Press Illustrating Service.

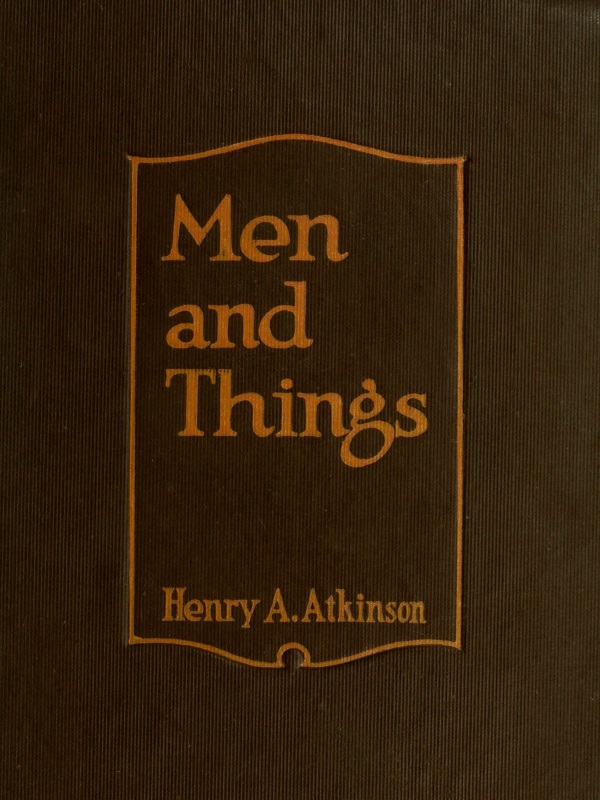

CUTTING STEEL FOR SHIPS WITH GIGANTIC SHEARS.

These workers are the servants of civilization and without them we would have no such trade as we have to-day.

BY

HENRY A. ATKINSON

SECRETARY, SOCIAL SERVICE DEPARTMENT OF THE CONGREGATIONAL CHURCHES

AND ASSOCIATE SECRETARY OF THE COMMISSION ON THE CHURCHES

AND SOCIAL SERVICE OF THE FEDERAL COUNCIL OF THE

CHURCHES OF CHRIST IN AMERICA

NEW YORK

MISSIONARY EDUCATION MOVEMENT

OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA

1918

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY

MISSIONARY EDUCATION MOVEMENT OF THE

UNITED STATES AND CANADA

CORRESPONDENCE CONCERNING MISSION STUDY Send the proper one of the following blanks to the secretary of your denominational mission board whose address is in the “List of Mission Boards and Correspondents” at the end of this book. ================================================================= We expect to form a mission study class, and desire to have any suggestions that you can send that will help in organizing and conducting it. Name ............................................................ Street and Number ............................................... City or Town ..................... State ........................ Denomination ..................... Church ....................... Text-book to be used ............................................ ================================================================= We have organized a mission study class and secured our books. Below is the enrolment. Name of City or Town .................... State ................. Text-book ......................... Underline auspices under which class is held: Denomination ...................... Church Y. P. Soc. Church ............................ Men Senior Women’s Soc. Intermediate Name of Leader .................... Y. W. Soc. Junior Sunday School Address ........................... Name of Pastor .................... Date of starting ............ State whether Mission Study Class, Frequency of Meetings ....... Lecture Course, Program Meetings, or Reading Circle ............... Number of Members ........... ................................. Does Leader desire Helps? ... Chairman, Missionary Committee, Young People’s Society ........... ............................................................ Address .................................................... Chairman, Missionary Committee, Sunday School .................... ............................................................ Address ....................................................

TO MY FATHER

THE REV. THOMAS A. ATKINSON

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Foreword | xiii | |

| I | The World of Work | 1 |

| II | The World of the Rural Workers | 17 |

| III | The World of the Spinners and Weavers | 33 |

| IV | The World of the Garment Workers | 49 |

| V | The World of the Miners | 65 |

| VI | The World of the Steel Workers | 79 |

| VII | The World of the Transportation Men | 95 |

| VIII | The World of the Makers of Luxuries | 113 |

| IX | The World of Seasonal Labor and the Casual Workers | 135 |

| X | The World of Industrial Women | 155 |

| XI | The World of the Child Workers | 173 |

| XII | The Message and Ministry of the Church | 191 |

| Bibliography | 211 | |

| Index | 215 |

| These workers are the servants of civilization | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

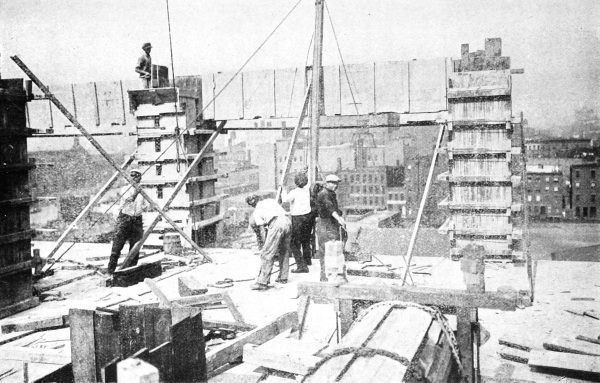

| The work which men do inevitably groups them together | 10 |

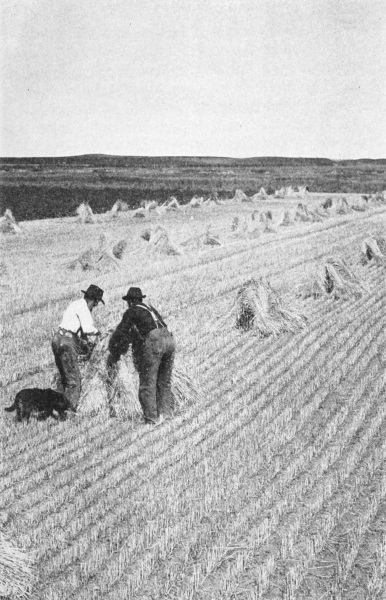

| Not many of us stop to consider the man who made possible the white bread that we eat | 18 |

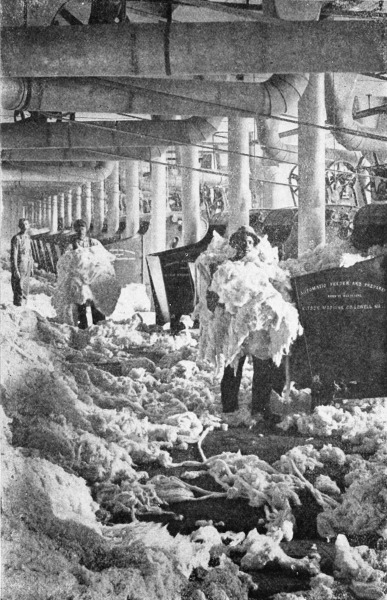

| The worker in these mills is a worker and little or nothing else | 42 |

| The workers on the sidewalks of Fifth Avenue | 50 |

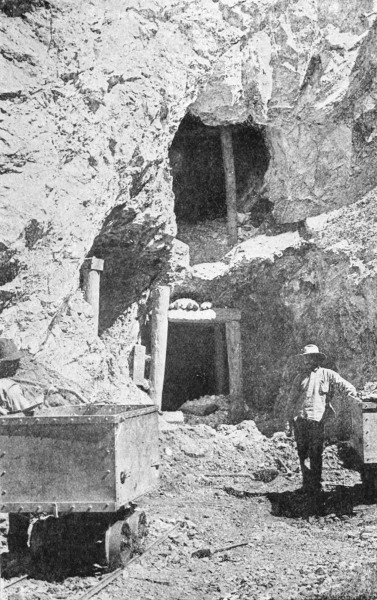

| We forget the men who are toiling underground | 66 |

| The New U. S. Bureau of Mines Rescue Car | 74 |

| Commerce and transportation are dependent upon the steel workers | 82 |

| The church must preach from the text “A man is more precious than a bar of steel” | 90 |

| Living upon the canal-boats and barges are the families of the workers | 106 |

| The cigarmakers carry no moral enthusiasm into their trade | 122 |

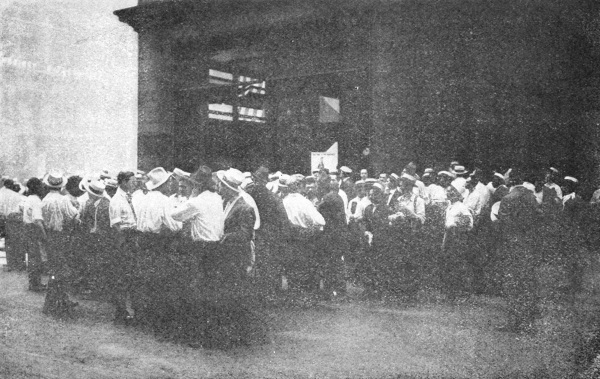

| The casual workers are the true servants of humanity | 146 |

| In the army of laborers the girl and the woman are drafted | 162 |

| Thousands of children in America are doing work which they ought not to do | 186 |

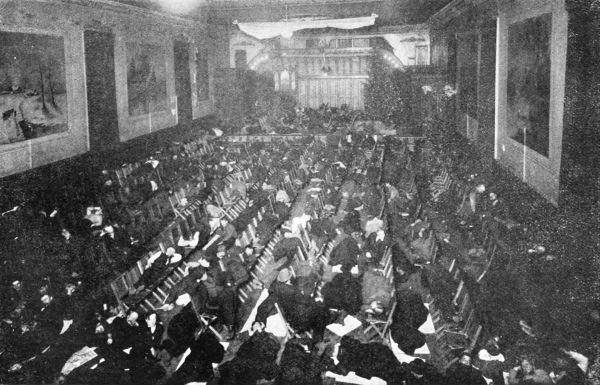

| A Russian Forum in session in the Church of All Nations, Boston | 194 |

| The Church of All Nations provided a sleeping place for the unemployed | 202 |

A friend said to me this last week, “There are two things that I instinctively distrust, one is prophecy, the other is statistics. Now that the war has lengthened into the fourth year and America has taken her place by the side of the Allies, I find my gorge rising every time any one attempts a prophecy and quotes statistics. All prophecies have proved false and statistics are utterly unreliable. Even the clocks have been made to lie by official decree.”

Granted that my friend is pessimistic, at the same time we must all sympathize with him in this feeling. In writing this book, I have tried to keep out of the realm of prophecy and have used just as few statistics as possible. Most of the facts were secured by investigations made prior to August, 1914. I have endeavored to check up every statement with all the reports I could secure from the Department of Labor at Washington, through the Survey and the New Republic, and through other sources. I feel reasonably certain that all the statements concerning conditions will bear investigation and are substantially correct. If there are discrepancies, it will be found after making due allowance for the judgment of others, that they are due to changes brought about by unusual conditions in industry. The principles are unchanged and it is upon these that I have attempted to place the most emphasis. Concrete facts are but illustrativeix of the principle involved. Conditions affect cases but leave principles undisturbed.

I am greatly indebted to the help in research given me by Miss Lucy Gardner, of Salem, Massachusetts. As far as possible I have given credit to the proper authorities for material used. If I have failed to do so I take this opportunity of acknowledging my indebtedness to all unknown authors and authorities who have contributed in any way.

This book goes forth to the young people of America in the hope that they will find in it some small inspiration that will prove an incentive to them to give themselves to the cause of humanity, realizing that through service, and through service alone, can any one make the fullest contribution to his generation.

“Men and Things,”—a nation is great only in its citizens. The great task before the church to-day is to help to readjust the conditions existing in all industries so that men and women may labor and enjoy the fruits of their labor and profit physically and spiritually in the wealth which they help to create.

Henry A. Atkinson.

New York, May, 1918.

One of the commonest sights in the city is that of the people going to work in the early morning; the streets are thronged with men carrying dinner pails, and girls and women carrying bundles. Many are hurrying with a worried look on their faces as if fearful of being a minute or two late. At night the same people are again on the streets with their faces turned in the opposite direction going home after the day’s work. A few hours’ rest, then a new day, and the same people may be seen in the same streets, hurrying to the ever unending tasks.

The country holds the same urge of work. Nothing is more interesting than a trip through the country early in the morning. With the first hint of dawn you see a thin pencil of smoke begin to stream from the chimneys of the farmhouses. Bobbing lanterns appear by the barn. You hear the clanking of chains and the rattle of harness as the teams are being made ready for the day’s toil. As the morning grows older, you meet the workers out on the road with their faces set sturdily toward the field of their labor.

All night long from a thousand centers massive trains are rushing toward other centers. In each engine two men, with nerves alert and eyes peering out into the darkness ahead, guide the power that pulls the train.2 Every few minutes the door of the firebox is opened and a gleam of light makes an arc through the darkness of the night as the fireman mends his fire.

During the daytime thousands of trackmen have inspected the rails; other thousands have been at work repairing the ties, putting in new rails, and improving the grade. Telegraphers are continuously flashing their messages along the wires; their invisible hands guide these flying trains. In factories, workshops, mills, mines, forests, on steamships, on the wharves, wherever there are human beings, there is work being done. Work is as ceaseless and persistent as life itself.

The Song of the World of Work. You remember, perhaps, the first time that you visited a big city. From your room in the hotel you could hear the roar of the streets. That roar is made up of hundreds of separate sounds. It is the voice of work from the throat of the city. It changes with each hour of the night. Just before dawn there is a lull and the voice is almost quiet but only for a short period; then it takes on a new volume of sound and grows in intensity to the full force of its noonday chorus. What is this voice saying? It is telling the story, and pouring out the complaint, and singing the song of the world of work. The idler or the parasite is the exception. People can live without working, but such is human nature that the person is rarely found who is willing to bear the odium of being a member of the class that never toils.

Work and Life. “What are you going to do when you grow up?” This is a common question asked of every girl and boy. Very early in our lives we begin to try to answer this question. Our environment shapes3 our attitude toward life, and helps us to choose the type of work to which we think we are adapted, but, having once settled the question of the kind of work we are to do, that choice eventually determines, in a large measure, our character. Work is so much a part of our lives that it marks us and puts us in groups. All ministers are very much alike, doctors are alike, lawyers are alike, business men are alike, business women resemble each other, so do miners and woodsmen. In fact, the work that we do groups us automatically with the others in the same profession or trade. Work creates our world for us and also gives us our vocabulary. A man who made his fortune on a big cattle-ranch in the West moved with his family to Chicago. His wife and daughter succeeded in getting into fashionable society and with the money at their command made quite a stir in the social world. Foolishly they were ashamed of their old life on the ranch. They had difficulty in living down their past, and the husband never reached a place where his family could be sure of him. He carried his old world with him into the new environment. One of the standing jokes among their friends was the way in which this man told his cronies at the club how his wife had “roped a likely critter and had him down to the house for inspection.” This was his description of a young man who was considered eligible for his daughter’s hand. The men who have been brought up in mining communities use the phraseology of the mines. One of the most prominent preachers in America was a miner until he was past twenty years of age. His sermons, lectures, and books are filled with the phrases learned in his early life. A preacher in a fishing village4 in the northern part of Scotland, in making his report to the Annual Conference, stated: “The Lord has blessed us wonderfully this year. In the spring, with the flood-tide of his grace, there was brought a multitude of souls into our harbor. We set our nets and many were taken. These we have salted down for the kingdom of God.” Needless to say, he and his people were dependent upon the fishing industry for a living.

Purpose of Work. Life is divided into work and play. Work is the exertion of energy for a given purpose. People accept the claim of life as they find it with little or no protest because one must work in order to eat. The compulsion of necessity determines the amount of work and the amount of play in the average life. Even a casual study of the industrial life of to-day convinces one that work absorbs a large part of the time and conscious energy of all the people. The letters T. B. M. meaning “Tired Business Man” are now used to typify a fact of modern life. Business takes so much time and effort that it leaves the individual so worn out at the end of every day that he is not able to think clearly, or to render much service to himself or to his friends. He is simply a run-down machine and must be recharged for the next day’s work.

In one of the American cities a group of nineteen girls formed themselves into a Bible study class, and met at the Young Women’s Christian Association building on Thursday nights. A light, inexpensive dinner was served and the pastor of one of the churches was asked to teach the group. All of these girls were members of the church and were engaged in work in the city. One was in a secretarial position, four were stenographers,5 two were saleswomen, and thirteen were employed in a department store. The hours of work were long for the majority of the class. On Saturday nights they were forced to work overtime. The average wage for the group was $7.25 a week. Out of this they had to buy their food, pay for their rooms, buy their clothes, and pay their car-fare. Whatever was left they could save or give away just as they pleased. After the classes had been meeting for about six weeks, it developed that only four of the girls went to church with any degree of regularity. Ten of them gave as a reason for not going that they were so tired on Sunday mornings that they could not do their work and get up in time to go to church. When they did get up, there were dozens of hooks and eyes and buttons that had to be sewed on, clothes which had to be mended, and the week’s washing to be done. In telling of their experiences one girl said, “Sunday is really my busiest day.” These girls can be taken as typical of a large number of workers, men and women. Life to the majority becomes simply the performance of labor. Work is the whole end of existence. All brightness and cheer is squeezed out by the compulsion of labor.

In a Pennsylvania coal town the employees of the company live in a little village built around the coke ovens. There is not a green thing in the whole village. A girl from Pittsburgh married one of the men who was interested in the mines. They moved to this town, and she took all her wedding presents and finery with her. In three weeks the smoke had ruined her clothes, had made the inside of her little home grimy, and the dirt and soot had ground itself into the carpets and floor,6 till she said, “I feel that all the beautiful life that Frank and I had planned to live together has become simply an incidental adjunct to the coke-ovens.” We often hear it said that the minds of people are stolid, stodgy, or indifferent, and that they do not appreciate the best things in life. The wonder is that the masses of the people appreciate them as much as they do.

The Purpose of Life. A well-known catechism teaches that, “The chief end of man is to glorify God and to enjoy him forever.” Herbert Spencer says, “The progress of mankind is in one aspect a means of liberating more and more life from mere toil, and leaving more and more life available for relaxation, for pleasure, culture, travel, and for games.” The struggle for existence consumes so much time that it becomes an end in itself. This ought not to be. The true purpose of life is not work, nor wealth, nor anything else that can be gained by human striving, but it is life itself. Therefore, the work that people do ought to contribute to an enrichment of life. We are indebted to Henry Churchill King for the splendid phrase, “The fine art of living.” William Morris said that whatever a man made ought to be a joy to the maker as well as to the user, so that all the riches created in the world should enrich the creator as well as those who profit by the use of the riches. Under the old form of production, where every man did his own work with his own tools, it was easy for him to take pleasure in the thing that he was making. The factory system breaks the detail of production into such small parts that no one worker can take very much pride in the actual processes of his work. It is not a very thrilling thing to stand by a machine and feed bars of7 iron into it for ten hours a day, and to watch the completed nuts or screws dropping out at the other end of the machine. The pleasure in the work must be secured from the conditions under which the work is performed—the cooperation in the production, and the feeling that the worker is a part, and is being blessed by being a part, of the modern industrial system.

Specialization in Work. Specialization has been carried so far that to-day there are very few skilled workers in the sense in which this term was used several years ago. Shoemakers very rarely know how to make shoes, for they now make only some one part of the shoe. The automobile industry, by methods of standardizing, is organized so that each worker performs some simple task. He repeats this over and over, but his task added to that done by the others, produces an automobile. In the glove factory one set of workers spend their lives making thumbs; another group stitch the back of the gloves. In the clothing industry some make buttonholes, others sew on buttons; some put in the sleeves, and others hem; each has a very small part to do. This specialization in industry has been carried so far that it is seldom that a worker knows anything about the finished product.

A study of the organization of labor shows to what extent specialization has been carried. One of the chief complaints of the American manufacturer is that his men and women are not loyal. There is undoubtedly ground for this complaint, but on the other hand it must be conceded that it is very difficult for a worker—in the garment trade, for instance—to be loyal to a long succession of buttonholes; and for glovemakers to be loyal8 to a multitude of thumbs. The lack of loyalty comes largely from the failure of the directors of modern industry to bring their workers into that relationship with the business which would give them a feeling that they are an essential part of the industry. Loyalty grows by what it feeds on. The specialization that has been going on has been the very force which has made the worker simply a part of the machine, and as such, detaches him from the business of which he ought to feel himself an integral part.

Unity of the Workers. The extent to which specialization has been developed has had another effect. While the process of differentiation has been carried on at a rapid pace, and the individual worker has known but little about the finished product, he has come to know a great deal about the other disintegrated units in the workshop, the mine, the factory, and the mill. Consequently, with the differentiation in the work there has been a growing solidarity or feeling of unity among the workers themselves. Evidence of this is found in the philosophy that there are only two classes of people in the world, the people who work and the people who do not work, and which is used by the revolutionary groups with tremendous force. We do not like to think of classes in America, but the forces of industrial life have created classes in spite of ourselves.

A World Apart. The workers live in a world apart. Unconsciously they drift together. They talk each other’s language; they understand each other’s point of view. In every town and city we find groups of the workers living to themselves. The work which men do inevitably groups them together; and social life centers9 so completely about their work that it is really the factory and mill that mark out the lines and define the limits within which the classes must live. Consequently, in our American cities we find such designations as these: “Shanty Town,” “Down by the Gas Works,” “Across the Tracks,” “Murphy’s Hollow,” “Tin-Can Alley,” “Darktown,” “On the Hill,” “Out by the Slaughter-Pen,” “Over on the West Side,” and “Down in the Bottoms.” Just think of your own town, and you probably can add some new phrase that tells where your laboring group lives. In one Western town the community was divided by the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks. The boys in the school on the north side of the tracks were all known as “Sewer Rats.” On the opposite side of the town they were known as “Depot Buzzards.” Whenever one group met the other there was always a war. A friend tells of a similar condition in a Canadian village where the Scotch boys were banded against the Irish and the Irish against the Scotch. Whenever the Macks met the Micks, or the Sandys met the Paddys, there was a row. A large part of this classification is temporary and need not be considered very seriously. Underlying it, however, is the deeper fact that we have come to recognize that there is a world of the workers, and that it is a world apart. In this world of the workers the rewards and the profits of toil are barely adequate to take care of the needs of the families of the workers.

It is assumed that in pre-war times it required from $800 to $900 a year to support a family in the average American community. Since 1914 the cost of living has increased approximately 60 per cent. It is estimated10 that even to-day with the advances that have been made in the wages by nearly all industries, 61 per cent. of the workers of America are receiving an average wage of less than $800 a year. “Shanty Town” and that section “Down by the Gas Works” have been built of poor material and allowed to become dilapidated not because the people living there like that sort of thing, but because the returns for the labor of these people are totally inadequate for their needs. The housing and living conditions of the people who live in the world of the workers is determined by the wages which they receive.

McGraw-Hill Company.

The work which men do inevitably groups them together.

The Interdependence of All. Now, if we do recognize that the world of work is a world apart, we must not fail to recognize also that behind this disintegration that has been going on, there is an integration of society more comprehensive than we have ever known before in the history of the world. While the people may be allowed to live by themselves in a part of the town that is less desirable as a dwelling-place than other parts, yet we are all dependent one upon the other. There is an old story which illustrates this point. A boy complained to his father about being poor and said that he wished that he had been born in a rich man’s home. The father told him that he was mistaken, for he really had wealth which he had never considered. That night the boy had a dream. It seemed to him that there came and stood at his bed a little fellow dressed like a farmer. The boy asked him who he was. He replied that he was the soul of all the farmers that were working to produce the flour that went into bread. Another little figure appeared beside the first, a black man with a turban on his head; he was the spirit of the workers in the tea11 and spice gardens of India. Another black man dressed in the rough clothes of a day-laborer joined the others; he was the spirit of the workers on a Southern plantation who make the cotton and produce the sugar. Other workers appeared so fast that the boy could hardly keep up with their approach—the coal-miner, the iron-miner, the woodsman, the carpenter, and the girl workers in the flax-mills of Dublin, who produce the linen in the rough, red-checked tablecloths. When they had all gathered together there was a multitude, and all were in reality the servants of this one boy.

Our dependence upon each other was clearly illustrated in the shut-down of non-essential industries on certain days in the winter of 1917–18. In order to keep people from starving and freezing, the government of the United States ordered the suspension of certain industries so that the conservation of fuel might protect the lives of the people.

The Good Neighbor. We are “members one of another.” The basic industries provide the necessities of our lives—feeding, housing, clothing, warmth, means of traveling, and the things which are part and parcel of our very being. The workers who are engaged in producing these things are true servants of humanity, and we are all under deep and abiding obligations to them. Just in the proportion that we produce something that adds to the wealth and happiness of the world, we are discharging the obligation which others by their labors have placed upon us. The division into classes, and the setting off of groups by themselves, the creating of the world of labor as a world apart, makes the practise of neighborliness a difficult thing. Now neighborliness12 is the very essence of Christianity. To be a friend of man ought to be the supreme desire of every individual. In the parable of the Good Samaritan Jesus defined the meaning of Christianity in terms of neighborliness. The church must answer this question: How can Christian people be good neighbors in modern industrial society?

Neighbor to the Group. We recognize the call to neighborliness in individual cases. If a man is knocked down by an automobile when he is crossing a street, people will run to help him to his feet, will call a cab or an ambulance, and he will be cared for just as carefully by the stranger as if he were a near relative. The individual idea of neighborliness is thoroughly appreciated. We have learned how to practise it. When it comes to a group, however, we find it difficult. The same men that would rush into the street to help an individual that is hurt, will live in a community and not appreciate the needs of the people living in the same block. The industrial class may be knocked down by adverse social conditions, and no one will recognize just what the situation means; or, recognizing it, will know how to apply the remedy, or even how to offer intelligent assistance.

In a small city in Ohio there lived an old man and his wife. Their children had married and moved away, leaving the old people to shift for themselves. The man was nearly blind and his wife was paralyzed and unable to take care of herself. The neighbors used to go to see them once in a while but no one felt any special responsibility for them and the community knew very little about the conditions under which they lived. One of the neighbors remarked one day that he had not seen13 anybody around the house and no smoke coming from the chimney. An investigation was made and it was found that the old man had been dead three days and was lying in bed with his paralyzed wife who could not help herself, nor could call for assistance. For three days she had been suffering unspeakable agony beside the form of her dead husband. The whole community was shocked. No one could believe that such a lack of neighborliness could exist. No one was particularly to blame; it was merely one of those things that occur because the man and his wife had dropped out of the main-traveled path of the city’s life.

The church is making every effort to meet the needs of the individual, but when it preaches the need of regeneration, it must meet the group needs as well, and the minister of a church for a world of labor must be minister to the group as well as to the individual. The world war has impressed upon us many facts, none with more insistence than this—that we are living in a very small world; and that nations, as well as groups of people everywhere, must learn to appreciate each other for what they are, and for the contribution which they are making to the well-being of humanity. Recognizing this, however, does not mean that we are all to try and think alike, to be alike, or to live alike. As Americans we are very likely to think that our way of doing things is entirely right, and that enlightenment comes in proportion to the degree in which other people copy our example in clothes, methods of living, and even our manner of speaking.

A Specialized Program for Group Needs. The church’s program for a world of work must be a specialized14 program. It must be based upon a thorough knowledge of the facts incident to the life of the people, an appreciation of their view-points, and must take into consideration the ultimate ends to be achieved, the means by which these ends can be reached, and a willingness to subordinate the program of the church to the needs of the group. The program of a city church appealing to well-to-do, middle-class people, will utterly fail in the average rural community. A program for a mining community must consider the needs as well as the character of the miners, and the quality of their work. The church is sharply challenged by the specialization in industry, and by the fact that there are classes who do not hear, or at least fail to heed its appeal. In the growing demand for democracy, the church must not only be the most democratic of all institutions but it must be the leader in setting before the people the ideals and in keeping before their minds the great ends of democracy.

Approach to the Subject. In the following chapters are set forth some of the conditions under which the workers in the basic industries toil and live; also the great needs of each group and what the church is doing, what it ought to do, and what it can do. We will consider each group in relation to the contribution it makes to the life of us all. Food is a first need of each individual, therefore, we will study the rural workers first, for they are the ones who feed the world. Next we will study the makers of our clothing; then the mines, for they provide for our warmth and shelter; then the steel workers, who are the real builders of our material civilization. We are a restless race, and demand the15 labor of thousands of men and women to move us from place to place, so we will study the lives of these providers of transportation. We will also think together of that large group who amuse us and who labor to produce the luxuries which we enjoy. There are certain groups that we will find in each of these larger groups, such as the seasonal workers, the women in industry who toil. We will take a glimpse at these.

Men and Things. Men produce things, and often the created thing seems to become greater than its creator. We will hope through these discussions to show that man is infinitely greater than all the things which he produces. We will also endeavor to arrive at some decision as to what constitutes a proper message and ministry for the church in the midst of a world of work, so that working men and women may be protected in their toil, and freed from the incessant and always present danger of becoming slaves to the wealth they create.

There have grown up on the western plains of Canada a number of large cities and a great many small villages and towns. These are the direct results of a process of civilization dependent upon the fertile soil from which vast quantities of wheat are reaped each year. Just before harvest the sea of grain extends as far as the eye can see. The first settlers built their little cabins, bought as much seed grain as was available, and planted it; doing nearly all of the work themselves. Improved methods of planting and harvesting have added thousands of acres to the wheat-fields. Railroads have been built to carry the wheat to the great shipping and milling centers. Cities such as Winnipeg have grown rich through being the connecting-links between the farmer, with his field and his wheat, and the breakfast tables all over the civilized world.

Our Daily Bread. The development of the grain-belt of western Canada is similar to that which has taken place in Minnesota, the Dakotas, and other Northwestern states. In California, Oregon, Washington, Oklahoma, and Kansas we find great areas devoted to the growing of wheat. The wheat that is put on the market is of two general varieties: what is known as winter wheat sown in the autumn, and spring wheat that is sown18 early in the spring. These great wheat areas have been called the bread-basket of the Western world. Few of us realized the importance of wheat to the life of the world until Mr. Hoover began to tell us that we must save it by having wheatless days and by eating more corn bread and war-breads of various kinds. The total annual consumption of wheat is 974,485,000 bushels, and of this amount the United States produced, in 1917, 678,000,000 bushels. The needs of the world have been figured as calling for about 20 per cent. advance upon all that is available under normal conditions.

Not many of us who live in cities stop to consider the man who made possible the roll or the piece of white bread that we eat with our meal. We forget the long day’s work, the painstaking toil, and the grim struggle of the pioneers who first worked the land. We seldom think of the planting and reaping year after year, the construction of transportation, the building of warehouses, the venturing of money in mill-building, until finally were developed not only the vast farms but also cities, railroads, wheat-carrying steamship lines, elevators, and the mills that go to make up the great bread-making industry. Only when the war interfered with the processes and threatened to cut off the supply of wheat, did we begin to realize how important the wheat farm is to the very life of the nation. If bread is the staff of life, wheat is the chief material out of which that staff is made. Other grains when used for bread, as we are forced to use them to-day, are all substitutes for wheat.

Press Illustrating Service.

Not many of us stop to consider the man who made possible the white bread that we eat at our daily meals.

The Cane-Sugar Makers. If we travel in a direction a little east of south from the wheat-fields of Canada, we come to the great plantations of Louisiana and Mississippi19 where sugar-cane is grown. Here we find people of a different type living under different conditions. Sugar-cane is grown in fields that have been won from the swamps by hard toil. In this rich soil, cultivated and ridged by the plow, the sugar-cane is laid in long parallel rows. After it has been buried a few days it begins to sprout, and from each one of the joints on the stalk of cane there grows up a new plant. These are tilled and come to maturity in October. The stalks grow from eight to fifteen feet high and at harvest-time are cut down and then stripped of their leaves by the workers, who take them up in their hands and with a flat knife slash off the long, bladelike leaves, leaving them clean and smooth. The stalks are piled in rows to be picked up later and put into wagons, taken to the siding, loaded into freight-cars, and hauled to the mill, where they are crushed between rollers, and the juice pressed out. The liquid so obtained is then put into large vats and evaporated, leaving brown sugar and molasses. The crude or brown sugar is sent to the refinery and passed through various processes until we get the white sugar that comes to our tables. Practically all of the work on the sugar plantation is done by Negroes. These people live in small cabins and work for a very small wage, ranging from 75 cents to a $1.25 a day. Their tiny houses, which are usually whitewashed and surrounded by a little plot of ground, are the property of the owners of the plantation. The Negro is expected to buy everything from the company’s stores. The prices are high and it is rarely that one finds a family that is not in a perpetual state of debt to the owner of the plantation.

When the migration of Negroes from the South to the20 North began some few years ago, a great concern was felt in many quarters as to what the result would be. A meeting was held in one of the Southern cities and the Negroes were invited to be present. One of the Negroes said: “If you let me tell you what I think, it is about like this. We-all have been working here for about 75 cents to $1 a day, but we never see the time when we have any money of our own. It takes more than we make for the things we use. Folks in Iowa, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Massachusetts offer us $15 to $18 a week, tickets for ourselves and our families, and a free house to live in with two weeks’ rations provided and in the house. Now none of us wants to leave Louisiana, and if you want to keep us here just raise our wages to $2 a day. We would a heap rather stay here than go North.”

Sugar from Beets. Not all the sugar that comes to our tables is made from the cane; in fact only a small proportion is cane-sugar. Most of it is produced from the beet which is grown in large quantities in the West. Montana, Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming, and California are the extensive sugar-beet producing states. The beets grow to an enormous size; they are planted in rows and cared for much as the beets that grow in our vegetable gardens. In California the Japanese are entering very largely into the sugar-beet culture.

The beet-fields call whole families to work. Several towns in the Northwestern states have sections made up entirely of Russians, and people from other lands, who have been attracted by the opportunities for employment offered by the beet industry. One family consisting of a father, mother, thirteen children, and the mother’s sister21 worked all last summer in one of the beet-fields. The youngest child was only five years old but he put in long hours every day. This family is typical of many. The statistics regarding child labor in the United States show that the vast majority of children employed in gainful labor are the children in the rural districts. Thus sugar comes to your table through two sources: from the workers, including a large number of children, in the beet-fields and the workers on the Southern plantations.

The Corn Belt. In the Middle states we have the great corn-producing areas. A great deal of the philosophy of this region is summed up in the reply of a farmer to the question as to why he was planting more corn than usual. He said: “So that I can feed more hogs.”

“What will you do with the hogs?” he was then asked.

“Sell them and buy more land to plant more corn to raise more hogs to buy more land.”

The price of hogs and the price of corn, in normal times, keep on a level with each other. When corn is high pork is high, and when corn falls we find that pork falls with it.

Food and the Land. It is impossible within the limits of this book to give more than a glimpse of a few of the great food-producing industries of America. The packing-houses and canneries contribute their share to the feeding of the people; but when all is said and done, we get back to the fact that even in this age when factory and city make claims, all values finally rest on the land. The growth of our cities has emphasized their22 dependence upon the country. People in the city must be fed, and the food comes from the soil. It is now claimed that the gravest mistake made by Kerensky, a leader of the Russian revolution, was in not giving sufficient attention to the food question in Russia. After the revolution became a fact Kerensky tried to spur the army to greater activity, but the people, unused to the new ways of freedom, failed to keep up the processes that would produce food. The railroads were congested; fuel was scarce; lacking fuel—the railroads and boats still further failed in their undertaking. The result was that the food supply became less and less in Petrograd and other centers. Behind the lines hungry people grew restless. Leon Trotzky would not have succeeded in overthrowing Kerensky but for the hunger of the people. These people were willing to accept any change of government because there was at least a hope, however desperate it might be, that the new government would furnish the food which they needed so badly. One writer dealing with this subject said: “Oratory and precepts failed to feed the hungry people.”

We have heard over and over again the phrase, “An army travels on its stomach.” It is also true that the civilian population of a country lives and labors on its stomach. Food is the foundation of life. “Give us this day our daily bread” is the first demand of man upon God and upon his fellow man. The solution of all our problems depends finally on the question of bread. “Who shall be king?” The answer to this question is very likely to be, “The one who will give us bread.” The peace of the world must finally be based upon an appreciation of economic values. Justice means that23 conditions will be such that in each nation food for all the people will be produced in abundance.

The Country and the City. Much has been said of the freedom and independence of farm life. The producer of food is a real benefactor of the race. The farmer works in the open air and lives a simple life, and so gains an opportunity for developing the very finest traits of human character. But when we compare the changes that have been taking place in the rural districts, we find strong reasons for the exodus from the country to the city. The city offers a more interesting and profitable life which makes it difficult to maintain the center of attraction on the farm. The history of humanity began in a garden and ends in a city. The word “city” comes from the old Latin word which means the citizen, the place where the citizen lived.

The city is really the center of authority and governmental power. It offers the best and at the same time the worst; has the best in intellect, which it attracts and claims for its own, and it has the best in amusement and entertainments. We have heard people say: “The country is a good place in which to rest and work, but the city is the place to have your fun.” The city has the best and the worst of morals, and the best and the worst health conditions. Side by side with the city mansion are the tumble-down hovels and the cramped, narrow tenements that are a disgrace to our land. The robust, strong man pushes his weaker fellow to the wall. The worst forms of disease and the most acute physical suffering are found in the city. In the city there are many intellectual giants and many half-sane intellectual weaklings. The man dwelling in the country has a greater24 independence than these. He can at least have three meals a day, and knows how to take care of himself. Hundreds of thousands of people in our cities have just brains enough and just education enough to do one thing; if hard times throws one of these out of his job, he is left utterly helpless—a derelict on the sea of humanity. The culprit is safer in the city than in the thickest forest. Men without character and women without principle huddle together in its sordid districts. The tides of the city wash up queer specimens to the light of day, and reveal to the passer-by the saddest and most gruesome sights, and the worst types of humanity.

The best in the city is matched by the worst. Philanthropy cures, or tries to cure, what rogues have created. Just as the incentive to goodness in the city is highest, so the temptations to the opposite course of life are of the strongest. The artificial life creates new and unusual wants, and together with the excitement caused by city conditions, makes temptations hard to resist. The city is the rich man’s paradise and the poor man’s hell. The lure of the city is strong upon us all. There are a thousand voices calling us there; and this is impoverishing our rural districts and making the question of food a more serious one every year. In the country one can plod along and with the present prices be independent, but this does not satisfy. The men of to-day think in thousands where their fathers thought in terms of hundreds. Hundreds of dollars are made on the farm and millions in the city. The city calls every young man and young woman. Everybody who is at all familiar with the small towns knows that one of the hardest facts which must be faced is that just as soon as the young25 people finish school they leave for the city. Church work is made hard by the continual drain on the best life in the community.

The Tenant and the Absentee Landlord. Over against this question of the lure of the city there is that of the tenant farmer. The Industrial Relations Commission, making its study of the rural conditions in America, finds that there is a very grave danger that America will produce a peasant class like that of some of the European countries. The independent landowners are decreasing; in Mississippi 62 per cent. of the land is tilled by tenants, in Louisiana 58 per cent., and Kansas 36 per cent. So many of the owners of the farms have moved to the city that the actual production of food has been left to the people who are known as “birds of passage.” Most of these tenants are here to-day and gone to-morrow. The retired farmer presents the problem of the absentee landlord. The tenant farmer suffers under the handicap of his limitation, and his poverty is often his undoing. The absentee landlord of the farm enjoys the fruits of the labor of another. We must not forget, however, that the retired farmer has contributed his share toward the development of our nation. He has helped to make his community. The man who actually remains on the soil to produce the food is producing less, and takes less interest in his community, than the man who owns the land and who made a success of production in years gone by. The tenant does not cultivate the land as intensively as it can be cultivated; he does not attempt soil conservation, and takes but little interest in the community and its institutions.

Study of a Rural Community. It is interesting to26 make a study of the rural community and to compare present conditions with those of the past. Such a study convinces one that the success of the church is closely bound up with the economic situation of the community. An investigation was made in three townships in the central part of Wisconsin just a few miles from the state capital.1 The land in this section is rich, the homes of the people are comfortable, the barns and sheds substantial, and everything about the farms well kept. Fences are up and all the buildings are neatly painted. The land produces anything that can be grown in a temperate climate: peas, grain, barley, potatoes, oats, hay, cattle, sheep, and hogs. Other parts of Wisconsin produce more milk and butter; but the large herds of Holstein cows and the number of creameries and cheese factories found in this part of the state convince the visitor that no small part of the farmer’s income is derived from this source.

1 Survey made by Social Service Department of Congregational Churches, 14 Beacon Street, Boston.

The state university is the Wisconsin farmer’s best friend. Through its instruction at Madison, its extension department, experimental stations, and institutes held throughout the state, it shows this friendship; and the splendid economic conditions found in rural Wisconsin prove that this friendship is not wasted. The land in these townships is valued at $100 to $150 an acre, but upon inquiry at a dozen or more farms it was learned that no one knew of any farm land that was for sale.

About 2,500 people live in the three townships described. Sixty years ago nearly all the people were27 Americans, many of them having emigrated from New York State. In later years the Americans have been supplanted by Germans and Scandinavians. The old settlers now lie at rest in the beautiful cemeteries which are taken care of by the communities with the same care and affection that is bestowed upon private homes and grounds. Many of the descendants of the first settlers are scattered far and wide throughout the United States. The Rev. Hubert C. Herring, Secretary of the National Council of the Congregational Churches of the United States, and one of the best known among home missionary leaders in America, was born and spent his early life in this section of Wisconsin. The school he attended is at the country cross-roads and near the school is the Presbyterian church which he joined. Dr. Herring’s first efforts at oratory were practised upon the neighboring boys and girls in the Philomathean Society, a country debating society, at that time a leading social and literary organization among the people of the community. Ella Wheeler Wilcox, one of the most popular and prominent of the magazine and newspaper writers, and who is well known to every reader in America, was born in this same township. Twelve other people who are influential nationally and internationally were born and reared in this community.

Most of the people hold their own farms and most of them have money on interest in the bank. The few families who rent farms are working, planning, and saving so that they can buy land and own their farms. The school-buildings are adequate and the grounds well kept; the teachers are efficient and intelligent; and the high school maintains an advanced standard. The young people28 go directly from these schools into the state university. Here, then, we have the material conditions that would seem to guarantee success in the work of the church. There is no poverty, and very few people can be said to be living on the fringe of the community. There is no overcrowding on the part of the churches, for there are only two American churches and they have a parish twelve miles wide and fifteen miles long, and the pastor serving both is the only English-speaking preacher in this whole district. Now what are the facts? One of these churches was closed for a number of years and now has services only once in every two weeks; the other was also closed for a number of years. One church has a Sunday-school with fifty members and a Christian Endeavor Society of thirty-six members; the church service is attended by twenty-five to forty people. One of the men in the community said: “Many of the people are foreign and have their own churches, of which there are seven in this district; but they have their troubles, for the children are breaking away from the old churches as they have broken from the old languages, and are beginning to come to our Sunday-school.” The community has a good moral record. There has never been a saloon, except at one point, and the two saloons that were located there were voted out years ago. The people are home-loving and law-abiding, but the two churches are not as successful as they were fifty years ago when they were filled at every service.

The first minister in the district was a graduate and honor man of Williams College, and the church was the center of the community life. People looked to the church, were helped and inspired; it sent out teachers,29 preachers, and other men and women trained in thoughtfulness, to enrich the world. Contributions of such a range cannot spring from the conditions in which the church finds itself to-day. What are the reasons? Some of the people blame the universities. When the young people return from college they seem to take no interest in the church. But the universities are really not to blame. The church fills so small a circle in the community that when the young man has finished his course at the university he cannot fit himself back into the narrow groove of the church activities. In sixty years the old methods of farming have changed. Tools and machinery are of another type. Conditions on the farm are totally different, because the farmers have recognized that new methods are demanded. When the old settlers have their picnics and reunions, one of the older men shows the young men how they used to “cradle” the grain. It is an interesting thing, but compared to the modern reaper the cradle is simply an archaic tool, and no man would think of harvesting his crop with it to-day. The fields of the church life of rural Wisconsin and in other sections of the country are “white to the harvest,” but the ministers are forced to use the old-fashioned “cradle” in harvesting the whole crop. The university is showing the church its opportunity and at the same time pointing out its failure. In the particular locality under discussion the churches have no program. Religion is limited to a very small part of life. The farm demands all the time of the people during six days of the week. On Sunday the work clothes are changed for Sunday clothes and part of the day given over to the church. This is religion. The line of demarkation between the30 sacred and the secular is much more clearly drawn in the country than anywhere else. The average minister of the country church is much more a man apart from the rest of the community.

The program of the church must be made a part of the whole life of the people. The church out in the districts where the people live who are producing the food for the world is responsible in a large degree for the pleasures of the people. Country people find it difficult to think in terms of the community. It is hard for them to cooperate. The church must shape its program with a clear understanding of the great facts of the community life, and appeal primarily from this standpoint and not simply from that of the needs of individuals.

Another rural study shows a community where 80 per cent. of the people were living on land owned by somebody else. There were five churches, and each of them was struggling for a pitiful existence. Less than 20 per cent. of the people had any connection with the church or any other organization. A minister was sent into this district to make a study of the situation with a view to possible work by the home mission board of his church. In his report he stated that the needs there were just as pressing and demanded just as much statesmanship as any field in India or China. He was furnished with sufficient money to put up a good church building, and the plans of the building provided for social and game rooms. He brought a doctor into the community and attached him to the church as a lay worker. He promoted an interest in better farming methods, and began with organized groups a course of lessons in31 thrift. Gradually this minister gained the interest of the boys and girls through baseball, basket-ball, singing school, and other community exercises and agencies. People began to come to church. They wanted to hear this preacher, for as one of the farmers said, “A feller who knows enough to talk about the things that we are interested in must know something about heaven. I want to hear what he’s got to say.” The church in this community succeeded, but its success was primarily dependent upon the program that considered the economic needs of the people, and studied to find a remedy for the bad, and to build up the good.

Socialism’s Message to the Church. Socialism has been sneered at as being a “stomach philosophy.” There is ground for this criticism, for a great deal of socialism is purely materialistic; but the fact that it interests itself in the feeding of the people is not a serious fault. Socialism has emphasized many things that the church has failed to appreciate. Consideration of the food problems and of the economic basis of our civilization is something that the church cannot afford to ignore. The great mass of workers who are producing the food of the world are truly ministers to the needs of humanity.

The World of Rural Workers. Figures are dull or they would be marshaled here to show that the producers of the world’s food live in a world to themselves. There are many divisions in this world, and many cross-sections of the life of the people. That the rural church is not succeeding is evident. Its sons and daughters of the past generation are the leaders in the world of finance, art, commerce, and letters; but are the conditions within it to-day such that may produce sons and daughters to fill32 the places of those who are now occupying the positions of trust and honor? The call and the opportunity of the church are urgent in that great part of the world of work which produces the things that we eat. Shall those who feed others themselves be denied the bread of life? It is a call for leadership, for statesmanship, for planning, for devotion, for sacrifice, and for heroic service.

“Now when we cross this bridge, look north and you will see the soul of our city symbolized in brick and mortar.” These were the words of a business man who had taken an afternoon off and was showing his friend the wonders of a New England city that had grown up about the textile industry. The soul of the city, as he thought of it, lived in the huge mills lining the banks of the canal which runs through the city. When his friend looked, he saw more than the mills. He saw a road beside the canal paved with cobblestones and, on the other side, the company houses overshadowed by the mills and factories. The towers and huge smokestacks threw shadows that completely covered the houses where many of the workers lived.

So thoroughly is this city dependent upon the mills and their output that a brilliant writer in a recent work of fiction said of it, that if there were bridges and a portcullis you could easily think of their being raised to protect the mills against an invasion from the workers; just as in medieval times the feudal castles were protected by the moat and bridge. The bells in the many towers and the siren whistles of the mills call the people from sleep in the morning, telling them when to begin work and when to quit. Within the mills are long34 lines of machines set in parallel rows down which the workers easily pass. Each worker tends eight to twenty machines. Here is a broken thread to be tied, and there a new pattern to be set up. The clatter and roar of the machinery is unceasing. It is a part of the composite voice of labor that is sounding around the world. As the shuttles fly the finished fabric is rolled up ready for inspection, and, when passed, goes to the market, and later is made into garments.

It is a huge task to clothe the modern world. No one realizes how much it means until he looks into the work of the textile-mills which have grown up in our own and in other countries. Cities like Lawrence, Lowell, and Fall River, Massachusetts, are what they are because of their great factories. In these places they produce miles of cloth every week.

Men and Clothes. Of all the animals in the world man is the only one that provides himself with artificial covering. All the others have perfectly fitting coats provided by nature, and these coats are adapted to the conditions under which the individual animal is forced to live. Man calls in the help of plant and animal life to supply himself with clothing for his protection against the cold of winter and the heat of summer. He also uses clothing as an adornment. We have come to consider clothing as a badge of civilization and a mark of man’s superiority to all the other animals. Those races that pay the least attention to clothing are the lowest in the scale of civilization. Such races are found in South America, in Central Africa, and on some of the islands of the South Seas. There is scarcely a trace of civilization to be found among them. They have a kind of35 community life, but they live in a most primitive fashion. Their food consists chiefly of roots, plants, fish, and game which can be easily secured. They have rude shelters or crude huts; wear very little clothing; and their religion is a belief in witches and evil spirits. Where they have idols they are of the most hideous workmanship, representing in a most grotesque way bad influences and vicious passions.

The Materials. The first clothing man wore was made from the skins of animals and from the bark of trees. Later on it was learned that wool could be spun, and that by using crude needles cloth could be sewed together. Wool, silk, cotton, linen, paper, and many others materials have come into common use. All of these are produced by groups of people of whose working conditions we are in ignorance and whose very existence is unknown to most of us. Among civilized people the use of wool has grown to such an extent that the sheep-raising industry has become one of the biggest businesses in all sections of America. The sheep-herder lives a lonely life and yet rarely complains, and is never happier than when out in the fields with his charges. At shearing time the sheep are brought into a shed, and after a few futile struggles in an effort to escape the process, they sit quietly head up while the fleece is taken from them. When they go into the shed they are grimy gray; after the shearing when they leave it they are a light yellowish white. Thousands of people are employed in the wool industry; in securing the product, spinning it, weaving it into cloth, and making it into garments for our use.

Silk has been used for many centuries in the manufacture36 of garments. A Chinese legend tells of a wife of one of the early emperors of China who lived more than thirty-five centuries ago and who learned to make silk from the cocoon of the caterpillar. From this discovery has come a great industry. The caterpillar lives upon the leaves of the mulberry tree, and it has to be fed and tended with infinite patience. The process of gathering the cocoons and of preparing them for spinning is a business that can be learned only by years of apprenticeship. Caring for the caterpillar is a task that does not always appeal to people, and yet it is one that engages the attention of a large number of workers.

Cotton was first used in India, but its cultivation and manufacture developed in three continents at just about the same time. In a Vedic hymn written fifteen centuries before Christ reference is made to “the threads in the loom,” which indicates that the manufacture of cloth was already well advanced. Cotton was used in China one thousand years before Christ. It was held to be so valuable that a heavy fine was imposed upon any one who stole a garment or any piece of cotton cloth. Alexander the Great found cotton in use when he invaded India, and tradition says that it was he who introduced its use into Europe. In Persia cotton was exclusively used before the days of Alexander. Thousands of years before the invention of machinery for the making of cotton cloth Hindu girls were spinning cotton on wheels, making it into yarn, and using frail looms for weaving these yarns into textiles. The beauty of the fabric was so striking that they were known as “Webs of the Woven Wind.”

Cotton and History. Cotton has played a large part37 in the history of the United States. It was just one hundred years after the discovery of America that the first cotton plant was introduced into the land. The short-staple cotton plant did not mean much until 1814 when an enterprising New Englander assembled in one building the several processes of spinning and weaving. His shop at Waltham was the first complete cotton factory in the world. The South made the mistake of turning its attention to the planting of cotton and allowing the North to do the manufacturing. Cotton became an important factor only when the cotton-gin was invented. This was in 1833. When cotton became profitable, Negro slavery took on an added meaning. The value of cotton was really the factor that led men to demand that slavery should continue as a national institution.

Why Increase Production? Having secured the material suitable to be made into cloth the next step was to improve the process of manufacture. The first wool that was woven was rolled in the hand, made into threads, and woven in a very crude loom. The task was a tedious one, and the cloth was produced very slowly. But, as time went on, man by practise learned more about weaving. He had been weaving linen from flax in the days when the Pyramids were being built in Egpyt, but it was not until the power-loom was invented that cloth-making could be carried on as a profitable industry. Early man had just about all he could do to provide himself with food, shelter, and the clothes that he needed. To-day these things are provided in quantities sufficient for all and with little exertion. Hence, we find the basis for the division of labor. A machine for spinning cotton can produce enough thread in a very38 few hours to make clothes for the families of all the men who are interested in operating the machine. This thread is then turned over to the operator of the power-loom; the machinery is started and the cloth begins to roll itself up into a huge bundle. Very soon enough is produced to clothe all of those who are interested and occupied with this operation. The cloth is then turned over to the garment-makers and the process of fashioning the clothes is carried forward so that each individual has his or her part to perform; and in a very short time there are enough garments fashioned and finished so that all the garment-makers can be provided with clothes. Now comes the question that is so often asked. If there is plenty of clothing for everybody, why should some people not have clothes enough? If a man interested in the production of cloth makes more than enough for him to wear, why should he go on working? The answer to this is that, in the modern world, man must trade off his specialized product in order to satisfy his own needs and those of his family.

The Machine. The enterprise of clothing the world is made possible by machinery. Man has never produced more marvelous results than in the development of the intricate, huge, and costly machines which fashion the fabrics from which we make our clothes. These tools give man a thousand hands where before he had only two. If each person did only a moderate amount of labor the people of every country that employed machinery would be provided with all the necessities of life. A supply could be insured without overworking any one, and a few hours’ work each day would be enough. In that time all that is necessary for each individual39 would be produced. The machine, then, is the instrument that increases the possibility for leisure; by the multiplied productive power it increases the number of things that a man may have, and at the same time it enlarges his possibilities for leisure. We accept the machine as we accept the weather. As a matter of fact it is not at all certain that since the machine has been with us we have been any happier because of the enormous production of our times. The machine has carried on the divisions in our industrial life. The new methods and improved devices save labor, time, and energy. At the same time they increase the output. A man’s hand is no more mighty than it was centuries ago, but backed by the tireless energy of machinery he can with slight effort turn out a production that a story-teller would not have credited to the mightiest giants of mythology.

The United States Bureau of Labor tells the story in figures. Five hundred yards of checked gingham can be made by a machine in 73 hours; by hand labor it would take 5,844 hours. One hundred pounds of sewing cotton can be made by a machine in 39 hours; by hand labor it would take 2,895 hours. The labor costs are proportionate. The increased effectiveness of a man’s labor aided by the use of machinery, according to these reports, varies from 150 per cent. all the way up to 2,000 per cent. Hence, we see that the machine is not so much a labor-saving device as it is a production-making device. As has been said already, it is man’s energy and strength multiplied many times. The machine has become so potent that the question is, “What relation shall the created thing be to the creator?” The machine sets the pace. The man or40 woman working with it must follow. It is exacting, implacable, produces through long hours; is set up in the midst of high temperatures, and is utterly indifferent to the fate of the individuals operating it. It works at night, it works by day and under conditions which are humanly impossible; but human beings are forced to keep the pace. The textile cities of America with their rows of tenements are practically built by the machinery in the mills and factories. The system has grown up, and men and women are forced to adjust themselves to this system. The welfare and happiness of the individuals working at the machines are very likely to be matters of secondary importance to the value of the production of the machinery itself.

The Workers. At the present time in the United States there are about 1,000,000 people employed in all the textile industries and about $500,000,000 a year paid in wages. About one and three quarter billions is the total value of the production. The worker in these mills is a worker and little or nothing else. The struggle for mere existence takes so much of his time that he has slight opportunity and but small inclination to take part in any social or civic affairs. He usually lives in a tenement or in a barrack type of building provided by the company for which he works.

The Southern Mill Village. In the Southern mill towns the companies usually own all the houses in which the people live. These houses are generally one-story buildings with a porch extending along the entire front. All of them are alike, and most of them are painted gray or drab. The streets of the mill village are unpaved and in most places cut into gullies by the41 rains. In a few places running water, bathtubs, electricity, and other modern conveniences have been provided, but these are the rare exceptions. More often the houses are barren of all comforts, and living is reduced to the lowest possible terms. The mill village has ordinarily but one store and this is owned or controlled by the company. The food eaten by the people is of the simplest kind; corn bread, pork side-meat, and coffee make up the staples of diet. Nearly all the members of the family work in the mill. At an investigation made by a state commission in Atlanta, Georgia, one of the men testified that he, his wife, five of his children, and his wife’s sister all worked in the mill; there were three younger children who stayed at home, the oldest one of the three acting as housekeeper and nurse. The improvements that most people expect as a matter of course, such as fire-proofing, sanitary plumbing, lighting, heating, storage, bathing, and washing facilities are utterly unknown. If you spent a day in one of these mill villages, you would find one or two members in almost every family sitting on the porch of the house and away from work because of sickness. If a neighbor happens to pass, you would hear some such conversation as this: “Howdy? How are you feeling?” “Poorly, thank you, I have never felt worse in my life; my victuals just don’t seem to agree with me, an’ I just feel like I was of no account.” The vitality of the people is being sapped by the insanitary conditions under which they live. It was discovered some years ago that hookworm is the cause of the illness that has been preying upon these workers for generations. The dangerous worms thrive in the midst of filth. A clean-up of the village and the42 building of better homes almost certainly eliminates the disease and its cause.

The people of the mill village find most of their recreation in the near-by city. Nearly all of the principal Southern cities have a number of these villages contributory to it. In many a home the only piece of finery is the tawdry dress made up in what is supposed to be the latest style—certainly the most exaggerated style—and usually in the most striking colors. This is the Sunday dress of the young lady of the house. When she is ready for her day off in the city, her costume will be completed by the addition of a hat of the most marvelous and striking make and color.

The Motion-Picture’s Contribution. The motion-picture theater has been a godsend to the people of the mill village. Most of these workers are very ignorant. Hard living and incessant toil have deprived them of the opportunity of attending school, and even if there were the will to get an education, the schools have not been accessible in many instances; consequently, the people have merely the rudiments of an education, and many of them can neither read nor write. Hundreds of homes in these villages have no books except an almanac and a Bible. The needs of the workers are almost overwhelming, so that one hardly knows where to begin even to tell about the changes that must be made in a community before much benefit can be secured in the lives of the individuals. The motion-picture has brought to these workers scenes from the outside world and has enlarged their ideas of life. Any one can understand the lesson a picture teaches.

Copyright, H. C. White Company.

In the cotton-mills a worker is a worker and little or nothing else.

The motion-picture furnishes amusement and recreation,43 and it gives a glimpse of larger aims and new motives. The girls who dress up in their fine clothes and gaudy hats and go to the city whenever they have a chance are trying to express themselves. Inherently they have fine traits of character, but out of their ignorance and lack of experience they are unable properly to balance the proportion of color and style and make these to fit in with the facts of every-day life. There is no one to teach them; they are unable to go to dressmakers for advice, and the people with whom they associate admire the kind of finery that they wear. But when they see these pictures presented on the screen they get a chance to know how people in other places really live and act. As one girl said: “I only learned how to be a lady when I got to see ladies’ pictures at the movies.”

Improvements. Some of the mills have built model villages, have furnished good schools, churches, playgrounds, and other recreational features. There have been discouraging failures made in attempting to lead the people to accept the better things; but the failures are insignificant when compared to the successes that have been achieved by the companies that have really had the welfare of the workers at heart. One mill owner has put in the finest kind of equipment in the homes of the people. The hours of labor have been materially reduced: first they began with eight, now they have seven, and this reformer says that he believes that they will be able to reduce the hours still further and make the six-hour day the standard. He intends to put on four shifts of workers for each twenty-four hours and believes that he will get a better result than could be44 achieved even with the eight-hour day. It is interesting to note that this man, by paying higher wages than others and by reducing the hours of labor, has been able to secure permanence among his workers; and at this period when other mills are shorthanded, he has all the labor that he needs. “It is not philanthropy but good sense” is his way of defining the splendid work he is doing.

Workers in the Northern Textile Cities. In the Northern textile cities we find a different situation, for most of the workers live in tenements. The stores, shops, and theaters are built and operated with the demands of the workers, rather than their needs in view. In one of these textile cities the average wage is $11.25 a week. Consider the case of just one family living in this city under these conditions. The family lives in a tenement with barely room enough for the father, mother, two daughters, and a son. The mother is devoted to the home; the father is a loom-fixer in the mill and a member of the union. All attend the Congregational church on Sundays. This man has been able to send his children through grammar school. His wages are above the average for the kind of work he is doing. The two girls started work just as soon as they finished school. The son also went to work, but he was so tired of the town where he had always lived that he went to New York and secured a position there. Everything went well for many years, and the prospects, while not bright for the future, were not especially dark. Then trouble came. First, the father was sick, and his illness dragged on through the whole winter, but by spring he was able to go back to work. It was the beginning of the slack season, however, when he applied for his old position.45 He went to work, but the wages were not as good as they had been when he left. The daughters found that in order to have any society they had to spend more money for clothes. “You can’t expect us to dress in a dowdy fashion, for if we do we never will have any friends,” was their assertion. Ten dollars was the wage of one of the girls and eight dollars the wage of the other girl. This amount did not go very far toward supporting them and buying the necessary clothes, and gave but little chance for a good time. Nothing was left to help the family fund. Before the winter was over a strike was called and the father lost his position. The family now became dependent upon the funds of the union to which the father belonged and the small amount the girls could squeeze out of their wages.

The winter passed as do all other mundane things and the strike came to an end. Those who were members of the union were not allowed to come back. The managers of the mill proclaimed that they had won a great victory for democracy and that the mill should be operated strictly as an “open shop.” The father found that “open shop” meant a closed shop to him until he tore up his union card and promised not to join any other labor organization. This he did in order to go back to work. He was forced to it, but he never quite gained the confidence of the foreman, for he was a marked man. Added to the hard struggle for existence with its attendant worries there is an increasing feeling of bitterness in the heart of this man, because he knows that he is being discriminated against for his former membership in the trade union. The family lives on, as thousands of others in the neighborhood are doing, but there is46 hostility toward the factory and all it represents. Not all the workers in the mill have this experience. Some have managed to save, and by good fortune have been able to save enough so that they are fairly comfortable and independent, owning their homes and living in comparative ease, although very simply. We must not think for a moment that there is only one side to this life and that always a disheartening one. The challenging thing, however, is that the men and women who are actually operating the machines are nearly all living harassed lives, with a heavy burden of trouble and worry, and are not finding the pleasure that should come from work well done.