|

| CHAP. | |

| I. | The S.S. "Donibristle" |

| II. | Hilda Vivian |

| III. | "Heave-to or I'll sink You" |

| IV. | Under Fire |

| V. | Captured |

| VI. | Under Hatches |

| VII. | Ramon Porfirio |

| VIII. | The Compound |

| IX. | The First Day on the Island |

| X. | Investigations |

| XI. | A Fight to a Finish |

| XII. | Plans |

| XIII. | "Getting on with It" |

| XIV. | The Vigil on the Cliffs |

| XV. | How Minalto Fared |

| XVI. | Captain Consett's Report |

| XVII. | The Scuttling of the "Donibristle" |

| XVIII. | Successful so Far |

| XIX. | A Dash for Freedom |

| XX. | The Voyage |

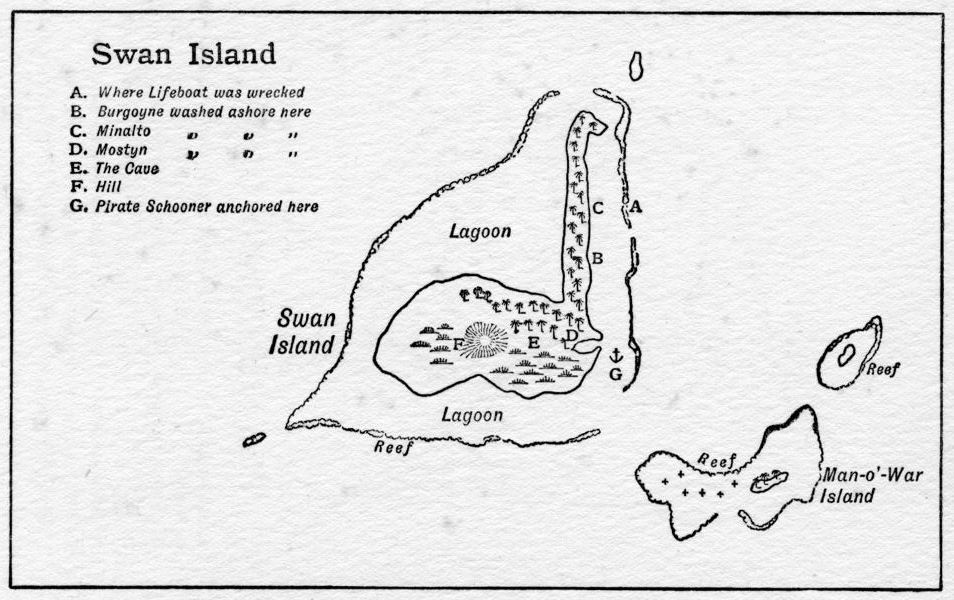

| XXI. | The Castaways |

| XXII. | Making the Best of It |

| XXIII. | Where the Pig Went |

| XXIV. | The Cave proves Useful |

| XXV. | The Tables Turned |

| XXVI. | The Fate of Ah Ling |

| XXVII. | Farewell to Swan Island |

| XXVIII. | The "Titania" |

| XXIX. | The Admiral's Promise |

| XXX. | THe End of the "Malfilio" |

| XXXI. | The Capture of the Secret Base |

| XXXII. | And Last |

Illustrations |

|---|

| She was a Light Cruiser of about 4000 Tons |

| Frontispiece |

| Black Strogoff addresses the "Donibristle's" Crew |

| A Dash for Freedom |

| The Fate of Ah Ling |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

To the accompaniment of a pungent whiff of hot oil, a miniature cascade of coal dust and frozen snow, and the rasping sound of the derrick chain, the last of the cargo for No. 3 hold of the S.S. Donibristle bumped heavily upon the mountain of crates that almost filled the dark confined space.

"Guess that's the lot, boss," observed the foreman stevedore.

"Thanks be!" ejaculated Alwyn Burgoyne, third officer of the 6200-ton tramp, making a cryptic notation in the "hold-book". "Right-o; all shipshape there? All hands on deck and get those hatches secured. Look lively lads!"

Burgoyne waited until the last of the working party had left the hold, then, clambering over a triple tier of closely-stowed packing-cases, he grasped the coaming of the hatch and with a spring gained the deck.

"What a change from Andrew!" he soliloquized grimly, as he surveyed the grimy, rusty iron deck and the welter of coal-dust and snow trampled into a black slime. "All in a day's work, I suppose, and thank goodness I'm afloat."

Three months previously Alwyn Burgoyne had been a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Navy; hence his reference to "Andrew", as the Senior Service is frequently designated by long-suffering bluejackets. Under peace conditions and in the knowledge that the greatest menace with which the British Empire was ever threatened was removed for all time, the Admiralty were compelled to make drastic reductions both in personnel and material. Numbers of promising young officers, trained from boyhood to the manners and customs of ships flying the White Ensign, had been "sent to the beach", or, in other words, their services had been dispensed with. Even the sum of money paid to these unfortunates was a sorry recompense for their blighted careers, since circumstances and the fact that they were of an awkward age to embark upon another profession were a severe handicap in life's race.

Burgoyne, however, was one of the luckier ones. Forsaking the lure of gunnery, torpedo, and engineering, he was specializing in navigation and seamanship when the "cut" came. Without loss of time he had sat for and obtained first a Mate's and then a Master's Board of Trade Certificate, and with these qualifications, aided by a certain amount of influence, he obtained the post of Fourth Officer in the British Columbian and Chinese Shipping Company.

On his first voyage in the S.S. Donibristle, from Vancouver to Shanghai, Burgoyne gained a step in promotion. Viewed from a certain point it was a regrettable promotion, since Alwyn had to step into a dead man's shoes. But Roberts, the Third Officer, disappeared on the homeward run—it was a pitch-dark night, and a heavy beam sea, and no one saw him go—and Burgoyne "took on" as Third.

To fill the vacant post, Phil Branscombe, a Devonshire lad who had come into the British Columbian and Chinese Shipping Company via a wind-jammer and a Barry collier, was appointed as Fourth Officer, and Branscombe was now about to start on his first voyage under the B.C. & C.S.C. house-flag.

The Donibristle was lying at Vancouver. She had been bunkered with Nanaimo coal; the last of her cargo—mostly Canadian ironmongery and machinery—was under hatches, and she was due to sail at daybreak.

"Cheerio, old thing!" exclaimed Branscombe as Burgoyne made his way aft, his india-rubber sea-boots slithering and squelching on the slush-covered deck. "All stowed? Good, same here. How about tea?"

As the chums made their way towards the companion, their attention was attracted by the arrival of three people who were on the point of stepping off the gangway, where the First Officer stood ready to receive them.

One was a middle-aged gentleman of a decidedly military bearing, obvious in spite of the fact that he wore a heavy greatcoat with turned-up fur collar. Clinging to his arm—a necessary precaution in view of the slippery state of the deck—was a lady, evidently his wife. The third member of the party, disdaining any extraneous support either animate or inanimate, was a girl of about nineteen or twenty. She wore a long fur travelling coat, a close-fitting velour hat, and thick fur gloves that reached almost to her elbows. As her collar was turned up, there was little of her profile visible, but what there was was enough to proclaim her to be a very good-looking girl.

"Passengers, eh?" remarked Burgoyne. "Didn't know we were taking any this trip."

"Eyes front, old man," exclaimed Branscombe in a low tone. "Dear old thing! Remember the path of duty——"

"Is slippery," rejoined the Third Officer, as the Fourth, skidding on the frozen snow in the midst of his homily, measured his length upon the deck. "And be thankful you haven't your No. 1 rig on."

Descending the companion, the two chums gained the alley-way out of which opened the officers' cabins. Here they encountered a stout, jovial-faced man carrying a tea-tray.

"Is there plenty of hot water on in the bathroom, steward?" asked Burgoyne. "Thanks—by the by, what names are on the passenger list?"

"Only five, sir," replied the steward. "There's a Mr. Tarrant, a Mr. Miles, Colonel and Mrs. an' Miss Vivian, sir.... Tea's ready, sir."

"Thanks; pour me out a cup and let it stand, please," said Alwyn, as he hurried off to the bathroom to remove all traces of five hours' hard work in No. 3 hold.

Twelve minutes later Burgoyne, having washed and donned his best uniform, entered the mess-room where the officers had all their meals with the exception of dinner. It was the custom on board ships of the British Columbian and Chinese Shipping Company for the officers to dine with the captain and passengers in the saloon. Although the Donibristle was primarily a cargo-boat, she had accommodation for twelve passengers. These she could carry without being obliged to have a Board of Trade passenger certificate, and since the Donibristle was by no means a fast boat there was no acute competition to secure passenger berths.

Most of the occupants of the mess-room—two engineers, the purser, and two deck officers—had finished tea and were "fugging" round a large stove. Branscombe, who had forestalled his chum by two minutes, was taking huge mouthfuls of bread and jam, and drinking copious draughts of tea with the rapidity of a man who never knows when he will be interrupted by the call of duty, while, in order to take every advantage of the brief spell of leisure, he was scanning a newspaper conveniently propped up against a huge brown earthenware teapot.

"Any news?" inquired Burgoyne.

"United Services draw with Oxford University."

"I'd liked to have seen the match," remarked the Third Officer. It recalled memories of a hard-played game in which Sub-Lieutenant Burgoyne, R.N., was one of the United Service team. That seemed ages ago, although only eight months had elapsed. "And the M.C.C.?" he inquired.

"No match. It was raining cats and dogs in Melbourne," replied Branscombe.

Having heard the latest of two great events in the world of sport that were taking place in almost diametrically opposite parts of the globe, Burgoyne exclaimed:

"Well, any more news? Don't be a mouldy messmate. Hand over half that paper—the part you've read."

"Take this one, Burgoyne," said Withers, the Second Engineer. "There's another boat missing—a week overdue. That's the second this month, an' both between 'Frisco and Kobe."

"Yes, the Alvarado," added the purser. "Wasn't that the vessel we sighted off the Sandwich Islands, Burgoyne?"

"Yes, I was officer of the watch," he replied.

"Well, she's gone without a trace as far as we know," said Withers. "And the Kittiwake went in similar circumstances. If the Alvarado had sent out an S.O.S. we should have got it, I suppose. What's the distance—ah, here's our Signor Marconi or our Mark Antony, whatever you please. Say, young fellah-me-lad, what's our wireless radius?"

This question was addressed to Mostyn, a tall slim youth who had just entered the mess-room. His uniform proclaimed him to be one of the wireless operators.

"Two hundred and fifty by day; six hundred by night," replied Mostyn, who then proceeded with the characteristic fervour of a wireless man to let fly a battery of technical terms and formulae.

"'Vast heaving, my lad," interrupted the Second Engineer, with a jovial laugh. "You've floored me. I feel like that young Canuk must have felt when he was shown over the ship last Monday."

"What was that?" inquired the purser.

"He showed great interest in my scrap heap," replied Withers. "The greatest interest. I explained every mortal thing in the engine-room—twenty-five minutes steady chin-wag. And when I'd finished he just asked: 'And do they work by steam or gasoline?' I've been off my feed ever since," he added pathetically.

"To get back to the Alvarado," said the purser "It's jolly strange for a vessel to drop out of existence nowadays and leave no trace. We can dismiss the mine theory. Fritz didn't try that game on in the North Pacific, and it's hardly likely that the mine laid by the Japs in '05 would be still barging about. Rammed a derelict? Blown up by internal explosion? Turned turtle during a hurricane?"

"A hurricane, perhaps," replied Burgoyne. "We had it a bit stiff just about that time—when Robert was lost overboard."

"Ships do vanish," continued the pessimistic purser. "Wireless and other scientific gadgets notwithstanding. I remember——"

"Chuck it, old man!" interrupted Branscombe.

"Don't try to give us all cold feet. It's cold enough on deck—an' it's my watch," he added dispassionately. The Fourth Officer pushed aside his cup and plate, struggled into his greatcoat, and left the mess-room. It was his job to superintend the clearing up of the decks after the cargo had been stowed, and the stevedores had taken their departure.

The rest of the mess relapsed into silence. Some were deep in the evening papers, others were reading torn and thumb-marked novels. A few, Burgoyne amongst them, retired to the more secluded part of the room in order to write to their relatives and friends, and send the mail ashore before the Donibristle got under way.

"Any passengers?" asked Withers, breaking the prolonged silence.

"Yes, young fellah-me-lad," replied Holmes, the purser. "Boiled shirts and stiff collars for everyone."

"Is that the menu, Holmes?" inquired Withers with well-feigned innocence.

"It will be for you if you don't take care," rejoined the purser severely. "We haven't a full passenger list, but we've got to keep our end up, even though we're not a crack liner."

"Who are they?" asked Mostyn.

"A Colonel Vivian and his wife and daughter," replied Holmes. "They are only going as far as Honolulu—dodging the Canadian winter I should imagine. There's a Mr. Tarrant. He's in the Consular Service, and is bound for Kobe. The last is Mr. Miles. I don't know what he is, but I rather fancy he's a drummer working for a Montreal drug store. Anyone know if the Old Man's aboard yet?"

"Yes, he came aboard with the Chief," replied the wireless officer, "about five minutes before I came below."

"Why on earth didn't you say so before?" demanded Withers, making a precipitate rush for the door. "I didn't expect Angus before eight bells, and——"

"Evidently friend Withers has left undone those things that he ought to have done," observed Holmes. "Get a move on, you fellows. Nothing like punctuality for meals, 'specially when I want a run ashore after dinner."

Twenty minutes later officers and passengers assembled in the saloon for dinner. Although lacking the luxurious trappings of a first-class liner's saloon, the Donibristle's was quite a comfortable, well-equipped apartment. Electric lights in frosted glass bulbs with amber shades threw a warm, subdued light upon the long table. The snow-white table-cloth looked dainty with glittering cutlery and plate. Choice Californian flowers—bought that afternoon in Vancouver by the messman, presumably to create a good initial impression upon the passengers—completed the display.

At the head of the table sat Captain Roger Blair, R.N.R., a short, thick-set Tynesider, whose war record included service in the North Sea, the AEgean, and outer patrol work on the edge of the Arctic Circle. He had been twice in collision and torpedoed on four occasions; yet, until the surrender of the German Fleet, he had never set eyes on a Hun submarine. He was inclined to be irritable as a result of the nervous strain of four and a half years in mine-infested waters under war conditions; but, in spite of being nearly fifty-four years of age, he was accounted one of the finest and most reliable skippers in the company's service.

On his right was Mrs. Vivian, a frail and rather subdued lady with a distinctly nervous manner. Next to her was Colonel Vivian, huge, burly, and bronzed. His features were clear cut, but a rather heavy chin and a military moustache gave the casual observer an impression that the colonel was a severe and stern man. In point of fact he was when in command of a regiment, but in retirement he was jovial and good-natured, and simply doted on his wife and daughter.

Hilda Vivian had been placed on the Captain's left, consequently Alwyn Burgoyne, far down the table, saw but little of her except a partial view of an attractive profile.

Mr. Tarrant, an aesthetic gentleman of about twenty-five or thirty, sat on Miss Vivian's left. Next to him was Miles, an undersized, white-faced individual with an unlimited amount of "push and go" as far as his calling was concerned, and almost a complete apathy towards everything else.

At the foot of the table was Mr. Angus, the Chief Engineer. He was, like the majority of chiefs in the Mercantile Marine, Scotch. His appearance, accent, and mannerisms all pointed to the undeniable fact that he hailed from the Clyde. Five feet ten in height, broad-shouldered, rugged-featured, and with sandy hair, he was both the terror and admiration of the crowd of rapscallions who comprised the rank and file of the Donibristle's stokeholds.

Angus was reported to be "near". If he spent a dollar he took good care to get a dollar's worth in return for his outlay. He never parted with a cent without due consideration—and lengthy consideration at that. But in greater matters he was generous in the extreme. Whenever a subscription list came round for some worthy cause—usually for the widow or dependent of one of the company's former servants—the scrawled initials "J. A." invariably appeared for a substantial amount from Jock Angus's funds. If a fireman, down on his luck, was unable to provide himself with a kit suitable for the climatic conditions and changes of the voyage, the Chief would stealthily interview the purser and see that the man got an outfit at the expense of dour Jock Angus.

And he knew his job from A to Z. Left alone with the necessary tools he could transform a scrap heap into a set of engines and guarantee a good head of steam. He had been in charge of the Donibristle's engines for two years of almost constant running, and never once had they broken down or stopped through mechanical defects.

Beneath the Scotsman's rugged exterior beat the heart of a kindly man. Almost everyone on board took his troubles to Angus, knowing that his confidence would be respected, and that the advice he received was blunt, sympathetic, and sound, while the relations between the Old Man and the Chief ran as smoothly as the well-tuned triple-expansion engines of the good ship Donibristle.

The rest of the officers, with the exception of a few actually on duty, were seated on either side of the long table—good and true men all, typical of the great Mercantile Marine, without which the British Empire would crumble into the dust. Most of them have already been brought to the reader's notice; and since it is yet too early to bring upon the stage the arch-villain Ramon Porfirio and his satellites and myrmidons, they must be temporarily detained in the wings.

At daybreak, in a strong off-shore wind, thick with snow, the S.S. Donibristle cast off and proceeded on her voyage. By noon, working up to eleven knots, she had passed through the broad strait of San Juan de Fuca—the waterway between Vancouver Island and the Federal State of Washington—and was rolling heavily in the following seas.

During his watch on the bridge Alwyn Burgoyne saw nothing of the passengers. Certainly it was not the kind of weather in which landsmen venture on deck. The whole aspect was a study in greys. The sea, as far as the driving snow permitted to be seen, was a waste of leaden-coloured waves flecked with tumbling grey crests. Overhead a watery sun almost failed to make its presence known through the sombre swiftly-moving clouds. Everything on deck was snow-covered, while wisps of steam mingled with an eddying volume of smoke from the salt-rimed funnels.

Crouched in the bows was the motionless figure of the look-out man, peering intently through the flurry of snow-flakes, and ready at the first sign of another craft to hail the bridge, where, always within easy distance of the engine-room telegraph, Burgoyne paced ceaselessly to and fro. For the time being the safety of the ship and all who sailed in her depended upon his judgment. An error on his part or even hesitation in carrying out the "Rules and Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea" might easily result in an appalling catastrophe.

Twice during his watch Alwyn had to alter course. Once to avoid a topsail schooner that suddenly loomed up, grotesquely distorted through the snow, at a distance of two cables on the starboard bow. The second occasion was called for by the sighting of a derelict—a timber-ship dismasted and floating just awash. A startled shout from the look-out man, a crisp order from the Third Officer, and the Donibristle, heeling under the effect of helm hard over, literally scraped past the waterlogged craft.

Five minutes later, Mostyn, the wireless operator, was sending out a general warning to the effect that at such and such a time, and in latitude and longitude so and so, the S.S. Donibristle had sighted a derelict highly dangerous to navigation.

At last, just as the sun was breaking through and the snow-storm had passed, Burgoyne's relief ascended the bridge ladder. Alwyn, having "handed over", went below, ate a hearty meal, and, relieved of all responsibility for the time being, turned in with the knowledge that before he took on again the Donibristle would be in a distinctly warmer climate.

He saw nothing of the passengers that evening. Their places at dinner were vacant. According to the steward, Mr. Tarrant was just able to sit up and take nourishment; while Mr. Miles, the Canadian commercial traveller, in a valiant attempt to ward off the dreaded mal de mer, had resorted to certain drugs from his sample case, and was now under the care of the steward. Colonel Vivian was attending to his wife, who was obliged to keep to her cabin, while he and his daughter for some unexplained reason were having dinner in the latter's state room.

At noon on the following day Burgoyne, having "shot the sun" and worked out the ship's position, was considerably astonished to see Hilda Vivian mounting the bridge with the utmost sang-froid.

"Good morning, Mr. Burgoyne!" she exclaimed; "or is it good afternoon? Quite warm, isn't it? A delightful change from yesterday. I've come to have a look round."

"I'm afraid I must tell you that you are trespassing, Miss Vivian," said Alwyn. "No passengers are allowed on the bridge, you know."

Hilda Vivian's eyes sparkled with ill-concealed mirth.

"That was what my father said," she rejoined. "I had a small bet with him on it. I've won, you see."

"But I can't let you——" began Burgoyne. "Company's regulations and all that sort of thing, you know."

"Supposing I refuse to go?" she inquired archly.

Alwyn pondered. It promised to be a tough proposition. He rather wondered what the Old Man would say to him if he happened to come on deck and espy a passenger—a lady passenger, and a young and pretty one at that—standing apparently without let or hindrance upon the bridge.

His colour deepened under his tan as he replied:

"You'll be getting me into a jolly hole if you persist."

It was a lame thing to say, he reflected. After all it seemed a bit futile to have to put forward an individual case to support the rights of deck-officers.

"I wouldn't do that," replied the girl earnestly. "It's all right. I asked Captain Blair, and he said I'd find somebody up here to show me round."

"Right-o," said Burgoyne, not at all sorry to have the opportunity. "But excuse me a moment while I finish working out our position."

He retired to the chart-house and shut the door, having first asked the quartermaster to show the compass and steam steering-gear to the passenger. He counted on a long and highly technical explanation from the old seaman, and in this he was not mistaken.

Alwyn used the respite profitably. He made no attempt to check his figures; that was a mere excuse. Taking up the telephone, he rang up the Captain's cabin. A brief conversation confirmed Miss Vivian's statement, not that he doubted her word, but it was desirable to obtain the Old Man's sanction.

"That leaves me a comparatively free hand," soliloquized the Third Officer, as he replaced the receiver. "There are worse ways of taking a trick than being in the company of a jolly girl."

Jolly she undoubtedly was. Without an atom of side, and utterly devoid of any trace of self-consciousness, Hilda Vivian was decidedly practical without sacrificing her femininity.

Burgoyne's watch passed only too quickly. The girl was a good conversationalist and a splendid listener. Without betraying the faintest sign of boredom she followed the Third Officer's somewhat stereotyped explanations of the various devices upon which the modern navigator depends in order to take his ship, with uncanny accuracy, across thousands of miles of trackless ocean.

And then conversation drifted into other channels. Hilda explained her presence on board. She was an only daughter; her brother had been wounded and missing at Messines, and her mother had never properly recovered from the shock. Colonel Vivian had been in command of a battalion in Egypt and Palestine, and on the homeward voyage the transport had been mined off Cape de Gata, in the course of which he had received an injury to his thigh that had incapacitated him from further active service.

"I know that bit," said Alwyn to himself. He felt pretty certain of it from the moment he saw the colonel board the Donibristle at Vancouver; but now there was no doubt on the matter. He made no audible remark, but allowed his fair companion to "carry on".

After the Armistice Colonel Vivian went on the retired list. He was not a rich man, having little means beyond his pension; and specialists' fees incurred by his wife's illness made a heavy drain upon the colonel's exchequer. One specialist expressed his opinion that the only thing likely to benefit Mrs. Vivian was a voyage round the world. Making sacrifices, Colonel Vivian was now engaged upon the protracted tour, taking passages in cargo-boats with limited accommodation in order to cut down expenses, and prolong the "rest cure" by breaking the voyage in various ports.

"I think the voyage is doing Mother good," continued the girl, "and I am enjoying it—every minute in fact. But I do wish I could have brought Peter——"

"And who is Peter?" asked Burgoyne, so abruptly that he could have bitten his tongue for having shown such a lively interest—or was it resentment?—towards Peter.

"He's simply a dear," replied Hilda. "A sheep-dog, you know. Of course, it was impossible to bring him, owing to quarantine restrictions and all that sort of thing, so we had to leave him with friends. Are you fond of dogs, Mr. Burgoyne?"

"Beagles," said Alwyn. "Hadn't much time for a dog of my own. We ran a pack of beagles at Dartmouth. Ripping sport."

"Were you at Dartmouth then?" asked Miss Vivian. "At the College?"

Burgoyne nodded.

"Then you were in the navy?"

"Yes," replied the Third Officer. "In the pukka Royal Navy. I came out some months ago, worse luck. But," he added, loyal to his present employers, "this line isn't half-bad—rather decent, in fact."

Miss Vivian made no audible comment. Burgoyne had apparently failed to arouse a sympathetic interest in his case. He felt himself wondering whether she would jump to the conclusion that he was a rotter who had been ignominiously court-martialled and dismissed the Service. But, before he could enlarge upon that particular point, Hilda steered the conversation into other channels until Phil Branscombe's arrival on the bridge brought Burgoyne's trick to a close.

"My relief," announced Alwyn.

Hilda made no attempt to leave the bridge. Branscombe smiled.

"I'm off duty," persisted the Third Officer. "Would you care to see our wireless cabin? It's a perfectly priceless stunt, and Mostyn, our budding Marconi, is quite harmless while under observation."

"Thanks," replied the girl calmly. "Another day perhaps; when it's not so fine. I'll stay here a little longer; I am interested to know what Mr. Branscombe did in the Great War."

Burgoyne accepted his dismissal with the best grace at his command. He had a certain amount of satisfaction in knowing that Miss Vivian had heard of a joke at the Fourth Officer's expense, although she may not have known the actual facts.

Phil Branscombe had been appointed midshipman, R.N.V.R., a fortnight previous to the signing of the Armistice, although it wasn't his fault that he hadn't been so earlier. Consequently by the time he joined his M.-L. in a Western port hostilities were at an end. One evening towards the end of November the commander of the M.-L. flotilla was dozing in his cabin, when certain of the younger officers thought it would be a huge joke to pour pyrene down the stove-pipe and put out the fire in the Senior Officer's cabin. Stealthily they emptied the contents of the extinguisher and beat a retreat, chuckling at the mental picture of the commander's discomfiture when he awoke to find that the stove had gone out and himself shivering in the cold cabin.

Twenty minutes later a signalman conveying a message to the commander found him unconscious. The oxygen-destroying properties of the pyrene had not only extinguished the fire, but had been within an ace of suffocating the occupant of the cabin. Fortunately the commander recovered. The culprits were discovered, but their victim, convinced that it had not been their intention to drive matters to extremes, accepted their apologies and regrets. But the case did not end there. The Admiralty got to hear of it, and Branscombe and two of his fellow-midshipmen were summarily dismissed.

"That's what I did in the Great War, Miss Vivian," said Branscombe at the end of his recital. "You see, I wasn't one of the lucky ones. This ship saw some service. She was armed with six 4.7's, and made fourteen double trips across the Atlantic. Angus, our Chief Engineer, was on board her part of the time. He might tell you some yarns if you get the right side of him. Once we had some Yanks on board, and one of them asked him the same question that you asked me about what he did in the Great War. Angus simply looked straight at him. 'Ma bit', he replied."

"The Donibristle hasn't guns on board now, I suppose?" inquired the girl.

"No," replied Branscombe. There was a note of regret in his voice. "The Merchant Service doesn't want guns nowadays. I can show you where the decks were strengthened to take the mountings. No, there's no need for guns on this hooker."

But Fourth Officer Philip Branscombe was a bit out in his reckoning.

Meanwhile, as Burgoyne was making his way aft, he encountered Colonel Vivian laboriously climbing the companion-ladder.

"Thanks, Mr. Burgoyne," exclaimed the colonel, as the Third Officer stood aside to allow him to pass. "By the by, are you any relation to Major Burgoyne of the Loamshires?"

"My uncle," replied Alwyn.

"Then I must have met you at Cheltenham," resumed Colonel Vivian. "Several times I thought I'd seen your face before."

Burgoyne shook his head.

"I haven't been in Cheltenham since I was twelve," he replied, "but I have an idea that I've seen you before, sir."

"Oh, where?"

"To the best of my belief about twelve miles sou'-sou'-west of Cape de Gata. You were wearing pale blue pyjamas and a wristlet watch. When we hiked you out of the ditch you were holding up a Tommy who couldn't swim, and——"

"By Jove! I remember you now," interrupted the Colonel. "You were in charge of one of the Pylon's boats. But I thought you were a midshipman R.N."

"I was," agreed Burgoyne. "I had to resign under the reduction of naval personnel stunt. And, by the by, sir, Miss Vivian asked me to tell you that she had been on the bridge for—" he glanced at his watch, "for the last three and a half hours."

"Hear that noise? Sounds like an aeroplane overhead," exclaimed Branscombe.

It was high noon. The Donibristle was approximately five hundred miles nor'-west of the Sandwich Islands. The sky was clear and bright. Air and sea were shimmering under the powerful rays of the sun.

"Hanged if I can," replied Burgoyne, "I think you're mistaken, old son. It's hardly likely that a seaplane would be buzzing round over this part of the Pacific."

Nevertheless he craned his neck and gazed at the blue vault overhead. The two chums, off duty, were standing aft. Close to them Messrs. Tarrant and Miles were engaged in a heated argument over the merits and demerits of the products of a certain firm of tabloid drug manufacturers. Colonel and Mrs. Vivian were seated in canopied deck-chairs under the lee of one of the deck-houses. Captain Blair and the Chief Engineer were pacing to and fro on the starboard side of the deck, earnestly discussing a technical point in connection with the distilling plant. Hilda Vivian happened to be "listening in" in the wireless cabin, hearing vague sounds which Peter Mostyn assured her were time signals from a shore station on the Californian coast.

"What's that," sang out Tarrant, overhearing the Third Officer's remark. "Aeroplane—what?"

Presently at least a dozen pairs of eyes were scanning the sky, but without success.

"Can you hear it now?" asked Burgoyne.

"No, I can't," replied Branscombe bluntly, "but I swear I did just now."

"Would it be the dynamos you heard?" inquired Angus.

"No; aerial motor," declared the Fourth Officer firmly. "In fact," he added, "I believe I can hear it now."

"Ye maun hae a guid pair o' lugs," observed Angus caustically.

Branscombe said nothing more, but hurried on to the bridge. An inquiry of the Fifth Officer and the two quartermasters resulted in a negative reply. Nothing had been seen or heard of an aircraft of any description.

"Good job I didn't bet on it," remarked Philip, when he returned and reported the result of his inquiries. "But no one can prove I didn't hear it," he added, with a marked reluctance to admit defeat.

"I certainly heard a buzz right overhead," announced Colonel Vivian. "I rather pride myself on my hearing, but I'm hanged if I saw anything. Besides, if there were a seaplane so far out from land, wouldn't it have come down to within a few hundred feet and had a look at us?"

"I haven't seen an aeroplane for months," said Withers plaintively. "At one time, when I was running from Southampton to Cherbourg and Havre during the war, the sky was stiff with 'em. Hardly ever bothered to look up at the things. Now they're becoming novelties again. It would seem like old times to see a Handley-Page again."

Meanwhile Mostyn was continuing to give practical lessons to Hilda Vivian.

"What an extraordinary noise," exclaimed the girl, removing the receivers from her ears. "Much fainter than before."

Mostyn took up the ear-pieces. There was a call, but in a different wave-length. He was "standing-by" on the 600-metre wave. Rapidly adjusting the "Billi" condenser he failed to attain the desired result. Apparently the sending-out apparatus was of a totally different tune. That discovery puzzled him, since almost every ship and station keeps within the narrow limit of the 600-metre wave. Disconnecting the pin of the receiving-gear, and placing the jigger-switch on the first stop, he connected up the short-wave earth terminal. The sounds were of greater intensity but still fell short of the desired result. Deftly Mostyn manipulated the rack-and-pinion gear of the "Billi" until the signal became coherent.

Unconscious now of the girl's presence, Mostyn grasped a pencil and almost mechanically wrote the message that came through ethereal space. To her it conveyed nothing, being apparently a meaningless jumble of letters.

"SK—finished," announced Mostyn, then, again aware of Miss Vivian's presence, he continued. "Code message—they often send it in that form. I'll decode it straight away."

He tried with every code-book at his command, but without success. None of the recognized books afforded a clue. It might be just possible that Captain Blair would have a key in his possession.

"Sail on the starboard bow!" hailed the look-out man, just as the wireless operator dispatched a messenger to the Old Man.

At the hail Hilda left the wireless-room and went to the rail. Few ships had been sighted during the last two or three days, and her curiosity was aroused by the appearance of the stranger. Branscombe, who was standing near her, hastened to offer her a pair of binoculars, at the same time pointing to a small black object, surmounted by a blurr of smoke, on the horizon.

"What is the name of the ship?" asked the girl.

"Sorry, Miss Vivian," replied the Fourth Officer gravely, "but I'm not a thought reader. She'll probably make her number when she passes us."

The Donibristle was logging eleven and a half knots, and since the stranger was making eighteen or twenty it did not take long for the latter to become clearly visible to the naked eye. She was a light cruiser of about 4000 tons, with two funnels and two short masts. From the deck of the Donibristle it was seen that she carried a gun for'ard, and three on her starboard broadside, so it was safe to conclude that her principal armament consisted of eight 4- or 6-inch weapons. Right aft, and visible only when the superstructure no longer screened it, flew the White Ensign.

"What is she?" inquired Colonel Vivian.

"I can't tell yet," replied Captain Blair, who, having finished his conversation with the Chief, was making his way to the bridge with Mostyn's "chit" in his hand. "I don't even know her class. The navy's developed so many weird and hybrid types during the war, that it would puzzle Solomon to know t' other from which. Had them all at my finger-ends at one time. S'pose you don't recognize yonder cruiser, Mr. Burgoyne?"

"No, sir," replied the Third Officer, lowering his binoculars. "She hasn't even her name painted on her lifebuoys. Hello! Her bunting tossers are busy."

From the cruiser's bridge the International E.C. fluttered up to the signal yard-arm.

"That means 'What ship is that?'," explained Branscombe to Hilda. They had now crossed to where Colonel Vivian, Burgoyne, and several of the ship's officers off duty were standing.

"How interesting," muttered the girl. "What do we do now?"

"Make your number," replied Alwyn, loth to keep out of the conversation. "There it is: KSVT."

"That's not a number," objected Hilda.

"We call it a number," persisted the Third Officer. "Those four flags signify that we are the S.S. Donibristle, 6200 tons, registered at Newcastle-on-Tyne. Now they are making the next hoist—ATVH. That means Vancouver, our port of departure, and—by Jove, there's the ID."

Without waiting to give Hilda the interpretation of the two-flag signal, Burgoyne made a dash for the bridge, followed by Branscombe as a good second. Yet it was quite apparent to Colonel Vivian, his daughter, and Mr. Tarrant, that there was something of extreme gravity in that signal. Mrs. Vivian, being a little farther away, had not noticed the general exodus, while the remaining passenger—the drug drummer—showed no interest in the appearance of the cruiser.

Almost every officer and man on the deck of the Donibristle knew the significance of the signal. They had not served in the Outer Patrol during the Great War, when the examination of neutral merchantmen was an everyday occurrence, without learning to understand the peremptory command: "Heave-to instantly, or I will fire into you".

Such a mandate coming from a vessel flying the White Ensign was not to be treated with levity or contempt. Deeply puzzled, Captain Blair stepped to the engine-room telegraph and was about to ring for "Stop" when a startled voice—the First Officer's, although it was hardly recognizable—shouted:

"They're not bluejackets, sir; they're Chinks."

Just then the cruiser, which was bearing broad on the Donibristle's starboard beam, ported helm. Turning sixteen points, and moving half as fast again as the merchantman, she rounded the latter's stern and settled down on a parallel course at a distance of a cable's length on the Donibristle's port side.

"Tell the operator to send out a general SOS call," ordered Captain Blair hurriedly, "add 'attacked by pirate' and give our position."

He gave a quick glance in the direction of the cruiser. She had now drawn slightly ahead, so that she overlapped the Donibristle by about half her length. Meanwhile she had diminished speed until both vessels were moving through the water at approximately the same rate.

Just then a man scrambled on to the cruiser's bridge-rail and held a pair of hand signal-flags at the "preparatory". Then, without further preamble he semaphored: "If you use wireless I sink you".

The Old Man bent his head and spoke through the engine-room speaking-tube.

"Mr. Angus," he said in level even tones, "can you give me an extra two knots?"

Apparently the reply was favourable, for the skipper replaced the whistle with a gesture of satisfaction.

"Get the passengers down below, Mr. Burgoyne," he added; "there'll be sparks flying in half a shake. Heave-to, indeed. I'll show 'em how I heave-to. Pass the word for the hands to take cover."

Alwyn hurried off the bridge. He had barely reached the foot of the ladder when the pirate, aware that their commands with reference to the wireless had been disobeyed, opened fire with one of the beam 4-inch guns.

At that extremely short range it was almost an impossibility to miss such an easy target. With a terrific crash the wireless cabin simply disappeared, while fragments of the shell killed the Chief Officer on the spot, severely wounded one of the quartermasters, and gashed Captain Blair's forehead from his right eyebrow to his right temple.

The Old Man staggered, fell against the binnacle, and slid struggling to the deck. Branscombe rushed to his aid, but before he could reach him the skipper regained his feet. Half-blinded with blood, and dazed by the concussion, his one thought was the safety of his ship.

With a bound the Old Man sprang to the wheel, thrust the dumbfounded helmsman aside, and rapidly manipulated the steam steering-gear until the helm was hard-a-starboard. As he felt the ship answer he became as cool and steady as a rock. Deliberately he "met" and steadied her, until her bows pointed almost at right angles to the pirate's beam.

It was an audacious manoeuvre. The iron-nerved, tough old skipper was about to ram his opponent and send the cruiser, with all her rascally crew, to the bottom of the Pacific.

When Alwyn reached that part of the deck where he had last seen the passengers he found it deserted. Miles, at the report of the cruiser's quick-firer, had bolted below. Young Tarrant, with the characteristic inquisitiveness that an Englishman often shows even in the most dangerous situations, had gone for'ard to investigate the result of the damage. Colonel Vivian, his daughter, and the steward were bending over the deck-chair on which Mrs. Vivian had been reclining. She was still reclining but in a very different condition, for as Burgoyne approached he heard the steward say:

"I can't do any more, sir. Weak heart... the sudden shock... no, sir, no sign of life. I'll have to be going. There's work for me to do up there." He indicated the bridge, where, between the gaping holes in the canvas of the bridge rails, could be seen prostrate writhing forms amidst the pungent eddying smoke. Grasping his first-aid outfit, the man ran along the deck, seemingly unmindful of the fact that more shells would soon be playing havoc with the devoted Donibristle.

The steward's words were only too true. The sudden and unexpected shock, when the cruiser dealt her cowardly blow, had deprived Mrs. Vivian of life. Never very strong, and suffering from a weak heart, she had died before either her husband or her daughter could get to her.

It was no time for expressions of regret. Alwyn's instructions were imperative. The passengers must be ordered below.

"As sharp as you can, Colonel Vivian," he said; "we don't know what that vessel will do next."

The colonel pointed to the deck-chair with its inanimate occupant. He was incapable of doing anything of a heavy nature by reason of his injured leg.

Alwyn glanced at Hilda. The girl understood and nodded silently. Raising the burdened chair they carried it down the companion-way, the colonel following as quickly as his crippled limb would allow.

"You'll be safe here, I think," he said, but in his mind he knew that there was no place on board the ship where immunity might be found from those powerful 4-inch shells. He could only hope that Providence would shield the gently-nurtured girl from those flying fragments of red-hot steel. "I must go on deck," he added. "I'll let you know when we're out of danger."

At the foot of the companion ladder he stopped and beckoned to the colonel.

"I may as well tell you," he said hurriedly, "the cruiser is a pirate, her crew mostly Chinese. She does two knots to our one. You'll understand?"

"I do," replied the colonel simply. He had faced peril and death many times, but never before had he done so with his wife and daughter.

"You know where Mostyn's cabin is," continued Burgoyne. "There are plenty of his things and I'm afraid he won't want them. Tell Miss Vivian to change into his clothes, cut her hair short, and disguise herself as much as she can. If it isn't necessary there's not much harm done; if it is—well, you know, sir."

The Third Officer gained the deck just as the Donibristle had completed her turning manoeuvre and was steadying on her helm. His quick glance took in the situation at a glance.

"The Old Man's going to ram her, by Jove!" he exclaimed. "That's the stuff to give 'em."

"Lie down, sir!" shouted a voice. "Skipper's orders."

The warning came from one of a group of men prone upon the deck. Alwyn was quick to obey. He realized the result of a deadweight of 6000 tons crashing into the side of a stoutly-built steel cruiser.

Full length upon the quivering planks, for Angus had risen to the occasion and the Donibristle's engines were pulsating harder than ever they had done before, Burgoyne could not resist the temptation to raise his head and watch the proceedings.

From his unusual point of vantage, for his eyes were only about eight inches above the deck, Burgoyne had the impression that he was looking at a cinematographic picture, as the light-grey hull of the pirate cruiser not only seemed to increase in size but also moved quickly from left to right.

"Now for it!" he thought, and braced himself anew to meet the shock.

But the impact never came. Without doubt the black-hearted villains who controlled the cruiser knew how to handle a vessel, for almost the moment the Donibristle starboarded helm, the pirate craft began to forge ahead. Rapidly gathering speed, she contrived to elude the merchantman's bluff bows by a matter of a few feet. It was close enough to enable some of the former's crew to hurl a couple of bombs upon the Donibristle's deck, where they burst with little material effect, although the double explosion caused a momentary panic amongst the prostrate men in the vicinity.

Captain Blair had shot his bolt. He realized the fact. Another opportunity to ram his opponent would not occur. He could only attempt to seek safety in flight, and that, he knew, was a forlorn hope, owing to the vast difference in speed between the two ships.

Giving the Donibristle full starboard helm until she heeled outwards a good fifteen degrees, the Old Man steadied her when she was heading in a totally different direction to that of her assailant. In addition she was dead in the eye of the wind, and the smoke pouring from her funnels, and from the three separate conflagrations on deck, served to put up a screen between her and the pirate. By the time the latter had turned in pursuit (she circled rapidly under the contrary action of her twin screws) the Donibristle had gained a good two miles.

"She'll be winging us in a brace of shakes," declared Captain Blair, as the steward deftly bound lint over the Old Man's forehead. "Clear out of this, Barnes. You fellows too. She's out to cripple us, not to sink the old hooker. I'll carry on by myself."

The officers, quartermaster, and hands on the bridge had no option. They protested unavailingly. Captain Blair had a way of getting his orders carried out. Reluctantly they obeyed. They knew that the bridge would be the principal objective of the hostile guns, that it was doomed to destruction, and that the rest of the ship would come off lightly.

Burgoyne received the Old Man's order when he was half-way up the bridge ladder. Full of admiration for the grim, resolute figure of the wounded skipper, standing in solitude upon the shell-wrecked bridge, he turned and gained the deck.

A figure, crawling on hands and knees from underneath a pile of shattered, smouldering woodwork, attracted the Third Officer's attention. To his surprise he recognized Mostyn, the senior wireless officer Until that moment Burgoyne, like everyone who had seen the wireless cabin disappear with the explosion of the 4-inch shell, had taken it for granted that its occupant had been blown to pieces; but by one of those freaks of fate Mostyn had not only survived, but had escaped serious injury. He had been temporarily stunned, bruised, and cut in a score of places, his one-time white patrol uniform was scorched, torn, and discoloured, but he had emerged wrathful if not triumphant.

"The blighters!" he muttered. "Another twenty seconds and I'd have got the message through. Can you get me something to drink, old son?"

"I'll get you below, out of it," said Alwyn. "They'll reopen fire soon, I'm afraid."

He bent to raise the wounded operator, but Mostyn expostulated vehemently.

"Don't," he exclaimed. "It hurts frightfully. I'll carry on by myself if you'll stand by."

He crawled painfully to the companion-way. There his bodily strength gave out, and he collapsed inertly against the coaming. Finding that Mostyn was insensible and no longer capable of feeling pain, Burgoyne literally gathered him in his arms and carried him below. Before he had handed over his burden to the care of the steward, the ship quivered from stem to stern, and a hollow roar reverberated 'tween decks. The pirate had reopened fire.

Burgoyne regained the open. He did not feel particularly happy at having to do so. It would have been preferable to remain in the comparative shelter afforded by the thin steel plates and bulkheads. There was no reason why he should not take cover except that some of his comrades were exposed to the far-flying slivers of steel.

The after funnel had carried away. Guided by the unsevered wire guys it had fallen inboard, and was lying diagonally across the riddled casings and a couple of boats that were slung inboard. Smoke pouring from the base of the funnel was sweeping aft, hiding the bridge and fore part of the ship in a pall of oil-reeking, black vapour.

He glanced astern. The pirate vessel was coming up hand over fist, and with a certain amount of caution had taken up a position on the Donibristle's starboard quarter. She thus achieved a double purpose. She was no longer impeded by the smoke from her intended prey; and there was no risk of her propellers fouling ropes and baulks of timber deliberately thrown overboard from the merchantman.

The pirate's bow gun spoke again, followed almost simultaneously by the for'ard quick-firer of the starboard battery. A heavy object crashed upon the Donibristle's deck from overhead. Owing to the smoke the Third Officer could not see what it was.

"Our other smoke-stack, I think," he soliloquized. "By Jove! What are those fellows up to?"

His attention was directed towards a group of men standing aft. With an utter disregard of danger, seven or eight men were throwing articles into one of the quarter-boats—their scanty personal belongings, tins of provisions, and kegs of fresh water.

"Belay there!" shouted Burgoyne. "Time enough when you get the order to abandon ship. Take cover."

Even as he spoke the staccato sound of a machine-gun came from the for'ard superstructure of the cruiser. The luckless men, caught in the open by the hail of nickel bullets, were swept away like flies. Nor did the machine-gun cease until every boat in davits on the Donibristle's port side was riddled through and through. Splinters of wood flew in all directions. Metal bullets rattled like hail against the steel framework of the deck-houses, and zipped like swarms of angry bees when they failed to encounter any resistance save that of the air.

By this time the speed of the Donibristle had fallen to a bare seven knots. The destruction of both funnels and consequent reduction of draught had counteracted the strenuous efforts of Angus and the engine-room staff to "keep their end up". Far below the water-line, working in semi-darkness owing to the fact that the hammering to which the boat had been subjected had broken the electric-light current, unable to see what was going on, the "black squad" toiled like Trojans in the unequal contest with the fast and powerfully armed pirate.

A glance astern showed the Third Officer that the Donibristle was steering a somewhat erratic course. The straggling wake was evidence of that. Perhaps it was intentional on the Old Man's part in order to baffle the pirate gun-layers; but Burgoyne decided to make sure on that point.

Crossing to the starboard side, so that the partly-demolished deck structure might afford a slight amount of cover, Alwyn ran for'ard. Scrambling over mounds of debris and crawling under the wrecked funnels he hurried, holding his breath as he dashed through the whirling wreaths of smoke.

At last he arrived at the starboard bridge ladder—or rather where the ladder had been. Only two or three of the brass-edged steps remained. Here he paused. The edge of the bridge hid the skipper from his view. He retraced his steps for a few paces and looked again. There was the Old Man still grasping the wheel. The sides of the wheel-house were shattered, daylight showed through the flat roof, but Captain Blair remained at the post of honour and danger.

It was evident that he had been hit again. One arm hung helplessly by his side. The white sleeve of his tunic was deeply stained.

Burgoyne hesitated no longer. He wondered why the Second Officer had not noticed the skipper's predicament, but the Second had followed the First, and was lying motionless across the dismounted binnacle.

Without waiting to cross over to the port side and ascend by the almost intact ladder, Burgoyne swarmed up one of the steel rails supporting the bridge, and gained the dangerously swaying structure.

The Old Man looked at him as he approached.

"Women aboard," he muttered, like a man speaking to himself. "Women aboard and the dirty swine are firing into us. Worse than Huns."

"Shall I carry on, sir?" asked Burgoyne.

"No," was the reply. "But—yes. Carry on, I've stopped something here. Feel a bit dazed."

He stood aside and allowed Alwyn to take his place at the wheel. In the absence of a compass there was nothing definite to steer by. The Donibristle, like a sorely-stricken animal, was merely staggering blindly along at the mercy of her unscrupulous pursuer.

Then it dawned upon the Third Officer that the cruiser had not fired for some minutes. It was too much to hope that the pirate, sighting another craft, had sheered off. He glanced aft, across the debris-strewn decks, tenanted only by the dead. The pirate cruiser was still there. She had closed her distance, and was about two cables' lengths on the merchantman's starboard quarter. She had lowered the White Ensign, and now displayed a red flag with the skull and crossbones worked in black on the centre of the field. This much Alwyn saw, but what attracted his immediate attention was the plain fact that he was looking straight at the muzzles of four of the pirate's quick-firers, and, as the cruiser forged ahead, those sinister weapons were trained so that they pointed at the merchantman's bridge and the two men on it.

Burgoyne realized that if those guns spoke he would not stand a dog's chance. Through long-drawn-out moments of mental torture he waited for the lurid flash that meant utter annihilation. He wanted to shout: "For Heaven's sake fire and finish with me."

Yet the quick-firers remained silent, although not for one moment did the weapons fail to keep trained upon the Donibristle's bridge. There were machine-guns, too, served by yellow, brown, and white featured ruffians, who were awaiting the order to let loose a tornado of bullets upon the defenceless merchantman.

The tension was broken by the appearance of a gigantic mulatto, who, clambering on to the domed top of the for'ard gun-shield, began to semaphore a message. He sent the words slowly, coached by a resplendently-garbed villain who spelt out the message letter by letter.

The signal as received read thus:

"Surrend ers hip savey our lifs. Ifno tuues ink shipa ndnoq uarta."

"What's that fellow signalling?" asked Captain Blair. Faint with loss of blood he could only just discern the slow motion of the coloured hand-flags.

Burgoyne signified that the message was understood, and bent to speak to the wounded skipper.

"They've signalled, 'Surrender the ship and save your lives; if not we will sink you and give no quarter'."

The Old Man raised himself on one elbow. The pulse on his uninjured temple was working like a steam piston.

"Surrender the ship!" he exclaimed vehemently. "I'll see them to blazes first."

"Very good, sir!"

Fired by the dogged bravery of the skipper, Alwyn stood erect and prepared to semaphore a reply of defiance, but before he could do so Captain Blair called to him.

"After all's said and done, Burgoyne," said the Old Man feebly, "we've put up a good fight. No one can deny that. And there are women aboard, though p'raps 'twould be best——"

His voice sank and he muttered a few inaudible sentences.

"I'm slipping my cable," he continued, his voice gaining strength, "so it doesn't much matter to me. There are the others to consider—what's left of them. Quarter, they promised?"

"Aye, aye, sir!"

"Then we'll chuck up the sponge. Tell the villains we'll surrender. If they don't keep their word (now make sure you understand) tell Angus to stand by, and if there's any shooting he's to open the Kingston valves."

"Aye, aye, sir," agreed the Third Officer. He realized that if the pirates failed to keep faith in the matter of quarter, then the Donibristle—the prize they so greatly desired—would be sunk by the simple expedient of opening the underwater valves.

"We surrender," semaphored Burgoyne.

It was a hateful task, but upon reflection he agreed with his skipper's amended decision. The Donibristle had not thrown up the sponge without a gallant resistance dearly paid for in human lives. It remained to be seen whether the terms of surrender would be honoured by the horde of polyglot pirates.

Gripping the bridge-rail Burgoyne shouted out the order: "All hands on deck."

The summons was obeyed promptly, but how few responded to it! There was Branscombe, with his arm in a sling and an ugly gash on his cheek; little Perkins, the Fifth Officer, who had never before smelt powder; Holmes, the purser, and Adams, the steward, both looking like butchers after tending the wounded; Heatherington, the junior wireless operator; and fifteen of the deck-hands, several of whom bore visible signs of the gruelling they had undergone. In addition were Withers and Nuttall and seventeen firemen of the "watch-below", the rest under Angus remaining at their posts in the engine- and boiler-rooms. Of the rest of the officers and crew eleven had been killed outright or mortally wounded, including the First and Second Officers, and close on twenty hit.

The officers and men who had fallen in on the boat-deck, unaware of the trend of events, were watching the pirate with puzzled looks.

Burgoyne went to the skipper to obtain further instructions before obtaining assistance in order to take him below. Captain Blair was unconscious. Wounded in half a dozen places, he had carried on until the ship was no longer his to command. As senior surviving deck officer, Alwyn was now responsible for the act of surrender.

"We've given in," he announced to the assembled men. "There was no help for it. The cruiser has promised us quarter. Lower the ensign."

As the torn, tattered, and smoke-begrimed Red Ensign was lowered and untoggled, wild yells burst from the throats of the ruffian crew. They did not know how to cheer; they could not if they did. It could only be compared with a concerted roar of a hundred wild beasts.

The shouts ceased, not abruptly, but in a long-drawn-out howl. The captain of the pirate cruiser was shouting himself hoarse in an endeavour to obtain silence. When comparative quiet had been gained, he stepped to the end of the bridge and raised a megaphone.

"Ship Donibristle!" he shouted. "Obtain way off ze ship an stan' by to receive boats."

"Aye, aye!" replied Burgoyne.

Hitherto the Donibristle had been forging ahead at her present maximum speed, which by this time was a bare five knots; while the pirate cruiser had slowed down to the same speed, causing her to yaw horribly.

For the first time Burgoyne noticed that the engine-room telegraph was no longer workable. The voice-tube, however, was intact.

"Mr. Angus," he began.

"Aye, it's Angus," replied that worthy's rolling voice "Is't Captain Blair speakin'?"

"No, Burgoyne," replied the temporarily promoted Third. "The skipper's hit. We're down and out. Stop both engines, and——"

"Weel?" asked the Chief Engineer with more alacrity than he usually displayed.

"Stand by the Kingston valves. The villains have promised to spare our lives, but you never know. So if you hear one blast on the whistle, open the valves and take your chance. Do you understand?"

"Deed aye," replied Angus.

Presently the throb of the twin propellers ceased. The Donibristle carried way for nearly a mile before she stopped. Her head fell off as she rolled gently in the trough of the long crestless waves. The cruiser also stopped, and a couple of boats were swung out, manned, and lowered.

Burgoyne had very little time to complete his preparations, but he made the best of those precious moments. Captain Blair was carried below, with the purser and the steward to attend him. The rest of the engine-room staff, with the exception of Angus, were mustered on deck. Calling one of the hands, a reliable and intelligent Cockney, Alwyn stationed him on the bridge, telling him to keep out of sight as much as possible.

"If those fellows start shooting us down," he said, "they won't waste much time about it. Now keep a sharp look-out. At the first sign tug that whistle lanyard for all you're worth, then shift for yourself if you can, and the best of luck."

Burgoyne's next step was to send Branscombe to bring the passengers on deck. He watched intently as they ascended the companion-ladder, Tarrant and the Fourth Officer assisting Colonel Vivian, and Miles furtively following. But to his keen disappointment and alarm there was no sign of Hilda Vivian. Mental pictures of the ruffianly horde finding the girl below filled him with apprehension.

"Where's Miss Vivian?" asked Alwyn anxiously. A suspicion of a smile showed itself on the Fourth Officer's features.

"It's all right, old man," he explained. "There she is; three from the end of the rear rank of firemen."

Burgoyne gasped.

"Thought I told her to shove on Mostyn's kit," he exclaimed. "Don't you see, she'll have to—to keep with the engine-room crowd."

"Jolly sight safer," declared Branscombe. "She'd attract attention with the few of us who are left. Her father agreed with me. 'Sides, all hands know, and they're white men, every man jack of 'em."

"P'raps you're right," conceded Burgoyne, and as he gave another look he felt convinced that the amended plan was the thing. Unless an unfortunate fluke occurred or, what was most unlikely, someone "gave her away" the pirates would never recognize the slender fireman with closely-cropped hair and begrimed features, and rigged out in an ill-fitting greasy suit of blue dungarees, as a girl of gentle birth. There was certainly nothing in her demeanour to betray her. She was standing in a line with the men, outwardly as stolid as the rest.

Drawing a small plated revolver from his hip-pocket—it was a six-chambered .22 weapon of neat workmanship—Burgoyne thrust it inside his sock, jamming the muzzle between the inside of his boot and his ankle. For the first time he felt grateful to the steward for having spilt ink over both pairs of deck-shoes, otherwise he would not have been wearing boots, and another hiding-place for the handy little weapon would not have promised to be so convenient.

The leading boat from the pirate cruiser ran alongside, and about twenty men, armed to the teeth, swarmed up the Donibristle's side, followed (not led) by a swarthy, black-bearded individual wearing a cocked hat, a blue tunic, with a lavish display of gold lace, a black and crimson scarf round his waist, and a pair of duck trousers with white canvas gaiters. From his belt hung a cavalry officer's sword, while in his kid-gloved right hand he grasped an automatic pistol.

The boarding-party consisted of men of half a dozen nationalities, and at least three totally distinct types of colour. There were Chinese, blue-smocked and wearing straw hats and black wooden shoes, negroes, bare to the waist, Creoles and half-breeds from various South American states, a couple of South Sea Island Kanakas, and a gigantic Malay armed with a kriss and a magazine rifle. Bunched together they eyed the motionless crew of the Donibristle so fiercely that Burgoyne momentarily expected to find them slashing, hewing, and shooting down their helpless, unarmed captives.

The pirate officer stepped forward in the most approved melodramatic manner.

"Me Pablo Henriques, tiente po—dat premier lieutenant—ob cruiser Malfilio," he announced. "Señor Ramon Porfirio him capitano. Now I take command ob de—de——"

He paused, unable to pronounce the name.

"—ob dis ship," he continued. "If you no give trouble den all vell. If you do, den dis."

He drew one finger across his throat with a guttural cluck and pointed significantly over the side. The stolid-faced prisoners hardly moved a muscle. With no immediate danger in prospect, provided the pirate kept his word, they were content to let events shape themselves, confident that in the long run the lawful keepers of the peace on the High Seas would adjust matters in the form of a running noose round the neck of each of the pirate crew.

"Now tell me," continued Henriques, addressing Burgoyne. "You no capitan; where am he?"

"Wounded," replied Alwyn briefly.

"Bueno. He make to ram us," rejoined the half-caste lieutenant. "Capitano Ramon Porfirio him angry, so we shoot. Say, is dis all der crew?"

"No," replied Burgoyne steadily. "There are several wounded below. Also the Chief Engineer is in the engine-room."

Henriques darted a glance of suspicion at the British officer.

"Wa for?" he demanded sharply.

Burgoyne returned his look calmly.

"He has to watch the steam-gauges," he replied. "It might be awkward for us if an explosion occurred."

It was an answer that served a two-fold purpose. Not only had Burgoyne given the pirate lieutenant a satisfactory reason for the Chief Engineer's presence in the engine-room, but he had, perhaps unknowingly, shown a certain amount of anxiety for the safety of the ship. Consequently any suspicion on the part of Pablo Henriques that the crew of the Donibristle had arranged to destroy the vessel, the boarding-party, and themselves was totally dispelled.

"Ver' good!" he exclaimed, satisfied with the explanation. "Now, wher' are de documentos—de papairs?"

Burgoyne shook his head and pointed to the wreckage of the chart-house. "Your fire was so accurate that the ship's papers are lost," he replied.

As a matter of fact Captain Blair had weighted them with a lead-line and sinker, and had dropped them overboard almost directly the Malfilio had hoisted the ID signal. They were several miles astern and fathoms deep in the Pacific.

A string of questions followed. What was the nature of the cargo? The amount of coal in the bunkers? Any infectious disease? How many passengers?

All these questions Burgoyne answered promptly He was anxious not to cause trouble and give the pirates an excuse for brutality and perhaps massacre.

"Four," he replied in answer to the last question. "One, a lady, lies dead below. She died during the firing."

Pablo Henriques shrugged his shoulders. That information interested him hardly at all.

"You vill tell your men," he ordered, "to give up all arms an knifes. If we find any after late, den' we kill 'em."

The young officer gave the word, and the crew deposited their knives upon the deck. Firearms they did not possess, but of the officers, Withers and Branscombe each gave up an automatic and a few rounds of ammunition. Burgoyne took the risk and retained his revolver.

"Now I make search every man," declared Henriques, smiling sardonically. "I jus' make certain."

Fortunately a signal was being made by the Malfilio, and Henriques' attention was diverted. By the time the message was completed and acknowledged, the pirate lieutenant had either forgotten his intention of having the prisoners searched, or else something of more pressing nature required attention.

Accompanied by three or four of the pirates Henriques went below. He was away for about five minutes, during which time the Malay ostentatiously whetted the already keen edges of his kriss. Noting the act, Burgoyne registered a vow that, should the pirates commence a massacre, he would take care that the yellow ruffian would be the recipient of the first of the six bullets in his revolver.

Presently the grotesquely attired Henriques returned with much sabre-rattling.

"De firemans here vill go below an' keep up de steam," he ordered. "Ebbery one of de firemans. De odders dey vill go prisoners on board de Malfilio."

"That's done it," ejaculated Burgoyne under his breath. "Why that ass Branscombe hadn't put Miss Vivian with the deck-hands passes my comprehension. She'll be separated from her father straight away."

He was furious but impotent. He pictured Hilda ordered below into the hot, steam-laden, dusty stokehold, imprisoned in an iron box, in which only hardened firemen could endure the discomforts, especially in latitudes approaching the tropics. He wondered whether Colonel Vivian would break the bonds of restraint and jeopardize the lives of all the passengers, or whether Hilda would give way under the parting, which might or might not be permanent.

The fact that Alwyn was now senior executive officer complicated matters. He was responsible for the safety of passengers and crew as far as lay in his power, and he was under the impression that Branscombe's ill-advised step reflected upon his own judgment and discretion. And Hilda Vivian's presence on board promised to lead to endless difficulties and additional dangers before the prisoners were rescued. As these thoughts passed rapidly through his mind Burgoyne watched Miss Vivian from a distance. She no doubt clearly understood the pirate lieutenant's order, even if the words were somewhat ambiguous; but the girl gave no sign or look to indicate her thoughts. She had dropped quite naturally into the stand-at-ease pose of her companions, all of whom were ready, if needs be, to give their lives to shield her from harm.

"After all," soliloquized Alwyn, "there'll be Angus and Withers to keep an eye on her. And there's less chance of the old Donibristle being sunk than the pirate, if a British or Yankee cruiser should appear."

There was a decided uncertainty about that "if". British cruisers were comparatively rare birds in that part of the North Pacific, and Uncle Sam was content to keep his cruisers within easy distance of the American seaboard, except on rare occasions when events in the Philippines or Hawaii required their presence. As for merchant vessels, they kept rigidly to the recognized routes. Sailing craft had perforce to wander from the narrow path, otherwise there were wide stretches of the Pacific where the blue seas were hardly ever disturbed by a ship's cutwater.

The Donibristle, when overhauled by the Malfilio, was on the recognized Vancouver-Honolulu route. She had cut and was well to the south'ard of the steamer track between 'Frisco and Yokohama, and still at some distance north-west of the converging track between 'Frisco and Honolulu. During the pursuit she had been forced some miles out of her course, so that any slight hope of being rescued by a chance war-ship was rendered still more remote.

Pablo Henriques signalled imperiously to Alwyn to put his orders into execution.

"Carry on, Mr. Withers," said Burgoyne, without a trace of emotion, although he felt like springing at the throat of the pirate lieutenant. "Get the firemen—both watches—below."

The men broke ranks and disappeared from view. With them went Hilda, descending the almost vertical slippery steel ladder without the faintest hesitation.

"You will lower boats," ordered Henriques.

"But," protested Burgoyne, pointing to the shattered and bullet-holed assortment of woodwork in the davits, "it is useless. They wouldn't keep us afloat a minute."

The pirate lieutenant shrugged his shoulders.

"That has noddin' to do with me," he remarked callously. "If dey no float you swim. It not far."

"That's one way of making us walk the plank, I suppose," thought Alwyn; then, without betraying his mistrust, ordered the boats to be swung out.

"We can make some of them seaworthy, lads," he added. "It's not far. Those boats that can keep afloat will have to make two trips. The passengers will go in No. 1 lifeboat. She's the safest I think."

As the seamen moved off to carry out the order, Colonel Vivian turned to the erstwhile Third Officer.

"Is there no chance of my remaining on board?" he asked hurriedly. "You see, my daughter—and my wife, lying dead below——"

"Miss Vivian will be safe enough, I think," replied Burgoyne. "That is provided her secret is kept. I quite understand your anxiety about Mrs. Vivian. Why not ask to be allowed to remain?"

Colonel Vivian limped away to make the request. It was humiliating for a British army officer to have to ask a favour of a rascally half-caste pirate, but the thought of having to abandon the body of his wife to be unceremoniously thrown overboard by this horde of coloured ruffians made him put aside his scruples.

"No," replied Henriques. "De order is all leave de ship. But I gif you fife minutes to perform de burial of de lady."

And so, setting to work rapidly yet reverently, Burgoyne, the purser, and the steward assisted the bereaved colonel to commit the remains to the deep. Under the watchful eyes of a couple of pirates, lest articles or documents of value should be disposed of at the same time, the corpse was swathed in a spare awning, lashed up, and weighted with a length of chain. The steward produced a Prayer Book and handed it to the temporary skipper. Burgoyne, noting that a bare ninety seconds remained, read a few portions of the burial service, then, with every man of the Donibristle's crew within sight knocking off work and standing bareheaded, the mortal remains of Mrs. Vivian were committed to the deep.

"Perhaps," thought Alwyn, as he turned away, "perhaps it was as well that Miss Vivian did go below. There are limits even to the endurance of human nature."

The voice of the pirate lieutenant bawling out orders in broken English attracted Burgoyne's attention. A signal had just been received from the Malfilio countermanding the previous order, and instructing Henriques to send the prisoners below and get under way. So the boats were swung in again and secured.

By the time that this work was completed, and before the British deck-hands and officers could be sent below, a faint buzzing that momentarily increased caused all hands to look skywards. Approaching the Malfilio at a high speed was a small seaplane. At first Burgoyne and many of his comrades thought that it was a naval scout, and that deliverance was at hand; but the fact that no hostile demonstration was made on the pirate cruiser quickly banished this hope.

The seaplane was winding in a wireless aerial as she circled round the Malfilio. Without the slightest doubt it was by this means that the Malfilio had been placed in touch with her prey. The fuselage was dumpy and the monoplane spare and small, and by the corrugations of the wings Burgoyne rightly concluded that they were of metal. She was of an earlier type with a single motor of comparatively low power —but quite sufficient to enable her to be a valuable adjunct to the pirate cruiser.

The "winding-in" completed, the seaplane alighted on the surface and "taxi-ed" alongside the Malfilio. A derrick swung outwards from the cruiser, and a steel wire rope was deftly shackled to the eyebolt of a "gravity band" round the fuselage. Even as the machine rose from the water, dangling at the end of a wire rope, her wings swung back and folded themselves against the body, and in this compact form the aerial scout vanished from sight behind the Malfilio's superstructure.

This much Burgoyne saw before he was compelled to follow the remaining officers and deck-hands, including the Cockney who had been told to stand by the whistle lanyard, and who, during the operation of swinging in the boats, had seen his officer's signal for recall.

Once 'tween decks, the men were herded for'ard and locked up in the forepeak, an armed pirate being stationed on the hatchway. The remnant of officers and the passengers were ordered aft, and secured in the steerage, where they found Captain Blair, Mostyn, and the other wounded. There were four cabins at their disposal, the whole separated from the rest of the ship by a transverse bulkhead in which was a single sliding door. Outside this a sentry was posted, while, as an additional precaution, that for some reason was not taken in the case of the men, four villainous-looking Orientals, armed to the teeth, were stationed with the prisoners. The dead-lights were screwed into the scuttles, and the captives warned that any attempt at tampering with them would be punishable with death; and, since the electric light had failed, the steerage was dimly illuminated by half a dozen oil-lamps.

The door had not been locked more than a couple of minutes before the prisoners heard the thresh of the twin propellers. The S.S. Donibristle under her new masters was steaming ahead, under greatly reduced speed, in the wake of the pirate cruiser Malfilio—but whither?

The reaction of the excitement and peril of the last few hours now set in, and a state of lethargy took possession of most of the prisoners. The hot, confined, ill-ventilated space, the reek of iodoform pervading everything, and a sheer hunger and fatigue all combined to suppress any desire for conversation. For some hours the silence was broken only by the moans of the wounded and the clank of the freshwater pump, as the parched men quenched their burning thirst with frequent and copious draughts, while constantly their Chinese guards, with their expressionless yellow faces and slanting eyes, paced to and fro, like sinister demons from another world.