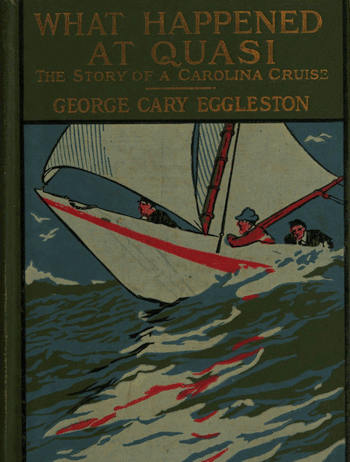

WHAT HAPPENED AT QUASI

THE STORY OF A CAROLINA CRUISE

BOOKS FOR BOYS

BY

GEORGE CARY EGGLESTON

Each Handsomely Illustrated. Price of Each Volume, $1.50

THE LAST OF THE FLATBOATS. A Story of the Mississippi and Its Interesting Family of Rivers.

CAMP VENTURE. A Story of the Virginia Mountains. Adventures among the “Moonshiners.”

THE BALE MARKED CIRCLE X. A Blockade-Running Adventure.

JACK SHELBY. A Story of the Indiana Backwoods.

LONG KNIVES. The Story of How They Won the West. A Tale of George Rogers Clark’s Expedition.

WHAT HAPPENED AT QUASI. The Story of a Carolina Cruise. A Tale of Sport and Adventure.

For Sale by All Booksellers, or Sent Postpaid on Receipt of Price by the Publishers

LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD CO., BOSTON

As Tom tugged hard at one of the larger roots, the keg suddenly fell to pieces.—Page 353.

WHAT HAPPENED AT QUASI

THE STORY OF A CAROLINA CRUISE

BY

GEORGE CARY EGGLESTON

ILLUSTRATED BY H. C. EDWARDS

BOSTON

LOTHROP, LEE & SHEPARD CO.

Published, April, 1911

Copyright, 1911

By Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co.

All rights reserved

What Happened at Quasi

NORWOOD PRESS

BERWICK & SMITH CO.

NORWOOD, MASS.

U. S. A.

I INSCRIBE THIS STORY WITH AFFECTION TO

GEORGE DUNN EGGLESTON

MY GRANDSON, IN THE BELIEF THAT WHEN HE GROWS OLD ENOUGH HE WILL WANT TO KNOW “WHAT HAPPENED AT QUASI,” AND WILL READ THE BOOK BY WAY OF FINDING OUT

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Interstate Chumming | 3 |

| II. | The Story of Quasi | 15 |

| III. | A Programme Subject to Circumstances | 25 |

| IV. | Tom Fights it Out | 30 |

| V. | A Rather Bad Night | 39 |

| VI. | A Little Sport by the Way | 54 |

| VII. | An Enemy in Camp | 67 |

| VIII. | Cal Begins to Do Things | 76 |

| IX. | A Fancy Shot | 89 |

| X. | Tom’s Discoveries | 97 |

| XI. | Perilous Spying | 108 |

| XII. | Tom’s Daring Venture | 119 |

| XIII. | Cal’s Experience as the Prodigal Son | 135 |

| XIV. | Cal Relates a Fable | 149 |

| XV. | Cal Gathers the Manna | 156 |

| XVI. | Fog-Bound | 164 |

| XVII. | The Obligation of a Gentleman | 174 |

| XVIII. | Fight or Fair Play | 182 |

| XIX. | Why Larry Was Ready for Battle | 191 |

| XX. | Aboard the Cutter | 197 |

| XXI. | Tom’s Scouting Scheme | 204 |

| XXII. | Tom Discovers Things | 212 |

| XXIII. | Tom and the Man With the Game Leg | 222 |

| XXIV. | The Lame Man’s Confession | 230 |

| XXV. | A Signal of Distress | 238 |

| XXVI.[x] | An Unexpected Interruption | 246 |

| XXVII. | The Hermit of Quasi | 258 |

| XXVIII. | Rudolf Dunbar’s Account of Himself | 265 |

| XXIX. | Tom Finds Things | 271 |

| XXX. | Dunbar Talks and Sleeps | 283 |

| XXXI. | Dunbar’s Strange Behavior | 295 |

| XXXII. | A Rainy Day With Dunbar | 306 |

| XXXIII. | A Great Catastrophe | 316 |

| XXXIV. | Marooned at Quasi | 331 |

| XXXV. | Again Tom Finds Something | 339 |

| XXXVI. | What the Earth Gave Up | 350 |

| XXXVII. | Tom’s Final “Find” | 360 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| As Tom tugged hard at one of the larger roots, the keg suddenly fell to pieces (Page 353) | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Dick, Cal, and Tom searched the man’s clothes | 72 |

| “In my haste I forgot to conceal my gun” | 126 |

| “Stand where you are or we’ll shoot” | 182 |

| “No, ’tain’t no use. I’ve got to take my medicine” | 226 |

| A minute more, it would have been too late | 320 |

WHAT HAPPENED AT QUASI

THE STORY OF A CAROLINA CRUISE

WHAT HAPPENED AT QUASI

THE STORY OF A CAROLINA CRUISE

I

INTERSTATE CHUMMING

It was hot in Charleston—intensely hot—with not a breath of air in motion anywhere. The glossy leaves of the magnolia trees in the grounds that surrounded the Rutledge house drooped despairingly in the withering, scorching, blistering sunlight of a summer afternoon in the year 1886. The cocker spaniel in the courtyard panted with tongue out, between the dips he took at brief intervals in the water-vat provided for his use. A glance down King Street showed no living creature, man or beast, astir in Charleston’s busiest thoroughfare.

In the upper verandah of the Rutledge mansion, four boys, as lightly dressed as propriety permitted, were doing their best to keep endurably cool and three of them were succeeding. The fourth was making a dismal failure of the attempt. He[4] was Richard Wentworth of Boston, and he naturally knew little of the arts by which the people of hot climates manage to endure torrid weather with tolerable comfort and satisfaction. He kept his blood excited by the exertion of violently fanning himself. While the others sat perfectly still in bamboo chairs, or lay motionless on joggling boards, Dick Wentworth was constantly stirring about in search of a cooler place which he did not find.

Presently he went for the fourth or fifth time to the end of the porch, where he could see a part of the street by peering through the great green jalousies or slatted shutters that barred out the fierce sunlight.

“What do you do that for, Dick?” asked Lawrence Rutledge in a languid tone and without lifting his head from the head-rest of the joggling board.

“What do I do what for?” asked Dick in return.

“Why run to the end of the verandah every five minutes? What do you do it for? Don’t you know it’s hot? Don’t you realize that violent exertion like that is unfit for weather like this? Why, I regard unnecessary winking as exercise altogether too strenuous at such a time, and so I don’t open my eyes except in little slits, and I do even that only[5] when I must. You see, I’m doing my best to keep cool, while you are stirring about all the time and fretting and fuming in a way that would set a kettle boiling. Why do you do it?”

“Oh, I’m only observing, in a strange land,” answered Dick, sinking into a wicker chair. “I’ll be quiet, now that I have found out the facts.”

“What are they, Dick?” asked Tom Garnett, otherwise known to his companions as “the Virginia delegation,” he being the only Virginian in the group. “What have you found out?”

“Only that the cobblestones, with which the street out there is paved, have been vulcanized, just as dentists treat rubber mouth plates. Otherwise they would melt.”

“I’d laugh at that joke, Dick, if I dared risk the exertion,” drawled Calhoun Rutledge, the fourth boy in the group, and Lawrence Rutledge’s twin brother. “Ah, there it comes!” he exclaimed, rolling off his joggling board and busying himself with turning the broad slats of the jalousies so as to admit the cool sea breeze that had set in with the turning of the tide.

Lawrence—or “Larry”—Rutledge did the same, and Tom Garnett slid out of his bamboo chair, stretched himself and exclaimed:

“Well, that is a relief!”

Dick Wentworth sat still, not realizing the sudden change until a stiff breeze streaming in through the blinds blew straight into his face, bearing with it a delicious odor from the cape jessamines that grew thickly about the house. Then he rose and hurried to an open lattice, quite as if he had expected to discover there some huge bellows or some gigantic electric fan stirring the air into rapid motion.

“What has happened?” he asked in astonishment.

“Nothing, except that the tide has turned,” answered Larry.

“But the breeze? Where does that come from?”

“From the sea. It always comes in with the flood-tide, and we’ve been waiting for it. Pull on your coat or stand out of the draught; the sudden change might give you a cold.”

“Then you don’t have to melt for whole days at a time, but get a little relief like this, now and then?”

“We don’t melt at all. We don’t suffer half as much from hot weather as the people of northern cities do—particularly New York.”

“But why not, if you have to undergo a grilling like this every day?”

“It doesn’t happen every day, or anything like every day. It never lasts long and we know how to endure it.”

“How? I’m anxious to learn. I may be put on the broiler again and I want to be prepared.”

“Well, we begin by recognizing facts and meeting them sensibly. It is always hot here in the sun, during the summer months, and so we don’t go out into the glare during the torrid hours. From about eleven till four o’clock nobody thinks of quitting the coolest, shadiest place he can find, while in northern cities those are the busiest hours of the day, even when the mercury is in the nineties. We do what we have to do in the early forenoon and the late afternoon. During the heat and burden of the day we keep still, avoiding exertion of every kind as we might shun pestilence or poison. The result is that sun strokes and heat prostrations are unknown here, while at the north during every hot spell your newspapers print long columns of the names of persons who have fallen victims.”

“Then again,” added Calhoun, “we build for hot weather while you build to meet arctic blasts. We set our houses separately in large plots of ground, while you pack yours as close together as possible. We provide ourselves with broad verandahs and bury ourselves in shade, while you are planning your[8] heating apparatus and doubling up your window sashes to keep the cold out.”

“It distresses me sorely,” broke in Larry, “to interrupt an interesting discussion to which I have contributed all the wisdom I care to spare, but the sun is more than half way down the western slope of the firmament, and if we are to get the dory into the water this afternoon it is high time for us to be wending our way through Spring Street to the neighborhood of Gadsden’s Green—so called, I believe, because some Gadsden of ancient times intended it to become green.”

The four boys had been classmates for several years in a noted preparatory school in Virginia. Dick Wentworth had been sent thither four years before for the sake of his threatened health. He had quickly grown strong again in the kindly climate of Virginia, but in the meanwhile he had learned to like his school and his schoolmates, particularly the two Rutledges and the Virginia boy, Tom Garnett. He had therefore remained at the school throughout the preparatory course.

Their school days were at an end now, all of them having passed their college entrance examinations; but they planned to be classmates still, all attending the same university at the North.

They were to spend the rest of the summer vacation[9] together, with the Charleston home of the Rutledge boys for their base of operations, while campaigning for sport and adventure far and wide on the coast.

That accounted for the dory. No boat of that type had ever been seen on the Carolina coast, but Larry and Cal Rutledge had learned to know its cruising qualities while on a visit to Dick Wentworth during the summer before, and this year their father had given them a dory, specially built to his order at Swampscott and shipped south by a coasting steamer.

When she arrived, she had only a priming coat of dirty-looking white paint upon her, and the boys promptly set to work painting her in a little boathouse of theirs on the Ashley river side of the city. The new paint was dry now and the boat was ready to take the water.

“She’s a beauty and no mistake,” said Cal as the group studied her lines and examined her rather elaborate lockers and other fittings.

“Yes, she’s all that,” responded his brother, “and we’ll try her paces to-morrow morning.”

“Not if she’s like all the other dories I’ve had anything to do with,” answered Dick. “She’s been out of water ever since she left her cradle, and it’ll take some time for her to soak up.”

“Oh, of course she’ll leak a little, even after a night in the water,” said Cal, with his peculiar drawl which always made whatever he said sound about equally like a mocking joke and the profoundest philosophy. “But who minds getting his feet wet in warm salt water?”

“Leak a little?” responded Dick; “leak a little? Why, she’ll fill herself half full within five minutes after we shove her in, and if we get into her to-morrow morning the other half will follow suit. It’ll take two days at least to make her seams tight.”

“Why didn’t the caulkers put more oakum into her seams, then?” queried Tom, whose acquaintance with boats was very scant. “I should think they’d jam and cram every seam so full that the boat would be water tight from the first.”

“Perhaps they would,” languidly drawled Cal, “if they knew no more about such things than you do, Tom.”

“How much do you know, Cal?” sharply asked the other.

“Oh, not much—not half or a quarter as much as Dick does. But a part of the little that I know is the fact that when you wet a dry, white cedar board it swells, and the further fact that when you soak dry oakum in water, it swells a great deal[11] more. It is my conviction that if a boat were caulked to water tightness while she was dry and then put into the water, the swelling would warp and split and twist her into a very fair imitation of a tall silk hat after a crazy mule has danced the highland fling upon it.”

“Oh, I see, of course. But will she be really tight after she swells up?”

“As tight as a drum. But we’ll take some oakum along, and a caulking tool or two, and a pot of white lead, so that if she gets a jolt of any kind and springs a leak we can haul her out and repair damages. We’ll take a little pot of paint, too, in one of the lockers.”

“There’ll be time enough after supper,” interrupted Larry, “to discuss everything like that, and we must be prompt at supper, too, for you know father is to leave for the North to-night to meet mother on Cape Cod and his ship sails at midnight. So get hold of the boat, every fellow of you, and let’s shove her in.”

The launching was done within a minute or two, and after that the dory rocked herself to sleep—that’s what Cal said.

“She’s certainly a beauty,” said Dick Wentworth. “And of course she’s better finished and finer every way than any dory I ever saw. You know, Tom,[12] dories up north are rough fishing boats. This one is finished like a yacht, and—”

“Oh, she’s hunky dory,” answered Tom, lapsing into slang.

“That’s what we’ll name her, then,” drawled Cal. “She’s certainly ‘hunky’ and she’s a dory, and if that doesn’t make her the Hunkydory, I’d very much like to know what s-o-x spells.”

There was a little laugh all round. As the incoming water floated the bottom boards, the name of the boat was unanimously adopted, and after another admiring look at her, the four hurried away to supper. On the way Dick explained to Tom that a dory is built for sailing or rowing in rough seas, and running ashore through the surf on shelving beaches.

“That accounts for the peculiar shape of her narrow, flat bottom, her heavy overhang at bow and stern, her widely sloping sides, and for the still odder shape and set of her centre board and rudder. She can come head-on to a beach, and as she glides up the sloping sand it shuts up her centre board and lifts her rudder out of its sockets without the least danger of injuring either. In the water a dory is as nervous as a schoolgirl in a thunder storm. The least wind pressure on her sails or the least shifting of her passengers or cargo, sends her heeling over almost[13] to her beam ends, but she is very hard to capsize, because her gunwales are so built out that they act as bilge keels.”

“I’d understand all that a good deal better,” answered Tom, laughing, “if I had the smallest notion what the words mean. I have a vague idea that I know what a rudder is, but when you talk of centre boards, overhangs, gunwales, and bilge keels, you tow me out beyond my depth.”

“Never mind,” said Cal. “Wait till we get you out on the water, you land lubber, and then Dick can give you a rudimentary course of instruction in nautical nomenclature. Just now there is neither time nor occasion to think about anything but the broiled spring chickens and plates full of rice that we’re to have for supper, with a casual reflection upon the okra, the green peas and the sliced tomatoes that will escort them into our presence.”

In an aside to Dick Wentworth—but spoken so that all could hear—Tom said:

“I don’t believe Cal can help talking that way. I think if he were drowning he’d put his cries of ‘help’ into elaborate sentences.”

“Certainly, I should do precisely that,” answered Cal. “Why not? Our thoughts are the children of our brains, and I think enough of my brain-children to dress them as well as I can.”

In part, Cal’s explanation was correct enough. But his habit of elaborate speech was, in fact, also meant to be mildly humorous. This was especially so when he deliberately overdressed his brain-children in ponderous words and stilted phrases.

They were at the Rutledge mansion by this time, however, and further chatter was cut off by a negro servant’s announcement that “Supper’s ready an’ yo’ fathah’s a waitin’.”

II

THE STORY OF QUASI

Major Rutledge entertained the boys at supper with accounts of his own experiences along the coast during the war, and incidentally gave them a good deal of detailed information likely to be useful to them in their journeyings. But he gave them no instructions and no cautions. He firmly believed that youths of their age and intelligence ought to know how to take care of themselves, and that if they did not it was high time for them to learn in the school of experience. He knew these to be courageous boys, manly, self-reliant, intelligent, and tactful. He was, therefore, disposed to leave them to their own devices, trusting to their wits to meet any emergencies that might arise.

One bit of assistance of great value he did give them, namely, a complete set of coast charts, prepared by the government officials at Washington.

“You see,” he explained to the two visitors, “this is a very low-lying coast, interlaced by a[16] tangled network of rivers, creeks, inlets, bayous, and the like, so that in many places it is difficult even for persons intimately familiar with its intricacies to find their way. My boys know the geography of it fairly well, but you’ll find they will have frequent need to consult the charts. I’ve had them encased in water-tight tin receptacles.”

“May I ask a question?” interjected Tom Garnett, as he minutely scanned one of the charts.

“Certainly, as many as you like.”

“What do those little figures mean that are dotted thickly all over the sheets?”

“They show the depth of water at every spot, at mean high tide. You’ll find them useful—particularly in making short cuts. You see, Tom, many of the narrowest of our creeks are very deep, and many broad bays very shallow in places. Besides, there are mud banks scattered all about, some of them under water all the time, others under it only at high tide. You boys don’t want to get stuck on them, and you won’t, if you study the figures on your charts closely. By the way, Larry, how much water does your boat draw?”

“Three feet, six inches, when loaded, with the centre board down—six inches, perhaps, when light, with the board up.”

“There, Tom, you see how easily the chart[17] soundings may save you a lot of trouble. There may be times when you can save miles of sailing by laying your course over sunken sandbars if sailing before the wind, though you couldn’t pass over them at all if sailing on the wind.”

“But what difference does the way of sailing make? You see, I am very ignorant, Major Rutledge.”

“You’ll learn fast enough, because you aren’t afraid to ask questions. Now to answer your last one; when you sail before the wind you’ll have no need of your centre board and can draw it up, making your draught only six or eight inches, while on the wind you must have the centre board down—my boys will explain that when you’re all afloat—so if you are sailing with the wind dead astern, or nearly so, it will be safe enough to lay a course that offers you only two or three feet of water in its shoalest parts, while if the wind is abeam, or in a beating direction, you must keep your centre board down and stick to deeper channels. However, the boys will soon teach you all that on the journey. They’re better sailors than I am.”

Then, turning to his own sons, he said:

“I have arranged with my bank to honor any checks either of you may draw. So if you have need of more money than you take with you, you’ll[18] know how to get it. Any planter or merchant down the coast will cash your checks for you. Now I must say good-bye to all of you, as I have many things to do before leaving. I wish all of you a very jolly time.”

With that he quitted the room, but a few minutes later he opened the door to say:

“If you get that far down the coast, boys, I wish you would take a look over Quasi and see that there are no squatters there.”

When he had gone, Cal said:

“Wonder if father hopes to win yet in that Quasi matter, after all these years?”

“I’m sure I don’t know,” answered Larry. “Anyhow, we’ll go that far down, if only to gratify his wish.”

“Is Quasi a town?” asked Dick, whose curiosity was awakened by the oddity of the name.

“No. It’s a plantation, and one with a story.”

Dick asked no more questions, but presently Cal said to his brother:

“Why don’t you go on, Larry, and tell him all about it? I have always been taught by my pastors and masters, and most other people I have ever known, that it is exceedingly bad manners to talk in enigmas before guests. Besides, there’s no secret about this. Everybody in South Carolina who ever[19] heard the name Rutledge knows all about Quasi. Go on and tell the fellows, lest they think our family has a skeleton in some one or other of its closets, and is cherishing some dark, mysterious secret.”

“Why don’t you tell it yourself, Cal? You know the story as well as I do.”

“Because, oh my brother, it was your remark that aroused the curiosity which it is our hospitable duty to satisfy. I do not wish to trespass upon your privileges or take your obligations upon myself. Go on! There is harkening all about you. You have your audience and your theme. We hang upon your lips.”

“Oh, it isn’t much of a story, but I may as well tell it,” said Larry, smiling at his brother’s ponderous speech.

“Quasi is a very large plantation occupying the end of a peninsula. Except on the mainland side a dozen miles of salt water, mud banks and marsh islands, separate it from the nearest land. On the mainland side there is a marsh two or three miles wide and a thousand miles deep, I think. At any rate, it is utterly impassable—a mere mass of semi-liquid mud, though it looks solid enough with its growth of tall salt marsh grass covering its ugliness and hiding its treachery. The point might as well be an island, so far as possibilities of approach[20] to it are concerned, and in effect it is an island, or quasi an island. I suppose some humorous old owner of it had that in mind when he named it Quasi.

“It is sea island cotton land of the very finest and richest kind, and when it was cultivated it was better worth working than a gold mine. There are large tracts of original timber on it, and as it has been abandoned and running wild for more than twenty years, even the young tree growths are large and fine now.

“That is where the story begins. Quasi belonged to our grandfather Rutledge. He didn’t live there, but he had the place under thorough cultivation. When the war broke out my grandfather was one of the few men in the South who doubted our side’s ability to win, and as no man could foresee what financial disturbances might occur, he decided to secure his two daughters—our father’s sisters, who were then young girls—against all possibility of poverty, by giving Quasi to them in their own right. ‘Then,’ he thought, ‘they will be comfortably well off, no matter what happens.’ So he deeded Quasi to them.

“When the Federals succeeded, early in the war, in seizing upon the sea island defences, establishing themselves at Beaufort, Hilton Head, and other[21] places, it was necessary for my grandfather to remove all the negroes from Quasi, lest they be carried off by the enemy. The place was therefore abandoned, but my grandfather said that, at any rate, nobody could carry off the land, and that that would make my aunts easy in their finances, whenever peace should come again. As he was a hard-fighting officer, noted for his dare-devil recklessness of danger, he did not think it likely that he would live to see the end. But he believed he had made his daughters secure against poverty, and as for my father, he thought him man enough to take care of himself.”

“The which he abundantly proved himself to be when the time came,” interrupted Cal, with a note of pride in his tone.

“Oh, that was a matter of course,” answered Larry. “It’s a way the Rutledges have always had. But that is no part of the story I’m telling. During the last year of the war, when everything was going against the South, grandfather saw clearly what the result must be, and he understood the effect it would have upon his fortunes. He was a well-to-do man—I may even say a wealthy one—but he foresaw that with the negroes set free and the industries of the South paralyzed for the time, his estate would be hopelessly insolvent. But like[22] the brave man that he was, he did not let these things trouble him. Believing that his daughters were amply provided for, and that my father—who at the age of twenty-five had fought his way from private to major—could look out for himself, the grim old warrior went on with his soldierly work and bothered not at all as to results.

“In the last months of the war, when the Southern armies were being broken to pieces, the clerk’s office, in which his deeds of Quasi to my aunts were recorded, was burned with all its contents. As evidence of the gift to his daughters nothing remained except his original deeds, and these might easily be destroyed in the clearly impending collapse of everything. To put those deeds in some place of safety was now his most earnest purpose. He took two or three days’ leave of absence, hurried to Charleston, secured the precious papers and put them in a place of safety—so safe a place, indeed, that to this day nobody has ever found them. That was not his fault. For the moment he returned to his post of command he sat down to write a letter to my aunts, telling them what he had done and how to find the documents. He had not written more than twenty lines when the enemy fell upon his command, and during the fight that ensued, he was shot through the head and instantly[23] killed. His unfinished letter was sent to my aunts, but it threw no light upon the hiding place he had selected.

“When the war ended, a few weeks later, the estate was insolvent, as my grandfather had foreseen. In the eagerness to get hold of even a little money to live upon, which was general at that time, my grandfather’s creditors were ready to sell their claims upon the estate for any price they could get, and two of the carrion crows called money-lenders bought up all the outstanding obligations.

“When they brought suit for the possession of my grandfather’s property, they included Quasi in their claim. When my father protested that Quasi belonged to his sisters by deeds of gift executed years before, he could offer no satisfactory proof of his contention—nothing, indeed, except the testimony of certain persons who could swear that the transfer had been a matter of general understanding, often mentioned in their presence, and other evidence of a similarly vague character.

“Of course this was not enough, but my father is a born fighter and would not give up. He secured delay and set about searching everywhere for the missing papers. In the meanwhile he was energetically working to rebuild his own fortunes, and he succeeded. As soon as he had money of his[24] own to fight with, he employed the shrewdest and ablest lawyers he could find to keep up the contest in behalf of his sisters. He has kept that fight up until now, and will keep it up until he wins it or dies. Of course he has himself amply provided for my aunts, so that it isn’t the property but a principle he is fighting for.

“By the way, the shooting ought to be good at Quasi—the place has run wild for so long and is so inaccessible to casual sportsmen. If the rest of you agree, we’ll make our way down there with no long stops as we go. Then we can take our time coming back.”

The others agreed, and after a little Dick Wentworth, who had remained silent for a time, turned to Larry, saying:

“Why did you say it wasn’t much of a story, Larry?”

III

A PROGRAMME—SUBJECT TO CIRCUMSTANCES

The Hunkydory was an unusually large boat for a craft of that kind. She was about twenty-five feet long, very wide amidships—as dories always are—and capable of carrying a heavy load without much increase in her draught of water. She was built of white cedar with a stout oak frame, fastened with copper bolts and rivets, and fitted with capacious, water-tight lockers at bow and stern, with narrower lockers running along her sides at the bilge, for use in carrying tools and the like.

She carried a broad mainsail and a large jib, and had rowlocks for four pairs of oars. Sitting on the forward or after rowing thwart, where she was narrow enough for sculls, one person could row her at a fair rate of speed, so little resistance did her peculiar shape offer to the water. With two pairs of oars, or better still, with all the rowlocks in use, she seemed to offer no resistance at all.

It was the plan of the boys to depend upon the sails whenever there was wind enough to make any progress at all, and ply the oars only when a calm compelled them to do so.

“We’re in no sort of hurry,” explained Larry, “and it really makes no difference whether we run one mile an hour or ten. There aren’t any trains to catch down where we are going.”

“Just where are we going, Larry,” asked Dick. “We’ve never talked that over, except in the vaguest way.”

“Show the boys, Cal,” said Larry, turning to his brother. “You’re better at coast geography than I am.”

“Hydrography would be the more accurate word in this case,” slowly answered Cal, “but it makes no difference.”

With that he lighted three or four more gas burners, and spread a large map of the coast upon the table.

“Now let me invoke your earnest attention, young gentlemen,” he began. “That’s the way the lecturers always introduce their talks, isn’t it? You see before you a somewhat detailed map of the coast and its waterways from Charleston, south to Brunswick, Georgia. It is grossly inaccurate in some particulars and slightly but annoyingly so[27] in others! Fortunately your lecturer is possessed of a large and entirely trustworthy fund of information, the garnerings, as it were, of prolonged and repeated personal observation. He will be able to correct the errors of the cartographer as he proceeds.

“We will take the Rutledge boathouse on the Ashley River near the foot of Spring Street as our point of departure, if you please. Enteuthen exelauni—pardon the lapse into Xenophontic Greek—I mean thence we shall sail across the Ashley to the mouth of Wappoo Creek which, as you see by the map, extends from Charleston Harbor to Stono Inlet or river, separating James Island from the main. Thence we shall proceed up Stono River, past John’s Island, and having thus disposed of James and John—familiar characters in that well-remembered work of fiction, the First Reader—we shall enter the so called North Edisto River, which is, in fact, an inlet or estuary, and sail up until we reach the point where the real Edisto River empties itself. Thence we shall proceed down the inlet known as South Edisto River round Edisto Island, and, by a little detour into the outside sea, pass into St. Helena Sound. From that point on we shall have a tangled network of big and little waterways to choose among, and we’ll[28] run up and down as many of them as tempt us with the promise of sport or adventure. We shall pass our nights ashore, and most of our days also, for that matter. Wherever we camp we will remain as long as we like. That is the programme. Like the prices in a grocer’s catalogue and the schedules of a railway, it is ‘subject to change without notice.’ That is to say, accident and unforeseen circumstances may interfere with it at any time.”

“Yes, and we may ourselves change it,” said Larry. “Indeed, I propose one change in it to start with.”

“What is it?” asked the others in chorus.

“Simply that we sail down the harbor first to give Dick and Tom a glimpse of the points of interest there. We’ll load the boat first and then, when we’ve made the circuit of the bay, we needn’t come back to the boat house, but can go on down Wappoo cut.”

The plan commended itself and was adopted, and as soon as the Hunkydory’s seams were sufficiently soaked the boat was put in readiness. There was not much cargo to be carried, as the boys intended to depend mainly upon their guns and fishing tackle for food supplies. A side of bacon, a water-tight firkin of rice, a box of salt, another of coffee, a tin[29] coffee-pot, and a few other cooking utensils were about all. The tools and lanterns were snuggled into the places prepared for them, an abundance of rope was bestowed, and the guns, ammunition and fishing tackle completed the outfit. Each member of the little company carried a large, well-stocked, damp-proof box of matches in his pocket, and each had a large clasp knife. There were no forks or plates, but the boat herself was well supplied with agate iron drinking cups.

It was well after dark when the loading was finished and the boat in readiness to begin her voyage. It was planned to set sail at sunrise, and so the crew went early to the joggling boards for a night’s rest in the breezy veranda.

“We’ll start if there’s a wind,” said Cal.

“We’ll start anyhow, wind or no wind,” answered Larry.

“Of course we will,” said Cal. “But you used the term ‘set sail.’ I object to it as an attempt to describe or characterize the process of making a start with the oars.”

“Be quiet, Cal, will you?” interjected Dick. “I was just falling into a doze when you punched me in the ribs with that criticism.”

IV

TOM FIGHTS IT OUT

Fortunately there was a breeze, rather light but sufficient, when the sun rose next morning. The Hunkydory was cast off and, with Cal at the tiller, her sails filled, she heeled over and “slid on her side,” as Tom described it, out of the Ashley River and on down the harbor where the wind was so much fresher that all the ship’s company had to brace themselves up against the windward gunwale, making live ballast of themselves.

The course was a frequently changing one, because the Rutledge boys wanted their guests to pass near all the points of interest, and also because they wanted Dick Wentworth, who was the most expert sailor in the company, to study the boat’s sailing peculiarities. To that end Dick went to the helm as soon as the wind freshened, and while following in a general way the sight-seeing course suggested by the Rutledges, he made many brief departures from it in order to test this or that peculiarity of[31] the boat, for, as Larry explained to Tom, “Every sailing craft has ways of her own, and you want to know what they are.”

After an hour of experiment, Dick said:

“We’ll have to get some sand bags somewhere. We need more ballast, especially around the mast. As she is, she shakes her head too much and is inclined to slew off to leeward.”

“Let me take the tiller, then, and we’ll get what we need,” answered Larry, going to the helm.

“Where?”

“At Fort Sumter. I know the officer in command there—in fact, he’s an intimate friend of our family,—and he’ll provide us with what we need. How much do you think?”

“About three hundred pounds—in fifty pound bags for distribution. Two hundred might do, but three hundred won’t be too much, I think, and if it is we can empty out the surplus.”

“How on earth can you tell a thing like that by mere guess work, Dick?” queried Tom in astonishment.

“It isn’t mere guess work,” said Dick. “In fact, it isn’t guess work at all.”

“What is it, then?”

“Experience and observation. You see, I’ve sailed many dories, Tom, and I’ve studied the behavior[32] of boats under mighty good sea schoolmasters—the Gloucester fishermen—and so with a little feeling of a boat in a wind I can judge pretty accurately what she needs in the way of ballast, just as anybody who has sailed a boat much, can judge how much wind to take and how much to spill.”

“I’d like to learn something about sailing if I could,” said Tom.

“You can and you shall,” broke in Cal. “Dick will teach you on this trip, and Larry and I will act as his subordinate instructors, so that before we get back from our wanderings you shall know how to handle a boat as well as we do; that is to say, if you don’t manage to send us all to Davy Jones during your apprenticeship. There’s a chance of that, but we’ll take the risk.”

“Yes, and there’s no better time to begin than right now,” said Dick. “That’s a ticklish landing Larry is about to make at Fort Sumter. Watch it closely and see just how he does it. Making a landing is the most difficult and dangerous thing one has to do in sailing.”

“Yes,” said Cal; “it’s like leaving off when you find you’re talking too much. It’s hard to do.”

The little company tarried at the fort only long enough for the soldiers to make and fill six canvas[33] sand bags. When they were afloat again and Dick had tested the bestowal of the ballast, he suggested that Tom should take his first lesson at the tiller. Sitting close beside him, the more expert youth directed him minutely until, after perhaps an hour of instruction, during which Dick so chose his courses as to give the novice both windward work and running to do, Tom could really make a fair showing in handling the sails and the rudder. He was still a trifle clumsy at the work and often somewhat unready and uncertain in his movements, but Dick pronounced him an apt scholar, and predicted his quick success in learning the art.

They were nearing the mouth of the harbor when Dick deemed it best to suspend the lesson and handle the boat himself. The wind had freshened still further, and a lumpy sea was coming in over the bar, so that while there was no danger to a boat properly handled, a little clumsiness might easily work mischief.

The boys were delighted with the behavior of the craft and were gleefully commenting on it when Larry observed that Tom, instead of bracing himself against the gunwale, was sitting limply on the bottom, with a face as white as the newly made sail.

“I say, boys, Tom’s seasick,” he called out.[34] “We’d better put about and run in under the lee of Morris Island.”

“No, don’t,” answered Tom, feebly. “I’m not going to be a spoil-sport, and I’ll fight this thing out. If I could only throw up my boots, I’d be all right. I’m sure it’s my boots that sit so heavily on my stomach.”

“Good for you, Tom,” said Larry, “but we’ll run into stiller waters anyhow. We don’t want you to suffer. If you were rid of this, I’d—”

He hesitated, and didn’t finish his sentence.

“What is it you’d do if I weren’t playing the baby this way?”

“Oh, it’s all right.”

“No, it isn’t,” protested Tom, feeling his seasickness less because of his determination to contest the point. “What is it you’d do? You shall do it anyhow. If you don’t, I’ll jump overboard. I tell you I’m no spoil-sport and I’m no whining baby to be coddled either. Tell me what you had in mind.”

“Oh, it was only a sudden thought, and probably a foolish one. I was seized with an insane desire to give the Hunkydory a fair chance to show what stuff she’s made of by running outside down the coast to the mouth of Stono Inlet, instead of going back and making our way through Wappoo creek.”

“Do it! Do it!” cried Tom, dragging himself up to his former posture. “If you don’t do it I’ll quit the expedition and go home to be put into pinafores again.”

“You’re a brick, Tom, and you shan’t be humiliated. We’ll make the outside trip. It won’t take very long, and maybe you’ll get over the worst of your sickness when we get outside.”

“If I don’t I’ll just grin and bear it,” answered Tom resolutely.

As the boat cleared the harbor and headed south, the sea grew much calmer, though the breeze continued as before. It was the choking of the channel that had made the water so “lumpy” at the harbor’s mouth. Tom was the first to observe the relief, and before the dory slipped into the calm waters of Stono Inlet he had only a trifling nausea to remind him of his suffering.

“This is the fulfillment of prophecy number one,” he said to Cal, while they were yet outside.

“What is?”

“Why this way of getting into Stono Inlet. You said our programme was likely to be ‘changed without notice,’ and this is the first change. You know it’s nearly always so. People very rarely carry out their plans exactly.”

“I suppose not,” interrupted Larry as the Stono[36] entrance was made, “but I’ve a plan in mind that we’ll carry out just as I’ve made it, and that not very long hence, either.”

“What is it, Larry?”

“Why to pick out a fit place for landing, go ashore, build a fire, and have supper. Does it occur to you that we had breakfast at daylight and that we’ve not had a bite to eat since, though it is nearly sunset?”

As he spoke, a bend of the shore line cut off what little breeze there was, the sail flapped and the dory moved only with the tide.

“Lower away the sail,” he called to Cal and Dick, at the same time hauling the boom inboard. “We must use the oars in making a landing, and I see the place. We’ll camp for the night on the bluff just ahead.”

“Bluff?” asked Tom, scanning the shore. “I don’t see any bluff.”

“Why there—straight ahead, and not five hundred yards away.”

“Do you call that a bluff? Why, it isn’t three feet higher than the low-lying land all around it.”

“After you’ve been a month on this coast,” said Cal, pulling at an oar, “you’ll learn that after all, terms are purely relative as expressions of human[37] thought. We call that a bluff because it fronts the water and is three feet higher than the general lay of the land. There aren’t many places down here that can boast so great a superiority to their surroundings. An elevation of ten feet we’d call high. It is all comparative.”

“Well, my appetite isn’t comparative, at any rate,” said Tom. “It’s both positive and superlative.”

“The usual sequel to an attack of seasickness, and I assure you—”

Cal never finished his assurance, whatever it was, for at that moment the boat made her landing, and Larry, who acted as commander of the expedition, quickly had everybody at work. The boat was to be secured so that the rise and fall of the tide would do her no harm; wood was to be gathered, a fire built and coffee made.

“And I am going out to see if I can’t get a few squirrels for supper, while you fellows get some oysters and catch a few crabs if you can. Oh, no, that’s too slow work. Take the cast net, Cal, and get a gallon or so of shrimps, in case I don’t find any squirrels.”

“I can save you some trouble and disappointment on that score,” said Cal, “by telling you now that you’ll get no squirrels and no game of any[38] other kind, unless perhaps you sprain your ankle or something and get a game leg.”

“But why not? How do you know?”

“We’re too close to Charleston. The pot-hunters haven’t left so much as a ground squirrel in these woods. I have been all over them and so I know. Better take the cartridges out of your gun and try for some fish. The tide’s right and you’ve an hour to do it in.”

Larry accepted the suggestion, and rowing the dory to a promising spot, secured a dozen whiting within half the time at disposal.

Supper was eaten with that keen enjoyment which only a camping meal ever gives, and with a crackling fire to stir enthusiasm, the boys sat for hours telling stories and listening to Dick’s account of his fishing trips along the northern shores, and his one summer’s camping in the Maine woods.

V

A RATHER BAD NIGHT

During the next two or three days the expedition worked its way through the tangled maze of big and little waterways, stopping only at night, in order that they might the sooner reach a point where game was plentiful.

At last Cal, who knew more about the matter than any one else in the party, pointed out a vast forest-covered region that lay ahead, with a broad stretch of water between.

“We’ll camp there for a day or two,” he said, “and get something besides sea food to eat. There are deer there and wild turkeys, and game birds, while squirrels and the like literally abound. I’ve hunted there for a week at a time. It’s only about six miles from here, and there’s a good breeze. We can easily make the run before night.”

Tom, who had by that time learned to handle the boat fairly well for a novice, was at the tiller, and the others, a trifle too confident of his skill perhaps,[40] were paying scant attention to what he was doing. The stretch of water they had to cross was generally deep, as the chart showed, but there were a few shoals and mud banks to be avoided. While the boys were eagerly listening to Cal’s description of the hunting grounds ahead, the boat was speeding rapidly, with the sail trimmed nearly flat, when there came a sudden flaw in the wind and Tom, in his nervous anxiety to meet the difficulty managed to put the helm the wrong way. A second later the dory was pushing her way through mud and submerged marsh grass. Tom’s error had driven her, head on, upon one of the grass covered mud banks.

Dick was instantly at work. Without waiting to haul the boom inboard, he let go the throat and peak halyards, and the sails ran down while the outer end of the boom buried itself in the mud.

“Now haul in the boom,” he said.

“Why didn’t you wait and do that first?” asked Tom, who was half out of his wits with chagrin over his blunder.

“Because, with the centre board up, if we’d hauled it in against the wind the boat would have rolled over and we should all have been floundering.”

“But the centre board was down,” answered Tom.

“Look at it,” said Cal. “Doubtless it was down when we struck, but as we slid up into the grass it was shut up like a jackknife.”

“Stop talking,” commanded Larry, “and get to the oars. It’s now or never. If we don’t get clear of this within five minutes we’ll have to lie here all night. The tide is just past full flood and the depth will grow less every minute. Now then! All together and back her out of this!”

With all their might the four boys backed with the oars, but the boat refused to move. Dick shifted the ballast a little and they made another effort, with no result except that Tom, in his well-nigh insane eagerness to repair the damage done, managed to break an oar.

“It’s no use, fellows,” said Larry. “You might as well ship your oars. We’re stuck for all night and must make the best of the situation.”

“Can’t we get out and push her off?” asked Tom in desperation.

“No. We’ve no bottom to stand on. The mud is too soft.”

“That’s one disadvantage in a dory,” said Dick, settling himself on a thwart. “If we had a keel[42] under us, we could have worked her free with the oars.”

“If, yes, and perhaps,” broke in Cal, who was disposed to be cheerfully philosophical under all circumstances. “What’s the use in iffing, yessing and perhapsing? We’re unfortunate in being stuck on a mud bank for the night, but stuck we are and there’s an end of that. We can’t make the matter better by wishing, or regretting, or bemoaning our fate, or making ourselves miserable in any other of the many ways that evil ingenuity has devised for the needless chastisement of the spirit. Let us ‘look forward not back, up and not down, out and not in,’ as Dr. Hale puts it. Instead of thinking how much happier we might be if we were spinning along over the water, let us think how much happier we shall be when we get out of this and set sail again. By the way, what have we on board that we can eat before the shades of night begin falling fast?”

“Well, if you will ‘look forward,’ as you’ve advised us all to do,” said Dick Wentworth, “by which I mean if you will explore the forward locker, you’ll find there a ten-pound can of sea biscuit, and half a dozen gnarled and twisted bologna sausages of the imported variety, warranted to keep in any climate and entirely capable of putting a[43] strain upon the digestion of an ostrich accustomed to dine on tenpenny nails and the fragments of broken beer bottles.”

“Where on earth did they come from?” asked Larry. “I superintended the lading of the boat—”

“Yes, I know you did, and I watched you. I observed that you had made no provision for shipwreck and so I surreptitiously purchased and bestowed these provisions myself. The old tars at Gloucester deeply impressed it upon my mind that it is never safe to venture upon salt water without a reserve supply of imperishable provisions to fall back upon in case of accidents like this.”

“This isn’t an accident,” said Tom, who had been silent for an unusual time; “it isn’t an accident; it’s the result of my stupidity and nothing else, and I can never—”

“Now stop that, Tom!” commanded Cal; “stop it quick, or you’ll meet with the accident of being chucked overboard. This was a mishap that might occur to anyone, and if there was any fault in the case every one of us is as much to blame as you are. You don’t profess to be an expert sailor, and we know it. We ought some of us to have helped you by observing things. Now quit blaming yourself, quit worrying and get to work chewing bologna.”

“Thank you, Cal,” was all that Tom could say in reply, and all set to work on what Dick called their “frugal meal,” adding:

“That phrase used to fool me. I found it in Sunday School books, where some Scotch cotter and his interesting family sat down to eat scones or porridge, and I thought it suggestive of something particularly good to eat. Having the chronically unsatisfied appetite of a growing boy, the thing made me hungry.”

“This bologna isn’t a bit bad after you’ve chewed enough of the dry out of it to get the taste,” said Larry, cutting off several slices of the smoke-hardened sausage.

“No,” said Dick, “it isn’t bad; but I judge from results that the Dutchman who made it had rather an exalted opinion of garlic as a flavoring.”

“Yes,” Cal answered, speaking slowly after his habit, “the thing is thoroughly impregnated with the flavor and odor of the allium sativum, and I was just revolving—”

“What’s that, Cal?” asked Larry, interrupting.

“What’s what?”

“Why, allium something or other—the thing you mentioned.”

“Oh, you mean allium sativum? Why, that is[45] the botanical name of the cultivated garlic plant, you ignoramus.”

“Well, how did you come to know that? You never studied botany.”

“No, of course not. I’ll put myself to the trouble of explaining a matter which would be obvious enough to you if you gave it proper thought. I found the term in the dictionary a month or so ago when you and I had some discussion as to the relationship between the garlic and the onion. I may have been positive in such assertions as I found it necessary to make in maintaining my side of the argument; doubtless I was so; but I was not sufficiently confident of the soundness of my views to make an open appeal to the dictionary. I consulted it secretly, surreptitiously, meaning to fling it at your head if I found that it sustained my contentions. As I found that it was strongly prejudiced on your side, I refrained from dragging it into the discussion. But I learned from it that garlic is allium sativum, and I made up my mind to floor you with that morsel of erudition at the first opportunity. This is it.”

“This is what?”

“Why, the first opportunity, to be sure. I’m glad it came now instead of at some other time.”

“Why, Cal?”

“Why because we have about eleven hours of tedious waiting time before us and must get rid of it in the best way we can. I’ve managed to wear away several minutes of it by talking cheerful nonsense and spreading it out over as many words as I could. I’ve noticed that chatter helps mightily to pass away a tedious waiting time, and I’m profoundly convinced that the very worst thing one can do in a case like ours is to stretch the time out by grumbling and fretting. If ever I’m sentenced to be hanged, I shall pass my last night pouring forth drivelling idiocy, just by way of getting through what I suppose must be rather a trying time to a condemned man.”

“By the way, Cal, you were just beginning to say something else when Larry interrupted you to ask about the Latin name of garlic. You said you were ‘just revolving.’ As you paused without any downward inflection, and as you certainly were not turning around, I suppose you meant you were just revolving something or other in your mind.”

“Your sagacity was not at fault, Tom, but my memory is. I was revolving something in my mind, some nonsense I suppose, but what it was, I am wholly unable to remember. Never mind; I’ll think of a hundred other equally foolish things[47] to say between now and midnight, and by that time we’ll all be asleep, I suppose.”

It was entirely dark now, and Dick Wentworth lighted a lantern and hoisted it as an anchor light.

“What’s the use, Dick, away out here?” asked one of the others.

“There may be no use in it,” replied Dick, “but a good seaman never asks himself that question. He just does what the rules of navigation require, and carries a clear conscience. If a ship has to stop in mid ocean to repair her machinery even on the calmest and brightest of days when the whole horizon is clear, the captain orders the three discs set that mean ‘ship not under control.’ So we’ll let our anchor light do its duty whether there is need of it or not.”

“That’s right in principle,” said Larry, “and after all it makes no difference as that lantern hasn’t more than a spoonful of oil in it. But most accidents, as they are called—”

Larry was not permitted to say what happened to “most accidents,” for as he spoke Tom called out:

“Hello! it’s raining!”

“Yes—sprinkling,” answered Larry, holding out his hand to feel the drops, “but it’ll be pouring in five minutes. We must hurry into our oilskins.[48] There! the anchor light has burned out and we must fumble in the dark.”

With that he opened a receptacle and hurriedly dragged the yellow, oil-stiffened garments out, saying as he did so:

“It’s too dark to see which is whose, but we’re all about of a size and they don’t cut slickers to a very nice fit. So help yourselves and put ’em on as quickly as you can, for it’s beginning to pour down.”

The boys felt about in the dark until presently Cal called out:

“I say, fellows, I want to do some trading. I’ve got hold of three pairs of trousers and two squams, but no coat. Who wants to swap a coat for two pairs of trousers and a sou’wester?”

The exchanges were soon made and the waterproof garments donned, but not before everybody had got pretty wet, for the rain was coming down in torrents now, such as are never seen except in tropical or subtropical regions.

The hurried performance served to divert the boys’ minds and cheer their spirits for a while, but when the “slickers” were on and closely fastened up, there was nothing to do but sit down again in the dismal night and wait for the time to wear away.

“Now this is just what we needed,” said Cal, as soon as the others began to grow silent and moody.

“What, the rain?”

“Yes. It helps to occupy the mind. It gives us something to think about. It is a thing of interest. By adding to our wretchedness, it teaches us the lesson that—”

“Oh, we don’t want any lessons, Cal; school’s out,” said Dick. “What I want to know is whether you ever saw so heavy a rain before. I never did. Why, there are no longer any drops—nothing but steady streams. Did you ever see anything like it?”

“Often, and worse,” Larry answered. “This is only an ordinary summer rain for this coast.”

“Well now, I understand—”

“Permit me to interrupt,” broke in Cal, “long enough to suggest that the water in this boat is now half way between my ankles and my knees, and I doubt the propriety of suffering it to rise any higher. Suppose you pass the pump, Dick.”

Dick handed the pump to his companion, who was not long in clearing the boat of the water. Then Tom took it and fitfully renewed the pumping from time to time, by way of keeping her clear. After, perhaps, an hour, the rain slackened to a[50] drizzle far more depressing to the spirits than the heavy downpour had been. The worst of the matter was that the night was an intensely warm one, and the oilskin clothing in which the boys were closely encased, was oppressive almost beyond endurance. Presently Dick began unbuttoning his.

“What are you doing, Dick? “Tom asked as he heard the rustle.

“Opening the cerements that encase my person,” Dick answered.

“But what for?”

“Why, to keep from getting too wet. In these things the sweat that flows through my skin is distinctly more dampening than the drizzling rain.”

“I’d smile at that,” said Cal, “if it were worth while, as it isn’t. We’re in the situation Charles Lamb pityingly imagined all mankind to have been during the ages before candles were invented. If we crack a joke after nightfall we must feel of our neighbor’s cheek to see if he is smiling.”

The desire for sleep was strong upon all the company, and one by one they settled themselves in the least uncomfortable positions possible under the circumstances, and became silent in the hope of catching at least a cat nap now and then. There was very little to be done in that way, for the moment one part of the body was adjusted so that[51] nothing hurt it, a thwart or a rib, or the edge of the rail, or something else would begin “digging holes,” as Larry said, in some other part.

Cal was the first to give up the attempt to sleep. After suffering as much torture as he thought he was called upon to endure he undoubled himself and sat upright. The rest soon followed his example, and Cal thought it best to set conversation going again.

“After all,” he said meditatively, “this is precisely what we came to seek.”

“What? The wretchedness of this night? I confess I am unable to take that view of it,” answered Larry almost irritatedly.

“That is simply because your sunny temper is enshrouded in the murky gloom of the night, and your customary ardor dampened by the drizzle. You are not philosophical. You shouldn’t suffer external things to disturb your spiritual calm. It does you much harm and no manner of good. Besides, it is obvious that you judged and condemned my thought without analyzing it.”

“How is that, Cal? Tell us about it,” said Dick. “Your prosing may put us to sleep in spite of the angularity and intrusive impertinence of everything we try to rest ourselves upon. Do your own analyzing and let us have the benefit of it.”

“Oh, it’s simple enough. I indulged in the reflection that this sort of thing is precisely what we set out on this expedition to find, and it is so, if you’ll only think of it. We came in search of two things—adventure and game. Surely this mud-bank experience is an adventure, and I’m doing my best to persuade you fellows to be ‘game’ in its endurance.”

“That finishes us,” said Dick. “A pun is discouraging at all times; a poor, weak-kneed, anæmic pun like that is simply disheartening, and coming at a time of despondency like this, it reduces every fibre of character to a pulp. I feel that under its influence my back bone has been converted into guava jelly.”

“Your speech betrayeth you, Dick. I never heard you sling English more vigorously than now. And you have regained your cheerfulness too, and your capacity to take interest. Upon my word, I’ll think up another pun and hurl it at you if it is to have any such effect as that.”

“While you’re doing it,” said Larry, “I’m going to get myself out of the sweatbox I’ve been in all night. You may or may not have observed it, but the rain has ceased, and the tide has turned and if I may be permitted to quote Shakespeare, ‘The glow-worm shows the matin to be near.’ In[53] modern phrase, day is breaking, and within about two hours the Hunkydory will be afloat again.”

With the relief of doffing the oppressive oilskins, and the rapidly coming daylight, the spirits of the little company revived, and it was almost a jolly mood in which they made their second meal on hard ship biscuit and still harder smoked bolognas.

VI

A LITTLE SPORT BY THE WAY

The day had just asserted itself when Larry, looking out upon the broad waters of a sound that lay between the dory and the point at which the dory would have been if she had not gone aground, rather gleefully said:

“We’ll be out of our trouble sooner than we hoped. The Hunkydory will float well before the full flood.”

“Why do you think so, Larry?” asked Tom, who had not yet recovered from his depression and was still blaming himself for the mishap and doubting the possibility of an escape that morning.

“I don’t think it; I know,” answered Larry, beginning to shift ballast in a way that would make backing off the mud bank easier.

“But how do you know?”

“Because there’s a high wind outside and it’s blowing on shore. Look at the white caps out there where the water is open to the sea. We’re in[55] a sort of pocket here, and feel nothing more than a stiff breeze, but it’s blowing great guns outside, and when that happens on an incoming tide the water rises a good deal higher than usual. We’ll float before the tide is at the full.”

“In my judgment we’re afloat now,” said Dick, who had been scrutinizing the water just around them. “We’re resting on the marsh grass, that’s all.”

“So we are,” said Cal, after scanning things a bit. “Let’s get to the oars!”

“Better wait for five or ten minutes,” objected Dick. “We might foul the rudder in backing off. Then we’d be in worse trouble than we were before.”

“That’s so, Dick,” answered Cal, restraining his impatience and falling at once into his peculiarly deliberate utterance. “That is certainly so, and I have been pleased to observe, Dick, that many things you say are so.”

“Thank you for the compliment, Cal, and for what it implies to the contrary.”

“Pray don’t mention it. Take a look over the bow instead and see how she lies now.”

In spite of their banter, that last ten minutes of waiting seemed tediously long, especially to Tom, who wanted to feel the boat gliding through the[56] water again before forgiving himself for having run her aground. At last the bow caught the force of the incoming flood, and without help from anybody the dory lifted herself out of the grass and drifted clear of the mud bank.

The centre board was quickly lowered, the sails hoisted, the burgee run up to the masthead, and, as the Hunkydory heeled over and began plowing through the water with a swish, her crew set up a shout of glee that told of young hearts glad again.

A kindly, gentle thought occurred to Dick Wentworth at that moment. It was that by way of reassuring Tom and showing him that their confidence in him was in no way shaken, they should call him to the helm at once. Dick signalled his suggestion to Larry, by nodding and pointing to Tom, whose eyes were turned away. Larry was quick to understand.

“I say, Tom,” he called out, “come to the tiller and finish your job. It’s still your turn to navigate the craft.”

Tom hesitated for a second, but only for a second. Perhaps he understood the kindly, generous meaning of the summons. However that might be, he promptly responded, and taking the helm from Larry’s hand, said, “Thank you, Larry—and all of you.”

That was all he said; indeed, it was all that he could say just then.

Suspecting something of the sort and dreading every manifestation of emotion, as boys so often do, Larry quickly diverted all minds by calling out:

“See there! Look! There’s a school of skipjacks breaking water dead ahead. Let’s have some fun trolling for them. We haven’t any appointed hours and we’re in no hurry, and trolling for skipjacks is prime sport.”

“What are they, anyhow?” asked Dick, who had become a good deal interested in the strange varieties of fish he had seen for the first time on the southern coast.

“Why, fish, of course. Did you think they were humming birds?”

“Well, I don’t know that I should have been greatly astonished if I had found them to be something of that kind. Since you introduced me to flying fish the other day, I’m prepared for anything. But what I wanted to know was what sort of fish the skipjacks are.”

“Oh, that was it? Well, they’re what you call bluefish up north, I believe. They are variously named along the coast—bluefish, jack mackerel, horse mackerel, skipfish, skipjacks, and by some other names, I believe, and they’re about as good[58] fish to eat as any that swims in salt water, by whatever name you call them.”

“Yes, I’ve eaten them as bluefish,” answered Dick. “They’re considered a great dainty in Boston and up north generally.”

“They’re all that,” answered Larry, “and catching them is great sport besides, as you’ll agree after you’ve had an hour or so of it. We must have some bait first. Tom, run her in toward the mouth of the slough you see on her starboard bow about a mile away. See it? There, where the palmetto trees stand. That’s it. She’s heading straight at the point I mean. Run her in there and bring her head into the wind. Then we’ll find a good place and beach her, and I’ll go ashore with the cast net and get a supply of shrimps.”

“Is it a wallflower or a widow you’re talking about, Larry?” languidly asked Cal, while his brother was getting the cast net out and arranging it for use.

“What do you mean, Cal? Some pestilent nonsense, I’ll be bound.”

“Not at all,” drawled Cal. “I was chivalrously concerned for the unattached and unattended female of whom you’ve been speaking. You’ve mentioned her six times, and always without an escort.”

“Oh, I see,” answered Larry, who was always quick to catch Cal’s rather obscure jests. “Well, by the pronouns ‘she’ and ‘her,’ I meant the good ship Hunkydory. She is now nearing the shore and if you don’t busy yourself arranging trolling lines and have them ready by the time I get back on board of her with a supply of shrimps, I’ll see to it that you’re in no fit condition to get off another feeble-minded joke like that for hours to come. There, Tom, give her just a capful of wind and run her gently up that little scrap of sandy beach. No, no, don’t haul your sheet so far—ease it off a bit, or she’ll run too far up the shore. There! That’s better. The moment her nose touches let the sheet run free. Good! Dick himself couldn’t have done that better.”

With that he sprang ashore, and with the heavily leaded cast net over his arm and a galvanized iron bait pail in his hand, hurried along the bank to the mouth of the slough, where he knew there would be multitudes of shrimps gathered for purposes of feeding. After three or four casts of the net he spread it, folded, over the top of his bait bucket to keep the shrimps he had caught from jumping out. Within fifteen minutes after leaping ashore he was back on board again with a bucket full of the bait he wanted.

“Now, then,” he said to Dick and Tom, “Cal will show you how to do the thing. I’ll sail the boat back and forth through the schools, spilling wind so as to keep speed down. Oh, it’s great sport.”

“Well, you shall have your share of it then,” said Dick, carefully coiling his line. “After I’ve tried it a little, and seen what sort of sailing it needs, I’ll relieve you at the tiller and you shall take my line.”

“You’ll do nothing of the kind,” said Cal with a slower drawl than usual by way of giving emphasis to his words. “Not if I see you first. After Larry has run us through the school two or three times, missing it more than half the time, I’ll take the tiller myself and give you a real chance to hook a fish or two.”

Dick knew Cal well enough to understand that he was in earnest and that there would be no use in protesting or arguing the matter. Besides that, he hooked a big fish just at that moment, and was jerked nearly off his feet. The strength of the pull astonished him for a moment. He had never encountered a fish of any kind that could tug like that, and for the moment he forgot that the dory was doing most of the pulling. In the meanwhile[61] he had lost his fish by holding his line too firmly and dragging the hook out of its mouth.

“That’s your first lesson,” said Cal, as deliberately as if there had been no exciting sport on hand, and with like deliberation letting his own line slip slowly through his tightened fingers. “You must do it as I am doing it now,” he continued. “You see, I have a fish at the other end of my line and I want to bring him aboard. So instead of holding as hard as a check post, I yield a little to the exigencies of the situation, letting the line slip with difficulty through my fingers at first and long enough to transmit the momentum of the boat to the fish. Then, having got his finny excellency well started in the way he should go, I encourage persistency in well doing on his part by drawing in line. Never mind your own line now. We’ve run through the school and Larry is heaving-to to let Tom and me land our fish. You observe that Tom has so far profited by his close study of my performance that—yes, he has landed the first fish, and here comes mine into the boat. You can set her going again, Larry; I won’t drag a line this time, but devote all my abilities to the instruction of Dick.”

On the next dash and the next no fish were[62] hooked. Then, as the boat sailed through the school again, Dick landed two beauties, and Tom one.

“That ends it for to-day,” said Larry, laying the boat’s course toward the heavily wooded mainland at the point where Cal had suggested a stay of several days for shooting.

“But why not make one more try?” eagerly asked Tom, whose enthusiasm in the sport was thoroughly aroused; “haven’t we time enough?”

“Yes,” said Larry, “but we have fish enough also. The catch will last us as long as we can keep the fish fresh, which isn’t very long in this climate, and we never catch more fish or kill more game than we can dispose of. It is unsportsmanlike to do that, and it is wanton cruelty besides.”

“That’s sound, and sensible, and sportsmanlike,” said Dick, approvingly. “And besides, we really haven’t any time to spare if we’re going to stop on the island yonder for dinner, as we agreed, and—”

“And as at least one appetite aboard the Hunkydory insists that we shall,” interrupted Cal. “It’s after three o’clock now.”

“So say we all of us,” sang Tom to the familiar after-dinner tune, and Larry shifted the course so as to head for an island nearly a mile away.

There a hasty dinner was cooked and eaten, but hasty as it was, it occupied more time in preparation than had been reckoned upon, so that it was fully five o’clock when the dory was again cast off.

In the meanwhile the wind had sunk to a mere zephyr, scarcely sufficient to give the heavy boat steerage way, and, late in the day, as it was, the sun shone with a sweltering fervor that caused the boys to look forward with dread to the prospect of having to resort to the oars.

That time came quickly, and the sails, now useless in the hot, still air, were reluctantly lowered.

A stretch of water, more than half a dozen miles in width, lay before them, and the tide was strong against them. But they pluckily plied the oars and the heavy boat slowly but surely overcame the distance.

They had found no fresh water on the island, and there was very little in the water kegs when they left it for their far-away destination. The hard work of rowing against the tide in a hot atmosphere, made them all thirsty, so that long before they reached their chosen landing place, the last drop of the water was gone, with at least two more hours of rowing in prospect.

“There’s a spring where I propose to land,” said Cal, by way of reassuring his companions. “As[64] I remember it, the water’s a bit brackish, but it is drinkable at any rate.”

“Are you sure you can find the spot in the dark, Cal?” asked Larry, with some anxiety in his voice. “For it’ll be pitch dark before we get there.”

“Oh, yes, I can find it,” his brother answered.

“There’s a deep indentation in the coast there—an inlet, in fact, which runs several miles up through the woods. We’ll run in toward the shore presently and skirt along till we come to the mouth of the creek. I’ll find it easily enough.”

But in spite of his assurances, the boys, now severely suffering with thirst, had doubts, and to make sure, they approached the shore and insisted that Cal should place himself on the bow, where he could see the land as the boat skirted it.

This left three of them to handle four oars. One of them used a pair, in the stern rowlocks, where the width of the boat was not too great for sculls, while the other two plied each an oar amidships.

In their impatience, and tortured by thirst as they were, the three oarsmen put their backs into the rowing and maintained a stroke that sent the boat along at a greater speed than she had ever before made with the oars alone. Still it seemed to them that their progress was insufferably slow.

Presently Cal called to them: “Port—more to port—steady! there! we’re in the creek and have only to round one bend of it. Starboard! Steady! Way enough.”

A moment later the dory slid easily up a little sloping beach and rested there.

“Where’s your spring, Cal?” the whole company cried in chorus, leaping ashore.

“This way—here it is.”

The spring was a small pool, badly choked, but the boys threw themselves down and drank of it greedily. It was not until their thirst was considerably quenched that they began to observe how brackish the water was. When the matter was mentioned at last, Cal dismissed it with one of his profound discourses.

“I’ve drunk better water than that, I’ll admit; but I never drank any water that I enjoyed more.” Then he added:

“You fellows are ungrateful, illogical, unfair, altogether unreasonable. That water is so good that you never found out its badness till after it had done you a better service than any other water in the world ever did. Yet now you ungratefully revile its lately discovered badness, while omitting to remember its previously enjoyed and surpassing[66] goodness. I am so ashamed of you that I’m going to start a fire and get supper going. I for one want some coffee, and it is going to be made of water from that spring, too. Those who object to brackish coffee will simply have to go without.”

VII

AN ENEMY IN CAMP

No sooner was the camp fire started than Cal went to the boat and brought away a piece of tarpaulin, used to protect things against rain. With this and a lighted lantern he started off through the thicket toward the mouth of the little estuary, leaving Dick to make coffee and fry fish, while Larry mixed a paste of corn meal, water and a little salt, which he meant presently to spread into thin sheets and bake in the hot embers, as soon as the fire should burn down sufficiently to make a bed of coals.

As Cal was setting out, Tom, who had no particular duty to do at the moment, asked:

“Where are you off to, Cal?”

“Come along with me and see,” Cal responded without answering the direct question. “I may need your help. Suppose you bring the big bait bucket with you. Empty the shrimps somewhere. They’re all too dead to eat, but we may need ’em for bait.”

Tom accepted the invitation and the two were quickly beyond the bend in the creek and well out of sight of the camp. As they neared the open water, Cal stopped, held the lantern high above his head, and looked about him as if in search of something. Presently he lowered the lantern, cried out, “Ah, there it is,” and strode on rapidly through the dense undergrowth.

Tom had no time to ask questions. He had enough to do to follow his long-legged companion.

After a brief struggle with vines and undergrowths of every kind, the pair came out upon a little sandy beach with a large oyster bank behind it, and Tom had no further need to ask questions, for Cal spread the tarpaulin out flat upon the sands, and both boys began gathering oysters, not from the solid bank where thousands of them had their shells tightly welded together, but from the water’s edge, and even from the water itself wherever it did not exceed a foot or so in depth. Cal explained that these submerged oysters, being nearly all the time under salt water, and growing singly, or nearly so, were far fatter and better than those in the bank or near its foot.

It did not take long to gather quite as many of the fat bivalves as the two could conveniently carry in the tarpaulin and the bait pail, and as Cal was[69] tying up the corners of the cloth Tom began scrutinizing the sandy beach at a point which the ordinary tides did not reach. As he did so he observed a queer depression in the sand and asked Cal to come and see what it meant.

After a single glance at it, Cal exclaimed gleefully:

“Good for you, Tom. This is the luckiest find yet.”

With that he placed the lantern in a favorable position, emptied the bait pail, hurriedly knelt down, and with his hands began digging away the sand.

“But what is it, Cal? What are you digging for?”

“I’ll show you in half a minute,” said the other, continuing to dig diligently. Less than the half minute later he began drawing out of the sand a multitude of snow-white eggs about the size of a walnut. As Tom looked on in open-mouthed wonder, he thought there must be no end to the supply.

“What are they, Cal?” the boy asked.

“Turtle’s eggs, and there’s a bait bucket full of them. You’ve made the luckiest find of all, Tom,” he said again in congratulation.

“Are they good to eat?”