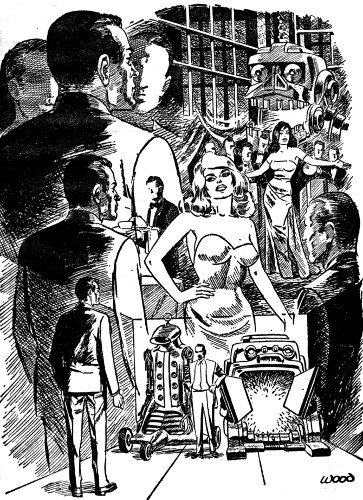

BY JACK SHARKEY

ILLUSTRATED BY WOOD

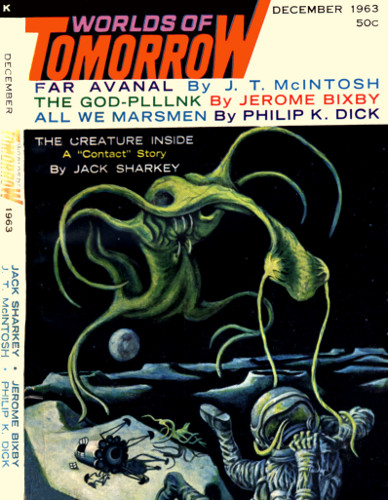

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of Tomorrow December 1963

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The room was small, but it held a whole

universe—and Norcriss had no place in it!

I

"How much did they tell you about the fix we're in?" said Dr. Alan Burgess to his visitor.

Lieutenant Jerry Norcriss shook his head. "They said you'd fill me in. They said it was urgent."

Burgess paused, lighted a cigarette, then belatedly offered one to Jerry, who declined. "Well," he said, interspersing his words with short nervous puffs of smoke, "about a year ago, I stumbled on a way to reverse the process of an electro-encephalograph, to play pre-recorded thoughts and experiences to a man's mind. You zoologists, with your Contact process for penetrating newly discovered fauna's minds, will be familiar with the process. Luckily for us."

Jerry eyed him. "Go on."

"My development involves an infinitely selective feedback. We give the subject a saturating dose of inflowing concepts. His mind is free to choose among them and to link them. Take 'bigness, affluence and danger' for an instance. The subject puts them together and fleshes them out. He could experience a large, expensive fission bomb falling onto him, or he could be sacrificed to an immense golden idol, or—Or anything that his inner mind chose."

"I begin to understand," said Jerry. "The overlay influences all the senses. The subject thinks he's really undergoing whatever he conjures up—and you use it for therapy, letting him work off his aggressions and frustrations in what seems to him an actual universe."

"Correct, except for the tense," said Alan Burgess. "I was doing that until Monday of this week." He leaned forward across the desk. "We screen the subjects carefully, because certain psychoses could be disastrous to the subject in my device. Paranoia, for instance. The man would be amid unutterable horrors, with danger on every side; he'd emerge a gibbering idiot, if he didn't die of heart failure first."

"Emerge?" asked Jerry, frowning. "I'd assumed you used a helmet, such as we do in Contact...."

Burgess sighed. "Unfortunately, I am paying the penalty of lone-wolf experimentation. I wish I'd had the sense to route the input to the brain through a helmet, but I didn't. Instead I installed the person in an observation room. The influencing factor was nutrition. Intravenous feedings wouldn't have served the purpose of the observer; sometimes the subject's choice of foodstuffs is significant. He had to be let move about, his mind in a make-believe world, but his body actually moving about a room we could see into. So—I had an atomic duplicator installed. The hospital got one last year for making radium, turning cancerous growths into normal flesh, regrowing bone and the like.

"Should the subject then grow hungry, the duplicator would be triggered by his conviction of eating. In his mind, he might be—hanging from a branch by his tail, for instance. The duplicator's production of bananas, coconuts or whatever would give us a further clue to his state of mind. You see?"

"So far, sound enough, Dr. Burgess," said Jerry. "So what went wrong? I assume something did, or I wouldn't be here."

"We made a terrible error. We tried observing a man named Anthony Mawson in our gadget. I'd diagnosed his case as simple inferiority complex. My fault. Wrong diagnosis. Mawson has megalomania, a gorgeous case of it ... of course, he's not the first such case to fool psychiatrists. You see, his outward shyness, soft-spoken voice and general gawkishness is due to feeling superior to others, not the reverse. He feels smarter, stronger, braver, etcetera, than everybody else in creation—but he also feels that nobody knows it but himself. Hence his indrawing, his brooding, taciturn gentility."

Jerry Norcriss prodded. "What happened with Mawson when you put him in your machine?"

"I don't know," said Burgess. "No one's been able to see into the machine since he entered it on Monday."

"He couldn't have escaped?"

"No! I wish he had. Anthony Mawson is still in that room, in his own private universe, and we can't get him out of it. We've tried cutting the power to the machine; the opacity inside the room remains. We sent two men in after him. They never came out."

"How could he possibly?" asked Jerry.

Burgess shook his head. "We can only guess. Our theory is that he's used the duplicator to make the entire room self-sustaining. Normally we could wait till he runs out of material to feed the duplicator, but—we can't wait on the lives of those two men. Nor can we chance his expanding his universe."

Norcriss frowned. "Expanding it?"

Burgess nodded. "By, perhaps, feeding the duplicator with the room itself. With a pickaxe, he can start hewing down the very walls, or even have the duplicator build a robot that will take care of its need for material to build with. Against this development, we have surrounded the room completely with a force-shield, limiting his outward progress to two feet of concrete in any direction. But the room is approximately thirty feet square, and twenty feet high. With all that mass he could exist in there for years."

"And my job is to get him out," said Jerry.

"Yes. The government feels that a Contact specialist's the only kind of man to send into this madman's world. You men are used to extra-somatic experiences—and you have learned to live with danger without losing your heads."

"Well," said Jerry, getting up, "I guess that sums up the situation sufficiently."

Burgess nodded, sadly. "Any further briefing is useless. Impossible, really. I've told you the situation, and you can certainly imagine the danger. But as for the solution, well.... You'll just have to feel your way, and do whatever you think best."

Jerry paused beside Burgess at the door to the hall. "One thing, though, Doctor; when I get into the influence of the machine, what kind of universe will I be in? Mine or Mawson's?"

"I can only theorize on that," said Burgess. "My guess would be that you'll find both in there, one vying for supremacy over the other. This fight won't be man to man. It will be universe against universe."

II

There had been no sensation at all as Jerry stepped through the flat sheet of grayness in the doorway; no more physical awareness than a blind man might feel when passing through the beam of a powerful light. Perhaps there was a slight sensation of the mere presence of the energies that kept the opacity in existence—but that sensation, Jerry knew, was psychological, not actual.

"Although," he realized, as his world became an infinity of opalescent gray, "in this place, a psychological awareness will be no different from a genuine physical sensation. Better be careful what I think about in this psychokinetic fog...."

The thought was barely formulated when the grayness changed. It became moist against his flesh, and started swirling in tendrils about him. "Damn it, be careful!" he belatedly cautioned his mind. "Now the stuff is fog!" Ahead of him in the swirling mist a brighter-than-gray glow led his footsteps forward.

He found himself standing beneath an overhanging marquee. Its black undersurface was runneled with condensed moisture amid the garish naked bulbs that haloed the wet cement sidewalk.

A red-coated doorman, resplendent behind rows of bright brassy buttons, gave him a smile as he pulled open the door that led to the club. Jerry nodded and went inside.

Thick crimson carpet cushioned his footfalls as he moved cautiously through an empty lobby, then down a white marble staircase toward the ballroom. Dimly, he was aware that the band at the far end of the mammoth room was playing music. What song he didn't know until a chance chording reminded him of a popular song of the day ... at which point that suddenly was the tune. The tables ringing the dance floor were covered with bright linen and shining silver. The tables were empty of patrons, however, until Jerry casually thought, "I should think business would be better—"

Suddenly a horde of laughing couples appeared in the chairs, with hurrying waiters bringing champagne, trays and menus to their guests.

The men wore tuxedos; the women were in evening dress. He looked suddenly at himself, and saw that his uniform was now the official dress uniform of the Space Corps. Before he could conquer it, his mind voiced a quick wish that he shouldn't be dining alone; and then a girl was rising from her place at a table beside the dance floor, hurrying to greet him, hands outstretched.

Her fingers were small and strong and warm. She smiled up at him. "Jerry, darling."

Despite her being only arm's length from him, he could not see her well at all. His impression was merely one of youth, loveliness and girl-ness. But then, as he tried to ascertain precisely what she looked like, hidden corners of his mind began to supply each detail an instant before his conscious quest for it and Jerry, in a few moments, was suddenly staggered with delighted shock.

Very few men are privileged to find a girl who lives up to all their dreams of perfection in a woman.

Hair as soft as cobweb, as fluffy as dancing clouds, as golden as flowing honey, cascaded down about a slender alabaster throat, and died in golden ripples on smooth white shoulders. Eyes the rich brown of raw chocolate gazed serenely at him from under red-gold brows and jet lashes, their patrician serenity permeated with a touch of twinkling impishness. Her lips were soft and not unlike berry-stained velvet, sweet and warm and tempting; her mouth generous and tilted at the corners into a smile of greeting—obviously the result of her subduing a frank laugh of joy at seeing him. Geometrically perfect teeth flashed white as porcelain between her lips. Her gown was a shimmering midnight blue, highlighted with random sprinkles of brightly coruscating gems.

Even as his lips parted to ask her name, Jerry knew it and spoke it softly. "Carol."

"Listen," she said softly, tilting her head toward where the band had begun a new song. Swift, urgent and rapturous, it floated through the room, surrounded the two of them, took possession of them. Then Carol was in his arms, and Jerry was dancing out onto the floor with her. The other couples were a blur of forgotten figures that swayed.

Jerry knew the melody. It was their song, their own private love song, the one that had been playing on the night when they both knew, suddenly, that there could be no one else for either of them but the other....

As they returned to their table, Jerry realized that Carol was now garbed in a white peasant blouse and bright flowered flaring skirt, and that her hair was drawn back at the temples to expose her ears, now adorned with golden hoops. The table was in a lattice-backed booth, covered with a red-and-white checkered cloth. The inner surface of the table held salt, pepper, grated cheese and breadsticks, matching cruets of pale olive oil and dark vinegar. The band was now a five-man gypsy ensemble.

"Remember the first time we came here, Jerry?" asked Carol, her eyes at once upon his face and distant, dreamy....

As she smiled, Jerry noticed with dull horror that one of her eyes was perceptibly lower than the other.

The teeth she flashed his way were mottled with brown stains. She took hold of his fingers with her own.

"Carol!" he said shakily, staring at the knuckly, red-raw hands that clutched at his. "What's happening?"

"Happening?" she said, her voice a raucous croak of amusement. "Nothing's happening! In fact, you're probably one of the dullest guys I ever got stuck with." She tossed her head petulantly. Coarse, straw-colored hair flipped away from her thick neck. Her breath was sour with wine and miasmic with garlic.

"Carol!" he cried.

"Don't whine!" she snapped, viciously. "I hate a guy who whines!" With that, she shoved out of the booth, and waddled toward the rear of the coffeehouse, one hand scratching at a bulge of flesh that overhung the too-tight girdle. Her black leotards were twisted and dull as she passed the flashing rainbow lights of the brassy jukebox.

Jerry shoved away from the table, overturning his coffee in its cracked china cup, and he wove his way through the reek and smoke toward the door through which she'd vanished.

When he got there, the door was a peeling poster on a bare brick wall, advertising some long-forgotten show. His fingers scrabbled on rough mortar for a moment. Then he turned and paced back to his cot, where he flopped on his back in the long shadows of the bars.

"Norcriss!" said the guard, coming into the cell. "This is it!" The brass uniform buttons flashed brightly.

Strong hands were lifting him from the cot, dragging him down a long corridor toward a steel door. As they got there, the door opened wide, and Jerry saw the gaping maw of hungry steel gears, while behind him a man's voice droned prayers.

Then, before the guard could shove Jerry forward into that waiting mechanical mouth, Jerry noticed the odd shimmer of grayness that lay between himself and the waiting teeth, and he remembered that he was in a world of illusion.

At precisely that moment he knew beyond a doubt that those waiting jaws were illusion in form only. An atomic duplicator does not have to chew its intake. It merely dissolves the atomic bonds with the rays that flash between its power plates on either side of the disruption platform. The waiting mouth and teeth were mere symbols in Jerry's mind of what was about to occur.

They were unreal—but they could be fatal.

He shut his eyes, shoved backward with his feet, and thought of Carol as he'd first glimpsed her.

When he opened his eyes once more, she was standing before him in her ballroom gown again, and the band was just beginning to play their song once more.

"Jerry," she said, taking his arm. "Dance with me."

"No. We're in danger here. Come on, I'll get your coat. We've got to go away quickly."

A spark of alarm showed briefly in her eyes. Then she nodded wordlessly and hurried up the marble staircase with him to the lobby. Jerry got her coat from the check-room—a marvelous silvery fur that covered her from neck to waist—and then they were heading out into the fog together.

"Good evening to you, sir," said the doorman, eyes and buttons bright.

Jerry grunted and led Carol off down the street into the fog.

"Where are we going?" she asked, breathlessly trying to keep pace.

"Away, I hope," he said. Even their movement from the ballroom could be sheer illusion. Jerry tried moving from the club entrance in the exact reverse of the motion in which he'd first approached it, trying to achieve the real doorway that led from the experimental room into the antiseptic hospital corridor where Burgess waited. But the fog continued to be fog. It would not take on the form of that intangible gray shimmering that guarded the entrance to Anthony Mawson's megalomaniac universe.

"If I could only see where—" he began.

Then every tendril of fog was gone.

Before him lay the cold blackness of outer space, pinpointed with hard, unwinking stars. Jerry recoiled from the viewplate, shaken, and turned around to see Carol. Her eyes were wide and startled as she glanced about at the metal confines of the control cabin. Jerry had just time enough to think how incongruous she looked in her fur jacket and long blueblack gown ... and then she was clothed in the neat gray uniform of the WASP, trim short-sleeved shirt and sharply creased shorts.

"Jerry," said Carol. She slipped her arm through his, staring at the infinite stars in the viewplate. "What are we running from?"

He tried to think, but could not remember. "There's—some danger behind us. We have to get away from it, Carol. It means complete destruction if we're caught."

Carol stared helplessly at the stars in the viewplate. "But where are we running to?"

Jerry shook his head. "Impossible to tell. Not without the help of a good astrogator. Out in space, stars shift and magnitudes change. I'm not even qualified to guess—"

"Sire," said the astrogator, handing a clipboard to Jerry, "we can reach any of these seven stars in a few hours. Just tell me where you'd prefer to go."

Jerry turned to the man, resplendent in his neat Space Corps uniform, jacket bright with brass buttons. When he tried to focus upon the man's features he could detect nothing.

"We'd better choose the quickest trip," Jerry said, after a moment's indecision. "No telling how much fuel we have left."

The astrogator nodded. "I'm afraid that's out of my department, all right, sir. But if you'd care to check the tanks?" Without waiting for a reply, the man turned and began to pick his way carefully toward the rear of the spaceship, stepping from girder to girder. The floor, Jerry noticed idly as he followed, was exposed to open space between the curving ribs of steel that formed the framework of the ship.

"Careful, now," he said, helping Carol along from one to the other. "That's vacuum out there. We don't want to fall through."

Ahead of Jerry, the implacable man with the brass buttons was nearly to the steel door masking the blast chamber where the components of fuel were mingled and ignited. Jerry, giddly aware of every hazardous step over the squares of star-speckled blackness, kept one hand on Carol's arm, the other on her chessboard.

"Don't spill any of the men!" she cautioned, as the diminutive plastic figures danced and rattled on the board. "I don't intend to search the whole cosmos for a pawn."

"Here you go, sir," said the politely insistent astrogator, opening the steel door. Before Jerry yawned an oval of intense white flame, the radiating heat crisping against his skin and hair.

"The fission rate," Jerry mumbled, consulting his wristwatch. "I've got to time it, or I won't be able to calculate the amount of fuel still in the bulkheads."

"Count it by steps, sir," suggested the astrogator.

"One," said Jerry, stepping out toward that blinding coruscation of heat. "Two," he said, feeling carefully for the next girder.

Then the toe of his boot slipped from the metal, and he realized, with a horrible lancing of adrenalin through his abdomen, that he was falling out the opening between the girders. The only salvation would be a shove with his still-braced rear foot, but that would carry him directly into the inferno of burning fuel. An eternity of falling through icy vacuum against an instant of intolerable searing pain....

"The fire—" gasped Jerry, toppling in inexorable slow motion toward starry darkness, a cloud of twirling chess pieces orbiting about his head. "I've got to make it into the fire...."

He tensed the muscles of the laggard leg for the spring that would carry him to destruction, and then he saw that the chess pieces were shimmering gray, and the oval frame of the doorway to the flaming fuel was shimmering gray, and even what had seemed hot white burning was cold gray waiting mist, and with a yell of remembrance, Jerry clamped shut his eyes and let himself plunge downward into nothingness....

III

"Are you all right, Norcriss?" Jerry blinked slowly, then focused on the face of Dr. Alan Burgess. He found himself lying on a narrow, white-sheeted cart, in the corridor outside the room where all the trouble had begun. "Mawson," he said groggily. "Is he—?"

Burgess nodded wearily. "Still in there, in full control of his one-man universe. What happened, Norcriss? You came tumbling out that door like a wild man, clawing the air and yelling. Then you went into shock. You've been unconscious for two hours."

"I—I thought I was falling," Jerry admitted. "The last thing I remember is stepping through the open space between a spaceship's supporting girders."

"What open space?" said Burgess, frowning curiously.

Jerry shook his head. "There isn't any such thing. But something happens to logic in that room. It's like having a dream, Doctor. Things that would startle you in everyday life seem correct. Even familiar. But there's a kind of pattern to events. At first, I'm in my universe, and mostly in control. Then little fragments of my pseudo-reality start slipping, changing into other things. The changes seem perfectly normal to me. Then, all at once, the guy with the brass buttons turns up—and I've managed in the nick of time, twice, to realize that I was about to be sent or led between the disrupting plates of your atomic duplicator."

"The man with the brass buttons," Burgess said slowly. "Do you think it's Mawson?"

"Either him or a robot he's made to keep his machine fed." When Burgess scowled, Jerry shrugged and appended, "It is his machine, for all practical purposes. He's the boss of that hungry electronic monster, Doctor, however the hospital feels about it."

"This Carol. Is she a real woman, or a figment of your imagination, wishful thinking?"

"She's real enough," Jerry sighed. "She's the personal secretary of the entire Space zoology program. I take her out sometimes. There's nothing special between us."

"But you wish there were," said Burgess.

Jerry stared at him. "What makes you think that?"

Burgess tilted his head toward the room where Mawson still maintained control. "Your visions in there. You must think a lot of her. You can kid yourself consciously; but nearly all you underwent in there came straight from your subconscious. And a subconscious just doesn't know how to lie."

Jerry changed the subject, "What's our next move? How soon can I go back after Mawson?"

"You can't. Mawson's knowledge of this Carol can easily be turned to your disadvantage. He can use her to lead you to dissolution in there. No, it's much too risky. You're lucky you got out when you did."

"But what about Mawson, then?"

Burgess tried to look confident. He failed. "We can ring up your headquarters and ask for another man. Or, if worse comes to worse, we can partition off this part of the hospital, and just sit it out until Mawson runs out of atomic building blocks."

"Which may take years," Jerry reminded him.

Burgess turned his palms upward. "What else can we do?"

"Send me again," said Jerry. "I know the score pretty well, now. I know what to watch out for. I'm sure that with one more try I can get Mawson out of there."

"Sorry," Burgess said, shaking his head. "As a medical man, I cannot permit it. You've had a bad shock. We'll try someone else, if your outfit will send someone, and see what happens. If he fails, or if they won't supply us with any more men, then—well, you can try again in a few weeks, if you're still game. But not now."

"Doctor, in a few weeks, Mawson will be so well in control of that universe that he may find a way to block the entrance. Have you thought of that?"

"His universe is not a real one—" Burgess began.

"But that duplicator is real enough. It can make anything he decides he needs. And at any time he may get the bright idea of simply mounting his machine right at the entrance, so anyone stepping into that gray field will be powdered into atoms, instantly."

"That's true enough," admitted Burgess. "But my diagnosis still stands. For now, you are off this assignment. When I feel you're ready—assuming nothing else has succeeded meantime—I'll contact you at the base."

"How do you know I won't be off on some other planet by then?" asked Jerry bitterly.

"I don't," said Burgess. "I hope you are not, but there isn't anything further I can do about it. I'm sorry."

"And what do I do in the meantime?"

Burgess grinned. "Call up this Carol and go out on the town."

Jerry shook his head at the last part. "No thanks. I prefer Carol to know nothing about it."

Burgess shrugged and gave it up. "All right, Norcriss. Rest here till you feel stronger, then you're free to go." Then he was striding off down the corridor.

After a bit, Jerry sat up cautiously, let the slight giddiness subside, then swung his legs off the side of the cart and got down.

Behind him, the door to Mawson's universe stood open on its wall of grayness. Jerry stared thoughtfully at it, then saw that the two internes who were guarding the opposite ends of this section of the hospital corridor were hesitantly half-starting toward him. Jerry knew he could be through that doorway and into the grayness before they got within ten feet of him....

IV

Then his shoulders slumped, and he turned and walked toward the elevators. Burgess was right. He felt worn out, and uninclined to make grandstand plays. Besides, he thought, thumbing the elevator button, it would be nice to see the real Carol again, after her nebulous pseudo-self. He wanted very much to put his arms around a girl who wouldn't suddenly turn into something horrible in his embrace.

The steel doors slid open before him, and the elevator boy leaned out to check the corridor for other passengers. "Down," he said. Jerry nodded and started into the elevator.

Then he hesitated, and looked back toward the room where Mawson reigned supreme, then back at the elevator boy. "Say," he said, uncertainly, "that's a strange outfit for an elevator attendant in a hospital. I'd have expected an orderly in an all-white getup."

The boy glanced down at his uniform, the bright blue pants, shined black shoes, and scarlet jacket bright with twin rows of brass buttons. "I suppose it is," he said. "But I don't usually run this elevator. I'm from the hotel next door. I'm just doing this while the regular guy takes his coffee break."

Jerry hesitated, then stepped toward the waiting elevator with its pale gray walls. And stopped again. His hand went to his forehead, bewilderedly. "There's something—" he said.

Then Carol was beside him, slipping her arm through his. "Come on, Jerry," she said urgently. "We'll be late for our date."

Jerry looked at her, then at the hotel corridor behind her, then again at the waiting elevator.

"I have the oddest feeling something's wrong," he said. "I—I don't remember coming over here for you."

"You didn't," she said promptly. "I came for you, Jerry. This is your hotel, remember? Doctor Burgess said you'd had a bad shock, but I didn't know how bad till now."

"Shock?" said Jerry. "What shock? What was bothering me?"

Carol smiled tightly. "Nothing. Nothing at all. Come on, Jerry, darling." Again she drew him toward the elevator.

"If I could only remember," he said, uneasily, on the brink of that open cube of bright grayness. Then his eyes focused upon the brass buttons fronting the boy's jacket, and at his own shadow as it passed across those glowing hemispheres. As the shadow crossed a button, the color would die, and the button would be dull crystal, and then glow bright and brassy again when the shadow had passed.

"Photoelectric cells!" said Jerry. "Light-sensitive cells. Those aren't buttons, they're eyes! Multiple robot eyes!" He staggered away from the boy. Carol stopped him.

The elevator boy, suddenly half again Jerry's height, was towering over him, long steel arms extending like hooked telescopes toward him. "Get in, Jerry, get in!" cried Carol, struggling to push him forward toward those invincible metal clamps.

In a fury of fear, Jerry fought her, grappled with her, twisted to avoid those extending robot hands that would drag him to destruction. And suddenly Carol was screaming his name, and her eyes were pools of terror and betrayal, and the leaping metal fingers had buried themselves in the soft flesh of her shoulders and dragged her back into grayness.

Incredible energies came alive about her, and then there was only a shimmer of dusty crystalline winds, and she was gone.

Jerry found himself standing before the still-warm plates of the atomic duplicator, in the room where Mawson had had his short-lived universe. Beside the machine, a squat cubic box dangled limp steel arms, its rows of photo-electric cells losing their golden glow.

And then, as Burgess came hurrying in through the door, he toppled over in a dead faint.

"So there is no such person as Carol?" said Burgess, standing at the foot of the hospital bed. "She was only the figment of your imagination?"

"Yes," said Jerry dully. "And all along, it was Mawson I was really with. He was clever, all right. She was certainly the last occupant of that crazy place I was likely to attack. If he had not tried attacking me himself—I might be atom dust by now. A little longer, and she—he, I mean—might have talked me into that elevator."

"Well," said Burgess, "I'm sorry this thing ended with Mawson's dissolution, but that can't be helped. You did your job well, Lieutenant."

"Thanks," said Jerry, expressionlessly.

"To come so near death so many times—" Burgess shuddered. "You have a remarkable constitution, not to have cracked under such a strain. Lieutenant, you're a lucky man."

And Jerry, his mind still filled with a vision of golden hair, soft brown eyes and warm, eager lips, could only echo wearily, "Very lucky."

END