Photo. Emery Walker

PROFESSOR AND MRS. FAWCETT

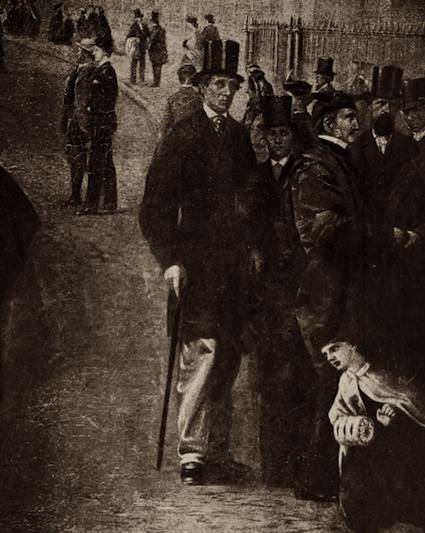

From the painting by Ford Madox Brown, now in the National Portrait Gallery

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: A Beacon for the Blind

Being a Life of Henry Fawcett, the Blind Postmaster-General

Author: Winifred Holt

Release Date: June 12, 2016 [eBook #52310]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A BEACON FOR THE BLIND***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cu31924028315400 |

Photo. Emery Walker

PROFESSOR AND MRS. FAWCETT

From the painting by Ford Madox Brown, now in the National Portrait Gallery

There has been no more striking example in our time of how self-reliance and strength of purpose can triumph over adverse fortune than that presented by the career of Henry Fawcett. The story of his life as it is to be told in this book will give ample illustrations of his fortitude and his perseverance. All that I, an old friend of his, need speak of is a quality hardly less remarkable than was his energy. I mean his cheerfulness. It was specially wonderful and admirable in one afflicted as he was. Nothing would seem so to cut a man off from his fellows as the loss of sight, nor would it appear possible to enjoy the charms of external nature without seeing them. Fawcett, however, delighted in society. He never moped. He loved to be among his friends, and found an inexhaustible pleasure in talk wherever he was, in his College (Trinity Hall, Cambridge), at London viiidinner-parties, in the lobbies or smoking-room of the House of Commons. If he had moments of sadness in solitude we knew nothing of them, for in company he was always bright. His greetings were joyous; his good spirits proverbial at Cambridge, and indeed in all the circles that knew him, making his friends feel, in any moments of depression that might come upon them, half ashamed to be less cheery than one with whom fate had dealt so hardly. Without this natural buoyancy of temper, even such a resolute will as his might have failed to achieve so much as he achieved. He seemed determined to hold on to every possible source of enjoyment he had ever known before sight was lost. That determination used to strike me most in his fondness for open-air nature and physical exercise. He loved not only walking but riding. I remember how once when I was staying with him in the same country house in Surrey, our host arranged a long excursion on horseback through the lanes and woods of the pretty country that lies on both sides of the North Downs, to the south-west of London. Fawcett insisted on being one of the party, and when he approached a place where the bridle-path ran through a wood of beeches, whose spreading boughs came down almost to the height of the horses’ heads, he said to me, ‘Tell me to duck my head ixwhenever we come to a spot where the branches are low.’ I felt uneasy, for if he had struck against one of the thick boughs, he might have been unhorsed and would certainly have been hurt. However, I went in front and warned him as he had desired. He rode on fearlessly, stooping low over the horse’s neck whenever I called out to him to do so, and he evidently enjoyed the fresh scent of the woods and the rustling of the leaves just as much as did all the rest of us.

His love of nature, joined to his sympathy with the masses of the people, made him eager to secure the preservation of public rights in commons and village greens and footpaths. He was one of the founders of that Commons Preservation Society which has done so much to save open spaces in England from the grasp of the spoiler; frequently attended its meetings, and was always ready to vote and speak in the House of Commons when any question involving popular rights in the land arose there.

At a time when extremely few non-official persons in Parliament interested themselves in the government and administration of India, Fawcett, though he had never visited the East, and had no family connection with it, felt, and set himself to impress upon others, the grave responsibility of Britain for the welfare of the peoples of xIndia. He studied with characteristic thoroughness and assiduity the facts and conditions of Indian life, the financial problems those conditions involve, the needs and feelings of the subject population. His speeches were of the greatest value in calling public attention to these subjects, and his name is gratefully remembered in India.

His mental powers were remarkable rather for strength than for subtlety. It was an eminently English intellect, forcible in its broad commonsense way of looking at things, and in its disposition to pass by side issues and refinements in order to go straight to the main conclusions he desired to enforce. This was what chiefly gave weight to his speeches in Parliament and on the platform. Debarred as he was from the use of writing, he formed the habit of thinking out fully beforehand both what he meant to say and the words in which he meant to say it, and thus he became a master of lucid statement and cogent argument, making each of his points sharp and clear, and driving them home in a way which every listener could comprehend. The same merits of directness and coherency are conspicuous in his writings on political economy, his favourite study. There were no dark corners in his mind any more than in his political creed, or indeed in his course of action as a statesman. In practical politics, it was said xiof him, to use a familiar phrase, that you always knew where to find him. That was one of the qualities which secured for him not only the confidence of his political friends but the respect of his political opponents. When he died prematurely he had reached a position in the House of Commons which would have secured his early admission to the Cabinet, and the only doubt I ever heard raised was whether his blindness, which would have made it necessary that documents, however confidential, should be read aloud to him, would have constituted a fatal obstacle.

The force of his character and the vigour of his intellect must have ensured him a distinguished career even had he been stricken by no calamity. That he should have been stricken by one which would have overwhelmed almost any other man, and should have triumphed over it by his cheerful and persistent courage, marks him out as an extraordinary man, worthy to be long remembered.

‘I wish we had Fawcett here to-day. At this crisis England needs him sorely.’ These words, said with much feeling by the late Lord Avebury, were spoken to the writer of this book only two years ago.

Fawcett is not needed only in England. His is the type of man needed sorely to-day and every day in every empire and democracy under the sun. His example of valour against odds is just as necessary for America as for the Mother Country, for the men who are now doing the world’s work as for the lads who will be at work to-morrow.

Sir Leslie Stephen said that while writing the biography of Fawcett, there was not a single fact which he had to conceal, nothing to explain away, nothing to apologise for, and he judged the best way to do his subject honour was to tell the plain story as fully and as frankly as he could.

Sir Leslie wrote with the reticent dignity of one recently grieving for the loss of his friend; the present writer will have executed her task if she has succeeded in throwing a more personal light on the heroic figure of Fawcett.

xivThis little book has no pretensions. It endeavours merely to preserve carefully and reverently glimpses and flashes—which might have otherwise been lost—of a great life, a life of deep significance not only to those who see, but especially to those who, like Fawcett, must depend for their vision on that inner eye which no calamity can darken.

When he lost his sight, Fawcett had his fixed manner of life, his tastes and ambitions, and he was painfully forced to readjust himself to altered aspects. The tracing of the beneficent effect of this necessity on a man of his strong mind, body and will, is a psychological study of deep interest.

His attitude towards questions that are still vital, such as the treatment of dependent peoples, the widening of the suffrage and the perfecting of its machinery, make his personality still unique, modern and absorbing.

A nearer view of the man, seen through the recollections and anecdotes of his friends, shows his intense love of fun, his high ideals and bravery, his tremendous industry and accomplishment.

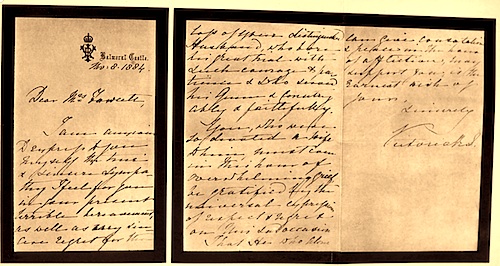

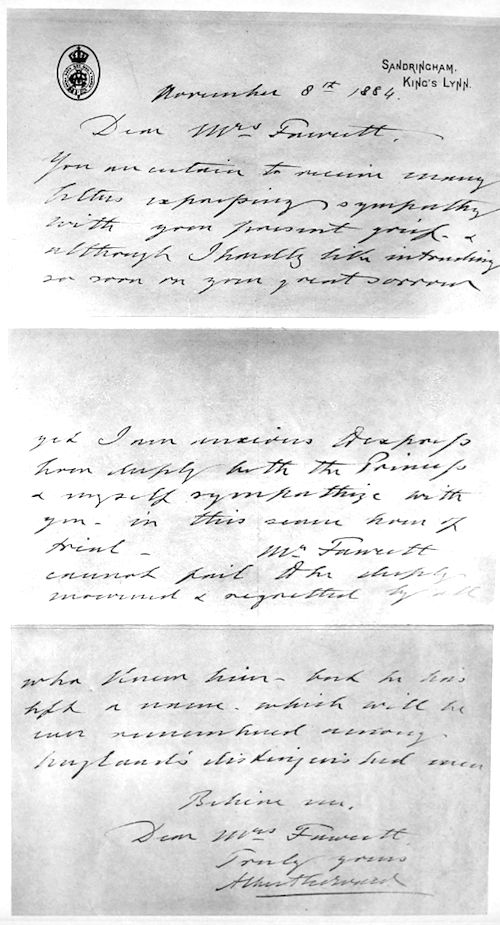

The author is grateful for permission to use the facsimiles of the letters of Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales (King Edward).

She is also deeply obliged for the help given by reminiscences and anecdotes from the Right xvHonourable the late Lord Avebury; Dr. Beck, Master of Trinity Hall, Cambridge; Dr. Henry Bond; the Right Honourable Viscount Bryce, late British Ambassador to America; Sir Francis Campbell; the late Robert Campbell, Esq.; the Honourable Joseph H. Choate, late American Ambassador to Great Britain; Lord and Lady Courtney; Sir Alfred Dale; the late Sir Robert Hunter; the late Sir William Lee-Warner, G.C.S.I.; the Right Honourable Viscount Morley; Lady Ritchie, Miss McCleod Smith; the Right Honourable the late James Stuart, Esq., and Mr. Sedley Taylor.

She is particularly indebted to Miss Fawcett, the sister of Mr. Fawcett, and to Mrs. Fawcett, his widow, for their assistance. Their interest in the book was a great stimulus towards its writing. Mr. F. J. Dryhurst, C.B., who from 1871 to 1884 was secretary to Mr. Fawcett, has been a great aid in preparing the book. The greatest assistance has been given by Miss de Grasse Evans and Miss Beatrice Taylor, without whose sympathy and help in various stages of the work its completion might have been impossible.

It has been inevitable that Sir Leslie’s biography should be largely quarried. His arrangement of facts has been followed as the simplest and most logical framework for the story, and descriptions xviof scenes which he and his friends witnessed, and stories of Fawcett not elsewhere given, have been used. The admiration and gratitude of the novice for help from the master biographer is here humbly recorded.

This book should enhance the interest of the older biography, which perhaps may be reintroduced after many years oblivion—as it has been out of print—by its younger and less formal companion.

The material to be had has been used and adapted as it might best serve, and the narrative has not been interrupted to give its source; it is believed that this policy will be in accordance with the wishes of those of Mr. Fawcett’s appreciators who have so generously helped.

The more we know about this brave, patient and humorous man, the more inspiration we get; and to help us to achieve and to rejoice—never was inspiration more sorely needed than to-day! It is in the hope of supplying a little of this great need that this brief story of a steadfast life is written.

| PAGE | |

| Foreword by the Right Hon. Viscount Bryce | vii |

| Introduction | xiii |

| Chapter I. Waterloo, the Mayor and the Baby | 3 |

|---|---|

| The Fisherman—The Battle of Waterloo—The Mayor of Salisbury—the Mayor’s Son—The Market-place—The Circus—Boarding-School and Fun—A Diary | |

| Chapter II. The Boy Lecturer | 11 |

| A Lecture on the Uses of Steam—Parliamentary Ambitions—King’s College—Politics in the Fifties—Cribbage and Cricket |

| Chapter III. The Tall Student | 25 |

|---|---|

| Peterhouse—Quoits and Billiards—Trinity Hall—A Fellowship—Lincoln’s Inn | |

| Chapter IV. A Set Back | 35 |

| A Trip to France—Wiltshire French—A Discouragement |

| Chapter V. Darkness | 43 |

|---|---|

| A Shooting Accident—Blindness—Readjustment | |

| Chapter VI. Happiness | 54 |

| The clear-sighted Man—A Scot’s Accent—Mountain Climbing—Skating—Riding, etc. | |

| Chapter VII. Distraction | 63 |

| Fishing—In the House of Commons—Need for Distraction—What Helen Keller thinks—Sir Francis Campbell—Leap Frog—Despair and Cheer—Paupers and Political Economy |

| Chapter VIII. The Problem of the Poor | 75 |

|---|---|

| A Prime Object—Lincoln—Leslie Stephen—Daily Life at Cambridge—Deepening interest in Social Questions | |

| Chapter IX. The Good Samaritan | 84 |

| ‘Ask Fawcett’—The Ancient Mariners and the Diplomat—Christmas Exceedings—Fawcett as Host—A Bore Foiled—The British Association | |

| Chapter X. The Young Economist | 94 |

| Championing Darwin—Darwin at Down—Salisbury gossip—Meeting Mill—Fawcett for Lincoln and the Union—John Bright’s Dog—Chair of Political Economy |

| Chapter XI. A Programme of Helpfulness | 111 |

|---|---|

| Triumphing over Blindness—The Professor’s Audience—Free Trade and Protection—The Luxury of Light—The Malady of Poverty | |

| Chapter XII. The Schools of the Poor | 119 |

| Need of non-secular Education—Charity and Pauperism—Friendship with Working-Men—The Voice that Linked | |

| Chapter XIII. The New M.P. and the Club | 127 |

| Thackeray and the Reform Club—The Popular M.P.—The Assassination of Lincoln—Marriage | |

| Chapter XIV. The Woman and the Vote | 135 |

| The Home in London—Sympathy with Woman Suffrage—The Blind Gardener—Clubs—Hatred of Flunkeyism |

| Chapter XV. Blind Superstitions | 143 |

|---|---|

| Speech before the British Association—Mill again—Bright and Lord Brougham—The Mythical Committee Room—Defeat at Southwark | |

| Chapter XVI. Pure Politics | 151 |

| Defeat at Cambridge and Brighton—Routing a Chimæra—Elected the Member for Brighton—The House of Commons | |

| xxChapter XVII. A Prophetic Question in Parliament | 162 |

| The Blind and Silent M.P.—His First Speech—Protecting Cattle, neglecting Children—Industry earns Penury—Mill ‘out’ | |

| Chapter XVIII. Gladstone Prime Minister | 173 |

| Opposition to Gladstone—‘The Most Thorough Radical Member in the House’—Growing Dissatisfaction with the Government—The Irish Universities Bill—Helping to Defeat his own Party |

| Chapter XIX. The Stolen Commons | 185 |

|---|---|

| The Disappearance of the English Playgrounds and Commons—Fawcett’s First Protest—The Annual Enclosure Bill stopped by his Energetic Action | |

| Chapter XX. The Fight for the Forest | 194 |

| The Commons Preservation Society—The Saving of Epping Forest—The Queen’s Rights—The Lords of the Manors’ Rights.—The People’s Rights | |

| Chapter XXI. For the People’s Woods and Streams | 203 |

| Saving the Forests—‘The Monstrous Notion’—Walking with Lord Morley—The Boat Race—Safeguarding the Rivers |

| Chapter XXII. What India Paid | 217 |

|---|---|

| India Pays for English Hospitality—Royal English Generosity to India paid for by India—How to Deal with an Angry Opponent—Indian Finance and the poor Ryot—Gratitude from India—How Fawcett Prepared his Speeches | |

| xxiChapter XXIII. The ‘One Man who cared for India’ | 227 |

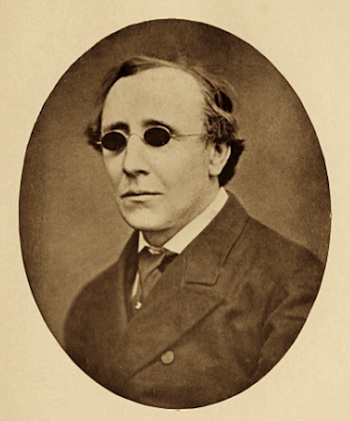

| Defeated at Brighton—Spectacles and the Man—Elected for Hackney | |

| Chapter XXIV. Famine, Turks and Indians | 234 |

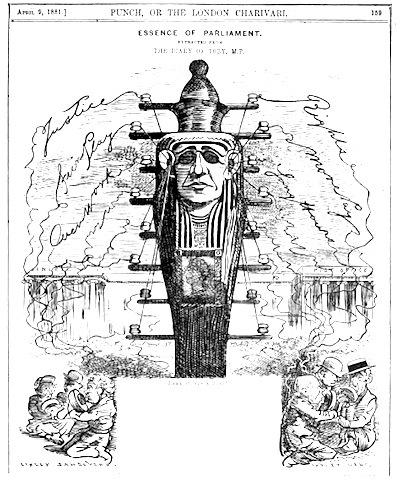

| Punch and Fawcett—The Indian Famine—Parliamentary Interest Aroused in India—Bulgarian Atrocities—Afghanistan War—Gladstone’s Faith in Fawcett—A £9,000,000 Mistake |

| Chapter XXV. Liberals in Power | 249 |

|---|---|

| General Expectation that Fawcett would join the Cabinet—Importance of a Fish—Postmaster-General—Queen Victoria Interested—Post Office Problems—Scientific Business Management Anticipated—Women’s Work—A Likeness to Lincoln | |

| Chapter XXVI. Fresh Air, Blue Ribbons and Postmen | 262 |

| A Day with the Postmaster-General—How he Worked—Reform—The Parcel Post | |

| Chapter XXVII. The Pennies of the Poor | 275 |

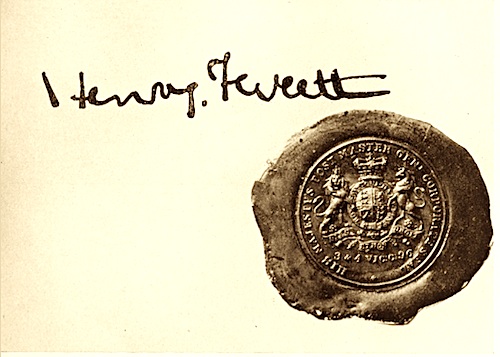

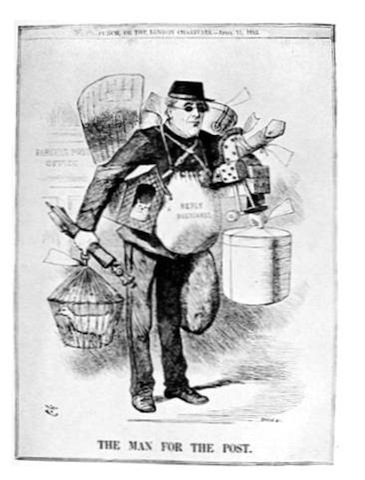

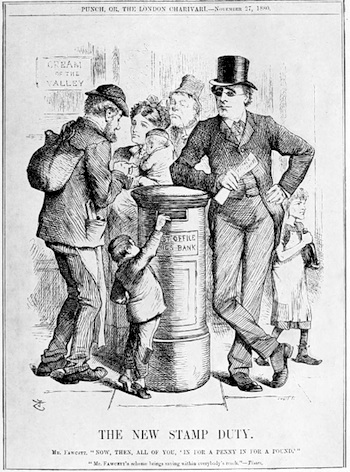

| Cheap Postal Orders—Savings Bank—Life Insurance—Two Post Office Pamphlets to Help the People—Cheap Telegrams—Telephones—‘The Man for the Post’—‘Words are Silver, Silence is Gold’ |

| Chapter XXVIII. At Home and at Court | 287 |

|---|---|

| Appreciating Opponents—Hackney Address—Proportional Representation—Justice for Women—A State Concert—Humble Friendships—Pigs—Salisbury again | |

| Chapter XXIX. A Grave Illness | 300 |

| Illness—Convalescence—Musical Discrimination | |

| Chapter XXX. Among the Blind | 306 |

| A Leader of the Blind—Honours—His Last Speech | |

| Chapter XXXI. Light | 311 |

| The Passing—The People Grieve—Sorrow in Parliament—The Nation’s Loss—Letters from Queen Victoria, the Prince of Wales (the late King Edward) and Gladstone—The Railroad Men’s Tribute—The Significance of his Life—India’s Loss—Fawcett’s Message | |

| Henry Fawcett, from ‘Punch’ | 327 |

| Appendix | 329 |

| Index | 335 |

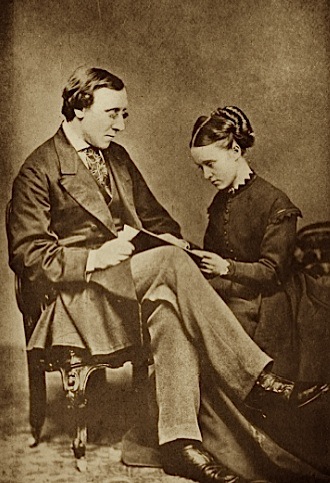

| Professor and Mrs. Fawcett | Frontispiece |

| Henry Fawcett’s Mother | Facing page 6 |

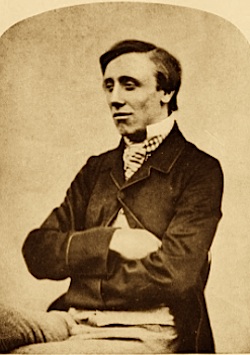

| Henry Fawcett before he was Blind | „ 26 |

| Miss Maria Fawcett | „ 50 |

| Henry Fawcett at Cambridge, 1863 | „ 102 |

| Henry Fawcett and Mrs. Fawcett | „ 130 |

| Henry Fawcett | „ 180 |

| Henry Fawcett and his Father | „ 204 |

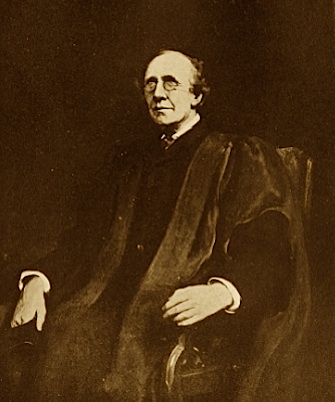

| Henry Fawcett | „ 224 |

| Fawcett’s Signature and Seal as Postmaster-General of England | „ 252 |

| The Man for the Post | „ 272 |

| The New Stamp Duty | „ 276 |

| Here stands a Post | „ 282 |

| Facsimile of a Letter from Queen Victoria to Mrs. Fawcett | „ 316 |

| Facsimile of a Letter from the Prince of Wales (King Edward VII.) to Mrs. Fawcett | „ 318 |

| Memorial in Westminster Abbey | „ 322 |

The Fisherman—The Battle of Waterloo—The Mayor of Salisbury—The Mayor’s Son—The Market-place—The Circus—Boarding-School and Fun—A Diary.

One midsummer day in 1815 a young draper’s assistant was gently fishing in the Salisbury Avon. William Fawcett was but lately come to Salisbury, yet he already knew his river. While trying a deep pool in the shadow of a bridge near the town he was startled by shouts from the roadway above. ‘News from the army! A great victory! Boney in flight!’

The fisherman forgot his fish, and hurried away to join the rejoicing crowd gathering in the market-place. There having been bustled to the roof of a stage-coach, and had the gazette containing the news thrust into his hands, he read out in his remarkably clear and resonant voice the account of the great battle of Waterloo.

Seventeen years later, when the shopkeeper had become the Mayor of Salisbury, he again led the town in rejoicings. The great Reform Bill had become law. Salisbury townsfolk were henceforth to have a voice in the councils of the nation, and the barren hill on which stood the pocket 4borough of old Sarum was no longer to mock them with its political power.

The town joyously prepared to celebrate the event. The houses were decorated. Elaborate illuminations were set up. Victory, assisted by Greek gods and goddesses, presided over a transparency in which Britannia throttled the hydra of corruption, while Wellington and Peel scowled in the background. Meat and beer were given to the poor; in the market-place, at great fires lighted in the open air, whole sheep were roasted. The smoke swirled blindly about the bustling crowd, and then surged up past the latticed windows of the Mayor’s house, to seek in ever thinning rifts the spire of the wonderful cathedral that for centuries has watched over the destinies of the town. The next day was held in the market-place a great banquet, at which the Mayor presided; and after dinner all adjourned to the Green Croft Cricket Ground, where his Worship led off the dance with a prominent and elderly lady of the town—the Mayor resplendent in plaited shirt frill and high stock, the buckles on his shoes twinkling as he cut ‘pigeon wings,’ the lady sedate in her wide brocade gown, her poke bonnet, and lace veil.

Fawcett’s heart was as light as his heels on that occasion. All his life he had been a reformer, a staunch Liberal, ardent for the extension of the franchise. It says much for his personal charm and worth that, in a close Tory borough such as 5Salisbury then was, he should have been chosen Mayor by his political opponents.

So dear to his heart was the spirit of freedom that the Mayor had forsooth to fall in love with the daughter of the solicitor who acted as agent for the Liberal party. Miss Mary Cooper was a good and clever woman, deeply interested in politics, and as ardent a reformer as the man she married.

The couple were sociable and humorous. They kept a good table, laid in an excellent stock of wine, and diffused such a pleasant atmosphere of hospitality that they became immensely popular, and many distinguished people sought their company. But William Fawcett was not only a good townsman, he was a good countryman as well, a great jumper, a keen sportsman, a good shot, and a renowned fisherman.

In 1833, when the Princess Victoria was fourteen years old, when the negro slaves were being freed throughout the British Colonies, when Stephenson had completed his locomotive and the first railroads had been started, when all things seemed to be pushing and striving for independence and progress, in the Mayor’s old low red-brick house overlooking the market-place, in a wonderful Elizabethan room, on 26th August, Henry Fawcett was born.

The baby seems to have been singularly like most other babies. He shared the uneventful placidity of his nursery with an older brother, 6William, and a sister, Sarah Maria. Six years later there came another brother, Thomas Cooper.

When Harry was four years old Queen Victoria, whom he was to serve in so distinguished a capacity, came to the throne. But it was still too early to find in Harry indications of the future statesman. He was delicate, and much spoiled at home, had a strong will of his own, and was on the whole rather selfish. He was not an imaginative child, though he loved at times, holding his sister Maria tightly by the hand, to venture into the great cathedral and see the coloured light as it filtered through the high windows, or to thrill in response to the thundering of the great organ. But more often we find him, still very tiny, standing squarely on his feet, inquiring with real interest the price of bacon, how much sheep and wool brought; or walking with his father and wearying him with ceaseless economic questions as to ‘Why are things cheaper to-day than last month?’ ‘Why does butter cost more than milk?’ until that patient man was heard to exclaim not too patiently, ‘Harry asks me so many questions that he quite worries me.’

HENRY FAWCETT’s MOTHER

He went to a Dame’s school, where his first teacher said that she had never had so troublesome a pupil, that his head was like a colander; but Harry puts the case more pathetically when he tells his mother that ‘Mrs. Harris says if we go on, we shall kill her, and we do go on,’ regretfully adding, ‘and yet she does not die.’ A 7schoolmate of these days says that Harry lisped very much, and that the boys used to tease him about it. He was also so slow about his lessons that they called him thickhead. But when school was out Harry entered the realms he loved. From his home on the market-place he had only to go outside the door to be at once in touch with the active world whose economic problems appealed to him so keenly. He made friends among the country folk, and talked of their crops and the money they would bring, and noted in his childish mind the rise and fall in the price of wheat.

Then to the same open space came all sorts of travelling shows. Sometimes the circus spread its mysterious tents, and when the children were dragged away from the wild beasts and the seductive freaks and put to bed, the little Fawcetts would stealthily creep to the bedroom window overlooking the market and see the lights shining on all the wonderful but forbidden marvels, and hear the hurdy-gurdy and the band mix their triumphal blare with the solemn striking of the clock in the near-by cathedral.

In 1841 Harry’s father took a delightful farmhouse at Longford, about three miles south of Salisbury, with delectable streams full of fish. Harry loved to fish every day, and hated lessons, but, alas! grim fate backed the lessons, and sent him ruthlessly to school. He went as a boarder to Mr. Sopp at Alderbury, a few miles away.

There are many tales showing that Harry loved 8the fleshpots and that he had been much indulged at home. He writes, ‘I have begun Ovid—I hate it.’ ‘This is a beastly school—milk and water, no milk—bread and butter, no butter. Please give a quarter’s notice.’

And still more heartrending was the prayer to his mother, ‘Please when the family has quite finished with the ham bone, send it to me.’ Imagination can supply the effect of this on the family circle, and guess what a well-covered ham bone was shipped to the starving Harry. Starving or no, he grew immensely stronger and larger, and though he never admitted that he got enough to eat at any school, he became ultimately reconciled to his exile.

He used to come home often for half-holidays, and to go to Longford and revel in all country delights. Then began the close friendships with the cottagers about him which meant so much to him and influenced all his life.

In the summer that completed his tenth year there came to Salisbury two men who also loved the common people and sought to make their lives easier. It was the year of the great Free Trade campaign in the agricultural districts, and the men were Cobden and Bright. They visited Harry’s father, and perhaps Harry himself met them then for the first time. Lord Morley has said in his life of Cobden that ‘the picture of these two men, leaving their homes and their business, and going over the length and breadth of the land 9to convert the nation, had about it something apostolic.’ In a home where they and their teachings were so reverenced, to even hear of their journeyings would make a strong impression on a boy of Harry’s interests, and perhaps helped to give a definite aim to his ambitions.

At Mr. Sopp’s school he began a diary, of which the penmanship is admirable. On some days the only record is the startling fact, ‘It was a very fine day.’ June 21st, 1847, however, is a very eventful day, for he lists the capture of the first fish that he took with a fly, which weighed ‘about three-quarters of a pound.’

Again, he is transported with joy by the gift of a hedgehog and four young ones, and he has a glorious time in going on board H.M.S. Howe, of one hundred and twenty guns. On one occasion he goes to the theatre, on another he is in court hearing a trial. He begins Greek, and this anguish is modified by the arrival of a cake for one of his schoolfellows, which Harry doubtless shares.

A change of scene is recorded in the diary when on 3rd August Henry becomes the first pupil at Queenwood College. In its previous career this temple of learning had been Harmony Hall, built by Robert Owen for his last socialist experiment. In 1817 it was opened as a school by Mr. Edmonson, a Quaker. Special emphasis was given to scientific training and English literature. The school seems to have been very congenial to Harry, and his intellect now began to develop rapidly.

10To continue from the diary, we learn that ‘we elected the various school officers. J. Mansergh and I were elected without opposition editors of the Queenwood Chronicle.’ He had been at Queenwood but a fortnight, and was fourteen years old when this great honour came to him. Mr. Fawcett was delighted at this good news, and offered because of it and because Harry had been ’studying most determinedly’ to take the boy to Stonehenge. His aversion to books had distressed his family, and this new interest in his studies gave his father great pleasure. On reading a composition which Harry had sent home, Mr. Fawcett exclaimed to his wife, ‘I really think, mother, after all that there is something in that boy!’ His literary performances at this time indicate an increasing imagination, but in the main he never deviated from the practical paths of thought shown when as a tiny child he studiously investigated the Salisbury market. His schoolmates report him as ‘tall for his age, loose-limbed, and rather ungainly.’ He had become much of a bookworm, and though later good at games, at this time he preferred to wander off by himself and read. He was strongest in mathematics; languages did not much appeal to him; but he liked to learn long passages of poetry by heart. There was a disused chalk-pit near Queenwood where he would take refuge and declaim his lines. The extravagance of his gesticulations might well cause unexpecting passers-by to consider him the village loony.

A Lecture on the uses of Steam—Parliamentary Ambitions—King’s College—Politics in the Fifties—Cribbage and Cricket.

Fawcett was interested in the scientific lectures, and he had a very good time. Professor Tyndall took them out surveying. Harry comments on a lecture at which he heard that there ‘is fire in everything, even ice’; he also records some chemical experiments in the laboratory.

In September the diary states, ‘I began writing my lecture on phonography, on the uses of steam without copying any of it.’

There is an error here, as these were two lectures, not one. That on steam, in a blue marbled-covered copy-book, lies before the writer. The title, inscribed in tall, shaded handwriting, contained within scrupulously ruled lines, is:

12The ink, which was black sixty-six years ago, is now much faded; but the essay of the fourteen-year-old schoolboy is still fresh and interesting, and so prophetic of the man that it is like a simple map indicating the chief features of the country we are about to see.

Henry writes in his careful penmanship, for which he must have been marked at least 9+ in a scale of 10, ‘Things which appear simple to an unobserving Person are to an observing Person the most complicated and beautifully formed ... such a simple Thing as a blade of Grass, has ever any Man been yet so wise as to tell what it is?’

Here is another curious sentence written by the bright-eyed youngster with the monumental dignity of the lecturer:

‘What can be so beautifully contrived and framed as the human Body, where there are innumerable Parts, acting all in Unity?... if one of the Parts go wrong, the whole Body is put out of Tune ... is there any one Part of our Body which we could dispense with?... I think the Answer “No” must be evident to every one.’

It is curious that Fawcett should have been called upon later by the loss of his eyesight to contradict this childish statement, and to prove not only that we can get along without some of our most precious faculties, but that the law of compensation so works that we may be able to accomplish more by reason of the loss.

13The essay proceeds to deal with railways, and contains all kinds of figures relating to tonnage, trains, traffics, the cost of railroad construction, etc., all with careful, correct figures; a complicated study for a railroad expert. This schoolboy is already coping with the figures and statistics of which he had later such a marvellous control. He dwells on the importance of the railroad to the Wiltshire farmer, who can sell his cheese at sevenpence a pound in London, when it is only worth sixpence where it is made. In this and similar statements we find the political economist foreshadowed: he speaks of the nobility who selfishly object to having railways, which he feels are the greatest help to the common people; and he adds, ‘A Man should sacrifice a little of his own Pleasure when he knows that by sacrificing that Pleasure he will benefit the People at large.’ We must note that pleasure is always spelt with a beautiful and exceptionally large P.

Later there are some intelligent remarks on the power of a railway to create traffic, so that ’some Railways have been made between two Places where there was not sufficient Traffic for a Coach, and yet when they are made, a Trade springs up, and they pay very well indeed.’

He further approves of the railway as a means of cheap transportation, and remarks, ‘Many a Person can avail himself of a Day’s Pleasure ...’ or, ‘Enjoy the beautiful Air of some Country Village.’ Here we have not only the keystone of 14Henry Fawcett’s character, but indications of the political activities in which he was to be so pre-eminent. His public career was one long, unbroken effort to do away with the monopolies and prerogatives of any class, and so to increase the independence and rights of the poor.

The essay continues by quoting from an article in the Quarterly Review written in 1825, which considers it impossible that an engine could travel eighteen miles an hour. With evident joy he quotes, ‘The gross Exaggerations of the Powers of the Locomotive Steam Engine, or to speak English, the Steam Carriage, may delude for a time, but must end in Mortification to those concerned. We should as soon expect the People of Woolwich to suffer themselves to be fired off in Congreve’s Ricochet Rockets, as to trust themselves to the Mercies of such a Machine going at such a rate.’ Harry himself then tells of the M.P. who insisted that the best possible locomotive could not compete with a canal boat. The scribe seems fully to appreciate the humour of this, and so foreshadows the love of fun and the vibrant laugh of the man to be.

Steam-engines lead to steamships. Our author now invites us to cross ‘the wide heaving Ocean,’ saying, ‘When you are on a Voyage in a Steam Vessel you feel none of that Inconvenience of having to remain at Anchor for two or three Weeks waiting for a favourable Wind ... you can proceed, for you are quite independent of the Winds, 15and the Speed of a Steam Vessel is very considerably greater than that of any other Vessel.’ A steam vessel went from Liverpool to Boston in eleven days and nine hours, and yet when steam navigation was struggling into existence ‘it struck the minds of our brave Captains as a poor mean mechanical Thing unworthy of the least Consideration.’... ‘I think you may almost remark’ (note the conservative discretion) ‘that the greatest and most useful inventions when they are struggling into Existence receive the greatest Opposition, because they make great changes, and most people, especially the ignorant, are generally very adverse to any changes.’

Now he boasts magnificently about the British navy and merchant marine, approves of Bonaparte’s wisdom in coveting the British sailors, and yet prudently warns all against pride, citing the lamentable consequence of lack of humility to Babylon and Nineveh. We are asked to consider the relative values of coal, diamonds, gold, and silver, and are informed that ‘every Difficulty can be overcome by steady Perseverance—some Persons will never scarcely be overcome by Difficulties—they say they will do it, and they will never rest till they have performed what they want to, and it is to Men like these that we are indebted.... No Improvements or Inventions will run into a Person’s Mind like Water will run into a Bottle, but they come from Years of Study and Perseverance.’

16We are asked, ‘Do you suppose that Sir Isaac Newton established the Laws of Gravitation without some trouble, do you suppose that such a Piece of Poetry as Milton’s “Paradise Lost” was written without a Moment’s Thought—or do you suppose that Watt improved the Steam Engine without some hard Labour?’ Our scribe then finishes his masterpiece with a stupendous finale, by the help of a bit of poetry culled from an American newspaper and entitled the ’song of Steam,’ a verse of which will be sufficient:

This magnum opus, being now successfully brought to completion, is signed in full, no longer, as on the title-page, with only the initial of his first name, but by Henry Fawcett, writ exceedingly large and clear, Queenwood College, October 12th, 1847. Every page in the marbled copy-book has been filled with various spellings, and only a very few erasures, between 27th September and 12th October.

We have quoted this delicious essay as fully as space would allow, not only on account of its unique charm, but because every page is coloured by a preoccupation with those subjects and a love for those traits of human nature which were later so characteristic of Henry Fawcett, the teacher and statesman. In fact, we may accept this essay on 17steam as his official debut. The lecture had an encore at Salisbury in the family circle, when, as Harry writes, all were ‘much pleased with it, and Papa promised to give me a sovereign for it.’

His lecture on phonography is much in the spirit of to-day, when simplified spelling is causing such ardent controversies. Harry comments that ‘out of fifty thousand Words in the language, only fifty are written as they are pronounced.’ We must note that in these writings his own inventions in spelling tend to change these statistics.

The range of his composition at this period is great. An article on ‘Angling and Sir Isaac Walton’ is in happy contrast to the account of a first visit to London. Another fragment contains the acute observation that ’statesmen depend upon their brains.’ In another essay called ‘Reflection’ an imaginary trip is taken past Spain, during which the author ponders on people who are ‘made poor by gold.’ Progressing to Egypt, we are told that Mahomet was ‘in many respects a worthy man.’ Arriving in India, our guide tells us of a company of men who, ‘occupying a house of no very considerable size in London, have entirely from their enterprise and powers of mind, got possession of many thousand acres of land.’ Does this refer to the East India Company, and had Harry seen the stately East India House in Leadenhall Street on that first visit to London?

The breathless exuberant feat of imagination and philosophy closes with quotations from Portia’s 18lines to Mercy and Cicero’s oration on Verres, both of which, the author truthfully says, ’show powers of reflection.’

Harry was writing and studying with a definite end in view. Already the youth had determined on a political career, and when the schoolboys discussed their plans for the future he invariably declared that he meant to be a Member of Parliament. The statement was received with roars of laughter, but Harry remained imperturbably sure.

He was at Queenwood for a year and a half, and then went to London, where he first attended King’s College School, and then King’s College. A schoolmate described him as ‘a very tall boy with pale whitey brown hair, who always stood at the bottom of the lower sixth class.’

He attended the school in his fifteenth and sixteenth years, and then went to lectures in the college until the summer of 1852, when he was nineteen years old.

Standing in the school was, in those days, entirely determined by knowledge of the classics, for which Fawcett showed a grand indifference; but he gained the arithmetic prize in 1849, also the class-work prize, the first prize in German, and the second in French in the same term. His knowledge of these languages was always so vague that we fear his teacher was over-partial in the award, or that the other boys were strangely deficient. In 1850 he carried off another honour for mathematics, and a first prize after that in the Michaelmas 19term. The masters noted Fawcett’s unusual mathematical power, and were also impressed by his ability to write English prose.

At Easter in 1851 he left school and worked only at the college for mathematics and classics. We hear that he made no particular mark; but he occasionally played billiards and cricket, and he was already an interested spectator in the gallery of the House of Commons.

During his stay in London he lived with some family connections, a Mr. and Mrs. Fearon. Mr. Fearon was a Chief Office Keeper at Somerset House, and lived there. Somerset House adjoins King’s College, and this was fortunate for Harry, who, when he first went to London, had much outgrown his strength. The hours spent in the little parlour tucked away in the vast building were not without charm for the home-loving boy. Sitting on the corner of the horse-hair sofa, with its relentless early Victorian back and its unyielding springs, trying, mostly in vain, not to disturb Mrs. Fearon’s best antimacassar, he would cheerfully play cribbage by the hour with his hostess, while his host expounded pungently on the questions of the day. Harry had passed from the Liberalism of the country home to the Liberalism of the metropolis. For both, Bright and Cobden were now leaders and standard-bearers, though Lord Palmerston was the Party Chief. Free Trade had been won, but neither Parliament nor country had settled down to it as a policy, and 20the need of another and more democratic Reform Bill was looming up on the political horizon.

These were the days that followed the abortive revolutions of ‘48. The battle for political independence was raging everywhere, but both leaders and rank and file were learning with bitterness to make haste slowly. None the less, hearts were glowing hotly for Freedom, and while Fawcett was in London, Kossuth, the Hungarian, was welcomed with enthusiasm. He followed Carl Schurz, that valiant apostle of Liberty, to America, where Garibaldi was already working at his soap factory on Staten Island. There was no doubt as to the heartiness of Kossuth’s reception across the Atlantic. The fire of Freedom burnt to high heaven there: was it not sufficient proof of this that the dandies of that land reverently encased their mighty brains in the Kossuth hat? Talk of these great men, of their vain endeavours, of the persecution of the poor, of the need of opening cages and letting in the light of Freedom, made its mark on Harry, and he often spoke afterwards of Fearon’s ‘quaint and forcible’ phrases.

In 1851 was the great Exhibition in Hyde Park. Did Harry’s tall head peer above the crowd that lined the streets as Queen Victoria drove in state to the opening of that proud achievement? One would like to think that once with seeing eyes Fawcett beheld the little lady who presided over England’s destinies throughout his working life.

And now Mr. Fawcett, senior, conscientiously 21counting his pennies, and the ability which his son had already shown as a student, went to his neighbour, the Dean of Salisbury. He showed the Dean Harry’s mathematical papers, and asked for advice about the next step. It was not customary for one of Harry’s social standing to go to a university, and the strain on the paternal purse to send him there would be considerable, but the Dean had no doubt that Cambridge offered the proper opening. The sacrifice was cheerfully made.

‘I count life just a stuff to try the soul’s strength on

—educe the man.’—Browning.

Peterhouse—Quoits and Billiards—Trinity Hall—A Fellowship—Lincoln’s Inn.

Harry knew that for his father’s sake it was necessary for him to be self-supporting as soon as possible, and therefore chose his college on purely financial grounds. He went to Peterhouse, where the fellowships could be held by laymen, and were reported to be of unusual value.

His great friend, Sir Leslie Stephen, saw him there for the first time. We cannot do better than quote from Sir Leslie’s biography of Fawcett the impression his subject then made upon him:

‘I saw Fawcett for the first time a few months after his entrance (in October 1852).... I could point to the precise spot on the bank of the Cam where I noticed a very tall, gaunt figure swinging along with huge strides upon the towing path. He was over 6 feet 3 inches in height. His chest, I should say, was not very broad in proportion to his height, but he was remarkably large of bone and massive of limb.

‘The face was impressive, though not handsome. The skull was very large; my own head vanished 26as into a cavern if I accidentally put on his hat. The forehead was lofty, though rather retreating, and the brow finely arched.

‘The complexion was rather dull, but more than one of his early acquaintance speaks of the brightness of his eye and the keenness of his glance. The eyes were full and capable of vivid expression, though not, I think, brilliant in colour. The features were strong, and, though not delicately carved, were far from heavy, and gave a general impression of remarkable energy. The mouth long, thin-lipped, and very flexible, had a characteristic nervous tremor as of one eager to speak and voluble of discourse....

‘A certain wistfulness was a frequent shade of expression. But a singularly hearty and cordial laugh constantly lighted up the whole face with an expression of most genial and infectious good-humour.[3-1]

3-1. Sir Leslie Stephen, speaking of the photograph reproduced to face p. 26, says, ‘The rather peculiar expression of the eyes results from the weakness of sight presently to be noticed which made him shrink from any strong light.’

‘On my first glimpse of Fawcett, however, I was troubled by a question of classification. I vaguely speculated as to whether he was an undergraduate, or a young farmer, or possibly somebody connected with horses at Newmarket, come over to see the sights. He had a certain rustic air, in strong contrast to that of the young Pendennises who might stroll along the bank to make a book upon the next boat race.

HENRY FAWCETT BEFORE HE WAS BLIND

27‘He rather resembled some of the athletic figures who may be seen at the side of a north-country wrestling-ring. Indeed, I fancy that Fawcett may have inherited from his father some of the characteristics of the true long-legged, long-limbed Dandie Dinmont type of north-countryman. The impression was, no doubt, fixed in my mental camera because I was soon afterwards surprised by seeing my supposed rustic dining in our College Hall. I insist upon this because it may indicate Fawcett’s superficial characteristics on his first appearance at Cambridge.

‘Many qualities, which all his friends came to recognise sooner or later, were for the present rather latent, or, maybe, undeveloped. The first glance revealed the stalwart, bucolic figure, with features stamped by intelligence, but that kind of intelligence which we should rather call shrewdness than by any higher name.’

At first the men of his own year were inclined to estimate Harry as an outsider in sports and games. His simple provincial ways gave little sign of expert skill. But he won his way in dramatic fashion. An undergraduate nick-named the ‘Captain’ challenged him to a game of quoits. Salisbury’s native game is quoits; Harry was well trained, and won easily. Then the battle shifted to billiards. Captain’s score pushed steadily ahead until in a game of a hundred points he had ninety-six to Harry’s seventy-five: four points more for the Captain, twenty-five for Harry. The 28onlookers vociferously offered ten to one on the Captain. Fawcett gravely took all the bets offered at this rate, and any others that he could get, and then calmly, in a single break, made the twenty-five necessary points.

Fawcett is quoted as having given this account, ‘Bets were forced on me; but the odds were really more than ten to one against my making twenty-five in any position of the balls, but I saw a stroke which I knew that I could make, and which would leave me a fine game.’ No matter by what magic the feat was achieved, it filled his pockets, and cleared for ever any doubts in his companions’ minds as to the capacity and shrewdness of ‘Old Serpent,’ as he was then dubbed, and by which nickname he went for a brief time.

He never gambled again. The story is paralleled in later years by an equally solitary financial speculation. He then showed the same quickness in seizing the facts and calculating the chances, the same boldness in acting on his own judgment, and the same restraint in not repeating the adventure.

He disapproved of gambling, and had a wholesome dislike of it. His sense of fun made it impossible for him ever to have a holier-than-thou attitude, but his common sense and natural goodness kept him singularly free from the failings so common among his associates. While anything but a Puritan, he ‘was in all senses perfectly blameless in his life.’

29He had a rare talent for friendship, attracting people to him as easily as he was attracted to them, and his faculty of making friends and keeping them held to the end. He was never known to lose a friend.

Those who knew him well appreciated his strong intellectual equipment. Perhaps his chief characteristics were his absolute normality, his remarkable freedom from self-consciousness, his common sense, and his ever-present sense of fun. These early years at the university, when the lank boy was emerging into the statesman, were years of great happiness and joviality. Fawcett found many congenial spirits, and formed intimacies among men destined to distinguished careers. Most of his associates were good workers, but not particularly given to intellectual subtleties. Music made slight appeal to him, and he was flagrantly ignorant of classics and modern languages, and made no pretence to culture. The young Cambridge men of this period were greatly afraid of sentimentality, and devotees of the ‘God of Things as they are.’

But there was one subject peculiarly attractive to the men with whom Fawcett consorted—political economy. And in those days political economy meant Mill. His book, gathering together all the last words of the science, had been written a very few years before Fawcett went to Cambridge. It had had a phenomenal success, and it and its author were enjoying a phenomenal 30authority. Edward Wilson, a brilliant Senior, well represented the feeling of his day, when he would confute all opposition by an apt quotation, leaving Mill triumphantly supreme, and then close his vindication with the cry, ‘Read Mill! Read Mill!’ Fawcett did, from early till late, until he knew the book by heart. As he was thoroughly inoculated with this cult, his reverence for Mill was one of his strong steadfast beliefs through life.

Fawcett begrudged time taken from his books, and never rowed in his college boat, although Sir Leslie Stephen writes:

‘That he occasionally performed in the second boat, I remember by this circumstance, that I can still hear him proclaiming in stentorian tones and in good vernacular from an attic window to a captain of the boat on the opposite side of the quadrangle, and consequently to all bystanders below, that he had a pain in his inside and must decline to row. I have some reason to think that he had felt bad effects from some previous exertions, and had been warned by a doctor against straining himself. I have an impression that there was some weakness in the heart’s action. Fawcett, like many men who enjoy unbroken health, was a little nervous about any trifling symptoms. One day we found him lying in bed, complaining lustily of his sufferings, and stating that he had dispatched a messenger to bring him at once the first doctor attainable. A doctor arrived, and his first question as to the 31nature of Fawcett’s last dinner resolved the consultation into a general explosion of laughter, in which the patient joined most heartily.’

It was characteristic of Fawcett that he treated all men as equals, and took from them the best of what they had to offer. He became intimate with men of all ages. Mr. Hopkins, a Peterhouse man, with whom Fawcett read, had received his B.A. in 1827, twenty-five years before Fawcett’s appearance at Cambridge; but this difference in age did not prevent a close bond. Fawcett never alluded to Hopkins without great enthusiasm, and in the days of his grave trial this friend was the most helpful of all. He was of great service in the first years at Cambridge, urging Fawcett to regard the mathematical studies necessary for taking a good degree as valuable intellectual gymnastics. Fawcett with his usual keenness and common sense was quite alive to the fact that a good degree was a distinct commercial asset, and said that he would rather be Senior Wrangler in the worst year than second to Sir Isaac Newton. His definite aim in life—a political career—made any wanderings into study for its own sake of no interest to him. He planned through life so to select that he might obtain.

From the days of declaiming in the chalk-pit at Queenwood, Fawcett had realised the value of public speaking.

The great Macaulay, Sir William Harcourt, and other distinguished men had tried their oratorical 32pinions in flights at the Debating Club called ‘The Union.’ Fawcett joined, and after some tentative efforts, despite his friends’ amusement and discouragement, boldly won his way, and became a good speaker. He worked over his orations carefully, and by great persistence gained an easy and fearless manner of speaking, and we find that he opened debates on National Education and University Reform.

In these years the events which led to the Crimean War provided the chief subjects of debate, such as the foreign policy of Austria and Prussia, the independence of Poland, and the character of the Emperor Nicholas. On these questions Fawcett did not share the views of John Bright, who was then making his great speeches on behalf of peace; but the undergraduate’s democratic sympathies are clearly shown in his advocacy of non-sectarian National Education, of a motion that ‘the party called “Cobdenites” have done the country good service,’ or in favour of a ‘considerable extension of the franchise,’ and of ‘University Reform.’

It was during this period of careful self-training that Fawcett gradually reduced his style of speaking to that simplicity and directness which became so marked throughout his career. There is a lingering trace of grandiloquence and schoolboy rhetoric in an essay written on the merit of Pope’s poetry, but that seems to have been his swan-song to elocution with frills.

33Fawcett left Peterhouse in his second year, and went to Trinity Hall as a pensioner, thus reducing the expense to his father. There chances for scholarship were alluring, and several immigrants from other colleges joined forces at Trinity Hall. There also he met Leslie Stephen, his lifelong friend and biographer, who speaks of this friendship as ‘one of the greatest privileges of my life.’

Fawcett set to work with a will to carry off the Senior Wranglership. We are told that in the Tripos, for the first and the last time in his life, Fawcett’s nerve failed. Though he got out of bed and ran round the college quadrangle to exhaust himself, he could not sleep, and failed to gain the success which meant so much to him. He sank to seventh; but in spite of his comparative failure he had shown marked ability, and made so great an impression by his work, that he was elected to a fellowship at Christmas 1856.

He adhered to his boyish ambition of entering Parliament, but there were still great obstacles in his way. Beyond his fellowship, which brought him £250 a year, he had no income of his own. His father was not a rich man, and the strain on his purse to support his other three children was sufficient. Harry resolved, therefore, to make his way by a career at the Bar, and while still at Cambridge entered Lincoln’s Inn. When he had won his fellowship he settled in London, and set himself to study law. No one who came in contact with him at this time had any doubt that he 34would arrive at his goal by main force. A friendly firm of solicitors had already promised that he should have opportunities, and his great talent for working well with all sorts of people, his genius for friendship, and his real business ability bid well for the success of his plan. His will was inflexible, his good-nature chronic, and his acuteness of mind and general ability far beyond the average.

In the mimic legislature of the Westminster Debating Society, which consisted of young barristers and journalists, Fawcett soon became the leader of the Radical party. The organisation followed the form of the House of Commons. It is said that Bulwer Lytton had once paid it a visit, and said afterwards that he had entered in a fit of abstraction, mistaking it for the House of Commons, and only discovered his error upon finding that there were no dull speeches and no one asleep, which seems to prove that it must have been a most remarkable society.

One of his contemporaries, who saw Fawcett in the height of these pseudo-Parliamentary triumphs, speaks of his ‘resonant voice, wild hair, and expressive eyes.’ But just at this point, when he seemed to be setting with full sail on the channel towards success, his eyes began to trouble him.

A Trip to France—Wiltshire French—A Discouragement.

In 1857 the great Critchett warned him against making any exertion, and forbade his reading. Though he appeared cheerful as usual with his family, a friend recalls that during his entire career he had never known him to be so depressed.

In 1857 he was glad to find occupation by taking a pupil to Paris. Miss Fawcett went with them. The pupil was to read mathematics and to learn French, while it was hoped that the master’s eyes might benefit under the care of foreign specialists, as well as by the change.

The oculists gave him some slight encouragement: one ordered low living, and the other high. It was characteristic of Fawcett that he frugally chose the former.

In Paris our long Wiltshire man seems to have been much of a fish out of water. The Latin morals and customs were naturally not sympathetic to his uncompromising though uncensorious nature. He could never cope successfully with a foreign language. There was even a 36frequent strong Wiltshire flavour about his English speech. The difference between ‘February’ and ‘Febuwerry’ never became apparent to him. At Alderbury he had learnt French with a pronounced English accent. In Paris he now delighted the French ladies at the pension where he stayed with his peculiar and unique speech. There was a Madame Palliasse there whom, much to her joy, he called Madame Peleas.

He came back from France with his eyes still in bad shape and his spirit totally unresponsive to the lure of Gaul.

On his return he was extremely tried by his inability to work. His real feelings about life at this time are well expressed in a letter to his dear friend, Mrs Hodding:

‘I regard you with such true affection that I have long wished to impart my mind on many subjects.... You know somewhat of my character; you shall now hear my views as to my future. I started life as a boy with the ambition some day to enter the House of Commons. Every effort, every endeavour, which I have ever put forth has had this object in view. I have continually tried, and shall, I trust, still try not only honourably to gratify my desire, but to fit myself for such an important trust. And now the realisation of these hopes has become something even more than the gratification of ambition. I feel that I ought to make any sacrifice, to endure any amount of labour, to obtain this position, because every day 37I become more deeply impressed with the powerful conviction that this is the position in which I could be of the greatest use to my fellow-men, and that I could in the House of Commons exert an influence in removing the social evils of our country, and especially the paramount one—the mental degradation of millions.

‘I have tried myself severely, but in vain, to discover whether this desire has not some worldly source. I could therefore never be happy unless I was to do everything to secure and fit myself for this position. For I should be racked with remorse through life if any selfishness checked such efforts. For I must regard it as a high privilege from God if I have such aspirations, and if He has endowed me with powers which will enable me to assist in such a work.’

This is an interesting revelation of a pure ambition. Fawcett wished to succeed for no self-regarding purpose. His ideals were noble, and his ambition their legitimate accompaniment.

About this time he shows a lively interest in the social condition of the people. After an expedition to some manufacturing towns he mentions an investigation of ‘gaols and ragged schools,’ and shows much interest in these sombre centres. He describes a meeting with a good gentleman whom he characterises as ’so fine and perfect an example of a venerable Christian.’

Even twelve hours spent in one day at the House of Commons does not seem to have been for him 38an overdose of politics. It did not tax his eyes, and it delighted his ears, though he writes, ‘No one need fear obtaining a position in the House of Commons now; for I should say never was good speaking more required. There is not a man in the Ministry can speak but Lord Palmerston; Disraeli is the support of the Opposition; but, although he was considered to have achieved a success that night, it was done by uttering a multitude of words and indulging in a great deal of clap-trap.

‘Gladstone made the speech of the evening, and he is a fine speaker. He never hesitates, and his manner and elocution are admirable; in fact, in this he resembles Bright, but is, in my opinion, inferior to Bright, in not condensing his matter.’

Towards the close of this letter there is an exceedingly interesting statement, prophetic of his future interests. He says that he feels that Australia must have in future a great effect on England, and adds these significant words, ‘India too is the land I much desire to see and know; and it ought to be by any one who takes part in public life.’

The doctor now forbade Fawcett all reading, for fear that he might lose his sight. He took this sentence philosophically, commenting that it came at an extremely favourable time, when he could best afford to take a holiday. He writes, ‘I cannot be sufficiently thankful that it has occurred just now, when perhaps I can spare the time with so 39little inconvenience.... Maria will resign her needle with great composure to devote herself to reading to me. I shall thus get quite as much reading as I desire, and I can well foresee that, far from being a misfortune, it may become an advantage, since it will perhaps for the next year induce me to think more than young men are apt to do: it will give me an opportunity to solidify and arrange my knowledge, and you will know how happy Maria and I shall be together.’

About this time a classmate writes of him: ‘We recognised as fully as at a later period his energy and keen intelligence. If we were still a little blind to some of his nobler qualities, we at least recognised in him the thoroughly good fellow, whose success would be as gratifying to his friends as it was confidently anticipated.’

Yes, anticipated and ardently hoped for; but could it be expected by Fawcett himself, doomed as he was to idleness by the condition of his eyes, his doctor’s warnings, and their orders for absolute rest—and unfitted as he now was for work, and able only to send an occasional letter to the papers on matters of current interest?

He was staying at his father’s house at Longford with such patience as he could muster. He, however, enjoyed sitting in the fields near Salisbury and listening to the sounds about him. The murmuring streams, the songs of birds, and the hum of drowsy insects seemed to bring him comfort and rest.

A Shooting Accident—Blindness—Readjustment.

Unfortunate as was the fate which condemned him to so much trouble with his eyes, it was a fortunate and strange preparation for what was to follow. Obedient to his physician’s injunctions to give up work, Fawcett remained with his family near Salisbury. On 15 September 1858, he went shooting with his father. Together they climbed Harnham Hill. Fawcett turned to look back at the glorious view, bathed in an autumn light, the trees, already turning to gold, the village nestled in the valley through which the river Avon wound, the spire of the great cathedral touched with glory by the setting sun. To Fawcett this was one of the loveliest views in England: he looked on all this beauty for the last time.

As they were crossing a field he advanced in front of his father, who, suffering from incipient cataract of the eye, did not see his son. A partridge rose and the father fired, hitting the bird, but some of the stray shot penetrated both the son’s eyes, blinding him instantly. To protect his eyes from the glare he was wearing tinted spectacles, both 44glasses were pierced, but the resistance which they offered to the shot prevented the charge entering the brain, and so probably saved his life. His first thought on being blinded was that he would never again see the beautiful view which he loved so dearly. There is a widely current story, which, however, we have been unable to verify, that after the accident his first words to his agonised father were, ‘This shall make no difference.’

He was taken back to his father’s house in a cart, and his first words to his sister as she received him there were, ‘Maria, will you read the newspaper to me?’ This way of taking his calamity sounded the key-note of his heroic acceptance of it from the first. His unflinching bravery gave the cue which he wished his family to follow. His calmness remained unaltered even when the doctors gave little encouragement. All knew that there was not much hope, though he was in such splendid physical condition that he suffered very little pain.

Mrs. Fawcett, whom her relations called ‘the brightness of the house,’ was having tea with some friends when her wounded son was brought in. When she saw him she bravely tried to control her grief, but it was so overwhelming that she took refuge in another room, and only appeared in the short intervals when she was able to master her distress.

In this crisis his sister Maria was a tower of strength. The poor father seemed more sorely 45stricken by the accident than the son. But for his daughter’s wisdom, he would probably have lost his reason. All through the night Maria kept him busy at small, useful tasks, and for several days occupied both her mother and him as fully as possible.

After a lapse of six weeks Fawcett was able for three days to perceive light, but after that the curtain fell for the rest of his life, and he remained in total darkness. In the following June he suffered some pain in one of his eyes, and later submitted to an operation which was unsuccessful, and put the final seal on his calamity. Perhaps the father deserves as much sympathy as the son. Their relations had been particularly affectionate, and were, if possible, more intensely so after the catastrophe. The elder Fawcett often said that his grief at having blinded Henry would be less, if ‘the boy’ would only complain. But this was perhaps the only way in his life that the son refused to gratify the parent whom he loved so tenderly. He was never known to complain of his loss of sight, and used to say that blindness was not a tragedy, but an inconvenience.

The life-long ambition of Fawcett to lend a hand in public affairs had been shared by his father, and the hope and pride which he felt in his son’s career added, if possible, to the tragedy of seeing it so suddenly broken. The indomitable pluck shown by more than one blind man which makes out of his stumbling-block a mounting-stone 46had yet to be proven. It did not then seem possible for him to win even greater triumphs than he might have won if he had not been forced to sharpen his courage because he had to fight his battle in the dark.

A friend who visited Fawcett a few weeks after the accident found him serene and cheerful, although his father was evidently heart-broken, and his appearance gave abundant evidence of it. Fawcett, though not much given to quotation, was fond at this time of repeating the phrase of Henry V. at the battle of Agincourt:

What Fawcett distilled from the evil thing which had befallen him was an iron determination, which triumphed over odds such as few have encountered on any battlefield.

But the blind man’s horizon had not yet cleared. His outlook, despite the loving care of his family, was still sad, and though he gave no sign, there was a fearful slough of despond still to be struggled through. Ten minutes after the accident, he had made up his mind to stick to his pursuits as much as possible, but how nearly possible was it for a blind man to succeed in Parliament, and to give a helpful impetus to the affairs of nations? This was still at Fawcett’s time in England untested and remained for him to show. He lacked fortune and social position to clear the road for him, and 47the letters of condolence that poured in mostly obstructed his path with futile sentimentality. He said, ‘they give more pain than comfort,’ and added that nothing pained him so much as these letters. The writers counselled resignation to the will of Providence, meekness, submission, and of course all implied inaction. But Fawcett asked what was the will of Providence. Why, without trying, should he suppose that inaction would be the nobler part for him to play. His sister read to him all the missives from the Job’s comforters, and he, though much saddened, listened, ‘in a fixed state of stoical calm.’

Into this atmosphere, heavy with grief, came the message of a friend. His dear old Cambridge teacher, Hopkins, wrote admitting that blindness is ‘one of the severest bodily calamities that can befal us,’ yet added cheerfully: ‘But depend upon it, my dear fellow, it must be our own fault if such things are without their alleviation.... Give up your mind to meet the evil in the worst form it can hereafter assume. Now it seems to me that your mind is eminently adapted to many of those studies which may be followed with least disadvantage without the help of sight....

‘I would suggest your directing your attention to subjects of a philosophical and speculative character, such as any branch of mental science and the history of its progress; the Philosophy of Physical Science, as Herschel’s work in Lardner’s Encyclopædia, Whewell’s Inductive Philosophy, etc., 48or any work treating on the general principles, views, and results of physical science. Political Economy, statistics, and social science in general are assuming interesting forms in the present day.

‘What a wide range of speculative study, full of interest, do these subjects present to us! For any part of which, if I mistake not, your mind is well qualified.

‘The evil that has fallen upon you, like all other evils, will lose half its terror if regarded steadfastly in the face with the determination to subdue it as far as it may be possible to do so.

‘Cultivate your intellectual resources (how thankful you may be for them!) and cultivate them systematically: they will avail you much in your many hours of trial. Under any circumstances I hope you will visit Cambridge from time to time. I’ll lend you my aid to amuse you by talking philosophy or reading an act of Shakespeare or a canto from Byron. I shall certainly avail myself of the first opportunity I have of paying you a visit at Longford, and shall engage you for my guide across the chalk hills. I may then perhaps find the means of indoctrinating you with a few healthy geological principles.’

Hopkins had struck the right chord. He roused his pupil from his depression and gave him new hope and ambition. ‘Keep that letter for me,’ he said to his sister, and from its arrival dated his returning zeal and the spontaneous cheerfulness 49which heretofore had been so skilfully assumed.

Though the sanity and wisdom of this letter aroused Fawcett as nothing had before, it is not to be understood that his taking up life again depended upon the spur given to his hope and self-confidence by his old friend, but this did come at the psychological moment. It enabled him to shoulder his burden with more courage, and to begin again climbing towards the ambitions he had entertained before his blindness. Unhelped he had planned to travel the road already begun, deviating as little as possible from the course before mapped out; and he would have done so without the comfort from his friend’s advice. But the letter was undoubtedly a first milestone on his race towards the goal which he had set himself.

Much has been said of the philosophy which is apt to accompany blindness, of the resignation and calm of those afflicted with it. The unusual feature in the bravery with which Fawcett met his calamity was his almost instantaneous resolution to disregard it, and to make good just as he would have made good without it. Too much honour cannot be given him for this extraordinary and immediate courage.

Very soon after the accident he took up walking, and at once showed his fearlessness while going between his brother and a friend who has recorded the brave adventure.

On leaving the house, he struck out at once with 50the long, quick strides of his old walking era, and naturally stumbled almost at the first step. One of the party caught him by the arm, and begged him to pick his steps more carefully. ‘Leave me alone!’ was his reply; ‘I’ve got to learn to walk without seeing, and I mean to begin at once—only tell me when I am going off the road.’ To say that he knew not fear would be to give an impression of callousness which would be entirely false; but it can be truly said that fear never kept him from carrying out his purpose.

An early glimpse of the hard conflict and longing of his soul was given when walking with his dearly loved sister. He turned to her suddenly as if he had been thinking, and asked if she knew Southey’s ‘Hymn before Sunrise in the Valley of Chamounix.’ When she replied that she did not, he astonished her by reciting the poem with rare beauty and fervour. The vibrant voice gathered intensity as, with that wistful expression so often on his newly blinded face, he repeated the last lines:

MISS MARIA FAWCETT

After his accident Fawcett took his meals with his sister from a tray in the drawing-room. When some weeks had passed, he was persuaded to 51venture out with her to a quiet supper at the home of friends. Finding that it was not a formidable undertaking after all, and that he had an extremely interesting time, he determined to see as much of people as possible, and resumed his social ways.

It was inevitable that at first his merriment and cheerfulness were a little bit laboured, but in an astonishingly short time they became invariable, and those closest to him detected no permanent depression. About everything but his sadness under his affliction, Fawcett was frank, but about this sadness he remained bravely reticent.

He soon began candidly to enjoy life, and he seems to have gotten infinitely more of its beauty and happiness than the average person who is without handicaps. He had only had one fear, which he confided to his sister: it would be unbearable for him if through loss of physical force he should become useless.

Despite very great difficulty, Fawcett for some time tried to keep up writing with his own hand, and there are still several of his autograph letters. But he found the effort so great that he soon gave it up and depended entirely on dictation. He was not entirely loath to do this, because he thought the practice of dictation useful to him as a speaker. He never mastered Braille or any other system of printing for the blind, but depended on being read to.

In many minor things Fawcett never acquired the dexterity possible to those who are blinded in 52youth. When his catastrophe came his habits were already too fixed, and he was too mature to adapt himself readily in unimportant matters. But his ingenuity in studying out scientific management of all the little problems of daily routine was marvellously practical and at times even comic. For example, he had all his clothes carefully and legibly labelled with numbers, placed so as not to show during wear. In this way his garments might easily be identified by any one not familiar with his wardrobe. If he came home in a great hurry to metamorphise his attire, directions like the following to his family or an aide-de-camp were not infrequent. He would call in his clarion, cheerful voice, probably from the door as he entered: ‘I must dress quickly. Please help. Coat one, vest six, collar one, trousers three; shoes and socks twelve and thirteen.’ The rest we will leave to imagination, but there was no detail, even to pocket-handkerchiefs, which did not have its allotted place and catalogue number.

He seems long to have remained faithful to his Salisbury tailor, a charming person of the old school who recently vouchsafed to the author the following recollections of his distinguished client: ‘Mr. Fawcett was very matter of fact and methodical. A very honest kind of man, a sterling man. He was very susceptible to cold, and was apt to carry changes of different underwear with him. He was particular about the material which he bought for his clothes, and always felt 53of it. He wouldn’t be humbugged. You couldn’t help liking him. He was that loose and easy in his walk, his limbs didn’t seem to belong to him. I often heard him at the hustings, he spoke to the point—he made a thorough impression.’

The Clear-sighted Man—A Scot’s Accent—Mountain Climbing—Skating—Riding, etc.

His friends all testify to his spirit, his normal view of life frequently making them forget the fact of his blindness. A distinguished writer and diplomat, who had known Fawcett, on being asked what impression had been produced on him, replied quickly and quite simply, ‘I think that he was an extraordinarily clear-sighted man.’ Stephen in his biography uses this sentence: ‘Fawcett had come to see more distinctly the real tendency of the proposal and to feel the full force of the objections to which he had never been blind.’ Such remarks illustrate Fawcett’s power of making people utterly forget his blindness.