Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 849. | two dollars a year. |

Though the Indians of New England were for many years vastly superior in numbers to the white men, they were never wholly united, and their cowardice and lack of discipline were weaknesses for which their treachery and deceit could not compensate. The long conflict between the races culminated in 1675 in King Philip's war, when the wily Wampanoag sachem succeeded in forming a confederation, embracing nearly all the New England tribes, for a final desperate struggle.

It seemed for a time as though the combination might succeed. At the end of the summer the scattered settlements, and especially those along the Connecticut River, which formed the outposts of the colonies, were panic-stricken. Everywhere the savage allies had been victorious. A dozen towns had been attacked and burned, bands of soldiers had been cut off, and isolated murders without number had been committed. Prowling bands of Indians lurked about the stockaded towns, driving off cattle and rendering impossible the cultivation of the fields, so that the settlers were called upon to face starvation as well as the scalping-knife and tomahawk.

There was no meeting the Indians face to face, except by surprise. They fought from ambush, or by sudden assault on unprotected points, and would be gone before troops could be brought to the scene. The white men were unable to follow them without Indian allies, and they were slow to adapt themselves to the Indian mode of fighting. Flushed by their success, the confederates became overconfident, and grew to despise their clumsy opponents. In the spring of 1676 more than five thousand of them were encamped on the Connecticut River, twenty miles north of Hadley. Here they planted their corn and squashes, and amused themselves with councils, ceremonies, and feasts, boasting of what they had done and what they would do. They judged the white men by themselves, and did not suspect the iron courage and stubborn determination that were urging the people in the towns below them "to be[Pg 326] out against the enemy." On the night of May 18th they indulged in a great feast, and after it was over, slept soundly in their bark lodges, all but the wary Philip, who, scenting danger, had withdrawn across the river.

On that same evening about two hundred and fifty men and boys gathered in Hadley street. Of this number fifty-six were soldiers from the garrisons of Hadley, Northampton, Springfield, Hatfield, and Westfield. The rest were volunteers, among whom was Jonathan Wells, of Hadley, sixteen years old, whose adventures and miraculous escape have been preserved.

The party was under the command of Captain William Turner, and the expedition which it was about to undertake was inspired by a daring amounting to rashness. The plan was to attack the Indian camp, which contained four times their number of well-armed braves. Defeat meant death, or captivity and torture worse than death. The march began after nightfall, so as not to attract the attention of the Indian scouts, and the little band made its way safely through swamps and forests, past the Indian outpost, and at daybreak arrived in the neighborhood of the camp. Here the horses were left under a small guard among the trees, while the men crept forward to the lodges of the enemy.

The surprise was complete. The panic-stricken savages, crying that the dreaded Mohawks were upon them, were shot down by scores, or, plunging into the river, were swept over the falls which now bear Captain Turner's name. The backbone of Philip's conspiracy was broken, and he himself was driven to begin soon afterward the hunted wanderings which were to end in the fatal morass.

But the attacking party, though victorious, was not yet out of danger. It was still heavily outnumbered by the surviving Indians. While the soldiers were destroying arms, ammunition, and food, or scattered in pursuit of the fleeing enemy, the warriors rallied, and opened fire upon them from under cover of the trees. Captain Turner became alarmed and ordered a retreat. The main body hastily mounted and plunged into the forest, seeking to shake off the cloud of savages who hung upon their flanks like a swarm of angry bees.

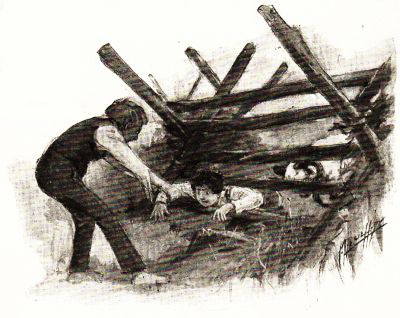

Young Jonathan was with a detachment of about twenty who were some distance up the river when the retreat began. They ran back to the horses and found their comrades gone. The Indians pressed upon them in numbers they could not hope to withstand. It was every man for himself. In the confusion the boy kept his wits about him, and managed to find his horse. As he plunged forward under the branches three Indians levelled their pieces and fired. One shot passed through his hair, another struck his horse, and the third entered his thigh, splintering the bone where it had been broken by a cart-wheel and never properly healed. He reeled, and would have fallen had he not clutched the mane of his horse. The Indians, seeing that he was wounded, pursued him; but he pointed his gun at them, and held them at bay until he was out of their reach. As he galloped on he heard a cry for help, and reining in his horse, regardless of the danger which encompassed him, found Stephen Belding, a boy of his own age, lying sorely wounded on the ground. He managed to pull him up behind, and they rode double until they overtook the party in advance. This brave act saved Belding's life.

The retreat had become a rout. All was panic and dismay. But Jonathan was unwilling to desert the comrades left behind. He sought out Captain Turner, and begged him to halt and turn back to their relief. "It is better to save some than to lose all," was the Captain's answer. The confusion increased, and to add to it the guides became bewildered and lost their way. "If you love your lives, follow me," cried one. "If you would see your homes again, follow me," shouted another, and the party was soon split up into small bands. The one with which Jonathan found himself became entangled in a swamp, where it was once more attacked by the Indians. He escaped again, with ten others, who, finding that his horse was going lame from his wound, and that he himself was weak from loss of blood, left him with another wounded man, and rode away. His companion, thinking the boy's hurt worse than his own, concluded that he would stand a better chance of getting clear alone, and riding off on pretense of seeking the path, failed to return. Jonathan was now wholly deserted. Wounded, ignorant even of the direction of his home, surrounded by bloodthirsty Indians, and weak with hunger, he pushed desperately on. He was near fainting once, when he heard some Indians running about and whooping near by; but they did not discover him, and a nutmeg which he had in his pocket revived him for a time.

After straying some distance further he swooned in good earnest, and fell from his horse. When he came to he found that he had retained his hold on the reins, and that the animal stood quietly beside him. He tied him to a tree, and lay down again; but he soon grew so weak that he abandoned all hope of escape, and out of pity loosed the horse and let him go. He succeeded in kindling a fire by flashing powder in the pan of his gun. It spread in the dry leaves and burned his hands and face severely. Feeling sure that the Indians would be attracted by the smoke and come and kill him, he threw away his powder-horn and bullets, keeping only ammunition for a single last shot. Then he stopped his wound with tow, bound it up with his neckcloth, and went to sleep.

In the morning he found that the bleeding had stopped, and that he was much stronger. He managed to find a path which led him to a river which he remembered to have crossed on the way to the camp. With great pain, and difficulty, leaning on his gun, the lock of which he was careful to keep dry, he waded through it, and fell exhausted on the further bank. While he lay there an Indian in a canoe appeared, and the boy, who could neither fight nor run, gave himself up for lost. But he remembered the three Indians in the woods, and putting a bold face on the matter, aimed his gun, though its barrel was choked with sand. The savage, thinking he was about to shoot, leaped overboard, leaving his own gun in the canoe, and ran to tell his friends that the white men were coming again.

Jonathan knew that pursuit was certain, and as it was broad daylight, and he could only hobble at best, he assured himself that there was no hope for him. Nevertheless he looked about for a hiding-place, and presently, a little distance away, noticed two trees which, undermined by the current, had fallen forward into the stream close together. A mass of driftwood had lodged on their trunks. Jonathan got back into the water so as to leave no tracks, and creeping between the trunks under the driftwood, found a space large enough to permit him to breathe. In a few minutes the Indians arrived in search of him, as he had expected. They ransacked the whole neighborhood, even running out upon the mat of driftwood over his head, and causing the trees to sink with their weight so as to thrust his head under water; but they could find no trace of him, and at last retired, completely outwitted.

The boy limped on, tortured by hunger and thirst, and so giddy with weakness that he could proceed but a short distance without stopping to rest. Happily he saw no more of the Indians, and at last, on the third day of his painful journey, he arrived at Hadley, where he was welcomed as one risen from the dead.

The story of his escape was told for years after around the wide fireplaces throughout the country-side, and was thought so remarkable that one who heard it, unwilling that the record of so much coolness and courage should be lost, wrote it down for future generations of boys to read.

Some years ago an ambitious but poorly equipped applicant for the position of teacher in one of the vacant schools in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, was asked to prepare a composition on the subject of "History." This was the result of his labor:

"History is an useful study. The world was created in sex days. Adam & Eve was the first mans by the creation. An single republick is better as towsand kingsdoms."

When I hear of the birth of a new republic in the family of nations, memory is certain to recall the Pennsylvania school-teacher's composition. There is no doubt, I say to myself, that the secret underlying the formation of so many little representative governments is to be found in the closing sentence, at once so eloquent and so musical—"An single republick is better as towsand kingsdoms." There are many republics that are not mentioned in the school-books, and in this article I have brought together some of the queerest facts concerning only a few of them.

About fifteen miles northeast of Sardinia is the smallest of the little republics—that is, the smallest in point of population. Tavolara is an island five miles long and about half a mile wide. It contains a population of 55 men, women, and children; and every six years the grown people of the republic, men and women together, go to the polls and elect a President and a Congress of six members. The island of Tavolara was a part of the kingdom of Sardinia until 1836, when the King presented it to the Bartoleoni family. From 1836 to 1882 the little monarchy was governed by King Paul I., but in the latter year he died, and in 1886 it became a republic. Its independence was recognized by Italy in 1887, and no doubt other great countries would have paid it a similar honor had they known of its existence. It is a very modest little republic, without army or navy, and its inhabitants, instead of troubling their neighbors, live the quiet lives of fishermen.

The republic smallest in area is Goust, which is less than one-third the size of Tavolara, although it has a population of 130 souls. It has been a republic since 1648, and enjoys the distinction of being recognized by France and Spain. Goust, with its territory of a mile in extent, covers the flat top of a mountain in the lower Pyrenees, and is governed by a President, who is elected every five years. He is also judge, tax-collector, and assessor. Goust has no church or clergyman, but worships in another country more than a mile away. All baptisms and marriages are performed there too, and all citizens of Goust who die are slid down to the cemetery in the Oasau valley and buried there.

East of Australia and north of New Caledonia is the republic of Franceville, an island with an area of about eighty-five miles. Its inhabitants number 550, of whom 40 are whites and 510 natives. It was once a colony of France, but in 1879 it was declared independent, and its people at once adopted a republican constitution. It is governed by a President and a council of eight elected by the people—black and white, men and women. Only white males hold office. The President elected recently is R. D. Polk, a native of Tennessee, and a relative of James K. Polk, one of the Presidents of our own republic.

In the western part of North Carolina is a perfectly organized republic independent of both State and national governments. It is known as the Qualla Reserve, and is the home of about 1000 of the Cherokee Indians belonging to the Eastern branch. The Reserve has an area of 50,000 acres, or 82 square miles, of the richest valley land of the State, lying along the Ocona, Lufta, and Soco creeks. The President of the little republic is elected every four years. He receives a salary of $500 a year, but when at Washington on business for the republic he gets $4 a day extra. He is called Chief, and none but a Cherokee of more than thirty-five years is eligible to the chieftainship. When he is absent his duties are performed by an Assistant Chief, whose salary is $250 a year. The Chief has a cabinet of three secretaries, and the Congress comprises two delegates from every 100 members of the tribe. All Cherokee males of sixteen and all white men who have Indian wives have the right to vote. The constitution provides for the maintenance of a public school, in which both English and Cherokee are taught. The inhabitants of the Reserve are intelligent, fairly well educated, law-abiding, and industrious.

The queer little Italian republic of San Marino, with its 33 square miles of territory and its population of 6000, lies up in the eastern spurs of the Apennine Mountains. It is governed by a Grand Council of 60, who are elected for life, and two Presidents, one of whom is appointed by the Council, the other elected by the people. The little republic has an army of 950 men, who are employed only as policemen. San Marino is the only country in the world that prohibits the introduction of the printing-press. The city of San Marino, with a population of 1700, is one of the queerest old towns in the world. It has undergone no change in 500 years. The republic of San Marino began in 1631.

A little bit larger than San Marino in population, but six times as large in area, is the republic of Andorra. It lies in a valley of the eastern Pyrenees between France and Spain. It became a free state in 819. It is governed by a Sovereign Council of 24 members, elected by the people, and a Syndic, or president, chosen for life by the Council. It has an army of 1100 men, and one big gun planted in the centre of the republic. This gun carries a ball twenty miles, and Europe trembles at the thought of its being fired. In Andorra, the capital, is the palace—a stone building several hundred years old. Here the Councilmen meet. The ground-door is the stable where their horses are kept and fed by their masters themselves. The floor above contains the dining-room, the Senate-chamber and the public school, and the dormitory is on the third floor. Here are kept the archives of the republic, which no one but a native can read. They are kept in a vault to which there are seven great keys, which are held by seven deputies. The schoolmaster of Andorra is the barber, and also the secretary of the Senate; the Mayor is a farmer; the barber shaves customers only on Sunday; and every citizen is a soldier of the republic at his own expense.

Another little republic, of which little can be said because so little is known of it, is Mansuet. It covers four square miles, and is tucked away between Aix-la-Chapelle and Vermus. There are 3000 people in Mansuet, but they are proud; they inhabit a lovely country, and they have enjoyed the rights of republican citizens since the year 1688. Mansuet is free and independent under the protection of Germany, and has an army of three soldiers. A President and a Council of five govern it.

The latest addition to the galaxy of little republics is Hawaii. It is very young yet, as it was born on our birthday—the Fourth of July. We'll hear more about it later on.

The elephant is painted blue, the lambs are painted red,

The zebra has rich carmine stripes upon his back and head.

The rooster's larger than the cow, the pigs are works of art,

And as for goats and lions, why, you can't tell them apart.

Shem, Ham, and Japhet look just like a row of wooden pegs,

With great long ulsters hanging down to cover up their legs.

In which they all resemble both their father and his wife,

And which is which I couldn't say—no, not to save my life.

The horses are both green and brown, and made, 'tis really true,

From just the same queer pattern as the bear and kangaroo;

And every dove and stork and chick in that strange wooden ark

Is modelled like the ostrich that they've got in Central Park.

And if you broke the horns and legs from off the yellow moose

You'd take him for a baby seal, or possibly a goose;

But spite of all I love that ark as well as any toy

That ever brought a bit of fun to any girl or boy.

But one queer thing that puzzles me, the ark, built for a boat,

When deluged in the bath-tub can't be got to stay afloat;

While all the beasts 'twas built to save instead of getting drowned,

Go floating gayly just as safe as when they're on the ground.

Carlyle Smith.

A group of merry girls and boys were talking with Mrs. General Washington one February evening, when one of the number suddenly inquired: "Did you ever get a valentine from the President?"

To which came the ready reply, "Of course I did!" as a conscious smile rippled over the still beautiful though now elderly face.

"And did you ever go to a valentine party when you were a girl?"

"Why, of course I did," and Mrs. Washington straightened herself more particularly in her high-back chair.

"Oh, do tell us all about it!"

And as she responded with a most indulgent smile, they gathered close to hear.

It was night in old Virginia when, for the entertainment of our visiting friends, grandmother laid aside her knitting, and glided slowly, stately, gracefully around the room. She was dancing the minuet.

Unexpectedly my maid entered, bearing a tray on which was a white envelope sealed with rose-colored wax imprinted with a laughing cupid. I was much embarrassed at receiving this before so many curious eyes, and warningly looked at the girl, but it was too late; indeed, her ready words made me only the more conspicuous.

"I 'member to watch, kase uver sence dey here"—with a nod of her head in the visitors' direction—"young misses mons'us quiet!"

Fearing she might become yet more garrulous, I hurriedly asked, "Nancy, did the carriage return from the King's Mill Plantation?" and the girl left the room to inquire.

It was St. Valentine's eve. And who had sent this beautiful valentine—for beautiful I knew it was—notwithstanding that as yet the seal remained unfastened! Would I open it before all these guests, or would I make excuse and go in hiding?

Grandmother settled the question by inquiring, "Valentine, dearie? Many's the one I got when I was a girl."

"I suppose you did, grandma, for you've told me you were much like your old friend Madam Ball—and she was a great belle;" and then continuing, foolish child that I was, with a quick rush of the red blood all over my face, even to the roots of my hair, "I've heard, too, that her daughter, when at my age, was just the comeliest maiden possible—so modest, so sensible and loving, with hair resembling flax, and cheeks like May-blossoms."

These words caused grandmother to come closer, and, scrutinizing my face, she asked, "Why, what's put Mary Ball into your head, child?" and, not waiting for reply, added, "You cannot deceive your old grandmother; you might as well give up now as at any other time;" and pointing to the still unopened valentine, while looking at the group of visitors, she tantalizingly said, "Open it, dearie, and see what George has sent you."

This was too much, and I fled from the room.

Grandmother was right, and I knew it, for I was learning to know George Washington's handwriting, and I was already planning how I would tease him when we met at the party to be given the following evening at the Oaklands, to which home we were both invited.

There had lately been a wedding at our house; a cousin of my mother's was the bride, and such a gay time as this excitement had brought! George Washington was among the guests, and I was much pleased because he danced with me several times.

Referring to an old Virginia wedding, there is nothing comparable to it, as the preparations go regularly on for successive nights and days—such preparations as ruffle-crimping, jelly-straining, cocoanut-grating, egg-frothing, silver-cleaning, to be ready for guests who arrive a few days before, and, as in our case, remain for a week or more afterwards. Nor do the guests arrive alone; they come in their private carriages, with horses and an army of negro servants to be entertained. Just think of the numberless rice-waffles, beat-biscuit, light bread, muffins, and laplands to be brought hot on the breakfast table! and the ham, dried venison, turkey, fried chicken, cinnamon cakes, quince marmalade on the tea table! Oh, a wedding meant an out-and-out stir in those days! But our house was a large old place in the midst of scenery both lovely and picturesque, and we owned many negroes, who had been taught all sorts of work, and therefore it was easy for us to prepare. Indeed, our head cook, Aunt Tamer, was a character, black and portly, but cleanly turbaned and white-aproned. I seem to hear her now praising her own concoctions, and she was especially proud of "bakin' de bes' beat-biscuit an' loaf bread."

But I was talking about my valentine and the party. Probably because the fête of St. Valentine belongs to nearly every country, and since the fifteenth century it was exceedingly popular in England and France, the girls were asked to wear fifteenth-century costume; my dress was of the finest white mull, as fine as a spider's web, and embroidered with lilies-of-the-valley. The boys' clothes were in exact copy of old English gentlemen, and they wore long queues tied with black ribbons, wide ruffled shirt fronts, short breeches, and knee-buckles. The decorations were elaborate—pink roses and rosebuds in solid banks of lavishness. Indeed, the large square rooms seemed transformed into flower-gardens. One exquisite effect was produced with magnolia leaves and wax candles. These leaves formed a cornice to the drawing-room ceiling, and the candles were so deftly placed that only the lighted tapers were seen. They shone like stars on a summer's night, for the dark green gloss on the large leaves acted as reflectors,[Pg 329] while suspended from the ceiling's centre were several rows of pink satin sash ribbon, each piece hanging so gracefully that when the ends were fastened, about four feet below the cornice, the ceiling was as effective and beautiful as the most critical fresco-painter could desire. Where each end was fastened there was a large bunch of magnolia leaves and candles assimilating a side-chandelier, and in the centre of the ceiling there were magnolia leaves in profusion.

No sooner was I in the drawing-room, than my friend George Washington gallantly advanced, and begged me to do him the honor of being his partner in the cotillion. After that there followed many other dances, all of which he would ask me to dance; but I did not forget he had sent me a valentine the night before, and therefore I decided to tease him by dancing with some of the other boys, especially with my particularly kind friend, young Custis.

OUR HOSTESS APPEARED AS THE GODDESS OF LOVE.

OUR HOSTESS APPEARED AS THE GODDESS OF LOVE.

We had reels, cotillions, and schottisches almost without number; but the dance just before supper was arranged for the occasion, and called St. Valentine. Our hostess suddenly appeared in soft fleecy white stuff, with spangled wings, as Venus, the goddess of love, her mother explained. First dancing one of the plantation dances that her old mammy had taught her, she sang a song about valentines; then taking a gilded basket, and coquetting through the drawing-room in the most graceful of reel steps, she gave a valentine to each guest. Then again dancing another of the plantation dances, she as gracefully withdrew.

A few moments later a musician's voice called, "Choose your partners by matching valentines"; and thus again George Washington advanced, and finding that his valentine really was the exact counterpart of mine, we walked to our places in the now rapidly forming minuet, and afterwards we marched together up and down the rooms and through the wide halls to supper.

After supper we played several games, one of which represented prominent characters, and some not so prominent—for example, making believe we were our own mothers or fathers. In this way, Colonel Ball of Lancaster, who was George Washington's grandfather, was taken, and Augustine Washington, his father. George Washington himself took the character of George III., while I took the character of Betty Washington, his sister. But some of the other boys and girls preferred representing Sir Walter Raleigh, Lord Fairfax, Governor Dimwiddie, Miss Burney, Hannah Ball, who married Raleigh Travers, of the same blood as Sir Walter Raleigh, and other titled gentlemen and women. Those who were to be guessed decided for themselves who they would be. Then all the guests asked questions, to which correct answer was given. If the name was not guessed within five minutes, it had to be told, for longer than five minutes made the game too tedious.

GOSSIP.

GOSSIP.

This game was followed by two of the girls taking seats in the middle of the room. They had previously withdrawn and put over their pretty dresses queer-looking old shawls, and covered their chestnut-brown curls with odd-looking bonnets tied under the chin. Then a cup of tea was given to each, and looking intently at one another, slowly stirring their tea meantime, one exclaimed in a high-pitched voice. "You don't say so!" whereupon our hostess inquired, "Who can tell what these girls represent?" and a number of voices replied, "Gossip." At this answer the girls rose, and laughingly threw aside their shawls and hats.

Then the youngest boy took one of the chairs made vacant by the girls. After seating himself, it was noticed that he put a big coat over his lap, and making a great show of threading his needle, he diligently sewed on a button. And the hostess asked, "What does Charley represent?" The children could hardly reply for laughing, for the boy looked so demure and industrious; but after a moment's hesitation there came the vigorous answer, "A bachelor."

Then Aunt Charlotte, an old negro woman, entered; she pretended to be a fortune-teller. And I afterwards learned her coming had been all arranged by the hostess, to whom I had been foolish enough to tell of the advent of my valentine.

She approached me first, and prostrated herself, face downwards, on the floor. "Why, Aunt Charlotte!" I exclaimed, "do get up."

"Lor', honey, I never specs to see de greates' ladie in de lan'."

"Well, stand up," was my agitated reply, "and explain what you mean."

"Bless de chile! I love to think I'm some 'count."

"Hurry!" was my impatient exclamation, "I can't wait." And all my young friends were grouped close around, zealously listening for what the old creature was about to say.

"I mean you'll make de grandes' marriage 'bout here."

"Whom will I marry?" were my now eager though venturesome words.

"Why, de young mars' who sent you de valentine."

I was so provoked with myself that I could have bitten my tongue off, though, after all, it was a most natural answer to give on St. Valentine's night; and thus having decided my future, Aunt Charlotte hurriedly turned to another, and yet another, as both girls and boys pressed forward for their turn. When she reached George Washington I listened closely. She told him he would ride in a coach and six, and that "we've nuver seen sich wondrous time as 'Mars George'll hav'."

When the fortune-telling was concluded, I learned that it was already considerably beyond the time to start home, and therefore speedily made my adieux; a few moments[Pg 330] later found me in our high-stepped carriage rapidly rolling out of the Oakland grounds.

"And thus ended the episode which I promised to tell you," said Martha Washington, the wife of the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental army and President of the United States, to the French officer De Grasse at the Peace Ball given in Fredericksburg.

"Pardon, madame; not ended, but rather begun," was the courtly response.

"Oh, what a lovely party!" was the exclamation from many of the attentive listeners. "And why couldn't we repeat it now?" was the immediate question.

"Indeed I shall," said one of the girls, with a decided shake of her long curls. "My very next party will be an old Virginia evening—dresses, dances, games, and all."

When Johnny was quite tired of making himself big pigs out of snowballs, and hammock-chairs for drawing the girls over the snow out of crotched sticks and old shawls, and Scandinavian skates out of barrel staves, he decided he would make an ice-boat, and all the more firmly because the whole family, except his pretty aunt Mamy, told him it was nonsense, and he never could, and an ice-boat was a dangerous thing if he could, and it was of no use anyway.

There were a lot of old skates in the garret, some big nails and some pieces of wood in the shed; his aunt Mamy could help him rig some sort of a sail. It was a pity if he couldn't make an ice-boat, and the river stretching away a glare of ice for twenty miles and more.

He ran down to the shed and chose for himself a board some five feet long, and a cross-board that he nailed on it a foot from the end. About a foot from the other end of the first board he nailed a bit of wood for a seat, the sides of it slanting out so that it was a little wider before than behind. That done, he nailed a couple of braces, slanting from just behind the seat nearly out to the ends of the cross-piece, and from the latter places two others, shorter ones, meeting on the extreme end of the long first board, beyond the cross-piece, so that the whole looked like the frame of a huge kite. He could have done without the braces, which were only stout three-inch-square sticks, but it seemed a little stronger and safer to have them, he said.

It seemed as if every one in the house had an errand for him to do that afternoon, and he almost gave up the idea of finishing his ice-boat at all. "When a fellow has such a piece of work as this in hand people might let him alone," he grumbled. And I don't know how he would have come out if he hadn't divined that his aunt Mamy was making mince patties for some use connected with himself.

But Johnny was up before the sun the next morning, and where the cross-piece of his frame rested on the longer board, in the very centre, he bored a hole for his mast—bored a lot of little holes close together, and worked them out with his jack-knife till he had one big hole. On either side of that he nailed a small block, and on the top of those he nailed a bit of board that just fitted the space, and then in the middle of that bit of board he made another hole just over the hole already bored, and there was a step for his mast, and his mast itself was ready in the shape of a good stout bean-pole that he had.

Very well pleased with himself so far, Mr. Johnny hurried through breakfast, and got out of the way before his grandmother could ask him to find her glasses, or his mother could suggest a few pages of history. His conscience was not easy, but then he would look for the glasses all a fore-noon another day, and learn a great many pages of history in the afternoon; and they really should consider, he thought, that one learns something in building an ice-boat; and if his heart smote him about the dear baby who cried for Johnny to play with him, the baby would cry at the other side of his mouth when he made a voyage in Johnny's ice-boat. So he took two of the old skates now, screwed the heel-screw of each into a bit of wood a foot long and three inches wide, and, working holes for the leathers, strapped the skates firmly, each to its own piece of wood, and then nailed the pieces securely under each end of the cross-piece, the skates there pointing forwards.

For the rudder then he took the third skate, screwed and strapped to a bit of wood as before, and nailed and screwed that bit of wood to the club end of a long round stick which he brought up through a hole already bored in the stern end of the main beam, or first long board; and he fitted this round stick to a handle by running it through a hole in something he had whittled out like the clothes-paddle or boiler-stick of washing-day.

"I've done well by the day, and the day's done well by me," said Johnny. "But now come needle and thread. I don't believe," said he, "that Aunt Mame is as hard-hearted as the rest." And by dint of hanging over the back of her chair with a good many judicious hugs and kisses—the little rogue really loved his aunt Mamy when there was nothing to gain by it—he induced her to coax a coarse and stout kitchen-table cloth from his mother's linen stores, to bind it with some strong tape, and then to cross the tape from corner to corner in order to strengthen it still more. When he had lashed his sail to his bean-pole with a stout twine, and made a gasket to hold his gaff, which was part of his bamboo fishing-rod, Johnny stopped to execute a brief war-dance, to hug his aunt again, to put on his reefer, and to stow away some mince patties. Then, securing the rope at the other corner of his sail, he dragged his tiny ice-boat free of the big blocks of ice along the shore, established himself upon the seat with his heels against the cross-piece, and waited for the wind.

It came along, with a little dust of snow upon its wings. It took Johnny's sail as if it were a puff of thistle-down; the rope slipped out through Johnny's fingers quick enough to burn them. His heart gave a great plunge, but he held fast, and the next moment a creak, a twist, a hiss, and he was moving. Moving? No—flying! Flying through the air even while he knew he was cutting with a sharp hiss into the ice—the razor-edge of the wind cutting with a sharp hiss, too, upon his cheek, and taking his breath away at first. And there he was speeding up the river so fast that his mother screamed and ran into the house, and his grandmother, looking from the window, began to blame every one else for letting him start out on such a hair-breadth undertaking, and his aunt Mamy declared it was like a great white bubble blowing up the sky, a great white spirit flashing up the river, and if he never came back she was glad to see the last of him that way—but he would be back all right. And so he was.

They said that little ice-boat went at the rate of forty miles an hour. Johnny always insists that it is eighty. But all I know about it is that the March maple-camp was twenty miles up river, and Johnny brought home a great parcel of the sweetest and richest morsels that the sunshine ever coaxed out of the earth through a maple-stem, that very sunset as he ran his ice-boat, "The Scarer," up the shore, and promised his mother he would never go half as fast as he could go in her, unless he had a mask to save his face from blistering, and his father was aboard.

"How did we ever consent to let our middle daughter stay away all these years, mother?" said Dr. Wainwright, addressing his wife.

"I cannot tell how it happened, father," she said, musingly. "I think we drifted into the arrangement, and you know each year brother was expected to bring her back[Pg 331] Harriet would plan a jaunt or a journey which kept her away, and then, Jack, we've generally been rather out at the elbows, and I have been so helpless, that, with our large family, it was for Grace's good to let her remain where she was so well provided for."

"She's clear grit, isn't she?" said the doctor, admiringly, stalking to and fro in his wife's chamber. "I didn't half like the notion of her giving readings; but Charley Raeburn says the world moves and we must move with it, and now that her object is not purely a selfish one, I withdraw my opposition. I confess, though, darling, I don't enjoy the thought that my girls must earn money. I feel differently about the boys."

"Jack dear," said his wife, tenderly, always careful not to wound the feelings of this unsuccessful man who was still so loving and so full of chivalry, "you needn't mind that in the very least. The girl who doesn't want to earn money for herself in these days is in the minority. Girls feel it in the air. They all fret and worry, or most of them do, until they are allowed to measure their strength and test the commercial worth of what they have acquired. You are a dear old fossil, Jack. Just look at it in this way: Suppose Mrs. Vanderhoven, brought up in the purple, taught to play a little, to embroider a little, to speak a little French—to do a little of many things and nothing well—had been given the sort of education that in her day was the right of every gentleman's son, though denied the gentleman's daughter, would her life be so hard and narrow and distressful now? Would she be reduced to taking in fine washing and hemstitching and canning fruit?"

"Canning fruit, mother dear," said Miriam, who had just come in to procure fresh towels for the bedrooms, "is a fine occupation. Several women in the United States are making their fortunes at that. Eva and I, who haven't Grace's talents, are thinking of taking it up in earnest. I can make preserves, I rejoice to say."

"When you are ready to begin, you shall have my blessing," said her father. "I yield to the new order of things." Then as the pretty elder daughter disappeared, a sheaf of white lavender-perfumed towels over her arm, he said: "Now, dear, I perceive your point. Archie Vanderhoven's accident has, however, occurred in the very best possible time for Grace. The King's Daughters—you know what a breezy Ten they are, with our Eva and the Raeburns' Amy among them—are going to give a lift to Archie, not to his mother, who might take offence. All the local talent of our young people is already enlisted. Our big dining-room is to be the hall of ceremonies, and I believe they are to have tableaux, music, readings, and refreshments. This will come off on the first moonlight night, and the proceeds will all go to Archie, to be kept, probably, as a nest-egg for his college expenses. That mother of his means him to go through college, you know, if she has to pay the fees by hard work, washing, ironing, scrubbing, what not."

"I hope the boy's worth it," said Mrs. Wainwright, doubtfully. "Few boys are."

"The right boy is," said the doctor, firmly. "In our medical association there's one fellow who is on the way to be a famous surgeon. He's fine, Jane, the most plucky, persistent man, with the eye, and the nerve, and the hand, and the delicacy and steadiness of the surgeon born in him, and confirmed by training. Some of his operations are perfectly beautiful, beautiful! He'll be famous over the whole world yet. His mother was an Irish charwoman, and she and he had a terrible tug to carry him through his studies."

"Is he good to her? Is he grateful?" asked Mrs. Wainwright, much impressed.

"Good! grateful! I should say so," said the doctor. "She lives like Queen Victoria, rides in her carriage, dresses in black silk, has four maids to wait on her. She lives like the first lady in the land, in her son's house, and he treats her like a lover. He's a man. He was worth all she did. They say," added the doctor, presently, "that sometimes the old lady tires of her splendor, sends the maids away to visit their cousins, and turns in and works for a day or two like all possessed. She's been seen hanging out blankets on a windy day in the back yard, with a face as happy as that of a child playing truant."

"Poor dear old thing!" said Mrs. Wainwright. "Well, to go back to our girlie, she's to be allowed to take her own way, isn't she, and to be as energetic and work as steadily as she likes?"

"Yes, dearest, she shall, for all I'll do or say to the contrary. And when my ship comes in I'll pay her back with interest for the loans she's made me lately."

The doctor went off to visit his patients. His step had grown light, his face had lost its look of alert yet furtive dread. He looked twenty years younger. And no wonder. He no longer had to dodge Potter at every turn, and a big package of receipted bills, endorsed and dated, lay snugly in his desk, the fear of duns exorcised thereby. A man whose path has been impeded by the thick underbrush of debts he cannot settle, and who finds his obligations cancelled, may well walk gayly along the cleared and brightened roadway, hearing birds sing and seeing blue sky beaming above his head.

The Ten took hold of the first reading with enthusiasm. Flags were borrowed, and blazing boughs of maple and oak, with festoons of crimson blackberry vine and armfuls of golden-rod transformed the long room into a bower. Seats were begged and borrowed, and all the cooks in town made cake with fury and pride for the great affair. The tickets were sold without much trouble, and the girls had no end of fun in rehearsing the tableaux which were decided on as preferable in an entertainment given by the King's Daughters, because in tableaux everybody has something to do. Grace was to read from Young Lucretia and a poem by Hetta Lord Hayes Ward, a lovely poem about a certain St. Bridget who trudges up to heaven's gate after her toiling years, and finds St. Peter waiting to set it wide open. The poor modest thing was an example of Keble's lovely stanza:

"Meek souls there are who little dream

Their daily life an angel's theme,

Nor that the rod they bear so calm

In heaven may prove a martyr's palm."

Very much astonished at her reception, she is escorted up to the serene heights by tall seraphs, who treat her with the greatest reverence. By-and-by along comes a grand lady, one of Bridget's former employers. She just squeezes through the gate, and then,

"Down heaven's hill a radiant saint

Comes flying with a palm,

'Are you here, Bridget O'Flaherty?'

St. Bridget cries, 'Yes, ma'am.'

"'Oh, teach me Bridget, the manners, please,

Of the royal court above,'

'Sure, honey dear, you'll aisy learn

Humility and love.'"

I haven't time to tell you all about the entertainment, and there is no need. You, of course, belong to Tens or to needlework guilds or to orders of some kind, and if you are a member of the Order of the Round Table, why of course you are doing good in some way or other, and good which enables one to combine social enjoyment and a grand frolic; and the making of a purseful of gold and silver for a crippled boy, or an aged widow, or a Sunday-school in Dakota, or a Good-will Farm in Maine, is a splendid kind of good.

This chapter is about cements and rivets. It is also about the two little schoolmarms.

"Let us take Mrs. Vanderhoven's pitcher to town when we go to call on the judge with father," said Amy. "Perhaps it can be mended."

"It may be mended, but I do not think it will hold water again."

"There is a place," said Amy, "where a patient old German man, with the tiniest little bits of rivets that you can hardly see, and the stickiest cement you ever did see, repairs broken china. Archie was going to sell the pitcher.[Pg 332] His mother had said he might. A lady at the hotel had promised him five dollars for it as a specimen of some old pottery or other. Then he leaped that hedge, caught his foot, fell, and that was the end of that five dollars, which was to have gone for a new lexicon and I don't know what else."

"It was a fortunate break for Archie. His leg will be as strong as ever, and we'll make fifty dollars by our show. I call such a disaster an angel in disguise."

"Mrs. Vanderhoven cried over the pitcher, though. She said it had almost broken her heart to let Archie take it out of the house, and she felt it was a judgment on her for being willing to part with it."

"Every one has some superstition, I think," said Amy.

NEW PUPILS AND NEW TEACHERS.

NEW PUPILS AND NEW TEACHERS.

Judge Hastings, a tall, soldierly gentleman with the bearing of a courtier, was delighted with the girls, and brought his three little women in their black frocks to see their new teachers.

"I warn you, young ladies," he said, "these are spoiled babies. But they will do anything for those they love, and they will surely love you. I want them thoroughly taught, especially music and dancing. Can you teach them to dance?"

He fixed his keen blue eyes on Grace, who colored under the glance, but answered bravely,

"Yes, Judge, I can teach them to dance and to play, not to count or to spell."

"I'll take charge of that part," said Amy, fearlessly.

Grace's salary was fixed at one thousand dollars, Amy's at four hundred, a year, and Grace was to come to her pupils three hours a day for five days every week, Amy one hour a day for five days.

"We'll travel together," said Amy, "for I'll be at the League while you are pegging away at the teaching of these tots after my hour is over."

If any girl fancies that Grace and Amy had made an easy bargain, I recommend her to try the same tasks day in and day out for the weeks of a winter. She will discover that she had earned her salary. Lucy, Helen, and Madge taxed their young teachers' utmost powers, but they did them credit, and each month, as Grace was able to add comforts to her home, to lighten her father's burdens, to remove anxiety from her mother, she felt that she would willingly have worked harder.

The little pitcher was repaired so that you never would have known it had been broken. Mrs. Vanderhoven set it in the place of honor on top of her mantel shelf, and Archie, now able to hobble about, declared that he would treasure it for his children's children.

One morning a letter came for Grace. It was from the principal of a girls' school in a lovely village up the Hudson, a school attended by the daughters of statesmen and millionaires, but one, too, which had scholarships for bright girls who desired culture, but whose parents had but very little money. To attend Miss L——'s school some girls would have given more than they could put into words; it was a certificate of good standing in society to have been graduated there, while mothers prized and girls envied those who could go there, for the splendid times they were sure to have.

"Your dear mother," Miss L—— wrote, "will easily recall her old schoolmate and friend. I have heard of you, Grace, through my friend, Madame Necker, who was your instructress in Paris, and I have two objects in writing. One is to secure you as a teacher in reading for an advanced class of mine. The class would meet but once a week; your office would be to read to them, interpreting the best authors, and to influence them in the choice of books adapted for young girls."

Grace held her breath. "Mother!" she exclaimed, "is Miss L—— in her right mind?"

"A very level-headed person, Grace, Read on."

"I have also a vacant scholarship, and I will let you name a friend of yours to fill it. I would like a minister's daughter. Is there any dear little twelve-year-old girl who would like to come to my school, and whose parents would like to send her but cannot afford so much expense? Because, if there is such a child among your friends, I will give her a warm welcome. Jane Wainwright, your honored mother, knows that I will be too happy thus to add a happiness to her lot in life."

Mother and daughter looked into each other's eyes. One thought was in both.

"Laura Raeburn," they exclaimed together.

Laura Raeburn it was who entered Miss L——'s, her heart overflowing with satisfaction, and so the never-shaken friendship between Wishing-Brae and the Manse was made stronger still, as by cements and rivets.

This short notice and warning was meant in the kindliest way. George knew that well, and read between the lines. But it was plain to see that the plot was frustrated by the force of circumstance. He pushed the missive into the glowing coals of the fire; it blazed up merrily, and disappeared into gray ashes.

Now for flight. It would certainly do him no good to stay longer within the camp of the enemy. He knew no method of communication with the outside, and it would be impossible for him to meet with the others who were supposed to be his fellow-conspirators. Although the furlough he had been granted had been for a month, he was all zeal to return and join his command, but determined not to do so empty-handed. If he could only find out the destination of the large army that was ready to be embarked at a word's notice, a great deal would be accomplished. Was it Albany, Boston, or Philadelphia that was Lord Howe's objective point? If he could overhear the conversation at the meeting that he knew must now be going on at Fraunce's, he would have something that would make his trip far from worthless.

When doubting, use caution, may be a good motto, but under some circumstances boldness will answer quite as well. In fact, it is often the only thing that will carry affairs to successful issues.

George determined to hear the result of that meeting if possible, and then put as many miles of land and water between himself and New York as he could accomplish with the remaining hours of darkness. It would be hard to get across the river, but he doubted not being able to find a skiff or a boat along the wharves.

Back in the town once more, he approached Fraunce's Tavern by a circuitous way, and at last reached the stable, the shed of which was closely under the windows of the private dining-rooms where many a gay party had been given, and where years and years ago the old Dutch Mynheers had met and toasted their one-legged Governor in fragrant schnapps.

It had been better for George if he had started at once for the red soil of his native State. The tribulations which Mrs. Bonsall had predicted were about to cloud his horizon.

Tall as he was, he was not able to look in at the window. He could hear the murmur and flutter of conversation coming from within the brightly lighted room. Placing his hands on the sill, and using all the strength of his muscular young arms, he managed to draw himself up until his head was level with the panes. It was a fine sight to behold. This was not a council of war, nor even a secret meeting. It was merely a gathering of officers to talk the situation over informally.

General Howe did not believe in hurrying. But often ideas and plans develop at meetings such as this that bear important results. The talk was so general that George could not at first make out a single connected sentence, and his arms were tired with holding himself in the constrained position; besides, his face was forced so closely to the window that it seemed certain that some one would see him from the inside of the room. He lowered himself to the ground, and searching the yard, found a tall barrel. Rolling it cautiously to the side of the house, he stepped upon it.

It was now plain sailing—at least, it seemed to be.

Through the window-blind, which, was partly closed, he could look without being seen. The window was lowered a little at the top to admit the air.

"Tis the strangest thing in the world," said the voice of a speaker, whom George could not see, as he was behind the angle of the wall. "He was a clever lad, well knit and straight; they say the heir to a vast property up the great river. Search high or low, no trace can be found of him. 'Tis known that he went to his room at the City Arms, and that was the last seen of him."

"So Rivington was telling me," spoke up a man facing the window. "And I saw him when he called on General Howe. Those despatches were of great importance. But it's the General's intention to leave Burgoyne to fight it out alone on the Hudson. Philadelphia must be taken; I am sure that is the plan."

George's nerves tingled. Here was something of importance to relate.

A red-faced officer arose. "Here comes the punch, gentlemen," he said. "And I propose as our first toast confusion to Mr. Washington, and may Satan fly away with him."

"On to Philadelphia!" George heard some one cry.

"Yes, and rout out their ratty Congress," said another.

Suddenly it seemed to George as if the earth's surface had opened to receive him, and that he dropped from untold heights. The fact was that the head of the barrel had given in, and he was thrown backwards onto the hard ground. He came down with a clatter. A side entrance to the tavern ran close to where he had been standing. In fact, he had been exposed to the view of any one who came up the walk. Just as he had fallen a party of five or six entered the yard from the outside, coming up the road by the stables.

"Hello! What's that out there?" said a voice. The window of the dining-room was thrown up and a white-wigged head thrust out. "I say, who's there?" was again repeated.

George arose to his feet. One of the party coming toward him stepped forward. "What is the matter here?" he said.

Now if he was called to explain his presence it might lead to his detection, and with a sense of horror George saw that one of the party was the heavy man who had been in his room at the City Arms—the uncle of Richard Blount, of Albany, whose bona fide nephew was in confinement in New Jersey.

He jumped to his feet and made a leap for the wall, to get over before the others could reach the gate.

"Stop him there!" said the voice from the window. "See who it is! Stop him!"

As he reached the top, and was about to throw himself on the other side, there were a flash and a report, and a strange pain ran through George's left arm. He lost his balance and fell.

When he came to, for he had been stunned a trifle by the second fall, he saw that quite a crowd was gathered over him.

"Does anybody know him?" some one asked.

"Yes, I do," was the answer. "It is the young man who tried to steal my time-piece the other day." The voice was Abel Norton's.

"Ay, and he took mine too, if it is the same," put in another. The last speaker was Schoolmaster Anderson.

"Turn him over to the watch," said an officer. "We cannot afford to have suspicious characters about. Ah, here he comes, for once in the right place."

"What means this disturbance, good people? Oh, is any one badly hurt?" As these words were spoken a caped figure with a lantern hurried up. He had a long pike in his hand, and a huge rattle hung by a leather thong about his neck.

Two or three bystanders helped raise the young man to his feet.

"He is wounded," said some one, noticing the useless left arm, which was numbed with pain, and which was bleeding.

"The prison surgeon is good enough for the likes of him," said another.

"Come with me, young man," said the watchman, putting his hand on George's shoulder. "You had better have that arm attended to. Oh! he's charged with crime, eh? That's very different."

Followed by Abel Norton, Schoolmaster Anderson, and a few idlers, the party moved down the street.

The "jig" was up now with a vengeance.

"COURAGE," SAID A LOW VOICE AT GEORGE'S ELBOW.

"COURAGE," SAID A LOW VOICE AT GEORGE'S ELBOW.

"Courage," said a low voice at George's elbow. "Act well your part." It was like Schoolmaster Anderson to quote even under these circumstances. "Do not fear coming to trial. They are too busy to think of little things like this. We will take care of you as well as we can. Know no one," he whispered.

The party had turned into Vine Street, and were heading for the old sugar-house on the corner, which, like many other gloomy buildings of that kind, had been turned for the nonce into a prison.

While Schoolmaster Anderson had been talking he had shaken his fist threateningly under our hero's nose, and had interlarded his talk with some epithets such as: "You young villain. Steal a watch, will you? Rascal!" and the like.

As they entered the narrow doorway of the sugar-house a portly man met them. He carried a large bunch of keys on a huge ring. Roughly he pushed back the crowd of curiosity seekers, and admitted only the watchman, Abel Norton, Mr. Anderson, and the prisoner into the court-yard. A smoky lamp flared from a bracket in the wall.

"What have you here?" he asked.

"Some one we wish you to look out for especially well and carefully," said Mr. Anderson. He took a bit of paper from his pocket; on it was scribbled "Secretary to the Governor." For some time, however, the schoolmaster had not held that important position. But this the jailer did not know. The watchman, who was a stupid fellow, here spoke up.

"'Tis naught but a thief, I take it," he growled.

"Say nothing. How do you know?" said Abel Norton, in a whisper. The heavy face above the cloak took on a wondrous-wise expression.

George had winced, but as he did so felt a reassuring pull at the back of his coat.

"He's wounded," said the jailer, noticing that the lad was supporting one arm with the other.

"We'll send a surgeon to him," said Abel Norton. "I may be a soft-hearted fellow; but I hate to see any one suffer."

"There's an empty cell on the second floor," put in the jailer. "I suppose you don't wish him to be placed in the main gallery with the others."

Mr. Anderson managed to whisper, as George was led away: "Courage. Two of your friends are with you. We are Numbers Two and Three."

Since his arrest the prisoner had not spoken a word. He did not know how badly he was hurt, and had not recovered entirely from the shock of the fall. The pistol-ball had entered his arm below the elbow. As he weakly followed the jailer up the stairway he passed a sentry, and, looking through an iron-barred door, caught a glimpse of a long room filled with a crowd of hungry-looking, half-clothed wretches. They were political prisoners mostly, but many of them had been soldiers who had so bravely defended Fort Washington a few months before.

"Prepare to receive another guest," said a voice from within the reeking room. "Fresh herring here! All ye salt mackerel!"

Several figures got up from the floor, but the party passed down the corridor and halted before a little cell scarcely six feet square. In one corner were a pile of straw and an old worn blanket.

Faint from the loss of blood, George was only too glad to sink down with his back against the wall. So this was what it had come to, the expedition which had apparently promised so well. What would good Mrs. Mack think of her boarder's sudden disappearance? There was one comforting thought, however. He had friends who were placing themselves in a position of danger in order to assist him. He would rather die than betray them. But how odd: Anderson and Norton—men who were known as Tories. That[Pg 335] they also possessed considerable influence was soon to be proved, for in the course of an hour a surgeon appeared and carefully dressed the wounded forearm.

"It's not serious," he said. "I will be in to see you again."

One of the safest places to hide in is a prison, and probably the knowledge of this fact influenced the actions of his supposed accusers, and in such a disturbed condition were the courts of the city that many prisoners arrested on suspicion were held for years without ever coming to trial, in fact, without any indictment being found against them, even the crime for which they had been committed having been forgotten.

As George tossed about uneasily that night in the straw, he now and then dreamed fitfully that he was back once more in camp drilling his company, and again that he was at Stanham Mills, setting traps with his brother along the banks of the roaring brook. Suddenly he felt something hard beneath him. It was the bag of gold! Prisoners who could pay lived in quite a different fashion from the impoverished wretches who were compelled to take what was given them.

He could not imagine why they had not searched his pockets, but the ceremony had been omitted. Running his hand beneath the straw, he found that one of the boards of the floor was loose, leaving a crack that ran almost the entire length of the wall. He took the guineas from the pouch one by one, and placed them in the crack.

When the under-jailer came to the iron grating of his cell the next morning with a stone jug of water in one hand and a loaf of mouldy bread in the other, George extended one of the gold pieces.

"Take this, my man," he said. "You can have more chance to use it than I just now." The man grasped it in his dirty hand, and transferred it quickly to his pocket. At the same time he glanced over his shoulder at the red-coated sentry on the stairway.

"Well, Mr. High and Mighty," he said, drawing back the loaf, "if this bread is not good enough for you, you can go hungry then." He turned as if to walk away, then, walking back, he thrust it through the bars.

"Let me hear no complaints," he went on in a loud tone of voice. "It is good enough fare for such as you."

George could scarcely swallow the rough food. But what was his surprise, in the course of an hour or two, to see the beetle-browed jailer once more before his cell.

"Ho, ho!" he said. "So you have come to your senses. Hand me that stone jug and hold your jaw." As the man extended his hand, George saw that he held a large piece of cold meat and a soft warm biscuit. He took it, and with a parting growl the jailer shuffled away with the empty pitcher.

It seemed to George that the day would never pass. Strange sounds echoed through the building—curses and ribald songs, and now and then the clanking of heavy iron-latched doors. He heard at times the voices of the guards as they exchanged their posts. The only light that entered his little cell came through the window, in the corridor. There was no outlook, and his wounded arm throbbed with pain. Late in the evening the surgeon came again, and the head jailer accompanied him, carrying in his hand a tin lantern. The dim light from the perforations danced in a hundred little spots along the gloomy walls.

After the surgeon had dressed the wound, which he did in silence, and the door had clanged again behind him, George heard him speak to the jailer further down the corridor.

"Take care of that young man," he said. "He is a prisoner of great importance. Answer no questions concerning him, but treat him well. It is necessary that his health should be preserved."

"I suspected quite as much," replied the head jailer. "I have brains. He is no common thief. They wish him for something else, hey?"

"Ay," said the doctor, "that is it. You will find it out in good time, but now I see that you are in the secret keep it close."

To his surprise, shortly after dark our prisoner heard a shuffling at the door of the cell. He had been shivering in the straw in a thin worn blanket.

"Who's there?" he said, his teeth rattling, and his eyes straining to catch a glimpse of what was going on. There was no answer, but as he put out his hand he touched a bundle. He drew it toward him. It was a heavy patch-work quilt. He drew it around him, grateful for the warmth, and thankful in his heart to his unknown benefactor. Immediately he fell asleep as softly as a child might in its cradle.

The days passed quickly. At first it seemed as if George would go wild for the lack of some one to talk to. If it were not for the voices that he could hear at times, and for a few rays of sunlight that shot down the corridor, he would have gone mad. But the jailers treated him kindly; his food was plain, and it was evident that extra attention was being paid to him.

When the man who had first taken the gold piece appeared at the end of the first week, George held another toward him.

"Get me a book, something to read, for pity's sake," he said.

The man had taken the gold piece. "Ay, growl," he said. "'Twill do you lots of good. Where do you suspect you are—at an inn, my friend?"

He had returned, however, later in the day, and thrust a volume quickly through the bars.

Latin and the classics had always appealed strongly to George Frothingham. In the short term at Mr. Anderson's he had made most wonderful progress. What, then, was his delight to see that the well-thumbed, dogeared book was a Virgil! Now how he treasured those few hours of daylight when he could read!

But imagine his astonishment when he found thrust well forward through the iron bars one morning a heavy King James Bible. As he opened it his fingers came across something hard in the back of the binding. He pulled it out—two thin files wrapped about with a bit of paper! On the latter were the familiar characters of the cipher. He had scarcely made this discovery when down the corridor he heard approaching many steps. He thrust the good book and its contents underneath the straw, and looking up, his heart almost failed him, for he caught a glimpse of red coats and gold lace.

"Who is this distinguished personage?" said a strange voice, ironically. It was one of the officers speaking.

"An important prisoner," returned the jailer.

George could see that the whole group had paused before the door. To his astonishment, he saw among them the face of Schoolmaster Anderson. He noticed that the latter plucked the jailer by the sleeve.

"He is here for some good cause. I know not what," the latter continued, hurriedly. "'Twill be divulged later, I suppose."

Two or three of the officers had glanced searchingly into the little den. One noticed the Virgil on the floor.

"Ah, he has some learning, I perceive," said one.

When they had gone, to his chagrin our hero found that the light was too dim to read the cipher message. He must wait until noon of the next day, when the sun would beat through the window around the corner of his cell.

On the day this visit of inspection had been made to the sugar-house prison his Majesty's frigate Minerva was bowling along merrily off the southern shore of Long Island. Again a group of officers were on her quarter-deck. A short man in a cocked hat swept the horizon to the northward with his glass.

"Ah, there it lies!" he said—"there's the new country which, we hope, will soon be flying our flag throughout its length and breadth."

It was a brilliant cloudless morning. Some near-shore gulls hovered overhead or dashed down in the frigate's wake.

Lieutenant William Frothingham felt the invigorating land breeze on his cheeks. He could make out now with the naked eye the low-lying hills. Home again. It was his country and the King's that lay off there, and somewhere,[Pg 336] his brother, whom he loved more than any one else on earth, was wearing the uniform of the forces that he soon would be opposed to, maybe in battle. Little did he know that George's horizon was confined by four black walls.

The Minerva, with a bone in her teeth and the wind just right to bring her in, swept past Sandy Hook at last, and blossoming out into some of her lighter canvas, she reached the quieter waters of the bay. Soon were brought to view the forests of masts and the great dark hulls of the fleet that had preceded her. Signals sprang out, and the flags rattled stiffly in the wind. As she passed the Roebuck a sheet of flame and white smoke burst from her side, and every frigate followed suit and welcomed her with a roaring salvo. She swept up the river, the bulwarks lined with the curious faces of the soldiery gazing at the crowded wharfs. At last anchor was dropped in the currents of the broad North River.

Early the next morning boats were manned, and the troops were disembarked. A huge band was there to meet them, and the new arrivals swept into Broadway between the lines of cheering soldiers and citizens. If disloyalty to the King was here it did not show.

The blood surged through William's veins as he walked at the head of his stalwart company and acknowledged the salute of a group of officers standing at the street corner. To his wonder as he went by a row of low brick houses he heard a voice call his name: "Mr. Frothingham! Is it you? Is it you? Is that the uniform?" he heard distinctly. He turned, but could see no one whom he recognized; it had seemed to him that it was a woman's voice, however. There was an odd figure standing there, a washer-woman, evidently; she had dropped a basket which she had been holding, and the ground at her feet was covered with frilled shirts. The crowd about her laughed. Her lips were moving, but the cheer that broke out drowned what she was saying. As the company halted, a figure came out into the street.

"Ah, Lieutenant Frothingham!" said a voice that made William start. "We have you here in the King's livery, I see."

William turned. It was a small man, very gorgeous in a red waistcoat and a heavy fur-lined coat.

"Pardon me for introducing myself. Your brother George was a pupil of mine. I knew who you were at a glance," he added. "You are alike as two pinfish."

"Have you seen aught of my brother?" was William's first exclamation.

"I think I have heard a rumor somewhere," replied the schoolmaster, with a frown, though his eyes twinkled in contradiction. "He was with Washington at Trenton and Princeton. My name is Anderson."

Of course the news of these two affairs had greeted the Minerva when she first arrived in port. It had caused a thrill of astonishment.

"What did I tell you?" had remarked Colonel Forsythe, upon this occasion. "The only people that can beat Englishmen are Englishmen themselves—and what else are these Yankees?"

The regiment took up the march, and William, heading his company, once more turned into a side street, at the end of which were the new quarters. The town swarmed with the red-coated soldiery.

As they had gone down the street, they had passed beneath the shadow of the sugar-house prison. George, from within, heard the loud rolling of the royal drums, and raised himself on his elbow to listen.

The wagon was about to start, and Mrs. Adams leaned out to say: "Now, Billy, stay close around here to-day, you and Dick, and take care of things, and don't let anybody get into the house. Water the hogs about twelve."

"And you'd better cut an armful of corn-tops and give the calves, too," added Billy's father.

"Yes, sir, I will," answered Billy, dutifully.

"Dick, I want you to be a good boy to-day, and not get into any trouble, whatever you do," cautioned Mrs. Dunlap, Dick's mother. She knew his proneness to mischief and accidents, and thinking it might be well to hold out some extra inducements, added, "If you behave yourself right nicely, maybe I'll buy you something the next time I go to town."

"Yes'm," was Dick's non-committal response. He had heard that promise a great many times before.

The wagon started. Mr. Adams and Mr. Dunlap occupied the spring seat in front, while their wives sat just behind them in straight-backed chairs. In the rear end five or six small children were sitting on straw on the bottom of the wagon-bed.

"Billy," called back Mrs. Adams, "you'll find some fried chicken for your dinner in the stove oven, and a pie in the safe, and some—" The rest was lost in the jolting of the wagon. That was of little consequence, however, for the two boys had no fears of not being able to find everything there was on the place to eat when the time came.

It was a morning in August. The people in the[Pg 337] wagon had started to a camp-meeting a few miles away, and did not expect to return till late at night. Twelve-year-old Billy had been left at home to look after things, and Dick had insisted upon staying to keep him company. The two were of the same age, but Billy was considerably the larger. Billy had on his every-day clothes, and was bare-footed, while Dick looked rather uncomfortable in his Sunday suit and shoes and stockings.

"Guess I'll take these off," he said, seating himself on the doorstep and beginning to untie his shoes. "There, that feels better," he added, as he put the superfluous articles in at the door and looked down at his bare feet. "What are we going to do?"

"I don't care. Anything you say."

"Then let's go swimming," suggested Dick. "Too hot to do anything else."

"Ma told me to stay pretty close about home. Somebody went into Mr. Lawson's house last week, when there wasn't anybody there, and took a whole lot of things. Guess she's afraid the same fellow will get into ours, whoever it was."

"Can't you lock the house?"

"Not from the outside. The front door will fasten on the inside, and so will the windows. But the kitchen door won't fasten at all. The lock is off."

After going through the house to see what could be done, Billy said: "I'll tell you what we'll do. We'll fasten everything but the kitchen door, and then bring old Ring down and tie him close to that. He won't let anybody get in."

Dick endorsed this plan, and they proceeded to carry it out. A stake was driven into the ground, and the dog's chain was fastened to it. Ring was part bull-dog, and rather too fond of using his teeth on strangers to be permitted to run at large.

"You'll keep 'em away, won't you, Ring?" said Billy, patting the dog's head. Then he brought a pan of water and placed it in Ring's reach, and they were ready to start.

Passing out through the gate, which they closed, but carelessly neglected to fasten, they crossed the prairie ridge that lay north of the house, and walked on slowly toward the swimming-place. The creek was more than a mile away. After reaching it, they amused themselves for an hour or two, then put on their clothes and started back.

Before coming in sight of the house they heard Ring barking furiously. Both started on a run to see what was the matter.

As soon as they came to where they could look over the ridge, Billy burst out laughing.

"It's Kizner's pet sheep. He's got into the yard, and Ring's barking at 'im. Just watch the old ram, will you, making out like he's going to butt Ring! He knows Ring's tied or he wouldn't be so bold. Just see Ring rear and charge! Wouldn't he like to get to 'im once?"

"Is it old Aleck?" asked Dick. "If it is, he's not afraid of any dog. Tommy Hendricks says he gets after their dog sometimes, and runs 'im back into the yard. He butts like everything, that old sheep does. Tommy's half scared to death of 'im."

"Huh!" exclaimed Billy, contemptuously. "Tommy may be, but I'm not. If he fools with me I'll give 'im rocks, and turn old Ring loose on 'im to boot. I'd just like to see 'im run him!"

"Better go slow," cautioned Dick. "You don't know that old ram. The Kizner boys taught 'im to butt when he was a little bit of a thing, and he's been getting worse and worse ever since. Why, my pa was going along over on the branch last spring, and found Aleck sticking in a mud-hole. So he up and helped 'im out, and was going ahead, when, zip! something took 'im behind. It was Aleck butting 'im. That's the kind of a sheep old Aleck is. And the old fellow was so poor then he could hardly walk. He's big and fat now, I guess."

Billy laughed heartily. "What did your pa do?" he asked.

"Why, he caught 'im and pitched 'im back into the mud-hole; but I guess he got out somehow."

"Well, I'm not afraid of 'im," declared Billy, and he began to fill his pockets with stones of a size suitable for throwing.

Taking courage from Billy, Dick did the same. Then they hurried in at the gate, and ran round to the back of the house, where the sheep and the dog were tantalizing each other.

Aleck was a vicious-looking old ram, large and strong, with curled horns, and a head made on purpose for butting. Perhaps he had received his name because of his fighting powers. At any rate, it suited him very well.

Both Ring and the sheep were out of temper. Ring was growling and barking and tugging at his chain, doing his best to get loose. Aleck charged toward him occasionally, and did not seem to be in the least afraid.

"Get out of here!" shouted Billy, as he rushed round the house and threw a stone at the ram, missing him.

Dick threw one also, with better aim, for it struck the ram on the side. Aleck promptly turned his attention to the new-comers. He was in just the right mood to deal with them.

What took place during the next few minutes the two boys had only a confused recollection of afterwards. Each was conscious of being knocked sprawling, and of trying to rise, and being knocked down again. Every time one of them started to get on his feet he was sent rolling over the hard ground. How the ram managed to move fast enough to keep both of them down they were too much excited to observe; but he did it easily, and would probably have kept a third boy down at the same time if there had been three.

At last, after being knocked and rolled some distance, they were near the stake-and-ridered fence which enclosed the large yard. Dick made a rush on his hands and knees, and succeeded in climbing the fence far enough to tumble through between the fence and the rider. Once on the other side, he was safe enough.