THE RIVER MOTOR BOAT BOYS ON THE YUKON

The River Motor Boat Boys on the Yukon

The Lost Mine of Rainbow Bend

Harry Gordon

AUTHOR OF

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the St. Lawrence,”

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Colorado,”

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Mississippi,”

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Amazon,”

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Columbia,”

“The River Motor Boat Boys on the Ohio”

A. L. Burt Company

New York

Copyright, 1915, by

A. L. Burt Company

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A.

CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCING OLD FRIENDS

II. A MYSTERY

III. THE MYSTERY DEEPENS

IV. JUST ODDS AND ENDS

V. STARTING

VI. A MURDEROUS ASSAULT

VII. THE GOLD FEVER

VIII. AN EXCITING TIME

IX. THE VISITORS

X. THE YUKON

XI. TRAPPED

XII. A CLOSE CALL

XIII. ON THE YUKON

XV. ANOTHER MISHAP

XVI. ESQUIMAUX

XVII. ABE

XVIII. THE TRADE

XIX. WINTER QUARTERS

XX. THE VISION

XXI. THE MYSTERY

XXII. SOLVING THE MYSTERY

XXIII. SOLVING THE MYSTERY

XXIV. GOOD-BYE

[Transcriber’s Note: As printed, there was no Chapter XIV and the titles of chapters XXII and XXIII are identical.]

THE RIVER MOTOR BOAT BOYS ON THE YUKON

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCING OLD FRIENDS

The motor boat Rambler lay moored securely fore and aft to a short pier in the South Branch of Chicago. Great care had been taken in the mooring, for the holding lines where they ran in over the side of the boat were thickly wrapped with soft cloth to prevent chafing and between her side and the dock’s rough piling, were placed huge, soft, rope bumpers to prevent the wearing by rubbing between boat and dock. Even in the dim light of the late April evening, the reason for this careful mooring was apparent at a glance. The Rambler was gay with a coat of fresh paint from cabin top to keelson. This gay, cleanliness did not stop with the exterior, for down below in the warm cosy cabin, the lights glistened on sides and ceiling freshly enameled in purest white. The four folding bunks along the sides were bordered with gilt and above their folded tops protruded the edges of clean sheets and soft warm blankets. Knobs of mahogany protruding from the lower sides of the wall showed where the occupants, or crew, kept their personal belongings, while in the racks on the ceiling above were suspended three glistening rifles and a large bore shot gun. Everything in the room bore testimony to careful, constant, well planned work. The back end of the room had been partitioned off into a cozy kitchen with an abundance of lockers to hold supplies. Back beyond the kitchen, under the after deck, were the powerful little motors which, when in action, drove the beautiful boat at a rapid pace.

But more interesting than the boat were its occupants gathered around the small table in the cozy cabin. They were three in number. The one at the end of the table was a tall lad with an intelligent, manly face. His name was Clayton Emmet, but he was commonly called Clay by his acquaintances. On Clay’s right sat a boy of about his own build, but of graver face, whose name, Cornelius Witters, had been shortened to Case. He was plucky and loyal, but gloomily-inclined and accustomed to prophesying the worst in any difficulty. Next to Case sat Alexander Smithwick, or Alex, smaller in size, but whose freckled face and grinning mouth told of a humorous, joking disposition. All three were engaged in a lively debate, Alex darting out every few minutes to stir up a stew which was sending out a savory odor from the tiny kitchen. Hurrying back from one of these trips he flung himself again into the discussion.

“We have just got to make another trip this summer. Look at all the work and expense we have been to repairing the Rambler this winter. We do not want to have all that wasted. Then think of all the fun we have had on our other trips. On the Amazon, the Mississippi, the Ohio, the Columbia, the St. Lawrence, and the Colorado. Why, every one of them has been chock full of fun, adventure and excitement.”

“I would like to go,” said Case gloomily, “but in the first place, we have explored all the best of the big rivers and, in the second place, we can not afford the time for any more trips. We have helped others to make money but I doubt if all our trips have brought us one thousand dollars. We had ought to keep steadily at work and lay up money for our future careers. You want to remember we are getting old.”

“Oh, yes, we are getting old,” Alex grinned. “I feel old age creeping upon me day by day, gray hairs amongst the gold, a touch of rheumatism, a gathering weakness in flesh and bone, and often a terrible aching pain in the stomach.”

“Those stomach pains are from over-eating,” retorted Case.

Alex turned to Clay. “What do you think about it? You are always the clearest headed one of the bunch.”

“I agree with what Case has said,” Clay declared, gravely. “We are all over seventeen years old and had ought to be beginning to try to get a start in life instead of wasting time and money in these summer trips, however pleasant they may be.”

Alex’s freckled face took on a look of gloom, while even Case did not look pleased at having his theory indorsed.

Clay smiled at their serious faces. “I have been thinking about this matter seriously all winter,” he said, quietly, “and have decided that we will have to give up mere pleasure trips for the future, but I see no reason why we should not go this summer if there is a way to make the trip profitable. How much money have we got altogether?”

“Why we have got that $1,000.00 in the bank,” said Case.

“I’ve saved $100.00 this summer,” declared Alex, eagerly.

“Oh, for that matter, I’ve hoarded up $125.00, if it’s needed,” Case confessed.

“I’ve had a pretty good position all winter,” Clay said. “I’ve managed to lay by $175.00. Let’s see what that brings the total up to. Why, $1,400.00, but I am afraid it will take all of that.”

“What is your plan?” demanded Alex, his eyes shining.

Clay hesitated. “It seems a bold one to propose, but I really believe our best chance lies in a trip up the Yukon.”

“Whew!” whistled Alex and Case together. “You mean for us to go up there and hunt for gold? We know nothing about mining,” said Case.

“It would be lots of fun,” Alex insisted, “but it’s some trip up there to the Yukon.”

“I did not mean for us to go merely for gold, although I think we could soon learn enough about it to try it out if we so desired,” Case explained. “My idea was to stock up with beads, trinkets and tobacco—especially tobacco—to trade with the Indians for skins, furs, and specimens of the far North. Even at the worst we could go to work and make big wages, for labor is scarce up there.”

“But will not the expense of such a trip be something fierce?” inquired the gloomy Case.

“It will. We would have to ship the Rambler by rail to Seattle and the cost of transportation for her and ourselves would be high. You see it is not so very long since gold was discovered in Alaska and the rush of people to get there enables the steamers to charge almost any price.”

“Keep still a second,” exclaimed Alex. “Isn’t that some one moving about up on deck?”

He darted for the cabin door, followed by his two companions. Coming from the brightly lighted cabin out into the night, they could not see ten feet in the inky darkness, but they could hear the retreat of hurried foot-steps going up the dock.

“No use trying to catch him in this darkness,” Clay remarked. “Probably it’s only a river thief. Let’s go down into the cabin.”

“Call him a river thief if you want to,” Case said, darkly, “but I doubt it. All our trips seem to start with a mystery.”

“All the more fun,” grinned Alex. “They help to make excitement, Gloomy Gus.”

“There will be no mystery this time. No one would want to join a trip like the one we are going to take,” Clay said.

“You’ll see,” Case said darkly.

“Let’s get back to our trip,” said the cheerful Alex. “What will we want to take with us?”

“First we will want to stock up with all the food we can carry, for food prices will be high in Alaska. Our guns are all right, but we had ought to have some warmer clothing and heavier blankets. Our heaviest expense, however, will be a new motor for the Rambler.”

“A new motor for the Rambler?” cried Case, in dismay. “Why, what’s wrong with our dear little motors? They have carried us thousands of miles without a hitch.”

“That’s just the trouble. They have about worn out their lives in faithful service for us. I have gone over them carefully this winter and I find that the cylinders have worn thin while the working parts are almost gone. Aside from that we could not carry enough gasoline for the trip and I do not expect we will find much, if any, gasoline on the Yukon.”

“Then what are we going to do?” demanded Alex, anxiously.

“I wish we could put in a wood engine and save the expense for fuel, but a steam engine which would do our work would be too heavy for the Rambler. The next best thing is a kerosene engine. They are not much heavier than a gas, and I feel sure we can get kerosene on the Yukon. It always follows closely the movements of civilized man. Well, what do you say? Shall we have a new motor or not?”

His companions recognized the wisdom of his arguments and gave ready assent, although they hated the idea of parting with their loyal little friends.

“If you have finished and all is settled, I would like to offer a few remarks,” said Alex, grinning as he rose from his chair with a twinkle in his eye. He paused for a moment while the other two looked up at him expectantly. “Gentlemen,” he began, “it gives me great pleasure to look over this vast sea of upturned faces. In them I see resolve, a resolution to do or die, a determination to conquer a frozen wilderness and wrench from it its golden treasures. Gentlemen, I propose a toast. Here’s to——”

“Whew! Don’t you smell something?” interrupted Case.

“Smell! Why I can almost hear it,” grinned Clay. “It seems to come from the kitchen.”

Alex, his speech forgotten, flew for the kitchen. In a moment he was back with a sheepish grin on his face. “Most of the coffee has boiled over, but there are two inches of stew which hasn’t stuck onto the pot,” he announced.

“You seem to forget everything else when you get to talking,” commented Case, gloomily.

“Oh! Alex means all right,” Clay said cheerfully. “The only trouble with Alex is that he is like the steamboat Abe Lincoln used to tell about. She had a four-foot engine and a five-foot whistle, so every time she blew the whistle the engine would stop.”

“I suppose your crude sarcasm is meant to imply that when I talk I have to stop everything else. Why, my dear companion, that’s a virtue. A man should not try to do more than one thing at a time,” Alex retorted impudently. “Why, if you two could whistle as well as I, you wouldn’t do anything else. Case does blow his own whistle a good deal, but it generally sounds like a fog horn with a frog in its throat—dismal—dismal—dismal.”

“Away with you and get us something to eat, you little imp,” laughed Case.

“Why, don’t you want to try some of this stew?” asked Alex hopefully. “It’s rich and there’s fully two inches of it that isn’t fast to the pan.”

“No, I don’t want to taste it, the smell is enough. Open up a can of beans and a can of salmon for Clay and I. You can keep all the stew for yourself. I don’t think there is enough of it for more than one anyway.”

“I never care for stews,” declared Alex promptly. “I’ll give it to Captain Joe. I forgot to cook up anything for him anyway.”

He advanced to where a big white bull dog lay asleep in the corner and placed the stew-pan close to his nose. The dog awoke instantly and began sniffing eagerly.

“Look at him. Watch him go to it. Captain Joe knows what’s good,” Alex exulted.

Captain Joe shoved his nose into the pan and took one good whiff, then gave the pan a shove with his paw and with a sniff of disgust, retired to the opposite corner and lay down again.

“Captain Joe is an intelligent animal,” Clay agreed with a grin. But hurry up Alex. Throw that stuff out and bring on the salmon and beans. I am hungry as a wolf.”

Alex meekly obeyed and soon all three were seated around the table eating their cold meal and eagerly discussing their proposed trip.

“How soon do you think we can start?” asked Alex eagerly.

“The sooner the better,” Clay replied. “It will take a long time to make the trip and the season is short up there. If we divide the labor equally we can soon be ready. Tomorrow, Alex can order the provisions. He’s authority on eatables. You, Case, can buy the heavier blankets and warmer clothing we will need, while I will try to find a good kerosene engine and buy the tobacco and trading trinkets. The buying had ought to take us all of tomorrow, for we want to be careful in our purchases. By working hard the next day we had ought to get the old motors out and the new installed. If so, there is no reason why we can not be off in three days from now.”

“Hurrah,” shouted the excited Alex. “That’s going some.”

“Keep still,” whispered Clay, “I can hear those footsteps right on deck again.

His two companions listened.

“We want to catch that fellow this time,” Clay said softly. “You fellows just keep right on talking and I’ll slip back to the back door. The steps are moving slowly back to the after deck. As soon as they come close to the door, I’ll throw it open and grab him, then you all come at once and the job is done.”

His two companions nodded assent to the plan and began talking loudly to each other, while Clay crept back to the door at the stern.

The soft muffled foot-steps came slowly nearer until they reached the narrow deck aft.

Clay flung the door open and with a shout sprung upon the dim figure outside. Alex and Case, with Captain Joe, came dashing out to his assistance. But there was no need of help. The stranger offered no resistance, instead he chuckled.

“Is this the way you always greet visitors?” he asked. “Gee, but you are a hospitable lot.”

“Come on down into the cabin where we can see who you are,” said Clay sternly, still retaining his grip on the stranger’s arm.

The stranger followed him willingly down into the cabin light, where Clay let go his arm as though the coat sleeves was red hot, while his chums howled at him with delight.

“Mr. Clay, but you’re a great detective,” Alex jaunted. “You go out to catch a thief and bring in a friend.”

But his jeers fell on deaf ears, for Clay was gazing at a slender, bright-eyed boy with abashment and recognition. “Why, it’s Ike Levis,” he cried.

“It’s a wonder you recognize him, Clay,” grinned the impudent Alex. “You’ve only known him for ten years.”

“I’ve only known him for five, but I can almost see a likeness,” smiled Case.

The bright-eyed stranger smiled at the joshing, but seemed to think it had gone far enough.

“I stole time to come down and get a look at your wonderful little ship, of which I had heard so much. Won’t you show me around, boys?”

CHAPTER II

A MYSTERY

The boys agreed to Ike’s request with delight. They were proud of the neat little Rambler that had carried them safely and surely over so many thousands of miles of water. They led him all around showing the clever contrivances of lockers, the folding bunks, the cozy kitchen, and how every inch of available space had been arranged for the handy storage of some article.

“You’ve got a daisy little craft, and have got her fixed up dandy,” Ike enthusiastically declared, as soon as they were seated. “Where do you expect to go this summer, and how soon are you going to start?”

“We are going to Alaska up on the Yukon,” Alex exclaimed. “We’re not going for fun exactly this time, although we expect to have a lot of that too. Our main object is to dig a ton or so of gold, fill up the balance of our cargo with rare and costly furs, and make our way back to the States before the ice sets.”

“There you go, hoodooing the trip before it’s started,” growled Case gloomily. “I was in hopes we might sneak back with a few hundred dollars. But with all the bragging you’ve begun already, I am doubtful if we get back with the boat.

“Now, Gloomy Gus”—a name he bestowed on Case during his gloomy spells—grinned Alex. “Isn’t it better a lot to think you are going to get rich when you start even if you do come back poor? It makes fun in the going anyway. Ain’t I right, Clay?”

“Don’t count your chickens before they are hatched,” quoted Clay with a smile.

“If we did not, there would be no chicken raisers,” Alex retorted with spirit. “They always expect a chicken for every egg until the shells begin to crack.”

“I hate to interrupt so much philosophy,” said Ike with a smile, “but I’m just itching to talk a little myself.”

“Take the floor,” smiled Clay, and his two companions lapsed into silence.

“What I want to say is just this,” began Ike in a brisk, business-like way. “I want to go up the Yukon with you fellows.”

“Hurray,” shouted Alex, “four is lots better than three.”

“Sure, come along,” said Case, cheerfully.

Only Clay did not join in the hearty replies and his two companions eyed him in wonder.

“It is going to be a very expensive trip,” Clay said at last.

“I expect it to be costly,” Ike replied, quietly. “But, boys, you know that little news stand I have been running for so many years has paid pretty well all the time. It paid the expenses of all of us when mother and father and baby brother were alive. Since they were all taken by the white sickness, there has been more money than I could use, you understand, so I put it in the banks. I can put in $1,000.00 for this trip and then some more if needed.”

“But why do you want to sell such a good paying stand as yours and waste a lot of money on a trip like this which may not bring in a cent?” Clay asked.

“I can put in a boy I know well, a good, honest boy, to run the stand while I am gone. You, Clay, do not understand. Every year you have vacations and have lots of fun. You come back well and happy and eager for work. For ten years I stand behind that little stand. Out in the snow and cold, the slush and rain, the dust and hot sun, and never once a play day. That is not right, that is not well. It makes a young man soon old, makes him look on life wrong. Now I can afford it I would like to have one long play time.”

“But there is but little fun we’ll have on the Yukon! With a $1,000.00 you could have all kinds of fun at some hunting or fishing resort closer home,” Clay still urged.

“I tell you another reason why I want most to go to the Yukon,” replied Ike, after a second’s hesitation. “I got uncle up there several years. He makes no good at the mining. I got no other relatives now, so I hunt up uncle and if prices are high we set up fine store. Uncle can sell goods in the store while I go out and trade for furs with the Indians. I think we make good money. But it seems you no want me to go with you, Clay—why?”

“But I do want you to go with us,” Clay declared, heartily, his face lightening. “We all of us want you to go. We start in tomorrow to buy our supplies and when that’s done move your things right down to the boat and become one of us.”

“Sorry, but I can’t do that,” Ike replied. “I’ll have to teach the new boy the business and settle up a few of my affairs. I am afraid I will not be able to come aboard until just before you start. But I will do a fair share of the work as soon as we are off. Call by my stand in the morning and I will hand you that $1,000.00. Put it into the general fund and get me an outfit just the same as you do for yourselves.”

“But a $1,000.00 apiece is more than we are putting up,” said Clay, honestly. “We have only $1,400.00 in cash altogether.”

Ike laughed. “You do not figure it right, my friend. I gets for my money not only a share in outfit and stores, but I get a trip up and down the Yukon which is worth much more than $500.00. And now, boys, it is getting late and I have to be up early in the morning to attend to my stand.”

Clay turned on the prow light to light up the prow and dock and the three boys followed their friend on deck where they parted with many good-nights and prophecies for the coming trip.

As soon as he had passed out of sight, the three descended to the cabin again, and Alex folding his arms, looked at Clay with as much scorn as his freckled, good-humored face could express. “You’re a fine one,” he grunted. “Why, you cross-questioned Ike as though he was a criminal and you the prosecuting attorney just because he wanted to go on this trip with us. I was afraid he would get disgusted with your questions and give up the notion. There’s no other boy I know who I had rather have go on this trip with us. Ike used to be mighty good to me when I was a little newsie. Ike is all right.”

“Yes,” Case agreed. “I have seen him many a time stop big boys who were abusing little ones, and leave his stand to help feeble old men and old ladies across the street.”

“I know him better than either of you,” Clay said, quietly, ignoring the storm that had burst upon him. “I remember the time when his family was dying of consumption. Why, all the time they were lingering on between life and death, he was like an angel to them. They had a doctor, a day nurse and any delicacy they thought they wanted. At night he would take the day nurse’s place. When at last they were dead and buried, there was little left of Ike but skin and bones, for he had eaten barely enough to keep him alive, so that the others might have more comforts. The money he had saved was all gone and there was little left of the news stand but a few bundles of the best selling newspapers. A boy who acts towards his folks like that simply can’t be a bad boy.”

“Then why didn’t you want him to go with us?” demanded Alex, still unsatisfied.

“I see I have got to tell it all,” Clay said wearily. “It isn’t so much, but it has made me a little curious. I was passing Ike’s stand one evening last fall and stopped to get a paper. Ike was at the other end of the stand talking with two strange-looking men who wore rough clothes and whose faces were covered with big blotches where they had been frost bitten. All three were talking friendly but eagerly, and often I could catch the words, ‘Alaska,’ ‘Yukon,’ ‘and great wealth,’ so I decided that the two men were miners just in from Alaska. Well, I could not hear much of what they said, they talked in such low tones. At last I got tired of waiting and called Ike and gave him the change for the paper and left. Now you all think it was my idea about this Yukon trip; you are wrong. It’s Ike’s plan. Ever since the day I saw him with those two men he has been trying to enthuse me about this Yukon trip.”

“Maybe he had learned something good about the Yukon country and wants that we should get the benefit of it,” Alex suggested.

“I thought that myself,” Clay said, sadly, “until this afternoon, when I passed Ike’s stand on my way home. There stood the two miners I had seen before and they and Ike were having a violent quarrel. In fact, they were coming to the point of blows. One of the men aimed a blow at Ike and I started to run to Ike’s assistance, yelling for the police. The yells for the police seemed to scare the two men for they took to their heels. I asked Ike what all the trouble was about and he said they were a couple of roughs who had bought a paper and gave him a nickel. When he gave them their change they had insisted on change for a dollar, which they claimed was the amount given him.”

“Great mystery all that,” Alex said scornfully. “Have you any more evidence to pile up, Mr. Sherlock Holmes?”

“Welt, Ike’s story rang rather flat to me,” Clay replied. “Neither man carried a paper or anything else when they took to their heels. I would not have thought much about these things if Ike had not come down tonight and wanted to go to Alaska with us. That seemed to string all those things together. I felt sure Ike was too much of a business chap to spend $1,000.00 on a pleasure trip to the Yukon. But when he said he wanted to go to hunt up his uncle, why that made things look better, for a Jew will go a long ways and do a lot for a relative.”

“Well, what are we going to do about it?” Alex demanded.

“I want him to go with us of course,” answered Clay. “I know Ike’s all right, but I was in hopes that my questions—about which you have been roasting me so—would clear up the things that had been puzzling me.”

“Ike might as well go as not,” Case agreed gloomily. “We always have to carry a nice fat mystery on each of our trips, and I’d rather Ike brought it along with him than to have some uninvited stranger smuggle it aboard.”

“You and Clay make me tired,” snapped Alex. “One of you is just as bad as the other. I guess I’ll have to call one of you Gloomy Gus 1, the other Gloomy Gus 2.”

“All right, you wait and see,” said Case darkly. “It’s only a nice gentle kitten-like mystery we start with on each trip, but before the trip is ended it grows to be as big as a grizzly bear.”

“That reminds me that one of us will have to bring Teddy Bear down to the boat. He’s getting pretty big but we must have him along with us for one more trip anyway.”

Teddy Bear was a grizzly cub the boys had captured on their trip on the Columbia. On their return from their last trip, they had turned him over to the zoo man as he had grown so big and had such a thieving appetite for sugar and other sweet things that they could not trust him in the Rambler while they were away at their work. Whenever they had a day of leisure, they would take Captain Joe along with them and go up to see their pet. They would put him through his tricks and slip him in a generous amount of sugar. So they kept themselves fresh in his memory. Teddy and Captain Joe were the greatest comrades and both rejoiced at these meetings. It was comical to see Captain Joe seated on his haunches, look up with one eye cocked as though saying, “Well, Old Chap, how are they treating you down here?” and Teddy Bear would with one eye wink back as though replying, “Pretty well, Joe, but it isn’t anything like life on the Rambler.”

Alex declared that he once heard Teddy tell Joe to sneak him down a pail of sugar the next time he came and Joe replied with vast scorn that he would not steal from his masters, but if Teddy had any good meat to exchange for sugar he’d manage it somehow. Clay, on hearing this story, had promptly placed Alex’s head down in an empty flour barrel until he confessed that he might have been mistaken.

When Clay spoke of bringing Teddy Bear down next day, Captain Joe arose in dignity from his corner and wabbled over to his side. Clay patted his head, “Yes, Joe, we are going to bring Teddy Bear tomorrow. Teddy Bear is going to stay on the boat now. You want Teddy Bear, Captain Joe?”

Captain Joe cocked his eyes and wagged his stump of a tail vigorously. He seemed to be saying, “I guess you’re talking straight, boss, but I don’t believe that guy’s going to leave all the good meat he’s getting if he can help it.” Captain Joe then rubbed his nose across Clay’s ankle, rose sedately, and made the rounds of the table rubbing his nose on each boy’s leg.

“He’s telling us that it is time to go to bed and stop disturbing his sleep with our chatter,” laughed Alex.

“He’s right, too,” Case agreed, “but listen, aren’t those more foot-steps on the dock close to the boat?”

Clay reached over and snapped on the prow light. Instantly there was a scamper of foot-steps up the wharf.

Clay laughed and shut off the light. “We seem to be having our share of visitors tonight,” he remarked, “but I am not anxious to make another capture tonight. I am going to bed and trust to Captain Joe to wake us up if any one tries to get in.”

The boys were all ready for bed and they were soon all asleep, leaving Captain Joe on guard.

CHAPTER III

THE MYSTERY DEEPENS

When Alex and Case awoke next morning it was to the savory odor of browned pancakes, fried bacon, and steaming coffee. Clay was just lifting the last pancake from the frying pan to the plate when the two jumped out of their bunks.

“Gee, that breakfast smells good. I really believe I can eat a bit this morning,” Alex announced.

“I never saw the time that you couldn’t,” retorted Clay. “But hurry up you fellows, if you don’t want to eat a cold breakfast. It won’t keep warm forever.”

This announcement brought great haste in the pulling on of clothes and the washing of hands and faces. Breakfast was dispatched amid a chatter of conversation concerning the purchases to be made.

“I have been thinking it over,” said Clay, during one of the lulls in the conversation, “and I do not believe we had ought to leave the Rambler with no one on board of her. It was all right to do so in the winter, for then she was frozen up and no one could make away with her, run her into some slip, paint her and with a few hours of alteration, make her into a different looking boat. Those foot-steps last night prove that the river thieves are beginning to gather around for their summer trade. I think one of us had better be on the Rambler all the time.”

His companions’ faces became downcast. Each had made a list of the things he was to buy and were eager to be off to their purchasing. Neither wanted to stay idle on board and lose their share of the fun. But Case spoke up manfully.

“I’ll stay,” he said, “my list is far the smallest and if neither of you get back in time, I’ll do my buying tomorrow.”

“Thanks,” said Clay, gratefully, “I would stay myself, but the new motor will be the first thing needed and I want to see to that myself for I have had some experience with them.”

As soon as the two were gone, Case set about the unpleasant task of washing the dishes and cleanup the cabin. This done, he strolled out on the wharf and sitting down on a box in the warm sunshine chatted with the aged dock tender who had been a sailor until age had compelled him to quit the sea. He could tell many strange tales of queer places and mysterious adventures and he was always willing to relate them to the boys who often on cold, stinging days invited him down into the Rambler’s cozy cabin to share their warm dinner or drink a cup of scalding hot coffee.

“Yep,” he answered, in reply to Case’s questions, “I’ve been to the Yukon once and once is enough for me. We were hunting seals and run into the river to get out of a gale and afore it moderated enough for us to get out we were froze in solid. Lord! what a winter we had. We had plenty of salt stuff but our potatoes soon went and the scurvy broke out and then came the long winter night, and all the time there was but white all around us. Nothing but white and a great everlasting silence—just like as though the whole world had gone dead never to come to life again. The silence and the whiteness got on our nerves and we got to quarreling with each other. There was a good many killed before the ice broke up. We had left only about half enough able men to work the ship. It wasn’t long though before we sighted a steamer and hoisted our distress signal and she stopped for us to board her. She was overloaded with the first bunch of gold seekers. Her captain let us have considerable potatoes, and, by slicing them up thin and chewing them up raw good and fine, what was left of us were nearly well when we got to San Francisco. My, but those raw potatoes tasted better than anything I ever ate,” and the old seaman smacked his lips over the recollection.

“I guess the winters up there are pretty rough?” Case assented, but we intend to be on our way home long before the river freezes over.”

“Sonny,” said the old sailor, earnestly. “You can’t calculate on the Yukon. Old timers and the Indians call it ‘The Never Know What’ on ’count of its contrary ways. Let me give you some good advice if you are bent on going. Take lots of tallow candles and potatoes with you. Course you can take all the fancy stuff you want, but a good meal of tallow keeps your human furnace running full blast and the taters keep off the scurvy. Look there, sonny, you’ve got a visitor.”

Case jumped up from his box just in time to see a man entering the Rambler’s open cabin. He grinned, “Captain Joe will look out for him all right, but I guess I had better go aboard and see what he wants.” He sauntered aboard leisurely and entered the cabin. The man was standing close to the opening looking as though he wanted to run but was afraid to turn around, for Captain Joe, with bared fangs and growling lowly, was stealthily advancing from the further end of the cabin.”

“Down, Captain Joe, down,” Case cried, just as the dog crouched lower for a spring. Captain Joe relaxed and retired sullenly to his corner.

The man whipped out a huge red handkerchief and wiped the beads of sweat from his brow. “Nice, pleasant little pet you’ve got there,” he remarked. “I reckon a biting dog is the only thing I’m afraid of.”

“Who are you, and what do you want?” demanded Case, his clear gray eyes on the other’s face. The man was dressed roughly and there were rents in his clothing, but his hands and face were clean and his face bore a good humored if determined expression.

The man twirled his hat for a moment before replying. “I had it all fixed in regular order what I wanted to say, but that dog has pretty near scairt it all out of my head. Are you the boss of this outfit?”

“We have no bosses, or rather, we are all bosses?” Clay smiled.

“Well, I guess you will do as well to talk to as any of the rest. I heard that you were going to the Yukon and I want to go along with you—me and my partner.”

“Where did you hear we were going to the Yukon?” demanded Case, sharply.

The man produced a soiled morning paper and laid a huge forefinger on an article in one corner.

Clay read it in silence and some bewilderment.

“The Rambler boys are soon to start off on another of their famous cruises. This time they have chosen the far-away Yukon as their goal. It’s a bold attempt, but they are all Chicago boys and we believe they will make it. At any rate, we wish them the best of good luck.”

Case kept his eyes on the paper for a moment after he finished reading the notice, pondering how it had appeared so soon. The paper had been published long before he and his companions had got up. Charley thought it had been inserted either by Ike or one of the mysterious eavesdroppers of the night before. But for what reason had it been inserted? He gave up the puzzle and looked up at the man who was watching him eagerly.

“Take a seat,” he said, pushing forward a stool and taking one himself. “That notice is right,” he remarked. I am sorry to say it, but I am sure my companions will agree with me, we can not take you and your partner. We will be four in number besides our pets and we are going to have a very heavy cargo. We’ll be overloaded as it is.”

“But we can be of lots of help to you,” urged the man, eagerly. We are both Old Timers—Sour Dough men. We know the country like a book. You’ll need a pilot on the ‘You Never Know What.’ There’s too many bars, hidden rocks, and rapids for a green horn to tackle. Bill can cook for you, an’ Bill’s a powerful good cook,” he said with pride.

Clay shook his head decidedly, although he was sorry for the man. “Why are you so anxious to get up there?” he asked.

“I’ll tell you the truth,” the man said desperately. “My partner and I had a couple of claims way up the Yukon and last summer we struck it rich. Not much free gold, you understand, such as you wash free with pan and water, but quartz rich enough to make your eyes stand out. But that kind of gold has to have mills, stamps, and all kind of machinery to set it free. So Bill and I gathered all the dust we had and came outside to find capital to develop our claims. We might as well have staid at home, for we could not get any one to put up the money. They just thought we was crazy when we told how rich our claims were. We have slept out in the cold many and many a night, and picked up odd jobs like shoveling snow to keep from starving. We are used to hardships up north but a man is treated like a human up there. It goes against the grain for a truthful, honest man to be hounded on by a policeman when he is only trying to warm himself over a grating.”

While the miner had been talking. Case had been looking him steadily in the eyes. He noted the subtle change of the iris which always marks the telling of a lie. He marked the man’s allusion to his honesty and thoughtfulness. He had often shrewdly observed in his life in the great city, that it is not the honest man who brags about his truthfulness and honesty. Clearly this fellow was lying in some part of his tale.

“It’s no go,” said Case, decisively. “We just simply can’t take you. We have barely enough money to take us there and bring us back.”

The man’s face became clouded with disappointment. “Tell you what I’ll do,” he offered. “We’ll give you a sixth interest in our claims. That will pay a dozen times over for the trip.”

“We have not the money to handle them even if they are as rich as you claim. I’ll tell you what I’ll do though,” Case said, pitying the man’s tragic face. “I’ll talk it over with my chums tonight and see what they have to say. If you and your partner want to take the trouble to come down in the morning, I’ll let you know what they decide. I am positive though that they will agree with me.”

The man rose and put on his hat. “We’ll come down in the morning all right. Sonny, you’ve treated me square and frank and I am much obliged to you. So long, until tomorrow.”

Case watched him out of sight and then began the preparations for dinner to which he intended to invite the aged docktender, for he wanted to learn all the old seaman knew about the country they were going to.

The two were just finishing their supper when a roaring sound steadily growing in volume stole in through the little cabin windows. “I wonder what that noise is,” said Case. “Sounds mighty queer.”

“Sounds just like waves dashing up on an iceberg,” the old seaman agreed. “Let’s go up to the end of the dock and take a look.”

When they reached the shore the boy and old man doubled up with laughter. It looked as though half of Chicago was crowding the little street, but steadily a wide path opened up and then closed again with jamming people. Down the wide path walked Teddy Bear, paws raised in an attitude of defense. Clay walked behind with a grin on his face.

“Teddy Bear is sure coming down in style,” chuckled Case. “He’s got a whole procession with him.”

The crowd followed the bear down to the boat and when he was led down into the cabin they departed with cheers and laughter.

CHAPTER IV

JUST ODDS AND ENDS

Captain Joe greeted Teddy Bear with delight. He circled around him snapping playfully at his legs and uttering short, joyous barks. Teddy dropped slowly down on all fours and gave Captain Joe a good-humored cuff that sent him clear to the other side of the cabin. This rebuke administered, he made his way over to where the sugar was kept in one of the kitchen lockers and tried hard to open it, but the boys had taken the precaution to add locks to all their lockers and his efforts were unavailing. At last he gave it up and made his way back into the main cabin and stood gazing at the boys reproachfully.

“You’ve got to stop your thieving, Teddy Bear,” said Case with a grin. “Get over there in your old place in the corner and I’ll get you a few lumps of sugar.”

Teddy meekly obeyed and quickly received the reward for his obedience.

“Well, I finished the best part of my purchases,” Clay remarked, “and I thought I had better come down and spell you for a while. I’ll have time to finish up my list tomorrow, for there will be part of the time when it will take only two of us to work on the motors. I’ve had the dandiest luck in getting a new motor. It’s a daisy and will burn either gasoline or kerosene. They promised to deliver it down here early this afternoon. I took Ike with me when I went to see about getting transportation, and let me tell you, that boy’s some bargainer. I could never have got as cheap rates as he did out of the freight agent. We are to have a flat car for the Rambler and live on board of her until we reach Seattle. But I am keeping you back. Hurry up and get your things before dark if you can.”

Case was off like a shot and was soon uptown in the shopping district where he spent a happy afternoon making his purchases. With a grin at his own foolishness, he added to his list a large box of tallow candles. “Of course we will never have to eat such stuff, but they will bring back more than their value, I guess, trading with the Indians,” he argued in justification. It was nearly dusk when he finished his list and arrived at the Rambler to find that Alex had arrived only just ahead of him.

Alex was excitedly talking to Clay who was busily preparing their evening meal.

“What’s all the fuss about?” Case demanded.

“Nothing much,” Clay said, calmly. “Alex’s just a little excited, that’s all. We’ll compare experiences while we’re eating supper. Wash up and get ready. I’ve got fried fish and that’s best when eaten piping hot.”

It was not until the first pangs of his hunger was satisfied, that Alex gave vent to his grievance, and then it was in milder tones. “I guess I’m a little touchy,” he confessed, “but it made me sore the way Ike jumped on me this morning, and for nothing too. Just about a little item that appeared in the morning paper about our trip. It took me a long time to convince him that none of us could have put it in, and, by the time I had done it, I was mad myself, while Ike seemed pretty well upset.”

“He spoke about that item to me when I went to see him just before noon,” Clay remarked, “but all he said was that he wondered who could have given it to the paper. All I could tell him about it was that there had been a couple of fellows prowling around our boat last night and they might have overheard part of our conversation, though why they should give it to the newspapers was more than I could figure out.”

“Would you fellows like to own an interest in two rich gold mines?” Case asked when Clay had finished.

“Oh, no,” retorted Alex. “We wouldn’t take one as a gift. Money is the root of all evil and we don’t want to get evil, do we?”

“It would not be exactly a gift,” Case replied, ignoring the irony, and he proceeded to tell them of his morning visitor.

“What kind of looking fellow was he?” Clay inquired, eagerly, when he had finished.

“A big, heavy man, with long, thick whiskers. He was not a bad appearing man. His face was good humored but determined looking. He didn’t impress me as a bad man.”

“Did he have a red scar on his right cheek?” Clay demanded.

“He did,” Case assented. “Looked to me like an old knife cut.”

“Then he is one of those men I told you about last night,” Clay remarked. “He’s the best appearing of the two. The other one could be hung for his looks. Queer how so many little things keep coming up that we can’t explain and which seem to have some connection with each other. First the first meeting between Ike and those men at the news stand, then Ike’s constant suggestions to me all winter about this Yukon trip, then the second meeting at the stand when they had their quarrel, then Ike’s wanting to go with us, then that queer notice in this morning’s paper, and right on top of it, all these men applying for passage. Makes a queer chain, doesn’t it?”

“Our little kitten of a mystery seems to be growing into quite a cub,” observed Case, delighted to feel that his prophecy of trouble seemed to promise to bear fruit.

“Oh, cut it out!” exclaimed Alex. “Let’s forget it all. Don’t let’s spoil our trip at the start by worrying over trifles that do not concern us anyway. Case, you make me tired. You’re one of those guys that are always looking at the hole while the other chaps are watching the doughnut.”

“I don’t know but what you are right,” Case replied shamefacedly. “I soon get rid of that habit when we get started on one of our trips, but the long, gloomy winter in the city seems to bring it back on me again. Just bear with me until we get started and I’ll be all right. But just remember one thing, young man. You have used enough slang the last few days to entitle you to do all the dishwashing from here to the Yukon and back.”

“We have all of us been using too much of it lately,” Clay remarked. “We had ought to make a more determined effort to stop it. It’s catchy, but the way we keep on adding new all the time it will not be so very long before our talk will sound like the chattering of a group of monkeys.”

“Well,” Alex grinned, “we had better stop our chattering right now and get to work. We have got a lot to do before we go to bed.”

Most of their stores had been brought down to the wharf during the afternoon and lay piled in a big heap beside the Rambler. As soon as the boys had hurried through the cleaning up, they turned on the prow light and lighting a couple of lanterns went at the task of stowing their cargo. Boxes and packages were carried below, broken open and their contents stowed in the lockers, while the emptied packages were thrown overboard. As each box was opened it was checked off their lists so as to make certain that they received every thing they had ordered. Although they worked hard and with zest, it was midnight when they got all the stuff, but their new motor, safely stored.

“I don’t know what we had better do about that motor,” Clay said, looking at it doubtfully. “I hate to put it down in our freshly-painted cabin because there is always such a lot of oil and grease on even a new engine, but we can’t risk leaving it up here all night.”

Case tried to lift up one side of it and failed. “I guess there is not much danger of any one running away with it,” he grinned. “It must weigh five hundred pounds.”

“Oh, they couldn’t get away with the engine very easily, but there’s a whole lot of brass and copper fittings which they could unscrew or wrench off.”

“I’ll tell you what to do,” Alex suggested. “Put a rope on Teddy Bear and tie him up to the engine. There will be no one bother it while he’s around. He has grown so big and strong that he’s got a punch like a prize fighter.”

But Teddy did not take kindly to the idea when they tried to lead him up out of the warm cozy cabin. Alex had to fill a big can with sugar and lead the way with it extended invitingly to induce him to leave the boat. While Clay tied him to the engine, Alex scattered the sugar all around in little piles so that it would take Teddy Bear some time to find and lap it all up.

This last job done the tired but happy boys turned in, agreeing to be up early in the morning.

It seemed as if they had only just fallen asleep when they were suddenly awakened by loud snarling and scuffling on the wharf, followed by a harsh yell.

“Wake up and hustle, you fellows,” shouted Clay, as he pulled on his pants and seized his automatic. “Teddy Bear is in trouble.” His two companions were beside him when he gained the dock and the three rushed for the place where Teddy had been tied. Alex had switched on the prow light before leaving the cabin and its rays lit up a circle around the engine where they could see Teddy Bear sitting close to the engine holding up his paws and whining pitifully. The boys looked and listened but could see or hear no one near.

“Whoever it was has had plenty of time to get off the dock since we first heard the noise,” Clay declared. “Let’s see what’s the matter with Teddy. I hope he has not been hurt badly.”

Teddy extended his left paw with a little whine and Case examined it gently. “Why, he’s been stabbed clear through the fleshy part,” he exclaimed. “Run down into the cabin, Alex, and get that bottle of peroxide, some cloth for bandages, and the box of salve. Now cheer up, Teddy, this isn’t going to hurt you much. It will heal up in a hurry. You don’t use tobacco or drink liquor, and you chew your food well, so your blood is just as pure and clean as blood can be. In a week you will not know you ever were hurt.”

Teddy put his head sideways and looked at him with a doubtful grin as though trying to understand what was said to him.

“I wish I knew what brute gave him that cut. I’d feel tempted to use my automatic on him,” declared Alex, wrathfully, as he watched Clay, assisted by Case, apply the peroxide until it stopped foaming, follow it up with a liberal application of the healing salve, and then bind up the paw with long strips of white cloth.

“What’s the matter with his other arm?” Case asked. “Look how he keeps it doubled up all the time. I believe he’s holding something in it. I can see a bit of black.”

“So there is,” Alex agreed. “Hold out your other arm, Teddy, and let’s see what you have got.”

But Teddy was reluctant to part with his treasure and it was only after repeated commands that he obeyed.

Alex seized the object and bore it down into the brighter light of the cabin, his companions following. He laid the object on the table and all three boys burst into laughter.

It was an old battered felt hat and across its top were several long rents where the bear’s claws had raked over; to one of the rents clung a generous patch of skin covered on the outside by long, coarse black hair.

“I guess Teddy Bear’s more than evened up things,” grinned Alex. “I am going to bring him down into the cabin and give it to him. It belongs to him. He earned it. That fellow will not prowl in the dark much for awhile.”

So Teddy was led below, and received the return of the hat and scalp lock with much satisfaction.

“It is near day-break so there is not much use of our going to bed again,” Clay said. “I’ll cook breakfast and we will get to work early. I don’t know what we are going to do about Teddy Bear,” he continued. “He is getting too strong for a pet. We can’t control him and he’s liable to hurt some of us even in play. Get out of here!” he ordered, as Teddy slowly worked his way up to the sugar locker. He raised the knife with which he was slicing bacon and pointed it at the bear to emphasize his command.

Teddy fled to the far end of the cabin, whining in fear.

“There’s your answer,” laughed Alex. “We have never punished Teddy like we ought, but he has learned by experience himself that knives hurt. I guess a little punishment now and then when he has done wrong will keep him under control. We began his education wrong, we should have started with discipline first.”

CHAPTER V

STARTING

As soon as the sun was up the boys were at work The first job was to remove the old motors to make place for the new. This was a dirty, greasy job but not hard. The nuts holding the motors to the solidly-built bed were unscrewed and the motors were carried out and stored in a corner of the big warehouse where the aged docktender had offered to keep an eye on them until the boys got back from their trip.

But the placing of the new motor was more of an undertaking. Strong as they were, the boys could not lift it aboard.

“We will have to have help and plenty of it,” Clay declared, after they had twice made the attempt and failed. “Of course we could get a plank and block and tackle and get it aboard, but if the rope or board slipped just a little bit it would go through the bottom of the Rambler as though the boards were made of paper. Then I can see now that the engine bed has got to be fixed. It’s too narrow for this new motor. Now I’ve got a few more things to buy, so I’ll run up town and get them. I’ll stop on my way up and send down a couple of good carpenters with plenty of hard wood to fix up that engine bed right. Then when I come down, I’ll bring four or five good husky men along with me and we’ll have that motor in its place in no time.”

He was not gone long before the two carpenters came down bearing their tools and several blocks of oak. The engine hold was a close place to work in, but they made good progress and soon had fitted in a new bed smooth and level to fit the new engine. They had just finished their job when Clay appeared, followed by a loaded wagon and four big strapping Irishmen.

With the aid of the Irishmen, and the help of the carpenters who had remained to watch, the motor was lowered down onto the new bed. This done, it only remained to fasten it down with six big bolts and connect the engine up with the shaft. A few minutes sufficed for this. Clay paid the Irishmen and the carpenters double wages for the time they had worked and they departed well pleased with their few hours’ labor.

The boys then turned to the task of stowing the load the wagon had brought down. Part of this consisted of three barrels of kerosene, two of which they emptied into the Rambler’s tank, the third was placed up on the forward deck. The boxes and packages were taken below and their contents emptied into the lockers. “We haven’t got space for a hundred pounds more stuff,” Alex announced when they finished. “We are just about filled up.”

“We are ready to start right now,” said Clay with satisfaction, “but of course we cannot go until tomorrow’s freight, and we can not go without Ike. I saw him this morning and he said he would be down tonight—likely would get down in time for supper. What do you say, boys, if we take a little spin just to try out our new motor and see if there’s anything the matter with it. Turn on the oil at the tank, Alex, and then both of you stand by to cast off when I give the word.”

The boys obeyed quickly, eager for the test, while Clay went back and fussed with the motor. Case and Alex waited long by the mooring lines for the signal to let go, but it did not come.

“Can’t you start it?” Alex at last shouted impatiently.

“Sure,” replied Clay, coolly. “I could start it right off, but it would be ruined in ten minutes without petting it up a little first. I’ve been filling up grease cups, putting oil in the lubricating tanks, and oiling up the working parts. You’ve got to watch those things closely with this kind of a motor or it will run hot and melt away its bearings. But I am about to start now. As soon as she starts throw off the lines, and you, Case, take the wheel.”

In a moment there came a series of sharp explosions from the engine room. The boys cast off the lines and Case jumped back to the wheel. The Rambler backed slowly away from the wharf. As soon as she was clear of the pier, Clay reversed the engine and the Rambler was headed up stream.

Clay remained in the engine pit tuning up his new charge, trying it out slowly like a new race horse, striving to bring each working part into harmony with its fellows, now turning on a little more oil, or a little more air, again screwing down for less oil and increasing the air; his keen ear attuned to the throb of the exhaust whose varying notes told the story of the changes his tinkering had wrought. It was stuffy in the engine hold and once he raised his head above the coaming for a deep breath of fresh air. He grinned at the scraps of conversation that floated back to him from up forward.

“The Rambler don’t go like she used to go,” Case was saying, gloomily, “every craft on the stream is passing us. Look at that Vixen behind. She is creeping right up on us now and the Rambler used to make two miles to her one.”

“Yes,” Alex agreed, dejectedly. “Clay has handed us a lemon all right. It has turned the Rambler into a floating hearse. Well, he meant it for the best and we must not show our disappointment. He’ll feel bad enough about it himself when he finds out the mistake he made.”

“Sure, there’s to be no roasting of Clay,” Case agreed, heartily. “He’s the best one of us three.”

Clay, still grinning, dropped down again into the hold and resumed his tinkering with air and oil tubes. He straightened up at last, and gave a sigh of satisfaction as his ear caught a new note in the throbbing exhaust, a low, mellow throb, throb, throb, regular and even. He had at last secured the right mixture of oil and air for the motor. He filed little notches on the air and oil cocks so that in the future the proper adjustments of air and oil could be made at a moment’s notice. This done, he climbed out of the hold and made his way forward.

“Well, how’s she doing?” he asked of the downcast two.

Alex tried to answer brightly. “She seems to go a wee mite slower than she used to, but maybe she’ll do better when the new engine gets limbered up a bit.”

“It feels dandy to be out in the Rambler once more, doesn’t it?” put in Case, hurriedly.

Clay turned aside to hide his grin. “Isn’t that the Dingbat coming down on us from ahead?” Didn’t we used to be able to outrun her?”

“No, she always used to beat us a little,” Alex said, gloomily.

“Well, it’s time we were turning back anyway,” Clay observed. “When she gets past you, Case, turn around and follow her.” He walked back to the hold grinning at the scraps of conversation that followed him.

“Think of him wanting to race the Dingbat, with this one-mule water wagon.”

“And the Dingbat is one of the swiftest motor boats around here.”

“Think of our hoping that he would tumble to his mistake by degrees and not get so rough a jar.”

“Well, he had to know it some time. He isn’t quite blind.”

Clay reached the hold and dropping down into it, stood with head above the hatch coaming watching. He saw the Dingbat sweep past like an arrow, and Case, obedient to order, swing the Rambler around in slow, clumsy pursuit. Then he reached down to the motor and shoving over the lever to make a quicker spark, turned on a little more oil and air. He could feel the Rambler leap forward as he clambered out of the hold and walked forward.

The boys’ faces were a study. Case, his mouth wide open, was handling the wheel and gazing ahead at the great foamy waves parting away from the bow.

Alex, leaning over the side, was watching the foam slip by while amazement and surprise stood out on his freckled face. “Clay,” he shouted, “pinch me and see if I’m asleep or just plain crazy. Five minutes ago I was in a hearse, and now I’m in a flying machine.”

“Oh, she isn’t flying yet, laughed Clay. “She’s only just getting off the ground. Face around and have a good look at the Dingbat.”

The Rambler swept past the Dingbat like a trolley car past a loaded wagon. The Dingbat’s captain in assumed rage, rose to his feet and shook his fist at them as they swept by.”

“Look here,” he shouted. “I’m willing to race any motor boat around these parts, but I’ll be hanged if I’ll match my boat against a hydroplane.”

“Want more speed, Case?” Clay inquired. “I’ve only got three-fourths of the power turned on.”

“More speed?” yelled Case as he nearly swamped a passing row boat with the high waves which the Rambler’s bows sent rolling away from her. “More power?” he repeated, when the curses heaped on him by the row boat’s crew had died away behind. “The balance of the power would drive her under water, loaded as she is.”

“No,” Alex grinned. “It would send all the water in the South Branch clean up into the city in a series of tidal waves.”

Clay prudently set the timer at half speed. They made the run back to the dock in less than half the time it had taken them to go. The boys were jubilant over the motor.

“I’ll bet she made 18 miles an hour on that first sprint,” Alex exulted.

“Under full power and laden light, I am sure we can get twenty-two miles an hour out of her,” Case said, confidently.

They found the two applicants for passage waiting on the wharf. “Hallo,” said the big man heartily. “We come as we said we would. This is my partner. Partner Bill, and a right good partner too he is. Me and him have been partners for a right smart number of years. Ain’t we, Bill?”

“Yes, Jed, but don’t talk too much,” growled Bill, who, though smaller than his partner, was a man of powerful build and heavily muscled, unlike Jed, however, his hands were dirty and his face bore the stamp of every evil passion.

“All right, Bill,” said Jed, good-naturedly. “I guess this chap,” indicating Case,” told you fellows about the talk I had with him yesterday.”

“Haven’t I seen you two somewhere before?” Clay demanded before Alex or Case could reply.

Bill looked startled and Jed shifted his feet uneasily before he answered. “You might have seen us somewhere,” he admitted, slowly. “We have been in Chicago all winter doing odd jobs to keep our bodies and souls together, ’till the spring thaw. Yes, you may have seen us working somewhere.”

“It was last fall at Ike’s news stand on the corner I first saw you,” Clay spoke slowly and watched the two faces. Jed squirmed uneasily but the other came promptly to the rescue.

“That’s where it was,” he exclaimed. “We was strangers to the city and we stopped there to ask some directions, and had a right pleasant chat with the boy before we left.”

“And I saw you there again,” Clay continued.

“Like as not,” interrupted the other. “We have hung around the stand a good deal this winter and Ike and us got to be real good friends.”

“Yes, you seemed mighty good friends the last time I saw you together,” Clay said, dryly. “It was only a couple of afternoons ago and you two were trying to rough house Ike and you might have done it too, if I hadn’t seen the fracas and called the police.”

Bill seemed at a loss for an answer for a second and then his reckless air came back. “We wasn’t going to hurt him none—just scare him. We asked him for a dime to get a bowl of soup, ’cause we were nearly starved, and that miserable whining Jew——”

“Stop right there,” Alex commanded. “Ike is a Jew but he is not miserable and he is not whining. He is manly and straight. He is one of our best friends and he is coming down this evening to go on this trip with us.”

Clay had shook his head vigorously at Alex but the boy would not be stopped until he said what he had to say.

The effect on the two men was amazing. Anger and evil passions played over Bill’s face like black clouds over a murky sky. Even Jed’s good-humored countenance became downcast and troubled.

“Come on, partner,” he said, plucking at Bill’s sleeve. “They don’t want you an’ me here. Let’s go and try somewhere else.”

Bill, with a string of oaths on his lips, suffered him to lead him off the end of the dock where he turned and shook his clenched fist at the boys on the Rambler.

“He would sure be a nice one to have along on a trip,” Alex grinned. “I’d be afraid to go to sleep for fear I’d wake up murdered.”

“I’m sorry you told them Ike was going with us,” Clay said severely. “If he had wanted them to know he would have told them, but he didn’t. You could see that by their faces when you blurted it out. Well, it’s done now and can’t be helped. It’s your turn to cook dinner, Case. After it is over, I’ll show you both how to run the new motor. It’s very simple. You’ll soon be able to handle it.”

CHAPTER VI

A MURDEROUS ASSAULT

As Clay had said, it took but a little while for Alex and Case to learn to handle the new motor and they soon became delighted with its simplicity.

“The only bad feature about it is that it has to be cleaned more frequently than a gas engine,” Clay observed. “The kerosene soots up the piston and coats the rings and then the motor does not work well. It ought to be cleaned thoroughly at least once a week. I’ve been thinking that we had ought to make the cleaning of it a new punishment for slang using. Our present penalty is too light—the dish washing has been tried and found wanting. After a man has spent a day down in that stuffy hold, covered with grease and oil, it will make him careful of his language for a long time.”

“All right,” agreed his companions, but Alex, with an eye to the present, past and future, added craftily: “Of course this doesn’t apply to past offences, nor to future ones. It only goes into effect when we are actually started on our trip up the Yukon?”

“That’s about it,” assented Clay.

“Then I want to say that we are a lot of boneheads running around wasting our precious oil. We are dippy, all of us. Case has got bats in his belfry, you have a few wheels in your head, and I’m not quite right in my upper story. Let’s go in and overhaul our stores instead of casting money.”

All the afternoon the boys labored on the more careful repacking of their hastily stored cargo and overhauling their personal belongings. When the afternoon began to wane, Alex betook himself to the kitchen to prepare the supper which they had agreed should be quite a spread in honor of Ike’s coming. As the sun went down, Case tied a rope around Teddy Bear and led him up on the dock, followed by Captain Joe. “I’m going up the street a bit and meet Ike,” he said. The animals need exercise and I guess Ike will be pretty tired with his luggage before he gets down here.”

Alex, assisted by Clay in the preparation of the feast, took but little notice of the passage of time until the cabin grew so dark that they had to turn on the lights to see.

“Gee, I wonder what’s keeping Ike so long,” Alex exclaimed. “If he doesn’t come pretty soon the supper will be spoilt.”

“Strange Case doesn’t come back,” Clay said uneasily. “He’s been gone over an hour. I hope he didn’t take Teddy up town. If he did, he’s liable to have got into trouble and Ike may be trying to help him out. One of us had better go up and see what’s the matter.”

He had scarcely spoken when there came the sound of slow foot-steps on the dock and Alex snapped on the prow light.

The first to come inside of the half circle of light was Teddy and Captain Joe, then followed Case, half carrying, half supporting a limp form.

Alex and Clay leaped to the wharf to receive the strange possession.

“It’s Ike,” said Case, as he stopped, and stood panting, but still supporting his heavy burden. “Give me a hand to get him down into the cabin. I’m about played out.”

The three carried him down into the cabin and laid him in a clean bunk, just taking off his shoes and loosening up his clothing so that he might rest easier. In the bright light, he looked ghastly, his face pale and many blood stained handkerchiefs around his head.

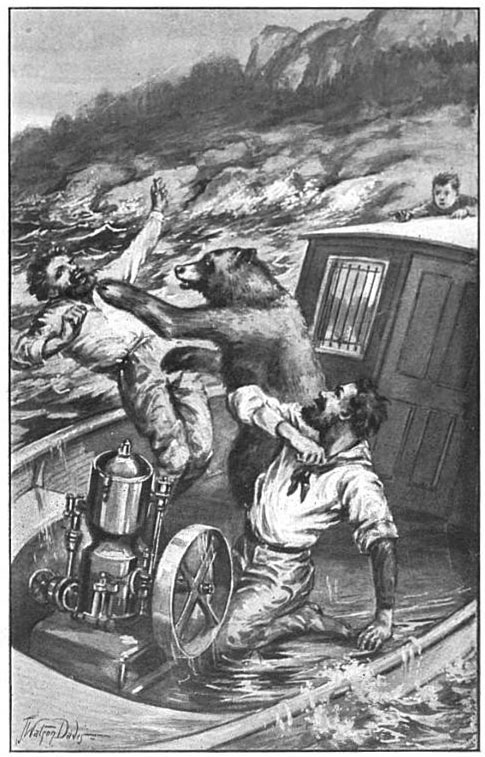

“Don’t look so scared,” said Case with a smile. “He is not going to die. He will be all right in a day or two. Let’s have supper and I’ll tell you all about it. The supper was placed upon the table and all three fell to eating while Case told his story. “I waited up the street a little ways until I began to feel uneasy and restless, then I moved further up the street, almost opposite that lumber yard. It was almost dark when I saw Ike coming. He was carrying a suitcase and walking fast. Just as he came to the other end of the lumber yard, two men sprang out on him. One hit him over the head and he went down like a stone. The other grabbed the suit case out of Ike’s hand, tore it open as though it was paper and dumped the contents out on the street. While he was pawing it over, the other fellow went through Ike’s pockets. For a full moment I was helpless with surprise, then I ran for the spot. Teddy and Captain Joe right behind me. The men saw me coming, but they stood their ground until I was about one hundred feet away. They evidently wanted to make a thorough search. When I got that close they ran and turned off the street into an alley.”

“Did you see their faces?” questioned Clay eagerly.

“I did,” Case replied. “They were the two men who wanted to take passage with us. Well, I did not follow them up. I got Ike laid out as comfortable as I could and called for the ambulance and then ran back to Ike. The ambulance got to him as quickly as I did. He soon came to under the doctor’s treatment. The doctor shaved his head, put ointment and sticking plaster on it, and bound it up. To save him a bad night of pain, the doctor gave him some sleeping, quieting dope, and then he ordered the driver to bring us down to the pier and pick him up on the way back. Well, the horses refused to go out over the water and we took Ike out of the wagon. I told the driver that I had a job on my hands. I guess the dope had taken good effect for he was unconscious and breathing heavily. I fairly had to carry him to the boat.”

“Did you notify the police?” Clay asked.

“No, Ike was conscious all right until the doctor gave him that dope and he begged me not to tell the police, for we might be held as witnesses so long that our trip would be spoilt.”

“Well,” said Alex. “I’ll be glad when we are off at last.”

“And that will be tonight,” Clay said. “I’m going to run the Rambler around tonight and anchor her close to the railroad dock. We start in the morning and it will be best to have her on hand. Besides I want to get out of here. There’s too much trouble going on around this pier. Do you think the noise of the motor would wake Ike, Chase?”

“You would have to hit him again with another pair of brass knucks—that’s what the doctor said was used on him—to wake him up,” laughed Case.

So the moorings were cast off. And the Rambler was run around close to the big railroad dock and anchored, while the boys, deciding that they had had enough excitement for one day, at once turned in. At daylight they were up again and tied up to the railroad dock. Here they passed strong ropes under the Rambler and fastening them above the boat had a strong, well-fixed sling, which would lift equally on all parts of the heavily-ladened boat, when the dock hoist was attached. This done there was nothing to do but wait until their train backed down to take them on.

Ike had been awakened by the noise on deck and, when the boys descended into the cabin, they found him sitting up on the edge of his bunk swinging his legs. “No, I ain’t sick, you understand,” he said in answer to their inquiries. “That low-life what hit me over the head he don’t do nothing but make my head ache some. Did them loafers steal anything from me when I no got my senses?”

“They broke open your suit case and scattered your things all over the pavement,” Case said. “I picked up all I could find but of course I did not know whether anything was missing.”

“Give me my clothes first,” Ike demanded. He examined the pockets of pants and coat and grinned. “They gets nothing here,” he said, “except a Canadian quarter, a lead half dollar, and a dime with a hole in it. I have a false lining here on the inside and it makes a dandy place to carry money, you understand.” He slapped the seat of his trousers and it gave back a crisp rustling as of stiff new bills. A careful examination of the torn suit case discovered nothing missing and Ike, feeling better in mind and spirit, declared he would like a bite to eat.

While Clay hustled around to cook him a slice of toast, some soft boiled eggs, and a cup of coffee, Alex ran up town and was soon back with a couple of morning papers.

They contained only a brief notice of the assault on Ike, probably given out by the ambulance surgeon, but flaring across on the first front page was:

“Chicago’s open season for hold-ups and murders has begun.” Then below the head lines followed.

“Mr. Austin, a rather prominent retail merchant, was on his way home last night when he was attacked by foot-pads who darted out on him from the old lumber yard on L street. Mr. Austin had been unable to get to the bank during the day and carried in a wallet in his breast pocket, over $1,000. While one man held him and choked him, the other relieved him of his money, and of the fat wallet. Then they tripped him up and took to their heels, escaping, as there are no policemen and few pedestrians on this lonely street. Mr. Austin describes the two as being very big, roughly clothed men, one of them having a red scar on one cheek. Of course they got away. Even if Mr. Austin had been able to obtain a good photograph of each it is doubtful if our bone-headed police would recognize the men if they accidentally met them.”

Just then came the rumble of a train coming down the dock. Clay pushed his head out of the window. “It’s our train,” he shouted. “Take those dishes off the table and set the pots off the stove. She may list a bit when they go to hoist her.”

A huge crane swung slowly over the Rambler and from it a huge hook attached to a chain was gently lowered. The boys quickly caught the hook in the sling. The chain slowly tightened and the Rambler was lifted bodily and lowered gently onto a flat car, where she was quickly shored up with timbers to keep her on an even keel.

It was only a few minutes before the train backed off the docks, switched onto the main track and began to crawl slowly out of the dingy city.

“Hurrah!” cried Alex in his joy. “We are off, off at last.” And the others joined him in his jubilation.

CHAPTER VII

THE GOLD FEVER

Four travel-weary looking boys stood on the hurricane deck of the steamer Arctic just landed at St. Michael’s Island which lies somewhat below the Arctic circle and close to the mouth of the great river Yukon. We spoke of the boys as standing, but that was incorrect, rather they were sitting, with legs swinging, on the deck of the motor boat Rambler, looking down at the strange scene going on below them. From one gang plank the Arctic’s passengers were pushing out eagerly to reach the shore, while up the other gang plank was struggling a line of curious humanity.

“Whew, if that’s what the gold-seeker gets to be like, then I don’t want to be one,” declared a boy gloomy looking, unless something exciting was going on around him. “Gee, they are a ghastly looking sight. See how some faces are disfigured by frost bites, and those others at the foot of the plank, notice how pale and wan their faces are, and notice the lines of suffering on them. Famine all winter I’ll bet caused that. See those three fellows coming up now, two with only one arm and one with one leg, been frozen or broken in accidents on the ice. Right behind them are two nearly dead with the scurvy; you can see the marks from here.”

“Well, maybe they have been well paid for their sufferings, Case,” observed Alex, whose good-humored, freckled face was always cheerful. “They’ll most of them get well quick as soon as they get to the States and get proper food and medicine.”

“They don’t look as though they make much money,” observed Ike, the Jew boy, dubiously. “Most of them has on rags and the best of them I could fit out better in a cheap second-hand shop.”

“You can’t tell a man by his clothes,” said Clay, the fourth boy, who was looking over at the distant town of Nome, a cluster of tents and rough shanties on the mainland.

“You’re right there,” said a voice behind them and the four wheeled around to find the captain of the steamer standing behind them. “No, you can’t judge those men by their looks or clothes. That fellow in rags has a claim up near Dawson that has turned him out over two million already. He wants a change. His folks have a kind of a farm up in the States. He’ll go there and lay around under the trees for a while and then drift back. That big man next to him is one of the richest miners in the north. He’ll go out for a month perhaps, spend a quarter of a million having what he calls a good time, then he’ll drift back. Maybe more than half of that crowd coming on board have made good stakes. Of the balance most are tenderfeet, who have simply got cold feet and have given up the game. But, boys, three-fourths of that crowd will be back in a year. I can’t understand it myself, but there is a lure to this Northland that seems to draw men back to her in spite of the awful punishments she gives. But all this isn’t what I came to see you about, boys. I wanted to say that we can lower your boat down any time, but its pretty rough now so I would advise you to wait until tomorrow.”

“Thank you, Captain,” said Clay, after a questioning glance at his companions. “We thank you very much, but we have been delayed so much on the journey that we have got to hustle to see much of the Yukon before the ice sets in. We want to see Nome this afternoon, and tomorrow begins our trip up the Yukon. I am sure the Rambler can ride those waves—she has gone over much bigger ones in her time. If the slings are placed right so that she will hit the water evenly, she will be all right.”

“All right, boys,” smiled the Captain. “Have your own way about it. Good-bye, and I hope it will be our fortune to go back on the same boat in the fall. I’ll send the boatswain right up to fix the slings. He’s an artist at that kind of work. We will have your boat in the water in a jiffy.”

He was gone but a moment when the boastswain appeared and with deft fingers adjusted the slings. At a signal the steamer’s big crane, hoisted high, swung in over their heads. The boys clambered aboard the Rambler and took their places—Case at the wheel, Clay at the motors, and Alex and Ike at the slings ready to cast off when the time came.

The big crane lifted them over the rail, held them poised for a minute, then lowered them gently down into the rough water below. The moment the slings slacked, Ike and Alex cast off the iron hooks that connected them to the crane. Clay started the motors, Case swung the wheel around, and the Rambler—like a bird freed from captivity—darted away, followed by the cheers of the steamer’s crew.

Alex danced up and down the deck, while the others could hardly refrain from joining him in their joy at being once more afloat on their beloved craft.

Case headed the Rambler for the straggling village. The little motor boat rode the sea valiantly and by mid-afternoon they were safely moored in the lea of a short pier running out from the beach. “Alex, you and Case run out and take in the sights while Ike and I stay by the boat,” Clay said. “We had not ought to leave the Rambler alone with all her valuable cargo. As soon as you get through with your sight-seeing, come back again and give Ike and me a chance. Better take Captain Joe and Teddy Bear with you. They need a walk after their long confinement. The two eagerly obeyed and Alex led Teddy away with Captain Joe at his heels.