|

List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

A GALLANT OF LORRAINE

VOL. II.

BY

H. NOEL WILLIAMS

AUTHOR OF “FIVE FAIR SISTERS,” “A PRINCESS OF INTRIGUE,”

“THE BROOD OF FALSE LORRAINE,” ETC.

IN TWO VOLUMES

With 16 Illustrations

VOL. II

LONDON : HURST & BLACKETT, LTD.

:: PATERNOSTER HOUSE, E.C. ::

| CHAPTER XXV | |

|---|---|

Offer of Schomberg, Saint-Géran and Marillac to take Montauban within twelve days—Advice of Père Arnoux—Diplomacy of Bassompierre—A humiliating fiasco—A second attempt meets with no better success—Bassompierre counsels the King to raise the siege, and it is decided to follow his advice—General exasperation against Luynes—Louis XIII begins to grow weary of his favourite—Conversation of the King with Bassompierre—The latter warns Luynes that he “does not sufficiently cultivate the good graces of the King”—Reply of the Constable—Louis XIII twits Luynes with the love of the Duc de Chevreuse for his wife—Puisieux, Minister for Foreign Affairs, and Père Arnoux, the King’s Jesuit confessor, conspire against the Constable—Disgrace of the latter—Bassompierre, at the head of the bulk of the Royal forces, lays siege to Monheurt—A perilous situation—Bassompierre falls ill of fever—He leaves the army and sets out for La Réole—He is taken seriously ill at Marmande—His three doctors—Approach of the enemy—Refusal of the townsfolk to admit him and his suite into the town—A terrible night—He recovers and proceeds to Bordeaux—Death of the Constable before Monheurt | |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

Who will govern the King and France?—The pretenders to the royal favour—Position of Bassompierre—The Cardinal de Retz and Schomberg join forces and secure for their ally De Vic the office of Keeper of the Seals—They propose to remove Bassompierre from the path of their ambition by separating him from the King—Bassompierre is offered the lieutenancy-general of Guienne and subsequently the government of Béarn, but declines both offices—He inflicts a sharp reverse upon Retz and Schomberg—Condé joins the Court—His designs—The rival parties: the party of the Ministers and the party of the marshals—Monsieur le Prince decides to ally himself with that of the Ministers—Mortifying rebuff administered by the King to the Ministers at the instance of Bassompierre—Failure of an attempt of the Ministers to injure Bassompierre and Créquy with Louis XIII—Arrival of the King in Paris—Affectionate meeting between him and his mother—Accident to the Queen{viii} | |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

Question of the Huguenot War the principal subject of contention between the two parties—Condé and the Ministers demand its continuance—Marie de’ Medici, prompted by Richelieu, advocates peace—Secret negotiations of Louis XIII with the Huguenot leaders—Soubise’s offensive in the West obliges the King to continue the war—Louis XIII advances against the Huguenot chief, who has established himself in the Île de Rié—Condé accuses Bassompierre of “desiring to prevent him from acquiring glory”—Courage of the King—Passage of the Royal army from the Île du Perrier to the Île de Rié—Total defeat of Soubise—Siege of Royan—The King in the trenches—His remarkable coolness and intrepidity under fire—Capitulation of Royan—The Marquis de la Force created a marshal of France—Conversation between Louis XIII and Bassompierre—Diplomatic speech of the latter | |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

Condé and his allies offer to secure for Bassompierre the position of favourite, if he will join forces with them to bring about the fall of Puisieux—Refusal of Bassompierre—Condé complains to Louis XIII of Bassompierre’s hostility to him—Bassompierre informs the King of the proposal which has been made him—Louis XIII orders Monsieur le Prince to be reconciled with Bassompierre—Siege of Négrepelisse—The town is taken by storm—Terrible fate of the garrison and the inhabitants—Fresh differences between Condé and Bassompierre—Discomfiture of Monsieur le Prince—Bassompierre, placed temporarily in command of the Royal army, captures the towns of Carmain and Cuq-Toulza—Offer of Bassompierre to resign his claim to the marshal’s bâton in favour of Schomberg—Surrender of Lunel—Massacre of the garrison by disbanded soldiers of the Royal army—Bassompierre causes eight of the latter to be hanged—Lunel in danger of being destroyed by fire with all within its walls—Bassompierre, by his presence of mind, saves the situation—Schomberg and Bassompierre—The latter is promised the marshal’s bâton | |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

Conditions of peace with the Huguenots decided upon—Refusal of the citizens of Montpellier to open their gates to the King until his army has been disbanded—Bullion advises Louis XIII to accede to their wishes, and is supported by the majority of the Council—Bassompierre is of the contrary opinion and urges the King to reduce Montpellier to “entire submission and repentance”—Louis XIII decides to follow the advice of Bassompierre, and the siege of the town is begun—A disastrous day for the Royal army—Death of Zamet and the Italian engineer Gamorini—Political intrigues—Bassompierre succeeds in securing the post of Keeper of the Seals for Caumartin, although the King has already promised it to d’Aligre, the nominee of Condé—Heavy losses sustained by the besiegers in an attack upon one of the advanced works—Condé quits the army and sets out for Italy—Bassompierre is{ix} created marshal of France amidst general acclamations—Peace is signed—Death of the Abbé Roucellaï—Bassompierre accompanies the King to Avignon, where he again falls of petechial fever, but recovers—He assists at the entry of the King and Queen into Lyons—He is offered the government of the Maine, but declines it. | |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

Fall of Schomberg—La Vieuville becomes Surintendent des Finances—His bitter jealousy of Bassompierre—He informs Louis XIII that the marshal “deserves the Bastille or worse”—Semi-disgrace of Bassompierre, who, however, succeeds in making his peace with the King—Mismanagement of public affairs by Puisieux and his father, the Chancellor Brulart de Sillery—La Vieuville and Richelieu intrigue against them and procure their dismissal from office—The Earl of Holland arrives in Paris to sound the French Court on the question of a marriage between the Prince of Wales and Henrietta Maria—Bassompierre takes part in a grand ballet at the Louvre—La Vieuville accuses the marshal of drawing more money for the Swiss than he is entitled to—Foreign policy of La Vieuville—Richelieu re-enters the Council—Bassompierre accused by La Vieuville of being a pensioner of Spain—Serious situation of the marshal—The Connétable Lesdiguières advises Bassompierre to leave France, but the latter decides to remain—Differences between La Vieuville and Richelieu over the negotiations for the English marriage—Arrogance and presumption of La Vieuville—Intrigues of Richelieu against him—The King informs Bassompierre that he has decided to disgrace La Vieuville—Indiscretion of the marshal—Duplicity of Louis XIII towards his Minister—Fall of La Vieuville—Richelieu becomes the virtual head of the Council | |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

Vigorous foreign policy of Richelieu—The recovery of the Valtellina—His projected blow at the Spanish power in Northern Italy frustrated by a fresh Huguenot insurrection—Bassompierre sent to Brittany—Marriage of Charles I and Henrietta Maria—Bassompierre offered the command of a new army which is to be despatched to Italy—He demands 7,000 men from the Army of Champagne—The Duc d’Angoulême and Louis de Marillac, the generals commanding that army, have recourse to the bogey of a German invasion in order to retain these troops—Bassompierre declines the appointment—Conversation between Bassompierre and the Spanish Ambassador Mirabello on the subject of peace between France and Spain—The marshal is empowered to treat for peace with Mirabello—Singular conduct of the Ambassador—News arrives from Madrid that Philip IV has revoked the powers given to Mirabello—Bassompierre is sent as Ambassador Extraordinary to the Swiss Cantons to counteract the intrigues of the house of Austria and the Papacy—His reception in Switzerland—Lavish hospitality which he dispenses—Complete success of his negotiations{x} | |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

Bassompierre goes on a mission to Charles IV of Lorraine—He returns to France—The Venetian Ambassador Contarini informs the marshal that it is rumoured that a secret treaty has been signed between France and Spain—Richelieu authorises Bassompierre to deny that such a treaty exists, but the same day the marshal learns from the King that the French Ambassador at Madrid has signed a treaty, though unauthorised to do so—Indignation of Bassompierre, who, however, refrains from denouncing the treaty, which it is decided not to disavow—Explanation of this diplomatic imbroglio—Growing strength of the aristocratic opposition to Richelieu—The marriage of Monsieur—The “Conspiration des Dames”—Intrigues of the Duchesse de Chevreuse—Madame de Chevreuse and Chalais—Objects of the conspirators—Arrest of the Maréchal d’Ornano—Indignation of Monsieur—Conversation of Bassompierre with the prince—Plot against the life or liberty of Richelieu—Chalais is forced by the Commander de Valençay to reveal it to the Cardinal—“The quarry is no longer at home!”—Alarm of Monsieur—His abject submission to the King and Richelieu—He resumes his intrigues—Chalais is again involved in the conspiracy by Madame de Chevreuse—Arrest of the Duc de Vendôme and his half-brother the Grand Prior | |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

Alarm of the conspirators at the arrest of the Vendômes—Chalais, at the instigation of Madame de Chevreuse, urges Monsieur to take flight and throw himself into a fortress—Monsieur and Chalais join the Court at Blois—The Comte de Louvigny betrays the latter to the Cardinal—Chalais is arrested at Nantes—Despicable conduct of Monsieur—Chalais, persuaded by Richelieu that Madame de Chevreuse is unfaithful to him, makes the gravest accusation against her, in the hope of saving his life—He is, nevertheless, condemned to death—He withdraws his accusations against Madame de Chevreuse—His barbarous execution—Death of the Maréchal d’Ornano—Marriage of Monsieur—Bassompierre declines the post of Surintendant of Monsieur’s Household—Indignation of Louis XIII against Anne of Austria—Public humiliation inflicted upon the Queen—Banishment of Madame de Chevreuse—Bassompierre nominated Ambassador Extraordinary to England—Differences between Charles I and Henrietta over the question of the young Queen’s French attendants—The Tyburn pilgrimage—Expulsion of the French attendants from England—Resentment of the Court of France | |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

Bassompierre arrives in England—His journey to London—He is visited secretly by the Duke of Buckingham—He visits the duke in the same manner at York House—Charles I commands him to send Père de Sancy back to France—Singular history of this ecclesiastic—Refusal of Bassompierre—His first audience of Charles I and Henrietta Maria at Hampton Court—Firmness of Bassompierre on the question of Père de Sancy—He visits the Queen at Somerset House—His private audience of the King—He reproves the{xi} presumption of Buckingham—Admirable qualities displayed by Bassompierre in the difficult situation in which he is placed—He succeeds in effecting a reconciliation between the King and Queen—His able and eloquent speech before the Council—An agreement on the question of the Queen’s French attendants is finally arrived at—Lord Mayor’s Day three centuries ago—Bassompierre reconciles the Queen with Buckingham—Stormy scene between Charles I and Henrietta Maria at Whitehall—Bassompierre speaks his mind to the Queen—Intrigues of Père de Sancy—Peace is re-established—Magnificent fête at York House—Departure of Bassompierre from London—He is detained at Dover by bad weather—England and France on the verge of war—Buckingham decides to proceed to France on a special mission and proposes to accompany Bassompierre—Embarrassment of the latter—He visits the duke at Canterbury and persuades him to defer his visit—A disastrous Channel passage—Return of Bassompierre to Paris—Refusal of the Court of France to receive Buckingham—An English historian’s appreciation of Bassompierre | |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

The Assembly of the Notables—Bassompierre nominated one of the four presidents—The “sorry Château of Versailles”—The ballet of le Sérieux et le Grotesque—Execution of Montmorency-Boutteville and Des Chapelles for duelling—Death of Madame—Preparations for war with England—Louis XIII resolves to take command of the army assembled in Poitou—The King falls ill at the Château of Villeroy—Bassompierre is prevented by Richelieu from visiting him—Intrigue by which the Duc d’Angoulême is appointed to the command of the army which ought to have devolved upon Bassompierre—Descent of Buckingham upon the Île de Ré—Blockade of the fortress of Saint-Martin—Investment of La Rochelle by the Royal army—Bassompierre, the King, and Richelieu at the Château of Saumery—The Cardinal assumes the practical direction of the military operations—Provisions and reinforcements are thrown into Saint-Martin—Refusal of the Maréchaux de Bassompierre and Schomberg to allow Angoulême to be associated with them in the command of the Royal army—Schomberg is persuaded to accept the duke as a colleague—Bassompierre persists in his refusal and requests permission of the King to leave the army—He is offered and accepts the command of a separate army, which is to blockade La Rochelle from the north-western side—He declines the government of Brittany—Dangerous situation of Buckingham’s army in the Île de Ré—Unsuccessful attempt to take Saint-Martin by assault—Disastrous retreat of the English | |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

Siege of La Rochelle begins—Immense difficulties of the undertaking—Unwillingness of the great nobles to see the Huguenot party entirely crushed—Remark of Bassompierre—Courage and energy of Richelieu—His measures to provide for the welfare and efficiency of the besieging army—The lines of circumvallation—Erection of{xii} the Fort of La Fons by Bassompierre—The construction of the mole is begun and proceeded with in the face of great difficulties—Responsibilities of Bassompierre—The Duc d’Angoulême accuses the marshal of a gross piece of negligence, but the latter succeeds in turning the tables upon his accuser—Louis XIII returns to Paris, leaving Richelieu with the title of “Lieutenant-General of the Army”—Critical state of affairs in Italy—Unsuccessful attempts to take La Rochelle by surprise—Intrigues of Marie de’ Medici and the High Catholic party against Richelieu—The King rejoins the army—Guiton elected Mayor of La Rochelle | |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | |

Arrival of the English fleet under the Earl of Denbigh—Its composition—Daring feat of an English pinnace—Retirement of the fleet—Probable explanation of this fiasco—Indignation of Charles I, who orders Denbigh to return to La Rochelle, but this is found to be impossible—The Rochellois approach Bassompierre with a request for a conference to arrange terms of surrender—The arrival of a letter from Charles I promising to send another fleet to their succour causes the negotiations to be broken off—La Rochelle in the grip of famine—Refusal of Louis XIII to allow the old men, women and children to pass through the Royal lines: their miserable fate—Movements in favour of surrender among the citizens suppressed by the Mayor Guiton—Terrible sufferings of La Rochelle—Bassompierre spares the life of a Huguenot soldier who had intended to kill him—Difficulties experienced by Charles I and Buckingham in fitting out a new expedition—Assassination of Buckingham—The vanguard of the English fleet, under the command of the Earl of Lindsey, appears off La Rochelle—Narrow escape of Richelieu and Bassompierre—The King takes up his quarters with Bassompierre at Laleu—Arrival of the rest of the English fleet—Feeble efforts of the English to force their way into the harbour—The Rochellois, reduced to the last extremity, sue for peace—Bassompierre conducts deputies from the town to Richelieu—Surrender of La Rochelle—Bassompierre returns with the King to Paris | |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII | |

The Duc de Rohan and the Huguenots of the South continue their resistance—Opposition of Marie de’ Medici and the High Catholic party to Richelieu’s Italian policy—The Cardinal’s memorial to Louis XIII—Monsieur appointed to the command of the army which is to enter Italy—The King, jealous of his brother, decides to command in person—Twelve thousand crowns for a dozen of cider—Combat of the Pass of Susa—Treaty signed with Charles Emmanuel of Savoy—Problem of the reception of the Genoese Ambassadors—Anger of Louis XIII at a jest of Bassompierre—Peace with England—Campaign against the Huguenots of Languedoc—Massacre of the garrison of Privas—“La Paix de Grâce”—Surrender of Montauban—Richelieu and d’Épernon—Bassompierre returns to Paris with the Cardinal—Their frigid reception by the Queen-Mother—Richelieu proposes to retire from affairs and the Court, but an accommodation is effected{xiii} | |

| CHAPTER XXXIX | |

Serious situation of affairs in Italy—Trouble with Monsieur—Richelieu entrusted with the command of the Army in Italy—It is decided to send Bassompierre on a special embassy to Switzerland—The marshal buys the Château of Chaillot—His departure for Switzerland—Mazarin at Lyons—Bassompierre’s reception at Fribourg—He arrives at Soleure and convenes a meeting of the Diet—His discomfiture of the Chancellor of Alsace—Success of his mission—He receives orders from Richelieu to mobilise 6,000 Swiss—The Cardinal as generalissimo—Pinerolo surrenders—Bassompierre joins the King at Lyons—Louis XIII and Mlle. de Hautefort—Successful campaign of Bassompierre in Savoy—His mortification at having to resign his command to the Maréchal de Châtillon—Increasing rancour of the Queen-Mother against Richelieu—Visit of Bassompierre to Paris—An unfortunate coincidence—Louis XIII falls dangerously ill at Lyons—Intrigues around his sick-bed—Perilous situation of Richelieu—Recovery of the King—Arrival of Bassompierre at Lyons—Suspicions of Richelieu concerning the marshal—The latter endeavours to disarm them—Question of Bassompierre’s connection with the anti-Richelieu cabal considered—His secret marriage to the Princesse de Conti | |

| CHAPTER XL | |

Peace is signed with the Emperor at Ratisbon—The Queen-Mother deprives Richelieu’s niece Madame de Combalet of her post of dame d’atours and demands of Louis XIII the instant dismissal of the Cardinal—The Luxembourg interview—“The Day of Dupes”—Triumph of Richelieu—Bassompierre’s explanation of his own part in this affair—His visit to Versailles—“He has arrived after the battle!”—He gives offence to Richelieu by refusing an invitation to dinner—He finds himself in semi-disgrace—Monsieur quarrels with the Cardinal and leaves the Court—The King again treats Bassompierre with cordiality—Departure of the Court for Compiègne—Bassompierre learns that the Queen-Mother has been placed under arrest and the Princesse de Conti exiled, and that he himself is to be arrested—The marshal is advised by the Duc d’Épernon to leave France—He declines and announces his intention of going to the Court to meet his fate—He burns “more than six thousand love-letters”—His arrival at the Court—Singular conduct of the King towards him—The marshal is arrested by the Sieur de Launay, lieutenant of the Gardes du Corps, and conducted to the Bastille | |

| CHAPTER XLI | |

Bassompierre in the Bastille—He is informed that he has been imprisoned “from fear lest he might be induced to do wrong”—Monsieur retires to Lorraine—The marshal’s nephew the Marquis de Bassompierre is ordered to leave France—After a few weeks of captivity, Bassompierre solicits his liberty, which is refused—He falls seriously ill, but recovers—Death of his wife the Princesse de Conti—Flight of the Queen-Mother to Brussels—Death of Bassompierre’s brother the Marquis de Removille—Execution of{xiv} the Maréchal de Marillac—Montmorency’s revolt—Trial and execution of the duke—Hopes of liberty, which, however, do not materialise—Arrest of Châteauneuf—Arrival of the Chevalier de Jars in the Bastille—A grim experience—Bassompierre disposes of his post of Colonel-General of the Swiss to the Marquis de Coislin—The marshal’s hopes of liberty constantly flattered and as constantly deceived—Malignity of Richelieu—The ravages committed by the contending armies upon his estates in Lorraine reduce Bassompierre to the verge of ruin—The marshal’s niece, Madame de Beuvron, solicits her uncle’s liberty of Richelieu—Mocking answer of the Cardinal—Some notes written by Bassompierre in the margin of a copy of Dupleix’s history are published under his name, but without his authority—The historian complains to the Cardinal—Arrest of Valbois for reciting a sonnet attacking Richelieu for his treatment of Bassompierre—Apprehensions of the marshal—His despair at his continued detention—Grief occasioned him by the death of a favourite dog—The Duc de Guise dies in exile | |

| CHAPTER XLII | |

Death of Richelieu—Bassompierre is offered his liberty on condition that he shall retire to his brother-in-law Saint-Luc’s Château of Tillières—He at first refuses to leave the Bastille, unless he is permitted to return to Court—His friends persuade him to alter his decision—He is authorised to reappear at Court—His answer to the King’s question concerning his age—He recovers his post as Colonel-General of the Swiss—His death—His funeral—His sons, Louis de Bassompierre and François de la Tour—His nephews | |

| Queen Henrietta Maria | Frontispiece |

| From the picture by Van Dyck at Dresden. | |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Louis XIII King of France | 346 |

| From an engraving by Picart. | |

| Charles, Marquis de La Vieuville | 402 |

| From a contemporary print. | |

| François, Seigneur de Bassompierre, Marquis D’Harouel | 430 |

| From a contemporary print. | |

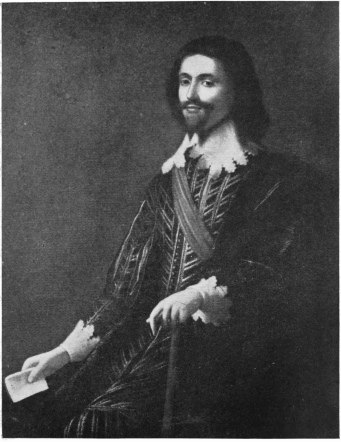

| Charles I | 470 |

| After the picture by Van Dyck at Dresden. | |

| George Villiers, First Duke of Buckingham | 518 |

| After the picture by Gerard Honthorst in the National Portrait Gallery. Photo by Emery Walker. | |

| Marie de’ Medicis, Queen of France | 564 |

| From an old print. | |

| Charlotte Louise de Lorraine, Princesse de Conti | 604 |

| From an engraving by Thomas de Leu. | |

Offer of Schomberg, Saint-Géran and Marillac to take Montauban within twelve days—Advice of Père Arnoux—Diplomacy of Bassompierre—A humiliating fiasco—A second attempt meets with no better success—Bassompierre counsels the King to raise the siege, and it is decided to follow his advice—General exasperation against Luynes—Louis XIII begins to grow weary of his favourite—Conversation of the King with Bassompierre—The latter warns Luynes that he “does not sufficiently cultivate the good graces of the King”—Reply of the Constable—Louis XIII twits Luynes with the love of the Duc de Chevreuse for his wife—Puisieux, Minister for Foreign Affairs, and Père Arnoux, the King’s Jesuit confessor, conspire against the Constable—Disgrace of the latter—Bassompierre, at the head of the bulk of the Royal forces, lays siege to Monheurt—A perilous situation—Bassompierre falls ill of fever—He leaves the army and sets out for La Réole—He is taken seriously ill at Marmande—His three doctors—Approach of the enemy—Refusal of the townsfolk to admit him and his suite into the town—A terrible night—He recovers and proceeds to Bordeaux—Death of the Constable before Monheurt.

During the next few days some progress was made by the Guards at Ville-Nouvelle; but the other two divisions seemed able to do little or nothing; while the garrison, strengthened by the accession of several hundred first-class fighting men, harassed them incessantly. On October 4, Louis XIII summoned another council of war at Picqueos, to which Bassompierre went. On his arrival he was met by Père Arnoux, the King’s Jesuit confessor, who said to him: “Well, Monsieur, Montauban is going to be given, so they say, to him who offers the lowest price for it, as they give the public works in France. In how many days do you offer to take it?” Bassompierre replied that no one would be so presumptuous as to name a day by which a place like Montauban could be taken, and that the duration of the siege would{322} depend on many circumstances. “We have bidders much more determined than you are,” rejoined the Jesuit. And he told him that the leaders of the Le Moustier division had pledged “their heads and their honour” to take Montauban in twelve days, provided that the Guards would hand over to them the greater part of their cannon; and that it was with the object of deliberating upon this proposal that the council had been summoned. He then advised Bassompierre, with whom he was on very friendly terms, that he and colleagues “would do a thing agreeable to the King and the Constable by not opposing it, unless they were prepared to pledge themselves to place Montauban in the King’s hands in an even shorter time.”

Bassompierre thanked the Jesuit, and drawing Praslin and Chaulnes aside, told them of the proposal which the leaders of the Le Moustier division—Schomberg, Saint-Géran and Marillac—intended to make at the council, though he did not tell them of the source of his information, which he allowed them to think was the King himself. He then pointed out that these officers, who had been in anything but good odour with the King and the rest of the army since their refusal to attack the bastion of Le Moustier, hoped to rehabilitate their reputation for courage by offering to accomplish a task which they must very well know to be impossible, even with the assistance of the Guards’ cannon. They undoubtedly believed, however, that Praslin and Chaulnes would refuse to surrender their artillery, in which event they would gain credit with the King for having made the offer, and, at the same time, throw the responsibility for being unable to carry it out upon the officers of the Guards’ division, of whom they were bitterly jealous. And he begged the two marshals “in God’s name” not to fall into the trap prepared for them by refusing to give up their cannon. The latter agreed to do as he advised, and they went into the room where the council was assembling.{323}

The Constable opened the proceedings in a lengthy speech, in which he exhorted the marshals and generals present to “lay aside all emulations, jealousies and envies,” and co-operate loyally together for the service of the King. Then he turned to the leaders of the Guards’ division and “inquired how long precisely they would require to take the town.” Bassompierre and the two marshals, after a pretence of consulting together, answered that they had done, and would continue to do, everything that was humanly possible to achieve this result, but that they were not prepared to name any definite time. The Constable then said that the officers from Le Moustier were ready to pledge themselves to take the town in twelve days; and Saint-Géran, turning to the King, exclaimed: “Yes, Sire, we promise it you upon our honour and upon our lives!”

Bassompierre and his colleagues applauded their resolution to render this great service to the King, and assured them that, as devoted servants of his Majesty, if there were any way in which they might contribute to the success of their enterprise, they had only to command them. Upon which the Constable said that the King wished them to send to Le Moustier sixteen of their siege-guns. To this they at once consented, and added that, if men were needed, they would willingly send 1,500 or 2,000, and Bassompierre himself would command them.

The officers from Le Moustier, much embarrassed, for they had counted with confidence on their demand for the Guards’ cannon being refused, thanked them, and said that their artillery was all that they required. The others then said to the Constable that, in view of the fact that they were surrendering practically the whole of their siege-guns, they presumed that the King would discharge them from the obligation of taking the town; and they were given to understand that all that would be required of them would be to divert the enemy’s attention from Le Moustier by occasional attacks and mines.{324}

Within the next forty-eight hours the Guards’ cannon was delivered at Le Moustier; but when Bassompierre went there on the 10th, on the pretext of visiting a friend of his who had been wounded, to see how matters were progressing, he found that the batteries were very badly placed, and that, notwithstanding the weight of gunfire, comparatively little impression had been made on the defences.

On the previous day, Bassompierre, catching sight of La Force on the ramparts of Ville-Nouvelle, had gone forward, under a flag of truce, to speak to him. He found the Huguenot chief eager for some arrangement which would put an end to this fratricidal struggle; and, at his suggestion, he spoke to Chaulnes and urged him to persuade the Constable to meet Rohan, who, La Force had given him to understand, would be willing to approach Montauban for that purpose, and discuss with him terms of peace. This Chaulnes agreed to do, and on October 13 an interview took place between Luynes and Rohan at the Château of Regnies, some four leagues from Picqueos. After a long consultation, terms were agreed upon, subject to the approval of the King and the Council, which, says Bassompierre, were “advantageous and honourable for the King and useful for the State.” But when the Council met, Schomberg urged that a decision should be postponed until after he and his colleagues at Le Moustier had made their attempt to take the town, which he was confident would be successful. In that event, he pointed out, they would be able to impose much more severe terms on the Huguenots. And he swore “on his honour and his life” that he would take Montauban within the time specified. The King and the Council, impressed by such unbounded confidence, agreed to do as he advised.

On the 17th, the Constable sent for Bassompierre to come to Le Moustier, where he had gone to dine with Schomberg, and inquired whether a mine which he had instructed him to prepare some days before were finished.{325} Bassompierre replied in the affirmative, upon which the Constable said: “It must be exploded to-morrow so soon as you receive the order from me, for, if it please God, to-morrow we shall be in Montauban, provided everyone is willing to do his duty.” Bassompierre answered that he could rely on the Guards’ division doing theirs, when Luynes told him that the explosion of the mine must be followed by a feint against the advanced-works of Ville-Nouvelle, in order to divert the enemy while the Le Moustier division stormed the town. Bassompierre had heard during the past two days a furious bombardment proceeding in that quarter, but when he scanned the defences, he could not perceive any practicable breach nor even the appearance of one. “Monsieur,” said he, “you speak with great confidence. May God grant that it may be justified!” Both the Constable and Schomberg appeared to regard the taking of the town as already assured, and, as he took leave of them, the latter said: “Brother, I invite you to dine with me the day after to-morrow in Montauban.” “Brother,” answered Bassompierre, “that will be a Friday and a fish-day. Let us postpone it until Sunday, and do not fail to be there.”

Bassompierre transmitted the order which he had received from the Constable to Chaulnes and Praslin, who instructed him to take charge of the mine, and to have everything in readiness for the diversion they were to make on the morrow.

The eventful day which, if Schomberg and his colleagues were to be believed, was destined to atone for all the toil and bloodshed of the past two months, arrived, and with it the King, the Constable, the Cardinal de Retz, Père Arnoux, Puisieux, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, and many other distinguished persons, who were conducted by them to carefully-selected positions from which they would be able to enjoy an uninterrupted view of the storming of the town. At the same time, they ordered their servants to pack up their plate, linen, and so{326} forth, as they intended to sup and sleep in Montauban. “And many other things they did more ridiculous than I shall condescend to write down.”

Early in the afternoon, the Guards’ division received orders “to begin the dance,” and Bassompierre fired his mine, which blew a big hole in the enemy’s advanced-works in that quarter and sent an unfortunate young officer of the Guards, the Baron d’Auges, into another world. Mines, in those days, appear to have had an unpleasant way of taking toll of both sides. The Guards occupied the crater, but, in accordance with their orders, did not advance any further. At the same time, the troops at Ville-Bourbon made a similar diversion.

The great assault, however, tarried. It tarried so long that at length the King grew impatient, and sent to Schomberg and his colleagues to inquire the reason why they did not advance. They replied that there was no breach that was practicable. Presently, he sent again, and was informed that, though there was a breach, scaling-ladders would be required, and these had not yet arrived. The scaling-ladders were brought, and once more the King wanted to know why they did not attack. The answer was that the delay had enabled the enemy to repair the breach; it would have to be reopened by a fresh bombardment.

“Finally,” says Bassompierre, “after having wasted the whole day up to six o’clock in the evening, and kept 600 gentlemen and a great number of people of note under arms all day, without doing or attempting to do anything, unless it were to kill a good many people of the town who showed themselves, they sent to tell the King that they had freshly reconnoitred the place where the attack must be delivered, and that truly it was not practicable. And upon that everyone went home.”

Next day, Louis XIII sent a message to Ville-Nouvelle requesting one of the two marshals or Bassompierre to come to Picqueos; and it was decided that Bassompierre{327} should go. He found the King in his cabinet with the Constable, the Cardinal de Retz, and Roucellaï, and it was plain that his Majesty was in a very ill-humour. “Bassompierre,” said he, “you have long been of opinion that nothing of any use would be accomplished on the side of Le Moustier.” “Your Majesty will pardon me,” answered Bassompierre, “but I never believed that everything that was proposed would succeed. Nevertheless, one must judge things by the results.” The King then told him that Schomberg and his colleagues had assured him that in five days they would be able to establish a battery of their heaviest guns on a knoll within a very short distance of the walls, and open a breach which would enable them to storm the town; and inquired what he thought about it. Bassompierre replied that, if they did succeed in establishing a battery there, the town must fall; but he very much doubted whether the enemy would allow them to do it. “And I,” exclaimed the King angrily, “refuse to wait for what they wish to do. For they are deceivers; and I will never believe anything they say again.” The Constable here interposed, and begged his Majesty to remember that the generals at Le Moustier were as much mortified as he was at the fiasco of the previous day. And he asked that they might be given another chance of redeeming their promise to take the town. To this the King agreed, and Bassompierre was told to arrange another diversion when the time for the assault to be delivered should arrive.

However, it never did arrive. During the next few days the knoll was fortified without any interference from the enemy, and nothing remained but to get the guns into position. But, on the early morning of the 25th, the garrison exploded a mine under the knoll which blew it up with its defences, and followed this up by a murderous sally against the Picardy Regiment, who were driven out of their trenches with heavy loss. Three nights later, they made another sortie, this time at the expense of the{328} Champagne Regiment, and, breaking right through it, penetrated to the besiegers’ battery-positions and destroyed one of their largest guns.

After this it was obviously impossible to continue the siege with the smallest hope of success; the winter was coming on; the army, badly paid and badly fed, with no confidence in its leaders, and harassed incessantly by a bold and resolute enemy, was becoming demoralised and was dwindling every day from death, sickness and desertion. Of 30,000 men who had encamped before Montauban at the end of August, only 12,000 effective combatants remained; and the division before Ville-Bourbon was now so weak that its leaders were obliged to ask the Guards for assistance to enable them to hold their trenches against the perpetual attacks to which they were exposed.

On the morrow, the Constable came to Le Moustier and summoned a council of war to decide what was to be done. “Everyone saw plainly,” says Bassompierre, “that we had no longer the means of continuing the siege; but no one wished to propose that it should be abandoned.” At length, Bassompierre took upon himself to do so and urged that they should “reserve the King, themselves and this army for a better future and a more convenient season.” To this the other leaders offered no opposition, and the Constable proceeded to communicate their decision to the King. Louis XIII, with tears in his eyes, directed Bassompierre to supervise the raising of the siege, and afterwards to march, with the greater part of the army, on Monheurt, a little town on the Garonne which had just revolted, as he and the Constable desired to terminate the campaign with a success, however unimportant it might be.

To raise the siege without the risk of incurring further losses was far from an easy task, as, unless every precaution were taken, there was grave danger that the garrison, flushed with success, might sally out and fall upon the{329} rear of the army while it was crossing the Tarn. However, Bassompierre appears to have made his arrangements with considerable skill, and on November 10 the last of the troops were withdrawn, with no more serious interference than a little skirmishing.

The disastrous result of the siege of Montauban caused general exasperation against Luynes, who met with a very bad reception from the people of Toulouse—numbers of whose relatives and friends had fallen during the siege—when he accompanied the King thither about the middle of November. The High Catholic party was particularly furious, and accused the Constable, not only of incapacity, but of treason. What was a more serious matter for him, was the fact that the King was growing weary of his favourite.

This change in Louis XIII’s attitude towards the man whom he had raised so high, and who had so long exercised such an absolute dominion over him, seems to have begun some months before; but it was at first carefully concealed from all but two or three of his intimates.

“One morning, after the siege of Saint-Jean-d’Angély,” says Bassompierre, “as the Constable was returning from dinner, and was about to enter the King’s lodging, with his Swiss and his guards marching before him, and the whole Court and the chief officers of the army following him, the King, perceiving his approach from a window, said to me: ‘See, Bassompierre, it is the King who enters.’ ‘You will pardon me, Sire,’ said I to him, ‘it is a Constable favoured by his master, who is showing your grandeur and displaying the honours you have conferred upon him to the eyes of everyone.’ ‘You do not know him,’ said he. ‘He believes that I ought to give him the rest, and wants to play the King. But I will certainly prevent him doing that, so long as I am alive.’ Upon that I said to him: ‘You are very unfortunate to have taken such fancies into your head; he is also unfortunate, because you have conceived these suspicions against him; and I still more so, because you have{330} revealed them to me. For, one of these days, you and he will shed a few tears, and then you will be appeased; and afterwards you will act as do husbands and wives who, when they have made up their quarrels, dismiss from their service the servants to whom they had confided their ill-will towards each other. Besides, you will tell him that you have not confided your dissatisfaction with him to any save to myself and to certain others; and we shall be the sufferers. And you have seen that, last year, the mere suspicion that he entertained that you might be inclined to favour me determined him to ruin me.’

“He [the King] swore to me with great oaths that he would never speak of it, whatever reconciliation there might be between them, and that he did not intend to open his mind to anyone on this matter, save Père Arnoux and myself, and that on my life I must engage never to open mine to anyone, save Père Arnoux, and only after he [the King] shall have spoken to him, and should command me to do it. I told him that he had but to command me, and that I had already given this command to myself, as it was of importance to my future and to my life.”

A few days after this conversation, Bassompierre was sent to Paris, at which he was much relieved, “since he found that confidences of the King were very dangerous”; and when, some weeks later, he rejoined the army at the beginning of the siege of Montauban, he took care never to approach his Majesty unless he were sent for.

“The resentment of the King against the Constable increased hourly, and the latter, whether it was that he felt assured of the King’s affection, or that the important affairs which he had upon his hands prevented him thinking about it, or that his grandeur blinded him, took less care to entertain the King than he had done formerly. In consequence, the displeasure of the King augmented greatly, and every time that he was able to speak to me in private, he expressed to me the most violent resentment.

“On one occasion when I had come to see him, the Milord de Hay, Ambassador Extraordinary of the King of Great Britain, who had been sent to intervene in favour{331} of peace between the King and the Huguenots, had his first audience of the King, at the conclusion of which he went to visit the Constable. Puisieux, according to custom, came to know from the King what the milord had said at the audience. Upon which the King called me to make a third in their conversation and said to me: ‘He [the Ambassador] is going to have audience of King Luynes!’ I was very astonished at him speaking to me before M. de Puisieux and pretended to misunderstand him; but he said to me: ‘There is no danger before Puisieux, for he is in our secret.’ ‘There is no danger, Sire!’ I exclaimed. ‘Now I am assuredly undone, for he is a timorous and cowardly man, like his father the Chancellor, who at the first lash of the whip will confess everything, and will, in consequence, ruin all his adherents and accomplices.’”

The King began to laugh, and told Bassompierre that he would answer for Puisieux’s discretion. Then he began a long tirade against his favourite, and appeared particularly indignant that the latter should, on the death of Du Vair, the Keeper of the Seals, which had occurred at the beginning of August, have persuaded him to give him the vacant post, notwithstanding that it was as contrary to usage as to common sense for a man to hold the Seals and the Constable’s sword.[1]

Bassompierre left the royal presence, feeling very uneasy. He saw clearly that Luynes was losing his hold over the King; but he knew that it might be some time before the young monarch would be able to summon up sufficient resolution to shake it off entirely; and, meanwhile, if Puisieux, whom he thoroughly distrusted, were to abuse the King’s confidence, and lead the Constable to believe that he was endeavouring to influence his Majesty against him, he would find himself in an even more difficult situation than he had the previous year. He{332} therefore decided that his safest course was “to make some representations to him [Luynes] on the subject, for his good,” without, however, allowing the Constable to suspect that the King had spoken to him. They would probably be well received, for, since his return from Spain, the favourite’s manner towards him had been very cordial, and he appeared most anxious that Bassompierre should identify his interests with his own by marrying his niece.

“Some days after this, happening to be in his cabinet with him, I told him that, as his very humble servant, devoted to his interests, I felt myself obliged to point out to him that he did not cultivate sufficiently the good graces of the King, and that he was not so assiduous in doing this as heretofore; that, as the King was increasing in age and in knowledge of things, and he in charges, honours and benefits, he ought also to increase in submission towards his King, his master, and his benefactor, and that, in God’s name, I begged him to take care and to pardon the liberty I had taken in speaking to him concerning it, since it proceeded from my zeal and passion for his very humble service.”

The favourite took Bassompierre’s warning in very good part, but made light of it:

“He answered that he thanked me and felt obliged for the solicitude which I had for the preservation of his favour, which would assuredly be very useful and profitable to me, and that I had begun to speak to him as a nephew, which he hoped I should be in a little while; that he wished also to answer me as an uncle, and to tell me that I might rest assured that he knew the King to the bottom of his soul; that he understood the means necessary to keep him, as he had known those to win him, and that he purposely gave him on occasion little causes for complaint, which served only to increase the warmth of the affection which he entertained for him. I saw clearly that he was of the same stamp as all other favourites, who believe that, once they have established their fortune, it will endure for ever, and do not recognise the approach of{333} their disgrace until they have no longer the means to prevent it.”

During the closing weeks of the siege of Montauban, whenever the King had an opportunity of speaking to Bassompierre privately, he “complained incessantly of the Constable.” The love—it was of a very innocent kind—which Louis had hitherto entertained for Luynes’s beautiful wife, Marie de Rohan, no longer protected her husband. This love had, in fact, changed into hatred, since his Majesty had perceived that the lady was accepting other attentions, without doubt less platonic than his.

And he took a particularly mean way of avenging himself.

“What made me think worse of him [the King],” writes Bassompierre, “was that all of a sudden the extreme passion that he entertained for Madame la Connétable was converted into such hatred, that he warned her husband that the Duc de Chevreuse was in love with her. He told me that he had said this, upon which I said to him that he had done very ill, and that to make mischief between a husband and wife was to commit sin. ‘God will pardon me for it, if it pleases Him,’ he answered; ‘but I have felt great pleasure in avenging myself on her and of inflicting this mortification upon him.’ And he went on to say several things against him, and, amongst others, that before six months had passed, he would make him disgorge all that he had taken from him.”

A few days after the siege of Montauban had been raised, the King’s other two confidants, the Jesuit Père Arnoux and Puisieux, the former of whom suspected Luynes of desiring to make peace with the Protestants on their own terms, joined forces to procure the downfall of the favourite. But they had underrated the power which habit and the fear of change exercised over the cold heart and indolent mind of Louis XIII. He betrayed them to Luynes, or, perhaps, the pusillanimous Puisieux may have{334} betrayed his fellow-conspirator. Anyway, Luynes learned of the intrigue and insisted on the Jesuit’s disgrace; and “the first news that I had from him [the King],” says Bassompierre, “was that he had been constrained to abandon Père Arnoux to the hatred of the Constable.” The King added that Bassompierre “might be assured that there was nothing against him.” Nevertheless, says that gentleman, “I did not fail to be in great apprehension, although I could say that every time that the King had spoken to me on the subject I had warded off his blows, and that I had been infinitely distressed that he had ever made me the recipient of his confidence.”

However, Bassompierre need not have been alarmed, as it was very soon to be beyond the power of Luynes to injure anyone.

On November 16 Bassompierre and his army encamped before Monheurt, and on the 18th the trenches were opened. A day or two later he had an exceedingly narrow escape of his life.

He was riding, followed by two aides-de-camp, from the trenches of the Piedmont Regiment, to those of the Normandy Regiment, a journey which he had made several times already without interference from the garrison, although it was well within musket-shot of the town, and “dressed in scarlet, with the cross on his cloak, and mounted on a white pony, he was easily recognisable.” Suddenly, the advanced bastion and counterscarp bristled with musketeers, who began firing at him and “with such fury that he heard nothing but balls whistling about him.” One ball struck the pommel of his saddle and another pierced his cloak, but he managed to reach a large tree without being hit, and took shelter behind it. Here he was in safety, though the enemy fired more than a hundred shots at it. At length, the firing ceased and, thinking that they had exhausted their ammunition, he mounted and galloped towards the{335} trenches of the Normandy Regiment. However, they had only been waiting for him to show himself, and, so soon as he did so, they began firing at him again as fiercely as ever. “But,” says he, “as my hour was not yet come, God preserved me against the attempt; though I believe I was never nearer death than I was on that occasion.”

The weather was very bad, rain falling incessantly, and the soldiers were nearly up to their knees in mud. Nevertheless, they worked well, and by the 22nd, on which day the siege-artillery arrived, they had pushed their trenches close to the walls.

Meanwhile, Bassompierre had received a secret communication from the Marquis de Mirambeau, the commander of the garrison, who offered to surrender Monheurt, in consideration of receiving a sum of 4,000 crowns and a formal pardon for his offence of having taken up arms against the King. The Maréchal de Roquelaure, lieutenant-general of Guienne, had lately arrived to take the nominal command of the siege operations. But he left their direction entirely in Bassompierre’s hands, and, as Mirambeau had requested that he should not be informed of his offer, it was communicated to Louis XIII, who was still at Toulouse. This decided the King and the Constable to come to Monheurt, “in order to have the honour of taking it.”

On the 23rd, Bassompierre, after inspecting one of his batteries, advanced a few paces in front of it to survey some point in the defences. “The gunners,” he says, “not thinking that I was there, discharged their pieces, the wind of which threw me very rudely to the ground, and left me with a singing in my right ear, accompanied by insupportable twinges.” Two hours later he was taken ill with fever, but he remained on duty all that day, during which the trenches were pushed up to the border of the moat. Next morning, however, he was so much worse that he wrote to the King and the Constable asking to be relieved of his command, and saying that he{336} proposed to go to La Réole, where he could secure skilled medical attention, for he was too prudent to trust himself to the care of the army surgeons. He also begged them to send him a doctor.

Next morning he received a very kind letter from the King, granting his request and informing him that he was sending a doctor, upon which he embarked in a boat, accompanied by his personal attendants and a guard of Swiss halberdiers, and set off down the Garonne towards La Réole.

On arriving at Tonneins, about midway between Monheurt and Marmande, he learned that a small force of cavalry was crossing the river to the right bank, and that they were the Constable’s own company of gensdarmes.

He sent for the officers in command to inquire where they were going, and was told that they had received orders from the Maréchal de Roquelaure to take up their quarters in a little town called Gontaud, about half-a-league from Marmande. He expressed his surprise that Roquelaure should send a small body of cavalry, unaccompanied by infantry, to an open town in the midst of the enemy’s country, where there was a great danger of their being surprised; and, aware that the King and the Constable would certainly cancel the order if they were informed of it, begged the officers to return, while he sent a message to the King requesting that they should be quartered at Marmande, which was a walled town. But the officers pointed out that the baggage had already been sent on to Gontaud; and, on their assuring him that they would keep a sharp look-out that night, and on the morrow ask to be transferred to safer quarters, he allowed them to proceed, although he felt very uneasy.

On reaching Marmande, he felt so much worse that he decided to remain there for the night, instead of continuing his journey to La Réole, and therefore had himself carried to an inn in the suburb, and sent for a doctor. But the only one who could be found was a country-practitioner,{337} to whose tender mercies Bassompierre did not feel inclined to entrust himself. However, shortly afterwards, a quack doctor named Duboure, whom the Baron d’Estissac had sent after him, arrived on the scene. Duboure was none too sober, but he possessed remedies which afforded the patient some temporary relief, and about nine o’clock in the evening one of the King’s own physicians, named Le Mire, whom his Majesty had sent, made his appearance. The great man, after consulting, for form’s sake, with his humble colleagues, “proceeded to scarify him and apply leeches to his shoulders, in order to remove the furious tingling which he had in the head.”

“This was about eleven o’clock, and, at the same time, we heard many pistol-shots in the street of the faubourg, which is on the bank of the Garonne. They were fired by the Constable’s gensdarmes, who were being pursued by the enemy, who had attacked them at Gontaud the same evening they arrived there. At this news, my servants hurriedly placed a napkin on my shoulders, which were covered with blood, put on my dressing-gown, and, in this state, had me carried away by four of my Swiss halberdiers and five or six other persons whom they had contrived to pick up. They accompanied me nearly to the gate of the town, and then ran back to barricade themselves in my lodging, to try and save themselves and my horses, plate and equipage. They believed that I had entered the town, and there only remained with me the four Swiss, the two doctors, Le Mire and Duboure, and two valets de chambre. But, as I approached the gate, the people of Marmande saluted me with several musket-shots, believing (as they told me afterwards) that I was the petard which the enemy were bringing to fasten to their gate. My people cried out that it was the general who commanded the army, whom they had come to welcome as he disembarked from his boat, and that, if they did not open, they would repent it. But, for all that, they could get nothing out of them, except permission for me to be placed in a little open{338} guard-house which was within the barrier. A man came to open the door and let me in, and at once closed it upon me, after which he threw himself upon a little drawbridge, which was forthwith raised. Thus, I found myself confined within this barrier, without being able to send any message to my servants, who, believing that I had entered the town, confined themselves to guarding my lodging; and the people of the town refused to open the gate until seven o’clock the next morning. I was stretched on a table, all covered with blood from my scarification, which congealed and clung to the napkin which had been placed over it, so that it galled me from time to time, while my head ached intolerably, for I was in a high fever; and I was covered only with a rather thin dressing-gown, in very cold weather, for it was the 26th of November. I can say that I was in the greatest torment and the most evil plight that I ever suffered in my life, which made me wish for death a hundred times.”

When morning dawned, the good citizens of Marmande, having satisfied themselves that there were no Huguenots lurking in the vicinity, at length summoned up courage to open their gates, and the unfortunate Bassompierre was carried to an inn and put to bed. Here he lay for a fortnight between life and death, “stricken with a purple fever,” and it was only his iron constitution which eventually turned the scale in his favour. The crisis once passed, however, he mended rapidly, and in a few days was sufficiently recovered to continue his journey to La Réole, and thence to Bordeaux, where he arrived on December 15, to await the King.

Louis XIII and the Constable had arrived at Monheurt on November 28, and had taken up their quarters at a village called Longuetille, about a league from the town. The place was taken on December 12; the lives of the inhabitants were spared, but the garrison was put to the sword, and the place pillaged and burned to the ground. Luynes, however, was not present to witness this sorry triumph. While the flames were devouring the{339} conquered town, he lay at Longuetille, in the grip of the same pestilential fever from which Bassompierre so narrowly escaped, and which was now ravaging the Royal army. The disasters of the campaign, and the unceasing anxiety as to the future to which he had been for some time a prey, had told upon his strength, and three days later he died, in his forty-fourth year. “He was little regretted by the King,” says Bassompierre; “while his death was hailed with joy by the bulk of the nation, with whom he had long been intensely unpopular. Even the Ultramontane party, whose cause he had so well served, received the news with satisfaction.” They had been infuriated by the belief that he intended to make peace with the Huguenots, and ascribed the Montauban fiasco to the fact that the Almighty refused to make use of so unworthy an instrument for the destruction of the heretics.{340}

Who will govern the King and France?—The pretenders to the royal favour—Position of Bassompierre—The Cardinal de Retz and Schomberg join forces and secure for their ally De Vic the office of Keeper of the Seals—They propose to remove Bassompierre from the path of their ambition by separating him from the King—Bassompierre is offered the lieutenancy-general of Guienne and subsequently the government of Béarn, but declines both offices—He inflicts a sharp reverse upon Retz and Schomberg—Condé joins the Court—His designs—The rival parties: the party of the Ministers and the party of the marshals—Monsieur le Prince decides to ally himself with that of the Ministers—Mortifying rebuff administered by the King to the Ministers at the instance of Bassompierre—Failure of an attempt of the Ministers to injure Bassompierre and Créquy with Louis XIII—Arrival of the King in Paris—Affectionate meeting between him and his mother—Accident to the Queen.

Luynes dead, who would govern the King and France? Such was the question which everyone was asking himself, for that Louis XIII, so jealous of his royal authority, yet too indolent to exercise it himself, would require someone to lean on was a foregone conclusion. There were many pretenders. There was Marie de’ Medici, who, now that the man who had estranged her son from her was no more, might hope to recover in time much of the influence she had once exercised over the King. And Marie’s triumph would mean that of Richelieu, who had now acquired so great an ascendancy over her that scandal asserted that he was her lover. There was the greedy and ambitious Condé, who had learned prudence from adversity, but was in other respects but little changed. Luynes, in the last months of his “reign,” had separated Condé from the King, and tricked Richelieu out of the cardinal’s hat which had been the secret condition of the prelate’s reconciliation with the favourite, addressing a formal demand for{341} it to Gregory XV, accompanied by a private request to his Holiness not to accord it. But now the lists were again open to them. Then there were the Ministers: the Cardinal de Retz, whom Luynes had made the nominal chief of the Council, and his ally Schomberg, Superintendent of Finance; the Chancellor Brulart de Sillery and his son Puisieux, the Minister for Foreign Affairs; and old Jeannin. And all these persons felt that they might have to reckon seriously with Bassompierre, in whose society the King undoubtedly took more pleasure than in that of any of them, and whom, they knew, the late Constable had regarded as his only dangerous rival.

It is certain that, had Bassompierre been so minded, he would have stood an excellent chance of succeeding to Luynes’s place as favourite, and that his elevation would have been well received, as he was exceedingly popular both at the Court and in the Army. But his epicurean wisdom rejected the idea of a life of gilded slavery; to be obliged to forgo the society of his “beautiful mistresses,” in order to dance attendance upon his youthful sovereign and make up his mind for him a dozen times a day, was not at all an attractive prospect to one who infinitely preferred pleasure to grandeur; the royal favour, without the responsibilities of power, was sufficient for him.

The Cardinal de Retz, Schomberg and Puisieux had the advantage of being near the King at the time of the Constable’s death. The first two at once joined forces against Puisieux and “aspired to become all-powerful and to restrain the King from doing anything except on their advice.” They secured a decided success by persuading Louis XIII to bestow the vacant office of Keeper of the Seals upon De Vic, a counsellor of State, who was devoted to their interests, and then put their heads together to find a means of separating the King from Bassompierre, whom they regarded as a serious obstacle in the path of their ambition. Louis XIII{342} arrived at Bordeaux on December 21, and shortly afterwards the two Ministers proposed to him to leave Bassompierre in Guienne as lieutenant-general of that province, in place of the Maréchal de Roquelaure, who was to be compensated for the loss of his post by a present of 200,000 livres and the government of Lectoure. Having obtained his Majesty’s consent to this arrangement, they sent Roucellaï to sound Bassompierre on the matter and “even offered to add to this charge that of marshal of France.” But Bassompierre preferred to wait upon events and to see into whose hands the management of affairs would fall, foreseeing that whoever might secure it would not be strong enough to maintain his position without support, and “being assured that he would be very pleased to have him for a friend, and to give him a larger share of the cake than they [Retz and Schomberg] were offering him.”

“When the King spoke to me of the lieutenancy-general [of Guienne], I answered that I should esteem myself more happy to occupy the post of Colonel-General of the Swiss near his person than any other away from it; that I was only just recovering from a severe illness which demanded three months’ repose, and that during that time I desired no other employment than that of my first office of Colonel-General. And to this his Majesty agreed.”

Although foiled in this attempt to get Bassompierre out of the way, Retz and Schomberg presently returned to the charge, and having persuaded the Maréchal de Thémines to surrender the government of Béarn, in exchange for the lieutenancy-general of Guienne, offered it to Bassompierre. The government of Béarn, though, in the present circumstances, it could scarcely be regarded as a bed of roses, was a very honourable and lucrative post. But its acceptance would, of course, entail an almost complete separation from the King, and from—what was more important in Bassompierre’s estimation—the Court{343} and Paris; and he therefore returned the same answer as he had in the case of Guienne.

A day or two later, Bassompierre had the satisfaction of inflicting a sharp reverse upon the two Ministers.

The Cardinal and Schomberg had urged the King to follow up the capture of Monheurt by the surprise of Castillon, on the Dordogne, which, they declared, could very easily be carried out and would have an excellent effect. Now, Castillon belonged to the Duc de Bouillon, who, at the outbreak of hostilities, had entered into a compact with Louis XIII, which stipulated that this and other towns within his jurisdiction should “remain in the service of the King, but without making war on those of the Religion”; while the King, on his side, promised that they should in no way be interfered with. To seize Castillon therefore would be a direct breach of this agreement, and could only be defended on the ground that the townsfolk had sent assistance to the Huguenots, of which there was no evidence of any value. Nevertheless, Louis XIII allowed himself to be persuaded by the two Ministers to consent to this being done, provided that the rest of the Council did not oppose it. When, however, the project was laid before the Council, Bassompierre rose and denounced it in a vigorous speech, in which he declared that, if executed, it would be a “great stain on the King’s honour and reputation,” after which he proceeded to give his Majesty some very wholesome advice on the danger of breaking his royal word.

“Sire,” said he, “it is easy for a man to deceive a person who trusts him, but it is not easy to deceive a second time. A promise badly observed only once deprives him who breaks it of the trust of the whole world.” And he stigmatized the counsel which had been given the King, of the source of which he pretended ignorance, as “interested, evil-intentioned and rash,” which, if followed, would probably result in driving Bouillon into rebellion, and with him numbers of{344} Protestants who had hitherto remained neutral, since they would feel that it was impossible to trust the word of the King.

One or two other members of the Council signified their agreement with the views expressed by Bassompierre, upon which the King announced that he had come to the same conclusion, to the great discomfiture of Retz and Schomberg, who were forced to recognise that their design of governing the young monarch was likely to prove a much more difficult task than they had bargained for.

Louis XIII left Bordeaux on the last day of the year, and travelled by easy stages towards Paris. At Château-neuf-sur-Charente, where he arrived on January 6, 1622, another pretender to Luynes’s shoes appeared upon the scene, in the person of Condé.

“Monsieur le Prince,” says Bassompierre, “who was extremely cunning and supple, was equally courteous to everyone, without inclining to any side, until he had perceived the tendency of the market. His design was to persuade the King to continue the Huguenot war, for three reasons, in my opinion: first, because of the ardent affection which he had for his religion and his hatred against the Huguenot party; secondly, because he thought that he could govern the King better in time of war than in time of peace, since he would undoubtedly be lieutenant-general of his army; and, lastly, in order to separate him from the Queen his mother, the Chancellor and the old Ministers, who were his antipathy.”

In order to ascertain the state of the Court, Condé addressed himself to the Abbé Roucellaï, an adroit and insinuating personage, who had been in turn the protégé of Concini, the Queen-Mother and Luynes, and who, now that the Constable was dead, had decided to seek a new patron in Monsieur le Prince. The abbé told him that there were two parties at the Court. On one side, were the three Ministers, Retz, Schomberg and the new Keeper of{345} the Seals, De Vic, “who desired to possess the King’s mind to the exclusion of everyone else”; on the other, the three marshals of France, Praslin, Chaulnes, and Créquy[2] and some others, who were resolved not to submit to this. He added that the King conversed frequently with Bassompierre and appeared to have a rather high opinion of him, and that, if the latter had any ambition to succeed to the favour of the late Constable, it might very well be realised. That, however, did not seem to be his desire, “although he was disposed to accept the share in the King’s good graces which his services might merit.” Bassompierre and the Ministers, he told the prince, were “not always of the same opinion,” and only a few days before he had spoken very bitterly against them before his Majesty in a council. Condé then inquired if Bassompierre were in favour of continuing the war against the Huguenots, and Roucellaï answered that he had pressed Luynes to enter into negotiations with Rohan, from fear that the Royal army would be obliged to raise the siege of Montauban. As a result of this conversation, the prince sent Roucellaï to Bassompierre to inform him that he wished to speak to him and ascertain his views in regard to the war.

Before seeing Bassompierre, however, Condé had an interview with the Ministers, whom he found in warlike mood, not because they believed that any useful purpose could be served by a continuance of this fratricidal strife, but for the same selfish reasons as he himself desired it, namely, “to keep the King so far as possible from Paris, in order the better to govern him.” He then approached Créquy, who answered that he was in favour of peace, provided that it could be obtained on advantageous and honourable terms. Bassompierre gave him a similar reply, when he spoke to him on the matter, and added that he would find Praslin and all other good servants of{346} the King of the same opinion. “It is singular,” said the prince; “all you men of war, who ought to desire it, and can only make your way by means of it, want peace; and the lawyers and statesmen demand war.” “I answered,” says Bassompierre, “that I desired war, and that it ought to bring me fortune and advancement, but only on condition that it was for the service of the King and the good of the State; and that otherwise I should esteem myself a bad servant of the King and a bad Frenchman, if, for my own private advantage, I were to desire a thing which must cause both so much evil and prejudice.”

After this sharp, if indirect, rebuke, Condé left him and told Roucellaï that, after sounding Créquy and Bassompierre, he found that he was likely to have more in common with the Ministers than with them.

During the remainder of the journey to Paris, skirmishes between the rival parties were of frequent occurrence, each doing everything possible to prejudice the King against the other. At Sauzé, where the Court arrived on the 10th, Bassompierre again scored at the expense of the Ministers.

Louis XIII was about to sit down to cards with Bassompierre and Praslin, when the three Ministers were announced.

“The King said to us as he saw them enter: ‘Mon Dieu, how tiresome these people are! When one is thinking of amusing oneself, they come to torment me, and most often they have nothing to tell me.’ I, who was very pleased to have the chance of giving them a rebuff in revenge for the ill turns they were doing me every day, said to the King: ‘What, Sire! Do these gentlemen come without being sent for by you, or without having first informed your Majesty that there is something of importance to deliberate upon, and then ask for your time?’ ‘No,’ said he, ‘they never inform me, and come when it pleases them, and most often when it does not please me, as they do now.’ ‘Jesus, Sire! is it possible?’ I replied. ‘That is to treat you like a scholar,

and make themselves your tutors, who come to give you a lesson when it pleases them. You ought, Sire, to conduct your affairs like a King, and every day, on your arrival at the place where you purpose to spend the night, one of your Secretaries of State should come to tell you if there be any news of importance which requires the assembling of your Council, and then you should send for them to come to you, either at that same hour, or at one which will be most convenient to you. And, if they have anything to tell you, let them inform you of it first, and then send them word when they are to come to you. It was thus that the late King your father conducted his affairs, and your Majesty ought to do likewise; and if they [the Ministers] should come to you otherwise [i.e., without being sent for], to send them away, and to tell them of your intention firmly, once for all.’

“The King took the representations I had made him in very good part, and said that, from that moment, he would put my counsel into practice; and he went on talking to the Maréchal de Praslin and myself. When our conversation had continued for some little time, Monsieur le Prince approached the King and said: ‘Sire, these gentlemen [the Ministers] await you to hold the council.’ The King turned to Monsieur le Prince with an angry countenance and exclaimed: ‘What council, Monsieur? I have not sent for them. I shall end by being their valet; they come when they please, and when it does not please me. Let them go away, if they wish to, and let them come only when I shall send for them; it is for them to consult my convenience and to send to inquire when that may be, and not for me to consult theirs. I desire that, at the end of each day’s journey, a Secretary of State should present himself at my lodging to inform me what news there is, and, if it be of importance, I will name a time to deliberate upon it; but I will never allow them to name it; for I am their master.’

“Monsieur le Prince was a little surprised at this response and was very curious to know from what shop it came. He went back to tell them [the Ministers], who requested him to inform the King that they were come merely to receive the honour of his commands, as courtiers, and not otherwise, and that if only his Majesty would{348} speak a word to them, they would go away. The King did so, but very brusquely, and it was:—

“‘Messieurs, I am going to play cards with this company.’ Upon which they made him a profound reverence and withdrew, very astonished.”

The Ministers soon ascertained whom they had to thank for the very mortifying rebuff which they had received from the King, and were more incensed than ever against Bassompierre. The latter, who had been on very friendly terms with the Cardinal de Retz until his Eminence’s designs upon the King had brought their interests into collision, went to see him the next day and assured him that, so far as he himself was concerned, he was still his very humble servant. But he told him that he had no love for his colleagues, Schomberg and De Vic, and wished them to know it. The Cardinal begged him to be reconciled with them, but within forty-eight hours two incidents occurred which removed all hope of this.

It happened that, the following evening, news arrived that the Maréchal de Roquelaure was dangerously ill and that his recovery was considered hopeless. “Upon which,” says Bassompierre, “these gentlemen [the three Ministers] and Monsieur le Prince went in a body to the King to demand the charge of marshal of France, which he [Roquelaure] had, for M. de Schomberg. The only answer which the King made them was to say: “And Bassompierre—what shall he become?” This crude reply deeply affected M. de Schomberg, and from that day we ceased to speak to one another.”[3]

The second incident, which followed closely upon the first, served to embitter still further the relations between these two gentlemen.{349}

“It happened on the morrow that the King only travelled one stage,[4] at which we [Créquy and himself] were annoyed, because we saw that these gentlemen [the Ministers] were purposely delaying the King’s arrival, thinking, if time were allowed them, to usurp the authority before he had seen the Queen his mother and the old Ministers. The Maréchal de Créquy and I, while warming ourselves in the King’s wardrobe, complained of these short journeys, upon which the Comte de la Roche-guyon told us that they were made out of consideration for the French and Swiss Guards, who otherwise would be unable to follow us. We said then that this consideration ought not to occasion such a long delay; that we, who were respectively in command of the two regiments of Guards, did not complain, that the Guards would march so far as the King pleased, and that we could make them do what we wished. Out of these last words, which were reported to the Ministers, they proceeded to compound three dishes for the King, saying that we boasted of making the two regiments of Guards do what we wished, and that we could turn them in whatever direction we pleased. They attacked the King on his weak side, and he was angry at seeing that we were compromising his authority.

“The evening before he arrived at Poitiers, he told me that he desired to speak to me on the following morning, and said to me: ‘I promised to tell you all that might be said to me concerning you. That is why, since it has been reported to me that you were boasting of being able to persuade the Swiss to do all that you wished, and even against my service, I desired to make you understand that I do not approve of such discourse being held, and less by you than by another, seeing that I have always had entire confidence in you.’

“‘God be praised, Sire,’ I answered, ‘that my enemies, seeking every means to injure me, are unable to find anything save what is easy for me to avert and bring to naught. This accusation is of that quality, and you can learn the truth from their own mouths, although it is{350} but little accustomed to issue from them. Ask them, Sire, on what subject I said that I would make the Swiss do what I wished, and if they do not tell you that it was on that of their making long or short marches, about which M. de Créquy and I were complaining to one another, since they make arrangements for your Majesty to travel a shorter distance each day to return to Paris than a parish procession would cover, I am willing to lose my life. And your Majesty can judge whether that touches you or not, and whether you ought to regard this discourse as a boast of being able to employ the Swiss against your service.’”