LEARN ONE THING

EVERY DAY

APRIL 1 1916

SERIAL No. 104

THE

MENTOR

GREAT GALLERIES

OF THE WORLD

THE NATIONAL

GALLERY

LONDON

By Professor

JOHN C. VAN DYKE

DEPARTMENT OF

FINE ARTS

VOLUME 4

NUMBER 4

FIFTEEN CENTS A COPY

“Knowledge gives power,” says the philosopher. “Knowledge enriches,” says the scholar. But the practical individual exclaims: “Special expert knowledge is a personal asset, but how does general knowledge enrich?”

“Knowledge makes life fuller and more interesting.” And what does that mean? It means that life, through knowledge, may be made a joy and a blessing in spite of what the cynics say. It means that through knowledge we learn to appraise things at their true value. Our eyes are opened to see other colors than purple and gold, our ears to hear understandingly other sounds than the roar of traffic, the shriek of an automobile horn, or syncopated music. Knowledge reveals to us the nicer shades of color that give us quiet satisfaction—the finer and gentler tones of Nature and of human life that afford us a lasting enjoyment. It teaches us that there are things more “worth while” than ourselves.

Why do some of us ignore fine art, dismiss good books with indifference, yawn at good music, speed through a ravishing landscape at sixty miles an hour, and neglect a friendship that would bring us self-improvement? The sky and mountains have a thousand messages for us, if we pause to listen to them. The sea is an oracle if we study it. A good book is a mine of information if we search it. A fine painting is an inspiration if we cherish it. Good music is a constant joy if we give attention to it. And the voices of our fellow creatures are filled with precious confidences if we give our ears and hearts to them.

Let us then seek knowledge with the eager mind of a child; for indeed, as Robert Louis Stevenson sang:

National Gallery, London

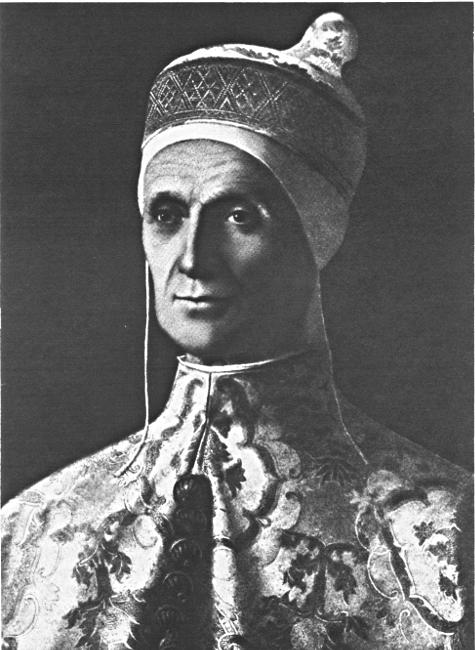

THE DOGE LOREDANO. By Giovanni Bellini

THE NATIONAL GALLERY

Monograph Number One in The Mentor Reading Course

There were three famous painters in the Bellini family. Jacopo Bellini was the father, and his two sons were Gentile and Giovanni (Jo-van´-nee), the latter being the younger and the greater.

He is supposed to have been born at Venice either in 1430 or 1431, and was brought up in his father’s house, serving with his brother as his father’s assistant until he was nearly thirty years old. However, Giovanni seems to have been influenced more by his brother-in-law, Mantegna, than by his father. This influence lasted until Mantegna departed for the Court of Mantua in 1460. In 1470 Giovanni was commissioned to paint a Deluge with Noah’s Ark. After this he painted many pictures, among them the famous altar-piece for the Church of S. Giovanni e Paolo, which was destroyed by a disastrous fire in 1867, along with Titian’s “Peter Martyr” and “The Crucifixion” by Tintoretto.

After 1480 a great deal of Giovanni’s time and energy was taken up by his duties as conservator of the paintings in the great hall of the Ducal Palace at Venice. His duties were to repair and renew the works of his predecessors. In addition, he was commissioned to paint a number of new subjects himself. These pictures illustrated the part played by Venice in the wars of Barbarossa. The works were much admired, but none of them survived the fire of 1577.

About the end of the year 1505 Giovanni painted the portrait of the Doge Loredano. This is the only portrait of his which has been preserved. It is one of the most masterly in the whole range of painting. Loredano was the man who carried the Venetian republic through the most trying period of its existence. He became the doge, or ruler, in 1501. France and Spain combined in an attempt to destroy his power, but in vain. This firm man fought hard, although Venice was impoverished and deprived of many of its possessions.

The last ten or twelve years of Bellini’s life were filled with more commissions than he could handle. Albrecht Dürer, the famous German painter, visited Venice for a second time in 1506. He reported that Bellini was still the best painter in the city, and he also spoke of the hospitality and courtesy of the artist. Bellini died in 1516.

As pupils he had many of the most famous artists of his time. Two of them, in fact, surpassed him later on—Giorgione and Titian. Bellini may be called the true founder of Venetian painting.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 4, No. 4, SERIAL No. 104

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

National Gallery, London

ARIOSTO. By Titian

THE NATIONAL GALLERY

Monograph Number Two in The Mentor Reading Course

One day a great emperor was watching an artist paint, when one of the painter’s brushes rolled to the floor. The king stooped and picked up the brush, saying as he did so, “It becomes Caesar to serve Titian.”

It was in such esteem that the Emperor Charles V held the great artist. “There are many princes, but there is only one Titian,” he said.

During the ninety-nine years of the life of Tiziano Vecello, or Titian (Tish-en), as he is known today, some of the greatest events in the history of mankind took place. The year that he was born, 1477, at Cadore in Italy, the first dated English book was printed on the press of William Caxton. When Titian was fifteen Columbus discovered America. Hardly twenty-five years later Charles V, King of Spain, was crowned Emperor of most of Europe. Then came the Reformation, with Luther as its leader, and toward the end of the artist’s life the great revolt of the Netherlands which freed them forever from the dominion of Spain. Living in such stirring times, it was natural that Titian gave to the world art that combined many truths of a universal nature.

Titian first studied at Venice. Giovanni Bellini, the great Venetian master, was one of his teachers. Later on Titian formed a partnership with Giorgione, the famous Italian painter. Albrecht Dürer, who visited Venice after Giorgione died, also made a great impression on Titian.

Titian’s style formed itself early. He was famous before the age of thirty. From this time on he lived in princely style, surrounded by friends, and with honors and commissions from all sides. He was considered the greatest portrait painter living; and he never let up in his work—he was still a powerful artist when most men fail in strength.

Lodovico Ariosto, the Italian poet, was one of Titian’s friends. This man was born at Reggio, in Lombardy, on September 8, 1474. He inclined strongly to poetry from his earliest years; but his father made him study law. At last, however, he was allowed to follow his inclination and overjoyed, he threw himself heartily into the study of the classics. He worked hard, but when his father died he was compelled to give up literature to manage his family, whose affairs were in a poor way.

But he managed to write at this time some comedies and prose, and a few lyrical pieces. Later on he was more successful, particularly when a brother of the Cardinal Ippolito d’Este took him under his patronage. He not only distinguished himself as a poet, but also as a diplomatist.

There is a story told of Ariosto that when walking one day in a deserted spot he fell in with bandits. They took him captive, but discovering that he was the author of “Orlando Furioso,” they humbly apologized for not having shown him the respect due him.

Ariosto spent the last part of his life at Ferrara, writing comedies, and correcting his “Orlando Furioso,” of which the complete edition was published only a year before his death, which occurred on June 6, 1533.

This was Titian’s friend and the man whose portrait is reproduced herewith. The great artist did not spend his last years in happiness. He lost his daughter, Lavinia, who had been his model for many beautiful pictures. Most of his companions had passed away. His son, Pomponio, was a worthless profligate; his son, Orazio, however, attended his father with true affection. In 1575 the plague struck Venice. The following year Titian was stricken. He died on August 27, and was buried with great honor in the Church of St. Maria dei Frari, for which he had painted his famous picture of the “Assumption.”

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 4, No. 4, SERIAL No. 104

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

National Gallery, London

THE DUCHESS OF MILAN. By Hans Holbein

THE NATIONAL GALLERY

Monograph Number Three in The Mentor Reading Course

It was at the end of the fifteenth century, about 1495, that one of the greatest geniuses in German painting was born at Augsburg. He is known as Hans Holbein the Younger, as his father is called Hans Holbein the Elder, for he too was an excellent artist.

Hans and his brother, Ambrosius, worked under Holbein the Elder until 1516. They undoubtedly helped their father on his pictures. Later the two brothers went to Basel, where Hans met his powerful patron, Jacob Meier, who commissioned him to paint a picture which is now considered one of his greatest works, “The Meier Madonna.”

In 1517 Hans Holbein left Basel for two years. He is supposed to have visited Italy in his travels, returning to Basel in 1519. There he met the learned Erasmus, whose friendship he gained. He also made a number of sketches for his book, “Praise of Folly.” Jacob Meier still continued to be his patron and turned many commissions his way. The artist at this time designed stained glass, decorated furniture, and illustrated books. His best illustrations were the drawings for the book “The Dance of Death.” These are supposed to have been made sometime before 1527.

It is as a portrait painter that Hans Holbein is best known. It was his fame as such that brought him to England in 1526, where he spent most of the last years of his life. To England Holbein had brought letters of introduction from Erasmus to Sir Thomas More. Through this gentleman he received many commissions. About 1536 he was appointed by Henry VIII “King’s Painter” with a salary of thirty-four pounds a year (in value today about $850) and rooms in the palace.

The last part of Hans Holbein’s life is enveloped in mystery. In 1543 the dreaded plague broke out in London once more. The city was still a dirty, crowded town of the Middle Ages. The streets were narrow and the houses and little shops were set close together. Consequently, London was just the kind of a city in which the plague might take its terrible course unchecked. On the 7th of October, 1543, Holbein made his will. This was found some years ago in London. Not long after making his will the great artist died. No one knows the details of his death, nor the place of his burial.

But though Holbein was dead, his works lived on. They are known and valued today as those of few other artists. He belongs among the immortals of German art.

His portrait of the “Duchess of Milan” is a marvel of beauty in its exquisite simplicity of rendering. “Both paint and painter are forgotten in looking at a work like this; you see only the incarnate spirit, and feel its very sphere. Though the woman is really not beautiful, her expression is fascinating in the highest degree. The rich brown eyes, with the yellow ring immediately around the pupil, seem to admit you to the secrets of her thoughts, and the full pouting lips irresistibly command admiration.”

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 4, No. 4, SERIAL No. 104

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

National Gallery, London

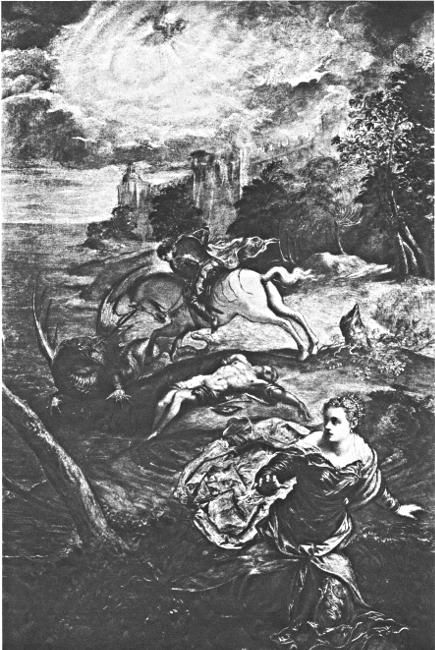

SAINT GEORGE AND THE DRAGON. By Tintoretto

THE NATIONAL GALLERY

Monograph Number Four in The Mentor Reading Course

Tintoretto was called by his contemporaries “Il Furioso,” or “the furious.” This was because of the passionate, fiery style which marked his work.

His real name was Jacopo Robusti. He received his nickname from the fact that his father was a dyer, or Tintore. Jacopo used to help him, and so they called him Tintoretto, or “little dyer.”

He was born in Venice in 1518. Even as a child he daubed pictures on the walls of his father’s dye house. His father soon noticed this, and took him around to the studio of Titian, to see if he could be trained as an artist. The famous old painter agreed to attempt it, but Jacopo had only been ten days in the studio when Titian sent him home for good. It is said that the great master did this out of jealousy, believing that the boy might become his rival. However, it may be fairer to presume that Titian really did not think that the young dyer would ever become an artist. It is a well-known fact, however, that Titian was a bad teacher.

Then Tintoretto began studying for himself. He obtained small copies of Michelangelo’s sculptures and drew from them as models. He worked night and day at this.

Many disappointments blocked his path. Titian dictated the public work among the painters of Venice, and he invariably passed by Tintoretto. Therefore, the young artist in order to make himself known, undertook to do great works without pay. He neglected no order, however humble, and he chose his subjects from all sources.

It was not until he was thirty years old that he received a commission to paint in the Ducal Palace in Venice—the desire of his heart. Hard times were then over for him. He married Faustina de’Vescovi, the daughter of a Venetian nobleman. She was a careful housewife and an excellent companion for her impetuous husband.

The next important event in Tintoretto’s life was the decoration of the Scuola di St. Marco. This was in 1560. About thirty years later he did the crowning production of his life. This was the huge “Paradise.” It is seventy-four feet by thirty feet, and is said to be the largest painting ever done upon canvas.

After the completion of this picture Tintoretto rested for awhile. Thereafter he never undertook any work of importance. In 1594 he was seized with an attack of sickness, and he died on May 31.

His daughter, Marietta, was also a portrait painter of some note. She died at the age of thirty, and Tintoretto grieved for her greatly. It is said that he painted her portrait as she lay dead.

Tintoretto hardly ever traveled out of Venice. He liked music, and as a youth played the lute and other instruments, some of which he invented himself. He liked to design theatrical costumes. He was an agreeable companion, but as he was a hard worker he lived a rather retired life, hardly admitting any, even his intimate friends, to his presence.

It is said that when the artist left the house his wife wrapped up money for him in a handkerchief. On his return she made him tell how it had been spent.

There are a number of Tintoretto’s works in England, among them being the spirited work “St. George and the Dragon.” He had few pupils.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 4, No. 4, SERIAL No. 104

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

National Gallery, London

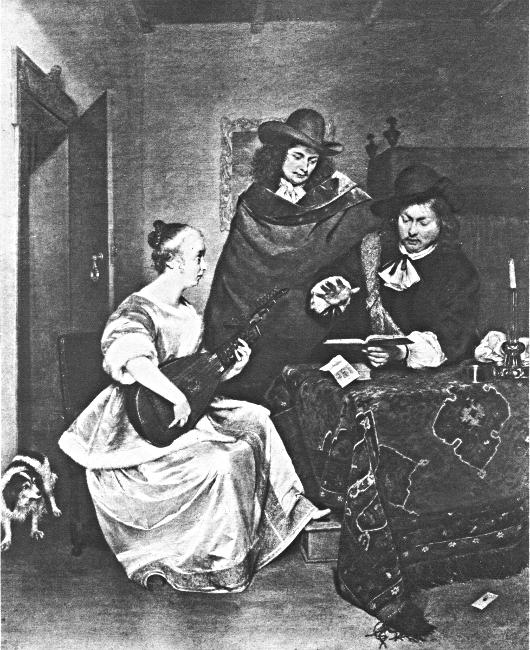

THE GUITAR LESSON. By Gerard Ter Borch

THE NATIONAL GALLERY

Monograph Number Five in The Mentor Reading Course

One of the most famous of the “Little Masters” of Holland was Gerard Ter Borch, or Terburg, as he is sometimes called. This artist, whose pictures are always full of color, loved to paint brilliant cloths and dazzling jewelry. His paintings are pictures pure and simple.

Ter Borch was born at Zwolle, Holland, in 1617. His father, who was also an artist, gave him a good education and developed the youth’s talent very early. The boy evidently was in Amsterdam in 1632, studying under C. Duyster or possibly P. Codde. Duyster’s influence can be traced in a picture bearing the date of 1638. Before this picture was painted, however, in 1634, he studied under Pieter Molyn in Haarlem.

About 1635 Ter Borch went to London and later on he traveled extensively in Germany, France, Spain and Italy. In 1641 he painted some small portraits on copper in Rome. Seven years later he was at Münster during the meeting of the congress which ratified the treaty of peace between Spain and the Netherlands. It was there that he did his famous little picture on copper of the assembled ministers. This picture, together with the “Guitar Lesson” and a “Portrait of a Man Standing,” is now in the National Gallery. The picture of the peace commissioners was bought by the Marquess of Hertford for $36,400, and presented to the gallery by Sir Richard Wallace.

About this time Ter Borch was invited to visit Madrid in Spain. There King Phillip IV gave him employment and honored him with knighthood. However, the artist became involved in an intrigue and was forced to return to Holland.

There he lived for a time at Haarlem. Later on he finally settled in Deventer, where he became a member of the town council. It is as a member of this body that he appears in the portrait now in the Gallery of the Hague. Ter Borch died at Deventer in 1681.

Some critics rank this artist very close to Rembrandt and Franz Hals. He liked to portray the higher social circles of his day with all the stately pomp that distinguished them. This took delicate technical skill in the representation of costly costumes, and in addition to all this, Ter Borch was able to give a poetic charm to the interior of the houses which he portrayed, throwing romantic interest over anything.

The paintings of Ter Borch are quite rare. Only about eighty have been catalogued. His work is free from the touch of grossness that characterized many of the Dutch artists of the time.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 4, No. 4, SERIAL No. 104

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

National Gallery, London

LADY COCKBURN AND CHILDREN. By Sir Joshua Reynolds

THE NATIONAL GALLERY

Monograph Number Six in The Mentor Reading Course

Sir Joshua Reynolds was one of the greatest of English portrait painters; and as a painter of childhood he has no superior. He was a rapid worker, and it is estimated by some authorities that he finished as many as 3,000 portraits. His career was one long series of successes, and he made an immense fortune by his painting.

Reynolds was born in Devonshire, England, on July 16, 1723. Thomas Hudson was his first teacher. Then the young artist visited Italy. There he studied carefully the works of the old masters. He returned to London and almost immediately was accorded first place among the portrait painters of the day. At the same time he became one of the leading members of the famous Literary Club, among whose members were Doctor Samuel Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith, the authors, David Garrick, the leading actor of the time, and other men prominent in the fields of art and letters.

The British Royal Academy was founded in 1768, and its first president was Reynolds. There he distinguished himself by delivering his famous “Discourses” on art. With these he proved himself to be as much a master of words as of the brush.

Reynolds’ success and prosperity naturally made his less fortunate rivals jealous of him; at the same time his attitude towards some of them was not altogether generous. In particular his relations with Gainsborough were not pleasant. Nevertheless, Reynolds went to Gainsborough’s deathbed, and there was an apparent reconciliation.

In 1784, at the death of Ramsay, Reynolds was appointed painter to the king. Two years before a stroke of paralysis had attacked him; but he was able to resume his painting after a month of rest. In the summer of 1789, however, his sight began to fail. Nevertheless, he continued to practise his art until about the end of 1790. But from then on he began to sink gradually. He suffered for only a few months, and on February 23, 1792, passed peacefully away.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, though a great artist, lacked academic education, and therefore he never could draw the human figure properly. He sacrificed this ability to secure a thorough knowledge of the great paintings of the world, their faults and their excellencies.

He also had a tendency to tamper with his pigments. It is said that one day the famous American artist, Gilbert Stuart, was copying one of Reynolds’ fine heads in a very warm room. Suddenly he noticed that one eye on the painting seemed to be moving downward. At first he thought his imagination was playing him false; but finally he was convinced that the eye was moving. He quickly removed the painting to a cold room, and gradually worked the eye back in place. It was then that he discovered that his great predecessor had used wax in his pigments. This explained something that had baffled artists for years—the brilliant transparency of many of Reynolds’ colors.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 4, No. 4, SERIAL No. 104

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

By JOHN C. VAN DYKE, Professor of the History of Art, Rutgers College

MENTOR GRAVURES

THE DOGE LOREDANO

By Giovanni Bellini

ARIOSTO

By Titian

THE DUCHESS OF MILAN

By Hans Holbein

MENTOR GRAVURES

SAINT GEORGE AND THE DRAGON

By Tintoretto

THE GUITAR LESSON

By Gerard Terborch

LADY COCKBURN AND CHILDREN

By Sir Joshua Reynolds

The National Gallery

Entered at the postoffice at New York, N. Y., as second-class matter. Copyright, 1916, by The Mentor Association, Inc.

THE MENTOR · DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS

APRIL 1, 1916

The National Gallery, whether the tourist sees it first or last in his trip around Europe, is sure to make an impression. It is one of the famous galleries of the world, and has a rarefied atmosphere about it, even to those who know the galleries by heart. The walk up the wide stone steps approaching the first room excites a wonder that is almost amazement. The pictures have a richness—a jewel quality about them—that seems preternaturally splendid. You have not perhaps noticed such depth and mellowness of color in other galleries. What does it mean? Well, in some cases it may mean merely that the pictures are framed under glass, and get a certain tone and richness from that; but it more often means that you are looking at very unusual pictures. The National Gallery is full of masterpieces.

THE VIRGIN AND CHILD, SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST AND SAINT NICHOLAS OF BARI

By Raphael

SAINT HELENA—THE VISION OF THE CROSS

By Paolo Veronese (vay-ro-nay´-zee)

Where did they come from? Out of the famous private collections of England. When nobility dies without an heir, or the heir himself needs money, then the pictures collected by the art-loving elders of perhaps a dozen generations come by bequest to the National Gallery, or find their way to the auction room and are purchased for the gallery. Thus it is that the National Gallery has been the natural inheritor of the rich collections of England. It started less than a hundred years ago (in 1824) with the Angerstein collection, and has been growing ever since with gifts of collections such as those of Vernon, Wynn Ellis, Vaughan, Salting. If it is found necessary to bid for a picture at auction, a government grant or the subscriptions of wealthy art patrons, or both, generally carries the day against any private collector. Thus such famous pictures as Raphael’s “Ansidei Madonna,” Titian’s (tish´-an) “Ariosto,” Holbein’s “Duchess of Milan” were bought for the gallery at enormous prices—the Raphael bringing over $350,000, and the others some $150,000 each.

There are now about 3000 pictures in the gallery, though, of course, all of them are not hung at any one time. There is not enough wall space for that, though the building is in a chronic state of enlargement. New rooms are added from year to year, and new editions of the catalogue are being continually issued. The gallery is very well arranged and lighted, and very well managed. Management of a gallery seems very easy to the public because there is apparently no friction, but the director has his trials. And the pictures have their perils, not only from accidents, but from fanatical visitors. The greatest perils however, are from dust, gas, the tooth of time, and the hand of the careless cleaner. The pictures in the European galleries have suffered more from drastic scrubbing and reckless restoration than from all the other causes combined. The cleaning room has been the graveyard of many a masterpiece.

Beyond doubt the Italian pictures here are the most important, both in quality and in quantity. No gallery in Europe quite equals that of London in its Renaissance masterpieces. And its Pre-Renaissance pictures are not to be despised. Of their kind nothing could be finer than the altar-piece by Orcagna (or-can´-ya) and the panels of Duccio (doo´-cho) or Monaco; but they are not carried so far, or so effectively, as the works of the later men—the “Doge Loredano” by Bellini, for example. Bellini is not the final word in art, but how perfect of its kind is this portrait of the Doge (doje) with its serene poise and supreme dignity! How devoid of anything like ostentation or display! And how direct it is in the revelation of the stern old warrior, who, when Doge of Venice, did not hesitate to wage war against France, Germany, and the Papacy—all three together. There are a number of attractive Madonnas by Bellini in the gallery, and an “Agony in the Garden” with a famous landscape at the back; but none of them quite comes up to the Doge in force or conviction of reality.

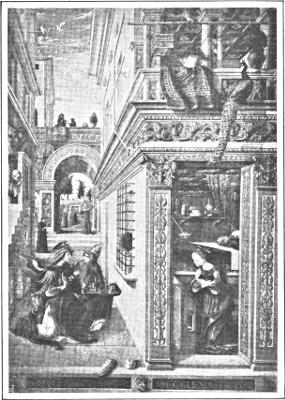

THE ANNUNCIATION

By Carlo Crivelli

In the same vein, but with less nobility and more detail, is the “Portrait of a Young Man” by Antonello da Messina and the “Young Venetian” by Basaiti—(ba-sa-ee´-tee) both contemporaries of Bellini in Venice. They were not his equals, however. Basaiti was his follower, as was also Catena, who is represented here by a large “Warrior Adoring the Infant Christ”—a notable picture for Catena. Among the early Venetians in the gallery Crivelli makes a distinct impression. There are half a dozen altarpieces by him, and one hesitates to say which is the best, so very perfect in workmanship are all of them. The “Annunciation” is perhaps the type, and for pure decorative charm few pictures go beyond it. The architecture of it, the rugs, curtains, bedspread, costumes, even the peacock and the children, are all put in for color effect and to carry out the scheme of making the picture beautiful to look at, as well as interesting in story. It fairly reeks with color. Crivelli’s pictures are the most brilliant and the best preserved in surface of any of the early Venetian works; and, oddly enough, they are all painted, not in oil, but in distemper—the medium used before the introduction of oil. It was the Antonello da Messina mentioned above who is credited with bringing oil-painting to Venice about 1470, but Crivelli declined to use it.

Bellini was as famous for his pupils as for his work, he having been the master, or the influencer, of almost all the great Venetians. Giorgione (Jor-jo´-nee) and Titian were his direct pupils, and the difference between the portrait of the “Doge Loredano” and the portrait of “Ariosto” by Titian is the difference between master and pupil. Both portraits are reproduced herewith in photogravure, and the student has a good opportunity to compare them. Bellini belonged to the Early and Titian to the High Renaissance, and, in a measure, the portraits emphasize a difference in time, though they may have been painted in the same year. Bellini lived to be old—lived into the High Renaissance—and must have painted this portrait after 1501, when Loredano became Doge; Titian was young, and probably painted the “Ariosto” about 1508; but the style of the one is early, the style of the other late. The “Doge” has great dignity, but with it rigidity of poise, sharpness of line, paucity of light and shade, thinness of color. It is emphatic rather than insinuating, and a little awkward in its positive truth. The “Ariosto,” on the contrary, is superb in its easy graceful poise, its inherent nobility of look, its perfect repose. The workmanship of it is infallibly right in its composition, its full light and shade, and its gamut of greys, browns and flesh colors. Compare the drawings of the robes for the difference between the men, and other differences will make themselves manifest. Both portraits are excellent, but they are by no means alike in point of view or method.

A YOUNG LADY AT A SPINET

By Jan Vermeer

PORTRAIT OF A TAILOR

By Giambattista Moroni

A MAN’S PORTRAIT

By Jan Van Eyck

Titian was perhaps the master-painter of the craft in Italy, and the “Ariosto” is not his only masterpiece in the National Gallery. There is an early “Madonna” and a “Christ and the Magdalen,” both of them excellent, and yet giving way in interest to his large “Ariadne and Bacchus,” the most considerable of his figure pictures north of the Alps. It is a little cold in its blue color, but perfect in workmanship, and a marvel of life and movement. Tintoretto’s “St. George and the Dragon” is a romantic canvas that in life and spirit presses the Titian very hard. It is not possible to pick flaws in it, which cannot be said about every Tintoretto. The charging St. George, the hurrying princess, the dead body, the sea, the sky, the distance, are quite as they should be. And what a beautiful piece of color! Tintoretto was a genius of exalted rank, as was also Paolo Veronese, some of whose best canvases are here—notably the large “Family of Darius at the Feet of Alexander.”

The “St. Helena” (reproduced herewith) is put down to Paolo in the catalogue, and, though it may not be by him, is, nevertheless, a fine picture in decorative arrangement and color. Lotto in a superb “Family Group” and Paris Bordone (bor-do´-nee) in the “Portrait of a Lady,” of a patrician type, are both extremely well represented in the gallery; but perhaps they do not attract so much attention as a more commonplace portraitist—Moroni. The reason of this is that the National Gallery has two of the very best works by Moroni—the “Tailor” and the “Lawyer.” The “Tailor” is very much admired, and justly so. He is shown standing at his cutting board, shears in hand, and as the door opens he looks up to see who has entered. What a very natural action! And what a serene, even noble, type of man! The portrait is modern enough in method to have been done today, only there is no painter of today who could do it. It is not, however, in the class with the Titian “Ariosto.” Compare them and you will see that intellectually the Titian is the more profound, as technically it is the more subtle.

“CHAPEAU DE PAILLE”

This portrait, known as “The Straw Hat,” by Peter Paul Rubens, is of Suzanne Fourment, his wife’s sister

The Florentines never had the fine color sense of the Venetians, but from that you will not infer that they never painted fine pictures. They were different from the Venetians, were more intellectual or romantic or pathetic, cared more for linear drawing than for light, shade or color. The Botticellis in the gallery illustrate this distinction. There are a number of them, and they all carry by pathetic sentiment or romance, and exhibit linear drawing primarily. The famous “Mars and Venus” shows the drawing and the “Nativity,” the sentiment. The round picture of the “Madonna, Child and St. John,” shown in the illustrations, is a school piece, but gives the Botticelli pathos in the girlish types and the sad faces. Do you notice how cleverly the circle is filled with lines and forms? Filippino, contemporary of Botticelli, (botte-chél-lee) and much influenced by him, has here an altar-piece that is admired and copied by students as it deserves to be; and put down to Lorenzo di Credi is a portrait of “Costanza de Medici” that is supremely fine not only in color but in character. An early Florentine, Paolo Uccello, (Oo-chél-lo) famous for his study of perspective, is here shown in his masterpiece, “The Rout of San Romano,” and Antonio and Piero Pollajuolo (pol-la-you-oh´-lo) by the “St. Sebastian,” their most important work. These are only the pictures that may justly be called great masterpieces. It is astonishing what a list may be made. The list should include the two wonderful panels by Piero della Francesca—the very noblest kind of fine art,—all the pictures by Cosimo Tura, the “Madonna” by Verrocchio, (ver-ro´-kee-o) though it is merely a school piece, the “Agony in the Garden” by Mantegna, and many another panel by Fra Filippo, or Pisanello, or Benozzo.

THE VIRGIN AND CHILD

By Sandro Botticelli

The Florentine trio—Michelangelo, Raphael and Leonardo—are represented here in rather dubious examples. The two Michelangelos are school pieces, though very good work, and the genuineness of the Leonardo da Vinci (vín-chee) “Madonna of the Rocks” is disputed by a similar picture in the Louvre. The London picture has much beauty about it, and no doubt Leonardo had some hand in its production, but he was probably assisted in it by a pupil. As for Raphael, there are several pictures assigned to him, but none of them gives much of an idea of that great artist. The “Ansidei Madonna” cost a great deal of money, and has renown; but it is a thin, cold work of Raphael’s youth. If you would see Raphael and judge him justly, you must go to Florence and Rome. Florence, too, is the proper place to see painters such as Andrea del Sarto, while Perugia is the spot for Perugino, and Parma for Correggio (kor-red´-jo). One’s opinion of an Italian painter is not to be formed from seeing one or more isolated examples of him in the northern galleries.

PORTRAIT OF AN OLD LADY

By Rembrandt

Among the Early Flemish painters there is nothing finer than the Arnolfini portraits by Jan Van Eyck, the pathetic “Deposition” by Bouts, or the two large panels by Gerard David (dah´-veed). Work of a similar nature is shown by Gerard of Haarlem (Geertgen tot Sint Jans) in his “Madonna and Child.” It is delicate, miniature-like work, and not painting in any Hals or Velasquez sense; but done with tremendous earnestness and sincerity and without a slip or flaw technically. A much later man, Gossart (or Mabuse) tried to elaborate the miniature method of the early men, and apply it to large canvases. The result is here shown in the large “Adoration of Kings,” wherein everything is so realized in surface appearance that you could pick up the tiles or hats or jewelled presents, so deceptively are they portrayed. This is, of course, considered a great feat in art, and ever since the picture was added to the gallery there have been many admirers about it. But art consists of something more than cats and fiddles to be picked up, as Sir Joshua Reynolds remarked many years ago.

CHRIST AT THE COLUMN

By Velasquez (ve-las´-keth)

The Later Flemings, Rubens and Van Dyck, did not despise a surface realism, but they spent no time on petty details. They struck out with a large brush, and sought to give also the body and bulk of things. Rubens, all told, had perhaps the most learned and facile brush of any of the great painters. He was more sure than Hals, more swift than Titian, more learned than Velasquez. He was the master craftsman of them all. His “Drunken Silenus,” “Judgment of Paris” and “Chapeau de Paille” in this gallery will give you an excellent idea of his skill, his color sense, his Flemish point of view. His pupil, Van Dyck, never reached up to him, and was not the greatest portrait painter of the world, though he occasionally did a great portrait. One of them is in this gallery, the “Portrait of Cornelius Van der Geest,” a perfect head, done in Van Dyck’s early period; and done so surely and truly that it will stand comparison with the best works of any period or country.

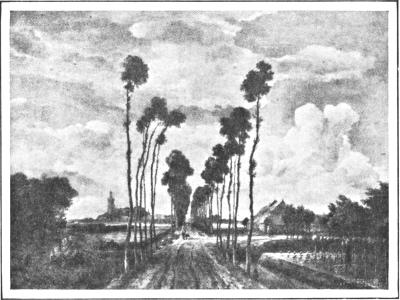

In Dutch art the name of Rembrandt usually leads all the rest, and here in the London gallery are many examples put down to him. The early “Portrait of an Old Lady,” herewith reproduced, is perhaps the most satisfactory of all, not only because of its wonderful rendering of an aged face, but because of the great humanity shown in it. The tremulous line of the lips and chin, the flabby cheeks of old age, the eyes that seem filled with tears, all suggest a life that has known sorrow. That appealed to Rembrandt very strongly. He was always sympathetic with the suffering because, perhaps, he had suffered himself. No painter could put more feeling or meaning into a face, a hand, an arm, a bent form than he. He was the great genius of Netherland art. Hals was a mere tavern-roysterer with a gift for painting, compared with him. The National Gallery, however, has no first-rate example of Hals, though several mediocre canvases are attributed to him. Nor is Steen, or Vermeer of Delft, or De Hooch seen here at his best. By Terborch there is a “Guitar Lesson” showing a young woman in white and yellow satin that is attractive, and a beautifully drawn “Portrait of a Gentleman.” Cuyp (kipe) is shown, in many examples, and better than in any other European gallery. This is also true of the sea-painter Jan van de Cappelle. There is a whole wall devoted to examples by Ruisdael, (rise´-dale) and among the many Hobbemas is one at least of commanding interest—“The Avenue, Middelharnis.” It is slate-grey in color, but its linear perspective and atmosphere have made it very popular.

THE GRACES DECORATING A FIGURE OF HYMEN

By Sir Joshua Reynolds

MARRIAGE A LA MODE

By William Hogarth

The National Gallery is not by any means complete in its representations of the Spanish painters, though it has a number of excellent pictures. By Velasquez one bust portrait alone, that of Philip, is worth a day’s journey to see. There probably never was a more perfect presentation. It not only shows the physical but the moral and mental in the sitter in a most convincing way. There are several full-length portraits here ascribed to Velasquez, but they are not entirely by his hand. The “Christ Bound to the Column” is a great picture and the Rokeby “Venus” is another masterpiece; but neither of them can be attributed with certainty to Velasquez. He was the master-painter of Spain, and Murillo, with his “Holy Family” and “St. John and the Lamb” looks very weak and sentimental beside him. Ribalta who preceded Velasquez, and Goya, who came long after him, were painters in the Velasquez tradition if they were not of his class.

The German pictures in the gallery are quite as limited as the Spanish with only one masterpiece of commanding importance. The large “Ambassadors” by Holbein is not that one, it being a rather commonplace affair for all its vastness; but the “Portrait of Christina of Denmark, Duchess of Milan,” makes amends for it. Here Holbein is at his simplest and his noblest. The lady is dressed in black velvet and silk with fur edgings, and is shown against a blue background. She stands there looking at us with a faint attempt at a smile, with her beautiful hands crossed in front of her. This is one of the ladies that Henry VIII wished to marry. He had this portrait of her painted by Holbein, but did not succeed in marrying her. The portrait is a wonder of good drawing and good taste. There is nothing of value by Dürer in the German collection, and the only other notable picture there is a portrait of a young girl by Lucidel.

HEAD OF A GIRL, LOOKING UP

By Jean Baptiste Greuze

PORTRAIT OF MRS. SIDDONS

By Sir Thomas Lawrence

THE PARSON’S DAUGHTER

By George Romney

Naturally the English pictures loom large in the National Gallery, though many of them in recent years have been transferred to the Tate Gallery. Here one sees Hogarth in his series “Marriage a la Mode” and in several portraits. He was the beginner in the school and one of its best painters. He, of course, had not the court and society following of Sir Joshua Reynolds who came after, with many full-length portraits of nobility painted to look a trifle nobler than reality. He was a famous master, and never did a better group than the “Lady Cockburn (co´-burn) Children.” He signed his name on the edge of the dress at the bottom, and told Lady Cockburn, with a courtier’s bow, that he could not neglect the opportunity to go down to posterity on the hem of her ladyship’s garment. The saying pleased him quite as much as his painting, for he repeated it to Mrs. Siddons when painting her portrait. It is not known whether the ladies compared notes, but if they did it probably resulted in a bad quarter of an hour for Sir Joshua.

THE AVENUE AT MIDDELHARNIS, HOLLAND

By Meindert Hobbema

PASTORAL LANDSCAPE

By Claude Lorrain

Gainsborough, the contemporary of Reynolds, also painted Mrs. Siddons, and made the more famous portrait of her. The color is a trifle cold in blues, and the surface is glassy; but the portrait has dignity, personality and style. This is the picture that Gainsborough had such difficulty in painting the nose that at last he exclaimed in a rage, and it is said with some mild profanity, “Madame, there seems to be no end to your nose.” Many excellent portraits by both Reynolds and Gainsborough, with their contemporaries Hoppner, Romney, and others are here. The best Romney is the celebrated “Parson’s Daughter,” and the best Lawrence, the sad-faced bust portrait of Mrs. Siddons.

The gallery some years ago had a very extensive collection of Turners, but many of them are now removed to the Tate Gallery. The celebrated ones, such as the “Frosty Morning,” “Crossing the Brook,” and “Rain, Steam and Speed,” are still here. When Turner died he left many canvases and about 19,000 sketches and drawings to the National Gallery. Among the canvases were a “Dido Building Carthage” and a “Sun Rising through Vapor” that Turner in his will requested should be hung between two large pictures by Claude Lorrain—the thought being to show how far Turner surpassed Claude. But the comparison is not wholly in Turner’s favor. He is flushed, hectic, a little spectacular, where Claude is cool, calm and serene. The Turners are more cunning in artifice, but they lack Claude’s simplicity and sincerity. Claude and Poussin (poo´-sang), by whom there are plenty of canvases here, were past masters in their time and it is somewhat dangerous for any modern to put himself in comparison with them. Art is not, after all, a thing that will bear comparisons so well as contrasts. It is supposed to reveal the individuality of the man behind the brush, and one great pleasure of the great galleries is that they show us these differing individualities—even as Turner and Claude.

RIVER SCENE

By Turner

| NEW GUIDES TO OLD MASTERS | |

| LONDON—THE NATIONAL GALLERY | By John C. Van Dyke |

| ART OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY | By J. deW. Addison |

| NATIONAL GALLERY | By A. A. Corkran |

| WHAT PICTURES TO SEE IN EUROPE | By Lorinda M. Bryant |

| Containing chapters on The National Gallery | |

| NATIONAL GALLERY | By P. J. Konody |

| LECTURES ON NATIONAL GALLERY | By J. P. Richter |

| THE NATIONAL GALLERY | By J. E. C. Flitch |

| MASTERPIECES IN THE NATIONAL GALLERY | |

| Reproductions from the paintings, with an introduction by Karl Voll | |

| GERMAN AND FLEMISH MASTERS IN NATIONAL GALLERY | By M. H. Witt |

⁂ Information concerning the above books may be had on application to the Editor of The Mentor

THE NATIONAL GALLERY

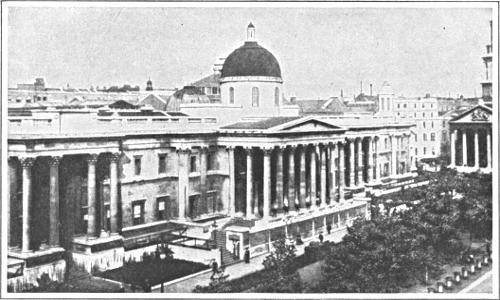

The National Gallery is situated on the north side of historic old Trafalgar Square. It is a long, low building more imposing in its proportions than beautiful. It was designed by Wilkins and is in the Grecian style. It was erected in the years between 1832 and 1838 at a cost of nearly $450,000. Since then it has been enlarged several times. It is now 460 feet in length, and it contains one of the finest collections of paintings in the world. The National Gallery was established by an act of Parliament in 1824, and at first the collection consisted of only 38 pictures, the gift of Mr. Angerstein, whose portrait by Thomas Lawrence hangs on the wall of the staircase in the entrance hall. As years passed by rich and important collections were contributed until now the National Gallery is composed of nearly 3,000 pictures. More than half of them, however, are not housed in the National Gallery building. About 1,100 are there. Most of the others are in the Tate Gallery, which is situated on Grosvenor Road. The great old masterpieces are in the National Gallery building, and that is naturally the part of the collection that the art student visits first. The Tate Gallery, which is under the management of the trustees of the National Gallery, is regarded as a branch of that institute. The Tate Gallery was built and presented to the nation by Sir Henry Tate in 1897, and the paintings there are chiefly those of modern British artists. If anyone wants to study the art work of English painters from the time of Turner down to the present day, he should go to the Tate Gallery. If the visitor is particularly interested in what has been called the modern “Pre-Raphaelite School,” he will find there a great wealth of representative work of G. F. Watts, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Ford Madox Brown, Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Holman Hunt, and Sir John E. Millais. These were the leaders of that circle of artists of fifty years ago which assumed the name of the “Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.” The members drew their title from the fact that their art was inspired by the simplicity and purity of feeling and the patient handiwork of the painters that preceded Raphael. This movement in art and the work of its brilliant leaders will receive attention later in The Mentor. The present number is devoted to the famous master works included in the collection in the National Gallery building.

W. D. Moffat

Editor

ESTABLISHED FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF A POPULAR INTEREST IN ART, LITERATURE, SCIENCE, HISTORY, NATURE, AND TRAVEL

THE ADVISORY BOARD

The purpose of The Mentor Association is to give its members, in an interesting and attractive way, the information in various fields of knowledge which everybody wants to have. The information is imparted by interesting reading matter, prepared under the direction of leading authorities, and by beautiful pictures, produced by the most highly perfected modern processes.

THE MENTOR IS PUBLISHED TWICE A MONTH

SUBSCRIPTION, THREE DOLLARS A YEAR. FOREIGN POSTAGE 75 CENTS EXTRA. CANADIAN POSTAGE 50 CENTS EXTRA. SINGLE COPIES FIFTEEN CENTS. PRESIDENT, THOMAS H. BECK; VICE-PRESIDENT, WALTER P. TEN EYCK; SECRETARY, W. D. MOFFAT; TREASURER, ROBERT M. DONALDSON; ASST. TREASURER AND ASST. SECRETARY, J. S. CAMPBELL

COMPLETE YOUR MENTOR LIBRARY

Subscriptions always begin with the current issue. The following numbers of The Mentor Course, already issued, will be sent postpaid at the rate of fifteen cents each.

Volume 2

Volume 3

Volume 4

NUMBERS TO FOLLOW

April 15, MASTERS OF THE VIOLIN—Joachim, Paganini, Ole Bull, Maud Powell, Ysaye, Kreisler, and others. By Henry T. Finch, Author and Music Critic.

May 1. AMERICAN PIONEER PROSE WRITERS. By Hamilton W. Mabie, Author and Editor.

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, Inc.

52 EAST 19th STREET, NEW YORK, N. Y.

THE MENTOR

Back numbers of The Mentor are as valuable now as at the date of issue. Each individual copy goes to form a cumulative library—The Mentor Library—comprising a collection of facts indispensable to any one who wants to be well informed.

In attractiveness, The Mentor Library cannot be surpassed. By graphically and vividly depicting interesting persons, places, events, and works of art, it makes it easy for you to accumulate a growing store of “worth while” knowledge.

An Opportunity to Complete Your Mentor Library

All but a few of our members have already completed their sets. Some, however, have delayed. This announcement is intended for these few. Please act quickly, for you may not have another opportunity to procure all the previous issues on these special terms.

| Issues Nos. 1 to 100 inclusive | $15.00 |

| Issues Nos. 1 to 90 inclusive | 13.50 |

| Issues Nos. 1 to 80 inclusive | 12.00 |

| Issues Nos. 1 to 70 inclusive | 10.50 |

| Issues Nos. 1 to 60 inclusive | 9.00 |

| Issues Nos. 1 to 50 inclusive | 7.50 |

| Issues Nos. 1 to 40 inclusive | 6.00 |

| Issues Nos. 1 to 30 inclusive | 4.50 |

| Issues Nos. 1 to 20 inclusive | 3.00 |

| Issues Nos. 1 to 10 inclusive | 1.50 |

SINGLE COPIES FIFTEEN CENTS EACH

Payable $1 on Receipt of Bill and $2 Monthly

SEND NO MONEY NOW! Merely assure your being among the possessors of complete Mentor Libraries by sending us your name and address, together with a statement of the issues that you desire.

THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

52 EAST NINETEENTH STREET—NEW YORK, N. Y.

MAKE THE SPARE

MOMENT COUNT