AROUND THE WORLD

FOR

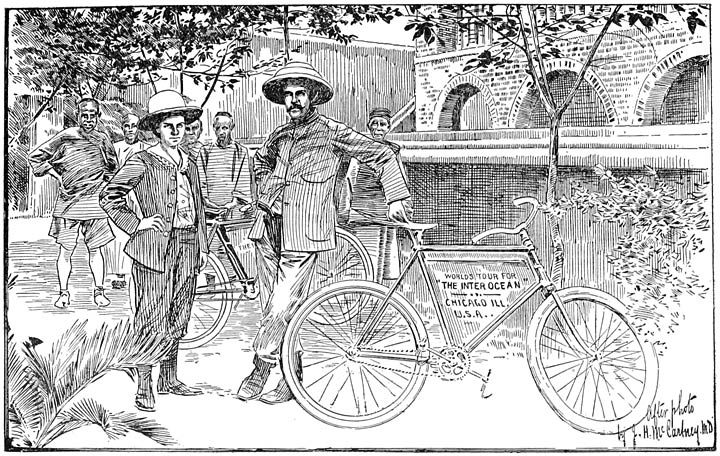

THE INTER OCEAN

IN FOREIGN LANDS

from April, 1895, to November, 1898.

[2]

THE TOUR AT A GLANCE.

INTRODUCTORY. PAGES.

Chicago Cyclists demonstrate their enthusiasm at the proposed World’s Tour awheel—Friends of the Inter Ocean endorse the project by giving the McIlraths letters to friends in foreign lands—The starting point left behind on April 10, 1895 5–7

Two and one-half days getting into Nebraska—Many friends made on the road—An unanswerable argument in favor of the “rational” costume for women—An encounter with the law at Melrose Park and what came of it 9–13

Hard cycling in a hailstorm—A speeder with one leg arouses the admiration of the World’s tourists—In Colorado at the one-time rendezvous of the famous James Boys and their gang—The 1,000 mile mark covered by May 3 13–18

Made wanderers at midnight through the whim of an unreasonable woman—Breaking a coasting record at Hot Springs, Colo.—Western railroad beds as dangerous as the Spanish Mines in Havana Harbor—An explosion and a badly lacerated tire 18–23

Lizards, snakes and swollen streams make traveling lively for tourists—Paralysis of hands and arms necessitates a week’s course of medical treatment—“Tommy Atkins,” most companionable of Englishmen, forced to desert the Inter Ocean cyclists 24–26

Vigilantes of Nevada mistake the wheelman for a notorious bandit—Saved by one’s gold teeth—Into Reno, where hospitality has its abode—Quick time to California, and then off for the Mikado’s land on Oct. 12 29–33

Quartered at the Club Hotel, Yokohama—Japan’s extraordinary credit system—At the funeral of a prince, and a few points noted on Japanese crowds—Uncle Sam’s people get the best of everything in Japan 33–38

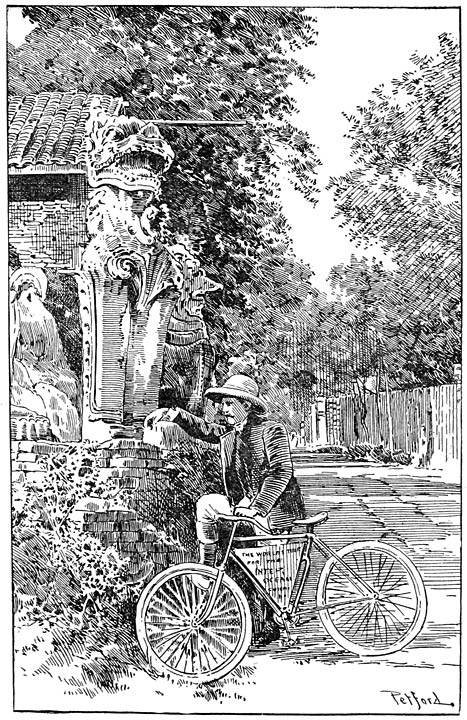

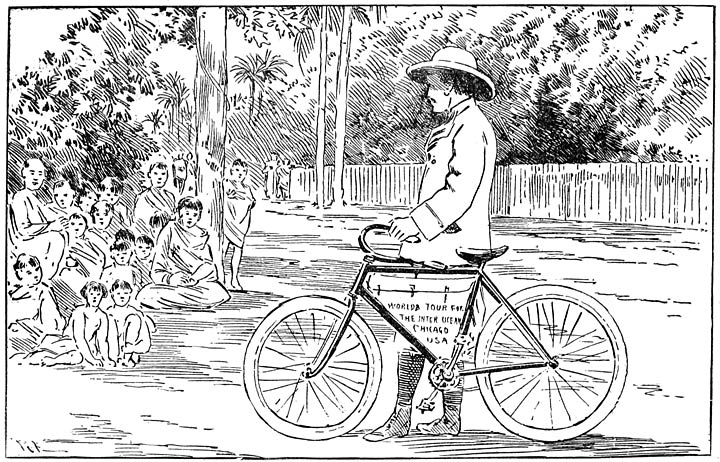

His Highness, the Emperor, objects to being “shot” by a camera—The war holidays at Shokausha Park, Kudan—By steamer to China—An effective “gun” for Chinese dogs—Cyclists the center of many inquisitive crowds 39–42

Guests at a Chinese wedding—The dark side of life in China sought and found—Indescribable horrors of a native prison—New Year extravagantly celebrated—Mrs. McIlrath’s pen picture of a Chinese lady of fashion 43–47

Received in state by the Tao Tai of Su Chow—Invited to witness the execution of a woman by the “Seng Chee” method—Debut of the bicycle along the Grand Canal—“Foreign devils” pursued by maddened mobs of natives 48–53

The American people’s able representative at Ching Kiang—A reminiscence of his pluck and courage in settling claims for his country—Wheeling by night in a strange country with mud up to the bicycle hubs 53–57

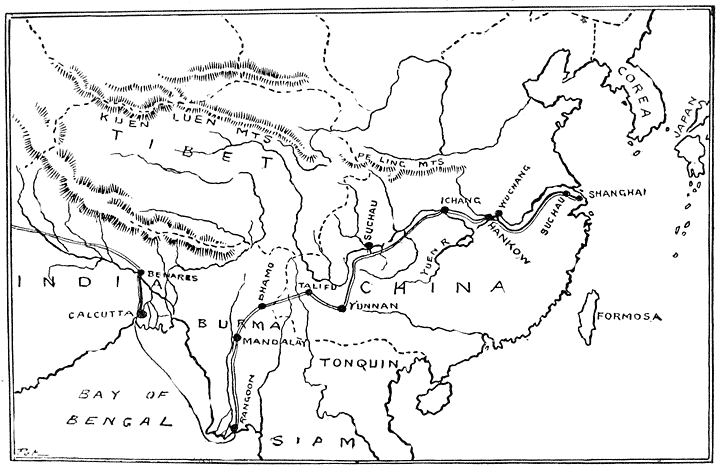

Saved by a Mandarin from the clutches of an Asiatic Shylock—Cyclists stray into the dangerous province of Hunan—Taken into Shaze, the city of blood and crimes—The Yang-Tse Kiang gorges from a houseboat 57–62 [4]

The Yang-Tse-Kiang in its fiercest mood turned to advantage by a native undertaker—An appreciative Tai Foo pays the tourists for calling upon him—Severe punishment of a grasping boatman—A forced march to Chung King 62–66

Coolie guides and luggage bearers desert the tourists—Opium the curse of the Chinese Empire—The most dangerous stage of the Chinese trip concluded at last—Chung King’s conjurer gives a remarkable street performance 67–71

Inter Ocean tourists become tramps through rain and snow, with the wheels carried on bamboo poles—Nearing the boundary line of China—Sudden change of climate and a narrow escape from the sunstroke—Chang, the Yunnan Giant 72–76

A toast to the United States on Burmese soil—“On the Road to Mandalay”—Entertained at a wedding of royalty, where a feature of the programme caused ladies to retire and bachelors to blush—Hospitable British officers 76–81

Rangoon suffers an attack of the bicycling fever—Native sports supplanted by corrupt horse-racing—A prize fight where rules do not count—Across the Bay of Bengal by steamer 81–88

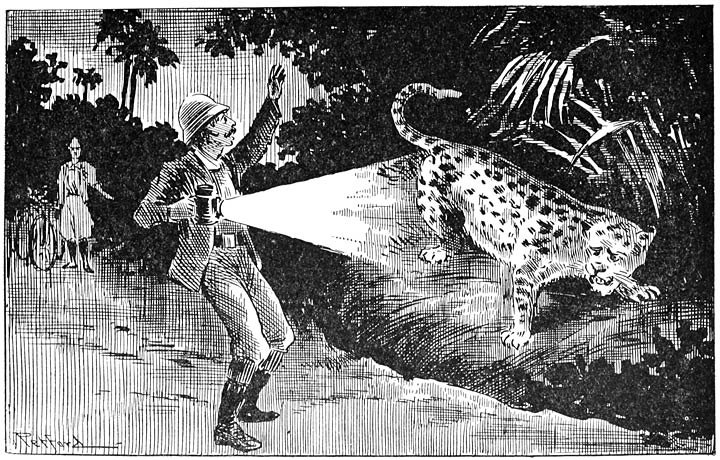

Arrival of the tourists causes great excitement at Benares—A pretty trio of supercilious British wheelmen—Guests of the Maharajah at Fort Ramnagar—A leap almost into the jaws of death 88–94

Pursued by a maddened herd of water buffalo—A joke ends in a race for life—The Yankee flag a conspicuous feature of the Queen’s Jubilee at Delhi—A reminder of the plucky but unfortunate Frank Lenz 94–96

Patriotism nearly lands McIlrath in a native prison—A night of terror attributed to Rodney, the pet monkey—Cyclists stricken with fever and become helpless invalids at Lahore—Bicycling much more comfortable than English national traveling 97–102

Last days in India spent during the dreaded monsoon season—The pet monkey’s appetite for rubber brings about an annoying delay—Officials refuse to let the Inter Ocean tourists follow out their plans and ride through Beloochistan 103–107

On board the “Assyria” bound for Persia—American firearms come in handy when road agents ask for “presents”—Climbing the Alps child’s play compared with crossing the Kotals of Persia 108–112

A visiting card left on the Porch of Xerxes—At the ruins of Persepolis—Some plain truths, as to the character of the Armenians—Lost in a snowstorm on the peak of a mountain—Mrs. McIlrath’s feet frozen badly 113–118

The most miserable Christmas day ever passed by man—The Sultan’s cavalrymen forced to admit the superiority of the bicycle—Deserted by a cowardly driver on the road to Teheran—The trip to Resht made by carriages 118–122

Landed in Russia three years after leaving Chicago—Easter Sunday in Tiflis, the “Paris of the Caucasus”—In sight of Mount Ararat—The pet monkey commits suicide in Constantinople—A Turkish newspaper joke—Roumania the next country entered 122–126

Saluted by the king of Roumania—A country where cyclists are in their glory—Splendid riding into Austro-Hungary—Vienna gives the Inter Ocean tourists the heartiest of welcomes—Munich and its art galleries 126–130 [5]

INTRODUCTORY.

PROPOSAL OF THE INTER OCEAN TOUR—ENTHUSIASTIC CHICAGO WHEELMEN ATTEND THE RECEPTIONS TO THE CYCLISTS—THE START ON APRIL 10.

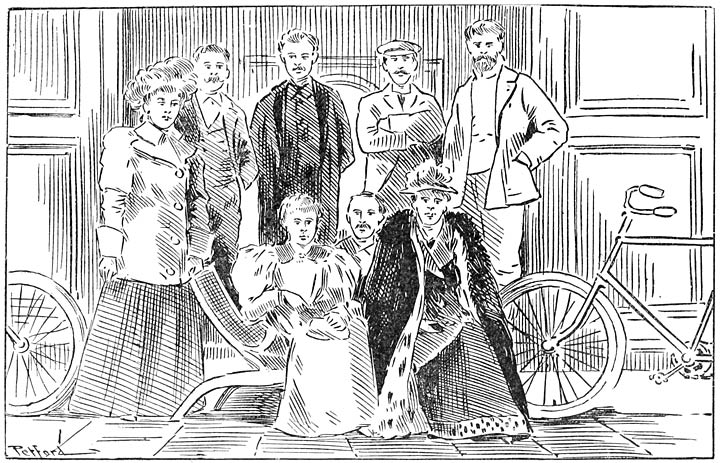

Beyond tests of speed involving championships and world’s records, there have been few performances in the recent history of cycling to attract more general notice than the world’s tour awheel of Mr. and Mrs. H. Darwin McIlrath. In the early Spring of 1895 the Chicago Inter Ocean, appreciating the great interest taken in cycling all over the country, planned this remarkable trip of more than 30,000 miles. From the moment of the first announcement of the McIlrath tour to the time of their home-coming, interest in and admiration for the Inter Ocean Cyclists never abated. Letters of inquiry at once began to come in so thick and fast to the Inter Ocean office, that to facilitate matters and more thoroughly acquaint the public with the details of the tour than could be done in the columns of the Inter Ocean, a series of receptions was tendered to the intrepid riders for several days prior to their start. The large room at 101 Madison Street, Chicago, was secured for the purpose, and for days Mr. and Mrs. McIlrath received their friends and admiring enthusiastic Chicago wheelmen. The crowds in front of the building became so great gradually that special policemen were detailed to keep the throng moving and traffic open. Among those who visited the McIlraths were:

Mrs. K. B. Cornell, President of the Ladies' Knickerbocker Cycling Club, Roy Keator of the Chicago Cycling Club, J. L. Stevens and W. C. Lewis of the Lincoln Cycling Club, Frank T. Fowler, Frank S. Donahue and Frank Bentson of the Illinois Cycling Club, O. H. V. Relihen of the Overland Cycling Club, Miss Annis Porter, holder of the Ladies' Century Record, Thomas Wolf, of Chicago-New York fame, Letter Carrier Smith, who has made the trip from New York to Chicago five times, David H. Dickinson, S. J. Wagner, O. Zimmerman (a cousin to the famous A. A.), Frank E. Borthman, R. B. Watson, Dr. and Mrs. W. S. Fowler, Mrs. J. Christian Baker, Mrs. L. Lawrence, John Palmer, President of Palmer Tire Co., Gus Steele, Yost racing team, C. Sterner and Grant P. Wright, Ashland Club, H. J. Jacobs, C. G. Sinsabaugh, editor of “Bearings,” Mesdames A. G. Perry, George E. Baude, Helen [6]Waters, D. W. Barr, C. Hogan, Mrs. Doctor Linden, George Pope, Robert Scott, Misses Kennedy, N. E. Hazard, Eva Christian, Mrs. Charles Harris, J. G. Cochrane, Pauline Wagner and Ada Bale.

Many of those who called, though utter strangers to the tourists, upon the strength of their friendship for the Inter Ocean brought letters of introduction for Mr. and Mrs. McIlrath to relations and acquaintances in the foreign lands to be visited. The itinerary as planned by the Inter Ocean was as follows:

Start from Chicago, April 10, 1895: Dixon, Ill.; Clinton, Cedar Rapids, Des Moines, Council Bluffs, Iowa; Omaha, Lincoln, Grand Island, Neb.; Denver, Pike’s Peak, Colo.; Cheyenne, Laramie, Green River, Wyoming; Salt Lake City, Ogden, Utah; Elko, Reno, Nev.; Sacramento, San Francisco, Cal.; steamer to Yokohama, Kioto, Osaka, Niko, Kamachura, Papenburg, Japan; steamer to Hongkong and Canton, China; the Himalayas, Bangkok, Siam, Rangoon, Burmah; Calcutta, Benares, Lucknow, Cawnpore, Agro, Lahore, India; Jask, Teheran, Tabriz, Persia; Erzeroum, Constantinople, Turkey; Athens, Greece; steamer to Italy; Turento, Pompeii, Rome, Florence, Venice, Milan and Nice, Italy; Toulon, Marseilles, France; Barcelona, Valencia, Carthagena, Gibraltar, Spain; steamer across channel to Tangier and Cadiz; return via steamer to Gibraltar, Lisbon, Portugal; Madrid, Spain; Bordeaux, Orleans, Paris, France; Brussels, Belgium; Frankfort, Germany; Vienna, Austria; Berlin, Germany; Warsaw, Poland; St. Petersburg, Russia; steamer to Stockholm, Sweden; Christiana, Norway; steamer to Great Britain, Scotland, England and Ireland; steamer to New York, Buffalo, Erie, Penn.; Cleveland and Toledo, Ohio; Fort Wayne, Ind.; and Chicago.

It had been intended for the tourists to depart from Chicago at 7 o’clock on the morning of April 10. After farewell receptions at the Illinois Cycling Club and the Lake View Cycling Club, it was decided, in view of the popular demand, that the hour for departure be changed until noon. So it was that as the clock in the Inter Ocean tower struck 12 on Saturday, April 1, the credentials and passport, which was signed by Secretary of State Gresham, were given to Mr. McIlrath, and in the midst of a crowd numbering thousands, and with an escort of hundreds of Chicago wheelmen, the Inter Ocean cyclists were faced west and started on their tour of the globe.

Captain Byrnes of the Lake Front Police Station and a detail of police made a pathway through the crowd on Madison Street to Clark. Cable cars had been stopped and the windows of the tall buildings on each side of the street were filled with spectators. A great cheer went up as Mr. and Mrs. McIlrath mounted their wheels to proceed. They could go only a few yards so congested was the street, and they were forced to lead their wheels to Clark Street, north to Washington and [7]west to Des Plaines. Here they mounted and the farewell procession was given its first opportunity to form. A carriage containing Frank T. Fowler, John F. Palmer, John M. Irwin and Lou M. Houseman, sporting editor of the Inter Ocean, led the way. Next came a barouche containing Mrs. Annie R. Boyer of Defiance, O., Mrs. McIlrath’s mother. The escort of cyclers, four abreast, followed, with the tourists flanked by the secretaries of the Illinois and Lake View Cycling Clubs. At the Illinois Club House came the leave-taking, and not until then could the tourists be said to be fairly started.

The unlooked for events of the three years following 1895, chief among which was the Spanish-American War, caused several material changes in the itinerary of the McIlraths as originally planned. Though accomplished successfully, the long trip across Persia, taken during the dead of winter, resulted in delays that had not been anticipated and after the cyclists had entered Germany, it was deemed best by the promoters of the enterprise to bring the tour to an end. Mr. and Mrs. McIlrath left Southampton, England, the first week in October, 1898. After landing in New York they took a rest of several days before starting overland to Chicago. The route from New York to Chicago led through the following cities: New York to Yonkers, Poughkeepsie, Hudson, Albany, Schenectady, Canajoharie, Utica, Syracuse, Newark, Rochester, Buffalo, Fredonia, New York; Erie, Penn.; Geneva, Cleveland, Oberlin, Bellevue, Bowling Green, Napoleon, Bryan, Ohio; Butler, Kendallville, Goshen, South Bend, La Porte Ind.; through South Chicago and Englewood to the Inter Ocean Office. [8]

[The McIlrath equipment consisted of truss-frame wheels made by Frank T. Fowler, of Chicago, fitted with Palmer tires and Christy saddles furnished by A. G. Spalding & Bro.] [9]