Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, JANUARY 28, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 848. | two dollars a year. |

"I'm going to have a shy at that gold when we get up to Potosi, Jack. I tell you forty thousand dollars in gold is worth looking for these days."

Ned Peterson leaned back in one of the great rocking-chairs on the upper gallery of the Hôtel de France, in Port of Spain, on the island of Trinidad, and puffed his cigar as complacently as though the gold were already in his trunk. He was fresh out of the School of Mines of Columbia College, and so felt at liberty to lay down the law to his fourteen-year-old brother Jack. They were both on their way into the heart of Venezuela, to the gold-mines of Naparima, of which their father was superintendent and part owner.

"Oh, that's just one of your romantic notions," Jack replied, standing by his brother and looking through the jalousie-blinds at the coolies squatting in the park across the street. "You want a chance to write to your chums in New York that you're searching for lost gold in the bottom of the Orinoco River. It sounds well, but it won't amount to anything."

"You don't know what you're talking about," the young man retorted, with great dignity. "We know the gold is there, and it will be an easy matter to find out just about where the canoe was when it capsized and dumped it into the river. Of course there has been a great deal of searching for it, but never under as favorable circumstances as we shall find. Last November, when the gold was lost, the water in the Orinoco was sixty feet higher than it is now. At this time of year, midwinter, it is so low that the steamers cannot go further up the river than the City of Bolivar. At Potosi the water is not more than three or four feet deep just now, and by sounding in the mud we will have an excellent chance of finding the box. Anyhow, it's worth trying for. Forty-one thousand three hundred and forty dollars is the exact value of it."

"You have it down fine!" Jack laughed. "Couldn't you take off a dollar or two?"

"Not a cent," Ned answered. "They send the gold down from the mines in bars, two bars in a box, and each bar weighing exactly 1000 ounces. I suppose you know that gold is worth $20.67 an ounce, always and in all countries.[Pg 302] That price never varies. So it is easy to calculate the value of the two bars. It was a great setback to father's management, the loss of those two bars right at the beginning."

"I've heard an awful lot about those two bars of gold," Jack said, "but I never quite understood the thing. How did they come to be lost?"

Ned was quite willing to show his superior knowledge by telling the story of the lost gold. "You see, father took charge of the mines at a very bad time," he began. "It had been a gilt-edged investment for a long time, and the two-hundred-dollar shares paid ten dollars a month in dividends. But the veins of ore contracted, and dividends went down to a dollar a month, and as father stepped in just at that time he got all the blame for the reduction. Then came the loss of the two bars, and that made matters worse.

"The mines, you know," he continued, "are on the Urubu River, a branch of the Orinoco, forty miles above Potosi. Potosi is a little native settlement at the junction of the two rivers, a hundred miles above Bolivar, and Bolivar, as you know, is two hundred and fifty miles up the Orinoco from here. They run the gold into bars at the mines, pack it two bars in a box, and send the box in a big canoe down to Potosi, with a guard of three or four armed men. From Potosi it goes in the steamer to Bolivar, and from Bolivar it is carried, along with other things, by great teams of forty and sixty bullocks over the mountains to Caracas, the capital, where it is coined in the mint.

"There was where father met his great misfortune," Ned went on, "in the shipping. The gold was all right, and the guard was all right, but father didn't know that it was customary to lash the box to two big timbers, so that if anything happened to the canoe the gold would float. The men didn't care, and they came down the Urubu all right into the Orinoco, and in five minutes more they'd have had the box aboard the steamer. But the swift current or something else struck the canoe; over she went, and down went the box like a flash, and it's never been seen since. The question is how far the current would carry it in that swift water, sixty feet deep, and how far it would sink in the muddy bottom. They have spent a good many hundred dollars in searching for it, but not a trace has ever been found, though that was several months ago, and the water is low enough now.

"So you see," he concluded, "what a grand thing it would be if we could find it on our way to join the folks. I wanted to try it sooner, but they would not let us start till I had finished my course at the School of Mines."

"It wouldn't belong to us if we did find it," Jack objected.

"No, nor to father either," Ned answered. "But they've offered two thousand dollars reward for its recovery, and if we could find it, it would smooth everything out. We've got to go past Potosi in a canoe anyhow. The steamer that starts to-morrow evening goes only to Bolivar, and there we are to buy a canoe and do the rest of the journey on our own hook. Then you'll have a chance to show what you're made of, young fellow, with a hundred and forty miles to paddle in a canoe."

"Don't brag, Mr. School of Mines," Jack laughed. "I guess when it comes to paddling you'll find I'm with you."

The young Americans were surprised to find that it was a good American steamboat that was to carry them up the Orinoco on Saturday evening—a boat called the Bolivar, of about 600 tons. They knew that it was only one section of the river they would see, for the Orinoco empties into the sea through a hundred mouths, some flowing into the Gulf of Paria, others emptying into the ocean as far down the coast as Point Barrima, 230 miles away. There was not much to be seen on Saturday evening, for the boat had a long sail across the Gulf of Paria before entering the river, down past San Fernando and the pitchy shores of La Brea, near the great pitch lake. When Sunday morning dawned they were in one of the many channels of the mighty Orinoco, and then there was even less to see than before. The river was nearly a mile wide, but the shores were low and covered with mangrove bushes, and there was no sign of life or habitation.

"Say, Ned," Jack exclaimed, after they had gone through scores of miles of this low wet country, "what do you think of Venezuela? It would be a funny racket if two great nations should go to war over the boundaries of a country like this."

"It's a matter of honor with us," Ned replied, still in his dignified way.

"A matter of chills, I should say, here along the coast," Jack retorted, "though it's hot enough to cook eggs in the sand. I don't think the thermometer went below 90° all last night."

All the way up to the City of Bolivar the river was much the same, except that occasionally they passed a bluff; and wherever there was a bluff there was a little settlement, the houses having no walls but the posts that supported the thatched roofs. Nowhere was there a sign of cultivation or any land that looked as if it could be cultivated, and the only human beings were the Guaranno Indians, who lived in the huts on shore. The river water was thick with yellow mud, and well spiced with alligators and giant lizards five or six feet long.

"It will be different when we reach Bolivar," Ned said, half apologetically. "You know Bolivar is the fourth city of Venezuela, and quite a large place."

At daylight on Monday morning the steamboat lay in front of Bolivar, or, rather, at the feet of Bolivar, for the city is built on a bluff a hundred feet high, and half-way up the hill is a strong stone wharf. But the water was so low that the boat lay fifty feet beneath the wharf, and it was hard to realize that in flood-time the water is almost up to the top of the hill.

"So this is the great City of Bolivar, is it?" Jack exclaimed, after they had climbed the steep hill and passed the city wall, and stood among the yellow-walled, flat-roofed houses. "There's too much grass growing in the streets to suit a New-Yorker."

There were few wheeled vehicles in the streets, but plenty of donkeys carrying burdens. The principal buildings were the cathedral, standing on the summit of a little hill, and the jail, about which some red-capped soldiers were on guard.

"I did want to see one of those great teams of sixty bullocks starting out," Jack said; "but now that we've seen the town, the quicker you can get a canoe and let us be off, the better."

Ned was disappointed too in the appearance of Bolivar, about which he had heard so much, and before the sun was high he had bought a small dug-out canoe for eight dollars, about double its value, and the boys were off for their hundred-mile paddle against the current to Potosi, with canned provisions enough to last them all the way to the mines.

In the forty-eight hours that this journey consumed they saw just three men, all half-breed Indians, out in canoes fishing; but they tired of counting the alligators sunning themselves on mud banks. When at last a turn of the river brought Potosi into view, they shouted with laughter at the appearance of the place, though both were tired and disgusted. The settlement stood on a high bluff, like Bolivar, but it consisted of four houses or huts, all without walls, and roofed with thatch.

"No matter," Ned laughed. "If there was nothing here but a cave I should stop, all the same, and find out where that gold was lost. You see there is hardly any water in the river. We will go up to the settlement and make inquiries, and it's a mighty good thing we have both studied Spanish. Even these half-breeds speak Spanish after a fashion."

"I guess they'll speak it better than we do," Jack replied. "I can read it all right, and I could understand them if they wouldn't talk so fast; they seem to rattle off about two or three hundred words a minute."

When they climbed the hill they found that, poor as the settlement was, it commanded a beautiful view of miles of the Orinoco and a long sweep of the Urubu, a much smaller stream, but more picturesque.

The occupant of the hut nearest the edge of the bluff professed to know all about the losing of the gold, and he agreed for a small consideration to give what information he could. He was willing, too, to take the young Americanos into his house to live during the two or three days[Pg 303] that they thought they might stay in Potosi. There was plenty of room, for the cooking-place was a fire under the nearest tree, and the beds were only hammocks swung from the wattles that answered for rafters. The custom was to turn into the hammocks "all standing," as Jack called it, without any change in the toilet, so that a large family could sleep conveniently under the one small roof.

The boy's new landlord, who called himself Felipe, lived alone in the hut with his daughter, a swarthy but handsome girl of about fifteen. Maria, the daughter, did all the work of the house, even to cutting the firewood; but the visitors soon had reason to believe that her father did not treat her very kindly. She was much interested in the newcomers, and did some little kindnesses for them. Of course Ned considered her entirely beneath his notice; but Jack saw that she had the soft brown eyes of her race, with the smooth copper-colored skin of our own Indians, though with more red in her cheeks, and a profusion of straight raven-black hair. He thought her a very pretty and intelligent-looking girl.

"Now, then, young chap," said Ned, after they had taken a short rest in the shade of the hut, "we're going to have a hunt for that gold. Felipe has gone out to cut some poles, and he's going with us in the canoe to point out the spot. It's a thousand dollars apiece to us, mind you, if we strike it, and a great help to father. Two thousand ounces of gold is only 125 pounds, and we can easily handle it if we can find it. Say," he went on, "I believe you've made a conquest, Jack. I notice that young Dago girl keeps looking at you and smiling at you half the time. I suppose she's not used to seeing such handsome kids as you."

"Get out!" Jack answered, blushing. "She wants to be hospitable to us, that's all. It makes me mad to see the way her father orders her around, for she's much more intelligent than he is."

"Humph!" Ned grunted, "Always keep on the right side of the cook; that's the advice of an old traveller."

Felipe was very liberal with his information when they went out in the canoe. There the steamer lay, here the boat was capsized and the box went down. The swift current was setting a little off shore at the time, so he pointed out the likeliest places for sounding the mud. "But think of sixty feet of water!" he exclaimed. The box might have been carried half a mile down stream before it touched bottom at all. The only chance was to make a thorough search over a large space.

"Say, Ned," Jack asked, in English, while they were prodding the mud with their poles, "if this fellow knows so well where the box went down, why didn't he get it himself?"

"I suppose because he couldn't find it, like the rest of them," Ned answered. "He seems to be an honest sort of fellow."

They kept up the search till noon without finding anything more valuable than a few big stones and water-soaked logs; and when they went up to the house to dinner the little girl squeezed a lime into a cup of cool water for each of the strangers, saying that they looked tired and hot.

"It's all on your account, Jack," Ned said, banteringly. "You're the attraction."

Jack made no reply; but after dinner he ran his hands through his pockets in search of some trifle that he might give the girl for her attentions to them. He could find nothing more suitable than his silver match-box; it made the little Indian's eyes sparkle when he handed it to her.

The afternoon's search was no more successful than the morning's, and early in the evening all the occupants of the hut lay down in their hammocks. Jack found that a small piece of mosquito-netting, large enough at any rate to cover his face, had been put in his hammock to help keep off the mosquitoes, and he saw that there was none in any of the other hammocks; but he made no remarks about it.

Before sunrise in the morning the others were all astir, but Jack felt sore and stiff, and he lay still.

"I'm afraid that hot sun rather knocked me out yesterday," he said to Ned. "I think I'll stay here a little while, and try to get another nap."

Ned anxiously felt his brother's temples and pulse, for such symptoms have to be watched in tropical countries; but finding no signs of fever, he went out and down the hill to look after the canoe before breakfast. Felipe also strolled out, leaving Maria in the hut getting the things ready for breakfast. In a few minutes, however, Felipe returned, and said something angrily to the girl. Receiving no reply, he seized her by the arm and gave her a violent shake, and slapped her on the side of the head.

Jack could not help seeing it, and his blood began to boil. He lay still a moment longer, however, till Felipe reached up into the thatching and drew out a long heavy switch that he had evidently used before. This was more than Jack could stand, and he sprang out of the hammock.

"Hi, you Greaser!" he cried, in English, for he was too mad to bother with Spanish, "if you hit that girl again I'll spread you all over the bluff!"

Felipe did not understand the words, but Jack's attitude was plain enough to him. The boy stood in front of him with fists clinched, ready for instant battle.

Although only fourteen, Jack was several sizes larger and much more muscular than the half-breed, and in a fist fight would have whipped him in a minute. Besides, he was an American boy defending a helpless girl, and his blood was up. But Felipe had no fancy for such an encounter. He let go his hold and retreated a step, and with the instinct of his race his right hand went up to his bosom, and he drew out a long knife.

For an instant Jack did not know what to do. He was entirely unarmed, for Ned carried the only revolver they had, and Felipe with a knife was a dangerous customer. But it was only for an instant, for his eye fell upon a machete sticking in a leather cleat against one of the posts that supported the roof.

A machete is a cutlass, a broadsword about two feet long, used by the South Americans for scratching the ground and felling small trees, and it makes a terribly effective weapon.

"That's your game, is it?" Jack exclaimed, snatching up the machete. "Then come on!" and in his excitement he advanced upon the Venezuelan without further ceremony.

Felipe's knife was a trifle compared with the machete; and with the young Americano boiling over with rage, and the machete cutting circles in the air dangerously near his head, it was no wonder that the half-breed turned and fled ignominiously.

The flight gave the affair a humorous turn that Jack was quick to see, and he followed the native at a lively pace, more for sport than in anger, but shouting and waving the cutlass as if he intended to cut him to pieces.

Down the hill Felipe ran like a deer, looking neither to the right nor the left till he was by the side of Ned and under his protection.

"Never mind, Felipe," Ned said, with a sly look at Jack, after explanations had been made; "if he should kill you with the cutlass I'd give him a good trouncing for it, so you'd be avenged anyhow."

This was quite satisfactory to the Venezuelan, for he knew as little about a joke as he did about using his fists. But as Jack turned and went back to the house, Felipe cautiously waited to return with Ned.

This caution of Felipe's meant a great deal to the young Americans, though they little suspected it. It gave Jack five minutes alone with Maria in the hut, and that five minutes was of great importance. She thanked him with her velvety eyes for rescuing her, but said no word about it; what she did say was of much more account.

"It's no use for you to look in the river where you have been looking," she said, keeping a bright lookout for her father's return. "He is showing you the wrong places."

"Is that so?" Jack exclaimed. "Can you show us the right place?"

"It's no use to look anywhere," she answered, "for the gold is not there."

"Not there? Then has it been found?"

"Yes," she replied.

"And do you know where it is?"

"It is here," she said, stamping her little bare brown foot upon the earth floor of the hut near one of the posts.

"Buried!" Jack exclaimed. "Who found it?"

"You must not ask me that," the girl replied. "I suppose they will kill me for what I have told you already."

"Not if I know myself, they won't!" Jack exclaimed. "Is this fellow your father?"

"Not exactly," Maria answered. "My father died, and Felipe married my mother. And he treats me very badly," she added.

"Then, we must get out of here to-night with the gold," Jack hurriedly said, "and take you along. My mother will be glad to have a girl like you in the house, and it is only forty miles up the river to the mines. Is Felipe a sound sleeper?"

"I will see to it that he sleeps well to-night," Maria answered, with more meaning in her words than Jack understood at the time. "Hush! They are coming!"

While Felipe slept soundly in his hammock that night under the influence of an herb that Maria added to his tea, the two Americanos paddled their canoe rapidly up the Urubu River toward the mines. Maria sat demurely in the bow; for she was not quite as heavy as the box of gold, so that was put in the stern. The thousand dollars that was her share of the reward made Maria one of the richest half-breed girls in Venezuela, and the boys still delight in counting over the five hundred dollars that fell to each of them. But Jack's mother says the greatest prize captured in that expedition was Maria, the copper-colored little Venezuelan.

| Madge. |

| Bess. |

| A Stranger. |

| A Salesman. |

| A Cash-boy. |

Scene.—The Upholstery Department of a fashionable shop. Screens, piles of rugs, sofa pillows, etc., in confusion. Three or four cane-seated chairs placed about at irregular distances. Across left end of stage extends a pole for the display of curtains. Behind these the actors may retire. There should be a second exit opposite, near back of stage. Right of centre an upright piano. As curtain rises, enter slowly, Cash-boy bearing check and small change.

[An impression of space may be produced in two ways, either by hanging a background canvas, whereon is painted a perspective of counters, draperies, potteries, etc., or by the use of mirrors. As scene-painters do not grow on every twig, the better plan is to borrow long mirrors from a house-furnishing establishment, and arrange them so that they reflect a section of the stage behind the curtained pole. This section can be made to look as if sales of small articles were going on at another end of the shop from that in the foreground of stage. But take care that no part of the real stage setting is reflected. A pantomimic repetition of the play would bring down the house, and as certainly disturb the performers. Do not crowd the stage.]

Cash-boy. Now where's 792 gone, I wonder? That's just the way with 'em; always yelling for "check," and when you come racing and tearing, they ain't there. Glad I ain't down-stairs, to have them girls hollering "Cosh! Cosh!" (mimicking) fit to bust your ears. Guess I better chase after 792. (Seats himself, and examines change.) I'll toss up to see where he is—heads, he's skipped to lunch; tails (enter, R., Madge and Bess unobserved), he'll gimme ginger for keeping him waiting.

[Sees girls, closes his hand over penny, and exits, making wry face.]

Bess (sighing). Poor boy! Evidently he has a cruel step-father who ill-uses him.

Madge. His case is less pitiable than ours, for one can at least occasionally escape the society of a man. Besides, men never make things so unpleasant at home.

Bess. "Home!" Oh, Madge! I could weep to think how we have looked forward to a home of our own, after ten years of boarding-school. (Enter, R., Stranger. She pauses on the threshold, listening.) And now to have everything spoiled by this hateful step-mother. It is too bad.

Madge. Papa writes that she is lovely, and will be as much a companion to us as to him.

Bess. Nonsense. Who ever heard of a step-mother being a companion? I am sure she is an ugly old maid who has no sympathy with anything under fifty years of age.

Madge. It was rather nice of her to ask papa to let us furnish our rooms in the new house, though.

Bess. Policy—mere policy. She wants to get rid of the trouble of doing it herself.

Madge. Well, for papa's sake I think we ought to try to like her.

Bess. Oh, you will like her fast enough, but I never, never can!

Stranger (approaching). There seems to be nobody in this department to wait on me; or perhaps a clerk is attending to your orders?

Madge. No; we were so busy talking that we forgot how much we have to do, and did not notice the absence of clerks.

Stranger. Ah! here is some one coming. Let us hail him at once. (Cash-boy loiters from behind curtains, L.) Boy, please bring a salesman as quickly as possible.

Cash-boy. 'Ain't 792 come yet? Well, he is taking a corking feed. Wish I was him.

Bess (compassionately). Do not you have enough to eat at home?

Cash-boy. Do I look like I'm suffering?

Bess. No; but I thought perhaps your step-father—

Cash-boy (thrusting his hands in his pockets and laughing). 'Ain't got no step-father. The old lady, she's a step, though.

Stranger. Don't you think you should speak more respectfully of old persons?

Cash-boy. I'm a jollying you. She ain't much older than you, and she don't act a bit like a step. She's prime, I tell you.

Bess (impatiently). Go call some one to wait on us, and don't stand talking all day.

[Exit Cash-boy, calling "Sales! Sales!"]

Stranger (rising and looking behind curtains, L.). It is provoking to sit idle in this way when one has the furnishing of a house on hand.

Madge. I should think so. With only two rooms to fit up, Bess and I feel our responsibilities weighing on us.

[Moves about among rolls of carpet, keeping near Stranger.]

Stranger. How sweet of your mother to allow you to select everything for yourselves!

Madge (softly). We have no mother.

Stranger. Poor children!

[Lays her hand on Madge's shoulder. They return thus to their seats. Bess walks over to R., and leans dejectedly against piano a moment, then turns impulsively.]

Bess. Have you daughters?

Stranger. None of my own; but I'm going to adopt two in a few weeks.

Madge. Do you love them so much?

Stranger. I shall when we know each other better.

Bess. And they?

Stranger. I fear they are a trifle prejudiced at present, but love begets love, and we shall eventually become friends.

Madge. It would be difficult not to become friendly with you.

Stranger. Thank you, my dear. (Again goes to curtains, L.) Here is our salesman at last, and as we are all on the same errand, we may save time by looking at carpets and hangings together. (To Bess.) You shall have first opportunity, however.

Bess. No, no; you are entitled to take precedence.

Stranger. Age before beauty—eh? Well, then we will[Pg 305] collectively examine rugs for your rooms. (To Salesman.) Something in delicate tints, please.

Salesman. What size, madam?

Bess (aghast). Size?

Madge. We did not once dream of measuring the floor.

Stranger. Never mind; we will not worry about such trifles as measurements. Let me see (reflecting); twelve feet square—no, twelve by fifteen will do. (Salesman unrolls two rugs.) That one is charmingly suggestive of spring-time and flowers. Just the thing for a débutante.

Bess. I think I prefer the other. What is the price?

Salesman. A hundred and fifty dollars.

Madge (springing up in surprise). A hundred and fifty! Goodness gracious! Why, we expected to furnish a whole room for less! How much is the other?

Salesman. Twenty-five.

Stranger. Don't let me influence your choice.

Bess. Imagine trampling on a hundred-and-fifty dollar rug.

Stranger. People trample on more valuable things every day.

Bess (aside). Now why should that speech make me uncomfortable? (To Madge.) Aren't we inconsiderate in taking the time of a stranger for our affairs?

Stranger. That depends upon the stranger.

Bess. Then shall we look at curtains? Those are handsome—aren't they?

Stranger. I'm afraid they are more expensive even than the rug. You might try dotted muslin, perhaps. I shall have them for my room.

Bess (reluctantly). Well. What are you giggling about, Madge?

Madge. I was thinking that you said this morning nothing could induce you to have dotted muslin curtains.

Bess. People may change their minds—mayn't they?

Stranger. I trust you may change yours some time when more is at stake. (To Salesman.) Will you kindly find some pale blue draperies that I ordered from the fancy-goods counter down-stairs, and bring them here?

[Exit Salesman.]

Bess (going toward piano). I wonder if we shall have a piano at home?

Stranger (absently). Oh yes!

Madge (surprised). Why, how can you know?

Stranger (recovering herself). On general principles, my dear. Every house must need a piano.

Bess. Of course you play or sing?

Stranger. My repertoire is limited, and not classical. Association with young people has led me to devote more time than I ought to dance-music and light opera.

Madge. Do play us a two-step now, just for fun.

[Stranger seats herself at piano and plays with spirit. The girls hesitate a moment, then push aside rugs and begin to dance.]

Bess (stopping breathless). How sweet of you! Such a fascinating two-step, and played as if you like to take a turn yourself.

Stranger. I was quite devoted to it, but now that I am an old maid I have no sympathy with anything under fifty years of age.

Madge (aside). That's what Bess says about our prospective step-mother.

[Enter Salesman with draperies.]

Stranger. Thank you. Yes, we have finished our shopping in this department. (To girls.) I must say good-by to you, as you probably wish to purchase bedroom furniture, and I will first look after my parlor.

Madge. I am so sorry we cannot go on as we have begun. We shall miss having you to advise and consult with.

Bess. You have been so very kind to help us.

Stranger. Policy, my dear—mere policy.

Bess (aside). How strange! She quotes my very words. (To her.) I will not believe there was a scrap of policy about it.

Madge. Nor I. You were simply lovely to two ignorant girls who thought they knew everything.

Stranger. Well, good-by. Possibly we may meet again some day.

Girls (in unison). I'm sure we hope so.

Salesman (as Stranger starts to leave). To whom shall I charge your curtains and rugs, madam?

Stranger. To Charles Rockwood.

Girls. Why, that is papa's name.

Stranger. Yes? Quite a coincidence—isn't it?

Salesman. The address, please?

Stranger. Thirty-three West Blank Street.

Girls (in great excitement). The number of our new house!

Stranger. Really?

Bess. What does it all mean?

Madge. How perfectly exciting!

Bess. Is it possible that—

Madge. This is our—

Stranger. Future step-mother? Who ever heard of a step-mother being a companion, my dear girls?

Bess. Forgive me. I did not know—

Stranger. The marplot that was to spoil everything when her daughters returned from boarding-school.

[Enter Cash-boy.]

Cash-boy. Sev—en—nine—ty—two!

Salesman. Here, check, take this to the office.

Madge. Wait a moment, boy. You see we have gained a "step," too.

Madge (embracing Stranger). I was sure I should like you.

Bess. And I—

Stranger. Never, never, never can.

Bess (taking her hand affectionately). I thought so once, but now I know that circumstances alter cases.

When I was last in the South, the gentleman at whose house I was visiting asked a trustworthy old colored man to get him a green boy from the country to be trained as a house servant. In a day or so the old man drove up to the door and put out of his wagon a sturdy-looking lad of fifteen or so, black as the ace of spades, and clad in raiment seemingly made of selections from a rag-bag. With a small bundle in his hand he approached the gallery—that is what a porch in some parts of the South is called—where I was sitting with my host, Mr. Prettyman. The boy took off his hat and made not a bow exactly but an inclination of his head, grinning from ear to ear, and displaying as white and useful a set of teeth as is often seen.

"What is your name?" Mr. Prettyman asked.

"Jim Dandy, sah," the boy answered.

"Whom do you live with?"

"I lives wid Aunty," the boy said, and his manner now showed that he was getting embarrassed, for he did not giggle, but smiled nervously.

"Where does Aunty live?" Mr. Prettyman inquired.

I suspect that this question made Jim Dandy fear that Mr. Prettyman did not have as much sense as a gentleman living in a fine house in town ought to have. He hesitated a moment, and then, moving his head sideways, said, "Aunty, she live over yonder."

This was most indefinite, but it was evidently the best that Jim Dandy could do for the moment, so Mr. Prettyman took him round to the kitchen at the back of the house and put him in charge of the cook, who was also the old housekeeper. And so Jim Dandy was engaged. In the course of an hour he was trying to learn his way about the house and feel comfortable in a suit of blue clothes with many brass buttons. But there was another ordeal for Jim Dandy. When Mrs. Prettyman reached home later in the day she decided that the new "buttons" must be called James. And so he was called on formal occasions, but with the children at least Jim Dandy stuck.

In a few days the new boy began to feel at home, and then set about justifying his worthiness of the distinguished name he had assumed. The first time he was sent down-town he came back in such a hurry that it seemed incredible that he could have done his errand. The next time he staid longer, and the third time—that was after he had been in service a week—he staid half a day. To one of the children he confessed that he had spent all his time in looking in the shop-windows. Hearing this, I felt a sympathy for Jim Dandy, for I waste much of my own time in that same occupation. But the shop-windows of this little Southern city seemed shabby and sorry to me after New York and Paris, and I felt sorry for Jim Dandy that such cheap splendors should make him forget his duty.

The fourth time Jim Dandy was sent into town he was told that he must not loiter on the way, but be back in a hurry. And, sure enough, he did not stay long. In less than an hour he was back. But he was not the smart-looking "buttons" who had started out shortly before. His clothes were muddy, his coat was slit in the back, his cap was gone, and there was blood on one of his cheeks. In appearance he looked sheepish and crestfallen. "Jim Dandy has had a licking," I said to myself, for I felt sure that some of the negro lads in town, envious of his whole clothes, had given the country boy a beating for revenge and for the fun of the thing. To inquiries Jim Dandy could make no intelligible reply. He went to the back of the house and sat on the kitchen steps. Tears rolled down his cheeks, and his great eyes were filled with trouble. Aunt Mandy, the cook, evidently diagnosed Jim Dandy's trouble as I had done, and she was voluble in her abuse of him for not "'tending to his own bizness."

It had not been long, however, before there was an explanation of Jim Dandy's adventure. The Mayor of the town called at Mr. Prettyman's to ask for the boy. As the Mayor was also a magistrate, we were afraid Jim Dandy must have done something very dreadful. This is what the Mayor said Jim had done:

A pony phaeton with four children in it was driving through Main Street. A trolley-car was approaching, and the pony took fright and became unmanageable, backing the phaeton on to the track. Jim was passing on his errand. Seeing the danger, he got behind the phaeton, and pushed it and the pony from the track. He was not so fortunate, for the fender of the car caught him and rolled him over and over in the mud until the car was stopped. This was how Jim Dandy's first suit of livery came to be spoiled. We were proud of Jim, and spoke to him as kindly as possible; but he was rather a sulky youth till his new suit of clothes arrived—a suit paid for, by-the-way, by the Mayor himself, for it was his children that Jim had saved from the trolley-car.

The first freshness had not been worn from Jim's new suit before we all went to a picnic on the banks of the little mountain river that flowed through the town. Jim was told to keep a sharp lookout on the younger children, who were fishing from the bank in shallow water. One of the little girls was a fidgety specimen of humanity, for she could never sit still two minutes at a time. Before she had been fishing ten minutes she fell into the river. The water was very shallow, but the current was swift, and there was surely enough water to drown little Margaret Prettyman, with a-plenty to spare. But Jim Dandy was there, and the child had hardly touched the water before he was in after her and had her in his arms. Not many seconds more had passed before Mrs. Prettyman had the very wet and much-frightened Margaret in her arms, and was weeping over that rescued infant.

Jim Dandy's smartness was again dimmed, and he was a sorry and bedraggled looking darky. Mr. Prettyman looked his "buttons" over carefully, and Jim was evidently embarrassed by the gaze.

"Well, James," his master said, "you are rightly named, for you are a Jim Dandy—every inch a Jim Dandy."

This is what the country boy did to justify his name during the two weeks that I staid at Mr. Prettyman's. It may be that he has gone on and on from adventure to adventure, so that when I hear about them I will have to send the record of them to Mr. Kirk Munroe, so that he may have a biographer worthy of a daring career. When I left I gave some money to little Margaret, to be divided among the servants. She came to the gate just as I was going to the carriage, and said, "Aunt Mandy's obliged, and Hannah's obliged, and Jim Dandy's obliged,' but Jim Dandy's obliged the most, 'cause he stood on his head."

"And so you are your papa's good fairy? How happy you must be! How proud!" Amy's eyes shone as she talked to Grace, and smoothed down a fold of the pretty white alpaca gown which set off her friend's dainty beauty. The girls were in my mother's room at the Manse, and Mrs. Raeburn had left them together to talk over plans, while she went to the parlor to entertain a visitor who was engaged in getting up an autumn fête for a charitable purpose. Nothing of this kind was ever done without mother's aid.

There were few secrets between Wishing-Brae and the Manse, and Mrs. Wainwright had told our mother how opportunely Grace had been able to assist her father in his straits. Great was our joy.

"You must remember, dear," said mamma, when she returned from seeing Miss Gardner off, "that your purse is not exhaustless, though it is a long one for a girl. Debts have a way of eating up bank accounts; and what will you do when your money is gone if you still find that the wolf menaces the door at Wishing-Brae?"

"That is what I want to consult you about, Aunt Dorothy." (I ought to have said that our mother was Aunt Dorothy to the children at the Brae, and more beloved than many a real auntie, though one only by courtesy.) "Frances knows my ambitions," Grace went on, "I mean to be a money-maker as well as a money-spender; and I have two strings to my bow. First, I'd like to give interpretations."

The mother looked puzzled. "Interpretations?" she said. "Of what, pray?—Sanscrit or Egyptian or Greek? Are you a seeress or a witch, dear child?"

"Neither. In plain English I want to read stories and poems to my friends and to audiences—Miss Wilkins's and Mrs. Stuart's beautiful stories, and the poems of Holmes and Longfellow and others who speak to the heart. Not[Pg 307] mere elocutionary reading, but simple reading, bringing out the author's meaning and giving people pleasure. I would charge an admission fee, and our dining-room would hold a good many; but I ought to have read somewhere else first, and to have a little background of city fame before I ask Highland neighbors to come and hear me. This is my initial plan. I could branch out."

To the mother the new idea did not at once commend itself. She knew better than we girls did how many twenty-five-cent tickets must be sold to make a good round sum in dollars. She knew the thrifty people of Highland looked long at a quarter before they parted with it for mere amusement, and still further, she doubted whether Dr. Wainwright would like the thing. But Amy clapped her hands gleefully. She thought it fine.

"You must give a studio reading," she said. "I can manage that, mother; if Miss Antoinette Drury will lend her studio, and we send out invitations for 'Music and Reading, and Tea at Five,' the prestige part will be taken care of. The only difficulty that I can see is that Grace would have to go to a lot of places and travel about uncomfortably; and then she'd need a manager. Wouldn't she, Frances?"

"I see no trouble," said I, "in her being her own manager. She would go to a new town with a letter to the pastor of the leading church, or his wife, call in at the newspaper office and get a puff; puffs are always easily secured by enterprising young women, and they help to fill up the paper besides. Then she would hire a hall and pay for it out of her profits, and the business could be easily carried forward."

"Is this the New Woman breaking her shell?" said mother. "I don't think I quite like the interpretation scheme either as Amy or as you outline it, though I am open to persuasion. Here is the doctor. Let us hear what he says."

It was not Dr. Wainwright, but my father, Dr. Raeburn, except on a Friday, the most genial of men. Amy perched herself on his knee and ran her slim fingers through his thick dark hair. To him our plans were explained, and he at once gave them his approval.

"As I understand you, Gracie," Dr. Raeburn said, "you wish this reading business as a stepping-stone. You would form classes, would you not? And your music could also be utilized. You had good instruction, I fancy, both here and over the water."

"Indeed yes, Dr. Raeburn; and I could give lessons in music, but they wouldn't bring me in much, here at least."

"Come to my study," said the doctor, rising. "Amy, you have ruffled up my hair till I look like a cherub before the flood. Come, all of you, Dorothy and the kids."

"You don't call us kids, do you, papa?"

"Young ladies, then, at your service," said the doctor, with a low bow. "I've a letter from my old friend Vernon Hastings. I'll read it to you when I can find it," said the good man, rummaging among the books, papers, and correspondence with which his great table was littered. "Judge Hastings," the doctor went on, "lost his wife in Venice a year ago. He has three little girls in need of special advantages; he cannot bear to send them away to school, and his mother, who lives with him and orders the house, won't listen to having a resident governess. All, this is the letter!" The doctor read:

"I wish you could help me, Charley, in the dilemma in which I find myself. Lucy and Helen and my little Madge are to be educated, and the question is how, when, and where? They are delicate, and I cannot yet make up my mind to the desolate house I would have should they go to school. Grandmamma has pronounced against a governess, and I don't like the day-schools of the town. Now is not one of your daughters musical, and perhaps another sufficiently mistress of the elementary branches to teach these babies? I will pay liberally the right person or persons for three hours' work a day. But I must have well-bred girls, ladies, to be with my trio of bairns."

"I couldn't teach arithmetic or drawing," said Grace. "I would be glad to try my hand at music and geography and German and French. I might be weak on spelling."

"I don't think that of you, Grace," said mother.

"I am ashamed to say it's true," said Grace.

Amy interrupted. "How far away is Judge Hastings's home, papa?"

"An hour's ride, Amy dear. No, forty minutes' ride by rail. I'll go and see him. I've no doubt he will pay you generously, Grace, for your services, if you feel that you can take up this work seriously."

"I do; I will," said Grace, "and only too thankful will I be to undertake it; but what about the multiplication table, and the straight and the curved lines, and Webster's speller?"

"Papa," said Amy, gravely, "please mention me to the judge. I will teach those midgets the arithmetic and drawing and other fundamental studies which my gifted friend fears to touch."

"You?" said papa, in surprise.

"Why not, dear?" interposed mamma. "Amy's youth is against her, but the fact is she can count and she can draw, and I'm not afraid to recommend her, though she is only a chit of fifteen, as to her spelling."

"Going on sixteen, mamma, if you please, and nearly there," Amy remarked, drawing herself up to her fullest height, at which we all laughed merrily.

"I taught school myself at sixteen," our mother went on, "and though it made me feel like twenty-six, I had no trouble with thirty boys and girls of all ages from four to eighteen. You must remember me, my love, in the old district school at Elmwood."

"Yes," said papa, "and your overpowering dignity was a sight for gods and men. All the same, you were a darling."

"So she is still." And we pounced upon her in a body and devoured her with kisses, the sweet little mother.

"Papa," Amy proceeded, when order had been restored, "why not take us when you go to interview the judge? Then he can behold his future schoolma'ams, arrange terms, and settle the thing at once. I presume Grace is anxious as I am to begin her career, now that it looms up before her. I am in the mood of the youth who bore through snow and ice the banner with the strange device, 'Excelsior.'"

"In the mean time, good people," said Frances, appearing in the doorway, "luncheon is served."

We had a pretty new dish—new to us—for luncheon, and as everybody may not know how nice it is, I'll just mention it in passing.

Take large ripe tomatoes, scoop out the pulp and mix it with finely minced canned salmon, adding a tiny pinch of salt. Fill the tomatoes with this mixture, set them in a nest of crisp green lettuce leaves, and pour a mayonnaise into each ruby cup. The dish is extremely dainty and inviting, and tastes as good as it looks. It must be very cold.

"But," Doctor Raeburn said, in reply to a remark of mother's that she was pleased the girls had decided on teaching, it was so womanly and proper an employment for girls of good family, "I must insist that the 'interpretations' be not entirely dropped. I'll introduce you, my dear," he said, "when you give your first recital, and that will make it all right in the eyes of Highland."

"Thank you, Doctor," said Grace. "I would rather have your sanction than anything else in the world, except papa's approval."

"Why don't your King's Daughters give Grace a boom? You are always getting up private theatricals, and this is just the right time."

"Lawrence Raeburn, you are a trump!" said Amy, flying round to her brother and giving him a hug. "We'll propose it at the first meeting of the Ten, and it'll be carried by acclamation."

"Now," said Grace, rising and saying good-afternoon to my mother, with a courtesy to the rest of us, "I'm going straight home to break ground there and prepare my mother for great events."

Walking over the fields in great haste, for when one has news to communicate, one's feet are wings, Grace was arrested[Pg 308] by a groan as of somebody in great pain. She looked about cautiously, but it was several minutes before she found, lying under the hedge, a boy with a broken pitcher at his side. He was deadly pale, and great drops of sweat rolled down his face.

"Oh, you poor boy! what is the matter?" she cried, bending over him in great concern.

"I've broke mother's best china pitcher," said the lad, in a despairing voice.

"Poof!" replied Grace. "Pitchers can be mended or replaced. What else is wrong? You're not groaning over a broken pitcher, surely."

"You would, if it came over in the Mayflower, and was all of your ancestors' you had left to show that you could be a Colonial Dame. Ug-gh!" The boy tried to sit up, gasped, and fell back in a dead faint.

"Goodness!" said Grace; "he's broken his leg as well as his pitcher. Colonial Dames! What nonsense! Well, I can't leave him here."

She had her smelling-salts in her satchel, but before she could find them, Grace's satchel being an omnium gatherum of remarkable a miscellaneous character, the lad came to. A fainting person will usually regain consciousness soon if laid out flat, with the head a little lower than the body. I've seen people persist in keeping a fainting friend in a sitting position, which is very stupid and quite cruel.

"I am Doctor Wainwright's daughter," said Grace, "and I see my father's gig turning the corner of the road. You shall have help directly. Papa will know what to do, so lie still where you are."

GRACE'S FLAG OF DISTRESS.

GRACE'S FLAG OF DISTRESS.

The lad obeyed, there plainly being nothing else to be done. In a second Doctor Wainwright, at Grace's flag of distress, a white handkerchief waving from the top of her parasol, came toward her at the mare's fastest pace.

"Hello!" he said. "Here's Archie Vanderhoven in a pickle."

"As usual, doctor," said Archie, faintly. "I've broken mother's last pitcher."

"And your leg, I see," observed the doctor, with professional directness. "Well, my boy, you must be taken home. Grace, drive home for me, and tell the boys to bring a cot here as soon as possible. Meanwhile I'll set Archie's leg. It's only a simple fracture." And the doctor, from his black bag, brought out bandages and instruments. No army surgeon on the field of battle was quicker and gentler than Doctor Wainwright, whose skill was renowned all over our country-side.

"What is there about the Vanderhovens?" inquired Grace that night as they sat by the blaze of hickory logs in the cheery parlor of Wishing-Brae.

"The Vanderhovens are a decayed family," her father answered. "They were once very well off and lived in state, and from far and near gay parties were drawn at Easter and Christmas to dance under their roof. Now they are run out. This boy and his mother are the last of the line. Archie's father was drowned in the ford when we had the freshet last spring. The Ramapo, that looks so peaceful now, overflowed its banks then, and ran like a mill-race. I don't know how they manage, but Archie is kept at school, and his mother does everything from ironing white frocks for summer boarders to making jellies and preserves for people in town, who send her orders."

"Is she an educated woman?" inquired Grace.

"That she is. Mrs. Vanderhoven is not only highly educated, but very elegant and accomplished. None of her attainments, except those in the domestic line, are available, unhappily, when earning a living is in question, and she can win her bread only by these housekeeping efforts."

"Might I go and see her?"

"Why yes, dear, you and the others not only might, but should. She will need help. I'll call and consult Mrs. Raeburn about her to-morrow. She isn't a woman one can treat like a pauper—-as well born as any one in the land, and prouder than Lucifer. It's too bad Archie had to meet with this accident; but boys are fragile creatures."

And the doctor, shaking the ashes from his pipe, went off to sit with his wife before going to bed.

"I do wonder," said Grace to Eva, "what the boy was doing with the old Puritan pitcher, and why a Vanderhoven should have boasted of coming over in the Mayflower?"

Eva said: "They're Dutch and English, Grace. The Vanderhovens are from Holland, but Archie's mother was a Standish, or something of that sort, and her kinsfolk, of course, belonged to the Mayflower crowd. I believe Archie meant to sell that pitcher, and if so, no wonder he broke his leg. By-the-way, what became of the pieces?"

"I picked them up," said Grace.

George was so near that the heavy man could have touched him with his hand, but after scratching about the door, he found the latch at last, and stumbled sleepily out into the hall. Owing to the darkness within the room George could now see out of the curtainless window. There was no one on the roof! However, he could not tarry where he was; he must take the risk; and slipping the miniature and cipher into his pocket, he opened the window and slid over the wall to the alley. It was turning freezing cold; the ground crunched under his feet, and the little gate to the widow's diminutive front yard creaked shrilly. The young spy knocked softly on the door.

"Who's there?" came a voice from the second story.

"'Tis I, George Frothingham," he answered. "Mrs. Mack, I pray you let me in."

The old woman in a minute admitted him into the hallway.

"You will have to hide me somewhere, my good friend," he said, "for I am in great danger."

"The very place! the little room that you used to have," was the whispered response. "No one would think of looking for ye there; and if they did, there's a small attic over-head. Why should they think of my house?" she added.

Once more George found himself in the little room where he had passed so many lonely hours reading and writing, recalling pleasant scenes, and drawing bright pictures of what he hoped might be, before the great changes had arrived. Thinking that it might attract attention to have a light burning in the room at such an hour, he refrained from trying to read the despatches, putting it off until morning. He tumbled into the little bed that he had slept in so often, and, despite the excitement of the night, fell fast asleep. When he awoke it was broad daylight—such a crisp sparkling day! Every twig on the trees shone like a branch of diamonds. The pools in the road were filled with white brittle ice that broke and shivered noisily beneath the feet of some school-boys going down the road.

"Oh, that I was only one of them!" thought George, looking out of the window. A curtain was tacked across the panes, and he could look out without being seen.

Suddenly he stopped, half dressed, although the room was intensely cold, and pulled out the despatch he had found in the hollow limb. There it was, neatly written in the cipher, and that also was at hand. But where were the magnifying-glass and the snuff-box? He could not find them, and strain his eyes to their utmost, he could not make out clearly the characters on the diminutive sheet of parchment. He hastily finished dressing, and called through the hallway for Mrs. Mack. There was no answer. Then he thought of a large round glass bowl that used to hang by a chain in the window below-stairs. He remembered that when filled with water it magnified extremely well. Mrs. Mack had evidently gone out, the house seemed deserted, so he slipped down the stairs, and found the bowl in its accustomed place. But as he reached it from the hook he paused. Two persons were softly talking at the back of the hall. He could feel, from the draught of air, that the door was open.

"'Tis very strange," said a man's voice; "but there's great excitement at the City Arms. I was there with the[Pg 310] milk this morning, and they say as how a young gentleman from up the river has disappeared—murdered, maybe, for all they know. They are looking in all directions for him."

"And what might be his name?"

George recognized Mrs. Mack's voice.

"I have forgotten," said the man; "but they say he was a handsome lad, and scattered his money as if he expected it to grow again."

Then followed some conversation about the milk, and the door was closed. Mrs. Mack started as she saw her guest approaching.

"You had better stay in your room, Mr. Frothingham," she said. "That is my neighbor, the milkman, an inquisitive blackguard."

"Mrs. Mack," responded George, "I am the young man who is missing from the City Arms. They must not find me."

"Shure you're safe here. But what are you doing with the bowl, sir?" inquired the woman.

"I am going to read with it," said George. "Will you fill it with water?"

Mrs. Mack looked at him as if she thought he had taken leave of his senses, but she complied, and brought the bowl up to his room. In a few minutes more George was easily able to decipher the despatch. It ran as follows:

"To you,—Your number is four; initial B. Observe. We are glad to hear from our brother in New Jersey, and that he approves of the plan. It can be done. We are not suspected, and your arrival is most opportune. You have been seen by us; you are the young man for our purpose. It must be done on Friday night. A dinner will be given at a place to which you will receive an invitation. It is but a few steps from the river. After the dinner, cards will be proposed. Tables will be arranged in such a way that he whom we wish will be seated near the door. A note will arrive requesting his presence with the fleet. There will be no moon. A man-of-war's boat will be waiting; once in mid-stream, he will never reach the ships, for we know who mans the boat. The only difficulty will be to disarm suspicion of those who accompany him. They must be detained. You and another, who will be made known to you, will be playing at the farther table. You back him heavily with gold and lose your wager. This will keep the officers' attention. They will endeavor to stay after he is gone. When we have ten minutes' start pretend to be enraged, upset the table. There will be great confusion. The party will break up at once. Leave through the alley behind the house; go to Striker's Wharf. There you will find an able skiff. New Jersey is to the westward. We leave the rest to you. If we can keep enough of his friends from following him, it will be easy to accomplish our end of the undertaking. To-morrow at five o'clock be walking down the left-hand side of Johnson's Lane. Some one will pass you who will strike three times on the lid of his snuff-box. Turn and follow him. We hold no meetings, but he will give you some instructions. Final orders at the limb. You are number Four of Seven. Remember."

George read the strange epistle through. It was of little use to him now; he could not show himself in his assumed character. Richard Blount and the manner of his disappearance must remain a mystery. So far as he was concerned, he could lend no assistance in the proposed scheme. He tore the letter up, burning the scraps; but, after considering, he determined, however, to keep the appointment with the man with the snuff-box that evening.

At five o'clock, with a worsted shawl of Mrs. Mack's bound tightly about his throat and a heavy fur cap drawn around his ears, he was stamping his heels together like a butcher's apprentice, a basket on his arm, at the corner of Johnson's Lane. Three or four people passed him, but he saw no signs of a man with a tendency to tap on his snuff-box. At last, as he looked down the lane, he perceived a small figure walking toward him with a quick nervous step. George did not know what to do, for he recognized at once that it was Mr. Anderson. Strange to say, as he was approaching he drew a snuff-box from his pocket. Then with a flood of light it dawned upon the lad that Mr. Anderson was one of the "Seven," and he understood why he had not been recognized, and also knew that there was an able hand at the helm.

As the little man approached, a tall figure also appeared about the corner, and strode after the schoolmaster with long swinging steps. George saw at once that it was the young officer who had breakfasted with him the day before. They would soon be within speaking distance. Taking a few hasty steps he darted about the corner, dropping his basket as he ran. So quick had been the movement that he was not in time to dodge a great lanky man who was walking quickly from the opposite direction, and he ran right into his arms. So great was his impetus that the man fell back against the wall of a brick house, and his huge watch flew out of his pocket and was dashed to pieces.

"FROTHINGHAM! FROTHINGHAM!" THE OLD CLERK TRIED TO SAY.

"FROTHINGHAM! FROTHINGHAM!" THE OLD CLERK TRIED TO SAY.

"You thieving villain! Stop thief—stop!" exclaimed the stranger, making a grasp for George's shoulder. But now the lad's great strength once more served him in good stead. He struck down the other's arm, and as he did so gasped, for the person he had run into was none other than Abel Norton, his old chief clerk. Abel's other hand had firm hold upon the woollen comforter, and George caught him by the throat and twisted him backwards across his knee. "Frothingham! Frothingham!" the old clerk tried to say.

Here was an added danger. He was recognized! The two men must now be almost at the corner. With a final effort George tore himself away, and started down the alley at a run. He knew that farther on there was a big lumber-yard that opened on the main street. If he could reach there ahead of the others, he might manage to escape.

Abel's first cries, however, had brought a number of people from the public-houses, and the young officer and Mr. Anderson came about the corner of the lane. George's fleeing figure was in plain sight.

"Stop thief!" the officer shouted, and leaped forward with the stride of a swift runner.

"Stop thief!" echoed Abel Norton, and strange to say, the old man caught up with the redcoat easily, and, stranger still, appeared to slip and fall upon his heels. Down they both went.

Schoolmaster Anderson in the mean time was at the head of four or five other pursuers, who had run from the tap-rooms. Before he reached the spot where the two leaders were gathering themselves together, he also tripped, and the two next fell over him. There was a general laugh, and by this time George had turned through the gateway into the lumber-yard. Here again he had to adapt himself to circumstances, for at the farther entrance was standing a group of soldiers throwing horseshoes at a peg in the frozen ground. He could not go out of that opposite gate without exciting suspicion. There were only two things left him to do; one to jump the fence to the left, or try to scale the high wall to the right. A glance at the latter decided matters. There was a clumsy-looking ladder leaning against the wall. He hastened up, and threw himself over the top, kicking the ladder from beneath him as he jumped. He came down in a little garden. He had doubled on his tracks, and could hear the pursuit going down the road behind him. Suddenly he glanced up at the small house; it bore a sign over the front door:

He tried the door, it was unlocked, and he stepped in without knocking. A strange-looking woman with a long face and pale blue eyes was sitting there. George knew her at a glance to be Luke Bonsall's mother. She looked up from her sewing.

"What means this?" she asked, in a deep, hollow voice.

"I am a friend of your son's in the army. I have a message—a message from him to you," said George, panting. "Take me where we can be alone, and I will tell you."

The woman got up and slipped the bolt into the door.

"A message from my son!" she repeated. "He is dead."

George started. There would be no necessity to break[Pg 311] the news. "I have a letter here," he said, fumbling in his pocket, "How did you know he died, might I ask, madam? It is true, and I was sorry to bear the tidings."

"I dreamed it," said the woman. "See, I am in black."

George handed her the letter. She read it carefully, but did not weep or show that it had touched her.

"It's good news," she said. "I told him that I could not be the mother of a coward."

"Indeed he was none such," answered George, quickly. "He died like a brave soldier, and would have made his mark."

"It was not to be," responded the woman. "The Fates would not have it so."

"What a strange creature is this!" thought George to himself. But had he known all, it would have seemed stranger still, for Mrs. Bonsall was a believer in occult signs, and long ago she had had her son's horoscope cast. She had been informed that the sickly, pale-eyed youth was to die in battle. The idea then would have seemed most amusing to any one else, but to Mrs. Bonsall it had been a reality, and Luke himself had gone to the front with this cloud about him. He was brave indeed.

George suddenly remembered his own position, and extended his hand. There had come a confused babble of voices out in the yard.

"Do you hear that, Mrs. Bonsall? They are after me! See," he said, "you must assist me. I must hide until dark, for if I am found my life is not worth a pine-tree shilling. They think I am a thief. I am not."

"Come," the woman said; "walk softly." She took him by the hand and led him back to a small stairway. They went up two flights until they reached a large empty hall. George stumbled over a heavy pair of boots, and looking through an open doorway on the right, he could see a cavalry sabre leaning against a chair.

"Sh! they have quartered them upon me," whispered Mrs. Bonsall. "But it's not for long, for despair and defeat await them. Ah yes! I know, I know!" Mrs. Bonsall pushed the fugitive into a little room beyond, and locked the door behind him.

He sat down on a chair near the window and looked out. He could see over the top of the wall that he had scaled. There were some soldiers and a number of men rummaging about the heaps of lumber. Then he heard a thump of the knocker on the door below. A rumbling sound followed. The strain was frightful on George's nerves.

"And think you I would shelter a pickpocket?" asked the woman, plainly.

George could not make out the reply, for a loud voice shouted, in a rich brogue: "Out, you fools! There's no one here. What do you take this spacious mansion for—a thieves' den? By the powers!"

"Don't let them in, Corporal Shaughnessy," pleaded the widow's voice.

The loud voice was now rumbling from below again. Some one in the crowd laughed, and George breathed easily as he heard them go out into the road.

It seemed to him now that it never would grow dark. He realized that he was very hungry, and he tried the door, but it was firmly locked. He was in Mrs. Bonsall's power, but he felt somehow that he could trust her. As he was deliberating whether to try the window or not, he heard the sound of footsteps.

"By the gun of Athlone!" said Corporal Shaughnessy's voice, "we will be moving soon, and sorry will I be, for though our landlady is the only female who ever failed to smile upon me, our quarters here are comfortable, and I would hate to be losing of them for a bed in the snows of the wilderness."

"They do be saying," put in another voice, "that it will be decided at the meeting to-night."

"And where's that to be held?" said the first speaker.

"At the Fraunces House. They always hold them there. I have been upon guard there."

"Come into me spacious apartment and have a pipe, McCune," said Shaughnessy.

The tones of the two men talking were familiar to George somehow. But when he heard the name "McCune," he recalled the whole thing to his memory. They were the two soldiers he and his brother had talked with years ago on that memorable day of parting.

The door closed behind them, and it had hardly done so when a soft grating of the key in the lock was heard. Mrs. Bonsall opened the door. Once more she took him by the hand and led the way down the stairs.

As they went through the front room the woman picked up a candle and looked intently at George's palm.

"Tribulations," she said; "but do not despair; success awaits you."

George did not smile, but gravely thanked her for all that she had done, and slipped out of the house.

It was pitch dark, and he remembered as he went along that he was far from accomplishing anything that he had made the perilous trip for. All his fine castles had tumbled about his ears, the smooth pathway that appeared to stretch before him had vanished, and nothing but obstacles loomed before his eyes. However, if he could not assist in the wild scheme of gaining possession of such a powerful hostage as Lord Howe or his brother, the General, any news that he could bring concerning the probable destination of the army would be of inestimable value to General Washington at Morristown. Why not find out as much as he could and get away?

So intently was he thinking, that he did not notice a figure that had stepped out of the doorway of a house and was walking, close at his heels.

"Oh, de ham fat it am good, an' de 'possum it am fine,"

hummed a voice.

George turned. "Cato, you imp of darkness," he said, "where did you come from?"

"From de State of New Jarsey," responded the old man, his white teeth gleaming plainly in the darkness. "Well, Mas'r George, I's done followed you, and it took de best horse on de place. I tink you mought need me."

"Then it was you that dodged over there in the road near West Point?"

"Yes, sah, I 'spect so. You come purty nigh gitting away from me once or twice, sah."

"How did you cross the river? How in the world?" exclaimed George, his astonishment driving all other thoughts out of his head.

"On a log raf, youn' mas'r, and it was purty col' work," answered the old negro.

"Cato," said George, impressively, "you must keep away from me, and you must get back as soon as you can."

"Can't I stay wid you, sah?" answered the old darky. "I'll be deaf, dumb, and blind. I knows you are here on some business dat—"

George interrupted him. "I hate to do it, Cato," he said; "but do you see that corner? You get back and around it as soon as you can, and if you meet me again, don't appear to know me, for by doing so you may place a rope around my neck."

The old man did not say another word, but scuttled off.

Now George determined upon a bold line of action. So well had he known the ins and outs of the town that he knew at once the room in which the officers were to meet, at Fraunces Tavern. He knew that through a stable in the rear he might gain a position from which he could hear or see something of the proceedings. But why not first go to the orchard? He had no sooner determined upon this plan than he had walked quickly to the north, and taking several short-cuts, reached the tree.

In the last few hours he had memorized the cipher until it was almost perfectly imprinted on his mind. There was a paper in the limb addressed to "No. 4." He drew it out, and finding where a fire had smouldered in the street, he picked out an ember and blew it into a flame. He made out the words: "B., Number Four, make your escape. Use all caution. We do not know you. It is for the best that you should be a stranger to us."

Twelve months have scarcely elapsed since Mr. Andrée, the Swedish balloonist, first published the details of his scheme for reaching the North Pole by the smooth and easy but crooked paths of cloudland. During this short period the clever and hardy aeronaut has had his proposals favorably received by the Swedish and French academies of sciences, and obtained the $36,000 required for his purpose from King Oscar, Mr. Nobel, and the Baron Oscar Dickson. Mr. Andrée has travelled all over Europe to consult the most competent specialists, and has completed all his preparations for the transportation of his huge balloon from Paris, where it is being constructed, to Spitzbergen early next May. The start will be made some time in July or at the beginning of August from Norskoärna, a small rocky and snowy archipelago situated on the northwestern coast of Spitzbergen, and the most accessible part of this famous territory. Norskoärna is almost under the eightieth parallel, and although sad and even grim in aspect, this remote spot will prove a convenient station for the departure, as the distance to the North Pole is only about 600 miles. Mr. Andrée's balloon, which will be called The Northern Pole, is to be made of triple French varnished silk, having a resistance of 250 pounds to the linear inch. It contains 130,000 cubic feet, and has a lifting power of more than 10,000 pounds. Besides the car and its three occupants—Messrs. Andrée, Ekholm, and Strindberg—the balloon will be supplied with scientific apparatus and 2000 prepared photographic plates, in charge of Dr. Strindberg. The Northern Pole will not carry sand for ballast, but use its large quantity of stores for throwing out in case of need. At Norskoärna the balloon can be kept waiting any length of time for a favorable wind. Held in place by sixteen tackles attached to the rocky soil, and connected by a system of ropes and pulleys with the whole netting, it can laugh at all the efforts of the strongest gale, and remain there for weeks ready for immediate despatch.

GRAPHIC PLAN OF THE NORTH POLE.

GRAPHIC PLAN OF THE NORTH POLE.Mr. Nils Ekholm, the celebrated meteorologist of Upsal University, will give the signal for the departure of this fearless expedition. This signal will not be given until Mr. Ekholm finds a northern breeze blowing briskly and with all the known signs of permanency—a frequent occurrence, however, in those regions and in such a season. As a professional aeronaut, I may be allowed to say that Mr. Ekholm will not be mistaken in his prognostications, and that, once started, Mr. Andrée's aerial craft will be carried away for hours in the direction of the North Pole. It would be almost unreasonable to hope that the aerial travellers will float exactly above the foremost point of our globe from the tropics. It would be enough for Mr. Andrée to make such a nearing as would enable him to bring back to civilization hundreds or thousands of photographs recording all the features of those unattainable regions. His most ambitious desires will be wholly satisfied, I am sure, if he obtains a clear view of the rocky mountains that Lieutenant Peary is said to have seen from the top of the Greenland glaciers on a far distant horizon.

SPITZBERGEN, THE STARTING-POINT.

SPITZBERGEN, THE STARTING-POINT.

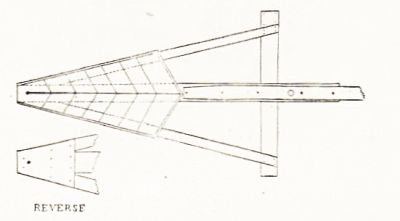

For my own part, I believe that the three aerial explorers will have no difficulty in running the greater part of the 600 miles separating Norskoärna from the North Pole. If by some unaccountable misfortune there should be a notable change in the moving paths of cloudland, it is certain that Mr. Andrée will be able to direct his balloon in a suitable siding. Then he will resort to his ingenious combination of guide-roping and sailing which I described in a previous article. Since his first trial, in 1894, he has realized great improvements, as will be seen by comparing the aspect of his new balloon with that of the Swea sailing above the Swedish lake country, already published in Harper's Round Table. Instead of using only one medium-sized guide-rope, he will drag in the Polar solitudes not less than three heavy hemp lines. With the aid of these gigantic and ponderous guide-ropes, each one measuring 1200 feet and weighing 600 pounds, he can set three sails, supplied with yards and moved by rigging, and attached to the upper part of the balloon, independent of the netting, so that they may receive their full expanse. Their total surface amounts to more than 700 square feet, and they will, if skilfully managed, impart a remarkable deviating power to the balloon. So The Northern Pole will skip along like a sailing-craft with a stern wind.

THE COURSE OF THE SUN IN THE ARCTIC REGIONS.

THE COURSE OF THE SUN IN THE ARCTIC REGIONS.

It must be remembered that in summer-time the winds and storms of the North Pole are far less treacherous than those of the most attractive parts of the tropical,[Pg 313] or even those of the temperate zones. The north polar regions are never visited by cyclones or thunder. The only danger to be encountered is a slight fall of snow, not more than four or five inches in the whole season. For meeting this almost trivial danger Mr. Andrée has had the upper part of his balloon covered with a silk canvas, so that the meshes of the net will be free from any accumulation of falling snowflakes.

In the desolate northern lands the sun is a trusty friend to the aeronaut. By constantly shining over the horizon during a number of months he develops almost a comfortable degree of heat, while without any intermission during the twenty-four hours of each day he supplies a sufficient quantity of light for all photographic purposes. In the mean time, owing to his moderate altitude, even when he crosses the meridian line at noon, he is never elevating the unfortunuate aeronaut against his will to a dangerous distance from the more than half-frozen soil.

The NORTHERN POLE.

The NORTHERN POLE.

The real difficulty is for the balloon, loaded with numberless precious documents, to find its way out before winter sets in with its long cold nights and horrors. This exit must be made at any cost by directing the balloon into a wind tending to some part of the south. Mr. Andrée will certainly not pay attention to the geographical position of the spot where he is to alight. He will not care whether he lands on land or on sea. It will make no difference to him whether he sets foot on rocks or on cracking ice. He will trust equally to the frozen Atlantic or to the congelated Pacific if he can descend from cloudland above the horizon of a whaler. Russia, Siberia, Alaska, or the Northern Dominions are as good as his own country, if it is not beyond his power to reach some locality inhabited by Esquimos, Laplanders, or Samoyeds. The main point is to see The Northern Pole afloat for a long period, say a month. At all events, Mr. Ekholm calculates that the balloon will remain in the air at least fifteen or twenty days, and that during this time it will have passed over a distance of nearly four thousand miles.

In order to be quite sure to navigate in the atmosphere twelve times longer than any aeronautical run performed up to the present day (the thirty-six hours' voyage made in 1892 by M. Maurice Mallet, who has drawn the accompanying sketches), Mr. Andrée is having his balloon made absolutely impermeable, of the best and most costly material, with a new varnish and exceptional sewing. He has replaced even the usual valve at the top by two others a great deal smaller and fixed to the equator of the balloon, to be used only for ordinary manœuvres during the prolongation of the voyage, for he is determined not to make any pause, decided to fall from cloudland like a thunderbolt to the very spot selected by instantly opening his monstrous sphere with a tearing rope, to which will be attached a dagger for the grand and final moment.