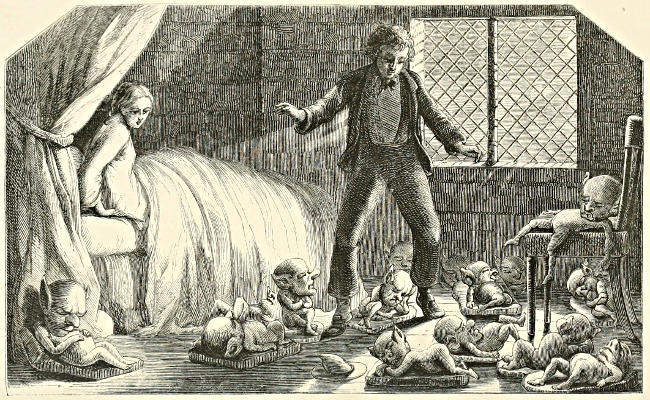

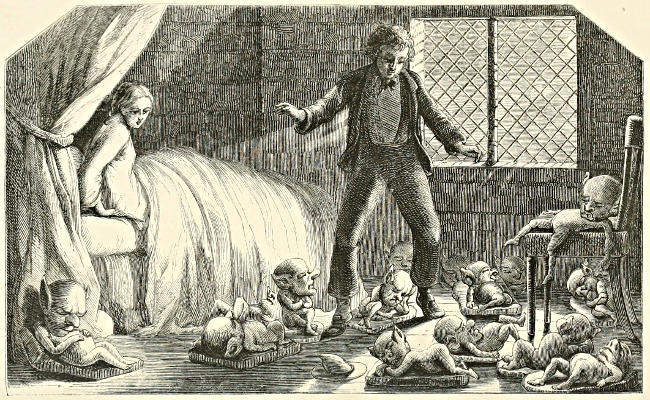

“He picked his way, with much circumspection, between the prostrate forms of the tiny people.”

T. G. J. Vol. I., p. 233.

“He picked his way, with much circumspection, between the prostrate forms of the tiny people.”

T. G. J. Vol. I., p. 233.

THE OXONIAN

IN

THELEMARKEN;

OR,

NOTES OF TRAVEL IN SOUTH-WESTERN NORWAY

IN THE SUMMERS OF 1856 AND 1857.

WITH GLANCES AT THE LEGENDARY LORE

OF THAT DISTRICT.

BY

THE REV. FREDERICK METCALFE, M.A.,

FELLOW OF LINCOLN COLLEGE, OXFORD,

AUTHOR OF

“THE OXONIAN IN NORWAY.”

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

HURST AND BLACKETT, PUBLISHERS,

SUCCESSORS TO HENRY COLBURN,

13, GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET.

1858.

[The right of Translation is reserved.]

LONDON:

SAVILL AND EDWARDS, PRINTERS, CHANDOS STREET,

COVENT GARDEN

In the neighbourhood of Bayeux, in Normandy, it is said that there still lingers a superstition which most probably came there originally in the same ship as Rollo the Walker. The country folks believe in the existence of a sprite (goubelin) who plagues mankind in various ways. His most favourite method of annoyance is to stand like a horse saddled and bridled by the roadside, inviting the passers-by to mount him. But woe to the unlucky wight who yields to the temptation, for off he sets—“Halloo! halloo! and hark away!” galloping fearfully over stock and stone, and not unfrequently ends by leaving his rider in a bog or horse-pond, at the same time vanishing with a loud peal of mocking laughter. “A heathenish and gross superstition!” exclaims friend Broadbrim. But what if we try to extract a jewel out of this[iv] ugly monster; knock some commonsense out of his head. Goethe turned the old fancy of Der getreue Eckart to good account in that way. What if a moral of various application underlies this grotesque legend. Suppose, for the nonce, that the rider typify the writer of a book. Unable to resist a strong temptation to bestride the Pegasus of his imagination—whether prose or verse—he ventures to mount and go forth into the world, and not seldom he gets a fall for his pains amid a loud chorus of scoffs and jeers. Indeed, this is so common a catastrophe, from the days of Bellerophon downwards (everybody knows that he was the author of the Letters[1] that go by his name), so prone is inkshed to lead to disaster, that the ancient wish, “Oh that mine adversary had written a book,” in its usual acceptation (which entirely rests, be it said, on a faulty interpretation of the original language), was really exceedingly natural, as the fulfilment of it was as likely as not to lead to the fullest gratification of human malice.

In defiance, however, of the dangers that[v] threatened him, the writer of these lines did once gratify his whim, and mount the goblin steed, and as good luck would have it, without being spilled or dragged through a horse-pond, or any mischance whatsoever. In other words, instead of cold water being thrown upon his endeavours, The Oxonian in Norway met with so indulgent a handling from that amiable abstraction, the “Benevolus Lector,” that it soon reached a second edition.

So far the author’s lucky star was in the ascendant. But behold his infatuation, he must again mount and tempt his fate, “Ay! and on the same steed, too,” cries Mr. Bowbells, to whom the swarming sound of life with an occasional whiff of the sewers is meat, and drink, and all things; who is bored to death if he sees more of the quiet country than Brighton or Ramsgate presents, and is about as locomotive in his tastes as a London sparrow.

“Norway again, forsooth—nous revenons à nos moutons—that horrid bleak country, where the cold in winter is so intense that when you sneeze, the shower from your olfactories rattles against the earth like dust-shot, and in summer you can’t sleep[vi] for the brazen-faced sun staring at you all the twenty-four hours. What rant that is about

and all that sort of thing. Give me Kensington Gardens and Rotten Row!”

Still—in spite of Bowbells—we shall venture on the expedition, and probably with less chance of a fiasco than if we travelled by the express-train through the beaten paths of central Europe. There, all is a dead level. Civilization has smoothed the gradients actually and metaphorically—alike in the Brunellesque and social sense. As people progress in civilization, the more prominent marks of national character are planed off. Individuality is lost. The members of civilized society are as like one another as the counters on a draft-board. “They rub each other’s angles down,” and thus lose “the picturesque of man and man.” The same type keeps repeating itself with sickening monotony, like the patterns of paper-hangings, instead of those delightfully varied arabesques with which the free hand of the painter used to diversify the walls of the antique dwelling.[vii]

But it is not so with the population of a primitive country like Norway. Much of the simplicity that characterized our forefathers is still existing there. We are Aladdined to the England of three centuries ago. Do you mean to say that you, a sensible man or woman, prefer putting on company manners at every turn, being everlastingly swaddled in the artificial restraints of society; being always among grand people, or genteel people, or superior people, or people of awful respectability? Do you prefer an aviary full of highly educated song-birds mewed up so closely that they “show off” one against another, filled with petty rivalries and jealousies, to the gay, untutored melody of the woods poured forth for a bird’s own gratification or that of its mate? Do you like to spend your time for ever in trim gardens, among standards and espaliers, and spruce flower-beds, so weeded, and raked, and drilled, and shaped, that you feel positively afraid of looking and walking about for fear of making a faux pas? Oh no! you would like to see a bit of wild rose or native heather. (Interpret this as you list of the flowers of the field, or a fairer flower still.)[viii] You prefer climbing a real lichened rock in situ, that has not been placed there by Capability Brown or Sir Joseph Paxton.

Indeed, the avidity with which books of travel in primitive countries—whether in the tropics or under the pole—are now read, shows that the more refined a community is, the greater interest it will take in the occupation, the sentiments, the manners of people still in a primitive state of existence. Our very over-civilization begets in us a taste to beguile oneself of its tedium, its frivolities, its unreality, by mixing in thought, at least, with those who are nearer the state in which nature first made man.

“The manners of a rude people are always founded on fact,” said Sir Walter Scott, “and therefore the feelings of a polished generation immediately sympathize with them.” It is this kind of feeling that has a good deal to do with urging men, who have been educated in all the habits and comforts of improved society, to leave the groove, and carve out for themselves a rough path through dangers and privations in wilder countries.

“You will have none of this sort of thing,” said Dr. Livingstone, in the Sheldonian theatre, while[ix] addressing Young Oxford on the fine field for manly, and useful, and Christian enterprise that Africa opens out,—“You will have none of this sort of thing there,” while he uneasily shook the heavy sleeve of his scarlet D.C.L. gown, which he had donned in deference to those who had conferred on him this mark of honour. Yes, less comforts, perhaps, but at the same time less red tape.

“Brown exercise” is better than the stewy, stuffy adipocere state of frame in which the man of “indoors mind” ultimately eventuates. Living on frugal fare, in the sharp, brisk air of the mountain, the lungs of mind and body expand healthfully, and the fire of humanity burns brighter, like the fire in the grate when fanned by a draught of fresh oxygen. Most countries, when we visit them for the first time, turn out “the dwarfs of presage.” Not so Norway. It grows upon you every time you see it. You need not fear, gentle reader, of being taken over beaten ground. “The Oxonian” has never visited Thelemarken and Sætersdal before. So come along with me, in the absence of a better guide, if you wish to cultivate a nearer acquaintance with the roughly forged, “hardware” sort of[x] people of this district, content to forget for a while the eternal willow-pattern crockery of home. Thelemarken is the most primitive part of Norway; it is the real Ultima Thule of the ancients; the very name indicates this, and the Norwegian antiquaries quote our own King Alfred in support of this idea. It is true, that on nearer inspection, its physical geography will not be found to partake of the marvellous peculiarities assigned to Thule by the ancient Greek navigator, Pytheas, who asserts that it possessed neither earth, air, or sea, but a chaotic mixture of all three elements. But that may emphatically be said to be neither here nor there. Inaccessible the country certainly is, and it is this very inaccessibility which has kept out the schoolmaster; so that old times are not yet changed, nor old manners gone, nor the old language unlearned under the auspices of that orthoepic functionary. The fantastic pillars and arches of fairy folk-lore may still be descried in the deep secluded glens of Thelemarken, undefaced with stucco, not propped by unsightly modern buttress. The harp of popular minstrelsy—though it hangs mouldering and mildewed with[xi] infrequency of use, its strings unbraced for want of cunning hands that can tune and strike them as the Scalds of Eld—may still now and then be heard sending forth its simple music. Sometimes this assumes the shape of a soothing lullaby to the sleeping babe, or an artless ballad of love-lorn swains, or an arch satire on rustic doings and foibles. Sometimes it swells into a symphony descriptive of the descent of Odin; or, in somewhat of less Pindaric, and more Dibdin strain, it recounts the deeds of the rollicking, death-despising Vikings; while, anon, its numbers rise and fall with mysterious cadence as it strives to give a local habitation and a name to the dimly seen forms and antic pranks of the hollow-backed Huldra crew.

The author thinks that no apology is needed for working in some of the legendary interludes which the natives repeated to him, so curious and interesting, most of which he believes never appeared before in an English dress, and several of them in no print whatever. Legends are an article much in request just now; neither can they be considered trifling when viewed in the light thrown upon the[xii] origin of this branch of popular belief and pastime by the foremost men of their time, e.g., Scott, and more especially Jacob Grimm. Frivolous, indeed! not half so frivolous as the hollow-hearted, false-fronted absurdities of the “great and small vulgar,” is the hollow-backed elf, with the grand mythological background reaching into the twilight of the earth’s history, nor so trifling the simple outspoken peasant, grave, yet cheery, who speaks as he thinks, and actually sometimes laughs a good guffaw, as the stuck-up ladies and gentlemen of a section of the artificial world, with their heartless glitter, crocodile tears, their solemn pretence, their sham raptures.

I must not omit to say that the admirable troll-drawing, which forms the frontispiece of the first volume, is one selected from a set of similar sketches by my friend, T. G. Jackson, Esq., of Wadham College, Oxford. It evinces such an intimate acquaintance with the looks of those small gentry that it is lucky for him that he did not live in the days when warlocks were done to death.

F. M.

Lincoln College, Oxford,

May, 1858.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The glamour of Norwegian scenery—A gentle angler in a passion—The stirring of the blood—A bachelor’s wild scream of liberty—What marriage brings a salmon-fisher to—Away, for the land of the mountain and the flood—“Little” circle sailing—The Arctic shark—Advantages of gold lace—A lesson for laughers—Norwegian coast scenery—Nature’s grey friars—In the steps of the Vikings—The Norwegian character—How the Elves left Jutland—Christiansand harbour | pp. 1-15 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Disappointed fishermen—A formidable diver—Arendal, the Norwegian Venice—A vocabulary at fault—Ship-building—The Norwegian Seaboard—Sandefjord, the Norwegian Brighton—A complicated costume—Flora’s own bonnet—Bruin at large—Skien and its saw-mills—Norway cutting its sticks—Wooden walls—Christopher Hansen Blum—The Norwegian phase of religious dissent—A confession of faith—The Norsk Church the offspring of that of Great Britain | pp. 16-28 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| A poet in full uniform—The young lady in gauntlet gloves again—Church in a cave—Muscular Christianity in the sixteenth century—A miracle of light and melody—A romance of bigotry—How Lutheranism came in like a lion—The Last of the Barons—Author [xiv]makes him bite the dust—Brief burial-service in use in South-western Norway—The Sörenskriver—Norwegian substitute for Doctors’ Commons—Grave ale—A priestly Samson—Olaf’s ship—A silent woman—Norwegian dialects—Artificial salmon-breeding—A piscatorial prevision | pp. 29-47 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Mine host at Dal—Bernadotte’s prudent benignity—Taxing the bill of costs—Hurrah for the mountains—Whetstones—Antique wooden church—A wild country—“Raven depth”—How the English like to do fine scenery—Ancient wood-carving—A Norwegian peasant’s witticism—A rural rectory—Share and chair alike—Ivory knife-handles—Historical pictures—An old Runic Calendar—The heathen leaven still exists in Norway—Washing-day—Old names of the Norsk months—Peasant songs—Rustic reserve—A Norsk ballad | pp. 48-68 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| A lone farm-house—A scandal against the God Thor—The headquarters of Scandinavian fairy-lore—The legend of Dyrë Vo—A deep pool—A hint for alternate ploughboys—Wild goose geometry—A memorial of the good old times—Dutch falconers—Rough game afoot—Author hits two birds with one stone—Crosses the lake Totak—A Slough of Despond—An honest guide—A Norwegian militiaman—Rough lodgings—A night with the swallows—A trick of authorship—Yea or Nay | pp. 69-81 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| No cream—The valley of the Maan—The Riukan foss—German students—A bridge of dread—The course of true love never did run smooth—Fine misty weather for trout—Salted provisions—Midsummer-night revels—The Tindsö—The priest’s hole—Treacherous ice—A case for Professor Holloway—The realms of cloud-land—Superannuated—An ornithological guess—Field-fares out of reach of “Tom Brown”—The best kind of physic—Undemonstrative affection—Everywhere the same—Clever little [xv]horses | pp. 82-96 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| An oasis—Unkempt waiters—Improving an opportunity—The church in the wilderness—Household words—A sudden squall—The pools of the Quenna—Airy lodgings—Weather-bound—A Norwegian grandpapa—Unwashed agriculturists—An uncanny companion—A fiery ordeal—The idiot’s idiosyncrasy—The punctilious parson—A pleasant query—The mystery of making flad-brod—National cakes—The exclusively English phase of existence—Author makes a vain attempt to be “hyggelig”—Rather queer | pp. 97-113 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Northwards—Social colts—The horse shepherd—The tired traveller’s sweet restorer, tea—Troll-work—Snow Macadam—Otter hunting in Norway—Normaends Laagen—A vision of reindeer—The fisherman’s hut—My lodging is on the cold ground—Making a night of it—National songs—Shaking down—A slight touch of nightmare | pp. 114-128 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| The way to cure a cold—Author shoots some dotterel—Pit-fall for reindeer—How mountains look in mountain air—A natural terrace—The meeting of the waters—A phantom of delight—Proves to be a clever dairymaid—A singular cavalcade—Terrific descent into Tjelmö-dal—A volley of questions—Crossing a cataract—A tale of a tub—Author reaches Garatun—Futile attempt to drive a bargain | pp. 129-141 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| The young Prince of Orange—A crazy bridge—At the foot of the mighty Vöring Foss—A horse coming downstairs—Mountain greetings—The smoke-barometer—The Vöring waterfall—National characteristics—Paddy’s estimate of the Giant’s Causeway—Meteoric water—New illustrations of old slanders—How [xvi]the Prince of Orange did homage to the glories of nature—Author crosses the lake Eidsfjord—Falls in with an English yacht and Oxonians—An innkeeper’s story about the Prince of Orange—Salmonia—General aspect of a Norwegian Fjord—Author arrives at Utne—Finds himself in pleasant quarters—No charge for wax-lights—Christian names in Thelemarken—Female attire—A query for Sir Bulwer Lytton—Physiognomy of the Thelemarken peasants—Roving Englishmen—Christiania newspapers—The Crown Prince—Historical associations of Utne—The obsequies of Sea Kings—Norwegian gipsies | pp. 142-160 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| From Fairy-lore to Nature-lore—Charming idea for stout folk—Action and reaction—Election-day at Bergen—A laxstie—A careless pilot—Discourse about opera-glasses—Paulsen Vellavik and the bears—The natural character of bears—Poor Bruin in a dilemma—An intelligent Polar bear—Family plate—What is fame?—A simple Simon—Limestone fantasia—The paradise of botanists—Strength and beauty knit together—Mountain hay-making—A garden in the wilderness—Footprints of a celebrated botanist—Crevasses—Dutiful snow streams—Swerre’s sok—The Rachels of Eternity—A Cockney’s dream of desolation—Curds-and-whey—The setting-in of misfortunes—Author’s powder-flask has a cold bath—The shadows of the mountains—The blind leading the blind—On into the night—The old familiar music—Holloa—Welcome intelligence | pp. 161-187 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| The lonely châlet—The Spirit of the hills—Bauta-stones—Battlefields older than history—Sand-falls—Thorsten Fretum’s hospitality—Norwegian roads—The good wife—Author executes strict justice—Urland—Crown Prince buys a red nightcap—A melancholy spectacle—The trick of royalty—Author receives a visit from the Lehnsman—Skiff voyage to Leirdalsören—Limestone cliffs—Becalmed—A peasant lord of the forest—Inexplicable natural phenomena—National education—A real postboy—A [xvii]disciple for Braham—The Hemsedal’s fjeld—The land of desolation—A passing belle—The change-house of Bjöberg—“With twenty ballads stuck upon the wall”—A story about hill folk—Sivardson’s joke—Little trolls—The way to cast out wicked fairies—The people in the valley—Pastor Engelstrup—Economy of a Norwegian change-house—The Halling dance—Tame reindeer—A region of horrors | pp. 188-214 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Fairy-lore—A wrestle for a drinking-horn—Merry time is Yule time—Head-dresses at Haga—Old church at Naes—Good trout-fishing country—A wealthy milkmaid—Horses subject to influenza—A change-house library—An historical calculation—The great national festival—Author threatens, but relents—A field-day among the ducks—Gulsvig—Family plate—A nurse of ninety years—The Sölje—The little fat grey man—A capital scene for a picture—An amazing story—As true as I sit here—The goat mother—Are there no Tusser now-a-days?—Uninvited guests—An amicable conversation about things in general—Hans saves his shirt—The cosmopolitan spirit of fairy-lore—Adam of Bremen | pp. 215-241 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| A port-wine pilgrimage—The perfection of a landlady—Old superstitious customs—Levelling effects of unlevelled roads—A blank day—Sketch of an interior after Ostade—A would-be resurrectionist foiled—The voices of the woods—Valuable timber—A stingy old fellow—Unmistakeable symptoms of civilization—Topographical memoranda—Timber-logs on their travels—The advantages of a short cut—A rock-gorge swallows a river—Ferry talk—Welcome—What four years can do for the stay-at-homes—A Thelemarken manse—Spæwives—An important day for the millers—How a tailor kept watch—The mischievous cats—Similarity in proverbs—“The postman’s knock”—Government patronage of humble talent—Superannuated clergymen in Norway—Perpetual curates—Christiania University examination—Norwegian students—The Bernadotte dynasty—Scandinavian unity—Religious parties—Papal propagandists at Tromsö—From fanaticism to field-sports—The Linnæa Borealis | pp. 242-276[xviii] |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Papa’s birthday—A Fellow’s sigh—To Kongsberg—A word for waterproofs—Dram Elv—A relic of the shooting season—How precipitous roads are formed in Norway—The author does something eccentric—The river Lauven—Pathetic cruelty—The silver mine at Kongsberg—A short life and not a merry one—The silver mine on fire—A leaf out of Hannibal’s book—A vein of pure silver—Commercial history of the Kongsberg silver mines—Kongsberg—The silver refining works—Silver showers—That horrid English | pp. 277-296 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| A grumble about roads—Mr. Dahl’s caravansary—“You’ve waked me too early”—St. Halvard—Professor Munck—Book-keeping by copper kettles—Norwegian society—Fresh milk—Talk about the great ship—Horten the chief naval station of Norway—The Russian Admiral—Conchology—Tönsberg the most ancient town in Norway—Historical reminiscences—A search for local literature—An old Norsk Patriot—Nobility at a discount—Passport passages—Salmonia—A tale for talkers—Agreeable meeting—The Roman Catholics in Finmark—A deep design—Ship wrecked against a lighthouse—The courtier check-mated | pp. 297-317 |

The glamour of Norwegian scenery—A gentle angler in a passion—The stirring of the blood—A bachelor’s wild scream of liberty—What marriage brings a salmon-fisher to—Away, for the land of the mountain and the flood—“Little” circle sailing—The Arctic shark—Advantages of gold lace—A lesson for laughers—Norwegian coast scenery—Nature’s grey friars—In the steps of the Vikings—The Norwegian character—How the Elves left Jutland—Christiansand harbour.

A strange attraction has Norway for one who has once become acquainted with it: with its weird rocks and mountains—its dark cavernous fjords—its transparent skies—its quaint gulf-stream warming apparatus—its “Borealis race”—its fabulous Maelstrom—its “Leviathan slumbering on the Norway foam”—its sagas, so graphically portraying the manners and thoughts of an ancient race—its[2] sturdy population, descendants of that northern hive which poured from the frozen loins of the north, and, as Montesquieu says, “left their native climes to destroy tyrants and slaves, and were, a thousand years ago, the upholders of European liberty.”

“Very attractive, no doubt,” interrupts Piscator. “In short, the country beats that loadstone island in the East hollow, which extracted the bolts out of the ships’ bottoms; drawing the tin out of one’s pockets, and oneself thither every summer without the possibility of resistance. But a truce to your dithyrambs on scenery, and sagas, and liberty. Talk about the salmon-fishing. I suppose you’re coming to that last—the best at the end, like the postscript of a young lady’s letter.”

Well, then, the salmon-fishing. A man who has once enjoyed the thrill of that won’t so easily forget it. Here, for instance, is the month of June approaching. Observe the antics of that “old Norwegian,” the Rev. Christian Muscular, who has taken a College living, and become a sober family man. See how he snorts and tosses up his head, like an old hunter in a paddock as the chase sweeps[3] by. He keeps writing to his friends, inquiring what salmon rivers are to be let, and what time they start, and all that sort of thing, although he knows perfectly well he can’t possibly go; not even if he might have the priest’s water on the Namsen. But no wonder Mr. Muscular is growing uneasy. The air of Tadpole-in-the-Marsh becomes unhealthy at that season, and he feels quite suffocated in the house, and prostrated by repose; and as he reads Schiller’s fresh ‘Berglied,’ he sighs for the mountain air and the music of the gurgling river.

But there are mamma and the pledges; so he must resign all hope of visiting his old haunts. Instead of going there himself, in body, he must do it in spirit—by reading, for instance, these pages about the country, pretty much in the same way as the Irish peasant children, who couldn’t get a taste of the bacon, pointed their potatoes at it, and had a taste in imagination. Behold, then, Mr. Muscular, with all the family party, and the band-boxes and bonnet-boxes, and umbrellas and parasols numbered up to twenty; and last, not least, the dog “Ole” (he delights to call the live things about him by[4] Norsk names), bound for the little watering-place of Lobster-cum-Crab. Behold him at the “Great Babel junction,” not far from his destination, trying to collect his scattered thoughts—which are far away—and to do the same by his luggage, two articles of which—Harold’s rocking-horse and Sigfrid’s pap-bottle—are lost already. Shall I tell you what Mr. Muscular is thinking of? Of “the Long,” when he shut up shop without a single care; feeling satisfied that his rooms and properties would be in the same place when he came back, without being entrusted to servants who gave “swarries” above-stairs during his absence.

Leaving him, then, to dredge for the marine monstrosities which abound at Lobster-cum-Crab, or to catch congers and sea-perch at the sunken wreck in the Bay—we shall start with our one wooden box, and various other useful articles, for the land of the mountain and the flood—pick up its wild legends and wild flowers, scale its mountains, revel in the desolation of its snowfields, thread its sequestered valleys—catching fish and shooting fowl as occasion offers; though we give fair notice that on this[5] occasion we shall bestow less attention on the wild sports than on other matters.

On board the steamer that bore us away over a sea as smooth as a mirror, was a stout English lady, provided with a brown wig, and who used the dredging-box most unsparingly to stop up the gaps in her complexion.

“A wild country is Norway, isn’t it?” inquired she, with a sentimental air; “you will, no doubt, have to take a Lazaroni with you to show you the way?” (? Cicerone).

“The scenery,” continued she, “isn’t equal, I suppose, to that of Hoban. Do you know, I was a great climber until I became subject to palpitations. You wouldn’t think it, so robust as I am; but I’m very delicate. My two families have been too much for me.”

I imagined she had been married twice, or had married a widower.

“You know,” continued she, confidentially, “I had three children, and then I stopped for some years, and began again, and had two more. Children are such a plague. I went with them to the sea, and[6] would you believe it, every one of them took the measles.”

But there was a little countrywoman of ours on board whose vivacity and freshness made up for the insipidity of the “Hoban lady.” She can’t bear to think that she is doing no good in the world, and spends much of her time in district visiting in one of the largest parishes of the metropolis. Not that she had a particle of the acid said to belong to some of the so-called sisters of mercy—reckless craft that, borne along by the gale of triumphant vanity, have in mere wantonness run down many an unsuspecting vessel—I mean trifled with honest fellows’ affections, and then suddenly finding themselves beached, in a matrimonial sense, irretrievably pronounce all men, without exception, monsters. And, thus, she whose true mission it was to be “the Angel in the House,” presiding, ministering, soothing, curdles up into a sour, uneasy devotee.

At sea, a wise traveller will be determined to gather amusement from trifles; nay, even rather than get put out by any delay or misadventure, set about performing the difficult task of constructing[7] a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. For instance, our vessel, being overburdened, steered excessively ill, as might be seen from her wake, which, for the most part, assumed the shape of zigzags or arcs of circles. This disconcerted one grumpy fellow uncommonly. But we endeavoured to restore his good humour by telling him that we were not practising the “great” but the “little” circle sailing. His mantling sulkiness seemed to evaporate at this pleasantry; and, subsequently, when, on the coal lessening, and lightening our craft astern, she steered straighter, he facetiously apostrophized the man at the wheel—

“You’re the man to take the kinks out of her course; we must have you at the wheel all night, and as much grog as you like, at my expense, afterwards.”

The captain, who was taken prisoner on returning from the Davis’ Straits fishery, during the French wars, and was detained seven years in France, gives me some information about the Arctic shark (Squalus Arcticus), which is now beginning to reappear on the coast of Norway.

“We used to call them the blind shark, sir—more by token they would rush in among the nets and seize our fish, paying no more attention to us than nothing at all. They used to bite pieces out of our fish just like a plate, and no mistake, as clean as a whistle, sir. I’ve often stuck my knife into ’em, but they did not wince in the least—they did not appear to have no feeling whatsomdever. I don’t think they had any blood in ’em; I never saw any. I’ve put my hand in their body, and it was as cold as ice.”

“By-the-bye, captain,” said I, to our commander, who was a fubsy, little round red-faced man, with a cheery blue eye, “how’s this? Why, you are in uniform!”

“To be sure I am. Th’ Cumpany said it must be done. Those furriners think more of you with a bit of gowd lace on your cap and coat. An order came from our governor to wear this here coat and cap—so I put ’em on. What a guy I did look—just like a wolf in sheep’s clothing.”

“Or a daw in borrowed plumes,” suggested I.

“But I put a bould face on’t, and came a-board,[9] and walked about just as if I had the old brown coat on, and now I’ve got quite used to the change.”

Now this little fellow is as clever as he is modest—every inch a seaman. I’ve seen him calm and collected in very difficult circumstances on this treacherous old North Sea.

Last year, in the autumn, the captain tells me he was approaching the Norwegian coast in the grey of the morning when he descried what he took to be a quantity of nets floating on the water, and several boats hovering about them. He eased the engine for fear of entangling the screw. Some Cockneys on board, who wore nautical dresses, and sported gilt buttons on which were engraved R. T. Y. C., laughed at the captain for his excessive carefulness. Presently it turned out that what had seemed to be floating nets were the furniture and hencoops of the ill-fated steamer Norge, which had just been run down by another steamer, and sunk with a loss of some half a hundred lives. A grave Norwegian on board now lectured the young men for their ignorance and bravado.

“They just did look queer, I’ll a-warrant ye,” continued our north-country captain. “They laughed on t’other side of their mouths, and were mum for the rest of the voyage.”

“What vessel’s that?” asked I.

“Oh! that’s the opposition—the Kangaroo.”

This was the captain’s pronunciation of Gangr Rolf (Anglicè, Rollo, the Walker), the Norwegian screw, which I hear rolls terribly in a sea-way.

“Hurrah!” I exclaimed. “Saall for Gamle Norge,” as we sighted the loom of the land. How different it is from the English coast. The eye will in vain look for the white perpendicular cliffs, such as hedge so much of old Albion, their glistening fronts relieved at intervals by streaks of darker hue, where the retreating angle of the wall-like rock does not catch the sun’s rays; while behind lie the downs rising gently inland, with their waving fields of corn or old pastures dotted with sheep. Quite as vainly will you cast about for the low shores of other parts of our island—diversified, it may be, by yellow dunes, with the sprinkling of shaggy flag-like grass, or, elsewhere, the flat fields terminating[11] imperceptibly in flatter sands, the fattening ground of oysters.

As far as I can judge at this distance, instead of the coast forming one sober businesslike line of demarcation, with no nonsense about it, showing exactly the limits of land and ocean, as in other countries, here it is quite impossible to say where water ends and land begins. It is neither fish nor fowl. Those low, bare gneiss-rocks, for instance, tumbled, as it were, into a lot of billows. One would almost think they had got a footing among the waves by putting on the shape and aspect of water. Well, if you scan them accurately you find they are unmistakeably bits of islands. But as we approach nearer, look further inland to those low hills covered with pine-trees, which somehow or other have managed to wax and pick up a livelihood in the clefts and crannies of the rocks, or sometimes even on the bare scarps. While ever and anon a bald-topped rock protruding from the dark green masses stands like a solitary Friar of Orders Grey, with his well shaven tonsure, amid a crowd of black cowled Dominicans.

“Surely that,” you’ll say, “is the coast line proper?”

“Wrong again, sir. It is a case of wheels within wheels; or, to be plain, islands within islands. Behind those wooded heights there are all sorts of labyrinths of salt water, some ending in a cul-de-sac, others coming out, when you least expect it, into the open sea again, and forming an inland passage for many miles. If that myth about King Canute bidding the waves not come any further, had been told of this country, there would have been some sense in it, and he might have appeared to play the wave-compeller to some purpose. For really, in some places, it is only by a nice examination one can say how far the sea’s rule does extend.”

The whole of the coast is like this, except between the Naze and Stavanger, rising at times, as up the West Coast, into magnificent precipices, but still beaded with islands from the size of a pipe of port to that of an English county. Hence there are two ways of sailing along the coast, “indenskjærs,” i.e., within the “skerries,” and “udenskjærs,”[13] or outside of the “skerries,” i.e., in the open sea. The inner route has been followed by coasters from the days of the Vikings. Those pilots on the Norwegian Government steam-vessels whom you see relieving each other alternately on the bridge, spitting thoughtfully a brown fluid into a wooden box, and gently moving their hand when we thread the watery Thermopylæ, are men bred up from boyhood on the coast, and know its intricacies by heart. The captain is, in fact, a mere cypher, as far as the navigation is concerned.

“You’ve never been in Norway before?” I inquired of the fair Samaritan.

“No; this is my first visit. I hope I shall like it.”

“I can imagine you will. If you are a lover of fashion and formality, you will not be at ease in Norway. The good folks are simple-minded and sincere. If they invite you to an entertainment, it is because they are glad to see you. Not to fill up a place at the table, or because they are obliged to do the civil, at the same time hoping sincerely you won’t come. Their forefathers were men of great[14] self-denial, and intensely fond of liberty. When it was not to be had at home, they did what those birds were doing that rested on our mast during the voyage, migrated to a more congenial clime—in their case to Iceland. The present Norwegians have a good deal of the same sturdy independence about them; some travellers say, to an unpleasant degree. It’s true they are rather rough and uncouth; but, like their forefathers, when they came in contact with old Roman civilization in France and Normandy, they will progress and improve by intercourse with the other peoples of Europe.

“Their old mythology is grand in the extreme. Look at that rainbow, yonder. In their eyes, the bow in the cloud was the bridge over which lay the road to Valhalla. Then their legends. Do you know, I think that much of our fairy lore came over to us from Norway, just as the seeds of the mountain-flowers in Scotland are thought by Forbes to have come over from Scandinavia on the ice-floes during the glacial period. If I had time, I could tell you a lot of sprite-stories; among others, one how the elves all left Jutland one night in an old wreck, lying on[15] the shore, and got safe to Norway. To this country, at all events, those lines won’t yet apply:—

“But here we are in Christiansand harbour, and yonder is my steamer, the Lindesnaes, which will take me to Porsgrund, whither I am bound; so farewell, and I hope you will not repent of your visit to Norway!”

Disappointed fishermen—A formidable diver—Arendal, the Norwegian Venice—A vocabulary at fault—Ship-building—The Norwegian Seaboard—Sandefjord, the Norwegian Brighton—A complicated costume—Flora’s own bonnet—Bruin at large—Skien and its saw-mills—Norway cutting its sticks—Wooden walls—Christopher Hansen Blum—The Norwegian phase of religious dissent—A confession of faith—The Norsk Church the offspring of that of Great Britain.

Two Englishmen were on board the Lindesnaes, who had been fishing a week in the Torrisdal Elv, and had had two rises and caught nothing; so they are moving along the coast to try another river. But it is too late for this part of Norway. These are early rivers, and the fish have been too long up to afford sport with the fly.

The proverb, “never too old to learn,” was practically brought to my mind in an old Norwegian gentleman on board.

“My son, sir, has served in the English navy.[17] I am seventy years old, and can speak some English. I will talk in that language and you in Norwegian, and so we shall both learn. You see, sir, we are now going into Arendal. This is a bad entrance when the wind is south-west, so we are clearing out that other passage there to the eastward. There is a diver at work there always. Oh, sir, he’s frightful to behold! First, he has a great helmet, and lumps of lead on his shoulders, and lead on his thighs, and lead on his feet. All lead, sir! And then he has a dagger in his belt.”

“A dagger!” said I; “what’s that for?”

“Oh! to keep off the amphibia and sea-monsters; they swarm upon this coast.”

As he spoke, the old gentleman contorted his countenance in such a manner that he, at all events, let alone the diver, was frightful to behold. Such was the effect of the mere thought of the amphibia and sea-monsters. Fortunately, his head was covered, or I can’t answer for it that each particular hair would not have stood on end like to the quills of the fretful porcupine. It struck me that he must have been reading of Beowulf, the Anglo-Saxon[18] hero, and his friend Breca, and how they had naked swords in their hands to defend them against the sea-monsters, and how Beowulf served the creatures out near the bottom of the sea (sae-grunde néah).

At Arendal, where the vessel stops for some hours, I take a stroll with a Norwegian schoolboy. Abundance of sycamore and horse-chesnut, arrayed in foliage of the most vivid hue, grow in the pretty little ravines about this Norwegian Venice, as it is called.

“What is the name of that tree in Norsk,” I asked of my companion, pointing to a sycamore.

“Ask, i.e. ash.”

“And of that?” inquired I, pointing to a horse-chesnut.

“Ask,” was again the reply.

Close to the church was the dead-house, where corpses are placed in winter, when the snow prevents the corpse being carried to the distant cemetery. In the little land-locked harbour I see a quantity of small skiffs, here called “pram,” which are to be had new for the small price of three[19] dollars, or thirteen shillings and sixpence English. The vicinity of this place is the most famous in Norway for mineralogical specimens. Arendal has, I believe, the most tonnage and largest-sized vessels of any port in Norway. Ship-building is going forward very briskly all along the coast since the alteration in the English navigation laws. At Grimstead, which we passed, I observed eight vessels on the stocks: at Stavanger there are twenty.

The reader is perhaps not aware that, reckoning the fjords, there is a sea-board of no less than eight thousand English miles in Norway—i.e., there is to every two and a half square miles of country a proportion of about one mile of sea-coast. This superfluity of brine will become more apparent by comparing the state of things in other countries. According to Humboldt, the proportion in Africa is one mile of sea-coast to one hundred and forty-two square miles of land. In Asia, one to one hundred. In North America, one to fifty-seven. In Europe, one to thirty-one.

With such an abundance of “water, water everywhere”—I[20] mean salt, not fresh—one would hardly expect to meet with persons travelling from home for the sake of sea-bathing. And yet such is the case. On board is a lady going to the sea-baths of Sandefjord. She tells me there is quite a gathering of fashionables there at times. Last year, the wife of the Crown Prince, a Dutch woman by birth, was among the company. She spent most of her time, I understood, in sea-fishing. Besides salt-water baths, there are also baths of rotten seaweed, which are considered quite as efficacious for certain complaints as the mud-baths of Germany. Landing at Langesund, I start for Skien on board the little steamer Traffic.

A bonder of Thelemark is on board, whose costume, in point of ugliness, reminds one of the dress of some of the peasants of Bavaria. Its chief characteristics were its short waist and plethora of buttons. The jacket is of grey flannel, with curious gussets or folds behind. The Quaker collar and wristbands are braided with purple. Instead of the coat and waistcoat meeting the knee-breeches halfway, after the usual fashion, the latter have to[21] ascend nearly up to the arm-pits before an intimacy between these two articles of dress is effected. Worsted stockings of blue and white, worked into stars and stripes, are joined at the foot by low shoes, broad-toed, like those of Bavaria, while the other end of the man—I mean his head—is surmounted by a hat, something like an hourglass in shape.

The fondness of these people for silver ornaments is manifest in the thickly-set buttons of the jacket, on which I see is stamped the intelligent physiognomy of that king of England whose equestrian statue adorns Pig-tail-place; his breeches and shoes also are each provided with a pair of buckles, likewise of silver.

Contrasting with this odd-looking monster is a Norwegian young lady, with neat modern costume, and pair of English gauntlet kid gloves. Her bouquet is somewhat peculiar; white lilies, mignionette, asparagus-flower, dahlias, and roses. Her carpet-bag is in a cover, like a white pillowcase.

Bears, I see by a newspaper on board, are terribly[22] destructive this year in Norway. One bruin has done more than his share. He has killed two cows, and wounded three more; not to mention sheep, which he appears to take by way of hors d’œuvres. Lastly, he has killed two horses; and the peasants about Vaasen, where all this happened, have offered eight dollars (thirty-six shillings) for his apprehension, dead or alive.

At the top of the fjord, fourteen English miles from the sea, lies Skien. The source of its prosperity and bustle are its saw-mills. Like Shakspeare’s Justice, it is full of saws. The vast water-power caused by the descent of the contents of the Nord-Sö is here turned to good account: setting going a great number of wheels. Two hundred and fifty dozen logs are sawn into planks per week; and the vessels lie close by, with square holes in their bows for the admission of the said planks into their holds. All the population seems to be occupied in the timber trade. Saws creaking and fizzing, men dashing out in little shallops after timbers that have just descended the foss, others fastening them to the endless chain[23] which is to drag them up to the place of execution; while the wind flaunts saw-dust into your face, and the water is like the floor of a menagerie. That unfortunate salmon, which has just sprung into the air at the bottom of the foss, near the old Roman Catholic monastery, must be rather disgusted at the mouthful he got as he plunged into the stream again.

But we must return to the modern Skien. This timber-built city was nearly half burnt down not long ago; but as a matter of course the place is being rebuilt of the old material. Catch a Norwegian, if he can help it, building his house of stone. Stone-houses are so cold and comfortless, he says. Since the fire, cigar-smoking has been forbidden in the streets under a penalty of four orts, or three shillings and fourpence sterling, for each offence.

The great man of Skien appears to be one Christopher Hansen Blum.

“Whose rope-walk is that?”

“Christopher Hansen Blum’s.”

“And that great saw-mill?”

“Christopher Hansen Blum’s.”

“And those warehouses?”

“Christopher Hansen Blum’s.”

“And that fine lady?”

“Christopher Hansen Blum’s wife.”

“And the other fine lady, my fair travelling companion with the gauntlet kid gloves?”

“Christopher Hansen Blum’s niece.”

This modern Marquis of Carabas (vide Puss in Boots) is also, I understand, one of the chief promoters of the canal which is being quarried out of the solid rock between Skien and the Nord-Sö; the completion of which will admit of an uninterrupted steam traffic from this place to Hitterdal, at the northern end of that lake, and deep in the bowels of Thelemarken.

A great stir has been lately caused at Skien by the secession from the establishment of Gustav Adolph Lammers, the vicar of the place. The history of this gentleman is one of the many indications to be met with of this country having arrived at that period in the history of its civilization which the other countries of Europe have passed many years ago;—we mean the phase of the first[25] development of religious dissent and a spirit of insubordination to the established traditions of the Church as by law established. We are transported to the days of Whitfield and Wesley. Lammers, who appears to be a sincere person, in spite of the variety of tales in circulation about him, commenced by inculcating greater strictness of conduct. He next declined to baptize children. This brought him necessarily into conflict with the church authorities, and the upshot was that he has seceded from the Church; together with a number of the fair sex, with whom he is a great favourite. The most remarkable part of the matter, however, is that he will apply, it is said, for a Government pension, like other retiring clergy. Whether the Storthing, within whose province all such questions come, will listen to any such thing remains to be seen.[2]

A tract in my possession professes to be the Confession of Faith of this “New Apostolic Church.” In the preamble they state that they wish to make proper use of God’s Word and Sacraments. But as they don’t see how they can do this in the State[26] Church, in which the Word is not properly preached, nor the Sacraments duly administered, they have determined to leave it, and form a separate community, in conformity with the Norwegian Dissenter Law of July 16, 1845. The baptism of infants they consider opposed to Holy Writ. All that the Bible teaches is to bring young children to Christ, with prayer and laying on of hands, and to baptize them when they can believe that Jesus Christ is the son of God, and will promise to obey his Gospel. Hence the elders lay hands upon young children, and at the same time read Mark x., verses 13-17. At a later period, these children are baptized by immersion. The Holy Communion is taken once a month, each person helping himself to the elements; confession or absolution, previously, are not required.

The community are not bound to days and high-tides, but it is quite willing to accept the days of rest established by law, on which they meet and read the Scriptures.

Marriage is a civil contract, performed before a notarius publicus.

The dead are buried in silence, being borne to the grave by some of the brethren; after the grave is filled up a psalm is sung.

All the members of the community agree to submit, if necessary, to brotherly correction; and if this is of no avail, to expulsion. Temporary exclusion from the communion is the correction to be preferred. These rules were accepted by ten men and twenty-eight women, on the 4th July, 1856—giving each other their right hand, and promising, by God’s help,

We have given the following particulars, because the state of the Christian religion in Norway must for ever be deeply interesting to England, if on no other account, for this reason, that in this respect she is the spiritual offspring of Great Britain. Charlemagne tried to convert Scandinavia, but he failed to reach Norway. The Benedictine monk, Ansgar of Picardy, went to Sweden, but never penetrated hither; in fact, the Norsk Christian Church[28] is entirely a daughter of the English. The first missionaries came over with Hacon the Good, the foster son of our King Athelstan; and though this attempt failed, through the tenacity of the people for heathenesse, yet the second did not, when Olaf Trygveson brought over missionaries from the north of England—Norwegian in blood and speech—and christianized the whole coast, from Sweden to Trondjem, in the course of one year—996-997.[3]

A poet in full uniform—The young lady in gauntlet gloves again—Church in a cave—Muscular Christianity in the sixteenth century—A miracle of light and melody—A romance of bigotry—How Lutheranism came in like a lion—The last of the Barons—Author makes him bite the dust—Brief burial service in use in South-Western Norway—The Sörenskriver—Norwegian substitute for Doctors’ Commons—Grave ale—A priestly Samson—Olaf’s ship—A silent woman—Norwegian dialects—Artificial salmon breeding—A piscatorial prevision.

Next day, at five o’clock, A.M., I drove off to the head of the Nord-Sö, distant half-a-dozen miles off, and got on board the steamer, which was crowded with passengers. An old gentleman on board attracted my attention. His dress was just like that of a livery servant in a quiet family in England—blue coat, with stand-up collar, and two rows of gold lace round it. This I find is the uniform of a sörenskriver. Konrad Swach—for that was his name—is a poet of some repute in this country. His most popular effusion is on the national flag of Norway,[30] which was granted to them by the present King, Oscar—a theme, be it remarked, which would have secured popularity for a second-rate poem among these patriotic Northmen. To judge from the poet’s nose, it struck me that some of his poetic inspirations is due to drink. The front part of the vessel is beset by Thelemarken bonders, male and female, in their grotesque dress.

The young lady in gauntlet gloves is also on board, whom I make bold to address, on the strength of our having journeyed together yesterday. As we steam along through the usual Norwegian scenery of pines and grey rocks, she points out to me the mouth of a curious cave.

“That is Saint Michael’s Church, as it is called. The opening is about sixteen feet wide, and about as many high, and goes some eighty feet into the cliff. In the Catholic times, it was used as a church, and became a regular place of pilgrimage, and was regarded as a spot of peculiar sanctity. In the sixteenth century, as the story goes, when the reformed faith had been introduced into the country, the clergyman of the parish of Solum, in which St.[31] Michael’s was situate, was one Mr. Tovel. Formerly a soldier, he was a man of strong will, zealous for the new religion, and a determined uprooter of ‘the Babylonian remnants of popery,’ as he phrased it. The church in the cave was now sadly come down in the world, and had been despoiled of all its valuables. But in the eyes of the bonders, who, with characteristic tenacity of character, adhered to the old faith, it had risen higher in proportion. Numerous pilgrims resorted to it, and miracles were said to be wrought at the spot. At night, it was said, soft singing might be heard, and a stream of light seen issuing from the orifice, which lies four hundred feet above the water.

“One autumn evening, the reverend Mr. Tovel was rowing by the place when the above light suddenly illumined the dark waters. The boatmen rested on their oars and crossed themselves. Tovel urged them to land, but in vain. Determined, however, on investigating the matter himself, he obtained the services of two men from a neighbouring village, who apparently had less superstitious scruples than his own attendants, and watched from[32] his abode, on the other side of the lake, for the reappearance of the light. On the eve of St. Michael he looks out, and sure enough the light was visible. Off he sets, with his two men, taking with him his Bible and sword. The night was still, with a few stars shining overhead. Reaching the foot of the rock, the priest sprang ashore, and invited the boatmen to accompany him, but not a step would they go. The superstition bred in the bone was not so easily to be eradicated, even by the coin and persuasion of Herr Tovel.

“‘Cowards! stay here, then,’ exclaimed his reverence, as he started up the steep ascent alone. After a hard scramble, he stood a foot or two below the cavern, when just as his head came on a level with its mouth the light suddenly vanished. At this trying moment, Tovel bethought him of the great Reformer, how he fought with and overcame the Evil One. This gave him fresh courage, and he entered the cavern, singing lustily Luther’s psalm—

“At the last words the light suddenly reappeared. An aged priest, dressed up in the full paraphernalia of the Romish church, issues from a hidden door in the interior of the cave, and greets Tovel with the words—

“‘Guds Fred,’ (God’s peace); ‘why should I fear those who come in God’s name?’

“‘What!’ exclaimed the astonished Tovel; ‘is it true, then, that Rome’s priests are still in the land?’

“‘Yes; and you are come sword in hand to drive out a poor old priest whose only weapon is a staff.’

“As he spoke, the door of an inner recess rolled back, and Tovel beheld an altar illuminated with iron lamps, over which hung a picture of St. Michael, the saint often worshipped in caves and mountains.

“‘It is your pestiferous doctrines against which I wage war, not against your person,’ rejoined Tovel. ‘Who are you, in God’s name?’

“‘I am Father Sylvester, the last priest of this Church. When the new religion was forced upon[34] the land, I wandered forth, and am now returned once more, to die where I have lived. The good people of Gisholdt Gaard have secretly supported me.’

“Moved with this recital, the Lutheran priest asks—‘And are you trying to seduce the people back to the old religion?’

“The aged man rejoins, with vehemence—

“‘It were an easy task, did I wish to do so; but I do not. It is only at night that I say prayers and celebrate mass in the inner sacristy there.’

“Tovel, thoroughly softened, when he finds that his beloved Reformed faith was not likely to suffer, finishes the conversation by saying—

“‘Old man, you shall not lack anything that it is in my power to give you. Send to me for aught that you may have need of.’

“The venerable priest points to the stars, and exclaims, solemnly—

“‘That God, yonder, will receive both of us, Protestant and Catholic.’

“After this they cordially shook hands. Tovel went home an altered man. Some time afterwards,[35] the light ceased to shine entirely. He knew why. Old Father Sylvester was no more.

“Mr. Tovel got off much better than many clergymen of the Reformed faith in those days. Old Peder Clausen, the chronicler, relates that he knew a man whose father had knocked three clergymen on the head. The stern old Norwegian bonders could ill brook the violence with which the Danes introduced Lutheranism; a violence not much short of that used by King Olaf in rooting out heathenism, and which cost him his life.”

I thanked the young lady for her interesting information.

Presently a curious figure comes out of the cabin. It was a fine-looking old man, with white hair, and hooked nose, and keen eyes, shadowed by shaggy eyebrows. His dress consisted of a blue superfine frock-coat, with much faded gold embroidery on a stand-up collar; dark breeches, and Hessian boots. On his breast shone the Grand Cross of the North Star. A decided case of Commissioner Pordage, of the island of Silver-Store, with his “Diplomatic coat.”

That’s old Baron W——, the last remnant of the Norsk nobility. He wears the dress of an Amtman, which office he formerly held, and loses no opportunity of displaying it and the star. He it was who in 1821 protested against the phævelse (abolition) of the nobility. The Baron was evidently quite aware of the intense impression he was making upon the Thelemarken bonders. On our both landing, subsequently, at a station called Ulefoss, I was highly diverted at seeing him take off his coat and star and deposit the same in a travelling-bag, from which he drew forth a less pretending frock, first taking care to fold up the diplomatic coat with all the precision displayed by that little man of Cruikshank’s in wrapping up Peter Schlemil’s shadow. We both of us are bound, I find, for the steamer on the Bandagsvand.

“Well, what are we waiting for?” said I, to the man who had brought my horse and carriole.

“Oh, we must not start before the Baron. People always make way for him. He won’t like us to start first.”

“Jump up,” said I, putting my nag in motion,[37] and leaving the Baron in the lurch, who was magniloquizing to the people around. All the bonders “wo-ho’d” my horse, in perfect astonishment at my presumption, while the Baron, with a fierce gleam of his eye, whipped his horse into motion. I soon found the advantage of being first, as the road was dreadfully dusty; and being narrow, I managed to keep the Baron last, and swallowing my dust for a considerable distance.

We were soon at Naes, on the Bandagsvand, where lay the little steamer which was to hurry us forty-two miles further into Thelemarken, to a spot called Dal. The hither end of the lake, which is properly called Hvide-sö (white-sea), is separated from the upper, or Bandagsvand, by a very narrow defile jammed in between tremendous precipices. We pass the church of Laurvig on the right, which is said to be old and interesting. The clergyman, Mr. H——, is on board. He tells me that the odd custom of spooning dust into a small hole (see Oxonian in Norway) is not usual in this part of Norway. The term used for it is “jords-paakastelse.” The burial-service is very brief; being[38] confined to the words, “Af Jord er du, Til Jord skal du blive, ud af Jord skal du opstaae.”

For his fee he receives from one ort = tenpence, to sixteen dollars, according to circumstances. In the latter case there would be a long funeral oration. Close by the church is the farm of Tvisæt (twice-sown), so called, it is said, because it often produced two crops a year. Although placed in the midst of savage and desolate scenery, the spot is so sheltered that it will grow figs in the open air.

The Sörenskriver is also on board, the next Government officer to the Amtman, or governor of the province. He is going to a “Skifte,” as it is called. This word is the technical expression for dividing the property of a deceased person among his heirs, and is as old as Harald Hârfager, the same expression being used in Snorro’s Chronicle of his division of his kingdom among his sons. In this simple country there is no necessity for Doctors’ Commons. The relatives meet, and if there is no will the property is divided, according to law, among the legal heirs: if there[39] is one, its provisions are carried out: the Sörenskriver, by his presence, sanctioning the legality of the proceeding.

He informs me that there is generally a kind of lyke-wake on the melancholy occasion, where the “grave öl” and “arve öl,” “grave ale,” or “heirship ale,” is swallowed in considerable quantities. In a recent Skifte, at which he presided, the executors charged, among the expenses to come out of the estate, one tonder malt and sixty-five pots of brantviin; while for the burial fee to the priest, the modest sum of one ort was charged. While the Sörenskriver was overhauling these items with critical eye, the peasant executor, who thought the official was about to take exception to the last item, or perhaps, which is more likely, wishing to divert his attention from the unconscionable charge for drink, observed that he really could not get the funeral service performed for less. The pastoral office would seem, from this, not to occupy a very high position among these clod-hoppers. Sixty-five pots, or pints, of brandy, a huge barrel of malt liquor, and ten-pennyworth of parson.

Mr. C., who is acquainted with Mr. Gieldrup, the priestly Samson of Aal, in Hallingdal, gives me some account of his taking the shine out of Rotner Knut, the cock and bully of the valley. It was on the occasion of Knut being married, and the parson was invited to the entertainment, together with his family. During the banquet, Rotner, evidently with the intention of annoying the priest, amused himself by pulling the legs of his son. Offended at the insult, Gieldrup seized the peasant, and hurled him with such force against the wooden door of the room, that he smashed through it. After which the parson resumed his place at the board, while Knut put his tail between his legs, as much abashed as Gunther, in the Nibelungenlied, when, at his wedding, he was tied up to a peg in the wall by his bride, the warrior virgin Brunhild.

It is customary in Hallingdal, where this occurred, to accompany the Hallingdance with the voice. One of the favourite staves in the valley had been—

It was now altered, and ran as follows, greatly to Knut’s chagrin,—

On another occasion, Gieldrup was marrying two or three couples, when one of the bridegrooms, impatient to be off, vaulted over the chancel rails, and asked what was to pay. In the twinkling of an eye the muscular parson caught him by the shoulders and hurled him right over the heads of the bystanders, who stood round the rails.

As we steam along, the Sörenskriver points out to me, on the top of the lofty rocks on the left, a rude representation in stone of a ship, which goes by the name of “Olaf’s skib.” Among other idiosyncrasies of the saint and martyr, one was, that of occasionally sailing over land. How his vessel came to be stranded here, I cannot learn. Further on, to the right, you see two figures in[42] stone, one of which appears to have lost its head, not metaphorically, but in the real guillotine sense.

The bonders will give you a very circumstantial account, part of which will not bear repetition here, how that this is a Jotul, who had some domestic unpleasantness with his lady, and treated her at once like the Defender of the Faith did Anne Boleyn (we beg pardon of Mr. Froude) casting her head across the water, where it is still lying, under the pine trees yonder, only that the steamer cannot stop to let us see it. The lady and gentleman were petrified in consequence.

“I see you speak Norsk,” said the Sörenskriver, “but you will find it of very little use yonder, at Dal. The dialect of Thelemarken, generally, is strange, but at Dal it is almost incomprehensible, even to us Norwegians. It is generally believed that the language here still possesses a good deal[43] of the tone and turn of the old Icelandic, which was once spoken all the country through.”

I did not, however, find it so difficult. The Norwegians look upon English, I may here remark, as hard to pronounce. On that notable occasion, say they, when the Devil boiled the languages together, English was the scum that came to the top. A criticism more rude than even that of Charles V.

As we approach the landing-place, to my astonishment, I perceive a gentleman fly-fishing at the outlet of the stream into the lake.

He turned out to be Mr. H——, who is traversing the country, at the expense of the Government, to teach the people the method of increasing, by artificial means, the breed of salmon and other fish. He tells me, that last year he caught, one morning here, thirty-five trout, weighing from one to six pounds each.

His operations in the artificial breeding-line have been most successful; not only with salmon, but with various kinds of fish. He tells me it is a mistake to suppose that the roe will only be[44] productive if put in water directly. He has preserved it for a long period, transporting it great distances without its becoming addle, and gives me a tract which he has published on the subject. As we are just now at home in England talking of stocking the Antipodal rivers with salmon, this topic is of no little interest. The method of transporting the roe in Norway is in a wooden box, provided with shelves, one above another, and two or three inches apart, and drilled with small holes. Upon these is laid a thin layer of clean, moist, white, or moor, moss (not sand), and upon that the roe, which has already been milted. This is moistened every day. If the cold is very great, the box is placed within another, and chaff placed in the interstices between the two boxes. In this way roe has been conveyed from Leirdalsören to Christiania, a week’s journey. Professor Rasch, who first employed moss in the transport, has also discovered that it is the best material for laying on the bottom of the breeding stews, the stalks placed streamwise. Moss is best for two reasons: first, it counteracts the tendency of the[45] water to freeze; and secondly, it catches the particles of dirt which float down the stream, and have an affinity rather for it than for the roe. The roe is best placed touching the surface of the stream, but it fructifies very well even when placed half, or even more, out of the water. Care is taken to remove from the stews such eggs as become mouldy, this being an indication that they are addle. If this is not done, the mouldiness soon spreads to the other good roe, and renders it bad. With regard to the nursery-ground itself, it is of course necessary to select a spring for this purpose which will not freeze in winter, and further, to protect the water from the cold by a roofing or house of wood.

I suppose the next thing we shall hear of will be, that roe that has been packed up for years will, by electricity or some sort of hocus-pocus, be turned to good account, just as the ears of corn in the Pyramids have been metamorphosed into standing crops. Mr. H——’s avocation, by-the-bye, reminds me of an old Norwegian legend about “The Fishless Lake” in Valders. Formerly[46] it abounded with fish; but one night the proprietor set a quantity of nets, all of which had disappeared by the next morning. Well, the Norwegian, in his strait, had recourse to his Reverence, who anathematized the net-stealer. Nothing more came of it till the next spring; when, upon the ice breaking, all the nets rose to the surface, full of dead fish. Since then no fish has been found in the lake. Mr. H—— might probably succeed in dissolving the charm.

“I see you are a fisherman,” said Mr. H——; “you’ll find the parson at Mö, in Butnedal, a few miles off, an ‘ivrig fisker’ (passionate fisherman)—ay! and his lady, too. They’ll be delighted to see you. They have no neighbours, hardly, but peasants, and your visit will confer a greater favour on them than their hospitality on you. That is a very curious valley, sir. There are several ‘tomter’ (sites) of farm-houses, now deserted, where there once were plenty of people: that is one of the vestiges of the Black Death.”

On second thoughts, however, he informed me[47] that it was just possible that Parson S—— might be away; as at this period of the summer, when all the peasants are up with their cattle at the Sæters, the clergy, having nothing whatever to do, take their holiday.

Mine host at Dal—Bernadotte’s prudent benignity—Taxing the bill of costs—Hurrah for the mountains—Whetstones—Antique wooden church—A wild country—“Raven depth”—How the English like to do fine scenery—Ancient wood-carving—A Norwegian peasant’s witticism—A rural rectory—Share and chair alike—Ivory knife-handles—Historical pictures—An old Runic calendar—The heathen leaven still exists in Norway—Washing day—Old names of the Norsk months—Peasant songs—Rustic reserve—A Norsk ballad.

Mine host at Dal, a venerable-looking personage, with long grey hair floating on his shoulders, was a member of the Extraordinary Meeting of Deputies at Eidsvold in 1815, when the Norwegians accepted the Junction with Sweden. I and the old gentleman exchanged cards. The superscription on his was—Gaardbruger Norgaard, Deputeret fra Norges Storthing—i.e., Farmer Norgaard, A Deputy from Norway’s Storthing.

Another reminiscence of his early days is a[49] framed and glazed copy of the Grundlov (Fundamental Law) of Norway, its palladium of national liberty, which a hundred and twelve Deputies drew up in six weeks, in 1814. Never was Constitution so hastily drawn up, and so generally practical and sensible as this.

The Crown Prince, the crafty Bernadotte, with his invading army of Swedes, had Norway quite at his mercy on that occasion; but the idea seems to have struck him suddenly that it was as well not to deal too hardly with her, as in case of his not being able to hold his own in Sweden, he might have a worse place of refuge than among the sturdy Norwegians. “I am resolved what to do, so that when I am put out of the stewardship they may receive me into their houses.” So he assented to Norway’s independence.

For my part, at this moment, I thought more about coffee than Norwegian liberty and politics; but as it was nine o’clock, P.M., the good people were quite put out by the request. Coffee in the forenoon, say they, tea in the evening. As it was, they made me pay pretty smartly for the accommodation[50] next morning. “What’s to pay?” said I, striding into the room, where sat the old Deputy’s daughter, the mistress of the house, at the morning meal. She had not long ago become a widow, and had taken as her second husband, a few days before, a grisly-looking giant, who sat by in his shirt-sleeves.

“Ask him,” said the fair Quickly, thinking it necessary, perhaps, just so recently after taking the vow of obedience, by this little piece of deference to her new lord to express her sense of submission to his authority. For my part, as an old traveller, I should rather say she did it for another feeling. English pigeons did not fly that way every day, and so they must be plucked; and the person to do it, she thought, was the Berserker, her awful-looking spouse. The charge was exorbitant; and as the good folks were regaling themselves with fresh mutton-chops and strawberries and cream, while they had fobbed us off with eggs and black bread and cheese—the latter so sharp that it went like a dagger to my very vitals at the first taste—I resolutely taxed[51] the bill of costs, and carried my point; whereupon we took leave of the Deputy and his descendants.

In one sense we had come to the world’s end; for there is no road for wheels beyond this. The footpath up the steep cliff that looks down upon the lake is only accessible to the nimble horses of the country. “Hurrah!” exclaimed I, as I looked down on the blue lake, lying hundreds of feet perpendicularly below us. “Hurrah for the mountains! Adieu to the ‘boppery bop’ of civilization, with all its forms and ceremonies, and turnpikes and twaddle. Here you can eat, and drink, and dress as and when you like, and that is just the fun of the thing, more than half the relaxation of the trip.” Why, this passion for mountain-travelling over the hills and far away is not peculiar to Englishmen. Don’t the ladies of Teheran, even, after their listless “vie à la pantoufle,” delight to hear of the approach of the plague, as they know they are sure to get off to the hills, and have a little tent-life in consequence? Didn’t that fat boy Buttons (not in Pickwick, but[52] Horace), cloyed with the Priest’s luscious cheesecakes, long for a bit of coarse black bread, and run away from his master to get it?

The precipitous path is studded at intervals with heaps of hones, or whet-stones. I find that about here is the chief manufacture in all Norway for this article. One year, a third of a million were turned out. The next quarry in importance is at Kinservik, on the Hardanger Fjord. Surmounting the ascent, we traverse swampy ground dotted with birch-trees, and presently debouch upon one of those quaint edifices not to be found out of this country—stabskirke (stave church), as it is called—of which Borgund and Hitterdal Churches are well-known specimens. It is so called from the lozenge-shaped shingles (staves), overlapping each other like fish-scales, which case the roof and every part of the outside. Smaller and less pretending than those edifices, this secluded place of worship was of the same age—about nine hundred years. The resinous pine has done its work well, and the carving on the capitals of the wooden pillars at the doorway[53] is in good preservation, though parts have lately been churchwardenized.

“That is Eidsborg church,” said a young student, who had volunteered to accompany me, as he was bound to a lone parsonage up the country, in this direction. “This is the church the young lady on board the steamer told you was so remarkable.”

After making a rough sketch of the exterior, we proceeded on our journey. The few huts around were tenantless, the inhabitants all gone up to the châlets. The blanching bear-skulls on the door of one of these showed the wildness of the country we are traversing; while a black-throated diver, which was busy ducking after the fish in the sedge-margined pool close by, almost tempted me to load, and have a long shot at him. As we proceed, I observe fieldfares, ring-ouzel, and chaff-finches, while many English wild flowers enliven the scene, and delicious strawberries assuage our thirst. Pursuing our path through the forest, we come to a post on which is written “Ravne jüv,” Anglicè, Raven depth.

“Det maa De see,” (you must see that,) said[54] my companion, turning off up a narrow path, and frightening a squirrel and a capercailzie, which were apparently having a confab about things in general. I followed him through the pine-wood, getting over the swampy ground by the aid of some fallen trunks, and, in two or three minutes, came to the “Ravne jüv.” It is made by the Sandok Elv, which here pierces through the mountains, and may be seen fighting its way thousands of feet below us. Where I stood, the cliff was perpendicular, or rather sloped inwards; and, by a singular freak of nature, a regular embrasured battlement had been projected forward, so as to permit of our approaching the giddy verge with perfect impunity.

Lying flat, I put my head through an embrasure, and looked down into the Raven’s depth.

“Ah! it’s deeper than you think,” said my companion. “Watch this piece of wood.”

I counted forty before it reached a landing-place, and that was not above half the way.

Annoyed at our intrusion, two buff-coloured hawks and a large falcon kept flying backwards and forwards within shot, having evidently chosen this frightful precipice as the safest place they could find for their young. Luckily for them, the horse and guide had gone on with my fowling-piece, or they might have descended double-quick into the sable depths below, and become a repast for the ravens; who, as in duty bound, of course frequent the recesses of their namesake, although none were now visible.

What a pity a bit of scenery like this cannot be transported to England. The Norwegians look upon rocks as a perfect nuisance, while we sigh for them. Fancy the Ravne jüv in Derbyshire. Why, we should have Marcus’ excursion-trains every week in the summer, and motley crowds of tourists thronging to have a peep into the dark profound, and some throwing themselves from the top of it, as they used to do from the Monument, and John Stubbs incising his name[56] on the battlements, cutting boldly as the Roman king did at the behests of that humbugging augur; and another true Briton breaking off bits of the parapet, just like those immortal excursionists who rent the Blarney Stone in two. Then there would be a grand hotel close by, and greasy waiters with white chokers, and the nape of their neck shaven as smooth as a vulture’s head (faugh!) and their front and back hair parted in one continuous straight line, just like the wool of my lady’s poodle. How strongly they would recommend to your notice some most trustworthy guide, to show you what you can’t help seeing if you follow your nose, and are not blind—the said trustworthy guide paying him a percentage on all grist thus sent to his mill. Eventually, there would be a high wall erected, and a locked gate, as at the Turk Fall at Killarney, and a shilling to pay for seeing “private property,” &c. &c. No, no! let well alone. Give me the “Raven deep” when it is in the silent solitudes of a Norwegian forest, and let me muse wonderingly, and filled with awe, at the stupendous engineering[57] of Nature, and derive such edification as I may from the sight.

At Sandok we get a fresh horse from the worthy Oiesteen, and some capital beer, which he brings in a wooden quaigh, containing about half a gallon.

On the face of the “loft,” loft or out-house, I see an excellent specimen of wood carving. “That,” said Oiesteen, “has often been pictured by the town people.” All the farm-houses in this part of the country used to be carved in this fashion. One has only to read the Sagas to know why all these old houses no longer exist. It is not that the wood has perished in the natural way; experience, in fact, seems to show that the Norwegian pine is almost as lasting, in ordinary circumstances, as stone, growing harder by age. The truth is, in those fighting days of the Vikings, when one party was at feud with another, he would often march all night when his enemy least expected him, and surrounding the house where he lay, so as to let none escape, set it on fire.

The lad who took charge of the horse next stage was called Björn (Bear), a not uncommon[58] name all over Norway. It was now evening, and chilly.

“Are you cold, Björn?” said the student.

“No; the Björn is never chilly,” was the facetious reply. The nearest approach to a witticism I had ever heard escape the mouth of a Norwegian peasant.

Two or three miles to the right we descry the river descending by a huge cataract from its birthplace among the rocky mountains of Upper Thelemarken. Presently we join what professes to be the high road from Christiania, which is carried some twenty miles further westward, and then suddenly ceases.