor did Te Whiwi meet with much greater encouragement at Maketu and Rotorua. The agitation, however, did not stop, the fire once kindled rapidly spread, ardent followers of the new idea sprang up, and their numbers soon increased, until finally, in 1854, a tribal gathering was convened at Manawapou, in the country of the Ngatiruanui tribe. Here a large runanga, or council-house, was erected, which was called Tai poro he nui, or the finishing of t[Pg 6]he matter, and after many points had been discussed, a resolution was come to among the assembled tribes that no more land should be sold to Europeans. A solemn league was entered into by all present for the preservation of the native territory, and a tomahawk was passed round as a pledge that all would agree to put the individual to death who should break it. In 1854 another bold stand was made, and Te Heuheu, who exercised a powerful sway over the tribes of the interior, summoned a native council at Taupo, when the King movement began in earnest. It was there decided that the sacred mountain of Tongariro should be the centre of a district in which no land was to be sold to the government, and that the districts of Hauraki, Waikato, Kawhia, Mokau, Taranaki, Whanganui, Rangitikei, and Titiokura should form the outlying portions of the boundary; that no roads should be made by the Europeans within the area, and that a king should be elected to reign over the Maoris.

In 1857 Kingite meetings were held at Paetai, in Waikato, and at Ihumatao and Manukau, at which it was agreed that Potatau Te Wherowhero, the most powerful chief of Waikato, should be elected king, under the title of Potatau the First, and finally, in June, 1858, his flag was formally hoisted at Ngaruawahia. Potatau, who was far advanced in life when raised to this high office, soon departed from the scene, and was succeeded by his son Matutaera Te Wherowhero, under the title of Potatau the Second.

The events of the New Zealand war need not here be recited, but it may be easily imagined that during the continuance of the fighting the extensive are[Pg 7]a of country ruled over by the Maori monarch was kept clear of Europeans. But in 1863 and 1864 General Cameron, at the head of about 20,000 troops, composed of Imperial and Colonial forces, invaded the Waikato district, and drove the natives southward and westward, till his advanced corps were at Alexandra and Cambridge. Then followed the Waikato confiscation of Maori lands and the military settlements. The King territory was further broken into by the confiscations at Taranaki and the East Coast, but no advance was, however, made, by war or confiscation, into the country which formed the subject of my explorations. The active volcano of Tongariro is tapu, or strictly sacred, in the eyes of the Maoris, and several persons who had attempted to ascend it were plundered by the natives, and sent back across the frontier. On the west of Taupo Lake lies the Tuhua country, whose people had from the first, from the nature of the district, been much secluded from European intercourse, and who besides had given refuge to many of the desperadoes of the other tribes; while to the south-west of Taupo Lake were the people of the Upper Whanganui country, who have always been suspicious and hostile, while for some considerable time, too, the whole district was in terror of Te Kooti and his marauding bands. It is from these causes that the vast and important area embraced by the King Country has remained closed to Europeans, and, all things considered, it is a fact which must ever remain one of the most singular anomalies of British colonization, that, after a nominal sovereignty of forty years over New Zealand, this portion of the colony should have remained a terra incognita up to [Pg 8]the present day, by reason of the hostility and isolation of the native race.

Having pointed out the leading causes which resulted in the closing of the King Country to European settlement, it will be interesting to glance at the endeavours which have been made by the different governments to break down the barrier of native isolation, and thus to throw open to the colonists an extensive area of the island, which is, in reality, as much a portion of British territory as is the principality of Wales. As is well known, since the termination of the lamentable war between the two races, the King natives have, on all occasions, jealously preserved their hostile spirit to Europeans; while the peculiar state of matters involved in the whole question, while unexampled in the history of any other part of the British Empire, has been naturally a source of annoyance and even danger to the several governments of the colony who have attempted from time to time to grapple with the native difficulty.

The New Zealand war concluded, or rather died out, in 1865, when the confiscated line was drawn, the military settlements formed, and the King natives isolated themselves from the Europeans. For ten years it may be said that no attempt was made to negotiate with them. They were not in a humour to be dealt with. About 1874 and 1875, however, it became evident that something would have to be done. The colony had greatly advanced in population, and a system of public works had been inaugurated, which made it intolerable that large centres of population should be cut off from each other by vast spaces of country which Europeans were not allowed even to traverse. From time to time during the whole period the awkward position of affairs had been forced on public attention by outrages and breaches of the law occurring on the border, the perpetrators of which took secure refuge by fleeing to the protection of Tawhiao, who then—as now—defied the Queen's authority within his dominions.[Pg 9]

Sir Donald McLean, while Native Minister, had several important interviews with the Kingites, with a view to bring about a better relationship between the two races, and as he was well known to the natives both before and during his term of office, his efforts had considerable effect in promoting a more friendly intercourse.

Again, Sir George Grey, when Premier of the Colony, attended two large native meetings in the King Country, in 1878, and opened up communication with the chiefs of the Kingites. At the second meeting at Hikurangi about seventeen miles beyond Alexandra, Sir George Grey laid before the natives definite terms of accommodation. He offered to give back to them the whole of the land on the west bank of the Waipa and Waikato rivers, and to confer certain honours on Tawhiao, the son of Te Wherowhero, who had succeeded to the kingship. At a subsequent meeting held at Te Kopua, in April, 1879, these offers were again made, but Tawhiao, for some reason which has never been satisfactorily explained, declined to accept them, and they were distinctly withdrawn.

With the advent of the Whitaker ministry into power, it was felt that another attempt should be made to deal with the Maori king, and accordingly, during the session of 1882, acts were carefully framed so as to facilitate the object. A Native Reserves Act was passed, under which natives could have placed any blocks of land they chose under a board which would have administered the property for the benefit of the owners.[Pg 10] An Amnesty Act was also put on the statute-book, under which the government could have issued pardons to those natives who had committed crimes and taken refuge among the Kingites. The most sanguine hopes were entertained that this difficulty would at last be settled, and in a way which would be satisfactory for both peoples. The terms which Mr. Bryce, as Native Minister, laid before Tawhiao and his people at the Kingite meeting, held at Whatiwhatihoe in October of the same year, were so liberal as to surprise the whole country. A large tract of the confiscated land on the west bank of the rivers Waipa and Waikato was offered to be restored, while Tawhiao was to be secured in all the lands which he could claim in the King Country, and the government were to endeavour to procure for him and his people a block of land from the Ngatimaniapoto tribe, the most extensive landowners in his dominions. Altogether the amount of land to be restored amounted to many thousands of acres, most of it fertile and well suited for the purposes of the natives, or that section of them known as the Waikatos, of whom Tawhiao was the hereditary chief.

What the government proposed to do was that the king's mana, or sovereign authority, should be removed by the best means, and that in doing so the utmost care should be taken that all of the natives of the king's tribe should be provided for. This step was the more necessary from the fact that Tawhiao, although the acknowledged head of the Maori race, and exercising a supreme authority over the King Country,[Pg 11] was, owing to the confiscation of his tribal lands which had taken place after the war, a comparatively landless monarch.

At the Kingite gathering at Whatiwhatihoe, Tawhiao, in view of the proposals made, was willing to take back the land, but objected to receive a salary from the government, to be called to the legislative council, or to be made a magistrate.[3] He, and those around him, saw that to have accepted these terms would have been equivalent to saying that he abdicated his position as king. That being, from the Native Minister's point of view, the all-important matter, the negotiations could go no further, and the memorable meeting at Whatiwhatihoe broke up with Tawhiao still reigning as absolute monarch over one of the most extensive and fertile portions of New Zealand.

With my reference to the geographical, historical, and political features of the King Country, I will here allude briefly to the physical and social position of the native race as I found it during my travels through that portion of the island where the inhabitants dwell in all their primitive simplicity.

There can be no doubt whatever that the Maori race is greatly on the decrease,[4] and that the three principal diseases conducing to this result are phthisis, chronic asthma, and scrofula; the two first principally brought about, I believe, by a half-savage, half-civilized mode of life, and the latter from maladies contracted since the first[Pg 12] contact of the people with Europeans. It is, however, clear that there is a large number of natives yet distributed throughout the King Country, and among them are still to be found, as of old, some of the finest specimens of the human race. A change of life, however, in every way different from that followed by their forefathers, has brought about a considerable alteration for the worse among the rising population, and, although during my journey I met and conversed with many tattooed warriors of the old school, and who were invariably both physically and intellectually superior to the younger natives, it was clear that this splendid type of savage would soon become a matter of the past.

I found the natives living much in their primitive style, one of the most pernicious innovations, however, of modern civilization amongst them being an immoderate use of tobacco among both old and young. Although most of the native women were strong and well-proportioned in stature, and apparently robust and healthy, there appeared to be a marked falling off in the physical development of the younger men, when compared with the stalwart, muscular proportions of many of the older natives—a result which may, no doubt, be accounted for by their irregular mode of life when compared with that usually followed by their forefathers, combined with the vices of civilization, to which many of them are gradually falling a prey. It is a notable fact, which strikes the observer at once, that many of the old chiefs and elders of the various tribes, with their well-defined, tattooed features and splendid physique, have the stamp of the "noble savage" in all his[Pg 13] manliness depicted in every line of their body, while many of them preserve that calm, dignified air characteristic of primitive races in all parts of the world before they begin to be improved off the face of the earth by raw rum and European progress. On the other hand, the rising generation has altogether a weaklier appearance, and, although I noticed many buxom lasses with healthy countenances and well-developed forms, not a few of the younger men were slight of build, with a thoughtful, haggard, and in many instances consumptive look about them.

In both their ideas and mode of life they appeared to cling to their old customs tenaciously, and seemed to know little of what was going on in the world beyond their own country, while their religion, what little they possessed, evidently existed in a kind of blind belief in a species of Hauhauism, in which biblical truths and native superstition were curiously mixed. In matters of politics affecting their own territory they invariably expressed a desire that matters might remain as they were, and that they might be allowed to live out their allotted term in their own lands. From one end of the country to the other they seemed to entertain an almost fanatical faith in the power of Tawhiao, and they appeared to regard his influence in the light of our own legal fiction, "that the king could do no wrong."

When I undertook to explore the King Country—being at the time only a new arrival in the colony—I found that it was a part of the British Empire of which I knew very little. I soon, however, learned that the extensive region ruled over by the Maori king was,[Pg 14] to all intents and purposes, an imperium in imperio, situated in the heart of an important British colony, a terra incognita, inhabited exclusively by a warlike race of savages, ruled over by an absolute monarch, who defied our laws, ignored our institutions, and in whose territory the rebel, the murderer, and the outcast took refuge with impunity. This fine country, embracing nearly one half of the most fertile portion of the North Island, as before pointed out, was as strictly tabooed to the European as a Mohammedan mosque, and all who had hitherto attempted to make even short journeys into it had been ruthlessly plundered by the natives, and sent back across the frontier, stripped even of their clothes.

At this time—in the early part of the year 1882—Te Wetere, Purukutu, Nuku Whenua, and Winiata, all implicated in the cruel murders of Europeans, were still at large, bands of native fanatics, excited to the point of rebellion against the whites, were massing themselves together in large numbers at Parihaka, and singing pæans to the pseudo-prophet, Te Whiti, who had for some time been inciting his followers to resist any attempt at incursion into their territory on the part of the European colonists who had acquired land and built settlements near the frontier. Thus it was that wars and rumours of wars were fast gathering around what was generally alluded to as the vexed Maori Question, while, to make matters still more unsatisfactory, it was known that the rebel Te Kooti, who had carried out the Poverty Bay massacre, after his marvellous escape from the Chatham Islands,[Pg 15] and who had more than once played the part of a New Zealand Napoleon during the war, was hiding, with a price set on his head, in his stronghold in the Kuiti, ready, it was believed, to take up arms at any moment. This was the state of the country which I then and there volunteered to explore.

The next point to consider was how the journey could be best set about. The matter was laid before Sir George Grey during the session of Parliament of 1882, and he, with a characteristic desire to advance an undertaking calculated to promote the interests of the colony, wrote a letter of introduction in my behalf to King Tawhiao, asking him to grant me his mana, or authority, to travel through the Maori territory. The letter was presented at a moment when the native mind was much disturbed in connection with the political relationship existing between the Kingites and the Europeans, and just at the time when the meeting at Whatiwhatihoe, before referred to, was about to be held between the Native Minister and Tawhiao, with a view to the opening of the country to settlement and trade. It is only right to state that the king received me on this occasion with every token of good feeling, and spoke, as indeed did all the natives, in the highest terms of Sir George Grey; but he advised me, as the native tribes were much disturbed in connection with the question about to be discussed between the Maoris and Europeans, not to set out on my journey until the meeting should be over.

Leaving Whatiwhatihoe before the termination of the gathering, I made no further appeal to Tawhiao, who subsequently left for an extended tour through the island.[Pg 16] The assemblage of the tribes broke up, as before shown, without any solution being arrived at with regard to the settlement of the native difficulty, and the question of the exploration of the King Country lay in abeyance for a few months, but the idea was always firmly fixed in my mind, although it was not until the 8th of March, 1883, that I left Auckland, en route for Tauranga, to explore the wonders of the forbidden land at my own risk.

[1] For the altitudes of the various mountains, see map.

[2] The word tapu is applied to all places held sacred by the Maoris; it is synonymous with the taboo of the South Sea Islanders. To interfere with anything to which the tapu has been extended is considered an act of sacrilege.

[3] A justice of the peace.

[4] In Cook's time the whole native population was estimated as exceeding 100,000; in 1859 it only amounted to 56,000, of this number 53,000 fell to the North Island, and only 2283 to the Middle Island; in 1881 the number had decreased to 44,099, of which 24,370 were males, and 19,729 females.

THE FRONTIER OF THE KING COUNTRY.

THE KING'S CAMP.[Pg 17]

Alexandra—Crossing the frontier—Whatiwhatihoe—The camp—King Tawhiao—The chiefs—"Taihoa."

Alexandra, the principal European settlement on the northern frontier of the King Country, lies about one hundred miles distant from Auckland, and a little less than eight miles to the west of the Te Awamutu terminus of the southern line of railway.

I reached Alexandra along a delightful road lined with the hawthorn and sweetbriar, and through a picturesque country, where quiet homesteads, surrounded by green meadows filled with sleek cattle and fat sheep, imparted to the aspect of nature an air of contentment and quiet repose. Indeed, when doing this journey in a light buggy drawn by a pair of fast horses, it seemed difficult to realize the fact that I was fast approaching the border-line of European settlement, and that a few minutes more would land me on the frontier of a vast territory which formed the last home of perhaps the boldest and most intelligent race of savages the world had ever seen. In fact, when approaching Alexandra from the Te Awamutu road,[Pg 18] with its neat white houses, embowered amidst gardens and groves of trees, and with its church-spire pointing towards heaven, I seemed to be entering a quiet English village; and had it not been that the eye fell now and again upon a dark, statuesque figure, wrapped in a blanket, and with a touch of the "noble savage" about it, it would have been somewhat difficult to dispel the pleasant illusion.

The township was not large, and a school-house, two hotels, several stores, a public hall, commodious constabulary barracks surrounded by a redoubt, a postal and telegraph station, a blacksmith's forge, and about fifty houses, built for the most part of wood, formed its principal features of Anglo-Saxon civilization.

On the day following my arrival at Alexandra I left, in company with a native interpreter, for Whatiwhatihoe, to present my credentials to the Maori king. Our ride across the frontier into Maoriland was a most delightful one. The steep, wooded heights of Mount Pirongia had cast off their curtain of mist, and stood revealed in their brightest hues; while the green, rolling hills at its base formed a pleasant contrast with the more sombre, fern-clad banks of the Waipa River, as it wound its devious course from the direction of Mount Kakepuku, which rose above the plain beyond in the form of a gigantic cone. The country for miles around lay stretched before the gaze, forming a varied picture of delightful scenery, and all nature appeared budding into life; while the prickly gorse, with its golden-yellow flowers, encircled Whatiwhatihoe like a chevaux de frise. The primitive whares[Pg 19][5] of the natives imparted a rustic appearance to the scene, as they stood scattered about the country to the south, while, as the eye wandered in the direction of the north, the white homesteads of the settlers served to mark the aukati[6]—frontier-line—separating the King Country from the territory of the pakeha.[7]

The king's settlement of Whatiwhatihoe was situated on the west or opposite bank of the Waipa from Alexandra, and on a broad alluvial plain running along the base of a range of fern-clad hills. As a rule the whares were built entirely of raupo,[8] and were scattered about the flat and on the low hills in its vicinity without any regard to regularity, and while some had a neat and even a clean look, others were less attractive both in their designs and general surroundings. They were mostly oblong in shape, with slanting roofs, which projected a few feet at one end of the building in the form of a recess, where the entrance, consisting of a low narrow doorway, was placed. Windows, in the form of small square apertures, were the exception and not the rule, and consequently the interior of these primitive domiciles was badly ventilated. A few blankets and native mats formed the principal articles of furniture, save where the owner, profiting by the advance of civilization, had gone in for articles de vertu on which the "Brummagem" hall-mark might be distinctly traced.[Pg 20]

As we approached the camp the whole place presented a very animated appearance; horsemen were riding about in every direction; long cavalcades of natives, men, women, and children, were arriving from all parts of the country, to take part in the korero[9] to be held on the morrow; while many old tattooed savages, swathed in blankets, and plumed with huia feathers to denote their chieftainship, were squatting about, puffing at short pipes with a stolid air, as they listened in mute attention to one of their number as, gesticulating wildly, and walking to and fro between two upright poles set a few paces apart, he delivered a fiery harangue upon the momentous question of throwing open their country to the advancing tide of civilization. Bevies of women and girls were busily engaged in preparing for the coming feast, and troops of children played and fought with countless pigs and innumerable mongrel dogs.

While pushing our way among the assembled crowds we were met by the king's henchman, a half-caste of herculean proportions, who conducted us to the whare runanga, or meeting-house, an oblong structure about eighty feet long by forty broad, solidly built out of a framework of wood, and thatched with raupo. It was capable of holding a large number of people, and the white rush mats covering the floor gave it a clean and comfortable appearance.

In the centre of this spacious hall sat the king flanked by his four wives, the principal and most attractive of whom was Pare Hauraki,[Pg 21] a fine buxom woman with oval features and artistically tattooed lips, habited in native costume, with a korowhai, or cape, bound with kiwi feathers, thrown carelessly across her shoulders, over which her dark raven hair fell in thick, waving clusters. A number of chiefs of the various tribes assembled, squatted in a semicircle in front of the king, who rose from his seat—a rush mat—as I approached, and motioned for me to be seated in front of him.

THE MAORI QUEEN PARE HAURAKI.

Tawhiao was habited in European attire, consisting of a pair of dark trousers, patent leather boots, and a grey frock-coat trimmed with red braiding about the sleeves, and which at the first glance reminded me of the redingote gris affected by Napoleon I., [Pg 22]and which obtained for him the sobriquet of the "little corporal." A black huia feather tipped with white adorned his hair, and in his left ear he wore a large piece of roughly polished greenstone,[10] and in his right a shark's tooth. In stature he was a little below the medium height, sparely made, but keenly knit, with a round, well-formed head; while his features, which were elaborately tattooed in a complete network of blue curved lines, were well defined in the true Maori mould; and although he had a cast in the left eye, his countenance was pleasant, and as he spoke in a slow deliberate way, he invariably displayed in his conversation a good deal of cool, calculating shrewdness.

Among the principal rangatiras, or chiefs, present were Tu Tawhiao, the king's son, Major Te Wheoro, Manga Rewi, Te Tuhi, Te Ngakau, Wahanui, Whitiora, Hone Te Wetere, and Hone Te One. Tu Tawhiao was a tall, slim youth, with a thin, sleek face and dark moustache, and with a meek expression of countenance. He affected European costume, and had none of the strong Maori type of feature so characteristic of his father. He did not appear to be a very gifted youth, but he had a pleasing manner, and might be considered as a fair type of the anglicized Maori. Major Te Wheoro was a short, thick-set man, with heavy features and a somewhat shrewd look. He ranged himself on the[Pg 23] European side during the war, when he gained his commission, and at the time of which I write he was one of the four Maori members of the House of Representatives. Manga Rewi, like Tawhiao, was a Maori of the old school, and with all the physical characteristics of the race about him. His chief influence appeared to arise from the fact that during the war he was one of the principal Kingite leaders. Te Ngakau was remarkably thick-set and muscular, with a firm-looking yet intelligent face. He was dressed half as a Maori and half as a European, and was remarkable for nothing so much as for the enormous development of the calves of his legs. Whitiora was an antiquated, tattooed warrior, who during the war had won his laurels when gallantly defending the Rangiriri Pa against the Imperial forces, while Hone Te Wetere was known to fame in a somewhat doubtful way in connection with the White Cliffs massacre.

The most notable, however, of all the chiefs present was undoubtedly Wahanui, of the Ngatimaniapoto tribe. Standing over six feet, and of enormous build, he had a peculiar air about him which seemed to mark him as one born to command. His features, slightly tattooed about the mouth—which was singularly large—bore a remarkable appearance of intelligence, while his head, covered with thick white hair, was round and massively formed. He impressed me very favourably during the interview, and when speaking, as he did at some length upon the political condition of the King Country, he seemed to possess not only a great power of language, but a singularly persuasive manner which was at once both courteous and dignified.[Pg 24] He appeared to exercise a weighty influence over the king, and to act in all matters as the "power behind the throne," but he had evidently a conservative turn of mind, and had he been born in England, I think he would have developed into a nobleman of very pronounced Tory principles.

WAHANUI.

(Chief of the Ngatimaniapoto Tribe.)

When the king had learned the object of my mission, and that I had come to obtain his authority to explore the Maori territory, he was careful to inquire what other countries I had visited, and whether I had before travelled in other parts of the world with no other view than to see mountains, rivers, and plains. [Pg 25]"The Maori," he remarked, "never undergoes fatigue for such a purpose as that, but I know," he continued, with a slight touch of naïveté, "the pakeha is different to the Maori, he has the 'earth hunger,' and likes to see new places. If you wish to go into the country, you may do so when the meeting is over, but it is not good that you should go until the Maori has spoken with the pakeha at the korero, therefore I say wait, 'taihoa.'"

MANGA REWI.

(A Chief of the Ngatimaniapoto Tribe.)

The latter word sounded somewhat unpleasant to my ears, as I knew with[Pg 26] the Maoris it was their gospel, and was synonymous with the Spanish proverb, "Never do to-day what may be done to-morrow." I took the king at his word, but before I left his presence I mentally recorded a vow that, if I could not get into the King Country at the north, I would get into it at the south, which I eventually did a few months afterwards, as the sequel of this narrative will show.

[5] Whare is the native name for a house or hut.

[6] The aukati signifies the boundary of a tapued or sacred district.

[7] Pakeha is a term used by the Maoris to designate Europeans; it means a stranger, or a person from a distant country.

[8] For a synopsis of the principal flora met with during the journey, see Appendix.

[9] The word korero (to speak) is here applied as a general term to the meeting.

[10] The pounamu, or greenstone (nephrite), a species of jade, is much prized by the Maoris as an ornament, either for the neck or ears. It is only found on the west coast of the Middle Island, the native name for which is Wahipounamu, or Land of the Greenstone.

THE KORERO.[Pg 27]

The Kingites—Half-castes—An albino—The King's speech—Maori oratory—The feast.

On the morrow after my interview with the king the meeting between the Native Minister and Tawhiao, with a view to bring about more friendly relations between the two races, was arranged to take place.

At the time fixed for the korero the Kingites, headed by their chiefs, assembled on the flat within the settlement. They squatted about in attractive groups, and the entire assembly formed a compact semicircle composed of men, women, and children of all ages; while the bright and almost dazzling colours of their varied, and, in many instances, eccentric costumes formed an interesting picture, in which were blended the most singular and striking contrasts. Some of the men were habited entirely in European attire, others affected more becoming native costumes, and had their heads decked with feathers, while not a few were got up in a style which seemed to indicate that they were undergoing what might be considered, from a Darwinian point of view, the "transition period" between savage and civilized life. The women, of whom there were many, had donned their holiday finery, and although their flowing skirts were evidently not designed after the most fashionable model, thi[Pg 28]s defect was made up in no small degree by the glowing effects of the bright colours of the variegated material out of which they were made. Crimson, yellow, and blue were the prevailing tints, and one by no means unattractive damsel had her lithe form swathed in a shawl on which were depicted all the various designs of a pack of cards.

MAJOR TE WHEORO, M.H.R.

There were many half-castes of both sexes among the throng, and the strain of European blood, which in most cases might be distinctly traced, had evidently, by one of those singular processes of nature which it[Pg 29] is difficult to understand, aided to produce in them here, as elsewhere, a robust and healthy race of people. Many of the girls of this class, with their swarthy complexions and well-rounded limbs, were very comely-looking, and one young lady, habited in a well-fitting purple silk dress, and with a very handsome native shawl of many colours thrown artistically across her gracefully formed shoulders, attracted the admiring glances of all present. She spoke English fluently, and with her fascinating air, dark eyes, and r[Pg 30]emarkable Spanish cast of countenance, she appeared more suited to grace the Prado of Madrid than the primitive marae[11] of Whatiwhatihoe. In singular contrast to this attractive daughter of the King Country was an albino woman, with light flaxen hair, pink eyes, and a complexion which, if it had been washed, might have rivalled the snowy whiteness of alabaster. Her lips were marked in the ordinary Maori fashion, and, so far as her outward appearance went, she was stout and well-built, and appeared to be as fine a specimen of her kind as I had seen in any part of the world.

TE TUHI.

(A Chief of the Waikato Tribe.)

[Pg 31]When Tawhiao appeared in the midst of his people, he had cast aside his European costume, and had swathed himself after the native fashion in a white blanket, with broad pink stripes upon it. At the moment of the arrival of the Native Minister the king was seated by the side of his wife Pare Hauraki, and in the centre of the semicircle formed by the Waikato chiefs and other natives, and as Mr. Bryce drew near he raised himself from the ground and approached to welcome him. As soon as the friendly greetings were over, the Native Minister and the king seated themselves upon the ground face to face, and, having regarded each other for some time with an air of mutual satisfaction, Tawhiao arose, and, resuming his original position in the midst of the natives, arranged his blanket in toga fashion across his breast, and raising his bare right arm, began his speech in slow, but well-delivered tones, and with the calm, confident air of one who had been accustomed to sway the multitude and to speak, as he expressed it in the figurative language of his race, "straight from his breast." His short harangue, however, was carefully framed with all the customary art of Maori diplomacy, and with a view to show that the occasion was simply one for the mutual expression of goodwill on both sides. Not the faintest reference at this time was made to his future line of policy, nor was there a single hint to indicate that any new departure was about to be initiated calculated to alter the political relationship existing between the Maori and Pakeha. It was in every sense a carefully worded discourse, and proved[Pg 32] beyond a doubt that the trite saying of Voltaire, that language was invented to disguise our thoughts, was equally appreciated by savage as by civilized races.

ALBINO WOMAN, KING COUNTRY.

Tawhiao's speech, however, when finally declining the proposals of the Native Minister, when, in face of all the inducements held out to him, he stoutly refused to resign his mana, or sovereign authority, is worthy a place here, not only as an interesting example of the Maori style of oratory, but likewise as a touching proof of the deep-rooted desire of the old king to remain at the head of his decaying race.

WHITIORA WIROUIRU TE KOMETE.

(A Chief of the Waikato Tribe.)

[Pg 33]Tawhiao, who spoke with evident emotion on this occasion, said: "My word is, do not speak at all; only listen" (addressed to his people). "The best way of speaking is to listen. If this European" (the Native Minister) "rises, the best thing to do is to listen. This is my word, hearken you" (to Mr. Bryce). "I approve of you administering affairs on that side—the European side. But my word is, I will jump on that side, and stand. I have nothing to say. My only reason for going on that side is to hear—to listen, so that I may know. I say I will remain in the positions of my ancestors and my parents in this island of Aotearoa.[12] I will remain here; and as for my proceedings, let me proceed along my own line. I have nothing to say; I have only to listen, so that I may know. After I have listened I will come back to this side of our line.[13] Say what you have to say. That is my thought, that I will remain here, in the place where my ancestors and fathers trod; but if I had trodden anywhere else, then I could be spoken to about it. I still adhere to the word that existed from the commencement. The queen was not divided; her rule has been obeyed. Now, say what you have to say. With me there is no trouble or darkness. What I have said to you is good; it has been said in the daylight, while the sun is shining. I do not mind falling, if only I do not fall as my cloak would fall. I can traverse all the words. This is another word of mine. I am teaching; I will remain here. You can remain on your side and[Pg 34] administer affairs, and I will remain on my side. Let me be here, on this side of our own line. Speak while the sun is shining. It has been said for a long time that the Europeans are against me. My reply to that is, that the pakeha is with me. But let me remain here at Aotearoa. I will direct my people this very day as we sit here. I will not go off in any new direction, but will be as my ancestors were."

PAORA TU HAERE.

(Head Chief of the Ngati Whatua Tribe.)

After the Native Minister had replied to the king's speech, the present of provisions given by the government, consisting of beef, flour, sugar, and biscuits, was hauled [Pg 35]to the front in bullock drays, and, after being piled into a heap, Major Te Wheoro stepped forward and acknowledged the donation on the part of the natives. When this ceremony was concluded, loud shouts of joyful voices were heard in the distance, and from each side of the marae two separate bands of about 200 women and girls came dancing along in variegated costumes, with small baskets in their hands made of plaited flax, and filled with cooked potatoes, roasted pork, and fish. They rounded up in front of the meeting with a measured step, between a skip and a hop, and when they had deposited their burdens in a heap, and grinned immensely, as if to show their white teeth, half a dozen stalwart men came forward with roasted pigs cut in twain, or rather amputated down the centre of the spine. When these sweet luxuries had swelled the dimensions of the kai,[14] Te Ngakau stepped forward, and, taking up a pronged stick, or roasting-fork, formally presented this token of hospitality to the government, which in its turn, according to custom, and to avoid the incubus of a "white elephant," returned it with thanks to the natives.

Feasting then became the order of the day, and joining the king's circle, we partook of the kindly fruits of the earth with unalloyed satisfaction; and as table requisites were not plentiful, we dispensed with those baubles of modern progress, and ate after the primitive mode of our forefathers.

[11] Marae, an open space in front of a native settlement.

[12] Aotearoa is the ancient native name for the North Island; it is equivalent to "land of bright sunlight."

[13] Meaning the Aukati or boundary-line separating the King Country from the European portion of the colony.

[14] Kai, Maori word for food.

ASCENT OF PIRONGIA.[Pg 36]

Mount Pirongia—Geological features—The ascent—A fair prospect.

HATI WIRA TAKAHI.

(Chief of the Ngapuhi Tribe.)

The steep, rugged heights of Mount Pirongia are at all times an attractive feature in the splendid landscape which stretches along the course of the Waikato River and thence through the valley of the Waipa to the very borders of the King Country. Rising to a height of 3146 feet above the level of the sea, the conical peaks of this grand mountain stand boldly out against the sky as they change and shift, as it were, with magical effect, when viewed from different points of vantage, now assuming the form of gigantic pyramids, now swelling into dome-shaped masses connected by long, sweeping ridges which lose themselves in deep ravines, and rolling slopes whose precipitous sides sometimes end in steep precipices, or open out into broad valleys covered from base to summit by a thick mantle of vegetation. When beheld from a distance, Pirongia appears to have been moulded by the hand of nature into the most subdued and graceful proportions, over which are constantly playing the most enchanting effects of light and shade, and it is not until one stands at the base of this stupendous mountain of[Pg 37] eruptive rock that one fully realizes the bold features of its rugged outline, as one contemplates in wonder the work of those terrific subterranean forces which, at some period or another, caused this volcanic giant to rear its rugged head above the surrounding plains. Beneath the bright morning light, or when evening spreads its mellow tints over the heavens, the mountain is seen to its best advantage; but when the heavily laden clouds from the west sweep in from the sea, they gather round the lofty summit of Pirongia in a thick pall of vapoury mist, and then, bursting into a flood of rain, roll down its steep sides to swell the current of the Waipa.

TAWHAO NGATUERE.

(A Chief of the Ngatikahunu Tribe.)

[Pg 38]When viewed from a geological point of view, Pirongia formed evidently at some remote period of its history the centre of an extended volcanic action to which the extensive ranges stretching from this point in many ramifications to the west coast, and thence in the direction of Whaingaroa harbour in the north and Kawhia harbour in the south, owe their origin. When standing upon the summit of the mountain, it may be plainly seen that the Pirongia ranges diverge in all directions from a common centre, formed by the most elevated portion of the volcanic cone which constitutes the highest point of the mounta[Pg 39]in chain. For a considerable distance to the north and south, and as far west as the coast, this mountainous system extends in an almost continuous line, and assumes an elevation which varies from nearly 2000 to 3000 feet above the level of the sea, but it gradually diminishes in altitude towards the east, in the form of low hills and undulating slopes which finally merge into the broad plains which mark the upper and lower valleys of the Waipa. Throughout these extensive ranges there is little or no open[Pg 40] country, but mountain top after mountain top, ridge after ridge, ravine after ravine, stretch away as far as the eye can reach in a confused rugged mass covered with a dense and almost impenetrable vegetation. The summit or highest point of Pirongia, which assumes the form of a large oval-shaped, though now much broken, crater, was evidently the central point of eruption of the volcanic forces which caused the various higher ranges and lower hills to radiate from this point and assume their serrated and disjointed form, and it is here, as well as in the numerous gullies and ravines which spring from it, that the geological features of the various rocks may be more distinctly traced. As in all formations of the kind in its vicinity, the igneous rocks predominate, and of these trachyte is the most common; huge masses of this rock cropping[Pg 41] up everywhere above the surface of the mountain. Scoria, obsidian, pumice, and other volcanic rocks likewise occur, their gradual decomposition serving to form a dark rich soil, which covers the sides of the mountain and gives life to its splendid vegetation.

A CHIEF OF THE NGATIPROA TRIBE.

When I made the ascent of Pirongia it was in the pleasant company of Mr. F.J. Moss, Member of the House of Representatives. The country around the eastern base of the mountain was composed of a series of low, fern-clad hills, intersected by small swamps and watercourses fed principally from the mountain springs.

PARATENE TE MANU.

(A Chief of the Ngatiwai Tribe.)

The moment we left the fern hills and entered the forest all the varied beauties of its rich growth burst upon the view. The steep ascent of the mountain began almost at once, and our path lay along the precipitous ridges which sweep down on every side from its summit, clothed with a thick growth of enormous trees, and rich in all the wondrous creations of a primeval vegetation. Among the many giants of the vegetable world was the rata, which, clothed with its curious growth of parasitical plants, towered high above its compeers of the forest. Many of these trees were of enormous size, especially when they grew in the low, damp gullies, where they attained to a height of considerably over a hundred feet, with a girth of from thirty to forty feet at their base. A few of these giants were scattered about the high ridges, but they appeared to thrive best, and to attain their greatest girth, near the low, damp beds of the small watercourses, which, bursting from the adamantine sides of[Pg 42] the mountain, and leaping along their rocky course, formed the only music that enlivened these bush-bound solitudes.

TUKUKINO.

(Head Chief of the Ngatitematera.)

When we reached the summit of the mountain, we emerged from the thick forest on to an open spot which commanded a delightful prospect. Turning[Pg 43] towards the west, we stood on the brink of a precipice which fell in a clear descent of 1000 feet into the ravine below; here and there a jutting mass of rock stood out in rugged grandeur from the adamantine wall of stone, but otherwise a thick growth of matted scrub covered the sides and bottom of this enormous fissure, and so dense and entangled was the vegetation as we looked down upon it, that it appeared quite possible to walk upon the tops of the trees without falling to the ground. Far beyond this, mountain after mountain rolled away in the distance, until the eye rested on the grand expanse of Kawhia Harbour, dotted with its broad inlets and numerous headlands, which rose in picturesque beauty above the deep-blue outline of the distant sea. North-westerly from this point the bright waters of Aotea Harbour lay embosome[Pg 44]d in a semicircle of hills, and, beyond again, Mount Karioi rose from the borders of the ocean to an altitude of 2300 feet. East and south of this the Whanga Ranges bounded the horizon, and right opposite to Pirongia the bold peaks of Maungakawa and Maungatautari rose into view. Between this wide area there were lower hills which radiated from the mountain ranges, but it could be plainly seen that the greater portion of the country was formed of level plains dotted here and there with small lakes and extensive swamps, through which the Waikato and the Waipa, with their numerous tributaries, could be traced as they wound for miles away in the distance. Here and there upon the cultivated flats the white houses of the settlers, embowered amidst orchards and gardens, dotted the landscape, while Alexandra, Kihikihi, Hamilton, and Cambridge, and numerous other settlements, served to mark the spots where future cities may ere long grow into existence, and add wealth and prosperity to this fertile land. It was, however, when gazing in the direction of the south, where the King Country lay stretched for miles before us in all the wide, rich beauty of a virgin country, that the grandest natural scenery burst upon the view, and charmed the imagination with the thought of a bright future. The aukati or boundary-line could be distinctly traced, on the one side by farms and homesteads, and on the other by the huts[Pg 45] of the natives; but beyond these features there was nothing to denote that the territory to the north was the abode of enlightenment, and that the land to the south was a primeval wilderness still wrapped in the darkness of primitive barbarism.

TE RAIA NGAKUTU TE TUMUHUIA.

(Head Chief of the Ngatitematera tribe. Last of the New Zealand

Cannibals.)

[Pg 46]AUCKLAND TO OHINEMUTU.

The flank movement—Auckland Harbour—Tauranga—Whakari—The tuatara—En route—The Gate Pa—All that remains—Oropi—A grand forest—Mangorewa Gorge—Mangorewa River—A region of eternal fire.

A little short of five months after the events which I have recorded in the previous chapters took place, I embarked on board the S.S. Glenelg, for Tauranga. I had selected to travel by this way as I had determined to reach the Lake Country by the East Coast, pass through the centre of the island, enter the King Country at its southern extremity, and, if possible, carry on my explorations northward to Alexandra. Owing to the unsatisfactory condition of the Native Question at that time, the undertaking appeared to be a hopeless one, but I resolved to give it a fair trial, and as the Glenelg glided over the calm waters of Auckland Harbour, half the difficulties which had previously presented themselves to my mind seemed to disappear with the fading rays of the sun as they played over the water, cast fitful shadows athwart the romantic islands of the bay, and lit up the tall spires of the receding city.

As we sped on in the golden twilight, some of the most attractive views were obtained of the renowned[Pg 47] harbour which places the northern capital of New Zealand at the head of all antipodean cities for grandeur of scenery, and as a mart for commerce, and which, in time to come, should transform it into the Naples of the Pacific. On every side the most delightful prospects unfolded themselves; the city with its forest of houses rising and falling over hill and valley, and clustering around the tall, grassy cones, once the scene of raging volcanic fires, next crowned with Maori pas, and now dotted with neat villas. Small inlets and jutting points of land came constantly before the gaze; the forest-clad mountains of Cape Colville and Coromandel mounted boldly above the sea; in the east, Kawau, the island home of Sir George Grey, rose in the north, backed by the rugged peaks of the Barrier Islands; while right in the centre of this grand picture the volcanic cone of Rangitoto towered to a height of 800 feet above the wide expanse of water. Every point, each sinuous bay and jutting headland, was rich in a varied vegetation of the brightest green, and as the softly tinted light—violet, crimson, and yellow—so characteristic of New Zealand sunsets, mingled with the deep blue of the sea as the shades of evening crept on, and the stars shone forth from above—the whole surroundings, as our vessel glided rapidly on her way, combined to form an ever-changing panorama of unrivalled beauty.

When, early on the following morning, we steamed into Tauranga Harbour, the sea was as smooth as a sheet of glass, the heavens were blue and cloudless, and the town, the fern-clad hills, and the mountains in the distance, completed one of the most attractive pictures of New Zealand scenery I had ever beheld. In fro[Pg 48]nt the neat white houses of the settlement rose from the very edge of the lake-like expanse of water, the country beyond lay stretched before the gaze in a broad expanse of green, whilst the bold outline of the coast, with its jutting headlands, extended for miles on either side.

WHAKARI, OR WHITE ISLAND.

Tauranga is not a large place, but its situation is delightful. It is built mostly along the west shore of the harbour, and commands a splendid view of the great ocean beyond, with its picturesque islands, which rise in fantastic shape, from the broad surface of the Bay of Plenty. The harbour, which is completely landlocked, and safe in all weathers, stretches out before the town in the form of an inland lake. The rugged islands of Tuhua, Karewha, and Motiti rise abruptly from the surrounding sea, while in the distan[Pg 49]ce, towards the east, the geysers and boiling springs of Whakari send up their clouds of steam.

THE TUATARA.

Whakari, or White Island, which lies about thirty miles from the shore in the Bay of Plenty, is a cone-shaped mountain rising abruptly from the sea to an altitude of 860 feet. The crater, about a mile and a half in circumference, is in the condition of a very active solfatara, whose numerous geysers and boiling springs evolve at all times dense volumes of steam and sulphurous gases. There are large deposits of sulphur surrounding the crater, and several small warm lakes of sulphurous water. It lies in the line of active thermal action which stretches across the North Island through the Lake Country to the volcano of Tongariro, with which, according to native tradition, it is supposed to be connected by a subterranean channel.

The small rocky island of Karewha in the Bay of Plenty is remarkable as being the only remaining abode of the tuatara (Hatteria punctata,[15]) the largest lizard i[Pg 50]n New Zealand. It is a non-venomous reptile, about eighteen inches long, with a ridge of sharp-pointed spines like a fringe down its back, and which it raises or depresses at pleasure.