The Project Gutenberg EBook of Dorothy South, by George Cary Eggleston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Dorothy South

A Love Story of Virginia Just Before the War

Author: George Cary Eggleston

Illustrator: C. D. Williams

Release Date: May 23, 2016 [EBook #52148]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK Dorothy SOUTH ***

Produced by David Edwards, Chuck Greif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Berwick and Smith

Printers

Norwood, Mass.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | TWO ENCOUNTERS | 11 |

| II. | WYANOKE | 25 |

| III. | DR. ARTHUR BRENT | 36 |

| IV. | DR. BRENT IS PUZZLED | 47 |

| V. | ARTHUR BRENT’S TEMPTATION | 62 |

| VI. | NOW YOU MAY CALL ME DOROTHY | 77 |

| VII. | SHRUB HILL CHURCH | 91 |

| VIII. | A DINNER AT BRANTON | 101 |

| IX. | DOROTHY’S CASE | 117 |

| X. | DOROTHY VOLUNTEERS | 135 |

| XI. | THE WOMAN’S AWAKENING | 150 |

| XII. | MAMMY | 156 |

| XIII. | THE “SONG BALLADS” OF DICK | 166 |

| XIV. | DOROTHY’S AFFAIRS | 175 |

| XV. | DOROTHY’S CHOICE | 184 |

| XVI. | UNDER THE CODE | 191 |

| XVII. | A REVELATION | 199 |

| XVIII. | ALONE IN THE CARRIAGE | 217 |

| XIX. | DOROTHY’S MASTER | 222 |

| XX. | A SPECIAL DELIVERY LETTER | 230 |

| XXI. | HOW A HIGH BRED DAMSEL CONFRONTED FATE, AND DUTY | 237 |

| XXII. | THE INSTITUTION OF THE DUELLO | 253 |

| XXIII. | DOROTHY’S REBELLION | 263 |

| XXIV. | TO GIVE DOROTHY A CHANCE | 270 |

| XXV. | AUNT POLLY’S VIEW OF THE RISKS | 286 |

| XXVI. | AUNT POLLY’S ADVICE | 295 |

| XXVII. | DIANA’S EXALTATION{6} | 306 |

| XXVIII. | THE ADVANCING SHADOW | 314 |

| XXIX. | THE CORRESPONDENCE OF DOROTHY | 322 |

| XXX. | AT SEA | 346 |

| XXXI. | THE VIEWS AND MOODS OF ARTHUR BRENT | 363 |

| XXXII. | THE SHADOW FALLS | 377 |

| XXXIII. | “AT PARIS IT WAS” | 391 |

| XXXIV. | DOROTHY’S DISCOVERY | 404 |

| XXXV. | THE BIRTH OF WAR | 424 |

| XXXVI. | THE OLD DOROTHY AND THE NEW | 429 |

| XXXVII. | AT WYANOKE | 435 |

| XXXVIII. | SOON IN THE MORNING | 441 |

| “Shall we have one of our old-time horseback rides ‘soon’ in the morning, Dorothy?” |

| (Frontispiece.) |

| “Who is your Miss Dorothy?” |

| (Page 17.) |

| “I won’t call you a fool because the Bible says I mustn’t.” |

| (Page 178.) |

| Dorothy South.) |

| (Page 304.) |

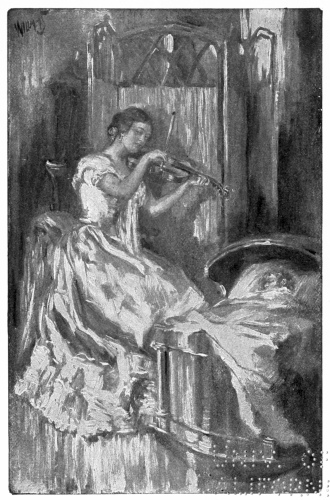

| “In that music my soul laid itself bare to yours and prayed for your love.” |

| (Page 417.) |

| “Aunt Polly!” he said abruptly, “I want your permission to marry Dorothy.”) |

| (Page 452.) |

IT was a perfect day of the kind that Mr. Lowell has celebrated in song—“a day in June.” It was, moreover, a day glorified even beyond Mr. Lowell’s imagining, by the incomparable climate of south side Virginia.

A young man of perhaps seven and twenty, came walking with vigor down the narrow roadway, swinging a stick which he had paused by the wayside to cut. The road ran at this point through a luxuriantly growing woodland, with borders of tangled undergrowth and flowers on either side, and with an orchestra of bird performers all around. The road was a public highway, though it would never have been taken for such in any part of the world except in a south side county of Virginia in the late fifties. It was a narrow track, bearing{12} few traces of any heavier traffic than that of the family carriages in which the gentle, high-born dames and maidens of the time and country were accustomed to make their social rounds.

There was a gate across the carriage track—a gate constructed in accordance with the requirement of the Virginia law that every gate set up across a public highway should be “easily opened by a man on horseback.”

Near the gate the young man slackened his vigorous pace and sat down upon a recently fallen tree. He remembered enough of his boyhood’s experience in Virginia to choose a green log instead of a dry one for his seat. He had had personal encounters with chigoes years ago, and wanted no more of them. He sat down not because he was tired, for he was not in the least so, but simply because, finding himself in the midst of a refreshingly and inspiringly beautiful scene, he desired to enjoy it for a space. Besides, he was in no hurry. Nobody was expecting him, and he knew that dinner would not be served whither he was going until the hour of four—and it was now only a little past nine.

The young man was fair to look upon. A trifle above the medium height, his person was{13} symmetrical and his finely formed head was carried with an ease and grace that suggested the reserve strength of a young bull. His features were about equally marked by vigor and refinement. His was the countenance of a man well bred, who, to his inheritance of good breeding had added education and such culture as books, and earnest thinking, and a favorable association with men of intellect are apt to bring to one worthy to receive the gift.

He seemed to know the spot wherein he lingered. Indeed he had asked no questions as to his way when less than an hour ago he had alighted from the pottering train at the village known as the Court House. He had said to the old station agent, “I will send for my baggage later.” Then he had set off at a brisk walk down one of the many roads that converged at this centre of county life and affairs. The old station master, looking after him, had muttered: “He seems to think he knows his way. Mebbe he does, but anyhow he’s a stranger in these parts.”

And indeed that would have been the instant conclusion of any one who should have looked at him as he sat there by the roadside enjoying the sweet freshness of the morning, and the exquisite abandon with which exuberant{14} nature seemed to mock at the little track made through the tangled woodlands by intrusive man. The youth’s garb betrayed him instantly. In a country where black broadcloth was then the universal wear of gentlemen, our young gentleman was clad in loosely fitting but perfectly shaped white flannels, the trousers slightly turned up to avoid the soil of travel, the short sack coat thrown open, and the full bosomed shirt front of bishop’s lawn or some other such sheer stuff, being completely without a covering of vest. Obviously the young pedestrian did not belong to that part of the world which he seemed to be so greatly enjoying.

That is what Dick thought, when Dick rode up to the gate. Dick was a negro boy of fourteen summers or about that. His face was a bright, intelligent one, and he looked a good deal of the coming athlete as he sat barebacked upon the large roan that served him for steed. Dick wore a shirt and trousers, and nothing else, except a dilapidated straw hat which imperfectly covered his closely cropped wool. His feet were bare, but the young man made mental note of the fact that they bore the appearance of feet accustomed to be washed at least once in every twenty four hours.{15}

“Does your mammy make you wash your feet every night, or do you do it of your own accord?” The question was the young man’s rather informal beginning of a conversation.

“Mammy makes me,” answered the boy, with a look of resentment in his face. “Mammy’s crazy about washin’. She makes me git inter a bar’l o’ suds ev’ry night an’ scrub myself like I was a floor. That’s cause she’s de head washerwoman at Wyanoke. She’s got washin’ on de brain.”

“So you’re one of the Wyanoke people, are you? Whom do you belong to now?”

“I don’t jes’ rightly know, Mahstah”—Dick sounded his a’s like “aw” in “claw.” “I don’t jes’ rightly know, Mahstah. Ole Mas’r he’s done daid, an’ de folks sez a young Yankee mahstah is a comin’ to take position.”

“To take possession, you mean, don’t you?”

“I dunno. Somefin o’ dat sort.”

“Why do you call him a Yankee master?”

“O ’cause he libs at de Norf somewhar. I reckon mebbe he ain’t quite so bad as dat. Dey say he was born in Ferginny, but I reckon he’s done lib in de Norf among the Yankees so long dat he’s done forgit his manners an’ his raisin.”

“What’s your name?” asked the young man, seemingly interested in Dick.{16}

“My name’s Dick, Sah.”

“Dicksah—or Dick?”

“Jes’ Dick, so,” answered the boy.

“Oh! Well, that’s a very good name. It’s short and easy to say.”

“Too easy!” said the boy.

“ ‘Too easy?’ How do you mean?” queried the young man.

“Oh, nuffin’, only it’s allus ‘Dick, do dis!’ ‘Dick do dat.’ ‘Dick go dar,’ ’Dick come heah,’ an’ ‘Dick, Dick, Dick’ all de day long.”

“Then they work you pretty hard do they? You don’t look emaciated.”

“Maishy what, Mahstah?”

“Oh, never mind that. It’s a Chinese word that I was just saying to myself. Do they work you too hard? What do you do?”

“Oh, I don’t do nuffin’ much. Only when I lays down in de sun an’ jes’ begins to git quiet like, Miss Polly she calls me to pick some peas in de gyahden, er Miss Dorothy she says, ‘Dick, come heah an’ help me range dese flowers,’ or Mammy, she says, ‘Dick, you lazy bones, come heah an’ put some wood under my wash biler.’ ”

“But what is your regular work?”

“Reg’lar wuk?” asked the boy, his eyes growing saucer-like in astonishment, “I ain’t{17}

got no reg’lar wuk. I feeds de chickens, sometimes, and fin’s hens’ nests an’ min’s chillun, an’ dribes de tukkeys into de tobacco lots to eat de grasshoppers an’ I goes aftah de mail. Dat’s what I’se a doin’ now. Leastways I’se a comin’ back wid de mail wot I done been an’ gone after.”

“Is that all?”

“Dat’s nuff, ain’t it, Mahstah?”

“I don’t know. I wonder what your new master will think when he comes.”

“Golly, so do I. Anyhow, he’s a Yankee, an’ he won’t know how much wuk a nigga ought to do. I’ll be his pussonal servant, I reckon. Leastways dat’s what Miss Dorothy say she tink.”

“Who is your Miss Dorothy?” the young man asked with badly simulated indifference, for this was a member of the Wyanoke family of whom Dr. Arthur Brent had never before heard.

“Miss Dorothy? Why, she’s jes’ Miss Dorothy, so.”

“But what’s her other name?”

“I dunno. I reckon she ain’t got no other name. Leastways I dunno.”

“Is Wyanoke a fine plantation?”

“Fine, Mahstah? It’s de very finest dey is.{18} It’s all out o-doors and I reckon dey’s a thousand cullud people on it.”

“Oh, hardly that,” answered the young man—“say eight or nine hundred—or perhaps one hundred would be nearer the mark.”

“No, Sir! De Brents is quality folks, Mahstah. Dey’s got more’n a thousan’ niggas, an’ two or three thousan’ horses, an’ as fer cows an’ hawgs you jes’ cawn’t count ’em! Dey eats dinner offen chaney plates every day an’ de forks at Wyanoke is all gold.”

“How many carriages do they keep, Dick?”

“Sebenteen, besides de barouche an’ de carryall.”

“Well, now you’d better be moving on. Your Miss Polly and your Miss Dorothy may be waiting for their letters.”

As the boy rode away, Dr. Arthur Brent resumed his brisk walk. He no longer concerned himself with the landscape, or the woods, or the wild flowers, or the beauty of the June morning, or anything else. He was thinking, and not to much purpose.

“Who the deuce,” he muttered, “can this Miss Dorothy be? Of course I remember dear old Aunt Polly. She has always lived at Wyanoke. But who is Dorothy? As my uncle wasn’t married of course he had no daughter.{19} And besides, if he had, she would be his heir, and I should never have inherited the property at all. I wonder if I have inherited a family, with the land? Psha! Dick invented Miss Dorothy, of course. Why didn’t I think of that? I remember my last stay of a year at Wyanoke, and everything about the place. There was no Dorothy there then, and pretty certainly there is none now. Dick invented her, just as he invented the gold forks, and the thousand negroes, and all those multitudinous horses, carriages, cows and hogs. That black rascal has a creative genius—a trifle ill regulated perhaps, but richly productive. It failed him for the moment when I demanded a second name for Dorothy. But if I had persisted in that line of inquiry he would pretty certainly have endowed the girl with a string of surnames as completely fictitious as the woman herself is. I’ll have some fun out of that boy. He has distinct psychological possibilities.”

Continuing his walk in leisurely fashion like one whose mind is busy with reflection, Dr. Arthur Brent came at last to a great gate at the side of the road—a gate supported by two large pillars of hewn stone, and flanked by a smaller gate intended for the use of foot farers like himself.{20}

“That’s the entrance gate to the plantation,” he reflected. “I had thought it half a mile farther on. Memory has been playing me its usual trick of exaggerating everything remembered from boyhood. I was only fifteen or sixteen when I was last at Wyanoke, and the road seems shorter now than it did then. But this is surely the gate.”

Passing through the wicket, he presently found himself in a forest of young hickory trees. He remembered these as having been scarcely higher than the head of a man on horseback at the time of his last visit. They had been planted by his uncle to beautify the front entrance to the plantation, and, with careful foresting they had abundantly fulfilled that purpose. Growing rather thickly, they had risen to a height of nearly fifty feet, and their boles had swelled to a thickness of eight or ten inches, while all undergrowth of every kind had been carefully suppressed. The tract of land thus timbered by cultivation to replace the original pine forest, embraced perhaps seventy-five or a hundred acres, and the effect of it in a country where forest growths were usually permitted to lead riotous lives of their own, was impressive.

As the young man turned one of the curves{21} of the winding carriage road, four great hounds caught sight of him and instantly set upon him. At that moment a young girl, perched upon a tall chestnut mare galloped into view. Thrusting two fingers of her right hand into her mouth, she whistled shrilly between them, thrice repeating the searching sound. Instantly the huge hounds cowered and slunk away to the side of the girl’s horse. Their evident purpose was to go to heel at once, but their mistress had no mind for that.

“Here!” she cried. “Sit up on your haunches and take your punishment.”

The dogs obediently took the position of humble suppliants, and the girl dealt to each, a sharp cut with the flexible whip she carried slung to her pommel. “Now go to heel, you naughty fellows!” she commanded, and with a stately inclination of her body she swept past the young man, not deigning even to glance in his direction.

“By Jove!” exclaimed Dr. Brent, “that was done as a young queen might have managed it. She saved my life, punished her hounds to secure their future obedience, and barely recognizing my existence—doing even that for her own sake, not mine—galloped away as if this superb day belonged to her!{22} And she isn’t a day over fifteen either.” In that Dr. Brent was mistaken. The girl had passed her sixteenth birthday, three months ago. “I doubt if she is half as long as that graceful riding habit she is wearing.” Then after a moment he said, still talking to himself, “I’ll wager something handsome that that girl is as shy as a fawn. They always are shy when they behave in that queenly, commanding way. The shyer they are the more they affect a stately demeanor.”

Dr. Arthur Brent was a man of a scientific habit of mind. To him everything and everybody was apt to assume somewhat the character of a “specimen.” He observed minutely and generalized boldly, even when his “subject” happened to be a young woman or, as in this case, a slip of a girl. All facts were interesting to him, whether facts of nature or facts of human nature. He was just now as earnest in his speculations concerning the girl he had so oddly encountered, as if she had been a new chemical reaction.

Seating himself by the roadside he tried to recall all the facts concerning her that his hasty glance had enabled him to observe.

“If I were an untrained observer,” he reflected, “I should argue from her stately dignity{23} and the reserve with which she treated me—she being only an unsophisticated young girl who has not lived long enough to ‘adopt’ a manner with malice aforethought—I should argue from her manner that she is a girl highly bred, the daughter of some blue blooded Virginia family, trained from infancy by grand dames, her aunts and that sort of thing, in the fine art of ‘deportment.’ But as I am not an untrained observer, I recall the fact that stage queens do that sort of thing superbly, even when their mothers are washerwomen, and they themselves prefer corned beef and cabbage to truffled game. Still as there are no specimens of that kind down here in Virginia, I am forced to the conclusion that this young Diana is simply the highly bred and carefully dame-nurtured daughter of one of the great plantation owners hereabouts, whose manner has acquired an extra stateliness from her embarrassment and shyness. Girls of fifteen or sixteen don’t know exactly where they stand. They are neither little girls nor young women. They have outgrown the license of the one state without having as yet acquired the liberty of action that belongs to the other.” Thus the youth’s thoughts wandered on. “That girl is a rigid disciplinarian,” he reflected. “How{24} sternly she required those hounds to sit on their haunches and take the punishment due to their sins! I’ll be bound she has herself been set in a corner for many a childish naughtiness. Yet she is not cruel. She struck each dog only a single blow—just punishment enough to secure better manners in future. An ill tempered woman would have lashed them more severely. And a woman less self-controlled would have struck out with her whip without making the dogs sit up and realize the enormity of their offence. A less well-bred girl would have said something to me in apology for her hounds’ misbehavior. This one was sufficiently sensible to see that unless I were a fool—in which case I should have been unworthy of attention—her disciplining of the dogs was apology enough without supplementary speech. I must find out who she is and make her acquaintance.”

Then a sudden thought struck him; “By Jove!” he exclaimed aloud, “I wonder if her name is Dorothy!”

Then the young man walked on.{25}

HALF an hour later Arthur Brent entered the house grounds of Wyanoke—the home of his ancestors for generations past and his own birthplace. The grounds about the mansion were not very large—two acres in extent perhaps—set with giant locust trees that had grown for a century or more in their comfortable surrounding of closely clipped and luxuriant green sward. Only three trees other than the stately locusts, adorned the house grounds. One of these was a huge elm, four feet thick in its stem, with great limbs, branching out in every direction and covering, altogether, a space of nearly a quarter acre of ground, but so high from the earth that the carpet of green sward grew in full luxuriance to the very roots of the stupendous tree. How long that aboriginal monarch had been luxuriating there, the memory of man could make no report. The Wyanoke plantation book, with its curiously minute record of{26} everything that pertained to the family domain, set forth the fact that the “new mansion house”—the one still in use,—was built in the year 1711, and that its southeasterly corner stood “two hundred and thirty nine feet due northwest of the Great Elm which adorns the lawn.” A little later than the time of Arthur Brent’s return, that young man of a scientific mental habit made a survey to determine whether or not the Great Elm of 1859 was certainly the same that had been named “the Great Elm” in 1711. Finding it so he reckoned that the tree must be many hundreds—perhaps even a thousand years of age. For the elm is one of the very slowest growing of trees, and Arthur Brent’s measurements showed that the diameter of this one had increased not more than six inches during the century and a half since it had been accepted as a conspicuous landmark for descriptive use in the plantation book.

The other trees that asked of the huge locusts a license to live upon that lawn, were two quick-growing Asiatic mulberries, planted in comparatively recent times to afford shade to the front porch.

The house was built of wood, heavily framed, large roomed and gambrel roofed. Near it{27} stood the detached kitchen in the edge of the apple orchard, and farther away the quarters of the house servants.

As Arthur Brent strolled up the walk that led to the broad front doors of the mansion his mind was filled with a sense of peace. That was the dominant note of the house and all of its surroundings. The great, self-confident locust trees that had stood still in their places while generations of Brents had come and gone, seemed to counsel rest as the true philosophy of life. The house itself seemed to invite repose. Even the stately peacock that strolled in leisurely laziness beneath the great elm seemed, in his very being, a protest against all haste, all worry, all ambition of action and change.

“I do not know,” thought the young man, as he contemplated the immeasurably restful scene, “what the name Wyanoke signifies in the Indian tongue from which it was borrowed. But surely it ought to mean rest, contentment, calm.”

That thought, and the inspiration of it, were destined to play their part as determinative influences in the life of the young man whose mind was thus impressed. There lay before him, though he was unconscious of the fact, a life struggle between stern conviction and{28} sweet inclination, between duty and impulse, between intensity of mind and lassitude of soul. There were other factors to complicate the problem, but these were its chief terms, and it is the purpose of this chronicle to show in what fashion the matter was wrought out.

Advancing to the porch, Arthur rapped thrice with the stick that he carried. That was because he had passed the major part of his life elsewhere than in Virginia. If such had not been the case he would have interpreted the meaning of the broad open doors aright, and would have walked in without any knocking at all.

As it was, Johnny, the “head dining room servant,” as he was called in Virginia—the butler, as he would have been called elsewhere—heard the unaccustomed sound of knocking, and went to the door to discover what it might mean. To him Arthur handed a visiting card, and said simply: “Your Miss Polly.”

The comely and intelligent serving man was puzzled by the card. He had not the slightest notion of its use or purpose. In his bewilderment he decided that the only thing to be done with it was to take it to his “Miss Polly,” which, of course, was precisely what Arthur Brent desired him to do. There was probably{29} not another visiting card in all that country side—for the Virginians of that time used few formalities, and very simple ones in their social intercourse. They went to visit their friends, not to “call” upon them. Pasteboard politeness was a factor wholly unknown in their lives.

Miss Polly happened to be at that moment in the garden directing old Michael,—the most obstinately obstructive and wilful of gardeners,—to do something to the peas that he was resolutely determined not to do, and to leave something undone to the tomatoes which he was bent upon doing. On receipt of the card, she left Michael to his own devices, and almost hurried to the house. “Almost hurried,” I say, for Miss Polly was much too stately and dignified a person to quicken a footstep upon any occasion.

She was “Miss Polly” to the negro servants. To everybody else she was “Cousin Polly,” or “Aunt Polly,” and she had been that from the period described by the old law writers as “the time whereof the memory of man runneth not to the contrary.” How old she was, nobody knew. She looked elderly in a comfortable, vigorous way. Gray hair was at that time mistakenly regarded as a reproach to women—a{30} sign of advancing age which must be concealed at all costs. Therefore Aunt Polly’s white locks were kept closely shaven, and covered with a richly brown wig. For the rest, she was a plump person of large proportions, though not in the least corpulent. Her dignity was such as became her age and her lineage—which latter was of the very best. She knew her own value, and respected, without aggressively asserting it. She had never been married—unquestionably for reasons of her own—but her single state had brought with it no trace or tinge of bitterness, no suggestion of discontent. She was, and had always been, a woman in perfect health of mind and body, and the fact was apparent to all who came into her comfortable presence.

She had a small but sufficient income of her own, but, being an “unattached female”—as the phrase went at a time when people were too polite to name a woman an “old maid,”—she had lived since early womanhood at Wyanoke; and since the late bachelor owner of the estate, Arthur Brent’s uncle, had come into the inheritance, she had been mistress of the mansion, ruling there with an iron rod of perfect cleanliness and scrupulous neatness, according to housekeeping standards from which she would{31} abate no jot or tittle upon any conceivable account. Fortunately for her servitors, there were about seven of them to every one that was reasonably necessary.

She was a woman of high intelligence and of a pronounced wit,—a wit that sometimes took humorous liberties with the proprieties, to the embarrassment of sensitive young people. She was well read and well informed, but she never did believe that the world was round, her argument being that if such were the case she would be standing on her head half the time. She also refused to believe in railroads. She was confident that “the Yankees” had built railroads through Virginia, with a far seeing purpose of overrunning and conquering that state and possessing themselves of its plantations. Finally, she regarded Virginia as the only state or country in the world in which a person of taste and discretion could consent to be born. Her attitude toward all dwellers beyond the borders of Virginia, closely resembled that of the Greeks toward those whom they self assertively classed as “the barbarians.” How far she really cherished these views, or how far it was merely her humor to assert them, nobody ever found out. To all this she added the sweetest temper and the most unselfish{32} devotion to those about her, that it is possible to imagine. She was very distantly akin to Arthur, if indeed she was akin to him at all. But in his childhood he had learned to call her “Aunt Polly,” and during that year of his boyhood which he had spent at Wyanoke, he had known her by no other title. So when she came through the rear doors to meet him in the great hall which ran through the house from front to rear, he advanced eagerly and lovingly to greet her as “Aunt Polly.”

The first welcome over, Aunt Polly became deeply concerned over the fact that Arthur Brent had walked the five or six miles that lay between the Court House and Wyanoke.

“Why didn’t you get a horse, Arthur, or better still why didn’t you send me word that you were coming? I would have sent the carriage for you.”

“Which one, Aunt Polly?”

“Why, there’s only one, of course.”

“Why, I was credibly informed this morning that there were seventeen carriages here besides the barouche and the carryall.”

“Who could have told you such a thing as that? And then to think of anybody accusing Wyanoke of a ‘carryall!’ ”

“How do you mean, Aunt Polly?”{33}

“Why, no gentleman keeps a carryall. I believe Moses the storekeeper at the Court House has one, but then he has nine children and needs it. Besides he doesn’t count.”

“Why not, Aunt Polly? Isn’t he a man like the rest of us?”

“A man? Yes, but like the rest of us—no. He isn’t a gentleman.”

“Does he misbehave very grossly?”

“Oh, no. He is an excellent man I believe, and his children are as pretty as angels; but, Arthur, he keeps a store.”

Aunt Polly laid a stress upon the final phrase as if that settled the matter beyond even the possibility of further discussion.

“Oh, that’s it, is it?” asked the young man with a smile. “In Virginia no man keeps a carryall unless he is sufficiently depraved to keep a store also. But I wonder why Dick told me we had a carryall at Wyanoke besides the seventeen carriages.”

“Oh, you saw Dick, then? Why didn’t you take his horse and make him get you a saddle somewhere? By the way, Dick had an adventure this morning. Out by the Garland gate he was waylaid by a man dressed all in white ‘jes’ like a ghos’,’ Dick says, with a sword and two pistols. The fellow tried to take the mail{34} bag away from him, but Dick, who is quick-witted, struck him suddenly, made his horse jump the gate, and galloped away.”

“Aunt Polly,” said the young man with a quizzical look on his face, “would you mind sending for Dick to come to me? I very much want to hear his story at first hands, for now that I am to be master of Wyanoke, I don’t intend to tolerate footpads and mail robbers in the neighborhood. Please send for Dick. I want to talk with him.”

Aunt Polly sent, but Dick was nowhere to be found for a time. When at last he was discovered in a fodder loft, and dragged unwillingly into his new master’s presence, the look of consternation on his face was so pitiable that Arthur Brent decided not to torture him quite so severely as he had intended.

“Dick,” he said, “I want you to get me some cherries, will you?”

“ ‘Cou’se I will, Mahstah,” answered the boy, eagerly and turning to escape.

“Wait a minute, Dick. I want you to bring me the cherries on a china plate, and give me one of the gold forks to eat them with. Then go to the carriage-house and have all seventeen of my carriages brought up here for me to look at. Tell the hostlers to send me one or two{35} hundred of the horses, too. There! Go and do as I tell you.”

“What on earth do you mean, Arthur?” asked Aunt Polly, who never had quite understood the whimsical ways of the young man. “I tell you there is only one carriage—”

“Never mind, Aunt Polly. Dick understands me. He and I had an interview out there by the Garland gate this morning. Mail robbers will not trouble him again, I fancy, now that his ‘Yankee Master’ is ‘in position,’ as he puts it. But please, Aunt Polly, send some one with a wagon to the Court House after my trunks.”{36}

ARTHUR BRENT had been born at Wyanoke, twenty seven years or so before the time of our story. His father, one of a pair of brothers, was a man imbued with the convictions of the Revolutionary period—the convictions that prompted the Virginians of that time to regard slavery as an inherited curse to be got rid of in the speediest possible way compatible with the public welfare. There were still many such Virginians at that time. They were men who knew the history of their state and respected the teachings of the fathers. They remembered how earnestly Thomas Jefferson had insisted upon writing into Virginia’s deed of cession of the North West Territory, a clause forever prohibiting slavery in all the fair “Ohio Country”—now constituting Indiana, Illinois and the other great states of the Middle West. They held in honor, as their fathers before them had{37} done, the memory of Chancellor George Wythe, who had well-nigh impoverished himself in freeing the negroes he had inherited and giving them a little start in the world. They were the men to whom Henry Clay made confident appeal in that effort to secure the gradual extirpation of the system which was the first and was repeated as very nearly the last of his labors of statesmanship.

These men had no sympathy or tolerance for “abolitionist” movements. They desired and intended that slavery should cease, and many of them impoverished themselves in their efforts to be personally rid of it. But they resented as an impertinence every suggestion of interference with it on the part of the national government, or on the part of the dwellers in other states.

For these men accepted, as fully as the men of Massachusetts once did, the doctrine that every state was sovereign except in so far as it had delegated certain functions of sovereignty to the general government. They held it to be the absolute right of each state to regulate its domestic affairs in its own way, and they were ready to resent and resist all attempts at outside interference with their state’s institutions, precisely as they would have resisted and resented{38} the interference of anybody with the ordering of their personal households.

Arthur Brent’s father, Brandon Brent, was a man of this type. Upon coming of age and soon afterwards marrying, he determined, as he formulated his thought, to “set himself free.” When Arthur was born he became more resolute than ever in this purpose, under the added stimulus of affection for his child. “The system” he said to his wife, “is hurtful to young white men, I do not intend that Arthur shall grow up in the midst of it.”

So he sold to his brother his half interest in the four or five thousand acres which constituted Wyanoke plantation, and with the proceeds removed those of the negroes who had fallen to his share to little farms which he had bought for them in Indiana.

This left him with a wife, a son, and a few hundred dollars with which to begin life anew. He went West and engaged in the practice of the law. He literally “grew up with the country.” He won sufficient distinction to represent his district in Congress for several successive terms, and to leave behind him when he died a sweetly savored name for all the higher virtues of honorable manhood.

He left to his son also, a fair patrimony, the{39} fruit of his personal labors in his profession, and of the growth of the western country in which he lived.

At the age of fifteen, the boy had been sent to pass a delightful year at Wyanoke, while fitting himself for college under the care of the same tutor who had personally trained the father, and whose influence had been so good that the father invoked it for his son in his turn. The old schoolmaster had long since given up his school, but when Brandon Brent had written to him a letter, attributing to his influence and teaching all that was best in his own life’s success, and begging him to crown his useful life’s labors with a like service to this his boy, he had given up his ease and undertaken the task.

Arthur had finished his college course, and was just beginning, with extraordinary enthusiasm, his study of medicine when his father died, leaving him alone in the world; for the good mother had passed away while the boy was yet a mere child.

After his father’s death, Arthur found many business affairs to arrange. Attention to these seriously distracted him, greatly to his annoyance, for he had become an enthusiast for scientific acquirement, and grudged every moment{40} of time that affairs occupied to the neglect of his studies. In this mood of irritation with business details, the young man decided to convert the whole of his inheritance into cash and to invest the proceeds in annuities. “I shall never marry,” he told himself. “I shall devote my whole life to science. I shall need only a moderate income to provide for my wants, but that income must come to me without the distraction of mind incident to the earning of it. I must be completely a free man—free to live my own life and pursue my own purposes.”

So he invested all that he had in American and English annuity companies, and when that business was completed, he found himself secure in an income, not by any means large but quite sufficient for all his needs, and assured to him for all the years that he might live. “I shall leave nothing behind me when I die,” he reflected, “but I shall have nobody to provide for, and so this is altogether best.”

Then he set himself to work in almost terrible earnest. He lived in the laboratories, the hospitals, the clinics and the libraries. When his degree as a physician was granted his knowledge of science, quite outside the ordinary range of medical study was deemed extraordinary by his professors. A place of honor in one of{41} the great medical colleges was offered to him, but he declined it, and went to Germany and France instead. He had fairly well mastered the languages of those two countries, and he was minded now to go thither for instruction, under the great masters in biology and chemistry and physics.

Two years later—and four years before the beginning of this story, there came to Arthur Brent an opportunity of heroic service which he promptly embraced. There broke out, in Norfolk, in his native state, in the year 1855, such an epidemic of yellow fever as had rarely been known anywhere before, and it found a population peculiarly susceptible to the subtle poison of the scourge.

Facing the fact that he was in no way immune, the young physician abandoned the work he had returned from Paris to New York to do, and went at once to the post of danger as a volunteer for medical service. Those whose memories stretch back to that terrible year of 1855, remember the terms in which Virginia and all the country echoed the praises of Dr. Arthur Brent, the plaudits that everywhere greeted his heroic devotion. The newspapers day by day were filled with despatches telling with what tireless devotion this mere boy—he{42} was scarcely more than twenty three years of age—was toiling night and day at his self appointed task, and how beneficent his work was proving to be. The same newspapers told with scorching scorn of physicians and clergymen—a very few of either profession, but still a few—who had quitted their posts in panic fear and run away from the danger. Day by day the readers of the newspapers eagerly scanned the despatches, anxious chiefly to learn that the young hero had not fallen a victim to his own compassionate enthusiasm for the relief of the stricken.

Dr. Arthur Brent knew nothing of all this at the time. His days and nights were too fully occupied with his perilous work for him even to glance at a newspaper. He was himself stricken at last, but not until the last, not until that grand old Virginian, Henry A. Wise had converted his Accomac plantation into a relief camp and, arming his negroes for its defence against a panic stricken public, had robbed the scourge of its terrors by drawing from the city all those whose presence there could afford opportunity for its spread.

Dr. Arthur Brent was among the very last of those attacked by the scourge, and it was to give that young hero a meagre chance for life{43} that Henry A. Wise went in person to Norfolk and brought the physician away to his own plantation home, in armed and resolute defiance alike of quarantine restrictions and of the protests of an angry and frightened mob.

Such in brief had been the life story of Arthur Brent. On his recovery from a terribly severe attack of the fever, he had gone again to Europe, not this time for scientific study, but for the purpose of restoring his shattered constitution through rest upon a Swiss mountain side. After a year of upbuilding idleness, he had returned to New York with his health completely restored.

There he had taken an inexpensive apartment, and resumed his work of scientific investigation upon lines which he had thought out during his long sojourn in Switzerland.

Three years later there came to him news that his uncle at Wyanoke was dead, and that the family estate had become his own as the only next of kin. It pleased Arthur’s sense of humor to think of a failure of “kin” in Virginia, where, as he well remembered, pretty nearly everybody he had met in boyhood had been his cousin.

But the news that he was sole heir to the family estate was not altogether agreeable to{44} the young man. “It will involve me in affairs again,” he said to himself, “and that is what I meant should never happen to me. There is a debt on the estate, of course. I never heard of a Virginia estate without that adornment. Then there are the negroes, whose welfare is in my charge. Heaven knows I do not want them or their value. But obviously they and the debt saddle me with a duty which I cannot escape. I suppose I must go to Wyanoke. It is very provoking, just as I have made all my arrangements to study the problem of sewer gas poisoning with a reasonable hope of solving it this summer!”

He thought long and earnestly before deciding what course to pursue. On the one hand he felt that his highest duty in life was to science as a servant of humanity. He realized, as few men do, how great a beneficence the discovery of a scientific fact may be to all mankind. “And there are so few men,” he said to himself, “who are free as I am to pursue investigations untrammeled by other things—the care of a family, the ordering of a household, the education of children, the earning of a living! If I could have this summer free, I believe I could find out how to deal with sewer gas, and that would save thousands of lives and immeasurable{45} suffering! And there are my other investigations that are not less pressing in their importance. Why should I have to give up my work, for which I have the equipment of a thorough training, a sufficient income, youth, high health, and last but not least, enthusiasm?”

He did not add, as a less modest man might, that he had earned a reputation which commanded not only the attention but the willing assistance of his scientific brethren in his work, that all laboratories were open to him, that all men of science were ready to respond to his requests for the assistance of their personal observation and experience, that the columns of all scientific journals were freely his to use in setting forth his conclusions and the facts upon which they rested.

“I wish I could put the whole thing into the hands of an agent, and bid him sell out the estate, pay off the debts and send me the remainder of the proceeds, with which to endow a chair of research in some scientific school! But that would mean selling the negroes, and I’ll never do that. I wish I could set them all free and rid myself of responsibility for them. But I cannot do that unless I can get enough money out of the estate to buy little farms for them as my father did with his negroes. I mustn’t{46} condemn them to starvation and call it freedom. I wish I knew what the debt is, and how much the land will bring. Then I could plan what to do. But as I do not know anything of the kind, I simply must go to Wyanoke and study the problem as it is. It will take all summer and perhaps longer. But there is nothing else for it.”

That is how it came about that Dr. Arthur Brent sat in the great hallway at Wyanoke, talking with Aunt Polly, when Dorothy South returned, accompanied by her hounds.{47}

DOROTHY came up to the front gate at a light gallop. Disdaining the assistance of the horse block, she nimbly sprang from the saddle to the ground and called to her mare “Stand, Chestnut!”

Then she gathered up the excessively long riding skirt which the Amazons of that time always wore on horseback, and walked up the pathway to the door, leaving the horse to await the coming of a stable boy. Arthur could not help observing and admiring the fact that she walked with marked dignity and grace even in a riding skirt—a thing so exceedingly difficult to do that not one woman in a score could accomplish it even with conscious effort. Yet this mere girl did it, manifestly without either effort or consciousness. As an accomplished anatomist Dr. Brent knew why. “That girl has grown up,” he said to himself, “in as perfect a freedom as those locust trees out there, enjoy. She is as straight as the straightest of{48} them, and she has perfect use of all her muscles. I wonder who she is, and why she gives orders here at Wyanoke quite as if she belonged to the place, or the place belonged to her.”

This last thought was suggested by the fact that just before mounting the two steps that led to the porch, Dorothy had whistled through her fingers and said to the negro man who answered her call:—“Take the hounds to the kennels, and fasten them in. Turn the setters out.”

But the young man had little time for wondering. The girl came into the hall, and, as Aunt Polly had gone to order a little “snack,” she introduced herself.

“You are Dr. Brent, I think? Yes? well, I’m Dorothy South. Let me bid you welcome as the new master of Wyanoke.”

With that she shook hands in a fashion that was quite child-like, and tripped away up the stairs.

Arthur Brent found himself greatly interested in the girl. She was hardly a woman, and yet she was scarcely to be classed as a child. In her manner as well as in her appearance she seemed a sort of compromise between the two. She was certainly not pretty, yet Arthur’s quick scrutiny informed him that in a year or two{49} she was going to be beautiful. It only needed a little further ripening of her womanhood to work that change. But as one cannot very well fall in love with a woman who is yet to be, Arthur Brent felt no suggestion of other sentiment than one of pleased admiration for the girl, mingled with respect for her queenly premature dignity. He observed, however, that her hair was nut brown and of luxuriant growth, her complexion, fair and clear in spite of a pronounced tan, and her eyes large, deep blue and finely overarched by their dark brows.

Before he had time to think further concerning her, Aunt Polly returned and asked him to “snack.”

“Dorothy will be down presently,” she said. “She’s quick at changing her costume.”

Arthur was about to ask, “Who is Dorothy? And how does she come to be here?” but at that moment the girl herself came in, white gowned and as fresh of face as a newly blown rose is at sunrise.

“It’s too bad, Aunt Polly,” she said, “that you had to order the snack. I ought to have got home in time to do my duty, and I would, only that Trump behaved badly—Trump is one of my dogs, Doctor—and led the others into mischief. He ran after a hare, and, of course,{50} I had to stop and discipline him. That made me late.”

“You keep your dogs under good control Miss—by the way how am I to call you?”

“I don’t know just yet,” answered the girl with the frankness of a little child.

“How so?” asked Arthur, as he laid a dainty slice of cold ham on her plate.

“Why, don’t you see, I don’t know you yet. After we get acquainted I’ll tell you how to call me. I think I am going to like you, and if I do, you are to call me Dorothy. But of course I can’t tell yet. Maybe I shall not like you at all, and then—well, we’ll wait and see.”

“Very well,” answered the young master of the plantation, amused by the girl’s extraordinary candor and simplicity. “I’ll call you Miss South till you make up your mind about liking or detesting me.”

“Oh, no, not that,” the girl quickly answered. “That would be too grown up. But you might say ‘Miss Dorothy,’ please, till I make up my mind about you.”

“Very well, Miss Dorothy. Allow me to express a sincere hope that after you have come to know what sort of person I am, you’ll like me well enough to bid me drop the handle to your name.”{51}

“But why should you care whether a girl like me likes you or not?”

“Why, because I am very strongly disposed to like a girl like you.”

“How can you feel that way, when you don’t know me the least little bit?”

“But I do know you a good deal more than ‘the least little bit,’ ” answered the young man smiling.

“How can that be? I don’t understand.”

“Perhaps not, and yet it is simple enough. You see I have been training my mind and my eyes and my ears and all the rest of me all my life, into habits of quick and accurate observation, and so I see more at a glance than I should otherwise see in an hour. For example, you’ll admit that I have had no good chance to become acquainted with your hounds, yet I know that one of them has lost a single joint from his tail, and another had a bur inside one of his ears this morning, which you have since removed.”

The girl laid down her fork in something like consternation.

“But I shan’t like you at all if you see things in that way. I’ll never dare come into your presence.”

“Oh, yes, you will. I do not observe for{52} the purpose of criticising; especially I never criticise a woman or a girl to her detriment.”

“That is very gallant, at any rate,” answered the girl, accenting the word “gallant” strongly on the second syllable, as all Virginians of that time properly did, and as few other people ever do. “But tell me what you started to say, please?”

“What was it?”

“Why, you said you knew me a good deal. I thought you were going to tell me what you knew about me.”

“Well, I’ll tell you part of what I know. I know that you have a low pitched voice—a contralto it would be called in musical nomenclature. It has no jar in it—it is rich and full and sweet, and while you always speak softly, your voice is easily heard. I should say that you sing.”

“No. I must not sing.”

“Must not? How is that?”

The girl seemed embarrassed—almost pained. The young man, seeing this, apologized:

“Pardon me! I did not mean to ask a personal question.”

“Never mind!” said the girl. “You were not unkind. But I must not sing, and I must never learn a note of music, and worst of all{53} I must not go to places where they play fine music. If I ever get to liking you very well indeed, perhaps I’ll tell you why—at least all the why of it that I know myself—for I know only a little about it. Now tell me what else you know about me. You see you were wrong this time.”

“Yes, in a way. Never mind that. I know that you are a rigid disciplinarian. You keep your hounds under a sharp control.”

“Oh, I must do that. They would eat somebody up if I didn’t. Besides it is good for them. You see dogs and women need strict control. A mistress will do for dogs, but every woman needs a master.”

The girl said this as simply and earnestly as she might have said that all growing plants need water and sunshine. Arthur was astonished at the utterance, delivered, as it was, in the manner of one who speaks the veriest truism.

“Now,” he responded, “I have encountered something in you that I not only do not understand but cannot even guess at. Where did you learn that cynical philosophy?”

“Do you mean what I said about dogs?”

“No. Though ‘cynic’ means a dog. I mean what you said about women. Where did{54} you get the notion that every woman needs a master?”

“Why, anybody can see that,” answered the girl. “Every girl’s father or brother is her master till she grows up and marries. Then her husband is her master. Women are always very bad if they haven’t masters, and even when they mean to be good, they make a sad mess of their lives if they have nobody to control them.”

If this slip of a girl had talked Greek or Sanscrit or the differential calculus at him, Arthur could not have been more astounded than he was. Surely a girl so young, so fresh, and so obviously wholesome of mind could never have formulated such a philosophy of life for herself, even had she been thrown all her days into the most complex of conditions and surroundings, instead of leading the simplest of lives as this girl had manifestly done, and seeing only other living like her own. But he forbore to question her, lest he trespass again upon delicate ground, as he had done with respect to music. He was quick to remember that he had already asked her where she had learned her philosophy, and that she had nimbly evaded the question—defending her philosophy as a thing obvious to the mind, instead of answering{55} the inquiry as to whence she had drawn the teaching.

Altogether, Arthur Brent’s mind was in a whirl as he left the luncheon table. Simple as she seemed and transparent as her personality appeared to him to be, the girl’s attitude of mind seemed inexplicable even to his practised understanding. Her very presence in the house was a puzzle, for Aunt Polly had offered no explanation of the fact that she seemed to belong there, not as a guest but as a member of the household, and even as one exercising authority there. For not only had the girl apologized for leaving Aunt Polly to order the luncheon, but at table and after the meal was finished, it was she, and not the elder woman who gave directions to the servants, who seemed accustomed to think of her as the source of authority, and finally, as she withdrew from the dining room, she turned to Arthur and said:

“Doctor, it is the custom at Wyanoke to dine at four o’clock. Shall I have dinner served at that hour, or do you wish it changed?”

The young man declared his wish that the traditions of the house should be preserved, adding playfully—“I doubt if you could change the dinner hour, Miss Dorothy, even if we all desired it so. I remember Aunt Kizzey, the{56} cook, and I for one should hesitate to oppose my will to her conservatism.”

“Oh, as to that,” answered the girl, “I never have any trouble managing the servants. They know me too well for that.”

“What could you do if you told Kizzey to serve dinner at three and she refused?” asked the young man, really curious to hear the answer.

“I would send for Aunt Kizzey to come to me. Then I would look at her. After that she would do as I bade her.”

“I verily believe she would,” said the young man to himself as he went to the sideboard and filled one of the long stemmed pipes. “But I really cannot understand why.”

He had scarcely finished his pipe when Dorothy came into the hall accompanied by a negro girl of about fourteen years, who bore a work basket with her. Seating herself, Dorothy gave the girl some instruction concerning the knitting she had been doing, and added: “You may sit in the back porch to-day. It is warm.”

“Is it too warm, Miss Dorothy, for you to make a little excursion with me to the stables?”

“Certainly not,” she quickly answered. “I’ll go at once.”

“Thank you,” he said, “and we’ll stop in{57} the orchard on our way back and get some June apples. I remember where the trees are.”

“You want me to show you the horses, I suppose,” she said as the two set off side by side.

“No; any of the negroes could do that. I want you to render me a more skilled service.”

“What is it?”

“I want you, please, to pick out a horse for me to ride while I stay at Wyanoke.”

“While you stay at Wyanoke!” echoed the girl. “Why, that will be for all the time, of course.”

“I hardly think so,” answered the young man, with a touch of not altogether pleased uncertainty in his tone. “You see I have important work to do, which I cannot do anywhere but in a great city—or at any rate,”—as the glamour of the easy, polished and altogether delightful contentment of Virginia life came over him anew, and its attractiveness sang like a siren in his ears,—“at any rate it cannot be so well done anywhere else as in a large city. I have come down here to Virginia only to see what duties I have to do here. If I find I can finish them in a few months or a year, I shall go back to my more important work.”{58}

The girl was silent for a time, as if pondering his words. Finally she said:

“Is there anything more important than to look after your estate? You see I don’t understand things very well.”

“Perhaps it is best that you never shall,” he answered. “And to most men the task of looking after an ancestral estate, and managing a plantation with more than a hundred negroes—”

“There are a hundred and eighty seven in all, if you count big and little, old and young together,” broke in the girl.

“Are there? How did you come to know the figures so precisely?”

“Why, I keep the plantation book, you know.”

“I didn’t know,” he answered.

“Yes,” she said, “I’ve kept it ever since I came to Wyanoke three or four years ago. You see your uncle didn’t like to bother with details, and so I took this off his hands, when I was so young that I wrote a great big, sprawling hand and spelled my words ever so queerly. But I wanted to help Uncle Robert. You see I liked him. If you’d rather keep the plantation book yourself, I’ll give it up to you when we go back to the house.”{59}

“I would much rather have you keep it, at least until you make up your mind whether you like me or not. Then, if you don’t like me I’ll take the book.”

“Very well,” she replied, treating his reference to her present uncertainty of mind concerning himself quite as she might have treated his reference to a weather contingency of the morrow or of the next week. “I’ll go on with the book till then.”

By this time the pair had reached the stables, and Miss Dorothy, in that low, soft but penetrating voice which Arthur had observed and admired, called to a negro man who was dozing within:

“Ben, your master wants to see the best of the saddle horses. Bring them out, do you hear?”

The question “do you hear?” with which she ended her command was one in universal use in Virginia. If an order were given to a negro without that admonitory tag to it, it would fall idly upon heedless ears. But the moment the negro heard that question he gathered his wits together and obeyed the order.

“What sort of a horse do you like, Doctor?” asked the girl as the animals were led forth. “Can you ride?”{60}

“Why, of course,” he answered. “You know I spent a year in Virginia when I was a boy.”

“Oh, yes, of course—if you haven’t forgotten. Then you don’t mind if a horse is spirited and a trifle hard to manage?”

“No. On the contrary, Miss Dorothy, I should very much mind if my riding horse were not spirited, and as for managing him, I’m going to get you to teach me the art of command, as you practise it so well on your dogs, your horse and the house servants.”

“Very well,” answered the girl seeming not to heed the implied compliment. “Put the horses back in their stalls, Ben, and go over to Pocahontas right away, and tell the overseer there to send Gimlet over to me. Do you hear? You see, Doctor,” she added, turning to him, “your uncle’s gout prevented him from riding much during the last year or so of his life, and so there are no saddle horses here fit for a strong man like you. There’s one fine mare, four years old, but she’s hardly big enough to carry your weight. You must weigh a hundred and sixty pounds, don’t you?”

“Yes, about that. But whose horse is Gimlet?”

“He’s mine, and he’ll suit you I’m sure. He{61} is five years old, nearly seventeen hands high and as strong as a young ox.”

“But are you going to sell him to me?”

“Sell him? No, of course not. He is my pet. He has eaten out of my hand ever since he was a colt, and I was the first person that ever sat on his back. Besides, I wouldn’t sell a horse to you. I’m going to lend him to you till—till I make up my mind. Then, if I like you I’ll give him to you. If I don’t like you I’ll send him back to Pocahontas. Hurry up, Ben. Ride the gray mare and lead Gimlet back, do you hear?”

“You are very kind to me, Miss Dorothy, and I—”

“Oh, no. I’m only polite and neighborly. You see Wyanoke and Pocahontas are adjoining plantations. There comes Jo with your trunks, so we shall not have time for the June apples to-day—or may be we might stop long enough to get just a few, couldn’t we?”

With that she took the young man’s hand as a little girl of ten might have done, and skipping by his side, led the way into the orchard. The thought of the June apples seemed to have awakened the child side of her nature, completely banishing the womanly dignity for the time being.{62}

DURING the next three or four days Arthur was too much engaged with affairs and social duties to pursue his scientific study of the young girl—half woman, half child—with anything like the eagerness he would have shown had his leisure been that of the Virginians round about him. He had much to do, to “find out where he stood,” as he put the matter. He had with him for two days Col. Majors the lawyer, who had the estate’s affairs in charge. That comfortable personage assured the young man that the property was “in good shape” but that assurance did not satisfy a man accustomed to inquire into minute details of fact and to rest content only with exact answers to his inquiries.

“I will arrange everything for you,” said the lawyer; “the will gives you everything and it has already been probated. It makes you sole executor with no bonds, as well as sole{63} inheritor of the estate. There is really nothing for you to do but hang up your hat. You take your late uncle’s place, that is all.”

“But there are debts,” suggested Arthur.

“Oh, yes, but they are trifling and the estate is a very rich one. None of your creditors will bother you.”

“But I do not intend to remain in debt,” said the young man impatiently. “Besides, I do not intend to remain a planter all my life. I have other work to do in the world. This inheritance is a burden to me, and I mean to be rid of it as soon as possible.”

“Allow me to suggest,” said the lawyer in his self-possessed way, “that the inheritance of Wyanoke is a sort of burden that most men at your time of life would very cheerfully take upon their shoulders.”

“Very probably,” answered Arthur. “But as I happen not to be ‘most men at my time of life’ it distinctly oppresses me. It loads me with duties that are not congenial to me. It requires my attention at a time when I very greatly desire to give my attention to something which I regard as of more importance than the growing of wheat and tobacco and corn.”

“Every one to his taste,” answered the lawyer,{64} “but I confess I do not see what better a young man could do than sit down here at Wyanoke and, without any but pleasurable activities, enjoy all that life has to give. Your income will be large, and your credit quite beyond question. You can buy whatever you want, and you need never bother yourself with a business detail. No dun will ever beset your door. If any creditor of yours should happen to want his money, as none will, you can borrow enough to pay him without even going to Richmond to arrange the matter. I will attend to all such things for you, as I did for your late uncle.”

“Thank you very much,” Arthur answered in a tone which suggested that he did not thank him at all. “But I always tie my own shoe strings. I do not know whether I shall go on living here or not, whether I shall give up my work and my ambitions and settle down into a life of inglorious ease, or whether I shall be strong enough to put that temptation aside. I confess it is a temptation. Accustomed as I am to intensity of intellectual endeavor, I confess that the prospect of sitting down here in lavish plenty, and living a life unburdened by care and unvexed by any sense of exacting duty, has its allurements for me. I suppose,{65} indeed, that any well ordered mind would find abundant satisfaction in such a life programme, and perhaps I shall presently find myself growing content with it. But if I do, I shall not consent to live in debt.”

“But everybody has his debts—everybody who has an estate. It is part of the property, as it were. Of course it would be uncomfortable to owe more than you could pay, but you are abundantly able to owe your debts, so you need not let them trouble you. All told they do not amount to the value of ten or a dozen field hands.”

“But I shall never sell my negroes.”

“Of course not. No gentleman in Virginia ever does that, unless a negro turns criminal and must be sent south, or unless nominal sales are made between the heirs of an estate, simply by way of distributing the property. Far be it from me to suggest such a thing. I meant only to show you how unnecessary it is for you to concern yourself about the trifling obligations on your estate—how small a ratio they bear to the value of the property.”

“I quite understand,” answered Arthur. “But at the same time these debts do trouble me and will go on troubling me till the last dollar of them is discharged. This is simply{66} because they interfere with the plans I have formed—or at least am forming—for so ordering my affairs that I may go back to my work. Pray do not let us discuss the matter further. I will ask you, instead, to send me, at your earliest convenience, an exact schedule of the creditors of this estate, together with the amount—principal and interest—that is owing to each. I intend to make it my first business to discharge all these obligations. Till that is done, I am not my own master, and I have a decided prejudice in favor of being able to order my own life in my own way.”

Behind all this lay the fact that Arthur Brent was growing dissatisfied with himself and suspicious of himself. The beauty and calm of Wyanoke, the picturesque contentment of that refined Virginia life which was impressed anew upon his mind every time a neighboring planter rode over to take breakfast, dinner, or supper with him, or drove over in the afternoon with his wife and daughters to welcome the new master of the plantation—all this fascinated his mind and appealed strongly to the partially developed æsthetic side of his nature, and at times the strong, earnest manhood in him resented the fact almost with bitterness.

There was never anywhere in America a{67} country life like that of Virginia in the period before the war. In that state, as nowhere else on this continent, the refinement, the culture, the education and the graceful social life of the time were found not in the towns, but in the country. There were few cities in the state and they were small. They existed chiefly for the purpose of transacting business for the more highly placed and more highly cultivated planters. The people of the cities, with exceptions that only emphasized the general truth, were inferior to the dwellers on the plantations, in point of education, culture and social position. It had always been so in Virginia. From the days of William Byrd of Westover to those of Washington, and Jefferson and Madison and John Marshall, and from their time to the middle of the nineteenth century, it had been the choice of all cultivated Virginians to live upon their plantations. Thence had always come the scholars, the statesmen, the great lawyers and the masterful political writers who had conferred untold lustre upon the state.

Washington’s career as military chieftain and statesman, had been one long sacrifice of his desire to lead the planter life at Mount Vernon. Jefferson’s heart was at Monticello while he penned the Declaration of Independence, and{68} it was the proud boast of Madison that he like Jefferson, quitted public office poorer than he was when he undertook such service to his native land, and rejoiced in his return to the planter life of his choice at Montpélièr.

In brief, the entire history of the state and all its traditions, all its institutions, all its habits of thought tended to commend the country life to men of refined mind, and to make of the plantation owners and their families a distinctly recognized aristocracy, not only of social prestige but even more of education, refinement and intellectual leadership.

To Arthur Brent had come the opportunity to make himself at once and without effort, a conspicuous member of this blue blooded caste. His plantation had come to him, not by vulgar purchase, but by inheritance. It had been the home of his ancestors, the possession and seat of his family for more than two hundred years. And his family had been from the first one of distinction and high influence. One of his great, great, great grandfathers, had been a member of the Jamestown settlement and a soldier under John Smith. His great, great grandfather had shared the honor of royal proscription as an active participant in Bacon’s rebellion. His great grandfather had been the{69} companion of young George Washington in his perilous expeditions to “the Ohio country,” and had fallen by Washington’s side in Braddock’s blundering campaign. His grandfather had been a drummer boy at Yorktown, had later become one of the great jurists of the state and had been a distinguished soldier in the war of 1812. His father, as we know, had strayed away to the west, as so many Virginians of his time did, but he had won honors there which made Virginia proud of him. And fortunately for Arthur Brent, that father’s removal to the west was not made until this his son had been born at the old family seat.

“For,” explained Aunt Polly to the young man, in her own confident way, “in spite of your travels, you are a native Virginian, Arthur, and when you have dropped into the ways of the country, people will overlook the fact that you have lived so much at the north, and even in Europe.”

“But why, Aunt Polly,” asked Arthur, “should that fact be deemed something to be ‘overlooked?’ Surely travel broadens one’s views and—”

“Oh, yes, of course, in the case of people not born in Virginia. But a Virginian doesn’t need{70} it, and it upsets his ideas. You see when a Virginian travels he forgets what is best. He actually grows like other people. You yourself show the ill effects of it in a hundred ways. Of course you haven’t quite lost your character as a Virginian, and you’ll gradually come back to it here at Wyanoke; but ‘evil communications corrupt good manners,’ and I can’t help seeing it in you—at least in your speech. You don’t pronounce your words correctly. You say ‘cart’ ‘carpet’ and ‘garden’ instead of ‘cyart’ ‘cyarpet’ and ‘gyarden.’ And you flatten your a’s dreadfully. You say ‘grass’ instead of ‘grawss’ and ‘basket’ instead of ‘bawsket’ and all that sort of thing. And you roll your r’s dreadfully. It gives me a chill whenever I hear you say ‘master’ instead of ‘mahstah.’ But you’ll soon get over that, and in the meantime, as you were born in Virginia and are the head of an old Virginia family, the gentlemen and ladies who are coming every day to welcome you, are very kind about it. They overlook it, as your misfortune, rather than your fault.”

“That is certainly very kind of them, Aunt Polly. I can’t imagine anything more generous in the mind than that. But—well, never mind.”{71}

“What were you going to say, Arthur?”

“Oh, nothing of any consequence. I was only thinking that perhaps my Virginia neighbors do not lay so much stress upon these things as you do.”

“Of course not. That is one of the troubles of this time. Since we let the Yankees build railroads through Virginia, everybody here wants to travel. Why, half the gentlemen in this county have been to New York!”

“How very shocking!” said Arthur, hiding his smile behind his hand.

“That’s really what made the trouble for poor Dorothy,” mused Aunt Polly. “If her father hadn’t gone gadding about—he even went to Europe you know—Dorothy never would have been born.”

“How fortunate that would have been! But tell me about it, Aunt Polly. You see I don’t quite understand in what way it would have been better for Dorothy not to have been born—unless we accept the pessimist philosophy, and consider all human life a curse.”

“Now you know, I don’t understand that sort of talk, Arthur,” answered Aunt Polly. “I never studied philosophy or chemistry, and I’m glad of it. But I know it would have been better for Dorothy if Dr. South had stayed{72} at home like a reasonable man, and married—but there, I mustn’t talk of that. Dorothy is a dear girl, and I’m fitting her for her position in life as well as I can. If I could stop her from thinking, now, or—”

“Pray don’t, Aunt Polly! Her thinking interests me more than anything I ever studied,—except perhaps the strange and even inexplicable therapeutic effect of champagne in yellow fever—”

“There you go again, with your outlandish words, which you know I don’t understand or want to understand, though sometimes I remember them.”

“Tell me of an instance, Aunt Polly.”

“Why, you said to me the other night that Dorothy was a ‘psychological enigma’ to your mind, and that you very much wished you might know ‘the conditions of heredity and environment’ that had produced ‘so strange a phenomenon.’ There! I remember your words, though I haven’t the slightest notion what they mean. I went upstairs and wrote them down. Of course I couldn’t spell them except in my own way—and that would make you laugh I reckon if you could see it, which you never shall—but I haven’t a glimmering notion of what{73} the words mean. Now I want to tell you about Dorothy.”

“Good! I am anxious to hear!”

“Oh, I’m not going to tell you what you want to hear. That would be gossip, and no Virginia woman ever gossips.”

That was true. The Virginians of that time, men and women alike, locked their lips and held their tongues in leash whenever the temptation came to them to discuss the personal affairs of their neighbors. They were bravely free and frank of speech when telling men to their faces what opinions they might hold concerning them; but they did that only when necessity, or honor, or the vindication of truth compelled. They never made the character or conduct or affairs of each other a subject of conversation. It was the very crux of honor to avoid that.

“Then tell me what you are minded to reveal, Aunt Polly,” responded Arthur. “I do not care to know anything else.”

“Well, Dorothy is in a peculiar position—not by her own fault. She must marry into a good family, and it has fallen to me to prepare her for her fate.”

“Surely, Aunt Polly,” interjected the young man with a shocked and distressed tone in his{74} voice, “surely you are not teaching that child to think of marriage—yet?”

“No, no, no!” answered Aunt Polly. “I’m only trying to train her to submissiveness of mind, so that when the time comes for her to make the marriage that is already arranged for her, she will interpose no foolish objections. It’s a hard task. The girl has a wilful way of thinking for herself. I can’t cure her of it, do what I will.”

“Why should you try?” asked Arthur, almost with excitement in his tone. “Why should you try to spoil nature’s fine handiwork? That child’s intellectual attitude is the very best I ever saw in one so young, so simple and so childlike. For heaven’s sake, let her alone! Let her live her own life and think in her own honest, candid and fearless way, and she will develop into a womanhood as noble as any that the world has seen since Eve persuaded Adam to eat of the tree of knowledge and quit being a fool.”

“Arthur, you shock me!”

“I’m sorry, Aunt Polly, but I shall shock you far worse than that, if you persist in your effort to warp and pervert that child’s nature to fit it to some preconceived purpose of conventionality.”{75}

“I don’t know just what you mean, Arthur,” responded the old lady, “but I know my duty, and I’m going to do it. The one thing necessary in Dorothy’s case, is to stop her from thinking, and train her to settle down, when the time comes, into the life of a Virginia matron. It is her only salvation.”

“Salvation from what?” asked Arthur, almost angrily.

“I can’t tell you,” the old lady answered. “But the girl will never settle into her proper place if she goes on thinking, as she does now. So I’m going to stop it.”

“And I,” the young man thought, though he did not say it, “am going to teach her to think more than ever. I’ll educate that child so long as I am condemned to lead this idle life. I’ll make it my business to see that her mind shall not be put into a corset, that her extraordinary truthfulness shall not be taught to tell lies by indirection, that she shall not be restrained of her natural and healthful development. It will be worth while to play the part of idle plantation owner for a year or two, to accomplish a task like that. I can never learn to feel any profound interest in the growing of tobacco, wheat and corn—but the cultivation of that child into what she should be is a nobler work{76} than that of all the agriculturists of the south side put together. I’ll make it my task while I am kept here away from my life’s chosen work.”

That day Arthur Brent sent a letter to New York. In it he ordered his library and the contents of his laboratory sent to him at Wyanoke. He ordered also a good many books that were not already in his library. He sent for a carpenter on that same day, and set him at work in a hurry, constructing a building of his own designing upon a spot selected especially with reference to drainage, light and other requirements of a laboratory. He even sent to Richmond for a plumber to put in chemical sinks, drain pipes and other laboratory fittings.{77}